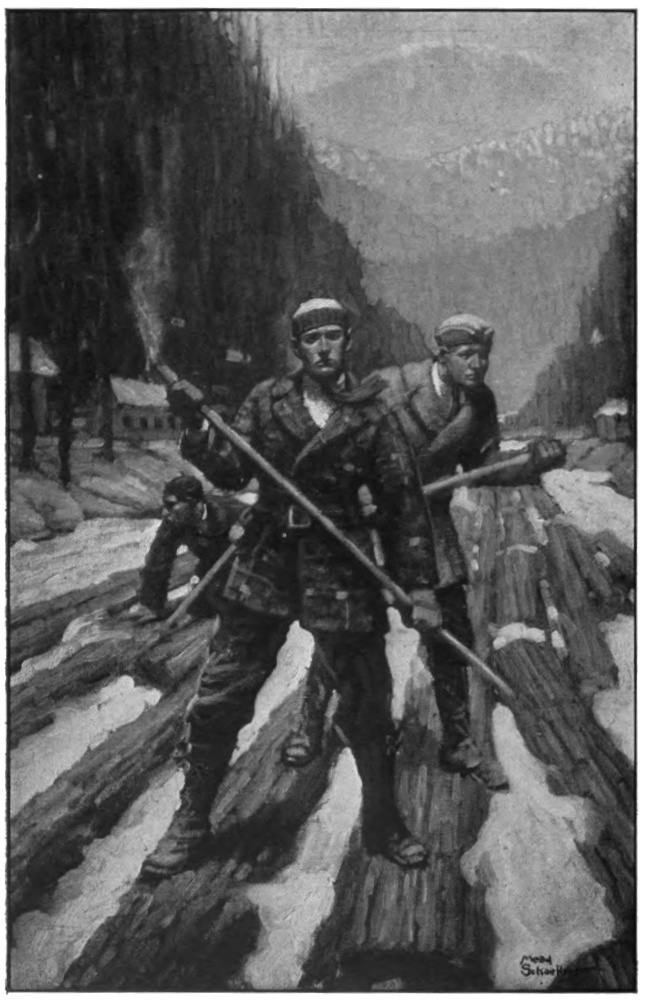

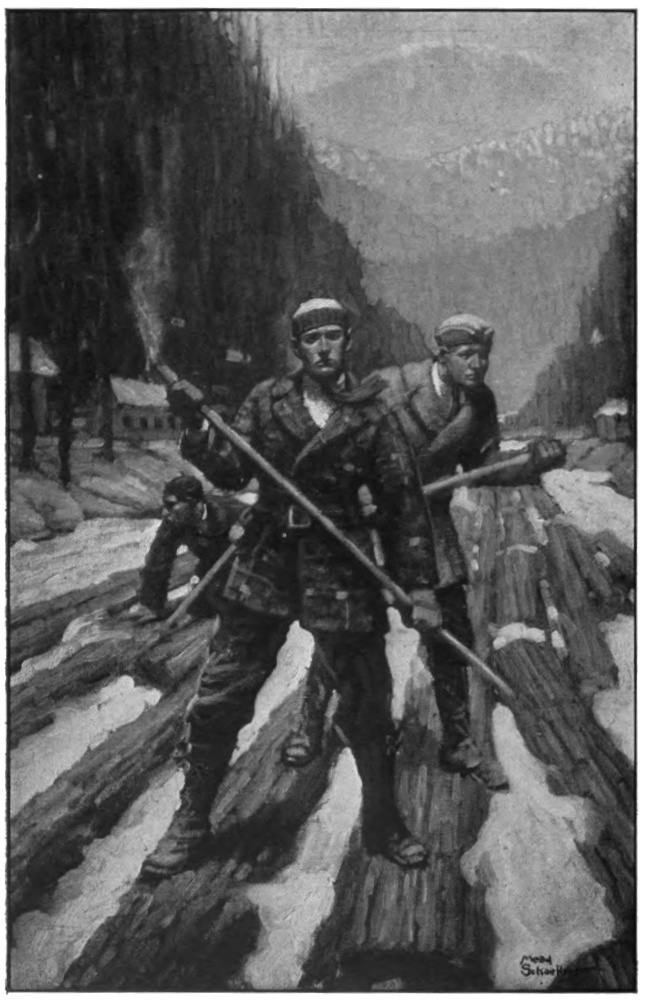

Rex had some trouble at first in keeping his balance, but he was quick to catch on to the knack.

Title: The Golden Boys on the River Drive

Author: L. P. Wyman

Illustrator: Mead Schaeffer

Release date: July 19, 2020 [eBook #62698]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

Rex had some trouble at first in keeping his balance, but he was quick to catch on to the knack.

“Hurrah! She’s breaking up.”

Two boys were standing on a little wharf looking out over the ice covered surface of Moosehead Lake in northern Maine. They were fine specimens of American boyhood. Bob Golden, nineteen years old, lacked but a trifle of standing six feet and was possessed of a body perfectly proportioned to its height. His brother Jack, a year younger, was not quite so tall but his body was as perfectly developed. Except when at school they had for years lived in the great out-of-doors, in the Maine woods and on the Maine lakes, and the free and open life coupled with the invigorating air of the Pine Tree State had given them “mens sana in corpore sano.”

They had arrived at the lumber camp belonging to their father the day before, having driven up from their home in Skowhegan, a small town about fifty miles to the south. The Fortress, a military college in Pennsylvania, where they were cadets, had closed for a three weeks’ vacation and they had lost no time in reaching the camp.

“She’s breaking up,” Jack repeated, dancing about like a wild man, on the end of the wharf. “Just look at that crack run out into the lake, will you,” he added, as a heavy booming sound reverberated through the vast forest.

“And just think,” Bob declared, as he grabbed his brother by the arm and held him fast, “by night there won’t be a speck of ice to be seen anywhere on the lake. I wonder where it all goes to so quickly.”

Jack was about to reply when the loud call of a horn rang through the air.

“I don’t know, but I do know where I’m going,” he cried as he turned and sprang for the shore. “Come on or I’ll eat all the flapjacks,” he called back, as he saw that his brother was still watching the ice.

“Be with you in a minute,” Bob shouted, his eyes still on the lake.

It was a fascinating sight, the ice slowly heaving with a suppressed restlessness as though loath to give up its sovereignty of the lake. But hunger soon overcame his desire to watch the lake and he was but a few minutes later than his brother in entering the long mess room.

Breakfast was on the long table, along the two sides of which about forty men were doing their best to make way with the huge piles of hot cakes and bacon and eggs, to say nothing of doughnuts and coffee.

“You ver’ near mees der grub, oui,” shouted big Jean Larue, as Bob took his seat beside Jack.

“Guess there’s plenty left,” he laughed, as he glanced about the table.

“Oui, dar’s allays pleenty der grub here,” declared another Kanuck, a huge six footer, named Pierre, from his seat near the foot of the table.

Pierre’s statement was correct, for Mr. Golden believed in giving his men good food and plenty of it, and there was never any fault found with the bill of fare in any of his camps.

“We geet the first raft heetched up tomorrow,” Jean said, as he helped himself to another pile of cakes.

“Sure we will, eef you not eat so mooch you no can stir,” Pierre shouted, and a roar of laughter filled the vast room in which Jean joined. His appetite was a standing joke with the men, and he really seemed to take pride in it.

“Dat all right,” he said, as the laughter subsided. “After breakfast I, Jean Larue, put you on your back ver’ queek. You tink I eat too mooch, hey?”

“You mean you try. What you call eet? You spell able once,” Pierre grinned, as another roar of laughter greeted his words.

“Better get a wiggle,” Jack advised his brother, as he helped himself to two more doughnuts. “I wouldn’t miss seeing that match for a farm.”

“Nor I, but I’ll be there. Don’t you worry,” Bob replied, as he reached for the plate of fresh cakes which the cook’s helper had just brought in.

Both boys knew that a wrestling match between Jean Larue and Pierre le Blanc would be worth going miles to see. Both were big men and well known for their deeds of strength and athletic ability. Pierre was a good-natured, generous fellow and was a favorite with his companions. Jean, at the beginning of the winter, had been the bully of the camp. An arrogant braggart, he had been feared and hated by the greater part of the crew. Just after Christmas Bob, who with his brother had come to the camp for their winter vacation, had had a fight with the Frenchman and, thanks to his superior knowledge of boxing, had given him a sound whipping. This seemed to have broken the man’s spirit; but, a short time later, the boys saved his life and to their great joy he became a different man. All his old arrogance was gone and he became one of the most popular members of the crew.

“Come on dar,” Pierre shouted, as he pushed back his chair. “You hav’ now eat enough for two men. Eef you eat mooch more eet will be no fun to put you on your back.”

“Huh, I, Jean Larue, will geeve you all der fun you want in one leetle minute,” Jean retorted, as he too jumped up from his chair and started for the door, followed by the entire crew.

The snow still lay deep in the woods, but in front of the bunk house it was packed hard, making a smooth although a slippery floor. Once outside in the crisp air, the two men quickly pulled off their heavy mackinaws and thick woolen shirts.

“My, what men,” Bob whispered, as they stood there stripped to the waist.

Physically, at least, they were deserving of the exclamation. Big and thick set, without an ounce of superfluous flesh on their torsos, the muscles played in ripples beneath the smooth skin.

No complicated set of rules governed an impromptu match of this kind. No getting of three points on the ground was necessary to win. The first man down was the loser, and in case both came down together, the man on top was the winner.

A stranger would have thought, from the appearance of the men, that it was to be a fight to the finish, but all present knew that the two were great friends and that the loser would take his defeat in good part and hope to win the next time. However, they had seen the two men wrestle before and knew that each would exert himself to the utmost to win.

For some moments the two giants circled around each other, watching with hawk-like keenness for an opening. The right hold meant half the battle, as they well knew, and a false hold might well mean defeat. Suddenly, seeing his chance, Pierre leaped forward and caught his opponent about the waist. And then the real struggle began.

“Just look at those muscles will you,” Jack whispered to Bob.

It was little wonder that the display excited the boy’s admiration. The huge muscles stood out like immense cords as the two men strained with all their might to upset each other. Pulling and pushing they whirled about on the smooth snow, neither seeming to be able to gain the advantage. Once Jean slipped, and the boys thought that he was going down, but he quickly recovered his footing and, in a second, seemed on even terms again. Both men were breathing hard and it seemed as though one or the other must yield soon, but as to which one it would be there was no indication.

Then suddenly the end came. The boys saw Jean’s powerful arms creep upward, then quickly he bent his back, and Pierre, taken by surprise, flew over his head, landing on his back nearly ten feet away. For a moment he lay there striving to regain his breath, which had been driven from his body. Then eager hands pulled him to his feet and he ran for Jean, who was already pulling on his shirt.

“Dat one ver’ bon hold,” he said as he grasped the victor by the hand.

“Oui, she one ver’ fine hold,” Jean agreed, accepting the outstretched hand with a broad grin. “I thot you had me one time,” he added as he drew on his mackinaw.

“Oui, I ver’ near geet you,” Pierre grinned as he began to dress.

“It’s fine that those men can go through a match like that and still be good friends,” Bob declared as he and Jack hurried away to the wharf.

Even they, accustomed as they were to the rapidity with which the ice breaks up when it once starts, were surprised at the change which one short hour had wrought. What had been a broad expanse of frozen surface now was a heaving mass of huge cakes of ice, interspersed with stretches of open water.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” Jack asked as he gazed at the sight.

“Nothing finer,” Bob agreed. “But come on, let’s get the rods and try for trout in some of those open stretches.”

The finest fishing in the lakes of northern Maine is just as the ice goes out. Then the big trout are hungry after the long winter beneath the ice, and lucky is the fisherman who is there at the time.

As the boys returned to the wharf with their rods it happened that there was an open space just out in front. Bob was first to have a fly lazily floating on the surface of the water, but it had hardly struck the surface before it disappeared and a tug at the line told the boy that he had hooked the first fish of the season. From the way the reel whined as the line ran out he knew that it was a big one. He pressed on the drag as hard as he dared but it seemed to have little effect.

“You’ll have to make it snappy or you’ll lose him,” Jack shouted. “That opening’s going to close in a minute or two, and if he gets under the ice, good night.”

Bob saw that what his brother had said was true, and, for the moment, was uncertain what was best to be done. But just then he noticed that the line was slacking and he hastened to reel in. He had recovered about half of the line when the fish darted off again and he was forced to let the line run.

“You’ll have to pull him,” Jack shouted. “He’ll be under that cake in another minute.”

Bob, realizing the truth of Jack’s statement, quickly lowered the light rod and caught hold of the line. Now it was simply a question of the strength of the line. Would it hold or would it break?

“It’s a good thing that’s a new line,” Jack cried, dancing about in his excitement as Bob began to pull in carefully, hand over hand.

“Nothing very sportsmanlike about this way of landing a fish,” he declared. “But we need that fellow for dinner.”

Slowly, foot by foot, the fish came in until finally it was flapping at their feet.

“Eight pounds if he’s an ounce,” Jack declared, as he picked the fish up by the gills and held it out at arm’s length.

For nearly two hours they fished, watching their chance whenever an open space gave them opportunity to cast. They lost several on account of the ice closing in before they could get them out, but more were landed successfully and by ten o’clock they had enough for dinner for the crew. They were all good-sized fish, none weighing less than three pounds, but the first one caught remained the prize of the lot by a good margin.

“Now I guess it’s up to us to clean ’em,” Jack said, as he reeled in his line. “That’s a dandy mess if I do say it.”

They had thrown the fish as they unhooked them into a packing box, and each taking hold of an end, they started for the mess house. They had stepped from the wharf when Jack chanced to look back toward the lake.

“What’s that out there?” he cried, setting his end of the box down on the snow.

“Looks like a man,” Bob replied, as he followed suit with his end.

“I’ll get the glasses,” Jack shouted, starting on the run for the office only a few rods away.

He was back in almost no time and, running to the end of the wharf, quickly raised the glasses to his eyes.

“It’s a man all right,” he declared after a moment, as he handed the glasses to his brother.

The man was probably a mile and a half from the shore, on a cake of ice about twenty feet in diameter. Bob could see that he was sitting in the center of the cake.

“I can’t see him move a bit,” he said, as he lowered the glass from his eyes.

“Don’t suppose he’s dead do you?” Jack asked anxiously.

“Seems to me that he’s sitting up too straight for that,” Bob replied slowly.

For a moment the two boys looked at each other. Each knew what was passing in the other’s mind. They well knew that the cake of ice which was supporting the man was liable to break up at any moment, and that the strongest swimmer could not live long in the icy water. All the men were off in the woods back of the camp, loading the last of the season’s cut. To go for them might mean that it would be too late.

“Let’s get the canoe quick,” Bob said, as he started on the run for the office slowly followed by Jack.

The canoe, which was in a little shed back of the office, was a small canvas affair, good enough for a short trip in smooth water, but far too frail to be safe amid the floating ice. But it was the only means they had of reaching the man and they did not hesitate. To get it down to the wharf was the work of but a few moments. Carefully they lowered it to the water, there being at the moment a large clear space in front of the wharf.

“This is going to be a mighty dangerous trip all right,” Bob declared, as he took his place in the stern while Jack crouched in the bow. “We’ve got to be careful of the ice or we’ll get a hole in her and then——”

There was no need to finish the sentence. They both knew what a hole in the frail canoe would mean.

The wind, which had been light during the morning, had freshened during the past hour and now was coming strong from the northwest, directly in their faces. All over the lake the huge cakes of ice were bobbing up and down, the spaces of clear water between them constantly increasing and decreasing in size.

From the start their progress was very slow, as they were obliged to follow a zigzag course wherever the open spaces would permit. In twenty minutes they were but a few hundred feet nearer the man than when they started.

“Can we ever do it?” Jack panted, as he dug his paddle deep in the water and exerted all his strength to avoid a cake which threatened to smash into the side of the canoe.

“We’ve got to,” Bob returned, a look of determination in his face. “We’ll do it if his cake holds out long enough,” he encouraged, as with a strong push he sent the canoe forward through a narrow lane between two large cakes.

Now the open spaces were larger and they were able to make better time. They were nearly half way to the man and urging the canoe between two immense floes when suddenly Jack realized that the cakes were rapidly approaching each other.

“Dig for all you’re worth or we won’t get through,” he shouted.

They did their best but it was not enough. Realizing that they could not make it, Jack stopped paddling and shouted:

“We’ll have to jump for it.”

Bob quickly took in the situation and, throwing his paddle to the bottom of the canoe, he too watched the huge floe as it approached. They saw that the cake to their right would reach the boat first.

“Make it snappy,” Bob shouted, as the cake was upon them.

With hands gripping the side of the canoe they crouched, waiting for the cake of ice to reach them.

“Now!” Bob shouted, and on the instant both sprang for the ice, then turned and dragged the canoe after them.

They were not a moment too soon for, as they drew the canoe from the water, the two floes met with a grinding crash.

“Mighty close call that,” Bob gasped, as he gazed about.

“Too close for comfort, but, thank God we made it,” Jack agreed. “But come on. There’s no time to lose. This ice looks mighty rotten to me, and that cake he’s on may be worse.”

The cake on which they found themselves was a large one, fully a hundred feet across. A glance told them that between their cake and that on which the man sat was mostly open water; and, encouraged by the sight, they began dragging the canoe over the ice. To get it again in the water and to embark without swamping the frail craft took all their skill. But working carefully, they finally accomplished it and pushed off just as, with a loud crack, the big floe broke up into a dozen smaller ones.

“Our lucky day all right,” Jack shouted, as he dug his paddle into the water. “Pray God it holds,” he added in a lower tone.

They now made good time, as only occasionally did a small cake cause them to change their course, and in a few minutes they were only a few rods away from their destination.

The stranded man had risen to his feet and as Jack raised his head he waved his arms vigorously.

“Look, Bob,” the boy shouted, as he recognized the man. “It’s Jacques Lamont.”

The words had hardly left his lips when a loud cracking sound reached their ears and, to their horror, the cake parted in the middle, and before the man had time to jump, the icy water had swallowed him. One moment he had been standing there waving his hand at them and the next he was gone.

By the time the boys had recovered from their first shock of horror, the space between the two halves of the ice floe had widened to several feet, and with powerful strokes they sent the canoe toward the lane of water.

“It was about here,” Bob shouted, as he stopped paddling and swung the canoe around.

At that moment the man’s head popped above the surface of the water only a few feet away. A few powerful strokes brought him quickly to the side of the canoe.

“Jacques,” cried both boys, as the man seized the side of the canoe with his hand.

“You come der right time, oui,” he said, his teeth chattering so that he could hardly speak.

“Get in as quick as you can,” Bob ordered.

Jacques Lamont was a large man and the canoe was small, barely large enough to carry three full-sized men. Under less skillful handling it would surely have upset, but the Frenchman knew just how to go about it, and the boys were but slightly less adept, and in almost no time he was in.

“You let me tak’ paddle,” he said to Jack. “Need work keep warm, oui.” Carefully the two changed places and in another moment the canoe was speeding back. Rapidly the lake was clearing of ice and only occasionally did they have to swerve from a straight course to avoid a floe, and soon they reached the wharf.

“Hurry up to the office now,” Bob ordered, as he sprang from the canoe.

Fortunately they found a good fire roaring in the office stove. Tom Bean, the camp foreman, was at the desk doing something with a big account book as they pushed open the door.

“Bejabbers, and it looks like ye’d been in the drink, so it does,” he declared, as he got up from his chair and greeted the big Frenchman with a hearty hand shake.

“Oui, dat water he ver’ wet,” Jacques grinned, as he stretched out his hands to the grateful heat of the stove.

“Got anything he can put on, Tom?” Bob asked. “He must get into something dry right away.”

“Sure and it’s meself thot’ll find something,” the Irishman assured him, as he disappeared into the little bedroom which opened out of the office.

Jacques Lamont was an old friend of the Golden boys. He had worked for their father many years, but this winter he had spent in trapping away up over the Canadian line. About fifty years old, his out-of-door life and clean living had caused the passing years to deal very lightly with him and he would readily have passed for fifteen years younger.

Tom was back in a few minutes with an armful of clothes.

“Thar, I gess thot’ll fix ye,” he declared, as he threw them on a chair. “They may be a bit small but they’re the biggest I’ve got.”

Jacques quickly stripped and, after a brisk rub with a coarse towel, proceeded to don the clothing which Tom had supplied.

“You haven’t told us how you came to be on the ice,” Jack said.

By this time Jacques was nearly dressed and told them how he had been down to Greenville, a small town about twenty miles down the lake, to sell his furs. He had come up to the Kineo House, a large summer hotel on the other side of the lake, the day before, to see a man on a matter of business. But the man was not there, and learning that he would not be there until the next day, he had started across the lake early that morning to see his friends at the camp.

“I tink der ice no go out so soon,” he explained. “But she bust up ver’ queek and I geet caught, oui. You boys save my life. I, Jacques Lamont, never forgeet heem.”

“That’s all right, old man,” Bob assured him, with a hearty slap on the back. “Just forget it.”

“Non, no forgeet,” the Frenchman insisted. “Some time I do sumtin for you, oui.”

“As if you hadn’t fifty times over,” Jack broke in. “But come on. There goes the dinner horn and I’m hungry enough to eat all the cook has got, so if you folks want anything, you’d better get a hustle on.”

“How about those trout?” Bob asked, as he started for the door.

“Guess they’ll have to wait for supper,” Jack called back. “I noticed that they were still down there in the box,” he added, as Bob caught up with him.

“Well, we’ll dress them after dinner and they’ll go pretty good tonight I reckon, even if I did have my mouth all made up for them for dinner.”

Dinner over, they, together with Jacques, cleaned the fish and took them to the kitchen where the cook promised to give them a big feast that night.

About four o’clock the three friends went down to the wharf for a look at the lake. Not a single bit of ice was to be seen.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” Jack asked, as he looked out over the heaving water. “Where do you suppose it all goes to so soon?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” Bob replied, and then asked: “How about it, Jacques? Where does the ice go?”

“Non, I not know. Eet jest goes, I tink.”

Both boys laughed at the Frenchman’s explanation, and just then Tom joined them.

“Thar, begorra, the last of the cut is hauled and termorrow we’ll begin rollin’ in and buildin’ the fust raft. The Comet’ll be up ’bout noon and I want ter have things ready so’s she kin begin towin’ as soon’s she gits here.”

The supper that night was all that the cook had promised. The big trout, baked with slices of bacon, were delicious; and the hot biscuits, so light that Jack declared they looked more like cream puffs, seemed to almost melt in the mouth. The crew were in high spirits and many was the joke thrown across the big table as the food disappeared.

“You’ve got to hump yourself, Bob, to beat these biscuits,” Jack declared, as he reached for his sixth.

“Yes, I’ll have to yield the palm to Joe,” Bob laughed. “He’s got me beaten six ways of Sundays.”

“Don’t you believe it,” Jack returned loyally. “You can make just as good ones, but I don’t think these can be beat.”

“Thanks for the flattery,” Bob smiled. “Pass the spuds down this way and we’ll let it go at that.”

As usual, breakfast the next morning was eaten by lamplight, and dawn was just breaking in the east when the crew started work by the side of the lake.

Some of the logs, enough to make the first raft, were already in the water, having been piled on the ice and fastened together here and there by ropes so that they would not float away.

“Now then, we’ll get at thot boom fust thing and swing her round these logs,” Tom shouted, as the boys joined him at the water’s edge.

About a dozen of the men had been told off for this work, while the rest of the crew started, with their peaveys, rolling the big spruce logs from the huge piles into the water.

A large spike was driven into the end of a log, and to this a short piece of strong rope was tied. The other end was then secured to another spike driven into the end of another log, leaving enough leeway between the ends for flexibility. This was continued until a boom was completed long enough to reach entirely around the raft. These rafts contain about 30,000 logs and will yield approximately 2,000,000 feet of lumber.

The boys, together with all the rest of the crew, had discarded their moccasins and were wearing heavy shoes, the soles of which were thickly studded with short but sharp brads, which prevented any possibility of slipping on the logs.

By a little past ten the boom was completed and fastened around the huge raft, which was then ready to be towed across the lake to the East Outlet, where the waters of the lake emptied into the Kennebec River.

“Hurrah! There she comes,” Jack shouted, a few minutes later, as his sharp eyes spied a thin stream of smoke far down the lake.

“Begorra, and ye kin depend on Cap’n Seth to git here in time for dinner,” Tom Bean laughed, as he picked up his sledge and started for the office.

The boys, from the little wharf, watched the approaching steamer, the Comet, one of the fleet of The Coburn Steamboat Company.

“There’s the Twilight, I’ll bet a nickle,” Bob declared, pointing to a second stream of smoke some distance behind the Comet. “I suppose she is going to tow Big Ben’s first raft across.”

“Probably,” Jack agreed. “I only hope that we can get across first and get our logs started ahead of his. He’ll, of course, do all he can to hold us up on the way down the river, and if he gets started ahead of us he can give us a lot of trouble.”

Big Ben Donohue, a man of Irish descent and a local political boss, owned a big lumber camp a few miles down the lake. Having been under-bid, in a large contract with The Great Northern Star Paper Company by Mr. Golden the summer previous, he had tried in many ways during the winter to delay their work, but thanks to the two boys, he had failed to accomplish his purpose.

“There’s Cap’n Seth,” Jack shouted, as a large middle-aged man swung his cap to them from the deck of the small steamer as she steamed up to the wharf.

“Hello, Cap’n Seth,” both boys shouted, as they heard the bell on the boat ring for “back water.”

Cap’n Seth was an old timer on Moosehead Lake. He had worked on the lake as boy and man as far back as he could remember, and no one knew the lake better than he.

“How’s the byes?” he greeted them, as he sprang to the wharf and threw a half hitch of the rope which he held in his hand about a stout post at the end of the wharf.

“Fine and dandy, and how’s yourself?” Bob asked, as he shook hands.

“If I felt any better I’d be scared,” Cap’n Seth declared, biting off a large hunk of “sailor’s delight.”

“Is the Twilight going to tow for Ben?” Bob asked, as they started toward the office.

“Ah huh, but I know what you’re a thinkin’ and ye needn’t worry. We’ll beat her across easy. He hasn’t got his boom mor’n half done and won’t get started ’fore ’bout three o’clock, an’ we ought ter be half way across by that time,” the captain assured them.

“We’re all ready fer ye to start, Cap’n,” Tom Bean said, as they entered the office where the foreman was busy putting some papers away. “’Spose ye’ve had yer dinner,” he added, with a wink at the boys.

“Wall neuw,” Cap’n Seth began scratching his head. “I kinder cal’lated to git a little snack ’fore we started. If this wind freshens up much more it’ll be a long trip an’ we’ll be hungry afore we get back.”

“Oh, quit your teasing, Tom,” Jack laughed, as he saw the wistful look in the captain’s face. “Don’t you mind him, Cap’n Seth. Dinner’ll be ready in about five minutes now, and we’re not going to start till we get filled up.”

Cap’n Seth, much relieved in his mind with the assurance that he would get his dinner, shook his fist in mock anger at the foreman. “I reckon ye think yer mighty smart scarin’ a feller outter a year’s growth with yer tomfoolery. Do ye ever read the Bible?” he asked suddenly, changing the conversation.

“Do I iver rade the Bible is it?” Tom almost shouted, for it was his proud boast that he was a great Bible scholar. “Sure and it’s meself thot fergits more about the Bible ivery night than ye iver knowed.”

“Is that so?” Cap’n Seth replied, a most serious look on his face. “Then mebby ye kin settle a pint fer me that’s bin givin’ me a lot o’ trouble.”

“Mebby I kin,” Tom assured him, sticking out his huge chest. “If it’s in the Bible ye’ve come ter the right man and don’t ye fergit it. What is it?”

“Wall,” Cap’n Seth began slowly, scratching his head. “It’s like this. I’ve wanted fer a long time ter know why Moses didn’t take iny giraffes inter the ark.”

The big foreman slowly and thoughtfully scratched his head. He felt that his reputation as a Bible scholar was at stake and did not want to make a mistake. He thought for a moment without speaking, then, a look of relief coming to his face, he asked:

“And how do yer know thot he didn’t?”

“Tom, I’m surprised at yer. I thought ye knew sumpin about the Scriptures and yer don’t even know that Moses didn’t take any giraffes inter the ark. Wall, wall, kin ye beat it?”

Tom, feeling more than ever uncertain of his ground, hastily endeavored to regain his lost prestige by saying:

“Ter be sure I knowed it, but I jest wanted ter be sure as how ye knowed it.”

“That’s a leetle too thin, Tom, but we’ll let it go if ye kin give me the rason,” Cap’n Seth declared, with a sly wink at the boys.

“Sure and that’s aisy,” he declared, after a moment’s deep thought. “It was because the blamed critters were too tall fer the ark, of course.”

“Too tall yer eye,” the captain snorted. “Ye got ter do better’n that or go ter the foot o’ the class.”

Tom, seeing that his answer had failed to satisfy and none too sure of his ground in his own mind, scratched his head for several moments in deep thought. Finally he said:

“It’s meself thot’ll bet a good five cent cigar thot thot ere question ain’t answered at all in the Bible.”

“An’ I’ll take the bet,” Cap’n Seth quickly replied. “An’ we leave it ter Bob ter say who wins.”

“Right ye are. Jest a minute and I’ll git me Bible,” Tom said, starting toward the bedroom which opened out of the office.

“Port yer helm there,” the captain shouted. “We don’t need nary Bible ter settle this bet.”

“And why not?” Tom asked, turning back.

“Because I kin give yer the answer,” the captain assured him.

“Oh, ye kin, eh? Wall, what is it?” Tom asked.

“Wall, ye see it’s like this, I reckon. Moses didn’t take any giraffes inter the ark cause Moses wasn’t born till about a thousand years after the ark had finished her voyage. Noah had charge o’ that cruise, ye poor fish.”

For an instant a puzzled expression stole over the face of the Irishman, and then, as the fact that he had been made the butt of a joke worked its way into his mind, he burst out laughing, and the boys joined in heartily. Great was the Irishman’s relief when he realized that, after all, his reputation as a Bible scholar had not suffered.

“I owe ye the cigar all right, all right,” he declared, as soon as he could speak. “Sure and thot’s a good one, so it is. I’ll spring thot on Father Maginnis the next time I see him, so I will.”

Just then the dinner horn sent its welcome blast through the vast forest and the captain quickly leaped to his chair and, followed by the others, started for the mess house. The meal was a hurried one, as they were anxious to get the big raft started despite the captain’s assurance that Big Ben would be far behind them. They all knew the advantage of getting the first raft of logs over the big dam at the outlet.

In addition to the captain, the Comet boasted of a crew of two. Tim Sullivan, engineer and fireman combined, was a big Irishman with red hair and was, of course, called Reds by all who knew him. The other member of the crew was a half-breed by the name of Joe Gasson. Joe was a small man, about thirty years old, but what he lacked in size he more than made up for in strength and quickness.

“That Joe, he’s quicker nor a cat,” Cap’n Seth was wont to say.

Joe Gasson was deck hand and general utility man.

“Can’t say as how I jest like the looks o’ that weather,” Cap’n Seth said to Bob, as he cast a weather eye toward the west.

“You think it’s going to storm?”

“Can’t say fer sartain this time o’ year, but I’m kinder afeard of it.”

The Comet had just left the wharf and was backing up to the raft.

“Hold her thar now,” Tom shouted from his position on the raft, where he stood holding the big three-inch hawser which was already fastened to the key of the raft. The stern of the steamer was now almost touching the log and Tom threw the rope to Joe who quickly made it fast to the snubbing post.

“All right now. Let her go,” Tom shouted, as he turned and ran over the logs toward the shore.

Slowly the steamer started forward, the hawser straightening out until there was a space of about fifty feet between the boat and the raft. Then it tightened and the steamer came to an abrupt stop. It takes a vast amount of pulling to overcome the inertia of 30,000 big logs and the water boiled and churned at the stern as the blades of the propeller beat it into foam. The Comet, built on the lines of a tug boat, was a powerful craft and soon began to move slowly through the water again, while the raft gradually took on the shape of a huge flatiron.

“Hurrah! She’s moving,” Jack shouted.

Bob and Jack, together with a half dozen of the men of the camp, were to cross with the raft, and the two boys were standing in the stern eagerly watching the starting of the logs. The big hawser, tight as a steel cable, groaned with the tremendous strain. Fortunately the wind, which had been blowing from the northwest, had died down to a light breeze. One would hardly think that an opposing wind would make much difference, as the logs lying so low in the water offer but a small surface to it; but when the surface of each log above the water line is multiplied by 30,000, the product is an enormous area. As a matter of fact, it is impossible for a boat to tow a raft against a very strong wind, and often, in spite of its great pulling power, the steamer is dragged backward sometimes at a rate of several miles an hour.

It was all of a half hour before the raft was fairly in motion and even then, as Jack declared, “you’d have to sight by a tree or something to be sure that you were moving.”

“Well, we’re off at last, Cap’n Seth,” Bob said, as the captain joined them in the stern.

“Yep, we’re on the move,” he replied, as he examined the hawser to see if it was securely fastened.

“How about the weather?” Jack asked.

“Wall neuw,” and the captain took a hasty glance toward the west. “I’m a thinkin’ we’ll have a bit o’ weather afore dark, but I’m hopin’ as how we may git across afore it strikes us. It’s twelve miles straight across to East Outlet an’ we kin make it in about five hours if the pesky wind don’t blow any harder nor it is neuw, but I don’t jest like the looks o’ that bank o’ clouds over thar,” and he pointed toward the west where the boys could see a heavy looking fringe of leaden colored clouds.

Very slowly the steamer gained speed until the captain assured them that they were making almost three miles an hour, which is considered very good unless the wind is in the right direction.

“That bank of clouds is getting higher all the time, Jack,” Bob declared, as for the hundredth time he cast an anxious glance toward them.

“And the wind is blowing harder than it was too,” Jack returned. “I don’t believe we’re making more’n a couple miles an hour.”

“We’re not exactly exceeding the speed limit,” Bob grinned, as he glanced down at the water.

They had been on the way for nearly two hours and were about a third of the way across. Off to the left, about a half a mile distant, was Sugar Island, the largest of the many islands which dot the lake. Sugar Island has an area of some 5,000 acres.

“We’re not going to make it before dark, that’s certain,” Bob said about an hour later. “We’re not making more’n a mile an hour I’ll bet and the wind is getting stronger every minute.”

The sky, which during the day had been nearly free of clouds, was now entirely overcast with dark rapidly moving banks of mist, and the wind had increased from a light breeze to a strong blow which came in fitful gusts.

“We’re jest barely holdin’ our own,” declared Cap’n Seth, who again joined them. “If she gits any stronger we’ll begin to drift. Ought ter had better sense than ter start out when my rheumatics kept tellin’ me that a storm was a comin’. Them ere rheumatics are better nor a barometer for ter tell when a storm’s a comin’. Never knew ’em ter tell a lie yet,” and he slowly shook his head as he glanced up at the sky.

Even as he spoke the first drop of the coming storm began to beat against their faces, and in less than five minutes the rain was coming down in earnest.

“Me for the engine room,” Bob shouted, as he left the stern and made his way forward followed by Jack and the captain.

“Givin’ her all ye got, Reds?” the latter asked, as he reached the open door of the engine room.

“Sure an’ I am thot,” Reds replied, glancing at the steam gage. “Faith an’ she’s pullin’ fer all she’s worth.”

“Gee, listen to that wind,” Jack said a little later, from his perch on the coal bin. “I’ll be a fig we’re not holding our own now,” he added, as he jumped down. “Come on Bob, let’s put on these rubber coats and go out and see what’s doing.”

Outside in the stern of the boat they found the captain and the rest of the men watching the big raft as it heaved and groaned in the heavy sea.

“We’ll hit Sugar Island in another ten minutes,” he shouted, as he caught sight of the boys.

The rain was now falling in torrents and the wind was roaring in furious blasts which shook the little steamer in all her timbers. Darkness was falling rapidly, although it was still light enough for them to see the island now only a few rods astern. Already the captain was loosening the hawser preparatory to casting it off as soon as the raft should strike.

“Will she break up, Cap’n?” Bob shouted.

“Dunno, she may hold together and she may not,” was the unsatisfactory reply.

At that moment the farther end of the big raft struck the beach and with a grinding crash the logs began to pile up as the wind drove them forward. At the same instant the captain slipped the last coil of the rope from the snubbling post and the boat, freed from its drag, leaped forward.

From Moosehead Lake to Waterville, by the way of the Kennebec River, is about one hundred miles. A log, starting from the lake and making the trip without a stop, would make the trip in from two to three days. The annual drive of logs, comprising upward of 100,000,000, usually starts the first of May, and on account of jams and other delays, it is usually a matter of several weeks before a given log reaches its destination.

The boys knew that their father had been very anxious to get that particular raft of logs over the dam and started down the river at the earliest possible moment, as the contract called for delivery of not less than ten thousand logs by the first of June.

“It’s too bad we couldn’t have got across with that raft,” Bob declared a few minutes later, after he had returned to the engine room accompanied by Jack and the captain. “What are we going to do now?” he asked, as he removed his dripping coat.

“I told Joe to head her back to the camp,” the captain replied. “It’ll prob’ly take several days ter git them logs off the island ready ter tow agin, an’ knowin’ as how yer dad is in a hurry, it’ll be quicker ter start with another one soon’s this storm blows out.”

It was as Jack declared, “dark enough to cut with a knife,” by the time they reached the wharf. The rain had ceased and the wind had nearly died down. A few stars were visible, dimly peeking through the rifts in the clouds, giving promise of a fair day on the morrow.

Tom Bean was on the wharf as Cap’n Seth carefully warped the steamer in.

“Did ye git the raft across?” he asked anxiously, as Bob jumped from the boat.

“Sure and I feared as mooch,” he said, after Bob had told him that the raft was beached on Sugar Island. “It’s too bad, so it is, but we got another one ready ter be towed afore the storm struck, but it’s meself as thought as how we were goin’ ter lose it entirely fer awhile when the wind was blowin’ the hardest. But we managed ter hold her and yer kin start the first thing in the morning.”

“Yes, we’ll have to let those logs rest there till we get some started down the river,” Bob said, as he glanced up at the sky. “I guess it’ll be a good day tomorrow and I don’t think the boom broke so I guess they won’t scatter any.”

It was intensely dark in the bunk house when Bob awoke. It was so unusual for him to wake up during the night that for a moment he lay wondering what had disturbed him. All was still except for a variety of snores from members of the crew, but he was used to them and knew that they were not responsible. A glance at the luminous face of his watch told him that it was but a little past two o’clock. He turned over and settled himself to go to sleep again, when suddenly he realized that he was very thirsty.

Pulling a small flashlight from beneath his pillow, he quietly slipped from the bunk and stole softly across the room toward the door which opened into the kitchen.

“Of course the pail is empty,” he muttered a moment later. “Well, that means that I’ve got to get dressed and go out to the pump. I can’t go to sleep till I get a drink, that’s sure.”

So stealing quietly back to his bunk, he quickly: drew on his clothes and a moment later the front door had closed quietly behind him.

The pump from which they obtained drinking water was close to the office building, some three hundred yards from the bunk house, and almost half that distance from the lake. It was not nearly as dark as in the early part of the night, as the moon was shining through the light clouds making it possible to see for some little distance.

Just before he reached the pump an opening in the woods gave him a view of the wharf.

“Well, what do you know about that?” he said aloud, as he came to a sudden stop. “Where in the world is the Comet?” and the next moment he was running rapidly down the path toward the lake.

His question was soon answered, for as he reached the end of the wharf he could see, in the dim light, the form of the boat some hundred yards off shore.

“Mighty funny how she got loose,” he muttered, as he looked about him. Then, seeing that the rope was still tied to the post, he stooped down and quickly pulled it in. It was a short job, as only a few feet of it remained. Eagerly he examined the end.

“Looks as though she had chafed it through,” he declared, as he saw the frayed end. “I don’t understand it though, as Cap’n Seth is too careful a man to tie up a boat so that it would chafe.”

A very light breeze was blowing and he could not, for the moment, see that the boat was moving; but, as he watched it, he realized that it was slowly drifting down the lake.

“Guess I’d better go get Cap’n Seth,” he thought, as he turned back toward the camp.

He was half way to the bunk house when he stopped as a thought struck him.

“Pshaw,” he said half aloud. “There’s no use in waking him up. I can take the canoe and bring her in myself. I know how to run her.”

He turned and ran back to the little shed behind the office where the canoe was kept, stopping only long enough at the pump to get his delayed drink. A few moments later he was sending the light craft rapidly through the water toward the drifting steamer.

“Guess I’d better be careful,” he thought, as he got to within a few yards of the boat. “It’s just possible that there might be someone aboard her.”

So for a time he let the canoe drift, as he strained his ears to listen. But no sound, save the soft lapping of the water against the side of the steamer came to him, and dipping his paddle noiselessly in the water, he soon grasped the side of the boat. Again he waited and listened.

“I guess it’s all right,” he thought, as he stepped softly into the stern of the steamer and lifting the light canoe from the water placed it bottom up across the back of the boat.

This accomplished, he crept softly forward toward the engine room, stopping every few feet to listen. The door of the engine room was closed, and as he reached it he again paused and placed his ear against it. Was it fancy or could he hear someone inside the room breathing?

“I don’t know whether I’m hearing things or not,” he thought as he stepped back a bit, “but it sounds as though there’s somebody in there asleep.”

After thinking the matter over for a few minutes, he drew the flashlight from his pocket and stepping forward, placed his hand on the door knob. Carefully, without making the slightest sound, he pushed open the door a few inches and again listened. No longer was there any doubt as to the room being occupied. The deep breathing of a man was plainly audible. He pushed the door open still farther and quickly threw the light of the flash within the room. There on the floor in front of the furnace, with his back against the coal bin, was a man fast asleep. Bob recognized him at once as an employee of Big Ben Donahue. A few months before, as recorded in a previous volume, Bob had prevented him from selling or giving liquor to the men of his father’s crew. It was the same man beyond the shadow of a doubt, and Bob grinned as he quietly closed the door, as the remembrance of his former encounter with the man flashed through his mind.

He had closed the door and crept back to the stern of the boat in order to have time to consider what was best to be done. There was not much doubt in his mind as to the way things lay. That it was a move on the part of Big Ben to delay them in getting a raft of logs started down the river he did not doubt. Knowing that the wind was blowing down the lake, he would figure that it would not be necessary to start the engine. The wind would carry the boat directly past his camp, where the man would be taken off and the steamer allowed to drift wherever the wind blew it after that. The man had frayed the end of the rope, thus making it appear that it had chafed in two. The one weak point in his scheme was that his man had fallen asleep on the job.

“So far so good,” Bob mused. “And now what’s the next move?” he asked himself.

For a moment he considered hitting him with a stick of wood just hard enough to stun him, but he immediately dismissed that plan knowing that he would never be able to bring himself to hit a sleeping man. He had been aware of a strong odor of cheap whiskey in the engine room and the knowledge that the man was undoubtedly drunk was, he considered, a point in his favor, and he determined to try to tie him up without waking him. He had, during the trip the previous day, noticed several pieces of small rope in the engine room, and had no doubt about being able to quickly find something to answer his purpose. His mind once made up, he hesitated no longer.

Quickly he stepped to the door and again pushed it open. His light showed him that the man had not moved. A bracket lamp was fastened to the wall just inside the door and making as little noise as possible he struck a match and lighted it. Still the man did not move. He found the bits of rope without difficulty and selecting two pieces suitable for his purpose he knelt in front of the sleeping man. Carefully he raised first one foot and then the other, and slipped the rope beneath them. He was congratulating himself that the man was too sound asleep to be easily awakened, when suddenly without the slightest warning, he sprang to his feet. Bob quickly followed his example and for an instant the two stood facing each other.

For only a moment however did the man hesitate, then stepping quickly forward he aimed a vicious blow at Bob’s head with his huge fist. Bob dodged the blow easily, and as the man’s impetus carried him slightly off his balance, the boy succeeded in getting in a good stiff punch just behind the ear. The blow staggered the man for an instant and he reeled against the side of the room. Had Bob followed up the blow he might have ended the fight at once, as the man was more or less dazed from the blow coming when he was only half awake. But he failed to take advantage of the opportunity and in another minute it was too late. The man quickly recovered himself, and maddened to the point of frenzy by the blow, he rushed at the boy. The room was so small that there was little space to dodge, and although Bob succeeded in getting in another blow on the nose, which started the blood, the man seized him about the waist in his powerful arms and in another instant they were rolling over and over on the floor.

Almost instantly Bob realized that so far as mere strength went he was no match for the burly Frenchman. He must pit his skill against the strength of his antagonist. Almost at once the Frenchman secured a grip on Bob’s throat, but he had managed to free himself before the man could shut off his wind. It was this hold that he feared and he exerted all his skill to prevent a recurrence of it and for a time was successful. But soon, despite his best efforts, the Frenchman again got his huge hand on his throat and this time the boy was not able to squirm free. Quickly the man’s grasp tightened and Bob realized that unless something happened the fight would soon be over. At that instant, just when the man’s grip had tightened so that he was hardly able to breathe, the thought of a trick which he had learned some years before, flashed into his mind.

The Frenchman had only one of his hands about Bob’s throat and the other was pressing against his left shoulder. Quickly working his right hand beneath the man’s arm, he seized hold of his wrist with both hands, and exerting all his strength, gave it a quick twist. The bone snapped with an audible crack and the man, with a cry of pain, leaped to his feet and Bob at once did likewise.

For a moment the Frenchman seemed too dazed to speak, then as he tried in vain to lift the injured arm, he whispered hoarsely:

“You hav’ bust dat arm.”

Bob saw at once that all the fight had been taken out of the man.

“It’s too bad it had to be done,” he said not unkindly, “but it was the only way I could keep you from choking me to death. Now,” he continued in a firm tone, as the Frenchman looked at him, his face contorted with both anger and pain, “if you want to save yourself a good deal of trouble with that arm you’ll not try to hinder me but let me get this boat back to the wharf as soon as possible.”

“Oui, I no bother you,” the man groaned, as he sank into an old chair.

Bob at once threw open the door of the furnace, and seeing that the fire was in fair shape, he put on a couple of shovelsfull of coal and opened the drafts. There was nothing more he could do until he had a head of steam.

“Arm pain you much?” he asked, as he sat down on the doorstep.

“Oui, she hurt plenty mooch,” the man growled.

“Why did you try to steal the boat?”

“Non. I no try steal boat,” the Frenchman denied. “I been up North East Carry. Geet lost comin’ back and ver’ tired. See boat, and geet in to tak’ rest. Dat rope she must bust. Boat drift off. I know nuttin ’bout it till I wake up, see you try tie me up.”

“Hum, it’s mighty strange how a boat could chafe an inch and a half rope in two with almost no wind blowing,” Bob returned shaking his head. “No, I’m afraid it won’t go down. I’m sorry about your arm, but I didn’t much fancy being choked to death. Tom Bean will set it for you and he can do as good a job as any doctor.”

“But I lose my wages,” the man whined.

“I suppose so,” Bob replied. “But that’s your fault. You tried to kill me and I had to protect myself.”

By this time a glance at the steam gage told Bob that there was enough steam to start the boat, and opening the valve he soon had the boat moving slowly through the water.

“Now I’ll have to go to the pilot-house to steer her,” he announced, “and if you try any funny business you’ll be a long time getting that arm fixed.”

Without waiting for the man to reply, Bob quickly made his way to the pilot-house. The boat was headed down the lake and he swung her in a long curve and soon had her pointed toward the camp. He had set the steam for slow speed and as the boat was within about a hundred feet of the wharf he rushed back to the engine room and shut it off. The man still sat in the chair and had apparently not moved. Quickly returning to the pilot-house, he saw that the boat had made more progress than he had judged she would, and realized that she would hit the wharf too hard for safety. So he had to throw the wheel over as far as he could. The boat responded nobly, but even so he missed the wharf by only a few inches.

“That was a bit too close for comfort,” he declared, as the boat moved slowly up the lake.

The steamer was fully a hundred feet from the wharf when she finally lost headway.

“It’s a whole lot harder to run a steamboat alone than I thought,” he said aloud. “I wonder if I can pole her in. Here goes for a try anyhow.”

Bob knew that there was a long pole out on the deck, and in another minute he was trying to use it but the water was too deep. He was unable to touch bottom.

“So near and yet so far,” he grinned, as he laid the pole down on the deck. “Guess I’ll have to wait till the wind carries her in a bit.”

Fortunately the wind, what there was of it, was in the right direction and soon he could see that the boat was slowly but surely getting nearer the wharf. He waited a few minutes and then tried again with the pole. This time he could easily touch bottom, and soon the bow of the boat gently hit the wharf. It was the work of but a moment to make her fast and then he returned to the engine room.

“All right now,” he greeted the Frenchman, who still sat in the chair looking, as he afterward told Jack, as though he had lost his last friend. “Come on and we’ll get Tom out of bed and he’ll set your arm.”

It was a little after four o’clock when they reached the office. The door was not locked, and opening it Bob stepped inside closely followed by his patient.

Tom Bean slept in a little bedroom which opened out of the office. The door of this room was closed, and as soon as he had a light going, Bob knocked loudly on it.

“Who’s there?” came a sleepy demand.

“It’s I, Tom,” Bob replied. “Can I come in?”

“Sure you kin,” and Bob pushed open the door and entered the room.

“Faith and what do yer mane by wakin’ an honest mon at this time o’ night?” Tom demanded as he sat up in bed.

Bob sat down on the edge of the bed and quickly told him what had happened.

“Well, I’ll be jiggered,” the foreman said, when he had finished. “Ye sure do bate the bugs when it comes ter gettin’ into scrapes, so yer does. But,” he added hastily, “Yere like a cat and allays land on yer fate.”

“But hurry up and get some clothes on, Tom. The poor fellow must be suffering and his arm needs looking after. I’ll get a fire going while you get dressed.”

It only took Tom a few minutes to get into his clothes, but by the time he was dressed Bob had a fire roaring in the stove.

“So ye’ve been tryin’ some more of yer dirty work, hey,” Tom said sternly, as he stepped close to the Frenchman who was standing near the stove.

“Non, non, I——” he began, but Tom stopped him.

“Sure and ye might as well save yer breath cause I wouldn’t belave yer on a stack o’ Bibles.” But although he spoke roughly, the kind-hearted Irishman was as gentle as a woman as he set about his work. It was not a bad break, he assured the man after a careful examination.

Setting a broken arm was nothing new to Tom, and, as Bob had declared, he could do it as well as a doctor. In the lumber camps of the Big Maine woods, broken arms and legs are common and in many cases it would be a long time before a doctor could be reached. So Tom had learned how to do the work, and in his years of lumbering had had considerable practice.

The Frenchman stood the operation with a sullen stoicism, although the pain must have been severe.

“Thar, begorra, thot’s as good a job as iny doc’d do,” Tom declared, as he finished binding the arm to a strip of board. “Ye’ll have as good a flipper as ever in three or four weeks, but if ye want to enjoy good health it’s meself as advises ye ter give us a wide berth.”

The Frenchman gave no word of thanks, but announced that he would be on the way. Bob helped him on with his coat and in another minute he was gone.

“He sure’s a hard nut,” Tom declared. “And you want ter look out fer him. He’ll do yer dirt if ever he gits a chance.”

It was nearly five o’clock and they decided that a game of checkers would be the best way to kill time until breakfast. So Bob got out the board and soon they were deep in the interest of the game.

“That’s three games to your four,” Bob announced a little later, as the loud blast of a horn told them that breakfast was ready.

“Sure and yer no nade ter rub it in. It’s meself as knows that yer now siven games ahead, but I’ll be after catchin’ up wid yer ’fore the spring’s over.” Tom grinned as he put the board away. “But come on, let’s be after makin’ it snappy. We want ter git started wid thot raft jest as soon as we kin, or Big Ben’ll be after gittin’ in forninst us.”

It was barely light when the Comet was hitched to the second raft ready for another try. Bob and Tom agreed that it would be best to say nothing about the adventure of the night to anyone except Jack and Cap’n Seth. The captain, of course, had to be told, as he was quick to notice that the steamer was not tied as he had left her, and Bob had no hesitation in telling his brother.

“That must have been a peach of a fight,” the latter declared, after Bob had told him about it.

“It was while it lasted,” Bob assured him. “I’m mighty sorry that I had to break his arm, but it was that or have the life choked out of me and——”

“You did just right, of course,” Jack interrupted. “No one could blame you, so don’t worry about it.”

“Look, Jack,” Bob suddenly cried, as he caught his brother by the arm.

“There’s the Twilight towing one of Ben’s rafts.”

“Sure’s your born,” Jack agreed. “It’s going to be a race to see who’ll get across first.”

“It’ll be a race all right,” Bob said quietly. “A race of snails at about two miles an hour.”

“That’s about the size of it,” Jack laughed. “But the Comet can beat the Twilight any day so I don’t think we need to worry.”

“I’m not so sure about that last part of what you said,” Bob replied soberly. “It’s true that the Comet is the faster boat in an even race, but unless I’m much mistaken, the Twilight is hitched on to a smaller raft than the one we’re towing.”

“Jimminy crickets, you’re right. I never thought about that,” and Jack too looked sober. “Let’s go and ask Cap’n Seth what he thinks about it.”

They found the captain in the pilot-house steering.

“I dunno,” he replied in answer to their question. “Course the Comet’s the faster boat, but if the Twilight’s hitched on to a smaller raft she might beat us. Reckon we’ll jest hav’ ter wait an’ see. Give her all she’ll stand, Reds,” he shouted through the speaking tube.

The wind, which was light, was with them this time, and they were making good progress, but so was the Twilight. The two boats were now about two miles apart and it was plain, from the dense clouds of black smoke, that they were issuing from the Twilight’s stack, that her captain also was pushing her to the limit.

“Cap’n Bill may be nuthin’ but a kid, but he knows how ter git out o’ the Twilight all the speed that’s in her,” Cap’n Seth told them as he cast an anxious eye from the window toward the other boat. “An’ he ain’t got more’n about 20,000 logs in that raft, an’ we’ve got thirty, an’ it takes a lot o’ power ter pull that extra 10,000 through the water, let me tell yer.”

An hour passed and still another, and it could not be seen that either boat had gained on the other. Their course toward the same goal was bringing them, all the time, closer together and now they were not more than a mile apart.

“Tom made a mistake when he didn’t fix up a small raft for us to tow across,” Bob declared, as he leaned on the rail and watched the other boat. “Then we’d have been there first without any trouble.”

“No doubt about that,” Jack agreed, “but it’s too late now and I believe we’ll win out at that.”

Two more hours slipped by without any change in the relative positions of the two boats. They were making about two miles an hour and were about half way across the lake.

During the last hour Bob had been in the pilot-house with Cap’n Seth, but now he joined his brother who was standing in the stern.

“Of all the slow races this takes the cake,” he grumbled, as he sat down on a coil of rope.

“Yep, it’s all of that and then some,” Jack agreed. “I don’t believe either boat has gained a foot in the last four hours. Suppose we both get there at the same time?”

“I don’t know what we’d do in that case unless we flipped a coin for it,” Bob smiled.

The boats were now not more than a mile apart and, in the clear air, the boys could see a number of men in the stern of the Twilight.

“I believe that’s Ben himself on board there,” Bob said.

“Not much doubt of that,” Jack replied. “There’s no one else up here as big as he is.”

The outlet of Moosehead Lake into the Kennebec River is closed by a large dam, near the center of which was a sluice through which the logs were emptied into the river ten or twelve feet below the level of the lake. Watertight gates close the passageway when desired, so that by throwing the gates open the water in the river can be raised a number of feet in a few minutes. During the latter part of the driving season, when the water in the river is low, these gates are usually opened once each day, sending what is called the “head” down the river.

Toward this dam the two boats were towing their rafts. Big Ben as well as the boys knew that it was a case of first come first served in the matter of getting the logs first through the sluice. Could he but get there first and get his logs started down the river ahead of the Golden logs, he felt sure that abundant opportunity would present itself to cause delays. He hated the Goldens, first because Mr. Golden had beaten him in bidding on a big contract the summer before, and also because Bob and Jack had frustrated his attempts during the winter to delay their work. Another sore point was in regard to a very valuable tract of timber land, situated between the two camps. He had found, a short time before the previous Christmas, Mr. Golden’s deed to the land, and instead of returning it had kept it, and by means of a forged deed had claimed the tract as his own. But the boys had found the missing deed and Mr. Golden had had little trouble in proving his title to the property.

Big Ben Donahue was pacing the deck of the Twilight chewing nervously on a big black cigar. Every minute or two his glance would stray to the Comet, as he paced slowly back and forth.

“We seem to be just about holding our own and no more,” he said to the captain, a young man in his early twenties, as he stopped by the pilot-house.

“Just about,” the latter replied, as he shifted the wheel a few points to the right. “They’ve got a bigger raft than we have, but the Comet is a faster boat.”

“Hum, well, it’ll be twenty dollars in your pocket if we get there ahead,” the man said, as he again glanced toward the other boat.

“Nothin’ doin,” the young captain replied quickly. “You hired this boat and it’s my duty to get your logs across as soon’s I can an’ I’m a doin’ it, but I don’t want your money.”

Big Ben’s eyes snapped as he looked the boy in the face, but the latter met his glance with a steady gaze and, without saying anything more, the men soon walked away.

“I hope we lose this race though I’ve got to do my best to win it,” the young captain muttered, as he too glanced at the Comet.

Big Ben stopped at the door of the engine room. The fireman was leaning back in a chair in front of the furnace door, and as his eyes were closed Ben judged that he was asleep.

“Hey, there,” he shouted. “What do you think this is, bed time?”

The fireman, a half-breed named Joe Cooley, slowly opened his eyes.

“I no sleep,” he stammered. “I jest restin’, oui.”

“Well, you tend to business and get some wood on the top of that coal and see if you can’t get a little speed out of this tub,” Big Ben ordered.

“She no stan’ more. She bust, you put on wood, oui,” the fireman asserted as he glanced at the steam gage.

“Bust your eye,” Big Ben snorted. “Why, you’ve only got thirty pounds there.”

“Cap’n, him say nev’ geet more thirty pounds, she bust sure. Dat safety valve, she no work, geet stuck, oui,” and the man shook his head.

“I believe the fellow’s lying,” Big Ben muttered to himself, as he walked toward the stern. “She ought to carry forty pounds all right.”

A few minutes later, as he again paused at the door of the engine room, he saw that no one was there. For a moment he hesitated as though undecided what to do; then, glancing quickly and seeing the coast was clear, he stepped into the room and threw open the furnace door.

“Hump, that’s not half a fire,” he muttered, as he glanced about him.

In a small bin to one side of the furnace he saw a few sticks of wood, and moving with great quickness he threw four of the largest pieces in on top of the coal.

“There, I guess that’ll get some action out of her,” he muttered, as he closed the furnace door and quickly left the room.

The action was not long in manifesting itself, but not in the way he desired. Big Ben was again up forward talking with the captain, when a dull explosion came to their ears.

“There, that old engine’s blown out a cylinder head again,” the captain declared, as he left the wheel and started for the engine room, closely followed by the angry man.

By the time they reached the room the engine had stopped and the room was filled with steam.

“We’ll have to wait till she cools down,” the captain declared. “Where’s Joe? I told him not to let her get above thirty pounds. She blows off at thirty-two and the valve’s been sticking lately. Haven’t had time to fix it yet.”

Big Ben, knowing that he had lost the race through his own foolish action, said nothing but turned away mentally kicking himself for a meddling fool.

“Oh, Bob, something has happend to the Twilight. See, she stopped,” Jack shouted to his brother, who at that moment was talking with the captain in the pilot-house.

Bob, hearing the shout, came running out.

“So she has,” he agreed, as soon as he got to his brother’s side. “Well, here’s hoping that she stays stopped till we get a good lead on her. Wonder what happened?”

“If Ben had any reason for wanting to get ahead of us except to make father lose out on his contract, I might feel sorry for him; but, as it is, I don’t think that I shall shed any tears in his behalf.” And Jack grinned cheerfully as he started toward the pilot-house.

It was just four o’clock when they arrived at the dam. After some discussion it was decided that it would be best to wait until morning before beginning to shoot the logs through the sluice. There was a fairly comfortable boarding house near the outlet and in it the boys stayed, together with the members of the crew, who had been chosen to drive this first batch of logs to its destination.

They were up early the following morning, and the sun was barely showing itself when the gates were thrown open and the big logs began to shoot down into the waters of the Kennebec. To the boys it was a glorious sight to see the logs taking their initial dive into the foaming water below the dam.

The drivers, with their calked boots, were running here and there on the logs, busy with their peaveys in keeping them running free so that there would be no jam in the sluiceway. In this work the boys took no part, as it was work requiring a high degree of skill, which could be acquired only by long experience. Often situations arose where a misstep or a moment’s hesitation would be fatal, as the current was very swift and to be drawn into the sluiceway meant almost certain death.

By nine o’clock the last log was through, and the river, below the dam, was filled with the floating logs. The boys were to assist in driving them down, and in a very short time after the last of them were out of the lake they found themselves, peaveys in hand, slowly floating down the river.

It was strenuous work to keep all the logs in motion. Those at the sides were forever catching along the bank of the river and must be pried loose, and there was always the likelihood of a jam resulting should any of the front logs catch on an obstruction in the river. Then the logs behind, urged on by the irresistible force of the current, would pile up in a tangled mass, often many deep. It was at such times that seconds counted. Could the key log be located and be pried out in time the mass would begin to move again, but often this would be impossible and dynamite would have to be used.

Big Jean Larue was in charge of the crew and, as Tom Bean often declared, a better river driver never handled a peavey.

A few miles from the lake the river makes a sharp bend. Here the current is very swift and it is a place dreaded by the drivers as it requires quick and hard work to avoid a jam. Shallow water and large rocks, many of which are only a short distance beneath the rapidly swirling water, add to the difficulties. But at this time of year the melting snow makes the river higher than usual, and all hoped that they would be able to get past the bend without trouble.

It was about the middle of the afternoon when the head of the drive reached the rapids.

“Now for some fun and a fast ride,” Jack shouted, as the speed of the log he was riding increased.

“You be mighty careful,” yelled Bob, who was on a big log some forty feet to the right. “This is a nasty place for a spill.”

The boys were within a few logs of the head of the drive, Jack being near the center of the river and Bob well over toward the right bank. Four of the men, including Jean, were near the left bank where they were having all they could do in keeping the logs from jamming up on the shore.

“They’re running mighty close,” Jack declared to himself, as he saw the head of the drive start to take the curve.

The river at this point was not more than a hundred feet wide and the words had hardly left his lips when the thing which they had all dreaded happened. The logs were crowded too closely together and as they reached the sharp bend they suddenly jammed.

“Back for your life,” Bob shouted; and Jack, quick to see what had happened, turned and ran from log to log diagonally back toward the right bank.

He reached the shore in safety, and as he stopped beside Bob he gasped:

“Just look at them pile up.”

“Some mess, I’ll say,” Bob returned, as he watched the huge logs, urged on by the rapid current, pile one on top of the other, until many of them were several feet above the level of the river.

It was all over in a few minutes, and where a short time before had been a scene of swiftly moving logs, now there was no motion visible, only a confused mass reaching from shore to shore, hiding the water, and stationary.

To be sure only at the head and reaching back a distance of some thirty feet were the logs piled up to any extent. Back of them the logs had been brought to a stop more gently and had not “climbed.” But it was bad enough and both boys looked sober as they waited for Jean, who was rapidly making his way across the logs toward them.

“I tink we hav’ one mess, oui,” he declared, as he joined them.

“I know it,” Bob agreed. “What are you going to do?”

“Mebby one log hold ’em,” he said, as he waved his hand to the rest of the crew who were still some distance away. “We find heem an’ geet heem loose, all the logs go mebby. No find heem we hav’ use der powder.”

As soon as the rest of the crew came up, they started for the middle of the river.

“She one ver’ bad jam,” Jean declared, as they reached the very front of the drive.

For an hour they all worked, first at one log and then at another, hoping to locate one which would prove to be the “key.” Several times they thought they had hit it as, a log being pried loose, they were conscious of a quiver in the mass. But each time it was a false alarm, and at the end of the hour Jean declared that it was no use to try any longer.

He called to Bob, who at the moment was a little to his right, and as soon as he came to his side he said:

“I tink we put ’bout three sticks right dar,” pointing to a place where several logs were closely massed together, “mebby she start, hey?”

“You’re the doctor,” Bob said, shaking his head. “But it looks to me as though nothing short of an earthquake would start them.”

“Well, we try heem,” Jean said, as he started back toward the rear of the drive.

He was back in a few minutes, carrying the dynamite together with a battery outfit which he had gotten from the big scow, which always accompanies the drive, loaded with supplies.

“Now we feex heem,” Jean declared, and in a short time the three sticks of dynamite had been placed where Jean thought they would do the most good.

Soon the wires were connected and laid over the logs to the shore, and all was ready to close the circuit.

“Let her go,” Jean shouted, and Bob pressed the button.

But, to their surprise, nothing happened. Again and again he closed the circuit, but with no result.

“Guess we got a bum connection somewhere,” he declared, as he began to inspect the wire.

“Every connection’s all right now,” he declared a few minutes later, after he had examined the last one.

But again nothing happened when he pressed the button.

“Must be the batteries are dead,” Jack volunteered.

“Shouldn’t wonder,” Bob agreed, as he began to examine the cells. “They look like old ones.”

“I go see eef Bill got more,” Jean said, and started back on a run.

“Heem no more have, but I got one bon piece fuse he had. I feex heem ver’ queek,” Jean said, as he returned a few minutes later.

It was the work of but a moment to substitute the fuse for the wire, and the boys from their position on the bank soon saw the Frenchman strike a match and apply the light to the end of the fuse which was about a foot long. Instantly it began to sputter, and turning quickly Jean started for the bank. He had made but three or four steps, however, when, to their horror, they saw him stumble and fall. A log had rolled beneath his feet.

“Make it snappy,” Bob shouted at the top of his voice.

“His foot’s caught,” Jack yelled, and Bob saw that what his brother had said was true.

They could see that the Frenchman was making Herculean efforts to free himself.

“He may not be able to do it in time,” Bob gasped, as he started on the run across the logs.

The boy knew that the fuse would burn but a short minute, and that if he failed to reach it in time, he as well as Jean would probably be killed. But the man was in the greatest danger and the boy never hesitated. As he jumped from log to log he breathed a prayer that he might get there in time. He could see the fuse sputtering fiercely and growing rapidly shorter. How heavy his feet felt. It seemed like some hideous nightmare. He could hear Jack shouting for him to come back, but he paid no heed to the commands. But one thought filled his mind. He must get to that fuse before the fire reached the dynamite.

“I must, I must,” he said aloud, as he took the logs with flying leaps.

The end of the fuse had disappeared as he reached the spot, and he knew that only an inch or two remained. Quickly he shoved his hand between the two logs, and grabbing hold of the fuse he gave it a sharp jerk and flung it far out into the water. As it went flying through the air, he could see that less than two inches remained.

A strange feeling of weakness stole over him as he realized how near he had been to death, and he sank down on a log and buried his face in his arms.

In another minute Jack had his arms about him, and the tears running down his cheeks was imploring him to look up. Bob had not fainted and after a moment his strength began to come back and he got slowly to his feet.

“It was close, awful close, Jack boy,” he whispered. “But thank God I made it in time.”

“And it was the bravest thing I ever saw,” Jack declared.

Then, as if by one impulse, the brothers knelt there on the logs, and, with arms about each other, they thanked God for His goodness.

“But we must see to Jean,” Bob cried, as he sprang to his feet.

They found the Frenchman still tugging to get his foot free.

“Just a minute, old fellow, and we’ll have you out,” Bob said, as he bent to examine the log which held the man prisoner. “Catch hold here, Jack, and when I give the word lift as hard as you can.”

It was a hard lift, but by exerting all their strength they were able to move the log enough to permit Jean to pull his foot out. Fortunately, except for a little skin rubbed off in his efforts to get the foot free, the man was uninjured.

“You save my life one more time, oui,” the Frenchman said soberly, as they made their way to the shore. “I, Jean Larue, never forgeet heem. Sometime I pay you back, oui.”

In spite of the protests of both Bob and Jack that he wait until they could get some new cells, Jean got another fuse from the scow and soon he was again speeding for the shore, leaving the sputtering fuse behind him. This time he reached the bank in safety, and a moment later the explosion came, with a roar which shook the earth beneath their feet. It seemed to the boys as though a mighty hand was tearing the huge logs apart. Breathlessly they waited to see what the result of the blast would be.

“Hurrah, she’s moving,” Jack shouted a moment later. “If only they don’t get caught again.”