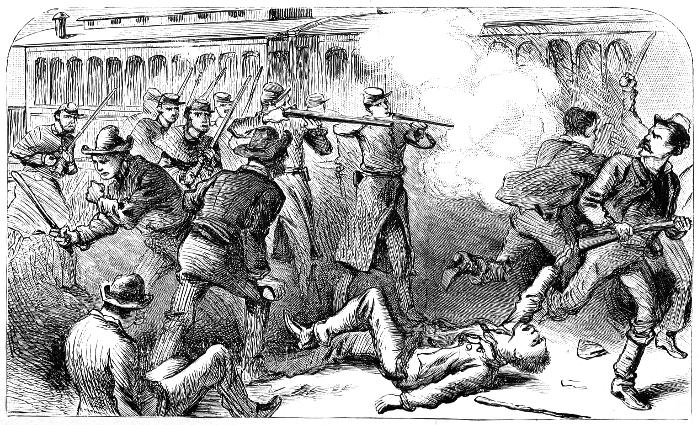

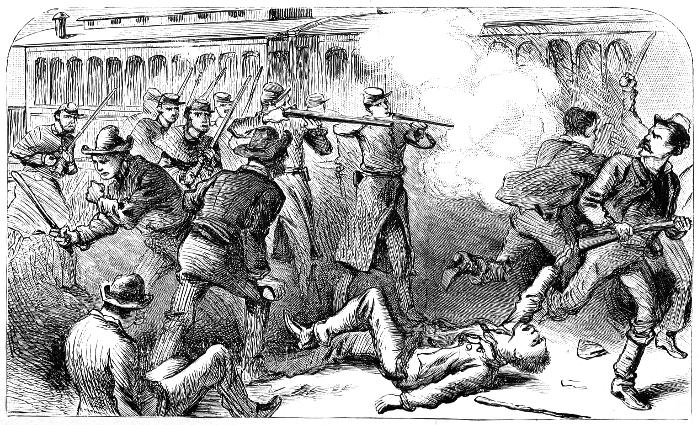

The Battle with the Strikers.

Title: The Rod and Gun Club

Author: Harry Castlemon

Release date: December 3, 2019 [eBook #60838]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The Battle with the Strikers.

ROD AND GUN SERIES.

THE

ROD AND GUN CLUB.

By HARRY CASTLEMON,

AUTHOR OF “THE GUNBOAT SERIES,” “BOY TRAPPER SERIES,”

“ROUGHING IT SERIES,” ETC.

THE JOHN C. WINSTON CO.,

PHILADELPHIA,

CHICAGO, TORONTO.

FAMOUS CASTLEMON BOOKS.

GUNBOAT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 6 vols. 12mo.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

SPORTSMAN’S CLUB SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

FRANK NELSON SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

BOY TRAPPER SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

ROUGHING IT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

ROD AND GUN SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

GO-AHEAD SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

FOREST AND STREAM SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 3 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

WAR SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. 5 vols. 12mo. Cloth.

Other Volumes in Preparation.

Copyright, 1883, by Porter & Coates.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. | |

| Some Disgusted Boys | 5 |

| Chapter II. | |

| Birds of a Feather | 25 |

| Chapter III. | |

| Lester Brigham’s Idea | 45 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| Flight and Pursuit | 66 |

| Chapter V. | |

| Don’s Encounter with the Tramp | 87 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| About Various Things | 108 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| A Test of Courage | 130 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| [iv]The Fight as Reported | 152 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| In the Hands of the Mob | 172 |

| Chapter X. | |

| Welcome Home | 194 |

| Chapter XI. | |

| Hopkins’ Experience | 217 |

| Chapter XII. | |

| Plans and Arrangements | 239 |

| Chapter XIII. | |

| The Deserters Afloat | 261 |

| Chapter XIV. | |

| Don Obtains a Clue | 284 |

| Chapter XV. | |

| Another Test and the Result | 307 |

| Chapter XVI. | |

| The Rod and Gun Club | 324 |

| Chapter XVII. | |

| Casting the Fly | 344 |

| Chapter XVIII. | |

| Conclusion | 360 |

“Well, young man, I will tell you, for your satisfaction, that I have got you provided, for, for four long years to come.”

The speaker was Mr. Brigham. As he uttered these words he placed his hat and gloves on the table, and looked down at his son Lester, who had just entered the library in obedience to the summons he had received, and who sat on the edge of the sofa, twirling his cap in his hands. The boy looked frightened, while the expression on his father’s face told very plainly that he was angry about something.

“I have had quite enough of your nonsense,” continued Mr. Brigham, in very decided tones. “Since we came to Mississippi you have done nothing but roam about the woods and fields with[6] your gun on your shoulder, and get yourself into trouble. You made yourself so very disagreeable that none of the decent boys in the settlement would have anything to do with you, and consequently you had to take up with such fellows as Bob Owens and Dan Evans. After setting fire to Don Gordon’s shooting-box, and being caught in the act of stealing David Evans’s quails, you had to go and mix yourself up in that mail robbery. Why, Lester, have you any idea where you will bring up if you do not at once begin to mend your ways?”

“Why, father, I had nothing to do with that,” exclaimed Lester, trying to look surprised and innocent; “nothing whatever. You know, as well as I do, that I was at home when those men who lived in that house-boat waylaid and robbed the mail-carrier.”

“I am aware that you took no active part in the work,” said his father. “If you had, you would now be confined in the calaboose. But you told Dan Evans about those checks for five thousand dollars that my agent sends me every month.”

“I didn’t,” interrupted Lester.

“Everything goes to prove that you did,” answered[7] Mr. Brigham. “If you didn’t, how does it come that Dan knew all about those checks? He made a full confession to Don Gordon. The story is all over the country, and the people about here are very angry at you. Suppose that Dan had shot Don Gordon, as he tried to do? What do you suppose would become of you? I really believe you would have been mobbed before this time. I wonder if you have any idea of the excitement you have raised in the settlement?”

No; Lester had not the faintest conception of it, for the simple reason that he had held no conversation with anybody, save the members of his own family, since the afternoon on which Dan Evans was overpowered and robbed of his mail-bag. When the full particulars of the affair came to his ears, he was as frightened as a boy could be, and live. He knew that he was in a measure responsible for the robbery, that it would never have been committed if he had held his tongue regarding his father’s money, and the fear that he had rendered himself liable to punishment at the hands of the law, nearly drove him frantic. His terror was greatly increased by his father’s last words. There had not been so much excitement in the[8] settlement since the war—not even when it became known that Clarence Gordon and Godfrey Evans had dug up a portion of the general’s potato patch, in the hope of unearthing eighty thousand dollars in gold and silver that were supposed to be buried there. Don Gordon had more friends than any other boy in the settlement, unless it was Bert, and the planters were enraged at the attempt that had been made upon his life. If Dan Evans’s bullet had found a lodgment in his body instead of going harmlessly through the roof, Dan and Lester Brigham, as well as the three flatboatmen who stole the mail, might have had a hard time of it.

Lester’s first care was to hide himself in the house, as he had done after he and Bob Owens burned Don’s old shooting-box. He earnestly hoped that the men would escape with their plunder; but when he learned that a strong party, led by General Gordon, had pursued them in Davis’s sailboat and captured them, he was ready to give up in despair. Judge Packard would have to look into the matter now through his judicial spectacles, and Lester did not want to be summoned to appear as a witness. Neither did Dan,[9] who, disregarding the advice Don Gordon had given him, took to the woods and hid there, just as he did after he picked his father’s pocket of the hundred and sixty dollars that David had made by trapping quails.

When Mr. Brigham saw that Lester took to staying in the house, and that he had suddenly lost all interest in hunting and shooting, his suspicions were aroused. He always kept his ears open when he went to the landing, and by putting together the disjointed scraps of conversation he overheard while he was waiting for his mail, he finally accumulated a mass of evidence against his son Lester that fairly staggered him.

“I couldn’t believe this of you until I went to Gordon and asked him what he knew about it,” continued Mr. Brigham. “Then the whole story came out. Lester, you will have to go away from here.”

“That’s just what I want to do,” exclaimed the boy, in joyous tones. “I never did like this place. It is awful lonely and dull, and there is no one for me to associate with. If I could only go off somewhere on a visit——”

“As I told you, at the start, I have got things[10] fixed for you for four years to come,” said Mr. Brigham. “You ought to have something to do—something that will occupy your mind so completely that you will have no time to be discontented or to think of anything wrong. I have decided to send you to school; and I am sorry I didn’t do it long ago.”

When Lester heard this he threw his cap spitefully down upon the floor, planted his elbow viciously upon the arm of the lounge, and looked very sullen indeed. School-rooms and school-books were his pet aversions.

“I don’t want you to do that,” said he, angrily. “I would much rather stay here.”

“Do you want to grow up in ignorance?” demanded his father.

If Lester had given an honest response to this question it would have been: “No, I don’t want to grow up in ignorance, but I do want to live at my ease. I desire to go to some place where I can find plenty to amuse me, and where I shall have no labor to perform, either mental or manual.” But he did not quite like to say that, and so he said nothing.

“You don’t know a single thing that a boy of[11] your age ought to know,” continued Mr. Brigham. “I have just had a long conversation with Gordon and his two boys.”

Lester looked up with a startled expression on his face. “You haven’t determined to send me to Bridgeport, have you?” he exclaimed.

“I have,” was the decided answer.

“To the military academy?” asked Lester, in louder and more incredulous tones.

“That’s the very place. The systematic drill and training you will there receive, will be of the greatest benefit to you, if you are only willing to profit by them. That school has made men of Don and Bert Gordon already.”

“I should say so,” sneered Lester, suddenly recalling some items of information that had come to him in a round-about way. “Don has been in a constant row with the teachers ever since he has been there.”

“That is not true. He got himself into trouble when he first entered the school, and lost his shoulder-straps by it; but he has toned down wonderfully under the influence of those three boys he brought home with him, and he is bound[12] to make his mark before his four years’ course is completed.”

“But, father, do you know that the teachers are awful hard on the boys—that if a student looks out of the wrong corner of his eye, or breaks the smallest one of the thousand and more rules that he is expected to keep constantly in mind, he is punished for it?” asked Lester, who was almost ready to cry with vexation. It was bad enough, he told himself, to be sent away to any school against his will; but it was worse for his father to select a military academy, and then to hold that embodiment of mischief and rebellion, Don Gordon, up to him as an object worthy of emulation. Lester had no desire to learn the tactics, and he dreaded the discipline to which he knew he would be subjected.

“I heard all about it during my talk with Don and Bert,” replied his father. “A strong hand and plenty of work are just what you need.”

“But do you know that Bert is first sergeant of the company to which I shall probably be assigned, and that one of its corporals is a New York boot-black? Do you want me to obey the orders of a street Arab?”

“He could not have attained to the position he holds unless he had proved himself worthy of it. The majority of the students, however, are the sons of wealthy men, and they are the ones I want you to choose for your associates. Make friends with them and bring some of them home with you, as Don and Bert did, or go home with them, if they ask you. My word for it, you will see plenty of sport there, if you will only do your duty faithfully. Gordon’s boys are impatient to go back; and yet there was a time when Don disliked school as heartily as you do.”

“When shall we start for Bridgeport?”

“A week from next Wednesday. New students are received up to the 13th of the month; so we must make our application two days before the school begins.”

“Of course we’ll not go up on the same boat with the Gordons?”

“Why not? Having been there before, they can save us a great deal of trouble by telling us just where to go and what to do.”

“But I don’t like the idea of traveling in their company. They will snub me every chance they get.”

“You need not borrow any trouble on that score. They have good reasons for disliking you, but if you conduct yourself properly, you will have nothing to fear from them. Now, Lester, promise me that, if you are admitted to that school, you will wake up and try to accomplish something. I will do everything I can to aid and encourage you, and I will begin by putting it in your power to hold your own with the richest student there.”

Lester perfectly understood his father’s last words, and he was considerably mollified by them. If there were anything that could reconcile him to becoming a member of the military academy, it was the knowledge of the fact that a liberal supply of spending money was to be placed at his disposal. Lester’s highest ambition was to be looked up to as a leader among his companions. He had failed to accomplish his object so far as the boys about Rochdale were concerned, but he was pretty sure that he would not fail at Bridgeport. He didn’t, either. His money, which Mr. Brigham might better have kept in his own pocket, brought him to the notice of some uneasy fellows at the academy, who joined him in a daring enterprise, the like of which had never been heard of before.[15] It gave the village people something to talk about, and furnished the law-abiding students with any amount of fun and excitement. In fact the whole school term was crowded so full of thrilling incidents, so many things happened to take their minds off their books, that when the examination was held, some of the best scholars narrowly escaped being dropped from their classes.

“I will do anything I can for you,” repeated Mr. Brigham, seating himself in the nearest chair and taking a newspaper from the table. “If you will go through the four years’ course with flying colors, and come out at the head of your class, I shall be highly gratified, and I assure you that you will lose nothing by it.”

Mr. Brigham fastened his eyes upon his paper, and Lester, taking this as a hint that he had nothing more to say just then, picked up his cap and went out. He made his way directly to his own room, and taking his squirrel rifle down from the antlers that supported it—purchased antlers they were, and not trophies of the boy’s own skill—he buckled a cartridge belt about his waist and left the house. He wanted to go off in the woods by himself and think the matter over; but it is hard[16] to tell why he took his rifle with him, for he had no intention of hunting, and he could not have killed anything if he had. Perhaps it was because he had fallen into the habit of carrying a weapon on his shoulder wherever he went, just as Godfrey and Dan did.

“It is some comfort to know that the governor is not disposed to put me on short allowance,” thought he, as he sat down on a log and rested his rifle across his knees, “and perhaps I can manage to stand it for a while. If I can’t, and father won’t let me come home, I’ll skip out, as Bob Owens did; only I’ll not go into the army. But it can’t be all work and no play up there. There must be some jolly fellows among the students who are in for having a good time now and then, and they are the ones I shall run with. I am sorry Bert is an officer, for he will tyrannize over me in every possible way. I feel disgusted whenever I think of that.”

Lester Brigham was not the only boy in the world who felt disgusted that day. There were three others that we know of. One of them lived away off in Maryland, and the others lived in Rochdale. The last were Don and Bert Gordon.

When their father came into the room in which they were sitting and told them that Mr. Brigham was waiting to see them in the parlor, they followed him lost in wonder, which gave place to a very different feeling when they learned that this visitor had come there to make some inquiries regarding the Bridgeport military academy, with a view of sending his son there. Bert gave truthful replies to all his questions, and so did Don, for the matter of that; but he did not neglect to enlarge upon the severity of the discipline, or to call Mr. Brigham’s attention to the fact that no boy need go to that school expecting to keep pace with his classes, unless he was willing to study hard. Believing that Lester would make trouble one way or another, Don did not want him there, and he hoped to convince Mr. Brigham that the academy at Bridgeport would not at all suit Lester; but he did not succeed. The visitor seemed to believe that military drill was just what his refractory son needed, asked the boys when they were going to start, thanked them for the information they had given him, and took his leave.

“Well, now, I am disgusted,” exclaimed Don;[18] while Bert went over to the window and drummed upon it with his fingers.

“I don’t see how you are going to help yourselves, boys,” said the general. “Lester Brigham has as much right to go to that school as you have.”

“I know that,” replied Don. “But I don’t want him there, all the same.”

“Neither do I,” said Bert. “He will be in my company, and if I make him toe the mark, he will say that I do it because I want to be revenged on him for burning Don’s shooting-box and getting Dave Evans into trouble.”

“Do your duty as a soldier, and let Lester say what he pleases,” said the general.

“Oh! he’ll have to,” exclaimed Don. “If he doesn’t, he will be reported. Bert’s got to walk a chalk line now, and if he makes a false step, off come his diamond and chevrons. It’s some consolation to know that we can’t introduce him to Egan and the rest. They would snub us in a minute if we did, and serve us right, too. A plebe must be content to wait until the upper-class boys get ready to speak to him.”

“Having passed four years of my life in that[19] academy I am not ignorant of that fact,” said the general, after a little pause, during which he recalled to mind how he had once had his face washed in a snow-drift by a couple of second-class boys whom he had presumed to address on terms of familiarity. “But I hope you will do all you can for Lester. Remember how lonely you felt when you first went there, and found yourselves surrounded by those who were utter strangers to you.”

“Oh, we will,” said Bert, while Don scowled savagely but said nothing. “If he will show us that he has come there with the determination to do the best he can, we’ll stand by him; won’t we, Don?”

Of course the latter said they would, but he gave the promise simply because his father desired it, and not because he had any friendly feeling for Lester Brigham.

The other disgusted boy was Egan, who, on this particular day, was pacing up and down the back veranda of his father’s house, shaking his fist at the surf that was rolling in upon the beach, and acting altogether like one whose reflections were by no means agreeable. What it was that had[20] happened to annoy him, we will let him tell in his own way.

Christmas, with its festivities, was now a memory. New Year’s day came and went, and Don and Bert, each in his own way, began making preparations for their return to Bridgeport. The latter, who was determined that the close of another school year should find him with at least one bar on his shoulder, devoted his morning hours to his books, while Don, to quote his own language, proceeded to put himself through a regular course of training. There was a long siege of hard study before him, but one would have thought, by the way he went to work, that he was preparing himself for a physical rather than an intellectual contest. He rode hard, hunted perseveringly, kept up his regular exercise with Indian clubs and dumb-bells, and looked, as he said he felt, as if he were good for any amount of work.

Knowing how valuable a little advice would have been to them when they first joined the academy, Don and Bert rode over to see Lester, intending to give him some idea of the nature of the examination he would have to pass before he would be received as a student, and to drop a few hints[21] that would enable him to keep out of trouble; but they never repeated the experiment. Lester was surly and not at all sociable; and he was so very independent, and seemed to have so much confidence in his ability to make his way without help from anybody, that his visitors took their leave without saying half as much to him as they had intended.

“I know what they are up to,” said Lester, who stood at the window watching Don and Bert as they rode away. “They have reasons for wishing to get on the right side of me. Somebody has probably told them that I am to have plenty of money to spend, and they intend that I shall spend some of it for their own benefit. I am going in for a shoulder-strap—I am not one to be satisfied with a sergeant’s warrant—and the first thing I shall do, after I get it, will be to take those stripes off Bert Gordon’s arms. He and his boot-black can’t order me around.”

This soliloquy will show that Lester had changed his mind in regard to the school at Bridgeport. He wanted to go there now. His father, who knew nothing about the academy beyond what Don and Bert had told him, and who judged it by the fashionable boarding-schools at which he had[22] obtained the little knowledge he possessed, had neglected no opportunity to impress upon Lester’s mind the fact that a rich man’s son would not be allowed to remain long in the ranks, and that there was nothing to prevent him from winning and wearing an officer’s sword, if he would only use a little tact in pushing himself forward. After listening to such counsel as this, it was not at all likely that anything that Don and Bert could say would have any influence with him.

“He thinks he is going to have a walk over,” said Don, as he stroked his pony’s glossy mane.

“It looks that way, but there’s where he is mistaken,” replied Bert. “Lester will be walking an extra before he has been at the academy a week.”

“Well, we’ll not volunteer any more advice, no matter what happens to him,” said Don. “We’ll let him go as he pleases and see how he will come out.”

The day set for their departure came at last, and Don and Bert, accompanied by Mr. Brigham and Lester, set out for Bridgeport, which they reached without any mishap. They rode in the same hack from the depot to the academy, and when they alighted at the door, they were surrounded[23] by a crowd of boys who had already reported for duty, and who made it a point to rush out of the building to extend a noisy welcome to every newcomer. School was not yet in session, and the first-class boys were not above speaking to a plebe.

Among those who were first to greet Don and Bert as they stepped out of the hack, were Egan, Hopkins and Curtis. As these young gentlemen had already completed the regular academic course, perhaps the reader would like to know what it was that brought them back. They came to take what was called the “finishing course,” and to put themselves under technical instruction. After that (it took two years to go through it) Hopkins was to enter a lawyer’s office in Baltimore; Egan intended to become assistant engineer to a relative who was building railroads somewhere in South America; while Curtis was looking towards West Point.

The boys who composed these advanced classes were privileged characters. They dressed in citizens’ clothes, performed no military duty, boarded in the village, and came and went whenever they pleased. When the students went into camp, they were at liberty to go with them, or they could[24] stay at the academy and study. If they chose the camp, they could ask to be appointed aids or orderlies at headquarters, or they could put on a uniform, shoulder a musket, and fall into the ranks. They held no office, and the boy who was lieutenant-colonel last year, was nothing better than a private now.

Don and Bert greeted their friends cordially, and as soon as the latter could free himself from their clutches, he beckoned to Mr. Brigham and Lester, who followed him through the hall and into the superintendent’s room.

“Which one of these trunks do you belong to, Gordon?” inquired a young second-lieutenant, whose duty it was to see that the students were assigned to rooms as fast as they arrived.

“The one with the canvas cover is mine,” replied Don.

“Any preference among the boys?” asked the lieutenant. “You can’t have Bert for a room-mate this term, you know. The second sergeant of his company will be chummed on him.”

Don replied that he didn’t care who he had for a companion, so long as he was a well-behaved boy; whereupon the lieutenant beckoned to a negro porter whom he called “Rosebud,” and directed him to take Don’s trunk up to No. 45, third floor.

“By the way, I suppose that that fellow who[26] has just gone into the superintendent’s room with Bert is a crony of yours?” continued the young officer.

“He is from Mississippi,” said Don. He did not wish to publish the fact that Lester Brigham was no friend of his, for that would prejudice the students against him at once. Lester was likely to have a hard time of it at the best, and Don did not want to say or do anything that would make it harder for him.

“All right,” said the officer. “I will take pains to see that he is chummed on some good fellow.”

“You needn’t put yourself to any trouble for him on my account,” said Don in a low tone, at the same time turning his back upon a sprucely-dressed but rather brazen-faced boy, who persisted in crowding up close to him and Egan, as if he meant to hear every word that passed between them. “He is nothing to me, and I wish he was back where he came from. He’ll wish so too, before he has been here many days. I said everything I could to induce his father to keep him at home, but he——”

“Let’s take a walk as far as the gate,” said Egan, seizing Don by the arm and nodding to[27] Hopkins and Curtis. “You stay here, Enoch,” he added, turning to the sprucely-dressed boy.

“What’s the reason I can’t go too?” demanded the latter.

“Because we don’t want you,” replied Egan, bluntly. “I told you before we left home, that you needn’t expect to hang on to my coat-tails. Make friends with the members of your own company, for they are the only associates you will have after school begins.”

“But they are all strangers to me, and you won’t introduce me,” said Enoch.

“Then pitch in and get acquainted, as I did when I first came here. You may be sure I’ll not introduce you,” said Egan, in a low voice, as he and his three friends walked toward the gate. “An introduction is an indorsement, and I don’t indorse any such fellows as you are.”

“What’s the matter with him?” asked Don, who had never seen Egan so annoyed and provoked as he was at that moment.

“Everything,” replied the ex-sergeant. “He’s the meanest boy I ever met—I except nobody—and if he doesn’t prove to be a second Clarence Duncan, I shall miss my guess.”

“The boy who came here with me will make a good mate for him,” said Don.

“This fellow’s father has only recently moved into our neighborhood,” continued Egan. “He went into ecstasies over my uniform the first time he saw it, and wanted to know where I got it, and how much it cost, and all that sort of thing. Of course I praised the school and everybody and everything connected with it; but I wish now that I had kept still. The next time that I met him he told me that when I returned to Bridgeport he was going with me. I was in hopes he wouldn’t stick, but he did.”

“Mr. Brigham crowded Lester upon Bert and me in about the same way,” said Don.

“Was that Lester Brigham?” exclaimed Curtis—“the boy who burned your old shooting-box and kicked up that rumpus while we were at Rochdale? We often heard you speak of him, but you know we never saw him.”

“He’s the very one,” replied Don.

“Then he will make a good mate for Enoch Williams,” said Egan. “Why, Don, this fellow has been caught in the act of looting ducks on the bay.”

Egan’s tone and manner seemed to indicate that he looked upon this as one of the worst offenses that could be committed, and both he and Hopkins were surprised because Don did not grow angry over it.

“What’s looting ducks?” asked the latter.

“It is a system of hunting pursued by the pot-hunters of Chesapeake bay, who shoot for the market and not for sport. A huge blunderbuss, which will hold a handful of powder and a pound or more of shot, and which is kept concealed during the day-time, is put into the bow of a skiff at night, and carried into the very midst of a flock of sleeping ducks; and sometimes the men who manage it, secure as many as sixty or seventy birds at one discharge. The law expressly prohibits it, and denounces penalties against those who are caught at it.”

“Then why wasn’t Enoch punished?”

“Because everybody is afraid to complain of him or of any one else who violates the law. It isn’t safe to say anything against these duck-shooters, and those who do it are sure to suffer. Their yachts will be bored full of holes, their oyster-beds dragged at night or filled with sharp[30] things for the dredges to catch on, their lobster-pots pulled up and destroyed or carried off, their retrievers shot or stolen—oh, it wouldn’t take long to raise an excitement down there that would be fully equal to that which was occasioned in Rochdale by that mail robbery.”

If the reader will bear these words in mind, he will see that subsequent events proved the truthfulness of them. The professional duck-shooters who played such havoc with the wild fowl in Chesapeake bay, were determined and vindictive men, and it was very easy to get into trouble with them, especially when there were such fellows as Enoch Williams and Lester Brigham to help it along.

The four friends spent half an hour in walking about the grounds, talking over the various exciting and amusing incidents that had happened while they were living in Don Gordon’s Shooting-Box, and then Don went to his dormitory to put on his uniform, preparatory to reporting his arrival to the superintendent. Every train that steamed into the station brought a crowd of students with it, and the evening of the 14th of January found them all snug in their quarters,[31] and ready for the serious business of the term, which was to begin with the booming of the morning gun. All play was over now. There had been guard-mount that morning, sentries were posted on the grounds and in the buildings, and the new students began to see how it seemed to feel the tight reins of military discipline drawn about them. Of course there were a good many who did not like it at all. Events proved that there was a greater number of malcontents in the school this term than there had ever been before. Bold fellows some of them were, too—boys who had always been allowed to do as they pleased at home, and who proceeded to get up a rebellion before they had donned their uniforms. One of them, it is hardly necessary to say, was Lester Brigham. On the morning when the ceremony of guard-mounting was gone through with for the first time, he stood off by himself, muffled up head and ears, and watching the proceeding. Presently his attention was attracted by the actions of a boy who came rapidly along the path, shaking his gloved fists in the air and talking to himself. He did not see Lester until he was close upon him, and then he stopped and looked ashamed.

“What’s the trouble?” asked Lester, who was in no very good humor himself.

“Matter enough,” replied the boy. “I wish I had never seen or heard of this school.”

“Here too,” said Lester. “Are you a new scholar? Then we belong to the same class and company.”

“I wouldn’t belong to any class or company if I could help it,” snapped the boy. “My father didn’t want me to come here, but I insisted, like the dunce I was, and now I’ve got to stay.”

“So have I; but I didn’t come of my own free will. My father made me.”

“Get into any row at home?” asked the boy.

“Well—yes,” replied Lester, hesitatingly.

“I don’t see that it is anything to be ashamed of. You look like a city boy; did the cops get after you?”

“No; I had no trouble with the police, but I thought for a while that I was going to have. I live in the canebrakes of Mississippi, and my name is Lester Brigham. I used to live in the city, and I wish I had never left it.”

“My name is Enoch Williams, and I am from Maryland,” said the other. “I don’t live in a[33] cane-brake, but I live on the sea-shore, and right in the midst of a lot of Yahoos who don’t know enough to keep them over night. Egan is one of them and Hopkins is another.”

“Why, those are two of the boys that Don Gordon brought home with him last fall,” exclaimed Lester. “Do you know them?”

“I know Egan very well. His father’s plantation is next to ours. If he had been anything of a gentleman, I might have been personally acquainted with Hopkins by this time; but, although we traveled in company all the way from Maryland, he never introduced me. Do you know them?”

“I used to see them occasionally last fall, but I have never spoken to either of them,” answered Lester. “By the way, the first sergeant of our company is a near neighbor of mine.”

“Do you mean Bert Gordon? Well, he’s a little snipe. He throws on more airs than a country dancing-master. I have been insulted ever since I have been here,” said Enoch, hotly. “The boys from my own State, who ought to have brought me to the notice of the teachers and of some good fellows among the students, have turned their backs upon me, and told me in[34] so many words, that they don’t want my company.”

“Don and Bert Gordon have treated me in nearly the same way,” observed Lester.

“But, for all that, I have made some acquaintances among the boys in the third class, who gave me a few hints that I intend to act upon,” continued Enoch. “They say the rules are very strict, and that it is of no earthly use for me to try to keep out of trouble. There are a favored few who are allowed to do as they please; but the rest of us must walk turkey, or spend our Saturday afternoons in doing extra duty. Now I say that isn’t fair—is it, Jones?” added Enoch, appealing to a third-class boy who just then came up.

Jones had been at the academy just a year, and of course he was a member of Don Gordon’s class and company. He was one of those who, by the aid of Don’s “Yankee Invention,” had succeeded in making their way into the fire-escape, and out of the building. They failed to get by the guard, as we know, and Jones was court-martialed as well as the rest. His back and arms ached whenever he thought of the long hours he had spent in walking extras to pay for that one night’s fun;[35] and he had made the mental resolution that before he left the academy he would do something that would make those who remained bear him in remembrance. He was lazy, vicious and idle, and quite willing to back up Enoch’s statement.

“Of course it isn’t fair,” said he, after Enoch had introduced him to Lester Brigham. “You needn’t expect to be treated fairly as long as you remain here, unless you are willing to curry favor with the teachers, and so win a warrant or a commission; but that is something no decent boy will do. I can prove it to you. Take the case of Don Gordon: he’s a good fellow, in some respects——”

“There’s where I differ with you,” interrupted Lester. “I have known him for a long time, and I have yet to see anything good about him.”

“I don’t care if you have. I say he’s a good fellow,” said Jones, earnestly. “There isn’t a better boy in school to run with than Don Gordon would be, if he would only get rid of the notion that it is manly to tell the truth at all times and under all circumstances, no matter who suffers by it. He’s as full of plans as an egg is of meat; he is afraid of nothing, and there wasn’t a boy in our set who dared join him in carrying out some[36] schemes he proposed. Why, he wanted to capture the butcher’s big bull-dog, take him up to the top of the building, and then kick him down stairs after tying a tin-can to his tail! He would have done it, too, if any of the set had offered to help him; but I tell you, I wouldn’t have taken a hand in it for all the money there is in America.”

“He must be a good one,” said Enoch, admiringly.

“Oh, he is. We had many a pleasant evening at Cony Ryan’s last winter that we would not have had if Don had not come to our aid; but when the critical moment arrived, he failed us.”

“You might have expected it,” sneered Lester, who could not bear to hear these words of praise bestowed upon the boy he so cordially hated.

“Well, I didn’t expect it. Don was one of the floor-guards that night, and he allowed a lot of us to pass him and go out of the building. When the superintendent hauled him up for it the next day, he acknowledged his guilt, but he would not give our names, although he knew he stood a good chance of being sent down for his refusal. I shall always honor him for that.”

“I wish he had been expelled,” said Lester, bitterly.[37] “Then I should not have been sent to this school.”

“Well, when the examination came off,” continued Jones, “Don was so far ahead of his class that none of them could touch him with a ten-foot pole; and yet he is a private to-day, while that brother of his, who won the good-will of the teachers by toadying to them, wears a first sergeant’s chevrons. Of course such partiality as that is not fair for the rest of us.”

“There isn’t a single redeeming feature about this school, is there?” said Enoch, after a pause. “A fellow can’t enjoy himself in any way.”

“Oh yes, he can—if he is smart and a trifle reckless. He can go to Cony Ryan’s and eat pancakes. I suppose Egan told you of the high old times we had here last winter running the guard, didn’t he?”

“He never mentioned it,” replied Enoch.

“Well, didn’t he describe the fight we had with the Indians last camp?”

“Indians!” repeated Enoch, incredulously, while Lester’s eyes opened with amazement.

“Yes; sure-enough Indians they were too, and not make-believes. We thought, by the way they[38] yelled at us, that they meant business. Why, they raised such a rumpus about the camp that some of our lady guests came very near fainting, they were so frightened. Didn’t Egan tell you how he and Don deserted, swam the creek, went to the show disguised as country boys, and finally fell into the hands of those same Indians who had surrounded the camp and were getting ready to attack us?”

No, Egan hadn’t said a word about any of these things to Enoch, and neither had Don or Bert spoken of them to Lester; although they might have done so if the latter had showed them a little more courtesy when they called upon him at his house. Some of the matters referred to were pleasant episodes in the lives of the Bridgeport students, and the reason why Egan had not spoken of them was because he did not want Enoch to think there was anything agreeable about the institution. He didn’t want him there, because he did not believe that Enoch would be any credit to the school; and so he did with him just as Don and Bert did with Lester: he enlarged upon the rigor of the discipline, the stern impartiality of the instructors, the promptness with which they[39] called a delinquent to account, and spoke feelingly of their long and difficult lessons; but he never said “recreation” once, nor did he so much as hint that there were certain hours in the day that the students could call their own.

“Tell us about that fight,” said Enoch.

“Yes, do,” chimed in Lester. “If there is any way to see fun here, let us know what it is.”

Jones was just the boy to go to with an appeal of this sort. He was thoroughly posted, and if there were any one in the academy who was always ready to set the rules and regulations at defiance, especially if he saw the shadow of a chance for escaping punishment, Jones was the fellow. He gave a glowing description of the battle at the camp; told how the boys ran the guard, and where they went and what they did after they got out; related some thrilling stories of adventure of which the law-breakers were the heroes; and by the time the dinner-call was sounded, he had worked his two auditors up to such a pitch of excitement that they were ready to attempt almost anything.

“You have given me some ideas,” said Enoch, as they hurried toward their dormitories in obedience[40] to the call, “and who knows but they may grow to something? I’ve got to stay here—I had a plain understanding with my father on that point—and I am going to think up something that will yield us some sport.”

“That’s the way I like to hear a fellow talk,” said Jones, approvingly; “and I will tell you this for your encouragement: we care nothing for the risk we shall run in carrying out your scheme, whatever it may be, but before we undertake it, you must be able to satisfy us that we can carry it out successfully. Do that, and I will bring twenty boys to back you up, if you need so many. We are always glad to have fellows like you come among us, for our tricks grow stale after a while, and we learn new ones of you. Don Gordon can think up something in less time than anybody I ever saw; but it would be useless to look to him for help. Egan and the other good little boys have taken him in hand, and they’ll make an officer of him this year; you wait and see if they don’t.”

“Jones gave me some ideas, too,” thought Lester, as he marched into the dining-hall with his company, and took his seat at the table; “but I[41] must say I despise the way he lauded that Don Gordon. Don seems to make friends wherever he goes, and they are among the best, too; while I have to be satisfied with such companions as I can get. I am going to set my wits at work and see if I can’t study up something that will throw that bull-dog business far into the shade.”

Unfortunately for Lester this was easy of accomplishment. He was not obliged to do any very hard thinking on the subject, for a plan was suggested to him that very afternoon. There was but one objection to it: he would have to wait four or five months before it could be carried out.

Lester’s room-mate was a boy who spelled his name Huggins, but pronounced it as though it were written Hewguns. He had showed but little disposition to talk about himself and his affairs, and all Lester could learn concerning him was that he was from Massachusetts, and that he lived somewhere on the sea-coast. He and Lester met in their dormitory after dinner, and while the latter proceeded to put on his hat and overcoat, Huggins threw himself into a chair, buried his hands in his pockets and gazed steadily at the floor.

“What’s the matter?” inquired Lester. “You act as if something had gone wrong with you.”

“Things never go right with me,” was the surly response. “There isn’t a boy in the world who has so much trouble as I do.”

“I have often thought that of myself,” Lester remarked. “Come out and take a walk. Perhaps the fresh air will do you good.”

“I don’t want any fresh air,” growled Huggins. “I want to think. I have been trying all the morning to hit upon something that would enable me to get to windward of my father, and I guess I have got it at last.”

“What do you mean by getting to windward of him?” asked Lester.

“Why, getting the advantage of him. If two vessels were racing, the one that was to windward would have the odds of the other, especially if the breeze was not steady, because she would always catch it first. I guess you don’t know much about the water, do you?”

“I don’t know much about boats,” replied Lester; “but when it comes to hunting, fishing or riding, I am there. I have yet to see the fellow who can beat me.”

“I am fond of fishing,” said Huggins. “I was out on the banks last season. We made a very fine catch, and had a tidy row with the Newfoundland fishermen before we could get our bait.”

“What sort of fish did you take?”

“Codfish, of course.”

“Do you angle for them from the banks?”

“I said on the banks—that is, in shoal water.”

“Oh,” said Lester. “I don’t know anything about that kind of fishing. Did you ever play a fifteen pound brook-trout on an eight-ounce fly-rod?”

“No; nor nobody else.”

“I have done it many a time,” said Lester. “I tell you it takes a man who understands his business to land a fish like that with light tackle. A greenhorn would have broken his pole or snapped his line the very first jerk he made.”

“You may tell that to the marines, but you needn’t expect me to believe it,” said Huggins, quietly. “In the first place, a fly-fisher doesn’t fasten his hook by giving a jerk. He does it by a simple turn of the wrist. In the second place, the Salmo fontinalis doesn’t grow to the weight of fifteen pounds.”

Lester was fairly staggered. He had set out with the intention of giving his room-mate a graphic account of some of his imaginary exploits and adventures (those of our readers who are well acquainted with him will remember that he kept a large supply of them on hand), but he saw that it was time to stop. There was no use in trying to deceive a boy who could fire Latin at him in that way.

“The largest brook-trout that was ever caught was taken in the Rangeley lakes, and weighed a trifle over ten pounds,” continued Huggins. “And lastly, the members of the order Salmonidæ don’t live in the muddy, stagnant bayous you have down South. They want clear cold water.”

“Why do you want to get to windward of your father?” inquired Lester, who thought it best to change the subject.

“To pay him for sending me to this school,” replied Huggins.

“And you think you know how to do it?”

“I do.”

Lester became interested. He took off his hat and overcoat and sat down on the edge of his bed.

“If one might judge by the way you talk and act, you didn’t want to come to this school,” said Lester.

“No, I didn’t,” answered Huggins. “I don’t want to go to any school. The height of my ambition is to become a sailor. I was born in sight of the ocean, and have snuffed its breezes and been tossed about by its waves ever since I can remember. I live near Gloucester, and my father is largely interested in the cod-fishery. He began life as a fisherman, but he owns a good sized fleet now.”

“Didn’t he want you to go to sea?” asked Lester.

“No. He allowed me to go to the banks now and then, but when I told him that I wanted to make a regular business of it, he wouldn’t listen to me. After I got tired of trying to reason with[46] him, I made preparations to run away from home; but he caught me at it, and bundled me off here.”

“What are you going to do about it?”

“I’m not going to stay. I’ve been to school before, but I was never snubbed as I have been since I came to Bridgeport. The idea that a boy of my age should be obliged to say ‘sir’ to every little up-start who wears a shoulder-strap! I’ll not do it.”

“You’d better. If you don’t you will be in trouble continually.”

“Let the trouble come. I’ll get out of its way.”

“How will you do it?”

Huggins shut one eye, looked at Lester with the other, and laid his finger by the side of his nose.

“Oh, you needn’t be afraid to trust me,” said Lester, who easily understood this pantomime. “Those who are best acquainted with me will tell you that I am true blue. I know just how you feel. I don’t like this school any better than you do; I was sent here in spite of all I could say to prevent it. I have been snubbed by the boys in the upper classes because I spoke to them before[47] they spoke to me, and when I see a chance to leave without being caught, I shall improve it.”

“I guess I can rely upon you to keep my secret,” said Huggins, but it is hard to tell how he reached this conclusion. One single glance at that peaked, freckled face, whose every feature bore evidence to the sneaking character and disposition of its owner, ought to have satisfied him that his room-mate was not a boy who could be confided in.

“You may depend upon me every time,” said Lester, earnestly. “I’ll bring twenty good fellows to help you.”

“Oh, I can’t take so many boys with me,” said Huggins, looking up in surprise. “I couldn’t find berths for them.”

“Are you going off on a boat?”

“Of course I am. Some dark night, when all the rest of the fellows are asleep, I am going to slip out of here, take my foot in my hand and draw a bee-line for Oxford; and when I get there, I am going to ship aboard the first sea-going vessel I can find.”

“As a sailor?” exclaimed Lester.

“Certainly. I shall have to go before the[48] mast; but I’ll not stay there, for I can hand, reef and steer as well as the next man, I don’t care where he comes from, and I understand navigation, too.”

Lester was sadly disappointed. He hoped and believed that his room-mate was about to propose something in which he could join him.

“I am sorry I can’t go with you,” said he; “but I don’t want to follow the sea.”

“Of course you don’t, for you belong ashore. I belong on the water, and there’s where I am going. Oxford is two hundred miles from Bridgeport, and that is a long distance to walk through snow that is two feet deep.”

“You can go on the cars,” suggested Lester.

“No, I can’t; unless I steal a ride. My father is determined to keep me here, and consequently he does not allow me a cent of money,” said Huggins; and he proved it by turning all his pockets inside out to show that they were empty.

“He is mean, isn’t he?” said Lester, indignantly. He was about to add that his father had given him a very liberal supply of bills before he set out on his return to Rochdale, but he did not[49] say it, for fear that his friend Huggins might want to borrow a dollar or two.

“But he will find that I am not going to let the want of money stand in my way,” added Huggins. “I saw several nice little yachts in their winter quarters when I was at the wharf the other day, and if it were summer we’d get a party of fellows together, run off in one of them, and go somewhere and have some fun. When the time came to separate, each one could go where he pleased. The rest of you could hold a straight course for home, if you felt like it, and I would go to sea.”

“That’s the very idea,” exclaimed Lester. “I wonder why some of the boys didn’t think of it long ago. When you get ready to go, count me in.”

“I shall not be here to take part in it,” replied Huggins. “I hope to be on deep water before many days more have passed over my head.”

“I am sorry to hear you say so, for you would be just the fellow to lead an expedition like that. But there’s one thing you have forgotten: if you intend to slip away from the academy, you will need help.”

“I don’t see why I should. I shall not stir until every one is asleep.”

“Then you’ll not go out at all. There are sentries posted around the grounds at this moment, and as soon as it grows dark, guards will take charge of every floor in this building. It is easy enough to get by the sentries—I know, for some of the boys told me so—but how are you going to pass these floor-guards when they are watching your room?”

“Whew!” whistled Huggins. “They hold a fellow tight, don’t they?”

“They certainly do; and it is not a very pleasant state of affairs for one who has been allowed to go and come whenever he felt like it. Your best plan would be to ask for a pass. That will take you by the guards, and when you get off the grounds, you needn’t come back.”

“But suppose I can’t get a pass?”

“Then the only thing you can do is to wait until some of your friends are on duty. They will pass you and keep still about it afterward.”

“I haven’t a single friend in the school.”

“You can make some by simply showing the boys that your heart is in the right place. I must[51] go now to meet an engagement; but I will see you later, and if you like, I will introduce you to a few acquaintances I have made since my arrival, every one of whom you can trust.”

As Lester said this, he put on his hat and overcoat and left the room. Huggins had given him an idea, and he wanted to get away by himself and think about it. He did not have time to spend a great deal of study upon it, for as he was about to pass out at the front door, he met Jones, who was just the boy he wanted to see. He was in the company of several members of his class, but a wink and a slight nod of the head quickly brought him to Lester’s side.

“Say, Jones,” whispered the latter, “I understand that there are a good many yachts owned in this village, and that they are in their winter quarters now. When warm weather comes, what would you say to capturing one of them, and going off somewhere on a picnic?”

“Lester, you’re a good one,” exclaimed Jones, admiringly.

“Do you think it could be done?”

“I am sure of it,” replied Jones, who grew enthusiastic at once. “It’s the very idea, and I[52] know the boys will be in for it hot and heavy. It takes the new fellows to get up new schemes. I can see only two objections to it.”

“What are they?” inquired Lester.

“The first is, that we can’t carry it out under four or five months. Couldn’t you think up something that we could go at immediately?”

“I am afraid not,” answered Lester. “Where could we go and what could we do if we were to desert now? We could not sleep out of doors with the thermometer below zero, for we would freeze to death. We must have warm weather for our excursion.”

“That’s so,” said Jones, reflectively. “I suppose we shall have to wait, but I don’t like to, and neither would you if you knew what we’ve got to go through with before the ice is all out of the river. The other objection is, that we have no one among us who can manage the yacht after we capture it.”

“What’s the reason we haven’t?”

“Can you do it?”

“I might. I have taken my own yacht in a pleasure cruise around the great lakes from Oswego to Duluth,” replied Lester, with unblushing[53] mendacity. “It was while I was in Michigan that I killed some of those bears.”

“I didn’t know you had ever killed any,” said Jones, opening his eyes in amazement.

“Oh, yes, I have. They are also abundant in Mississippi, and one day I kept one of them from chewing up Don Gordon.”

“You don’t say so. You and Kenyon ought to be chums; there he is,” said Jones, directing Lester’s attention to a tall, lank young fellow who looked a great deal more like a backwoodsman than he did like a soldier. “He is from Michigan. His father is a lumberman, and Sam had never been out of the woods until a year ago, when he was sent to this school to have a little polish put on him. But he is one of the good little boys. He says he came here to learn and has no time to fool away. Shall I introduce you?”

“By no means,” said Lester, hastily. He did not think it would be quite safe. If his friend Jones made him known to Kenyon as a renowned bear-hunter, the latter might go at him in much the same style that Huggins did, and then there would be another exposure. He could not afford to be caught in many more lies if he hoped to[54] make himself a leader among his companions. “Since Kenyon is one of the good boys, I have no desire to become acquainted with him,” he added. “And, while I think of it, Jones, don’t repeat what I said to you.”

“About the bears? I won’t.”

“Because, if you do, the fellows will say I am trying to make myself out to be somebody, and that wouldn’t be pleasant. After I have been here awhile they will be able to form their own opinion of me.”

“They will do that just as soon as I tell them about this plan of yours,” said Jones. “They’ll say you are the boy they have been waiting for. But you will take command of the yacht, after we get her, will you not?”

“Yes; I’ll do that.”

“It is nothing more than fair that you should have the post of honor, for you proposed it. I will talk the matter up among the fellows before I am an hour older.”

“Just one word more,” said Lester, as Jones was about to move off. “My room-mate is going to desert and go to sea. If I will make you acquainted[55] with him, will you point out to him the boys who will help him?”

“I’ll be glad to do it,” said Jones, readily. “But tell him to keep his own counsel until I can have a talk with him. If he should happen to drop a hint of what he intends to do in the presence of some boys whose names I could mention, they would carry it straight to the superintendent, and then Huggins would find himself in a box.”

“If he runs away, will they try to catch him?” asked Lester.

“To be sure they will. Squads of men will be sent out in every direction, and some of them will catch him too, unless he’s pretty smart. Tell him particularly to look out for Captain Mack. He’s the worst one in the lot. He can follow a trail with all the certainty of a hound, and no deserter except Don Gordon ever succeeded in giving him the slip. Now you take a walk about the grounds, and I will see what my friends think about this yacht business. I will see you again in fifteen or twenty minutes.”

So saying Jones walked off to join his companions, while Lester strolled slowly toward the gate.[56] The latter was highly gratified by the promptness with which his idea (Huggins’s idea, rather) had been indorsed, but he wished he had not said so much about his ability to manage the yacht. He knew as much about sailing as he did about shooting and fishing, that is, nothing at all. He had never seen a pleasure-boat larger than Don Gordon’s. If anybody had put a sail into a skiff and told him it was a yacht, Lester would not have known the difference.

“It isn’t at all likely that my plan will amount to anything,” said Lester, to himself. “I suggested it just because I wanted the fellows to know that there are those in the world who are fully as brave as Don Gordon is supposed to be. But if Jones and his crowd should take me at my word, wouldn’t I be in a fix? What in the name of wonder would I do?”

It was evident that Lester was sadly mistaken in the boys with whom he had to deal, and he received another convincing proof of it before half an hour had passed. By the time he had taken a dozen turns up and down the long path, he saw Jones and Enoch Williams hurrying to meet him. The expression on their faces told him that they[57] had what they considered to be good news to communicate.

“It’s all right, Brigham,” said Jones, in a gleeful voice. “The boys are in for it, as I told you they would be, and desired us to say to you that you could not have hit upon anything that would suit them better. I have been counting noses, and have so far found fifteen good fellows upon whom you can call for help any time you want it. They all agreed with me when I suggested that you ought to have the management of the whole affair.”

“Where did you learn yachting, Brigham?” asked Enoch.

“On the lakes,” replied Lester.

“Then you must be posted. I have heard that they have some hard storms up there occasionally.”

“You may safely say that. It is almost always rough off Saginaw bay,” answered Lester; and that was true, but he did not know it by experience. He had heard somebody say so.

“I am something of a yachtsman myself,” continued Enoch. “I brought my little schooner from Great South Bay, Long Island, around into Chesapeake bay. Of course my father laid the[58] course for me, and kept his weather eye open to see that I didn’t make any mistakes; but I gave the orders myself, and handled the vessel.”

Lester, who had been on the point of entertaining his two friends by telling of some thrilling adventures that had befallen him during his imaginary cruise from Oswego to Duluth, opened his eyes and closed his lips when he heard this. He saw that his chances for making a hero of himself were growing smaller every hour. He was afraid to talk about fishing in the presence of his room-mate; he dared not speak of bears while he was in the hearing of Sam Kenyon; and it would not be at all safe for him to enlarge upon his knowledge of seamanship, for here was a boy at his elbow who had sailed his own yacht on deep water. He was doomed to remain in the background, and to be of no more consequence at the academy than any other plebe. He could see that very plainly.

“There’s a splendid little boat down there near the wharf,” continued Enoch, who was as deeply in love with the water and everything connected with it as Huggins was, although he had no desire to go before the mast. “I bribed her keeper to[59] let me take a look at her the other day, and I tell you her appointments are perfect. I should say that her cabin and forecastle would accommodate about twenty boys. But this is cutter-rigged, and I don’t know anything about vessels of that sort; do you?”

“I’ve seen lots of them,” answered Lester.

“I suppose you have; but did you ever handle one?”

Lester replied that his own boat was a cutter; and when he said it, he had as clear an idea of what he was talking about as he had of the Greek language.

“Then we are all right,” said Enoch. “They look top-heavy to me, and I shouldn’t care to trust myself out in one during a gale, unless there was a sailor-man in charge of her. But if we get her and find that she is too much for us, we can send the yard down and make a sloop of her. It wouldn’t pay to have her capsize with us.”

Lester shuddered at the mere mention of such a thing; and while Enoch continued to talk in this way, filling his sentences full of nautical terms, that were familiar enough to him and quite unintelligible to Lester, the latter set his wits at work to[60] conjure up some excuse for backing out when the critical time came. He was not at all fond of the water, he was afraid to run the risk of capture and punishment, and he sincerely hoped that something would happen to prevent the proposed excursion.

“Of course we can’t decide upon the details until the time for action arrives,” said Jones, at length. “But you have given us something to think of and to look forward to, and we are indebted to you for that. Now, let’s call upon your room-mate and see what we can do to help him.”

Lester led the way to his dormitory, and as he opened the door rather suddenly, he and his companion surprised Huggins in the act of making up a small bundle of clothing. He was startled by this abrupt entrance, and he must have been frightened as well, for his face was as white as a sheet.

“It’s all right, Huggins,” said Lester, who at once proceeded with the ceremony of introduction. “You needn’t be afraid of these fellows.”

“Of course not,” assented Jones. “We know that you intend to take French leave, but it is all right, and if there is any way in which we can[61] help you, we hope you will not hesitate to say so.”

Huggins did not seem to be fully reassured by these words. The pallor did not leave his face, and the visitors noticed that he trembled as he seated himself on the edge of his bed.

“I am obliged to you, but I don’t think I shall need any assistance. This will see me through the lines, will it not?” said Huggins, pulling from his pocket a piece of paper on which was written an order for all guards and patrols to pass private Albert Huggins until half-past nine o’clock. The printed heading showed that it was genuine.

“Yes, that’s all you need to take you by the guards,” said Jones. “And when half-past nine comes, you will be a long way from here, I suppose.”

“I shall be as far off as my feet can carry me by that time,” replied Huggins. “But don’t tell any one which way I have gone, will you?”

“If you were better acquainted with us you would know that your caution is entirely unnecessary,” said Jones. “But you are not going to walk two hundred miles, are you? Why don’t you go by rail?”

“How can I when I have no money?”

“Are you strapped?” exclaimed Enoch. “I can spare you a dollar.”

“I’ll give you another,” said Jones, looking at Lester.

“I’ll—I’ll give another,” said the latter; but he uttered the words with the greatest reluctance. He was always ready to spend money, but he wanted to know, before he parted with it, that it was going to bring him some pleasure in return. As he spoke he made a step toward his trunk, but Huggins earnestly, almost vehemently, motioned him back.

“No, no, boys,” said he, “I’ll not take a cent from any of you. I am used to roughing it, and I shall get through all right. All I ask of you is to keep away so as not to direct attention to me. How soon will my absence be discovered?”

“That depends upon the floor-guard,” answered Jones. “If he is one of those sneaking fellows who is forever sticking his nose into business that does not concern him, he will report your absence to the officer of the guard when he makes his rounds at half-past nine. If the floor-guard keeps his mouth shut, no one will know you are gone[63] until the morning roll is called. In any event no effort will be made to find you until to-morrow.”

“And then I may expect to be pursued, I suppose?”

“You may; and if you are not caught, it will be a wonder. Every effort will be made to capture you, for don’t you see that if you were permitted to escape, other boys would be encouraged to take French leave in the same way? Now, listen to me, and I will give you some advice that may be of use to you.”

If his advice, which was given with the most friendly intentions, had been favorably received, Jones would have said a good deal more than he did; but he very soon became aware that his words of warning were falling on deaf ears. Huggins was not listening to him. He was unaccountably nervous and excited, and Jones, believing that he would be better pleased by their absence than he was with their company, gave the signal for leaving by picking up his cap. He lingered long enough to shake hands with Huggins and wish him good luck in outwitting his pursuers and finding a vessel, and then he went out, followed by Enoch and Lester.

“How strangely he acted!” said the latter.

“Didn’t he?” exclaimed Enoch. “He seemed frightened at our offer to give him a few dollars to help him along. What was there wrong in that? If I had been in his place I would not have refused. Now he can take his choice between begging his food and going hungry.”

“I don’t envy him his long, cold walk,” observed Jones. “And where is he going to find a bed when night comes? The people in this country don’t like tramps any too well, and the first time he stops at a farm-house he may be interviewed by a bull-dog.”

Lester did not find an opportunity to talk with his room-mate again that day. They marched down to supper together, and as soon as the ranks were broken, Huggins made all haste to put on his hat and overcoat, secure his bundle and quit the room. He would hardly wait to say good-by to Lester, and didn’t want the latter to go with him as far as the gate.

“He’s well out of his troubles, and mine are just about to begin,” thought Lester, as he stood on the front steps and saw Huggins disappear in the darkness. “I would run away myself if I[65] were not afraid of the consequences. It wouldn’t be safe to try father’s patience too severely, for there is no telling what he would do to me.”

Lester strolled about until the bugle sounded “to quarters,” and then he went up to his room, where he passed a very lonely evening. No one dared to come near him, and if he had attempted to leave his room, he would have been ordered back by the floor-guard. He knew he ought to study, but still he would not do it. It would be time enough, he thought, to take up his books, when he could see no way to get out of it.

Lester went to bed long before taps, and slept soundly until he was aroused by the report of the morning gun, and the noise of the fifes and drums in the drill-room. Having been told that he would have just six minutes in which to dress, he got into his clothes without loss of time, and fell into the ranks just as the last strains of the morning call died away.

“Fourth company. All present or accounted for with the exception of Private Albert Huggins,” said Bert Gordon, as he faced about and raised his hand to his cap.

“Where is Private Huggins?” demanded Captain Clayton.

“I don’t know, sir. He had a pass last night, and he seems to have abused it. At any rate he is not in the ranks to answer to his name.”

Captain Clayton reported to the adjutant, who in turn reported to the officer of the day, and then the ranks were broken, and the young soldiers hurried to their dormitories to wash their hands and faces, comb their hair, and get ready for morning inspection. While Bert and his room-mate were thus engaged, an orderly opened the door long enough to say that Sergeant Gordon was wanted in the superintendent’s office.

“Hallo!” exclaimed Sergeant Elmer—that was the name and rank of Bert’s room-mate—“you are going out after Huggins, most likely. If you have the making up of the detail don’t forget me.”

Bert said he wouldn’t, and hastened out to obey the summons. As he was passing along the hall he was suddenly confronted by Lester Brigham, who jerked open the door of his room and shouted “Police! Police!” at the top of his voice.

“What’s the matter with you?” exclaimed Bert, wondering if Lester had taken leave of his senses.

“I’ve been robbed!” cried Lester, striding up and down the floor, in spite of all Bert could do to quiet him. “That villain Huggins broke open my trunk and took a clean hundred dollars in money out of it.”

Lester’s wild cries had alarmed everybody on that floor, and the hall was rapidly filling with students who ran out of their rooms to see what was the matter.

“Go back, boys,” commanded Bert. “You have not a moment to waste. If your rooms are not ready for inspection you will be reported and punished for it. Go back, every one of you.”

He emphasized this order by pulling out his note-book and holding his pencil in readiness to write down the name of every student who did not yield prompt obedience. The boys scattered in every direction, and when the hall was cleared, Bert seized Lester by the arm and pulled him into his room.

“No yelling now,” said he sternly.

“Must I stand by and let somebody rob me without saying a word?” vociferated Lester.

“By no means; but you can act like a sane boy and report the matter in a quiet way, can’t you? Now explain, and be quick about it, for the superintendent wants to see me.”

“Why, Huggins has run away—he intended to do it when he got that pass last night—and he has taken every dollar I had in the world to help himself along. Just look here,” said Lester, picking up the hasp of his trunk which had been broken in two in the middle. “Huggins did that yesterday, and I never knew it until a few minutes ago. I went to my trunk to get out a clean collar, and then I found that the hasp was broken, and that my clothes were tumbled about in the greatest[69] confusion. I looked for my money the first thing, but it was gone.”

“Don’t you know that it is against the rules for a student to have more than five dollars in his possession at one time?” asked Bert. “If you had lived up to the law and given your money into the superintendent’s keeping, you would not have lost it.”

“What do I care for the law?” snarled Lester.

“You ought to care for it. If you didn’t intend to obey it, you had no business to sign the muster-roll.”

“Well, who’s going to get my hundred dollars back for me? That’s what I want to know,” cried Lester, who showed signs of going off into another flurry.

“I don’t know that any one can get it back for you,” said Bert quietly. “It is possible that you may never see it again.”

“Then I’ll see some more just like it, you may depend upon that,” said Lester, walking nervously up and down the floor and shaking his fists in the air. “I was robbed in the superintendent’s house, and he is bound to make my loss good.”

“There’s where you are mistaken. You took your own risk by disobeying the rules——”

“The money was mine and the superintendent had no more right to touch it than you had,” interrupted Lester. “My father gave it to me with his own hands, because he wanted I should have a fund by me that I could draw on without asking anybody’s permission.”

“Well, you see what you made by it, don’t you? How do you know that Huggins has run away?”

“He told me he was going to. I offered to give him a dollar to help him along, and so did Jones and Williams.”

“You ought not to have done that.”

“I don’t care; I did it, and this is the way he repaid me. I’ll bet he had my money in his pocket when he refused my offer. I thought he acted queer, and so did the other boys.”

“Do you know which way he intended to go?”

“He said he was going to draw a bee-line for Oxford, and ship on the first vessel he could find that would take him to sea. Are you going after him?” inquired Lester, as Bert turned toward the door. “Look here: if you will follow him[71] up and get my money back for me, I’ll—I’ll lend you five dollars of it, if you want it.”

Lester was about to say that he would give Bert that amount, but he caught his breath in time, and saved five dollars by it. He knew very well that Bert would never be obliged to ask him for money.

The sergeant hurried down to the superintendent’s office, where he found the officer of the day, who had just been making his report.

“I understand that Private Huggins abused my confidence, and that he stayed out all night on the pass I gave him yesterday,” said the superintendent, after returning Bert’s salute. “Perhaps you had better take a corporal with you, and look around and see if you can find any traces of him.”

Bert was delighted. Here was an opportunity for him to win a reputation.

“Shall I go to Oxford, sir?” said he.

“To Oxford?” repeated the superintendent, while the officer of the day looked surprised.

“Yes, sir. There’s where he has gone.”

“How do you know?”

“His room-mate told me so. He has run away intending to go to sea.”

“Well, well! It is more serious than I thought,” said the superintendent, while an expression of annoyance and vexation settled on his face. “He must be brought back. Was he going to walk all that distance or steal a ride on the cars? He has no money, and his father took pains to tell me that none would be allowed him.”

“He has plenty of it, sir,” replied Bert. “He broke into Private Brigham’s trunk and took a hundred dollars from it.”

The superintendent could hardly believe that he had heard aright.

“That is the most disgraceful thing that ever happened in this school,” said he, as soon as he could speak. “I didn’t suppose there was a boy here who could be guilty of an act of that kind. Sergeant,” he added, looking at his watch, “you have just fifteen minutes in which to reach the depot and ascertain whether or not Huggins took the eight o’clock train for Oxford last night. Learn all you can, and go with the squad which I shall at once send in pursuit of him.”

“Very good, sir,” replied Bert.

“Can I go?” asked Sergeant Elmer, as Bert[73] ran into his room and snatched his overcoat and cap from their hooks.

“I hope so, but I am afraid not. The superintendent will make up the detail himself or appoint some shoulder-strap to do it, and it isn’t likely that he will take two sergeants from the same company. You will have to act in my place while I am gone.”

“Well, good-by and good luck to you,” said the disappointed Elmer.

Bert hastened down the stairs and out of the building, and at the gate he found the officer of the day who had come there to pass him by the sentry. As soon as he had closed the gate behind him, he broke into a run, and in a few minutes more he was walking back and forth in front of the ticket-office, conversing with a quiet looking man who was to be found there whenever a train passed the depot. He was a detective.

“Good morning, Mr. Shepard,” said Bert. “Were you on duty when No. 6 went down last night?”

No. 6 was the first southward bound train that passed through Bridgeport after Huggins left the academy grounds.

“I was,” answered the detective. “Was that fellow I came pretty near running in last night on general principles one of your boys?”

“I can’t tell until you describe him,” said Bert.

“There was nothing wrong about his appearance, but I didn’t like the way he acted,” observed the detective. “He looked as though he had been up to something. He didn’t buy a ticket, and he took pains to board the train from the opposite side. He wore a dark-blue overcoat, Arctic shoes, seal-skin cap, gloves and muffler, and had something on his upper lip that looked like a streak of free-soil, but which, perhaps, on closer examination might have proved to be a mustache.”

“That’s the fellow,” said Bert. “Did he go toward Oxford?”

“He did. Do you want him? What has he been doing?”

“I do want him, for he is a deserter,” replied Bert. He said nothing about the crime of which Huggins was guilty. The superintendent had not told him to keep silent in regard to it, but he knew he was expected to do it all the same.

“Then I am glad I didn’t run him in,” said Mr. Shepard. “You boys always see plenty of fun[75] when you are out after deserters. But you can’t take that big fellow alone. He’ll pick you up and chuck you head first into a snow-drift.”

“There are one or two fellows in that squad whom he can’t chuck into a snow-drift,” said Bert, pointing with his thumb over his shoulder toward the door.

The detective looked, and saw a party of students coming into the depot at double time. They were led by Captain (formerly Corporal) Mack, who, having been permitted to choose his own men, had detailed Curtis, Egan, Hopkins, and Don Gordon to form his squad. A long way behind them came the old German professor, Mr. Odenheimer, who was very red in the face and puffing and blowing like a porpoise. The fleet-footed boys had led him a lively race, and they meant to do it, too. They didn’t want him along, for his presence was calculated to rob them of much of the pleasure they would otherwise have enjoyed. He was jolly and good-natured when off duty, but still pompous and rather overbearing, and if Huggins were captured and Lester Brigham’s money returned to him, the honor of the achievement would fall to him, and not to Captain Mack and his men.