Title: History of the Ordinance of 1787 and the Old Northwest Territory

Editor: Harlow Lindley

Contributor: George Jordan Blazier

Federal Writers' Project

Editor: Milo Milton Quaife

Norris F. Schneider

Other: Northwest Territory Celebration Commission

Release date: April 23, 2020 [eBook #61909]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Sogard and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

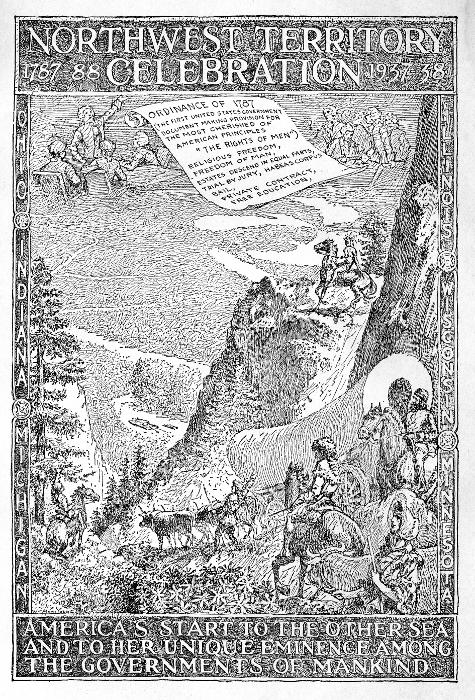

THIS CARTOGRAPHIC MAP OF NORTHWEST TERRITORY

WITH THE ORDINANCE OF 1787 ON THE MAP BACK

In full color, this attractive pictorial map 18″×24″, shows how the United States came into possession of the territory and how the states developed from it—more history in easily understandable form than is usual in a book.

Under the celebration plan, the supplying of these maps to school students in a state is a function of the State Commissions for Northwest Territory Celebration. Where the state commissions do not provide these maps, they may be procured from the Federal Northwest Territory Celebration Commission, Marietta, Ohio, at the following prices:

25 maps—50 cents postpaid 100 maps—$1.50 postpaid

(A Supplemental Text for School Use)

Prepared for the

NORTHWEST TERRITORY CELEBRATION COMMISSION

under the Direction of a Committee Representing the States

of the Northwest Territory:

Harlow Lindley, Chairman

Norris F. Schneider

and

Milo M. Quaife

The Federal Writers’ Project Cooperating

Northwest Territory Celebration Commission

Marietta, Ohio

1937

PRINTED IN U. S. A.—1937

This book is distributed free to the school and college teachers of Northwest Territory through the state departments of education of the various states. It is offered to all others, along with an 18″×24″ cartographic map of Northwest Territory in full color and art copy of Ordinance of 1787, at ten cents per copy, postpaid (coin, no stamps) by

NORTHWEST TERRITORY CELEBRATION COMMISSION

Marietta, Ohio

HOW TO MAKE A BEAUTIFUL HOME DECORATION OF THE CARTOGRAPHIC MAP OF NORTHWEST TERRITORY

The pictorial maps available are very popular for home decoration, especially when “antiqued.” Splendid wall pieces, lamp shades, wastebasket covers, etc., can be made from them. Similar pieces in the art stores sell at $1.00 to $5.00.

INSTRUCTIONS FOR ANTIQUING

Stretch the map flat, using thumbtacks at its corners. With a soft brush apply two coats of orange shellac. Let each dry thoroughly. Other antique effects can be secured by the use of umber, burnt sienna, Vandyke brown, etc., ground in oil and thinned with turpentine. To mount the map on wallboard or other background, apply flour paste to back; let the paper stretch thoroughly; apply carefully and rub out all wrinkles.

| PAGE | |||

| Introduction | 6 | ||

| Foreword | 7 | ||

| Chapter | I— | Pre-Ordinance Summary | 9 |

| Chapter | II— | History of the Ordinance of 1787 | 16 |

| Chapter | III— | The First Settlement of the Northwest Territory under the Ordinance of 1787 | 30 |

| Chapter | IV— | The Beginnings of Government | 45 |

| Chapter | V— | Growth of Settlements | 50 |

| Chapter | VI— | Evolution of the Northwest Territory | 66 |

| Chapter | VII— | Significance of the Ordinance of 1787 | 75 |

| Bibliography | 85 | ||

| School Contests | 91 | ||

The Northwest Territory Celebration Commission, created by Congress to design and execute plans for commemorating the passage of the Ordinance of 1787 and the establishment of the Northwest Territory, takes pleasure in presenting this brief outline of the history involved, to the public, and particularly to the schools, whose students of today will be our citizens almost before we realize it.

Through the study of the thinking and the deeds of ordinary American people during the formative—usually called “critical”—period of our nation’s history, even though not so exciting or colorful as were battles and heroes, we may find some understanding of how this nation attained greatness, and provide inspiration to our own and future generations.

Through the years vast amounts of material and substantiating evidence have come to light, and as historians have been able to view this formative period in perspective, it has assumed an ever-increasing importance in the foundation upon which our civilization rests.

As yet, that accumulating recognition is largely scattered through a vast number of specialized studies and books, as various authorities have unearthed important and vital related facts.

And so this commission has asked the state historians of the states of the Northwest Territory, with Dr. Harlow Lindley as chairman, and with such acceptable assistance as they might secure, to digest the available material into this brief but coordinated summary.

It is impracticable and unnecessary, for the purposes of this book, to go into further original research. There is ample accurate material now available for these pages, the prime purpose of which is to give a fundamental knowledge to all whom it may reach, and to inspire a further study by those so inclined, to the end that America may know why America is, and what it really rests upon, and what may be our surest and soundest path for progress to the continued betterment of mankind through government.

Northwest Territory Celebration Commission,

George White, Chairman

E. M. Hawes, Executive Director

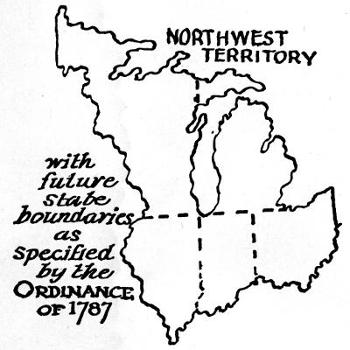

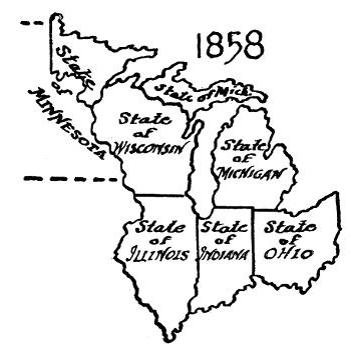

This brief elementary textbook presenting the history of the Ordinance of 1787 and the establishment of civil government in the old Northwest Territory out of which was created later the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota, has been prepared at the suggestion of the Northwest Territory Celebration Commission for supplementary study in the schools.

Under the instructions of the commission, and according to our own concepts of the purposes of this book, it has seemed impossible to attempt original research or study into less substantiated phases of the history covered. Rather, it has been our purpose to digest in correlated form, and briefly, the fund of material which already has been developed by countless individual studies and writings.

This available material, although now generous in amount and amply authenticated, requires some explanation. It is to be remembered that the people of our early westward movement and, to a great extent, of all our early history, were makers of history, rather than writers of it. There were settled communities of individuals who summarized the more humble events of life, even though these events might be more substantial and indicative than colorful armies and battles.

Resultantly, research into this history of necessity has been largely confined to the casual and incidental records of the time—letters, diaries, the meager public records and scarce newspapers and publications. This has so far resulted in many specialized studies which are available. The need now is that these be brought together into a correlated record of an epoch, which will fit itself into the fabric of our national history.

Hence this book.

Attention is called to the bibliography, which is included as an aid to further study. Even this list of published material is necessarily abridged from the more complete bibliography which is available.

Some repetition is experienced in the text, as is likely with subjects involving many ramifications and treated by different writers.

Those immediately in charge of this work have consulted with representatives of various historical agencies and a number of prominent educators in each of the states concerned.

Harlow Lindley, secretary, editor and librarian of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, as chairman of the committee appointed by the commission, has been responsible for collecting and organizing the material. The executive director of the Northwest Territory Celebration Commission prepared Chapter I and the latter part of Chapter V. Mr. Norris F. Schneider of the Zanesville (Ohio) High School, has written Chapter III. Dr. Milo M. Quaife, secretary and editor of the Burton Historical Collection in the Detroit Public Library, not only has represented the state of Michigan in making the plans for the book, but also has contributed Chapter VII.

One unique feature of the project is the fact that most of the illustrations are the work of students in the schools of the states which evolved from the old Northwest Territory. These were made possible as a result of an illustration contest sponsored by the commission.

The readers of this book are referred to the pictorial map of the Northwest Territory issued by the Northwest Territory Celebration Commission to which reference is made on page 4. This map tells the story of the evolution of the old Northwest Territory and also contains a copy of the Ordinance of 1787.

Harlow Lindley, Chairman.

Columbus, Ohio

July 1, 1937

While much of the history of the American colonies has been ably presented in other school history texts, and it is not the province of this book to rehearse it, there is reason for a brief summary which will place in the mind of the reader the background for the events of which this book treats.

It is not easy to value or even to understand the forces which were at work in America unless we consider what types of people were involved. While most of the colonies were settled by Englishmen, this did not mean that they were always congenial. The Puritans of New England, radical in their beliefs and zealous in their doctrines, had little in common, even while they were in England, with their fellow countrymen who settled Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. In between these discordant groups were the Dutch of New York, the Swedes of Delaware, the Catholics of Maryland, and the Quakers and Germans of Pennsylvania.

Beyond these national and social differences were the trends brought about by their environments in this new land. The rocky and discouraging soils of the northern colonies, even the climate itself, tended to widen the gulf between these people and the pleasure-loving folk of the South, with its broad fertile acres and mild climate. It was inevitable that the New Englanders should turn to manufacture and trade, while the South should remain agrarian, and equally inevitable that this should result in jealousy and rivalry.

But a still more vital force was at work to encourage distrust and dislike. People of that day took their religious beliefs very seriously. Even those who fled from a state church could not escape the idea of state and religion being inexorably related.

Although the Puritans of Massachusetts had fled England to gain “religious freedom,” they might better have said to gain freedom for their own sort of religion, for they were as intolerant of other religious beliefs as had been the Church of England of theirs. Indeed, Connecticut and Rhode Island were split off from the Massachusetts colony because of religious disputes. The southern colonies, still clinging to the state church of the mother country, were anathema to New England and New England to them. With the Quakers in Pennsylvania, and the Catholics in Maryland—and all zealous for their own religious contentions—the tendency[10] was even further from, rather than toward, the building of a common nation.

And so, with diverse nationalities, religious and economic and moral distinctions; with widely varying charters from the king and jealousies between rival groups of European “owners,” we may well wonder that the colonies got along together at all.

For a century and a half the population increased, and with it the discordant feeling between at least many of the colonies. They had only one thing in common—an increasing distrust of and rebellious spirit toward the mother country and the king. This could result in the joining of forces against a common and more powerful enemy. And so it did finally. But in all this there had been no proposal for a new nation, or, more particularly, for a new theory and plan of government. True enough, there had been a convention called at Albany in 1754 for united effort against the Indians, but the colonies were not strongly in favor of it, and the king would not tolerate the union.

As lands along the coast became more occupied and therefore higher priced, and the political uncertainties more acute, the more adventurous colonists, perhaps irked by the restraint of individual freedom which any government imposes, struck out for the wilderness westward.

MARQUETTE

Drawn by Howard Petrey, Superior, Wisconsin

Also, because we are trying here to study what was in the minds of men, why they did this or that, it must be remembered that the world was still looking for the Northwest Passage to Cathay. As late as the outbreak of the Revolution, and even later, England was subsidizing efforts to locate this short route to the fabled East. Thus the same urge which had led Columbus to the discovery of America played a part in the development of colonial plans.

From the seventeenth century onward, French missionaries and fur traders had extended their explorations and their scattered posts, effecting[11] alliances with the Indians, and inciting violent resistance to English and colonial approach. As late as 1749 Celoron led a considerable expedition down the Ohio River, up the Great Miami and to the Lakes, tacking notices on trees and planting leaden plates claiming possession in the name of the king of France. This had an ominous meaning, in that the French had done almost nothing in settling Ohio, whereas it was in this very direction that English settlement pressed.

During this period, which culminated in the French and Indian War, the colonies did not cooperate, although, as has already been said, the need for united effort was first publicly urged at the Albany convention. After the French and Indian war was over, and the title to the Northwest had been ceded to England, she herself became suspicious of westward American settlement, and forbade it, even to the extent of giving to the province of Quebec the lands she had previously given to the American colonies.

The rugged and fearless individualists who were most likely to settle the West were the least inclined to conform to stabilized government, especially if that government were objectionable in any of its phases. And, removed beyond the Alleghany Mountains, they would be beyond hope of subjection. Those who had already migrated to the West asked nothing from the colonies except help in defense against the Indians—and of this received very little. They were free men—perhaps the freest of any considerable group of individuals in ages of history. Ahead of them lay a wide continent, blessed with God’s bounties, and, as law and restraint caught up with them, all that was necessary was to move farther westward to seemingly endless lands and natural resources—and freedom.

ROBERT CAVALIER DE LA SALLE

Drawn by Marie Kellogg, Superior, Wisconsin

In 1776 Virginia, in the fervor of her revolt, did give indication of the trend of her people’s feelings through her “Bill of Rights,” and this undoubtedly expressed the long restrained but culminating American idea. When revolt mounted to the utterance of the Declaration of Independence, that great document set forth in fervid terms the general principles of the rights of man. But there was nothing discernible in it as to what specific form or type of government should make those principles effective.

The Articles of Confederation, which immediately followed, were but the forced cooperation of the colonies for defensive purposes.

The soldiers, realizing fully that they probably never would be paid in sound money, with their own meager fortunes ruined by their years of struggle, and disgusted with the politics, the compromises, and ineffectiveness of the Continental Congress, turned to the idea of western lands. At least, their almost worthless pay certificates could be used in buying land from the government which had issued such money. In these far-off wildernesses they would find the freedom they craved and escape from the seeming ineffectiveness of government under the Articles of Confederation.

Congress had actually voted at the very beginning of the war, and long before the nation owned a square foot of these lands, to give western lands as bounties for military service. The separate colonies, especially Virginia, had given such bounties for service in the earlier wars against Indians and French. Washington had made a trip to the Ohio country in 1770 to select such bounty lands, and had been so impressed that he chose some 40,000 acres of his own. As hero of the troops, and the greatest single factor in preventing their mutinies, it seems certain that his enthusiasm for these lands heightened that of the soldiers.

Washington, too, saw that a western frontier peopled by veterans whose earnestness of purpose and abilities could not be questioned, would form the safest bulwark against attack by the Indians, or by the British—who if they gave up title at all, would do so unwillingly and with tongues in their cheeks. But, as yet, there was no determination, or even clearly defined suggestion as to the form of government which would apply to the United States. The Articles of Confederation were unwieldy, undependable, and, if anything, were working against the idea of representative government.

In 1783, while the troops were in camp awaiting the signing of the Treaty of Paris, and on the verge of being discharged to go to—they knew not what—with no money, and with the rebuilding of their worlds yet before them, they expressed in writing their hopes and aspirations for their own and America’s future.

This humble document, recorded by Timothy Pickering as scribe, and signed by 283 leaders of the men, set forth not only their desire for lands in the West, but for certain principles of government as fundamental to their hopes, ambitions and plans. This plan became known to history variously as the Pickering Plan, the Newburgh Petition, and the Army Plan.

Essentially, it was the innermost determination of ordinary Americans who had proved their sincerity of purpose. It was probably the first crystallized expression from the men who had fought to establish the new[13] nation as to what its tenets of government should be. A study of this document will disclose a striking similarity to the Ordinance of 1787, when we get to that point in our history.

We must now go back to another phase of the nation’s development, which was altogether human, and which is with us today. This was the element of hope for riches and private profit. In those days it was specifically called “land hunger.”

All of the earliest westward colonization schemes for America were what we might call “land grabbing schemes” of various merits. To discourage this tendency many plans were evolved for the development of the West. From about 1750 one plan followed another in rapid succession. Each was an improvement over the one preceding it. One is particularly significant—that of Peletiah Webster who proposed the surveying into townships of the lands adjoining the colonies—now states—on the west, and their sale in small lots only, and one range at a time to the westward. This would have established a strong and well-settled frontier, without large speculative holdings, and would have conserved for orderly growth the great untold areas of the West.

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK WADING SWAMPS WITH TROOPS

Drawn by Merle June Dehls, Vincennes, Ind.

After the Revolutionary War was over, the United States had only in effect a quitclaim deed from England to the lands north and west of the Ohio.

But the colonies now asserted their individual claims more vociferously than ever. There were now 13 states, in effect different and independent nations, each with a desire for expansion westward. Virginia had, of her own volition, sent George Rogers Clark into the West during the Revolution to drive the British from what were ostensibly her lands in the Illinois country. Clark had done a superb job—and claims are made that he not only acquired these lands by conquest for Virginia, but destroyed the budding Indian conspiracy that the British under Henry Hamilton were[14] fomenting, and which, by attack from the rear, would have destroyed the entire American cause.

Connecticut and Massachusetts refurbished their charter claims and New York, through its treaty with the Iroquois Indians, made indeterminate but extensive demands to the territory.

And, lastly, there were the undeniable rights of the Indians to be acquired by purchase or by conquest.

Under pressure of states whose colonial charter boundaries had been more restricted, principally Maryland, the states with wide-flung claims were urged to cede all their western lands to the nation at large. The contention was that these lands had been won from the British by common effort and should therefore be common property. Here, at last, was a definite indication that development was to be toward one nation, rather than an alliance of 13 smaller independent governments. How strong this point really was is not certain, however, for one of the great objectives was to lessen the common debt, and thus relieve each of the states of its obligations.

However, the unified nation movement was gaining strength. Intermingling of men in the army, common purposes in defense, and now, property held in common were breaking down the old animosities.

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Drawn by Sam Delaney, Marietta, Ohio

New York took the lead in ceding her claims in 1780. Virginia, richest, most populous and with best substantiated claims, followed in 1784. This was immediately followed by the Ordinance of 1784, the first plan to be evolved for the West, that made any reference to the principles of government. This ordinance, although passed by Congress, never became effective because it made no provisions for acquisition or ownership of land, and, in fact, there still remained the necessity of Massachusetts and Connecticut cessions and the acquisition of title from the Indians. Massachusetts and Connecticut finally ceded their rights, but there still were no clearly indicative signs of what American principles of government were to become, beyond a broader right of franchise.

Later, Congress passed the Ordinance of 1785—commonly called the “Land Ordinance.” This did provide for the survey and sale of lands. It[15] contained some of the proposals of wise old Peletiah Webster, made years before, for township surveys, sale by succeeding western ranges, and in plots small enough to prevent large speculation. But it said nothing about laws to go with the land, and it, too, became largely ineffective in its purpose.

And so was enacted the Ordinance of 1787 with all its portent for government built primarily for man, rather than man for government.

As the ordinance was passed by the Continental Congress sitting in New York, the Constitutional Convention was sitting in session at Philadelphia. Two months later the United States Constitution was adopted by that convention and submitted to the states for ratification. In that great document as submitted to the states there were no provisions for these rights of men.

But the people of the United States were not at all indefinite as to their wishes and interests. Only by assurance that the bill of rights would be included was it possible to obtain ratification of the Constitution.

The Ordinance of 1787 was now in effect. America had started westward under a law of highest hope and modern ideals.

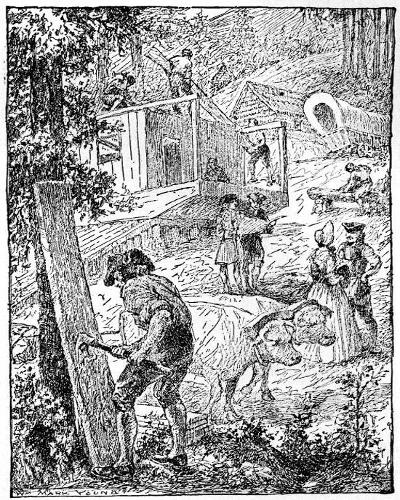

INDIAN TREATY

Drawn by William R. Willison, Marietta, Ohio

Most of the humanitarian provisions of the Ordinance of 1787 became part of the United States Constitution in the first amendments made four years later—1791—and one of the greatest found its way into our organic law 78 years afterward, when slavery was abolished by the thirteenth amendment.

This is not, however, the whole story of the Ordinance of 1787 and “How this Nation?” As Abraham Lincoln later said,

“The Ordinance of 1787 was constantly looked to whenever a new Territory was to become a State. Congress always traced their course by that Ordinance.”

Every state constitution subsequently adopted as the nation marched across the continent to the Pacific Ocean reflected the influence of that great ordinance. Thus, the concepts of Americans, which perhaps were planted with the first colonists but which bore fruit in the Ordinance of 1787, determined the most cherished fundamentals of this nation today.

A century and a half ago, on the thirteenth day of July, 1787, the Congress of the United States, in session at New York, among its last acts under the Articles of Confederation, enacted an ordinance for the government of the territory of the United States northwest of the Ohio River. We know of no legislative enactment, proposed and accomplished in any country, in any age, by monarch, by representatives, or by the peoples themselves, that has received praise so exalted, and at the same time so richly deserved, as has this same Ordinance of 1787.

It has been lauded by our great statesmen, great jurists, great orators, and great educators.

In his notable speech in reply to Robert Young Hayne, delivered in the United States Senate in January, 1830, Daniel Webster said of it:

“We are accustomed to praise the law-givers of antiquity; we help to perpetuate the fame of Solon and Lycurgus; but I doubt whether one single law of any law-giver, ancient or modern, has produced effects of more distinct, marked, and lasting character than the Ordinance of 1787. We see its consequences at this moment, and we shall never cease to see them, perhaps, while the Ohio shall flow.”

Judge Timothy Walker, in an address delivered in 1837 at Cincinnati, spoke upon this subject in the following words:

“Upon the surpassing excellence of this ordinance no language of panegyric would be extravagant. It approaches as nearly to absolute perfection as anything to be found in the legislation of mankind; for after the experience of fifty years, it would perhaps be impossible to alter without marring it. In short, it is one of those matchless specimens of sagacious forecast which even the reckless spirit of innovation would not venture to assail. The emigrant knew beforehand that this was a land of the highest political, as well as national, promise, and, under the auspices of another Moses, he journeyed with confidence to his new Canaan.”

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase said of it:

“Never, probably, in the history of the world, did a measure of legislation so accurately fulfill, and yet so mightily exceed, the anticipations of the legislators. The Ordinance has well been described as having been a pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night in the settlement and government of the Northwestern States.”

Peter Force, in 1847, in tracing its history, declared:

“It has been distinguished as one of the greatest monuments of civil jurisprudence.”

George V. N. Lothrop, LL.D., in an address delivered at the annual commencement of the University of Michigan, June 27, 1878, said substantially:

“In advance of the coming millions, it had, as it were, shaped the earth and the heavens of the sleeping empire. The Great Charter of the Northwest had consecrated it irrevocably to human freedom, to religion, learning, and free thought. This one act is the most dominant one in our whole history, since the landing of the Pilgrims. It is the act that became decisive in the Great Rebellion. Without it, so far as human judgment can discover, the victory of free labor would have been impossible.”

Notwithstanding the high praises that have been bestowed upon the ordinance, and the many and great benefits that have flowed from it, its authorship was, for nearly a century, a matter of dispute. No less than four different persons have had claims to authorship advanced for them by their friends.

Who, if any one man, was primarily the author of the ordinance, is uncertain, and now of little moment. The long contention which was waged as to its authorship serves its greatest purpose in emphasizing the importance which was then and has since been attributed to the document.

Because of the geographic implications later involved it is worth while, however, to consider briefly the various assertions of authorship.

Webster, in his famous two-day speech in reply to Hayne, gives to Nathan Dane, of Massachusetts, the entire credit for devising the ordinance, and such was the confidence in Webster’s statement, that many writers since have accepted it as a demonstrated fact.

Thomas H. Benton, in the debate following Webster’s speech, replied:

“He [Webster] has brought before us a certain Nathan Dane, of Beverly, Mass., and loaded him with such an exuberance of blushing honors as no modern name has been known to merit or claim. So much glory was caused by a single act, and that act the supposed authorship of the Ordinance of 1787, and especially the clause in it which prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude. So much encomium and such greatful consequences it seems a pity to spoil, but spoilt it must be; for Mr. Dane was no more the author of that Ordinance, sir, than you or I.... That Ordinance, and especially the non-slavery clause, was not the work of Nathan Dane of Massachusetts, but of Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.”

Charles King, president of Columbia College, in 1855 published a paper on the Northwest Territory in which he claimed for his father, Rufus King, the authorship of the non-slavery clause.

Ex-Governor Edward Coles, in a paper on the “History of the Ordinance of 1787,” prepared for the Pennsylvania Historical Society in 1850, disputed Webster’s claim for Dane, and asserted the claim of Thomas Jefferson.

Force undertook to gather from the archives of Congress materials for a complete history of this document, but he found nothing that settled the question of authorship; and although he probably knew more of the original documents pertaining to the Northwest Territory than any other man since its adoption, he died in ignorance of the real author.

Hon. R. W. Thompson, in an eloquent address on “Education,” ascribed the ordinance to the wise statesmanship and the unselfish and far-reaching patriotism of Jefferson.

Lothrop, in his Ann Arbor address in 1878, on “Education as a Public Duty,” said:

“It was a graduate of Harvard, who, in 1787, when framing the Great Charter for the Northwest, had consecrated it irrevocably to Human Freedom, to Religion, Learning, and Free Thought. It was the proud boast of Themistocles, that he knew how to make of a small city a great state. Greater than his was the wisdom and prescience of Nathan Dane, who knew how to take pledges of the future, and to snatch from the wilderness an inviolable Republic of Free Labor and Free Thought.”

In 1876, a year in which many buried historical facts were unearthed, William Frederick Poole, in an admirable article published in the North American Review, presented the history of the Ordinance in a most scholarly manner. But discarding the absoluteness of the claims heretofore set forth, he presents, as the chief actor in this mysterious drama, Dr. Manasseh Cutler, of Massachusetts.

Following, in a general way, the line of argument laid down by Poole, it is interesting to examine the foregoing claims in the light of the known facts. In January, 1781, Thomas Jefferson, then Governor of Virginia, acting under instructions from his state, ceded to the general government Virginia’s claims to that magnificent tract of country known as the Northwest Territory, which had been acquired by Virginia by king’s charter and also as a result of its conquest by George Rogers Clark in 1778-79. The Virginia cession, regarded as the most crucial of the necessary relinquishments of state claims, was not completed in form satisfactory to the United States until 1784. On the first of March of the same year Jefferson, then a member of Congress and chairman of a committee appointed for the purpose, presented an ordinance for the government of all the territory lying westward of the 13 original states to the Mississippi River. There were two notable features in this paper; first, it provided for the exclusion of slavery and involuntary servitude after the year 1800; second, it provided for[19] Articles of Compact, the non-slavery clause being one of them. By this provision there were five articles that could never be set aside without the consent of both Congress and the people of the territory. The non-slavery article was rejected by Congress, and the rest was adopted with some unimportant modifications, on the twenty-third of April, 1784. Whether even this ordinance was actually drafted by Jefferson is disputed, because it was an almost identical copy of the plan submitted by David Howell of Rhode Island in the previous year. However, on the tenth of May, 17 days after the Ordinance of 1784 was adopted, Jefferson resigned his seat in Congress to assume the duties of United States Minister to France. As the Ordinance of 1787 was not adopted until three years after Jefferson had gone to France, and since he did not return until December, 1789, more than two years after its passage, there is serious question as to his possible influence upon it.

Moreover, careful comparison of the Ordinance of 1784 with that of 1787, shows no similarity, except in the two points referred to above: the anti-slavery provision, and the articles of compact. The Ordinance of 1784 contains none of those broad provisions found in the later document concerning religious freedom, fostering of education, equal distribution of estates of intestates, the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, trial by jury, moderation in fines and punishments, the taking of private property for public use, and interference by law with the obligation of private contracts. No provision was made for distribution or sale of lands, and under this Ordinance of 1784 no settlements were ever made in the territory.

MANASSEH CUTLER

Drawn by Marie Kellogg, Superior, Wisconsin

In 1785, on motion of Rufus King, an attempt was made to re-insert some sort of anti-slavery provision, but it was not carried. This, so far as we can learn, is the extent of the grounds for King’s claims to authorship.

In March, 1786, a report on the western territory was made by the grand[20] committee of the House, which, proving unsatisfactory, resulted in the appointment of a new committee. It reported an ordinance that was recommitted and discussed at intervals until September of the same year, when another committee was appointed. Of this, Dane was a member. A report was made which was under discussion for several months. In April, 1787, this same committee reported another ordinance which passed its first and second readings, and the tenth of May was set for its third reading, but for some reason final action was postponed. This paper came down to the ninth of July without further change. Poole has given us the full text as it appeared only four days before the final passage of the great ordinance. This bears less likeness to the finally adopted version than does the Ordinance of 1784.

Force, in gathering up the old papers, found this July 9 version in its crude and unstatesmanlike condition, and wondered how such radical changes could have been so suddenly effected; for in the brief space of four days the new ordinance was drafted, passed its three readings, was put upon its final passage, and was adopted by the unanimous vote of all the states present.

This rapid and fundamental change in the ordinance tends to discredit all of the foregoing claims.

Authorship of public documents which attain greatness is usually a matter for later dispute.

Such documents have probably never been the work of any one author, but are rather the coordinated expressions of thought which have developed over long periods of time and in many men’s minds. Least of all entitled to credit is the “Scribe” who merely recorded the thought propounded by others, but whose name often becomes associated with the document.

At the close of the Revolutionary War, Congress, in adjusting the claims of officers and soldiers, gave them interest-bearing continental certificates. The United States Treasury was in a state of such depletion and uncertainty, that these certificates were actually worth only about one-sixth of their face value. At the close of the war many of these officers were destitute, notwithstanding the fact that they held thousands of dollars in these depreciated “promissory notes” of the government.

On the eve of the disbandment of the army in 1783, 288 officers petitioned Congress for a grant of land in the western territory. Their petition went beyond a request for lands, however, and set forth certain provisions of government as essential to their petition. In this humble and little-known document known variously as the “Pickering” or “Army” Plan, were contained many of the proposals which later found their way into the Ordinance of 1787. Included for instance was the then radical prohibition of slavery clause. This document bears a closer resemblance in principles[21] and in wording, to the Ordinance of 1787 when it was adopted than does any other contemporary document. Among the petitioners was General Rufus Putnam. It was his plan, if Congress should comply with the petition, to form a colony and remove to the Ohio Valley. On the sixteenth of June, 1783, Putnam addressed a letter to General George Washington elaborating the soldiers’ plan and setting forth the advantages that would arise if Congress should grant the petition, and urged him to use his influence to secure favorable action upon it. This letter is of great interest in the development of the history of the Northwest. It is printed in full in Charles M. Walker’s History of Athens County, Ohio, pp. 30-36.

The chief advantages of this project, as set forth by Putnam were, the friendship of the Indians, secured through traffic with them; the protection of the frontier; the promotion of land sales to other than soldiers, thus aiding the treasury; and the prevention of the return of said territory to any European power. There were, in the letter, other suggestions of far-reaching interest; (1) That the territory should be surveyed into six-mile townships, one of the first suggestions for our present admirable system of government surveys; (2) that in the proposed grant, a portion of land should be set apart for the support of the ministry; and (3) that another portion should be reserved for the maintenance of free schools.

One year later Washington wrote to Putnam that, although he had urged upon Congress the necessity and the duty of complying with the petition, no action had been taken. The failure of this plan led to the development of another and better one. It is interesting to note, however, that the men under whose sponsorship and virtual insistence the Ordinance of 1787 was finally evolved had been subscribers to the Pickering Plan of 1783.

In 1785, Congress adopted the system of surveys suggested by Putnam, and tendered him the office of Government Surveyor. He declined, but through his influence, his friend and fellow-soldier, General Benjamin Tupper, was appointed. In the fall of 1785, and again in 1786, Tupper visited the territory and in the latter year he completed the survey of the “seven ranges” in eastern Ohio. In the winter of 1785-86 he held a conference with Putnam at the home of the latter, in Rutland, Massachusetts. Here they talked over the beauty and value of “the Ohio country” and devised a new plan for “filling it with inhabitants.” They issued a call to all officers, soldiers, and others, “who desire to become adventurers in that delightful region” to meet in convention for the purpose of organizing “an association by the name of The Ohio Company of Associates.” The term “Ohio” as used here related to the “Ohio country” or the “Territory north and west of the River Ohio,” as the present state of Ohio was then of course non-existent.

Also the name, “Ohio Company of Associates,” is not to be confused with the earlier “Ohio Company” of the 1750’s which had been one of the[22] earlier land schemes, operating south of the Ohio River. No man in the “Ohio Company of Associates” had been a part of the former Ohio Company, and there was no relation between the two companies.

Delegates from various New England counties met at Boston, March 1, 1786. A committee, consisting of Putnam, Cutler, Colonel John Brooks, Major Winthrop Sargent, and Captain Thomas H. Cushing was appointed to draft a plan of association. Two days later they made a report, some of the most important points of which were: (1) That a stock company should be formed with a capital of one million dollars of the Continental Certificates already mentioned; (2) that this fund should be devoted to the purchase of lands northwest of the River Ohio; (3) that each share should consist of one thousand dollars of certificates, and ten dollars of gold or silver to be used in defraying expenses; (4) that directors and agents be appointed to carry out the purposes of the company.

Subscription books were opened at different places, and at the end of the year, a sufficient number of shares had been subscribed to justify further proceedings. On the eighth of March, 1787, another meeting was held in Boston, and General Samuel Holden Parsons, Putnam, Cutler and General James M. Varnum were appointed directors, and were ordered to make proposals to Congress for the purchase of lands in accordance with the plans of the company. Later, the directors employed Cutler to act as their agent and make a contract with Congress for a body of land in the “Great Western Territory of the Union.”

To those who have studied this transaction of the Ohio Company of Associates in its various bearings, there can be no doubt that through it the Ordinance of 1787 came to be. The two were intimately related parts of one whole. Either studied alone presents inexplicable difficulties; studied together each explains the other. Through the agency of Cutler the purchase of land was effected and those radical changes in the ordinance were made between the ninth and thirteenth of July, 1787.

Cutler was born at Killingly, Connecticut, May 3, 1742. At the age of twenty-three he graduated from Yale. The two years following were devoted to the whaling business and to storekeeping at Edgartown, on Martha’s Vineyard. He did not enjoy this occupation, however, and studied law in his spare time. In 1767 he was admitted to the Massachusetts bar. This profession proved little more congenial, and he determined to study theology. In 1771 he was ordained at Ipswich, where he continued preaching until the outbreak of the Revolution, when he entered the army as a chaplain. In one engagement he took such an active and gallant part that the colonel of his regiment presented him with a fine horse captured from the enemy. Cutler returned to his parish before the war closed and decided to study medicine. He received his M.D. degree, and for several years[23] served in the double capacity of minister and doctor. He was now a graduate in all the so-called learned professions—law, divinity, and medicine. In scientific pursuits he was probably the equal of any man in America, excepting Benjamin Franklin, and perhaps Benjamin Rush. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and several other learned bodies. Two years before his journey to New York, he had published four articles in the memoirs of the American Academy, dealing with astronomy, meteorology and botany. The last mentioned was the first attempt made by any one to describe scientifically the plants of New England. Employing the Linnaean system, he classified 350 species of plants found in his neighborhood. His articles brought him prominence among learned groups throughout the country, and secured for him a cordial welcome into the literary and scientific circles of New York and Philadelphia. Cutler was well fitted, therefore, to become, as has already been related, a leading spirit in the enterprise of the Ohio Company. In 1795 Washington offered him the judgeship of the Supreme Court of the Northwest Territory, which he declined. He became a member of the Massachusetts Legislature, and from 1800 to 1804 served his district as its Representative in Congress. He declined re-election and returned to his pastorate. At the time of his death in 1820 he had served there for nearly 50 years.

He was a man of commanding presence, “stately and elegant in form, courtly in manners, and at the same time easy, affable, and communicative. He was given to relating anecdotes and making himself agreeable.” His character, attainments, manners and knowledge of men fitted him admirably for the task of uniting the diverse elements of Congress to promote the scheme he was sent there to represent. How he accomplished this is an interesting story.

Cutler’s diary reveals that he left his home in Ipswich, 25 miles northwest of Boston, on Sunday, June 24, 1787. He preached that day in Lynn, and spent the night at Cambridge. He also stopped at Middletown to confer with Parsons. Here the plan of operations was perfected, and he pursued his journey, arriving at New York on the afternoon of July 5, 1787. He had armed himself with about 50 letters of introduction. One of these he delivered immediately to a well-to-do merchant of the city, who received him very cordially and insisted that Cutler stay with him as long as he remained in the city.

The next morning Cutler was on the floor of Congress early, presenting letters of introduction to the members. He was particularly anxious to become acquainted with southern men, and they received him with much warmth and politeness. He was so genteel in his manners, and so much more like a southerner than a New England clergyman, that they took a fancy to him at once.

During the morning he prepared his applications to Congress for the proposed purchase of western land for the Ohio Company. He was introduced to the House by Colonel Edward Carrington, after which he delivered his petition, and proposed terms of the purchase. A committee was appointed to discuss terms of negotiation.

It must be remembered that Cutler was employed not only to make a purchase of land, but to see that the frame of government for the territory was acceptable to his constituents. Thus he had a motive in making himself agreeable to the southern men. Among the New England members there existed some antagonism toward the Ohio Company’s scheme, since its success would cause many enterprising citizens to leave that section. Massachusetts had a large tract of land in Maine, and she desired to turn the tide of emigration in that direction; for this reason Massachusetts members stood in the way of the western movement. Cutler felt, however, that their support of the company’s scheme might be relied upon when brought to a test.

Cutler was invited to dinners and teas, where his engaging manner made him the center of attraction. He used every occasion as a means of setting before the members the great advantages that would follow consummation of the proposed plan.

In the first place, Congress could thus pay a large amount of the national debt to its most worthy creditors without money. Again, it would open up the Northwest to settlement, thus insuring large sales of land to civilians. Further, it would establish a barrier between older settlements and the western Indians, thus furnishing protection without expense to the government.

In three or four days he had so fully succeeded in enlisting the favor of Congress that by July 9 a new committee was appointed to prepare a frame of government for the territory. It was at this point that the ordinance under consideration bore so little resemblance to the final document which was adopted four days later. This committee was composed of Carrington, Nathan Dane of Massachusetts, Richard Henry Lee and two others. It is quite probable that the members of this committee were selected in accordance with Cutler’s wishes.

The next morning after the committee was appointed, it called Cutler into its councils, having previously sent him a copy of the ordinance, which had already passed two readings. He was asked to make suggestions and propose amendments, which he did, returning the paper to the committee with his suggestions.

On July 10, he left for Philadelphia to visit his scientific correspondents, Franklin and Rush, and also to look in upon the Constitutional Convention, which was then in session.

The day following his departure, the committee presented to Congress a new ordinance prepared in accordance with Cutler’s suggestions. If Force could have had access to Cutler’s diary in writing up the history of the Ordinance of 1787, the mystery of the radical changes that he found between the ninth and the eleventh of July would have been solved.

On the eighteenth Cutler was again in New York. On the nineteenth he made this entry in his diary:

“Called on members of Congress very early in the morning, and was furnished with the ordinance establishing a government in the western Federal territory. It is, in a degree, new modeled. The amendments I proposed have all been made except one, and that is better qualified.”

The frame of government having been satisfactorily settled, Congress proceeded to state the conditions on which the sale of lands should be based. On the twentieth these terms were shown to Cutler, who rejected them. He said:

“I informed the committee that I should not contract on the terms proposed; that I should greatly prefer purchasing lands from some of the states, who would give incomparably better terms; and therefore proposed to leave the city immediately.”

Thus it appears quite certain that the distinctive flavor of the ordinance and the provisions which have given it greatness among all the credos of mankind were injected into it after July 9, and after Cutler had been requested to make suggestions and amendments.

But that these vital changes were not original with Cutler is evidenced by his later statement, “I only represented my principals, who would accept nothing less.”

And so the real responsibility for authorship of the ordinance may be traced to the men at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern, to the signers of the Pickering Plan, to the sober-minded and unsung men who had fought and thought a new nation into potential greatness.

At this time a number of other leading persons who held government certificates proposed to make Cutler their agent for the purchase of lands for themselves. This would give him control of some four millions more of the debt with which to influence Congress. He agreed to act for them, on the condition that the affair be conducted secretly. The next day several members called on him. They found him unwilling to accept their conditions, and proposing to leave immediately. They assured him that Congress was disposed to give him better terms. He appeared very indifferent, and they became more and more anxious. His ruse was working admirably. He finally told them that if Congress would accede to his terms, he would extend his proposed purchase. In this way, Congress could pay more than four millions of the public debt. He explained that the intention[26] of his company was an immediate settlement by the most robust and industrious people in America, which would instantly enhance the value of federal lands. He proposed to renew the negotiations on his own terms, if Congress was so disposed.

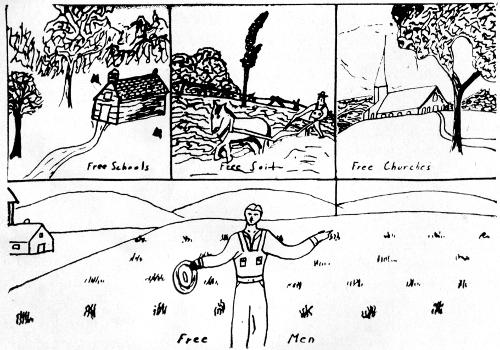

On the twenty-fourth he wrote out his terms and sent them to the Board of Treasury, which had been empowered to complete the contract. These terms specified that the general government should survey the tract at its expense, stated the method of payment, number of payments, and the time at which the deed should be given. The most striking provisions of the contract set apart the sixteenth section of each township for the support of free schools, the twenty-ninth section of each township for the ministry; and two entire townships for the establishment and maintenance of a university.

These terms called forth much opposition, and taxed Cutler’s lobbying powers to their utmost. He said:

“Every machine in the city that it was possible to set to work, we now set in motion. My friends made every exertion in private conversation to bring over my opponents. In order to get at some of them so as to work powerfully on their minds, we were obliged to engage three or four persons before we could get at them. In some instances we engaged one person, who engaged a second, and he a third, and soon to the fourth before we could effect our purpose. In these maneuvers I am much beholden to Col. Duer and Maj. Sargent.”

It had been the purpose of the company to secure the governorship of the new territory for Parsons, but it became known that General Arthur St. Clair, the president of the Continental Congress, wanted the position. St. Clair was withholding his influence. Cutler sought an interview with him. “After that,” said Cutler, “our matters went on much better.” It will be remembered that St. Clair became the first Governor of the Northwest Territory.

On the twenty-seventh, Congress directed the Board of Treasury “to take order and close the contract.” That evening Cutler left New York for his home, authorizing Sargent to act in his stead. On the twenty-ninth of August he made a report to the directors and agents at a meeting in Boston. A great number of proprietors attended, and all fully approved of the proposed contract and it was finally executed October 27, 1787.

The Ordinance of 1787 undoubtedly represented the most advanced thought of that time on the subject of free government.

This ordinance irrevocably fixed the character of the immigration, and determined the social, political, industrial, educational, and religious institutions of the territory.

As soon as it was adopted by Congress, it was sent to the Constitutional[27] Convention at Philadelphia, and some of its most important provisions were embodied in the new Constitution. Notable among these was one in the second Article of Compact, in the ordinance, stating that, “for the just preservation of rights and property, no law ought ever to be made, or have force in said Territory, that shall, in any manner whatever, interfere with, or affect private contracts or engagements, bona fide, and without fraud, previously formed.” This appears in Paragraph 1, Section 10, Article 1 of the Constitution, prohibiting a state from passing any “law impairing the obligation of contracts.” This is said to be the first enactment of the kind in the history of constitutional law.

The fact that the Constitutional Convention included this one proviso in the draft of the Constitution, indicates that consideration was given the provisions of the ordinance, and thereby suggests their deliberate omission from the Constitution, for reasons unknown, inasmuch as the debates of that convention were, by agreement, not recorded.

However, after the Constitution was submitted to the states for ratification it quickly became apparent that the people were determined upon specific provision for the rights of men in their fundamental law, and while ratification of the Constitution by nine states was accomplished in 1789, it was only possible by assurance that such provisions would be immediately added as amendments.

In some form, every one of the states admitted from the Northwest Territory later embodied similar provisions in their fundamental law. The adoption or rejection of these principles was not left to the discretion of the states; being “Articles of Compact,” they could not be discarded without the consent of Congress.

The sixth article of this compact prohibited slavery forever, within the bounds of the Northwest Territory. But for this form of compact in the ordinance, it is perhaps possible that Indiana and Illinois would have entered the Union as slave states. In 1802 General William Henry Harrison, then Governor of Indiana Territory, called a convention of delegates to consider the means by which slavery could be introduced into the territory, and he himself presided over its deliberations. In the language of Poole,

“The Convention voted to give its consent to the suspension of the sixth article of the compact, and to memorialize Congress for its consent to the same. The memorial laid before Congress stated that the suspension of the sixth article would be highly ‘advantageous to the Territory’ and ‘would meet with the approbation of at least nine-tenths of the good citizens of the same.’ The subject was referred to a committee of which John Randolph of Virginia was chairman, who reported adversely as follows: ‘That the rapidly increasing population of the State of Ohio evinces in the opinion of your committee, that the labor of slaves is not necessary to promote[28] the growth and settlement of colonies in that region. That this labor, demonstrably the dearest of any, can only be employed to advantage in the cultivation of products more valuable than any known in that quarter of the United States; that the committee deem it highly dangerous and inexpedient to impair a provision wisely calculated to promote the happiness and prosperity of the northwestern country, and to give strength and security to that extensive frontier. In the salutary operation of this sagacious and salutary restraint, it is believed that the inhabitants of the[29] Territory will, at no very distant day, find ample remuneration for a temporary privation of labor and of emigration.’”

When Ohio was admitted to the Union, the advocates of slavery made strenuous efforts to secure its introduction, but were defeated. Indiana and Illinois territories later asked that the anti-slavery provision be set aside. More than one committee reported in favor of repealing it, but Congress firmly maintained the compact.

The enlightened provisions of the ordinance attracted the thrifty Yankee from New England, the enterprising Dutchman from Pennsylvania, the conscientious Quaker from Carolina and Virginia, and some of the sturdiest pioneer stock from the frontier of Kentucky. Even the light-hearted French contributed to this great melting pot.

Some historians refer to the spirit of the Northwest Territory as the “first American civilization,” brought about by welding into a national entity the diverse and imported civilizations of the earlier colonies.

Northwest Territory

The First Colony of the United States

It is at least an interesting speculation as to whether the newly born United States would have prevailed as one nation, except for the opportunity given by the Northwest Territory with its new lands, common problems, and forward looking government for this merging of the older states’ discordant traditional concepts of government and social relations.

Comparison of the social, industrial, and educational conditions in the states of the Old Northwest with those in neighboring states not born under the influence of the ordinance creates further evidence of the value of the principles enunciated by the ordinance.

If, in 1861, the principles and institutions of Kentucky and Missouri, instead of those of the Ordinance of 1787, had prevailed in the five states formed from the Northwest Territory, it would have required no seer to predict another end for the great struggle between the states. As Lothrop says, “It [the Ordinance of 1787] is the act that became decisive in the Great Rebellion. Without it so far as human judgment can discover, the victory of Free Labor would have been impossible.”

While it is not claimed that the ordinance was the source of all the blessings that have crowned these states, still it is certain that it was the germ from which many of them have been developed. Neither is it claimed that all the ills of the Southern States arose from the absence of similar provisions; however, their presence and influence on the one hand, and their absence on the other, tended to widen the gulf between North and South and, when the final struggle came, had a determining influence on the result.

When George Washington said farewell to his officers at the end of the Revolutionary War, he gave them this admonition:

“The extensive and fertile regions of the West will yield a most happy asylum to those who, fond of domestic enjoyment, are seeking for personal independence.”

While Washington did not become a shareholder in the Ohio Company of Associates, several circumstances give evidence as to his having been active in its planning.

Having personally visited the Ohio country in 1770 for the purpose of studying and selecting lands, his selection of some 40,000 acres in Virginia and Ohio for himself; and the comments in his journal of the trip give ample evidence of his enthusiasm for this part of the West. His repeated statement during the Revolution that in case of failure to achieve independence the troops should “retire to the Ohio Country and there be free”; his long and earnest efforts to open up routes to the West by canal and by road; his great friendship and admiration for Rufus Putnam; and his later decisive steps in sending Anthony Wayne to put a final end to the question of Indian land titles and warfare; all these indicate far more than a casual interest in the plans for and success of this first western colony.

Washington had himself earlier attempted to establish a colony on the Great Kanawha River south of the present town of Point Pleasant, West Virginia. We can readily imagine that he may have deliberately refrained from becoming an Ohio Company Associate because of the implications of personal interest which might follow. But when, on April 7, 1788, a group of his former officers made the first settlement in the Northwest Territory, at Marietta, Washington exclaimed:

“No colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices as that which has just commenced on the banks of the Muskingum. Information, property, and strength will be its characteristics. I know many of the settlers personally, and there never were men better calculated to promote the welfare of such a community.”

The founders of Marietta settled in the West to regain the fortunes[31] they had lost in the Revolution. Some of them earned nothing from their professions during the eight years of the war. They received little or no pay for their military services, because Congress had no power to raise money by levying taxes. Finally, they were paid with certificates issued by the Continental Congress. Because these notes were worth only about twelve cents on the dollar the expression, “not worth a Continental,” became a by-word. In desperation the officers looked to the public land of the West with its fertility, timber, fur, and game as a place to find the necessities of life. They were not speculators; they were pioneers in search of homes for themselves and their children.

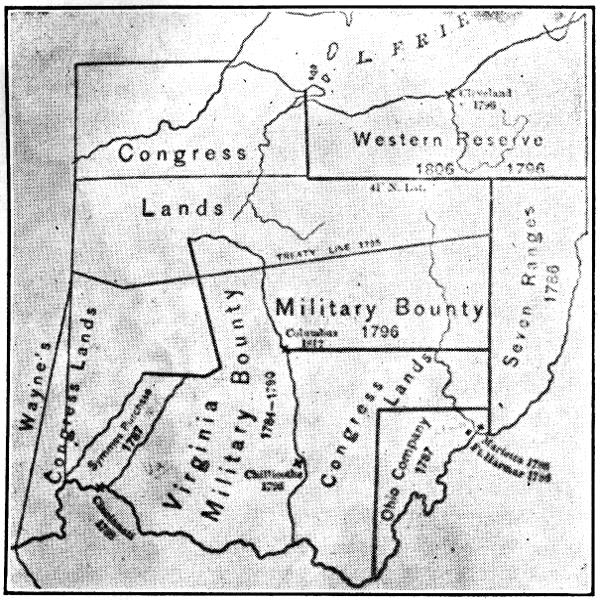

Several unsuccessful attempts had been made by the soldiers to secure land in the West before Congress finally granted them a place to settle. As early as September, 1776, Congress tried to encourage enlistment by offering bounties of land—five hundred acres to a colonel, 100 acres to a private, and other ranks in proportion. At the time this offer was made, the government owned no public land, nor did it until the winning of the Northwest by George Rogers Clark, the cession of land claims by the states, and Indian treaties had provided a public domain. In hope of securing grants in this presumed domain Colonel Timothy Pickering in 1783 formulated “Propositions for Settling a New State by Such Officers and Soldiers of the Federal Army as Shall Associate for that Purpose.” He suggested that Congress purchase lands from the Indians and give tracts to soldiers in fulfillment of the bounty promises of 1776. In the hands of Putnam this suggestion became the “Newburgh Petition,” which was forwarded to Congress with the signatures of about 288 officers in the Continental Line of the Army. With this petition Putnam sent a letter to Washington in which he asked support for the appeal of the signers and outlined their plan. His letter included such wise suggestions as the exchange of land for public securities, the adoption of the township system of survey, and the advantage of settlements of soldiers in the West as outposts against danger from the Indians or from the English in Canada. In a belated response to these demands Congress enacted on May 20, 1785, “An Ordinance for ascertaining the mode of disposing of lands in the Western Territory,” which applied to the lands won from England, ceded by the states and now purchased from the Indians. This ordinance made no provision for government in the West, and, although the “seven ranges” just west of the Pennsylvania border were surveyed and offered for sale according to its provisions, but little land was sold and this attempt at westward settlement was a comparative failure.

This further reflects the determination of the American people to have an acceptable and agreed-upon form of government upon which to build a new country.

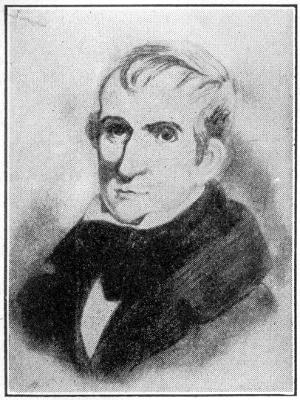

RUFUS PUTNAM

Drawn by Herbert Krofft, Zanesville, Ohio

In these efforts of the officers to secure western lands, Putnam was the leader. Putnam had been well taught in the school of experience. After his father’s death, he had gone, at the age of nine, to live with his stepfather, who made him work hard and would not permit him to go to school. “For six years,” Putnam said, “I was made a ridecule of, and otherwise abused for my attention to books, and attempting to write and learn Arethmatic.” At the age of 16 he was bound as apprentice to a millwright. Three years later he decided to escape from the severity of his master and seek adventure by joining the English army in the French and Indian War. He returned home from his second enlistment in disgust, because he had been made to work in the mills when he wanted to fight the French and Indians. After working seven years as a millwright, he turned to farming and surveying. Soon after the outbreak of the Revolution he was appointed military engineer. Later in the war he constructed the fortifications at West Point and suggested that place for a military school. He retired from the army a brigadier general and returned to farming and surveying. Putnam was appointed by Congress surveyor on the seven ranges of townships provided for by the Land Ordinance of 1785; but he resigned to survey lands in Maine for his own state and recommended Brigadier General Benjamin Tupper for the position in Ohio.

Tupper was so closely associated with Putnam in western plans that the two men have been called twin brothers. It has been suggested that the two men deliberately investigated land available for purchase in two different regions to compare their advantages. Tupper was stopped at Pittsburgh by Indian trouble, but he heard favorable reports of the Ohio country, which made him enthusiastic for settlement. He hurried eastward and arrived at Rutland on January 9, 1786. Before the blazing fireplace in Putnam’s home the two men talked all night about their dream of settlement in the West. When the morning light gleamed through the windows of the kitchen, the ineffectual hopes of the army officers had been forged[33] into a practical plan of action by the enthusiasm of Putnam and Tupper. On January 25, 1786, Massachusetts newspapers published an invitation to officers and others interested in western settlement to meet in their respective counties and appoint delegates to convene at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern in Boston to form an organization for the purpose.

Although this call was sent out three years after the Newburgh Petition, the prompt response of the officers showed that there had been no decline in interest. The Ohio Company of Associates resulted from this meeting.

It has been pointed out that most of those attending were also members of the military Society of the Cincinnati, so named because the Revolutionary soldiers thought they resembled the Roman soldier Cincinnatus in leaving their farms and work to save their country. No doubt the hope of western migration had been kept alive by discussion at the meetings of the Cincinnati. Most of those men also belonged to the Masonic Lodge, and this association also unified and perpetuated the ideas included in the Newburgh Petition of which most of them had been signers.

At the meeting in Boston on March 1 the delegates elected Putnam chairman and Major Winthrop Sargent clerk. One thousand “shares” were planned, and no person was permitted to hold more than five shares or less than one share, except that several persons could own one share in partnership. To facilitate the transaction of business, one agent was elected by each group of 20 shares to represent their interest at meetings of the company. Putnam, Manasseh Cutler, and General Samuel Holden Parsons, were appointed directors to manage the affairs of the company. Sargent was elected secretary and later General James M. Varnum was made a director and Colonel Richard Platt treasurer. All land was to be divided equally among the shares by lot. One year after the organization of the company 25 shares had been subscribed, and Parsons, Putnam, and Cutler were appointed to purchase a tract of land from Congress.

Although largely responsible for shaping the beginning of the new colony, Cutler did not move to the tract he purchased; he later visited the infant settlement, however, and his sons, Ephraim, Jervis, and Charles, became pioneer residents of the Northwest Territory.

Cutler contracted to purchase for the Ohio Company a million and a half acres at one dollar per acre, less one third of a dollar for bad lands and the expenses of surveying. Because the public securities with which payment was to be made were worth only twelve cents on the dollar, the actual purchase price was eight or nine cents per acre. The tract was bounded on the east by the Seven Ranges, which had been surveyed and offered for sale under the Land Ordinance of 1785, on the south by the Ohio River, and on the western side by the seventeenth Range; it extended far enough north to include in addition to the purchase one section of 640 acres in each[34] township for the support of religion, one section for the support of schools, two entire townships for a university, and three sections for the future disposition of Congress. An interesting phase of this provision of the contract with the government was that the Ordinance of 1787 itself made no specific provision for public school lands, lands for support of religion, or for university purposes. The Land Ordinance of 1785 had provided for the setting aside of one section in each township for public schools, but for neither religion nor universities. But, so earnest of purpose were the men who had written into the Ordinance of 1787 “Religion, morality and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall be forever encouraged,” that in their bargaining with the land commissioners, insistence was made upon these specific reservations. And so, perhaps outside the formal tenets of law, was furthered a public land policy which has done much to make our public school and university educational system an integral and distinctive feature of this government.

Five hundred thousand dollars was to be paid when the contract was signed and the same amount when the United States completed the survey of the boundary lines of the tract. The contract was signed on October 27, 1787, by Cutler and Sargent for the Ohio Company, and by Samuel Osgood and Arthur Lee for the Treasury Board, as commissioners of public lands. Because the company could not pay the second installment when it was due, the tract was reduced in size from a million and a half acres to 1,064,285 acres when the patent was issued on May 20, 1792. By giving 100,000 acres for donation lands to actual settlers, Congress reduced the final purchase to 964,285 acres.

In conformity with the Articles of Association the shareholders received equal divisions of the purchase. Instead of the 1000 shares originally expected, 822 were subscribed. When the final apportionment was made, each share received a total of 1,173.37 acres in seven allotments of eight acres, three acres, a house lot of .37 acres, 160 acres, 100 acres, a 640 acre section, and 262 acres.

Had army pay certificates been worth par, the maximum holding for any individual would have been about $5900, and from that amount down to a fractional part of $1173. In such sized holdings there could be little suggestion of either speculation or monopoly. The army certificates being depreciated in value as they were, the real value of holdings, in hard money, varied from about $700 down to a few dollars. On such vast capital was America started across a continent!!

The Ohio Company purchase was located on the Muskingum River for several reasons. Since the Associates of this Company expected to engage in farming, and since they were the first settlers, many have wondered[35] why they did not choose a level tract rather than the hilly section of the Muskingum. The answers are several: Although they were the first settlers, they did not have first choice. Southern Ohio was the only part of the territory to which the United States could give clear title. Connecticut withheld her Western Reserve of three and a quarter million acres east of the Fort McIntosh Treaty line. The western land lying between the Scioto and Little Miami Rivers was under Virginia option. Since a location west of the Little Miami would have been too far from the settled part of the country, a tract of suitable size for the Ohio Company could be found only in the southeast part of the present state of Ohio. The southern location just west of the Seven Ranges was closer to New England and was on the then greatest thoroughfare of western travel, the Ohio River. Furthermore, the Muskingum region was as far distant as possible from the Indian settlements farther west. Another advantage was the protection afforded by Fort Harmar, which had been constructed in 1785 by United States troops under command of Major John Doughty for the purpose of stopping illegal occupation of the land. Also, the settlers would have as neighbors 13 families on the patent of Isaac Williams, which lay on the Virginia side of the Ohio, opposite the mouth of the Muskingum. In making his choice of location, Cutler considered all these factors as well as the advice of Thomas Hutchins, geographer of the United States, who told him that the Muskingum Valley was, in his opinion, “the best part of the whole of the western country.”

As soon as the purchase was assured, the Ohio Company started systematic preparation for settlement. Putnam was elected superintendent. Plans were made in Boston for a city of 4000 acres with wide streets and public parks at the mouth of the Muskingum. One hundred houses were to be constructed on three sides of a square for the reception of settlers. For making surveys and preparing for immigrants, the superintendent was ordered to employ four surveyors and 22 assistants, six boat builders, four house carpenters, one blacksmith, and nine laborers. Each man was required to furnish himself with rifle, bayonet, six flints, powder horn and pouch, half a pound of powder, one pound of balls, and one pound of buckshot. Surveyors were to receive $27 a month, and laborers $4 per month and board. Although these plans were made when it was midwinter and travel was difficult, no time was to be lost. These were men of action. They had waited over three years for Congress to make it possible to carry out their purposes. Putnam decided to lead an advance expedition to the Muskingum to be ready for surveying and building and planting early in the spring, and in five weeks after the land contract was signed, they were on their way.

There is a substantial lesson in this for us who today profess heartfelt[36] desires and intensities of purpose. Ahead of these men lay months of winter, severe enough in the settled communities but far more to be feared in the hazardous wilderness of the Alleghany Mountains. Travel by foot, for 800 miles with a plodding ox team for part of their baggage, over the roughest of roads and uncharted trails, and across swollen streams was to be their lot. So severe was the risk that no women could accompany the party. During the trip and at its end possible Indian attacks endangered them. Such was their prospect which they faced cheerfully, unflinchingly and enthusiastically.

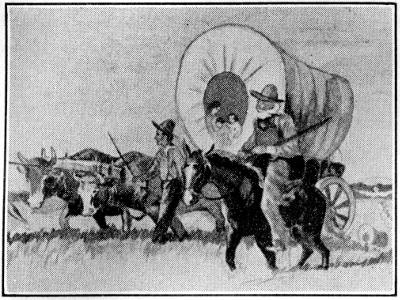

PIONEER PARTY

Drawn by Betty Kimmell, Vincennes, Ind.

The company of 48 men was divided into two parties. The boat builders and their assistants, 22 in number, met at Cutler’s home in Ipswich, Massachusetts, on December 3, 1787. Cutler not only helped to fashion the government for the Ohio Company of Associates; he also provided for their migration a wagon covered with black canvas and lettered with his own handwriting “For the Ohio Country.” At dawn the men paraded to hear an address from Cutler, fired three volleys with their rifles, and went to Danvers, Massachusetts, where Major Haffield White assumed command. With their plodding ox team they took a route south and then southwest over stage coach roads, mountain trails, or cutting their own path as they went, to the old Glade Road westward through Pennsylvania. After a toilsome journey, they reached Sumrill’s Ferry on the Youghiogheny River 30 miles southeast of Pittsburgh on January 23, nearly eight weeks after leaving home. At this place (now West Newton, Pa.) they started to build boats in readiness for the arrival of the other party.