Title: The Tank Corps

Author: Clough Williams-Ellis

Amabel Williams-Ellis

Author of introduction, etc.: Hugh Jamieson Elles

Release date: August 8, 2020 [eBook #62881]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note

This book uses footnote anchors at the beginning of some quoted text to refer to footnotes crediting the sources of those quotes. It also uses mid-paragraph footnote anchors to refer to other kinds of footnotes.

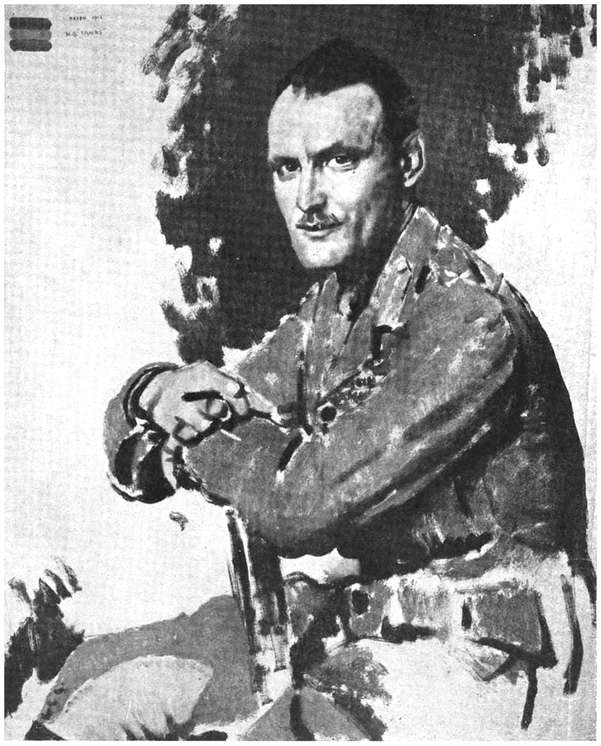

MAJOR-GENERAL HUGH ELLES, C. B., D. S. O.

FROM A PORTRAIT BY SIR WILLIAM ORPEN, A. R. A.

THE TANK CORPS

BY

Major CLOUGH WILLIAMS-ELLIS, M.C.

AND

A. WILLIAMS-ELLIS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

Major-General H. J. ELLES, C.B., D.S.O.

COMMANDER OF THE TANK CORPS

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

NEW  YORK

YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1919,

BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

5

My dear Williams-Ellis,

You ask me for a foreword to your history, and invite me, too, to agree to, criticise, or even refute the conclusions of your Epilogue.

The first task I undertake with pleasure, though I feel it would be more justly and more skilfully done either by one of the pioneers who sowed that we might reap, or by the rare thinker who in our own time has contributed so much to keep us on the lines of clear understanding and progress.

As to the second task I must decline a direct reply, and for many reasons I can no more than touch generally upon the questions you have dealt with in so interesting a way. I find them, however, not yet sufficiently remote in time, either to be clear themselves, or to be distinctly placed in a picture itself still obscure.

Of the early days of the Tanks, and of the early struggles, difficulties and hopes of the pioneers, I have no first-hand knowledge—to comment at any length upon them would be out of place. They do, however, represent a remarkable effort of persistent and courageous faith, of determination to succeed in the face of lukewarmness and even scepticism, of the overcoming of many practical difficulties. Above all, they present a great clearness of vision on the part of three men in particular—Swinton, Stern and d’Eyncourt.

It is remarkable that one of the first official papers on the tactical use of Tanks, written by General Swinton early in 1915, should have been almost literally translated into action on August 8, 1918.

To General Swinton, too, is due the implanting, into all ranks, of the fundamental idea of the Tank as a6 weapon for saving the lives of infantry. This idea was indeed the foundation of the moral of the Tank Corps, for it spread from the fighting personnel to the depots and workshops, and even to the factories.

More than anything else, it was this sentiment which kept men ploughing through the mud of 1917, in the dark days when often the chance of reaching an objective had fallen to ten per cent.; which kept workshops in full swing all round the clock on ten and eleven hour shifts for weeks and, once, for months on end; which, finally, secured from the factories an intensive and remarkable output.

Sir Albert Stern brought to his labours a whole-hearted energy and enthusiasm unsurpassed. But more practical than this alone, he ensured initial production by a contempt for routine and material difficulties and a resilience to rebuff as fortunate as they were courageous.

To Sir Eustace d’Eyncourt, the only member of the original Committee still officially connected with us, a great debt is due. We have been fortunate to have had at our disposal an engineer of his wide practical experience, who devoted much of his scanty leisure to our guidance both in policy and in detail, whose sagacious counsels have more than once checked the impetuosity of some of his associates.

Before passing to the aspects of Tank history with which I have been directly concerned, I wish to make reference to two organisations vital to the Tank Corps in the field. For if that represented the point of the spear, they combined to form a most solid and dependable shaft.

The first of these two was the Training Organisations set up in England to produce the men; second, the manufactories which produced the machines.

The task of the Training Centre and the cadet schools was particularly onerous. The organisation of any new instructional centre in the haste and pressure of7 the time was no easy task—its work was often thankless and subject to much ill-informed and light-hearted criticism.

The Training Centre of the Tank Corps had additional difficulties. There was no guidance as to training—the entire system had to be thought out from the beginning, and continually modified by the experience of the battlefield—instructors had not only to be found but trained—esprit de corps and discipline had to be built up; and all this against time.

It may perhaps be a compensation to the many officers and men who lived laborious days, and were not rewarded by seeing the results of their work in the field, to know that “France” has never been under any illusion as to the great thoroughness of their work.

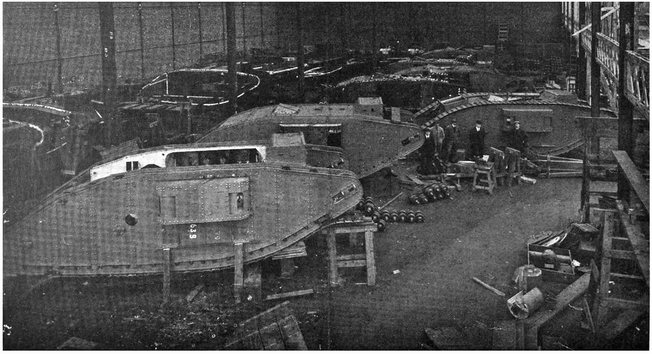

The work carried through in the munitions factories, and the ingenuity and solid labour that backed the efforts of the soldier in the field, are perhaps not yet fully appreciated by the fighting men. In France one might hear of sporadic unrest, but till one met with it, one realised nothing of the genuine faithful grind at production of objects of whose destination the worker often knew nothing, of the blind patience under duress of shortage, and of crowded accommodation; of hope deferred.

The Tank Corps was fortunate indeed in having established at an early date close relations with its workers, and more fortunate still at a critical time in being able to declare a substantial dividend on the capital of wealth, labour and brains entrusted to it by its section of industrial Britain.

Once touch was obtained with the worker himself, the interest taken by J. Bull in the factory, in T. Atkins in the field, was more than fully proved, not only by the demand for copies of accounts of Tank actions, but by the steadily increased output that was maintained.

The thing is only natural. Put a man or a woman to turn out bolts from a machine for eight hours a8 day, and you will get a certain result. Tell her or him that the bolts will go into a Tank that will fight probably in six weeks’ time; that the Tank will save lives and slay Huns; that yesterday Tanks did so-and-so; that last week No. 10567, made in Birmingham, and commanded by Sergeant Jones of Cardiff, rounded up five machine-guns ... you will get quite a different result; moreover, it is John Bull’s right and due to be told these things.

We had not got quite a complete result in this direction, but we were getting near it, and perhaps our co-operation of the back and the front was as nearly a microcosm of an ideal national co-operation in war as has been achieved. We aimed at Team Work.

You who have coped in a short compass with the whole story of Tanks can well realise the difficulties of dealing concisely, even by comment, with the kaleidoscopic events of two and a half crowded years—with the questions of organisation, training, personnel, design, supply, fighting, reorganisation, workshops, experiments, salvage, transportation, maintenance.

I shall attempt no more than to supplement your admirably drawn narrative as to one or two points which appear to me to be of major importance or interest.

The employment of Tanks in the field was one long conflict between policy and expediency. Policy seemed always to demand that we should wait until all was prepared, until sufficient masses of machines should be ready to use in one great attack that would break the German defensive system. Expediency necessitated the employment of all available forces at dates predetermined, and in localities fixed for reasons other than their suitability as Tank country. Battles are not won with Tanks alone, and in early 1917, for example, the Tank was still a comparatively untested machine. Indeed,9 the later issues of the Mark I. developed weaknesses in detail so alarming as to preclude anything more than a short-lived effort in battle.

Not until the Mark IV. machine was well into delivery could a guarantee as to its degree of mechanical reliability be given, and by that time the trend of the year’s campaigning was unalterably fixed.

And so it was that it was our fate up to the first Cambrai battle to “chip in when we could” in conditions entirely unfavourable.

The employment of Tanks in Flanders has often been criticised, without intelligent appreciation of the fact that had they not fought in Flanders they would have probably fought nowhere. Better, therefore, that they should fight and pull less than half their weight, and still save lives, than that they should stand idle while tremendous issues were at stake.

If employment in the field was a struggle between policy and expediency, the principles of production and design represented a direct conflict of opposing policies, resulting happily in compromise. The fighting man, conscious of the weaknesses of the earlier weapons, and visualising development which he believed to be obtainable, and knew to be necessary, and the soldier-engineer overburdened with difficulties of maintenance and cursed with the nightmare of Spares and Spares and more Spares—both cried aloud from France for rapid progress in design.

In England the other side of the picture was presented with equal force. The process of bulk production necessitates orders placed long in advance, materials were difficult to obtain, plans of track work and workshop organisation are not susceptible of change without delay, change, too, entailing irritation of factory staffs and workmen. Production once agreed to and embarked upon, a very complicated machinery is with difficulty set in motion. To stop or change this machinery results often in a loss of output which is in10 no way compensated by the improvements ultimately obtained.

The same problem must have occurred in many branches of war production. The best, however, is only the enemy of the good, if the good is good enough.

You have portrayed the difficulties arising from these conditions in Chapter V. The picture you draw belongs to the earlier stages, when the two sides worked rather upon regulation than upon formula. The later stages of the war saw a very full appreciation of each other’s point of view and the growth of a very sturdy spirit of co-operation, which carried us over more than one difficulty to meet which special appliances or special construction were necessary.

The Tank, as a weapon, has been threatened with several crises. Some have been averted by intelligent forecast in specification. Some have been dealt with by the improvisations of the engineers both in France and in England. Some have disappeared before a general improvement in design. You, I think, have touched on one crisis only—the mud crisis. The mud crisis was defeated at long last, but the swamp crisis, never. Although none of the other troubles was of long duration, any one of them, unless cured, would have caused a permanent disappearance of the arm.

Failure of rollers was succeeded by failure of sprockets. Sprockets and rollers were hardly cured when the Germans produced a very reliable armour-piercing bullet. This after a very short innings was defeated by the arrival of the Mark IV. Tank. The Mark IV. Tank was barely rescued from the mud of Flanders by the invention of the unditching beam, when we discovered that the Hindenburg trenches were about one foot too wide to cross without some form of help to the Tank. This difficulty was overcome, but about this time the effect of concentrated machine-gun fire upon Mark IV. Tanks must have become known to the11 Germans, as also their vulnerability to the ordinary field gun. The position with regard to both splash and casualties from guns firing over the sights, was becoming serious when the arrival of Mark V. Tank, with its increased handiness and speed, put an end to the splash difficulty for ever, and defeated the field gun for a good long time.

So on to the last days of the war, when we were able to look forward to 1919 with a certain knowledge that we had much in hand against any measure of opposition—short of a superior Tank—that the enemy could produce.

The idea undoubtedly exists still in the minds of certain people that the particular form of Tank which they have seen or fought with represents the latest word in design. It does not. The latest Tank produced in any bulk was the type that marched through London on July 19. It has never fought, and it represents the last word only of the elementary series of Tanks of which Mark I. was the original.

If finality in design has by no means been approached in the war, the same may be said as regards the employment of the then existing types. This depended, after due consideration of their limitations and powers, on the training of personnel, not only of the Tank Corps, but essentially of infantry too. Lack of time, lack of opportunity, and wastage of trained personnel were the great difficulties which confronted commanders of every arm and formation in their efforts to reach even average standards of skill in only a few of the commoner phases of warfare. With the Tank Corps the additional difficulties of mechanical training were no more than balanced by freedom from the trench routine of troops employed for defence. For the infantry Tank, the training of Tank personnel alone is not sufficient. In the assault, Tanks are no more than a part of infantry, an integral part of the troupes d’assaut. For real success, i.e., cheap success, not only must the two12 arms train and re-train together, but they should live together, feed together, and drink together.

Much was attempted and much was done to supplement the lack of opportunity by demonstration, lectures, attachments. But by reason of the incomplete military education of our hastily-trained troops it was necessary to limit manœuvre and tactics on the battlefield to the simplest elements. Anything in the nature of finesse had to be avoided. Skilful use of ground and mutual fire support were things hoped for more often than achieved.

It was a question of bulk production against time, but the results obtained only prove how much more could be achieved with the same material had conditions of training been those of peace time with its long service and rigorous and plentiful supervision.

The preceding paragraph may seem ungracious from one who has had the privilege of commanding a great force of citizen soldiers. It is nevertheless true that soldiering, like any other trade, takes time and experience to learn—that though there may be many who, being engineers, or advocates, or business men, or farmers, learn soldiering with great aptitude, the great bulk of any body of men, call them regular soldiers or citizen soldiers, require a deal of training under the best instructors, if they are to draw the full advantage from the ever varying conditions of the battlefield.

I have alluded above to the Tank Corps as a citizen force. It was, indeed, peculiarly so, for of the 20,000 odd souls that went to compose it, perhaps not more than two or three per cent. were professional soldiers; and, while the General Staff officers on H.Qs. were almost without exception regulars, the whole of the Administrative and Engineering staffs with one solitary exception were drawn from various civil vocations.

Moreover, units as they came into being were built13 up, not on any old-time tradition of a parent regiment, but each one very much around the personality of its own commanding officer. And it has indeed been interesting to watch the development of particular idiosyncrasies of whole battalions and companies from the characters of their leaders.

Your record has faithfully set forth what has been accomplished by these troops. They are well able to sustain criticism in the light of their achievements.

I have alluded before to the esprit de corps, founded as it was upon the sentiment of saving of life—a sentiment to which appeal has never failed. Other factors went to strengthen it. It was braced by a high standard of results demanded, by the determination to make good in spite of partial first successes. But the strongest element in it was the faith in our weapon—the machine necessary to supplement the other machines of war, in order to break the stalemate produced by the great German weapon, the machine-gun—our mobile offensive answer to the immobile defensive man-killer.

It is indeed a curious reflection that the Germans before committing themselves to their great final offensive, should not have followed to their logical conclusion the preparations which they made for the preceding phases of the war with such meticulous forethought. In 1914, they removed from the path of their attacking infantry the prepared obstacles of permanent fortification by means of specially-constructed machines—siege cannon of unprecedented size. Later, they developed the machine-gun in bulk, and so modified the preconceived course of warfare to their own advantage for defence. It is astonishing that for their final offensive effort, they should not have equipped their men with armament for overcoming the very defence in depth supported by the very machine-guns from which they had reaped so much advantage in the previous years.

And yet we see them in March, 1918, reverting after14 an initial attack, powerfully covered by artillery fire, to the same attempt to break through with men that had failed in 1914. Although machine-gun support was stronger, there was little help from the other arms beyond scanty artillery support and considerable frightfulness of day and night bombing and long-range bombardment. The German infantry was well, often magnificently, led, whether in Picardy or Flanders; and one could not watch the work of the strong offensive patrols without intense admiration of their skill and courage.

The Germans failed against defence in depth. The elements that were wanting were those of continuous mobility necessary to overcome such defence, against which infantry without powerful support and plentiful supply sooner or later become powerless. The Germans lacked the means to move and to supply their guns rapidly. They lacked Tanks to produce surprise or to carry forward the battle as an alternative to guns. They lacked lorries, they lacked cross-country vehicles.

With us, when the tide turned, the converse was the case, and it was at least a part reason of success against an enemy who fought bravely and often bitterly almost to the end.

Whether you justly appraise the contribution of the Tank Corps towards the final victory is for history to declare—at some interval yet—but I am hardy enough to give you a parable in the terms of a great national pastime.

Rugby football of all games affords the closest analogy to war—to warfare on the Western Front the parallel, without labouring the detail, is remarkable.

In the early nineties the accepted tactics of the game demanded a distribution of the team into nine forwards and six backs. The orthodox believed in forward play, and in emergency sometimes even a tenth forward would be added at the expense of one back.

At this time there occurred in the annual matches15 between two countries an uninterrupted series of defeats for one. As a measure of resource or despair, I do not know which, a new distribution was made in its forces. Instead of nine, eight forwards were played, one back was added—the fourth three-quarter.

The tactics were for the forwards to hold the opposing attack and for the backs to play offensively. The game is historic. For three-quarters of the match the nine forwards pressed the eight heavily, and these were very hard put to it to maintain their lines. In the last phase of the game one of the four three-quarters got away unmarked, the game was won and lost.

That was twenty-five years ago. The rules of the game remain unchanged, but the distribution of the players has been modified and the tactics of teams have developed on the lines of that historic match and beyond.

Whether the parallel of the Tank Corps to the extra three-quarter is a completely true one history will record in due season. What, however, we may claim is that the fourth three-quarter after a nervous start, in which perhaps he was sometimes out of his place, nevertheless on more than one occasion got away unmarked; that he ran straight even when he was being heavily tackled and drew the opposition for his side; that he went down well to the rushes of the German forwards; and that, finally, he more than once handled the ball in the great combined run which took his team from within its own twenty-five over the opponents’ goal line.

Yours sincerely,

United Service Club,

July 28, 1919.

17

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | v | |

| I | A Brief Account of the Tank, Its Crew and Its Tactical Functions, As They Were at the Date of the Armistice | 25 |

| II | The Earliest Tanks, General Swinton, Admiral Bacon,—the Holt Tractor and the Evolution of the “Land Cruiser” | 31 |

| III | The Tank Corps in Embryo | 46 |

| IV | The First Tank Battles—The Attack on Morval, Flers, the Quadrilateral, Thiepval, and Beaumont-Hamel | 57 |

| V | Winter Training, Expansion and Readjustments | 77 |

| VI | The Battles of Arras and Bullecourt | 89 |

| VII | The Battle of Messines and the “Hush” Operation | 110 |

| VIII | The Flanders Campaign—Preparations for the Third Battle of Ypres | 124 |

| IX | The Third Battle of Ypres | 138 |

| X | The First Battle of Cambrai | 160 |

| XI | Three New Types of Tank—The Depot—Central Workshops | 190 |

| XII | The French Tank Corps—American Tanks and British Tanks in Egypt | 209 |

| XIII | Suspense—The “Savage Rabbits” Episode—The Enemy’s Intentions | 235 |

| XIV | The March Retreat | 243 |

| XV | The Equilibrium—Minor Actions—Hamel—The Ballon D’Essai | 265 |

| XVI | With the French—The Battle of Moreuil | 280 |

| XVII | The Battle of Amiens, or Battle of August 8 | 288 |

| XVIII | The German Attitude—“Man-Traps and Gins”—The Battle of Bapaume | 323 |

| XIX | Breaking the Drocourt-Quéant Line—The Battle of Epehy | 34118 |

| XX | The Second Battle of Cambrai, or the Battle of Cambrai-St. Quentin | 361 |

| XXI | The Second Battle of Le Cateau—The Running Fight | 380 |

| XXII | The Rout—Mormal Forest—The Battle of the Sambre—The Armistice | 392 |

| Epilogue | 402 | |

| Index | 417 |

19

| Major-General Hugh Elles, C.B., D.S.O. From a portrait by Sir William Orpen, A.R.A. |

Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

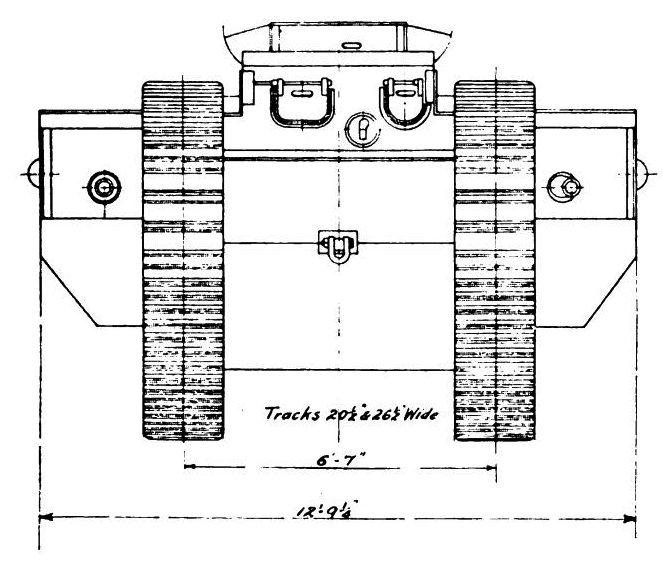

| General Arrangements of Mark V. Tank—Front View | 28 |

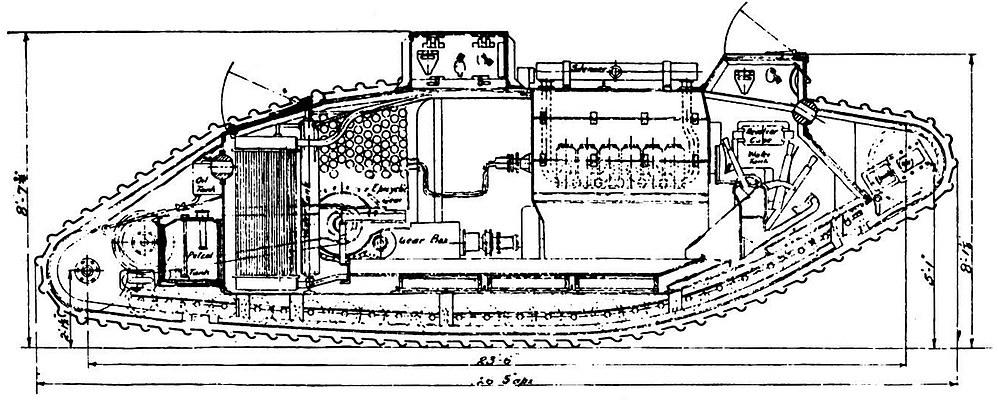

| General Arrangement of Mark V. Tank—Sectional Elevation | 28 |

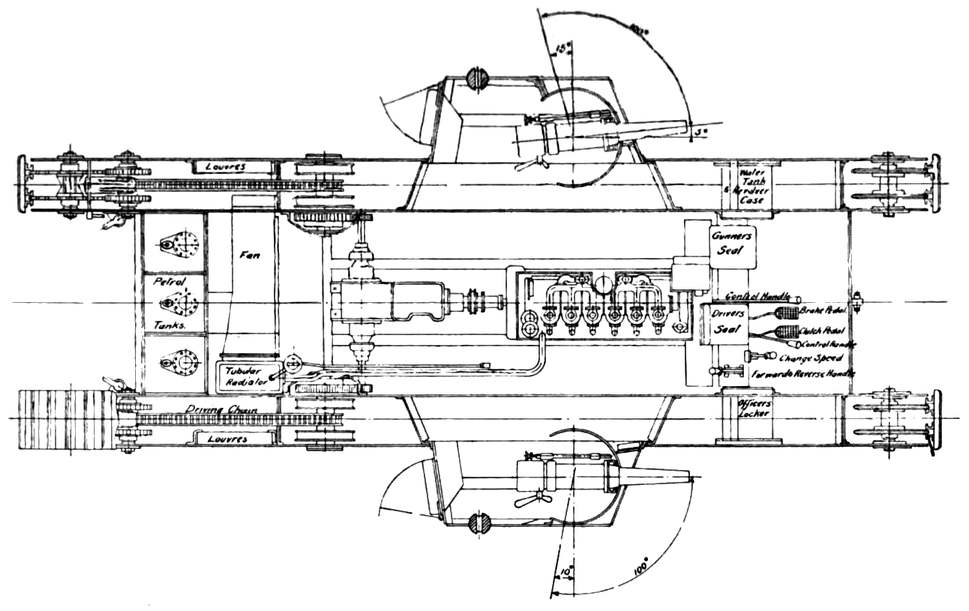

| General Arrangement of Mark V. Tank—Sectional Plan | 29 |

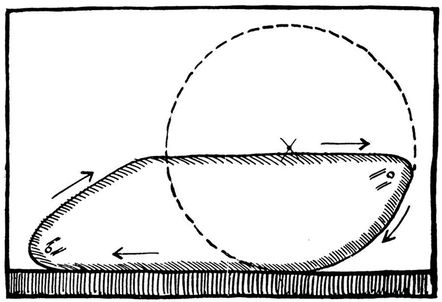

| Diagram Showing Adaptation to the “Large-Wheeled Tractor” Idea | 29 |

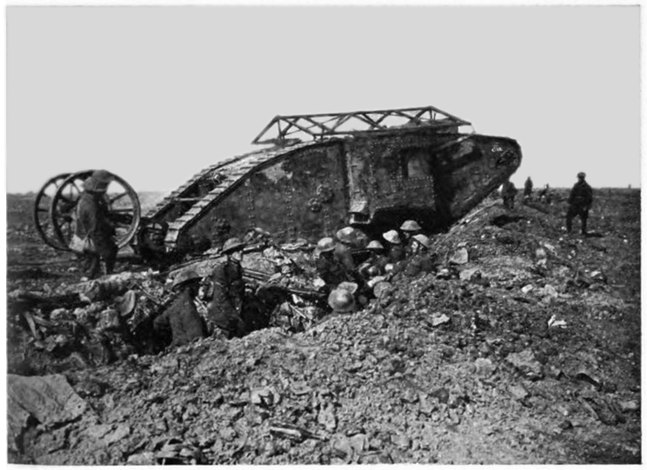

| The Original Thiepval Mark I. Tank with Anti-Bomb Roof and “Tail” | 64 |

| Field Camouflage | 64 |

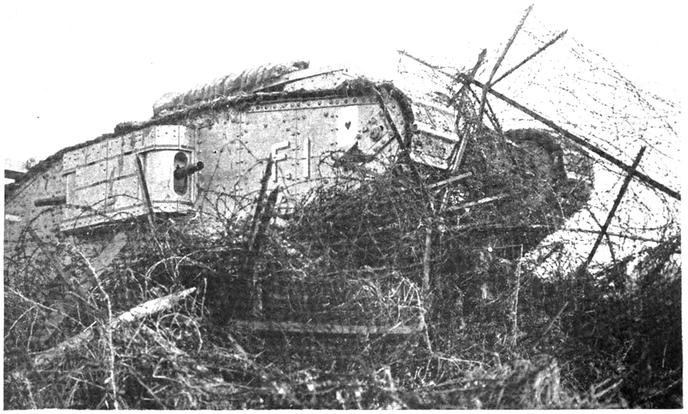

| A Derelict. Valley of the Scarpe | 96 |

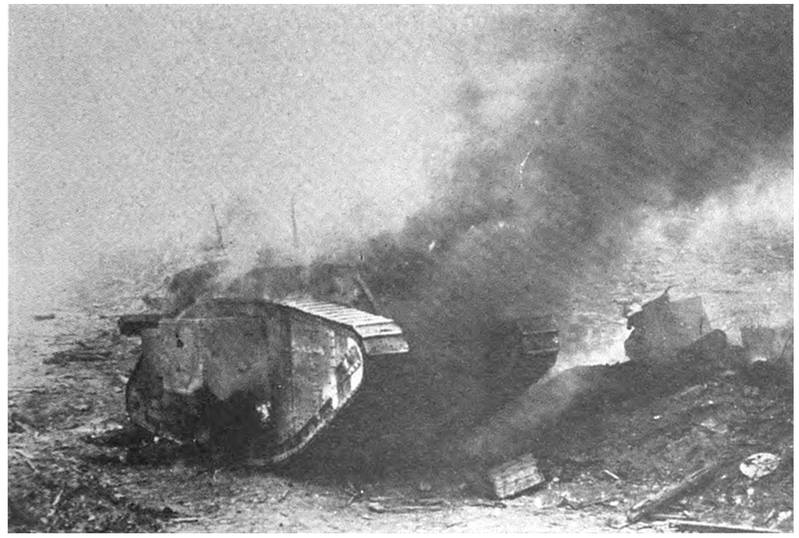

| A Burning Tank | 96 |

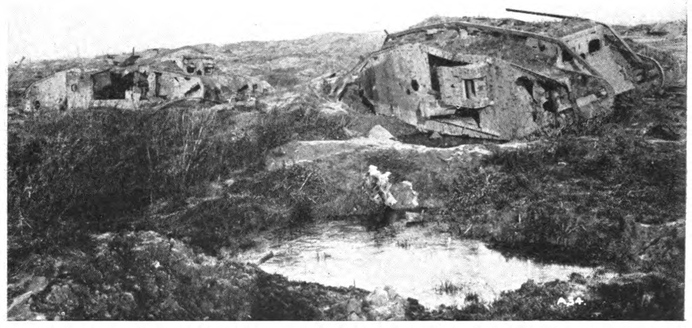

| “Direct Hits” | 97 |

| Bellied on a Tree-Stump and Subsequently Hit | 97 |

| A Flanders Pill-Box | 132 |

| The Unditching Beam in Action | 132 |

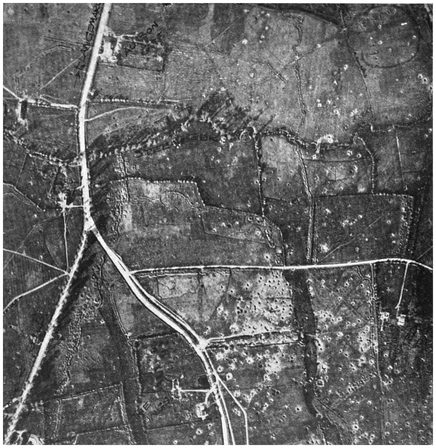

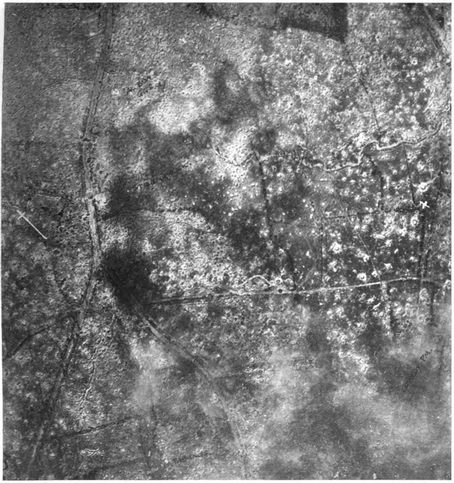

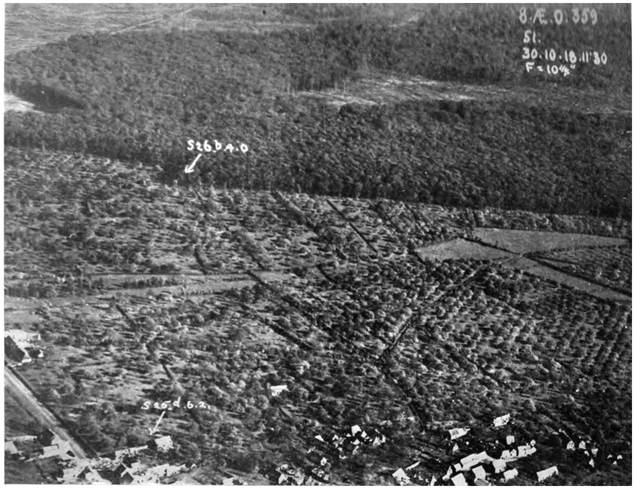

| The Steenbeek Valley Before the Battle | 133 |

| The Steenbeek Valley After Bombardment | 133 |

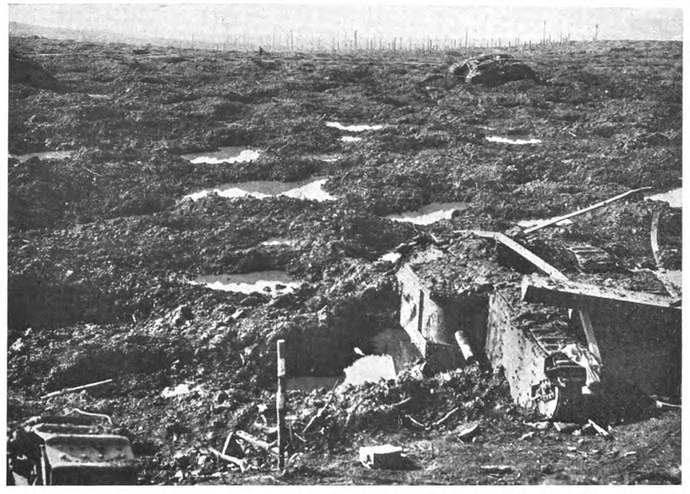

| A Deadly Swamp (the Wrecks of Six Tanks May Be Counted) | 144 |

| “Clapham Junction” Near Sanctuary Wood | 145 |

| “The Salient” | 145 |

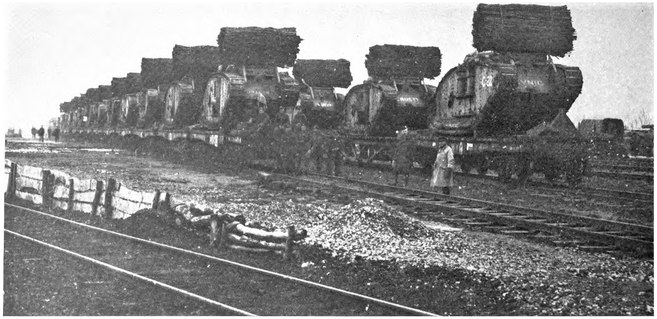

| Preparing for Cambrai. A Train of Tanks with Fascines in Position | 176 |

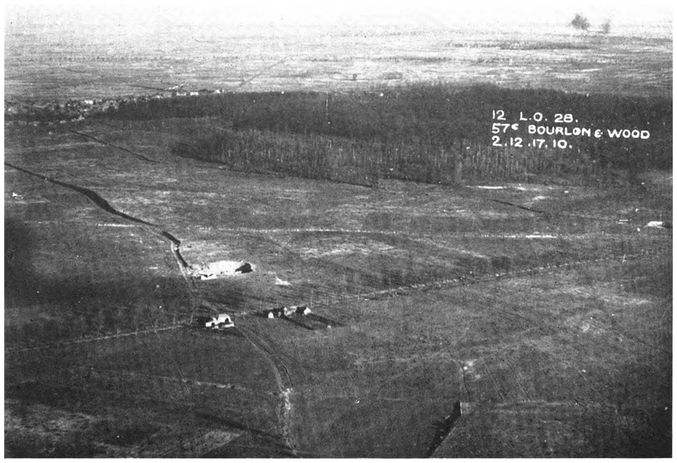

| The Bapaume-Cambrai Road | 177 |

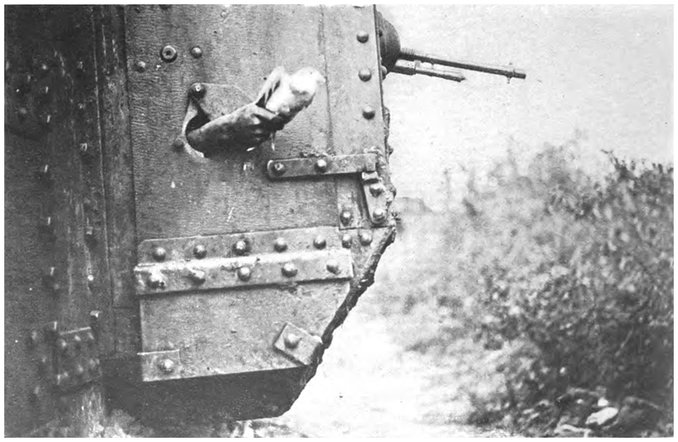

| A Tank Crushing down the Enemy’s Wire | 177 |

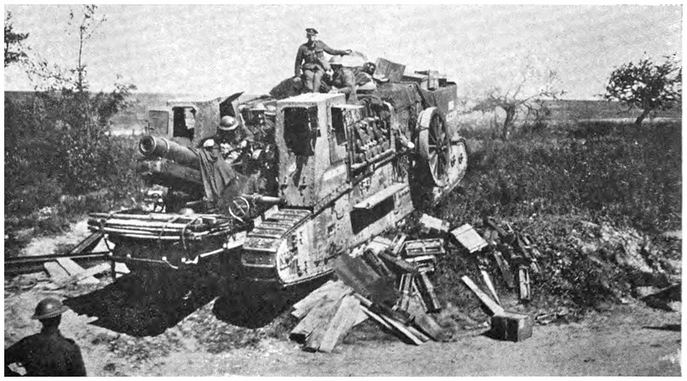

| Sledge Towing Tank Taking up Supplies | 20020 |

| Bermicourt Chateau near St. Pol. Tank Corps Main Headquarters | 200 |

| Gun-Carrying Tank Taking up a Howitzer | 201 |

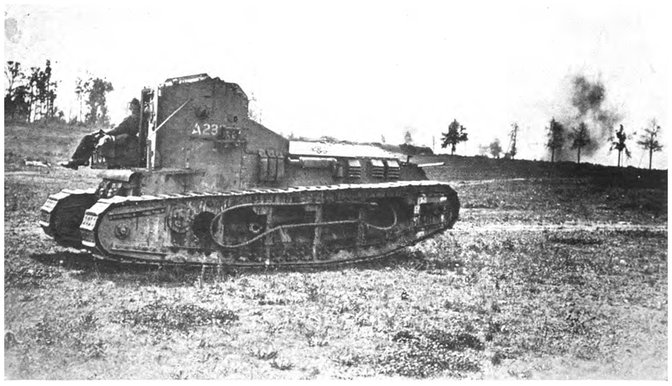

| A Whippet Going In | 201 |

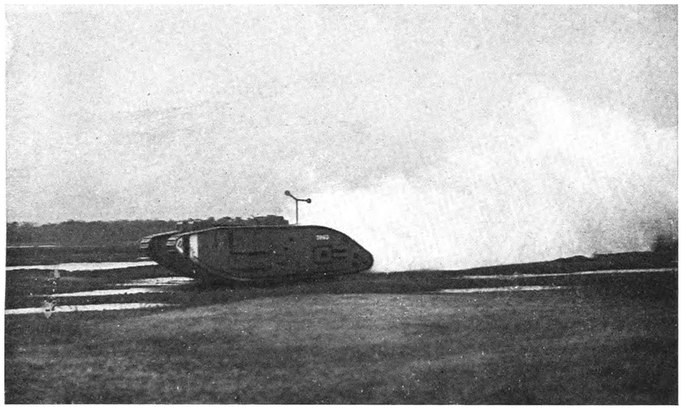

| Smoke Screen and Semaphore | 304 |

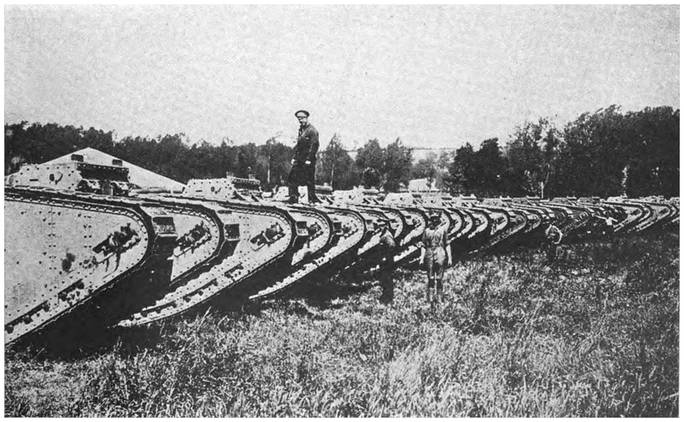

| A Tankadrome | 304 |

| Moving Up. Battle of Amiens | 305 |

| The Armoured Cars Going Up | 305 |

| German Anti-Tank Gunners. (From a photograph found on a prisoner) | 336 |

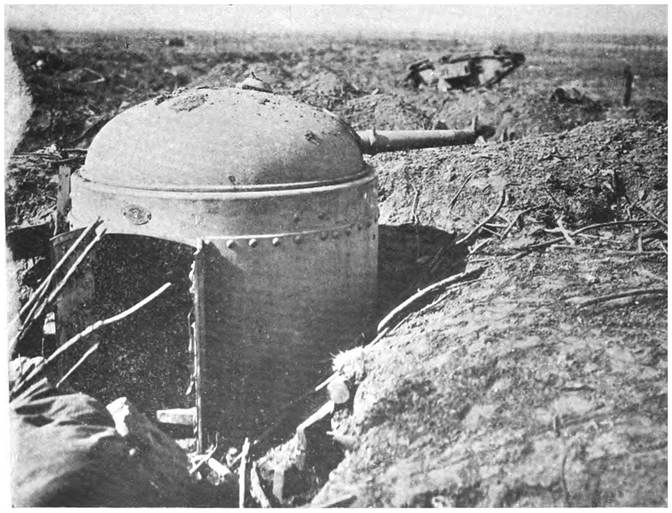

| An Anti-Tank Gun in a Steel Cupola (Ypres) | 336 |

| A Captured German Tank | 337 |

| A German Anti-Tank Rifle | 337 |

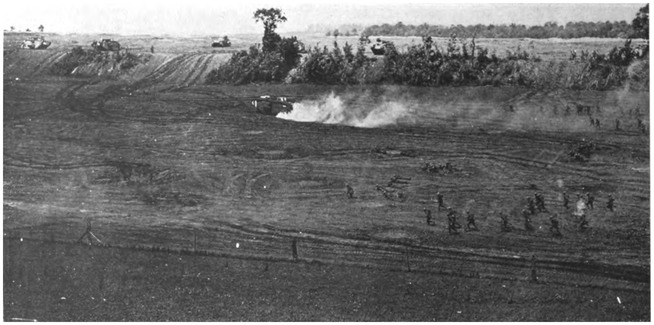

| Infantry Advancing Behind Tanks. A Practice Attack at Bermicourt | 368 |

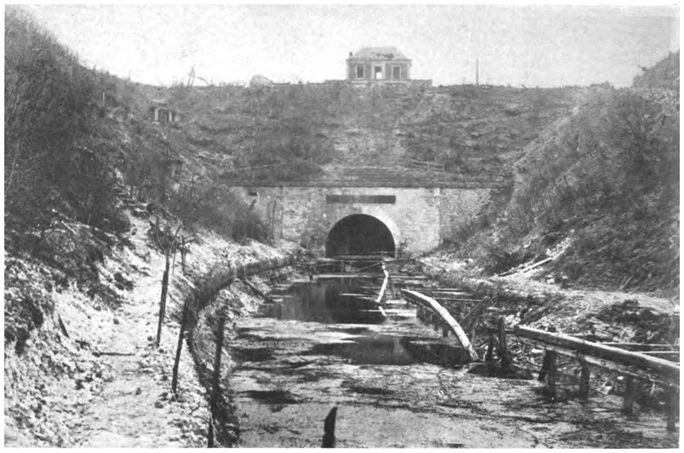

| The St. Quentin Canal Tunnel, Bellicourt | 369 |

| Carrier Pigeon Being Released | 369 |

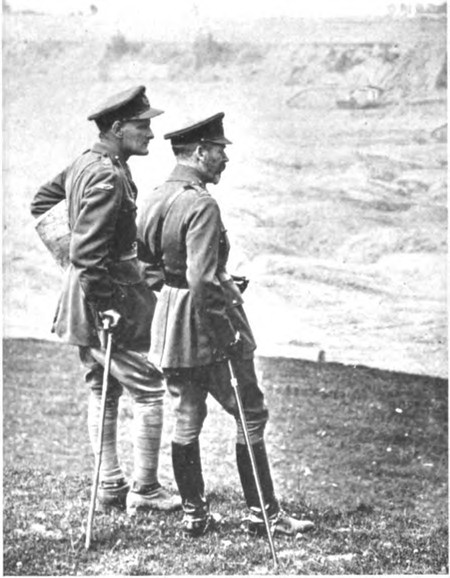

| His Majesty the Colonel-in-Chief and General Elles | 384 |

| Manufacture | 385 |

| The Western Edge of Mormal Forest | 396 |

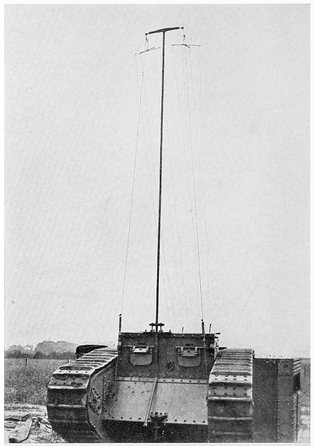

| A “Wireless” Tank | 397 |

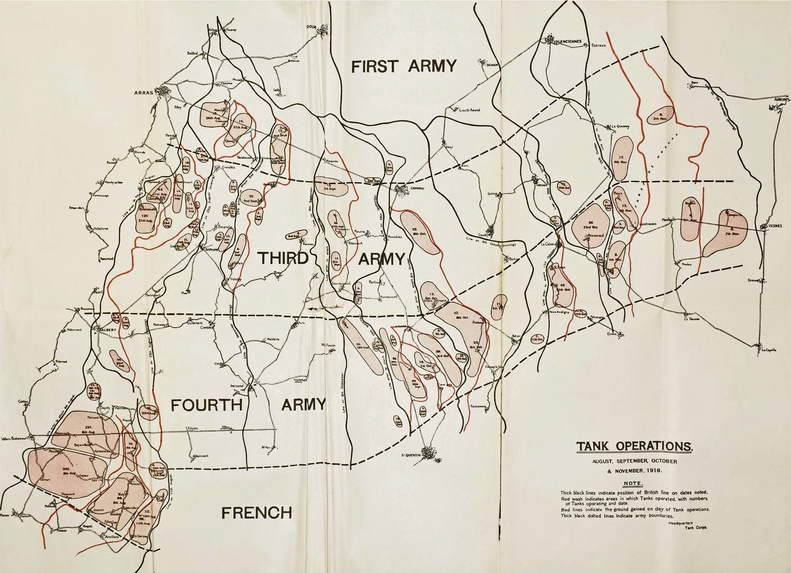

| Map of Tank Operations, August–November, 1918 | 416 |

25

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE TANK, ITS CREW AND ITS TACTICAL FUNCTIONS, AS THEY WERE AT THE DATE OF THE ARMISTICE

The secrets of the Tank Corps have been so well kept that there are few civilians who even now know anything of Tanks or their crews beyond what might be learned from photographs, or a distant view of “Egbert” or some other War Bond or Olympian Tank.

The Censorship has seen to it that the civilian has had no opportunity of making himself familiar with the tactical opportunities and problems that the use of Tanks has introduced or with the conditions under which Tank crews fight.

It is for the civilian reader that the present chapter is intended. He is to be given some idea of the oak tree before he is invited to dissect the acorn.

If he has no idea of the appearance and habits of the Tanks that fought at the Canal du Nord or that pushed back the enemy at Mormal, he cannot be expected to thrill as he should over the vicissitudes of the first converted Holt Tractor. For to one who had never seen the engine of a through express the history of “Puffing Billy” would almost certainly prove insufferably tedious.

The authors, therefore, propose to deal, very briefly,26 with the modern Tank before plunging the reader into the dark ages of 1914, where, to pursue our analogy, Watt’s kettle-lid and the “Rocket” dwell obscurely.

Every detail of Tank Corps’ training, equipment, and tactics has been modified in view of some limitation or opportunity arising from the structure of the Tank itself. Therefore, though this book is principally concerned with the development of the Tank Corps rather than with the intricate evolution of the Tanks themselves, the reader will find it necessary to have a general idea of the construction and workings of the different types of machine.

It would indeed be as idle to describe the anatomy of a snail or a lobster without mention of its shell, as to endeavour to separate the story of the Tank Corps from that of its Tanks.

When the War ended in November, 1918, there were, besides obsolete types which were still used for such work as carrying and the towing of supply sledges, three main types of Tank. First, the Mark V., which was 26 ft. long, 8 ft. 4 in. wide, weighed 27 tons, and had a horse-power of 150. The Male Tanks carried two 6-pounder guns, and one Hotchkiss gun. The Female carried five Hotchkiss machine-guns and no 6-pounder guns.

The Mark V. Star.—This Tank resembled the Mark V., except that it had a length of 32 ft. 6 in., and was designed for the transport of infantry and for the traversing of trenches too wide for the Mark V. Each had a normal speed of about five miles an hour, and was protected by armour up to five-eights of an inch thick.

They were both so designed as to turn easily at their27 maximum speed, and carried attachments for use on soft ground, which increased the grip of the tracks.

Each was fought by a crew consisting of a subaltern and seven men, three drivers (two of whom normally fought the Hotchkiss guns), and three gunners.

The third type was the Whippet. The tracks were nearly as long as those of a heavy Tank, but the body had been reduced to a small cab perched at the back, rather as an urchin rides a donkey. It was armed with two machine-guns, managed by a crew of three men, and developed a speed of seven miles an hour. Whippets were designed for use as raiders and in conjunction with cavalry. In practice, however, the cavalry was seldom able to act with them. Partly in consequence of this, partly owing to the state of open warfare being of such short duration, the Whippets, though having brilliant feats to their credit (see the exploits of “Musical Box,” Chapter XIII), remained creatures of promise rather than of achievement.

As a rule Male Mark V. Tanks were used against Pill-Boxes and other “strong points,” while the special work of Female Tanks was to deal with hostile infantry (for example, by sitting astride and thus enfilading their trenches), and then to finish the process of flattening the enemy’s wire which the Male Tanks had begun.

All three types of Tank were capable of going across country. That is to say they could, for example, follow a pack of hounds anywhere, except perhaps in the Fens.

Ditches, heavy plough, banks, walls, hedges, or fences could all be negotiated.

Tanks could also go over many obstacles—notably28 over wire—where the Field, even were they willing “to take a windmill in the harbour of the chase,” must go round.

But as a moment’s reflection will show, there must remain in every country certain features which will prove absolute barriers to the progress of Tanks.

Chief among these are canals and deep rivers (unless spanned by strong bridges), very steep railway cuttings, railway embankments, marsh, or woods in which the trees are too strong to be pushed over, and too dense-set to be steered through.

Besides these natural, or at least civilian, obstacles, there will be inevitable military obstacles in any country that has been fought over.

For example, old half-blown-in trench systems make ground “awkward,” and Tanks operate at extreme disadvantage in country like that round Ypres, which was by 1917 a continuous network of water-logged shell and mine craters, with no original ground left at all.

Again, by the close of hostilities the number of anti-Tank devices employed by the Germans was very considerable. They paid the new arm the compliment of an intricate system of defence and counter-offence which included concealed Tank traps made on the model of elephant-pits, formidable double-traversed trenches, a branch of special anti-Tank artillery, heavily reinforced concrete stockades, and an elaborate system of land mines.

With so many obstacles to avoid or to negotiate, with their fate often hanging upon a prompt and accurate use of their guns, the crew inside the Tank were doomed by the conditions under which they fought to an almost incredibly limited view of the surrounding world.

When the flaps were closed (see diagram showing29 interior of a Mark V. Tank), as they had to be directly the Tank came under close fire, the crew were in almost complete darkness, and had to rely upon their periscope or, alternatively, upon minute eye-holes (about the size of the capital O’s used in this text) bored through the armour-plating. If the fire was at all heavy the periscope was usually quickly put out of action, and the officer and gunners had only the extremely limited view afforded by these holes.

They were thus almost entirely dependent upon their maps, the special Tank compass, and upon the information which a preliminary reconnaissance of the ground had given them.

This circumstance not only profoundly modified the training of the officers and crews, but also necessitated the organisation of what was almost a new service. This service was the “Reconnaissance” branch of the Intelligence. When the Tank Corps was ordered to take part in an attack, the Reconnaissance Staff was responsible for the preliminary survey of the proposed battle site for a report as to where and how Tanks could best operate, and finally for a series of detailed maps and sketches. In these maps and sketches the route of every individual Tank was set forth from landmark to landmark, together with the assigned objectives of each machine and the obstacles which it was likely to encounter. These maps and sketches were compiled from aerial surveys, captured German maps and documents, information gained from local inhabitants, accounts given by prisoners, the original Ordnance survey, and from personal reconnaissance. By 1918 this system had been so developed that the infantry came to rely almost entirely upon their accompanying Tanks for direction.

This added greatly to the importance and responsibility30 of the work both of Tank Reconnaissance officers and of commanders.

Topographical information can only be adequately conveyed to a more or less trained receiver, and it was therefore found necessary to add an elementary course on Reconnaissance to the already long list of subjects in which the members of every Tank crew must train. The crew were an assemblage of experts.

An average of about a month was spent by every soldier at the training depots and battle-practice grounds. Here each man did about ten days’ course as a driver or gunner, learned revolver-shooting, signalling, and the management of carrier pigeons, and went through a gas course. In view of the probability of casualties, each man was also given a working knowledge of every other man’s job. But most vital of all—the conditions under which Tank crews fought being out of the common trying and arduous—the scheme of training aimed at creating a high sense of discipline; that esprit de corps and that tradition of valour which teaches men to endure the unendurable.

This supreme end it achieved, as a perusal of the Tank Corps Honours List will show.

Such, then, were the Tanks and their crews in the autumn of 1918.

In the pages which follow, the reader will see from how crude an embryo the Tank sprang, and through what hair-breadth escapes alike from official overlaying and annihilation by the enemy, it passed in the four years of which we are about to relate the history.

31

THE EARLIEST TANKS—GENERAL SWINTON—ADMIRAL BACON—THE HOLT TRACTOR AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE “LAND CRUISER”

The War had only been in progress for a few weeks when the first idea of the first Tank was born almost simultaneously in the minds of General E. D. Swinton, Major Tulloch, Captain Hetherington and Mr. Diplock, and—if we are to believe rumour and their own account of the affair—of several hundreds of other gentlemen.

“Born” is perhaps not quite the appropriate word. At any rate it is to be understood, if not in a Pickwickian, at least in a Pythagorean sense.

For by 1914 the Tank had successively passed through several tentative and inconclusive incarnations.

In 1482 Leonardo da Vinci invented a kind of Tank;1 a wooden “War Cart” was used by the Scottish in the fifteenth century.2

There were designs for a Tank for the Crimea, but the project of this weapon was abandoned as being barbarous. Lastly, a really practical design for a kind of “Caterpillar” to be driven by steam was made in 1888.32 A trial machine was even constructed. But Fate decreed that all trace of design and model should be instantly lost, only apparently to be rediscovered after the modern Tank had been thought out afresh.

Why, if the Tank was constantly being invented, did it as constantly disappear? The reason appears to have been that, like the early aeroplanes, all these abortive machines had failed in one particular.

The engine was not powerful enough. The steam Tank had not in the least answered the riddle. The horse-power could, it is true, be almost indefinitely increased, but, like a kind of Old Man of the Sea, the engine weight would have increased proportionately and the “free” power have been no more.

Indeed till the invention of the petrol engine the Tank was doomed to be unpractical. Its three essentials—armour-plating, guns, and ability to surmount obstacles and traverse open country—demanded a large amount of this “free” power.

Only, therefore, when an engine was produced whose proportion of power to weight was about 100 H.P. to every ten hundredweight, did the Tank become a possible and effective engine of war.

Thus, till the time was ripe the Tank had been doomed to enjoy very brief excursions into the actual, and to sojourn, long forgotten, beyond the waters of Lethe.

Does memory survive transmigration? Were General Swinton and his co-inventors aware of the Crimea Tank and the 1888 Tractor? In any case the matter is not one of great importance, for—to put it briefly—ultimately their Tank went, and the others did not.

By October, 1914, Colonel Swinton and Captain Tulloch had independently worked out the details of an engine of war. Like the other early inventors, they33 imagined a machine that was to “arise” out of a cross between an armoured car and an agricultural tractor. It was to be slower, more formidable and far heavier than any armoured car that had yet been seen, a kind of “Land Cruiser” capable of plodding on its caterpillar feet across country right up to the enemy’s gun positions. Like the other early “mobile machine-gun destroyers,” it was to be strongly armed with guns and machine-guns, and so heavily steel-plated as to be impervious to shrapnel, H.-E. fragments and rifle bullets. It was to cross trenches with ease, and was to be capable either of cutting or of flattening the enemy’s wire in the mere act of its progress.

By November Colonel Swinton and Captain Tulloch were in close touch with one another, and the child of their fancy descended from the clear regions of pure thought to battle its slow way forward amid the fogs and thornbrakes of actual experiment and official memoranda.

Well-informed readers will perhaps wonder why the present authors have singled out Captain Tulloch and Colonel Swinton from amid “the press of knights.” Do they intend to lay the laurel on their brows? To declare that they alone invented the Tank?

The chroniclers pretend to no such judicial powers. Be theirs rather the genial rôle of the Dodo in Alice in Wonderland, who at the end of the Caucus-race allotted one of Alice’s comfits to each of the competitors.

As far, however, as they can disentangle the complexities of the evidence, it does appear to have been through these two enthusiasts that the Tank idea first took tangible shape. The notion was in the air, perhaps it took unsubstantial form in other minds before34 October, 1914,—it seems probable that it did in Mr. Diplock’s and Mr. McFee’s, for example. Perhaps, too, in other minds it was later to take clearer and more practical shape.

But it does seem to have been Colonel Swinton and Captain Tulloch who, first of the band of pioneers, had the courage and the practical energy to forward a somewhat startling notion in official quarters.

For Mr. Diplock’s first “Pedrail” machine, whose plans he laid before Lord Kitchener and Mr. Winston Churchill in November, 1914, was a Gun Tractor, not a fighting machine. It was not till February 1915 that Mr. Diplock (in conjunction with a Committee appointed by Mr. Churchill) officially so much as contemplated the building of a “Land Cruiser.”

Fortunately one of the first of the Swinton memoranda was submitted through Colonel Sir Maurice Hankey, Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence, who was an early and active friend to the idea of the new arm.

Difficulties, however, abounded. Many were actual, some were imaginary.

For example, it was urged that to design and build such machines would take over a year. Surely the war would be over!

Then when the counsels of those kill-joys prevailed who believed that the war would “hold,” and it was decided to experiment with the “mobile machine-gun destroyers,” various technical difficulties arose.

It was difficult to procure some of the essentials without elaborate manufacture and the making of special tools, and makeshift parts were, therefore, substituted. Fitted with these makeshifts, the Land Cruisers were a disappointment.

The first tests were carried out in February 1915,35 when Captain Tulloch’s adaptation of the Holt Tractor was given a trial. It did not prove a complete failure, and much was learned from the experiment. For example, the machine was unexpectedly effective in rolling in the wire which it had been originally intended that its automatic “lobster-claw” wire-cutters should alone deal with.

In June Admiral Bacon’s Forster-Daimler Tractor of 155 H.P., fitted with a self-bridging apparatus, was experimented with.

This, too, proved disappointing, in so far as the device was to fulfil the proposed functions of a Land Cruiser. It refused to cross trenches, though it proved a practical Tractor, and it was later used in “trams” of eight machines for the transport of 15-in. guns.

The position, therefore, in June 1915, as far as the War Office was concerned, was as follows: Proposals had been put forward by Colonel Swinton, Admiral Bacon, and Captain Tulloch, and submitted to the War Office; certain trials had been made, the result of which was, in the view of the authorities, to emphasise the engineering and other difficulties. It was only in June that the War Office ascertained that investigations on similar lines were being carried out by the Admiralty.

For the Admiralty, with a large land force at its disposal, had been for some time casting about for means whereby the men of that force might go into battle more in Navy fashion, that is (to misquote the “heroic Spanish gunners”) with something better than serge, “joined to their own invincible courage,” between them and the enemy’s bullets.

Mr. Churchill had, as early as January 1915, written a letter to the Prime Minister expressing his entire36 agreement with Colonel Hankey’s remarks “on the subject of special mechanical devices for taking trenches.”

The idea of employing a large armoured shield on wheels, or of using ordinary steam tractors on which a small bullet-proof shelter had been fitted, had been considered. Mr. Churchill interested himself personally in the scheme, and he and his expert, Major Hetherington of the R.N.A.S.—the third independent inventor—worked hard to evolve and then “push” a practical machine.

In the early spring of 1915 a Committee, called the Land Ship Committee, was appointed,3 and many designs of wheel and caterpillar tractors were submitted to it. One of these designs was especially interesting not only for its astonishing appearance, but for the influence which it exerted upon the “profile” of the future Tank. The curious will find a brief account of it in the Note at the end of the chapter. It was Mr. Churchill’s Committee who called in Major Wilson, Mr. Tritton, and Mr. Tennyson d’Eyncourt as consultants, “when a design was evolved which embodied the form finally adopted for Tanks.”

Thus, while the honour of the first designs and experiments belongs to the War Office, it was to the enterprise of this Admiralty Committee that most of the credit of the evolution of the Mark I. Tank was due.

It was, as we have said, apparently not until the Admiralty Committee had been at work for some time that the Director of Fortifications and Works, on behalf of the War Office, ascertained that the Admiralty had designs for a “Land Cruiser” in hand.

The two Departments met at Wormwood Scrubs to37 witness the Admiralty’s trials of a Killen-Straight tractor. It was a remarkable occasion, for a number of men who were destined profoundly to influence the history of the Tanks now saw a foreshadowing of such an engine for the first time.

Among them were Lord Kitchener, Mr. Lloyd George, Mr. Balfour, and Mr. McKenna. Mr. Winston Churchill was also there, but to him an armoured tractor was no novelty.

After this gathering the Tank enthusiasts of the two Departments fell upon each other’s necks, swore eternal friendship, and in the middle of June formed a Joint Committee, of which Lieutenant Stern was Secretary.

Tanks—when any existed which would work—were to be a military service in the Department of the Master-General of Ordnance.

The Admiralty was to continue its work of designing, was to provide cash for experiments, and Mr. Churchill, its late First Lord, was to continue his invaluable work as a propellant. All seemed prosperous, for the representatives of the two Services appear to have worked pretty harmoniously, and the better informed and more progressive heads of Departments on both sides showed an interested benevolence.

But unfortunately—especially at the War Office—there appear to have been a certain number of obstructionists.

One senior Officer, fearing, one supposes, to be diverted from his ideal of the official attitude by the sight of these ungodly engines, refused so much as to attend the trials. The Adjutant-General (then no doubt, poor man, sufficiently harassed) rigidly refused a single man for the new arm. Fortunately, the Joint Committee was resourceful, and, after a preliminary appeal to Mrs.38 Pankhurst for militant suffragists,4 they induced the Admiralty to turn over to them the 20th Squadron of the Armoured Car Reserve, and to increase the strength of this unit from 50 to 600 men.

By July Colonel Swinton—another of the Tank’s best sources of power—had returned to France. G.H.Q. was later to be more propitious, but now the taste of those inconclusive experiments was still in its mouth, and their chief technical adviser had begun to have horrid doubts about the whole affair. “Caterpillars,” he remarked, that he had lately seen “could only go at the rate of 1½ miles an hour on roads, were very slow in turning, and nearly every bridge in the country would require strengthening to carry them.” “It was necessary to descend from the realms of imagination to solid fact.”

Colonel Swinton explained and exhorted and expostulated.

Meanwhile the Joint War Office and Admiralty Committee system was too simple to last.

From August 1915 to August 1917, when the “New” Tank Committee was formed, the control and administration of Tank manufacture and design were extraordinarily tentative and shifting. Necessarily so. The home organisation had to expand very rapidly, and constantly to adapt itself to changed conditions of Tank tactics abroad and Tank manufacture at home.

Even the multiplicity of the authorities concerned seems to have been to a great extent inevitable. The Tank had, of course, initially complicated its early history39 by starting life in Infantry puttees and a south-wester.

At the point we have reached, its story plunges into a whirling quicksand of departments, branches, committees, and conferences, which were reorganised and rearranged—changed hats and functions with bewildering frequency. This tangle of activity Colonel Swinton throughout made it his hobby to understand and his business to co-ordinate.

The present historians, on the contrary, feel tempted to adopt the simple method of their Hebrew predecessor, who, having picked out one plum, so often blandly continues: “And the rest of the acts of the Trench Warfare Department and all that they did, are they not written in the book of the archives of the War Office?”

However, it is possible that the Hebrew historian honestly believed that the lost books of the Chronicles were really available to the inquiring reader. The present authors have no such illusion about War Office papers, and therefore propose to give at least an outline of the vicissitudes and fluctuations of early Tank control.

The chief persons of the Drama remain throughout:

The War Office: (1) In its capacity as Ordnance, and (2) in its capacity as General Staff. Later (3) as the Tank Department, War Office.

G.H.Q.: (1) In its main capacity, and as (2) The Experiments Committee.

Later, the H.B.M.G.C.

Finally, the Tank Corps.

The Admiralty: (1) In its capacity as the Land Ship Committee, and (2) as Squadron 20 of the R.N.A.S.

The Ministry of Munitions: (1) In its capacity as the40 Trench Warfare Department; (2) in its capacity as the Inventions Department. (3) Later, as the Mechanical Warfare Supply Department (really another Tank Committee). (4) Later still, as the Tank Supply Department.

The successive Main Tank Committees: (1) The Joint Naval and Military Committee (which did not survive Act I.). (2) The Tank Supply Committee, afterwards called the Advisory Committee of the Tank Supply Department, and divided into a main committee and a sub-committee. (It was this sub-committee which afterwards formed the backbone of the very active and occasionally criticised M.W.S.D., before referred to). Later, (3) after a gap, the First Tank Committee; (4) the Second reconstructed Tank Committee.

Grand Chorus of Directors General, Interdepartmental Conferences, Manufacturers, and Workshop Personnel.

We find that the period from August 1915 to February 1916 constitutes a kind of Act I. in the history of Tank administration and manufacture, for the 1914 and early 1915 period is too dim and legendary to serve as anything but prologue.

During the whole of the Act I. period it was the Admiralty and the Joint Land Ship Committee which played the “leads.”

It was the Admiralty which defrayed the whole cost of the extensive experimental work and provided the necessary personnel, and it was by members of the Joint Committee in consultation that the Mark I. Tank, “Mother,” was ultimately designed.

On September 11, two months after Colonel Swinton’s41 visit, the Experiments Committee, G.H.Q., laid down in an excellent and far-sighted memorandum what were the qualities which they desired should be aimed at in designs for the caterpillar cruiser and what were the tactical purposes which it must serve.

By September 28 the Joint Committee had so far perfected the design of “Mother” as to have had a wooden dummy (officially described as a “mock-up”) made, and on that day her counterfeit was inspected at Wembley by an Interdepartmental Conference, and approved.

Some weeks elapsed while the Joint Committee worked out the further details of their machine, and about December 3 Mr. Churchill wrote a Memorandum entitled “Variants of the Offensive,” in which he paradoxically accentuated the value of defensive armour as a preservative of mobility. There was to be a new form of attack. It was to be launched at night under the guidance of searchlights. Caterpillar Tractors were to breach the enemy’s line, and then turn right and left. The Infantry were to follow them closely under cover of bullet-proof shields.

On Christmas Day Sir Douglas Haig (who had lately taken over from Sir John French, and who as yet “knew not Joseph”) read the paper with interest, and pinned a pencil slip upon it, “Is anything known about the Caterpillar referred to in para. 4, page 3?”

No time was lost in finding out, and a few days later G.H.Q. sent an officer to England to inquire into the matter. This officer was Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Elles, who was afterwards to be the first Tank General.

By the end of January 1916 the experimental machine—no pasteboard simulation, but “Mother” herself—was complete, and on February 2 the official trial was42 held at Hatfield, before the Army Council and a representative of G.H.Q.

“Mother” made good, and G.H.Q. asked to be supplied with a certain number of the Land Cruisers. A small Executive Tank Supply Committee with much fuller powers than the old Joint Committee, was formed under the Presidency of Lieutenant (now Colonel Sir Albert) Stern, and orders were at once given to begin manufacture.

So ended Act I.

The first scene of Act II. (March to mid-August) was occupied with one of the most dramatic achievements of the War.

This was the manufacture at Lincoln of the first 150 “Land Ships” ordered by the Government, in the space of six months, and in absolute secrecy.

The public discussed the phantom Russians who travelled through England by night. It discussed the Germans who nightly signalled to each other throughout the inland counties. But it did not discuss the large water-tanks or cisterns that were being made for Petrograd, Egypt, or Mesopotamia, or some such place.

That this vital secrecy was kept for months by hundreds of people was chiefly due to the happy effect of copious and imaginative lying.

There was no mystery about these grotesque armour-plated creatures! They were not really for Mesopotamia at all. Every one knew that.

The Russian Government had ordered them. They were ridiculous things? Of course they were. It was a Russian design. Was there not even an inscription in Russian characters on them? At least they might43 frighten the Germans if they served no other useful purpose.

Tradition relates that when the first drawings were brought to the manager’s office of the factory which had been selected for the manufacture of the “water-carriers,” the manager and his staff expressed themselves as being seriously concerned for the sanity of the designers, and of those who submitted such drawings to practical men like themselves.

They were, however, let into the secret of the real part which Tanks were to play, and though still profoundly incredulous, decided, like good citizens, to carry out whatever work was asked of them. The vital necessity of secrecy having been impressed upon them, they were asked—tradition continues—what arrangements they would like made about sentries and the isolation of their workpeople. After a little consideration they answered that they would only guarantee that the secret should be kept on condition that they were given a completely free hand and not interfered with.

They proposed to have no sentries, no “isolated area” to proclaim trumpet-tongued, “Here is a secret!”

They desired merely to propound a satisfactory system of lies, to give an “alternative explanation”—to put it more delicately—and to carry out their work with a disarming publicity.

After some hesitation the authorities consented to this strange system. We shall see how, on September 15, “wisdom was justified of her children.”

The factory where these curious interviews are reported to have taken place was that of Messrs. Forsters, Agricultural Implement Manufacturers of Lincoln. We almost literally beat our ploughshares into swords.

In London, changes in Tank administration were44 going on as usual. The trend as far as supply and manufacture were concerned was towards centralisation.

A Tank Supply Department was created at the Ministry of Munitions, and the Tank Supply Committee changed its name to “Advisory Committee of the Tank Supply Department.” In August this Committee—gradually, as it were—turned into the Mechanical Warfare Supply Department before alluded to. Lieutenant (by now Colonel Stern was at its head.)

In the M.W.S.D. were now concentrated three separate functions:

They were Tank designers; they were responsible for supply; they were responsible for the final inspection of machines. The future was to show that such concentration had some drawbacks as well as many obvious advantages.

Note.—The genesis of the “large-wheeled tractor” was as follows: Trenches with a parados and parapet about 4 ft. high were being constructed by the enemy in Flanders.

The engineers consulted by the Land Ship Committee gave it as their considered opinion that if these obstacles were to be crossed, a wheel of not less than 15 ft. diameter would be necessary.

Machines with these gigantic wheels were actually ordered, but the wooden model that was knocked together as a preliminary at once convinced even its best friends that the design was fantastic, and that any machine of the kind would be little better than useless on account of its conspicuousness and vulnerability.

However, the “big wheel” idea did not utterly die, for in the upturned snout of the Mark I. Tank we have,45 as it were, its “toe” preserved, the track turning sharply back at about axle level, instead of mounting uselessly skyward, as would have been the case had not the old wheel idea been supplanted by that of the sliding track.

46

THE TANK CORPS IN EMBRYO

Not till Act III. do we get the opening of the main plot of our drama. For it was only at the end of March, 1916 that recruiting for the new arm began, and therefore that “The Fighting Side” first appeared.

5“At the end of March certain officer cadets with engineering experience and drawn from the 18th, 19th, and 21st Royal Fusiliers, were asked to volunteer their services for what they were given to understand was an experimental armoured car unit. (The Armoured Car Section of the Motor Machine Gun Corps.)

“Those who decided to throw in their lot with the new Service were interviewed by Colonel Swinton and Colonel Bradley, who, in the course of their examination, threw out no hints as to further details relative to the new unit. Results of these interviews were communicated on the Thursday before Easter Friday, when successful volunteers were informed that they were to be granted temporary commissions in the M.M.G.C., and were despatched the same morning to report to the M.M.G.C. Headquarters at Bisley. Upon arrival further information was received from the Adjutant that short leave would be granted for the purpose of obtaining kit, and that all officers would report their return with kit, on the following Tuesday evening.

“During the week that followed Easter the two first selected Companies, i.e., ‘K’ and ‘L,’ were formed, officers being posted to one or other of the Companies.”

Specially selected officers and men of the original47 M.M.G.C. formed the nucleus of these Companies, and the Companies were formed into a Battalion as further reinforcements arrived. On the Monday after Easter Bank Holiday training began, instructions being given in the use of the Vickers and Hotchkiss .303 Machine Guns and later in the Hotchkiss 6-pounder Naval gun.

An officer who arrived in about the second batch tells how he and another man from the same regiment were sent down to Bisley after the usual brief but formidable interview with Colonel Swinton. They arrived at Brookwood Station only to be told that the ever mysterious Motor Machine Gun Corps had left two days before for Siberia.

Tableau!

“Siberia” proved, however, to be a camp not so far from Bisley as to be beyond the radius of the station cab in which they both presently set off.

No Tanks were, of course, yet available for training, and therefore instruction was concentrated upon the use of the three guns, “each officer, N.C.O. and man being required to pass out at the examination.”

6“With the above exception, physical drill and an occasional route march, no further training of military character was imposed; thus in the early summer of 1916 practically all the personnel of the new branch of the service were efficient in the manipulation of the three guns in question. During the whole of the foregoing period no further information other than widely different rumours could be obtained by the junior personnel of the Unit as to the purposes for which they, or the experimental armoured car, would be used.”

About June it became increasingly evident that if the48 Land Cruisers were to be fought that year, production must be accelerated.

“A very limited number of officers, N.C.O.’s and men, totalling about one dozen, were despatched to Lincoln and other centres, where they were employed in connection with what they later understood to be Tank production.”

Meanwhile, a very carefully chosen and elaborately prepared training area had been organised on Lord Iveagh’s estate near Thetford, and as soon as information came that the first machines would soon be available for training, the Battalion was again moved.

This time the still mystified companies found themselves in a camp more ringed about than was the palace of the Sleeping Beauty, and more zealously guarded than the Paradise of a Shah. Three rows of plantations and shelter belts guarded them from the eyes of the profane, and the intruder or the breaker of camp must pass six lines of sentries assisted by cavalry patrols.

A highroad which ran through the training ground was closed, and all inhabited farms within the area were evacuated. No civilians were allowed under any pretext to pass the guard, nor were troops allowed to leave the area except on production of special passes which were very difficult to get.

Once an aeroplane from a neighbouring aerodrome flew over, moved by a friendly spirit of inquiry. It was immediately greeted with a hail of machine-gun bullets and was obliged to depart in some haste.

For now the Tanks had to appear in their true character as fighting machines, and needed a better screen49 than Russian Fairy Tales. The machines had been long expected. Almost daily some one in the camp had “heard” an unfamiliar engine throb, and when this happened the entire camp would rush out to see if “they” had come.

The wildest rumours were afoot.

The car could climb trees! It could swim! It could jump like a flea!

Any one who has lived in an ordinary camp where there were no secrets and remembers what rumours flourished on the most ethereal food, can imagine their growth in a camp where there was a real mystery.

But at last, towards the beginning of June, a limited number of Mark I. machines were detrained at a special railhead within the area.7 The training of the Battalion now began in earnest. Machines and men were destined to be launched in little over six weeks’ time into the then newly begun Somme offensive.

Two types of Tank were detrained, “Big Willie” and “Little Willie.” The Mark I. (Big Willie) was very different from the Mark V. machine described in Chapter I.

It took four men to drive it. It had an unwieldly two-wheeled tail, or to give this appendage its official name, a “Hydraulic Stabiliser.” By this device it could let itself down gently over a drop of over 5 ft., and partly with the aid of it, the machine was steered.

In practice, compared with the handy Mark V., the whole steering arrangement of the Mark I. was extraordinarily clumsy and laborious. She would not turn sharply at all on rough ground, and had to be coaxed to any change of direction. Her engine and tracks also50 needed constant adjustment, the rollers being an everlasting source of trouble. Drivers and mechanics who have handled both machines, seem to regard the running of a Mark V. as child’s-play after struggling with the caprices of “Mother.”

“Little Willie” was used only as a training Tank, as in practice he was found to have a defective balance. His centre of gravity was misplaced, and he was, besides, too short for the work of crossing trenches.

But there were other than technical problems awaiting solution.

It would be difficult to over-estimate the difficulties which confronted those officers who were responsible for the preliminary training of the Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps; no one had ever actually fought inside a Tank, and it was, therefore, upon the spirit of prophecy alone that they must rely in their preparations. There was no manual to help them. They had, however, one very excellent official document, the secret Notes on the Employment of Tanks, which was issued in February 1916 (signed “E. D. S.”8), which gave an extraordinarily good forecast of what the rôle of Tanks would probably be when in action.

But the paper was very short and very objective, and was more concerned with an analysis of the place of the Tanks in the orchestra of battle than with the difficulties presented by their individual score.

This was where the training of the first Tank crew fell short—almost inevitably. Their teachers had a rather hazy mental picture of the actuality of battle. They did not squarely face the essential question upon51 whose answer all specific training and all specific preparation depend, the question, that is, “What is it going to be like?”

Thus, though they did teach most of the essentials, they left out half a dozen subjects of which an accurate knowledge was, as we shall see, ever afterwards held to be absolutely necessary.

One of their difficulties was the shortness of the time. What must the crews know? Would physical fitness or map reading prove more important when the day came? Signalling or esprit de corps? Visual training or revolver drill? There was no time for everything. There were, however, obviously three or four essentials. Most of the officers and men were already first-rate engineers or mechanics, but they must be trained exactly in the strange machine they were to use. They must understand the peculiarities of Tanks, and, if possible, of their individual Tank, the monster which they had to render animate.

They must be thoroughly at home with their Vickers guns, be accurate shots with them, be able to remedy all stoppages, and to strip their weapons with speed and accuracy. Above all, crews must train together, be accustomed to work under their officer, each with his special work as brakeman, gearsman, driver or gunner, but each still part of an organic whole. They must also attain to a certain physical level, must undergo some visual training, and must know how to fire a revolver.

All this and more was achieved, for the men were picked individuals of more than ordinary intelligence, and soon became extraordinarily keen on their work.

9“If anything went wrong with the Tank, they used to look upon it not as a bore but as a pleasure to put it52 right.... We felt a terrific pride in our Company and Section, and also as a Tank crew against other crews. There was always healthy competition, and this competition carried us right out to France.... Besides that, Tank Commanders had the very great advantage of training their crews themselves.... We knew our men thoroughly.”

But, as another Tank Commander wrote afterwards:

“The first Company to go out had to work at tremendous speed. The Tanks did not arrive till the last minute, and I and my crew did not have a Tank of our own the whole time we were in England ... as our Tank went wrong the day it arrived.... Again we had no reconnaissance or map reading ... no practices or lectures on the compass.... We had no signalling ... and no practice in considering orders. This was a thing I very much missed when I got out to France. When you work with a Division you get very long orders, and you have to analyse these orders to discover what concerns you and what does not.... We had no knowledge of where to look for information that would be necessary for us as Tank Commanders, nor did we know what information we should be likely to require.”

No one, in short, had sat down to imagine a Tank in action from within.

We had official painters in France, but alas! we had no official writers of prophetic fiction.

The history of the attack on Morval shows that this probably inevitable lack of, say, an official clairvoyant, this dependence upon methods of trial and error, though it ultimately did little to hurt the development of Tanks, did very much to prevent the Tank personnel from feeling satisfied by their début.

53

It must have been with some sense of having taken a momentous step that the authorities sanctioned the manufacture of 150 Tanks after witnessing the trials at Hatfield.

We were short of men and short of steel, and to divert steel from shells and men from the infantry was a grave decision. Our rulers were for a moment, perhaps, granted the gift of prevision. They saw that the new weapon might prove the sword that was ultimately to tip the level balance, and to break the intolerable equilibrium which had settled on the line from the Alps to the sea.

This prophetic mood did fitfully visit the authorities.

For a few months they would, as it were, have faith, and personnel would be granted and machines would be ordered.

Then perhaps for half a precious year they would relapse and backslide and revert, till Colonel Swinton, the Fighting Side, and all the other missionaries and preachers of the Tank Corps almost despaired.

But in February 1916 there was much to uphold them. The situation demanded some desperate remedy.

The balance hung deadly level. We could hold the Germans now, but for how long? The race for the coast had been a draw, and the First Battle of Ypres had ended open warfare on the Western Front.

10“Quick-firing field guns and the machine-guns used defensively, proved too strong for the endurance of the54 attackers, who were forced to seek safety by means of their spades rather than through their rifles. Whole fronts were entrenched, and, except for a few small breaks, a man could have walked by trench, had he wished to, from Nieuport almost into Switzerland.”

The Germans were dug in.

11“And with the trench came wire entanglements—the horror of the attack—and the trinity of trench, machine-gun, and wire made the defence so strong that each offensive operation was brought to a standstill.

“The problem which then confronted us was a two-fold one:

“Firstly, how could the soldier in the attack be protected against shrapnel, shell-splinters and bullets? Helmets were reintroduced, armour was tried, shields were invented, but all to no great purpose.

“Secondly, even if bullet-proof armour could be invented, which it certainly could, how were men laden down with it going to get through the wire entanglements which protected every position?”

It was, in fact, impossible for infantry alone to attack such positions without the most extensive artillery preparation. The enemy and his trenches and his wire must be blown out of the ground. This was the accepted answer to the problem of the deadlock. But as yet we had not got the shells. We were straining every nerve to reach the solution by bombardment, but in February 1916 we had not got the necessary ammunition. Was there no other answer to the problem? Nothing that could be done meanwhile?

This was the mood in which the missionaries of the “mobile machine-gun destroyer” found the High Command. Had we had shells in February 1916 we should not have had the Tank. We must have waited another55 year for it, till, in fact, we had found out the defects of the hoped-for solution by bombardment.

The German, who was full fed with ammunition, felt at this early date no urging to go out and seek any such fantastic remedy. His High Command would have laughed at the idea of Tanks as Dives may have laughed at hungry Lazarus’ antics over broken victuals.

So, while our shells were making, we built Tanks. And Fate, whose taste in humour is not ours, and who knew what we did not, namely, that the Tank and prolonged artillery preparation are alternative weapons, decreed that both shells and Tanks should be ready for the Somme offensive.

It was thus upon a “substructure” of the new artillery preparation that we gaily imposed the Tank. We were to take fourteen months in working out the proposition that they could never be effectively used together.

The Tanks had been designed for the sort of conditions which had prevailed at Loos. Their training grounds had been carefully modelled on the “Loos” pattern. By the time Tanks could be put into the field, a year later, our artillery superiority had completely changed the nature of the fighting.

At Beaumont-Hamel in November 1916, for example, we fired off as much ammunition as was expended in three weeks at the Battle of Loos.

On the Somme—owing to our having advanced—four miles of churned-up, shell-pitted ground had to be crossed before the front line could be reached. It had also—to state the case after the manner of the author of Erewhon—become the fashion, just before the day of battle, for the attacking side to blast the ground which56 they were about to cross to the condition of plum pudding on stir-up Sunday. This blasting process, moreover, necessarily gave the enemy several days’ warning of any proposed attack.

It had also incidentally had another effect upon the industrious German. When we were bombarded our chief idea was retaliation; when the German was shelled he dug.

So it had come about that on the Somme, everywhere behind the German lines, were great electrically-lit and comfortably warmed dug-outs, where a company or so could lie secure thirty or forty feet below ground and there wait for the bombardment to “blow over.” Then they would emerge ready to welcome our infantry. Thus the system of the, say, six days’ artillery preparation, though it did very much to raise our moral and depress that of the enemy in time resulted in an almost complete system of enemy counter-measures, and in a state of the battle-ground which caused attackers and attacked to be almost immobile. The system, necessary as had been our adoption of it, had not solved the problem of the deadlock.

The Tank, as we have said, had been intended for use on reasonably sound ground. It was also to be a surprise weapon. Not once for the next fourteen months did we omit to give the enemy at least five days’ notice of our proposed attacks, nor did we decline to co-operate with his artillery in reducing the intended battle-ground to a morass. It was, therefore, not till the First Battle of Cambrai, when we did adopt other tactics, that Tanks came by their own.

57

THE FIRST TANK BATTLES—THE ATTACK ON MORVAL, FLERS, THE QUADRILATERAL, THIEPVAL AND BEAUMONT-HAMEL

It was not till the Somme offensive, which was launched on July 1, 1916, had been in progress for two months and a half, that it was found possible for the new arm to take its place in the fighting. We have seen how, secretly, urgently, behind a rich curtain of ingenious and circumstantial lies, the manufacture of the Tanks had been going on. How, secretly, urgently, the crews had been training for their unknown job.

Of the fifty Tanks which were destined to take part in the battle of September 15, about thirteen left England on August 15, and the rest followed at intervals and in driblets as the limited transport allowed. The last batch arrived on August 30 and, like its fellows, proceeded to the training centre at Yvrench. Here trenches had been dug and wire entanglements erected, and machine-gun and 6-pounder practice could be carried out after a fashion. But there was no staff of instructors, the ranges were too short, and the conditions for battle practice quite unlike those which prevailed on the Somme. But it had to suffice. The Tanks were wanted at once, and by September 10 “C” and “D” Companies had arrived in the forward area, their H.Q. being established at the Loop. It was thus within a week of their arrival forward that Tanks were called upon to take part in the attack.

The battle had now been in progress for nearly ten58 weeks. We had advanced and occupied a depth of four miles of devastated country.

Most of the men and many of the officers had not been to France before. They found themselves in a strange world. Endless lines of transport crawled over incredibly bad roads bordered by gaunt stumps of trees and by a sordid and tragic litter of dead men and horses, rags, tin cans, rotting equipment, and derelict transport.

The enemy was counter-attacking over the whole of the thirty-mile front, and the sound of our guns was everywhere. At night the stream of lorries never ceased, and at some point or other in our line, far away, a star shell could always be seen sailing up from behind a rise of ground, giving some fringe of shattered wood, or ruined sugar factory, a fleeting silhouette against its cold white light.

All ranks were desperately busy, from the mechanics who had new spare engine parts to adjust, to those in command who had their own minds and those of several Major-Generals to make up. Colonel Brough had commanded when the Tanks disembarked, but had now handed over to Colonel Bradley, and he and the Army Corps, and Divisional Commanders with whom he conferred on the 13th seem, perhaps inevitably, to have been as uncertain how to wield the new weapon as were the Tank Commanders of such details as how to fit their new camouflage covers or anti-bombing nets.

In an advance when ought a Tank to start? If it started too soon it would draw the enemy barrage; if it started too late the infantry would reach the first objective before it, and it would be of no use.

This and other similar dilemmas darkened their counsels, and it was finally decided that the Tanks’ start59 should be so timed that they reached the first objective five minutes before the infantry, and, further that Tanks should be used in twos and threes against strong points. No special or detailed reconnaissance work had been done, and a somewhat indigestible mass of aerial photographs was presented by the Divisional Staff to the bewildered Tank Commanders, many of whom had never seen such things before.12

Much more useful were a series of maps with routes marked out and annotated with the necessary compass bearings, and a detailed time-table with full barrage and other particulars. At least they would have been more useful had not all orders been changed in such a way at the last moment as to invalidate almost every route and hour which they showed.

Meanwhile the Tank crews and commanders had been enjoying three or four days of almost comically complete nightmare. In the first place, they had all manner of mechanical preoccupations—newly arrived spare engine parts to test, new guns to adjust, box respirators to struggle with, and an astounding amount of “battle luggage” to stow away. But worst of all, they found themselves regarded as the star variety-turn of the Western Front.

Already, before leaving Thetford, they had given a demonstration before the King and several members of the Cabinet. At Yvrench they had performed before General Joffre, Sir Douglas Haig, and the greater part of the G.H.Q. Staffs,13 but on reaching the Loop they60 found to their horror that it was to be “Roses, roses, all the way.” A Tank Commander wrote bitterly: