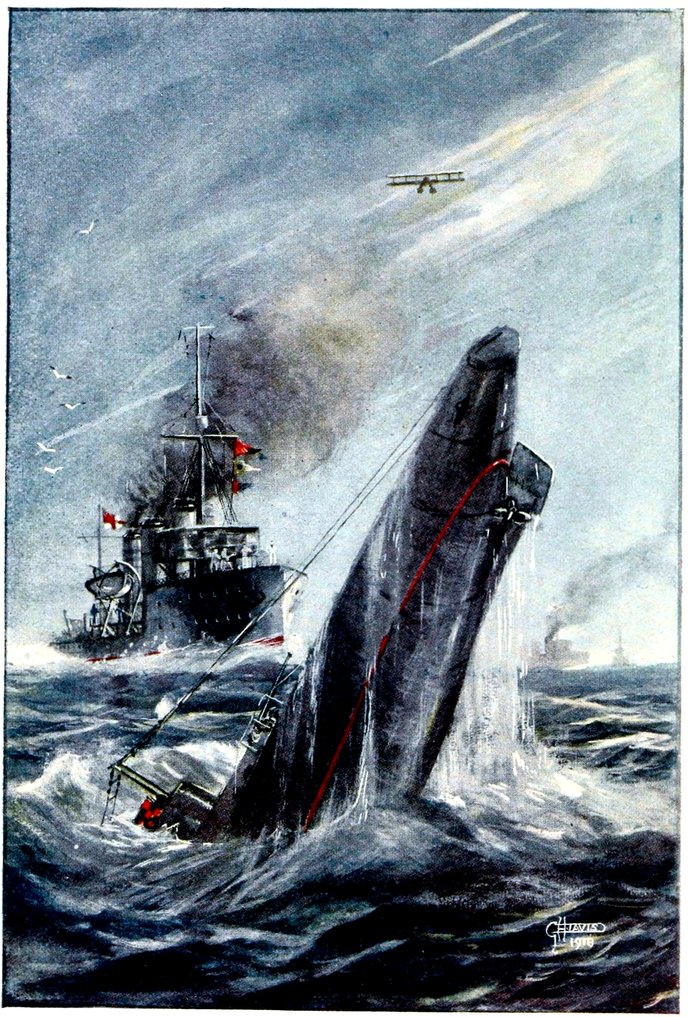

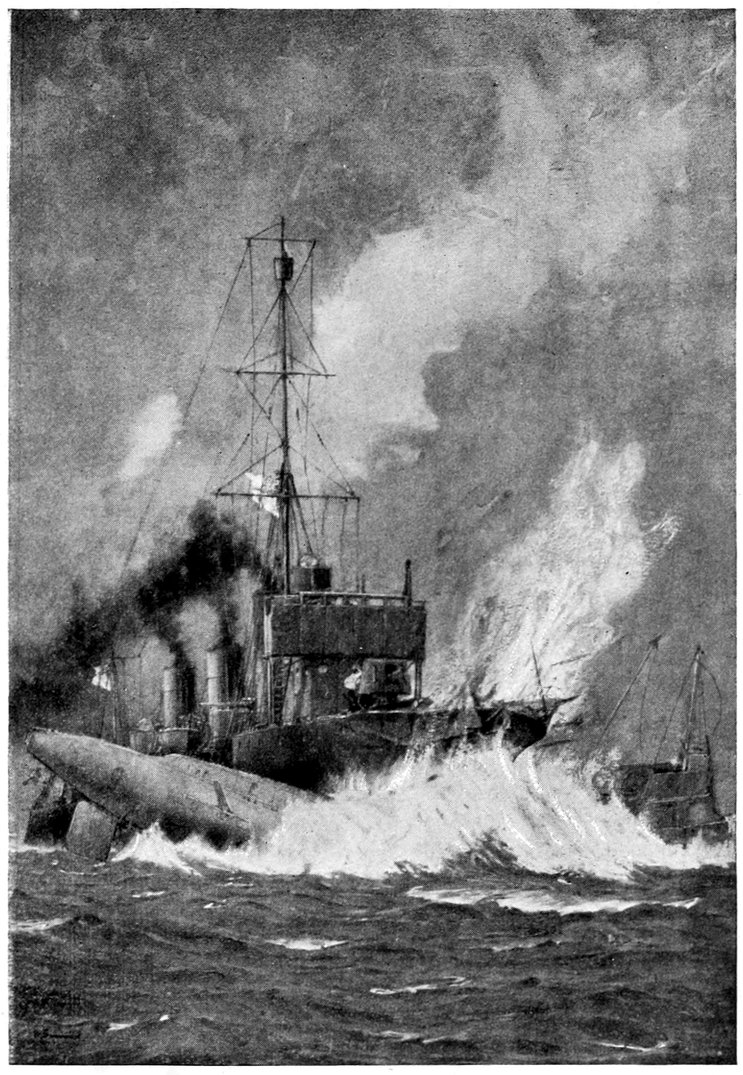

The Last of a Pirate

G. H. Davis

Title: War in the Underseas

Author: Harold Wheeler

Release date: August 27, 2020 [eBook #63060]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Chris Curnow, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Last of a Pirate

G. H. Davis

IN THE SINCERE HOPE THAT IF OPPORTUNITY BE HIS HE MAY EMULATE THE DARING OF HIS FATHER, WHOSE ACHIEVEMENT AT ZEEBRUGGE AND OSTEND WILL BE RELATED BY OLD BOYS TO THEIR JUNIORS UNTIL THE OCEAN HIGHWAY IS AS DRY AS A DUSTY ROAD

Sea-power strangled Germany and saved the world. Even when the Kaiser’s legions were riding roughshod over the greater part of Europe its grip was slowly throttling them. Despite the murderous mission of mine and U-boat, it kept the armies of the Allies supplied with men and munitions, and scoured the world for both. When the British Fleet took up its war stations in the summer of 1914 it became the Heart of Things for civilization. It continued to be so when the major portion of the swaggering High Sea Fleet came out to meet Beatty under the white flag in the chilly days of November 1918. It remains so to-day.

The officers and men of the Royal Navy whose march is the Underseas played a perilous and noble part in the Great Conflict. British submarines poked their inquisitive noses into the wet triangle of Heligoland Bight three hours after hostilities were declared; they watched while the Men of Mons crossed 8the Channel to stay the hand of the invader; they pierced the Dardanelles when mightier units remained impotent; they threaded their way through the icy waters of the Baltic despite the vigilance of a tireless enemy; they fought U-boats, a feat deemed to be impossible; they dodged mines, land batteries, and surface craft, and depleted the High Sea Fleet of many valuable fighting forces. In addition, they had to contend with their own peculiar troubles—shoals, collisions, breakdowns, and a hundred and one ills which a landsman never suspects. Some set out on their duties and failed to come back. They lie many fathoms deep. Their commanders have made their last report. Sea-power has its price.

I am under special obligation to several officers of British submarines for assistance willingly rendered, despite the arduous nature of their duties. Their generous enthusiasm exhibits that “real love for the Grand Old Service it is an honour and pleasure to serve in,” as Admiral Beatty wrote to me the other day.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Clearing the Decks | 13 |

| II. | Life as a Latter-day Pirate | 52 |

| III. | Germany’s Submersible Fleet | 69 |

| IV. | Pygmies among Giants | 84 |

| V. | Tragedy in the Middle Seas | 105 |

| VI. | Horton, E 9, and Others | 120 |

| VII. | Submarine v. Submarine | 137 |

| VIII. | A Chapter of Accidents | 148 |

| IX. | Sea-hawk and Sword-fish | 165 |

| X. | U-Boats that Never Returned | 192 |

| XI. | Depth Charges in Action | 209 |

| XII. | Singeing the Sultan’s Beard | 222 |

| XIII. | On Certain Happenings in the Baltic | 241 |

| XIV. | Blockading the Blockade | 272 |

| XV. | Bottling up Zeebrugge and Ostend | 297 |

| XVI. | The Great Collapse | 310 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The Last of a Pirate | Frontispiece |

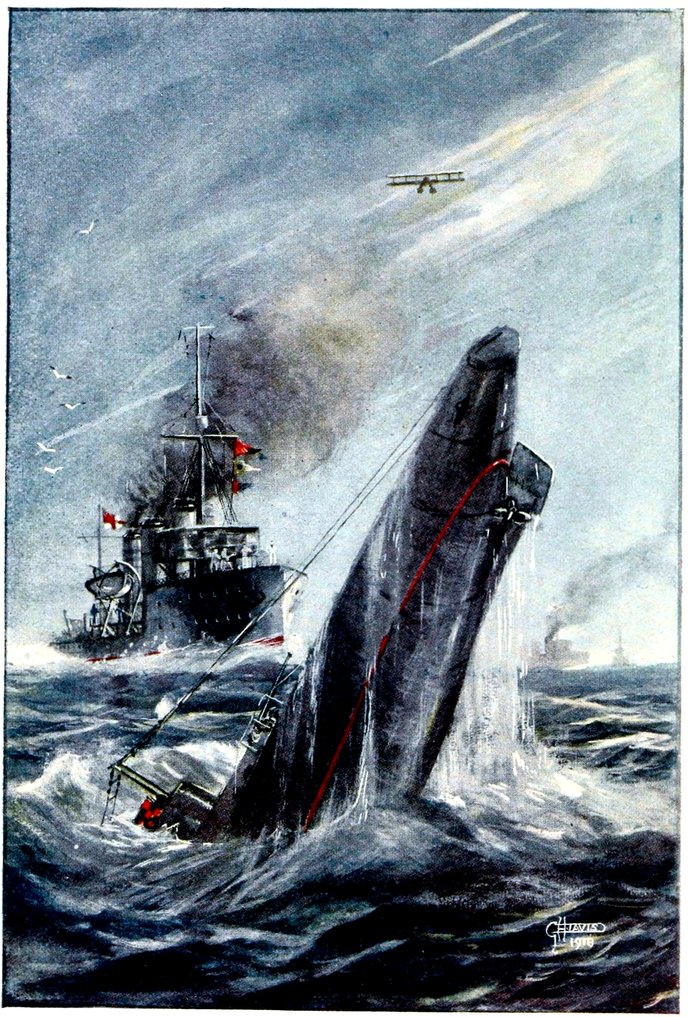

| Unrestricted Submarine Warfare | 48 |

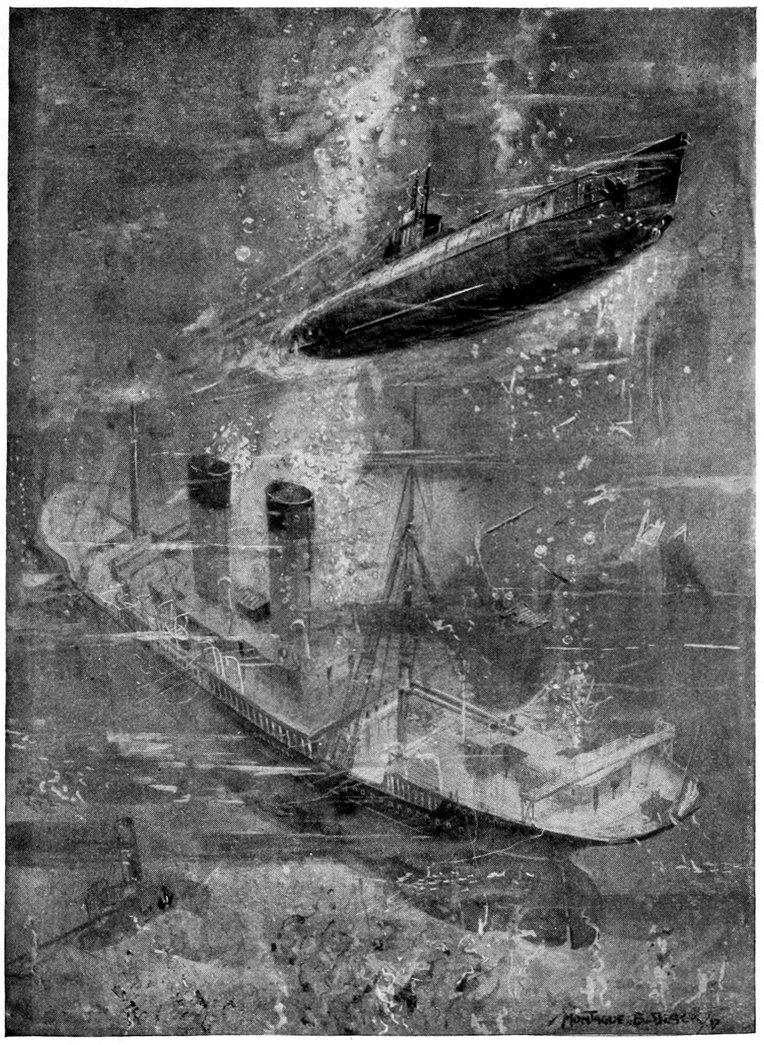

| The Interior of a German Submarine | 72 |

| The Second Exploit of E 9 | 126 |

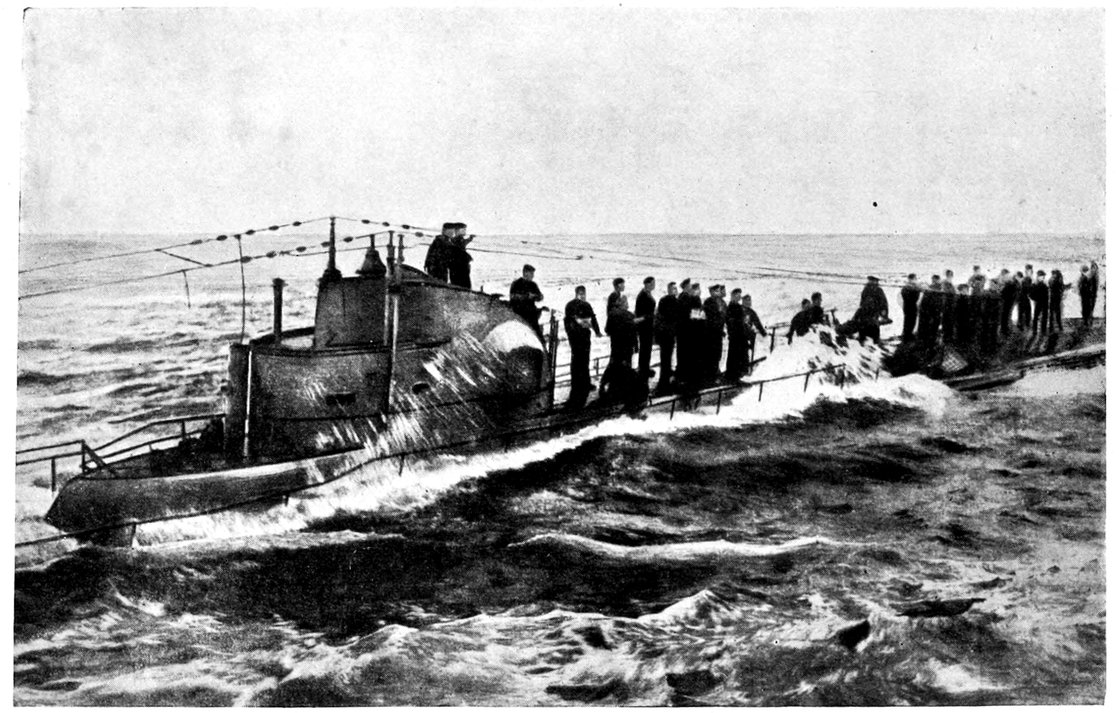

| “Kamerad! Kamerad!” | 154 |

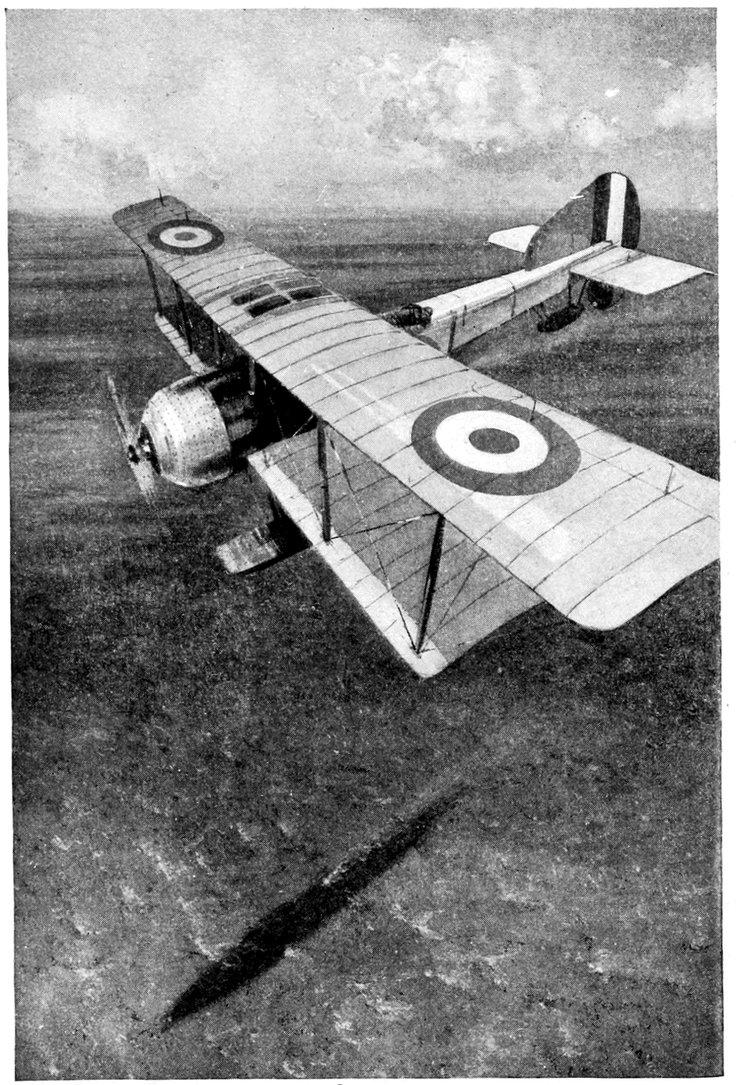

| A Seaplane of the R.N.A.S. | 188 |

| The Destroyer’s Short Way with the U-Boat | 218 |

| C 3 at Zeebrugge Mole | 298 |

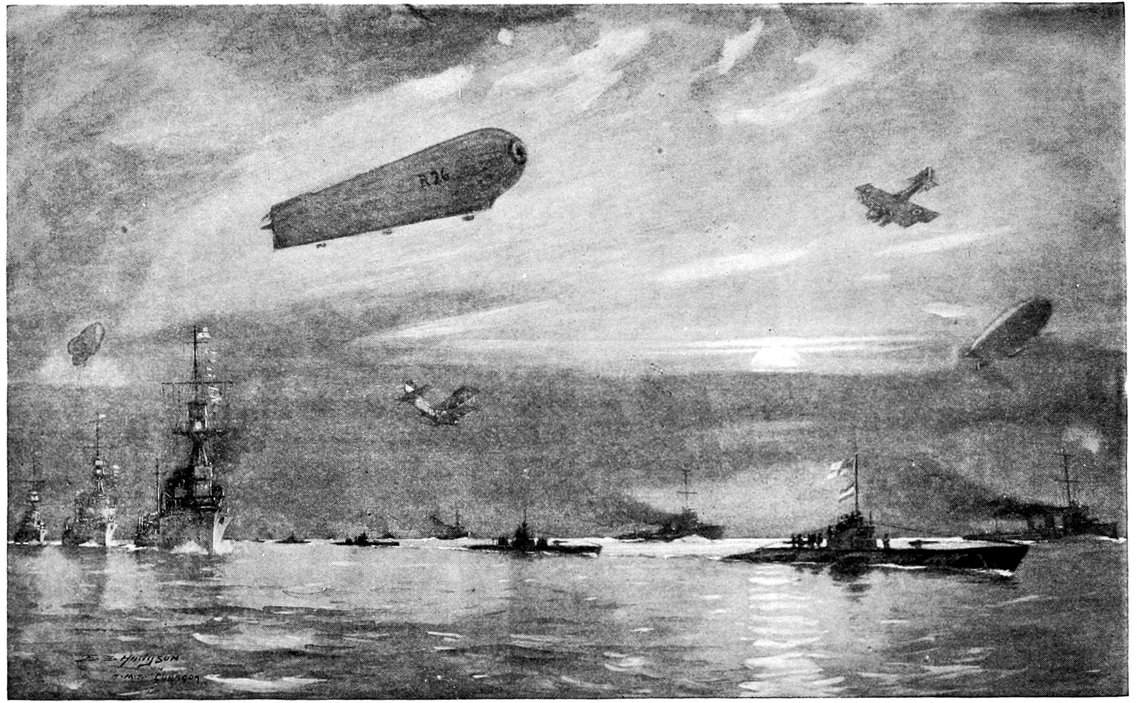

| Entry of the Surrendered U-Boats into Harwich | 310 |

“Society must not remain passive in face of the deliberate provocation of a blind and outrageous tyrant. The common interests of mankind must direct the impulses of political bodies: European society has no other essential purpose.”—Schiller.

Surprise is the soul of war. The submarine illustrates this elemental principle, and its astounding development is the most amazing fact of the World Struggle. Given favourable circumstances it can attack when least expected, pounce on its prey at such time as may be most convenient to itself, and return to its lair without so much as being sighted. What has become a vital means to the most important military ends was once described by the British Admiralty as “the weapon of the weaker Power.” To a large extent, of course, it is par excellence the type of vessel necessary to bidders for Sea Supremacy who would wrest maritime predominance from a stronger Power. On the other hand, it has rendered yeoman service to the British Navy, 14as many of the following pages will show. Germany, a nation of copyists but also of improvers, diverted the submersible from the path of virtue which previous to the outbreak of hostilities it was expected to pursue. It is safe to say that few people in Great Britain entertained the suspicion that underwater craft would be used by any belligerent for the purpose of piracy.

Up to August 1914 the submarine was intimately associated in the public mind with death and disaster—death for the crew and disaster for the vessel. It is so easy to forget that Science claims martyrs and Progress exacts sacrifice. These are two of the certainties of an uncertain world. The early stages of aviation also were notable for the wreck of hopes, machines, and men. To-day aircraft share with submarines and tanks the honour of having altered the aspect of war. The motor-car, once the laughing-stock of everybody other than the enthusiast, and now grown into a Juggernaut mounting powerful guns, is the foster-father of the three, for the perfection of the internal combustion engine 15alone made the submarine and the aeroplane practicable.

For good or for ill, the underwater boat has passed from the experimental to the practical. In the hands of the Germans it became a particularly sinister and formidable weapon. The truth is not in us if we attempt to disguise the fact. When there was not so much as a cloud the size of a man’s hand on the European sky, and the Betrayer was pursuing the path of peaceful penetration all undisturbed and almost unsuspected, the submarine was regarded by many eminent authorities as a somewhat precocious weakling in the naval nursery. They refused to believe that it would grow up. Even Mr H. G. Wells, who has loosed so many lucky shafts, unhesitatingly damned it in his Anticipations. He saw few possibilities in the craft, and virtually limited its use to narrow waterways and harbours.

There were others, however, who thought otherwise, and the controversy between the rival schools of thought was brought to a head by a fierce battle fought in Printing House Square. Sir Percy Scott, who had previously 16held more than a watching brief for the heavy fathers of the Fleet, bluntly told the nation through the columns of the Times that the day of the Dreadnought and the Super-Dreadnought was over. With a scratch of the pen he relegated battleships to the scrap-heap—until other experts brought their guns to bear on the subject. Almost on the conclusion of this war of words the war of actuality began. I do not think I am wrong in saying that the former ended in an inconclusive peace. Practice has proved the efficiency of both surface and underwater craft, but particularly of vessels that do not submerge.

Admiral Sir Percy Scott’s prophecy remains unfulfilled. The big-gun ship has asserted itself in no uncertain language. It is interesting to note, however, that the ruling of one who took part in the discussion, and whose personal experience in the early stages of the evolution of a practical submarine entitled him to special consideration, has been entirely negatived. Rear-Admiral R. H. S. Bacon,[1] 17the principal designer of the first British type, asserted that “the idea of attack of commerce by submarines is barbarous and, on account of the danger of involving neutrals, impolitic.” It is obvious from this that the late commander of the Dover Patrol never contemplated any departure from the acknowledged principles of civilized warfare. The unexpected happened, as it is particularly liable to do in war. One of the main purposes of the enemy’s submarines in the World War was piracy, unrestrained, unrestricted, and unashamed. It failed to justify Germany’s hope.

Probably Lord Fisher was the first seaman holding high position to actually warn the British Government of the likelihood of Germany’s illegitimate use of the submarine. Early in 1914 he handed to Mr Asquith and the First Lord of the Admiralty a memorandum pointing out, among other things, that the enemy would use underwater boats against our commerce.[2] His prescience was forestalled thirteen years before by Commander Sir Trevor 18Dawson, who had prophesied that the enemy would attack our merchant fleet in much the same way as the Boers were then attacking the army in the Transvaal. “Submarine boats,” he told a meeting of engineers, “have sufficient speed and radius of action to place themselves in the trade routes before the darkness gives place to day, and they would be capable of doing almost incalculable destruction against unsuspecting and defenceless victims.”

Originally Germany was by no means enamoured of the new craft. Her first two submarines did not appear until 1905–6; Great Britain’s initial venture was launched at Barrow-in-Furness in 1901. The latter, the first of a batch of five, was ordered on the advice of Lord Goschen. Even then the official attitude was sceptical, not altogether without reason. Mr H. O. Arnold-Forster, speaking in the House of Commons on the 18th March, 1901, after admitting that “there is no disguising the fact that if you can add speed to the other qualities of the submarine boat, it might in certain circumstances become 19a very formidable vessel,” adopted what one might call a misery-loves-company attitude. “We are comforted,” he averred, “by the judgment of the United States and Germany, which is hostile to these inventions, which I confess I desire shall never prosper.”

Dr Flamm, Professor of Ship Construction at the Technical High School at Charlottenburg, who should and probably does know better, has aided and abetted certain other publicists in foisting on the public of the Fatherland the presumption that the submarine is a German invention. This is not the place for a full history of the underwater craft from its early to its latest stages, but perhaps it is permissible to give a few particulars regarding the toilsome growth of this most formidable type of vessel.

The first underwater craft of which there is anything approaching authentic record was the invention of Cornelius Drebbel, a Dutchman who forsook his own country for England. According to one C. van der Woude, writing in 1645, Drebbel rowed in his submerged boat from Westminster to Greenwich. Legend or 20truth has it that this “Famous Mechanician and Chymist” managed to keep the air more or less sweet in his craft by means of a secret “Chymical liquor,” and that the structure was covered with skin of some kind to make it watertight. Drebbel, who also professed to have discovered the secret of perpetual motion, is stated to have hit upon the idea of his invention by the simple process of keeping his eyes open. He noticed some fishermen towing behind their smacks a number of baskets heavily laden with their staple commodity. When the ropes were not taut the vessels naturally rose a little in the water. He came to the conclusion that a boat could be weighted in much the same way to remain entirely below the surface, and propelled by means similar to a rowing-boat. It is even said that King James travelled at a depth of from twelve to fifteen feet in one of the two vessels constructed by Drebbel, whose invention is referred to in Ben Jonson’s Staple of News.

The submarine may be said to have remained in this essentially elementary stage until 1775, 21when David Bushnell, an American, launched a little one-man submarine after five years of planning and preparation. The shape of the vessel resembled a walnut held upright, the torpedo being carried outside near the top. At the bottom was an aperture fitted with a valve for admitting water, while a couple of pumps were provided for ejecting it. About 200 lb. of lead served as ballast, which could be lowered by ropes for the purpose of giving immediate increase of buoyancy should emergency require it. “When the skilful operator had obtained an equilibrium,” Bushnell writes, “he could row upward and downward, or continue at any particular depth, with an oar placed near the top of the vessel, formed upon the principle of the screw, the axis of the oar entering the vessel; by turning the oar one way he raised the vessel, by turning it the other way he depressed it.” A similar apparatus, worked by hand or foot, whichever was the more convenient, propelled the submarine forward or backward. The rudder could also be utilized as a paddle.

Bushnell provided his little wooden craft 22with what he called a crown and we should designate a conning-tower. In this there were several glass windows. Neither artificial light nor means of freshening the air was carried, though the submarine could remain submerged for thirty minutes before the condition of the atmosphere made it necessary to ascend sufficiently near the surface to enable the two ventilator pipes to be brought into action. The water-gauge and compass were rendered discernible by means of phosphorus.

The torpedo—Bushnell termed it a magazine—was an oak box containing 150 lb. of gunpowder and a clockwork apparatus which was set in operation immediately the affair was unshipped. It was attached to a wooden screw carried in a tube in the brim of the ‘crown.’ Having arrived beneath an enemy vessel, the screw was fixed in the victim’s hull from within the submarine, and the ‘U-boat’ made off. At the time required the mechanism fired what to all intents and purposes was a gun-lock, and the torpedo blew up.

The wooden screw was the least successful 23of the various appliances. An attempt was made in 1776 to annihilate H.M.S. Eagle, then lying off Governor’s Island, New York. The operator apparently tried to drive his screw into iron, and quite naturally failed. Writing to Thomas Jefferson on the subject, Bushnell suggests that had the operator shifted the submarine a few inches he could have carried out his operation, even though the bottom was covered with copper. Two other unsuccessful trials were made in the Hudson River. Owing to ill-health and lack of means, the inventor then abandoned his submarine, though in the following year he attempted to ‘discharge’ one of his magazines from a whaleboat, the object of attack being H.M.S. Cerberus. It failed to reach the British frigate, and blew up a prize schooner anchored astern of her. Washington was fully alive to the possibilities of Bushnell’s invention, but was evidently of opinion that it was too crude to warrant his serious attention. Writing to Jefferson, he says: “I thought, and still think, that it was an effort of genius, but that too many things were necessary to be combined to expect 24much from the issue against an enemy who are always upon guard.” Incidentally this was a remarkable testimonial to the men on look-out duty on the British vessels. Keen sight is still a recognized weapon against submarine attack.

In 1797 Robert Fulton, also an American, brought his fertile brain to bear on the submarine, possibly on hearing or reading of David Bushnell’s boat. One would have anticipated that the era of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars would be propitious for the introduction of new plans and methods calculated to bring a seemingly never-ending state of hostilities to an end. Novel propositions were certainly brought forward; few were utilized. Fulton, an artist by profession, simply bubbled over with ideas connected with maritime operations. Moreover, he had extraordinary tenacity and enthusiasm. Set-backs seemed to give him added momentum. He tried to do business with Napoleon in France, with Pitt in England, with Schimmelpenninck on behalf of Holland, not always without success, before returning to the United States and 25running the steamer Clermont at five miles an hour on the Hudson.

At the end of 1797 the enterprising American proposed to the French Directory to construct a submarine, to be christened the Nautilus, or, as he frequently spelled it, the Nautulus. So great was his faith in the project for “A Machine which flatters me with much hope of being Able to Annihilate” the British Navy, that he was willing to be remunerated by results, viz., 4000 francs per gun for every ship of forty guns and upward that he destroyed, and half that amount per gun for smaller vessels. All captures were to become the property of “the Nautulus Company.” A little chary of being caught red-handed by the enemy and dealt with as a pirate, he asked that he might be given a commission in the Service, which would ensure for him and his crew the treatment of belligerents. Pléville le Pelley, Minister of Marine, deeming that such warfare was “atrocious,” and yet not altogether unkindly disposed toward it, refused the latter request, which would obviously give the submarine official sanction. The proposed 26payment by results he reduced by fifty per cent. All the arrangements were subsequently cancelled.

Nothing further was done until July 1798, when Bruix was Minister of Marine. Fulton renewed his proposition, and certain inquiries by scientists of repute were made at the instigation of Bruix. The report was distinctly favourable, but again there was disagreement as to terms. Fulton, impatient of delay, built the Nautilus. This little vessel, twenty feet long and five feet beam, was launched at Rouen in July 1800. On the trial trip the inventor and two companions made two dives in the boat, the time of submersion varying from eight minutes to seventeen minutes. Proceeding to Havre, Fulton made various improvements in the Nautilus, including the introduction of a screw propeller worked by hand, and the addition of wings placed horizontally in the bows for the purpose of ascending or descending. While at Havre the submarine remained below over an hour at a depth of fifteen feet with her crew and a lighted candle. On another occasion the Nautilus 27was submerged for six hours, air being supplied by means of a little tube projecting above the water.

For sailing on the surface the boat was fitted with a single jury-mast carrying a mainsail jib, which could be unshipped when submarine navigation was required. By admitting water she sank to the required depth, and was then propelled by the method already referred to. A glass dome, a compass, a pump for expelling the water when necessary, and a gauge for testing depth, which Fulton called a bathometer, constituted the ‘works.’ The torpedo was an apparatus made of copper filled with gunpowder, “arranged in such a manner that if it strikes a vessel or the vessel runs against it, the explosion will take place and the bottom of the vessel be blown in or so shattered as to ensure her destruction.”[3] The weapon was to be fixed to the bottom of the victim by means of a barbed point on the chain used for towing it.

Fulton approached Napoleon, who authorized Forfait, the latest Minister of Marine, 28to advance the sum of 10,000 francs for the purpose of perfecting the Nautilus. He also granted Fulton an interview. When, in the autumn of 1801, he expressed a wish to see the submarine, the vessel had been broken up. Here the matter ended, and the ingenious American turned his thoughts in the direction of steam navigation. The Nautilus was his one and only experiment in underwater craft.[4]

The first ship to be actually sunk during hostilities by submarine was the Federal 13–gun frigate Housatonic, of 1264 tons. She went down off Charleston on the 17th February, 1864, during the American Civil War, as the result of being attacked by a spar-torpedo carried by the Confederate submarine Hunley, so named after her designer, Captain Horace L. Hunley. Unfortunately the underwater boat was also a victim, and she carried with her her fourth crew to meet with death as a consequence 29of misadventure. On the first occasion the boat was swamped and eight men were drowned, on the second a similar disaster overtook her, with the loss of six of her crew, on the third she descended and failed to come up. Small wonder that the Hunley came to be known as ‘the Peripatetic Coffin.’

The shape of the Hunley was cylindrical. For’ard and aft were water ballast tanks operated by valves, and additional stability was given by a sort of false keel consisting of pieces of cast iron bolted inside so as to be easily detachable should it be necessary to reach the surface quickly. On each side of the propeller, worked by the hand-power of eight men, were two iron blades which could be moved so as to change the depth of the vessel. The pilot steered from a position near the fore hatchway.

The torpedo, a copper cylinder containing explosive and percussion and primer mechanism, was fired by triggers. It was carried on a boom, twenty-two feet long, attached to the bow. The speed was seldom more than four miles an hour on a calm day. As there was 30no means of replenishing the air other than by coming to the surface and lifting one of the hatchways, it was obviously a fair-weather ship.

On the afternoon of the 17th February, 1864, the Hunley set out on her final trip. While attacking the submarine was only partly submerged, and one of the hatches was uncovered; why will never be known. She made straight toward the Housatonic, with the evident intention of striking the vessel near the magazines with her torpedo. There was an explosion, the ship heeled to port, and went down by the stern. When divers examined the extent of her injuries the plucky little Hunley was found with her nose buried in the gaping wound in her victim’s hull. Her crew were dead, but apparently the officer was saved.

Other submarines or partly submersible boats were used by the defenders of the Southern cause. They were usually termed ‘Davids’ because they were built to sink the Goliaths of the Federal Navy. The New Ironsides, the Minnesota, and the Memphis were all damaged as a result of their operations.

31The only weapon of the submerged submarine is the torpedo. The World War brought no surprise in this direction. For surface work the calibre of the guns mounted on the disappearing platforms has increased very considerably. In 1914 a 14–pdr. was considered ample armament. With added displacement, gun-power has grown enormously. Some German underwater craft in 1918 carried 5.9–in. guns—that is to say, weapons larger than those used by many destroyers.

During the past decade torpedoes and submarines have made almost parallel progress. Of the various types of the former, the Whitehead is first favourite in the Navies of Great Britain, Japan, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, while France uses both the Whitehead and the Schneider, and Germany was exclusively devoted to the Schwartzkopf (Blackhead). The extreme effective range of each may be taken as from 10,000 to 12,000 yards. The essential difference between a torpedo and the usual run of naval ammunition for guns is that the torpedo retains its propellant, while the shell does not. The torpedo is really an explosive submarine 32mine forced through the water at a rate varying from 28 knots to 42 knots by twin-screws worked by compressed air engines. Any deviation from the course is automatically corrected by a gyroscope. Some torpedoes are now fitted with an apparatus which causes the torpedo to go in circles should it miss its mark and meet with the wash of passing ships. There is the added possibility, therefore, that the weapon may strike a vessel at which it was not aimed when a squadron is proceeding in line ahead.

To a certain extent the submarine has enabled the torpedo to come into its own. It is not at all an easy task to hit a rapidly moving ship from a platform also ploughing the water at a great rate. Among other things the speed and distance of the opponent have to be taken into consideration, and the missile aimed ahead of the enemy so that it and the target shall arrive at a given point at the same moment. The late Mr Robert Whitehead’s invention, an improvement on that of Commandant Lupuis, of the Austrian Navy, who had sold his patent to the former, was tested 33by the British Admiralty at Sheerness in 1871. Although extremely crude when compared with its successor of to-day, the sum of £15,000 was paid for the English rights. It was first put to a practical test in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877, when Lieutenant Rozhdestvensky, who afterward suffered defeat at the hands of the Japanese in May 1905, sank a Turkish warship by its means.

Viscount Jellicoe has told us that the arrival of the submarine led to certain alterations in strategy. I quote from an interview which the former First Sea Lord granted to a representative of the Associated Press in the spring of 1917. Sir John, as he then was, said: “The most striking feature of the change in our historic naval policy resulting from the illegal use of submarines, and from the fact that the enemy surface ships have been driven from the sea, is that we have been compelled to abandon a definite offensive policy for one which may be called an offensive defensive, since our only active enemy is the submarine engaged in piracy and murder.” Mr Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty in 34August 1914, put the matter a little more bluntly. “But for the submarine and the mine.” he wrote, “the British Navy would, at the outset of the war, have been able to force the fighting to an issue on their old battleground—outside the enemy’s ports.”

This did not mean that every other type of ship had been rendered obsolete or even obsolescent by the coming of the vessel that can float on or under the waves. Admiral von Capelle, Secretary of State for the German Imperial Navy, told the Main Committee of the Reichstag that the submarine was an “important and effective weapon,” but added that “big battleships are not wholly indispensable. Their construction depends on the procedure of other nations.”[5] For instance, the submarine has emphasized the importance of the torpedo-boat destroyer, which some seamen thought it would supersede. The T.B.D. has more than maintained its own. Not only is it useful for acting independently, fighting its own breed, but as the safeguard of the battleships and battle-cruisers at sea, 35and also as the keenest weapon against submarines, the naval maid-of-all-work has proved extraordinarily efficient.[6]

In the general operations of naval warfare it cannot be said that the enemy U-boats were particularly successful. In the five battles that were fought the work of German submarines was negligible so far as actual fighting was concerned. In two of them, namely Coronel and the Falklands, they were unrepresented on account of the actions taking place many thousands of miles from European waters. This limitation of range of action is a difficulty that time and experiment were beginning to solve when hostilities came to an abrupt conclusion.

The battles of Heligoland Bight and Dogger Bank are profoundly interesting to the student of War in the Underseas. Sir David Beatty, who commanded the Battle Cruiser Squadron in the first big naval engagement in which submarines were used, while admitting that he did not lose sight of “the risk” from them, says in his dispatch that “our high speed ... 36made submarine attack difficult, and the smoothness of the sea made their detection comparatively easy.” These two antidotes will be noted by the reader. The same distinguished officer, perched on the fore-bridge of the Lion in his shirt-sleeves while pursuing the German Fleet near the Dogger Bank, personally observed the wash of a periscope on his starboard bow. By turning immediately to port he entirely upset the calculations of the enemy commander, who was not afforded a further opportunity to torpedo the flagship. A like manœuvre defeated a similar projected attack on the Queen Mary in the Bight. The helm is therefore a third instrument of defence. Apparently the service rendered by enemy U-boats at these two battles was worthless. If they fired at all they missed. On the other hand, any attempt to sink them likewise failed.

In the dispatches on the Battle of Jutland, which a well-known Admiral tells me were severely edited before publication, there are several references to enemy submarines, none to our own. The first attempted attack took 37place about half an hour after Sir David Beatty had opened fire, and immediately following the entry of the 5th Battle Squadron into the fight. The destroyer Landrail sighted a periscope on her port quarter. With the Lydiard she formed a smoke-screen which “undoubtedly preserved the battle-cruisers from closer submarine attack.” The light cruiser Nottingham also reported a submarine to starboard. We are also informed that “Fearless and the 1st Flotilla were very usefully employed as a submarine screen during the earlier part of May 31.” The Marlborough, flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir Cecil Burney’s First Battle Squadron, after having been torpedoed—whether by submarine or other craft is not mentioned—drove off a U-boat attack while proceeding to harbour for repairs. “The British Fleet,” adds Sir John Jellicoe, “remained in the proximity of the battlefield and near the line of approach to German ports until 11 a.m. on June 1, in spite of the disadvantages of long distances from fleet bases and the danger incurred in waters adjacent to enemy coasts from submarines and torpedo 38craft.” In the British list of enemy vessels put out of action, one submarine figures as sunk.

Admiral Beatty justly remarks that the German losses were “eloquent testimony to the very high standard of gunnery and torpedo efficiency of His Majesty’s ships.” Of the twenty-one vessels lost or severely damaged, it would appear as though nine were accounted for by torpedoes, although this does not necessarily mean that they had not been engaged by gunfire as well. At Dogger Bank, it may be recollected, a torpedo finally settled the Blücher, which had already been rendered hors de combat by shell fired from more old-fashioned weapons.

The German High Sea Fleet adopted a prolonged attitude of caution after Jutland, but the All-Highest thought it well to issue an Imperial Order calculated to inspire the officers and men of the submarine flotillas. “The impending decisive battle” mentioned in the following message, which is dated Main Headquarters, 1st February, 1917, evidently refers to the ‘unlimited’ phase of U-boat warfare 39and not to a general action, as one might imagine at first glance. This highly interesting document runs:

In the impending decisive battle the task falls on my Navy of turning the English war method of starvation, with which our most hated and most obstinate enemy intends to overthrow the German people, against him and his Allies by combating their sea traffic with all the means in our power.

In this work the submarine will stand in the first rank. I expect that this weapon, technically developed with wise foresight at our admirable yards, in co-operation with all our other naval fighting weapons, and supported by the spirit which during the whole course of the war has enabled us to perform brilliant deeds, will break our enemy’s war designs.

The defensive policy of the Imperial Navy was summed up by a writer in the Deutsche Tageszeitung seven months after the publication of the above. “Above all else,” he wrote, “the German High Sea Fleet has rendered possible the conduct of the submarine war. Without it the enemy would have threatened our submarine bases and restricted our submarine warfare, or made it impossible.” It 40was not a valorous rôle to play, but there was wisdom in it.

The submarine campaign passed through several phases. In its earliest stages it was mainly directed by Grand Admiral von Tirpitz, the predominant personality associated with the growth of the Imperial Navy. In December 1914 this Bluebeard of the Seas asserted that as England wished to starve Germany, “we might play the same game and encircle England, torpedoing every British ship, every ship belonging to the Allies that approached any British or Scottish port, and thereby cut off the greater part of England’s food supply.” The ‘game’ was started on the 18th February, 1915, and enthusiastically applauded throughout the German Empire. All the waters surrounding the United Kingdom, and “all English seas,” were declared to be a war area. Every vessel of the British Mercantile Marine was to be destroyed, “and it will not always be possible to avoid danger to the crews and passengers thereon.”[7] Peaceful shipping was warned that there was a possibility of neutrals 41being “confused with ships serving warlike purposes” if they ventured within the danger zone. Great Britain had declared the North Sea a military area in November 1914, and every care was taken to respect the rights of neutral shipping. The enemy, on the contrary, speedily showed utter disregard of international law. The submarine programme was started before the day advertised for the opening performance.

The sinking of the Lusitania on the 7th May, 1915, with the loss of 1225 lives, showed in no uncertain way that the Germans intended nothing less than an orgy of cold-blooded devilry. In the following month the always strident German Navy League stated that the fleet which it had done so much to bring into being “was not in a position to break the endless chain of transports carrying munitions in such a manner as blockade regulations had hitherto required.” To search ships was “in most cases impossible.” In the same manifesto the sinking of the giant Cunarder was ‘explained’ by arguing that as submarines had no means to compel vessels to stop, and 42there was ammunition on board, sinking without warning was justified. “Such must continue to be the case, and the Army has a just claim to this service of the Fleet.”

As a protest against armed traders, the campaign was intensified on the 1st March, 1916. These ships were “not entitled to be regarded as peaceful merchantmen.” The plain English of the move was that Germany wanted some kind of excuse for ordering her submarines to sink vessels at sight. According to her, none other than naval ships had the least excuse to assume so much as the defensive. In President Wilson’s so-called Sussex note of the 18th April, 1916, attention is called to the “relentless and indiscriminate warfare against vessels of commerce by the use of submarines without regard to what the Government of the United States must consider the sacred and indisputable rules of international law and the universally recognized dictates of humanity.”

The third phase was that of “unlimited submarine war,” announced on the last day of January 1917. “Within the barred zones 43around Great Britain, France, Italy, and in the Eastern Mediterranean, all sea traffic will henceforth be oppressed by all means.” Neutral ships in those areas would traverse the waters “at their own risk.” To a large extent they had done so before. Notwithstanding repeated ‘regrets’ and pledges given by Germany to the United States, murder on the high seas was now to be an acknowledged weapon of German warfare. It culminated in a declaration of war on the part of the United States on the 6th April, 1917, by which time over 230 Americans had lost their lives by the enemy’s illegal measures. The date is worth remembering; it will loom big in the history books of to-morrow. Zimmermann, Germany’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, had already expressed the opinion that ruthless submarine warfare promised “to compel England to make peace in a few months.”[8] In this expectation, as in several others, he miscalculated.

The Lord Chancellor declared that submarine warfare, as carried on by the enemy, was 44absolutely illegal by international law, and was mere piracy.[9] As to mines, which were also greatly favoured by the Huns and sown by their U-boats, it may be mentioned that such weapons laid to maintain a general commercial blockade are equally illegal, although perfectly legitimate outside naval bases. This was a small matter to the Kaiser and his satellites, who were out to win at any and all costs. No British mines were placed in position until many weeks after the declaration of hostilities, although the enemy had scattered them indiscriminately in the trade routes either before or immediately following the outbreak of war. When we resorted to the use of mines they were anchored in all cases, and constructed to become harmless if they broke loose.

The reply of England and of France to these measures was to stop supplies from entering Germany by means of a blockade controlled by cruiser cordon. “The law and custom of nations in regard to attacks on commerce,” to quote the British Declaration to Neutral 45Governments,[10] “have always presumed that the first duty of the captor of a merchant vessel is to bring it before a Prize Court, where it may be tried, where the regularity of the capture may be challenged, and where neutrals may recover their cargoes.” With delicate consideration for the convenience of neutrals, which some folk held to be wisdom and others lunacy, the British Government declared their intention “to refrain altogether from the exercise of the right to confiscate ships or cargoes which belligerents have always claimed in respect of breaches of blockade. They restrict their claim to the stopping of cargoes destined for or coming from the enemy’s territory.”[11]

Much ado was made about the stoppage of food for the civil population of the Central Empires. It was barbarous, inhuman, and so on. Yet the principle had been upheld by both Bismarck and Caprivi, and practised at the siege of Paris. As Sir Edward Grey delightfully put it, this method of bringing 46pressure to bear on an enemy country “therefore presumably is not repugnant to German morality.”[12]

A great deal has been said and written to show that the Prussian Government was not the German People, that instead of Representation there was Misrepresentation. It is still extremely difficult to secure reliable information on any subject connected with intimate Germany, and the contemporary views of so-called neutrals are often more than suspect. A study of German newspapers at the time certainly led one to believe that opposition to the submarine campaign had been more or less negligible. A change of view only came when the people realized that ruthlessness did not pay, and it was the business of the British Navy to demonstrate this—as it did. Meantime the German official accounts of sinkings were grossly exaggerated, and the nation had no means of discovering the loss of submarines other than when relatives serving in them failed to return to their families. There was no one to contradict the grossly exaggerated statement 47made by Dr Helfferich, Minister for the Interior, that in the first two months of unrestricted U-boat warfare over 1,600,000 tons of shipping had been sunk at the cost of the loss of a mere half-dozen submarines.[13]

Dr Michaelis, a more noisy sabre-rattler than his predecessor in the Chancellorship, asserted that “the submarine warfare is accomplishing all, and more than all, that was expected of it.”[14] Like many other of his countrymen, to him the crews of the Imperial Pirate Service were more of the nature of soldiers than of sailors. Certainly their callous behaviour suggested that they were strangers to the proverbial comradeship of the sea, and one with the glorious band that hacked a way through Belgium, drove their bayonets through babies, and crucified their prisoners. Loud cheers followed the remark that “We can look forward to the further labours of our brave submarine warriors with complete confidence,” and also to a reference to greetings sent home to the Fatherland by “our troops on all fronts 48on land and sea, in the air and under the sea.”

As to the thoroughness with which commanders of U-boats performed their task, there is no need to speak. There is plentiful evidence to prove that so elementary a duty as that of examining a ship’s papers seldom interested them. They had no respect for law or life. Witness a case[15] that has a direct bearing on this matter. It arose in connexion with the salving of the s.s. Ambon, a neutral vessel bound for the Dutch East Indies, after having been torpedoed on the 21st February, 1916, when about seven miles off Start Point. A shell was fired from an enemy submarine. Immediately the engines of the steamship were stopped, a lifeboat was lowered, and the chief engineer sent off with the ship’s papers and instructions. The latter included a copy of a telegram from the owners advising that the steamer was to call at a certain port on a specified day, in accordance with an agreement between the Dutch and German Governments. The German commander did not so much as look at the documents, and peremptorily told the crew to leave the Ambon. “My orders admit of no variation,” he remarked. They were “to sink every ship in the blockade area.” The steamer was then torpedoed, but did not founder, and was subsequently towed into Plymouth.

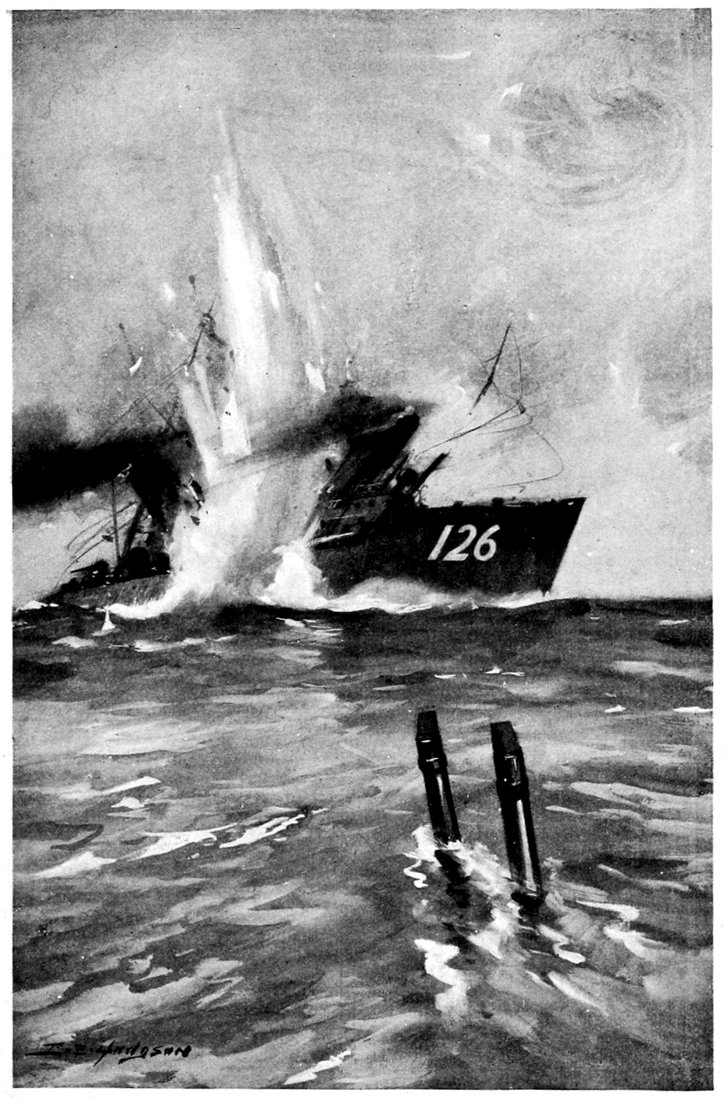

Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

A U-boat gliding, submerged, over her victim.

Montague Black

49No reliance whatever could be placed on Germany’s word, as neutrals early discovered to their cost. Having provided a so-called ‘safe’ zone, the Dutch steamer Amsterdam was torpedoed within it. At Germany’s own suggestion, an International Committee, composed of Dutch, Swedish, and German naval officers, was formed to investigate the circumstances. Their finding was that the vessel had been sunk in the ‘safe’ zone.

There was a time when the French authorities seemed to be in favour of the submarine above all other types of naval ships. The result was that France lost her position in the race for second place in the world’s fleets, though it is to her credit that in 1888 she launched the Gymnote, the first modern submarine to be 50commissioned. Nordenfeldt, of gun fame, had already achieved a certain amount of success with steam-driven underwater boats, but they had many disadvantages when compared with those of Mr John P. Holland, who hailed from the same country as Fulton. The first submarines built for the British Government were of the Holland type, of 120 tons displacement when submerged, and having a speed of five knots when travelling below. Germany’s pioneer U-boat was built in 1890. In 1918 she boasted giant diving cruisers of 5000 tons, with a radius of action of 8000 miles, and mounting 5.9–in. guns.

As to the vexed question of the number of submarines possessed by Great Britain and Germany respectively at the beginning of the war, one can only say that authorities differ. According to an interview granted by Mr Winston Churchill to M. Hugues le Roux which appeared in Le Matin in the first week of February 1915, we then had more underwater boats than the enemy, but Lord Jellicoe afterward asserted that in August 1914 “the German Navy possessed a great many more 51oversea submarines than we did.”[16] Unless there is a subtle distinction between the general term used by the then First Lord and the oversea type referred to by the former Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, it is impossible to reconcile the two statements, for it is obvious that the leeway mentioned by the latter cannot have been made up in five months.

According to the Berlin official naval annual Nautilus, published in June 1914, the total number of completed German submarines up to the previous month was twenty-eight. Commander Carlyon Bellairs, R.N., M.P., estimated them at “fifty built, building, and projected.” Austria had six ready, four under construction at Pola, and five on the stocks in Germany. In the five years immediately preceding the beginning of the struggle Germany certainly spent more on underwater craft than Great Britain, the figure for the former being £5,354,206, and for the latter £4,159,670.

“The unrestricted U-boat war means a very strong naval offensive against the Entente.”—Admiral von Capelle.

Writing in the early summer of 1915, a neutral who visited the once busy ports of Danzig, Stettin, Hamburg, and Bremen remarked that “wherever one goes in these cities, wherever one takes one’s meals, one hears the word Unterseeboot. Amazing, and often untrue, stories are told of the number of submarines that are being constructed, the size and speed of the latest ones, and the great number of English ships that have been sunk, but whose loss has been ‘concealed from the British public.’” The submarine barometer was Set Fair. It soon dropped to Change.

Within six months the industrious and outspoken Captain Persius was confessing in the Berliner Tageblatt that “regarding the effectiveness of our U-boats in the trade war, one hears frequently nowadays views that 53bear little resemblance to the views uttered a year ago. Then, alas, hopes were extravagant, owing to a disregard of facts which the informed expert, indeed, observed, but which remained concealed from the layman”—a confession of failure, notwithstanding the offer of substantial rewards for every merchant vessel sunk, and pensions for each man in a submarine which destroyed a transport.

Twenty months later Admiral von Scheer asserted that German submarine losses were more than equalized by new construction. Note the definite acknowledgment of losses and of the necessity for replacing them. In April 1918 Admiral von Capelle, Imperial Secretary of State for the Navy, endeavoured to explain the declining maritime death-rate of the enemy by assuring the Main Committee of the Reichstag that the average loss of British ships from submarine attacks alone, during 1917, was 600,000 tons per month. The truth of the matter was that the average loss from all causes was not more than 333,000 gross tons. According to an official statement 54circulated to the German Press on the 4th of the following June, food conditions in England were “extraordinarily bad,” because the U-boat campaign was “having the intended result of constantly diminishing England’s food supply.” In actual fact, the U-boats were then having a particularly rough time. So far as the German Independent Socialists were concerned, they did not “look forward with complete confidence,” as Dr Michaelis had professed to do in July 1917, “to the further labours of our brave submarine warriors.” Herr Vogtherr, a member of the party, bluntly remarked that “it cannot be seen that U-boat warfare has brought peace nearer. Meanwhile we continue to destroy tonnage which we shall need after the war in order to obtain necessary raw materials.” As to the latter clause, the British Mercantile Marine has already had something to say. It lost 14,661 gallant fellows through enemy action.

According to the statement of a member of the crew of the British destroyer which rammed U 12, some of the prisoners at least were 55thankful to be in despised England. They said that the coxswain had been a North Sea pilot for fifteen years previous to the outbreak of war, and though the veriest tyro in matters relating to underwater craft, was compelled to take service, presumably because he was well acquainted with the east coast of the United Kingdom. The story of crews being forced with the gentle persuasion of a revolver to board other U-boats while their own was docked to undergo repairs was not necessarily exaggerated. There is evidence that on occasion German seamen were shot for refusing to go on board a submarine. The mate of the Brazilian steamer Rio Branco, when taking the ship’s papers to the commander of an enemy U-boat, asked a member of the crew what life was like as a latter-day pirate. He replied in a single word usually taken to denote eternal misery, and added that although he and his mates would like to mutiny, opportunity was never afforded them, because they were shot on the slightest pretext. There is no reason to doubt that crews were sent to sea with insufficient training, and that their 56moral steadily declined as Allied efforts to tackle the foe developed.

With a stoical philosophy which may have been specially intended for neutral consumption,[17] Lieutenant-Commander Claus Hansen informed the Kiel representative of the New York World that “We need neither doctors nor undertakers aboard U 16; if anything goes wrong with our craft when below no doctor can help; and we carry our coffin with us.” One can thoroughly appreciate his remark that the work “is fearfully trying on the nerves. Every man does not stand it.”

The same article also furnishes other interesting particulars of the life of a modern pirate which bear prima facie evidence of truth. “We steer entirely by chart and compass,” the commander averred. “As the air heats it gets poor, and, mixed with odours of oil from machinery, the atmosphere becomes fearful. An overpowering sleepiness often attacks new men, who require the utmost will-power to remain awake. Day after day in such cramped quarters, where there is 57hardly room to stretch the legs, where one must be constantly alert, is a tremendous strain on the nerves. I have sat or stood for eight hours with my eyes glued to the periscope, peering into the brilliant glass until my eyes and head have ached. When the crew is worn out, we seek a good sleep and rest under the water, the boat often rocking gently, with a movement like that of a cradle. Before ascending I always order silence for several minutes, to determine whether one can hear any propellers in the vicinity through the shell-like sides of the submarine, which act like a sounding-board.”

Hansen gave the interviewer to understand that lying dormant many fathoms deep was not exactly a treat to his crew. “When the weather or the proximity of the enemy make it necessary to remain down so long that the air becomes unusually bad, every man except those actually on duty is ordered to lie down, and to remain absolutely quiet, making no unnecessary movements, as movement causes the lungs to use more oxygen, and oxygen must be saved, just as the famished man in 58the desert tries to make the most of his last drop of water. As there can be no fire, because fire burns oxygen, and the electric power from the accumulators is too precious to be wasted for cooking, we have to dine cold when cruising.” This chat, it is necessary to add, took place in March 1915. Since then many improvements have been made in submarines, including ventilation and roominess.

At this particular period everything possible was being done to arouse the enthusiasm of the German nation for the Underseas War. Carefully written articles by naval men, syndicated by official or semi-official Press bureaux, made their appearance with almost bewildering frequency. German submarines had found their way to the Dardanelles, a feat attended by much metaphorical trumpet-blowing and flag-waving. To quote Captain von Kühlewetter, a devout worshipper at the shrine of Tirpitz:

“The layman can hardly imagine what it means for a craft of only 1000 tons displacement, about 230 feet long and 19 or 20 feet beam at its widest point, to make with a 59crew of thirty a trip as far as from Hamburg to New York. The little vessel can only travel at moderate speed in order that the petrol may last. It is always ready to meet the enemy without help of any kind on a journey through hostile waters for the entire distance. And these submarines did meet the enemy often.”

There is a charming naïveté about the narrative of a U-boat man who spent some time reconnoitring the coast of Scotland. His vessel left her base in company with several others, including U 15, which failed to return. “She fell before the enemy” is his pathetic little epitaph to her memory. Each of the ten days spent on the trip was divided into four shifts for alternate sleep and work. For variety there was “a little while under, a little while on top.” The only sensational phase of the cruise appears to have been when “one after another had to leave his place for a minute and take a peep through the periscope. It was the prettiest picture I ever saw. Up there, like a flock of peaceful lambs, lay an English squadron without a care, as if 60there were no German sea-wolves in armoured clothing. For two hours we lay there under water on the outposts. We could with certainty have succeeded in bringing under a big cruiser, but we must not. We were on patrol. Our boat had other work to do. It was a lot to expect from our commander. So near to the enemy, and the torpedo must remain in its tube! He must have felt like a hunter who, before deer-stalking begins, suddenly sights a fine buck thirty paces in front of him.”

The reference to British cruisers resembling peaceful lambs is delicious. The writer seems to have forgotten that so far as ‘armoured clothing’ goes they are considerably better provided than the toughest submarine afloat. And what kind of a wolf was it to let such easy prey escape? One surmises a reason connected with the British patrol rather than with its German counterfeit.

An American sailor-boy was taken on board U 39 after that submarine had torpedoed his ship. The lad afterward characterized the unenviable experience as “a dog’s life in a 61steel can,” accompanied by a constant succession of rings of the gong that sent every member to his appointed station as though the Last Trump had blown. The usual menu was stew and coffee, the liquid refreshment being varied on occasion by the substitution of raspberry juice.

Three captains—a Briton, an American, and a Norwegian—were made prisoners on U 49. For days they were confined in a tiny cabin containing three bunks. They took turns in the solitary chair that was the only furniture other than a folding table. As no light was allowed, conversation and change of position were their only occupations. They found plenty to talk about, but even desultory chatter becomes irksome when it is centred around the topic, What will happen? Still, misery loves company, even if it does not appreciate cramp. The prisoners were kept in this Dark Hole of the Underseas except for occasional airings on deck when the craft was running awash and there was ‘nothin’ doin’’ in the piracy or anti-piracy line. Even then they were closely watched by 62armed guards. Their rations consisted of an unpalatable concoction called stew, black bread, rancid butter, and alleged marmalade, any one of which might have been guaranteed to engender mal de mer.

When off the coast of Spain the commander of U 49 hailed a Swedish steamer. The captain must have been deeply relieved when he found that his services were merely required as temporary gaoler. He was peremptorily told to take charge of the prisoners, and land them in the neighbourhood of Camarina. Neither ship nor cargo was interfered with. Never were mariners more pleased to set foot on solid earth.

This particular barbarian was not quite so callous as the presiding genius of U 34. Four of the crew of the trawler Victoria, of Milford, which he had sunk, were picked up by the submarine. Six of their comrades had passed to where there is no sea, and required no favours from enemy or friend. As though they were not sufficiently well acquainted with the ways of U 34, the survivors were summoned on deck the following morning to 63receive a further object-lesson in humanity as the Hun understands it. They were compelled to watch the death and burial of a Cardiff trawler. “England,” explained one of the German officers, “began the war, and we shall sink every ship we see flying the British flag.” When the latest victim of U 34 had gone to her watery grave, the men were given a handful of biscuits, placed in a boat, and left to the mercy of the sea.

Apparently U-boats were not keen on fine weather. “A smooth sea and a lull in the wind are very disagreeable for U-boats,” said Dr Helfferich, the Vice-Chancellor, “especially in view of the enemy’s defensive measures, particularly as regards aircraft. Some U-boat commanders are of opinion that U-boat warfare can be carried on with still better results when the weather is not too fine and the nights are longer.”

A certain submarine left her lair at Zeebrugge a few days before Vice-Admiral Sir Roger Keyes and his band of heroes gave an enforced holiday to those that remained. She had not proceeded any great distance before she 64encountered a mine. It did not completely put her ‘out of mess,’ but sent her staggering backward in inky darkness to the bottom. The electric light had failed with the quickness of a candle meeting a sudden draught. To restore the current was obviously the first thing to do. It was not easy working with the aid of torches, the boat tipped up on end, her stern buried deep in the bed of the sea. Primitive man, his tail not yet worn off, would have fared better. Eventually the supply was restored, and it became possible to make a more thorough survey of the damage. The engineers found that the shock had paralysed the nervous system of the machinery. Not only was the boat leaking badly, but the pumps refused to blow out the ballast tanks.

On an even keel the problem would be easier to tackle. The men were therefore ordered to assemble in the stern and rush forward on the word of command. Their combined movement had the desired effect. Slowly the extra weight in the bow caused the ooze to loose its grip. The submarine sank down with languid grace. There was now nothing 65to hamper movement. Each member of the crew had a pair of hands ready for service instead of having to employ one for the purpose of hanging on.

The engineers tried to start the motors. They refused to budge. Sea-water found its way into the accumulators, adding a further terror to the overwrought men by the introduction of poison gas in an atmosphere already charged with death. Pirates might laugh when they saw British sailors struggling for life in icy water, might derive entertainment from shelling frail craft laden to the gunwale with survivors from ships sunk in pursuance of the German cult of frightfulness, but they failed to appreciate the humour of the situation when they were the victims and the tragedy was enacted 100 feet beneath the surface. The traditional Nero would never have fiddled had he felt the scorch of the flames that burnt Rome. There is little enough of the alleged glory of war in being trapped like a rat. Much of its glamour in any circumstance is imaginary, and exists chiefly in the minds of scribblers. This is not pacificism, but fact.

66The sea mounted higher and higher in the lonely prison cell. Officers and crew tried to staunch the inflow, to stop the leaks with tow and other likely material. These devices held for a little, then burst away. Some sought to make their escape through the conning-tower, as Goodhart of the British Navy had done;[18] others tried to force a way out via the torpedo-tubes. Bolts were wrenched off, fastenings filed through. The doors held firm. The mighty efforts of the men met with no reward. They fell back exhausted and covered with sweat. The pressure from without would have thwarted a score of Samsons. The hatches remained immovable.

They read the handwriting on the curved walls of their prison: “No hope!” The crew must have cursed the Hohenzollerns then. Despair robbed them of reason. One fellow went mad, then another, followed by a third. A man plunged into the water, now up to his knees. His overwrought brain could stand the terrible strain no longer. He 67drowned in two feet of water. Nobody moved to pull him out. The place became a Bedlam. A comrade tried to shoot himself. The revolver merely clicked. In a passion of rage he flung both weapon and himself into the rising flood. Death was the most desired of all things.

A plate burst, letting in a Niagara. The swirl of waters increased the pressure of air against the hatches. One of them burst open. Those who remained alive were carried off their feet and hurled through the aperture. The blind forces of Nature succeeded where man had failed. A mangled mass of human flotsam was flung to the surface. Two maimed bodies alone had life in them when a British trawler steamed by. A boat was lowered, the half-dead forms fished out of the sea. Then the enemy, potential victims of these men but an hour before, did what they could to alleviate their agony. That is the spirit and the tradition of the British Sea Service, though the sufferer be the Devil himself.

A survivor of a neutral ship blown up by a U-boat, who was kept swimming about for 68ten minutes before being rescued because the officers wanted to take some snap-shots, avowed that he and his mates were compelled to lend a hand with the ammunition. That was the Huns’ method of making them pay their way. Their ‘dungeon,’ to quote the narrator, was “furnished with tubes, pressure gauges, flywheels, torpedoes, and the floor paved with shells.” The life he characterized as “monotonous.” During their stay of twelve days five vessels were sunk.

As “a recognition of meritorious work during the war” the Kaiser created a special decoration for officers, petty officers, and crews of submarines on the completion of their third voyage. That did not make them any the more enamoured of mines and wasserbomben.

“The submarine is the hunted to-day.”—Sir Eric Geddes.

In the first phase of the Underseas War torpedoes were the favourite weapons of the U-boat. The work was done more effectively and quicker than was possible with the comparatively small guns then mounted. Later, the number of ships attacked by shellfire rapidly increased. This was due to several reasons. The second method of attack was considerably less expensive, for a torpedo costs anything from £750 to £1000. Comparatively few merchant vessels had any means of defence, for ramming was seldom practicable, and other dodges, such as obscuring the vessel by voluminous smoke from the funnels, and steering stern on, thus presenting a relatively small target, were equally uncertain. Altogether the submarine had things very much her own way. She could carry an augmented provision of ammunition, and the 70difficulties of supply were more easily met. It takes longer to make a torpedo than to turn a shell; to train a torpedo expert than a gunner. If no British patrol were at hand, the German commander could safely risk waging war on the surface. He did not have to return to his base so frequently for the purpose of replenishing empty magazines, and he was saving money for the dear Fatherland. With increasing range of action the necessity for conserving torpedoes became more pronounced. The menace grew to such proportions in the Mediterranean that it was found necessary to send vessels by the long Cape route instead of via the Suez Canal.

When slow-moving John Bull at last bestirred himself and decided to arm merchantmen, the risks of an exposed U-boat were considerably increased. The torpedo again came into her own. As Mr Winston Churchill told the House of Commons,[19] “the effect of putting guns on a merchant ship is to drive the submarine to abandon the use of the gun, 71to lose its surface speed, and to fall back on the much slower speed under water and the use of the torpedo. The torpedo, compared with the gun, is a weapon of much more limited application.”

Germany’s maritime faith being based on the U-boat, despite the Kaiser’s dictum that “our future lies on the water,” many keen scientific brains there had a part in its recent evolution. Whereas in 1914 the latest type, such as U 30, could travel 300 miles submerged or 3500 miles entirely on the surface—the latter trip an impossibility, of course, with the British Navy in being—at least 8800 miles were traversed by the submarine which in 1918 bombarded Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, on the west coast of Africa. This is assuming that she returned to her home port in Europe.

The following table, in which round figures are used, will help us to appraise Germany’s progress in the construction of U-boats previous to the outbreak of hostilities. It is based on what is considered to be reliable evidence, although the difficulty of obtaining accurate 72figures will be appreciated. I shall refer to the larger types later.

U 1 (1905).—Submerged displacement, 236 tons. Surface engines, 250 H.P.; electric motors, 100 H.P. Speed, 10 knots on surface, 7 knots submerged. Surface range, from 700 to 800 miles. Armament, one torpedo-tube in bow. Complement, nine officers and men.

U 2–U 8 (1907–10).—Submerged displacement, 250 tons. Surface engines, 400 H.P.; electric motors, 160 H.P. Speed, 12 knots on surface, 8 knots submerged. Surface range, 1000 miles. Armament, two torpedo-tubes in bow. Fitted with submarine signalling apparatus. Complement, eleven officers and men.

U 9–U 18 (1910–12).—Submerged displacement, 300 tons. Surface engines, 600 H.P. Speed, 13 knots on surface, 8 knots submerged. Surface range, 1500 miles. Armament, two torpedo-tubes in bow, one torpedo-tube in stern. With U 13 anti-aircraft weapons were introduced.

U 19–U 20 (1912–13).—Submerged displacement, 450 tons. Surface engines, 650 H.P.; electric motors, 300 H.P. Speed, 13½ knots on surface, 8 knots submerged. Surface range, 2000 miles. Armament, two torpedo-tubes in bow, one torpedo-tube in stern, two 14–pdr. Q.F. guns. Complement, seventeen officers and men.

U 21–U 24 (1912–13).—Submerged displacement, 800 tons. Surface engines, 1200 H.P.; electric motors, 500 H.P. Speed, 14 knots on surface, 9 knots submerged. Surface range, 3000 miles. Armament, two torpedo-tubes in bow, two torpedo-tubes in stern, one 14–pdr. Q.F. gun, two 1–pdr. anti-aircraft guns. Complement, twenty-five officers and men.

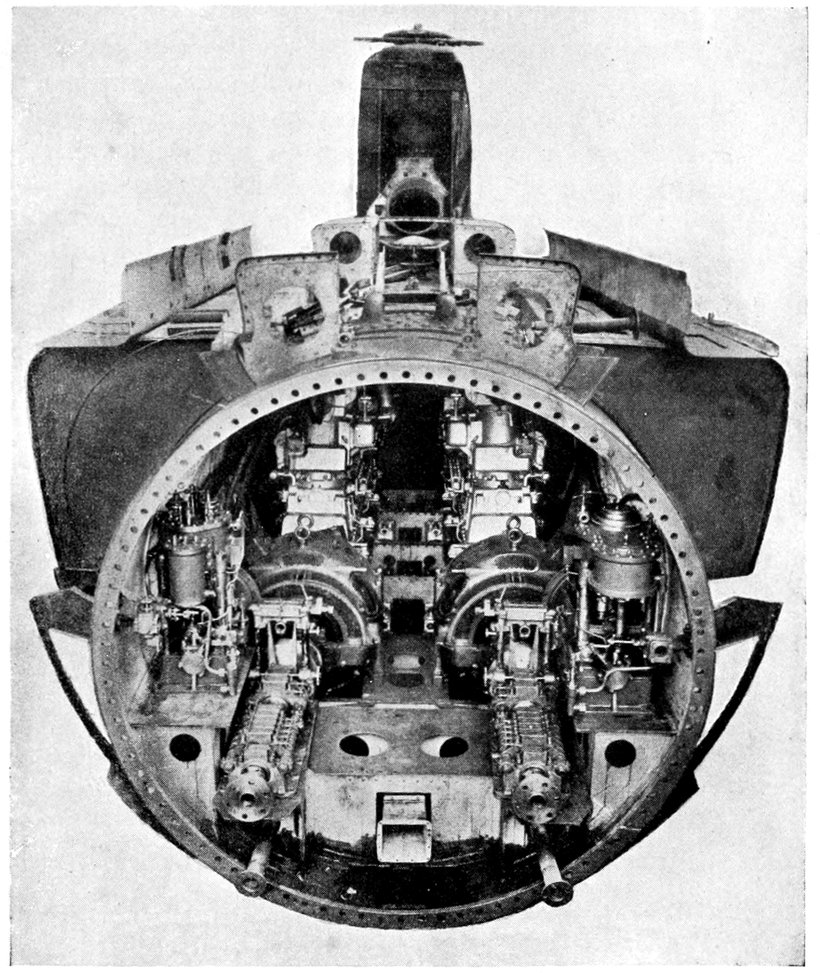

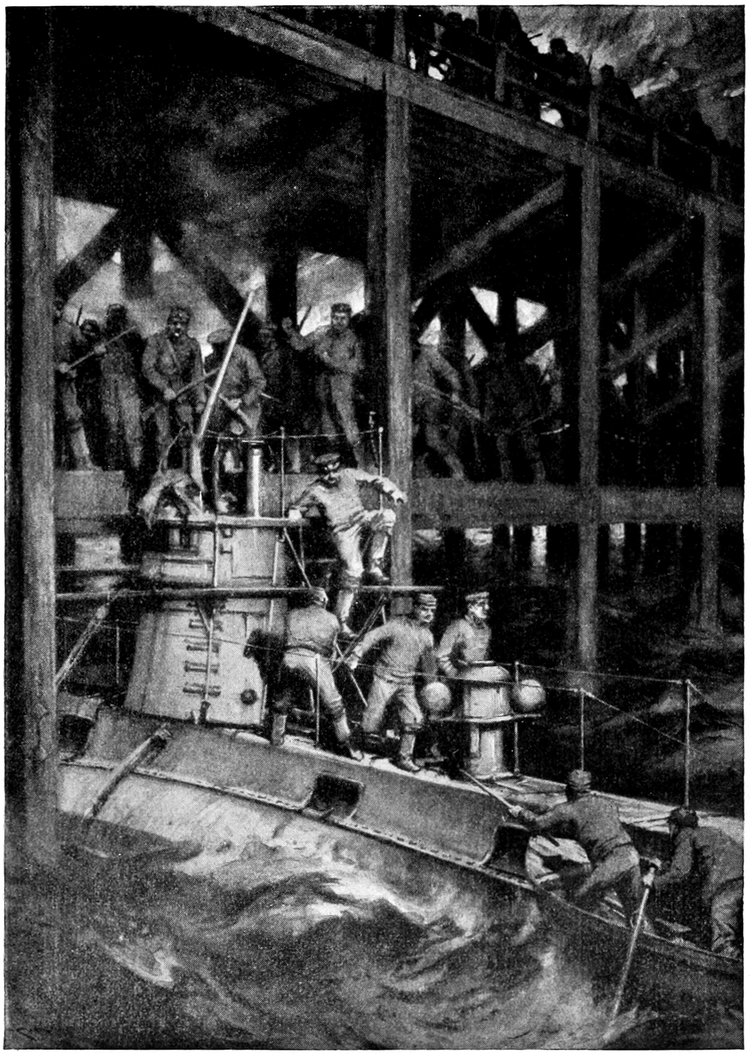

The Interior of a German Submarine

Showing the internal combustion engines for surface work, and the motor-generators for driving the propellers when submerged.

73U 25–U 30 (1913–14).—Submerged displacement, 900 tons. Surface engines, 2000 H.P.; electric motors, 900 H.P. Speed, 18 knots on surface, 10 knots submerged. Surface range, 4000 miles. Submerged range, 300 miles. Armament, two torpedo-tubes in bow, two torpedo-tubes in stern, two 14–pdr. Q.F. guns, two 1–pdr. anti-aircraft guns. Complement, thirty to thirty-five officers and men. Upper works lightly armoured. Fitted with wireless.

German U-boats are really submersibles. That is to say, the outer shell conforms to the shape of an ordinary ship, with a broad deck, whereas British submarines resemble a fat cigar. Internally they are cylindrical, the space intervening between the compartments and the shell affording accommodation for the ballast tanks. The theory is that vessels built to this design are more seaworthy and easier to handle. U 36, which was building when war broke out, was divided into ten compartments, below which were the steel cylinders containing compressed air for freshening the atmosphere, oil fuel, lubricating oil, and water-ballast tanks, and the accumulators for driving the dynamos when travelling 74beneath the surface. The officers’ combined ward-room and sleeping quarters were for’ard, immediately behind the bow torpedo compartment. Adjoining were the crew’s quarters, divided by a steel bulkhead from the control chamber, situated below the conning-tower. In the control chamber the steering wheel, periscope, projection table on which a surface view was thrown after the manner of a camera obscura, water-pressure dial, and other delicate and necessary instruments for the safety and navigation of the ship were distributed. Proceeding toward the stern, the petty officers’ quarters, the machine-room with its heavy oil engines for surface work and electric motors for progression when submerged, and the stern torpedo compartment were to be found. U 36 was one of the “new Super-Dreadnought submarines,” to quote an American correspondent who saw them under construction at Kiel. On these, he added, “the Germans appear to be banking.”

The autumn of 1915 witnessed the introduction of mine-laying submersibles. The trotyl-filled cylinders were dropped on recognized 75trade routes without the slightest regard for the rights of neutrals. The mines were kept in a special chamber, ingeniously contrived so that it could be flooded without the water entering elsewhere, and released through a trap-door. Thus another weapon was added to the submarine’s armoury. It answered all too well. “They can follow your mine-sweeper,” said Sir Edward Carson, “and as quickly as you sweep up mines they can lay new ones without your knowing or suspecting.” In 1914 the enemy had only one means of sowing these canisters of death, namely, by surface vessels. It will be recollected that the Königin Luise was sunk in the North Sea on the morning of the 5th August while on this hazardous duty. Germany’s opportunity for hurting us in this manner was of short duration. The British Navy asserted itself, with the result that the enemy was perforce compelled to find a new method. He resorted to the use of specially fitted submarines.

In due course 4.1–in. guns, mounted on disappearing platforms, made their début, 76followed by U-boats provided with two 5.9–in. guns. With increase of gun-power came a necessary increase in size, and with both several distinct advantages and disadvantages. The boats were less easy to manœuvre, required augmented crews, and offered a larger area for attack. Against these minus qualities must be set those of increase of cruising range, and the possibility of spoil, the sole excuse of the old-time pirate. Hitherto his more scientific successor could only sink his victim. Now, given favourable conditions, he might carry off goods useful to the Fatherland. One German U-boat secured twenty-two tons of copper from merchantmen destroyed during a 5000–mile cruise.

Germany waxed particularly enthusiastic over her diving cruisers. These boats displaced 5000 tons, were from 350 feet to 400 feet long, had a much accelerated submerged and surface speed, were protected by an armour belt of tough steel plate, and mounted a couple of 5.9–in. guns. Some of these submersibles seem to have been driven by steam when in surface trim, others by the usual Diesel engines. On the 11th May, 1918, a British Atlantic escort 77submarine came across one of these fine fellows travelling awash, likely enough anxious to have a shot at the merchant convoy which the representative of His Majesty’s Navy was on her way to pick up. A heavy sea was running at the time, but at intervals between the waves the periscope revealed the position of his rival to the British commander. One torpedo sufficed. The Tauchkreuzer went down, carrying with her the sixty or seventy men who constituted her company. There were no survivors. She had the distinction of being the first of the type to be destroyed.

Germany’s merchant service, prizes of war, or driven off the seven seas and growing barnacles in neutral or home ports, virtually ceased to exist at the outbreak of hostilities. The mammoth liners which formerly competed with our own no longer sailed the seas with their holds full of cheap goods and their saloons alive with travellers bent on ‘peaceful penetration’—and other things. It rankled in the bosoms of her shipping magnates that the much-vaunted High Sea Fleet was impotent to prevent Britain ‘carrying on’ commercially 78while conducting campaigns in all parts of the world. It was true that Germany’s U-boats were making inroads on the maritime resources of her enemy, that when hostilities were over they might compete on more than even terms because of these losses, but to-day rankled though to-morrow was full of hope. Likewise the Economic Conference in Paris had declared its firm intention to impose special conditions on German shipping after the war. After the war! The Director-General of the North German Lloyd Line said that the English were not so unpractical as to reject a favourable freightage or passage.

I cannot give you the name of the man or woman who first suggested the possibilities of the submarine for business purposes. The idea was certainly not a particularly novel one. All I can say definitely is that the concern which owned the pioneer vessels was called the Ocean Navigation Company, and that the president was Herr Alfred Lohmann. If British merchantmen could use American ports, why not German commercial submarines? The Deutschland was built with this object in 79view. Officially she was described as “a vessel engaged in the freight trade between Bremen and Boston and other Eastern Atlantic ports.”

She left Heligoland on the 23rd June, 1916, and arrived at Norfolk News, Virginia, seventeen days later. The German Press quite naturally went into ecstasies over the achievement. Yet it was not quite such a unique event as they imagined. Ten submarines built in Montreal had crossed the Atlantic nine months before. The Deutschland duly discharged her cargo, stayed three weeks or so, and returned to Germany. The Kaiser showed his pleasure by conferring decorations on Herr Lohmann and the crew. Germany was again a maritime nation—of sorts.

The submersible had travelled no fewer than 8500 nautical miles. She made a second voyage to America in October. This time her port of arrival was New London, Connecticut. When starting on her return journey she managed to get in collision with one of the escorting tugs, which sank with the loss of seven of her crew. The Deutschland was the 80pioneer of seven similar boats said to be in course of construction. A sister vessel, the Bremen, was launched and started on a voyage. She is now some two years overdue.

Official Germany revealed no great faith in the possibilities of the commercial submarine, though this does not necessarily mean that the autocrats of the Wilhelmstrasse showed their real belief. It sometimes suited them to lie. According to the Frankfurter Zeitung, £15,000,000 per annum was earmarked for the fostering of Germany’s moribund merchant service in the next decade.

In October 1916 the depredations of U 53 off the American coast were hailed by the population of Berlin and other German towns as a sure prelude to peace. She was the first armed U-boat to cross the Atlantic, but the German nation saw her multiplied by scores, if not by hundreds. Many optimistic folk held the belief, based on the wonderful tales that were told of huge Allied shipping losses, that the war would be over before the dawn of a new year. Britons are not the only people who have hugged delusions. After 81having put in at Newport News for a few hours and been visited by various notabilities, U 53 took up a position off the Nantucket Lightship, so well known to all Atlantic voyagers. She then calmly proceeded to sink half a dozen ships—British, Dutch, and Norwegian—under the nose of U.S. destroyers. According to accounts that were published in American newspapers at the time, the submersible had four torpedo-tubes, one 4–in. gun forward and one 3–in. gun aft, three periscopes, wireless apparatus, and engines of 1200 h.p. that enabled her to travel on the surface at eighteen knots. Her submerged speed was understood to be some four knots less.

U-boats were built at the Vulkan and Blohm and Voss shipyards of Hamburg; at Hoboken, in the former yards of the Société John Cockerill;[20] at Puers, near Termonde; and at the great naval bases of Kiel and Wilhelmshaven. Here the parts were assembled, for it is fairly evident that the thousand and one units of a modern submersible were constructed 82on many lathes in many parts of the Fatherland. For example, it is believed that UC 5, the small mine-layer of 200 tons displacement captured by the British Navy and exhibited off the Thames Embankment, was brought in sections to Zeebrugge and put together there.

When German liners were compelled to keep in American ports owing to the pressure of British sea-power, there seemed not the slightest likelihood that the United States would become an active participant in the war. In 1917 these selfsame steamers were traversing 3000 miles of ocean with armed tourists bound for Germany, giving the lie direct to the Imperial Chancellor’s hopeful message that Uncle Sam could not “send and maintain an army in Europe without injuring the transport and supply of the existing Entente armies and jeopardizing the feeding of the Entente people.” The mercantile marine of the United States is small, but with the aid of former German vessels and British ships her troops defied the submarine menace and were landed by the hundred thousand in France 83as America’s splendid contribution toward the liberation of the world. The spectacular appearance of the Deutschland and U 53 fade into insignificance before this amazing triumph.

Speaking at a luncheon given in London[21] in honour of American Press representatives visiting England, Vice-Admiral Sims remarked that some of his countrymen regarded it as a miracle of their Navy that it had got a million and a half troops across the Atlantic in a few months and had protected them on the way. “We didn’t do that,” he avowed. “Great Britain did. She brought over two-thirds of them and escorted a half. We escort only one-third of the merchant vessels that come here.”

America has been most generous in her appreciation of the part played by Britain in the war.

“This is the first time since the Creation that all the world has been obliged to unite to crush the Devil.”—Rudyard Kipling.

Two weeks after the declaration of war Count von Reventlow was cock-a-hoop regarding the “attitude of reserve” of what he was kind enough to term the “alleged sea-commanding Fleet of the greatest naval Power in the world.” “This fleet,” he asserted, “has now been lying idle for more than a fortnight, so far from the German coast that no cruiser and no German lightship has been able to discover it, and it is repeatedly declared officially, ‘German waters are free of the enemy.’”