Title: Japan and the Pacific, and a Japanese View of the Eastern Question

Author: Manjiro Inagaki

Release date: January 7, 2020 [eBook #61126]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Richard Tonsing, MFR, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Japan and the Pacific, by Manjiro Inagaki

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/japanpacificandj00inagrich |

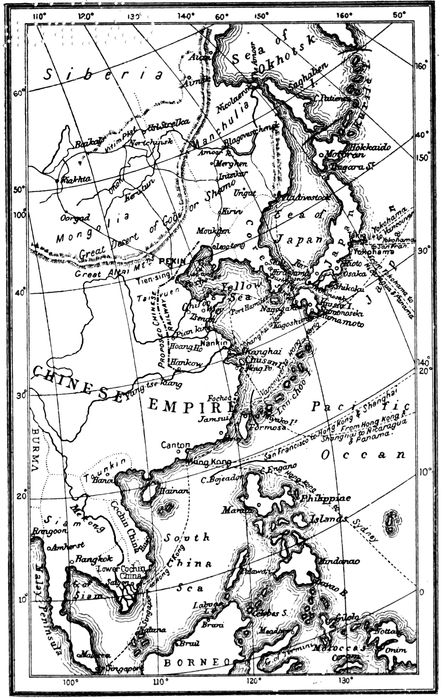

Japan & the North Pacific.

I feel that some explanation is due when a Japanese ventures to address himself to English readers; my plea is that the matters on which I write are of vital importance to England as well as to Japan. Though I feel that my knowledge of English is so imperfect that many errors of idiom and style and even of grammar must appear in my pages, yet I hope that the courtesy which I have ever experienced in this country will be extended also to my book.

My aim has been twofold: on the one hand, to arouse my own countrymen to a sense of the great part Japan has to play in the coming century; on the other, to call the 10attention of Englishmen to the important position my country occupies with regard to British interests in the far East.

The first part deals with Japan and the Pacific Question: but so closely is the latter bound up with the so-called Eastern Question that in the second part I have traced the history of the latter from its genesis to its present development. Commencing with a historical retrospect of Russian and English policy in Eastern Europe, I have marked the appearance of a rivalry between these two Powers which has extended from Eastern Europe to Central Asia, and is extending thence to Eastern Asia and the Pacific. This I have done because any movement in Eastern Europe or Central Asia will henceforth infallibly spread northwards to the Baltic and eastwards to the Pacific. An acquaintance with the Eastern Question in all its phases will thus be necessary for the statesmen of Japan in the immediate future. I have confined my view to England and Russia because their interests in Asia and the North Pacific are so direct and so important that 11they must enter into close relations with my own country in the next century.

I cannot claim an extensive knowledge of the problems I have sought to investigate, but it is my intention to continue that investigation in the several countries under consideration. By personal inquiries and observations in Eastern Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, China, and the Malay Archipelago, I hope to correct some and confirm others of my conclusions.

I have to thank many members of the University of Cambridge for their help during the writing and publication of my book. To Professor Seeley especially, whose hints and suggestions with regard to the history of the eighteenth century in particular have been so valuable to me, I desire to tender my most hearty and grateful thanks. To Dr. Donald Macalister (Fellow and Lecturer of St. John’s College) and Mr. Oscar Browning, M.A. (Fellow and Lecturer of King’s College) I owe much for kindly encouragement and advice and assistance in many ways, while I am indebted to Mr. G. 12E. Green, M.A. (St. John’s College), for his labour in revising proofs and the ready help he has given me through the many years in which he has acted as my private tutor.

The chief works which I have used are Professor Seeley’s “Expansion of England,” Hon. Evelyn Ashley’s “Life of Lord Palmerston,” and Professor Holland’s “European Concert in the Eastern Question.” The latter I have consulted specially for the history of treaties.

| PART I. | ||

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| JAPAN AND THE PACIFIC | 21 | |

| England and Asia—The Persian war—The Chinese war—Russian diplomacy in China—Singapore and Hong Kong—Labuan and Port Hamilton—Position of Japan; its resources—Importance of Chinese alliance to England—Strength of English position in the Pacific at present—Possible danger from Russia through Mongolia and Manchooria—Japan the key of the Pacific; her area and people; her rapid development; her favourable position; effect of Panama Canal on her commerce—England’s route to the East by the Canadian Pacific Railway—Japanese manufactures—Rivalry of Germany and England in the South Pacific—Imperial Federation for England and her colonies—Importance of island of Formosa—Comparative progress of Russia and England—The coming struggle. | ||

| PART II. | ||

| THE EASTERN QUESTION. | ||

| I. | ||

| Foreign Policy of England during the Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Centuries | 73 | |

| 14 | The Spanish Empire, its power, and its decline—Commercial rivalry of England and Holland—The ascendency of France; threatened by the Grand Alliance—The Spanish succession and the Bourbon league—England’s connection with the war of the Austrian succession—The Seven Years’ War—Revival of the Anglo-Bourbon struggle in the American and Napoleonic wars. | |

| II. | ||

| Foreign Policy of Russia during the Reigns of Peter, Catherine, and Alexander | 95 | |

| Peter the Great, and establishment of Russian power on the Baltic—Consequent collision with the Northern States and the Maritime Powers—Catherine II. and Poland—First partition—Russia reaches the Black Sea—Russo-Austrian alliance against Turkey opposed by Pitt—Second and third partitions of Poland—Rise of Prussia—Alexander I. and the conquest of Turkey—Treaty of Tilsit—Peace of Bucharest—Congress of Vienna—French influence in the East destroyed. | ||

| III. | ||

| The New European System | 114 | |

| The concert of the Great Powers; its aims—It does not protect small states from its own members, e.g., Polish Revolution—How far can it solve the Turkish question? | ||

| IV. | ||

| Greek Independence | 120 | |

| The Holy Alliance—The Greek insurrection—Interference of the Three Powers—Battle of Navarino—Treaty of Adrianople—The policy of Nicholas I.; Treaty of Unkiar Ikelessi—Turkey only saved by English and French aid—Palmerston succeeds to Canning’s policy. | ||

| 15V. | ||

| The Crimean War | 131 | |

| Nicholas I. alienates France from England by the Egyptian question—Mehemet Ali and Palmerston’s convention against him—Nicholas I. in England—The Protectorate of the Holy Land; breach between Russia and France—Proposed partition of Turkey—War of Russia and Turkey—The Vienna Note—Intervention of France and England to save Turkey—Treaty of Paris; Russia foiled—Correspondence between Palmerston and Aberdeen as to the declaration of war—National feeling of England secures the former’s triumph—French motives in joining in the war. | ||

| VI. | ||

| The Black Sea Conference | 164 | |

| French influence destroyed by the Franco-Prussian War—Russia annuls the Black Sea clauses of the Treaty of Paris—Condition of Europe prevents their enforcement by the Powers—London Conference; Russia secures the Black Sea; England’s mistake—Alsace and Lorraine destroy the balance of power. | ||

| VII. | ||

| The Russo-Turkish War of 1878 | 172 | |

| Bulgarian atrocities—The Andrassy Note; England destroys its effect—The Berlin Memorandum; England opposes it—Russia prepares for a Turkish war—Conference of Constantinople—New Turkish Constitution—Russo-Turkish War—Treaty of San Stefano—Intervention of the Powers—The Berlin Congress—Final treaty of peace. | ||

| VIII. | ||

| Remarks on Treaty of Berlin | 195 | |

| 16 | The position of affairs—The Salisbury-Schouvaloff Memorandum and its disastrous effect on the negotiations at Berlin—Russia’s gain—England and Austria the guardians of Turkey—Austria’s vigorous and straightforward Balkan policy—Thwarted in Servia but triumphant in Bulgaria—Relations of Greece to Austria—Solution of the Crete question—Neutrality of Belgium threatened—Importance of Constantinople to Russia; the Anglo-Turkish Convention—England’s feeble policy in Asia Minor—The question of Egypt—A new route to India by railway from the Mediterranean to Persian Gulf—England’s relation to Constantinople. | |

| IX. | ||

| Central Asia | 227 | |

| Rise of British power in India—Rivalry of France—Aims of Napoleon—Russian influence in Central Asia—Its great extension after the Crimean War—And after the Berlin Congress—Possible points of attack on India—Constantinople the real aim of Russia’s Asiatic policy—Recent Russian annexations and railways in Central Asia—Reaction of Asiatic movements on the Balkan question—Dangerous condition of Austria—Possible future Russian advances in Asia—England’s true policy the construction of a speedy route to India by railway from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf—Alliance of England, France, Turkey, Austria, and Italy would effectively thwart Russian schemes. | ||

| 1. | JAPAN AND THE NORTH PACIFIC | Frontispiece |

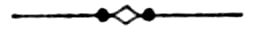

| 2. | THE PACIFIC AND ITS SEA ROUTES | 46 |

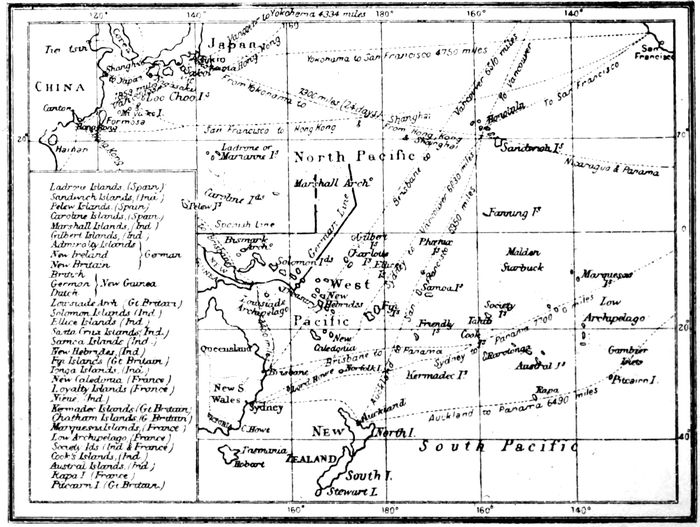

| 3. | THE EXPANSION OF RUSSIA IN EUROPE | 97 |

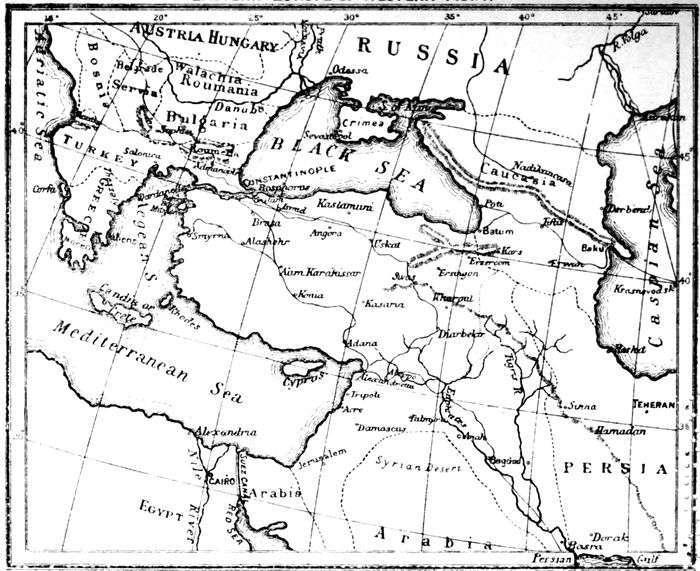

| 4. | EASTERN EUROPE AND WESTERN ASIA | 115 |

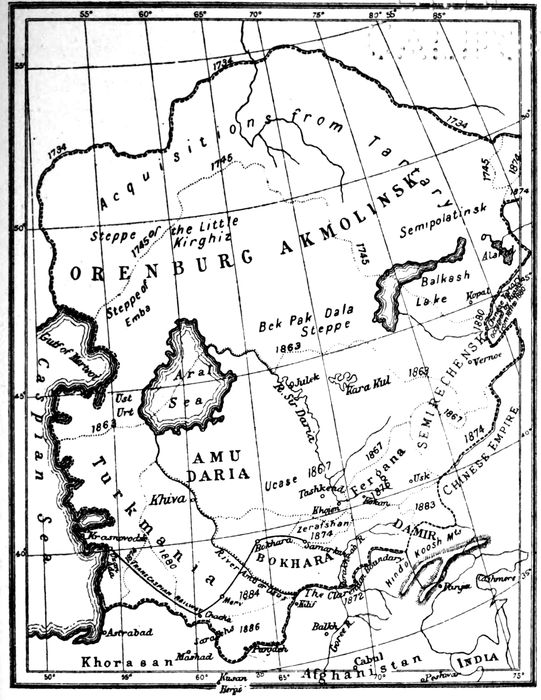

| 5. | THE EXPANSION OF RUSSIA IN ASIA | 233 |

England and Asia—The Persian war—The Chinese war—Russian diplomacy in China—Singapore and Hong Kong—Labuan and Port Hamilton—Position of Japan; its resources—Importance of Chinese alliance to England—Strength of English position in the Pacific at present—Possible danger from Russia through Mongolia and Manchooria—Japan the key of the Pacific; her area and people; her rapid development; her favourable position; effect of Panama Canal on her commerce—England’s route to the East by the Canadian Pacific Railway—Japanese manufactures—Rivalry of Germany and England in the South Pacific—Imperial Federation for England and her colonies—Importance of island of Formosa—Comparative progress of Russia and England—The coming struggle.

Without doubt the Pacific will in the coming century be the platform of commercial and political enterprise. This truth, however, escapes the eyes of ninety-nine out of a hundred, just as did the importance of Eastern 22Europe in 1790, and of Central Asia in 1857. In the former case England did not appreciate the danger of a Russian aggression of Turkey, and so Pitt’s intervention in the Turkish Question failed. It was otherwise in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the Crimean War and the Berlin Congress proved great events in English history. In 1857 the national feeling in England was not aroused as to the importance of defending Persia from foreign attack. Lord Palmerston had written to Lord Clarendon, Feb. 17, 1857, “It is quite true, as you say, that people in general are disposed to think lightly of our Persian War, that is to say, not enough to see the importance of the question at issue.” How strongly does the Afghan question attract the public attention of England at the present day?

It is very evident that in 1857 very few in England were awake to the vital importance of withstanding Russian inroads into the far East, viz., the Pacific.

After defeating Russia miserably in the Crimean War and driving her back at the 23Balkans by the Treaty of Paris, Lord Palmerston’s mind was now revolving and discussing the following serious thought: “Where would Russia stretch out her hands next?”

I think I am not wrong in stating the following as Lord Palmerston’s solution of the problem:—

(a) That Russia was about to strike the English interests at Afghanistan by an alliance with Persia.

(b) That she would attack the Afghan frontier single-handed.

(c) That an alliance would be formed with the Chinese, and a combined hostility against Britain would be shown by both.

(d) She would extend her Siberian territory to the Pacific on the north, thereby obtaining a seaport on that ocean’s coast, and make it an outpost for undermining English influence in Southern China.

Therefore in 1856 Lord Palmerston declared war against Persia remarking that “we are beginning to reveal the first 24openings of trenches against India by Russia.”[1]

This policy proved a winning one. The Indian Mutiny of 1857, however, scarcely gave Palmerston time to mature his Afghan Frontier scheme, consequently his views with regard to that country were to a great extent frustrated by Russia.

In the autumn of 1856, the Arrow dispute gave Palmerston his long-wished for opportunity of gaining a stronghold in the South China Sea. He declared war on China. The causes of this dispute on the English side were morally unjust and legally untenable. Cobden brought forward a resolution to this effect—that “The paper laid on the table failed to establish satisfactory grounds for the violent measure resorted to.” Disraeli, Russell, and Graham all supported Cobden’s motion. Mr. Gladstone, who was also in favour of the motion, said, at the conclusion of his speech, “with every one of us it rests to show that this House, which is the first, 25the most ancient, and the noblest temple of freedom in the world, is also the temple of that everlasting justice without which freedom itself would only be a name, or only a curse, to mankind. And I cherish the trust that when you, sir, rise in your place to-night to declare the numbers of the division from the chair which you adorn, the words which you speak will go forth from the halls of the House of Commons as a message of British justice and wisdom to the farthest corner of the world.”

Mr. Gladstone, it certainly seems to me, only viewed the matter from a moral point of view. If we look at it in this light, then the British occupation of Port Hamilton was a still more striking example of English “loose law and loose notion of morality in regard to Eastern nations.”

Palmerston was defeated in the House by sixteen votes, but was returned at the general election by a large majority backed by the aggressive feelings of the English nation.

He contended that “if the Chinese were right about the Arrow, they were wrong 26about something else; if legality did not exactly justify violence, it was at any rate required by policy.”[2] He described this policy in the following way—“To maintain the rights, to defend the lives and properties of British subjects, to improve our relations with China, and in the selection and arrangement of those objects to perform the duty which we owed to the country.”

This is easy to understand, and showed at any rate a disposition, in fact a wish, for the Anglo-Chinese alliance.

The Treaty of Pekin was finally concluded in 1860, the terms of which were—Toleration of Christianity, a revised tariff, payment of an indemnity, and resident ambassadors at Pekin.

Whatever might have been the policy of Palmerston in the Chinese War, Russia took it as indirectly pointed at herself.

General Ignatieff[3] was sent to China 27immediately as Russian Plenipotentiary. It is said that he furnished maps to the allies, in fact did his very best to bring the negotiations to a successful and peaceful close, and immediately after the signing of the agreement, he commenced overtures for his own country, and succeeded in obtaining from China the cession of Eastern Siberia with Vladivostock and other seaports on the Pacific (1858).

Lord Elgin asked Ignatieff why Russia was so anxious to obtain naval ports on the Pacific. He replied: “We do not want them for our own sake, but chiefly in order that we may be in a position to compel the English to recognize that it is 28worth their while to be friends with us rather than foes.”

Here began the struggle between England and Russia in the Pacific.

In 1859 Russia obtained the Saghalien[4] Island, in the North Pacific, from Japan, in exchange for the Kurile Island, while England was bombarding[5] Kagoshima, a port in South Japan (1862), but the English were virtually repelled from there.

Previous to this period the English policy in Asia was to establish a firm hold of Indian commerce with the South China Sea, for she could not find so large and profitable a field 29of commerce elsewhere. Therefore the English attention for the time being was entirely directed in that quarter.

In 1819 the island of Singapore, as well as all the seas, straits, and islands lying within ten miles of its coast, were ceded to the British by the Sultan of Johor. It then contained only a few hundred piratical fishermen, but now it is on the great road of commerce between the eastern and western portions of Maritime Asia, and is a most important military and naval station.

Hong Kong, an island off the southern coast of China, was occupied by the English, and in 1842 was formally handed over by the Treaty of Nankin. It has now become a great centre of trade, besides being a naval and military station.

In 1846 Labuan, the northern part of Borneo, was ceded to Great Britain by the Sultan of Borneo, and owing to the influence of Sir James Brooke a settlement was at once formed. Now it also, like Singapore, forms an important commercial station, and transmits to both China and Europe the 30produce of Borneo and the Malay Archipelago.

Owing to the opening of seaports in Northern China for foreign trade in 1842, the growing Russian influence in the Northern Pacific and many other circumstances caused England to perceive the necessity of having a naval depôt and commercial harbour on the Tong Hai and on the Yellow Sea. England was doubtless casting her eyes upon the Chusan Island or some other island in the Chusan Archipelago, but did not dare to occupy any one of them lest she should thereby offend the chief trading nation of that quarter, viz., China.

However, in 1885 England annexed Port Hamilton, on the southern coast of the Corea, during the threatened breach with Russia on the Murghab question.

“Port Hamilton,” said the author of “The Present Condition of European Politics,”[6] “was wisely occupied as a base from which, with or without a Chinese alliance, Russia 31could be attacked on the Pacific. It is vital to us that we should have a coaling station and a base of operations within reach of Vladivostock and the Amoor at the beginning of a war, as a guard-house for the protection of our China trade and for the prevention of a sudden descent upon our colonies; ultimately as the head station for our Canadian Pacific railroad trade; and at all times, and especially in the later stages of the war, as an offensive station for our main attack on Russia.”

Port Hamilton forms the gate of Tong Hai and the Yellow Sea; it cannot, however, become a base of operations for an attack on the Russian force at Vladivostock and the Amoor unless an English alliance is formed with Japan. The above writer shows an ignorance of the importance of the situation of Japan in the Pacific question. Japan holds the key of the North China Sea and Japan Sea in Tsushima.[7] 32She has fortified that island, and placed it in direct communication with the naval station of Sasebo, also with the military forces of Kumamoto. She also can send troops and fleets from the Kure naval station and the garrison of Hiroshima. She would also, if required, have other naval stations on the coast of the Japan Sea ready for any emergency. In this manner she would be able to keep out the British fleet from attacking Vladivostock and the Amoor through the Japan Sea. Even if she might not be able to do this single-handed she certainly could by an alliance with Russia.

If also Japan occupied Fusan, on the south-eastern shore of the Corea, the Japan Sea would be rendered almost impregnable from any southern attack.

33Again, Port Hamilton would be useless as a head station for the Canadian Pacific Railway trade without an Anglo-Japanese alliance. If you look at the map, you can easily appreciate the situation. Japan, with many hundreds of small islands, lies between 24° and 52° in N. lat., its eastern shores facing the Pacific and cutting off a direct line from Vancouver’s Island to Port Hamilton. It must therefore depend mainly upon Japan as a financial and political success.

Japan is now divided into six military districts, while the seas around it are divided into five parts, each having its own chief station in contemplation. The Government are now contemplating establishing a strong naval station at Mororan in Hokkukaido, for the defence of the district and also the shore of the northern part of the mainland, especially of the Tsugaru Strait. The strait of Shimonoseki also has been fortified and garrisoned on both sides, and has close communication from the Kure naval station, and with Hiroshima, and Osaka. Railway communication has also made great strides 34during the last few years, and rapid transit has consequently greatly improved throughout the empire.

If the Kiushiu, the Loo Choo, and the Miyako Islands are well looked after by the Japanese fleet from the Sasebo naval station, then Japan would be able to sever the communication between Vancouver’s Islands and Port Hamilton, and also between the former place and Hong Kong to a certain extent. The San-Francisco-Hong Kong route would be injured, and Shanghai-Port-Hamilton line would be threatened. Without doubt Japan is the Key of the Pacific.

Reviewing the discussion, we find that Port Hamilton is rather useless with regard to the Japan Sea and the Canadian Pacific railway road without a Japanese alliance, but it would be of immense importance in withstanding a Russian attack on the British interests from the Yellow Sea through Mongolia or Manchooria. It is also an excellent position for any offensive attack upon China in case of war breaking out.

The British occupation of Port Hamilton 35was very galling to the Chinese nation, in fact, quite as disagreeable as the occupation of Malta and Corsica was to Italy, and the annexing of the Channel Islands and Heligoland to France and Germany. It has therefore somewhat shaken the Anglo-Chinese alliance.

A Chinese alliance, however, is of far greater importance for English interests than the occupation of Port Hamilton. If relations became strained a severe blow would be dealt to English trade and commerce in that part. The main portion of the commercial trade of China is with the United Kingdom and her colonies; for instance, in 1887, the imports of China from Great Britain, Hong Kong, and India amounted to about 89,000,000 tael, while the exports to the same countries were 48,000,000 tael. It is hardly possible to find two countries more closely connected by trade than England and China.[8] The Hamilton 36scheme was wisely abandoned in 1887, and the English Government obtained a written guarantee from China against a Russian occupation in future years.

Viscount Cranbrook said in his reply to a question asked by Viscount Sidmouth: “That the papers to which he referred did contain a written statement, and a very long written statement on the part of the Chinese Government giving the guarantee in question. It was not a mere verbal statement by the Chinese Government, but a very deliberate note. It was found that the Chinese had received from the Russian Government a guarantee that Russia would not interfere with Corean territory in future if the British did not, and the Chinese Government were naturally in a position, on the faith of that guarantee by the Russian Government, to 37give a guarantee to the British Government. The Marquess of Salisbury, on the part of her Majesty’s Government, had accepted it as a guarantee in writing from the Chinese Government.”

This policy was undoubtedly an exceedingly wise and good one. By this England not only regained a firm and complete commercial alliance, but also maintained and strengthened a political alliance against Russian attacks from the Corea and indirectly from Manchooria and Mongolia.

England also saved money by the abandonment of the Port Hamilton scheme, and saved her fleet from being, to a certain degree, scattered in such a far-off quarter of the globe.

England now holds complete sway both commercially and navally in the Pacific. Lord Salisbury’s policy is worthy of all praise, together with Mr. Gladstone’s original scheme. If the scheme had never been originated there would not have been so firm an Anglo-Chinese alliance as there now is.

38England’s power at the present time is three times as great as that of Russia in the Pacific; in fact Russia has always been overweighted in that respect. Therefore it is selfevident she could never be able to withstand the combined Anglo-Chinese fleets.

It seems to me that the only feasible plan for a Russian attack on Anglo-Chinese alliance would be from Mongolia and Manchooria by means of an alliance with the Mongolian Tartars. This would be preferable to coping with England face to face in the Pacific.

Chinese history plainly tells us that the Chinese could not withstand an attack of the brave Mongol Tartars from the north, and that they have proved a constant source of dread to them.

The Great Wall which stretches across the whole northern limit of the Chinese Empire from the sea to the farthest western corner of the Province of Kansal, was built only for the defence of China against the northern “daring” Tartars.

Ghenghis Khan (1194), the rival of Attila, 39in the extent of his kingdom, who overran the greater part of China and subdued nearly the whole of N. Asia, who carried his arms into Persia and Delhi, drove the Indians on to the Ganges, and also destroyed Astrakhan and the power of the Ottoman, was a Mongolian Tartar.

In the thirteenth century Kokpitsuretsu invaded China from Mongolia and formed the Gen dynasty which ruled over the whole eastern part of Asia except Japan (1280 to 1368). The founder of the present Chinese dynasty was a Manchoorian. Both, however, were of Mongolian extraction, and well kept up the fame of the Tartars for boldness and general daring. Since their times the Tartars have fully maintained their title of being the most warlike tribe in Asia.

Therefore if Russia were allied with the Mongol Tartars she would be able at least to reach the Yellow Sea, even if she were not able to do China serious harm.

Her best policy would be to extend the Omsk-Tomsk Railway[9] to Kiakhta viâ Kansk 40and Irkutsk, and from there to Ust Strelka and Blagovestchensk through Nertchinsk; a branch also might be thrown off from Kiakhta to Oorga, in the direction of Pekin, the metropolis of China; two branches might also be constructed from Nertchinsk—(a) to Isitsikar, through the western boundary of Manchooria, with the ultimate object of reaching some convenient harbour on the Gulf of Leaotong, or the Yellow Sea, viâ Kirin[10] and Moukden—(b) to L. Kulon through the northern boundary of Mongolia in the direction of Pekin; and to construct a branch line from Blagovestchensk to Isitsikar viâ Merghen.

By these means Russia would not only open sources of untold wealth in Siberia, but also secure a larger field of commerce in Manchooria and Mongolia than she has done by the opening of the Trans-Caspian Railway. 41It is clear that there would be more political and strategical advantages in this quarter, than in Central Asia. Should Russia ever be able to get possession of a seaport in the Gulf of Leaotong or in the Yellow Sea, she would deal a heavy blow against the Anglo-Chinese alliance, and ultimately frustrate, to a great extent, British aspirations in the East.

Russia, however, has worked in quite a different way, and is strengthening the defences at Vladivostock both in military and naval forces, and is acting towards the Corea in a gradually-increasing aggressive spirit, which had succeeded in Europe and Central Asia previously for more than one hundred and fifty years.

Lord Derby well described the Russian tactics in the following speech:—“It has never been preceded by storm, but by sap and mine. The first process has been invariably that of fomenting discontent and dissatisfaction amongst the subjects of subordinate states, then proffering mediation, then offering assistance to the weaker party, then declaring the independence of that 42party, then placing that independence under the protection of Russia, and finally, from protection proceeding to the incorporation, one by one, of those states into the gigantic body of the Russian Empire.”

But Russia should remember that a Russian annexation of Corea—“the Turkey” in Asia—would necessitate an alliance of England, China, and Japan, who all possess common interests in the Pacific and Yellow Sea; also that it might cause a second Crimean war in the Pacific instead of on the Black Sea.

Japan was comparatively unknown until Commodore Perry, of the United States, introduced her to European society in 1854. Since that date a “wonderful metamorphosis” has taken place in every branch of civilization.

The total area of Japan is about 148,742 square miles, or nearly a quarter greater than that of the United Kingdom, while the population is about 38,000,000. The climate is very healthy, while the natural resources are many.

Japanese patriotism is very keen, and their 43love of country stands before everything; they are brave, honest, and open-minded. The following facts bear out the above statement: In 1281 the “Armada of Mongol Tartars” reached the Japanese shores, only to be easily repulsed in Kiushiu by the Japanese fleet. Hideyoshi in the sixteenth century conquered the Corea, and General Saigo defeated and subjugated eighteen of the resident chiefs with all their followers in Formosa (1873).

One of the great traits in the Japanese character is that they never hesitate to adopt new systems and laws if they consider them beneficial for their country. Feudalism was abolished in 1871 without bloodshed. In 1879 city and prefectural assemblies were created, based on the principle of the election. The new Constitution was promulgated in 1889, and new Houses of Peers and Commons will be opened this year (1890).

Railways are rapidly growing, over 1,000 miles already having been laid, and soon the whole country will be opened out by the “iron horse.” All the principal towns are 44connected by telegraph[11] with one another and with Europe. The postal system[12] is carried out on English lines, while the police force is strong and very efficient. The standing army consists of about forty-three thousand men, which, however, could be quickly increased to two hundred thousand in case of war, all trained and equipped under the European system. The navy consists of thirty-two ships, including several protected cruisers, and in this or next year it will be reinforced by three more ironclads and five or six gunboats. The Japanese navy is organized chiefly upon the pattern of the English navy.

The Pacific & Its Sea Routes.

47The geographical situation and condition of Japan are very favourable to her future prosperity, both commercially and from a manufacturing point of view. Look at a map of the world—the country lies between two of the largest commercial nations, viz., the United States and China, the former[13] being England’s great commercial rival of the present day, while the latter offers a large field for trade and commerce.

If M. de Lesseps’ scheme of the Panama Canal should happen to be completed on his Suez Canal line, undoubtedly the Pacific Ocean would be revolutionized in every way. Up to now the waterway from Europe to the Pacific has been from the West, viz., viâ the Suez Canal, or the Cape of Good Hope.

But in case of the “gate of the Pacific” being open, then European goods could be transported in another direction, and the nations in the Pacific would have two sea routes. Japan would be placed practically in the centre of three large markets—Europe, Asia, and America—and its commercial prosperity would be ensured.

48If, however, the Panama scheme failed from one cause or another there would be another sea route.[14]

49In 1887 the American Senate sanctioned the creation of a company for the construction of a maritime canal across Nicaragua,[15] 50and the actual work was begun in October, 1889.

The President of the country, which has a 51surplus of 57,000,000 dollars, alluding to the commencement of the Nicaragua Canal said in his message to the Senate:—

“This Government is ready to promote 52every proper requirement for the adjustment of all questions presenting obstacles to its completion.” It is therefore pretty sure, sooner or later, to be completed, and would take the place of the Panama Canal and give the same advantages with regard to the Pacific and Japan.

“In the school of Carl Ritter,”[16] said Professor Seeley, “much has been said of three stages of civilization determined by geographical conditions—the potamic, which clings to rivers; the thalassic, which grows up around inland seas; and lastly, the oceanic.” He also traced the movements of the centre of commerce and intelligence in Europe, and at last found out why England had attained her present greatness.

Without doubt, since the discovery of a new world the whole world has become the oceanic.

But the discoveries of Watt and Stephenson, seem to me to have added another stage to general civilization, viz., the railway; and 53it seems also to me that we might call the present era “the railway-oceanic.”

The Canadian Pacific Railway scheme was completed in 1887. It has a total length of at least 3,000 miles, starting from Quebec and finishing at Vancouver’s Island on the Pacific. Its marvellous success will also considerably change the general tenor of the Pacific even more than the Panama or Nicaragua scheme will do. An express train can cross in five days, while the voyage from Vancouver to Yokohama in Japan, would only occupy twelve days steaming at the rate of fourteen or fifteen knots an hour. From England the whole journey to Shanghai and Hong Kong by this route would take only thirty-four or thirty-five days, and Australia now has direct communication with the mother country through a sister colony.

Last of all, Japan would have much better communication with the European markets generally than is possible at the present time, if the English proposed[17] mail steamers 54should run, and it is said that the Canadian Pacific route would bring Japan within twenty-six or twenty-seven days’ reach of England.

On the other hand, if the Russian Siberian Railway scheme should be carried out to the Pacific at Vladivostock, it would open a very large field of trade and commerce with inland Siberia to Japan. It would be still more so if the Chinese railways were extended so as to open the entire empire.[18]

Japan has not only a splendid future before her with regard to commercial greatness, but has every chance of rising to the head of manufacturing nations. In the latter respect she has advantages over Vancouver’s Island and New South Wales, her rivals on the Pacific. She is known to possess valuable 55mineral resources, having good coal mines at Kiushiu and Hokkukaido. The climate of Japan varies in different localities, but on the whole is exceedingly healthy. Consisting as the country does of numerous islands she has many good harbours and trading ports. Wages are low though they might rise if a corresponding increase of labour is required. The credit system is fairly well carried out[19] and is growing day by day. There are about four hundred banks, including the Bank of Japan; and the medium of exchange has a regular standard. The principal exports are silk, tea, coal, and rice. Japan is not the producer of raw goods for manufacturing purposes, but simply works them up. Her area is not in comparison 56with the commercial greatness which she will attain in the future. She may import raw goods from America, Australia, and the Asiatic countries, in the same way that England does. Her position enables her also to obtain wool from Australia and California, also cotton from China, Manchooria, India, and Queensland. All these imports are worked up into different manufacturing goods. She has an advantage here over England, for she has not so far to send her manufactured goods, and does not need, like England, to send them all round the world.

Thus we see Japan has ample scope from a commercial point of view, and has plenty of friendly countries close at home for the production of her raw material, and has great advantages in sea routes to America and Australia.

The Japanese are born sailors, being islanders.

There are several large steamship companies[20] whose ships are continually 57plying along her own shores[21] and also to the mainland of China, and one company contemplates shortly opening communication with North and South America. It has often puzzled me why Japan does not hold closer relations with Australia, especially as Australia is becoming one of her most important neighbours in commerce. I can certainly predict that if this suggestion comes to pass, that together they will in the future hold the key of the Pacific trade.

Australia and her near colonies have already begun to play an important part in the affairs of the Pacific; and why should she not, considering their natural wealth and general progress? European Powers have begun to take great interest, both commercially and diplomatically, in these colonies. England, France, Spain, and Holland long ago saw the advantage of having secured coaling stations in the Pacific, and England and France have always taken great care in selecting posts in the immediate vicinity of 58the sea route between America and Australia; and since the working of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Panama Canal, they have begun to annex those islands which lie near the route from Panama to the Australian colonies, and from the latter to Vancouver. The French occupation of Tahiti and the Rapa (both containing good harbours) in 1880 was with the distinct object of controlling the sea route from Panama to Sydney, Brisbane, and Auckland. England also began to fortify Jamaica in 1887, and she is now casting her eyes on Raratonga. The dispute regarding the New Hebrides and the Samoan Conference[22] were simply for the protection of the Vancouvan-Australian-San-Franciscan sea-ways. England has lately annexed the Ellice Islands and undoubtedly will shortly occupy the Gilbert and Charlotte Islands.

59Germany also has been considering the Asiatic-Australian routes, foreseeing that the whole Pacific question rests on that basis. In 1884 she annexed New Guinea, and the Bismarckian policy proved a severe blow to the British power in the North and West Pacific. There are three great sea routes from New South Wales to Hong Kong and other parts of the North Pacific; one travels eastward of the Solomon Islands and New Caledonia (6,000 miles) and the other two westward of the above-mentioned islands (5,500 and 5,000 miles).

The German occupation of New Guinea actually resulted in her having the entire control of these three important sea routes. The English possession of the Treasury Islands, the depôt made there, and of the Louisiade Archipelago is certainly not strong enough to protect these routes, though they are very important for the defence of the Australian colonies. Even the trade route from Vancouver’s Island to Brisbane has to a certain extent been endangered. It would be policy on England’s part to annex the 60Solomon Islands if she means to regain the prestige which she has lost owing to the Germanic policy of annexation in the Pacific.

In order to firmly establish her power in this quarter, Germany, in 1885, raised a quarrel with Spain concerning the sovereignty of the Caroline and Pelew Islands, but this quarrel was composed by the mediation of the Pope.

Frederick the Great “preferred regiments, as a ship cost as much as a regiment.” Bismarck preferred “the Greater Germany,” and his policy was “the German trade with the German flag” (i.e., the German flag shall go where German trade has already established a footing). This policy proved very successful, not only in the West Pacific, but also in the North Pacific and the eastern coast of Africa. Germany now is the chief colonizing rival of England.

In 1883 Mr. Chester annexed all the parts of New Guinea with the adjacent islands lying between 141 deg. and 155 deg. of E. long. Lord Derby; however, annulled this 61annexation, regarding it as an unfriendly act, and he also assured the Colonial Government that “Her Majesty’s Government are confident that no foreign power contemplates interference in New Guinea.” This occurred in May, 1884. But this prognostication did not prove true, for in November of the same year Germany occupied New Guinea.

This caused much public indignation in the English colonies against the Home Government, and the public of England recognized that the reasons and complaints of the Australian Colonies were right and just.

The movement of Imperial Federation sprang up in England, the chief object of which was “a closer association between the Colonies and Great Britain and Ireland for common national purposes such as colonial and foreign policy, defence and trade.” The result of this was the Colonial Conference in 1887; and Lord Salisbury, offering a hearty welcome to the Colonial delegates, said: “I do not recommend you to indulge in schemes of Constitution making;” but also said: “It will be the parent of a long progeniture, 62and distant councils of the empire may, in some far-off time, look back to the meeting in this room as the root from which their greatness and beneficence sprang.”

The following subjects were submitted for discussion: (1) The local defence of ports other than Imperial coaling stations; (2) the naval defence of the Australian Colonies; (3) measures of precaution in relation to the defences of colonial ports; (4) various questions in connection with the military aspects of telegraph cables, their necessity for purpose of war, and their protection; (5) questions relating to the employment and training of local or native troops to serve as garrisons of works of defence; and, lastly (6), the promotion of commercial and social relations by the development of our postal and telegraphic communication.

Thus, by means of this Conference, the military federation of the British Empire was established. By its efforts the English squadron in the China Sea and in the Australian seas are more closely connected together than they have been before, and, if 63needed, the English forces in the North Pacific would be reinforced by Australian troops. We saw an instance of this in the late Egyptian campaign.

One more question remains to be ventilated, viz., whether England is able to secure absolute power in the North Pacific with the naval and military forces she has at her command there, using Hong Kong as the centre of war preparations.

I answer in the negative. It could be maintained only by an occupier of the Island of Formosa, the “Malta” of the North Pacific, which lies between the North China Sea and the South China Sea. Its area is estimated at 14,978 square miles. It has a healthy climate, tempered by the influence of the sea and its mountains. Coal is to be found in considerable quantities, although not of the best quality. Its natural products are plentiful, such as sugar, tea, and rice. It possesses several good harbours, one of which, Tam-sui, or Howei, is surrounded by hills upwards of 2,000 feet high, and has a depth of 3½ fathoms with a bar of 7½ feet.

64From this island, with a good navy, any power almost might be exerted over the North and South China Seas, and over the Pacific highways from Hong Kong to Australia, Panama, Nicaragua, San Francisco, Vancouver, Japan, Shanghai. All these are in fairly close proximity to Formosa, and the Shanghai route to Hong Kong actually runs between the island and the China mainland.

There remain still two or three more facts which must not be neglected in order to obtain a fair view of this important question.

(a) It is a fine post for any offensive attack upon China, and also a stronghold for an attack upon the British power in the Pacific. If fortified and defended by a navy from any other power, Formosa would prove a great rival to Hong Kong, which would lose at least half of its importance, commercially and strategically, and which has already been somewhat weakened by the French occupation of Cochin China, in 1882.[23]

65(b) In case of Asiatic complications, England would naturally expect reinforcements from Australia, and from the mother country by the Canadian Pacific Railway, but after they arrive at Vancouver, and are on transport, they will be at the mercy either of Japan or the occupier, whoever it may be, of Formosa. Even the Bismarckian policy re New Guinea would be broken down, i.e., all commercial and strategical communication between Hong Kong and Australia would be seriously incommoded by the occupation of Formosa.

(c) If China herself occupied Formosa thoroughly,[24] and allied with Japan who 66occupies the Loo Choo Islands, they would be impregnable in the sea above 20° of N. lat.

Again, if the occupier of the Loo Choo Islands[25] also occupied Formosa on a military basis, she again would have nearly absolute control of the North Pacific. England would be supreme if she held both Hong Kong and Formosa; Germany if the holder would not only complete the Bismarckian policy in New Guinea, but would start a new Germanic policy in the North Pacific.

Thus we see that Japan, China, England, and Germany, might become important actors in the China Sea, while Russia and China would be actors behind the scenes in Manchooria and Mongolia.

The whole result of a historical study of the foreign policy of England and Russia tells us that Russia has increased her influence by 67annexing and conquering in every[26] direction of the compass with Moscow as the centre of the Empire. Peter the Great started in the direction of the Baltic, i.e., north-west; Catherine II. towards the Crimea and Poland in a south and westerly direction; Alexander I. confined his attention to the Balkans and Caucasus, while Nicholas improved on the same directions, and marched into Central Asia, and since 1858 the Russian attention has been turned on the East, i.e., the Pacific.

England, on the other hand, has added to her fame by establishing the following naval and coaling stations along the great highways of trade:—

Heligoland in the North Sea, the Channel Islands, Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus, Perim, Aden, Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong and Labuan; the Accession Islands, St. Helena, 68and the Cape of Good Hope, in Africa; the Bermuda Islands, Halifax, the West Indies, especially Jamaica, and the Falkland Islands in America, besides many important islands in the South and West Pacific.

By means of these, in the present days of steam, she has been able to maintain her place as the Queen of the Maritime World—a position superior to Russia, although the latter country is lord of one-seventh of the globe.

With such great rivals, we can surely predict that at some future time Russia will work her way into Manchooria and Mongolia to the Yellow Sea and attack the North Pacific. “Everything is obtained by pains,” said Peter the Great, in 1722; “even India was not easily found after the long journey round the Cape of Good Hope.”[27] To this Soimonf, who afterwards devoted himself for seventeen years to the exploration of Siberia, and was its governor, said that “Russia had a much nearer road to India, and explained the water system of 69Siberia, how easily and with how little land carriage goods could be sent from Russia to the Pacific and then by ships to India.” Peter replied, “It is a long distance and of no use yet awhile.” But in the present days of telegraphy and railroads it is not a great distance at all.

England will without doubt occupy Formosa in order to uphold her power in the same quarter. The result it would be almost impossible to foretell. But this fact remains a certainty that will one day come to pass, that England and Russia will at some future period fight for supremacy in the North Pacific. Japan lies between the future combatants!

The Spanish Empire, its power, and its decline—Commercial rivalry of England and Holland—The ascendency of France; threatened by the Grand Alliance—The Spanish succession and the Bourbon league—England’s connection with the war of the Austrian succession—The Seven Year’ War—Revival of the Anglo-Bourbon struggle in the American and Napoleonic wars.

Charles V. of Spain in the height of his power reigned over almost the whole of Western Europe. Besides being King of Spain he was Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, and Lord of Spanish-America. “The Emperor,” said Sir William Cecil, “is aiming at the sovereignty of Europe which cannot be obtained without the suppression 74of the reformed religion, and unless he crushes the English nation he cannot crush the Reformation.” Perceiving this important fact, Charles directed his attention to England, and offered the hand of his son Philip to Mary of England who was anxious to bring back the Catholic Faith into England.

Their marriage took place in 1554, and proved a great help towards re-establishing the Papal supremacy in England, besides making Spain and England strong political allies.

Charles V. abdicated in 1555 and spent the rest of his life in seclusion at San Yusti, and the great part of his dominions, viz., the Colonies, Italy, and the Netherlands descended to his son, Philip II., who was by his marriage with Mary nominal King of England.

On the childless death of Mary the English crown descended to Elizabeth in 1558. Philip thereupon offered marriage to her, but the virgin queen wisely declined. England was by this refusal emancipated from Papal interference and the tyrannies of Philip, and Elizabeth resolved to carry out her 75religious and political views independently. Her doctrinal[28] reform and foreign policy naturally made Spain her bitter enemy.

In the Netherlands Philip’s general conduct raised the inhabitants to revolt, and under the leadership of the Prince of Orange they soon obtained a strong position, and eventually, in 1648, after a long and protracted struggle, their independence was recognized.

Thus the two great sea powers of Philip’s age were both common enemies against the arrogance of Spain and were consequently united.

In France a similar religious struggle, fierce and bitter, was raging. Civil war was rampant and atrocities numerous, the massacre on St. Bartholomew’s Day being a notable example. In 1585 the Catholic party formed the “League,” whose main objects were the annihilation of the reformed party, and the 76elevation of the Guises to the French throne through an alliance with Philip II. of Spain. Its manifesto stated that French subjects were not bound to recognize a prince who was not a Catholic. The death of Henri III. made the situation worse, for two candidates for the French throne appeared,—Henry of Navarre, who was supported by the Huguenots and the Cardinal of Bourbon, whom the Leaguers followed, while Philip II. laid claim to the throne on behalf of his daughter by his third marriage with Elizabeth of Valois, sister of Henri III. Hence, after the accession of the House of Bourbon, a coalition of England, Holland, and France was formed against Philip II. of Spain, and from 1600 to 1660 the European coalition was England, Holland, and France, versus the Spanish Empire.

In the meantime Spain had acquired Portugal in 1580, by which both countries became one state, and Philip II. sovereign of the whole oceanic world. Portugal for sixty years remained a dependency of Spain, and then the Spanish Empire had attained to vast 77and unwieldy dimensions. She could no longer defend her colonies from foreign invasion and plunder. The Dutch established themselves wherever they pleased, and plundered and occupied most of the Portuguese possessions. It has been truly said that the Colonial Empire of Holland was founded at the expense first of Portugal, and ultimately of Spain.[29]

England at this time was rapidly rising into the front rank of European nations. In 1588 the “Invincible Armada” appeared in the English Channel and was annihilated and disgraced. This was the introduction to that English colonial greatness on which the sun never sets.

78Then came the beginning of the fall of the Spanish Empire. In 1640 Cardinal Richelieu, the ablest French statesman, provoked Portugal to rebel, his object being the aggrandizement of his own country abroad. The revolt proved successful under John of Braganza, and again Portugal posed as a nation. This proved a deadly blow to Spanish power, and Cromwell finally crushed her power by his invincible foreign policy. He seized Jamaica while Charles II. acquired Bombay.

This gradual decay of Spain had a corresponding inspiriting effect on England and Holland. Both became commercial and colonial rivals one with another. Ashley Cooper said, “Holland is our great rival in the ocean and in the New World. Let us destroy her though she be a Protestant Power; let us destroy her with the help of a Catholic Power.”[30]

79The great naval victories of England and the Navigation Acts, 1651, 1663, and 1672,[31] crushed the Dutch carrying trade and navy, and England now began to assume the supremacy of the whole oceanic world which has from that time never departed from her.

However, France gradually filled the breach left by Holland and Spain, and became a great naval rival of England. The strength of all the nations round her had been considerably weakened by the Thirty Years’ War, while her commercial and manufacturing progress soon made her one of the strongest European Powers.

From 1660 to 1672 may be regarded as the 80period of the great national rise of France. Louis XIV. laid claim to Belgium and Burgundy in 1665 on the death of Philip IV. of Spain, and in order to enforce his claim his army entered Flanders and Burgundy, but owing to the pressure of the Triple Alliance[32] the unfavourable Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle was concluded.

However, later on Louis broke the Triple Alliance and secured the valuable assistance of England and Spain, and with the assistance of the former nation he made a concerted attack upon Holland. France had now reached the topmost rung of the ladder between 1678 and 1688.

About this period the struggle against absolute monarchy was nearly concluded in England, and was further strengthened in 1689 by the Declaration of Rights. The English crown was offered to William of Orange and Mary and accepted by them. Already this personal union had caused an alliance to be formed between England and Holland, at that time the two great Protestant 81Powers of Europe, against France the great Roman Catholic upholder.

If France had remained quiet during the above-mentioned internal discord, England would have been unable to form the “Grand Alliance.” Thus Louis committed a great error in assuming an offensive attitude against the two Protestant Powers. This caused a coalition to be formed against him of England, Holland, Spain, and Austria.

This new system in Europe existed from 1688 to 1700. Then new complications arose, for Charles II., King of Spain, died childless, and the extinction of the Spanish House of Hapsburg seemed to be near at hand. The question of a Spanish successor now occupied the minds of the European cabinets after the Peace of Ryswick.

There were three claimants: Louis XIV., Leopold I., and the Electoral Prince of Bavaria. The dominions of the Spanish sovereign were still extensive, viz., Spain itself, the Milan territory, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spanish-America. To unite the Spanish monarchy with that of France or 82Austria, would destroy the European balance of power. Consequently a general council with regard to the succession took place, and the First Partition Treaty was drawn up. Charles II. of Spain, however, made a will, appointing Louis’ grandson, Philip of Anjou, as his successor, so Louis XIV. determined to uphold the will rather than the treaty.

In 1701 the Duke of Anjou was peacefully proclaimed king as Philip V. Louis XIV. on hearing this boasted that “Il n’y a plus de Pyrenees.” This Bourbon succession in Spain changed the European system, and henceforth we have England, Holland, and Austria, as opposed to France and Spain.

The Duke of Marlborough, who combined the qualities of a general, diplomatist, and minister skilfully together, was the leader of the Second Grand Alliance against the Houses of Bourbon.

The inability of France to defend the Spanish Empire, followed by the War of the Spanish Succession, paved the way for the Peace of Utrecht (1713). By this treaty the Bourbons lost Italy and the Low Countries, but 83retained the throne of Spain, thus still leaving that country open to the influence of France. Hence the permanent alliance of France and Spain was formed in the eighteenth century.

Meanwhile Holland had fallen into decay through internal exhaustion caused by her struggle against foreign enemies; thus England had taken her place as the great maritime and colonial power. Thus we see the struggle between England and France (supported by Spain) for the oceanic world in the eighteenth century.

By the Utrecht Treaty, France ceded to England Newfoundland, Arcadia, and Hudson’s Bay territory, while Spain also ceded Gibraltar, the Minorca Island, and the Asiento, the occupation of the two former making another bitter enemy to England.

Spain had already a hatred of English trade with her colonies in America, so that only a single English ship was conceded by the Treaty of Utrecht, giving thereby only a limited right of trade in South America to England. But this was evaded by a vast 84system of smuggling which arose and proved a constant source of dispute between England and Spanish revenue officers and rendered peace almost impossible.

In 1733 the first secret pacte de famille had been concluded between France and Spain for the ruin of English maritime trade. The American coast was keenly watched, and the result was “The Jenkins’ Ear War,” 1739.

Charles VI., having no son, established an order of succession by the Pragmatic Sanction, signed by nearly all the European Powers, by which his daughter, Maria Theresa, was to succeed to all the hereditary dominions of Hapsburg. But on his death two claimants appeared on the scene—the Elector of Bavaria and Philip V. of Spain.

Walpole did his best to form a Grand Alliance between Hanover and Prussia, also between England, Holland, and Austria. However, Frederick’s claim to Silesia being refused by Austria, the French and Prussian armies crossed the Rhine, 1741. Thus France began the War of the Austrian Succession. In 1743 the Battle of Dettingen 85was fought between England and France, the former fighting on behalf of Maria Theresa, and as yet feeling her way carefully before she was brought into direct conflict with the latter Power.

After the Treaty of Worms the question at issue was changed to that of naval supremacy, and the War of the Austrian Succession fell into the background.

In 1744, after an attempted invasion of England on behalf of the Pretender, France declared war against both England and Austria. This was bad policy, for if she had fought against one enemy at a time she would have stood a far better chance of crushing England’s power. Professor Seeley says, “If we compare together those seven wars between 1688 and 1815, we shall be struck with the fact that most of them were double wars, and that there is one aspect between France and England, another between France and Germany.... It is France,” says he, “that suffers by it.”[33]

England and Holland firmly allied with 86one another, and German troops were subsidized by England.

Against this alliance the second secret pacte de famille was founded.

Battles were fought on all sides, by land and sea, both in Europe and America. In spite of French successes at Fontenoy and Laufeldt, she was severely defeated both on the sea and in America. Louisburg fell, Cape Breton Island was captured, and many other losses sustained. At length the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle brought a nominal peace into the oceanic world, in 1748.

In 1756 this nominal peace came to an end, and the Seven Years’ War[34] was fought out, both in the Old and New Worlds; Pitt 87the elder then appeared as a great actor on England’s side, and used his great talents to crush down the French Colonial Empire, and to obtain for his country the sole mastery of the oceanic world.

He was essentially a war Minister: “The war was vigorously carried on throughout 1758 in every part of the globe where French could be found, and in 1759 Pitt’s energy and his tact in choosing men everywhere were rewarded by the extraordinary success by land and sea.”[35]

The glorious death of Wolfe on the Heights of Abraham was followed by the surrender of Montreal and the brilliant victory of Plassey in India by Clive over the French. Pitt assured his countrymen that “they should not be losers” (in giving pecuniary assistance to Frederick the Great) “and that he would conquer America for them in Germany.”

88This proved true. In 1762 the fall of the French Colonial Empire occurred, and England obtained Canada and India.

This wonderful statesman[36] undoubtedly made England the first country in the world.

“A height of prosperity and glory unknown to any former age,”[37] was reached in England during the administration of Chatham. Now the tide of fortune began to run against England.

The passing of the famous Stamp Act, and many other “repeated injuries and usurpations,”[38] made the relations between England 89and the American Colonies virtually hostile. At last the Colonies revolted, and it gave Spain and France the long-wished-for opportunity of taking revenge upon England. France and Spain formed the third pacte de famille, and assisted the insurgent Colonies, and the independence of the United States was acknowledged in 1783.

In 1789 the French Revolution broke out, and the first effect felt in England was the breaking-up of the Whig party.

In 1792 Austria and Prussia invaded France in order to put down the Republicans in that country. In retaliation France determined to declare war against all countries governed by kings, which principle she established by the “Decree of November 19th,” and in 1793 she declared war against England and Holland.

The younger Pitt had now come to the front. He was an economist and advocated a peace policy. In the spring of 1792 he reduced the navy and confidently looked forward to at least fifteen years of peace. There is no doubt that if France had 90remained quiet his hopes would have proved correct, and that the west bank of the Rhine would now be under French rule.

But France was eager to revenge past injuries put upon her by England; and, as if in answer to her desires, the second Alexander the Great appeared in Napoleon, and began “alarming the Old World with his dazzling schemes of aggrandizement.”

Against England his whole energies were directed. “Let us be masters,” said he, “of the Channel for six hours and we are masters of the world.”[39] In 1798, he captured Malta, occupied Egypt, and undertook a campaign in Syria, as a furtherance to his desires of obtaining India, at the same time retaining his ideas with regard to 91England. Malta to Egypt, Egypt to India, India to England.

In 1802 a momentary universal peace occurred. But Napoleon could not rest, his ambition spurred him on. His anger was again kindled by the English retention of Malta, after his defeat in Egypt, and he saw if Malta was wrested from him his lofty schemes would be undermined. In 1803 he again declared war against England and Holland. He arrested all the English residents in France between the ages of sixteen and sixty and kept them confined.

The younger Pitt was just the statesman fit to cope with him, and frustrate his aims. He aimed at a European coalition,[40] by which all threatening dangers from the overwhelming greatness of one nation might be averted.

92On October 21, 1805, the glorious victory at Trafalgar, the outcome and consummation of Nelson’s inspiring command, “England expects every man to do his duty,” broke the naval power of France. And yet this was followed by the capitulation of Ulm, the defeat at Austerlitz, and the subsequent Treaty of Presburg, which broke up the coalition of England, Russia, and Austria, and seriously affected Pitt’s health thereby. Truly, “Austerlitz killed Pitt.”[41]

At once Napoleon proceeded to turn the whole forces he had on the Continent against England, especially after the Peace of Tilsit, (1807). He first attacked England with the “Continental System,” i.e., he prohibited all direct and indirect European trade with the 93British Isles. This he confirmed by the Decrees of Berlin (1806) and Milan (1807).

In 1812 he invaded Russia and entered the famous city with the cry of “Moscow! Moscow!” Even at that moment, however, his real aim of attack was England, across the Channel.

England was ever uppermost in his thoughts. “He conquers Germany, but why? Because Austria and Russia, subsidized by England, march against him while he is brooding at Boulogne over the conquest of England. When Prussia was conquered, what was his first thought? That now he has a new weapon against England, since he can impose the Continental System upon all Europe. Why does he occupy Spain and Portugal? It is because they are maritime countries, with fleets and colonies that may be used against England.”[42]

Napoleon was driven out of Moscow by fire, and his return march turned literally into a defeat, while his plan of a direct attack in 94England, through Belgium, three years after, was frustrated at Waterloo.

Thus the scene of the great Napoleonic drama in English history closed on June 18, 1815.

Peter the Great, and establishment of Russian power on the Baltic—Consequent collision with the Northern States and the Maritime Powers—Catherine II. and Poland—First partition—Russia reaches the Black Sea—Russo-Austrian alliance against Turkey opposed by Pitt—Second and third partitions of Poland—Rise of Prussia—Alexander I. and the conquest of Turkey—Treaty of Tilsit—Peace of Bucharest—Congress of Vienna—French influence in the East destroyed.

The Russian territory now extends over one-seventh of the globe, and Alexander III. rules over more than 100,000,000 souls. Russia is a powerful political rival not only of England alone, but of all the European Powers.[43]

96However, on Peter the Great’s accession to the throne, his country covered an area of only 265,000 square miles, and no harbours were to be found either on the Baltic or the Black Sea. This was felt to be a serious obstacle for a rising Power. Peter himself said, in the preface to the “Maritime Regulations”: “For some years I had the fill of my desires on Lake Pereyaslavl, but finally it got too narrow for me. I then went to the Kubensky Lake, but that was too shallow. I then decided to see the open sea and began often to beg the permission of my mother to go to Archangel.”[44] His first and great object was to establish harbours on the Baltic or the Black Sea.

The Turks were the preliminary object of his attack. The first campaign against Azof (1695) proved a failure, but a new campaign was started again in 1696, and the Czar’s “bravery and his genius” were rewarded with a great victory over Azof. Here begins the modern history of Russia.

The Expansion of Russia in Europe.

99Immediately after the capture of Azof Peter determined to carry out his design of creating a large fleet on the Black Sea. For the purpose, “no sooner had the festivities in Moscow ended than, at a general council of the boyars, it was decided to send 3,000 families of peasants and 3,000 streltsi and soldiers to populate the empty town of Azof and firmly to establish the Russian power at the mouth of the Don. At a second council Peter stated the absolute necessity for a large fleet, and apparently with such convincing arguments, that the assembly decided that one should be built. Both civilians and clergy were called upon for sacrifices.”[45]

Peter also sent fifty men of the highest families in Russia to Italy, Holland, and England, to study the art of ship-building. Peter himself visited Holland and England that he might learn ship-building. “One thing, however, he could not learn there, and 100that was the construction of galleys and galliots, such as were used in the Mediterranean, and would be serviceable in the Bosphorus and on the coast of the Crimea. For this he desired to go to Venice.”[46] This clearly shows us that Peter had conceived the idea of establishing a strong navy on the Black Sea.

The revolt of the streltsi recalled him home; however, he found no difficulty in suppressing the insurrection.

After this, he sent an envoy to the Ottoman Empire to obtain permission for the Russian fleet to enter the Black Sea, to which the Porte replied: “The Black Sea and all its coasts are ruled by the Sultan alone. They have never been in the possession of any other Power, and since the Turks have gained sovereignty over this sea, from time immemorial no foreign ship has ever sailed its water, nor ever will sail them.”

Meanwhile Charles XII., King of Sweden, began to assume an attitude of hostility to Peter, and the Battle of Narva was fought, 101where Peter was miserably defeated. After this war, Charles made Russia the great object of his attack instead of Poland. He said, “I will treat with the Czar at Moscow.” Peter replied, “My brother Charles wishes to play the part of Alexander, but he will not find me Darius.” The Battle of Pultawa (1709) soon decided Peter’s superiority, and the Peace of Nystadt (1721) added the Baltic provinces and a number of islands in the Baltic to Russia.

In 1703 “a great window for Russia to look out at Europe”—so Count Algaratti called St. Petersburg—was made by Peter on the marshes of the Neva. This step firmly established Russian power on the Baltic.

But to establish Russian power on the Baltic at all was as great a mistake as ever has been committed by so shrewd a statesman as Peter the Great. The predominance of Russia in the Baltic with her strong navy threatened the interest of the commerce and carrying-trade of the English and Dutch. Hence it was natural enough that England and Holland, two great maritime powers, 102should have joined to protect their interest in the Baltic as well as the integrity of Sweden against Russian aggression. In the case of the Northern War, England had formed an alliance with Sweden and sent her fleet to the Baltic under command of Admiral Norris to prevent the Russian sway on those waters.

Had Peter thought less of the importance of the Baltic, and concentrated his energies on obtaining a sure foothold in the Crimea, Constantinople would now be a Russian southern capital.

The Seven Years’ War had been brought to a finish when Catherine II. ascended the Russian throne. The next great European complication was brought about by the affairs of Poland.

On the death of Augustus III., Stanislaus Poniatowski was elected King of Poland, and at the request of Prussia and Russia the dissenters, adherents of the Greek Church and the Protestants, received all civil rights.

103In opposition to this a Confederation of Bar was formed in 1768, with the object of dethroning the King. Catherine now began to interfere with Poland on behalf of the Greek Christians, and supported the King with her Russian army. This interference made her practically mistress of Poland. Turkey, an ally of the Confederacy, being alarmed at the growing Russian influence and being urged on by France, declared war upon Russia in order to resist the progress of Catherine in Poland; but this proved disastrous, as she was miserably defeated, both on land and sea, and brought to the verge of ruin. This Russian success alarmed Western Europe, and especially the two neighbouring Christian Powers, Prussia and Austria, each of whom had a special interest in the existence of Poland and Turkey. Catherine would not make peace without acquiring territory as a compensation for her exertions and outlay, while Prussia and Austria would not allow her to do this unless they acquired a certain amount of territory themselves. Hence the First Partition of 104Poland took place, by which the three Powers secured equal aggrandizement, Russia receiving the eastern part of Lithuania as her share.

In 1774 the Treaty of Kutschouk Kainardji was concluded with Turkey, by which the independence of the Mongol Tartars in the Crimea was acknowledged by the Sultan; Russia obtained the right of protection over all the Christian subjects of the Porte within a certain limit, and also the right of free navigation in all Turkish waters for trading vessels. This treaty firmly planted Russia on the northern coasts of the Black Sea.

In 1783 the Crimea was incorporated with Russia, and in 1787 Catherine visited the southern part of Russia as far as Kherson, on the Black Sea. Joseph II. of Austria, on hearing of her approach to his dominions, hastened to meet her, and together they journeyed through the Crimea, the Czarina unfolding to the Emperor both her own plans and those of Potemkin, her favourite, viz., to expel all the Turks from Europe, re-establish the old Empire of Greece, and 105place her younger grandson Constantine on the throne of Constantinople. Joseph fell in with her view, and it was hinted that something like a Western Empire should be also constituted and placed under the Austrian sway. In this way a division of the Ottoman Empire was contemplated between the two countries. This soon aroused the suspicions of Turkey, and war was again declared. But now it was two against one, and the fate of Turkey again seemed sealed.

William Pitt was the first statesman who directly opposed Russia and tendered assistance to Turkey against Russian encroaching power. His foreign policy of opposition to Russia has been followed more or less by generations of English Ministers. The Triple Alliance of England, Prussia, and Holland was formed by Pitt against the “Colossus of the North,” in order to preserve the balance of power in Europe, and the death of Joseph. II., saved Turkey again. Pitt, by means of this Alliance, demanded that a peace be made between Russia and Turkey on the status quo ante bellum, and threatened to 106maintain his demand by arms. The English people, however, cared very little about a Russian invasion of Turkey, while Catherine disregarded Pitt’s threats.

Soon after a peace between Russia and Turkey was concluded at Jassy, by which Turkey ceded Oczakow and the land between the Dnieper, Bug, and Dniester, containing several good harbours, and notably Odessa; the protectorate of Russia over Tiflis and Kartalinia was also recognized.

By the above-mentioned acquisitions she felt certain that very soon Constantinople would be in her hands. However, a nearer, and, in her opinion, a more important matter engaged her attention. In 1792 the new Constitution of Poland was drawn up by Ignaz Potocki, converting the Elective Monarchy into an hereditary one, the House of Saxony supplying a dynasty of kings. The Confederacy of Jargowitz, which was formed in opposition to this new Constitution, called in the help of Russia.

This now seemed to be a grand opportunity for Russia to finally annex Poland, 107because the deaths of Frederick the Great (1786) and Joseph (1790), and the French Revolution, which occupied the attention of all Western Europe, set the Czarina free from her most watchful rivals. A Russian army invaded Poland, and the new Constitution was repealed. Prussian troops also entered Poland under the pretence of suppressing Jacobinism, and Russia again found herself frustrated, and concluded a Second Partition (1793) with Prussia, by which she received Lithuania, Volhynin, and Podolia.

In 1795 the Polish nation rebelled, under the leadership of Xoscruscko, and this led to a Third Partition between Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and the former Power added 181,000 square miles, with 6,000,000 inhabitants, together with Curland, to her already vast dominions.

By this last Partition a road of aggression was open towards Sweden on the north-west, and towards Turkey on the south.

Many combined circumstances led Russia to assume an aggressive policy towards Turkey specially. Sweden, or rather Finland, 108was not of sufficient importance as a prey to the “northern bear”—a warmer climate was also wanted. Catherine had already discovered the mistaken policy of Peter the Great, who had spent all his energy in getting the strongholds of the Baltic in opposition to Charles XII. of Sweden. Russian sway on the Baltic meant a direct opposition from two great sea Powers, viz., England and Holland, whose interests would suffer thereby. A striking proof of the opposition was seen in the case of the Northern War.

The Partition of Poland produced another stray Power in the Baltic, to wit, Prussia.

Previous to the Partition of Poland, Prussia Proper and her dominions, Brandenberg and Silesia, were separated, Poland being between them. The First Partition joined the Prussian kingdom to the main body of the Monarchy; by the Second and Third Partitions Prussia obtained the then South Prussia and East Prussia, thereby uniting all into one compact body.

Thus unconsciously a powerful Russian 109enemy was being formed in the Baltic. Thus Russia had three great enemies—England, Holland, and Prussia, joined by Sweden and Denmark, on the Baltic.

Catherine had already obtained a firm footing on the Black Sea coast, and was confident of her ability to occupy Constantinople and make it a Russian southern capital; the French Revolution attracting the attention of Western Europe, the Ottoman Empire was left at the mercy of Russia. Again a Russian occupation would give a fine prospect of extending Russian authority into Danubian territory, Central Asia, and Asia Minor.

So we may conclude that Catherine’s annexation of Poland was only a step towards attaining her great aim, and gave her time to mature her plans.

At this juncture Catherine died, and was succeeded by Paul (1796). He reversed his mother’s policy by concluding an alliance with Turkey against Napoleon, seeing that the latter’s policy was to destroy the Turkish Empire for the benefit of France. He changed his policy later, however, after his 110unsuccessful campaign in Holland, and threw himself into Napoleon’s arms by establishing an armed neutrality in the north against England.