Title: Eleanor Ormerod, LL. D., Economic Entomologist : Autobiography and Correspondence

Author: Eleanor A. Ormerod

Editor: Robert Wallace

Release date: March 11, 2020 [eBook #61597]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Fay Dunn, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

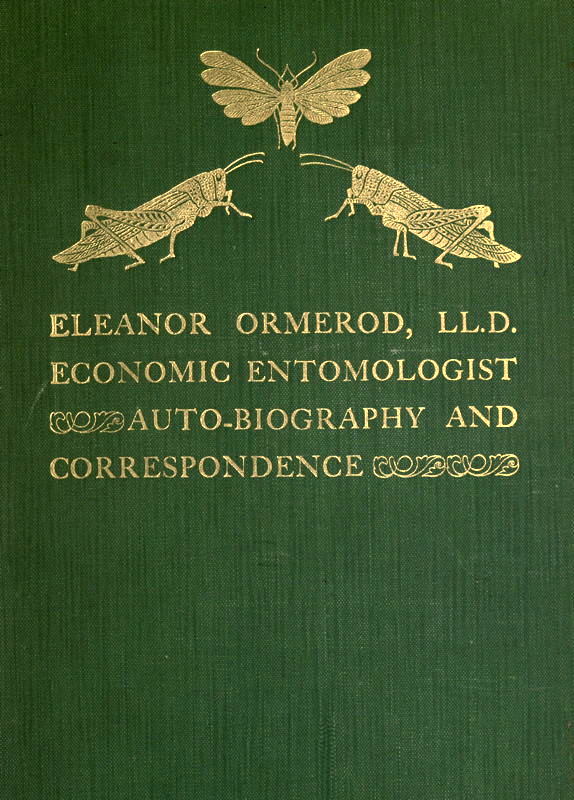

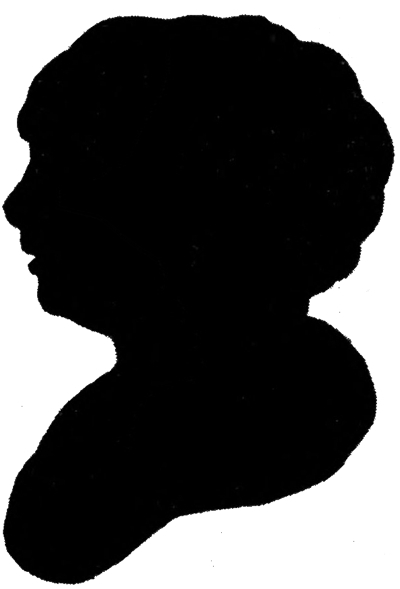

Elliott & Fry. Photo Walker & Cookerell Ph. So.

Eleanor A. Ormerod

The idea that Miss Ormerod should write her biography originated with the present writer during one of many visits paid to her at St. Albans. Miss Ormerod had unfolded in charming language and with admirable lucidity and fluency some interesting chapters of her personal experiences and reminiscences. The first working plan of the project involved the concealment of a shorthand writer behind a screen in the dining-room while dinner was proceeding, and while the examination of ethnological specimens or other attractive objects gave place for a time to general conversation on subjects grown interesting by age. Although the shorthand writer was selected and is several times referred to in letters written about this period (pp. 304-307), Miss Ormerod, on due reflection, felt that the presence, though unseen, of a stranger at these meetings in camera would make the position unnatural, and dislocate the association of ideas to the detriment of the narrative.

She then bethought herself of the method of writing down at leisure moments, from time to time as a suitable subject occurred to her, rough notes (p. 318) to be elaborated later, and when after a time a subject had been exhausted, the rough notes were re-written and welded into a narrative (pp. 304-321). Some four or five of the early chapters were thus treated and then typewritten, but the remainder of the Autobiography was left in crude form, requiring much piecing together and editorial trimming. Had the book been produced on the original plan, it was proposed to name it “Recollections of Changing Times.”[1] It would have dealt with a number of subjects of general interest, such as the history of the Post Office, early records of floods and viearthquakes, as well as newspapers of early date. The introduction of Miss Ormerod’s letters to a few of her leading correspondents was made necessary by the lack of other suitable material. The present volume is still mainly the product of Miss Ormerod’s pen, but with few exceptions general subjects have been eliminated; and it forms much more a record of her works and ways than it would have done had she been spared to complete it. From the inception of the idea the present writer was appointed editor, but had Miss Ormerod lived to see the book in the hands of the public his share of work would have been light indeed. Armed with absolute authority from her (p. 318) to use his discretion in the work, he has exercised his editorial license in making minor alterations without brackets or other evidences of the editorial pen, while at the same time the integrity of the substance has been jealously guarded.

As in Miss Ormerod’s correspondence with experts only scientific names for insects and other scientific objects were employed, it was found expedient to introduce the common names within ordinary or round brackets. Much thought and care have been given to the arrangement of the letters, and a sort of compromise was adopted of three different methods that came up for consideration, viz., (1) according to chronological order, (2) according to the subjects discussed, and (3) grouping under the names of the individuals to whom they were addressed. While the third is the predominant feature of the scheme the chronological order has been maintained within the personal groups, and precedence in the book was generally given to the letters of the oldest date. At the same time, to complete a subject in one group written mainly to one correspondent, letters dealing with the subject under discussion have been borrowed from their natural places under the heading of “Letters to Dr. ——” or “Letters to Mr. ——.” While Miss Ormerod’s practice of referring to matters of minor importance and of purely personal interest in correspondence dealing mainly with definite lines of scientific research, has not been interfered with in a few instances, in most of the other groups of letters on technical subjects editorial pruning was freely practised to prevent confusion and to concentrate the subject matter. The chief exceptions occur in the voluminous and interesting correspondence with Dr. Fletcher, in her specially confidential letters to Dr. Bethune, and in the very general correspondence with the editor. It was felt that to remove more of the friendly viireferences and passing general remarks to her correspondents would have been to invalidate the letters and show the writer of them in a character alien to her own.

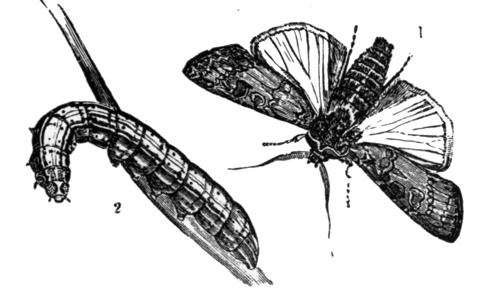

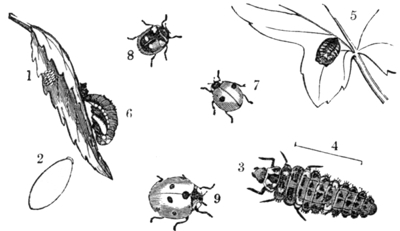

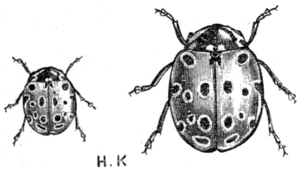

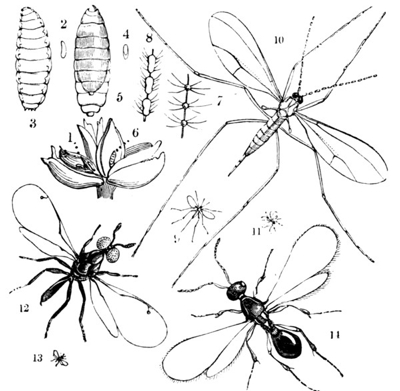

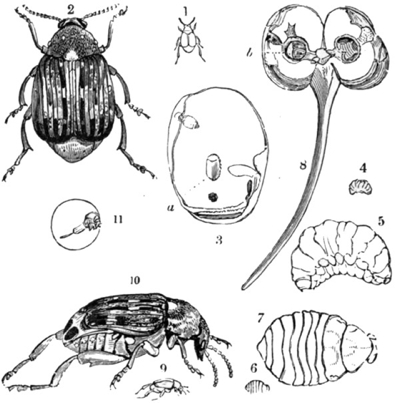

The figures of insects which have been introduced into the correspondence, to lighten it and increase its interest to the reader, have been chiefly borrowed from Miss Ormerod’s published works; and among them will be found a number of illustrations from Curtis’s “Farm Insects,” for the use of which her acknowledgments were fully given to Messrs. Blackie, the publishers.[2] The contents of this volume will afford ample evidence of Miss Ormerod’s intense interest in her subject, of the infinite pains she took to investigate the causes of injury, and of the untiring and unceasing efforts she employed to accomplish her object; also that her determinations relative to the causes and nature of parasitic attacks upon crops, give proof of soundness of judgment, and her advice, chiefly connected with remedial and preventive treatment, was eminently sensible and practical. Mainly by correspondence of the most friendly kind she formed a unique connecting link between economic entomologists in all parts of the world; and she quoted their various opinions to one another very often in support of her own preconceived ideas.

The three biographical chapters, III., XI., and XII., were added to the autobiographical statements which she had left, with the object merely of supplying some missing personal incidents in an interesting life. Other deficiencies in the Autobiography are made up by Miss Ormerod’s correspondence, and the history of her work is permitted to evolve from her own letters.

A strong vein of humour runs through many parts of her writings, notably in the chapter on “Church and Parish.” The reader will not fail to notice the splendid courtesy and deference to scientific authority, as well as the fullest appreciation of and unselfish sympathy with the genuine scientific work of others, which pervades all she wrote. Prominent among these characteristics of Miss Ormerod should be placed her scrupulous honesty of purpose in acknowledging to the fullest extent the work of others.

The work of collecting material, sifting, and editing has been going on for nearly two years, and could never have been accomplished but for the kindly help rendered by so many of Miss Ormerod’s correspondents, all of whom I viiinow cordially thank for invaluable sympathetic assistance. Special acknowledgments are due to Sir Wm. Henry Marling, Bart., the present owner of Sedbury Park, and to Miss Ormerod’s nephews and nieces, who have been delighted to render such assistance as could not have been found outside the family circle. Besides Mr. Grimshaw, Mr. Janson, Dr. Stewart MacDougall, Professor Hudson Beare, and Mr. T. P. Newman who read the proofs critically, last, but not least, do I thank Mr. John Murray, whose friendly reception of the first overtures made to him as the prospective publisher of this volume brightened some of the dark moments near the close of Miss Ormerod’s life. I have had as editor the much appreciated privilege of drawing, in all cases of difficulty, upon Mr. Murray’s great literary experience.

In making these pleasing acknowledgments I in no way wish to shift the responsibility as Editor from my own shoulders for defects which may be discovered or for the general scheme of the work, which was, with slight modifications, my own. If it be said in criticism that the Editor is too little in evidence, I shall be all the more satisfied, as that has been throughout one of his leading aims.

University of Edinburgh,

1904.

Page 70, line 31, for “Tenebroides” read “Tenebrioides”.

Page 130, line 11, for “Ceutorhyncus” read “Ceuthorhyncus”.

Page 130 in description of Fig. 14, for “Ceutorhyncus” read “Ceuthorhyncus”.

Page 144, line 7, for “importad” read “imported”.

Page 185, line 1, for “Lucania” read “Leucania”.

Transcriber’s note:

These errata have been applied to this Project Gutenberg text.

| PAGE | |

| BIRTH, CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION: Born at Sedbury Park, May, 1828—recollections of early childhood—First insect observation—Girlish occupations—Education of the family—Eleanor Ormerod’s education at home by her mother—Interests during hours of leisure. | 1 |

| PARENTAGE: Localities of Sedbury Park and Tyldesley, the properties of George Ormerod—Roman remains—The family of Ormerod since 1311—Three George Ormerods of Bury—Reference to “Parentalia” by George Ormerod—The alliance of the family with the heiress, Elizabeth Johnson of Tyldesley—“Tyldesley’s” experiences during the Stewart rebellion in 1745—Descent from Thomas Johnson of Tyldesley—George Ormerod, father of Miss Ormerod—John Latham, fellow and president of the Royal College of Physicians, London, maternal grandfather of Miss Ormerod—Connection with the Ardernes of Alvanley and descent from Edward I.—The right of the Ormerod family to the “Port Fellowship” of Brasenose College. | 7 |

| REMINISCENCES OF SEDBURY BY MISS DIANA LATHAM: The Ormerod family of ten—The father and mother and their respective interests in literature and art—Sedbury Park and the hobbies of its inmates—Paucity of congenial neighbours—Annual visit to London—Drives and Excursions—The elder and the younger sections of the family—Eleanor Ormerod’s favourite sister, Georgiana—Interest in natural history and medicine—Miss Ormerod at twenty-five—Routine of life at Sedbury—Drawings by Mrs. Ormerod—The Library—Music—Models—Separation of the family. | 14 |

| CHURCH AND PARISH: Tidenham parish church—Leaden font—The Norman Chapel of Llancaut—The history of Tidenham Church—Curious practices in neighbouring churches—The church as schoolroom—Pretty customs on special occasions—The discomforts of the usual service—The choral service on high days—No reminiscences of precocious piety—Impressions of sermons by Scobell and Whately—Clerical eccentricities in dress, &c.—The Oxford Movement—Dr. Armstrong—Raising the latch of the chancel door with a ruler—The woman’s Clothing Club of the parish—Lending library instituted and successfully managed by Miss G. E. Ormerod—Her accomplishments and merits as a philanthropist. | 20 |

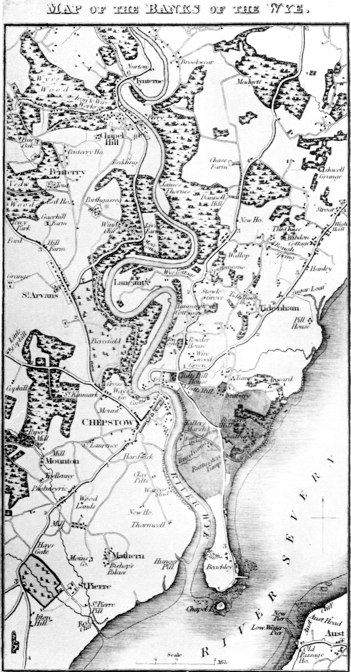

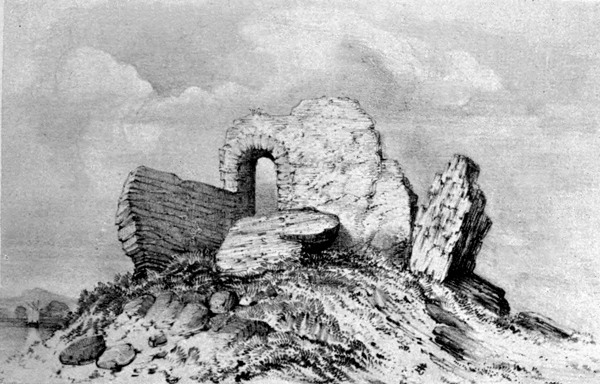

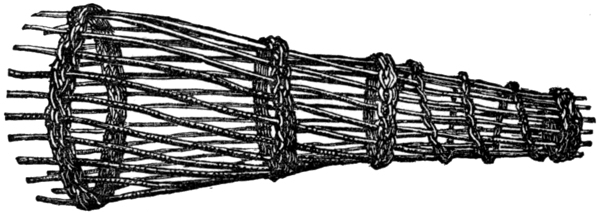

| SEVERN AND WYE: “Forest Peninsula” between Severn and Wye—Ruined chapel of St. Tecla—Muddy experiences—Scenery on the Severn—Rise of Tides—Colour and width of the river—Sailing merchant fleet to and from Gloucester—A “pill” or creek—Salmon fishing from boats—“Putcher” or basket fishing—Disorderly conduct by fishermen—Finds of Natural History specimens in fishing baskets—Severn clay or “mud”—A bottle-nosed whale—Seaweeds—Fossils from Sedbury cliffs—Saurian remains—Dangers of the cliffs. | 33 |

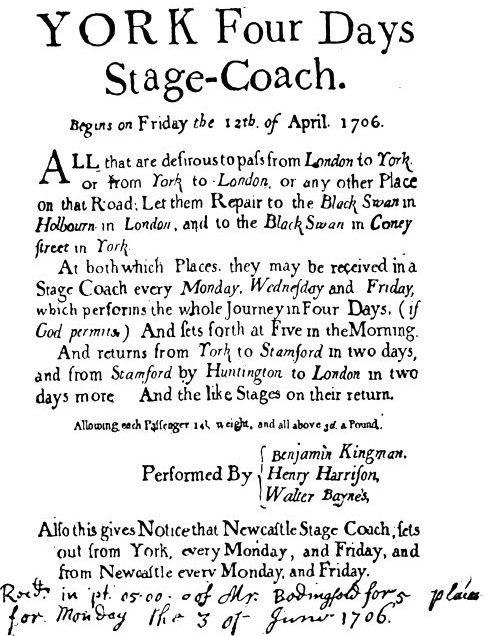

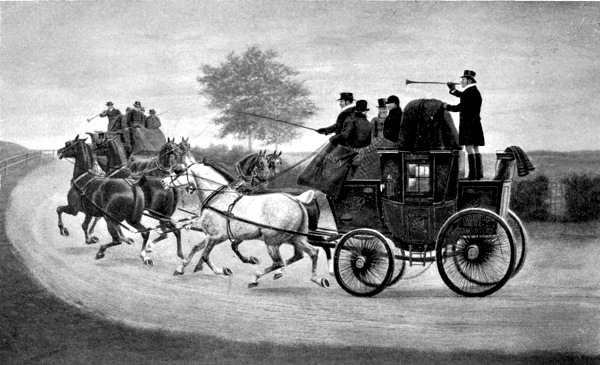

| TRAVELLING BY COACH, FERRY, AND RAILWAY: Many coaches passing Sedbury Park gates—Dangers of travelling—View of the Severn valley—The Old Ferry passage of the Severn—Swamping of a sailing boat in 1838—A strange custom when rabies was feared—Window-shutter-like ferry telegraph—The ferry piers—The first railways—Curious early train experiences. | 43 |

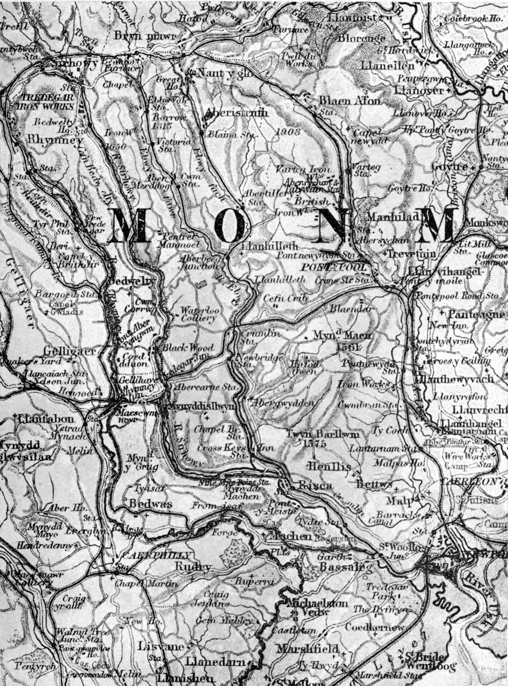

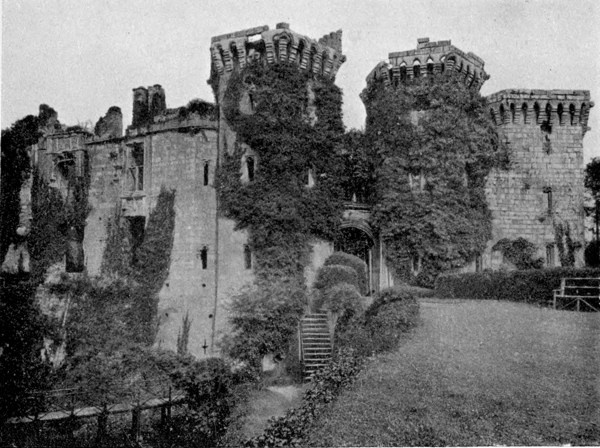

| CHARTIST RISING IN MONMOUTHSHIRE IN 1839: Chartist rising in Monmouth under John Frost, ex-draper of Newport—Home experience—Defenceless state of Sedbury house—Trial and sentence of the leaders—Reminiscences of troubles—Attorney-General’s address to the jury—Physical features of the disturbed area—Plan of the rising—Prompt action of the Mayor of Newport—Thirty soldiers stationed in the Westgate Hotel—Advance of 5,000 rioters—Their spirited repulse and dispersal—Arrest and punishment of Frost and other leaders. | 47 |

| BEGINNING THE STUDY OF ENTOMOLOGY, COLLECTIONS OF ECONOMIC ENTOMOLOGICAL SPECIMENS, AND FAMILY DISPERSAL: Beginning of Entomology 1852—A rare locust—Purchase of Stephen’s “Manual of British Beetles”—Method of self-instruction—First collection of Economic Entomology specimens sent to Paris—Facilities at Sedbury for collection—Aid given by labourers and their children in collecting—Illness and death of Miss Ormerod’s father—Succession and early death of Venerable Thomas J. Ormerod—Succession of the Rev. G. T. B. Ormerod—Miss Ormerod’s brothers—Especial copy of “History of Cheshire” presented to the Bodleian Library—A family heirloom. | 53 |

| COMMENCEMENT AND PROGRESS OF ANNUAL REPORTS OF OBSERVATIONS OF INJURIOUS INSECTS: Preliminary pamphlet issued in 1877—Explanation of the objects aimed at—Approval of the public and of the press—Changes in the original arrangement of the subject matter—Classification of facts under headings arranged in 1881—Sources of information stated and fully acknowledged—Adoption of plain and simple language—Illustrations of first importance—Blackie & Sons supply electros of wood engravings from Curtis’s “Farm Insects”—The brothers Knight assist—Accumulation of knowledge—General Index to Annual Reports by Newstead—Manual of Injurious Insects and other publications—Notice of the discontinuance of the Annual Reports in the Report for 1900—“Times” notice of “Miss Ormerod’s partial retirement from Entomological Work,” in Appendix B. | 59 |

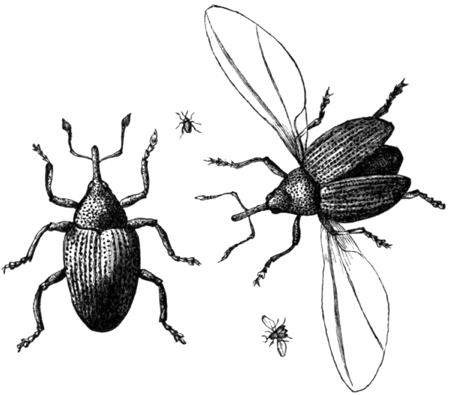

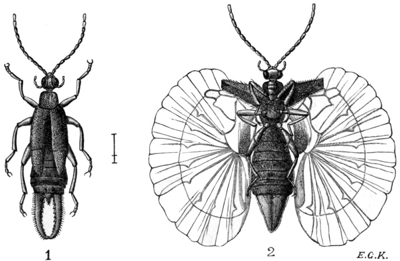

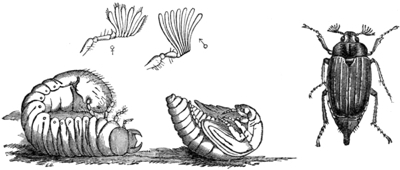

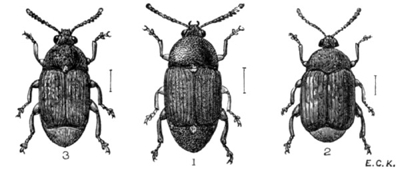

| SAMPLES OF LEGAL EXPERIENCES: First employment as an expert witness in 1889—Case of Wilkinson v. The Houghton Main Colliery Company, Limited—Form of subpœna—Rusty-red flour beetle infestation in a cargo of flour transported from New York to Durban—Report on insect presence—Confirmed by Oliver Janson and a Washington expert—A compromise effected—Case of granary weevil infestation in a cargo of flour from San Francisco to Westport—Letter of thanks from William Simpson of R. & H. Hall, Limited. | 68 |

| xiiBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH BY THE EDITOR: Reasons for changes of residence—Intimacy with Sir Joseph and Lady Hooker at Kew—Interesting people met there—Appointed Consulting Entomologist to the Royal Agricultural Society of England—Insect diagrams—Serious carriage accident—Methods adopted in doing entomological work—As a meteorological observer—Professor Westwood as friendly mentor—Appreciation of work by foreign correspondents. | 73 |

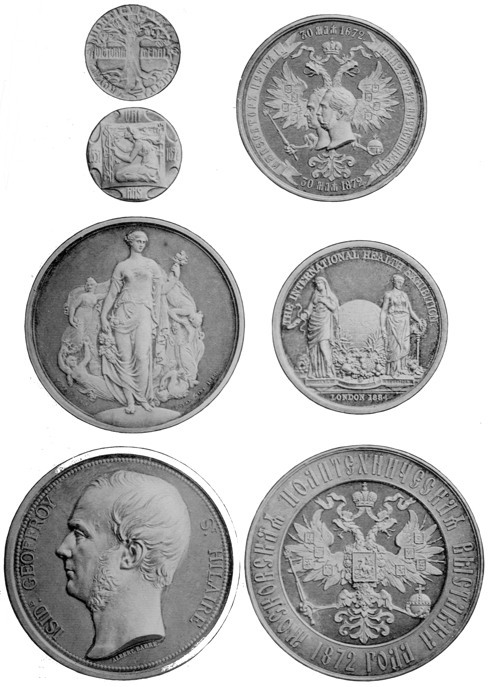

| BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH BY THE EDITOR (continued): Public lectures at the Royal Agricultural College—Reasons why lecturing was ultimately discontinued—Lectures at South Kensington and other places—The Economic Entomology Committee—Simplicity of Miss Ormerod’s home life before and after her sister’s death—Programme of daily work—Welcome guests—Intimate friends—Sense of humour—Story of a hornet’s capture—Proofs of courage—Historical oaks at Sedbury—Fond of children and thoughtful of employees—Charity—Public liberality—Subsidiary employments and amusements—Made LL.D.—Fellowships of societies—Medals—Treatment of letters. | 83 |

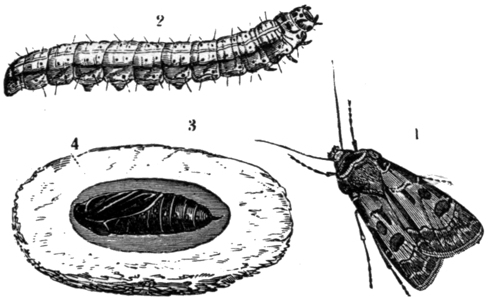

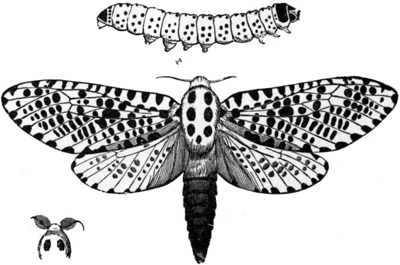

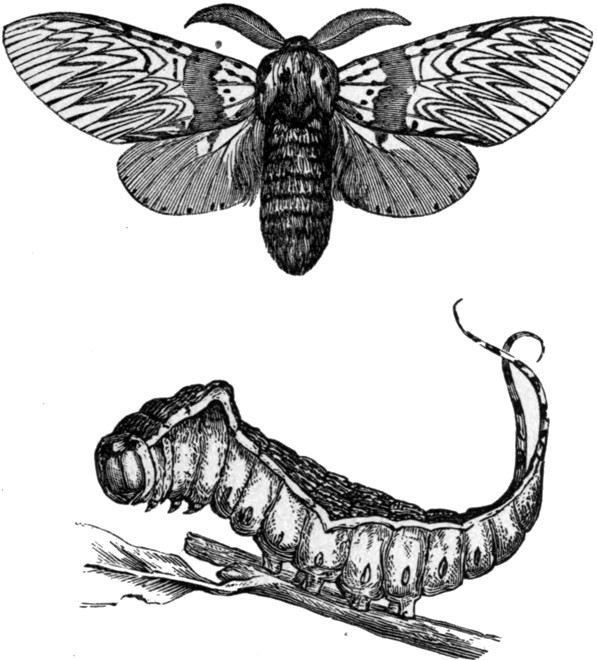

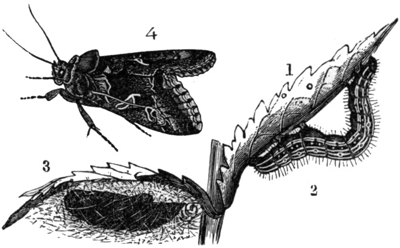

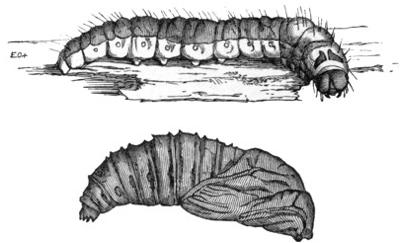

| LETTERS TO COLONEL COUSSMAKER AND MR. ROBERT SERVICE: (Coussmaker) Insect diagrams Royal Agricultural Society—Surface caterpillars—Wood leopard moth—Puss moth. (Service)—Paper by “Mabie Moss” on hill-grubs of the Antler moth—The pest checked by parasites. | 99 |

| LETTERS TO MR. WM. BAILEY: Mr. Bailey’s letter to H.G. the Duke of Westminster on Ox warble fly—Letter showing the destruction of Ox warbles by the boys—R.A.S.E. recognition—Annual letter and cheque for five guineas for prizes in insect work—Looper caterpillars—Mr. Bailey’s method of teaching agricultural entomology—Economic entomology exhibit at Bath and West Society’s Show, St. Albans—Examinership at Edinburgh University—The royal party at the show—Cheese-fly maggot—Copies of Manual for free distribution—Presentation slips—LL.D. of the University of Edinburgh—Discontinuing colleagueship. | 109 |

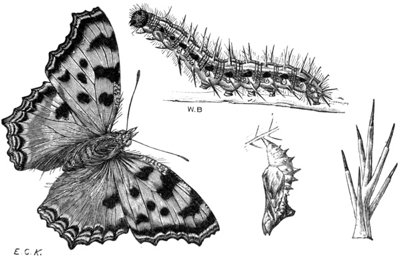

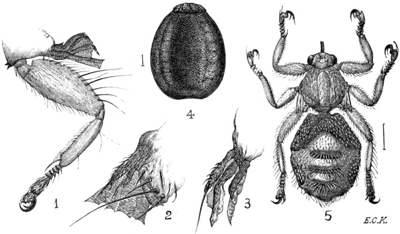

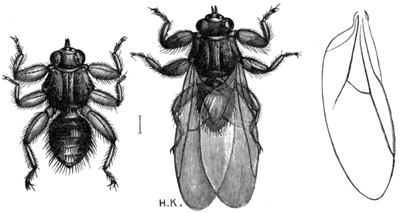

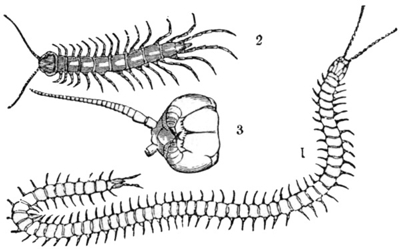

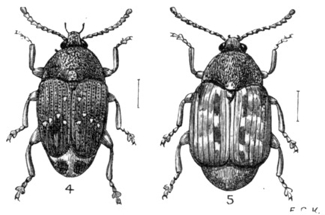

| xiiiLETTERS TO MR. D. D. GIBB: Great tortoiseshell butterfly infestation—Charlock weevil—Gout fly—Forest fly—Structure of its foot—Great gadfly—Horse breeze flies—Deer forest fly in Scotland—Sheep forest fly—Hessian fly and elbowed wheat straw—Bean-seed beetles—Millepedes—American blight—Brickdust-like deposit on apple trees—Insect cases for the show at St. Albans—Specimens of forest fly chloroformed—Death from fly poisoning—Looper caterpillars—Diamond-back moth—Corn sawfly. | 128 |

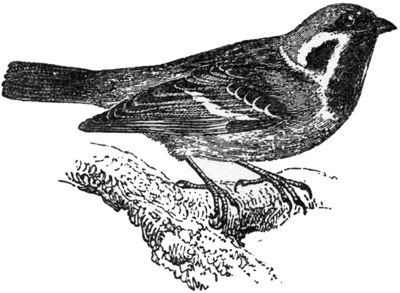

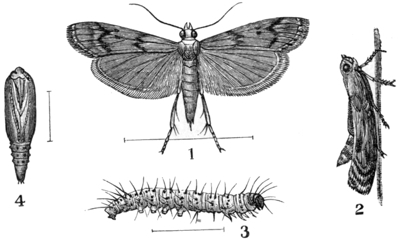

| LETTERS TO MR. GRIMSHAW, MR. WISE, AND MR. TEGETMEIER (Grimshaw) The Red-bearded botfly—Deer forest fly—Ox and deer warble flies. (Wise) Case of caddis worms injuring cress-beds—Enemies and means of prevention—Moles—Black currant mites—Biggs’ prevention—Dr. Nalepa’s views—Attack-resisting varieties of currants from Budapest—Dr. Ritzema Bos’s views—Mite-proof currants—Woburn report on gall mites—Narcissus fly—Lappet moth caterpillars. (Tegetmeier) Scheme of Miss Ormerod’s leaflet on the house sparrow plague—Earlier authorities—Enormous success of the free distribution of the leaflet—Miss Carrington’s opposition pamphlet—One hundred letters in a day received—Unfounded nature of opposition exposed, including Scripture reference to sparrows—Fashionable support—1,500 letters classified and 100 filed for future use—“The House Sparrow” by W. B. Tegetmeier, with Appendix by Eleanor A. Ormerod. | 149 |

| LETTERS TO MR. MARTIN, MR. GEORGE, MR. CONNOLD, AND MESSRS. COLEMAN AND SONS: (Martin) Elm-bark beetle—Ash-bark beetle—Large ash-bark beetle—Galleries—Preventive measure. (George) Mason bee—Roman coin found near Sedbury—Samian cup—The family grave. (Connold)—Pocket or bladder plums—Professor Ward describes the fungus—Dr. Nalepa’s publications. (Coleman and Sons) Attack of caterpillars of the silver Y-moth—Origin of the name. | 169 |

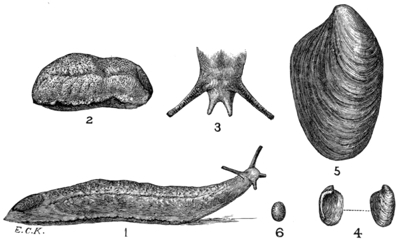

| LETTERS TO PROFESSOR RILEY AND DR. HOWARD: (Riley) Flour moth caterpillars—Differences of mineral oils—Trapping the winter moth—Orchard growers Experimental Committee. (Howard) John Curtis, Author of “Farm Insects”—Advance of Economic Entomology—C. P. Lounsbury, Cape Town—Sparrow Leaflet—Shot-borer beetles—Fly weevil—Lesser earwig—Handbook of Orchard Insects—General Index—Flour Moths—Snail-slug—Flat-worm—Tick—Degree of LL.D. of Edinburgh University. | 179 |

| LETTERS TO DR. J. FLETCHER: Dr. Voelcker’s gas lime pamphlet—Honorary membership of Entomological Society of Ontario—Ostrich fly—“Silver-top” in wheat—The “Crowder”—Mill or flour moth—Shot-borers—Progress of Agricultural Entomology—Paris-green as an insecticide—End of Board of Agriculture work—“Manual of Injurious Insects”—Fruit-growers’ associations—Lesson book for village schools—Entomology lectures in Edinburgh—Stem eel-worms—Miss Georgiana’s insect diagrams—Mr. A. Crawford’s death in Adelaide—Diamond-back moth—Insects survive freezing—Resigned post of Consulting Entomologist of R.A.S.E.—Finger and toe—Baroness Burdett-Coutts—Gall and club-roots—Currant scale—Mustard beetle—Professor Riley. | 195 |

| LETTERS TO DR. J. FLETCHER (continued) AND TO DR. BETHUNE: (Fletcher) Foreign authorities in correspondence—Dr. Nalepa’s books—Silk moths—Red spider—Formalin as a disinfectant—Professor Riley’s resignation—“Agricultural Zoology” by Dr. Ritzema Bos—Ground Beetles on Strawberries—Timberman beetle—Proposal to endow Agricultural lectureship in Oxford or Cambridge—Legacy of £5,000 to Edinburgh University—Woburn Experimental Fruit Grounds—Insects in a mild winter—Index of Annual Reports—“Recent additions” by Dr. Fletcher—Proposed book on “Forest Insects” conjointly with Dr. MacDougall. (Bethune) Proffered help after a fire—Eye trouble—Locusts in Alfalfa from Buenos Aires—Handbook of Orchard Insects—Rare attacks on mangolds and strawberries—Pressure of work—Death of Dr. Lintner—Sympathy to Mr. Bethune. | 217 |

| xvLETTERS FROM DRS. RITZEMA BOS, SCHÖYEN, REUTER, AND NALEPA, MR. LOUNSBURY AND MR. FULLER: (Ritzema Bos) Stem eel-worms—Cockchafer—Root-knot eel-worm—Black lady-bird feeding on Red spider—Eyed lady-bird—Professor Westwood on larvæ of Staphylinidæ. (Schöyen) Explanation of resignation of R.A.S.E. work—Wheat midge—Hessian fly—Wasps—San José scale—Mr. Newstead’s opinion. (Reuter) Hessian fly—Accept reports on Economic Entomology—Norwegian dictionary received and successfully used—Antler moth—Paris-green pamphlet—Swedish grammar—Work on Cecidomyia by Reuter—Forest fly—“Silver-top” in wheat probably due to thrips. (Nalepa) Gall mites. (Lounsbury) Boot beetle—First report from Capetown—Supplies electros for future reports—Mr. Fuller goes to Natal—Pleased to receive visits from entomological friends. (Fuller) Experiences in publishing technical literature. | 232 |

| LETTERS TO MR. JANSON AND MR. MEDD: (Janson) Deer forest flies—Identification confirmed by Professor Joseph Mik—Flour or mill moth—Granary Weevils—Shot-borer beetles—Pine beetles—Contemplated removal to Brighton—Grouse fly from a lamb—Cheese and bacon fly—Case of rust-red flour beetle—Willow beetles—White ants—Bean-seed beetles—Sapwood beetle—Death of Professor Mik. (Medd) Agricultural Education Committee joined reluctantly on account of pressure of Entomological work—Sympathy expressed with desire to improve “nature teaching” in rural districts—One hundred copies of the Manual and many leaflets presented—Proposed simple paper on common fly attacks on live stock—Objection to the Water-baby leaflet of the committee—Paper on wasps in the “Rural Reader”—Retiral from the Agricultural Education Committee. | 259 |

| LETTERS TO PROFESSOR ROBERT WALLACE BEFORE 1900: “Indian Agriculture”—Wheat screening and washing—Text books of injurious insects—Grease-banding trees—Dr. Fream—Mosley’s insect cases—Professor Westwood of Oxford—“Australian Agriculture”—Text-book “Agricultural Entomology”—Entomology in Cape Colony—Appointment as University Examiner in Agricultural Entomology—Presentation of Economic Entomology Exhibit to Edinburgh University—Death of Miss Georgiana Ormerod—Pine and Elm beetles—Index of the first series of Annual Reports. | 275 |

| LETTERS TO PROFESSOR WALLACE ON THE LL.D. OF THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH: Proposal of the Senatus of Edinburgh University to confer the LL.D. on Miss E. A. Ormerod as the first woman honorary graduate—Great appreciation of the prospective honour as giving a stamp of the highest distinction to her life’s work—Detailed arrangements preparing for graduation—Miss Ormerod’s books presented to the University Library—Successful journey to Edinburgh—Stay at Balmoral Hotel—Letter of thanks for personal attention sent after the event—Howard’s views of the honour to Economic Entomology, and of the value of the Edinburgh LL.D.—Slight chill on the return journey. | 287 |

| LETTERS TO PROFESSOR WALLACE AFTER THE GRADUATION: Congratulations by the London Farmers’ Club—Agricultural education and how to help it—Painting in oil of Miss Ormerod for the Edinburgh University—Copies of “Manual of Injurious Insects” for free distribution—Book of sketches for the University—Photographs by Elliott and Fry—Proposed “Handbook of Forest Insects” in collaboration with Dr. MacDougall—Proposed “Recollections of Changing Times”—Pamphlet on “Flies Injurious to Stock”—Graduation book—Proofs of “Stock Flies”—Thanks for “Quasi Cursores”—Digest of an inaugural address on “Famine in India”—Presentation of the oil painting—Re Sulphate of copper for Professor Jablonowski—Gall mite experiments on black-currants—Appreciation of the company in which the oil painting of Miss Ormerod hangs in the Court Room of the University. | 299 |

| LETTERS TO PROFESSOR WALLACE (concluded): Papers of “Reminiscences” sent to the editor—Details of letterpress material and of subjects for plates—Photo of oil painting taken by Elliott and Fry—Proclamation of the King—Publisher for “Reminiscences”—Return of papers to Miss Ormerod—One of several visits to St. Albans—“Taking in sail” by discontinuing the Annual Report—Illness becoming alarming—Material for “Reminiscences” consigned to the editor with power of discretion as to use—Continued weakness—Proposed week-end visit shortened—Taking work easier—First chapters of “Reminiscences” typewritten—Dr. MacDougall as collaborateur—Serious relapse—Proposal of a pension misappropriate—Improvement in health followed by frequent relapses—Pleasure of looking up “Reminiscences” in bed—Medical consultation with Dr. J. A. Ormerod—Liver complications—Fifteenth relapse—Touching farewell letters written in pencil—Obituary notices in the “Times” and the “Canadian Entomologist.” | 313 |

| APPENDICES: A. Salmon fishing, from the “Log Book of a Fisherman”—B. “Times” notice of partial retirement—C. Insect cases and their contents presented to Edinburgh University—D. Note on Xyleborus dispar—E. Obituary notice of Professor Riley. | 327 |

| INDEX | 337 |

| FOOTNOTES | 359 |

| PAGE | |

| PUTCHER FOR CATCHING SALMON | 36 |

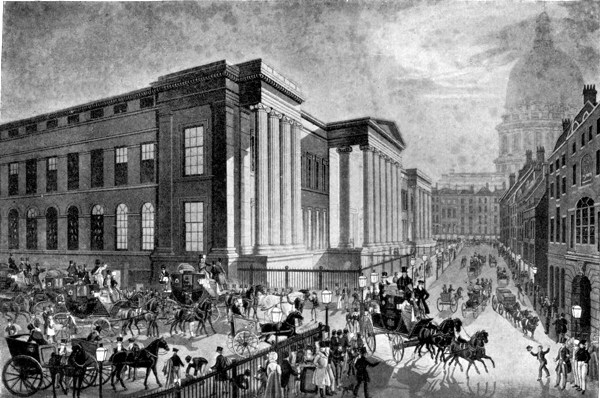

| TIME-TABLE: TRAVELLING 200 YEARS AGO | 44 |

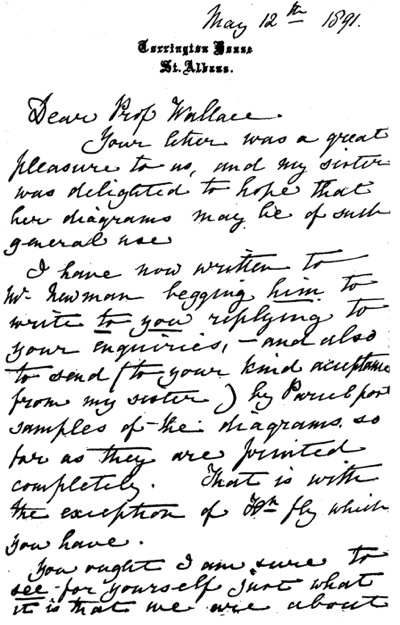

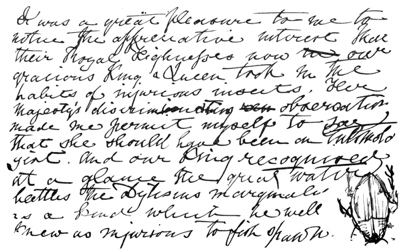

| FACSIMILE OF MISS ORMEROD’S HAND-WRITING | 89 |

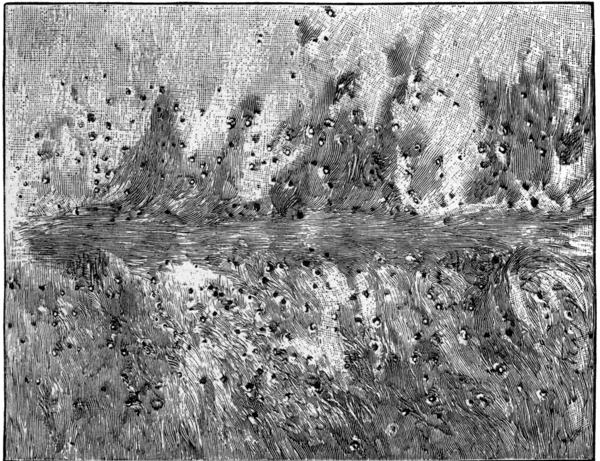

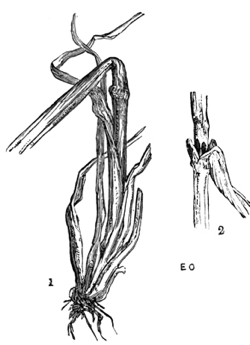

| SURFACE CATERPILLARS | 101 |

| WOOD LEOPARD MOTH | 102 |

| PUSS MOTH | 103 |

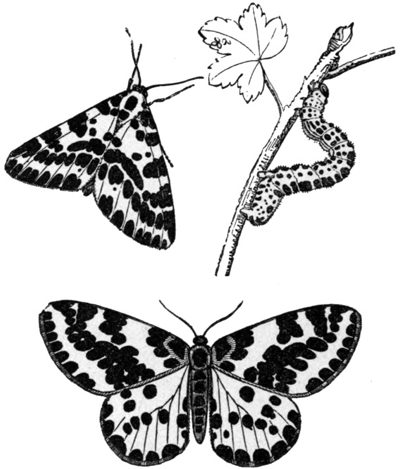

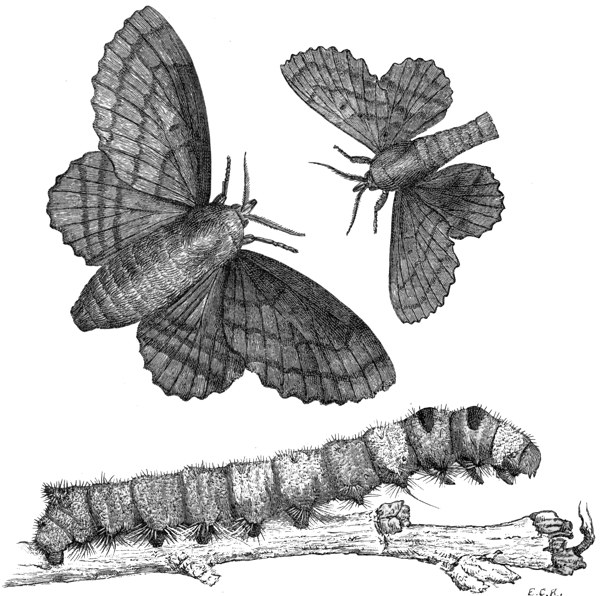

| ANTLER MOTH AND CATERPILLARS | 105 |

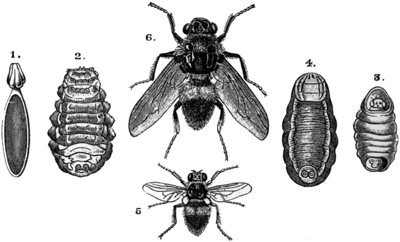

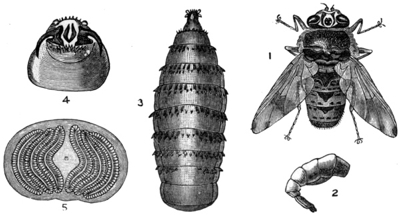

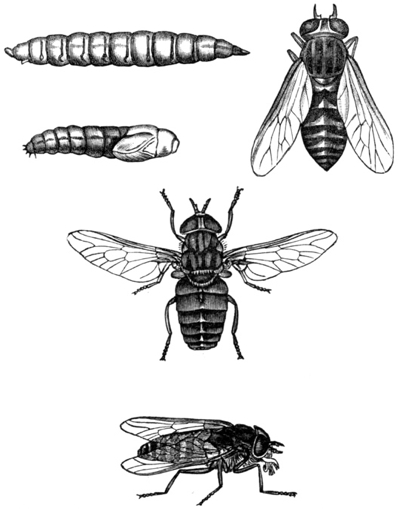

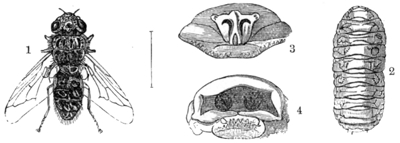

| OX WARBLE FLY, OR BOT FLY | 110 |

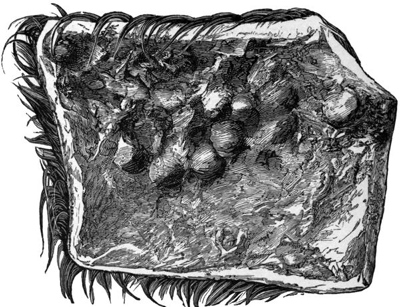

| PIECE OF SKIN WITH 402 WARBLE-HOLES | 111 |

| PIECE OF WARBLED HIDE | 112 |

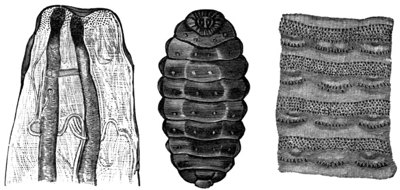

| BREATHING TUBES OF WARBLE MAGGOT, AND OUTSIDE PRICKLES | 112 |

| MAGPIE MOTH | 114 |

| HORSE BOT FLY, OR HORSE BEE | 117 |

| FACSIMILE NOTE RELATING TO THE KING AND QUEEN | 122 |

| WATER BEETLE | 124 |

| CHEESE AND BACON FLY | 125 |

| GREAT TORTOISE-SHELL BUTTERFLY | 129 |

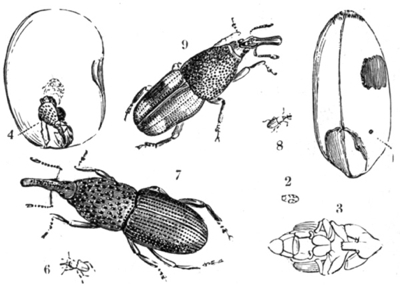

| CHARLOCK WEEVIL | 130 |

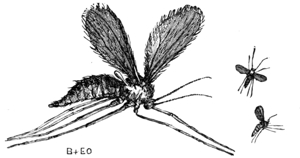

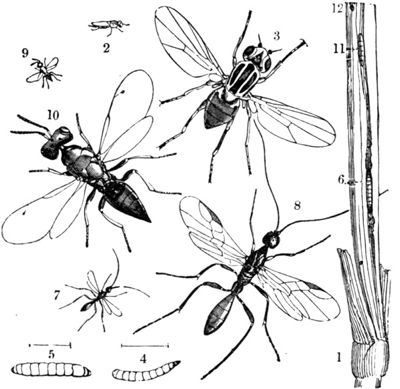

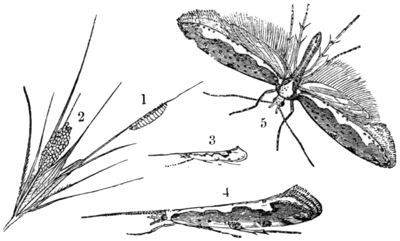

| HESSIAN FLY | 131 |

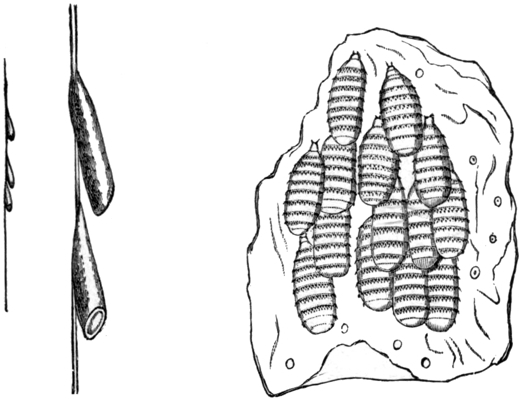

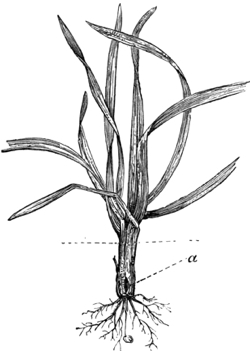

| HESSIAN FLY MAGGOT ON YOUNG WHEAT AND ON BARLEY | 132 |

| HESSIAN FLY ATTACK ON BARLEY | 132 |

| GOUT FLY, OR RIBBON-FOOTED CORN FLY | 133 |

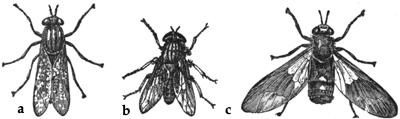

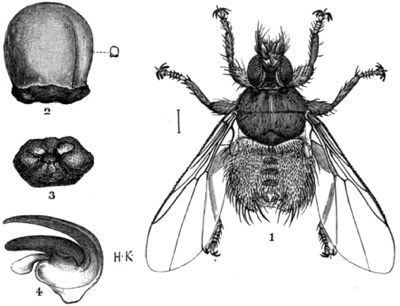

| FOREST FLY | 134 |

| GREAT OX GADFLY | 135 |

| BREEZE FLIES | 136 |

| SADDLE FLY ATTACK ON BARLEY | 137 |

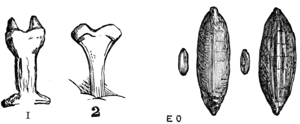

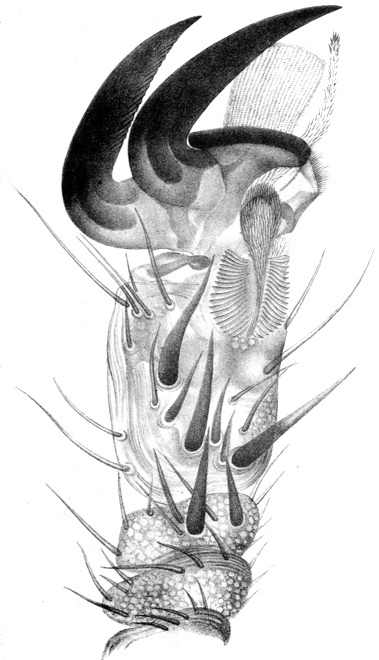

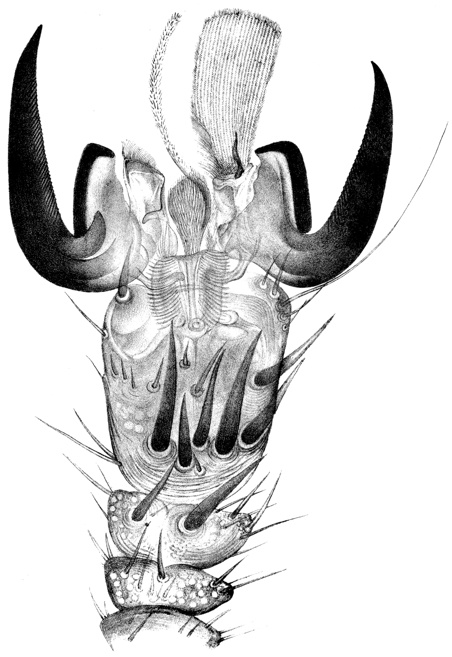

| FOOT OF FOREST FLY | 139 |

| xviiiDEER FOREST FLY | 140, 141 |

| SHEEP SPIDER FLY | 141 |

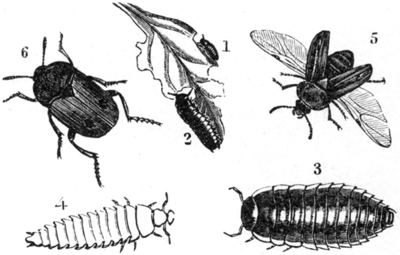

| BEET CARRION BEETLE | 142 |

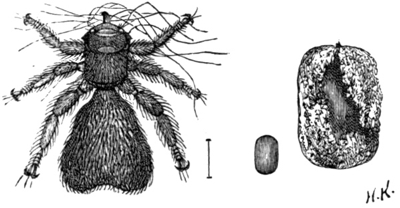

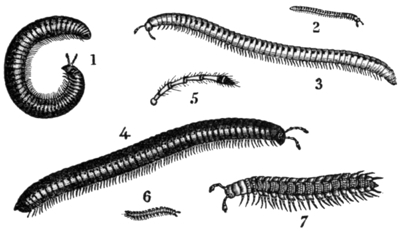

| CENTIPEDES AND A MILLEPEDE | 143 |

| AMERICAN BLIGHT OR WOOLLY APHIS | 144 |

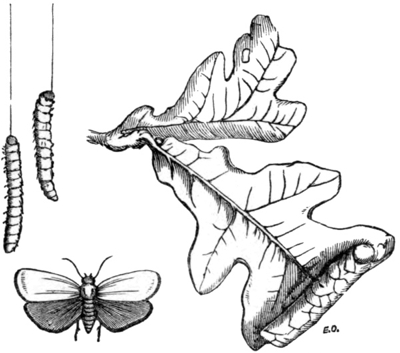

| OAK-LEAF ROLLER MOTH | 145 |

| LOOPER CATERPILLARS; WINTER MOTH AND MOTTLED UMBER MOTH | 146 |

| CORN SAWFLY | 147 |

| RED-BEARDED BOTFLY | 150 |

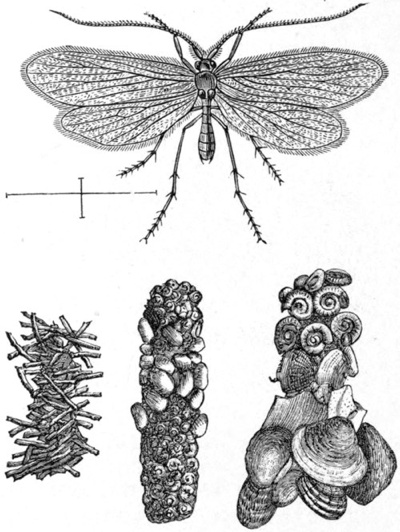

| WATER MOTH AND CADDIS WORMS | 152 |

| LAPPET MOTH | 158 |

| HOUSE SPARROW | 160 |

| TREE SPARROW | 162 |

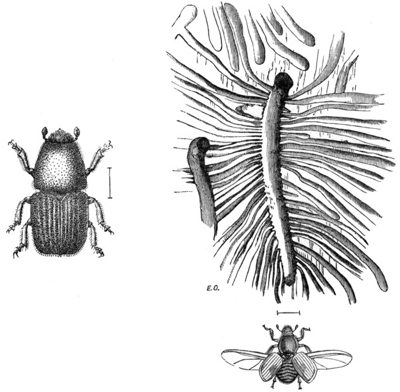

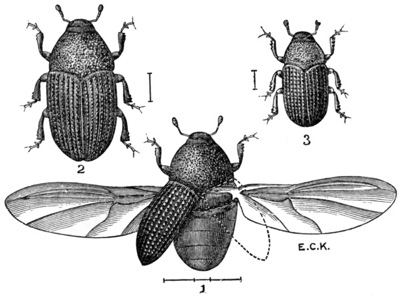

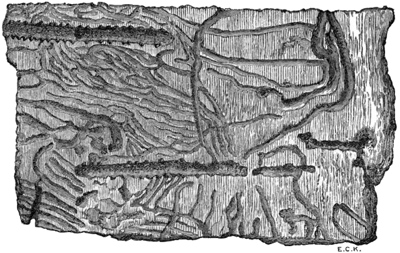

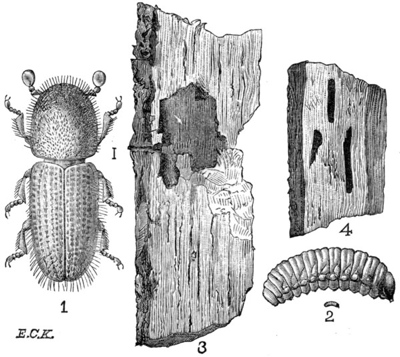

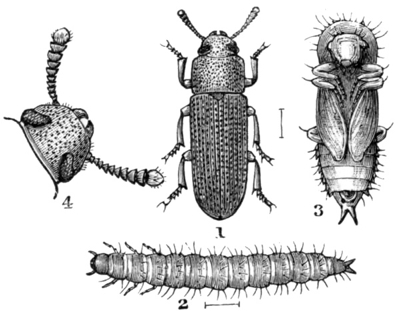

| ELM-BARK BEETLE | 170 |

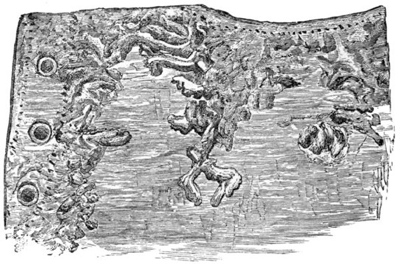

| TUNNELS OF ASH-BARK BEETLE | 171 |

| GREATER ASH-BARK BEETLE | 172 |

| PIECE OF ASH-BARK WITH BEETLE GALLERIES | 173 |

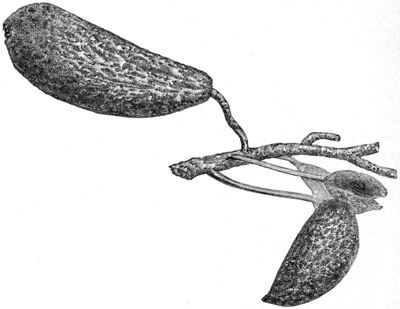

| POCKET OR BLADDER PLUM | 176 |

| SILVER Y-MOTH | 178 |

| MEDITERRANEAN FLOUR MOTH | 180 |

| ANGOUMOIS MOTH, OR FLY WEEVIL | 188 |

| LESSER EARWIG | 189 |

| SNAIL-SLUG | 191 |

| FLATWORM, LAND PLANARIAN | 192 |

| SHOT-BORER BEETLES | 199 |

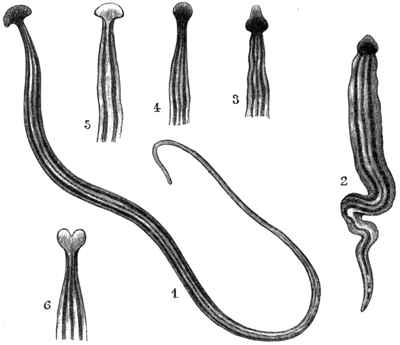

| STEM-EELWORMS | 209 |

| DIAMOND-BACK MOTHS | 211 |

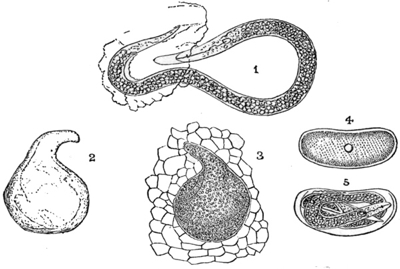

| TOMATO ROOT-KNOB EELWORM | 213 |

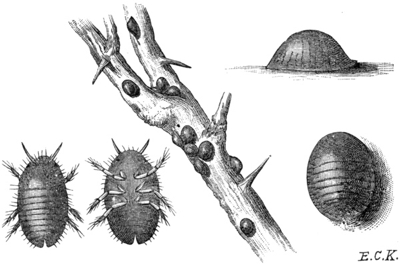

| CURRANT AND GOOSEBERRY SCALE | 214 |

| MUSTARD BEETLE | 215 |

| GOOSEBERRY AND IVY RED SPIDER | 221 |

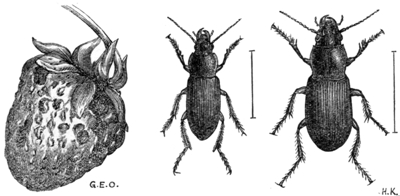

| GROUND BEETLES | 223 |

| TIMBERMAN BEETLE | 224 |

| SOUTH AMERICAN MIGRATORY LOCUST | 229 |

| PIGMY MANGOLD BEETLE | 230 |

| xixSPINACH MOTH | 231 |

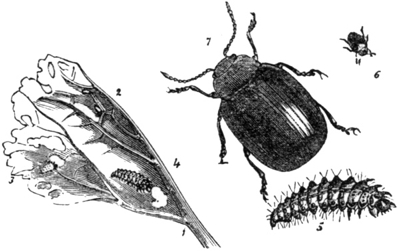

| COCKCHAFER | 233 |

| LADY-BIRDS | 234 |

| LONG-HORNED CENTIPEDES | 235 |

| EYED LADY-BIRD | 237 |

| WHEAT MIDGE | 239 |

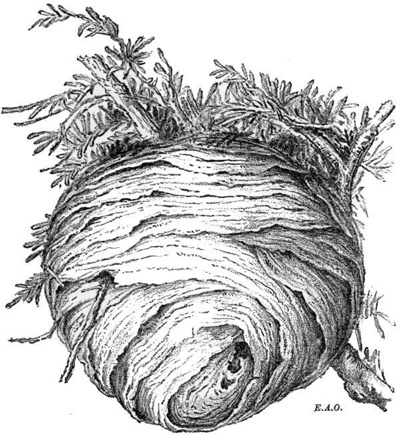

| NEST OF TREE WASP | 241 |

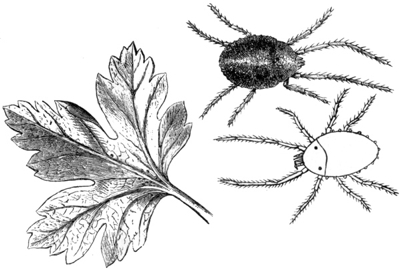

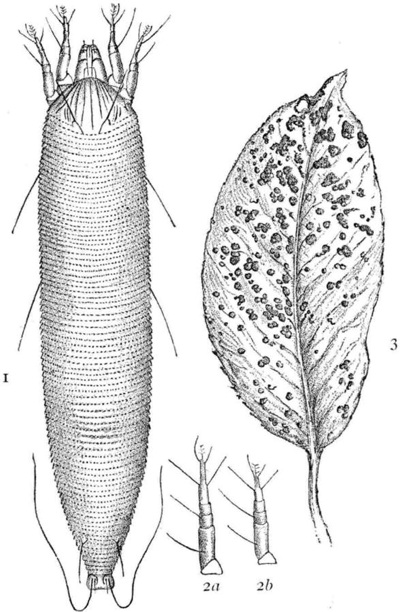

| PEAR LEAF BLISTER MITE | 249 |

| CURRANT GALL MITE | 251 |

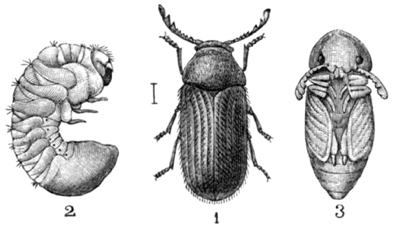

| BREAD, PASTE, OR BOOT BEETLE | 253 |

| BOOT INJURED BY PASTE BEETLE MAGGOT | 254 |

| GRANARY WEEVIL | 262 |

| GROUSE FLY | 265 |

| RUST-RED FLOUR BEETLE | 266 |

| MOTTLED WILLOW WEEVIL | 267 |

| GOAT MOTH | 268 |

| PEA AND BEAN WEEVILS | 269 |

| BEAN BEETLES | 270 |

| “SPLINT,” OR SAP-WOOD BEETLE | 271 |

| SHEEP’S NOSTRIL FLY | 305 |

| PLATE | ||

| ELEANOR ANNE ORMEROD, LL.D. | Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | ||

| I. | SEDBURY PARK HOUSE AND GROUNDS | 6 |

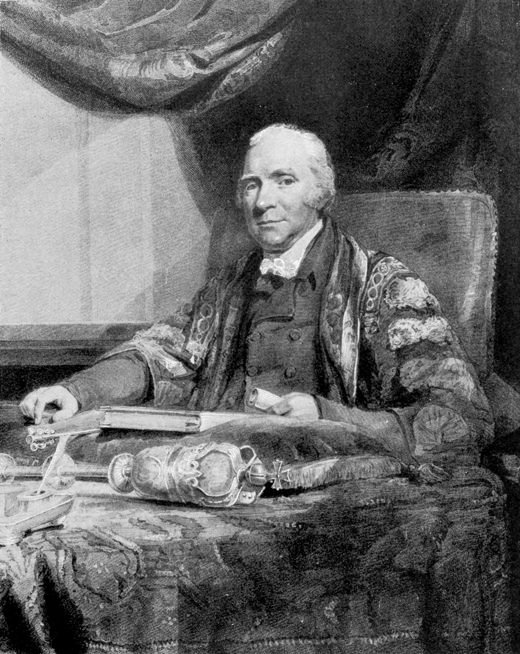

| II. | GEORGE ORMEROD, ESQ., D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S., F.S.A. | 8 |

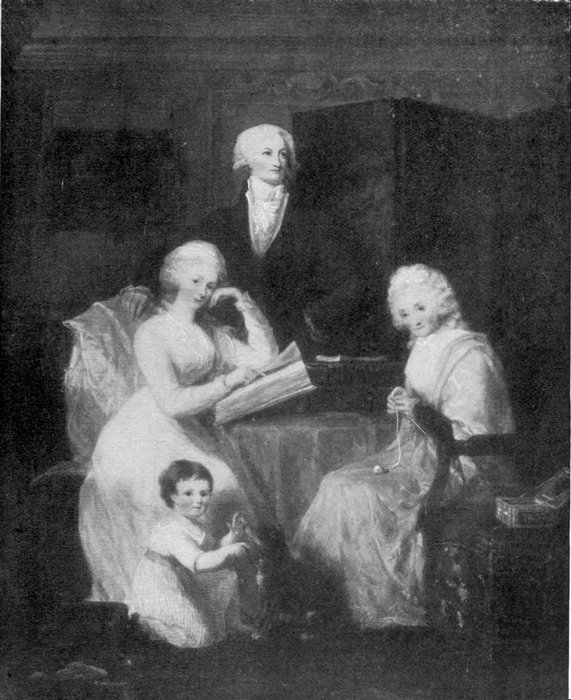

| III. | FAMILY GROUP—GEORGE ORMEROD AS A CHILD, AND HIS MOTHER, UNCLE, AND GRANDMOTHER | 10 |

| IV. | JOHN LATHAM, ESQ., M.D., F.R.S., PHYSICIAN | 12 |

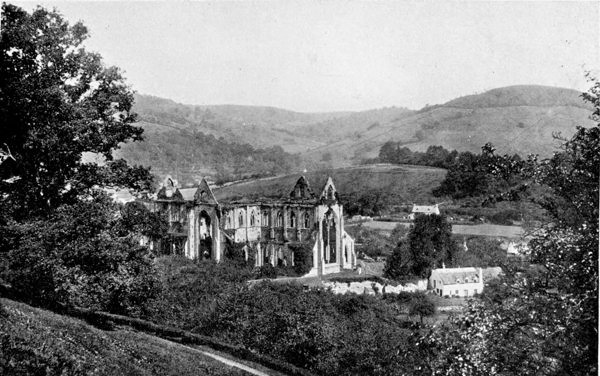

| V. | RUINS OF TINTERN ABBEY, MONMOUTHSHIRE | 16 |

| VI. | NORMAN WORK FROM CHEPSTOW PARISH CHURCH | 18 |

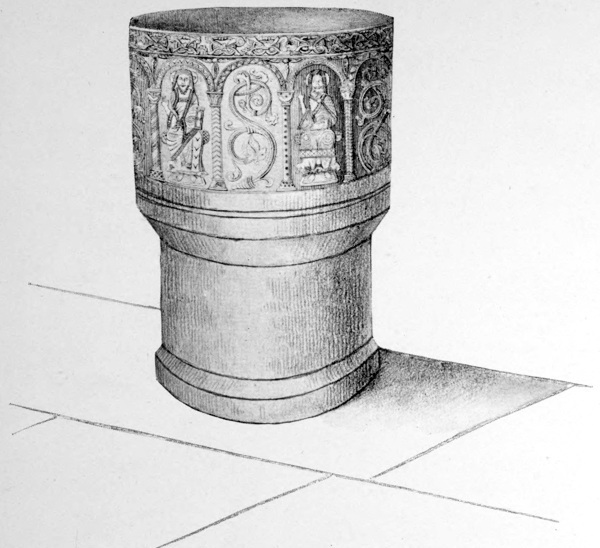

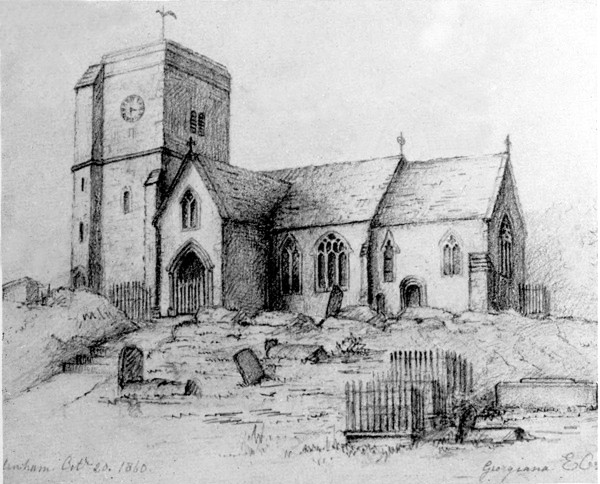

| VII. | LEADEN FONT IN TIDENHAM CHURCH, GLOUCESTERSHIRE, AND CHURCH OF ST. MARY THE VIRGIN, TIDENHAM | 20 |

| xxVIII. | NORMAN CHAPEL, LLANCAUT, WYE CLIFFS | 22 |

| IX. | MAP OF THE BANKS OF THE WYE | 32 |

| X. | RUINED ANCHORITE’S CHAPEL OF ST. TECLA, AND SEVERN CLIFFS, SEDBURY PARK | 34 |

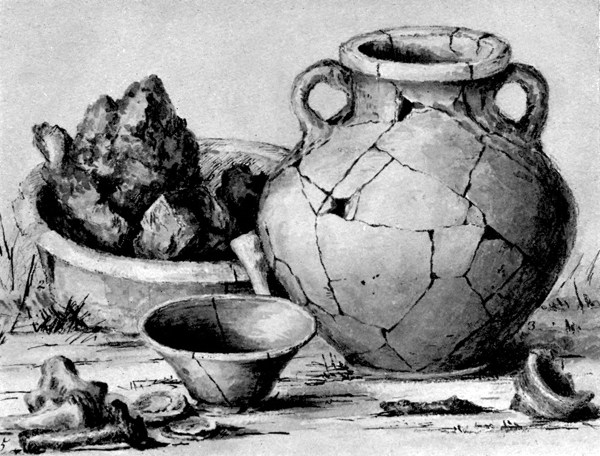

| XI. | ROMAN POTTERY, FOUND IN SEDBURY PARK, AND SAURIAN FROM LIAS, SEDBURY CLIFFS | 40 |

| XII. | ROYAL MAIL, OLD GENERAL POST OFFICE, LONDON | 42 |

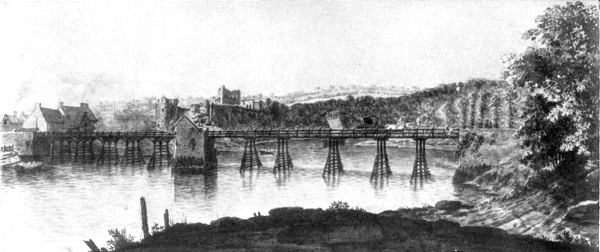

| XIII. | OLD CHEPSTOW BRIDGE, WITH POST-CHAISE CROSSING IT | 45 |

| XIV. | A WEST OF ENGLAND ROYAL MAIL, en route | 46 |

| XV. | MAP OF DISTRICT OF THE CHARTIST RISING IN MONMOUTH | 50 |

| XVI. | CHEPSTOW CASTLE, MONMOUTHSHIRE | 52 |

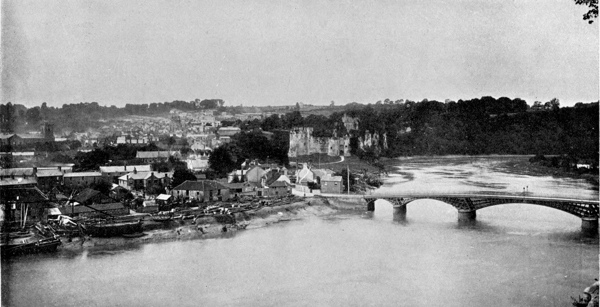

| XVII. | CHEPSTOW WITH THE BRIDGE OVER THE WYE AND CHEPSTOW CASTLE ON THE RIVER BANK | 54 |

| XVIII. | ANTIQUE CARVED CHEST, AN HEIRLOOM | 58 |

| XIX. | TORRINGTON HOUSE, ST. ALBANS, HERTS. | 74 |

| XX. | MISS ORMEROD’S METEOROLOGICAL STATION | 80 |

| XXI. | HEDGEHOG OAK, SEDBURY PARK, AND AP ADAM OAK, SEDBURY PARK | 92 |

| XXII. | MISS ORMEROD’S MEDALS, RECEIVED 1870 TO 1900 | 98 |

| XXIII. | FOOT OF FOREST FLY—SIDE VIEW | 138 |

| XXIV. | FOOT OF FOREST FLY—SEEN FROM ABOVE | 138 |

| XXV. | RUINS OF CHEPSTOW CASTLE, MONMOUTHSHIRE | 174 |

| XXVI. | RAILWAY BRIDGE OVER THE WYE, NEAR CHEPSTOW | 208 |

| XXVII. | MISS GEORGIANA ELIZABETH ORMEROD | 284 |

| XXVIII. | ORMEROD HOUSE, LANCASHIRE | 300 |

| XXIX. | ELEANOR ANNE ORMEROD, LL.D., F.R.MET.SOC. | 312 |

| XXX. | MISS ORMEROD’S FATHER, AT FIVE YEARS OLD, AND MISS ORMEROD IN CHILDHOOD | 324 |

I was born at Sedbury Park, in West Gloucestershire, on a sunny Sunday morning (the 11th of May, 1828), being the youngest of the ten children of George and Sarah Ormerod, of Sedbury Park, Gloucestershire, and Tyldesley, Lancashire. As a long time had elapsed since the birth of the last of the other children (my two sisters and seven brothers), my arrival could hardly have been a family comfort. Nursery arrangements, which had been broken up, had to be re-established. I have been told that I started on what was to be my long life journey, with a face pale as a sheet, a quantity of black hair, and a constitution that refused anything tendered excepting a concoction of a kind of rusk made only at Monmouth. The very earliest event of which I have a clear remembrance was being knocked down on the nursery stairs when I was three years old by a cousin of my own age. The damage was small, but the indignity great, and, moreover, the young man stole the lump of sugar which was meant to console me, so the grievance made an impression. A year later a real shock happened to my small mind. Whilst my sister, Georgiana, five years my senior, was warming herself in the nursery, her frock caught fire. She flew down the room, threw herself on the sheepskin rug at the door, and rolled till the fire was put out. But she was so badly burnt that the injuries required dressing, and this event also made a great impression on me. Other reminiscences of pleasure and of pain come back, in thinking over those long past days, but none of such special and wonderful interest as that of being held up to see King William IV. Little as I was, I had been taken to one of the theatres, and my father carried me along one of the galleries, and raised me in his arms that I might look through the glass window 2at the back of one of the boxes and see His Majesty. I do not in the least believe that I saw the right man. However, it is something to remember that about the year 1835, if I had not been so frightened, I might have seen the King.

In regard to any special likings of my earliest years it seems to me, from what I can remember or have been told, that there were signs even then of the chief tastes which have accompanied me through life—an intense love of flowers; a fondness for insect investigation; and a fondness also for writing. In my babyhood, even before I could speak, the sight of a bunch of flowers was the signal for both arms being held out to beg for the coveted treasure, and the taste was utilised when I was a little older, in checking a somewhat incomprehensible failure of health during the spring visit of the family to London. Some one suggested trying the effect of a supply of flower roots and seeds for me to exercise my love of gardening on, and the experiment was successful. I can remember my delight at the sight of the boxes of common garden plants—pansies, daisies, and the like; and I suppose some feeling of the restored comfort has remained through all these years to give a charm (not peculiarly exciting in itself) to the smell of bast mats and other appurtenances of the outside of Covent Garden market.

My first insect observation I remember perfectly. It was typical of many others since. I was quite right, absolutely and demonstrably right, but I was above my audience and fared accordingly. One day while the family were engaged watching the letting out of a pond, or some similar matter, I was perched on a chair, and given to watch, to keep me quiet at home, a tumbler of water with about half a dozen great water grubs in it. One of them had been much injured and his companions proceeded quite to demolish him. I was exceedingly interested, and when the family came home gave them the results of my observations, which were entirely disbelieved. Arguing was not permitted, so I said nothing (as far as I remember); but I had made my first step in Entomology.

Writing was a great pleasure. A treat was to go into the library and to sit near, without disturbing, my father, and “write a letter” on a bit of paper granted for epistolary purposes. The letter was presently sealed with one of the great armorial seals which my father wore—as gentlemen did then—in a bunch at what was called the “fob.” The whole affair must have been of a very elementary sort, but 3it was no bad application of the schoolroom lessons, for thus, quite at my own free will, I was practising the spelling of easy words, and their combination into little sentences, and also how to bring pen, ink, and paper into connection without necessitating an inky deluge. In those days children were not “amused” as is the fashion now. We neither went to parties, nor were there children’s parties at home, but I fancy we were just as happy. As soon as possible a certain amount of lessons, given by my mother, formed the backbone of the day’s employment. In the higher branches requisite for preparation for Public School work, my mother was so successful as to have the pleasure of receiving a special message of appreciation of her work sent to my father by Dr. Arnold, Head master of Rugby. All my brothers were educated under Dr. Arnold, two as his private pupils, and the five younger as Rugby schoolboys, and he spoke with great appreciation of the sound foundation which had been laid by my mother for the school work, especially as regarded religious instruction. From the fact of my brothers being so much older than I, the latter point is the only one which remains in my memory; but I have a clear recollection of my mother’s mustering her family class on Sunday afternoons, i.e., all whose age afforded her any excuse to lay hands on them. Whether in the earlier foundation or more advanced work, my mother’s own great store of solid information, and her gift for imparting it, enabled her to keep us steadily progressing. Everything was thoroughly learned, and once learned never permitted to be forgotten. Nothing was attempted that could not be well understood, and this was expected to be mastered. In playtime we were allowed great liberty to follow our own pursuits, in which the elders of the family generally participated, and as we grew older we made collections (in which my sister Georgiana’s love of shells laid the foundation of what was afterwards a collection of 3,000 species), and carried on “experiments,” everlasting re-arrangement of our small libraries, and amateur book-binding. All imaginable ways of using our hands kept us very happily employed indoors. Out of doors there was great enjoyment in the pursuits which a country property gives room for, and I think I was a very happy child, although I fancy what is called a “very old-fashioned” one, from not having companions of my own age.

On looking back over the years of my early childhood, 4the period when instruction—commonly known as education—is imparted, it seems to me that this followed the distinction between education and the mere acquirement of knowledge (well brought out by one of the Coleridges), and embraced the former much more fully than is the case at the present day. There was no undue pressure on bodily or mental powers, but the work was steady and constant. The instruction, except in music, was given by my mother, who had, in an eminent degree, the gift of teaching. Although at the present time home education is frequently held up to contempt, still some recollections of my own home teaching may be of interest. The subjects studied were those included in what is called a “solid English education.” First in order was biblical knowledge and moral precepts, practical as well as expository, which seem to have glided into my head without my being aware how, excepting in the case of the enormity of any deviation from truth. In each of the six week-days’ work came a chapter of Scripture, read aloud, half in English, and half in French, by my sister and me. The “lessons,” i.e., recitation, inspection of exercises, &c., followed. The subjects at first were few—but they were thoroughly explained. Geography, for example, was taken at first in its broad bearings, viz., countries, provinces, chief towns, mountains, rivers, and so on (what comes back to my mind as corresponding to “large print”), and gradually the “small print” was added, with as minute information as was considered necessary. Use of the map was strictly enforced, and repetition to impress it on the memory. I seem to hear my mother inculcating briskness in giving names of county towns—“Northumberland? Now then! quick as lightning, answer.” “Newcastle, Morpeth and Alnwick, in Northumberland”; and to enforce attention a tap of my mother’s thimble on the table, or possibly, if stupidity required great rousing, with more gentle application on the top of my head. If things were bad beyond endurance, the book was sent with a skim across the room, which had an enlivening effect; but this rarely happened. My mother gave the morning hours to the work (unless there was some higher claim upon them, such as my father requiring her for some purpose or other) but she always declared that she would have nothing to do with the preparation of lessons in the afternoon. If all went fairly well, as usual, the passage for next day’s lesson was carefully read over at my mother’s side, and difficulties explained, and 5then I was expected to learn it by myself. What we knew as “doing lessons”—which now I believe passes under the more advanced name of “preparation”—was left to my own care, and if this proved next morning not to have been duly given I had reason to amend my ways. The preparation hour was from four to five o’clock, but if the lessons had not been learned by that time they were expected to be done somehow, though I think my mother was very lenient if any tolerably presentable reason were given for short measure. If the work were completed in less than the allotted time, I was allowed to amuse myself by reading poetry, of which I was excessively fond, from the great volume of “Extracts” from which my lesson had been learned. This plan seems to me to have had many advantages. For one thing, I carried the morning’s explanations in my head till called upon, and for another, I think it gave some degree of self-reliance, as well as a habit of useful, quiet self-employment for a definite time. This was, in all reason, expected to be carefully adhered to, and I can well remember when I had hurried home from a summer’s walk how the muscles in my legs would twitch whilst I endeavoured to learn a French verb.

One educational detail which, as far as my experience goes, appears to have been much better conducted in my young days than at present, was that reading aloud to the little people had not then come into vogue. I have no recollection of being allowed to lie about on the carpet, heels in the air, whilst some one read a book to me. There was also the peculiarity to which, if I remember rightly, Sir Benjamin Brodie attributes in his autobiography some of his success in life, viz., work was almost continuous. There was never an interval of some weeks’ holidays. A holiday was granted on some great occasion, such as the anniversary of my father and mother’s wedding-day and birthdays, and on the birthdays of other members of the family, but (if occurring on consecutive days) somewhat under protest; and half-holidays were not uncommon in summer. These consisted of my being excused the afternoon preparation of lessons, and as the pretext for asking was generally the weather’s being “so very fine,” I conjecture it was thought that an extra run in the fresh air was perhaps a healthy variety of occupation. Any way, the learning lost must have been small, for excepting the written part of the work the lessons were expected to appear next morning in perfect form, however miscellaneously 6acquired. One way or other there were occasional breaks by pleasant episodes such as picnics, on fine summer days, to one of the many old ruined castles, or disused little Monmouthshire churches, or Roman remains in the neighbourhood, where my father worked up the material for some forthcoming archæological essay and my mother executed some of her beautiful sketches (plate VI.). The carriage-load of young ones enjoyed themselves exceedingly, and prevented the work from becoming monotonous or burdensome. And there were joyful days before and after going from home, and now and then, when it was impossible for my mother to give her morning up to the work, if she had not appointed one of the elder of the young fry her deputy for the occasion. I remember, too, that I took my book in play hours, when and where I wished; sometimes on a fine summer afternoon the “where” might be sitting on a horizontal bough of a large old Portugal laurel in the garden. And I fancy that the perch in the fresh air, with the green light shimmering round me, was as good for my bodily health (by no means robust) as my entertaining little book for my progress in reading.

It was remarkable the small quantity of food which it was at one time thought the right thing for ladies to take in public. I suppose from early habit, my mother, who was active both in body and mind, used to eat very little. At lunch she would divide a slice of meat with me. Although now the death, in her confinement, of the Princess Charlotte, “the people’s darling,” which plunged the nation in sorrow, is a thing only of history, yet it is on record how she almost implored for more food, the special desire being mutton chops. Though not in any way connected with the Royal Family, my mother held in memory the unhappy event from its consequences. Sir Richard Croft, whose medical attentions had been so inefficient to the Princess, was shortly after called to attend in a similar capacity on Mrs. Thackeray, wife of Dr. Thackeray, then or after Provost of King’s College, Cambridge. For some reason or other he left his patient for a while, and the story went that, finding pistols in the room where he was resting, he shot himself. Miss Cotton—Mrs. Thackeray’s sister—was a friend of my mother. Miss Thackeray, the infant who was ushered into the world by the death of both her mother and the doctor, survived, and in her young-lady days was particularly fond of dancing; and I have the remembrance of my first London ball being at her aunt’s house.

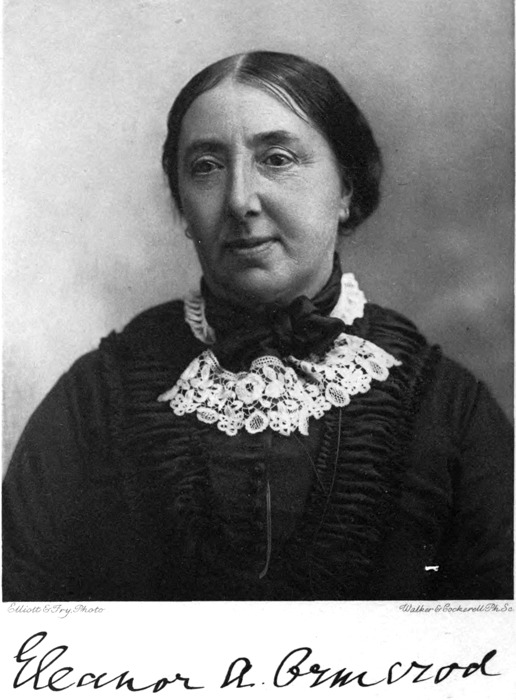

PLATE I.

Sedbury Park House and Grounds, distant view.

The situation of Sedbury (plate I.), rising to an elevation of about 170 feet between the Severn and the Wye, opposite Chepstow, was very beautiful, and the vegetation rich and luxuriant. My father purchased the house and policy grounds from Sir Henry Cosby about 1826, and it was our home till his death in 1873. He retained Tyldesley, his other property in Lancashire, with its coal mines, but we did not reside there, as the climate was too cold for the health of my mother and for the young family.

[The original purchase was called Barnesville, and earlier still Kingston Park, and it consisted of a moderate-sized villa with the immediately adjoining grounds. The property was added to by purchases from the Duke of Beaufort, and it was renamed Sedbury Park after the nearest village. To the house the new owner added a handsome colonnade about 10 feet wide, and a spacious library. Sir Robert Smirke, the architect of all the improvements, was the man who designed the British Museum, the General Post Office, &c.[3] Barnes Cottage on the property, at one time ‘Barons Cottage,’ was kept in habitable repair because it secured to the estate the privilege of a seat in church.]

About sixteen miles from Sedbury Park are still to be seen the interesting ruins of the Great Roman station of this part of the country, Caerwent or the white tower, the Venta Silurum of Antonine’s “Itinerary.”[4] Its trade and military 8importance were transferred to Strigul, now known as Chepstow, after the Norman Conquest. Sedbury Park is believed to have been an outlying post of this chief military centre, and it was occupied by soldiers “guarding the beacon and the look-out over the passages” of the Severn. Considerable finds of Roman pottery (plate XI.) were discovered about 1860, while drains about 4 feet deep were being cut near to the Severn cliffs. They consisted chiefly of fragments of rough earthenware—cooking dishes and cinerary urns, &c. There was also a small quantity of glazed, red Samian cups and one piece of Durobrivian ware and great quantities of animals’ teeth and bones, but no coins (p. 174). After the death of my father it was found that much of the best ware had been stolen.

My father (plate II.) is well known for the high place he takes amongst our English County historians, as the author of “The History of the County Palatine, and City of Chester,” published in 1818. He came of the old Lancashire family of Ormerod of Ormerod, a demesne in the township of Cliviger, a wild and mountainous district, situated along the boundaries of Lancashire and Yorkshire. The varied watershed (transmitting the streams to the eastern and western seas); the beauties of the rocks and waterfalls; the shaded glens, and the antique farmhouses (where fairy superstition still lingered till the beginning of the past century), have been written about by Whitaker in his “History of Whalley.”[5] There, in the year 1810, in an elevated position, amongst aged pine and elm trees, and surrounded by high garden walls of dark stone, the mansion, (plate XXVIII.)—since greatly enlarged by the family of the present proprietor—stood in a dingle at the side of a mountain stream, which rushed behind it at a considerable depth. Beyond the stream, the rise of the ground to the more elevated moors includes a view of the summit of Pendle Hill, of exceedingly evil repute for meetings of witches and warlocks, and congenerous unpleasantnesses, in the olden time.

The family of Ormerod was settled in the locality from which they took their name, as far back as the year 1311, the estates continuing in their possession until, in 1793 (by the marriage of Charlotte Ann Ormerod, sole daughter and heiress of Laurence Ormerod, the last of the generation of the parent stem in direct male descent), they passed to Colonel John Hargreaves; and by the marriage of his eldest 9daughter and co-heiress, Eleanor Mary, with the Rev. William Thursby, they became vested in the Thursby family,[6] represented until recently by Sir John Hardy Thursby, Bart., of Ormerod House, Burnley, Lancashire, and Holmhurst, Christchurch, Hants. Sir John showed thoughtful, philanthropic feeling to his Lancashire district, by presenting the land for a public park to Burnley, and, in connection with his family, he also gave the site for the neighbouring “Victoria Hospital.” In 1887, he served as High Sheriff of Lancashire, and was created Baronet. Dying on March 16, 1901, he was succeeded by his eldest son, John Ormerod Scarlett Thursby, of Bankhall, Burnley, who, in his surname and baptismal names, keeps alive the connection with the old family stock and the families with which the last two co-heiresses of Ormerod were connected by marriage. With these matters of possessions, however, the collateral branch of Ormerod, of Bury in Lancashire (from the special founder of which my father was descended in direct male line), had nothing to do. From Oliver Ormerod, who became permanently resident at Bury shortly after the close of the seventeenth century, descended his only son, George Ormerod of Bury, merchant. From him descended George Ormerod (an only child), who died on October 7, 1785, a few days before the birth of his only child—my father—yet another George Ormerod. In a mere statement of the names of the representatives of successive generations, of whom no specially distinguishing points appear to have been recorded, there is, perhaps, little of general interest. But possibly some amount of interest attaches to the proofs of representatives of one family having lived quietly on from generation to generation in one locality since the early part of the fourteenth century. The connections and intermarrying of the Ormerods with many of the Lancashire families of former days give the subject a county interest to those who care to search out the genealogical, historical and heraldic details given at great length in my father’s volume of “Parentalia.” Here and there some member of the family appears to have come before the world, as in the case of Oliver Ormerod, M.A., noted as a profound scholar, theologian, and Puritan 10controversialist, and author of two polemical works—one entitled “The Picture of a Puritan,” published in 1605, and the other “The Picture of a Papist,” published in 1606. Oliver Ormerod was presented to the Rectory of Norton Fitzwarren, Co. Somerset, by William Bourchier, third Earl of Bath, and afterwards to the Rectory of Huntspill in the same county, where he died in the year 1625.

Something, however, occurred in 1784 of much interest to our own branch of the family, leading subsequently to great increase of property, and likewise in some degree, connecting us with the Jacobite troubles of 1745. This was the marriage of my grandfather with Elizabeth, second daughter of Thomas Johnson, of Tyldesley. Thomas Johnson (my great grandfather) having married, secondly, Susannah, daughter and co-heiress of Samuel Wareing, of Bury and Walmersley, got with her considerable estates, inherited from the Wareings, the Cromptons of Hacking, and Nuthalls of Golynrode. On the occasion of the march of Charles Stewart to Manchester in 1745, “Tyldesley”—to use the form of appellation often given from property in those days—suffered many hardships. As one of the five treasurers who had undertaken to receive Lancashire subscriptions in aid of the reigning monarch, King George the Second, and as an influential local friend of the cause, he was one of those who suffered the infliction of domiciliary military visitation, and also threat of torture by burning his hands to induce him to give up government papers and money in his possession. I have still in my house (1901) the large hanging lamp of what is now called “Old Manchester” glass, which lighted the dining-room when my great grandfather stood so steadily to his trust that although the straw had been brought for the purpose of torture (or to terrify him into submission) extremities were not proceeded to. He was ultimately left a prisoner on parole, in his house, until released in December, 1745, in consequence of the retreat of the rebel army. But disagreeable as this state of things must have been at the best, it was to some degree lightened by kindness (or at least absence of unnecessary annoyance) on the part of the Jacobite officers, of whom stories remained in the family to my own time. One especial point was their kindness to my eldest great aunt,[7] then a little child, whom they used to take on their knees to show her what she described as their “little guns.” The drinking of the healths of the rival 11princes, which probably often led to a less peaceful ending, was mentioned by my father in his History of Cheshire, as a notable instance of consideration.

PLATE III.

Family Group—George Ormerod as a child; his Mother seated behind him; her brother, Thomas Johnson, Esq., of Tyldesley, Lancashire, standing; and their Mother seated on the right.

Composition from miniature, circa 1780.

“On one occasion when the Scotch officers who caroused in their prisoner’s house, had given their usual toast King James, and the host on request had followed with his, and undauntedly proposed King George, some rose, and touched their swords; but a senior officer exclaimed, ‘He has drunk our Prince, why should we not drink his? Here’s to the Elector of Hanover.’”[8]

During the disturbed time, when any one bearing the appearance of a messenger would assuredly have been seized with the papers which he carried, the difficulty of transmitting information was met by the employment at night of two greyhounds trained for the service. The documents were fastened to the animals and thus carried safely to the adherent’s house, from which as opportunity offered they could be passed on. The greyhounds, having been well fed as a reward and encouragement to future good behaviour, were started off on their return journey. In the present day this plan of transmission would very soon be discovered, but in those times the nature of the country, the nocturnal hours chosen, and also the deeply-rooted superstitions of the district, all helped to make the four-footed messengers very trusty carriers.

In 1755 Thomas Johnson served as Sheriff of Lancashire. He died in 1763, leaving a widow (who survived him until 1798), one son, and three daughters—the only survivors of a family of eleven children, of whom seven died in infancy, three on the day of their birth. Of the four children who reached maturity, Elizabeth, the second daughter (plate III.) married my grandfather, George Ormerod of Bury, at the Collegiate Church, Manchester, on the 18th of October, 1784. He died in 1785, a fortnight before the birth of my father, who was the sole issue of this marriage.

My father, George Ormerod (plate II.), heir to his grandfather, was born October 20, 1785. He was co-heir of, and successor to the estates of his maternal uncle in 1823, and sole heir to his surviving maternal aunt in 1839. He was D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S., F.S.A., and a magistrate for the counties of Cheshire, Gloucester, and Monmouth. On August 2, 1808, he married my mother, Sarah, eldest daughter of John Latham, Bradwall Hall, Cheshire, Fellow 12and sometime President of the Royal College of Physicians, Harley Street, London.[9]

My grandfather in the female line, John Latham, M.D., F.R.S. (plate IV.), the eldest son of the Rev. John Latham, came of an old family stock, and was born in 1761 in the rectory house at Gawsworth, Cheshire. He was educated first at Manchester Grammar School, and thence proceeded (with the view of studying for orders) to Brasenose College, Oxford, but the strong bent of his own wishes towards the medical profession induced him to alter his plans, and he took his degree of M.D. on October 10, 1788. “His first professional years were passed at Manchester and Oxford, where he was physician to the respective infirmaries. In 1788 he removed to London, was admitted Fellow of the College of Physicians, and elected successively physician to the Middlesex, the Magdalen, and St. Bartholomew Hospitals. In 1795 he was appointed Physician Extraordinary to the Prince of Wales, and reappointed to the same office on the Prince’s accession to the throne as George IV. In 1813 Dr. Latham was elected President of the College of Physicians; in 1816, founded the Medical Benevolent Society; and in 1829 finally left London, retiring to his estate at Bradwall Hall, where he died on April 20, 1843, in the eighty-second year of his age.”

He indulged in the practical pleasures of country life, and maintained a home farm, on which he kept a dairy of sixty cows. He was a man of great force of character and of decisive action. On one occasion a man who had been told that if he returned he would be summarily ejected, came back to crave an audience. On being reminded of the fact he pleaded, “Oh! doctor, you do not really mean it.” “Yes, I do,” was the prompt reply as an order was given to the butler to turn the intruder out.

PLATE IV.

John Latham, Esq., M.D., F.R.S., Physician Extraordinary to George IV., maternal grandfather of Miss Ormerod, in his robes as President of the Royal College of Physicians, 1813 to 1819.

Dr. Latham married, in 1784, Mary, eldest daughter and co-heiress of the Rev. Peter Mayer, Vicar of Prestbury, Cheshire, by whom he had numerous children, of whom three sons and two daughters lived to maturity. My 13mother, his eldest daughter, survived him, as did also her brothers. Of these the second son, Peter Mere Latham, M.D., of Grosvenor-street, Westminster, one of Her Majesty’s Physicians Extraordinary, was long well known as an eminent consulting physician regarding diseases of the chest, until his own severe sufferings from asthma obliged him to retire to Torquay, where he died on July 20, 1875.

From our being related to John Latham and his wife, Mary Mayer (although in point of rank the difference was so enormous between the head from whom we could trace and ourselves), it is permissible to allude to our connection with the family of Arderne of Alvanley, and consequent descent from King Edward the First and his wife, Eleanor of Castile. This gave us our claim of “founder’s kin” in the election to the “Port Fellowship” of Brasenose College, to which distinction in my time my brother— Rev. John Arderne Ormerod—was elected. He was the last Port Fellow on the above foundation. The record of each generation will be found in the genealogical table of “Arderne” in my father’s “Parentalia,” and also on reference to the pedigrees of the many families of which members are named in the “History of Cheshire.”

My cousin Eleanor Anne Ormerod was the youngest of a family of ten—seven brothers and three sisters—all clever, energetic creatures, and gifted with a strong sense of humour. A large family always creates a peculiar atmosphere for itself; it also breaks up into detachments of elder and younger growth, and the elder members are beginning to take places in the world before the younger are out of the schoolroom. Eleanor’s eldest brother was a Church dignitary while she was still a child, teased and petted by her young medical student brothers, and the darling of her elder sister Georgiana. The father and mother of this numerous flock were both remarkable people. Mr. Ormerod, historian and antiquary, always occupied with literary or topographical research, was an autocrat in his own family and intolerant of any shortcomings or failings that came under his notice. He could, however, on occasion, relax and tell humorous stories to children. The family discipline was strict; the younger members were expected to yield obedience to the elders, and it was said that the spaniel Guy (he came from Warwick), who ranked as one of the children, always obeyed the eldest of the family present. My aunt had a large share of the milk of human kindness added to much practical common sense and a touch of artistic genius in her composition; it was from her that her daughters inherited their eye for colour and dexterity of touch. Mr. Ormerod was a neat draughtsman of architectural subjects, but my aunt had taste and skill and a delight in her own branch of art—flower painting—that lasted all her life.

Sedbury Park (plate I.) was a beautiful home; the house, a handsome family mansion with comfortable old-fashioned 15furniture, good and interesting pictures, old china, and a splendid library, afforded also ample space for its inmates to follow their various hobbies, and many were the arts and crafts practised there at various times. The carpenter’s bench, the lathe, wood-carving, electro-typing, modelling and casting for models each had their turn, and in all this strenuous play Eleanor had her full share. Society played a very secondary part in life at Sedbury; calls were exchanged with county neighbours at due intervals, and there was some intimacy with Copleston, Bishop of Llandaff, the Bathursts of Lydney Park, and the Horts of Hardwicke. But though Mr. Ormerod attended to his duties as magistrate, and went duly to meetings of the bench at Chepstow, he was quite without sympathy for field sports and the pursuits of his brother magistrates. He was absorbed in his own studies, and something of a recluse by nature.

[Miss Ormerod has herself written of the elaborateness of the arrangements and the great formality which were associated with the regular county dinner party, the chief method of entertainment at Sedbury sixty years ago. She referred to the anxieties experienced lest the coach should not arrive in time with the indispensables including fish—“the distance of Sedbury from London involving twenty-four hours or more of transmission in weather favourable or otherwise.” Miss Ormerod continues:—

“One very important matter in the far gone past times in the arrangement of the dinner table, was the removal of the great cloth and of two cloths laid, one at each side, just wide enough to occupy the uncovered space before the guests, and long enough to reach from one end of the table to the other. The removal required a deal of care and dexterity, and I do not think it was practised at many other houses in our neighbourhood. When the table was to be cleared for dessert of course everything was removed, including the great tablecloth itself—one of the handsomest of the family possessions, and of considerable length when there were the usual number of about eighteen or twenty guests. The operation was performed as follows:—The butler placed himself at the end of each strip successively, and a few of the house servants or of those who came with guests along each side. The butler drew the slips in turn and the servants took care there should be no hitch in the passage of the cloths, and so each was nicely gathered up.

“But the removal of the great tablecloth which was the 16next operation was a more difficult matter. The great heavy central epergne of rosewood had to be lifted a little way up by a strong man-servant or two, whilst the tablecloth was slipped from beneath it and the cloth was started on its travels down the table till it came into the hands of the butler, who gathered it up. The beautifully polished table then appeared in full lustre. The shining surface sparkled excellently and presently reflected the bright silver and glass and the fruit and flowers with a brilliance which to my thinking was much more beautiful than the arrangement of later days.”]

The annual visit to London was a great delight to my aunt, who enjoyed meetings with her own family and friends, and visits to exhibitions, &c. Her husband had always occupation in the British Museum, and her daughters took painting and other lessons. Mary, the eldest, was a pupil of Copley Fielding; Georgiana (plate XXVII.), and Eleanor later, had lessons from Hunt and learnt from him how to combine birds’ nests and objects of still life with fruits and flowers into very lovely pictures. Both were excellent artists with a slight difference in style: Georgiana’s pictures had great harmony of colour and composition; Eleanor’s had more chic. Hunt was a very touchy little man—almost a dwarf—and if by any chance my aunt did not see him and bow as she drove past he cherished resentment for days after. At Sedbury driving tours or picnic excursions to the ruined castles and other objects of interest (plates V., XVI., XXV.), in the neighbourhood were frequent, and the sketches that resulted were often reproduced as zincographs. Now and then a tour abroad was achieved, but such tours were few and far between. The beautiful copy of Correggio’s “Marriage of St. Catherine” which ultimately became Eleanor’s property, was acquired on a visit to Paris and the Louvre.

This self-contained family life did not lead to the marriage of the daughters, and three only of the seven sons married—one very late in life. Mary, the Princess Royal of the family, was the centre of the first group—herself and four brothers; Georgiana that of the second, consisting of two brothers older than herself, one younger, and Eleanor. Georgiana was a most lovable person; she always believed in her younger sister’s capacity and in her projects, which were not approved of nor taken seriously by some of her elders, and could not have been carried out until after the break up of the home on the death of Mr. Ormerod. Meantime, 17the naturalist element in Eleanor was free to lay up knowledge for future use, and her country life gave leisure and opportunity for observation of bird, plant, and insect life, to say nothing of reptiles. Any snake killed on the estate was brought to Eleanor, and if it was remarkable for size or beauty she took a cast of it to be afterwards electrotyped, or had it buried in an ant-hill in order to set up its skeleton when the ants had cleaned the bones. The casts, which resembled bronze, were sometimes attached to slabs of green Devonshire marble, and made handsome paper weights. Wasps were at one time a subject of special study and interest to her brother Dr. Edward Ormerod, and she and Georgiana once conveyed a wasp’s nest to him at Brighton. I believe he did not allow the wasps to exceed a certain number, out of consideration for the neighbouring fruiterers.

The premature deaths of Edward and William, physician and surgeon, were heartfelt sorrows to the two sisters nearest in age. If Eleanor’s lot had been cast in later days she might have become a lady doctor of renown; she had many qualifications for the medical profession and a liking for domestic surgery; she had strong nerves and inspired confidence and used to say that she never went a journey without some fellow-passenger going into a detailed account of all her ailments. Besides strong nerves she had strong eye-sight and a delicate but firm touch. Her brothers did not encourage anatomical studies, but she could prepare sections of teeth and other objects for the microscope as beautifully as any professional microscopist. Some of my cousins were strong sighted and very short-sighted, and much inclined to be sceptical as to my long-sighted vision.

My last visit to Sedbury was in the autumn of 1853 in company with my step-sister Margaret Roberts, then just beginning to try her powers as an authoress. Eleanor must then have been twenty-five or twenty-six, but was considered to be quite young by her family, and in some respects was really so. She no longer played such pranks as embarking in a tub to navigate the horse pond, but her fine dark eyes would shine with mischief, and she was the licensed jester to the family circle.

PLATE V.

Ruins of Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire.

Frith photo.

The routine of life at Sedbury usually began, on the part of the younger members of the family, with a walk after breakfast prefaced by a visit to the poultry yard and greenhouses. Georgiana was chief hen-wife, and kept an account of the eggs and chickens. The park, lying on high ground between the Severn and the Wye, had beautiful 18points of view and fine timber, and there were lovely views beyond its precincts. “Offa’s Dyke” ran through a corner of the estate, and the discovery of some Roman pottery in its neighbourhood had given my cousins much occupation in sticking broken fragments together and re-building them into vases (plate XI.). Our most beautiful walk, rather too long for the morning strolls, was to the “double view,” a projecting promontory above the Wye where the river curves and from whence a lovely view is visible both up and down the stream. From the morning walk we always brought back something from hedge or field for my aunt to draw as she lay on her sofa with her drawing table across it. She was then in failing health, but still able to draw, and she used to make studies of flowers in pencil on grey paper, touching in the high light with Chinese white. Each drawing when finished was shut up in a large book, and there kept until some gathering of the family took place, when the drawings were produced and a lottery ensued, each person choosing a drawing in turn according to the number on the ticket they had drawn. I have a book of these beautiful drawings (plate VI.) which I greatly prize. In her youthful days she had painted in oils, and there were some fine copies of Dutch flower pictures in the drawing-room made by her. In later life the care of her large family left scant time for Art, but she cherished it in her daughters, and it was again a resource in her advanced age. The great sculptor Flaxman was a friend of her father and had encouraged her youthful efforts in Art. She had amazing industry and had copied many of his designs on wood as furniture decorations.

PLATE VI.

Portion of Norman Work from Chepstow Parish Church.

From a drawing by Mrs. Ormerod, 1844.

(p. 6.)

Georgiana and Eleanor usually had some painting or other industry on hand, or copying to do for their father. In the afternoon we often took a drive and were taken to see Tintern or the Wynd Cliff or some other point of interest. After dinner we sat in the library, a fine room with a splendid collection of books shut up in wire bookcases. Each member of the family had a key to the imprisoned books, but a visitor felt that to get one extracted for personal use was rather a ceremony. The beautiful illustrated books were brought out for the evening’s entertainment and then safely housed again. On Sundays we walked or drove to Tidenham Church, a “little grey church on a windy hill” (plate VII.). We took a walk in the afternoon, and in the evening Mr. Ormerod read a sermon in the library to us and the servants. Such was the routine of life that autumn at Sedbury. At the time of our visit, the Gloucester Musical 19Festival was going on, but there was no thought of going to hear it. In later years Eleanor possessed a good piano and studied the theory of music, but I think that was prompted by her general cleverness and activity of intellect rather than by any special gift for music. She was teaching herself Latin during our visit, and as time went on she acquired other languages. She made beautiful models of fruits by a process of her own invention. A collection of these was sent to an International Exhibition at St. Petersburg and she acquired sufficient knowledge of Russian to correspond with the department of the Exhibition receiving them.

After the break-up of the Sedbury home, consequent on the death of Mr. Ormerod, who survived his wife[11] for many years, Mary bought the lease of a house in Exeter and settled there for the rest of her life; the two younger sisters took a house for three years in Torquay, where we were then living as well as their, and our, old and beloved uncle, Dr. Mere Latham. Wishing to be nearer London, they removed to Isleworth and some years later to Torrington House, St. Alban’s, where they spent the remaining years of their lives.

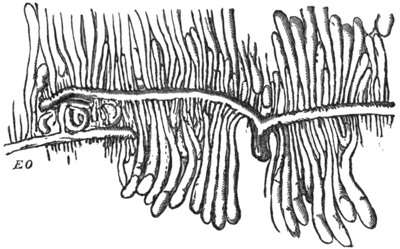

Our Parish Church (plate VII.), that is to say, the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Tidenham, Gloucestershire, in which parish my father’s Sedbury property was situated, was of considerable antiquarian interest, as, although the hamlet of Churchend in which it stands is not mentioned in the Saxon survey of 956, the original church was in existence in the year 1071. The fabric of the church when I knew it was of later date, and, as shown by the accompanying sketch, chiefly in the architecture of the fourteenth century, excepting the south doorways of the nave and chancel and the tall narrow trefoil-headed windows in the north aisle. The chief point of archæological interest, however, lies in its possession of a leaden font (plate VII.) in perfect repair, referable from its style to the transition period of Saxon and Anglo-Norman architecture, and considered not likely to be more recent in date than the eleventh century. The subject derives additional interest from the circumstance of the precise correspondence of this font in Tidenham Church with the leaden font in the church of the adjoining small parish of Llancaut, making it demonstrably certain that both the fonts were cast from the same mould.[12] The decorations 21on the fonts are in mezzo relievo. These consist of figures and foliage ranged alternately, in twelve compartments, under ornamental, semi-circular arches resting on pillars; the design—two arches containing figures alternating with two arches containing foliage—being thrice repeated. The details will be better understood from the accompanying plate than from verbal description, but may be stated as representing respectively under each of the two thrice-repeated arches a venerable figure seated on a throne, the first of the two holding a sealed book, the second raising his hand as in the act of benediction, after removal of the seal from a similar book which is grasped in his hand. Each of these figures was considered to represent the Second Person of the Trinity.[13] On this point I am not qualified to offer an opinion, but whatever may be the case as to ecclesiastical adaptation in the representation in the second of the two figures, the first of the throned figures appears to coincide with the description of the vision of the Deity, given in the “Revelation” of St. John, chap. V. verse 1,[14] rather than with any representation of “The Lamb” that “stood,” as it had been slain, and “came and took the book out of the right hand of him that sat upon the throne” (verses 6 and 7 of the chapter quoted).

PLATE VII.

Leaden Font in Tidenham Church.

Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Tidenham, Gloucestershire.

The vault on S.E. side of the Church, about 15 ft. square,

is the grave of Miss Ormerod’s Father and Mother.

From a sketch by Miss Georgiana E. Ormerod.

The illustration is taken from very careful “rubbings” of the Tidenham Font. The Llancaut font has suffered considerable damage, and likewise the loss of two of the original twelve compartments. These had presumably been removed to make the font more suitable to the exceedingly small size of the little Norman chapel (plate VIII.). This church, which in my time was almost disused, measured only about 40 feet in length by 12 in breadth, and possessed nothing of an architectural character, excepting one small round-headed window at the east end, with plain cylindrical side shafts without capitals, and a small cinquefoil piscina. The situation, on one of the crooks of the Wye, and just above the river, is romantic in the extreme. The ground rapidly slopes down to it from above, clothed with woodland from the level of the top of the precipitous cliffs which rise almost immediately beside it to a great height above the 22river. Access on that side is thus only possible by boat, or by a rough way, known as the Fisherman’s Path, along the front of the cliffs. Nevertheless, because of the exceeding picturesqueness of the spot, it was a favourite resort on the twelve Sundays in the year on which (I believe under some legal necessity) service was there, in my time, performed. The scene, on the only occasion I was ever present (when our parish church was closed), might have furnished an excellent subject for a painting, as the congregation (far too many for the little church to hold), in their bright Sunday dress, emerged from the sloping glades or woodland, to the open space close by the church. Comfort was a matter of minor importance. Those who disposed themselves on the grass, where they had full enjoyment of the fresh summer air, and heard, through the open door, as much of the service as they chose to listen to, doubtless enjoyed themselves, but within it was not so agreeable. The squire’s family were of course installed in the pew, and there we were packed as tightly as could be managed, so that we all had to get up and sit down together. We had a “strange clergyman,” reported to be of vast learning; and my juvenile terror, along with my physical condition from squeezing, has imprinted the morning’s performance on my recollection as something truly wretched.

There being no resident population the chapel has since fallen into ruin, and the font and bell have been removed to the mother parish of Woolastone, the bell now doing duty at the day-school there. In 1890 Sir William H. Marling, Bart. (patron of the living) carefully restored the font and placed within it a brass plate bearing the following inscription:—

“Perantiquum hunc fontem baptismalem e ruinis sacelli scī Jacobi Lancaut in comū Gloucē servatum refecit Guls̄ Hes̄ Marling Bars̄ A.D, 1890.”

The venerable relic stands in the hall at Sedbury Park.

PLATE VIII.

Norman Chapel, Llancaut, Wye Cliffs.