![[The image of the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: The City of Dreadful Night

Author: Rudyard Kipling

Illustrator: Charles D. Farrand

Release date: April 14, 2020 [eBook #61834]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif, MFR and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

By

R U D Y A R D K I P L I N G

With Illustrations by

CHARLES D. FARRAND

![[colophon]](images/colophon.png)

ALEX. GROSSET & CO.

11 East Sixteenth St., New York

1899

Copyright, 1899

BY

ALEX. GROSSET & CO.

{3}

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| A Real Live City, | 5 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Reflections of a Savage, | 14 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Council of the Gods, | 25 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| On the Banks of the Hugli, | 37 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| With the Calcutta Police, | 49 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The City of Dreadful Night, | 58 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Deeper and Deeper Still, | 72 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Concerning Lucia, | 82 |

We are all backwoodsmen and barbarians together—we others dwelling beyond the Ditch, in the outer darkness of the Mofussil. There are no such things as commissioners and heads of departments in the world, and there is only one city in India. Bombay is too green, too pretty, and too stragglesome; and Madras died ever so long ago. Let us take off our hats to Calcutta, the many-sided, the smoky, the magnificent, as we drive in over the Hugli Bridge in the dawn of a still February morning. We have left India behind us at Howrah Station, and now we enter foreign parts. No, not wholly foreign. Say rather too familiar.

All men of certain age know the feeling of caged irritation—an illustration in the Graphic, a bar of music, or the light words of a friend{6} from home may set it ablaze—that comes from the knowledge of our lost heritage of London. At home they, the other men, our equals, have at their disposal all that town can supply—the roar of the streets, the lights, the music, the pleasant places, the millions of their own kind, and a wilderness full of pretty, fresh-colored Englishwomen, theatres, and restaurants. It is their right. They accept it as such, and even affect to look upon it with contempt. And we, we have nothing except the few amusements that we painfully build up for ourselves—the dolorous dissipations of gymkhanas where every one knows everybody else, or the chastened intoxication of dances where all engagements are booked, in ink, ten days ahead, and where everybody’s antecedents are as patent as his or her method of waltzing. We have been deprived of our inheritance. The men at home are enjoying it all, not knowing how fair and rich it is, and we at the most can only fly westward for a few months and gorge what, properly speaking, should take seven or eight or ten luxurious years. That is the lost heritage of London; and the knowledge of the forfeiture, wilful or forced, comes to most men at times and seasons, and they get cross.

Calcutta holds out false hopes of some return.{7} The dense smoke hangs low, in the chill of the morning, over an ocean of roofs, and, as the city wakes, there goes up to the smoke a deep, full-throated boom of life and motion and humanity. For this reason does he who sees Calcutta for the first time hang joyously out of the ticca-gharri and sniff the smoke, and turn his face toward the tumult, saying: “This is, at last, some portion of my heritage returned to me. This is a city. There is life here, and there should be all manner of pleasant things for the having, across the river and under the smoke.” When Leland, he who wrote the Hans Breitmann Ballads, once desired to know the name of an austere, plug-hatted redskin of repute, his answer, from the lips of a half-breed, was:

“He Injun. He big Injun. He heap big Injun. He dam big heap Injun. He dam mighty great big heap Injun. He Jones!” The litany is an expressive one, and exactly describes the first emotions of a wandering savage adrift in Calcutta. The eye has lost its sense of proportion, the focus has contracted through overmuch residence in up-country stations—twenty minutes’ canter from hospital to parade-ground, you know—and the mind has shrunk with the eye. Both say together, as{8} they take in the sweep of shipping above and below the Hugli Bridge: “Why, this is London! This is the docks. This is Imperial. This is worth coming across India to see!”

Then a distinctly wicked idea takes possession of the mind: “What a divine—what a heavenly place to loot!” This gives place to a much worse devil—that of Conservatism. It seems not only a wrong but a criminal thing to allow natives to have any voice in the control of such a city—adorned, docked, wharfed, fronted and reclaimed by Englishmen, existing only because England lives, and dependent for its life on England. All India knows of the Calcutta Municipality; but has any one thoroughly investigated the Big Calcutta Stink? There is only one. Benares is fouler in point of concentrated, pent-up muck, and there are local stenches in Peshawur which are stronger than the B.C.S.; but, for diffused, soul-sickening expansiveness, the reek of Calcutta beats both Benares and Peshawur. Bombay cloaks her stenches with a veneer of assafœtida and huqa-tobacco; Calcutta is above pretence. There is no tracing back the Calcutta plague to any one source. It is faint, it is sickly, and it is indescribable; but Americans at the Great Eastern Hotel say that it is something like the{9} smell of the Chinese quarter in San Francisco. It is certainly not an Indian smell. It resembles the essence of corruption that has rotted for the second time—the clammy odor of blue slime. And there is no escape from it. It blows across the maidan; it comes in gusts into the corridors of the Great Eastern Hotel; what they are pleased to call the “Palaces of Chouringhi” carry it; it swirls round the Bengal Club; it pours out of by-streets with sickening intensity, and the breeze of the morning is laden with it. It is first found, in spite of the fume of the engines, in Howrah Station. It seems to be worst in the little lanes at the back of Lal Bazar where the drinking-shops are, but it is nearly as bad opposite Government House and in the Public Offices. The thing is intermittent. Six moderately pure mouthfuls of air may be drawn without offence. Then comes the seventh wave and the queasiness of an uncultured stomach. If you live long enough in Calcutta you grow used to it. The regular residents admit the disgrace, but their answer is: “Wait till the wind blows off the Salt Lakes where all the sewage goes, and then you’ll smell something.” That is their defence! Small wonder that they consider Calcutta is a fit place for a permanent Viceroy. Englishmen who can calmly extenu{10}ate one shame by another are capable of asking for anything—and expecting to get it.

If an up-country station holding three thousand troops and twenty civilians owned such a possession as Calcutta does, the Deputy Commissioner or the Cantonment Magistrate would have all the natives off the board of management or decently shovelled into the background until the mess was abated. Then they might come on again and talk of “high-handed oppression” as much as they liked. That stink, to an unprejudiced nose, damns Calcutta as a City of Kings. And, in spite of that stink, they allow, they even encourage, natives to look after the place! The damp, drainage-soaked soil is sick with the teeming life of a hundred years, and the Municipal Board list is choked with the names of natives—men of the breed born in and raised off this surfeited muck-heap! They own property, these amiable Aryans on the Municipal and the Bengal Legislative Council. Launch a proposal to tax them on that property, and they naturally howl. They also howl up-country, but there the halls for mass-meetings are few, and the vernacular papers fewer, and with a zubbardusti Secretary and a President whose favor is worth the having and whose wrath is undesirable, men are kept clean despite them{11}selves, and may not poison their neighbors. Why, asks a savage, let them vote at all? They can put up with this filthiness. They cannot have any feelings worth caring a rush for. Let them live quietly and hide away their money under our protection, while we tax them till they know through their purses the measure of their neglect in the past, and when a little of the smell has been abolished, bring them back again to talk and take the credit of enlightenment. The better classes own their broughams and barouches; the worse can shoulder an Englishman into the kennel and talk to him as though he were a khidmatgar. They can refer to an English lady as an aurat; they are permitted a freedom—not to put it too coarsely—of speech which, if used by an Englishman toward an Englishman, would end in serious trouble. They are fenced and protected and made inviolate. Surely they might be content with all those things without entering into matters which they cannot, by the nature of their birth, understand.

Now, whether all this genial diatribe be the outcome of an unbiased mind or the result first of sickness caused by that ferocious stench, and secondly of headache due to day-long smoking to drown the stench, is an open question. Any{12}way, Calcutta is a fearsome place for a man not educated up to it.

A word of advice to other barbarians. Do not bring a north-country servant into Calcutta. He is sure to get into trouble, because he does not understand the customs of the city. A Punjabi in this place for the first time esteems it his bounden duty to go to the Ajaib-ghar—the Museum. Such an one has gone and is even now returned very angry and troubled in the spirit. “I went to the Museum,” says he, “and no one gave me any gali. I went to the market to buy my food, and then I sat upon a seat. There came a chaprissi who said: ‘Go away, I want to sit here.’ I said: ‘I am here first.’ He said: ‘I am a chaprissi! nikal jao!’ and he hit me. Now that sitting-place was open to all, so I hit him till he wept. He ran away for the Police, and I went away too, for the Police here are all Sahibs. Can I have leave from two o’clock to go and look for that chaprissi and hit him again?”

Behold the situation! An unknown city full of smell that makes one long for rest and retirement, and a champing naukar, not yet six hours in the stew, who has started a blood-feud with an unknown chaprissi and clamors to go forth to the fray. General orders that, whatever may{13} be said or done to him, he must not say or do anything in return lead to an eloquent harangue on the quality of izzat and the nature of “face blackening.” There is no izzat in Calcutta, and this Awful Smell blackens the face of any Englishman who sniffs it.

Alas! for the lost delusion of the heritage that was to be restored. Let us sleep, let us sleep, and pray that Calcutta may be better to-morrow.

At present it is remarkably like sleeping with a corpse.{14}

Morning brings counsel. Does Calcutta smell so pestiferously after all? Heavy rain has fallen in the night. She is newly-washed, and the clear sunlight shows her at her best. Where, oh where, in all this wilderness of life, shall a man go? Newman and Co. publish a three-rupee guide which produces first despair and then fear in the mind of the reader. Let us drop Newman and Co. out of the topmost window of the Great Eastern, trusting to luck and the flight of the hours to evolve wonders and mysteries and amusements.

The Great Eastern hums with life through all its hundred rooms. Doors slam merrily, and all the nations of the earth run up and down the staircases. This alone is refreshing, because the passers bump you and ask you to stand aside. Fancy finding any place outside a Levée-room where Englishmen are crowded together to this extent! Fancy sitting down seventy strong to tâble d’hôte and with a deafening{15} clatter of knives and forks! Fancy finding a real bar whence drinks may be obtained! and, joy of joys, fancy stepping out of the hotel into the arms of a live, white, helmeted, buttoned, truncheoned Bobby! A beautiful, burly Bobby—just the sort of man who, seven thousand miles away, staves off the stuttering witticism of the three-o’clock-in-the-morning reveller by the strong badged arm of authority. What would happen if one spoke to this Bobby? Would he be offended? He is not offended. He is affable. He has to patrol the pavement in front of the Great Eastern and to see that the crowding ticca-gharris do not jam. Toward a presumably respectable white he behaves as a man and a brother. There is no arrogance about him. And this is disappointing. Closer inspection shows that he is not a real Bobby after all. He is a Municipal Police something and his uniform is not correct; at least if they have not changed the dress of the men at home. But no matter. Later on we will inquire into the Calcutta Bobby, because he is a white man, and has to deal with some of the “toughest” folk that ever set out of malice aforethought to paint Job Charnock’s city vermillion. You must not, you cannot cross Old Court House Street without looking carefully to see that you stand no{16} chance of being run over. This is beautiful. There is a steady roar of traffic, cut every two minutes by the deeper roll of the trams. The driving is eccentric, not to say bad, but there is the traffic—more than unsophisticated eyes have beheld for a certain number of years. It means business, it means money-making, it means crowded and hurrying life, and it gets into the blood and makes it move. Here be big shops with plate-glass fronts—all displaying the well-known names of firms that we savages only correspond with through the V. P. P. and Parcels Post. They are all here, as large as life, ready to supply anything you need if you only care to sign. Great is the fascination of being able to obtain a thing on the spot without having to write for a week and wait for a month, and then get something quite different. No wonder pretty ladies, who live anywhere within a reasonable distance, come down to do their shopping personally.

“Look here. If you want to be respectable you musn’t smoke in the streets. Nobody does it.” This is advice kindly tendered by a friend in a black coat. There is no Levée or Lieutenant-Governor in sight; but he wears the frock-coat because it is daylight, and he can be seen. He also refrains from smoking for the same rea{17}son. He admits that Providence built the open air to be smoked in, but he says that “it isn’t the thing.” This man has a brougham, a remarkably natty little pill-box with a curious wabble about the wheels. He steps into the brougham and puts on—a top-hat, a shiny black “plug.”

There was a man up-country once who owned a top-hat. He leased it to amateur theatrical companies for some seasons until the nap wore off. Then he threw it into a tree and wild bees hived in it. Men were wont to come and look at the hat, in its palmy days, for the sake of feeling homesick. It interested all the station, and died with two seers of babul flower honey in its bosom. But top-hats are not intended to be worn in India. They are as sacred as home letters and old rosebuds. The friend cannot see this. He allows that if he stepped out of his brougham and walked about in the sunshine for ten minutes he would get a bad headache. In half an hour he would probably catch sunstroke. He allows all this, but he keeps to his hat and cannot see why a barbarian is moved to inextinguishable laughter at the sight. Everyone who owns a brougham and many people who hire ticca-gharris keep top-hats and black frock-coats. The effect is curious, and at first fills the beholder with surprise.{18}

And now, “let us see the handsome houses where the wealthy nobles dwell.” Northerly lies the great human jungle of the native city, stretching from Burra Bazar to Chitpore. That can keep. Southerly is the maidan and Chouringhi. “If you get out into the centre of the maidan you will understand why Calcutta is called the City of Palaces.” The travelled American said so at the Great Eastern. There is a short tower, falsely called a “memorial,” standing in a waste of soft, sour green. That is as good a place to get to as any other. Near here the newly-landed waler is taught the whole duty of the trap-horse and careers madly in a brake. Near here young Calcutta gets upon a horse and is incontinently run away with. Near here hundreds of kine feed, close to the innumerable trams and the whirl of traffic along the face of Chouringhi Road. The size of the maidan takes the heart out of anyone accustomed to the “gardens” of up-country, just as they say Newmarket Heath cows a horse accustomed to more shut-in course. The huge level is studded with brazen statues of eminent gentlemen riding fretful horses on diabolically severe curbs. The expanse dwarfs the statues, dwarfs everything except the frontage of the far-away Chouringhi Road. It is big—it is impressive. There{19} is no escaping the fact. They built houses in the old days when the rupee was two shillings and a penny. Those houses are three-storied, and ornamented with service-staircases like houses in the Hills. They are also very close together, and they own garden walls of pukka-masonry pierced with a single gate. In their shut-upness they are British. In their spaciousness they are Oriental, but those service-staircases do not look healthy. We will form an amateur sanitary commission and call upon Chouringhi.

A first introduction to the Calcutta durwan is not nice. If he is chewing pan, he does not take the trouble to get rid of his quid. If he is sitting on his charpoy chewing sugarcane, he does not think it worth his while to rise. He has to be taught those things, and he cannot understand why he should be reproved. Clearly he is a survival of a played-out system. Providence never intended that any native should be made a concierge more insolent than any of the French variety. The people of Calcutta put an Uria in a little lodge close to the gate of their house, in order that loafers may be turned away, and the houses protected from theft. The natural result is that the durwan treats everybody whom he does not know as a loafer, has an in{20}timate and vendible knowledge of all the outgoings and incomings in that house, and controls, to a large extent, the nomination of the naukar-log. They say that one of the estimable class is now suing a bank for about three lakhs of rupees. Up-country, a Lieutenant-Governor’s charprassi has to work for thirty years before he can retire on seventy thousand rupees of savings. The Calcutta durwan is a great institution. The head and front of his offence is that he will insist upon trying to talk English. How he protects the houses Calcutta only knows. He can be frightened out of his wits by severe speech, and is generally asleep in calling hours. If a rough round of visits be any guide, three times out of seven he is fragrant of drink. So much for the durwan. Now for the houses he guards.

Very pleasant is the sensation of being ushered into a pestiferously stablesome drawing-room. “Does this always happen?” No, “not unless you shut up the room for some time; but if you open the jhilmills there are other smells. You see the stables and the servants’ quarters are close too.” People pay five hundred a month for half-a-dozen rooms filled with attr of this kind. They make no complaint. When they think the honor of the city is at stake they say defiantly: “Yes, but you must remember{21} we’re a metropolis. We are crowded here. We have no room. We aren’t like your little stations.” Chouringhi is a stately place full of sumptuous houses, but it is best to look at it hastily. Stop to consider for a moment what the cramped compounds, the black soaked soil, the netted intricacies of the service-staircases, the packed stables, the seethment of human life round the durwans’ lodges, and the curious arrangement of little open drains means, and you will call it a whited sepulchre.

Men living in expensive tenements suffer from chronic sore-throat, and will tell you cheerily that “we’ve got typhoid in Calcutta now.” Is the pest ever out of it? Everything seems to be built with a view to its comfort. It can lodge comfortably on roofs, climb along from the gutter-pipe to piazza, or rise from sink to verandah and thence to the topmost story. But Calcutta says that all is sound and produces figures to prove it; at the same time admitting that healthy cut flesh will not readily heal. Further evidence may be dispensed with.

Here come pouring down Park Street on the maidan a rush of broughams, neat buggies, the lightest of gigs, trim office brownberrys, shining victorias, and a sprinkling of veritable hansom cabs. In the broughams sit men in {22}top-hats. In the other carts, young men, all very much alike, and all immaculately turned out. A fresh stream from Chouringhi joins the Park Street detachment, and the two together stream away across the maidan toward the business quarter of the city. This is Calcutta going to office—the civilians to the Government Buildings and the young men to their firms and their blocks and their wharves. Here one sees that Calcutta has the best turn-out in the Empire. Horses and traps alike are enviably perfect, and—mark the touchstone of civilization—the lamps are in the sockets. This is distinctly refreshing. Once more we will take off our hats to Calcutta, the well-appointed, the luxurious. The country-bred is a rare beast here; his place is taken by the waler, and the waler, though a ruffian at heart, can be made to look like a gentleman. It would be indecorous as well as insane to applaud the winking harness, the perfectly lacquered panels, and the liveried saises. They show well in the outwardly fair roads shadowed by the Palaces.

How many sections of the complex society of the place do the carts carry? Imprimis, the Bengal Civilian who goes to Writers’ Buildings and sits in a perfect office and speaks flippantly of “sending things into India,” meaning thereby{23} the Supreme Government. He is a great person, and his mouth is full of promotion-and-appointment “shop.” Generally he is referred to as a “rising man.” Calcutta seems full of “rising men.” Secondly, the Government of India man, who wears a familiar Simla face, rents a flat when he is not up in the Hills, and is rational on the subject of the drawbacks of Calcutta. Thirdly, the man of the “firms,” the pure non-official who fights under the banner of one of the great houses of the City, or for his own hand in a neat office, or dashes about Clive Street in a brougham doing “share work” or something of the kind. He fears not “Bengal,” nor regards he “India.” He swears impartially at both when their actions interfere with his operations. His “shop” is quite unintelligible. He is like the English city man with the chill off, lives well and entertains hospitably. In the old days he was greater than he is now, but still he bulks large. He is rational in so far that he will help the abuse of the Municipality, but womanish in his insistence on the excellencies of Calcutta. Over and above these who are hurrying to work are the various brigades, squads, and detachments of the other interests. But they are sets and not sections, and revolve round Belvedere, Government House, and Fort{24} William. Simla and Darjeeling claim them in the hot weather. Let them go. They wear top-hats and frock-coats.

It is time to escape from Chouringhi Road and get among the long-shore folk, who have no prejudices against tobacco, and who all use pretty nearly the same sort of hat.{25}

He set up conclusions to the number of nine thousand seven hundred and sixty-four ... he went afterwards to the Sorbonne, where he maintained argument against the theologians for the space of six weeks, from four o’clock in the morning till six in the evening, except for an interval of two hours to refresh themselves and take their repasts, and at this were present the greatest part of the lords of the court, the masters of request, presidents, counsellors, those of the accompts, secretaries, advocates, and others; as also the sheriffs of the said town.

—Pantagruel.

“The Bengal Legislative Council is sitting now. You will find it in an octagonal wing of Writers’ Buildings: straight across the maidan. It’s worth seeing.” “What are they sitting on?” “Municipal business. No end of a debate.” So much for trying to keep low company. The long-shore loafers must stand over. Without doubt this Council is going to hang some one for the state of the City, and Sir Steuart Bayley will be chief executioner. One does not come across Councils every day.{26}

Writers’ Buildings are large. You can trouble the busy workers of half-a-dozen departments before you stumble upon the black-stained staircase that leads to an upper chamber looking out over a populous street. Wild chuprassis block the way. The Councillor Sahibs are sitting, but anyone can enter. “To the right of the Lât Sahib’s chair, and go quietly.” Ill-mannered minion! Does he expect the awe-stricken spectator to prance in with a jubilant warwhoop or turn Catherine-wheels round that sumptuous octagonal room with the blue-domed roof? There are gilt capitals to the half pillars, and an Egyptian patterned lotus-stencil makes the walls decorously gay. A thick-piled carpet covers all the floor, and must be delightful in the hot weather. On a black wooden throne, comfortably cushioned in green leather, sits Sir Steuart Bayley, Ruler of Bengal. The rest are all great men, or else they would not be there. Not to know them argues one’s self unknown. There are a dozen of them, and sit six-a-side at two slightly curved lines of beautifully polished desks. Thus Sir Steuart Bayley occupies the frog of a badly made horse-shoe split at the toe. In front of him, at a table covered with books and pamphlets and papers, toils a secretary. There is a seat for the Reporters, and that is all. The{27} place enjoys a chastened gloom, and its very atmosphere fills one with awe. This is the heart of Bengal, and uncommonly well upholstered. If the work matches the first-class furniture, the inkpots, the carpet, and the resplendent ceiling, there will be something worth seeing. But where is the criminal who is to be hanged for the stench that runs up and down Writers’ Buildings staircases, for the rubbish heaps in the Chitpore Road, for the sickly savor of Chouringhi, for the dirty little tanks at the back of Belvedere, for the street full of smallpox, for the reeking gharri-stand outside the Great Eastern, for the state of the stone and dirt pavements, for the condition of the gullies of Shampooker, and for a hundred other things?

“This, I submit, is an artificial scheme in supersession of Nature’s unit, the individual.” The speaker is a slight, spare native in a flat hat-turban, and a black alpaca frock-coat. He looks like a vakil to the boot-heels, and, with his unvarying smile and regulated gesticulation, recalls memories of up-country courts. He never hesitates, is never at a loss for a word, and never in one sentence repeats himself. He talks and talks and talks in a level voice, rising occasionally half an octave when a point has to be driven home. Some of his pe{28}riods sound very familiar. This, for instance, might be a sentence from the Mirror: “So much for the principle. Let us now examine how far it is supported by precedent.” This sounds bad. When a fluent native is discoursing of “principles” and “precedents,” the chances are that he will go on for some time. Moreover, where is the criminal, and what is all this talk about abstractions? They want shovels, not sentiments, in this part of the world.

A friendly whisper brings enlightenment: “They are plowing through the Calcutta Municipal Bill—plurality of votes you know; here are the papers.” And so it is! A mass of motions and amendments on matters relating to ward votes. Is A to be allowed to give two votes in one ward and one in another? Is section 10 to be omitted, and is one man to be allowed one vote and no more? How many votes does three hundred rupees’ worth of landed property carry? Is it better to kiss a post or throw it in the fire? Not a word about carbolic acid and gangs of domes. The little man in the black choga revels in his subject. He is great on principles and precedents, and the necessity of “popularizing our system.” He fears that under certain circumstances “the status of the candidates will decline.” He riots{29} in “self-adjusting majorities,” and the “healthy influence of the educated middle classes.”

For a practical answer to this, there steals across the council chamber just one faint whiff. It is as though some one laughed low and bitterly. But no man heeds. The Englishmen look supremely bored, the native members stare stolidly in front of them. Sir Steuart Bayley’s face is as set as the face of the Sphinx. For these things he draws his pay, and his is a low wage for heavy labor. But the speaker, now adrift, is not altogether to be blamed. He is a Bengali, who has got before him just such a subject as his soul loveth—an elaborate piece of academical reform leading no-whither. Here is a quiet room full of pens and papers, and there are men who must listen to him. Apparently there is no time limit to the speeches. Can you wonder that he talks? He says “I submit” once every ninety seconds, varying the form with “I do submit.” “The popular element in the electoral body should have prominence.” Quite so. He quotes one John Stuart Mill to prove it. There steals over the listener a numbing sense of nightmare. He has heard all this before somewhere—yea; even down to J. S. Mill and the references to the “true interests of the ratepayers.” He sees what is coming next.{30} Yes, there is the old Sabha Anjuman journalistic formula—“Western education is an exotic plant of recent importation.” How on earth did this man drag Western education into this discussion? Who knows? Perhaps Sir Steuart Bayley does. He seems to be listening. The others are looking at their watches. The spell of the level voice sinks the listener yet deeper into a trance. He is haunted by the ghosts of all the cant of all the political platforms of Great Britain. He hears all the old, old vestry phrases, and once more he smells the smell. That is no dream. Western education is an exotic plant. It is the upas tree, and it is all our fault. We brought it out from England exactly as we brought out the ink bottles and the patterns for the chairs. We planted it and it grew—monstrous as a banian. Now we are choked by the roots of it spreading so thickly in this fat soil of Bengal. The speaker continues. Bit by bit. We builded this dome, visible and invisible, the crown of Writers’ Buildings, as we have built and peopled the buildings. Now we have gone too far to retreat, being “tied and bound with the chain of our own sins.” The speech continues. We made that florid sentence. That torrent of verbiage is ours. We taught him what was constitutional and what was un{31}constitutional in the days when Calcutta smelt. Calcutta smells still, but we must listen to all that he has to say about the plurality of votes and the threshing of wind and the weaving of ropes of sand. It is our own fault absolutely.

The speech ends, and there rises a gray Englishman in a black frock-coat. He looks a strong man, and a worldly. Surely he will say: “Yes, Lala Sahib, all this may be true talk, but there’s a burra krab smell in this place, and everything must be safkaroed in a week, or the Deputy Commissioner will not take any notice of you in durbar.” He says nothing of the kind. This is a Legislative Council, where they call each other “Honorable So-and-So’s.” The Englishman in the frock-coat begs all to remember that “we are discussing principles, and no consideration of the details ought to influence the verdict on the principles.” Is he then like the rest? How does this strange thing come about? Perhaps these so English office fittings are responsible for the warp. The Council Chamber might be a London Board-room. Perhaps after long years among the pens and papers its occupants grow to think that it really is, and in this belief give résumés of the history of Local Self-Government in England.

The black frock-coat, emphasizing his points{32} with his spectacle-case, is telling his friends how the parish was first the unit of self-government. He then explains how burgesses were elected, and in tones of deep fervor announces: “Commissioners of Sewers are elected in the same way.” Whereunto all this lecture? Is he trying to run a motion through under cover of a cloud of words, essaying the well-known “cuttle-fish trick” of the West?

He abandons England for a while, and now we get a glimpse of the cloven hoof in a casual reference to Hindus and Mahomedans. The Hindus will lose nothing by the complete establishment of plurality of votes. They will have the control of their own wards as they used to have. So there is race-feeling, to be explained away, even among these beautiful desks. Scratch the Council, and you come to the old, old trouble. The black frock-coat sits down, and a keen-eyed, black-bearded Englishman rises with one hand in his pocket to explain his views on an alteration of the vote qualification. The idea of an amendment seems to have just struck him. He hints that he will bring it forward later on. He is academical like the others, but not half so good a speaker. All this is dreary beyond words. Why do they talk and talk about owners and occupiers and burgesses{33} in England and the growth of autonomous institutions when the city, the great city, is here crying out to be cleansed? What has England to do with Calcutta’s evil, and why should Englishmen be forced to wander through mazes of unprofitable argument against men who cannot understand the iniquity of dirt?

A pause follows the black-bearded man’s speech. Rises another native, a heavily-built Babu, in a black gown and a strange head-dress. A snowy white strip of cloth is thrown jharun-wise over his shoulders. His voice is high, and not always under control. He begins: “I will try to be as brief as possible.” This is ominous. By the way, in Council there seems to be no necessity for a form of address. The orators plunge in medias res, and only when they are well launched throw an occasional “Sir” toward Sir Steuart Bayley, who sits with one leg doubled under him and a dry pen in his hand. This speaker is no good. He talks, but he says nothing, and he only knows where he is drifting to. He says: “We must remember that we are legislating for the Metropolis of India, and therefore we should borrow our institutions from large English towns, and not from parochial institutions.” If you think for a minute, that shows a large and healthy knowledge{34} of the history of Local Self-Government. It also reveals the attitude of Calcutta. If the city thought less about itself as a metropolis and more as a midden, its state would be better. The speaker talks patronizingly of “my friend,” alluding to the black frock-coat. Then he flounders afresh, and his voice gallops up the gamut as he declares, “and therefore that makes all the difference.” He hints vaguely at threats, something to do with the Hindus and the Mahomedans, but what he means it is difficult to discover. Here, however, is a sentence taken verbatim. It is not likely to appear in this form in the Calcutta papers. The black frock-coat had said that if a wealthy native “had eight votes to his credit, his vanity would prompt him to go to the polling-booth, because he would feel better than half-a-dozen gharri-wans or petty traders.” (Fancy allowing a gharri-wan to vote! He has yet to learn how to drive!) Hereon the gentleman with the white cloth: “Then the complaint is that influential voters will not take the trouble to vote. In my humble opinion, if that be so, adopt voting papers. That is the way to meet them. In the same way—The Calcutta Trades’ Association—you abolish all plurality of votes: and that is the way to meet them.” Lucid, is it not? Up flies{35} the irresponsible voice, and delivers this statement: “In the election for the House of Commons plurality are allowed for persons having interest in different districts.” Then hopeless, hopeless fog. It is a great pity that India ever heard of anybody higher than the heads of the Civil Service. The country appeals from the Chota to the Burra Sahib all too readily as it is. Once more a whiff. The gentleman gives a defiant jerk of his shoulder-cloth, and sits down.

Then Sir Steuart Bayley: “The question before the Council is,” etc. There is a ripple of “Ayes” and “Noes,” and the “Noes” have it, whatever it may be. The black-bearded gentleman springs his amendment about the voting qualifications. A large senator in a white waistcoat, and with a most genial smile, rises and proceeds to smash up the amendment. Can’t see the use of it. Calls it in effect rubbish. The black frock-coat rises to explain his friend’s amendment, and incidentally makes a funny little slip. He is a knight, and his friend has been newly knighted. He refers to him as “Mister.” The black choga, he who spoke first of all, speaks again, and talks of the “sojorner who comes here for a little time, and then leaves the land.” Well it is for the black choga that the sojourner does come, or there would be no{36} comfy places wherein to talk about the power that can be measured by wealth and the intellect “which, sir, I submit, cannot be so measured.” The amendment is lost, and trebly and quadruply lost is the listener. In the name of sanity and to preserve the tattered shirt-tails of a torn illusion, let us escape. This is the Calcutta Municipal Bill. They have been at it for several Saturdays. Last Saturday Sir Steuart Bayley pointed out that at their present rate they would be about two years in getting it through. Now they will sit till dusk, unless Sir Steuart Bayley, who wants to see Lord Connemara off, puts up the black frock-coat to move an adjournment. It is not good to see a Government close to. This leads to the formation of blatantly self-satisfied judgments, which may be quite as wrong as the cramping system with which we have encompassed ourselves. And in the streets outside Englishmen summarize the situation brutally, thus: “The whole thing is a farce. Time is money to us. We can’t stick out those everlasting speeches in the municipality. The natives choke us off, but we know that if things get too bad the Government will step in and interfere, and so we worry along somehow.” Meantime Calcutta continues to cry out for the bucket and the broom.{37}

The clocks of the city have struck two. Where can a man get food? Calcutta is not rich in respect of dainty accommodation. You can stay your stomach at Peliti’s or Bonsard’s, but their shops are not to be found in Hasting Street, or in the places where brokers fly to and fro in office-jauns, sweating and growing visibly rich. There must be some sort of entertainment where sailors congregate. “Honest Bombay Jack” supplies nothing but Burma cheroots and whisky in liqueur-glasses, but in Lal Bazar, not far from “The Sailors’ Coffee-rooms,” a board gives bold advertisement that “officers and seamen can find good quarters.” In evidence a row of neat officers and seamen are sitting on a bench by the “hotel” door smoking. There is an almost military likeness in their clothes. Perhaps “Honest Bombay Jack” only keeps one kind of felt hat and one brand of suit. When Jack of the mercantile marine is sober, he is very sober. When he is drunk he is—but{38} ask the river police what a lean, mad Yankee can do with his nails and teeth. These gentlemen smoking on the bench are impassive almost as Red Indians. Their attitudes are unrestrained, and they do not wear braces. Nor, it would appear from the bill of fare, are they particular as to what they eat when they attend tâble d’hôte. The fare is substantial and the regulation peg—every house has its own depth of peg if you will refrain from stopping Ganymede—something to wonder at. Three fingers and a trifle over seems to be the use of the officers and seamen who are talking so quietly in the doorway. One says—he has evidently finished a long story—“and so he shipped for four pound ten with a first mate’s certificate and all, and that was in a German barque.” Another spits with conviction and says genially, without raising his voice: “That was a hell of a ship; who knows her?” No answer from the panchayet, but a Dane or a German wants to know whether the Myra is “up” yet. A dry, red-haired man gives her exact position in the river—(How in the world can he know?)—and the probable hour of her arrival. The grave debate drifts into a discussion of a recent river accident, whereby a big steamer was damaged, and had to put back and discharge cargo. A burly{39} gentleman who is taking a constitutional down Lal Bazar strolls up and says: “I tell you she fouled her own chain with her own forefoot. Hev you seen the plates?” “No.” “Then how the —— can any —— like you —— say what it —— well was?” He passes on, having delivered his highly flavored opinion without heat or passion. No one seems to resent the expletives.

Let us get down to the river and see this stamp of men more thoroughly. Clark Russell has told us that their lives are hard enough in all conscience. What are their pleasures and diversions? The Port Office, where live the gentlemen who make improvements in the Port of Calcutta, ought to supply information. It stands large and fair, and built in an orientalized manner after the Italians at the corner of Fairlie Place upon the great Strand Road, and a continual clamor of traffic by land and by sea goes up throughout the day and far into the night against its windows. This is a place to enter more reverently than the Bengal Legislative Council, for it houses the direction of the uncertain Hugli down to the Sandheads, owns enormous wealth, and spends huge sums on the frontaging of river banks, the expansion of jetties, and the manufacture of docks costing two{40} hundred lakhs of rupees. Two million tons of sea-going shippage yearly find their way up and down the river by the guidance of the Port Office, and the men of the Port Office know more than it is good for men to hold in their heads. They can without reference to telegraphic bulletins give the position of all the big steamers, coming up or going down, from the Hugli to the sea, day by day, with their tonnage, the names of their captains, and the nature of their cargo. Looking out from the verandah of their offices over a lancer-regiment of masts, they can declare truthfully the name of every ship within eye-scope, with the day and hour when she will depart.

In a room at the bottom of the building lounge big men, carefully dressed. Now there is a type of face which belongs almost exclusively to Bengal Cavalry officers—majors for choice. Everybody knows the bronzed, black-moustached, clear-speaking Native Cavalry officer. He exists unnaturally in novels, and naturally on the frontier. These men in the big room have its cast of face so strongly marked that one marvels what officers are doing by the river. “Have they come to book passengers for home?” “Those men! They’re pilots. Some of them draw between two and three thousand rupees a{41} month. They are responsible for half-a-million pounds’ worth of cargo sometimes.” They certainly are men, and they carry themselves as such. They confer together by twos and threes, and appeal frequently to shipping lists.

“Isn’t a pilot a man who always wears a pea-jacket and shouts through a speaking-trumpet?” “Well, you can ask those gentlemen if you like. You’ve got your notions from home pilots. Ours aren’t that kind exactly. They are a picked service, as carefully weeded as the Indian Civil. Some of ’em have brothers in it, and some belong to the old Indian army families.” But they are not all equally well paid. The Calcutta papers sometimes echo the groans of the junior pilots who are not allowed the handling of ships over a certain tonnage. As it is yearly growing cheaper to build one big steamer than two little ones, these juniors are crowded out, and, while the seniors get their thousands, some of the youngsters make at the end of one month exactly thirty rupees. This is a grievance with them; and it seems well-founded.

In the flats above the pilots’ room are hushed and chapel-like offices, all sumptuously fitted, where Englishmen write and telephone and telegraph, and deft Babus forever draw maps of the shifting Hugli. Any hope of understand{42}ing the work of the Port Commissioners is thoroughly dashed by being taken through the Port maps of a quarter of a century past. Men have played with the Hugli as children play with a gutter-runnel, and, in return, the Hugli once rose and played with men and ships till the Strand Road was littered with the raffle and the carcasses of big ships. There are photos on the walls of the cyclone of ’64, when the Thunder came inland and sat upon an American barque, obstructing all the traffic. Very curious are these photos, and almost impossible to believe. How can a big, strong steamer have her three masts razed to deck level? How can a heavy, country boat be pitched on to the poop of a high-walled liner? and how can the side be bodily torn out of a ship? The photos say that all these things are possible, and men aver that a cyclone may come again and scatter the craft like chaff. Outside the Port Office are the export and import sheds, buildings that can hold a ship’s cargo a-piece, all standing on reclaimed ground. Here be several strong smells, a mass of railway lines, and a multitude of men. “Do you see where that trolly is standing, behind the big P. and O. berth? In that place as nearly as may be the Govindpur went down about twenty years ago, and began to shift out!” “But that{43} is solid ground.” “She sank there, and the next tide made a scour-hole on one side of her. The returning tide knocked her into it. Then the mud made up behind her. Next tide the business was repeated—always the scour-hole in the mud and the filling up behind her. So she rolled and was pushed out and out until she got in the way of the shipping right out yonder, and we had to blow her up. When a ship sinks in mud or quicksand she regularly digs her own grave and wriggles herself into it deeper and deeper till she reaches moderately solid stuff. Then she sticks.” Horrible idea, is it not, to go down and down with each tide into the foul Hugli mud?

Close to the Port Offices is the Shipping Office, where the captains engage their crews. The men must produce their discharges from their last ships in the presence of the shipping master, or, as they call him, “The Deputy Shipping.” He passes them as correct after having satisfied himself that they are not deserters from other ships, and they then sign articles for the voyage. This is the ceremony, beginning with the “dearly beloved” of the crew-hunting captain down to the “amazement” of the identified deserter. There is a dingy building, next door to the Sailors’ Home, at whose{44} gate stand the cast-ups of all the seas in all manner of raiment. There are Seedee boys, Bombay serangs and Madras fishermen of the salt villages, Malays who insist upon marrying native women, grow jealous and run amok: Malay-Hindus, Hindu-Malay-whites, Burmese, Burma-whites, Burma-native-whites, Italians with gold earrings and a thirst for gambling, Yankees of all the States, with Mulattoes and pure buck-niggers, red and rough Danes, Cingalese, Cornish boys who seem fresh taken from the plough-tail, “corn-stalks” from colonial ships where they got four pound ten a month as seamen, tun-bellied Germans, Cockney mates keeping a little aloof from the crowd and talking in knots together, unmistakable “Tommies” who have tumbled into seafaring life by some mistake, cockatoo-tufted Welshmen spitting and swearing like cats, broken-down loafers, gray-headed, penniless, and pitiful, swaggering boys, and very quiet men with gashes and cuts on their faces. It is an ethnological museum where all the specimens are playing comedies and tragedies. The head of it all is the “Deputy Shipping,” and he sits, supported by an English policeman whose fists are knobby, in a great Chair of State. The “Deputy Shipping” knows all the iniquity of the river-side, all the ships,{45} all the captains, and a fair amount of the men. He is fenced off from the crowd by a strong wooden railing, behind which are gathered those who “stand and wait,” the unemployed of the mercantile marine. They have had their spree—poor devils—and now they will go to sea again on as low a wage as three pound ten a month, to fetch up at the end in some Shanghai stew or San Francisco hell. They have turned their backs on the seductions of the Howrah boarding-houses and the delights of Colootolla. If Fate will, “Nightingales” will know them no more for a season, and their successors may paint Collinga Bazar vermillion. But what captain will take some of these battered, shattered wrecks whose hands shake and whose eyes are red?

Enter suddenly a bearded captain, who has made his selection from the crowd on a previous day, and now wants to get his men passed. He is not fastidious in his choice. His eleven seem a tough lot for such a mild-eyed, civil-spoken man to manage. But the captain in the Shipping Office and the captain on the ship are two different things. He brings his crew up to the “Deputy Shipping’s” bar, and hands in their greasy, tattered discharges. But the heart of the “Deputy Shipping” is hot within him, be{46}cause, two days ago, a Howrah crimp stole a whole crew from a down-dropping ship, insomuch that the captain had to come back and whip up a new crew at one o’clock in the day. Evil will it be if the “Deputy Shipping” finds one of these bounty-jumpers in the chosen crew of the Blenkindoon, let us say.

The “Deputy Shipping” tells the story with heat. “I didn’t know they did such things in Calcutta,” says the captain. “Do such things! They’d steal the eye-teeth out of your head there, Captain.” He picks up a discharge and calls for Michael Donelly, who is a loose-knit, vicious-looking Irish-American who chews. “Stand up, man, stand up!” Michael Donelly wants to lean against the desk, and the English policeman won’t have it. “What was your last ship?” “Fairy Queen.” “When did you leave her?” “’Bout ’leven days.” “Captain’s name?” “Flahy.” “That’ll do. Next man: Jules Anderson.” Jules Anderson is a Dane. His statements tally with the discharge-certificate of the United States, as the Eagle attesteth. He is passed and falls back. Slivey, the Englishman, and David, a huge plum-colored negro who ships as cook, are also passed. Then comes Bassompra, a little Italian, who speaks English. “What’s your last ship?” “Ferdi{47}nand.” “No, after that?” “German barque.” Bassompra does not look happy. “When did she sail?” “About three weeks ago.” “What’s her name?” “Haidée.” “You deserted from her?” “Yes, but she’s left port.” The “Deputy Shipping” runs rapidly through a shipping-list, throws it down with a bang. “’Twon’t do. No German barque Haidée here for three months. How do I know you don’t belong to the Jackson’s crew? Cap’ain, I’m afraid you’ll have to ship another man. He must stand over. Take the rest away and make ’em sign.”

The bead-eyed Bassompra seems to have lost his chance of a voyage, and his case will be inquired into. The captain departs with his men and they sign articles for the voyage, while the “Deputy Shipping” tells strange tales of the sailorman’s life. “They’ll quit a good ship for the sake of a spree, and catch on again at three pound ten, and by Jove, they’ll let their skippers pay ’em at ten rupees to the sovereign—poor beggars! As soon as the money’s gone they’ll ship, but not before. Every one under rank of captain engages here. The competition makes first mates ship sometimes for five pounds or as low as four ten a month.” (The gentleman in the boarding-house was right, you see.) “A first mate’s wages are seven ten or eight,{48} and foreign captains ship for twelve pounds a month and bring their own small stores—everything, that is to say, except beef, peas, flour, coffee, and molasses.”

These things are not pleasant to listen to while the hungry-eyed men in the bad clothes lounge and scratch and loaf behind the railing. What comes to them in the end? They die, it seems, though that is not altogether strange. They die at sea in strange and horrible ways; they die, a few of them, in the Kintals, being lost and suffocated in the great sink of Calcutta; they die in strange places by the waterside, and the Hugli takes them away under the mooring chains and the buoys, and casts them up on the sands below, if the River Police have missed the capture. They sail the sea because they must live; and there is no end to their toil. Very, very few find haven of any kind, and the earth, whose ways they do not understand, is cruel to them, when they walk upon it to drink and be merry after the manner of beasts. Jack ashore is a pretty thing when he is in a book or in the blue jacket of the Navy. Mercantile Jack is not so lovely. Later on, we will see where his “sprees” lead him.

In the beginning, the Police were responsible. They said in a patronizing way that, merely as a matter of convenience, they would prefer to take a wanderer round the great city themselves, sooner than let him contract a broken head on his own account in the slums. They said that there were places and places where a white man, unsupported by the arm of the law, would be robbed and mobbed; and that there were other places where drunken seamen would make it very unpleasant for him. There was a night fixed for the patrol, but apologies were offered beforehand for the comparative insignificance of the tour.

“Come up to the fire lookout in the first place, and then you’ll be able to see the city.” This was at No. 22, Lal Bazar, which is the{50} headquarters of the Calcutta Police, the centre of the great web of telephone wires where Justice sits all day and all night looking after one million people and a floating population of one hundred thousand. But her work shall be dealt with later on. The fire lookout is a little sentry-box on the top of the three-storied police offices. Here a native watchman waits always, ready to give warning to the brigade below if the smoke rises by day or the flames by night in any ward of the city. From this eyrie, in the warm night, one hears the heart of Calcutta beating. Northward, the city stretches away three long miles, with three more miles of suburbs beyond, to Dum-Dum and Barrackpore. The lamplit dusk on this side is full of noises and shouts and smells. Close to the Police Office, jovial mariners at the sailors’ coffee-shop are roaring hymns. Southerly, the city’s confused lights give place to the orderly lamp-rows of the maidan and Chouringhi, where the respectabilities live and the Police have very little to do. From the east goes up to the sky the clamor of Sealdah, the rumble of the trams, and the voices of all Bow Bazar chaffering and making merry. Westward are the business quarters, hushed now, the lamps of the shipping on the river, and the twinkling lights on the Howrah{51} side. It is a wonderful sight—this Pisgah view of a huge city resting after the labors of the day. “Does the noise of traffic go on all through the hot weather?” “Of course. The hot months are the busiest in the year and money’s tightest. You should see the brokers cutting about at that season. Calcutta can’t stop, my dear sir.” “What happens then?” “Nothing happens; the death-rate goes up a little. That’s all!” Even in February, the weather would, up-country, be called muggy and stifling, but Calcutta is convinced that it is her cold season. The noises of the city grow perceptibly; it is the night side of Calcutta waking up and going abroad. Jack in the sailors’ coffee-shop is singing joyously: “Shall we gather at the River-the beautiful, the beautiful, the River?” What an incongruity there is about his selections! However, that it amuses before it shocks the listeners, is not to be doubted. An Englishman, far from his native land, is liable to become careless, and it would be remarkable if he did otherwise in ill-smelling Calcutta. There is a clatter of hoofs in the courtyard below. Some of the Mounted Police have come in from somewhere or other out of the great darkness. A clog-dance of iron hoofs follows, and an Englishman’s voice is heard soothing an agitated{52} horse who seems to be standing on his hind legs. Some of the Mounted Police are going out into the great darkness. “What’s on?” “Walk-round at Government House. The Reserve men are being formed up below. They’re calling the roll.” The Reserve men are all English, and big English at that. They form up and tramp out of the courtyard to line Government Place, and see that Mrs. Lollipop’s brougham does not get smashed up by Sirdar Chuckerbutty Bahadur’s lumbering C-spring barouche with the two raw walers. Very military men are the Calcutta European Police in their set-up, and he who knows their composition knows some startling stories of gentlemen-rankers and the like. They are, despite the wearing climate they work in and the wearing work they do, as fine five-score of Englishmen as you shall find east of Suez.

Listen for a moment from the fire lookout to the voices of the night, and you will see why they must be so. Two thousand sailors of fifty nationalities are adrift in Calcutta every Sunday, and of these perhaps two hundred are distinctly the worse for liquor. There is a mild row going on, even now, somewhere at the back of Bow Bazar, which at nightfall fills with sailormen who have a wonderful gift of falling foul{53} of the native population. To keep the Queen’s peace is of course only a small portion of Police duty, but it is trying. The burly president of the lock-up for European drunks-Calcutta central lock-up is worth seeing-rejoices in a sprained thumb just now, and has to do his work left-handed in consequence. But his left hand is a marvellously persuasive one, and when on duty his sleeves are turned up to the shoulder that the jovial mariner may see that there is no deception. The president’s labors are handicapped in that the road of sin to the lock-up runs through a grimy little garden-the brick paths are worn deep with the tread of many drunken feet-where a man can give a great deal of trouble by sticking his toes into the ground and getting mixed up with the shrubs. “A straight run in” would be much more convenient both for the president and the drunk. Generally speaking—and here Police experience is pretty much the same all over the civilized world-a woman drunk is a good deal worse than a man drunk. She scratches and bites like a Chinaman and swears like several fiends. Strange people may be unearthed in the lock-ups. Here is a perfectly true story, not three weeks old. A visitor, an unofficial one, wandered into the native side of the spacious ac{54}commodation provided for those who have gone or done wrong. A wild-eyed Babu rose from the fixed charpoy and said in the best of English: “Good-morning, sir.” “Good-morning; who are you, and what are you in for?” Then the Babu, in one breath: “I would have you know that I do not go to prison as a criminal but as a reformer. You’ve read the Vicar of Wakefield?” “Ye-es.” “Well, I am the Vicar of Bengal-at least, that’s what I call myself.” The visitor collapsed. He had not nerve enough to continue the conversation. Then said the voice of the authority: “He’s down in connection with a cheating case at Serampore. May be shamming. But he’ll be looked to in time.”

The best place to hear about the Police is the fire lookout. From that eyrie one can see how difficult must be the work of control over the great, growling beast of a city. By all means let us abuse the Police, but let us see what the poor wretches have to do with their three thousand natives and one hundred Englishmen. From Howrah and Bally and the other suburbs at least a hundred thousand people come in to Calcutta for the day and leave at night. Also Chandernagore is handy for the fugitive law-breaker, who can enter in the evening and get{55} away before the noon of the next day, having marked his house and broken into it.

“But how can the prevalent offence be housebreaking in a place like this?” “Easily enough. When you’ve seen a little of the city you’ll see. Natives sleep and lie about all over the place, and whole quarters are just so many rabbit-warrens. Wait till you see the Machua Bazar. Well, besides the petty theft and burglary, we have heavy cases of forgery and fraud, that leave us with our wits pitted against a Bengali’s. When a Bengali criminal is working a fraud of the sort he loves, he is about the cleverest soul you could wish for. He gives us cases a year long to unravel. Then there are the murders in the low houses—very curious things they are. You’ll see the house where Sheikh Babu was murdered presently, and you’ll understand. The Burra Bazar and Jora Bagan sections are the two worst ones for heavy cases; but Colootollah is the most aggravating. There’s Colootollah over yonder—that patch of darkness beyond the lights. That section is full of tuppenny-ha’penny petty cases, that keep the men up all night and make ’em swear. You’ll see Colootollah, and then perhaps you’ll understand. Bamun Bustee is the quietest of all, and Lal Bazar and Bow Bazar, as you can see{56} for yourself, are the rowdiest. You’ve no notion what the natives come to the thannahs for. A naukar will come in and want a summons against his master for refusing him half-an-hour’s chuti. I suppose it does seem rather revolutionary to an up-country man, but they try to do it here. Now wait a minute, before we go down into the city and see the Fire Brigade turned out. Business is slack with them just now, but you time ’em and see.” An order is given, and a bell strikes softly thrice. There is an orderly rush of men, the click of a bolt, a red fire-engine, spitting and swearing with the sparks flying from the furnace, is dragged out of its shelter. A huge brake, which holds supplementary hoses, men, and hatchets, follows, and a hose-cart is the third on the list. The men push the heavy things about as though they were pith toys. Five horses appear. Two are shot into the fire-engine, two—monsters these—into the brake, and the fifth, a powerful beast, warranted to trot fourteen miles an hour, backs into the hose-cart shafts. The men clamber up, some one says softly, “All ready there,” and with an angry whistle the fire-engine, followed by the other two, flies out into Lal Bazar, the sparks trailing behind. Time—1 min. 40 secs. “They’ll find out it’s a false alarm, and come{57} back again in five minutes.” “Why?” “Because there will be no constables on the road to give ’em the direction of the fire, and because the driver wasn’t told the ward of the outbreak when he went out!” “Do you mean to say that you can from this absurd pigeon-loft locate the wards in the night-time?” “Of course: what would be the good of a lookout if the man couldn’t tell where the fire was?” “But it’s all pitchy black, and the lights are so confusing.”

“Ha! Ha! You’ll be more confused in ten minutes. You’ll have lost your way as you never lost it before. You’re going to go round Bow Bazar section.”

“And the Lord have mercy on my soul!” Calcutta, the darker portion of it, does not look an inviting place to dive into at night.{58}

The difficulty is to prevent this account from growing steadily unwholesome. But one cannot rake through a big city without encountering muck.

The Police kept their word. In five short minutes, as they had prophesied, their charge was lost as he had never been lost before. “Where are we now?” “Somewhere off the Chitpore Road, but you wouldn’t understand if you were told. Follow now, and step pretty much where we step—there’s a good deal of filth hereabouts.”

The thick, greasy night shuts in everything.{59} We have gone beyond the ancestral houses of the Ghoses of the Boses, beyond the lamps, the smells, and the crowd of Chitpore Road, and have come to a great wilderness of packed houses—just such mysterious, conspiring tenements as Dickens would have loved. There is no breath of breeze here, and the air is perceptibly warmer. There is little regularity in the drift, and the utmost niggardliness in the spacing of what, for want of a better name, we must call the streets. If Calcutta keeps such luxuries as Commissioners of Sewers and Paving, they die before they reach this place. The air is heavy with a faint, sour stench—the essence of long-neglected abominations—and it cannot escape from among the tall, three-storied houses. “This, my dear sir, is a perfectly respectable quarter as quarters go. That house at the head of the alley, with the elaborate stucco-work round the top of the door, was built long ago by a celebrated midwife. Great people used to live here once. Now it’s the—Aha! Look out for that carriage.” A big mail-phaeton crashes out of the darkness and, recklessly driven, disappears. The wonder is how it ever got into this maze of narrow streets, where nobody seems to be moving, and where the dull throbbing of the city’s life only comes faintly and by snatches. “Now it’s the{60} what?” “St. John’s Wood of Calcutta—for the rich Babus. That ‘fitton’ belonged to one of them.” “Well it’s not much of a place to look at.” “Don’t judge by appearances. About here live the women who have beggared kings. We aren’t going to let you down into unadulterated vice all at once. You must see it first with the gilding on—and mind that rotten board.”

Stand at the bottom of a lift and look upward. Then you will get both the size and the design of the tiny courtyard round which one of these big dark houses is built. The central square may be perhaps ten feet every way, but the balconies that run inside it overhang, and seem to cut away half the available space. To reach the square a man must go round many corners, down a covered-in way, and up and down two or three baffling and confused steps. There are no lamps to guide, and the janitors of the establishment seem to be compelled to sleep in the passages. The central square, the patio or whatever it must be called, reeks with the faint, sour smell which finds its way impartially into every room. “Now you will understand,” say the Police kindly, as their charge blunders, shin-first, into a well-dark winding staircase, “that these are not the sort of places

{61} to visit alone.” “Who wants to? Of all the disgusting, inaccessible dens—Holy Cupid, what’s this?”

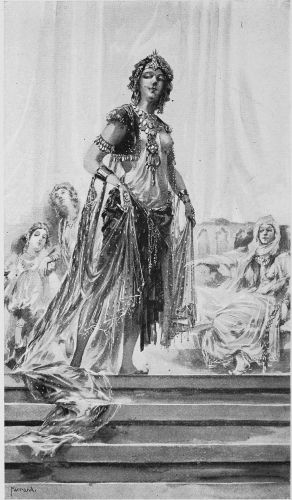

A glare of light on the stair-head, a clink of innumerable bangles, a rustle of much fine gauze, and the Dainty Iniquity stands revealed, blazing—literally blazing—with jewelry from head to foot. Take one of the fairest miniatures that the Delhi painters draw, and multiply it by ten; throw in one of Angelica Kaufmann’s best portraits, and add anything that you can think of from Beckford to Lalla Rookh, and you will still fall short of the merits of that perfect face. For an instant, even the grim, professional gravity of the Police is relaxed in the presence of the Dainty Iniquity with the gems, who so prettily invites every one to be seated, and proffers such refreshments as she conceives the palates of the barbarians would prefer. Her Abigails are only one degree less gorgeous than she. Half a lakh, or fifty thousand pounds’ worth—it is easier to credit the latter statement than the former—are disposed upon her little body. Each hand carries five jewelled rings which are connected by golden chains to a great jewelled boss of gold in the centre of the back of the hand. Ear-rings weighted with emeralds and pearls, diamond nose-rings, and how many other{62} hundred articles make up the list of adornments. English furniture of a gorgeous and gimcrack kind, unlimited chandeliers and a collection of atrocious Continental prints—something, but not altogether, like the glazed plaques on bonbon boxes—are scattered about the house, and on every landing—let us trust this is a mistake—lies, squats, or loafs a Bengali who can talk English with unholy fluency. The recurrence suggests—only suggests, mind—a grim possibility of the affectation of excessive virtue by day, tempered with the sort of unwholesome enjoyment after dusk—this loafing and lobbying and chattering and smoking, and, unless the bottles lie tippling among the foul-tongued handmaidens of the Dainty Iniquity. How many men follow this double, deleterious sort of life? The Police are discreetly dumb.

“Now don’t go talking about ‘domiciliary visits’ just because this one happens to be a pretty woman. We’ve got to know these creatures. They make the rich man and the poor spend their money; and when a man can’t get money for ’em honestly, he comes under our notice. Now do you see? If there was any domiciliary ‘visit’ about it, the whole houseful would be hidden past our finding as soon as we turned up in the courtyard. We’re friends—to a certain{63} extent.” And, indeed, it seemed no difficult thing to be friends to any extent with the Dainty Iniquity who was so surpassingly different from all that experience taught of the beauty of the East. Here was the face from which a man could write Lalla Rookhs by the dozen, and believe every work that he wrote. Hers was the beauty that Byron sang of when he wrote—

“Remember, if you come here alone, the chances are that you’ll be clubbed, or stuck, or, anyhow, mobbed. You’ll understand that this part of the world is shut to Europeans—absolutely. Mind the steps, and follow on.” The vision dies out in the smells and gross darkness of the night, in evil, time-rotten brickwork, and another wilderness of shut-up houses, wherein it seems that people do continually and feebly strum stringed instruments of a plaintive and wailsome nature.

Follows, after another plunge into a passage of a court-yard, and up a staircase, the apparition of a Fat Vice, in whom is no sort of romance, nor beauty, but unlimited coarse humor. She too is studded with jewels, and her house is even finer than the house of the other, and more infested with the extraordinary men who speak such good English and are so deferential{64} to the Police. The Fat Vice has been a great leader of fashion in her day, and stripped a zemindar Raja to his last acre—insomuch that he ended in the House of Correction for a theft committed for her sake. Native opinion has it that she is a “monstrous well-preserved woman.” On this point, as on some others, the races will agree to differ.

The scene changes suddenly as a slide in a magic lantern. Dainty Iniquity and Fat Vice slide away on a roll of streets and alleys, each more squalid than its predecessor. We are “somewhere at the back of the Machua Bazar,” well in the heart of the city. There are no houses here—nothing but acres and acres, it seems, of foul wattle-and-dab huts, any one of which would be a disgrace to a frontier village. The whole arrangement is a neatly contrived germ and fire trap, reflecting great credit upon the Calcutta Municipality.

“What happens when these pigsties catch fire?” “They’re built up again,” say the Police, as though this were the natural order of things. “Land is immensely valuable here.” All the more reason, then, to turn several Hausmanns loose into the city, with instructions to make barracks for the population that cannot find room in the huts and sleeps in the open{65} ways, cherishing dogs and worse, much worse, in its unwashen bosom. “Here is a licensed coffee-shop. This is where your naukers go for amusement and to see nautches.” There is a huge chappar shed, ingeniously ornamented with insecure kerosene lamps, and crammed with gharriwans, khitmatgars, small store-keepers and the like. Never a sign of a European. Why? “Because if an Englishman messed about here, he’d get into trouble. Men don’t come here unless they’re drunk or have lost their way.” The gharriwans—they have the privilege of voting, have they not?—look peaceful enough as they squat on tables or crowd by the doors to watch the nautch that is going forward. Five pitiful draggle-tails are huddled together on a bench under one of the lamps, while the sixth is squirming and shrieking before the impassive crowd. She sings of love as understood by the Oriental—the love that dries the heart and consumes the liver. In this place, the words that would look so well on paper have an evil and ghastly significance. The gharriwans stare or sup tumblers and cups of a filthy decoction, and the kunchenee howls with renewed vigor in the presence of the Police. Where the Dainty Iniquity was hung with gold and gems, she is trapped with pewter and glass;{66} and where there was heavy embroidery on the Fat Vice’s dress, defaced, stamped tinsel faithfully reduplicates the pattern on the tawdry robes of the kunchenee. So you see, if one cares to moralize, they are sisters of the same class.

Two or three men, blessed with uneasy consciences, have quietly slipped out of the coffee-shop into the mazes of the huts beyond. The Police laugh, and those nearest in the crowd laugh applausively, as in duty bound. Perhaps the rabbits grin uneasily when the ferret lands at the bottom of the burrow and begins to clear the warren.

“The chandoo-shops shut up at six, so you’ll have to see opium-smoking before dark some day. No, you won’t, though.” The detective nose sniffs, and the detective body makes for a half-opened door of a hut whence floats the fragrance of the black smoke. Those of the inhabitants who are able to stand promptly clear out—they have no love for the Police—and there remain only four men lying down and one standing up. This latter has a pet mongoose coiled round his neck. He speaks English fluently. Yes, he has no fear. It was a private smoking party and—“No business to-night—show how you smoke opium.” “Aha! You{67} want to see. Very good, I show. Hiya! you”—he kicks a man on the floor—“show how opium-smoking.” The kickee grunts lazily and turns on his elbow. The mongoose, always keeping to the man’s neck, erects every hair of its body like an angry cat, and chatters in its owner’s ear. The lamp for the opium-pipe is the only one in the room, and lights a scene as wild as anything in the witches’ revel; the mongoose acting as the familiar spirit. A voice from the ground says, in tones of infinite weariness: “You take afim, so”—a long, long pause, and another kick from the man possessed of the devil—the mongoose. “You take afim?” He takes a pellet of the black, treacly stuff on the end of a knitting-needle. “And light afim.” He plunges the pellet into the night-light, where it swells and fumes greasily. “And then you put it in your pipe.” The smoking pellet is jammed into the tiny bowl of the thick, bamboo-stemmed pipe, and all speech ceases, except the unearthly noise of the mongoose. The man on the ground is sucking at his pipe, and when the smoking pellet has ceased to smoke will be half way to Nibhan. “Now you go,” says the man with the mongoose. “I am going smoke.” The hut door closes upon a red-lit view of huddled legs and bodies,{68} and the man with the mongoose sinking, sinking on to his knees, his head bowed forward, and the little hairy devil chattering on the nape of his neck.

After this the fetid night air seems almost cool, for the hut is as hot as a furnace. “See the pukka chandu shops in full blast to-morrow. Now for Colootollah. Come through the huts. There is no decoration about this vice.”

The huts now gave place to houses very tall and spacious and very dark. But for the narrowness of the streets we might have stumbled upon Chouringhi in the dark. An hour and a half has passed, and up to this time we have not crossed our trail once. “You might knock about the city for a night and never cross the same line. Recollect Calcutta isn’t one of your poky up-country cities of a lakh and a half of people.” “How long does it take to know it then?” “About a lifetime, and even then some of the streets puzzle you.” “How much has the head of a ward to know?” “Every house in his ward if he can, who owns it, what sort of character the inhabitants are, who are their friends, who go out and in, who loaf about the place at night, and so on and so on.” “And he knows all this by night as well as by day?{69}” “Of course. Why shouldn’t he?” “No reason in the world. Only it’s pitchy black just now, and I’d like to see where this alley is going to end.” “Round the corner beyond that dead wall. There’s a lamp there. Then you’ll be able to see.” A shadow flits out of a gully and disappears. “Who’s that?” “Sergeant of Police just to see where we’re going in case of accidents.” Another shadow staggers into the darkness. “Who’s that?” “Man from the fort or a sailor from the ships. I couldn’t quite see.” The Police open a shut door in a high wall, and stumble unceremoniously among a gang of women cooking their food. The floor is of beaten earth, the steps that lead into the upper stories are unspeakably grimy, and the heat is the heat of April. The women rise hastily, and the light of the bull’s eye—for the Police have now lighted a lantern in regular “rounds of London” fashion—shows six bleared faces—one a half native, half Chinese one, and the others Bengali. “There are no men here!” they cry. “The house is empty.” Then they grin and jabber and chew pan and spit, and hurry up the steps into the darkness. A range of three big rooms has been knocked into one here, and there is some sort of arrangement of mats. But an average country-bred is more{70} sumptuously accommodated in an Englishman’s stable. A home horse would snort at the accommodation.

“Nice sort of place, isn’t it?” say the Police, genially. “This is where the sailors get robbed and drunk.” “They must be blind drunk before they come.” “Na—Na! Na sailor men ee—yah!” chorus the women, catching at the one word they understand. “Arl gone!” The Police take no notice, but tramp down the big room with the mat loose-boxes. A woman is shivering in one of these. “What’s the matter?” “Fever. Seek. Vary, vary seek.” She huddles herself into a heap on the charpoy and groans.

A tiny, pitch-black closet opens out of the long room, and into this the Police plunge. “Hullo! What’s here?” Down flashes the lantern, and a white hand with black nails comes out of the gloom. Somebody is asleep or drunk in the cot. The ring of lantern light travels slowly up and down the body. “A sailor from the ships. He’s got his dungarees on. He’ll be robbed before the morning most likely.” The man is sleeping like a little child, both arms thrown over his head, and he is not unhandsome. He is shoeless, and there are huge holes in his stockings. He is a pure-{71}blooded white, and carries the flush of innocent sleep on his cheeks.