![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Angels in Art

Author: Clara Erskine Clement Waters

Release date: April 22, 2020 [eBook #61896]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif, deaurider and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

ANGELS IN ART

| Art Series |

| THE MADONNA IN ART |

| Estelle M. Hurll. |

| CHILD LIFE IN ART |

| Estelle M. Hurll. |

| ANGELS IN ART |

| Clara Erskine Clement. |

| LOVE IN ART |

| Mary Knight Potter. |

| L. C. PAGE AND COMPANY |

| (INCORPORATED) |

| 196 Summer Street, Boston, Mass. |

BY

CLARA ERSKINE CLEMENT

AUTHOR OF

“A HANDBOOK OF LEGENDARY ART,”

“PAINTERS, SCULPTORS, ARCHITECTS, AND ENGRAVERS,”

“ARTISTS OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY,”

ETC.

Illustrated

LONDON

DAVID NUTT

1899

{6}

Colonial Press:

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U. S. A.

ANGELS IN ART.

NGELS and archangels, cherubim and seraphim, and all the glorious hosts

of heaven were a fruitful source of inspiration to the oldest painters

and sculptors whose works are known to us, while the artists of our more

practical, less dreamful age are, from time to time, inspired to

reproduce their conceptions of the guardian angels of our race.

NGELS and archangels, cherubim and seraphim, and all the glorious hosts

of heaven were a fruitful source of inspiration to the oldest painters

and sculptors whose works are known to us, while the artists of our more

practical, less dreamful age are, from time to time, inspired to

reproduce their conceptions of the guardian angels of our race.

The Almighty declared to Job that the creation of the world was welcomed with shouts of joy by “all the sons of God,{12}” and the story of the words and works of the angels written in the Scriptures—from the placing of the cherubim at the east of the Garden of Eden, to the worship of the angel by John, in the last chapter of Revelation—presents them to us as heavenly guides, consolers, protectors, and reprovers of human beings.

What study is more charming and restful than that of the angels as set forth in Holy Writ and the writings of the early Church? or more interesting to observe than the manner in which the artists of various nations and periods have expressed their ideas concerning these celestial messengers of God? What more fascinating, more stimulating to the imagination and further removed from the exhausting tension of our day and generation?

The Old Testament represents the angels as an innumerable host, discerning good and evil by reason of superior intel{13}ligence, and without passion doing the will of God. Having the power to slay, it is only exercised by the command of the Almighty, and not until after the Captivity do we read of evil angels who work wickedness among men. In fact, after this time the Hebrews seem to have added much to their angelic theory and faith which harmonizes with the religion of the Chaldeans, and with the teaching of Zoroaster.

The angels of the New Testament, while exempt from need and suffering, have sympathy with human sorrow, rejoice over repentance of sin, attend on prayerful souls, and conduct the spirits of the just to heaven when the earthly life is ended.

One may doubt, however, if from the Scriptural teaching concerning angels would emanate the universal interest in their representation, and the personal{14} sympathy with it, which is commonly shared by all sorts and conditions of men, did they not cherish a belief—consciously or otherwise—that beings superior to themselves exist, and employ their superhuman powers for the blessing of our race, and for the welfare of individuals. Evidently Spenser felt this when he wrote:

As early as the fourth century the Christian Church had developed a profound belief in the existence of both good and evil angels,—“the foul fiends” and “bright squadrons” of Spenser’s lines,{15}—the former ever tempting human beings to sin, and the indulgence of their lower natures; the latter inciting them to pursue good, forsaking evil and pressing forward to the perfect Christian life. This faith is devoutly maintained in the writings of the Fathers of the Church, in which we are also taught that angelic aid may be invoked in our need, and that a consciousness of the abiding presence of celestial beings should be a supreme solace to human sorrow and suffering.

It remained for the theologians of the Middle Ages to exercise their fruitful imaginations in originating a systematic classification of the Orders of the Heavenly Host, and assigning to each rank its distinctive office. The warrant for these discriminations may seem insufficient to sceptical minds, but as their results are especially manifest in the{16} works of the old masters, some knowledge of them is necessary to the student of Art; without it a large proportion of the famous religious pictures of the world are utterly void of meaning.

Speaking broadly, this classification was based on that of St. Paul, when he speaks of “the principalities and powers in heavenly places,” and of “thrones and dominions;” on the account by Jude of the fall of the “angels which kept not their first estate;” on the triumphs of the Archangel Michael, and a few other texts of Scripture. Upon these premises the angelic host was divided into three hierarchies, and these again into nine choirs.

The first hierarchy embraces seraphim, cherubim, and thrones, the first mention being sometimes given to the cherubim. Dionysius the Areopagite—to whom St. Paul confided all that he had seen, when transported to the seventh heaven—ac{17}cords the first rank to the seraphim, while the familiar hymn of St. Ambrose has accustomed us to saying, “To Thee, cherubim and seraphim continually do cry.” Dante gives preference to Dionysius as an authority, and says of him:

The second hierarchy includes the dominations, virtues, and powers; the third, princedoms, archangels, and angels. The first hierarchy receives its glory directly from the Almighty, and transmits it to the second, which, in turn, illuminates the third, which is especially dedicated to the care and service of the human race.

From the third hierarchy come the ministers and messengers of God; the second is composed of governors, and the first of councillors. The choristers{18} of heaven are also angels, and the making of music is an important angelic duty.

The seraphim immediately surround the throne of God, and are ever lost in adoration and love, which is expressed in their very name, seraph coming from a Hebrew root, meaning love. The cherubim also worship the Creator, and are assigned to some special duties; they are superior in knowledge, and the word cherub, also from the Hebrew, signifies to know. Thrones sustain the seat of the Almighty.

The second hierarchy governs the elements and the stars. Princedoms protect earthly monarchies, while archangels and angels are the agents of God in his dealings with humanity. The title of angel, signifying a messenger, may be, and is, given to a man bearing important tidings. Thus the Evangelists are represented with wings, and John the Baptist is, in this{19} sense, an angel. The Greeks sometimes represent Christ with wings, and call him “The Great Angel of the Will of God.”

Very early in the history of Art a system of religious symbolism existed, a knowledge of which greatly enhances the pleasure derived from representations of sacred subjects. In no case was this symbolism more carefully observed than in the representations of angels. The aureole or nimbus is never omitted from the head of an angel, and is always, wherever used, the symbol of sanctity.

Wings are the distinctive angelic symbol, and are emblematic of spirit, power, and swiftness. Seraphim and cherubim are usually represented by heads with one, two, or three pairs of wings, which symbolize pure spirit, informed by love and intelligence; the head is an emblem of the soul, the love, the knowledge, while the wings have their usual significance.{20}

This manner of representing the two highest orders of angels is very ancient, and in the earliest instances in existence the faces are human, thoughtful, and mature. Gradually they became child-like, and were intended to express innocence, and later they degenerated into absurd little baby heads, with little wings folded under the chin. These in no sense convey the original, spiritual significance of the seraphic and cherubic head.

The first Scriptural mention of cherubim with wings occurs after the departure of the Israelites from Egypt, Exodus xxv., 20: “And the cherubim shall stretch forth their wings on high, covering the mercy seat.” Isaiah gives warrant for six wings, as frequently represented in Art, and so vividly described by Milton:

In Ezekiel we read that “their wings were stretched upward when they flew; when they stood they let down their wings.” There is, no doubt, Scriptural authority for representing angels’ wings in the most realistic manner, since Daniel says “they had wings like a fowl.” Is it not more desirable, however, to see angel-wings rather than bird-wings? The more devout and imaginative artists succeeded in overcoming the commonplace in this regard by various devices. For example, Orcagna, in the Campo Santo at Pisa, makes the bodies of his angels to end in delicate wings instead of legs; in some old pictures the wings fade into a cloudy vapor, or burst into flames. In one of{24} Raphael’s frescoes in the Vatican, we see fiery cherubs, their hair, wings, and limbs ending in glowing flames, while their faces are full of spirit and intelligence. Certainly, if anywhere purely impressionist painting is acceptable and fitting, it is in the portrayal of heavenly wings.

Mrs. Jameson, in writing of this subject, says, “Infinitely more beautiful and consistent are the nondescript wings which the early painters gave their angels: large,—so large that, when the glorious creature is represented as at rest, they droop from the shoulders to the ground; with long, slender feathers, eyed sometimes like the peacock’s train, bedropped with gold like the pheasant’s breast, tinted with azure and violet and crimson, ‘Colors dipp’d in Heaven,’—they are really angel-wings, not bird-wings.”

It is interesting to note that wings were used by the artists of ancient{25} Egypt, Babylon, Nineveh, and Etruria as symbols of might, majesty, and divine beauty.

The representation of great numbers of angels, surrounding the Deity, the Trinity, or the glorified Virgin, is known as a Glory of Angels, and is most expressive and poetical when æsthetically portrayed. A Glory, when properly represented, is composed of the hierarchies of angels in circles, each hierarchy in its proper order. Complete Glories, with nine circles, are exceedingly rare. Many artists contented themselves with two or three, and sometimes but a single circle, thus symbolizing the symbol of the Glory.

The nine choirs of angels are represented in various ways when not in a Glory, and are frequently seen in ancient frescoes, mosaics, and sculptures. Sometimes each choir has three figures, thus symbolizing the Trinity; again, two fig{26}ures stand for each choir, and occasionally nine figures personate the three hierarchies; in the last representation careful attention was given to colors as well as to symbols.

The Princedoms and Powers of Heaven are represented by rows and groups of angels, all wearing the same dress and the same tiara, and bearing the orb of sovereignty and wands like sceptres.

One of the most important elements in the proper painting of seraphs and cherubs was the use of color, while greater freedom was permitted in the portrayal of other angelic orders. In a Glory, for example, the inner circle should be glowing red, the symbol of love; the second, blue, the emblem of light, which again symbolizes knowledge.

Angelic symbolism in its purity makes the “blue-eyed seraphim” and the “smiling cherubim” equally incorrect, since the{27} seraph should be glowing with divine love, and the face of the cherub should be expressive of serious meditation,—as Milton says, “the Cherub Contemplation.” The familiar cherubim beneath Raphael’s famous Madonna di San Sisto, in the Dresden Gallery, are exquisite illustrations of this thoughtfulness.

The colors of the oldest pictures, of the illuminated manuscripts, the stained glass, and the painted sculptures were most carefully considered. Gradually, however, the color law was less faithfully observed, until, at the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth centuries, it was not unusual to see the wings of cherubim in various colors, while cherub heads were represented as floating in clouds with no apparent wings.

Two pictures of world-wide fame illustrate this change,—Raphael’s Madonna,{28} mentioned above, and Perugino’s Coronation of the Virgin. In the first, the entire background is composed of seraphs and cherubs apparently evolved from thin blue air, and in constant danger of disappearing in the golden-tinted background. In the second, the multi-colored wings of the floating cherubim are beautiful and the harmony of tones is exquisite, but they represent an innovation to which one must become more and more accustomed as artists are less reverent in their work.

The five angelic choirs which follow the seraphim and cherubim are not familiar to us in works of art, although they were painted with great accuracy in the words of the mediæval theologians.

When archangels are represented merely as belonging to their order, and not in their distinctive offices, they are in complete armor, and bear swords with the points upwards, and sometimes a trumpet also.{29}

Angels are robed, and are represented in accordance with the work in which they are engaged. Strictly speaking, the wand is the angelic symbol, but must be frequently omitted, as when the hands are folded in prayer, or musical instruments are in use, and in a variety of other occupations.

All angels are said to be masculine. They are represented as having human forms and faces, young, beautiful, perfect, with an expression of other-worldliness. They are created beings, therefore not eternal, but they are never old, and should not be infantile. Such representations as can be called infant angels should symbolize the souls of regenerate men, or the spirits of such as die in infancy,—those of whom Jesus said that “in heaven their angels do always behold the face of my Father.”

Angels are changeless; for them time{32} does not exist; they enjoy perpetual youth and uninterrupted bliss. To these qualities should be added an impression of unusual power, wisdom, innocence, and spiritual love.

In the earliest pictures of angels the drapery was ample, and no unusual attitudes, no insufficient robes, nor unsuitable expression was seen in such representations so long as religious art was at its best.

White should be the prevailing color of angelic drapery, but delicate shades of blue, red, and green were frequently employed with wonderful effect. The Venetians used an exquisite pale salmon color in the drapery of their angels; but no dark or heavy colors are seen in the robes of angels in the pictures of the old Italian masters. The early German painters, however, affected angelic draperies of such vast expanse and weighty coloring, em{33}broidery, and jewels, that apparently their angels must perforce descend to earth, and never hope to rise again without a change of toilet.

I shall presently speak of angels in their offices of messengers, guardians, choristers, and comforters. At present I am thinking of the multitudes of angels which were introduced into early religious pictures to indicate a “cloud of witnesses.” They lend an element of beauty and of spiritual emotion to the scenes honored with their presence. Their effectiveness has appealed to many Christian architects who have fully profited by the example of Solomon, who “carved all the walls of the house—temple—with carved figures of cherubim,” and he made the doors of olive-tree, and he carved on them figures of cherubim.

In the same manner, in many old churches, angels carved in marble, stone{34} or wood, and painted on glass, in frescoes on walls, and in smaller pictures, fill all spaces, and are everywhere beautiful. So long, however, as the stricter theological observances prevailed, angels were not permitted as mere decorations, but were so placed as to illustrate some solemn and significant portion of the belief and teaching of the Church.

Angels were only second to the persons of the Trinity at this period, and preceded the Evangelists. They were represented as surrounding divine beings, and the Virgin Enthroned, or in Glory.

What was known as a Liturgy of Angels was most effective and beautiful. It consisted of a procession of angels on each side of the choir, apparently approaching the altar, all wearing the stole and alba of a deacon, and bearing the implements of the mass. The statues of kneeling angels, not infrequently placed{35} on each side the altar, holding tapers, or the emblems of the Passion of Christ, were not mere decorations, but symbolized the angelic presence wherever Christ is worshipped. In short, either processions or single figures of angels, in any part of a church, and apparently approaching the altar, are symbols of the glorious hosts of heaven who evermore praise God.

During the first three centuries of Christianity the representation of angels was not permissible, and it is interesting to observe the crude and curious manner in which they were pictured in the illuminated manuscripts and the mosaics of the fifth century. Indeed, until the tenth century the angels in Art were curiously formed, and more curiously draped.

Giotto first approached the ideal representation of angels, and, naturally, his pupils excelled him in their conception{36} of what these celestial beings should be. It was, however, Angelico who first—and shall we not say last?—succeeded in portraying absolutely unearthly angels,—angels who must have appeared to him in his holy dreams, and impressed themselves on his pure spirit in such a wise that with mere paints and brushes he could picture a superhuman purity.

Not an angel of Angelico’s resembles any man, while in the angels of other masters, beautiful, seraphic, and charming as they may be, we often fancy that we see a beautiful boy, or a happy child, who might have served the artist as an angel-making model.

Wonderfully celestial as Angelico’s angels seem to be, they are feminine, almost without exception. In his time this criticism was held to be a serious one; but since angels are sexless,—according to the religious teaching on which this{37}

spiritually-minded monk relied,—I fail to see ground for disapprobation of his work.

The angels of Giotto and Benozzo Gozzoli, with all their beauty, are also feminine, while the great Michael Angelo, whose angels have not yet attained to wings, failed to represent such celestial beings as one would choose as personal attendants.

Leonardo’s angels almost grin; Correggio reproduced the lovely children who did duty as his angels; almost the same may be said of Titian; while in the pictures by Francesco Albani, Guido Reni, and the Caracci, the angels are simply attractive and even elegant boys, as may be seen in our illustration of the child Jesus with angels, by Albani. It is so difficult to distinguish the angels of some artists from their cupids, that one can only decide between them by learning{40} the titles of their pictures. These are characteristics of the works of these masters as a whole, with rare exceptions, rather than of single pictures.

To whom, then, may one look for satisfactory angels? For myself, I answer, to Raphael, and especially to his later works. His angels are sexless, spiritual, graceful, and, at the same time, the personification of intelligence and power, as may be seen in our illustration of the Archangel Michael. Witness also the three angels in the Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, in the Stanza della Signatura, in the Vatican. They are without wings, and none are needed to emphasize their godlike wrath against the thief who robbed the widow and orphan in the very temple of the Most High. The celestial warrior on his celestial steed,—believed to be St. Michael, in his office of Protector of the Hebrews,—the deadly{41} mace drawn back ready to strike the fallen robber, and his two rapidly gliding attendants, with streaming hair and swift, spirit-like movement, are such conceptions and personifications of superhuman power as can scarcely be paralleled in any other work of Art.

Rembrandt, too, painted wonderful angels. No adjective ordinarily applied to such pictures is suited to these. They are poetical, unearthly apparitions, and once studied, can no more be forgotten than can some of Dante’s and Shakepeare’s immortal lines.

Modern artists have, speaking generally, wisely followed the examples of old masters in their treatment of angels. The poet Blake, however, is a notable exception to this rule. He painted angels that surely “sing to heaven,” while they float upon the air which their diaphanous drapery scarcely displaces, and seem about{42} to vanish and become a portion of the ether which surrounds them.

I cannot better close this chapter than by quoting what Mr. Ruskin writes of the earlier and later representations of angels.

He says of the earlier pictures that there is “a certain confidence in the way in which angels trust to their wings, very characteristic of a period of bold and simple conception. Modern science has taught us that a wing cannot be anatomically joined to a shoulder; and, in proportion as painters approach more and more to the scientific, as distinguished from the contemplative state of mind, they put the wings of their angels on more timidly, and dwell with greater emphasis on the human form, with less upon the wings, until these last become a species of decorative appendage,—a mere sign of an angel.

“But in Giotto’s time an angel was a{43}

complete creature, as much believed in as a bird, and the way in which it would, or might, cast itself into the air, and lean hither and thither on its plumes, was as naturally apprehended as the manner of flight of a chough or a starling.

“Hence, Dante’s simple and most exquisite synonym for angel, ‘Bird of God;’ and hence, also, a variety and picturesqueness in the expression of the movements of the heavenly hierarchies by the earlier painters, ill-replaced by the powers of foreshortening and throwing naked limbs into fantastic positions, which appear in the cherubic groups of later times.{46}”

HE archangels alone have names, and being known to us by them, as well

as in connection with certain important events in heaven and on earth,

we involuntarily think of them with a more intimate and, at the same

time, a more reverent and sympathetic feeling than we can possibly have

for the numberless nameless angels of the heavenly choir.

HE archangels alone have names, and being known to us by them, as well

as in connection with certain important events in heaven and on earth,

we involuntarily think of them with a more intimate and, at the same

time, a more reverent and sympathetic feeling than we can possibly have

for the numberless nameless angels of the heavenly choir.

In works of Art, these last are always beautiful, always smiling, and ever ready to appear in greater or lesser numbers whenever any notable religious event is{47} taking place, thus apparently justifying those who believe that we are always surrounded by these celestial beings. They are a most decorative audience of witnesses, and when they are playing upon their musical instruments, or with open lips and upturned, rapturous eyes are singing praises to God, they contribute an enchanting element to the representation.

But the story of the archangels and their wonderful deeds, as told in Scripture and in the sacred legends, impresses us with a vivid sense of their marvellous power and wisdom, as well as of their tender sympathy for the human beings whom they protected and served in their office of guardians and defenders. The official duties that have been assigned them by the theologians have the effect of giving them a place, so to speak, in which we may think of them; and this{48} serves to make them more positively existent to our minds than other angels are. In comparison with such a personality as we must involuntarily give to St. Michael, the hovering, musical angels are so intangible, such veritable airy visions, that they elude all practical thought of them, and appear to be evolved upon occasion from the air into which they vanish.

Michael (like unto God) is the captain-general and leader of the heavenly host; the protector of the Hebrew nation, and the conqueror of the hosts of hell; the lord and guardian of souls, and the patron saint and prince of the Church militant. His attributes are the sceptre, the sword, and the scales.

Gabriel (God is my strength) is the guardian of the celestial treasury; a bearer of important messages; the angel of the Annunciation, and the preceptor of the{49} Patriarch Joseph. His symbol is the lily.

Raphael (the medicine of God) is the chief of guardian angels, and was the conductor of the young Tobias. He bears the staff and gourd of a pilgrim.

Uriel (the light of God) is regent of the sun, and was the teacher of Esdras. His symbols are a roll and book.

Chamuel (one who sees God) is believed by some to be the angel who wrestled with Jacob, and who appeared to Christ during the agony in the garden. Others believe the latter to have been Gabriel. Chamuel bears a cup and staff.

Jophiel (the beauty of God) is the guardian of the Tree of Knowledge, who drove Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden; the protector of seekers for truth; the preceptor of the sons of Noah; the enemy of those who pursue vain knowledge. His attribute is a flaming sword.{50}

Zadkiel (the righteousness of God) is sometimes said to have stayed the hand of Abraham from the sacrifice of Isaac, while others believe this to have been the work of Michael. The sacrificial knife is the symbol of Zadkiel.

When the archangels are represented merely as such, without reference to their distinctive offices, they are in complete armor, holding swords with the points upwards, and sometimes bearing trumpets also. They are of a twofold nature, since they are powers, as are the princedoms, and fulfil the duties of messengers and ministers, as do the angels.

Although each of the seven archangels has been many times represented in works of Art, I know of no example in which they are seen together, and can be distinguished by name. There are occasional instances of the representation of seven angels, blowing trumpets, which are in{51}tended to illustrate the text in Revelation, “And I saw the seven angels which stand before God, and to them were given seven trumpets.”

In pictures of the crucifixion, and of the Virgin with the body of her dead son,—known as the Pietà,—the instruments of the Passion are frequently borne by seven angels, and the same number appear in pictures of the last judgment. But as neither the Eastern or Western Church acknowledged the seven archangels, it is probable that these pictures represent the angels of Revelation.

A most interesting example of artistic symbolism is seen in a picture painted in 1352 by Taddeo Gaddi, and now in the Church of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence. Here seven angels attend on St. Thomas Aquinas, and bear the symbols of the distinguished virtues of this reverend and learned saint. The symbols{52} are a church—Religion; a crown and sceptre—Power; a book—Knowledge; a cross and shield—Faith; an olive branch—Peace; flames of fire—Piety and Charity; and a lily—Purity.

The Hebrews believed that Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel sustain the throne of God. The first three are reverenced as saints in the Catholic Church; and their divine achievements and celestial beauty have been a fruitful inspiration to painters and sculptors, resulting in the creation of many immortal works of art.

The Archangel Michael is reverenced as the first and mightiest of all created beings. He was worshipped by the Chaldeans, and the Gnostics taught that he was the leader of the seven angels who created the universe. After the Captivity the Hebrews regarded him as all that is implied by the Prophet Daniel when he{53}

says, “Michael, the great prince which standeth for the children of thy people.” It is believed that he will be privileged to exalt the banner of the Cross on the Judgment Day, and to command the trumpet of the archangel to sound; it is on account of these offices that he is called the “Bannerer of Heaven.”

As captain of the heavenly host, it devolved on Michael to conquer Lucifer and his followers, and to expel them from heaven after their refusal to worship the Son of Man; and terrible was the punishment he inflicted on them. Chained in mid-air, where they must remain until the Judgment Day, they behold all that happens on earth. Man, whom they disdained, has flourished in their sight, and wields a power that they may well envy, while the souls of the redeemed constantly ascend to the heaven which is closed to them. Thus are they constantly tor{56}mented by hate, and a desire for revenge, of which they must ever despair.

St. Michael is represented in art as young and severely beautiful. In the earliest pictures his drapery is always white and his wings of many colors, while his symbols, indicating that his conquests are made by spiritual force alone, are a lance terminating in a cross, or a sceptre. Later, it became the custom to represent him in a costume and with such emblems as indicated the nature of the work in which he was engaged; and except for the wings, his picture might often be mistaken for that of a celestially radiant knight, since he is clothed in armor, and bears a sword, shield, and lance. But his seraphic wings and his bearing mark him as a mighty spiritual power; and this impression is increased rather than lessened, when in all humility he is in the act of worship before the{57} Divine Infant, or stands in reverent attitude near the Madonna, as if to guard her and her heaven-sent son.

When conquering Satan the treatment is varied, but the subject is easily recognized. More frequently than otherwise, the archangel stands on the demon, who is half human and half dragon, wearing a suit of mail, and is about to pierce the evil spirit with a lance or bind him in chains.

Such pictures date from the earliest attempts in religious painting, and the same subject was represented in ancient sculpture. Some of these works are so crude as to be absurd, but for their manifest reverence and sincerity. An early sculpture in the porch of the Cathedral of Cortona, probably dating from the seventh century, presents the archangel in long, heavy robes, reaching to his feet; he stands solidly on the back of the dragon, and as if to make the footing more secure,{58} the beast curls his tail in air and lifts his head as high as possible, holding his mouth wide open, into which St. Michael presses his lance without a struggle. The whole effect is that of some calm and commonplace occurrence, and is in striking contrast with the spirit of the conflict which is represented, as well as with the superhuman combat depicted by later artists.

The dragon is personified by a variety of horrible reptilian forms. Some artists even attempted to follow the apocalyptic description. “For their power is in their mouth, and in their tails: for their tails were like unto serpents, and had heads, and with them they do hurt.”

Lucifer is not always alone, but is sometimes surrounded by demons, who crouch with him at the feet of St. Michael, before whom a company of angels kneel in adoration.{59}

During the sixteenth century the pictures of this archangel took on the military aspect, to which I have referred, and but for the wings would have represented St. George, or a Crusader of the Cross, as suitably as the great Warrior Angel.

An exquisite small picture of this type, now in the Academy at Florence, was painted by Fra Angelico. The lance and shield and the lambent flame above the brow are the only emblems; the latter symbolizing spiritual fervor. The rainbow-tinted wings are raised and fully spread, meeting above and behind the head; the armor is of a rich dark red and gold. The pose and the expression of the countenance indicate the reserved power and the godlike tranquillity of the celestial warrior, and fitly represent him as the patron of the Church Militant.

The representations of St. Michael conquering Lucifer are so numerous and so{60} interesting technically, that any adequate account of them and of their artistic and theological development would fill a volume, and might be considered rather tiresome. I shall speak especially of two examples which are very generally accepted as the most satisfactory of them all.

The first, painted by Raphael when at his best, is in the Louvre. It was a commission from Lorenzo dei Medici, who presented it to Francis I. The subject was doubtless chosen by Raphael as a compliment to the sovereign, who was the Grand Master of the Order of St. Michael, the military patron saint of France.

It was painted on wood, and sent with three other pictures, packed on mules, to Fontainebleau, where Lorenzo was visiting, in May, 1518. The picture was somewhat injured on the journey. In 1773 it was transferred to canvas, and “restored” three years later, but at the{61} beginning of this century the restorations were removed. We must believe that the picture has suffered from these chances and changes, but the fact remains that it is still a glorious work by a great master.

The beautiful young angel does not stand upon the fiend beneath him, but, poised in air, he lightly touches with his foot the shoulder of the demon in vulgar human form, fiery in color, having horns and a serpent’s tail. The expression of the angel is serious, calm, majestic, as he gazes down upon the writhing Satan, whose face, as he struggles to raise it, is full of malignant hate. This detail is lost in the black and white reproductions.

Michael grasps the lance with both hands, and so natural is the action, so easy and graceful, that the beholder instinctively waits to see the weapon do its work, while flames rise from the earth as if impatient to engulf the disgusting{62} demon. The head of the angel, with its light, floating hair is against the background of the brilliant wings, in which blue, gold, and purple are gloriously mingled; his armor is gold and silver; a sword hangs by his side, and an azure scarf floats from his shoulders. His legs are bare, and his feet shod with buskins, which leave the toes uncovered. The contrast between the exquisite, angelic flesh tints, rosy in hue, and the brown coloring of the demon, effectively emphasizes the beauty of purity and the loathsomeness of evil.

The St. Michael of Guido Reni so closely resembles that of Raphael in general treatment, that it is more nearly just to compare these works than is usually the case with pictures of the same subject by different masters. The attitude of Guido’s saint is like that of a dancing-master when contrasted with the pose of Raphael’s,{63}

and his demon is simply low and base, devoid of malignity or any supreme evil.

But the head and face of Guido’s Michael make his picture wonderful; they adequately express divine purity and beauty, while the studied and fictitious qualities of Guido’s art—here at their best—serve to enhance the exquisite effect of this angelic warrior, and the picture is justly esteemed as one of the treasures of the Cappucini at Rome.

Outside of Italian art, the St. Michael of Martin Schoen is well worth notice. The figure is fully draped in a long, flowing robe and mantle; the pose is most graceful, and the bearing of the angel dignified and unruffled. The demon is made up of fins, a savage mouth, and numerous claws with which to seize its victims; an entirely emblematic and most repulsive figure.

There are occasional pictures of the{66} “Fall of the Angels,” in which St. Michael contends against the entire company of rebellious spirits. These are illustrative of the text, “When Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon fought and his angels, and the great dragon was cast out.”

The painting of such a picture at Arezzo, about 1400, caused the death of Spinello d’Arezzo, whose mind so dwelt upon the demons he had painted that he went mad, and fancied that Lucifer appeared to him, and cursed him for having represented the fiend and his angels in so revolting a manner. The horror of the artist induced a fever of which he died.

The smaller of the two pictures of this subject by Rubens, in Munich, is esteemed a miracle of art. It displays the inventive power of the great Flemish master in a wonderful tour de force, for the rebel{67} angels are not fallen, but falling, and tumbling headlong out of heaven, down, down,—in such confusion and affright as only Rubens could portray.

In some cases Raphael and Gabriel are represented as witnesses of the combat between Michael and Lucifer. To my taste, these figures, with their abundant white draperies, detract from the simplicity and dignity of this impressive scene. Not only these archangels, but apostles and saints are sometimes introduced, in spite of the evident anachronism, as observers of this great spiritual struggle, while hosts of angels are above and around the picture.

In short, the representations of this subject, in one form and another, are almost numberless, and can scarcely be too many, when they are regarded as embodying the great truth of the spiritual triumph over evil.{68}

Mrs. Jameson says: “This is the secret of its perpetual repetition, and this the secret of the untired complacency with which we regard it ... and if to this primal moral significance be added all the charm of poetry, grace, animated movement, which human genius has lavished on this ever-blessed, ever-welcome symbol, then, as we look up at it, we are ‘not only touched, but wakened and inspired,’ and the whole delighted imagination glows with faith and hope, and grateful triumphant sympathy,—so, at least, I have felt, and I must believe that others have felt it, too.”

The representations of St. Michael as the Lord of Souls are less numerous than those of the subjects just mentioned, but are very interesting. In some votive pictures he appears as the protector of those who have struggled with evil, and gained a victory. In such pictures the angel{69} has his foot upon the dragon, or holds a dragon’s head in his hand, and bears the banner of victory.

Again, Michael is represented with his scales engaged in weighing the souls of the dead; in such pictures he is unarmed, and bears a sceptre ending in a cross. The souls are typified by little naked human figures; the accepted spirits usually kneel in the scales, with hands clasped as in prayer; the attitude of the rejected souls expresses horror and agony, which is sometimes emphasized by the figure of a demon, impatient for his prey, who reaches out his talons, or his devil’s fork, to seize the doomed spirits.

Leonardo da Vinci represented the angel as presenting the balance to the Infant Jesus, who has the air of blessing the pious soul in the upper scale. Signorelli, about 1500, painted a picture of this subject, which is in the church of San{70} Gregorio at Rome, in which the archangel, in a suit of mail, stands with his wings spread out, and the balance with full scales held above a fierce, open-mouthed dragon. The lance of the archangel has pierced through the under jaw of the beast and entered his body, making an ugly wound, and a hideous little demon, resting on his tiny black wings, is clutching the condemned spirits in the lower scale.

In pictures of the Assumption or Glorification of the Virgin, if St. Michael is present, it is in his office of Lord of Souls, as the legends of the Madonna teach that he received her spirit, and guarded it until it was again united with her sinless form.

As Lord of Souls it is taught that St. Michael conducted the spirits of the just to heaven, and even cared for their bodies in some instances. The legend of St.{71}

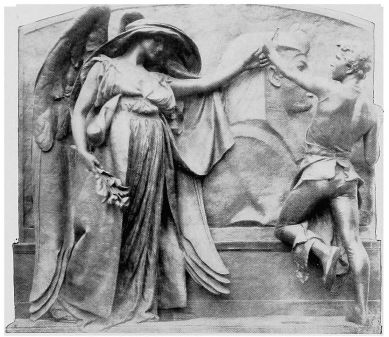

Catherine of Alexandria teaches that her body was borne by angels over the desert and sea to the top of Mount Sinai, where it was buried; and later a monastery was built over her sepulchre. In the picture of the “Translation of St. Catherine,” which we give, St. Michael is one of the four celestial bearers of the martyr saint.

In rare instances St. Michael was represented without wings. Such a figure standing on a dragon is a St. George, unless the balance is introduced. When the archangel stands upon the dragon with the balance in his hand, he appears in his double office as Conqueror of Satan and Lord of Souls. Memorial chapels and tombs were frequently decorated with this subject, a notable instance being that on the tomb of Henry VII., in Westminster Abbey.

In pictures of the Last Judgment, St.{74} Michael is sometimes seen in the very act of weighing souls, and, although I have nowhere found this explanation, it has seemed to me that the souls being thus weighed at the last hour should symbolize those of whom St. Paul said, “We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trump: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed.”

Since the Archangel Michael was made the guardian of the Hebrew nation, he was naturally an important actor in many scenes connected with their history. It was he who succored Hagar in the wilderness (Genesis xxi., 17), who appeared to restrain Abraham from the sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis xxii., 11). He brought the plagues on Egypt and led the Israelites on their journey. The Jews and early Chris{75}tians believed that God spake through the mouth of Michael in the Burning Bush, and by him sent the law to Moses on Mount Sinai. When Satan would have entered the body of Moses, in order to personate the prophet and deceive the Jews, it was Michael who contended with the Evil One, and buried the body in an unknown place, as is distinctly stated by Jude. Signorelli chose this as the subject of one of his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, and I have seen no other representation of it, although I believe that a few others exist.

It was Michael who put blessings instead of curses into Balaam’s mouth (Numbers xxii., 35), who was with Joshua in the plain of Jericho (Joshua v., 13), who appeared to Gideon (Judges vi., 2), and delivered the three faithful Jews from the fiery furnace (Daniel iii., 25). This last subject is one of the earliest in Christian{76} art, and was a symbol of the redemption of man by Jesus Christ. There are still other like offices which St. Michael filled as the protector of the Jews, while several important works are attributed to him in the Apochrypha and in the Legends of the Church.

For example, in the apochryphal story of Bel and the Dragon, it is related that when King Cyrus had thrown the prophet Daniel into the lions’ den, and he had been six days without food, the angel of the Lord appeared to the prophet Habakkuk in Jewry, when he had prepared a mess of potage for the reapers in his field, and the angel commanded Habakkuk to carry the potage to Babylon and give it to Daniel.

“Then Habakkuk said, ‘Lord, I never saw Babylon; neither do I know where the den is.’ Then the angel of the Lord took Habakkuk by the hair of his head, and set him in Babylon over the lions{77}’ den; and Habakkuk cried, saying, ‘O Daniel, Daniel, take the dinner which God hath sent thee,’—and the angel again set Habakkuk in his own place.”

At one period this subject was represented on sarcophagi; but I have only seen it in prints after the Flemish artist, Hemshirk.

In the legends of St. Michael we read that in the sixth century, when the plague was raging in Rome, and processions threaded the streets chanting the service since known as the Great Litanies, the Archangel Michael appeared, hovering over the city. He alighted on the summit of the Mausoleum of Hadrian and sheathed his sword, from which blood was dripping. From that hour the plague was stayed, and from that day the Mausoleum, which is surmounted by a statue of the Archangel, has been called the Castle of Sant’ Angelo.

The legends also give an account of two{78} appearances of St. Michael when he commanded the erection of churches; one at Monte Galgano, on the east coast of Italy, and the second at Avranches in Normandy. The first site was found to cover a wonderful stream of water, which cured many diseases, and made the church of Monte Galgano a much frequented place of pilgrimage.

The church in Normandy is on the celebrated Mont Saint Michael, and is famous in all Christian countries. From the time when the angel appeared to St. Aubert, the bishop, and commanded him to build the church, this saint was greatly venerated in France, and was made patron of France and of the order which St. Louis instituted in his honor.

The first church erected here was small, but Richard of Normandy and William the Conquerer raised a magnificent abbey, which overlooked the most{79}

picturesque scenery, and for this reason, if no other, remains a much frequented spot.

The old English coin called an angel was so named from the representation of St. Michael which was stamped upon it.

The pictures of St. Michael announcing to the Virgin Mary the time of her death, bear so strong a resemblance to those of the Annunciation, that it is necessary to remember that these have the symbols of a palm on a lighted taper in the hand of the angel, instead of the lily of the Archangel Gabriel, as is seen in our illustration of a beautiful picture in the Florentine Academy.

The legend relates that on a certain day the heart of Mary was filled with an inexpressible longing to see her Son, and she wept sorely, when lo! an angel clothed in light appeared before her, saluting her, and saying, “Hail, O Mary! blessed by{82} Him who hath given salvation to Israel! I bring thee here a branch of palm gathered in paradise; command that it be carried before thy bier in the day of thy death; for in three days thy soul shall leave thy body, and thou shalt enter into paradise where thy Son awaits thy coming.” Mary answering, said: “If I have found grace in thy sight tell me thy name, and grant that the Apostles may be reunited to me, that in their presence I may give up my soul to God. Also, I pray thee, that after death my soul may not be affrighted by any spirit of darkness, nor any evil angel be given power over me.” And the archangel replied: “My name is the Great and Wonderful. Doubt not that the Apostles shall be with thee to-day, for he who transported the prophet Habakkuk by the hair of his head to the lions’ den, can also bring hither the Apostles. Fear thou not the evil spirit, for{83} thou hast bruised his head, and destroyed his kingdom.” And the angel departed, and the palm branch shed light from every leaf and sparkled as the stars of heaven.

And the duty of the archangel was thus fulfilled until he should again appear as Lord of Souls to receive the spirit of the Virgin, to guard it until it should again inhabit her sinless body.{84}

HE Archangel Gabriel is mentioned by name but twice in the Old

Testament. First in Daniel viii., 16, when he explained the vision which

the prophet had seen, and again in Daniel ix., 21, when Gabriel appeared

to Daniel to give him skill and understanding.

HE Archangel Gabriel is mentioned by name but twice in the Old

Testament. First in Daniel viii., 16, when he explained the vision which

the prophet had seen, and again in Daniel ix., 21, when Gabriel appeared

to Daniel to give him skill and understanding.

Likewise in the New Testament he is twice mentioned, in Luke i., 19 and 26, when he announced to Zacharias the birth of John the Baptist, and to the Virgin Mary that she was favored of the Lord, and blessed among women. On each of these occasions he filled the office of a{85} messenger or bearer of important tidings. It is believed to have been Gabriel who fought with the Angel of the Kingdom of Persia for twenty-one days, when Michael came to his relief, and Gabriel again visited Daniel to strengthen him, and explain “that which is noted in the scripture of truth,” and to announce that the king of Græcia should overcome the king of Persia. After which Gabriel returned to his battle with the Angel of Persia.

The contest with the angel of Persia is a subject which offers unusual opportunities in its artistic representation; it is, however, much the same in spirit as the struggle between Michael and Lucifer, and the preference was given to the latter by the painters of religious subjects.

St. Gabriel has been many times portrayed as the messenger announcing the birth of John the Baptist and that of{86} Jesus Christ. In the apochryphal legends he also foretells the birth of Samson, and that of the Virgin Mary. From these frequently repeated messages which foretold important births, Gabriel naturally came to be regarded as the angel who presides over childbirth.

The great number of representations of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary make it difficult to select those of which to speak. The earliest pictures of this event portray it with great simplicity, purity, and grace. A spiritual mystery is being depicted, and is handled with sincere reverence and the utmost delicacy.

The scene is usually the portico of an ecclesiastical edifice. When seated, the Virgin is on a species of throne, but she is more frequently represented as standing. The archangel is at some distance from her, not infrequently quite outside the porch. He is majestic and beautiful;{87} is clothed in white, wearing the tunic and pallium, or archbishop’s mantle. His wings are large, and brilliant with many colors, and his abundant hair is bound with a jewelled tiara. He bears either the sceptre of power or a lily in one hand, while the other is extended in benediction. Sometimes he holds a scroll inscribed with the words, “Ave Maria, gratia plena,” Hail! Mary, full of grace, which words Dante represents Gabriel as constantly repeating in paradise.

The angel is the chief figure in this scene in the earlier pictures; he is joyfully triumphant, announcing the coming of the Saviour, while the Virgin is all humility and submission; in some cases her head is covered, an extreme expression of lowliness, and she is always self-effacing in attitude and expression.

An early custom in churches was to place the picture of the Virgin on one{88} side of the altar, and that of the angel on the other side; or, if both figures were in the same frame, a division was made by an architectural pillar, or a conventional ornament between them. In many cases the Virgin and the Archangel were placed separately above, or on each side of some scene from the life of Jesus, usually an altar piece. The picture by Fra Filippo Lippi, which we give, is a very fine example of the so-called “divided Annunciations.” It is in the Florentine Academy. This picture is very beautiful, and fittingly expresses the humility and surprise of the Virgin and the reverence of the heavenly messenger. It is also a good example of Fra Filippo’s style; his draperies were graceful, abundant, and usually much ornamented with designs in gold, of which we have here enough for elegance, while it is not overdone as in other works of this artist.{89}

A very ancient Annunciation, of peculiar and elaborate arrangement, dating from the fifth century, is in mosaic, over the arch in front of the choir in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, in Rome. The classical treatment of the dresses, and of the entire composition, makes this work so different from the usual conception of the subject as to be worthy of observation. There are two scenes: in the first, the archangel is sent on his mission, and is rapidly flying towards the earth, as if in haste to utter his joyous salutation, “Hail! thou art highly favored! Blessed art thou among women!”

The second scene presents Gabriel standing before the Virgin, who is seated on a throne, behind which are two guardian angels. This representation is so utterly unlike what is known as Christian art as to make a lasting impression, by{92} reason of its classical treatment; all the details have an air of belonging to an earlier period than that known as mediæval, and the figures might be those of ancient Greeks.

It is extremely curious and interesting to observe the various methods of representing the Archangel Gabriel in pictures of the Annunciation. At times he might be mistaken for the ambassador of a proud and powerful earthly potentate. He is clothed in gorgeous raiment, with a rich train, sometimes borne by one, and again by three page-like angels, while he carries himself with majestic haughtiness.

We do not wonder that the difference between the estate of an archangel sent by God, and the humility of the Virgin of Galilee, should have misled some artists; or that with them the angel held the first place, especially as it was only thus that any element of splendor could be intro{93}duced into their pictures. Indeed, we have engravings after a picture by Raphael, in which the Virgin is kneeling before the angel, who raises the right hand in benediction.

But the gradual increase in the veneration accorded to the Virgin, and the titles of Queen of Heaven, and Queen of Angels, which were bestowed on her, soon changed the spirit of the representations of the Annunciation; and while the Virgin loses none of her humility and submission, the angel bows, and even kneels to her, thus emphasizing his acknowledgment of her superior holiness,—since an archangel could only kneel before spiritual perfection.

It was well that the patriarchs and prophets should acknowledge the superiority of the angels sent to them,—but the glory of the Mother of Christ should be represented as commanding the rever{94}ence of even the highest of created being—only thus could the faith of the Church, for which these religious pictures were painted, be fittingly illustrated.

Thus it became customary to omit the sceptre in the hand of the angel, and to give him the lily alone, or the lily and the scroll. Indeed, there are notable pictures in which Gabriel has no symbol, but with hands clasped over his breast, and head inclined, he seems to worship the Virgin while declaring his mission to her. There are, however, few Annunciations in which the lily does not appear. It is the special symbol of the purity of Mary, to whom is applied the verse from the Song of Solomon: “I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys.” In some pictures the lily is seen in a vase near the Virgin.

Occasionally the symbol of peace is introduced in pictures of the Annunciation by placing a crown of olive on the head{95}

of the archangel, or an olive branch in his hand. Here Gabriel is presented as announcing the “Peace on earth and good will towards men,” which Raphael and his attendant angels chanted to the shepherds on the birth of Jesus.

The early German painters were fond of picturing Gabriel in priestly robes, heavily embroidered, and rich in color. This dress supplied the same gorgeous effect as was given by the princely trains of which I have spoken. In these pictures Gabriel usually kneels,—his ample robes falling on the pavement around him,—thus avoiding the proud bearing of the regally vestured messenger.

The simplicity of the scene, when Gabriel is appropriately draped in the filmy white robe,—which is the usual conception of an angel’s dress,—is far more satisfactory and harmonious with the spirit of the miraculous Annuncia{98}tion than any splendid vestments can possibly be.

The earliest pictures of the Annunciation, however, in spite of unsuitable costumes, and of certain technical imperfections, are more acceptable to the reverent mind than are those of a later time, in which the angel is scantily draped and is apparently conscious of his physical beauty, while the Virgin is entirely wanting in grace or dignity. Such a rendering of this scene is most offensive; all the more so that these pictures are frequently well executed, and were they not presented as representations of this sacred subject, but given some appropriate title, they would have claims to a certain artistic approbation.

Other artists, like Allori, in our illustration, represent an all too conscious Virgin, an angel who apparently poses for a picture, and a mass of utterly{99} inappropriate detail. This Annunciation, which is in the Florentine Academy, affords an excellent example of this objectionable style, and its faults are emphasized when it is compared with the serious dignity of Fra Filippo’s picture and that which follows, by Fra Angelico. By such comparisons the great difference between true sentiment and affectation in Art becomes apparent.

There are some Annunciations in which the Virgin is represented as starting up from fear or surprise, quite as one might fancy that a tragedy queen would do, were her privacy unceremoniously disturbed.

Again the Virgin Mary is fainting from emotion, and thus could not have replied to the angel in the Scriptural words, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.”

Not infrequently, in representations of this scene, the Holy Spirit, as a dove,{100} hovers above or near the Virgin, or flies in through a window; again the Almighty is seen in the clouds, surrounded by a celestial light, and sometimes attended by celestial spirits. In rare instances the Eternal Father sends the Infant Jesus down from the sky bearing a cross, and preceded by a dove. These extremely symbolic Annunciations are usually of an early date.

Fra Angelico painted the Annunciation with intense reverence and simplicity. We have an illustration of his fresco on the wall of the corridor in his convent of San Marco, in Florence, which is, to my mind, one of the most beautiful and spiritual Annunciations in existence. It tells the sacred story faithfully; there is nothing introduced that does not essentially belong here. The Virgin gives the impression of being equal to the angel in purity and goodness; he is superior only in knowledge.{101}

Angelico believed that he was divinely directed in his work, which he began with prayer, and for this reason he would never change his original design. His care in the finish of his pictures was phenomenal; his draperies were dignified; his color and composition were harmonious. It has well been said of his works: “Every part contributed to that unity of tenderness, inspiration, and religious feeling which marks his pictures, and which are such as no one man had ever succeeded in accomplishing.” Angelico knew nothing of human anxieties and struggles, and could not paint them; he could not depict the hatred of the enemies of Christ; martyrdoms and persecutions were feebly represented by him, but to annunciations, coronations of the Virgin, and kindred subjects he imparted a sweetness and a spiritual fervor that has rarely, if ever, been surpassed. We can imagine him rising{104} from his prayers with his conceptions of the Virgin and the archangel as distinct in his mind’s eye as they are to our vision in his pictures, and it is easy to understand that the man who lived in his atmosphere would be void of ambition, and refuse to be made Archbishop of Florence, as he did.

Gabriel is reverenced by the Jews as the chief of the angelic guards, and the keeper of the celestial treasury. The Mohammedans regard him as their patron saint; their prophet believed this archangel to be his inspiring and instructing spirit. Thus he is important in the faith and legends of Christians, Jews, and Mohammedans alike. Milton may have had the Jewish tradition in mind when he represented Gabriel as the guardian of paradise:

HE Archangel Raphael is esteemed as the guardian angel of the human

race. He especially protects the young and innocent, and guards pilgrims

and travellers from harm. It was he who warned Adam of the danger of

sin, and declared to him its dread consequences. Milton thus interprets

the message:

HE Archangel Raphael is esteemed as the guardian angel of the human

race. He especially protects the young and innocent, and guards pilgrims

and travellers from harm. It was he who warned Adam of the danger of

sin, and declared to him its dread consequences. Milton thus interprets

the message:

That Raphael’s language was benevolent and sympathetic, as imagined by the poet, appears in Adam’s farewell to the angel:

Representations of St. Raphael are far less numerous than are those of St. Michael and St. Gabriel. They are always pleasing, and present him as a benign, sympathetic, and companionable friend to those whom he serves. His symbol is habitually a pilgrim’s staff; as a guardian he wears a sword, and has a small casket or vase, containing the{107} “fishy charm” against evil spirits. He wears a pilgrim’s dress, has sandals on his feet, and a pilgrim bottle or wallet hangs from his belt. His flowing hair is bound by a diadem, and his beautiful face expresses the benevolence of his character and mission.

Many chapels and some churches are dedicated to the Archangel Raphael, as the chief of celestial guardians, and in these are numerous pictures commemorating his benevolent deeds. The greater part of the representations of this archangel are so connected with the history of Tobias, that it is necessary to know his story, in order to enjoy or understand these pictures. I will give this beautiful Hebrew narrative as concisely as possible:

Tobit was a rich man, and just; and he and his wife, Sara, were carried into captivity by the Assyrians. He gave alms to all his people, lived justly, and{108} ate not the bread of the Gentiles. His misfortunes, however, increased; he had but his wife and his son, Tobias, left to him, when he became blind, and prayed for death.

At the same time a man named Raguel, who dwelt in Ecbatane, was afflicted with a daughter who was persecuted by an evil spirit. She had married seven husbands, and each one had been killed by the fiend, as soon as he entered the bridal chamber. The maiden was accused of these murders, and, like Tobit, she prayed for death.

God then sent the Archangel Raphael to cure the blindness of Tobit, and take away the reproach of the unhappy daughter of Raguel of Ecbatane.

At this time Tobit desired his son, Tobias, to go to Gabael in Media to receive ten talents, which Tobit had left in trust with Gabael. Tobias asked,{109} “How can I receive the money, seeing I know him not?” Tobit gave Tobias the handwriting, and bade him seek a guide for his journey. Raphael then offered to guide the young man, who knew not that he spoke with an archangel. Tobias led Raphael to his father, and they agreed upon the wages the guide should receive, and Tobit gave directions concerning the journey, while he and Sara, his wife, were greatly afflicted at parting with Tobias.

At evening the travellers came to the river Tigris, and when Tobias went to bathe, a fish leapt out at him. Raphael told the youth to take out the liver and gall of the fish and preserve it carefully, which being done, they roasted the fish and ate it. When Tobias asked why he should keep the liver and the gall, the angel told him that the heart and liver would cure a person vexed with an evil{110} spirit, if a smoke from them was made before the person; and the gall would cure the blindness of one afflicted with whiteness of the eyes.

In our illustration from the picture by Andrea del Sarto, in the Belvedere, Vienna, Tobias carries the fish, and it appears to represent the moment when Raphael is making his explanation of its purpose.

As they proceeded Raphael said: “Brother, to-day we shall lodge with Raguel, who is thy cousin; he hath but one daughter, named Sara; I will ask her as a wife for thee: she belongs to thee by law, and is fair and wise, and you can marry her when we return.” Then Tobias, who knew the fate of the seven husbands, was filled with fear lest he too should die, and thus afflict his parents, who had no other child.

But Raphael assured Tobias that Sara{111}

was the wife that the Lord intended for him, and that when he entered the marriage chamber the evil spirit would flee at the smoke he should make with the liver of the fish, and would never return. When Tobias heard this he loved the maiden, and his heart was effectually joined to her.

When they came near Ecbatane, they met Sara, and she led them to her parents, who rejoiced to see them, and wept when they heard of the blindness of Tobit. While the servants of Raguel prepared a supper, Tobias said to the angel, “Speak of those things of which thou didst talk, and let this business be despatched.” Then Raphael asked Raguel to give Sara to Tobias; but the father was sore distressed, and told of the death of the seven who had already married her; but as Sara belonged to Tobias by the law of Moses, his request could not{114} be denied, and before they did eat together, Raguel joined their hands, and blessed them.

Then the marriage chamber was prepared, and the maiden wept; but her mother comforted her, and when Tobias entered and made the smoke as the angel had directed, the evil spirit fled. Tobias and Sara knelt in thankfulness, and Tobias prayed as Raphael had told him, and Sara said, “Amen.”

In the morning Raguel dug a grave, for he wished to bury Tobias quickly, that no one should know what had happened; but when he sent to see if he were dead, it was found that the young husband was quietly sleeping. Then there was great rejoicing, and a wedding feast was made, which lasted fourteen days. Meanwhile, Raphael went to Gabael and received from him the ten talents, and when the feast ended, the angel{115} conducted Tobias and Sara to Tobit, and Raguel bestowed on Sara half his wealth.

As they approached Nineveh, Raphael said to Tobias, “Let us haste before thy wife, to prepare the house: and take thou the gall of the fish.” The mother of Tobias was watching for his return, and was greatly alarmed at his long absence. When she saw him with his guide, and the little dog which he had taken away, she ran to Tobit with the news, and they rejoiced greatly. Raphael now said to Tobias, “I know that thy father will open his eyes; therefore anoint them with the gall, and being pricked therewith, he shall rub them, and the whiteness shall fall away, and he shall see thee.” And so it was, and Tobit was blind no more, and they all rejoiced and blessed God.

Then Tobias recounted all that had happened, and his parents went out with him to meet his wife, and her servants,{116} and cattle, and all she had brought with her. And the people were filled with wonder to see that Tobit was blind no more, and they rejoiced greatly with him during seven days when he kept a feast.

Tobit bade his son to call his guide and give him more than the wages that had been named. And Tobias wished to give the angel half of all he had brought back with him, and Tobit said, “It is due unto him.” But when Raphael knew their intentions he commanded them to glorify God for all his goodness, and told Tobit that his goodness and sorrows and those of the daughter of Raguel had been known in heaven, and God had sent him to heal all these troubles; and added, “I am Raphael, one of the seven holy angels, which present the prayers of the saints, and go in and out before the glory of the Holy One.”

Our illustration after the picture of{117}

Giovanni Biliverti in the Pitti Gallery, Florence, places before us the scene, when, refusing reward, the Archangel declared himself. The beauty of the angel, the affectionate enthusiasm of Tobias, and the sincere and reverent gratitude of the old Tobit are wonderfully portrayed, while the young wife and the aged mother in the background complete the group of those who have been delivered from their sorrows by the messenger of the Most High.

From the time when the angel left them Tobit and Raguel prospered, and after Tobit and Sara died, Tobias removed to Ecbatane and inherited the wealth of Raguel; he lived with honor to be an hundred and seven and twenty years old, and to hear of the destruction of Nineveh.

Milton thus refers to the story of Tobias:{120}

Raphael is frequently represented without wings when leading Tobias, who—in order to emphasize the contrast between an angel and a mortal—is made very small, and is thus manifestly out of keeping with the story. When the wings appear there is no reason for dwarfing Tobias, and the picture is far more satisfactory. It is not difficult to discern that if the story of Tobias is considered as an allegory, the young man personates the Christian, guided and guarded through life by God’s mercy.

There is, in Verona, in the Church of St. Euphemia, a most impressive chapel which was decorated with pictures illustrating the story of Tobias, by Carotto, a pupil of Mantegna, who seems to have{121} painted more in the manner of Leonardo than in that of his master.

Various incidents of the story are effectively pictured, but the famous altar-piece, the greatest work by Carotto, is the most important of the number. It represents the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael,—three exquisite wingless figures,—the latter being in the centre, and the only one having an aureole. He is leading Tobias, and looking down at the youth with an expression of tenderness.

St. Michael is on the right; one hand rests on his great sword, while with the other he lifts his crimson robe. His countenance, serious and indomitable in expression, fitly indicates the characteristics that his titles imply. He is the Lord of Souls and the Angel of Judgment, so far as human imagination can picture so exalted a celestial being.{122}

St. Gabriel, on the left, holding a lily, and gazing heavenward in adoration, is a beautiful, angelic figure, far less powerful than the other archangels, and quite in harmony with his office.

The impression on my mind, made by this picture, is that Gabriel realizes that his blessed office has been fulfilled, his active work is done, and adoration is now his duty and his joy; but Michael and Raphael have still their great missions to perfect; they are still battling against evil, and guiding men in the paths of righteousness.

Carotto was a native of Verona, and his pictures are rarely seen elsewhere. His color is warm and well blended, while his drawing is severe. It is said that he was but twenty-five years old when he decorated the Chapel of St. Raphael, in 1495. He was of a quick wit, and when told that the legs of his angels were{123}

too slender, he instantly replied, “Then they will fly the easier.”

A very famous and wonderful picture of the three archangels with Tobias, by Botticelli, is in the Academy of Florence. The angels of this artist are frequently criticised for a certain stiffness, but their beautiful faces more than redeem any fault in their figures, and have a sweetness and depth of expression that appeals to the heart and makes one forget less important details.

A picture of St. Raphael leading Tobias, in the Church of St. Marziale in Venice, is said to be the earliest remaining work by Titian. For this reason it is most interesting, but it is certainly not so beautiful as that of Carotto, nor as that of Raphael, called the Madonna del Pesce,—the Madonna of the Fish,—in the Madrid Gallery, in which the master pictures the archangel whose name he bore.{126}

Of this last picture Passavant says, “Here Christian poetry has found its highest expression; for it is poetry which touches all nations the most deeply, and beauty alone can give an idea of divinity.”

In the famous Madonna del Pesce, the Virgin is seated on a throne with the child; the young Tobias, holding a fish in his hand, and led by the Archangel Raphael, comes to implore Jesus to cure his father’s blindness. The Infant Saviour looks at Tobias, while his hand is on an open book which St. Jerome holds before him; the symbolic lion crouches at the feet of the saint. The background of the picture is principally formed by a curtain, but on the right a small opening of sky is seen.

The whole picture is executed in the best style of the artist’s mature power, while it is full of the fervent piety of his{127} earlier works. The Virgin is the ideal of purity and loveliness; the child is radiant with divine beauty; the angel is celestial in his bearing and his countenance, while the head of the reverend saint is grand and noble in expression.

Raphael’s Madonnas sometimes seem to be but simple domestic women, gifted with beauty; in them no trace of a mystical or spiritual nature appears; but the Madonna del Pesce, like the Madonna di San Sisto, and the Madonna di Fuligno, justifies the eulogy of Vasari, when he says, “Raphael has shown all the beauty which can be imagined in the expression of a Virgin; in the eyes there is modesty, on the brow there shines honor, the nose is of a very graceful character, the mouth betokens sweetness and excellence.” The color of the Madonna del Pesce is admirably clear and harmonious, even for this great master.{128}

This Madonna was originally painted for the Church of San Domenico Maggiore, at Naples, in which church a chapel had been erected as an especial place of worship for the numerous Neapolitans who suffer from diseases of the eye; it was not, however, permitted to serve its intended purpose, and has had an interesting history.

It is said that the Duke of Medina, when Viceroy of Naples, took the picture from the Dominicans without the consent of the government, and when the prior complained to the Pope, Medina had him escorted to the frontier by fifty horsemen, and expelled from the kingdom. In 1644 the Duke took the Virgin with the Fish to Spain, and Philip IV. placed it in the Escurial. In 1813, when the French were compelled to leave Spain, they took this picture, with many others, to Paris.{129}

It was painted on a panel and was in bad condition, and Bonnemaison was commissioned to transfer it to canvas. This work was not completed in 1815, when other pictures which had been taken from Spain were returned, and this Madonna remained in France until 1822. Naturally, it must have lost something of its original excellence, but it still holds a place of honor in the wonderful Italian Gallery of the Madrid Museum; it is a rival of the famous Dresden Madonna—di San Sisto—in the regard of many connoisseurs in art.

The various scenes from the story of Raphael and Tobias have been represented in the works of artists of all nations. Rembrandt four times painted the parting of Tobias from his father and mother, and several other incidents in the story. His picture in the Louvre, of the departure of the Archangel, is{130} remarkable for its spirited action. As the angel ascends, flying through the air, he seems to part the clouds as a strong swimmer passes through the breakers of the sea.

There have been many curious conceits introduced into some of the early religious pictures, and I have seen two instances in which little seraphim and angels are perched on trees, near the Virgin and Holy Child. The idea seems to be that these “Birds of God”—as Dante calls the angels—are making music and singing for the Divine Infant, some of them also praying for his solace.

Occasionally a series of pictures called the Acts of the Holy Angels has been painted. It consists of eleven strictly Scriptural subjects, usually as follows, but varied in some instances by the introduction of other motives of the same{131} character, as, for example, the angel appearing to Hagar and to Elijah:

| I. | The Fall of Lucifer. |

| II. | The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. |

| III. | The Visit of Three Angels to Abraham. |

| IV. | The Angel Preventing the Sacrifice of Isaac. |

| V. | The Angel Wrestling with Jacob. |

| VI. | Jacob’s Dream. |

| VII. | The Deliverance of the Three Children from the Fiery Furnace. |

| VIII. | The Angel Slays the Host of Sennacherib. |

| IX. | The Angel Protects Tobias. |

| X. | The Punishment of Heliodorus. |

| XI | . The Annunciation to the Virgin. |

I have already said that of the seven archangels to whom Milton refers, when he says:

but three are recognized by the Christian Church; and when three archangels are{132} seen together, they are Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. In the Greek Church this representation is regarded as typical of the military, civil, and religious power, and, accordingly, the costumes indicate a soldier, a prince, and a priest.

But Uriel has not been entirely ignored, even by the Christian Church, and an early tradition teaches that this archangel, and not Christ, accompanied the two disciples on their way to Emmaus. In the book of Esdras we read, “The angel that was sent unto me, whose name was Uriel.” His office was that of interpreter of judgments and prophecies, which Milton recognizes thus:

In several ancient churches four archangels are represented in the architectural{133} decoration. An example in which they are very splendid is that in the mosaics above the choir arch in the Cathedral of Monreale, Palermo. These colossal, armed figures are impressive, not only from their size, but also because of their apparent realization of their illustrious rank in the order of created beings.