Title: Sebastopol

Author: graf Leo Tolstoy

Translator: Francis Davis Millet

Release date: February 12, 2020 [eBook #61388]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

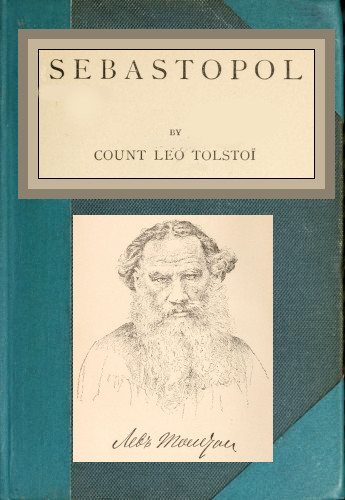

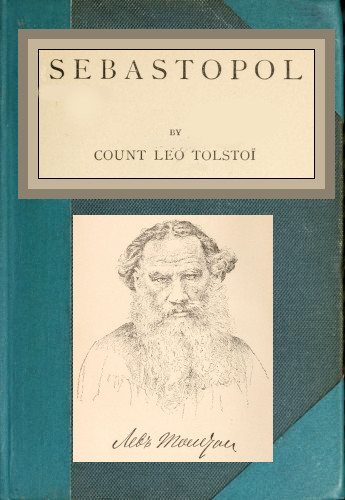

LEO TOLSTOÏ.

SEBASTOPOL.

SEBASTOPOL IN DECEMBER, 1854.

SEBASTOPOL IN MAY, 1855.

SEBASTOPOL IN AUGUST, 1855.

BY

COUNT LEO TOLSTOÏ

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

BY

FRANK D. MILLET

WITH INTRODUCTION BY W. D. HOWELLS

WITH PORTRAIT

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE

1887

Copyright, 1887, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

When I read in the excellent essay of M. Ernest Dupuy that “Count Leo N. Tolstoï was born on the 28th of August, 1828, at Yasnaya Polyana, a village near Inla, in the government of Inla,” I have a sense of lunar remoteness in him. It is as if these geographical expressions were descriptive of localities in the ungazetteered regions of the moon; and yet this far-fetched Russian nobleman is precisely the human being with whom at this moment I find myself in the greatest intimacy; not because I know him, but because I know myself through him; because he has written more faithfully of the life common to all men, the universal life which is the most personal life, than any other author whom I have read. This merit the Russian novelists{6} have each in some degree; Tolstoï has it in pre-eminent degree, and that is why the reading of “Peace and War,” “Anna Karenina,” “My Religion,” “Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth,” “Scenes at the Siege of Sebastopol,” “The Cossacks,” “The Death of Ivan Illitch,” “Katia,” and “Polikouchka,” forms an epoch for thoughtful people. In these books you seem to come face to face with human nature for the first time in fiction. All other fiction at times seems fiction; these alone seem the very truth always.

The facts of Tolstoï’s life, as one gathers them from the essays of M. Dupuy and of M. Melchoir de Voguë, are briefly that he studied Oriental languages and the law at the University of Kazan; then entered the army, served in the Crimean war, resigned at its close; gave himself up to society and literature in St. Petersburg; and finally left the capital for his estates, where he has since lived the life of lowly usefulness which he believes to be the true Christian life. The man whose career was in camps, in{7} courts, and in salons, now makes shoes for peasants, and humbly seeks to instruct them and guide them by the little tales he writes for them in the intervals of his great work of newly translating the gospels. He married the daughter of a German physician of Moscow, and his wife and children share his toils and ideals. Not much more is known of the retirement of this very great man; but I heard that an American traveller who lately passed a day with him found him steadfast in the conviction that withdrew him from society—the conviction that Jesus Christ came into the world to teach men how to live in it, and that He meant literally what He said when He forbade us luxury, war, litigation, unchastity, and hypocrisy. His latest book, “Que Faire,” is a relentlessly searching statement of the facts and reasons which forced this conviction upon him.

It is a sorrowful comment on our Christianity that this frank acceptance of Christ’s message seems eccentric and even mad to the world. But it is the “increasing pur{8}pose” which runs through all Tolstoï’s work from first to last; it is what makes him great above all others who have written fiction. It does not much matter where you begin with him; you feel instantly that the man is mighty, and mighty through his conscience; that he is not trying to surprise or dazzle you with his art, but that he is trying to make you think clearly and feel rightly about vital things with which “art” has often dealt with diabolical indifference or diabolical malevolence.

I do not know how it is with others to whom these books of Tolstoï’s have come, but for my own part I cannot think of them as literature in the artistic sense at all. Some people complain to me, when I praise them, that they are too long, too diffuse, too confused, that the characters’ names are hard to pronounce, and that the life they portray is very sad and not amusing. In the presence of these criticisms I can only say that I find them nothing of the kind, but that each history of Tolstoï’s is as clear, as orderly, as brief, as something I have lived{9} through myself; as for the names, they are necessarily Russian. It is when some one tells me they are “pessimistic” that I really despair. I have always supposed pessimism to be the doctrine of the prevalence of evil, and these books perpetually teach me that the good prevails, and always will prevail whenever men put self aside, and strive simply and humbly to be good. We are all so besotted with dreams and vanities that we have come to think that the right will accomplish itself spectacularly, splendidly; but Tolstoï makes us know that it never can do so. He teaches such of us as will hear him that the Right is the sum of each man’s poor little personal effort to do right, and that the success of this effort means daily, hourly self-renunciation, self-abasement, the sinking of one’s pride in absolute squalor before duty. This is not pleasant; the heroic ideal of righteousness is more picturesque, more attractive; but is this not the truth? Let any one try, and see! I cannot think of any service which imaginative literature has done the race so great as that which Tolstoï{10} has done in his conception of Karenin at that crucial moment when the cruelly outraged man sees that he cannot be good with dignity. This leaves all tricks of fancy, all effects of art, immeasurably behind.

In fact, Tolstoï brings us back in his fiction, as in his life, to the Christ ideal. “Except ye become as little children”—that is what he says in every part of his work; and this work, so incomparably good æsthetically, to my thinking, is still greater ethically. You will not find its lessons put at you, any more than you will those of life. No little traps are sprung for your surprise; no calcium light is thrown upon this climax or that; no virtue or vice is posed for you; but if you have ears to hear or eyes to see, listen and look, and you will have the sense of inexhaustible significance.

I happened to begin with “The Cossacks”—that epic of nature, and of a young man’s sorrowful, wandering desire to get into harmony with the divine scheme of beneficence; then I read “Anna Karenina”—that most tragical history of loss and ruin to brilliancy{11} and loveliness, out of which the good can alone save itself; then I came to “Peace and War,” that great assertion of the sufficiency of common men in all crises, and the insufficiency of heroes; I found some chapters of the “Scenes at the Siege of Sebastopol,” and I read them with a yet keener sense of this truth; “Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth” made me acquainted for the first time in literature with the real heart of the young of our species; “The Death of Ivan Illitch” expressed the horror and the stress of mortality, with its final bliss, and made it a part of Nature as I never had realized it before; “Polikouchka,” slight, broken, almost unconcluded, was perfect and powerful and infinite in its scope of mercy and sympathy.

I know very well that I do not speak of these books in measured terms; I cannot. As yet my sense of obligation to them is so great that I neither can make nor wish to make a close accounting with their author, and I am not disposed to exploit them for the reader’s entertainment. As often as I have tried to do this their æsthetic interest{12} has escaped me. I have been ashamed to tag them with the tattered old adjectives of praise, and I have found myself thinking of them on their ethical side. But they exist increasingly in English and in French, and the best way, the only way, to get a due sense of them is to read them.

W. D. Howells.

{13}

Dawn tinges the horizon above Mount Sapouné; the shadows of the night have left the surface of the sea, which, now dark blue in color, only awaits the first ray of sunshine to sparkle merrily; a cold wind blows from the fog-enveloped bay; there is no snow on the ground, the earth is black, but frost stings the face and cracks underfoot. The quiet of the morning is disturbed only by the incessant murmuring of the waves, and is broken at long intervals by the dull roar of cannon. All is silent on the men-of-war; the hour-glass has just marked the eighth hour. Towards the north the activity of day replaces little by little the tranquillity of night. On this side a detachment of soldiers is going to relieve the guard, and the click of their guns can be heard; a surgeon{16} hurries towards his hospital; a soldier crawls out of his hut, washes his sunburned face with icy water, turns towards the east, and repeats a prayer, making rapid signs of the cross. On that side an enormous, heavy cart with creaking wheels reaches the cemetery where they are going to bury the corpses heaped almost to the top of the vehicle. Approach the harbor and you are disagreeably surprised by a mixture of odors; you smell coal, manure, moisture, meat. There are thousands of different objects: wood, flour, gabions, beef, thrown in heaps here and there; soldiers of different regiments, some provided with guns and with bags, others with neither guns nor bags, crowd together; they smoke, they quarrel, and they bear loads upon the steamer stationed near the plank bridge and ready to sail. Small private boats, filled with all sorts of people—soldiers, sailors, merchants, and women—are constantly arriving and departing. “This way for Grafskaya!” and two or three retired sailors rise in their boats and offer you their services. You choose the nearest one, stride over the half-decomposed body of a black horse lying in the mud two steps from{17} the boat, and seat yourself near the helm. You push off from the shore; all around you the sea sparkles in the morning sun; in front of you an old sailor in an overcoat of camel’s-hair cloth and a lad with blond hair are diligently rowing. You turn your eyes upon the gigantic ships with scratched hulls scattered over the harbor, upon the shallops,—black dots on the sparkling azure of the water—upon the pretty houses of the town, to whose light-colored tones the rising sun gives a rosy tinge, upon the hostile fleet standing like light-houses in the crystalline distance of the sea, and, at last, upon the foaming waves, where play the salt drops which the oars dash into the air. You hear at the same time the regular sound of voices which comes over the water, and the grand roar of the cannonade at Sebastopol, which seems to increase in strength as you listen.

At the thought that you, you also, are in Sebastopol, your whole soul is filled with a sentiment of pride and of valor, and your blood runs quicker in your veins.

“Straight towards the Constantine, your excellency,” says the old sailor, turning{18} around to the direction you are giving to the helm.

“Look! she has still got all her cannons,” remarks the lad with the blond hair as the boat glides along the side of the ship.

“She is quite new, she ought to have them. Korniloff lives on board,” repeats the old man, examining in his turn the man-of-war.

“There! it has burst!” cries the lad, after a long silence, his eyes fixed upon a small white cloud of drifting smoke suddenly appearing in the sky above the south bay, and accompanied by the strident noise of a shell explosion.

“They are firing from the new battery to-day,” adds the sailor, calmly spitting in his hand. “Come along, Nichka; pull away. Let’s pass the shallop.”

And the small boat moves rapidly over the undulating surface of the bay, leaves the heavy shallop behind laden with bags and with soldiers, unskilful rowers who are pulling awkwardly, and at last lands in the middle of a great number of boats moored to the shore in the harbor of Grafskaya. A crowd of soldiers in gray overcoats, sailors{19} in black jackets, and women in motley gowns comes and goes on the quay. Some peasants are selling bread; others, seated beside their samovars, offer to customers warm drink.

Here, on the upper steps of the landing, are strewn about, pell-mell, rusty shot, shell, canister, cast-iron cannon of different calibres; there, farther away, in a great open square, are lying enormous joists, gun-carriages, sleeping soldiers. On one side are wagons, horses, cannon, artillery caissons, stacks of muskets; farther on, soldiers, sailors, officers, women, and children are moving about; carts full of bread, bags, and barrels, a Cossack on horseback, a general in his droschky, are crossing the square. A barricade looms up in the street to the right, and in its embrasures are small cannon, beside which a sailor is sitting quietly smoking his pipe. On the left stands a pretty house, on the pediment of which are scrawled numerals, and above can be seen soldiers and blood-stained stretchers. The dismal traces of a camp in war-time meet the eye everywhere. Your first impression is, doubtless, a disagreeable one; the strange amal{20}gamation of town life with camp life, of an elegant city and a dirty bivouac, strikes you like a hideous incongruity. It seems to you that all, overcome by terror, are acting vacuously; but if you examine the faces of those men who are moving about you, you will think differently. Look well at this soldier of the wagon-train who is leading his bay troitka horses to drink, humming through his teeth, and you shall find that he does not go astray in this confused crowd, which in fact does not exist for him, for he is full of his own business, and will do his duty, whatever it is—will lead his horses to the watering-place or drag a cannon with as much calm and assured indifference as if he were at Toula or at Saransk. You notice the same expression on the face of this officer, with his irreproachable white gloves, who is passing before you, of that sailor who sits on the barricade smoking, of the soldiers who wait with their stretchers at the door of what was lately the Assembly Hall, even upon the face of the young girl who crosses the street, leaping from stone to stone for fear of soiling her pink dress. Yes, a great deception awaits you on your arrival at Se{21}bastopol. In vain you seek to discover upon any face traces of agitation, fright, indeed even enthusiasm, resignation to death, resolution; there is nothing of all that. You see the course of every-day life; see people occupied with their daily toils, so that, in fact, you blame yourself for your exaggerated exaltation, and doubt not only the truth of the opinion you have formed from hearsay about the heroism of the defenders of Sebastopol, but also doubt the accuracy of the description which has been given you on the north side and the sinister sounds which fill the air there. Before doubting, however, go up to a bastion, see the defenders of Sebastopol on the very place of the defence, or rather enter straight into this house at whose door stand the stretcher-bearers. You will see there the heroes of the army, you will see there horrible and heart-rending sights, both sublime and comic, but wonderful and of a soul-elevating nature. Enter this great hall, which before the war was the hall of the Assembly. Scarcely have you opened the door before the odor exhaled from forty or fifty amputations and severe wounds turns you sick. You{22} must not yield to the feeling which keeps you on the threshold of the room, it is an unworthy feeling; go boldly in, and not blush at having come to look at these martyrs. You may approach and speak with them. The wretches like to see a pitying face, to relate their sufferings, and to hear words of charity and sympathy. Passing down the middle between the beds, you look for the face which is the least rigid, the least contracted by pain, and on finding it decide to go near and put a question.

“Where are you wounded?” you hesitatingly ask an old, emaciated soldier, seated on his bed, watching you with a kindly look, and apparently inviting you to approach. You have, I say, put this question hesitatingly, because the sight of the sufferer inspires not only a lively pity, but also a sort of dread of hurting his feelings, joined with a profound respect.

“On the foot,” replies the soldier; and nevertheless you notice by the folds of the blanket that his leg has been cut off above the knee.

“God be praised!” he adds, “I shall be discharged.{23}”

“Were you wounded long since?”

“It is the sixth week, your excellency.”

“Where do you feel badly now?”

“Nowhere only in my calf when it is bad weather; nothing but that.”

“How did it happen?”

“On the fifth bastion, your excellency, in the first bombardment. I had just sighted the cannon, and was going quietly to the other embrasure, when suddenly something struck my foot. I thought I had fallen into a hole. I looked—my leg was gone!”

“You didn’t have any pain at first, then?”

“None at all, only just as if I had scalded my leg; that’s all.”

“And afterwards?”

“None afterwards, only when they stretched the skin; that was a little rough. First of all things, your excellency, we mustn’t think. When we don’t think we don’t feel. When a man thinks, it is the worse for him.”

Meanwhile, a woman dressed in gray, with a black kerchief tied around her head, approaches, joins in the conversation, and begins to give a detailed account of the sailor: how he has suffered, how his life was de{24}spaired of for four weeks, how, when wounded, he made them stop the stretcher on which he was being carried to the rear in order to watch the discharge of our battery, and how the grand-dukes had spoken with him, had given him twenty-five rubles, and how he had replied that, not being able to serve any more himself, he would like to come back to the bastion to train the conscripts. The good woman, her eyes sparkling with enthusiasm, relates this in one breath, looking at you and then at the sailor, who turns away and pretends not to hear, busy with picking lint from his pillow.

“It is my wife, your excellency,” says the sailor at last, with an intonation of voice which seems to say, “You must excuse her; all that is woman’s foolish prattle, you know.”

You then begin to understand what the defenders of Sebastopol are, and you are ashamed of yourself in the presence of this man. You would have liked to express all your admiration for him, all your sympathy, but the words will not come, or those which do come are worthless, and you can only bow in silence before this unconscious gran{25}deur, before this firmness of soul and this exquisite shame of his own merit.

“Ah, well, may God speedily cure you!” you say, and you stop before another wounded man lying on the floor, who, suffering horrible pain, seems to be awaiting his death. He is blond, and his pale face is much swollen. Stretched on his back, his left hand thrown up, his position indicates acute suffering. His hissing breath escapes with difficulty from his dry, half-open mouth. The glassy blue pupils of his eyes are rolled up under the eyelids, and a mutilated arm, wrapped in bandages, sticks out from under the tumbled blanket. A nauseating, corpse-like odor rises to your nostrils, and the fever which burns the sufferer’s limbs seems to penetrate your own body.

“Is he unconscious?” you ask of the woman who kindly accompanies you, and to whom you are no longer a stranger.

“No; he can still hear, but he is very bad;” and she adds, under her breath, “I have just made him drink a little tea. He is nothing to me, only I have pity on him; indeed, he has only been able to swallow a few mouthfuls.{26}”

“How do you feel?” you ask him.

At the sound of your voice the wounded man’s eyes turn towards you, but he neither sees nor understands.

“That burns my heart!” he murmurs.

A little farther on an old soldier is changing his clothes. His face and his body are both of the same brown color, and as thin as a skeleton. One of his arms has been amputated at the shoulder. He is seated on his bed, he is out of danger, but from his dull, lifeless look, from his frightful thinness, from his wrinkled face, you see that this creature has already passed the greater part of his existence in suffering.

On the opposite bed you see the pale, delicate, pain-shrivelled face of a woman whose cheeks are flushed with fever.

“It is a sailor’s wife. A shell hit her on the foot while she was carrying dinner to her husband in the bastion,” says the guide.

“Has it been amputated?”

“Above the knee.”

Now, if your nerves are strong, enter there at the left. It is the operating-room. There you see surgeons with pale and serious countenances, their arms blood-splashed to the{27} elbows, beside the bed of a wounded man, who, stretched on his back with open eyes, is delirious under the influence of chloroform, and utters broken phrases, some unimportant, some touching. The surgeons are busy with their repulsive but beneficent task, amputation. You see the curved and keen blade penetrate the healthy white flesh. The wounded man suddenly comes to himself with heart-rending cries, with curses. The assistant surgeon throws the arm into a corner, while another wounded man on a stretcher who sees the operation turns and groans, more on account of the mental torture of expectation than from the physical pain he feels. You will witness these horrible, heart-rending scenes; you will see war without the brilliant and accurate alignment of troops, without music, without the drum-roll, without standards flying in the wind, without galloping generals—you will see it as it is, in blood, in suffering, and in death! Leaving this house of pain, you will experience a certain impression of well-being, you will take long breaths of fresh air, and will be glad to feel yourself in good health; but at the same time the contemplation of these{28} misfortunes will have convinced you of your own insignificance, and you will go up into a bastion without hesitation. What are the sufferings and the death of an atom like me, you will ask yourself, in comparison with these innumerable sufferings and deaths? Besides, in a short time the sight of the pure sky, of the bright sun, of the pretty city, of the open church, of the soldiers coming and going in all directions, raises your spirits to their normal state. Habitual indifference, preoccupation with the present and with its petty interests, resume the ascendant. Perhaps you will meet on your way the funeral cortege of an officer—a red coffin followed by a band and by unfurled standards—and perhaps the roar of the cannonade on the bastion will strike your ear, but your thoughts of a few moments before will not come back again. The funeral will only be a pretty picture for you, the growl of the cannon a grand military accompaniment, and there will be nothing in common between this picture, these sounds, and the clear, personal impression of suffering and death called up by the sight of the operating-room.

Pass the church, the barricade, and you{29} enter the most animated, the liveliest quarter of the city. On both sides of the street are shop signs, eating-house signs. Here are merchants, women with men’s hats or with handkerchiefs on their heads, officers in elegant uniforms. Everything testifies to the courage, the assurance, the safety of the inhabitants.

Enter this restaurant on the right. If you want to listen to the sailors’ and the officers’ talk, you will hear them relate the incidents of the night before, of the affair of the 24th; hear them grumble at the high price of the badly cooked cutlets, and mention the comrade recently killed.

“Devil take me! we are badly off where we are now,” says the bass voice of a pale, blond, beardless, newly appointed officer, his neck wrapped in a green knit scarf.

“Where is that?” some one asks.

“In the fourth bastion,” replies the young officer; and at this reply you attentively look at him, and feel a certain respect for him. His exaggerated carelessness, his violent gestures, his too loud laughter, which would shortly before have seemed to you impudent, become in your eyes the index of{30} a certain kind of combative spirit common to all young people who are exposed to great danger, and you are sure he is going to explain that it is on account of the shells and the bullets that they are so badly off in the fourth bastion. Nothing of the kind! They are badly off there because the mud is deep.

“Impossible to get up to the battery,” he says, pointing to his boots, muddied even to the upper-leathers.

“My best gun captain was instantly killed to-day by a ball in his forehead,” rejoins a comrade.

“Who was it? Mituchine?”

“No, another man.—Look here! are you never going to bring me my chop, you villain?” says he, speaking to the waiter.—“It was Abrossinoff, as brave a man as lived. He took part in six sorties.”

At the other end of the table two infantry officers are eating veal cutlets with green pease washed down by sour Crimean wine, by courtesy called Bordeaux. One of them, a young man with red collar and two stars on his coat, is telling to his neighbor with a black collar and no stars the details of the{31} fight on the Alma. The first is a little the worse for liquor. His frequently interrupted tale, his uncertain look, which reflects the lack of confidence which his story inspires in his auditor, the fine part he gives himself, the too high color of his picture, lead you to guess that he is wandering away from the absolute truth. But you haven’t anything to do with these tales, which you will hear for a long time yet in the farthest corners of Russia; you have one wish alone, that is, to go straight to the fourth bastion, which you have heard so many and so varied reports about. You will notice that whoever tells you he has been there says it with pride and satisfaction; that whoever is getting ready to go there either shows a little emotion or affects an exaggerated sangfroid. If one man is joking with another, he will invariably tell him, “Go to the fourth bastion!” If a wounded man on a stretcher is met, and he is asked where he comes from, he will answer, almost without fail, “From the fourth bastion!” Two completely different notions of this terrible earthwork have been circulated; the first by those who have never put their foot upon it, and for whom{32} it is the inevitable tomb of its defenders, the second by those who, like the little blond officer, live there and simply speak of it, saying it is dry or muddy there, warm or cold.

During the half hour you have been in the restaurant the weather has changed and the fog which spread over the sea has risen. Thick, gray, moist clouds hide the sun. The sky is gloomy, and a fine rain mixed with snow is falling, wetting the roofs, the sidewalks, and the soldiers’ overcoats. After passing one more barricade you go along up the broad street. There are no more shop-signs; the houses are uninhabitable, the doors fastened up with boards, the windows broken. On this side the corner of a wall has been carried away, on that side the roof has been broken in. The buildings look like old veterans tried by grief and misery, and stare at you with pride, one might say with disdain even. On the way you stumble over cannon-balls and into holes, filled with water, which the shells have made in the rocky ground. You pass detachments of soldiers and officers. You occasionally meet a woman or a child, but here the woman does not wear a hat. As for the{33} sailor’s wife, she wears an old fur cloak, and has soldiers’ boots on her feet. The street now leads down a gentle declivity, but there are no more houses around you, nothing but shapeless masses of stones, of boards, of beams, and of clay. Before you, on a steep hill, stretches a black space, all muddy, and cut up with ditches. What you are looking at is the fourth bastion.

Passers become rare, no more women are met. The soldiers walk with rapid step. A few drops of blood stain the path, and you see coming towards you four soldiers bearing a stretcher, and on the stretcher a face of a sallow paleness and a bloody coat. If you ask the bearers where he is wounded, they will reply, with an irritated tone, without looking at you, that he has been hit on the arm or on the leg. If his head has been carried away, if he is dead, they will keep a morose silence.

The near whiz of balls and shells gives you a disagreeable impression while you are climbing the hill, and suddenly you have an entirely different idea from the one you recently had of the meaning of the cannon-shots heard in the city. I do not know{34} what placid and sweet souvenir will suddenly shine out in your memory. Your intimate ego will occupy you so actively that you will no longer think of noticing your surroundings. You will permit yourself to be overcome by a painful feeling of irresolution. However, the sight of a soldier who, with extended arms, is slipping down the hill in the liquid mud, and passes near you, running and laughing, silences your small inward voice, the cowardly counsellor which arises in you in the presence of danger. You straighten up in spite of yourself, you raise your head, and you, in your turn, scale the slippery slope of the clay hill. You have scarcely gone a step before musket-balls hum in your ears, and you ask yourself if it would not be preferable to go under cover of the trench thrown up parallel with the path. But the trench is full of a yellow, fetid, liquid mud, so that you are obliged to go on in the path; all the more since it is the way everybody goes. At the end of two hundred paces you come out on a place surrounded by gabions, embankments, shelters, platforms supporting enormous cast-iron cannon, and heaps of symmetrically{35} piled cannon-balls. These heaps of things give you the impression of a strange and aimless disorder. Here on the battery assembles a group of sailors; there in the middle of the enclosure lies a dismounted cannon, half buried in the sticky mud, through which an infantryman, musket in hand, is going to the battery, pulling out with difficulty first one foot and then the other. Everywhere in this liquid mud you see broken glass, unexploded shells, cannon-balls—every trace of camp life. You seem to hear the noise of a cannon-ball falling only two yards away, and from all sides come the sound of balls, which sometimes hum like bees, sometimes groan and split the air, which vibrates like a violin-string, the whole dominated by the sinister rumbling of cannon, which shakes you from head to foot and fills you with terror.

This is, then, the fourth bastion, this really terrible place, you say to yourself, feeling a little pride and a great deal of repressed fear. Not at all! You are the sport of an illusion. This is not yet the fourth bastion; it is the Jason redoubt, a place which, comparatively, is neither dangerous nor fright{36}ful. In order to reach the fourth bastion you enter the narrow trench which the infantryman follows, stooping over. You will perhaps see more stretchers, sailors, soldiers with spades, wires leading to the mines, earth-shelters equally muddy, into which only two men can crawl, and where the battalions of the Black Sea Sharpshooters live, eat, smoke, and put their boots on and off, in the midst of the débris of cast-iron of every form thrown here and there. You will perhaps find here four or five sailors playing cards in the shelter of the parapet, and a naval officer, who, seeing a new face come up, and a spectator at that, will be really pleased to initiate you into the details of the arrangements and give you an explanation of them. This officer, seated on a cannon, is rolling a cigarette with such coolness, passes so quietly from one embrasure to another, and talks with you with such natural calmness, that you recover your own sangfroid, in spite of the balls which are whistling here in greater numbers. You ask him questions, and even listen to his tales. The sailor will describe to you, if you will only ask him, the bombardment of the 5th, the{37} state of his battery with a single serviceable cannon, his men reduced to eight, and, moreover, on the morning of the 6th, the battery fired with every gun. He will tell you also how, on the 5th, a shell penetrated a bomb-proof and struck down eleven sailors. He will show you, through the embrasure, the enemy’s trenches and batteries, which are only thirty or forty fathoms distant. I fear, however, that, leaning out of the embrasure in order to examine the enemy better, you will see nothing, or that, if you perceive something, you will be very much surprised to learn that this white and rocky rampart a few steps away, and from which are spouting little clouds of smoke, is really the enemy—“him,” as the soldiers and sailors say.

It is very possible that the officer, either through vanity or simply, without reflection, to amuse himself, will be willing to have them fire for you. At his order the captain of the gun and the men, fourteen sailors all told, gayly approach the cannon to load it, some chewing biscuit, others cramming their short pipes in their pockets, while their hobnailed shoes clatter on the platform. No{38}tice the faces of these men, their bearing, their movements, and you will recognize in each of the wrinkles of their sunburned faces with high cheek-bones, in each muscle, in the breadth of the shoulders, in the thickness of the feet shod with colossal boots, in each calm and bold gesture, the principal elements that make up the strength of Russia—simplicity and obstinacy. You will also see that danger, misery, and suffering in the war will have imprinted on these faces the consciousness of their dignity, of high thoughts, of a sentiment.

Suddenly a deafening noise makes you quake from head to foot. You hear at the same instant the shot whistling away, while a thick powder-smoke envelops the platform and the black figures of sailors moving about. Listen to their conversation, notice their animation, and you will discover among them a feeling which you would not expect to meet—that of hatred of the enemy, of vengeance. “It fell straight into the embrasure; two killed. Look! they are carrying them away,” and they shout for joy. “But he is getting angry now, he is going to hit back,” says a voice, and in truth you{39} see at the same instant a flash and spurting smoke, and the sentinel on the parapet calls, “Cannon!” A ball whizzes in your ears and buries itself in the ground, digging it up and casting around a shower of earth and stones. The commander of the battery gets angry, renews the order to load a second, a third gun. The enemy replies, and you experience interesting sensations. The sentinel again calls, “Cannon!” and the same sound, the same blow, and the same throwing up of earth are repeated. If, on the other hand, he cries, “Mortar!” you will be struck by a regular, not disagreeable hissing, which has no connection in your mind with anything terrible. It comes nearer and with greater rapidity. You see the black ball fall to the ground, and the bomb-shell burst with a metallic cracking. The pieces fly in air, whistling and screeching; stones hit each other, and mud splashes over you. You feel a strange mixture of pleasure and fright at these different sounds. At the instant the projectile reaches you, you invariably think it will kill you. But pride keeps you up, and no one notices the dagger that is digging into your heart. So{40} when it has passed without grazing you, you live again; for an instant a feeling of indescribable sweetness possesses you to such a degree that you find a special charm in danger, in the game of life and death. You would like to have a ball or a shell fall nearer, very near you. But the sentinel announces with his strong, full voice, “Mortar!” The hissing, the blow, the explosion are repeated, but accompanied this time by a human groan. You go up to the wounded man at the same time with the stretcher-bearers. He has a strange look, lying in the mud mingled with his blood. Part of his chest has been carried away. In the first moment his mud-splashed face expresses only fright and the premature sensation of pain, a feeling familiar to man in this situation. But when they bring the stretcher to him, and he unassisted lies down on it on his uninjured side, an exalted expression, elevated but restrained thoughts, enliven his features. With brilliant eyes and shut teeth he raises his head with an effort, and at the moment the stretcher-bearers move he stops them, and addressing his comrades with trembling voice, says, “Good-by, brothers!{41}” He would like to say something more, he seems to be trying to find something touching to say, but he limits himself to repeating, “Good-by, brothers!” A comrade approaches the wounded man, puts his cap on his head for him, and turns back to his cannon with a gesture of perfect indifference. At the sight of your terrified expression of face the officer, yawning, and rolling between his fingers a cigarette in yellow paper, says, “So it is every day, up to seven or eight men.”

You have just seen the defenders of Sebastopol on the very place of the defence, and, strange to say, you will retrace your steps without paying the least attention to the bullets and balls which continue to whistle the whole length of the road as far as the ruins of the theatre. You walk with calmness, your soul elevated and strengthened, for you bring away the consoling conviction that never, and in no place, can the strength of the Russian people be broken; and you have gained this conviction not from the solidity of the parapets, from the ingeniously combined intrenchments, from the number of mines, from the cannon heaped{42} one on the other, and all of which you have not in the least understood, but from the eyes, the words, the bearing, from what may be called the spirit of the defenders of Sebastopol.

There is so much simplicity and so little effort in what they do that you are persuaded that they could, if it were necessary, do a hundred times more, that they could do everything. You judge that the sentiment that impels them is not the one you have experienced, mean and vain, but another and more powerful one, which has made men of them, living tranquilly in the mud, working and watching among the bullets, with a hundred chances to one of being killed, contrary to the common lot of their kind. It is not for a cross, for rank; it is not that they are threatened into submitting to such terrible conditions of existence. There must be another, a higher motive power. This motive power is found in a sentiment which rarely shows itself, which is concealed with modesty, but which is deeply rooted in every Russian heart—patriotism. It is now only that the tales that circulated during the first period of the siege{43} of Sebastopol, when there were neither fortifications, nor troops, nor material possibility of holding out there, and when, moreover, no one admitted the thought of surrender—it is now only that the anecdote of Korniloff, that hero worthy of antique Greece, who said to his troops, “Children, we will die, but we will not surrender Sebastopol,” and the reply of our brave soldiers, incapable of using set speeches, “We will die, hurrah!”—it is now only that these stories have ceased to be to you beautiful historical legends, since they have become truth, facts. You will easily picture to yourself, in the place of those you have just seen, the heroes of this period of trial, who never lost courage, and who joyfully prepared to die, not for the defence of the city, but for the defence of the country. Russia will long preserve the sublime traces of the epoch of Sebastopol, of which the Russian people were the heroes!

Day closes; the sun, disappearing at the horizon, shines through the gray clouds which surround it, and lights up with purple rays the rippling sea with its green reflections, covered with ships and boats, the{44} white houses of the city, and the population stirring there. On the boulevard a regimental band is playing an old waltz, which sounds far over the water, and to which the cannonade of the bastions forms a strange and striking accompaniment.{45}

Six months had rolled by since the first bomb-shell thrown from the bastions of Sebastopol ploughed up the soil and cast it upon the enemy’s works. Since that time millions of bombs, bullets, and balls had never ceased flying from bastions to trenches, from trenches to bastions, and the angel of death had constantly hovered over them.

The self-love of thousands of human beings had been sometimes wounded, sometimes satisfied, sometimes soothed in the embrace of death! What numbers of red coffins with coarse palls!—and the bastions still continued to roar. The French in their camp, moved by an involuntary feeling of anxiety and terror, examined in the soft evening light the yellow and burrowed earth of the bastions of Sebastopol, where the black silhouettes of our sailors came and went; they counted the embrasures bristling with fierce-looking cannon. On the telegraph tower an{48} under-officer was watching through his field-glass the enemy’s soldiers, their batteries, their tents, the movements of their troops on the Mamelon-Vert, and the smoke ascending from the trenches. A crowd composed of heterogeneous races, moved by quite different desires, converged from all parts of the world towards this fatal spot. Powder and blood had not succeeded in solving the question which diplomats could not settle.

A regimental band was playing in the besieged city of Sebastopol; a crowd of soldiers and women in Sunday best was promenading in the avenues. The clear sun of spring had risen upon the English works, had passed over the fortifications, over the city, and over the Nicholas barracks, shedding everywhere its just and joyous light; now it was setting into the blue distance of the sea, which gently rippled, sparkling with silvery reflections.

An infantry officer of tall stature and with a slight stoop, busy putting on gloves of doubtful whiteness, though still presentable, came out of one of the small sailor-{49}houses built on the left side of Marine Street. He directed his steps towards the boulevard, fixing his eyes in a distracted manner on the toe of his boots. The expression of his ill-favored face did not denote a high intellectual capacity, but traits of good-fellowship, good sense, honesty, and love of order were to be plainly recognized there. He was not well-built, and seemed to feel some confusion at the awkwardness of his own motions. He had a well-worn cap on his head, and on his shoulders a light cloak of a curious purplish color, under which could be seen his watch-chain, his trousers with straps, and his clean and well-polished boots. If his features had not clearly indicated his pure Russian origin he would have been taken for a German, for an aide-de-camp, or for a regimental baggage-master—he wore no spurs, to be sure—or for one of those cavalry officers who have been exchanged in order to take active service. In fact, he was one of the latter, and while going up to the boulevard he was thinking of a letter he had just received from an ex-comrade, now a landholder in {50}the Government of F——; he was thinking of his comrade’s wife, pale, blue-eyed Natacha, his best friend; he was especially recalling the following passage:

“When they bring us the Invalide,[A] Poupka (that was the name the retired uhlan gave his wife) rushes into the antechamber, seizes the paper, and throws herself upon the sofa in the arbor[B] in the parlor, where we have passed so many pleasant winter evenings in your company while your regiment was in garrison in our city. You can’t imagine the enthusiasm with which she reads the story of your heroic exploits! ‘Mikhailoff,’ she often says in speaking of you, ‘is a pearl of a man, and I shall throw myself on his neck when I see him again! He is fighting in the bastions, he is! He will get the cross of St. George, and the newspapers will be full of him.’ Indeed, I am beginning to be jealous of you. It takes the papers a very long time to get to us, and although a thousand bits of news fly from mouth to mouth, we can’t believe all of them. For example: your good{51} friends the musical girls related yesterday how Napoleon, taken prisoner by our cossacks, had been brought to Petersburg—you understand that I couldn’t believe that! Then one of the officials of the war office, a fine fellow, and a great addition to society now our little town is deserted, assured us that our troops had occupied Eupatoria, thus preventing the French from communicating with Balaklava; that we lost two hundred men in this business, and they about fifteen thousand. My wife was so much delighted at this that she celebrated it all night long, and she has a feeling that you took part in the action and distinguished yourself.”

In spite of these words, in spite of the expressions which I have put in italics and the general tone of the letter, Captain Mikhaïloff took a sweet and sad satisfaction in imagining himself with his pale, provincial lady friend. He recalled their evening conversations on sentiment in the parlor arbor, and how his brave comrade, the ex-uhlan, became vexed and disputed over games of cards with kopek stakes when they succeeded in starting a game in his study, and how{52} his wife joked him about it. He recalled the friendship these good people had shown for him; and perhaps there was something more than friendship on the side of the pale friend! All these pictures in their familiar frames arose in his imagination with marvellous softness. He saw them in a rosy atmosphere, and, smiling at them, he handled affectionately the letter in the bottom of his pocket.

These memories brought the captain involuntarily back to his hopes, to his dreams. “Imagine,” he thought, as he went along the narrow alley, “Natacha’s joy and astonishment when she reads in the Invalide that I have been the first to get possession of a cannon, and have received the Saint George! I shall be promoted to be captain-major: I was proposed for it a long time ago. It will then be very easy for me to get to be chief of an army battalion in the course of a year, for many among us have been killed, and many others will be during this campaign. Then, in the next battle, when I have made myself well known, they will intrust a regiment to me, and I shall become lieutenant-colonel, commander of the Order{53} of Saint Anne—then colonel—” He was already imagining himself general, honoring with his presence Natacha, his comrade’s widow—for his friend would, according to the dream, have to die about this time—when the sound of the band came distinctly to his ears. A crowd of promenaders attracted his gaze, and he came to himself on the boulevard as before, second-captain of infantry.

He first approached the pavilion, by the side of which several musicians were playing. Other soldiers of the same regiment served as music-stands by holding before them the open music-books, and a small circle surrounded them, quartermasters, under-officers, nurses, and children, engaged in watching rather than in listening. Around the pavilion marines, aides-de-camp, officers in white gloves were standing, were sitting, or promenading. Farther off in the broad avenue could be seen a confused crowd of officers of every branch of the service, women of every class, some with bonnets on, the majority with kerchiefs on their heads; oth{54}ers wore neither bonnets nor kerchiefs, but, astonishing to relate, there were no old women, all were young. Below in fragrant paths shaded by white acacias were seen isolated groups, seated and walking.

No one expressed any particular joy at the sight of Captain Mikhaïloff, with the exception, perhaps, of Objogoff and Souslikoff, captains in his regiment, who shook his hand warmly. But the first of the two had no gloves; he wore trousers of camel’s-hair cloth, a shabby coat, and his red face was covered with perspiration; the second spoke with too loud a voice, and with shocking freedom of speech. It was not very flattering to walk with these men, especially in the presence of officers in white gloves. Among the latter was an aide-de-camp, with whom Mikhaïloff exchanged salutes, and a staff-officer whom he could have saluted as well, having seen him a couple of times at the quarters of a common friend.

There was positively no pleasure in promenading with these two comrades, whom he met five or six times a day, and shook hands with them each time. He did not come to the band concert for that.{55}

He would have liked to go up to the aide-de-camp with whom he exchanged salutes, and to chat with those gentlemen, not in order that Captains Objogoff, Souslikoff, Lieutenant Paschtezky, and others might see him in conversation with them, but simply because they were agreeable, well-informed people who could tell him something.

Why is Mikhaïloff afraid? and why can’t he make up his mind to go up to them? It is because he distrustfully asks himself what he will do if these gentlemen do not return his salute, if they continue to chat together, pretending not to see him, and if they go away, leaving him alone among the aristocrats. The word aristocrat, taken in the sense of a particular group, selected with great care, belonging to every class of society, has lately gained a great popularity among us in Russia—where it never ought to have taken root. It has entered into all the social strata where vanity has crept in—and where does not this pitiable weakness creep in? Everywhere; among the merchants, the officials, the quartermasters, the officers; at Saratoff, at Mamadisch, at Vi{56}nitzy—everywhere, in a word, where men are. Now, since there are many men in a besieged city like Sebastopol, there is also a great deal of vanity; that is to say, aristocrats are there in large numbers, although death, the great leveller, hovers constantly over the head of each man, be he aristocrat or not.

To Captain Objogoff, Second-captain Mikhaïloff is an aristocrat; to Second-captain Mikhaïloff, Aide-de-camp Kalouguine is an aristocrat, because he is aide-de-camp, and says thee and thou familiarly to other aides-de-camp; lastly, to Kalouguine, Count Nordoff is an aristocrat, because he is aide-de-camp of the Emperor.

Vanity, vanity, nothing but vanity! even in the presence of death, and among men ready to die for an exalted idea. Is not vanity the characteristic trait, the destructive ill of our age? Why has this weakness not been recognized hitherto, just as small-pox or cholera has been recognized? Why in our time are there only three kinds of men—those who accept vanity as an existing fact, necessary, and consequently just, and freely submit to it; those who consider{57} it an evil element, but one impossible to destroy; and those who act under its influence with unconscious servility? Why have Homer and Shakespeare spoken of love, of glory, and of suffering, while the literature of our century is only the interminable history of snobbery and vanity?

Mikhaïloff, not able to make up his mind, twice passed in front of the little group of aristocrats. The third time, making a violent effort, he approached them. The group was composed of four officers—the aide-de-camp Kalouguine, whom Mikhaïloff was acquainted with, the aide-de-camp Prince Galtzine, an aristocrat to Kalouguine himself, Colonel Neferdoff, one of the Hundred and Twenty-two (a group of society men who had re-entered the service for this campaign were thus called), lastly, Captain of Cavalry Praskoukine, who was also among the Hundred and Twenty-two. Happily for Mikhaïloff, Kalouguine was in charming spirits; the general had just spoken very confidentially to him, and Prince Galtzine, fresh from Petersburg, was stopping in his quarters, so he did not find it compromising to offer his hand to a second-captain. Praskoukine did{58} not decide to do as much, although he had often met Mikhaïloff in the bastion, had drunk his wine and his brandy more than once, and owed him twelve rubles and a half, lost at a game of preference. Being only slightly acquainted with Prince Galtzine, he had no wish to call his attention to his intimacy with a simple second-captain of infantry. He merely saluted slightly.

“Well, captain,” said Kalouguine, “when are we going back to the little bastion? You remember our meeting on the Schwartz redoubt? It was warm there, hey?”

“Yes, it was warm there,” replied Mikhaïloff, remembering that night when, following the trench in order to reach the bastion, he had met Kalouguine marching with a grand air, bravely clattering his sword. “I would not have to return there until to-morrow, but we have an officer sick.” And he was going on to relate how, although it was not his turn on duty, he thought he ought to offer to replace Nepchissetzky, because the commander of the eighth company was ill, and only an ensign remained, but Kalouguine did not give him time to finish.

“I have a notion,” said he, turning tow{59}ards Prince Galtzine, “that something will come off in a day or two.”

“But why couldn’t something come off to-day?” timidly asked Mikhaïloff, looking first at Kalouguine and then at Galtzine.

No one replied. Galtzine made a slight grimace, and looking to one side over Mikhaïloffs cap, said, after a moment’s silence,

“What a pretty girl!—yonder, with the red kerchief. Do you know her, captain?”

“It is a sailor’s daughter. She lives close by me,” he replied.

“Let’s look at her closer.”

And Prince Galtzine took Kalouguine by the arm on one side and the second-captain on the other, sure that by this action he would give the latter a lively satisfaction. He was not deceived. Mikhaïloff was superstitious, and to have anything to do with women before going under fire was in his eyes a great sin. But on that day he was posing for a libertine. Neither Kalouguine nor Galtzine was deceived by this, however. The girl with the red kerchief was very much astonished, having more than once noticed that the captain blushed as he was passing her window. Praskoukine marched{60} behind and nudged Galtzine, making all sorts of remarks in French; but the path being too narrow for them to march four abreast, he was obliged to fall behind, and in the second file to take Serviaguine’s arm—a naval officer known for his exceptional bravery, and very anxious to join the group of aristocrats. This brave man gladly linked his honest and muscular hand into Praskoukine’s arm, whom he knew, nevertheless, to be not quite honorable. Explaining to Prince Galtzine his intimacy with the sailor, Praskoukine whispered that he was a well-known, brave man; but Prince Galtzine, who had been, the evening before, in the fourth bastion, and had seen a shell burst twenty paces from him, considered himself equal in courage to this gentleman; also being convinced that most reputations were exaggerated, paid no attention to Serviaguine.

Mikhaïloff was so happy to promenade in this brilliant company that he thought no more of the dear letter received from F——, nor of the dismal forebodings that assailed him each time he went to the bastion. He remained with them there until they had visibly excluded him from their conversa{61}tion, avoiding his eye, as if to make him understand that he could go on his way alone. At last they left him in the lurch. In spite of that, the second-captain was so satisfied that he was quite indifferent to the haughty expression with which the yunker[C] Baron Pesth straightened up and took off his hat before him. This young man had become very proud since he had passed his first night in the bomb-proof of the fifth bastion, an experience which, in his own eyes, transformed him into a hero.

No sooner had Mikhaïloff crossed his own threshold than entirely different thoughts came into his mind. He again saw his little room, where beaten earth took the place of a wooden floor, his warped windows, in which the broken panes were replaced by paper, his old bed, over which was nailed to the wall a rug with the design of a figure of{62} an amazon, his pair of Toula pistols, hanging on the head-board, and on one side a second untidy bed with an Indian coverlet belonging to the yunker, who shared his quarters. He saw his valet Nikita, who rose from the ground where he was crouching, scratching his head bristling with greasy hair. He saw his old cloak, his second pair of boots, and the bundle prepared for the night in the bastion, wrapped in a cloth from which protruded the end of a piece of cheese and the neck of a bottle filled with brandy. Suddenly he remembered he had to lead his company into the casemates that very night.

“I shall be killed, I’m sure,” he said to himself; “I feel it. Besides, I offered to go myself, and one who does that is certain to be killed. And what is the matter with this sick man, this cursed Nepchissetzky? Who knows? Perhaps he isn’t sick at all. And, thanks to him, a man will get killed—he’ll get killed, surely. However, if I am not shot I will be put on the list for promotion. I noticed the colonel’s satisfaction when I asked permission to take the place of Nepchissetzky if he was sick. If I don’t get the rank of major, I shall certainly get the{63} Vladimir Cross. This is the thirteenth time I go on duty in the bastion. Oh, oh, unlucky number! I shall be killed, I’m sure; I feel it. Nevertheless, some one must go. The company cannot go with an ensign; and if anything should happen, the honor of the regiment, the honor of the army would be assailed. It is my duty to go—yes, my sacred duty. No matter, I have a presentiment—”

The captain forgot that he had this presentiment, more or less strong, every time he went to the bastion, and he did not know that all who go into action have this feeling, though in very different degrees. His sense of duty which he had particularly developed calmed him, and he sat down at his table and wrote a farewell letter to his father. In the course of ten minutes the letter was finished. He arose with moist eyes, and began to dress, repeating to himself all the prayers which he knew by heart. His servant, a dull fellow, three-quarters drunk, helped him put on his new coat, the old one he was accustomed to wear in the bastion not being mended.

“Why hasn’t that coat been mended?{64} You can’t do anything but sleep, you beast!”

“Sleep!” growled Nikita, “when I am running about like a dog all day long. I tire myself to death, and after that am not allowed to sleep!”

“You are drunk again, I see.”

“I didn’t drink with your money; why do you find fault with me?”

“Silence, fool!” cried the captain, ready to strike him.

He was already nervous and troubled, and Nikita’s rudeness made him lose patience. Nevertheless, he was very fond of the fellow, he even spoiled him, and had kept him with him a dozen years.

“Fool! fool!” repeated the servant. “Why do you abuse me, sir—and at this time? It isn’t right to abuse me.”

Mikhaïloff thought of the place he was going to, and was ashamed of himself.

“You would make a saint lose patience, Nikita,” he said, with a softer voice. “Leave that letter addressed to my father lying on the table. Don’t touch it,” he added, blushing.

“All right,” said Nikita, weakening under the influence of the wine he had taken, at{65} his own expense, as he said, and blinking his eyes, ready to weep.

Then when the captain shouted, on leaving the house, “Good-by, Nikita!” he burst forth in a violent fit of sobbing, and seizing the hand of his master, kissed it, howling all the while, and saying, over and over again, “Good-by, master!”

An old sailor’s wife at the door, good woman as she was, could not help taking part in this affecting scene. Rubbing her eyes with her dirty sleeve, she mumbled something about masters who, on their side, have to put up with so much, and went on to relate for the hundredth time to the drunken Nikita how she, poor creature, was left a widow, how her husband had been killed during the first bombardment and his house ruined, for the one she lived in now did not belong to her, etc., etc. After his master was gone, Nikita lighted his pipe, begged the landlord’s daughter to fetch him some brandy, quickly wiped his tears, and ended up by quarrelling with the old woman about a little pail he said she had broken.

“Perhaps I shall only be wounded,” the captain thought at nightfall, approaching{66} the bastion at the head of his company. “But where—here or there?”

He placed his finger first on his stomach and then on his chest.

“If it were only here,” he thought, pointing to the upper part of his thigh, “and if the ball passed round the bone! But if it is a fracture it’s all over.”

Mikhaïloff, by following the trenches, reached the casemates safe and sound. In perfect darkness, assisted by an officer of the sappers, he put his men to work; then he sat down in a hole in the shelter of the parapet. They were firing only at intervals; now and again, first on our side and then on his, a flash blazed forth, and the fuse of a shell traced a curve of fire on the dark, starlit sky. But the projectiles fell far off, behind or to the right of the quarters in which the captain hid at the bottom of a pit. He ate a piece of cheese, drank a few drops of brandy, lighted a cigarette, and having said his prayers, tried to sleep.

Prince Galtzine, Lieutenant-colonel Neferdorf, and Praskoukine—whom nobody{67} had invited, and with whom no one chatted, but who followed them just the same—left the boulevard to go and drink tea at Kalouguine’s quarters.

“Finish your story about Vaska Mendel,” said Kalouguine.

Having thrown off his cloak, he was sitting beside the window in a stuffed easy-chair, and unbuttoned the collar of his well-starched, fine Dutch linen shirt.

“How did he get married again?”

“It’s worth any amount of money, I tell you! There was a time when there was nothing else talked about at Petersburg,” replied Prince Galtzine, laughingly.

He left the piano where he had been sitting, and drew near the window.

“It’s worth any amount of money! I know all the details—”

And gayly and wittily he set about relating the story of an amorous intrigue, which we will pass over in silence because it offers us little interest. The striking thing about these gentlemen was, that one of them seated in the window, another at the piano, and a third on a chair with his legs doubled up, seemed to be quite different men from what{68} they were a moment before on the boulevard. No more conceit, no more of this ridiculous affectation towards the infantry officers. Here between themselves they showed out what they were—good fellows, gay, and in high spirits. Their conversation continued upon their comrades and their acquaintances in Petersburg.

“And Maslovsky?”

“Which one—the uhlan or the horse-guardsman?”

“I know them both. In my time the horse-guardsman was only a boy just out of school. And the oldest, is he a captain?”

“Oh yes, for a long time.”

“Is he always with his Bohemian girl?”

“No, he left her—”

And the talk went on in this tone.

Prince Galtzine sang in a charming manner a gypsy song, accompanying himself on the piano. Praskoukine, without being asked, sang second, and so well too that, to his great delight, they begged him to do it again.

A servant brought in tea, cream, and rusks on a silver tray.{69}

“Give some to the prince,” said Kalouguine.

“Isn’t it strange to think,” said Galtzine, drinking his glass of tea near the window, “that we are here in a besieged city, that we have a piano, tea with cream, and all this in lodgings which I would be glad to live in at Petersburg?”

“If we didn’t even have that,” said the old lieutenant-colonel, always discontented, “existence would be intolerable. This continual expectation of something, or this seeing people killed every day without stopping, and this living in the mud without the least comfort—”

“But our infantry officers,” interrupted Kalouguine, “those who live in the bastion with the soldiers, and share their soup with them in the bomb-proof, how do they get on?”

“How do they get on? They don’t change their linen, to be sure, for ten days at a time, but they are astonishing fellows, true heroes!”

Just at this moment an infantry officer entered the room.

“I—I have received an order—to go to{70} general—to his Excellency, from General N——” he said, timidly saluting.

Kalouguine rose, and without returning the salute of the new-comer, without inviting him to be seated, begged him with cruel politeness and an official smile to wait a while; then he went on talking in French with Galtzine, without paying the slightest attention to the poor officer, who stood in the middle of the room, and did not know what to do with himself.

“I have been sent on an important matter,” he said at last, after a moment of silence.

“If that is so, be kind enough to follow me.” Kalouguine threw on his cloak and turned towards the door. An instant later he came back from the general’s room.

“Well, gentlemen, I believe they are going to make it warm to-night.”

“Ah! what—a sortie?” they all asked together.

“I don’t know, you will see yourselves,” he replied, with an enigmatic smile.

“My chief is in the bastion, I must go there,” said Praskoukine, putting on his sword.{71}

No one replied; he ought to know what he had to do. Praskoukine and Neferdorf went out to go to their posts.

“Good-by, gentlemen, au revoir! we will meet again to-night,” cried Kalouguine through the window, while they set out at a rapid trot, bending over the pommels of their Cossack saddles. The sound of their horses’ shoes quickly died away in the dark street.

“Come, tell me, will there really be something going on to-night?” said Galtzine, leaning on the window-sill near Kalouguine, whence they were watching the shells rising over the bastions.

“I can tell you, you alone. You have been in the bastions, haven’t you?”

Although Galtzine had only been there once he replied by an affirmative gesture.

“Well, opposite our lunette there was a trench”—and Kalouguine, who was not a specialist, but who was satisfied of the value of his military opinions, began to explain, mixing himself up and making wrong use of the terms of fortification, the state of our works, the situation of the enemy, and the plan of the affair which had been prepared.{72}

“There! there! They have begun to fire heavily on our quarters; is that coming from our side or from his—the one that has just burst there?” And the two officers, leaning on the window, watched the lines of fire which the shells traced crossing each other in the air, the white powder-smoke, the flashes which preceded each report and illuminated for a second the blue-black sky; they listened to the roar of the cannonade, which increased in violence.

“What a charming panorama!” said Kalouguine, attracting his guest’s attention to the truly beautiful spectacle. “Do you know that sometimes one can’t tell a star from a bomb-shell?”

“Yes, it is true; I just took that for a star, but it is coming down. Look! it bursts! And that large star there yonder—what do they call it? One would say it was a shell!”

“I am so accustomed to them that when I go back to Russia a starry sky will seem to me to be sparkling with bomb-shells. One gets so used to it.”

“Ought I not to go and take part in this sortie?” said Prince Galtzine, after a pause.{73}

“My dear fellow, what an idea! Don’t think of it. I won’t let you go; you will have time enough.”

“Seriously—do you think I ought not to?”

At this moment, right in the direction these gentlemen were looking, could be heard above the roar of artillery the rattle of a terrible fusillade; a thousand little flames spurted and sparkled along the whole line.

“Look, it is in full swing,” said Kalouguine. “I can’t calmly listen to this fusillade; it stirs my soul! They are shouting ‘Hurrah!’” he added, stretching his ear towards the bastion, from which arose the distant and prolonged clamor of thousands of voices.

“Who is shouting ‘Hurrah’—he or we?”

“I don’t know; but they are surely fighting at the sword’s point, for the fusillade has stopped.”

An officer on horseback, followed by a Cossack, galloped up under their window, stopped, and dismounted.

“Where do you come from?”

“From the bastion, to see the general.{74}”

“Come, what is the matter? Speak!”

“They have attacked—have taken the quarters. The French have pushed forward their reserves—ours have been attacked—and there were only two battalions of them,” said the officer, out of breath.

It was the same one who had come in the evening, but this time he went towards the door with confidence.

“Then we retreated?” asked Galtzine.

“No,” replied the officer, in a surly tone, “a battalion arrived in time. We repulsed them, but the chief of the regiment is killed, and many officers besides. They want reinforcements.”

So saying, he went with Kalouguine into the general’s room, whither we will not follow them.

Five minutes later Kalouguine set out for the bastion on a horse, which he rode in the Cossack fashion, a kind of riding which seems to give a particular pleasure to the aides-de-camp. He was the bearer of certain orders, and had to await the definite result of the affair. As to Prince Galtzine, he, agitated by the painful emotions which the signs of a battle in progress usually ex{75}cite in the idle spectator, hastily went out into the street to wander aimlessly to and fro.

Soldiers carried the wounded on stretchers, and supported others under the arms. It was very dark in the streets; here and there shone the lights in the hospital windows or in the quarters of a wakeful officer. The uninterrupted sound of the cannonade and the fusillade came from the bastions, and the same fires still lighted up the black sky. From time to time could be recognized the gallop of a staff-officer, the groan of a wounded man, the steps and the voices of the stretcher-bearers, the exclamations of doting women who stood on the thresholds of their houses and watched in the direction of the firing.

Among these last we find our acquaintance Nikita, the old sailor’s widow with whom he had made up, and the little daughter of the latter, a child of ten years.

“Oh, my God! holy Virgin and Mother!” murmured the old woman, with a sigh; and she followed with her eyes the shells which{76} flew through space from one point to another like balls of fire. “What a misfortune! what a misfortune! The first bombardment was not so hard. Look! one cursed thing has burst in the outskirts of the town right over our house!”

“No, it is farther off; they are falling in Aunt Arina’s garden,” said the child.

“Where is my master! where is he now!” groaned Nikita, still drunk, and drawling his words. “No tongue can tell how I love my master! If, God forbid, they commit the sin of killing him, I assure you, good aunt, I won’t be answerable for what I may do! Really, he is such a good master that—There is no word to express it, you see. I wouldn’t exchange him for those who are playing cards inside, true. Pooh!” concluded Nikita, pointing to the captain’s room, in which the yunker Yvatchesky had arranged with the ensigns a little festival to celebrate the decoration he had just received.

“What a lot of shooting-stars there are! what a lot of shooting-stars there are!” cried the child, breaking the silence which followed Nikita’s speech. “There! there!{77} another one is falling! What is that for? Say, mother.”

“They’ll destroy our cabin!” sighed the old woman, without replying.

“To-day,” resumed the sing-song voice of the little prattler—“to-day I saw in uncle’s room, near the wardrobe, an enormous ball; it had come through the roof and had fallen right into the room. It is so large that they can’t lift it.”

“The women who had husbands and money are gone away,” continued the old woman. “I have only a cabin, and they are destroying that! Look! look how they are firing, the wretches! Lord, my God!”

“And just as we were coming out of uncle’s house,” the child went on, “a bomb-shell came straight down; it burst, and threw the earth on all sides; one little piece almost struck us!”

Prince Galtzine met in constantly increasing numbers wounded men borne on stretchers, others dragging themselves along on foot or supporting each other, and talking noisily.{78}

“When they fell upon us, brothers,” said the bass voice of a tall soldier who carried two muskets on his shoulder—“when they fell upon us, shouting ‘Allah! allah!’[D] they pushed one another on. We killed the first, and others climbed over them. There was nothing to be done; there were too many of them—too many of them!”

“You come from the bastion?” asked Galtzine, interrupting the orator.

“Yes, your Excellency.”

“Well, what happened there? Tell me.”

“This happened, your Excellency—his strength surrounded us; he climbed on the ramparts and had the best of it, your Excellency.”

“How? the best of it? But you beat them back?”

“Ah yes, beat them back! But when all his strength came down upon us, he killed our men, and no help for it!”

The soldier was mistaken, for the trenches were ours; but, strange but well-authenticated fact, a soldier wounded in a battle al{79}ways believes it a lost and a terribly bloody one.

“I was told, nevertheless, that you beat him back,” continued Galtzine, good-naturedly; “perhaps it was after you came away. Did you leave there long ago?”

“This very moment, your Excellency. The trenches must belong to him; he had the upperhand—”

“Why, aren’t you ashamed of yourselves? Abandon the trenches! It is frightful,” said Galtzine, irritated by the indifference of the man.

“What could be done when he had the strength.”

“Ah, your Excellency,” said a soldier borne on a stretcher, “why not abandon them, when he has killed us all? If we had the strength we would never have abandoned them! But what was to be done? I had just stuck one of them when I was hit—Oh, softly, brothers, softly! Oh, for mercy’s sake!” groaned the wounded man.

“Hold on; far too many are coming back,” said Galtzine, again stopping the tall soldier with the two muskets. “Why don’t you go back, hey? Halt!{80}”

The soldier obeyed, and took off his cap with his left hand.

“Where are you going to?” sternly demanded the prince, “and who gave you permission, good-for—” But coming nearer, he saw that the soldier’s right arm was covered with blood up to the elbow.

“I am wounded, your Excellency.”

“Wounded! where?”

“Here, by a bullet,” and the soldier showed his arm; “but I don’t know what hit me a crack there.” He held his head down, and showed on the back of his neck locks of hair glued together by coagulated blood.

“Whose gun is this?”

“It is a French carbine, your Excellency; I brought it away. I wouldn’t have come away, but I had to lead that small soldier, who might fall down;” and he pointed to an infantryman who was walking some paces ahead of them leaning on his gun and dragging his left leg with difficulty.

Prince Galtzine was cruelly ashamed of his unjust suspicions, and conscious that he was blushing, turned around. Without questioning or looking after the wounded{81} any more, he directed his steps towards the field-hospital. Making his way to the entrance with difficulty through soldiers, litters, stretcher-bearers who came in with the wounded and went out with the dead, Galtzine entered as far as the first room, took one look about him, recoiled involuntarily, and precipitately fled into the street. What he saw there was far too horrible!

The great, high, sombre hall, lighted only by four or five candles, where the surgeons moved about examining the wounded, was literally crammed with people. Stretcher-bearers continually brought new wounded and placed them side by side in rows on the ground. The crowd was so great that the wretches pushed against one another and bathed in their neighbors’ blood. Pools of stagnant gore stood in the empty places; from the feverish breath of several hundred men, the perspiration of the bearers, rose a heavy, thick, fetid atmosphere in which candles burned dimly in different parts of the hall. A confused murmur of groans,{82} sighs, death-rattles, was interrupted by piercing cries. Sisters of Charity, whose calm faces did not express woman’s futile and tearful compassion, but an active and lively interest, glided here and there in the midst of bloody coats and shirts, sometimes striding over the wounded, carrying medicines, water, bandages, lint. Surgeons with their sleeves turned up, on their knees before the wounded, examined and probed the wounds by the flare of torches held by their assistants, in spite of the terrible cries and supplications of the patients. Seated at a little table beside the door a major wrote the number 532.

“Ivan Bogoïef, private in the third company of the regiment from C——, fractura femuris complicata!” shouted the surgeon, who was dressing a broken limb at the other end of the hall. “Turn him over.”

“Oh, oh, good fathers!” gasped the soldier, begging them to leave him in peace.

“Perforatio capites. Simon Neferdof, lieutenant-colonel of the infantry regiment from N——. Have a little patience, colonel. There is no way of—I shall be obliged to leave you there,” said a third, who was fum{83}bling with a sort of hook in the head of the unfortunate officer.

“In Heaven’s name, get done quickly!”

“Perforatio pectoris. Sebastian Sereda, private—what regiment? But it is no use, don’t write it down. Moritur. Carry him off,” added the surgeon, leaving the dying man, who with upturned eyes was already gasping.

Forty or fifty stretcher-bearers awaited their burdens at the door. The living were sent to the hospital, the dead to the chapel. They waited in silence, and sometimes a sigh escaped them as they contemplated this picture.

Kalouguine met many wounded on his way to the bastion. Knowing by experience the bad influence of this spectacle on the spirit of a man who is going under fire, he not only did not stop them to ask questions, but he tried not to notice those he met. At the foot of the hill he ran across a staff-officer coming down from the bastion full speed.

“Zobkine! Zobkine! one moment!{84}”

“What?”

“Where do you come from?”

“From the quarters.”

“Well, what is going on there? Is it hot?”

“Terribly!”