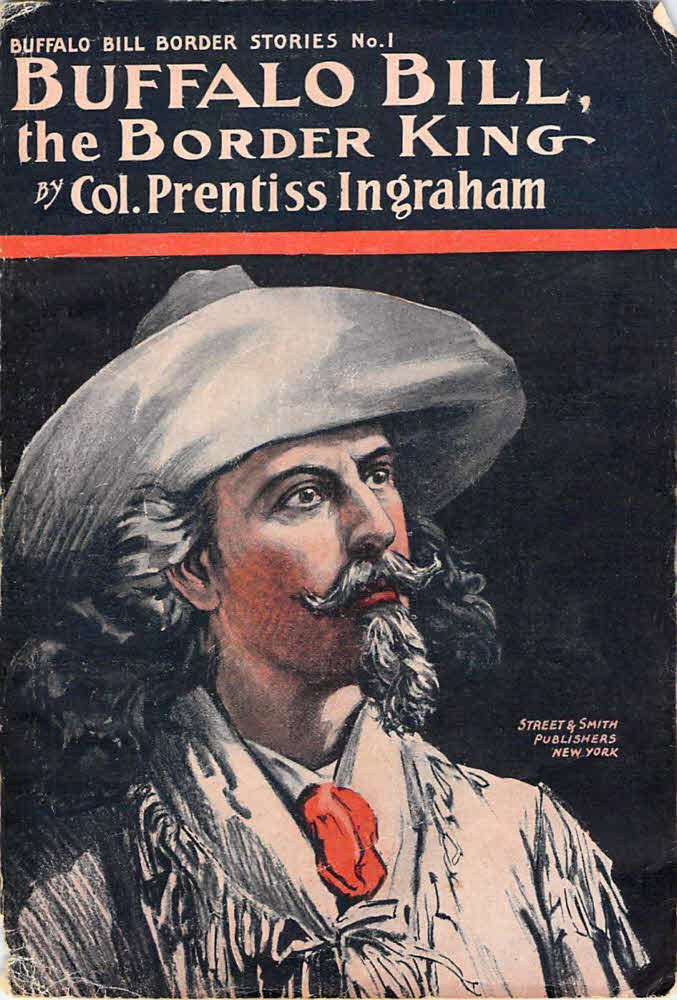

Title: Buffalo Bill, the Border King; Or, Redskin and Cowboy

Author: Prentiss Ingraham

Release date: July 14, 2020 [eBook #62638]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

In Appreciation of William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill).

Chapter I. Running the Death-gantlet.

Chapter III. The King of the Sioux.

Chapter IV. Buffalo Bill’s Plot.

Chapter V. The Desperate Venture.

Chapter VI. The Dash of the Scouts.

Chapter VII. The Ace of Clubs.

Chapter IX. Breaking Through the Red Circle.

Chapter X. The Ride to the Rescue.

Chapter XIII. The Chase of the White Antelope.

Chapter XIV. A Startling Discovery.

Chapter XV. The Treasure Chest.

Chapter XVI. The Bandits of the Overland Trail.

Chapter XVII. A Friend in Need.

Chapter XVIII. The Race With Death.

Chapter XIX. Danforth’s Hand Is Stayed Again.

Chapter XXI. The Cave in the Mountain.

Chapter XXII. The Night Prowlers.

Chapter XXIII. More Than They Bargained For.

Chapter XXIV. Chased by the Flames.

Chapter XXV. The Telltale Crow.

Chapter XXVII. “The Death Killer.”

Chapter XXVIII. The White Antelope Interferes.

Chapter XXXI. Buffalo Bill’s Great Shot.

Chapter XXXII. The Border King’s Pledge.

Chapter XXXIII. Tracking the Mad Hunter.

Chapter XXXIV. Red Knife Loses His “Medicine.”

Chapter XXXV. The Search For New Medicine.

Chapter XXXVIII. White Antelope’s Peril.

Chapter XXXIX. A Cry For Help.

Chapter XL. The Freight-train.

Chapter XLIII. Man to Man at Last.

Chapter XLIV. The Fight to Gain the Island.

Chapter XLV. War to the Knife.

Chapter XLVI. And the Knife to the Hilt.

OR,

REDSKIN AND COWBOY

BY

Col. Prentiss Ingraham

Author of “Buffalo Bill”

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1907

By STREET & SMITH

Buffalo Bill, the Border King

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian.

[1]

It is now some generations since Josh Billings, Ned Buntline, and Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, intimate friends of Colonel William F. Cody, used to forgather in the office of Francis S. Smith, then proprietor of the New York Weekly. It was a dingy little office on Rose Street, New York, but the breath of the great outdoors stirred there when these old-timers got together. As a result of these conversations, Colonel Ingraham and Ned Buntline began to write of the adventures of Buffalo Bill for Street & Smith.

Colonel Cody was born in Scott County, Iowa, February 26, 1846. Before he had reached his teens, his father, Isaac Cody, with his mother and two sisters, migrated to Kansas, which at that time was little more than a wilderness.

When the elder Cody was killed shortly afterward in the Kansas “Border War,” young Bill assumed the difficult role of family breadwinner. During 1860, and until the outbreak of the Civil War, Cody lived the arduous life of a pony-express rider. Cody volunteered his services as government scout and guide and served throughout the Civil War with Generals McNeil and A. J. Smith. He was a distinguished member of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry.

During the Civil War, while riding through the streets of St. Louis, Cody rescued a frightened schoolgirl from a band of annoyers. In true romantic style, Cody and Louisa Federci, the girl, were married March 6, 1866.

In 1867 Cody was employed to furnish a specified amount of buffalo meat to the construction men at work on the Kansas Pacific Railroad. It was in this period that he received the sobriquet “Buffalo Bill.”

In 1868 and for four years thereafter Colonel Cody[2] served as scout and guide in campaigns against the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. It was General Sheridan who conferred on Cody the honor of chief of scouts of the command.

After completing a period of service in the Nebraska legislature, Cody joined the Fifth Cavalry in 1876, and was again appointed chief of scouts.

Colonel Cody’s fame had reached the East long before, and a great many New Yorkers went out to see him and join in his buffalo hunts, including such men as August Belmont, James Gordon Bennett, Anson Stager, and J. G. Heckscher. In entertaining these visitors at Fort McPherson, Cody was accustomed to arrange wild-West exhibitions. In return his friends invited him to visit New York. It was upon seeing his first play in the metropolis that Cody conceived the idea of going into the show business.

Assisted by Ned Buntline, novelist, and Colonel Ingraham, he started his “Wild West” show, which later developed and expanded into “A Congress of the Roughriders of the World,” first presented at Omaha, Nebraska. In time it became a familiar yearly entertainment in the great cities of this country and Europe. Many famous personages attended the performances, and became his warm friends, including Mr. Gladstone, the Marquis of Lorne, King Edward, Queen Victoria, and the Prince of Wales, now King of England.

At the outbreak of the Sioux, in 1890 and 1891, Colonel Cody served at the head of the Nebraska National Guard. In 1895 Cody took up the development of Wyoming Valley by introducing irrigation. Not long afterward he became judge advocate general of the Wyoming National Guard.

Colonel Cody (Buffalo Bill) died in Denver, Colorado, on January 10, 1917. His legacy to a grateful world was a large share in the development of the West, and a multitude of achievements in horsemanship, marksmanship, and endurance that will live for ages. His life will continue to be a leading example of the manliness, courage, and devotion to duty that belonged to a picturesque phase of American life now passed, like the great patriot whose career it typified, into the Great Beyond.

BUFFALO BILL, THE BORDER KING.

Fort Advance, a structure built of heavy, squared timbers and some masonry, with towers at the four corners, commanding the deep ditches which had been dug around the walls, stood in the heart of the then untracked Territory of Utah. It was the central figure of a beautiful valley—when in repose—and commanded one of the important passes and wagon trails of the Rockies.

A mountain torrent flowed through the valley, and a supply of pure water from this stream had been diverted into the armed square which, commanded by Major Frank Baldwin, was a veritable City of Refuge to all the whites who chanced to be in the country at this time.

For the valley of Fort Advance offered no peaceful scene. The savage denizens of the mountain and plain had risen, and, in a raging, vengeful flood, had poured into the valley and besieged the unfortunate occupants of the fort. These were a branch of the great Sioux tribe, and, under their leading chief, Oak Heart, fought with the desperation and blind fanaticism of Berserkers.

A belt of red warriors surrounded Fort Advance,[6] cutting off all escape, or the approach of any assistance to the inmates of the stockade, outnumbering the able-bodied men under Major Baldwin’s command five to one! Among them rode the famous Oak Heart, inspiring his children to greater deeds of daring. By his side rode a graceful, beautiful girl of some seventeen years, whose face bore the unmistakable stamp of having other than Indian blood flowing in her veins. Long, luxurious hair, every strand of golden hue, contrasted strangely with her bronze complexion, while her eyes were sloe-black, and brilliant with every changing expression.

This was White Antelope, a daughter of Oak Heart, and she held almost as much influence in the tribe as the grim old chief himself. Because of her beauty, indeed, she was almost worshiped as a goddess. At least, there was not a young buck in all the Utah Sioux who would not have attempted any deed of daring for the sake of calling the White Antelope his squaw.

But while the red warriors were so inspired without the walls of the fortress, within was a much different scene. Major Baldwin’s resources were at an end. Many of his men were wounded, or ill; food was low; the wily redskins had cut off their water-supply; and there were but a few rounds of ammunition remaining. Fort Advance and its people were at a desperate pass, indeed!

After a conference with his subordinate officers, Major Baldwin stood up in the midst of his haggard, powder-begrimed men. They were faithful fellows—many of them bore the scars of old Indian fights.[7] But human endurance has its limit, and there is an end to man’s courage.

“Will no man in this fort dare run the death-gantlet and bring aid to us?” cried the major.

It was an appeal from the lips of a fearless man, one who had won a record as a soldier in the Civil War, and had made it good later upon the field as an Indian fighter. The demand was for one who would risk almost certain death to save a couple of hundred of his fellow beings, among them a score of women and children.

The nearest military post where help might be obtained was forty miles away. Several brave men had already attempted to run the deadly gantlet, and had died before the horrified eyes of the fort’s inmates. It seemed like flinging one’s life away to venture into the open where, just beyond rifle-shot, the red warriors ringed the fort about.

Such was the situation, and another attack was about due. The riding of the big chief and his daughter through the mass of Indians, was for the purpose of giving instructions regarding the coming charge. Ammunition in the fort might run out this time. Then over the barrier would swarm the redskins, and the thought of the massacre that would follow made even Major Baldwin’s cheek blanch.

So the gallant commander’s appeal had been made—and had it been made in vain? So it would seem, for not a man spoke for several moments. They shifted their guns, or changed weight from one foot to the other, or adjusted a bandage which already marked the redskin’s devilish work.

[8]

They were brave men; but death seemed too sure a result of the attempt called for; it meant—to their minds—but another life flung away!

“Was it not better that all should die here together, fighting desperately till the last man fell?” That was the question these old scarred veterans asked in their own minds. The venture would be utterly and completely hopeless.

“Look there!”

The trumpet-call was uttered by an officer on one of the towers of the stockade. His arm pointed westward, toward a ridge of rock which—barren and forbidding—sloped down into the valley facing the main gateway of Fort Advance.

At the officer’s cry a score of men leaped to positions from which could be seen the object that occasioned it. Even Major Baldwin, knowing that the cry had been uttered because of some momentous happening, hurriedly mounted to the platform above the gate. He feared that already his demand for another volunteer was too late. He believed the redskins were massing for another charge.

All eyes were strained in the direction the officer on the watch-tower pointed. A gasp of amazement was chorused by those who saw and understood the meaning of the cry.

A horseman was seen riding like the wind toward the fort—and he was a white man!

The Indians who had already beheld this rash adventurer were dumb with amazement. They were as much surprised by his appearance as were the inmates of the fort.

[9]

The unknown rider was leading a packhorse. The horse he bestrode was a magnificent animal, and the packhorse flying along by its side was a racer as well, for both came on, down the long tongue of barren rock, at a spanking pace.

From whence had the man come? Who was he? How had he gotten almost through the Indian lines undiscovered?

He certainly had all but run the gantlet of the red warriors, for no shot, or no arrow, had been fired at him until he was discovered by the officer on the watch-tower of the fort.

Then it was that he spurred forward like the wind, and floating to the ears of the whites who watched him so fearfully came the long, tremolo yell of the Sioux warriors as they started in pursuit of the daredevil rider. He was heading directly for the large gates of the fort.

That he had chosen well his place to break through the Indian death-circle was evident, for there were few braves near him as he fled along the sloping ridge into the valley. His rifle he turned to right, or to left, firing with the same ease from either shoulder, while his mount, and the packhorse tied to its bridle, guided their own feet over the rocky way.

When he pulled trigger the bullet did not miss its mark. The rifle rang out a death-knell, or sent a wounded brave out of action.

The ponies of the Indians were feeding in the valley, with only a guard here and there, and there were no mounted warriors near to close in on the reckless rider, or to head him off. Hark! Their vengeful[10] yells, as they observed the possibility of the daring man’s escape, were awful to hear. They were in a frenzy of rage at the desperate act of the horseman.

Rifles and bows sent bullets and shafts at him, but at long range. If he was hit he did not show it. The horses still thundered on, down into the valley, as recklessly as frenzied buffalo.

Oak Heart, the great war chief, heard the commotion and saw the speeding white man. The chief was mounted, and he lashed his horse into a dead run for the point where the reckless paleface was descending into the valley. With him rode the White Antelope, and their coming spurred the braves to more strenuous attempts to reach, or capture, or kill, the daredevil rider.

The occupants of the fort—those who beheld this wonderful race—were on the qui vive. Their exclamations displayed the anxiety and uncertainty they felt.

“He can never make it!”

“The Indian guard are driving in the ponies to bar his way!”

“Who is he?”

“How he rides!”

“God guard the brave fellow!” cried a woman’s voice.

One of the gentler sex had climbed to the platform over the gate, and this was her prayer.

Other women had dropped to their knees, and were fervently praying God to spare the splendid fellow who was daring the gantlet of death. A cheer rose from the soldiery. This unknown was showing them the way that they had not dared to go.

[11]

“That packhorse is wounded. Why doesn’t he leave it?” cried one of the officers. “It is delaying him—can’t the fellow see it?”

At that moment the commander shouted:

“Captain Keyes, take your troop to the rescue of that brave fellow!”

“With pleasure, sir! I was about to ask your permission to do just that,” declared the junior officer.

The bugle sounded, but its notes were drowned in a sudden wild shout of joy that rose from the two hundred inmates of the fort. Another officer, with a field-glass at his eye, had suddenly turned and shouted:

“It is Buffalo Bill, the Border King!”

The wild cheers that greeted the recognition of the daring gantlet runner came in frenzied roars, the piping voices of children, the treble notes of women, and the deep bass of the men mingling in a swelling chorus that rose higher and higher.

The Border King, as he had been called, heard the sound. He understood that it was in his welcome, and he fairly stood up in his stirrups and waved his sombrero, while the horses dashed on at the same mad pace.

Buffalo Bill, or William F. Cody, as was his real name, was the chief of scouts at this very fort, and he was a hero—almost a god—in the eyes of the soldiers and his brother scouts.

[12]

A week before he had started for Denver with important despatches, but had returned in a few hours to report signs of a large band of Indians on the move. He had warned Major Baldwin that Oak Heart and his braves might be intending a concerted attack upon Fort Advance; but duty called Buffalo Bill to the trail again, and he had hurried away on his Denver mission.

That the danger he had dreaded was real, the surrounding of the fort several days later by the Sioux proved. Scouts had been sent for aid, but too late. None had gotten through the belt of redskins, and that belt was tightening each hour. The ammunition was low, and the awful end was not far off if help from some quarter did not appear.

Even the appearance of Buffalo Bill inspired the beleaguered whites with hope. It seemed an almost hopeless attempt to reach the fort, for the red warriors were closing in upon him. Yet he rode on unshakenly.

Down the ridge he sped, and out upon the plain. He was seemingly coming from the sunshine of life into the valley of death’s shadow!

Why did he do it? Why did he risk his life so recklessly when only forty miles away he could have obtained help from the military post? There was some reason behind his daring act, and some cause for his delaying his effort by dragging the packhorse, now wounded, with him.

All in the fort knew what this hero of the border had done to win fame among the mighty men of the frontier. He was chief and king among them. Yet what could he do now to help the besieged in the[13] fortress, even did he reach the gate? That was the question!

But hope revived, nevertheless, in every heart. Even the commandant, Major Frank Baldwin, began to look more hopeful as the scout drew closer to the fort. He had known Buffalo Bill long and well, and he knew of what marvels he was capable!

Buffalo Bill had been born in a cabin home on the banks of the Mississippi River in the State of Iowa, and from his eighth year he had been a pioneer—an advance agent of civilization. At that age his father had removed to Kansas, and as a boy Billie Cody saw and took part in the bloody struggles in Kansas between the supporters of slavery and those who believed that the soil of Kansas should be unsmirched by that terrible traffic in human lives.

Cody’s father, indeed, lost his life because of his belief in freedom, and the boy was obliged to help support the family at a tender age. He went to Leavenworth, and there hired out to Alex Majors, who of that day was the chief of the overland freighters into the far West.

The boy was eleven years old—an age when most youngsters think only of their play and of their stomachs. But Billie Cody had seen his father shot down; he had nursed him and hidden him from his foes, and from the dying pioneer had received a sacred charge. That was the care of his mother and sister. It was necessary for him to earn a man’s wage, not a boy’s. And to get it he must do a man’s work. He was a splendid rider, even then—one of those horsemen who seem a part of the animal he bestrode, like the Centaurs[14] of which Greek mythology tells us. Alex Majors needed a messenger to ride from train to train along the wagon-trail, and he entrusted young Cody with the job.

It was one that might have put to the test the bravery of a seasoned plainsman. Indians and wild beasts were both very plentiful. There were hundreds of dangers to threaten the lone boy as he rode swiftly over the trails. Yet even then he began to make his mark. He had several encounters with the Indians during his first season. As he says himself, the first redskin he ever saw stole from him, and he had to force the scoundrel—boy though he was—to give up the property at the point of the rifle. This incident, perhaps, gave the youth a certain daring in approaching the reds which often stood him well in after adventures. And the reds learned to respect and fear Billie Cody. He allowed his hair to grow long, to show the Indians that he was not afraid to wear a “scalp-lock”—practically daring any of his red foes to come and take it!

So from that early day he had been active on the border. All knew him—red as well as white. He had been an Indian fighter from his eleventh year, the hero of hundreds of daring deeds, thrilling adventures, and narrow escapes. He was as gentle as a woman with the weak, the feeble, or with those who claimed his protection; but he was as savage in battle as a mountain lion, and had well earned the title bestowed upon him by his admiring friends—the Border King. His coming to the fort now—if he could make it safely—was worth in itself a company of reenforcements, for it put heart into all the besieged.

[15]

“Never mind, Keyes! it is Cody, and he will get through,” called out Major Baldwin to Captain Keyes, as the men were mounting.

Captain Edward L. Keyes was a splendid type of cavalry officer, and he was anxious for another brush with the redskins at close quarters. He was disappointed, but as the man making the attempt to reach Fort Advance was Buffalo Bill, the captain agreed with Major Baldwin that “he would get through.”

The Border King had turned his rifle now upon the Indian guards who were trying to head him off by blocking his way with the large herd of half-wild ponies which had been feeding in the valley. Indian ponies are not broken like those used by white men. They are pretty nearly wild all their days. The red man merely teaches his mount to answer to the pressure of his knees, and to the jerk of the single rawhide thong that is slipped around the brute’s lower jaw. And these lessons are further enforced by cruelty.

The odor of a white person is offensive to an Indian pony. A white man has been known frequently to stampede a band of Indian mounts; and not infrequently the mob of wild creatures has turned upon the unfortunate paleface and trampled him to death under their unshod feet.

Therefore, this opposition of the ponies was no small matter. They were a formidable barrier to Buffalo Bill’s successful arrival at the gate of the stockade fort.

His rifle rattled forth lively, yet deadly, music, and his aim was wonderfully true for that of a man riding at full speed. Emptying the gun, he swung it quickly over his shoulder, and drawing the big cavalry pistols[16] from their holsters the daring scout began to fairly mow a path through the herd of ponies. The slugs carried by the large-caliber pistols were as effective as the balls from his rifle. The mob of squealing, kicking, biting ponies broke before his charge, and swept on ahead of him. Another cheer from the watchers in the fort signaled this fact. The ponies were stampeding directly toward Fort Advance.

“Out and line ’em up!”

“We’ll corral the ponies if we kyan’t th’ Injuns!”

“Throw open the gates!” commanded Major Baldwin, his voice heard above the tumult.

The command was obeyed, and Captain Keyes and his men galloped out to meet the mob.

In vain did the Indian guards try to head off the stampede. By having left their ponies in the valley where the grass was sweet and long, they had been caught in this trap. Instead of capturing Buffalo Bill it looked as though he and the other whites would capture the bulk of the Indian ponies!

Oak Heart and the White Antelope, with a few mounted reds at their back, thundered across the level plain and up the rise toward the fort. But the pony herd and Buffalo Bill were well in the lead.

The king of the border turned in his saddle, and waved his sombrero in mockery at the Indian chief. Then the ponies dashed into the gateway and were corraled, while the scout, still leading his packhorse, swept in behind them.

“On guard, all! The redskins will charge on foot to try and get their ponies!” shouted the scout, as he came through the gate.

[17]

His voice rose above the turmoil and brought the delighted men to their duty. Major Baldwin echoed Buffalo Bill’s advice, ordering everybody to their posts.

“Be careful of the expenditure of powder and lead, men!” warned the major, from his stand on the platform. “Remember we are running short.”

“Don’t you believe it, major!” cried the voice of the scout, as he dismounted in the middle of the enthusiastic throng.

“What’s that, Cody?”

“Strip the packhorse. I have brought you a-plenty of ammunition until reenforcements can be had.”

“God bless you, Cody, for those words! You have saved us,” cried Major Baldwin, and there was a tremor in his voice as he glanced toward the group of women and children.

He came down from the platform, and wrung the scout’s hand, as he asked:

“In the name of Heaven, Cody, where did you get ammunition? Surely, you did not bring it all the way from Denver?”

“No, indeed. I cached this over a year ago, major,” the scout replied cheerfully. “It will hold those red devils off until help arrives. You’ve sent to Fort Resistence, I presume?”

“Sent, alas! But five men have died in the attempt.”

“And not one got through?” cried Buffalo Bill.

“Not one, Cody.”

Buffalo Bill’s face assumed a look of anxiety—an expression not often seen there.

“I had called for another volunteer when you were[18] discovered coming. It was a splendid dash you made, Cody, and a desperate one as well.”

“Aye,” said the scout gravely. “Desperate it was, indeed. But it must be made again. This ammunition I have brought you may last till morning; but the reds must be taken on the flank or they’ll hold you here till kingdom come!

“I’ll try to get through again, Major Baldwin. You must have help,” declared the Border King sternly.

Scarcely had Buffalo Bill uttered these cheering words when a babble of cries arose from the watchers on the towers and the platform over the gate. The redskins were gathering for a concerted charge, maddened by his escape and the loss of their ponies.

Saving a few chiefs, beside Oak Heart and the White Antelope none of the reds were mounted. However, they were so enraged now that they ignored the whites’ accuracy of aim and came on within rifle-shot of the stockade.

The ammunition brought on the packhorse led by the scout was hastily distributed among the defendants of the fort, with orders to throw no shot away. They were to shoot to kill, and Major Baldwin advised as did “Old Put” at the first great battle in United States history—the Battle of Bunker Hill—“to wait till they saw the whites of the enemies’ eyes!”

Powder was as precious to that devoted band as gold-dust, and bullets were as valuable as diamonds.

[19]

Major Baldwin took his position on the observation platform above the gate, Buffalo Bill by his side, repeating rifle in hand, and near them stood a couple of young officers as aids, and the bugler. All were armed with rifles, and every weapon for which there was no immediate need in the fort was loaded and ready. The women were in two groups—one ready to reload the weapons tossed them by the men, and the other to assist the surgeon with the wounded.

The Indians came swarming across the valley in a red tidal wave. They were decreasing their circle, and expected to rush the stockade walls in a cyclonic charge.

They quickened their pace as they came, and the weird war-whoop deafened the beleaguered garrison. They came with a rush at last, showering the walls with arrows and bullets, some of which found their way into the loopholes.

It was a grand charge to look upon; it was a desperate one to check.

The whites had their orders and obeyed them. Not a rifle cracked until the Indians were under the stockade walls, scrambling through the ditch. Then the four six-pounders roared from the block-towers, their scattering lead and iron mowing down the yelling redskins in the ditches.

Then volley upon volley of carbines, repeating rifles, and muskets echoed the rolling thunder of the big guns.

Not a few of the bullets and arrows entered the loopholes, and many dead and wounded were numbered among the whites; but the carnage among the redskins was awful to contemplate.

[20]

The thunder of the big guns, the popping of the smaller firearms, the screaming of the wild ponies corraled in the fort, and the demoralized shrieks of the Indians themselves made a veritable hell upon earth!

Above all rose the notes of the bugle sending forth orders at Major Baldwin’s command. Now and then that piercing, weird war-cry of the Border King was heard—a sound well known and feared by the Indians. They recognized it as the voice of he whom they called Pa-e-has-ka—“The Long Hair.”

Indian nature was not equal to facing the deadly hail of iron and lead, and the red wave broke against the stockade and receded, leaving many still and writhing bodies in the ditches which surrounded the fort, and scattered upon the plain. Slowly at first the redskins surged backward under the galling fire of the whites but finally the retreat became a stampede.

The rout was complete. All but the dead and badly wounded escaped swiftly out of rifle-shot, save one mounted chief. He was left alone, struggling with his mount, trying to force the animal to leave the vicinity of the fort gate.

This was Oak Heart himself, the king of the Sioux, and his mount was a great white cavalry charger that he had captured months before. This was no half-wild Indian pony; yet the Indian chief, without spurs and a proper bridle, could not control the beast. The horse had heard the bugle to which he had been so long used. He was determined in his equine mind to rejoin the white men who had been his friends, instead of these cruel red masters, and he made a dash for the gate of the fortress.

[21]

In vain did Chief Oak Heart try to check him. He would have flung himself from the horse’s back, but the creature was so swift of foot and the ground was so broken here, that such an act would have assured Oak Heart’s instant death. Besides, being the great chief of his tribe, Oak Heart had bound himself to the horse that, if wounded or killed, he would not be lost to his people which—according to Indian belief—would be shame.

Oak Heart had lost his scalping-knife, and could not cut the rawhide lariat that held him fast. He writhed, yelling maledictions in Sioux upon the horse; but he could neither check the brute nor unfasten the lariat.

His warriors soon saw Chief Oak Heart’s predicament, and they charged back to his rescue. The White Antelope led them on, for she was as brave as her father.

Buffalo Bill had been first to see the difficulty into which the chief had gotten himself, and springing down from the platform he threw himself into the saddle, shouted for the gates to be opened, and spurred his horse out of the fort.

“Don’t shoot the girl!” the scout yelled to the soldiers lining the walls above him. “Have a care for the girl!”

But there was scarcely chance for the whites to fire at all at the oncoming White Antelope and her party, before Buffalo Bill was beside the big white charger and the struggling king of the Sioux.

Out flashed the scout’s pistol, and he presented it to the red man’s head.

[22]

“Oak Heart, you are my prisoner! Yield yourself!” he cried, in the Sioux tongue.

At the same moment he seized the thong by which the Indian was wrenching at the jaw of the white horse, snatched it from Oak Heart’s grasp, and gave the big charger his head. The white horse sprang forward for the open gate of the fort, and Buffalo Bill’s mount kept abreast of him. The redskins dared not fire at the scout for fear of killing Oak Heart.

A volley from the soldiery sent the would-be rescuers of the chief back to cover. Only the beautiful girl, White Antelope, was left boldly in the open, shaking her befeathered spear and trying to rally her people to the charge. The white men honored Buffalo Bill’s request and did not shoot at her, or the Sioux would have lost their mascot as well as their great chieftain.

In a moment the scout with his prisoner dashed through the open gates, which were slammed shut and barred amid the deafening acclamations of the garrison. Major Baldwin was on hand to grasp Buffalo Bill’s hand again, and as he wrung it he cried:

“Another brave deed to your credit, Cody! It was cleverly done.”

He turned to the chief whom the scout was freeing from the lariat that had been the cause of his capture. The redskin king had accepted his fate philosophically. His look and bearing was of fearlessness and savage dignity. He had been captured by the palefaces, and so humbled in the eyes of a thousand braves; but he was defiant still, and his features would not reveal his heart-anguish to those foes that now surrounded him with flushed faces.

[23]

The stoical traits of the Indian character cannot but arouse admiration in the white man’s breast. From babyhood the redskin is taught—both by precept and instinct—to utter no cry of pain, to reveal no emotion which should cause a foe pleasure. When captured by other savages, the Indian will go to the fire, or stand to be hacked to pieces by his enemies, with no sound issuing from his lips but the death-chant.

And this Spartan fortitude is present in the very papooses themselves. A traveler once told how, in walking through an Indian village, he came upon a little baby tied in the Indian fashion to a board, the board leaning against the outside of a wigwam. The mother had left it there and the white man came upon it suddenly. Undoubtedly his appearance, and his standing to look at the small savage, frightened it as such an experience would a white child. But his voice was not raised. Not a sound did the poor little savage utter; but the tears formed in his beady eyes and ran down his fat cheeks. Infant that he was, and filled with fright of the white man, he would not weep aloud.

Oak Heart, the savage king, looked abroad upon his enemies, and his haughty face gave no expression of fear. He was a captive, but his spirit was unconquered.

“This is a good job, Cody,” whispered Baldwin, glancing again at the chieftain. “We can make use of him, eh?”

“We can, indeed, major,” returned the scout.

“But that crowd out yonder will be watching us all the closer now. How under the sun anybody can get through them after this——”

[24]

“Leave it to me, major,” interrupted Buffalo Bill firmly. “I am ready to make the trial—and make it now!”

There was a look on Buffalo Bill’s face as he spoke that informed Major Baldwin that the scout had already formed some plan which he wished to make known to him. So the officer said:

“Come to my quarters, Cody, and we will talk it over. Captain Keyes, kindly take charge of the chief and see that he is neither ill-treated or disturbed. Some of these boys feel pretty ugly, I am sure. We have lost a number of good men, and two of the children have been frightfully wounded by arrows coming through the lower loopholes.”

When the major and the scout reached the former’s office, Baldwin said:

“Are you in earnest in this attempt, Cody?”

“Never more so, Major Baldwin. Help we must have.”

“No man knows the danger better than you do. I need not warn you.”

“Quite needless, sir. I know the game from A to Z.”

“Very true. But there are great odds against you.”

“No man, I believe, sir, stands a better chance of getting through than myself.”

“That is so; yet, while many good men might be spared to make the attempt, you are the one who cannot be replaced.”

[25]

“Thank you, sir; but my life is no more to me than another man’s is to him. If I’d been thinking of the chances of getting shot up all these years, I reckon I’d turned up my toes long ago. I never think of death if I can help it.”

“It’s true, Cody!” exclaimed the major. “You act as though the bullet wasn’t molded that could kill you.”

“So the redskins say, I believe,” responded the scout grimly.

“Yet your place cannot easily be filled,” the major said again. “If you can get some other volunteer I wish you would. I don’t want to lose you, Bill.”

“Captain Keyes is anxious to go, sir, but——”

“Oh, yes; Keyes is a daredevil whom nothing will daunt; but I refused his request and those of my few other officers.”

“Then I must go, sir.”

“First, tell me about your mission,” said the major abruptly.

“I delivered your despatches, sir,” said Cody, “and here are others for you. On coming within a few miles of the fort I saw that several large parties of Indians had passed, all seemingly making in this direction. I knew what was up at once. I suspected that unless you had been lucky enough to get a supply of ammunition before the reds closed in on you, you’d run short; but there was that horse load we had to bury last year when I was on the expedition with Captain Ames. So I went over there and found it all in good shape.

“I came mighty near losing it all, however,” added the scout, smiling, “for in the very act of uncovering[26] the stuff I was come upon by a redskin on a good horse. It was kill or be killed, and before he could either shoot me or knife me I had laid him out.

“His war-bonnet and rigging made a pretty good disguise for me. And certainly his horse came in handy. The animal was not a wild pony, but had Uncle Sam’s brand on him. Where the red got him, Heaven only knows. Some poor white man probably lost his life before he lost his horse.

“However, I dressed up as near like an Injun as I could, and packed the ammunition on the dead man’s mount. I made a détour so as to come up from the west, and be opposite the main gate; for I knew about how the red devils would swarm about you here. And I was not interfered with until, coming out on that ridge, I had to throw aside my disguise, or run the risk of being made a target of by some of your fellows in the stockade here. I knew they could shoot better than the redskins,” and Cody laughed.

“So here I am,” the scout added, “little the worse for wear, major.”

“And a more gallant ride I never saw. You have done nobly, Cody. The ammunition will keep us going for some hours.”

“Unless the redskins rush you too hard.”

“You think they will try to charge again—and without their horses?”

“Sure thing. Our capture of Oak Heart will stir ’em up worse than ever.”

“They won’t wait until dark, then?”

“I don’t believe so. That half-wild girl, White Antelope, will give them no peace until they try to rescue her father.”

[27]

“But you warned my men not to shoot her.”

“That’s right. She’s Injun now,” said Buffalo Bill sadly. “But her mother wasn’t a redskin, and perhaps some day, when old Oak Heart passes in his chips, she may be gotten away from the savages.”

“You knew her mother, then, Cody?”

“Yes. And a noble woman she was.”

“Yet she went to the wigwam of a dirty redskin?”

“Ah! you don’t know the circumstances. It is a sad story, Major Baldwin, and some day I’ll tell it to you. But don’t blame the mother—or the unfortunate child of this strange union. She would make a beautiful woman if she were civilized, cross-blood though she be.”

“Well, well! It’s a sad case, as you say. I’ll pass the word to the officers to instruct their men to spare the White Antelope wherever they may meet her.”

“Thank you,” said Buffalo Bill simply. “My scouts already know my wishes on the subject. And now, major, I must get ready for my dash through that mob again.”

“It seems a wicked shame to let you go, Cody! Yet—we can’t beat off many more charges even with this access of ammunition.”

“You surely can’t. I must go.”

“You have devised a plan, I can see.”

“I have, sir.”

“Well, sit here and tell me. The mess cook is preparing a hearty meal for you. You can talk while you eat, Cody.”

“Thanks for your thoughtfulness, major. I am a little slim-waisted, not daring to build a fire since yesterday.”

[28]

“Just like you to neglect your own needs when others demand your services.”

“Ha, ha!” laughed the scout. “I had some desire to keep my scalp, as well. The reds are too thick hereabout to make fire-building a safe occupation.”

“Well, sir, your plan?” queried the officer.

“Why, it came to me when I saw old Oak Heart mixed up with that blessed old white horse, you know. That old fellow is an ancient friend of mine. I recognized him at once. And he never did love an Injun. I wonder how Oak Heart managed to ride him at all.”

“The horse, you mean?”

“Sure. Well, as for the chief, we have him; but we never can make terms with his tribe for his release.”

“You think not?”

“I know so. The chief is a true Sioux. He would never allow his people to make terms for his life. You could hack him to pieces on that scaffolding yonder, where all the reds could see, and it would not change the attitude of the crew a mite, excepting to make them more bloodthirsty.”

“Yes?”

“So we can’t make terms with him.”

“What do you advise, then?”

“That you have a talk with Oak Heart. He understands English very well, and what he doesn’t understand I’ll interpret for him.”

“Go ahead, Cody,” said the major, laughing. “What are my further instructions?”

“Why, sir——”

“You know very well, scout, that you are bossing[29] your superior officer. But it isn’t the first time. What shall I say to this red rascal?”

Cody’s smile widened and his eyes twinkled.

“Just tell him that he has proved himself too brave an enemy to be either kept in captivity, or punished.”

“And set him free!”

“Sure.”

“But why?”

“Because I can use him in just that way, sir.”

“How?”

“Let me explain. I’ll mount his horse—or the one he rode. I know the splendid fellow well, as I told you. He belonged to Colonel Miles, and a faster or better enduring animal is not now on the frontier.

“I’ll put Oak Heart on my old black. The poor fellow is foundered and will never again be of much value. We will ride out side by side.”

“You will!”

“Somebody must return Oak Heart to his people, you know. And I crave permission to do that.”

“All very well, Cody; but I don’t see your plan.”

Cody laughed again.

“I’ll make it plainer then, sir, by saying that I propose to paint and rig up as old Oak Heart himself, and put him in my togs.”

“Jove, scout! That is a perilous scheme.”

“It’s a good one.”

“But you’ll be shot when they find you out.”

“When they do I’ll be a mile away. I’m going to ride on ahead toward the mouth of the cañon. It’s the nearest road to Fort Resistence. I’ll wave back the tribe as I advance, and they’ll think it is Oak Heart ordering them. They’ll obey him, all right. Then I’ll[30] make a break for it, and you can wager I’ll get through all right, and with that white hoss under me nothing in that outfit can head me off or catch me!”

“And the chief?”

“Hold him back a bit at the stockade. When my horse begins to run, let him go. If the beggars shoot him, it will serve the old scoundrel right. At least, it will confuse the reds.”

“A good idea!” exclaimed Baldwin. “And I really believe it is feasible.”

“Sure it is.”

“There doesn’t seem any better way to break through their lines.”

“That’s right! Strategy must aid pluck in this game.”

“Aye, and you’re the one to make the effort. But may I suggest an amendment, scout?”

“Just put it up to me, Major Baldwin. You haven’t been chasing Injuns all this time without having learned a trick or two yourself.”

“Thank you, Cody. Here’s my idea: Oak Heart will see through your scheme and possibly signal his people the truth before you can reach the cañon.”

“I’ll have to run that risk.”

“No use running any more risk than necessary. Why not take a second man with you?”

“Ah!”

“Yes. One of you represent Oak Heart and the other be yourself. We’ll hold the real chief back until you and your mate get to the cañon. Then, by turning Oak Heart loose, we will add to the reds’ confusion, as you say.”

“Glorious! Fine, major! And I’ll take Texas Jack[31] with me and let him play Oak Heart’s part. He makes a better Injun than I should. And then—I know Jack. One of us will be sure to get through and reach Resistence.”

“Jack has been on duty night and day, Cody,” objected Major Baldwin. “He volunteered to make the attempt before, but I vetoed it. I needed his presence and advice. To let you both go is like putting all my eggs in one basket and sending them to a dangerous market.”

“He’s the man I want,” said Buffalo Bill firmly.

“All right! Let Omohondreau be sent for,” the major said, turning to an orderly.

Texas Jack’s real name was Jean Omohondreau, and he came of a wealthy and noble French family, although he was born in America. It is said that he had refused the title of “Marquis of Omohondreau,” although later he was known as “The White King of the Pawnees,” having been adopted into that tribe and completely winning the confidence of the red men.

At this time Jack was smooth shaven, and with his deeply bronzed features and piercing eyes and black hair he did not look unlike an Indian. Besides, he had lived among the savages even more than Buffalo Bill himself, and had that imitative faculty so general in French people. He could “take off” the savage to the life.

When Texas Jack came sleepily enough from his[32] bunk, it took but a few words from Cody to wake his old pard up. The moment Jack understood what was wanted of him, he was in for the plan, heart and soul.

Oak Heart, who had been entertained—possibly to his great surprise, although he had not shown such emotion in his hard old face—by the younger officers with food and drink, and some of the paleface’s real tobacco, instead of dried willow bark, was now given a uniform and slouch hat in place of his war-bonnet and beaded and befeathered buckskin suit and gay blanket.

The natural acquisitiveness of the Indian character, and the childish joy they have in new finery, possibly made the chief ignore what was done with his old garments. Texas Jack made himself look the Indian brave to the life, put on Chief Oak Heart’s abandoned finery, and, mounting the splendid white cavalry charger—but with saddle hidden by his blanket—was ready to accompany Buffalo Bill.

The latter sprang into the saddle of his claybank—“Buckskin”—and led the way through the open gate. Behind them was the surprised Oak Heart upon Buffalo Bill’s old black, and the soldiers were ready to set him free the moment the two scouts had crossed the danger zone.

The Indians had retired sullenly after Oak Heart’s capture, and White Antelope had as yet been unable to rally them to another charge upon the stockade. Their last charge had been disastrous, and they had not only lost their principal chief, but had been unable to bring back to their camping lines many of the dead and injured. But the belt of red humanity still encircled the fort, and it was plain that they proposed to abide there until such time arrived as could compass their revenge.

[33]

Those of the less seriously wounded had dragged themselves back toward their companions; but the others had been removed inside the fort and were being cared for by the surgeon, after he had ministered to the wounded whites. The dead redskins were let lie where they had fallen for the time being.

Oak Heart had noted the care taken of his wounded braves by the white medicine-man. If this charity impressed him his immobile face showed no emotion. He sat the horse that had been given him like a graven image.

Now the moment had arrived for the departure of the two scouts from the fort. As the pair dashed through the open gateway many good wishes followed them. But the troops had been warned not to cheer. That might apprise the redskins that some desperate venture was about to be made.

“Good-by, Bill, and may God guard you!” cried Major Baldwin. “And you, too, Texas Jack! I hope to see you both again.”

Cody turned and waved his hand to him; but Jack, in the character of the captured chief, looked straight ahead over his horse’s ears, and he made no gesture.

“We’ll bear toward the left, Jack, for our best plan is to strike for the cañon,” said Buffalo Bill.

“Right you are, pard. But don’t let’s make a dash till we hafter. We’ll gain everything by keeping them red devils guessing.”

“Sure’s you live, Jack! The moment the reds make a move for us, you sign for them to go back. Keep ’em at a distance if you can.”

“I will,” assured Texas Jack.

[34]

“Sit up stiff, old man, and play the part right,” admonished Buffalo Bill with a laugh.

These courageous men could laugh in the face of almost certain death!

“What d’ye suppose they think of it, Bill?” asked Jack. “They’re awake, all right. I wonder what they think at seeing you bringing their supposed chief back to them?”

“I’d give a good deal to know just what they are going to think,” said Cody, more gravely. “But we’ll soon know.”

“Betcher we will!”

“It’s unnecessary to ask you, Jack, if you’ve got your shooting irons ready?”

“Ready and loaded, Bill.”

The two scouts were as watchful as antelopes, and as cautious. But they appeared to ride along at an easy lope, and in a most careless fashion. This is the coolness born of long familiarity with peril; they could meet death itself without the quiver of a nerve.

They progressed but slowly, and the eyes of most of the red men were fixed upon them. It was plain that the savages did not understand just what was going forward when they saw he who appeared to be their king riding thus quietly, and armed and caparisoned, with Long Hair, the white scout. They could not understand why he was coming back to them in company with Pa-e-has-ka.

Soon they began to move forward in a body to meet the coming “chief” and his comrade.

“Give ’em the sign language, Jack. It’s time,” muttered Buffalo Bill.

Omohondreau was an adept at this wonderful means[35] of communication, which was really a general language understood by the members of all the red tribes. He raised first one hand, palm outward, and then the other, and motioned the red men back. The warriors hesitated—then obeyed.

But a mounted figure came dashing from another part of the field, and this silent sign manual did not retard it.

“Face of a pig!” ejaculated Texas Jack, in the patois of the French Canadian, and which he sometimes lapsed into in moments of excitement. “Here comes that gal, Bill!”

“The White Antelope!” exclaimed Cody. “I had forgotten her.”

“Shall I warn her away?”

“I’m afraid if you turned to face her she would see that you are not Oak Heart.”

“Quicker, then, Pard Cody!”

“No. They might suspect.”

“Heavens, Bill! What will you do when the girl overtakes us?”

“Whatever comes handiest.”

“I could put a bullet through her without turning,” muttered Jack.

“You wouldn’t be so cruel, old man.”

“Hang it, man!” exclaimed Jack in disgust. “She’s only a ’breed.”

“No. You’ll not injure her. I have your promise, Jack,” said Cody confidently.

“But she’ll finish us if she suspects. I think she has a pistol,” said Jack.

“We’ll see.”

“Hang it, Bill Cody! You’re the coldest proposition[36] I ever came across. I’ll eat this old war-bonnet—and it’s about as digestible as a wreath of prickly pear—if we don’t have trouble with that gal.”

Evidently White Antelope was much amazed by the fact that her father did not even look in her direction, for she called some welcome to him in Sioux. Neither of the scouts made reply, but both kept watch of her out of the corners of their eyes. The girl, puzzled by the mystery, half drew in her pony.

The mob of Indians waited. That they were puzzled was evident; but as long as they remained inactive the scouts’ chances were increased.

“Can we make it, Pard Cody?” muttered Texas Jack.

“If the girl doesn’t suspect too quick.”

“She’ll queer us—sure!”

“I hope not,” and Buffalo Bill looked grave.

“If she comes nearer we’ll have to do something, Bill—as sure as thunder she’s coming!”

It was true. White Antelope had again spoken to her pony, and the animal leaped forward. She came from the left, and Texas Jack rode nearest her.

“Keep on, Jack!” exclaimed Bill under his breath.

He pulled back Buckskin and got around so as to ride between the supposed Indian chief and the girl. Instantly White Antelope seemed to suspect that all was not right. She raised her voice, crying in her native tongue:

“Why does the great chief not speak to his child? Oak Heart, my father, it is I, your daughter, White Antelope, who calls you!”

She was all the time riding nearer. There seemed no way to stop her, and she must soon be near enough[37] to observe that the supposed Oak Heart was a false Indian.

Fortunately the tribesmen were some hundreds of yards away from the two scouts. But they heard something of what White Antelope said, and they began to move forward, murmuring among themselves. They did not for a moment suspect that this was not their great chief, but they believed that something was wrong with him, and that Pa-e-has-ka had Oak Heart in his power.

“They’re coming, Cody!” whispered Texas Jack. “They’ll make a rush in a moment.”

“Sign them again!” commanded Buffalo Bill. “It’s our only chance.”

“Think it will work?”

“It must work. We need a few moments more before we make a dash for the cañon.”

“But that gal——”

“I’ll ’tend to her,” exclaimed Buffalo Bill. “Signal the reds to keep back.”

Again Texas Jack raised his hands and made the well understood sign. But the Indians hesitated. They saw White Antelope still riding toward the supposed chief and the scout, crying to her father to answer her.

“Keep on for the cañon, Jack!” muttered Buffalo Bill beneath his breath.

He jerked his horse to one side, turning to meet the Indian maiden. As she rode down toward the scouts, her golden hair flying in the wind, her lips parted, her eyes shining, she was indeed a beautiful creature. Her beauty alone would have made any old Indian hunter withhold his hand. And Buffalo Bill had a deeper reason[38] for wishing no harm to befall the half-breed daughter of Oak Heart.

“What is the white chief, Pa-e-has-ka, doing with Oak Heart?” the girl cried in Sioux, urging her pony toward the scouts.

Buffalo Bill was riding with the rein of the claybank horse lying upon its neck, and guiding him with his knees. His rifle lay across his saddle, the muzzle pointing in the direction of White Antelope as she rode near. He did not raise his voice, nor change the expression of his face, for the scout knew that he was being closely watched by the crowd of redskins in the background. But into his voice as he spoke he threw all the threatening, venimous tone of a madman thirsting for blood.

“The White Antelope, like her father, Chief Oak Heart, is in my power. Do not make a single motion to show that you are startled, White Antelope, for if you do my first bullet shall be driven through your heart, and my second shall cleave the heart of your father!”

These words, spoken with such wicked emphasis, seemed to come from a veritable fiend instead of the placid-looking white scout. The White Antelope’s great eyes opened wider, and she half stopped her pony.

“None of that!” snapped Buffalo Bill in English, which he knew the girl understood quite well. “Make a false move at your peril—and at your father’s!”

“My father——” began the startled maiden gaspingly.

“Ride closer. Keep beside me, Oak Heart! I forbid you speaking to your child!”

[39]

Buffalo Bill’s commanding tone was most brutal. His eyes flashed into the Indian maiden’s own as though he meant every word of his recent threat. But the supposed Oak Heart’s shoulders shook. However, he kept his head turned religiously away from his “daughter.”

The seconds were slipping by, and the scouts were approaching very near to the place where they would be obliged to turn sharply and make their dash for the cañon. Despite their bearing off so far toward the left, their course had been apparently toward the Indian lines.

White Antelope, all the rich color receded from her cheeks, rode beside Buffalo Bill on his left hand. She was not only frightened by the scout’s threat, which he seemed to be able to fulfil, but she was puzzled at her father’s inaction and seeming helplessness. She tried to force her pony forward slyly so as to obtain a look at Oak Heart’s features.

“None o’ that!” commanded Buffalo Bill in quite as brutal and threatening a tone as before.

At the moment a wild yell rose from their rear—from the direction of the fort. The girl turned swiftly to look. And so surprised were the scouts to hear a disturbance in that direction, that they glanced around, too.

Out of the gateway appeared a black horse, and on its back a figure in uniform and wide-brimmed hat. But as the horse dashed on the figure snatched off the uniform hat, displaying the long, flying hair of an Indian, and he broke into a shrill and terrible Indian war-whoop!

On the heels of this another roar burst from the[40] fort, and out of the gateway piled a troop of mounted men—those soldiers that were first to get upon their horses to pursue the wily Oak Heart. The latter saw his daughter and knew her danger. Following his war-whoop, he shrieked a warning to White Antelope. She understood the words he uttered, although the scouts could not.

The girl turned swiftly and saw Texas Jack’s painted face.

“False paleface!” she cried. “You are not Oak Heart. The great chief is there!” and she pointed back at the flying figure on the black horse.

“It’s all up, Cody!” cried Texas Jack.

Buffalo Bill leaned suddenly from his saddle and snatched from the maiden’s belt the revolver which she cherished above most of her possessions. He feared her ability to use this.

“Off with you, Jack!” he cried. “Now’s our time!” and setting spurs to his claybank he raced after Texas Jack toward the opening of the defile which they had been so gradually and cautiously approaching.

So interested had the officers and garrison of Fort Advance become in the attempt of the courageous scouts to reach the cañon entrance, that they had quite neglected to watch the king of the Sioux. That he understood fully the trick that Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were attempting to play upon his people was proven by the outcome.

[41]

The savage chief sat his black horse in motionless gloom, and as though his eyes saw nothing. Captain Edward Keyes had kept his file of men in the saddle ready to make a break from the fort should the scouts fall in need of some attempt at rescue. Otherwise, everybody was crowding forward to look out of the gate, or, from the platform and watch-towers, to view the work of the brave men who had gone from them.

The black horse, on which Buffalo Bill had ridden so many times, but which he had now been obliged to abandon because of its age and the fact that he had been ridden too hard on one or two occasions, missed its master. It had seen Buffalo Bill and his companion ride out of the fort, and it desired to follow. Perhaps the horse did not approve of the Indian that now backed him.

However it was, it danced about a good deal, and champed at the bit, and seemed to give the stoical chief considerable trouble. Twice it started for the gate, and the soldiers headed it off. Likewise Oak Heart drew it in hard with his hand on the bridle. It seemed as though the chief had no expectation of leaving the fort until his white captors were ready.

But that was all the savage cunning of the chief. It was his cunning, too, perhaps, that made the horse so nervous. He doubtless slyly spurred him with his toe or heel, and kept the animal on the qui vive all the time.

Oak Heart could follow Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack with his eyes, and he doubtless understood—now, at least—just what they were about. Suddenly the White Antelope came into view, riding like the wind down upon the two scouts. Oak Heart’s face did not[42] change a muscle, but just then his mount made a sidelong leap, and when he became manageable again the black charger was just within the open gateway.

Several moments passed. The white men’s attention was strained upon the little comedy being enacted by the two scouts and the Indian maiden. They could not hear, of course, but they could imagine that the situation had become mighty “ticklish” for the scouts, knowing Buffalo Bill’s objection to injuring the Sioux maiden.

It was at this minute that the black horse made a final charge through the gateway. Two men were knocked down, and Oak Heart threw himself over to one side of the galloping horse, shielding himself with its body from the guns of the surprised white men in the stockade.

His wild yells had already apprised White Antelope of the deception. Buffalo Bill had disarmed her, and the two scouts spurred on toward the cañon.

The hearts of the watching people at the fort were in their throats. A general cry of dread burst from them as they saw the Border King and Texas Jack turn abruptly toward the cañon. The Indians saw the act, too, but for a few seconds did not comprehend it. They were slower than White Antelope in understanding that the supposed warrior with Pa-e-has-ka was a white man in disguise, and that the person careering across the plain on the black charger was the real Oak Heart.

The signals of Texas Jack in his character of Oak Heart had drawn many of the Indians away from the cañon’s mouth toward the place for which the supposed chief and Buffalo Bill seemed to be aiming.[43] There were very few left in the path of the reckless scouts. Yet those few must be settled with.

There were no mounted warriors near the cañon entrance. The great scout had chosen his place of attack wisely. And there were few ponies in the vicinity, anyway—not over two dozen at the most. The earlier stampeding of the ponies had almost entirely dismounted Oak Heart’s braves. The ponies that might follow, should the scouts get through safely, neither of them feared, mounted as they were on such splendid animals.

“Let ’em out, Jack!” cried Buffalo Bill, as they made directly for the cañon.

“I hear you!” returned Texas Jack, smiling recklessly, and settling himself more firmly in his saddle.

The two were off like frightened deer. For some moments the Indians were almost dumb with amazement. Then the war-whoop of Oak Heart was answered by wild cries from all about the field. The reds knew that the Border King had outwitted them, and as one man the mob of redskins made for the entrance to the cañon, firing as they ran.

The scouts did not return the fire. They kept their bullets for targets nearer the path their horses followed. The nearer Indians were converging swiftly at the mouth of the cañon.

Behind, and nearest to the scouts, came Oak Heart and White Antelope, who had waited to join her father. But neither of them were armed. When Buffalo Bill snatched the revolver from the girl’s belt he had made a good point in the game, for she was an excellent shot with the small gun—for an Indian.

Suddenly The Border King raised his rifle, and shot[44] after shot rang out. He fired at the Indians directly in front of him, gathering to bar the way. There were now a score of them near enough to be dangerous.

The repeating rifle sang deadly music, for several of the braves fell. With the last shot from Buffalo Bill’s weapon, Texas Jack’s gun took up the tune and rattled forth the death notes. They were now close to the group of reds, and the shots forced the Indians to scatter.

Instantly the scouts slung their guns over their shoulders and drew the big pistols from the saddle-holsters. With one of these in each hand, the scouts rode on.

Theirs was indeed a desperate charge, and, although now hidden by the nature of the ground from the bulk of the Indians, the encounter was visible from the fort.

The chorus of wild yells, the rattle of revolvers, the heavier discharges of the old muzzle-loaders of the redskins, and the resonant war-cries of the scouts themselves, were heard by the besieged. The Border King and Texas Jack were having the running fight of their lives. Would they get through alive?

Suddenly a chorused groan arose from the white onlookers, while a shriek of exultation came from those Indians who saw the incident. Buffalo Bill’s horse gave a sudden convulsive leap ahead, then fell to his knees. The scout loosened his feet in the stirrups, and, as the brave Buckskin rolled over upon its side, dead, the scout stood upright, turning his revolvers on his foes. Texas Jack, on the white charger, tore on into the mouth of the cañon.

Buffalo Bill had emptied the pistols which he had carried in his saddle-holsters. Now, he stood beside[45] his dead horse, with the pistols drawn from his belt in either hand. He stood boldly at bay, and the redskins went down before his deadly aim.

The redskins’ triumph was short-lived. Texas Jack, seeing his partner’s peril, turned his great white charger as quickly as might be. Back he rushed to Cody’s side.

“Up with yuh, pard!” he shouted.

He whirled the big horse again. With a leap, Buffalo Bill sprang up behind Texas Jack, his back to that of his partner, and again the horse was headed for the cañon’s mouth. The four revolvers of the scouts spit death into their foes at every jump of the horse.

Those redskins who opposed the way either crumpled up and fell to the rocks or dodged behind the boulders for safety. It seemed as though their numbers were sufficient to make the scouts’ escape impossible; the odds against the white men were all of ten to one!

But the redskins’ shooting was wild, while the accuracy of the white men’s aim was phenomenal. Many a red, just as he had drawn bead upon the scouts, was struck by a pistol ball, and either knocked over completely or his own shot diverted.

The cheering of the garrison as they saw Texas Jack return for his partner inspired the scouts. The last Indian went down before them and was trampled under the hoofs of the charger that bore them both, and as they shot out of sight into the gloom of the cañon’s mouth Buffalo Bill removed his sombrero and waved it to the watchers on the fort stockade, while his well-known war-cry rang over the field of battle!

[46]

“We’ve got through, Jack!”

“We sure have, Pard Cody.”

“Anybody hurt?”

“I got a couple of nicks from the pesky arrows,” said Omohondreau. “But, shucks! them Injuns can’t shoot with a white man’s gun worth a hoot in a rainwater barrel.... Yuh lost Buckskin, Cody.”

“And sorry enough I am to lose the poor creature. He’s been a good nag.”

“How about you, Pard Cody?”

“A scratch from a bullet in my left shoulder. It’s bleeding a little, but I won’t stop to fool with it now. And I got four arrows through my clothes. Oh, we were lucky!”

“Betcher life! We’ve been favored mightily.”

“Thank God for it,” said Buffalo Bill devoutly. “I don’t expect often to come through two such circuses in one day—and have nothing worse to show for it.”

“Right. Now, old man, what’s the program?”

“Keep on. I don’t feel safe as long as we’re at the bottom of this hole in the hills.”

“That’s all right. But we haven’t got but one horse——”

“I was thinking of that.”

“And your thoughts?”

“We can’t both ride this horse, good as he is, all the way to Fort Resistence.”

“Right again!”

[47]

“One of us must push on for help about as fast as the horse can go.”

“Sure.”

“There isn’t much danger of the reds following us far, for their ponies aren’t to be compared with this fellow—and they all know what he can do.”

“Well?”

“Then you’d better let me go on, as soon as we come to the creek ahead and shape ourselves up a bit, and you can scout around until I return with help from Fort Resistence.”

“Pard Bill!”

“Yes?”

“They need every rifle they can git in the fort, yuh know.”

“They certainly do.”

“Scouting around yere all night, I can’t do much good, and that’s a fact.”

“Very true, Jack! Very true.”

“And I’ve got nothing to eat, while the maje and the folks at Advance will be mighty anxious tuh know if yuh got through all right—ain’t that so?”

“Reckon you’re right, Jack.”

“Then I’m goin’ to take a sneak back and try to git through the lines after dark.”

“No, you won’t, Jack Omohondreau. I veto that.”

“Put the kibosh on it, do yuh?” asked Jack, leering back at his partner over his shoulder.

“I certainly do!”

“Why, pard?”

“There’s no danger going on now for help, so I’ll return to the fort myself, while you strike out for[48] Resistence and help. I got you into this. I’m not going to shoulder the heavy part of the job off onto you.”

“That’s like you, Cody! Always lookin’ for trouble to git into yourself. But I’m going back.”

“I say no,” replied Buffalo Bill firmly.

“Now, see here!” exclaimed Jack, in some heat. “It’s my idea to go back, and I’m going.”

“Well, you needn’t stop here,” laughed Cody, as Jack, in his excitement, brought the horse down to a walk.

“You listen to reason!” exclaimed Texas Jack. “I speak the lingo all O. K.”

“I admit that.”

“And I’m already playing Injun.”

“Pshaw! That may be, but I can soon change my colors.”

“You’re as obstinate as a mule, Cody!”

“See here, Jack, I admit that the folks need us back there at the fort, and one had better return, but I should be the one.”

“Tell you what, pard!” exclaimed Jack, smitten with a sudden thought.

“Well?”

“We’ll draw lots to see who goes.”

“I’ll beat you at that game, Jack!” cried Cody, with a laugh.

“Don’t yuh crow too loud, old man,” said Texas Jack gaily. “When we git to the creek we’ll see who’s who!”

“I’ll go you, for my luck is good.”

“I’m sure a child of fortune myself,” laughed Jack.

They soon reached the creek, which cut across the cañon at its widest part, spurting from under a ledge[49] on one side, and disappearing with a tinkle of falling water through a crack on the other—one of those underground streams often found in the Rockies, which only by chance ever come to the light of day.

The scouts dismounted, making sure that all pursuit had been abandoned by their mounted foes, at least, and washed and dressed their slight wounds. In each man’s pouch was Indian salve, certain valuable herbs, dried, and bandages rolled for them by the women of Fort Advance. Your old frontiersman was no mean surgeon, and many a man to-day, whose early years were spent on the border, owes his life to some rough but prompt bit of surgery on the part of a pard with powder-stained fingers.

“Now, we’ll draw lots to see who goes back,” said Cody. “Wish we had a pack of cards.”

“I got what th’ boys call a Sing Sing Bible,” observed Texas Jack, drawing the pack from his pouch.

“Good! We can’t take the time to play any game, but I’ll shuffle, you cut, and the one who holds the ace of clubs goes back to Advance.”

“Agreed. Shuffle ’em good, old man—though I feel I’m going to win right now.”

“You’re too cock-sure,” laughed Buffalo Bill.

The scouts spoke in a light-hearted way, but each realized the terrible ordeal that might fall to the one who attempted to return to Fort Advance. Major Baldwin needed one of them as an adviser—and his rifle would be an acquisition as well, for both Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were dead shots.

The uncertainty and impatience of the entire garrison would be relieved, too, if they were informed that one of the scouts had gone on to Resistence and would[50] surely bring help the next day. This knowledge would put heart in the defenders of Fort Advance when the Indians attacked, as they surely would after nightfall.

The cards were shuffled by the chief scout, and then he held them in his open palm. Texas Jack cut at a point about half-way down the pack. One after another the pasteboards were discarded, and Buffalo Bill had already displayed two aces, when suddenly his partner chuckled and slammed down another card, face up. It was the fatal card—the ace of clubs.

“Got yuh that time, Pard Cody!” exclaimed Texas Jack in delight.

Buffalo Bill looked regretful, while his partner was triumphant.

“I told yuh I was a child of fortune,” laughed Texas Jack.

“I yield, old man,” said Cody. “May your luck carry you through in safety.”

“I’ll git there—or the reds will know I tried,” said Jack with emphasis.

“Aye, that they will. Now I must be off, Jack. The horse is rested, and he’s got a hard road to travel this night. I’ll be back with help as soon as possible.”

“You ought to make it by morning with any kind of luck.”

“I’ll do my best,” declared Buffalo Bill. “And now good-by, old pard! If you go under I’ll see that there are plenty of those red devils on the trail to the happy hunting grounds to make up for your loss.”

They wrung each other’s hands, and, although the spoken word was light, the look in each man’s eyes showed a deeper feeling. Buffalo Bill walked quickly to where the great white horse was feeding, and, vaulting[51] into the saddle, the horse, without urging, started into his easy lope.

Once the mounted scout looked back. Texas Jack stood in the middle of the trail looking more like an Indian chief than ever, he was so silent and stern of feature.

They waved their hands briefly—a last farewell. Then the Border King disappeared around a turn in the trail, and Texas Jack prepared for his attempt, night now being not far away.

Texas Jack had been a ranchman in Texas since early boyhood. His sentiments and affiliations were Southern, and when the war broke out he joined the Confederate Army as a scout. He was a reckless, daredevil fellow, yet high-minded, honorable to foe as well as friend. The noble blood of the Omohondreaus showed through the rough manner of the hardy frontiersman.

It was Jack Omohondreau who came so near dealing an irreparable blow to the Northern cause by capturing President Lincoln and taking him South as a prisoner. How near the daring scout came to accomplishing this very thing nobody but those few Confederates in the secret—and possibly Lincoln himself—ever knew.

However, when the Civil War was ended, Buffalo Bill, who had scouted for the other side, found Jack in Kansas, and it was through his influence that the young French-American was enlisted in the Federal Army.

[52]

He was of cheery nature, fearless to recklessness, strong as a grizzly, and possessed of a handsome presence. Such was the man who had determined to return through the ring of enraged Sioux to give comfort and help to the besieged garrison of Fort Advance.

He knew all that he had to risk, but, in his Indian disguise, and under cover of the early darkness, he hoped to accomplish his purpose. If captured by the redskins he well knew that death by the most frightful torture would be his portion. The Sioux hated him almost as fiercely as they hated Buffalo Bill.

That he could speak their language was in Jack’s favor. And he knew that if he chanced upon any bunch of the reds a word or two might pass him through all right. Oak Heart had gathered several different branches of the tribe together, and many of the braves must be strangers to each other.

The scout had already formed his plan of return to the fort. He had reloaded his rifle and revolvers, seen that his knife was still in its scabbard, and, after another long swig at the clear, running water and a tightening of his belt, Texas Jack climbed one side of the cañon with infinite caution. He could not return through the gorge itself, for he did not know how near pursuit might be. And he wormed his way up the steep ascent like a serpent, that he might not be observed from below.

Night came upon him as he arrived on the summit of the timbered ridge. The forest was a tangled wilderness, but he knew how to pass through it without making the slightest disturbance, and, as he might come upon the Indians at any moment, he was glad of the darkness and the thicket. A few miles along this[53] ridge and he would come out upon a bluff that overlooked the valley in which Fort Advance was situated.

He strode on lightly, yet swiftly—threading his way through the trackless forest with a confidence which brought him straight to his destination. And as yet he had not passed an Indian.

The dash of the scouts into the cañon had drawn all the outposts from the hills, and the redskins were either guarding the lower passes, ringing the fort, or gathered about the camp-fires where the main encampment had been established.

When Texas Jack came out upon the bluff he could see these camp-fires twinkling on the other side of the valley, although it was still light enough for him to see all who moved below him. The encampment was at the base of the southern hills, some two miles from the fort. Some half-hundred ponies were feeding in the valley, with the guards about them doubled. The loss of the bulk of the herd had been a severe blow to the redskins, and Texas Jack knew that the Indians would put forth every effort to retake them, should opportunity arise.

Jack decided that Chief Oak Heart was probably at the encampment, counseling with his old men and the other chiefs regarding the next blow to be struck at Fort Advance. That plans of deviltry and cunning were being hatched the scout was certain.

Then he thought of the Border King flying along the trail to Resistence for help, and he regained his courage.

Awaiting with the stolid patience of a redskin for the night to deepen, the scout finally pursued his march[54] into the valley. He had carefully weighed all chances for and against his success. Now he was ready to take them.

Night spread its wings over the valley. It hid its scars and wounds and the stark bodies of the dead, lying under the fortress walls. In the gloaming it might have been the most peaceful valley in all the Rockies. One coming upon it suddenly, and unwarned, would never have suspected the blood so recently spilled there and the threatening aspect of the situation at that very moment!

Texas Jack stole down the declivity with a step as light as the fall of a leaf. The savage whom he imitated could have moved no more lightly, and as he came into the valley itself he crouched and crept along like a shadow.