“Suppose we have a club.”

Title: Adele Doring of the Sunnyside Club

Author: Grace May North

Illustrator: Florence Liley Young

Release date: May 16, 2020 [eBook #62151]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

“Suppose we have a club.”

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | The Sunnyside Club |

| II | The Secret Sanctum |

| III | A Jolly Scrubbing-Party |

| IV | Adele’s Secret |

| V | Pleasant Plans |

| VI | A Surprise Party |

| VII | A Birthday Feast |

| VIII | More Surprises |

| IX | The Mother Goose Play-House |

| X | Preparing for Examinations |

| XI | Vacation Days |

| XII | The Fudge Party |

| XIII | The Two Dryads |

| XIV | Pine Island |

| XV | An Exciting Adventure |

| XVI | More Mystery |

| XVII | The Little Bear |

| XVIII | A Fish Supper |

| XIX | A Trip to the City |

| XX | Amanda Brown |

| XXI | The Ball Game |

| XXII | The King’s Highway |

| XXIII | School-Days Again |

| XXIV | The House by the Wood |

| XXV | A Visit to the Poorhouse |

| XXVI | A Mystery Solved |

| XXVII | A Really, Truly Home |

| XXVIII | The New Pupil |

| XXIX | Eva Begins a New Life |

| XXX | Eva Humiliated |

| XXXI | Something Unexpected |

| XXXII | A Happy Meeting |

| XXXIII | Farewell to the Orphanage |

There was spring in the air,

Though the woods were still bare.

There was fragrance all about,

Though not a flower was out.

There were seven girls so gay

Off for a holiday.

Across the April meadows they danced, a long row, hand in hand. Another month and the brown fields would be gold-and-white with daisies and buttercups.

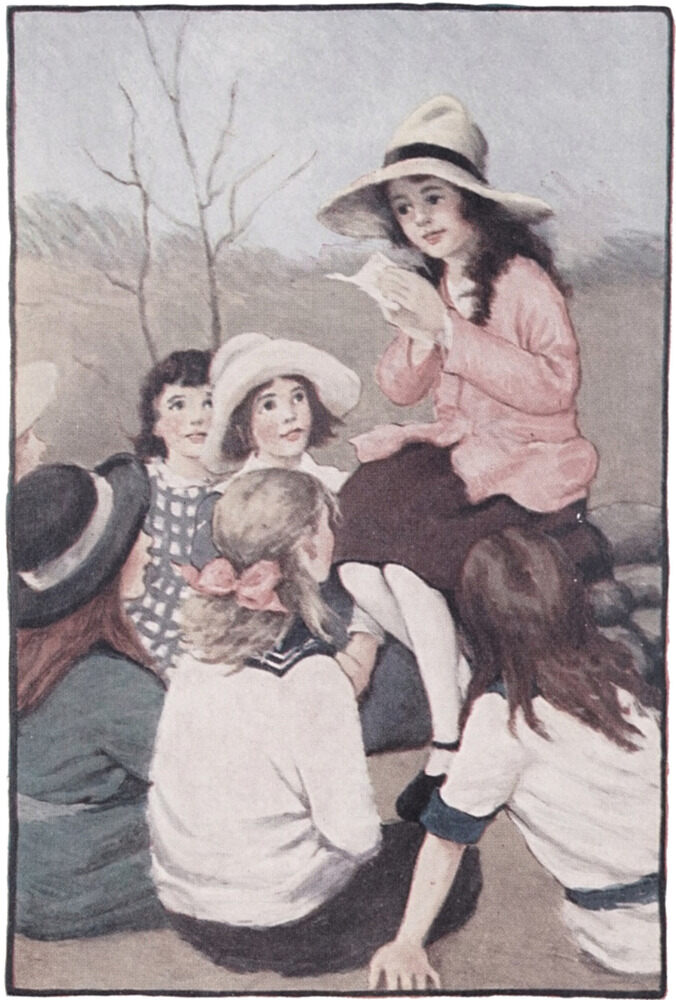

“Look! Look! The pussy-willows are out!” Adele Doring called, as, with a shout of glee, she darted ahead of the rest, toward a bush which grew close to a low stone wall and not far from a sparkling brook.

When the others came up, they caught hold of hands and danced about the bush while Adele sang:

“‘Little Pussy-willow, harbinger of spring,

We are glad to welcome you, such good news you bring.’”

“Adele,” drawled Rosamond Wright when they had paused for breath, “I’m powerful worried about you, for fear you are going to grow up to be a poet or something queer like that.”

Adele laughed as she perched on the low stone wall and fanned herself with her broad-brimmed hat.

“No fear of my being a poet!” exclaimed Doris Drexel, as she and the other girls sat down on the warm brown grass. “Why I couldn’t even make ‘curl’ rhyme with ‘girl’ without being prompted.”

Then Adele, having put her hand in the pocket of her rose-colored sweater-coat, gave a sudden exclamation as she drew out a piece of folded paper.

“Girls!” she cried. “Lend me your ears! I have a secret plan to reveal.”

“Aha!” quoth Bertha Angel. “So you had a sinister motive, as Bob says, for bringing us to this lonely, forsaken spot.”

“You were wise to do so, if it’s a secret,” Rosie declared, “for even the walls have ears.”

“Well, if this old stone wall wants to hear what I have to say,” laughed Adele, “it may listen and welcome.”

“Do hurry and tell us!” cried the impatient Betty Burd. “Your plans are always such jolly fun.”

“Well, then,” said Adele, mysteriously, “I’ve been reading a book.”

“But there is nothing remarkable about that,” Doris Drexel exclaimed. “You are almost always reading a book.”

Adele, not heeding the interruption, continued: “And in this book dwell several maidens of about our own age. They belong to a secret society and they have the best times ever. Now my plan is this. Since we seven girls are continually together, suppose we have a club.”

“Wouldn’t that be fun, though!” exclaimed Peggy Pierce. “I’ve always wanted to belong to one.”

“I choose to be treasurer!” declared Betty Burd mischievously.

“Oh, Betty, you treasurer!” cried Doris Drexel in mock horror. “Then we never would know how our funds stood.”

“Don’t you have enough of mathematics in school, little one?” Adele asked with twinkling eyes.

“Don’t I, though! Oh, girls!” Betty exclaimed dismally. “I just know that you are all thinking of yesterday. Wasn’t it terrible when I was at the board doing that problem and those visiting ladies came in and said that they were interested in watching the progress made by the young. I was so scared that every figure looked like a Chinese character to me, and how I did wish that a trap-door would open under my feet and let me gently down into the cellar. Luckily, Miss Donovan had no desire to be disgraced, and so she bade me take my seat and let Bertha do the problem.”

“I hate math., too,” Doris Drexel declared. “I’m like the little boy who said he could add the naughts all right but the figures bothered him.”

“In truth,” said Gertrude Willis, “there is just one of us who was born to be the treasurer of this club, and that one is Bertha Angel,—‘the only pupil in Seven B who can add and subtract with unvarying accuracy,’ as Miss Donovan so recently remarked.”

“Good!” cried Adele. “Bertha Angel, you are elected treasurer, but your duties will not be heavy, for at present there is no money to count.”

“I accept the responsibility,” said Bertha brightly, as she sprang up and made a bow.

“Now,” Adele inquired, “who would like to be secretary?”

“Secretary!” repeated Betty Burd blankly. “I thought that was a piece of furniture. My Uncle George has one in his study and it looks like a writing-desk.”

“So it is, fair maid,” drawled Rosamond Wright, “but didst thou never hear of one word having two meanings? The secretary which we want is a person to write down the clever things that we say and do.”

“I vote for Gertrude Willis,” called Doris Drexel. “Any one who could write such a composition as she read yesterday in assembly on the ‘Rights of the Indian’ surely ought to be recognized as a genius in our midst.”

“Thanks kindly,” laughed Gertrude; “I’ll do my little best.”

“Girls,” exclaimed Adele, “our club is now the happy possessor of a secretary and a treasurer, but it has neither a name nor a president!”

Peggy Pierce was on her feet in an instant, exclaiming, “There is only one among us who could be our president, and she is”—“Adele Doring!” the five others shouted in enthusiastic chorus.

“You see,” laughed Peggy, as she resumed her seat, “the vote is unanimous.”

Adele, rising, made a deep bow as she recited with mock gravity, “Ladies and gentlemen, I thank you for the honor which this day you have conferred upon me, and I hope that my future acts and deeds will in no way betray the confidence which you have placed in me.”

“Oho!” Bertha Angel declared. “That speech was in last week’s history lesson.”

“I was hoping you’d all forgotten it,” Adele laughingly replied, as she sat again on the low stone wall.

“Well, I had, you may be sure!” Betty Burd exclaimed. “But what is the club to be named?”

“I had an inspiration last night,” said Adele, “so I wrote it down. I thought we might name the club after our beautiful suburban town of Sunnyside, and then I wrote this rhyme as a sort of pledge for us all to sign:

“We promise to look on the Sunnyside

And be kind and cheerful each day;

To help the needy or lonely or sad,

Whom we happen to meet on our way.”

“Oh, Adele!” moaned Betty Burd in pretended dismay. “Why didn’t you tell us in the beginning that we had to be saints to belong to your club? If I should turn into a cherub too suddenly, my mamma dear wouldn’t know me.”

“Don’t worry about that,” laughed Adele. “We aren’t any of us in danger of sprouting wings just at present.” And then she added seriously, “But I do think that a club ought to stand for something more worth while than just fun and frolic. Of course we’ll have that, too; we always do.”

“You are right, Adele,” exclaimed Gertrude Willis warmly. “I think it is a beautiful pledge, and I wish to be the first one to sign it.”

Adele produced a stub of a pencil, and the paper went the rounds, each girl writing her name thereon.

“Now,” said Adele, “only one thing remains to be decided upon, and that is, where we shall have our Secret Sanctum.”

“Our which?” asked the irrepressible Betty Burd.

“A place where we may hold our secret meetings,” Adele explained.

“You may use our attic if you wish,” drawled Rosamond, “but, I warn you, it’s powerful warm up there in the summer, and cobwebby.”

“An attic is all right on rainy days,” Adele replied, “but the blue sky is the roof for me, now that spring is here.”

While she was talking, Adele’s eyes were roving the meadow. Suddenly she saw something, and, leaping to the ground, she skipped about with delight, to the amazement of the others.

“Adele,” protested Peggy Pierce, “tell us, so we may dance, too.”

“Ohee!” sang out Adele, catching hold of Peggy and whirling her around. “I’ve just thought of the dan-di-est place for a Secret Sanctum, but I’m not going to tell until I find out if we may have it. Meet me Monday morning under the elm-tree and then I will tell you.”

So ended the first meeting of the Sunnyside Club, which was destined, in the months to come, to bring cheer and happiness into many lives.

The town of Sunnyside lay in a wide valley, beyond which were sloping hills, and among them, clear and blue, nestled Little Bear Lake.

To the south of the village there was a field which was so yellow in summer that it had been called Buttercup Meadows. Near it was a maple wood, and through the wood and across the field rippled a merry little brook.

Now, in the meadow and near the wood, and close to the laughing brook, stood a picturesque old log cabin. Years before, when the nearest town had been ten miles away, Adele Doring’s grandfather had owned all of the land that one could see from the top of Lookout Hill, and in this log cabin his sheep-herders had lived.

The sheep and the herders had long since passed away, but the old log cabin was still standing, and Adele’s father now owned it, and, too, he owned the Buttercup Meadows and the maple wood and the laughing brook and Lookout Hill.

It was that log cabin which Adele had seen on the day when the Sunnyside Club had been formed by the seven girls who were always together. They had been wondering where they could hold their meetings, when Adele had spied the log cabin, and she had thought at once that it would make an ideal Secret Sanctum, but she did not want to tell the others until she had asked her Giant Father’s advice and consent.

The next morning, after breakfast, Adele revealed her plan. “May you have the log cabin, Heart’s Desire?” her Giant Father asked with twinkling eyes. “Why, of course you may! Uncover yonder ink bottle and I will deed it to you this very moment.”

“Oh, Daddy!” Adele laughingly exclaimed. “I don’t want to own it that way. I just want your permission and mother’s to do with it as I like.”

Mrs. Doring beamed on them both as she replied, “If your father is willing, daughter, then so am I.”

“Oh, you darlings!” Adele exclaimed, joyously hugging them. “Thank you so much.” Then catching up her hat and books, away she skipped to school.

The trysting-place was a big spreading elm-tree which stood in the middle of the girls’ side of the school-yard. Under it was a circular bench, and here the seven maidens waited each morning until all had gathered.

When Adele rounded the high hedge which bordered the school-grounds, she was greeted with a joyous chorus from the six who were already there.

“Three cheers for the president of the Sunnyside Club!” cried Betty Burd, the irrepressible.

“Hush! Hush!” laughed Adele, looking quickly about. “Don’t you remember that it is a secret society?”

“Luckily there is no one here but ourselves and the elm-tree,” Rosamond said.

“Adele!” Gertrude Willis exclaimed. “Why are your eyes so shining and bright? Have you good news to tell?”

“Indeed I have,” Adele replied gayly. “Just think, girls, we may have it!”

“Have what?” asked the puzzled six.

“O dear, how stupid of me!” laughed Adele. “Of course I hadn’t told you about it, had I? Well, you know that we wanted a place in which to hold our club-meetings, and I said I had thought of one if we might have it.” The six nodded eagerly.

“Well, then, we may, and it’s the loveliest, idealest place for a Secret Sanctum that ever could be thought of.”

“Oh, Adele, do tell us where it is,” begged Peggy Pierce. “I am ’most consumed with curiosity.”

“Well, then, I will end your suspense by telling you that it is the log cabin over in Buttercup Meadows. It belongs to my dad, and he is glad to let us have it, and so is mumsie.”

“Ohee!” squealed Betty Burd. “How I do wish that there was no school to-day, so that we might go right over to look at our newest possession.”

“Let’s go at three!” exclaimed Adele; “that is, if our nice mothers do not need us after school.”

The mothers not only did not need them, but one and all were glad to have their daughters out of doors as much as possible in the pleasant spring weather, and so, as soon as the afternoon session was over, the seven maidens went hippety-skipping across the brown meadows.

Adele was armed with a good-sized key, which was rusty with age, but which proved that its days of usefulness were not over, for, when it was slipped in the padlock, it turned with a creak and the door swung open.

As first it was so dark within that they could see nothing, but soon their eyes, becoming accustomed to the dimness, noted several objects about.

“Oh, do look!” cried Doris Drexel in delight. “Here is rustic furniture which must have been made by the sheep-herders many years ago.”

“Can’t we get some light on the subject and a little air as well?” exclaimed Bertha Angel. “It’s stifling in here. Good! Here’s a window,” she added as she pulled a leather thong from a nail and threw back a rude wooden blind, thus uncovering a square opening, and through it came, not only a fresh breeze, but also the slanting rays of the afternoon sun.

“There! Now we can breathe,” said Adele, “and examine our possessions more closely.”

There was a rude bed-couch, a rustic table, and several three-legged stools. These were fashioned out of the trunks of small trees, with the bark still on them.

“Oh, but this will make an adorable Secret Sanctum,” exclaimed Betty Burd.

“Girls,” drawled the romantic Rosamond Wright, “if only this furniture could talk, what tales of sheep-herder’s life it could reveal!”

“The place is so musty and cobwebby,” said the practical Bertha, “we shall have to scrub every inch with warm soap-suds.”

“Oh, Burdie, how could you throw soapy water on my poetical dreams!” moaned Rosamond, who did not even like to hear a scrubbing-brush mentioned, much less entertain the idea of wielding one.

“Tut! Tut! My children!” Adele intervened. “Now all listen to me. You know the spring examinations are due in a few weeks, and we must study, study, study, and cram, cram, cram, so let’s forget that the cabin exists until next Saturday, and then let’s come out here with all the needed utensils, and, with Bertha to superintend the task, we will soon have the place as clean as a whistle.”

“Oh-h!” moaned Rosamond, and then she added mischievously, “I do believe that I’m going to be confined to my bed all day next Saturday with overstudyitis.”

“Don’t worry about that,” laughed Doris Drexel. “You may have overtattingitis, Rosie, but never overstudyitis.”

Rosamond had made yards and yards of tatting, which she said would some day adorn her wedding finery, and the other six often teased her about it, for, as yet, to them boys were playmates and brothers and nothing else.

Then Rosamond dramatically exclaimed: “Girls, I will not fail you in the hour of need. Armed with my mother’s best feather-duster, to be used on pianos only, I will be here Saturday next at the appointed hour.”

“Well, I’ll bring an extra scrubbing-brush, Rosie,” said Bertha teasingly.

“And let’s bring our lunches and stay all day if our nice mothers are willing,” Peggy Pierce remarked.

“That we will!” exclaimed the six. The door was again closed and the key hidden under a log which served as a step. Then, hand in hand, the Sunny Seven, as Adele called them, hippety-skipped homeward, chattering like magpies and laying wonderful plans for the adornment of their Secret Sanctum, which, in the summer to come, was to be the scene of many a jolly lark.

The sky is always bluer,

And the songs of birds more gay,

And the meadow blossoms sweeter,

Upon a Saturday.

A week of lessons over,

And long golden hours for play.

Saturday dawned sunny and blue, and Adele was up at an early hour and down in the kitchen before Kate had set the water to boil.

“The top of the morning to you!” Adele called to the kindly Irish woman who had been cook in the Doring family since before Jack was born.

“And it’s you, Colleen,” said Kate, “and some merriness you’re planning, to be up this early.”

“Right you are!” the girl gayly replied. “I’m going to a picnic, and I want to borrow a mop and a scrubbing-brush and a pail and some rags.”

Kate held up her hands in pretended horror as she exclaimed, “And a picnic do you call it?”

“It truly is,” laughed Adele, “and I want some sandwiches and pickles and some of those darling little cakes which you made yesterday morning, and—”

“Take anything that you can find, Colleen,” said Kate, as she busied herself with breakfast preparations.

So Adele put up a bountiful lunch in a covered basket which she kept for the purpose. Jack, who was a year older than Adele, sauntered out into the kitchen and helped himself to one of the chocolate cupcakes as he exclaimed: “Say, Della, why don’t you ever ask us fellows to these picnics of yours? It isn’t fair for you girls to eat all the good things by yourselves.”

“Maybe we will some day,” Adele replied. And then she added merrily, “But you wouldn’t want to be asked to-day.”

“I should say not,” Kate began, “with brooms and mops and pails—” But she said no more, for Adele, springing up, whispered, “Hush, Kate! It’s a secret!”

After breakfast Adele ran down to the barn, and Terrence, Mr. Doring’s handyman, hitched her black pony, Firefly, to the little red cart. Into this were stowed the lunch and cleaning utensils, and then Adele drove out of the yard, waving to her mother and Kate.

The homes of the other six were soon visited, as they were all in the same neighborhood, and each girl appeared with scrubbing-brush and apron and pail.

“We’ll take turns riding,” said Adele, as she leaped lightly to the ground. “Betty, you may drive, and Gertrude Willis, you climb in and ride and keep an eye on the scrubbing-brushes, lest they attempt to hop out over the sides. The rest of us will trudge along behind.”

Gertrude had not been strong during the winter, and that was why thoughtful Adele had suggested that she should ride; and as for little Betty Burd, the youngest of the seven, to own a pony like Firefly was the dearest desire of her heart, but her widowed mother felt that other luxuries were more necessary. Adele, knowing this, took every opportunity which offered to give Betty the pleasure of riding or driving Firefly.

Across the meadow they went, a gay cavalcade. Like all young things in spring, their hearts were filled with joy and they wanted to dance and sing. During the week the maple wood had changed from brown to silvery green, and there were patches of fresh grass along the banks of the laughing brook.

“Hark!” cried Adele with glowing eyes, as she stopped and held up one hand. “Did I hear it or did I not?”

They all listened, and from a clump of bushes near there arose, sweet and clear, the morning song of a robin. Then, with a rushing of wings, the redbreast was up and away.

“Cheerily! Cheerily! The robins sing.

We’ve come to tell you. It’s spring! It’s spring!”

Adele sang happily.

“I hope you all wished on the first robin,” Rosamond exclaimed, “for that wish is sure to come true.”

“Well,” said Adele thoughtfully, “I don’t believe that there’s a thing in the whole world that I have to wish for. I’ve mother and father and Jack and a happy home and such nice friends. What is there left for one to desire?”

“Lucky Adele!” Betty Burd said almost wistfully; and then Adele remembered how lonely Betty and her mother were for the loved one who so recently had been taken away; but brave little Betty, sensing this, called cheerily, “Trot along, Firefly! Let’s run them a race!” and Firefly did trot along at such a gay pace that the brushes and pails rattled about and Gertrude had quite a time to keep them from bobbing out, while the girls on foot had to run and skip to keep up, and so, gayly, they soon reached the Secret Sanctum.

Adele unhitched Firefly, with Betty helping, and then the pony was allowed to roam, for he never wandered far away from his mistress.

The door and window of the cabin were soon open, and Bertha, who had been appointed director-in-chief of the scrubbers’ brigade, began to issue orders. “Somebody fill the pails at the brook,” she said, “and somebody else be gathering sticks for a fire. Hot water gets things much cleaner than cold.”

And so the girls skipped about, finding wood, and filling pails, and starting a fire, for, of course, Bertha had some matches.

“Did any one think of scouring-powder?” asked Peggy Pierce, as she rolled up her sleeves and donned her big apron.

Silently Bertha produced the required article.

“Burdie, what an orderly brain you must have,” Rosamond exclaimed in wonder and admiration. “I never would have thought of soap-powder in a thousand years.”

“You’d have brought the latest song or a bit of tatting, wouldn’t you, Rosie?” Doris Drexel asked, to tease. But Adele, fearing that Rosamond might be hurt, hastily added, “We need all sorts of people in this world to keep it balanced. Now a story-book is much more to my liking than soap-powder, but Rose and I are going to show you young ladies that we are as good scrubbers as any of you.”

Rosamond smiled lovingly at her champion, and then, as Bertha was giving further orders, they all gathered about to listen.

“I think,” the director-in-chief was saying, “that it would be better to carry the rustic furniture all out by the brook, and then it can be washed there and dried in the sun, and that will clear the cabin floor and make it easier to scrub. Now, Gertrude, you take charge of the outdoor work, but don’t you lift a thing, and Rosamond and Peggy will help you while the rest of us do the inside.”

Then the girls took hold of the rustic table, and, by turning it sidewise, it soon stood near the brook; the rustic bed-couch followed, and, with six to lift, it was not heavy for any. Gertrude protested that she was really much stronger than she had been, but they would not allow her to help.

By this time the water in the pails was hot, and Betty Burd impulsively stooped to lift one of them from the fire, when Bertha warned: “Don’t you touch that handle, Betty. It will burn you. Wait! I’ll show you how.” Then, taking the broom, Bertha slipped it under the hot handle. Betty took hold of the other end, and together they lifted the pail from the fire and placed it on the grass. The soap-powder was added, and, when the water was cool enough, the brushes were dipped in and the rustic furniture was drenched and scrubbed.

“If there are any little bugs living in this bark,” Peggy said, “we bid them come forth.”

“They’ll be drowned little bugs before many minutes,” Rosamond added, as she threw a pail of fresh water from the brook over the table, to rinse off the soap-suds. This they also did to the couch-bed and the stools, and then the rustic furniture was left in the warm noon sunshine to dry and sweeten.

Meanwhile, the inside of the cabin was being thoroughly scoured, and many a startled spider darted out into the meadow, never to return.

At last the four maidens appeared in the doorway, and Adele threw herself down on the warm ground as she exclaimed, “Well, if scrub-ladies get as weary as this in their bones, I’m glad that I’m planning to take up a different profession.”

“Oh, you girls had the hardest part of it,” Gertrude declared. “Scrubbing the furniture was really like play.”

“Well,” said Adele, “we seven have banded together with the firm resolve of looking on the sunny side of things, and the sunny side of this scrubbing is—”

“That it’s done,” Rosamond interrupted.

“I’ll agree that is one sunny side to it,” laughed Adele, “and the other is, that we’ll enjoy our Secret Sanctum so much more, now that it is sweet and clean—”

“And bugless,” put in Betty Burd.

Adele, heeding not the interruption, continued, “And you know a thing that’s worth having is worth working for.”

“Oh, Della,” cried Peggy Pierce, “would you mind postponing the lecture until after we have our lunch? I’m positively famished.”

“So am I,” Rosamond declared.

“Well, since we’re hungry, suppose we eat,” said the practical Bertha.

“Hurrah for our treasurer!” cried Betty Burd, springing up and dancing toward the little red cart with a sprightliness which did not suggest weariness of bones. Then, climbing up, she handed out the seven baskets, and soon a tempting repast was spread on the paper table-cloth which Rosamond had brought.

“Did ever sandwiches taste so good before?” muttered Peggy Pierce, with a mouth full of bread and cold chicken.

“Who said olives?” asked Adele, as she sighted a little pile in front of Rosamond.

“Pardon me for not passing them sooner,” Rosamond exclaimed, with elaborate politeness as she lifted the paper napkin on which they were heaped, but, this being moist, the olives fell through and rolled about on the table-cloth.

“Grabbing isn’t manners!” Doris Drexel called, as Betty Burd pounced upon one.

“There are two olives apiece,” said Rosamond, “so you might as well grab that many if you wish.”

“I did have a chocolate cup-cake apiece for us,” moaned Adele, “but that brother Jack of mine came out into the kitchen, and, without as much as saying ‘by your leave,’ he ate the biggest, and when I went back to the jar for more, nary a one was left.”

“Never mind, Della,” Bertha condoned, “I have an extra sugar cookie,—they’re made out of real cream—and you shall have it.”

“Yum-m!” murmured Rosamond as she took a bite of her sugar cookie. “Aren’t they delicious! I suppose you made them, Burdie.”

“I did that,” Bertha replied, expecting again to hear how practical she was.

“You’ll make a good wife for a poor man, a missionary or somebody like that,” said Doris Drexel, as she nibbled daintily on her cookie, to make it last as long as she could.

“Marry!” said Bertha scornfully. “I’m not going to marry anybody.”

“Well, you needn’t be so snappy about it,” laughed Doris. “I didn’t mean right away, to-morrow. I know you’re only thirteen, though tall for your age.”

“Girls!” the sentimental Rosamond exclaimed. “Which one of us do you suppose will have the first romance?”

“Not I,” laughed Adele, as she sprang up and shook the crumbs from her lap; and then she added reproachfully, “There’s somebody at this picnic who hasn’t had a bite to eat and it’s a shame, so it is. He’s coming now to tell us what he thinks about it.”

The girls looked around and there stood Firefly, gazing reproachfully at them.

“I choose to feed him,” cried Betty Burd, springing up; and dancing again to the cart, she called gayly, “Come on, you darling Firefly. Here’s the nicest hay for you, and some oats and a lump of sugar for your dessert.”

The other girls repacked the baskets and tossed the papers on the dying embers of their fire. It had been made close to the brook, so that they could put it out quickly if the dry grass began to burn.

Then, to their delight, they found that the floor of the cabin was dry, and so the warm, clean furniture was carried back in, and then Adele exclaimed, as she brought forth a pad and pencil, “Sit down everybody, and, since your brains are rested, I shall expect them to produce brilliant ideas. Now gaze about our Secret Sanctum and tell what it needs.”

“There’s a green fly coming in at the window,” Doris Drexel announced. “We ought to tack up mosquito-netting.”

“Good,” exclaimed Adele, as she wrote down the suggestion. “We’ll call that item one.”

“I think we ought to make a sort of mattress for this hard couch,” Peggy remarked, “if it’s intended for comfort.”

“And sofa-pillows we need in plenty,” said the rather indolent Rosamond, who liked things luxurious.

“I’ll contribute a pine pillow,” Doris volunteered. “I have such a fragrant one, and it’s just the thing for a rustic place like this.”

“We need a bowl for flowers,” said Rosamond. “Mother has a big blue one with a chip in it, and it would look adorable on the center-table filled with buttercups and ferns.”

“Fine!” cried Adele brightly; “item five. And in every one of our pantries, on top shelves or in out-of-the-way places, there is apt to be chipped or cracked china. With our mothers’ consent, let’s bring it over here and have a china-closet. Then, when we wish to give a party, we shall have plenty of dishes.”

“But where’s the closet?” asked Betty Burd, looking about as though she expected one to appear like magic before her.

“We’ll make one,” Adele announced.

“Make a china closet?” repeated Betty Burd in amazement. “Out of what?”

“Orange boxes, no less, little one,” Adele replied. “I made a book-case once and covered it with flowered chintz, and it was just ever so pretty.”

“Dad will let us have the boxes,” said Bertha Angel, whose father was the leading grocer in town.

“And my dear papa will contribute the cloth, I am sure,” Peggy declared. Mr. Pierce owned the Bee Hive department store.

“Some magazines would look homey scattered around on the top of the table,” Gertrude remarked. “And then, we must have a bank in which to keep our funds.”

“And you must have a little blank-book, Trudie, and write down in it all that we say and do,” Betty Burd declared.

“Gertrude will certainly be kept busy if she does that,” laughed Doris Drexel, “for some of us could out-chatter a poll-parrot.”

“Naming no names,” said Betty Burd, making a merry face at Doris. There was one delightful thing about their youngest member, she always took teasing good-naturedly and joined in a laugh, even though it were about herself, as gayly as did the rest.

“And then, when our Secret Sanctum is all finished and furnished we must have a house-warming party,” Rosamond declared.

“Oh, won’t that be fun, though!” exclaimed Betty Burd, whirling around like a top.

“And we’ll invite Bob and Jack and all of the Jolly Pirates’ Club,” Doris Drexel added.

These happy girls were soon to give a party at their Secret Sanctum, though it was to be very different from the one which they were so gayly planning.

A secret! A secret!

Who can guess the secret?

There’s blue in it and green in it,

And bird-song lilting gay,

There’s dancing and there’s laughter

And there’s mirth and merry play.

One Friday, after the Secret Sanctum had been furnished as the girls had planned, the six were waiting for Adele under the elm-tree in the school-yard.

“Didn’t we have fun last Saturday!” chattered Betty Burd. “But I don’t know what we would have done if Bob Angel and Jack Doring had not carted those heavy things to the cabin for us.”

Bob Angel assisted his father after school-hours by delivering groceries, and he had readily consented to cart the mattress and boxes to the cabin for his sister, Bertha, and her friends.

“I’m so glad I found those bright-colored prints up in our attic,” said Doris Drexel. “They are some my grandmother had, and, with their queer, old-fashioned frames, they are just suited to our Sanctum.”

“I can’t get over admiring the china-closet and the book-case,” Betty declared. “I never dreamed that such pretty things could be made out of just orange boxes.”

Rosamond glanced at her wrist-watch as she exclaimed: “Here it is five minutes to the last bell. I never knew Adele to be so late before. What can have happened?”

“If Adele is late to-day,” said Doris Drexel, “it will break her perfect record. She hasn’t even been tardy a moment this whole term.”

“Ho! Here she comes now!” cried Peggy Pierce with a sigh of relief, for the girls would have been as sorry as Adele herself if the perfect record had been broken.

“What ever kept you so long, Della?” Rosamond called. “We’ve been waiting here for almost fifteen minutes.”

“Did you break a shoe-lace?” Doris Drexel inquired.

“Nary a bit of it,” laughed Adele when she could get her breath. “I happened to see a clump of violets in a sunny corner and I dug them up, roots and all, and took them over to Granny Dorset. She told me last week that she was eager for the first violets to bloom; that somehow the ache in her bones got better then, and since she can’t leave her bed to get them for herself, I thought that I would take them to her, and she was so pleased! I wish you might have seen her dear old eyes twinkle.”

“Oh, Adele, you’re always thinking of kind things to do,” Betty Burd declared. “I wish I were that way!”

“There’s the last bell!” called Peggy Pierce. “Forward! March!” But Adele detained them, exclaiming: “Wait, girls; I have the most beau-ti-ful secret to tell you, but I’ll have to keep it now until after school! Meet me under the elm-tree just as soon as ever you can.”

Then into their class-room they went, but all through the morning session they kept wondering and wondering what new fun Adele was planning. In fact, Betty Burd was thinking so much about it that she could not keep her mind on her lesson, and when Miss Donovan suddenly asked her to name the capital of England, Betty was so confused that she answered, “Oh, it’s a secret!”

“A secret?” exclaimed the mystified Miss Donovan. Poor Betty blushed as crimson as a poppy, and the other six girls just had to laugh.

Then Betty explained that she had meant to say that London was the capital of England, but that she had been thinking of a secret.

When at last the class was dismissed, the Sunny Seven, as Adele called them, hurried out to the elm-tree, and Betty Burd exclaimed: “Wasn’t Miss Donovan a dear not to keep me in! I was so afraid that she would, and then I couldn’t have heard the secret.”

“Like as not you deserved to be kept in,” Bertha Angel remarked, “but we are glad that you weren’t.”

“Now, Adele, do tell us that secret,” pleaded Peggy Pierce, and they all listened with eager anticipation.

“Look at me hard,” Adele said, “and see if you can guess my secret.”

The six girls turned her around and even examined the big ribbon bows on her golden-brown braids, but they couldn’t find a clue to the secret.

“Don’t I look a little bigger or older or something?” Adele asked.

“Oho-ho! I know!” cried Doris Drexel, clapping her hands gleefully. “Adele, it’s your birthday.”

“You are warm,” Adele replied, “but it isn’t my birthday yet. It’s just going to be. Think of it, girls! Next week I shall be thirteen years old and almost a young lady.”

“Shall you do your hair up?” asked Rosamond Wright, whose dearest desire was to wear her curls twisted on high.

“Dear me, no,” laughed Adele. “I shall wear braids until I’m twenty, I guess.”

“Oh, Della, I do hope you’re going to have a party,” exclaimed Peggy Pierce. “I have the sweetest new dress. It’s white muslin, all scattered over with pink rosebuds, and I’m just pining to be asked to a party so that I can wear it.”

“Yes, I’m going to have a party,” Adele replied, “but you won’t be able to wear that dress to it, Peggy; it’s going to be a different sort of party.”

“Oh-o-o!” came a wailing chorus. “Aren’t we going to be invited?”

“Not exactly,” laughed their favorite, “and yet I shall expect you all to be there.”

“Oh, Adele!” Bertha Angel exclaimed. “You are so mysterious and so provoking! Do you expect us to come to your party without an invitation?”

“Of course not,” Adele replied, “and I won’t keep you guessing any longer. This is the way of it. Yesterday I went over to the orphan asylum to read stories to the very little children, as I do every Sunday, and when I was coming out I passed what I supposed was an empty class-room. The door was open a crack, and I thought that I heard some one crying inside. I looked in and saw a girl of about our own age sobbing as hard as ever she could. I had never seen her before. I went nearer and said, ‘Little girl, can I do something to help you?’ At first she only cried the harder, but I sat down beside her, and at last she told me that her mother and father were both dead and that the people she had been living with couldn’t keep her any longer, and so they had sent her to the orphans’ home. I told her that she would like it there because the matron was so kind.

“‘Yes,’ she sobbed, ‘I shall like it, I guess, but next week Saturday will be my birthday, and mother always gave me a party, but now nobody cares.’

“I felt as though I would have to cry, too, but I knew that would not be the way to cheer her up, so I asked her to take a walk with me and I showed her the pleasant places around the Home. She loved the woods, she said, and when we went back, an hour later, I guess she felt better, but right then and there I decided that this year, instead of having a party for myself, I would give a surprise birthday-party for Eva Dearman.”

“Oh, Adele!” Gertrude Willis exclaimed. “I am so sorry for that poor orphan girl. May we help give the party?”

“That’s just what I hoped that you would want to do,” said Adele happily. “I must skip home now and do my practicing, but to-morrow will be Saturday, so let’s meet in our Secret Sanctum at three o’clock and make our plans.”

The Secret Sanctum log cabin stood

In Buttercup Meadows beside the green wood,

And the birds at nest-building would pause and sing

That joyous song which they carol in spring,

And the brook as it purled on its fern-edged way,

And the daisies and buttercups golden and gay,

Were all of them telling, “It’s May! Lovely May!”

And there the maids of the Sunny Clan

Met one Saturday a party to plan.

“Girls,” said Rosamond Wright, as she looked out of the cabin for the twentieth time, “it is quarter-past three and Adele not yet come.”

“Oh, I forgot,” Betty Burd exclaimed, as she placed a bowl of daisies on the rustic center-table, “Adele asked me to tell you that she might be a little late, as she had to go on a very important errand!”

“There is some one coming now on horseback,” Peggy Pierce remarked as she came up from the brook with a pitcher of sparkling water.

“All that I can make out is a cloud of dust,” said Bertha Angel, as she shaded her eyes to look.

“It is Adele!” cried Betty Burd. “She’s turning into the meadow lane now.”

The six girls ran out eagerly to meet the lassie, who came galloping up on Firefly. Leaping lightly to the ground, Adele let the pony go wherever he wished to browse, knowing that he would return to her when she whistled.

The girls pounced upon their favorite and led her into the cabin, where she sank down among the soft-pillows, exclaiming, “I’ve ridden so fast, I’m ’most out of breath, but I knew that you girls would be waiting here, and so I came on a gallop. Now be seated and I’ll tell you all about it.”

Down on the floor the Sunny Six sat, tailor-fashion, and Adele began: “I’ve been over to the Orphans’ Home to see the matron, Mrs. Friend. She’s a dear! She was so pleased to hear that we wanted to give Eva Dearman a birthday party, and what do you think? That little girl was brought up just as nicely as we have been. Her father was a wealthy broker, but he lost his money, and then both of her parents died. Some neighbors took care of Eva until her money was all gone and then they sent her to the orphanage.”

“Heartless wretches!” exclaimed the impulsive Betty Burd. “Seems like it wouldn’t have cost them much to have given the poor motherless girl a corner in their home.”

“Well, they didn’t,” Adele continued, “and Mrs. Friend says that all Eva Dearman has to her name is the deed to some worthless desert property in Arizona.”

“Oh, girls,” exclaimed the romantic Rosamond Wright, “what if there should be gold on that desert land, and what if our Orphans’ Home girl should turn out to be an heiress!”

“Such things only happen in story-books,” said the practical Bertha Angel. “Now don’t let’s interrupt Adele again. We want to hear the plans for the party.”

“Mrs. Friend told me that there are twelve girls in the Home who are just about our own age. One of them, Amanda Brown, is so surly and disagreeable that none of the others like her, and the matron said that we need not ask her unless we wish, but of course we would not think of leaving her out.”

“Perhaps a party is just what she needs,” suggested Gertrude Willis, the minister’s daughter.

“And now,” said Adele, “don’t you think it would be nice to give a present to each one of the Home girls?”

“It would be a nice thing to do, surely,” Gertrude answered. “How much money have we in the club treasury?”

The girls had each given what they could to start a Sunnyside fund, and Doris Drexel, whose father was a bank president, had contributed a small bank in which to keep their wealth.

Bertha Angel rose and said gayly, “I’ll go and get the bank and then we’ll count our money.”

Now, back of the log cabin was a shed, and, one of the boards in the floor being loose, the girls had hidden their bank in a dark hole which they had found underneath it. The shed was then padlocked and the precious fund they believed was surely safe. It would have been safe enough had it been locked in the log cabin, as the girls well knew, but Rosamond had declared that it was much more romantic to steal out to the shed and place it in the dark hole under the loose board, and so, to please her, this had been done.

Bertha took the rusty key and ran around to the shed. When the door was open, the girl noticed that the board was slightly lifted, and that the stone which they usually placed on it had been rolled away. What could it mean? Kneeling, she lifted the board higher and thrust her hand into the dark hole. But the bank was not there.

Springing up, she ran back to the cabin, calling excitedly, “Girls! Girls! What do you suppose has happened?”

The startled six rushed out of the cabin door. “Why, Bertha, what is the matter?” Adele exclaimed. “You look as though you had seen a ghost.”

“It’s worse than a ghost,” said Bertha dismally. “Our bank is gone.”

“Gone!” echoed all of the girls in amazement.

“Then we can’t give the party or the presents or anything,” wailed Betty Burd.

“And I’ve spent all of my allowance for two months to come,” moaned Adele.

The girls reached the shed and each one felt in the dark hole under the loose board.

“It must have been a tramp,” Doris Drexel declared.

“Maybe he’s hiding in the woods this very moment,” said Rosamond fearfully.

“It couldn’t have been a tramp,” Bertha remarked thoughtfully, “because the door was locked and there is no window.” Then suddenly she burst into a peal of merry laughter. The other six looked at her in puzzled amazement.

“Why, Bertha,” Adele exclaimed, “surely there is nothing funny about it!”

“Yes there is,” Bertha replied, her eyes dancing. “Don’t you remember that, at our last business meeting, we decided that our bank might be stolen, and that we would change its hiding-place?”

“Oh, of course,” said Peggy Pierce. “And that very day I took it down-town and asked father to keep it in his safe. I’ve been cramming so hard for examinations, I guess, that now I can’t remember anything.”

“Never mind, Peggy,” said Adele, as she slipped her arm around the crestfallen girl. “Our memories all play strange pranks at times.” Then, turning to the others, she called, “Come on; let’s don our hats and finish this meeting down at the Bee Hive, because, of course, we would buy the birthday presents there anyway.”

Firefly came on a gallop when Adele whistled, and whinnying for the lump of sugar which his mistress always had for him.

“Gertrude, would you like to ride?” Adele asked. But Gertrude said that she wasn’t a bit tired and would much rather walk with the others.

“Well then, Betty,” Adele began, and the others laughed at the happy eagerness with which that small girl clambered up on the pony’s back. Betty was only eleven, though she would soon be twelve. She was petite and dark and sparkling, and everybody’s pet. Away she galloped over Buttercup Meadows, her hair flying out like a mantle about her shoulders.

Half an hour later the six who were walking reached the Bee Hive, and found Betty, flushed from her gay ride, awaiting them. Luckily at that hour of the day the store was not as busy as its name implied, and jolly Mr. Pierce gave his whole attention to the flock of happy girls. How he laughed when he heard the story of the lost bank. Out of the safe it was taken and the money was counted by the treasurer.

“Exactly six dollars and thirty-three cents,” she announced. “Now the question is, will that amount of money purchase suitable birthday presents for twelve guests?”

The girls had not noticed that during the counting Peggy, the darling of her father’s heart, had beckoned him to the back of the store and had begged him to be a dear and give them something extra nice for the orphans. Had the girls known about this, they would not have been as surprised as they were when Mr. Pierce stepped forward with a tray on which were ever so many necklaces with lockets of different designs.

“Oh-h!” breathed the six with delighted sighs. “But, Mr. Pierce, we never could purchase twelve of these adorable chains for six dollars and thirty-three cents.”

“The cause is such a good one,” said Mr. Pierce, with a twinkle at Peggy, “that you may have them at cost.”

Then followed a rapturous fifteen minutes, during which the girls selected twelve necklaces and lockets.

“Orphans always have to wear things just alike,” Adele declared, “and so I am sure that they would like to have these different.”

“I suppose that we ought to give them stockings or handkerchiefs or something useful,” suggested Bertha Angel, the practical.

“Maybe so,” said Adele, “but this time the poor things are going to have just what we would like for ourselves,—something useless and pretty.”

When at last the twelve necklaces were chosen, each was placed in a little square white box lined with pink silk. The Sunny Seven thanked Mr. Pierce and then away they went with their treasures. The twelve orphans, busily working at the Home, little dreamed of the pleasure that was in store for them.

The eventful Saturday dawned bright and sunny. Adele awoke as soon as did Robin Red, who lived in the blossoming apple tree close to her window. Perched on a teetering twig, he caroled his good-morning song and Adele listened with a happy heart.

“Such a beautiful, sunny day for our party,” she thought joyously as she hurriedly dressed, tiptoeing about, that she need not awaken the rest of the family. The Sunny Seven had agreed to rise at dawn and meet at the log cabin as early as they possibly could, for there were many things to be done to make ready for their guests.

Meanwhile, in the orphan asylum, which was a mile out on the Lake Road, the morning tasks were begun. The atmosphere of the place was home-like, due to the kindly, mothering heart of the matron. Windows were thrown open, and sunshine, fragrant breeze, and bird-song drifted in.

Eva Dearman, upon awakening, had slipped a photograph from under her pillow, and, gazing at the sweet pictured face, she had whispered softly, “Mumsie, dear, this is my birthday, and I’m going to think that you are with me all day, and I’m going to try to be brave and happy, just as I know you would want me to be.”

An hour later the older girls in the Home stood in line, waiting for the morning tasks to be allotted to them. Eva was next to Amanda Brown. To Amanda fell the task of sweeping and dusting the study-hall, while to Eva Dearman was given the pleasanter one of sweeping the verandas, raking the gravelly walks, and tidying up the summer-house.

“That’s always the way,” grumbled Amanda, as the girls turned to get brooms and brushes. “You have the easy work given to you, but they give me that horrid old study-room to clean.”

“I’ll tell you what,” Eva replied brightly, “I’ll hurry up with my work, and if there’s any time before sewing-class, I’ll help you with yours.”

Amanda stared in amazement. Eva had not been long in the Home, and the girls were barely acquainted with her.

Amanda Brown could not believe that any one really intended to be kind to her. She knew that the other girls did not like her, and she tried to think that she didn’t care, and so, instead of thanking Eva, she rudely retorted, “Seeing’s believing,” and away she went.

Eva sang a little song softly to herself as she swept the front porch thoroughly and as quickly as she could. Then the garden-walks were raked until not a stray leaf or twig could be found. When her task was finished, Eva paused to listen to a bird-song as she thought: “Poor Amanda! It is hard to be shut in that dreary study-hall this bright morning. I’ve half an hour left to do as I like.”

Almost longingly, she looked over toward the little wood where she loved to go when her task was done, but instead she skipped into the Home, and, dancing down the hall, burst into the study-room, exclaiming gayly: “Ho there, Amanda! Seeing is believing!”

Amanda looked up in surprise. Indeed she could hardly believe her eyes when she saw Eva pounce upon the teacher’s desk and dust it thoroughly and vigorously. In fifteen minutes the work was finished, and Amanda knew that she ought to say “Thank you,” but her stubborn spirit rebelled. However, just at that moment one of the younger girls appeared in the doorway and said: “Oh, Eva Dearman, here you are! I’ve been hunting everywhere for you. Mrs. Friend wants you to come to her study at once, and she wants you, too, Amanda Brown.”

Puzzled, and wondering if they had done anything wrong, the two girls went down the corridor and Eva rapped on Mrs. Friend’s door.

A kindly voice bade them enter. In the study were ten other girls, who looked flushed and excited. What could it mean?

“Eva,” said Mrs. Friend, putting her arm about the girl and kissing her on the forehead, “we want to congratulate you on this your thirteenth birthday.”

Eva blushed rosily as she replied happily, “Oh, thank you, Mrs. Friend.”

Then the matron continued, “Because it is Eva’s birthday, I am going to give you other girls who are near her own age a half-holiday, and so you may go now and take your baths and put on your best white dresses.”

“Oh, goodie! goodie!” cried several of the girls, as they clapped their hands gleefully. Then out of the door they went, remembering to be quiet in the halls. An hour later, fresh from the bath, they donned their best white dresses and their butterfly hair-ribbon bows, which their matron had given to them at Christmas.

Eva, like a princess among her maidens, beamed on them all as she exclaimed: “You girls do look so pretty, every one of you! But,” she added suddenly, “where is Amanda Brown?”

No one knew. She had not been in the bath-room, nor had she dressed, for her white gown was still lying on her cot.

A bell was ringing, which called the girls below. Eva, alone, lingered behind, looking everywhere for Amanda. At last, pausing to listen, she heard a faint sobbing, which seemed to come from the linen-closet. Eva opened the door, and there on the floor lay Amanda in a miserable heap of brown calico. She looked up with eyes that were red and swollen.

“Go away!” she said sullenly, but Eva leaned over and took hold of her hot hand.

“Amanda,” she said gently, “please come out. Do you want to spoil my party?”

“I’d spoil your party if I went to it,” sobbed Amanda. “Jenny Dixon said I would. She said that I am so cross and homely, she doesn’t see why I was invited.”

“Did Jenny Dixon say that to you?” asked Eva with a white face.

“No-o, she didn’t say it to me,” Amanda replied. “She whispered it to Mabel Hicks, but she knew that I would hear, and I won’t go to your party! I won’t! I won’t!”

“Very well,” said Eva firmly, “then neither will I! Amanda Brown, do you suppose that I would enjoy my birthday-party for one minute if I knew that some one was left out and unhappy?”

Amanda found it hard to understand Eva. “I don’t see why you should care about me,” she replied; “nobody else does.”

“But I do care,” Eva said sincerely. “Now please hurry, Amanda, and I will help you to dress.”

With a strange new happiness in her heart, Amanda crept from the dark closet, and half an hour later the two girls went down-stairs to the dining-room arm in arm. Amanda, in her white dress, with the crimson bows on her black braids, looked very different from the Amanda who that morning had been dusting in the study-hall.

After dinner Mrs. Friend told the twelve to put on their best hats and go out in the front yard and watch for something to come down the road.

“Oh! Oh!” cried Sadie Bell. “I do believe that we are going somewhere. I supposed that the party was to be right here at the Home.”

The twelve girls stood on the front lawn, Eva with her arm shelteringly about Amanda’s waist. Eagerly they watched down the road for—they knew not what.

“Look! Look!” cried Jenny Dixon excitedly. “Here comes something queer. Whatever can it be?”

The girls ran to the gate and beheld a very strange vehicle coming.

Twelve little orphan girls in white,

Hearts a-brimming with delight,

Watched with eager, dancing eyes

For what? They knew not!

A surprise!

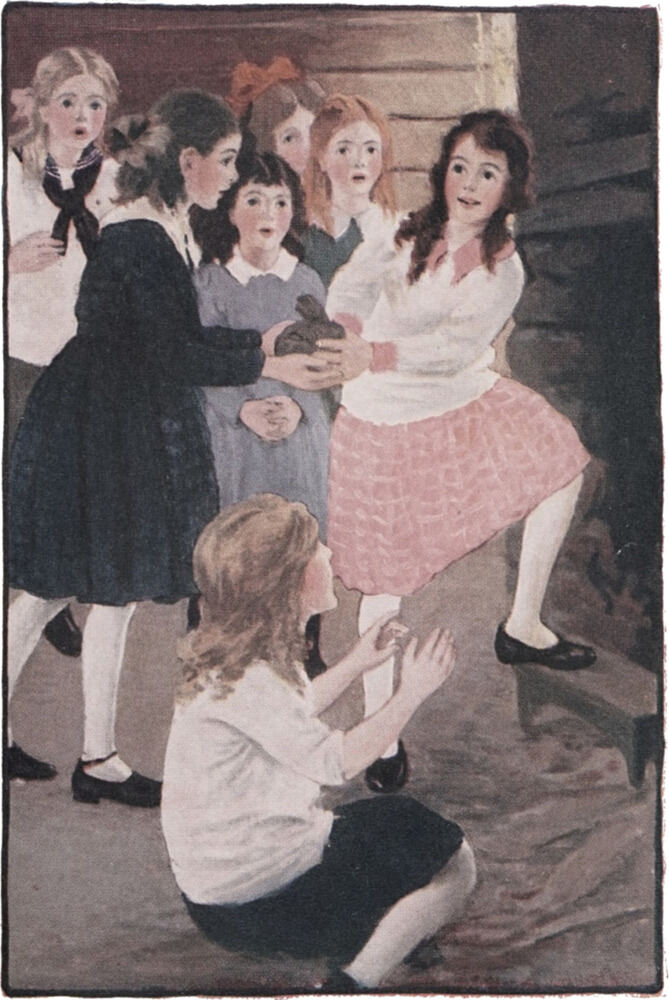

The twelve girls, flushed and excited, were peering down the country road at the strangest vehicle which they had ever seen. It was, in truth, a hay-rack covered with garlands of daisies and buttercups and drawn by two white horses with daisy wreaths about their necks. On the front seat was the driver, Bob Angel, with Adele at his side, while in the wagon part the Sunny Six sat on the soft new-mown hay. They were all dressed in white, and, to the surprise of the twelve orphans, the wonderful equipage stopped at their own gate. In a twinkling Adele was on the ground, and, taking both of Eva’s hands, she kissed her on the cheek, exclaiming, “Lovely Queen o’ May! Your carriage has come to take you away on this your thirteenth natal day.”

Tears rushed to Eva’s eyes as she exclaimed, “Oh, Adele, you were so good to plan all this for me.” Then, brushing them away, she said brightly, “I’d reply in rhyme if I could, for I do suppose that one should.”

“Oho!” laughed Betty Burd. “Eva, you’re a poet and don’t know it.”

“Come now,” said Adele, who was Mistress of Ceremonies, “we must start on our journey. Eva, you are to sit in state with the driver, and all the rest of us are to scramble up on the hay, because we are not so important to-day.”

“More rhymes,” laughed Peggy Pierce.

Into the daisy-covered hay-rack the girls climbed, looking as pretty as the flowers themselves. Then Bob started the horses, Jerry and Jingo, and somehow they seemed to know that the spirit of fun was abroad, for they galloped down the road at a merry pace and the girls laughed and sang. Soon they turned into the meadow-lane. “What a darling log cabin!” Eva exclaimed, as they neared the Secret Sanctum.

“Just wait until you see the inside of it,” said Adele. Then the horses stopped and out of the hay-rack the girls leaped, not waiting for Bob’s proffered assistance. Adele threw open the cabin-door and the guests entered with exclamations of pleasure.

Bertha hung back for a few last words with her brother Bob, after which he drove the equipage over near the wood, unhitched, and turned the horses out to graze. Then he took a short cut to the town.

Soon the merry fun began. There were whirling and singing and dancing games, and after an hour of rollicking, Adele invited the guests to take a walk with her in the maple wood, so away they went, little dreaming of the delightful surprise that would await them when they returned to the cabin.

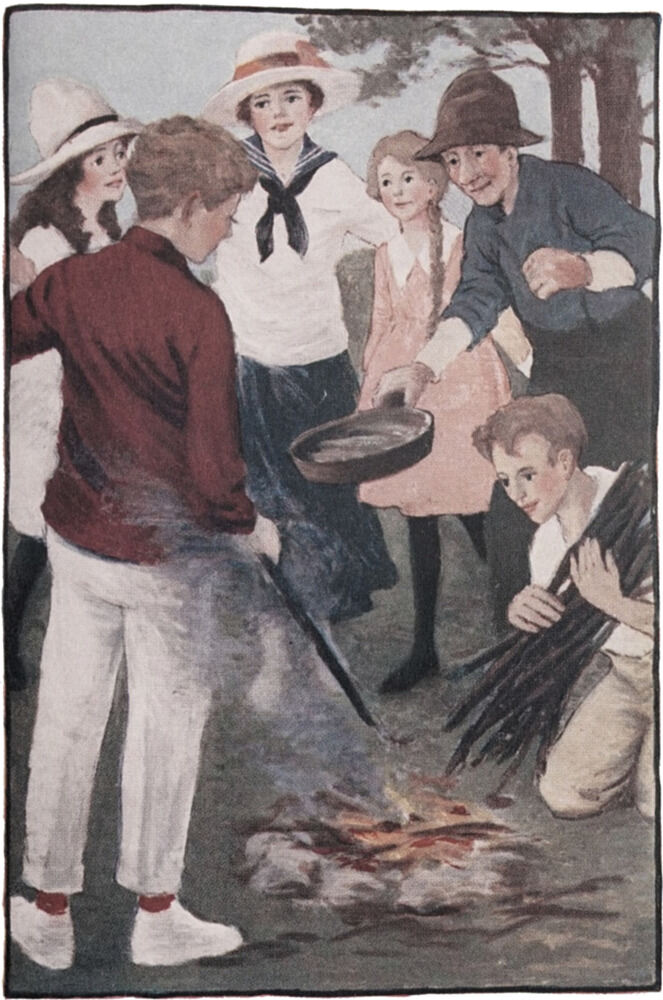

When the last gleam of white had disappeared among the trees, all was hustle and bustle in Buttercup Meadows.

“Quick now!” exclaimed Bertha Angel, who was Mistress of Ceremonies in Adele’s absence. “We must hurry if we are to have everything ready in fifteen minutes, and Adele never can keep the orphans in the woods longer than that.”

“The boys ought to be here this very second, if they are going to help us,” said Betty Burd.

“Bob and Jack promised to be here promptly at four,” Rosamond remarked, “and it’s powerful close to that now.”

“Well, you can depend on Bob,” Bertha exclaimed. “He is never even a fraction of a moment late. Being my brother, I know his virtues and otherwise.”

“What is the otherwise?” asked Peggy Pierce, as the girls donned their big aprons and darted about at various tasks.

“Oh,” laughed Bertha, as she heaped lettuce sandwiches on a big blue plate which had a crack in it, “Bob’s besetting sin is teasing me, and such pranks as he can invent!”

“Well,” exclaimed Rosamond Wright, as she glanced at her wrist-watch, “your model brother is late to-day, for it is four to the second and there is no one in sight.”

“Oh, yes, there is,” said Betty Burd, as she came in from the brook with a bucket of sparkling water. “There are two colored men coming across lots just below here.”

Doris Drexel looked out of the door, and then she sprang back with a startled cry. “They are negroes, and, oh, girls, what if they should be tramps? I do wish that Bob had been here on time.”

“They are coming right this way,” whispered Betty Burd. “Hadn’t we better close the door and lock it?”

“Let me look,” said Bertha Angel, as she stepped fearlessly into the meadow. Then, to the surprise of the others, she called gayly, “Well, Rastus, do hurry up! We’ve wasted time enough as it is.”

“Why, Bertha!” exclaimed Peggy Pierce in surprise. “Do you know those colored men?”

“Know them? I should say that I do,” Bertha laughingly replied. And then she ran right up to one of them, and, shaking her finger at him, she exclaimed: “Aha, Bob Angel, now I know why you wanted to borrow my red silk handkerchief.”

Then the other girls, their fear changed to laughter, trooped out of the cabin.

“Jack Doring and Bob Angel!” Betty Burd exclaimed. “I never would have known you boys in a hundred years.”

“We-all heard you wanted some waiters,” Bob drawled, trying to talk in negro dialect, “and we-all came to apply.”

“Well, you-all are engaged,” laughed Bertha, “and now please do hustle.”

Then every one bustled about. The boys made a long table with boards and sawhorses, and benches on each side were fashioned with boxes and more boards. Soon the tables were covered with flower-bordered paper table-cloths, and there were napkins to match. Two bowls of daisies and buttercups and ferns adorned the ends of the table, and in the very center was placed a huge birthday cake, which Mrs. Doring had made for Adele. It was frosted with white, and on it were thirteen pink candy roses, for Eva and Adele that day were both thirteen.

Mrs. Drexel had sent chicken salad, and the girls themselves had made lettuce sandwiches, which were piled in tempting array. Rastus, as they called Bob Angel, was just filling the last tumbler with pink lemonade when Rosamond Wright exclaimed, “Here comes Adele!”

There was a chorus of delighted exclamations from the orphans as they approached.

“I didn’t know a table could look so beautiful,” Amanda whispered to Eva, as Adele motioned them to their places. Soon the festive board was surrounded with laughing, happy faces, and then Bob and Jack, as black as burnt cork could make them, greatly added to the merriment with their antics. They wore small white aprons, and each had a folded towel flung over one arm. They passed things with a flourish and talked a string of nonsense, trying, with more or less success, to imitate the negro dialect.

The heaps of delicious sandwiches disappeared rapidly, the pink lemonade was often replenished, and never before had a chicken salad been more appreciated.

At last Adele called gayly, “Girls, we must leave a corner for the ice-cream and cake.”

“That’s right,” laughed Gertrude Willis, while at the mention of ice-cream the orphans looked as though their fondest dreams were being fulfilled.

“Garçon!” called Adele, who was just learning a bit of French. “You may clear the table.”

The waiters put their black heads out of the cabin-door and cried, “Law, chile, wait a minute!” Later, when they did appear, each carried a partly eaten sandwich, for the boys did not intend to miss any of the good things themselves.

Adele, to save Eva from embarrassment, agreed to cut the birthday cake, but first she counted noses.

“Say, Miss Doring,” Jack drawled, “I’ll be ’bleeged to tell you, ma’am, I’se got two noses.”

How the girls laughed, for it is easy to laugh when the heart is light. So Adele allowed two pieces for each boy. When the cake had been cut and the generous slices passed, the waiters appeared with pyramids of frosty ice-cream. Then, when this had disappeared, Rastus came out with a basket lined with flowers, but piled in the center of it were little white boxes tied with pink and blue baby-ribbon. It was first passed to Eva, who chose the wee box which was nearest, and then waited until each orphan had drawn forth one of the dainty packages.

“Now,” said Adele, with shining eyes, “open them all together.”

How eagerly the ribbons were untied and the little boxes opened, and then what a chorus of rejoicing there was! Eva had chosen just the one that Adele had hoped she would, a slender golden chain and a locket wreathed with pearls. When it was fastened about her neck Eva exclaimed, “Oh, Adele, how can I thank you!”

But Amanda called their attention to her locket, which was set with pretty red stones. “I never owned a trinket before in all my life,” she said softly to Eva, who sat at her side. Then, almost wistfully, she asked, “Is it to be mine for keeps?” Eva fastened the chain about Amanda’s neck and softly assured her that it was to be her very own. The other ten orphans were equally pleased, and pretty the lockets looked as they hung around the necks of their new owners.

Soon Adele rose and the girls sauntered about until the flower-bedecked equipage reappeared and they donned their hats.

Eva held out both hands to Adele as she exclaimed gratefully, “If I live to be a hundred years old, I never can have a happier day.”

“You and I are going to have many happy days together,” Adele replied warmly. And then the Sunny Seven, who were staying behind to clear up, waved to the guests as long as the hay-rack and its black drivers were in sight.

During the day Adele had often wondered why none of the girls had congratulated her on its being her birthday as well as Eva’s, but she was of too generous a nature to feel hurt, and so she soon forgot all about it, but her friends had not forgotten, as you shall hear.

When Adele reached home after the orphans’ surprise-party, she found a note telling her that her father and mother had gone for a ride into the country. Jack Doring, having taken a bath, was changed from black to white again. Then, donning his very best suit, he announced that he might not be in until late; and, since this was Kate’s evening out, Adele was soon left all alone in the big rambling house.

Up to her room she went, just a bit weary from the long, busy day. Leaning back in her comfortable lounging-chair, Adele thought to herself, “It seems strange that even mumsie and dad have forgotten that this is my birthday, and Jack hasn’t said a word about it. But then, I could not have had a nicer time if I had had a party all for myself.”

Then, closing her eyes, she drowsily listened to the evening song of the robins who lived in the apple-tree just outside her open window. The crooning melody seemed to grow fainter and fainter to Adele; a warm, fragrant breeze from the garden brushed against her cheek, and soon she fell asleep. It was dark when she awakened, and she sat up with a start. What could it have been that had aroused her? Probably her father and mother were returning. The girl listened intently. Suddenly something fell with a crash in the room below. Springing to her feet, she turned on the light, and, running to the top of the stairs, she called: “Mother! Father! Is that you?”

There was no reply, and for one brief moment Adele’s heart stopped beating. There surely was some one down-stairs, but who could it be? Then Adele remembered that her big white Persian cat had been asleep on its cushion when she left the library. Of course it must be Fluff prowling about, and perhaps he had tipped over a bowl of roses. She ran lightly down the stairs and switched on the library lights. The white cat rose from his cushion and yawned sleepily, so Fluff had not made the noise. Adele had a strange feeling that some one was in the room, hidden and watching her.

“I hope that I am not growing timid,” she thought to herself; and then, deciding that she would read for a while, she went out into the dining-room, where she had left her book. She was only gone one moment, but when she returned, the library was in total darkness and she knew that she had left it lighted. Before she could be very much frightened, however, there was a rushing, rustling noise, and snap! the lights were on again. Great was Adele’s surprise at finding the room filled with laughing friends. “Happy Birthday!” they shouted.

Adele sank down on a chair and looked so white and strange that Jack ran to her side and exclaimed, “Oh, Della, did we frighten you too much? I didn’t realize that it would be so scary.”

“I was afraid that we should frighten Adele,” Gertrude said remorsefully, as she knelt beside her friend. “That’s why I suggested that we go to the front door and ring.”

But Adele, quickly regaining her composure, sprang up with a laugh, and the color returned to her cheeks as she said: “No, you did not frighten me too much. I guess I am just surprised, and that is what one should be at a surprise-party, isn’t it?”

Then, quite herself again, she chattered on gayly: “Do look at you all, in your pretty best! And Peggy has her heart’s desire—a chance to wear her new muslin with the rosebuds on it. It’s as pretty as can be, Peggy, and your pink sash is adorable. Well, now I must run up-stairs and dress.”

“I’ll go with you and be your maid,” said Gertrude Willis, who was Adele’s dearest friend. “You other girls may stay and entertain the boys.”

With Jack as Master of Ceremonies, the fun soon began. Meanwhile Adele bathed and dressed in her prettiest. From below came the merry strains of the victrola, playing waltzes and hops. When the two girls descended the stairway, they found that the library had been cleared of furniture. Mrs. Doring, having returned from her drive, had made this good suggestion.

Then what a merry hour they had. Suddenly the front-door bell rang and Adele skipped to open it. An expressman stood outside and he inquired, “Does Adele Doring live here?”

“Yes, she does,” that wondering young lady replied, and then into the hall the expressman brought a wooden box, which he deposited on the floor. When he was gone Adele exclaimed eagerly, “Oh! Oh! What do you suppose is in it?”

“I’ll get the hammer and then we will find out,” Jack said. A moment later he was prying off the cover. There, among soft tissue papers, lay ever so many books, all bound in pale blue, and the set was called “Stories That Girls Like Best.” Indeed, there was every title among them that a girl of thirteen could wish to possess. Adele clasped her hands and exclaimed rapturously, “Who could have sent me such a beautiful gift?”

“Here’s a card,” Jack said, as he handed it to her, and eagerly she read:

“I just knew it!” cried their happy hostess, “and I do wish that I had arms long enough to hug you all at once.”

“Adele!” exclaimed Betty Burd. “Don’t make such a terrible wish. An old witch might be lurking around and it might come true.”

“Well, I hope not,” laughed Adele, “for my beauty would surely be spoiled if my arms dragged on the floor.”

Jack and Bob carried the pretty blue books into the library and placed them on the center-table, and then the merry fun was renewed, when suddenly the side-door bell clanged and Adele skipped to open it, but there was no one outside.

“Some one is playing a prank, I guess,” she laughingly said. But Jack suggested that they turn on the porch light, and when this was done Adele saw a low bird’s-eye-maple table on which stood a beautiful drooping fern. When the boys had carried it into the library Adele gleefully clapped her hands as she exclaimed, “It’s just what I need for the bay-window in my room.”

The little card which hung on the fern informed her that this was a gift from her brother Jack and his six boy friends, who called themselves the Jolly Pirates. Adele thanked them with shining eyes.

“Now,” she said, “surely the surprises are over,” but just that very moment Mrs. Doring called from the top of the stairs, “Adele, come up here a moment and bring the girls with you.” And so up the stairs they flocked, looking for all the world like a bevy of butterflies in their pretty muslin dresses and their many-colored sashes.

“Maybe it’s another surprise,” exclaimed Betty Burd, who was enjoying Adele’s happiness as much as did that girl herself.

Adele’s room was brilliantly lighted, and her adorable mother and her Giant Daddy were standing in the door, waiting. Into the room the girls trooped, and Adele gave a cry of joy when she saw a bird’s-eye-maple writing-desk, on which were rose-colored blotters and a silver ink-stand and scratcher, and holders for both pen and pencil.

The card fastened to the desk read:

These were the pet names which they had for each other. How Adele hugged him! And then he laughingly exclaimed, “Now put on your spectacles, for there is something else in this room for you to find.”

Adele looked about, high and low. Suddenly she spied a water-color painting in a rustic frame. It was a picture of their very own log cabin, painted when the meadow was yellow-and-white with daisies and buttercups. There were fleecy clouds over a sunny blue sky, and the woods in the background were fresh and green, and, as for the laughing brook, you could fairly see it sparkle and hear it gurgle as it danced along.

“From Mother,” a little card told her.

“Mumsie!” Adele cried. “An artist from the city painted it, didn’t he? I watched him one day when he was just beginning on the brook, and how I loved it, but I never even dreamed that I was to own it.”

Now, just at that very moment bells began ringing all over the house: the front-door bell, the side-door bell, the Chinese gongs, the little silver tea-bell clanged and jingled. What could it mean?

“More surprises!” laughed Adele. “Come along, girls; let’s fathom the mystery.”

So down the stairs the Sunny Seven trooped. Bob Angel stood in the lower hall, ringing a dinner-bell, as he chanted:

“Ding, dong, dell!

Hark to the bell—ll—ll!

Come, follow me,

And see what you will see!”

“Bob’s happy now,” his sister Bertha jokingly exclaimed. “Like all little boys, he loves to make a big noise.”

The girls trooped after the bell-ringer, and as they entered the library, the folding-doors slid silently open, and such a festive scene as they beheld in the room beyond!

A mahogany table was decked with shining silver and sparkling glass, and in the center was a frosted cake with thirteen candles ablaze. Pretty name-cards told each guest where to sit, and of course Adele was at the head of the table and Bob at the foot. Kate, with her kindly Irish face aglow, appeared in the kitchen doorway and then Mrs. Doring came in to help pass the good things.

“Two feasts in one day!” exclaimed Bob Angel. “I wish I had the capacity of Giant Blunderbuss of fairy lore.”

The first course soon disappeared, and then the cake, with its twinkling candles, was placed in front of Adele to be cut.

“Thirteen is going to be my lucky number hereafter,” Adele laughed, and then she puckered up her mouth and blew the lights out. “Oho, here’s a card on the cake,” she called gayly, and then she read aloud, “For my little Colleen, from Kate.”

“Another present!” cried the delighted girl, “Thank you, Kate, and when your birthday comes, I’ll make you a cake.”

“Poor Kate!” Jack Doring said in mock sympathy. “I wouldn’t have a birthday soon if I were you, Kate, but if you do have one, be sure to hide the salt-box. You know why.”

Adele laughed good-naturedly as she exclaimed, “Just because I put salt in one cake instead of sugar is no sign that I am going to do it forever after.”

When the generous slices were passed, Betty Burd gave a squeal of delight. “Oh, do look!” she cried. “There are things in the cake to tell our fortunes.”

“Mine is a piece of straw,” Dick Jensen chuckled. “So I am to be a farmer, I suppose. Well, I’d like nothing better.”

“Alas and alack!” moaned Doris Drexel. “I have a thimble, and I just hate sewing, but I suppose that I shall have to be resigned to my fate.”

“See what I have!” Jack Doring exclaimed, as triumphantly he held aloft a silver dime. “I just felt in my bones that I was going to be rich some day.”

“Not if you have to work for it,” teased Adele, for Jack was rather inclined to be indolent.

“I wasn’t planning to work,” Jack replied calmly. “I shall find a gold mine or some little thing like that.”

“Poor little me!” moaned Rosamond Wright. “There doesn’t seem to be a thing in my piece of cake.”

Rosamond, in her pink dress, with her flushed face and short golden curls, looked as pretty as the flower after which she had been named.

“Don’t give up, Rosie,” Bob Angel called. “Seems to me I see a glint of gold there in the frosting.”

Eagerly Rosamond broke the cake where the glint was, and out fell a wedding ring.

“Congratulations!” cried Adele. “Rosie is to be our first bride.”

When each future had been prophesied and the boys and girls had eaten their ice-cream and cake, the merry party returned to the library, and soon after, as the hour was late, they took their departure.

When they were gone Adele nestled in her mother’s arms, as she said softly, “Mumsie, this has been the happiest day of my life.”

“That is because you have given others so much happiness,” her mother replied.

There’s many a high-chair put away

For the baby that came, but could not stay.

There’s many a mother-heart yearning still,

And arms that a motherless babe might fill.

There’s many a home that’s sad and drear,

That a prattling child might bless and cheer.

It was Sunday, the day after the eventful Saturday which would be so long remembered by the Sunny Seven, as well as by the twelve orphans who had been made so happy.

Adele, dressed in pretty white muslin and wearing her daisy-wreathed hat, tripped down the road toward the orphan asylum. She was so deep in thought that she did not notice some one standing on the corner and evidently waiting for her, until a pleasant voice called, “May I go with you, my pretty maid?”

“Oh, Gertrude Willis!” Adele exclaimed. “I was thinking of you that very moment and wishing that you were going with me, and here you are.”

These two friends were especially dear to each other. They walked on together, and Gertrude said, “Adele, I think it so nice of you to go every Sunday afternoon to tell stories to the little children at the Orphans’ Home. I have often wanted to go with you, but usually father has a young people’s meeting at the church and he likes me to be there, but to-day he himself suggested that I go with you.”

“I’m so glad!” Adele replied, giving her friend’s arm a loving squeeze. Then they talked of Eva Dearman, and decided that they would try to be like sisters to the little girl who had no home-people of her own in all the world.

“I just can’t imagine what that would be like,” Gertrude remarked, as she thought of the parsonage in which there were five merry children, watched over by a loving, if dignified, father, and the dearest mother in all the world.

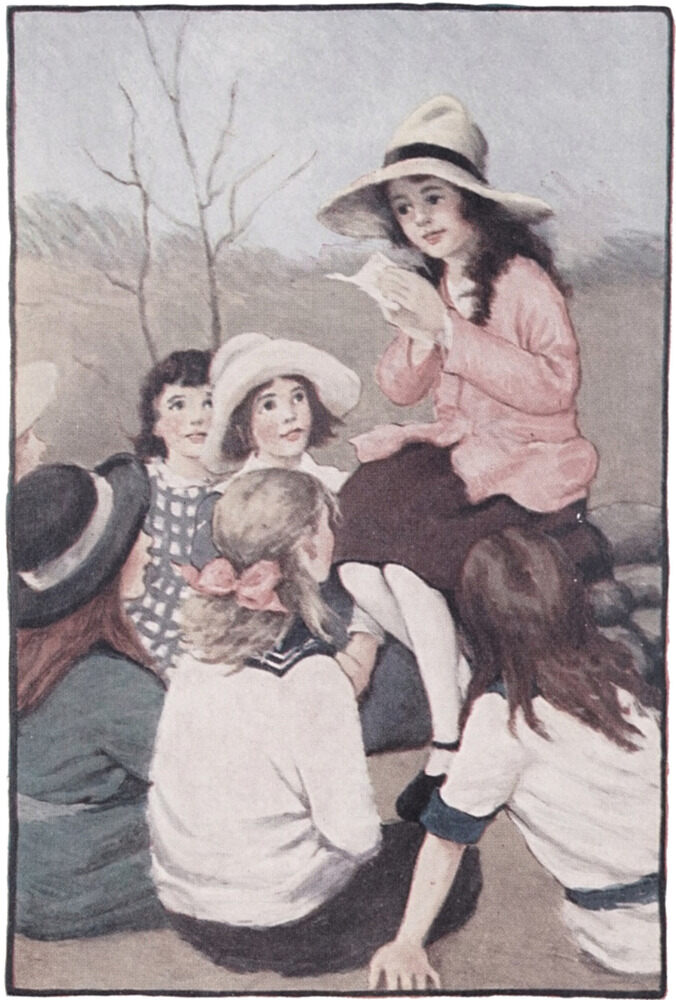

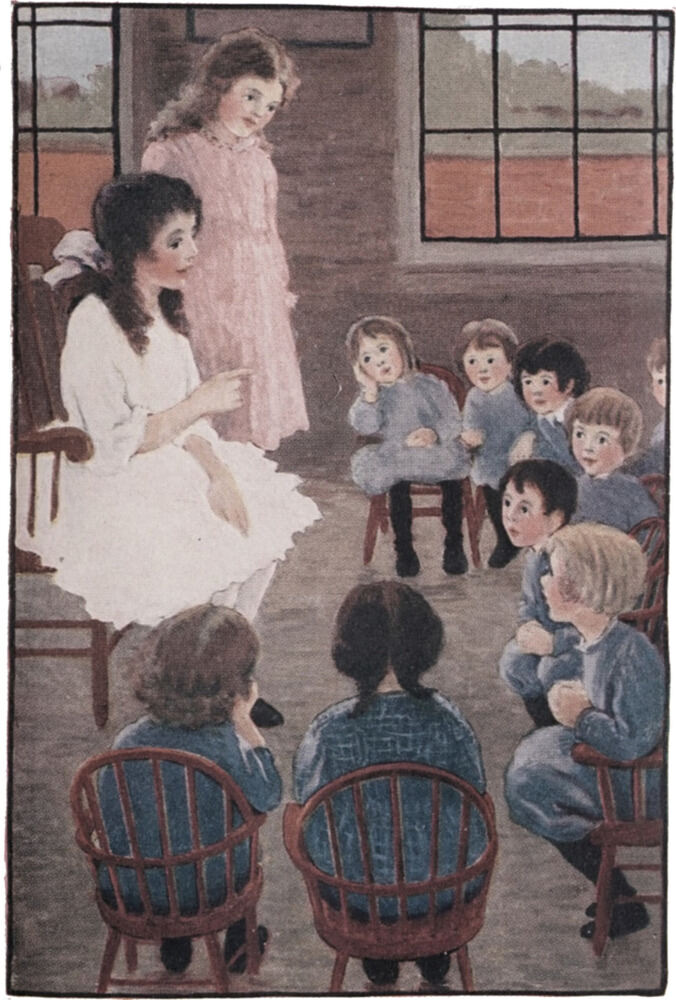

Mrs. Friend, the matron of the Home, greeted them pleasantly, and led them to the large, barren room where, on little red chairs, twenty small children were seated.

Their round, eager eyes were watching the door, and when they saw Adele, their faces brightened, and it seemed as though sunshine had suddenly entered the rather gloomy room.

The children, ranging from five years to eight, arose, and, standing beside their chairs, made funny little bobbing curtsies, and they piped out, like so many chirping birds, “Good afternoon, Miss Adele.”

“Good afternoon, little sunbeams,” Adele replied. “I have brought a friend with me to-day. Miss Gertrude is her name.”

Then the tiny tots bobbed another curtsy, and with solemn faces they piped, “Good afternoon, Miss Gertrude.”

“The little darlings!” Gertrude exclaimed softly, and tears rushed to her eyes. It made her heart ache to think of all those babies and not a mother to cuddle them, and then she thought of the childless homes to which these very little ones might bring so much joy and happiness.