QUEEN ELIZABETH

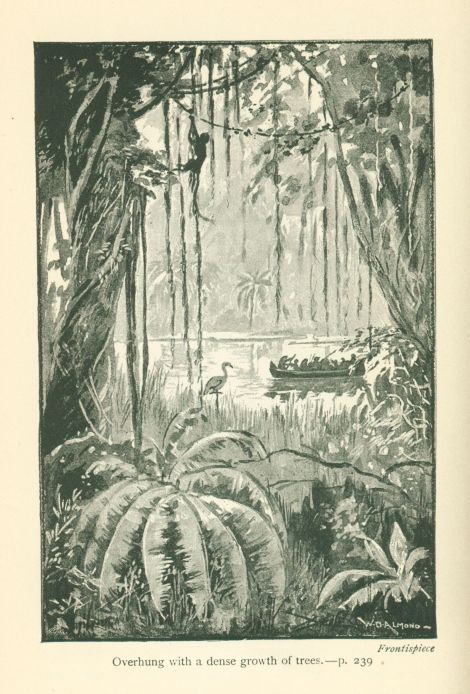

Title: For God and Gold

Author: Julian Stafford Corbett

Release date: May 20, 2020 [eBook #62184]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

BY

JULIAN CORBETT

AUTHOR OF 'THE FALL OF ASGARD'

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1900

All rights reserved

First Edition 1887

Reprinted 1900

FOR GOD AND GOLD

CALLING ON THIS AILING AGE TO ESCHEW THE SINS AND IMITATE

THE VIRTUES OF

MR. JASPER FESTING

SOMETIME FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE IN CAMBRIDGE, AND LATE AN OFFICER

IN HER MAJESTY'S SEA-SERVICE

BY THIS SHOWING FORTH OF

Certain noteworthy passages from his Life in the said University and

elsewhere, and especially his connection with the beginning of

The Puritan Party

Together with a particular relation of his Voyage to

Nombre de Dios

Under that renowned Navigator

THE LATE

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE, KNIGHT

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF

AND NOW FIRST SET FORTH

PREFACE

It is not to be denied that the usual practice in ushering into the world a long-hidden manuscript has been to give some account of its existence in its former state, and of the manner in which it came to light. For sufficient reasons that course will not be followed in the present case.

Should any one in consequence be brought to doubt the genuineness of these memoirs, it is hoped that it will be sufficient to refer him to a curious little work entitled Sir Francis Drake Revived, which contains a very sprightly account of that renowned navigator's so-called Third Voyage to the Indies, being that in which he attempted Nombre de Dios, and which, as the title-leaf recites, is 'faithfully taken out of the report of Master Christopher Ceely, Ellis Hixom, and others who were in the same voyage with him, by Philip Nichols, Preacher; Reviewed also by Sir Francis Drake himself before his death, and much holpen and enlarged by divers notes with his own hand here and there inserted, and set forth by Sir Francis Drake (his nephew), now living, 1626.'

So closely do the present memoirs follow that account that it cannot reasonably be doubted that Mr. Festing was one of those 'others' who had a hand in Preacher Nichols's book, although neither he nor Mr. Waldyve are mentioned as being of the expedition. When we consider the circumstances under which they sailed, it is only natural to suppose that they made it a condition of their assistance that their names should be suppressed in the published narrative; and, in view of this supposition, it is not unworthy to be noted that Nichols makes no mention of a 'captain of the land-soldiers' or a 'merchant' as sailing with Drake, although it is known that these officials formed part of all well-ordered expeditions to the Spanish Main.

Of course some small discrepancies will be found between the two accounts, but they are unimportant, and seem rather to confirm the general accuracy of Mr. Festing's memoirs than to cast any suspicion upon them. For instance, Nichols gives the name of the man who 'spoiled all' in the first attempt on the recuas as Pike, but there can be no doubt that, by an obvious word-play which would commend itself to an Elizabethan punster, the name of the infantry weapon was substituted for that of Culverin out of tenderness for the old Sergeant's memory.

Such instances might be multiplied indefinitely, but it appears better to suffer the curious to note and comment upon them for themselves. Should any such be tempted to pursue the subject farther, he will find an interesting account of Signor Giampietro Pugliano in a letter of Sir Philip Sidney's, who describes the esquire of the Emperor's stables in much the same terms as those which Sergeant Culverin was in the habit of using.

In fact, Mr. Festing's memoirs receive confirmation from contemporary sources too numerous to set out here. He mentions indeed only one event of any historical or biographical importance which has not been found either related or referred to by other trustworthy writers, and that is the piratical attack of Drake upon the Antwerp caravel—an exploit about which all parties concerned no doubt took good care to keep their own counsel.

These considerations, it is felt, will be enough to carry conviction to what Mr. Festing would have called 'all honest kindly readers.' To the merciful dealing of such his memoirs are now therefore committed without further excuse, defence, or apology.

J. C.

THAMES DITTON,

October 1887.

FOR GOD AND GOLD

Erasmus, in his Praise of Folly, has uttered a sharp note against those scribbling fops who think to eternise their memory by setting up for authors, and especially those who spoil paper in blotting it with mere trifles and impertinences. Yet have I, that was none before, resolved to turn author, and set down certain passages in my life that I have thought not unworthy to be remembered.

Many who share my respect for him who is rightly called the honour of learning of all our time, forgetting therein, as it must be said, all tenderness for me, have marvelled openly that I listen not to his wisdom, but will still be spending paper, time, and candles upon such trifles and impertinences as he condemns. It were better, say they, for a scholar to take in hand some weighty matter of religion, or philosophy, or civil government.

But stay, good friends, till I bid you show me how it were better. Such treatises are ordnance of power; and are we sure that of late years scholars have not been forging too many weapons for dunces to arm themselves withal in these wordy wars that now be? A harquebuss is a dangerous toy in unskilled hands, and so I know may be a discourse of religion, or philosophy, or civil government to unlearned controversialists, of whom, God knows, there is a mighty company in this present time.

So, I pray you, consider whether Erasmus has not here a little dishonoured his scholarship and sounded his note false. Should he not rather have placed amidst all other folly that he praises these very trifles and impertinences also with which a scholar may seek to comfort his solitude?

I am the more moved to the part I have chosen because it is not clear that all I have to tell shall be found wholly trifling and impertinent. Indeed I think it may contain something noteworthy, not in respect of myself, or even of that noble gentleman whose story this is as much as mine, but rather in respect of that very mirror and pattern of manhood who was my good friend in those days, though now with God, and whom of all I ever knew or heard of I honour as in courage unsurpassed, in counsel unequalled, and in constancy passing all I ever deserved.

So much by way of preface or apology; and now, with a good wish on all honest, kindly readers, let me to my tale.

As with many others, my life, it may be said, began with my father's death. Till then I had been kept in so great subjection that, save in my books, I had hardly lived. For he was an austere, grave man of the Reformation party, and one whom the fires of Mary's reign had hardened against all Popery, so that towards the end of his life he became what is now called a Puritan, ay, and that of a strict sort too.

Outwardly to his great friends in the county he was still good company. For, not to speak more, because of the honour I bear him, he was a worldly man, and not one to use a shoe-horn to drag ill-fitting opinions on to men of quality, nor in any way to seek a martyr's crown. His chiding and severity were kept for me and his servants and tenants, who were all hard-pressed, though, in truth, not beyond what justice would warrant were mercy laid aside.

It was a hard case for me, because of my mother I had not even a memory. The same hour that I was born she died, leaving my father alone in the world save for me. It was then that he most changed, they told me, but in no respect showed his grief so much as in misliking me.

Yet I think I loved him, for all his chiding and sharpness. Indeed I had so little else to love. At least I know that I was sobbing bitterly when my old nurse came to tell me that his short sickness had come suddenly to an end: for he had but a little time past been seized with a quartan ague, which carried off so many that same glorious year that our great Queen came to her throne.

It was a cold, gray afternoon in January. I was sitting, hungry and forgotten, in my favourite nook in the dim old library. It was an ancient, low room, which my father had left standing when he had rebuilt the rest of the place in the new style soon after he had purchased it. It had been a house of Austin Canons which fell to the lot of some spendthrift courtier in King Henry's time, which gentleman, getting past his depth in my father's books with over much borrowing, was at last driven to release the place to him. So it was that the old monastery became our dwelling, but this, the Canons' refectory, was all that was left of the former buildings.

At one end there was a deep recess, where I could sit and see the dreary darkness settling down on the distant Medway, and the Upchurch Marshes, and the Saltings. It was but a sad prospect at any time in winter, and made me sad, though I would never sit elsewhere with my books. I must have loved it because my father never came to chide me there, and because on that cold stone sill I could sit and sob undisturbed over the sorrows of men long dead, as I now sat sobbing over my own, when Cicely came hurriedly to me.

'The Lord has taken him, Master Jasper,' she cried, as well as her sobs would allow. 'The Lord has taken him, before I could call you to see how sweet an ending he made. God-a-mercy on him, for he was a just and upright gentleman, and one that dallied not with mercy, and died a good Reformation man. Ay, that he did, and would see never a priest of them all, with their hocus-pocus and Jack-in-the-box, and their square caps and their Latins. When the end was coming he cried out, "God-a-mercy on me and all usurers," once or twice he did, for the usurers seemed to trouble him. So I opened the windows, and bade him not trouble himself with the rogues at such a time, but get on sweetly with his dying. That was a comfort to him, I know, for he grew quiet then, and passed away with but one more cry for mercy on them. May the rogues be better for a good man's prayers, that he shall pray no more! For 'tis all passed, 'tis all passed; and you are Squire of Longdene now, Master Jasper; and maybe your worship would like to see how your father lies.'

I dried my tears then, for I had been dreading the summons to see him die, and felt glad that I was spared the sight. I was able to follow Cicely into the great chamber where he lay, and look bravely for the last time on the wise, hard face.

It was when I came out that I felt indeed my life had begun. For there stood old Miles, our steward, who had married my nurse, bowing respectfully.

'A wise man has gone this day, sir,' he said, 'and a godly and a rich. May the Lord in His mercy give your worship strength to bear his loss and walk in his footsteps.'

It lifted me up strangely to hear him speak thus; for I was but fourteen years old, and had never been called 'your worship' before, except sometimes on Saturdays by the Medway fisher lads, who knew I had groats in my wallet then. To hear Miles thus call me was a thing I could hardly understand. He who had barely a word for me, except to scold when he caught me bird-nesting in the orchard, or swear after me in breathless chase when I flew my hawk at his pigeons, as happened more than once when Harry came to see me and my father was away.

It is time I should tell of Harry, my friend and rival, my almost brother; for his life was, and, I thank God for His mercy, still is, in spite of all the wrong I did, so bound up in mine, that I cannot tell my tale without unfolding his.

He was the only son of Sir Fulke Waldyve, a gentleman of good estate and ancient family near Rochester, in Kent, and a good neighbour of ours. Ever since my father had come to live at Longdene, Sir Fulke and he had been fast friends. Not that they had much to make them so. For Sir Fulke was an old soldier and courtier of King Henry's day, and had named his only son after him as the pattern of manhood. From the like cause he swore roundly rasping Tudor oaths at all that displeased him, ay, and much that he loved too, from mere habit, but above all at Puritans and those who thought Reformation should go further than his idol King Henry had carried it. In all ways the knight was a man of the old time, while my father was held one of the new men, whom many thought to be ruining the country. He had been a wool merchant in London, and had made much money at trading and by other ways that merchants use.

Even I used to wonder to see them so friendly, and used to watch them by the hour together through a hole I knew of in the yew hedge, as they sat drinking in our orchard after dinner in the summer-time. Sir Fulke was so round and red, with his curly beard and his sunburnt face and his merry blue eyes, and my father was so pale and spare and grave. I wondered how men could be so little alike, and wondered how it would have been with me if that rough old knight had been my father instead of the courtly merchant by his side.

'By this light,' I have heard Sir Fulke burst out in the midst of their talk, 'I marvel every day what a God's name makes me love you, Nick. Your sour face should be as much a rebel in my heart as your damned French claret is in my stomach. Were it not that you are so good a tippler, I would say that at heart you were no better than a pestilent, pragmatical rogue of a Calvinist.'

'Nay, Fulke,' my father would say quickly in his courtly way, being, as it seemed, in no way offended that the old knight should speak to him so roughly, for they always said my father, like other merchants who have thriven, was slow to take offence with men of ancient lineage and good estate; 'what matter that our outward seeming is different? That is only because our lots were cast differently. Not what we are, but what we love, is the talk of friends.'

'Ay, by God's power,' Sir Fulke would cry, 'you have hit it now most nicely, Nick. You love a long fleece, and so do I. You love a fair stretch of meadowland, and so do I. You love a well-grown tree, and so do I; ay, and, you rogue, you love a full money-bag, and so, by this light, do I. Mass, but I run myself out of breath with our likings, and sack must run me back again.'

'Indeed,' my father would answer, 'were it only our delights that we share, I think it would be bond enough, without a common sorrow to help it.'

'Ay, ay, Nick; that is it,' the old knight would murmur, sad in a moment, for Harry's mother, too, had died in childbed. 'But speak not of that. God rest her sweet soul! What is there divided that she could not bring together?'

And so they would fall into silence awhile, till Sir Fulke's eye was dry again, and his thoughts had wandered away from the beautiful woman whom, late in life, he had loved and married and lost, to some new plan he had for mending his estate upon which he wanted his friend's counsel.

It is little to be wondered at, then, that a great friendship grew up also between Harry and me. We were little more alike, I think, than our fathers. For on Harry descended all the sunny beauty of his mother. Indeed, afterwards, when as a page at Court he personated the Princess Cleopatra in a masque before the Queen's grace, an old lord who was in presence swore it must be the gentle Lady Waldyve alive again. He was lithe and active too, and of quick and nimble wit, and as long as I can remember could always give the fisher lads more than he took, either with fist or tongue. But more than all this, it was his gentle, loving spirit that won and kept my love in spite of all our boyish quarrels, ay, and of a greater thing than that. When I think of his noble nature, which never allowed him to turn a span's breadth from the path of honour, the lofty patience wherewith he bore my shortcomings, the tender sympathy I won from him in all my troubles, I can still kneel down and thank God that gave me such a friend to carry a light before me in the way a gentleman should walk.

So what wonder then that I loved him as I loved no one else—save one, of whom I shall forbear yet to speak, until my tale compels me. Then I must, seeing it was surely God's will that tried me so sore.

Had Harry been other than he was, at the time at least of which I now speak, I must yet have loved him, for it was my father's will that I should.

'Jasper,' he would say to me sometimes when I had been reading at home, 'close your book and ride over to Ashtead to bid young Waldyve go a-hawking with you to-morrow. You must see more of him. For know, I would have you no merchant, or parson, or plain scholar, but a gentleman. You will have money, and he shall teach you how to spend it like a gentleman. Make him your friend, and be you his, or you shall smart for it.'

So away I would go blithely enough; for those days with Harry were the only happy ones I knew, though it must be said they often ended sadly with a rebuke and even chastisement from old Miles, till one day my father, seeing him, told him he would not have gainsaid any prank I played in company with Sir Fulke's son.

This I told Harry next day he came, thinking to strangely delight him; but instead he looked grave, and swore one of his father's oaths that he would never fly hawk at Miles's pigeons again.

Such was my friend Harry Waldyve when, in the first year of our most glorious Queen's reign, whom God bless with fullest measure, my father died, and I began my life.

It was not till the morning after my father's death that Sir Fulke rode over from Ashtead with Harry. The old knight was redder in the face than ever. There were tears in his eyes, too, as he took my hand and sat down by the great hearth in the hall without speaking.

As for Harry, he threw his arms about my neck and shyly pressed into my hand his set of gilded hawk bells—the most precious thing he had. I had long envied him the toys, and his kindness set my tears flowing fast again.

'Don't grieve, Jasper,' he said. 'You must not grieve. Dad will be your father now. He said he would as we rode along. He told me to tell you he was your guardian now, and we are really brothers at last, Jasper.'

I looked at Sir Fulke, but he only nodded his head. His face was very red, and I knew he could not have spoken without sobbing. So Harry and I talked on in low tones till the old knight found his voice. He spoke angrily at last, but I did not mind his chiding, for somehow I knew it was only to hide his grief, lest we boys should see his weakness.

'Yes, I am your guardian, lad,' said he; 'and since I am, why, in God's name, did you not send for me before, instead of letting your father lie all night like a dog that none cares to bury?'

'Please you, sir,' said I, 'Miles rode out an hour after he died, as I thought, to bring the news to you.'

'An hour after his death!' cried Sir Fulke. 'On what devil's errand went he then, for he came not to me till six o'clock this morning?'

'Whither rode Miles last night?' I asked then of Cicely, who was sobbing hard by. 'Know you, and has he come back?'

'Nay, I know not, your worships,' she said, 'save that he went to your worship, as he said, and—and——'

'And what, woman?' cried Sir Fulke testily.

'On an errand of his dead master's, please your worships,' whimpered Cicely; 'an errand, by your worship's leave, into Chatham.'

'And what, o' God's name,' cried the knight, 'took him there?'

'Nay, I know not,' replied Cicely, with a look of that sort of humility, much used by her class, which is very near of kin to defiance. 'Unless it were to take order for his poor worship's funeral with the elect that be there.'

'What say you?' roared Sir Fulke, 'you pestilent, canting scrag-end of Eve's flesh! What, by the fat of the fiend, has your Calvinistic knave of a husband to do with a gentleman's funeral? Knows he not, the dog, that it is I who shall order his master's affairs? Is this all that comes of Festing's boasted discipline? I told him he was wrong, he was always wrong; and here's the end of it. The elect, too,—the elect knaves, the elect devils! Do you think, you canting jade, that because Mary is dead you shall play what pranks you like with a gentleman's body? By this light, you misjudge Henry's and Mistress Anne's daughter if your thick heads think that.'

By this time Sir Fulke had railed himself clean out of breath, and as he ceased we could hear the sound of horses' feet in the courtyard.

'Run, lads,' said Sir Fulke, 'and if that be Miles bring him before me.'

To the door we went, and sure enough found Miles had returned, but not alone. Dismounting from their shabby jades were two men, dressed all in black. One of them I knew by sight, having seen him about Chatham and Rochester. He had a round, red face, with a shrewd, solid look in it, and dancing blue eyes full of merriment, which even now, though I think he tried to look as grave as he could, he was unable to get master of. His companion was a grave, dark-eyed man, of dull complexion, whose look repelled me as much as the other's attracted.

'Peace be on this house,' the two men chimed when they had finished tumbling off their horses, which they did in so clumsy a manner as even then, almost made me laugh. 'Peace; and be its sorrow comforted.'

The red-faced man then came forward up the steps, and took my hand so kindly that I felt at once that I had found a new friend.

'Master Festing,' said he, 'I know you, and desire your worship's better acquaintance. Me you know not, though I was your good father's friend. He would not have it so known; but let that pass. Know me for Master Drake, of Chatham, sometime preacher to his Majesty's fleet, and soon to be again, let us hope, now the evil times be overpast and joyful days be come again for all true Reformation men.'

His black clothes were very shabby, and of old-fashioned cut, and there came with him up the steps and into the hall a savoury smell of tar and the sea.

'Yes, my lad,' went on Mr. Drake, for 'your worship' was quite out of tune with his kind, fatherly way, 'this is an hour of sorrow for you, but one of joy for England. A weight is lifted from England's heart, and yours shall rise with hers. For, saving a decent grief for your father's loss, no true Englishman should weep when his country claps her hands and leaps with gladness.'

I did not well understand him then, though I knew he meant to comfort me. For in those days we knew little of what was coming, when such words as Mr. Drake's would be on every one's lips. England was crushed and broken then, shuddering still under the curse of Rome and Spain. I was no more a prophet than the rest, and could ill understand why this little red-faced preacher should draw himself up in his shabby clothes, with glittering eyes, till he almost looked as though he had come out of my Plutarch, best loved of books. I was glad when he stopped and turned to his friend.

'I had forgot,' said Mr. Drake. 'Be better acquainted with my right-worshipful and approved good friend, Mr. Death. One of the faithful flock, Mr. Festing, that through the bloody times, which now be past, has watched and prayed for England beyond the seas, in Frankfort; withstanding steadfastly all backsliders there, and helping Mr. Knox to file away the Popish rust that still clung to King Edward's service-book.'

He seemed to think that because my father had been a secret but active Puritan, I must be one too, and well versed in all those unhappy controversies with which the English exiles made their banishment doubly hard, and laid the seeds of many troubles that even now grow each day ranker.

'Ay, that I did,' said Mr. Death, unfastening his hard lips, 'and should have prevailed at last against that bad, factious Erastian, Dr. Cox, had he not so traitorously procured us to be driven forth by the Gallios of that city.'

'If any man has dealt traitorously with you, Mr. Death,' said Harry, 'it were well you should come within and speak with my father, who is a Justice, and will see you righted, I doubt not.'

'Ay,' echoed I, 'come within and speak with my guardian, who will surely welcome all my father's friends.'

Our words had quite another effect to that which we had expected. For both the preachers stopped short before the door, looking hard at each other. Mr. Death seemed to grow more pale than before, and to be at a loss what to do. But Mr. Drake's face I saw grow to so stern a look of resolution as only in one other have I seen equalled.

'Come, brother,' said he, 'we have a blow to strike, so let us strike quick and hard,' and with that he strode across the hall to where Sir Fulke was sitting, who sprang up fiercely when he saw the preachers.

'Drake!' cried he, 'what in the devil's name make you here?'

'In the devil's name I make nothing, Sir Fulke,' answered Drake unflinchingly; 'but come to stay you marring, in the devil's name, a dead man's wishes; and in God's name to charge you to deliver up to me the body of Nicholas Festing for burial.'

I verily believe that had it been the sour-faced Mr. Death that had given their errand he would there and then have been sent forth with such a dish of blows seasoned with hot railing as would have kept him satisfied for many a day. But Sir Fulke, like King Henry and our blessed Queen, knew a man when he saw him, and surprised me by his quiet answer.

'You open your mouth wide, Drake,' said he; 'by what authority do you expect me to fill it?'

'Here is one,' answered Drake, 'that you will be the last to gainsay, if men know you for what you are,' and with that he took from his breast a paper and handed it to Sir Fulke. He carefully examined the signature and writing, and then gave it back to Drake.

'Nicholas Festing wrote that, I doubt not,' said he; and then, looking Drake hard in the face, went on, 'Read it to me, and read it truly, if you are a man.'

Without wincing a jot under Sir Fulke's stare, Mr. Drake took the paper and read as follows:—'Know all men whom it may concern, and above all Sir Fulke Waldyve of Ashtead, knight, to whom I have given care of all my earthly affairs, that it is my last will that in all which concerns the spiritual and heavenly part of me no man shall meddle, save as my approved friend Mr. Drake, preacher, of Chatham, shall direct; and him I charge to deliver my soul to God, and my body to earth, after the manner of the reformed Church, and free from Popish, idolatrous, and superstitious ceremonies, saving always the laws of this realm. For I would have all men know that I die, as I have lived, in the purified and ancient Church of Christ, in testimony whereof, above all, I desire to be buried without jangling of bells, or mistrustful prayers, or conjuring with incense, as though my happy state with God were doubtful, and reverently laid in the earth, with thanks to God, in certain hope of a glorious resurrection.'

For a moment Sir Fulke looked at me, as though he would ask me to read the paper too, but almost immediately he stared hard again at Mr. Drake, and was satisfied.

'Enough,' he said, plainly much pained. 'How will you bury him?'

'By the rites in use amongst the true English remnant at Geneva,' croaked Mr. Death, who, seeing all danger was over, now came forward. 'There alone is found the true law of God, there alone has the threshing-floor been swept clean of——'

'Peace, fool,' said Sir Fulke sharply. 'If Nicholas Festing wishes to be put under the sod like a canting Calvinistical knave, by God's head, he shall be, saving always, as he said, the laws of this realm. I want no pestilent, heretical sermons from you, but only information to lay before the Council, whither I ride this very day, according to my duty as a Justice of the Queen's most excellent Majesty. And, look you, Drake, promise me to do nothing till I return.'

'My hand on that, Sir Fulke,' said Drake, heartily holding out a hand not unstained with pitch, which my guardian, after a moment's hesitation, took.

With that the preachers departed, and Sir Fulke soon after followed them on his way to London, much saddened, as I think, to see what manner of man his friend had been.

Whether he was heard by the Council or not I cannot tell. Certain it is, however, that on his return he took no steps to prevent the funeral. I expect, if the truth were known, his zeal won little encouragement from the Council. For in the early days of our wise Queen's reign, in spite of an ordinance against using new doctrines or ceremonies without authority, and the proclamation against King Edward's service-book, which had been given out the month before, things were left to go on with as little mud-stirring as possible, until Parliament could be brought together.

I doubt not the poor old knight lamented bitterly the high-handed days of his old master, King Henry; but he was helpless, and a day was fixed for the funeral to take place at our little church.

Well I remember that sunny January morning, and how I dreaded what was to come. At an early hour great numbers of people came flocking out of Rochester, Sittingbourne, and the villages around to Longdene. For, since this was but the first year of the Queen's reign, no one knew as yet of a certainty what order would be taken in ecclesiastical matters, and the news that a gentleman was to be buried after a new and reformed manner attracted many, since these things, being the first that had been seen in Kent, were accounted strange at the time, and somewhat boldly done, when as yet the old religion was still in force.

The people came rejoicing, with baskets of food, as though to a wedding or glutton mass rather than to a funeral. To me alone, in all that multitude, it was an occasion of sadness. It was the first time the people had had brought home to them that the days of England's shame and bondage were over, and when I looked upon the crowd, before the gate, eating and drinking and laughing, as they waited for the body to come forth, I began to know what Mr. Drake had meant, when he said that a weight was lifted from England's heart, though it only made heavier the load on mine.

So brightly shone the sun, and so radiant were those happy people, scarce one of whom had not lost a friend or kinsman in poor Wyatt's mad attempt to do by force what God had now done so quietly by Mary's death, that I alone of all the world seemed sad, and in my utter loneliness I turned away and wept bitterly.

Mr. Drake was in the room, talking in high spirits to a knot of preachers who had just arrived. Many, I was told, had come down from London to do honour to the great occasion, as they called it, but I forget their names, if I ever knew them.

Good Mr. Drake must have heard my sobs, for he came forward out of the gloomy throng and spoke to me very kindly.

'Come, lad, come,' said he, with his tarry hand on my shoulder; 'have a stout heart. This is a proud day for you, a day of rejoicing in the Lord, that it is given you to bear witness of England's new life, and not, as was vouchsafed to me and others here, to bear witness of her slow cankering death. All England will praise you for this day's work. Ay, and beyond the seas too, many a poor Fleming, and Frenchman, and German who was losing heart will smile happily when he hears Nicholas Festing's name, and envy his son the part God gave him to play.'

Hearing Mr. Drake's words, the preachers gathered round us and vied with each other in giving me drafts of comfort, rather, as it seemed to me, for their own glorification in each other's eyes, by showing their cunning in the brewing of such phrases, than from any desire to console me.

'Affliction, Master Festing,' said a fat, pale-faced man, 'is the mustard of the spirit; for even as that excellent sauce maketh the stomach lusty to receive meat, so doth sorrow stir up the heart to a desire for the Word,' and with that he smacked his lips and looked towards the sideboard, which Cicely was already furnishing with meat against our return.

'Rejoice, too, my boy, in your tears,' said Mr. Death, 'for they be the water to drive the mill which shall grind in pieces the stumbling-blocks of your soul.'

'And groaning, sir,' said another, 'is the portion of the elect, who, being predestined to the eternal company of God, must not defile their spirit with the joy of the world, which fills the stomachs of the eternally damned.'

'Softly, softly, sir,' interposed a heady-looking man; 'comfort the boy, if you will, but comfort him according to the Word.'

'And who are you,' retorted the other angrily, 'to teach me what is according to the Word, and what is not?'

'Brethren, brethren,' cried a mild, grave-looking man with a refined and scholarly face, 'I pray you remember on what errand you are. On a day of triumph like this, is it for the victors to quarrel? Moreover, it is time we departed. Mr. Drake, I pray you order our manner of proceeding.'

With that we started, to my no small joy, for I was longing to be alone in the old library again, and none of those men, save Mr. Drake, brought any comfort to my aching heart.

It must have been a strange sight, when I come to think of it now, as we crossed the sunlit court and sallied out between the crowds of eager faces that lined the way. Instead of the throng of clerks in gay attire who used to precede the coffin at burials of persons of note, swinging censers, and singing for the soul of the departed, there were none but the black company of preachers in their gowns and Geneva caps.

The people joined in behind me where I walked with Miles and Cicely, and the long line wound down to the church in the valley between the frosty hedgerows and the young woods my father had planted.

I knew the little moss-grown church well, for it was a favourite resting-place for Miles's pigeons. They, I think, were the only living things that cared for it, except a few ill-tempered jackdaws and one or two old bent women, who came to mutter prayers upon their beads amongst the mouldering stones.

I do not think there had been a parson there since King Henry's time, certainly none that I could remember, except on rare occasions when one came out of Rochester to shiver through a homily or a funeral, as well as the jackdaws and the chilling damp would allow.

It was a place all shunned for its ghostliness, unless they had a special call to go there, which indeed was seldom; for there was not even a door upon which the parish notices could be fixed. The wood had long ago gone to make fires, and the wide-spreading hinges, all bent and rusty, hung down with an air of mourning.

But the pigeons and the jackdaws quarrelled for the place. It was a pleasant spot for them. All that savoured of Popery, which was all the church contained, had been torn down, I think, in Edward's days. Rood-screen and all were gone—perhaps to cook a Reformation pot with the door. Thus the birds could fly in and out as they liked, and rest out of the way of stones and hawks, till Harry hustled them out.

The little painted windows still remained. They were very Popish things, with the Virgin and I know not what saints upon them. But it did not matter, for the spiders and the ivy—good reformers they—had nearly hidden them from sight, so, as it was thought too costly to replace them with white glass, they had been allowed to remain.

A grave had been prepared for my father at the end of the north aisle, where once was a chapel of St. Thomas, and where were still to be seen, moss-grown and time-stained, two or three tombs of the Abbots of Longdene. There was great difficulty, I remember, in getting the coffin so far, because the pavement was all loose, and in some part quite thrust out of place by the rats and the fungus.

As many of the people as there was room for thronged in after us, and jostled each other for the best places with many a rude jest. Such irreverence was very hard for me to bear, but I do not wish to condemn them for it. It was done from no ill-will to me or my father, but only from that same exuberant spirit of joy which was beginning to fill all men's hearts when each day they saw more clearly that England's night was done.

The preachers alone seemed in earnest; for they, good men, had suffered much, and this thing that we were now upon must have seemed too serious and heaven-sent for idle gaiety.

I was more at ease when the scholarly-looking gentleman began the service. His soft, full voice quieted the people directly, and the beautiful words he spoke kept them in rapt attention in spite of their crowding to see what was to be done.

No wonder, for now they heard, many for the first time in God's House, the voice of prayer go up in their own sweet English tongue. The preacher began with a collect, in which he commended the dead man's soul to God, and prayed that his sins committed in this world might be forgiven him, that the gates of heaven might be opened to him, and his body raised up upon the last day. So lovely did the well-balanced, earnest words sound in our dear old speech that I saw tears in many an eye before he had done, and the amen, in which all joined at its end, was half choked with sobs.

Incontinently they lowered then the coffin in the grave, and covered it with earth, while the old preacher read an epistle taken from 1 Thessalonians iv.

Deeper and deeper grew the silence, and less and less my pain, as the heart-stirring words fell upon the listening throng. 'I would not, brethren, have you ignorant concerning them which are asleep, that ye sorrow not, even as other which have no hope. For if we believe that Jesus is dead and is risen, even so them which sleep in Jesus will God bring with him.'

So the solemn periods marched on to the end. 'Wherefore comfort yourselves one another with these words,' and therewith the white-haired scholar kneeled down, and began with a loud, full voice to sing in English the Paternoster.

A sound, as it seemed to me, like the rustle of angels' wings filled the mouldering church as the whole throng with one accord kneeled with the preacher and joined him as he sang, women and all. Neither I nor any there, I think, save the preachers, had heard such a thing before. And surely it was the sweet women's voices that made our singing sound so holy in my ears, and lifted up my heart with such a heaven-born content that at last I could feel indeed that it was not a day for sorrow, but one in which I too must rejoice with England.

Our Paternoster was followed by a sermon, in which, after a few words on death and eternal life, the preacher fell to exhorting the people to be earnest in carrying out the work, and not to be content with a pretended evangelical reformation, suffering such things to be obtruded on the Church as should make easy the returning back to Popery, superstition, and idolatry. They had seen, he said, in Germany the evil of suffering, under colour of giving small offence, many stumbling-blocks, which after the first beginnings were hard to get removed at least not without great struggling.

But, indeed, I remember little of what the good man said; for I was but a boy then, and my mind would ever be fixing itself on the jagged ends of the rood-screen, which had been left sticking from the wall when it had been hewn away.

'Pity it is,' I said to my thoughts, 'they were not clean rooted out. Even now they might wound a man's limbs who was passing unawares, and time will come when they will grow corrupt, and as they rot away make the arch unstable.'

Little I thought then how true a type those same poor beam-ends would prove of all that was to come on England ere many years were gone.

It would be wearisome for me to relate all that passed in the weeks that followed my father's funeral, even if I could. But indeed I remember little, except confusedly about men of law who came from London and had long speech with my guardian.

In the business of setting my father's affairs in order I too was a good deal mixed.

'You cannot know too soon,' Sir Fulke said to me, 'what your estate will be. I am one who thinks a lad cannot learn too early to be a good steward, and so thought your father too, Jasper. So from the first I would see you have a say in your own affairs.'

Thus it came about that I was always present when the lawyers came, and though at first I found it irksome, I soon began to take interest in my estate.

Yet one event of these days I must relate, seeing that it was the beginning of things which afterwards played so great a part in my life.

I rode into Rochester one day to see a man of law who dwelt there. As we descended the steep hill that leads from off the downs to the low-lying ground, the whole district was stretched out like a map below us. We could see straight before us the compact little city of Rochester, a mass of red roofs girded with a soft belt of trees, and crowding round the Cathedral and the great Castle, still grim and solid in its decay. About it ran the yellow river in one grand sweep from the bridge to where it turned again between Upnor Castle and the dock at the growing village of Chatham. Right in front of us, where the road was swallowed up between the two round towers of the city gate, was a great crowd. It was no strange thing to see, for hither were wont to gather the mariners from the fleet which rode between the bridge and Upnor and the workmen from the dockyard, that they might gossip and drink at the taverns which lined the way without the gate. To-day, however, it was a greater crowd than usual; so great indeed that we could not pass and had to draw rein.

'What, in the fiend's name,' cried Sir Fulke, 'brings all these stockfish gaping here to block a gentleman's path?'

''Tis Drake, 'tis preaching Drake,' said a good-humoured, weather-beaten sailor who stood by. And sure enough it was; for no sooner were the words out of our friend's mouth than Mr. Drake's jolly red face appeared above the heads of the crowd, as he mounted a stool close to the gate.

'Come, hearken, mariners,' he cried, 'hearken to the Word of God and the whistle of the Lord's boatswain. For the Word of God is like unto a capstan. You can turn it about and about till you tear up the anchor that binds you to earth. Come, then, my lads, and turn it about with me till you tear up the crooked anchor of sin, whereby the devil would moor you to the things of this world.'

This was as much as Sir Fulke could bear, and he cried out, 'What kennel preaching is this? Have you nothing better to liken the blessed Word of God to than a capstan?'

'And wherefore should I not?' cried Drake, not noticing from whom the interruption came. 'What ell of tar-yarn is this, that will take upon him to reprove the similitudes of a preacher to her Majesty's navy? Wherefore, I pray you, should not the Word of God be likened to a capstan, when that blessed servant of the Lord, even Hugh Latimer, did not himself scruple to liken the Mother of God to a saffron-bag?'

'Well, I'll grant you the similitude is right enough,' Sir Fulke called out again. 'For, by God's truth, it seems that a preacher nowadays can turn the Word about and about till he make it pull up anything he will.'

This sally produced a laugh from the rougher part of Drake's audience, and many began to cry out, 'What say you to that, master preacher? Has he not got you now?'

'What have I to say to it?' said Drake, turning fiercely on them. 'Know you not your own trade, you lubberly, roeless sons of herrings? Know you not that when you man a capstan you go but one way, like asses, that you are, in a clay-mill? So it is with the Word. There is one right way, that shall profit you to turn it, and if you twist it another it shall spin you heels over ears in a heap, like the ungodly in the bottomless pit. My similitude was right enough, yet would I have defended it with greater courtesy had I known who challenged it. Make way, lads, make way for Sir Fulke Waldyve; for next under God you shall reverence our blessed Queen and all who hold her commission. Make way, and let me ask pardon for my discourtesy to our most worthy magistrate.'

'Enough, Drake, enough,' said Sir Fulke good-humouredly; 'you outrun me no less in courtesy than wit. Were all preachers such as you there would be little call from Injunctions against preaching without authority, but since such there be, I must even, in virtue of my office, bid you cease, and all this company disperse.'

That they did contentedly, with three cheers for the old knight, who was well known, and loved as much as known, at Rochester.

Mr. Drake was bidden to the 'Crown' by my guardian to take a cup of wine; for it was always his custom to try and part in friendship with those whom he had had occasion to chide.

'But what of the Injunctions about which you are so tender, Sir Fulke?' laughed Drake. 'You forget I am an ecclesiastical person, and may not haunt or resort to taverns or alehouses, vide Injunction No. 7.'

'"Save for your honest necessities,"' returned Sir Fulke. 'So run the words; and your peace-making I hold, in my capacity of Justice, to be a most honest necessity. So come, with no more words, and save your tenderness for less honest occasions.'

So we went to the inn, and there they talked of the times quietly enough till the lawyer came in. Mr. Drake craved leave to carry me home with him when our business was done, that I might see his boys, of whom he seemed very proud, and fish with them on the morrow.

Sir Fulke demurred at first, but when Mr. Drake urged that it would cheer me a little, and perhaps bring the colour back to me, for I was but very poorly after my days of sorrow, my guardian at last consented.

Towards evening, then, Mr. Drake came back for me, and we sallied out together, Sir Fulke crying out as we left that Mr. Drake was not to send me back with any pestilent Calvinistic ideas in my head.

I was surprised that we went across the road down to the landing-stage just below the bridge. For I knew not where Mr. Drake's house could be if we must go to it by water, but I did not say anything till we had taken his boat and were clear of the turmoil which the fast-ebbing tide caused as it fought its way angrily through the narrow arches of the noble bridge.

'Where is your house, Mr. Drake?' I asked, as we reached the stiller water.

'Where is it, my boy?' answered he, chuckling to himself, as if vastly tickled by my question. 'Where, but on no man's land.'

'And where may that be?' asked I, not at all understanding his merriment.

'Why, in God's free tide-way, my lad,' said Mr. Drake, chuckling more heartily than ever. 'Where could an Englishman, and above all a Devonshire man, live better than there, where there are no landlords and no taxes, and every one is his own king? You will know it some day, I hope. Frank knows it. My boys know it.'

I could not quite make out what he meant, and least of all who Frank was, and what he had to do with it. And no wonder, for then I did not know his strange habit of speaking of his sons as 'Frank and my boys.' I did not like to question him more, and was content to listen to him as he told me the names and services of the Queen's ships which we passed. There were a good many of them moored between the bridge and Upnor Castle, whereof some came to great renown afterwards, but then they were few and ill kept compared with what a man may see in the reach to-day.

Clean past Chatham and the one little dock that it then had we went, till we made the reach that runs toward Hoo. Here Mr. Drake stopped rowing and pointed down the river.

'Look, Master Festing,' cried he. 'There she lies, there ride her jolly old bones over no man's land. That is my house, that is my castle, that is where I live with Frank, when he is at home, and my boys.'

I looked to where he pointed, and saw an old hulk, after the fashion of King Henry VII.'s time, moored just out of the fair-way. A handsome vessel she must have been once, but was dismasted and plainly very old. I noted this to Mr. Drake.

'Ay,' he said, 'she is old, but trim and staunch yet. They say Cabot sailed in her to the Indies once; the first man who touched the mainland, let the Spaniards say what they will. I know it, and Frank knows it, and so do my boys, and we are proud of it, as we ought to be, for he sailed from England in an English ship.'

'But why do you live there?' I asked.

'Well,' said he, 'I have a reason, and I may as well tell you now as later. I lived once near Tavistock, in beautiful Devon, on the banks of our sweet Tavy, and there I might be dwelling now, but that I began to smell the Word of God and know it from the stinking breath of the beast of Rome. Then the Lord sent me trials, which, I thank Him day and night, He gave me strength to bear. The Justices of Devon were, for the most part, very earnest for the old religion, and persecution grew hot for those who would not sign the Six Articles. I thank God I was one to whom He showed the filthy error of that first most pestilent and damnable doctrine concerning transubstantiation. For, look you, lad, they would have made us like unto themselves, who are worse than the cannibal savages of the Indies. They, in their devilish ignorance, do but eat the flesh of their enemies; but these, in their most pernicious self-will, would pretend to fill their lewd bellies with the flesh of their Redeemer. Even as I speak to you of it, lad, my words seem like poison that will blister my lips, and I shudder each time I think of it, that Christian men are found to set such wanton contumely upon their sweet Lord. Come what might, I was no man to sink my soul in the filth of such a hell-born superstition as that; so I rose up and fled from the destroyer hither to Kent, where I knew true men were to be found. Here God showed me yonder hulk, which I purchased with the store of money I had saved. There dwelt I in peace till, in the fulness of time, King Henry died, and the godly men who stood around the throne of his son made me a preacher to the Royal Navy. So I continued reaping plenteously in the harvest of the Lord, until Edward's death thrust England once more down into the black pit of papacy and superstition.'

'But the day has broken again, now,' I said, remembering his former words, and wishing to win him back to the genial mood from which he had talked himself. He had been getting more and more like a great boy as we neared the ship and he talked of his sons, and I was sorry to have made him gloomy by my foolish questions.

'So it has, lad, so it has,' he cried, looking up quickly with the twinkle in his eyes again. 'It is growing brighter every hour; you shall help to brighten it, with God's good will, and so shall Frank, so shall my boys. But here we are almost alongside. Ahoy! ahoy! ahoy!'

No one answered to his shout, but as we came close alongside we could hear a strange commotion in the waist of the ship, into which, however, we could not see.

'They are about it again,' said Mr. Drake, with a chuckle; 'my boys are.'

'About what?' asked I.

'Fighting!' replied Mr. Drake, with increasing pride and delight. 'I know the sound. My boys fight as much as any man's sons in all Rochester. Not many days pass without them getting about it.'

'But what do they fight about?' I asked.

'Don't bother your head with that,' replied Mr. Drake; 'they don't.'

With that we went aboard, and I saw the cause of all the hubbub. Stripped to the waist were two sturdy lads of about twelve and thirteen years of age. They were fighting furiously with their fists, to the great delight of nine other boys of all ages, varying from a little fellow not more than three years old to a lad of scarce less growth than the smaller of the two fighters. The onlookers were cheering each telling blow, and hounding on their brothers to further efforts. Each time the others shouted I noticed that the baby cried out too, as loudly as his little lungs would allow, and beat on the deck with an old sword-hilt, which seemed to be his favourite and only plaything.

'There, Master Festing,' said Mr. Drake to me, beaming all over his round face, 'there are boys for a father to be proud of. Well done, Jack! 'Tis Jack and Joe,' he went on. 'You could not have had better luck; they are pretty fighters both.'

My answer was drowned in a fresh shout from the boys as they caught sight of their father.

'Come on, dad, come on,' they cried. 'Jack is winning again, but you shall still see some good sport before 'tis ended.'

They crowded round Mr. Drake to drag him by his cloak to where the two boys were still belabouring each other. Thither I think he would have gone, for he seemed as excited over it as the baby, but just then a thin, weary-looking woman, with eyes red with weeping, came running out of the cabin in the poop, and took Mr. Drake wildly by the arm.

'Stop them, Ned,' she said, 'stop them, for God's sake; they have been fighting this hour. For what black sin has Heaven given me such sons?'

'Tut, tut,' answered Mr. Drake; 'would you have a nosegay of milksops to call you mother? Rejoice that God has given us sons with whom, when the time is come, we shall not fear to speak with our enemies in the gate.'

'I know, I know,' she pleaded again; 'but stop them, Ned, this once. Look at their bloody faces; and I am so a-weary. Frank would stop them if he were here.'

'Ay, though he loves to see them fight,' answered her husband; 'I think sometimes he cares too much for you, and not enough for the cause. Still, for his sake, I will stop them. Peace, lads, peace!' he cried then; 'enough for to-day. It has been well fought, but now I bring you a visitor. Look to him, while I shift my boots within.'

The boys ceased fighting instantly, and after wiping their faces they shook hands, and then came up to where Mr. Drake had left me with the rest. John Drake, being the eldest there, welcomed me, but in a way that fell a good deal short of good manners.

'Can you fight?' said he, with a contemptuous look at my black broadcloth doublet.

'I can fight with sword and buckler,' I answered, 'a little.'

'Then you are a gentleman?' asked Joe.

'Yes.'

'Frank is going to be a gentleman. He says so. He is going to make all of us gentlemen, too.'

'Who is Frank?' asked I.

'Don't you know Frank?' said Joe, while all the rest laughed at my ignorance. 'Frank is our brother, our eldest brother. He is a sailor now. He's 'prentice to a shipmaster, who trades to Zeeland and France. He will be a master soon, and have a ship of his own. He says so. And then he will sail with us against Calais, and win it back, and the Queen will make us gentlemen.'

'That is much to do, and will take some doing,' said I, smiling, I am afraid; for I could not but be merry over the way they spoke of what a poor smack-lad was going to do.

'What are you grinning at?' cried Jack, firing up in a moment. 'Do you doubt Frank will do what he says? Take that, then,' and he struck me a hard blow on the chest that made me reel again.

I am sorry it made me angry to be struck so, for I returned his blow so heartily that, being younger than I, he was spun over on the deck somewhat heavily. Yet I think he did not mind, for when he picked himself up from where he fell, he came to me quite quietly and felt my arm.

'Who would have guessed,' said he, 'that you could strike so shrewd a blow,—you with a pale face like that; but Frank could thrash you, and so he shall when he comes home, and then we will ask him to let you sail with us against Calais.'

I could not laugh at him any more, for I began to take a great liking to the sturdy lad, with his broad, flat face and curly hair, since I had knocked him down, and could quite forgive him for talking so big about his brother Frank.

'I am sorry I struck so hard,' said I.

'Nay, sir,' answered he, 'be not sorry. It is not every one can fell me like an ox, and besides, dad says England will want strong arms ere long. Won't she, dad?'

'Ay, that she will,' said Mr. Drake, who now came out from under the poop; 'and Mr. Festing will use his for her. But come to supper now.'

'Art going to be a soldier, lad?' he said to me, as soon as we were seated.

'I think I shall be scholar,' answered I. 'Sir Fulke says I am to go to Cambridge soon. It was my father's wish.'

'Well, he was a wise man,' said Mr. Drake, 'and doubtless knew best. But it seems to me that England will need pikes and swords sooner than books. Still, let that pass.'

'Don't let him be a scholar, dad,' said Jack. 'He must be a sailor, and sail with us to the Indies, and find new kingdoms, like the Spaniards, and bring back a cargo of gold and pearls. Tell him about the Indies, dad.'

So Mr. Drake, with a right good will, fell to talking of the wonders of the West, and we twelve boys sat round him, open-eyed, greedily devouring his words, while he spoke of the gilded king that was there, who ruled over mountains of gold; and of the Indians that hunted fish in the sea, as spaniels did rabbits; and of the great whelks that were three feet across; and of trees with leaves so big that one could cover a man, and almonds as large as a demi-culverin ball. I know not what other wonders he related, just as he heard them from the mariners who came thence, but we all grew greatly excited by his tales, and went to bed to dream things yet stranger than the truth.

Such was my first meeting with the Drake family, and fast friends we boys became, and though continually fighting amongst themselves for the lightest causes, they never offered to attack me again. Francis I never saw at this time. He was nearly always abroad, and when he returned it so happened that I could not get to see him. Still, whenever we got a day away from our grammar, Harry and I always slipped off with our crossbows, to sail with the Drakes in their boat and fish and shoot wild-fowl.

Those were our happiest days. So greatly did the Drake boys take to Harry, after a fight or two, and so much did we take to the sea, that all our old pleasures were forsaken, and the pigeons and the jackdaws were left in quiet possession of the crumbling old church.

Nor were Mr. Drake's stories of the West the least cause of our love for the Medway and that aged hulk. Harry was never tired of questioning the old navy preacher about it, and soon we began to worry our old tutor to tell us more.

For I must relate that I was now living almost entirely at Ashtead with Harry, that I might share with him the tutor whom Sir Fulke had secured for us. Poor old long-suffering Master Follet! How I wish I could know thee now! Surely when I look back to those days of patience, I know thou must have been the sweetest pedant that ever said his prayers to Aristotle. But then in my folly I knew thee not. I knew thee not for the gentle scholar thou wast, for the well-rounded compendium thou hadst made thyself of that old learning which is fast passing away,—the old, pure learning, which a man could seek so pleasantly when learning was books and naught but books, and he who knew them best was accounted wisest.

If Eve had not tempted nor Adam sinned, God might have given us that richest gift—to see the hours of our youth, as they pass, with the eyes that we look back upon them withal when they are gone. Alas! such wit I lacked and knew thee not, my gentle master, nor the hours in which I was free to rifle the treasure-house of thy polished wisdom. Had I but known, I might have tasted, ere they were yet dead, the sweets of those days when he who sought wisdom and would be accounted wise might sit out his life in the window-seat of his library, drinking in the voice of the mighty dead, while the world without glimmered softly in through the painted lattices upon the folio before him, and wandered thence to kiss its sister volumes sleeping in the shelves.

Now that has changed, with much besides. Now must not a scholar be content with the light that comes softened and tender-hued through a library window if he would pass for wise amongst men. Now must he plunge out into the day and seek for the new wisdom amongst the haunts of thronging men, where the sunlight beats fierce and bright upon the world to show to him who fears not all its beauty, and all its baseness too.

Such wisdom was not our tutor's portion, and his want of it, instead of increasing our love for him, as now it would, was our chief ground of difference. We each day grew more full of the wonders of the West, not alone from what Mr. Drake told us, but also from what we heard direct from mariners, with whom groats could win us speech in Chatham and Rochester.

Well I remember how he answered when, having drunk dry our other wells, we made bold to try what we could find in our tutor.

'I am glad, my boys,' said he, with an anxious look in his delicate, wizened face and clear, brown eyes, 'that you have come to me in your trouble; for I perceive you have been speaking with some ignorant fellows, who have filled your heads with the folly that is now everywhere afloat. Beware of it as you would beware the fiend. So strong is this madness that has seized on men, and even scholars (if indeed they still deserve the name), that in so great a place as Paris even Aristotle has been called in question.'

He looked at us as he said this, pausing long with uplifted eyebrows to watch the effect which this announcement, to him so terrible, would have on us. I did not know what to say, so prayed him civilly to proceed.

'You may well be pained,' he continued, though it must be said that I don't think we were at all, 'but you will rejoice to hear that these things will not continue long. I have here a goad which will soon drive these dull-witted cattle back to the right path.'

So saying he laid his hand on a bundle of manuscript, which we knew only too well, and leaning fondly over it read slowly, as though it were a sweetmeat in his mouth, the title-leaf at the top. Its name was in Greek, not because the work was written in that tongue, but merely out of a fashion used commonly amongst such men to increase their appearance of wisdom.

'It is a work,' the good old man said,—we had heard it a score of times before,—'upon which I am labouring, entituled, "'H Aristotéleia Apología; or, Ramus Ransacked, being a British Blast against Gaulish Gabies, wherein all the preposterous, fantastical opinions of late grown current amongst the Dunces of Paris are fully set forth, withstood, and refuted by Christoph: Follet." It begins with a sharp note against——'

'But, please you, sir,' Harry interrupted,—and I was glad he did, for I saw the old man was running out of his course, as he always did when he got astride his 'Apology,'—'were it not well first to show us how the knowledge of this New World, of which we were asking you, had so set things awry?'

'Knowledge of the New World, say you?' said our tutor, evidently a little pained. 'Know, my boys, there is no knowledge of this pretended New World. No man can know what does not exist: the New World does not exist, ergo, no man hath knowledge of it.'

'Far be it from me to dispute your syllogism,' said I, for logic was his chief delight to teach us, 'yet, saving your premises, I have many times spoken with them that have been there and seen it.'

'My boy, my boy,' answered Mr. Follet sadly, 'in what a perilous case do I find you! What hope can I have of your scholarship if you will set the eyes of moderns against the wits of the ancients? How can they have seen this New World of which they are so ready to prate? Had it existed, Aristotle would have written of it. Forget you for how many years, and for how many and great sages, the whole sum of human understanding has been contained within the compass of the writings of that great man, and will you seek to increase it by the babbling of drunken sailors?'

'But, please you,' said Harry, 'the honest mariners who told me were not drunk.'

'The greater liars they, then,' answered Mr. Follet, a little testily. 'Or rather, I should say, the more pitiable their ignorance; for let me not be carried beyond good manners, which are a sweet seasoning of scholarship too often forgotten nowadays in the dishes men compound of their wits.'

'Save you sir, for that most excellent conceited figure,' said Harry gravely; for the mad knave always knew how to bring his tutor back to a fair ambling pace when he grew restive.

'Well, lad, indeed I think it was not amiss,' answered Mr. Follet, with a complacent smile. 'It is an indifferent pretty trick I have, and one I could doubtless in some measure rear in you; but not if you suffer the vulgar to plant weeds in the gardens I am tilling with such labour, that I may in due course see you both bring forth a plenteous crop of the fruits of scholarship. If you have a desire to make yourself learned in cosmography, I myself, who have no small skill in it, will teach you. But listen no more to idle sailors' tales, whose only guide is experience, wherewith they foolishly seek to explain the hidden wonders of the world, seeing they have no skill to learn the truth from books.'

'Is it Aristotle, then, alone we must read?' asked Harry, a little disheartened at the prospect before us.

'I will not say that,' answered our tutor. 'Though for the wise the Stagirite is all-sufficient, yet it cannot be denied but that there be some authors who, having reverently and afar-off walked in the footsteps of the master, have in a manner amplified, extended, and explained, and as it were diluted his vast learning, so as to make it more palatable, medicinable, and digestible to the unlearned, such as you and Jasper. Therefore, because of your weakness, I would suffer you to read the works of Strabo, Seneca, and Claudius Ptolemæus, amongst the ancients; and among the moderns, the Speculum Naturale of Vicenzius Bellovacensis, the Liber Cosmographicus de Natura Locorum of Albertus Magnus, together with certain works of our own Roger Bacon; but these with circumspection, and under my guidance, seeing he was a speculator who erred not from too little boldness, or too great respect for Aristotle.'

With this we had to rest content, though I think Harry found little comfort in it, seeing that his love for books was never so great as mine. As for me, I laid aside my Plutarch, and devoured greedily all my tutor advised. Nor did I stop there; for, rummaging in the library at home, I found other works on cosmography, such as the Imago Mundi of Honoré d'Autun, and that of Cardinal Alliacus, together with not a few others which some abbot of the later times had collected, being, as I imagine, interested in the science.

In these I read constantly, and carried what I found there to Mr. Drake and his boys, and my friends amongst the sailors. Hour by hour I told them of the dread ocean, where was eternal night, with storms that never ceased; of the magic island of Antilia or Atlantis; of the marvellous hill in Trapobana, which had the property of drawing the nails from a ship which sailed near it, and so wrecking it; and, above all, of the Earthly Paradise, of which I loved best to muse.

Again and again I poured into their wondering ears the tale of that blessed land which lay beyond the Indies, the first region of the East, where the world begins and heaven and earth are hand in hand; the land where is raised on high a sanctuary which mortals may not enter, and which everlasting bars of fire have closed since he who first sinned was driven forth. I told them of the wonders of that land; how in it there was neither heat nor cold, and four great rivers went forth to fill the place with all manner of sweetness and water the Wood of Life, the tree whereof if any man eat the fruit he shall continue for everlasting and unchanged.

Some laughed at me, saying I was blinded by too much book-learning, but most of the mariners, and especially Drake's boys, listened with great respect, caring little, as I think, after the manner of seafaring folk, whether the tales they heard were true or not, so long as they were strange.

So passed by the full days of my boyhood; I living, as I have said, chiefly at Ashtead in Harry Waldyve's company.

It was not alone in devouring grammar, and such dry bones of cosmography as Mr. Follet allowed us to pick, that our time was spent. Sir Fulke was not a man to keep boys wholly to such work. Although he had managed to acquire some show of skill in theology when King Henry brought it into fashion at Court, yet even that I soon saw had fallen into sad confusion in his mind, and in no sense was he a scholar.

Yet in all such pastimes and pleasant labours as are used in open places and the daylight, which in respect of peace or war are not only comely and decent, but also very necessary for a courtly gentleman to use—in these he still showed the remains of his former high skill, or at least a happy trick of imparting to us his great knowledge of their mysteries.

Almost every day he would have us out and exercise us under his own eye at riding, running at the ring and tilt, and in playing with weapons, being especially careful of our fence with the sword and spiked target. Like his master King Henry, he had a great love and skill for using the bow. This he taught us to use, and less willingly also the harquebuss.

We had little time for the sea—an element, as my guardian was wont to say, which sorted less with what pertained to a gentleman than the land. Yet he did not forbid it, and whenever he went up to the Court, which was not seldom, we laid aside awhile our courtly exercises, and were continually amongst the marshes and Saltings with Mr. Drake's boys, 'Isti dracones horrendi,' as Mr. Follet was wont to ease his mind by calling them.

After Sir Fulke's returns from Court it was always our scholarship that had the upper hand. For he was wise enough to see how things were changing at Court, and came back overflowing with praises of the young Queen's beauty and learning.

''Slight, lads,' he would say, 'she puts you both to shame, and goes beyond all young gentlemen of her time in the excellency of her learning. I tell you it is a sight to make England weep for joy to see her stand up, so fair and courteous, and make her speech in Latin, or French, or Spanish, or Italian, to the jabbering foreigners that come. And as for the Greek; why, Mr. Roger Ascham tells me she reads more of it with him in a day at Windsor than any prebendary of the church doth Latin in a week; he should know, seeing he had the setting forward of all her most excellent gifts of learning.'

'Then must we be double courtiers, sir,' said Harry, 'and court learning and the Queen as well, if we want to keep the Court, or the Queen shall have but half-courtiers.'

'Half-courtiers or double courtiers,' said Sir Fulke, 'I know that he who is out of learning will soon find himself out of Court.'

'Then is he in an evil case,' laughed Harry, 'for he that is out of Court is out of his suit, and he that is out of his suit shall be shamed unless he quickly suit himself with another. Come, Jasper, let us get Mr. Follet to make us breeches to go to Court with.'

And away he would run to his work, while Sir Fulke laughed at his boy's trick of turning words upside down. For he soon got the ways of that tripping wit which, it must be said, has since come to make far better passwords to places at Court than ever a hard-witted scholar could learn, did he read twice as much Greek as Mr. Ascham himself.

I say not this in envy, though I was too hard-witted ever to come by the trick. Harry's gifts were dearer to me than my own, and, God knows, I loved him for them, and never in my life envied him anything, except once, but for the present time let that pass.

Some three years after my father's death thus passed away before the sad day came when Harry and I were forced to separate, since our paths led diversely. It was high time that I should go to Cambridge, according to my father's wish. Sir Fulke's faith in scholarship was not large enough for him to suffer Harry to do the like. For him a place was found in the household of that most godly and warlike nobleman, Sir Francis Russell, Earl of Bedford, who was godfather to Frank Drake, since his renowned father, the first earl, being very earnest for the Reformation party, had been a good friend of Mr. Drake's when he lived at Tavistock.

Since my father's death I had known no day so sad as that on which I took my departure for Cambridge in company with Mr. Follet, who at my charges was to install me safely in Trinity College.

Harry rode with us as far as Gravesend, where we were to take the river for London. Mr. Drake, too, joined us at Rochester, and, riding by my side on his shaggy cob, beguiled the way with much good advice as to how I should bear myself at the University.

'I am, in a great measure,' said he, 'out of my former opinion against your becoming a scholar, not only because of the excellent parts I can see in you, which it were a sin to swathe in a napkin, but also because you will find that certain stout hearts amongst the godly, to whom I have written concerning you, are fast getting the upper hand at Cambridge. So that, I doubt not, you shall find yourself set amongst many goodly plants, with whom you shall grow to bear fruit medicinable for the purging away of all the clogging papistical humours that still be left to fester in the stomach of Reformation.'

'He were but a bitter tree,' laughed Harry, 'did he bear but purges.'

'A most wrong conclusion, my malapert Hal,' answered Mr. Drake; 'for your bitter pill is a sovereign sweetening of the inwards; and you shall find, moreover, that much fruit which grows at Court, though sweet in the mouth, is, for the most part, most bitter in the belly.'

'Then,' cried Harry, 'have I learnt a most notable piece of science, and can henceforth tell why courtiers' tongues are sweet and scholars' bitter. Still, I will be a courtier with a tongue tuned to sweet courtesy, and leave bitter railing to scholars.'

'Go, thou madcap,' chuckled Mr. Drake, whom Harry could never offend; 'go cry "Words, come and play with me," for surely thou wast born their play-fellow.'

Mr. Drake then fell to tell me, as he had a score of times before, that Trinity was the worthiest college in England, since it was that which his good friend, the renowned Earl of Bedford, had chosen for Frank's godfather, Lord Russell.

So largely did he speak of this and of the shining light that the young Earl had proved himself there, that his talk carried us all the way to Gravesend, where, most sadly, we bade adieu to him and Harry. As the strong flowing tide carried us up the beautiful Thames my spirits grew lighter; for I was not without comfort to soften the grief of my first parting with my brother.

As I never attained to his wit and skill in courtly exercises, being in no way apt thereto either by birth or nature, so I may say, since all men know it, in things pertaining to scholarship he was but a child beside me. I know not if I was unduly proud of all I had attained to under Mr. Follet's guidance, yet of a surety I know he was unduly proud to bring me to Cambridge.

'Were it not unworthy of a scholar, Jasper,' said the worthy man, as we sat in the tilt-boat that was carrying us to London, 'I could bring my heart to envy you the many and great delights that await you whither we are going. Most profitably have you attended to my precepts, and eschewing the light of experience, by which the vulgar walk, have trusted to books, which are the only true guide. Such well-fashioned vessels as I have made you it is now again the delight of Alma Mater to fill with her choicest nectar.'

'Did she, then, once choose other vessels?' asked I.

'Alas, dear discipulus, yes,' answered Mr. Pellet, with a little flush on his wan cheek; 'and then it was that I was cast forth. It was when those Elysian days, whereof the memory is a sweet savour to me still, were ended—the days when it was my happy fortune to find a place amongst that unmatched garland of fellows and scholars with which Dr. Medcalfe crowned St. John's College when he was Master, and afterwards when I was chosen out to be a most unworthy member of the new-founded house of Trinity. It was an honour I had little hoped to win; for (not to speak too much, because of the love I still bear to my old and dear college) this royal Trinity which our glorious King Henry founded, that colonia of St. John's, that matre pulchra filia pulchrior, to which you, I hope most humbly and reverently, are about to belong, I hold, above all foundations, learned or unlearned, that the world has ever seen, to be the most noble, princely, and magnificent.'

'What made you, then, leave so honourable a state?' asked I as he paused, as if lost in musing on the glories of our college.

'That is soon told,' said he sadly. 'The days I speak of ended with the most precious life of our scholar king. It was there, if I may make free with the fine figure of my most worthy friend, Mr. Roger Ascham, that the Hog of Rome passed over the seas into that most fair garden of Cambridge, and set to to root out the fair plants that were growing there, and tread them under his cloven feet. Then the blighting breath of idolatry carried seeds of tares thither, which, taking root, throve most rankly amidst the pollution that beast had made, till ignorance choked out scholarship, and I fled.'

'Surely, sir,' said I, for much talk with Mr. Drake had increased the hot opinions that were born in me; 'surely the breath of the beast of Rome is no better than the vapours from the mouth of hell.'

'Soft and fair, Jasper,' said the old scholar, 'soft and fair. Such words sit ill on a scholar's lips. Carry not the rancour of these present times into the holy shrine whither you go. The memory of the ruin that befell that fair-built fabric did somewhat carry me beyond the terms of good manners. Do not you follow me. As you love learning, help to guard the doors of yonder dear place against the savage turmoil of these shifting times.'

'Must a scholar, then,' said I, 'forget his religion and what he owes to his God?'