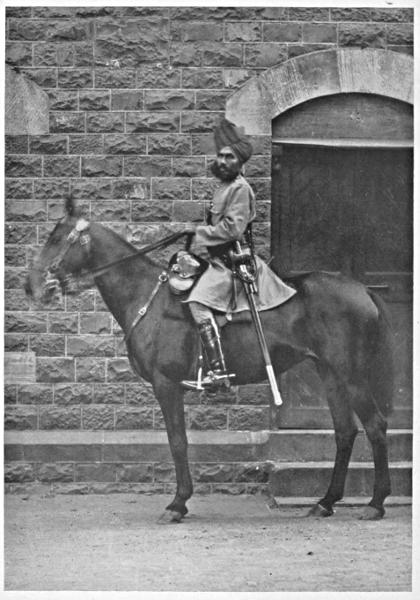

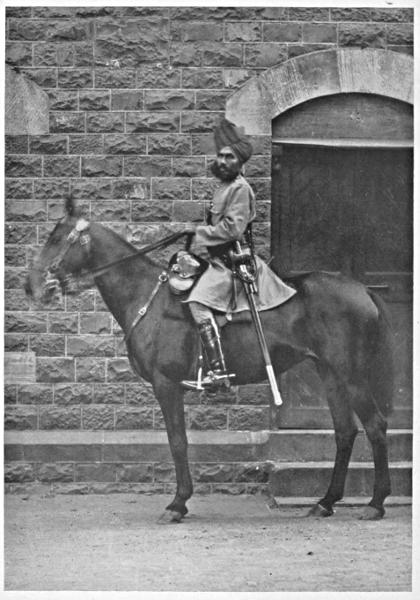

Mounted Police Constable

Bombay City

Title: The Bombay City Police: A Historical Sketch, 1672-1916

Author: S. M. Edwardes

Release date: July 31, 2020 [eBook #62798]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by ellinora and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE BOMBAY CITY POLICE

Mounted Police Constable

Bombay City

THE BOMBAY CITY POLICE

A HISTORICAL SKETCH

1672-1916

BY

S. M. EDWARDES, C.S.I., C.V.O.,

formerly of the Indian Civil Service and sometime

Commissioner of Police, Bombay

HUMPHREY MILFORD

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS

1923

I have been prompted to prepare this brief record of the past history and growth of the Bombay Police Force by the knowledge that, except for a few paragraphs in Volume II of the Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island, no connected account exists of the police administration of the City. Considering how closely interwoven with the daily life of the mass of the population the work of the Force has always been, and how large a contribution to the welfare and progress of the City has been made by successive Commissioners of Police, it seems well to place permanently on record in an accessible form the more important facts connected with the early arrangements for watch and ward and crime-prevention, and to describe the manner in which the Heads of the Force carried out the heavy responsibilities assigned to them.

The year 1916 is a convenient date for the conclusion of this historical sketch; for in September of that year commenced the violent agitation for Home Rule which under varying names and varying leadership, and despite concessions and political reforms, kept India in a state of unrest during the following five or six years.

Other considerations also suggest that the narrative may close most fitly in the year preceding the memorable pronouncement in Parliament, which ushered in the recent constitutional reforms. No one can foretell what changes may hereafter take place in the character and constitution of the City Police Force; but it is improbable that the Force can remain unaffected by the altered character of the general administration. Ere old conditions and old landmarks disappear, it seems to me worth while to compile a succinct history of the Force, as it existed before the era of “democratic” reform.

I am indebted to the present Acting Commissioner of Police for the photographs of the portraits hanging in the Head Police Office and of the types of constabulary; to the Record-Keeper at the India Office for giving me access to various police reports and official papers dating from 1859 to 1916; and to Mr. Sivaram K. Joshi, 1st clerk in the Commissioner’s office, who spent much of his leisure time in making inquiries and framing answers to various queries which the Bombay Government kindly forwarded at my request to the Head Police Office.

S. M. EDWARDES

London, 1923

| Page | ||

| I | The Bhandari Militia, 1672-1800 | 1 |

| II | The Rise of the Magistracy, 1800-1855 | 20 |

| III | Mr. Charles Forjett, 1855-1863 | 39 |

| IV | Sir Frank Souter Kt., C. S. I., 1864-1888 | 54 |

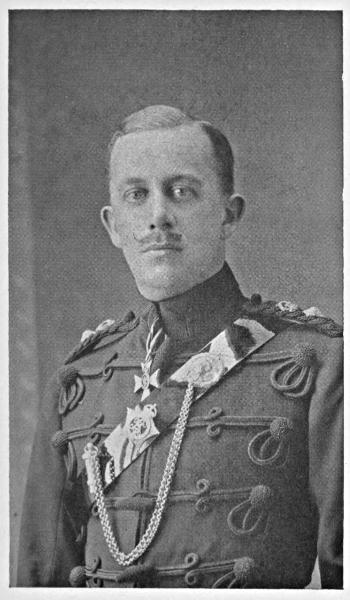

| V | Lieut-Colonel W. H. Wilson, 1888-1893 | 79 |

| VI | Mr. R. H. Vincent, C. I. E., 1893-1898 | 90 |

| VII | Mr. Hartley Kennedy, C. S. I., 1899-1901 | 107 |

| VIII | Mr. H. G. Gell, M. V. O., 1902-1909 | 120 |

| IX | Mr. S. M. Edwardes, C. S. I., C. V. O., 1909-16 | 148 |

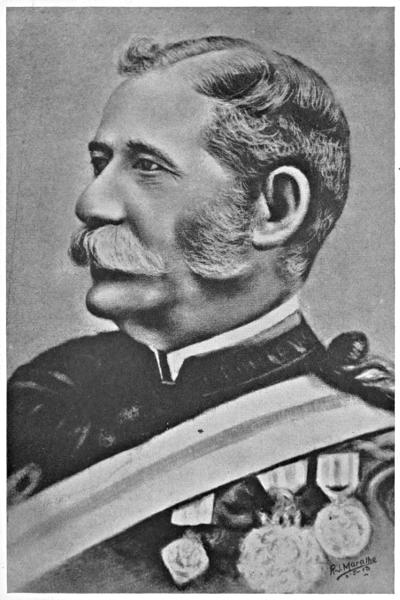

| Mounted Police Constable | Frontispiece | ||

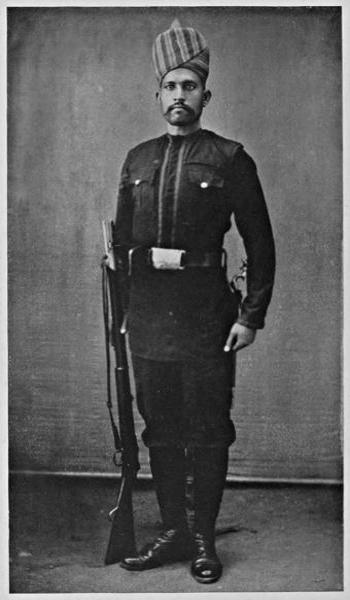

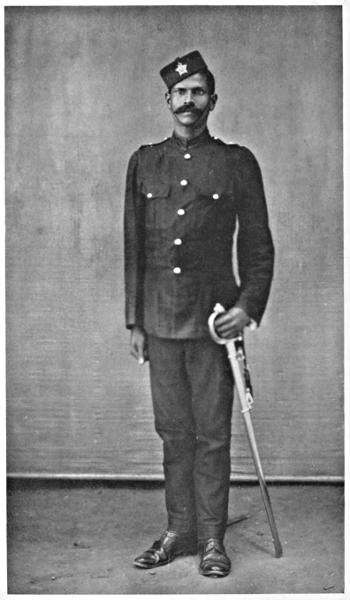

| Armed Police Constable | To face | page | 9 |

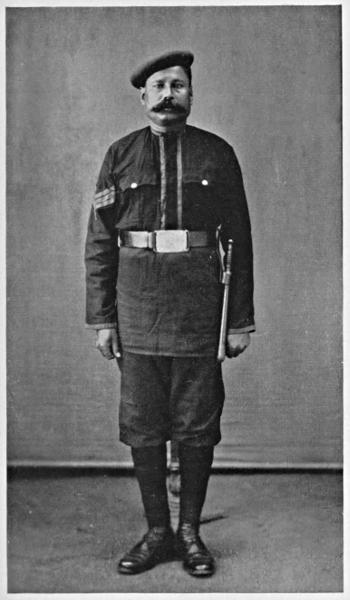

| Police Constable | ” | ” | 34 |

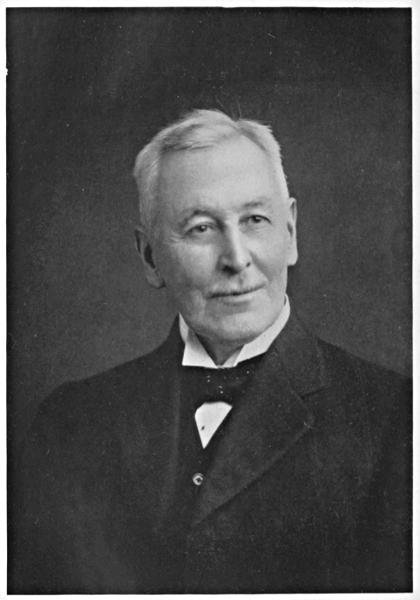

| Sir Frank Souter | ” | ” | 54 |

| Armed Police Jamadar | ” | ” | 59 |

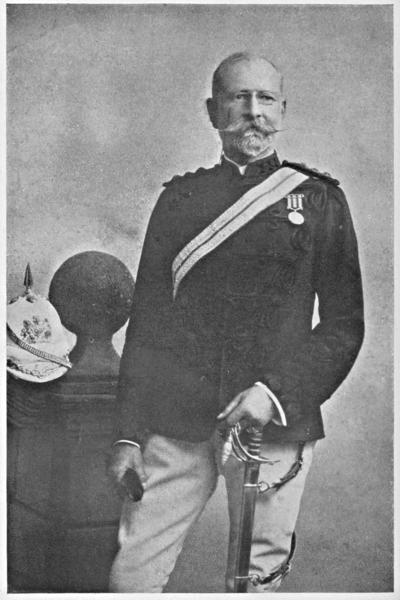

| Lieut-Col. W. H. Wilson | ” | ” | 79 |

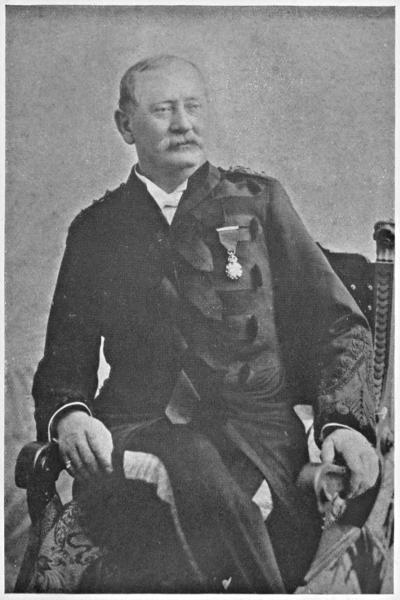

| Mr. R. H. Vincent | ” | ” | 90 |

| Khan Bahadur Sheikh Ibrahim Sheikh Imam | ” | ” | 97 |

| Mr. Hartley Kennedy | ” | ” | 107 |

| Mr. H. G. Gell | ” | ” | 120 |

| Rao Sahib Daji Gangaji Rane | ” | ” | 133 |

| Mr. S. M. Edwardes | ” | ” | 148 |

A perusal of the official records of the early period of British rule in Bombay indicates that the credit of first establishing a force for the prevention of crime and the protection of the inhabitants belongs to Gerald Aungier, who was appointed Governor of the Island in 1669 and filled that office with conspicuous ability until his death at Surat in 1677. Amidst the heavy duties which devolved upon him as President of Surat and Governor of the Company’s recently acquired Island,[1] and at a time when the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Mogul, the Sidi and the Marathas offered jointly and severally a serious menace to the Company’s trade and possessions, Aungier found leisure to organize a rude militia under the command of Subehdars, who were posted at Mahim, Sewri, Sion and other chief points of the Island.[2] This force was intended primarily for military protection, as a supplement to the regular garrison. That it was also employed on duties which would now be performed by the civil police, is clear from a letter of December 15, 1673, from Aungier and his council to the Court of Directors, in which the chief features of the Island and its administrative arrangements are described in considerable[2] detail.[3] After mentioning the strength of the forces at Bombay and their distribution afloat and ashore, the letter proceeds:—

“There are also three companies of militia, one at Bombay, one at Mahim, and one at Mazagon, consisting of Portuguese black Christians. More confidence can be placed in the Moors, Bandareens and Gentus than in them, because the latter are more courageous and show affection and good-will to the English Government. These companies are exercised once a month at least, and serve as night-watches against surprise and robbery.”

A little while prior to Aungier’s death, when John Petit was serving under him as Deputy Governor of Bombay, this militia numbered from 500 to 600, all of whom were landholders of Bombay. Service in the militia was in fact compulsory on all owners of land, except “the Braminys (Brahmans) and Bannians (Banias),” who were allowed exemption on a money payment.[4] The majority of the rank and file were Portuguese Eurasians (“black Christians”), the remainder including Muhammadans (“Moors”), who probably belonged chiefly to Mahim, and Hindus of various castes, such as “Sinays” (Shenvis), “Corumbeens” (Kunbis) and “Coolys” (Kolis).[5] The most important section of the Hindu element in this force of military night-watchmen was that of the Bhandaris (“Bandareens”), whose ancestors formed a settlement in Bombay in early ages, and whose modern descendants still cherish traditions of the former military and political power of their caste in the north Konkan.

The militia appears to have been maintained more or less at full strength during the troubled period of Sir John Child’s governorship (1681-90). It narrowly escaped[3] disbandment in 1679, in pursuance of Sir Josia Child’s ill-conceived policy of retrenchment: but as the orders for its abolition arrived at the very moment when Sivaji was threatening a descent on Bombay and the Sidi was flouting the Company’s authority and seizing their territory, even the subservient John Child could not face the risk involved in carrying out the instructions from home; and in the following year the orders were rescinded.[6] The force, however, did not wholly escape the consequences of Child’s cheese-paring policy. By the end of 1682 there was only one ensign for the whole force of 500, and of non-commissioned officers there were only three sergeants and two corporals. Nevertheless the times were so troubled that they had to remain continuously under arms.[7] It is therefore not surprising that when Keigwin raised the standard of revolt against the Company in December 1683, the militia sided in a body with him and his fellow-mutineers, and played an active part in the bloodless revolution which they achieved. Two years after the restoration of Bombay to Sir Thomas Grantham, who had been commissioned by the Company to secure the surrender of Keigwin and his associates, a further reference to the militia appears in an order of November 15th, 1686, by Sir John Wyborne, Deputy Governor, to John Wyat.[8] The latter was instructed to repair to Sewri with two topasses and take charge of a new guard-house, to allow no runaway soldiers or others to leave the island, to prevent cattle, corn or provisions being taken out of Bombay, and to arrest and search any person carrying letters and send him to the Deputy Governor. The order concluded with the following words:—

“Suffer poor people to come and inhabit on the island; and call the militia to watch with you every night, sparing the Padre of Parel’s servants.”

The terms of the order indicate to some extent the dangers and difficulties which confronted Bombay at this epoch; and it is a reasonable inference that the duties of the militia were dictated mainly by the military and political exigencies of a period in which the hostility of the neighbouring powers in Western India and serious internal troubles produced a constant series of “alarums and excursions”.

The close of the seventeenth and the earlier years of the eighteenth century were marked by much lawlessness; and in the outlying parts of Bombay the militia appears to have formed the only safeguard of the residents against robbery and violence. This is clear from an order of September 13, 1694, addressed by Sir John Gayer, the Governor, to Jansanay (Janu Shenvi) Subehdar of Worli, Ramaji Avdat, Subehdar of Mahim, Raji Karga, Subehdar of Sion, and Bodji Patan, Subehdar of Sewri. “Being informed,” he wrote, “that certain ill people on this island go about in the night to the number of ten or twelve or more, designing some mischief or disturbance to the inhabitants, these are to enorder you to go the rounds every night with twenty men at all places which you think most suitable to intercept such persons.”[9] The strengthening of the force at this period[10] and the increased activity of the night-patrols had very little effect in reducing the volume of crime, which was a natural consequence of the general weakness of the administration. The appalling mortality among Europeans, the lack of discipline among the soldiers of the garrison, the general immorality to which Ovington, the chaplain, bore witness,[11] the prevalence of piracy and the lack of proper laws and legal machinery, all contributed to render Bombay “very unhealthful” and to offer unlimited scope to the lawless section of the population.

As regards the law, judicial functions were exercised at the beginning of the eighteenth century by a civil officer of the Company, styled Chief Justice, and in important cases by the President in Council. Neither of these officials had any real knowledge of law; no codes existed, except two rough compilations made during Aungier’s governorship: and justice was consequently very arbitrary. In 1726 this Court was exercising civil, criminal, military, admiralty and probate jurisdiction; it also framed rules for the price of bread and the wages of “black tailors”.[12] Connected with the Court from 1720 to 1727 were the Vereadores,[13] a body of native functionaries who looked after orphans and the estates of persons dying intestate, and audited accounts. After 1726 they also exercised minor judicial powers and seem to have partly taken the place of the native tribunals, which up to 1696 administered justice to the Indian inhabitants of the Island.[14] So matters remained until 1726, when under the Charter creating Mayors’ Courts at Calcutta, Bombay and Madras the Governor and Council were empowered to hold quarter sessions for the trial of all offences except high treason, the President and the five senior members of Council being created Justices of the Peace and constituting a Court of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery.

For purposes of criminal justice Bombay was considered a county. The curious state of the law at this date is apparent from the trial of a woman, named Gangi, who was indicted in 1744 for petty treason in aiding and abetting one Vitha Bhandari in the murder of her husband.[15] She was found guilty and was sentenced to be burnt. Apparently the penalty for compassing a[6] husband’s death was the same as for high treason: and the sentence of burning for petty treason was the only sentence the Court could legally have passed. Twenty years earlier (1724) an ignorant woman, by name Bastok, was accused of witchcraft and other “diabolical practices.” The Court found her guilty, not from evil intent, but on account of ignorance, and sentenced her to receive eleven lashes at the church door and afterwards to do penance in the building.[16]

The system, whereby criminal jurisdiction was vested in the Governor and Council, lasted practically till the close of the eighteenth century. In 1753, for example, the Bombay Government was composed of the Governor and thirteen councillors, all of whom were Justices of the Peace and Commissioners of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery. They were authorised to hold quarter sessions and make bye-laws for the good government etc. of Bombay: and to aid them in the exercise of their magisterial powers as Justices, they had an executive officer, the Sheriff, with a very limited establishment.[17] In 1757 and 1759 they issued proclamations embodying various “rules for the maintenance of the peace and comfort of Bombay’s inhabitants”; but with the possible exception of the Sheriff, they had no executive agency to enforce the observance of these rules and bye-laws, and no body of men, except the militia, for the prevention and detection of offences. When, therefore, in 1769 the state of the public security called loudly for reform, the Bombay Government were forced to content themselves and their critics with republishing these various proclamations and regulations—a course which, as may be supposed, effected very little real good. In a letter to the Court of Directors, dated December 20th, 1769, they reported that in consequence[7] of a letter from a bench of H. M.’s Justices they had issued on August 26, 1769, “sundry regulations for the better conducting the police of the place in general, particularly in respect to the markets for provisions of every kind”; and these regulations were in due course approved by the Court in a dispatch of April 25, 1771.[18]

Police arrangements, however, were still very unsatisfactory, and crimes of violence, murder and robbery were so frequent outside the town walls that in August, 1771, Brigadier-General David Wedderburn[19] submitted proposals to the Bombay Government for rendering the Bhandari militia[20], as it was then styled, more efficient. His plan may be said to mark the definite employment of the old militia on regular police duties. Accordingly the Bombay Bhandaris were formed into a battalion composed of 48 officers and 400 men, which furnished nightly a guard of 12 officers and 100 men “for the protection of the woods.” This guard was distributed as follows:—

| 4 | officers | and | 33 | men | at Washerman’s Tank (Dhobi Talao). |

| 4 | ” | ” | 33 | ” | near Major Mace’s house. |

| 4 | ” | ” | 34 | ” | at Mamba Davy (Mumbadevi) tank. |

From these posts constant patrols, which were in communication with one another, were sent out from dark until gunfire in the morning, the whole area between Dongri and Back Bay being thus covered during the night. The Vereadores were instructed to appoint not less than 20 trusty and respectable Portuguese fazendars to attend singly or in pairs every night at the various police posts.[8] All Europeans living in Sonapur or Dongri had to obtain passes according to their class, i.e. those in the marine forces from the Superintendent, those in the military forces from their commanding officer, all other Europeans, not in the Company’s service, but living in Bombay by permission of the Government, from the Secretary to Government, and all artificers employed in any of the offices from the head of their office.

The duties of the patrols were to keep the peace, to seize all persons found rioting, pending examination, to arrest all robbers and house-breakers, to seize all Europeans without passes, and all coffrees (African slaves) found in greater numbers than two together, or armed with swords, sticks, knives or bludgeons. All coffrees or other runaway slaves were to be apprehended, and were punished by being put to work on the fortifications for a year at a wage of Rs. 3 per month, or by being placed aboard cruisers for the same term, a notice being published of their age, size, country of origin and description, so that their masters might have a chance of claiming them. If unclaimed by the end of twelve months, they were shipped to Bencoolen in Sumatra.

The standing order to all persons to register their slaves was to be renewed and enforced under a penalty. The Company agreed to pay the Bhandari police Rs. 10 for every coffree or runaway slave arrested and placed on the works or on a cruiser; Re. 1 for every slave absent from his work for three days; and Rs. 2 for every slave absent from duty for one month; Re. 1 for every soldier or sailor absent from duty for forty-eight hours, whom they might arrest; and 8 annas for every soldier or sailor found drunk in the woods after 8 p.m. The money earned in the latter cases was to be paid at once by the Marine Superintendent or the Commanding Officer, as the case might be, and deducted from the pay of the defaulter; and the total sum thus collected was to be divided once a month or oftener among the Bhandaris on duty.

Armed Police Constable

Bombay City

The officers in charge of the police posts and the Portuguese fazendars, attached thereto, were to make a daily report of all that had happened during the night and place all persons arrested by the patrols before a magistrate for examination. The Bhandari patrols were to assemble daily at 5 p.m. opposite to the Church Gate (of the Fort) and, weather permitting, they were to be taught “firing motions and the platoon exercise, and to fire balls at a mark, for which purpose some good havaldars should attend to instruct them, and the adjutant of the day or some other European officer should constantly attend.”

These Bhandari night-patrols, as organized by General Wedderburn, were the germ from which sprang the later police administration of the Island. We see the beginnings of police sections and divisions in the three main night-posts with their complement of officers and men; the forerunner of the modern divisional morning report in the daily report of the patrol officer and the fazendar; and the establishment of an armed branch in the fire-training given to the patrols in the evening. The presence of the fazendars was probably based on the occasional need of an interpreter and of having some advisory check upon the exercise of their powers by the patrols. In those early days the fazendar may have supplied the place of public opinion, which now plays no unimportant part in the police administration of the modern city.

Notwithstanding these arrangements, the volume of crime showed no diminution. Murder, robbery and theft were still of frequent occurrence outside the Fort walls: and in the vain hope of imposing some check upon the lawless element, the Bombay Government in August, 1776, ordered parties of regular sepoys to be added to the Bhandari patrols. Three years later, in February, 1779, they decided, apparently as an experiment, to supplant the Bhandari militia entirely by patrols of sepoys, which were to be furnished by “the battalion[10] of sepoy marines”. These patrols were to scour the woods nightly, accompanied by “a peace officer”, who was to report every morning to the acting magistrate.[21] Still there was no improvement, and the dissatisfaction of the general public was forcibly expressed at the close of 1778 or early in the following year by the grand Jury, which demanded a thorough reform of the police.[22] In the course of their presentment they stated that “the frequent robberies and the difficulties attending the detection of aggressors, called loudly for some establishment clothed with such authority as should effectually protect the innocent and bring the guilty to trial”, and they proposed that His Majesty’s Justices should apply to Government for the appointment of an officer with ample authority to effect the end in view.[23]

This pronouncement of the Grand Jury was the precursor of the first appointment of an executive Chief of Police in Bombay. On February 17, 1779, Mr. James Tod (or Todd) was appointed “Lieutenant of Police”, on probation, with an allowance of Rs. 4 per diem, and on March 3rd of that year he was sworn into office; a formal commission signed by Mr. William Hornby, the Governor, was granted to him, and a public notification of the creation of the office and of the powers vested in it was issued. He was also furnished with copies of the regulations in force, and was required by the terms of his commission to follow all orders given to him by the Government or by the Justices of the Peace.[24]

Tod had a chequered career as head of the Bombay police. The first attack upon him was delivered by the very body which had urged the creation of his appointment. The Grand Jury, like the frogs of Æsop who demanded a King, found the appointment little to their liking, and were moved in the following July (1779) to present “the[11] said James Todd as a public nuisance, and his office of Police as of a most dangerous tendency”; and they earnestly recommended “that it be immediately abolished, as fit only for a despotic government, where a Bastille is at hand to enforce its authority”.

The Government very properly paid no heed to this curious volteface of the Grand Jury, and Tod was left free to draft a new set of police regulations, which were badly needed, and to do what he could to bring his force of militia into shape. His regulations were submitted on December 31, 1779, and were approved by the Bombay Council and ordered to be published on January 26th, 1780. They were based upon notifications and orders previously issued from time to time at the Presidency and approved by the Justices, and were eventually registered in the Court of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery on April 17, 1780. Between the date of their approval by the Council and their registration by the Court, Tod revised them on the lines of the Police regulations adopted in Calcutta in 1778.[25] It was further provided at the time of their registration that “a Bench of Justices during the recess of the Sessions should be authorized from time to time to make any necessary alterations and amendments in the code, subject to their being affirmed or reversed at the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace next ensuing”. Tod’s regulations, which numbered forty-one, were the only rules for the management of the police which had been passed up to that date in a formal manner. They were first approved in Council, as mentioned above, by the authority of the Royal Charter of 1753, granted to the East India Company, and were then published and registered at the Sessions under the authority conveyed by the subsequent Act (13 Geo. III) of 1773. They thus constituted the earliest Bombay Police Code.

Meanwhile Tod found his new post by no means a bed of roses. On November 30th, 1779, he wrote to the Council stating that his work as Lieutenant of Police had created for him many enemies and difficulties. He had twice been indicted for felony and had been honourably acquitted on both occasions: but he still lived in continual dread of blame. “By unremitting and persevering attention to duty I have made many and bitter enemies”, he wrote, “in consequence of which I have been obliged in great measure to give up my bread.” He added that his military title of Lieutenant of Police had proved obnoxious to many, and he offered to resign it, suggesting at the same time that, following the precedent set by Calcutta, he should be styled Superintendent of Police. Lastly he asked the Council to fix his emoluments. The censure of the Grand Jury, quoted in a previous paragraph, indicates clearly the opposition with which Tod was faced; and one cannot but sympathize with an officer whose endeavours to perform his duty efficiently resulted in his arraignment before a criminal court. That he was honourably acquitted on both occasions shows that at this date at any rate he was the victim of malicious persecution.

As regards the style and title of his appointment, the Bombay Council endorsed his views, and on March 29th, 1780, they declared the office of Lieutenant of Police annulled, and created in its place the office of Deputy of Police on a fixed salary of Rs. 3,000 a year. Accordingly on April 5th, 1780, Tod formally relinquished his former office and was appointed Deputy of Police, being permitted to draw his salary of Rs. 3,000 a year with retrospective effect from the date of his first appointment as “Lieutenant”. On the same day he submitted the revised code of police regulations, which was formally registered in the Court of Oyer and Terminer on April 17th. In abolishing the post of Lieutenant the Bombay Government anticipated by a few months the order of[13] the Court of Directors, who wrote as follows on July 5th, 1780:—

“Determined as we are to resist every attempt that may be made to create new offices at the expense of the Company, we cannot but be highly displeased with your having appointed an officer in quality of Lieutenant of Police with a salary of Rs. 4 a day. Whatever sum may have been paid in consequence must be refunded. If such an officer be of that utility to the public as you have represented, the public by some tax or otherwise should defray the charges thereof.”

Before leaving the subject of the actual appointment, it is to be noted that at some date previous to 1780 the office of High Constable was annexed to that of Deputy of Police; for, in his letter to the Court of Sessions asking for the confirmation and publication of his police regulations, Tod describes himself as “Deputy of Police and High Constable”. No information, however, is forthcoming as to when this office was created, nor when it was amalgamated with the appointment of Deputy of Police.[26]

The actual details of Tod’s police administration are obscure. At the outset he was apparently hampered by lack of funds, for which the Bombay Government had made no provision. On January 17th, 1780, he submitted to them an account of sums which he had advanced and expended in pursuance of his duties as executive head of the police, and also informed the Council that twenty-four constables, “who had been sworn in for the villages without the gates”, had received no pay and consequently had, in concert with the Bhandaris, been exacting heavy fees from the inhabitants. Tod requested the Government to pay the wages due to these men, or, failing that, to authorize payment by a general assessment on all heads of families residing outside the gates of the town. The Council reimbursed Tod’s expenses[14] and issued orders for an assessment to meet the cost of the constabulary.

While allowing for the many difficulties confronting him, Tod cannot be held to have achieved much success as head of the police. His old critics, the Grand Jury, returned to the charge at the Sessions which opened on April 30th, 1787, and protested in strong terms against “the yet inefficient state of every branch of the Police, which required immediate and effectual amendment”. “That part of it” they said, “which had for its object the personal security of the inhabitants and their property was not sufficiently vigorous to prevent the frequent repetition of murder, felony, and every other species of atrociousness—defects that had often been the subject of complaint from the Grand Jury of Bombay, but never with more reason than at that Sessions, as the number of prisoners for various offences bore ample testimony.”

They animadverted on the want of proper regulations, on the great difficulty of obtaining menial servants and the still greater difficulty of retaining them in their service, on the enormous wages which they demanded and their generally dubious characters. So far as concerned the domestic servant problem, the Bombay public at the close of the eighteenth century seems to have been in a position closely resembling that of the middle-classes in England at the close of the Great War (1914-18). The Grand Jury complained also of the defective state of the high roads, of the uncleanliness of many streets in the Town, and of “the filthiness of some of the inhabitants, being uncommonly offensive and a real nuisance to society”. They objected to the obstruction caused by the piling of cotton on the Green and in the streets, to the enormous price of the necessaries of life, the bad state of the markets, and the high rates of labour. They urged the Justices to press the Bombay Government for reform and suggested “the appointment of a Committee of Police with full powers to frame regulations and armed with sufficient authority to carry them into[15] execution, as had already been done with happy effect on the representation of the Grand Juries at the other Presidencies.”

The serious increase of robbery and “nightly depredations” was ascribed chiefly to the fact that all persons were allowed to enter Bombay freely, without examination, and that the streets were infested with beggars “calling themselves Faquiers and Jogees (Fakirs and Jogis)”, who exacted contributions from the public. The beggar-nuisance is one of the chief problems requiring solution in the modern City of Bombay: and it may be some consolation to a harassed Commissioner of Police to know that his predecessor of the eighteenth century was faced with similar difficulties. The Grand Jury were not over-squeamish in their recommendations on the subject. They advocated the immediate deportation of all persons having no visible means of subsistence, and as a result the police, presumably under Tod’s orders, sent thirteen suspicious persons out of the Island.[27]

Three years later, in 1790, Tod’s administration came to a disastrous close. He was tried for corruption. “The principal witness against him (as must always happen)”, wrote Sir James Mackintosh, “was his native receiver of bribes. He expatiated on the danger to all Englishmen of convicting them on such testimony; but in spite of a topic which, by declaring all black agents incredible, would render all white villains secure, he was convicted; though—too lenient a judgment—he was only reprimanded and suffered to resign his station”.[28] Sir James Mackintosh, as is clear from his report of October, 1811, to the Bombay Government, was stoutly opposed to the system of granting the chief executive police officer wide judicial powers, such as those exercised by Tod and his immediate successors: and his hostility to the system may[16] have led to his overlooking the exceptional difficulties and temptations to which Tod was exposed. The Governor and his three Councillors, in whom by Act XXIV, Geo. III, of 1785 (“for the better regulation and management of the affairs of the East India Company and for establishing a Court of Judicature”), the supreme judicial and executive administration of Bombay were at this date vested, realized perhaps that Tod’s emoluments of Rs. 250 a month were scarcely large enough to secure the integrity of an official vested with such wide powers over a community, whose moral standards were admittedly low, that Tod had done a certain amount of good work under difficult conditions, and that the very nature of his office was bound to create him many enemies. On these considerations they may have deemed it right to temper justice with mercy and to permit the delinquent to resign his appointment in lieu of being dismissed.

The identity of Tod’s immediate successor is unknown. Whoever he was, he seems to have effected no amelioration of existing conditions. In 1793 the Grand Jury again drew pointed attention to “the total inadequacy of the police arrangements for the preservation of the peace and the prevention of crimes, and for bringing criminals to justice.” Bombay was the scene of constant robberies by armed gangs, none of whom were apprehended. The close of the eighteenth century was a period of chaos and internecine warfare throughout a large part of India, and it is only natural that Bombay should have suffered to some extent from the inroads of marauders, tempted by the prospect of loot. A system of night-patrols, weak in numbers and poorly paid, could not grapple effectively with organized gangs of free-booters, nurtured on dangerous enterprises and accustomed to great rapidity of movement. The complaints of the Grand Jury, however, could not be overlooked, and led directly to the appointment of a committee to consider the whole subject of the police administration and suggest reform.

This committee was in the midst of its enquiry when Act XXXIII, Geo. III. of 1793 was promulgated and rendered further investigation unnecessary. Under that Act a Commission of the Peace, based upon the form adopted in England, was issued for each Presidency by the Supreme Court of Judicature in Bengal. The Governor and his Councillors remained ex officiis Justices of the Peace for the Island, and five additional Justices were appointed by the Governor-General-in-Council on the recommendation of the Bombay Government. The Commission of the Peace further provided for the abolition of the office of Deputy of Police and High Constable, and created in its place the office of Superintendent of Police.

The first Superintendent of Police was Mr. Simon Halliday, who just prior to the promulgation of the Act above-mentioned had been nominated by the Justices to the office of High Constable. So much appears from the records of the Court of Sessions; and one may presume that after the Act came into operation in 1793 Mr. Halliday’s title was altered to that of Superintendent. His powers were somewhat curtailed to accord with the powers vested in the Superintendent of Police at Calcutta, and he was bound to keep the Governor-in-Council regularly informed of all action taken by him in his official capacity.

Mr. Halliday was in charge of the office of Superintendent of Police until 1808. His assumption of office synchronized with a thorough revision of the arrangements for policing the area outside the Fort, which up to that date had proved wholly ineffective. Under the new system, which is stated in Warden’s Report to have been introduced in 1793 and was approved by the Justices a little later, the troublesome area known as “Dungree and the Woods” was split up into 14 police divisions, each division being staffed by 2 Constables (European) and a varying number of Peons (not exceeding 130 for the whole area), who were to be stationary in[18] their respective charges and responsible for dealing with all illegal acts committed within their limits.

The disposition of this force of 158 men was as follows:—

| Name of Chokey | Number of Constables | Number of Peons | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Washerman’s Tank (Dhobi Talao) | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Back Bay | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Palo (Apollo i.e. Girgaum Road) | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Girgen (Girgaum) | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Gowdevy (Gamdevi) | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Pillajee Ramjee[29] | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Moomladevy (Mumbadevi) | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Calvadevy (Kalbadevi) | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Sheik Maymon’s Market (Sheik Memon Street?) | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Butchers (Market?) | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Cadjees (Kazi’s market or post) | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Ebram Cowns (Ibrahim Khan’s market or post) | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Sat Tar (Sattad Street) | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Portuguese Church (Cavel) | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| 28 | 130 | 158 |

The names of the police-stations or chaukis (chokeys) show that the area thus policed included roughly the modern Dhobi Talao section and the southern part of Girgaum, most of the present Market and Bhuleshwar sections and the western parts of the modern Dongri and Mandvi sections. In fact, the expression “Dongri and the Woods” represented the area which formed the nucleus of what were known in the middle of the nineteenth[19] century as the “Old Town” and “New Town”. At the date of Mr. Halliday’s appointment, this part of the Island was almost entirely covered with oarts (hortas) and plantations, intersected by a few narrow roads; and if one may judge by the illustration “A Night in Dongri” in The Adventures of Qui-hi (1816),[30] a portion of this area was inhabited largely by disreputable persons.

Simultaneously with the introduction of the arrangements described above, an establishment of “rounds” hitherto maintained by the arrack-farmer, consisting of one clerk of militia, 4 havaldars and 86 sepoys, and costing Rs. 318 per month, was abolished. Mahim, which was still regarded as a suburb, had its own “Chief,” who performed general, magisterial and police duties in that area; while other outlying places like Sion and Sewri were furnished with a small body of native police under a native officer, subject to the general supervision and control of the Superintendent. In 1797 the condition of the public thoroughfares and roads was so bad that, on the death in that year of Mr. Lankhut, the Surveyor of Roads, his department was placed in charge of the Superintendent of Police; while in 1800 the office of Clerk of the Market was also annexed to that of the chief police officer, in pursuance of the recommendations of a special committee. In the following year, 1801, the old office of Chief of Mahim was finally abolished, and his magisterial and police duties were thereupon vested in the Superintendent of Police. To enable him to cope with this additional duty, an appointment of Deputy Superintendent, officiating in the Mahim district, was created, the holder of which was directly subordinate in all matters to the Superintendent of Police. The first Deputy Superintendent was Mr. James Fisher, who continued in office until the date (1808) of Mr. Halliday’s retirement when he was succeeded by Mr. James Morley.

As has been shown in the preceding chapter, the importance of the office of Superintendent of Police had been considerably enhanced by the year 1809. Excluding the control of markets and roads, which was taken from him in that year, the Superintendent had executive control of all police arrangements in the Island, exercised all the duties of a High Constable, an Alderman and a Justice of the Peace, was Secretary of the Committee of Buildings, a member of the Town Committee, and a member of the Buildings Committee of H.M.’s Naval Offices in Bombay. He had been appointed a Justice of the Peace at his own request, on the grounds that he would thereby be enabled to carry out his police work more effectively. His deputy at Mahim was also appointed a Justice of the Peace on the publication of Act XLVIII, Geo. III. of 1808.

The year 1809 marks another crisis in the history of Bombay’s police administration, to which several factors may be held to have contributed. In the first place crime was still rampant and defied all attempts to reduce it. Bodies of armed men continued to enter the Island, as for example in 1806 and 1807, and to terrify, molest and loot the residents; and though these gangs remained for some little time within the Superintendent’s jurisdiction, they were never apprehended by the police.[31] In his report of November 15, 1810, Warden refers also to an attack by “Cossids”, i.e. Kasids or letter-carriers, who must have been induced to leave for the moment their ordinary duties as postal-runners and messengers by the apparent immunity from arrest and punishment[21] enjoyed by the bands of regular thieves and free-booters. In consequence of the general lawlessness traffic in stolen goods was at this date a most lucrative profession, and obliged the Justices in 1797 to nominate individual goldsmiths and shroffs as public pawnbrokers for a term of five years, on condition that they gave security for good conduct and furnished the police regularly with returns of valuable goods sold or purchased by them.[32] Another source of annoyance to the authorities was the constant desertion of sailors from the vessels of the Royal Navy and of the East India Company. These men were rarely arrested and the police appeared unable to discover their haunts. The peons, i.e. native constables were declared to be seldom on duty, except when they expected the Superintendent to pass, and to spend their time generally in gambling and other vices. In brief, the police force was so inefficient and crime was so widespread and uncontrolled that public opinion demanded urgent reform.

In the second place, the old system whereby the Governor and his Council constituted the Court of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery disappeared on the establishment in 1798 of a Recorder’s Court. The powers of the Justices, who were authorized to hold Sessions of the Peace, remained unimpaired, and nine of them, exclusive of the Members of Government, were nominated for the Town and Island. It was inevitable that the constitution of a competent judicial tribunal, presided over by a trained lawyer, should, apart from other causes, lead to a general stock-taking of the judicial administration of Bombay, and incidentally should direct increased attention to the subject of the powers vested in the Police and the source whence they drew their authority.

The powers of the Superintendent of Police at this epoch were very wide. First, he had power to convict offenders summarily and punish them at the police office.[22] This procedure, in the opinion of the Recorder, Sir James Mackintosh (1803-11), was quite illegal, inasmuch as the punishments were inflicted under rules, which from 1753 to 1807 were not confirmed by the Court of Directors and had therefore no validity. The rules made between 1807 and 1811 were likewise declared by the same authority to be invalid, as they had not been registered in the court of judicature. On other grounds also the police rules authorizing this procedure were ultra vires. Secondly, the Superintendent inflicted the punishment of banishment and condemned offenders to hard labour in chains on public works. Between February 28, 1808, and January 31, 1809, he (i.e. Mr. Halliday) banished 217 persons from Bombay, and condemned 64 persons to hard labour in the docks. During the three years, 1807-1809, about 200 offenders were thus condemned to work in chains. On the other hand, the Superintendent frequently liberated prisoners before the expiry of their sentence, and in this way released 26 persons on December 20, 1809, without assigning any reason. He condemned persons also to flogging. He kept no record of his cases. “He may arrest 40 men in the morning”, wrote Sir James Mackintosh, “he may try, convict and condemn them in the forenoon; and he may close the day by exercising the Royal prerogative of pardon towards them all.” It is hardly surprising that the mind of the lawyer revolted against the system, and that in his indignation he characterized the powers of the Superintendent as “a precipitate, clandestine and arbitrary jurisdiction.”[33]

In the third place, the powers of the Governor-in-Council to enact police regulations for Bombay were defined anew and enlarged by Act XLVII, Geo. III. of 1808, under the provisions of which the Government was empowered to nominate 16 persons, exclusive of the members of the Governor’s Council, to act as Justices of the Peace. The promulgation of this Act, which was[23] received in Bombay in 1808, rendered necessary a thorough revision of the conditions and circumstances of police control.

In consequence, therefore, of the prevalence of crime and the notorious inefficiency and corruption of the Police, the hostility of the new Recorder’s Court to the existing system of administration, and the need of a new enactment under Act XLVII, the Bombay Government appointed a committee in 1809 to review the whole position and make suggestions for further reform. The President of the committee was Mr. F. Warden, Chief Secretary to Government, who eventually submitted proposals in a letter dated November 15, 1810. The urgent need of reform was emphasized by the fact that the Superintendent of Police, Mr. Charles Briscoe, who had succeeded Mr. Halliday in 1809, was tried at the Sessions of November, 1810, for corruption, as Tod had been in 1790, and that complaints against the tyranny and inefficiency of the force were being daily received by the authorities. Sir James Mackintosh was only expressing public opinion when in 1811 he recommended Government “in their wisdom and justice to abolish even the name of Superintendent of Police, and to efface every vestige of an office of which no enlightened friend to the honour of the British name can recollect the existence without pain.”

Warden’s proposals were briefly the following. He advocated the adaptation to Bombay of Colquhoun’s system for improving the police of London, and suggested the appointment on fixed salaries of two executive magistrates for the criminal branch of the Police, to be selected from among the Company’s servants or British subjects—“one for the Town of Bombay, whose jurisdiction shall extend to the Engineer’s limits and to Colaba, and to offences committed in the harbour of Bombay, with a suitable establishment; and a second for the division without the garrison, including the district of Mahim, with a suitable establishment.” Both these[24] magistrates were to have executive and judicial functions, and were also to perform “municipal duties”.[34] The active functions of the police were to be performed by a Deputy, while “the control, influence, and policy” were to be centred in a Superintendent-General of Police, aided by the two magistrates. The latter officer was to be responsible for the recruitment of the Deputy’s subordinates, and the Mukadams (headmen) of each caste were to form part of the police establishment.

Warden dealt at some length with the qualifications and powers which the chief police officer should possess. He proposed that the Superintendent’s power of inflicting corporal punishment should be abolished, and that his duties should extend only to the apprehension, not to the punishment, of offenders; to the enforcement of regulations for law and order; to the superintendence of the scavenger’s and road-repairing departments; to watching “the motley group of characters that infest this populous island;” and to the vigilant supervision of houses maintained for improper and illegal purposes. “He should be the arbitrator of disputes between the natives, arising out of their religious prejudices. He should have authority over the Harbour, and should be in charge of convicts subjected to hard labour in the Docks, and those sent down to Bombay under sentence of transportation. He should not be the whole day closeted in his chamber, but abroad and active in the discharge of his duty; he should now and then appear where least expected. The power and vital influence of the office, and not its name only, should be known and felt. He ought to number among his acquaintances every rogue in the place and know all their haunts and movements. A character of this description is not imaginary, nor difficult of formation. We have heard of a Sartine and a Fouché; a Colquhoun exists; and I am informed that the character of Mr. Blaqueire at Calcutta, as a Magistrate, is equally efficient.” Warden, indeed,[25] demanded a kind of “admirable Crichton,”—strictly honest, yet the boon-companion of every rascal in Bombay, keeping abreast of his office-work by day and perambulating the more dangerous haunts of the local criminals by night. It is only on rare occasions that a man of such varied abilities and energy is forthcoming: and nearly half a century was destined to elapse before Bombay found a Police Superintendent who more than fulfilled the high standard recommended by the Chief Secretary in 1810.

The upshot of the Police Committee’s enquiry and of the report of its President was the publication of Rule, Ordinance and Regulation I of 1812, which was drafted by Sir James Mackintosh in 1811, and formed the basis of the police administration of Bombay until 1856. Under this Regulation, three Justices of the Peace were appointed Magistrates of Police with the following respective areas of jurisdiction:—

(a) The Senior Magistrate, for the Fort and Harbour.

(b) The Second Magistrate, for the area between the Fort Walls and a line drawn from the northern boundary of Mazagon to Breach Candy.

(c) The Third Magistrate, with his office at Mahim, for all the rest of the Island.[35]

Included in the official staff of these three magistrates were:—

| a Purvoe (i.e. Prabhu clerk) | on | Rs. | 50 | per | month | |

| a Cauzee (Kazi) | ” | ” | 8 | ” | ” | |

| a Bhut (Bhat, Brahman) | ” | ” | 8 | ” | ” | |

| a Jew Cauzee (Rabbi) | ” | ” | 12 | ” | ” | |

| an Andaroo (Parsi Mobed) | ” | ” | 6 | ” | ” | |

| Two Constables | each | ” | ” | 9 | ” | ” |

| One Havildar | ” | ” | 8 | ” | ” | |

| Four Peons | each | ” | ” | 6 | ” | ” |

The executive head of the Police force was a Deputy of Police and High Constable on a salary of Rs. 500 a month, while the general control and deliberative powers were vested in a Superintendent-General of Police. All appointments of individuals to the subordinate ranks of the force were made by the Magistrates of Police, who with the Superintendent-General met regularly as a Bench to consider all matters appertaining to the police administration of Bombay. European constables were appointed by the Justices at Quarter Sessions, and the Mukadams or headmen of each caste formed an integral feature of the police establishment.

The strength and cost of the force in 1812 were as follows:—

| 1 | Deputy of Police and Head Constable | Rs. | 500 | per | month |

| 2 | European Assistants (at Rs.100 each) | Rs. | 200 | ” | ” |

| 3 | Purvoes (Prabhus, clerks) | Rs. | 110 | ” | ” |

| 1 | Inspector of Markets | Rs. | 80 | ” | ” |

| 2 | Overseers of Roads (respectable natives at 50 each) | Rs. | 100 | ” | ” |

| 12 | Havaldars (at Rs. 8 each) | Rs. | 96 | ” | ” |

| 8 | Naiks (at Rs. 7 each) | Rs. | 56 | ” | ” |

| 6 | European Constables | Rs. | 365 | ” | ” |

| 50 | Peons (at Rs. 6 each) | Rs. | 300 | ” | ” |

| 1 | Battaki man | Rs. | 6 | ” | ” |

| 1 | Havaldar and 12 Peons for the Mahim patrol | Rs. | 80 | ” | ” |

| Harbour Police. | |||||

| 7 | Boats i.e. 49 men | Rs. | 300 | ” | ” |

| 1 | Purvoe | Rs. | 50 | ” | ” |

| 4 | Peons (at Rs. 6 each) | Rs. | 24 | ” | ” |

| Contingencies | Rs. | 74 | ” | ” | |

Thus, including the Deputy of Police, the land force comprised 10 Europeans, one of whom was in charge of the markets, and 86 Indians, of whom two were inspectors[27] of roads. The clerical staff consisted of three Prabhus. The water-police consisted of 53 Indians and one clerk. The cost of the force, including the water-police, amounted to Rs. 27,204 a year, to which had to be added Rs. 888 for contingencies, Rs. 1425 for the clothing of havaldars and peons, and Rs. 2000 for stationery.[36]

The inclusion in the magisterial establishment of “a Cauzee” etc. requires brief comment. Down to 1790 the administration of criminal justice in India was largely in the hands of Indian judges and officials of various denominations, though under European supervision in various forms; and even after that date, when the native judiciary had ceased to exist except in quite subordinate positions, the law that was administered in criminal cases was in substance Muhammadan law, and a Kazi and a Mufti were retained in the provincial courts of appeal and circuit as the exponents of Muhammadan law and the deliverers of a formal fatwa. The term Kazi on this account remained in formal existence till the abolition of the Sadr Courts in 1862.[37] The object of associating Kazis with the Bombay magistrates of police at the opening of the nineteenth century was doubtless to ensure that in all cases brought before them, involving questions of the law, customs and traditions of the chief communities and sects inhabiting the Island, the magistrates should have the advantage of consulting those who were able to interpret and give a ruling on such matters. The Kazi proper was the authority on all matters relating to the Muhammadan community; the “Jew Cauzee” on matters relating to the Bene-Israel, who from 1760 to the middle of the nineteenth century contributed an important element to the Company’s military forces;[38] the Bhat presumably gave advice on[28] subjects affecting Hindus of the lower classes; while the “Andaroo” (i.e. Andhiyaru, a Parsi priest) was required in disputes and cases involving Parsis, whose customs in respect of marriage, divorce and inheritance had not at this date been codified and given the force of law.

The Regulation of 1812 effected little or no improvement in the state of the public security. Gangs of criminals burned ships in Bombay waters to defraud the insurance-companies; robberies by armed gangs occurred frequently in all parts of the Island;[39] and every householder of consequence was compelled to employ private watchmen, the fore-runners of the modern Ramosi and Bhaya, who were often in collusion with the bad characters of the more disreputable quarters of the Town.[40] Even Colaba, which contained few dwellings, was described in 1827 as the resort of thieves.[41] The executive head of the force at this date was Mr. Richard Goodwin, who succeeded the unfortunate Briscoe in 1811 and served until 1816, when apparently he was appointed Senior Magistrate of Police, with Mr. W. Erskine as his Junior.

The proceedings of both the magistrates and the police were regarded with a jaundiced eye by the Recorder’s Court, and Sir Edward West, who filled the appointment, first of Recorder and then of Chief Justice, from 1822 to 1828, animadverted severely in 1825 upon the illegalities perpetrated by the magisterial courts, presided over at that date by Messrs. J. Snow and W. Erskine[42]. His successor in the Supreme Court,[43] Sir J. P. Grant, passed equally severe strictures upon the[29] police administration at the opening of the Quarter Sessions in 1828.

“The calendar is a heavy one. Several of the crimes betoken a contempt of public justice almost incredible and a state of morals inconsistent with any degree of public prosperity. Criminals have not only escaped, but seem never to have been placed in jeopardy. The result is a general alarm among native inhabitants. We are told that you are living under the laws of England. The only answer is that it is impossible. What has been administered till within a few years back has not been the law of England, nor has it been administered in the spirit of the law of England; else it would have been felt in the ready and active support the people would have given to the law and its officers, and in the confidence people would have reposed in its efficacy for their protection.”[44]

The punishments inflicted at this date were on the whole almost as barbarous as those in vogue in earlier days. In 1799, for example, we read of a Borah, Ismail Sheikh, being hanged for theft: in 1804 a woman was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for perjury, during which period she was to stand once a year, on the first day of the October Sessions, in the pillory in front of the Court House (afterwards the Great Western Hotel), with labels on her breast and back describing her crime: and in the same year one Harjivan was sentenced to be executed and hung in chains, presumably on Cross Island (Chinal Tekri), where the bodies of malefactors were usually exposed at this epoch. One James Pennico, who was convicted of theft in 1804, escaped lightly with three months’ imprisonment and a public whipping at the cart’s tail from Apollo Gate to Bazaar Gate; in 1806 a man who stole a watch was sentenced to two years’ labour in the Bombay Docks.[45] The public pillory and flogging were punishments constantly inflicted during the early years of the nineteenth century.[30] The pillory, which was in charge of the Deputy of Police, was located on the Esplanade in the neighbourhood of the site now occupied by the Municipal Offices. The last instance of its use occurred in 1834, when two Hindus were fastened in it by sentence of the Supreme Court and were pelted by boys for about an hour with a mixture composed of red earth, cowdung, decayed fruits and bad eggs. At intervals their faces were washed by two low-caste Hindus, and the pelting of filth was then resumed to the sound of a fanfaronade of horns blown by the Bhandaris attached to the Court.[46] Meanwhile the English doctrine of the equality of all men before the law was gradually being established, though the earliest instance of a Brahman being executed for a crime of violence did not occur until 1846. The case caused considerable excitement among orthodox Hindus, whose views were based wholly upon the laws of Manu.[47]

The early “thirties” were remarkable for much crime and for a serious public disturbance, the Parsi-Hindu riots, which broke out in July, 1832, in consequence of a Government order for the destruction of pariah-dogs, which at this date infested every part of the Island. Two European constables, stimulated by the reward of eight annas for every dog destroyed, were killing one in the proximity of a house, when they were attacked and severely handled by a mob composed of Parsis and Hindus of several sects. On the following day all the shops in the Town were closed, and a mob of about 300 roughs commenced to intimidate all persons who attempted to carry out their daily business. The bazar was deserted; and the mob forcibly destroyed the provisions intended for the Queen’s Royals, who were on duty in the Castle, and stopped all supplies of food and water for the residents of Colaba and the shipping in the harbour. As the mob continued to gather strength, Mr. de Vitré, the Senior Magistrate of Police, called for[31] assistance from the garrison, which quickly quelled the disturbance.[48]

The Press of this date recorded constant cases of burglary and dacoity. “The utmost anxiety and alarm prevail amongst the inhabitants of this Island, especially those residing in Girgaum, Mazagon, Byculla and the neighbourhood, in consequence of the depredations and daring outrages committed by gangs of robbers armed with swords, pistols and even musquets, who, from the open and fearless manner in which they proceed along the streets, sometimes carrying torches with them, seem to dread neither opposition nor detection, and to defy the police.” It was even said that sepoys of the 4th Regiment of Native Infantry, then stationed in the Island, joined these gangs of marauders, and when two men of the 11th Regiment were arrested on suspicion by a magistrate, their comrades stoned the magistrate’s party. “It would be far better that the Island should be vacated altogether by the sepoy regiments,” said the Courier, “than that it should be exposed repeatedly to these excesses.” Fifty men of the Poona Auxiliary Force had to be brought down to aid the police and to patrol the roads at night.[49]

According to Mrs. Postans, the police administration had improved and robberies had become less frequent at the date of her visit, 1838. “The establishment of an efficient police force,” she writes, “is one of the great modern improvements of the Presidency. Puggees (Pagis i.e. professional trackers) are still retained for the protection of property: but the highways and bazaars are now orderly and quiet, and robberies much less frequent.”[50] The authoress admitted, however, that the Esplanade—particularly the portion of it occupied by the[32] tents of military cadets—was the resort of “a clique of dexterous plunderers,” who during the night used to cast long hooks into the tents and so withdraw all the loose articles and personal effects within reach.[51] The prevalence of more serious crime is indicated by her remarks about the Bhandari toddy-drawers:—

“It appears that in many cases of crime brought to the notice of the Bombay magistracy, evidence which has condemned the accused has been elicited from a Bundarrie, often sole witness of the culprit’s guilt. Murderers, availing themselves of the last twilight ray to decoy their victims to the closest depths of the palmy woods and there robbing them of the few gold or silver ornaments they might possess, have little thought of the watchful toddy-drawer, in his lofty and shaded eyry.”[52]

That the improvement was not very marked is also proved by the fact that in 1839, the year after Mrs. Postans’ visit, the Bench of Justices increased their contribution to Government for police charges to Rs. 10,000, the additional cost being declared necessary owing to the rapid expansion of the occupied urban area, and to the grave inadequacy of the force for coping with crime. So far as watch and ward duties were concerned, the police must have welcomed the first lighting of the streets with oil-lamps in 1843. Ten years later there were said to be 50 lamps in existence, which were lighted from dusk to midnight, and the number continued to increase until October, 1865, when the first gas-lamps were lighted in the Esplanade and Bhendy Bazar. On the other hand drunkenness was a fruitful source of crime, and the number of country liquor-shops was practically unlimited. “On a moderate computation” wrote Mrs. Postans “every sixth shop advertises the sale of toddy.” With such facilities for intoxication, crime was scarcely likely to decrease.

But other and deeper reasons existed for the unsatisfactory state of the public peace and security. Throughout the whole of the period from 1800 to 1850, and in a milder form till the establishment of the High Court in 1861, there was constant friction, occasionally of an acute character, between the Supreme Court and the Company’s government and officials. Moreover, the original intention of the Crown that the Supreme Court should act as a salutary check upon the Company’s administration was frustrated by several periods of interregnum between 1828 and 1855, the Court being represented frequently by only one Judge and on one occasion being entirely closed owing to the absence of judges. This antagonism between the highest judicial tribunal and the executive authority could not fail to react unfavourably on the subordinate machinery of the administration, and coupled with inadequacy of numbers, insufficiency of pay, and a general lack of integrity in the Police force itself, may be held to have been largely responsible for the comparative freedom enjoyed by wrong-doers and their manifest contempt for authority.

Contemporary records indicate that the Police Office at this period (1800-1850) was located in the Fort; the court of the Senior Magistrate of Police was housed in a building in Forbes Street, and the court of the Second Magistrate in a house in Mazagon. The powers of both Magistrates were limited, and all cases involving sentences of more than six months’ imprisonment, or affecting property valued at more than Rs. 50, had to be sent to the Court of Petty Sessions or committed to the Recorder’s, subsequently the Supreme Court. The Court of Petty Sessions was composed of the two Magistrates of Police and a Justice of the Peace (the Superintendent-General of Sir J. Mackintosh’s draft Regulation), and sat every Monday morning at 10 a.m. at the Police Office in the Fort. The constitution of this Court was afterwards amended by Rule, Ordinance and Regulation 1 of 1834, which, though not registered in the[34] Supreme Court as required by Act XLVII, Geo. III, was subsequently legalized by India Act VII of 1836. By that Ordinance the Court was composed of not less than three Justices of the Peace, one of whom was a Magistrate of Police, the second was a European, and the third was a Native of India, not born of European parents. It remained in existence, with extended powers, until the year 1877, when, together with three Magistrates of Police, it was superseded by the Presidency Magistrates Act.

A word may here be said on the subject of the well-known uniform of the Bombay constabulary, the bright yellow cap and the dark blue tunic and knickers, which once caused a wag to style the Bombay police-sepoy “the empty black bottle with the yellow seal.” The origin of the uniform is obscure; but it was certainly in use in 1838, for Mrs. Postans describes the dress of the men as “a dark blue coat, black belt, and yellow turban.”[53] An illustration in The Adventures of Qui-Hi, entitled “A Night in Dongri,” shows that the uniform was worn at a still earlier date. In the background of the picture two persons are obviously having an altercation with a police-constable, and the latter is depicted wearing the flat yellow cap and blue uniform familiar to every modern resident of Bombay. The dress of the constabulary must therefore have been adopted at some date prior to 1816, and it is probably a legitimate inference that it dates back to the reorganization of 1812, and was possibly adapted from an older dress worn at the end of the eighteenth century. In any case the distinctive features of the dress of the Bombay police-constable of to-day are well over one hundred years old.

Police Constable

Bombay City

When Thomas Holloway relinquished the office of High Constable in 1829, his place was taken by one José Antonio, presumably a Portuguese Eurasian, who had been serving as Constable to the Court of Petty[35] Sessions. José Antonio seems to have performed the duties of executive police officer until 1835, when Captain Shortt was appointed “Superintendent of Police and Surveyor etc. etc.” Between 1829 and 1855 the following officials were responsible for the police administration of Bombay:—

| Period of Office | Senior Magistrate | Junior Magistrate | Constable or Supdt. of Police |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1829-33 | J. D. de Vitré | H. Gray | José Antonio. |

| 1834 | J. Warden | Do. | Do. |

| Supdt. of Police | |||

| 1835-39 | J. Warden | H. Willis | Capt. Shortt |

| 1840 | J. Warden | E. F. Danvers | Capt. Burrows |

| 1841-45 | P. W. Le Geyt | Do. | Do. |

| 1846 | G. L. Farrant | Do. | Capt. W. Curtis |

| 1847-48 | G. Grant | Do. | Do. |

| 1849 | Do. | Do. | Capt. E. Baynes |

| 1850-51 | A. Spens | Do. | Do. |

| 1852-53 | Do. | L. C. C. Rivett | Do. |

| 1854-55 | A. K. Corfield | T. Thornton | Do. |

It will be apparent from this list that from 1835 to 1855 the executive control of the Police force was entrusted to a series of junior officers belonging to the Company’s military forces, who probably possessed little or no aptitude for police work, were poorly paid for their services, and had no real encouragement to make their mark in civil employ. Consequently, despite increased expenditure on the force, these military Superintendents of Police secured very little control over the criminal[36] classes, and effected no real improvement in the morale of their subordinates. In 1844, for example, a succession of daring robberies was carried out in the Harbour by gangs of criminals, who sailed round in boats from Back Bay. The most notorious of them was known as the Bandar Gang[54]; and their unchecked excesses led to the formation of a separate floating police-force under the control of a Deputy Superintendent on Rs. 500 a month. House-breaking was of daily occurrence in Colaba, Sonapur, Kalbadevi and Girgaum,[55] and constant complaints of dishonesty among the European constables and of the gross inefficiency of the native rank and file were made to the authorities by both public bodies and private residents.[56] Corruption was prevalent in all ranks of the force, and most of the subordinate officers, both European and Indian, were in secret collusion with agents and go-betweens, some of them members of the higher Hindu castes, who assisted their acts of extortion and blackmail and shared with them the proceeds of their venality. Bands of ruffians infested the thoroughfares and lanes of the native city, and no respectable resident dared venture unprotected into the streets after nightfall.

The period immediately preceding the year of the Mutiny was also remarkable for two serious breaches of the public peace. The earlier occurred at Mahim in 1850, on the last day of the Muharram festival, in consequence of a dispute between two factions of the Khoja community, and resulted in the murder of three men and the wounding of several others.[57] The later riots broke out in October, 1851, between the Parsis and Muhammadans, in consequence of a very indiscreet article on the Muhammadan religion which was published in the Gujarati, a Parsi newspaper. The Muhammadans, incensed at the statements made about the Prophet,[37] gathered at the Jama Masjid on October 17th in very large numbers, and after disabling a small police patrol, stationed there to keep the peace, commenced attacking the Parsis and destroying their property. The public-conveyance stables at Paidhoni, which at that date belonged to Parsis, were wrecked, liquor-shops were broken open and rifled, shops and private houses were pillaged. Captain Baynes, the Superintendent of Police, and Mr. Spens, the Senior Magistrate, managed with a strong force to disperse the main body of rioters, capturing eighty-five of them: but towards evening, as there were signs of a fresh outbreak and the neighbourhood of Bhendy Bazaar was practically in a state of siege, the garrison-troops were marched down to Mumbadevi and thence distributed in pickets throughout the area of disturbance. This action finally quelled the rioting, and the annual Muharram festival, which commenced ten days later, passed off without any untoward incident.[58]

In the year 1855 the post of Senior Magistrate was held by Mr. Corfield, Messrs. T. Thornton and N. W. Oliver being respectively Junior and Third Magistrates. In that year the public outcry against the police had become so great, and the general insecurity had been reflected in so constant a series of crimes against person and property, that Lord Elphinstone’s government determined to institute a searching enquiry into the whole subject. With this object they appointed to the immediate command of the force in 1856 Mr. Charles Forjett, who was serving at the moment as Deputy Superintendent. Through his energy and activity, they were able to satisfy themselves fully of the prevalence of wholesale corruption in the force. Drastic executive action was at once taken; and this was followed by the drafting and promulgation of Act XIII of 1856 for the future constitution and regulation of the Police Force. At the same time Mr. Corfield was succeeded as Senior Magistrate by Mr. W. Crawford. The credit for the[38] introduction of the reforms and for the restoration of public confidence belongs wholly to Charles Forjett, whose successful administration during a period fraught with grave political dangers deserves to be recorded in a separate chapter. His appointment in 1855 may be said to inaugurate the régime of the professional police official as distinguished from the purely military officer, and to mark the final disappearance of an antiquated system, under which inefficiency and crime flourished exceedingly. Henceforth a new standard of administration was imposed, whereby the Bombay Police Force was enabled to maintain the public peace effectively and also to acquire by degrees a larger share of the confidence and co-operation of the general body of citizens.[59]

Charles Forjett[60], who was appointed Superintendent of Police in 1855, was of Eurasian (now styled Anglo-Indian) parentage and was brought up in India. His father was an officer of the old Madras Fort Artillery and had been wounded at the capture of Seringapatam in 1799. In Our Real Danger in India, which he published in 1877, some few years after his retirement, Forjett states that he served the Bombay Government for forty years, first as a topographical surveyor and then successively as official translator in Marathi and Hindustani, Sheriff, head of the Poona police, subordinate and chief uncovenanted assistant judge, superintendent of police in the Southern Maratha Country, and finally as Commissioner of Police, Bombay. He first earned the favourable notice of the Bombay Government by his reform and reorganization of the police in the Belgaum division of the Southern Maratha Country; and there is probably considerable justification for his own statement that the peace and security of the southern districts of the Presidency during the period of the Mutiny were chiefly due to his constructive work in this direction.

He owed his later success as a police-officer to three main factors, namely his great linguistic faculty, his wide knowledge of Indian caste-customs and habits, and his masterly capacity for assuming native disguises. Born[40] and bred in India, he had learnt the vernaculars of the Bombay Presidency in his youth, and had been familiar from his earliest years with those subtle differences of belief and custom which the average home-bred Englishman knows nothing about and can never master. His black hair and sallow complexion—in brief, the strong “strain of the country” in his blood—enabled him, when disguised, to pass among natives of India as one of themselves. A story is told to illustrate his powers of disguise. He once told the Governor, Lord Elphinstone, that in spite of special orders prohibiting the entrance of any one and in defiance of the strongest military cordon that His Excellency could muster, he would effect his entrance to Government House, Parel, and appear at the Governor’s bedside at 6 a.m. Lord Elphinstone challenged him to fulfil his boast and took every precaution to prevent his ingress. Nevertheless Forjett duly appeared the following morning in the Governor’s bedroom—in the disguise of a mehtar (sweeper). With these special qualifications for police work were combined a strong will and great personal courage.

Forjett’s fame rests mainly upon his action during the Mutiny, and one is apt to overlook the great but less sensational services which he rendered to Government and the public in subduing lawlessness and crime in Bombay. As mentioned in the previous chapter, he was serving as Assistant or Deputy Superintendent of Police for some few months before Lord Elphinstone placed him in control of the force, and during that period he set himself to test the extent of the corruption which was believed to prevail widely among all ranks. By means of his disguises he managed to get into close touch with the men who were acting as go-betweens and receivers of bribes, and even dined with one of them, a high-caste Hindu, without betraying his identity. Through these men he also contrived on various occasions to test the integrity of individual members of the force. In consequence[41] he was able in a very short time to expose the whole system of corruption and to furnish Government with the evidence they required for a drastic purging of the upper and lower grades.

That duty accomplished, he turned his attention to the criminal classes.[61] “At a time” wrote the late Mr. K. N. Kabraji in his Reminiscences of Fifty Years Ago, “when the public safety was quite insecure, when the city was infested by desperate gangs of thieves and other malefactors, Forjett had to use all his wonderful energy and acumen to break their power and rid the city of their presence. He strengthened and reformed the Police, which had been powerless to cope with them. There was a notorious band of athletic ruffians in Bazar Gate Street, consisting chiefly of Parsis. They used to occupy some rising ground, from which they swooped down on their prey. Their daily acts of crime and violence were committed with impunity, and their names were whispered by mothers to hush their children to silence.

“I may here give a personal instance of the insecurity of the times. As I was returning one night with my father from the Grant Road theatre in a carriage, a ruffian prowling about in the dark at Falkland road snatched my gold-embroidered cap and ran away with it. The road had been newly built and ran through fields and waste land. Khetwadi, as its name implies, was also an agricultural district. Grant road, Falkland road and Khetwadi were then lonely places on the outskirts of the City, and it is no wonder that wayfarers in these localities could never be secure of purse or person. But on the Esplanade, under the very walls of the Fort, occurred instances of violence and highway robbery, which went practically unchecked. Not a few of the offenders were soldiers. They used to lie in wait for a likely carriage with a rope thrown across the road, so that the horse stumbled and fell, and then they rifled the occupants of the carriage at[42] their leisure. It was Mr. Forjett, whose vigilance and activity brought all this crying scandal to an end.”[62]

The rapid change for the better which followed Forjett’s appointment to the office of Superintendent is illustrated by the fact that whereas in 1855 only 23 per cent of property stolen was recovered, in 1856 the percentage had risen to 59. Mr. W. Crawford, “Senior Magistrate of Police and Commissioner of Police”, in his annual return of crime for the year 1859 remarked that “the total continued absence of gang and highway robbery is most satisfactory”, and drew pointed attention to the efficiency of the “executive branch of the police” under Mr. Forjett.[63] In the following year, 1860, there were only three cases of burglary, and although the value of property stolen amounted to Rs. 187,000, the police managed to recover property worth Rs. 73,000. Serious offences against the person also seem to have decreased in number during Forjett’s régime. The Senior Magistrate observed with satisfaction that “the debasing spectacle of a public execution was not called for” during the year 1859; and such records as still exist of the later years of Forjett’s administration point to the same conclusion.[64]