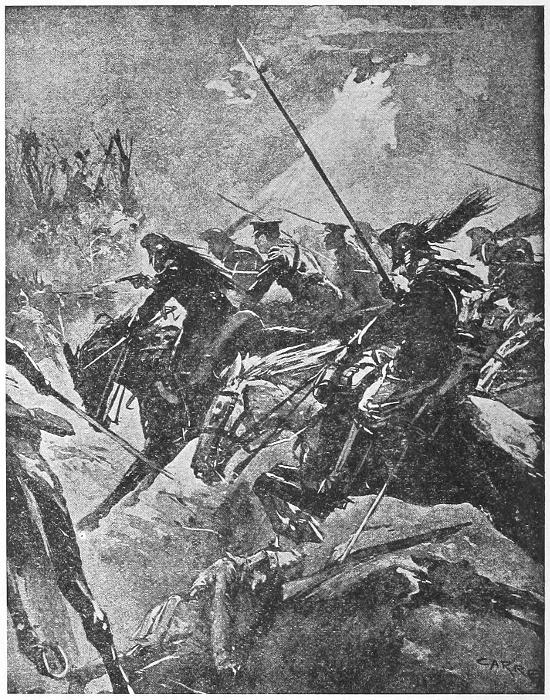

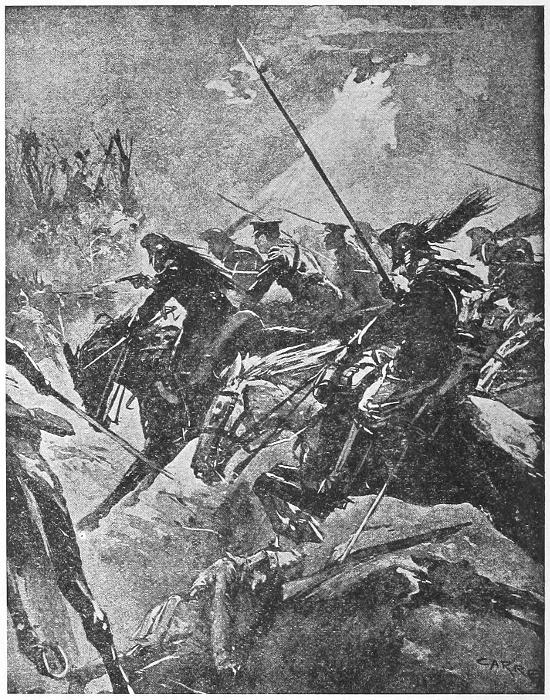

Night Charge of the 22nd Dragoons, Sept. 10-11, 1914.

Title: Impressions and Experiences of a French Trooper, 1914-1915

Author: Christian Mallet

Release date: July 12, 2020 [eBook #62629]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

IMPRESSIONS AND EXPERIENCES OF

A FRENCH TROOPER, 1914-15

Night Charge of the 22nd Dragoons, Sept. 10-11, 1914.

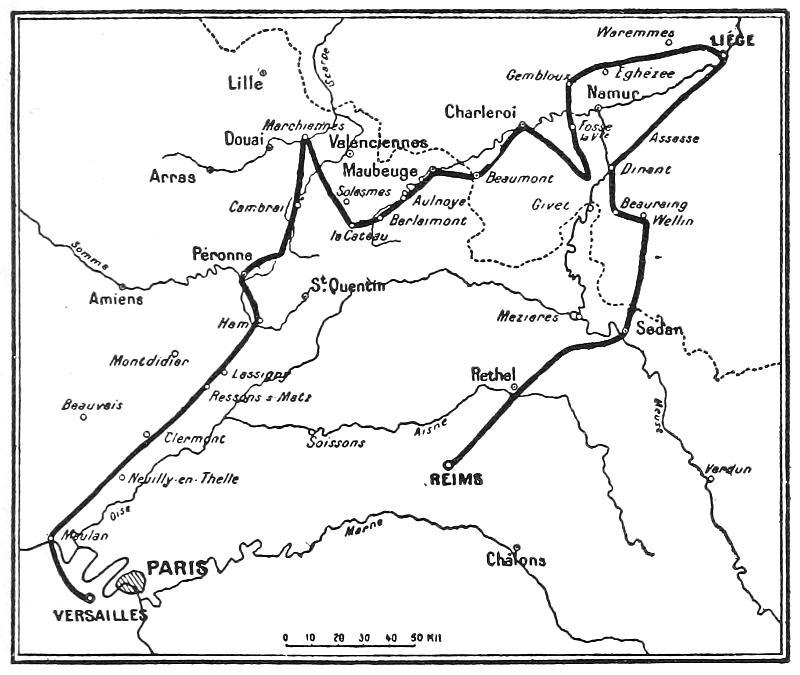

Map illustrating the Route followed by the 22nd Regiment of Dragoons.

IMPRESSIONS AND

EXPERIENCES OF A

FRENCH TROOPER

1914-1915

BY

CHRISTIAN MALLET

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

1916

Copyright, 1916

by

E. P. DUTTON & CO.

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

In Memoriam

TO MY CAPTAIN

COUNT J. DE TARRAGON

AND

TO MY TWO COMRADES

2nd LIEUT. MAGRIN and 2nd LIEUT. CLÈRE

WITH WHOM

MANY PAGES OF THIS BOOK ARE CONCERNED

WHO FELL

ALL THREE ON THE FIELD OF HONOUR

IN DEFENCE

OF THEIR COUNTRY

“Dragons que Rome eut pris pour des Légionnaires.”

| PAGE | ||

| Frontispiece | 9 | |

| The 22nd Regiment of Dragoons | 11 | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | —Mobilisation—Farewells—We leave Rheims | 13 |

| II. | —Across the Border into Belgium—Life on Active Service from Day to Day—After the Germans had Passed through—The Retreat | 26 |

| III. | —How we Crossed the German Lines—The Charge of Gilocourt—The Escape in the Forest of Compiègne | 43 |

| IV. | —Verberie the Centre of the Rally—The Epic of a Young Girl—Mass in the Open Air—From Day to Day | 74 |

| V. | —The Two Glorious Days of Staden | 97 |

| VI. | —The Funeral of Lord Roberts—Nieuport-Ville—In the Trenches—Ypres and the Neighbouring Sectors—I Transfer to the Line | 110 |

| VII. | —The Attack at Loos | 144 |

| Index | 165 |

This picture by Carrey represents the night charge of a squadron of 22nd Dragoons against German trenches near Compiègne. During the night of September 9th, the squadron leader, who had received orders to endeavour to intercept and capture a large enemy convoy, suddenly came under a hot fire from German trenches. In the darkness it was impossible to choose his country, but the position before him must be attacked, and, signalling the charge, he led his squadron at the trenches. As the first line rose to the jump the Germans scuttled out in panic, only to be ridden down and destroyed. With the 22nd are shown two troopers of the 4th Dragoon Guards, belonging to the 2nd British Cavalry Brigade. Both had fought at Mons, but during the retirement had lost their regiment, and after wandering about for some days fallen in with the 22nd Dragoons and fought for some weeks in their ranks. Whilst still under heavy fire, one of these Englishmen, throwing the reins of his horse to his companion, dismounted and ran to and rescued a French trooper whose horse had fallen dead and pinned him to the ground; on rejoining their own regiment their French commanding officer gave them the following certificate of service:

“I, the undersigned, certify that T..... and B....., troopers, belonging to the 4th Dragoon[10] Guards, lost themselves in the neighbourhood of Péronne on the 20th August, and joined up with my squadron, and have since then formed part of it and engaged in all its operations. On the night September 10-11 my squadron received orders to capture a German convoy, and found itself surrounded by the retreating enemy.

“T..... and B..... took part in a charge by night against entrenched infantry, and helped in the fighting on the outskirts of the forest of Compiègne.

“They are both men of fine courage and high training, and have given me every satisfaction.

“(Signed) A. De S.,

“Captain, 22nd Dragoons.”

(Le Temps.)

| AUSTERLITZ | 1805 |

| JENA | 1806 |

| EYLAU | 1807 |

| OPORTO | 1809 |

The 22nd Regiment of Dragoons was raised in 1635 under the name of “The Orleans Regiment,” and took part from 1639 to 1756 in all the great wars in which the French were engaged before the Revolution. From 1793 to 1814 the regiment was continually at work, first under the Republic and then in Napoleon’s armies.

It saw service in the Army of the Sambre and Meuse, 1794-1796; the Army of the Rhine, 1800; the Grande-Armée, 1805; in the war in Spain, 1808-1813; the Campaign in Saxony, 1813; the Campaign in France, 1814.

The regiment was disbanded in May, 1815, and was not raised again until September, 1873.

MOBILISATION—FAREWELLS—WE LEAVE RHEIMS

Of all my experiences, of all the unforgettable memories which the war has woven with threads of fire unquenchable in my mind, of all the hours of feverish expectancy, joy, pain, anguish and glorious action, none stands out—nor ever will—more clearly in my recollection than the day when we marched out of Rheims. Nothing remains, except a confusion of disconnected memories of the days of waiting and of expectation, days nevertheless when one’s heart beat fast and loud. A bugle-call sounding the “fall-in” lifts the curtain on a new act in which, the empty years behind us, we are spurring our horses on into the eternal battle between life and death.

On the thirtieth of July, 1914, I did not believe in the possibility either of war or of mobilisation—nor even of partial mobilisation—and I refused to let my thoughts dwell on it.

The good folk of Rheims, excited and anxious, gathered from time to time in dense crowds outside the building of the Société Générale, on the walls of which the latest telegrams were posted up, then broke up into knots of people who discussed the situation with anxiety and even consternation. At the Lion d’Or, where I turned in for dinner on the terrace under the very shadow of the cathedral, I called for a bottle of Pommery, saying jocularly that I must just once more drink champagne; a message telephoned from a big Paris newspaper reassured me, and in the peaceful quiet of a fine summer’s night I returned to my quarters with a light heart.

As I was turning into bed I caught a glimpse through the barrack window of the two Gothic towers of the cathedral, standing high above the city as if in the act of blessing and guarding it.

All was quiet: the silence was only broken from time to time by the cry of the swallows as they skimmed through the clear air.

War, I repeated to myself, it is foolish even[15] to think of, and this talk of war is but the outcome of some disordered pessimistic minds; and with that I went to sleep on my hard little webbed bed ... for the last time.

Towards midnight I woke with a start, as though someone had shaken me roughly. Yet all was still: the barracks were rapt in sleep. Near by me only the loud and heavy breathing of the twelve men who made up the number occupying the room could be heard, as I lay on my back, wide awake, waiting, for I now felt that the signal would surely come which should turn the barracks into a very hive of bees.

Five minutes passed—perhaps ten—then a deafening bugle call which made the very walls vibrate, calling first the first squadron, growing in volume as it called the second, louder still the third, like the roar of some beast of prey as it summoned ours; then it died away as it got farther off across the barrack square where the fifth squadron was quartered.

It was the call to arms.

The sleepy troopers, half awake, sat up in their beds with a start—“Hulloa!—what? What is the matter?... Are we really mobilising?”

Then followed the sound of heavy boots in[16] the corridors, heavy knocks on the doors, the silence of the night was a thing of the past and had given place to deafening clatter.

In a few seconds every man was on his feet without any clear idea as to what was forward. The sergeant-major called to me: “Mallet—run and warn the officers of the squadron to strap on their mess tins with their equipment and assemble in barracks as quickly as possible.”

So it’s serious, is it? and in a flash the truth, the very reverse of what I had been trying to believe, forced itself upon me and paralysed all other power of thought. Whether it breaks out to-morrow or in a month’s time, it is war—relentless war—that I seem to see like a living picture revealed.

The impression masters my mind as I turn each corner of the dark streets and open spaces, and the cathedral with its twin towers, so peacefully standing there, is transformed into a giant fortress watching over the safety of the country-side.

A man comes out of a house on the place and runs after me, I hear his heavy shoes striking the pavement behind me; breathless he blurts out the question, “Is war declared?”

“War ... yes ... that is to say, I don’t know.”

I continue on my way to carry out my orders with enough time left to run up to my own rooms and get some money and clean linen.

I got back to barracks as dawn was spreading over the sky, and found our commandeered horses being brought in by civilians and soldiers in fatigue overalls. An elderly non-commissioned officer shrugged his shoulders and said in a low voice, “Commandeered horses being brought in already!—that does not look very healthy.”

At the time of the Agadir affair things did not get as far as that, and the incident forced itself on my mind as proof that war was inevitable.

Packing and preparation were over and the men, waiting for orders, were wandering about the square, and in the canteen, which they filled—still half dark as it was—one heard shouts of joy and high-pitched voices telling the oldest and most threadbare stories.

But the canteen-keeper—friend of us all—with red eyes and shaking voice, was talking of Bazeille, her own village, burned by the Germans in 1870, where her old father and mother still lived. She is horrified at the thought of another invasion of the soil of France.

“The Bosches here? No, indeed, Flora, you[18] are talking wildly; never you doubt, we will send them to the right-about and back to Berlin at the point of our toes—give us another glass of white wine—the best—that’s better worth doing.”

“Well, well!”

At the table where I sat with my own particular friends, all were in high spirits, all talking the greatest nonsense, becoming intoxicated with their own words as they romanced of heroic charges, of wonderful forced marches and highly fantastic battles; I alone remained somewhat serious and heavy of heart, and abused myself for being less free of care than they in the face of this triumph of manliness and youthful high spirits; yet in spite of myself, I watched them, these comrades of mine, day in, day out, to whom I should become more closely allied still by war, and tried to pierce the mists of the future, grey and threatening, and to discern what was to be the fate of each.

There they sat: Polignac, who was to be taken prisoner a short four weeks later, and who still languishes in a Westphalian fortress; Laperrade, who was to fall dead with a lance head through his chest as he defended his officer; Magrin, fated to die, when spring came, with a bullet through his heart; Clère,[19] whom death was to claim three days after having heroically won his commission, and all the rest of them, too many to name here, but of all of whom I cherish in my heart a recollection not only tender but full of pride that they were my friends.

Yet the day passed in a fever of expectation and excitement. The smallest piece of news, or the greatest absurdity told by the latest man from the guard-room of the 5th, or the stables of the 2nd, or by “the adjutant’s orderly,” flew like the wind round the barracks, increased in volume, became distorted, took shape no one knew how and in the end was believed by all—until some still more ridiculous tale took its place.

There were waggish fellows, too, who wandered from group to group with a serious look on their faces, saying, “Well, it’s come now; I have just heard the Colonel give the order to stand to horses,” and until evening, when we were again crowded inside the canteen, it was the same hunger for news, the same excitement, the same desperate longing to know what was happening.

Only at seven o’clock did we get the official news, and although it came as no surprise, the whole barrack was stunned by it. Squadron orders issued at seven o’clock gave us three[20] hours to prepare to march, as prescribed by the rules governing the movements of covering troops, to which we belonged. In three hours we should be on the way to an unknown destination; to ourselves fell the honour of being the advance guard; to us the task of guarding and watching the frontiers whilst the rest of the army was mobilising; and with keen pride in the fact, we held up our heads and thrust out our chests, whilst our faces took on a look of confidence in our power to conquer. Even the humblest trooper seemed transfigured, and in that moment I realised, perhaps for the first time, the high soul of France.

But the news soon spread beyond the barracks. Rheims, although some twenty minutes’ walk away, somehow learned it, and almost immediately all the town flocked to the barrack gates. I say all the town because all classes together hurried there pell-mell—not only those with a brother or son or a friend amongst the troops about to set off, but those who were drawn by ties of friendship with the regiment, and those who came from mere curiosity. The crowd, which got larger and larger, beat upon the iron gates like waves breaking vast and black on a rocky shore. Old women came to give a last kiss to their[21] sons; old men, too, pensioners who had fought in ’70, whose hands trembled as they pressed those of their boys, distracted little shop girls who held their lovers passionately in their arms—silk frocks and broadcloth mingled together in one vast crowd swayed by deep emotion, brave and placid, though its heart was near breaking—every sob was stifled, every mouth drawn with sorrow yet tried to laugh, and it was cheerily that the last partings took place, the last touching and heartfelt “God speed” was said.

How great a country to possess such children! Soon the gates could no longer bar the passage of the crowd which swept like a torrent through the outer square, overwhelmed the sentries, and threatened to engulf everything.

As the hour of departure grew nearer, the farewells became more animated. Then the bugles sounded through the barracks the order for “majors to join the Colonel,” next captains and others of commissioned rank; there was a scurrying of officers to and fro before the orderly room, and Colonel Robillot himself could be seen standing on the doorstep watching the scene with a look of pride and indulgence in his eyes.

At nine o’clock, as I was standing some[22] distance apart in a corner of the square with friends who had come to bid me a last farewell, a non-commissioned officer, touching me on the shoulder, warned me that my troop was about to fall in, and I had to break off my adieux.

From that moment I was to think no more of myself. All was over with affairs that bound heart or fancy. The supreme moment had come when words no longer count, and when the eyes try to fill themselves with one last gaze upon those whom one is leaving—goodbye to family, to love, to self, to the joy of the living—all one’s soul goes out in this last gaze.

This look would say, “Farewell, I will be brave, never doubt it, don’t cry, don’t suffer regrets.” This look embraces all that life has meant up to now, whether of joy or sorrow. It is final—a farewell, a promise—it signifies the end—all one’s very soul is in one’s eyes.

And, in effect, no sooner was my back turned and I stood at my horse’s side than all other thoughts left me. I forgot that I had perhaps said a last farewell, in face of the essential importance of assuring myself that nothing of my equipment should be forgotten, that my horse is soundly shod, of tightening[23] up the girths and seeing that my blanket was properly folded, and, automatically, I went on repeating to myself, “Let me see ... I have my lance, my sword, my carbine[1] ... have I thought of everything?” and seemed to look disaster in the face on finding that I had no water-bottle—what was I to do? The very bottle that Flora, the canteen-keeper, had filled with boiling soup in her motherly way—“Oh, my water-bottle”—a real calamity it seemed—empires might crumble; I should have no soup to-morrow morning—all my outlook on war is shrouded in gloom.

Still it was no time to behave like a child. One by one each trooper led his horse into the huge barrack square, where spots of light from electric torches carried by the officers indicated where each troop was to take up its position.

On the chalky ground of the square, showing grey in the darkness, what looked like parallel black lines were growing longer. They were lines of troops, growing into squadrons and increasing until they became the whole regiment. Behind them were the baggage waggons, the travelling forges, machine-guns, commandeered carts, the cyclists’ detachment and all the rest.

The riding school lay between us and the outer square, which was filled with light and alive with the impatient crowd crushing forward to see us ride out of the narrow way kept open for us, and the time dragged as we waited for every man to be in his place and for the signal to move out.

The horses, impatient at standing still, would paw the ground, and now and again a long-drawn neigh would break the silence. At last a figure appeared in silhouette—it was the Colonel.

“Mount!” The two majors repeated the command, and in each half-regiment its two captains, first, then the subalterns and non-commissioned officers repeated it.

A wave seemed to flow from troop to troop like an eddy in a pool, and, sitting rigid in our saddles, our lances held upright, we waited the final order, which was to decide our future and direct us towards the unknown.

“March!” Quitting the dim light of the inner, we came suddenly into the brightly lit outer square, where thousands of hands were held up to bid us a frenzied farewell.

A cry from the crowd followed as we dragoons, sitting like statues, our helmets drawn well down over our faces lest we should betray any sign of emotion, passed out of the barracks[25] which many were never to see again, amid the cheers of a multitude, and the noise of thousands of feet which grew less and less distinct as we rode on.

“I say, old pals, don’t forget your sweethearts,” cried a little street girl standing on the edge of the foot-path, and that was the last word I heard as Rheims became more and more indistinct in the darkness, whilst we pushed on towards the east.

ACROSS THE BORDER INTO BELGIUM—LIFE ON ACTIVE SERVICE FROM DAY TO DAY—AFTER THE GERMANS HAD PASSED THROUGH—THE RETREAT

6th August to 5th September, 1914

It was on the 6th of August that we crossed the frontier into the Walloon district of Belgium at Muno, to bring succour to the Belgians whose territory had just been violated by the German Army.

In turning over my diary, I select this incident from among many others and stop to describe it, for it seems but right to recall the enthusiastic and touching welcome with which the whole people greeted us—a people now, alas, crushed under the German heel. We were welcomed with open arms—they gave without counting the cost, they threw open their doors to us and could not do enough for the French who had come to join forces with them and bring them succour.

There is not a trooper in my regiment, not a soldier in our whole army, who does not recall that day with feelings of profound emotion.

From the time we left Sedan, our ears still ringing with the cheers that had sent us on our way from Rheims, we received the heartiest of welcomes and good wishes at every village we passed through, but once across the frontier we were acclaimed—prematurely, as it turned out—as veritable conquerors.

Cavalry on the march, squadron after squadron, has a marked effect on people, and takes the semblance of an invincible rampart against which any enemy must go down.

After seventeen hours in the saddle, with helmet, lance, carbine, sword and full kit, now by a night-time more than disagreeable by reason of an icy cold fog, now under a tropical sun which scorched us, all the while in a cloud of dust, tormented by swarms of midges and horse-flies which hung about us, and tortured by the sight of cherry trees heavy with fruit, which hung over the road, but the branches of which were out of our reach, we approached the frontier.

On the road we passed all the vehicles in the district which had been requisitioned by the military, interminable convoys of them, amongst which, irrespective of class, were[28] humble peasant carts, old-fashioned shaky barouches, motor-cars, with the crests of their owners blazoned on the doors, all filled with oats and forage.

Aëroplanes followed us and passed ahead of us flying all-out towards the east. Every now and again we had to draw to the side of the road to allow streams of motor omnibuses drawn from the streets of Paris, filled with chasseurs[2] and infantry, to pass by; and our teeth crunched the fine dust that we incessantly breathed.

At length we passed by a fir wood, and a post, painted yellow and black, showed us that we were in Belgium; then we came in sight of a village, almost a hamlet, from which, as we drew near, there rose a noise, the sound of singing, growing louder as we drew near—the Marseillaise, sung in welcome by all the folk from the country-side, gathered at their country’s gateway to greet us.

All joined in, women, children with shrill voices, even the old men. They ran along after us till we reached the place, when the song ceased and a thousand voices cried: “Vive la France! Vive les Français!” with such vigour that the horses were startled and cocked their ears in alarm.

One and all brought us gifts, each according to his or her means, fruit, bread, jam, cakes, cigars and cigarettes, pipes and tobacco. I should fill a page with a list of what was thrust upon us. To our parched lips women held flagons of wine or beer, which refreshed us more perhaps when it ran down our cheeks, caked with dust, even than when it found its way down our throats, as the jolting of our horses caused us to spill the precious liquid. It taxed us to stuff away all the dainties in our already overfull pockets, and we stuck cigars into our tunics between the buttons, and flowers in the buttonholes.

A number of French nuns with white head-dresses, like huge white birds, presented us with sacred medallions. I shall always retain graven on my memory the agony depicted in the beautiful, sad eyes of an elderly nun with white hair, who held out to me the last of her collection, a scapular of the Virgin in a brown wrap, and as she did so, said to me, “God guard you, my child.”

And in each village we passed through, that day and the days which followed, we met with the same welcome and the same generosity. It was the same at Basteigne, at Bertrix, at Rochefort, Beauraing, and Ave; indeed everywhere, in the towns as in the villages,[30] the crowd hailed us and fed us. Belgians have handed me boxes of as many as fifty cigarettes.

After exhausting days of twelve or fourteen hours in the saddle I noticed that the troopers, worn out with fatigue, suffering from the heat, from hunger and thirst and intolerable stiffness, sat up in their saddles instinctively as we approached a village, prompted by an unconscious sense of pride in holding up their heads, and I can say, for my part, that such a welcome as we received always banished any feelings of fatigue.

One of our bitterest regrets was having to pass again through Belgium in the reverse direction and to read the dumb surprise on the faces of the people who had thought us unconquerable, but whose great hearts were full only of commiseration for us, worn out as we were, and who, forgetful of their own anxieties, did all in their power to help us.

A peasant woman, I remember, gave us the whole of her provisions, everything that remained in her humble dwelling. The enemy were then advancing on our heels in a threatening wave, and, on my expressing astonishment that she should strip her shelves bare in this fashion, she shook her fist towards the horizon in a fury of rage and exclaimed: “Ah, sir,[31] I prefer that you should eat my provisions rather than leave them a crumb of bread.”

Up till the 19th August we had advanced in Belgium; the retreat of the division commenced that same day from Gembloux. We kept on seeking, without success, to get in touch with the German cavalry. Nothing but petty combats took place with insignificant details, a troop at most, but more often with patrols, reconnaissance parties and little groups who surrendered on our approach in a contemptible fashion.

I saw a German major, Prince R——, accompanied by two or three troopers, surrender themselves while still some two hundred mètres from one of our weak patrols. They threw down their arms and put up their hands. It was a sickening sight.

Everywhere the enemy’s cavalry gave ground, vanished in smoke, became a myth for our regiment, in spite of our forced marches. Each day we spent ten, fifteen, twenty hours in the saddle. One day we actually covered a hundred and thirty kilomètres in twenty-two hours, and reached our culminating point to the east, almost under the walls of Liége.

Although we hardly saw any Germans during this first month, we could, per contra, follow them by the traces of their crimes.

By day, from village to village, lamentations spread from one horizon to the other, and I regret not having noted the names of the places which were the scenes of the atrocities of which I saw the sequels. I regret not having taken the names of the unhappy women whose children, brothers and husbands had been tortured and shot without motive, not to speak of the outrages which they themselves had undergone, not to speak of the assaults of lechery and Sadism of which they had been the victims. They alluded to these in a fury of rage or made an involuntary confession in an agony of humiliation and grief.

By night a furrow of fire traced the enemy’s path. The Germans burnt everything that was susceptible of being burnt—ricks, barns, farms, entire villages, which blazed like torches, lighting the country-side with a weird light.

We entered villages of which nothing remained except smoking and calcined stones, before which families, who had lost their all, grieved and wrung their powerless hands at the sight of some black débris which had once been all their joy, their hearth and home.

I wish particularly to insist that these deeds were not the result of accident, for we were daily witnesses of them for a whole[33] month. I still shiver when I think of the confidences which I have received. The pen may not write down all the facts, all the abominations, all the hateful things, all the lowest and most degrading filthiness inspired by the imagination of crazy erotomaniacs. It was always Sadism which seemed to guide their acts and predominate amongst their misdeeds.

Here a mother mourned a child, shot for some childish prank; there a young girl grieved for her fiancé, hung because he was of military age; farther on a helpless old man had had his house pillaged and had been brutally treated because he had nothing else to offer. At every step we heard the story of crime, and those guilty deserve to be hung. Such are the things of which such an enemy was capable—an enemy who refused combat, who advanced hastily under cover of night to rob and burn a defenceless village, and who seemed to vanish like smoke at the approach of our troops, leaving in our hands hardly more than some drunken stragglers unable to regain their army, or some robbers who had waited behind to rob a house or to violate a woman, and had been taken in the act.

We passed through all that in our endless quest, always in the saddle, sleeping two or[34] three hours at night, in an exasperating search for the German cavalry, which was constantly reported to be within gun-shot, but which disappeared by enchantment each time we approached. To give an idea of what we endured, I have transcribed word for word the notes from my field pocket-book describing some of these August days. These notes were written in most cases on horseback by the roadside during a halt.

7th August.—Torrential rain; twelve hours in the saddle; we are worn out with fatigue; put up at Basteigne; arrived at night. My troop is on guard. I mount duty at the bridge; we are fed by the populace, nothing to eat from rations.

8th August.—Réveillé 3 o’clock, mounted a last turn of duty at the bridge till 5 o’clock. Departure; rested at midday in an open field for dinner. While we are eating, enemy is reported near; we follow immediately towards Liége. Don’t come up with them. March at night till one in the morning; have done one hundred and thirty kilomètres and twenty hours on horseback, sleep in an open field from two to four.

9th August.—Torrid heat, men and horses done up; billeted at Ave after twelve hours[35] in the saddle. First squadron ambushed. Lieutenant Chauvenet killed. The Germans flee, burning the villages, killing women and children.

11th August.—Leave Ave at 5 o’clock. The heat appears to increase, not a breath of air. For two hours we trot in clouds of blinding dust. A regiment of Uhlans is reported. The Colonel masses us behind a hill and we think we are going to deliver battle; but the enemy steals away once more. Thirst is a torture, my water-bottle lasts no time. Arrive at Beauraing at six o’clock. Thirteen hours in the saddle.

12th August.—We onsaddled at 5 o’clock. False alarm; wait at Beauraing.

14th August.—Alarm, the regiment moves off; I am left behind to accompany a convoy of reservists. The village is barricaded, the enemy is quite near. Only a handful of men are with the convoy. Wait at the side of the road with Fuéminville and Lubeké. Five dismounted men arrive, without helmets, done up, limping, prostrated, grim as those who have seen a sight which will for ever prevent them from smiling; the fact is that the remains of the 3rd squadron of the 16th have been caught in an ambush by the German infantry concealed in a wood. They[36] have been shot down at point-blank range without being able to put up a fight. Never have I seen human waifs more lamentable and more tragic. They had seen all their comrades fall at their side and owed their lives only to the fact that they had themselves fallen under their dead horses and to a flight of 40 kilomètres through the woods. Montcalm is amongst the killed. The convoy marched out at half-past nine at night, at the walk, an exasperating pace of 4 kilomètres an hour. We took all night to do 23 kilomètres. I ask myself when we are likely to rejoin the 22nd, even whether the 22nd still exists.

15th August.—We bivouac near the village of Authée, with the convoys of the 61st and 5th Chasseurs. It is dark and cold, and this night has tired me more than my longest marches. The waiting about unnerves us, and my blood boils when I think that the 22nd must be on the eve of having a fight. The Germans lay siege to Dinant eight kilomètres off. One hears the guns as if they were alongside. Our turn is near, I think. No one is affected thereby, and we prepare our soup to the whistling of shells. The cannonade seems to redouble, they are giving and taking hard knocks, and some[37] there will be who won’t answer their names to-night.

Ten o’clock.—The different convoys move off. 16th, 22nd, 9th, 28th, 32nd Dragoons, etc. All at once we are stupefied by seeing a battalion of the 33rd of the line, or rather what remains of the battalion, some thirty terrifying beings, livid, stumbling along, with horrible wounds. One has his lips carried away, an officer has a crushed hand, another has his arm fractured by a shell splinter. Their uniforms are torn, white with dust and drip with blood. Amongst the last comers the wounds are more villainous; in the waggons one sees bare legs that hang limp, bloodless faces. They come from Dinant, where the French have fought like lions. Our artillery arrived too late, but they had the fine courage to charge the German guns with the bayonet. The guns spit shell without cease and the crackle of musketry does not stop. We go across country to billet at Florennes. These last days of tropical heat give place to damp cold. It is raining. We meet long convoys of inhabitants who, panic-stricken, quit their houses to go and camp anywhere at all. It is lamentable. Two kilomètres from Florennes we “incline.” The cold is biting, in spite of the cloak I wear. We arrive in black darkness[38] at a village where we bivouac in spite of the torrential rain. I rejoin the regiment with infinite trouble; clothes, kit, horses are dripping wet. They must stay so all night. I do a stable guard at three in the morning without a lantern. The horses are tied up by groups to a horseshoe. They kick and rear, upsetting the kit and the lances in the mud; I dabble about and lose myself in the night. The village is called Biesmérée.

Sunday, 16th August.—The weather has cleared up. I leave again with the regiment. We are going to put up at Maisons-Saint-Gérard. Just before arriving there a storm bursts and wets us through; the water runs down into our breeches. I am as wet as if I had been dipped in a river; and one must sleep like that ... and yet one does not die!

17th August.—Off at 5 o’clock. We bivouac at Saint-Martin in the meadow between two small streams. I have hurt my left foot badly, and at times I feel an overpowering fatigue, but one must carry on all the same. The bivouac is admirable. Big fires warm up the soup for the troops. The little stream shimmers, all red, and encircles the bivouac. The day ends; splendid. Some Cuirassiers bivouac a little higher up on the village green. We hear them singing the Marseillaise. We[39] sleep in a barn in heaps one on the top of the other.

19th August.—The 4th squadron is on reconnaissance. We start alone, at a venture. We are in the saddle all day. At night we make a triumphal entry into Gembloux and we are baited with drinks and food. The Germans are at the gates of the town and the crowd is wildly excited. The sun goes down without a cloud, round as a wafer. I forget the day’s fatigues and we venture across the plain and the woods. It is an agonising moment; we hide ourselves behind a long rick of flax; the enemy is some hundreds of mètres off and all night we have sentries out. I slept two hours yesterday, to-day I am passing the whole night on foot. The cold is cruel. Now and then my legs give way and I nearly fall on my knees. We have had nothing to eat but bread, the chill damp gets into our bones. Some Taubes pass, sowing agony.

20th August.—I am one of the point party under Lieutenant Chatelin. We fire on some horsemen at 600 mètres. The squadron is still on reconnaissance. One could sit down and cry from fatigue. We advance towards Charleroi, whose approaches are several kilomètres long. A population of miners. Everywhere are foundries, mines, factories, and for[40] two hours unceasing acclamation. We arrive at a suburb of Charleroi, done up, falling out of our saddles. Interminable wait on the place; night falls. The camp kit comes up at last, but the march is not yet over, we are camping five kilomètres farther on. It is enough to kill one. We get to Landelies. Rest at last, we bivouac. I share a bed, with Delettrez, for the first time for three weeks. In a bed at one side a fat old woman is sleeping. No matter, it is an unforgettable night.

21st August.—Landelies; rest; we satisfy our hunger; we expect to pass a quiet day and night. At four o’clock we are off to an alarm; we are in the saddle all night and arrive in a little village, whose name I forget, half dead with hunger and cold. The peasants give us bread. We have been all day on horseback.

22nd August.—Are we going to have a little rest? No, we were out of bed all night and we are at it again. We do not understand the movements we are carrying out. Are we retreating? The fatigue is becoming insupportable. We get to Bousignies at three in the morning. On the road I lost my horse during a halt and I found myself alone in the night and on foot. I had all the trouble in the world to catch up the squadron on foot.[41] We slept two hours in the rain in a field of beetroot. Off again at 9 o’clock. Loud firing twenty kilomètres off. All the peasants are clearing out. They say that Charleroi is on fire.

And so it goes on each day till the end of the month. The 26th we marched in the direction of Cambrai; we put up at Epehy, which the enemy burnt the following day. The peasants replied by themselves setting fire to the crops to prevent their falling into the enemies’ hands.

At Roisel, a whole train of goods blazed in the midday heat. We went on to Péronne. The 28th we were at Villers-Carbonel, where I was present at an unforgettable artillery combat. I saw shells throw some French skirmishers in the air by groups of three and four at a time. We left Villers-Carbonel in flames, and, from that moment, we beat a rapid retreat towards Paris, passing by Sourdon, Maisoncelle, Beauvais, Villers-sur-Thère, Breançon, Meulan, Les Alluets-le-Roi, and, after a last and painful stage, we put up at Loges-en-Josas, four kilomètres from Versailles, where the fortune of war brought me to one of our own estates.

Thus it came about that my mother, who[42] believed me to be at the other end of Belgium, caught sight of me one fine morning coming up the central drive to the château on foot, leading my horse, my lance on my shoulder, followed by a long file of troopers.

HOW WE CROSSED THE GERMAN LINES—THE CHARGE OF GILOCOURT—THE ESCAPE IN THE FOREST OF COMPIÈGNE

6th to 10th September, 1914

Having left Versailles we arrived at Saint-Mard on the 6th of September to find ourselves in the thick of the battle of the Marne. The struggle extended all around us, from one horizon to the other, and if it was incomprehensible to our officers it was still more so to us private soldiers. In the evening, from Loges-en-Josas, where we had been billeted, we heard the guns. Everyone was sure that Paris would be invested within the next two days, and then we were suddenly sent off to be stranded some forty kilomètres to the north-east of Paris. We were ignorant of the movements going on, and we were amazed and quite out of our reckoning, hardly daring to believe that the enemy, who the evening before was thought to be at the gates of Paris, was now in retreat.

For my own part I preserve only a confused and burning recollection of the days of the 6th and 7th of September, days memorable amongst all others, since they saw the beginning of the victorious offensive of the armies of Maunoury, of Foch, of French and of Langle de Cary. The heat was suffocating. The exhausted men, covered with a layer of black dust adherent from sweat, looked like devils. The tired horses, no longer off-saddled, had large open sores on their backs. The air was burning; thirst was intolerable, and there was no possibility of procuring a drop of water. All around us the guns thundered. The horizon was, as it were, encircled with a moving line of bursting shells, and we knew nothing, absolutely nothing.

In the torrid midday heat we kept advancing, without knowing where or why. We passed a disturbed night rolled in our cloaks in an open field, without rations and already suffering from hunger. The next day was a repetition of the last and was passed in the same hateful state of physical exhaustion and of moral inquietude. From time to time, behind some hill, beyond some wood, quite near, a sudden and violent musketry fire broke out; the gun fire redoubled in[45] intensity and we heard the whistle of the shrapnel passing high over us, and the noise of the bursting shell. There, we said to ourselves, is the fighting; there, no, there, and then there on the left, on the right; it was everywhere. Repeatedly our column had to make sudden detours to avoid artillery fire. Still we knew nothing, and we continued our march as in a dream, under the scorching sun, gnawed by hunger, parched with thirst and so exhausted by fatigue that I could see my comrades stiffen themselves in the saddle to prevent themselves from falling. The sun went down with a splendour that no one thought of admiring. Little by little, insensibly, our figures bent forward till they touched the wallets on our saddles, and we gave way to a sort of torpor. Then a long tremor ran along the ranks. Above the village of Troène we fell into the thick of the fight. This happened so quickly that I preserve only a visual image of it. We had slowly climbed a hill, whose shadow concealed the setting sun from us. As we came out on the crest of the hill, we caught a sudden glimpse of a regiment of chasseurs-à-cheval, silhouetted in black against the immense red screen of the sky, charging like a whirlwind, with drawn sabres.

A “75” gun on our flank fired without interruption. I can see now a wounded chasseur who rose from the grass where he lay almost under the muzzle of the gun, and who fell back, as if struck by lightning, from the displacement of air caused by the shell. A second later nothing was to be seen except a confused mêlée behind a small wood. The noise was terrible, and was made up of a thousand different sounds. An officer of chasseurs, with a bullet through his chest, bareheaded, all splashed with blood, came down the hill leaning on his sword, and leaving behind him a long trail which reddened the grass. Then the sun seemed to perish as the immense uproar died down; all the noises died away, and we continued our road in the rapidly falling darkness, having had a sudden and fugitive vision of one scene amongst the thousands which compose the drama of a great battle.

All night we had marched without repose, without food. In our exhaustion we had become the spectres of our former selves, and our hearts were breaking from discouragement. We did not know that right alongside of us the most victorious offensive in the history of the world was commencing. We did not suspect that, under pressure from General[47] Maunoury, the German 4th Reserve Corps was giving way, and that this must assure the rout and the final defeat of Von Kluck’s army.

From the 8th we began to play an active part in the great battle. The 5th Cavalry Division was ordered to surprise a German convoy and to seize it. The officers told us of this mission. At last we were going to do something; our time of waiting was at an end, and there was to be no more wandering about the burnt-up country, devoured by thirst and discouraged at feeling ourselves lost and forgotten in the great struggle we had set our hand to. The convoy would be four kilomètres long, and we could already imagine the attack, the taking of the booty. It was going to be a romantic and amusing episode, and the dragoons sat up in their saddles, forgetting their fatigue and their hunger, and full of joy at the thought of the promised combat.

In my inner self I could not share the general enthusiasm; I felt that we had been exactly marked down by the enemy’s aircraft which flew over us each moment, insolently bidding defiance to our rifle and machine-gun fire.

The expedition, however, started off well. A young dragoon, sent forward as scout,[48] penetrated into a farm and there found fifteen Prussian Staff Officers engaged in stuffing themselves with food. He calmly pointed his revolver at them and advised them to surrender. “My regiment will be here directly; any resistance is useless.” In reality he had to keep them under the muzzle of his revolver for a long quarter of an hour, for the regiment was still far off. A major having shown signs of moving, the dragoon blew out his brains at point-blank range, and he succeeded in keeping them all terrorised until our arrival. This capture stimulated still further the general good humour. I can still see six of the fourteen prisoners file past the flank of the column, each between two dragoons, a forage cord tied to the reins of their horses, and I can see again the cunning and furious look of a “hauptmann” still bloated with the feast which we had prevented him from completing. I remember the gay, frank laugh of the whole regiment, its light-heartedness at having laid hands on these fat eaters of choucroute, who were too astonished even to be insolent.

A few moments afterwards three German motor-cars were sighted three hundred mètres off, going at a prudent pace. At once the ranks were broken and we galloped furiously[49] at them, each straining hard to be the first to get there; but, by quickly reversing their engines, the three chauffeurs succeeded in turning and made off at top speed, riddled by machine-gun fire, but out of range for us. The last of them, however, was destined to fall into our hands next morning, having been damaged by a shot in its petrol tank. We had to set it on fire so as not to abandon it to the enemy, who were pressing us on all sides. Half my regiment was now detached from the division and charged with the task of capturing, unaided, the tail of a convoy which was reputed to have broken down on the road.

At nightfall we entered the forest of Villers-Cotterets, under the command of Major Jouillié, and I was assailed by an acute presentiment of misfortune. I parted from the other half of the regiment and from the other regiments of the division with the clear and irresistible intuition that I would not see them again for a long time, and shortly afterwards we melted like shadows under the trees of the great dark forest.

Then commenced, for me, one of the most painful episodes of the whole war. The silence of the forest was lugubrious. A Taube persisted in flying over us, quite near to the ground, like a great blackbird. Its shadow[50] grazed us, one might have said, and nothing was more harassing and more demoralising than this enemy that followed us and kept persistently on our track. At a cross-roads, as we came out into a large clearing, it let fall three long coloured smoke balls to signal our presence to its artillery, which was doubtless quite near but of whose position we were ignorant. Then it disappeared with a rapid flight, and the night fell black as ink around us.

The voices of the officers seemed grave. The continual thrusts which the column made, its returns on its tracks, gave me to understand that we were groping our way, not knowing which to take. We descended in double file a terribly steep narrow path, preceded by the machine-guns, which had only just room enough to pass. The soft soil sunk in like a marsh. Then there was a sudden halt and, quite near me, I saw the Major’s face, full of anxiety. Addressing Captain de Tarragon in a choking voice he said, “The machine-guns are done for.” The rest of the phrase was lost, but I heard the words “bogged, engulfed, impossible to get them out....”

We were ordered to incline, and we climbed up again to the forest. All the men were alarmed at the loss of the machine-guns, abandoned[51] in the marsh, and the face of Desoil, the non-commissioned officer with the machine-guns, was heart-breaking. His mouth worked but no words came.

With this discouragement all of us felt a renewal of hunger which was painfully acute. Thirst too burnt our throats, and fatigue weighed down our exhausted limbs. Ah, how I envied the horses which nibbled the leaves and the grass. For two days our water-bottles had been empty, we had already finished our reserve rations and this contributed to the gloom on our faces.

Towards midnight, the village of Bonneuil-en-Valois was vaguely outlined in the night at the edge of the forest. The hungry and tired horses stumbled at each step; almost all the men were dozing on their wallets, and we committed the irreparable fault of dismounting and of sleeping heavily on the open ground, instead of utilising the cover of night to join one of the neighbouring divisions by a forced march. A small post composed of a corporal and four men was the only guard for our bivouac. Each of us had passed his horse’s reins under his arm, and all of us slept, officers and men alike, like tired brutes. We did not suspect that our sentinels were posted hardly three hundred mètres from the[52] German sentries, who were concealed from us by a fold in the ground which held a regiment of Prussian infantry, who had chanced to get there, within rifle range, just at the same time as we.

At dawn a neighing horse, some clash of arms, probably gave away our position, and the alarm was given in the enemy’s camp, which was separated from us only by a field of standing lucerne. The troopers slept on, and the German scouts crept up, absolutely invisible.

A sudden musketry fire woke us up, and the German infantry was on us. I cannot think of these moments without giving credit to the admirable presence of mind which saved the situation by the avoidance of all panic. The horses were not girthed up, many of the kits had slipped round, reins were unbuckled; no matter, we had to mount. I have a crazy recollection of my loose girth, of my saddle slipping round, of the blanket which had worked forward on to my horse’s neck; no matter, “Forward! Forward!” a second’s delay might be our ruin. A hail of bullets fell amongst us. Alongside of me, Alaire, a quite young non-commissioned officer, was hit in the belly. He was the first in the regiment whom I had seen fall. God![53] what a horrible toss he took, dragged by his horse, maddened by fear, crying out, “Rolland, Rolland, don’t abandon me.” Then, in a last contortion, his foot came out of the stirrup and he died convulsed by a final spasm. Near me, the Captain’s orderly gave a loud shout; horses, mortally wounded, galloped wildly for some mètres and then suddenly fell as if pole-axed.

I saw a man who, as if seized with madness, sent his wounded horse headlong to the bottom of a ravine and then threw himself after.

“Forward! Forward!” I followed the others, who made off towards the village. My horse trod on a German whose throat, gashed by a lance thrust, poured out such a stream of blood that the earth under me was red and streaming with it. “Forward! Forward!”

We were not going to view them then, these enemies who killed us without our seeing them, so hidden were they amongst the grass that they blended with the soil? Yes we were though, and suddenly surprise stopped short the rush of the squadrons. Before us, some mètres off, and so near that we could almost touch it with our lances, an aëroplane got up, like a partridge surprised in a stubble. A cry of rage burst from every throat. We[54] tried to charge it with our lances in the air, but it mocked our efforts, and our rearing horses were on the spot ten seconds too late. The enemy seemed also to have flown. All that remained were two or three grey corpses that strewed the soil. We trotted into the village with our heads down, humiliated at having been fooled like children.

After having passed the first few isolated farms along our road, an enemy’s section came for us, exposing themselves entirely this time, while a line of recumbent skirmishers fired a volley into us from our right, almost at point-blank range. There was nothing for it but to retire, unless we wanted to remain there as dead men, and at the gallop, the more so because a machine-gun was riddling the walls of a farm with little black points. We passed before it like a whirlwind; and, happily, its murderous fire was too high to hit us. I can still recall the sight of an isolated German, caught between the fire of his regiment and the charge of our horses. I turned my head and laughed with joy at seeing a comrade pierce him with his lance in passing.

The Germans were all round us, and our only line of retreat was by the forest, into which we all plunged in a common rush[55] without waiting for orders. The forest, at least, represented safety for the moment. It was a sanctuary calculated to protect us from an entire army, until we died of hunger. For a long time we marched in silence, cutting across the wood, avoiding the beaten path, for our intention was to attain the very heart of the forest, or some impenetrable spot where we could not be discovered, where we could regain our breath and where our officers could deliberate and take a decision. The whole half-regiment took shelter at last in an immense ravine, where we were sheltered from aircraft. We were covered by a thick vault of leaves in a sort of prehistoric gorge, which seemed far from all civilisation and lost in an ocean of verdure, and there we dismounted. The Major sent patrols to explore the issues from the forest, and we waited some mortal hours without daring to raise our voices.

Our situation was almost desperate. For three days we had touched not a morsel of bread, not a biscuit, our horses not a handful of corn. The reserve rations were exhausted; and the patrols, which came in one after the other, brought sad news. The Germans were masters of all the issues from the forest, and we were taken in a vice, prisoners in this gulf of trees and reduced to dying of hunger[56] and thirst. A little way off, the officers—Major Jouillié, Captain de Salverte, Captain de Tarragon, Monsieurs Chatelin, Cambacérès, Roy and de Thézy—deliberated with glum faces. Each stood near his horse so as to be able to jump on in case of surprise. In spite of everything the men’s spirits remained admirable. All had a jest on their lips, and the more serious amongst them wrote a line to their wives or mothers. Leaning against the trunk of a tree, I scribbled on two letter-cards, found in my wallets, two short notes of adieu. The day passed with depressing slowness.

Towards four o’clock two officers of Uhlans appeared on a little road which, so to speak, hung above us. At once all eyes were fixed on these two thin silhouettes. They advanced, talking quietly, with their reins loose on their horses’ necks. How great was the temptation to shoulder one’s carbine, take steady aim, feel one’s man at the end of the muzzle and kill him dead with a ball through the heart! Everyone understood, however, that it was necessary to keep quiet and let off the prey so good a mark was it, for doing so would have given the alarm and signalised our presence. Now they were right on us, so near that we could have touched them,[57] and yet they did not know that there were two hundred carbines which could have knocked them over at point-blank range. Even now I can distinctly see the face of the first, as if it were photographed on my brain. He was quite young, with an eye-glass well screwed into the eye, his face was red and insolent, just as the Prussian officer is always represented. He had a whip under his arm, and he even had a cigar. Suddenly his face and that of his companion contracted, as if confronted by some apparition. This French regiment must have seemed to them a phantom of the forest, some impossible and illusory vision seen in the shadow of the leaves. Their horses stopped short and, for the space of a second, their riders looked like two figures in stone. Then in a flash they understood and fled at full speed. For an instant we heard the stones fly under their horses’ shoes, but the sound grew fainter and fainter, and a deep silence reigned again.

The alarm had been given, the danger had still further increased, and, now that our place of concealment had been discovered, we had to start off again across the thicket and rock on our poor done-up horses. On reflecting over it, my mind refuses to believe that such a cross-country ride was possible. To throw[58] the enemy off the scent it was necessary to pass where no one would have imagined that a horse could go, and that involved a ride into the abyss in the deepening night, plunges into black gulfs, intersected by trunks of trees, to the foot of which some horsemen and their horses rolled like broken toys.

I felt my old horse, Teint, curl up and tremble between my legs. His hair stood on end and his nostrils opened and shut. On, on, ever on ... to the very heart of the old forest, whose most secret solitudes we troubled, frightening the herds of deer, which fled terrified before our cavalcade. For a moment it seemed as if we were at some monstrous hunt on horseback with men for quarry, and in spite of myself, a mortal fatigue seized on me. I shut my eyes and waited for the “Gone away.” Better it were to be finished quickly, since the game was lost.

The troops had got mixed and I found myself again for a moment amongst the 3rd squadron by the side of Lieutenant Cambacérès, and we exchanged a few brief words. Almost timidly, so absurd did the idea appear that one of us could escape, I asked him to write a line home if it were my luck to be done for and if he came out safe. I promised him the same service, if the rôles were reversed.[59] To such an extent does gaiety enter into the composition of our French nature, we even joked for a few moments and we shared a last tablet of chocolate, which he had preserved in his wallet, a service for which I shall always be grateful to him, for hunger was causing me insupportable pain. We were now going at a slow pace over a carpet of dead leaves, amongst trees which were singularly thinned out. Our object being to gain the heart of the forest, we had ended up by reaching its border, and we remained glued to the spot, holding our breath at the sudden vision seen through the branches.

The famous convoys that the division was out to take were there, in front of us, on a stretch of some eight kilomètres of road. Waggons of munitions, provision carts, water-carts, lorries of all sorts, were moving gaily along at an easy walk, and the rumbling noise was continuous.

In the calm of the evening each spoken word, each order given by the guides came to us clear and distinct. Then came the last vehicles, the last country carts, some stragglers tailing out into a confusion of cyclists and horsemen; and so the interminable convoy went on its way. The vehicles at its head had the appearance of toys on the horizon,[60] of toys designed with the pen on the gold of the sky; and the personnel looked like insects finely traced in the clear atmosphere. The whole thing went quietly on its way like a slow caravan. One would have said that here was a people coming to settle in conquered country and arriving at the end of its journey in the peace of a lovely evening.

The same day, at the same moment, General Foch, pushing the thin end of his wedge between the armies of Bülow and those of Hausen, enlarged that fissure which was to prove fatal to the German army which had almost arrived at the Marne. The pursuit was about to begin. These same convoys, whose peaceful aspect wounded our hearts from the insolence of their air of possession on French soil (we were ignorant of course that the dawn of a great victory was about to break)—these same convoys, lashed by terror and by the breath of panic, were going to follow beaten armies in a headlong and wild retreat, leaving on the road their waggons and stores.

From this moment a vague hope sprang up in our hearts and, as is often the case, we gathered courage when the worst of catastrophes seemed to be heaping on our heads.

Night fell little by little. It was impossible[61] to remain where we were. We were well within the German lines, of this there was no doubt, since we had the enemy’s troops behind us, while their convoys were on in front of us; but, under cover of night we might attempt a desperate stroke, and anything was better than dying of hunger. Towards ten at night our column came bravely out of the forest—a silent column whose members looked like phantoms. Cutting across country, we avoided Haramont, Eméville, Bonneuil-en-Valois, Morienval. As night fell a sombre gloom seized on us. All those silent villages, which we dared not approach, had a threatening appearance; lights appeared suddenly, more or less distant; a succession of luminous points was moving slowly, like a moving train going slowly. I was ill at ease, and this was causing me physical pain; my saddle girth was too loose and had allowed my horse’s blanket to slip till it threatened to fall off. No matter, for nothing in the world would I dismount. It seemed as if hands came out of the shadows and stretched forth to seize me. A breath of superstitious terror blew over us, and, in the deep surrounding silence, a single persistent and regular noise made us start with the fear of the unknown. It was the screech of the owl,[62] an unnatural cry which seemed like a signal replied to in the distance; and it made us shudder. My eyes eagerly searched the shadow to discover a hidden enemy. Twice I could have sworn that I saw a group of German uniforms, two mounted Uhlans, another on foot; but I mistrusted my eyes, hallucinations being of common occurrence at night, and I tried to pluck up courage.

While crossing a road a sudden noise and a cry of “Help!” rang out, a cry choked with agony and terror. It came from one of our men, whose horse had struck into mine and had rolled into the ditch. I turned and saw in a flash a brief struggle which the night at once blotted out. This time I had made no mistake. There really were two Germans struggling with our comrade; but I was carried on by the forward movement, and profound silence reigned again. If we were surrounded by enemies, why this conspiracy of silence? The horrid screech of the owl never ceased, imparting panic to our disordered imaginations, making us think that even a catastrophe was preferable to this maddening incertitude, to this agony of doubt. During this time I lived the worst hours of my life.

We advanced, however, marching from west to east, and soon we entered the great black[63] mass of the forest of Compiègne, from whence arose four or five bird-calls as we approached. No matter; for the second time the forest represented safety for us, and under the impenetrable shade of its tall trees we followed its edge in the direction of Champlieu, sometimes followed, sometimes preceded by the hooting which announced, as we learnt later, our approach and our passage.

At the moment when our agony was at an end, when hope revived, when, even, certain men giving way to fatigue had bent down on to their wallets drunk with sleep,—at that moment we fell definitely into the mouse-trap into which the Germans had methodically decoyed us, and a desperate attack was made on us from all sides. The drama took place so rapidly that I can remember only detached shreds of it. The clouds parted, letting fall a flood of moonlight; somewhere a cry resounded in the night, and the black forest seemed to spit fire. Thousands of brief flashes lit up each thicket, a hail of bullets thinned the column, and mingled with this were cries and a terrible neighing from the horses, some of which reared, while others lay kicking on the ground, dragging their riders and their kits in a spasm of terrible agony. Instinctively each trooper made a “left turn” and galloped[64] furiously to get out of range of this murderous fire which decimated our ranks. In a few seconds we had put two hundred mètres between the forest and us, and the two squadrons rallied under cover of a slight mist.

As we rode a squadron sergeant-major, Dangel, gave a groan, as his horse carried him off after the others. Then I saw him collapse, pitch forward on his nose on to his horse’s fore shoulder and fall to the ground, to be dragged. I leapt from my horse and managed to disengage his foot. Holding him in my arms, I begged him to show a little pluck. “We must clear out of this or we will be taken prisoners. For God’s sake get on your horse.” His only response was a long sigh, then his heavy body collapsed in my arms, and he dragged me to the ground. For a second I was perplexed. The others were far off, and I alone remained behind with a dying man in my arms, who clasped me in desperate embrace. At last his arms let go, and a spasm stretched him dead at my feet. I laid him piously on the grass with his face to the sky, and when I had finished this last duty to a comrade, I raised my head and saw a whole line of skirmishers fifty mètres off. For a moment a feeling[65] possessed me that I could not get away; but, damme, they were not going to take me alive. An extraordinary calm came over me.

I remounted slowly, made sure that I had picked up all four reins and lowered my lance. Now, by the grace of God ... now for it. A volley greeted my departure, but it was written that I was to escape. Several bullets grazed me, not one hit me. Soon I was out of range and concealed by a curtain of fog. I rejoined the two squadrons, many of whose troopers were without horses. Two hundred mètres farther on a fresh fusillade came from the invisible trenches and decimated our already thinned ranks. Captain de Tarragon, whose horse had been wounded, pitched forward and remained pinned under his horse. I passed by him at the gallop hardly seeing him, and I heard a shout that seemed to illumine the very darkness: “Charge, my lads.” This shout, repeated by all, swelled, increased and became a savage clamour, which must have paralysed the enemy, for the fusillade ceased and cries of “Wer da” were heard at different points.

Afterwards I shut my eyes and tried to remember, but for some moments everything was mixed up. I recall a furious gallop at the dark holes where the Germans had gone to[66] earth. A high trench embankment faced us and my horse got to the other side after a monstrous scramble. Before me and on my right and left I saw horses taking complete somersaults; I could not say whether it lasted a minute or an hour. The pains and the privations of the last three days culminated in a moment of madness. We had to get through, cost what it might; we had to bowl over everything, break through everything, but get through all the same, and our hot and furious gallop grew faster under the heedless moon, which bathed the country with its pale and gentle light. Three times we charged, three times we charged down on the obstacle without knowing its nature, until the remains of the two squadrons found themselves, breathless, in a little depression at the edge of a wood, before an impassable wall of barbed wire.

Impatient voices shouted for wire-cutters, and during the delay before these were forthcoming, a few panic-mongers blurted out false news, which soon circulated and which all believed: “The enemy is advancing in skirmishing order.” “We are going to be shot down at point-blank range,” etc.... Had the news been true, I would not have given much for our skins. Huddled together like a[67] flock of sheep before the gap which some of our men were exerting themselves to open up for our passage, a handful of resolute infantry could have killed every one of us.

At last the gap was made and I descended a steep slope between the thin stems of the birches, having been sent forward as scout by my Major, whom I was never to see again. Below, a figure in silhouette and bareheaded was resting on his sword in the middle of a clearing bathed in moonlight. He watched me coming, and I was astonished to recognise in him the officer of my troop. For a brief moment each had taken the other for an enemy, and at twenty mètres off we were each ready to fall on the other. Our mutual recognition was none the less cordial. M. Chatelin refused my horse, which I offered to him, deciding to try to regain our lines on foot under cover of night (which he did after having knocked over two German sentries). He warned me expressly against some skirmishers concealed in a thicket behind me, and after a hearty handshake and a “good luck,” which sounded supremely ironical between two such isolated individuals, lost in the heart of German “territory,” I watched his thin silhouette melt into the darkness.

I made my way back to give an account of[68] my mission and to tell the Major that this route was impracticable for the two squadrons. Above, the plain extended to infinity, white in the moonlight, with no vestige of a human being! All that was to be seen were two horses which galloped wildly to an accompaniment of clashing stirrups, and the uneasy neighs of lost animals—that whinny of the horse which has something so human in it gave me a shudder. How was it that two squadrons had had the time, during my brief absence, to melt and disappear?

What road have they found? Why have they abandoned me? The terror of desolation took the place of my former calm. To die with the others in the midst of a charge would have been fine; but to feel oneself lost and alone in all this mystery, in this endless night, in the midst of thousands of invisible enemies, was a bit too much. It was a childish nightmare and, seized with the same panic as the lost horses, I too spurred mine till his flanks bled, and I set off straight before me galloping like a madman. Luck, or perhaps my horse who scented his stable companions, brought me all at once to a small contingent of dragoons,—Captain de Salverte and eleven men, with whom I joined up. I questioned the Captain, who could tell me nothing.[69] He had found himself detached and lost like me, and he had put himself at our head to try to get us out of this inextricable position. We walked on gloomily through a country cut up by hedges and streams. Shortly, we found ourselves within a few mètres of an enemy’s bivouac, the fires of which made the shadows dance on our drawn faces. A stupid sentry was warming himself, and had his back turned to us. What was the good of struggling? Why cheat oneself with chimerical illusions? The day would dawn and we would be ingloriously surprised and sent to some prisoner’s camp in the centre of Germany, unless, choosing to die rather than yield, we kept for ourselves the last shot in our magazines.

However, we reached the forest. In the maze of dark paths we lost the Captain and Sergeant Pathé. With Farrier Sergeant-Major Delfour, and Sergeant-Major Desoil of the machine-gun section, nine of us were left, and we were determined to try a last effort, spurred by an awakening of that instinct of self-preservation which stiffens the desire to live in the very face of death.

Deep in the forest we passed the night concealed in a thicket, taking pity on our horses, which would have died had we demanded[70] a further effort of them. Soon we were overpowered by sleep, sleep so profound that the entire German army might have surprised us, without our raising a little finger to get away.

At daybreak we continued our way, with stiff and benumbed limbs and soaking clothing. It was a beautiful autumn day. Wisps of pink mist wrapped to the tree tops. A large stag watched our coming with uneasy surprise, standing in the middle of a paved road on his slim legs. He disappeared with a bound into a clump of bushes, whose swaying branches let fall a shower of silver drops. A divine peace possessed all space. In a clearing some thirty loose horses had got together. The larger number were saddled and carried the complete equipment of regiments of dragoons and of chasseurs. The lances lay on the ground, together with complete sets of kit and mess tins. Surely the enemy had not passed this way or he would have laid hands on all this material so hurriedly abandoned; and yet no human being was about who could tell us anything, not even a lost soldier. There was no one but ourselves and the immense tranquil forest, gilded by early autumn, splashed with the dark green of the oaks and with every shade of colour from ardent purple to the white leaf of the aspen.

That glorious dawn shone on the greatest victory the world had ever seen. The battle was over for the armies of Maunoury, of French, of Franchet, of d’Estrey, of Foch, and of Langle de Cary. The pursuit was beginning, and the whole extent of country, where we were now wandering, pursued and tracked like wild beasts, was going to be cleared within a few hours of the last German who had sullied its soil.

More than thrice during the morning we came unexpectedly on German detachments, isolated parties, lost patrols or stragglers, and each time we cut across the wood to escape them at the risk of breaking our necks. Then we got to a long straight path at the lower end of which a fine limousine motor-car had been abandoned, and at the end of the path we reached a village which appeared to be empty. We consulted together for a moment, being in doubt what to do; but all of us were loth to return to the forest. This was the fifth day of our fast; so much the worse for us; it was time to put an end to it, so we made our way to an abandoned farm. We sheltered there for two hours, scanning the surrounding country for signs of life. Everything seemed dead. We could see no peasant, no civilian, not even an animal, and this waiting was one torment[72] the more, but it was to be the last. Not till ten o’clock, over there, very far off, did I catch sight of the thin black caterpillar of a column of soldiers coming our way during my turn of sentry-go. My heart beat violently, but I refrained from giving the news to my comrades from the fear of raising false hopes. My eyes burnt like flame and my teeth chattered. If these were Germans the game was up. If they were French, oh! then!

I looked, I looked with my eyes pressing out of my head. At times, as I strained my eyes, everything grew misty and I could see nothing; then, a second later, I again found this growing caterpillar and I began to distinguish details. There were squadrons of cavalry, but I could not yet make out the colour; and my body, from being icy cold, turned to burning hot. At times I forced myself not to look. I looked again, counted twenty, and then devoured space with my eyes.

A patrol had been detached, and approached rapidly at the trot; this time I recognised French Hussars. Then all strength of will, and all my effort to remain calm disappeared. I turned my reeling head towards my comrades and I fell on the grass crying, crying[73] like a madman, in words without sequence. The fatigue of these five days without food or drink, almost without sleep, and the living in a perpetual nightmare, brought on a nervous crisis, and my whole body was racked with spasms. My comrades, not having as yet understood, looked at me with astonishment. With a gesture I pointed out the approaching column, the pale blue of which contrasted brightly with the gold of the leaves. All of them, as soon as they had seen it, were overcome as I had been, each in his own way. Some burst into brusque convulsive sobs, others danced, waving their arms like madmen or rather like poor wretches who have passed days of suffering and agony on a raft in mid-ocean, and who suddenly see a ship approaching to their rescue.

VERBERIE THE CENTRE OF THE RALLY—THE EPIC OF A YOUNG GIRL—MASS IN THE OPEN AIR—FROM DAY TO DAY

10th September to 20th October, 1914

The battle finished on the tenth, and then the pursuit of the conquered army commenced and kept the whole world in suspense, with eyes fixed on this headlong flight towards the north, which lasted till the end of the month, and which was to be the prelude of the great battles of the Yser.

The region round Verberie was definitely cleared of Germans and was become once more French. The little town for some days presented an extraordinary spectacle.

We entered the town after having received the formal assurance of the 5th Chasseurs, who went farther on, that all the country was in our hands. Some divisional cyclists were seated at the roadside. We asked them for news of the 22nd, and their reply wrung our[75] hearts. They knew nothing definite, but they had met a country cart full of our wounded comrades, who had told them that the regiment had been cut up.

No one could tell us where the divisional area was to be found. The division itself appeared to have been dismembered, lost and in part destroyed. We thought that we were the only survivors of a disaster, and, once the horses were in shelter in an empty abandoned farm stuffing themselves with hay, we wandered sadly through the streets destroyed by bombardment and by fire in search of such civilians as might have remained behind during the invasion.

A little outside the town we at last found a farm where two of the inhabitants had stayed on. The contrast between them was touching. One was a paralysed old man unable to leave his fields, the other was a young girl of fifteen, a frail little peasant, and rather ugly. Her strange green eyes contrasted with an admirable head of auburn hair, and she had heroically insisted on looking after her infirm grandfather, though all the rest of the family had emigrated towards the west. She had remained faithful to her duty in spite of the bombardment, the battle at their very door and the ill-treatment of[76] the Bavarian soldiers who were billeted in the farm. Distressed, yet joyous, she prepared a hasty meal and busied herself in quest of food, for it was anything but easy to satiate eleven men dying of hunger when the Germans, who lay hands on everything, had only just left.

She wrung the neck of an emaciated fowl which had escaped massacre, and, by adding thereto some potatoes from the garden, she served us a breakfast, washed down with white wine, which made us stammer with joy, like children. One needs to have fasted for five days to have felt the cutting pains of hunger and of thirst in all their horror, to appreciate the happiness that one can experience in eating the wing of a scraggy fowl and in drinking a glass of execrable wine tasting like vinegar. She bustled about, and her pitying and motherly gestures touched our hearts. While we ate she told us the most astonishing story that ever was, a story acted, illustrated by gestures, which made the scenes live with remarkable vividness.

She told us how, faithful to her oath, she was alone when the Bavarians came knocking at her door, how she lived three days with them, a butt for their innumerable coarsenesses, sometimes brutally treated when the[77] soldiers were sober, sometimes pursued by their gross assiduities when they were drunk; how one night she had to fly half naked through the rain, slipping out through the vent-hole of the cellar, to escape being violated by a group of madmen, not daring to go to bed again, sleeping fully dressed behind a small copse; how at last French chasseurs had put the Bavarians to flight and had in their turn installed themselves in the farm, and how among them she felt herself protected and respected.