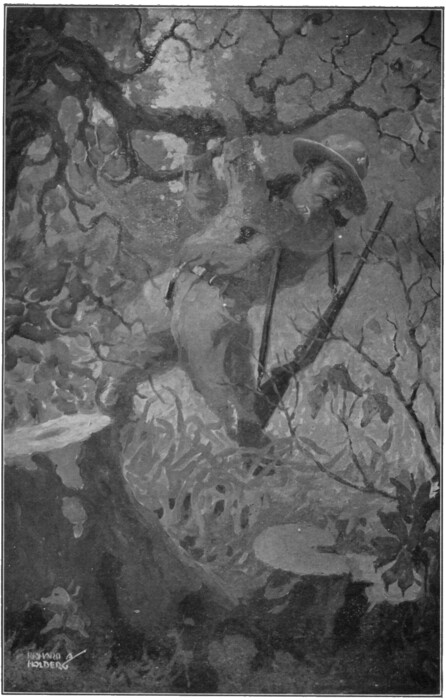

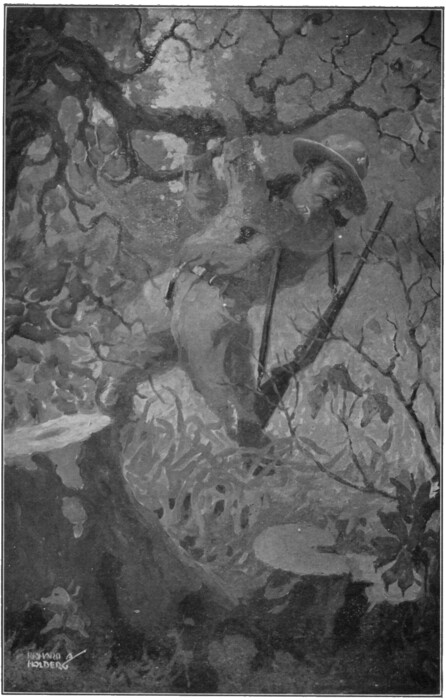

HE MANAGED TO GET HOLD OF A BRANCH OF A SCRUB OAK.

Title: Westy Martin

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh

Release date: January 6, 2020 [eBook #61118]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Westy Martin, by Percy Keese Fitzhugh, Illustrated by Richard A. Holberg

HE MANAGED TO GET HOLD OF A BRANCH OF A SCRUB OAK.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | A Shot |

| II | A Promise |

| III | The Parting |

| IV | The Sufferer |

| V | A Plain Duty |

| VI | First Aid—Last Aid |

| VII | Little Drops of Water |

| VIII | Barrett’s |

| IX | On the Trail |

| X | Luke Meadows |

| XI | Westy Martin, Scout |

| XII | Guilty |

| XIII | The Penalty |

| XIV | For Better or Worse |

| XV | Return of the Prodigal |

| XVI | Aunt Mira and Ira |

| XVII | The Homecoming |

| XVIII | A Ray of Sunshine |

| XIX | Pee-Wee on the Job |

| XX | Some Noise |

| XXI | One Good Turn |

| XXII | Warde and Westy |

| XXIII | Ira Goes A-Hunting |

| XXIV | Clews |

| XXV | A Bargain |

| XXVI | The Marked Article |

| XXVII | Enter the Contemptible Scoundrel |

| XXVIII | Proofs |

| XXIX | The Rally |

| XXX | Open to the Public |

| XXXI | Shootin’ Up the Meetin’ |

| XXXII | The Boy Edwin Carlisle |

| XXXIII | Mrs. Temple’s Lucky Number |

| XXXIV | Westward Ho |

| XXXV | The Stranger |

| XXXVI | An Important Paper |

| XXXVII | Parlor Scouts |

| XXXVIII | Something “Real” |

A quick, sharp report rent the air. Followed several seconds of deathlike silence. Then the lesser sound of a twig falling in the still forest. Again silence. A silence, tense, portentous. Then the sound of foliage being disturbed and of some one running.

Westy Martin paused, every nerve on edge. It was odd that a boy who carried his own rifle slung over his shoulder should experience a kind of panic fear after the first shocking sound of a gunshot. He had many times heard the report of his own gun, but never where it could do harm. Never in the solemn depths of the forest. He did not reach for his gun now to be ready for danger; strangely enough he feared to touch it.

Instead, he stood stark still and looked about. Whatever had happened must have been very near to him. Without moving, for indeed he could not for the moment move a step, he saw a large leaf with a hole through the middle of it. And this hung not ten feet distant. He shuddered at the realization that the whizzing bullet which had made that little hole might as easily have blotted out his young life.

He paused, listening, his heart in his throat. Some one had run away. Had the fugitive seen him? And what had the fugitive done that he should flee at the sight or sound of a human presence?

Suddenly it occurred to Westy that a second shot might lay him low. What if the fugitive, a murderer, had sought concealment at a distance and should try to conceal the one murder with another?

Westy called and his voice sounded strange to him in the silent forest.

“Don’t shoot!”

That would warn the unseen gunman unless, indeed, it was his purpose to shoot—to kill.

There was no sound, no answering voice, no patter of distant footfalls; nothing but the cheery song of a cricket near at hand.

Westy advanced a few steps in the dim, solemn woods, looking to right and left....

Westy Martin was a scout of the first class. He was a member of the First Bridgeboro Troop of Bridgeboro, New Jersey. Notwithstanding that he was a serious boy, he belonged to the Silver Fox Patrol, presided over by Roy Blakeley.

According to Pee-wee Harris of the Raven Patrol, Westy was the only Silver Fox who was not crazy. Yet in one way he was crazy; he was crazy to go out west. He had even saved up a hundred dollars toward a projected trip to the Yellowstone National Park. He did not know exactly when or how he would be able to make this trip alone, but one “saves up” for all sorts of things unplanned. To date, Westy had only the one hundred dollars and the dream of going. When he had saved another hundred, he would begin to develop plans.

“I’ll tell you what you do,” Westy’s father had said to him. “You go up to Uncle Dick’s and spend the summer and help around. You know what Uncle Dick told you; any summer he’d be glad to have you help around the farm and be glad to pay you so much a week. There’s your chance, my boy. At Temple Camp you can’t earn any money.

“My suggestion is that you pass up Temple Camp this summer and go up on the farm. By next summer maybe you’ll have enough to go west, and I’ll help you out,” he added significantly. “I may even go with you myself and take a look at those geezers or geysers or whatever they call them. I’d kind of half like to get a squint at a grizzly myself.”

“Oh, boy!” said Westy.

“I wish I were,” said his father.

“Well, I guess I’ll do that,” said Westy hesitatingly. He liked Temple Camp and the troop, and the independent enterprise proposed by his father was not to be considered without certain lingering regrets.

“It will be sort of like camping—in a way,” he said wistfully. “I can take my cooking set and my rifle——”

“I don’t think I’d take the rifle if I were you,” said Mr. Martin, in the chummy way he had when talking with Westy.

“Jiminies, I’d hate to leave it home,” said Westy, a little surprised and disappointed.

“Well, you’ll be working up there and won’t have much time to use it,” said Mr. Martin.

Westy sensed that this was not his father’s true reason for objecting to the rifle. The son recalled that his father had been no more than lukewarm when the purchase of the rifle had first been proposed. Mr. Martin did not like rifles. He had observed, as several million other people had observed, that it is always the gun which is not loaded that kills people.

The purchase of the coveted rifle had not closed the matter. The rifle had done no harm, that was the trouble; it had not even killed Mr. Martin’s haunting fears.

Westy was straightforward enough to take his father’s true meaning and to ignore the one which had been given. It left his father a little chagrined but just the same he liked this straightforwardness in Westy.

“Oh, there’d be time enough to use it up there,” Westy said. “And if there wasn’t any time, why, then I couldn’t use it, that’s all. There wouldn’t be any harm taking it. I promised you I’d never shoot at anything but targets and I never have.”

“I know you haven’t, but up there, why, there are lots of——”

“There’s just one thing up there that I’m thinking about,” said Westy plainly, “and that’s the side of the big barn where I can put a target. That’s the only thing I want to shoot at, believe me. And I’ve got two eyes in my head to see if anybody is around who might get hit. That big, red barn is like—why, it’s just like a building in the middle of the Sahara Desert. I don’t see why you’re still worrying.”

“How do you know what’s back of the target?” Mr. Martin asked. “How do you know who’s inside the barn?”

“If I just tell you I’ll be careful, I should think that would be enough,” said Westy.

“Well, it is,” said Mr. Martin heartily.

“And I’ll promise you again so you can be sure.”

“I don’t want any more promises about your not shooting at anything but targets, my boy,” said Mr. Martin. “You gave me your promise a month ago and that’s enough. But I want you to promise me again that you’ll be careful. Understand?”

“I tell you what I’ll do, Dad,” said he. “First I’ll see that there’s nobody in the barn. Then I’ll lock the barn doors. Then I’ll get a big sheet of iron that I saw up there and I’ll hang it on the side of the barn. Then I’ll paste the target against that, see? No bullet could get through that iron and it’s about, oh, five times larger than the target.”

“Suppose your shot should go wild and hit those old punky boards beyond the edge of the iron sheet?” Mr. Martin asked.

“Good night, you’re a scream!” laughed Westy.

Mr. Martin, as usual, was caught by his son’s honest, wholesome good-humor.

“I suppose you think I might shoot in the wrong direction and hit one of those grizzlies out in Yellowstone Park,” Westy laughed. “Safety first is your middle name all right.”

“Well, you go up to Uncle Dick’s and don’t point your gun out west,” said Mr. Martin, “and maybe we can talk your mother into letting us go to Yellowstone next year.”

“And will you make me a promise?” asked Westy.

“Well, what is it?”

“That you won’t worry?”

The farm on which Westy spent one of the pleasantest summers of his life was about seventy miles from his New Jersey home and the grizzlies in Yellowstone Park were safe. But he thought of that wonderland of the Rockies in his working hours, and especially when he roamed the woods following the trails of little animals or stalking and photographing birds. The only shooting he did on these trips was with his trusty camera.

Sometimes in the cool of the late afternoon, he would try his skill at hitting the bull’s eye and after each of these murderous forays against the innocent pasteboard, he would wrap his precious rifle up in its oily cloth and stand it in the corner of his room. No drop of blood was shed by the sturdy scout who had given his promise to be careful and who knew how to be careful.

The only place where he ever went gunning was in a huge book which reposed on the marble-topped center table in the sitting room of his uncle’s farmhouse. This book, which abounded in stirring pictures, described the exploits of famous hunters in Africa. The book had been purchased from a loquacious agent and was intended to be ornamental as well as entertaining. It being one of the very few books available on the farm, Westy made it a sort of constant companion, sitting before it each night under the smelly hanging lamp and spending hours in the African jungle with man-eating lions and tigers.

We are not to take note of Westy’s pleasant summer at this farm, for it is with the altogether extraordinary event which terminated his holiday that our story begins. His uncle had given him eight dollars a week, which with what he had brought from home made a total of something over a hundred dollars which he had when he was ready to start home. This he intended to add to his Yellowstone Park fund when he reached Bridgeboro.

He felt very rich and a little nervous with a hundred dollars or more in his possession. But it was not for that reason that he carried his rifle on the day he started for home. He carried it because it was his most treasured possession, excepting his hundred dollars. He told his aunt and uncle, and he told himself, that he carried it because it could not easily be put in his trunk except by jamming it in cornerwise. But the main reason he carried it was because he loved it and he just wanted to have it with him.

He might have caught a train on the branch line at Dawson’s which was the nearest station to his uncle’s farm. He would then have to change to the main line at Chandler. He decided to send his trunk from Dawson’s and to hike through the woods to Chandler some three or four miles distant. His aunt and uncle and Ira, the farm hand, stood on the old-fashioned porch to bid him good-by.

And in that moment of parting, Aunt Mira was struck with a thought which may perhaps appeal to you who have read of Westy and have a certain slight acquaintance with him. It was the thought of how she had enjoyed his helpful visit and how she would miss him now that he was going. Pee-wee Harris, with all his startling originality, would have wearied her perhaps. Two weeks of Roy Blakeley’s continuous nonsense would have been enough for this quiet old lady.

There was nothing in particular about Westy; he was just a wholesome, well-balanced boy. She had not wearied of him. The scouts of his troop never wearied of him—and never made a hero of him. He was just Westy. But there was a gaping void at Temple Camp that summer because he was not there. And there was going to be a gaping void in this quiet household on the farm after he had gone away. That was always the way it was with Westy, he never witnessed his own triumphs because his triumphs occurred in his absence. He was sadly missed, but how could he see this?

He looked natty enough in his negligee khaki attire with his rifle slung over his shoulder.

“We’re jes going to miss you a right good lot,” said his aunt with affectionate vehemence, “and don’t forget you’re going to come up and see us in the winter.”

“I want to,” said Westy.

Ira, the farm hand, was seated on the carriage step smoking an atrocious pipe which he removed from his mouth long enough to bid Westy good-by in his humorous drawling way. The two had been great friends.

“I reckon you’d like to get a bead on a nice, big, hissin’ wildcat with that gol blamed toy, wouldn’ yer now, huh?”

“You go ’long with you,” said Aunt Mira, “he wouldn’ nothing of the kind.”

Westy smiled good-naturedly.

“Wouldn’ yer now, huh?” persisted Ira. “I seed ’im readin’ ’baout them hunters in Africa droppin’ lions an’ tigers an’ what all. I bet ye’d like to get one—good—plunk at a wildcat now, wouldn’ yer? Kerplunk, jes like that, hey? Then ye’d feel like a reg’lar Teddy Roosevelt, huh?” Ira accompanied this intentionally tempting banter with a demonstration of aiming and firing.

Westy laughed. “I wouldn’t mind being like Roosevelt,” he said.

“Yer couldn’ drop an elephant at six yards,” laughed Ira.

“Well, I guess I won’t meet any elephants in the woods between here and Chandler,” Westy said.

“Don’t you put no sech ideas in his head,” said Aunt Mira, as she embraced her nephew affectionately.

Then he was gone.

“I don’t see why you want ter be always pesterin’ the poor boy,” complained Aunt Mira, as Ira lowered his lanky legs to the ground preparatory to standing on them. He had been a sort of evil genius all summer, beguiling Westy with enticing pictures of all sorts of perilous exploits out of his own abounding experiences on land and sea. “You’d like to’ve had him runnin’ away to sea with your yarns of whalin’ and shipwrecks,” Aunt Mira continued. “And it’s jes a parcel of lies, Ira Hasbrook, and you know it as well as I do. Like enough he’ll shoot at a woodchuck or a skunk and kill one of Atwood’s cows. They’re always gettin’ into the woods.”

“No, he won’t neither,” said her husband.

“I say like enough he might,” persisted Aunt Mira. “Weren’t he crazy ’baout that book?”

“I didn’ write the book,” drawled Ira.

“No, but you told him how to skin a bear.”

“That’s better’n bein’ a book agent and skinnin’ a farmer,” drawled Ira.

“It’s ’baout the only thing you didn’t tell him you was,” Aunt Mira retorted.

Acknowledging which, Ira puffed at his pipe leisurely and contemplated Aunt Mira with a whimsical air.

“I meant jes what I said, Ira Hasbrook,” said she.

“The kid’s all right,” said Ira. “He couldn’ hit nuthin further’n ten feet. But he’s all right jes the same. We’re goin’ ter miss him, huh, Auntie?”

But they did not miss him for long, for they were destined to see him again before the day was over.

In truth, if this were a narrative of Ira Hasbrook’s adventures, it might be thought lively reading of the dime novel variety. He had not, as he had confided to Westy, limited his killing exploits to swatting flies.

He was one of those universal characters who have a way of drifting finally to farms. And he had not abridged his tales of sprightly adventure in imparting them to Westy. He had been to sea on a New Bedford whaler. He had shot big game in the Rockies. He had lived on a ranch. His star performance had been a liberal participation in the kidnapping of a despotic king in a small South Sea island.

Naturally, so lively an adventurer had nothing but contempt for a pasteboard target. And though he did not wilfully undertake to alienate Westy from his code of conduct, he had so continually represented to him the thrilling glories of the chase, that Aunt Mira had very naturally suffered some haunting apprehensions that her nephew might depart impulsively on some piratical cruise or Indian killing enterprise.

These vague fears had simmered down at the last to the ludicrous dread that her departing nephew (whom she had come to know and love) might, under the inspiration of the satanic Ira, celebrate his departure from the country by laying low some innocent cow in attempting to “drop” an undesirable woodchuck. She had come to have a very horror of the word drop which occurred so frequently in Ira’s tales of adventure....

But Aunt Mira’s fears were needless. Westy had been Ira’s companion without being his disciple. In his quiet way he had understood Ira thoroughly, the same as in his quiet way he understood Roy Blakeley and Pee-wee Harris thoroughly. The cows, even the woodchucks, were safe. The shot which turned the tide of Westy Martin’s life was not out of his own precious rifle.

He had not taken many steps after hearing the shot when he came upon the effect of it. A small deer lay a few feet off the trail. The beautiful creature was quite motionless and though it lay prone on its side with the head flat upon the ground, its gracefulness was apparent, even striking. It lay in a sort of bower of low hanging foliage and had a certain harmony with the forest which even its stricken state and somewhat unnatural attitude could not destroy.

As Westy first glimpsed this silent, uncomplaining victim, a feeling (which could hardly be called a thought) came to him. It was just this, that the cruelty which had wrought this piteous spectacle was doubly cruel for that the creature had been laid low in its own home. The friendly, enveloping foliage revealed this helpless denizen of the woods as a sorrowing mother might show her dead child to a sympathizing friend. Such thoughts did not take form in the mind of the tremulous boy but he had some such feeling. He was thoughtful enough, even at the moment, to wonder how he could have taken such delight in stories of wholesale killings. One sight of the actual thing aroused his anger and pity.

He approached a little nearer, this scout with a rifle over his shoulder, and beheld something which startled, almost unnerved him. He could see only one of the eyes, for the deer lay on its side, but this eye was soft and seemed not unfriendly; it was not a startled eye. The beautiful animal was not dead. He did not know how much it might be suffering, but at all events its suffering was not over, and there was a kind of resignation in the soft look of that single eye; just a kind of silent acceptance of its plight which went to the boy’s heart.

Who had done this thing, against the good law of the state, and in disregard of every humane obligation? Who had fled leaving this beautiful inhabitant of the quiet woods in agony? The leaves stirred gently above it in the soothing breeze. A gay little bird chirped a melody in the overhanging branches as if to beguile it in its suffering. And the soft, gentle eye seemed full of an infinite patience as it looked at Westy.

He was face to face with one of the sporting exploits of that horrible toy, the rifle. For just a moment it seemed as if the stricken deer were looking at his own rifle as if in quiet curiosity. Then he noticed a tiny wound and a little trickle of blood on the creature’s side. It made a striking contrast, the crimson and the dull gray....

...And the great hunter crouching behind the rock brought his trusty rifle to bear upon the distant stag. The keen-eyed marksman looked like a statue as he knelt, waiting.

Westy recalled these words in the mammoth volume on the sitting room table at the farm. He had admired, even been thrilled at the heroic picture of the great hunter whose exploits in the Maine woods were so flatteringly recorded. It had not at the time occurred to him that the noble stag might have looked like a statue too. Well, here was the actual result of such flaunted heroism, and Westy did not like it. It was quite a different sort of picture.

Then, suddenly, it occurred to him that he was to blame for this pitiful spectacle. He who shoots does not always kill. But he who shoots intends to kill. If the fugitive had failed of his purpose it was because he had been frightened at the sound of some one near at hand. The shooting season was not on, it had been a stolen, lawless shot.

A feeling of anger, even of hate, was aroused in Westy’s mind, against the ruthless violator of the law who had been forced to save himself by flight before his lawless deed was completed. He had probably thought the footfalls those of a game warden. To shoot game out of season was bad enough as it seemed to the scout. To shoot living things seemed now bereft of all glory to the sensitive boy. But to shoot and not kill and then run away seemed horrible. This poor deer might suffer for hours.

Westy had seen a little demonstration of the kind of thing he had been reading and hearing about. Through the medium of the alluring printed page, he had been present at buffalo hunts, he had seen kindly, intelligent elephants laid low, and here he was seething with rage that the blood of this harmless, beauteous creature had been shed, and shed to no purpose.

But Westy was more than a sensitive boy, he was a scout. And a scout has ever a sense of responsibility. It was futile to consider what some stranger had done while this poor creature lay suffering. All that he had read and heard about hunting big game and all such stuff was forgotten in the consciousness of a present duty. He, Westy Martin, must put this deer out of its suffering; he must kill it.

The owner of the precious rifle, all shiny and oily, shuddered. He, scout of the first class, must finish the work which some criminal wretch had begun.

He was too essentially honest to take refuge in his promise not to shoot at anything but a target. He had a momentary thought of that, and then was ashamed of it. Phrases familiar to him ran through his head. Serious boy that he was, he had always been a reader of the Handbook. A scout is helpful. A scout is friendly to all.... A scout is kind. He is a friend to animals. He will not kill nor hurt....

Yet he was not friendly to all. He was enraged at the absent destroyer, who had made it necessary for him to do something he could not bear to do. He wished that Ira were there to do it instead. He who had admired the great hunter crouching behind a rock, wished now that the mighty hunter might be present to attend to this miserable business. He had never dreamed of such an emergency, of such a duty. He wished that one or other of the sprightly youngsters in the advertisements, who were so ready with their firearms, might shoot for once in this humane cause.

Poor Westy, he was just a boy after all....

He never in all his life felt so nervous, and so much like a criminal, as when he reached with trembling hand for the innocent rifle with which he was to shed more crimson blood and destroy a life. He looked guiltily at the deer whose eye seemed to hold him in a kind of gentle stare. It seemed as if the creature trusted him, yet wondered what he was going to do.

There was a kind of pathos in the thought that came to him that the suffering deer did not recognize the rifle as the sort of thing which had laid him low. The creature’s innocence, as one might say, went to the boy’s heart.

He backed away from the stricken form, three yards—five yards. He felt brutal, abominable. The cautious little bird had withdrawn to a tree somewhat farther off where it still sang blithely. Westy paused, listening to the bird. Then he stole toward the tree trying to deceive himself that he wanted to see what kind of a bird it was, when in plain fact all he was doing was killing time. The bird, disgusted with the whole affair as one might have fancied, made a great flutter and flew away to a more wholesome atmosphere. The bird was not a scout, it had no duties....

Westy advanced a few paces, his rifle shaking in his hand. It was simple enough what he had to do, yet there he was absurdly calculating distances. Oh, if it had only been the white target there before him with its black circles one inside another, the only hunting ground or jungle Westy knew. Strange, how different he felt now.

He could not bear that soft eye contemplating him so he walked around to the other side of the deer where the eye could not see him. Then he felt sneaky, like one stealing up behind his victim. And through all his immature trepidation hate was in his heart; hate for the brutal wretch who had fled thinking only of his own safety, and leaving this ungrateful task for him to do.

Suddenly it occurred to Westy that he might run to Chandler and tell the authorities what he had found. That would be his good turn for the day. Ira had always “guyed” him about good turns. That would seem like running away from an unpleasant duty. To whom did he owe the good turn? Was it not to this stricken, suffering creature?

So Westy Martin, scout of the first class, did his good turn to this dumb creature in its dim forest home. The dumb creature did not know that Westy Martin was doing it a good turn. It seemed a queer sort of good turn. He could never write it down in his neat little scout record as a good turn. He would never, never think of it in that way. If the deer could only understand....

The way to do a thing is to do it. And it is not the part of a scout to dilly-dally. When a scout knows his duty he is not afraid. But if the deer could only know, could only understand....

Westy approached the creature with bolstered resolution. He lifted his gun, his arms shaking. Where should it be? In the head? Of course. He held the muzzle within six inches of the head. A jerky little squirrel crept part way down a tree, turned suddenly and scurried up again. It was very quiet about. Only the sound of a busy woodpecker tapping away somewhere. Westy paused for a moment, counting the taps....

Then there was another sound; quick, sharp, which did not belong in the woods. And the woodpecker stopped his tapping. Westy saw the deer’s forefoot twitch spasmodically. And a little stream of blood was trailing down its forehead.

Westy Martin had done his daily good turn....

The feeling now uppermost in Westy’s mind was that of anger at the unknown person who had made it necessary for him to do what he had done. He felt that he had been cheated out of keeping his promise about shooting. He knew perfectly well that what he had done was right and that only technically had he broken his promise to his father. But he had done something altogether repugnant to him and it turned him against guns not only, but particularly against the sneak whose lawless work he had had to complete.

It must be confessed that it was not mainly the fugitive’s lawlessness or even his cruel heedlessness that aroused Westy. It was the feeling that somehow this work of murder (for so he thought it) had been wished on him. It had agitated him and gone against him, and he was enraged over it.

He had not been quite the ideal scout in the matter of readiness to kill the deer; he might have done that job more promptly and with less perturbation. But he was quite the scout in his towering resolve to track down the culprit and tell him what he thought of him and bring him to justice.

It was characteristic of Westy, who was a fiend at tracking and trailing, that this course of action appealed to him now, rather than the tamer course of going direct to the authorities. There was something very straightforward about Westy. And besides, he had the adventurous spirit which prefers to act without cooperation.

“By jumping jiminies. I’ll find that fellow!” he said aloud. “I should worry about catching the train. I’ll find him all right, and I’ll tell him something he won’t forget in a hurry—I will. I’ll track him and find out who he is. Maybe after he’s paid a hundred dollars fine, he won’t be so free with his blamed rifle.”

It was odd how he had balked at putting an end to the wounded deer, and then had not the slightest hesitancy to pursue, he knew not what sort of disreputable character, and denounce him to his face and then report him. Westy would not show up with the authorities, not he; not till he had first called the marauder a few names which he was already deciding upon. They were not the sort of names that are used in the language of compliment. It is not to be supposed that Westy was perfect....

He was all scout now. Yet he was puzzled as to which way to turn. It is sometimes easier to follow tracks than to find them. No doubt the fugitive had been some distance from the deer when he had shot it. Where had he been then? Near enough for Westy to hear the patter of his footfalls, that was certain. Also another thought occurred to him. The man’s shot had not been a good one, at least it had not proved fatal. He was either a very poor marksman or else he had fired from a considerable distance.

Westy’s mind worked quickly and logically now. He had easily the best mind of any scout in his troop. Not the most sprightly mind, but the best. He tried hurriedly to determine where the man had stood by considering the position of the wound on the deer’s body. But he quickly saw the fallacy of any deduction drawn from this sign since the deer might have turned before he dropped. Then another thought, a better one, occurred to him. The animal had been shot below its side, almost in its belly. Might not that argue that the huntsman had been somewhat below the level of the deer?

The conformation of the land thereabouts seemed to give color to this surmise. The ground sloped so that it might almost be said to be a hillside which descended to the verge of a gully. Westy went in that direction for a few yards and came to the gully. He scrambled down into it and found himself involved in a tangle of underbrush. But he saw that from this trenchlike concealment, the animal might easily have been struck in the spot where the wound was.

His deduction was somewhat confirmed by his recollection that it was from this direction he had heard the receding footfalls. A path led through this miniature jungle and up the other side where the pine needles made a smooth floor in the forest.

Presently all need of nice deducing was rendered superfluous by a sign likely to prove a jarring and discordant note in the woodland studies of any scout. This was a crumpled tinfoil package which on being pulled to its original size revealed the romantic words so replete with the spirit of the silent woods:

The tinfoil package was empty and destined to delight no more. But it was not even wet, and had not been wet, and had evidently been thrown away but lately.

It was immediately after throwing this away that Westy noticed something else which interested him. It was nothing much, but bred as he was to observe trifling things in the woods, it made him curious. The rank undergrowth near him was besprinkled with drops as if it had been rained on. This was noticeable on the large, low-spreading plantain leaves near by. Surely in the bright sunshine of the morning any recent drops of dew or rain must have dried up. Yet there were the big flat leaves besprinkled with drops of water.

Westy remembered something his scoutmaster had once said. Everything that happens has a cause. Little things may mean big things. Nine boys out of ten would not have noticed this trivial thing, or having noticed it would not have thought twice about it. But Westy approached and felt of the leaves and as he did so, he felt his foot sinking into swampy water. He tried to lift it out but could not. Then, he felt the other foot sinking too. He hardly knew how it happened, but in ten seconds he was down to his knees in the swamp. Frantically he grasped the swampy weeds but they gave way. He could not lift either foot now. He felt himself going down, down....

So this was to be the end; he would be swallowed up and no one would know what had become of him. The silent, treacherous marsh would consume him. He was in its jaws and it would devour him and the world would never know. Nature, the quiet woods that he had loved, would do this frightful thing.

Then he ceased to sink. He was in above his knees. One foot rested on something hard. But it was not that which supported him. The marshy growth below held him up. He was not in peril but he had suffered a shocking fright. He managed to get hold of a crooked branch of scrub oak which overhung the gully and drew himself up. It was hard to do this for the suction kept him down. It was evidently a little marshy pool concealed by undergrowth that he had stepped into.

For no particular reason, he purposely got one foot under the submerged thing it had descended upon. He thought it was a stick. It came up slantingways till with one hand he was able to get hold of it. It was hard and cold. For this reason, he was curious about it and he kept hold of it with one hand while he scrambled clear of the tiny morass. It was dripping with mud and green slime. But he knew what he was holding long before it was clear of its slimy, green disguise. It was a rifle.

Then Westy knew the explanation of the wetness on the leaves. The rifle had not been there long. It had probably been thrown there in panic haste and the water had splashed up onto the low, dank growth which concealed the frightful hole. The gun would never have been found but for Westy’s observant eye and consequent mishap.

He wiped the dripping slime from the rifle and examined his find. The gun was old and had evidently seen much service. On the smooth-worn butt of it was something which interested him greatly and seemed likely to prove more helpful than any footprints he might hope to find. This was the name Luke Meadows, evidently burnt in with a pointed tool, possibly a nail. Printed in another direction on the rifle butt, so that it might or might not have borne relation to the name, were the letters very crudely inscribed Cody Wg.

Even in his surprise, Westy recognized a certain appropriateness in the word Cody burnt into a rifle butt; it seemed a fitting enough place on which to perpetuate the true name of Buffalo Bill. At the time he could not conjecture what the letters Wg stood for. But it seemed likely enough that Luke Meadows was the name of the owner of the rifle.

The gun had certainly not been in the swamp long for no rust was upon it. He believed that the owner of it, fearing to be overtaken with it in his possession, had flung it into the little swamp before fleeing.

He was not so intent now on finding footprints. Surely the person who had hidden the gun was the culprit, and it seemed a reasonable enough inference that he belonged in the neighborhood. The quest seemed greatly simplified; so simplified that Westy began formulating what he would say to the marauder. Of one thing he was resolved, and that was that the man should pay the penalty of his lawlessness.

Westy did not burden himself with two guns; he hid the one he had found in the bushes, then bent his course eastward through the woods. If he had been going straight to Chandler to catch the train, he would have cut through the woods southeast, emerging at the edge of the town. But he changed his course now and went directly east because he wanted to reach the little settlement known as Barrett’s. This was on the road which bordered the woods to the east and ran south into Chandler.

Westy would not exactly be going out of his way, he would simply be losing the advantage of a short cut. Barrett’s was the nearest and seemed the likeliest place from which one given to illicit hunting would come. At Barrett’s he would inquire for Luke Meadows.

The name on the rifle saved him the difficulties and delays of tracking. For with the culprit’s name, Westy felt that he could easily be found.

In about fifteen minutes, he emerged from the woods at Barrett’s. He had been there before, but one sight of the place now made him glad that he had not brought the telltale rifle with him. He felt that if he had, Meadows or Meadows’ cronies might relieve him of it and put an end to its availability as evidence. It was safe where it was....

Barrett’s was one of those places that grow up around a factory and subsist on the factory. Sometimes quite pretentious little villages grow up in this way and attain finally to the dignity of “GO SLOW” signs and traffic cops. But in this case the factory having put Barrett’s on the county map closed up its door and left Barrett’s sprawling. There was a settlement and no factory to support it.

When the Barrett Leather Goods Company stopped making leather goods, a couple of dozen men and as many more girls were thrown out of employment. With the leather goods factory closed there was nothing for the working people of Barrett’s to do but move away or subsist as best they could by hook or crook. The better sort among the inhabitants moved away. Those that remained soon became a dubious set whose professional activities were, at the least, shady.

Barrett’s was a sort of hobo among villages, an ill-kept, prideless, lawless place, having all the characteristics of a shiftless man who had gone to the bad. The countryside shunned it. And it was not considered a safe place for the youth of the surrounding villages, especially at night. Every now and then, some one from Barrett’s was taken to Chandler and thence sent to jail....

Barrett’s was not accustomed to visits from nattily attired boy scouts with rifles slung over their shoulders and the lolling youths of the settlement stared at him and commented audibly as he passed.

“Hey, what’s that you got over your shoulder?” one of them called.

“That, oh, that’s a soup spoon,” said Westy, quite unperturbed. “Do you know where Luke Meadows lives?”

“What d’yer want ’im fer?” one of the natives asked.

“Oh, I just wanted to see him,” said Westy.

“Whatcher want ter see ’im fer?”

“Oh, just for fun. Do you know where he lives?”

“He lives in that white house up the road,” said a rather more accommodating boy. “Do you see the house with the winder broken? The one with the chimney gone? He lives there, only he ain’t home.”

“He is too,” contradicted another informer. “I seen him go in his back door half an hour ago; he come around through the fields from the woods.”

“Thanks,” said Westy.

If Luke Meadows lived in the house indicated and had indeed returned home through the fields, then he must have emerged from the woods at a considerable distance from his home, an unnecessary thing to do except upon the theory that he wished to throw some one off his track, or at least avoid being seen. Westy thought he could sense the position in which this man stood toward the game wardens of the county. He thought it likely that there had been previous encounters between them. Hunting game out of season is a pursuit which is pretty apt to be chronic.

Now that Westy was about to encounter this man, he felt just a little trepidation. Perhaps it would have been better to go to Chandler first. But then the matter would have been out of his hands. He wished first to tell this man a thing or two which scouts know....

As he went along the narrow, dusty road, his uneasiness increased. He was not exactly afraid but he was beginning to balk a little at the prospect of denouncing a person who was probably many years his senior.

The little houses along the road, which must have been hopelessly unsightly from the beginning, had fallen into a state of disrepair and squalor which seemed in striking discord with the surrounding countryside. A slum in the city is bad enough; in the fair country it is shockingly grotesque.

These little houses were double, each holding two families, and some of them were in blocks of three or four. They seemed to nestle under the shadow of the big wooden factory back in the field. Every window of the big factory was broken and a more forlorn picture of disuse and dilapidation could scarcely be imagined. From this factory a rusty railroad track disappeared into the woods; it had probably once joined the main line at Chandler.

Beyond these little rows of cheap frame houses was one which stood by itself. Its chimney was indeed gone and its window broken, but at least it stood by itself, was of a different color and architecture from the others, and had, in its shabby way, a character of its own. A little girl was swinging on the fence gate, or would have been swinging if the hinges had not been broken. A dried and curling woodchuck skin was nailed to the clapboards beside the door, a dubious hint of the predilections of the householder.

“Does Luke Meadows live here?” Westy asked.

“Yes, sirrr,” said the little girl with a strong roll of her r’s.

“Could I see him?”

“I reckon you can,” said the little girl, then without going to the trouble of entering the house, she called, “Dad, thar’s a boy wants to see you.”

These were the first samples Westy had of that characteristic way of saying reckon and thar which he had soon to associate with new friends in a free, vast, far-off region. It occurred to him that if Meadows wished to lie low, as the saying is, it might go hard with the little girl who was so ready to admit his presence to a stranger.

The appearance and reputation of Barrett’s, as well as the unlawful shooting, had conjured up a picture in Westy’s mind which had made him apprehensive about his reception. And now he felt that the little girl might also feel something of the hunter’s displeasure.

His kindly fear for her was quite superfluous, for presently there appeared from within the house a youngish man who absently, as it seemed, placed his arm around the child’s shoulder and drew her toward him as he waited for Westy to make his business known.

The man was tall and raw-boned and wore nothing but queer-looking moccasins, corduroy trousers and a gray flannel shirt. His cheek-bones were high and he was as brown as a mulatto. What caught Westy and somewhat disconcerted him, was the stranger’s eyes, which were gray and of a clearness and keenness which he had never seen in the eyes of any human being before. They were the eyes of the forest and the plains, the eyes that see and read and understand where others see not. The eyes that speak of silent and lonely places and bespeak a competence which only rugged nature can impart. Such eyes Daniel Boone may have had.

At all events, they disconcerted Westy and knocked the beginning of his fine speech clean out of his head. The man was calm and patient, the little girl wriggled playfully in his strong hold, and Westy stood like a fool and said nothing. Then he found himself.

“Are you Lu—— Are you Mr. Luke Meadows?” he asked.

“Reckon I am,” drawled the man.

“Well, then,” said Westy, gathering courage, “I came to tell you that I know what you did in the woods because I—because I was the one that was there—I was the one that shouted.”

“Yer seed me, youngster?” the man drawled, not angrily.

“No, I didn’t see you,” said Westy, “but gee, you don’t have to see a person to find them out. You shot a deer and you know as well as I do it isn’t the season. And then you hid your gun—I guess you thought I was a game warden or something. But I found it, I’ll tell you that much and I saw your name on it.

“Do you know what you made me do?” he added, becoming vehement as his anger gave him courage. “You made me kill a deer, that’s what you made me do! You made me kill a deer after I promised I’d never shoot at anything but a target—that’s what you made me do,” he shouted in boyish anger. “You didn’t even kill it, you didn’t! Now you see what you did, sneaking and shooting game out of season! Now you see what you made me do!”

There was something so naïve and boyish in putting the injury on personal grounds that even Meadows could not repress a smile.

“I made a promise to my father, that’s what I did,” said Westy indignantly.

The man neither confessed nor denied his guilt. It seemed strange to Westy that he did not deny it since criminals always protest their innocence. At the moment the man’s chief concern seemed to be a certain interest in Westy. He just stood listening, the while holding the little girl close to him and playfully ruffling her hair. Perhaps his dubious standing with the authorities made him lukewarm about protestations of innocence.

“Waal?” was all he said.

“And you’re not going to get away with it either,” said Westy.

Meadows drew a tinfoil package from his trousers pocket, took some tobacco from it and replaced the package in his pocket. Westy saw that the package was a new one and that it bore the MECHANICS DELIGHT label.

“You left the other package in the woods,” Westy said triumphantly, “and that’s how I happened to find your gun.”

“Yer left the gun thar, youngster?”

“Yes, I did,” said Westy angrily, “and I know where it is all right.” Then the true Westy Martin got in a few words. “The only reason I came here first,” he said, “was because I didn’t want to seem sneaky. I didn’t want you to think that I had to go and get the—the constables or sheriffs—I didn’t want you to think I was afraid to face you alone. I didn’t want to go and tell on you till I saw you first, that’s all.”

“Waal, naow yer see me,” drawled Meadows.

“And I’m going to do what I ought to do, no matter what,” Westy flared up.

“S’posin’ yer run an’ play,” said Meadows to the little girl. Then, as she moved away. “An’ what might yer ought ter do?” he asked quietly.

“You admit you shot that deer?” Westy asked. “Jiminies, you can’t deny it,” he added boyishly.

“Waal?” said Meadows.

“Do you see this badge?” said Westy, pulling the sleeve of his scout shirt around so as to display the several merit badges that were sewn there. “That top one,” he said in a boyish tone of mingled pride and anger, “is a conservation badge; it’s a scout badge.”

“Yer one of them scaouts, huh?”

“Yes, I am and I won that badge. It means if I know of anybody breaking the game laws, I’ve got to report it, that’s what it means. I’ve got to do it even if it seems mean——”

“Seems mean, huh?”

“No, it doesn’t,” Westy forced himself to say. “Because what right did you have to do that? Gee, I don’t say you wanted to leave the deer suffering, I don’t say that.” He had been fully prepared to charge the offender with that but now that he was face to face with him, he found it hard to do so. He put the whole responsibility for his purpose on his conservation badge, in which Meadows seemed rather interested.

“What’s that thar next one?” he asked.

“That’s the pathfinder’s badge,” said Westy.

“Yer a pathfinder, huh?”

“Yes, I am,” said Westy, “but I guess maybe I’m not as good at it as you are. But anyway, if you know all about those things—shooting and the woods and all that—jiminies, you ought to know enough not to shoot game out of season. Maybe that deer was a very young one, or maybe——”

“Haow ’baout my young un?” Meadows asked calmly. “How ’baout that li’l gal yer seed?”

“Well, what about her?” demanded Westy angrily.

“What makes yer say maybe I’m good at that sort of thing?” asked Luke Meadows.

“I don’t know,” said Westy; “just sort of you seem that way. But anyway, that hasn’t got anything to do with what I have to do, has it? I got that merit badge by passing six tests, if anybody should ask you. And the last one of those tests is doing something that helps enforce the game laws, and you can bet I’m going to keep on doing that too. You’ll have to pay a fine, that’s what you’ll have to do, and it serves you right.”

“Yer goin’ ter tell ’em in Chandler haow yer found my gun near the spot?”

“Yes, I am and it serves you right,” said Westy. “You broke the law and you made me shoot—— Do you think it was fun for me to do that?” he flared up angrily.

“Waal, I reckon that’ll be enough fer ’em,” said Meadows. “It’ll cook my goose. They’ve got the knife in me, as you easterners say.”

He sat down on the top step of his miserable home and seemed to meditate. “Mis Ellis over yonder, I reckon she’ll look out fer the kid,” he said. “’Tain’t been nuthin but carnsarned trouble ever sence we come from Cody. If I could get one—jes one—good aim—jes—one—good—shot—at the man that told me ter come east and work in that thar busted up factory! The wife, she worked in it till she got the flu last winter and died. And here we are, me ’n’ the kid—stranded like play-actin’ folk. I can’t shoot them factory people nor that thar loon I run into in Cody, so I get off in the woods ’n’ shoot. Yer can get ten dollars fer a deerskin if yer kin get through without them game sharks catchin’ yer. Yer a pretty likely sort o’ youngster, yer are. Never had that thar flu, did yer?”

He said no more, only sat with his hands on his knees, occasionally spitting. And for a few moments there was silence.

“Is Cody a town?” Westy asked.

“In Wyoming,” Meadows answered.

And again there was silence.

“That’s where Yellowstone Park is,” said Westy.

“’Baout thirty or forty mile,” said Meadows.

“That’s where I’m going to go,” said Westy.

Still again there was silence, and Westy felt uncomfortable. He felt that he would like to know a little more about this man. And that was strange seeing that he was going to Chandler to report him. It seemed odd that Meadows did not threaten or try to dissuade him.

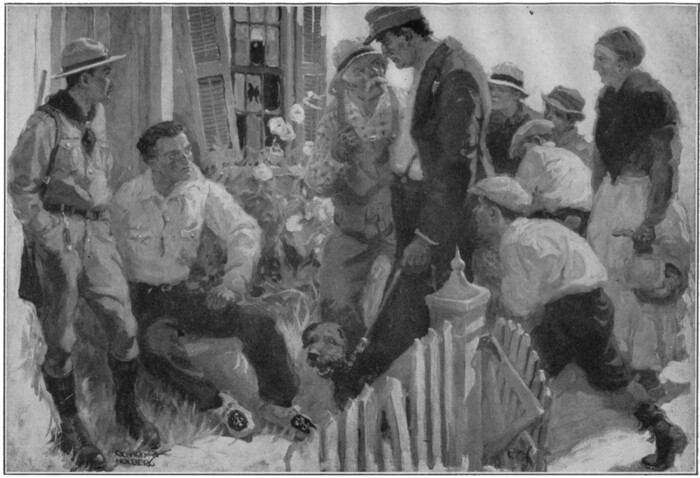

Then, suddenly the whole matter was roughly taken out of Westy’s hands. Two men, with a leashed dog, came diagonally across the road. They had evidently come out of the woods and their importance and purpose were manifested by the group representing Barrett’s younger set which followed them in great excitement, running to keep up and be prompt upon the scene. There was no mistaking the air of vigorous assurance which the men bore. But if this were not enough the badge upon the shirt of one of them left no doubt of his official character. It was this one who held the dog and the tired beast was panting audibly.

“Well, Luke, at it again, hey?” said the game warden, in that counterfeit tone of sociability which police officials acquire.

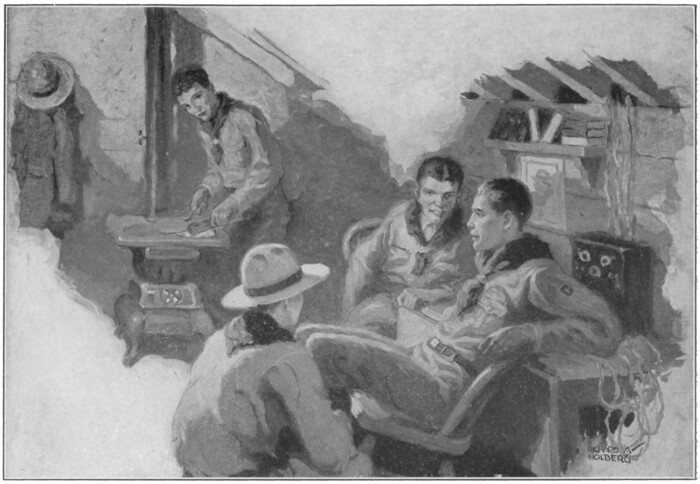

“WELL, LUKE, AT IT AGAIN, HEY?” SAID THE GAME WARDEN.

“H’lo, Terry,” drawled Luke, not angrily.

Surrounding the two men stood the gaping throng of curious boys. One or two slatternly women gave color to the scene. Somewhat apart from the group, a frightened, pitiful little figure, stood the child, Luke’s daughter.

“You run over to Mis Ellis’,” Luke said to her. But the little girl did not run over to Mrs. Ellis. She just stood apart, staring with a kind of instinctive apprehension.

“Well, Luke,” said the game warden, “seems like you got some explainin’ to do this time. What was you doin’ in the woods? Killin’ another deer, hey? When was you goin’ back to get him, Luke? Better get your hat, Luke, and come along with us. Farmer Sands here seen you comin’ out through the back fields——”

Then the little girl interrupted the game warden’s talk by rushing pell-mell to her father. Luke put his big, brown hand about her and then Westy noticed that his forearm was tattooed with the figure of a buffalo.

“You run along over t’ Missie Ellis,” said Luke, “and she’ll show yer them pictur’ books; you run like——”

Here he arose, slowly, deliberately, as if with the one action to dismiss her and place himself in the hands of the law. Then, suddenly, he lifted her up and kissed her. In all the long time that Westy was destined to know Luke Meadows, this was the only occasion on which he was ever to see him act on impulse.

But Westy Martin’s impulse was still quicker. Before the little child was down upon the ground again he spoke, and his own voice sounded strange to him as he saw the gaping loiterers all about, and the astonished gaze of Terry, the game warden. In the boy’s trousers pocket (which is the safe deposit vault pocket with boys) his sweaty palm clutched the hundred and three dollars which he was taking home to save for his trip to the Yellowstone He had kept one hand about it almost ever since he left the farm, till his very hand smelled like the roll of bills. But he clutched it even more tightly now. His voice was not as sure as that unseen clutch.

“If you’re hunting for the fellow who killed the deer over in the woods,” he said, “then here I am. I’m the one that killed the deer and—and if—if you’re going to take—arrest—anybody you’d better arrest me—because I’m the one that did it. I killed the deer—I admit it. So you better arrest me.”

For a few seconds no one spoke. Then, and it seems odd when you come to think of it, the dog pulled the leash clean out of Terry the game warden’s hand, and began climbing up on Westy and licking his hand....

He took his stand upon the simple confession that it was he who had killed the deer. He knew that he could not say more without saying too much. And all the king’s horses and all the king’s men could not make him say more. Fortunately, he did not have to say more, or much more, because Farmer Sands availed himself of the occasion to preach a homily on the evil of boys carrying firearms.

“Who you be, anyways?” he demanded shrewdly.

Westy’s one fear was that Luke would speak and spoil everything. For a moment, he seemed on the point of speaking. Probably it was only the sight of his little daughter that deterred him from doing so. It was a moment fraught with peril to Westy’s act. Then, it was too late for Luke to speak and Westy was glad of that.

He was on his way to Chandler between the game warden and the farmer.

“Well, who you be, anyways?” Farmer Sands repeated.

It was Terry, the game warden, who answered him across Westy’s shoulder.

“Why, Ezrie, he’s jus’ one of them wild west shootin’, Indian huntin’, dime novel readin’ youngsters what oughter have some sense flogged inter him. I’d as soon give a boy of mine rat poison to play with as one of these here pesky rifles. It’s a wonder he hit him, but that’s the way fools allus do. What’s your name, kid? You don’t b’long round here?”

Westy, albeit somewhat frightened, was self-possessed and shrewd enough not to beguile his escort with an account of himself.

“I told you all I’m going to,” he added. “I was going through the woods and I saw the deer and killed him. Then, I went through to Barrett’s and I was going to come along this road to Chandler. If I have to be taken to a judge, I’ll tell him more if he makes me. Please take your hand off my shoulder because I’m not going to try to run away.”

“Yer been readin’ Diamond Dick?” asked Farmer Sands, squinting at him with a look of diabolical sagacity.

“No, I haven’t been reading Diamond Dick,” said Westy.

“Wasn’t yer stayin’ up ter Nelson’s place?” the game warden asked.

“Yes, he’s my uncle,” said Westy.

“He know yer got a gun?”

“Sure, he does.”

“Well, you’d better ’phone him when you get to Chandler if you don’t want ter spend the night in a cell.”

Westy balked at the sound of this talk, but he only tightened his sweaty palm in his pocket and said, “He didn’t kill the deer. Why should I ’phone to him?”

Farmer Sands poked his billy-goat visage around in front of Westy’s face and stared but said nothing.

In Chandler, the trio aroused some curiosity as they went through the main street and Westy felt conscious and ashamed. He wished that Mr. Terry would conceal his flaunting badge. As they approached the rather pretentious County Court House, he began to feel nervous. The stone building had a kind of dignity about it and seemed to frown on him. Moreover in the brick wing he saw small, heavily barred windows, and these were not a cheerful sight.

What he feared most of all was that once in the jaws of that unknown monster, the law, he would spoil everything by saying more than he meant to say. He was probably saved from this by the dignitary before whom he was taken. The learned justice was so fond of talking himself that Westy had no opportunity of saying anything and was not invited to enlarge upon the simple fact that he had killed a deer. Probably if the local dignitary had known Westy better he would have expressed some surprise at the boy’s act but since, to him, Westy was only a boy with a gun (always a dangerous combination) there was nothing so very extraordinary in the fact of his shooting a deer. Fortunately, he did not ask questions for Westy would not have gone to the extreme of actually lying.

He stood before the desk of the justice, one sweaty palm encircled about his precious fortune in his pocket, and felt frightened and ill at ease.

“Well, my young friend,” said the justice, “those who disregard the game laws of this state must expect to pay the penalty.”

“Y-yes, sir,” said Westy nervously.

“It’s an expensive pastime,” said the justice, not unkindly.

“Yes, sir,” said Westy.

“I can’t understand why you did it, a straightforward, honest-looking boy like you.”

Westy said nothing, only set his lips tightly as if to safeguard himself against saying too much or giving way to his feelings.

“A boy that is honest enough to speak up and confess—to do such a thing—I can’t understand it,” the justice mused aloud, observing Westy keenly.

“It’s lettin’ ’em hev guns that’s to blame,” observed the game warden.

“It’s dressin’ ’em all up like hunters an’ callin’ ’em scaouts as duz it,” said Farmer Sands. “They was wantin’ me ter contribute money fer them scaouts, but I sez—I sez no, ’tain’t no good gon’ ter come of it, dressin’ youngsters up ’an givin’ ’em firearms an’ sendin’ ’em out ter vialate the laws.”

“They seem to know how to tell the truth,” said the justice, apparently rather puzzled.

“He was gon’ ter hide in Luke Meadows’ place when we catched him red-handed an’ he wuz sceered outer his seven senses an’ that’s why he confessed,” said Farmer Sands vehemently.

“Nobody can scare me into doing anything,” said Westy, defiantly. “I told because I wanted to tell and the reason you didn’t give money to the boy scouts was because you’re too stingy.”

This was the second time on that fateful day that Westy had shot and hit the mark. It seemed to amuse both the judge and the game warden.

“Has your uncle a telephone?” the justice asked, not unkindly.

“No, sir,” said Westy. “Anyway, I wouldn’t want to telephone him.”

“Could you get your father in Bridgeboro by ’phone?”

“He’d be in New York, and anyway, I don’t want to ’phone him.”

“Hum,” mused the judge. “Well, I’m afraid I haven’ much choice then, my boy. The fine for what you did is a hundred dollars. I’ll have to turn you over to the sheriff, then perhaps I’ll get in communication——”

Westy’s sweaty, trembling hand came up out of his pocket bringing his treasure with it. Boyishly, he did not even think to remove the elastic band which was around the roll of bills, but laid the whole thing upon the justice’s desk.

“Here—here it is,” he said nervously, “—to—to pay for what I did. There’s more than what you said—there’s three dollars more.”

There was a touch of pathos in the innocence which was ready to pay the fine with extra measure—and to throw in an elastic band as well. Farmer Sands looked shrewdly suspicious as the justice removed the elastic band and counted the money; he seemed on the point of hinting that Westy might have stolen it.

“Where did you get this?” the justice asked, visibly touched at the sight of the little roll that Westy had handed over.

“I had about twenty-five dollars when I came,” said Westy, “and the rest my uncle paid me for working for him on his farm.”

“There seems to be three dollars too much,” the justice said, handing that amount back to Westy. The boy took it nervously and said, “Thank you.”

The crumpled bills and the elastic band lay in a disorderly little heap on the justice’s desk, and the local official, who seemed very human, contemplated them ruefully. Perhaps he felt a little twinge of meanness. Then he rubbed his chin ruminatively and studied Westy.

The culprit moved from one foot to the other and nervously replaced the trifling remainder of his fortune in his trousers pocket. He was afraid that now something was going to happen to spoil his good turn. He hoped that the justice would not ask him any more questions.

“Well, my young friend,” said that dignitary finally, “you’ve had a lesson in what it means to defy the law. I blame it to that rifle you have there more than to you. Does your father know you have that rifle?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Approves of it, eh?”

“N-no, sir; I promised him I wouldn’t shoot at anything but a target.”

“And you broke your promise?”

“Yes, sir.”

Still the judge studied him. “Well,” said he, after a pause, “I don’t think you’re a bad sort of a boy. I think you just saw that deer and couldn’t refrain from shooting him. I think you felt like Buffalo Bill, now didn’t you?”

“I—yes—I—I don’t know how Buffalo Bill felt,” said Westy.

“And if Mr. Sands hadn’t got in touch with Mr. Terry and found that deer, you would have gone back home thinking you’d done a fine, heroic thing, eh?”

Westy did think he had done a good thing but he didn’t say so.

“But you had the honesty to confess when you saw that an innocent man was about to be arrested. And that’s what makes me think that you’re a not half-bad sort of a youngster.”

Westy shifted from one foot to the other but said nothing.

“You just forgot your promise when you saw that deer.”

“I didn’t forget it, I just broke it,” said Westy

“Well, now,” said the judge, “you’ve had your little fling at wild west stuff, you’ve killed your deer and paid the penalty and you see it isn’t so much fun after all. You see where it brings you. Now I want you to go home and tell your father that you shot a deer out of season and that it cost you a cold hundred dollars. See?”

“Yes, sir,” said Westy.

“You ask him if he thinks that pays. And you tell him I said for him to take that infernal toy away from you before you shoot somebody or other’s little brother or sister—or your own mother, maybe.”

Westy winced.

“If I were your father instead of justice of the peace here, I’d take that gun away from you and give you a good trouncing and set you to reading the right kind of books—that’s what I’d do.”

“I wouldn’ leave no young un of mine carry no hundred dollars in his pockets, nuther,” volunteered Farmer Sands.

“Well, it’s good he had it,” said the justice, “or I’d have had to commit him.” Then turning to Westy, he said, “Maybe that hundred dollars is well spent if it taught you a lesson. You go along home now and tell your father what I said. And you tell him I said that a rifle is not only a dangerous thing but a pretty expensive thing to keep.”

“Yes, sir,” said Westy.

“Are you sorry for what you did?”

“As long as I paid the fine do I have to answer more questions?” asked Westy.

“Well, you remember what I’ve said.”

“Yes, sir,” said Westy.

“Did you ever hear of Lord Chesterfield’s letters to his son?”

“N-no—yes, sir, in school.”

“Well, you get that book and read it.”

Westy said nothing. To lose his precious hundred dollars seemed bad enough. To be sentenced to read Lord Chesterfield’s letters to his son was nothing less than inhuman.

It was now mid-afternoon. The boy who had gone to work on his uncle’s farm so as to earn money to take him to Yellowstone Park, stood on the main street of the little town of Chandler with three dollars and some small change in his pocket. This was the final outcome of all his hoping and working through the long summer. He had just about enough money to get home to Bridgeboro.

And there only disgrace awaited him. For he would not tell the true circumstances of his killing the deer. He had assured Luke Meadows of his freedom; he would not imperil that freedom now by confiding in any one. His father might not see it as he did and might make the facts of the case known to these local authorities. Westy thought of the little, motherless girl clinging to her father, and this picture, which had aroused him to rash generosity, strengthened his resolution now. Westy was no quitter; he had done this thing, and he would accept the consequences.

What he most feared was that at home they would question him and that he would be confronted with the alternative of telling all or of lying. He thought only of Luke Meadows and of the little girl. And being in it now, for better or worse, he was resolved that he would stand firm upon the one simple, truthful admission that he had killed a deer.

Yet he was so essentially honest that he could not think of returning to Bridgeboro without first going back to the farm to tell them what he had done. He knew that this would mean questioning and might possibly, through some inadvertence of his own, be the cause of the whole story coming to light. But he could not think of going to Bridgeboro, leaving these people who had been so kind to him to hear of his disgrace from others. He would go back himself and tell his aunt; he would be in a great hurry to catch the later train and that would save him from being questioned. Yet it seemed a funny thing to do to go back and hurriedly announce that he had killed a deer and as hurriedly depart. Poor Westy, he was beginning to see the difficulties involved in his spectacular good turn.

He wandered over to the railroad, worried and perplexed. Wherever he might go there would be trouble. He would have to face his aunt and uncle, then his father and mother. And he could not explain. How could he hope to run the gauntlet of all these people with just the one little technical truth that he had killed a deer?

It was just beginning to dawn on him that truth is not a technical thing at all, that to stick to a technical truth may be very dishonest. Yet, he had (so he told himself) killed the deer. And that one technical little truth he had invoked to save Luke Meadows.

He would not, he could not turn back now.

He could catch a train to Bridgeboro in half an hour and leave the thunderbolt to break at the farm after he was safely away. Or he could return to the farm and still catch a train from Chandler at eight-twenty. He decided to do this.

He lingered weakly in the station for a few minutes, killing time and trying to make up his mind just what he would say when he reached the farm. The station was dim and musty and full of dust and aged posters. One of these latter was a glaring advertisement of an excursion to Yellowstone Park. It included a picture of Old Faithful Geyser, that watery model of constancy which is to be seen on every folder and booklet describing the Yellowstone. Westy looked at it wistfully. “See the glories of your native land,” the poster proclaimed. He read it all, then turned away.

The ticket office was closed, and in his troubled and disconsolate mood it seemed to him as if even the railroad shut him out. Not a living soul was there in the station except a queer-looking woman with spectacles and a sunbonnet and an outlandish bag at her feet. Westy wondered whether she were going to New York.

Then he wondered whether, when he reached Bridgeboro, he might not properly say that he was very sleepy and let his confession go over till morning. Then it occurred to him that he was just dilly-dallying, and he strode out of the station and through the little main street where farming implements were conspicuous among the displays. He paused to glance at these and other things in which he had never before had an interest. Never before had he found so many excuses for pausing along a business thoroughfare.

He intended to return through the woods but a man in a buckboard with a load of clanking milk cans gave him a lift and set him down at the crossroads near the farm. He cut up through the orchard because he had a queer feeling that he did not want any one to see him coming. It seemed very quiet about the farm; he had an odd feeling that he was seeing it during his own absence. It looked strange to see his aunt stringing beans on the little porch outside the kitchen and Ira sitting with his legs stretched along the lowest step. His back was against the house and he was smoking his pipe. The homely, familiar scene made Westy homesick for the farm.

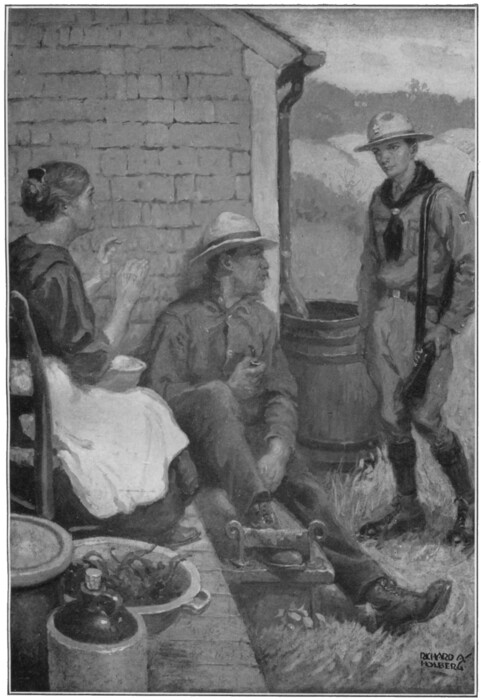

“Mercy on us, what you doin’ here?” Aunt Mira gasped. “Westy! You near skeered the life out of me!”

“MERCY ON US, WHAT YOU DOIN’ HERE?” GASPED AUNT MIRA.

Ira removed his atrocious pipe from his mouth long enough to inquire without the least sign of shock. “What’s the matter, kid? Get lost in the woods and missed your train?”

“No, I didn’t get lost in the woods,” said Westy, with a touch of testiness.

“Land’s sake, Iry, why can’t you never stop plaguin’ the boy,” said Aunt Mira.

“I came back,” said Westy rather clumsily. “I came back to tell you something. I’ve got something I want to tell you because I—because I want to be the one to tell you——”

“You lost your money,” interrupted Aunt Mira. “I told your uncle he should have made you a check.”

“Scouts and them kind don’t carry no checks,” said Ira.

“I came back,” said Westy, “because I want to tell you that I shot a deer in the woods and killed him. It’s true so you needn’t ask me any questions about it because—because I shot him because I had good reasons—anyway, because I wanted to, so there’s no good talking about it.”

Aunt Mira laid down her work and stared at Westy. Ira removed his pipe and looked at him keenly yet somewhat amusedly. Aunt Mira’s look was one of blank incredulity. Ira could not be so easily jarred out of his accustomed calm.

“Where’d yer shoot ’im?” he asked.

“In the woods,” said Westy; “in—in—do you mean where—what part of him? In his head.”

“Plunked ’im good, huh? Ye’ll have Terry after you, then you’ll have ter give ’im ten bucks to hush the matter up. Just couldn’t resist, huh?”

“Ira, you keep still,” commanded Aunt Mira, concentrating her attention on Westy. “What do you mean tellin’ such nonsense?” she questioned.

“I mean just that,” said Westy; “that I killed a deer and I did it because I wanted to. Then I went through the woods to Barrett’s because I decided to go to Chandler that way, and while I was talking to a man there the game warden and another man came along because they must have been—they must have known about it or something.

“Anyway, I told them I did it—killed the deer. So then I got arrested and they took me to Chandler and the judge or justice of the peace or whatever they call him, he said I had to pay a hundred dollars, so I did. I’ve got enough left to get home with, all right. But anyway, I didn’t want you to hear about it because I wanted to tell you myself. I’ve got to stand the blame because I killed him and so that’s all there is to it.”

It was fortunate for Westy that Aunt Mira was too dumfounded for words. As for Ira, his face was a study during the boy’s recital. He watched Westy shrewdly, now and then with a little glint of amusement in his eye as the young sportsman stumbled along with his boyish confession. Only once did he speak and that was when the boy had finished.

“Who was the man you was talkin’ with in Barrett’s, kid?”

“His name is Meadows,” Westy answered.

“Hmph,” was Ira’s only comment.

Indeed he had no opportunity for comment for Aunt Mira was presently upon him and her incisive commentary on Ira’s qualities probably saved Westy the discomfort of further questioning. He was such a thoroughly good boy that now when he confessed to doing wrong, Aunt Mira felt impelled to lay the blame to some one else. And Ira was the victim....

“Now you see, Iry Hasbrook, where your boastin’ and braggin’ and lyin’ yarns has led to,” said Aunt Mira, after Westy had gone. It had proved impossible to detain him, and he had marched off after his sensational disclosure with a feeling of infinite relief that no complications had occurred. But he might have seen danger of complications in Ira’s shrewd, amused look if he had only taken the trouble to notice it.

“He’s a great kid,” said Ira.

“A pretty mess you’ve got him in,” said Aunt Mira, “with your droppin’ this and droppin’ that. Now he’s dropped his deer and I hope you’re satisfied. ’Twouldn’t be no wonder if he ran away to sea and you to blame, Ira Hasbrook. It’s because he’s so good and trustin’ and makes heroes out of every one, even fools like you with your kidnappin’ kings and rum smugglin’ and what all.”

“How ’bout the book in the settin’ room?” Ira asked.

Aunt Mira made no answer to this but she at least paid Ira the compliment of rising from her chair with such vigor of determination that the dishpan full of beans which had been reposing in her lap was precipitated upon the floor. She strode into the sitting room where the “sumptuous, gorgeously illustrated volume” lay upon the innocent worsted tidy which decorously covered the marble of the center table.

Laying hands upon it with such heroic determination as never one of its flaunted hunters showed, she conveyed it to the kitchen and forthwith cremated it in the huge cooking stove. Then she returned to the back porch with an air that suggested that what she had just done to the book was intended as an illustration of what she would like to do to Ira himself. But Ira was not sufficiently sensitive to take note of this ghastly implication.

“Yer recipe for makin’ currant wine was in that book,” was all he said.

For a moment, Aunt Mira paused aghast. It seemed as if, in spite of her spectacular display, Ira had the better of her. He sat calmly smoking his pipe.

“Why didn’t you call to me that it was there?” she demanded sharply.

“You wouldn’t of believed me, I’m such a liar,” said Ira quietly.

“I don’t want to hear no more of your talk, Iry,” said the distressed and rather baffled lady. “I don’t know as I mind losin’ the recipe. What I’m thinkin’ about is the hundred dollars that poor boy worked to get—and you went and lost for him.”

She had subsided to the weeping stage now and she sat down in the old wooden armchair and lifted her gingham apron to her eyes and all Ira could see was her gray head shaking. Her anger and decisive action had used up all her strength and she was a touching enough spectacle now, as she sat there weeping silently, the string beans and the empty dishpan scattered on the porch floor at her feet.

“He’s all right, aunty,” was all that Ira said.

“I thank heavens he told the truth ’bout it least-ways,” Aunt Mira sobbed, pathetically groping for the dishpan. “I thank heavens he come back here like a little man and told the truth. I couldn’t of beared it if he’d just sneaked away and lied. He won’t lie to Henry—if he wouldn’t lie to me he won’t lie to Henry. I do hope Henry won’t be hard with him—I know he won’t lie to his father, ’tain’t him to do that. He was just tempted, he saw the deer and his head was full of all what you told him and that pesky book I hope the Lord will forgive me for ever buyin’. I’m goin’ to write to Henry this very night and tell him I burned up the book and prayed for forgiveness for you, Iry Hasbrook—I am.”

Ira puffed his horrible pipe in silence for a few moments, and in that restful interval could be heard the sound of the bars being let down so that the cows might return to their pasture. The bell on one wayward cow sounded farther and farther off as Uncle Dick, all innocent of the little tragedy, drove the patient beasts into the upper meadow.

The clanking bell reminded poor Aunt Mira to say, “You told him he couldn’t even shoot a cow, you did, Iry.”

“He’s just about the best kid that ever was,” was all that Ira answered.

“I’m goin’ to write to Henry to-night and I’m goin’ to tell him, Iry, just what you been doin’, I am. I’m goin’ to tell him that poor boy isn’t to blame. I know Henry won’t be hard on him. I’m goin’ to tell him about that book and ask him to forgive me my part in it,” the poor lady wept.

“Ask him if he’s got a good recipe for currant wine,” drawled Ira.

Aunt Mira’s tearful prayers were not fully answered, not immediately at all events. Westy’s father was “hard on him.” His well advertised prejudice against rifles as “toys” seemed justified in the light of his son’s fall from grace. Westy did not have to incur the perils of a detailed narrative.

Mr. Martin, notwithstanding his faith in his son, had always been rather fanatical about this matter of “murderous weapons” even where Westy was concerned. He was very pig-headed, as Westy’s mother often felt constrained to declare, and the mere fact of the killing of the deer was quite enough for a gentleman in his state of mind. Fortunately, he did not prefer a kindly demand for particulars.

“I just did it and I’m not going to make any excuses,” said Westy simply. “I told you I did it because I wouldn’t do a thing like that and not tell you. You can’t say I didn’t come home and tell you the truth.”

The memorable scene occurred in the library of the Martin home, Westy standing near the door ready to make his exit obediently each time his father thundered, “That’s all I’ve got to say.” First and last Mr. Martin said this as many as twenty times. But there seemed always more to say and poor Westy lingered, fending the storm as best he could.

It was the night of his arrival home, his little trunk had been delivered earlier in the day, and on the library table were several rustic mementos of the country which the boy had thought to purchase for his parents and his sister Doris. A plenitude of rosy apples (never forgotten by the homecoming vacationist) were scattered on the sofa where Doris sat sampling one of them. Mrs. Martin sat at the table, a book inverted in her lap. Mr. Martin strode about the room while he talked.

They had all been away and the furniture was still covered with ghostly sheeting. About the only ornaments at large were the little birch bark gewgaws and the imitation bronze ash receptacle which Westy had brought with him. This latter, which seemed to mock the poor boy’s welcome home had Greetings From Chandler printed on it and was for his father.