![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Some Artists at the Fair

Author: Francis Davis Millet

W. Hamilton Gibson

Will H. Low

John Ames Mitchell

Francis Hopkinson Smith

Release date: May 2, 2020 [eBook #61989]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

| Frank D. Millet | J. A. Mitchell |

| Will H. Low | W. Hamilton Gibson |

| F. Hopkinson Smith | |

New York

Charles Scribner’s Sons

1893

SOME ARTISTS AT THE FAIR

| Frank D. Millet | J. A. Mitchell |

| Will H. Low | W. Hamilton Gibson |

| F. Hopkinson Smith | |

New York

Charles Scribner’s Sons

1893

{vi}

Copyright, 1893, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

| PAGE | |

| THE DECORATION OF THE EXPOSITION | 1 |

| TYPES AND PEOPLE AT THE FAIR | 43 |

| THE ART OF THE WHITE CITY | 59 |

| FOREGROUND AND VISTA AT THE FAIR | 81 |

| THE PICTURESQUE SIDE | 100 |

THE grand style, the perfect proportions, and the magnificent dimensions of the buildings of the World’s Columbian Exposition, excite a twofold sentiment in the mind of the visitor—wonder and admiration at the beauties of the edifices, and regret and disappointment that they are not to remain as monuments to the good taste, knowledge, and skill of the men who built them, and as a per{2}manent memorial of the event which the Exposition is intended to celebrate. This complex feeling is a natural one, and is perfectly comprehensible in the presence of the noble porticos and colonnades, the graceful towers, superb domes, and imposing façades. Previous exhibitions, with the possible exception of that in Vienna in 1873, have been confessedly ephemeral in the character of their construction, and have shown a distinctly playful and festal style of architecture, with little attempt at seriousness or dignity of design. The monumental character of the group of Exposition buildings in Chicago is not the result of accident, but of deliberate forethought and wise judgment.

In the heat of the fever of construction, which has spread like a contagion from the rocks of Mount Desert to the white sands of the Pacific coast, a new race of architects has sprung up, fertile in resources and clever in execution, but with little well-grounded knowledge of the real principles of their art. Beginning with the bulbous conglomerations of material which have been forced upon a long-suffering public by the Government architects, and ending with consciously picturesque structures that hint more of the terrors of mediæval dungeons than of the comforts of domestic life, and bear the title of villa but the aspect of military strongholds, the architecture of the past two decades has, with some{4}{3}

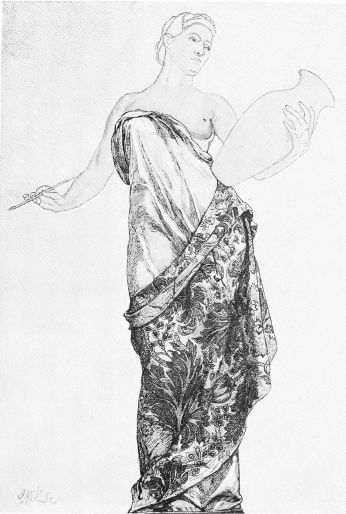

FIGURE EMBLEMATIC OF THE TEXTILE ARTS, BY ROBERT REID, IN ONE OF THE DOMES OF THE MANUFACTURES BUILDING.

notable exceptions, been distinguished by increasing ingenuity in imitation rather than the development of skill in adaptation. It would be worse than foolish to demand that an architect should be thoroughly original, as it would be to ask an artist to cut loose from all the proven principles and traditions of his profession, and invent an entirely new method and a novel system. What may be reasonably asked of an architect is that he have an individual point of view, and modernize the adaptation of old principles without disturbing the real spirit of the same; that he develop and extend these principles to meet the requirements of modern life; that, in fact, he work as nearly as possible in the same direction that the masters of ancient architecture would have done if they had been dealing with modern problems of design, plan, and construction. There are certain immutable laws of harmony and proportion which have always governed and will always rule in architecture as in art, and though they are disregarded and tampered with for the sake of novelty and so-called originality, this faithlessness always meets its just punishment in the result. The majority of modern architects have, in these days of abundant photographs, models, and measurements, been led to cater to the vanity of half-educated clients, and have engrafted French châteaux on Romanesque palaces, have invented wonderfully in{6}genious but viciously hybrid combinations, one of which has been aptly described as “Queen Anne in front and Mary Ann in the back.” The precept and example of the scholarly men in the profession have been powerless to stem this tide of ill-considered design, and nothing short of gradual regeneration and slow revulsion of sentiment against this tendency has been hoped for until the present year.

Mr. D. H. Burnham, the Director of Works of the World’s Columbian Exposition, took the first important step toward the renaissance of the true spirit of architecture in this country by ignoring all precedents of competition, and selecting as associates certain architects and firms whose records established their position as true leaders of the profession. These architects, after studious contemplation of the situation, decided on the adoption of a general classical style for the buildings, subject, of course, to such modifications as were found necessary by the requirements of each individual case. The result is a satisfactory and sufficient proof of the wisdom of Mr. Burnham’s action, and there is now before the country a more extensive and instructive object-lesson in architecture than has ever been presented to any generation in any country since the most flourishing period of architectural effort. The educational importance of this feature of the great Exposition can scarcely be over-esti{7}mated,

ALLEGORICAL FIGURE OF “NEEDLE-WORK,” BY J. ALDEN WEIR, IN ONE OF THE DOMES OF THE MANUFACTURES BUILDING.

and its salutary influence on the future architecture of this country can be prophesied with absolute certainty. The scheme has not been considered complete, however, nor the lesson properly emphasized, without the necessary adjuncts of the two arts so closely allied to architecture, sculpture and painting, both of which have been drawn upon with freedom and good judgment to supplement and enrich the architectural features. Sculpture has been employed far more extensively than its sister art, for the very good reason that few of the buildings have been constructed with any intention of carrying the interiors to any high degree of finish. It would have been impracticable, under the circumstances, to bring the interiors up to the same perfection as the exteriors, even with the cheapest material, for it would have added an enormous per cent to the cost of construction. The architects have, therefore, in most cases frankly accepted the situation and confined their efforts at embellishment to the façades, considering the buildings simply as great sketches of possible permanent structures, confessedly utilitarian as to the interior, but as sumptuous and suggestive in exterior treatment as the conditions permitted. Indeed, this was the only reasonable view to take, both because of the enormous size of the buildings and the complex uses for which they are intended. The exhibits themselves{10} are necessarily such prominent features of the interiors that they only need a background of more or less simple character to complete, with the elaborate installation which is being carried on, quite as agreeable a decoration scheme as might be reasonably expected on such an enormous scale.

Without going into details of construction, it is proper to call attention to one feature of the interiors, notably of the Machinery and Manufactures and Liberal Arts buildings, where the architect and the engineer have joined forces and produced a result far ahead of anything before accomplished. I refer to the wonderfully beautiful iron-work of these buildings, which satisfies to an eminent degree both the utilitarian and æsthetic requirements. Mr. C. B. Atwood, Designer in Chief, co-operated with Mr. E. C. Shankland, Chief Engineer, in working out a plan of construction of the immense trusses with the connecting girders, purlins, and braces, which has been carried out in great perfection. The ugly forms of ordinary bridge-builders’ construction, which have hitherto been endured as necessary for rigidity and strength, have been largely eliminated, and graceful curves, well-balanced proportions, and harmonious lines unite to make the iron-work, beautiful in itself, a distinctly ornamental feature of the interiors. Thus, without flourish of trumpets, a great advance has been made, and the great truth promulgated{11}

that the useful may be beautiful even in engineering. Painting of an artistic character has been confined for the most part to a few domes and panels in various pavilions, to wall spaces under colonnades and porticos, and to the two or three interiors in which there is sufficiently high finish to permit of mural decoration.

The Administration Building, by Mr. Richard M. Hunt, which was built for the uses of the World’s Columbian Commission with the numerous branches of its executive force, is the real focus of the group of buildings, not only from its position in the centre of a grand plaza of enormous extent, but on account of its monumental character. The portals and the angles of this building are adorned with groups of sculpture by Mr. Carl Bitter, of New York, and spandrels and panels, both outside and inside, are enriched by designs by the same sculptor. The dome, which is two hundred and sixty-five feet high, is truncated at the top and is lighted by a great eye forty feet in diameter. The interior of this dome around the great eye, a surface of the approximate dimensions of 35 x 300 feet, is to be covered with a figure composition painted by Mr. W. L. Dodge, representing in general terms the figure of a god on a high Olympian throne crowning with wreaths of laurel the representatives of the arts and sciences, and flanked by figures of Agriculture, Commerce,{14}

“MUSICIANS,” FRAGMENT FROM THE PROCESSION, BY W. L. DODGE, IN THE DOME OF THE ADMINISTRATION BUILDING.

and Peace. A Greek canopy, supported by flying female figures, contrasts agreeably with the clear blue of the sky background, against which the principal groups are shown in strong relief. Three winged horses drawing a vehicle with a model of the Parthenon, troops of warriors cheering the victors in the peaceful strife of the arts, and a wealth of minor figures, make up the composition, which is bold and imposing not only in magnitude but in line. The interior walls of the great Rotunda are tinted so as to give the effects of colored marbles and mosaics and under the outside the massive white Doric columns have a background of Pompeian richness{15}

“CERAMIC PAINTING,” BY KENYON COX, IN A DOME OF THE EAST PORTAL, MANUFACTURES BUILDING.

(From an unfinished sketch.)

of tone. With the exception of Mr. Dodge’s composition in the Administration Building, neither of the other buildings fronting on the grand plaza has any purely artistic decoration, although the hemicycle and portions of the Electricity Building, and the extensive arcades of the Machinery Building, are all treated with flat colors to supplement this architectural ornament, the former by Mr. Maitland Armstrong, the latter by Mr. E. E. Garnsey, of F. J. Sarmiento & Co. Across the south canal, however, a blaze of richly colored panels in the pavilions of the Agricultural Building, with here and there a figure of an animal half hidden by the superb Corinthian columns, shows where Mr. G. W. Maynard and his assistant, Mr. H. T. Schladermundt, have converted, by the magic of their art, the uninteresting plaster surfaces into a series of elaborate pictures. This decoration has been planned with great attention to the appropriate character of its individual features. There are two pavilions at either end of the building, with a large doorway breaking the wall into two panels, each one of which has a dado of elaborate ornament, a narrow border of conventionalized Indian corn on each side, and great garlands of fruit on top framing an oblong rectangle of rich Pompeian red with a colossal female figure of one of the seasons. Above the two panels, and connecting them by a band of color, is{18}

a frieze with rearing horses, bulls, oxen drawing a cart of ancient form, and other small groups of agricultural subjects. The focus of the decorative scheme is naturally at the main portico, the entrance to the Rotunda, called the Temple of Ceres, with the statue of the goddess in the mysterious twilight of the graceful and impressive interior. The portico is treated on much the same plan as the side pavilions, but as it provides a much greater area of wall surface, Mr. Maynard has been able to introduce a richer combination of colors and a greater variety of figures. “Abundance” and “Fertility,” two colossal{19}

female figures, occupy, with the richly ornamented borders, great flat niches on either side of the entrance, and are flanked in turn on the side-walls by the figure of King Triptolemus, the fabled inventor of the plough, and the goddess Cybele, symbolical of the fertility of the earth, the one in a chariot drawn by dragons, the other leading a pair of lions. These figures, as well as those in the four porticos, are treated in a broad, simple manner, so that they carry perfectly to a great distance and at the same time lose nothing by close inspection.

The sumptuousness of the color decoration is balanced by the lavish abundance of sculpture work which fills the pediments and crowns the piers and pylons, and, in general terms, the main features of the façades. The main pediment is by Mr. Larkin G. Mead; and the other statues—figures of abundance with cornucopiæ, a series of graceful maidens holding signs of the Zodiac, groups of four females representing the quarters of the globe supporting a horoscope, and various colossal agricultural animals—are all by the hand of Mr. Philip Martiny, who joins Mr. Olin L. Warner in supplementing the architectural ornamentation of the Art Building with various figures and bas-reliefs. Dominating the grand outlines of the edifice, perched high on the flat dome, is the gilded figure of Diana, by Mr. Augustus St. Gaudens, familiar as the finial of the{22} tower of the Madison Square Garden in New York, a fitting apex of the monumental structure.

The north front of the Agricultural Building, with the Peristyle and the south façade of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, form a grand court of honor, so to speak, facing the Administration Building, which may be appropriately termed the Gateway of the Exhibition, for it rises directly in front of the Terminal Station, a building of vast proportions and noble aspect, designed to accommodate the thousands of visitors who reach the Fair by the numerous lines of railways concentrated at this point. Six rostral columns, surmounted by a figure of Neptune, by Mr. Johannes Gelert, accent this court at different points. Mr. Frederick MacMonnies’s fin-de-siècle colossal fountain fills the west end of the basin with a busy group of symbolical figures and a flood of rushing water. Opposite, at the east end of the glittering sheet of water which reflects the architectural glories of the colonnades, the dignified, simple statue of the Republic, by Mr. D. C. French, towers high in air, relieved against the beautiful screen of the Peristyle, with its forest of columns showing clear cut against the blue waters of the lake. Every column and every pier of the Peristyle has its crowning figure, the work of Mr. Theodore Baur, and the great central arch, or Water-Gate supports a colossal Quadriga executed{23}

by Mr. D. C. French and Mr. Edward C. Potter, the former undertaking the figure work, and the latter the horses. Two pair of horses, led by classical female figures, draw a high chariot with a male figure symbolizing the spirit of discovery of the fifteenth century, and pages on horseback flank the chariot on either side, enriching the composition so that it presents a well-sustained mass from every possible point of view. This group is an achievement well worthy of its situation as the dominating embellishment of the great court with its wealth of sculpture and ornament.

The terraces afford another inviting field for open-air decoration. Numerous pedestals have tempted the skill of the sculptors of the Quadriga to produce distinguished types of the horse and the bull, and formal antique vases on the balustrade and reproductions of the masterpieces of ancient statuary break the long lines of parapet and greensward. The graceful bridges spanning the canals are guarded by sculptured wild animals native of the United States, part of them by Mr. Edward Kemeys, others by Mr. A. P. Proctor, in appropriate contrast to the classicality of their surroundings and suggesting future possibilities in sculpture inspired by similar motives. The eye cannot take in at a glance the sumptuous beauties of this grand court, even in its ragged state of partial finish, but roves from statue to column,{26} portal to terrace, resting agreeably on broad masses of rich color and on the gleaming reflections in the basin. Imagination can scarcely picture the scene with the addition of the festal features of fluttering banners, rich awnings, gayly decorated craft giving life and movement to the water front, and everywhere the crowd of visitors all on recreation bent.

The casual observer might well be pardoned for failing at first to mark how the grand pavilions and porticos of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building are accented by frequent spaces covered with artistic decoration. In each of the four corner pavilions there are two tympana, those on the south side having been given to Mr. Gari Melchers and Mr. Walter MacEwen to fill with a decorative design. Both these artists have made elaborate compositions representing, in general terms, “Music” and “Manufactures” and “The Arts of Peace,” and “The Chase and the Manufacture of Weapons,” respectively.

In the foreground of “Music,” at the left, a group of Satyrs pipes to a dancing cluster around the Muse Euterpe, and with various other personages make up a composition of great distinction of live and skilful arrangement. The second panel, which illustrates manufactures or textiles, is equally rich in groups, and in the background of both compositions is continued a procession in the honor of{27} Pallas Athena, who was credited by the Greeks with the invention of spinning. The general color gamut is light with an intricate harmony of delicate tones. The procession is silhouetted in bluish tones against a warm sky with the colors of early evening, the golden reflections touching the figures with beautiful lines of light. Mr. Melchers has followed out much the same general plan of color in a varied but well-sustained composition, so that the four tympana make, in a sense, a series of harmonious pictures.

The four grand central portals of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building recall triumphant arches of Roman times. Each of these portals has a lofty central entrance with rich bas-reliefs by Mr. Bitter and smaller side arches under pendentive domes. These eight domes have been filled with figure decorations, each by a different artist. Those on the south front of the building have been painted by Mr. J. Alden Weir and Mr. Robert Reid, who, with distinctly individual compositions, have harmonized their designs in a remarkably agreeable and skilful manner. Mr. Weir has chosen allegorical female figures of “Decorative Art,” “The Art of Painting,” “Goldsmith’s Art,” and the “Art of Pottery.” Each of these figures is seated on a balustrade and is relieved against a sky of pale broken blue tones. Flying draperies and capitals of four orders of architecture serve to connect the lines of{28} the composition, which is further enriched by a cupid holding a tablet inscribed with the different arts and decorated with a wreath. The figures are large and simple in line, and the general scheme of color is pale blue varied with purple and green, a combination suggested by the evanescent hues of Lake Michigan. Mr. Reid has also selected seated allegorical figures to carry out his ideas, with the addition of four youths, one on the keystone of each arch, holding high above their heads wreaths and palm branches which meet and cross so as to form a band of decorative forms around the upper part of the dome. A semi-nude figure of a man with an anvil and wrought-iron shield represents “Ironworking;” a young girl in white resting one arm on a pedestal and the hand of the other arm touching a piece of carved stone, signifies “Ornament;” another in purple, finishing a drawing of a scroll, suggests the principle of “Design,” as applied to mechanical arts, and the fourth figure is readily interpreted as honoring the “Textile Arts.” In the east portal Mr. E. E. Simmons has placed a single figure of a man in each pendentive of the dome, symbolizing “Wood Carving,” “Stone Cutting,” “Forging,” and “Mechanical Appliances.” The general scheme is pale gray and flesh-colored tones relieved and accentuated by the forms of the tools and accessories appropriate to each figure. The{29}

composition is bold in line, firm in outline, and original in conception. Mr. Kenyon Cox in the adjacent dome has worked so far in harmony with Mr. Simmons that he has decorated the pendentives rather than the upper part of the vault, placing a standing female figure in each against a balustrade and foliage. Above the heads, graceful banderoles, bearing the subjects illustrated, convert each pendentive into a shield-shaped space. A robust woman in buff jacket testing a sword, suggests “Steel Working.” A graceful girl in blue and white drapery holding a rare vase needs no title to show that she represents “Ceramic Painting.” “Building” is symbolized by a tall and shapely damsel in golden green robes, standing near an uncompleted wall, and “Spinning” by a stately maiden of fair complexion dressed in rose-colored stuffs, with the significant accessory of a spider-web. In the north portal Mr. J. Carroll Beckwith has illustrated the subject of Electricity as applied to Commerce. Four female figures occupy the pendentives. The “Telephone” and the “Indicator” are personified by a woman standing holding a telephone to her ear and surrounded by tape issuing from the ticker; “The Arc Light” by a figure kneeling holding aloft an arc light; “The Morse Telegraph” by a woman in flying draperies seated at a table upon which is the operating machine,{32} while she reads from a book; and “The Dynamo” by a woman of a type of the working-class seated upon the magnet with a revolving wheel and belt at her feet. Above, in the upper dome, is placed the “Spirit of Electricity,” a figure of a boy at the top of the dome from which radiate rays of lightning, to which he points. Mr. Walter Shirlaw, who has decorated the neighboring dome, shows distinct originality of conception in his four allegorical figures, “Gold,” “Silver,” “Pearl,” and “Coral,” symbolizing the abundance of the land and the sea. The maiden representing “Gold” steps forward freely, her mantle of yellow falling as she advances. A silver-gray cloak, fastened with silver disks, distinguishes the figure of “Silver.” “Pearl” stands erect with glistening pearls around her neck and on her garments. “Coral,” with raised arms, places a coral ornament in her hair. A spider’s web in decorative pattern connects the figures and occupies the central surface of the dome. White, green, and gold, treated in monotones, form the color plan.

The figure on page 29 is taken from a sketch of one of Mr. C. S. Reinhart’s figures in the south dome of the West Portal, and was materially changed in the enlargement, and improved in action and accessories. The effort of the artist has been to bring all the separate tones into harmony with each other, making the design and color appropriate{33}

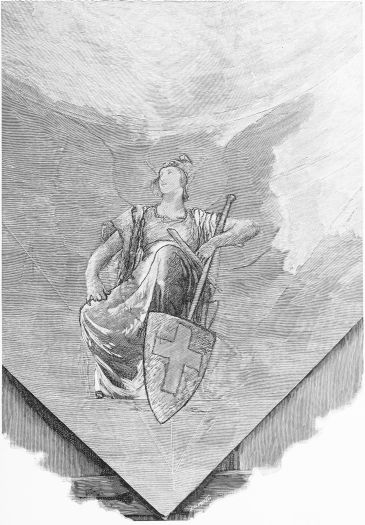

“THE ARMORER’S CRAFT,” ONE OF FOUR FIGURES BY E. H. BLASHFIELD, REPRESENTING THE ARTS OF METAL WORKING.

to the purposes of the building, the architecture, and the construction of the pendentive dome itself. A white-marble terrace describes a complete circle just above the four arches of the dome, the railing of which is a repetition of the actual one which finishes the top of the walls of the building itself; above a vibrating blue sky, with touches of salmon pink; in the pendentives four seated female figures, representing the Arts of Sculpture, Decoration, Embroidery, and Design. Between the figures and above the arches are urns with cactus, from which vines and flowers are trailing, thus uniting the composition. The treatment is mural—broad, flat tones within the severe contours. Above, in the sky, faint in color and harmonizing with the sky itself, four cherubs are having a merry-go-round with pale ribbons.

The pendentives of the adjacent dome, painted by Mr. E. H. Blashfield, are filled by four winged genii, representing the “Arts of Metal Working.” The “Armorer’s Craft” is personified by a helmeted figure; the “Brass Founder” and “Iron Worker” by two half-nude youths, one holding an embossed trencher, the other a hammer, while a maiden, in the closely clinging gown of the fifteenth century, with a statuette in her hand, symbolizes the “Art of the Goldsmith.” The extreme points of the pendentives are filled by appropriate attributes, a{36} pair of gauntlets, brass workers’ tools, a horse-shoe, and a medal. Behind the figures, and a little above their heads, is a frieze of Renaissance scroll work, and the whole composition is bound together by flying banderoles and by the sweep of the widely extended wings. The centre of the dome is occupied by two winged infants supporting a shield. The general color scheme comprises a series of peacock blues, greens, and purples, brilliant white tones in wings and frieze, and pale blue of the sky as a background to the composition.

The sculpture groups on the roof of the Woman’s Building, and the elaborate pediments executed by Miss Alice Rideout, with the Caryatides, by Miss Enid Yandell, were early finished and in place. The same is true of Lorado Taft’s graceful groups and friezes which adorn the Horticultural Building, and of Mr. John J. Boyle’s realistic and expressive embodiments of ideas suggested by the fertile theme of Transportation, and ranged in almost bewildering profusion around the building which bears that name. The regiment of statues on the Machinery Building, by Mr. M. A. Waagen and Mr. Robert Kraus, those on the Electricity Building, by Mr. J. A. Blankingship and Mr. Henry A. MacNeil, the statue of Franklin, by Mr. Carl Rohl-Smith, together with scores of other works of more or less importance, would, if listed, make a long catalogue of{37}

interesting objects of the sculptor’s art. The immense numbers of these works, proportionate, of course, to the colossal magnitude of the Exposition, forbid even the bare mention of them in detail. In addition to this great mass of sculpture work executed for the special purpose of supplementing the archi{38}tecture, it is intended to place at different places, notably in the Grand Court and on the grounds, and in the colonnades of the Art Building, selected examples of ancient sculpture, various reproductions of antique monuments.

An essential part of the decoration of the building is, of course, the architectural details, the models of which have been executed by various parties, notably Ellin & Kitson, of New York, and Evans, of Boston, with distinguished taste and skill. The capitals, mouldings, and ornaments of Greek and Roman buildings have been accurately copied on a scale and in a manner never before attempted. A few short months ago there was in this country but a very limited number of full-sized reproductions of any of the notable details of ancient architecture. The cast of the great Jupiter Stator capital was, it is said, found in but a single architect’s office. Now the whole range of details, from the beautiful Ionic capitals of the Temple of Minerva Polias to the mouldings of the Arch of Titus, are practically at the command of any architect and student.

Much has been said and much written about the proper color to be given to the exteriors of the great edifices. Experience shows, even if reason had not already dictated the decision, that the nearer they are kept to white the better for the architecture. Every experiment which has been made to produce{39}

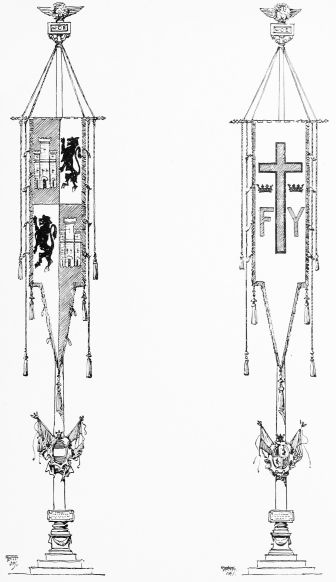

BANNER ADOPTED FROM THE STANDARD OF SPAIN UNDER FERDINAND AND ISABELLA. |

BANNER ADOPTED FROM THE EXPEDITIONARY FLAG OF COLUMBUS. |

æsthetic effects of texture suggested by the usual treatment of plaster objects has resulted in partial or in total failure, and every time the warm white of the staff has been meddled with, its glory has departed. But the conditions imposed by the climate, by the impossibility of securing a homogeneous surface, and by the exposure and consequent discoloration of a certain portion of the work, have made it necessary to apply some sort of paint to all the buildings. Ordinary white-lead and oil have been found to give the best results, for the irregular absorption of the staff and the weathering rapidly produce an agreeable, not too montonous an effect, and the surface deteriorates less rapidly after this treatment. The single notable exception to this simple scale of color is found on the Transportation Building, which was given to Healy and Millet, of Chicago, to cover with a polychromatic decoration, carrying out the original intention of the architects, and making it unique and splendid in appearance. All the statuary of this building was treated with bronze and other metals, the great portal, commonly called the “Golden Door,” was exceedingly rich and gorgeous in effect, and the intricate ornamentation of the architectural relief decoration had an echo in the flat surfaces covered with rich designs.

The decoration of the Exposition would be incomplete without careful attention to the informal{42} and festive features, such as flags and awnings. Every building presented new conditions, and demanded special study and design. A large proportion of the flag-staffs carried gonfalons or banners, but a certain number were reserved, naturally, for the United States flag and the flags of all nations. At various points large poles were planted in the ground, most of them for the purpose of displaying the Stars and Stripes, and a group of three poles, with ornate bases, elaborate flutings, and proper finials were placed in front of the Administration Building. The middle pole to carry a United States flag of large dimensions, and flanked on either side by a large and sumptuous banner, one adapted from the expeditionary banner of Columbus, the other from the standard of Spain at the time of the discovery of America.{43}

IT is no reflection on the Columbian show to confess that perhaps the pleasantest moments are those spent in resting one’s rebellious limbs upon a bench and in watching the crowd. It may be less novel and possibly less instructive than some other exhibits, but it is often more amusing. One realizes in studying this infinite stream of humanity how little he really knows, personally, of his own countrymen. New types seem to have sprung into existence for the sole purpose of appearing at this fair. It gives one a startling realization of the varying effects of climate, food, and mode of life upon our brothers and sisters. Voice, manner, color, size,{44} shape, and mental fittings are so widely different as to surest varieties in race. But we are all Americans, and those from the interior are more American than the others.

If the native Indian were of a reflective turn of mind, all this might awaken unpleasant thoughts. Judging from outside appearance, however, he has no thoughts whatever. He stalks solemnly about the grounds with a face as impassive as his wooden counterparts on Sixth Avenue. And yet he is the American. He is the only one among us who had ancestors to be discovered. He is the aboriginal; the first occupant and owner; the only one here with an hereditary right to the country we are celebrating. Perhaps the native realizes this in his own stolid fashion. As he stalks about among the dazzling structures of the Fair, and tries, or more likely, does not try, to grasp the innumerable wonders of art and science that only annoy and confuse him, it may require a too exhausting mental effort to recall the fact that his own grandfather very likely pursued the bounding buffalo over the waste of prairie now covered by the city of Chicago. He, at least, if his education permitted it, could claim historic connection with the country when Columbus came so near discovering it; whereas our own connection with the discoverer is certainly remote, and sometimes suggests (with the fact that he from whom we have{45} named the Fair never actually saw this particular country) that we are taking liberties with his name.

The unconquerable American desire to do things on a bigger scale than anybody else, which often results in our “biting off more than we can chew,” has again run away with us. There are many illustrations of this gnawing hunger at the World’s Fair. In fact the Fair itself, as a whole, comes painfully near being an illustration in point. A colossal enterprise too vast and complex to permit of its attain{46}ing a perfect finish in the time allowed, seems to give more joy to our occidental spirits than any possible perfection on a smaller scale. Crudity has little terror for us. The whole scheme is so vast and comprehensive, and the scale so hopelessly magnificent, that the visitor finds he has neither the spirit, spine, nor legs to even partially take it in. In fact the farther he goes the more he realizes the futility of the undertaking. And the hapless enthusiast who proposes to see, even superficially, the more important exhibits, should be fitted with a wrought-iron spine, nerves of catgut, and one more summer. In all the departments, from the fine arts to canned tomatoes, there is more than enough in numbers and in area to wear out the energy and paralyze the brain. To visit the Fair with profit or comfort you must leave your sense of duty behind. Whoever goes there with intent to thoroughly “do it,” is laying up for himself anguish of mind and the complete annihilation of his muscular and nervous force. It is far too big for any question of conscience to be allowed to enter in. Its bigness is beyond description. No words or pictures can tell the story of its size. Experience alone can teach it. You must go there day after day, to return at night with tired eyes and aching limbs, and with the bitter and ever-increasing knowledge that as an exhibition you can never grasp it. Where other exhibitions{47} have been satisfied with a display of an hundred cubic feet of any special article, Chicago must have at least an acre. Of whatever the world has seen before this time it now sees larger specimens and more of them. This means for the visitor more steps, more fatigue, more confusion, more time, and more money.

But there is a good side to all this, if one can forget his physical fatigue. Few of us fully realize what the Fair is doing for this country æsthetically. Not so much by its art collections, for the average American sees, or can see, enough good paintings in the course of a year to bring up his standard to a respectable level if he so elects, but by the architecture of the buildings themselves. Unless the aforementioned “Average American” is an undeserving{48} barbarian who has made up his mind to prefer the wrong thing, these impressive monuments cannot fail to do him good. The honest beauty of their design ought to stamp itself with sufficient force upon his dawning reason to make him see the crudity of the United States architecture in which he has wallowed up to date. No praise is too high for what Chicago has achieved in this direction. There are, of course, at the Fair some painful examples of what the untamed American architect loves to do, but he is fortunately in the minority. And the very contrast he offers works for progress in the cause of good art and a higher standard. The United States Building, designed by a Government architect, is a melancholy warning.

The more intimate one becomes with this particular fair, the more forcibly he realizes the fact that we are, above all else, a practical people. After being duly impressed by the gigantic proportions and artistic excellence of the buildings, for which no praise is too high, we come gradually to learn, as we meander among the exhibits, that those things which excite our surprise and curiosity are generally the results of ingenuity and manual skill. In those departments, for instance, relating to art, literature, and history, there is little to startle the traveller who is at all familiar with previous international shows. The best in the art galleries is, as usual,{49} from Europe. There is no dodging the fact that the average American is not overladen with the artistic sense. His enthusiasm runs in other directions. When it comes to the outward manifestations of human ingenuity, he is “on deck;” he is “in it” and “with you.” The application of electricity to filling teeth, or converting sawdust into table-butter, kindles in his bosom an excitement he never experienced in the art department. It certainly seems, after a visit to the electricity and machinery, that human hands can do nothing that is not more quickly accomplished by some machine. Not only this, but time and distance count for nothing, and, if we keep on as we have started, the day will soon be here when the man in Maine can shake hands with his friend in Arizona. Already the sun is a hard-working slave. Light, air, water, and in fact all nature, seems cruelly overworked. If she ever strikes, it will be an awkward period for us. These mechanical and scientific surprises make it interesting to speculate as to possible sights at our next grand exhibition, say twenty years hence. The man in China, for instance, need not go to the future fair at all. He will probably be able to see and hear it all at home. If he does go he can return to Shanghai for his lunch.

But the American as seen at this fair, although {50}first of all practical, is not, from another point of view, so far behind in his artistic sense as we are in the habit of considering him. In the first place, he is found, as a rule, standing before the best paintings and passing by the poorer ones. Those galleries containing the finest works are invariably the most crowded. And this is the greatest compliment we can pay ourselves. If, on the other hand, enthusiastic groups collected about the impressionists, and took pleasure in the purple and yellow “effects,” that are sprinkled about the French and American sections, there would be cause for anxiety. But such is not the case. That the impressionists still count their warmest admirers among themselves, their wives, sisters, and aunts, is a hopeful sign. As a people, we take many things less seriously than some of our contemporaries, but in matters of art we like it with a purpose. Too little clothing still strikes us as frivolous and improper. Blood, violence, and all unpleasantness are sometimes historically instructive, but, as a rule, we are fond of comfortable subjects. We still like a taste of sugar in our art.

But the brightest sign of all is the universal and hearty appreciation by the multitude of the buildings themselves. The expressions of delight by those who see for the first time these marvels of architectural beauty, indicate at least a capacity for artistic enjoyment. In fact, the American who steps for{51} the first time upon the borders of the Grand Basin, and looks upon the scene before him without a tingle of pride and pleasure is not of the stuff he should be. No words can give a just idea of the magnificence and restful beauty of this gigantic achievement. Rome and Greece were of marble and built for a more serious purpose. This is a city for a single summer. As such it is a complete and glorious triumph.

There is nothing like a colossal exhibition to emphasize the disastrous effects of wealth upon the human spirit. Your friend with plenty of money goes to the Fair because others do and because he hates to be “out of it.” He reaches Chicago in a palace car, occupies luxurious rooms at a comfortable and expensive hotel, takes a carriage when others walk, and at the exhibition itself derives pleasure only from those things that are unexpectedly novel. And to him such sights are few and such sensations rare. What he does realize, however, continually and with force, is the enormity of the crowd with its thoughtless persistence in holding the best places in front of those exhibits he wishes to see himself. Moreover, there is an ever-increasing sense of physical discomfort, and that is something your moneyed friend is slow to forgive. But he does his duty, and he is glad above all to get home again.{52}

But how different with your less prosperous friend, who has been economizing for months in order to get there! It being an expensive business, his time is limited, and he drinks it in through all his senses, excitedly and with large gulps. It is hard work, but how interesting! That dull pain which overtakes the great majority of sightseers soon catches him in the back of his neck, but as long as he can see, hear, and walk, he profits by his opportunities. And he goes to his home mentally refreshed, a broader and a wiser man. He has gained an experience he would not exchange for many dollars.

An unlooked-for feature of the exhibition is the profusion of newly married couples. Whether all this individual ecstasy adds gayety or mournfulness to the Fair depends, of course, entirely upon the point of view from which the victims are regarded. It is evident that many happy grooms have considered this a chance to kill two birds with one stone, and, as far as one can judge results from outward appearances, there is no question as to the practical working of the scheme. The happy couple find themselves in a sort of fairy land, wandering about among countless strangers, whose very{53} numbers seem to lend security and to harden the over-sensitive soul. The crowd also seems to create a feeling of isolation which the innermost recesses of a virgin forest could never supply. Moreover, there is here so much else to occupy the attention of the usually obnoxious public that the bride and groom can hold hands with absolute security and be as bold or blushing as their temperaments may demand.

The rolling-chairs that run about the grounds and through the buildings are the salvation of many a fainting spirit. To thousands of human beings with nothing but a human back and human legs the fair would be a failure without them. They are support for the weary, strength for the weak, and hope and a new life for the despairing. The guides who navigate them are, as a rule, college students, profiting by this opportunity to see the fair and to secure additional dollars toward completing their studies. The result is, for the occupant of the chair, an intelligent and agreeable companion, who is ready and willing to give any information he may possess. And besides, they are neither sharks nor liars, but fair and honorable respecters of truth. There is sometimes a contrast in manners and education between the occupant of the chair and the man behind that is not in favor of the former. When one sees what is evidently a citizen with far more money than{54} brains, and without the faintest appreciation of the beauties that encompass him, wheeled about at seventy-five cents an hour by a youth so far his superior that any comparison is impossible, it causes one to realize that Fortune is indeed an irresponsible flirt, who is never so happy as when doing the wrong thing.

A not uncommon sight, and one of the countless illustrations of what an excellent husband the American becomes when properly trained, is that of the weary, uninterested man, lingering patiently among laces, china, and views of Switzerland. His heart all the while is off with the machinery, possibly with that more than human little machine that winds the cotton on the spools. Such cases are, of course, offset by the devoted women who wear themselves out in tramping through soulless acres of agricultural products, locomotives, wagons, models of ships, and all the other follies that appeal to man.

The burning question of the hour for the visitor from another city is the question of finance. He who is worth his million and intends spending a fortnight in Chicago, will do well to take his million with him. He may bring some of it away, but that will depend entirely upon his own capacity for economy. Before registering at the hotel let him be sure to secure his return ticket, for it is a long walk from Chicago to New York. These remarks are not intended to discourage all who are not millionaires from visiting the exhibition. It can be done with less money. The writer has himself accomplished it. In fact, it is only fair to say that many of the stories of extortion which have come from the White City are much exaggerated. The most successful brigands are in the city of Chicago, and not at the Fair.

The writer can testify, from his own personal experience, that a very good lunch can be procured in the State of Illinois for less than one hundred dollars. Thirty dollars is more than enough for a sandwich, and a glass of water can be purchased anywhere for less than ninety cents. While to walk by the cafés and restaurants and look upon others who are eating, costs the promenader nothing whatever. But these moderate prices do not obtain at your hotel. The object of keeping a hotel is, like some other occupations, partly to make money. The Chicago hotel-keeper does not ignore this fact.{56}

His ideas of the relation of profit to expenditure are well calculated to startle the guest of reasonable expectations. If the guest is not overweeningly ambitious and is satisfied to sleep in a closet or hang from the stairs, his expenses need be no greater than if he occupied a handsome suite of rooms at any first-class New York hotel. But if he insists on having a real chamber, larger even than his own bathroom at home, and with a real window in it, then he must pay. And it is then that he begins to discover why his landlord keeps a hotel. Any previous extravagances in the way of horses, real estate,{57} or precious stones are as nothing to the present outlay. He finds that the rate per diem is, as far as he can judge, based upon the supposition that the hotel is to be closed to-morrow and must be paid for to-day. And real estate is high, even in Chicago. In matters of nourishment, the wealth of Ormus is of no avail, unless the waiter receives a tip exceeding in value the handsomest Christmas present ever given to a dearest friend.

Within the grounds there is little extortion, thanks to the firmness of the ruling powers.

But let not the Chicagoan whose eye may fall upon these lines suppose for an instant that they are intended as reflections on his character. The city that secured the prize is simply fulfilling its inevita{58}ble destiny. Had New York drawn the plum we should have witnessed a worse extortion, with the added mortification of a much inferior exhibition. Moreover, there is no public spirit in New York, and there is a great deal of it in Chicago. This sentiment alone is more than enough to make the difference between success and failure. The woods are full of citizens willing to begin at sunrise and discourse to you until midnight of the wonders of Chicago. In ordinary times this burning desire to impart just that kind of information is not always appreciated by the outside world; but in times of fairs the spirit that prompts it becomes a mighty engine. It was soon demonstrated that these citizens could work as well as talk, and as a result the White City has risen as from a fairy’s wand.

The important question for the individual citizen is whether it is worth his while to go to this fair. And this, of course, depends altogether upon his purse, his stomach, his back, his legs, nerves, wife, children, and business. He may never have another such opportunity for mental expansion and physical discomfort. It is a marvel of architectural beauty. It is days of instruction, of art and science, of surprise and exasperation, of mental development, fatigue, and financial ruin. In the end his personal preferences, however, will probably have little to do with it. All the world are going, and he must go too.{59}

ON the way west to the White City, to “the stately pleasure-dome decreed,” where the arts of civilization by the unwritten law of International Expositions hold their court, the observant traveller finds abundant food for thought. Beyond Niagara, assuming his point of departure to be New York, he sees in the landscape through which he is whirled a continuous sweep of flat farming land, but little water; fences everywhere, trees sparsely scattered, and plain box-like houses telling only of shelter; abundant barns differing little from the dwellings, and from time to time towns of varied nomenclature ranging from Delhi to Kalamazoo. Through the horizontal blur caused by the speed of the train through which all this is seen, there appear, principally about the stations, figures which lend a languid interest to the dead level of monotony.

The human interest of the picture, however, tells the same story as the landscape—a story of hard work, of material reward, an acquiescence in the law{60} by which labor gains bread and shelter, and little else. Occasionally, in the immediate vicinity of the stations, there is some attempt at adornment, generally confined to “tidying up” the surroundings; but around the farm-houses few or no flowers, little or no attempt to beautify the home, nothing of the almost frantic suburban effort of the East which has made the country kaleidoscopically varied with color, for the most part bad, yet giving hope that the next generation will do better, and pointing at least to a desire for beauty. Individual effort, unseen along the route, may be slandered by the preceding, but such for many monotonous miles seemed the foreground of the picture we were journeying to see.

At last a plain, varied by marshes, through which boarded walks running at right angles, with an occasional house here and there, testified to the various suburban excrescences of a great city; then a dome or two, towers, flags fluttering in the sun, innumerable trains, clangor of bells and shrieking of whistles; and with Chicago seven miles away, hidden in a pall of smoke, the White City was at hand.

There are certain mastering impressions in one’s life, certain scenes which stamp the memory, and, like the priceless kakemono which the reverent Japanese withdraws from hiding when in the mood to{61}

enjoy it, rise obedient to one’s thought in aftertime. Such a memory is that of a first sunny morning in Paris: a ride from the Madeleine across the Place de la Concorde, along the Tuileries Gardens and the Louvre, across the Seine with the island and Notre Dame in the distance, and then through older Paris to the gardens of the Luxembourg. Or again, a certain early moonlit evening in Florence, with the Duomo looming at the end of the street, Giotto’s Campanile standing sentinel at its side, the narrow street to the Piazza della Signoria with its Palazzo Vecchio and the Loggia dei Lanzi, thence by the side of the Uffizi to the Arno and across the Ponte Vecchio up to the Pitti Palace. These memories, common to so many, are often gained on ground made familiar through study of guide-books and photographs which, instead of dulling realization, add to it the zest of more thorough appreciation. In like manner, study, discussion, photographs, and engravings prepare one for the Columbian Exposition; but the first few hours of living in its architectural dreamland gives reality to the shadowy preconception, and adds the priceless gift of another masterpiece to memory’s picture-gallery.

It is probably impracticable in any case, and when we think of the transformation that this prairie has witnessed in two short years, quite impossible, in the case of the Exposition, to keep the approaches{64} of a great popular resort in any degree beautiful. Here we have on the land side of the Fair the usual assemblage of cheap shows, lemonade venders, and the like, which line the unsightly fence and make up what a friend has dubbed the Sideway Unpleasant. The fence is hard to pardon in a land where energy is predominant, desire to do the best not wanting, and staff abundant. A high white wall enclosing the substantial fabric of their dream would have done much to give the western approach something of the festal magnificence which the architects have given to the entrance by the Peristyle at the lake side.

But once within, to pick flaws criticism must take a higher flight than one, frankly astonished at the goodness of it all, is disposed to permit it to. Nothing is perfect in this mundane sphere, but this effort on lines as yet untrodden by these States has such{65} measure of success that one is proud to feel that this has been done in our own time, in one’s own country, by men of one’s own race—the race that peoples our seaboard, fills our manufacturing towns, tills our great farms, and stretching westward extracts precious metals here and cultivates orange-groves and vineyards there; the race which is daily urged, on the “whaleback” steamer from the city to the Fair, to purchase its chewing-gum before the boat starts, as none is sold after leaving the pier; the race that is so cosmopolitan, so made up from strange and opposing elements, and is withal so homogeneous, so American—and proud, above all, to feel that this curious people have had, at the crucial moment, the good sense to be inconsistent, to make haste slowly, to defer to the few, to make their Exposition the most beautiful before setting to work to make it, as things needs must be here, the biggest in all creation.

To be of this race and a follower of the arts; to have noted for years the growth of public desire for{66}

art and the frequent lapses to indifference on its part; to have seen that our artists as they grow in strength and numbers claimed the right to do something larger and finer and better than the private house, the portrait statue, or the genre picture; and then to come here, where for the first time they have found opportunity, and where the alliance of architecture, sculpture, and painting has produced its first work, to find that first work surprisingly good, is to feel proud not alone for the valiant craftsmen who have produced this result, but for the country at large which has stood behind them, and above all{67} for the solid men of the city of Chicago who have planned the work so bravely and so wisely. So many elements enter into an enterprise of this kind that to a community like ours (unaided by a parental government which, as in France, takes upon itself, as one of its functions, the provision of public pageant and amusement, and keeps as it were all the material in stock) the problem was more than difficult, and the solution, solved as it has been, most surprising. Eighteen months ago in Paris, as I stood with a French friend in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, he said, indicating the colossal construction, “I suppose that at Chicago you will have a tower bigger than that, and that your exposition will be a triumph of that sort of thing.” “I suppose that it may,” was the answer; but the tower which is such a blot on Paris, diminishing in scale her most beautiful monuments, is nowhere to be seen in Chicago, and though the bones and sinews of the Liberal Arts building may be a “triumph of that sort of thing,” its flesh of staff effectively covers and adorns it without concealment of construction or strength, but with due consideration paid to beauty.

To house the exhibits, to provide for instruction, and to make a pleasure-ground for the people (it could be urged from a utilitarian point of view) might indeed have been done more simply, or, as the phrase runs, in a more “business-like” way.{68} One rugged old farmer I overheard, as I stood leaning on the balustrade at the back of the MacMonnies fountain, as he pulled his wife away from the contemplation of the charming group of mermaids and sea-babies who disport themselves in the wake of Columbia’s triumphal galley, “Come along, Maria, I never see no use in them things; women with fishes’ tails.” Maria went along, but I fancied that Maria’s daughter lingered a moment, and she may have found the “use” of the artist in the social system. At any rate, the Chicago business man who individually and collectively represents the controlling power of this vast enterprise knew the use of beauty, and with the sagacity born of commercial success called to his aid the men most eminent in their professions, and then—left them alone.

Arguing without absolute knowledge, is it not easy to imagine that many times during the two years spent in constructing these superb structures, the heart of the business man must have failed him in seeing this child of his creation grow in beauty and strength to be sure, but at a cost of so many millions? No record exists, it is safe to say, of any questioning. The artists had been called in, they were doing their work loyally; and no less loyally, through financial crisis, business depression, and public indifference, the business man performed his part of the contract. He had pledged himself to the{69} whole country to do his best, the pledge had been given and accepted in the hour when he bore the coveted privilege to hold the Exposition away from competing cities, and the Court of Honor shows how well the pledge has been kept. A detail of organization, one of the many which would make the history of the Exposition most interesting if written, was told the other day, and is so characteristic of the spirit in which the Fair has been put through, that it is worth incorporating here. At a time when the Exposition had reached the limits of all possible insurance, when every sound insurance company in the world was carrying all the risks it was able to take, the Exposition concluded to do its own insurance, the details of which procedure need not be gone into here. At this time there were a number of pictures, about nine in all, which had been promised for the Loan Collection of Foreign Masterpieces, and were not forthcoming because of the inability of the Exposition to procure special insurance policies which had been promised when, long before, the owners of the pictures had consented to lend them. There seemed no way out of the difficulty, when the simple question was asked of the head of the Art Department, if it was essential to the completeness of the Loan Collection that these pictures should be in it? To which was answered, that if not essential, it was at least desir{70}able; whereat this business man gave instructions that the owners of the pictures be at once communicated with and informed that he would personally guarantee them against loss if they would allow the pictures to come. As this little show of public spirit involved a personal liability of over two hundred thousand dollars, the figures may be considered eloquent enough to find place in such a paper as this.

The wisdom of a large policy is to be found on every hand. The Exposition has been called a dream, and as it is so soon to vanish may well be one; but if the intent had been to deceive, it could hardly have been made more deceptive. To one in the gondolas or the launches speeding between these walls, they stand as though for all time; and for one walking in the long arcades, detail and veracity of construction force themselves on the attention most plausibly. It has been too often described how the architects, adopting certain dimensions, have obtained a conformity of effect; but that once obtained, they have shown the greatest freedom, and though all of them are men of many works, they have never perhaps been more happily inspired. The Administration building is the appropriate crown to the buildings leading up to it, and Mr. McKim’s Agricultural building is characterized by great charm of proportion, and though heavily charged with sculptured decoration is in nowise{71} overloaded. In addition to the very decorative sculptures due to Mr. Martiny, there is on this building some of the most satisfactory ornament in purely classical vein that I can remember on any modern structure. In fact, though the treatment of this group of buildings is thoroughly classic, it is pleasant to record the belief that in no other country would the traditions have been so well observed and at the same time so revivified as in ours. Our men owe their education to the Old World, chiefly to France; but it seems as though a certain separation from the influences of their schools had given them an independence which their foreign schoolmates lack. It is probable that had Paris in 1889 adopted the programme followed here the result would have been as correct, as thorough, as noble as this; but the result as a whole would have been colder, and lacking in the individual character observable here, where every man seems to continue the tradition rather than follow it. Mr. Post had long accustomed us to his capacity to build big and well; but never to build so big and so well as in the Liberal Arts building. When sailing along the lake-front one appreciates the immensity of the structure, which seems to equal that of all the other buildings combined; but near at hand one feels its beauty more than its bigness, and the simplicity by which this result is arrived at. The portals, taking almost all{72} the decorative features, are admirable. Mr. Atwood’s Fine Arts building is perhaps the best where all is so good, owing almost nothing to its decorative features—which, as the building is to be permanent, one may hope to see changed. The frieze of the Parthenon should hardly be borrowed to grace so fine a modern building. At night Mr. Atwood’s building is seen in all its beauty of proportion, and the nights when it is illuminated best of all. The torches running along the top of the building burn great flames of natural gas, and the illumination is at once simple and effective. On the roof of the Administration building something of the same effect is obtained in conjunction with the electric light outlining the dome; but as the torches on the Fine Arts building are seen against the sky, the effect is finer.

Night and electric light play a great part in the spectacular side of the Fair. Solomon in all his glory never saw such a sight as the plain people of this continent have had on illumination nights this summer. Innumerable incandescent lights sparkle along the cornices and pediments; the top of the wall inclosing the grand basin is outlined in fire; search-lights from the top of the Liberal Arts building cut their wide swaths of light in gigantic circles, resting for a moment here and there to bring out now this detail or to throw into dazzling relief a{73}

sculptured figure or beast. It lingers longest on MacMonnies’s fountain, the fitting jewel resting lightly on the bosom of this Venetian beauty whom but yesterday we called Chicago; and well it may, as in a degree the fountain is the clou of the Exposition. It seems but fair to call this fountain the most important of all the decorative sculptures. Every exposition has its great fountain, and the choice of Mr. MacMonnies to execute this one was most happy. Our sculptors as a rule have had too little opportunity to exercise the decorative side of their art, and we do not possess as does France a small army of sculptors who can be, as they were in ’89, turned loose to decorate a great exposition with groups and figures. It demands not only a decorative instinct but practice as well, a certain habit of and delight in handling huge masses of form which men who are capable perhaps of graver and more ponderated work may lack or have lost. Thus fifteen years ago Saint-Gaudens, fresh from school and filled with its traditions, would have in the course of natural selection been the man for the work; but with years and widening experience it is a question whether he would have undertaken to design and carry out in the short space of time that which his brilliant pupil has undertaken and carried through with all the audacity and fire of youth, tempered by a delicacy of taste which gives it after all its greatest value. Anything{76} more typical of the youth and hope which we fondly believe to be the characteristic of our nation is hard to conceive; and if, as is to be so greatly desired, the monument is to be made permanent (which the completeness of the modelling of individual parts, an unusual quality in works like this, would render easy), it might well stand to represent an era. Mr. French’s massive and dignified figure of America may be taken as the matron of this generation, tried and made strong through war; but MacMonnies’s epitome of youth represents the future of our as yet experimental civilization, and though the boat is propelled by the arts and sciences, it is the young girl who fills such a large part in our experiment who is really to the fore. It is Smith and Wellesley who row with the young girl enthroned; and vogue la galère, with pleasant waters ahead and a safe port at last!

Of Mr. Saint-Gaudens we have only a figure of Columbus, which he has signed in collaboration with another of his pupils, Miss Mary G. Lawrence. It is a good exemplification of what has already been said that at the first glance this figure seems almost out of place here. It is of a character—the highest character—of work which depends on the most serious study. Conception and pose are reduced to the simplest, almost archaic form, and while it does not seem quite as successful, it is of the same family as the Lincoln here in Chicago or the Deacon Chapin{77} in Springfield. The best of the sculpture here, while subject to the limitations twice mentioned, has perhaps gained a quality more essentially American by the absence of what may be called the ready-made decorative quality. The quadriga on the Peristyle, by French & Potter, the Indian girl and the bull, and indeed all the figures and animals at which these artists have worked together, are thoroughly satisfactory as decoration, and more native and appropriate to our soil than the lighter touch and greater facility of the sculpture at the exhibition on the Champ de Mars would have been.

The painters of the band of allied artists had the more difficult task. In the first place our country has arbitrarily forced our painters to work on a miniature scale, and with little exception our men affronted their task with theory and enthusiasm as their preparation. The sculptors had at least the practice of modelling large works; but with the exception of Mr. Maynard, who has taken Pompeian motives and given us under the porches of the Agricultural building a thoroughly architectural and adequate decoration in which his past experience has rendered him service, the painters were virtually winning their first spurs. Taking this into consideration their success is marked. Tried by the standard that the space allotted to a decoration should be filled, and filled by a composition which could not{78} serve within any other shaped space than that for which it is devised, Mr. Blashfield’s seems the most successful. In addition to this quality it has great charm of color and dignity of conception, which latter quality, combined with clean, workmanlike drawing, is shared by Mr. Cox. Mr. Reid’s and Mr. Weir’s domes also have charming qualities, while Mr. Shirlaw’s gives one the impression of a complete mastery of his scheme and intention. At the southern end of the Liberal Arts building, Mr. Melchers and Mr. McEwen have large compositions, those of the latter being marked perhaps by the greater individuality; but while they are all (each painter having two compositions) executed in a very able manner, they seem somewhat lacking in spontaneity. In another part of the grounds in the Women’s building the feminine contingent makes a brave show. Mrs. MacMonnies here leads the van with a composition sober in line and excellent in color. Miss Cassatt, having apparently defied the laws of decoration, has divided her space in three parts, in each of which she has painted pictures which, from her previous work, must be judged to be of excellent quality, but which, from the height at which they are seen and by reason of the small scale of the figures, are virtually lost. But this partial and cursory enumeration of what may be seen at the Fair could be continued beyond the limits of an article like this, and still leave unnamed{79} and apparently unappreciated much that is admirable and more that is hopeful. Of the delights of living in the midst of this, of seeing our people in holiday trim and, albeit, taking their pleasure somewhat sadly and getting as much instruction combined with it as possible, still enjoying it, much could be said. No mention has been made of the State buildings, which give, however, so much character to the grounds. New York’s imperial palace, bright and luxurious, is flanked on one side by Massachusetts’s staid and trim reproduction of John Hancock’s mansion, with additions of a character which must temper the smile of gentle reproof with which it regards its frivolous neighbor; while on the other stands Pennsylvania’s broad piazzaed home which shelters the Liberty bell. New Jersey reproduces a colonial “Head-quarters” mansion, and Washington is big and new and booming; California shows her fruits and extols her wines in a lowlying structure which recalls the adobe missions of her first settlers; and each and every State has here its home, first for its own people and then for the neighbors. Strange neighbors we have too, for the Midway Plaisance is not far away with its turbaned, sandalled, greased, and befeathered inhabitants, with its German and Austrian bands, its great difference of tongues and great similarity of cuisine. The outdoor life which is made so much of in Europe here{80} seems unappreciated; the numberless cafés and out-of-door restaurants which make up so much of the comfort with which one sees an exposition there still “leave to be desired” here. But these are details and of things earthy. The moral of the tale is short and easily read.

Our work-a-day nation awakened, it has been frequently said, to knowledge of the existence of art as a factor in life at Philadelphia seventeen years ago, and here and now attains as it were its majority. We may leave out our exhibit in the Fine Arts building proper, with the mere registration of the fact that by general consent it holds its own as well or better than close students of our art have known that it has done for several years past. The exhibition, or that part controlled by the Columbian Commission, is our best sign of progress, nay, of achievement. It has proved that throughout the land when occasion arises to build, to carve, or to paint, we have the men to do it. Art hath her victories no less than commerce; the qualities which have given us our place among nations, now that the struggle is past, are turned in gentler paths; and that which was prophecy so short a time ago is now truth realized:

BY the time this brief sketch shall have appeared in print the world’s greatest international fair will have thrown open its gates to the impatient multitudes, and millions will have looked with rapture upon its impressive perspectives of palaces and enjoyed their treasures. Even to the great general public, who are as yet awaiting with eager anticipation the indispensable outing at the Fair, its surpassing architectural features are already enticingly familiar. The “White City” is already a heritage of delight and inspiration to a vast multitude who have spent their available days beneath the spell of its enchantment.

It is no small thing thus to have penetrated the veil, as it were, as is here actually done for many{82}—to have materialized a vision—to have embodied a paradise. The “Heavenly City,” the “New Jerusalem,” with gates of gold and pearl, which in one questionable shape or another hovers in the hopeful, faithful fancy of so many of the sons of Adam will here find a realization, supplanting or exalting the ideal which has hitherto not always been to the glory of Heaven.

But in thus paying tribute to the architect we are perhaps unconsciously crediting him with more than his due; certainly more than he would himself claim. Of what avail were beautiful palaces if they could not be seen? and how easily might such an assemblage of heroic structures such as these at Jackson Park, as in previous similar expositions, have been so disposed, with relation to each other and their environment, as to have completely lost not only their individual impressiveness but the infinite advantage of their imposing ensemble.

We traverse the winding lagoon for an hour in continual delight, every passing moment, every quiet turn of our launch or gondola beneath arching bridge or jutting revetement opening up in either direction new and ravishing vistas of architectural beauty. Yet how little have we considered that the very means of our enjoyment, the pure blue waterway upon which our gondola so listlessly floats, is the crowning artifice by which the work of the archi{83}tect is glorified—a very triumph and inspiration in the great scheme of landscape—say rather waterscape—gardening, which has made this Columbian Fair a unique model for all others of its kind. I think it is conceded by the architects of the Fair that in no way are its buildings to be seen to such satisfaction or full effect as from the lagoon. And it is well to remember, if only as an instructive object-lesson, as we glide upon this liquid street, how much of our present enjoyment is due to the forethought of a supreme design, which, even before a single foundation-wall was laid, had taken into account the most effective grouping of the architectural features.

More than this, too, how many of these fortunate architects must have realized the rare satisfaction of having builded better than they knew, when for the first time they viewed their works from the vantage point afforded by their collaborator, the landscape artist, and saw these superb creations given back to them in twofold beauty from the clear mirror of the lagoon. The unique character and important innovation of this lagoon feature may be inferred when we consider that we have here an Exposition covering over five hundred and fifty acres, comfortably filled to its limits with the ample buildings, and yet no vehicles are to be allowed within its enclosure, and none will be required. The circuitous elevated{84}

railroad will of course transport the multitudes; while by the interior skilful distribution of the water-ways, rippling with gayly caparisoned gondolas by the score, and a hundred trim electric launches and other equally picturesque craft, every portion of the grounds will be easily accessible. The entire circuit on this water-course, from any given point, will occupy nearly an hour. The luxurious tourist arriving at his destination is invited at the water’s edge by ascending terraces of marble steps, their balustrades on either side overtopped by picturesque masses of tropic{85} and other luxuriant vegetation. Huge bronze-like agaves surmount the lofty marble urns; cannas, musas, caladiums, in most effective and artistic groups, are dispersed among broad expanses of velvety sward, begemmed with parterres of brilliant bloom.

But it is not alone in these picturesque settings of lawn and garden which everywhere abound throughout the grounds that we find our fullest appreciation of the landscape art. In the spell of these imposing structures, towering above the revetement walls on each side as we traverse the lagoon, we had utterly ignored another feature of its banks, or perhaps had our attention only momentarily inveigled thither by the invitation of the bevy of snowy ducks or geese or graceful swans hastening from our prow, and gliding beneath the overhanging boughs of feathery gray willows. Here indeed is a haven for a tired soul, a fairy realm whose modest charms are apt to be overlooked in the claims of the overwhelming architectural surroundings. But sooner or later its restful refuge will be discovered and welcomed. How many a foot-sore mortal, weary from the very excess of enthusiasm, will seek this quiet retirement, content for the moment to consign the architect to the accessory place of vista and horizon, while he roams and pries and muses among the labyrinthian paths, fragrant bowers, and{86} shadowy glades, and along the reedy flowery borders of this sylvan fairy island, which the artistic genius of Olmsted and Codman has here, in two short years, conjured up like magic from the muddy, dreary marsh.

Connected to the mainland by a half-dozen spans of bridges, it is readily accessible from any approach. It is a realm of strange inconsistencies and surprises, harmonies and pleasant discords, unified with the rarest skill. The familiar park or garden at one moment, its curving walks encircling more or less—generally less—conventional parterre, diversified with closely bedded mosaic of bright blossoms; and now a path leading us between high walls of blossom-laden shrubbery, skirting a rustic arbor, or winding beneath the shade of tall, dense branches of trees, which, however at home they may appear, so wonderfully has the skill of the landscapist concealed his artifice, are still almost as much strangers to the soil as ourselves; the adjustment and grouping giving the complete illusion of nature’s random planting.{87}

Only a very few of the thousands of trees upon this “wooded island”—medium-sized white-oaks—are native tenants of the place. Only two years ago isolated in the more elevated dunes of a great morass, they now find themselves in strange company; the soil from the bed of the lagoon, having levelled the former slopes about their feet, is now peopled with individuals as large as themselves. Many a rare nook upon the island’s borders would defy the critical scrutiny of the botanist or artist to detect a single tell-tale evidence of artifice. Would you step from the conventional park to the wild garden in{88}