Title: Ralph Osborn, Midshipman at Annapolis: A Story of Life at the U.S. Naval Academy

Author: Edward L. Beach

Illustrator: Frank T. Merrill

Release date: March 13, 2020 [eBook #61610]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Ralph Osborn—Midshipman at Annapolis

A STORY OF LIFE AT THE

U. S. NAVAL ACADEMY

By LIEUT. COMMANDER

EDWARD L. BEACH, U. S. NAVY

Author of “An Annapolis Youngster,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

FRANK T. MERRILL

W. A. WILDE COMPANY

BOSTON CHICAGO

Copyrighted, 1909

By W. A. Wilde Company

All rights reserved

Ralph Osborn—Midshipman at Annapolis[5]

The purpose of this story is to bring before the American youth who read it a correct portrayal of midshipman life at Annapolis, to bring out in story form the routine of drills, studies and customs of our Naval Academy, the discipline there undergone by American midshipmen and the environment in which they live and which controls them from the time they enter.

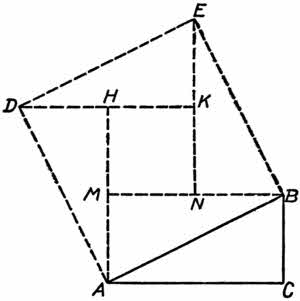

“The Osborn Demonstration” of the Pythagorean problem may not be new. It hardly seems reasonable that such a simple solving of this ancient problem should be discovered at this late date. However, it is certainly shorter and more graphic than any given in present day geometry text-books. Some search has been made, but up to the present no evidence has been found showing previous knowledge of this method of demonstration.

Should this story create any interest in Ralph Osborn and his friends it may here be stated that they have all lived. They were not the first nor will they be the last to have trials and triumphs at Annapolis.

Edward Latimer Beach,

Lieutenant-Commander,

United States Navy.

United States Ship Montana.

| I. | A Competitive Examination for the Naval Academy | 11 |

| II. | Mr. Thomas G. Short and His Man | 21 |

| III. | Short’s Method of Passing an Examination | 33 |

| IV. | Short’s Naval Career is Short | 44 |

| V. | Himskihumskonski | 55 |

| VI. | The Summer Practice Cruise Begins | 65 |

| VII. | Man Overboard | 76 |

| VIII. | Bollup’s Watch in a Queer Place | 88 |

| IX. | “Indignant Fourth Classman” | 101 |

| X. | “The Osborn Demonstration” | 113 |

| XI. | Third Classman Osborn | 122 |

| XII. | Chief Water Tender Hester | 132 |

| XIII. | Oiler Collins Jumps Ship | 145 |

| XIV. | Ralph is Kidnapped | 156 |

| XV. | Ralph Breakfasts with His Captain | 164 |

| XVI. | A Boiler Explosion | 173 |

| XVII. | Third Classmen Elect Class Officers | 187 |

| XVIII. | “Professor Moehler is a Liar and a Fool” | 198 |

| XIX. | “Osborn Never Wrote It, Sir” | 209 |

| XX. | Himski Saves Ralph | 219 |

| XXI. | “Creelton, I Believe You are the Man” | 230 |

| XXII. | Ralph at Bollup’s Home | 241 |

| XXIII. | Ralph Saves Bollup from Dismissal | 252 |

| XXIV. | Ralph has a Joke Played on Him by a Candidate | 262[8] |

| XXV. | Ralph Court-Martialed for Hazing | 275 |

| XXVI. | Ralph is Dismissed by Sentence of General Court Martial | 289 |

| XXVII. | Himski and Company are Joyfully Astonished | 300 |

| XXVIII. | First Class Leave at Hampden Grove | 309 |

| XXIX. | “Turn Out On This Floor. Turn Out, Turn Out” | 320 |

| XXX. | The Thief Unmasked | 333 |

| XXXI. | Ralph’s Lost Watch is Found | 346 |

| XXXII. | Ralph Finds His Uncle at Last | 359 |

[11]

Ralph Osborn—Midshipman

at Annapolis

“Father,” said Ralph Osborn, looking up from the book he had been reading, “I want to go to the Naval Academy.”

“Why, Ralph, how did you happen to think of that?” asked his father putting down his paper and giving to the earnest youth at his side his sympathetic attention; “what has attracted you to the naval life?”

“Father, you’ve always talked about my going to college and studying to be a lawyer. I’d much rather be a naval officer than a lawyer, and besides I don’t see how you can afford to send me to college. I’ll finish high school in a few months and then must look for some position; you can’t hope to be able to send me to college next year.”

“I’m afraid not, Ralph,” returned his father;[12] “but you might go into a lawyer’s office; many of our best lawyers have never been to college.”

“That was the old way, father, but nowadays practically all lawyers are college graduates. A lawyer of to-day who has not had college training is tremendously handicapped and must be a genius to be really successful. And besides, father, I have never felt I wanted to be a lawyer; my tastes are more mathematical.”

“Well, what has mathematics got to do with being a naval officer?” queried the father, Ralph Osborn senior.

“Why, father, Jack Farrer says, and he ought to know, that engineering, and electricity, and ship-building, are founded upon mathematics, and the naval officer has everything to do with these sciences. And if I could go to the Naval Academy I’d get a splendid education without its costing you anything. And after I was graduated if I didn’t want to be an officer I’d have a splendid profession. Now, father, won’t you please help me?”

Mr. Osborn sighed. “I wish I could, Ralph,” he said, “but I don’t know how I could. It’s a difficult thing to get into the Naval Academy; you must get the congressman of your district to appoint you, and we don’t even know our congressman. Such an appointment is generally given by a congressman to the son of some close friend, and——”

[13]

“Yes,” interrupted Ralph, eagerly, “but sometimes the congressman orders a competitive examination. Now Jack Farrer finally graduates from the Naval Academy next June; you know it is a six years’ course, four at the Academy and then two years at sea aboard a cruising ship, and his graduation will make a vacancy at Annapolis for the Toledo district. Now, father, won’t you get some friend of yours who knows Congressman Evans to write to him and ask the appointment for me? And if Mr. Evans won’t do that, ask that the appointment be thrown open to competitive examination? Please do, father.”

Ralph’s brown eyes more than his words imploringly begged his father. The latter was silent for a few moments, then said: “Ralph, I’ll ask my employer, Mr. Spencer, to write to Mr. Evans to-morrow, but don’t be too hopeful. There will undoubtedly be many others who have greater claims upon Mr. Evans.”

“Oh, thank you, father,” cried the now delighted Ralph. “If Mr. Evans won’t give me the appointment but opens it to a competitive examination I’m sure I’ll have a good chance of winning it.”

“Well, I’ll see Mr. Spencer to-morrow. By the way, Ralph, to-day I received a letter and a present from your Uncle George.”

“From my Uncle George!” exclaimed the young man, in great surprise. “Why, I’d forgotten[14] I had an Uncle George; I’ve never seen him, and you haven’t spoken of him for years. What did he say in his letter, and where is he? Tell me something about him.”

“Here is his letter. I hadn’t heard from or of him for ten years. His letter is absolutely brief. He says he is well and is doing well. He enclosed a check for two hundred dollars as a remembrance. He says that for the next week only his address will be the general delivery of the New York City post-office.”

“Two hundred dollars!” repeated Ralph, enthusiastically. “Why, father, if I am admitted to the Naval Academy that is just the amount I will have to deposit for my outfit. But why have you never told me anything about my Uncle George?”

“It’s a sad story,” replied Mr. Osborn, “and there isn’t much to tell. He was one of the most attractive young men in the city of Toledo, twenty years ago. Your grandfather was strict with him, and at times harsh, too harsh, I now think. However, one day about twenty years ago, your grandfather sent your Uncle George with two thousand dollars to deposit in a bank. Well, George turned up two hours later and said he had been robbed. Your grandfather became very angry and said that George had been drinking and gambling. Your uncle indignantly denied this, and your grandfather in a passion struck him. It was an awful time. George left the house, said he would never[15] return. I’ll never forget his white face. He asked me if I believed he had gambled that money away. I assured him I did not. He said: ‘I thank God for your belief in me, Ralph.’ Those were the last words he ever spoke to me.

“We never knew where he went or what became of him. At long intervals letters would come from him, each one enclosing a draft. In each letter he stated the amount he sent was to be applied to what he termed his financial indebtedness to his father, but he always maintained the money had been stolen from him. In about ten years the entire amount, with interest, was repaid to your grandfather. Until this letter came to-day I had not heard from him for ten years.”

“But, father, were not his letters enclosing the drafts acknowledged; did you not write to him?”

“Of course, but each letter was returned to us.”

“Where were these letters from?”

“From different places; your Uncle George has evidently been a great traveler. During those ten years several of his letters came from New York; two, I think, from Norfolk, Virginia. I remember one came from San Francisco, one from London, and one from Yokohama, Japan.”

“Now isn’t that interesting?” remarked Ralph. “Why, it almost seems like a mystery. Perhaps he’s a millionaire and some time will come to Toledo in his private car. But, father, what is your idea of it all?”

[16]

“I don’t know what to think, Ralph; your uncle was very proud as a young man, and my notion is that he has had a hard time of it like the rest of us; that he would come back here for a visit if he could do so in style, but would not like to come back without the evidences of prosperity. But I shall write to him immediately and ask him to visit us. You know he may have a notion that people here imagine he used that two thousand dollars gambling, whereas the fact is the matter was never discussed outside of our family. Twenty years ago people wondered at his departure but none ever learned the cause of it.”

“Father, if I get the appointment to Annapolis may I have the two hundred dollars Uncle George has sent? I have been wondering where we would get the money to deposit. And I would need about one hundred dollars more; I must have some for traveling expenses and for board in Annapolis, and I would like to go to the preparatory school there for a month.”

Mr. Osborn smiled. “Indeed you may have the two hundred, Ralph,” he replied, “and I will manage to find another hundred for you. But aren’t you getting ahead a little fast? You appear to take it for granted that there is no doubt of your getting that appointment.”

“Bully,” cried Ralph; “I’m going to get the appointment, I feel sure of that. And I’m going to write to Uncle George right away and tell him[17] I’m going, or at least that I hope to go to the Naval Academy. And I’ll tell him how grateful we are for the two hundred. Good-night, father.”

One evening, a week later, Mr. Osborn handed his son a letter, saying: “Here’s something that may interest you, Ralph.” The latter read the letter with great eagerness. It was as follows:

“My Dear Spencer:—

“In reply to yours of the 9th instant would say I will have an appointment for Annapolis next June. I will throw this open to competitive examination, and if your young friend, Mr. Ralph Osborn, wins, and is recommended by the board of examiners, I will appoint him with pleasure.

“Yours very truly,

“John H. Evans.”

“Hurrah!” shouted Ralph. “Now I’m going in to win. I’ve several months ahead and I’m going to study hard and review everything. I’m going to leave high school to-morrow and study at home. Now, father, keep quiet about this; don’t advertise the fact there’s going to be a competitive examination. Everybody has the same chance I have to learn about the vacancy to Annapolis and the coming competitive examination, but it isn’t necessary that I should stir up people to try to beat me out.”

At this time Ralph Osborn was about eighteen years old. He was of medium height and build; his eyes were brown; in them was a steadfast[18] earnestness that always attracted friendships and inspired confidence. His salient characteristics were truthfulness and determination. Except when his mother died no sorrow had ever been a part of Ralph’s life. Time had dimmed that sorrow, and to him his mother was now a beautiful, tender memory. His affection for his father was unbounded. The Osborns were a good family; there had never been a better one in Toledo, but Mr. Osborn had not been successful as a business man and now depended for his support entirely upon the salary he earned as bookkeeper.

Ralph wrote to his uncle, and received the following letter in reply:

“Dear Nephew Ralph:—

“I was much pleased to receive your letter, and interested to discover I have a nephew. I know something of Annapolis, and recommend it for you. I am leaving New York now but will write you later, and shall look forward to meeting you.

“Your affectionate uncle,

“George H. Osborn.”

Mr. Osborn also received a letter from his brother in which the latter expressed the intention of visiting Toledo, but at some future time.

“Well,” said Ralph, disgustedly, “I found a nice uncle, and now I’ve lost him, and don’t even know where to write to him.”

For the next three months Ralph devoted himself[19] to his studies. He imagined the competitive examination would be in arithmetic, grammar, geography, and spelling, and these he thoroughly reviewed.

The day came when announcement was made that there would be a competitive examination for the Naval Academy at Annapolis, and this was held in April. Ralph found that he had twenty-two competitors. It is doubtful if any had done such thorough reviewing as Ralph had. The examination lasted three days and Ralph felt he had done well.

“Father, the examination is all over,” cried Ralph, when Mr. Osborn returned home that evening. “I suppose the results will not be published for several days. There were twenty-three of us in all, and it will take some time to examine and mark all the papers that were handed in. Oh, I’m so anxious to see who gets the highest marks, I can hardly wait.”

“Do you think you have won, Ralph?”

“I’m certain I did well. I felt I knew every question that was asked, but of course some one may have done better.”

A few days later Ralph opened the evening newspaper, and the first thing that met his eyes was his own name in big head-lines. It was as follows: “Ralph Osborn, Jr., wins the Competitive Examination for Annapolis.” And then followed a description of Ralph that was most pleasing[20] to that young man. He was wild with joy, and could not contain himself. Before the night was over he had read that article hundreds of times. And Mr. Osborn, seeing his only child in such transports of happiness, was himself filled with joy.

Ralph received congratulations from hundreds of friends, and soon commenced to make preparations to leave for Annapolis.

As Ralph bade Mr. Osborn good-bye in the station, little did he dream that it was the last time he was to see that dear father alive.

Ralph Osborn arrived in Annapolis in May, just a month before the entrance examinations were to take place. He secured room and board at the price of eight dollars a week, and immediately enrolled himself for one month’s tuition in Professor Wingate’s preparatory school. Here the special instruction given consisted in studying previous examination questions, and Ralph soon felt he was well prepared for his coming ordeal.

At this time Annapolis was full of visitors, and the number of these increased daily. There were here many of the friends and relations of the midshipmen soon to graduate, and also more than a hundred and seventy candidates were distributed in the different boarding-houses of the old town. One of these aspirants came into immediate notoriety because apparently he possessed enormous wealth and made much noise in spending his money. His name was Short; he arrived in Annapolis in a private car and immediately rented a handsome, well-furnished house in which he installed a retinue of servants. Short was an orphan. He had inherited millions, and though[22] nominally under the control of a guardian, he actually ruled the latter with an imperious will that brooked neither check nor interference. Though he was not aware of it, Short as a midshipman was an impossible contemplation. First, he was utterly unprincipled; secondly, he was uncontrollable. But he made an effort to prepare himself, engaged special tutors, and promised them large bonuses if he passed the examinations successfully. A week before the examinations were held he was frankly told he would certainly fail in mathematics. Short immediately went to the telegraph office and sent several messages to New York. The next day two flashily-dressed men came to Annapolis, had several long talks with Short and received money from him.

Short enjoyed company and soon after he was domiciled in Annapolis he had invited several of the candidates to live with him as his guests. As these young men were earnestly preparing for their examinations, their presence probably influenced Short to study more than he otherwise would have done.

A few mornings before the day set for the commencement of the examinations, Short at breakfast asked one of his guests to come with him to the library. With them was also one of the men who had come down from New York. Short was in particular good humor.

As soon as they reached the library, Short[23] turned to the young candidate, and without any preliminary words said abruptly, “The jig is up. I’ve got you.”

The young man spoken to turned pale and trembled violently. “What do you mean?” he gasped.

Short laughed. “I mean you’re caught,” he replied. “I’ve been missing things of late and spotted you for the thief. The two hundred dollars you took at two o’clock this morning was a plant for you. Every bill was marked, and there were two detectives hidden in the room who saw you steal the money. I’ve a warrant for your arrest; you’ll land in the pen for this instead of becoming a midshipman.”

The young man addressed dropped helplessly into a near-by chair, and hysterically cried, “I didn’t do it. This is a put up job.”

Short grinned. “Perhaps,” he said. “But I hate to be hard on a chum. There’s a way out of it for you, though, if you will do exactly what I say.”

“I didn’t do it; you can’t prove I did,” exclaimed the young man.

“I’m not going to try to prove it,” smiled Short, in reply. “I’m just going to have you locked up in jail; the prosecuting attorney of Annapolis and a jury will take charge of you; but I guess you’ll live at public expense for a few years. It’s a clear case, my boy, but I bear you no[24] ill will; two hundred dollars or so isn’t much to me. But I told you there was a way out of it for you, and an easy way out of it, too.”

“What do you mean? Oh, Short, you wouldn’t disgrace me, you wouldn’t ruin me?” implored the young man in trembling tones.

“Stop your sniveling,” commanded Short. “Now do you want to get out of this and have no one know anything about it or do you want to go to jail? Take your choice, and be quick about it.”

“I’ll do anything. What do you want me to do?”

“First, I want you to write a confession stating you stole the two hundred dollars and other amounts from Thomas G. Short.”

“I’ll not do it.”

“Oh, well, then, go to jail; I’m tired of bothering with you.”

“Oh, Short, don’t. What would you do with that confession?”

“I don’t mind telling you. I’d lock it up and no one would ever see it. But I’d own you, do you understand? I’m going to be the most popular man at the Academy; I’m going to be class president and cut a wide swathe here. Now you’d help me and I’ll need help. That’s all you’ll have to do. And there’ll be a lot of money and good times in it for you. Come, write me that confession. You’ll never hear of it again; you’ll[25] simply know I’m your boss and you’ll have to do what I tell you.”

The hapless young candidate immediately brightened up and taking pen and paper rapidly wrote a few lines. Short read what he had written, and then, in a satisfied manner, said, “That’s sensible. You’ll never regret it.”

The young man then said, “Short, here’s your two hundred. Thank you so much for your goodness to me; but I can’t help taking things, I really can’t; I’m what they call a kleptomaniac.”

“Oh, keep the two hundred,” said Short, folding up the paper the young man had written, and putting it in his pocket. “Now see here, I can’t afford to have my right-hand man get caught stealing and you surely will be if you keep it up. Whenever the feeling comes over you again come to me and I’ll give you fifty or so. Now skip out. I’ve some private matters I want to talk over with my friend here.”

The young candidate returned the two hundred dollars to his pocket and left the room in an apparently happy frame of mind. With him the crime of a thing was not in the guilty act but in the publicity and punishment following detection.

“You’ve got that fellow good and hard,” remarked the other man who had remained in the room with them.

“Yes, and he’ll stay got,” returned Short, drily.[26] “Well, what have you to report? Are you going to get the math exam for me?”

“You bet, we’ll have it to-night sure thing. We’ve got it located, have a complete plan of the building, and Sunny Jim, the greatest safe cracker in the world, will get it to-night. Nothing less than a burglar-proof time-lock could keep him out. He’ll get here to-night on the six o’clock train and you’ll have a copy of your mathematical examination before this time to-morrow, and no one will ever be the wiser unless you choose to tell. Sunny Jim will not know who it’s for and he’ll lock up everything behind him when he leaves. He’ll not leave a trace behind him and no one will suspect the building has been entered.”

“Good. I’ll depend upon you. I can pass in the other subjects, and will in mathematics if I get hold of the examination several days ahead of time. That’s all for the present.”

The examinations were to begin on Monday, the first of June. Ralph Osborn felt well prepared and confident, yet he dreaded the ordeal and longed for it to be over.

On Friday night preceding the examinations, Ralph was in his room studying. At nine o’clock there was a sharp rap at his door.

“Come in,” he called out; and a man he had never seen before entered and said: “Mr. Osborn?”

[27]

“Yes; what can I do for you?” replied Ralph, feeling an instinctive dislike for the coarse-featured man he was addressing, and wondering what could have brought him to his room.

“You are a candidate, I believe, Mr. Osborn?”

“Yes,” replied Ralph, “and I’m very busy studying my mathematics.”

“Just so,” said the stranger with a knowing look, and taking a step nearer. “And your mathematics examination is going to be difficult. I’m sure you’ll not pass—unless you get my assistance.”

“Who are you, and what are you talking about?” asked Ralph sharply.

“Never mind who I am,” retorted the stranger, unfolding a paper, “but do you see this? It is the examination in mathematics. You can have it for fifty dollars.”

Ralph sprang at the stranger, his eyes dilated with wondering indignation, his soul aflame at the infamous proposal made to him. His breath came short and he almost choked. Nothing like this had ever entered his life and he was utterly unprepared with word or thought.

“The examination in mathematics!” he stammered as he started toward him.

“Take it easy,” smiled the stranger; “others have it, why shouldn’t you?”

At that moment there came a rap at the door and a black, woolly head was thrust into the room.

[28]

“Mistah Osborn,” said the intruder, “dere’s a telegram boy what’s got a telegraph fo’ you; he says dere’s fo’ty cents to collec’.”

“Excuse me for a minute,” said Ralph to the stranger, “while I see the telegraph messenger.” As he hurried out of the room and down the stairs, he felt glad of the interruption as it gave him time to gather his scattered thoughts. What should he do? He was in a terrible quandary. Somehow he did not doubt the fact that the stranger’s claim to possess the examination was correct. His whole nature revolted at the notion of passing an examination by such underhand means; he was horrified, but he did not know what to do. If he refused to take the examination the stranger would leave with it. And if he reported the occurrence without proof other than his unsupported word he was afraid nothing would come of his report.

He received the telegram which was of little importance, and still in perplexity as to what to do, he started to return when his eyes fell upon a telephone in the hall. A sudden inspiration came to him. He took down the receiver and said: “Central, give me the house of the superintendent of the Naval Academy immediately.”

Soon a voice came which said: “This is the superintendent; what is it?”

“Is this the superintendent of the Naval Academy?”

[29]

“It is. What do you want with him?”

“I am Ralph Osborn, a candidate.”

“What is it, Mr. Osborn?”

“Sir, I am at number twenty-six Hanover Street. There is a man in my room who has a paper which he says is the examination in mathematics the candidates are to have next Monday morning. He wants to sell it for fifty dollars. What shall I do, sir?”

“Keep him there. Offer a less price, haggle with him, but keep him there. Lock your door if you can, and open it when you hear four loud, distinct knocks.”

“All right, sir.”

Ralph immediately went to his room. His mind was now perfectly clear and determined. He had to kill time and he proposed to do it. First he deliberately rearranged the chairs; then he made a great pretence of getting ice-water for his visitor. Then he engaged in conversation, and asked all kinds of questions. Finally his visitor became impatient. “Do you want it or not?” he cried. “If you don’t, say so. I’ve no time to fool away.”

“Yes, I want it, but not for fifty dollars.”

The stranger got up to leave. Ralph begged him to reduce the price. When Ralph saw he could not delay the man longer, he jumped to the door, locked it and quickly put the key in his pocket.

[30]

“What are you doing?” angrily demanded the intruder, advancing upon Ralph.

“I’m going to get that paper at a cheaper price,” returned Ralph, picking up a heavy andiron with both hands. “Now keep away or you’ll get hurt.”

“You’ll have a big job if you think you can stop me from leaving,” shouted the man with a curse. “Open that door or I’ll break your head.”

“Keep off, or I’ll brain you,” cried Ralph, excitedly, but with menacing determination; just then there were four loud knocks on the door. Ralph quickly unlocked the door and threw it open. In walked two officers, one of magnificent presence, with two silver stars on his coat collar and broad gold bands on his sleeves. With the officers were two Naval Academy watchmen and an Annapolis policeman.

The superintendent, for it was he, looked at Ralph, who, with flushed face and panting breath, the irons in hand, now felt much relieved. The superintendent then addressed the stranger. “Who are you, sir?” he demanded.

“A free American citizen,” returned the man sulkily, “about my own business.”

“Officer, arrest that man on a charge of burglary. Go through his pockets and let me see what papers he has in them.”

“I protest against this indignity,” cried the man; “you’ll pay for this;” but his protests were[31] unavailing. He was searched, and in a moment a paper was handed the superintendent.

“Professor,” asked the superintendent, “is this the examination the candidates are to have Monday?”

The officer with the superintendent looked at the paper and instantly replied, “It is indeed, sir.”

“Very well; officer, I’d like to have you lock that man up over night. I’ll prefer charges against him to-morrow. The watchmen will go with you to help take him to the jail.”

And then the superintendent looked at Ralph; his steel gray eyes seemed to pierce him through and through. He then offered Ralph his hand and said: “Good-night, Mr. Osborn. I congratulate you; you have done well, sir. Continue as you have begun and you will be an honor to the Navy.”

Ralph, overcome with feeling at the superintendent’s words of commendation, could stammer but unintelligibly in reply. And for some time after the superintendent had left, Ralph stood in the middle of his room, andiron still firmly grasped, wondering at the exciting events he had just experienced.

The bars of the Annapolis jail may be sufficiently strong to keep securely negro crap shooters, but they were hardly child’s play to the skilful Sunny Jim, who had broken through and was far away long before morning.

[32]

A searching investigation developed no clue as to how the examination questions had gotten adrift, but a new examination was immediately made out and substituted for the one previously made. All in the ignorance of Mr. Thomas G. Short, who marched to the examination Monday morning believing that he was to make close to a perfect mark in mathematics.

On Monday morning the candidates flocked by scores to the room in the Naval Academy where they were to be examined. After the inspection of their appointments each candidate was assigned to a numbered desk. Ralph Osborn found himself at a desk numbered 153. On the desk was a pad of paper on which he was to do his work, pencils, and the written examination questions which this first day were in arithmetic, and algebra as far as quadratics. Ralph picked the examination paper up and eagerly scanned it; but in a moment a bell rang, and he heard a loud cry of: “Attention,” uttered in an authoritative manner by an officer in lieutenant’s uniform, who said, when complete quiet existed: “Each candidate will number each sheet of his work in the upper left-hand corner with the number of his desk. In no case will the candidate write his name on any sheet; when you have finished leave all your papers on your desk. Now go ahead with your work; you have four hours and you’ll need it.”

There was immediately a shuffle of papers and a stirring in seats as the candidates commenced[34] their first test. Ralph Osborn looked the examination paper rapidly over, and a feeling of confidence came over him as he read. “It’s easy,” he said to himself; “I can do it all.”

He commenced to work rapidly and had just finished the first problem when his attention was attracted by some whispered imprecations close to, and just behind him. There at a desk numbered 155 was the candidate whom Ralph had seen riding behind a handsome pair of horses, but to whom he had never spoken.

It was Short; and his face was convulsed with rage, and blank with disappointment. In his two hands was clenched the examination paper. His eyes seemed to dart from their sockets. He looked utterly confounded.

Ralph was surprised but didn’t have any time to waste on the young man behind him, so he resumed his work. He had finished the third question when he felt his chair kicked from behind, and then heard a whispered voice say:

“Sh. Don’t look around. Lend me your papers; I wish to compare your answers with mine.”

“I’ll do nothing of the kind,” returned Ralph, indignantly.

When Ralph had finished the fourth question, he felt his chair kicked again, and then the whispered words:

“Let me have your papers for a moment. No[35] one will see. The lieutenant is in the other end of the room. I’ll give you one hundred dollars if you’ll let me look at them.”

Ralph turned squarely around and deliberately eyed the young man who had made this dishonorable proposal. He was silent a moment and then in a low tone said: “How much did you pay for the examination you had stolen for you, you scoundrel? Speak to me again and I’ll report you.”

Short’s whole body trembled, and fierce hatred shone from his moody eyes. In his whole life he had never received such a defeat and such contemptuous treatment. His feelings were almost beyond his small powers of endurance, and this state of feeling was aggravated by a feeling of utter powerlessness. After that he made no further effort to speak to Ralph, and he was too far from the other candidates, and was also afraid to try to attract their attention.

Short tried to work but only made poor headway. Even had he been in a good humor he could not have passed the examination.

Ralph found the problems all easy and made rapid progress. After a while Short left his seat and approached the lieutenant in charge and asked him some trivial question. In returning, as he passed Ralph’s desk his eyes looked at the number 153, painted in white letters on the front of it, and a gleam of satisfaction passed over his[36] face. “I’ll fix that fellow, the hound, if he leaves this room before I do,” he remarked to himself. After that Short worked fitfully, occasionally glancing up at Ralph. He noticed with much approval that Ralph apparently finished his work an hour before the time allowed had expired, and was impatient when Ralph started to read his papers over, deliberately stopping at some places to make corrections.

Half an hour before the time was up a number of the candidates had finished and were leaving the examination room. Ralph was one of these. He folded his papers neatly, placed them on one side of his desk, and left the room entirely confident he had passed the examination.

As soon as Ralph Osborn had left the room Short began to arrange his papers, and started to number each sheet. The number of his desk was 155, but instead of writing this number on the pages of his work, he wrote on each of them the number 153, which he had seen on Ralph’s desk. He then gathered his papers together and walked to the lieutenant in charge. “Shall I sign my name at the bottom?” he asked.

“No, number each page with your desk number,” was the reply.

Short returned to his desk, but just as he reached Ralph’s desk he apparently stumbled, and for a moment rested both of his hands on it, still holding his own papers. In doing this he[37] attracted no one’s attention, but when he had straightened up he had Ralph’s papers in his hand. He had quickly substituted his own for Ralph’s papers and the papers left on Ralph’s desk, though numbered 153, were in reality Short’s. Short now carefully erased the upper part of the figure three, of the number 153, on each page of Ralph’s papers, and made a five out of it. He then carefully and neatly arranged these papers on his desk, and with an exultant feeling of success and gratified revenge, he left the room. He knew his own papers would never pass him, and rightly judged from the rapid way in which Ralph had worked that the latter would be successful.

The examinations were all finished Wednesday, and Ralph was confident he had passed, and therefore was exultant. But late that afternoon he received a telegram as follows:

“Your father has been seriously injured in an accident. But little hope. Come home at once.”

This was signed by his father’s friend, Mr. Spencer.

In anguish of grief and fear Ralph left by the next train; and late the next night was in Toledo but only to see the dear father in his coffin. The boy’s grief was pitiable. He felt he would never be comforted. The funeral was held two days later, and then the saddened young man returned[38] to Annapolis. There was no question in his mind but what he had been completely successful in his examinations.

Upon his return, which was Monday, he immediately went into the Academy grounds and there met a young man, dressed in civilian’s clothes with uniform cap. He recognized him as a candidate he had known in the preparatory school, Bollup by name.

“Hello, Bollup,” said Ralph. “I see you’ve passed all right. I knew you would, in spite of the way you used to talk.”

“Thanks, Osborn,” returned Bollup. “I’m awfully sorry you didn’t get through. I hope you’ll get another appointment next year. That nine-tenths in math of yours was certainly a big surprise to me, and to you, too, I guess; you thought you had done so well in it.”

“What are you talking about?” asked Ralph, hastily. “I’m sure I passed in everything, but I couldn’t wait to see the marks; I had to go to my father’s funeral in Toledo.” And Ralph’s eyes filled with tears. “What do you mean about my nine-tenths in mathematics? Surely that wasn’t my mark; why, that’s utterly ridiculous.”

“Look here, old fellow,” said Bollup, uneasily, “I don’t want to be the one to spread bad news, but on the bulletin-board in main quarters, you are credited with having made nine-tenths only in math, and are marked as having been rejected[39] for that reason by the Academic Board of the Academy.”

“My heavens,” ejaculated Ralph, thunderstruck at this information. “Look here, Bollup, there’s a mistake about that. I’ll bet I got over three-fifty on that math exam. Nine-tenths? Why that’s simply preposterous. Let’s look at that bulletin.”

It may here be remarked that at the Naval Academy marks range from 0, a total failure, to 4.00, which is perfect. 2.50, equal to 62 1/2 per cent, is the passing mark in all subjects.

Ralph and Bollup were soon standing before the bulletin-board and then Ralph realized that Bollup’s news was only too true.

“Too bad, old fellow,” commiserated Bollup. “I’m awfully sorry and disappointed.”

“There’s a mistake, I tell you,” returned Ralph, with staring eyes. “If my published mark had been two-thirty I might doubt my own judgment, but nine-tenths,—why that’s entirely impossible.”

“I do hope so, Osborn; but what are you going to do about it?”

“I’m going direct to the superintendent. I don’t know what else to do.”

“What, the superintendent himself? He won’t see you. I wouldn’t dare to go to see him myself.”

“That’s just where I’m going,” said Ralph, determinedly, “and I’m going right away, too.”

In a few minutes Ralph was at the door of the[40] superintendent’s office, and said to the orderly: “Will you ask the superintendent if he will please see Ralph Osborn on a matter of great importance?” A moment later he was told to walk in.

The distinguished officer greeted Ralph kindly. “I’m sorry you failed, Mr. Osborn,” he commenced. “I was so impressed with the way you handled that stolen examination affair that I wanted you to pass, and I personally ordered the result of your examination to be sent to me. You made excellent marks in everything except mathematics; had you made anything over a two in that I would have waived a slight deficiency. But with only a nine-tenths in mathematics it was impossible to pass you.”

“Sir,” said Ralph, “I wish to report that a great mistake has been made. I ought to have been given at least three-five on that examination. Of this I’m absolutely certain. I worked correctly nearly every problem. I compared my answers with those of other candidates and I can state positively that I made at least three-five on that examination. I cannot be mistaken in this matter.”

“The papers are marked independently by two different officers, Mr. Osborn; it’s not possible such a glaring mistake could be made by two different people.”

“I can’t explain it, sir; but I know I got the right answer to nearly all the questions.”

[41]

“Why have you been so late in reporting this matter?” inquired the superintendent, looking at him keenly.

“I have just learned it, sir. My father was killed in an accident and I left the day the examinations were finished and have just returned.” There was a break in Ralph’s voice as he spoke.

“I’m very sorry indeed. I’ll look into this matter. Be at my office at two o’clock.”

“Thank you, sir; I will.”

Ralph was there at the time appointed and was immediately called before the superintendent. “Mr. Osborn,” said the latter, “I have had your mathematical papers read over again by a third officer who did not know the original mark given them, and he marked them eight-tenths. He says they are very poor. I’m sorry, but I can do nothing more for you. Good-day, sir.”

There was an air of finality in the superintendent’s manner and voice.

“Sir,” said Ralph, now desperate, “I have to report that I answered nearly every question correctly,”—a look of displeasure crossed the superintendent’s face,—“I beg of you to let me see my papers.”

“I will do so immediately. Take a seat outside, please.” Then sending for his aide, a lieutenant, he said, “Telephone for the head of the department of mathematics, Professor Scott, to bring to my[42] office immediately Candidate Ralph Osborn’s examination papers in mathematics.”

A few minutes later an officer came in with some papers in his hand. “Admiral, these are Candidate Osborn’s papers,” he said.

“Professor, will you please convince Mr. Osborn that those papers are worth no more than nine-tenths?” said the admiral, continuing his writing.

“That will be easy,” smiled the professor in reply. “Now, Mr. Osborn, see here.”

Ralph went eagerly to the professor’s side, and took the papers from his hand. “Oh!” he cried, in a tone that startled the professor and the superintendent. “Are these the papers, sir, which have caused my rejection?” he demanded in a breathless tone.

“Why, yes, of course they are; they are your papers.”

“They are not my papers, sir. That is not my work. The handwriting is not mine. I never saw these papers before, sir.” And turning to the admiral, his face aglow with excitement and indignation, he said, “Surely you will not keep me out of the Academy on account of this poor work which belongs to some other person.”

“These are your papers,” maintained the professor, looking indignant. “They were on your desk; each one, you see, is numbered 153, your number.”

[43]

“They are not my papers,” insisted Ralph, “and no person on earth can prove them to be. Sir, I request this matter be further investigated.”

“A mistake is impossible,” exclaimed the professor.

“Is it possible for an examination paper to be stolen before the examination occurs?” asked Ralph suddenly.

“By George, Mr. Osborn, we’ll look into this matter,” said the superintendent, now full of interest. “I’ll send for your other papers and compare the writing. But can you imagine how this could have happened?”

Then came vividly to Ralph’s mind the angry, revengeful face of the man behind him in the examination room the week before. Recalling the number of the desk back of his, a thought flashed through him.

“Yes, sir, I can,” he quietly said. “I can imagine how a person doing poorly could have marked his sheets with my desk number, and then could have exchanged his papers with mine, erased my desk number, and on my sheets write his own number. I would ask that the papers of number 155 be brought here.”

“Why do you ask for the papers marked 155?” inquired the superintendent.

“That was the number of the desk nearest my own, the desk just behind mine,” explained Ralph.

“Did you have any conversation with the candidate at desk number 155? Was there anything in his manner, or did he do anything that now leads you to believe he might have exchanged his papers for yours?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What was it, please? Tell all the circumstances.”

“Soon after I commenced my work last Monday morning,” began Ralph, “my attention was attracted by a noise of heavy breathing, and I heard some whispered swearing. I turned around. The candidate behind me looked wild with anger. Then he whispered to me to let him have my sheets as I finished with them, to compare the answers, he said, but I wouldn’t do it. Then a little later he kicked my chair and whispered to me that he would give me one hundred dollars if I would give him my papers.”

[45]

“What did you say to that?”

“I called him a scoundrel and asked him what he paid for the examination he had had stolen, and told him if he said anything more to me I would report him.”

“You should have done so anyway, Mr. Osborn.”

“Yes, sir, I know I should, but I was thinking of nothing but my examination.”

“Do you know the candidate’s name?”

“I think it’s Short, sir; I don’t know anything about him except I have heard people say he is a millionaire.”

“Mr. Osborn, please sit down at that desk and write a complete statement of what you have just told me.” And calling his aide, he directed that all of the entrance examination papers of Candidates Short and Osborn be brought to him. “Did Mr. Short pass the other examinations?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” replied the professor, “and he was sworn in as a midshipman and is now aboard the Santee.”

“Send for Mr. Short,” directed the superintendent.

By the time Ralph had finished writing the statement required, the examination papers which the superintendent had sent for were brought to the office.

“Here are Mr. Short’s mathematical papers, admiral,” remarked the professor. “He did very well indeed; he made 3.63.”

[46]

“May I look at those papers, sir?” asked Ralph, eagerly. He took but one rapid glance at them, and then said simply, but with glistening eyes: “That is my work, sir; I left those papers on my desk. Each sheet was marked 153 when I left the room.”

“They are marked 155, sir,” said the professor.

“Will you please see if the last figure on each sheet does not look as though it had been erased?” asked Ralph.

The superintendent took the sheets, and without remark, deliberately examined each number with a magnifying glass. Then he said slowly: “Professor, the last figure of the number 155 shows evidence on each sheet of having been erased. There is no doubt whatever of this fact. And on some of the pages you can plainly see that the figure 3 was erased and made into a 5. See for yourself.”

“This is unquestionably so,” remarked the professor, after deliberate scrutiny.

“Now compare these papers,” continued the superintendent, “with the examinations in the other subjects; they are all here, I believe.”

The two officers were much interested. After a few moments, the admiral said: “It is certain that the mathematical papers marked 155 were written by the same person who wrote these papers on my left hand. Now we’ll see who are credited with having written these respective piles.”

[47]

It was soon evident to whom the respective piles belonged, and the superintendent, turning to Ralph, said, “Mr. Osborn, there isn’t a doubt but what you are entitled to 3.63 on your examination in mathematics; and it is certain that Mr. Short should have received the nine-tenths. But I’ll make a further test. Professor, please send for the officer who was in the examination room when these young men were examined.”

“Yes, sir. It was Lieutenant Brooks; I’ll have him here in a moment.”

Before long Lieutenant Brooks appeared in the superintendent’s office: and a moment later the orderly came in, saluted, and said: “Sir, there be a new midshipman, Mr. Short, sir, who says he was directed to report to you.”

“Show him in immediately.”

Short entered, dressed in civilian’s clothes and midshipman cap. On seeing Ralph he gave a start and turned pale, and seemed to tremble.

“Are you Midshipman Short?” demanded the superintendent.

“Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Brooks, have you ever seen this midshipman before?”

Lieutenant Brooks looked intently at the young man. Then he said: “Yes, sir, I remember that half an hour before his examination in mathematics had finished, last Monday, he came up to me with his papers and asked me if he should sign[48] his name. I told him no; there was really no need whatever for his question; full instructions had been given.”

“Thank you; that’s all, Mr. Brooks. Now, professor, you will take these two young men and give them immediately the same examination they had last Monday, and when they have finished, bring the papers to me.”

Ralph was exultantly happy. Terror was exhibited in every feature of Short’s face; he was nervous and frightened, and hesitation and uncertainty were in every motion he made.

“Wh—wh—what’s the matter, sir?” he faltered. “I—I have finished my examination in mathematics; I made 3.63, sir.”

“Which is your paper, sir?” demanded the superintendent, “this numbered 153, or this numbered 155?”

“This, this one, sir,” indicating the latter.

“Then will you please tell me why the number 155 bears evidence of erasure on every sheet? And can you explain why the handwriting of the papers marked with your number and which you claim as your own, should be in such utterly different handwriting from that of your papers in geography, grammar and history? Are not these your papers, sir?” And the superintendent handed him the mathematical papers marked 153, for which Ralph Osborn had received the mark of nine-tenths. “These papers are certainly[49] in the exact handwriting of your papers in the other subjects, and yet they are charged against Mr. Osborn.”

Short was unable to speak, and he stood before the superintendent awkward and abashed. He dared not, could not answer.

“Professor,” continued the superintendent, “start these two young men on this same examination immediately; take them into the board room across the hall.”

Ralph started in vigorously with exuberant joy in his heart. Having once worked the questions they were now doubly easy; and he figured away with enthusiasm.

Short fidgeted about in a most unhappy way. In a little over two hours Ralph reported he had finished. The professor took his papers to the superintendent’s office where they were compared with the papers marked 155.

“Professor, there is not the slightest doubt but young Short handed in Mr. Osborn’s paper as his own. It is certainly fortunate that this young villain’s naval career has been nipped early. But get his papers and we’ll compare what he has done with the papers that were accredited to Mr. Osborn.”

In a few moments Short was called into the superintendent’s office.

“You have done a low, dastardly act,” exclaimed the superintendent, as soon as he had entered;[50] “you are a thief. Before I leave my office to-night I shall recommend your dismissal to the Secretary of the Navy.”

“I will resign, sir.”

“Indeed you’ll not resign. You will be dishonorably dismissed. I have given orders you are to be kept in close confinement until word of your dismissal comes from Washington. I now am certain that you are the scoundrel who stole the examination questions in mathematics.” Then turning to a midshipman who was now in his office, he continued, “Are you the midshipman officer of the day?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Short is in arrest. You will march him to quarters and deliver him to the officer in charge.”

“Aye, aye, sir. Come along, Mr. Short.”

They marched out, Mr. Short presenting a most crestfallen, contemptible figure.

“Now, professor, I’ll call a special meeting of the Academic Board,” said the superintendent, “at ten o’clock to-morrow morning and we’ll make a midshipman out of Mr. Osborn. Good-night, Mr. Osborn; I congratulate you. If you pass your physical examination to-morrow you’ll be a midshipman before twenty-four hours have passed.”

“Good-night, sir, and thank you so much for everything,” replied Ralph, picking up his hat[51] and leaving the office, probably as happy a young man as Annapolis has ever seen.

His feelings were much to be envied that night. He had passed through a most anxious time with defeat staring him in the face, but had emerged triumphantly successful.

By noon the next day he had passed the severe physical test which all candidates to Annapolis undergo, and had been sworn in as a midshipman, and was happily walking about the decks of the old Santee where the enlisted men employed at the Naval Academy and recently sworn-in midshipmen are quartered, feeling that the most glorious thing was to be a midshipman in the Navy.

Mere words are incapable of expressing Short’s state of mind. Wild rage possessed him. Bitter hatred against Ralph Osborn filled his heart, enveloped his whole being. After the examinations had been completed he had been somewhat nervous, but became reassured when he heard that Ralph had suddenly left town that Wednesday evening. And as Short’s name was reported as having passed and he was sworn-in as a midshipman, he soon became confident that his cheating would never become known. He was feeling particularly pleased with himself at the instant he was directed to report to the superintendent. He was somewhat uneasy when these summons came, yet could not believe he had been found out.

[52]

And what a difference on his return! Black, wicked passion so possessed him that all other feelings were driven from his mind.

Upon his return to the Santee he was informed he was to be kept in close arrest until further orders, and was to hold no communication with other midshipmen.

A little before nine that night while Short was brooding and planning schemes for revenge against Ralph Osborn, a midshipman passed near and whispered: “What’s the matter, Short?”

“I want to talk with you,” replied Short. “Be at the forward gun-port on the starboard side at about eleven o’clock to-night.”

“I can’t. No one is allowed to speak to you. I’d get into trouble if I did.”

“You’ll get into more trouble if you don’t,” whispered Short. “You will be there to-night or you’ll be in the Annapolis jail to-morrow; take your choice,” and Short turned away.

At ten o’clock taps were rung out by the bugler, and the new midshipmen turned into their hammocks. Soon after all lights were put out and everything was quiet aboard the Santee. At eleven o’clock two dark forms quietly slipped out of their hammocks and crept to an open gun-port. Here they had a whispered conversation that lasted till after midnight. Then one handed the other a roll of bills; the latter said: “Thank you, Short; you may depend upon me. I understand[53] what you want done and I’ll do it. I’m glad you’ve given me more than one year. He would feel it much worse four years from now than he would to-day.”

“I suppose so,” grumbled Short. “He’s the superintendent’s white-haired boy now and it would be useless to try anything just at present. But mind you, if you let up on him when the time comes, or play me false, I’ll have you landed in jail as sure as my name is Short. Have no false notions on that subject.”

“All right, Short, I’ll remember; you need have no fear of me. I guess everything is understood, so good-night.”

They separated, and each returned to his hammock.

Three days later, at dinner formation, Midshipman Short was directed to stand in front of his classmates. Then the acting cadet officer, who mustered the new midshipmen at all formations, himself one who had been turned back into this class, read the following order which was signed by the Secretary of the Navy.

“Order.

“For having been guilty of the most dishonorable, contemptible action, for being in effect a thief, thereby proving himself to be unfit for any decent association, Midshipman Thomas G. Short is hereby dishonorably dismissed from the Naval Academy and the naval service. Two[54] hours after the publication of this order he will be marched to the Naval Academy gate, and hereafter he will never be permitted to enter the Naval Academy grounds.”

Astonishment was depicted on the faces of most of Short’s erstwhile classmates, for though much speculation had been indulged in as to the nature of Short’s trouble, the exact facts had not been divulged and were known to but few people at the Naval Academy.

Before eleven o’clock Tuesday morning, Ralph Osborn had been duly sworn in as a midshipman, and was directed to report to the paymaster for the purpose of depositing the money for his outfit, and to draw required articles from the midshipmen’s store. This did not take very long. At the store the first thing Ralph received was a uniform cap. He immediately put this on and regarded himself in the mirror with unconcealed satisfaction. Then he was given a great number of different articles; duck working suits, rubber coat and boots, flannel shirts, underclothing, shoes, towels, sheets, blankets, collars, cuffs, shirts, and so on. These he dumped heterogeneously together in a clothes bag, and with this heavily-filled bag thrown over his shoulder he started for the Santee, the old ship where his already admitted classmates were quartered. The first person he saw aboard the Santee was Bollup. The latter rushed toward him enthusiastically. “Hello, Osborn,” he cried. “You are a sure enough midshipman, aren’t you? I can see that by your cap. Well, I’m delighted, old chap; you were right about[56] there being a mistake in that nine-tenths, weren’t you? But I wasn’t giving much for your chances yesterday at this time, I can tell you. Now how was the mistake made? Tell me all about it.”

Bollup’s greeting was most warm and cordial and it was very pleasant to Ralph. The latter had been warned by the superintendent not to talk about Short’s dastardly act, so he merely said: “Oh, there was a mistake somewhere. My papers were examined again and were found to be satisfactory after all; so they let me in. But I tell you I was awfully blue for a while, old man. But I’m happy enough now! It seems awfully good to be a midshipman; I’ll probably never enjoy another bit of uniform as much as I do this cap. Now put me on to the ropes; what’s the first thing I must do?”

“I’ll take you to see old Block; he’s the chief master-at-arms; he’ll give you a mattress and hammock and a locker for your clothes and things. Come along, there’s the old man now.”

A little distance away was a man of enormous build berating an ordinary seaman for the neglect of some order. “You’re not fit to be an afterguard sweeper,” he roared. “Polish up this handrail properly or I’ll have you lose all your liberties for a month. Get a move on you, you alleged sailorman, or——”

“Block,” interrupted Bollup, “here is another young gentleman for you; he wants a mattress[57] and a hammock, and a locker. Can you fix him up right away?”

“Indeed I can. What’s your name, young sir?”

“Ralph Osborn, sir.”

“Avast your sir, when you’re talking to any one forrud of the mast, Mr. Osborn. This is your first lesson in man-of-war manners. Keep your ‘sirs’ and your ‘misters’ for the quarter-deck; they’ll be mightily missed there if you don’t put them on. Do you smoke cigarettes, Mr. Osborn?”

“I neither smoke nor chew, sir.”

“Never mind the ‘sir,’ sir. I’m glad you don’t smoke cigarettes; I report all midshipmen who do that. They’re regular coffin nails, but chewing is healthy; no sensible man ever objects to a person chewing; and a pipe now and then is a good thing for anybody. But no cigarettes, mind you, no cigarettes.” And Chief Master-at-Arms Block glared at Ralph in a way that would have surely intimidated him had he been guilty of the habit Block so heartily despised.

“Now this way,” continued the huge and formidable-appearing, yet kindly chief master-at-arms. “Here’s your locker key, No. 57, and I’ll send that make-believe sailorman down to you with your mattress, hammock and hammock clews, and I’ll tell him to put in the clews for you and show you how to swing the hammock. And, Mr. Osborn, I’m glad to know you; your classmates are a fine lot of young men, the best I’ve[58] known in the thirty years I’ve been aboard the Santee.”

“Thank you, Block, you’re very kind; I’ll get along, I’m sure.”

Bollup took Ralph down to his locker and immediately they were surrounded by a group of Ralph’s new classmates.

“Here, fellows, here is Osborn,” cried Bollup; “he got in after all. Why, when they saw what sort of a man they were losing they just naturally slipped a three in front of that nine-tenths of his. ‘You’ve made a mistake,’ says Osborn to the supe, ‘I made more than nine-tenths; send for my papers and read them over again.’ ‘To be sure I did,’ says the supe, ‘but a mistake that’s easily remedied; here, give me my pen and I’ll make your mark 3.9 instead of .9. I don’t need to read your papers over again; I remember them perfectly.’”

Everybody laughed at Bollup’s remarks, and they crowded about Ralph, giving him a hearty welcome. “Here, Osborn,” continued Bollup, “here’s Himski; you remember him, Osborn; never mind the rest of his name—it’s as long as a main to’ bowline, though what that is I don’t know, but it sounds good. I heard old Block this morning tell an ordinary seaman his face was as long as a main to’ bowline; but I’m sure there never was a face as long as Himski’s name is. And here is Creelton; you know him, don’t you, Os?”

[59]

“I never had the pleasure. I’m glad to meet you, Mr. Creelton,” replied Ralph, laughing in great good humor at Bollup’s nonsense.

“There are no misters here, Osborn,” replied Creelton, a pleasant-faced, blue-eyed youth. “I see Bollup has nicknamed you Os, already, and everybody in our class calls me Creel.”

“And William Hamm wants to make your acquaintance, Os,” continued Bollup; “now, William, make your politest bow and tell of the great pleasure you experience in making Mr. Osborn’s acquaintance. Mr. Osborn, Mr. Hamm; Mr. Hamm, Mr. Osborn. Smith M. T. and Smith Y. N., shake with Osborn; Taylor, you and Os are old friends. Herndon, give Os the glad hand. Murphy, you old sinner, don’t be shy about greeting a new classmate.”

Bollup proved to be a regular master of ceremonies and in a short time Ralph found several scores of intimate friends. While yet a candidate Ralph had known Bollup and Taylor fairly well but now he felt he was on terms of great intimacy with them. He had known casually in Annapolis at the preparatory school quite a number of the candidates who were now his classmates; but none well except Bollup and Taylor. But now they all seemed friends of the most intimate nature. And Bollup seemed to be the leader of them all. The spirit of the new class centered in Bollup.

While Ralph was putting away his things and[60] talking volubly with his new friends at the same time the harsh notes of a bugle were heard sounded on the deck overhead.

“The bugle has busted, fellows,” shouted Bollup; “break away from Os, or he’ll be late to formation. That’s for dinner formation, Os,” he continued. “Now hurry; we’ve only five minutes before muster; here, let me pack your locker for you; I’m an experienced packer.”

Bollup pushed Ralph out of the way and proceeded to finish putting his things away. He threw the remaining articles in pell-mell without regard to order, in about thirty seconds. “There, I told you I was an experienced packer, Os; now let’s beat it to formation.”

They rushed up to the upper deck and reached the formation just in time to avoid being marked late. Ralph was much interested. Here was his entire class gathered together, over a hundred young men, all dressed in uniform caps and civilian clothes; they had been measured for their midshipman uniforms but it would be several days before the uniforms would be ready. In the meantime they were anything but military in appearance. A midshipman in uniform was apparently in charge. He had been turned back into this new class for failure in his studies.

The midshipmen were mustered, absentees were reported, and then, in a column of twos, were marched off the Santee to main quarters at the[61] other end of the Academy grounds. Here they were halted, were dismissed and told to stand by to fall into ranks with the battalion at the regular dinner formation.

The new midshipmen stood about in groups feeling ill at ease in their new surroundings. All about them were hundreds of other midshipmen, waiting for formation. Many of these, evidently upper classmen, paid no attention whatever to the newcomers. Others, more youthful in appearance, and evidently of the lowest class, about to be made third classmen, glanced at Ralph’s incongruously attired classmates with unconcealed gratification. They were serving the remaining few days of their plebedom and they gloated over the young men who were not yet even plebes.

One of them came up to Ralph and said: “Mister, what’s your name?”

“Ralph Osborn.”

“Never mind your first name, and always say sir, when addressing an upper classman. Try it again. Now what’s your name?”

“Osborn, sir.”

“Where are you from?”

“Toledo, Ohio, sir.”

“Never mind the town; just name your state. Now try it again!”

“From Ohio, sir.”

“That’s better. Why have you entered the[62] Navy; for money, glory, patriotism or an education?”

“I don’t know how to answer, sir; I like everything about it.”

“Say sir when you end a sentence to an upper classman. Now try it again.”

Ralph did as directed.

“What is history in its highest and truest sense?”

“I don’t know, sir.”

“Well, you’d better learn before next February, or you’ll bilge upon the semi-an,” commented the young man, gruffly. And turning to the midshipman standing next to Ralph, he said: “What’s your name?”

“Bollup, sir, from Virginia, sir, one of the Bollups of that state, sir; a descendant of the Lieutenant-Colonel Bollup who was on General Washington’s staff, sir. I came into the Navy, sir, because my father told me to, sir; and I can’t tell you about that history question, sir; history was always my weak point, sir; I nearly bilged on history in my entrance examination, sir, and I hope you’ll excuse me from it, sir.”

The questioner glared upon Bollup, and demanded, “What are you trying to do, mister? Are you trying to run me?”

“Not at all, sir; I was just trying to save you from the trouble of asking me the questions you asked Mr. Osborn.”

[63]

“I’m inclined to think you’re cheeky. I’ll take it out of you if you are, with more trouble to you than to me. Can you stand on your head?”

“Oh, yes, sir, just watch me.” And instantly Boll up was standing on his head with his heels high in the air, to the overwhelming consternation of his questioner.

“Get up, get up, mister,” he shouted; “do you want to bilge me?”

“Oh, no, sir,” returned the now erect Bollup, innocently. “I just wanted to prove to you that I could stand on my head, sir; that was all, sir.”

“Well, I’ll give you plenty of chance to prove that, but not under the eyes of the officer in charge.” And then he said to the midshipman next to Bollup: “What’s your name, mister?”

“Himskihumskonski, sir.”

“Hold on there, that’s enough. Suffering Moses, mister, where on earth did you ever pick up such a name?”

“It was my father’s name, sir, and my grandfather’s before that; I’m a Jew, sir.”

“Well, you’re a blame good man, Mister Himski and so forth. Shake hands, will you? And if you want a friend just send for ‘Gruff’ Smith. You’ll find a Jew at this school is as good as anybody else if he’s got the stuff in him. And what is your name, mister?” continued “Gruff” Smith, turning to a small, round-faced, blue-eyed little fellow.

[64]

“William Hamm, sir.”

“The next time anybody asks you your name tell him it’s Billy Bacon; now don’t forget. There’s the bugle for formation and you’d better get in ranks or you’ll hit the pap for being late.”

It was in this manner that Ralph Osborn received his introduction to the battalion of midshipmen.

On Friday of this week the senior or first classmen were to be graduated, and each of the lower classes was to be promoted one class. Up to this time Ralph’s classmates were derisively called fifth classmen and functions. Though the upper classmen, from the midshipmen point of view, esteemed fourth classmen, or plebes, to be the lowest things in the Navy, having no privileges and but few rights, yet the new midshipmen had not even yet arrived to that low estate.

These young gentlemen looked upon every upper classman as a possible enemy from whom brutal hazing might be expected. But the actual hazing proved to be very different from what had been anticipated. Ralph Osborn found himself standing on his head several times and sang several songs, but these acts, though certain to cause the dismissal of the perpetrators if detected, were always done in a spirit of fun, and were as much enjoyed by Ralph as by the hazers. Naturally Bollup received more hazing, or running, as it is called at the Naval Academy, than any of his classmates. Bollup deliberately determined to have as much fun out of the hazing as he could, and his zeal in always doing[66] more than the hazer demanded, and his antics and absurd answers created much merriment and gave him a reputation as being “a fresh plebe.” He frequently intentionally forgot to add the word “sir” in replying to questions. This was always insisted upon as expressive of a proper respect toward his seniors.

“You must never forget to say sir, Mr. Bollup,” gravely ordered Mr. Smith, who was well known as “Gruff” Smith by all midshipmen.

“Must I even think it, sir?” demanded Bollup, innocently.

“Yes, you must always think it, even to yourself; the first training a midshipman receives is to respect his seniors.”

“All right, sir; you’ll find I’m always the most respectful midshipman at the Academy.”

“Put on a sir at the end of your sentence, Mr. Bollup.”

Bollup did so, and before the end of the week he used the word sir in every possible way when speaking to an upper classman.

In this week preceding graduation day, Ralph Osborn’s classmates were exercised in the mornings, first at infantry, in which they were drilled as recruits, and after that in the gymnasium. Each afternoon they were sent out in cutters for rowing exercise. By night all of these midshipmen were thoroughly tired. The purpose of this was to harden them physically in preparation for the approaching[67] summer cruise and to initiate them in naval beginnings. It was after supper, while strolling about the grounds, that the cases of hazing occurred.

Friday was graduation day; the next day the midshipmen were to embark aboard the practice ships for the summer cruise. The Chesapeake and Monongahela, both sailing ships, were to be used this summer. Half of Ralph’s class were to go on each ship, and Ralph found he was billeted for the Chesapeake.

At breakfast formation, Friday, an order was read out that there would be no drill that day for the new fourth class; that all were to mark the jumpers of their working suits with their names in indelible ink; the name in each case was to be in black letters an inch high. After the return from breakfast to the Santee the new fourth classmen distributed themselves on the gun-deck with their working jumpers and with pen and ink and started to mark their jumpers.

“Hello, Himski,” called out Bollup as he was passing the former. “Why don’t you get busy? What are you so blue about?”

Himskihumskonski looked hopelessly at the six jumpers about him.

“I wish you’d tell me how to mark my name,” he replied; “part of it will be on the front and part on the back of my coat, and I’ll be forever turning around so that these third classmen can[68] read it. I can just imagine myself spinning around all day long. Can’t you help me out, Bollup?”

“Surely I can,” returned that youth, cheerily. “Here, give me a piece of paper; thank you.” Bollup wrote rapidly. “Now, just fix up your jumpers that way and you’ll be all right.”

“Thank you,” replied the other, smiling. “It’s worth trying.”

The new fourth class took no part in the beautiful graduation ceremonies nor in the grand ball of Friday night. The next morning they were conveyed with members of the first and third classes to the practice ships, and the summer cruise commenced. The second classmen were to remain at Annapolis during the summer for practical work in the shops.

As soon as Ralph was aboard the Chesapeake he was directed to stand in line in front of a small office. Here he gave his name, and then received a small piece of paper which gave him information where he was to eat, where to sleep, at what gun he was to drill, and what part of the ship he was to work in. He then was told to shift into working clothes immediately and to stow his locker. This latter proved very difficult, for Ralph had an enormous lot of clothes and the locker was very small. When he had finished, his locker was jammed so full that its door could be closed only with difficulty. This finally done, Ralph went up[69] on deck and there in the port gangway was Bollup and Himskihumskonski surrounded by many upper classmen, all of whom were laughing heartily. On the front of Bollup’s jumper was printed, in great block letters,

“Bollup, sir,”

and on his companion’s jumper was printed,

“Himski, etc.”

This amused Ralph. “It’s just like Bollup,” he remarked to his classmate, Taylor.

On Monday morning the Chesapeake weighed anchor and got under way for New London. The first and third classmen fell into their places easily. Ralph and his classmates at first were much bewildered with the strange things about them, the multiplicity of ropes and the jargon of strange sounds that constantly were dinned into their ears. The lieutenant in charge of the deck would shout some unintelligible order in loud, harsh tones. Then piercing, shrill whistles would be blown, followed by the screaming of the boatswain’s mates; and then everybody would jump up from whatever he was doing and rush to one end or other of the ship. Here Ralph would always find some men leading out a rope, and some first classman would gruffly say: “Fist onto that rope, mister, and put your weight on it.” Ralph would always join in the rush, and before long he commenced to understand the[70] orders that were shouted and soon the meaning of them.

The Chesapeake anchored each of the six nights she was in Chesapeake Bay, and a little mild fun was indulged in by the upper classmen.

“Bring me something to read, Mr. Bollupsir,” said First Classman Baldwin, one evening soon after the Chesapeake had left Annapolis, to Bollup.

After some minutes the latter returned and said: “I’ve hunted everywhere, sir, but can find nothing, sir; I’m sorry, sir; I did the best I could, sir.”

“Well, Mr. Bollupsir,” returned Baldwin in menacing tones, “you’ll bring me something to read within the next few minutes or you’ll stand on your head every night for a week. Get me something; I don’t care what it is.”

“Say, Os,” said Bollup soon afterward, “for heaven’s sake give me a book or a paper, anything will do; I’ve got to get Baldwin something to read or stand on my head for a week.”

“I’m sorry, old fellow!” replied Ralph. “I wish I could but I haven’t a thing.”

“Yes, you have; I see a book and a paper in your locker; let me have them, quick.”

“Help yourself,” said Ralph, smiling, “but I’m afraid what you see is not what Baldwin wants.”

“Anything will do,” shouted Bollup, snatching[71] the book and paper from Ralph’s locker and running aft without looking at them, fearing he would receive condign punishment for being so long on his errand.

“Here, sir,” cried Bollup a moment later to Baldwin, “I’ve hunted the whole ship over and this is all I can find,” and he quickly handed Baldwin the book and paper.

Baldwin looked at them and then at the plebe in front of him. “I think these will be very interesting to you, Mr. Bollupsir,” he remarked quietly. “This paper is The Sunday-School Herald; it has a number of things in it, some articles and some poems. I’m quite fond of poetry. Suppose you learn all of these poems by heart, commencing with this one, entitled: ‘Our Beautiful Sunday-School;’ there are only twenty-two verses to it. And this is a very valuable book you have brought me; I know it well; it helped me get into the Academy three years ago. It is ‘Robinson’s Practical Arithmetic.’ Now when you are tired of learning poetry you may work out some problems, there are hundreds of them, and commence at the first. And every night you’ll please report to me at seven o’clock.”

Bollup was aghast. But Baldwin was determined and directed Bollup to commence immediately. And for the rest of the summer cruise for part of each day Bollup was to be seen on[72] the berth deck by Baldwin’s side industriously working problems or committing some part of the Sunday-School Herald to memory. This created lots of fun for everybody except poor Bollup. His own classmates plagued him unmercifully and he was in constant demand by the third classmen to recite “Our Beautiful Sunday-School.” In this recitation, performed hundreds of times, Bollup became impassioned and created uproarious laughter.

On the afternoon of the day of Bollup’s misadventure, Baldwin passed Ralph who was standing by his locker and said: “Here you, take this rubber coat and keep it in your locker for me, and whenever it rains bring me my coat on the run. Do you understand? And what’s your name?”

“Yes, sir, I understand and my name is Osborn; but my locker is now so jammed I can’t get all of my own things in it, sir; I’m afraid I can’t do it, sir.”

“Never say ‘can’t’ when your senior gives you an order, Mr. Osborn,” said Baldwin severely, throwing his rubber coat to Ralph and walking on.