Title: Jed's Boy: A Story of Adventures in the Great World War

Author: Warren Lee Goss

Illustrator: Harry T. Fisk

Release date: August 17, 2020 [eBook #62956]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

CIVIL WAR STORIES BY WARREN LEE GOSS

IN THE NAVY, (7th Thousand) Illustrated, 399 Pages, A Story of naval adventures during the Civil war.

“The Marine Journal” says of it: “The author, takes as usual for his fiction, a foundation of reality, and therefore the story reads like a transcript of real life. There are many dramatic scenes, such as the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac, and the reader follows the adventures of the two heroes with a keen interest that must make the story popular especially at the present time.”

TOM CLIFTON, A story of adventures in Grant and Sherman’s armies. (13th Thousand) Illustrated, 480 pages. 12mo. Cloth.

“The Detroit Free Press” says of it, “The book is the very epitome of what the young soldiers, who helped to save the Union, felt, endured and enjoyed. It is wholesome, stimulating to patriotism and manhood, noble in tone, unstained by any hint of sectionalism, full of good feeling; the work of a hero who himself did what he saw and relates.”

JACK ALDEN: Adventures in the Virginia Campaigns, 1861-65. (12th Thousand) Illustrated, 404 pages.

“The New York Nation” says of it: “It is an unusually interesting story. Its pictures of scenes and incidents of army life, from the march of the 6th Massachusetts regiment through Baltimore to the surrender at Appomattox, are among the best that we can remember to have read.”

JED. A boy’s adventures in the army. (28th Thousand) Illustrated, 402 pages. 12mo. Cloth.

“The Boston Beacon” among other complimentary remarks about this book says: “Of all the many stories of the Civil War that have been published—and their name is legion—it is not possible to mention one which for sturdy realism, intensity of interest, and range of narrative, can compare with Jed.”

A LIFE OF GRANT FOR BOYS AND GIRLS. Illustrated. 12mo. Cloth.

“The Christian Advocate” (Cincinnati) says of it: “One of the best lives of U. S. Grant that we have seen—clear, circumstantial, but without undue and fulsome praise. The chapters telling of the clouds of misfortune and suffering over the close of his life are pathetic in the extreme.”

THE BOY’S LIFE OF GENERAL SHERIDAN. Illustrated. 12mo. Cloth.

The “Living Church” (Milwaukee) says of it: “The story of the dashing officer in his war career and also afterwards—in his campaigns among the Indians, form a thrilling story of American leadership. The book contains a thorough review in thrilling language of the various campaigns in which Sheridan made his mark.”

Order from your bookseller. Send for Catalogue.

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY, NEW YORK

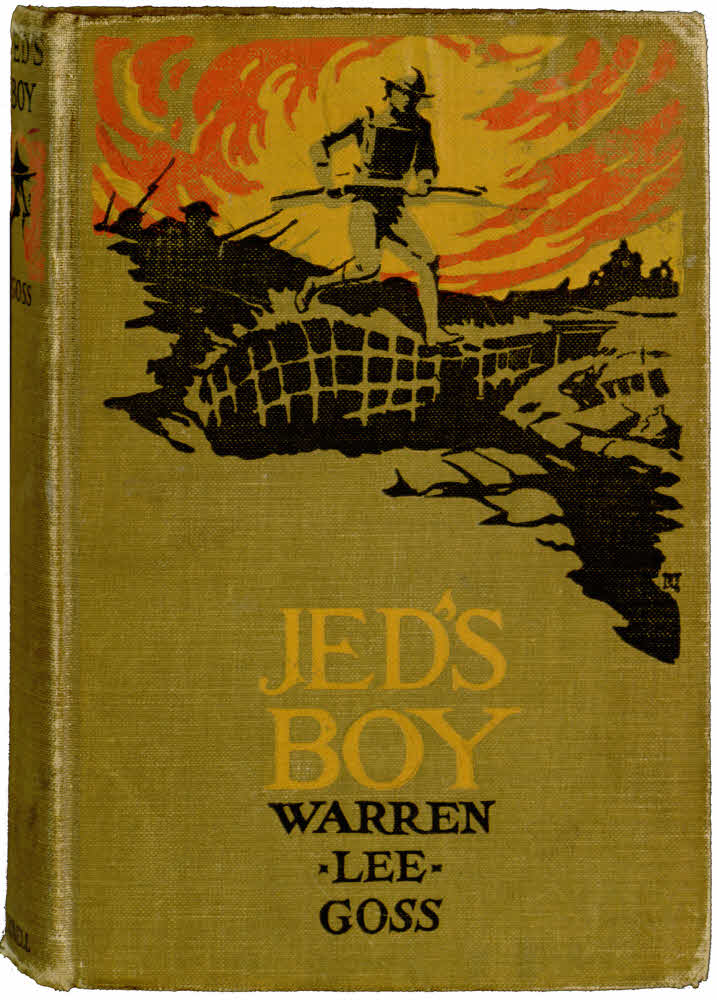

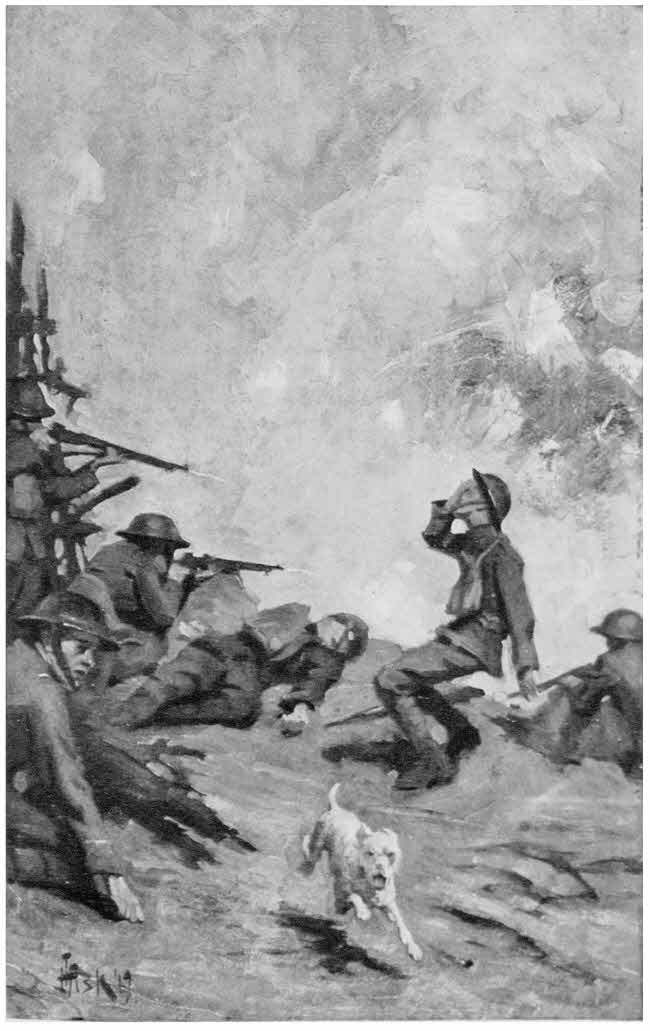

Frontis. “I GRIPPED MY NERVE AND SHUT MY TEETH. COULD I REACH A PLACE OF SAFETY?”—Page 111.

A STORY OF ADVENTURES IN

THE GREAT WORLD WAR

BY

WARREN LEE GOSS

AUTHOR OF “JED,” “JACK ALDEN,” “TOM CLIFTON,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1919, by

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

DEDICATED

TO THE SOLDIERS AND SAILORS

OF THE GREAT WORLD WAR

[v]

During the progress of the Great War, the writer has been often requested by his boy friends and others, both by letter and verbally, to write a book like “Jed” (“A Boy’s Adventures in the Army, ’61-’65”) depicting the scenes of this later war. Some of them have even suggested that he recreate some of the characters therein. To do this, of course, was a logical impossibility, since those not killed in that story would be too old for military service. Prompted, however, by that demand, he has taken a nephew of Jed as the hero of this story. Incited by his mother’s patriotism, and her recital of her brother Jed’s heroism, he enlists and serves his country on the battlefields of France.

The author’s main purpose in writing this book, as with his other books, is to stimulate a true spirit of Americanism. Patriotism thrives best where it is best nourished, and is not a plant of accidental growth. The Posts of the Grand Army of the Republic through their exercises on Memorial and other patriotic days, and their teachings of patriotism in the public schools, have been springs of liberty flowing throughout the land nourishing a love of country in our youth. That all this has borne fruit is shown by the spirit in which the boys of to-day have sprung to the defence of human liberty in the great conflict of their own time.

[vi]

We have been privileged to see the last shreds of hatred left over from our Civil War burned away in a fervor of patriotism, that has sent the sons of the Gray shoulder to shoulder with the sons of the Blue to the defence of liberty on the fields of France and Belgium.

If the writer has made clear that the young manhood of America has the same spirit to-day as had their fathers, in our great conflict of the sixties, and as had the Nathan Hales of the Revolution, he will have satisfied his own aspirations.

W. L. G.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Tramp Boy | 1 |

| II. | Working on the Farm | 9 |

| III. | Impending War Clouds | 15 |

| IV. | With the Colors | 22 |

| V. | From Camp to Transport | 31 |

| VI. | In Beautiful France | 43 |

| VII. | In the Trenches | 53 |

| VIII. | “Who Comes There?” | 64 |

| IX. | A Call Returned | 73 |

| X. | In Rest Billet | 83 |

| XI. | A Six Weeks’ Hike Through France | 91 |

| XII. | On the Battle Lines | 99 |

| XIII. | In the Tide of Battle | 106 |

| XIV. | The Croix de Guerre | 114 |

| XV. | On Leave of Absence | 120 |

| XVI. | A Strange Desertion | 128 |

| XVII. | Another Deserter | 136 |

| XVIII. | A Raid on the Enemy | 143 |

| XIX. | The German Peace Storm | 151 |

| XX. | An Adventure of Arms | 161 |

| XXI. | In the Hands of the Enemy | 169 |

| XXII. | Held by the Enemy | 176 |

| XXIII. | A Hazard of Fortune | 183 |

| XXIV. | Loose Among the Boches | 190 |

| XXV. | An Unexpected Encounter | 198 |

| XXVI. | A Hospital Case | 208 |

| XXVII. | The Mix-Up of Battle | 217 |

| XXVIII. | A Mystery Solved | 224 |

| XXIX. | The Supreme Sacrifice | 230 |

[1]

JED’S BOY

It was November, in the year 1914. The snow had come with the gloom of twilight, and an angry wind whistled over the Western Massachusetts hills.

I was then a lad, trying to fill his father’s place on the farm. I had just finished milking when I heard Bill Jenkins, our hired man, call out in rasping tones, “No, there’s no work for you here, I tell you!”

Turning, I saw at the barnyard gate the person to whom Bill had spoken. He was a tall slim boy apparently near my own age, fourteen.

“What is it, Bill?” I said; “what does he want?”

“You run along with your milkin’ pail,” said Bill. “I’ll ’tend to him. You don’t know nothin’ ’bout dealin’ with tramps.”

I repeated my question, and the boy answered, “I am looking for work.”

“An’ I told you there’s no work here for you,” said Bill roughly. “An’ if you can’t understand such plain words as them air, you’ll have to get a dictionary.”

[2]

“Can’t I stay here over night?” persisted the boy. “I can pay for my lodging. It’s getting dark, and these parts are strange to me.”

There was something in the high-pitched voice that told me the lad was weak as well as cold, and the trembling tones appealed to me more strongly than the request itself. There was, too, a peculiar accent in them that excited my curiosity. So before Bill could again interfere I answered,

“Yes, you can stay; and if there is no other bed, you can sleep with me. I am sure mother will be willing.”

“You are soft and foolish. You don’t understand folks that go traipsing ’round the country,” growled Bill. But ignoring his protests I led the way to the house, with the strange boy following.

When we reached the kitchen and the lights were brought, Bill, with a surly air, carried the pail to the milk room. Mother coming in saw the boy and asked, “Who is this, David?”

“A boy who wants to stay all night, Mother,” I replied, “and I have invited him to sleep with me. Can he?”

“What’s your name?” asked mother, turning to the boy and looking him over with an inquiring glance that meant more than words.

“Jonathan Nickerson—they call me Jot for short. That is not my whole name, only a part of it. My father is ’way off, I don’t know just where, and my mother is dead; I couldn’t agree with the folks she has been staying with, so I must find work or go hungry.”[3] As he spoke of his mother, his voice grew husky as though he were keeping back the tears.

There was a straightforwardness in his answer that pleased mother, as I knew it would, for she liked direct answers to questions. This may account for her keeping Bill Jenkins in her service most of the time since the Civil War, where he had served as a drummer for three months. He had appeared at her father’s door, ragged and disgusted with military life, after the battle of Bull Run, from which he had beaten his way with some of the rest of those who had got back to Washington.

Mother looked at the boy keenly from over her spectacles, but made no remarks, while I summed him up, as follows: He was very dark, thin in feature and in person, his eyes dark and bright, chin prominent; and notwithstanding thin-patched clothes and apparent weakness, there was a manner of independence and decision that cannot be expressed in words.

“Come here, Mother!” I said, turning to another room.

“What do you want now?” asked mother.

“Don’t turn him away in the cold and dark,” I pleaded. “Suppose I had no place to sleep tonight, out in the wind and snow.”

“He looks clean, if he is patched and darned, and seems a decent boy,” she said in an undertone, as though thinking aloud, and then added, “Yes, David, he can sleep in the ell bedroom. It is cold there, but there are plenty of good comforters, and I guess he can put up with it, if we can; and as our Master said,[4] ‘Inasmuch as ye have done it to the least—’” and she left the quotation unended.

Supper was ready, and mother said to the boy, “Yes, you can stay here tonight, and if you have not had your supper, sit up to the table with us.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” he replied sturdily, “but I have no money to pay for my supper—only enough to pay for my lodging—only twenty five cents at that.

“I did not say anything about pay,” said mother; “you are welcome to your supper.”

“Mother told me never to take anything without paying in some way for it,” he protested; “and I am not very hungry.”

Mother gave him another searching look, as if to learn whether there was any purpose back of his words, and then as though satisfied, said with softening voice, “Never mind about that, my boy; if you are not afraid of work, you may pay for your supper and breakfast too. There is plenty to do here.”

When he asked for a place to wash, and had gone to the kitchen sink for that purpose, mother remarked, “The pail is empty and the pump doesn’t work; so you must go to the well for some water.”

When supper was ended, Jonathan asked, “May I try to fix your pump, m’am?”

Mother hesitated, glanced at Bill, and then replied with a smile, “Yes, you may try. At any rate you can’t make it any worse than it has been, since Bill fussed with it.”

Jonathan went to work with his jackknife and such tools as were at hand. He had not more than started,[5] however, when Bill came in with an armful of wood for the kitchen stove. Stopping at the pump he said in his dictatorial tones, “You can’t do nothin’ with that pump! I’ve tried it, an’ I tell you it’s past mending by any botch or boy. An’ I tell Miss Stark it will be cheaper to buy a new one, by gosh! For I put in a half a day tryin’ to fix it.”

Jonathan, without reply, kept on with his mending and, to our surprise, after half an hour had the pump working.

“Where did you learn to fix pumps?” mother inquired in a pleased manner.

“Our pump got out of order once, and the man who fixed it explained its working to me, and I have learned about them otherwise since.”

“That pump,” said the disgruntled Bill, “will be out of order again as quick as scat, or I miss my guess.”

“You see,” said Jot, ignoring Bill, “that piece of leather is a valve and must fit quite tight. When the air is pumped out, the water comes up to fill the partial vacuum. All I have done is to limber and adjust the valve so that it fits tighter.”

“My!” said mother trying the pump, “it works quite well, and it does not matter where you learned it; you have earned your supper and breakfast too, for we would have had to send to Chester for a man to repair it, besides the inconvenience of waiting.”

The next morning mother asked Jot what pay he would want to do the chores and other light work about the place. “I will work a month,” he replied, “and you shall say how much I am worth.”

[6]

The answer pleased mother since it seemed to insure faithful service.

Thus it was that Jonathan Nickerson came to work on the Stark farm.

My father, Captain David Stark, had been a soldier in the Civil War. He had enlisted when only sixteen years of age and, by military aptitude and bravery, had won a captain’s commission, before he was twenty-one.

Over the mantel of our front room, secluded from light and flies except when we had company, hung a sword which had been presented to him, so its inscription read, by his admiring officers and men.

He had married my mother some years younger than he, quite late in life, and I was their only child. He had died before I remembered much about him.

One day Jot noticed the sword and read its inscription. He removed his hat reverently and said: “I would like to be a brave soldier like him. My mother’s only brother, Lieutenant Jedediah Hoskins, was killed while leading a charge, just before the surrender at Appomattox. She was but a little child when that occurred, but she had his back pay and other property to help us, and often called me Jed’s Boy, hoping that I would be like him.”

Jonathan, or Jot as we began to call him, was careful and handy; he repaired locks, and even put in running order a disregarded mowing machine that Bill, who didn’t like “new fangled farming,” declared was good for nothing. We soon began to regard him as one of the family, and mother liked him because, as she said, he was both honest and careful and “had not a lazy bone in his body.”

[7]

Bill usually read the weekly newspaper in the evening, sometimes commenting aloud on what he read. One evening while reading he looked up exclaiming, “Gosh!”

“What is it, Bill,” I asked, “anybody dead?”

“Matter! The Germans are marching on Paris”, he answered, “and there has been the all-firedest fightin’ you ever heard tell of.” Then Bill read aloud the news of the first fighting in the Great World War.

“I believe,” he concluded excitedly, “that I shall have to go myself and help lick them consarned Dutch.”

“I wouldn’t,” said mother with a gleam of fun in her eyes, for she liked to tease Bill, “You might wear yourself out, as you did at Bull Run, scampering back.”

“Well,” acknowledged Bill with a grimace, “I am getting old, and I like farmin’ a consarned sight better than I do fightin’; but when I read ’bout them Germans tryin’ to run over everybody, it makes my dander rise, darned if it don’t!” And Bill was not the only one of us who felt that way.

Then we got Bill to tell us about his experience in the Bull Run campaign. So he gave his version of that battle—even the running away, which, however does not concern this narrative.

“Didn’t you think it a shame,” asked mother, “to run away?”

“Well,” admitted Bill, “as a matter of glory it was, but as we fightin’ fellers see it then, it looked like common sense, plagued if it didn’t! A man will get sca’t at things he ain’t used to. Them fellers that run[8] wouldn’t do it again—if the other fellers didn’t. I wouldn’t wonder if I would stand to the rack an’ take the fodder that was coming, myself, if I was in another fight. And then my time was most eout, and I was all the time thinkin’ ’twas best to go home on my legs instead of in a box, when my time was up.”

“Were you scared, Bill?” I asked.

“Gosh, yes! the fust of it, my hair stood up so straight that I thought it would take my hat off. But I had spunk to stand it, in spite of being sca’t—’till the others run. D’ yo’ know that I think it takes more courage f’r a sca’t man to stand fire, than it does for a brave man.”

And I have since learned, from experience, that it is indeed a brave man who, being frightened, still keeps his place in battle.

[9]

The winter school had closed, and my spring work on the farm had begun. Boys of my age in New England, at least farmer boys, did not, as a rule, attend school in summer: it was thought that winter schooling was enough. My mother, however, intended for me to graduate in the high school later. Like most New England people, mother believed in the potency of work as a needful part of a boy’s or girl’s education. Work, she declared never hurt any one; while laziness and the feeling that one is too good to work were the foundation of shiftlessness and poverty. People must fight for anything worth having, and farming is a fight with the soil to make it yield a living.

“Your father,” she would say, “was a farmer and a good one; he believed as religiously in fighting the soil and keeping down the weeds, as he believed in fighting the Confederates and putting down the Rebellion. If you expect this farm to be yours, and to pay off the mortgage on it,” she would add, “you have got to learn about the work, or the rocks and weeds will get the best of you, and it will be of no use when you get it. You will be selling it, and spending the money, and become a shack of a man like some others who think they are too good to work.”

[10]

“But you have succeeded in working the farm,” I argued, “without knowing the work practically.”

“Yes,” she admitted, “but I was brought up on this farm and have learned what it will best raise. I know the business part; but if I understood the farm better I wouldn’t have to stand Bill Jenkins’ dictation, when he wants to have his way instead of mine.”

“What makes you keep him,” I asked; “he growls about what you ought to do, instead of taking your orders and obeying them.”

“He is faithful,” she replied, “and is to be trusted. If you can’t trust a man, he is of no use to you anywhere.”

Although Jot had now been with us long enough to receive several months’ pay, he still wore the same suit of clothes as when he came to the Stark farm. I afterward learned it was because he had been paying for his mother’s sickness and funeral. He was still reticent about his father, and would give no account of himself, except a general one. He talked, however, quite freely about his mother, and about his uncle Jed, and was intensely patriotic.

“I would like to fight for this country, as my uncle did,” he would sometimes say, “if I should ever be needed.”

We continued to read the news of the war as it came across the sea. Our hearts were thrilled at even the meagre recital given in our weekly paper, of that great adventure of arms, when like a lion the great French general with his brave army, stood in the path of German invasion and said, “They shall not pass!”

[11]

On the farm, meanwhile, Jot had been proving the correctness of mother’s judgment that he would be worth more than his keep. Among other traits brought out by acquaintance was one striking one. He was passionately fond of animals, and had a control over them that was seemingly the result of sympathy. In mowing time, when I would be tired enough to be resting, he would often be playing with our two year old colt, Jack; and he seldom came into the pasture without an apple or some dainty for him. The colt was of Hambletonian stock, high spirited, and when with Jot full of play.

One day, after we had been mowing hay, mother said, “Bill, there is a shower coming up, and you had better give the boys a little rest.”

“Well, Miss Stark, I guess it will be a good plan, while we are loafing, to give Jack a little training. He’s about the hardest scamp of a colt I ever see.”

But as Bill in his former attempts to train Jack had lost his temper and struck and kicked him, he found it hard to catch him.

“Let me try to catch him for you, Mr. Jenkins,” said Jot.

“What do you know about colts?” said Bill crossly.

“I got acquainted with him down in the pasture, and will try and catch him for you, if you are willing.”

Jot’s respectful manner mollified Bill and he assented, saying:

“Well, go ahead with your sleight of hand with the critter; but I can tell you, he is awful skeetish.”

Jot called the colt to him in coaxing tones, holding[12] out his hand with a lump of sugar, and Jack came circling around him with flowing mane and streaming tail; dropping his tail, snuffed at Jot’s hand, let him take hold of his fetterlock and, yielding to his caresses, allowed him to slip the bridle over his head and to be led around.

But when Bill attempted to take the colt in charge, he couldn’t manage him.

“Bill,” said mother, “Jonathan seems to understand him; hadn’t you better let him try to break him; for I am afraid you’ll spoil him; so please let him try.”

After he had led Jack around the yard for a while, Jot said to mother, “I think that will do for this time, Mrs. Stark.” And then, with a little more petting and another lump of sugar, sent the colt scampering away.

“My!” said mother, “I didn’t think you could do it.”

In one of our visits to Chester we acquired a dog, or more truthfully, a dog acquired us.

We had no dog on the place; for Bill hated dogs; said they killed sheep, and had fleas, and declared, with some truth, that if a dog didn’t kill sheep, he attracted those who did. But on this day as we were coming from a store where we had been making purchases, a dog with tin things tied to his tail came ki-yi-ing piteously from a near-by shed where some rowdy boys were congregated.

Jot coaxed the dog to him, got him in his arms, took off the tin cans that had been pinched to his tail, and holding the creature in his arms, said to the boys: “Who owns this dog?”

[13]

“No one owns him,” one of them answered; “he’s been hanging around here for quite a while.”

We took the frightened creature to the wagon and, when half a mile away, put him down to shift for himself. The dog would not be deserted by his new-found friends, but followed the team and, at every attempt to drive him away, would roll over on his back and implore in doggish fashion, to go with us. So at last, when we arrived at home, the dog was with us.

Bill, of course, strenuously objected to having the dog on the place; but after much pleading I got mother to allow us to keep him, though she also did not like dogs.

“I won’t have him underfoot,” she declared, “so you must keep him away from the house—out at the barn;” to which we agreed.

We were delighted, for what boy does not love a dog?

Jot taught him several cunning tricks, among other things, to bring home the cows at milking time. Because of his color we called him “Muddy.”

I have told these simple things not alone to reveal Jonathan’s compassionate nature, but because they were not without influence in scenes of greater importance, in our later lives, as you shall see.

Jot worked faithfully on the farm, and with its healthy food and work, had grown to be a strong though slight young man. He had attended school several winters, learning rapidly.

Meanwhile the war was claiming more and more of our attention, and we read about it with such interest[14] that we had begun taking a daily newspaper. When the news came of the sinking of the great passenger ship, the Lusitania, with its hundreds of passengers, it seemed too dreadful to believe. Though public indignation was at white heat over this cruel deed, it was soon toned to soberness by thoughts of our own possible war with this relentless military power.

Soon after the sinking of the Lusitania, a great personal sorrow befell me in the loss of my mother. She passed away after only a few days’ illness of heart failure. After her burial in the Stark private burial plot, my Aunt Joe and her husband came to take charge of the farm. Jonathan continued to work with us, but Bill left to work elsewhere; for he declared he wouldn’t stand bossing from any one.

The farm did not seem like home to me after mother’s death, and I fell into such melancholy at times, that Aunt Joe gave me what she called a good talking to, saying, “I guess your mother is glad to have her boy care for her; but it is just as natural to die, as it is to be born, and it don’t do a speck of good to be blue when we lose our friends.”

To illustrate her philosophy, she then sat down and had a good cry with me.

[15]

It was October, 1916. The harvests were gathered, and the fall ploughing was done; the frost was in the ground, and the hills were ablaze with the scarlet and gold of Autumn.

I was debating with Jot whether I would attend school or not, that winter.

“Of course,” answered Jot, “you will go to school just as if your mother were here to tell you to go.”

To this good advice Uncle Jim assented by a decided nod of approval. Now Uncle Jim, I had discovered, had a will of his own and very decided opinions. As Aunt Joe said, “though mild as skim milk in his ways, he is as sot as a rock.” And knowing this I thought it best to do as I was advised.

I began my studies at once when the winter term opened, but was discontented, and did not take so much interest in them as usual. When I brought my books home to study, Jot read them eagerly, and asked me many questions about the lessons. I think I learned more in trying to answer his questions than I did by the study of them in the books; for there is a difference between committing a lesson to memory, and giving a sensible answer to questions to one in earnest to know[16] about them—for one is an act of memory, but the other requires thought and reasoning.

Our interest in the war was growing in intensity day by day. Our neighbors often came in of an evening to hear the news and discuss the war, and among them there was a Mr. Larkin, who was a pacifist. He was well informed and well read, for a farmer, and though in the main patriotic had as Uncle Jim said, “a pacifist crook in his mind that needed straightening.”

At one of the evening gatherings, after we had dwelt upon the relentless cruelty of the German army in dealing with Belgium and France, Larkin said:

“They had better stop this war at once; for war is so dreadful that it should not have a place in any Christian country.”

“Well,” said Uncle Jim, in his slow and drawling tones, “I don’t much admire war, but if any darned crowd should break into this house and begin smashin’ things and threaten to kill the folks, am I a goin’ to sit here like an idiot and see ’em do it without liftin’ my hand to stop it? No, sir! I am goin’ to stop such works if I break their necks.”

“But don’t the Master say that we should return good for evil?” replied Mr. Larkin, “and when smitten on the right cheek that we should turn the left?”

“Well,” replied Uncle Jim slowly, “I suppose he did say so; an’ I suppose if the majority of folks would do so, it would be better. But it seems to me that I have read somethin’ about the Master’s getting riled at some wretches that had turned the Temple into a[17] sort of pawnbroker’s shop, and then drivin’ them out with horse whips, because they had made it a den of thieves. Now what do you suppose he would have done, if he had been in Belgium, and had seen them Germans setting fire to churches, and killin’ women and children?”

“That,” said Mr. Larkin, “only proves my assertion, that everybody should set themselves against war; you speak, as though to keep the peace with all your power, was degrading.”

“No, no,” said uncle; “you misunderstand me. What I mean is, that when a bully hits you, you must hit him back so hard that he will never want to hit you again. To do the contrary would be to encourage him. Such folks would soon rule the world, if you did not make them take a back seat.”

After Germany had violated her agreement with the United States not to sink any more of our ships sailing the ocean on peaceful missions, our President declared war, to “make the world safe for democracy.” Then came the first call for volunteers, to fill up the ranks of the National army. Men were quiet, but determined, in supporting the President, and a deep undercurrent of war spirit prevailed in our little community.

I had the war fever mighty bad. But uncle said: “Wait awhile an’ see how that cat is a goin’ to jump—for ’taint best to be in a hurry about important matters.”

There were some who differed about the wisdom of declaring war, and, of course, our neighbor Larkin was among them.

[18]

“Don’t you think,” he said to Uncle Jim, “that it would have been better if our President had not been so hasty?”

“No,” replied uncle decidedly, “I think that, instead of trying to keep us out so hard, if we had ridged up our backs in the fust place, and had begun to get a big army together, Germany would never have dared to provoke us to war. We have a right to sail the seas wherever we choose, on peaceful business—that was decided in the war of 1812—an’ no nation on earth has a right to say we shan’t.”

During all this talk and excitement Jot was mostly silent with a constraint that I did not understand—though I had full faith in his patriotism. At one time, before the declaration of war, it had been proposed by my cousin Will Edwards that they should go to Canada and enlist. But Jot had gravely replied: “I should like to fight under the flag of this free nation, if she should ever need me; as my Uncle Jed did in the Civil War.”

There was something, even in this remark, of reticence, as though there were other ties that bound him of which he was inclined to make no mention.

Soon after the declaration of war, a horse trader accompanied by Bill Jenkins, and another man, came to the Stark farm to bargain for horses. The prices they were willing to pay seemed large, and uncle sold one of our extra horses. Then Bill said, “Why don’t you sell the colt, Jack? He won’t be good for much for quite a while, an’ I guess you’ll need the money before long on this place.”

[19]

I did not like the freedom of Bill’s remark and neither did I wish the colt sold. “Well,” said the trader, “it will be no harm to look him over.” So we went down to the pasture where Jack had been let loose for his spring feed.

Our colt was now full grown and broken to saddle, but not to harness. Muddy, the dog, and Jack were great friends. The dog slept in the same stall with the colt and they often frolicked together in the pasture. When we reached the pasture the colt and dog were on a frolic—the colt jumping and wheeling and prancing, while Muddy jumped, barked and capered in front of him.

Turning to my uncle the trader said: “I will give you two hundred dollars for that colt. He isn’t worth it; but I know just where I can sell him.”

My uncle refused to sell, and the man handing uncle his business card, said: “Well, when you get ready to sell, let me know.”

After he had started away I turned to speak to Jot, but found he had disappeared. Later I came upon him behind the barn talking to the man who had accompanied the horse trader, and I overheard him using some words strange to me—seemingly in some foreign language—at any rate not common English. As I came upon them they parted, and when I asked Jot what they were talking about he made no definite reply, but said, “I am so glad they didn’t sell Jack.”

His evasion made me angry, and I turned away to go to the house. Jot called after me, but I refused to speak or turn back; and that night we went to bed[20] without a good-night greeting as was usual with us.

The first thing, after I awoke, I went to Jot’s room, but he was gone. Then I went down to breakfast, expecting to find him at the table; but he was not there.

“Where is Jot?” I asked Uncle Jim.

With provoking deliberation he removed his pipe from his lips saying “Gone.”

“Where has he gone?” I asked impatiently.

“Don’t know—suspect he has gone to enlist—said something about it.” And that was all I could learn—though I half suspected that uncle was keeping something back,—something he didn’t think it good for me to know.

After this I became more dissatisfied than ever, but still continued my work on the farm, expecting to have a letter from Jot. But no tidings of him came.

I constantly pestered Uncle Jim, who was made my guardian, to let me enlist. But he put me off by saying: “Time enough—wait awhile.”

Later on, uncle said to me, “I guess we shall have to sell Jack after all; I have been offered a good price for him by Colonel Walker. The interest on the mortgage is coming due this month, and I am a little short of money.”

So Jack was sold, and that made me still more discontented, and not long after I “broke out,” as Aunt Joe called it, by saying, “Uncle, I want to enlist. If I don’t enlist they will, like as not, draft me. Just think of a Stark being drafted! I am bigger than Jot, and just as good for a soldier. They will take me, and I am lonesome without Jot.”

[21]

Uncle Jim had finished his breakfast, pushed back from the table, and began smoking his pipe as was his custom after the morning meal.

I knew by his long deliberate puffs that he was thinking it over. Then with shorter puffs, he finished his smoke and I knew he had reached a decision.

“What d’ye think, Josephine? David won’t be good for anything at school or on the farm now; and it is natural for the Starks to want to serve their country when there is a war on hand. Like’s not, if we don’t give our consent he will go without it, and that would be worse for him and us too. What do you think?”

“But, Jim,” said my aunt dolefully, “We are in Sister Emily’s place. Would she consent if she were here?”

I felt that I had won over Uncle Jim, for when he said, “Well, Josephine, we will talk it over,” I knew that his mind was made up.

So the next morning at breakfast—uncle slowly and deliberately said, “Your aunt and I have been considering about giving our consent to your enlistment.” And then, after a long pause, “If you are still of the same mind, you may go. I understand that there will be a draft here—and you might have to go finally anyway—an’ to be made to do a thing isn’t pleasant, as you say, for a Stark.” So it was settled. I was to go.

[22]

A few weeks later I had enlisted in the Infantry and, with other recruits, among whom was Sam Jenkins, arrived at one of the training camps.

Its size astonished me. It was a city of barracks. Broad streets designated by letters, with each barrack numbered, stretched out in endless succession, covering hundreds of acres and miles in length and breadth.

On being assigned to barracks, we drew our “property,” including uniform, blankets, sweaters, and other equipments, usually issued to a “rookie,” besides a rifle and its belongings.

I had supposed that the life of a soldier in camp was one of comparative leisure, but there is where I made a mistake—a delusion common to the uninitiated. Our duties, or work, seemed unending. There was a rule to fit every hour of the day.

Reveille calls the rookie out of bed. Then after putting on his uniform he takes a position near the line and, at the first sergeant’s command of “Fall in” takes his place and assumes the first position of a soldier—which means, heels on the same line, toes turning outward, chest out, body thrown forward, thumbs at the seams of his trousers, legs straight, but[23] not stiff, and the weight of the body resting lightly upon the soles of his feet.

After reveille, he makes his bed, puts everything in order, then washes for breakfast, or as it is called “Mess,” after which he puts his equipments in order for drill. His rifle belts and uniform must be neat and clean as possible, or he gets a reprimand. Then comes “sick call”; then “drill call”; at which call he is expected to put everything in exact order in his quarters, then take his place in ranks for two hours’ drill.

Then comes another “Mess” call, which means fall in for dinner. After dinner there is a short rest, then comes drill call again, after which there is another short rest, during which he is expected to bathe, shave, and make himself neat, and ready for retreat—which is the dress occasion of the day. The next call is “Taps” when lights must be out.

This is, however, but simply an outline of the routine that one must follow during each day.

I, however, liked the military drill and, as Sam declared, learned it as though it was something that I was made for. But there were many petty exactions, which looked to me, as it doubtless has to every other raw soldier since the beginning, needlessly fussy; and the drill sergeant was exasperating. But there is a difference in men. Some, when invested with brief authority, have always been bullies.

But it was when I went on my first “hike” with full pack, that I thought I was killed. If there has ever been an invention, since the beginning of soldiering,[24] that has made a soldier boy regret his wealth of possessions, it is this first regular “hike.”

It was a beautiful day in July when I fell into line with others, some seasoned vessels of war—but mostly not. I had admired the pack while I was learning the minutiæ of making one, for it certainly is a wonderful invention, and the first half mile I kept up a martial air, with my sweat-provoking and back-aching pack galling me. Then I began to want a rest—and didn’t get it! The sweat ran down my face and saturated me with a sticky moisture. I fully agreed with Sam when he said, in undertone, “Isn’t it a grunter?” I certainly never knew the sweetest word in English until, at last, came the order, “Halt!” When I got through that “practice march,” I recognized that carrying a nine-pound rifle on my shoulder, and a heavy pack—however admirable the invention—was not amusing.

It was, however, not many weeks before my sturdy farmer-boy shoulders became more accustomed to the pack. Poor Sam, however, who was short and fat, for a long time persisted in his first opinion, that it was a “grunter”! He said he had heard Civil War soldiers tell of throwing away their blankets and overcoats on a march and now understood the reason of it!

Some weeks later, when I had learned the drill, and had even been complimented by a non-commissioned superior who declared that I took to soldiering “like a duck to water,” I thought there might be something in inherited qualities.

One thing, common to all new soldiers, was that I[25] suddenly found myself unexpectedly fond of home, and couldn’t hear from the folks often enough. Home never seemed to my mind quite so lovely, as now that I was away from it. I was, as may be inferred, not a little homesick.

I have forgotten to say, in its proper place, that Muddy had accompanied me from home to camp, and was hailed by my comrades as a companion worthy of the khaki with which nature had clothed him. He was soon adopted as the Company Mascot; and to a homesick boy his companionship cannot be over-estimated.

On coming to the Cantonment I had endeavored, from the first, to find Jot; but not a thing could I learn about him. To find any one in this big city was, as Sam said, “like looking for a collar button in a pasture.” It was more difficult to find a person in this great city of barracks perhaps, than in an ordinary city, because of the uniformity of its buildings and the sameness of its uniforms.

One day I had left Muddy in charge of the mess sergeant and had gone to the Y. M. C. A. to write to Uncle Jim and Aunt Joe, when the door opened, and Muddy, like a whirlwind of hair and tail, came yelping and jumping upon me.

I looked up to scold him, for dogs were not allowed there, when “Jot” stood smiling down upon me. He threw his arms around me with a big hug, and slap on the back, which I returned with interest, notwithstanding my cool New England habit of reserve.

During all this time, Muddy had been yelping and wagging both body and tail with doggish delight and[26] approval, at having brought his friends together, until the superintendent reminded us of the rules.

Then I inquired of Jot, “How did you find me?”

“I didn’t find you,” he replied, “it was Muddy.”

“Yes; but how did you find my barracks and company?”

“It was Muddy, I tell you;” he said. “I was on my way to the quartermaster’s office, when I heard a yelping and he flew like a mad dog out of one of the barracks; and yelped and whined and dragging me by my trouser leg as much as to say, ‘Come this way!’ And I understood enough of his dog talk to know that you were somewhere around here. So I followed him.”

It was not until we were on the way to the quartermaster’s that I noticed, that he wore the chevrons of a “Top Sergeant” (first sergeant) and learned that his quarters were only a short distance from mine.

How it was that Muddy knew that Jot was in the street is one of the mysteries of the dog intellect—or instinct;—for the incident is true.

Afterwards, I told Jot of the sale of Jack to Colonel Walker, and that I believed he was in the same encampment. But Jot said he had learned that he was in one of the more Southern camps—perhaps Camp Green, in North Carolina.

“Why was it,” I queried, “that you did not tell Uncle Jim or me where you were going?”

To this he replied, “Though your uncle did not tell me not to let you know that I was going to enlist, he intimated very plainly that he did not want you to[27] know. He said, ‘If David knows where you have gone, there’ll be no living with him; and he will follow you as sure as you stand there.’” I was quite angry with uncle at first, but when Jot said, “I think he did what he thought was best,” I saw, in part, an excuse for him.

Among other things that I learned, during my soldier experience, was one, that trouble is often brewing when we feel the safest. Now it was about to overtake me and my dog. I was showing off Muddy’s accomplishments one day to some dog admirers, when an officer came up and inquired: “Whose dog is that?”

“He is mine!” I proudly replied, “isn’t he a dandy, Mister?”

“You must address officers by their title, he said stiffly, and salute them.”

I had been so engaged, that I had not observed before, that he was an officer. I at once stood at attention and saluted.

He glanced at me seemingly through and through and then, as though satisfied, said, returning the salute,

“About that dog—just keep him out of sight and there will be no trouble;” and then as Muddy came fawning on him, patted him and passed on.

“That,” said one of the men, “is a West Pointer. He is as full of rules and orders as a book on tactics.”

“I guess he likes a dog, himself,” said Sergeant Bill, “or he would have ordered you to put him out of camp; for he is one of them highbrow officers that live by rule. Them West Pointers are a bundle of rules and regulations and eat blue books and general orders and such things instead of grub.”

[28]

It was shortly after the foregoing incident, that an order appeared in substance, as follows:

“After the 10th inst. all dogs, not licensed, will not be allowed in barracks, squad rooms, or mess halls.”

But as Muddy had a home license and wore a collar showing it, I was not concerned until, shortly after, there appeared the following:

“After this date, all dogs, whether licensed or not, will be turned over to the camp police.” To which some wag had added, “and thereafter will be included among the missing.” This was thought to be “rough” on those who had adopted dogs as mascots, and there were several companies that had, but as the mess sergeant said: “What can we do about it?”

I had been on guard at post one, in front of the commandant’s office, and in my distress, at the thought of losing my dog, determined on the hazardous expedient of interviewing the commandant, to get permission to keep Muddy.

So, brushing up my uniform and looking my neatest, I went to the office of that dread personage.

I passed the guard, got into the office, and when the commandant had turned from his desk where he was engaged in writing, I stood at attention and saluted. Then I saw that it was the same officer I have before mentioned as being a West Point man, but whom I did not know was the commandant.

“State your errand briefly,” he said coldly.

I was nervously stating my errand when in rushed Muddy, as though to argue his own case. I picked him[29] up for fear of what further damage he might do, and as a matter of habit with me, held in my arms.

“What is your name?” he inquired in a tone of severity that boded ill for my request.

I told him, and, in answer to other questions following, said my father was an officer during the Civil War in a Massachusetts regiment. I saw his face change from severity to interest, as he said pleasantly,

“Was your father Captain Stark of the —th Massachusetts?”

“Yes, sir,” I replied. “Did you know him there?”

“I am afraid not,” he replied, smiling for the first time; “but my father did,” and added, “They were friends.” After a pause he added, “I must grant this request to the son of my father’s friend.”

I do not know whether this incident had anything to do with a promotion which I soon after received as corporal; but I am sure it did not hinder it. And I was prouder of that promotion than any that I ever received—unless a decoration received long after from the French can be called one.

I found, however, that the duties of even this small office carried with it not a little responsibility.

Possibly I magnify the office when I say that to be a good corporal, in charge of new men, required some rare qualities. He should be icy calm, have dignity like a judge and eyes like a gimlet, and good humor in profusion; or he won’t get much work out of his men. I was on a detail shortly after my promotion, hauling provisions for the Regimental Ware House, and I couldn’t turn my head without losing a man.

[30]

When I told Jot about it he smiled and replied: “You did well not to send men after those you lost, or you would have lost more men.” And I knew by that remark, that he had once been a corporal.

[31]

Shortly after the incidents narrated in the foregoing chapter, I, with several others, among them Jot and Sam, was granted a leave of absence of fifteen days to visit our homes. This, we believed, meant that we were soon to be sent to France where, from the first, we desired to be.

When we reached the little village near our homes, we were curiously viewed by the people, who up to that time had seen little of the present day soldiers in khaki. We were hospitably treated by our people, and those who knew us gathered around to ask questions, as is the habit of New England folks.

On our arrival home, it is needless to say, we were greeted with hearty enthusiasm. Neighbors flocked in to see us, and Aunt Josie expressed her interest and love, after the usual manner of New England self-contained matrons, by a big dinner. Even Muddy was treated with affection and, for the first time in his home experience, was not considered as being “under foot” and in the way.

“How straight you are!” said Aunt Joe. “I declare I think you have grown an inch, and you were a big hulking fellow when you went away from here.”[32] Six months of military discipline had certainly left its impress upon all of us. Jot had filled out in chest and shoulders and, though not so tall and “bulking” as I, as Aunt Joe called it, was a fine-looking soldierly youth, lithe and active. Even Sam’s rather rotund form, was reduced to soldierly proportions.

“Gosh!” said his father anxiously, “you ain’t got any belly hardly at all. Hev’ they been starvin’ you?”

“No, Dad, we have all we want to eat in camp, and we have the wust kind of appetite after one o’ them drills. I guess you don’t know what they do to a feller down here to take the fat off him and the kinks out of him?”

“Yes, I do, Sam,” responded his father; “guess I’ve been trained a lot myself.”

“Did y’ ever go through the settin’ up drill?” asked Sam.

“Yes, Sam, I have set up nights a lot, but I never had to drill it. I got sort of used to it when I was courtin’.”

“I guess, Dad, you don’t understand; now I will give the orders and drill you.” And then Sam put his father through enough of the physical exercise to show him what he meant and until Uncle Jim smiled to see him puff.

The months of drill had certainly improved us physically. The difference between slouching country boys and soldierly youth, was written all over each of us.

Muddy, too, had his receptions; and even Bill[33] Jenkins who was again working on the farm, said: “Well, he’s a pretty good dog, and will do well enough now that he’s been trained.”

My aunt was a proud woman when she took Jot and me to church with her, and introduced us to the new minister. The old church where my mother and father had worshipped was filled, and we were greeted on every side by friendly people, especially by the teachers and members of the Sunday School to which Jot and I had been constant attendants when at home.

One of the young ladies of the class was Miss Emily Grant, of whom, in former times, I had been an ardent, though shy admirer. She introduced both Jot and me to a visiting friend, Miss Rose Rich, whom she had brought home with her from a Massachusetts boarding school.

Jot, usually so reticent, showed his approval of her, by saying: “Isn’t she fine? Her father is a doctor and she is going to take up Red Cross work.”

The friendliness of the two was observable to others besides myself. Miss Grant said to me, “Rose seems much taken with your friend.”

“He is the smartest noncommissioned officer,” I replied, “in the training camp. He’s top sergeant, and that means something, I can tell you.”

I told Uncle Jim about Colonel Burbank and what he said about my father. And Uncle Jim said, “Seems to me I heard your father mention him. I wonder if it was him that your father brought from between the lines badly wounded durin’ the Winchester fight? Shouldn’t wonder if it was.”

[34]

But I had never heard about it.

When Jot and I had visited, for the last time, the familiar scenes of the farm, and he had petted and talked to the horses and cows, we left our home for the camp again. A boy never realizes what a home means to him until he is leaving it, possibly forever; for I had a dim perception of what was possibly before me.

Several friends, besides my aunt and uncle, were at the station to bid us good-bye. Among them were Emily Grant and Rose Rich.

With the usual leave takings and waving of handkerchiefs from friends, the engine puffed, the train clanked out from the station, and we were off.

Back at camp we entered upon another course of training in company, regimental and battalion drill, with bayonet exercises, machine-gun fire, and the digging of trenches, as a preliminary to participation in modern warfare.

An old Civil War veteran, who had viewed our preparations, said to me, “If Grant had had these machine guns and other arms, he could have made the Rebs howl and ended the war in short order. Why, there is as great a difference between the equipments of this new army and our old Union Army as there is between a stage coach and an express train.”

Jot had been transferred to our regiment, at his request, and became first sergeant of a company. At one of our meetings at the Y. M. C. A. he said to me, “Don’t say anything about it, but I think that we are likely to break camp soon and go to France.”

“What makes you think so?” I asked.

[35]

“Well,” he said, “they have been making shipping lists for the regiment; and then the furloughs they have been giving, and other little things make me think so.”

I soon found that a rumor of the same purport was all around camp. Like most youngsters, I was hungry for a change; so when the top sergeant ordered us to be ready to move within a few hours, I was glad at the prospect of the change to some other place. Yet I thought of submarines and other scarey unpleasant possibilities, that night, before I slept.

The order came at last—it was on Sunday—for an army has no days more sacred than duty. Though we were not supposed to know where we were going, we all guessed—the Yankee birthright—and guessed France. Our outfit consisted of two suits of Olive Drab, canvas leggins, two woolen shirts, woolen underwear and stockings, two pairs of garrison shoes, a Mackinaw short overcoat, a belt, three blankets, and a comforter, all of which were carried in our packs. On top of the pack roll was the haversack, containing our kits, which consisted of a long handled aluminum fold pan with removable cover, in which were a knife and fork and spoon; two oblong cases for meat, hard bread, sugar and coffee. The ammunition belt was hung to this pack, and a canteen nesting in the cup hung from it. There was also a barrack bag belonging to our outfits, but this was carried by motor truck to the station.

This I remember to my sorrow, as did others in similar cases, for I did not see it again until our arrival in France, though it contained goodies from home, and[36] chocolates. Others did not see their cigarettes and tobacco again until long after.

At dark, with our packs strapped upon our backs, we moved to the station and were embarked on board of ordinary passenger cars—a noncommissioned officer at the doors of each car to see that none went out and that no one not belonging there went in. Each commissioned officer had a list that showed the place of each man and saw that he stayed there.

The next morning we found our train at a big New York terminal, and had our breakfast—of sandwiches and hot coffee that had been prepared for us the day before.

From there we were embarked on a ferry boat. Our company was on the top deck where we could see the tugs, steamers and ferry boats, busily moving on the stream, as we swung up the broad Hudson to the piers where several big transports lay.

Sailing lists of every man’s name in order of formation had been made in duplicate, one for our officers and another in the hands of the embarking officer. So he knew just how many of us there were, and had already designated a berth for each man.

The railroad transport officer met us with the inquiry: “Is Company —— of —— Regiment on this boat?”

“Yes, sir!”

“Colonel Burbank?”

“Here, sir!”

“Good. Disembark at once, sir. Your transport sails in half an hour. Form your men on the dock opposite the freight clerk.”

[37]

“Yes, sir!”

“A loading detail of ten men!”

“Yes, sir!”

We disembark; but before the first company could be formed a transportation officer without saying by your leave marched us on board. He is the supreme officer on the dock—no matter if the general commanding be present the officer is the boss.

Along the deck we went in column and on board the huge transport.

“Your sailing list, sir!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Are you formed in order of list?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good! Load the company, Mr. Blank.”

The clerk, with a lieutenant by his side with a duplicate list, calls out, “First Sergeant Smith.”

“Here, sir.”

The sergeant is handed a ticket, goes up the gangplank where he meets another sailor who sends him below; there he meets another sailor who sends him still further below, and so on until he is at the bottom of the ship where the bilge water smells. The others follow until the ship is stowed with a human freight of three thousand five hundred men.

Every man has his bunk of collapsible iron tubing which stand in tiers three high, with a passage way between. Later on, the top sergeant gets a second class room. No dogs allowed; but I smuggled Muddy in under my big coat.

We were all on board by night, and slept in our new[38] quarters, but were surprised to awake in the morning and find our ship still at the dock. We were allowed to go ashore for exercise on the dock, and the ship routine began. Our canteens were ordered to be filled but not to be used except in an emergency.

Before daylight, next morning, we swung out into the river and down into the broadening harbor, to the sea. We were all allowed on deck. As I stood viewing the scene on every side, of brilliantly lighted cities and towns, Jot came up, touched me on the shoulder and, with a sweep of his hand, said, “Don’t it put you in mind of that verse in the Bible,—‘Gazar and her towns and villages, unto the river of Egypt and the great sea and the border thereof?’” Then, as we waved an adieu to the Statue of Liberty he added, “We are the vanguard of the army to make good the meaning of that Statue that France has prophetically placed there. We go to deliver France and the world.”

The land began to fade as daylight brightened. The broad sea spread out before us and with it a possible broader vista of life’s great drama and of the freedom of men as yet unborn, whose destinies we were perhaps carrying across the sea.

The naval officers were in supreme command of all on board and we soldiers were put to ship routine at once.

“It looks to me,” said Sergeant Nickerson, “like a huge job to feed all of us in this one dining room.”

“But it isn’t our business,” I replied, “so long as we get the grub.”

“But it may be everybody’s business if they don’t[39] get it; and that’s what I am thinking about.” The difficulty was solved in this way. The men were marched to the room, and ate standing in line or at long tables. As fast as one batch was fed, another took its place. By the time breakfast was over, lunch began. It was a sort of endless chain made up of men, moving on schedule time.

Men began to growl—growling is a soldier’s safety valve, and his privilege ever since soldiering first began.

“Sure,” said Pat Quinn, “it’s ating tactics we are being drilled in. Ye’s open ye’s mouths so many toimes and then swallow—one toime and three motions!”

“What are you growling about?” said Private Shaw. “There’ll likely be another motion on this ship soon, so that you can’t swallow at all!”

So with rough jokes and gibes we ate our first breakfast on board ship. Then ship drill began. Each man was assigned to a boat or raft, and we learned the ship calls. When the bugle sounded “Assembly” every man was to go on deck and take his place at his boat or raft. At “Abandon Ship,” the boats and rafts were supposed to be got into the water. “Quarters” meant every man below, to his bunk.

We go through the motions—only—of getting the boats and rafts over the side of the ship. When our instructor said that a raft was safer than a boat, but that we were never to climb onto one, but hang on with both hands, we were skeptical about it.

“He wants to keep a boat for himself,” said Sam. “That is what he is preaching it for.”

[40]

We knew, however, that the safety of all on board might depend upon our efficiency at this drill.

With boat drill—mornings and afternoons—scrubbing decks, eating, and seasickness, our time was pretty fully occupied. I was dreadfully sick for a time, and did not care whether a submarine sunk us or not, but got over it before long. It was very close below decks, where we were mostly confined, and a hardship to those accustomed to the free air.

Our company was so fortunate as to be detailed as extra deck watch, and a group of us were on duty at all hours, day and night. It was an autocratic job—we were “It.” We could refuse to take orders or answer questions from even the colonel! Our post for this duty was a little box of a pen where, with fine binoculars, we kept watch for submarines. I liked the duty; it was a change and much like guard duty.

Before entering the danger zone we got detailed instructions against lights. Every match and flashlight on the ship had to be given up, and all hatches were closed at twilight. Even illuminated wrist watches were forbidden on deck at night.

One day a submarine was actually sighted. I was on duty in the watch box with several of my company, when I saw something sticking out of the water like a small flag staff.

“Submarine!” I yelled excitedly. Just then “bang!” went the forward deck gun and the periscope disappeared. Soon it was seen again at another quarter and another gun banged at it. Sam took up his rifle to shoot at it, but was restrained, though he[41] declared he could put a bullet through it. Then “bang” went another of our guns, and we were told that she was sunk, but I doubted it.

“Shucks!” growled Sam, “how can we shoot a Boche if we have to wait for orders? He will get away from us, before we can get them!”

There was no excitement, though a young lieutenant rushed around saying, “Be calm, men! be calm!” But some of us thought he was not living up to his own orders.

Soon after this Colonel Burbank sent for me to come to his cabin. After several kind inquiries about my folks, especially my father, he said, casually, “Sergeant Nickerson, I learn, has lived at your home? What do you know about him or his people?”

I told him all that I knew about him, and said, among other things, that he had told my mother that Nickerson was only a part of his name. And I interspersed with this information not a little praise of Jot, to camouflage the fact that I didn’t actually know much about him.

The purpose of these inquiries the colonel did not, of course, reveal. I was not a little surprised, however, when he said: “He looks like a German officer I once knew. I infer, from what you have told me, that he does not talk much about himself or his business. It’s a very soldierly quality!”

As I went to my quarters below decks this remark was buzzing in my head like a bumble bee in a haying field. As the colonel had not instructed me to the contrary, I informed Jot, when I again saw him, about[42] the colonel’s remarks—all except the last one, about the German officer.

Jot stood for a moment, as though in thought, and then said, “It will do no harm to tell you that I can speak a little German which I learned from my father and his people. The first words I ever spoke were German; but mother didn’t like it.” Here he stopped as though he had already said too much, then, putting his hands affectionately on my shoulders, added, “Does it really make any difference to you, David, who my father was, when you know me so well?” And I knew that it would be useless to ask him further questions on that subject.

We soon began to meet ships and fishing craft, mine sweepers, and tankers, which showed that we were nearing the coast. Next came a point of land like a cloud on the horizon, and then the top of a lighthouse appeared.

Was it France or England? It was France.

We learned that we were the first American transport to land at this port.

Entering a narrow channel which widened out into a broad harbor, we were safe in France!

“No one lands until ordered to do so by the commander of the port,” was the next order.

It was not until the next day that the colonel, and some other officers were ordered ashore to see the port commodore; then, after some more waiting, we were told to get ready for landing. Shortly after, we saw the lighters coming up on which we were to disembark.

[43]

Our first view of the land we had come to rescue was not prepossessing. Some men were standing on the sidewalks, as we marched through the narrow street ankle deep in mud.

“Are we in France, or in the mud?” facetiously queried one soldier. As we marched through the narrow streets there was much cheering—not like American cheers, long drawn out, but sharp and not all together. There were some personal allusions in English.

“I give you a kees;” said a girl. “You big fine Americans!”

The salutations were as unlike our home calls as were the city and its buildings. The buildings were crowded together as though land were scarce, they were of stone with carvings and copper ornaments, which even the soldier would notice, they were so fine.

We wanted to break loose and see France and talk to the people, but discipline held us in line. To men who had been confined for three weeks in narrow, stifling ship quarters, the air was invigorating.

We reached the station on schedule time, and were embarked on third class cars, a squad of eight men to a[44] compartment. No dogs were allowed, but I got Muddy in all the same, the guard taking pains not to see him.

To Americans, accustomed to our large coaches, these little box-like cars seemed like toys.

“Sho!” said Sam, “do they intend to give us one apiece? They are like baby carriages!”

They were, however, fairly comfortable, but after jolting along for several hours, when the train stopped, naturally every one wanted to get out. Our officers had a full-sized man’s job to get them back again on time.

Peter Beaudett, a French Canadian Yankee, protested, “I was saying something to a fine leetle girl; she speak de French to me.”

Then we steamed on again, and after some hours we stopped at a station for hot coffee, then rode all night.

“I didn’t suppose,” said Sam Jenkins, “that France was big enough for so much travel.”

At last we stopped, and were told that we had reached our destination.

We had reached the “Base Station,” or “Rest Camp,” and went into quarters. They consisted of low, one-story, portable barracks, lightly built with dirt floors, white oiled cotton cloth for windows, and with wooden cots similar to those in our home barracks. Though not as luxurious by a big sight, they were comfortable. It was one of several similar camps on the outskirts of an inland historic city.

We took our ease for a few days, slept, ate, and[45] visited the town when we could get a pass. None was allowed out of our well-guarded camp without one, and all must return at 9.30 P. M. or be punished. Then we began the routine of drill again, with French officers to teach us the new methods of fighting, such as bomb throwing and trench duty.

At retreat one afternoon we were informed that we were to be reviewed the next day. So after mess we shaved, bathed, brushed up our equipments and uniforms with unusual care, and with a French regiment for escort, marched and countermarched, with the stars and stripes flying and bands playing; and then marched some more!

The contrast between the French escort and our men was great. The French were different in many ways, some of them impossible to express in words. They were of inferior stature, many of them being not over five feet, two inches, and by contrast our men seemed giants. Their step was quick and brisk, while the strides of the Americans was a long, swinging stride, the step of men accustomed to hills and rough land, not that of good roads and pavements.

We were greeted heartily by the crowds of people gathered on the sidewalks and at the windows of the buildings. Cries of “vive les Amerique!” and other calls, that I did not comprehend, were heard. Flowers were thrown at us. But there were no long-drawn-out cheers such as we were accustomed to hear at home on similar occasions. After much marching and parading there came the order:

“Halt! Right dress! Front! Present arms!”

[46]

We were being reviewed by that great French soldier who, when the German hordes were marching on Paris, threw himself like a lion in their path and turned the current of the battle, General Pétain.

Some of us had read of him and looked with intense interest at this soldier of France. He was an erect martial figure, a little stout; with eyes keen, steady and penetrating, a white mustache, all the whiter by contrast with the darkening tan that told of long service in the field. No one could mistake him for other than a soldier; he bore that undefinable stamp of long service, discipline, and command of men.

Then we passed in review with our wagon trains, cannon, and machine guns, the people cheering in their way, and showering us with wreaths and flowers.

Even our mules, because they were American, came in for a share of attention. One fractious animal, that on account of bad conduct had been taken from a baggage wagon, drew attention by standing on his front feet and waving his hind legs and tail in the upper air, as though trying to make holes in the sky, and paint his displeasure with his tail. He was saluted with applause and laughter.

One thing was preeminently seen, we American soldiers held the hearts and minds of all. Later in camp we came to know more of our hosts.

The enlisted man has this advantage of his officers in learning to speak a language. He is not kept from trying to speak, by fear of making mistakes. He blunders on, and at last makes himself understood, though he makes fearful mistakes.

[47]

I was not long in the camp before I was hailed by a poilu who spoke the “American language.” He greeted me by saying, “How is little old New York?” He told me that he had lived there, but had come back when the war started to fight for his country.

One day while I was writing a letter to the home folks, with Muddy lying by my side, Jot, accompanied by a woman, the English-speaking poilu, and with a little girl in his arms, came to me saying:

“Dave, I want to show the dog to this baby and its mother.” So Muddy was put through his cunning tricks, and was played with and petted to his doggish heart’s delight.

At this time I was in my eighteenth year—broad shouldered, and five feet eleven and one-half inches in height. My uniform emphasized my stalwart form, now filled out and straightened by military training. Though I was never considered a big man at home, I felt myself, by the side of the smaller French soldiers, somewhat of a giant.

I stood up and saluted the little sad-faced woman and the “poilu”, and heard, or rather saw that she had asked some question about me.

“What is it she is saying?” I inquired.

“She wants to know,” replied the poilu, “if I knew the blond giant in America. Our people don’t know what a big country America is. They think it mostly New York city. You Americans are taller than our people but,” he added proudly, “my countrymen are big in courage and spirit.”

I remarked upon the large number of women who[48] wore long crepe veils, when he replied, “Yes; there are many in mourning for their dead. This little woman had already lost two sons in this war, and has just now got word that her only remaining son had been killed in battle.”

“She is not crying,” I said.

“No,” he replied. “Her loss is too deep for tears, and she is consoled by knowing that she has given them to France.”

“Express to her my sympathy,” I said, and Jot added, “Tell her that we are very sorry indeed for her.”

Then seeing that she had made some reply, we asked what she had said.

“She said: ‘God gave them to me, and I have given them to France.’”

While this conversation was going on, a man came up and stood apparently intent on watching the child and dog, and seeming to give no attention to our talk. Then touching Jot on the shoulder and drawing him out of hearing, he began to talk to him, as though trying to get his consent to some proposal, and then moved away with him towards the colonel’s quarters in a nearby château. He looked to me like the same man I had seen talking to Jot at home when the horse trader visited us. I wondered at this, for Jot was not given to making chance acquaintances. Then I saw them disappear in the large house where the colonel had his quarters.

After undergoing intensive training for several weeks, we were thought fit to receive more practical[49] and strenuous duties and practice, by being moved to real war trenches within reach of the guns of the enemy.

We in the ranks knew that something was up. The Eagle (colonel) had summoned our Skipper (captain), a clerk had copied a list of names that had been given him, and now all the officers were in with the eagle. The supply sergeant was already nailing up boxes, and the mess sergeant had been heard to say:

“I can’t see how the oven can be moved again”—all of which were signs to any soldier that our regiment was about to “pull out.”

We were all on tiptoe when the order came.

Every man whose shoes did not fit him got a chance to change them. Then a list of promotions was published and, to my surprise and pleasure, I was promoted to be a sergeant in place of one reduced. I was assigned to a loading detail by the top, and with nineteen men went to the quartermaster’s depot with an auto, and loaded up with ten days’ traveling rations, and hauled them to the depot. By ten o’clock the barrack bags came down, seven days’ rations were put in a freight car, and three laid out on the platform.

All was ready, and after dark the companies marched down to the station to entrain. I fell in line in my place on the platform with the rest. Then the mess sergeant and cooks dealt out enough “chow” (rations) for the corporals, so that each man had for his squad a can of beans, two cans of Willy (corn beef), and four packages of hard bread, and a can of jam.

[50]

“It has got to last you three days,” cautioned the mess sergeant; “so go easy on it.”

The top came along and checked every squad as it embarked. The officers shook hands with the railroad transportation officer and, together with the French interpreter, climbed aboard.

They were little box cars, and painted on the outside “32 hommes, 8 cheveaux.” There were portable benches at each end and a good lot of straw.

“Sure,” said Pat who was in my car, “it is comfortable enough for a pig.”

“Aw!” rejoined Shaw, “Cheveaux means horses, you wild Irishman!”

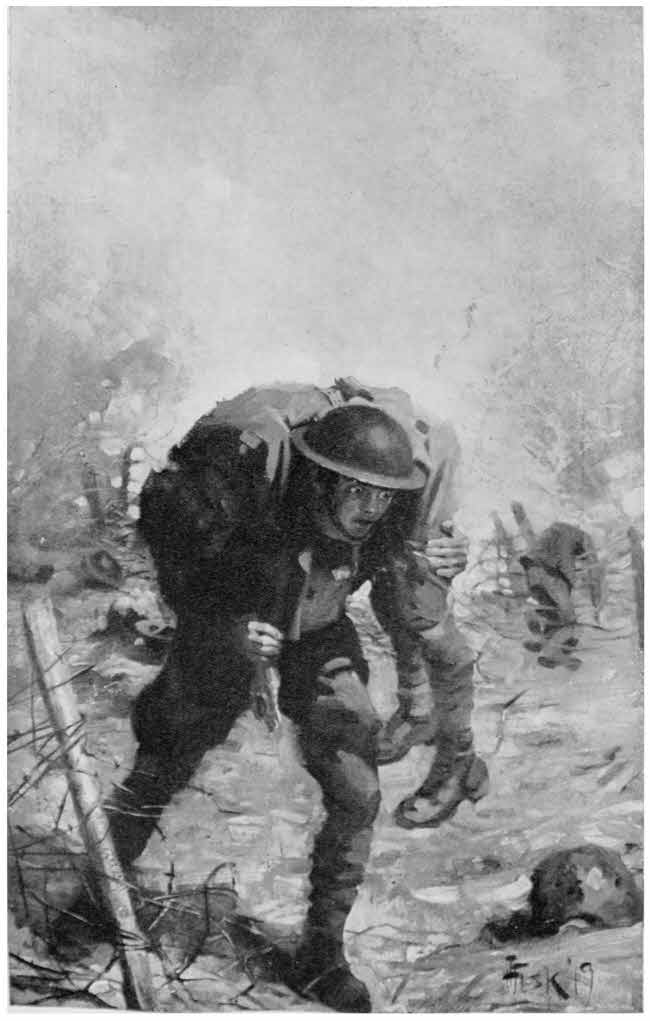

“AW!” REJOINED SHAW, “CHEVEAUX MEANS HORSES, YOU WILD IRISHMAN!”—Page 50.

Then we settled into the car; rifles in place, kits hung up on the sides, a lantern swung in the center. We were, despite all the growling, very comfortable. There was a seat for every man. All voted that it beat third class cars.

We reached a coffee station, and lined up outside the car in double ranks, and each man got a cup full of French coffee. Then came an all night ride. The men took off their boots and, with a haversack for a pillow, slept snug as bugs in a rug.

I slept, sitting up, with my back against the door, querying to myself if the buck private’s job was not easier than that of a sergeant. And I thought, possibly the skipper himself did not have so easy a time as I had sometimes thought.

The scenery was beautiful. We followed the course of a river. On the banks were old castles, beautiful châteaus, villages with red topped roofs, and always stone bridges.

[51]

“Say, boys!” exclaimed Sam, “we would have to pay big money for this sight seeing excursion, before the war.”

It was getting so interesting that we forgot to eat.

“Where are we going, Sergeant?”

“Don’t know.”

“How long will it take to get there?” inquired another inquisitive Yankee.

“Don’t know,” I replied, “there are three days’ rations on board, and seven in a freight car.”

“Don’t the skipper or eagle know?”

“Guess not; we are travelling on confidential orders; perhaps the eagle does know.”

So on through France we travelled, to heaven knows where!

At last we halted at a small station. An officer met us and inquired for the commanding officer. The train pulled in to a high platform, where we unloaded. We had reached the limits of our railroad travel. It was dark, and we were tired and hungry, with prospects of cold grub for supper.

We were assigned to billets by an American officer—stables, barns, stores and lofts. Some big galvanized cans of hot coffee were sent us by the officer of an American regiment already established.

“Thanks!” I heard the colonel say. “I hope to return the compliment some time.”

“You can return the coffee out of your ration tomorrow; it is the rule here to help each other.”

The most expressive part of our location was that for the first time, we were within sound of guns. We[52] heard a dull boom! boom! and at times thought we heard the sharper sound of rifles. We were near the front at last, and were to get practical experiences in the trenches, further to fit us for the grim duties of soldiering.

[53]

I, with others, was billeted in a house and barn tenanted by a little French woman with a brood of several young children, whose husband was fighting for France. Others were billeted, by the town major, in warehouses, lofts, and other places.

After a few days’ rest in our billets, we were marched to the trenches.

The American front in France at this time, so far as there was any front, was in Lorraine. In reality there was no American front, because our army had not had the training to hold one. While we had received the drill of ordinary soldiering, we lacked experience in the prevailing war methods then in use.

While my regiment is marching forward to take up trench duties in front of the enemy’s lines, let us take a look at what constitutes that part of a modern army known as an infantry regiment; for infantry is the body and mainstay of an army.