Title: Harper's Round Table, February 23, 1897

Author: Various

Release date: November 24, 2019 [eBook #60764]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 1897. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 904. | two dollars a year. |

Author of "Rick Dale," "The Fur-Seal's Tooth," "Snow-Shoes and Sledges," "The Mate Series," etc.

As far as the eye could see, and for leagues beyond the reach of vision, one of the most wonderful landscapes of the world was outspread in every direction. Castles of massive build with battlemented towers, Greek temples, slender spires, columns, arches, and walled cities with lofty buildings rising tier above tier met the view on every side. Not only were these structures of the most graceful modelling, but they were of such a brilliancy and variety of coloring as may only be seen in that land of wonders. While the prevailing tints were red or crimson, these were toned and contrasted with every shade of yellow from orange to buff, by greens, purples, and pinks, white, brown, and in fact every variety and combination of color known to nature. Some of the slender columns were even frosted as with silver, while others were surmounted by groups of statuary.

Broad avenues wound in and out among these gaudily tinted structures, and from them wide terraces—red, yellow,[Pg 402] pink, or white—swept back and up smooth and regular, as though built of squared marble blocks. Apparently interspersed among these beautiful objects were shady groves, blue lakes, rippling streams, and cool, snow-capped mountains; but these were of such a curious nature that they came and went like the moving pictures of a vitascope. Even the solid objects that one might be certain were real were so sharply reflected in the heated atmosphere above them that it was impossible to discern where substance ended and its pictured counterfeit began.

In thorough keeping with these wonders was another close at hand, which was the strangest of all. It was nothing more nor less than a forest of prostrate trees lying in the wildest confusion, as though levelled by a hurricane. Although they were broken and scattered over a wide area, everything was there to prove that they had once been of vigorous growth and noble proportions. Great trunks, limbs, branches, and even twigs, many of them still retaining their covering of bark, were strewn on every side; but all, even to the tiniest sliver, were turned into stone. Not ordinary gray stone such as appears in the more common fossil forms, but stone of the most exquisite color and shading, such as red jasper, clouded agate, opalescent chalcedony, shaded carnelian, or banded onyx. These substances are deemed precious even in the palace of a Czar, but here they appeared in greatest profusion, many of them retaining so clearly the markings and general aspect of wood that they could not be mistaken for anything else. It was a fossil forest of what had been in some dimly remote geologic age stately pine-trees, with waving tops and whispering branches, perhaps filled with joyous birds, and sheltering the strange animal life of a prehistoric world.

Now all was silent and motionless, with no more sign of life among the fossil trees or their gorgeous surroundings than if the whole region lay beneath the spell of some evil magic. Not a blade of grass was to be seen, nor a living green thing of any kind. There was no sound of running waters, nor of birds, nor of human activity. A sky of pale blue arched overhead, and from it the sun poured down a parching heat that rose in glimmering waves above tower and turret, battlement and spire.

These things are not imaginary, nor are they located in some remote and unheard-of corner of the world, but they exist to-day right here in our own land, as terribly beautiful and changeless at the close of the nineteenth century as they were when first seen by a European nearly four hundred years ago. They are the same as when the long-vanished cliff-dwellers roamed amid their wonders, and gazed on them with reverent awe ages before history began, for this is the Painted Desert of Arizona. It is a region almost as little known as the deserts of the moon, and one shunned with superstitious dread by the Indian tribes who dwell on its borders as a place of departed spirits. So desolate is it, and so void of life or the means of sustaining life, that not more than a score of white men have ever gazed on its marvels and lived to tell of them. It is a place to be avoided by all men, and yet we must penetrate to its very heart, for there, with the opening of this story, shall we find our hero.

He is a boy not more than seventeen years of age, seated on a fossil tree trunk that, turned into jasper, resembles a huge stick of red sealing-wax, and he is gazing with despairing eyes at the terrors by which he is surrounded. Beside him, with drooping head, stands a clean-limbed pony, bridled and saddled. A rifle, a roll of blankets, a picket-rope, and a canteen are attached to the saddle, and one of the boy's arms is slipped through the bridle-rein. He is clad in a gray flannel shirt, a pair of blue army trousers that are protected to the knees by fringed buck-skin leggings, a broad-brimmed white sombrero, and well-worn walking-shoes. A silk handkerchief is loosely knotted about his neck, and a belt of cartridges, from which also depends a hunting-knife, is buckled about his waist.

The lad's name is Todd Chalmers, his home is in Baltimore, and on the day before our introduction to him he was a member of a well-equipped scientific expedition that was traversing the valley of the Colorado Chiquito in the interests of a great Eastern college. Mortimer Chalmers, Todd's elder and only brother, and a distinguished geologist, is in charge of the expedition. Our lad, who is an honest, well-meaning fellow, but of an adventurous disposition and extremely impatient of control, had never been West until now, and only by persistent effort had he induced his brother to allow him to accompany his exploring party and remain with it during the long summer vacation. Three-fourths of the journey to their point of destination had been made by rail, and only ten days have elapsed since the party left the cars at Holbrook, where they purchased an equipment of pack and saddle animals. From there they set forth on their independent progress into the wild regions of the Colorado Chiquito, whose valley bounds the Painted Desert on the south.

For a few days, or until the first novelty of this new life wore off, all went well with Todd, who proved obedient to orders and attentive to the duties devolving upon him. Then came trouble. One of the party left camp on a private hunting expedition, became lost, and was only found after a long delay and much organized searching. To provide against further accidents of a similar nature, Mortimer Chalmers ordered that thereafter no member of the party should stroll alone more than one hundred yards from camp, or from the pack-train when it was in motion, without receiving permission from him.

Now Todd was passionately fond of hunting, and, as already stated, was impatient of restraint. He had anticipated unrestricted opportunities for indulging in his favorite sport on this expedition. At the same time not being a paid member of the party he did not feel bound in quite the same way as the others to obey the orders of one whom he regarded with the familiarity of a brother rather than with the respect due one in authority. Therefore the order regarding hunting had hardly been issued before he disobeyed it by galloping half a mile from the pack-train in pursuit of a jack-rabbit, which he finally got, and with which he returned in triumph.

In answer to his brother's query why he had thus disobeyed orders, the boy replied that he did not suppose that particular order applied to him, and that at any rate he was perfectly well able to take care of himself.

"Do you mean, Todd, that you intend to continue in your disobedience of orders?" asked the chief of party, sternly.

"Certainly not, when they are reasonable," answered the lad, flushing at the other's tone. "But you know, Mort, I came out here especially for the hunting, and it does seem rather hard—"

"No matter how it seems," interrupted the other. "I asked you if you intended to continue in your disobedience of my orders."

"And I gave you my answer," replied Todd.

"Which means that you propose to pass your own judgment on them, and then obey them or not, as seems to you best?"

"You can think as you please about it," retorted the other, angrily. "I know, though, that I am not going to submit to being treated like a child by my own brother just because he happens to be a few years older than I am."

"Very well," replied the chief of party, calmly; "unless you will promise implicit obedience to any order I may see fit to issue for the welfare of the party, I shall disarm you, at the same time forbidding you to borrow any other rifle or go upon any sort of a hunting expedition until you do promise what I ask."

"I certainly sha'n't promise to obey any order so foolish as the one in question, and if you choose to play the tyrant, why, you can, that's all. Only remember, if anything unpleasant happens in consequence, the fault will be wholly yours." Thus saying, the lad flung himself out of the tent in which this unhappy interview had taken place, and strode angrily away.

So the boy's cherished rifle was taken from him, and, filled with mingled rage, mortification, and repentance, he passed a very unhappy night. Although impatient and quick-tempered, he was not of a sullen disposition, nor one who could long cherish anger. He was manly enough to acknowledge to himself that he was wholly in the wrong, but was too proud, or rather too cowardly—which is what[Pg 403] so-called pride generally means—to confess his fault to his brother and ask his forgiveness.

In vain did Mortimer Chalmers gaze wistfully at his younger brother on the following morning, and long for a reconciliation. As for himself, he could not weaken his authority by showing partiality toward any one member of his party, and must be even more strict with Todd than with the others because of the relationship between them. Thus his position forbade his making the first friendly advances, and when the younger brother, assuming a careless cheerfulness that he did not feel, pointedly avoided him, the other turned to his own duties with a heavy heart.

In the early afternoon of that day, when the leader was riding at some distance in advance of his party, a small herd of black-tailed deer, alarmed by the echoes behind them, suddenly sprang from a small side cañon or ravine, halted abruptly on the edge of the bottom-land, gazed for a moment in startled terror at the strange beings not fifty yards from them, and then dashed madly back into the place whence they had come.

"Give me a shot—quick!" cried Todd to his nearest neighbor, and snatching the other's rifle as he spoke, he fired wildly at the retreating animals. Then clapping spars to his pony, he bounded after them in hot pursuit.

Carried away by the enthusiasm and excitement of the moment, Todd did not in the least realize what he was doing, or remember that he was disobeying his brother's clearly expressed orders. He only knew that the first deer he had ever seen alive and in their native haunts were scampering away from him, and that it seemed just then as though nothing in the world could compare in importance with getting one of them.

So, bending low in the saddle and firing as he rode, he spurred his broncho pony to frantic exertions, and dashed away up the ravine after the flying animals. Several others of the party spurred after the boy as though to join in the exciting chase; but after a short run, either because they remembered their chief's orders or because they found themselves hopelessly left behind, they returned to the train, and its slow line of march was resumed.

More than five minutes elapsed after Todd was lost to view behind a sharp bend of the ravine before Mortimer Chalmers, attracted by the sound of firing, hastened back to learn the cause of disturbance. When it was explained his face darkened, though more with anxiety than anger, and he ordered the party to go into camp where they were, there to await his return. Then calling to one of the best mounted of his assistants to see that his canteen was full of water and to follow him, the chief of the party clapped spurs to his own horse, and set off up the ravine in the direction taken by his impetuous young brother.

Until nearly sunset of the following day did the party in camp await, with ever-increasing anxiety, the return of those who had thus left them. Then their leader and his companion rode wearily back into the valley. They were haggard, covered almost beyond recognition with the dust of desert sands, and utterly exhausted, while their steeds were ready to drop with thirst and fatigue.

Mortimer Chalmers's first words announced the failure of his search, for as he entered camp he asked, "Has the boy come back?" Upon being answered in the negative, a look of utter despair settled over the man's face, though he turned away to hide it from the pitying gaze of his men.

From his companion it was learned that when, on the preceding day, they had emerged from the ravine, they found themselves on a vast plain of shifting sands, void of vegetation and dotted with great fortresslike mesas or lofty bluffs of the most vivid and varied coloring. In the distance they had descried a rider whom they believed to be Todd, but though they fired their rifles and waved sombreros to attract his attention, he failed either to see them or took no notice of their signals, and a few seconds later disappeared behind a distant butte. Hastening to that point, they found and followed his trail until it was lost in the wind-blown sands. Even then they kept on in the same general direction, firing their rifles at short intervals, until darkness compelled a halt. During the long cheerless night, without fire or food, and comforted by only a few mouthfuls of water from their canteens, they still fired occasional shots, but without receiving any answer.

At daybreak they were again in the saddle and moving in a great sweeping arc that embraced many miles of the terrible desert, back toward the river. Until reaching it they had hoped against hope that the missing lad might in some way have been led back to the point from which he had started. Now, however, there was no doubt that he was indeed lost in that fearful wilderness of sand and towering rocks.

This was the opinion of the whole party; but though it was fully shared by Mortimer Chalmers, he was off again before daylight of the following morning, accompanied by five of his most experienced men. These were to explore the desert by twos in different directions, as far as their strength and that of their animals would allow them to penetrate, though on no account were they to remain from camp longer than two days.

This expedition was as fruitless as the first, and when on the second evening the six searchers returned to camp empty-handed there was no longer a doubt but that poor Todd, lost and bewildered, had wandered beyond recovery, and met his death amid the horrors of the Painted Desert.

Although there was no longer any hope that he would ever again be seen alive, the party remained encamped at that place another day before moving on, and scouts were kept constantly posted along the edge of the plateau, whence they could command a great sweep of the interior country in case any tidings of the lost one should be miraculously wafted in that direction.

Even when the sad little camp was finally broken and the expedition resumed its melancholy march down the valley of the muddy river, these same scouts followed the edge of the bluffs, though often being obliged to make long and fatiguing detours to head precipitous cañons.

In this manner the party had proceeded but a few miles when Mortimer Chalmers, who, alone with his grief and self-accusing reflections, rode in advance, was seen to suddenly clap spurs to his horse and dash off down the valley. He had discovered a riderless pony grazing on the coarse herbage of the bottom, and was filled with a momentary hope that by some means his dearly loved brother might after all have found his way back to the river.

When the others overtook him they at once recognized the animal which was cropping the tough grasses with starving avidity as the broncho that had borne Todd Chalmers from their sight six days before. Its belly was bloated with water, of which it had evidently drunk a prodigious quantity, but it was otherwise gaunt from hunger. It still wore a broken bridle, and the saddle was found at no great distance away. To this were still attached the rifle, now broken, the roll of blankets, soiled and torn, and the empty canteen, that had belonged to the poor lad, of whose fate they brought melancholy tidings. A fragment of picket-rope still remained attached to the pony's neck, but its frayed end, worn with long dragging through sand and over rocks, showed that the animal must have traversed many miles of desert since the time when last he bore his young master.

The broncho's trail was discovered and followed to the distant brow of the bluffs, but beyond that it had been obliterated by wind-swept sands, and offered no further clew.

As no one of the party would ever care to use that broken saddle, and as it was all that was left to them of the merry lad who was lost, they buried it where they found it, with all its accoutrements. When they turned silently from the little mound of earth that covered it, all felt with Mortimer Chalmers as though they were leaving the grave of his light-hearted, hot-headed, affectionate, and impetuous young brother.

And now let us see what had really become of the lad whom his recent comrades mourned so sincerely, and who we left sometime since gazing anxiously at the gaudily decked monuments of the Painted Desert.

When in his thoughtless race after the coveted prize of[Pg 404] a black-tailed deer, Todd emerged from the ravine that led to the plateau, and gained a wide range of vision, he was sorely disappointed to see the animals he was pursuing skimming across the sands more than a mile away and approaching a tall mesa, behind which he knew they would in another moment disappear. He was about to give over the chase with a sigh of disappointment, when, to his surprise, one of the fleeing deer seemed to fall, though it almost immediately regained its feet and followed after its companions.

"Hurrah!" shouted Todd, again urging his pony to the chase. "One of them is wounded, and I'll have it yet. Mort will forgive me when I bring fresh venison into camp."

Just before reaching a rocky buttress of the mesa the lad heard shots behind him and, with a backward glance, saw two horsemen in hot pursuit. One of them he knew to be his brother, and both of them were waving to him to come back.

"I won't go without something to show for my hunt if I can help it," muttered the boy to himself, as he dashed around a corner of the rocky wall, and also disappeared from view. He had hoped to find his wounded deer there, but neither it nor the others were in sight, though he could still distinguish their tracks. Following these, he was led through a narrow and crooked valley that finally divided into several branches. The deer had taken one of these that led sharply to the right amid a confused mass of rocks.

"They are making a circuit back toward the river," thought the young hunter, "and that suits me exactly, for I shall be able to reach it and regain camp without being caught by Mort like a naughty child. That I couldn't stand, and I would rather stay out all night than submit to anything so humiliating."

Thus thinking, the lad continued to ride in the direction he thought the deer had taken, though he could no longer distinguish their tracks. Nor did he discover any sign of the wounded one, which for more than an hour he expected to do with each moment. By this time he was beginning to feel a little uneasy at not coming to the river toward which he was confident he was circling. The speed of his pony was now reduced to a walk, and Todd was greatly bewildered by the labyrinth of walls, columns, and fantastic rock forms into which he had wandered.

With the waning day the sky became overcast, and a strong wind, blowing in gusts, so shifted the desert sands, piling them into ridges and whirling their eddies, that when the boy finally determined to retrace his own trail he found, to his dismay, that even a few paces behind him it had wholly disappeared. At this discovery the terrible knowledge that he was lost came into his mind like a flash, and for a full minute he sat stunned and motionless.

Then he pulled himself together, laughed huskily, and said aloud: "Don't lose your head, old man. Keep cool. Camp right where you are until daylight, and then climb the highest point you can find. From it you will surely be able to get your bearings, for the river can't be more than a mile away."

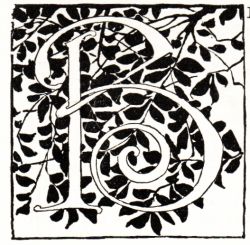

ear-hunting varies according to the kind of bear you are hunting. If black bear, it is rather tame sport, but if it is grizzly, cinnamon, or silver-tip, as the several species of the grizzly are called, then it becomes big-game hunting indeed, and is sport for only the most experienced.

Grizzly-bear hunting is not boys' play. It is men's work, and only for the most experienced at that; no boy should be permitted to go grizzly-bear hunting, either alone or in the company of other boys, or even in the company of most men who claim to be sportsmen.

No boy of mine should ever go after a grizzly unless he was accompanied by a hunter whose nerves had been tried by "Old Ephraim," and whose experience was undoubted. The grizzly is such an uncertain beast in his temperament, and is so ferocious and so dangerous when once his ugly temper is aroused, that it is not safe to take any liberties with him, and it is certainly not safe for boys to take any chances about venturing into his country. For this reason I do not think boys ought to go bear-hunting, even for the black, in localities frequented by the grizzly. As a rule, grizzly and black bear do not live in the same localities, although in some parts of the Rocky Mountains, in Colorado and New Mexico, I have killed both within twenty-five miles of each other.

If, having your father's permission to hunt grizzly, you set out with an experienced sportsman, the latter will advise you as to your rifle. There are many different opinions on this rifle question. I have always used a .45-90-300 or a .45-110-340, preferably the latter. The dangerous feature of grizzly-hunting is the bear's wonderful vitality. If you were certain, absolutely, of putting a ball through his brain every time you fired at him, there would be no need of such concern as to your rifle, for a much smaller calibre would answer the purpose equally as well as the larger; but rarely are you in a position to put a ball into his brain, even if you are a sufficiently expert shot to do so. You may fire at 75, 100, or 150 yards—you will more often see him at the shorter distance than at the longer—but the chances of your dropping him in his tracks are not good. Occasionally you may do so, but not often. Now this is the danger. When you put that bit of lead into the grizzly, no matter how thoroughly it may do its work, most frequently "Old Ephraim" is going to make a bee-line for you; and, what is more disquieting, he is likely to sustain life long enough to reach you, unless meanwhile you stop him. I know of a case where a grizzly was shot through the heart twice at close range, and yet got to the hunter and fearfully injured him before the bear fell dead.

I have seen many illustrations of the inefficacy of lighter charges of powder, and known several instances where, had men using them been alone, they would have fared very badly from the wrath of the grizzly. My own experience has taught me that the heavy charge is desirable. I certainly should not go after a grizzly with anything less than a .45-90. That is why I have always advocated plenty of powder back of the ball when you come to tackle "Old Ephraim." Lately a cartridge has been put on the market, a .30-40, of smokeless powder, which is said to be very killing. Theodore Roosevelt has used it on antelope, and tells me that it does splendid execution—certainly as good as, if not better than, any of the heavier charges. Archie Rogers, who is a noted bear-hunter, also used the gun out West last season, and killed a bear with it. These are two of the most experienced sportsmen in the country; but a gun in the hands of Archie Rogers after grizzly is a very different matter from its being in the hands of the ordinary sportsman, to say nothing of a tyro. The next time I go after bear I shall take along one of these guns and try it, but it seems to me it has not yet had sufficient trial against the grizzly to warrant its being advised for inexperienced hunters or for boys. The boy who reads this article and starts for grizzly, and values my advice, will provide himself with the old reliable .45-110-340. For black bear the .45-90 is sufficiently powerful, and many rifles of smaller calibre have been used on this member of the bruin family.

The best time to hunt bear is in the spring, when they have just come out of their winter's holes, in which they have been sleeping away the coldest months. They are then very hungry, and constantly on the move, and to be seen in the open more than at any other season of the year. This is the time, too, when their fur is long and silky, and of very much better quality than later, for very soon after coming out of their holes the fur becomes thinner and coarser. It is at this time of the year that the bear is a meat-eater; and, in fact, he is almost any kind of an eater, being so ravenous as to take what he can. If in the neighborhood of a ranch, he will prey on the live-stock, particularly on pigs and chickens. A few months later, when summer comes on, he goes up from the foot-hills into the high mountain plateaus, where he lives on vegetable matter, grasses, and weeds, and becomes a very diligent seeker after beetles, and all the insect life that lives under stones and logs. The true time of plenty for bear, and certainly when you are most likely to get a shot at him, is in the last of the summer, during the berry season. This is when you must hunt for him on the sloping sides of the hills that are covered with berry bushes, and frequently they are so absorbed in devouring the luscious fruit as to be rather easy of approach, although do not get the idea it is too easy; a bear is never easy to approach, and approach is only a small part of the game. Later on in the autumn he again goes up on the high plateaus, where game is plenty, and again becomes a meat-eater. When the winter sets in, and the heavy snows come, he seeks a cavernous hole in the hill-side, or some natural cave in the mountains, among rocks, where he remains sleeping until spring.

It is very difficult to still hunt bear; in fact, it is the experience of most hunters that bear have been more frequently come upon unexpectedly when out hunting for other game. You will probably have to make many trips before you see signs or before you get sight of a bear, and yet again you are apt to go out and stumble on to one. It takes the most careful hunting, because a bear, once aware of your presence in his vicinity, is very difficult to approach; he is certain to secure a position from which he can view an approaching enemy. And when you are looking for bear be very careful how you go through brush. It is not often a bear will charge you without your molesting him, unless it happens to be a female who has cubs near by. But nevertheless, as I have said, the grizzly is so uncertain in his temperament that he is just as apt to charge you as not to do so; and, at any rate, it is best not to run any chances, and therefore advisable to be very careful in going through heavy brush or any place in which he might be lurking. Bear-hunting is not popular with the average man who goes out with a rifle, because reward is so long delayed; it takes lots of time and plenty of patience and experience and skill to get your bear, and it is not every hunter who has this combination.

A GRIZZLY AT BAY.

A GRIZZLY AT BAY.

Bear are baited, but I have never cared very much for that sort of sport. It seems to me that to lay behind a stump awaiting the approach of your victim to the bait you have put out to lure him takes all the hunting out of it. You are simply there to kill, and all the pleasure of pitting your woodcraft and skill against the animal is entirely lost.

See that your rifle is clean and in good working order, and be very chary how you follow a wounded grizzly into cover. It is an old dodge of "Ephraim's," when he does not attack openly, to slink into cover and lie in wait for the hunter who rushes in after him in the thought that he is retreating. Go slow; and do not do any hurried shooting. You should not hunt grizzly unless you are a good shot; and being so, take careful aim before you press the trigger. A painfully wounded grizzly is a dangerous beast.

am not afraid of you," said the Rev. William P. Marsh. "You know very well that I am an American missionary and that you dare not touch me."

Karin the son of Artog looked somewhat ruefully at Oglou the son of Kizzil. "The infidel dog speaks truth," said he. "We must be careful, or the Vali's soldiers will hear of it, and it will take much bakshish to free us. What shall we do with him?"

Before Oglou the son of Kizzil could reply, the Rev. William P. Marsh took a small Bible from his pocket. "The subject of my discourse," he remarked, tucking a horse-blanket over his feet to keep off the cold, and comfortably resting his back against the side of the mountain—"the subject of my discourse this evening will be on the sinfulness of taking what does not belong to us. I shall be enabled to put more vigor into my remarks from the fact that you have robbed me of all my money, have likewise stolen my horse and saddle-bags. As I came to this country just to look after your miserable souls, it's pretty mean of you. However, we will now consider the subject in its primary aspects; thence we will touch upon original sin; and after that I propose to present for your prayerful consideration the subject of Kurdish sin, which seems to be a pretty big variety in itself."

He deliberately turned over the leaves of his well-thumbed Bible in search of an appropriate text for these two ruffians who had waylaid and robbed him within five miles of Kharput. Karin the son of Artog looked irresolutely at Oglou the son of Kizzil.

"It would be simpler to cut this missionary pig's throat," he suggested, stroking his long mustache. "Perhaps the Vali would be only too glad to get rid of him."

"I should like to; I have not killed any one for a week," rejoined Oglou the son of Kizzil, with much fervor. "But—" He hesitated.

The missionary did not understand Kurdish, and spoke in Armenian. "It would be more becoming," he remarked, "for you to sit down and listen to me without interruption. You may never have such another chance."

The quick eyes of Karin the son of Artog caught a glimmer of arms in the plain below them. All around the mountain pass was flecked with snow. "Proclaimed by all the trumpets of the sky," fresh masses began to fall. Their own village was a good many miles away. This mad hodga would continue to preach until he talked them to death. The Turkish zaptiehs, winding slowly up from the plain below, might ask inconvenient questions and appropriate all the plunder.

"After all, it is only four liras," suggested Oglou the son of Kizzil. "If we cut his throat, the zaptiehs will come after us, and our horses are done up. Better tell him we repent and give him back the money."

"When Allah, the All Great, has given us this money," sententiously said Karin the son of Artog, "it is showing ourselves thankless to throw it aside. But—perhaps it is as well. We can always catch him again when there aren't any zaptiehs about. Let us repent and get away before we are caught by these sons of burnt mothers, the zaptiehs."

Hence it was the Rev. William P. Marsh felt that his efforts at conversion had been suddenly blessed. "Maybe I was a bit hard on you," he said, affably, as the two Kurds helped him into the saddle. "If ever you show yourselves in Kharput, just come and see me and let me know how you're getting on. I don't want either of you to backslide after this act of grace, for I know how badly you must feel at giving back this money. I could see just now that nothing but the fear of the Lord prevented you from cutting my throat. If that stops you from cutting your neighbors' throats in your usual hasty fashion, you'll be very glad you tried to rob me by the way, and were brought to repentance. Now here's this Bible of mine, beautifully printed in Armenian. Maybe some one could read it to you when you feel inclined to go out and plunder your neighbors after the fashion of these parts. If you like to have it just say so, and I'll make you a present of it."

"Some day we will bring it back to you, Effendi," obsequiously said Karin the son of Artog, as the two picturesque-looking villains helped the infirm old missionary into the saddle. "Where is your house?"

"By the big college; you can't mistake it," said the old missionary, cheerfully. "Just ask for me, and you shall have a square meal first and some square truth afterwards. But I must get on." He jogged his patient old horse with one spurless heel, and shuffled away in the direction of Kharput, lifting up his voice in a hymn of praise as he disappeared in the gathering night.

Karin the son of Artog and Oglou the son of Kizzil watched the receding old man with a grin. "Four liras!" said the one. "Four liras!" echoed the other. "Now for the zaptiehs." The two cronies turned in the direction of the approaching force, but it was not to be seen.

"They've turned off, and are not coming up the mountain at all," mournfully suggested Karin the son of Artog.

"Oh, if we had only known, sons of dead asses that we are!" wrathfully replied Oglou the son of Kizzil.

"We would have cut his throat and kept the money," they added, simultaneously.

But the good old missionary jogged up the steep incline to Kharput, feeling that he had not lived in vain, and that the mission report for that year of grace, 1880, would contain the first authentic instance of the sudden conversion to Christianity of two Kurd desperadoes.

"Allah is with him" (an Eastern equivalent for stating that a man is mad), said Karin the son of Artog, leaping on his wiry pony and digging his shovel-shaped stirrups into its hairy sides.

"We must have been mad too," suggested Oglou the son of Kizzil, as he galloped down the mountain-side after his friend, "to give him back four liras when I would have cut his throat for a medjidieh!"

HE MADE A VICIOUS THRUST AT HIS FRIEND'S HEART.

HE MADE A VICIOUS THRUST AT HIS FRIEND'S HEART.

A few days later Karin the son of Artog had a slight difference of opinion with Oglou the son of Kizzil. No one knew how the quarrel originated, but it ended in Karin the son of Artog drawing an extremely sharp and crooked sword and rushing upon Oglou the son of Kizzil with the indecorous observation that he would slice out his liver. Although Karin the son of Artog was theoretically acquainted with the position of the human liver he had no practical knowledge of the fact, and, consequently, made a vicious thrust at his old friend's heart. Fortunately for Oglou the son of Kizzil, the point of the sword caught in the cover of the old missionary's Bible, and whilst Karin the son of Artog futilely endeavored to get it out again, Oglou the son of Kizzil, with the neat and effective back-stroke which was his one vanity, cut off the head of Karin the son of Artog. Oglou the son of Kizzil had placed the Bible over his heart as an amulet; hence, this providential instance of its powers more than ever convinced him of its utility as a charm to ward off misfortune. However this may have been, it could not protect the son of Kizzil from the somewhat inopportune attentions of his late friend's clan. The relations, with that blind haste which generally distinguishes the actions of relatives, promptly assumed that Oglou the son of Kizzil had been the aggressor, and demanded "blood-money." Here again arose another difference of opinion. Oglou the son of Kizzil, whilst willing to testify to the admirable qualities of his late friend Karin the son of Artog, felt inclined to rate those qualities at a lower[Pg 407] market value than seemed becoming to the dead man's friends. Three liras and a pony seemed to Oglou the son of Kizzil an adequate tribute to the virtues of the defunct warrior. He was willing, as a concession to sentiment, to throw in a praying-carpet with the pony, but was not prepared to do more. As a tribute to old friendship, however, he would marry the widow and take over the household. To this ultimatum the widow, through the medium of a white-haired old chief, her father, replied that Oglou the son of Kizzil had insulted her by supposing that she could ever have married a man whose "blood-money" would scarcely suffice for the funeral expenses, and that it would be well, in view of the circumstances, for Oglou the son of Kizzil to put his house in order and bid farewell to a world which he had too long disgraced by his presence.

With feminine unfairness, the widow of Karin the son of Artog did not give Oglou the son of Kizzil a start, for his relations were scattered about on different plundering expeditions, and were much too busy to attend to their kinsman's sudden call for aid. One morning, that darkest hour before the dawn in which ill deeds are done, Oglou the son of Kizzil was awakened by a smell of burning thatch.

"Ugh!" he grunted, feeling to see whether his yataghan was in order. "She's set her relations on to me. I should like to marry that woman. I wonder how many of them are outside."

Whilst he was still pondering, a bullet came through the wall of the hut, and scattered little pellets of mud all round. This seemed to Oglou the son of Kizzil a hint that it was about time for him to be off. With characteristic forethought he had tethered his pony in the hut. Picking up his small one-year-old son, the joy of his heart and the pride of his eyes, Oglou the son of Kizzil mounted his pony, rushed through the crazy door, tumbling against a crowd of Kurds who were waiting to receive him, and the next moment was madly galloping through the darkness in the direction of Kharput.

Recovering from their momentary panic, the relations of Karin the son of Artog charged after their former friend, headed by the widow, who, lance in hand and mounted en cavalier, resolved to revenge the slights which her pride had suffered. But Oglou the son of Kizzil had a good pony, the shovel edges of his stirrups were sharp enough to rake even that much-enduring animal's hide, and he sped up the mountain, guiding the animal with his knees, holding his little son on the saddle before him with one hand, and brandishing his yataghan with the other, as if he were slicing an imaginary foe with the same famous stroke which had killed Karin the son of Artog.

But the way was long, the ascent steep, and the one-year-old Artin, so rudely awakened from slumber, began to cry.

"Hush, little warrior," said his father, tenderly. "Little sheep's heart, be still."

As they toiled up the steep mountain path, the wiry pony going at each sudden rise in the broken ground with an impetuous rush, the clatter of falling stones served as a guide to the pursuers, and they came on, headed by the widow, brandishing her husband's lance.

"I shall have to turn and fight them presently," said Oglou to his son. "They'll never let me alone now."

Suddenly he gave a wild yell, and mercilessly prodded the pony.

"The house next the college! That is the place. Inshallah, I shall have time to get there and back to the top of the pass before they catch up with me. But unless I can get back in time I'm done for. It all depends upon the pony."

In answer to this appeal the gallant little beast bounded up the precipitous path like a wild goat. The piercing shriek of the widow died away, and the loud breathing of the pony, as he neared the top of the pass alone, broke the stillness. Once on the level ground, Oglou the son of Kizzil gave a peculiar cry, and the pony skimmed along, his belly almost touching the earth.

Hastily taking off his thick lamb-skin coat, Oglou the son of Kizzil wrapped it round the child, tied the missionary's Bible to his breast, sprang from his pony, hammered vigorously on the door of a little house next the college, and left the boy there. When the Rev. William P. Marsh opened the window, Oglou the son of Kizzil was already moving away.

"What does the rascal mean by having religious doubts at this hour of the morning," grumbled the good missionary, preparing to shut down the window. "Perhaps he has brought back the Bible I gave him."

Little Artin, snugly wrapped up in the lamb-skin, rolled off the door-step and began to howl. "When a baby howls," thought the good missionary, "the best thing is to call one's wife." He awoke his better half and explained the circumstances to her. "What would you advise me to do?" he inquired, as she sat up in bed.

"Fetch the child, and bring it up to our warm bed," she said, promptly. "Fancy wasting all this time, and on such a bitter night."

As Oglou the son of Kizzil reached the top of the pass, the gray dawn began to break. Only one of his pursuers was in sight; whereupon, Oglou the son of Kizzil urged the tired pony forward, took a firmer grip of his yataghan, and prepared to demolish his plucky adversary.

"Stop," shouted the widow of Karin the son of Artog. "I've changed my mind; a live donkey is better than a dead lion. Kill your son, and I will marry you. You shall be the head of our tribe."

"You are stronger than Rustam, fairer than a gazelle," said Oglou the son of Kizzil. "Inshallah, but it is kismet. My son dropped over the precipice as I rode along."

And they went back together.

Sixteen years later Oglou the son of Kizzil, much stouter and a little dirtier than of yore, cautiously rose from his couch without awakening his spouse, slipped out from the hut, and rode swiftly away through the darkness towards Kharput. Oglou the son of Kizzil was much troubled, for his interests lay in different directions. The little boy Artin had grown up to be a fine stalwart lad, with a strong vocation for the ministry, and an equally strong affection for the old cutthroat, who dare not openly acknowledge his son. Three or four times a year the Kurd galloped up to Kharput, whistled beneath his son's window, and the two would ride away together, the lad longing for the wild life of his father's folk, and yet restrained by his knowledge that he would one day be called to minister to them.

On this particular night Oglou the son of Kizzil was much perturbed. "These Armenian pigs will all be slaughtered to-morrow like sheep," he said. "It is the Sultan's will. We begin early in the morning, and the looting is to last for three days. But if the old hodga hears of it, he will go to the Vali, and the Vali will know that he has been betrayed."

Then young Artin thought for a moment. "Is there no way of stopping the massacre?" he asked. "You know people think I am an Armenian."

Oglou the son of Kizzil shrugged his shoulders. "There will be much plunder. We shall walk our horses through blood," he said, as if that settled the matter.

"And what shall I do?" inquired Artin.

"If the hodgas (schoolmasters) keep within their houses they will be safe; but we shall kill all their servants, and not leave an Armenian alive in the place, the dogs."

Artin knew that it would be useless to argue with the old robber, his father. "I suppose I had better get away with Mr. Marsh, or else take refuge with the British Consul at Sivas? He is staying with Mr. Marsh, but leaves to-morrow."

"It is the will of Allah that these dogs should die the death," said the Kurd, with pious resignation for other people's sufferings. "Joy of my heart, get away early in the morning, or you might be hurt when we attack the place. If we didn't obey orders we should have the troops let loose on us; and even my wife is afraid of that."

He embraced Artin fondly, shook his shaggy hair, and galloped swiftly away, leaving the young man in a brown[Pg 408] study. Artin went back to the college, roused up every slumbering pupil, and hunted among the Consul's travelling things for one particular article. When Mr. Marsh came down to breakfast, three hours later, there were fifteen thousand Armenians huddled together within the Mission walls.

"What does this all mean?" asked the English Consul, as he entered the breakfast-room. "I can hear firing in the town."

"The Sultan has ordered a massacre of all the Armenians to be found here," said Artin, quietly. "The Kurds are beginning now."

"I'll go to the Vali," cried Mr. Marsh, starting up in horror.

"It is no good," said Artin, with a touch of fatalism. "What will be, will be. I have done all I could. We have several thousands here already."

"But these cutthroat scoundrels will soon break into the college grounds," said the Consul. "Why didn't you warn people to fly, if you knew what was coming?"

"It was too late. There was only one thing to be done."

"And that was—?"

"To collect as many as the place would hold."

"Of course you will interfere to protect these poor people," suggested Mr. Marsh to the Consul.

"I have no instructions," said the Consul. "My action might bring about a war between Turkey and England."

"But if you do not, you will have the blood of thousands of innocent people on your soul;" and the good missionary paced the room in his agitation. "Then you must act!"

"The Consul has already interfered," said Artin.

"What do you mean?" testily asked the Consul.

"The English flag is flying from the top of the college," said Artin. "I took it out of your baggage and put it up. Now, for the honor of your country, you can't haul it down again."

The Consul's face cleared. "It's a fearful responsibility you've forced on me."

Accompanied by Mr. Marsh and Artin, he went into the court-yard. The Kurds were already beginning to batter in the gates.

The gates soon came down with a crash, the Turkish regulars outside looking on with an amused grin, and licking their lips at the thought of what was to follow.

But the English Consul strode out through the gates. He was unarmed, and his life hung on a thread. Then a Turkish officer came forward. "Effendi, this is no business of yours. You had better leave."

The Consul pointed to the British flag flying from the college tower. "Whilst that flag is flying here," he said, proudly, "this is English ground. Now enter if you dare."

After a hurried consultation with the Turkish officer the disappointed Kurds drew off, and rode into the town to continue their butchery.

"I did all I could directly I knew what was going on," said Artin the Kurd, to Mr. Marsh the American.

The missionary put his hand affectionately on the lad's shoulder. "To think," he mused—"to think that one small Bible should have been the means of saving the lives of all this multitude of people! If your father hadn't carried that Bible, his enemy's sword would have pierced his heart, and he would never have brought you here. Now we must try to feed the women and children until this slaughter ceases."

But Oglou the son of Kizzil, in the very act of shearing off an Armenian's head with his characteristic back stroke, sighed as if all the savor of slaughter had gone out of him. "Alas that I should raise up seed for the wife of mine enemy, and my own son rides not at his father's bridle-hand!"

s I stood there, not knowing what to do, I saw the fingers of a man come over the edge of the cabin window; then a face appeared, and, seeing who it was, I leaned forward and laid hold of the carpenter by the back of his shirt to help him. He murmured something inarticulate, and I saw the reason why he could not get in through the window. He had his cutlass in his teeth, and I had to relieve him of it and do some powerful hauling before I had him inside lying on his back on the cabin deck. I closed my hand over his mouth, and bending my head close to his, whispered: "Hush for your life! There's a sleeping man within touch of us!"

But now the hilt of another cutlass appeared at the window. I took it, and enjoining silence on those below in the boat, the carpenter and I hauled in another man. We must have made some noise, but the deep breathing went on undisturbed until every man jack of us had come in through that window. But it was no place to hold a consultation. With my finger to my lips, I stepped to the passageway, took down the lantern from its hook, and came back with it. The sleeper was snoring, and we saw that he was in a bunk behind a half-closed curtain. And now the reason for his sound rest was apparent; as we pulled aside the cloth, ready to jump on him if he made a sound, we smelt the strong odor of rum, and perceived that the man had clasped in his arms a big black bottle, much in the way a child in a cradle might fall asleep with a doll.

"You can't wake him," said the carpenter, who was called "Chips" by the crew, and if I had not stopped him, I think he would have tweaked the sleeper's nose.

"One of you stay down here and guard him," I said. "Mr. Chips, you and those three men close the forward hatch. I and these five men will take care of the man at the wheel and the watch. Now, steady! Make no noise!"

They followed me out to the little passageway that led to the foot of the ladder, and I went up it softly. I saw but two moving figures on deck—a man forward leaning with both elbows on the rail, and aft, the binnacle light reflecting on the face of an old sailor with a growth of long white whiskers; his eyes were half closed, and his fingers were grasped tightly around the spokes. Followed by the three men I had detailed, I jumped up on deck. The old seaman at the wheel made no outcry, for danger was probably the last thing he had in his mind. (He took us for some of the crew, I found out afterwards.) When he looked at the pistol that I pointed at his head, however, his jaw dropped, and without a word his legs gave way and he sat down backwards on the deck.

In the mean time the carpenter had clapped a pistol to the head of the man leaning over the rail, two others found sleeping on the forward deck were held quiet in the same manner, and I heard the slam of the hatch with satisfaction.

I had command of the brig, without a word having been spoken above a breath.

I say I had command of the brig right enough, but there[Pg 410] was to be a little trouble, after all, which came near to putting me out of the game altogether; but of that later.

In obedience to the plan, the side lights had been extinguished, the yards swung about, the helm put down, and we were steering northeast by east according to the compass.

I was standing by the man at the wheel, trembling with the agitation of pent self-congratulation. I would have given a great deal to have relieved my feelings by a cheer.

"Who are you? Pirates?" said a shaking voice at my side. I looked around. There stood the old sailor with his knees half bent, as if they refused to straighten.

"We're Yankee privateersmen," I said, grinning at him.

"Much the same thing," he muttered—"pirates! What are you going to do with us?"

"Treat you kindly, if you make no noise," I answered, rather amused than otherwise.

This appeared to relieve the old man greatly. The carpenter now came aft.

"I've bucked and gagged the men I found on deck," he said. "You don't want to heave them overboard, do you?" he added, chuckling.

"No!" I answered, quickly.

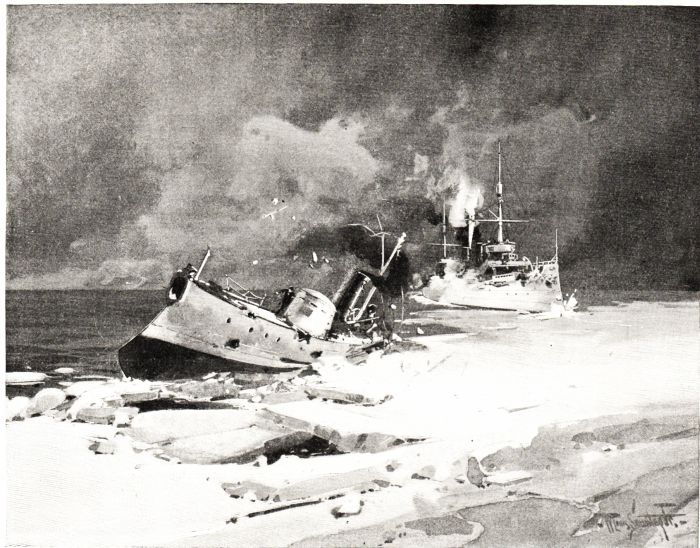

I had no time to find out whether the man was joking or not in asking this, for a flash of red fire tore out against the darkness less than a mile astern of us. Then a crash reached our ears. Some more flashes and reports in criss-cross, and then a burst of flame so bright that I could make out the outlines of a vessel from her lower yards to the water!

"By the great sharks, Mr. Hurdiss," cried the carpenter, "old Smiler has run afoul of a frigate, and no less! That's the end of him."

As we learned afterwards, that broadside was the end of poor Captain Gorham, and the tight little Yankee also. But we soon had affairs of our own to look after, and I myself had my hands full.

The report of the first shot had caused something of a commotion below. I heard the sound of a cry and an oath, and rushing to the head of the companion ladder, I was almost knocked down by a great man who came up it on the jump. He was bleeding from a gash the full length of his face, but I recognized him as the one who had been asleep in the berth below.

"Demons! Devils!" he shrieked, and avoiding my grasp, he jumped for the side, and went overboard head first, with a wild, unearthly scream.

I knew that a struggle must have taken place in the cabin, and calling the carpenter to follow me, I jumped down the steps, and here is where the unexpected happened. The lantern I had left there had been extinguished. All was pitch dark, but I could hear a faint groaning to the right. I felt along the passageway with my hand, and as I extended it I touched something that moved. At the same moment my wrist was caught in a tight grasp and a hand fumbled up my chest as if reaching for my throat.

"Who are you?" said a voice, in unmistakable English accents.

For reply I laid hold of the reaching hand, and thus the strange man and I stood there close together. I could not reach my pistol, or I would have shot him dead.

"Who are you?" he repeated, hoarsely.

I said nothing, but endeavored to wrench my hand free. The man, at this, began to shout.

"Ho, Captain Richmond, mutiny!" he cried, and threw his whole weight upon me, as if to bear me down. "Ho, Richmond! You drunken fool, the men have risen!" he roared again.

I had wrestled with many of my fellow-prisoners at Stapleton, but I had never been against such a man as this heretofore. I almost felt my ribs go as he grasped me, but I got my hip against him, and we came down together, completely blocking up the passageway. I fumbled for my pistol, but could not reach it, and taking me off my guard, the man shifted his grasp to my throat. I tried to evade it, but it was too late. I caught him by both wrists, and for a second managed to keep his thumbs from choking me.

"Get a light! A light!" I cried.

I had got my knee wedged in the pit of the man's stomach, and was pushing him with all my might, but even with this and the aid of my hands I could not break away. Gradually my breath stopped, lights flashed and danced before my eyes. I could feel my chest heaving as if my heart would come out of my body; then it seemed to me I heard an explosion far above me, and I knew no more.

When I drifted back to the sense of knowing that I was alive, it took me some minutes to gather the strings of my mind and haul in my ideas. At first I could not have told who I was, and for a long time my whereabouts were a puzzle to me. It might be the first question of any one to whom I should tell this to ask why I did not speak, and thus find out the condition of affairs. But let me assure you I was doing my best to form words and sentences, and the only result was a whistling, wheezing sound in my throat. My voice was gone! At last I found strength to raise my hand, and I felt that I was in a box of some kind, and this puzzled me still more until I heard voices talking to one side of me, and I recognized Chips, the carpenter, saying:

"It was a quick funeral, Dugan. And how is the young gentleman?"

Then the whole situation came back to me clearly, and I knew where I was and all about it. I put out my other hand this time, pulled aside the curtains, and it was as I supposed; they had placed me in one of the cabin-bunks; it was the very one, by-the-way, in which the drunken Captain had been sleeping.

"Well, sir," said the carpenter, "so you've come back to join us? It isn't every one who's been so near the great gate and returned."

I tried to answer something, and it must have been an odd sight to have seen me sitting there dizzy and swaying, working my mouth without a sound forth-coming. Something was choking me. At last I made a motion; they understood that I wished a drink of water, and Dugan went to fetch it for me. It pained me much to swallow or to move my head; I can truly sympathize with any man who has been hanged.

They had put something in the drink, however, that made me feel a bit stronger, and I motioned for Chips to come close to me.

"Have we come about?" I whispered.

"Yes, Captain," he replied, nodding his head and smiling encouragement, the way one addresses an invalid. "We came about some time ago, and are now holding a course southwest-by-south-half-south. Is that right, sir?"

I nodded. All I knew was that if we held this course long enough we would fetch up somewhere on the coast of the United States.

But the man's addressing me as "Captain" pleased me. Yes, surely, I was the prize-master of the brig, and the men looked to me to manage her. But I did not even know her name as yet, and there were many things that I wished to find out. So, taking Chips's arm, I made a sign telling him that I wished to go on deck.

The cabin had been lighted by the lantern hanging above our heads. As we went down the passageway I saw that another light was coming from a small door that opened into a little closetlike space which contained two bunks. A horn lantern was suspended from the deck beam, and a man with his head bound up in a bloody cloth was in the lower bunk.

"It's Fisher, the man we left guarding the drunken skipper," said Chips. "He was struck on the head with a bottle."

We were at the foot of the ladder, and I saw that it was from this place that the man with whom I had had the struggle had emerged. It was right here where I was standing that we had been fighting, and it was there we lay. I looked down and saw that the passageway had been lately slushed out, for a sopping squilgee had been tossed in the corner.

"Where is he?" I asked.

The carpenter shrugged his shoulders. I understood with a shudder, and did not repeat the question. What was the use?

By the motion of the vessel I knew that the wind must be light, and glancing up as I came to the top of the ladder, I saw that the carpenter was well up in his business, and that in him I had an able lieutenant.

The brig had every stitch of canvas set, and despite the fact that she was very old-fashioned and bluff in the bows, we were making good headway, and rolling out two rippling waves that seethed and tumbled on either side of us.

It would soon be dawn. The sky was growing light in the east, and the glow was spreading every minute, so that I judged it must be in the neighborhood of four o'clock in the morning. I sat down on the edge of the cabin sky-light and rested my elbows on my knees; and in that attitude I gave thanks that my life had been spared, and prayed that strength would be given to me to meet any danger that might come before me.

The dawning of a day is a very beautiful and holy thing to watch, especially at sea, with the red edge of the sun creeping slowly up against the horizon, and the expanding sense that one feels in his soul at the world's awakening. Had I a gifted pen, I should love to describe the sight I have seen so often—the growing of color in the water, from black to gray, from gray to green and blue; the red-tipped clouds, and all—but I shall not attempt it; I should fail. Even this day I noticed the beauty of it, but I began to worry about my throat (I was in great pain again), and wondered whether the pressure of the man's fingers had destroyed my larynx. But if I had lost power of speech, I knew that the carpenter would carry out my intentions, and that he probably could give the orders in much better fashion than I could. So it was not necessary for me to borrow trouble, although I hated to think of whispering for the rest of my existence.

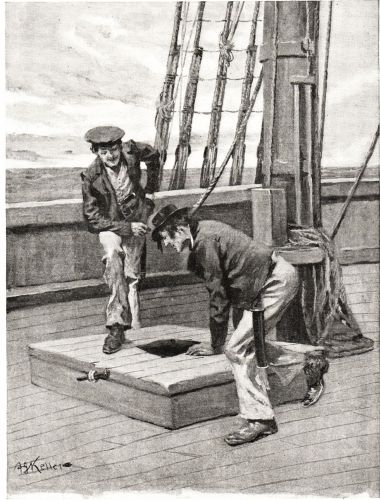

HE LEANED HIS FACE OVER THE HOLE AND SHOUTED.

HE LEANED HIS FACE OVER THE HOLE AND SHOUTED.

Suddenly I thought of the prisoners penned in the forecastle, and I approached the carpenter, who was chatting with the man at the wheel, and asked him about them—whether he had held converse with them, and how many were they. He informed me that there were eight fore-mast hands and the second and third mates cooped up below, and that the only way they could get out was through the forward hatch, which he had nailed down. I walked to the bow with him, and saw that he had cut a square hole in the middle of the hatch cover big enough to admit air and to permit of talking with those below. He leaned his face over the hole and shouted:

"Below there, ye Johnny Bulls! How fares it?"

The reply was a chorus of cursing. But at last one man succeeded in hushing the others, and I could hear his words distinctly. He spoke with a strong Scotch burr.

"Who are ye? Where are ye takin' us?" he asked.

"We're Yankees," answered Chips, "and you know that right well. We're taking you for a trip to the land of liberty. If you behave yourselves, and stop your low talk and your blaspheming, you'll have your breakfast soon. We're Christians."

There was no further conversation, and at this instant I was seized with a hemorrhage from my throat, and the carpenter insisted upon my turning in in the cabin, which I was not loath to do, as moving about seemed to start the blood in my throat. I went below, and lay there all the morning, suffering not a little. They brought me food, but I was unable to swallow it; but when I fell asleep at last, I was awakened in a few minutes, it seemed to me, by Chips touching me on the shoulder.

"It's near meridian, Captain Hurdiss," he said. "Hadn't you better take a squint at the sun? The wind is getting up a bit too, sir," he said, "and the glass has fallen."

I endeavored to get my feet, but the motion started the trouble in my throat, and I fell back, weakly.

"Never mind; you'd better keep to your bunk," the carpenter said. "To-morrow you'll be up and about, I'll warrant. I'll leave this bottle for you, sir."

I detected an anxious look in his face as he handed me a glass of water and spirits. Again I fell asleep, and awoke some time late in the afternoon, feeling much better.

The brig had a great motion on her, and every plank and timber was groaning and creaking. I took a sip out of the bottle, which was wedged in the corner of the bunk, and although it scalded and burned me, it seemed to give me strength, and I crawled out, and stumbling to the foot of the ladder, made my way up on deck. The sky had grown black and angry. We were on the starboard tack under reefed topsails, and everything was wet with flying spray. The Duchess of Sutherland, for that was the brig's name, belonged to an era of shipbuilding when they believed that every breeze must blow over a vessel's stern, I should think. The way she kept falling off was a caution. She appeared to go as fast sideways as she did ahead, and such a pounding and thumping as she made of it I have never seen equalled. Most of the crew were on deck, and one of them, a fine seaman named Caldwell, saw me standing holding on to the hatch combing. He came up, touching his forehead in salute.

"She's a bug of a ship, Captain Hurdiss," he said.

I nodded, and glanced up at the aged time-seamed masts.

"It won't pay to carry much more sail, sir," the man said, as if in suggestion.

I beckoned him to put his head close to mine, and gave an order to take in the foresail, for it was holding us back more than helping us. The man bawled out the order, and jumped with the rest to obey it. I felt so weak that once more I sought the cabin. I took a glance at the barometer as I went by, and saw that it was still falling; that we were in for a hard blow or a storm I did not doubt.

But the rolling and tumbling increased, and the groaning and complaining of the timbers led me to believe that the old craft was working like a basket, which was exactly what she was doing. Suddenly she gave a lurch so hard and sharp to port that I was almost spilled out of the berth, and fear giving me strength, I crawled up on deck on all fours. The man at the wheel was doing his best to bring the brig's head up in the wind, the jib had blown out and was tearing into streamers, the men in the forecastle were working away at something, and I heard a wail from the prisoners below.

It looked as if we were bound to capsize, but at this moment the topsail blew out of the bolts and we righted. But the storm was upon us; the tops of the seas blew off and scudded along the surface like drifting snow; there was a fiendish howling in the rigging. I motioned with my hand for the helmsman to swing her off. He understood, and soon we were before it, scudding under bare poles toward the north. But even then the Duchess made bad weather of it, yawing and plunging badly. Dugan, whom I had appointed second mate, came up to me.

"It's safer to run, Captain," he said, shouting in my ear. "Go below, sir; Chips and I will keep the deck."

As I could be of no use, I took his advice, and crawled into the bunk again, trying to assure myself that all was well. It had grown very dark, although it was but seven o'clock, and I had lain there but a half-hour or so, when the carpenter came rushing in. Even in the dim light I could see the terror in his blanched face.

"Heaven help us, Captain!" he said. "I've just sounded the well, sir, and there's three feet of water in the hold!"

The editor of a petty newspaper in France was extremely sad. He sat in his office with bowed head and troubled brow. Long had he fought against Adversity's strides, but at last they had overtaken him, and now, with no money to bring out the future issue, his only alternative was to cease publishing. The once paying circulation had dwindled to a mere nothing, and the wielder of the blue pencil and scissors racked his brains for an honorable excuse for quitting. It took hours, and at last he jumped up.

"Jacques," he called to his printer, "we will get out one more issue, and that will be the last. I will devote every page of it to the festivities occasioned by the visit of the Czar of Russia, and on the head of the sheet put in large display type this line:

"In commemoration of his illustrious Majesty the Czar of Russia, this paper, always an exponent of the nation's welfare, will cease publication."

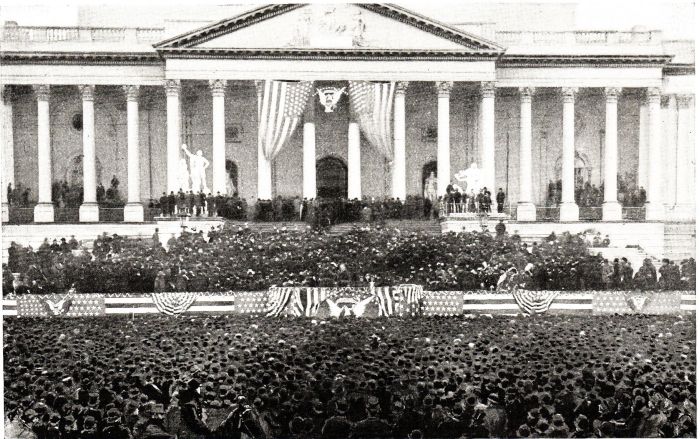

nce in every four years Washington witnesses a sight the parallel of which is only to be seen in the great court pageants of monarchical Europe. The inauguration of a President is always made a great ceremony; it is accompanied with such a display, the stage settings for this performance are so gorgeous, and so unlike anything else we are accustomed to in other cities, that one must go to Washington to see a ceremonial so impressive in the lesson it conveys and so interesting from the personages who are the central figures. There are often seen larger parades than those which march down historic Pennsylvania Avenue on the morning of the 4th of March, but none which so truly represents the greatness of the Union and draws from every corner of the country. On the 4th of March the President and the President-elect drive from the White House to the Capitol and back, and in the evening there is a grand ball. This sounds simple enough, but for months before that day hundreds of the leading citizens of Washington, and scores of men in other places, have been working many hours a day to perfect the details, and on their labors depends whether the great occasion shall be a success or spoiled by an awkward mishap. So soon as the election is over, the chairman of the National Committee of the successful candidate appoints a prominent citizen of Washington to be chairman of the inaugural committee, and he in turn appoints the other members of the committee. These men are the principal bankers, merchants, lawyers, newspaper men, and other public-spirited citizens, without regard to party, as the inauguration is a national affair, and all men are ready to show their respect to the President. Everything relating to the inauguration is left to these committees. The first thing they have to do is to raise a guarantee fund for the necessary expenses—the decoration of the ballroom, the music, and such other things. This year the committee fixed the amount at $60,000, all of which has been contributed by private persons. With the exception of providing the room in which the ball is held and building a stand or two, the government defrays none of the expenses, the entire cost being met by private contributions.

The committees have to decide what organizations and troops shall be in the parade and the places they are to occupy; they superintend the decoration of Pennsylvania Avenue, the main thoroughfare of Washington, leading from the White House to the Capitol; the erection of stands from which the thousands of people who come to the city to take part in the pageant may witness it; arranging for accommodations for the strangers, and the selection of the grand-marshal of the procession. This last is a very important matter. Necessarily the marshal must be a military man who has been used to the handling of large bodies of men, as on that day he commands an army larger than that of the regular force of the United States, and it requires great military skill and cool judgment to make of the parade a success, instead of a failure, as it would be in the hands of an incompetent man. General Horace Porter, who has a distinguished military record, will lead the hosts this year.

THE CROWD LISTENING TO THE INAUGURAL ADDRESS.

THE CROWD LISTENING TO THE INAUGURAL ADDRESS.

It is the custom for the President-elect to arrive in Washington a few days before the inauguration. Rooms are engaged for him at one of the hotels. Shortly after his arrival he drives to the White House and pays his respects to the man whose successor he is so soon to be. When Mr. Cleveland paid his first visit to the White House Mr. Arthur was President. Mr. Cleveland was then a bachelor, and his late political rival escorted him over the house, and recommended to him his sleeping-room as being the quietest and most comfortable in the mansion. Later in the same day the President returns the call, the visits in both cases being[Pg 413] very short, and official rather than social. While the President-elect is waiting to be sworn into office his time is generally very fully occupied in receiving public men, many of whom he meets for the first time, and sometimes in completing his cabinet. It has happened on more than one occasion that after the President-elect reached Washington he finally made up his mind as to a particular member of the cabinet.

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TROOPS IN THE INAUGURAL PARADE.

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TROOPS IN THE INAUGURAL PARADE.

At last comes the great day. The city is thronged with strangers. All Washington has been hoping for months that the sky will be blue and the air balmy, which is often but not always the case. There have been inaugurations when the weather was so warm overcoats were superfluous; at other times rain has fallen in torrents, snow has been piled up on the sidewalks, and men who escorted the President to the Capitol have had their ears and fingers badly frost-bitten. But whether fine or gloomy, from an early hour the capital of the nation takes on an air of unwonted activity. Orderlies and aides in gay uniforms are seen dashing in all directions, bands march up one street and down another, companies and regiments wend their way to their appointed positions, thousands of sight-seers pack the sidewalks, fill the stands and the windows on the line of the procession. Four years ago, when Mr. Cleveland was inaugurated for the second time, the weather was so cold that many of the men in the parade were frost-bitten, and several deaths resulted from the exposure. The night before it snowed heavily, which early the following morning turned into slush, and later in the day froze. But despite the forbidding weather the usual numbers were on the streets to see the new President, and men and women sat for hours on exposed stands rather than give up their places after having paid for them. Four years before that, when General Harrison was inducted into office the rain fell with pitiless fury, and yet under a sea of umbrellas people stood on the east front of the Capitol, and heard the new President deliver his first official pronouncement to the country. Many paid for their curiosity with their lives.

Whether the sun shines, or it rains in torrents, or the snow covers everything in its poetical but moist mantle, the President and the President-elect must ride to the Capitol in an open carriage. That is a penalty greatness has to pay to popular custom, and it has often been wondered at that the drive has not been fatal to one or both of the men. Nearly all the time during what is often a most unpleasant drive the new President has his hat off, bowing his acknowledgments to the applause which is never silent for one moment. It roars and rolls like a great salvo of artillery, in its intensity at times drowning even the music of the bands, and there are scores of them, all playing at the same time. Attended by a committee of Congress, regular infantry and artillery, thousands of militia from various States, and an even greater number of civic organizations, the President and President-elect drive in an open carriage, drawn by four horses, to the Capitol. Here everybody prominent in official life awaits them. In the Senate-chamber are the Senators, members of the House of Representatives, the Chief Justice and the associate justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, the members of the diplomatic corps, and the members of the cabinet.

The Vice-President precedes the President-elect to the Senate, and will have taken the oath of office while Major McKinley is en route. As soon as Mr. Hobart has been sworn in, he and the other personages who have[Pg 414] been in the Senate-chamber proceed to the platform erected on the east front of the Capitol, and to which the President-elect has been escorted. Here, confronting an immense assemblage, the oath is administered by the Chief Justice, and then, by this simple ceremony Major McKinley having become President, and Mr. Cleveland being an "ex," the new President reads his inaugural address. When that is finished, Major McKinley is once more escorted to his carriage and driven to a reviewing-stand erected in front of the White House, where for several hours he has to salute and be saluted by the thousands as they sweep past him. It is usually late in the afternoon before the new President is able to leave the stand and enjoy a short rest before once more taking part in one of the features of the inauguration day. It is worthy of note how quickly the transformation is effected from the great power of the President to the private life of the citizen. When the ex-President leaves the White House in the morning to drive with his successor to the Capitol, it is seldom that he re-enters his former residence. Some Presidents have been known to drive direct from the Capitol to the railroad station and start on their journey home; while General Arthur remained in Washington for some days after Mr. Cleveland's inauguration, but as the guest of ex-Secretary of State Frelinghuysen, John Adams was so exasperated by the election of his successor, that he refused to accompany him to the Capitol, and left Washington early on the morning of the fourth. Curiously enough, his son was equally as discourteous, and so was President Johnson. But with the administering of the oath to the new President, the man who five minutes before was the Chief Magistrate of the nation has become merely a private citizen. There is no courtesy shown to the man who has been. He drives to the station or to his friend's house unattended, without escort, without any one anxious to see him. When Mr. and Mrs. Cleveland leave Washington early in March it will be just as any other persons do.

There has been little change in the general details of inaugurations from the time of George Washington to the present. Jefferson, according to tradition, rode to the Capitol on horseback, tied his steed to a paling, and took the oath in a very democratic fashion. But if history is to be believed, Jefferson rode because the fine new coach he ordered for the occasion was not finished in time, and had it been finished, six horses would have drawn the chariot. When Jackson returned to the White House after the ceremony at the Capitol, the doors were thrown wide open and punch served to every one. The scene that followed is almost indescribable. Furniture was smashed, carpets destroyed, and the dresses of women ruined in the mad rush to drink the President's punch, and that, I believe, was the last time the attempt was made to keep open house on the 4th of March. President Arthur was twice inaugurated. Immediately on receipt of a telegram announcing the death of General Garfield, he sent for one of the New York judges and took the oath, his son and only one other person being present. The scene was very pathetic. Later he publicly took the oath in the Capitol, Chief-Justice Waite administering it. At one time it was thought that only the Chief Justice of the United States could swear in the President. But this is a mistake. The oath taken before a notary public or any other person competent to administer it is legal. On the death of Mr. Lincoln, Andrew Johnson took the oath privately in his room. After Mr. Lincoln's family left the White House, he entered it without any ceremony.

THE BALL IN THE PENSION BUILDING.