Title: The Jeffersonians, 1801-1829

Editor: Richard B. Morris

James Leslie Woodress

Release date: December 6, 2019 [eBook #60854]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

VOICES FROM AMERICA’S PAST

WEBSTER PUBLISHING COMPANY

ST. LOUIS ATLANTA DALLAS

The selections by Margaret Bayard Smith, from Forty Years of Washington Society, edited by Gaillard Hunt, which begin on pages 2 and 22, were reprinted through the courtesy of Charles Scribner’s Sons.

The picture on the cover and the picture on page 1, of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, were reprinted through the courtesy of the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company of Boston, Massachusetts. The picture on page 22, of the Constitution and the Guerrière, was reprinted through the courtesy of the New York Public Library. The picture of a political speaker on the Fourth of July on page 37 and the picture of John Quincy Adams on page 56 were reprinted through the courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The early part of the last century was an exciting time to live in America. The signers of the Declaration of Independence and the framers of the Constitution, mostly old men by now, saw that their experiment in republican government had turned out to be a success. The nation was flourishing in these years like a healthy adolescent. There were growing pains, to be sure, but no one doubted now that the youngster would reach manhood. The question was: What is he going to be like?

The party battles of John Adams’ administration left the Federalist Party in ruins, and Thomas Jefferson succeeded to the presidency with an overwhelming popular mandate. During his first term, Jefferson increased his popularity through buying from France the enormous Louisiana Territory which doubled the size of the United States. By the time the Lewis and Clark Expedition returned from exploring the new land, people began to realize the immense possibilities that the Louisiana Purchase held for the future of the United States.

Jefferson’s second term was beset by foreign problems that culminated eventually in the War of 1812, during James Madison’s administration. Despite George Washington’s advice in his Farewell Address to stay out of entangling foreign alliances, America could not avoid being affected by events abroad. She was caught between the hammer and the anvil during Napoleon’s wars with the rest of Europe. The War of 1812 settled no issues but, soon afterward, the main Anglo-American problems left over from the Revolution were adjusted. Napoleon’s downfall at Waterloo removed France as an obstacle to American development.

The period known as the “Era of Good Feeling” followed the War of 1812. During the two terms of James Monroe, internal matters were the main concern of the country: tariffs, banking, domestic improvements, the admission of new states into the Union. With the Monroe Doctrine, which warned Europe to respect the independence of Latin America, the United States began to emerge as a power in the world. Even more important was the appearance of storm warnings heralding the eventual coming of the Civil War. The Missouri Compromise, which drew a line between slave and free territory, established an uneasy truce between the North and the South.

By the time John Quincy Adams became the sixth President, sectionalism was rapidly developing, and the balance of power between the East and the West, the industrial North and the agricultural South, was beginning to shift. The two-party system, which had largely disappeared with the collapse of the Federalists in 1800, was revived. In 1828 the long monopoly that Virginia and Massachusetts had enjoyed in supplying American Presidents came to an end with the election of Andrew Jackson of Tennessee and a new era began.

The selections in this booklet reflect most of the significant events of these years from 1801 to 1829. The Louisiana Purchase, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the War of 1812, the Missouri Compromise, all are represented. In addition we have included accounts of some small events and background descriptions which give the flavor of the age. A proper notion of this period requires not only a knowledge of the major issues, such as understanding the Embargo Act or the significance of the Marbury vs. Madison decision, but also an appreciation of the quality of the experience of being an American in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Hence we have used such documents as Lorenzo Dow’s diary describing the life of a frontier preacher and Morris Birkbeck’s account of settling in Illinois.

In editing the manuscripts in this booklet, we have followed the practice of modernizing punctuation, capitalization, and spelling only when necessary to make the selections clear. We have silently corrected misspelled words and typographical errors. Wherever possible we have used complete selections, but occasionally space limitations have made necessary cuts in the original documents. Such cuts are indicated by spaced periods. In general, the selections appear as the authors wrote them.

Richard B. Morris James Woodress

The Lewis and Clark expedition

On election day in 1800, Thomas Jefferson won a clear victory over John Adams but almost did not became President. The Constitution required that presidential electors cast two ballots; the winner became President and the runner-up became Vice-President. Jefferson’s running mate, Aaron Burr, who had been nominated for Vice-President, received 73 electoral votes, the same number as Jefferson. This strange situation occurred because the Constitutional Convention had not anticipated the rise of party politics. When John Adams had defeated Jefferson in 1796, Jefferson, as the runner-up, was elected Vice-President. If parties had not developed by 1800, Adams, as Jefferson’s opponent, would surely have become Vice-President. But because parties had arisen, all 2 of Jefferson’s electors gave Burr their second vote. (A repetition of this kind of deadlock was avoided for future elections by the Twelfth Amendment.)

The Constitution stated that if the two leading candidates were tied, the election should be decided by the House of Representatives. The trouble was that in 1800 the House was controlled by the Federalists and not by Jefferson’s party. The Federalists nearly elected Burr President because they disliked him less than they disliked Jefferson.

Fortunately for the country, Federalist Alexander Hamilton, who knew Burr was unfit to be President, opposed his party’s plan to defeat Jefferson. But while this crucial decision was being made, the nation waited breathlessly. The excitement in Washington is recorded in the following selection from the notebook of Margaret Bayard Smith, wife of the editor of the National Intelligencer.

It was an awful crisis. The people, who with such an overwhelming majority had declared their will, would never peaceably have allowed the man of their choice to be set aside and the individual they had chosen as Vice-President to be put in his place. A civil war must have taken place, to be terminated in all human probability by a rupture of the Union. Such consequences were at least calculated on and excited a deep and inflammatory interest. Crowds of anxious spirits from the adjacent county and cities thronged to the seat of government and hung like a thunder cloud over the Capitol, their indignation ready to burst on any individual who might be designated as President in opposition to the people’s known choice. The citizens of Baltimore, who from their proximity were the first apprised of this daring design, were with difficulty restrained from rushing on with an armed force, to prevent—or if they could not prevent, to avenge this violation of the people’s will and in their own vehement language to hurl the usurper from his seat.

Mr. Jefferson, then President of the Senate, sitting in the midst of these conspirators, as they were then called, unavoidably hearing their loudly whispered designs, witnessing their gloomy and restless machinations, aware of the dreadful consequences which must follow their meditated designs, preserved through this trying 3 period the most unclouded serenity, the most perfect equanimity. A spectator who watched his countenance would never have surmised that he had any personal interest in the impending event. Calm and self-possessed, he retained his seat in the midst of the angry and stormy, though half-smothered passions that were struggling around him, and by this dignified tranquility repressed any open violence. Though insufficient to prevent whispered menaces and insults, to these, however, he turned a deaf ear and resolutely maintained a placidity which baffled the designs of his enemies.

The crisis was at hand. The two bodies of Congress met, the Senators as witnesses, the Representatives as electors. The question on which hung peace or war, nay, the union of the states was to be decided. What an awful responsibility was attached to every vote given on that occasion. The sitting was held with closed doors. It lasted the whole day, the whole night. Not an individual left that solemn assembly; the necessary refreshment they required was taken in rooms adjoining the Hall. They were not like the Roman conclave legally and forcibly confined; the restriction was self-imposed from the deep-felt necessity of avoiding any extrinsic or external influence. Beds, as well as food, were sent for the accommodation of those whom age or debility disabled from enduring such a long-protracted sitting. The balloting took place every hour—in the interval men ate, drank, slept or pondered over the result of the last ballot, compared ideas and persuasions to change votes, or gloomily anticipated the consequences, let the result be what it would.

With what an intense interest did every individual watch each successive examination of the ballot-box; how breathlessly did they listen to the counting of the votes! Every hour a messenger brought to the editor of the National Intelligencer the result of the ballot. That night I never lay down or closed my eyes. As the hour drew near its close, my heart would almost audibly beat, and I was seized with a tremour that almost disabled me from opening the door for the expected messenger....

For more than thirty hours the struggle was maintained, but finding the Republican phalanx impenetrable, not to be shaken in their purpose, every effort proving unavailing, the Senator from Delaware [James A. Bayard—actually a Representative], the 4 withdrawal of whose vote would determine the issue, took his part, gave up his party, for his country, and threw into the box a blank ballot, thus leaving to the Republicans a majority. Mr. Jefferson was declared duly elected. The assembled crowds, without the Capitol, rent the air with their acclamations and gratulations, and the conspirators, as they were called, hurried to their lodgings under strong apprehensions of suffering from the just indignation of their fellow citizens.

The dark and threatening cloud which had hung over the political horizon rolled harmlessly away, and the sunshine of prosperity and gladness broke forth and ever since, with the exception of a few passing clouds, has continued to shine on our happy country.

As the author of the Declaration of Independence and many memorable state papers, Thomas Jefferson was, with Abraham Lincoln, one of our two greatest presidential writers. The following speech, which he delivered on March 4, 1801, is an eloquent statement of democratic principles. Jefferson approached the office of President with humility and a conciliatory attitude towards his opponents. The simplicity and directness of his prose contrast greatly with the flowery and lengthy eloquence of most speakers in his day.

Friends and Fellow Citizens:

Called upon to undertake the duties of the first executive office of our country, I avail myself of the presence of that portion of my fellow citizens which is here assembled to express my grateful thanks for the favor with which they have been pleased to look towards me, to declare a sincere consciousness that the task is above my talents and that I approach it with those anxious and awful presentiments which the greatness of the charge and the weakness of my powers so justly inspire.

A rising nation spread over a wide and fruitful land, traversing all the seas with the rich productions of their industry, engaged in commerce with nations who feel power and forget right, advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of mortal eye; when I contemplate 5 these transcendent objects and see the honor, the happiness, and the hopes of this beloved country committed to the issue and the auspices of this day, I shrink from the contemplation and humble myself before the magnitude of the undertaking.

Utterly indeed should I despair, did not the presence of many whom I here see remind me that in the other high authorities provided by our Constitution, I shall find resources of wisdom, of virtue, and of zeal, on which to rely under all difficulties.

To you then, gentlemen, who are charged with the sovereign functions of legislation and to those associated with you, I look with encouragement for that guidance and support which may enable us to steer with safety the vessel in which we are all embarked amidst the conflicting elements of a troubled sea.

During the contest of opinion through which we have passed, the animation of discussions and of exertions, has sometimes worn an aspect which might impose on strangers unused to think freely and to speak and to write what they think.

But this being now decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the Constitution, all will of course arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good. All too will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable: that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate would be oppression.

Let us then, fellow citizens, unite with one heart and one mind; let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection, without which liberty and even life itself are but dreary things.

And let us reflect that having banished from our land that religious intolerance under which mankind so long bled and suffered we have yet gained little, if we countenance a political intolerance as despotic, as wicked, and capable of as bitter and bloody persecution.

During the throes and convulsions of the ancient world, during the agonized spasms of infuriated man, seeking through blood and slaughter his long lost liberty, it was not wonderful that the agitation of the billows should reach even this distant and peaceful 6 shore; that this should be more felt and feared by some, and less by others, and should divide opinions as to measures of safety.

But every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called, by different names, brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans: we are all federalists.

If there be any among us who wish to dissolve this union, or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed, as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.

I know indeed that some honest men have feared that a republican government cannot be strong; that this government is not strong enough. But would the honest patriot, in the full tide of successful experiment abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm, on the theoretic and visionary fear that this government, the world’s best hope may, by possibility, want energy to preserve itself?

I trust not. I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest government on earth.

I believe it the only one where every man, at the call of the law, would fly to the standard of the law; would meet invasions of public order, as his own personal concern.

Sometimes it is said that man cannot be trusted with the government of himself. Can he then be trusted with the government of others? Or have we found angels in the form of kings to govern him? Let history answer this question.

Let us then pursue with courage and confidence our own federal and republican principles, our attachment to union and representative government.

Kindly separated by nature, and a wide ocean, from the exterminating havoc of one quarter of the globe; too high-minded to endure the degradations of the others; possessing a chosen country, with room enough for our descendants to the thousandth and thousandth generation; entertaining a due sense of our equal right, to the use of our own faculties, to the acquisitions of our own industry, to honor and confidence from our fellow citizens resulting not from birth, but from our actions and their sense of them, enlightened by a benign religion, professed indeed and practiced in various 7 forms, yet all of them inculcating honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude, and the love of man, acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here and his greater happiness hereafter.

With all these blessings, what more is necessary to make us a happy and a prosperous people? Still one thing more, fellow citizens, a wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.

This is the sum of good government, and this is necessary to close the circle of our felicities.

The feud between Hamilton and Burr preceded the election of 1800, in which Hamilton opposed Burr’s election to the presidency. The rivalry between these two New Yorkers actually had begun during the Revolution and had continued throughout their political careers, but it reached a special intensity in 1800. As Vice-President under Jefferson, Burr had reached the peak of his career, but Jefferson, realizing that Burr almost had schemed his way into the presidency, undermined his influence in the Republican Party. In 1804, Hamilton again thwarted Burr’s ambitions by helping to defeat him for governor of New York. The duel soon followed.

Hamilton had no intention of firing at Burr and seems to have expected to die, for he made his will and arranged his affairs before crossing the Hudson River to New Jersey for the fatal duel on July 11, 1804. Burr had great charm and undenied ability, but it might have been better for him if he had died that day instead of Hamilton. He was an unscrupulous intriguer, and his subsequent career tarnished his reputation. In 1805, he tried to establish a political empire in the Mississippi Valley but he was captured and tried for treason. Though he was acquitted, he had to spend the next four years in exile. He later returned to an obscure law practice in New York.

In the selection that follows, David Hosack, the physician who attended Hamilton at the duel, describes the scene immediately after Burr 8 fired the fatal shot. He writes to William Coleman, editor of the New York Post, the paper Hamilton had founded.

To comply with your request is a painful task; but I will repress my feelings while I endeavor to furnish you with an enumeration of such particulars relative to the melancholy end of our beloved friend Hamilton, as dwell most forcibly on my recollection.

When called to him, upon his receiving the fatal wound, I found him half sitting on the ground, supported in the arms of Mr. Pendleton. His countenance of death I shall never forget. He had at that instant just strength to say, “This is a mortal wound, Doctor”; when he sunk away, and became to all appearance lifeless. I immediately stripped up his clothes, and soon, alas! ascertained that the direction of the ball must have been through some vital part. His pulses were not to be felt; his respiration was entirely suspended; and upon laying my hand on his heart, and perceiving no motion there, I considered him as irrecoverably gone. I however observed to Mr. Pendleton that the only chance for his reviving was immediately to get him upon the water.

We therefore lifted him up, and carried him out of the wood, to the margin of the bank, where the bargemen aided us in conveying him into the boat, which immediately put off. During all this time I could not discover the least symptom of returning life. I now rubbed his face, lips, and temples, with spirits of hartshorn, applied it to his neck and breast, and to the wrists and palms of his hands, and endeavored to pour some into his mouth. When we had got, as I should judge, about fifty yards from the shore, some imperfect efforts to breathe were for the first time manifest. In a few minutes he sighed, and became sensible to the impression of the hartshorn, or the fresh air of the water. He breathed; his eyes, hardly opened, wandered, without fixing upon any objects. To our great joy he at length spoke: “My vision is indistinct,” were his first words. His pulse became more perceptible; his respiration more regular; his sight returned.

... Soon after recovering his sight, he happened to cast his eye upon the case of pistols, and observing the one that he had 9 had in his hand lying on the outside, he said, “Take care of that pistol; it is undischarged, and still cocked; it may go off and do harm.—Pendleton knows (attempting to turn his head towards him) that I did not intend to fire at him.” “Yes,” said Mr. Pendleton, understanding his wish, “I have already made Dr. Hosack acquainted with your determination as to that.”... Perceiving that we approached the shore, he said, “Let Mrs. Hamilton be immediately sent for. Let the event be gradually broken to her; but give her hopes.”

Looking up, we saw his friend Mr. Bayard standing on the wharf in great agitation. He had been told by his servant that General Hamilton, Mr. Pendleton, and myself, had crossed the river in a boat together, and too well he conjectured the fatal errand, and foreboded the dreadful result. Perceiving, as we came nearer, that Mr. Pendleton and myself only sat up in the stern sheets, he clasped his hands together in the most violent apprehension; but when I called to him to have a cot prepared, and he at the same moment saw his poor friend lying in the bottom of the boat, he threw up his eyes and burst into a flood of tears and lamentation. Hamilton alone appeared tranquil and composed. We then conveyed him as tenderly as possible up to the house. The distresses of this amiable family were such that till the first shock was abated, they were scarcely able to summon fortitude enough to yield sufficient assistance to their dying friend.

... During the night he had some imperfect sleep; but the succeeding morning his symptoms were aggravated, attended, however, with a diminution of pain. His mind retained all its usual strength and composure. The great source of his anxiety seemed to be in his sympathy with his half-distracted wife and children. He spoke to her frequently of them. “My beloved wife and children,” were always his expressions. But his fortitude triumphed over his situation, dreadful as it was. Once, indeed, at the sight of his children brought to the bedside together, seven in number, his utterance forsook him. He opened his eyes, gave them one look, and closed them again till they were taken away. As a proof of his extraordinary composure of mind, let me add that he alone could calm the frantic grief of their mother. “Remember, my Eliza, you are a Christian,” were the expressions with which he frequently, 10 with a firm voice, but in a pathetic and impressive manner, addressed her. His words, and the tone in which they were uttered, will never be effaced from my memory. At about two o’clock, as the public well knows, he expired.

The duel between the former Secretary of the Treasury and the Vice-President provided high drama, but far more important was an event that had occurred the year before in Washington. This event was a Supreme Court decision written by Chief Justice Marshall, the decision known as Marbury vs. Madison. It established the principle that the Supreme Court may declare unconstitutional any law passed by Congress that conflicts with the Constitution. This principle has become so well accepted today that we can hardly realize it ever had to be stated. Its effect, however, was to strengthen the system of checks and balances between the three main branches of our government.

Marbury was an obscure justice of the peace, appointed by President Adams just before his term expired. The lame-duck Federalist administration went out of office before Marbury received his commission, and Marbury appealed to the Supreme Court to force James Madison, the new Secretary of State, to give it to him. The Supreme Court declared that Marbury deserved his commission but that it could not grant it. The reason was that the law saying the Court could do this was contrary to the Constitution and therefore invalid. In the portion of the decision that follows, Chief Justice Marshall argues the principle that Congress may not give powers not specifically authorized by the Constitution to the courts or to anyone else.

The question whether an act, repugnant [opposed] to the Constitution, can become the law of the land is a question deeply interesting to the United States but, happily, not of an intricacy proportioned to its interest. It seems only necessary to recognize certain principles, supposed to have been long and well established, to decide it.

That the people have an original right to establish, for their 11 future government, such principles as, in their opinion, shall most conduce to their own happiness is the basis on which the whole American fabric has been erected. The exercise of this original right is a very great exertion; nor can it, nor ought it, to be frequently repeated. The principles, therefore, so established are deemed fundamental. And as the authority from which they proceed is supreme, and can seldom act, they are designed to be permanent.

This original and supreme will organizes the government and assigns to different departments their respective powers. It may either stop here or establish certain limits not to be transcended by those departments.

The government of the United States is of the latter description. The powers of the legislature are defined and limited; and that those limits may not be mistaken or forgotten, the Constitution is written. To what purpose are powers limited, and to what purpose is that limitation committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time, be passed by those intended to be restrained? The distinction between a government with limited and unlimited powers is abolished if those limits do not confine the persons on whom they are imposed, and if acts prohibited and acts allowed are of equal obligation. It is a proposition too plain to be contested that the Constitution controls any legislative act repugnant to it or that the legislature may alter the Constitution by an ordinary act.

Between these alternatives there is no middle ground. The Constitution is either a superior paramount law, unchangeable by ordinary means, or it is on a level with ordinary legislative acts and, like other acts, is alterable when the legislature shall please to alter it.

If the former part of the alternative be true, then a legislative act contrary to the Constitution is not law; if the latter part be true, then written constitutions are absurd attempts, on the part of the people, to limit a power in its own nature illimitable.

Certainly, all those who have framed written constitutions contemplate them as forming the fundamental and paramount law of the nation, and, consequently, the theory of every such government must be, that an act of the legislature repugnant to the Constitution is void.

Marshall goes on to refute the argument that the Supreme Court should concern itself only with interpreting the law, regardless of the Constitution. Then he quotes specific passages from the Constitution:

It is declared that “no tax or duty shall be laid on articles exported from any state.” Suppose a duty on the export of cotton, of tobacco, or of flour; and a suit instituted to recover it. Ought judgment to be rendered in such a case? Ought the judges to close their eyes on the Constitution and only see the law?...

“No person,” says the Constitution, “shall be convicted of treason, unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court.” Here the language of the Constitution is addressed especially to the courts. It prescribes directly for them, a rule of evidence not to be departed from. If the legislature should change that rule and declare one witness, or a confession out of court, sufficient for conviction, must the constitutional principle yield to the legislative act?

From these, and many other selections which might be made, it is apparent that the framers of the Constitution contemplated that instrument as a rule for the government of courts as well as of the legislature.

Why otherwise does it direct the judges to take an oath to support it? This oath certainly applies in an especial manner to their conduct in their official character. How immoral to impose it on them if they were to be used as the instruments, and the knowing instruments, for violating what they swear to support!

At the end of the decision the Chief Justice concluded that the language of the Constitution confirmed and strengthened the principle essential to all written constitutions “that a law repugnant to the Constitution is void.”

The great event of Jefferson’s first term was the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory, that vast tract of land extending from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, from the Canadian border to the Gulf of 13 Mexico. The purchase of this land from Napoleon was not a premeditated act but rather the result of seizing an opportunity that presented itself. President Jefferson started out merely to buy New Orleans from France but ended up with more than 800,000 square miles. The agreed-on price was about $15,000,000, or something like two cents per acre.

Napoleon had forced Spain to give Louisiana back to France after Spain had held the territory nearly forty years. Just before the letter in the following account was written, the Spanish Intendant (director) of New Orleans, who had not yet turned over the city to France, closed the port to American commerce. Because most of the produce of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys reached eastern and foreign markets via New Orleans, closing the port seemed almost an act of war against the United States. At this point Jefferson sent James Monroe to Europe as special minister to buy New Orleans. It turned out just then that Napoleon needed money to renew his war against England, and the entire territory was purchased within a few weeks. The events which led to the purchase are described in the following letter that Jefferson wrote on February 3, 1803, to Robert Livingston, the American minister to France.

A late suspension by the Intendant of New Orleans of our right of deposit there, without which the right of navigation is impracticable, has thrown this country into such a flame of hostile disposition as can scarcely be described. The western country was peculiarly sensible to it as you may suppose. Our business was to take the most effectual pacific measures in our power to remove the suspension, and at the same time to persuade our countrymen that pacific measures would be the most effectual and the most speedily so. The opposition caught it as a plank in a shipwreck, hoping it would enable them to tack the western people to them. They raised the cry of war, were intriguing in all the quarters to exasperate the western inhabitants to arm and go down on their own authority and possess themselves of New Orleans, and in the meantime were daily reiterating, in new shapes, inflammatory resolutions for the adoption of the House.

As a remedy to all this we determined to name a minister extraordinary to go immediately to Paris and Madrid to settle this 14 matter. This measure being a visible one, and the person named peculiarly proper with the western country, crushed at once and put an end to all further attempts on the Legislature. From that moment all has become quiet; and the more readily in the western country, as the sudden alliance of these new federal friends had of itself already began to make them suspect the wisdom of their own course. The measure was moreover proposed from another cause. We must know at once whether we can acquire New Orleans or not. We are satisfied nothing else will secure us against a war at no distant period; and we cannot press this reason without beginning those arrangements which will be necessary if war is hereafter to result.

For this purpose it was necessary that the negotiators should be fully possessed of every idea we have on the subject, so as to meet the propositions of the opposite party, in whatever form they may be offered; and give them a shape admissible by us without being obliged to await new instructions hence. With this view, we have joined Mr. Monroe to yourself at Paris, and to Mr. Pinckney at Madrid, although we believe it will be hardly necessary for him to go to this last place.

Exploring the Missouri River Valley and the Rocky Mountain area long had been a cherished project of President Jefferson. He had talked about it periodically since the Revolution, and when he became President he set about to make his dream come true. Even before the United States owned the Louisiana Territory, Capt. Meriwether Lewis, Jefferson’s secretary, and William Clark, younger brother of George Rogers Clark, had been picked to head an expedition to explore the West.

The journey did not begin, however, until May, 1804, when the expedition left St. Louis. Capt. Lewis led his explorers up the Missouri River to what is now North Dakota, and before cold weather set in they built huts and a stockade for winter quarters. The next spring they moved on up the river in dugout canoes (pirogues) towards the mountains. The following selection from Capt. Lewis’ journal of the expedition was set down on April 13, 1805, when the party was at the junction of the Missouri and the Little Missouri rivers, still in North Dakota.

15Being disappointed in my observations of yesterday for longitude, I was unwilling to remain at the entrance of the river another day for that purpose, and therefore determined to set out early this morning; which we did accordingly; the wind was in our favour after 9 A.M. and continued favourable until 3 P.M. We therefore hoisted both the sails in the White Pirogue, consisting of a small square sail and spritsail, which carried her at a pretty good gait, until about 2 in the afternoon when a sudden squall of wind struck us and turned the pirogue so much on the side as to alarm Charbonneau [the interpreter], who was steering at the time. In this state of alarm he threw the pirogue with her side to the wind, when the spritsail gibing was as near oversetting the pirogue as it was possible to have missed. The wind, however, abating for an instant, I ordered Drouillard [also an interpreter] to the helm and the sails to be taken in, which was instantly executed, and the pirogue being steered before the wind was again placed in a state of security. This accident was very near costing us dearly. Believing this vessel to be the most steady and safe, we had embarked on board of it our instruments, papers, medicine, and the most valuable part of the merchandise which we had still in reserve as presents for the Indians. We had also embarked on board ourselves, with three men who could not swim, and the squaw [Sacajawea, the Shoshone wife of Charbonneau, who showed the party the way across the Continental Divide and obtained horses and protection for them from the Shoshones] with the young child, all of whom, had the pirogue overset, would most probably have perished, as the waves were high, and the pirogue upwards of 200 yards from the nearest shore; however, we fortunately escaped and pursued our journey under the square sail, which shortly after the accident I directed to be again hoisted.

By the end of May the expedition had moved halfway across Montana, still following the Missouri River:

Today we passed on the starboard [right] side the remains of a vast many mangled carcasses of buffalo which had been driven 16 over a precipice of 120 feet by the Indians and perished; the water appeared to have washed away a part of this immense pile of slaughter and still there remained the fragments of at least a hundred carcasses. They created a most horrid stench. In this manner the Indians of the Missouri destroy vast herds of buffalo at a stroke; for this purpose one of the most active and fleet young men is selected and disguised in a robe of buffalo skin, having also the skin of the buffalo’s head with the ears and horns fastened on his head in form of a cap. Thus caparisoned he places himself at a convenient distance between a herd of buffalo and a precipice proper for the purpose, which happens in many places on this river for miles together; the other Indians now surround the herd on the back and flanks, and at a signal agreed on all show themselves at the same time moving forward towards the buffalo.

The disguised Indian or decoy has taken care to place himself sufficiently nigh the buffalo to be noticed by them when they take to flight, and running before them they follow him in full speed to the precipice, the cattle behind driving those in front over and seeing them go do not look or hesitate about following until the whole are precipitated down the precipice forming one common mass of dead and mangled carcasses. The decoy in the meantime has taken care to secure himself in some cranny or crevice of the cliff which he had previously prepared for that purpose.

By August 13 the expedition was crossing the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass on the border between Montana and Idaho. In the selection that follows, Capt. Lewis describes the party’s meeting with the Shoshone Indians.

We had not continued our route more than a mile when we were so fortunate as to meet with three female savages. The short and steep ravines which we passed concealed us from each other until we arrived within 30 paces. A young woman immediately took to flight; an elderly woman and a girl of about 12 years old remained. I instantly laid by my gun and advanced towards them. They appeared much alarmed but saw that we were too near for them to escape by flight; they therefore seated themselves on the 17 ground, holding down their heads as if reconciled to die, which they expected no doubt would be their fate. I took the elderly woman by the hand and raised her up, repeated the word tab-ba-bone and stripped up my shirt sleeve to show her my skin; to prove to her the truth of the assertion that I was a white man, for my face and hands, which have been constantly exposed to the sun, were quite as dark as their own. They appeared instantly reconciled, and the men coming up, I gave these women some beads, a few moccasin awls, some pewter looking-glasses, and a little paint.

I directed Drouillard to request the old woman to recall the young woman who had run off to some distance by this time, fearing she might alarm the camp before we approached and might so exasperate the natives that they would perhaps attack us without enquiring who we were. The old woman did as she was requested and the fugitive soon returned almost out of breath. I bestowed an equivalent portion of trinket on her with the others. I now painted their tawny cheeks with some vermillion, which with this nation is emblematic of peace. After they had become composed I informed them by signs that I wished them to conduct us to their camp, that we were anxious to become acquainted with the chiefs and warriors of their nation. They readily obeyed and we set out, still pursuing the road down the river.

We had marched about 2 miles when we met a party of about 60 warriors mounted on excellent horses, who came in nearly full speed. When they arrived, I advanced towards them with the flag, leaving my gun with the party about 50 paces behind me. The chief and two others who were a little in advance of the main body spoke to the women, and they informed them who we were and exultingly showed the presents which had been given them. These men then advanced and embraced me very affectionately in their way, which is by putting their left arm over your right shoulder, clasping your back, while they apply their left cheek to yours and frequently vociferate the word ah-hi-e, ah-hi-e, that is, I am much pleased, I am much rejoiced. Both parties now advanced and we were all caressed and besmeared with their grease and paint till I was heartily tired of the national hug.

I now had the pipe lit and gave them smoke; they seated themselves in a circle around us and pulled off their moccasins before 18 they would receive or smoke the pipe. This is a custom among them, as I afterwards learned, indicative of a sacred obligation of sincerity in their profession of friendship, given by the act of receiving and smoking the pipe of a stranger. Or which is as much as to say that they wish they may always go barefoot if they are not sincere; a pretty heavy penalty if they are to march through the plains of their country.

After crossing the Continental Divide, the expedition descended the Columbia River to the Pacific Coast, where they built a fort and spent the winter of 1805-1806. The next year they retraced their steps across the wilderness and returned to St. Louis in September, 1806, having been gone twenty-eight months. The expedition not only was a great adventure, but it also captured the imagination of the country. Not long afterwards fur traders began tapping the rich resources of the area, and by the middle of the century settlers were crossing the plains and mountains via the Oregon Trail.

Although Jefferson was re-elected in 1804 by a landslide victory, his popularity diminished greatly during his second term. The source of his troubles lay in Europe, where England and France were involved in the long, bitter Napoleonic Wars. England could not defeat Napoleon on land, but her navy was superior. Hence she blockaded the continent. France retaliated by counter-blockades. The United States, with a large merchant fleet but scarcely any navy, was caught in the middle. Hundreds of American ships were seized and their cargoes confiscated. Both England and France violated American neutral rights, but England, with the world’s strongest navy, was the chief offender. When a British warship, the Leopard, fired on and impressed American seamen from an American frigate, the Chesapeake, off the coast of Virginia, the United States was ready to fight.

President Jefferson, however, was determined to avoid war and answered the Chesapeake incident with a proclamation excluding British warships from American waters, but the British would not agree to stop impressing American seamen. In addition, to deal with the seizure of American ships, Jefferson persuaded Congress to pass the Embargo Act. 19 This act forbade American ships to leave for foreign ports. The result was that American ships rotted in the harbors and depression hit American business. Yet England and France were not hurt enough to come to terms. The Embargo Act had to be repealed.

About the time the Embargo Act was repealed, Washington Irving, America’s first important man of letters, wrote his History of New York. This book is a burlesque account of the old Dutch period in New York history, a very funny book, full of comic pictures of the Dutch governors and the early settlers. The book also contains some contemporary political satire in the chapters devoted to William the Testy. In the selections which follow you will see obvious references to the Chesapeake incident, the Embargo Act, and President Jefferson’s actions.

As my readers are well aware of the advantage a potentate has in handling his enemies as he pleases in his speeches and bulletins, where he has the talk all on his own side, they may rest assured that William the Testy did not let such an opportunity escape of giving the Yankees what is called “a taste of his quality.” In speaking of their inroads into the territories of their High Mightinesses, he compared them to the Gauls who desolated Rome, the Goths and Vandals who overran the fairest plains of Europe; but when he came to speak of the unparalleled audacity with which they of Weathersfield had advanced their [onion] patches up to the very walls of Fort Goed Hoop, and threatened to smother the garrison in onions, tears of rage started into his eyes, as though he nosed the very offense in question.

Having thus wrought up his tale to a climax, he assumed a most belligerent look, and assured the council that he had devised an instrument, potent in its effects, and which he trusted would soon drive the Yankees from the land. So saying, he thrust his hand into one of the deep pockets of his broad-skirted coat and drew forth, not an infernal machine, but an instrument in writing, which he laid with great emphasis upon the table.

The burghers gazed at it for a time in silent awe, as a wary housewife does at a gun, fearful it may go off half-cocked. The document in question had a sinister look, it is true; it was crabbed in text, and from a broad red ribbon dangled the great seal of the 20 province, about the size of a buckwheat pancake. Still, after all, it was but an instrument in writing. Herein, however, existed the wonder of the invention. The document in question was a PROCLAMATION, ordering the Yankees to depart instantly from the territories of their High Mightinesses, under pain of suffering all the forfeitures and punishments in such case made and provided. It was on the moral effect of this formidable instrument that Wilhelmus Kieft calculated, pledging his valor as a governor that, once fulminated [thundered] against the Yankees, it would in less than two months drive every mother’s son of them across the borders.

The council broke up in perfect wonder, and nothing was talked of for some time among the old men and women of New Amsterdam but the vast genius of the governor and his new and cheap mode of fighting by proclamation.

As to Wilhelmus Kieft, having dispatched his proclamation to the frontiers, he put on his cocked hat and corduroy small clothes, and, mounting a tall rawboned charger, trotted out to his rural retreat of Dog’s Misery....

Never was a more comprehensive, a more expeditious—or, what is still better, a more economical—measure devised than this of defeating the Yankees by proclamation—an expedient, likewise, so gentle and humane there were ten chances to one in favor of its succeeding, but then there was one chance to ten that it would not succeed: as the ill-natured Fates would have it, that single chance carried the day! The proclamation was perfect in all its parts, well constructed, well written, well sealed, and well published; all that was wanting to insure its effect was, that the Yankees should stand in awe of it; but, provoking to relate, they treated it with the most absolute contempt, applied it to an unseemly purpose, and thus did the first warlike proclamation come to a shameful end—a fate which I am credibly informed has befallen but too many of its successors.

So far from abandoning the country, those varlets [rascals] continued their encroachments, squatting along the green banks of the Varsche River, and founding Hartford, Stamford, New Haven, and other border towns. I have already shown how the onion patches of Pyquag were an eyesore to Jacobus Van Curlet and his 21 garrison; but now these moss-troopers increased in their atrocities, kidnaping hogs, impounding horses, and sometimes grievously rib-roasting their owners. Our worthy forefathers could scarcely stir abroad without danger of being outjockeyed in horseflesh or taken in in bargaining, while in their absence some daring Yankee peddler would penetrate to their household and nearly ruin the good housewives with tinware and wooden bowls....

It was long before William the Testy could be persuaded that his much-vaunted war measure was ineffectual; on the contrary, he flew in a passion whenever it was doubted, swearing that though slow in operating, yet when it once began to work it would soon purge the land of these invaders. When convinced, at length, of the truth, like a shrewd physician he attributed the failure to the quantity, not the quality, of the medicine, and resolved to double the dose. He fulminated, therefore, a second proclamation, more vehement than the first, forbidding all intercourse with these Yankee intruders, ordering the Dutch burghers on the frontiers to buy none of their pacing horses, measly port, apple sweetmeats, Weathersfield onions, or wooden bowls, and to furnish them with no supplies of gin, gingerbread, or sauerkraut.

Another interval elapsed, during which the last proclamation was as little regarded as the first, and the non-intercourse was especially set at naught by the young folks of both sexes, if we may judge by the active bundling which took place along the borders.

Irving concludes this satire of William the Testy’s proclamation by a comic account of how the Yankees captured Fort Goed Hoop. They sneaked into the fort while the Dutch soldiers were sleeping off their dinner, gave the defenders a kick in the pants, and sent them back to New Amsterdam.

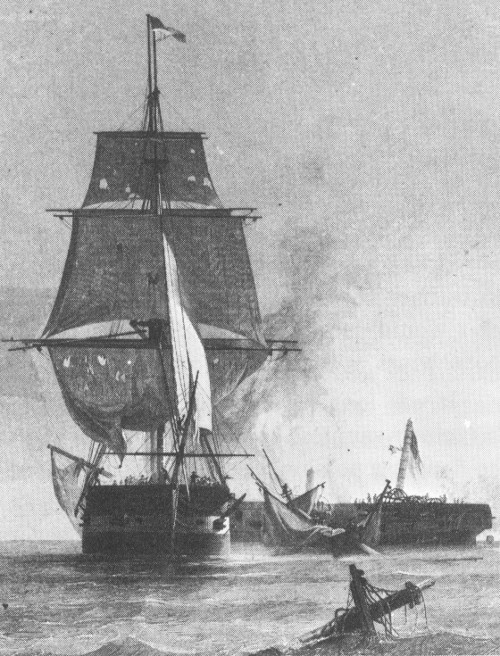

The Constitution and the Guerrière

Despite the unpopularity of the Embargo Act, James Madison, Jefferson’s choice to succeed him in the presidency, was elected by a large margin. Madison had served a long career in public life, beginning with the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention and more recently serving as Secretary of State under Jefferson. In the following selection Margaret Bayard Smith again reports the Washington scene, this time the events of March 4, 1809, Inauguration Day. Note that she mixes up the sequence of events by starting with the reception after the inauguration before describing the inauguration.

Today after the inauguration we all went to Mrs. Madison’s. The street was full of carriages and people, and we had to wait near half an hour before we could get in—the house was completely filled, parlours, entry, drawing room and bed room. Near the door of the drawing room Mr. and Mrs. Madison stood to receive 23 their company. She looked extremely beautiful, was dressed in a plain cambric dress with a very long train, plain round the neck without any handkerchief, and beautiful bonnet of purple velvet, and white satin with white plumes. She was all dignity, grace and affability.

Mr. Madison shook my hand with all the cordiality of old acquaintance, but it was when I saw our dear and venerable Mr. Jefferson that my heart beat. When he saw me, he advanced from the crowd, took my hand affectionately, and held it five or six minutes; one of the first things he said was, “Remember the promise you have made me, to come to see us next summer; do not forget it,” said he, pressing my hand, “for we shall certainly expect you.” I assured him I would not, and told him I could now wish him joy with much more sincerity than this day 8 years ago.

“You have now resigned a heavy burden,” said I.

“Yes indeed,” he replied, “and am much happier at this moment than my friend.”

The crowd was immense both at the Capitol and here; thousands and thousands of people thronged the avenue. The Capitol presented a gay scene. Every inch of space was crowded and there being as many ladies as gentlemen, all in full dress, it gave it rather a gay than a solemn appearance—there was an attempt made to appropriate particular seats for the ladies of public characters, but it was found impossible to carry it into effect, for the sovereign people would not resign their privileges and the high and low were promiscuously blended on the floor and in the galleries. Mr. Madison was extremely pale and trembled excessively when he first began to speak, but soon gained confidence and spoke audibly.

Mrs. Smith now interrupts her letter (to her sister-in-law) and finishes it the next day. The event she describes is the inauguration ball at Long’s Hotel.

Last evening, I endeavored calmly to look on, and amidst the noise, bustle and crowd, to spend an hour or two in sober reflection, 24 but my eye was always fixed on our venerable friend [Jefferson]. When he approached my ear listened to catch every word, and when he spoke to me my heart beat with pleasure. Personal attachment produces this emotion, and I did not blame it. But I have not this regard for Mr. Madison, and I was displeased at feeling no emotion when he came up and conversed with me. He made some of his old kind of mischievous allusions, and I told him I found him still unchanged. I tried in vain to feel merely as a spectator; the little vanities of my nature often conquered my better reason.

The room was so terribly crowded that we had to stand on the benches; from this situation we had a view of the moving mass; for it was nothing else. It was scarcely possible to elbow your way from one side to another, and poor Mrs. Madison was almost pressed to death, for every one crowded round her, those behind pressing on those before, and peeping over their shoulders to have a peep of her, and those who were so fortunate as to get near enough to speak to her were happy indeed. As the upper sashes of the windows could not let down, the glass was broken, to ventilate the room, the air of which had become oppressive.

The War of 1812, like the Korean war of this century, was a conflict that neither side won. The young United States Navy scored some notable victories at sea but could not prevent the overwhelming naval power of the British from blockading American coasts and cutting off American commerce. The United States Army, with a few notable exceptions, was badly generaled and was outfought. General Hull surrendered Detroit without a fight, and General Dearborn, who set out to attack Montreal, marched to the Canadian border, lost his nerve, and turned back.

The War of 1812 was also like the Korean war in that it was unpopular with the political party out of office. Federalist New England refused to support it, calling the conflict “Mr. Madison’s War,” and seriously talked of secession. New England merchants traded with the enemy, and when Maine was occupied by the British, many Americans quickly took an oath of allegiance to the king. The Czar of Russia’s 25 offer to act as mediator between England and America was eagerly accepted. The peace talks, however, dragged on for nearly two years before a settlement, leaving things just as they were before the war, was agreed upon.

Although neither side won, the War of 1812 did have some important consequences. Historians see it as America’s second war for independence. The Revolution severed American ties with England. The War of 1812 removed any doubts in the minds of European powers that the United States was here to stay. Also, in the years following the war, America was able to settle her grievances with England and to force the Spanish out of Florida. And, for the first time, the United States could concentrate on internal problems.

The frigate Constitution, captained by Isaac Hull, already had a distinguished history when the War of 1812 began. She had been built in Boston during the trouble with France in 1797 and had taken part in the war with the Barbary pirates. The peace treaty with Tripoli had been signed in the captain’s quarters on the gun deck. A trim, fast, graceful ship, the frigate had been made from timbers of solid live oak, hard pine, and red cedar. The bolts, copper sheathing, and brass-work had been supplied by Paul Revere. This ship now is preserved as a museum at the Boston Navy Yard.

Congress declared war on England in June, 1812, and the next month Capt. Hull sailed from Chesapeake Bay. In August he encountered the British ship Guerrière, and the action that followed he reports in his dispatch to the Secretary of the Navy. Thus, the war began with a resounding sea victory.

Sir,

I have the honour to inform you, that on the 19th instant, at 2 P.M. being in latitude 41, 42, longitude 55, 48, with the Constitution under my command, a sail was discovered from the masthead bearing E. by S. or E.S.E. but at such a distance we could not tell what she was. All sail was instantly made in chase, and soon found we came up with her. At 3 P.M. could plainly see that she was a ship on the starboard tack, under easy sail, close on a 26 wind; at half past 3 P.M. made her out to be a frigate; continued the chase until we were within about three miles, when I ordered the light sails taken in, the courses hauled up, and the ship cleared for action. At this time the chase had backed his main top-sail, waiting for us to come down.

As soon as the Constitution was ready for action, I bore down with an intention to bring him to close action immediately; but on our coming within gunshot she gave us a broadside and filled away, and wore, giving us a broadside on the other tack, but without effect; her shot falling short. She continued wearing and maneuvering for about three-quarters of an hour, to get a raking position, but finding she could not, she bore up, and ran under top-sails and gib, with the wind on the quarter.

I immediately made sail to bring the ship up with her, and 5 minutes before 6 P.M. being along side within half pistol shot, we commenced a heavy fire from all our guns, double shotted with round and grape, and so well directed were they, and so warmly kept up, that in 15 minutes his mizen-mast went by the board, and his main-yard in the slings, and the hull, rigging, and sails very much torn to pieces. The fire was kept up with equal warmth for 15 minutes longer, when his main-mast, and fore-mast went, taking with them every spar, excepting the bowsprit; on seeing this we ceased firing, so that in 30 minutes after we got fairly along side the enemy she surrendered, and had not a spar standing, and her hull below and above water so shattered, that a few more broadsides must have carried her down.

After informing you that so fine a ship as the Guerrière, commanded by an able and experienced officer, had been totally dismasted, and otherwise cut to pieces, so as to make her not worth towing into port, in the short space of 30 minutes, you can have no doubt of the gallantry and good conduct of the officers and ship’s company I have the honour to command. It only remains, therefore, for me to assure you, that they all fought with great bravery; and it gives me great pleasure to say, that from the smallest boy in the ship to the oldest seaman, not a look of fear was seen. They all went into action, giving three cheers, and requesting to be laid close along side the enemy.

Enclosed I have the honour to send you a list of killed and 27 wounded on board the Constitution, and a report of the damages she has sustained; also, a list of the killed and wounded on board the enemy.

The naval campaigns of the War of 1812 were fought on the Great Lakes as well as in the Atlantic. Because British troops were based in Canada, the northern border of the United States inevitably became a battle line. Commodore Perry won another important sea victory a year after the Constitution defeated the Guerrière when his squadron defeated and captured a British squadron on Lake Erie. This was the battle which Perry reported to General William Henry Harrison in his famous remark: “We have met the enemy, and they are ours.” In the two dispatches that follow, Perry gives a full account of the action to the Secretary of the Navy.

Sir,

It has pleased the Almighty to give to the arms of the United States a signal victory over their enemies on this lake. The British squadron, consisting of two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop, have this moment surrendered to the force under my command, after a sharp conflict.

Sir,

In my last I informed you that we had captured the enemy’s fleet on this lake. I have now the honour to give you the most important particulars of the action. On the morning of the 10th instant, at sunrise, they were discovered from Put-In-Bay, when I lay at anchor with the squadron under my command. We got under weigh, the wind light at south-west, and stood for them. At 10 A.M. the wind hauled to south-east and brought us to windward; formed the line and bore up. At 15 minutes before 12, the enemy commenced firing; at 5 minutes before 12, the action commenced on our part.

Finding their fire very destructive owing to their long guns, and its being mostly directed at the Lawrence, I made sail, and directed the other vessels to follow, for the purpose of closing with the enemy. 28 Every brace and bowline being soon shot away, she became unmanageable, notwithstanding the great exertions of the sailing master. In this situation, she sustained the action upwards of two hours within canister distance, until every gun was rendered useless, and the greater part of her crew either killed or wounded. Finding she could no longer annoy the enemy, I left her in charge of Lieutenant Yarnall, who, I was convinced, from the bravery already displayed by him, would do what would comport with the honour of the flag.

At half past two, the wind springing up, Captain Elliot was enabled to bring his vessel, the Niagara, gallantly into close action. I immediately went on board of her, when he anticipated my wish by volunteering to bring the schooner which had been kept astern by the lightness of the wind, into close action. It was with unspeakable pain that I saw, soon after I got on board the Niagara, the flag of the Lawrence come down, although I was perfectly sensible that she had been defended to the last, and that to have continued to make a show of resistance would have been a wanton sacrifice of the remains of her brave crew. But the enemy was not able to take possession of her, and circumstances soon permitted her flag again to be hoisted.

At 45 minutes past 2, the signal was made for “close action.” The Niagara being very little injured, I determined to pass through the enemy’s line, bore up and passed ahead of their two ships and a brig, giving a raking fire to them from the starboard guns, and to a large schooner and sloop, from the larboard side, at half pistol shot distance. The smaller vessels at this time having got within grape and canister distance, under the direction of Captain Elliot, and keeping up a well-directed fire, the two ships, a brig, and a schooner surrendered, a schooner and sloop making a vain attempt to escape.

Probably the most humiliating military defeat ever inflicted on the United States occurred in August, 1814, when British troops marched into Washington and burned the public buildings. This was a punitive action designed to teach the Americans a lesson and to demoralize the country. Official Washington fled at the approach of the British, and 29 in the following letter Dolly Madison, the President’s wife, describes her activities on the day before and her flight from the White House on the day of the British invasion.

Dear Sister—My husband left me yesterday morning to join General Winder. He inquired anxiously whether I had courage or firmness to remain in the President’s house until his return on the morrow, or succeeding day, and on my assurance that I had no fear but for him, and the success of our army, he left, beseeching me to take care of myself, and of the Cabinet papers, public and private. I have since received two dispatches from him, written with a pencil. The last is alarming, because he desires I should be ready at a moment’s warning to enter my carriage, and leave the city; that the enemy seemed stronger than had at first been reported, and it might happen that they would reach the city with the intention of destroying it. I am accordingly ready; I have pressed as many Cabinet papers into trunks as to fill one carriage; our private property must be sacrificed, as it is impossible to procure wagons for its transportation. I am determined not to go myself until I see Mr. Madison safe, so that he can accompany me, as I hear of much hostility towards him. Disaffection stalks around us. My friends and acquaintances are all gone, even Colonel C. with his hundred, who were stationed as a guard in this inclosure. French John [a faithful servant], with his usual activity and resolution, offers to spike the cannon at the gate, and lay a train of powder, which would blow up the British, should they enter the house. To the last proposition I positively object, without being able to make him understand why all advantages in war may not be taken.

Wednesday Morning, twelve o’clock. Since sunrise I have been turning my spy-glass in every direction, and watching with unwearied anxiety, hoping to discover the approach of my dear husband and his friends; but, alas! I can descry only groups of military, wandering in all directions, as if there was a lack of arms, or of spirit to fight for their own fireside.

Three o’clock. Will you believe it, my sister? we have had a battle, or skirmish, near Bladensburg, and here I am still, within 30 sound of the cannon! Mr. Madison comes not. May God protect us! Two messengers covered with dust come to bid me fly; but here I mean to wait for him.... At this late hour a wagon has been procured, and I have had it filled with plate and the most valuable portable articles belonging to the house. Whether it will reach its destination, the Bank of Maryland, or fall into the hands of British soldiery, events must determine. Our kind friend, Mr. Carroll, has come to hasten my departure, and in a very bad humor with me, because I insist on waiting until the large picture of General Washington is secured, and it requires to be unscrewed from the wall. This process was found too tedious for these perilous moments; I have ordered the frame to be broken, and the canvas taken out. It is done! and the precious portrait placed in the hands of two gentlemen of New York, for safe keeping. And now, dear sister, I must leave this house, or the retreating army will make me a prisoner in it by filling up the road I am directed to take. When I shall again write to you, or where I shall be tomorrow, I cannot tell!

Dolly.

British General Robert Ross landed with about four thousand men and marched into Washington without much opposition. The scene that took place during the burning is vividly described by a British officer, George Gleig, in A Narrative of the Campaigns of the British Army.

While the third brigade was thus employed [burning buildings], the rest of the army, having recalled its stragglers and removed the wounded into Bladensburg, began its march towards Washington. Though the battle was ended by four o’clock, the sun had set before the different regiments were in a condition to move; consequently this short journey was performed in the dark. The work of destruction had also begun in the city, before they quitted their ground; and the blazing of houses, ships, and stores, the report of exploding magazines, and the crash of falling roofs informed them, as they proceeded, of what was going forward. You can conceive nothing finer than the sight which met them as they drew near to the town. The sky was brilliantly illuminated by the 31 different conflagrations, and a dark red light was thrown upon the road, sufficient to permit each man to view distinctly his comrade’s face. Except the burning of St. Sebastian’s, I do not recollect to have witnessed ... a scene more striking or more sublime.

I need scarcely to observe that the consternation of the inhabitants was complete, and that to them this was a night of terror. So confident had they been of the success of their troops, that few of them had dreamed of quitting their houses or abandoning the city; nor was it till the fugitives from the battle began to rush in, filling every place as they came with dismay, that the President himself thought of providing for his safety. That gentleman, as I was credibly informed, had gone forth in the morning with the army, and had continued among his troops till the British forces began to make their appearance. Whether the sight of his enemies cooled his courage or not, I cannot say, but, according to my informer, no sooner was the glittering of our arms discernible, than he began to discover that his presence was more wanted in the Senate than with the army; and having ridden through the ranks, and exhorted every man to do his duty, he hurried back to his own house, that he might prepare a feast for the entertainment of his officers, when they should return victorious.

For the truth of these details, I will not be answerable; but this much I know, that the feast was actually prepared, though, instead of being devoured by American officers, it went to satisfy the less delicate appetites of a party of English soldiers. When the detachment sent out to destroy Mr. Madison’s house entered his dining parlor, they found a dinner table spread and covers laid for forty guests. Several kinds of wine, in handsome cut-glass decanters, were cooling on the sideboard; plate-holders stood by the fireplace, filled with dishes and plates; knives, forks, and spoons were arranged for immediate use; in short, everything was ready for the entertainment of a ceremonious party. Such were the arrangements in the dining room, whilst in the kitchen were others answerable to them in every respect. Spits, loaded with joints of various sorts, turned before the fire; pots, saucepans, and other culinary utensils stood upon the grate; and all the other requisites for an elegant and substantial repast were exactly in a state which indicated that they had been lately and precipitately abandoned.

32You will readily imagine that these preparations were beheld by a party of hungry soldiers with no indifferent eye. An elegant dinner, even though considerably overdressed, was a luxury to which few of them, at least for some time back, had been accustomed, and which, after the dangers and fatigues of the day, appeared peculiarly inviting. They sat down to it, therefore, not indeed in the most orderly manner, but with countenances which would not have disgraced a party of aldermen at a civic feast, and, having satisfied their appetites with fewer complaints than would have probably escaped their rival gourmands, and partaken pretty freely of the wines, they finished by setting fire to the house....

But, as I have just observed, this was a night of dismay to the inhabitants of Washington. They were taken completely by surprise; nor could the arrival of the flood be more unexpected to the natives of the antediluvian world than the arrival of the British army to them. The first impulse of course tempted them to fly, and the streets were in consequence crowded with soldiers and senators, men, women, and children, horses, carriages, and carts loaded with household furniture, all hastening towards a wooden bridge which crosses the Potomac. The confusion thus occasioned was terrible, and the crowd upon the bridge was such as to endanger its giving way. But Mr. Madison, having escaped among the first, was no sooner safe on the opposite bank of the river than he gave orders that the bridge should be broken down; which being obeyed, the rest were obliged to return and to trust to the clemency of the victors.

In this manner was the night passed by both parties; and at daybreak next morning, the light brigade moved into the city, while the reserve fell back to a height about a half mile in the rear. Little, however, now remained to be done, because everything marked out for destruction was already consumed. Of the Senate house, the President’s palace, the barracks, the dockyard, etc., nothing could be seen except heaps of smoking ruins; and even the bridge ... was almost wholly demolished.

Despite the general incompetence of the American leadership in the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson emerged from the campaigns as a 33 genuine war hero. The Battle of New Orleans, which ironically was fought after the peace treaty had been signed in Europe, was a great victory. Jackson’s troops, greatly outnumbered, barricaded themselves behind cotton bales and earthworks and mowed down the British as they stormed the American positions. In the two selections that follow, we print first the account of the battle by the British officer George Gleig and then General Jackson’s terse report to the Secretary of War.

OFFICER GLEIG:

The main body armed and moved forward some way in front of the pickets. There they stood waiting for daylight and listening with the greatest anxiety for the firing which ought now to be heard on the opposite bank. But this attention was exerted in vain, and day dawned upon them long before they desired its appearance. Nor was Sir Edward Pakenham disappointed in this part of his plan alone. Instead of perceiving everything in readiness for the assault, he saw his troops in battle array, indeed, but not a ladder or fascine [bundle of sticks to fill ditches] upon the field. The 44th, which was appointed to carry them, had either misunderstood or neglected their orders and now headed the column of attack without any means being provided for crossing the enemy’s ditch, or scaling his rampart.

The indignation of poor Pakenham on this occasion may be imagined, but cannot be described. Galloping towards Colonel Mullens, who led the 44th, he commanded him instantly to return with his regiment for the ladders, but the opportunity of planting them was lost, and though they were brought up, it was only to be scattered over the field by the frightened bearers. For our troops were by this time visible to the enemy. A dreadful fire was accordingly opened upon them, and they were mowed down by hundreds, while they stood waiting for orders.

Seeing that all his well-laid plans were frustrated, Pakenham gave the word to advance, and the other regiments, leaving the 44th with the ladders and fascines behind them, rushed on to the assault. On the left a detachment of the 95th, 21st, and 4th stormed a three-gun battery and took it. Here they remained for some time in the expectation of support; but none arriving, and 34 a strong column of the enemy forming for its recovery, they determined to anticipate the attack and pushed on. The battery which they had taken was in advance of the body of the works, being cut off from it by a ditch, across which only a single plank was thrown. Along this plank did these brave men attempt to pass; but being opposed by overpowering numbers, they were repulsed; and the Americans, in turn, forcing their way into the battery, at length succeeded in recapturing it with immense slaughter.

On the right, again, the 21st and 4th being almost cut to pieces and thrown into some confusion by the enemy’s fire, the 93d pushed on and took the lead. Hastening forward, our troops soon reached the ditch; but to scale the parapet without ladders was impossible. Some few, indeed, by mounting one upon another’s shoulders, succeeded in entering the works, but these were instantly overpowered, most of them killed, and the rest taken; while as many as stood without were exposed to a sweeping fire, which cut them down by whole companies. It was in vain that the most obstinate courage was displayed. They fell by the hands of men whom they absolutely did not see; for the Americans, without so much as lifting their faces above the rampart, swung their firelocks by one arm over the wall, and discharged them directly upon their heads. The whole of the guns, likewise, from the opposite bank, kept up a well directed and deadly cannonade upon their flank; and thus were they destroyed without an opportunity being given of displaying their valour, or obtaining so much as revenge.

Poor Pakenham saw how things were going, and did all that a General could do to rally his broken troops. Riding towards the 44th which had returned to the ground, but in great disorder, he called out for Colonel Mullens to advance; but that officer had disappeared, and was not to be found. He, therefore, prepared to lead them on himself, and had put himself at their head for that purpose, when he received a slight wound in the knee from a musket ball which killed his horse. Mounting another, he again headed the 44th, when a second ball took effect more fatally, and he dropped lifeless into the arms of his aide-de-camp.

Nor were Generals Gibbs and Keane inactive. Riding through the ranks, they strove by all means to encourage the assailants and recall the fugitives, till at length both were wounded and 35 borne off the field. All was now confusion and dismay. Without leaders, ignorant of what was to be done, the troops first halted and then began to retire, till finally the retreat was changed into a flight, and they quitted the ground in the utmost disorder. But the retreat was covered in gallant style by the reserve. Making a forward motion, the 7th and 43d presented the appearance of a renewed attack; by which the enemy were so much awed, that they did not venture beyond their lines in pursuit of the fugitives.

GENERAL JACKSON’S REPORT:

During the days of the 6th and 7th, the enemy had been actively employed in making preparations for an attack on my lines. With infinite labour they had succeeded on the night of the 7th, in getting their boats across from the lake to the river, by widening and deepening the canal on which they had effected their disembarkation. It had not been in my power to impede these operations by a general attack: added to other reasons, the nature of the troops under my command, mostly militia, rendered it too hazardous to attempt extensive offensive movements in an open country, against a numerous and well disciplined army.