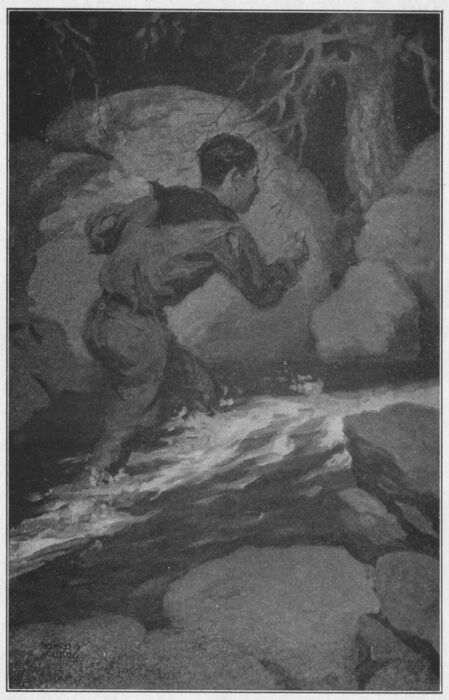

HOW CHEERING IT WAS—LIKE A FRIEND FROM HOME.

Title: Westy Martin in the Yellowstone

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh

Release date: January 5, 2020 [eBook #61114]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Westy Martin in the Yellowstone, by Percy Keese Fitzhugh, Illustrated by Richard A. Holberg

HOW CHEERING IT WAS—LIKE A FRIEND FROM HOME.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | Mr. Wilde and the Three Scouts |

| II | Mr. Wilde Holds Forth |

| III | The Knockout Blow |

| IV | The Chance Comes |

| V | The Shadow of Mr. Wilde |

| VI | Stranded |

| VII | Hopes and Plans |

| VIII | On the Way |

| IX | The Rocky Hill |

| X | The Camping Site |

| XI | Alone |

| XII | In the Twilight |

| XIII | Warde and Ed |

| XIV | The Master |

| XV | The Haunting Spirit of Shining Sun |

| XVI | A Desperate Predicament |

| XVII | Sounds! |

| XVIII | Westy’s Job |

| XIX | The Way of the Scout |

| XX | A Fatal Move |

| XXI | In the Darkness |

| XXII | The Friendly Brook |

| XXIII | The Cut Trail |

| XXIV | Downstream |

| XXV | Little Dabs of Gray |

| XXVI | Movie Stuff |

| XXVII | The Advance Guard |

| XXVIII | The Garb of the Scout |

| XXIX | The Polish of Shining Sun |

| XXX | Visitors |

| XXXI | No Escape |

| XXXII | Off to Pelican Cone |

| XXXIII | Hermitage Rest |

| XXXIV | Vulture Cliff |

| XXXV | Disappointment |

| XXXVI | Off the Cliff |

| XXXVII | Ed Carlyle, Scout |

| XXXVIII | The Wounded Stranger |

| XXXIX | Westy’s Descent |

| XL | Warde Meets a Grizzly |

| XLI | A Scout Mascot |

When Westy Martin and his two companions, Warde Hollister and Ed Carlyle, were on their long journey to the Yellowstone National Park, they derived much amusement from talking with a man whose acquaintance they made on the train.

This entertaining and rather puzzling stranger caused the boys much perplexity and they tried among themselves to determine what business he was engaged in.

For a while they did not even know his name. Then they learned it was Madison C. Wilde. And because he kept a cigar tilted up in the extreme corner of his mouth and showed a propensity for “jollying” them they decided (and it was a likely sort of guess) that he was a traveling salesman.

Mr. Wilde had the time of his life laughing at the good scouts, and, moreover, he humorously belittled scouting, seeming to see it as a sort of pretty game for boys, like marbles or hide-and-seek.

He had his little laugh, and then afterward the three boys had their little laugh. And he who laughs last is said to have somewhat the advantage in laughing.

Mr. Wilde told the three scouts that Yellowstone Park was full of grizzlies. “Oh, hundreds of them,” he said. “But they’re not as savage as the wallerpagoes. The skehinkums are pretty wild too,” he added.

“Is that so?” laughed Westy.

“You didn’t happen to see any killy loo birds while you were there, did you?”

Mr. Madison C. Wilde worked his cigar over to the corner of his mouth, contemplating the boys with an expression of cynical good humor. “Do they let you use popguns in the Boy Scouts?” he asked. “Because it isn’t safe to go in the woods without a popgun.”

“Oh, yes,” said Warde Hollister, “and we carry cap pistols too to be on the safe side. Scouts are supposed to be prepared, you know.”

“Some warriors,” laughed Mr. Wilde. “You’ll see the real thing out here, you kids,” he added seriously. “No running around and getting lost in back yards. If you get lost out here you’ll come pretty near knowing you’re lost.”

“What could be sweeter?” Ed Carlyle asked.

The foregoing is a fair sample of the kind of banter that had passed back and forth between Mr. Wilde and the boys ever since they had struck up an acquaintance. They had told him all about scouting, tracking, signaling and such things, and he had derived much idle entertainment in poking fun at them about their flaunted skill and resourcefulness.

“I’d like to see some boy scouts up against the real thing,” he said. “I’d like to see you get really lost in the mountains out west here. You’d all starve to death, that’s what would happen to you—unless you could eat that wonderful handbook manual, or whatever you call it, that you get your stunts out of.”

“We eat everything,” said Westy.

“Yes?” laughed Mr. Wilde. “Well, I’m pretty good at eating myself, but there’s one thing I can’t swallow and that’s the stories I hear about scouts saving drowning people and finding kidnapped children and all that kind of stuff. You kids seem to have the newspapers hypnotized. I read about a kid that put out a forest fire and saved a lot of lives at the risk of his own life. How much do you suppose the scout people pay to get that kind of stuff into the papers?”

“Oh, vast sums,” said Warde.

Mr. Wilde contemplated the three of them where they sat crowded on the Pullman seat opposite him. There was great amusement twinkling in his eyes, but approval too. He did not take them too seriously as scouts, real scouts, but just the same he liked them immensely.

“I bet you’ve been to the Yellowstone a lot of times,” said Ed Carlyle.

“Oh, a few,” said Mr. Wilde. “I’ve been up in woods off the trails where little boys don’t go—without their nurse girls.”

“I’ve heard there are bandits in the park,” said Westy.

“Millions of them,” said Mr. Wilde. “But don’t be afraid, they don’t hang out at the hotels where you’ll be.”

“Is it true there are train robbers out this way?” Westy asked.

“Getting scared? Why, I thought boy scouts could handle train robbers.”

“We can’t even handle you,” Warde said.

Indeed the three boys seemed on the point of giving Mr. Wilde up for a hopeless case.

“Why? Do you want to go hunting train robbers?” the exasperating stranger asked.

“Well,” said Westy, rather disgusted, “we wouldn’t be the first boy scouts to help the authorities. Some boy scouts in Philadelphia helped catch a highway robber.”

This seemed greatly to amuse Mr. Wilde. He screwed his cigar over from one corner of his mouth to the other and looked at the boys good-naturedly, but seriously.

“Well, I’ll tell you just how it is,” he said. “There are really two Yellowstone Parks. There’s the Yellowstone Park where you go, and there’s the Yellowstone Park where I go. There’s the tame Yellowstone Park and the wild Yellowstone Park.

“The park is full of grizzlies and rough characters of the wild and fuzzy West, but they don’t patronize the sightseeing autos. They’re kind of modest and diffident and they stay back in the mountains where you won’t see them. You know train robbers as a rule are sort of bashful. You kids are just going to see the park, and you’ll have your hands full, too. You’ll sit in a nice comfortable automobile and the man will tell you what to look at and you’ll see geysers and things and canyons and a lot of odds and ends and you’ll have the time of your lives. There’s a picture shop between Norris and the Canyon; you drop in there and see if you can get a post card showing Pelican Cone. That’ll give you an idea of where I’ll be. You can think of me up in the wilderness while you’re listening to the concert in the Old Faithful Inn. That’s where they have the big geezer in the back yard—spurts once an hour, Johnny on the spot. I suppose,” he added with that shrewd, skeptical look which was beginning to tell on the boys, “that if you kids really saw a grizzly you wouldn’t stop running till you hit New York. I think you said scouts know how to run.”

“We wouldn’t stop there,” said the Carlyle boy. “We’d be so scared that we’d just take a running jump across the Atlantic Ocean and land in Europe.”

“What would you really do now if you met a bandit?” Mr. Wilde asked. “Shoot him dead, I suppose, like Deadwood Dick in the dime novels.”

“We don’t read dime novels,” said Westy.

“But just the same,” said Warde, “it might be the worse for that bandit. Didn’t you read——”

Mr. Wilde laughed heartily.

“All right, you can laugh,” said Westy, a trifle annoyed.

Mr. Wilde stuck his feet up between Warde and Westy, who sat in the seat facing him, and put his arm on the farther shoulder of Eddie Carlyle, who sat beside him. Then he worked the unlighted cigar across his mouth and tilted it at an angle which somehow seemed to bespeak a good-natured contempt of Boy Scouts.

“Just between ourselves,” said he, “who takes care of the publicity stuff for the Boy Scouts anyway? I read about one kid who found a German wireless station during the war——”

“That was true,” snapped Warde, stung into some show of real anger by this flippant slander.

“I suppose you don’t know that a scout out west in Illinois——”

“You mean out east in Illinois,” laughed Mr. Wilde. “You’re in the wild and woolly West and you don’t even know it. I suppose if you were dropped from the train right now you’d start west for Chicago.”

The three boys laughed, for it did seem funny to think of Illinois being far east of them. They felt a bit chagrined too at the realization that after all their view of the rugged wonders they were approaching was to be enjoyed from the rather prosaic vantage point of a sightseeing auto. What would Buffalo Bill or Kit Carson have said to that?

Mr. Wilde looked out of the window and said, “We’ll hit Emigrant pretty soon if it’s still there. The cyclones out here blow the villages around so half the time the engineer don’t know where to look for them. I remember Barker’s Corners used to be right behind a big tree in Montana and it got blown away and they found it two years afterward in Arizona.”

It is said that constant dripping wears away a stone. At first the boys held their own good-humoredly against Mr. Wilde’s banter. He seemed to be only poking fun at them and they took his talk in the spirit in which it was meant. He seemed to think they were a pretty nice sort of boys, but he did not take scouting very seriously.

Now Westy was a sensitive boy and these continual allusions to the childish character of boy scouting got on his nerves. Then suddenly came the big shock, and this proved a knockout blow for poor Westy.

It developed in the course of conversation that Mr. Madison C. Wilde was engaged in a most thrilling kind of business. In the most casual sort of way he informed these boys that he was connected with the movies. Not only that, but his business connected itself with nothing less than the interesting work of photographing wild animals in their natural haunts for representation upon the screen. He was none other than the adventurous field manager of educational films, at which these very boys had many times gazed with rapt interest.

Nor was this all. Mr. Wilde (heartless creature that he was) casually brought forth from the depths of a pocket a mammoth wallet containing such a sum of money as is only known in the movies and, affectionately unfolding a certain paper, exhibited it to the spellbound gaze of his three young traveling acquaintances. This document was nothing less than a permit from the Commissioner of National Parks at Washington authorizing Mr. Wilde to visit the remotest sections of the great park, to stalk wild life on a truly grand scale, on a scale unknown to Boy Scouts who track rabbits and chipmunks in Boy Scout camps!

But here was the knockout blow for poor Westy. Mr. Wilde explained that waiting for him at the hotel near the Gardiner entrance of the park was a real scout whose services as guide and stalker had been arranged for with some difficulty. This romantic and happy creature was an Indian boy known in the Far West as Shining Sun. He was not, as Mr. Wilde explained, a back-yard scout. He was the genuine article. And he was going to lead Mr. Wilde and his associates into the dim, unpeopled wilderness.

And while Shining Sun, the Indian boy, was engaged in this delightfully adventurous task, Westy Martin and his two companions would be riding around on the main traveled roads on a sightseeing auto!

Was it any wonder that Westy was disgusted? Was it any wonder that in face of these startling revelations he began to see himself as just a nice sort of boy from Bridgeboro, New Jersey? A back-yard scout?

Truly, indeed, there were two Yellowstone Parks! Truly, indeed, thought poor Westy, there were two kinds of scouts.

And he, alas, was the other kind.

Then it was that Westy Martin, thoroughly disgusted with fate and thoroughly dissatisfied with himself and boy scouting generally, arose, just as the trainman called out: “Emigrant! Emigrant is the next stop!” And Westy Martin, leading the way, went headlong into the adventurous field of “big scouting”—never knowing it.

The three of them sat down disconsolately on one of the steps of the rear platform of the last car while the train paused at Emigrant, a deserted hamlet almost small enough to put in one’s pocket. Warde and Ed had followed Westy through the several cars, not fully sharing his mood, but obedient to him as leader. They made a doleful little trio, these fine boys who had been given a trip to the Yellowstone Park by the Rotary Club of America in recognition of a heroic good turn which each had done. Alas, that this glib stranger, Mr. Wilde, and that other unknown hero, Shining Sun, the Indian boy, should have destroyed, as it were with one fell blow, their wholesome enjoyment of scouting and their happy anticipations. Poor Westy.

I must relate for you the conversation of these three as they sat in disgruntled retirement on the rear platform of the last car nursing their envy of Shining Sun.

“I remind myself of Pee-wee Harris tracking a hop-toad,” grouched Westy.

“Just the same we’ve had a lot of fun since we’ve been in the scouts,” said Warde. “If we hadn’t been scouts we wouldn’t be here.”

“We’ll be looking at geysers and hot springs and things while they’re tracking grizzlies,” said Westy. “We’re boy scouts all right! Gee whiz, I’d like to do something big.”

“Just because Mr. Wilde says this and that——” Ed Carlyle began.

“Suppose he had gone to Scout headquarters in New York for a scout to help him in the mountains,” said Westy. “Would he have found one? When it comes to dead serious business——”

“Look what Roosevelt said about Boy Scouts,” cheered Warde. “He said they were a lot of help and that scouting is a peach of a thing, that’s just what he said.”

“Why didn’t you tell Mr. Wilde that?” Ed asked.

“Because I didn’t think of it,” said Warde.

“Just because I got the tracking badge that doesn’t mean I’m a professional scout like Buffalo Bill,” said Ed. “We’ve had plenty of fun and we’re going to see the sights out in Yellowstone.”

“While they’re scouting—doing something big,” grouched Westy.

“We should worry about them,” said Ed.

Westy only looked straight ahead of him, his abstracted gaze fixed upon the wild, lonesome mountains. A great bird was soaring above them, and he watched it till it became a mere speck. And meanwhile the locomotive steamed at steady intervals like an impatient beast. Then, suddenly, its voice changed, there were strain and effort in its steaming.

“Guess we’re going to go,” said Warde, winking at Ed in silent comment on Westy’s mood. “Now for the little old Yellowstone, hey, Westy, old scout?”

“Scout!” sneered Westy.

“Wake up, come out of that, you old grouch,” laughed Ed. “Don’t you know a scout is supposed to smile and look pleasant? Who cares about Stove Polish, or Shining Sun, or whatever his name is? I should bother my young life about Mr. Madison C. Wilde.”

“If we never did anything real and big it’s because there weren’t any of those things for us to do,” said Warde.

Westy did not answer, only arose in a rather disgruntled way and stepped off the platform. He strolled forward, as perhaps you who have followed his adventures will remember, till he reached the other end of the car. He was kicking a stone as he went. When he raised his eyes from the stone he saw that the car stood quite alone; it was on a siding, as he noticed now. The train, bearing that loquacious stranger, Mr. Madison C. Wilde, was rushing away among the mountains.

So, after all, Westy Martin had his wish (if that were really desirable) and was certainly face to face with something real and big and with a predicament rather chilling. He and his two companions, all three of them just nice boy scouts, were quite alone in the Rocky Mountains.

Westy’s first supposition was that the coupling had given way, but an inspection of this by the three boys convinced them that the dropping of this last car had been intentional. They recalled now the significant fact that it had been empty save for themselves. It was a dilapidated old car and it seemed likely that it had been left there perhaps to be used as a temporary station. They had no other surmise.

One sobering reflection dominated their minds and that was that they had been left without baggage or provisions in a wild, apparently uninhabited country, thirty odd miles from the Gardiner entrance of Yellowstone Park.

As they looked about them there was no sign of human life or habitation anywhere, no hint of man’s work save the steel rails which disappeared around a bend southward, and a rough road. Even as they looked, they could see in the distance little flickers of smoke floating against a rock-ribbed mountainside.

Warde was the first to speak: “I don’t believe this is Emigrant at all,” he said. “I think the train just stopped to leave the car here; maybe they’re going to make a station here. Anyway this is no village; it isn’t even a station.”

“Well, whatever it is, we’re here,” said Ed. “What are we going to do? That’s a nice way to do, not lock the door of the car or anything.”

“Maybe they’ll back up,” said Westy.

“They might,” said Warde, “if they knew we were here, but who’s going to tell the conductor?”

It seemed quite unlikely that the train would return. Even as they indulged this forlorn hope the distant flickers of smoke appeared farther and farther away against the background of the mountain. Then they could not be seen at all.

The three honor boys sat down on the lowest step of the old car platform and considered their predicament. One thing they knew, there was no other train that day. They had not a morsel of food, no camping equipment, no compass. For all that they could see they were in an uninhabited wilderness save for the savage life that lurked in the surrounding fastnesses.

“What are we going to do?” Warde asked, his voice ill concealing the concern he felt.

Ed Carlyle looked about scanning the vast panorama and shook his head.

“What would Shining Sun do?” Westy asked quietly. “All I know is we’re going to Yellowstone Park. We know the railroad goes there, so we can’t get lost. Thirty miles isn’t so much to hike; we can do it in two days. I wouldn’t get on a train now if one came along and stopped.”

“Mr. Wilde has got you started,” laughed Ed.

“That’s what he has,” said Westy, “and I’m going to keep going till I get to the park. I’m not going to face that man again and tell him I waited for somebody to come and get me.”

“How about food?” Warde asked, not altogether captivated by Westy’s proposal.

“What we have to get, we get,” said Westy.

“Well, I think we’ll get good and tired,” said Ed.

“I’m sorry I haven’t got a baby carriage to wheel you in,” said Westy.

“Thanks,” laughed Ed, “a scout is always thoughtful.”

“He has to be more than thoughtful,” said Westy. “If it comes to that, if we had been thoughtful we wouldn’t have come into this car at all. It’s all filled up with railroad junk and it wasn’t intended for passengers.”

“They should have locked the door or put a sign on it,” said Warde.

“Well, anyway, here we are,” Westy said.

“Absolutely,” said Warde, who was always inclined to take a humorous view of Westy’s susceptibility. “And I’ll do anything you say. I’ll tell you something right now that I didn’t tell you before. Ed and I agreed that we’d do whatever you wanted to do on this trip; we said we’d follow you and let you be the leader. So now’s our chance. We agreed that you did the big stunt and we voted that we’d just sort of let you lead. I don’t know what Shining Sun would do, but that’s what we agreed to do. So it’s up to you, Westy, old boy. You’re the boss and we’ll even admit that we’re not scouts if you say so. How about that, Ed?”

“That’s me,” said Ed.

“We’re just dubs if you say so,” Warde concluded.

The three sat in a row on the lowest step of the deserted car, and for a few moments no one spoke. Looking northward they could see the tracks in a bee-line until the two rails seemed to come to a point in the direction whence the train had come. Far back in that direction, thirty miles or more, lay Livingston where they had breakfasted. There had been no stop between this spot and Livingston, though they had whizzed past an apparently deserted little way station named Pray.

Southward the tracks disappeared in their skirting course around a mountain. The road went in that direction too, but they could not follow it far with their eyes. It was a narrow, ill-kept dirt road and was certainly not a highway. The country was very still and lonesome. They had not realized this in the rushing, rattling train. But they realized it now as they sat, a forlorn little group, on the step and looked about them.

To Westy, always thoughtful and impressionable, the derisive spirit of Mr. Wilde made their predicament the more bearable. The spirit of that genial Philistine haunted him and made him grateful for the opportunity to do something “big.” To reach the park without assistance would not, he thought, be so very big. It would be nothing in the eyes of Shining Sun. But at least it would be doing something. It would be more than playing hide-and-seek, which Mr. Wilde seemed to think about the wildest adventure in the program of scouting. It would, at the least, be better than coming along a day late on another train, even supposing they could stop a train or reach the stopping place of one.

“It’s just whatever you say, Westy, old boy,” Warde said musingly, as he twirled his scout knife into the soil again and again in a kind of solitaire mumbly peg. “Just—whatever—you—say. Maybe we’re not——”

“You needn’t say that again,” said Westy; “we—you are scouts. You just proved it, so you might as well shut up because—but——”

“All right, we are then,” said Warde. “You ought to know; gee whiz, it’s blamed seldom I ever knew you to be mistaken. Now what’s the big idea? Hey, Ed?”

“After you, my dear Sir Hollister,” said Ed.

“Well, the first thing,” said Westy, “is not to tell me you’re not scouts.”

“We’ll do that little thing,” said Warde.

“New conundrum,” said Ed. “What is a scout?”

“You are,” said Westy. “I wish I’d never met that Mr. Wilde.”

“Forget it,” said Warde.

“All right, now we know the first thing,” said Ed. “How about the second? Where do we go from here?”

Westy glanced at him quickly and there was just the least suggestion of something glistening in his eyes. “Are you willing to hike it?” he asked.

“You tell ’em I am,” said Ed Carlyle.

“Well, we know which direction to start in, and that’s something,” said Westy.

“And we’re not hungry yet, and that’s something else,” said Warde. “We ought to be able to walk fifteen miles to-day and the rest of the way to-morrow. And if we can’t find enough to eat in Montana to keep us from starving——”

“Then we ought to be ashamed to look Mr. Wilde in the face,” said Westy.

“I wish I knew something about herbs and roots,” said Ed. “The only kind of root that I know anything about is cube root and I don’t like that; I’d rather starve. I wonder if they have sassafras roots out this way. I’ve got my return ticket pinned in my pocket with a safety-pin so we ought to be able to catch some fish.”

“How about a line?” Warde asked.

“I can unravel some worsted from my sweater,” said Ed. “Oh, I’m a regular Stove Polish. Maybe we can find some mushrooms; I’m not worrying. I know one thing, I’d like to go up on Penelope’s Peak with Mr. Wilde and those fellows.”

“Pelican Cone,” said Westy.

“My social error—Pelican Cone,” said Ed.

“He’d about as soon think of taking us as he would our grandmothers,” said Westy. “That’s what gets me; they take an Indian boy who maybe can’t even speak English, because he can do the things we’re supposed to be able to do. I don’t mean just you and I. But wouldn’t you think there’d be some fellow in the scout organization—— Gee, I should think out west here there ought to be some who could stalk and things like that. You heard what he said about amateurs and professionals. He’s right, that’s the worst of it.”

“He’s right and we’re wrong as he usually is,” said Ed. “Believe me, I’m not worrying about what he thinks. We have plenty of fun scouting. What’s worrying me is whether we should follow the tracks or the road. I believe in tracking and I’d say follow the tracks only suppose they go over high bridges and places where we couldn’t walk. It’s not so easy to track railroad tracks. But the trouble with the road is we don’t know where it goes.”

“I don’t believe it knows itself,” said Warde, “by the looks of it.”

“We want to go south; we know that,” said Westy. “Gardiner is south from here.”

“I thought we were on our way out west,” said Warde. “I wish we had a compass, I know that.”

“Do you suppose Shining Sun has a compass?” Westy asked.

“Now listen,” said Ed. “I mean you, Westy. You’ve got the pathfinder’s badge and the stalker’s badge and a lot of others; you’re a star scout. You should worry about Dutch Cleanser or Stove Polish or whatever his name is——”

“Shining Sun,” said Westy.

“All right, when the shining sun comes up a little higher we’ll find out which is north and south and east and west and up and down and in and out and all the other points of the compass including this and that. How do you know we want to go south from here? Tell me that and I’ll find out where south is.”

“Silver Cleaner, the Indian boy!” shouted Warde. “Grandson of the old Sioux Chief Gold Dust Twins. I’ll tell you why we have to go south. Livingston, where we ate our last meal on earth, is north of here. We turned south at Livingston; this is a branch that goes down to the Gardiner entrance of the Park. If we go south from here we’re sure to strike the Park even if we don’t strike Gardiner. The Park is about fifty miles wide. I don’t know whether there’s a fence around it or not. Anyway, if we go south from here we’re sure to get into the Park.”

“Maybe we’ll land on Pelican’s Dome,” said Ed.

“Come face to face with Mr. Wilde, hey?” said Warde. “We’ll say to Stove Polish, ‘Oh, we don’t know, when it comes to picking trails——’”

“Come on, let’s start,” said Westy.

“Sure,” said Warde, “maybe they’ll be naming canoes after us yet—Hiawatha, Carlylus, Wesiobus, Martinibo——”

“I wonder what Indian they named Indian meal after?” said Ed.

“You’re worse than Roy Blakeley,” said Warde; “they named it after the Indian motorcycle, didn’t they, Westy, old scout?”

“You say you think the road runs south?” Westy asked.

“I say let’s follow the road,” said Westy. “We’re pretty sure to come to some kind of a settlement that way. If we follow the tracks we might come to a place where we couldn’t go any farther, like a high trestle or something like that. I wish we had a map. The road goes south for quite a distance, you can see that. What do you say?”

“Just whatever you say, Westy,” said Ed.

“Same here,” said Warde.

“Only I don’t want to be blamed afterward,” said Westy, looking about him rather puzzled and doubtful.

When he thought of Shining Sun, thirty miles seemed nothing. But when he gazed about at the surrounding mountains, the distance between them and the Park seemed great and filled with difficulties. He was already wishing for things the very existence of which was doubtless unknown to the Indian boy who had become his inspiration.

“Anyway,” said Westy, “let’s make a resolution. You fellows say you made one and left me out of it. Now let’s make another one, all three of us. Let’s decide that we’ll hike from here to the Gardiner entrance without asking any help of any one. We’ll do it just as if we didn’t have anything with us at all.”

“We haven’t,” said Warde.

“I mean even our watches and matches and things like that,” said Westy. “Just as if we didn’t even have any clothes; you know, kind of primitive.”

“Don’t you think I’d better hang onto my safety-pin?” Ed asked. “Safety first. An Indian might—you know even an Indian might happen to have a safety-pin about him.”

Westy could not repress a smile, but for answer he pulled his store of matches out of his pocket and scattered them by the wayside. Warde, with a funny look of dutiful compliance, did the same. Ed, with a fine show of abandon and contempt for civilization, pulled his store of matches out of one pocket and put them in another. “May I keep my watch?” he asked. “It was given to me by my father when I became a back-yard scout.”

“Back-yard scout is good,” said Westy.

“Thank you muchly,” said Ed.

“I mean all of us,” Westy hastened to add.

It was funny how poor Westy was continually vacillating between these two good scouts who were with him and that unknown hero whose prowess had been detailed by the engaging Mr. Wilde. He was ever and again being freshly captivated by Ed’s sense of humor and whimsical banter and impressed by Warde’s quiet if amused compliance with this new order of things by which it seemed that the primitive was to be restored in all its romantic glory.

It never occurred to Westy to wonder what kind of a friend and companion his unknown hero, Shining Sun, would really be. What he was particularly anxious to do, now that the chance had come, was to show that cigar-smoking Philistine, Mr. Wilde, that boy scouts were really good for something when thrown on their own resources.

Pretty soon the first simple test of their scouting lore was made when they took their bearing by that vast, luminous compass, the sun. It worked its way through the dull, threatening sky bathing the forbidding heights in gold and contributing its good companionship to the trio of pilgrims. It seemed to say, “Come on, I’ll help you; it’s going to be nice weather in the Yellowstone.”

“That’s east,” said Westy. “We’re all right, the road goes south and if it stops going south, we’ll know it.”

“If it’s the kind of a road that does one thing one day and another thing the next day I have no use for it anyway,” said Warde.

“When it’s twelve o’clock I know a way to tell what time it is,” said Ed. “Remind me when it’s twelve o’clock and I’ll show you.”

The sun, which had not shown its face during the whole of the previous day, brightened the journey and raised the hopes of the travelers. To Westy, now that they were started along the road and everything seemed bright, their little enterprise seemed all too easy. He was even afraid that the road went straight to the Gardiner entrance of the park. He wanted to encounter some obstacles. He wanted this thing to have something of the character of an exploit.

Poor Westy, thirty miles over a wild country seemed not very much to him. It would be just about a two-days’ hike. But he cherished a little picture in his mind. He hoped that Mr. Madison C. Wilde would be still at the Mammoth Hotel when he and his companions reached there, having traversed—having traversed—thirty miles of—having forced Nature to yield up——

“We can catch some trout and eat them, all right,” he said aloud.

“Oh, we can eat them, all right,” said Ed. “When it comes to eating trout, I’ll take a handicap with any Indian youth and beat him to it.”

“It’s going to be pleasant to-night,” said Westy. “We can just sleep under a tree.”

“I hope it won’t be too pleasant,” said Ed.

“You make me tired,” laughed Westy.

To be sure, a hike of thirty miles is no exploit, not in the field of scouting, certainly. If the road went straight to the park, then the boys could hardly hope to face that doubter, Mr. Wilde, with any consciousness of glory.

On the time-table map which Westy had left in the train, the way from Livingston to Gardiner seemed very simple. A little branch of the Northern Pacific Railroad connected the two places with a straight line. And a road seemed to parallel this.

But maps are very seductive things. You have only to follow a road with your lead pencil to reach your destination. Nature’s obstacles are not always set forth upon your map. Lines parallel on a map are often not within sight of each other on the rugged face of Nature. A little, round dot, a village, is seen close to a road. But when you explore the road the village is found to nestle coyly a mile or two back.

So if what the boys had undertaken was not so very big, at least it held out the prospect of being not so very little. But big or little, something big did happen among those lonely mountains that very day, an exploit of the first order. It was a bizarre adventure not uncommon in the Far West and it had an important bearing on the visit of these three scouts to the Yellowstone Park. And Westy Martin, hiking along that quiet, winding, western road, dissatisfied with himself because of what a chance acquaintance had said to him, was face to face with the biggest opportunity in all his young scout life. He did not know it, but he was walking headlong into it.

He had been proud when he had won the stalking badge. He was soon to know that this badge meant something and that it was no toy or gewgaw.

“I suppose it’s pretty wild on Pelican Cone,” said Warde, as they hiked along.

They were all cheerful for they were sure of their way for the present and were not disposed to borrow trouble. It was a pleasant summer morning, the sun shone bright on the rock-ribbed mountains, a fresh, invigorating breeze blew in their faces, birds sang in the neighboring trees, all Nature seemed kindly disposed toward their little adventure.

As the railroad line left the roadside and curved away into a mountain pass, they felt a momentary lonesomeness, the trusty rails had guided them so far on the long journey. It was like saying good-by to a friend, a friend who knew the way. For a minute they conferred again on whether they should “count the ties,” but they decided in favor of the road. So they went upon their adventure along the road, just as the great, thundering, invincible train had gone upon its adventure along the shining tracks.

“Yellowstone Park is just about like this,” said Westy; “I mean the wild parts. Of course there are things to see there like geysers and all that, but I mean the wild parts; it’s wild just like this. I suppose there are trails,” he added with a note of wistfulness in his voice. “I suppose they know just where to go if they want to get a look at grizzlies. I’d be willing to give up the other things, you bet, if I could go on a trip like that. I was going to ask Mr. Wilde, only I knew he’d just guy me about it.”

“We can see the film when it comes out anyway,” said Ed, always cheerful and optimistic. “We can go up on Mount what-do-you-call it, Pelican——”

“Pelican Cone,” said Westy. Already that hallowed mountain was familiar to him in imagination and dear to his heart. “Can’t you remember Cone?”

“I can remember it by ice cream cone,” said Ed. “What I was going to say was if that film comes to Bridgeboro we can go up on that cone for thirty cents and the war tax. What more do we want?”

“Sugar-coated adventures,” said Warde.

“Sugar-coated is right,” said Westy disgustedly.

“Now you’ve got me thinking about candy,” said Ed. “I hope we can buy some in the Park.”

“Do you suppose they have merry-go-rounds there?” Warde asked.

“Gee whiz, I hope so,” said Ed. “I’m just crazy for a sight of wild animals. Imitation ones would be better than nothing, hey, Westy?”

“Imitation scouts are better than no kind,” said Warde. “We’re pretty good imitations.”

“I wouldn’t admit it if I were you,” said Westy with the least suggestion of a sneer.

“A scout that gives imitations is an imitation scout,” said Ed. “Dutch Cleanser is an imitation scout; he imitates animals, Mr. Wilde West said so. That proves everybody’s wrong. What’s the use of quarreling? None whatever. Correct the first time. You can be a scout without knowing it, that’s what I am.”

“Nobody ever told you you were Daniel Boone, did they?” Westy sulked.

“They don’t have to tell me, I know it already,” said the buoyant Ed.

“Come on, cheer up, Westy, old boy,” said Warde. “We came out here to see Yellowstone Park and now you’re grouching because a funny little man with a cigar as big as he is that we met on the train says we’re just playing a little game, sort of. What’s the matter with the little game? We always had plenty of fun at it, didn’t we? Are you going to spoil the party because a little movie man wouldn’t take us up in the forest with him? Gee whiz, I wouldn’t call that being grateful to the Rotary Club that wished this good time on us. I wouldn’t call that so very big; I’d call it kind of small.”

Westy gave him a quick, indignant glance. It was a dangerous moment. It was the ever-friendly, exuberant Ed who averted angry words and perhaps prevented a quarrel. “If there’s anything big anywhere around and it wants to wait till I get to it, I’ll do it. I won’t be bullied. I’m not going to run after it, it will have to wait for me. I’m just as big as it is—even more so. It will have to wait.”

They all laughed.

They picked blackberries along the way during the hour or so preceding noon and made bags of their handkerchiefs and stored the berries in them. At noontime they sat down by the wayside and made a royal feast.

The country was rugged and in the distance were always the great hills with here and there some mighty peak piercing the blue sky. There was a wildness in the surroundings that they had never seen before. Perhaps they felt it as much as saw it. For one thing there were no distant habitations, no friendly, little church spires to soften the landscape. The towering heights rolled away till they became misty in the distance, and it seemed to these hapless wayfarers that they might reach to the farthest ends of the earth.

But the immediate neighborhood of the road was not forbidding, the way led through no deep ravines nor skirted any dizzy precipices and it was hard for the boys to realize that they were in the Rocky Mountains. They lolled for an hour or so at noontime and talked as they might have talked along some road in their own familiar Catskills.

One thing they did notice which distinguished this storied region from any they had seen and that was the abundance of great birds that flew high above them. They had never seen birds so large nor flying at so great a height. They appeared and disappeared among the crags and startled the quiet day with their screeching, which the boys could hear, spent and weak by the great distance. They supposed these birds to be eagles. Their presence suggested the wild life to be encountered in those dizzy fastnesses. The boys saw no sign of this, but their imaginations pictured those all but inaccessible retreats filled with grizzlies and other savage denizens of that mighty range. As Westy looked about him he fancied some secret cave here and there among the mountains, the remote haunt of outlaws and of the storied “bad men” of the West.

They hiked all day assured of their direction by the friendly sun. Now and again they passed a house, usually a primitive affair, and were tempted to verify the correctness of their route by comforting verbal information. But Westy thought of Mr. Madison C. Wilde and refrained. They were not often tempted, for houses were few and far between. Once they encountered a lanky stranger lolling on the step of a shabby little house. He seemed to be all hat and suspenders.

THEY HIKED ALL DAY ASSURED OF THEIR DIRECTION BY THE FRIENDLY SUN.

“Shall we ask him if this is the way?” Warde cautiously asked.

“No,” said Westy.

“I’m going to ask him,” said Ed.

“You do——” said Westy threateningly, “and——”

But before he had a chance to complete his threat, the blithesome Ed had carried out his fiendish purpose.

“Hey, mister, is this the way?” he said.

“Vot vay?” the stranger inquired.

“Thanks,” said Ed.

“You make me tired,” Westy said, constrained to laugh as they hiked along. “If that man could have spoken English——”

“All would have been lost,” said Ed, “and we would be sure of going in the right direction; we had a narrow escape. That’s because I was a good scout; I saw that he was a foreigner; I remembered what it said in my school geography. ‘Montana has been settled largely by Germans who own extensible—extensive farms—in this something or other region. The mountains abound in crystal streams which are filled with trout—that can easily be caught with safety-pins.’ It’s good there’s one scout in the party. If we had some eggs we’d fry some ham and eggs if we only had some ham; I’m getting hungry.”

“Now that you mentioned it——” said Warde.

“How many miles do you think we’ve hiked?” asked Westy.

“I don’t know how many you’ve hiked,” said Ed, “but I’ve hiked about ninety-seven. I think we’ve passed Yellowstone Park without knowing it, that’s what I think. Maybe we went right through it; the plot grows thicker. I hope we won’t walk into the Pacific Ocean.”

It was now late in the afternoon and they had hiked fifteen or eighteen miles. Once in the midafternoon they had heard, faint in the long distance, what they thought might be a locomotive whistle and this encouraged them to think that they were still within a few miles of the railroad line.

Westy would not harbor, much less express, any misgivings as to the reliability of the sun as a guide. Perhaps it would be better to say that he would not admit any inability on his part to use it. Yet as the great orb began to descend upon the mountain peaks far to the right of their route and to tinge those wild heights with a crimson glow, he began to imbibe something of the spirit of loneliness and isolation which that vast, rugged country imparted. After all, amid such a fathomless wilderness of rock and mountain it would have been good to hear some one say, “Yes, just follow this road and take the second turn to your left.”

“That’s West, isn’t it?” Westy asked, as they plodded on.

“You mean where the sun is setting?” asked Warde. “Oh, absolutely.”

“It sets there every night,” said Ed, “including Sundays and holidays.”

“Well then,” said Westy, feeling a little silly, “we’re all right.”

“We’re not all right,” said Warde; “at least I’m not, I’m hungry.”

“Well, here’s a brook,” said Westy. “Do you see—look over there in the west—do you see a little shiny spot away up between those two hills? Away up high, only kind of between the two hills? It’s only about half a mile or so. It’s the sun shining on this brook away up there. That shows it comes down between those two hills.”

They all paused and looked. Up among those dark hills in the west was a little glinting spot like gold. It flickered and glistened.

“Maybe it’s a bonfire,” said Warde.

“I think it’s the headlight of a Ford,” said Ed. “A Ford can go anywhere a brook can go.”

“You crazy dub,” said Westy.

“My social error,” said Ed.

“What do you say we go over there?” Westy said. “Do you see—notice on that hill where all the rocks are—do you see a big tree? If one of us climbed up that tree I bet we could see for miles and miles; we could see just where the road goes. It’s only about fifteen or twenty miles to the entrance of the park; maybe we could see something—some building or something. Then we could camp for the night up there and catch some fish. Wouldn’t you rather not reach Gardiner by the road? Maybe we can plan out a short-cut. Anyway, we can see what’s what. What do you say?”

“The fish part sounds good to me,” said Ed.

“How are we going to cook the fish?” Warde asked.

Ed pulled out a handful of matches and exhibited them, winking in his funny way at Warde.

“I thought you threw them away,” said Westy. “Do you think we couldn’t get a fire started without matches?”

“A scout never wastes anything,” said Ed. “The scouts of old never wasted a thing, I learned that out of the Handbook. Again it shows what a fine scout I am. Do you suppose Mr. Madison C. Wild West lights his cigars with sparks from a rock?”

“The Indians——” began Westy.

“The Indians were glad enough to sell Massachusetts or Connecticut or Hoboken or some place or other for a lot of glass beads,” said Ed. “They would have sold the whole western hemisphere for a couple of matches. You make me weary with your Indians! I wish I had a chocolate soda now, that’s what I wish. The Indians invented Indian summer and what good is it? It comes after school opens, deny it if you dare. Hey, Warde? If I’d lived in colonial days I bet I could have got the whole of Cape Cod for this safety-pin of mine.”

“Well, what do you say?” laughed Westy. “Shall we go up there and camp? And that will give us a chance to get a good squint at the country.”

“Decided by an unanimous majority,” said Ed.

“When do we eat?” said Warde.

“Leave it to me,” said Ed slyly. And again he went through that funny performance of appearing to throw his matches away by pulling them nonchalantly from one pocket and depositing them in another. “If there are no trout up there I’ll never believe the school geography again. I may even never go to school again, I’ll be so peeved.”

They left the road and made their way across country toward the hills whose lofty peaks were now golden with the dying sunlight. They followed the brook which had flowed near the roadside up to where it came through a rocky cleft between two hills.

As they climbed up to the spot, the glinting light which had been their beacon faded away and only the brook was there, rippling cheerily over its stony bed. It seemed as if it had bedecked itself in shimmering gold to guide these weary travelers to this secluded haunt.

To be sure they had not penetrated far from the unfrequented road, but they were able now to think of themselves as being in the Rocky Mountains. The cleft through which the brook flowed was wide enough for a little camping site at its brink and here, with the rushing water singing its soothing and incessant lullaby, they resolved to rest their weary bodies for the night.

One side of this cleft was quite precipitous and impossible of ascent. But the side on which the boys chose their camp site sloped up from the flat area at the brook side and was indeed the side of a lofty hill. It was on this hill that Westy had noticed the tree from the upper branches of which he had thought that he might scan the country southward, which would be in the direction of the park. A very much better view might have been obtained from neighboring mountain peaks, but the ascent of such heights would have been a matter of many hours and fraught with unknown difficulties. From the hill the country seemed comparatively low and open to the south.

“This is some spot all right,” said Warde. “It looks as if Jesse James might have boarded here.”

“Or William S. Hart,” said Ed. “Anyway I think there are some fish getting table board here; it’s a kind of a little table-land. If we can’t get any trout we can kill some killies. I wonder if there’s any bait in the Rocky Mountains? I bet the angle-worms out here are pretty wild.”

“Hark—shh!” said Westy.

“I’m shhhhing. What is it?” asked Ed.

“I thought I heard a kind of a sound,” said Westy.

“I hope it isn’t a grizzly,” said Warde. “Do you suppose they come to places like this? Come on, let’s gather some branches to sleep on; I know how to make a spring mattress. Is it all right to sleep on branches, Westy?”

It was funny to see Ed sitting on a rock calmly unraveling some worsted from his sweater, all the while with his precious safety-pin stuck ostentatiously in the shoulder of his shirt.

“It’s good you happened to have your sweater on,” said Warde.

“I hope I don’t lose my railroad ticket now,” said Ed. “I had it pinned in. I tell you what you do. Big Chief,” he added, addressing Westy, and all the while engrossed with his unraveling process; “you climb up that hill and take a squint around and look for a patch of yellow in the distance. That will be Yellowstone Park. Look all around and if you see any places where they sell hot frankfurters let us know. By the time you get back we’ll have supper ready, what there is of it, I mean such as it is. I’m going to braid this stuff, it’s too weak. Look in the sink and see if there are any sinkers, Wardie.”

“All right,” said Westy, “because if I wait till after supper it might be too dark.”

“If you wait till after supper,” said Ed, “maybe the tree won’t be there. We may not have supper for years. How do I know that fish are fond of red. I always told my mother I wanted a gray sweater, same color as fish-line, and she goes and gets me a red one. I wonder what Stove Polish catches fish with.”

“Maybe with the string that Mr. Wilde West was stringing us with,” said Warde.

“I guess I’d better go,” laughed Westy.

Westy was still laughing as he climbed the hill. He was thinking that these two companions of his were pretty good scouts after all. In his mood of dissatisfaction with himself and modern scouting, it had not occurred to him that being a good scout consists not in getting along with nothing, but in getting along with what you happen to have.

A little way up the hill he looked back and could see Ed sitting on a rock, one foot cocked up in the air with several strands of worsted about it. He seemed to be bent on the task of braiding these and there was something whimsical about the whole appearance of the thing which amused Westy and made him realize his liking for this comrade who was of another troop than his own.

Reaching the summit of the hill he saw that the tree he had seen from below was not as isolated as it had looked to be. It was a great elm and rose out of a kind of jungle of brush and rock and smaller trees. These near surroundings had not been discernible from the distant road. A given point in Nature is so different seen from varying distances and from different points of view.

But the hill was not disappointing in affording an extensive view southward. There was no object in that direction which gave any hint of Yellowstone Park, but probably much of the wild scenery he beheld was within the park boundaries. It was significant of the vastness of the Park and of the smallness of Westy’s mental vision that he had expected to behold it as one may behold some local amusement park. He had thought that upon approach he might be able to point to it and say with a thrill, “There it is!” He had not been able to fix it in his mind as a vast, wild region that just happened to have a tame, civilized name—Park.

There was something very peculiar about this great tree and Westy wondered if some terrific cyclone of years gone by might have caused it. Evidently it had once been uprooted, but not blown down. At all events a great rock was lodged under its exposed root, causing the tree to stand at an angle. It seemed likely that the same wind-storm which had all but lain the tree prone had caused the rock to roll down from a slight eminence into the cavity and lodge there. Great tentacles of root had embraced the rock which seemed bound by these as by fetters. And under a network of root was a dark little cave created by the position of the rock.

Westy poked his head between the network of roots and peered into this dank little cell. It smelled very damp and earthy. Some tiny creature of the mountains scampered frantically out and the stir it caused seemed multiplied into a tumult by the darkness and the smallness of the place. Westy weakened long enough to wish he had a match so that he might make a momentary exploration of this freakish little hole.

His first impulse was to throw off his jacket before climbing the tree, but he did not do this. He was good at climbing and he shinned up the tree with the agility of a monkey. He rested at the first branch and was surprised to see how even here the view seemed to expand before him. He felt that at last he was doing something free from the contamination of roads and railroad tracks. He was alone in the Rockies. He had once read a boys’ book of that title, and now he reflected with a thrill that he, Westy Martin, was, in a sense, alone in the Rockies. Not in the perilous depths, perhaps, but just the same, in the Rockies. He wondered if there might be a grizzly within a mile, or two or three miles of him. The Rockies!

He ascended to the next branch, and the next. Slowly he climbed and wriggled upward to a point beyond which he hesitated to trust the weight of his body. And here he sat in a fork of the tree and looked southward and eastward where a vast panorama was open before him.

To the north and west was a near background of towering mountains, making his airy perch seem low indeed. But to the south and east he saw the West in all its glory and majesty. Mountains, mountains, mountains! Magnificent chaos! Distance unlimited! Wildness unparalleled! Such loneliness that a whisper might startle like a shout. It needed only the roar of a grizzly to complete this boy’s sense of tragic isolation and to give the scene a voice.

From where he sat, Westy could look down into the cosy little cleft and see Ed Carlyle standing clearly outlined in the first gray of twilight; standing like a statue, hopefully angling with his converted safety-pin and braided worsted. Warde was gathering sticks for their fire. Westy’s impulse was to call to them, but then he decided not to. He preferred not to call, nor even see them. For just a little while he wanted to be alone in the Rockies.

So he did not call. He looked in another direction and as he did so his heart jumped to his throat and he was conscious of a feeling of unspeakable gratitude to the saving impulse which had kept him silent. For approaching up the hill from the direction in which he now looked were the figures of two men. And one glimpse of them was enough to strike horror to Westy Martin’s soul.

It required but one look at these two men to cause Westy devoutly to hope that they had not seen him. They were rough characters and of an altogether unpromising appearance.

One preceded the other and the leader was tall and lank and wore a mackinaw jacket and a large brimmed felt hat. But for the mackinaw jacket he might have suggested the adventurous western outlaw. But for the romantic hat with flowing brim he might have suggested an eastern thug. The man who followed him wore a sweater and a peaked cap, that dubious outfit which the movies have taught us to associate with prize fighters and metropolitan thugs.

But a more subtle difference distinguished these strangers from each other. The leader walked with a fine swinging stride, the other with that mean carriage effected by short strides and a certain tough swing of the arms. He had a street-corner demeanor about him and a way of looking behind him as if he were continually apprehending the proximity of “cops.” He had an East-Side, police-court, thirty-days-on-the-island look. His companion seemed far above all that.

WESTY MOVED NOT A MUSCLE, SCARCELY BREATHED.

Westy moved not a muscle, scarcely breathed. The tree was evidently the destination of these strangers for they approached with a kind of weary satisfaction, which in the smaller man bespoke a certain finality of exhaustion. The leader evidently sensed this without looking behind him, for he referred to it with a suggestion of disgust.

“Yer tired?”

“I ain’t used ter chasin’ aroun’ the world ter duck, pal,” said the other.

“Jes’ roun’ the corner; some cellar or other I reckon?” said the leader.

“Dat’s me,” replied the other.

By this time Westy was satisfied that they had not seen him before or during his ascent, and it seemed to him a miracle that they had not. Ludicrously enough he was conscious of a sort of disappointment that the taller man had not seen him, and this together with the deepest thankfulness for the fact.

There was something inscrutable about this stranger, a suggestion of efficiency and assured power. If Westy could have believed, without peril to himself, that his presence could not escape this man’s eagle vision it would have rounded out the aspect of lawless heroism which the man seemed to have. It was rather jarring to see the fellow fail in a matter in which he should have scored. And this, particularly in view of his subsequent conversation. But Westy’s dominant feeling was one of ineffable relief.

“There ain’t no trail up here?” the smaller man asked, as he looked doubtfully about him.

“I never hide ’long no trails,” the taller man drawled, as he seated himself on the rocky mound which was the roof of the little cave. “I telled yer that, pardner. I ony use trails ter foller others. Long’s I can’t fly I have ter make prints, but yer seen how I started. Prints is no use till yer find ’em. But ready-made trails ’n sech like I never use—got no use fer ’em. Nobody ever tracked me; same’s I never failed ter track any one I set out ter track. When yer see me a-follerin’ a reg’lar trail yer’ll know I’m pursuin’, not pursued, as the feller says. Matter, pardner? Yer sceered?”

“A dog could track us all right,” said the other. “He could scent us along the rails, couldn’t he? Walkin’ the rails for a mile might kid the bulls all right, but not no dog.”

“Nobody never catched me, pardner, an’ nobody never got away from me,” drawled the other man grimly.

“They put dogs on, don’t they?” the smaller man asked. He seemed unable to remove this peril from his mind.

“Yere, an’ they take ’em off again.”

“Well, I guess you know,” the smaller man doubtingly conceded.

“I reckon I do,” drawled the other.

“I ain’t scared o’ nobody gettin’ up here,” said the one who was evidently a pupil and novice at the sort of enterprise they had been engaged in. “But you said about dogs; sheriff’s posse has dogs, yer says.”

“They sure do,” drawled the other, lighting a pipe, “an’ they knows more’n the sheriffs, them hound dogs.”

“Well, yer didn’ cut the scent, did yer? Yer says ’bout cuttin’ scents, but yer didn’ do it, now did yer?”

For a few moments the master disdained to answer, only smoked his pipe as Westy could just make out through the leaves. The familiar odor of tobacco ascended and reached him, diluted in the evening air. It was only an infrequent faint whiff, but it had an odd effect on Westy; it seemed out of keeping with the surroundings.

“I walked the rail,” said the smoker very slowly and deliberately, “till I come ter whar a wolf crossed the tracks. You must have seed me stoop an’ look at a bush, didn’t yer? Or ain’t yer got no eyes?”

“I got eyes all right.”

“Didn’t yer see me kinder studyin’ sumthin’? That was three four gray hairs. Then I left the rail ’n cut up through this way. It’s that thar wolf’s got ter worry, not me ’n you.”

“Well, we done a pretty neat job, I’ll tell ’em,” said the smaller man, apparently relieved.

“Well, I reckon I knowed what I was sayin’ when I telled yer it was easy; jes’ like doin’ sums, that’s all; as easy as divvyin’ up this here swag. Ten men that’s a-sceered ain’t as strong as one man that ain’t a-sceered. All yer gotter do is git ’em rattled. Ony yer gotter know yer way when it’s over.”

“Yer know yer way all right,” said the other, with a note of tribute in his voice.

“Yer ain’t looked inside yet,” said the master. “Neat little bunk fer a lay-over, I reckon. Ony kinder close. ’Tain’t fer layin’ low I likes it ’cause I like it best outside, ’n we’re as safe here. Ony in case o’ sumthin’ gone wrong we got a hole ter shoot from. With me inside o’ that nobody’d ever git inside of three hundred feet from it. I could turn this here hill inter a graveyard, I sure reckon. Yer hungry?”

“Supposin’ any one was to find this here place?” the other asked. “You said ’bout sumthin’ goin’ wrong maybe.”

“Well, he wouldn’ hev the trouble o’ walkin’ back,” said the tall man grimly.

Just then Westy, who had scarce dared to breathe, took advantage of the stirring of the strangers to glance toward his friends in the cleft. The little camping site looked very cosy and inviting. But even as he looked his blood ran cold and he was struck with panic terror. For standing at the brink of the rivulet was Warde Hollister, his hands curved into a funnel around his mouth, ready to call aloud to him.

Westy held his breath. His heart thumped. Every nerve was tense. Then he heard the screeching of one of those great birds flying toward the crags in the twilight. He waited, cold with terror. . . .

“Don’t call to him,” said Ed. “As long as we haven’t got our fire started yet, what’s the use calling? He likes to be alone, sometimes; I know Westy all right. Don’t call.”

It was this consideration on the part of Ed for the mood and nature of his friend that saved Westy at the moment. And incidentally it saved Warde and Ed themselves from discovery. Westy knew his peril, but they did not know theirs.

Ed stood at the brink of the stream fishing, his partly unraveled sweater tied around his waist, giving a Spanish touch to his appearance. It was a funny habit of his to wear clothes the wrong way. He was always springing some ludicrous effect by freakish arrangement of his apparel. Warde was gathering sticks for their fire.

“Here’s another killie,” said Ed. “Small, but nifty. That makes seven so far, and about ’steen of these other kind, whatever they are. Don’t call till you have to. Westy had this little lonely stroll coming to him ever since Mr. Wilde West sprung that stuff on us. He likes to communicate with Nature, or commune or commute or whatever you call it. He’s imagining he’s hundreds and hundreds of miles off now—I bet he is. He’s thinking what a punk scout he is. He likes to kid himself; let him alone, don’t call.”

“There’s one thing I want to say to you,” said Warde, “now we’re alone. I guess you never quarreled with a fellow, did you?”

“Here’s another killie—a little one,” said Ed.

“Well, all I wanted to say was,” said Warde, “I’d like to let you know that I think you’re about as good an all-round scout as any there ever was, Indians, or I don’t care what. Understanding everything in nature is all right, but understanding all about people is something, too. Isn’t it?”

“I suppose it must be if you say so,” said Ed.

“This pin’s only good for the little ones——”

“I mean you understand Westy, you know just how to handle him,” said Warde. “Scouts have to deal with men, maybe wild men, just the same as they have to deal with nature, I guess. You can read Westy like a—a—like a trail. Gee, in the beginning I was hoping Westy and I could come out here alone. Now I just can’t think of the trip without you along. Do you ever get mad?”

“I get mad every time this blamed worsted breaks,” said Ed.

“I know Westy’s kind of—you know—he’s kind of sensitive. He’s awful serious about scouting. That Mr. Wilde just got him. Now he’ll do something big if it kills him. And what good will it do him? That’s what I say. Mr. Wilde will never see him again. You can’t make Indians out of civilized white people, can you? Now he thinks none of us are regular scouts. And that’s just what I want to tell you now while we’re alone. I want to tell you that you’re my idea of a scout; he is too, but so are you. What’s your idea of a scout, anyway? I was kind of wondering; you’re all the time joking and never say anything about it.”

“I guess you might as well start the fire now,” said Ed. “Thank goodness, he isn’t here to see you using matches; he’s mad at matches. Get the fire started good and then we’ll give him a war-whoop. I’ll clean the fish.”

Westy knew that he was in great peril. He knew that these two men were desperadoes, probably train robbers, and that they would not suffer any one to know of their mountain refuge and go free. He believed that the odds and ends of conversation he had overheard related to one of those bizarre exploits of the Far West, a two-man train robbery; or rather a one-man train robbery, for it seemed likely that one of the men had not been an expert or even a professional.

For the leader of this desperate pair Westy could not repress a certain measure of respect; respect at least for his courage and skill. The other one seemed utterly contemptible. There is always a glamour about the romantic bad man of the West, dead shot and master of every situation, which has an abiding appeal to every lover of adventure.

Here was a man, long, lanky, and of a drawling speech, whose eye, Westy could believe, was piercing and inscrutable like the renowned Two Pistol Bill of the movies. This man had said that no one could trail him and that no trail was so difficult that he could not follow it. Truly a most undesirable pursuer. One of those invincible outlaws whose skill and resource and scouting lore seems almost to redeem his villainy.

Westy knew that he was at the mercy of this man, this lawless pair. He knew that his safety and that of his friends hung on a thread. One forlorn hope he had and that was that darkness would come before the boys started their fire. Then these ruffians might not see the smoke. And perhaps they would fall asleep before Warde or Ed shouted. Then he could take his chance of descending and rejoining them. All this seemed too good to be possible and Westy had one of those rash impulses that seize us all at times, to put an end to his horrible suspense by making his presence known. One shout and—and what?

He did not shout. And he prayed that his friends would not shout. If he could only free himself and let them know! But even then there was the chance of this baffler of dogs trailing him and his companions and shooting them down in these lonely mountains. And who would ever know?

And just then he learned the name of this human terror who was smoking as he lolled in the dusk on the rock below. He was evidently a celebrity.

“That’s why they call me Bloodhound Pete,” drawled the man. “Nobody can corral me up here; thar ain’t no trail ter this place ’n nobody never knowed it. But I knowed of it. I ain’t never come to it from the road, allus through the gulch ’n roun’ by Cheyenne Pass, like we done jes’ now. But if you wus here I could trail yer, even if I never sot eyes on the place afore. I could trail yer if yer dealed me the wrong trick, no matter whar yer wuz.”

“I ain’t dealin’ yer no wrong trick,” said the other.

“That’s why I ony has one pard in a big job,” said Bloodhound Pete grimly. “’Cause in a way of speakin’ I ain’t fer bloodshed. I’d ruther drop one pardner than two or three. I don’t kill ’less thar’s need to, ’count o’ my own safety.”

Westy shuddered.

“Me ’n you ain’t goin’ ter have no scrap over the swag,” said the other man.

“N’ ye’ll find me fair as summer,” said the bloodhound. “Fair and square, not even sayin’ how I give the benefit to a pardner on uneven numbers.”

“Me ’n you ain’t a-goin’ ter have no quarrel,” said the other. “Yer wuz goner drop that there little gent, though, I’m thinkin’,” he added, “when he tried ter hold yer agin’ the car door. He wuz game, he wuz.”

“That’s why I didn’ drop ’im,” said the bloodhound. “Yer mean him with the cigar? Yere, he was game—him an’ the conductor. They was the ony ones. Them an’ the woman—she was game. Yer seed her, with the fire ax. I reckon she’d a used it if I didn’t take it from ’er. That thar little man had a permit or a license or sumthin’ to ketch animals down over ter the Park. Here ’tis in his ole knapsack an’ money enough ter buy a couple o’ ranches.”

“How much?” asked the other.

“I ain’t usin’ no light,” said the bloodhound, “’count er caution. We’ll sleep an’ divvy up fair an’ square in the mornin’.”

“Suits me,” said the other.

“And jes’ bear in mind,” drawled Bloodhound Pete, “that I allus sleep with one eye open an’ I can track anything ’cept a airplane.”

Westy shuddered again. He fancied the lesser of those two desperadoes shuddering. Bloodhound Pete seemed quite master of the situation.

This was the kind of man that Westy had to get away from. For he found it unthinkable that he and his companions should be shot down and left in that wild region, a prey to vultures. He tortured himself with the appalling thought that perhaps the great bird he had just seen and heard was one of those horrible creatures of uncanny instinct waiting patiently among its aerial crags for the bodies of the slain; for him, Westy Martin!

He had been able to realize, or rather to believe, that he was alone in the Rockies. He had, in the few moments that he had been there, indulged the thrilling reflection that he was actually in the storied region where grizzlies prowled, and other savage beasts woke the echoes with their calls, where eagles screamed in their dizzy and inaccessible domains. He had thrilled to the thought that he was at least within the limits of that once trackless wonderland of adventure where guides and trappers, famed in his country’s romantic lore, had wrought miracles renowned in the annals of scouting.

But Westy had not carried these reflections so far as to include the reality which now confronted him. He had been a trapper for a few sweet moments; he had penetrated the wilds after Indians—in his imagination, which is always a safe place to hunt. And now suddenly here he was, actually trapped in the Rocky Mountains; the victim of cold-blooded desperadoes. His life hung by a thread. His killing would be a trifling incident in the aftermath of a typical western train robbery.

It was odd how ready his imagination had been to feast upon the perils of the Wild West and how his blood turned cold at this true Western adventure into which he was drawn. The day before, in his comfortable seat in the speeding train, he would have said that such a thing as this was just impossible. It would have been all right in the books; but as involving him, Westy Martin, why, the very thought of it would have been absurd.

Yet there he was. There he was, the thing was a reality, and he knew that every chance was against him. He wondered what Shining Sun, the red boy, that silent master of the forest, would have done in this predicament. Then his thoughts wandered away from that exploited hero to his own pleasant home in Bridgeboro and he pictured his father sitting by the library table reading his evening paper. He pictured his father telling his sister Doris for goodness’ sakes to stop playing the Victrola till he finished reading. Then Doris strolling out onto the porch and ejecting himself and Pee-wee Harris from the swinging seat and sitting down herself to await the arrival of Charlie Easton. . . .

He looked anxiously in the direction of the cleft, fearful that at any minute smoke would arise out of it or voices be audible there. The two men were talking below, but he could not see them now nor hear what they said. The whole thing seemed so strange, so incredible, that Westy could not appreciate the extraordinary fact that the very property, the wallet of his traveling acquaintance, Mr. Wilde, was in possession of these outlaws.

One slight advantage (it was not even a forlorn hope) seemed to be accruing to him. It was growing dark. This at least might prevent the smoke from the distant fire being seen. As for the blaze, that could not be seen from the foot of the tree because of the precipitous descent at the base of the hill. From his vantage point in the tree Westy would have been able to see the fire. But there was no blaze to be seen and he wondered why, for surely, he thought, they must have been able to catch some sort of fish.

Then in his distraction, he found a measure of relief in thinking of matters not pertinent to his desperate situation. He thought how after all Ed’s safety-pin and braided worsted had probably not made good. This aroused again his morbid reflections about boy scouting. Shining Sun, without so much as a safety-pin, would have been able to catch fish, probably with his dexterous hands.

Westy was disgusted with himself and all his claptrap of scouting, when he thought of this primitive little master of the woods and water. Frightened as he was, he was reflective enough to be indignant at Mr. Wilde for that skeptic’s irreverent use of the name of Stove Polish. Shining Sun was all but sacred to serious Westy.

The peril from visible smoke was gone, but there was small comfort in this. Warde and Ed had probably not succeeded in catching any fish and a fire was therefore useless. Presently one or other of them would shout or come to investigate. And what then? Westy’s life and the lives of his comrades seemed to hang on a thread.

He roused himself out of his silent fear and suspense and realized that if he were going to do anything he must act quickly. He was between two frightful perils. If he were to act, do something (he knew not exactly what), it must be before his friends called, yet not till the men below had fallen asleep. Haste meant disaster. Delay meant disaster. When should he act? And what should he do? If he had only a little time—a little time to think. What would the Indian boy do?

He listened fearfully, his heart in his throat, but there was no sound. He was thankful that Ed Carlyle was not such a good scout—no, he didn’t mean exactly that. He was glad that Ed was not exactly what you would call a real—no, he didn’t mean that either. He was glad that Ed had not been scout enough—had not been able to catch any fish. There are times when not being such a marvelous super-scout is a very good thing.

Silence. Darkness. And the minutes passed by. He was jeopardizing his life and his companions’ lives, and he knew it. If he waited till they shouted all three of them would be—— He could not bear to think of it. Would be killed! Shot down! He, Westy Martin, and his two pals.

What would Shining Sun do?

Well, he, Westy Martin, would act at once. He would take a chance, be brave, die game. He would, if need be, be killed in the Rockies, like so many heroes before him. He would not be a parlor scout. He had dreamed of being in peril in the Rockies. Well, he would not falter now. He could not be a Shining Sun, but at least he could be worthy of himself. He would not be wanting in courage, and he would use such resource as he had.

He could not afford to wait for a shout from the cleft. He must descend and trust to the men being asleep. He wished that Bloodhound Pete had not made that remark about sleeping with one eye open. He wished that that grim desperado had not unconsciously informed him that he could track anything but an airplane. Then it occurred to him that he might disclose his presence to these men, promise not to tell of their hiding place, and throw himself on their mercy. Perhaps they—the tall one at least—would understand that a scout’s honor——

Honor! A scout’s honor. What is that? Shining Sun was a scout, a real scout. What would he do? He would escape!

Westy listened but heard no sound from below. He hoped they were in the little cave, but he doubted that; it was too small and stuffy. A place to shoot from and hold pursuers at bay, that was all it was.

Silently, with an arm around an upright branch, he raised one foot and unlaced a shoe, pausing once or twice to listen.

No sound from below or from afar. Only the myriad voices of the night in the Rocky Mountains, an owl hooting in the distance, the sound of branches crackling in the freshening breeze, the complaining call of some unknown creature. . . .

He hung the shoe on a limb, releasing his hold on it easily, then listened. No sound. Then he unlaced the other shoe and hung it on the branch. Strange place for a Bridgeboro, New Jersey, boy to hang his shoes. But Shining Sun wore no shoes, perish the thought! and neither would Westy. He removed his scout jacket with some difficulty and hung it on a limb, then he removed the contents of its pockets.

Westy Martin, scout of the first class, First Bridgeboro Troop, B. S. A., Bridgeboro, New Jersey, had won eleven merit badges. Nine of these were sewed on the sleeve of the khaki jacket in which he had traveled. This had been his preference, since he was a modest boy, and was disinclined to have them constantly displayed on the sleeve of his scout shirt which he usually wore uncovered. But two of the medals had been sewed on the sleeve of his shirt at some time when the jacket was not handy. These were the pathfinder’s badge and the stalker’s badge. So it happened that he carried these two treasured badges with him, when he left his jacket hanging in the tree and started to descend upon his hazardous adventure.

He had received these two honors with a thrill of pride. But throughout this memorable day they had seemed to him like silly gewgaws, claptrap of the Boy Scouts, signifying nothing. They were obscured by the haunting spirit of Shining Sun.

For another moment he listened, his nerves tense, his heart thumping. Then he began ever so cautiously to let himself down through the darkness. A long, plaintive moan was faintly audible far in the mountain fastnesses. . . .

Half-way down he thought he heard voices, but decided it was only his imagination taunting him. There was no sound below. He was fearful, yet relieved, when he reached the lowest branch; now there would be no branches squeaking, no crackling twigs, sounding like earthquakes in the tense stillness.