THE GIRL’S OWN PAPER

Vol. XX.—No. 1019.]

[Price One Penny.

JULY 8, 1899.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

SHEILA’S COUSIN EFFIE.

VARIETIES.

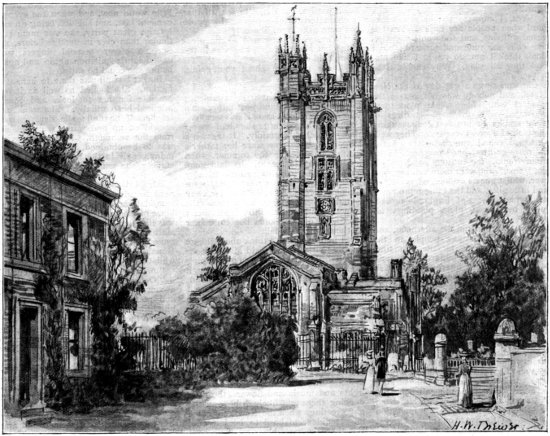

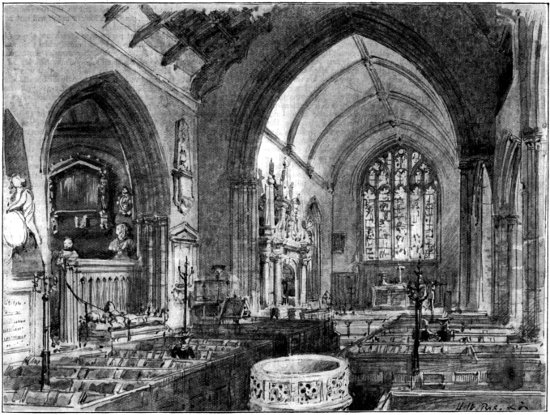

THE HOME OF THE EARLS POULETT.

LESSONS FROM NATURE.

THE COURTSHIP OF CATHERINE WEST.

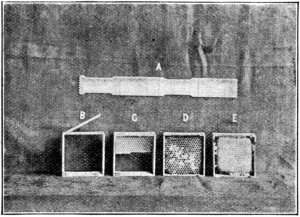

THE PLEASURES OF BEE-KEEPING.

THE HOUSE WITH THE VERANDAH.

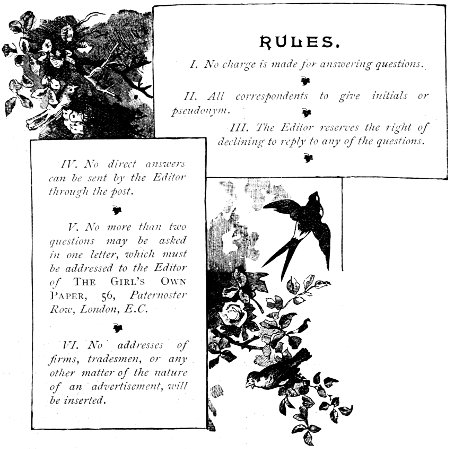

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.