Title: A Maid in Arcady

Author: Ralph Henry Barbour

Illustrator: Frederic J. Von Rapp

Release date: November 2, 2019 [eBook #60612]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A MAID IN ARCADY

BY

AUTHOR OF “KITTY OF THE ROSES”

“AN ORCHARD PRINCESS”

ETC.

With Illustrations by

Copyright, 1906

By J. B. Lippincott Company

Published, September, 1906

Electrotyped and Printed by

J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, U. S. A.

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

XII.

XIII.

XIV.

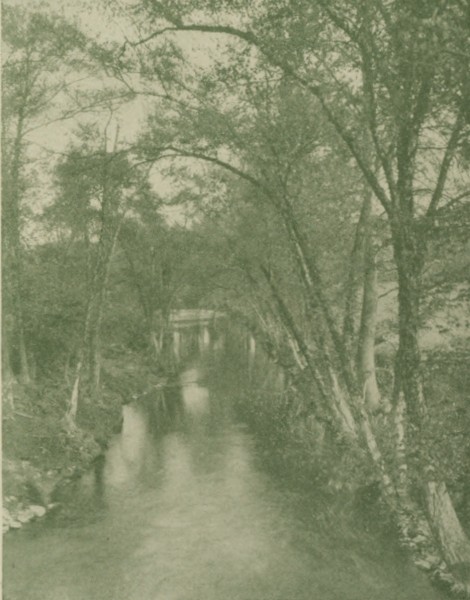

The clear water of the little river, in which the willows were mirrored quiveringly, shallowed where a tiny bar of silver-white sand thrust the ripples aside. Thus confined, the stream sulked for a moment in a deep, pellucid pool, and then, with sudden rush and gurgle, swept through a miniature narrows and swirled about the naked roots of the willows.

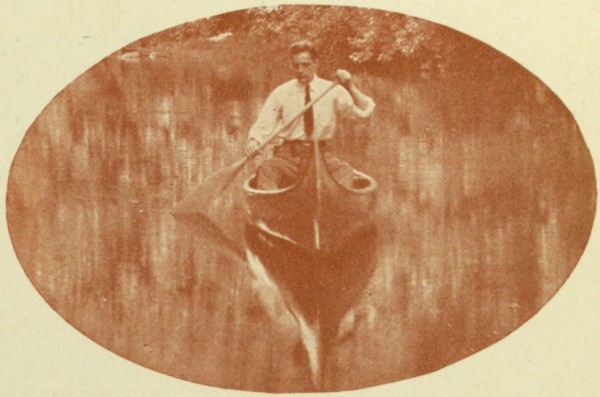

With a quick plunge of the paddle Ethan guided the canoe past the threatening bar. A drooping branch[10] swept his face caressingly as the craft gained the quiet water beyond. Here, as though repentant of its impatience, the river loitered and lapped about a massive granite bowlder, tugging playfully at the swaying ferns and tossing scintillant drops upon the velvety moss. To the left, the fringe of woodland which, in friendly gossip, had followed the little river for a quarter of a mile, parted where a second stream, scarcely more than a brook, flowed placidly into the first. Reinforced, the river widened a little and went slowly, musically on under the drooping branches, alternately sun-splashed and shadowed, until it disappeared at a distant turn. But the canoe did not follow. Instead it rocked lazily by the bowlder, while the ripples broke gently against its smooth sides.

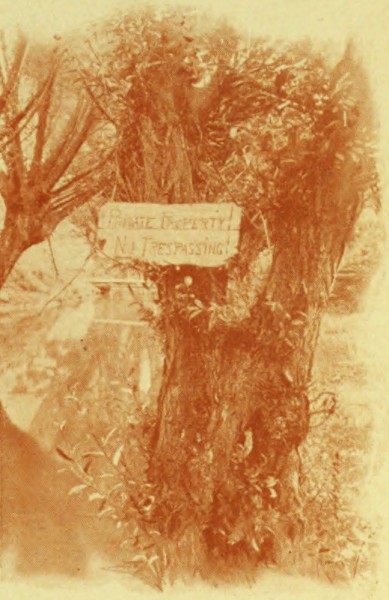

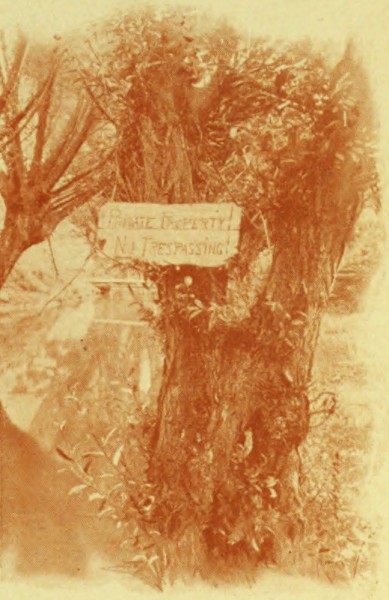

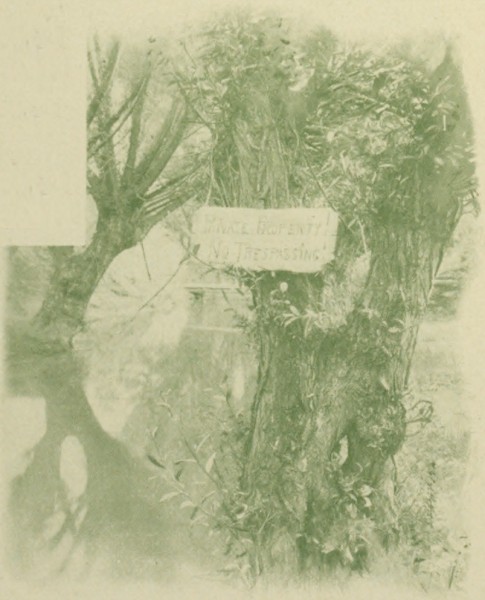

To the bole of an old willow which dropped its leaves in autumn upon the white sand-bar was nailed a weather-gray board, on which faded letters stated:

PRIVATE PROPERTY!

NO TRESPASSING!

Ethan observed the warning meditatively. In view of his later course of action let us credit him with that hesitation. At length, with a faint smile on his face, he turned the nose of the canoe toward the smaller stream and his back to the sign.

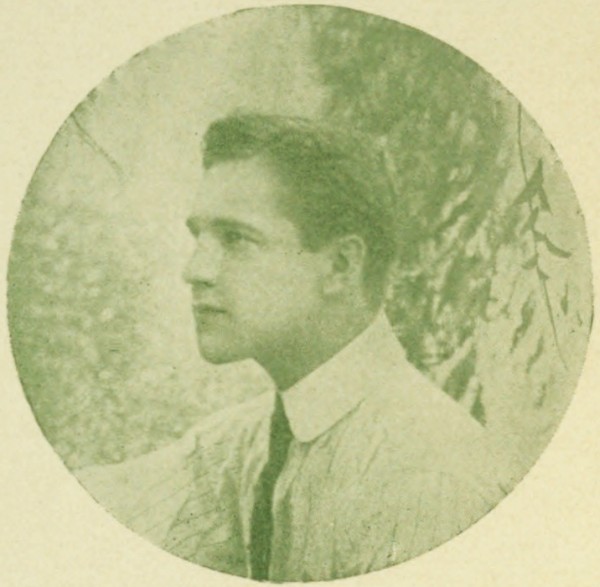

To have observed him one would scarcely have believed him capable of deliberately committing the dire crime of trespass. There was something about his good-looking face which bespoke honesty. At least, it would have[12] been difficult to credit him with underhand methods; it seemed easier to believe that if he ever did commit a crime it would be in such a superbly open and above-board fashion as to rob it of half its iniquity. Not that there was anything of classical beauty about his face. His eyes were a shade of brown, his nose was perhaps a trifle too short to reach the standard of the Grecians, his mouth, unhidden by any mustache, did not to any great extent suggest a Cupid’s bow. His chin was aggressive. For the rest, he had the usual allowance of hair of a not uncommon shade of brown, and showed, when he laughed which was by no means infrequently—a set of very white and very capable looking teeth. And yet I reiterate my former adjective; good-looking he was; good-looking in a healthy, frank,[13] happy and rather boyish way that was eminently satisfying.

If the sign on the old willow was right, and he really was trespassing, I have no excuse to offer, or at least none that my conscience will allow me to suggest. I can’t plead ignorance for him, for the simple reason that he had seen the sign and read it and that he knew all about trespass—or as much as was taught in the three-year course at the Harvard Law School, which he had finished barely a fortnight ago.

Meanwhile he has been sending the canoe quietly along the winding water path, dipping the paddle with easy, rhythmic swings of his shoulders, pushing the blade astern through the clear water and swinging it, flashing and dripping, back for the next stroke. He had tossed his light cloth cap into[14] the bottom of the canoe and had laid his coat over a thwart. The summer morning sunlight, slanting through the branches, wove quickly vanishing patterns in gold upon his brown hair. The tiny breeze, just a mere breath from the southwest, fragrant with the odor of damp, sun-warmed soil and greenery, stirred the sheer white shirt he wore and laid it in folds under the raised arm.

The brook was rather shallow; everywhere the pebbled bottom was visible. It was a whimsical brook, full of sudden turns and twistings; rounding tiny promontories of alder and sheepberry, dipping into quiet bays where bush honeysuckles were dripping sweetness from their pale yellow funnels, skirting curving beaches of white sand where standing armies of purple flags held themselves[15] stiffly at attention and restrained the invasion of the eager, swaying fern-rabble.

He had gone several hundred yards by this time against the slow current, and now there was evident a change in the foliage lining the banks, even in the banks themselves. Artifice had aided nature. Pink and white and yellow lilies dotted the stream, while at a little distance a slender, graceful stone bridge arched from shore to shore. Woodbine clustered about it and threw cool, trembling leaf-shadows against the sunlit stones. The arch framed a charming vista of the brook beyond. The canoe slipped noiselessly under the bridge and the strip of shadow rested gratefully for an instant on Ethan’s face. On the left there was a momentary break in the foliage and a brief glimpse of a[16] wide expanse of velvety turf. Then another turn, the canoe brushing aside the broad lily-pads, and the end of the journey had come, and, sitting with motionless paddle, he gazed spellbound.

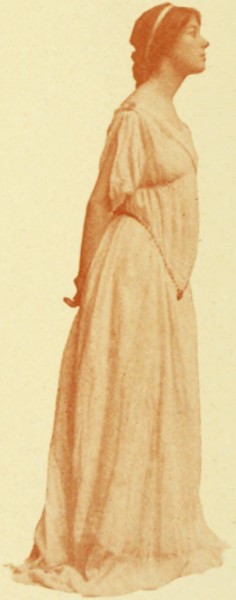

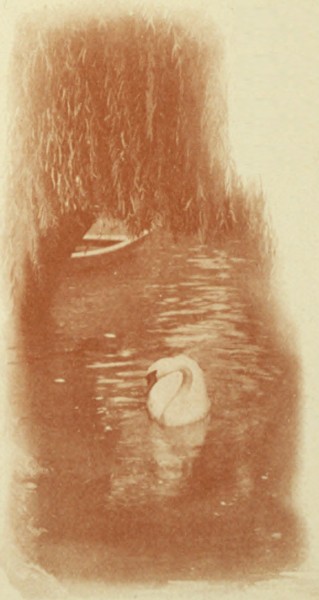

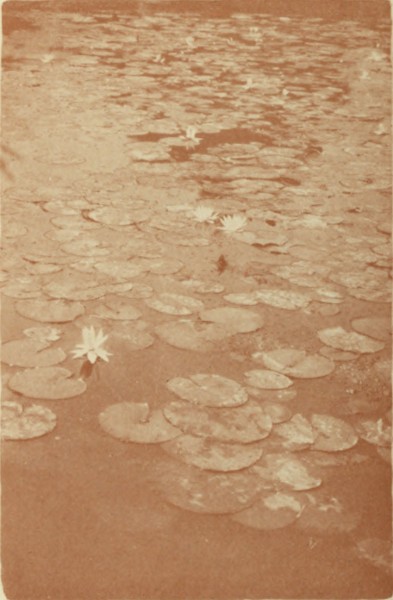

The banks of the stream fell suddenly away on either side and the canoe glided slowly and softly into a miniature lake. It was perhaps twenty yards across at its widest place and much more than that in length. Occasionally a far-reaching branch threw trembling shadows on the water, but for the most part the trees stood back from the margin of the pool and allowed the fresh green turf to descend unhampered to the water’s edge. At a point farthest from where Ethan had entered a little cascade tumbled. On all sides the ground[18] sloped slightly upward, and in one place a group of larches crowned the summit of a knoll and mingled their delicate branches far above the neighboring maples. Almost concealed among them an uncertain gleam of white caught at moments through the trees to the right suggested a building of some sort—perhaps the marble temple of the divinity, who, seated on the bank with her bare sandaled feet crossed before her, observed the intruder with calm, dreamy, almost smiling unconcern.

It was a beautiful scene into which Ethan had floated. Overhead was a blue sky against which a few soft white clouds hung seemingly motionless as though, like Narcissus, they had become enamored of their reflections in the pool there below. On a tiny islet in the pool, dwarf willows[19] caressed the water with the tips of their pendulous branches. Further on a trio of white swans sunned themselves, and about the margin the bosom of the pool was carpeted with lily-pads and starred with a multitude of fragrant blooms, white, rose-hued, carmine, pale violet, sulphur-colored and blue. The gauze wings of darting dragon-flies caught the sunlight, insects hovered above the flower-cups and in the branches around many a feathered cantatrice was singing her heart out. And for background there was always the varied green of encircling trees.

Yes, it was very beautiful, but Ethan had no eyes for it. With paddle still suspended between gunwale and water he was staring in a fashion at once depicting surprise, curiosity, and admiration at the figure on the[20] grass. And what wonder? Who would have thought to find a Grecian goddess under New England skies? Ethan’s thoughts leaped back to mythology and he sought a name for her. Diana? Minerva? Venus? Iris? Penelope?

And all the while—a very little while despite the telling—his eyes ranged from the sandaled feet to the warm brown hair with its golden fillet. A single garment of gleaming white reached from the feet to the shoulders where it was caught together on either side with a metal clasp. The arms were bare, youthfully slender, aglow in the sunlight. And yet it was to the eyes that his gaze returned each time. “Minerva!” his thoughts triumphed, “‘Minerva, goddess azure-eyed!’” And yet in the next instant he knew that while her eyes were undeniably[21] blue she was no wise Minerva. Such youthful softness belonged rather to Iris or Daphne or Syrinx.

And all the while—just the little time it took for the canoe to glide from the stream well into the pool—she had been regarding him tranquilly with her deep blue eyes, her bare arms, stretching downward to the grass, supporting her in an attitude suggesting recent recumbency. And now, as the craft brushed the lily-pads aside, she spoke.

“Do you not fear the resentment of the gods?” she asked gravely. “It is not wise for a mortal to look upon us.”

“I crave your mercy, O fair goddess,” he answered. “Blame rather this tiny argosy of mine which, propelled by hands invisible, has brought me hither. I doubt not that the gods[22] hold me in enchantment.” He mentally patted himself on the back; it wasn’t so bad for an impromptu!

She leaned forward and sunk her chin in the cup of one small hand, viewing him intently as though pondering his words.

“It may be so,” she answered presently. “What call you your frail vessel?”

“From this hour, Good Fortune.” Her gaze dropped.

“Will you deign to tell me your name, O radiant goddess?” he continued. She raised her eyes again and he thought a little smile played for a moment over her red lips.

“I am Clytie,” she answered, “a water-nymph. I dwell in this pool. And you, how are you called?”

He answered readily and gravely: “I am Vertumnus, clad thus in[23] mortal guise that I may gain the presence of Pomona. Long have I wooed her, O Nymph of the Pool.”

“I too love unrequited,” she answered sadly. “Apollo has my heart. Though day by day I watch him drive his fiery chariot across the heavens he sees me not.”

She arose and turned her face upward to the sun. Slowly she raised her white arms and stretched them forth in tragic appeal.

“Apollo!” she cried. “Apollo! Hear me! Clytie calls to you!”

Such a passion of melancholy longing spoke in her voice that Ethan thrilled in spite of himself. Unconsciously his gaze followed hers to the blazing orb. The light dazzled his eyes and blinded him for a moment. When he looked again toward the bank it was empty, but between the trees,[24] along the slope, a white garment fluttered and was lost to sight.

“Clytie!” he called in sudden dismay. And again.

“Clytie!”

A wood-thrush in a nearby tree burst into golden melody. But Clytie answered not.

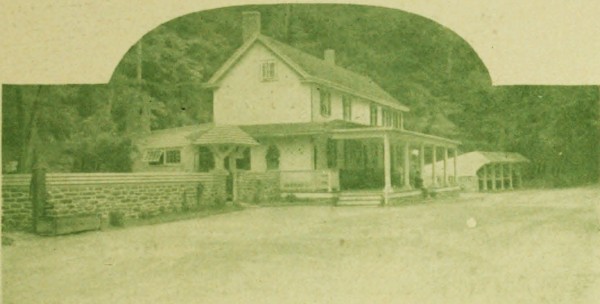

The Roadside Inn at Riverdell sprawls its white length along the old post-road over which many years ago the coaches swayed and rattled between New York and Boston. The Roadside, known in those days as Peppit’s Tavern, has changed but little. The front room over the porch, has held notable guests: Washington, Hancock, Adams, Lafayette and many more. On the tap-room windows you may still find the diamond-etched initials of by-gone celebrities. And much of the old-time atmosphere remains.

The room into which Ethan had his[26] bag taken after his return from his adventure in Arcady was low-ceilinged and dim. The two small windows, one overlooking the dilapidated orchard at the rear and the little river beyond, the other revealing the murmuring depths of a big elm, afforded little light. The floor was delightfully uneven; Ethan went downhill to the washstand and uphill again to the old mahogany bureau. The wide fire-place held a pair of antique andirons coveted by many a visitor, and the narrow shelf above was adorned with an equally desirable brass candlestick and a couple of opaque white glass vases which, ancient as they were, post-dated the shelf itself by half a hundred years. The bedstead, of mahogany, with rolling footboard, had made concessions to modernity. The pegs along the side, from which ropes[27] had once been stretched, remained, but an up-to-date wire spring and hair mattress had superseded the olden furnishings.

Ethan lighted a cigarette, unstrapped his bag and took out a leathern portfolio. With this on his knee, he sat at one of the open windows and scrawled a note.

“Dear Vin, I am sending my man Farrell on to you with the machine with orders to place it at your disposal. Make what use you can of it. I think it is all right now, though it went back on us this morning about two miles north of here. Funny place for it to bust, wasn’t it; looks as though it meant me to pay a visit here, eh? Well, I’m humoring it. I’ve decided to stay here for a day or two at the Roadside. I want to brush up a bit on mythology. Very interesting subject, mythology, Vin. Just when I’ll follow the machine I can’t say yet; possibly in a day or two. Make my excuses to your mother and sisters; invent any old story you like. You might say, for instance, that Vertumnus, fickle god, has transferred his affections[28] from Pomona to a water-nymph. But you needn’t if you’d rather not. I don’t care what you say. Expect me when you see me.

“Yours,

“Ethan.”

With a smile as he thought of his friend’s perplexity on reading the note, Ethan folded it and tucked it into an envelope. Then addressing it to “Mr. Vincent Graves, The Boulders, Stillhaven, Mass.,” he sealed it, dropped it into his pocket and made his way downstairs to dinner.

After dinner a big blue touring-car chugged its way southward along the shaded road, with Farrell at the wheel and Ethan’s note in Farrell’s pocket. Ethan watched it disappear. Then, drawing a chair to the edge of the porch, he set himself in it, put his heels on the railing, stuffed his hands into his pockets and asked himself with a puzzled smile why he had done it.

The grass grew tall and lush under the gnarled old apple-trees back of the Inn, and the straggling footpath which led to the landing was a path only in name. By the time he had gained the river Ethan’s immaculate white shoes were slate-colored with dew. The canoe rested on two poles laid from crotches of the apple trees, which overhung the stream. Ethan lifted it down and dropped it into the water. With paddle in hand he stepped in and pushed off down-stream.

On his left the orchard and garden of the Inn marched with him for a[30] way, giving place at length to a neck of woodland. On his right, seen between the twisted willows, stretched a pleasant view of meadows and tilled fields in the foreground, and, beyond, the gently rising hills, wooded save where along the base the encroaching grasslands rose and dipped. A couple of sleepy-looking farmhouses were nestled in the middle-distance and the faint whir-r-r of a mowing machine floated across the meadows. In the high grass daisies were sprinkled as thickly as stars in the Milky Way, and buttercups thrust their tiny golden bowls above the pendulous plumes of the timothy, foxtail, and fescue. The blue-eyed grass, too, was all abloom, like miniatures of the blue flags which congregated wherever the spring floods had inundated the meadows.

The sand-bar came in sight and the[31] little river began to fuss and fret as it gathered itself for what it doubtless believed to be an awe-inspiring rush. The canoe bobbed gracefully through the rapids and swung about in the pool below. Ethan winked soberly at the sign on the willow tree and dipped his paddle again. The canoe breasted the lazy current of the brook.

It was just such a day as yesterday. The little breeze stirred the rushes along the banks and brought odors of honeysuckle. Fleecy white clouds seemed to float on the unshadowed stretches of the stream. On one side a sudden blur of deep pink marked where a wild azalea was ablossom. Again, a glimpse of white showed a viburnum sprinkling the ground with its tiny blooms. Cinnamon ferns were pushing their pale bronze “fiddle-heads” into the air. Now and then[32] a wood lily displayed a tardy blossom. Near the stone bridge a kingfisher darted downward to the brook, broke its surface into silver spray and arose on heavy wing.

Once past the bridge and with only a single winding of the brook between him and the lotus pool, Ethan trailed his paddle for a moment while he asked himself whether he really expected to find the girl waiting for him. Of course he didn’t, only—well, there was just a chance——! Nonsense; there was not the ghost of a chance! Oh, very well; at least there was no harm in his paddling to the lotus pool—barring that he was trespassing! He smiled at that. He smiled at it several times, for some reason or other. Then he dipped his paddle again and sent the “Good Fortune” gliding swiftly over the sunlit water[33] of the pond. And when he looked there she was, seated on the bank, just as—and he realized it now—he had expected all along that she would be!

But it was not Clytie he saw; not unless the fashions have changed considerably and water-nymphs may wear with perfect propriety white shirtwaist suits and tan shoes. It was not impossible, he reasoned; for all he knew to the contrary, the July number of the Goddesses’ Home Journal—doubtless edited by Minerva—might prescribe just such garments for informal morning wear. At all events, being less bizarre than the flowing peplum of yesterday, Ethan—whose tastes in attire were quite orthodox—liked it far better. The effect was quite different, too. Yesterday she might have been Clytie; to-day reason cried out against any such possibility;[34] she was a very modern-appearing and extremely charming young lady of, apparently, twenty or twenty-one years of age, with a face, at present seen in profile, piquant rather than beautiful. The nose was small and delicate, the mouth, under a short lip, had the least bit of a pout and the chin was softly round and sensitive. This morning she wore her hair in a pompadour, while at the back the thick braids started low on her neck and coiled around and around in a perfectly delightful and absolutely puzzling fashion. Ethan liked her hair immensely. It was light brown, with coppery tones where the sunlight became entangled. She was seated on the sloping bank, her hands clasped about her knees and her gaze turned dreamily toward the cascade which sparkled and tinkled at the upper curve of the pool. As the[35] canoe had made almost no sound in its approach, she was, of course, ignorant of Ethan’s presence. And yet it may be mentioned as an interesting if unimportant fact that as he gazed at her for the space of half a minute a rosy tinge, all unobserved of him, crept into her cheeks. He laid his paddle softly across the canoe, and,——

“Greetings, O Clytie!” he said.

She turned to him startledly. A little smile quivered about her lips.

“Good morning, Vertumnus,” she answered. Perhaps his gaze showed a trifle too much interest, for after a brief instant hers stole away. He picked up the paddle and moved the canoe closer to the shore.

“I’m very glad to find you have not yet taken root,” he said gravely.

“Taken root?” she echoed vaguely.

“Yes, for that was your fate at the last, wasn’t it? If I am not mistaken you sat for days on the ground, subsisting on your tears and watching the sun cross the heavens, until at last your limbs became rooted to the ground and you just naturally turned into a sunflower. At least, that’s the way I recollect it.”

“Oh, but you shouldn’t tell me what my fate is to be,” she answered smilingly.

“Forearmed is forewarned; no, I mean the other way around!” he replied. “Maybe if you just keep your feet moving you’ll escape that fate. It would be awfully uncomfortable, I should say! Besides, pardon me if it sounds rude, sunflowers are such unattractive things, don’t you think so?”

“Yes, I’m afraid they are. The[37] fate of Daphne or Lotis or Syrinx would be much nicer.”

“What happened to them, please?”

“Why, Daphne was changed to a laurel; have you forgotten?”

“No, but how about the other ladies?”

“Lotis became a lotus and Syrinx a clump of reeds. Pan gathered some and made himself pipes to play on.

“Shelley, for a dollar,” he said questioningly.

She shook her head smilingly. “Keats,” she corrected.

“Oh, I have a way of getting them mixed, those two chaps.” He paused. “Do you know, it sounds odd nowadays[38] to hear anyone quote poetry?”

“I suppose it does; I dare say it sounds very silly.”

“Not a bit of it! I like it! I wish I could do it myself. All I know, though, is

and so on. I used to recite that at school when I was a youngster; knew it all through; and I think there were five or six pages of it. I was quite proud of that, and used to stand on the platform Saturday mornings and just gallop it off. I think the humor appealed to me.”

“It must have been delightful!” she laughed. “But you haven’t got even that quite right!”

“Haven’t I? I dare say.”

“No, Sir Thomas was her lord, not my lord, and it was his cough that was short instead of his breath.”

“Shows that my memory is failing at last,” he answered. “But, tell me, do you know every piece of poetry ever written?”

“No, not so many. I happen to remember that, though. Besides, we dwellers on Olympus hold poetry in rather more respect than you mortals.”

“You forget that I am Vertumnus,” he answered haughtily.

“Of course! And you puzzled me with that yesterday, too. I had to go home and hunt up a dictionary of mythology to see who Vertumnus was.”

“I—I trust you found him fairly respectable?” he asked. “To tell the truth, I don’t recollect very much[40] about him myself; and some of those old chaps were—well, a bit rapid.”

“Vertumnus was quite respectable,” she replied. “In fact, he was quite a dear, the way he slaved to win Pomona. I never cared very much about Pomona,” she added frankly.

“I—I never knew her very well,” he answered carelessly.

“I think she was a stick.”

“You forget,” he said gently, “that you are speaking of the lady of my affections.”

“Oh, I am so sorry!” she cried contritely. “Please forgive me!”

“If you will let me smoke a cigarette.”

“Why not? Considering that I am on shore and you on the water it hardly seems necessary——”

“Well, of course it’s your own private pool,” he said. “I thought perhaps[41] nymphs objected to the odor of cigarette-smoke around their habitations.”

“This nymph doesn’t mind it,” she answered.

He selected a cigarette from his case very leisurely. He had had several opportunities to see her eyes and was wondering whether they were really the color they seemed to be. He had thought yesterday that they were blue, like the sky, or a Yale flag or—or the ocean in October; in short just blue. But to-day, seen from a distance of some fifteen feet, and examined carefully, they appeared quite a different hue, a—a violet, or—or mauve. He wasn’t sure just what mauve was, but he thought it might be the color of her eyes. At all events, they weren’t merely blue; they were something quite different, far more[42] wonderful, and infinitely more beautiful. He would look again just as soon as he had the cigarette lighted, and——

“Were you surprised to find me here this morning?” she asked suddenly. There was no hint of coquetry in her tone and he stifled the first reply occurring to him.

“I—no, I wasn’t—for some reason,” he answered honestly. “I dare say I ought to have been.”

“I came on purpose to meet you,” she said calmly.

“Er—thank you—that is——!”

“I wanted to explain about yesterday. You see I didn’t want you to think I was just simply insane. There was—method in my madness.”

“But I didn’t think you insane,” he denied, depositing the burnt match carefully on a lily-pad and raising his[43] gaze to hers. “I thought—that——”

“Yes, go on,” she prompted. “Tell me what you did think when you found me here in that—that thing!”

“I thought I was in Arcadia and that you were just what you said you were, a water-nymph.”

“Oh,” she murmured disappointedly; “I thought you were really going to tell me the truth.”

“I will, then. Frankly, I didn’t know what to think. You said you were Clytie, and far be it from me to question a lady’s word. I was stumped. I tried to work it out yesterday afternoon and couldn’t, and so I came back to-day in the hope that I might have the good fortune to see you again.”

“It was rather silly,” she answered. “And I ought to have run[44] away when I saw your canoe coming. But it was so unexpected and sudden, and I was bored and—and I wondered what you would look like when I told you I was a water-nymph!” She laughed softly. “Only,” she went on in a moment, with grievance in her tones, “you didn’t look at all surprised! I might just as well have said ‘I am Mary Smith’ or—or ‘Laura Devereux!’”

(“Aha!” quoth Ethan to himself, “I am learning.”)

“You were very disappointing,” she concluded severely.

“I am sorry, really. I realize now that I should have displayed astonishment and awe. Perhaps if you had said you were Laura—Laura Devereux, was it?—I would have really shown some emotion.”

“Why?” she questioned.

“Well, don’t you think—Laura, now, is—I’m afraid I can’t just explain.” He was watching her intently. She was studying her clasped hands. “I suppose what I meant was that Laura is such an attractive name, so—so musical, so melodious! And then coupled with Devereux it is even—even—er—more so!”

“Is it?” She didn’t look at him and her tone was almost icy.

(“I fancy that’ll hold you for awhile,” he said to himself. “My boy, you’re inclined to be a little too fresh; cut it out!”)

“I never thought Laura especially melodious,” she said.

“Perhaps you are prejudiced,” he suggested amiably.

“Why should I be?” she asked, observing him calmly. He hesitated and paid much attention to his cigarette.

“Oh, no reason at all, I suppose,” he answered finally. He looked up in time to surprise a little mocking smile in her eyes. Nonsense! He’d show her that she couldn’t bluff him down like that! “To be honest,” he continued, “what I meant was that some folks take a dislike to their own names; in which case they are scarcely impartial judges.” He looked across at her challengingly. She returned the look serenely.

“So you think that is my name?” she asked.

“Isn’t it?”

“I don’t see why you should think so,” she parried. “I might have found it in a novel. I’m sure it sounds like a name out of a novel.”

“But you haven’t denied it,” he insisted.

“I don’t intend to,” she replied,[47] the little tantalizing smile quivering again at the corners of her mouth. “Besides, I have already told you that my name is Clytie.”

He tossed the remains of his cigarette toward where one of the swans was paddling about. The long neck writhed snake-like and the bill disappeared under the water. Then with an insulted air and an angry bob of the tail, the swan turned her back on Ethan and sailed hurriedly back to her family.

“I understand,” he said. “I will try not to forget hereafter that this is Arcadia, that you are Clytie and that I am Vertumnus.”

“Thank you, Vertumnus,” she said. “And now I must tell you what I came here to tell. You must know, sir, that I am not in the habit of sitting around on the grass in broad daylight[48] dressed—as I was yesterday. If I did I should probably catch cold. Yesterday morning we—a friend and I—dressed up in costume and took each other’s pictures up there under the trees. Afterwards the fancy took me to come down here and—and ‘make believe.’ And then you popped on to the scene all of a sudden.”

“I see. Very rude of me, I’m sure. Of course, as we are in Arcady, and you are a nymph and I a—a god, I don’t understand at all what you are talking about; but I would like to see those pictures!”

“I’m afraid you never will,” she laughed.

“I’m not so sure,” he said thoughtfully. “Strange things happen in—Arcady.”

“Weren’t you the least bit surprised[49] when you saw me? And when I—acted so silly?”

“I certainly was! Really, for a while—especially after you had gone—I was half inclined to think that I had been dreaming. You did it rather well, you know,” he added admiringly.

“Did I?” She seemed pleased. “Didn’t it sound terribly foolish when I spouted that about Apollo?”

“Not a bit! I—I half expected the sun to do something when you raised your hands to it; I don’t know just what; wink, perhaps, or have an eclipse.”

“You’re making fun of me!” she said dolefully.

“But I am not, truly! However, I don’t think you treated your audience very nicely. To get me sun-blind and then steal away wasn’t kind. When I looked around you had simply disappeared,[50] as though by magic, and I—” he shivered uncomfortably—“I felt a bit funny for a moment.”

“Really?” She positively beamed on him, and Ethan felt a sudden warmth at his heart. “I suppose every person has a sneaking desire to act,” she went on. “I know I have. Ever since I was a little girl I’ve loved to—to ‘make believe.’ That’s why I did it yesterday.”

“Have you ever considered a stage career?” he asked gravely. She leaned her chin in one small palm and observed him doubtfully.

“I never seem to know for certain,” she complained, “whether you are making fun of me or not. And I don’t like to be made fun of—especially by——”

“Strangers? I don’t blame you, Miss—Clytie. I wouldn’t like it myself.”

She continued to study him perplexedly, a little frown above her somewhat impertinent nose. Ethan smiled composedly back. He enjoyed it immensely. The sunlight made strange little golden blurs in her eyes. They were very beautiful eyes; he realized it thoroughly; and he didn’t care how long she allowed him to look into them like this. Only, well, it was a bit disquieting to a chap. He could imagine that invisible wires led from those violet orbs of hers straight down to his heart. Otherwise how account for the tingling glow that was pervading the latter? Not that it was unpleasant; on the contrary——

“I beg your pardon?” he stammered.

“I merely said that I had no idea of the stage,” she replied distantly, dropping her gaze.

“Oh!” He paused. It took him a moment to get the sense of what she had said through his brain. Plainly, Arcadian air possessed a quality not contained in ordinary ether, and its effect was strangely deranging to the senses. “Oh!” he repeated presently, “I am glad you haven’t. I shouldn’t want you to—er——”

But that didn’t appear to be just the right thing to say, judging from the sudden expression of reserve which settled over her countenance. Ethan shook himself awake.

“It is time for me to go,” she said, getting to her feet. Ethan made an absurdly futile motion toward assisting her. “I think I have explained matters, don’t you?”

“You have explained,” he answered judicially, “but there is much[53] more that would bear, that even demands elucidation.”

“I don’t see that there is,” she replied a trifle coldly.

“Oh, of course, if you prefer to have me place my own interpretation on—things——!”

“What things?” she demanded curiously.

“What things?” he repeated vaguely. “Oh, why—er—lots,” he ended lamely.

She turned her back.

“Good morning,” she said.

He took a desperate resolve.

“Good morning. Now that I know who you are——”

“You don’t know who I am!” she retorted, facing him defiantly.

“Pardon me, but——”

“I didn’t say my name was—that!”

“And I know more besides,” he added mysteriously.

“You don’t!”

“Oh, very well.” He smiled superiorly.

“How could you?”

“You forget that we gods have powers of——”

“Oh! Well, tell me, then.”

“Not to-day,” he answered gently. “To-morrow, perhaps.”

He raised his paddle and turned the canoe about.

“But you will not see me to-morrow,” she said, stifling the smile that threatened to mar her severity.

“You are not thinking of leaving Arcady?” he asked in surprise. “Where, pray, could you find a more delightful pool than this? Observe those swans! Observe the lilies! Besides, even in Arcady one[55] doesn’t move so late in the season.”

She regarded him for a moment with intense gravity. Then,

“You really think so?” she asked musingly.

“I really do.”

He waited, wondering at himself for caring so much about her decision. At last,

“Perhaps you are right,” she said. “Good morning.”

“And I, shall see you to-morrow?” he cried eagerly.

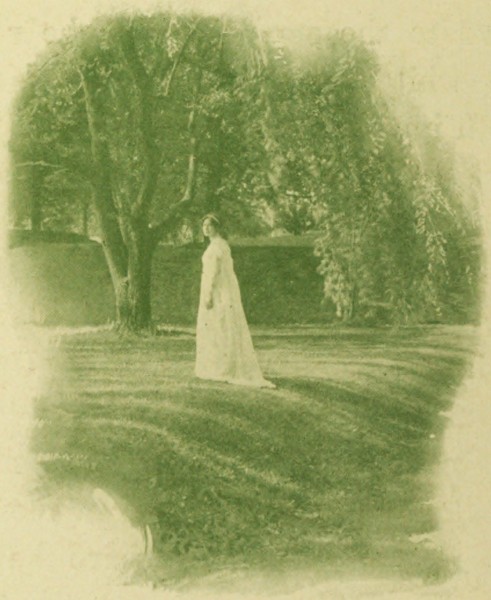

She turned under the first tree. The green shadows played over her hair and dappled her white gown with tremulous silhouettes.

“That,” she laughed softly, tantalizingly, “is in the hands of the gods.”

Her dress showed here and there[56] through the trees for a moment and then was lost to sight. Ethan heaved a sigh. Then he smiled. Then he seized the paddle and shot the canoe toward the outlet.

“Well,” he muttered, “I know how this god will vote!”

Ethan laid aside his paddle and mopped his face with his handkerchief. The canoe, left to its own devices, poked its nose against the meadow bank and allowed its stern to float slowly around in the languid current. He gazed across the fields over which the heat-waves danced and shimmered and addressed himself to his cigarette case.

“Providence,” he said, “showed great wisdom when it arranged that the Pilgrims should land on the coast of Massachusetts. ‘From what I’ve seen of these folks and what I’ve heard about them,’ says Providence, ‘I don’t believe they’re going to be much of an acquisition to the New[58] World. But I’ll give ’em a fair show. I’ll see that they land at Plymouth and if they can survive a Massachusetts winter and a Massachusetts summer I’ll have nothing more to say. Those of them alive a year from now will be entitled to prizes in the Endurance Test and will have qualified to become Hardy Pioneers and build up the country.’”

He mopped his face again, lighted a cigarette and took up his paddle.

“One would think that this state might show moderation at some season of the year,” he added disgustedly. “But not content with her Old Fashioned Winters, Backward Springs and Early Falls she has to try and wrest the Hot Weather blue ribbon from Arizona! No wonder they say a Bostonian isn’t contented in Heaven; doubtless he finds the[59] weather frightfully equable and monotonous!”

He righted the canoe and went on, with a glance at the sky above the hills.

“We’re probably in for a jolly good thunder-storm this afternoon,” he muttered.

By the time he had reached the entrance to the brook his forehead was again beaded with perspiration and his thin negligée shirt showed a disposition to cling to his shoulders. It was one of those intensely hot and exceedingly humid days which the early summer so often visits upon New England. Even the birds seemed to feel the heat and instead of singing and darting about across the shadowed stream were content to flutter and chirp drowsily amidst the branches. The hum of the insects held a lethargic[60] tone that somehow, like a locust’s clatter in August, seemed to increase the heat. Ethan went slowly up the winding stream with divided opinions on the subject of his own sanity. To sit in a canoe in the broiling sun on a morning like this merely to talk to a girl was rank idiocy, he told himself. Then he recalled her eyes, her tantalizing little laugh, the soft tones of her voice, the provocative ghost of a smile that so often trembled about her red lips, and owned that she was worth it. After he had slipped under the stone footbridge it suddenly occurred to him that perhaps the girl would object quite as strongly as he to making a martyr of herself in the interests of polite conversation! Perhaps she wouldn’t come at all! In which case he would have had his journey for naught—and possibly a sunstroke[61] thrown in! The more he considered that possibility the more reasonable it became, until, when he had shot the canoe into the little pond, and saw that the bank was empty of aught save a pair of the swans who were stretching their wings in the sunlight, he was not surprised.

“She certainly has more sense than I have,” he muttered.

Not a breath of air stirred the leaves of the encircling fringe of trees. The little lake was like an artist’s palette set with all the tender greens and pinks and whites and yellows of summer.

“I hope you like my pool?” inquired a voice.

Ethan turned from his survey of the scene and saw that the girl was standing under the shade of a willow a little distance up the slope. She was all in[62] white, as yesterday, but a broad-brimmed hat of soft white straw hid her hair and threw a shadow over her face. Ethan raised his own less picturesque panama and bowed.

“It’s looking fine to-day, I think,” he answered. “Perhaps just a little bit ornate, though. There’s such a thing as over-decorating even a lotus pool.”

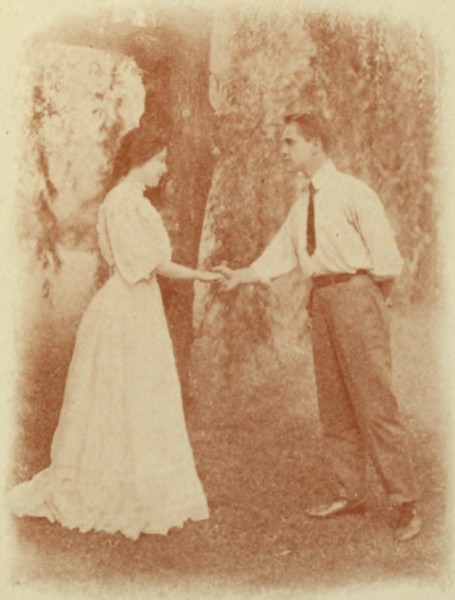

He turned the bow of the canoe toward the bank, swung it skilfully and stepped ashore. The girl watched him silently. When he had pulled the nose of the craft onto the grass and dropped his paddle he walked toward her. A little flush crept into her cheeks, but her eyes met his calmly.

“This is all dreadfully wrong, you know,” she said gravely. He stopped a few feet away and fanned himself with his hat.

“Yes, very warm, isn’t it?” he agreed affably.

“In the first place,” she went on severely, “you are trespassing.”

“I beg your pardon?” he asked as though he had not comprehended.

“I said you are trespassing.”

“Oh! Yes, of course. Well, really, you couldn’t expect me to sit out there in that hot sun, could you now? I—I have a rather delicate constitution.”

“But you were trespassing before! Coming up here only makes it worse.”

“Better, I call it,” he answered, turning to look back unregretfully at the pool.

“And then—then it is equally wrong for me to stay here and talk to you.”

“Oh come now!” he objected. “Nymphs in my day were not so conventional!”

“So I shall leave you,” she continued, unheeding and turning away.

“Then I shall go with you.”

“You wouldn’t dare!” she cried.

“Why not? Really, Miss Clytie, I am fairly respectable and I know of no reason why you shouldn’t be seen in my company. I have never done murder and never stolen less than a million dollars at a time. To be sure, I hope to become a practising attorney in the course of a year or so, but as yet my honor is unsullied.”

She hesitated, her eyes turned in the direction of the house.

“Besides,” he added hastily, “I was going to tell you what I know about you.”

“Then,” she answered reluctantly, “I’ll stay—a minute.”

“Thank you. And shall we be comfortable during that minute? ‘Come,[65] let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings.’”

She shook her head.

“Please!” he begged. “You will never be able to stand during all I have to tell you. Besides, you forget my delicate physique; I have been repeatedly warned against over-exertion.”

She sank gracefully to the grass in a billowing of white muslin, smiling and frowning at once as though annoyed by his persistence, yet too amiable to refuse. All of which produced its effect, Ethan realizing that she was doing him a great favor and becoming duly grateful. He followed her example, seating himself on the turf in front of her, paying, however, less attention to the disposition of his feet. Unconsciously his hand sought a[66] pocket, then dropped away again. She laughed softly.

“Please do,” she said.

“You’re sure you don’t mind?”

“Not at all,” she answered. So he produced his cigarette case and then his match-box and finally blew a breath of gray smoke toward the motionless branches overhead.

“Feel better?” she asked sympathetically.

“Much, thank you.”

“Then you may begin.”

“Begin——?”

“Tell me what you know about me.”

“Oh! To be sure. Well, let me see. In the first place, your name is Laura Devereux. I am right?”

She smiled mockingly.

“I haven’t agreed to tell you that.”

“Oh! But I know I am. I haven’t[67] asked any questions, for that would have been taking an unfair advantage, I fancy. But I happened to overhear yesterday afternoon at the Inn that a family by the name of Devereux had taken The Larches. And, as I have been in Riverdell before, I know where The Larches is—are—. Would you say is or are?”

“I am only a listener.”

“Then I shall say am, to be on the safe side; I know where The Larches am. You are living at The Larches.”

“No, I—I am merely staying there.”

“For the summer; exactly. That’s what I meant. When you are at home you live in Boston. I won’t tell you how I discovered that, but it was quite fairly.”

“Do I—are you sure I am a Bostonian?”

“Hm! Now that you mention it—I am not. Perhaps your family moved to Boston from somewhere else?”

“Yes?”

“From—let me see! Pennsylvania? But no, you don’t talk like a Pennsylvanian. Maryland? No again. Where, please?”

“But I haven’t acknowledged the correctness of any of your premises yet,” she objected.

“But you don’t dare tell me I’m wrong,” he challenged.

“At least, I am not going to tell you so,” she answered.

“That is as good as an admission!”

“Very well,” she replied serenely. “And now that you know so much about me—that is all, by the way?”

“So far,” he replied.

“Then don’t you think I ought to know something about you?”

“I am flattered that you care to.” He laid a hand over his heart and bowed profoundly.

“My curiosity is of the idlest imaginable,” she responded cruelly.

“I regret that bow,” he said. “However, I shall tell you anyhow. I am like the prestidigitateur in that I have nothing to conceal. And,” he added ruefully, “mighty little to reveal. My name is Parmley, surnamed Ethan. I am holding nothing back there, for I have no middle name. It has been a custom in our family since the days of the disreputable old Norman robber from whom we are descended to exclude middle names. I was born in this same Commonwealth of Massachusetts of well-to-do and honest parents, both of whom have[70] been dead for some years. I was an only child. Pray, Miss Devereux, consider——”

“If you don’t mind,” she interrupted, “I’d rather you didn’t call me that. I haven’t owned to it, you know.”

“Pardon me! I was about to ask you, Miss Clytie, to consider that fact when weighing my faults. As a child I was intensely interesting; I have gathered as much from my mother. I passed successfully through the measles, mumps, scarlet fever and whooping-cough. I also had the postage-stamp, bird-egg and autograph manias. Later I wriggled my way through a preparatory school—a sort of hot-house for tender young snobs—and later managed, by the skin of my teeth and a condition or two, to enter college. As it has been the custom[71] for the Parmleys to go to Harvard, I went there too. I am boring you frightfully?”

“No.”

“I succeeded in completing a four-year course in five. Some chaps do it in three, but I didn’t want to appear arrogant. I took it leisurely and finished in five. Then, as there had never been a lawyer in the family, I decided to study law. I entered the Harvard Law School and graduated a few weeks ago. I am now spending a hard-earned vacation. In September I am to enter a law firm in Providence as a sort of dignified office-boy.

“I am the possessor of some worldly wealth, not a great deal, but enough for one of my simple tastes. I am even a member of the landed gentry, since I own a piece of land with a house on it. I also own an automobile, and it is[72] that I have to thank for this pleasant meeting.”

She smiled a question.

“I left Boston bright and early Monday morning with Farrell. Farrell calls himself a chauffeur, in proof of which he displays a license and a badge. If it wasn’t for that license and that badge I’d never suspect it. Farrell’s principal duty seems to be to hand me wrenches and screw-drivers and things when I lie on my back in the road and take a worm’s-eye view of the machine. All went as nice as you please until we reached a spot some two miles north of this charming hamlet. There things happened. I won’t weary you with a detailed list of the casualties. Suffice it to say that I walked into Riverdell and Farrell followed an hour later leaning luxuriously back in the car and watching[73] that the tow-rope didn’t snap. I ate a supplementary breakfast at the Inn while Farrell entertained the blacksmith, and then, having nothing better to do, I dropped the canoe into the water and paddled downstream. Ever since I stole my first apple forbidden territory has possessed an unholy fascination for me, and that is why, perhaps, I roamed up the brook and stumbled, as it were, into Arcady.”

“What color is your machine?” she asked.

“Exceedingly blue.”

“And—isn’t it almost repaired?”

“Er—almost, yes.”

“It is taking a long while, seems to me.”

“Well, its malady was grave. I think it had tonsillitis, judging from the sounds it made.”

“Indeed? But it seemed to go very well.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I said that it seemed to go very well.”

“You have seen it?”

“Yes, it passed the house yesterday at about two o’clock.”

“There are a great many blue cars in the world,” he defended.

“Has it returned yet?” she asked, unheeding.

“No. The fact is, I was on my way to Stillhaven to visit friends there, so I sent the car on for them to use. I have observed that, failing my presence, the car does fairly well for my friends.”

“What a pessimist! And you are staying in Riverdell?”

“For a few days, yes; at the Roadside.”

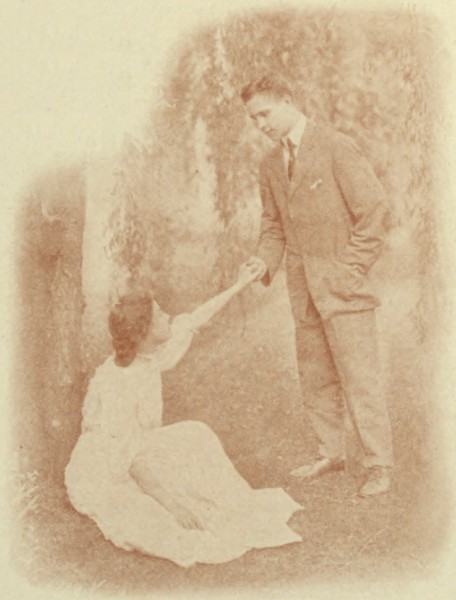

“Riverdell should feel flattered to find that you prefer it to Stillhaven as a summer resort.” She gathered her skirts together with one hand and started to rise. Ethan jumped to his feet and enjoyed the intoxicating felicity of feeling her hand in his.

“Thank you,” she murmured, smoothing her gown. Then, with a return of that provoking, mocking little smile, “Would it be a terrible blow to your vanity,” she asked, “if I were to tell you that your guesses are all wrong?”

“Terrible,” he answered anxiously.

“Then I won’t tell you,” she said soothingly.

“But—but—they’re not wrong, are they?”

“‘Where ignorance is bliss——’” she murmured.

“But I’d rather know! Tell me the worst, please!”

She shook her head smilingly.

“Good-bye,” she said.

“Aren’t you going to let me see you again?” he asked dolefully. Again she shook her head.

“I have had the offer of a new pool,” she said, “one with all modern improvements, and I think I shall move.”

“But—now, look here, it isn’t fair! What am I to do? It’s evident you’ve never spent a holiday in Riverdell, or else you’d appreciate my plight. There’s nothing to do save paddle around on that idiotic little river. And every time I’m afraid the water will leak out when I’m not watching it and leave me high and dry. If only for charity, please let me come here and see you now and then—just for a[77] moment! I’ll be very good, really; I’ll even agree to stay in the canoe and frizzle before your eyes!”

“You speak,” she answered perplexedly, “as though I had invited you to come to Riverdell, or at least as though I were to blame for your remaining here!”

He resisted the words that sprang to his lips.

“I beg your pardon then. I wouldn’t for the world imply anything so absolutely criminal. But I am here and I am bored; and surely you haven’t so many excitements, so many engagements in the mornings but that you can spend a few moments communing with nature here at the pool? Of course, I don’t recommend myself as an excitement; perhaps I’m more of a narcotic; but I’ll do anything in my power to amuse you! I’ll—I’ll even[78] tell you fairy stories or sing to you; and I’ve never done either in my life!”

“That is indeed an inducement then,” she laughed. “But—good-bye.”

“You won’t?”

“Do you think it likely?” she asked a trifle haughtily.

“Not when you look like that,” he answered dismally.

“Good-bye,” she said again, moving away.

“Good morning,” he answered. His eyes were on the ground where she had been sitting. He took a step forward. From there he watched her pass up the slope under the trees. At the last she turned back and looked regretfully at the pool shimmering in the noontide heat.

“I shall be sorry to leave it,” she[79] said softly, yet distinctly. “Perhaps—I shall change my mind.”

Then she went on, passing from shadow to sunlight, until the trees hid her. When she was quite out of sight Ethan lighted a cigarette, smiling the while. Then he flicked aside the charred match, lifted his left foot, stooped and picked up a little white wad which, as he gently shook it out, became a dainty white handkerchief. He looked at it, held it to his nose, touched it to his lips, folded it carefully and clumsily and placed it in his pocket. Then he turned toward the pool and the canoe.

“She’s a coquette,” he muttered, “an arrant coquette. But—but she’s simply—ripping!”

Ethan finished his second cigarette and tossed it hissing into the pool. The nearest swan immediately paddled over to investigate. Ethan sighed exasperatedly.

“Go ahead, then, you old idiot!” he muttered. “You won’t like it any better than you liked the last one; they’re out of the same box; but try it if you want to. There, I told you so! Oh, that’s it; blame me now! Blessed if you aren’t almost human!”

He looked for the twentieth time toward where the corner of the white pergola gleamed through the trees and for the twentieth time turned his gaze disappointedly away again. He had been there almost three-quarters of an hour, and he wasn’t going to[81] stay another minute! If she didn’t want to come, all right! Only she wouldn’t get her handkerchief if she didn’t! He had begun to doubt this morning whether she had dropped that article on purpose, as he had suspected yesterday. If it had been an accident she had probably returned already and searched for it, and he could not base his hopes of seeing her on the score of the handkerchief. It was quite evident, anyhow, that she wasn’t coming. That farewell remark of hers which he had translated to his own liking meant nothing, after all. He would throw his things into his bag and go on to Stillhaven after dinner. He had been a comical ass to fool around here like this tagging after a girl who didn’t want to be bothered with him and risking dyspepsia at the Inn! And what the deuce was he[82] thinking about women for, anyway? Hadn’t he taken a solemn vow on the occasion of his first, last and only affair to leave them severely alone? He grinned reminiscently.

That had been a desperate affair, brief and tragic. It had occurred in his freshman year. She was a “saleslady” in a florist’s shop on the Avenue. She had cheeks like one of the bridesmaid roses she sold, a tip-tilted nose, sparkling gray eyes and a mass of black hair which stood up from her forehead in a mighty rolling billow and smelled headily of violet perfume when she pinned a carnation to his coat. It had been love at first sight with Ethan, and he had seldom appeared in public without a flower in his button-hole. He remembered with something between a shudder and a sigh the exaltation of pride and joy[83] with which he had accompanied her to the theatre that first time! When he had returned from his Christmas vacation to find her engaged to the red-haired drug-clerk on the next corner he had promptly become a confirmed misogynist. During the seven years which had elapsed between that time and this he had relented somewhat, had gone through more than one mild flirtation and had kept his heart. There had been so many, many other things to occupy him that love had remained unconsidered. And now, what was he doing here, sitting in a canoe in a lily pond when he ought of right to be at Stillhaven helping Vincent sail the “Sea Lark” in the club races? Wasn’t he making a fool of himself again? Then something white moved toward him between the trees and the question went unanswered.

“I think I must have lost a handkerchief here yesterday,” she announced by way of greeting and explanation.

“A handkerchief?” he cried. “Let me help you search.”

“Oh, don’t bother! It doesn’t matter, of course, only—I thought that if it was here I’d get it.”

But Ethan was already out of the canoe.

“Er—what was it like?” he asked.

“Rather plain, I think; just a narrow lace edge.”

They looked diligently over the grass. Plainly it was not there. She raised her head, brushed a stray lock of hair from her forehead and laughed.

“I’m always losing them,” she said apologetically.

“Perhaps,” he suggested, “it might be well to offer a reward.”

“A splendid idea!” she cried. “We’ll post it on this tree here. Have you a piece of paper? And a pencil?”

“Both.” He tore the front from an envelope and handed her his pencil. She accepted them and set herself down on the grass.

“Oh, dear, what shall I write on? The canoe paddle? Thanks. Now let me see. What shall I say?”

“You must start by writing ‘Lost!’ in big letters at the top. That’s it.” Ethan’s rôle of adviser carried delicious privileges. It allowed him to kneel quite close behind her and observe the pink lobe of one small ear from a position of disquieting proximity.

“And then what?”

“I beg your pardon!” he said, with a start. “Why, then—er—let me see. ‘Lost’——”

“I have that,” she said demurely.

“A small handkerchief belonging——”

“How did you know it was small?” she asked with smiling interest.

“They always are,” he answered. “Where was I?”

“‘A small handkerchief belonging’——”

“That doesn’t sound quite shipshape. Let’s try again. ‘Lost, a small lady’s’——”

They laughed together as though it was a most novel and excellent joke.

“I don’t care to advertise my smallness,” she objected.

“Well, once more now. ‘Lost, a small handkerchief with a funny little lace border and an embroidered D in[87] the left-hand lower corner. Finder——’”

“An embroidered D?” she asked puzzledly.

“Wasn’t it a D?”

“Perhaps it was,” she allowed. She leaned a little farther forward, for the brief glance she had cast toward him had revealed the fact that his head was startlingly near. “And—and the reward?” she asked a trifle constrainedly.

“Finder may keep same for his honesty!”

“But—but that’s ridiculous!” she cried. “What’s the use of advertising at all?”

“To save the finder from committing theft,” he answered soberly. “Think of his conscience!”

“How do you know it’s a ‘him’?” she asked carelessly.

“I used the masculine gender merely in a—er—general way.”

“Oh!”

“Yes. Have you written that?”

“No, what’s the good of it? If the finder is dishonest enough to keep it he may look after his own conscience!”

“That’s unchristian,” he answered sadly.

“I’ll do this, though,” she said. “If the finder will produce it I will allow him to keep it on one condition.”

“And that?” he asked suspiciously.

“If there is a D on it he may have it. Otherwise——”

The finder produced it, unfolded it and looked at the “left-hand lower corner.”

“Well?” she asked, smilingly. He frowned.

“It—it looks more like an H,” he answered.

“It is an H! Now may I have it?”

“But it ought to be a D,” he said. “H stands neither for Devereux, Laura, nor Clytie.”

“I never said it did!”

“This is quite plainly not your property,” he went on, refolding it. “Being unable to find the owner, I shall retain possession of it.”

“But it’s mine!” she cried.

“Yours? What does the H stand for, then?”

She hesitated and flushed.

“I never said my name was Laura Devereux,” she murmured.

“No, but you see I happen to know that it is.” He replaced the handkerchief in his pocket. Then he reached forward and took the paper and envelope from her lap.[90] “I shall write an advertisement myself,” he said.

She watched him while he did so, biting her lip in smiling vexation. When it was done he passed the composition across to her.

“FOUND!”

“A lady’s lace-bordered handkerchief bearing the initial H in one corner. Owner may recover same by proving ownership and rewarding finder. Apply to Vertumnus, care Clytie, Lotus Pool, Arcadia, between ten and twelve.”

“What’s the reward?” she asked. He shook his head thoughtfully.

“I haven’t decided yet. Something—rather nice, I fancy.”

A faint flush crept into her cheeks and she turned her gaze toward the pool.

“It is much cooler to-day,” she said.

“Yes, last night’s thunder-storm cleared the air,” he replied, in a similar conversational tone. She glanced at the tiny watch hanging at her belt. Then she murmured something and sprang lightly to her feet before Ethan could go to her assistance.

“You are not going?” he asked in dismay.

She nodded gravely.

“But it’s quite early!”

“I don’t think it right to associate with dishonesty,” she answered severely. “You know very well that that handkerchief is mine!”

“Yes, I do,” he answered. “That is, I saw you drop it yesterday. Probably it belongs really to someone else. Unless—” he smiled—“unless you bought it at a bargain sale? In which case the initial didn’t really matter, I suppose.”

“Will you give it to me?” she asked unsmilingly.

“But it’s such a little thing!” he pleaded earnestly. “You have so many more that surely the loss of this one won’t inconvenience you. And I—I’ve taken a fancy to it.”

“That’s a convenient excuse for theft!” she answered.

“It’s the only one I have to offer,” he replied humbly.

“But—it’s so absurd!” she cried impatiently. “What can you want with it?”

He was silent a moment. She glanced furtively at his face and then moved a few steps toward the house.

“I wonder if you really want me to tell you?” he mused.

“Tell me what?” she asked uneasily.

“Why I want to keep it.”

“I don’t think I am—especially interested,” she answered coldly. “Are you going to return it?”

“Maybe; in a moment. You don’t want to hear the reason?”

“I—Oh, well, what is the reason?” she asked impatiently.

“A very simple one. As a handkerchief merely it doesn’t attract me especially. I have seen more beautiful ones, I think——”

“Well!” she gasped.

“My desire to keep it arises from the simple fact that it is yours, Clytie.”

She strove to meet his gaze with one exhibiting the proper amount of haughty resentment. But the attempt was a failure. After the first glance her eyes fell, the blood crept into her face and she turned quickly away.

“May I keep it, please?” he asked softly.

She went swiftly up the little slope under the trees.

“Clytie!” he called. She paused, without turning, to listen.

“May I keep it?”

Clytie dropped her head and passed quickly from sight.

Ethan stretched his arms, chastely clad in striped blue and white madras, yawned expansively, kicked his legs loose from the sheet in which they were entangled, and awoke; awoke to find the sunlight dancing across the room and making radiant blurs of his brushes on the old mahogany bureau; awoke to find a robin fervently launching his brief ballad in through the window from the branches just outside; awoke to find himself in a new and very wonderful world, a world populated by a girl with violet eyes, a reiterating robin, and himself!

He was in love!

Knowledge of the fact came to him with a heart-clutching abruptness.[96] He had gone to sleep last night without premonition; he awoke now to a startling illumination of mind. Whence had the tidings come? From the dancing sunlight streaming across the old boards? From the scented breeze that stirred the leaves out there? From the perfervid gossip of the swelling throat? Who could tell? And yet there it was, that knowledge, as real as the green summer earth awaiting him, as much a part of his life as the breath he drew!

He lay for a long while with his hands clasped under his head and gazed out into the beautiful green and golden and azure world, with a happy smile on his face, thinking new and ineffable thoughts. It is a glorious thing to find oneself really, wholly in love for the first time, glorious, wonderful, absorbing....

The robin ceased his pæan and was silent, with his head cocked attentively. Perhaps his ears were better than yours or mine and he heard a song sweeter and more triumphant than any of his own, for after a moment of listening he spread his wings and floated down across sunlit spaces to the orchard.

I wonder if the safety razor was not invented for the man in love. Certain it is that Ethan could never have used any other sort this morning. At times, driven by a mad impatience to be out and away, he shaved frantically, as though he feared that Nature would roll up her landscape and be gone ere he could reach it; at times he stood motionless, gazing unseeingly at the tip of his nose reflected in the old mirror. Now he whistled blithely, only to stop in the middle[98] of a note and relapse into a silent gravity. In short, he exhibited all the symptoms, mental and physical, usually accompanying his disease; temperature increased, pulse at once full and fluttering, respiration erratic, pupils of the eyes slightly dilated, mind apparently affected.

He dressed with unusual care, bewailing the fact that his choice of garments was limited to two suits. Neither blue serge nor gray homespun seemed fitted for the occasion; his heart hankered after purple and fine linen. But at last he was dressed and was hurrying down the creaking staircase to a late breakfast. Forty minutes later he was floating amidst the lilies of Arcady.

* * * * *

That line of stars, dear reader, is the typographic equivalent of three[99] wasted hours in the life of Ethan Parmley,—three empty unhappy hours spent in and about a silly old puddle smelling like an apothecary shop (I am using his own language now) with only a trio of idiotic swans to talk to. The Nymph of the Violet Eyes came not.

And yet he saw her that day, after all; caught a fleeting glimpse of her that at once assuaged and sharpened his hunger. He was on the porch of the Inn after dinner smoking, morosely, when a smart trap swept by from the direction of The Larches. It contained a coachman and two ladies. One of the ladies had violet eyes, though, as her head was turned away from him and partly hidden by a white parasol, he could not have proved it at the moment. As for the other, he couldn’t have said whether[100] she was young or old, fair or dark. The pair of glistening, well-groomed bays left Ethan scant time for observation. In a twinkling the carriage and its precious burden were gone. And although he never left the porch for more than a minute at a time all the rest of that interminable summer afternoon he found no reward. There were other roads leading to The Larches.

The evening mail brought him a note from Vincent Graves:

“Farrell showed up here Monday with the car and your note. I tried to find out from him what you were up to, but he either didn’t know or exercised a discretion I never credited him with. I hope it is nothing more than sunstroke; folks have been known to recover from that with their minds almost as good as new. Anyhow, I am coming over in a few days to see for myself. I know all about mythology—accent on the myth. But look here, no poaching[101] on my preserves! I finished third yesterday on time-allowance; would have done better if I hadn’t carried away my jib at the outer mark. No wind to speak of. Can’t you come on for Saturday’s race? We’ve had the car out once or twice. There’s something wrong with it. Farrell has it in hospital to-day. My compliments to her, but tell her I need you here.

“Yours,

“Vincent.”

After supper Ethan drew a chair to the open window of his room, set the lamp precariously on the bureau where the light would fall upon the portfolio in his lap, and replied to Vincent:

“My dear Vincent (he wrote), life moves sweetly in Arcadia. Clytie, she who beside her blossom-starred pool has so long gazed, enamored, upon the fiery Apollo, now hearkens to the wooing tones of green-garlanded Vertumnus. No more she fills the leafy hollow with her[102] tears and soft reproaches, but reclined where shading branches defy the sun god’s fiercest rays, she smiles betimes upon Vertumnus. And he, bathing his heart in the warm blue pools of her eyes, forgets and forswears the too-coy Pomona. So, friend, runs the drama of Clytie the dawn-eyed Nymph of the Lotus Pool; of Apollo, radiant and unapproachable Lord of the Sun; and of Vertumnus, humble and enamored God of the Seasons. Friend, for love of me, petition fair Venus to aid my cause!

“And now Jove be with you! The night wind steals sweetly through Arcadia’s moonlit glades and bears to my nostrils the heart-stirring fragrance of lily and of lotus. It is Clytie’s breath upon my cheek. Ah, my friend, I weep for you that you can never know the love of a god for a nymph in Arcady! May Somnus, gentlest of the gods, send thee sweet dreams. Farewell.

“Vertumnus.”

“And now, having read this over, I see clearly that it is beyond your understanding, my friend, and so it may be that it will never reach your eyes.”

It never did.

It sometimes rains even in Arcady.

When Ethan arose the next morning he found that Apollo was taking a rest and that Jupiter was having things all his own way. At the foot of the orchard the little river was foaming and boiling with puny ferocity. The grass was beaten and drenched and the foliage was adrip. But in the shelter of the elm outside the window a robin chirped cheerfully, thinking doubtless of gustatory joys to come.

“Well, you’re taking it philosophically, my friend,” muttered Ethan, “and I might as well follow your example, even though I have a soul above fat worms. It’s got to stop[104] sometime, and I might as well make the best of it meanwhile. Still,” he added ruefully, “a whole day in this ramshackle old ark doesn’t appeal to me much.”

He dressed leisurely, ate breakfast slowly, and afterward sought to kill time with a book by a window in the tap-room. The volume, a paper-clad novel left by some former guest, answered well enough. It is doubtful if he could have given undivided attention to the most engrossing story ever written. The rain, streaking down the tiny panes, caught strange hues from the old glass and the light from the crackling logs in the fire-place. Sometimes they were green like tender new apple leaves in May, sometimes blue like rain-drenched violets, like—no, not like but, rather, reminiscent of, certain eyes! Ah, there was[105] food for thought! The novel was turned face-downward on his knee, the cigarette drooped thoughtfully from the corner of his mouth and his hands went deep into his pockets. Those eyes! Rain-drenched violets? By jove, yes! No simile, no comparison could be better! Rain-drenched violets touched by the yellow light of the sun stealing back through gray clouds! Rather an elaborate description, he thought with a smile at his sentimentalism. The smile deepened as he recalled the infinitesimal blue circle under the left eye, a little blue vein showing with charming distinctness against the warm pallor of the skin like a vein in soft-toned marble. It was a little thing to recall, little in all ways, but it seemed to him a veritable triumph of the memory! By half closing his eyes he could almost see it.

Slam!

The paper-covered novel fell to the floor and lay fluttering its leaves in helpless appeal. He rescued it and sought his place again, smiling with real amusement over his foolishness.

“I’m certainly behaving like an idiot,” he thought. “I never knew being in love was so—so deuced unsettling. First thing I know, if I don’t keep a pretty steady hand on the reins, I’ll be writing poetry or roaming around the place cutting hearts and initials in the tree-trunks! H’m; let me see now; where was I? Ah, here we have it!

“‘Garrison laid the diamond trinket gently back on the desk and puffed slowly at his cigar. Presently he turned with disconcerting abruptness to Mrs. Staniford. “There is no possibility of mistake?” he asked.[107] “None,” was the firm reply. “You could swear to the identity of this jewel in court?” “Yes.” Garrison whipped a small round, black object from his pocket and settled it against his eye. Then he took up the trinket again and bent over it closely. “My dear madam,” he said softly, “if you did that you would be making a grave mistake.” “What do you mean?” she cried fiercely. “I mean,” was the smiling response, “that this is not one of your jewels,—unless——” “Well?” she prompted impatiently. “Unless, my dear madam, you wear paste!” A sharp involuntary exclamation of surprise startled them. They turned quickly. Lord Burslem was crossing the library with white, set face.’

“Pshaw! I knew all along the things were paste,” sighed Ethan.[108] “Singleton is Mrs. Staniford’s son by a former marriage and she has pinched the stones and given them to him to get him out of a scrape, something to do with that lachrymose Miss Deene, maybe; at least, something she knows about. Laurence is as innocent as the untrodden snow, or whatever the correct simile is, and if I keep on to the last chapter I’ll find out that fact. But I prefer to believe him guilty. He wore a gardenia in his buttonhole, and that settles it. I can’t stand for a man who wears gardenias. I insist that he is guilty.”

He tossed the book half-way across the room, arose, stretched his long arms above his head and stared out of the window. The rain was falling straight down from the dark sky in a manner that would doubtless have pleased Isaac Newton greatly, showing[109] as it did so perfectly the attraction of gravitation. The drops were of immense size, and when one struck the window pane it spread itself out into a very pool before it trickled down to the sash. Ethan watched for awhile, then yawned, glanced at his watch and lounged in to dinner.

About three o’clock the sky lightened somewhat and the torrential downpour gave way to a quiet drizzle. He donned a raincoat and sought the road. It was not bad walking, for the surface was well drained, and he had put three-quarters of a mile behind him before he had considered either distance or destination. Then, looking around and finding the highway lined on the right by an ornamental iron fence through which shrubs thrust their wet leaves, he smiled and shrugged his shoulders.

“I didn’t mean to come here,” he said to himself, “but now that I’m here I might as well go on and tantalize myself with a look at the house.”

Another minute brought him to a broad gate, flanked by high stone pillars. A well-kept drive-way swept curving back to a large white house, a house a little too pretentious to entirely please Ethan. On one side,—the side, as he knew, nearest the lotus pool,—an uncovered porch jutted out, and from this steps led to a white pergola. The latter was a recent addition and as yet the grapevines had not succeeded wholly in covering its nakedness. From one of the windows on the lower floor of the house a dull orange glow emanated.

“They’ve got a fire there,” said Ethan, “and she’s sitting in front of it. Wish I was!”

He settled the collar of his raincoat closer about his neck to keep out the drops, and sighed.

“You know,” he went on then, somewhat defiantly, addressing himself apparently to the residence, “there’s no reason why I shouldn’t walk right up the drive, ring the bell and ask for—for Mr. Devereux. I’ve got the best excuse in the world. And once inside it would be odd if I didn’t see Her. I’ve half a mind to do it! Only—perhaps she’d rather I wouldn’t. And—I won’t.”

He took a final survey of the premises and turned away with another sigh. Before he had reached the Inn the clouds had broken in the south and a little wind was shaking the raindrops from the leaves along the road.

“A good sailing breeze,” he thought. “And, by the bye, this is[112] Saturday. I ought to be at Stillhaven helping Vin win that race. I suppose I’ve disappointed him. However, a fellow can’t be in two places at once; he ought to know that.”

The little breeze had held all night, and this morning the trees and shrubs were quite dry again, but looking better for their bath. It was Sunday, and as the canoe floated into the harbor of the lotus pool a distant church bell was ringing. Perhaps, he told himself with a sudden sinking of the heart, he was doomed to another day without sight of Clytie; for it might be that the family would drive to church. But the first fair look about him dispelled his forebodings. She was standing at the border of the pool throwing crumbs of bread to the swans. She saw him at almost the same moment and smiled.

“Don’t come any nearer, please,” she said. “You’ll scare them.”

He dipped his paddle obediently and sat silent in the rocking craft until the last crumb had been distributed and she had brushed the crumbs from her outstretched hands. Stooping, she picked a book from the grass and faced him.

“May I come ashore?” he asked.

“You are already trespassing dreadfully,” she objected.

“‘In for a penny, in for a pound,’” he replied, sending the canoe forward. “‘Might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb.’ And if I could think of any other proverbs applicable to the matter I’d quote them.” He jumped out and pulled the bow of the canoe onto the turf.

“You won’t mind, however, if I[115] decline to stay and be hung with you?” she asked.

“On the contrary, I should mind very much. In fact, I demand that you remain and go bail for me in case I’m apprehended.”

“I fear I couldn’t afford it,” she answered.

“Doubtless your word would serve,” he said. “Perhaps, if you told them the excellent character I bear, you might get me off scot-free.”

“But I don’t think I know enough about your character.”

“There’s something in that,” he allowed. “Perhaps you had better observe me closely for the next hour or two. One can learn a great deal about another person’s character by observation.”

“How can I do that if I go to church?”

“You can’t. That’s one reason why you’re not going to church.”

“Oh! And—are there other reasons?”

“Yes.”

“Perhaps you had better give a few of them. I don’t think the first one is especially convincing.”

“Well, another one is that I haven’t seen you for three days.”

She shook her head gravely.

“Go on, please.”

“Not good enough? Well, then, another reason is that you haven’t seen me for three days.”

She laughed amusedly.

“Worse and worse,” she said.

“I didn’t think you’d care much for that argument,” he responded cheerfully. “It was somewhat in the nature of an experiment, you see. But the real unanswerable reason is this:[117] I have missed seeing you very much, I have been very dull, you are naturally kind-hearted and would not unnecessarily cause pain or disappointment, and I beg of you to give me a few moments of your cheerful society! Is that—better?”

“I don’t particularly care for it.”

“Miss Devereux——”

“What have I told you?” she warned.

“I beg pardon! But—now, really, please let me call you by a Christian name! I—I’d like to graduate from mythology.”

“I don’t think it would be proper for you to call me by my Christian name,” she answered demurely.

“A Christian name, I said,” he answered patiently. “Tell me why you don’t want me to address you as Miss Devereux, please.”

“Because——” She stopped and dropped her gaze. “We’ve never been properly introduced, have we?”

“True! Allow me, pray! Miss Devereux, may I present Mr. Parmley? Mr. Parmley, Miss Devereux!” He stepped forward, smiling politely and murmuring his pleasure, and ere she knew what was happening he was shaking hands with her. “Awfully glad to meet you, Miss Devereux!” he assured her cordially.

She backed away, striving to draw her hand from his, and laughing merrily.

“Is that what you call a proper introduction?” she asked.

“Well, it’s the best I could do under the circumstances,” Ethan answered. “Having no mutual acquaintances handy, you see——”

“Don’t you think—you might let go[119] now?” she asked, her laughter dying down to a nervous smile.

“Let go?” he echoed questioningly.

“Please! You have my hand!”

He looked down at it in mild surprise; then into her face.

“Isn’t that the strangest thing? I was never so surprised——!”

“But—Mr. Parmley, please let go,” she begged.

“You don’t mean to say that I still have it?” He tried to seem at ease and to speak carelessly, but his heart was pounding as though striving to do the Anvil Chorus all by itself, and his voice wasn’t quite steady.

“I do,” she answered coldly, biting her lip a little. A disk of red burned in each cheek. Her eyes were fixed on his imprisoning hand. “Besides, you are hurting me,” she added, falling[120] back upon the fib which is a woman’s last resource in such a quandary. But he shook his head soberly.

“Pardon me, but that’s impossible. You will observe that my hand is quite loose about yours. Accuse me of unlawful detention, if you wish, but not of cruelty.”

“But—but it is my hand,” she protested faintly.

“Well, that is nothing to boast of,” he replied smiling somewhat tremulously. She had kept her eyes from him all along and he was determined to see them before he gave up. “Look at mine; it’s twice as big!”