Title: The Music of Spain

Author: Carl Van Vechten

Release date: August 31, 2020 [eBook #63085]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Andrés V. Galia, Donal Wheeler and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

The book cover has been modified by the Transcriber and was added to the public domain.

The spelling of Spanish names and places in Spain mentioned in the text has been adjusted to the rules set by the Academia Real Española.

A number of words in this book have both hyphenated and non-hyphenated variants. For the words with both variants present the one more used has been kept.

Punctuation and other printing errors have been corrected.

The Music of Spain

BOOKS BY CARL VAN VECHTEN

MUSIC AFTER THE GREAT WAR 1915

MUSIC AND BAD MANNERS 1916

INTERPRETERS AND INTERPRETATIONS 1917

THE MERRY-GO-ROUND 1918

THE MUSIC OF SPAIN 1918

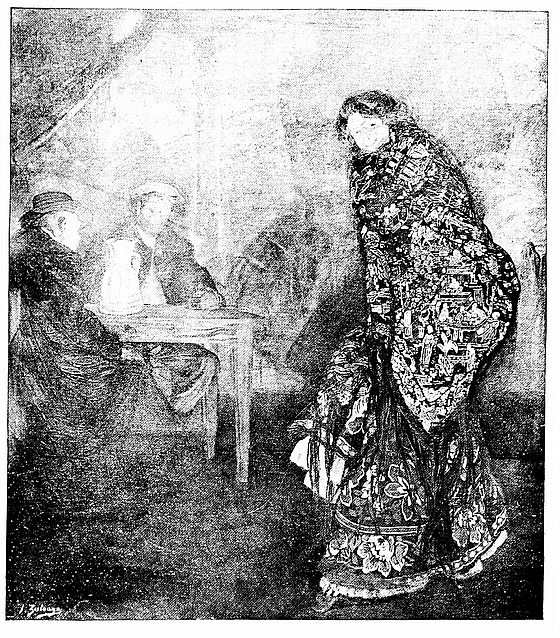

from a photograph by Mishkin

Mary Garden As Carmen, Act IV

CARL VAN VECHTEN

New York Alfred A. Knopf

MCMXVIII

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY

ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Pour Blanchette

Preface

When the leading essay of this book, "Music and Spain," first appeared it was, so far as I have been able to discover, the only commentary attempting to cover the subject generally in any language. It still holds that distinction, I believe. Little enough has been published about Spanish music in French or German, little enough indeed even in Spanish, practically nothing in English. It has been urged upon me, therefore, that its republication might meet with some success. This I have consented to although no one can be more cognizant of its faults than I am. The subject is utterly unclassified; there is no certain way of determining values at present. It is almost impossible to hear Spanish music outside of Spain; not easy even in Spain, unless one is satisfied with zarzuelas. Worse, it is impossible even to see most of it. Many important scores remain unpublished and our music dealers and our libraries have not an extensive collection of what is published. Under the circumstances I have worked under great difficulties, but my enthusiasm has not slackened on that account. My main purpose has been to open the ears of the world to these new sounds, to create curiosity regarding the music of the Iberian Peninsula. When more of this music is familiar will be time enough to write a more critical and more comprehensive work.

As "Music and Spain" is printed from the original plates I have made only slight typographical changes in the text; some of these are important, however. But I have added very voluminous notes incorporating information that has come to me since I wrote "Music and Spain." There is much new material included therein about Spanish dancing and modern composers and the index will make it possible for any one to find what he may be looking for in short order. The essay on Carmen, too, was written for this book and that on The Land of Joy, being entirely apposite, I have lifted from "The Merry-Go-Round." Mr. John Garrett Underhill has suggested many valuable changes and additions and I am deeply indebted to him.

The preparation of this book has given me an extraordinary interest in and a real love for the Iberian Peninsula. If I have succeeded in communicating a little of this feeling to my reader I shall be content.

CARL VAN VECHTEN.

New York, June 26, 1918.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Spain and Music

"Il faut méditerraniser la musique."

Nietzsche.

It has seemed to me at times that Oscar Hammerstein was gifted with almost prophetic vision. He it was who imagined the glory of Times (erstwhile Longacre) Square. Theatre after theatre he fashioned in what was then a barren district—and presently the crowds and the hotels came. He foresaw that French opera, given in the French manner, would be successful again in New York, and he upset the calculations of all the wiseacres by making money even with Pelléas et Mélisande, that esoteric collaboration of Belgian and French art, which in the latter part of the season of 1907-8 attained a record of seven performances at the Manhattan Opera House, all to audiences as vast and as devoted as those which attend the sacred festivals of Parsifal at Bayreuth. And he had announced for presentation during the season of 1908-9 (and again the following season) a Spanish opera called La Dolores. If he had carried out his intention (why it was abandoned I have never learned; the scenery and costumes were ready) he would have had another honour thrust upon him, that of having been beforehand in the production of modern Spanish opera in New York, an honour which, in[Pg 14] the circumstances, must go to Mr. Gatti-Casazza. (Strictly speaking, Goyescas was not the first Spanish opera to be given in New York, although it was the first to be produced at the Metropolitan Opera House. Il Guarany, by Antonio Carlos Gomez, a Portuguese born in Brazil, was performed by the "Milan Grand Opera Company" during a three weeks' season at the Star Theatre in the fall of 1884. An air from this opera is still in the répertoire of many sopranos. To go still farther back, two of Manuel García's operas, sung of course in Italian, l'Amante Astuto and La Figlia dell'Aria, were performed at the Park Theatre in 1825 with María García—later to become the celebrated Mme. Malibran—in the principal rôles. More recently an itinerant Italian opéra-bouffe company, which gravitated from the Park Theatre—not the same edifice that harboured García's company!—to various playhouses on the Bowery, included three zarzuelas in its répertoire. One of these, the popular La Gran Vía, was announced for performance, but my records are dumb on the subject and I am not certain that it was actually given. There are probably other instances.) Mr. Hammerstein had previously produced two operas about Spain when he opened his first Manhattan Opera House[Pg 15] on the site now occupied by Macy's Department Store with Moszkowski's Boabdil, quickly followed by Beethoven's Fidelio. The malagueña from Boabdil is still a favourite morceau with restaurant orchestras, and I believe I have heard the entire ballet suite performed by the Chicago Orchestra under the direction of Theodore Thomas. New York's real occupation by the Spaniards, however, occurred after the close of Mr. Hammerstein's brilliant seasons, although the earlier vogue of Carmencita, whose celebrated portrait by Sargent in the Luxembourg Gallery in Paris will long preserve her fame, the interest in the highly-coloured paintings by Sorolla and Zuloaga, many of which are still on exhibition in private and public galleries in New York, the success here achieved, in varying degrees, by such singing artists as Emilio de Gogorza, Andrés de Segurola, and Lucrezia Bori, the performances of the piano works of Albéniz, Turina, and Granados by such pianists as Ernest Schelling, George Copeland, and Leo Ornstein, and the amazing Spanish dances of Anna Pavlowa (who in attempting them was but following in the footsteps of her great predecessors of the nineteenth century, Fanny Elssler and Taglioni), all fanned the flames.

The winter of 1915-16 beheld the Spanish blaze. Enrique Granados, one of the most distinguished of contemporary Spanish pianists and composers, a man who took a keen interest in the survival, and artistic use, of national forms, came to this country to assist at the production of his opera Goyescas, sung in Spanish at the Metropolitan Opera House for the first time anywhere, and was also heard several times here in his interpretative capacity as a pianist; Pablo Casals, the Spanish 'cellist, gave frequent exhibitions of his finished art, as did Miguel Llobet, the guitar virtuoso; La Argentina (Señora Paz of South America) exposed her ideas, somewhat classicized, of Spanish dances; a Spanish soprano, María Barrientos, made her North American début and justified, in some measure, the extravagant reports which had been spread broadcast about her singing; and finally the decree of Paris (still valid in spite of Paul Poiret's reported absence in the trenches) led all our womenfolk into the wearing of Spanish garments, the hip-hoops of the Velasquez period, the lace flounces of Goya's Duchess of Alba, and the mantillas, the combs, and the accroche-coeurs of Spain, Spain, Spain.... In addition one must mention Mme. Farrar's brilliant success, deserved in some degree, as Carmen, both[Pg 17] in Bizet's opera and in a moving picture drama; Miss Theda Bara's film appearance in the same part, made with more atmospheric suggestion than Mme. Farrar's, even if less effective as an interpretation of the moods of the Spanish cigarette girl; Mr. Charles Chaplin's eccentric burlesque of the same play; the continued presence in New York of Andrés de Segurola as an opera and concert singer; María Gay, who gave some performances in Carmen and other operas; and Lucrezia Bori, although she was unable to sing during the entire season owing to the unfortunate result of an operation on her vocal cords; in Chicago, Miss Supervia appeared at the opera and Mme. Koutznezoff, the Russian, danced Spanish dances; and at the New York Winter Garden Isabel Rodríguez appeared in Spanish dances which quite transcended the surroundings and made that stage as atmospheric, for the few brief moments in which it was occupied by her really entrancing beauty, as a maison de danse in Seville. The tango, too, in somewhat modified form, continued to interest "ballroom dancers," danced to music provided in many instances by Señor Valverde, an indefatigable producer of popular tunes, some of which have a certain value as music owing to their close allegiance to the folk-dances and songs of[Pg 18] Spain. In the art-world there was a noticeable revival of interest in Goya and El Greco.

But if Mr. Gatti-Casazza, with the best intentions in the world, should desire to take advantage of any of this réclame by producing a series of Spanish operas at the Metropolitan Opera House—say four or five more—he would find himself in difficulty. Where are they? Several of the operas of Isaac Albéniz have been performed in London, and in Brussels at the Théâtre de la Monnaie, but would they be liked here? There is Felipe Pedrell's monumental work, the trilogy, Los Pireneos, called by Edouard Lopez-Chavarri "the most important work for the theatre written in Spain"; and there is the aforementioned La Dolores. For the rest, one would have to search about among the zarzuelas; and would the Metropolitan Opera House be a suitable place for the production of this form of opera? It is doubtful, indeed, if the zarzuela could take root in any theatre in New York.

The truth is that in Spain Italian and German operas are much more popular than Spanish, the zarzuela always excepted; and at Señor Arbós's series of concerts at the Royal Opera in Madrid one hears more Bach and Beethoven than Albéniz and Pedrell. There is a growing interest[Pg 19] in music in Spain and there are indications that some day her composers may again take an important place with the musicians of other nationalities, a place they proudly held in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, no longer ago than 1894, we find Louis Lombard writing in his "Observations of a Musician" that harmony was not taught at the Conservatory of Málaga, and that at the closing exercises of the Conservatory of Barcelona he had heard a four-hand arrangement of the Tannhäuser march performed on ten pianos by forty hands! Havelock Ellis ("The Soul of Spain," 1909) affirms that a concert in Spain sets the audience to chattering. They have a savage love of noise, the Spanish, he says, which incites them to conversation. Albert Lavignac, in "Music and Musicians" (William Marchant's translation), says, "We have left in the shade the Spanish school, which to say truth does not exist." But if one reads what Lavignac has to say about Moussorgsky, one is likely to give little credence to such extravagant generalities as the one just quoted. The Moussorgsky paragraph is a gem, and I am only too glad to insert it here for the sake of those who have not seen it: "A charming and fruitful melodist, who makes up for a lack of[Pg 20] skill in harmonization by a daring, which is sometimes of doubtful taste; has produced songs, piano music in small amount, and an opera, Boris Godunow." In the report of the proceedings of the thirty-fourth session of the London Musical Association (1907-8) Dr. Thomas Lea Southgate is quoted as complaining to Sir George Grove because under "Schools of Composition" in the old edition of Grove's Dictionary the Spanish School was dismissed in twenty lines. Sir George, he says, replied, "Well, I gave it to Rockstro because nobody knows anything about Spanish music."—The bibliography of modern Spanish music is indeed indescribably meagre, although a good deal has been written in and out of Spain about the early religious composers of the Iberian peninsula.

These matters will be discussed in due course. In the meantime it has afforded me some amusement to put together a list (which may be of interest to both the casual reader and the student of music) of compositions suggested by Spain to composers of other nationalities. (This list is by no means complete. I have not attempted to include in it works which are not more or less familiar to the public of the present day; without boundaries it could easily be extended into[Pg 21] a small volume.) The répertoire of the concert room and the opera house is streaked through and through with Spanish atmosphere and, on the whole, I should say, the best Spanish music has not been written by Spaniards, although most of it, like the best music written in Spain, is based primarily on the rhythm of folk-tunes, dances and songs. Of orchestral pieces I think I must put at the head of the list Chabrier's rhapsody, España, as colourful and rhythmic a combination of tone as the auditor of a symphony concert is often bidden to hear. It depends for its melody and rhythm on two Spanish dances, the jota, fast and fiery, and the malagueña, slow and sensuous. These are true Spanish tunes; Chabrier, according to report, invented only the rude theme given to the trombones. The piece was originally written for piano, and after Chabrier's death was transformed (with other music by the same composer) into a ballet, España, performed at the Paris Opéra, 1911. Waldteufel based one of his most popular waltzes on the theme of this rhapsody. Chabrier's Habanera for the pianoforte (1885) was his last musical reminiscence of his journey to Spain. It is French composers generally who have achieved better effects with Spanish atmosphere than men of other nations,[Pg 22] and next to Chabrier's music I should put Debussy's Iberia, the second of his Images (1910). It contains three movements designated respectively as "In the streets and roads," "The perfumes of the night," and "The morning of a fête-day." It is indeed rather the smell and the look of Spain than the rhythm that this music gives us, entirely impressionistic that it is, but rhythm is not lacking, and such characteristic instruments as castanets, tambourines, and xylophones are required by the score. "Perfumes of the night" comes as near to suggesting odours to the nostrils as any music can—and not all of them are pleasant odours. There is Rimsky-Korsakow's Capriccio Espagnole, with its alborado or lusty morning serenade, its long series of cadenzas (as cleverly written as those of Scheherazade to display the virtuosity of individual players in the orchestra; it is noteworthy that this work is dedicated to the sixty-seven musicians of the band at the Imperial Opera House of Petrograd and all of their names are mentioned on the score) to suggest the vacillating music of a gipsy encampment, and finally the wild fandango of the Asturias with which the work comes to a brilliant conclusion. Engelbert Humperdinck taught the theory of music in the Conserva[Pg 23]tory of Barcelona for two years (1885-6), and one of the results was his Maurische Rhapsodie in three parts (1898-9), still occasionally performed by our orchestras. Lalo wrote his Symphonie Espagnole for violin and orchestra for the great Spanish virtuoso, Pablo de Sarasate, but all our violinists delight to perform it (although usually shorn of a movement or two). Glinka wrote a Jota Aragonese and A Night in Madrid; he gave a Spanish theme to Balakirew which the latter utilized in his Overture on a theme of a Spanish March. Liszt wrote a Spanish Rhapsody for pianoforte (arranged as a concert piece for piano and orchestra by Busoni) in which he used the jota of Aragón as a theme for variations. Rubinstein's Toreador and Andalusian and Moszkowski's Spanish Dances (for four hands) are known to all amateur pianists as Hugo Wolf's Spanisches Liederbuch and Robert Schumann's Spanisches Liederspiel, set to F. Giebel's translations of popular Spanish ballads, are known to all singers. I have heard a song of Saint-Saëns, Guitares et Mandolines, charmingly sung by Greta Torpadie, in which the instruments of the title, under the subtle fingers of that masterly accompanist, Coenraad V. Bos, were cleverly imitated. And Debussy's Mandoline and Delibes's Les Filles de Cadix (which in this country belongs both to Emma Calvé and Olive Fremstad) spring instantly to mind. Ravel's Rapsodie Espagnole is as Spanish as music could be. The Boston Symphony men have played it during the season just past. Ravel based the habanera section of his Rapsodie on one of his piano pieces. But Richard Strauss's two tone-poems on Spanish subjects, Don Juan and Don Quixote, have not a note of Spanish colouring, so far as I can remember, from beginning to end. Svendsen's symphonic poem, Zorahayda, based on a passage in Washington Irving's "Alhambra," is Spanish in theme and may be added to this list together with Waldteufel's Estudiantina waltzes.

Four modern operas stand out as Spanish in subject and atmosphere. I would put at the top of the list Zandonai's Conchita; the Italian composer has caught on his musical palette and transferred to his tonal canvas a deal of the lazy restless colour of the Iberian peninsula in this little master-work. The feeling of the streets and patios is admirably caught. My friend, Pitts Sanborn, said of it, after its solitary performance at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York by the Chicago Opera Company, "There is musical atmosphere of a rare and penetrating kind; there is colour used with the discretion of a master; there are intoxicating rhythms, and above the orchestra the voices are heard in a truthful musical speech.... Ever since Carmen it has been so easy to write Spanish music and achieve supremely the banal. Here there is as little of the Spanish of convention as in Debussy's Iberia, but there is Spain." This opera, based on Pierre Louÿs's sadic novel, "La Femme et le Pantin," owed some of its extraordinary impression of vitality to the vivid performance given of the title-rôle by Tarquinia Tarquini. Raoul Laparra, born in Bordeaux, but who has travelled much in Spain, has written two Spanish operas, La Habanera and La Jota, both named after popular Spanish dances and both produced at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. I have heard La Habanera there and found the composer's use of the dance as a pivot of a tragedy very convincing. Nor shall I forget the first act-close, in which a young man, seated on a wall facing the window of a house where a most bloody murder has been committed, sings a wild Spanish ditty, accompanying himself on the guitar, crossing and recrossing his legs in complete abandonment to the rhythm, while in the house rises the wild treble cry of a frightened[Pg 26] child. I have not heard La Jota, nor have I seen the score. I do not find Emile Vuillermoz enthusiastic in his review ("S. I. M.," May 15, 1911): "Une danse transforme le premier acte en un kaléidoscope frénétique et le combat dans l'église doit donner, au second, dans l'intention de l'auteur 'une sensation à pic, un peu comme celle d'un puits où grouillerait la besogne monstreuse de larves humaines.' A vrai dire ces deux tableaux de cinématographe papillotant, corsés de cris, de hurlements et d'un nombre incalculable de coups de feu constituent pour le spectator une épreuve physiquement douloureuse, une hallucination confuse et inquiétante, un cauchemar assourdissant qui le conduisent irrésistiblement à l'hébétude et à la migraine. Dans tout cet enfer que devient la musique?" Perhaps opera-goers in general are not looking for thrills of this order; the fact remains that La Jota has had a modest career when compared with La Habanera, which has even been performed in Boston. Carmen is essentially a French opera; the leading emotions of the characters are expressed in an idiom as French as that of Gounod; yet the dances and entr'actes are Spanish in colour. The story of Carmen's entrance song is worth retelling in Mr. Philip Hale's words ("Boston Symphony Orchestra Programme[Pg 27] Notes"; 1914-15, P. 287): "Mme. Galli-Marié disliked her entrance air, which was in 6-8 time with a chorus. She wished something more audacious, a song in which she could bring into play the whole battery of her perversités artistiques, to borrow Charles Pigot's phrase: 'caressing tones and smiles, voluptuous inflections, killing glances, disturbing gestures.' During the rehearsals Bizet made a dozen versions. The singer was satisfied only with the thirteenth, the now familiar Habanera, based on an old Spanish tune that had been used by Sebastian Yradier. This brought Bizet into trouble, for Yradier's publisher, Heugel, demanded that the indebtedness should be acknowledged in Bizet's score. Yradier made no complaint, but to avoid a lawsuit or a scandal, Bizet gave consent, and on the first page of the Habanera in the French edition of Carmen this line is engraved: 'Imitated from a Spanish song, the property of the publishers of Le Ménestrel.'"

There are other operas the scenes of which are laid in Spain. Some of them make an attempt at Spanish colouring, more do not. Massenet wrote no less than five operas on Spanish subjects, Le Cid, Chérubin, Don César de Bazán, La Navarraise and Don Quichotte (Cervantes's novel has[Pg 28] frequently lured the composers of lyric dramas with its story; Clément et Larousse give a long list of Don Quixote operas, but they do not include one by Manuel García, which is mentioned in John Towers's compilation, "Dictionary-Catalogue of Operas." However, not a single one of these lyric dramas has held its place on the stage). The Spanish dances in Le Cid are frequently performed, although the opera is not. The most famous of the set is called simply Aragonaise; it is not a jota. Pleurez, mes yeux, the principal air of the piece, can scarcely be called Spanish. There is a delightful suggestion of the jota in La Navarraise. In Don Quichotte la belle Dulcinée sings one of her airs to her own guitar strummings, and much was made of the fact, before the original production at Monte Carlo, of Mme. Lucy Arbell's lessons on that instrument. Mary Garden, who had learned to dance for Salome, took no guitar lessons for Don Quichotte. But is not the guitar an anachronism in this opera? In a pamphlet by Don Cecilio de Roda, issued during the celebration of the tercentenary of the publication of Cervantes's romance, taking as its subject the musical references in the work, I find, "The harp was the aristocratic instrument most favoured by women and it would appear to be regarded in Don Quixote as[Pg 29] the feminine instrument par excellence." Was the guitar as we know it in existence at that epoch? I think the vihuela was the guitar of the period.... Maurice Ravel wrote a Spanish opera, l'Heure Espagnole (one act, performed at the Paris Opéra-Comique, 1911). Octave Séré ("Musiciens français d'Aujourd'hui") says of it: "Les principaux traits de son caractère et l'influence du sol natal s'y combinent étrangement. De l'alliance de la mer et du Pays Basque (Ravel was born in the Basses-Pyrénées, near the sea) est née une musique à la fois fluide et nerveusement rythmée, mobile, chatoyante, amie du pittoresque et dont le trait net et précis est plus incisif que profond." Hugo Wolf's opera Der Corregidor is founded on the novel, "El Sombrero de tres Picos," of the Spanish writer, Pedro de Alarcón (1833-91). His unfinished opera Manuel Venegas also has a Spanish subject, suggested by Alarcón's "El Niño de la Bola." Other Spanish operas are Beethoven's Fidelio, Balfe's The Rose of Castile, Verdi's Ernani and Il Trovatore, Rossini's Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Mozart's Don Giovanni and Le Nozze di Figaro, Weber's Preciosa (really a play with incidental music), Dargomijsky's The Stone Guest (Pushkin's version of the Don Juan story. This opera, by the way, was one of the many retouched[Pg 30] and completed by Rimsky-Korsakow), Reznicek's Donna Diana—and Wagner's Parsifal! The American composer John Knowles Paine's opera Azara, dealing with a Moorish subject, has, I think, never been performed.

The early religious composers of Spain deserve a niche all to themselves, be it ever so tiny, as in the present instance. There is, to be sure, some doubt as to whether their inspiration was entirely peninsular, or whether some of it was wafted from Flanders, and the rest gleaned in Rome, for in their service to the church most of them migrated to Italy and did their best work there. It is not the purpose of the present chronicler to devote much space to these early men, or to discuss in detail their music. There are no books in English devoted to a study of Spanish music, and few in any language, but what few exist take good care to relate at considerable length (some of them with frequent musical quotation) the state of music in Spain in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, the golden period. To the reader who may wish to pursue this phase of our subject I[Pg 31] offer a small bibliography. There is first of all A. Soubies's two volumes, "Histoire de la Musique d'Espagne," published in 1889. The second volume takes us through the eighteenth century. The religious and early secular composers are catalogued in these volumes, but there is little attempt at detail, and he is a happy composer who is awarded an entire page. Soubies does not find occasion to pause for more than a paragraph on most of his subjects. Occasionally, however, he lightens the plodding progress of the reader, as when he quotes Father Bermudo's "Declaración de Instrumentos" (1548; the 1555 edition is in the Library of Congress at Washington): "There are three kinds of instruments in music. The first are called natural; these are men, of whom the song is called musical harmony. Others are artificial and are played by the touch—such as the harp, the vihuela (the ancient guitar, which resembles the lute), and others like them; the music of these is called artificial or rhythmic. The third species is pneumatique and includes instruments such as the flute, the douçaine (a species of oboe), and the organ." There may be some to dispute this ingenious and highly original classification. The best known, and perhaps the most useful (because it is easily accessible) history of[Pg 32] Spanish music is that written by Mariano Soriano Fuertes, in four volumes: "Historia de la Música Española desde la venida de los Fenicios hasta el año de 1850"; published in Barcelona and Madrid in 1855. There is further the "Diccionario Técnico, Histórico, y Biográfico de la Música," by José Parada y Barreto (Madrid, 1867). This, of course, is a general work on music, but Spain gets her full due. For example, a page and a half is devoted to Beethoven, and nine pages to Eslava. It is to this latter composer to whom we must turn for the most complete and important work on Spanish church music: "Lira Sacro-Hispana" (Madrid, 1869), in ten volumes, with voluminous extracts from the composers' works. This collection of Spanish church music from the sixteenth century through the eighteenth, with biographical notices of the composers is out of print and rare (there is a copy in the Congressional Library at Washington). As a complement to it I may mention Felipe Pedrell's "Hispaniae Schola Musica Sacra," begun in 1894, which has already reached the proportions of Eslava's work. Pedrell, who was the master of Enrique Granados, has also issued a fine edition of the music of Victoria.

The Spanish composers had their full share in the process of crystallizing music into forms of[Pg 33] permanent beauty during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Rockstro asserts that during the early part of the sixteenth century nearly all the best composers for the great Roman choirs were Spaniards. But their greatest achievement was the foundation of the school of which Palestrina was the crown. On the music of their own country their influence is less perceptible. I think the name of Cristofero Morales (1512-53) is the first important name in the history of Spanish music. He preceded Palestrina in Rome and some of his masses and motets are still sung in the Papal chapel there (and in other Roman Catholic edifices and by choral societies). Francisco Guerrero (1528-99; these dates are approximate) was a pupil of Morales. He wrote settings of the Passion choruses according to St. Matthew and St. John and numerous masses and motets. Tomás Luis de Victoria is, of course, the greatest figure in Spanish music, and next to Palestrina (with whom he worked contemporaneously) the greatest figure in sixteenth century music. Soubies writes: "One might say that on his musical palette he has entirely at his disposition, in some sort, the glowing colour of Zurbaran, the realistic and transparent tones of Velasquez, the ideal shades of Juan de Juanes and Murillo. His mys[Pg 34]ticism is that of Santa Theresa and San Juan de la Cruz." The music of Victoria is still very much alive and may be heard even in New York, occasionally, through the medium of the Musical Art Society. Whether it is performed in churches in America or not I do not know; the Roman choirs still sing it....

The list might be extended indefinitely ... but the great names I have given. There are Cabezón, whom Pedrell calls the "Spanish Bach," Navarro, Caseda, Gomes, Ribera, Castillo, Lobo, Durón, Romero, Juarez. On the whole I think these composers had more influence on Rome—the Spanish nature is more reverent than the Italian—than on Spain. The modern Spanish composers have learned more from the folk-song and dance than they have from the church composers. However, there are voices which dissent from this opinion. G. Tebaldini ("Rivista Musicale," Vol. IV, Pp. 267 and 494) says that Pedrell in his studies learned much which he turned to account in the choral writing of his operas. And Felipe Pedrell himself asserts that there is an unbroken chain between the religious composers of the sixteenth century and the theatrical composers of the seventeenth. We may follow him thus far without believing that the theatrical composers of the sev[Pg 35]enteenth century had too great an influence on the secular composers of the present day.

All the world dances in Spain, at least it would seem so, in reading over the books of the Marco Polos who have made voyages of discovery on the Iberian peninsula. Guitars seem to be as common there as pea-shooters in New England, and strumming seems to set the feet a-tapping and voices a-singing, what, they care not. (Havelock Ellis says: "It is not always agreeable to the Spaniard to find that dancing is regarded by the foreigner as a peculiar and important Spanish institution. Even Valera, with his wide culture, could not escape this feeling; in a review of a book about Spain by an American author entitled 'The Land of the Castanet'—a book which he recognized as full of appreciation for Spain—Valera resented the title. It is, he says, as though a book about the United States should be called 'The Land of Bacon.'") Oriental colour is streaked through and through the melodies and harmonies, many of which betray their Arabian origin; others are flamenco, or gipsy. The dances, almost invariably accompanied by song, are generally in 3-4 time or its variants such as 6-8 or 3-8; the tango, of course, is in 2-4. But the dancers evolve the most elaborate inter-rhythms out of these simple measures, creating thereby a complexity of effect which defies any comprehensible notation on paper. As it is on this fioritura, if I may be permitted to use the word in this connection, of the dancer that the sophisticated composer bases some of his most natural and national effects, I shall linger on the subject. La Argentina has re-arranged many of the Spanish dances for purposes of the concert stage, but in her translation she has retained in a large measure this interesting complication of rhythm, marking the irregularity of the beat, now with a singularly complicated detonation of heel-tapping, now with a sudden bend of a knee, now with the subtle quiver of an eyelash, now with a shower of castanet sparks (an instrument which requires a hard tutelage for its complete mastery; Richard Ford tells us that even the children in the streets of Spain rap shells together, to become self-taught artists in the use of it). Chabrier, in his visit to Spain with his wife in 1882, attempted to note down some of these rhythmic variations achieved by the dancers while the musicians strummed their guitars, and he was partially successful. But all in all he only succeeded in giving in a single measure each variation; he did not attempt to weave them into the intricate pattern which the Spanish women contrive to make of them.

There is a singular similarity to be observed between this heel-tapping and the complicated drum-tapping of the African negroes of certain tribes. In his book "Afro-American Folksongs" H. E. Krehbiel thus describes the musical accompaniment of the dances in the Dahoman Village at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago: "These dances were accompanied by choral song and the rhythmical and harmonious beating of drums and bells, the song being in unison. The harmony was a tonic major triad broken up rhythmically in a most intricate and amazingly ingenious manner. The instruments were tuned with excellent justness. The fundamental tone came from a drum made of a hollowed log about three feet long with a single head, played by one who seemed to be the leader of the band, though there was no giving of signals. This drum was beaten with the palms of the hands. A variety of smaller drums, some with one, some with two heads, were beaten variously with sticks and fingers. The bells, four in number, were of iron and were held mouth upward and struck with sticks. The players showed the most remarkable rhythmical sense and skill that ever came under my notice. Berlioz in his supremest effort with his army of drummers produced nothing to compare in artistic interest with the harmonious drumming of these savages. The fundamental effect was a combination of double and triple time, the former kept by the singers, the latter by the drummers, but it is impossible to convey the idea of the wealth of detail achieved by the drummers by means of exchange of the rhythms, syncopation of both simultaneously, and dynamic devices. Only by making a score of the music could this have been done. I attempted to make such a score by enlisting the help of the late John C. Filmore, experienced in Indian music, but we were thwarted by the players who, evidently divining our purpose when we took out our notebooks, mischievously changed their manner of playing as soon as we touched pencil to paper."

The resemblance between negro and Spanish music is very noticeable. Mr. Krehbiel says that in South America Spanish melody has been imposed on negro rhythm. In the dances of the people of Spain, as Chabrier points out, the melody is often practically nil; the effect is rhythmic (an effect which is emphasized by the obvious harmonic[Pg 39] and melodic limitations of the guitar, which invariably accompanies all singers and dancers). If there were a melody or if the guitarists played well (which they usually do not) one could not distinguish its contours what with the cries of Olé! and the heel-beats of the performers. Spanish melodies, indeed, are often scraps of tunes, like the African negro melodies. The habanera is a true African dance, taken to Spain by way of Cuba, as Albert Friedenthal points out in his book, "Musik, Tanz, und Dichtung bei den Kreolen Amerikas." Whoever was responsible, Arab, negro, or Moor (Havelock Ellis says that the dances of Spain are closely allied with the ancient dances of Greece and Egypt), the Spanish dances betray their oriental origin in their complexity of rhythm (a complexity not at all obvious on the printed page, as so much of it depends on dancer, guitarist, singer, and even public!), and the fioriture which decorate their melody when melody occurs. While Spanish religious music is perhaps not distinctively Spanish, the dances invariably display marked national characteristics; it is on these, then (some in greater, some in less degree), that the composers in and out of Spain have built their most atmospheric inspirations, their best pictures of popular life in the Iberian peninsula. A good[Pg 40] deal of the interest of this music is due to the important part the guitar plays in its construction; the modulations are often contrary to all rules of harmony and (yet, some would say) the music seems to be effervescent with variety and fire. Of the guitarists Richard Ford ("Gatherings from Spain") says: "The performers seldom are very scientific musicians; they content themselves with striking the chords, sweeping the whole hand over the strings, or flourishing, and tapping the board with the thumb, at which they are very expert. Occasionally in the towns there is some one who has attained more power over this ungrateful instrument; but the attempt is a failure. The guitar responds coldly to Italian words and elaborate melody, which never come home to Spanish ears or hearts." (An exception must be made in the case of Miguel Llobet. I first heard him play at Pitts Sanborn's concert at the Punch and Judy Theatre (April 17, 1916) for the benefit of Hospital 28 in Bourges, France, and he made a deep impression on me. In one of his numbers, the Spanish Fantasy of Farrega, he astounded and thrilled me. He seemed at all times to exceed the capacity of his instrument, obtaining a variety of colour which was truly amazing. In this particular number he not only plucked the keyboard[Pg 41] but the fingerboard as well, in intricate and rapid tempo; seemingly two different kinds of instruments were playing. But at all times he variated his tone; sometimes he made the instrument sound almost as though it had been played by wind and not plucked. Especially did I note a suggestion of the bagpipe. A true artist. None of the music, the fantasy mentioned, a serenade of Albéniz, and a Menuet of Tor, was particularly interesting, although the Fantasia contained some fascinating references to folk-dance tunes. There is nothing sensational about Llobet, a quiet prim sort of man; he sits quietly in his chair and makes music. It might be a harp or a 'cello—no striving for personal effect.)

The Spanish dances are infinite in number and for centuries back they seem to form part and parcel of Spanish life. Discussion as to how they are danced is a feature of the descriptions. No two authors agree, it would seem; to a mere annotator the fact is evident that they are danced differently on different occasions. It is obvious that they are danced differently in different provinces. The Spaniards, as Richard Ford points out, are not too willing to give information to strangers, frequently because they themselves lack the knowledge. Their statements are often mis[Pg 42]leading, sometimes intentionally so. They do not understand the historical temperament. Until recently many of the art treasures and archives of the peninsula were but poorly kept. Those who lived in the shadow of the Alhambra admired only its shade. It may be imagined that there has been even less interest displayed in recording the folk-dances. "Dancing in Spain is now a matter which few know anything about," writes Havelock Ellis, "because every one takes it for granted that he knows all about it; and any question on the subject receives a very ready answer which is usually of questionable correctness." Of the music of the dances we have many records, and that they are generally in 3-4 time or its variants we may be certain. As to whether they are danced by two women, a woman and a man, or a woman alone, the authorities do not always agree. The confusion is added to by the oracular attitude of the scribes. It seems quite certain to me that this procedure varies. That the animated picture almost invariably possesses great fascination there are only too many witnesses to prove. I myself can testify to the marvel of some of them, set to be sure in strange frames, the Feria in Paris, for example; but even without the surroundings, which Spanish dances demand, the diablerie, the shiver[Pg 43]ing intensity of these fleshly women, always wound tight with such shawls as only the mistresses of kings might wear in other countries, have drawn taut the real thrill. It is dancing which enlists the co-operation not only of the feet and legs, but of the arms and, in fact, the entire body.

The smart world in Spain today dances much as the smart world does anywhere else, although it does not, I am told, hold a brief for our tango, which Mr. Krehbiel suggests is a corruption of the original African habanera. But in older days many of the dances, such as the pavana, the sarabande, and the gallarda, were danced at the court and were in favour with the nobility. (Although presumably of Italian origin, the pavana and gallarda were more popular in Spain than in Rome. Fuertes says that the sarabande was invented in the middle of the sixteenth century by a dancer called Zarabanda who was a native of either Seville or Guayaquil.) The pavana, an ancient dance of grave and stately measure, was much in vogue in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. An explanation of its name is that the figures executed by the dancers bore a resemblance to the semi-circular wheel-like spreading of the tail of a peacock. The gallarda (French, gaillard) was usually danced as a relief to the pavana (and indeed[Pg 44] often follows it in the dance-suites of the classical composers in which these forms all figure). The jacara, or more properly xacara, of the sixteenth century, was danced in accompaniment to a romantic, swashbuckling ditty. The Spanish folias were a set of dances danced to a simple tune treated in a variety of styles with very free accompaniment of castanets and bursts of song. Corelli in Rome in 1700 published twenty-four variations in this form, which have been played in our day by Fritz Kreisler and other violinists.

The names of the modern Spanish dances are often confused in the descriptions offered by observing travellers, for the reasons already noted. Hundreds of these descriptions exist, and it is difficult to choose the most telling of them. Gertrude Stein, who has spent the last two years in Spain, has noted the rhythm of several of these dances by the mingling of her original use of words with the ingratiating medium of vers libre. She has succeeded, I think, better than some musicians in suggesting the intricacies of the rhythm. I should like to transcribe one of these attempts here, but that I have not the right to do as I have only seen them in manuscript; they have not yet appeared in print. These pieces are in a sense the thing itself—I shall have to fall back on descriptions of[Pg 45] the thing. The tirana, a dance common to the province of Andalusia, is accompanied by song. It has a decided rhythm, affording opportunities for grace and gesture, the women toying with their aprons, the men flourishing hats and handkerchiefs. The polo, or ole, is now a gipsy dance. Mr. Ellis asserts that it is a corruption of the sarabande! He goes on to say, "The so-called gipsy dances of Spain are Spanish dances which the Spaniards are tending to relinquish but which the gipsies have taken up with energy and skill." (This theory might be warmly contested.) The bolero, a comparatively modern dance, came to Spain through Italy. Mr. Philip Hale points out the fact that the bolero and the cachucha (which, by the way, one seldom hears of nowadays) were the popular Spanish dances when Mesdames Faviani and Dolores Tesrai, and their followers, Mlle. Noblet and Fanny Elssler, visited Paris. Fanny Elssler indeed is most frequently seen pictured in Spanish costume, and the cachucha was danced by her as often, I fancy, as Mme. Pavlowa dances Le Cygne of Saint-Saëns. Marie-Anne de Camargo, who acquired great fame as a dancer in France in the early eighteenth century, was born in Brussels but was of Spanish descent. She relied, however, on the Italian classic style for her success rather than[Pg 46] on national Spanish dances. The seguidilla is a gipsy dance which has the same rhythm as the bolero but is more animated and stirring. Examples of these dances, and of the jota, fandango, and the sevillana, are to be met with in the compositions listed in the first section of this article, in the appendices of Soriano Fuertes's "History of Spanish Music," in Grove's Dictionary, in the numbers of "S. I. M." in which the letters of Emmanuel Chabrier occur, and in collections made by P. Lacome, published in Paris.

The jota is another dance in 3-4 time. Every province in Spain has its own jota, but the most famous variations are those of Aragón, Valencia, and Navarre. It is accompanied by the guitar, the bandarria (similar to the guitar), small drum, castanets, and triangle. Mr. Hale says that its origin in the twelfth century is attributed to a Moor named Alben Jot who fled from Valencia to Aragón. "The jota," he continues, "is danced not only at merrymakings but at certain religious festivals and even in watching the dead. One called the 'Natividad del Señor' (nativity of our Lord) is danced on Christmas eve in Aragón, and is accompanied by songs, and jotas are sung and danced at the crossroads, invoking the favour of[Pg 47] the Virgin, when the festival of Our Lady del Pilar is celebrated at Saragossa."

Havelock Ellis's description of the jota is worth reproducing: "The Aragonaise jota, the most important and typical dance outside Andalusia, is danced by a man and a woman, and is a kind of combat between them; most of the time they are facing each other, both using castanets and advancing and retreating in an apparently aggressive manner, the arms alternately slightly raised and lowered, and the legs, with a seeming attempt to trip the partner, kicking out alternately somewhat sidewise, as the body is rapidly supported first on one side and then on the other. It is a monotonous dance, with immense rapidity and vivacity in its monotony, but it has not the deliberate grace and fascination, the happy audacities of Andalusian dancing. There is, indeed, no faintest suggestion of voluptuousness in it, but it may rather be said, in the words of a modern poet, Salvador Rueda, to have in it 'the sound of helmets and plumes and lances and banners, the roaring of cannon, the neighing of horses, the shock of swords.'"

Chabrier, in his astounding and amusing letters from Spain, gives us vivid pictures and interesting[Pg 48] information. This one, written to his friend, Edouard Moullé, from Granada, November 4, 1882, appeared in "S. I. M." April 15, 1911 (I have omitted the musical illustrations, which, however, possess great value for the student): "In a month I must leave adorable Spain ... and say good-bye to the Spaniards,—because, I say this only to you, they are very nice, the little girls! I have not seen a really ugly woman since I have been in Andalusia: I do not speak of the feet, they are so small that I have never seen them; the hands are tiny and well-kept and the arms of an exquisite contour; I speak only of what one can see, but they show a good deal; add the arabesques, the side-curls, and other ingenuities of the coiffure, the inevitable fan, the flower and the comb in the hair, placed well behind, the shawl of Chinese crêpe, with long fringe and embroidered in flowers, knotted around the figure, the arm bare, and the eye protected by eyelashes which are long enough to curl; the skin of dull white or orange colour, according to the race, all this smiling, gesticulating, dancing, drinking, and careless to the last degree...

"That is the Andalusian.

"Every evening we go with Alice to the café-concerts where the malagueñas, the Soledas, the[Pg 49] Sapateados, and the Peteneras are sung; then the dances, absolutely Arab, to speak truth; if you could see them wriggle, unjoint their hips, contortion, I believe you would not try to get away!... At Málaga the dancing became so intense that I was compelled to take my wife away; it wasn't even amusing any more. I can't write about it, but I remember it and I will describe it to you.—I have no need to tell you that I have noted down many things; the tango, a kind of dance in which the women imitate the pitching of a ship (le tangage du navire) is the only dance in 2 time; all the others, all, are in 3-4 (Seville) or in 3-8 (Málaga and Cadiz);—in the North it is different, there is some music in 5-8, very curious. The 2-4 of the tango is always like the habanera; this is the picture: one or two women dance, two silly men play it doesn't matter what on their guitars, and five or six women howl, with excruciating voices and in triplet figures impossible to note down because they change the air—every instant a new scrap of tune. They howl a series of figurations with syllables, words, rising voices, clapping hands which strike the six quavers, emphasizing the third and the sixth, cries of Anda! Anda! La Salud! eso es la Maraquita! gracia, nationidad! Baila, la chiquilla! Anda! Anda! Consuelo! Olé, la[Pg 50] Lola, olé la Carmen! qué gracia! qué elegancia! all that to excite the young dancer. It is vertiginous—it is unspeakable!

"The Sevillana is another thing: it is in 3-4 time (and with castanets).... All this becomes extraordinarily alluring with two curls, a pair of castanets and a guitar. It is impossible to write down the malagueña. It is a melopœia, however, which has a form and which always ends on the dominant, to which the guitar furnishes 3-8 time, and the spectator (when there is one) seated beside the guitarist, holds a cane between his legs and beats the syncopated rhythm; the dancers themselves instinctively syncopate the measures in a thousand ways, striking with their heels an unbelievable number of rhythms.... It is all rhythm and dance: the airs scraped out by the guitarist have no value; besides, they cannot be heard on account of the cries of Anda! la chiquilla! qué gracia! qué elegancia! Anda! Olé! Olé! la chiquirritita! and the more the cries the more the dancer laughs with her mouth wide open, and turns her hips, and is mad with her body...."

As it is on these dances that composers invariably base their Spanish music (not alone Albéniz, Chapí, Bretón, and Granados, but Chabrier,[Pg 51] Ravel, Laparra, and Bizet, as well) we may linger somewhat longer on their delights. The following compelling description is from Richard Ford's highly readable "Gatherings from Spain": "The dance which is closely analogous to the Ghowasee of the Egyptians, and the Nautch of the Hindoos, is called the Olé by Spaniards, the Romalis by their gipsies; the soul and essence of it consists in the expression of a certain sentiment, one not indeed of a very sentimental or correct character. The ladies, who seem to have no bones, resolve the problem of perpetual motion, their feet having comparatively a sinecure, as the whole person performs a pantomime, and trembles like an aspen leaf; the flexible form and Terpsichore figure of a young Andalusian girl—be she gipsy or not—is said, by the learned, to have been designed by nature as the fit frame for her voluptuous imagination.

"Be that as it may, the scholar and classical commentator will every moment quote Martial, etc., when he beholds the unchanged balancing of hands, raised as if to catch showers of roses, the tapping of the feet, and the serpentine quivering movements. A contagious excitement seizes the spectators, who, like Orientals, beat time with their hands in measured cadence, and at every[Pg 52] pause applaud with cries and clappings. The damsels, thus encouraged, continue in violent action until nature is all but exhausted; then aniseed brandy, wine, and alpisteras are handed about, and the fête, carried on to early dawn, often concludes in broken heads, which here are called 'gipsy's fare.' These dances appear, to a stranger from the chilly north, to be more marked by energy than by grace, nor have the legs less to do than the body, hips, and arms. The sight of this unchanged pastime of antiquity, which excites the Spaniard to frenzy, rather disgusts an English spectator, possibly from some national malorganization, for, as Molière says, 'l'Angleterre a produit des grands hommes dans les sciences et les beaux arts, mais pas un grand danseur—allez lire l'histoire.'" (A fact as true in our day as it was in Molière's.)

On certain days the sevillana is danced before the high altar of the cathedral at Seville. The Reverend Henry Cart de Lafontaine ("Proceedings of the Musical Association"; London, thirty-third session, 1906-7) gives the following account of it, quoting a "French author": "While Louis XIII was reigning over France, the Pope heard much talk of the Spanish dance called the 'Sevillana.' He wished to satisfy himself, by ac[Pg 53]tual eye-witness, as to the character of this dance, and expressed his wish to a bishop of the diocese of Seville, who every year visited Rome. Evil tongues make the bishop responsible for the primary suggestion of the idea. Be that as it may, the bishop, on his return to Seville, had twelve youths well instructed in all the intricate measures of this Andalusian dance. He had to choose youths, for how could he present maidens to the horrified glance of the Holy Father? When his little troop was thoroughly schooled and perfected, he took the party to Rome, and the audience was arranged. The 'Sevillana' was danced in one of the rooms of the Vatican. The Pope warmly complimented the young executants, who were dressed in beautiful silk costumes of the period. The bishop humbly asked for permission to perform this dance at certain fêtes in the cathedral church at Seville, and further pleaded for a restriction of this privilege to that church alone. The Pope, hoist by his own petard, did not like to refuse, but granted the privilege with this restriction, that it should only last so long as the costumes of the dancers were wearable. Needless to say, these costumes are, therefore, objects of constant repair, but they are supposed to retain their identity even to this day. And this[Pg 54] is the reason why the twelve boys who dance the 'Sevillana' before the high altar in the cathedral on certain feast days are dressed in the costume belonging to the reign of Louis XIII."

This is a very pretty story, but it is not uncontradicted.... Has any statement been made about Spanish dancing or music which has been allowed to go uncontradicted? Look upon that picture and upon this: "As far as it is possible to ascertain from records," says Rhoda G. Edwards in the "Musical Standard," "this dance would seem always to have been in use in Seville cathedral; when the town was taken from the Moors in the thirteenth century it was undoubtedly an established custom and in 1428 we find the six boys recognized as an integral part of the chapter by Pope Eugenius IV. The dance is known as the (sic) 'Los Scises,' or dance of the six boys who, with four others, dance it before the high altar at Benediction on the three evenings before Lent and in the octaves of Corpus Christi and La Purissima (the conception of Our Lady). The dress of the boys is most picturesque, page costumes of the time of Philip III being worn, blue for La Purissima and red satin doublets slashed with blue for the other occasion; white hats with blue and white feathers are also worn whilst[Pg 55] dancing. The dance is usually of twenty-five minutes' duration and in form seems quite unique, not resembling any of the other Spanish dance-forms, or in fact those of any other country. The boys accompany the symphony on castanets and sing a hymn in two parts whilst dancing."

From another author we learn that religious dancing is to be seen elsewhere in Spain than at Seville cathedral. At one time, it is said to have been common. The pilgrims to the shrine of the Virgin at Montserrat were wont to dance, and dancing took place in the churches of Valencia, Toledo, and Jerez. Religious dancing continued to be common, especially in Catalonia up to the seventeenth century. An account of the dance in the Seville cathedral may be found in "Los Españoles Pintados por si Mismos" (pages 287-91).

This very incomplete and rambling record of Spanish dancing should include some mention of the fandango. The origin of the word is obscure, but the dance is obviously one of the gayest and wildest of the Spanish dances. Like the malagueña it is in 3-8 time, but it is quite different in spirit from that sensuous form of terpsichorean enjoyment. La Argentina informs me that "fandango" in Spanish suggests very much[Pg 56] what "bachanale" does in English or French. It is a very old dance, and may be a survival of a Moorish dance, as Desrat suggests. Mr. Philip Hale found the following account of it somewhere:

"Like an electric shock, the notes of the fandango animate all hearts. Men and women, young and old, acknowledge the power of this air over the ears and soul of every Spaniard. The young men spring to their places, rattling castanets, or imitating their sound by snapping their fingers. The girls are remarkable for the willowy languor and lightness of their movements, the voluptuousness of their attitudes—beating the exactest time with tapping heels. Partners tease and entreat and pursue each other by turns. Suddenly the music stops, and each dancer shows his skill by remaining absolutely motionless, bounding again in the full life of the fandango as the orchestra strikes up. The sound of the guitar, the violin, the rapid tic-tac of heels (taconeos), the crack of fingers and castanets, the supple swaying of the dancers, fill the spectators with ecstasy.

"The music whirls along in a rapid triple time. Spangles glitter; the sharp clank of ivory and ebony castanets beats out the cadence of strange, throbbing, deafening notes—assonances un[Pg 57]known to music, but curiously characteristic, effective, and intoxicating. Amidst the rustle of silks, smiles gleam over white teeth, dark eyes sparkle and droop, and flash up again in flame. All is flutter and glitter, grace and animation—quivering, sonorous, passionate, seductive. Olé! Olé! Faces beam and burn. Olé! Olé!

"The bolero intoxicates, the fandango inflames."

It can be well understood that the study of Spanish dancing and its music must be carried on in Spain. Mr. Ellis tells us why: "Another characteristic of Spanish dancing, and especially of the most typical kind called flamenco, lies in its accompaniments, and particularly in the fact that under proper conditions all the spectators are themselves performers.... Thus it is that at the end of a dance an absolute silence often falls, with no sound of applause: the relation of performers and public has ceased to exist.... The finest Spanish dancing is at once killed or degraded by the presence of an indifferent or unsympathetic public, and that is probably why it cannot be transplanted, but remains local."

At the end of a dance an absolute silence often falls.... I am again in an underground café in Amsterdam. It is the eve of the Queen's birth[Pg 58]day, and the Dutch are celebrating. The low, smoke-wreathed room is crowded with students, soldiers, and women. Now a weazened female takes her place at the piano, on a slightly raised platform at one side of the room. She begins to play. The dancing begins. It is not woman with man; the dancing is informal. Some dance together, and some dance alone; some sing the melody of the tune, others shriek, but all make a noise. Faster and faster and louder and louder the music is pounded out, and the dancing becomes wilder and wilder. A tray of glasses is kicked from the upturned palm of a sweaty waiter. Waiter, broken glass, dancer, all lie, a laughing heap, on the floor. A soldier and a woman stand in opposite corners, facing the corners; then without turning, they back towards the middle of the room at a furious pace; the collision is appalling. Hand in hand the mad dancers encircle the room, throwing confetti, beer, anything. A heavy stein crushes two teeth—the wound bleeds—but the dancer does not stop. Noise and action and colour all become synonymous. There is no escape from the force. I am dragged into the circle. Suddenly the music stops. All the dancers stop. The soldier no longer looks at the woman by his side; not a word is spoken. People[Pg 59] lumber towards chairs. The woman looks for a glass of water to assuage the pain of her bleeding mouth. I think Jaques-Dalcroze is right when he seeks to unite spectator and actor, drama and public.

In the preceding section I may have too strongly insisted upon the relation of the folk-song to the dance. It is true that the two are seldom separated in performance (although not all songs are danced; for example, the cañas and playeras of Andalusia). However, most of the folk-songs of Spain are intended to be danced; they are built on dance-rhythms and they bear the names of dances. Thus the jota is always danced to the same music, although the variations are great at different times and in different provinces. It is, of course, when the folk-songs are danced that they make their best effect, in the polyrhythm achieved by the opposing rhythms of guitar-player, dancer, and singer. When there is no dancer the defect is sometimes overcome by some one tapping a stick on the ground in imitation of resounding heels.

Blind beggars have a habit of singing the songs, in certain provinces, with a wealth of florid orna[Pg 60]ment, such ornament as is always associated with oriental airs in performance, and this ornament still plays a considerable rôle when the vocalist becomes an integral part of the accompaniment for a dancer. Chabrier gives several examples of it in one of his letters. In the circumstances it can readily be seen that Spanish folk-songs written down are pretty bare recollections of the real thing, and when sung by singers who have no knowledge of the traditional manner of performing them they are likely to sound fairly banal. The same thing might be said of the negro folk-songs of America, or the folk-songs of Russia or Hungary, but with much less truth, for the folk-songs of these countries usually possess a melodic interest which is seldom inherent in the folk-songs of Spain. To make their effect they must be performed by Spaniards, as nearly as possible after the manner of the people. Indeed, their spirit and their polyrhythmic effects are much more essential to their proper interpretation than their melody, as many witnesses have pointed out.

Spanish music, indeed, much of it, is actually unpleasant to Western ears; it lacks the sad monotony and the wailing intensity of true oriental music; much of it is loud and blaring, like the hot sunglare of the Iberian peninsula. However,[Pg 61] many a Western or Northern European has found pleasure in listening by the hour to the strains, which often sound as if they were improvised, sung by some beggar or mountaineer.

The collections of these songs are not in any sense complete and few of them attempt more than a collocation of the songs of one locality or people. Deductions have been drawn. For example it is noted that the Basque songs are irregular in melody and rhythm and are further marked by unusual tempos, 5-8, or 7-4. In Aragón and Navarre the popular song (and dance) is the jota; in Galicia, the seguidilla; the Catalonian songs resemble the folk-tunes of Southern France. The Andalusian songs, like the dances of that province, are the most beautiful of all, often truly oriental in their rhythm and floridity. In Spain the gipsy has become an integral part of the popular life, and it is difficult at times to determine what is flamenco and what is Spanish. However, collections (few to be sure) have been attempted of gipsy songs.

Elsewhere in this rambling article I have touched on the villancicos and the early song-writers. To do justice to these subjects would require a good deal more space and a different intention. Those who are interested in them may[Pg 62] pursue these matters in Pedrell's various works. The most available collection of Spanish folk-tunes is that issued by P. Lacome and J. Puig y Alsubide (Paris, 1872). There are several collections of Basque songs; Demófilo's "Colección de Cantos Flamencos" (Seville, 1881), Cecilio Ocón's collection of Andalusian folk-songs, and F. Rodríguez Marín's "Cantos Populares Españoles" (Seville, 1882-3) may also be mentioned.

After the bull-fight the most popular form of amusement in Spain is the zarzuela, the only distinctive art-form which Spanish music has evolved, but there has been no progress; the form has not changed, except perhaps to degenerate, since its invention in the early seventeenth century. Soriano Fuertes and other writers have devoted pages to grieving because Spanish composers have not taken occasion to make something grander and more important out of the zarzuela. The fact remains that they have not, although, small and great alike, they have all taken a hand at writing these entertainments. But as they found the zarzuela, so they have left it. It must be conceded that the form is quite distinct from[Pg 63] that of opera and should not be confused with it. And the Spaniards are probably right when they assert that the zarzuela is the mother of the French opéra-bouffe. At least it must be admitted that Offenbach and Lecocq and their precursors owe something of the germ of their inspiration to the Spanish form. Today the melody chests of the zarzuela markets are plundered to find tunes for French revues, and such popular airs as La Paraguaya and Y ... Como le Vá? were originally danced and sung in Spanish theatres. The composer of these airs, J. Valverde fils, indeed found the French market so good that he migrated to Paris, and for some time has been writing musique mélangée ... une moitié de chaque nation. So La Rose de Grenade, composed for Paris, might have been written for Spain, with slight melodic alterations and tauromachian allusions in the book.

The zarzuela is usually a one-act piece (although sometimes it is permitted to run into two or more acts) in which the music is freely interrupted by spoken dialogue, and that in turn gives way to national dances. Very often the entire score is danced as well as sung. The subject is usually comic and often topical, although it may be serious, poetic, or even tragic. The[Pg 64] actors often introduce dialogue of their own, "gagging" freely; sometimes they engage in long impromptu conversations with members of the audience. They also embroider on the music after the fashion of the great singers of the old Italian opera (Dr. de Lafontaine asserts that Spanish audiences, even in cabarets, demand embroidery of this sort). The music is spirited and lively, and in the dances, Andalusian, flamenco, or Sevillan, as the case may be, it attains its best results. H. V. Hamilton, in his essay on the subject in Grove's Dictionary, says, "The music is ... apt to be vague in form when the national dance and folk-song forms are avoided. The orchestration is a little blatant." It will be seen that this description suits Granados's Goyescas (the opera), which is on its safest ground during the dances and becomes excessively vague at other times; but Goyescas is not a zarzuela, because there is no spoken dialogue. Otherwise it bears the earmarks. A zarzuela stands somewhere between a French revue and opéra-comique. It is usually, however, more informal in tone than the latter and often decidedly more serious than the former. All the musicians in Spain since the form was invented (excepting, of course, certain exclusively religious composers), and most of the[Pg 65] poets and playwrights, have contributed numerous examples. Thus Calderon wrote the first zarzuela, and Lope de Vega contributed words to entertainments much in the same order. In our day Miguel Echegaray, brother of José Echegaray, has written one of the most popular zarzuelas, Gigantes y Cabezudos (the music by Caballero). The subject is the fiesta of Santa María del Pilar. It has had many a long run and is often revived. Another very popular zarzuela, which was almost, if not quite, heard in New York, is La Gran Vía (by Valverde, père), which has been performed in London in extended form. The principal theatres for the zarzuela in Madrid are (or were until recently) that of the Calle de Jovellanos, called the Teatro de Zarzuela, and the Apolo. Usually four separate zarzuelas are performed in one evening before as many audiences.

La Gran Vía, which in some respects may be considered a typical zarzuela, consists of a string of dance-tunes, with no more homogeneity than their national significance would suggest. There is an introduction and polka, a waltz, a tango, a jota, a mazurka, a schottische, another waltz, and a two-step (paso-doble). The tunes have little distinction; nor can the orchestration be considered brilliant. There is a great deal of noise and[Pg 66] variety of rhythm, and when presented correctly the effect must be precisely that of one of the dance-halls described by Chabrier. The zarzuela, to be enjoyed, in fact, must be seen in Spain. Like Spanish dancing it requires a special audience to bring out its best points. There must be a certain electricity, at least an element of sympathy, to carry the thing through successfully. Examination of the scores of zarzuelas (many of them have been printed and some of them are to be seen in our libraries) will convince any one that Mr. Ellis is speaking mildly when he says that the Spaniards love noise. However, the combination of this noise with beautiful women, dancing, elaborate rhythm, and a shouting audience, seems to almost equal the café-concert dancing and the tauromachian spectacles in Spanish popular affection. (Of course, as I have suggested, there are zarzuelas more serious melodically and dramatically; but as La Gran Vía is frequently mentioned by writers as one of the most popular examples, it may be selected as typical of the larger number of these entertainments.)

H. V. Hamilton says that the first performance of a zarzuela took place in 1628 (Pedrell gives the date as October 29, 1629), during the reign of Felipe IV, in the Palace of the Zarzuela (so[Pg 67] called because it was surrounded by zarzas, brambles). It was called El Jardín de Falerina; the text was by the great Calderon and the music by Juan Risco, chapelmaster of the cathedral at Cordova, according to Mr. Hamilton, who doubtless follows Soriano Fuertes on this detail. Soubies, following the more modern studies of Pedrell, gives Jóse Peyró the credit. Pedrell, in his richly documented work, "Teatro Lírico Español anterior al siglo XIX," attributes the music of this zarzuela to Peyró and gives an example of it. The first Spanish opera dates from the same period, Lope de Vega's La Selva sin Amor (1629). As a matter of fact, many of the plays of Calderon and Lope de Vega were performed with music to heighten the effect of the declamation, and musical curtain-raisers and interludes were performed before and in the midst of all of them. Lana, Palomares, Benavente and Hidalgo were among the musicians who contributed music to the theatre of this period. Hidalgo wrote the music for Calderon's zarzuela, Ni Amor se Libre de Amor. To the same group belong Miguel Ferrer, Juan de Navas, Sebastian Durón, and Jerónimo de la Torre. (Examples of the music of these men may be found in the aforementioned "Teatro Lírico.") Until 1659[Pg 68] zarzuelas were written by the best poets and composers and frequently performed on royal birthdays, at royal marriages, and on many other occasions; but after that date the art fell into a decline and seems to have been in eclipse during the whole of the eighteenth century. According to Soriano Fuertes the beginning of the reign of Felipe V marked the introduction of Italian opera into Spain (more popular than Spanish opera there to this day) and the decadence of nationalism (whole pages of Fuertes read very much like the plaints of modern English composers about the neglect of national composers in their country). In 1829 there was a revival of interest in Spanish music and a conservatory was founded in Madrid. (For a discussion of this later period the reader is referred to "La Opera Española en el Siglo XIX," by Antonio Peña y Goñi, 1881.) This interest has been fostered by Fuertes and Pedrell, and the younger composers today are taking some account of it. There is hope, indeed, that Spanish music may again take its place in the world of art.

Of course, the zarzuela did not spring into being out of nowhere and nothing, and the true origins are not entirely obscure. It is generally agreed that a priest, Juan del Encina (born at Sala[Pg 69]manca, 1468), was the true founder of the secular theatre in Spain. His dramatic compositions are in the nature of eclogues based on Virgilian models. In all of these there is singing and in one a dance. Isabel la Católica in the fifteenth century always had at her command a troop of musicians and poets who comforted and consoled her in her chapel with motets and plegarias (French, prière), and in the royal apartments with canciones and villancicos. (Canciones are songs inclining towards the ballad-form. Villancicos are songs in the old Spanish measure; they receive their name from their rustic character, as supposedly they were first composed by the villanos or peasants for the nativity and other festivals of the church.) "It is necessary to search for the true origins of the Spanish musical spectacle," states Soubies, "in the villancicos and cantacillos which alternated with the dialogue in the works of Juan del Encina and Lucas Fernández, without forgetting the ensaladas, the jácaras, etc., which served as intermezzi and curtain-raisers." These were sung before the curtain, before the drama was performed (and during the intervals, with jokes added) by women in court dress, and later created a form of their own (besides contributing to the creation of the zar[Pg 70]zuela), the tonadilla, which, accompanied by a guitar or violin and interspersed with dances, was very popular for a number of years. H. V. Hamilton is probably on sound ground when he says, "That the first zarzuela was written with an express desire for expansion and development is, however, not so certain as that it was the result of a wish to inaugurate the new house of entertainment with something entirely original and novel."

We have Richard Ford's testimony that Spain was not very musical in his day. The Reverend Henry Cart de Lafontaine says that the contemporary musical services in the churches are not to be considered seriously from an artistic point of view. Emmanuel Chabrier was impressed with the fact that the music for dancing was almost entirely rhythmic in its effect, strummed rudely on the guitar, the spectators meanwhile making such a din that it was practically impossible to distinguish a melody, had there been one. And all observers point at the Italian opera, which is still the favourite opera in Spain (in Barcelona at the Liceo three weeks of opera in Catalan is given after the regular season in Italian; in Madrid[Pg 71] at the Teatro-Real the Spanish season is scattered through the Italian), and at Señor Arbós's concerts (the same Señor Arbós who was once concert master of the Boston Symphony Orchestra), at which Brandenburg concertos and Beethoven symphonies are more frequently performed than works by Albéniz. Still there are, and have always been during the course of the last century, Spanish composers, some of whom have made a little noise in the outer world, although a good many have been content to spend their artistic energy on the manufacture of zarzuelas—in other words, to make a good deal of noise in Spain. In most modern instances, however, there has been a revival of interest in the national forms, and folk-song and folk-dance have contributed their important share to the composers' work. No one man has done more to encourage this interest in nationalism than Felipe Pedrell, who may be said to have begun in Spain the work which the "Five" accomplished in Russia. Pedrell says in his "Handbook" (Barcelona, 1891; Heinrich and Co.; French translation by Bertal; Paris, Fischbacher): "The popular song, the voice of the people, the pure primitive inspiration of the anonymous singer, passes through the alembic of contemporary art and one obtains thereby its[Pg 72] quintessence; the composer assimilates it and then reveals it in the most delicate form that music alone is capable of rendering form in its technical aspect, this thanks to the extraordinary development of the technique of our art in this epoch. The folk-song lends the accent, the background, and modern art lends all that it possesses, its conventional symbolism and the richness of form which is its patrimony. The frame is enlarged in such a fashion that the lied makes a corresponding development; could it be said then that the national lyric drama is the same lied expanded? Is not the national lyric drama the product of the force of absorption and creative power? Do we not see in it faithfully reflected not only the artistic idiosyncrasy of each composer, but all the artistic manifestations of the people?" There is always the search for new composers in Spain and always the hope that a man may come who will be acclaimed by the world. As a consequence, the younger composers in Spain often receive more adulation than is their due. It must be remembered that the most successful Spanish music is not serious, the Spanish are more themselves in the lighter vein.