Title: One Thousand Ways to Make a Living; or, An Encyclopædia of Plans to Make Money

Author: Harold Morse Dunphy

Release date: May 25, 2020 [eBook #62231]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MFR, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images

made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

HAROLD M. DUNPHY, LL. B.

Graduate of the University of Michigan, 1906

Attorney at Law

Collated and Edited

by

Harold M. Dunphy, LL. B.

FIRST EDITION

SPOKANE, WASHINGTON

1919

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF

TRANSLATION INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES

Copyright, 1919

BY

H. M. DUNPHY

SPOKANE, WASHINGTON

[iii]

The contents of this book have taken years to gather. They have been collected from every corner of this vast continent, and in some cases from Europe. The literary style, no doubt, from the reviewer’s point of view, will leave much to be desired. This, from the very start, was pointed out to the editor, Mr. H. M. Dunphy, who, however, determined that his object was to give a plain, unvarnished story of how to make a livelihood, and not to produce a book of a high literary character. His exact words every time were: “My position as editor of this work is simply to take the matter as handed in to me from time to time, see that nothing objectionable or prohibited by the States laws is allowed to be published. So far as the literary style is concerned, it would not be difficult for me, a lawyer of long practice, to fall into line with the orthodox. But I prefer to give the different information just as sent in to me, with certain exceptions I have mentioned.

“I did not arrive at this decision in haste, but after due deliberation. It was a choice of altering—and placing almost every experience I received—into literary phraseology, or allowing same to pass for publication in the language of the people. I choose the latter.” We think Mr. Dunphy is right. This book’s aim is the people rather than the classes; although we have no doubt it will appeal to many people of high education with slender means.

However, the language in every case is understandable by the people, so, while no excuse is offered, we think the reviewers and the higher educated public should be given an explanation.

Not only from a business point of view, but for the betterment of the conditions of the people, we desire this work to have a wide circulation. There is no need for people to call aloud about lack of employment if they will not consult this book.

One way to make a livelihood has been omitted in the edition of this work, and we feel sure he will excuse us for drawing attention to the fact. We want agents in every part of the country—and we don’t want those agents to handle the work without proper compensation.

Write us for terms.

The title of this book speaks for itself and should require no foreword from me. However, the able compiler and editor thinks otherwise, so I gladly fall in with his wishes.

I grasp the opportunity, because I think when doing so, I can benefit a great number of my fellow-countrymen and country-women, who to-day have the constant shadow of unemployment confronting them.

This is not a “get-rich-quick” book. It is a work to teach people how to get a livelihood. Of course, a great many people who commence in business through reading this book, and adopting one or more of the plans, will naturally push ahead and accumulate wealth. That, however, is not the object of the book. If it were, I certainly should not sponsor its sale. I maintain, as all decent citizens must believe, that every soul on this planet has a right to a decent existence. But it grieves me to see so many people, young and old, foot-sick, walking about looking for a “job,” which employers of labor are unable to offer. If these people would only look around and try to help themselves a little, the world would be a happier place in which to live.

There is work everywhere to be done, and this book tells how to go about it. It is a book that should be in every public reference library in the country, for the use of those who are unable to buy it.

The various plans for making a living are set forth in such detail that they can be understood by all. They do not cater only to the person who is out of employment, but they are also valuable to the man in business, who through competition may find he is not doing as well as he should. They are a great storehouse of general business knowledge. I, myself, am what people would call a “successful business man.” Yet the book is invaluable to me from the point of view of an investor. If I had had in my possession “Protection against Fraud and Wildcat Schemes” only three years ago—and acted upon it, I should have saved myself from entering into a bad speculation. This chapter is undoubtedly worth ten times the price asked for the whole book.

Out-of-door folk such as farmers and market gardeners, are firm believers in the theory of luck. I suppose it is because there is no more speculative occupation than the cultivation of the soil. Well, I don’t grudge them their theory, but I will say this: If they will only consult this book and act upon its plans, they will find their “luck” has been increased considerably.

But to come back to the unemployed; to the man or woman who is looking for work. It is these people I personally wish to benefit, and it is to them I would particularly address myself. Of the sincerity of their desire for work, there is no shadow of doubt; and since the only remedy for unemployment is employment, its discovery is the duty of man.

Well, here in this book we have it, of that I am convinced. Only co-operation must come from the unemployed. Let them select one of the plans at once and get to business. I’m sure they will succeed if only they put their[vi] heart and soul into it. After a little effort, if everything does not prosper at once, they must not lapse like Watts’ sluggard did: “’Tis the voice of the sluggard, I hear him complain. You’ve waked me too soon—I must slumber again.”

That won’t do. In this life, whatever it may be in the next, if we wish to live, we must work. There will be plenty of time for slumber later on.

And now, a final word. If there should be one person who reads this foreword and who does not believe every word I have written, I ask one favor: Let him individually select one of the plans set forth, and give it a fair trial. I give this advice, knowing full well that all I have written will be found to be true.

This book has my very best wishes for a large sale.

[vii]

The following article, “The Way to Wealth” was published by one of the greatest of Americans, Benjamin Franklin, in his famous “Poor Richard’s Almanac,” in the year 1757. This article is especially strong, as it represents the observations of Benjamin Franklin after twenty-five years of publishing “Poor Richard’s Almanac.” There is, perhaps, no other of Franklin’s writing that won for him more reputation than the following:

“The Way to Wealth” is run in the same form as it was originally written. “The Way to Wealth” should be regarded as the constitution of this book and should be read and followed with each and every plan.

I have heard that nothing gives an author so great a pleasure as to find his work respectfully quoted by others. Just, then, how much I must have been gratified by an incident I am going to relate to you. I stopped my horse lately where a great number of people were collected at an auction of merchant goods. The hour of the sale not being come they were conversing on the badness of the times; and one of the company called to a plain, clean, old man, with white locks: “Pray, Father Abraham, what think you of the times? Will not these heavy taxes quite ruin the country? How shall we ever be able to pay them? What would you advise us to do?” Father Abraham stood up and replied: “If you would have my advice, I will give it to you in short; for a word to the wise is enough, as Poor Richard says.” They joined in desiring him to speak his mind, and gathering around him he proceeded as follows:

“Friends,” said he, “the taxes are indeed very heavy, and if those laid on by the government were the only ones we had to pay, we might more easily discharge them, but we have many others and much more grievous to some of us. We are taxed twice as much by our idleness, three times as much by our pride, and four times as much by our folly, and from these taxes the commissioners cannot ease or deliver us by allowing an abatement. However, let us hearken to good advice and something may be done for us: ‘God helps those who help themselves,’ as Poor Richard says.

“I. It would be thought a hard Government that would tax its people one-tenth part of their time to be employed in its service, but idleness taxes many of us much more; sloth by bringing on disease, absolutely shortens life. ‘Sloth, like rust, consumes faster than labor wear, while the used key is always bright,’ as Poor Richard says. ‘But dost thou love life? if so then do not squander time, for that is the stuff life is made of,’ as Poor Richard says. How much more than is necessary do we spend in sleep, forgetting that the ‘sleeping fox catches no poultry,’ and that ‘there will be sleeping enough in the grave,’ as Poor Richard says.

“‘If time be of all things the most precious, wasting time must be,’ as[viii] Poor Richard says, ‘the greatest prodigality,’ since, as he elsewhere tells us, ‘lost time is never found again, and what we call time enough always proves little enough.’ Let us then be up and doing, and doing to the purpose; so by diligence shall we do more with less perplexity. ‘Sloth makes all things difficult, but industry all things easy; and he that rises late, must trot all day, and shall scarce overtake his business at night: while laziness travels so slowly that poverty soon overtakes him. Drive thy business, let not thy business drive thee; and early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise,’ as Poor Richard says.

“So what signifies wishing and hoping for better times? We may make these times better if we but bestir ourselves. ‘Industry need not wish, and he that lives upon hope will die fasting. There are no gains without pains; then help, hands, for I have no lands; or if I have they are smartly taxed. He that hath a trade hath an estate, and he that hath a calling hath an office of profit and honor,’ as Poor Richard says. But then the trade must be worked at and the calling followed, or neither the estate nor the office will enable us to pay our taxes. If we are industrious we shall never starve, for ‘at the working man’s house hunger looks in but dares not enter.’ Nor will the bailiff nor the constable enter, for industry pays debts, while despair increases them. What, though you have found no treasure, nor have any rich relations left you a legacy, ‘diligence is the mother of good luck, and God gives all things to industry. Then plow deep while sluggards sleep, and you shall have corn to sell and to keep.’ Work while it is called today, for you know not how much you may be hindered tomorrow. ‘One today is worth two tomorrows,’ as Poor Richard says; and further, ‘never leave that till tomorrow which you can do today.’ If you were a servant would you not be ashamed that the good master should catch you idle? Are you then your own master? Be ashamed to catch yourself idle when there is so much to be done for yourself, your family, your country and your king. Handle your tools without mittens; remember that ‘the cat in gloves catches no mice,’ as Poor Richard says. It is true that there is much to be done, and perhaps you are too weak-handed, but stick to it steadily and you will see great effects; for ‘constant dropping wears away stones; and by diligence and patience the mouse ate in two the cable; and little strokes fell great oaks.’

“Methinks I hear some of you say: ‘Must a man afford himself no leisure?’ I will tell thee, my friends, what Poor Richard says: ‘Employ thy time well, if thou meanest to gain leisure, and since thou art not sure of a minute, throw not away an hour.’ Leisure is time for doing something useful; thus, leisure the diligent man will obtain, but the lazy man never; for ‘a life of leisure and a life of laziness are two things. Many, without labor would live by their wits only, but they break for want of stock’; whereas industry gives comfort and plenty and respect. ‘Fly pleasures, and they will follow you. The diligent spinner has a large shift; and now I have a sheep and a cow, everybody bids me good morrow.’

“II. But with our industry we must likewise be steady, settled and careful, and oversee our own affairs with our own eyes, and not trust too much to others; for, as Poor Richard says:

[ix]

“And again, ‘three removes are as bad as a fire.’ And again, ‘keep thy shop and thy shop will keep thee.’ And again, ‘if you would have your business done, go; if not, send.’ And again, ‘He that by the plow would thrive, himself must either hold or drive.’ And again, ‘the eye of the master will do more work than both his hands.’ And again, ‘want of care does us more damage than want of knowledge.’ And again, ‘not to oversee workmen is to leave them your purse open. Trusting too much to others is the ruin of many; for in the affairs of this world men are saved, not by faith, but by want of it.’ But a man’s own care is profitable; for, ‘if you would have a faithful servant, and one that you like, serve yourself. A little neglect may breed great mischief; for want of a nail the shoe was lost; for want of a shoe the horse was lost; and for want of a horse the rider was lost, being overtaken and slain by the enemy; all for want of a little care about a horseshoe nail.’

“III. So much for industry, my friends, and attention to one’s own business; but to these we must add frugality, if we would make our industry more certainly successful. A man may, if he knows not how to save as he gets, keep his nose all his life to the grindstone and die not worth a groat at last. ‘A fat kitchen makes a lean will; and many estates are spent in the getting. Some women for tea forsook spinning and knitting. And men for punch, forsook hewing and splitting. If you would be wealthy, think of saving as well as getting. The Indies have not made Spain rich, because her outgoes are greater than her incomes.’ Away then with your expensive follies, and you will not have so much cause to complain of hard times, heavy taxes and chargeable families; for, ‘Women and wine, game and deceit, make the wealth small and the wants great.’ And further, ‘What maintains one vice would bring up two children.’ You may think, perhaps, that a little tea, or punch now and then, diet a little more costly, clothes a little finer, and a little entertainment now and then, can be of no great matter; but, remember, ‘Many a little makes a mickle.’ Beware of little expenses. ‘A small leak will sink a great ship,’ as Poor Richard says; and again, ‘who dainties love, shall beggars prove;’ and moreover, ‘Fools make feasts, and wise men eat them.’ Here you are all got together at this sale of finery and nicks-nacks. You call them goods; but if you do not take care, they will prove evils to some of you. You expect they will be sold cheap, and perhaps it may be less than they cost; but if you have no occasions for them, they must be dear to you. Remember what Poor Richard says: ‘Buy what thou hast no need of, and ere long thou shalt sell thy necessaries.’ And again, ‘At a great pennyworth, pause awhile.’ He means, that perhaps the cheapness is apparent only, and not real; or the bargain, by straightening thee in thy business, may do thee more harm than good. For in another place he says, ‘Many have been ruined by buying good pennyworths.’ Again, ‘it is foolish to lay out money in a purchase of repentence,’ and yet this folly is practiced every day at auctions for want of minding the Almanac. Many a one for the sake of finery on the back, has gone with a hungry belly and half starved his family. ‘Silks and satins and scarlets and velvets put out the kitchen fire,’ as Poor Richard says.

[x]

“These are not the necessaries of life; they can scarcely be called the conveniences; and yet, only because they look pretty, how many want to have them! By these and other extravagances, the genteel are reduced to poverty and forced to borrow from those whom they formerly despised, but who, through industry and frugality, have maintained their standing; in which case it appears plainly that: ‘A plowman on his legs is higher than a gentleman on his knees,’ as Poor Richard says. Perhaps they had a small estate left them, which they knew not the getting of; they think, ‘it is day, and will never be night;’ that a little to be spent out of so much is not worth minding; but ‘always taking out of the meal-tub, and never putting in, soon comes to the bottom,’ as Poor Richard says; and then, ‘when the well is dry, they know the worth of water.’ But this they would have known before, had they taken his advice. ‘If you would know the value of money, go and try to borrow some;’ for ‘he that goes a borrowing, goes a sorrowing,’ as Poor Richard says. And indeed so does he that lends to such people, when he goes to get it again. Poor Dick further advises and says: ‘Fond pride of dress is sure a very curse; ere fancy you consult, first consult your purse.’ And again, ‘Pride is as loud a beggar as want, and a great deal more saucy.’ When you have bought one fine thing, you must buy ten more, that your appearance may be all of a piece; but poor Dick says, ‘It is easier to suppress the first desire than to satisfy all that follow it. And it is as truly folly for the poor to ape the rich, as for the frog to swell in order to equal the ox.’

“It is, however, a folly soon punished; for, as Poor Richard says, ‘Pride that dines on vanity, sups on contempt. Pride breakfasted with plenty, dined with poverty, and supped with infamy.’ And after all, of what use is this pride of appearance, for which so much is risked, so much suffered? It cannot promote health, nor ease pain; it makes no increase of merit in the person; it creates envy; it hastens misfortune.

“But what madness must it be to run in debt for these superfluities? We are offered by the terms of this sale six months’ credit; and that perhaps, has induced some of us to attend it, because we cannot spare the ready money, and hope now to be fine without it. But ah! think what you do when you run in debt; you give to another power over your liberty. If you cannot pay at the time, you will be ashamed to see your creditor; you will be in fear when you speak to him; you will make poor, pitiful, sneaking excuses, and by degrees come to lose your veracity and sink into base, downright lying; for ‘the second vice is lying, the first is running into debt,’ as Poor Richard says; and again, to the same purpose, ‘Lying rides upon Debts back;’ whereas a free-born Englishman ought not to be ashamed nor afraid to see or speak to any man living. But poverty often deprives a man of all spirit and virtue. ‘It is hard for an empty bag to stand upright.’

“What would you think of that prince or government who should issue an edict forbidding you to dress like a gentleman or gentlewoman, on pain of imprisonment and servitude? Would you not say that you were free and had the right to dress as you please; that such an edict would be a breach of your privileges, and such a government tyrannical? And yet you are about to put yourselves under such tyranny when you run in debt for such dress! Your[xi] creditor has authority, at his pleasure to deprive you of your liberty by confining you in gaol till you shall be able to pay him. When you have got your bargain, you may perhaps think little of payment; but, as Poor Richard says, ‘Creditors have better memories than debtors; creditors are a superstitious sect—great observers of set days and times.’ The days come around before you are aware, and the demand is made before you are prepared to satisfy it; or, if you bear your debt in mind, the term which at first seems so long will, as it lessens, seem extremely short. Time will seem to have added wings to his heels as well as to his shoulders. ‘Those have a short Lent who owe money to be paid at Easter.’ At present, perhaps, you may think yourselves in thriving circumstances, and that you can spare a little extravagance without injury, but, ‘for age and want save while you may—no morning sun lasts a whole day.’ Gain may be temporary and uncertain, but ever, while you live, expense is constant and certain; and ‘it is easier to build two chimneys than to keep one in fuel,’ as Poor Richard says; so, ‘rather go to bed supperless than rise in debt.’ ‘Get what you can, and what you get, hold; ’Tis the stone that will turn all your lead into gold.’ And when you have got the philosopher’s stone, surely you will no longer complain of bad times, or the difficulty of paying taxes.

“IV. This doctrine, my friends, is reason and wisdom, but, after all, do not depend too much on your own industry and frugality and prudence, though excellent things, for they all may be blasted, without the blessing of heaven; and therefore ask that blessing humbly, and be not uncharitable to those that at present seem to want it, but comfort and help them. Remember Job suffered and afterwards was prosperous.

“And now, to conclude, ‘Experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other,’ as Poor Richard says, and ‘scarce in that, for it is true we may give advice, but we cannot give conduct.’ However, remember this, ‘They that will not be counseled cannot be helped,’ and further, that ‘if you will not hear reason, she will surely rap your knuckles,’ as Poor Richard says.”

Thus the Old Gentleman ended his harangue. The people heard it and approved the doctrine, and immediately practiced the opposite, just as if it had been a common sermon; for the auction opened and they began to buy extravagantly. I found the good man had thoroughly studied my Almanac, and digested all I had dropped on these topics during the course of twenty-five years. The frequent mention he made of me, must have tired anyone else, but my vanity was wonderfully delighted with it, though I was conscious that not a tenth part of the wisdom was my own which he ascribed to me, but rather the gleaning I had made of the sense of all ages and nations. However, I resolved to be the better for the echo of it, and though I had at first determined to buy stuff for a new coat, I went away, resolved to wear my old one a little longer. Reader, if thou wilt do the same, thy profit will be as great as mine. I am, as ever, thine, to serve thee.

Richard Saunders.

[xii-

xiii]

Thousands of men and women, who have lost their savings of years through the skillfully manipulated schemes of men who make a profession of robbing the unwary, might still be in comfortable circumstances had they been forewarned and forearmed against these people by the timely advice of some one who knew the crooks and turns by which they approach their victims with honeyed words and roseate pictures of fortunes quickly and easily made.

Women who have come into the possession of considerable sums of money, through inheritance, or as beneficiaries of husbands, fathers or brothers, are the special objects of exploitation. It is estimated that fully 90 per cent of the women thus provided for, lose the entire amounts within three to six months.

Many of these women succumb to flatteries accompanying offers of marriage, and willingly turn over every dollar that some loyal and devoted husband and father has made untold sacrifices to provide. Once in possession of the money, however, these villains usually disappear, to seek new fields and swindle other women by the same contemptible methods.

The greater part of the fraudulent schemes through which women with little savings are swindled, consists of plausible plans for making “profitable” investments. The writer of this chapter is reliably informed that in a certain city of over 100,000 inhabitants, more than sixty-five men engage in this business.

Women, however, are not the only victims, for men are also easily persuaded to part with their savings.

The man or woman known to have acquired any considerable sum of money, or even a few hundred dollars, is skillfully approached and asked to make an investment that is “sure to double your money in six months,” or guaranteed to pay 1,000 per cent dividends within a year, and every year thereafter, and the alluring picture thus held out is usually a veritable gem of literary and artistic skill.

Perhaps it is a choice piece of real estate, which the owner will sell at a “great sacrifice,” as his health requires a removal to a “milder climate.” Or it may be a block of mining or industrial stock, represented by a gorgeously engraved certificate, embellished with an elaborate seal and is advertised as a “real snap,” as only a few dollars of additional capital will start the enterprise to grinding out dividends. Whatever it is, there is a dazzling certainty about its future that is perfectly bewildering to the poor investor, who is made to see him- or herself soon very wealthy. And how easy it is to make an inexperienced woman—or man, either—believe that her or his few hundred dollars can so easily be turned into a channel that will bring a swift and sure reward.

The bait may be a first mortgage on a piece of farm land, “worth many times the small indebtedness it represents,” bears a high interest rate, and which, if foreclosed by the holder, would make him well to do.

Oftentimes these seductive offerings come through a friend, who offers—for a commission—to guide the faltering steps of the investor to certain wealth, as a personal favor.

The valuable farm land is found to be upon a mountain top or in the middle of a swamp, where no one could live or nothing can grow. It is worthless. But the mortgage, which showed some one had loaned a large sum of money on it? Oh, that was a mortgage made for the purpose. No real money was ever loaned on it.

[xiv]

And the stock in that wonderful mine, almost ready to pay dividends? Why, that consists principally of a set of location stakes, with perhaps a 10-foot hole in the ground, representing the first year’s assessment work on a very poor “prospect.” Anybody can see that it never will make a mine.

But the industrial enterprise—that surely must have a bright and promising future. Well, maybe, but as yet it has no equipment, no raw material, no franchise, no location—nothing but a certificate of incorporation, authorizing a few comparatively unknown men, with no capital whatsoever, to do a certain kind of manufacturing or other business—if they can raise a little money with which to make a start. At last, when the money is gone and it is too late, the poor investor begins to realize what has happened. His money is lost.

It is bad enough for the one who has been thus defrauded, but it is many times worse when little children are made to suffer. It may be that the widow should pay the penalty of her foolishness but the innocent, helpless little children are the ones who suffer most.

How to guard against the depredations of these people, and protect one’s self, is the object of this chapter. By following the plan here outlined, any man or woman can be assured of comparative safety. It has been successfully employed, and has saved thousands of dollars.

First of all, you must learn to do your own thinking, instead of becoming confused by the advice that is offered you, for no two of your friends or acquaintances will advise you alike. Use your own judgment, and carefully weigh every suggestion.

Suppose you are approached with a proposition to invest your money. No matter how attractive the prospect may look, adopt this as a slogan: “Investigate before investing,” and do this thoroughly, because the “snap” will not be gone if you delay a little while. Make sure that your investigation is as complete as possible. This will not only protect you from fraudulent and wild-cat schemes but will enable you to find a really meritorious proposition. It may cost you from $25 to $50 as expense for investigation purposes, but this is far better than losing $5,000 to $10,000. Make it a rule to test all propositions on which you are solicited—to never act until you have full information before you. When approached by the person desiring you to invest tell him before going into a discussion as to the investment you wish to be informed about his company. Copy all the following questions and submit them to him, requesting that each question be carefully answered, and that after the answers are made they shall be signed by the corporation, individual, company or partnership. If his proposition is all right, and he believes in it, he will gladly co-operate; but if he is doubtful whether or not it will stand the test, he will endeavor to persuade you not to put the company to the trouble of answering so many unnecessary questions. Adhere to your resolution to have the information first. These questions alone will eliminate nine-tenths of the fraudulent investments and all weak propositions.

1. Give full name of corporation, partnership or association.

2. If partnership, has your firm name been properly filed of record?

3. If corporation, when were you incorporated?

4. Have you paid your last annual license fee to the state?

5. What is your capitalization?

6. In how many shares is the company divided?

7. Is the stock assessable or non-assessable?

[xv]

8. Do you have common or preferred stock?

9. If you have common or preferred stock, how much common and how much preferred stock have you?

10. State the object of the company in issuing these two kinds of stock.

11. What advantage has the preferred over the common?

12. What is the preferred stock selling for? Also the common? How much have you sold to date of each?

13. What are the names of the present stockholders and their addresses and how much cash have they paid for the stock they hold?

14. If they have not paid cash—what did they give for their stock?

15. Has any stock or interest in the company been given for the promotion of the company? If so, how much or what interest?

16. Give the names, addresses and businesses, also amount of stock held by each of the officers, trustees or directors of said corporation or company, also did they pay cash for their stock—if so, how much? If service was rendered for stock, what was the service?

17. Is the stock of the company paid for in full? If so, state how or in what manner it was paid for.

18. When and where do you hold your annual meetings?

19. Do your trustees meet regularly and transact their business and have they done so from the inception of the corporation?

20. Have you a list of articles of incorporation and by-laws printed? If so, please furnish me with a copy of them.

21. Please state where I can see the minutes of your meeting.

22. Will you allow my attorney to go over the minutes of your meetings?

23. Have you real estate? If you answer yes, set forth the legal descriptions of all the real estate now owned by you, whether in this state or in other states.

24. Is the above described property free and clear of all incumbrances?

25. If you answer no, state in detail the kind of incumbrance, amount, and date it is due.

26. Please state the present value of each piece of property and state whether or not it is improved.

27. If you answer that the land is improved, state clearly how and in what manner it is improved and set forth clearly what the improvements are on said land.

28. What income has said lands and what is the gross expense of the property?

29. What net profit is made from land each year by your company?

30. What other assets has the company? And if there are other assets, where are they kept? Please set forth these assets in full, their present value and whether or not they are free and clear of all incumbrances.

31. What bank or trust company do you bank with? How long have you banked with it.

32. How much have you now on hand with said bank or trust company?

33. Please give the name and address of your lawyer and how long he has represented you.

34. What salaries are paid to officers of the company?

35. What are the total debts of the company at the present time? Please state to whom they are due and how long they have been owing.

36. Are there any judgments now on record or in existence against your company?

37. Are there any lawsuits now pending? If you answer yes, please give case number, name and address of plaintiff’s attorney and amount involved.

[xvi]

38. Is there any contemplated suit against the company which you have any knowledge of? If you answer yes, state the facts concerning it.

39. Please furnish me with a detailed statement of the affairs of the company. Showing the present income and expense and net profit or loss made to date.

40. Have you as yet paid dividends on your stock?

41. Please furnish me with a complete statement in writing as to what your company plans to do this year and the immediate future and what profits are reasonably possible from such operations.

42. If I invest $——, please state to what use my money will be put.

43. If it is to be used for a certain purpose, state how much of my money will go to the company and how much will go out on commissions.

44. Will the money I have subscribed be sufficient or will other money be necessary for the company successfully to carry out its plans? If you answer no, how much more will be necessary?

In the event of the above list of questions being answered in full, inform the salesman that you will familiarize yourself with the report and will later call upon him to go over the matter.

First look into the reputation of the men connected with the company. Also the reputation of the trustees and officers. Also obtain the financial standing of the large stockholders. This can be done in cities of over 50,000 by consulting reporting companies. See some prominent merchant and find out the best reporting company in the city. Call or write the reporting company and ascertain from them whether the above parties are good pay and whether they are the kind of men that are successful in carrying out plans. This report is important; it will cost you so much per name but it is well worth the fee to you. If the majority of these men are unknown—or have a poor reputation and are bad pay—it would be unnecessary to go further in your investigations as your chances would be very poor in such a company. Oftentimes this investigation alone will show the promotors have suits pending against them and even judgments on record.

However, if these investigations show the above-referred-to men O. K., submit the signed report to a banker not named as the company banker and obtain as complete a report as possible in writing from the bank and pay for the trouble; if the bank will not give a written report obtain a verbal report and write it down later yourself. If their advice is for or against the investment, obtain their reasons, and if none is given do not give it any thought.

Now see a lawyer and have him give you an exhaustive written report on your signed report, and pay him for it. Remember that it is far better to pay $25 to $50 and know where your investment is to go, than take a chance of losing all you possess. These last two reports will be very valuable to you. I suggest that they be put in writing so that when you are alone in your home you will be able to consider more carefully their report and advice.

Now make a copy of the real property and write the assessors of the county in which the land lies for a report concerning this land and its improvements. This information will be furnished you free of charge. If it be farm property, they can inform you quite well the kind of land and its value and also give you what improvements, if any, are on the land and their nature. And the same is true of city property. While the assessor’s estimate may be a little below the real value of the land it is far better to have the land at too conservative a figure than an excessive figure.

In the event that the company is in possession of mortgages, have a detailed report from the county assessor’s office as to the mortgaged property. This will give you the character of the mortgage security.

[xvii]

The writer in the last two years has saved more than $5,000 to his clients by checking up the property used as a security for the mortgage.

In one case my client requested me to prepare a deed and have it ready for him at three o’clock, the time of request being about 1:30 P. M., that he had decided to accept a $1,500 mortgage. The mortgage ran for three years—two years having elapsed—and the interest had been paid to date. He permitted me, by way of caution, to call the county assessor’s office, some hundred miles away, by long distance, which revealed that the land securing the mortgage was above the snow line up in a mountain region and worthless.

Armed with the above information you are prepared to talk and question the salesman. If he is sincere he will endeavor to answer fully your questions. After you talk with the salesman do not give your answer at once but inform him that you will give him your final answer in two or three days.

With the various reports before you—and the salesman’s answers to your questions which you should jot down—as judge of your own affairs decide your course of action. If your decision is to invest your money you will be an asset to the company as you will be familiar with its workings. Oftentimes ignorant investors in a company will destroy a good proposition.

If your decision is favorable, put away the signed report of the company, along with all the data, you have secured, and in case the future develops that the facts stated in the company’s report is untrue, you can lay the representation made, before an attorney and your case will be clear.

[1]

ONE THOUSAND WAYS TO MAKE A LIVING

In presenting these one thousand tried and tested plans for making a living, the author hopes and believes that he will be the means of helping many people to better methods of earning money; by pointing out to them the occupations to which they are better adapted, and in which their chances of success may be greatly increased.

Especially will the opportunities thus presented be welcomed by the families of those who have sacrificed their lives for their country, and those who return from the war wounded, or otherwise incapacitated from following their former callings.

They will find in this book many valuable suggestions for the taking up of other lines of work, and profiting by the experiences of those who have successfully worked the various plans herein set forth.

It should be borne in mind, however, that those adopting any of the plans herein outlined must combine in the execution of the same the elementary essentials of earnestness, honesty and perseverance, coupled with a strong will power and a determination to win success. Let them make this their one definite aim, and they will find that what others have done, they can do, and thereby bring to themselves and their families that much desired end—prosperity and happiness.

It was the clever idea of a woman that prompted her to dig ferns out of the woods of her native state, and put them in attractive raffia baskets woven by herself. The florists of her neighboring city gladly pay good prices for all of these she can bring in. In the winter she fills these same baskets with holly, attaches a bow of red ribbon to the side of each basket, and sells them as fast as she can turn them out. Other plants can be used to the same advantage in other localities.

A young girl who possessed a pleasing personality, but had no capital, created a profitable profession for herself by announcing to the young mothers of her neighborhood that she would take charge of children’s parties at the low price of two dollars for an afternoon. She arranged the menu and planned the entertainment for the youngsters, and did it so well that she soon had all the orders she could fill.

From this small beginning, she enlarged her activities by planning parties for grown people as well, at a much higher remuneration, and she is now receiving orders for conducting all kinds of entertainment, and it pays her well.

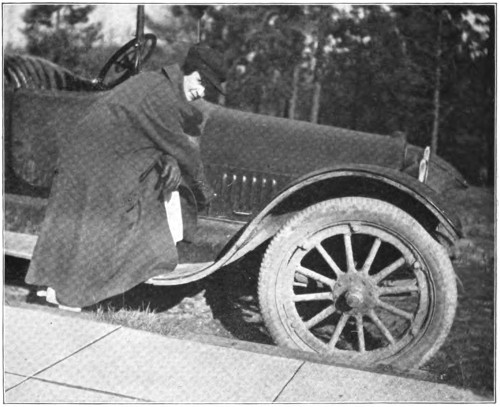

One of the teachers of a Seattle school was obliged by ill-health temporarily to suspend teaching, and, for outdoor exercise, engaged to run an auto carrying children from a distance to and from the school. She soon found this work so healthful and pleasant that she bought a machine, carried passengers for a while[2] at a good profit, and finally, in partnership with her brother, an expert mechanic, went into the automobile business as a regular occupation.

Plan No. 3. A School Teacher’s Way

She makes considerable money by giving lessons to women in the management of a car.

Just after the panic of 1893, when jobs were not to be had, an advertising man made a contract with a Denver daily newspaper to conduct a column of small reading notices, on a commission of forty per cent. He went among the small merchants who were not advertising in the display columns, and found they were willing to spend a little money each month in that sort of publicity, though not able to advertise extensively.

He wrote attractive items for each one, and had them set up in the form of news matter. By keeping his column free from display lines and other indications of advertising, he soon built up a very handsome column, which many merchants were willing to patronize, as the cost was small and the results extremely satisfactory.

He also wrote special articles that looked and read exactly like news items, and even secured columns of interviews, at regular rates, with leading business men concerning general trade conditions, thereby aiding in restoring public confidence following that panicky period. His commissions during that year of hard[3] times averaged forty dollars per week, and he had made many thousands of dollars for the paper besides.

This plan is not so easy to work as it was then, as all paid articles must now be followed by the word “adv,” meaning advertisement; and yet, even with that handicap, reading notices are still regarded by many people as more effective than display advertisements, and the man who has a talent for writing that class of matter can still make good money by doing so.

Here is the case of a woman who, though having only a few hundred dollars, had a lot of foresight and energy, and these qualities enabled her to originate a plan that paid.

Thousands of vacant lots in her city were covered with weeds that were an eyesore to their respective neighborhoods, and detracted from their appearance when shown to prospective purchasers. She went to the agents for these lots, made contracts with them under which she was to keep them clean of weeds the entire season for $3 per one hundred feet frontage, bought a mowing machine with her $100, and went to work. She also contracted to mow the lawns of a large number of people, hiring thirty men at $1.50 per day to do the work, and charging $2 per day for the work done by each man. The profits of her first month’s work paid for her mowers and her advertising, but after that all the profit was hers. The summer’s work, after paying all expenses, including her own board and clothes, netted her $1,200. The next season she contracted to keep the weeds from city lots that aggregated 2,000 acres, at $3 per one hundred feet frontage, plowed those lots all up, sowed them in wheat, kept fifty men employed, mowed more lawns, cut and threshed her wheat, and found she had made $11,000, with good prospects of making a great deal more the next year.

And all she had to start on was a few hundred dollars and a plan.

No capital, and but little space, is required for growing mint on a profitable scale. One woman, who is making and saving money for the education of her children, goes at it in a very methodical manner. She lays out her ground in beds with walks between, and each variety is given a separate bed. Each bed has a border of sage or other herb plants that find a ready sale. The soil should be loose and fine, and well fertilized, to obtain the best results. She not only supplies customers in her nearest town, but, as her business increases, is shipping a great deal of it to the city markets, where it is in constant demand from hotels, cafes, druggists, candy makers, etc. What she does not sell, she utilizes at home in the making of candy, delicious sweets and aromatic vinegars. Crystallized and candied mint leaves, mint sprays, mint vinegar and other products of this herb are much sought after, and to the resourceful person who has a taste for this class of work there is a mint of money in mint.

The woman who has a taste for literary or club work can turn many an honest penny by starting a small clipping bureau of her own.

One lady who made a success of this, both socially and financially, procured some large envelopes, and put all the clippings she made from magazines, newspapers,[4] etc., on any one subject, into one envelope, duly labeled, until she had accumulated an extensive variety. Realizing that material for papers to be read at the meetings of women’s clubs are always eagerly sought for, she specialized on those subjects that engrossed the attention of club women, particularly biographical sketches, entertainments, plans for special holidays, and table decorations, place cards, games, amusements, etc. Then she let it be known that for a small fee, she would furnish the material for properly entertaining the club, and found her clippings in constant demand.

This is a good plan, that can be carried out with considerable profit, and one that requires no capital to start or operate it.

Here is how a lady who knew her business made a lot of pin money from what she called her “One-Cow Dairy.” There were three in the family and their available capital consisted of an excellent cow, with an average butter production of one pound per day the year round, besides supplying the family with plenty of milk and cream. They also had a small cream separator, which cost considerable to begin with, but more than paid for itself, even with the output of a single cow, as it insured clean milk, more and better cream, and required less work as well as but little space.

For a butter worker, they had a ten-gallon V-shaped barrel churn, also a four-gallon stone jar for holding the cream, and a good pair of balance scales. Her husband built a dairy, 8x12 feet, with cemented floor, on the shady side of the house, covering it with vines, thus assuring a cool place always. She bought an iceless cooler, made entirely of galvanized iron, which is placed outside for holding the cream, and in which, the night before churning, she puts two pails of water, to preserve an even temperature. She sells her butter the year around, to regular customers, at forty cents per pound, and has demands for more than she can produce.

When the cow is about to go dry, she puts away, in brine, strong enough to float an egg, all the butter the family will need for that period, and having tied the pieces of butter up in muslin thoroughly sterilized, it keeps as fresh and sweet as the day it was made.

The total cost of establishing her dairy, exclusive of the separator, was $26.25, and with the present equipment she is ready to add one or two more cows to her dairy, whenever she finds those that are as good as the one she already has. She will thus be at but little additional expense, while greatly increasing her revenue.

Many good business men write very poor business letters, and anyone having a taste and a talent for this class of work can make the writing of such letters a permanent and profitable profession. A former newspaper man in a western city took it up, and found in it a much larger income than even the liberal salary he had formerly received.

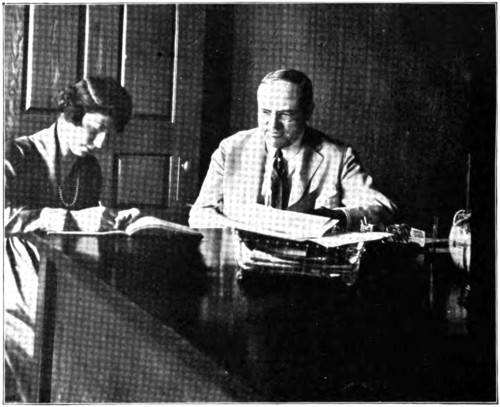

Living in a town of about 50,000 inhabitants, and having a rather extensive acquaintance, he called upon a number of the leading merchants and offered to come at a certain hour each day and dictate the answers to all letters received from out-of-town customers. As most of these firms did a large mail order business, and the heads of the concerns in many cases lacked either the time or the ability to give the correspondence the attention it deserved, they were glad to turn it over to a man who could handle it in a thorough manner.

[5]

This man found that he could easily dictate one hundred or more letters per day, among the various firms engaging his services, and could well afford to do the work for five cents per letter, thus making at least thirty dollars per week, with but little effort. He also prepared form letters for many of his patrons, for which he charged from five to ten dollars each, and thus increased his income to over fifty dollars per week. It is readily seen, therefore, that this is not only a very genteel profession for anyone adapted to it, but one that also pays well, besides being a good thing for the merchants who have their letters written by someone who knows how.

An Illinois woman tells an interesting story of how she helped her husband rise from a $20-a-week clerk to proprietor of a fine office business netting them $5000 a year, but she furnished the plan.

Both were employed in an advertising agency, and patronized a nearby delicatessen store kept by a German woman who prepared palatable foods, but never had used any form of publicity concerning them.

The lady with the idea was fond of the home-baked beans and the salads sold at this place, but had no means of knowing on what days they were to be had. So, instead of asking the German lady what days she had these on sale, she suggested the idea of furnishing her with attractive window-cards and appropriate decorations showing each day’s specialties in a way that drew favorable attention—and an increased volume of trade. Later she asked her patron to allow her to write and place in the local papers notices regarding her specialties, and this greatly added to the incomes of all concerned. But it was the results of those display cards in the window, “Today is Baked-Bean Day,” and “If You Like Potato Salad, You’ll Like Ours,” that turned the trick and got things going.

Soon after this, the husband and wife joined forces and made a “drive” for other lines of business, with the result that in six years they were occupying a handsome four-room suite of offices, with two large national advertisers and twenty-seven smaller ones for a clientele, were employing a rather extensive corps of assistants, and clearing up $5,000 per year net profits.

It was a woman’s plan that made this a success.

From a position as a small-salaried clerk in a Missouri wholesale dry-goods store to the ownership of a good-paying store of their own, is told by a wife, who first conceived the idea of the enterprise.

Needing some ginghams for her little girls’ school dresses, she learned that gingham stocks in all the retail stores were extremely limited, the clerks telling her that the firms purchased cheap wash goods only once a year, and they were practically out.

On her way home, she passed an attractive storeroom in a good location, and suddenly she formulated a plan by which she and her husband would start something new—A GINGHAM STORE!

She talked the matter over with her husband that night, and he was very favorably impressed with the idea. The firm by which he was employed also thought it would be a splendid thing and offered him very liberal terms on whatever purchases of stock he might desire from them. What money they had they invested in stocks, improvements, rent, advertising, etc., the wife selecting every[6] piece of gingham that went into the store, putting herself in the place of the woman who would want to buy ginghams for any purpose.

A handsome electric sign announced “The Gingham Shop”; as did the lettering on the windows, the bill-boards and in the street cars, and ads. in all the papers told the story of “The Gingham Shop.” They advertised a dolly’s gingham apron free to every little girl who came to their opening accompanied by her mother. That brought the mothers, and they kept coming, more and more of them every day, for they managed to keep the gingham idea before all the people all the time, in a thousand different ways, until every one who thought of ginghams at all thought of “The Gingham Shop.” Their store became the fad, so that they had practically all the gingham trade of the town and for many miles around. They sold strictly for cash, and thereby eliminated bookkeeping, collecting and bad debts.

Noticing a very pretty doll’s crocheted sack in a store, and hearing the proprietor say he feared he could get no more like it, as the lady who made those things for him had not been in the store for some time, a young lady who had ideas of her own decided to take up the work herself.

She bought some worsted, went home and proceeded to make a number of dolls’ sacks, hoods, capes, booties, caps, slippers, muffs, etc., put some baby ribbon on most of them, and, after figuring up the cost, put a price on each article and returned to the store. The proprietor was so well pleased that he gave her a large order, as did also several others in that and nearby towns. Then she learned where she could buy the worsted and ribbon at wholesale prices, and until after the holidays her spare time was all spent in crocheting dainty things for dolly, when she found she had made a profit of nearly $100 in odd moments. Later she began taking orders for crocheted scarfs, shawls, fascinators, etc., and made it a regular business for it continued to pay well. And it required very little time, capital or labor to make it a success.

Making and selling ready-to-wear aprons is the means a woman may employ to earn a good many extra dollars, without interfering very much with her regular household duties. She can turn her parlor into a work- and sales-room, where she can exhibit every description of aprons, in sizes and patterns, and offer them at attractive prices. A woman we know, now has a large list of regular patrons and has found it necessary to employ help in doing her housework, so that she can devote the larger portion of her time to this new enterprise.

Making canvas gloves would not seem to be a very good way to earn money, but a woman who lived near a small mining town, where the demand for canvas gloves was much greater than the supply, found she could live very comfortably on it.

She had a sewing machine, and having ripped an old pair of gloves open to get the pattern, found that it was merely a matter of sewing seams on the machine, so she turned them out very rapidly, and earned many dollars by doing so.

One need not live in a mining town to find a demand for canvas gloves, for they are used by thousands of other people—railroad men, mechanics, teamsters,[7] lumber workers, gardeners—indeed, nearly everybody who works needs them, so why should not other women of slender means also improve this humble but better-than-nothing means of making a living?

A college girl with a limited allowance had just enough spare cash to pay for a new blue-gray tailor-made suit, but not enough more to pay for a pair of spats to match, which the tailor offered to make for $2. However, she had a small piece of the goods left over when the suit was finished, and by ripping an old pair of spats to note the pattern, she proceeded to make a pair of new ones herself; silk-lined, but with the old buttons. They were so well made, and presented so neat an appearance, that all the other girls in the college implored her to make spats to match their suits. She did so and earned sufficient to pay her college expenses.

It was the sound of children’s voices raised in shouts of glee, as they reveled in the delights of a six-passenger, hand-propelled merry-go-round in the back yard of a friend, that gave to a young man, temporarily out of a position, an idea which he promptly enlarged to the dignity of a community affair, and imparted a world of pleasure to hundreds of children, while adding very largely to his own bank account.

The small merry-go-round in the private grounds of his friend was operated upon strictly business principles by the hopeful scions of the household, and every other youthful pleasure seeker was obliged to contribute some toy or other article of small value in return for the privilege of a few dizzy whirls in the small-sized machine, while being regaled with music from a miniature organ that played certain lively tunes while the machine was in motion. The “admission fee” was a book, pencil, knife, rubber ball, or anything that represented value to the young proprietors, but it had to be something, and everybody was happy.

The young man who was a witness of the performance began at once to enlarge upon the idea of entertaining children for a merely nominal sum, but which in the aggregate would amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars; and, having a little available capital, he rented a vacant corner containing several lots, in a central location, and began systematically to equip it. He bought a 12-seated merry-go-round, three swings, four see-saws, three “Irish Mails”, two tricycles, two velocipedes, and $100 worth of awnings to cover the entire scene of gaiety, and protect the little guests from both sunshine and rain.

He constructed a sand pit, installed rag-doll games, etc., and built a board walk around it all for the racing of the tricycles, velocipedes and “Irish Mails.”

He hired a carpenter to build a fence around the property, with an arch over the entrance for the name of the play-ground, and considered a few booths for the sale of candy, soda water and other soft drinks. His entire expense, including advertising and incidentals, was $382, and he placed the price of admission, which entitled the visitor to all the attractions of the place at five cents.

From the day the gates were opened the place was filled with children, for parents were glad to have their little ones participate in the clean and healthful entertainment it afforded. Within the first three months the enterprising proprietor had taken in enough to pay all the expense of establishing and conducting the play-ground, and noted that he had earned a net profit of $210 besides. When winter came, he turned the place into a skating rink, and made a profit several times larger than it had brought as a summer play-ground for children.

[8]

The daily drudgery of cooking is a nightmare; the horror and the despair of the ordinary housewife. And no wonder; for no other member of the family would ever stand for it. Therefore, any reasonable and economical plan that will free the wife and mother from this thraldom, and at the same time assure equally satisfactory service in the matter of food, at possibly less cost, is sure of a cordial welcome.

The co-operative kitchen not only solves this vexed problem for the housewife in general, but at the same time it affords a comfortable living to the two or three or half-dozen women who have the energy to give it a start in almost any community, and the culinary skill to keep it going good after it is started.

If women have sufficient capital to establish such a business in the right way, so much the better, but if they have not, they may incorporate for that purpose, and thus secure the necessary equipment for making it a going concern.

As a private enterprise it would produce a handsome and permanent income for its originators, while as an incorporated concern it would greatly reduce the household expenses of its members.

What is known as the Montclair plan provides for the serving of hot meals at any time desired, in the homes of the patrons or members, and according to the menu sent in by each individual in each family. Thermos bottles for the liquids, and Swedish containers for the meats, solve the problem of keeping food either hot or cold for an indefinite period, and the plan, if properly worked, is certain to grow in popular favor wherever it is tried. There’s money in it for somebody. During the war England learned its practicability and great advantage.

To start a tea room, and start it right, will require an amount of capital ranging all the way from $500 to $1,000, according to the locality and the amount of competition, either of other tea rooms, or of the service offered by various larger enterprises that use this as a side line.

A lady in Denver gives her experience in the following condensed statement:

She was fortunate in securing a location where the advent of a tea room was joyously hailed as a much desired innovation, and where the conditions obviated the necessity for an extensive publicity campaign, so that her little capital of $500 was sufficient to launch the enterprise in fairly good shape.

She started with a limited menu, fully intending to extend it as she gained experience and patronage. To begin with, she served tea, coffee, chocolate, broths, toasts, muffins, sandwiches, salads, fresh eggs, cake, cold meats, together with simple desserts, such as rice pudding, tarts, baked apples and stewed prunes, with whipped cream. She made it a special point to see that every item was of the best quality, properly prepared, and served with delicacy and tact, while cleanliness pervaded every nook and corner of her dainty little establishment. At the same time she guarded zealously against waste, and showed excellent judgment in providing just the exact amount of each material that could be utilized to advantage. She hired a neat, pretty and attractively attired maid as waitress, who was tactful in her demeanor towards guests. The prompt, courteous and refined service of this maid proved a valuable asset, as she soon became a general favorite with the patrons of the place, through her earnest endeavor to please.

The taking and filling of large orders for outside affairs—such as sandwiches, salads, etc., as well as the renting of her china, table silver and other[9] accessories, also proved a source of considerable revenue. Sometimes the tea-room itself would be rented out for social functions, such as card parties, church and lodge affairs or wedding feasts. On such occasions the proprietress did practically all of the catering, and was well paid for her services and accommodations.

During the first year she kept on display and for sale a line of antiques, art novelties, embroideries, confectionary, fine stationery, and other articles that commanded a ready sale, and thereby added considerably to her income during that trying period of making a beginning. As her regular patronage increased, however, she gradually discarded these side-lines, and concentrated all her efforts upon steadily and permanently increasing the scope of her trade.

She showed decided originality and talent in the preparation of her menu cards, and gave them an artistic effect which was at once striking and vastly different from the ordinary. Her prices, while extremely reasonable, afforded a satisfactory profit on every item, and at the end of the first year she had not only paid all expenses, but had a comfortable balance left over with which to begin the second year on a much more extensive scale.

Many men lose their positions, from one cause or another, but it isn’t every one of them who has a resourceful, skilful and determined wife to help him out. Here is one who had:

This man who had been a salesman was “let out” because his firm could no longer manufacture the goods he had been selling, and, as times were hard, another position could not be obtained. The family had never saved anything, and, their grocer changing suddenly to the cash system, left them with only half a dozen potatoes, a few pounds of flour, half a pound of lard, a cup of sugar, a little salt—and three hungry boys, to say nothing of the parents.

It was then that the plucky wife and mother rose to the occasion and saved the day. But it required a lot of grit and hard work. She peeled, sliced and boiled three of the six precious potatoes, adding water as the boiling went on. Then she put into a pan three tablespoonfuls of flour, one of sugar, and one of salt, scalding them with the hot water in which the potatoes had been boiled, and adding two quarts of cold water, making the mixture lukewarm.

Five cents from the small hoard of the family bought yeast one-half of which was saved for the next time, after moistening it with water and pouring it into the mixture. Covering the pan tightly, she set it aside until morning while the family went supperless to bed.

The hustling little woman was up at five o’clock the next morning and put twelve pounds of flour into a large pan, mixed in two heaping tablespoonfuls of lard, two of sugar and two of salt, then added the yeast mixture, which made an ordinary bread dough, and set it in a warm place to rise.

At eight a. m. she molded the dough into rolls, twelve rolls to each pound, two and one-half inches across and pressed down to an inch in thickness. These she put into a greased pan, not allowing them to quite touch each other, as they sell better when baked separately. By ten o’clock her eldest boy, who rode a wheel, had been excused from school, came home to do the selling. With five dozen light brown rolls in a basket, he started out to sell them at 10 cents a dozen.

In less than half an hour he was back for three dozen more, and returned in a short time with an order for the remainder, which the mother refused to accept, as she was keeping those for her own hungry family.

[10]

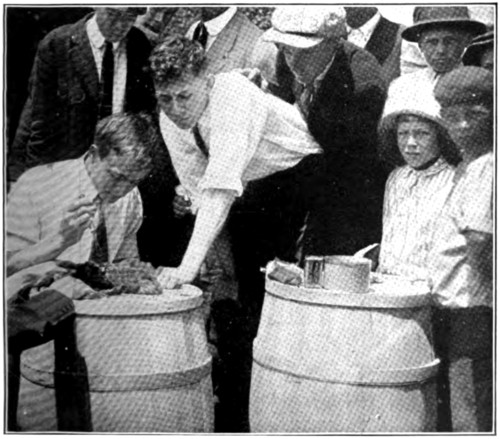

Plan No. 19. God helps those who help themselves

The next day she went through with the same program, except on a larger scale, and still was unable to supply the demand for her beautifully browned hot rolls that were ready for delivery just before meal time, and looked so tempting.

Her boy being out of school on Saturday, she mixed two pans of cake dough, one white and one brown, and spread them into a large bread pan so as to marble brown and white, and making a cake one and one-half inches thick, when baked.

Iced thinly, in plain white, and cut into two and one-half-inch squares, these sold readily for 20 cents a dozen, and were delicious. At the end of four days the little woman had made $10, and Monday morning her husband, still out of a position, offered to do the selling and delivering—greatly to her delight and the profit of both—for the sales increased until they had more demands for their products than they could supply.

She also began to bake delicious bread and pies, as well as rolls and cakes, and sold every article at a good price, that meant a handsome profit. This was the beginning of a successful bakery business for this family.

The teacher who finds the sharpening of pencils for her pupils a large and disagreeable part of her daily duties, will welcome this plan as a perfect godsend: that the plan, when properly operated by a live man, is a money-maker, is demonstrated by the fact that a Chicago man made big profits out of it.

[11]

He bought a large number of that botanical wonder known as the Resurrection Plant, or Anasta-tica, which can be obtained at a cost of 2 cents each, or less, when ordered in large quantities, and even when retailed at as low a price as 10 cents each, yield an enormous profit. To those not familiar with this remarkable plant, it may be well to explain that, altho it stays green while kept in water changed often enough to prevent it becoming stagnant or rancid, when taken out of the water it dries and curls up and goes to sleep, remaining in this state for years, and re-awakening or being “resurrected” immediately upon being placed in water again, when it will open up and commence to grow in half an hour or less. When tired of seeing it grow, you simply take it out of the water, let it “go to sleep” again, and re-awaken or resurrect it at any time you desire. Many people would gladly pay several dollars for a simple plant, but in the operation of this plan you can well afford to sell them at 10 cents each, as you realize a profit of 8 cents apiece, and one in every schoolroom in the land will prove a constant source of delight, as well as of educational value.

This is the way the Chicago man works the plan to the pleasure of teachers and pupils, and his own profit of something like $300 per week: he not only buys thousands of these Resurrection Plants, at, say, 2 cents each, but also a number of the best pencil sharpening machines, which cost him about 90 cents each. He consigns one of these machines and thirty of the Resurrection Plants to each teacher in a public school and requests her to announce that the pencil sharpener will belong to that particular room, for the full use of all of them, if each pupil will take home one of the plants and bring 10 cents back to her the next morning, explaining to them the peculiar characteristics of the plant. Of course, every child gladly performs this small service, and the teacher then remits to the consigner, the $3.00 collected, and he has exactly doubled his money, as both the pencil sharpener and the thirty plants cost him but $1.50. If there are over thirty pupils in the room, that simply means more plants and more profits, for with the second consignment of thirty plants it is not necessary to send the pencil sharpener, and the Chicago man’s profit on that transaction is therefore $2.40 instead of $1.50.

As there are many thousands of public schools in this country, and nearly all of them have a number of rooms, anyone who is good at figures can easily make a reasonable calculation as to the probable profits.

“The touch of a woman’s hand” is what turned eight and one-half acres of unattractive, idle land on the shores of Long Island Sound into a productive little farm that is now netting it’s owner a profit of over $5,000 a year! Don’t believe it? Listen!

To be sure, she had a few hundred dollars—just enough to buy it and improve it with a cheap little cottage, a small barn and some poultry sheds, and plant it to fruit trees, besides every sort of vegetable that enjoyed the greatest demand. She now has an orchard containing the best varieties of fruit trees, 1,000 apple, 500 peach, 100 pear, 100 quince, 100 cherry—besides one-fourth acre in grapes, one-half acre in raspberries, blackberries, etc., and still has plenty of room left for vegetables, planting them between the rows of fruit trees, thus affording ample cultivation for all. She employs one man regularly at $40 per month, and hires extra help in the busy seasons of the year.

To supply the immediate demand for the less common garden products she grew okra, French finochio, endive, chicory, etc., getting many ideas from seed[12] catalogues, Government publications that are sent for the postage. She plants large quantities of all vegetables, and cultivates every foot of the ground, fertilizers are freely used, and crops changed from year to year. She finds early asparagus and peaches the most profitable of all the things she raises, and while her first garden was growing she wrote letters to her friends in the city, asking them if they would not like a few samples of her fresh vegetables. They did and said so, and each one became a regular customer. As she produced more, she kept increasing her list of patrons by the same means, and to these she ships her products in “knock-down” crates that cost her 21⁄2 cents each, and, unless otherwise ordered, she fills these crates half with fruit and half with vegetables. The crates each hold six great basketfuls of produce, and cost the customer $1.50, besides 25 cents each for expressage.

By picking her products early in the morning, she has them delivered in the city for dinner, while they are fresh and much preferred to those bought at corner groceries. Having her own horse and wagon, the cost and labor involved in shipping is very small, and 500 crates easily net her $750.

Realizing from her own experience, the longing of city women for a quiet, rural spot in which to spend the week-ends, she informed a limited number of her lady friends in town that for $1.50 per day she would give them room, board and transportation, to and from the station, and so many of them gladly accepted her invitation that the capacity of her small cottage was soon taxed to the utmost. But she will not take regular boarders, and thus has the greater portion of her time to herself, to be devoted to such activities as best suit her. Those women who are given the privilege of spending the week-end on the farm not only cheerfully pay the moderate charges, but many of them render valuable assistance by working in her garden, as a pleasant means of relaxation and an agreeable change from the exacting requirements of city life.

The little 81⁄2 acre farm wasn’t much to look at when she first took it over, but she has made it a veritable bower of beauty, a haven of rest, and a revenue producer to the extent of $5,000 a year, all set down in the column marked “net profits.”

Politics is always an interesting subject, particularly to politicians, whether of large or small calibre, and the man who can formulate a plan by which to “aid the party,” and at the same time insure an income for himself has certainly “picked a winner.” We know of a man who did this, most successfully, and this is the way he did it:

His city, like all others, had political organizations of varying degrees of efficiency and influence, and desiring to assist in placing his own political party in the lead, while devising a good revenue from his activities at the same time, he hit upon the plan of a manual giving a resume of the main issues of the campaign, his party’s position regarding the same, the various ward and precinct boundaries, the names and addresses of all precinct committeemen, as well as those of the chairman and secretary of the central committee, the location of each polling place, dates of registration, of primaries and general election, and data of every character which would be interesting to voters.

Instead of leaving it to the secretary to compile and issue this manual, and having it printed and distributed at the expense of the committee, this man sought and obtained the authority of the committee for the publication of the same without cost to them, had them indorse it as the official publication, and proceeded to have it issued in attractive form. Most of the candidates for office on his party ticket[13] were glad to give him half tone portraits of themselves, with a declaration of the principles for which they stood and pay him from $25 to $50 each for the publicity thus obtained. Besides, practically all the merchants belonging to that particular party also gave him large advertisements, as the manual reached all the voters of the ward or county, regardless of party affiliations, and proved an excellent advertising medium.

Finding the plan so successful in his own county, he extended it to other counties, and finally to the entire state.

In many cities the theatrical managers arrange in some way to compile a list of theatre goers, and send them, by mail, neatly printed postal cards announcing the attractions billed for their houses several days in advance of their appearance. This plan has proved successful in most cases, but a man in one city of the middle west improved greatly upon it by publishing a weekly that embraced all the theatres and amusement places, and gave them all very much wider publicity, at no cost to any of them.

He arranged with the manager of each theatre and motion picture house in his city to furnish him with all the data concerning engagements for a week or two in advance, obtaining details of coming attractions, with portrait cuts and personal sketches of the most prominent actors and actresses billed for appearance at each house, a synopsis of the play, or any other feature that would naturally create a desire to see it. Write-ups and notes of local interest were also an excellent feature in this weekly, and it was so well edited and printed that nearly all copies were carefully preserved by those receiving them.

Instead of going to the trouble and expense of mailing, these weeklies were distributed at all the theatres and movie houses at every performance, and thus afforded each patron an opportunity to plan his amusement program ahead.

Having saved the theatre managers the expense of a program for each house, they were glad to allow him all the profits of the extensive advertising he secured, and he soon built up a business that netted several thousand dollars a year.

Every orchardist stands in mortal terror of the multitude of pests that infest both fruit and shade trees in practically all parts of the country, and as but few really understand how to prevent or destroy these persistent plagues, or have the time to do it properly, it affords some one in each community an excellent opportunity to make a good living by doing it for them. All he needs is to know exactly how.

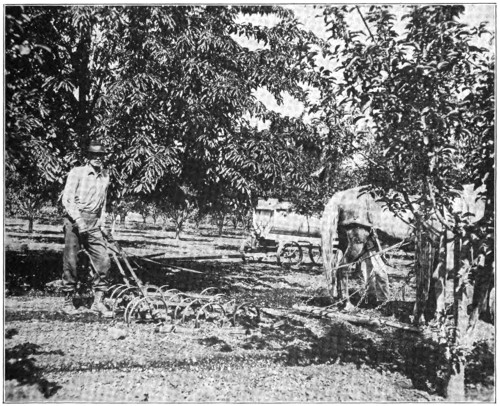

An enterprising young man in one of the irrigated fruit districts of the Northwest thought of a good plan along this line and proceeded to put it into execution, with entire satisfaction to the fruit growers, and a corresponding profit to himself.

The leading hardware merchant in his town was not only a good friend of the young man, but was thoroughly familiar with all the really effective methods of destroying tree pests through the spraying process. He sold him one of the best makes of spraying machine, gave him accurate instructions as to its use, as well as the various materials for spraying, and advised him to get busy at once.