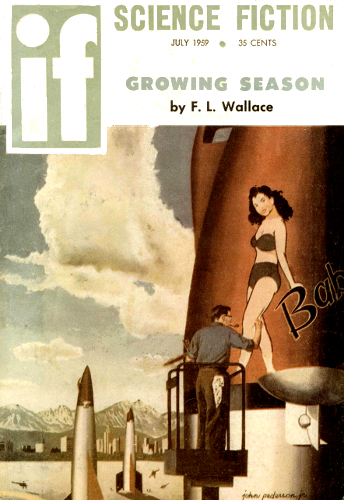

Title: Growing Season

Author: F. L. Wallace

Release date: November 15, 2019 [eBook #60693]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Why would anyone want to kill a tender

of mechanized vegetation—with, of all

things, a watch and a little red bird?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, July 1959.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The furry little animal edged cautiously toward him, ready to scamper up a tree. But the kernel on the ground was tempting and the animal grabbed it and scurried back to safety. Richel Alsint sat motionless, enjoying himself greatly.

Outside the park in every direction were many tiers of traffic. He was the only person in the park; it was silent there except for birds. One in particular he noticed, all body, or entirely wing—it was impossible to say which at this distance—soared effortlessly overhead, a small bundle of bright blue feathers. The wings, if it had wings, didn't move at all; the bird balanced with remarkable skill on air currents. Everything about it might be small, but the voice wasn't, and it made good use of every note.

Alsint twisted his hand slowly toward the sack beside him.

In that position the ship watch was visible. There was no need to look; it was connected to the propulsion processes of the ship and would signal long before he had to be back. Nevertheless he did glance at it.

In sudden alarm, he jumped up, scattering the contents of the sack. The circle of animals fled into the underbrush and the birds stopped singing and flew away.

He left everything on the bench. It was untidy, but his life would be more untidy if he missed the ship. He ran to the aircar parked in the clearing and fumbled at the door. The bright blue bird was changing to red, but he didn't notice that.

He bounced the car straight up, sinking into the cushions with the acceleration. High above the regular levels of traffic, he located the spaceport in the distance and jammed the throttle forward. The ship was there, and as long as it was, he had a chance. Not much, though. The absence of activity on the ground indicated they were getting ready.

He dropped the aircar down as close as he could get and left it. There was no time to take the underground passage that came up somewhere near the ship. The guard at the surface gate stopped him.

"You're too late," said the attendant.

"I've got to get in!" Alsint said.

The guard recognized the uniform, but, sitting in the heavily reinforced cubicle, made no move to press the button which would allow the gate to swing open. It was a high gate and there was no way to get over it.

He grinned sourly. "Next time you'll pay attention to the signal."

There were worse times and places to argue about it, but Alsint couldn't remember them. "There wasn't any signal," he said. He caught the cynical expression on the guard's face and extended his hand. "See for yourself."

The watch was working, indicating time till takeoff, but the unmistakable glow and the irritating tingle, guaranteed to wake any man out of a sleep this side of the final one, were missing.

The guard blinked. "Never heard of that ever happening," he said. "Tell you what—I'll testify that it wasn't your fault. That'll clear you. You can get a job on the next ship and catch up with your own in a month at the most."

It wasn't that easy, nor so simple. Alsint glanced frantically at the watch. Minutes left now, though he couldn't be sure. If the signal wasn't functioning, maybe the time was wrong too. "I'll never get on that one again," he said. "It's a tag ship."

The guard scrutinized him more closely, differentiating his uniform from others similar to it. "In that case you'd better go to the traffic tower," he said reluctantly. "They'll stop it for you."

They would, but he'd waste half an hour getting past the red tape at the entrance. There were a number of reasons why he couldn't let the ship leave without him. "I know our crew," he said. "They'll be waiting for me. Let me try to get on."

The guard shrugged. "It's your funeral." Slowly the gate swung open.

Alsint dashed through. He had to hurry, but it wasn't as dangerous as the guard imagined. The watch had failed, but inside the ship was a panel which indicated the presence or absence of any crew member. That panel was near the pilot. He wouldn't take off without clearing it.

Besides, there was standard takeoff procedure—always someone at the visionport, watching for latecomers, of which there were usually a few. Alsint raised his head as he ran. He couldn't see anyone at the visionport.

Breathing heavily, he brushed against the ship. Late, but not too late. He turned the corner at the vane.

He didn't like what he saw. The ramp was up and the outer lock was closed. They were waiting for clearance from the spaceport.

His composure slipped a little. If the clearance came within the next few minutes, he'd be dead. Not that the clearance would come. A ship just didn't lift off, leaving one of the crew behind—or he hoped it didn't.

He pounded on the lock and shouted, though it was useless. Inside, they couldn't hear him. The noise frightened a little red bird which had been hovering nearby. It flew around his head, squawking shrilly.

Alsint scowled at it. It reminded him unpleasantly of the park. If he hadn't gone there, he'd be safe inside the ship. True, parks were rare, and people who went to them even more rare. After so many months in the ship, it had been a great temptation—for him, not the others. No one else had been interested.

Now he had to get in. A tremor ran through the hull and he realized how urgent it was. A little more of this and he would be caught under the rockets.

The airlock was smooth, but he located the approximate latching point on the outside and stripped off the watch, holding it against the ship by the band. He tried to remember and thought the face should be turned inward. He held it that way and hoped he was right. He closed his eyes and swung hard with his fist.

His hand exploded with pain and he could feel the flash on his face. The energy, which was sufficient to drive the instrument for a thousand years, dissipated in much less than a second. An instant later the hand which held the strap reacted to the heat. He dropped the useless watch and opened his eyes.

He had figured it right and he was also lucky. The energy had turned inward, as he had hoped, otherwise he'd have no hand, and the latching mechanism had been destroyed. The resulting heat had buckled the plate outward. The hull was trembling with greater violence as the takeoff rockets warmed up.

The airlock was still very hot. His fingers sizzled as he grasped the curled edge and pulled out. It moved a little. He shifted his hands for a better grip and heaved. It opened.

He scrambled inside and shut it behind him, latching it with the emergency device. Close, but it didn't matter as long as he'd made it. The ship began to rise and the acceleration forced him to kneel in the passageway between the outer and inner lock. He kept thinking of the little red bird he'd seen outside. Burned, no doubt, as he would have been.

Finally the rockets stopped and the heaviness disappeared. They were out of the atmosphere and hence the ship had shifted to interstellar drive. The heat from the rockets began to abate. He was grateful for that.

He got to his feet and staggered to the inner lock and leaned against it. That didn't open, either. He shouted. It might take time, but eventually someone would come close enough to hear him.

There was air in the passageway and he knew he could survive. It had been too hot; now it was getting cold. He shivered and shook his head in bewilderment.

None of this was the way it ought to be. It had never been difficult to get on the ship. If he didn't know better, he'd say—

But this was not the time to say that.

He didn't hear the footsteps on the other side. The lock swung in and he fell forward. His burned hands were too cold to hurt as he checked his fall.

Scantily clad, Larienne stood over him. "Playing hiding games?" she asked. She got a better look and knelt by his side. "You're hurt!"

So he was, but mostly he was tired. In the interval before he accepted the luxury of unconsciousness, the thought flashed across his mind before he could disown it: Someone on the ship was trying to take the plant away, or wanted him to fail.

Either would have been accomplished if he had been left behind.

He sat in his room, thinking. He wished he knew more about the crew. Six months was enough to give him wide acquaintance, but not the deep kind. They were a clannish lot on the ship. His own assistant he knew well enough, and the doctor. The captain he hardly ever saw. The rest of them he knew by sight and name, but not much else: the few married couples, the legally unattached girls, and the larger number of male technicians.

None of them, as far as he could see, had any incentive to engineer the mixup which had nearly caused him to miss the ship. Of course he might be reading into it more than was there. It could have happened that way accidentally. And then maybe it didn't.

His thoughts were interrupted by a knock. "Who's there?" he called.

Larienne walked in. "Nobody asks who," she said. "It's always come in. Even I know that, and I've been on this traveling isolation ward a mere three years."

She dropped into a chair and draped her legs, long legs that were worth showing off. She had a certain air of impartiality that attracted attention. She was smart, though, and knew when to discard impartiality.

She eyed him curiously. "I'm trying to discover the secret of your popularity. That damn plant is pining for you."

"It's not me," he said. "You have to know how to handle it."

"Thanks," she said dryly. "I don't know how. But Richel Alsint, boy plant psychologist, does. He knows when to increase the circulation, when to give it an extra shot of minerals, and when, on the other hand, to scare the damn thing out of its wits, which I sometimes believe it actually has."

"Don't personalize it," he warned. "It's partly plant and partly a machine. Your mistake is that you treat it as if it were wholly a machine."

"Seems to me I've heard that before. What should I do that I don't?"

"Cycles," he said. "Rhythm. A machine doesn't need that kind of treatment, but a plant does. Normally it starts as a seed, grows to maturity, produces more seeds, and eventually dies. Our plant isn't like that, of course. It never produces seeds, and, if we're careful, doesn't die. Yet it does have something that faintly corresponds to the original cycles."

She sighed. "It might help if I knew what it was—geranium, or sunflower, or whatever."

He had told her, but apparently she didn't want to remember. "It isn't one plant. It's been made from hundreds; even I don't know what they were. One best feature from this, another strong feature from something else. We've taken plants apart and recombined them into something new. This is just—plant."

Larienne dropped her legs to a more comfortable if less esthetic position. "Hydroponics was simpler," she objected.

"It was," he said. "And if you want to know, old-fashioned dirt farming was even simpler. Our combination plant and machine is merely a step and a half ahead of hydroponics."

"Suppose you come out and tell me what I've done wrong," she said, getting up.

"One last thing," he said. "Remember that plants evolved on planets. No matter what we do, we can't convince the plant that it's still on a planet. Light's the easiest. As far as we know, it will grow indefinitely under our artificial light. Artificial gravity is different. I don't know the difference, and neither do the physicists, but the plant does. It can live in the ship just so long and then has to be taken out for a rest. There are other things that affect it, vibration, noise, and maybe more. You know how I have to keep after the pilot to dampen his drive. All these things change the cycle it has to have."

"Agreed," she said impatiently, meaning mostly that she didn't care. "Let's go out and look at it."

The plant was a machine and the machine was a plant. It occupied a large space in the center of the ship. And it wasn't wasted space; properly cared for, the plant could supply food for the crew indefinitely.

The plant machine evolved from earlier attempts to convert raw material and energy into food. Originally algae were used because they were hardy and simple to control. But the end product had to be processed and algae did not produce the full scale of nutrients in the proper proportion for the human diet.

Certain cells of more highly evolved plants were far more efficient in the conversion of raw materials into proteins, vitamins and the like. Originally, inedible parts were produced too, the stalk, which might or might not be used for food, and the leaves and roots. On a planet with plenty of room, this made little difference. But on an overcrowded planet, or one with a poisonous atmosphere, and especially on a ship where space was at a premium, normal methods could not be used.

In the plant machine were certain cells which had been selected because of their ability to produce a variety of nutrients. The inedible parts of the plant were replaced by machinery. Instead of roots to draw water and minerals from the soil, there were pumps and filters. Instead of stems to elevate that material to the leaves, there were hoses. Instead of entire leaves to perform photosynthesis, there were only those cells most efficient at the process. There were no seeds, tubers, roots, nor fleshy stalks to store the food. Collecting trays replaced them. There was no waste space; nothing was produced that couldn't be eaten.

There was an additional problem of reconciling the various cell fluids and different rates of growth. In part, that was accomplished by the plant machinery; the rest depended on the plant mechanic. His job was akin to that of a factory manager. In a sense, the plant machine was nothing more than a highly organized and complex factory, of which the productive units were the actual cells.

Alsint went along the aisles. Dials and gauges everywhere—a continuous record was kept of every stage. Each record was important, but nothing that could be reduced to a formula. The plant was not in bad shape, considering. At his instructions, Larienne made certain adjustments.

"Why reduce the light?" she asked. "I thought this unit grew better with stronger light."

"It does, within limits."

"I was within those limits."

"You were, but consider this. The plant from which these cells came grow fastest in early summer, but it isn't edible at that time. In late summer, it is. The light change merely corresponds to original conditions."

Partly convinced, she nodded. "What kind of plant was it?"

He smiled. "I don't know. It's the nth cellular descendant of some plant that once grew on Earth."

She touched a dial she had adjusted. "And on this one you reduced the fluid flow into it, and switched the output to another unit I've never seen it connected to."

"Same thing. The input corresponds to the difference between the dry and rainy seasons."

"But things grow faster with more water."

"They do, unless it happens to be a cactus."

She shook her head. "I give up. Cactus yet."

"I didn't say it was cactus. It might be, and, if so, could be very efficient in preparing water and soil minerals for use by the leaves. There aren't any leaves, of course, but that doesn't change the principle."

"Don't think I'll ever understand it," she said. "Enough to get by, but not the way you do."

She stood at his side. It was pleasant to have her there. Other things were pleasant to imagine too, but he refrained. There were married couples on the ship, just as there were unattached men and women. But when the men outnumbered the women three to one, certain conclusions were inevitable, and he had made them the first few days aboard. Unlike many of the others, he didn't expect to stay on the ship forever. In a year and a half he would either prove his point or fail.

Then he would leave. Would Larienne come with him? Maybe, but it wasn't a good bet. A liaison, no matter how easy it was to enter into, was not always easy to break. There would be time to decide about that later.

"Is everything all right?" she asked.

He glanced over the dials and mentally added them up. "Reasonably so. Yes."

"Good," she said. "Unless you need me sooner, I'll be back in about ten hours."

He nodded and she left. It was unnecessary to ask where she was going. He could tell that from her manner. They had raised a hitherto unmarked solar system and she was helping tag it.

His injured hands were aching with the effort, though Larienne had done most of the actual work. He started toward his room, and then, on another thought, turned into the dispensary. Franklan he knew better than anyone except Larienne, and he might get a fresh viewpoint from him.

Franklan was waiting. He had a doctor's degree from some planet, but on the ship titles were largely ignored. "The wounded hero comes back, holding our food supply precariously in his skilled hands," he said as Alsint entered.

The sarcasm was not altogether friendly, Alsint decided. Without comment, he laid his hands on the table. He did not pretend to be a hero and he was not even particularly stubborn. He had put together a plant in a better way, one that ought to withstand the rigors of tag ship service, and he intended to see that it got a fair trial.

"What do you know about ship watches?" he asked cautiously.

"Fifteen years on a tag ship, and I've never personally seen a failure. I suppose it can happen." Franklan glanced up. "It's too bad you had to destroy yours to get in. I'd like to see what an examination by our technicians would show."

The same thought that he had, though Franklan seemed to have attached the opposite meaning to it. "Interesting, isn't it?" Alsint said evenly. "But I was thinking of the connection it has to the crew panel."

Franklan bit his lip. "I hadn't considered that."

"I have. The pilot had to check the crew panel before he could take off. If he did, and saw that I was missing, why didn't he wait? If he didn't see that I wasn't inside the ship, then the panel was defective too. It's hard to believe."

Franklan filled a small tank with fluid and motioned toward it. Alsint dipped his hands in. It stung, but he could see that it had a pronounced healing effect.

Franklan was watching him narrowly. "Service on a tag ship is voluntary. It has to be, considering all the solitude we have to take. Any man can withdraw any time he wants. A lot of them do, especially in the first three years. However, bear this in mind. You've practically accused someone on the ship of trying to leave you behind. I know you do think that. And if you can produce evidence, I'll believe you. But there is one person on whom suspicion will fall first."

That was what Alsint wanted to hear. He'd gone over it in his mind and couldn't find anyone to suspect. Any clue was welcome.

"Who?" he asked.

"You," said Franklan. "If I wanted to leave the tag ship service, I'd see to it that I made as graceful an exit as possible. Forced out by an accident, of course. I'd want to tell people that."

He might have expected that kind of attitude. Franklan was proud of the work he was associated with. Nothing wrong with that; everyone had that right. In fact, if he didn't, he had no business doing it.

However, it made things difficult for Alsint. He was on a tag ship for other reasons. He had evolved several strains of plant cells that should be especially suited for use on tag ships.

For some reason the plants on tag ships were always dying. Ships returned to inhabited planets for refueling with the machines intact but with the plants dead. The plant cells had to be replaced. It was not that the actual material was expensive. It wasn't. But the process of getting the strange cells to work together as a new unit was time-consuming and enormously costly. That was where the trouble came. The plant couldn't be fitted together like an engine.

Alsint had evolved cells that were far more viable, but the only way to test that was in actual use. He had received permission from the Bureau of Exploration to install his plant in a ship and try it for two years. If at the end of that time the plant was still alive, he had something really worthwhile. The only stipulation was that no one on the ship should know that it was a test, since they might, out of consideration for him, modify the service the ship normally went through. It had to be a true rough, tough test.

And he was getting it, in more ways than he had expected. Unless he could stay with his plant for the next year and a half, all his work would go for nothing.

He drew his hands out of the fluid. "Do you think I'm trying to run out?" he asked quietly. He had proof that he wasn't, but he couldn't use it.

Franklan shrugged. "Honestly, I don't. But I'm not blinding myself to what the others will think." He squinted professionally at the burns and dried the hands with a gentle blast of air. He picked up a large tube and squeezed a substance on them which was absorbed almost instantly. "There. You'll be all right in a few days."

"Thanks," Alsint said laconically and stood up.

As he went out the door, Franklan called after him. "If I see the captain, I'll tell him I don't think you tried to jump ship. I doubt that he'll ask. As I said, service on this ship is voluntary."

Personally, Alsint didn't care what Franklan told the captain. However, he was at a definite disadvantage. Next time they came to a planet, if he were to disappear, nobody would be overly inquisitive.

The tagging operation was far from complete—seven planets in the system and each had to be thoroughly investigated. Long-range investigation, of course. A tag ship rarely landed, and then only when the planet under consideration seemed extremely desirable for colonization, enough to warrant closer observation.

It didn't matter whether it had a breathable atmosphere or not, whether it was ice-bound or blazing hot. These were minor difficulties and engineering ingenuity could overcome them. There were other criteria, and it was for these that they were checked.

Alsint went out into the ship. There was a lot of activity, but much of it was invisible, electronic in nature, affecting only instruments. The ship had slipped into an orbit, the plane of which intersected the axis of planetary revolution at the most effective angle. The ship went around twice while the planet revolved three times. In that period the mineral resources were plotted and the approximate quantities of each were determined.

Larienne looked up as he came near. "This is a real find," she said cheerfully.

"I suppose you've located the heavy stuff," he said, knowing that it was a superfluous statement.

"What else would we look for?" She bent over the small torpedo shape she was working on. "Not just one, either. This is the second planet in the system with enough heavy elements to be worth settling."

"What's the gravity?" He didn't always share the enthusiasm others had for their discoveries.

"The first was 1.6. This is about 2.3. A little high for personal comfort, but with the mineral resources there, the settlers can manage."

"What about atmosphere?"

"The first hasn't much, frozen mostly. This one has chlorine in it." She grinned at him. "Your old theme, huh?"

It was an old theme, though he didn't argue it. He was entitled to personal reactions. "Maybe. Would you like to live on either of them?"

"Don't have to," she said, making an adjustment on the torpedo. "Never get out on a planet more than twice a year. In fact, I've almost forgotten what a year means."

That was the point, possibly, though there was no use to discuss it. "Anything else of interest?"

"We're coming to a smaller planet. Land, oceans, warm enough, and with an atmosphere we can probably breathe as is. Don't know the composition of the solid matter yet, but from our mass reading, it's a good bet that there won't be enough heavy stuff to justify settlement." She made a final delicate adjustment on the torpedo and began wheeling it to a launching tube. "This one's in a rich system, though, and will probably be used as an administration planet—vacation spot too. It won't go to waste, if that is what's worrying you."

In a way, it was. It was too bad that so many planets that were otherwise ideal for human habitation had to be passed over because they lacked the one essential. There was no help for it, of course. To settle planets, spaceships were necessary—and heavy elements to drive those ships. Nothing else mattered in the least.

Larienne snapped the torpedo in place and pressed a stud. The dark shape disappeared. Out in space, it fell into an orbit which eventually would land it safely on the planet.

"There," she said with quiet satisfaction. "It's tagged, and it will stay tagged until somebody digs it up."

It might be a month, or a hundred years, before Colonization got around to it. Meanwhile the torpedo was there, broadcasting at intervals the information that the tag ship had discovered. Somewhere in a remote planning center, a new red dot appeared in a three-dimensional model of space, to be accounted for in a revised program of expansion.

Larienne brushed the hair out of her eyes. There was a smudge on her face. "I'm busy," she said. "But I can get out of this if you need me."

As long as she was more interested in what she was doing, he'd rather not have her. He shook his head. "I'll manage," he said, and headed toward the plant.

The instant he entered, something seemed wrong. He couldn't say what it was without investigation. It was a big complex machine as well as a plant, and even reading all the dials was not enough; visual inspection was necessary too. He started at one end and worked toward the other. The gauges indicated nothing out of the ordinary, but the plant was in bad condition.

It was something like a tree, the trunk and leaves of which were sound enough, no discernible injuries, but nevertheless dying. At the roots, of course. This plant had no roots, merely a series of tanks and trays, each connected to others in a bewilderingly complex fashion. In that series, though, was something which corresponded to roots.

He was near the end of the first row before he spotted part of the trouble. A flow-control valve was far out of adjustment. His hands were bandaged and clumsy, but he tried to reset it. It was jammed tight and he couldn't move it.

He could call Larienne, but she was busy. So was the rest of the crew. With sufficient leverage he could turn the valve. He looked around for something he could use. A small metal bar leaning against the wall nearby seemed adequate.

He picked it up—and the bar burned into the bandages. He knew what it was; he didn't have to think. He could hear the sparks as well as feel it. Fortunately his shoes were not good conductors and not much of the charge got through.

With an effort he relaxed his convulsive grip, and still the bar stayed in his hand. It had fused to the bandage and he couldn't shake it off. The bar was glowing red; only the relatively nonconductive properties of the bandage—heat as well as electricity—had prevented his instant electrocution. And the bar was sinking deeper into the bandage. If it ever touched his flesh, the charge would be dissipated—through his body.

He had to ground it. The metal tanks which held the plant would do that, but also crisp the plant beyond salvage. He had to make a fast choice.

Holding the bar at arm's length, he ran through the aisle, and, at the far end, thrust it against the side of the ship.

The resulting flash staggered him, but he stayed on his feet. Though the metal began cooling rapidly, it remained fused to the bandage. He laid one end on the floor and stepped on it, tearing it loose.

It was a plain metal bar, made into a superconductor, with an unholy charge stored in it. This couldn't be an accident. It took work to turn ordinary metal into a superconductor at room temperature. Also it couldn't be placed just anywhere. If the charge were to remain in it, a special surface had to be prepared.

The trap had been set up for him, and he had walked into it. The bandage had saved him, nothing else. That was the one thing the unknown person hadn't taken into account.

Who? Larienne? She had access to the plant. But so did anyone else, just by walking in.

Not Larienne. She had her ugly moments and might try to kill him in a fit of anger, but she wouldn't plan it coldly, nor go through with the scheme if she planned it. It didn't take special knowledge to sabotage the plant. Any control could be moved drastically and the plant would suffer. The only technical knowledge required was that of making the bar into a superconductor, and that knowledge she didn't have. True, she could ask someone to do it for her. But she wouldn't.

Alsint sat down. The actual physical damage from the electrical shock wasn't great. The certainty that someone had tried to kill him was.

Why? Violent personal hatred for himself he could rule out. He'd been careful in his contacts with the crew. Only a psychotic could manufacture a reason to hate him, and psychotics didn't last long on a tag ship.

It had to be connected to the plant. Someone on the ship was trying to take it away from him, or one of his competitors had hired one of the crew to see that he didn't survive. The last was unlikely.

He had no proof that his plant was better, merely a belief that it was. It seemed illogical that anyone would want to eliminate him on the strength of an untested belief.

But except for Larienne, no one had enough knowledge to nurse the plant along for the required two years. Unless he remained alive, no one would benefit.

He shook his head. It was difficult to add up and arrive at a sensible answer. One thing he knew, though—hereafter, he'd have to be on his guard at all times.

He could go to the captain with his story. He considered and rejected that in the same instant. He'd have to tell the captain everything, which would invalidate the test. He'd have to handle this by himself.

He got up and continued his inspection of the plant, making minor adjustments to compensate for the damage. Except for that one valve, nothing seemed far out of line.

That done, he limped to the dispensary. His hand was aching where he had torn the bar loose and ripped the flesh.

"Back again?" said Franklan. "Any new information on the enemy?"

By itself, that was a suspicious statement. How could he know about the latest incident? The easiest answer was that he didn't. He was referring to the time Alsint had nearly missed the ship.

"Not a thing," Alsint muttered. Unless he wanted to reinforce Franklan's original opinion, he'd better keep this to himself.

Franklan looked at his hand. "Whatever you've done, I don't recommend it. It's not the way to get well fast—or at all."

"Grabbed something hot," Alsint said. Might as well say that. The bar was now just a bar and no examination would reveal that it had been a superconductor. Same with the insulation it had rested on. He couldn't prove anything.

Franklan rattled the instruments. "Nothing serious. This'll heal on schedule, but it's going to hurt while I fix it." He administered a local anesthetic below the elbow.

It made Alsint dizzy. He sat down and closed his eyes while Franklan worked. He relaxed more than he intended and then deliberately opened his eyes because he was drowsy and didn't want to fall asleep.

Over Franklan's shoulder, behind the window that swung out from the dispensary to the corridor, was a little red bird. It was much like the one that had fluttered around as he had tried to get on the ship. Perhaps it had come in with him and hidden in some quiet place until now. It was possible.

Franklan looked up. "What are you staring at?"

Alsint's tongue was fuzzy. "Outside the window behind you is a little red bird," he said, speaking distinctly to overcome the side-effects of the anesthesia.

Franklan went on swabbing, not bothering to glance behind him. "You're tired," he said. "And look again at that bird outside the window. For my sake, tell it to put on a spacesuit. If it doesn't, it will die in a matter of seconds."

Startled, Alsint looked around. He was mixed up in his directions. He was facing the visionport, plain empty space, not the corridor.

He blinked his eyes frantically, but the bird wouldn't go away and it didn't die. There was no air out there, millions of miles from the nearest planet. The bird flapped its wings in the airless space and went through the motions of singing.

It was ridiculous. There was nothing to carry the sound. But he could imagine hearing it anyway, through the thick armorglass of the visionport—a bird singing in space.

Resolutely he closed his eyes and kept them closed. He had enough trouble without taking on hallucinations.

Franklan finished the new bandage and tapped his shoulder. "You can come out of it now."

Alsint tried not to, but he couldn't resist. He stared past Franklan toward the visionport.

"Is it gone?" asked Franklan. His voice was quiet.

"It's gone," Alsint said in relief.

"Good. These things happen occasionally. As long as you can adjust back to reality, you have nothing to worry about." Franklan rummaged through the medical supplies. "Take these. They may help you."

Wordlessly, Alsint took the packet and went back to his room. He was sweating and shaken.

Franklan hadn't seen it because he hadn't looked, but there had been a bird out there, or there hadn't. If not, Alsint's contact with reality was precarious and he'd have to watch himself. Franklan had hinted at that. Maybe he wanted Alsint to believe it.

But it didn't mean there hadn't been an actual bird. It could be put there in a plastic bubble that wasn't visible against the blackness of space. If so, it was an ingenious way of harassing him.

He relaxed at that formulation. It hadn't been worth the effort, but it did prove one thing—his unknown antagonist had an excellent imagination.

Time passed—days, perhaps, though that unit had little meaning on the ship. It was the work period which counted and nobody had bothered to tell him how long that was. The last planet of the system was analyzed and the permanent markers sent down. The star was tagged and the ship proceeded on its way.

What the destination was, Alsint didn't know and didn't inquire. They were going somewhere, to uncatalogued stars, and that was enough to know.

His hands healed and the bandages were removed. Larienne was reassigned to help him. The rest of the crew, whatever they guessed, or sensed, said nothing and the normal pattern of life on the tag ship seemed re-established.

His anxiety faded. It was not, he was sure, the end of the attempts to remove him, but he had time to think, to plan countermeasures.

He was not wholly prepared. He and Larienne were approaching the plant. The door was open and he could see inside. He glanced casually at the row on row of mechanism, and stopped.

"What's the matter?" asked Larienne.

He moistened his lips. "Go around to the other side and close the door. Be quiet about it, but close the door quickly."

She stared at him curiously and started to go inside.

He grabbed her arm. "Around, I said. Not through."

She shrugged and went around. In time he could see the other door close. Then she came back.

"What's inside?" she whispered, adopting his own attitude.

"Something I want you to see."

She peered in. "I can't see anything."

"It's out of the line of vision now, but it's still in there." He swung the door nearly shut. "Inside, fast. I'll show you."

Obediently she went in and he followed, closing the door behind him. She waited.

"The bird," he said. "I want you to verify that it is in here."

"Bird?" She was puzzled and dismayed. "How did a bird get in here?"

"I don't know. I'll figure that out later." There was no need to whisper, since it couldn't escape; nevertheless he did. "It's a psychological stunt. The best way to stop it is to catch the bird."

She drew away uncertainly. "You saw it in here?"

"I did, and I want you to be with me when I find it."

"Then we should make a lot of noise. It will fly up if it's frightened."

"Good. You take that aisle and I'll take this. Yell when you see it."

They separated. He hunted carefully, moving everything that could be moved, looking for the flash of red wings. The bird was shy and had hidden.

They met in the center aisle.

In answer to his unspoken query, she shook her head. "I didn't see it."

"It's here," he said stubbornly. "I can't be mistaken."

She started to say something and changed her mind. "Let's look again," she suggested. It was not what she intended to say. What she thought was plain from the expression on her face.

Again they went through the plant machine, searching. Every crevice, every hidden corner was examined. He peered into the machinery, the tanks and the trays, above and below. They looked, but there was no bird.

Larienne stood beside him and glanced up at the ceiling. "Maybe it got out through the ventilators."

"It couldn't," he said harshly. The ventilators were also filters; a microbe would have difficulty getting through. She was trying to give him a way out, but he couldn't take it.

The room in which the plant machine was housed was not a simple open space; there was structure throughout. But it was inconceivable that something as large as a bird, even a small bird, could escape detection.

"I'll take care of the plant," he said quietly. "I want to think."

She left. He knew how she felt. It was worse because she did feel that way.

He had scored against himself. Larienne would say nothing to the rest of the crew, but it would come out. Emotional reactions couldn't be hidden. And if there was ever an inquiry, she'd have to tell her story.

Franklan would see that there was an inquiry. That was his job. There was nothing particularly arduous about life on a tag ship, yet not everyone was suited to it. Monotony—and each person had to adjust to the others as well as the ship. There was no room for a person who saw things.

It was a most effective attack, without danger for the man or men behind it. Twice he had seen something that wasn't there, and there were witnesses to testify against him. It would be enough to remove him from the ship. The subsequent treatment wouldn't harm him, but the ship would be gone and he'd never get back on. Tag ships were just too unpredictable; they came and they went as they pleased, and no one could say where they would next arrive.

Baffled, he tried to catalogue the crew. Not Larienne. She'd live with him if he wanted, more readily now than before. Ordinary rules didn't apply to her; sympathy counted for most.

Nor was it Franklan. Bluntly he'd given his opinion, but that didn't mean he was responsible for this. The person who was behind it was keeping well hidden.

Alsint went wearily down the line, adjusting and readjusting.

On one of the handles was—a tiny red feather.

He stared at it, relief forming nebulously in his mind. A bird had been there. How it had gotten in and then out again through closed doors, he didn't know. That part was unimportant. It had been there.

It wasn't a hallucination, though for a time he'd almost believed it himself. Now he knew.

Gingerly he picked up the feather. It was no proof, except to himself. That was enough. He could do something about it.

The trap for him was set, but wouldn't be closed immediately. The ship would not go out of the way except in extreme emergency. In another four months it would run low on fuel and material for the tagging operation, assuming normal conditions. The ship would then return to the nearest inhabited planet.

That was the way tag ships operated. Unlike other ships, freight or passenger, their objective was not to get from one inhabited planet to another as fast as possible, but to stay away as long as they could. For that reason, of all ships, they alone had to have the plant. No other food supply was so economical of space and weight.

Once they reached a planet, he'd be referred to the authorities for psychiatric examination. Eventually he'd be cleared, but by then it would be too late. Unless he could forestall it.

There was a way to do that, though it was dangerous for him, and he stood a chance of ruining the plant.

He made up his mind and went back down the line of controls. Larienne might question some of the new settings, but she'd defer to his judgment.

It took two weeks for the plant to decline so even the captain could see that it was impossible to go on. As master of the ship, he disliked abandoning tagging operations even temporarily, but the crew had to eat.

It was a planet. Nothing out of the ordinary, there were many planets like Earth. Not many that were settled, though; almost uniformly, that kind of planet lacked the heavy elements that made colonization economically feasible.

It was pleasant and sunny, great grassy glades and an equal amount of forests. No intelligent life on it, so there was nothing to worry about on that score. Animals, big and little, but ordinary weapons would discourage them.

Half a mile away was the ship, ready for instant flight. Not that there was anything to flee from. That was the way it had to come down if it was ever to rise again.

The plant had been stripped to components and spread over the ground. An extensive layout, but it was necessary if the plant was going to get full benefit of planetary conditions. It had been put together to facilitate disassembly, and it hadn't taken long to remove it from the ship.

A transparent canopy covered it, protection from the elements. A sudden rainstorm could drastically alter the concentration of the vital fluids. There was also an electrified fence to keep out stray animals.

Everything except root cells was exposed to the sun and wind. Under these conditions the plant began to recover from the deliberate injury he had done it. Why plants should recover so easily was still a mystery, but generations of plant mechanics had discovered that they always did.

Alsint took the sundown shift. The plant could be left alone at night, locked up with the knowledge that nothing big enough to damage it could get in. It was better if there was someone to make minute adjustments from time to time, but that was not the reason he was there.

Sundown or sunrise, and sundown was better. Either time, men were outside the ship who didn't have to account for their whereabouts. More were out at sundown. And one of them, sooner or later, would be the person he wanted.

The plan was simple. Give the man every opportunity to kill him, make it irresistible—but shoot first. If the man lived, he would talk. If he didn't, there would be some clue in his personal effects. Dangerous, but if Alsint wanted to profit from his plant, he had no choice.

Days passed and no one came near. He could and did retard the regrowth of the plant, but in that respect he was limited. He couldn't be too obvious about it. The time came when he couldn't stall any longer. In reply to the captain's blunt question, he had to admit that in the morning the plant would be in as good condition as he could get it.

He sat that night in the enclosure, knowing this was his last chance. It grew dark and night sounds intruded. The lights in the ship went out. Only the light near him remained. He was careful to sit at the edge of illumination, visible, but a poor target.

Animals snuffled in the brush near the electrified fence. They had learned quickly and knew better than to touch it. And there was another sound—no animal.

He quietly shifted his arm and held the light in readiness. He listened. Someone was crawling through the brush. He had to wait. It was hard on his nerves, being bait.

He flashed the light on suddenly.

The man was half hidden behind a bush and Alsint couldn't see his face, but the gun in his hand glittered through the leaves.

"Surprise," said Alsint. "Don't try anything."

The man stood there, but he didn't drop his gun.

Alsint didn't like it. He couldn't identify the man. If he ran back into the forest, Alsint wouldn't know any more than he had in the beginning. He fingered the gun. "Come out where I can see you," he said.

The man didn't move—waiting until his eyes adjusted to the light shining on him, decided Alsint. As a choice, his own life came first. He raised the gun.

Before he could fire, a red bird attacked his eyes, squawking wildly.

He didn't drop the light. He tried to bat the bird away from his face, but it clung to his hair. Before he could crush it, he heard the whoosh of a gas gun. And the sound came from behind him. That was his mistake. There was more than one of them.

He breathed once and then felt himself fall forward.

It was morning when he awakened, bright sunlight streaming into his eyes. That was not the reason his head hurt, though he could be thankful the man or men had used a gas pellet instead of a projectile. Whoever he or they were.

He got up and staggered toward the ship. A few steps were all he took. The ship wasn't there. He leaned against a tree and looked wildly around. The plant was gone too.

Shakily he fumbled for a cigarette. Smoke didn't help much. They had taken the plant aboard while he was unconscious. They had left him alone on an uninhabited planet.

A pretty planet and a useless one. No ship ever stopped here except to revive a plant, and that wouldn't happen often. It would be several lifetimes before another ship came, if one ever did.

He stared miserably into the bright blue distance and thrust his hands into his jacket, and made a discovery. They'd left him a gun, at least, and ammunition. He'd be able to keep himself alive at a minimum level.

There was a whistle in the distance. His head came up. He wasn't alone. Larienne?

It couldn't be. From the direction of the sound, if it was Larienne, she was hiding in a nearby tree. But Larienne didn't like trees.

"Richel Alsint," said a loud voice. Behind him this time.

He turned around. There was no one there. Nothing but a red bird sitting on a branch. He started. The same red bird that had flown mysteriously in and out of his life. If it weren't for that creature, he'd be safely on the ship. He raised the gun.

From one foot to another, the bird hopped on the branch. "Birds can't talk," it screeched. "Birds can't talk."

The implication was clear. "Since you can talk, you're not a bird." The gun was still leveled. "Then what are you?"

"I could tell," said the bird. It had stopped hopping and was watching him calmly. It was red, but sometimes blue. The colors wouldn't remain fixed.

He lowered the gun in defeat. He couldn't kill a harmless creature just for the sake of killing. It hadn't been responsible for this.

"Don't be so sure, Richel Alsint. Don't be so sure." The bird burst into a wild trilling song.

He glared at it speechlessly. Bird it wasn't. Either it could read his thoughts or it had been taught a patter that fitted his present situation with remarkable precision.

"What do you think?" said the bird, cocking its head.

He forgot about the bird. It was only a momentary diversion. "I've been marooned," he said dully.

"It's happened before. It will happen again," chirruped the bird. "Don't worry, I'm here."

It was, but he wished it would go away.

"There is a note. Why don't you read, read, read?" sang the bird.

He looked, catching a glimpse of sunlight on metal. They had left something. He ran over to it, a few hundred yards away.

And there was a note. He seized it feverishly.

I made them leave this. You may not need it, but you deserve to know the answers.

Don't you understand? You were infuriating everyone, even me, and I liked you better than anyone on the ship. You were always changing things for the sake of that damn plant! It was too dry, so we had to have more humidity than we liked. Or the pilot had to keep the drive from vibrating. Or this, or that, on and on and on! Who cares, really?

A good plant mechanic ought to keep the plant alive for five months and then let it die. We can live the last month off the remains. We have to go back every six months for supplies anyway. It's expensive, I know, but until you can get a plant that reacts as we do, it will just have to die and be replaced.

I thought of staying with you, but I couldn't stand all those changes—rain and sun—all the things an uncontrolled planet has. And then there was that story of the bird. That was too much!

Don't think too badly of me. At least I kept them from killing you.

There was no signature, but there was no doubt who had written it.

"All of them," he muttered. Not just one man. Everyone, from the captain down. Larienne too. And they were safe. Who would bother to look for him when the captain recorded in the log that Richel Alsint had deserted because his plant was a failure? And, of course, it was going to fail.

"The crew of the craft was daft, and you were the only one who was sane?" said the bird. "Don't you believe it. There are people on countless planets just like them."

It was true. The crew was part of the civilization. On those planets where it was possible to have parks, no one went to them. They stayed in the cities as the crew stayed in the ship. And on other planets—roofed over against poisonous gases, and inhabitants who never saw the sun—those planets were not much better than spaceships. He was the one who was different, not they. They had a mechanical culture and they liked it.

He could see how he had irritated the crew in ways he didn't suspect. They had wanted to get rid of him and they had.

He looked down at the machine they had left him, robbed, at Larienne's insistence, from the major plant. Small, just large enough to supply one man, but containing all the necessary parts. A plant machine in miniature.

She really hadn't understood. He could live on the food this provided. But would he, on a world teeming with animals and covered with plants, real plants? He laughed bitterly.

"Now you know," said the bird. "In the past there were others marooned. Just like you. I came from them."

He looked up wonderingly. "Here? On this planet?" he asked eagerly.

A brilliant butterfly wandered past. The bird eyed it longingly and shivered into a rainbow of colors and darted away after it.

"Come back!" Alsint shouted. He couldn't find them unaided. He had to have directions.

The bird didn't return immediately. It played with the butterfly, flashing around it. Presently it tired of the sport and came back to the branch it had perched on. "Pretty bit of fluff," it said breathlessly.

"Never mind that," said Alsint impatiently. "What about those people? Are they on this world?"

"Oh, not here," said the bird. "A thousand planets away."

Alsint groaned. The bird had been trained by a mad-man and was alternately raising his hopes and crushing them.

"Not so," said the bird. "Here's history: a hundred and forty years ago, a couple, plant mechanics, were marooned—for the same reason." It flew from the perch and alighted on the plant machine, dipping its bill in a collecting tray. "Good stuff," it said, clattering its beak.

Alsint said nothing. It would tell him when it got ready, not before.

"The plant machine's fine," said the bird. "It's a plant that's been taken apart. Can you put it back together?"

"No more than it is," said Alsint. "No one can."

"No one you know," said the bird. "Here's more history: A hundred and forty years ago, this couple learned how to put it together—and it grew. A hundred and thirty years ago, they knew how to take an animal apart and keep it alive. A hundred and twenty years ago, they put the animal together and made it work in a new way."

The bird sidled along the branch. "What's the difference between plant and animal?" it asked.

There were countless differences, on any level Alsint wanted to think about. Cellular, organizational, whatever he named. But the bird had something simple in mind.

"There are some plants which can move a little," Alsint said slowly. "And there are some animals that hardly move at all. But the real difference, if there is any, is motion."

"Right. You'll get along fine," said the bird. "A hundred and twenty years ago, this couple—who by then had several children—put an animal together in a new way and got—pure motion."

That was what had been puzzling him, and now he knew. "Teleports," he said. "They can teleport."

"They can't," said the bird. "The mind's best for thinking—they say. And they've kept theirs uncluttered." The bird cocked a glittering eye. "I don't know about minds. I never had one."

If they couldn't teleport, how had the bird got here?

Alsint glanced at the bird. It wasn't perched on the plant machine and the wings were folded. Six feet off the ground it hovered, and not a breath of air stirring.

"Behind you," said the bird.

It didn't twitch a feather, but it was behind him now and he hadn't seen it move.

"Teleports, yes," said the bird. "But they can't do it. We do it for them."

The bird had been outside the visionport of the spaceship. If it could teleport itself, why not air too?

That was only part of it. The bird had followed him, but how had it foreseen this end?

"Did you know this would happen?" he asked.

"Plant mechanics are always getting marooned," said the bird. "We've gathered up quite a few. They work with the plant and a plant belongs on a planet. The rhythm is different from that of a machine."

He knew that. He could feel it, though he had never put it into words. "Go tell them where I am," he said. "I can live until they send a ship."

"A ship?" said the bird. "So slow? They don't believe in waiting. They've got all the beautiful planets that men don't want—just for the asking, though they don't have to ask. They need the right kind of people to live on them."

They didn't believe in waiting. A shadow fell across his face. Alsint looked up. Something was dropping down from the sky. Not a ship—not the conventional kind, anyway. It was the kind they would use. On planets on which all the food was grown naturally and no heavy elements were needed, what would be transported? People.

Not moving a wing, it came down, first fast and then slow. It stood in front of him, towering, a giant abstract figure of a woman with wings. There was frost on it.

He went to it and it covered him with wings.

There was no sensation at all except cold, which lasted only a few seconds. When he opened his eyes, the strange, beautiful ship was dropping down on another planet, more pleasant than the last. Men and women were coming out of the houses to meet him. One of them looked something like Larienne.