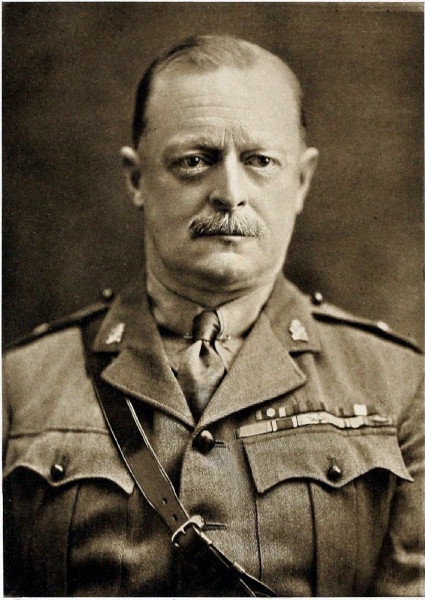

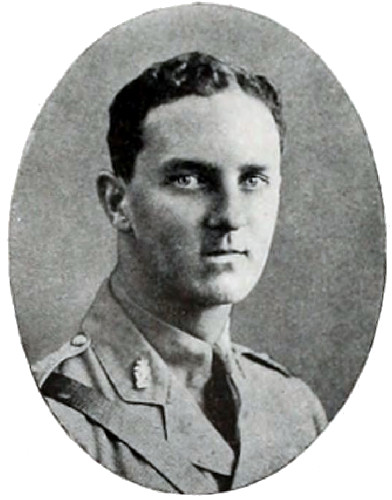

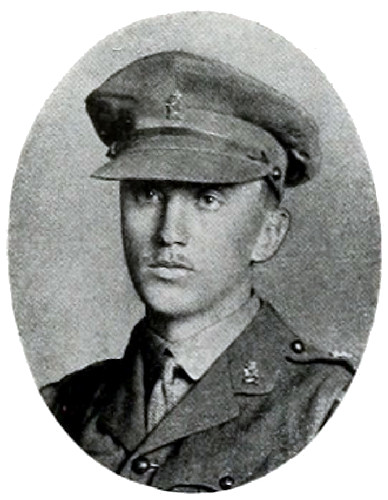

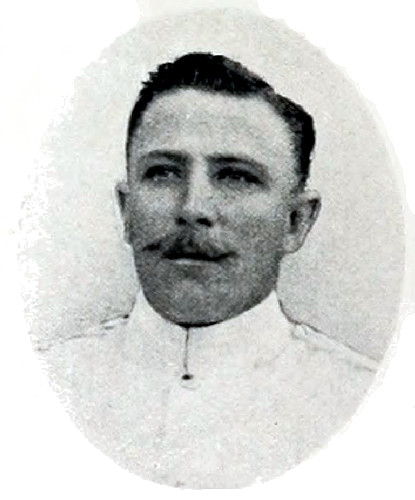

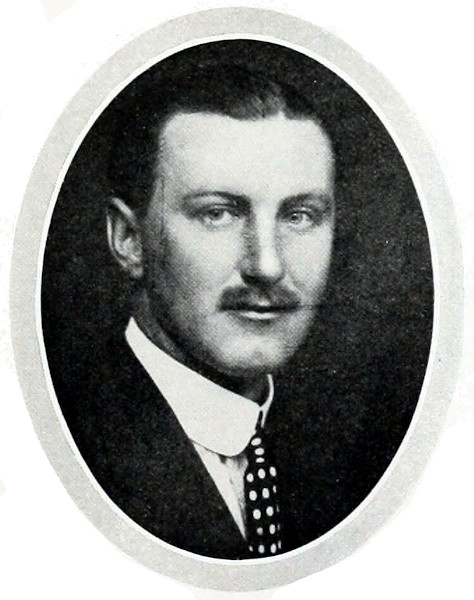

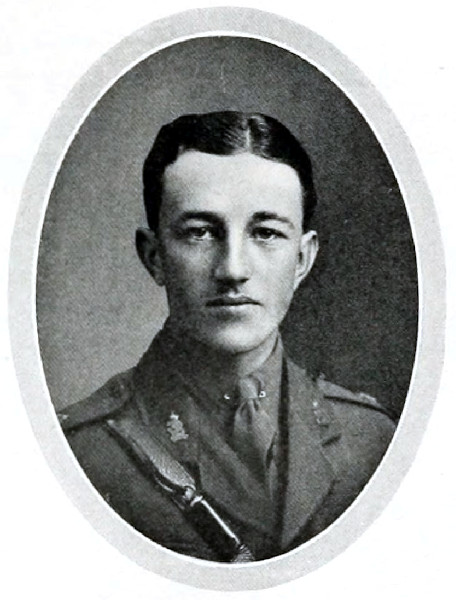

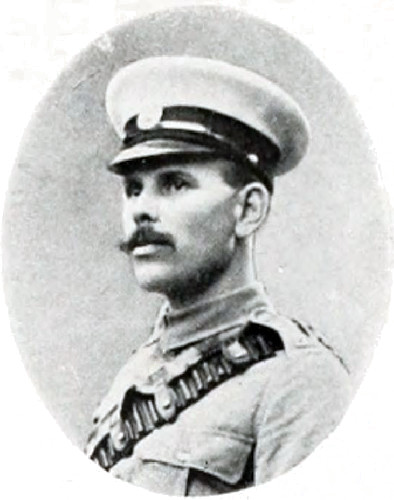

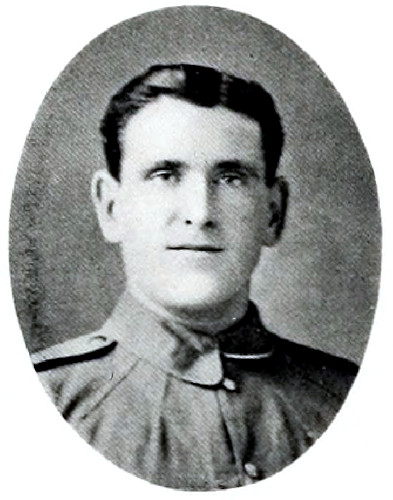

From a photograph by The Mendoza Galleries.

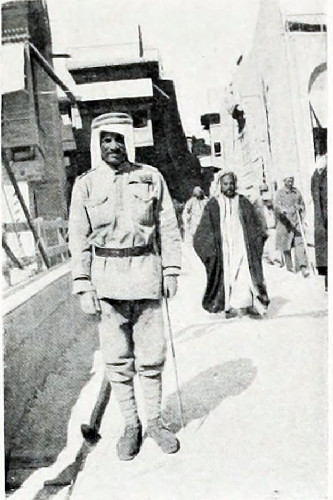

Lt. Col. J. J. Richardson. D.S.O.

Commanding 13th Hussars from August 1915

to the present time.

Title: The Thirteenth Hussars in the Great War

Author: H. Mortimer Durand

Release date: April 6, 2020 [eBook #61769]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

i

ii

From a photograph by The Mendoza Galleries.

Lt. Col. J. J. Richardson. D.S.O.

Commanding 13th Hussars from August 1915

to the present time.

iii

iv

v

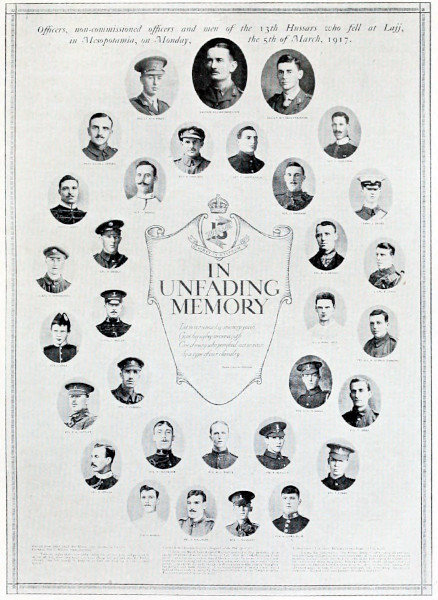

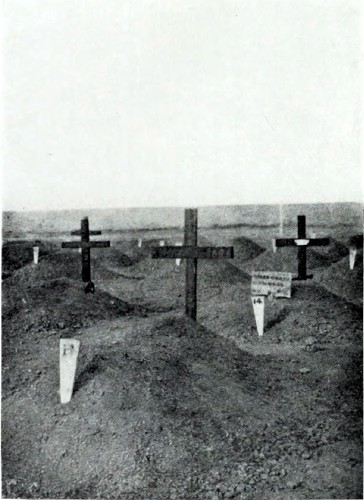

To the Unfading Memory of the

OFFICERS, NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS, AND MEN

OF THE REGIMENT WHO LAID DOWN THEIR

LIVES DURING THE GREAT WAR

1914-1918.

vi

vii

viii

ix

Thanks are tendered to Messrs. Elliott & Fry, to Messrs. Gale & Polden, and others, for permission to copy some of the portraits reproduced in this work. xiv 1

The main object of this book is to give an account of the services rendered by the Thirteenth Hussars during the last ten years, especially in the war which has just come to an end.

The earlier history of the Regiment has already been written, and very fully written. On this subject the standard authority must always be Barrett’s valuable work, which takes up the story from the beginning and carries it on to 1910, a period of nearly two hundred years. In order that readers of the present narrative may start with a general knowledge of the Regiment and its past, a chapter relating to this period has been introduced. As will be seen, it touches upon most of the wars waged by Great Britain since the days of Marlborough. But it is a mere summary, chiefly drawn from Barrett, and contains little new matter.

In ordinary circumstances this summary would open the book, but any account of the part played by a British Cavalry regiment in the late war must of necessity have some bearing upon the larger question of the part likely to be played by the mounted arm in any wars of the future; and just now this question is of special interest, for it has been freely asserted that recent changes in military conditions, notably the vast increase in the size of armies and the development of the aeroplane, have made Cavalry an obsolete and 2 useless arm; and it is important for us to know whether they have done so, or are likely to do so. Therefore it has been thought desirable to give at the beginning a brief review of the history of Cavalry before this war, and at the close a few remarks upon the lessons of the war with regard to the value of the arm under present conditions.

Perhaps the services of the Thirteenth Hussars will not lose in interest if considered to some exten/spat from this point of view. 3

For thousands of years the horse has been the companion of man in war.

It is significant that when Job gives us his wonderful description of the strong things of earth and sea and air, he speaks of the horse in this connection, as rejoicing in the sound of the trumpet, and smelling the battle afar off, the thunder of the captains, and the shouting. “He goeth out to meet the armed men. He mocketh at fear, and is not dismayed; neither turneth he back from the sword. The quiver rattleth against him, the flashing spear and the javelin. He swalloweth the ground with fierceness and rage.” And in many passages of the Bible, in poetry and in narrative, we have mention of the chariot and the horseman.

Representations of them are to be found in the carvings and tablets of long-vanished dynasties and nations. To take a single instance, they are shown in Assyrian carvings dating nearly a thousand years before Christ, which can be seen now in the British Museum.

Apparently the chariot came into the field earlier than the horseman usually so called, and the first use of the horse in war was to take up to the front in chariots warriors who got down to fight on foot, as the Greek chiefs did in the siege of Troy. But ere long Scythians or other nomads learned to mount the horse himself, and then began that close conjunction and sympathy between man and horse which made the two almost one creature, the Centaur of the fable.

The subject has been touched by many writers. There is perhaps 4 no need to consider here the uses and gradual disappearance of the war-chariot. For present purposes it is sufficient to note that long before the historical age the armed hosts of the great Eastern Empires were composed in part of mounted men, who marched, and often fought, on horseback. The chariots and the people attached to them may have been the first “Cavalry”; but the word as used in this book refers to mounted men only—riders,—and riders who did some part at least of their fighting from the backs of horses.

If the use of mounted men in war began in the East, to which Western nations owe so much, including even their religion, it soon extended to Europe. In the first conflict between East and West on a large scale of which we have any real knowledge, nearly five hundred years before Christ, the Persian invaders of Greece found that the Greeks had little Cavalry to oppose to the thousands of horsemen whom they brought with them. The men of Athens and Sparta fought on foot at Marathon and Thermopylæ. Even at Mount Cithæron, where Masistius in his golden cuirass charged and died, the Greek army was an army of footmen. Nevertheless there were some horsemen in Greece even then, especially on the plains of Thessaly; and the frieze of the Parthenon, of not much later date, shows helmeted Greek soldiers riding spirited horses. The horses are small, apparently not more than thirteen or at most fourteen hands, and are ridden barebacked, but they are evidently war horses. Then we have Xenophon’s well-known treatise on Cavalry, a thoroughly practical work, which must have been written in the first half of the next century; and after that the organisation of the Greek Cavalry is fairly well known.

It was Alexander the Great who first showed what horsemen could do in war if properly trained and led. Until his time Cavalry seem to have fought mostly in loose swarms, rather as skirmishers and bowmen than as solid squadrons using the weight of the horse itself to overthrow and destroy bodies of footmen. He saw the value of “shock tactics,” and taught his Cavalry to use them, so that when he invaded Persia in 334 B.C. the famous horsemen of Persia went down again and again before his fiery onsets. They had themselves, according to Herodotus, some notion of charging in squadron on the battlefield, but they had never seen Cavalry 5 used in mass, and neither they nor the Persian foot could stand against it.

In the impetuous rapidity of all his movements, especially perhaps in the closeness and vigour of his pursuits, Alexander was in fact a model leader of horse, and his conquests were largely due to his Cavalry, which he not only wielded with dash and power against the Cavalry of the enemy, but kept thoroughly in hand even after a successful charge, and threw into the scale wherever they might be most required to help his foot soldiers.

Ever since those days, for more than twenty centuries, the history of war on land has been the history of a struggle for pre-eminence between horsemen and footmen. The rivalry has been complicated by the invention of Artillery, and of late years by the development of fighting in the air; but it has gone on unceasingly, and can hardly be said to have come to an end even now. In the course of it there has often been a tendency to lose sight of the fact that combined effort for one purpose by all arms, and not rivalry between them, is the secret of success in war. But the long dispute and its vicissitudes form an interesting study.

By the Romans the effective use of Cavalry was for a long time not well understood. Though they had their “Equites” from early days, they got to rely more and more for serious fighting upon their wonderful legions, and it was not until the Punic Wars that they learned their lesson. Hannibal, like Alexander, was a born leader of horse, and when a hundred years after Alexander’s death he invaded Italy by way of the Alps, he at once taught Western Europe what Alexander had taught the Greeks and Persians, that in the existing condition of military armament, Cavalry well trained and boldly used in masses could do great things on the battlefield. The successive victories which he gained in Italy, with very inferior numbers, over the proud and confident troops of Rome, were due in large measure to his skilful use of his horsemen. At Cannæ, for example, his wild Numidian light horse, riding without saddle or reins, and his heavier squadrons from Spain and the North, began by driving off the weak Roman Cavalry opposed to them, and then, wheeling inwards upon the rear of the advancing legions, enclosed them in a circle of steel from which there was no escape. Fifty thousand of them are said to have 6 fallen, and for a time Rome seemed to be, perhaps really was, at his mercy. Every one knows the story of his long struggle against hopeless odds, and of his final defeat. When at last he was conquered the superiority in horsemen had passed to the Romans, and he was overwhelmed and crushed by his own methods. He had taught his enemies to fight.1

As time went on they forgot in a measure the lesson they had learnt from him, and they suffered some heavy reverses in consequence—for example, in their wars with the Parthians which stopped their expansion eastward; but happily such enemies were rare, and gradually the legions won for Rome the empire of the Western world. It lasted as long as the spirit and discipline of their incomparable Infantry remained unimpaired.

In the closing centuries of Imperial Rome the bulk of her enemies marched against her on horseback, and her own armies came to be composed more and more of Cavalry. Her last great battle was against Attila the Hun, whose people lived on their horses. It was a victory; but it was a Cavalry victory, and won by the help of the Goths. Her Infantry had long since failed her, and the Imperial City had been herself in the hands of the Barbarians. Her fall had been due to the woeful corruption and degeneration of the legions, not to any inherent superiority of the horseman over the footman; but the fact remains that at this time Cavalry was everywhere regarded as the more important arm of the two.

There followed a long period during which the predominance of the horseman grew more and more undisputed. With the collapse of Rome scientific warfare on a large scale became a lost art, and in the disorderly welter of the Dark Ages the fighting power of the footman, which depends so much upon organisation and discipline, sank lower and lower. To deal it a final blow came, a thousand years or so after Christ, the institution of Chivalry, which to a considerable extent undermined national feeling and exalted in its 7 place the individual prowess of the Knight. Having its origin in a praiseworthy attempt to set up a higher standard of right and wrong, to resist cruelty and injustice, to honour woman as she should be honoured, and to make courage and courtesy the aim of men, it did much good, and has left to succeeding ages some noble aspirations and examples. Even now there is surely no better thing one can say of a man than that he is chivalrous—chevaleresque—like a knight of old. The horseman had given his name to a new social order and a splendid ideal. In practice Chivalry was not always what it should have been, but the glamour of it lies upon all our poetry and literature. Even the free-lance or the moss-trooper, unprincipled ruffian as he often was, remains to our eyes a picturesque figure. There is still a gleam on his helmet and spear that time cannot take away. The war-horse and his rider had reached in those days the climax of their power and reputation.

Then, very gradually, came a change in the opposite direction. The knights and their retainers had been practically the only fighting men who counted, and were accustomed to ride down with ease and contempt any footmen who ventured to stand against them. Bows and arrows and axes and knives seemed of little avail against the spearman with his almost impenetrable armour and his thundering steed. As Colonel Maude puts it, “the knight in full armour had borne about the same relation to the infantry as an ironclad nowadays bears to a fleet of Chinese junks.” But little by little it began to be recognised, first it is said in the Crusades, when the knights had to take or defend fortresses and otherwise fight on foot, that there were operations in war for which the heavily armoured horseman was not well fitted. Bodies of footmen began to be raised again for such purposes, and even to be brought into the open field as archers or cross-bowmen for use in broken ground. They often suffered horribly, but now and then they gained some successes, and as time went on they developed greater skill and confidence. Eventually, at Crécy and Poictiers and Agincourt, the English archers, with their cloth-yard shafts and their bristling defence of pointed stakes, won astonishing victories over the Chivalry of France, and proved to Europe that the horseman was no longer invincible on the battlefield. The 8 lesson had very nearly been taught by the English three hundred years earlier, on the field of Hastings; but the time had not then come. Lured from their stockades, the footmen had been cut to pieces, and the French Cavalry had conquered England. At Crécy the English footmen turned the tables. And elsewhere, about the same period, the Swiss Infantry won almost equal honour.

The Cavalry of Europe nevertheless fought hard for their old pre-eminence, and it was long before they could be brought to see that they would never again be the undisputed masters in battle. But it was a lesson they had to learn. As time went on they found their charges repelled by serried squares of pikemen, from which came showers of arrows and cross-bolts; and later the invention of firearms weighted the scale still further against them. The only offensive weapons of the horsemen were the weight of their horses and the lance or sword; and if the horses failed to break the rows of eighteen-foot pikes, the arme blanche could do nothing. At last, after many attempts by the Cavalry to meet these new conditions, by using firearms themselves and other devices, it came to be generally recognised that against confident and steady infantry armed with the pike, deliberate frontal assault by horsemen was practically hopeless, and that for the future Cavalry must depend to some extent upon surprise and stratagem to give them victory. The defence had in some measure triumphed over the attack, and the essentially offensive arm had lost its pride of place.

This is not to say that for the future Cavalry was to be useless on the battlefield—far from it. The range of the unwieldy arquebus, or of the smooth-bore musket which followed it, was not so great as to keep Cavalry out of striking distance; and their speed, if they were led with decision and dash, would yet give them many opportunities of riding down the footmen. They could no longer do so whenever they pleased, but they were still a formidable part of the fighting line.

This was shown very clearly in our own Civil War. The armies of both King and Parliament were largely composed of horsemen, and in fight after fight it was they who were most conspicuous. Finally, the emergence of a great leader of Cavalry turned the scale in favour of the Roundheads. Cromwell’s Ironsides, thoroughly trained, and used as in old days the Cavalry of Alexander and 9 Hannibal had been used, not only with dash but with coolness and self-control, proved too strong for the Royalists, cavaliers though they were. Unlike Prince Rupert, Cromwell kept his horsemen firmly in hand, throwing them into the fight wherever they were most required, and the result was to make him master of England.

On the Continent too Cavalry was still largely used in battle. The Turkish horsemen were numerous and formidable. Before our civil conflicts, in the Thirty Years’ War, Gustavus Adolphus had wielded Cavalry with much effect, and while Cromwell was fighting in England the great Condé had sprung into fame by the achievement of his horsemen at Rocroy. Under him and other commanders the French Cavalry gained an enduring reputation, and the same may be said for the Germans under Pappenheim and Montecuculi. The Infantry was now perhaps the leading arm in battle, and it was growing stronger as its firearm improved, while the rise of a more or less effective Artillery was adding to the difficulties of the Cavalry attack; but at the close of the seventeenth century the horseman was still a power in the field.

Throughout the first half of the eighteenth century this state of things continued. In Marlborough’s wars Cavalry was used in large numbers, and with great effect. At Blenheim, and other notable fights, his horsemen practically decided the issue between him and the French Marshals. How important the arm was considered may be judged from the fact that at Ramilies the forces on both sides were little stronger in foot than in horse. Between them the opposing armies numbered only 75,000 Infantry to 64,000 Cavalry.

About the same time Charles XII. of Sweden was also using Cavalry in large numbers; and when, under Peter the Great, Russia began to make her mark among the military powers of the world, not the least formidable part of her army was the Cavalry, which, including the afterwards famous Cossacks, amounted at one time to more than 80,000 men.

Then came the crowning period for Cavalry in modern war. In spite of their recognised place on the battlefield, and their many successes, the horsemen of the European armies had not until the middle of the eighteenth century attained to a full comprehension of their possible influence. Awed to some extent by the reputation which the Infantry had gained at their expense in the course of the 10 last three centuries, the Cavalry had become a less swift and dashing arm. They had learnt to rely in large measure upon their fire, and even to fight dismounted as dragoons. “In fact,” according to their historian Denison, “the cavalry of all European States had degenerated into unwieldy masses of horsemen, who, unable to move at speed, charged at a slow trot and fought only with pistol and carbine.” Even so they were more mobile than Infantry, and had great achievements to their credit; but they had failed to see that a recent change in armaments had thrown the game into their hands. The Infantry, growing over-confident, had discarded the long pike for the bayonet—a very poor substitute—and the Cavalry had once more a chance of riding down their enemy in fair fight by the speed and weight of their horses. Their power was now to be taught them by a keen-sighted soldier, Frederick the Great of Prussia.

When he came to the throne in 1740, and began the career of unscrupulous aggression which was to make Prussia one of the leading nations of Europe, he soon saw that his Cavalry was not all it should have been. “They were,” says Denison, “large men mounted upon powerful horses, and carefully trained to fire in line both on foot and on horseback,” but they were quite incapable of rapid movement, and never attacked Infantry by the ancient method. “His first change was to prohibit absolutely the use of firearms mounted, and to rely upon the charge at full speed, sword in hand.” Marlborough had shown the advantage of using great bodies of Cavalry in mass, and Marshal Saxe had advocated their being taught to move at speed for a mile or more in good order. Frederick now took over both ideas, and by careful and incessant training evolved a Cavalry which was capable of manœuvring in thousands together at full pace, even over rough ground, without disorder or loss of control. Such a force, led by men like Seidlitz and Ziethen, proved to be almost irresistible. Against Austrians and Russians and Frenchmen alike, it had astonishing success. “Out of twenty-two great battles fought by Frederick, his Cavalry won at least fifteen of them. Cavalry at this time reached its zenith.”

Frederick’s system was copied by all the great military nations of Europe, and at the close of the eighteenth century the influence of horsemen in the field was greater than it had ever been since the battle of Crécy. 11

Then came Napoleon, and though the Cavalry had not such a pre-eminent place in his armies as in those of Frederick the Great, for it was not as efficient, yet it was used in vast numbers and at times with tremendous effect. Murat was perhaps the most conspicuous figure among all Napoleon’s Marshals, and other Cavalry leaders made great names for themselves. At Marengo, at Austerlitz, and in many more of Napoleon’s famous battles, the French horsemen won undying renown; and if at last his Cuirassiers had to recoil before the fire of the British squares at Waterloo, every one knows with what magnificent courage and devotion they strove again and again to cut their way to victory.

Among Napoleon’s enemies too, Prussian and Austrian, Russian and British, the Cavalry did much fine work throughout; and it is not perhaps too much to say that the Russian horsemen, especially the Cossacks, by destroying his famous squadrons in the great retreat, were among the most notable causes of his downfall. This much is certain, that when he fell the Cavalry of Europe held a high place in the battlefield. Infantry had become the backbone of most armies, and the power of Artillery had vastly increased, but Cavalry was still a powerful and necessary arm.

Then came another marked change in the conditions of war. A generation after the Conqueror’s death the rifle took the place of the smooth-bore musket in the hands of the Infantry, and the same principle was applied to cannon. The result was that the power of firearms was greatly increased in range and accuracy, and that the value of Cavalry in battle was proportionately lowered. Soon afterwards the introduction of breech-loading gave the rifled weapons a vastly greater rapidity of fire, which also told heavily against the mounted arm. It was one thing for Cavalry to remain out of range, a few hundred yards away, and then to charge against the slow and inaccurate fire of a smooth-bore musket. It was a very different thing for them to advance from a much greater distance, against a rifle which not only carried three times as far as the musket, but shot straight, and could be loaded in a quarter of the time. From the middle of the nineteenth century it began to be held, at all events in France and England, that the chance of a successful attack by Cavalry armed only with the 12 sword or lance upon Infantry in the battlefield, except under very unusual circumstances, was practically at an end. It seemed a fatal blow to the system of Frederick, and to the hope of the horseman in his long rivalry with the foot soldier.

That conclusion was not shaken by the wars waged by European nations during the remainder of the century. Some successes were gained by Cavalry in various parts of the world outside Europe. For example, the British Cavalry did fine work against the Sikhs in 1846 and 1849; a Persian square was broken and destroyed by a charge of British Indian Cavalry in 1856; and British Cavalry were very useful in the Mutiny soon afterwards, and against the Chinese; but neither in the Crimea, nor in the war between France and Austria in 1859, nor in the war between Prussia and Austria in 1866, nor in the Franco-German War of 1870, nor in the Russian War against Turkey a few years later, could the Cavalry claim to have struck such blows in battle as they had been used to strike in the days of Napoleon. Colonel Henderson in that fascinating book, ‘The Science of War,’ writing of the “shock tactics” lately prevailing, reviews the achievements of Cavalry under that system. “Such is the record,” he says: “one great tactical success gained at Custozza; a retreating army saved from annihilation at Königgratz; and five minor successes, which may or may not have influenced the ultimate issue—not one single instance of an effective and sustained pursuit; not one single instance, except Custozza, and there the Infantry was armed with muzzle-loaders, of a charge decisive of the battle; not one single instance of Infantry being scattered and cut down in panic-flight; not one single instance of a force larger than a brigade intervening at a critical moment. And how many failures! How often were the Cavalry dashed vainly in reckless gallantry against the hail of a thin line of rifles! How often were great masses held back inactive, without drawing a sabre or firing a shot, while the battle was decided by the infantry and the guns!”

Truly, the day of Cavalry seemed to be over, and this was the opinion frequently expressed at the end of the century. Their day was not over.

It will probably have been noticed that so far we have been 13 dealing only or mainly with the question of Cavalry on the battlefield. But their work lies not only on the battlefield—indeed, it may be doubted whether their work there, however great, has not always been of less value than the services they have been able to render in other ways.

The operations of war are generally treated by military writers as consisting of two distinct branches—those leading up to battle, and those of battle itself. The former are of great variety and scope, involving all the preparations and manœuvres which will result in bringing upon the battlefield an army with “every possible advantage of numbers, ground, supplies, and moral” over the army of the enemy. These operations are the province of “strategy.” The operations of the battle itself, when the opposed armies have actually come into touch, are the province of “tactics.” The latter are the more picturesque, and naturally appeal to the fighting spirit of the soldier; but the former are often, if not usually, of the greater importance to the issue of a war. “Strategy,” says Henderson, “is at least one half, and the more important half, of the art of war”; and he says elsewhere: “An army may even be almost uniformly victorious in battle, and yet ultimately be compelled to yield.”

Now it may safely be asserted that with regard to strategical operations there has never been any serious question as to the great value of Cavalry in any war confined to the land. To quote Colonel Denison, in “their fitness for scouting, reconnoitring, raiding, &c., Cavalry have always been the foremost arm and without rival. In covering an advance, in pursuing a retreating foe, their capacity has always been unequalled.” Henderson, himself an Infantry officer, states that “the Cavalry is par excellence the strategical arm,” that “it depends on the Cavalry, and on the Cavalry alone, whether the Commander of an army marches blindfold through the ‘fog of war,’ or whether it is the opposing General who is reduced to that disastrous plight.” And Von Bernhardi, discussing the future of Cavalry, says, “It is in the strategical handling of the Cavalry that by far the greatest possibilities lie.” He admits that on the battlefield and in retreat their rôle can only be a subordinate one. “But for reconnaissance and screening, for operations against the enemy’s 14 communications, for the pursuit of a beaten enemy, and all similar operations of warfare, the Cavalry is, and remains, the principal arm.” These passages were written before the aeroplane was used in war, but they show clearly that until then—that is, throughout the nineteenth century—Cavalry was still as necessary as ever for the proper working of a campaign.

And further, it may be pointed out that even with regard to the battlefield, horsemen armed and trained in a different way might conceivably be of greater use than horsemen depending solely or mainly upon shock and the arme blanche.

This was proved, though the majority of Continental soldiers would never open their eyes to the fact, by the fighting in the American Civil War. Henderson, with clearer vision, writes of this great conflict: “So brilliant were the achievements of the Cavalry, Federal and Confederate, that in the minds of military students they have tended in a certain measure to obscure the work of the other arms.” No doubt many of these achievements were rather of a strategical than a tactical nature, but many were not. The American Cavalry was from first to last constantly used for actual fighting, and in numberless instances its value as a battle arm was amply demonstrated. It would be impossible to enumerate them here, but Henderson expressly declares, for example, that “there is no finer instance ... of effective intervention (by Cavalry) on the field of battle than Sheridan’s handling of his divisions, an incident most unaccountably overlooked by European tacticians, when Early’s army was broken into fragments, principally by the vigour of the Cavalry, in the valley of the Shenandoah.” The fact was that, adapting themselves to the new conditions brought about by rifled firearms, the Americans had created a mounted service which could fight both on foot and on horseback, with the rifle or the sword or the pistol; “they used fire and l’arme blanche in the closest and most effective combination, against both Cavalry and Infantry.” Assuredly Cavalry was not yet a negligible arm in battle.

The closing years of the century saw the beginning of another war in which the horse and his rider were again very prominent. The Boers, who made so gallant and protracted a fight against the vast resources of England, were all mounted men, and it was not until the British forces opposed to them also consisted in a large measure 15 of mounted men that their resistance was broken down. They differed in many respects from the American Cavalry. The latter were trained to fight on foot if necessary, but preferred fighting on horseback whenever they could, though they fought with the pistol rather than the sword. The Boers fought mainly, almost entirely, on foot. Their arms and training were inconsistent with fighting from the saddle. They were in fact rather mobile riflemen than anything else. Nevertheless the fact remains that they were mounted men, and that a large part of their value lay in their being so. For many of the essential duties of Cavalry, for scouting and collecting information, for raids on their enemy’s communications, for the capture of his trains and guns, for covering a retirement, they were exceptionally well fitted. Henderson, writing of the duties of Cavalry, says: “But most important perhaps of all its functions are the manœuvres which so threaten the enemy’s line of retreat that he is compelled to evacuate his position, and those which cut off his last avenue of escape. A Cavalry skilfully handled, as at Appomattox or Paardeberg, may bring about the crowning triumph of grand tactics—viz., the hemming in of a force so closely that it has either to attack at a disadvantage or surrender.” The example of Paardeberg is one in which the triumph was due to the British Cavalry, but the Boers had some triumphs of the same kind, for instance at Nicholson’s Nek, and they were very near to gaining one which might have shaken the Empire. If Ladysmith had fallen, with its garrison of 12,000 men, as at one time seemed probable, the disaster would undoubtedly have been due in the main to the mobility of the Boers, whose rapid movements on horseback enabled them not only to drive in and besiege White’s troops, but afterwards to hold up for months, with inferior numbers, Buller’s relieving force, while still maintaining their grip on the starving garrison. In fact it may be said that even on the actual field of battle they fought partly as Cavalry—Von Bernhardi goes so far as to say “exclusively as Cavalry,”—for though they almost invariably dismounted to use their rifles, yet it was by the speed of their horses that they were able to extend their flanks, and, galloping out to any threatened point, form a fresh front against any turning movement. Our slow-moving Infantry had no chance of getting round and enveloping them, but was forced time after time to undertake desperate frontal attacks 16 upon the lines, often more or less entrenched, which their rapidity of manœuvre had made it possible for them to take up. Altogether, the fighting value of the 50,000 Burghers with whom Paul Kruger set out to defy Great Britain, was doubled or trebled by the fact that they were mounted men. It made them in their own country, and perhaps would have made them anywhere, a formidable fighting force.

This was not clearly understood on the Continent of Europe, but it was understood in England. It had a great effect upon the views of our leading soldiers with regard to the future of Cavalry, and the subsequent Russo-Japanese War did not in any way contradict the lessons drawn from the campaigns in America and South Africa.

To sum up this chapter, it may be said with confidence that when the Great War broke out the value of Cavalry, both as a strategical arm and on the field of battle, had been demonstrated by the experience of three thousand years. During that time it had fluctuated, especially with regard to the battlefield, but it had always been great. For some centuries, especially since the development of efficient firearms, the tendency had been for the Infantry to oust the horsemen from their pride of place in the actual shock of armies, and by the end of the nineteenth century the supremacy of the Infantry in this respect had been generally acknowledged. But even so it had not been shown that Cavalry, properly armed and trained, were incapable of joining with effect in the decision of battles, and the American and South African Wars had given reason to believe that it certainly could do so. Its great strategical value was not disputed. Clearly, therefore, Cavalry was still a necessary and important part of any efficient army—one of the most important. Whether for strategical duties or for full victory in battle, the other arms could not do without the horsemen.

No doubt the value of Cavalry might be altered in the future, as it had been in the past, by new developments in the art of war, but such was the position at that time.

We may now turn to the Thirteenth Hussars. 17

Before the war of 1914 the Regiment now known as the Thirteenth Hussars had, like most Regiments of the British Army, served in various parts of the world. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it had borne a part in nine wars of one kind or another, and had made acquaintance not only with the Continent of Europe, but with Asia, America, and Africa.

The Regiment was raised in the year 1715. The Duke of Marlborough was then still living, but his long series of victories had been brought to a close by the Treaty of Utrecht two years before, and thirty thousand of the veterans who had won them for him had been ruthlessly disbanded.

After the accession of George I., in 1714, it was seen that this step had been a hasty and dangerous one, for the Jacobite party was strong, and the reduction of the small British Army had given them fresh hopes. It soon became evident that the exiled Stuarts meant to take advantage of their opportunity, and the British Government was obliged to raise fresh troops in place of those so recently thrown away. Among the new Regiments were to be several of Dragoons, and in July 1715 the raising of one of these was entrusted to Brigadier Richard Munden, an officer on half-pay who had served with some distinction under Marlborough.

It appears that Munden had no difficulty in finding recruits, for within three months the Regiment had been raised, and was assembled at Northampton. There it received orders to march to Leeds, and soon afterwards Brigadier Munden was informed that his Regiment, with others, was to be under the orders of Major-General 18 Wills, whom His Majesty had appointed “to command several of his forces on an expedition.”

At this time a Dragoon Regiment in the British Army consisted of 6 troops, and its strength was between 200 and 300, including 19 “Commission” officers. It was not a Regiment of “Horse,” though it was mounted, and regarded as Cavalry. The men were armed with the same firearm as the Infantry, or practically the same, and were expected to fight on foot as well as on horseback. This, it will be remembered, was the period when European Cavalry depended largely on their fire, and had not been trained to the system of Frederick the Great, the charge at speed with the arme blanche. The officers of Munden’s Dragoons, including Munden himself, had almost all served in Regiments of Foot.

The Regiment was “officially declared to be a disciplined force belonging to the regular army on 31st October 1715.” It had not to wait long before seeing service, for early in November General Wills learned that the Jacobite “rebels” were over the Scottish border, and marching on Lancaster. He at once drew together his forces at Manchester, and marched thence to Wigan. On the 12th November Munden’s Dragoons were in presence of their first enemy, who had advanced as far as Preston, and was in occupation of the town.

It is significant that when General Wills left Wigan with his force to attack the rebels, the order of march was as follows: The advance-guard consisted of fifty musketeers and fifty dismounted dragoons. After the advance-guard came a Regiment of Foot, then three Brigades of Cavalry consisting of one Regiment of “Horse” and five of Dragoons. Evidently Cavalry was not regarded as the eyes of an army.

The action which followed was at first indecisive. The enemy, superior in numbers, and aided by some guns and barricades, repulsed one or two attacks made by Infantry and dismounted Dragoons. But on the following day General Carpenter having come up with three more Regiments of Dragoons, the rebels gave in and surrendered. Their assailants had lost in all one hundred and thirty killed and wounded, so the fighting had not been very severe. Nevertheless Preston was an affair of some importance, for 19 with the indecisive battle of Sheriffmuir, fought the same day by other troops, it sufficed to put an end to the First Jacobite Rebellion and to establish the House of Hanover on the British throne. Munden’s Dragoons had only four wounded during the fight, but they seem to have behaved well. Munden himself is said to have led a storming party, and to have been thanked for his gallant conduct. After the fight, the Regiment seems to have been employed in escorting to jail the unfortunate prisoners, whose fate was a sad one.

It may be noted that among the troops who served at Preston was Dormer’s Regiment of Dragoons, afterwards the Fourteenth Hussars. Thus began a comradeship between the two Regiments which was afterwards very close.

Then followed for Munden’s Dragoons, who about this time became known as the Thirteenth Dragoons, a long period of peace service. In 1718 there was again a reduction of the Army, and some Regiments having been disbanded in Ireland, the Thirteenth were sent over to take the place of one of them. The Irish military establishment was then separate from the British. The pay of the troops was somewhat less, and their circumstances in other respects were very unsatisfactory. It was forbidden to enlist any native of the country, so that men were hard to get, and the barrack accommodation was so scanty that the troops were scattered about in small detachments, to the woeful detriment of their discipline and efficiency. It apparently became the custom for officers to overstay their leave, or absent themselves without leave, and everything got slack in proportion. It was possibly not the fault of the Regiments that their arms were in most cases insufficient and bad; but in every way their condition was deplorable. The Thirteenth Dragoons seem to have suffered like the rest, and probably when their Colonel, Munden, was transferred to another Regiment in 1722, they were not in a very efficient condition.

Munden was one of the officers who followed the body of the great Duke of Marlborough when he was borne to his grave in Westminster Abbey. He died himself, a Major-General, three years later, and Colonel William Stanhope became Colonel of the Thirteenth. This officer, afterwards the Earl of Harrington, was appointed a Secretary of State in 1730. 20

The stay of the Regiment in Ireland came to an end in 1742, when it was transferred to Great Britain, and in the following year the command of it was bestowed upon Lieut.-Colonel James Gardiner of the Inniskilling Dragoons, then serving in Germany. Thus when the Second Jacobite Rebellion took place, in 1745, the Thirteenth, under this well-known officer, was among the Regiments at the immediate disposal of the Government, and was fortunate, or unfortunate, enough to find itself engaged once more on active service.

When Bonnie Prince Charlie unfurled his standard at Glenfinnan, Sir John Cope, the British General commanding in Scotland, was very weak in the number and quality of his troops. He had no gunners to man his few guns, and the force at his disposal to meet the advancing rebel army, after providing some small garrisons, amounted to about twenty-five companies of foot and two Regiments of Dragoons. One of these two was the Thirteenth. Provisions and transport were very scarce.

It is a curious coincidence that the Regiment came to blows with its second enemy at another Preston, this time in Scotland. Close to it was the house of their Colonel, Gardiner. The Thirteenth had had some trying work during the preceding weeks, when Cope withdrew his small force from Inverness to Dunbar, abandoning Edinburgh to the rebels; and the Regiment was not in good condition, many men and horses being physically unfit for duty.

The result of the battle is well known. The enemy, chiefly Highlanders, attacked on the early morning of 18th September. Cope having no gunners, a Lieut.-Colonel Whiteford and an old Master Gunner of the name of Griffiths fired a few rounds from the guns and cohorns, “none of whose shells would burst,” and then the guns were rushed by the Highlanders. It was a fine chance for the Cavalry, as the rebels were in confusion, but the chance was not taken. To tell the simple truth, neither of the two Dragoon Regiments, Hamilton’s or Gardiner’s, which seem to have numbered six hundred men between them, could be induced to charge, and their only inclination was to gallop off the field. By the exertions of their officers and other gentlemen, about three-quarters of them were stopped, and brought into Berwick 21 next day; but it must be admitted that their behaviour was anything but creditable, and the battle ended in the total defeat of the King’s force. This much is to be said in favour of the Regiments, that their officers fought gallantly. The ill-fated Gardiner, who was seriously ill, was wounded at the beginning of the engagement; and later, when his men refused to charge, he received several other wounds, from which he died. His Lieutenant-Colonel, Whitney, was also wounded in trying to rally the men. But the fight of “Prestonpans” was certainly what Brigadier Fowke called it, “an unhappy affair.”

After Gardiner’s death the command of the Thirteenth was given to Colonel Ligonier, a brave officer who had served under Marlborough, and in the following January it took part in another battle and another defeat at Falkirk Muir. The same two Regiments of Dragoons which had been engaged at Prestonpans, and another, Cobham’s, formed at Falkirk a Brigade of Cavalry under Ligonier’s orders. This affair was not so discreditable as the former. The Cavalry, very gallantly led by Ligonier, did charge the enemy, and it is said penetrated their first line. But they failed to break the second line, and the charge ended in a confused retreat. Lieut.-Colonel Whitney, wounded at Prestonpans, was killed, and the gallant Ligonier also paid for his courage with his life. Suffering from an attack of pleurisy, he insisted on getting out of bed to command his Brigade in the battle, which was fought in a storm of wind and rain. His exertions in rallying the Dragoons and covering the retreat during the following night were too much for him, and a week later he died.

The Thirteenth saw no further fighting. When the Duke of Cumberland broke the Highland clans at Culloden and put an end to the rebellion, the Regiment was not present. It had been left in Edinburgh to patrol the roads, and intercept any communications between the English and Scottish Jacobites. Its share in the campaign, therefore, had not been a very satisfactory one. Perhaps it was not to be blamed for the second defeat at Falkirk, but certainly it had not won much distinction on the battlefield.

All that can be said is that no troops are likely to do well in the great ordeal of war unless their discipline and general condition 22 have been steadily maintained in peace. History abounds in such lessons. The Regiment was to do great things later under more favourable conditions, and win a fine name for itself as a fighting corps. Its time was not yet come.

In 1748 the Thirteenth was once more transferred to Ireland, and there it remained for a second score of years. A Dragoon Regiment at this time seems to have been very weak in numbers, considerably under two hundred all told, officers and men, with one hundred and fifty horses. The prohibition against Irishmen had apparently been withdrawn, and by 1767 the men were almost all Irish. But none were Roman Catholics, the enlistment of these being still absolutely forbidden. The men were fine, most of them from five foot nine to five foot eleven, and “tolerably well appointed.” The officers too were mostly Irish. The barrack accommodation was still very poor, and the Regiment was scattered in detachments as before. The arms were very bad at times.

About 1777 the Thirteenth were converted into Light Dragoons, and much smaller men were enlisted. The example of Frederick the Great was now being followed on the Continent, and Cavalry was being trained for greater speed and hand-to-hand fighting. The Infantry firearm of the Thirteenth gave place to a short carbine, and some changes were made in the uniform, the old three-cornered hat making way for a Cavalry helmet. Bayonets were still carried, but evidently there was some idea of making the Dragoon more of a horseman and less of a foot soldier.

Nevertheless the state of the British Cavalry at that time as to equipment and drill was very antiquated. “The military value of their training,” says Barrett, “was practically nil.” And, to add to their disadvantages, they were now cursed with the system of “proprietary Colonels.” How this system came about is not clear, but towards the end of the eighteenth century it was in full force. In Munden’s day the Colonel had been “the active officer in command, and always present, unless on leave, whether at home or in the field.” Sixty years later, when the old traditions of Marlborough’s time had been lost, the Regiment was really commanded by the Lieutenant-Colonel, while the Colonel had become an absentee, seeing the Regiment perhaps once or twice a year. 23 Yet it was in a sense looked upon as his private property. “The system,” says Barrett, “was a bad one. To bad Colonels were due the crying abuses of the pay system as well as those of the clothing system—the systematic robbery of the soldier, the mean frauds by which an income was literally swindled out of Government or sweated off the backs of the men; and the abuse of the power of the lash was owing to the same cause.” In 1787 the Colonel of the Thirteenth, a member of Parliament, “lived mainly in London while the Regiment was in Ireland.” Arms were bad, desertions frequent, and the duties of the Regiment consisted chiefly of hunting down members of the various lawless societies in Ireland, Whiteboys and Peep-o’-Day Boys, and the like. In spite of all these heartbreaking drawbacks the regimental officers seem to have done something to make the men efficient, for at times the reports of inspecting Generals are good enough, though evidently the standard was not high; and in 1794, no doubt because of the French Revolution and the outbreak of war on the Continent, the strength had been increased to 446 men and 393 horses.

The Thirteenth, however, was not yet to be employed in the Continental war. It was now, after its two campaigns against the Jacobites, followed by fifty years of peace duty, to have its first taste of service abroad, but this was not to be in warfare against a civilised enemy.

In the island of Jamaica the “Maroons,” originally runaway negro slaves, had long been giving trouble, and it had now become urgently necessary to suppress them. They held a difficult mountain country, full of densely wooded glens, from which they had been wont for many years to raid the lowlands and plantations, plundering and murdering. After some partial settlements they had again risen, and had openly defied the white men to war. Their numbers were not large, perhaps 1200 all told, but as Great Britain was already fighting the French in the West Indies the complication was serious, and Lord Balcarres, the Governor, was assembling a considerable force to blockade the revolted highlands.

It is remarkable to find, considering the nature of the ground, that in addition to three Regiments of Infantry and some local militia, this force was to consist of five Dragoon Regiments, of which two were the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Light Dragoons. 24

The Thirteenth was brought over from Ireland to England in 1795, and a couple of troops sailed for Jamaica in advance, the remainder of the Regiment remaining in England until the following February, when, on the 9th of the month, the Headquarters sailed in the Concord, which formed part of a fleet numbering more than five hundred sail. In spite of all the circumstances of its peace service, the Regiment seems then to have been in a condition of discipline and efficiency very creditable to officers and men. Fortunate that this was so, for both were soon to be severely tested. A violent storm scattered the fleet three days after sailing, and in the Bay of Biscay the Concord took fire, some pitch used for fumigation having been upset by the rolling of the vessel, and blazed up. As the fire was immediately over nineteen casks of powder, the danger was great. It is pleasant to read how the ship’s company behaved in this sudden contingency. The Captain, who was writing in his cabin, ran on deck “with his pen across his mouth.” An officer was sent down to the hold to cover the powder barrels with wet blankets and mattresses. “Scores of men, with their mattresses held in front of them,” threw themselves on the flames and smothered them, while the officer below spread a sailcloth over the barrels and kept it wet under a shower of sparks from the deck above. Eventually, after really heroic exertions, the fire was brought under, and the ship escaped destruction. Soon afterwards she sprang a leak, and had to put back to Cove, but all damage was set to rights in a few days, and on the 26th February the fleet put to sea again. This time all went well, and on the 1st April the fleet was assembled in Barbadoes.

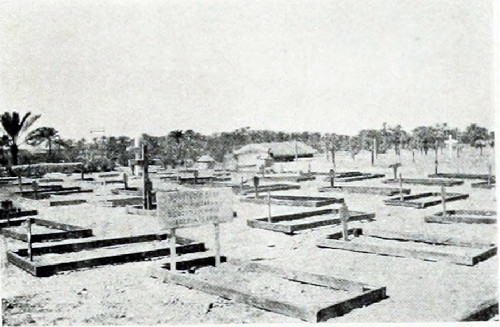

After a short stay there, the Thirteenth was sent on to San Domingo, in which island it remained for some months, helping to put down a rising of brigands. While doing this work the Regiment, which till then had been very healthy, was attacked by the scourge of the West Indies—yellow fever. Much has been written about the awful ravages of the disease in those days. It is only necessary to say here that the Thirteenth suffered as others did. Men died daily, and at last the Regiment was so reduced that it had to apply to the Fifty-sixth Foot for help to bury its dead. How many were left alive does not appear, but by the end of the year the remains of the Regiment had arrived in Jamaica. 25

It is not easy to follow in detail the course of the campaign against the Maroons; but it seems that though only two troops of the Thirteenth were employed in it, the command of the whole expedition was eventually given to Lieut.-Colonel the Hon. George Walpole of this Regiment, and that after some hard jungle fighting and mutual ambuscades the Maroons surrendered to him, on a promise that they should not be deported. The Jamaica Government broke this engagement, and voted Walpole a sword of honour, which in the circumstances was naturally declined.

The Regiment remained in the West Indies until August 1798, when, after transferring some 95 men to the Jamaica Dragoons, all that were left, 52 in number, chiefly non-commissioned officers, sailed under the command of a Lieutenant for England. Of these 52, many were found on arrival to be totally unfit for service, and were invalided. Most of those not immediately invalided were “completely exhausted and worn out,” and were gradually discharged. The Regiment had in fact ceased to exist. During the two years and six months of its absence, though it had lost only one man killed in action, it had left behind it, dead of disease, 19 officers, 7 quartermasters, 2 volunteers, and 287 non-commissioned officers and men. Such were the conditions of service at that time in the West Indies.

But the war with France was now in full course, and Cavalry was necessary, so the Commander-in-Chief gave orders that the Thirteenth be augmented to a strength of 641 men with the same number of horses. As practically nothing remained of the old Regiment but a few officers, this meant raising a new one. Nevertheless, by August 1799, the task had been accomplished, and two years later the strength had reached 902. The short-lived Peace of Amiens in 1802 caused it to be reduced again, after the custom of the times, by about one-half, but the reduction was as short-lived as the peace, and in 1805, when Napoleon had assembled his great army at Boulogne for the invasion of England, the Regiment stood at the highest strength it ever reached, 1064 men, and the same number of horses. From this time on until 1810 the Thirteenth was kept at home. It was then no longer an Irish Regiment, but a trace of its old connection remained in the fact that it now had as one of its squadron commanders Colonel 26 Patrick Doherty, who had sailed with it for the West Indies in 1796, and that two of his sons were serving in his squadron.

So far the war record of the Thirteenth can hardly be said to have been fortunate. In the ninety-five years of their existence they had served with no special distinction in the two Jacobite rebellions, and in one campaign abroad, where their chief enemies had been climate and disease. But this long period of inglorious and yet trying service was now over. In the next five years, before their first century came to an end, they were to cross swords again and again with the finest soldiers in the world, to learn the lessons of war under the greatest of English commanders, and to win for themselves imperishable renown.

In February 1810 the Regiment was ordered to prepare 8 troops for immediate service abroad, and before the end of the month they were on board ship. They left behind 2 troops in depot at Chichester, and parted with their Commanding Officer, Colonel Bolton, who had done much to raise and shape the new Regiment after the West Indian campaign. He had just been promoted, and was succeeded by Colonel Head from the Twelfth Dragoons. The 8 troops for active service each numbered 85 men and 85 horses, or 680 men with officers. Before the end of March they had disembarked at Lisbon.

The Thirteenth were about to take part in the famous Peninsular War. Wellington had already given the French some rude shocks in this quarter, and was soon to establish his reputation as one of the first soldiers in Europe. He had clearly recognised the power of offence given to Great Britain by her Navy, which was now supreme, and he believed that by clinging on to a foothold in Portugal, he would in time be able to deal a heavy blow to the military strength of Napoleon, which must be strained by a protracted struggle at this distant point of the Empire. It was a fine conception, and the event proved that he had judged correctly. But at the moment his prospects seemed to be very doubtful, if not hopeless. Napoleon had large armies in Spain, fully 300,000 men, commanded by some of his most famous Marshals, while the British force in Portugal was not a tenth of that number, and badly organised. The Spaniards were evidently incapable of defending their country, or of giving any effective help in defending 27 it; and Portugal was not strong enough, or united enough, to do much against such an enemy. Wellington himself was as yet a man of no great weight in Europe, a mere sepoy General, to use Napoleon’s words, who was regarded as fit only to fight Asiatics. He was thwarted and decried in England, where such successes as he had gained were minimised by party rancour. Some of his countrymen even wished to omit his name from the vote of thanks accorded to the troops under his command, and the force itself was full of complaints and discontent, chiefly on the part of the officers. It belonged to an Army which had been discredited by almost constant failure since the War of American Independence. Even in its own country it was not highly regarded. And if the British Infantry was now beginning, under Wellington’s command, to win some measure of the reputation it was soon to gain as the best in Europe, the British Cavalry was, both in numbers and training, greatly inferior to the magnificent squadrons of France. When the Thirteenth landed in Lisbon there seemed little likelihood of a brilliant future for them. Happily the British soldier is not greatly disturbed by the prestige of his enemies, and individually both men and horses were better than the French. Above all, our troops had now a leader whose indomitable spirit was proof against all discouragements.

The Thirteenth were soon in the thick of the fighting, but at first they seem to have been rather helpless. It is recorded that in July of that year, 1810, the Regiment for the first time found itself in bivouac, “and both the officers and men were perfectly ignorant what to do.... Nobody knew what was to be done for food, forage, &c. Provisions were served out to the men by the Commissary, but how to cook them was another matter.” They were soon taught how to find shelter and feed themselves, but this was the doubtful beginning of a campaign in which they were to oppose the war-seasoned troops of Napoleon. Nevertheless, within a few weeks of that date some of them had twice successfully encountered the enemy’s horsemen, a troop of the Thirteenth on the second occasion charging through and capturing more than fifty French Dragoons.

After this, during the summer, the Regiment suffered severely from sickness, which, however, did not prevent them from being 28 present at the battle of Busaco on the 26th September 1810, when Masséna was met and severely checked in his famous invasion of Portugal. They were not actually engaged, but were observing the plain in the left rear of the force while the battle was fought. As every one knows, Masséna was eventually stopped by the lines of Torres Vedras, and had to retreat. During the autumn and winter the Thirteenth remained in the country not far from Lisbon, watching the French and learning their work in many a rough march.

For some time it is said French and English Dragoons lay on opposite sides of the Tagus, and the retreat being for the time at an end, the Thirteenth used to have frequent field-days on a plain by the river. The vedettes by mutual arrangement refrained from firing on each other, and the French officers used to come and look on, sometimes when the river was low exchanging conversation with their friendly enemies. It was in some ways a chivalrous warfare, in which, however, the unfortunate Portuguese suffered terribly from the wasting of the country and exhaustion of supplies.

Then, in the spring of 1811, the enemy retired to the northward and westward; and a force under Marshal Beresford was sent to intercept communications from the south. The Thirteenth formed part of this force, and while under Beresford’s orders it had the luck to be engaged in a brilliant affair which has since formed the subject of much controversy. The town of Campo Mayor had been taken by the French under Latour Maubourg, and was occupied by a force of 1200 Infantry and over 800 Cavalry, with some Horse Artillery and a battery train of sixteen heavy guns. On Beresford’s approach this force evacuated Campo Mayor and retreated on Badajos, ten miles away. The British Cavalry was sent in pursuit and overtook the enemy. The action that ensued is not altogether easy to understand; but the Thirteenth charged, and after some very gallant hand-to-hand fighting, broke the opposing French Cavalry, pursuing them up to the gates of Badajos, capturing the whole siege train, with great quantities of waggons and stores, and leaving the rest of the garrison to be followed up and secured by Beresford’s heavy Cavalry and guns. The Thirteenth were naturally pleased and proud at their success against a very superior enemy; but, by a mistake 29 which was not fully explained at the time, the advance was stopped, and the Thirteenth given up for lost. They rejoined the force in safety; but Beresford, misled by false information, believed they had shown want of discipline after the charge, and reported in that sense. Wellington, at a distance, and as Fortescue says, “always justly sensitive over the ungovernable ardour of his Cavalry,” accepted Beresford’s view, and referred to the Thirteenth in stinging words. “Their conduct,” he wrote, “was that of a rabble, galloping as fast as their horses could carry them over a plain after an enemy to which they could do no mischief after they were broken.... If the Thirteenth Dragoons are again guilty of this conduct, I shall take their horses from them, and send the officers and men to do duty at Lisbon.” This threat was not communicated to the Regiment, Beresford having meanwhile learnt something of the truth; but the Thirteenth were nevertheless severely censured for impetuosity and want of discipline. This censure, as may be supposed, they deeply resented. Napier, in his ‘History of the Peninsular War,’ says that “the unsparing admiration of the whole army consoled them.” No doubt to some extent it did, but not entirely.

Fortescue, after a detailed examination of the incident, sums it up as follows: “Of the performance of the Thirteenth, who did not exceed 200 men, in defeating twice or thrice their numbers single-handed, it is difficult to speak too highly. Indeed, I know of nothing finer in the history of the British Cavalry.”... “But more important than all was the admission of the French that they could not stand before the British Cavalry.” Yet, owing to the mistakes of their superiors, the Thirteenth never received for their feat the honour they deserved, or indeed, officially, anything but blame. It was a signal instance of the ill-fortune which sometimes attends upon the noblest conduct.

Whatever may be said of this, the Thirteenth had, at all events, the satisfaction of knowing that they had been thoroughly successful. They were not always to be so, for on the 5th April, less than a fortnight later, a troop of the regiment was surprised by French Cavalry during the night. They were not on outpost duty, having been regularly relieved, and they supposed that their front had been secured by the relieving squadron, a body of Portuguese Cavalry 30 under British officers. The men of the Thirteenth had eaten nothing for two days, and were faint for want of food. After getting a meal, they lay down by their horses, and were sleeping peacefully when the French, who were retiring and came upon them by chance, dashed suddenly among them with the sabre. Two officers and twenty men escaped in the darkness, but the other two officers with practically all the rest of the men were taken prisoners. It is characteristic of warfare in those days that among them was the wife of one of the troopers.

Then there was another turn of the wheel. Ten days after the surprise it was reported that a body of French Cavalry was at Los Santos, levying contributions. The British Cavalry advanced to attack them, and Marshal Beresford himself rode with the Thirteenth, whom he had so severely censured less than a month before. A sharp fight ensued, ending in the rout of the enemy, who were pursued for about nine miles and lost some hundreds of prisoners. The loss of the Thirteenth was very small.

The next month saw the bloody battle of Albuera, which forms the subject of one of Napier’s most famous chapters. During the day the Thirteenth were employed in holding off the enemy’s Cavalry. They were exposed to severe fire from Infantry and guns, but were successful in carrying out their duty without heavy loss.

There was much hard work for the Thirteenth during the remainder of this year, 1811, and one incident is noteworthy. On the 21st November, Lieutenant King, a fine young officer, was shot by Spanish guerillas when carrying a flag of truce to the fortress of Badajos. His body was recovered by the French and buried with all military honours on the ramparts, General Philippon assembling the whole garrison under arms for the purpose.

During 1812 the Thirteenth again saw some rough service. They shared in the advance to Madrid and Alva de Tormes, and then in the retreat back to Portugal, during which their horses suffered terribly from hardship and starvation.

In April 1813 the British army advanced again, and again reached Alva de Tormes. In June the French took up their position at Vittoria, and the famous battle ensued. The share of the Thirteenth in this combat was interesting. After some sharp fighting they captured King Joseph’s carriages and equipment, and then pressed 31 on in pursuit of the beaten enemy, whose losses were great, including over a hundred and fifty guns. Vittoria was in fact the break-up of Napoleon’s power in Spain, for many of his commanders and troops had been withdrawn the year before to strengthen his army for the Russian campaign, and he was never able to replace them.

Then followed the march to the French frontier and the battles of the Pyrenees. In November the Thirteenth crossed the border.

The winter was a hard one for the Cavalry. Hilly country intersected by deep ravines, exhausted of supplies, and obstinately defended by Soult and his veterans, was a rough scene for outpost duty. There were many small affairs, especially between foraging parties. The weather was very bad, and the troops had constantly to bivouac in the mud, under torrents of rain, sometimes in snow. There was often no corn or straw for the horses, nothing procurable but gorse, which, pounded and made into a sort of paste, Irish fashion, just kept the poor beasts alive.

One incident which occurred near Orthes, on the 27th February 1814, is striking. The Thirteenth there came in contact with Soult’s Cavalry, and charged. At their head rode their Lieutenant-Colonel, Patrick Doherty, with his sons, Captain and Lieutenant Doherty, three abreast. The charge was completely successful, and many prisoners were taken, among them two officers.

Napier has told us how, through the spring of 1814, that fierce fighting went on, in snow and rain and misery—the French, now overmatched, losing battle after battle and many thousands of men, but still, under their indomitable leader Soult, turning to bay again and again. Then at last came the battle of Toulouse, and the white cockade began to show itself, and on the 13th April it was known that peace had been declared. Napoleon had fallen. Soult fought on for five days more, but then it was announced in general orders that hostilities had ceased, and the British Cavalry in pursuit beyond Toulouse desisted from further action.

The Thirteenth had fought almost without interruption for four years, in the long struggle that began at Lisbon and ended at Toulouse. They now had a few weeks’ rest, and it was badly needed. Numbers of horses, worn out by want and hard work, had to be destroyed, and the men were in rags. No clothing had been issued during the winter. “Overalls patched with cloth of all sorts of 32 colours, and most frequently of red oilskin—fragments of baggage-wrappers by the way—were universal or almost so.” They were indeed “The Ragged Brigade,” as they and their old comrades of the Fourteenth had been named. But, starting in May, they marched up through France, and arriving at Boulogne on the 5th July, embarked for England. By the 8th July the Regiment had all been landed in Ramsgate. During an absence of four years and five months the Thirteenth had marched 6000 miles, and had been engaged in twelve battles and thirty-two “affairs,” many sharply contested. They had lost by death six officers and 270 men. But the Regiment had now made its mark, and was thenceforward one of the foremost fighting corps of the British Cavalry.

After their return from France the Thirteenth spent some months in England and Ireland, but their enjoyment of peace was short. In February 1815 Napoleon escaped from Elba, and war again broke out. On the 20th April, having meanwhile received royal authority to bear on its guidons and appointments the word “Peninsula,” the Regiment was ordered to prepare six troops for immediate service, and soon afterwards the number was increased to ten. In May the Thirteenth were in Ostend (with twenty-eight women and nine children), and by the end of the month they formed part of a force of 6000 Cavalry, under Lord Uxbridge, which was inspected by Wellington and Blücher.

Then followed Quatre Bras and Waterloo. The movements of the Thirteenth up to the morning of the decisive battle are of no special interest, but it seems that having been ordered to join a Brigade consisting of the Seventh and Fifteenth Hussars under Major-General Grant, the Regiment arrived at Quatre Bras on the night of the 16th June, and shared in the retreat of the 17th June to Waterloo. It was a dreary day, for the rain was heavy and they got no food—a bad preparation for the coming battle. Then followed “a dreadful rainy night, every man in the Cavalry wet to the skin,” and at four o’clock in the morning of the 18th, the Thirteenth “turned out and formed on the field of battle in wet corn and a cold morning without anything to eat.” Their commanding officer, the gallant old veteran Colonel Doherty, had broken down and was lying ill in Brussels, so the Regiment was commanded on the 18th by Lieut.-Colonel Boyse. The Brigade to which it belonged was posted on the right centre 33 of the army, in rear of Byng’s Brigade of Guards, who held the house and garden of Hougomont. From this position the Thirteenth witnessed the furious fighting which ensued between the Guards and their French assailants, and they came themselves under heavy Artillery fire, which caused them some loss. Colonel Boyse had his horse killed under him by a cannon-shot, and was severely hurt, the command devolving on Major Lawrence. Two other officers were wounded. There was also severe and repeated Cavalry fighting, in which the Thirteenth did their share, charging more than once the enemy’s horsemen, and on one occasion dispersing a square of French Infantry. In this fighting they lost three officers killed or mortally wounded,2 and two more wounded by sabre cuts. Towards evening the French made another desperate attack with both Cavalry and Infantry, and the Thirteenth charged again, losing three more officers wounded, among whom were both the Doherty brothers. Before the enemy finally gave way almost every officer of the Regiment had lost one horse at least, and Major Lawrence had lost three. When at last the French broke, the Brigade was sent in pursuit, and pressed the routed enemy until nine o’clock. Then it was halted, and the pursuit was handed over to the Prussians. “The last charge,” wrote an officer of the Thirteenth, “was literally riding over men and horses, who lay in heaps.” And the account goes on to say that “when the Regiment mustered after the action at 10 P.M. that night, we had only 65 men left out of 260 who went into the field in the morning.”

Many rejoined later, and these figures do not represent the actual losses as afterwards ascertained, but so far as can be judged the total of killed and wounded was close upon a hundred, of whom eleven were officers.

After Waterloo, the Thirteenth marched to Paris, where they remained some weeks, and then they were sent northward again. At or near Hazebrouck, a name now so familiar, they remained some months. In May 1816 the Regiment returned to England, arriving at Dover on the night of the 13th. During the past year it had lost in killed, died, and discharged, 3 officers and 65 men.

With Waterloo ended the first century of the Regiment’s service. If ninety-five years of it had been rather colourless, the 34 last five had certainly been as full of fighting as any one could have desired.

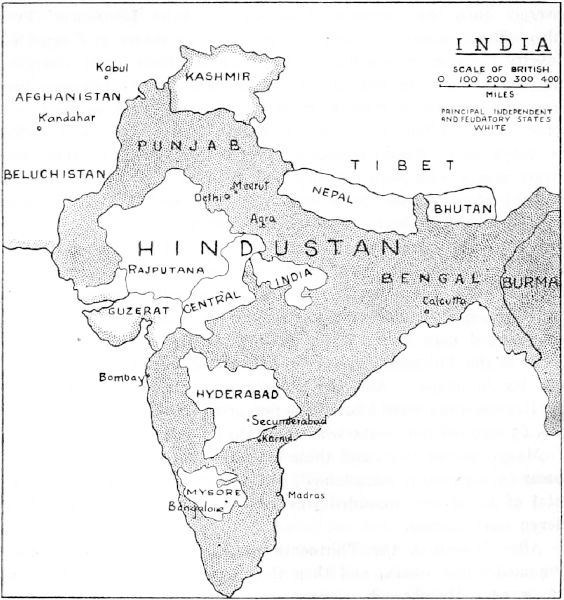

INDIA

For about three years after its return the Thirteenth remained in England. The times which followed the war were bad, and the Regiment was often employed maintaining order among the civil population, always a detestable duty for soldiers, but nothing of note occurred. On the 9th February 1819 the Regiment sailed for India, and for the next twenty years it rested peacefully in Eastern cantonments.

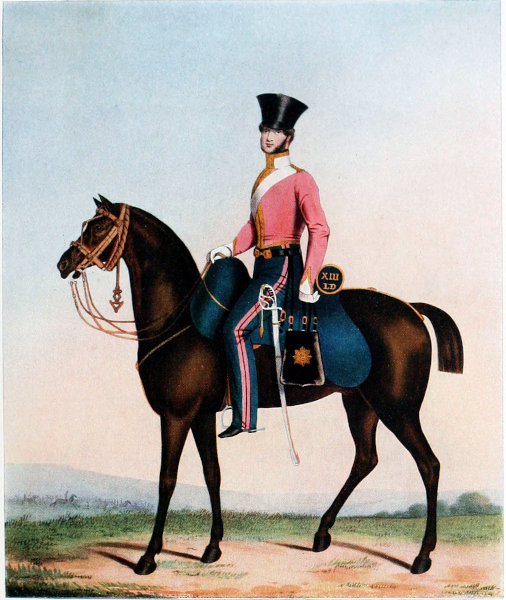

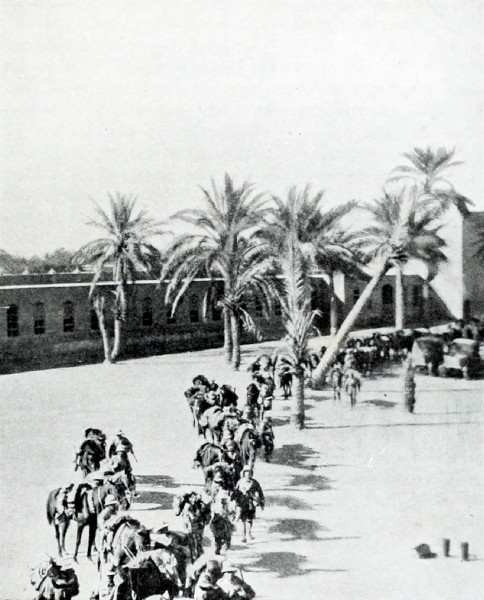

OFFICER OF THE 13TH LIGHT HUSSARS

1830-1836

In India, as well as in Europe, the beginning of the century had been a time of hard fighting in various fields, and when the 35 Thirteenth went out, the supremacy of the British among the Indian country powers had hardly been established. It was only sixteen years since Sir Arthur Wellesley had routed the Maratha armies at Assaye, and gained his first great victory. After that time other powers had challenged the British, and been with difficulty overthrown. Even in 1819 there remained serious elements of disorder, and it was not until seven years later that a period of complete peace began. Nevertheless, it may be said that the period of general war closed in Asia as in Europe soon after the fall of Napoleon.

The Thirteenth at all events had no fighting to do. They were sent to the extreme south of India, where the name of their old chief was very familiar, and the provinces about Bangalore, where they were quartered, had many fighting traditions; but nothing occurred to test the spirit of the Regiment. In that very pleasant place, and other stations not far distant, the Thirteenth remained year after year, with little to disturb them except inspections and reviews, enjoying plenty of sport, after the manner of British Cavalry Regiments in the East, and maintaining their efficiency in so far as it could be maintained without service in the field. In 1832 a formidable plot was discovered for a native rising in Bangalore. The Thirteenth with a British Infantry Regiment, the Sixty-Second, and a detachment of European Artillery, were to be suddenly attacked at night and massacred, after which the conspirators hoped that a general mutiny of the Native Army would follow. But the plot was revealed by a faithful native officer, and was crushed without any fighting.

Nevertheless it had shown that there was disaffection among the Indian population, and a few years later this came to a head. In 1839 it was found that a certain Mahomedan chief, the Nawab of Karnul, had collected in secret a large quantity of military stores, including some “hundreds” of guns, and that he had in his employ a considerable number of sturdy fighting men, Arabs, Rohillas, and Pathans from the North-West of India—the turbulent mercenaries who had for generations made India a vast battlefield. The matter was considered so serious that a force of 6000 men, of which two squadrons of the Thirteenth formed part, was sent to Karnul. Action had been taken in time, and the fighting on the part of the enemy at Karnul and the neighbouring village of Zorapur, 36 though brave enough, was soon over. A few British officers and men were killed and wounded. The Thirteenth lost more than thirty men, chiefly from cholera, on this expedition, but none by the sword. It was one of the countless forgotten skirmishes upon which the Indian Empire has been built up.3

Early in 1840, after twenty-one years spent in the country, the Thirteenth sailed for home. They had seen little fighting, but those were days when India claimed a terrible toll from British troops, and during the short march from Bangalore to the coast at Madras the Regiment lost from cholera forty more men, as well as many women and children. Cholera is no longer the scourge that it was to our countrymen, but the thousands of graves that one finds scattered over the face of the land, often in the loneliest places, are a sad reminder of the price Great Britain has paid for her Eastern dominion.

On return to England the Regiment was very weak, for in addition to its losses from disease, it had left behind many men who had volunteered for other Regiments in India; but it was soon in good order again. It was to be replaced in India by the Fourteenth, and in 1841 the two Regiments, “The Ragged Brigade” of the Peninsular War, met again in Canterbury. There can have been few officers in either who had served together in that war, but the old traditions were still alive, and in remembrance of them the Fourteenth presented to the sister Regiment their mess-table, which had been originally captured by the Thirteenth at Vittoria with King Joseph’s household.

During the next ten years and more the Thirteenth served in the United Kingdom, and there is little to record of their doings. In 1852 they formed part of the troops who followed the funeral of their old chief, the Duke of Wellington, and in the next year they attended the first camp of exercise held in England. The Duke had originated the idea. The camp was a success, and proved to be the precursor of many more such gatherings. But something more than camps of exercise was now before the Regiment. In 1854 came war with Russia, and the Thirteenth were warned for service in the field. By the middle of May they had sailed for 37 the East. It is memorable that they were now once more commanded by a Lieut.-Colonel Doherty.

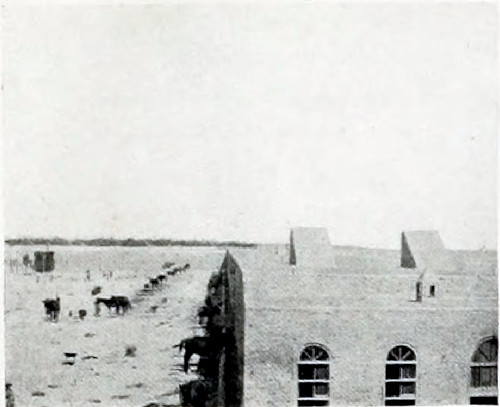

OFFICER OF THE 13TH LIGHT HUSSARS

(undress)

1830-1836