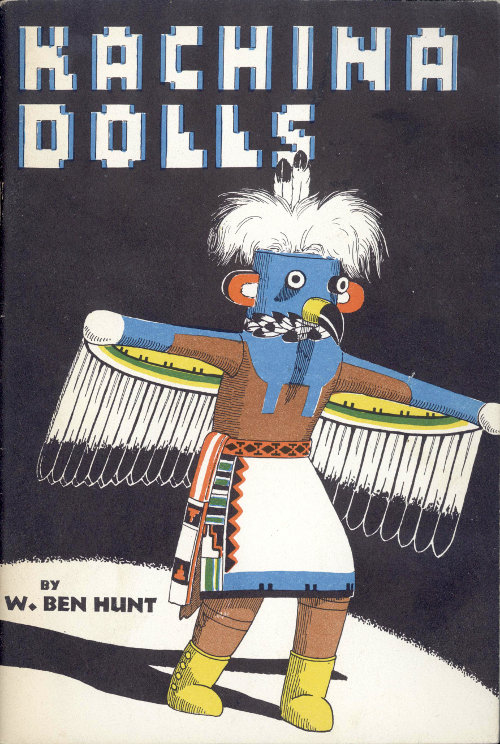

Title: Kachina Dolls

Author: W. Ben Hunt

Author of introduction, etc.: Robert E. Ritzenthaler

Release date: May 30, 2020 [eBook #62286]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

KACHINA DOLLS

BY

W. BEN HUNT

MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM

POPULAR SCIENCE HANDBOOK SERIES NO. 7 SEPTEMBER 1957

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

©1953 MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM

by ROBERT E. RITZENTHALER

Curator of Anthropology

On the sentinel-like mesas in the semi-desert land of northeastern Arizona dwell some 3,500 of one of our most colorful Indian tribes of today, the Hopi. Living in their traditional adobe, multi-storied “apartment houses,” called “Pueblos,” they practice many of their old ways and customs, and remain one of the tribes least affected by the white man. Agriculturalists they were and agriculturalists they are, filling the fields at the base of the mesas, raising corn, beans, and squash, but above all, corn. In this area where land is good, but moisture is all-important, the Hopi have developed a religion much concerned with prayers and ceremonies to bring rain and good crops. During the Snake Dance, for example, snakes are held in the mouths of the dancers and then released into the desert as messengers to the gods to inform them that the Hopi need rain.

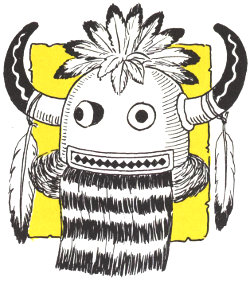

Less widely known to the world than the Snake Dance, but very important to the Hopi as a spiritual means of petitioning for rain, good weather, bountiful crops, and other blessings, is the Kachina cult. The Hopi believe that the Kachinas are a band of supernatural beings who live in the nearby mountains and pay visits to the villages at intervals during the first half of each year. At these times the men don the masks and costumes representing particular Kachinas, and perform dances and ceremonies in their honor. By wearing these costumes the men not only physically impersonate the Kachinas, but also assume their spirits. The dances and ceremonies take place both in the underground chambers, called kivas, where only men are allowed, and out on the village plazas where all may watch. During the latter, the dancers follow the leader in single file to the plaza where they line up facing east. The leader, at the center, begins the singing to the rhythm of his rattle; then the others join in, and the dancing begins. For the next song the dancers face north, then west, after which they distribute gifts, usually a bow and arrow for a 2 boy and a Kachina doll for a girl. They then retire to a secluded area to unmask, relax, and prepare for the next set of songs and dances.

In some of the dances 30 or 40 men will be dressed alike; in others a variety of Kachinas participate. Besides the serious dances there are humorous ones put on by clowns, or “mudheads” as they are popularly called. The mudheads are distinguished by their distinctive, mud-colored masks and provoke much laughter with their impromptu pranks and burlesquing of both Indian and white man, and even of the Kachina dances.

While the term “Kachina” refers to the mythological beings, and to the masked dancers who impersonate them, it is also used to refer to the dolls, which are miniature but accurate reproductions of them. Kachina dolls are made by the men to be given to the girls during the Kachina ceremonies. Children eagerly await the Giver Kachina, the counterpart of our Santa Claus, who wears a blue mask and carries a bundle of gifts on his back. His arrival is announced by a herald stationed on a roof top. He passes among the crowd distributing gifts to the children, such as candy, bows and arrows, and the especially desired Kachina dolls. Each girl receives at least one, and some may receive as many as a half dozen. They are played with as dolls, often being carried about in miniature cradles. They also, however, serve a useful purpose in acquainting the Hopi children with the names, kinds, details of costumes, and religious lore of the Kachinas. In a very real sense, then, they are the educational toys of the Hopi. The dolls are never worshipped and are not to be considered idols, but rather serve as constant reminders of the Kachinas, especially during the summer and fall when the Kachinas have returned to their mountain home. They are handled and carried about the village by the girls, but for the most part they will be seen hanging from the walls or rafters of the pueblo rooms.

The dolls described in this booklet are but a few of the many types. Not even the Hopi can tell you how many different Kachinas there are, but their number has been estimated at 250. Only about 200 are in current use, and these change with the years as new ones are added, and others disappear from usage.

Our Southwest is a veritable treasure chest of interesting things made by clever Indian craftsmen. Here and there, at Indian trading posts or Indian roadside stands along the way, among the rugs, sashes, pottery, and silver and turquoise jewelry, you will find Kachina dolls. Not too many. Up until a few years ago they were quite scarce in the trading posts, but could be bought at the various Hopi pueblos, where the best ones are made. While they were originally made for their little girls, as stated in the preface, they produced even more of them when it was discovered that tourists prized them. And like everything else, someone saw a chance to earn a dollar and started to manufacture them. Some years ago the Japanese even went so far as to make them of papier-mache. Many of them are machined and given a quick coat of paint. But you can still buy good Kachina dolls both on the mesas and at trading posts.

All in all the Hopi-made dolls are good, and usually when you find one a bit worn, with a cord around its neck, you can figure that at one time it adorned a pueblo wall. The Hopi Kachina makers take great pride in their work. Their dolls are made out of cottonwood roots, which gives them that sort of rough texture that is pleasing to the eye. Some of the very old dolls have cloth and buckskin clothing to make them more realistic, but for the most part they are made entirely of wood with the exception of feathers and fluffs, as shown in the following pages.

As mentioned before, there are about 250 different Kachinas, but the Hopi do not make that many different dolls. There are certain Kachinas that lend themselves better to carved dolls, and it is with these that we will deal.

Years ago, when starting out boys and girls in whittling, I made it a practice to give them Kachina dolls to whittle, for various reasons. It acquainted them with the feel of wood and the meaning of grain. It taught them how to sharpen a knife, and how to use it. And best of all, they whittled figures without having to worry about human faces, which are the bugaboo of all whittling novices, and a lot of others, too.

This booklet will mainly show how Kachina dolls are whittled and painted, and to what use they can be put. This is not an ethnological thesis, but is written for the craft-minded who like to whittle, and who like Kachina dolls. I do not imagine that anyone will make all of the objects listed and described, but there may be one or more of them that you will enjoy making.

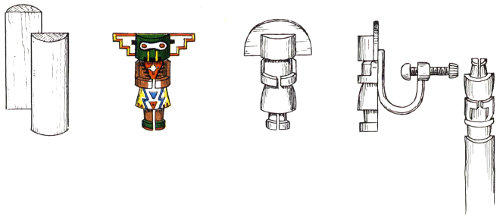

The first thing you will need is a piece of wood. Since it would be rather difficult to obtain cottonwood roots, our next best bet is a piece of straight-grained soft wood. I have used sections of green, knot-free basswood, willow, and poplar saplings or branches with good results. A piece of wood about 1½ inches in diameter is of a proper size to start out with. The green wood whittles easily and, due to the short lengths and deep cuts, it is not likely to check. And of course it is already round.

Also, white pine, sugar pine, and basswood can usually be bought at a lumber yard or millwork shop. It should be cut in rectangular sections and then rounded.

Then, of course, you will need a knife that holds an edge. A good quality of pocket knife is best, and all the whittling I have ever done has been with a small blade, from 1¼ to 1½ inches long. As the knife comes from the store it is not sharp enough for whittling. So get a small abrasive stone, and a piece of leather to strop it on, and sharpen it until you cannot see the edge; as long as you can see a “white” line or spot on the edge, your knife is not sharp. Thereafter, keep it sharp at all times.

You will also need sandpaper to sand down the knife cuts in the wood.

Now for the part that worries most beginners: painting the dolls. If you have a fairly steady hand, and use a good brush, this should not be too much of a problem. I have often said that it a person can pare a potato without wasting it, and can write fairly well, he or she can make a Kachina doll.

We use water colors for painting. That is what the Hopi use, and water colors are not so messy. While any good brand of water colors will do the trick, you will have the best success with poster or show-card colors. They are opaque and cover better than transparent water colors. Although many of the old Kachina makers use brushes made out of yucca leaf stems, chewed and trimmed to the sizes required, you can pick up a couple or three small brushes that will do a better job. Sable-hair brushes are best, but also more expensive.

Painting the dolls is not as difficult as one may think. Remember—you don’t have to paint faces, and the masks are all more or less abstract or symbolic in design. And furthermore you don’t have to do any shading or blending. It is all flat work.

There are two methods of painting. Most of the old-time Kachina makers give the entire doll a coat of white paint first, and the rest is painted over that. But usually, with good poster colors to work with, it is easier to lay out and paint each color directly on the bare wood. The colors dry rather rapidly and, if used rather thick (not too much water), they will not be apt to run or bleed where colors overlap. So don’t let the painting stop you. I have seen cub scouts make some very nice looking dolls.

The Indian does nothing to preserve the painted surface and the water colors are apt to smudge and wear off. On the other hand, a glossy surface on a doll looks awful, and is not in character. So we suggest that you use a light spray coat or two of Krylon, or Spray-fix, or any other crystal-clear spray, such as come in bomb cans. Krylon is a crystal-clear plastic spray, and Spray-fix is a fixative (in a bomb can) such as is used by artists to prevent smudging of pencil, charcoal, or pastel drawings. But whatever you use to preserve the water color, it should be “water white” and should not be sprayed on to impart a shiny surface, except where stated otherwise in the following pages.

Naturally, questions arise as to where one can get ideas for more difficult kinds of Kachina dolls, or Kachina costumes. Here are a couple of good books which contain such information: Hopi Kachinas, by Edward Kemrard; Ceremonial Costumes of the Pueblo Indians, by Virginia Roediger.

Moreover, Kachina dolls are shown from time to time in Arizona Highways Magazine and there are many crayon drawings of Kachinas, made by a Hopi Indian, in the 1899-1900 Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

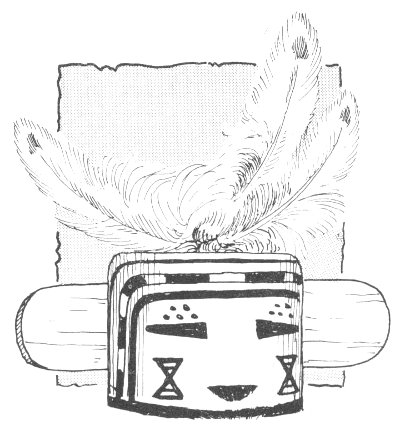

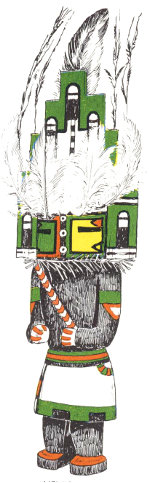

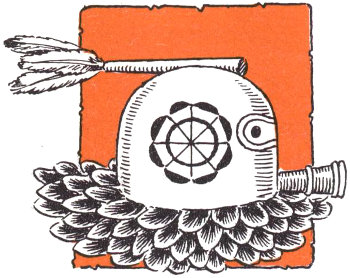

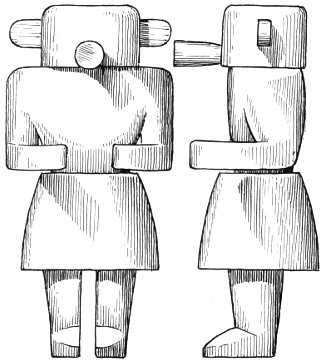

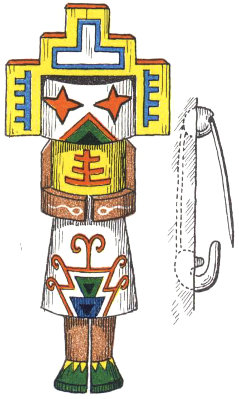

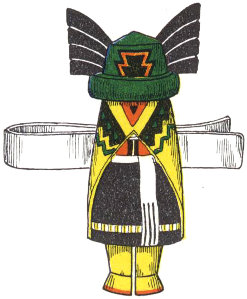

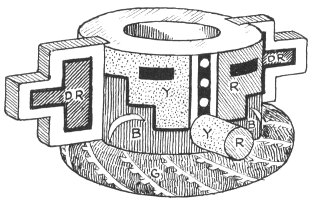

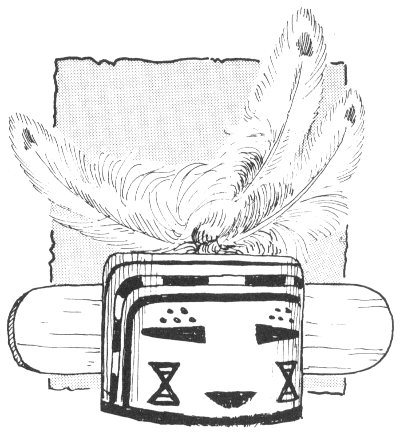

PALAH’IKO MANA

HEMIS

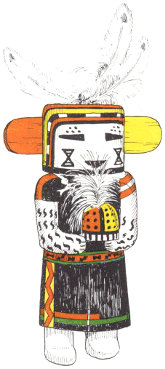

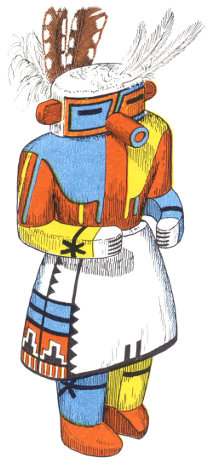

PAK IOKWICK

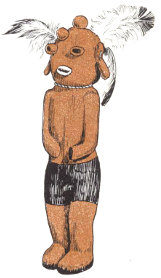

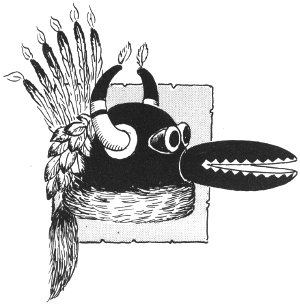

MUDHEAD

The dolls shown {above} were carefully drawn from old specimens in the collection in the Milwaukee Public Museum. Each one has a cord around the neck with a loop at the back for hanging on a wall.

All the bodies were made from cottonwood roots. The tablets are of other woods whittled thin. It is said that the Kachina doll makers, and also the makers of the actual Kachina masks, pay the most attention as a rule to the masks. While the rest of the costumes may vary, the masks usually hold true to ancient traditional forms and designs.

These dolls will also acquaint the beginner with the different methods of whittling, particularly the moccasins and arms. Colors also vary, depending on what colors are on hand. Today many of the dolls are painted with poster colors because they are easier to obtain than formerly.

Most of these old dolls are slightly wider than they are thick, or shall we say, slightly flattened from front to back. The Hemis Kachina is shown here with a green background on the tablet, whereas recent books show it to be blue: otherwise, the traditional characteristics are preserved. Indians often confuse these two colors.

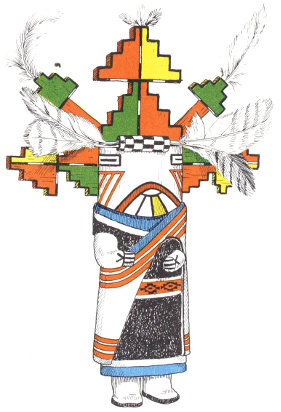

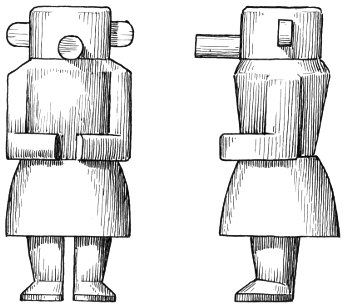

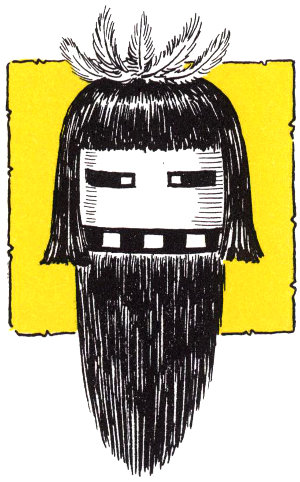

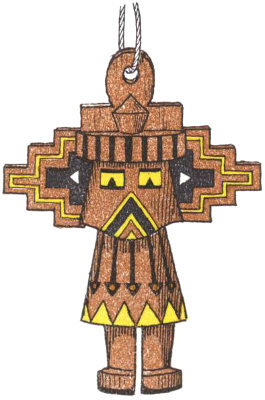

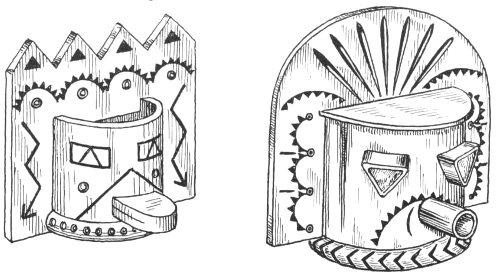

KEME

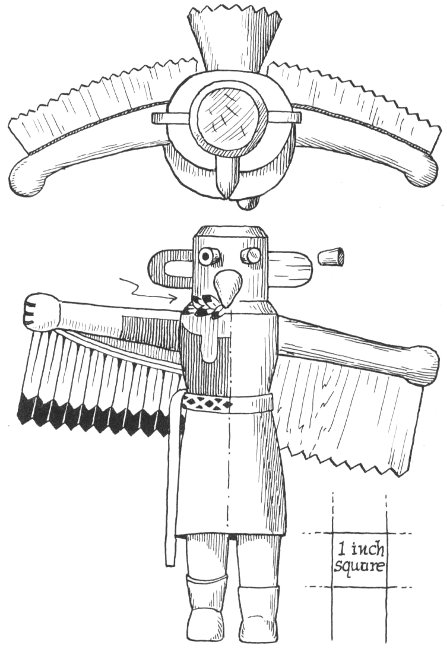

CROW

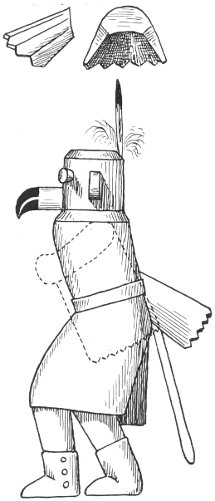

HOT’E

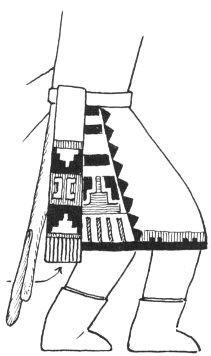

The {Keme} doll shown is an old one brought to me by a trader. It was in rather poor condition. The paint was smeared and rubbed off in places. By carefully matching the original colors, I went over the entire doll. Note the feet. They are different from those of any of the five on the preceding page.

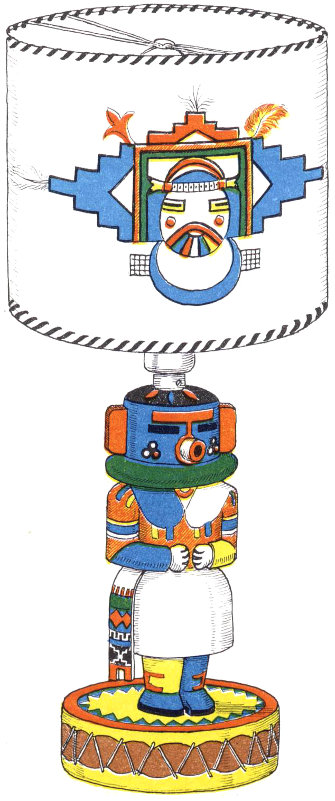

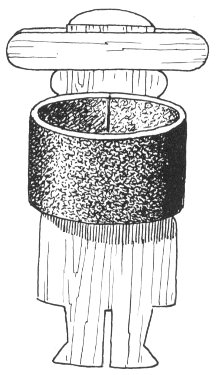

The Crow Kachina is one that I selected for a lamp base. In the actual costume there are real crow wings attached to the mask, but these dolls are also made with wings of wood in several different styles.

The Hot’e Kachina is often used for doll designs, and here, too, some dolls have small feathers attached to the mask, while others have wooden symbolic feathers. Some Hoté dolls have a miniature concha belt made of tin and a thin strip of black leather. The bow and rattle, of course, are slipped respectively into a notch and a hole in the hands.

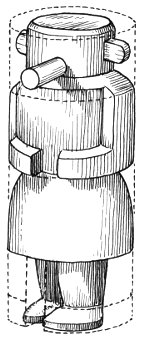

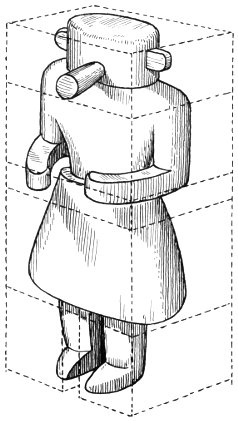

Saw out slot for legs

This is the simplest way of whittling Kachina dolls from a round piece of wood. Mark as shown at left and cut out piece between the feet and legs.

Slot for legs. Dotted lines show how block is marked with pencil.

Ears and nose are set into mortices.

This is an old Indian method of whittling dolls. Note that the upper body is quite flat, and that the head and skirt are oval in cross-section.

For the most part, Indians tend to make their doll bodies flat, especially figures ten inches or more in height. About the only sawing that is done is in cutting the space between the legs. For the beginner we have shown two types, the round and the flat. The different sections are marked as shown by dotted lines, and from there on in it is just a case of whittling. Arms, as shown in the lower doll, are whittled out, but occasionally they are whittled separately and tacked and glued on. All other appendages, such as nose, mouth, eyes, ears, and tablets are set into mortices cut to fit, and glued. While plastic cements dry quickly, it is better to use a glue that water color will adhere to. Regular hide glue or Elmer’s glue are fine. You will note that there are a great many ways of whittling feet. That seems to be a matter of choice.

Figures should be sandpapered, preferably with medium-grit sandpaper. The finish can be made to look very much like the rough texture of cottonwood root.

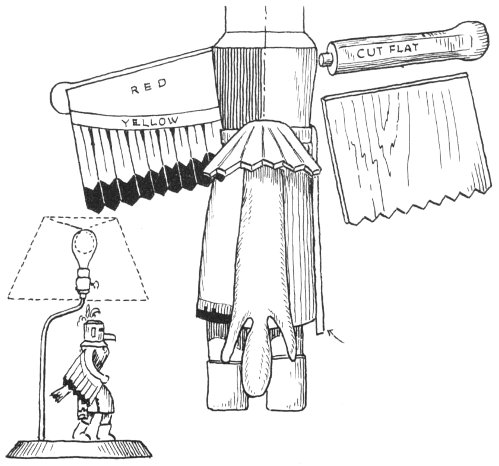

Ruff of painted feathers.

The tail is merely black-tipped eagle feathers like the wings.

Use a quick-drying glue rather than cement to fasten parts together.

The fox skin can be painted a reddish-buff. Sash is made separate and glued on.

Dolls of this type are not found in many of the western trading posts, and where you do find one it will have quite a price tacked to it.

To make this one, which is about eight inches high, you’ll need for the body a soft wood block about 2½ by 3 by 8 inches in dimensions. By enlarging with squares, the sizes of the various parts can be ascertained. The wings should be of thin wood, preferably ³/₃₂ inch thick. If a quick-drying glue is used, such as Elmer’s Glue-all, no brads are required. I like to use glue rather than cement, because water color paints will stick to places where glue appears, but will not stick to cement.

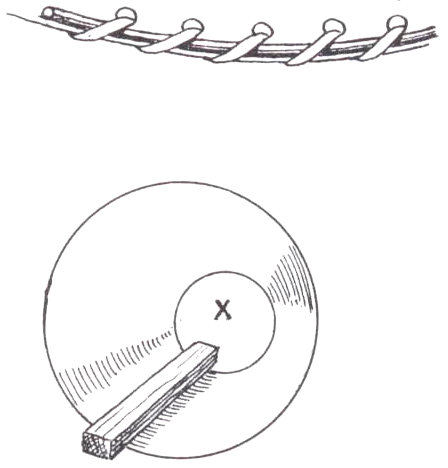

These dolls are sometimes glued to a base of some sort, and so make beautiful lamp bases. However, when used for that purpose, the doll is not drilled for wiring. Instead a piece of ⅜-inch brass tubing is used, bent as shown in the small sketch in the lower left-hand corner. Of course, a suitable shade should be made, one with a Pueblo Indian design.

EAR ORNAMENTS

LAPEL PIN

half round

Safety-pin set in plastic wood

TIE CLASP

half round

Set in plastic wood

ZIPPER PULL

half round

NECKLACE

Dolls for necklace are made round.

Use wood or glass pony beads.

If you want to please a lady or a girl, make her some of these. They are colorful, to say the least, and decorative.

The ear ornaments and the necklace are made of birch dowel rod, which is easy to whittle in miniature. Plastic screw clamps can be bought at almost any notion counter, and they are simply cemented onto the backs of the dolls. Do not make them more than 1 inch high. The necklaces, also rather unique, should be strung with wooden beads if possible to reduce the weight.

For these pieces, several coats of clear nail polish are used, or clear lacquer. Unlike the larger figures, they should have a good glossy finish. Owing to the smallness of some of these figures, it is best to whittle each on the end of a longer piece of dowel rod, and then cut it off with a fine coping or jeweler’s saw (See drawing {above}). Then cement on the clamp in order to have something to hold to while painting it.

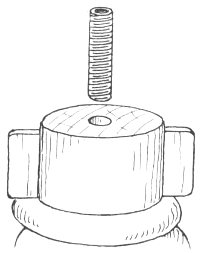

All drilling should be done before starting to whittle. The hole in the doll should be slightly smaller than the nipple. To insert nipple soak the wood around the hole with shellac and screw the nipple in. It will cut its own thread in the wood and the shellac will keep it from turning.

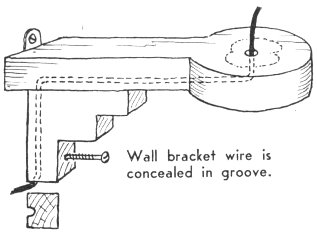

Wall bracket wire is concealed in groove.

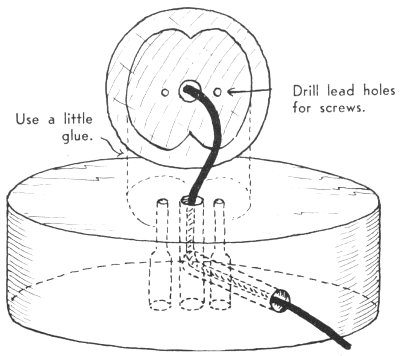

Drill lead holes for screws.

Use a little glue.

It is much simpler to insert the cord before fastening the

doll to the base.

I enjoy making lamps, and have made many Kachina doll lamps, each different from the others—different dolls, different bases, and different shades. The dolls should be made out of at least 2-inch wood. A 2½-inch size is better, the over-all base and doll measuring about 9 inches in length. This is a good proportion.

In making bracket lamps, the doll can be set right on the bracket, as shown at lower left, and the brackets can be painted to harmonize with the doll, or stained or painted to match the woodwork of the house.

I have also made totem pole lamps on this same principle, using Northwest Coast Indian designs on base and shade.

In making the drum base shown here, either of two methods may be used. When I have a lot of time, I lace rawhide over the block and paint it. Usually, however, I simply paint the circular base to resemble an Indian tom-tom.

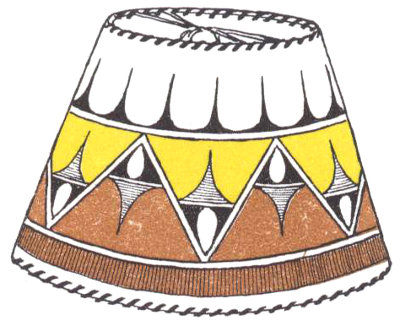

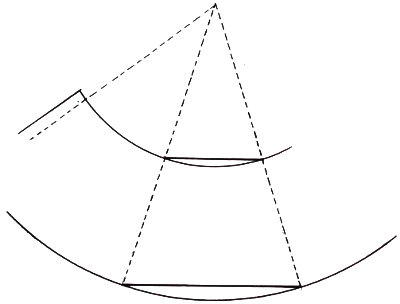

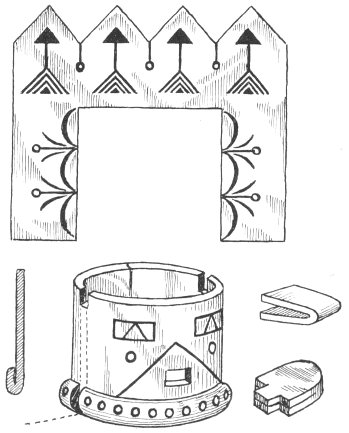

Paper lamp shades are rather easy to make after you know how to go about it. Of course a wire frame is required. These can sometimes be bought, but as a rule a frame can be taken from a discarded shade of the proper size. Only the top and bottom rings are required for the round shades.

Design taken from pottery.

Use a round shade with a round base.

This is the conventional shape. If you can not get a pattern from the former covering, a new one can be easily laid out as follows:

PROCEDURE

Remember:

Diameter × pi (3.1416) gives

you the circumference. Allow

½ inch for gluing.

Punch holes about ¼ inch from edge and lace with plastic or leather lace.

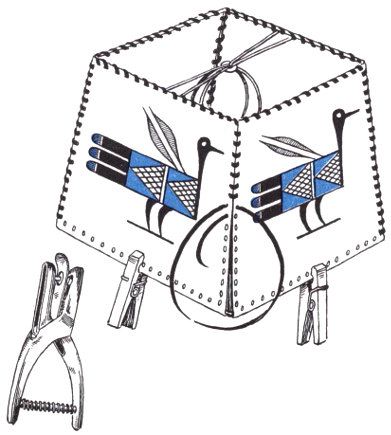

Frames for square shades should have wire uprights at corners.

A square shade is the proper thing to use on a lamp with a square base. This is usually covered with four separate pieces laced together at the corners and the top and bottom.

Since shades, in order to harmonize with Kachina doll lamps, cannot be bought in stores, they will have to be made. There are three types of shade that will look good: the cylindrical shade; the conventional round, tapered shade; and the square shade. Round shades should be selected for round bases, and square shades for square bases.

Use smooth three-ply drawing or bristol board, and transparent water colors are better than poster colors.

Shades can be parchmentized by applying a mixture of one part turpentine and two parts mineral oil. Apply the mixture to both sides with a wad of absorbent cotton, and wipe off the surplus. This is done after the shade is painted and glued together, since glue will not adhere to any oiled surface.

I prefer to leave the paper white, just giving it several light coats of clear plastic spray to prevent soiling.

Designs for shades should be appropriate. Southwest Pueblo designs fit in well, such as thunder birds, rain birds, Kachina masks, etc. Your library will no doubt be able to furnish many ideas along these lines.

If you object to lacing shades to the wire frame, you can use passe partout binding tape which is already gummed and only has to be moistened before applying.

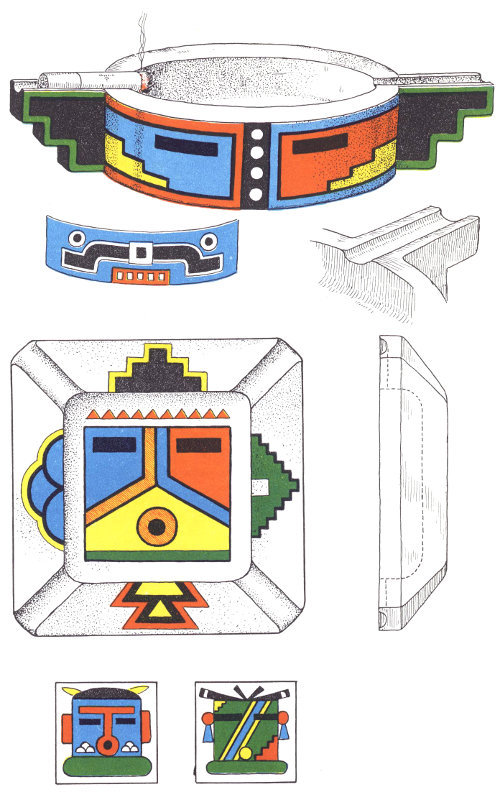

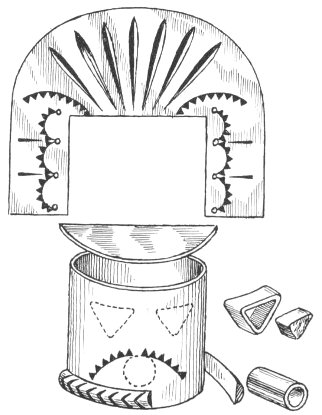

This is one item that is becoming quite popular through the West and there seems to be no limit in what can be done along these lines. You will probably get a lot of ideas when traveling, but here are a couple that are slightly “different.”

The top tray can be made of Mexican modeling clay or some other clay that does not require firing. In that case the top and inside are not decorated, and the outside decoration is put on with poster color and covered with several coats of plastic or clear lacquer to give it a kiln-dried ceramic appearance.

A cigarette box can also be made in the shape of a Kachina mask as a companion piece to the tray. While the lower tray has the conventional general shape, it could also be made with vertical sides.

A few years ago it was rather difficult to obtain a good turquoise blue, but it is now on the market.

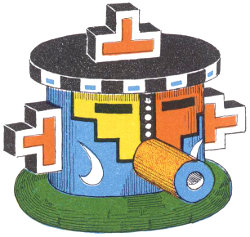

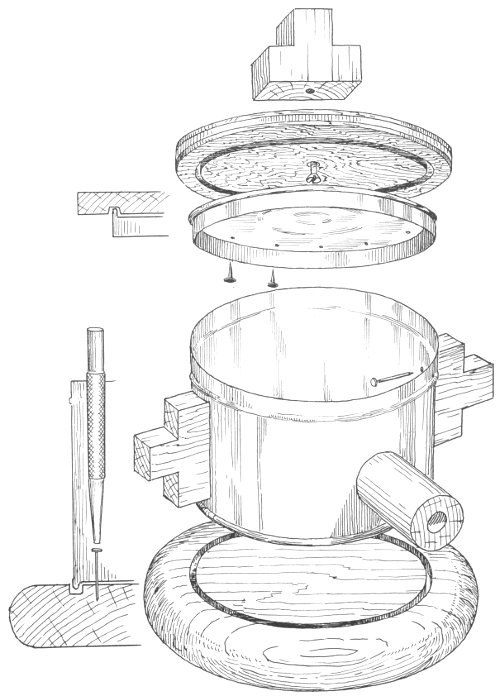

A one-pound coffee can is just right.

For better painting, scrape off all printed matter and wipe from can before starting other work.

Can be painted with enamels, colored lacquer, or dope, but do not try to use both on one job. They do not mix.

Fasten together with glue and one screw.

The grooves in the cover and the base can be cut on a lathe, using a face plate.

Fasten the cover to plywood with tacks. Put some thick shellac in the groove.

“Nose” and “ears” should fit snug to can. Punch holes in tin and put a coat of thick shellac on the wood when nailing ears to can.

Fasten base by pulling shellac in groove and fasten with small brads.

Use a nail set and drive brads into base.

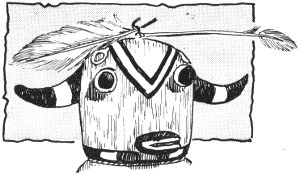

This canister speaks for itself. There is this much to be said for it: the lady of the house isn’t so apt to hide it when she is preparing for guests.

As with any Kachina project, there is practically no limit to what can be done in regard to design. You can take your pick of masks, and can select the appendages that you like best.

Coffee cans have just about the proper shape and proportions for these canisters, and the covers fit tightly. Be sure to smooth down the edges of the can, using fine emery or other abrasive cloth.

The inside of the can should be given a coat of clear lacquer to prevent rust from forming, since many brands of tobacco are slightly damp.

Mask slides are easily made. Bore a ¾-inch hole for the neckerchief first and the proceed as with any other mask.

For a full figure slide, use only a half round piece of wood, and glue a loop of leather to the back of it.

ALUMINUM

This aluminum slide can be made without welding. The snout is riveted in before bending the mask.

SILVER

Beautiful slides can be made of sterling silver, and since it is easily soldered, more can be added than with other materials. The eyes are inset with turquoise forced into the bezel and then ground off flush.

When the tablette is forced down over the mask it holds everything securely.

Slides are always in demand in scouting, and we show here four different methods of making them.

Those made of wood are very colorful. In making the full figure, only the vertical, front half of the form is used, and a ring of any material may be attached to the back.

Metal slides require a little more work. Aluminum is a good metal for youngsters. This requires no welding, but the tablet is fastened to the mask with a tight drive fit.

Silver, of course, is for the finished craftsman, and anyone familiar with silver soldering methods can easily produce one like that shown at the bottom of the page. If turquoise is used, so much the better.

These metal slides are eye-catchers, since they are not to be found in stores.

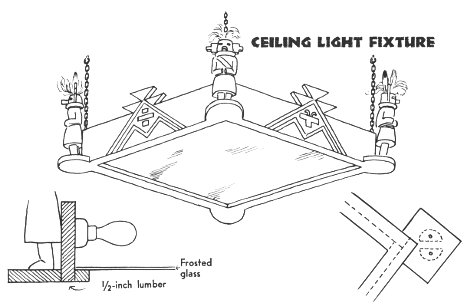

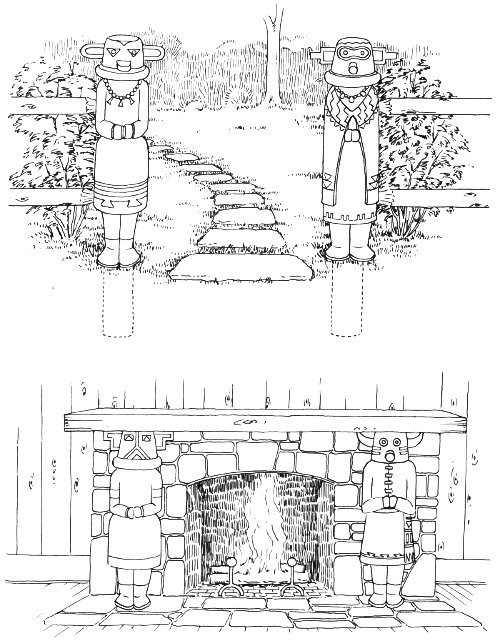

CEILING LIGHT FIXTURES

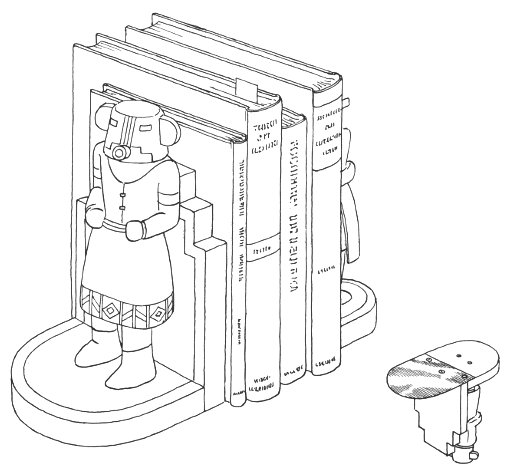

BOOK ENDS

It is necessary to add a metal base such as this on light-weight bookends. Be sure there are no sharp edges on it that might scratch the furniture.

Probably your thought on this fixture will be, “You can’t put that in a living room.” Not in any or every living room, but I know a beautiful large living room where a similar one is hung and it certainly sets off the Navaho rugs and Indian baskets and pottery in that room. This fixture would be ideal in a den or recreation room.

A cluster of four light bulbs should light it, or a socket can be set on each of the four sides. Frosted, or better still, an opal glass should be used. The side pieces are taken from the woven designs on Hopi women’s dresses, predominantly black.

These can also be made without the back or upright; that is, the doll would be set flush with the back edge of the base. But the metal base must be added unless the wooden base is well weighted with lead. I have made them that way, but prefer the thin metal piece instead. Twenty-gauge brass works out nicely. To fasten it, use small flat-head screws, countersunk, and give the metal a coat of thin shellac where it fits into the wood. Wood and metal must be flush along the bottom.

KACHINA DOLL POSTS

These attractive gate posts are rather easy to make. I used sections of old electric-line or telephone poles. They are of cedar and will withstand the weather. After cleaning the surface of the post with a drawknife, it is worked with a small hand ax, chisel, and mallet. Note the 2-foot or 3-foot projection left on the bottom to set it.

Paint with ordinary house paint and, if you wish, finish with a coat of clear varnish to protect the paint. I used water colors and finished with two coats of clear spar varnish. But house paints are easier to obtain.

The hearth posts may be flattened somewhat at the back to fit tightly against the fireplace. Telephone poles make the best material as they are well seasoned. The mantel shelf should be at least 2 inches thick. Three inches would be better, and could be effected by gluing a 3-inch piece of ⅞-inch lumber around the front and two ends to give it the appearance of a solid 3-inch plank.