Title: British Butterflies

Author: Alexander Morrison Stewart

Editor: Charles A. Hall

Release date: April 30, 2020 [eBook #61981]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Paul Mitchell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

References in the book to its illustrations are by “Plate” with Roman numerals. The illustrations themselves are labelled “Plate” with Arabic numerals. A plate’s number in Roman numerals is equal to a plate’s number in Arabic numerals. In several instances the author has spelled words differently to the accepted way. That spelling is retained in this transcription. The illustration on the book’s cover is referred to in the text as Plate 16.

Plate 16

FRONT COVER

PEEPS AT NATURE

EDITED BY

The Rev. Charles A. Hall

PUBLISHED BY

A. AND C. BLACK, LTD., 4, 5 AND 6, SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W. 1

AGENTS

| AMERICA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY |

| 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK | |

| AUSTRALASIA | OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS |

| 205 Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE | |

| CANADA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. |

| St. Martin’s House, 70 Bond Street, TORONTO | |

| INDIA | MACMILLAN & COMPANY, LTD. |

| Macmillan Building, BOMBAY | |

| 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA |

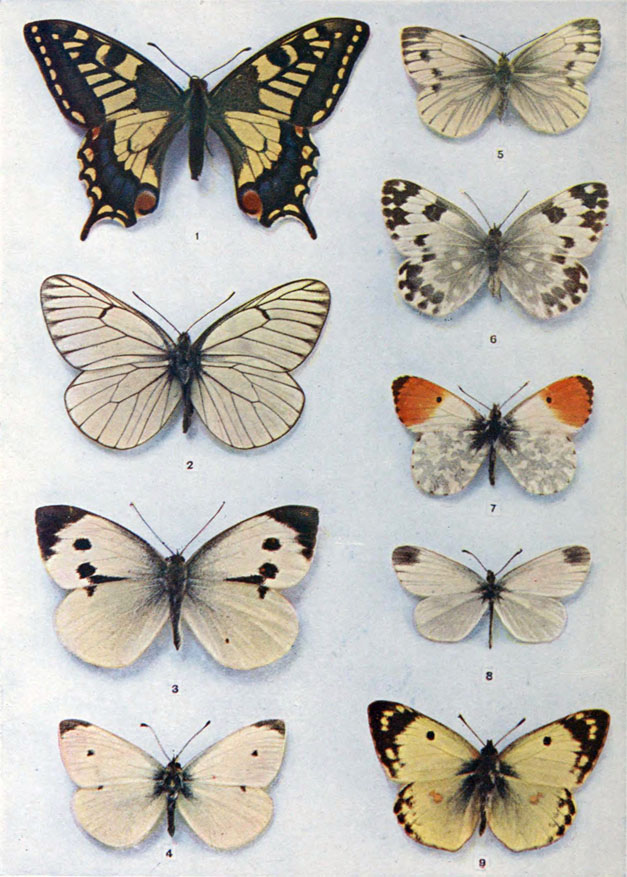

PLATE 1.

1. Swallow Tail

2. Black-veined White

3. Large Garden White (Female)

4. Small Garden White (Male)

5. Green-veined White (Female)

6. Bath White (Male)

7. Orange Tip

8. Wood White (Male)

9. Pale Clouded Yellow

First published May, 1912

I take it that this little “Peep at Nature,” needs no apology; the exquisite coloured plates, produced direct from natural butterflies by the three-colour process, are a sufficient justification of its appearance.

The author is a practical entomologist of many years’ standing. He writes from the fulness of a rich experience in the fields. He justly advocates the “Paisley” method of setting insects. I know it to be the more expeditious, and less calculated to damage specimens, than the ordinary process. His notes on the preservation of larvæ will be welcome in many quarters.

The publishers desire me to express their indebtedness to Messrs. Watkins and Doncaster, 36, Strand, W.C., for kindly arranging and lending the specimens from which the coloured plates have been produced.

CHARLES A. HALL.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY EDITORIAL NOTE | v | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | vii | |

| I | THE LIFE-HISTORY OF A BUTTERFLY | 1 |

| II | THE CAPTURE AND PRESERVATION OF BUTTERFLIES | 13 |

| III | THE BRITISH BUTTERFLIES DESCRIBED | 29 |

| INDEX | 88 |

| PLATE | ||

| I. | SWALLOW-TAIL—BLACK-VEINED WHITE—LARGE GARDEN WHITE—SMALL GARDEN WHITE—GREEN-VEINED WHITE—BATH WHITE—ORANGE-TIP—WOOD WHITE—PALE CLOUDED YELLOW* | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | ||

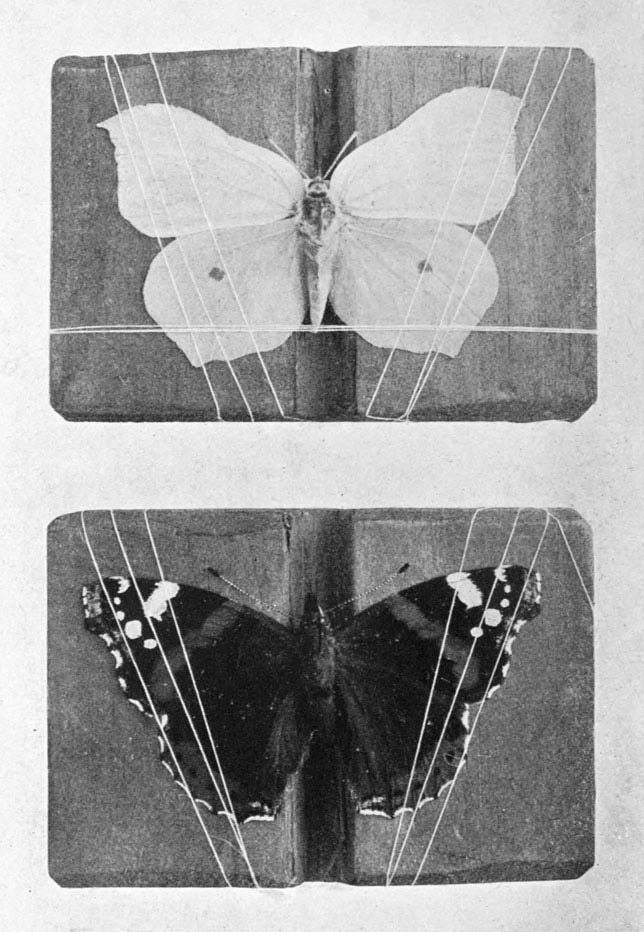

| II. | METHOD OF SETTING WITH BRISTLE AND BRACES | 9 |

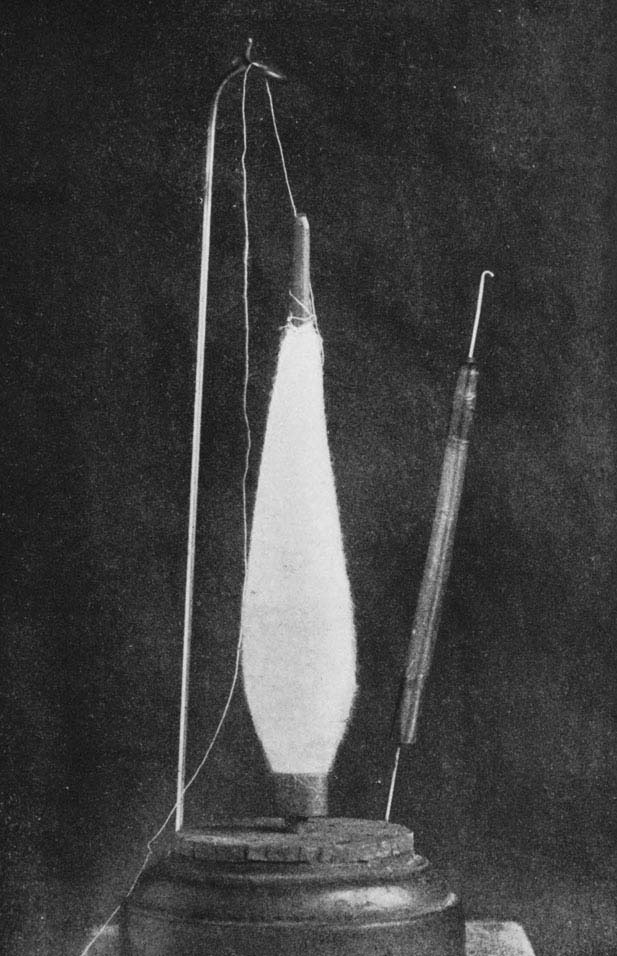

| III. | “COP” OF 120’S COTTON ON STAND, AND SETTING-NEEDLE FOR “PAISLEY” METHOD OF SETTING | 16 |

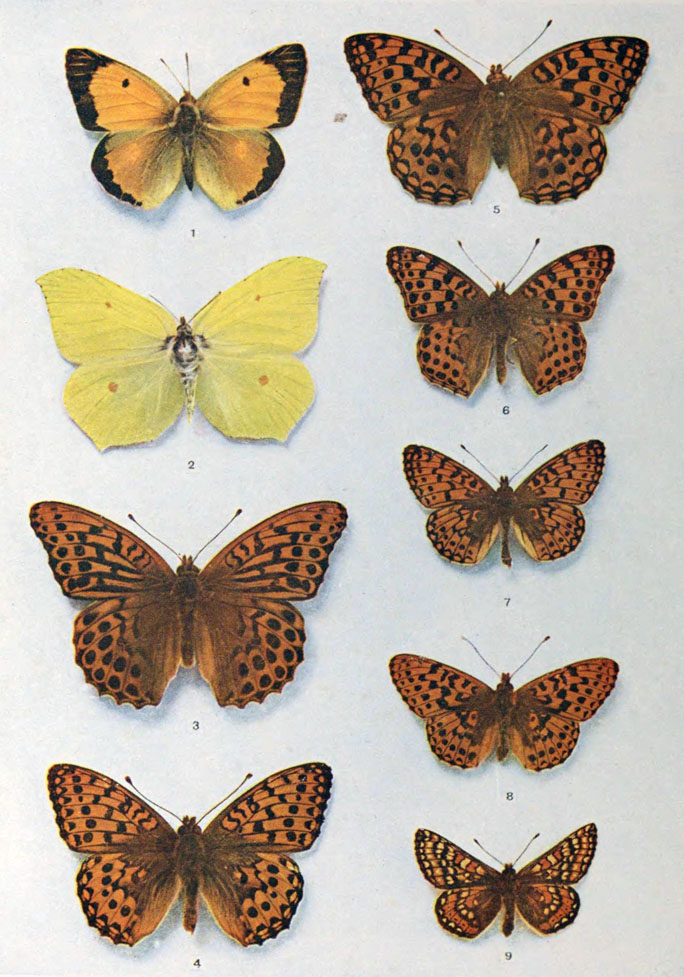

| IV. | CLOUDED YELLOW—BRIMSTONE—SILVER-WASHED FRITILLARY, ETC.* | 25 |

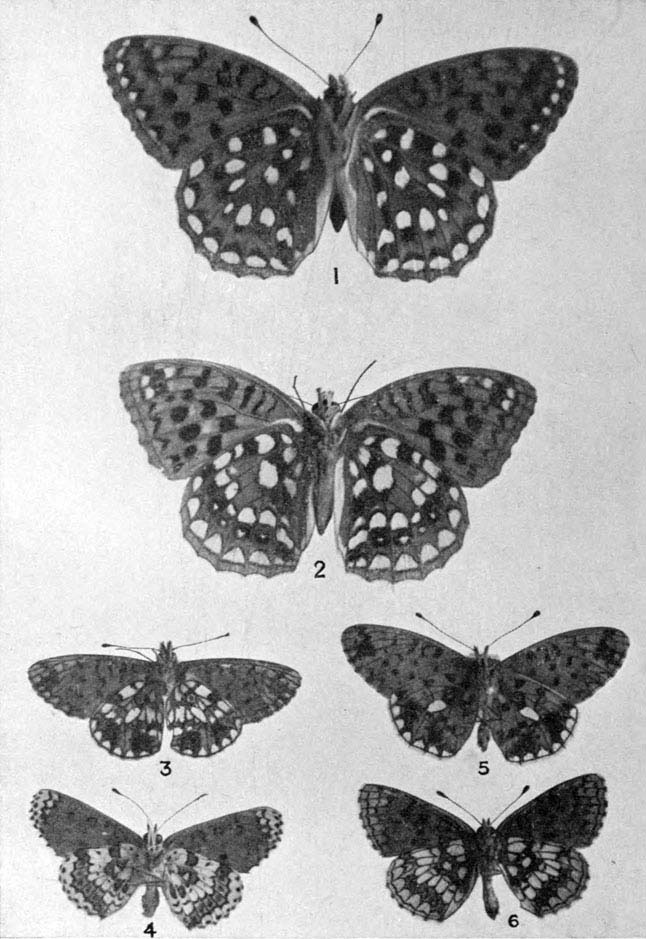

| V. | GLANVILLE FRITILLARY—HEATH FRITILLARY, ETC.* | 32 |

| VI. | “PAISLEY” METHOD OF SETTING | 35 |

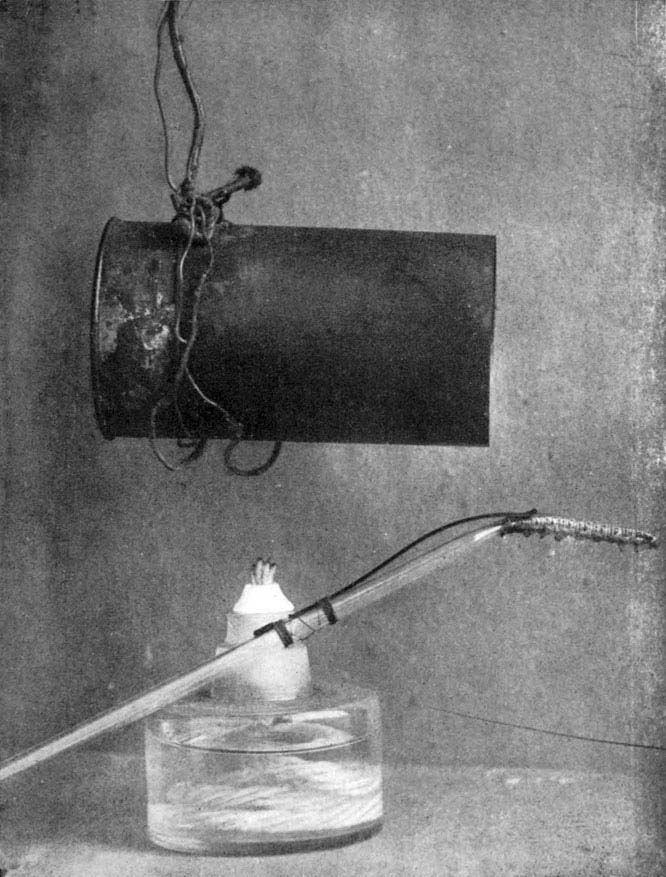

| VII. | APPARATUS FOR PRESERVING LARVÆ | 38 |

| VIII. | RED ADMIRAL—PAINTED LADY—MILK-WEED, ETC.* | 41 |

| IX. | MARBLED WHITE—MOUNTAIN RINGLET—SCOTCH ARGUS, ETC.* | 48 |

| X. | DARK GREEN FRITILLARY—HIGH BROWN FRITILLARY, ETC. | 51 |

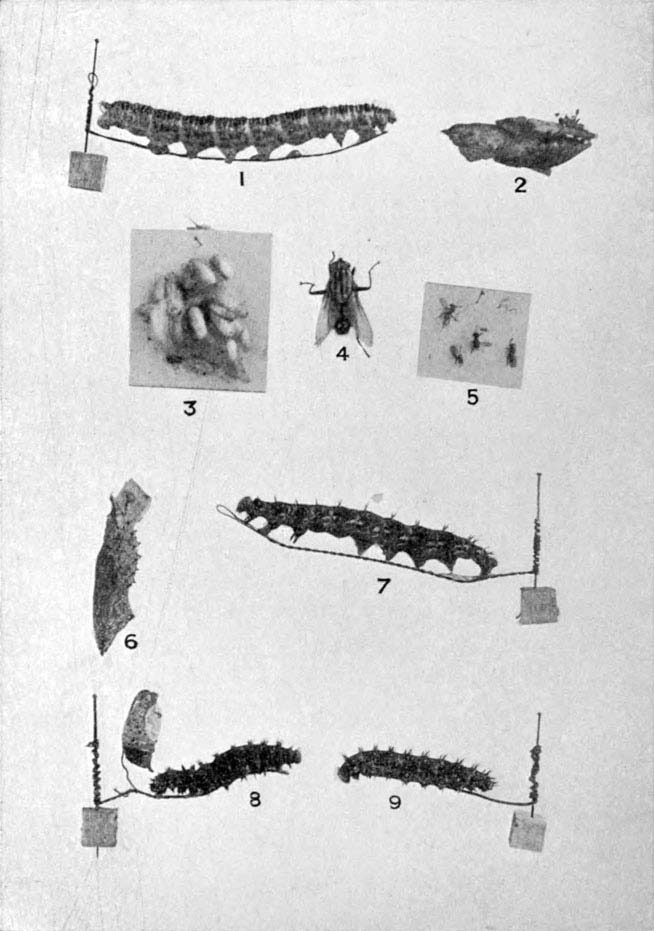

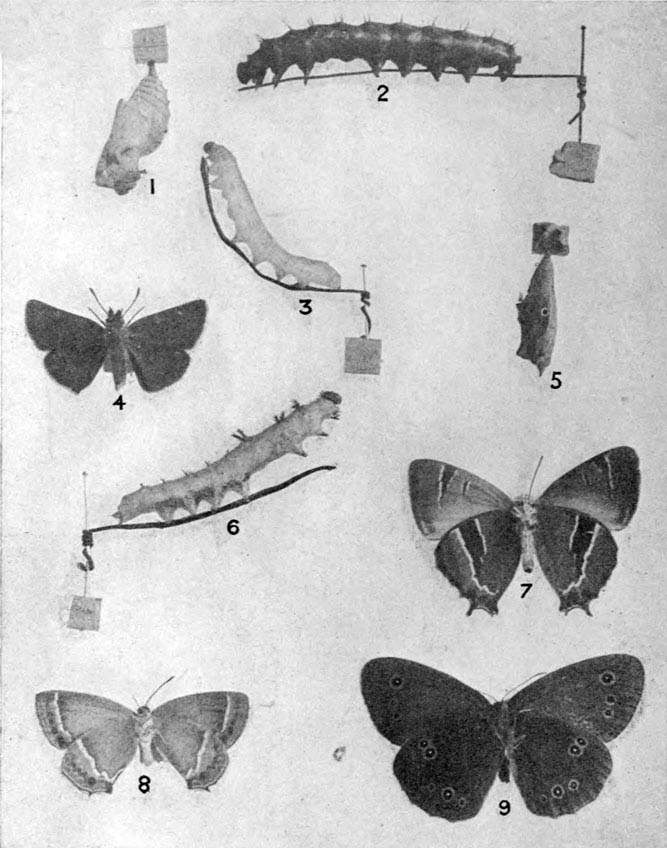

| XI. | LARVA OF LARGE GARDEN WHITE—PUPA OF LARGE GARDEN WHITE, ETC. | 54 |

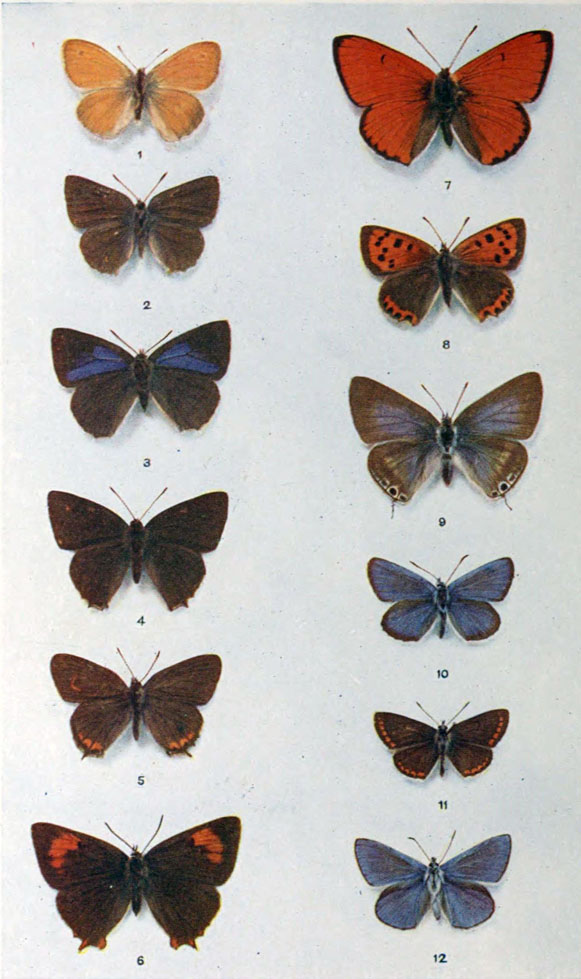

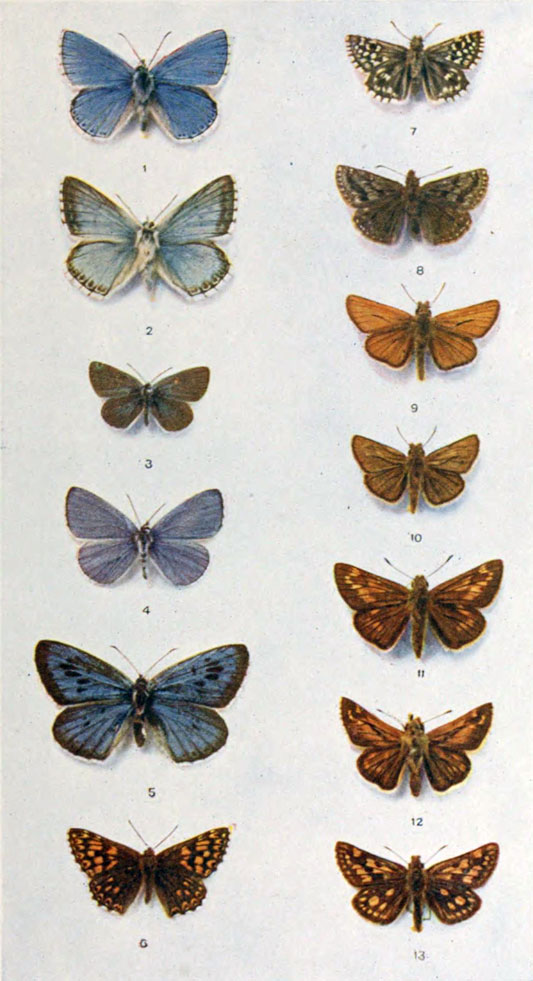

| [Pg viii]XII. | SMALL HEATH—GREEN HAIRSTREAK—PURPLE HAIRSTREAK, ETC.* | 57 |

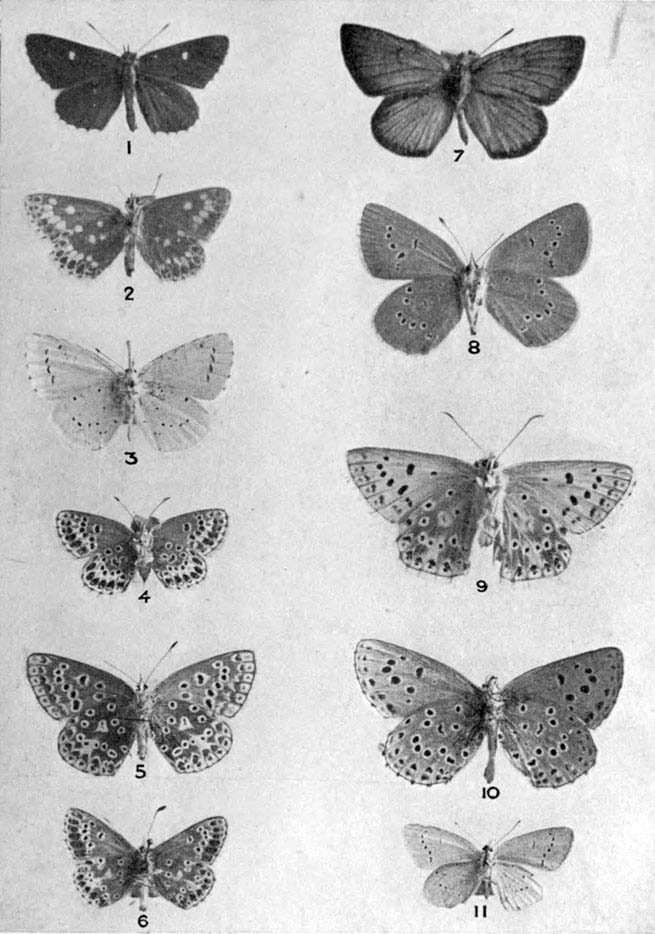

| XIII. | ADONIS BLUE—CHALK-HILL BLUE—LITTLE BLUE, ETC.* | 64 |

| XIV. | PUPA OF RED ADMIRAL—LARVA OF RED ADMIRAL, ETC. | 73 |

| XV. | BROWN ARGUS—AZURE BLUE—SILVER-STUDDED BLUE, ETC. | 80 |

| XVI. | LIFE-HISTORY OF SMALL TORTOISESHELL BUTTERFLY: OVA—LARVÆ—PUPA—MALE INSECT (TO RIGHT)—FEMALE(LEFT)—FOOD-PLANT (NETTLE)* | On the cover |

*These eight illustrations are in colour; the others are in black and white.

What is the difference between a butterfly and a moth, and how am I to distinguish between them? is a question very often put to the student of insect life—the entomologist.

Butterflies and moths both belong to the Natural Order, Lepidoptera, or scale-winged insects. Butterflies may be distinguished as day flyers, and the moths fly by night. The main physical difference between them appears in the forms of the antennæ, or horns; in the butterflies these organs are club-shaped at the extreme ends. But the antennæ of the various species do not all follow a common pattern. In some the knob is abrupt and much smaller, after the manner of a drum-stick; in others, the thickening commences well down the shaft, and is gradually increased until it very much resembles an Indian club. The antennæ of the moths, on the other hand, show much diversity of form, and in a great many species they are totally different in the male and female. A very common and beautiful form[Pg 2] is the feathered, or comblike, antenna; another is long and threadlike, and some show a combination of these two forms; others, again, seem to be striving after the butterfly type, and approach the club shape. It should be noted that not a few moths fly during the day, but it is rare, exceedingly rare, to find a butterfly abroad after sundown. With a little practice in observation, the novice soon learns to distinguish between the two.

The stages of development of butterflies and moths are practically the same: first the egg; next the caterpillar, or larva; then the pupa, or chrysalis; and, lastly, the imago, or perfect insect.

The eggs of the Lepidoptera are surpassingly beautiful. Are they like birds’ eggs? Not at all! In the first place they are too minute for comparison with the larger product of the birds; both in colour and form they more nearly resemble small shells or pearls, as a great many of them are beautifully opalescent, especially when empty. A good hand-lens will reveal a great deal of their beauty, but the low power of an ordinary compound microscope will be necessary to enable you to see all the nice detail of pattern sculptured on their surfaces. Each species of butterfly, or moth, produces eggs of particular shape and ornamentation, so it is quite possible, in most cases, to say to which species an egg belongs. How long the egg may remain unhatched depends a good deal upon which butterfly’s egg it is, the season of the year, and the temperature. Not many butterflies pass the winter in this country in the egg state, that season being usually passed either as[Pg 3] a half-fed hibernating caterpillar, or as a chrysalis; and in a few cases it is only the female which passes the winter in some secure retreat, to emerge again in the spring, and then deposit her eggs on the fresh-growing verdure. But, generally speaking, eggs laid during the summer hatch out in from ten to sixteen days. And it is well to be on the lookout for the young larvæ even earlier, if you intend to rear some species in confinement. If you have secured eggs to rear from, watch them from day to day to see if they darken, as they often assume a dark leaden hue immediately before hatching. This is a useful warning, and serves as a hint to have plenty of fresh food ready for the young family about to arrive.

The caterpillars are ravenous eaters; you will not notice this fact particularly at first, because they are then such tiny creatures, but in proportion to their size their eating capacity is enormous. They grow at an exceedingly rapid rate and to such an extent that they literally burst their skins! In a very short time—three or four days—the old skin bursts and out comes Mr. Caterpillar with a brand-new one. And this is the manner of their growth; several times (five or six) this skin-shedding process is repeated. And then the creature prepares for the last and final change before turning into a butterfly.

There are one or two more points I would ask you to notice about our caterpillar ere we pass on to consider his next stage. The legs are generally sixteen in number. There are six true legs, one pair on each of[Pg 4] the first three body-segments behind the head; four more pairs near the anal end, and the last segment carries another pair, known as the “anal claspers.” The first six may be said to represent the same legs in the perfect insect. Note also the breathing holes, or spiracles, placed in a row along either side of the larva. The head seems to carry very large eyes, but it does not really do so; the real eyes are very minute, and it requires a good strong pocket-lens to make them out. There are twelve of them all told, and they are not all of equal size. There are six on either side of the mouth, and the three larger ones on each side are not very difficult to find. The mouth is furnished with strong mandibles for biting and chewing food, and also contains the spinneret for the production of the silk used on various occasions. All these details should be carefully noted—the head, the eyes, the breathing spiracles, the mandibles, the fore-legs and claws, and the hind- or pro-legs. Mark the totally different types of feet which terminate these two sets of legs. You will need to use your lens for this observation, and to enable you to see the beautiful structure of the pro-leg foot, it will be necessary for you to examine it through a compound microscope. It is well for the young entomologist to know these more prominent features of a caterpillar’s economy, if for no other reason than to be able to answer the questions that are sure to be put to him on these and many other points.

But only a small percentage of the larvæ that are born into the world live to become butterflies; some[Pg 5] seasons a larger number than usual may escape, and then we have a butterfly year, but the relentless ichneumon flies soon restore the balance. They, too, have their young to provide for, and a strange mode of existence they have. Once you get to know these ichneumons at sight, you will be astonished at the number of them. All the summer through you will find them hawking about the trees, bushes, nettles, and heather, and, indeed, wherever larvæ are to be found, there, too, you will find these flies. There are many species of them. Once a female has discovered a larva its doom is sealed. The ordinary larva has very few defensive weapons; he may wriggle and squirm and look terrifying, but all the same the ichneumon sets about her task of placing one or two, and in many cases a dozen or two, of her eggs either upon or under his skin. These eggs soon hatch, and the little white maggots pass their existence inside the doomed creature, eating all the tissues away, at first avoiding the vital organs, which they leave until the last. When they have reached their allotted span, and are about to change to the pupa state themselves, they soon finish off their victim, and all that remains of what might have been a brilliant butterfly is a little shrivelled bit of skin and a host of little—or it may be a few big—black, brown, or grey flies. Sentiment apart, these parasitic flies are extremely useful. When you consider the large number of eggs laid by a single female butterfly or moth—from two to six hundred is a fair average—you will realize that if this enormous progeny were to survive and go [Pg 6]on increasing without any check, the vegetation of the world would very soon prove quite inadequate to support the vast army of caterpillars, to say nothing of you and me.

You may at some time find a dozen or two larvæ of some particular species of butterfly or moth, and at the time of collecting them they may seem healthy and all right, but weeks afterwards you may discover that only a very small number will change to chrysalids, the ichneumons having had the rest. If you can catch and induce a female butterfly to give you a batch of eggs in captivity, then you may be sure, providing your treatment of them has been right, that all your brood will arrive at the perfect state.

The next stage we have to consider we will pass over briefly. The change from the larva to the chrysalis is always a very fascinating performance to watch, not that one could sit and see the whole performance right through from start to finish, the time occupied is too long for that. Generally the process lasts a day or two, but by watching at frequent intervals, where several individuals are engaged at the same operation and each at its own stage of the work, it is not difficult to follow the whole process of the transformation. Try it with the larva of the Large Garden White butterfly, perhaps the commonest, and therefore the easiest to procure; you will gather plenty of “stung” or “ichneumoned” examples, but still a sufficient number should be clean to serve your purpose.

We will not enter into all the details of the “spinning-up”[Pg 7] process and describe how an attachment is secured at the anal extremity, and how our little friend “loops the loop.” Some species, such as the Tortoiseshell, get over this part of their difficulty by omitting the loop altogether, and therefore hang head downward, suspended only by the hooks and silk at the tail. Concealment during this stage is the creature’s only hope and chance of survival; other defence they have none. Their colour may occasionally protect them by virtue of making them harmonize beautifully with their surroundings. The ichneumons seldom molest them during the chrysalis stage; but birds and small animals have sharp eyes when foraging for food, so it is usually far more difficult to discover these chrysalids than to find the feeding caterpillars.

The time passed as a chrysalis is very variable; ten days to a fortnight in summer is sufficient for many species; others pass over the whole winter, like the spring brood of our common white butterflies, so that these can be sought for during the winter months under the overhanging portion of palings, walls, outhouses, and in similar situations. The cold does not seem to injure them; it may, and generally does, retard their emergence, and possibly has some effect on the colours of the wings, but it cannot change their ultimate pattern. Experiments have been tried with various chrysalids, part of a brood being hatched out after being submitted to a very low temperature, and another part of the same brood after being treated with a high temperature. Speaking generally, the coloration of those subjected[Pg 8] to the cold treatment was brightened and intensified, and Nature does the same thing in her own way. The early summer butterflies, which pass through the winter as chrysalids, are almost invariably larger and brighter than the midsummer or autumn brood of the same species.

But suppose our caterpillar to have successfully run the gauntlet—ichneumon, bird, beast, and beetle—and to have become a healthy pupa, and that the time has arrived when he must make the last and greatest transformation in his short and interesting career. Several days prior to his exit as a butterfly taking place, a noticeable change occurs in the apparent colour of the chrysalis.

As a matter of fact it is not the chrysalis shell which is changing colour, but the developing insect, the colours of which are beginning to show through it, at first rather faintly; but latterly the pattern of the wings can be distinctly seen, and the whole body surface gets darker. When this stage is reached, the advent of our butterfly is not long delayed. The hour chosen is usually early in the morning, so that by the time the sun is high and the fresh perfumed flowers are nodding in the breeze, our little butterfly has expanded and dried his wings, and is now quite prepared for the beautiful and consummating act in the wonderful drama of his existence.

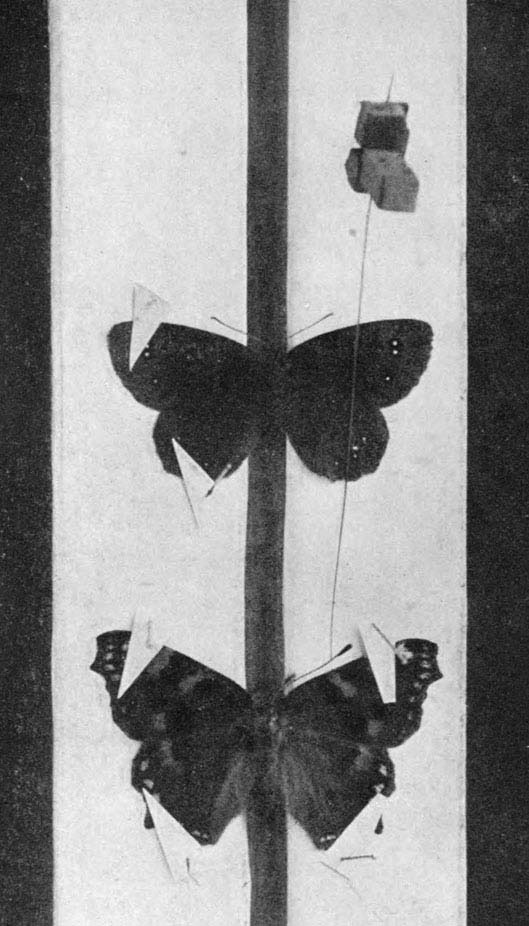

PLATE 2.

Method of Setting with Bristle and Braces

While he is drying his wings and preparing for a life amongst sunshine and flowers, we might spend a few minutes with him ere he leaves us, and the more so, as[Pg 9] now he looks his very best, arrayed in all his new-found finery. Such wings! no wonder he looks proud as he slowly opens and closes them, repeating this action over and over again as if to prove their smooth working before he launches forth upon the air.

And the wonderful pattern of these wings is all built up of tiny scales placed as regularly as the slates on a roof. Your pocket-lens will show you much of this, but to examine the individual scales, their various shapes and structure, you will require a compound microscope. These scales are the “dust” you will find on your finger and thumb if ever you pick up a butterfly in such an unscientific manner. You will notice, too, that the under sides of the wings bear quite a different design from the upper sides; this is nearly always the case, and in many foreign butterflies this difference between the two sides is so very remarkable as to be quite startling in its effect. Well I remember an old sergeant-major, who had spent many years in India, and had done a lot of “butterfly dodging” in his day, telling me of this wonderful effect. He said one would come upon an open piece of meadow-land blazing with flowers and butterflies, but, on being disturbed, the whole crowd of insects would rise in the air, and then, he would say, they looked like a different set altogether. When you capture a few specimens of any species, examine closely the under sides, and in any case, if you wish to preserve them, always set one of each sex with the under side uppermost.

Next to the wings the head claims our attention; it[Pg 10] supports three very essential organs—the eyes, the horns, or antennæ, and the tongue, or sucker.

The antennæ are undoubtedly the organs of smell, which is perhaps the most highly developed sense in the Insect World. That the eyes are a marvel of beauty, and that the tongue is a finely finished little instrument for its work no one can question; but the sense of smell has a much longer range than even the eye, with all its facets. And you will generally find, in relation to the faculty which any animal or insect has to exert most so as to procure its food and propagate its kind, the organ of that faculty reaches the highest point of development and service.

The eyes of the condor and the gannet must be marvellous in range and penetrating power. I have watched scores of the latter birds sailing and hovering 150 feet and more above a troubled sea. Suddenly there would be a slight pause, and then a rocket-like dive right down into the waves below. To see a fish on the surface from such a height would be a great feat, but to see and catch one a dozen feet deep in a broken sea as a gannet can do, is wonderful indeed.

With butterfly and moth the sense of smell is of the greatest importance. Their vision is good, but short in range; so to find the flowers wherein lies their food the sight is good, but the power to detect them by scent must be far better. “Over the hedge is a garden fair,” and if a butterfly cannot see through the hedge, he can at least smell through it. He could fly over it?[Pg 11] Yes, but if his sense of smell says there is nothing there for him, you see he is saved the time and trouble; and his life is short.

“Assembling” and “treacling” for moths are two methods employed by insect-hunters to secure an abundance of specimens otherwise difficult to obtain, and in both cases it is this same wonderful sense of smell which is the insect’s undoing.

For “assembling,” a captive virgin female is taken at dusk to the locality where the species is likely to occur, and if males are about they very soon make their appearance. The female being in a gauze-covered box, they will swarm over it in their efforts to find an entrance, and when thus engaged can be easily captured. As for the subtle odour emitted by the lady, you or I could never detect it, yet these moths come swarming from far and near. I once witnessed a curious phase of this instinct on a hillside in Arran. My attention was arrested by a number of males of Bombyx Quercus (variety, Callunæ), keeping near and flying over a certain spot, and, thinking a female might be about, I went over to investigate. It was a female, but a dead and crushed one; how it had met its end I could only conjecture; but evidently, although the insect was mutilated, the scent still lingered, and brought the males circling round. This large moth flies boldly during the day, and in Arran the larvæ feed on the heather.

The eyes of a butterfly are large and of the usual insect pattern—i.e., compound, being made up of a number of tiny lenses, hexagonal in shape, like the[Pg 12] honeycomb of the domestic bee. Roughly, about three thousand of these lenses go to make up the two eyes. As pointed out, their range of vision is comparatively short, but within their range vision must be very keen—before, behind, above, and below. I once saw a sparrow try to capture a Large Garden White in a street in the town; he darted at it again and again, much in the manner of the ordinary spotted flycatcher, but the butterfly seemed to have no difficulty in evading him, and eventually he gave up the game.

A small portion of the eye makes a good slide for the microscope, but the individual lenses are hardly visible through an ordinary hand-glass. On the top of the head are one or two small simple eyes, which do not look as if they could be of much service, but one never knows, and the butterflies will not tell, although they have long tongues.

The tongue is a very pretty structure; when not in use it lies coiled up in spiral fashion like a watch-spring, and is then well protected by two little side-covers called the “palpi.” Needless to say, the tongue cannot sting. No moth or butterfly has a stinging organ; the tongue is too delicate for any “cut and thrust” work. It is not difficult to mount a butterfly’s tongue for the microscope, and its examination well repays the trouble. Particularly noticeable under the microscope are the little bell-shaped suckers placed in long rows near the tip. If you wish to make and examine a cross section, take the head of a freshly killed specimen and extend the tongue in a little melted paraffin wax;[Pg 13] when this is thoroughly set, cut it across in very thin slices with a sharp razor; place one on a glass slide, then on to the microscope stage, and there you are! You will soon discover that the simple-looking tube is a very complicated affair, and quite a little study in itself.

We will not linger over what remains of the anatomy of our butterfly. The legs are six in number, but occasionally the first pair are useless for walking, and only the middle and last pairs are fully developed. Always remember the maximum number of legs for all insects is six. Caterpillars may have more or less; they occur as footless grubs with no legs at all, while some have as many as sixteen legs.

The last, or abdominal, section of a butterfly’s body carries the sexual organs; it is usually more slender in the males than in the females.

In the rearing of butterflies from eggs and in watching them all through their larval stages, we learn a great deal concerning their life and habits, and finally secure perfect specimens for the cabinet. But the glories of the chase and the charm of the country ramble weigh more in the balance with the naturalist, and the story of a captured specimen is often far more interesting than the record of a bred one.

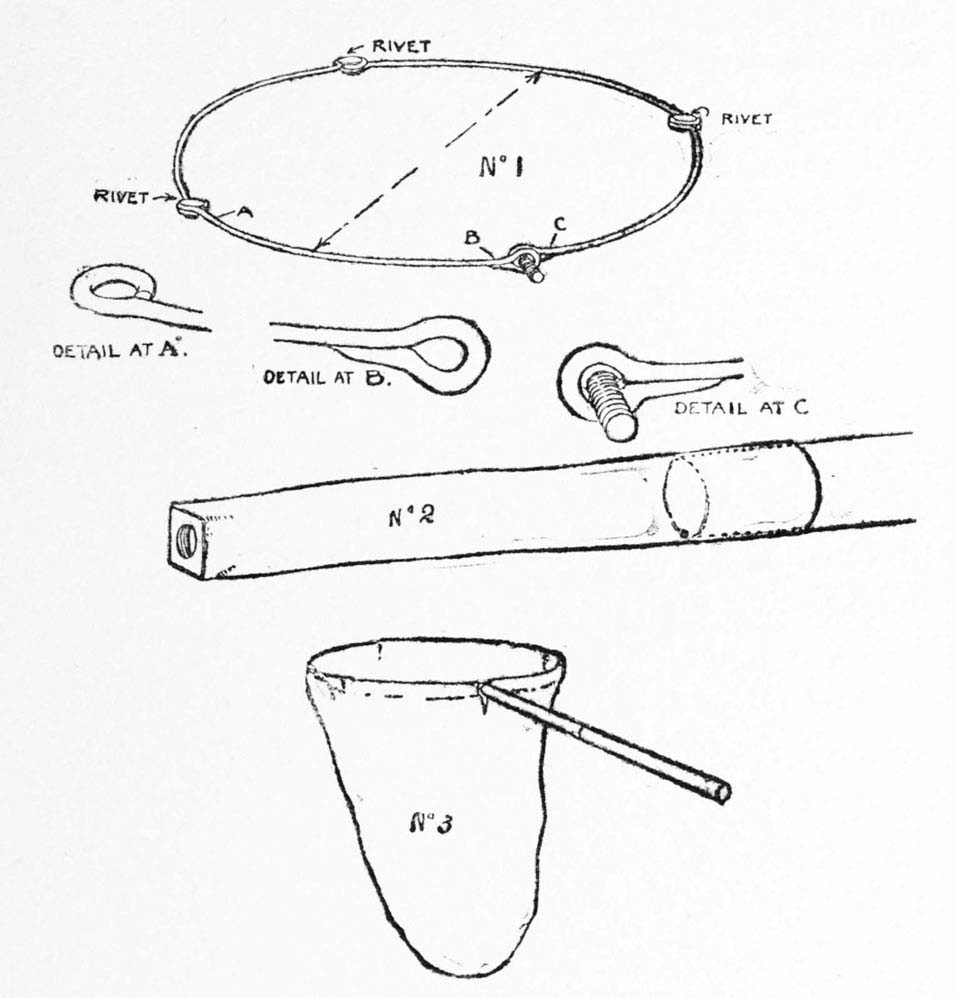

[Pg 14]Of butterfly nets used in the chase there are many and varied patterns in the market. I made my own and a better balanced one it would be hard to find. Having seen and handled a few in my time, my experience has been that they are mostly too heavy, have too many loose parts, and their weight is badly distributed. Indeed, I saw one lately which felt more like a hammer in one’s hand. I think if you try to get one made after the pattern here described and figured on p. 15, you will not be disappointed with it.

Now, it is one of the avowed purposes of this little book to make the study and collecting of butterflies cost all the time a boy can spare, and little, or, at least, not much in money. The requirements for a ring folding net are 2 yards of steel wire, rather less than 1/8 inch in thickness (cost about threepence); three copper rivets and washers, 3/16 inch by 3/8 inch long (cost one penny); one 1/4-inch iron screw-head bolt and nut (one penny). Cut the wire into two pieces, each 20 inches long, and two pieces 16 inches long. If you can get a tinsmith friend to turn the eyes for you, so much the better; you will thus avoid the most difficult part of the operation, but you would lose some valuable lessons and the satisfaction of having made the whole thing yourself.

The accompanying cut will show you how the eyes are turned and riveted, and how the nut is fixed in the tube which the tinsmith will make for you, and he will also solder the nut in the narrow end for a few coppers. Or you can get him to make the whole[Pg 15] concern, as I have done for a friend of mine. I simply gave the tinsmith mine for a pattern, and in a few days he handed me over an exact duplicate, and only charged one shilling and sixpence for it.

Details of Folding-Net.

1, Ring open, about 16 inches diameter; 2, tin tube with nut soldered in at narrow end; 3, net complete, showing wooden handle fitting into tin tube. Detail A shows how eyes are turned; B, larger eye for passing over screw; C, screw soldered in position.

The net itself is easily made. You will need 1-1/2[Pg 16] yards of the best and strongest muslin and a piece of stout twilled cotton, with which to make the hollow binding round the wire for strength. This binding must be at least 2 inches deep, so as to slip off and on the ring easily when you wish to repair the ring or wash the net. Get green muslin if you care for it; I tried green, too, but speedily gave it up, as I found the white net more effective for seeing and handling moths in after dark.

Do not shape the net down to too fine a point; rather make it more of a cup-shape and nearly the depth of your arm. And, lastly, while we are on the subject of the net, always carry a few strips of gum paper with you on an excursion; they are very handy and effective for repairing a damage, say, after contact with a bramble-bush.

Most butterflies are very impatient in the net, and strongly resent their imprisonment, so either double your net over the instant a capture is made, or catch the net by the neck, so to speak, with your left hand, leaving your right free for the pinching process. Pinching must be very carefully done, or your specimen may be spoiled. It can be done only when the wings are closed; you give the insect a sharp nip between your finger and thumb nails, right under the junction of the wings and the body—i.e., on the under side of the thorax, always taking care not to crush or mangle the specimen. Do not attempt to actually kill it; just give a sufficient pinch to stun it; then you may open the net, remove your specimen, and pin it in your[Pg 17] collecting box, which should be as nearly air-tight as you can make it, and lined with sheet cork. Place some freshly pounded laurel-leaves secured in a piece of muslin at one end of your box. The fumes given off by the bruised leaves soon kill the insects. Don’t use ammonia for killing butterflies; it alters their colours, and, in fact, ruins some altogether. Cyanide of potassium or laurel-leaves are the best killing agents, and the latter are by far the safest for boys to handle, as cyanide is very poisonous.

PLATE 3.

“Cop” of “120’s” Cotton on Stand, and Setting-Needle for “Paisley” Method of Setting

Specially-made entomological pins can be purchased from all dealers in naturalists’ requisites. Black enamelled pins are the vogue just now, and they last longer than the silvered or gilt ones, and resist “grease” better. Many insects, you should know, have a small, and some a large, amount of oil in their bodies, which gradually makes its presence seen, first in the abdomen, and later it spreads (if not checked) to the wings. The oil, coming in contact with the white or yellow pin, soon corrodes it through; the black enamel resists its action longest. Try to check this “greasing” of your specimens on its first appearance on the body, and if you notice it before it has spread to the wings all may be well. Break the abdomen off at once, and drop it into benzine, where you can let it remain a day or two. Then transfer it to a box of fine dry plaster of Paris for another day or so, and you will be surprised how beautiful and clean it will come out. Another hint: Push a little pin into each body when broken off, and attach a white thread to the pin; now you can do[Pg 18] what you like with the body without touching it with your fingers; lastly, replace each body, sticking it in position with a dab of entomological gum, to be had from Messrs. Watkins and Doncaster, 36, Strand, W.C.

Supposing you have arrived home with a few butterflies, and wish to set them. This is best done as soon as possible after they are killed. They may remain unset a few days if kept damp and yet properly aired; you must prevent them from hardening on the one hand, and getting mouldy on the other, through too long and close keeping; so have a watchful eye on them until set.

Setting-boards can be either bought or made. This is a question for each worker to determine for himself. Some collectors may have special facilities for making them, while others may have a profusion of pocket money wherewith to buy them. When I was a boy I made my own. It was a work of necessity. As a lad I had always so many specimens to set in summer-time that it would have been sheer ruination to have bought all the boards required.

On Plate II. you have an illustration of a setting-board, and the photograph is in itself an indication of how butterflies are to be set before being placed in the permanent collection. Note the setting-bristle mounted in a cube of cork. This is used to hold the wing in position while the card braces are being placed. The collector can easily mount a bristle for himself. A cat, badger, or other whisker will serve; do not try to push[Pg 19] it through the cube of cork, but glue it between two pieces; by doing so you will save your bristle from being spoiled and make a firmer job.

Keep your old thin postcards, from which to cut braces, and always have a boxful of various sizes handy, and in the same box, in a separate compartment, have an abundance of small, thin pins. Good setting, like other operations, is largely a matter of practice. Be careful not to injure the wings in any way, and place your braces on them so that they will not leave marks. I find a common fault with beginners is that they do not lower the specimen far enough down into the groove of the setting-board, with the result that the wings are bent and deformed by the braces pressing them down. See that the wings of your specimens lie flat and naturally spread out over the surface of the board on either side of the groove.

A setting-needle is sometimes an exceedingly useful tool. A very neat one can be made in a few minutes with a goose quill, a little sealing-wax, and the finest sewing-needle you can secure. Melt the wax and fill one end of the quill for half an inch or so, heat the eye end of the needle until nearly red-hot, and push it into the wax. This tool is very useful for adjusting a wing as occasion demands.

Let your insects remain as long as possible on the boards; they should be left on for a fortnight in warm, dry weather, but longer in the spring and autumn. The wings of imperfectly dried specimens are liable to spring up, or droop.

[Pg 20]There is another method of setting Lepidoptera which only requires to be more widely known to quickly supersede the use of braces and bristle. It is sometimes called the “Northern” method, but I prefer to call it the “Paisley,” because it was first used in that town. Its advantages are: Greater speed, less apparatus, less expense, and less liability to damage the specimens. Instead of the usual setting-board, a block is used—that is to say, your setting-boards are cut up into short pieces, in length a little less than the width of the board. Thus, a board 2-1/2 inches wide should be cut into pieces 1-3/4 inches long. As no corked surface is needed these blocks can be made or bought very cheaply; the usual cost, from a joiner, is about two shillings per hundred. The only other requisite is a cop of very fine cotton “1208” or even finer if you can get it. This you will be able to obtain from a cotton-spinner or his agent; by-and-by, as this method of setting becomes more widely known the dealers will probably stock a few of these fine cotton-yarn cops.* Plate III. will show you how to construct a stand for the cop. The rest is easy. Pin your insect in the same way as you would do for braces; place it on the block with wings well down on its surface, holding the block in your left hand. Give your cotton a turn round the extreme edge of the block, then bring it directly above your insect. Now blow the[Pg 21] wing on the left side as far forward as you wish it to go, and, while it is held extended by your blowing, bring the cotton down gently across it and there you have it, secured in position. Give two or three extra turns to hold it safe and repeat the operation for the other wing. If the wings should be stiff and refuse to go far enough forward, secure them as far forward as they will blow, with one turn of the cotton only, then gently assist them farther with a setting-needle. When in a satisfactory position, give the few extra turns of the cotton. I can set from sixty to one hundred and twenty insects in an hour by this method.

*Readers desirous of adopting this most excellent method of setting, and yet experiencing difficulty in getting suitable cotton-yarn, should communicate with the author, Mr. A. M. Stewart, 38, Ferguslie, Paisley.—Editor.

In removing an insect from a block, draw a sharp knife across the back of the block and lift off all the cotton at once. If the body of the specimen being set needs support, as sometimes happens, give the cotton two or three cross turns, and with your setting-needle raise the body on to this as shown on Plate VI. One hint more: See that your lines diverge from near the body at the bottom to near the tip of the wings at the top; the reason for this is that if you have to slip the wing forward under a turn of the thread it will not be damaged if the thread is arranged as indicated, whereas if your thread be laid on, say, from the outer bottom corner in towards the head, it would then scrape the wing, and be sure to remove some of the scales, thus damaging the specimen. The correct method is shown on Plate VI. With ordinary care and usage a good cop should last a year or two.

After your insects are set, by whatever method, they[Pg 22] need to be put aside in a dry, airy place to harden, and be secured against the ravages of mice and spiders. For their better protection, it is usual to place them in a “drying case,” which need not be an elaborate affair. My drying case was constructed out of an empty box obtained from the grocer; judging from the legend on the outside it had once contained tins of preserved apples. This is set up on end with the bottom removed and made into cross shelves. Light muslin cloth is tacked on in place of the bottom, so as to admit air but exclude dust. On the front, where the lid was originally nailed, is a hinged frame, covered with the same material, acting as a door. This drying house is not exactly pretty, but it has served its purpose admirably for many years.

A representative of the larva of each species is now considered essential to a complete collection of butterflies, and it is rendered even more perfect if egg-shells and chrysalis cases can also be included.

We now have a fairly easy and reliable process for preserving larvæ, a process which any aspiring young collector can carry through without much trouble or expense. It is really very simple and costs little. True, one can purchase apparatus specially made for the work for ten, or even five, shillings, but equally good results can be obtained with the expenditure of a few pence and a little ingenuity. I strongly advise young folk to make their own apparatus; by so doing they develop resourcefulness, and a handy youngster is not likely to make a failure of his life.[Pg 23]

In the first place you will need a hot-air chamber. Any empty toffee-tin will serve this purpose; one somewhere about 6 inches long by 4 inches in diameter will be a handy size. Get a piece of copper or soft iron wire, such as milliners use; give the wire two or three turns round the tin, twisting it as tightly as you can: then give the two free ends a turn or two round a gas-bracket near the burner, so as to bring your tin, with the open end next you, just over the burner. Or you may mount the tin over a spirit-lamp, in which event you will not be troubled with soot gathering on the outside of your oven. You now have an oven which you can make as hot as you want it by regulating your flame; you will soon discover the right temperature in which to dry a skin quickly without burning it. The skins of small, thin-skinned caterpillars dry very quickly, whilst those of large moths, such as the Oak Eggar, dry more slowly even with more heat.

Your next requirement is a glass blowpipe: this you can purchase at the chemist’s for a copper. Ask for a glass tube about a foot long and a quarter of an inch in diameter. Now, this tubing is made of a very soft and pliable kind of glass, and by heating it over a flame you should have no difficulty in drawing out one end of the tube into a fine point, not too long and not too abrupt; the illustration (Plate VII.) will show you the right length of the point. Hold the end over the gas-jet, keep turning it round, and in a minute it will become red and soft; remove the end of the tube from the flame, grasp it with a pair of forceps, and gently[Pg 24] and steadily pull the heated portion until it is drawn to a point of the required length. Nip off the part you caught with the forceps, and your tube is ready. Or another way is to heat the tube in the middle, and pull the two ends apart; this will give you two blowpipes, and you can make a fine point to one for small caterpillars and a wider aperture to the other for large ones. I used to know a friendly chemist who would “point” as many tubes as I wanted at his Bunsen burner in a few minutes. To complete your blowpipe, you will need about 2 inches of a watch-spring—any watch-repairer will give you a broken spring. The photograph on Plate VII. shows how the piece of spring is placed and used; it is bent to the required shape while heated, and bound in position with fine copper wire. The wire I use is the same as that required for mounting dried larva skins; it can be obtained at any shop where electrical appliances are sold; it is an extremely fine wire covered with green silk thread.

Your larva-preserving outfit is completed with a sheet of blotting-paper and an ordinary lead pencil. I will now describe the process.

PLATE 4.

1. Clouded Yellow (Male)

2. Brimstone (Male)

3. Silver-washed Fritillary (Male)

4. Dark-green Fritillary (Male)

5. High Brown Fritillary

6. Queen of Spain Fritillary

7. Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary

8. Pearl-bordered Fritillary

9. Greasy Fritillary

There could be no better species to begin with than the caterpillar of the Large Garden White butterfly; get one as nearly full-grown as possible, lay it out on the blotting-pad before you, place the lead pencil across it gently, but firmly, just behind the head, and roll it towards the tail. This kills the larva instantly, and empties out its internal organs by the anal orifice. Roll your pencil over it again to make sure the skin is[Pg 25] thoroughly clean inside; then insert your blowpipe into the anal orifice, letting the spring down on the last segment so as to hold the skin on; apply your mouth to the other end of the blowpipe, blow the skin out gently, and insert in the hot-air oven. Keep blowing gently for a few seconds; watch progress; touch the skin with your finger to see if it is getting hard and dry. Don’t blow too hard and make it look like a bursting sausage; try to keep it as natural in appearance as possible. In a few minutes it will be quite hard and dry; when dry, raise the spring, and a slight touch with the thumb-nail will liberate it from the blowpipe. The skin is now ready for mounting on silk-covered wire or a thin dry twig with a little entomological gum or seccotine. Our specimen is now ready to take its place in the collection.

We now have to face the problem of storing the collection. It is probably beyond the means of a young collector to purchase a cabinet with drawers, costing ten shillings per drawer, and he will be well advised to keep his specimens in store-boxes which he may be able to make for himself. I made some very serviceable ones with scented soap-boxes got from our grocer. Any size will do, but it is best to have your boxes all of one size if possible, say 10 inches by 14 inches by 4 inches. Get a few light deal boxes about these dimensions, nail on the lids, paper them all over the outside with good stout brown packing-paper having a glossy surface; paste it on with thin glue; set aside a day or two to dry. When dry, take a sharp saw and[Pg 26] cut the boxes round the sides and ends, so that each box is divided into two equal traylike halves. Glue a stout cardboard shell round the inside of one half, and attach the other half by two small brass hinges. The cardboard shell rises above the sides of the tray, and when the other half of the box is folded over it “stays put,” as the Yankee says; and, in addition, you have a fairly air-tight construction. These store-boxes fold after the manner of a book-form chess or draught board. Each half requires to be lined on the inside with sheet cork, which you can get from dealers in entomologists’ sundries, and finally covered with thin white paper. Such a store-box costs less than one and sixpence. Keep two or three boxes for duplicate specimens, and as many for your permanent collection. By-and-by you will want glass-topped cases, but by the time you have arrived at that stage you should have gained sufficient experience to enable you to know where to buy them.

See that every specimen before being transferred to your permanent collection bears with it a small label setting forth the date and place of capture, thus:

Keep these tickets as inconspicuous as possible and with the writing or printing in such a position as to be easily read without requiring to remove the insect.

The following list of British butterflies is thoroughly modern, and in labelling your specimens you should[Pg 27] adopt its nomenclature, and also follow the order given in arranging your collection. Both Latin and English names are included, but if you wish to be a thorough entomologist you should accustom yourself to use the scientific names. The Latin name is the same everywhere “from China to Peru.” If you use an English name of a butterfly in writing to a foreign collector he will probably fail to recognize the species referred to, but if you give the scientific name he will know it at once.

LIST OF BRITISH BUTTERFLIES

ARRANGED IN THEIR FAMILIES AND GENERA, WITH

THEIR SCIENTIFIC AND

POPULAR NAMES.

The remaining pages of this volume will be devoted to a description of the species mentioned in the foregoing list, together with notes on habits and other points. Assisted by the splendid coloured plates, which are produced from actual specimens, and the notes in the following pages, the young collector should have no difficulty in identifying the specimens he secures.

The Swallow-Tail (Papilio Machaon), Plate I., Fig. 1.—I find, in Scotland, where I live, that the first question put by friends looking over one’s insect treasures[Pg 30] usually refers to this butterfly. “Is that a British butterfly?” they ask; and on being assured that it is, they tender the information that they never saw one like it in this neighbourhood; and it takes much explanation to make them understand how rare and local some butterflies and moths are.

Alas! he is our one and only Swallow-Tail—the connecting link between our small island family and the great host of tropical and subtropical Swallow-Tails that flaunt their gorgeous colours under sunnier skies. And we hope he may long remain with us. The incentive to travel and capture this butterfly in his native haunts is not so great as it may have been half a century ago. For a few pence, or by exchange, the larva or chrysalis can be had from a dealer, and with ordinary care and attention it is not a difficult species to rear, and thus see alive.

That this species is already getting scarcer should be a warning to all who are interested in the preservation of our native fauna. Its extermination might not be a very difficult task; and although it is common in many places on the Continent, its reintroduction into England would certainly be attended with great trouble and difficulty.

Two years ago (1909) an experiment was made, under very favourable conditions, to “naturalize” a colony of this fine butterfly at Easton, near Dunmow, in Essex, the property of Lord Warwick. Lord Warwick and Professor Meldola laid down a large number of chrysalids which duly hatched, and, although the surrounding[Pg 31] marsh land had been liberally stocked with the food-plant, yet no eggs or larvæ were found after the butterflies had passed their season, nor have any been seen since.

Doubtless the butterfly has many natural enemies, and when we consider the draining, burning, and rush-cutting that go on in these fen lands, it will be apparent that the time cannot be far distant when an effort will need to be made, such as at Wicken, to provide “Cities of Refuge,” for many of our rare and persecuted little friends. I speak for birds, butterflies, flowers and ferns. An educated public taste would do more for them all than any amount of Acts of Parliament.

The Swallow-Tail measures fully 3 inches across the expanded wings; the prevailing tint is a pale primrose yellow, with bars and masses of black, the latter powdered with yellow scales on the fore-wings, and with pale blue on the hind-wings. There are also two red eye spots on the inner angle of the hind-wings near the tails. The under side looks not unlike a washed-out version of the upper, with a little more red on the hind-wings.

The caterpillar, too, is very beautiful, being green in colour, belted with black, and the black is studded with red spots. It thrives well on various members of the carrot family—carrot, parsley, fennel, celery; it has occasionally been found feeding on the common carrot leaves in rural gardens in neighbourhoods where the insect abounds.

The chrysalis, in which form the insect passes through the winter, is hung up in quite the orthodox manner,[Pg 32] belted round the back and attached at the tail. If you should find chrysalids in this position during the winter months and wish to remove them, cut away the whole support, and set them up again in your hatching cage, as you found them. Always avoid unnecessary handling of these delicate objects.

There are certainly two, and probably three, broods during a favourable summer, so this butterfly may be captured from May to August. Its headquarters are in the Fen counties of Cambridge and Norfolk, and it is found in many similar localities in fewer numbers.

Black-veined White (Aporia Cratægi), Plate I., Fig. 2.—This is one of the rarest of our butterflies, though why it should be so is rather difficult to say. As it feeds upon hawthorn in the larval state the puzzle is all the greater, as a commoner or more widely distributed plant it would be hard to find. It may be also found on blackthorn, cherry, plum, apple, and pear. It is not difficult to distinguish this fine insect from all the other “Whites” on our list. The wings are rather thinly scaled; you can note this by holding the insect up to the light, and looking through the wing with an ordinary pocket-lens. Do the same with its near neighbour, the Large Garden White, and you will see a difference—the Black-Veined White is semi-transparent, while the other is quite dense.

The almost black network of veins is another unmistakable feature, as is the entire absence of a fringe to the wings. Two and a half inches is the average expanse of the extended wings.

PLATE 5.

1. Glanville Fritillary

2. Heath Fritillary

3. Comma

4. Small Tortoiseshell

5. Large Tortoiseshell

6. Camberwell Beauty

7. Peacock

The caterpillar is rather hairy, dull-coloured underneath, black on the back, with two lines of broad red spots running from head to tail. When you find this caterpillar, you generally get a whole brood of them, as they are gregarious and live under a web until nearly fully fed.

The chrysalis is of a bright straw colour, spotted and streaked with black, and is not so angular as the chrysalis of the Large Garden White.

The butterfly is out in midsummer, and is rarely seen outside of the most southern counties, and even there it seems to prefer the coast. In Continental gardens it sometimes attacks the fruit-trees in such numbers as to constitute a plague.

The Large Garden White Butterfly (Pieris brassicæ) Plate I., Fig. 3, is well known to everybody. Town and country seem to be the same to him; indeed, I do believe he lives and thrives best in the town and village gardens; only twice have I met with the larva in a really wild situation, once finding a few caterpillars on a lonely shore in Arran, and I once got a chrysalis on a beech-tree trunk on the border of a large wood. Cabbage, kale, savoy, and cress, are the plants which the female usually selects as the most suitable to lay her eggs on, but as the caterpillars grow towards maturity there are few plants they will not attack, especially if they are driven by hunger and a lack of their usual food. The butterfly hardly needs description; suffice it to say that the female, besides having a rather larger expanse of black at the tip of the fore-wing, has also[Pg 34] two black spots and a dash (see figure) on the same wing. These are entirely wanting on the upper side of the male, but are present on the under side. The male is a little smaller than the female. Beyond question this butterfly is the most destructive of all the British species; fortunately it is largely held in check by ichneumon flies. Once I brought home a dozen or two caterpillars of this species from an isolated locality on the Mull of Kintyre, hoping to obtain some possible varieties. Not one butterfly did I hatch; they had all been stung, and mostly by a large grey dipterous fly (Plate XI., Fig. 4), although some few contained the little blackish imp which is their usual parasite. This little fellow it is who spins the small cocoons round the shrivelled skin of the victim (see Plate XI., Figs. 3, 5).

The eggs are laid singly or in small groups on the backs of leaves, and are somewhat long; they are straw-coloured, and stand up on end, so they are not difficult to find and collect, or destroy if too numerous. The caterpillar is yellow, speckled with black, and slightly spiny; it is also one of the easiest and most satisfactory to preserve. The chrysalis may be found during the winter attached to walls and fences. The butterfly is common throughout the summer.

Small Garden White (Pieris rapæ), Plate I., Fig. 4.—This butterfly is very like the last, but much smaller. Both species are generally found together. On the wing and in the caterpillar state they find the same nooks and corners in which to pass the winter as chrysalids.

PLATE 6.

But the caterpillars are very different in appearance. In this species the colour is a soft velvety green, with a faint yellow line down the back. Stretched at full length on the midrib of a cabbage-leaf, it is by no means a conspicuous object, and may be quite easily overlooked; but if you see the leaves riddled with holes, and find excrement lying between them and at the base, don’t cease looking until you find the culprit, sometimes deep in a cabbage, or on the back of the outer leaves.

Other caterpillars besides those of the Large and Small Whites may be present in force, notably those of the Cabbage moth (Mamestra brassicæ), large stout caterpillars varying from green to black; they are far too numerous, so have no compunction about destroying all you find. The caterpillar is apt to lose its colour in preserving, as is the case with all green caterpillars.

Green-Veined White (Pieris napi), Plate I., Fig. 5.—Unlike the last two species, this White is more often found in the country than the town, and in my experience it is only a casual visitor to suburban gardens. I have never found the caterpillars there.

To distinguish it from the last species it is only necessary to examine the under side, where both fore- and hind-wings are strongly veined with greyish-black, the female particularly so. On the upper side the veins are distinctly marked, but the line is finer.

In a rather wet meadow where Ladies’ Smock abounds in early June, I have seen this butterfly in profusion,[Pg 36] and not at all easy to capture when the sun was high. But when King Sol is sinking in the west, and all decent butterflies have gone to rest, a turn through the same meadow while the light still lingers reveals the Veined Whites all at rest on the flower-heads of the Ladies’ Smocks. It is then quite easy to select a few of the best, and search for varieties, until in the deepening twilight butterflies and flowers became so blended as to present only a whitish blurr to the eye. There are two broods—one out in June, the other in August.

The caterpillar is green, with yellow spots on the sides, and may be found on various plants of the cruciferous order, the cress group in particular. I have found it on the Ladies’ Smock (Cardamine pratense) and on the large-flowered Bitter Cress (Cardamine amara). For your collection always mount at least one of each sex with the under side uppermost. The specimen figured is a female; the male has only one round spot on each fore-wing.

Bath White (Pieris Daplidice), Plate I., Fig. 6.—This is the rarest of all our Whites; indeed, it is doubtful if it breeds in this country at all. A few specimens are taken annually on the south-east coast and neighbourhood, and the likelihood is that they are migrants from the Continent.

On the other hand, it is just possible that on account of its close resemblance to the Green-Veined White when on the wing, it is often passed over when mixed up with and flying amongst a number of that species.

The sexes are easily distinguished by the female having the upper side of the hind-wings broadly checkered with a double band of black spots, which is entirely wanting in the male. The under side, however, of both sexes is beautifully marbled in dark green on a creamy white ground. The caterpillar is a dull green with yellow lines on back and sides, and may be fed on cabbage or Dyer’s Rocket. The chrysalis is very similar to that of the Small Garden White.

The butterfly may be met with in May and June, and again in August and September.

The Orange-Tip Butterfly (Euchloë Cardamines), Plate I., Fig. 7.—This is the only member of its genus inhabiting this country, though there are several others met with on the Continent. It has a wide range in Britain and may be met with from Aberdeenshire to the south coast of England, although it appears to be becoming scarcer and more local in the northern half of the kingdom. The ground colour of the upper side of the wings is white, with a large orange patch occupying almost the outer half of the fore-wing, relieved by a black tip and a black spot. In the female these black marks are larger, but the orange is entirely wanting. The under side of the fore-wing is like the upper, but the under side of the hind-wing is beautifully marbled in dark green, an effect obtained by the commingling of black scales on a yellow ground.

The caterpillar is green, with a white line on the sides, and feeds on various species of Cardamine; hence meadow-lands are its favourite resorts, and there the[Pg 38] curious sharp-looking little chrysalis may be found hung up to some dead stem during winter.

The butterfly appears in early June and does not generally survive that month.

The Wood White Butterfly (Leucophasia sinapis), Plate I., Fig. 8.—This is the smallest and most fragile of our white butterflies. The wings are white with a black tip on the fore-wing, and the under side of the hind-wing clouded with black scales. The body is long, slender, and a little flattened laterally. It is not a common species, and is very local where it does occur. It has been found as far north as the Lake District, and down to the south coast. It is unrecorded for Scotland, but has been taken in Ireland.

The caterpillar is green, with yellow lines on the sides; it feeds on various members of the pea family—Vetch, Trefoil, etc. It appears on the wing in May, and sometimes a second brood occurs in August; so you may look for the caterpillar in June and again in September.

The Pale Clouded Yellow Butterfly (Colias Hyale), Plate I., Fig. 9.—I think there can be little doubt that this fine butterfly is on the increase with us; from all over the southern counties come records of its comparative plenty. In the Entomologist (October, 1911) I read of over one hundred being seen or captured by various collectors. Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Kent, Bucks, are amongst the favoured places, and Lucerne- or Clover-fields are the attractions.

PLATE 7.

Apparatus for Preserving Larvæ

The question of the migration of this and the following[Pg 39] species is still very far from being satisfactorily settled. That we do get a swarm over from the Continent when conditions are favourable is a matter of common knowledge, but whether we have resident and permanent colonies of our own is still doubtful. In any case this year (1911) has been a Hyale year, and we give thanks. The ground colour of this butterfly is a pale primrose-yellow. There is a broad black border beginning at the tip of the fore-wing and continuing on to the hind-wing, where it gradually dies out at the bottom angle; placed on this band of black are a few yellow spots. There is also a black spot on the fore-wing, and a faint orange spot near the middle of the hind-wing. The under side is more of a yellow shade, and a line of brown spots runs round the outer margin of both wings. There is a silvery spot in the centre of the hind-wings, like a figure 8 bordered with pinkish brown, and in fine fresh specimens the fringe is of the latter colour. The female is a shade lighter in ground colour and also shows more black.

The caterpillar may be looked for in June and July on Clover and Lucerne; it is green, with yellow lines running along the back and sides. The chrysalis is green with a single yellow line.

The latter half of August and the first half of September cover the best period of its flight in this country; on the Continent there is a spring brood.

The Clouded Yellow (Colias Edusa), Plate IV., Fig. 1.—As with the last species, we have still much to learn of the habits of this fine butterfly. Some years[Pg 40] it is plentiful, while in others hardly a specimen will be seen—and as for the caterpillars, we never hear of them being successfully searched for. The probability is that from a few spring visitors from the Continent we get a number of descendants in August, when a great many more arrive from across the Channel and mingle with them. The distribution of nearly all animals is regulated by the food-supply, the climate, or their enemies; yet none of these seem to satisfactorily account for the disappearance and reappearance of Edusa with us. It is a strong flying insect with a roving disposition, and on quite a few occasions it has been noted as far north as Arran and the Ayrshire coast, in Scotland. The brilliant orange and black wings make its identity unmistakable. Not so, however, with the light sulphur-coloured female variety, which very nearly approaches the typical female form of Hyale, but it may be distinguished by the broader black band on both fore- and hind-wings, and a heavy sprinkling of black scales near the base of the former, and all over the latter. The orange spot too, in the centre of the hind-wing is deeper, and, being on a darker ground, looks much brighter. There is no corresponding male variation.

The caterpillar is dark green, with a light line on each side, varied with yellow and orange touches. It feeds on various plants of the pea order—vetches, trefoils, clovers, etc. The chrysalis is brown spotted, and is striped with a yellow line. The butterfly appears with us during August and September.

PLATE 8.

1. Red Admiral

2. Painted Lady

3. Milk Weed

4. White Admiral

5. Purple Emperor (Male)

The Brimstone Butterfly (Gonepteryx rhamni), Plate IV., Fig. 2.—When I glance at this beautiful butterfly, I always feel inclined to laugh, not at the butterfly—oh dear no!—but at a practical joke I once saw through, much to the astonishment of a soldier friend. He had brought home a large assortment of fine butterflies from India, and in going over the stock my attention was arrested by the peculiar pattern on one of them. For ground colour and outline it certainly resembled our own Brimstone, but what weird markings! Turning the hand-glass on it revealed the fact that it was hand-painted. I asked the sergeant who did this, and then he suddenly remembered, and gave vent to a loud guffaw. “The scamps, by Jove! That carries me back to a certain mess-room at Darjeeling when this insect was handed over to me by a certain young officer as a great rarity. He was sure there was not another like it in the camp; and he was right. Lots of our fellows went ‘butterfly dodging,’ and had big collections to take home; but not one of them had this one. They named it ‘The Officer’s Fancy.’ Now, I recollect seeing this same officer out sketching and fooling around with a box of paints. It’s clever, though, isn’t it? He took us all completely in.” This was hardly to be wondered at! The colours had been very delicately laid on, and the pattern adopted was of the eye-spot and streak order, so that the whole effect was quite harmonious and in good taste.

But the Brimstone requires no artificial aids to make it a warm favourite with all butterfly lovers; if it lacks[Pg 42] variety of colouring, it more than makes up for it in the beautiful sweeping outlines of the wings. No other butterfly on our list can show such sweet harmony of line and contour. Like a breeze-blown daffodil, he greets us on our early spring rambles, just when the opening blossoms and leafy buds are all doubly welcome, in that we have missed their friendly presence through the long days of winter. The female hibernates in all sorts of out-of-the-way corners—in dense holly-bushes, piles of brushwood, chinks of walls, etc., coming forth again in May or even earlier to deposit her eggs on the Buckthorn and its allies. The antennæ are rather short and more like a club than a drum-stick, while the beautiful white silken mane along the back is quite a noticeable feature. The female is of a much lighter tint than the male.

The caterpillar is green, with paler sides, along which runs a white line: it may be found on the Buckthorn from May till July. The chrysalis, which is supported on the tail and band principle, is green and yellow, and rather oddly shaped. It hatches in the course of about three weeks. This butterfly is a plentiful insect south of the Border, but we have yet to record it for Scotland.

The Small Pearl-Bordered Fritillary (Argynnis Selene), Plate IV., Fig. 7.—Like all the members of its family the ground colour of the wings of this insect is a reddish-brown, marbled and spotted with black. For size it differs little from the next species, and the upper surface of the two being so much alike, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between them. The under side[Pg 43] (Plate X., Fig. 3), especially of the hind-wings, however, renders the task of identification comparatively easy: the ground colour is a deeper brown in this species and causes the pearl border to stand out in stronger relief; besides, numerous other pearl spots brighten its surface. It is a local butterfly, with a wide range of distribution both in England and Scotland; and where it does occur it is generally common. In the South it may be double brooded, but in the North the June flight is all we see of it for the year.

The caterpillar is black, with an interrupted white line along the back; the spines are brown; it feeds on the dog violet (Viola canina). The chrysalis is ash-coloured.

The Pearl-Bordered Fritillary (Argynnis Euphrosyne), Plate IV., Fig. 8.—Perhaps this is the commoner of these twin butterflies, though its range of distribution is much the same as the foregoing. In its case, also, the under side of the hind-wings furnishes us with the main points of distinction. Here the markings are a warm mid-red shade on an ochreous ground; the pearl border is very pronounced, and in the middle of the wing a single pearl reposes. Nearer the body there is another smaller spot hardly so bright. If you set several of these two species with the under side uppermost, you will soon get quite familiar with the difference between them. Plate X., Figs. 3, 5, shows this distinction.

The caterpillar is similar to the last species and prefers Viola as a food-plant, but I have found it in[Pg 44] little colonies where it most certainly must have fed on other plants, as Violas of any species were distinctly rare in the district, which is wet and marshy. For Scotland there is a single brood in June, while in the South it is double-brooded—May and August.

The Queen of Spain Fritillary (Argynnis Lathonia), Plate IV., Fig. 6.—This is, unfortunately, the rarest of all our Fritillaries; unfortunately, because it is the most beautiful and brilliant. In outline the fore-wing differs from that of the two preceding species, being slightly concave on the outer margin, while the hind-wing bears a slight trace of scalloping. But it is on the under side where all the treasures lie. A row of seven pearl spots adorns the outer margin of the hind-wing; then comes a row of small dark spots, each with a pearl-spot in its centre; then a profusion of large and small glittering patches completes this beautiful wing. The under side of the fore-wing has only three (or sometimes a tiny fourth) pearl spots near the tip. This butterfly is taken occasionally in clover-fields in our south-eastern counties. The specimens taken there are possibly migrants from the Continent.

The caterpillar is dark, with a white line on the back, yellow lines on the sides, and is clothed with short red spines. It may be found on Violas. As this insect is double-brooded on the Continent, it is well to look out for it during the whole summer from May to September.

The Dark Green Fritillary (Argynnis Aglaia), Plate IV., Fig. 4.—The only claim this handsome species has to be called green lies in the fact that the under side[Pg 45] of the hind-wing has for its ground colour a delightful tawny green. But the main attraction is the lovely rows of pearl spots ornamenting the under side (Plate X., Fig. 1); and there are four of these rows. One, and it is perhaps the finest, runs round near the outer margin, and consists of nine gems; the next, a little nearer the body, has eight, and is slightly irregular; the next row has only three, rather widely apart; and the fourth, and last, has also three very small ones quite near the base of the wing. The under sides of the fore-wings have also their pearl spots. Near the outer margin you will find a row with eight of them, beginning boldly near the tip; they gradually fade until the last of the row is barely visible. On some male specimens there are two silvery spots also near the tip, but on other specimens these are absent. The under side of the fore-wing has very little green to show; the tip of the wing is just tinted, and this tint is carried along the costal margin. I have described the under side in some detail, as I have seen it described as having only three rows of spots on the hind-wing, and no pearl spots at all on the fore-wing; and for another reason, I want you always to confirm your captures by a good textbook, as by so doing you will learn some valuable lessons in comparison and observation, and in noting details; and also it will enable you, perhaps, to add some fine variations to your collection.

The caterpillar lives on various species of wild Viola, and may be found on them in the early summer, but as the butterfly has a wide range of distribution, season[Pg 46] and locality make it vary a good deal in the time of its appearance. It has been found from the North of Scotland to the South of England. July is the month to look for it. I always find it more abundant near the coast. It is a bold flying species, and often difficult to capture; but in good settled weather I have taken it frequently at rest on thistle-tops at sundown.

The High Brown Fritillary (Argynnis Adippe), Plate IV., Fig. 5.—In this and the foregoing we have again two species very easy to confound, and all the more so when we note that stable characters are somewhat hard to find on the upper surface of the wings—in general the ground colour in Adippe is richer and darker, and the outer margin of the fore-wing is not so rounded as in Aglaia, being either straight or very slightly concave. The arrangement of the second row of spots, which runs round near the outer margin of both wings, is different in the two species, but they are very inconstant and even vary in the sexes; so the under side must be again consulted (Plate X., Fig. 2). And here we have an unfailing test. In Adippe, on the under side of the hind-wing near the outer margin, there is a row of dark red spots lined internally with black, and in the centre there is a small pearl spot. These eyelike spots are never present in Aglaia. The general green tint, too, of Aglaia is absent in Adippe. The silvery spots on the under side of the fore-wing of Aglaia are rarely to be seen in this species. In some females of Adippe three shadowy spots are visible near the tip. I have never seen these on a male; so we have it that, in the[Pg 47] great majority of specimens of Adippe, the under side of the fore-wing is devoid of silvery spots. While Adippe may be fairly common in the South, it is by no means so widely distributed, nor does it range so far north as Aglaia. In Scotland it is unknown.

The caterpillar is dark grey, with a whitish line along the back, and is covered with rust-red spines. It feeds on Viola. The butterfly appears in July.

The Silver-Washed Fritillary (Argynnis Paphia), Plate IV., Fig. 3.—This is the largest of our native Fritillaries, and is easily distinguished from the others by an entire absence of the silvery spots so characteristic of this genus. The upper surface of the male is of a warm, orange-brown, streaked and dotted with black on both wings; the under side of the fore-wing is much lighter, the spots on it are smaller, and the tip is marked with olive; the hind-wing under side bears a fine combination of pale olive with faint lavender and silver streaks, while its outer margin is distinctly scalloped. The female is quite different. In it the ground colour of the upper side of the fore-wings is much paler, and the black streaks along the veins are absent. The hind-wings have the same pale tint, but with a more decided tinge of olive, while the under sides of both wings, and especially of the hind ones, are pale olive green, and the scalloping round the outer margin of both wings is more pronounced. In the female variety Valesina, the upper surface has a dark olive ground shading out towards the tip of the fore-wings. This, with the black spots lying on it, gives the butterfly[Pg 48] quite a black appearance at a little distance. This variation is mostly found in the New Forest. The butterfly is common in many districts of England, but is rare in Scotland.

The caterpillar is covered with long spines, nearly black, and has a pale line along the back and sides; it feeds on Dog Violet and Wild Raspberry. The chrysalis is rather stout, hangs by the tail, and is greyish, with shining points. The perfect insect is out in July and August.

The Greasy Fritillary (Melitæa aurinia), Plate IV., Fig. 9.—This may not seem a pretty or poetical name for a butterfly. Beauty, poetry, and the “fitness of things,” might have suggested a more appropriate title; but, as Dickens has said, “the wisdom of our ancestors is not to be disturbed by unhallowed hands,” and as the technical name is in this instance some compensation, we may have to let it go at that. “Greasy” the butterfly is not, but only looks as if it were, when slightly worn; and, owing to some peculiarity in the arrangement of its scales, this slight wearing is very soon accomplished. Happily it is not a difficult insect to rear, and fine specimens without a suspicion of greasiness in their appearance can thus be had for the cabinet. This butterfly is quite distinct from any other British Fritillary, inasmuch as it has two very distinct ground colours on the upper side of its wings, a rich orange-brown and a pale ochreous yellow. The bands of this latter shade are bordered with dark brown; a reference to the coloured figure will show how these[Pg 49] colours are disposed. It is a rather variable species, and is widely distributed. It is found in glens and damp meadows and is generally abundant where found, though local.

PLATE 9.

1. Marbled White

2. Mountain Ringlet

3. Scotch Argus

4. Speckled Wood

5. Wall Brown

6. Grayling (Male)

7. Meadow Brown (Female)

8. Small Meadow Brown

9. Ringlet

10. Marsh Ringlet

The caterpillar is black, with a greyish line along the sides, and a small white dot above this between each segment. The chrysalis is ashen, with red and black spots; it is rather “dumpy,” and may be found on various low plants early in the summer, and again, in some southern localities, in the autumn. Like nearly all the Fritillaries the larvæ hibernate while very small, so it is best to leave them in their natural state until fairly well fed. Narrow-leaved Plantain, Scabious, and, some observers say, Foxglove and Speedwell, are its favourite foods. The times of flight are May and August. In many Scotch localities, Argyllshire, Ayrshire, etc., this species is abundant.

The Glanville Fritillary (Melitæa Cinxia), Plate V., Fig. 1.—This little butterfly is one of the “threatened species.” If due care and discretion be not exercised, there is a possibility of its becoming extinct in this country. “Threatened people live long,” but it were wise not to push our little friend too far; and wiser still if collectors who live in or near its favourite haunts would not only try to preserve it, but also make some attempt to spread its range into other localities apparently suitable for its propagation. We have far too few native butterflies to run the risk of losing any we have. And as the food-plant is the Ribbed or Narrow-leaved Plantain, it follows that even were this[Pg 50] species as abundant as its food would warrant, it could not possibly do any harm to anyone, either gardener or farmer. The ground colour might be called Fritillary brown, relieved with the usual black bands and spots; the hind-wings show a distinct row of black spots on a light ground running round near the outer margin. But the under side (Plate X., Fig. 4) is more striking and unmistakable, especially that of the hind-wing. The fringe itself is dotted at intervals with black; then follows a line of crescent spots on a cream-coloured ground; a fulvous band scalloped with a black outline traverses the wing, and on this band are dark spots edged with red. Then there is a cream band with black spots, and a broken-up band of fulvous spots edged with black. There is cream again next the body, with a few more black spots. The under side of the upper wing is a light orange-brown, and cream towards the tip, and bears a few black spots.

The caterpillar is black, with dark red between the segments; head and pro-legs red; spines short, crowded, black. The chrysalis is stout, yellowish-grey, dotted with black, and is sometimes enclosed in a loose web. The chrysalids I have reared always adopted this mode of concealment and protection. I have also been much impressed with the strong resemblance of the caterpillar to the flower-heads of the Narrow-leaved Plantain, amongst which it lives. The Isle of Wight appears to be the headquarters of the species, and it is found in a few other localities on the mainland. It appears in May and June.

PLATE 10

1. Dark Green Fritillary (under side)

2. High Brown Fritillary (under side)

3. Small Pearl Bordered Fritillary (under side)

4. Glanville Fritillary (under side)

5. Pearl Bordered Fritillary (under side)

6. Heath Fritillary (under side)

The Heath Fritillary (Melitæa Athalia), Plate V., Fig. 2. —There is more black, or dark brown, on the upper surface of this species, hence the insect looks darker in general aspect than any of the foregoing Fritillaries. The under side, too (Plate X., Fig. 6), is marked very like Cinxia, but the light bands on the hind-wings are more of a yellow tint, and the line of black spots through the central band are wanting; the veins are also more prominent and black. Altogether it is not difficult, on comparing the two under sides, to at once distinguish them.

It is also a rather local species, being confined to the South of England and Ireland. Both caterpillar and chrysalis are very like those of the last species; the spines, however, are rust-coloured. It feeds on Plantain. The perfect insect is out from May to July.