Title: Forest, Lake and Prairie

Author: John McDougall

Illustrator: J. E. Laughlin

Release date: March 23, 2020 [eBook #61658]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

KA-KAKE AND THE BUFFALO—(See page 155).

TWENTY YEARS OF FRONTIER LIFE

IN WESTERN CANADA—1842-62.

BY

JOHN McDOUGALL

SECOND EDITION

TORONTO:

WILLIAM BRIGGS

1910

Entered, according to the Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year

one thousand eight hundred and ninety-five, by WILLIAM BRIGGS, Toronto,

in the Office of the Minister of Agriculture, at Ottawa.

TO

My Dear Mother

THIS BOOK

is

AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

BY

THE AUTHOR.

CONTENTS.

Childhood—Indians—Canoes—"Old Isaiah"—Father goes to college

Guardians—School—Trip to Nottawasaga—Journey to Alderville—Elder Case—The wild colt, etc

Move into the far north—Trip from Alderville to Garden River—Father's work—Wide range of big steamboat—My trip to Owen Sound—Peril in storm—In store at Penetanguishene—Isolation—First boat—Brother David knocked down

Move to Rama—I go to college—My chum—How I cure him—Work in store in Orillia—Again attend college—Father receives appointment to "Hudson's Bay "—Asks me to accompany him.

From Rama to St. Paul—Mississippi steamers—Slaves—Pilot—Race

Across the plains—Mississippi to the Red—Pemmican—Mosquitoes—Dogs—Hunting—Flat boat—Hostile Indians

From Georgetown on the Red to Norway House on the Nelson—Old Fort Garry—Governor MacTavish—York boats—Indian gamblers—Welcome by H. B. Co. people

New mission—The people—School—Invest in pups—Dog-driving—Foot-ball—Beautiful aurora

First real winter trip—Start—Extreme fatigue—Conceit all gone—Cramps—Change—Will-power—Find myself—Am as capable as others—Oxford House—Jackson's Bay

Enlarging church—Winter camp—How evenings are spent—My boys—Spring—The first goose, etc

Opening of navigation—Sturgeon fishing—Rafting timber—Sawing lumber

Summer transport—Voyageurs—Norway House—The meeting place of many brigades—Missionary work intensified

Canoe trip to Oxford—Serious accident

Establish a fishery—Breaking dogs—Dog-driving, etc.

Winter trip to Oxford—Extreme cold—Quick travelling

Mother and baby's upset—My humiliation

From Norway House to the great plains—Portaging—Pulling and poling against the strong current—Tracking

Enter the plains—Meet a flood—Reach Fort Carlton

The Fort—Buffalo steak—"Out of the latitude of bread"

New surroundings—Plain Indians—Strange costumes—Glorious gallops—Father and party arrive

Continue journey—Old "La Gress"—Fifty miles per day

Fort Pitt—Hunter's paradise—Sixteen buffalo with seventeen arrows—"Big Bear"

On to White-fish Lake—Beautiful country—Indian camp—Strike northward into forest land

The new Mission—Mr. Steinhauer—Benjamin Sinclair

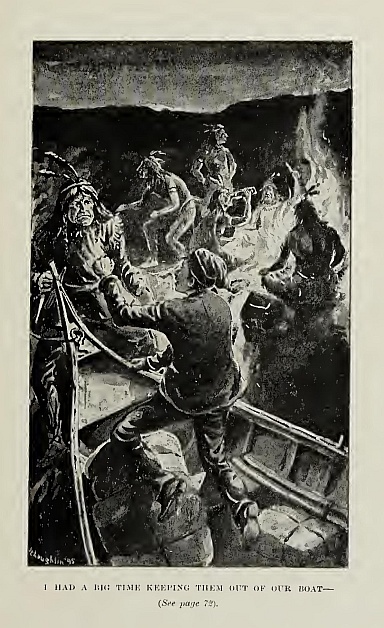

Measurement of time—Start for Smoking Lake—Ka-Kake—Wonderful hunting feat—Lose horse—Tough meat

Mr. Woolsey—Another new mission

Strike south for buffalo and Indians—Strange mode of crossing "Big River"—Old Besho and his eccentricities—Five men dine on two small ducks

Bear hunt—Big grizzlies—Surfeit of fat meat

The first buffalo—Father excited—Mr. Woolsey lost—Strike trail of big camp—Indians dash at us—Meet Maskepetoon

Large camp—Meet Mr. Steinhauer—Witness process of making provisions—Strange life

Great meeting—Conjurers and medicine-men look on under protest—Father prophesies—Peter waxes eloquent as interpreter—I find a friend

The big hunt—Buffalo by the thousand—I kill my first buffalo—Wonderful scene

Another big meeting—Move camp—Sunday service all day

Great horse-race—"Blackfoot," "Moose Hair," and others—No gambling—How "Blackfoot" was captured

Formed friendships—Make a start—Fat wolves—Run one—Reach the Saskatchewan at Edmonton

Swim horses—Cross in small boat—Dine at officers' table on pounded meat without anything else—Sup on ducks—No carving

Start for new home—Miss seeing father—Am very lonely—Join Mr. Woolsey

William goes to the plains—I begin work at Victoria—Make hay—Plough—Hunt—Storm

Establish a fishery—Build a boat—Neils becomes morbid—I watch him

Lake freezes—I go for rope—Have a narrow escape from wolf and drowning—We finish our fishing—Make sleds—Go home—Camp of starving Indians en route

Mr. O. B.—The murderer—The liquor keg

William comes back—Another refuge seeker comes to us—Haul our fish home—Hard work

Flying trip to Edmonton—No snow—Bare ice—Hard travel—A Blackfoot's prayer

Midnight mass—Little Mary—Foot-races—Dog-races, etc.—Reach my twentieth birthday—End of this book

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

Ka-Kake and the buffalo ... Frontispiece

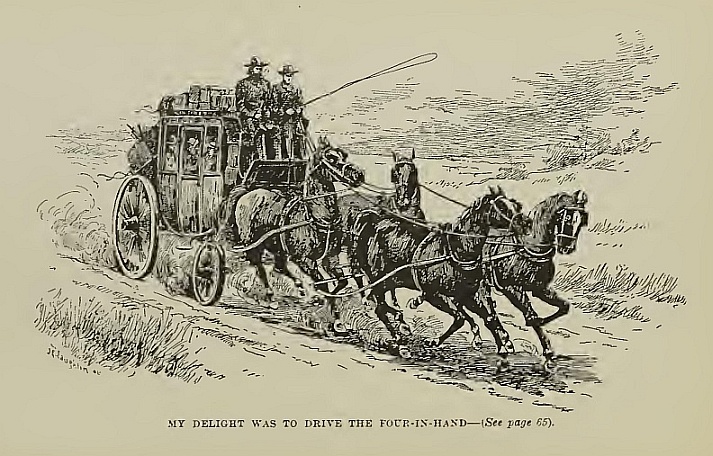

My delight was to drive the four-in-hand

I had a big time keeping them out of our boat

I lose my balance—and some conceit

Buffalo and hunters disappeared in the hills from our view (missing from book)

We were surprised by a troop of Indian cavalry

When the camp moved, parallel columns were formed

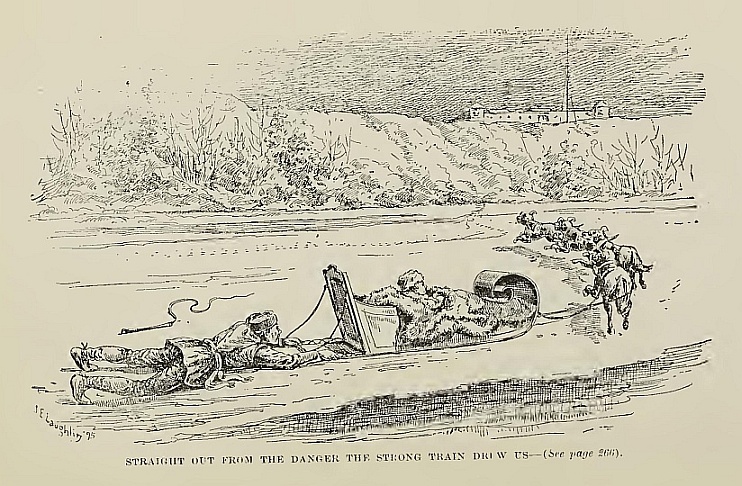

Straight out from the danger the strong train drew us

FOREST, LAKE AND PRAIRIE.

Childhood—Indians—Canoes—"Old Isaiah"—Father goes to college.

My parents were pioneers. I was born on the banks of the Sydenham River in a log-house, one of the first dwellings, a very few of which made up the frontier village of Owen Sound. This was in the year 1842.

My earliest recollections are of stumps, log heaps, great forests, corduroy roads, Indians, log and birch-bark canoes, bateaux, Mackinaw boats, etc. I have also a very vivid recollection of deep snow in winter, and very hot weather and myriad mosquitoes in summer.

My father was first settler, trapper, trader, sailor, and local preacher. He was one of the grand army of pioneers who took possession of the wilderness of Ontario, and in the name of God and country began the work of reclamation which has ever since gone gloriously on, until to-day Ontario is one of the most comfortable and prosperous parts of our great country.

God fitted those early settlers for their work, and they did it like heroes. Mother was a strong Christian woman, content, patient, plodding, full of quiet, restful assurance, pre-eminently qualified to be the companion and helper of one who had to hew his way from the start out of the wildness of this new world. My mother says I spoke Indian before I spoke English.

My first memories are of these original dwellers in the land. I grew up amongst them, ate corn-soup out of their wooden bowls, roasted green ears at their camp-fires, feasted with them on deer and bear's meat, went with them to set their nets and to spear fish at nights by the light of birch-bark flambeaux, and, later on, fat pine light-jack torches. Bows and arrows, paddles and canoes were my playthings, and the dusky forest children were my playmates.

Father, very early in my childhood, taught me how to swim, and, later on, to shoot and skate and sail. Many a trip I had with my father on his trading voyages to the Manitoulin and other islands of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, where he would obtain his loads of fish, furs and maple sugar, and sail with these to Detroit and other eastern and southern ports. Father had for cook and general servant a colored man, Isaiah by name. Isaiah was my special friend; I was his particular charge. His bigness and blackness and great kindness made him a hero in my boyish mind. My contact with Isaiah, and my association with the Indians, very early made a real democrat of me. I never could bear to hear a black man called a "nigger," nor yet an Indian a "buck." Isaiah was an expert sailor, as also a good cook, but it was his great big heart that won me to him, and which to-day, though nearly fifty years have passed since then, brings a dampness to my eye as I remember my "big black friend."

On some of his voyages father had a tame bear with him. This bear was a source of great annoyance to Isaiah, for Bruin would be constantly smelling around the caboose in which the stove and cooking apparatus were placed, and where Isaiah would fain reign supreme. One evening Isaiah was cooking pancakes, and was, while doing so, absent-minded—perhaps thinking of those old slavery days when he had undergone terrible hardships and great cruelty from his ignorant and selfish brothers, who claimed to own him, "soul and body." Whatever it was, he forgot to watch his cakes sufficiently, for Mr. Bear was whipping them off the plate as fast as Isaiah was putting them on. Father and a fellow-passenger were looking on and enjoying the fun. By and by Isaiah was heard to say, "Guess he had enough for the gentlemans to begin with;" but, lo! to his wonderment when he went to take the cakes, they were gone; and in his surprise he looked around, but there was no one near but the bear, and he looked very innocent. So Isaiah seemed to conclude that he had not made any cakes, and accordingly went to work in earnest, but, at the same time, determined that there should be no mistake in the matter. Presently he caught the thief in the act of taking the cake from the plate, and then he went for the bear with the big spoon in his hand, with which he was dipping and beating the batter. The chase became exciting. Around the caboose, across the deck, up the rigging flew the bear. Isaiah was close after him, but finally found that the bear was too agile for him, for presently he came back, a wiser and, for the time, a more watchful man.

When I was six years of age I had two little brothers, one between three and four, and the other a baby boy, about a year old—the older one named David, who is still living, and is now my nearest neighbor. The other we called Moses; he was a beautiful little fellow, and father almost idolized him. Once we lost him. What excitement we had, and also great alarm! By and by I found him in a sort of store-room behind the door, digging into a "mo-kuk," or bark vessel of maple sugar, face and hands smeared with it. What joy there was over the little innocent!

But one summer, while father was away on one of his fishing and trading trips, our baby boy "sickened and died." This was my first contact with death; it was terrible to witness baby's pain and mother's grief. We buried our loved one in the Indian burying-ground at Newash (now Brook).

Two years ago I looked in vain for the grave; it is lost to view, but never will I forget those sad days and nights during my little brother's sickness. Our Indian neighbors did all they could to help and comfort. Neither will I forget the hard time of meeting father at the beach, when he came ashore and found that his darling boy was dead and buried. Often since then have I come into contact with death in many shapes, but this first experience stamped itself on my brain.

Sometimes I went with father to his appointments to preach in the homes of the new settlers. What deep snow, what narrow roads, what great, dark, sombre woods we drove through! How solemn the meetings in those humble homes! How poor some of the people were—little clearings in great forests; rough, unhewn logs, with trough roofs. How those people did sing! What loud amens! I almost seem to hear them now.

I had an uncle settled in the bush not far from Owen Sound. I remember distinctly going with him and his family to meeting one winter's day. We had a yoke of oxen and a big sleigh. "Whoa! Haw! Gee!" and the old woods rang as we drove slowly to that "Gospel meeting" through the deep, deep snow in those early days. Then, as now, the cursed liquor traffic was to the front, and many a white man went by the board and ruined himself and family under its baneful influence. Many a poor Indian was either burned, or drowned, or killed in some other way, because of the trade which was carried on through this death-dealing stuff. The white man's cupidity, and selfishness, and gross brutality too often found a victim in his weaker red brother.

Very early in my childhood I was made to witness scenes and listen to sounds which were more of "hell than earth," and which made me, even then, a profound hater of the vile stuff, as also of the viler traffic.

My father, who was a strong temperance man, had many a "close call" in his endeavors to stop this trade, and to save the Indians from its influence, incurring the hatred of both white and red men of the vilest class.

Once when I was walking with him through the Indian village of Newash, I saw an Indian under the influence of liquor come at us with his gun pointed. I was greatly startled, and wondered what father would do; but he merely stood to face him, and, unbuttoning his coat, dared the Indian to shoot him. This bold conduct on father's part made the drunken fellow slink away, muttering as he went. Ah! thought I, what a brave man father is! and this early learned object-lesson was not lost on the little boy who saw it all.

Whiskey, wickedness and cowardice were on one side, and on the other, manliness, pluck and righteousness.

About this time, when I was between six and seven years of age, my father arranged to go to college. He left my brother David with our uncle, who lived up in the bush, and myself with a Mr. Cathey, who taught the Mission School at Newash.

I well remember the stormy winter's morn, when father and mother started for the long journey, as it seemed to me, through the forests of Ontario, from Owen Sound to Cobourg. I thought my little heart would break, and mother was quite broken up with grief at the parting from her boys, and, no doubt, father felt it as keenly; but his strong will was master, and believing in Providence, he took this step, as he thought, in the path of duty and in the interest of each one of us.

Guardians—School—Trip to Nottawasaga—Journey to Alderville—Elder Case—The wild colt, etc.

My guardians were good and kind people, and I never can forget the interest they took in me; but they believed in industry and thrift, and indeed had sore need to, for the salary of a teacher on an Indian mission in those days was very small. My time was spent in going to school, in carrying wood and water, and running errands.

During this time my guardians made a trip to the Nottawasaga country, and I went along. Our mode of transport was an open boat, and we coasted around Cape Rich and down the bay past Meaford and Thornbury. I remember one night we camped on the beach where the town of Collingwood now stands. There was nothing then but a "cedar swamp," as near as I can recollect. Finally we came to the mouth of the Nottawasaga River, where we left our boat, and made a walking trip across country to Sunnidale; and while to-day the whole journey is really very short by rail or steamboat, then, to my boyish mind, the distance was great and the enterprise something heroic.

Those deep bays, those long points, those great sand-hills, how big then, and long, this all seemed to me; and yet, how all this has dwindled down with the larger experience of life.

While at Sunnidale, I spent some of my time fishing for "chubb" in a small mill-pond, and one day, to my great surprise, caught a most wonderful fish or animal, I could not tell which. It finally turned out to be a "mud-turtle." How to carry it home puzzled me. However, eventually I succeeded in bringing the strange thing to the house. Somebody told me to put it down and stand on its back, and it was so strong and I so little that it could move with my weight.

Often since then I have seen a big Indian, with a big saddle and load of buffalo meat, all on the back of a small pony, and I have thought of my "mud-turtle" and my ride on its back.

Father did not remain very long at college. An opening came to him to go to Alderville and become the assistant of Elder Case, in the management of an industrial school situated at that place.

Father in turn opened the way for my guardian, Mr. Cathey, who became teacher at this institution, and accordingly we moved to Alderville.

This was a great trip for me—by steamboat from Owen Sound to Coldwater, by stage to Orillia, by steamboat to Holland Landing, by stage to Toronto, and by steamboat from Toronto to Cobourg. All this was an eye and mind opener—those wonderful steamboats, the stagecoach, the multitude of people, the great city of Toronto, for even in 1850 this was to me a wonderful place. To be with mother and father once more, what joy! New scenes, a new world, had opened to my boyish imagination. I felt pity for the people away there in Owen Sound, shut in by forests and rocks. I commiserated my little brother in thought, left as he was on the bush farm, under the limestone crags. What did he know? What could he see? Why, I was away up in experience and knowledge. In vain folks might call me "little Johnnie." I was not little in my own conceit, for I had travelled; I was somebody.

Here I saw the venerable Elder Case, whom I may safely call the Apostle of Indian Missions in Canada. He took me on his knee, and placing his hand on my head, gave me his blessing. Then there was his sweet womanly daughter. She was as an "angel of grace" to my boyish heart. She lifted me into the realm of chivalry. I would have done all in my power at her bidding. These memories have been as a benediction all through life, and kept me from going astray many a time in my youth.

In the meantime a little sister was born. We named her Eliza, after Miss Case. The Indians called her No-No-Cassa, or humming-bird, for she was a great crier; nevertheless, she grew to womanhood, became the wife of a Hudson's Bay Company's officer, who later on was made an Honorable Senator. To-day my sister is a widow, and is living near the historic city of Edinburgh, overseeing the education of her youngest son, who is attending one of the famous schools of old Scotland.

Father's life at Alderville was a busy one: the boys to manage, and some of those grown into young men were very unruly; the farm to run, coupled with circuit and mission work. Many a ride I had with him to meetings in that vicinity. Elder Case had a fine mare; no one else could handle her like father. She had a colt, now grown to be a great big horse, black as coal and wild also. He had broken all his halters heretofore, but father made one of strong rope which held him, and then proceeded to break him in.

One day as father was leading this colt, he called me to him, and lifted me on his back. Fear and pride alternated in my mind, but finally the latter ruled, for I was the first one to ride him. Many a broncho have I broken since then, but I never forget the ride on Elder Case's black colt.

Move into the far north—Trip from Alderville to Garden River—Father's work—Wide range of big steamboat—My trip to Owen Sound—Peril in storm—In store at Penetanguishene—Isolation—First boat—Brother David knocked down.

Our stay at Alderville was not a long one. Within a year my father was commissioned by the Church to open a mission somewhere in the north country, among the needy tribes who frequented the shores of lakes Huron and Superior.

After prospecting, he determined to locate near the confluence of the "Soo" and Garden rivers.

Behold us, then, moving out by wagon, on to Cobourg, and taking steamboat from there to Toronto; thence staging across to Holland Landing. Then going aboard the steamer Beaver, we landed one evening at Orillia, took stage at once, and pounded across many corduroy bridges to Coldwater, where, in the early morning, we went aboard the little side-wheeler Gore, and then out to Owen Sound, where my brother David joined us, and we sailed across Georgian Bay, up through the islands into the majestic river which connects these great lakes, and landed at the Indian village of Garden River.

I am now in my ninth year, and, as father says, quite a help.

We rented a small one-roomed house from an Indian, and into this we moved from the steamboat. Whiskey was king here. Nearly all the Indians were drunk the first night of our arrival. Such noise and din! We children were frightened, and very glad when morning dawned.

Things became more quiet, and now we went to work to build a mission house, a church, and a school-house.

Father was everywhere—in the bush chopping logs, among the Indians preaching the Gospel, and fighting the whiskey traffic. I drove the oxen and hauled the timber to its place. I interpreted for father in the home and by the wayside. My brother and myself fished, picked berries, did anything to supplement our scanty fare, for father's salary was only $320, and prices were very high. In our wanderings after berries I had to be responsible for my brother. The Indian boys would go with us. Every little while I would shout, "David, come on!" They would take it up, "Dape-tic-o-mon!" This was how the sounds came to their ears. This they would shout; and this they named my brother, and the name still sticks to him in that country.

My Indian name was "Pa-ke-noh-ka" ("the Winner"). I earned this by leaving all boys of my age in foot-races. After some months of hard work we got the home up, and moved into it. Then the school-house was erected.

A wonderful change was going on in the meantime. The people became sober. To see any drunk became the exception. A strong temperance feeling took hold of the Indians. Many of them were converted. Though but a boy, I could not help but see and note all the changes. What meetings I attended with father in the houses, and camps, and sugar-bushes of the people!

Our means of transport were, in summer, by boat and canoe, and in winter, by sleigh and snow-shoes.

Many a long trip I had with father in sail or Mackinaw boat, away up into Lake Superior, then down to the Bruce Mines, calling en route and preaching to a few Indians who lived at Punkin Point. We sailed when the wind would let us. Then father would pull and I would steer, on into the night, across long stretches and along what seemed to me interminable shores.

How sleepy I used to be! Often I wondered if father ever became tired. He would preach, and pray, and sing, and then pull, as if he were fresh all the time.

Then, in winter, with our little white pony and jumper, which my father had made, we would take the same trips. Sometimes the ice would be very dangerous, and father would take the reins out of the rings and give them to me straight from the horse's mouth, saying, "If she breaks through, John, keep her head above water if you can." And then father would take the axe he carried and run ahead, trying the ice as he ran. And thus we would reach those early settlements and Indian camps, where father was always welcome.

In summer, in coming to or from Lake Superior, we always portaged at the "Soo," on the American side.

Coming down father would put me ashore at the head of the rapids, and he would run them.

While we were in that country the Americans built their canal.

Father was chaplain for the Canal Company for a time.

I saw a big "side-wheeler" being portaged across for service on Lake Superior. It took months to do this. By and by I saw great vessels "locking" through the canal.

Our Indians got out timber for the canal. Some of my first earnings I made in taking out timber to floor the canal.

Father became well acquainted with the Canal Company. Once a number of the directors with the superintendent came to Garden River in one of their tugs, and prevailed on father to join the party. He took me along.

Away we flew down the river, and when near the mouth on the American side, we met a yawl pulling up stream. Who should be in it but the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, Sir George Simpson. He stood up in his boat and hailed us, and told us that a big steamer named the Traveller was aground over between the islands. She had started to cross over to the Bruce Mines and come up the other channel. He said, "You will confer a great favor if you go over and give her all the help you can. She is loaded with passengers, and they are running great risks should a storm come on before she is got off."

Accordingly we went to the rescue, and as a messenger from Providence were we welcomed by the great ship. We launched a nice little log canoe that father had taken along, and he got into it and felt and sounded a way for us, for our small vessel drew almost as much water as the big one; but father piloted our tug close to the great vessel. Soon we had a big hawser hitched to the stern of the steamer.

I well remember the time, for I was in the cabin at supper when our tug, with all steam on and with a jump, gathered in all the slack. What a jerk! and then snap went the big rope as though it had been so much thread, and away I went to the other end of the small cabin. Crockery, cutlery, and boy brought up in a promiscuous heap. Then we broke another big rope in vain, and it was concluded that the most of our passengers should go on to the steamer, and father should pilot the tug over to the Canadian side, where there was a big scow or lighter, and bring the latter, and thus lighten the ship.

Darkness was now on the scene, and the big ship, all lit up, presented a weird sight stuck on a bar and in great danger if the wind should come off the lake; which fortunately it did not.

Father started with the tug at first peep of day, and about two o'clock in the afternoon came back to us with the big barge in tow. This was placed alongside the steamer, and all hands went to work to lighten her.

In the meantime two anchors were got out astern. One of these was to be pulled upon by the windlass, and the other by the passengers—for there were some three hundred on board. Everybody worked with a will, and soon all was ready. Steam up on the steamer, our tug hitched to her ready to pull, the passengers ranged along the rope from one anchor away astern, the other rope from another anchor on the windlass. Some of the crew rolled the ballast barrels to and fro, to cause the ship to roll, if possible. When all was ready the whistle blew, and all steam was put on both big and little ships, the passengers pulled as for life, the capstan turned, the big vessel seemed to quiver and straighten, and after moments of great suspense began to move backwards off the shoal. What shouting, what cheering, once more the huge ship was afloat!

As it was now late we started for the Bruce Mines, our tug taking the lead and the steamer following. About dark we reached the docks at the Bruce Mines, where we lay all night.

Our watchman slept at his post, and allowed the big ship to get away ahead of us in the morning, but when we did start, we flew. Our superintendent was determined to overhaul her before she could reach the "Soo," and so he did, overtaking and passing her in Big Lake George, while she was scratching her way over the shoal, which at that time was not dredged out as now.

Then, when the last boat went east in the fall, all that western and upper country was left without communication until spring opened again.

Under these circumstances you can imagine with what eagerness we looked for the first boat of the season.

I well remember I was hauling timber to the river bank with a yoke of oxen, some little ways down from the Mission, when the boat came along. All I could do was to wave my gad and shout her welcome. Looking up the river, I saw my brother Dave, with father's double-barrelled gun, standing to salute the first steamer. Dave either did not know or had forgotten that father had put in an unusual big charge for long shooting, and when the boat came opposite to him he fired the first barrel, and the gun knocked him over. The passengers and crew of the steamer cheered him, and, nothing daunted, he got up, fired the second barrel, and again was knocked over. This was great fun for the steamboat people, and they cheered David, and threw him some apples and oranges, which he, dropping the gun, and running to the canoe, was soon out in the river gathering.

Some of this time mother was very sick, and David and I had all the work to do about the house—wash, scrub, bake, cook, inside and outside. We found plenty to do. When not wanted at home we went fishing and hunting. Then I found employment in teaming.

I worked one winter for an Indian, hauling saw-logs out of the woods to the river bank. He gave me fifty cents per day and my board. In the summer I sometimes sold cordwood on commission for Mr. Church, the trader, and when he put up a saw-mill, a couple of miles down the river, I several times got out a lot of saw-logs and rafted them down to the mill.

I also hauled cordwood on to the dock with our pony and a sleigh, for there were no carts or wagons in the country at that time, nor yet had we the means to buy them.

I think I made a good investment with my first earnings, a part of which I expended in the purchase of a shawl for my mother, and a part I saved for the next missionary meeting as my subscription thereto.

Father was stationed for six years at Garden River.

During this time he sent me down to Owen Sound for one winter, in order that I might attend the public school, there being none nearer to which I might have access. I must have been eleven or twelve years of age at this time. My parents put me on the steamer—the Kalloola. I was placed in care of the mate, and away we went for the east. All went well until we reached Killarney; then we struck out into the wide stretch of Georgian Bay. It must have been the middle of the afternoon that we took our course out into the "Big Lake." In the evening the wind freshened, the sky became dark, the scuds thickened, and there was every indication of a storm. The captain shook his head; old Bob, the mate, looked solemn; everything was put ship-shape.

Down came the storm, and for some hours it seemed doubtful whether we should weather it. Some of the bulwarks of our side-wheeler were smashed in. Our vessel labored heavily. Passengers were alarmed; some of them who had been gambling and cursing and swearing during the previous fine portion of the voyage, were the most excited and alarmed of the lot. The captain had to severely reprimand them at last.

Again I took mental note that loudness and profanity are not evidences of pluck or manliness.

Old Bob was about to lock me in my stateroom, but I pleaded to be allowed to remain with him on deck. Signals of distress were made. The captain thought we were in the vicinity of an island, and if we could be heard, some fishermen might light a beacon-fire, and thus we might be saved by getting under the lee of the island.

The danger was imminent. Anxiety and sustained suspense were written on every face, when suddenly through the black night and raging storm there flashed in view a glimmer of light. Presently this assumed shape, and the captain was right—we were near an island; and in a little while, by dint of strong effort, we were in the lee of the same and safe for the while. Then I went to sleep, and when I awoke we were far on our course, and in due time reached Owen Sound. I went to my uncle's, about two miles in the country, but still it was hard to distinguish very much between town and country.

From my uncle's kind but humble home I wended my way every school-day to the old log school-house in Owen Sound. The teacher believed in "pounding it in," for, like now, "Children's heads were hollow." I saw a great deal of flogging, but somehow or another missed being flogged at that school. Through the rain and mud, through the snow and slush, through the winter's cold, I plodded back and forth morning and evening from school to the little log-house under the limestone cliffs.

This last autumn, in company with my cousin, Captain George MacDougall (who was born in this log-house), we drove out to look at the spot once more. The farm, hill, and cliffs were there, but the house was gone. Here we had sheltered and played and grown, and felt it was home—now it was gone. A strange home was built near the spot, stranger people lived in it, and with feelings of melancholy we turned away.

Twice during that winter I had intermission from school. Another uncle came along and took me down to Meaford, where my grandparents lived, and this gave me a delightful visit and a holiday as well.

Another time I was chopping and splitting wood in the morning, before starting for school, when the axe slipped, and I cut my foot almost in two. Alas! I had my new boots on—long boots at that. No one knows how much sacrifice my father and mother made to provide me with those boots. I went and got my measure taken. Every other day or so I went to see if the village shoemaker had finished them. At last, after weary waiting, they were finished. How proudly I carried them home! With what dignity I walked to school with them on! Very few boys in those days had "long boots," and now alas! alas! I had cut one of them almost in two. That was the thought that was uppermost in my mind, while my aunt was dressing my foot and saying "Poor Johnnie," and pitying me with her big heart; and I was, so far as my foot was concerned, rather glad, because it bespoke another holiday from school. But my boot—could it ever be mended? would it ever look as it had? Oh, this worried me a lot.

Early next summer I went back to Garden River, and was delighted to be home again. Then father found a place for me in the store of Mr. Edward Jeffrey, at Penetanguishene, to which place I went on the same old steamer. We happened to reach there late one evening, when the whole town was in a blaze of burning tallow. Every window had a candle in it, and we on the boat, as we steamed up the bay, could not help but wonder what had happened. Presently as we neared the wharf someone shouted across to us, "Sebastopol is taken; Sebastopol is taken!"

Here was a "national" spirit in earnest. Away in the heart of Europe British soldiers were in conflict; they and their allies won a victory, and out here in the heart of this continent, a hamlet on the shore of this distant bay is aflame with joy. Why, I walked from the wharf to my future home amid a blaze of light. Every seven-by-nine had a tallow-dip behind it.

Here, for about nine months, I worked in the store and on the farm. The greater part of our customers were French, and I soon picked up the vernacular, and became quite at home in serving them.

One day when I was in the store alone, a drunken Indian came in and wanted me to give him something; in fact, demanded it. I refused, and he drew his long knife and started around the counter after me. When he came near I vaulted over the counter, and for some time we kept this up, I hoping someone would come in, and failing that, I wanted time to reach the door, which I finally secured, and throwing it open, called for help, when the crazy fellow took to his heels. I would have thankfully informed on the man who gave him the liquor, but did not like to punish the poor Indian.

Here I was given one suit of clothes and my board for my work, which always was so much; besides I learned much which has been useful to me all through life.

Summer came, and with it my father, who took me home with him. This time we drove to Barrie, and then took the train to Collingwood.

This was my first ride on a railroad; my thought was, how wonderfully the world is progressing.

Move to Rama—I go to college—My chum—How I cure him—Work in store in Orillia—Again attend college—Father receives appointment to "Hudson's Bay"—Asks me to accompany him.

After six years of great toil, and a good deal of privation, father was moved to Rama, and now a bright new field was opening before me, for father had determined to send me to Victoria College. I was now nearly fourteen years old, and would have been better suited at some good public school, but father had great faith in "old Victoria," and at that time there was a preparatory department in connection with the college. So, soon after we were settled at Rama, I went on to Cobourg.

I was early, and it was several days before college opened. Oh, how lonesome I was, completely lost in those strange surroundings. I had a letter to Dr. Nelles, and because of my father he received me graciously, and I felt it was something to have a grand, good father, such as I had; but it was days before I became in any way acquainted with the boys.

I was looked upon as an Indian; in fact, I was pointed out by one boy to another as the "Indian fellow." "Oh," said the other boy, "where does he come from?" and to my amazement and also comfort, for it revealed to me that these very superior young gentlemen did not know as much as I gave them credit for, the other said, "Why, he comes from Lake Superior at the foot of the Rocky Mountains;" and yet this boy was about voicing the extent of general knowledge of our country in those days.

I was given a chum, and he was as full of mischief and conceit as boys generally are in the presence of one not so experienced as they are.

My father thought I might be able to go through to graduation, and therefore wanted me to take up studies accordingly.

Latin was one of the first I was down for, this was in Professor Campbell's room.

We filed in the first morning, and he took our names, and said he was glad to see us, hoped we would have a pleasant time together, etc., and then said, "Gentlemen, you can take the first declension for to-morrow."

What was the first declension, what did you do with it, how learn it, how recite it? My, how these questions bothered me the rest of the day! I finally found the first declension. I made up my mind that I would be the first to be called on to-morrow. Oh, what a stew I was in! I dared not ask anybody for fear of ridicule, and thus I was alone. I staid in my room, I pored over that page of my Latin grammar, I memorized the whole page. I could have repeated it backwards. It troubled me all night, and next day I went to my class trembling and troubled; but, to my great joy, I was not called upon, and without having asked anyone, I saw through the lesson, and a load went off my mind.

After that first hour in the class-room, I saw then that after all I was as capable as many others around me, and was greatly comforted. But my rascal of a chum, noticing that I stuck to my Latin grammar a great deal, one day, when I was out of the room, took and smeared the pages of my lesson with mucilage and shut the book, thus destroying that part for me, and putting me in another quandary.

However, I got over that, and "laid low" for my chum, for he was soon at his tricks again. This time he knotted and twisted my Sunday clothes, as they hung in the room.

And now my temper was up. I went out on to the playground, found him among a crowd, and caught him by the throat, tripped him up and got on him, and said, "You villain! You call me an Indian; I will Indian you, I will—scalp you!" And with this, with one hand on his throat, I felt for my knife with the other, when he began to call "Murder!" The boys took me off, and I laid my case before them, and showed them how the young rascal had treated me. And now the crowd took my part, and I was introduced.

After that everybody knew me, and I had lots of friends.

Before long I "cleaned out" the crowd in running foot-races, and proved myself the equal of any at "long jump" and "hop, step and jump." This made me one of the boys, and even my chum began to be proud of me.

But my greatest hardship was lack of funds, even enough to obtain books, or paper and pencils. Once I borrowed twenty-five cents from one of the boys, and after a few days he badgered me for it, and kept it up until I was in despair and felt like killing him. Then I went to one of the "Conference students" and borrowed the twenty-five cents to give to my persecutor; and then daily I wended my way to the post-office, hoping for a remittance, but none came for weeks, and when one came, it had the great sum of one dollar in it. How gladly I paid my twenty-five cents debt, and carefully hoarded the balance of my dollar. Christmas came, and most of the boys went home; but though I wanted to go home and my parents wanted me very much, and though it took but a few dollars to go from Cobourg to Barrie, the few were not forthcoming, and my holidays were to go back to Alan-wick amongst my father's old friends, those with whom he had worked during his time under Elder Case, and who received me kindly for my father's sake.

Soon the busy months passed, and then convocation and holidays, and I went back to Rama and enjoyed a short holiday in canoeing down to Muskoka, having as my companions my cousin Charles and my brother David.

We had a good time, and when we came home I engaged to work for Thomas Moffatt, of Orillia, for one year, for $5.00 per month and my board.

My work was attending shop, and one part especially was trading with the Indians.

Of these we had two classes—those who belonged to the reserve at Rama, and the pagans who roamed the "Muskoka country." Having the language and intimate acquaintance with the life and habits of these people, I was as "to the manner born," and thus had the advantage over many others.

Many a wild ride I have had with those "Muskoka fellows." If we heard of them coming, I would go to meet them with a big team and sleigh, and bring them and their furs to town, and after they had traded would take them for miles on their way.

While in town we would try and keep them from whiskey, but sometimes after we got started out some sly fellow would produce his bottle, and the drinking would begin, and with it the noise and bluster; and I would be very glad when I got them out of my sleigh and had put some distance between us.

Right across from us was another store, the owner of which had been a "whiskey trader" the greater part of his life.

One morning I was taking the shutters off our windows, when a man galloped up in great haste and told me he was after a doctor, that there was someone either freezing or frozen out on the ice in the bay, a little below the village; and away he flew on his errand.

The old "whiskey trader" happened just then to come to the door of his store, and I told him what I had heard. With a laugh and an oath he said, "John, I'll bet that is old Tom Bigwind, the old rascal." (Poor Tom, an Indian, was the victim of drunkenness, and this man had helped to make him so.) "He owes me, and I suppose he owes you also. Well, I will tell you what we will do; you shall take his old squaw, and I will take his traps."

My boyish blood was all ablaze at this, but as he was a white-headed old man, I turned away in disgust.

I then went in to breakfast, and when I came out I had an errand down the street, and presently met the old trader, all broken up and crying like a child. I said, "What is the matter?" and he burst out, "Oh, it is George! Poor George!" "What George?" I asked; and he said, "My son! my son!" And then it flashed upon me—for I knew his son, like old Tom, the Indian, had become a victim of the same curse.

Ah! thought I, this is retribution quick and sharp.

I went on down to the town hall, into which the lifeless body had been brought, and there, sure enough, was poor George's body, chilled to death out on the ice while drunk!

One of the gentlemen present said to me, "John, you must go and break this sad event to his wife."

I pleaded for someone else to go, but it was no use. I was acquainted with the family, had often received kind notice from this poor woman who now in this terrible manner was widowed, and with a troubled heart I went on my sad errand.

What had spoken to her? No human being had been near the house that morning, and yet, with blanched face, as if in anticipation of woe, she met me at the door.

I said, "Be calm, madam, and gather your strength," and I told her what had happened. It seemed to age me to do this; what must it have been to this loving wife to listen to my tale! She sat as dead for a minute, and then she spoke. "John, I will go with you to my husband;" and, leaning and tottering on my arm, I took her to where her dead husband lay.

It is awful to stand by the honorable dead when suddenly taken from us while in the prime and vigor of life, but this seemed beyond human endurance. No wonder I hate this accursed traffic.

I was very busy and happy during my stay in Orillia. My employer and his good wife were exceedingly kind, and I became acquainted with many whose friendship I value and esteem to-day. At the end of the year I had saved all but $10 of my $60 salary, and with this to the good and with father's hearty encouragement, I started for college once more.

This time I was at home at once. Even the old halls and class-rooms seemed to welcome me. Dr. Nelles took me by the hand in a way which, in turn, took my heart. I received great kindness from Dr. Harris and Dr. Whitlocke, Mr. (now Dr.) Burwash and Mr. (now Dr.) Burns. I had these grand men before me as ideals, and I strove to hold their friendship.

That year at college, 1859-60, is a green spot in my memory. It opened to me a new life; it gave me the beginnings of a grip of things; it originated, or helped to originate, within me a desire to think for myself. Everywhere—on the playground, in the class-rooms, in the college halls, in the students' room—I had a good time. I was strong and healthy, and, for my age, a more than average athlete. I could run faster and jump farther than most of the students or townboys. I knew my parents were making sacrifices to keep me at college, and I studied hard to make the most of my grand opportunity.

Thus the months flew almost too quickly, and college closed and I went home; and, being still but a young boy, was glad to see my mother and brothers and sisters, and to launch the canoe and fish by the hour for bass and catfish, and even occasionally a maskinonge.

Why, even now I seem to feel the thrill of a big black bass's bite and pull.

What excitement, what intense anxiety, and what pride when a big fellow was safely landed in my canoe!

One day I was lazily paddling around Limestone Point. The lake was like a mirror. I was looking into the depths of water, when presently I saw some dark objects. I slowly moved my canoe to obtain a right light, so as to see what they were, when to my surprise I made out the dark things to be three large catfish.

Quietly I baited my hook and dropped it down, down, near the mouth of one. They seemed to be sleeping. I gently moved my baited hook, until I tickled the fellow's moustache. Then he slowly awoke and swallowed my hook. I pulled easily, and without disturbing the others put him in my canoe, and repeated this until the trio were again side by side.

This was great sport—this was great luck for our table at home.

In a little while Conference sat, and my father was appointed to Norway House, Hudson's Bay.

This news came like a clap of thunder into our quiet home at Rama. Hudson's Bay—we had a very vague idea where that was; but Norway House, who could tell us about this?

Now, it so happened that we were very fortunate, for right beside us lived Peter Jacobs. Peter had once been a missionary, and had been stationed at Norway House and Lac-la-Pliue; therefore to Peter I went for information. He told me Norway House was north of Lake Winnipeg, on one of the rivers which flow into the Nelson; that it was a large Hudson's Bay Company's fort, the head post of a large district; that our mission was within two miles of the fort; that the Indians were quiet, industrious, peaceable people; "in fact," said he, "the Indians at Norway House are the best I ever saw."

All this was comforting, especially to mother. But as to the route to be travelled, Peter could give but little information.

He had come and gone by the old canoe route, up the Kaministiqua and so on, across the height of land down to Lake Winnipeg.

We were to go out by another way altogether. I began to study the maps. This was a route I had not been told anything about at school.

In the meantime father came home. And though I did hope to work my way through college, when my father said, "My son, I want you to go with me," that settled it, and we began to make ready for our big translation.

From Rama to St. Paul—Mississippi steamers—Slaves—Pilot—Race.

Early in July, 1860, we started on our journey. I was then in my seventeenth year. We sailed from Collingwood on an American propeller, which brought us to Milwaukee, on Lake Michigan. Here we took a train through a part of Wisconsin to Lacrosse, on the Mississippi River, which place we reached about midnight, and immediately were transferred to a big Mississippi steamer.

Here everything was new—the style and build of the boat, long and broad and flat, made to run in very shallow water.

The manner of propelling this huge craft was a very large wheel, as wide as the boat, and fixed to the stern, and which in its revolutions fairly churned the waters in her wake.

The system of navigation was so different; the pilot steered the boat, not by his knowledge of the fixed channel, but by his experience of the lights and shadows on the water which by day or night indicated to him the deep and shallow parts.

Passengers and mails had no sooner been transferred, than tinkle! tinkle! went the bells, and our big steamer quivered from stem to stern, and then began to vibrate and shake as if in a fit of ague, and we were out in the stream and breasting the current of this mighty river.

Dancing was going on in the cabin of the boat when we went on board; but soon all was quiet except the noise of the engines and the splash of the paddles.

Next morning we were greeted with beautiful river scenery. Long stretches, majestic bends, terraced banks, abrupt cliffs, succeeded each other in grand array.

During the day we came to Lake Pepin, and here were joined to another big steamer. The two were fastened together side by side to run the length of the lake, and also to give the passengers of the other boat opportunity to come aboard ours, and be entertained by music and dancing.

The colored steward and waiters of our boat were a grand orchestra in themselves.

One big colored man was master of ceremonies. Above the din of machinery and splashing of huge paddles rose his voice in stentorian tones: "Right!" "Left!" "Promenade!" "Change partners!" "Swing partners!" And thus the fun went on that bright afternoon; while, like a pair of Siamese twins, our big stern-wheelers ploughed up the current of the "Big River," this being the literal translation of the word Mississippi.

Both boats had crowds of Southern people and their slaves as passengers; and if what we saw was the whole of slavery, these were having a good time. But, as the colored barber on our boat said to me, "This is the very bright side of it."

And then he asked me if we were not English. And when I told him we were Canadians, he wanted me to ask father to help some of these slaves to freedom. But it was not long after this when the mighty struggle took place which resulted in the freeing of all the slaves.

These were the days of steamboats on the Mississippi, which Mark Twain has immortalized.

From port to port the pilot reigned supreme. What a lordly fellow he was! As soon as the boat was tied to the bank the captain and mate took the reins, and they drove with a vengeance, putting off or taking on freight at the stopping-places, and taking in cordwood from the barge towed alongside in order to save time.

They made those "roust-abouts" jump. The captain would cuff, and the mate would kick, and the two would vie with each other in profanity, and thus they rushed things; and when ready, the pilot with quiet dignity would resume his throne.

When the channel narrowed our boats parted, and to change the excitement began a race.

Throw in the pitch pine-knots, fling in the chunks of bacon! Make steam! more steam! is the meaning of the ringing of bells and the messages which follow each other down from the pilot-house to the engine-room.

This time we seemed as yet to be about matched, when our rival pilot undertook to run between us and the bar, and in doing so ran his boat hard and fast in the sand.

We gave him a parting cheer and went on, reaching St. Paul some twenty-four hours ahead.

St. Paul, now a fine city, was then a mere village.

Across the plains—Mississippi to the Red—Pemmican—Mosquitoes—Dogs—Hunting—Flat boat—Hostile Indians.

We had reached the prairie country, woodland and plain intermixed.

We were now at the end of our steam transport service for this trip.

We did hope to catch the only steamer on the Red River of the North, but in this were disappointed.

The next question was how to reach the Red River. Hundreds of miles intervened.

We found on inquiry that there were two means of crossing the country in sight—one by stage-coach, the other by Red River cart.

A brigade of these latter having just then come in from the north, father and I went out to the camp where these carts were, and the sight of them soon made father determine not to travel with them. Our first sight of these Red River chariots was not favorable. I climbed into one, but did so carefully, fearing it would collapse with my weight. All the iron on it was a thin hoop on the hub, the whole thing being bound together with rawhide. "No, gentlemen, we were as yet too much 'tender-feet' to risk such vehicles."

Imagine mother and my sisters jogging hundreds of miles in those springless carts!

Father then went to interview the proprietors of the stage line, and concluded a bargain with them to take us from St. Paul to Georgetown, which place is on the Red River. Accordingly, one morning bright and early, and long before breakfast, we were rolling away up the eastern bank of the Mississippi—father, mother and sisters inside the coach, and myself up with the driver. Our pace was good, the country we were travelling through beautiful in its scenic properties.

We stopped for the first stage at St. Anthony's Falls. Here we had our breakfast.

If anyone that morning had said, "Just across yonder will stand one of the finest cities in America, and that before many years," all the pessimists in the party would have laughed at such a prophecy, but I verily believe, father would have said, "Yes, it is coming."

Our drive that day took us across the Mississippi to the village of St. Cloud, where father, learning that the steamer on the Red River would not come up to Georgetown for some time, concluded to stay over until the next coach, one week later.

In the meantime we made a tent, and hunted prairie chicken, and studied German, or rather Germans, for these made up the greater part of the population.

Taking the next coach the following week, we continued our journey. Soon we left settlement behind, the people of the stage-houses and stopping-places being the only inhabitants along the route.

Many of these were massacred in the Sioux rising which took place shortly afterwards.

Our stages ranged from twelve to twenty miles, and we averaged seventy miles per day.

A great part of the route was beautifully undulating, and fresh scenes were before us all the while.

MY DELIGHT WAS TO DRIVE THE FOUR-IN-HAND

My delight was to drive the four-in-hand, and the good-natured drivers would give me many an opportunity to do so.

It seemed like living to hold those reins, and swing around those hills and bowl through those valleys at a brisk trot or quick gallop.

By and by we reached the beginning of the Red River. We were across the divide; we were coursing down the country northward.

Hitherto it had been "up north" with us, but now, for years, it would be "down north."

These waters flowed into Hudson's Bay.

Presently we were on the great flat plain, which largely constitutes the valley of the Red River.

At the stopping-place, on the edge of this flat country, the stage people were about to leave the coach and hitch on to a broad-tired, springless wagon, but father simply put his foot down and we went on with our coach.

Talk about mosquitoes! They were there by the million. Such a night as we put in on the Breckinridge flats!

The stopping-place was unique of its kind—a dugout with a ridge-pole and small poles leaned against this on two sides, with earth and sods placed over these poles, and some canvas hung at either end. The night was hot, the dugout, because of the cook-stove, hotter still, and the mosquitoes in countless numbers.

Mother and my sisters were in misery; indeed, we all were, but we comforted each other with the thought that it was for one night only, and that respite would come in the morning.

My bed was under the table on the mud floor. My companion for the night was the proprietor of this "one-roomed mud hotel." The next morning the driver for that day said to me, "Now, young man, make a good square meal, for to-night we will reach Georgetown, and you will have only dogs and pemmican to cat." I asked him what pemmican was, but he could not tell me. All he could do was to talk about it.

All day we drove over this great flat plain—rich soil, long grass; the only break was the fringing of timber along the river.

We had dinner and then supper, and again the driver would admonish us to partake heartily of bacon and bread, for to-night, said he, "we reach the land of pemmican."

My curiosity was greatly excited as to what pemmican might be.

Late in the evening we reached Georgetown. Here we were on the banks of the Red River, and at the end of our stage journey, where we hoped to find a steamer to take us down to Fort Garry. Georgetown was situated a little north of the junction of Buffalo Creek with the Red River. The town consisted of one dwelling house and a storehouse, both belonging to the Hudson's Bay Company.

Here, though not yet in the Hudson's Bay country, we were already in touch with this great company whose posts reached far on to the Arctic and dotted the country from Labrador to the Pacific coast.

The gentleman in charge, a Mr. Murray, learning of our destination, with the usual courtesy of the Hudson's Bay Company's officers, welcomed us heartily, and gave up his room to our family, while he took up quarters with me in our tent, which we speedily pitched near the bank of the river.

That night, before we went to sleep, I inquired of Mr. Murray if he knew anything about pemmican, and with a laugh he replied, "Yes, my boy, I was made acquainted with pemmican many years ago, and will be pleased to introduce you to some in the morning." I would fain have inquired about dogs, but my kind friend was already snoring. I could not sleep so soon. This strange, wild, new country we had travelled through for days, these Indian, and buffalo, and frontier stories I had listened to at the stopping-places, and heard from the drivers as we travelled—though born on the frontier yet all this was new to me. Such illimitable plains, such rich soil, such rank grass—there was a bigness about all this, and I could not help but speculate upon its future.

With the early morn we were up, and using the Red River as our wash-dish, were soon ready to investigate our new surroundings.

The first thing was pemmican. Mr. Murray took me to the storehouse, and here, sure enough, was pemmican in quantity. Cords of black and hairy bags were piled along the walls of the store. These bags were hard, and solid, and heavy. One which had been cut into was lying on the floor. Someone had taken an axe and chopped right through hair and hide and pemmican, and here it was spread before me. My friend stooped and took some and began to eat, and said to me, "Help yourself," but though I had not eaten since supper yesterday, and we had driven a long way after that, still the dirty floor, the hairy bag, the mixture of the whole, almost turned my stomach, and I merely said, "Thank you, sir." Ah! but soon I did relish pemmican, and for years it became my staple food.

It was a wonderful provision of Providence for the aboriginal man and the pioneer of every class.

For days we waited for the steamer; not a word reached us from anywhere. In the meantime, father and I hunted and fished; we shot duck and prairie chicken, and caught perch and pickerel and catfish and mud-turtles, and explored the country for miles, though we were cautioned about Indians, a war-party of whom one might strike anywhere and any time.

The Red River was a sort of dividing line between the Ojibways and the Sioux, the former to the east and the latter to the west of this long liquid line of natural division.

By and by the steamer came, and, to our great disappointment, the captain said he could not run her back down as the water was too low.

This captain was not of the kind of pioneer men who laugh at impossibilities.

The next thing was to load a flat-bottomed barge and float her down.

We were allowed to erect our tent on a portion of the deck of the scow, and soon we were moving down stream, having as motive power human muscle applied to four long sweeps.

Day and night, with change of men, our scow kept on down this slow-currented and tortuous stream. The only stop was to take on wood for our cooking stove. Here I learned to like pemmican.

From Georgetown on the Red to Norway House on the Nelson—Old Fort Garry—Governor MacTavish—York boats—Indian gamblers—Welcome by H. B. Co. people.

I think it was the sixth day out from Georgetown that we again entered Canada. Late in the evening of the eighth day we rounded the point at the mouth of the Assiniboine, and landed at Fort Garry.

It was raining hard, and mud was plentiful.

I climbed the banks and saw the walls and bastions of the fort, and looked out northward on the plains and saw one house.

Where that house stood, now stands the city of Winnipeg.

Fortunately for us a brigade of York boats was then loading to descend the rivers and lakes, and cross the many portages to York Factory on Hudson's Bay.

Father lost no time in securing a passage in one of these, which was to start the next morning. In the meantime, Governor MacTavish invited father and mother and sisters to quarters in his own home for the night.

My work was to transfer our luggage to the York boat, and then stay and look after it, for it was evident that our new crew were pretty well drunk.

Near dark we heard a strange noise up the Red, and one of the boatmen said, "Indians coming!" And sure enough a regular fleet of wild Red Lake Ojibways hove in sight, and, singing and paddling in time, came ashore right beside us. Painted and feathered, and strangely costumed, these were real specimens of North American Indians.

As was customary, the Hudson's Bay Company served them out a "regale" of rum, and very soon the night was made hideous with the noise of their drunken bout.

I had a big time keeping them out of our boat, but here my acquaintance with their language served me in good turn.

I HAD A BIG TIME KEEPING THEM OUT OF OUR BOAT

Until near morning I kept my vigil in the bow of our boat, and then our steersman woke up, and was sufficiently sobered to relieve me, and I took his blanket and slept a short time.

Early in the day we made our start for Norway House. This we trusted was our last transfer.

Our craft was an agreeable change to the clumsy barge. This was more like a bateau built and used on our eastern lakes, but lighter and stronger, capable of standing a good sea, and making good time under sail. The boat was manned with eight men and a steersman. One of the eight was the bowman.

With our eight big oars keeping stroke, we swept around the point and again took the Red for Lake Winnipeg and beyond. Our quarters in the open boat were small, and, for our party, crowded, but we hoped to reach our destination in a few days.

We had but four hundred miles more to make to what was to be our new home.

We were now passing through the old Red River settlement, St. John's, St. Boniface, Kildonan, the homes of the people on either bank, many of these making one think that these folk literally believed in the old saw, "Man wants but little here below, nor wants that little long." Here, as everywhere in the North-West, the influence of the great herds of buffalo on the plain, and big shoals of fish in the lakes and rivers, was detrimental to the permanent prosperity of a people. You cannot really civilize a hunter or a fisherman until you wean him from these modes of making a livelihood.

We passed Stone Fort and Archdeacon Cowley's Mission, where for a lifetime this venerable servant of God labored for the good of men; then on to the mouth of the Red, which we camped at the second day. We had many delays coming through the settlements, but now were fairly off.

Up to this time father and I had not let our crew know that we understood the Ojibway, or, as it was termed here, the Salteaux.

Often had we been much amused at the remarks some of these men had made about us, but seeing a muskrat near the boat, I forgot all caution and shouted in Indian to a man with a gun to shoot it. The man let the muskrat go because of his wonder at my use of the language. "Te wa," said he, "this fellow speaks as ourselves;" and then we became great friends.

Here for the first time in my life I found myself amongst Indian gamblers.

Whenever we were wind-bound, some of the various crews (for there were a number of boats) would form gambling circles, and with drum and song play "odd or even," or something similar.

Here the man most gifted with mind-reading power would invariably come off the winner.

Our men seemed passionately fond of this kind of gambling, and it was one of the habits the missionary had to contend against, for to the Indian there was associated with this the supernatural and heathenish, and often these gambling circles would break up for the time with a stabbing or shooting scrape.

Sometimes wind-bound, sometimes sailing, sometimes pulling, merely calling at Berens River post, where some ten or twelve years later Rev. E. R. Young began a mission, and presently we had gone the greater part of the length of Lake Winnipeg, had entered one of the outward and sea-bound branches of the Nelson, had crossed the island-dotted and picturesque Play-green Lake, had come down the Jack River, and on the tenth day from Fort Garry, pulled up at Norway House, and met a very kind welcome from the Hudson's Bay Factor and his lady, and indeed from everybody.

We were still two miles from Rossville. Our new friends manned a boat and took us over. Here we found the Rev. Robt. Brooking and family; and as no news had preceded us, we brought them word of their being relieved. Great was their joy, and ours was not a little, for we had now reached our objective point for the present. Here was our home, and here were we to work and labor, each according to his ability.

New mission—The people—School—Invest in pups—Dog-driving—Foot-ball—Beautiful aurora.

Rossville is beautifully situated on a rocky promontory which stretches out into the lake. All around are coves, and bays, and islands, and rivers. The water is living and good, the fish are of first quality, and in the season fowl of many kinds were plentiful. Canoe and boat in summer, dog-train in winter—these were the means of transport.

The only horse in the country belonged to the Mission, had been brought there by James Evans, and was now very old. We used him to plough our garden, and sometimes haul a little wood, but he was really a "superannuate."

The Indians were of the Cree nation, and spoke a dialect of that language, known as the Swampy Cree.

As there is a strong affinity between the Ojibway and the Cree, I began very soon to pick it up. As Peter Jacobs had told me, these Indians were the best we had ever seen—more teachable, more honest, more willing to work, more respectful than any we had as yet come across.

Their occupation was, in summer, boating for the Hudson's Bay Company and free traders, and in winter, hunting.

There were no better, no hardier tripmen in the whole Hudson's Bay country than these Norway House Indians.

Between Lake Winnipeg and York Factory there are very many portages, and across these all the imports and exports for this part of the country must be carried on men's backs, and across some these big boats must be hauled. No men did the work more quickly or willingly than the men from our Mission at Rossville.

When we went to them their great drawback was the rum traffic. This was a part of the trade, but I am glad to say that soon after this time of which I write, the Hudson's Bay Company gave up dealing in liquor among the Indians.

This was greatly to their credit.

No wonder the Indian drank, for almost all white men with whom he came in contact did so; and even some of our own missionaries, greatly to my surprise, had brought into this Indian country those Old Country ideas of the use of stimulants.

But father soon inaugurated a new régime, and many of the Hudson's Bay people respected him for it, and helped him in his efforts against this truly accursed traffic.

In a few days Mr. Brooking and family left on their long journey to Ontario, and we settled down to home-life at Rossville.

My work was teaching, and I had my hands full, for my daily average was about eighty.

I had no trouble, the two years I taught at Norway House, to gather scholars. They came from the mainland and from the islands and from the fort, by canoe and dog-train.

My scholars were faithful in their attendance, but the responsibility was a heavy one for me, a mere boy. However, I was fresh from being taught and from learning, and I went to work enthusiastically, and was very much encouraged by the appreciation of the people.

After school hours I either took my gun and went partridge-hunting, or went and set my net for white-fish, to help make our pot boil.

On Saturdays I took one of my boys with me in my canoe, and we would paddle off down the lake or up the river, hunting ducks and other fowl.

When winter came—which it does very early out there—I got some traps and set them for foxes.

Many a winter morning I rose at four o'clock, harnessed my dogs and drove miles and back in visiting my traps, reaching home and having breakfast before daylight, as it was necessary, for a part of the winter, to begin school as soon as it was good daylight.

Soon after we arrived I invested in four pups. I paid the mission interpreter, Mr. Sinclair, £2 sterling for the pups on condition that he fed them until they were one year old.

In the meantime, for the first winter, Mr. Sinclair kindly lent me some of his dogs. Everybody had dogs, and my pups promised to make a good train when they grew.

All my boy pupils were great "dog-drivers." Many a Saturday morning, bright and early, my boys would rendezvous at the Mission, and we would start with staked wood-sleighs across the lake or up the river to the nearest dry wood bluff.

This, in my time, was three or four miles away, and what a string we would make—twenty-five or thirty boys of us, each with three or four dogs, all these hitched tandem; bells ringing, boys shouting, whips cracking, dogs yelping—away we would fly as fast as we could drive. What cared we for cold or storm!

When we reached the wood we would race as to who could chop and split and load first. What shouting and laughter and fun! and, when all were loaded, back across the ice as fast as we could go, all running.

Then we would pile our wood at the schoolhouse or church, and, again agreeing to meet at the mission house in the afternoon, away home to their dinner my boys would drive, and by and by turn up, this time with flat sleds or toboggans; and now we would race across to the Hudson's Bay Company's fort, every man for himself, and when we got there we would challenge the Company's employees to a game of foot-ball, for this was the national game of the North-West, and my boys were hard to beat.

Then back home by moon or Northern Light, making this ice-bound land like day. Ah! those were great times for the cultivation of wind and muscle and speed—and better, sympathy and trust.

Father, when home, held an English service at the fort once a week, and the largest room available was always full. Then we organized a literary society, which met weekly at the fort. Thus many a night we drove to and fro with our quick-moving dogs.

At times we were surrounded by the "Aurora." Sometimes they seemed to touch us. One could hear the swish of the quick movement through the crisp, frosty atmosphere. What halos of many-colored light they would envelop us in! Forest and rock, ice and snow, would become radiant as with heavenly glory. One would for the time almost forget the intense cold.

No wonder the Indian calls these wonderful phenomena "The Dancers," and says they are "the spirits of the departed." After all, who knows? I do not.

First real winter trip—Start—Extreme fatigue—Conceit all gone—Cramps—Change—Will-power—Find myself—Am as capable as others—Oxford House—Jackson's Bay.

During our first winter I accompanied father on a trip to Jackson's Bay and Oxford House. This is about 180 miles almost due north of Norway House, making a trip of 360 miles.

Our manner of starting out on the trip was as follows: William Bundle, father's hired man, went ahead on snow-shoes, for there was no track; then came John Sinclair, the interpreter, with his dogs hitched to a cariole, which is a toboggan with parchment sides and partly covered in, in which father rode, and on the tail of which some of the necessary outfit was tightly lashed; then came my train of dogs and sleigh, on which was lashed the load, consisting of fish for dogs and pemmican and food for men; kettles, axe, bedding—in short, everything for the trip; then myself on snow-shoes, bringing up the rear.

Now, the driver of a dog-sleigh must do all the holding back going down hill; must right the sleigh when it upsets; keep it from upsetting along sidehills, and often push up hills; and, besides all this, urge and drive the dogs, and do all he can to make good time.

This was my first real winter trip with dogs, and I very soon found it to be no sinecure, but, on the contrary, desperately hard work.

Many a time that first day I wished myself back at the Mission.

The hauling of wood, the racing across to the fort—all that had been as child's play; this was earnest work, and tough at that.

The big load would cause my sleigh to upset; my snow-shoes would likewise cause me to upset. The dogs began to think—indeed, soon knew—I was a "tenderfoot," and they played on me.

Yonder was William, making a bee-line for the north, and stepping as if he were going to reach the pole, and that very soon, and Mr. Sinclair was close behind him; and I, oh! where was I, but far behind? Both spirit and flesh began to weaken.

Then we stopped on an island and made a fire; that is, father and the men had the fire about made when I came up. Father looked mischievous. I had bothered him to let me go on this trip.

However, the tea and pemmican made me feel better for a while, and away we went for the second spell, between islands, across portages, down forest-fringed rivers and bluffs casting sombre shadows. On my companions seemed to fly, while I dragged behind. Oh, how heavy those snow-shoes! Oh, how lazy those dogs! Oh, how often that old sleigh did upset! My! I was almost in a frenzy with mortification at my failure to be what I had presumed to think I was. But I did not seem to have enough spirit left to get into a frenzy about anything.

When are they going to camp? Why don't they camp? These were questions I kept repeating to myself. We were going down a river. It was now late. I would expect to find them camped around the next point, but, alas! yonder they were disappearing around another point. Often I wished I had not come, but I was in for it, and dragged wearily on, legs aching, back aching, almost soul aching.

Finally they did camp. I heard the axes ringing, and I came up at last.

They had climbed the bank and gone into the forest. I pushed my sleigh up and unharnessed my dogs, and had just got the collar off the last one in time to hear father say, "Hurry, John, and carry up the wood." Oh, dear! I felt more like having someone carry me, but there was no help for it.

Carrying ten and twelve foot logs, and you on snow-shoes, is no fun when you are an adept, but for a novice it is simply purgatory. At least I could not just then imagine anything worse than my condition was.

By great dint of effort get the log on to your shoulder and then step out; snow deep and loose; bushes and limbs of trees, and your own limbs also all conspiring, and that successfully, to trip and bother. Many a fall is inevitable, and there are a great many logs to be carried in, for the nights are long and cold.

William felled the trees and cut them into lengths, and I grunted and grumbled under their weight in to the pile beside the camp.

At last I took off my snow-shoes and waded in the deep snow.

Father and his interpreter, in the meanwhile, were making camp, which was no small job. First, they went to work, each with a snowshoe as a shovel, to clear the snow away for a space about twelve feet square, down to the ground or moss; the snow forming the walls of our camp. These walls were then lined with pine boughs, and the bottom was floored with the same material; then the fire was made on the side away from the wind. This would occupy the whole length of one side; except in the case of a snow-storm, there would be no covering overhead.

If the snow was falling thick some small poles would be stuck in the snow-bank at the back of the camp, with a covering of canvas or blankets, which would form the temporary roof of the camp.

At last we were done; that is, the camp was made, the wood was carried, the fire was blazing.

Then the sleighs must be untied and what you wanted for that time taken from them, and then carefully must you re-wrap and re-tie your sleigh, and sometimes even make a staging on which to hang it to keep it and its contents from your dogs.