Title: Harper's Young People, November 7, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: October 22, 2019 [eBook #60554]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| PERIL AND PRIVATION. |

| BUSY BIRDS. |

| NAN. |

| VENOMOUS SNAKES. |

| THE TRAIN BOY'S FORTUNE. |

| THE SINGING LESSON. |

| THE MULATTO OF MURILLO. |

| THE DUCK HAT. |

| ART. |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| vol. iv.—no. 158. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, November 7, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Of all the sufferers from shipwrecks, women are the most to be pitied; for children do not know the full extent of their danger until death relieves them, while women usually overestimate it. Their mental agonies are therefore greater than those endured by men, while their physical privations are as great, without the same strength to bear them.

Mrs. Bremner, wife of the Captain of the Juno, bound from Rangoon to Madras, had perhaps as terrible an experience of shipwreck as ever fell to the lot of any of her sex. The ship's crew consisted chiefly of Lascars, with a few Europeans, among whom was John Mackay, the second mate, who tells this story.

Soon after the Juno set sail she sprang a leak, which increased more and more on account of the sand ballast choking the pumps, until on the twelfth evening she settled down. From the sudden jerk all imagined they were going to the bottom, but she only sank low enough to bring the upper deck just under water.

All hands scrambled up the rigging to escape instant destruction, "moving gradually upward as each succeeding wave buried the ship still deeper. The Captain and his wife, Mr. Wade and myself, with a few others, got into the mizzentop. The rest clung about the mizzen-rigging.[Pg 2] Mrs. Bremner complained much of cold, having no covering but a couple of thin under-garments, and as I happened to be better clothed than her husband, I pulled off my jacket and gave it her."

On the first occurrence of these calamities such unselfishness is not uncommon; it is the continuous privation which tries poor human nature. But it must be said to John Mackay's credit that he behaved most unselfishly throughout, and stood by this poor woman like a man.

The ship rocked so violently that the people could hardly hold on, and though excessive fatigue brought slumber to some eyes, Mr. Mackay did not snatch a wink. "I could not," he says, "sufficiently compose myself, but listened all night long for a gun, several times imagining I heard one; and whenever I mentioned this to my companions, each one fancied he heard it too." It is noteworthy that the same thing happened throughout the calamity as to seeing land. When one would imagine that he saw it, the others were persuaded that they saw it too.

The prospect at dawn was frightful: a tremendous gale; the sea running mountains high; the upper parts of the hull going to pieces, and the rigging giving way that supported the masts to which seventy-two wretched creatures were clinging.

After three days, during which their numbers were much diminished, the pangs of hunger became intolerable. "I tried to doze away the hours and to induce insensibility. The useless complaining of my fellow-sufferers provoked me, and, instead of sympathizing, I was angry at being disturbed by them." He had read of similar scenes, and his dread of what might be was at first more painful than his actual sufferings. Presently, however, he learned by bitter experience that imagination falls short of reality.

For the first three days the weather was cold and cloudy, but on the fourth the wind lowered, and they found themselves exposed to the racking heat of a powerful sun. Mackay's agonies, especially his sufferings from thirst, then became terrible. The only relief from them was afforded by dipping a flannel waistcoat which he wore next his skin from time to time in the sea. He writes, however, that he always "found a secret satisfaction in every effort I made for the preservation of my life." On the fifth day the first two persons died of actual starvation, their end being attended by sufferings which had a most sorrowful effect on the survivors.

As the sea was now smooth, an attempt was made to fit out a raft (the boats having been rendered useless), but this being insufficient to contain the whole crew, the stronger beat off the weaker. Though Mackay succeeded in getting on board, Mrs. Bremner did not, and he asked to be put back again, which was readily done. He resumed his place by her in the mizzentop. Her husband had by this time lost his wits, and would not even answer when addressed. "At first the sight of his wife's distress seemed to give him pain as having been the cause of her sufferings, and he avoided her; but now he would barely permit her to quit his arms, so that they were sometimes even obliged to use force to rescue her from his embraces." His frenzy (as often happens in such cases) took the form of seeing an imaginary feast, and wildly demanding to be helped to this or that dish. On the twelfth day he died, and it was with the utmost difficulty that they threw the body into the sea, after stripping off a portion of his clothing for his wife's use.

There were two boys on board the Juno, who were among the earliest victims. Their fathers were both in the foretop, and heard of their sons' illness from those below. One of them—it was the thirteenth day of their misery—answered with indifference that he "could do nothing" for his son. The other hurried down as well as he could, and, "watching a favorable moment, scrambled on all fours along the weather gunwale to his child, who was in the mizzen-rigging. By that time only three or four planks of the quarter-deck remained, and to them he led the boy, making him fast to the rail to prevent his being washed away. Whenever the lad was seized with a fit of sickness, the father lifted him up and wiped away the foam from his lips, and if a shower came, he made him open his mouth and receive the drops, or gently squeezed them into it from a rag. In this terrible situation both remained five days, until the boy expired. The unfortunate parent, as if unwilling to believe the fact, raised the body, looked wistfully at it, and when he could no longer entertain any doubt, watched it in silence until it was carried off by the sea. Then, wrapping himself in a piece of canvas, he sank down and rose no more, though he must have lived—as we judged from the quivering of his limbs when a wave broke over him—a few days longer." In all the annals of shipwreck I know no more pathetic picture than this.

But for showers of rain all would have been dead long since. They had no means of catching the drops save by spreading out their clothes, which were so wet with salt-water that at first it tainted the fresh. Mackay, however, before these timely supplies arrived, had had a very unusual experience. Maddened by the fever which consumed him, and in spite of the ill consequences he expected to happen, he had gone down and drank two quarts of sea-water. "To my great astonishment, though this relaxed me violently, it revived both my strength and spirits. I got a sound sleep, and my animal heat abated." Another expedient for getting some moisture into their mouths was to chew canvas or even lead. Shoes they had none, as leather dressed in India is rendered useless by water, and Lascars never use any shoes. There were, indeed, some bits of leather about the rigging but the smell and taste of it were found "too offensive to be endured." The rains and their fatigue made them very cold at night. In the morning, as the heat increased, "we exposed first one side and then the other to it, until our limbs became pliant; and as our spirits revived, we indulged in conversation, which sometimes even became cheerful. But as mid-day approached, the scorching rays renewed our torments, and we wondered how we could have wished the rain to cease."

It must be understood that the ship, though its hull was under water, was moving on all this time. On July the 10th, being the twentieth day from its partial sinking, one of the people, as had often before happened, cried out, "Land!" His cry was now heard without emotion, though, "on raising my head a few minutes afterward," says Mackay, "I saw many eyes turned in the direction indicated." Mrs. Bremner inquired of him whether he thought it might be the coast of Coromandel, which seemed to him so ridiculous that he answered that if it was, "they ought to be exhibited as curiosities in the Long Room at Madras under the pictures of Cornwallis and Meadows."

It was, however, really the land, though they had small chance of reaching it. Indeed, before evening, the ship, under water as it already was, struck on a rock. The tide having fallen, the remaining beams of the upper deck were left bare, and Mackay and the gunner tried to get Mrs. Bremner down to them, "but she was too weak to help herself, and we had not strength to carry her." The Lascars—for the raft had come back with them, as it could make no headway—offered to help if she gave them money. She happened to have thirty rupees about her, which was afterward of great use, and she did not stint it in helping her preservers. They brought her down for eight rupees, and insisted on being paid on the spot. With that exception, it is pleasant to read that their conduct was excellent throughout, and their behavior to Mrs. Bremner singularly kind and delicate.

In the gun-room, which they could now reach through[Pg 3] a hole in the deck, were found some cocoa-nuts, which one would have expected the finders to retain. On the contrary, they shared them, and insisted only upon keeping the milk in the nuts. This consisted of only a few drops of rancid oil; nor had the solid part of the cocoa-nuts—a fact to be remembered by those who buy them out of barrows—the least nourishment in it. They found themselves rather worse than better for eating them.

They were past the worst pains of hunger by this time, but the frenzied desire for water still continued. "Water, fresh-water," says Mackay, "was what perpetually haunted my imagination; not a short draught which I could gulp down in a moment—of that I could not endure the thought—but a large bowlful, such as I could hardly hold in my arms. When I thought of victuals, I only longed for such as I could swallow at once without the trouble of chewing."

Hope now began to animate them, and though it was the twenty-first day of their sufferings, it is noteworthy that no one died after they first saw land. Toward evening six of the stoutest Lascars, though indeed they were all shadows, tied themselves to spars, and reached the shore. They found a stream of fresh-water, of which those on board could "see them drinking their fill." In the morning they beheld these men surrounded by natives, and were all attention to see what sort of treatment they met with. The natives "immediately kindled a fire, which we rightly concluded was for dressing rice, and then came down to the water's edge, waving handkerchiefs to us as a signal that we should come ashore. To describe our emotions at that moment is impossible."

But these poor folks could not get on shore, and least of all the poor woman. Boats there were none, and if there had been, there was such a surf between the ship and the land that no boat could live in it. But to remain was certain death. "I felt myself called upon," says Mackay, "to make the attempt." With great difficulty he got out a spar and tied it to him with a rope. He then took leave of Mrs. Bremner, who was of course utterly helpless. "She dismissed me with a thousand good wishes for my safety." While they were speaking, the spar broke loose, and floated away. He paused one moment, then plunged into the sea. Though he could "hardly move a joint" before, his limbs immediately became limber in the water, and the spar helped to sustain him; but "being a perfect square, it turned round with every motion of the water, and rolled me under it." Eventually, however, a tremendous wave carried him to land.

Some natives, speaking in the Moorish tongue—"at which I was overjoyed, for I feared we were beyond the Company's territories, and in those of the King of Ava"—observing his ineffectual efforts to rise laid hold of him and bore him along. As they passed a little stream he made signs to be set down. "I immediately fell on my face in the water and began to gulp it down." His bearers finally dragged him away lest he should drink too much. They took him to a fire, round which the Lascars were sitting, and gave him some boiled rice, "but after chewing it a little I found I could not swallow it." One of the natives, seeing his distress, dashed some water in his face, which, washing the rice down, almost choked him, but "caused such an exertion of the muscles that I recovered the power of swallowing. For some time, however, I was obliged to take a mouthful of water with every one of rice. My lips and the inside of my mouth were so cracked with the heat that every motion of my jaws set them a-bleeding and gave me great pain."

As soon as he was a little recovered, his first care was for Mrs. Bremner, and on pointing out that she had some money about her, the natives were persuaded to take her off the ship. This was accomplished only a few hours before it parted in two. She was totally unable to walk, but her remaining rupees, joined to liberal promises, to be performed on her reaching her journey's end, procured her a litter, in which she was conveyed to Chittagong.

No woman probably ever went through such an experience and survived it as this unhappy lady. Mackay, having no money—for Mrs. Bremner had no more to give him—had to walk, and speedily broke down. The natives left him behind without a scruple. He fell in, however, with a party of Mugs, the chief of whom was full of human kindness. He washed Mackay's wounds, which were filled with sand and dirt, supplied him with rice, and endeavored to teach him how to make fire by rubbing two pieces of bamboo together. Mackay finally arrived at Chittagong, though in a pitiable condition.

In a postscript to this miserable story he says, "With respect to the fate of my companions in misfortune, Mrs. Bremner, having recovered her health and spirits, was afterward well married." So it seems that with time and courage one really does get over almost everything.

A broad green marsh, with sullen pools

Of brackish water here and there,

With mounds of hay on wooden piles,

And squares of yellow flowers like tiles,

And swamp-rosemary everywhere.

The straight road stretches, gray with dust,

From distant pine-trees to the hill;

The warm breath of an autumn day

Prevails, and with its languid sway

Keeps every little song-bird still.

But all along the wire line

That telegrams unnumbered brings,

Small chirping birds are perched secure,

With down-bent head and mien demure,

And gray brown lightly folded wings.

And do you ask, dear girls and boys,

What calls these flatterers from home,

Why restlessly they care to roam

Far from the foliage-guarded nest?

A new idea has come to me;

I wonder if you will agree

To what I'm going to suggest.

When in some quite mysterious way

A trifling fault strikes mamma's ears,

I'm confident you must have heard

Of that communicative bird

Who's always telling all he hears.

A little bird told me, she says,

Of what I never should suspect.

Suppose these listening songsters light

Upon the wires there in sight

To get the latest news direct!

If they're the gossips of bird land,

Reporters for the "Night-hawk Press,"

Then very likely they indulge

In other meddling, and divulge

The tiny secrets so few guess.

They hover near the open door

In summer; past the eaves they dart,

And very likely understand

When any hidden mischief's planned,

And straightway hasten to impart,

To those, they think it may concern,

Their interesting items. Why,

I seem to see their bright eyes shine,

Their cunning heads sideways incline

Inquisitively, full of joy.

The only way I know is this—

To always try to do so well

That when the busy birds appear

To carry secrets through the air,

They won't have anything to tell

Except those messages that bless

Obedience and truthfulness.

A LITTLE PHILOSOPHER.

A LITTLE PHILOSOPHER.

Nan's visitor, Miss Rolf, left the little shop, and walked away in the winter's dusk up the main street, and down one of the more secluded streets, where the "upper ten" of Bromfield lived. Bromfield was a large dull town, full of factories and smoke, and had a general air of business and money-making. The houses on the pretty street to which Miss Rolf directed her steps seemed to be shut away from all the dust and noise of the town, and Mrs. Grange's gateway was the finest and most aristocratic-looking one in the row. Miss Rolf went in at the gate, past a pretty lawn dotted with cedars, to the side entrance of a long low stone house, within the windows of which lights were already twinkling. She had a curious, amused smile on her face as she went down the hall, and it had not faded when she entered the parlor fronting the garden and the lawn.

Three people were seated in the fire-light—an elderly lady with a pale sweet face, a tall boy of fifteen, and a gentleman whose face was like Miss Rolf's in regularity of feature, but much softer in expression.

In the luxurious room Miss Rolf looked much more in her place than in Mr. Rupert's butter shop, and if Nan could have seen her "second cousin Phyllis" there, she would have been more than ever certain that she belonged to those who had the money.

Miss Rolf was greeted by all three occupants of the room at once.

"Well, Phyllis?"—from the gentleman.

"Did you see her?"—this from the boy.

"Well, what happened?"—this from the lady.

Miss Rolf sank into one of the many easy-chairs, and, leaning back, began to draw off her long gloves.

"Yes, I saw her," she answered, smiling. "It was really very interesting. Quite like something in a story. There was the horrible little store, and Mrs. Rupert, a vulgar sort of woman; and then the little girl came in—dreadfully untidy and dowdy-looking, but really not at all so common as I feared. She has the hazel eyes every one admired so in her father."

"And did you tell her that her aunt Letitia wants her to go to Beverley?" said the boy, eagerly.

"No, I didn't," rejoined Miss Rolf. "I thought I'd do that when I went to-morrow. There was no time to discuss the matter. Besides, I wanted to see the child alone first."

"Why not send for her to come here?" Mrs. Grange said, gently.

"Not a bad idea," said Miss Rolf, sitting upright. "She might come to-morrow, instead of my going there."

"I can't help thinking Letitia will regret it," said the gentleman, who was Miss Rolf's father.

"Why should she, papa?" said the boy, quickly. "Surely it is only fair. Her father was left out of Cousin Harris's will just for a mere caprice, and why should Cousin Letty have everything, and this child nothing? I don't see the justice of that."

"But to remove her from a low condition; to place her among people she never knew—I am afraid it is unwise," said Mr. Rolf, shaking his head. "You don't understand it, Lance; I don't expect you to. Just wait, and see my words come true."

Lance, or Lancelot Rolf, laughed brightly. He seemed quite prepared to take the risks on Miss Letitia Rolf's venture. While Miss Rolf wrote her letter to little Nan, the boy watched her earnestly. He was intensely interested in this new-found cousin, and, had he known where to go, would certainly have paid a visit to the cheese-monger's family himself.

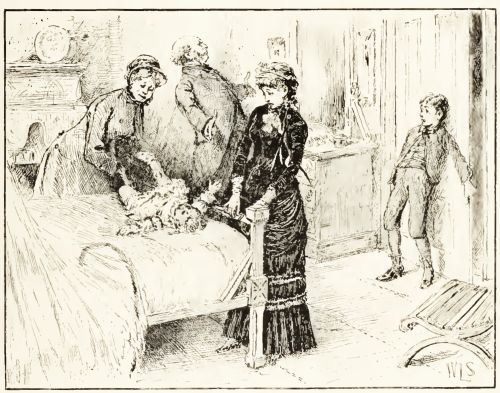

"NAN WAS DRESSED BY MRS. RUPERT AND MARIAN."

"NAN WAS DRESSED BY MRS. RUPERT AND MARIAN."

He would have found an excited little party had he done so, for by eight o'clock Mrs. Rupert had indulged in every possible speculation about Nan's future. Mr. Rupert, a tall, thin, weather-beaten man, had come in for tea, and was told of the visitor, and obliged to hear all Mrs. Rupert's ideas and hopes on the subject, while Nan herself was the only quiet member of the party. She sat at the tea-table, for once in her life very quiet and repressed. Just what she hoped or thought she could not have told you; but it seemed to her as if something like her old life with her parents might be coming back. Could it be she was to go away, and leave Bromfield, the cheeses and butter and eggs, her aunt's loud voice, Marian's little airs of superiority, and Phil's rough kindness, forever behind her?

"Come, Nan, you may as well help with the tea-things,[Pg 5] if you are going to see your rich relations," said her aunt's voice, sharply recalling her to her duties, and Marian laughed scornfully.

"I don't suppose we'll know Nan, or she us, by to-morrow night," she said, with a shrug of the shoulders.

Early the next morning a man-servant from Mrs. Grange's brought a note for Nan, which she read in the little untidy parlor, surrounded by all the family. It was from Miss Rolf, requesting Nan to come as soon as possible to Mrs. Grange's house, and it produced a new flutter in the household. Nan was dressed by Mrs. Rupert and Marian in everything that either of the girls' scanty wardrobe possessed worth putting on for such a visit. Had she but known it, a much simpler toilet would have been far more appropriate and becoming, for her purple merino dress and Marian's red silk neck-tie, her "best" hat with its green feathers, and Mrs. Rupert's soiled lavender kid gloves, were a very dreadful combination. Nan, as she walked up Main Street, did not feel entirely satisfied with the costume herself. If her head had not been so dazed by what the Ruperts already called her "good fortune," she would have felt it all more keenly. As it was, she went into Mrs. Grange's gateway feeling herself in a dream, and wondering how and where she would wake up.

Nan was admitted by a very grave-looking man-servant, who, on hearing her name, led her down the softly carpeted hall, and upstairs to the door of a cozy little sitting-room, where Miss Rolf was waiting for her. The many luxuries of the room, its brightness and air of refinement, made Nan half afraid to go farther, and suddenly she seemed to feel the vulgarity of her own dress; but her "second cousin," Miss Rolf, smiled very pleasantly upon her from the window, and coming up to the little girl, kissed her affectionately.

Miss Rolf in the morning light, and in a long dress of pale gray woollen material, looked to Nan like nothing less than a princess. She was apparently about twenty one or two, with a fair face, soft waves of blonde hair, and eyes that looked to Nan like stars, they were so bright, and yet soft with all their sparkle. Nan scarcely noticed the imperious curve of her new cousin's pretty mouth or the disdainful pose of the head. She thought of nothing then but her beauty and grace and charming manners.

"Well, my dear," this dazzling princess said, "take off your hat and cloak, and sit down by the fire. I want to have a talk with you." Nan, very much subdued by everything she saw about her, obeyed, while Miss Rolf seated herself in a low chair, and looked at her little cousin critically.

"Now, Nan," she said, gravely, "do you know that your father would have been a very rich man but for an absurd quarrel with his elder brother?"

"I knew there was something," said Nan, who was afraid of her own voice.

"Well, then," continued Miss Rolf, "when your grandfather died, he left everything to his elder son and daughter. The son, your uncle Harris, is a confirmed invalid—indeed, he is not altogether right in his mind—but your aunt Letitia, your father's older sister, is strong and well, and they live together at Beverley. Miss Letitia has suddenly taken it into her head to hunt you up, and as my father and I were coming here on a visit, she asked me to try and find you."

Miss Rolf paused, and Nan, who sat very still, her hazel eyes fixed on the young lady's face, nodded, and said, in a sort of whisper, "Thank you."

"Your aunt," continued Phyllis, smiling pleasantly, "told me that I was to invite you, in her name, to come on a visit, to Beverley. Mind, Nan, don't get it into your head that it is more than a visit—unless you prove so nice and pleasant a little visitor that she will want you to stay always."

Nan's face broke into a smile that made her really pretty.

"I'll try and be pleasant," she said, brightly.

"So you would like to go?" said Miss Phyllis, looking at her earnestly. "Wouldn't you miss—the Ruperts?"

Nan's face flushed.

"Yes," she said, looking down, "I shall miss aunt—and Philip."

Miss Phyllis said nothing for a moment. She had more to tell, but she thought it as well not to say it now. She had taken a sudden fancy to Nan; she wanted the child to come to Beverley, and perhaps, if she told her all, Nan would refuse; at least, looking at the child's honest, fearless[Pg 6] eyes, she felt it more prudent to say no more. So Nan was told that she was to go, if she liked, in a week, to her grandfather's and her father's old home.

"Your aunt thought," said Miss Phyllis, "that you might need some new clothes. You see, you will have to dress more at her house than here in Bromfield, and so we will take a week to get you ready. Perhaps it would be as well for you to stay here to-day, and go out with me."

Nan's eyes danced. Never but once since she lived in Bromfield had she owned an entirely new dress. Everything she wore had been "made over" from Mrs. Rupert's or Marian's, and she faintly understood that new clothes of Miss Phyllis's buying would be something unthought of in the Rupert mind.

"I'll leave you here a little while, Nan," said the young lady, "and you can amuse yourself with the books and papers."

But Nan needed nothing of the kind. When the door was closed, she uttered a little half-scream of delight, and jumped up, walking over to the window, where she looked out at the dull town lying smoky and hazy in the distance, and which she felt sure she was about to leave forever. She hardly heard Miss Phyllis returning, and felt startled by the sound of her voice, saying, "Nan, are you ready?" And there was the beautiful young lady in her furs and broad-brimmed hat, with a purse and a little note-book in her hand, ready to lead Nan into the first scene of her enchantment.

Venomous snakes are those which have two hollow teeth in the upper jaw through which they inject poison into the wound made by their bite. The great majority of snakes are not venomous, but nevertheless there are more venomous snakes in the world than most men really require.

There are two classes of venomous snakes—those whose bite is certain death, and those whose bite can be cured. The only venomous snake inhabiting Europe is the viper, but its bite is seldom fatal. In the United States, with the possible exception of New Mexico and Arizona, there are only three venomous snakes—the rattlesnake, the copperhead, and the moccasin. All our other snakes are harmless. In some places the copperhead is known as the flat-headed adder, but the other species of snakes, to which the name "adder" is often given by country people, are as harmless as the pretty little garter-snake.

Central and South America have many venomous snakes whose bite is always fatal. Among these the best-known are the coral-snake, the tuboba, and the dama blanca. A British naval vessel, on its way up a South American river a few years ago, anchored for the night, and a number of the officers thought they would go ashore, and sleep in a deserted shanty that stood on the bank, where they fancied that the air would be cooler than it was on board the vessel. When they reached the shanty, one of them said he thought he would go back to the ship, and all the others, with one exception, said that they would follow him. The officer who determined to stay swung his hammock from the beams of the roof, and was soon asleep. He woke early in the morning, and, to his horror, found that three snakes were sleeping on his body, and that others were hanging from the rafters or gliding over the floor. He recognized among them snakes whose bite meant death within an hour or two, and he did not dare to move a finger. He lay in his hammock until the sun grew warm and the snakes glided back to their holes. His companions had noticed that the place looked as if it was infested with snakes, but had cruelly refrained from warning him. The officer was one of the bravest men that ever lived, but he could never speak of his night among the snakes without a shudder.

In one of the West India Islands—Martinique—there is a snake called the lance-headed viper, which is almost as deadly as the coral-snake. The East Indies are full of venomous snakes, and in British India nearly twenty thousand persons are killed every year by snake bites. Of the East Indian snakes whose bite is incurable the cobra is the most numerous, but the diamond snake, the tubora, and the ophiophagus are also the cause of a great many deaths. The British government has offered a large reward for the discovery of an antidote to the poison of the cobra, but no one has yet been able to claim it.

Africa, like all tropical countries, has many species of venomous snakes. The horned cerastes is the snake from whose bite Cleopatra is said to have died, and from its small size, and its habit of burying itself all but its head in the sand, it is peculiarly dreaded by the natives. The ugliest of these snakes is the great puff-adder, which often grows to the length of five or six feet, and whose poison is used by the natives in making poisoned arrows.

It is a very curious fact that the poison of venomous snakes can not be distinguished by the chemist from the white of an egg. And yet one kind of snake poison will produce an effect entirely unlike that produced by another kind. The blood of an animal bitten by a cobra is decomposed and turned into a thin, watery, straw-colored fluid, while the blood of an animal bitten by a coral-snake is solidified, and looks very much like currant jelly. Nevertheless, the poison of the cobra and that of the coral-snake seem to be precisely alike when analyzed by the chemist, and are apparently composed of the same substances in the same proportion as is the white of an egg.

"Papers! Harper's Weekly! Bazar! All the monthly magazines!"

Jim Richards wished that he might have a dollar for every time he had repeated that cry. He was sure he had said it, during the three years he had been train-boy on the road between Philadelphia and New York, as many as fifty thousand times. Even ten cents each time would give him five thousand dollars. What could he not do with as much money as that? His mother should have a new dress, for one thing. He would give little Pete for his birthday the box of tin soldiers in the toy-shop window; and Lizzie, for hers, the doll on which her heart was set. Then they would all move into a new house somewhere in the country, instead of their wretched tenement in New York. Jim himself would give up his place as train-boy and go into the company's machine shop, which he could not do now, because his earnings from the sale of the papers were pretty good, while the machine-shop wages would be for some time small. But these were dreams; the train was approaching Trenton, where Jim would find the New York evening papers, and he had still to go through the last car. It was Saturday evening, and he must make enough to buy his mother's Sunday dinner.

"Papers!" he cried, slamming the door after him, and beginning to lay them one by one in the laps of the passengers. The first passenger was an old gentleman, and in his lap Jim laid a copy of a weekly paper.

"Take it away!" exclaimed the old man. "I don't want it."

Jim, in his hurry, had passed on without hearing.

"What! You won't, eh?" the old man went on, provoked by Jim's seeming inattention. "Then I'll get rid of it myself."

Crumpling it up into a ball, he turned around and threw[Pg 7] it violently down the aisle, narrowly missing Jim's head, and landing it in the lap of an old lady on the opposite side.

"You won't lay any more papers in my lap, I guess," he added, shaking his head threateningly as Jim came back.

Jim was angry. He picked up the paper and smoothed it out as well as he could, but it was hopelessly damaged, and no one would think of buying it.

"You'll have to pay me ten cents for that," he exclaimed.

The train was now slacking, and the old gentleman, who was evidently bound for Trenton, had risen from his seat.

"Not a cent," he declared; "not a single cent. You hadn't any business to put it in my lap. I told you not to, but you persisted in leaving it there. You train-boys are a nuisance. It'll be a lesson to you."

"But I'll have to pay for it myself," cried Jim.

"Serve you right. You'll have ten cents less to spend for cigarettes."

By this time the train had stopped, and the passengers were crowding out. The old man was already on the platform, and Jim was standing by the seat, angrily uncertain whether to follow him out or stay and pick up the few papers he had distributed before returning to the baggage-car. In his moment of uncertainty he happened to look down upon the floor. There in the shadow of the seat lay a long leather pocket-book. No one but the old gentleman could have dropped it. Jim stooped and picked it up. Here was a chance to pay off his venerable friend.

In another instant, though, a better impulse came to him.

"What would mother say?" he thought. He threw down his papers, rushed to the door, jumped from the steps, and ran along the platform through the crowd in pursuit of the old man. In the confusion and darkness it was not easy to find anybody. Jim thought he saw him a little way ahead, but at the same moment the bell rang for the train to start. Should he follow the man or not? There must be time, he thought. In a moment more he had caught up with the person, but it was not his man at all. It was too bad, but he had done his best. He did not know that where he had failed, two other persons—dark-looking men, whom he had noticed getting off the car—had succeeded, and were now following the old gentleman along the passageway that leads up to the street.

Still uncertain what to do, Jim turned around, only to see the train moving off. It was but a few steps back to the track, and Jim ran with all his speed. But when he got there, the rear platform of the last car was a hundred yards away, and all that he could see was the red lantern winking at him, as it seemed, through the darkness.

The train had gone off with all his papers, including those which he had expected to sell between Trenton and New York. There would be no Sunday dinner to-morrow; indeed, Jim would be lucky if he were not discharged from his place.

"$5000!"

"$5000!"

For a moment Jim was bewildered. Then he bethought himself of the pocket-book. He would, at any rate, find out what was in that, only no one must see him do it.

So he walked down the track until he was quite out of sight, and by the light of a match carefully opened the leather flap. On the inside, in gilt letters, was the owner's name—John G. Vanderpoel, 11 Sycamore Street, Trenton. Jim had no excuse now for not returning it at once.

The sight of the name, though, brought back his anger.

"Old screw!" he said, half aloud. "I guess if he'd only known what was going to happen, he'd have paid me my ten cents. Let's see what's in it, anyhow."

The match had gone out, but Jim had another. Striking it, he looked into the pockets, one of which seemed to contain something green. Jim pulled it out with a beating heart. Yes, it was money—a package of greenbacks—and the label on the outside, though Jim's hands shook so that he could hardly make it out, read "$5000."

Not only was Jim ignorant that the old gentleman was being followed, but Mr. Vanderpoel did not know it himself. He walked out of the station with a firm, brisk step, his overcoat tightly buttoned over the place where he supposed his money to be, and congratulating himself that he had at length collected the debt which it represented.

It was not far to his house, which was in a side street, and occupied several lots of ground. A long path led up from the front gate, lined with shrubbery, and lighted only by the pale rays that gleamed from the front door. Alongside of the path stretched a little duck pond. It was a quiet, retired street, and when Mr. Vanderpoel turned into it, he left the crowd behind. He did not leave, however, the two men who had kept him in sight all the way from the station, and who now quickened their steps so that when he stopped at his gate they were not more than a few feet in the rear. Mr. Vanderpoel opened the gate, and went in. The gate swung back on its hinges, and was held open by one of the men, while the other entered. Not hearing the latch click, Mr. Vanderpoel turned around, and was met face to face by the intruder.

"Well, what do you want?" he demanded, angrily.

For an answer the old gentleman's arms were promptly seized and pinioned behind his back, and he himself was laid at full length along the garden path.

"Keep still now," hissed a rough voice. "We ain't no idea o' hurtin' ye, but what we want is them five thousand dollars."

It was not the slightest use to struggle. One man held him fast, while the other went through his pockets. Presently the first inquired of his partner,

"Where do you s'pose he's hid it?"

If it was the money they were speaking of, Mr. Vanderpoel knew perfectly well where he had hid it. It was, or ought to be, in the very pocket which the man was now searching—the breast pocket of his overcoat—and he waited breathlessly for the man's answer.

"Don't know," growled the thief, after a moment. "'Tain't here."

Mr. Vanderpoel almost jumped. If it were not there, where could it be? He had certainly put it in that pocket. He was glad, of course, that the thieves could not find it, but that did not relieve his mind as to its safety. However, if it had already been stolen, or if he had lost it, he could afford to lie still and enjoy what promised to be a humorous situation. Indeed, he felt almost inclined to laugh; and the robbers themselves, it seemed, began to realize that they were the victims of a sell.

"'Tain't on him nowhere," gruffly remarked the one who had been making the search.

"Feel in his breeches pocket," suggested the other.

The man transferred his hand from the coat to the trousers without success. "'Tain't there neither," he growled. "I don't believe he fetched it tonight."

"There's his shoes," observed the first man, who was evidently the more persevering of the two. "See if it ain't in them."

The other tore open the gaiters and dragged them off. The cold air struck Mr. Vanderpool's stocking feet very unpleasantly, and filled him with dismal visions of rheumatism and gout; but he bore it bravely, and by a tremendous effort stopped a threatening sneeze.

"I tell yer he ain't got it," declared the first man. "We're left; that's what it is. What'll we do with the old chap?"

His partner scowled. "Chuck him into the pond."

He chucked into a pond at his time of life, and with his rheumatism! It would be the death of him. The prospect of a ducking loosened his tongue.

"Help! murder! thieves!"

At this moment the gate clicked. Both men heard the sound, and started for the shrubbery at the side of the path. Almost before the old gentleman was aware that they had gone, their retreating footsteps were echoing down the street.

Mr. Vanderpoel felt that he was saved. He would have risen to his feet but for the fact that his shoes were off. The person who had come in the gate, and who was now standing before him, was a lad dressed, as it seemed to Mr. Vanderpoel's confused sight, in the District Telegraph uniform.

"Well, young man," he exclaimed, "I guess you've saved my life. Just help me on with my shoes, will you, and we'll go into the house."

It was some time before Jim could take in the situation, and he stood gazing at the old man without saying a word.

"What are you staring at?" cried Mr. Vanderpoel, hotly. "Do you suppose I'm sitting here in my stocking feet for amusement? I've been knocked down and robbed—or I would have been robbed if some one else hadn't done it already. If anything could reconcile one to the thought of being robbed by one set of thieves, it would be that they left nothing for the next set. But I certainly believe they would have killed me if you hadn't come up. Easy, now"—as the boy drew the gaiter over the old man's knobby foot—"look out for that corn. Now the other one. There! never mind the buttons. Lend me your arm, will you? I'm lame and bruised where I fell. It was lucky I didn't hit my head. Well, I'm sorry I lost the money, but I'm mighty glad those fellows didn't get it."

"Was it much?" asked the boy, briefly. They had now gone up the steps, and, while Mr. Vanderpoel drew out his latch-key, were standing in the light that gleamed through the door. As Mr. Vanderpoel turned around, he recognized, as he had not done before, the boy's features.

"HE HANDED OVER THE BOOK, WHICH MR. VANDERPOEL

SEIZED."

"HE HANDED OVER THE BOOK, WHICH MR. VANDERPOEL

SEIZED."

"Hello!" he cried, "you're that train boy. Yes, it was a good deal. Do you know anything about it?"

Jim's face took on a non-committal look.

"Well," he said, "I found something in the cars. Perhaps you'd better identify it. Prove property, you know."

"Come in," said Mr. Vanderpoel, drawing Jim inside and closing the door. "Was it a pocket book you found?"

Jim nodded.

"With money in it?" eagerly.

Jim nodded again.

"Five thousand dollars?" Mr. Vanderpoel whispered.

"I didn't count it," said Jim, briefly. "There it is."

He handed over the book, which Mr. Vanderpoel seized and breathlessly opened. The money was in fifty dollar bills, and did not take long to count. When counted it proved to be all right.

"Yes," said Mr. Vanderpoel, delightedly. "It's all there. It must have dropped out of my pocket when I threw that paper at you in the car. Served me right for making such a lunatic of myself! But what a sell!" rubbing his hands gleefully. "What a tremendous sell on those villains that they didn't get a penny of it! Now come in to dinner"—leading the way through the hall—"and tell me all about yourself. You saved my life, and I'm going to do the correct thing."

And so the train-boy came into his fortune. In the end it amounted to a good deal more than $5000, for Mr. Vanderpoel's ideas of correctness turned out to be on a liberal scale. The family was brought to Trenton and put in a neat little cottage; Pete had all the tin soldiers that he could use, and Lizzie more dolls than she could possibly take care of; the mother got her dress, and Jim had his heart's desire, by being put, not in the company's machine-shop, but in a great deal better one, in which Mr. Vanderpoel was interested, and where Jim himself will no doubt one day be an owner. But better than all is the sense which Jim has of having fought against and overcome a great temptation. And this sense, I think, is the train-boy's fortune.

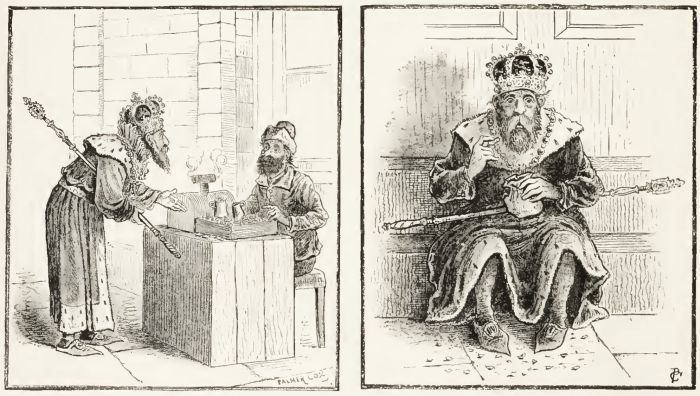

What an interesting picture they make, the old music master and his young pupil! By his cowled head we see that the teacher is a monk, and we remember to have read in our histories about the convents, where, during the fierce conflicts of the Middle Ages, holy men lived peaceful lives, wrote books, painted pictures, and set beautiful Latin hymns to lovely music. Those times were wild and dark enough. The brave young men who put on the armor of knighthood and rode forth to defend the weak and right the oppressed found plenty to do. Ladies sat in their castles, working endless pieces of tapestry in stitches which have lately been revived. Boys found pleasure in learning all sorts of manly sports. Here and there one would be found who was quiet and gentle, and he would perhaps be taught to read and write, and would be regarded as a wonderful scholar.

From the sweet rapt look on the face of this little chorister we see that he is one of the pure and noble natures which would not care for fighting, or pitching quoits, or rushing along with hawk and hounds. He loves art, and puts his whole soul into its study.

The gray-bearded master has trained many boys, and while kind and tender, is severe in requiring his pupils to do their best. The score on which the boy's eyes are resting is familiar to him through long years of use, and he feels that it is sacred. He shivers with horror when a note is flatted, as it sometimes is by a giddy singer whose ear is not accurate or whose voice is not disciplined.

The little fellow to whom the master is listening so critically while the sweet full tone chords so perfectly with the long-drawn note on the violin will be only one among a multitude of others in the great cathedral. But when the choir uplifts the Te Deum or the Inflammatus with its waves of melody floods every nook and corner of the grand church, one voice untrained and out of tune might mar the harmony.

One beautiful summer morning, about the year 1630, several youths of Seville approached the dwelling of the celebrated painter Murillo, where they arrived nearly at the same time. After the usual salutation they entered the studio. Murillo was not yet there, and each of the pupils walked up quickly to his easel to examine if the paint had dried, or perhaps to admire his work of the previous evening.

"Pray, gentlemen," exclaimed Isturitz, angrily, "which of you remained behind in the studio last night?"

"What an absurd question! Don't you recollect that we all came away together?"

With these words Mendez, with a careless air, approached his easel, when an exclamation of astonishment escaped him, and he gazed in mute surprise on his canvas,[Pg 10] on which was roughly sketched a most beautiful head of the Virgin.

At this moment some one was heard entering the room. The pupils turned at the sound, and all made a respectful obeisance to the great master.

"Look, Señor Murillo, look!" exclaimed the youths, as they pointed to the easel of Mendez.

"Who has painted this—who has painted this head, gentlemen?" asked Murillo, eagerly. "Speak; tell me. He who has sketched this head will one day be the master of us all. Murillo wishes he had done it. What skill! Mendez, my dear pupil, was it you?"

"No, señor," replied Mendez, in a sorrowful tone.

"Was it you, then, Isturitz, or Ferdinand, or Carlos?"

But they all gave the same reply as Mendez.

"I think, sir," said Cordova, the youngest of the pupils, "that these strange pictures are very alarming. To tell the truth, such wonderful things have happened in your studio that one scarcely knows what to believe."

"What are they?" asked Murillo, still lost in admiration of the beautiful head by the unknown artist.

"According to your orders, señor," answered Ferdinand, "we never leave the studio without putting everything in order; but when we return in the morning, not only is everything in confusion, our brushes filled with paint, our palettes dirtied, but here and there are sketches, sometimes of the head of an angel, sometimes of a demon, then again a young girl, or the figure of an old man, but all admirable, as you have seen yourself, señor."

"This is certainly a curious affair, gentlemen," observed Murillo, "but we shall soon learn who is this nightly visitant. Sebastian," he continued, addressing a little mulatto boy about fourteen years old, who appeared at his call, "did I not desire you to sleep here every night?"

"Yes, master," said the boy, with timidity.

"And have you done so?"

"Yes, master."

"Speak, then; who was here last night and this morning before these gentlemen came?"

"No one but me, I swear to you, master," cried the mulatto, throwing himself on his knees in the middle of the studio, and holding out his little hands in supplication before his master.

"Listen to me," pursued Murillo. "I wish to know who has sketched this head of the Virgin and all the figures which my pupils find every morning here on coming to the studio. This night, in place of going to bed, you shall keep watch, and if by to-morrow you do not discover who the culprit is, you shall have twenty-five strokes from the lash. You hear! I have said it. Now go and grind the colors; and you, gentlemen, to work."

From the commencement until the termination of the hour of instruction Murillo was too much absorbed with his pencil to allow a word to be spoken but what related to their occupation; but the moment he disappeared conversation began, and naturally turned to the subject in which they were all interested.

"Beware, Sebastian, of the lash," said Mendez, "and watch well for the culprit; but give me the Naples yellow."

"You do not need it, Señor Mendez; you have made it yellow enough already; and as to the culprit, I have already told you that it is the Zombi."

"Are these negroes fools with their Zombi?" said Gonzalo, laughing. "Pray what is a Zombi?"

"Oh, an imaginary being, of course. But take care, Señor Gonzalo," continued Sebastian, with a mischievous glance at his easel, "for it must be the Zombi who has stretched the left arm of your St. John to such a length that if the right resembles it he will be able to untie his shoe-strings without stooping."

"Do you know, gentlemen," said Isturitz, as he glanced at the painting, "that the remarks of Sebastian are extremely just, and much to the point? Who knows but that from grinding the colors he may one day astonish us by showing he knows one from another?"

It was night, and the studio of Murillo, the most celebrated painter in Seville, was now as silent as the grave. A single lamp burned upon a marble table, and a young mulatto boy, whose eyes sparkled like diamonds, leaned against an easel. Immovable and still, he was so deeply absorbed in his meditations that the door of the studio was opened by one who several times called him by name, and who, on receiving no answer, approached and touched him. Sebastian raised his eyes, which rested on a tall and handsome negro.

"Why do you come here, father?" he asked, in a melancholy tone.

"To keep you company, Sebastian."

"There is no need, father; I can watch alone."

"But what if the Zombi should come?"

"I do not fear him," replied the boy, with a sad smile.

"He may carry you away, and then the poor negro Gomez will have no one to console him in his slavery."

"Oh, how sad! how dreadful it is to be a slave!" exclaimed the boy, weeping bitterly.

"It is the will of God," replied the negro, with an air of resignation.

"God!" ejaculated Sebastian, as he raised his eyes to the dome of the studio, through which the stars glittered—"God! I pray constantly to Him, my father (and He will one day listen to me), that we may no longer be slaves. But go to bed, father; go, go, and I shall go to mine there in that corner, and I shall soon fall asleep. Good-night, father, good-night."

"Good-night, my son;" and having kissed the boy, the negro retired.

The moment Sebastian found himself alone he uttered an exclamation of joy. Then suddenly checking himself, he said: "Twenty-five lashes to-morrow if I do not tell who sketched these figures, and perhaps more if I do. Oh, my God, come to my aid!" and the little mulatto threw himself upon the mat which served him for a bed, where he soon fell fast asleep.

Sebastian awoke at daybreak; it was only three o'clock. "Courage, courage, Sebastian," he exclaimed, as he shook himself awake; "three hours are thine—only three hours; then profit by them; the rest belong to thy master. Slave! Let me at least be my own master for three short hours. To begin, these figures must be effaced," and seizing a brush, he approached the Virgin, which, viewed by the soft light of morning, appeared more beautiful than ever.

"Efface this!" he exclaimed—"efface this! No; I will die first. Efface this—they dare not—neither dare I. No—that head—breathes—speaks; it seems as if her blood would flow if I should offer to efface it, and that I should be her murderer. No, no, no; rather let me finish it."

Scarcely had he uttered these words, when, seizing a palette, he seated himself at the easel, and was soon totally absorbed in his occupation. Hour after hour passed unheeded by Sebastian, who was too much engrossed by the beautiful creation of his pencil, which seemed bursting into life, to mark the flight of time.

But who can describe the horror and consternation of the unhappy slave, when, on suddenly turning round, he beheld all the pupils, with his master at their head, standing beside him!

Sebastian never once dreamed of justifying himself, and, with his palette in one hand and his brushes in the other, he hung down his head, awaiting in silence the punishment he believed that he justly merited.

Murillo having, with a gesture of the hand, imposed silence on his pupils, and concealing his emotion, said in a cold and severe tone, while he looked alternately from the beautiful picture to the terrified slave,

"Who is your master, Sebastian?"

"You," replied the boy, in a voice scarcely audible.

"I mean your drawing-master," said Murillo.

"You, señor," again replied the trembling slave.

"It can not be; I never gave you lessons," said the astonished painter.

"But you gave them to others, and I listened to them," rejoined the boy, emboldened by the kindness of his master.

"And you have done better than listen; you have profited by them," exclaimed Murillo, unable longer to conceal his admiration. "Gentlemen, does this boy merit punishment or reward?"

At the word punishment Sebastian's heart beat quick; the word reward gave him a little courage; but fearing that his ears deceived him, he looked with timid and imploring eyes toward his master.

"A reward, señor," cried the pupils, in a breath.

"That is well; but what shall it be?"

Sebastian began to breathe.

"Speak, Sebastian," said Murillo, looking at his slave. "Tell me what you wish for; I am so much pleased with your beautiful composition that I will grant any request you may make. Speak, then; do not be afraid."

"Oh, master, if I dared—" And Sebastian, clasping his hands, fell at the feet of his master.

With the view of encouraging him, each of the pupils suggested some favor for him to demand.

"Ask gold, Sebastian."

"Ask rich dresses, Sebastian."

"Ask to be received as a pupil, Sebastian."

A faint smile passed over the countenance of the slave at the last words, but he hung down his head and remained silent.

"Come, take courage," said Murillo, gayly.

"The master is so kind," said Ferdinand, half aloud, "I would risk something; ask your freedom, Sebastian."

At these words Sebastian uttered a cry of anguish, and raising his eyes to his master, he exclaimed, in a voice choked with sobs, "The freedom of my father! the freedom of my father!"

"And thine also," said Murillo, who, no longer able to conceal his emotion, threw his arms round Sebastian, and pressed him to his breast. "Your pencil," he continued, "shows that you have talent; your request proves that you have a heart; the artist is complete. From this day consider yourself not only as my pupil, but as my son. Happy Murillo! I have done more than paint. I have made a painter."

Murillo kept his word, and Sebastian Gomez, better known under the name of the Mulatto of Murillo, became one of the most celebrated painters in Spain. There may yet be seen in the churches of Seville the celebrated picture which he had been found painting by his master, and others of the highest merit.

Dick Smith's home was in the West, and as the incident I am about to relate happened a good many years ago, he must have been then only thirteen or fourteen years old. He was a brave, hearty lad, full of enthusiasm and love of adventure, but especially abounding with ingenuity, and always doing something new and curious. Thus he has been known all his life as an "inventor," and still shows the same quality.

He lived on the bank of a river, and being fond of the water, became an expert swimmer and oarsman. Although he had no gun, yet with cunning traps and many original devices he caught considerable game, some for its fur, and some for its meat. It is about one of his boyish inventions that I am going to tell you.

At certain seasons of the year great flocks of ducks came into the river, and staid many days eating the Indian rice (Zizania aquatica) that grew in the shallow water. But as Dick's father had no shot-gun or any convenient way of capturing them, the ducks came and went unmolested.

At length ingenious Dick set to work to contrive some method of catching them. He obtained a section of thin bark from some tree, and arranged so that it would just slip over his head and rest on his shoulders, like the crown of a large old-fashioned hat, the top of it reaching several inches above his scalp.

In this he cut holes for his eyes and mouth, so that he could see and breathe. He also fastened leaves and vines on the top and around it to partly conceal it.

When this was done, he put it on and started for the ducks. Reaching a thicket on the river's brink near the game, he laid aside his clothes and took to the water. He had often been in the river where the rice grew, and knew just what difficulties he would have to overcome in swimming and wading. Out he went, and as he came near the ducks he moved very slowly and cautiously so as not to alarm them.

Pretty soon he was in the midst of an immense flock, and although they were extremely wary and quite suspicious of the vine-covered bark, yet within a short time he succeeded in grasping quite a number by the legs, and jerking them under the water. When he had secured all he could fairly manage, he quietly made his way home. His catch proved most delicious eating, and was very acceptable to the family, as it came at a time in the year when no other meat was generally available. Frequently while the wild rice lasted did he repeat the operation, bringing home the fattest specimens that came to the river.

But one day as he sat beneath the bushes on the edge of the water about a quarter of a mile from home, examining some ducks just caught, his little dog by his side, suddenly a huge panther pounced down from the high bank above, and rushed for the dog. Away went the dog for dear life, and the panther after him. But Dick knew well enough that the dog, which was very fleet, would escape, and that the great cat would soon give up the race and come back for himself. But the lad had no notion of affording the panther a boy for dinner; and so, perfectly cool and brave, set to thinking how to escape. If he should run away, the animal would follow his track and soon overtake him, for he could not equal the dog in speed; if he should climb a tree, the creature could excel him in climbing; if he should wade or swim into the river and the panther should see him, she might follow and get him there. But Dick was not to be caught so easily; what worked so well in deceiving ducks might do even better with the panther. And so, instantly slipping on his "duck hat," as he called it, he waded rapidly into the water a few rods, and settled down so that he could just breathe and see, and turning around, watched the shore. Hardly had he reached this position when the panther pounced down as before from the high bank and began smelling and looking for the boy. Failing to detect his whereabouts, she pawed over the ducks Dick had left; and since she could not have dog or boy for dinner, she decided to take duck.

Dick felt quite certain that when his dog reached home in fright and excitement the attention of the family would be attracted, and his father would shoulder his rifle and start out to investigate the matter. And Dick was not mistaken. In a very few minutes he saw his father in the canoe swiftly paddling along the shore, peering sharply for his boy. But the spot occupied by the panther was around a little curve in the bank, where she would not see the man until he was close upon her.

Before Mr. Smith reached this place he saw the lad's "duck hat," and Dick contrived to lift one hand carefully above the water and point where the creature was dining.

The father understood the signal, and giving the canoe a strong pull, seized the gun, and prepared to fire the instant he saw anything to fire at. A moment more the[Pg 12] rifle's sharp crack rang out, the panther sprang into the air, and fell back among the ducks, dead as they were.

Even yet, Dick, now elderly "Mr. Richard Smith," delights in telling how he escaped in a "duck hat" from a panther.

Our town has been very lively this winter. First we had two circuses, and then we had the small pox, and now we've got a course of lectures. A course of lectures is six men, and you can go to sleep while they're talking, if you want to, and you'd better do it unless they are missionaries with real idols or a magic lantern. I always go to sleep before the lectures are through, but I heard a good deal of one of them that was all about art.

Art is almost as useful as history or arithmetic, and we ought all to learn it, so that we can make beautiful things and elevate our minds. Art is done with mud in the first place. The art man takes a large chunk of mud and squeezes it until it is like a beautiful man or woman, or wild bull, and then he takes a marble grave-stone and cuts it with a chisel until it is exactly like the piece of mud. If you want a solid photograph of yourself made out of marble, the art man covers your face with mud, and when it gets hard he takes it off, and the inside of it is just like a mould, so that he can fill it full of melted marble which will be an exact photograph of you as soon as it gets cool.

This is what one of the men who belong to the course of lectures told us. He said he would have shown us exactly how to do art, and would have made a beautiful portrait of a friend of his, named Vee Nuss, right on the stage before our eyes, only he couldn't get the right kind of mud. I believed him then, but I don't believe him now. A man who will contrive to get an innocent boy into a terrible scrape isn't above telling what isn't true. He could have got mud if he'd wanted it, for there was mornamillion tons of it in the street, and it's my belief that he couldn't have made anything beautiful if he'd had mud a foot deep on the stage.

As I said, I believed everything the man said, and when the lecture was over, and father said, "I do hope Jimmy you've got some benefit from the lecture this time"; and Sue said, "A great deal of benefit that boy will ever get unless he gets it with a good big switch don't I wish I was his father O! I'd let him know," I made up my mind that I would do some art the very next day, and show people that I could get lots of benefit, if I wanted to.

I have spoken about our baby a good many times. It's no good to anybody, and I call it a failure. It's a year and three months old now, and it can't talk or walk, and as for reading or writing, you might as well expect it to play base-ball. I always knew how to read and write, and there must be something the matter with this baby, or it would know more.

Last Monday mother and Sue went out to make calls, and left me to take care of the baby. They had done that before, and the baby had got me into a scrape, so I didn't want to be exposed to its temptations; but the more I begged them not to leave me, the more they would do it, and mother said, "I know you'll stay and be a good boy while we go and make those horrid calls," and Sue said, "I'd better or I'd get what I wouldn't like."

After they'd gone, I tried to think what I could do to please them, and make everybody around me better and happier. After a while I thought that it would be just the thing to do some art, and make a marble photograph of the baby, for that would show everybody that I had got some benefit from the lectures, and the photograph of the baby would delight mother and Sue.

I took mother's fruit basket and filled it with mud out of the back yard. It was nice thick mud, and it would stay in any shape that you squeezed it into, so that it was just the thing to do art with. I laid the baby on its back on the bed, and covered its face all over with the mud about two inches thick. A fellow who didn't know anything about art might have killed the baby, for if you cover a baby's mouth and nose with mud it can't breathe, which is very unhealthy, but I left its nose so it could breathe, and intended to put an extra piece of mud over that part of the mould after it was dry. Of course the baby howled all it could, and it would have kicked dreadfully, only I fastened its arms and legs with a shawl strap so that it couldn't do itself any harm.

"THE MOMENT THEY SAW THE BABY THEY SAID THE MOST DREADFUL

THINGS."

"THE MOMENT THEY SAW THE BABY THEY SAID THE MOST DREADFUL

THINGS."

The mud wasn't half dry when mother and Sue and father came in, for he met them at the front gate. They all came upstairs, and the moment they saw the baby they said the most dreadful things to me without waiting for me to explain. I did manage to explain a little through the closet door while father was looking for his rattan cane, but it didn't do the least good.

I don't want to hear any more about art or to see any more lectures. There is nothing so ungrateful as people, and if I did do what wasn't just what people wanted, they might have remembered that I meant well, and only wanted to please them and elevate their minds.

"I hate to apologize; I do not like to admit that I was in the wrong."

I do not know who the speaker was. I did not even see his face as he passed the window where I was sitting, resting in the shadow of the curtain, and thinking, dear children, about you. I am sure that he was a boy, however, for such a fresh, decided voice, and such a quick step, could belong to nobody in the world but a boy.

Somehow I felt very sorry indeed when I thought about what he had said: "Hate to apologize! Not like to confess one's self to have been in the wrong!" Why, that is not noble.

Every one of us—you, Elsie, at your pretty embroidery, you, Dora, at your map drawing, you, Horace, over your chemistry, you, Theobald, deep in Virgil, I, the Post mistress, with my heaps of letters—every one of us, my dears, is liable sometimes to be in the wrong. We say something hastily, and hurt somebody's feelings, and then we are sorry. We do something which is foolish, and which we regret. The only brave course—the only course open to honorable people—is to apologize, to ask pardon, if necessary, of the person whom we have vexed or annoyed. It is always manly in a boy to own up and bear the blame if he has made a mistake. Many of the troubles and heart aches that people have to bear would be done away with if everybody who did wrong was willing to admit it, and if those who were wronged would be forgiving.

And now for the good things with which this number of the Post-office Box is fairly overflowing.

San Francisco, California.

I live in San Francisco. I often drive out to the beach with papa and mamma. A little way from the shore there is a large pile of rocks, and upon them you can see hundreds of sea-lions climbing about, and can plainly hear them barking or roaring. I often drive through the Golden Gate Park too. It is beautifully laid out with flowers, and at the large conservatory the beautiful "Victoria Regia" is in bloom now—a lily whose blossoms open three times, the first day a pure white, with a large white crown in the centre, then closes to open the next day a pale pink, then closes to open the last time almost purple. The leaves are saucer-shaped, about one yard across, and will bear the weight of a child three or four years old standing on them. But I must stop now, so good-by. I am nine years old, and study at home.

Birdie.

Thank you, dear, for your description of the superb Victoria Regia.

Mount Vernon, Ohio.

I am a little girl nearly nine years old. I go to school every day. We have but one pet; it is a kitty, and its name is Amorita. I am working a motto. It is my first, and my friends think it very nicely done. Mount Vernon is the county-seat of Knox County, Ohio. I have two sisters, Anna and Ruth, and one brother, Budge. On rainy days we have very pleasant times playing with dolls and books and sleds. To-night we had a circus in the parlor. Budge and Ruth were the lions, and I was the keeper; but soon they became unmanageable, and were sent to bed. It is drawing near my bed-time, and I will ask you to please print this, for I enjoy reading the letters, and want to see my own name in the Post-office Box. Good night.

Cinda B.

Savana La Mar, Jamaica, West Indies.

This is my first letter. We live in Jamaica, West Indies, and I like to read the letters from other boys and girls.

I am twelve years old, and have five brothers and two sisters. One brother is in England at the Blue-Coat School; the others learn lessons here at home. We have black people to do our work.

Harry M.

Butternut Lake, Wisconsin.

My sister Kate and I send you some yellow violets which we picked this afternoon while we were out walking. Is that not good for so far north? We are about fifty-three miles from Lake Superior. I love Young People very much, and I like the Post-office Box best.

Kate B. and Fannie T. M.

Brave little violets, and bright eyes that found them! Thank you, Kate and Fannie, for sending the pretty flower to me.

New York City.

I have taken Young People from the first number, and enjoy it very much. I returned from the sea-shore not long ago, and brought with me many pretty shells. I also brought a piece of sea-weed, which is a very good weather guide. When it is soft you may know it will be clear, and when it is hard it will be stormy.

Lulu L.

I suppose you will ask your sea-weed to tell you in the morning whether or not to wear your water-proof and overshoes to school. If it is doubtful, and papa says the wind is in the east, the safest way will be to wear them in New York.

Thomasville, Georgia.

Last Christmas my papa presented me with Harper's Young People, and it has afforded me a great deal of pleasure, and I intend to continue reading it always. I am eight years old, and since last fall have gone to school. I am now in the Fifth Reader, and work sums in fractions; but somehow I still love to play, and ride my velocipede, while my sister Sadie, who is five years, and Edna, nineteen months, amuse themselves with dolls. We live in a town quite famous as a winter resort, and many come here to escape the cold North and West, and to enjoy our pine regions.

Herbert J. H.

Belden, Texas.

I am a little boy nine years old. I have been taking Young People since last November. I have several pets. I have a dog, a pony, a pig, and three chickens; but the sweetest pet of all is my little baby brother; his name is Charley, but we call him Carly. I want to tell about my pig, he is so smart he thinks he is a dog. Everywhere the dogs go, the pig goes too. He helped me drive the horses to water yesterday. I live on a farm. I do not go to school; mamma teaches me at home.

Walter J. M.

A very remarkable pig. It must be funny to see him trotting off after the dogs and their little master.

New York City.

I am a little girl thirteen years old. I have a little dog, but he is very homely. We have three little kittens, and they are pretty. My brother found them in the garden. The cats and the dog do not fight. I have a papa and a mamma, and an auntie, and two big brothers. My auntie reads all the little letters to me. I have taken Harper's Young People since the first number.

Nettie B. M.

Monticello, New York.

Have you, dear Postmistress, ever been to Monticello? I think it is a lovely place. And there are such beautiful views. If I look to the north, I see quite a stretch of woods and hills, and away off in the distance a ridge of very high hills. I am staying on a farm where there are seven cows and four calves. Their names are Bessie, Brownie, Bright-eyes, and Bunker Hill. They are just as gentle as lambs. In the house there is a cat called Manners, and she has two kittens, Miss Muffet and Pussy Tiptoes. Tiptoes (or Tip, as she is called) has white-tipped paws, and a bib of white just under her chin. Muffet is gray and white.

I want to tell you about the County Fair. The grounds are two miles and a half from here. We rode up, and staid all day. First we went into the poultry house, which was full. What do you suppose we saw? Two little tiny hens, each with five little chickens no bigger than a medium-sized egg. After that we entered the domestic building. Dear! how full it was! Cake, jelly, pies, preserves, and fruit occupied an entire side of it. The other side was filled with art, fancy-work, and such things. The vegetable tent was next, and some one said the display of vegetables was larger than that at the state Fair. I can't begin to tell how many cattle, pigs, and sheep there were. We ate our lunch in the wagon, and it tasted very good. I was very tired when we got home, but we had a pleasant day and lovely weather.

A few weeks ago we drove to Katrina Falls. We went down into the basin, and saw the water come rushing down from fifty feet above, with high rocks and woods all around, and it made as wild a scene as I ever saw. I picked a fern and leaf to bring home and press.

Effie E. H.

Diddie, Dumps, and Tot were three little girls who lived on a plantation in Mississippi many years ago. Their real names were Madeleine, Elinor, and Eugenia, but nobody ever called them by anything except their funny pet names. The three little girls had three little colored maids, who waited on them, shared their plays, and went with them everywhere. The pet who gave them so much trouble on the afternoon of this story was a sheep, who had belonged to Diddie since he was a lamb. Then he had been very gentle, but he had grown cross and stubborn with age, though Diddie kept on loving him dearly.

You may all look at his picture on the cover of this number of Young People. They were playing that he was Lord Burgoyne, and that a feast was being made in his honor. But, alas! his lordship objected to being carried to the entertainment.

"You, Dumps, an' Tot, an' Dilsey, an' all of yer, I've got er letter from Lord Burgoyne, an' he'll be here to-morrow, an' I want you all to go right into the kitchen an' make pies an' cakes." And so the whole party adjourned to a little ditch where mud and water were plentiful (and which on that account had been selected as the kitchen), and began at once to prepare an elegant dinner.

Dear me! how busy the little housekeepers were! and such beautiful pies they made, and lovely cakes all iced with white sand, and bits of grass laid around the edges for trimming! and all the time laughing and chatting as gayly as could be.

"Ain't we havin' fun?" said Dumps, who, regardless of her nice clothes, was down on her knees in the ditch, with her sleeves rolled up, and her fat little arms muddy to the elbows; "an' ain't you glad we slipped off, Diddie? I tol' yer there wa'n't nothin' goin' to hurt us."

"And ain't you glad we let Billy come?" said Diddie. "We wouldn't er had nobody to be Lord Burgoyne."

"Yes," replied Dumps, "an' he ain't behaved bad at all; he ain't butted nobody, and he ain't runned after nobody to-day."

"'Ook at de take," interrupted Tot, holding up a mud-ball that she had moulded with her own little hands, and which she regarded with great pride.

And now, the plank being as full as it would hold, they all returned to the hotel to arrange the table. But after the table was set the excitement was all over, for there was nobody to be the guest.

"Ef Ole Billy wa'n't so mean," said Chris, "we could fotch 'im hyear in de omnibus. I wush we'd a let Chubbum an' Suppum come; dey'd er been Lord Bugon."

"I b'lieve Billy would let us haul 'im," said Diddie, who was always ready to take up for her pet; "he's rael gentle now, an' he's quit buttin'; the only thing is, he's so big we couldn't get 'im in the wheelbarrer."

"Me 'n' Chris kin put 'im in," said Dilsey. "We kin lif 'im, ef dat's all;" and accordingly the omnibus was dispatched for Lord Burgoyne, who was quietly nibbling grass on the ditch bank at some little distance from the hotel.

He raised his head as the children approached, and regarded them attentively. "Billy! Billy! po' Ole Billy!" soothingly murmured Diddie, who had accompanied Dilsey and Chris with the omnibus, as she had more influence over Old Billy than anybody else. He came now at once to her side, and rubbed his head gently against her; and while she caressed him, Dilsey on one side and Chris on the other lifted him up to put him on the wheelbarrow.