DRAWING COVER

Title: The Handy Horse-book

Author: Maurice Hartland Mahon

Release date: August 21, 2020 [eBook #62993]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE

HANDY HORSE-BOOK

OPINIONS OF THE PRESS.

“Most certainly the above title is no misnomer, for the ‘Handy Horse-Book’ is a manual of driving, riding, and the general care and management of horses, evidently the work of no unskilled hand.”—Bell’s Life.

“As cavalry officer, hunting horseman, coach proprietor, whip, and steeplechase rider, the author has had long and various experience in the management of horses, and he now gives us the cream of his information in a little volume, which will be to horse-keepers and horse-buyers all that the ‘Handy Book on Property Law,’ by Lord St Leonards, has for years past been to men of business. It does not profess to teach the horse-keeper everything that concerns the beast that is one of the most delicate as well as the noblest of animals; but it supplies him with a number of valuable facts, and puts him in possession of leading principles.”—Athenæum.

“The writer shows a thorough knowledge of his subject, and he fully carries out the object for which he professes to have undertaken his task—namely, to render horse-proprietors independent of the dictations of ignorant farriers and grooms.”—Observer.

“We need only say that the work is essentially a multum in parvo, and that a book more practically useful, or that was more required, could not have possibly been written.”—Irish Times.

“He propounds no theories, but embodies in simple and untechnical language what he has learned practically; and a perusal of the volume will at once testify that he is fully qualified for the task; and so skilfully is the matter condensed that there is scarcely a single sentence which does not convey sound and valuable information.”—Sporting Gazette.

“We can cordially recommend it as a book especially suited to the general public, and not beneath the attention of ‘practical men.’”—The Globe.

“Contains a very great modicum of information in an exceedingly small space.... There can be little doubt that it will, when generally known, become the established vade mecum of the fox-hunter, the country squire, and the trainer.”—Army and Navy Gazette.

“A useful little work.... In the first part he gives just the amount of information that will enable a man to work his horse comfortably, check his groom, and generally know what he is about when riding, driving, or choosing gear.”—Spectator.

“This is a book to be read and re-read by all who take an interest in the noble animal, as it contains a most comprehensive view of everything appertaining to horse-flesh; and is, moreover, as fit for the library and drawing-room as it is for the mess-table or the harness-room.”—Sporting Magazine.

“By all means buy the book; it will repay the outlay.”—Land and Water.

DRAWING COVER

THE

HANDY HORSE-BOOK

OR

PRACTICAL INSTRUCTIONS IN DRIVING, RIDING,

AND THE GENERAL CARE AND

MANAGEMENT OF HORSES

BY

A CAVALRY OFFICER

FOURTH EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED

With Engravings

WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

MDCCCLXVIII

The Right of Translation is reserved

TO

MAJOR-GENERAL LORD GEORGE PAGET, C.B.

Inspector-General of Cavalry,

SON OF THE DISTINGUISHED HORSEMAN AND HERO WHO COMMANDED THE CAVALRY AT WATERLOO, AND HIMSELF A LEADER AMONG THE “IMMORTAL SIX HUNDRED,”

THIS BOOK IS BY PERMISSION INSCRIBED,

IN TRIBUTE TO HIS SOLDIERLY QUALITIES, AND TO HIS CONSIDERATION FOR THE NOBLE ANIMAL WHICH HAS CARRIED THE BRITISH CAVALRY THROUGH SO MANY DANGERS TO SO MANY TRIUMPHS,

BY HIS LORDSHIP’S OBEDIENT SERVANT,

“MAGENTA.”

Finding myself a standing reference among my friends and acquaintance on matters relating to horse-flesh, and being constantly in the habit of giving them advice verbally and by letter, I have been induced to comply with repeated suggestions to commit my knowledge to paper, in the shape of a Treatise or Manual.

When I say that my experience has been practically tested on the road, in the field, on the turf (having been formerly a steeplechase rider, as well as now a hunting horseman), with the ribbons, and in a cavalry regiment, I must consider that, with an ardent taste for everything belonging to horses thus nourished for years, I must either have sadly neglected my opportunities, or have[viii] picked up some knowledge of the use and treatment of the animal in question.[1]

Born and bred, I may say, in constant familiarity with a racing-stable, and having been always devotedly attached to horses, the wrongs of those noble animals have been prominently before my eyes, and I have felt an anxious desire to see justice done to them, which, I am sorry to say, according to my observation, is but too seldom the case; indeed, I have often marvelled at the tractability of those powerful creatures under the most perverted treatment by their riders and drivers.

My object, therefore, in offering the following remarks, is not to trench upon the sphere of the professional veterinary surgeon or riding-master, but to render horse-proprietors independent of the dictation of ignorant farriers and grooms. Intending this little work merely as a useful manual, I have purposely avoided technicalities, as belonging exclusively to the professional man, and endeavoured to present my dissertations on disease in the most comprehensive terms possible, proposing only simple remedies as far as they go; though, for the satisfaction of my readers, I may mention that, as an amateur, I have myself devoted much time and thought to the study of anatomy, and that any treatment of disease herein recommended has been carefully perused and approved by a veterinary surgeon. Theories are excluded, and I confine myself simply to practical rules founded on my own experience.

Hints and remarks are here offered to the general public, which, to practical men, will appear trifling and unnecessary; but keen and extended observation, carried on as opportunity offered, amongst all classes and in many countries and climates, has given me an insight into the want of reasoning[x] exhibited by men of every station in dealing with the noble and willing inmates of the stable, and has assisted in suggesting the necessity for just such A B C instructions as are herein presented by the Public’s very humble servant,

“MAGENTA.”[2]

Increased attention having been directed to the necessity for greater vigilance with regard to the breeding and production of good and useful horses, many readers have expressed a wish that I would give some decided views on these subjects; and concurring with them as to the exigency of the case, I have ventured, in an additional chapter in this new and Third Edition, to make a few remarks, which, although doubtless patent to practical men, are naturally looked for by the public in this Manual, which has been so favourably received.

“MAGENTA.”

The Third Edition of this little work, published so recently as April last, being already out of print, the Author, in presenting a new one, feels called upon gratefully to acknowledge this unusual mark of favour on the part of the public.

London, November 1867.

| PAGE | |

| PART I. | |

| BREEDING, | 1 |

| SELECTING, | 2 |

| BUYING, | 6 |

| STABLING, | 8 |

| GROOMING, | 12 |

| HALTERING, | 16 |

| CLOTHING, | 18 |

| FEEDING, | 20 |

| WATERING, | 25 |

| GRAZING, | 26 |

| TRAINING, | 28 |

| EXERCISING, | 31 |

| WORK, | 33 |

| BRIDLING, | 38 |

| SADDLING, | 43 |

| RIDING, | 49 |

| HARNESSING, | 56 |

| DRIVING, | 65 |

| DRAWING, | 72[xiv] |

| SHOEING, | 75 |

| VICE, | 84 |

| SELLING, | 89 |

| CAPRICE, | 90 |

| IRISH HUNTERS, AND THE BREEDING OF GOOD HORSES, | 93 |

| PART II. | |

| DISEASES, | 101 |

| OPERATIONS, | 102 |

| TO GIVE A BALL, | 104 |

| TO GIVE A DRENCH, | 105 |

| PURGING, | 106 |

| THE PULSE, | 109 |

| DISEASES OF THE HEAD AND RESPIRATORY ORGANS, | 109 |

| DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE AND URINARY ORGANS, | 120 |

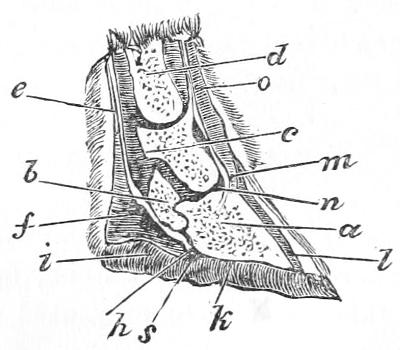

| DISEASES OF THE FEET AND LEGS, | 127 |

| LOTIONS, PURGES, BLISTERS, ETC., | 158 |

| INDEX, | 164 |

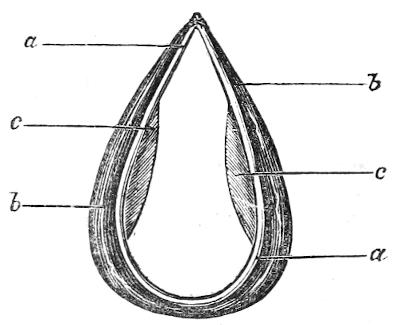

| DRAWING COVER, | frontispiece. | |

| THE HACK, | page | 4 |

| THE WEIGHT-CARRYING HUNTER, | ” | 6 |

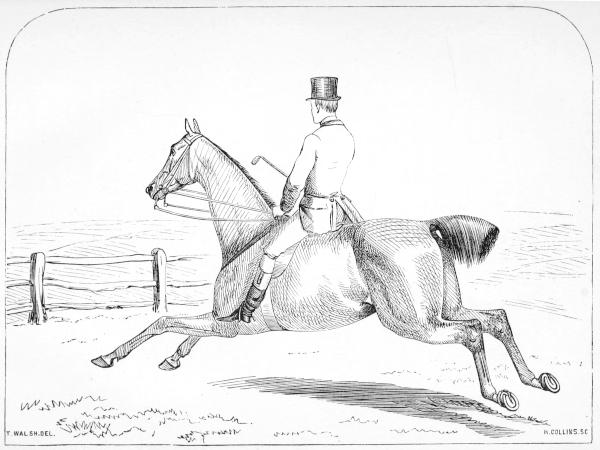

| RIDING AT IT, | ” | 53 |

| THE PROPER FORM, | ” | 95 |

| PREPARATORY CANTER, | ” | 99 |

A few words only of observation would I make on this subject.[3] Palpably our horses, especially racers and hunters, are degenerating in size and power, owing mainly, it is to be feared, to the parents being selected more for the reputation they have gained as winners carrying feather-weights, than for any symmetrical development or evidence of enduring power under the weight of a man. We English might take a useful lesson in selecting parental stock from the French, who reject our theory of breeding from animals simply because they have reputation in the racing calendars, and who breed from none but those which have shape and power, as well as blood and performance, to recommend them. They are also particular to avoid using for stud purposes such animals as may exhibit indications of any constitutional unsoundness.

In selecting an animal, the character of the work for which he is required should be taken into consideration. For example, in choosing a hack, you will consider whether he is for riding or for draught. In choosing a hunter, you must bear in mind the peculiar nature of the country he will have to contend with.

A horse should at all times have sufficient size and power for the weight he has to move. It is an act of cruelty to put a small horse, be his courage and breeding ever so good, to carry a heavy man or draw a heavy load. With regard to colour, some sportsmen say, and with truth, that “a good horse can’t be a bad colour, no matter what his shade.” Objection may, however, be reasonably made to pie-balls, skew-balls, or cream-colour, as being too conspicuous,—moreover, first-class animals of these shades are rare; nor are the roan or mouse-coloured ones as much prized as they should be.

Bay, brown, or dark chestnuts,[4] black or grey horses, are about the most successful competitors in the market, and may be preferred in the order in which they are here enumerated. Very light chestnut, bay, and white horses are said to be irritable in temper and delicate in constitution.[5]

Mares are objected to by some as being occasionally uncertain in temper and vigour, and at times unsafe in harness, from constitutional irritation. More importance is attached to these assumed drawbacks than they deserve; and though the price of the male is generally from one-fourth to one-sixth more than that of the female, the latter will be found to get through ordinary work quite as well as the former.

To judge of the Age by the Teeth.—The permanent nippers, or front teeth, in the lower jaw, are six. The two front teeth are cut and placed at from two to three years of age; the next pair, at each side of the middle ones, at from three and a half to four; and the corner pair between four and a half and five years of age, when the tusks in the male are also produced.

The marks or cavities in these nippers are effaced in the following order:—At six years old they are worn out in the two centre teeth, at seven in the next pair, and at eight in the corner ones, when the horse is described as “aged.”

After this, as age advances, these nippers appear to change gradually year by year from an oval to a more detached and triangular form, till at twenty their appearance is completely triangular. After six the tusks become each year more blunt, and the grooves, which at that age are visible inside, gradually wear out.

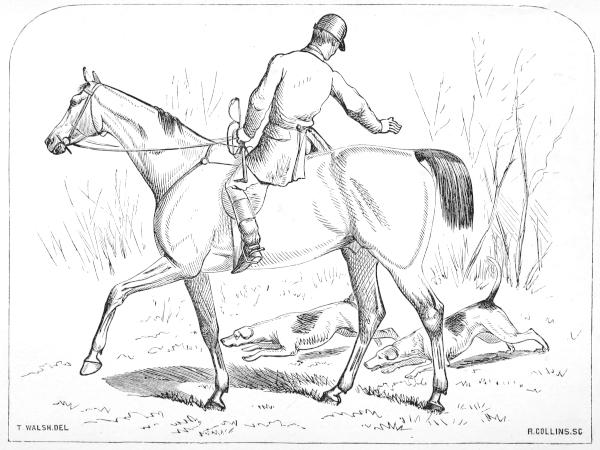

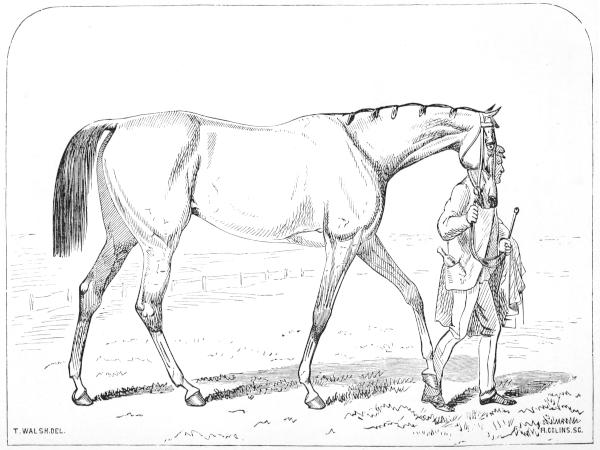

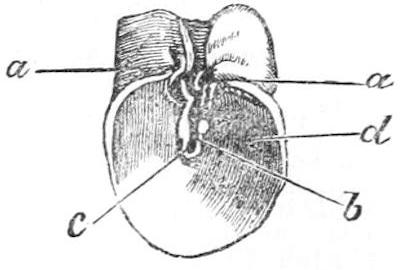

The Hack to Ride.—A horse with a small well-shaped head seldom proves to be a bad one; therefore such, with small fine ears, should be sought in the first instance.

It is particularly desirable that the shoulder of a riding hack should be light and well-placed. A high-withered[4] horse is by no means the best for that purpose. Let the shoulder-blades be well slanted as the horse stands, their points light in front towards the chest. Nor should there be too wide a front; for such width, though well enough for draught, is not necessary in a riding-horse, provided the chest and girth be deep.

As a matter of course the animal should be otherwise well formed, with rather long pasterns (before but not behind),—the length of which increases the elasticity of his movement on hard roads. His action should be independent and high, bending the knees. If he cannot walk well—in fact, with action so light that, as the dealers say, “he’d hardly break an egg if he trod on it”—raising his legs briskly off the ground, when simply led by the halter (giving him his head)—in other words, if he walks “close to the ground”—he should be at once rejected.

With regard to the other paces, different riders have different fancies: the trot and walk I consider to be the only important paces for a gentleman’s ordinary riding-horse. It is very material, in selecting a riding-horse, to observe how he holds his head in his various paces; and to judge of this the intending purchaser should remark closely how he works on the bit when ridden by the rough-rider, and he should also pay particular attention to this point when he is himself on his back, before selection is made.[6]

THE HACK

Respecting soundness, though feeling fully competent myself to judge of the matter, I consider the half-guinea fee to a veterinary surgeon well-laid-out money, to obtain his professional opinion and a certificate of the state of an animal, when purchasing a horse of any value.

The Hack for Draught ought to be as well formed as the one just described; but a much heavier shoulder and forehand altogether are admissible.

No one should ever for a moment think of putting any harness-horse into a private vehicle, no matter what his seller’s recommendation, without first having him out in a single or double break, as the case may be, and seeing him driven, as well as driving him himself, to make acquaintance with the animal—in fact, to find him out.

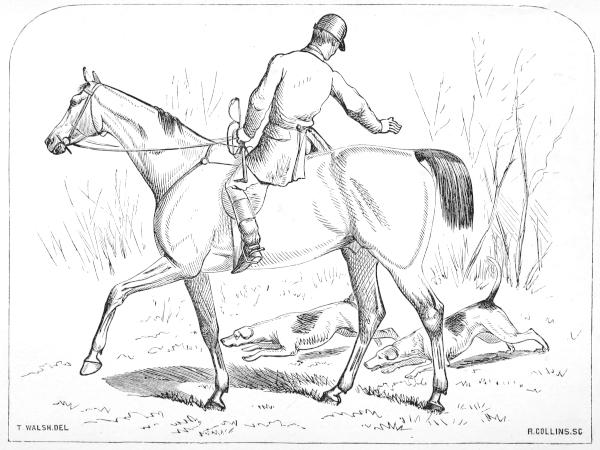

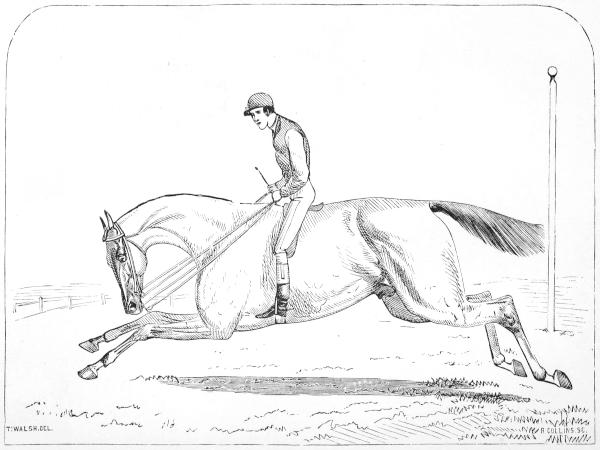

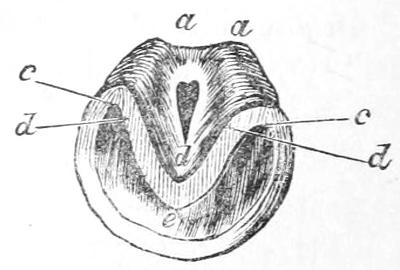

The Hunter, like the hack, should be particularly well-formed before the saddle. He should be deep in the girth, strong in the loins, with full development of thigh, short and flat in the canon joint from the knee to the pastern, with large flat hocks and sound fore legs. This animal, like the road-horse, should lift his feet clear of the ground and walk independently, with evidence of great propelling power in the hind legs when put into a canter or gallop.

A differently-shaped animal is required for each kind of country over which his rider has to be carried. In the midland counties and Yorkshire, the large three-quarter or thorough-bred horse only will be found to have pace and strength enough to keep his place. In close countries, such as the south, south-west, and part[6] of the north of England, a plainer-bred and closer-set animal does best.

In countries where the fences are height jumps—a constant succession of timber, or stone walls—one must look for a certain angularity of hip, not so handsome in appearance, but giving greater leverage to lift the hind legs over that description of fence.

A hunter should be all action; for if the rider finds he can be carried safely across country, he will necessarily have more confidence, and go straighter, not therefore requiring so much pace to make up for round-about “gating” gaps and “craning.”[7]

If you propose purchasing from a dealer, take care to employ none but a respectable man. It is also well to get yourself introduced to such a one, by securing the good offices of some valuable customer of his for the purpose; for such an introduction will stimulate any dealer who values his character to endeavour by his dealings to sustain it with his patron.

THE WEIGHT-CARRYING HUNTER

Auction.—An auction is a dangerous place for the uninitiated to purchase at. If, however, it should suit you to buy in that manner, the best course to pursue is to visit the stables on the days previous to the sale, for in all well-regulated repositories the horses are in[7] for private inspection from two to three days before the auction-day. Taking, if possible, one good judge with you, eschewing the opinions of all grooms and others—in fact, fastening the responsibility of selection on the one individual—make for yourself all the examination you possibly can, in or out of stable, of the animal you think likely to suit you. There is generally a way of finding out some of the antecedents of the horses from the men about the establishment.

Fairs.—To my mind it is preferable to purchase at fairs rather than at an auction: indeed, a judge will there have much more opportunity of comparison than elsewhere.

Private Purchase.—In buying from a private gentleman or acquaintance, it is not unusual to get a horse on trial for three or four days. Many liberal dealers, if they have faith in the animal they want to dispose of, and in the intending purchaser, will permit the same thing.

Warranty.—As observed under the head of “Selecting,” it is never wise to conclude the purchase of a horse without having him examined by a professional veterinary surgeon, and getting a certificate of his actual state. If the animal be a high-priced one, a warranty should be claimed from the seller as a sine qua non; and if low-priced, a professional certificate is desirable, stating the extent of unsoundness, for your own satisfaction.[8]

Ventilation is a matter of the first importance in a stable. The means of ingress and egress of air should be always three or four feet higher than the range of the horses’ heads, for two simple reasons: first, when an animal comes in warm, it is not well to have cold air passing directly on the heated surface of his body; and, in the second place, the foul air, being the lightest, always ascends, and you give it the readiest mode of exit by placing the ventilation high up. The common louver window, which can never be completely closed, is the best ordinary ventilator.

Drainage ought to be closely investigated. The drains should run so as to remove the traps or grates outside the stable, or as far as possible from the horses, in order to keep the effluvium away from them. All foul litter and mass should be removed frequently during the day; straw and litter ought not to be allowed to remain under a horse in the daytime, unless it be considered expedient that he should rest lying down, in which case let him be properly bedded and kept as quiet as possible. In many cases the practice of leaving a small quantity of litter in the stall is a fine cloak for deposit and urine left unswept underneath, emitting that noxious ammonia with which the air of most stables is so disagreeably impregnated that on entering them from the fresh air you are almost stifled.

Masters who object to their horses standing on the[9] bare pavement can order that, after the stall is thoroughly cleaned and swept out, a thin layer of straw shall be laid over the stones during the daytime. In dealers’ and livery stables, and indeed in some gentlemen’s, the pavement is sanded over, which has a nice appearance, and prevents slipping.

When the foul litter is abstracted, and the straw bedding taken from under the horse, none of it should be pushed away under the manger; let it be entirely removed: and in fair weather, or where a shed is available, the bedding should be shaken out, to thoroughly dry and let the air pass through it.

Wheaten is more durable than oaten straw for litter: but the fibre of the former is so strong that it will leave marks on the coat of a fine-skinned animal wherever it may be unprotected by the clothing; however, this is not material.

Light should be freely admitted into stables, not only that the grooms may be able to see to clean the horses properly, and to do all the stable-work, but if horses are kept in the dark it is natural that they should be more easily startled when they go into full daylight,—and such is always the consequence of badly-lighted stables. Of course, if a horse is ailing, and sleep is absolutely necessary for him, he should be placed separate in a dark quiet place.

Stalls should be wide, from six to seven feet across if possible, yielding this in addition to other advantages, that if the partitions are extended by means of bars to the back wall, either end stall can be turned into a loose-box sufficiently large to serve in an emergency.

A Loose-Box is unquestionably preferable to a stall[10] (in which a horse is tied up all the time he is not at work in nearly the same position), and is indispensable in cases of illness. Loose-boxes should be paved with narrow bricks; and when prepared for the reception of an animal whose shoes have been removed, the floor should be covered with sawdust or tan, or either of these mixed with fine sandy earth, or, best of all, peat-mould when procurable,—any of which, where the indisposition is confined to the feet only, may be kept slightly moistened with water to cool them.

In cases of general illness, straw should be used for bedding; and where the poor beast is likely to injure himself in paroxysms of pain, the walls or partitions should be well padded in all parts within his reach, and as a further precaution let the door be made to open outwards, and be fastened by a bolt, as latches sometimes cause accidents.

Partitions should be carried high enough towards the head to prevent the horses from being able to bite one another, or get at each other’s food.

With regard to stable-kickers, see the remarks on this subject under the head of “Vice” (page 85).

Racks and Mangers are now made of iron, so that horses can no longer gnaw away the manger piecemeal. Another improvement is that of placing the rack on a level with and beside the manger, instead of above the horses’ heads; but notwithstanding this more reasonable method of feeding hay when whole, it is far preferable to give it as manger-food cut into chaff.

Flooring.—In the construction of most stables a cruel practice is thoughtlessly adopted by the way of facilitating drainage (and in dealers’ stables to make horses look large), viz., that of raising the paving towards[11] the manger considerably above the level of the rear part. It should be borne in mind that the horse is peculiarly sensitive to any strain on the insertions of the back or flexor tendons of his legs. Thus in stalls formed as described, you will see the creature endeavouring to relieve himself by getting his toes down between the flags or stones (if the pavement will admit) with the heels resting upon the edges of them; and if the fastening to the head be long enough he will draw back still farther, until he can get his toes down into the drain-channel behind his stall, with the heels upon the opposite elevation of the drain. Proper pavement in your stable will help to alleviate a tendency towards what is called “clap of the back sinew.”—See page 143.

The slope of an inch and a half or two inches is sufficient for purposes of drainage in paving stables; but if the drainage can be managed so as to allow of the flooring being made quite level, so much the better.

Should my reader be disposed to build stabling, he cannot do better than consult the very useful and practical work entitled ‘Stonehenge, or the Horse in the Stable and in the Field.’

The horse being a gregarious animal, and much happier in society than alone, will, in the absence of company of his own species, make friends with the most sociable living neighbour he can find. A horse should not be left solitary if it can be avoided.

Dogs should never be kept in the stable with horses, or be permitted to be their playfellows, on account of the noxious emissions from their excrement. Cats are better and more wholesome companions.

I do not profess to teach grooms their business, but to put masters on their guard against the common errors and malpractices of that class; and with a view to that end, two or three general rules are added which a master would do well to enforce on a groom when hiring him, as binding, under pain of dismissal.

1. Never to doctor a horse himself, but to acquaint his master immediately with any accident, wound, or symptom of indisposition about the animal, that may come under his observation, and which, if in existence, ought not to fail to attract the attention of a careful, intelligent servant during constant handling of and attendance on his charge.

2. Always to exercise the horses in the place appointed by his master for the purpose, and never to canter or gallop them.

3. To stand by while a horse is having its shoes changed or removed, and see that any directions he may have received on the subject are carried out.

4. Never to clean a horse out of doors.

These rules are recommended under a just appreciation of that golden one, “Prevention is better than cure.”

If the master is satisfied with an ill-groomed horse, nine-tenths of the grooms will be so likewise; therefore he may to a great extent blame himself if his bearer’s dressing is neglected.

Grooms are especially fond of using water in cleaning the horse (though often rather careful how they use it with themselves, either inside or out): it saves them[13] trouble, to the great injury of the animal. The same predominating laziness which prompts them to use water for the removal of mud, &c., in preference to employing a dry wisp or brush for the purpose, forbids their exerting themselves to employ the proper means of drying the parts cleaned by wet. They will have recourse to any expedient to dry the skin rather than the legitimate one of friction. Over the body they will place cloths to soak up the wet; on the legs they will roll their favourite bandages. It is best, therefore, to forbid the use of water above the hoof for the purpose of cleaning—except with the mane and tail, which should be properly washed with soap and water occasionally.

When some severe work has been done, so as to occasion perspiration, the ears should not be more neglected than the rest of the body; and when they are dried by hand-rubbing and pulling, the horse will feel refreshed.

As already recommended, cleaning out of doors should be forbidden. If one could rely on the discretion of servants, cleaning might be done outside occasionally in fine weather; but licence on this score being once given, the probability is that your horse will be found shivering in the open air on some inclement day.

The groom always uses a picker in the process of washing and cleaning the feet, to dislodge all extraneous matter, stones, &c., that may have been picked up in the clefts of the frog and thereabouts; he also washes the foot with a long-haired brush. In dry weather, after heavy work, it is good to stop the fore feet with what is called “stopping” (cow-dung), which is not difficult to procure. Wet clay is sometimes used in[14] London for the purpose in the absence of cow-dung. Very useful, too, in such case will be found a stopping composed of one part linseed-meal to two parts bran, wetted, and mixed to a sticking consistency.

The evidence of care in the groomed appearance of the mane and tail looks well. An occasional inspection of the mane by the master may be desirable, by turning over the hairs to the reverse side; any signs of dirt or dandriff found cannot be creditable to the groom.

Bandaging.—When a hunter comes in from a severe day, it is an excellent plan to put rough bandages (provided for the purpose) on the legs, leaving them on while the rest of the body is cleaning; it will be found that the mud and dirt of the legs will to a great extent fall off in flakes on their removal, thus reducing the time employed in cleaning. When his legs are cleaned and well hand-rubbed, put on the usual-sized flannel bandages. They should never remain on more than four or six hours, and when taken off (not to be again used till the next severe work) the legs should be once more hand-rubbed.

Bandages ought not to be used under other circumstances than the above, except by order of a veterinary surgeon for unsoundness.

In some cases of unsoundness—such as undue distension of the bursæ, called “wind-galls,” the effect of work—a linen or cotton bandage kept continually saturated with water, salt and water, or vinegar, and not much tightened, may remain on the affected legs; but much cannot be said for the efficacy of the treatment.

For what is called “clap,” or supposed distension of the back sinew (which is in reality no distension of[15] the tendon, as that is said to be impossible, though some of its fibres may be injured, but inflammation of the sheath through which the tendon passes), the cold lotion bandaging just described, in connection with the directions given under the head of “Shoeing” (page 82), will be found very serviceable.

Grooms’ Requisites are usually understood to comprise the following articles:—a body-brush, water-brush, dandriff or “dander” brush, picker, scraper, mane-comb, curry-comb, pitchfork, shovel and broom, manure-basket, chamois-leather, bucket, sponges, dusters, corn-sieve, and measures; leather boot for poultices, clyster syringe (requiring especial caution in use—see page 159, note), drenching-horn, bandages (woollen and linen); a box with a supply of stopping constantly at hand; a small store of tow and tar, most useful in checking the disease called thrush (page 135) before it assumes a chronic form; a lump of rock-salt, ready to replace those which should be always kept in the mangers to promote the general health of the animals as well as to amuse them by licking it; a lump of chalk, ready at any time for use (in the same manner as rock-salt) in the treatment of some diseases, as described, pages 154 and 160.

Singeing, there is little doubt, tends to improve the condition of the animal; so much so, that timid users do well to remember that animals which, before the removal of their winter coat, required perpetual reminders of the whip, will, directly they are divested of that covering, evince a spirit, vigour, and endurance which had remained, perhaps, quite unsuspected previously. In fact, in most cases, the general health and appetite seem to be improved.

Singeing, when severe rapid work is done, enables the horse to perform his task with less distress, and when it is over, facilitates his being made comfortable in the shortest possible space of time.

Singeing, if done early in the winter, requires to be repeated lightly three or four times during the season.

Clipping has exactly the same effect as the above, and is preferable to it only in cases where, the animal’s coat being extremely long, extra labour, loss of time, and flame, are avoided by the clipping process. Singeing is best with the lighter coats, but sometimes thin skinned and coated animals are too nervous and excitable to bear the flame near them for this purpose, in which case the cause of alarm ought obviously to be avoided, and clipping resorted to.

It is worth while to employ the best manipulators to perform these operations.

With horses intended for slow and easy work, and liable to continued exposure to the weather, singeing or clipping only the under part of the belly, and the long hairs of the legs, will suffice. Unless neatly and tastily done, this is very unsightly on a gentleman’s horse. Clipping, if not done till the beginning of December, seldom requires repetition.

In stony and rough countries, it is the habit of judicious horsemen to leave the hair on their hunters’ legs from the knees and hocks down, as a protection to them.

The Head-Stall should fit a horse, and have a proper brow-band; it is ridiculous to suppose that the same[17] sized one can suit all heads. Ordinary head-stalls have only one buckle, which is on the throat-lash near-side; and if the stall be made to fit, that is sufficient. Otherwise there should be three buckles, one on each side of the cheek-straps, besides the one on the throat-lash.

Let the fastening from the head-stall to the log be of rope or leather. Chain fastenings are objectionable, because, besides being heavy, they are very apt to catch in the ring, and they make a fearful noise, especially where there are many horses in the stable. By having rope or leather as a fastener, instead of chain, the log may be lighter (of wood instead of iron), and the less weight there is to drag the creature’s head down, the less the distress to him. Poll-evil (page 117), it is said, has frequently resulted from the pressure of the head-stall on the poll, occasioned by heavy pendants.

Chains are more durable, and that is all that can be said in their favour, except that they may be necessary for a few vicious devils who are up to the trick of severing the rope or leather with their teeth.

See that the log is sufficiently heavy to keep the rope or leather at stretch, and that the manger-ring is large enough to allow the fastening to pass freely. If the log is too light, or the manger-ring too small, the likely result will be that the log will remain close up under the ring, the fastening falling into a sort of loop, through which the horse most probably introduces his foot, and, in his consequent alarm and efforts to disentangle his legs, chucks up his head, and away he goes on his side, gets “halter-cast,” most likely breaks one of his hind legs in his struggles to regain his footing, or at least dislocates one of their joints.

Opinions differ materially as to the amount of clothing that ought to be used in the stable. My view of the matter is, that a stable being, as it should be, thoroughly ventilated, necessitates the horses in it being to a certain extent kept warm by clothing. An animal that has not been divested of his own coat by clipping or singeing, will require very little covering indeed; for nature’s provision, being sufficient to protect him out of doors, ought surely to suffice in the stable, with a very slight addition of clothing. If he has been clipped or singed, covering enough to make up for what he has lost ought to be ample: by going beyond this the horse is only made tender, and more susceptible of the influences of the atmosphere when he comes to be exposed to it with only a saddle on his back.

In parts of North America, I have observed, where the stables are built roughly of wood, with many fissures to admit the weather, horses are seldom, if ever, sheeted. They are certainly rarely divested of their coats; but during work, as occasion may require, it is usual for the rider, when stopping at any place, to leave his horse “hitched” (as they call it) to any convenient post or tree, in all weathers, and for any length of time, and these horses scarcely ever catch cold.

The best Sheet is formed of a rug (sizeable enough to meet across the breast and extend to the quarters), by simply cutting the slope of the neck out of it, and fastening the points across the breast by two straps and buckles.

The Hood need only be used when the horse is at[19] walking exercise, or likely to be exposed to weather, or for the purpose of sweating, when a couple of them, with two or three sheets, may be used.—See page 32.

Horse-clothing should be, at least once a-week, taken outside the stable, and well beaten and shaken like a carpet.

Rollers should be looked to from time to time, to see that the pads of the roller do not meet within three or four inches (over the backbone),—in other words, there should be always a clear channel over it, nearly large enough to pass the handle of a broom through, so as to avoid the possibility of the upper part of the roller even touching the sheet over the spinal ridge, which, if permitted, will be sure to cause a sore back, to the great injury of the horse and his master, arousing vicious habits in the former to resent any touch, necessary or unnecessary, of the sore place on so sensitive a part, and rendering him irritable when clothing, saddling, or harnessing, or if a hand even approach the tender place.

This is so troublesome a consequence of not paying attention to the padding of rollers, that a master will do well to examine them himself for his own satisfaction.

Knee-Caps.—On all occasions when a valuable horse is taken by a servant on road or rail, his knees should be protected by caps. The only way to secure them is to fasten them tightly above the knee, where elastic straps are decidedly preferable, leaving the fastening below the knee slack.

A Leather Boot, lined with sponge, or one of felt with a strong leather sole, should be ready in every stable to be used as required, in cases of sudden foot-lameness.

The cavalry allowances are 12 lb. hay, 10 lb. oats, and 8 lb. straw daily, which, I know by experience, will keep a healthy animal in condition with the work required from a dragoon horse, of the severity of which none but those acquainted with that branch of the service have any idea.

Until he is perfectly fit for the ranks, between riding-school, field-days, and drill, the troop-horse has quite work enough for any beast. I may add that few horses belonging to officers of cavalry get more than the above allowance, unless when regularly hunted, in which case additional corn and beans are given.

With severe work, 14 lb. to 16 lb. of oats, and 12 lb. of hay, which is the general allowance in well-regulated hunting-stables, ought to be sufficient. Beans are also given in small quantity.

Some persons feed their horses three times a-day, but it is better to divide their food into four daily portions, watering them, at least half an hour before each feed.

The habit which some grooms have of feeding while they are teazing an animal with the preliminaries of cleaning, is very senseless, as the uneasiness horses are sure to exhibit under anything like grooming causes them to knock about their heads and scatter their food. On a journey, according to the call upon the system by the increased amount of work, so should the horse’s feeding be augmented by one-third, one-fourth, or one-half more than usual. A few beans or pease may well be added under such circumstances.

In stables where the stalls are divided by bales or swinging-bars, the horses when feeding should have their heads so tied as to prevent them from consuming their neighbour’s food, or the result would be that the greedy or more rapid eaters would succeed in devouring more than their fair share, while the slower feeders would have to go on short commons.

Oats ought always to be bruised, as many horses, whether from greediness in devouring their food, or from their teeth being incapable of grinding, swallow them whole; and it is a notorious fact that oats, unless masticated, pass right through the animal undigested.

When supplies have been very deficient with forces in the field, the camp-followers have been known to exist upon the grain extracted from the droppings of the horses.

It should be remembered that not more than at the utmost two days’ consumption of oats should be bruised at a time, as they soon turn sour in that state, and are thus unfit for the use of that most delicate feeder, the horse. All oats before being bruised should be well sifted, to dispose of the gravel and dust which are always present in the grain as it comes from the farmer. Unbruised oats, if ever used, should be similarly prepared before being given in feed.

Hay ought always to be cut into chaff or may be mixed with the corn, which is the only way to insure the proper proportion being given at a feed. When the hay is not cut but fed from the rack, never more than 3 lb. should be put in the rack at a time. If desirable to give as much as 12 lb. daily, let the rack be filled six times in twenty-four hours.

Beans must be invariably split or bruised. It is[22] better to give a higher price for English beans than to use the Egyptian at any price; the latter are said to be impregnated with the eggs of insects, which adhere to the lining of the horse’s stomach, causing him serious injury. In India horses are principally fed on a kind of small pea called “gram”—in the United States their chief food is maize; the oat-plant not succeeding well in either of those regions.

Bran.—Food should be varied occasionally, and all horses not actually in training ought to have a bran-mash once a-week. The best time to give this is for the first feed after the work is done, on the day preceding the rest day, whenever that may be.

Even hunters, after a hard day, will eat the bran with avidity, and it is well to give it for the first meal. Its laxative qualities render it a sedative and cooler in the half-feverish state of system induced by the exertion and excitement of the chase; and according to my experience, if given just after the work is done, the digestive process, relaxed by the bran, has full time to recover itself by the grain-feeding before the next call is made on the horse’s powers. If the bran is not liked, a little bruised oats may be mixed through it to tempt the palate. Whole grains of oats should never be mixed with bran, as they must of necessity be bolted with the latter, and passed through the animal entire.

Mash.—When only doing ordinary work, the following mash should be given to each horse on Saturday night after work, supposing your beasts to rest on Sunday:—

Put half a pint of linseed in a two-quart pan with an even edge; pour on it one quart of boiling water, cover it close, and leave to soak for four hours.

At the same time moisten half a bucket of bran with a gallon of water. When the linseed has soaked for four hours, a hole must be made in the middle of the bran, and the linseed mass mixed into the bran mass. The whole forms one feed. Should time be an object, boil slowly half a pint of linseed in two quarts of water, and add it to half a bucket of bran which had been previously steeped for half an hour or an hour in a gallon of water.

If a cold is present, or an animal is delicate, the bran can be saturated with boiling water, of which a little more can be added to warm it when given.

Carrots, when a horse is delicate, will be found acceptable, and are both nutritious and wholesome as food. In spring and summer, when vetches or other green food can be had, an occasional treat of that sort conduces to health where the work is sufficiently moderate to admit of soft feeding. When horses are coating in spring or autumn, or weak from fatigue or delicacy, the addition to their food of a little more nutriment may be found beneficial. The English white pea is milder and not so heating as beans, and may be given half a pint twice daily, mixed with the ordinary feeding, for from one to three or four weeks, as may be deemed advisable.

When an animal is “off his feed,” as it is called, attention should be immediately directed to his manger, which is often found to be shamefully neglected, the bottom of it covered with gravel, or perhaps the ends and corners full of foul matter, such as the sour remains of the last bran-mash and other half-masticated leavings.

The introduction of any greasy or fetid matter into[24] a horse’s food will effectually prevent this dainty creature from touching it. It used to be a common practice at hostelries in the olden time, to rub the teeth of a traveller’s horse with a tallow candle or a little oil; thus causing the poor beast to leave his food untouched for the benefit of his unfeeling attendant.

Again, the oats or hay may be found, on close examination, to be musty, which causes them to be rejected by the beast.

Where no palpable cause for loss of appetite can be discovered, reference should be made to a qualified veterinary surgeon, who will examine the animal’s mouth, teeth, and general state of health, and probably report that the lining of the cheeks is highly inflamed in some part, owing to undue angularity or decay of the teeth, and he will know how to act accordingly.

When horses are on a journey, or a long ride home after hunting, some people recommend the use of gruel; but, from experience, I prefer giving a handful of wetted hay in half a bucket of tepid water, or ale or porter.—See page 37.

Feeding on Board Ship should be confined to chaff and bran, mixed with about one-fourth the usual quantity of bruised oats.

Though horses generally look well when “full of flesh,” there are many reasons why they should not be allowed to become fat after the fashion of a farmer’s “stall-feds.” Some really good grooms think this form of condition the pink of perfection. They are mistaken. An animal in such a state is quite unfit to travel at any fast pace or bear continued exertion without injury, and may therefore be considered so far useless.

He is also much more liable to contract disease, and[25] if attacked by such the constitution succumbs more readily.

Moreover, the superfluous weight of the cumbrous flesh and fat tends to increase the wear and tear of the legs; and if the latter be at all light from the knee to the pastern, they are more likely to suffer.

On the other hand, it may be well to observe, by way of caution, that it is by no means good management to let a horse become at any time reduced to actual leanness through overwork or deficient feeding. It is far easier to pull down than to put up flesh.

These hints on feeding may be closed with a remark, that in all large towns contractors are to be found ready and willing to enter into contract for feeding gentlemen’s horses by the month or year. This is a very desirable arrangement for masters, but one frequently objected to by servants, who, however, in such cases can easily be replaced by application to the dealer, he having necessarily excellent opportunities of meeting with others as efficient.

Contractors should not be allowed to supply more than two or three days’ forage at a time.

Horses are greater epicures in water than is generally supposed, and will make a rush for some favourite spring or rivulet where water may have once proved acceptable to their palate, when that of other drinking-places has been rejected or scarcely touched.

The groom’s common maxim is to water twice a-day, but there is little doubt that horses should have access[26] to water more frequently, being, like ourselves or any other animal, liable from some cause—some slight derangement of the stomach, for instance—to be more thirsty at one time than another; and it is a well-known fact that, where water is easily within reach, these creatures never take such a quantity at a time as to unfit them for moderate work at any moment. If an arrangement for continual access to water be not convenient, horses should be watered before every feed, or at least thrice a-day, the first time being in the morning, an hour before feeding (which hour will be employed in grooming the beast); and it may be observed that there is no greater aid to increasing their disposition to put up flesh, than giving them as much water as they like before and after every feed.

A horse should never be watered when heated, or on the eve of any extraordinary exertion. Animals that are liable to colic or gripes, or are under the effect of medicines, particularly such as act on the alimentary canal, and predispose to those affections, should get water with the chill off.

Watering in Public Troughs, or places where every brute that travels the road has access, must be strictly avoided. Glanders, farcy, and other infectious diseases may be easily contracted in this way.

The advantage of grazing, as a change for the better in any, and indeed in every, case where the horse may be thrown out of sorts by accident or disease, becomes very questionable, on account of the artificial state in[27] which he must have been kept, to enable him to meet the requirements of a master of the present day in work. If the change be recommended to restore the feet or legs, this object may be attained, and much better, by keeping the creature in a loose-box without shoes, on a floor covered with sawdust or tan, kept damp as directed (page 10), to counteract whatever slight inflammation may be in the feet and legs, or, best of all, covered with peat-mould, as this does not require to be damped, and the animal can lie down on it; besides, the properties of the peat neutralise the noxious ammonia, and it does not consequently require to be so often renewed. In the loose-box also he can take quite as much exercise as is necessary for an invalid intended to be laid up, and there he can be supplied with whatever grain, roots, or succulent food may be deemed necessary.

As for any other advantage to be derived from a run at grass, unless for the purpose of using the herb as an alterative, I never could see it: and even this end, unless the horse has a paddock to himself, can hardly be gained; for if there are too many beasts for the production of the ground, the fare must be scanty, and each animal half starved.

The disadvantages of changing a horse to grass from the artificial state of condition are the following:—

1. That condition is sure to be lost (at least as far as it is necessary to fit for work, especially to go across country at a hunting pace, with safety to himself and his rider), and not to be regained for a considerable time, and at great cost.

2. The horse is exceedingly liable to meet with accident from the playfulness or temper of his companions.

3. Worms of the most dangerous and pertinacious description are picked up nowhere but at grass.

4. Many ailments are contracted from exposure and hardship or bad feeding; and owing to the animal being removed from under immediate inspection, such ailments gain ground before they are observed. Moreover, at grass the horse is more exposed to contagious and epidemic diseases.

5. Horses suffer great annoyance from flies in summer time, not having long tails like horned cattle to reach every part of their body; and wherever any superficial sore may be present, the flies are sure to find it out.

As to aged animals, it is sheer cruelty (practised by some masters with the best intentions and worst possible results) to turn them out to grass. Such creatures have probably been accustomed in the earlier part of their lives to warm stables, their food put under their noses, good grooming, and proper care. You might just as well turn out a gentleman in his old age among a tribe of friendly savages, unclad and unsheltered, to exist upon whatever roots and fruits he could pick up, as expose a highly-bred and delicately-nurtured old horse to the vicissitudes and hardships of a life at grass.

The principle of this system is that of overpowering the horse that may in some instances have even become dangerous and useless, from having learned the secret[29] that his strength gives him an advantage over his master—man. Unconsciously deprived of his power of resistance, his courage vanishes; the spirit which rose against all accountable efforts to subdue it, that would scorn to yield to overweight, pace, work, or any other evidence of man’s power, and which in the well-dispositioned animal causes him to strain every nerve to meet what is required of him rather than succumb, is by Rarey’s system subdued through a ruse so effected that the power which overwhelms all the creature’s efforts at resistance appears to originate and be identified with the man who can thus, for the first time, take liberties with him, which he has lost the power of resenting; and man thenceforward becomes his master. The method pursued by Mr Rarey in subduing such a vicious and ungovernable horse as Cruiser, is this: Placing himself under a waggon laden with hay, to which the animal is partly coaxed, partly led by guide-ropes, and stealing his fingers through the spokes of the waggon-wheel, he raises and gently straps up one fore leg, and fastens a long strap round the fetlock of the other, the end of which he holds in his hand and checks when necessary. The beast, thus unconsciously tampered with, is quite disposed to resent in his usual style the subsequent impertinent familiarities of his tamer; but being by the foregoing precautions cast prostrate on his first attempt to move, and finding all his efforts to regain his liberty and carry out reprisals abortive, worn-out and hopeless, he at length yields himself helplessly to his victor’s obliging attentions, of sitting on him as he lies, drumming and fiddling in his ears, &c., and is thenceforward man’s obedient and tractable servant.

There is no doubt that Mr Rarey’s plan of thus overcoming the unruly or vicious beast by mild but effectual means, is the right one to gain the point, as far as it goes; but breaking him in to saddle or draught, improving his paces, or having ability in riding or driving any horse judiciously, must be considered another affair, and only to be acquired through more or less competent instruction, and by practice combined with taste.

In training, the use of a dumb jockey[9] will be found most serviceable to get the head into proper position, and to bend the neck. Two hours a-day in this gear, while the horse is either loose in a box or fastened to the pillar-reins if in a stall, will not at all interfere with his regular training, exercise, or work, and will materially aid the former result.

I greatly advocate the use of the dumb jockey without springs, even with formed horses, who, being daily used to it, need no such adjuncts as bearing-reins, but will arch their necks, work nicely on the bit, and exhibit an altered show and style in action that is very admirable in a gentleman’s equipage.

Should my reader be much interested in breaking-in rough colts, I recommend him to consult ‘Stonehenge,’ by J. H. Walsh, F.R.C.S., editor of the ‘Field.’

Training for Draught.—Before the first trial in the break-carriage, give your horse from half-an-hour to an hour’s quiet ringing in the harness, to which he should have been previously made accustomed by wearing it for a couple of hours the two or three preceding days. The first start should be in a regular break, or strong[31] but inexpensive vehicle, and stout harness, with also saving-collar, knee-caps, and kicking-strap—no bearing-rein. He should be led by ropes or reins (in single harness on both sides of the head), and tried on a level, or rather down than up a slight inclination. The place selected should be one where there is plenty of unoccupied roadway.

Better begin in double harness, and let the break-horse with which the driver is to start the carriage be strong and willing, so as to pull away the untried one.

The Neck usually suffers during the first few lessons in training to harness; and until that part of it where the collar wears becomes thoroughly hardened by use, it should be bathed with a strong solution of salt and water before the collar is taken off, that there may be no mistake about its being done at once. Should there be the least abrasion of the skin, do not use salt and water, but a wash of 1 scruple chloride of zinc to 1 pint of water, dabbed on the sore every two or three hours with fine linen rag, and give rest from collar-work till healed; then harden with salt and water; and when the scab has disappeared, and the horse is fit for harness, chamber the collar over the affected part, and employ for a while a saving-collar. A sore neck will produce a jibbing horse, and therefore requires to be closely attended to in his training.

It is desirable that a master should appoint a particular place for the exercising of his horses, coupled with[32] strict injunctions to his groom on no account to leave it. No master should give his servants the option of going where they please to exercise, their favourite resort being often the precincts of a public-house, with a sharp gallop round the most impracticable corners to make up the time. An occasional visit of the master to the exercising ground is a very salutary check upon such proceedings.

The best possible exercise for a horse is walking—the sod or any soft elastic surface being better than the road for the purpose; and if the latter only is available, use knee-caps as a safeguard.

Two hours’ daily exercise (if he gets it) at a fast walk will be enough to keep a hack fit for his work; and it is usual with some experienced field-horsemen never to allow their hunters, when once up to their work, to get any but walking exercise for as much as four hours daily, two hours at a time—that is, when they desire to keep them “fit.”

Ladies’ and elderly gentlemen’s horses ought most particularly to be exercised, and not overfed, to keep them tame and tractable, and to guard against accidents.

The foregoing directions refer to the preparations for the master’s work, and are what I should give my groom.

Sweating.—In case it is desirable to prepare an animal for any extraordinary exertion, the readiest, safest, and most judicious means is by sweating, carefully proceeded with, by using two or three sets of body-clothes, an empty stomach being indispensable for the process, and a riding-school, if available, the best place for the necessary exercise,—a sweat being thus sooner obtained free from cold air, and the soft footing of such a place[33] saving the jar on the legs more even than the sod in the field, unless it happen to be very soft.

Sweating is a peculiarly healthy process for either man or beast; and to judge of the benefit derived by a horse through that means, from the effect of a heavy perspiration through exercise on one’s self, there seems little doubt that it is very renewing to the physique.

Ringing or Loungeing with a cavesson, though not ordinarily adopted, except by the trainer, is nevertheless most useful as a means of exercise. It is a very suitable manner of “taking the rough edge off,” or bringing down the superabundant spirits of horses that have been confined to the stable for some time by weather or other similar cause producing restiveness, and is peculiarly adapted for exercising harness-horses where it may not be safe or expedient to ride them.

The master on the road or in the field using his bearer for convenience or pleasure, will do him less injury in a day than a thoughtless ignorant servant will contrive to accomplish in an hour when only required to exercise the beast.

To the advice already given, never to allow your horses to be galloped or cantered on a hard surface, it is well to add, refrain from doing so yourself. On the elastic turf these paces do comparatively little harm; but for the road, and indeed all ordinary usage, except hunting or racing, the trot or walk is the proper pace. My impression coincides with that of many experienced sportsmen, that one mile of a canter on a hard surface[34] does more injury to the frame and legs of a horse, than twenty miles’ walk and trot: for this reason, that in the act of walking or trotting the off fore and near hind feet are on the ground at the same moment alternately with the other two, thus dividing the pressure of weight and propulsion on the legs more than even ambling, which is a lateral motion; while in anything approaching to the canter or gallop, the two fore feet and legs have at the same moment to bear the entire weight of man and horse, as well as the jar of the act of propulsion from behind.

Ambling is a favourite pace with the Americans, whose horses are trained to it; also with the Easterns. It is, as before mentioned, a lateral motion, much less injurious to the wear and tear of the legs than either canter or gallop on the hard road, the off fore and hind being on the ground alternately with the near fore and hind legs.

Though unsightly to an Englishman’s eyes, this pace is decidedly the easiest of all to the rider, and may be accelerated from four to six or eight miles an hour without the least inconvenience. Some American horses are taught to excel in this pace, so as to beat regular trotters.

By trotting a horse you do him comparatively little injury on the road; but observe the animal that has been constantly ridden by ladies (at watering-places and elsewhere), who are so fond of the canter: he stands over, and is decidedly shaky on his legs, although the weight on his back has been generally light. Observe, on the contrary, the bearer of the experienced horseman; although the weight he had to carry may have been probably what is called “a welter,” his legs are right enough.

The softness of the turf, as fitting it for the indulgence of a gallop, is indicated by the depth of the horse-tracks; there is not much impression left on a hard road.

It should be always borne in mind that “it is the pace that kills,” and unless the wear and tear of horse-flesh be a matter of no consideration, according as the pace is increased from that of five or six miles per hour, so should the distance for the animal’s day’s work be diminished.

For instance, if you require him to do seven miles in the hour daily, that seven miles must always be considered as full work for the day; if you purpose going eight miles per hour, your horse should only travel six miles daily at that rate; if faster still, five miles only should be your bearer’s limit; if at a ten-mile rate, then four miles; or at a twelve-mile rate, three miles per day. But of course such regulations apply to daily work only, as a horse is capable of accomplishing a great deal more without injury, if only called upon to do so occasionally.

A man may require to do a day’s journey of thirty miles, or a day’s hunting, and such work being only occasional, no harm whatever to the animal need result; but about eight or ten miles a-day at an alternate walk or trot (say six-miles-an-hour pace) is as much as any valuable animal ought to do if worked regularly.

No horse ought to be hunted more than twice a-week at the utmost.

The work of horses, especially when ridden, ought to be so managed that the latter part of the journey may be done in a walk, so that they may be brought in cool.

A horse in the saddle is capable of travelling a hundred miles, or even more, in twenty-four hours, if required; and if the weight be light, and the rider judicious, such feats may be done occasionally without injury: but if a journey of a hundred miles be contemplated, it is better to take three days for its performance, each day’s journey of over thirty miles being divided into two equal portions, and got through early in the morning and late in the afternoon; the pace an alternate walk and trot at the rate of about five miles an hour, to vary it, as continuous walking for so long as a couple of hours when travelling on the road, may prove so tiresome that horses would require watching to keep them on their legs; and it is good for both horse and man that the latter should dismount and take the whole, or nearly the whole, of the walking part on his own feet, thus not only relieving his bearer from the continual pressure of the rider’s weight on the saddle on his back, but as a man when riding and walking brings into play two completely distinct sets of muscles, he will, though a little tired from walking, find himself on remounting positively refreshed from that change of exercise.

This recommendation is equally applicable to the hunting-field at any check, or when there is the least opportunity. So well is the truth of the above remark known to the most experienced horsemen, that some of them, steeplechase riders, make it a practice before riding a severe race to walk rapidly from five to ten miles to the course, in preference to making use of any of the many vehicles always at their disposal on such occasions.

It is only surprising that the expediency of making[37] dragoons dismount and walk beside their horses on a march, at least part of the way, for distances of one or two miles at a time, is not more apparent to those in authority (many of them practical men), in whose power it lies to make a regulation so very salutary for both man and horse. The more the beneficial effect of such an arrangement is considered, the more desirable it would appear to be, especially in dry weather. The great occasional relief to an overweighted horse of being divested of his rider now and then, would rather serve than injure the latter, on account of the variety of exercise, as before remarked, while his handling of the horse would decidedly be enlivened by the change.

Signals of Distress on increased pace.—Prominently may be mentioned a horse becoming winded, or, as sportsmen call it, having “bellows to mend,” which in proper hands ought seldom to occur, even in the hunting-field, as there are tokens which precede it—such as the creature hanging on his work, poking his head backwards and forwards, describing a sort of semicircle with his nose, gaping, the ears lopping, &c.

Some horsemen are in the habit of giving ale or porter (from a pint to a quart of either) to their horses during severe work. This is not at all a bad plan, if the beast will take it; and as many masters are fond of petting their animals with biscuit or bread, a piece of either being occasionally soaked in one of the above liquids when given, will accustom the creature so trained to the taste of them.

After the work is over a little well-made gruel is a great restorative; and when a long journey is completed, a bran-mash might be given, as mentioned under the head of “Feeding,” page 22.

One of the worst results to be dreaded from a horse going long journeys daily, is fever in the feet (page 132), which may be obviated by stopping the fore feet directly they are picked and washed out at the end of each day’s journey.—See page 13.

After a long journey, it would be desirable to have the animal’s fore shoes at least removed.

The saddle ought not to be taken off for some time after work; the longer it has been under the rider, and the more severe the work, the longer, comparatively, it should remain on after use, in order to avoid that frightful result which is most like to ensue from its being quickly removed—viz., sore back. With cavalry, saddles are left on for an hour or more after the return from a field-day or march.

A numna or absorbing sweat-cloth under the saddle is in cases of hard or continued work a great preservative against sore back.

When an extraordinary day’s work has been done, after the horse is cleaned and fed he should be at once bedded down, and left to rest in quiet, interrupted only to be fed.

Every horseman before he mounts should observe closely whether his horse is properly saddled and bridled.

Bits must be invariably of wrought steel, and the mouthpiece in all bits should fit the horse’s mouth exactly in its width: the bit that is made to fit a sixteen-hands-high is surely too large for a fourteen-hand cob. The bit ought to lie just above the tusk in a[39] horse’s jaw, and one inch above the last teeth with a mare.

It must be adapted to the mouth and temper of the horse as well as to the formation of his head and neck. A riding-master, or the rider, if he has any judgment, ought to be able to form an opinion as to the most suitable bit for an animal.[10]

The ordinary Bridoon (or Double bridle, as it is called in the North) is best adapted to the well-mouthed and tempered horse, and is the safest and best bridle for either road or field. Unfinished gentlemen as well as lady equestrians, when riding with double reins to the bits, are recommended to tie the curb-bit rein evenly in a knot on the horse’s neck (holding only the bridoon-rein in the hand), provided his temper and mouth be suitable to a snaffle. This is a practice pursued by some even good and experienced horsemen where the temper of a horse is high, in order to have the curb-bit to rely upon in case he should happen to pull too hard on the bridoon or snaffle, which otherwise would be quite sufficient and best to use alone.

The Curb-chain, when used, should be strong and tight; it should invariably be supported by a lip-strap, an adjunct that is really most essential, but which grooms practically ignore by losing. The object of the lip-strap is to prevent the curb, if rather loose, from falling over the lip, thus permitting the horse to get hold of it in his mouth and go where he pleases; it also guards against a trick some beasts are very clever at, of catching the cheek or leg of the bit in their teeth, and making[40] off in spite of the efforts of any rider. If the curb be tight, the lip-strap is equally useful in keeping it horizontally, and preventing its drooping to too great a pressure, thus causing abrasion of the animal’s jaw. The curb ought to be pretty tight, sufficiently so to admit one finger between it and the jaw-bone.

The Snaffle with a fine-mouthed horse is well adapted for the field—the only place where I would ever dispense altogether with the curb-bit, and then only in favour of a fine-mouthed well-tempered beast disposed to go coolly at his fences.

On the road a horse may put his foot upon a stone in a jog-trot, or come upon some irregularity; and unless the rider has something more than a snaffle in his hand, he is exceedingly likely to suffer for it. Many a horse that is like a foot-ball in the field, full of life and elasticity, and never making a mistake, will on the road require constant watching to prevent his tumbling on his nose.[11]

At the same time, a horse should by no means be encouraged to lean on the bit or on the rider’s support, which most of them will be found quite ready to do; a disposition in that direction must be checked by mildly feeling his mouth (with the bit), pressing your legs against his sides, and enlivening him gently with the whip or spur.

The Martingal.—The standing or head martingal is a handsome equipment—safe and serviceable with a[41] beast that is incorrigible about getting his head up, but should be used in the street or on the road only.

The Ring-Martingal is intended solely for the field with a horse whose head cannot be kept down; but it requires to be used with nice judgment, and handling of the second or separate rein, which should pass through it, especially when the animal is in or near the act of taking his fences, when, with some horses, comparative freedom may be allowed to the head, which should, however, be brought down to its proper place directly he is safely landed on his legs again by the use of this second martingal-rein, which is attached to the bridoon bit.

N.B.—If this second rein be attached to the snaffle by buckles (and not stitched on as it ought to be), the buckles of the rein should be defended from getting into the rings of the martingal by pieces of leather larger than those rings. Most serious accidents have occurred from the absence of this precaution: the buckle becoming caught in the ring, the horse’s head is fixed in one position, and not knowing where he is going, he proceeds, probably without any control from the rider, till both come to some serious mishap. The rein stitched to the ring of the bit is the safest.

The Running-Rein, or other plan of martingal (from the D in front of the saddle above the rider’s knee through the ring of the snaffle to his hand), should only be used by the riding-master or those competent to avail themselves of its assistance in forming the mouth of a troublesome or untrained animal. Some experienced horsemen, however, when they find they cannot keep the nose in or head down with ordinary bits, instead of using a martingal of any denomination, employ[42] (especially in the field) with good effect a ring, keeping the bridoon or snaffle-reins under the bend of the neck; or a better contrivance is a bit of stiff leather three or four inches long, with two D’s or staples for the reins to pass through on each side.

The Chifney Bit is the most suitable for ladies’ use, or for timid or invalid riders: it at once brings up a hard-pulling horse, but requires very gentle handling. I have known more than one horse to be quite unmanageable in any but a Chifney bit.

The more severe bits are those that have the longest legs or cheeks, giving the greatest leverage against the curb. By the addition of deep ports on the mouthpiece of the bit much severity is attained (especially when the port is constructed turned downwards, in place of the usual practice of making it upwards), which can be increased to the utmost by the addition of a tight noseband to prevent the horse from easing the port by movement of his tongue or jaws.

It is almost needless to observe, that the reverse of the above will be the mildest bits for tender-mouthed, easy-going horses.

Twisted Mouthpieces are happily now almost out of fashion, and ought to be entirely discountenanced; their original intention was to command hard-mouthed horses, whose mouths their use can only render harder.

The Noseband, if tightened, would be found very useful with many a hard-pulling horse in the excitement of hunting, when the bit, which would otherwise require to be used, would only irritate the puller, cause him to go more wildly, and make matters worse. I have known some pullers to be more under control in the[43] hunting-field with a pretty tight noseband and a snaffle than with the most severe curb-bit.

The Throat-lash is almost always too tight. Grooms are much in the habit of making this mistake, by means of which, when the head is bent by a severe bit, the throat is compressed and the respiration impeded, besides occasioning an ugly appearance in the caparison.

It may be remarked also that, if not corrected, servants are apt to leave the ends of the bridle head-stall straps dangling at length out of the loops, which is very unsightly: the ends of the straps should be inserted in these loops, which should be sufficiently tight to retain them.

A Saddle should be made to fit the horse for which it is intended, and requires as much variation in shape, especially in the stuffing, as there is variety in the shapes of horses’ backs.[12] An animal may be fairly shaped in the back, and yet a saddle that fits another horse will always go out on this one’s withers. The saddle having been made to fit your horse, let it be placed gently upon him, and shifted till its proper berth be found. When in its right place, the action of the upper part of the shoulder-blade should be quite free from any confinement or pressure by what saddlers call the “gullet” of the saddle under the pommel when the animal is in motion. It stands to reason that any interference with the action of the shoulder-blade must,[44] after a time, indirectly if not directly, cause a horse to falter in his movement.

N.B.—A horse left in the stable with his saddle on, with or without a bridle, ought always to have his head fastened up, to prevent his lying down on the saddle and injuring it.

Girths.—When girthing a horse, which is always done upon the near or left-hand side, the girth should be first drawn tightly towards you under the belly of the horse, so as to bring the saddle rather to the off side on the back of the beast. This is seldom done by grooms; and though a gentleman is not supposed to girth his horse, information on this as well as on other points may happen to be of essential service to him; for the consequence of the attendant’s usual method is, that when the girths are tightened up, the saddle, instead of being in the centre of the horse’s back, is inclined to the near or left-hand side, to which it is still farther drawn by the act of mounting, so that when a man has mounted he fancies that one stirrup is longer than the other—the near-side stirrup invariably the longest. To remedy this he forces down his foot in the right stirrup, which brings the saddle to the centre of the animal’s back.

All this would be obviated by care being taken, in the process of girthing, to place the left hand on the middle of the saddle, drawing the first or under girth with the right hand till the girth-holder reaches the buckle, the left hand being then disengaged to assist in bracing up the girth. The outer girth must go through the same process, being drawn under the belly of the horse from the off side tightly before it is attached to the girth-holder.

With ladies’ saddles most particular attention should be paid to the girthing.

(It must be observed that, with some horses having the knack of swelling themselves out during the process of girthing, the girths may be tightened before leaving the stable so as to appear almost too tight, but which, when the horse has been walked about for ten minutes, will seem comparatively loose, and quite so when the rider’s weight is placed in the saddle.)

Stirrup-Irons should invariably be of wrought steel. A man should never be induced knowingly to ride in a cast-metal stirrup, any more than he ought to attempt to do so with a cast-metal bit.

Stirrup-irons should be selected to suit the size of the rider’s foot; those with two or three narrow bars at the bottom are decidedly preferable, for the simple reason, that in cold weather it is a tax on a man’s endurance to have a single broad bar like an icicle in the ball of his foot, and in wet weather a similar argument may apply as regards damp; besides, with the double bar, the foot has a better hold in the stirrup, the rings being, of course, indented (rasp-like), as they usually are, to prevent the foot from slipping in them.

This description of stirrup, with an instep-pad, is preferable for ladies to the slipper, which is decidedly obsolete.

Latchford’s[13] ladies’ patent safety stirrup seems to combine every precaution for the security of fair equestrians.

A balance-strap to a side-saddle is very desirable, and in general use.

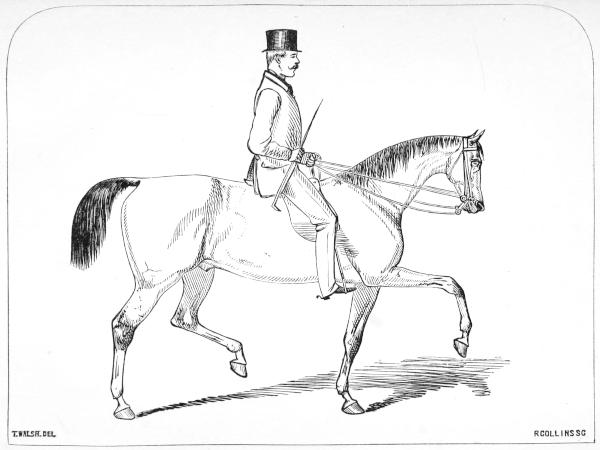

Where expense is no object, stirrups that open at the[46] side with a spring are, no doubt, the safest for gentlemen in case of any accident.