Title: Stories Pictures Tell. Book 7

Author: Flora L. Carpenter

Release date: September 10, 2020 [eBook #63171]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Garcia, Larry B. Harrison, Barry

Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at https://www.pgdp.net

| PAGE | ||

| “The Fighting Téméraire” | Turner | 1 |

| “Joan of Arc” | Lepage | 11 |

| “The Syndics of the Cloth Hall” | Rembrandt | 23 |

| “The Last Supper” | Da Vinci | 33 |

| “Alexander and Diogenes” | Landseer | 45 |

| “Rubens’s Sons” | Rubens | 59 |

| “Song of the Lark” | Breton | 69 |

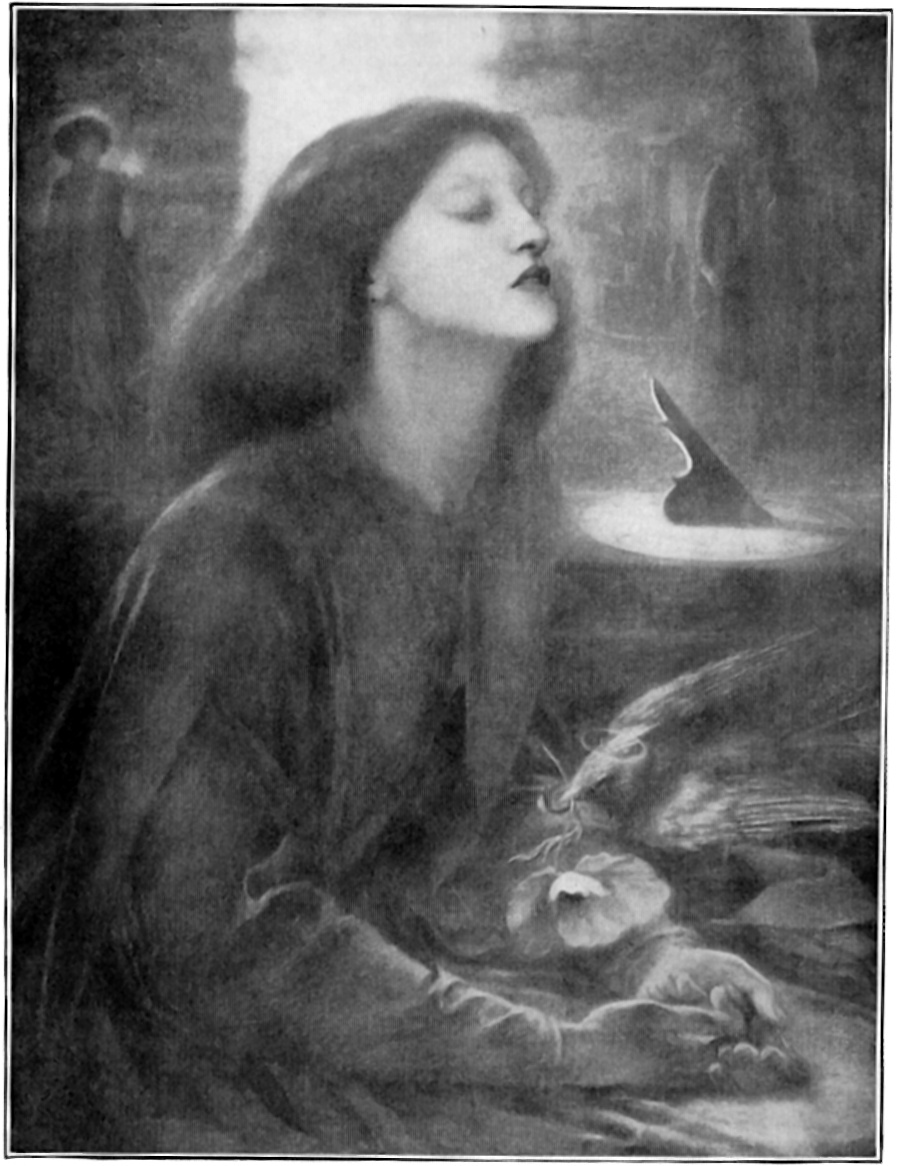

| “Beata Beatrix” | Rossetti | 77 |

| Review of Pictures and Artists Studied | ||

| The Suggestions to Teachers | 93 |

Art supervisors in the public schools assign picture-study work in each grade, recommending the study of certain pictures by well-known masters. As Supervisor of Drawing I found that the children enjoyed this work but that the teachers felt incompetent to conduct the lessons as they lacked time to look up the subject and to gather adequate material. Recourse to a great many books was necessary and often while much information could usually be found about the artist, very little was available about his pictures.

Hence I began collecting information about the pictures and preparing the lessons for the teachers just as I would give them myself to pupils of their grade.

My plan does not include many pictures during the year, as this is to be only a part of the art work and is not intended to take the place of drawing.

The lessons in this grade may be used for the usual drawing period of from twenty to thirty minutes, and have been successfully given in that time. However, the most satisfactory way of using the books is as supplementary readers, thus permitting each child to study the pictures and read the stories himself.

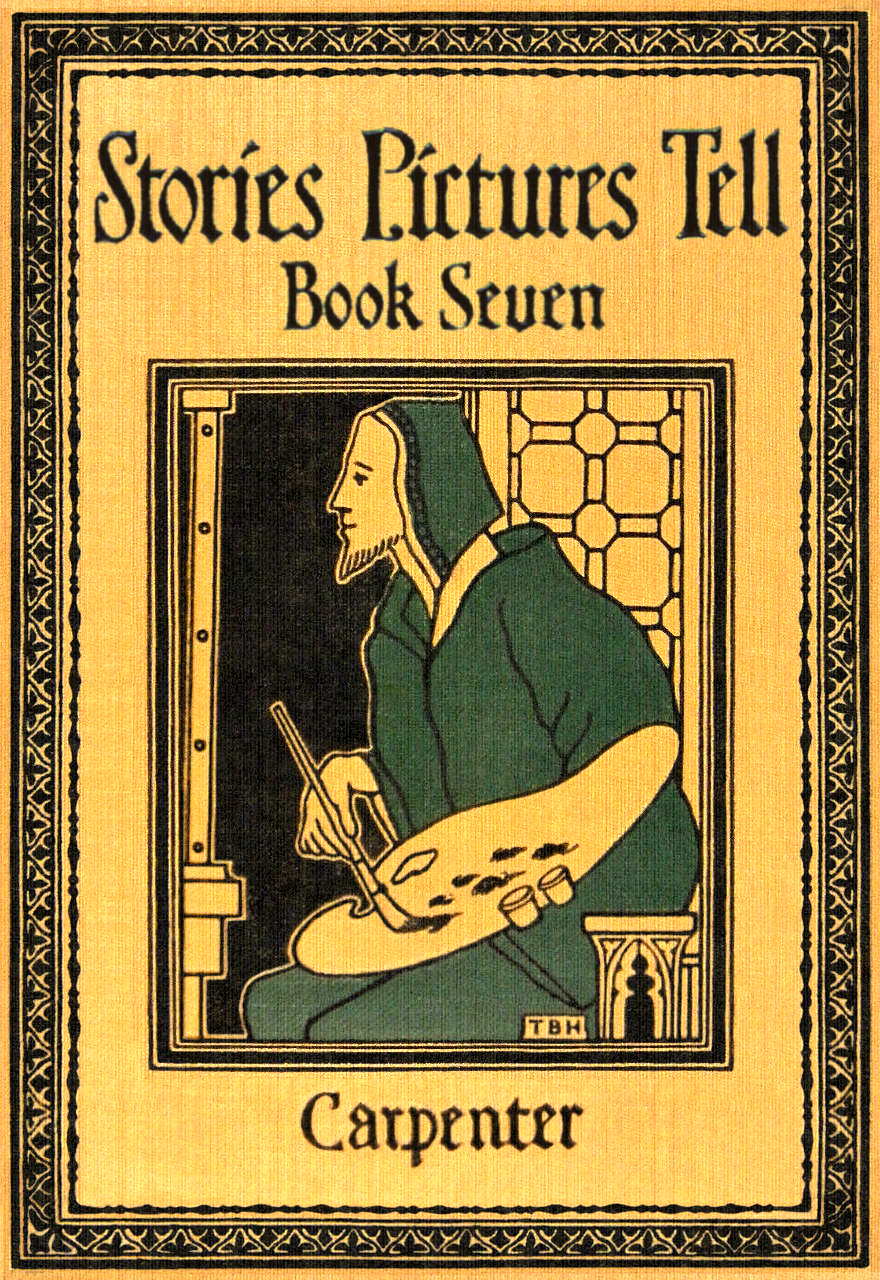

Questions to arouse interest. What is represented in this picture? Which boat is the Téméraire? What smaller boat is towing it? Why do you think it needs to be towed? What is the time of day? What makes you think so? Is the ship moving or stationary? Why does it float so high in the water? What other boats can you see in this picture? What can you see in the background? What is the condition of the water? What kind of a feeling does this picture give you? Why do you like the picture?

The story of the picture. One evening when the artist, Mr. Turner, and a party of friends were sailing down the river Thames in London, there suddenly loomed before their astonished gaze the dark hull of the famous ship called the Téméraire. They had heard and read of the many great victories won by this noble vessel, and the glory it had brought to England. Its name Téméraire means “the one who dares.” Now its days of usefulness were over, and it was being towed to its last place of anchor to be broken up.

At first they gazed in silence, for it was a sad and solemn sight to watch this feeble old boat creeping along like a disabled soldier, its former glories fading like the setting sun. The silence was broken by the exclamation of one of the young men, “Ah, what a subject for a picture!”

And yet we must remember that at the time Turner painted this picture it was considered just as commonplace and uninteresting to paint a sailing vessel as it would be for our artists to paint a bicycle or a wagon.

But Turner painted something more than a picture of a boat. He has made us feel not only the sadness in this parting scene but also all the glories of the splendid victories won in former days. Again we recall the Battle of the Nile, when the English commander, Lord Nelson, won the victory over Napoleon’s fleet and captured the Téméraire from the French. We remember how Nelson, then a young man but having already lost an arm and an eye in battle, was put in command of the English fleet and sent against the French; how after a severe storm the two fleets, going in opposite directions, passed each other in the fog, Nelson reaching Italy and Napoleon landing in Egypt. Then the older naval officers in England, who thought they should have been appointed to this important command, said all they could about the folly of sending so young a man as Nelson, and told how much better they could have done. So the people were dissatisfied and finally the order for extra supplies and provisions was countermanded just as Nelson heard where Napoleon was and wanted to start out. Then Lady Hamilton, the wife of the English minister to Italy, used her influence in his behalf, and the provisions were furnished secretly. We do not care to dwell long on that fierce Battle of the Nile, which began after six o’clock in the evening and lasted all night. Only the flashes of the guns told the positions of the different boats until the burning of the French flagship made a more terrible illumination. It was a great victory for the English.

For forty years after this the Téméraire remained in active service. It took part in the famous victory at the Battle of Trafalgar; it was the second ship in line, and the first to catch Nelson’s well-known words, “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Many lives were lost in this battle, among them that of the great commander.

At length the good old ship was considered unfit for active service. Then for several years it was used as a training ship for cadets. Now, no longer fit for that either, it was to be broken up for lumber. At the time when the Téméraire was captured all war vessels used sails, but less than twenty-five years later they began to use steam. That, too, was a reason why the Téméraire was to be destroyed.

To Turner, who was born near the river Thames and grew up among boats and sailors, the sight of this old boat made a strong appeal, not only because he was an artist, but because he was also a patriotic Englishman full of pride in the ship’s great victories.

The setting sun casts a parting glow upon the great, empty vessel as it stands high out of the water. The sky is ablaze with rosy light, which is reflected in the quiet surface of the Thames, but our eyes are drawn at once to the great Téméraire. We glance at the long, dark shadows and reflections of the two vessels, but soon find our eyes wandering to the brilliantly lighted masts, to the gorgeous sunset sky, and back again to the proud old boat. In the dark smoke of the tug there is a touch of brilliant red.

The small boats scattered here and there help to bring out the distance from that faraway shore so unconscious of the passing of the great ship. At least three fourths of the picture is sky.

All of Turner’s first paintings were in tones of blues and grays, so soft and delicate they were often indistinct. It was not until after he had traveled through Italy, and spent many days in Venice, where all is brilliant color, that he began to make his pictures blaze with color. He had completely mastered the pale shades, so it needed but a touch of brilliant color here and there to make his whole picture glow. In “The Fighting Téméraire” more than half the picture is painted in the soft gray colors of dusk, but the sunset and the touch of red in the smoke of the tug seem to set the whole picture aflame. A gentleman once said to Turner, after looking at this picture, “I never saw a sunset like that.” Turner replied, “No, but don’t you wish you could?”

In Turner’s day water colors were very popular, and Turner painted a great many of them. His water colors are much better preserved than his oil paintings. The “Téméraire” was painted in oils. The sky has faded considerably in the original picture, and others of his oil paintings have become indistinct. It is believed that this is because he so often used poor materials.

Turner himself considered this picture, “The Fighting Téméraire Tugged to Her Last Berth to be Broken Up,” as he called it, his best work, and bequeathed it to the National Gallery in London, refusing to sell it for any price.

You will remember that later, when America proposed a similar fate for our battleship, Constitution, the people raised a protest and the plan was given up. It was then that Holmes wrote his famous “Old Ironsides,” which might have applied equally well to the Téméraire.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. How did the artist happen to see this ship? What does the name “Téméraire” mean? For what was this vessel famous? Tell about Lord Nelson and the Battle of the Nile. From whom did he capture the Téméraire? When was this battle fought? Tell about the Battle of Trafalgar. What saying of Nelson’s has become famous? Who won the victory? What became of the Téméraire then? Why was it now to be broken to pieces? Before the use of steam, how were vessels propelled? How was the Téméraire propelled? To what did Turner compare this old ship? Why was it a sad sight to him? What colors did he use in this picture? How did the artist consider this painting? To whom did he leave it? Why did Americans object when it was proposed that the battleship Constitution be broken up?

To the Teacher: A description of the picture may be prepared by a pupil and given orally to the class. This may be followed by a written description of the picture and a short biography of the artist, as a class exercise in connection with the English composition work.

The story of the artist. Joseph Mallord William Turner was born, lived, and died in London. His father was a jolly little barber who curled wigs and dressed the hair of English dandies, as did all the barbers in those days. He was very popular because he was so good-natured and full of fun. He was also very ambitious for his little son, who had been left to his care by the death of the mother.

The story is told that one day, when Joseph was six years old, his father was called to the home of a wealthy patron, and, having no one with whom to leave the child, he took the boy with him. At the patron’s home the little boy climbed up into a big chair and waited patiently, but it seemed a very long time indeed before his father could satisfy the exacting customer. Finally the boy became interested in studying a carved lion on a silver tray lying on the table near by. He studied this lion so carefully that when they reached home, and while his father was preparing their supper, he drew a lion in full action, and brought the drawing to show his father. It was decided then and there that Joseph should be an artist. The father also wished that his son might receive an education. But Turner did not learn much at school, for as soon as the boys and girls found he could draw wonderful pictures they offered to do his sums for him and helped him with his lessons while he drew pictures for them in return.

The jolly little barber was so pleased with his son’s drawings that he put them up in his shop. His patrons began to inquire about the little artist, and when the proud father put a price mark on the drawings, they were soon sold. Later, Turner was apprenticed to an architect to learn architectural drawing, but he was not successful. He did not seem to be able to understand the theory of perspective or even the first steps in geometry. However, he finally must have mastered these subjects, for some years later he became Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy.

Later in life Turner traveled in France, Germany, and Italy, and it was then he began to use those brilliant colors which we always associate with his work. Turner rarely sold any of his paintings. He called them his “children,” and was unwilling to part with them. But his engravings and illustrations made him very wealthy.

Of Turner’s many pictures of the sea, perhaps the best known is “The Slave Ship.” Other famous pictures by Turner are “Rain, Steam, and Speed, the Great Western Railway,” “Steamer off Harbour’s Mouth Making Signals,” “Approach to Venice,” “Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus,” “Sun Rising in a Mist,” and “Shade and Darkness—The Evening of the Deluge.”

Questions about the artist. Where was the artist born? What did his father do for a living? How did Turner happen to draw his first picture? Why did he not learn much at school? What did his father do with his drawings? What subject proved difficult for the boy artist to learn? Was he ever able to master it? Where did Turner travel? What colors did he use in his paintings? Why would he not sell his pictures? How did he become wealthy?

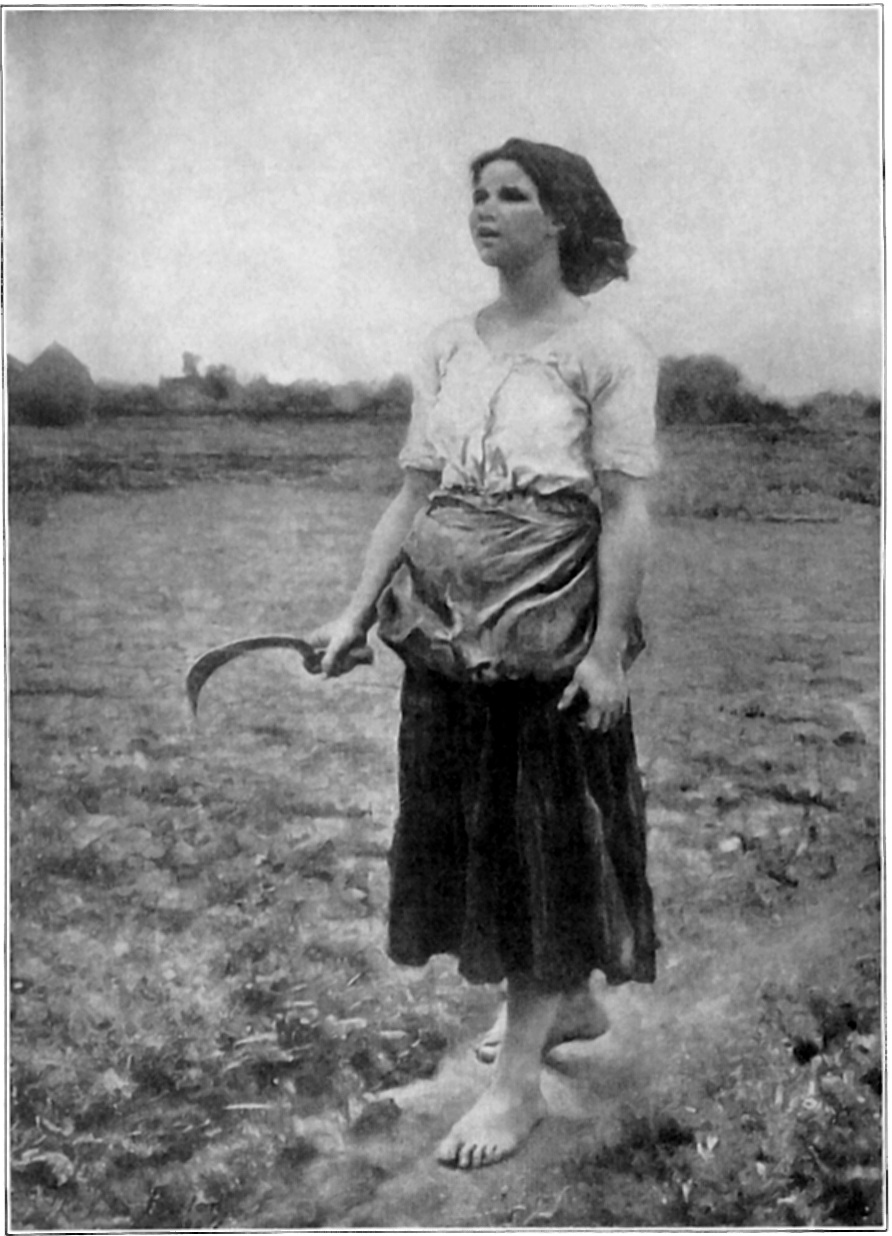

Questions to arouse interest. What is represented in this picture? Where is it supposed to be? What is the girl doing? How many figures can you see faintly suggested against the trees and the house? Why do you think they are not real like the girl? What can you see in the distance? What can you tell about Joan of Arc? Where does she seem to be looking? How is she dressed? What is there about her that makes you think she is used to hard work? that she is serious and thoughtful? that she must be very much in earnest? that she is forgetful of self? Where does the light in the picture seem to come from?

The story of the picture. Far away among the wild hills of France, in the village of Domremy, lived Joan of Arc, the “Maid of Orleans.” Her father was a small farmer, and all her people were working people. Joan’s life was not an idle one, for we are told that she was an expert at sewing and spinning, that she tended the sheep and cattle, and rode the horses to and from the watering places. But she could neither read nor write, as she had received no education. When she wished to send a letter she would dictate it to some one who could write, and then make the mark of a cross at the top. As she was of an intensely religious nature, she often wandered off by herself and remained in prayer for hours, sometimes in the fields or the great forest near by, and sometimes in the village church.

About this time France was frequently invaded by the English, and even the small village in which Joan lived had been entered and plundered.

There had been so many intermarriages between the royal houses of France and England that it was doubtful who was the rightful heir to the throne. France was divided into two factions, yet all agreed in their hatred of the English who had taken possession of the northern part of the country. Worst of all, the queen mother Isabella supported the claims of her grandson, an Englishman, against those of her own son, Charles, the French prince.

This agreed with an old prophecy known to the country people, that France should be lost by a woman and saved by a woman. The queen, Isabella, who finally secured the crown for her English grandson, was regarded as the woman who lost France; and later it became generally believed that Joan of Arc was the woman who saved France.

Joan prayed constantly for the deliverance of her country from the English. At last one day she told her father that she had seen an unearthly light and heard a voice telling her that she was to go and help the French prince. Again the vision appeared, and this time she said she had seen St. Michael, St. Catherine, and St. Margaret, who told her that she was appointed by heaven to go to the aid of Prince Charles. Her father tried to laugh her out of her “fancy,” as he called it, and did all he could to dissuade her, but Joan was resolute and declared she must go.

The village people were very superstitious, and when they heard of Joan’s wonderful visions they were immediately convinced. An uncle of Joan’s, who was a wheelwright and cartmaker, offered to take her to a high nobleman who, according to the vision, should bring her before the prince. This nobleman laughed at her, but later on became sufficiently convinced to give her a horse, a suit of armor, and two guards to escort her to Prince Charles.

After traveling eleven days through a wild country, constantly on the watch for the enemy, she finally reached Chinon, where Charles was staying. Although he was dressed exactly like the men about him, Joan picked him out immediately, and told him she had been sent by heaven to conquer his enemies and see him crowned king at Rheims. She also told him several things supposed to be secret, known only to himself, and so she was able to gain his confidence.

She told him too that in the Cathedral of St. Catherine, some distance away, he would find an old sword, marked on the blade with five crosses, which the vision had told her she should wear. No one had ever heard of this old sword, and it seemed very wonderful that Joan should know about it; but it was found in the cathedral just as she had said.

Charles then asked the opinion of all the wise men about him, and all agreed that Joan was inspired by heaven. This put new life into the French soldiers, but discouraged the English, who thought Joan was a witch.

And then it was that Joan rode on to the Siege of Orleans in which, as we know, the French were victorious. She rode on a beautiful white war horse, her armor glittering so in the sun that she could be seen for a great distance, and she carried a white flag. Twice she was wounded during the terrible battle which followed, but each time she was soon up and at the head of the French again, the English fleeing before them.

We know how the French fought their way to Rheims, where Charles VII was crowned; and how Joan then declared her work completed and begged to be allowed to return to her home; but King Charles would not consent. We do not like to think of how this weak king did nothing to help her when she was finally taken prisoner and sold by the Duke of Burgundy to the English, who burned her at the stake as a heretic and witch. It was not until ten years later that Charles VII publicly recognized the service she had done, and declared her “a martyr to her religion, her country, and her king.”

In the picture we see the “Maid of Orleans” listening to the voices. As she sat in the shade of the great apple tree winding yarn, she had suddenly heard voices, and then a vision of St. Michael, St. Margaret, and St. Catherine, the saints to whom she had prayed so often in the little church, appeared before her. She trembled, and rising, walked forward. Now, leaning against a tree, she gazes at the vision. She imagines herself clad in armor and presented with a sword by the saints, who tell her that heaven commands her to free France from the English.

With its fruit trees, flowers, and vegetables, the French garden represented in the picture was painted from nature. In the distance we see a suggestion of the great forest in which Joan used to wander in solitude and prayer. A simple peasant girl, poorly dressed, there is little about her to please or attract us until we look at the eyes. Then we begin to understand why this picture is considered a masterpiece. Those great, far-seeing, melancholy eyes seem to look far beyond us, and their ecstatic gaze inspires us with some of that same confidence in her which so possessed her soldiers.

The vision which so inspired Joan is partly visible to us amid the tangle of the trees and shrubbery. The figures of the three saints silhouetted against the rude peasant hut add to the confusing details of the background, and yet by them our eyes are led back to the one restful part of the picture—Joan herself. She is not beautiful, only earnest and good, and we feel a great pity for this girl who is so soon to suffer a dreadful fate for an ungrateful king and people.

The sunlight falls full upon her face and outstretched arm. The curve of this arm harmonizes with the branches of the trees above, and her upright figure with the straight tree trunks. Her firm chin tells us something of the determination and courage which carried her through to the end.

We are told that she had a deep, strong voice which was capable of great sweetness, and that her honesty and goodness compelled the respect of even the rudest soldiers.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Who was Joan of Arc? Why was she called “The Maid of Orleans”? Tell something of her life. In what country did she live? What were her duties? What education had she received? What was her nature? For what did she pray constantly? What vision did she have? What did her father say? How did the village people feel about it? Who helped her go to Prince Charles? How did the nobleman receive her at first? What were some of the difficulties of her journey? What did she do that made Prince Charles believe in her? How did Joan’s coming affect the French soldiers? the English soldiers? Tell about the Siege of Orleans. When did Joan consider her work done? Why would not King Charles VII let her go home? What became of Joan? What has the artist represented Joan as doing in this picture? What vision appeared to her? What does she lean against? What else can you see in this garden? How does the tangled, somewhat confusing background bring out the figure of Joan? What kind of a voice had Joan? Why did all the soldiers respect her?

To the Teacher: Different pupils may be asked to study this lesson under the following topics:

The story of the artist. Jules Bastien-Lepage was born in Damvillers, France. His parents were people of means, and as his father was an artist he received his first art instructions from him. As a young man Jules held a position in the post office, and his duties there kept him busy every morning. But all his afternoons were devoted to study under an artist who lived near by.

Then during the Franco-Prussian war he joined the army in the defense of Paris. He was never very strong, and the constant exposure and hardships forced him to return home on sick leave; that was the end of his experience as a soldier. His health somewhat recovered, he began painting in earnest. He desired above all things to be a great historical painter and, if possible, to paint these pictures at the very places where the historical events occurred.

He had a very fine studio fitted up on the second floor at home, but most of his painting was done out of doors.

We cannot read much of his life without finding some mention of his grandfather, for it was the old man’s delight to work or sit beside his grandson while the young man was painting. The grandfather is usually described as wearing a brown skull cap and spectacles, and carrying his snuffbox and large checked handkerchief much in evidence. He took care of their garden and orchard, and one of the very first pictures Lepage painted that caused most favorable comment was a portrait of his grandfather in a corner of the garden. This picture, together with another of a young peasant girl, exhibited at the same time, marked the beginning of the artist’s popularity.

Born in the same country as Millet and like him understanding the religious enthusiasm and the superstitions of the peasants, we are not surprised that he should love to paint the French peasant and that Joan of Arc’s life and history should have appealed to him so strongly. This subject had been a favorite theme for painters for several hundred years, and most of the artists had represented Joan as a saint or as a maid of great beauty. Lepage, however, represented her as a simple peasant girl, dressed as such, and showing evidence in her face and her coarse hands of the rough farm work she had been doing.

This painting of Joan of Arc is considered the artist’s masterpiece. Another noted picture by him is “The Hay Makers.”

Bastien-Lepage became very popular indeed, and the people vied with each other to obtain his paintings and to get an opportunity to work in his studio. He worked very hard, and this, with the excitement of so much publicity, finally wore him out. He died at the age of thirty-six years.

Questions about the artist. Who painted this picture, and where was he born? Where is the original painting? Tell about Jules Bastien-Lepage and his early training. Why did he not remain in the army? What kind of a painter did he most desire to be? Where did he usually paint? Who went with him? Describe the old grandfather. What picture marked the beginning of the artist’s popularity? Why did the life of Joan of Arc appeal to him so strongly? In what way did his representation of Joan differ from that of other artists?

Questions to arouse interest. What are these men doing? How are they dressed? What makes you think some one has interrupted them? At whom are they looking? Why do you suppose the one syndic has risen? Why do you think the man standing behind the others wears no hat? What do you think his duties were? Which man looks the oldest? the youngest? How has the artist avoided a stiff arrangement of the figures in this painting?

The story of the picture. This picture represents the syndics of the Cloth Merchants’ Guild, in a room of their Guild House, busy going over their accounts. In these days of great corporations and societies of all kinds, it is easy for us to understand what a Cloth Merchants’ Guild might be.

History tells us that as far back as the time of the Romans there were what were called merchants’ corporations or guilds organized for mutual aid and protection. Among the very first known was a fishermen’s guild, in which all the members met and decided the rights of the various members to use the water front, and also, no doubt, planned to take away the privilege from all who were not members.

In the Netherlands the guilds were many and very influential. Besides the general officers usually appointed by the king, there were a certain number of officers whom the members themselves chose, called masters, deans, wardens, or syndics. It was the duty of these syndics to visit the workshops and salesrooms of all members of the guild, at all hours, to see that the rules were enforced. They were also expected to examine candidates for apprenticeship and mastership. Each guild had its own costume or uniform. Even to this day a remnant of these old customs remains, and in England every twenty years a few of the cities celebrate, by a very important and imposing parade, what is known as “guild day.” Many cities still have the old Guild Houses where these meetings were held, and there is not a cathedral or church building of any importance in the Netherlands or Belgium in which some great event connected with these guilds is not represented by either a painting or a sculptured monument. And so it is little wonder that Rembrandt should paint such a picture as this.

It is as if we opened the door suddenly upon the syndics, who look up to see what has disturbed them. One man has half risen from his chair. All five are dressed in the uniform of the guild—black coats, broad white collars, and large black felt hats. Each figure is a complete portrait in itself and bears, it is said, a speaking likeness to the syndic painted.

Some time before this, Rembrandt had had an unfortunate experience. He had painted a wonderful picture called the “Night Watch.” But in that great painting he had allowed his feelings as an artist, and his love of a fine composition, to make him forget man’s vanity. So, although a great many prominent men had posed for this picture, he had neglected to paint them all in conspicuous positions. Those upon whom the bright light fell were delighted with the picture, but the majority, who were in the shadow, did not like it at all and so refused to pay any money toward buying it. The truth is they had each expected a good portrait, and instead he had painted a masterpiece in composition.

So in this later picture he was careful to make a good likeness of each of the syndics, as well as to make an interesting composition.

These five syndics are gathered around a table covered with a rich oriental cloth woven on a dark red ground. The plain paneled walls of the room are brown, filling the picture with that rich golden-brown tone for which Rembrandt is famous and which gives to his pictures their mysterious and peculiar charm.

It is said that the other portraits in the Ryks Museum, Amsterdam, where this picture is hung, look dull and lifeless beside it. And, strange to say, it was painted when Rembrandt was fast losing his eyesight and when, too, he was in great financial difficulties. The order for the picture was given him by an old friend who thought first of his need, but later of his great genius. It was Rembrandt’s last important order before his death in 1669.

Although these men are looking toward us, no two are in exactly the same position. The light from the window falls full on the face of each syndic; even the servant is not placed in the shadow. Suppose these men had been represented as of exactly the same height; that would have given us a straight horizontal line across the picture even straighter than that of the wainscoting above, which is broken by the corner of the room. Thus we would have had a stiff, uninteresting arrangement.

Art students from all over the world go to the Art Museum to study and copy parts of this wonderful painting. Joseph Israels tells us he made a copy of his favorite figure, which was “the man in the left-hand corner with the soft gray hair under the steeple hat.”

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Where are these men? Why have they met here? What is their trade? For what purpose were the guilds formed? Tell about the first guilds and their purpose. In what country were these guilds most popular? Where do they still exist? Who were the syndics? What were some of their duties? What was the place called where they met? What do we have in our country in the place of syndics and guilds? Of what benefit are they? How are the syndics in this picture dressed? At whom are they looking? What can you say of the man standing behind the syndics? Which syndic seems to be the most important? What unpleasant experience had the artist had that influenced him in painting this picture? In what ways do the positions of the six men differ? What can you say of the composition of this picture? the light and shade? What qualities of greatness do you find in this picture? How did Rembrandt happen to paint it? What colors did he use? Where is the original painting?

The story of the artist. Rembrandt was born in Leiden, the Netherlands, in 1606. In those days, when there were no newspapers and no one cared to set down the daily events in the lives of great men, it was only what the man actually accomplished that was recorded. So we know very little of the early life of Rembrandt. Some authorities declare he was born in a windmill, but most agree that as his father was a prosperous miller, the son was no doubt born in a very comfortable if not elegant home. However that may be, we know that Rembrandt spent many happy hours with his brothers and sisters high up in this windmill, and here it is believed he first studied the effect of light and shade on objects.

From the small window in the tiny room at the top of the mill little light could be expected, and as he did much of his painting here his studies were mostly in shadow. Often he must have looked from this little window down upon the quaint city of Leiden, built upon its ninety islands joined by at least a hundred and fifty bridges; upon its wide streets, rose-bordered canals, houses built in rows, each with its own windmill, and the picturesque rows of trees. The largest building of all was the University, for which Leiden is still famous. Rembrandt attended this university, we are told, and as he looked at it he must have recalled its history and how bravely the Dutch people fought when the Spanish army tried to capture the city—how they braved famine and pestilence as they awaited the arrival of Prince William of Orange. As a reward for their courage, William offered his people either a great gift of gold or a university; and, although the people needed the money to rebuild their houses, they chose the university.

Rembrandt is one of the great artists who is known to the world by his first name. His father’s name was Gerrit Harmens and he was called Harmens van Rijn (by the Rhine). According to a custom of those days the name frequently told where the man lived. His son was called Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, meaning Rembrandt, son of Harmens by the Rhine.

Rembrandt’s great love for good pictures, and his desire to draw, caused his parents to send him to an artist to study. He studied with this teacher at home for three years. Then he spent several months in Amsterdam studying, but finally decided that nature should be his teacher. He was then only sixteen years old, but he fitted up the little room in the mill as a studio, and here he continued his study. He painted his father, his mother, and his brothers and sisters many times. Then he painted his own portrait by looking in a mirror, and, by assuming various attitudes and different expressions, he received much valuable practice which, later on, helped him greatly.

His first great work was a portrait of his mother, painted when he was twenty-three years old. Two years later he went to Amsterdam, where his pictures brought large prices and pupils flocked to him from all parts of Europe. Once he painted a window with a servant standing near it that was so real it deceived every one.

About this time he married the beautiful Saskia, whose picture he has painted so many times. His home was furnished extravagantly, and nothing was too good to give Saskia.

There are three great paintings by Rembrandt which mark three epochs in his life. The first was “The Anatomy Lesson,” painted for Doctor Tulp, representing the Professor of Anatomy lecturing to his class. It is said that Rembrandt hid behind a curtain and, without their knowledge, observed the class during several lessons that he might secure natural expressions and positions. This picture was painted shortly after his marriage to Saskia, and through it he became famous. It marks the beginning of the happiest part of his life.

The second great painting was the “Night Watch,” which was not appreciated because he failed to give all the figures equal prominence. This picture marks the beginning of his fall from favor, and it was about this time that his wife, Saskia, died.

Crushed by both sorrow and misfortune, Rembrandt still continued to paint. His choice of subjects, however, changed noticeably. He now painted more of the sorrow, poverty, and distress of life. His house, with all its beautiful furnishings, was sold.

Then came his great painting, “The Syndics of the Cloth Hall,” in which he seems to have concentrated all his wonderful genius. But, masterpiece that it is, the picture won no popularity, and so the last years of Rembrandt’s life were spent in increasing poverty and sadness.

Other noted pictures by Rembrandt are: “Christ Blessing Little Children,” “Sacrifice of Abraham,” “Portrait of an Old Woman,” “The Mill,” “Saskia,” and “Supper at Emmaus.”

Questions about the artist. Who painted this picture? Why was he so named? Why do we know so little about him? Where is it believed that Rembrandt first studied light and shade? What other training did he have? How did he paint his own portrait? What was his first great painting? Tell something which illustrates how well he could paint. Was the greatness of “The Syndics of the Cloth Hall” appreciated when it appeared?

Questions to arouse interest. What does this picture represent? Where do the figures seem to be? Why do you suppose the artist placed all his figures on one side of the table? What makes you think the disciples are excited? How many do not look excited? Which is the central figure? How is our attention directed toward the central figure? How does the position of the hands aid in this? Which one is Judas? Why do you think so? Which one is John? What expressions do you see upon the different faces?

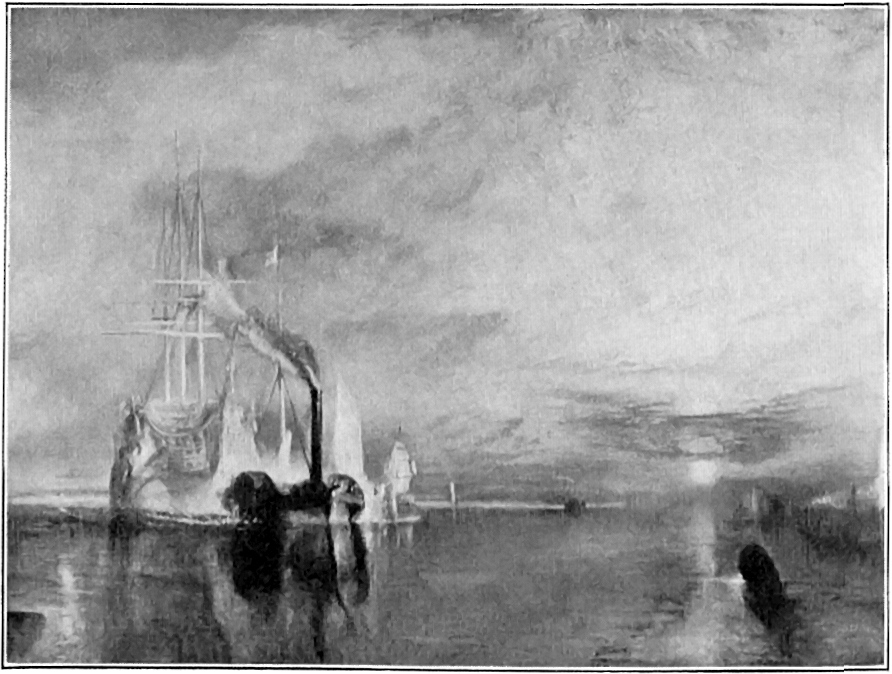

The story of the picture. Beatrice, the good and beautiful wife of the Duke of Milan, had visited most of the many convents in Italy, but her favorite among them all was the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. When the great dining room of this beautiful convent was being finished, the monks felt that it lacked nothing except a suitable decoration for the end wall; so they appealed to the duke and his wife for at least one fine painting by the most popular artist of the time, Leonardo da Vinci. And so it came about that Leonardo began this great work, which was to be his masterpiece. It was so placed that the monks seated at their meals could see the long table as if it were in their own room and but slightly raised above the rest.

Many stories are told of the artist while working on this great painting. Often he worked from early morning until dusk, quite unconscious of the flight of time, of his meals, or of the hushed voices of the monks and visitors who came to watch him paint. Then again he would not paint for several days, but would sit for hours quietly studying his painting. The prior of the monastery began to think he would never finish the picture, and at last he appealed to the duke to speak to Leonardo about it. The artist told the duke that while he sat thinking he was doing his best work, for it was necessary for him to have a complete picture in his mind before he could paint one. Of course he was told to do it in his own way. He completed the painting in two years, which was an unusually short time for so great a masterpiece, when we consider how much study was necessary, and that the figures were larger than life. Leonardo also had other work which had to be done.

Mr. William Wetmore Story has given us the prior’s complaint to the duke in verse, from which we have selected these extracts:

It is said that Leonardo threatened to paint the face of the complaining prior as the Judas in his picture, but we know that he did not.

He has chosen for his subject the moment following the words of Christ to his disciples: “One of you shall betray me.” On their faces he has shown the surprise, consternation, and distress which would naturally follow the realization that there is a traitor among them.

We recognize at once the calm, beautiful face of the figure in the center as that of the Christ. Leonardo spent more time on this head than on any other part of the picture. He made a great many sketches, and in each he tried to represent Christ as looking at us, but all his efforts failed to satisfy him. At last he consulted a friend, who advised him to give up trying to paint the expression of the eyes, but to represent Christ looking down; and this seems to have been the last touch needed to make the face perfect.

On both sides we see the disciples in four groups of three each. If we study any one of these groups we will find it complete in itself, yet all four groups are held together by the expression on the faces and especially by the position of the hands. So wonderfully have the hands been painted that some critics have spoken of this picture as “a study of hands.”

If we begin at the left-hand side of the picture we see Bartholomew standing at the end. In his astonishment, he has risen so quickly that his feet are still crossed as they were when he was seated. He looks toward Christ as if he thought his ears must have deceived him.

Next to Bartholomew is James (the less), who reaches behind Andrew to touch the arm of Peter and urge him to ask the meaning of it all. Andrew’s uplifted hands express horror, while his face is turned anxiously toward the Master. Peter is greatly excited, but feels that John is the one to ask the question; so we see him leaning toward John, his hand resting on John’s shoulder as he eagerly urges him to ask who it is of whom Christ spoke. In his right hand Peter grasps his knife ready to defend his Lord.

Between Peter and John we see the traitor Judas, vainly attempting to appear innocent and unconcerned. As he leans forward, he clasps his money bag tighter, but at the first sudden movement of alarm he has overturned the salt upon the table. It is said that after the face of the Christ, Leonardo found that of Judas the most difficult to paint. It was hard to imagine a man so wicked.

The gentle, sorrowful face of John seated next to the Christ is in strong contrast to the startled, guilty look on the dark face of Judas.

To the right of the Master, we see James (the great), whose arms are outstretched as he looks at the Master and eagerly asks, “Lord, is it I?”

Just behind James is Thomas, with one finger lifted threateningly as if he must know who the traitor is that he may cast him out at once.

Philip, standing beside James, places his hands on his heart as he says, “Thou knowest, dear Lord, it is not I.” The three disciples at the end of the table are in earnest conversation. Matthew points with his arms to the Saviour as if explaining to the elder disciple, Simon, what has just been said. His face asks a question and expresses wonder, while that of Thaddeus, next to him, is worried and troubled. Simon holds his hands out and looks appealingly to Christ for an explanation.

The table itself was like that used in the dining room of the convent; even the tablecloth and china were the same. Three windows form a background for the picture, and the middle one frames the face of the Christ.

But the picture was painted in tempera upon damp walls, and it soon began to fade and even to peel off. If it had not been for an Italian who made an engraving of this picture shortly after it was finished, we should have little idea of the real beauty of the original. At one time the convent was used as a stable, and a door was cut right through the middle and lower part of the picture. Naturally, in the course of time, the picture lost most of its original splendor. Many attempts were made to preserve it, but without success. Then, not many years ago, an artist was found who succeeded in restoring the picture to some degree of perfection.

The painting is twenty-eight feet long, and the figures are all larger than life.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Where is the original painting? Why was this convent chosen? In what room is it? In what way did it become a part of the furniture of the room? How long did it take Leonardo to paint this picture? Why did the prior feel so anxious? What reply did the artist make to him? What does the picture represent? Which is the central figure? How is it made to appear the most important? How are the disciples arranged? Which is John? Which is Judas? What has Christ just said that causes such excitement? What expressions do you see on the different faces? What can you say of the composition of this picture? How do the hands of each disciple express his feelings? What has become of this painting? About how large is it?

The story of the artist. Leonardo da Vinci was born in the little village called Vinci, about twenty miles from Florence, Italy. His father was a country lawyer of considerable wealth.

Very little is known of Leonardo’s boyhood, except that he grew up on his father’s estate and early displayed remarkable talents. He was good-looking, strong, energetic, and an excellent student. He was especially good in arithmetic, and liked to make up problems of his own which even his teacher found interesting and difficult. Above all he loved to wander out in the great forest near the palace and to tame lizards, snakes, and many kinds of animals. Here he invented a lute upon which he played wonderful music of his own composing. Then, too, he sang his own songs and recited his own poems.

He loved to draw and paint because he could both represent the things he loved and use his inventive genius as well. He seemed to be gifted along so many lines, and was of such an inquiring mind, that it was difficult for him to work long enough at one thing to finish it. We read of him as musician, poet, inventor, scientist, philosopher, and last, but most important to us—as artist.

When he was fifteen years old he made some sketches which were so very clever that his father took them to a great artist, Verrocchio, who was delighted with them and was glad to take Leonardo as his pupil. The story is told that when Verrocchio was painting a large picture he asked Leonardo to paint one of the angels in the background. The boy spent much time and study on this work, and finally succeeded in painting an angel which was so beautiful that the rest of the picture seemed commonplace. It is said that Verrocchio felt very sad at the thought that a mere boy could surpass him, and declared he would paint no more pictures, but would devote his life to design and sculpture.

One time one of the servants of the castle brought Leonardo’s father a round piece of wood and asked him to have his son paint something on it that would make it suitable for a shield, like the real shields that hung in the castle hall. Leonardo wanted to surprise his father. So he made a collection of all the lizards, snakes, bats, dragonflies, and toads that he could find and painted a picture, in which he combined their various parts, making a fearful dragon breathing out flame and just ready to spring from the shield. Coming suddenly upon the shield on his son’s easel, the father was indeed startled. Studying the picture carefully, he declared it was far too valuable a present for the servant; so another shield had to be painted and the first was sold at a great price. No one knows what finally became of it.

Leonardo spent seven years with Verrocchio; then he opened a studio of his own in Florence, Italy.

Later Pope Leo X invited him to Rome to paint for him, but most of his work there was left unfinished. The story is told of how one day the pope found him busily engaged in making a new kind of varnish with which to finish his picture. “Alas,” said the pope, “this man will do nothing, for he thinks of finishing his picture before he begins it.”

From Rome, Leonardo went to Milan, where, with the Duke of Milan as patron, he painted his masterpiece, “The Last Supper.” He also made a model for an equestrian statue which, though never executed, was regarded as equal to anything the Greeks had ever done.

Leonardo da Vinci proved to be a great addition to the duke’s court; his fine appearance and his many talents made him very popular indeed. He played skillfully on a beautiful silver lyre and charmed the people with his music and songs. He also helped the duke found and direct the Academy at Milan, and gave lectures there on art and science. So his time was divided, as usual, among his many interests.

When the duke was driven out of Milan by the new French king, Leonardo spent several years in Florence, where he painted the famous “Mona Lisa,” and other portraits. Then followed a few years of travel through Italy. At the request of the French king, Francis I, Leonardo joined his court in France, and there he spent the last years of his life, regarded with great reverence and respect, and loved by all.

Among the other great pictures painted by Leonardo da Vinci are: “Mona Lisa,” “The Christ,” “Madonna of the Rocks,” “St. Anne,” and “John the Baptist.”

Questions about the artist. Tell what you can of the boyhood of Leonardo da Vinci. What talents did he have? How did these sometimes prevent his completing his work? Tell the legend about the angel he painted for Verrocchio; the wooden shield. What did the pope say of Leonardo? why? Where was “The Last Supper” painted? In what way was Leonardo an addition to the duke’s court? How was Leonardo regarded as a sculptor? What are some of his most famous paintings?

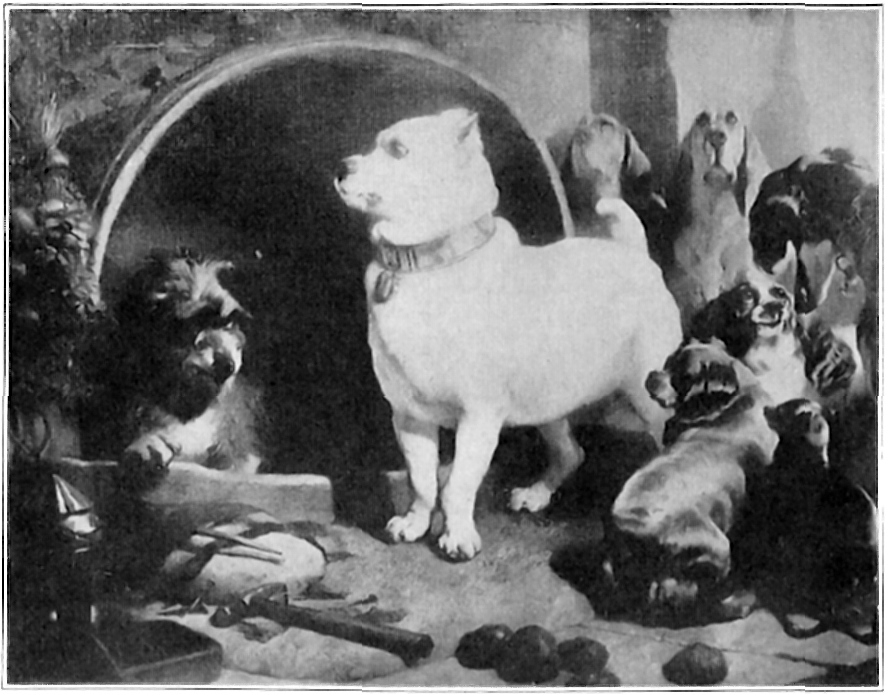

Questions to arouse interest. Where are these dogs? Which one seems at home? In what is he lying? What makes you think the sun is shining brightly? Which dog looks the best cared for? How does he seem to feel toward the first dog? To which class do the other dogs in the picture belong? What seems to be their attitude toward the two principal dogs? Which dog looks the proudest? the most content? the vainest? What different kinds of dogs are represented in this picture? How many know the story about Alexander and Diogenes? Why was this picture so named?

The story of the picture. Into the streets of Athens, bright with the life and brilliant colors of its gayly dressed people, came the uncouth figure of the philosopher Diogenes, ridiculing all that the Athenian held most dear. On his head he carried the tub in which he ate and slept. At first he also carried a cup, but after seeing a boy drink from the hollow of his hand, he broke his cup on the pavement, preferring the “simpler way.” His ugly, cynical face, awkward figure, bare feet, and ragged clothing made him an object of astonishment and ridicule. Independent, surly, and ill-natured, he continued to be an outcast throughout his long life. He taught in the streets as did many of the philosophers in those days, and spoke so plainly and so contemptuously of the life of the people that but for his ready wit he must have been driven out of the city. He himself cared nothing for abuse and insult, and went so far in showing his contempt for pride in others that he acquired the same fault himself, and grew proud of his contempt for pride. He loved to show the contempt he felt for all the little courtesies of polite society.

The story is told that Diogenes came, uninvited and unannounced, to a dinner which Plato, a great philosopher, was giving to a select number of his friends, and, rubbing his dirty feet on the rich carpets, called out, “Thus I trample on the pride of Plato.” To which that philosopher quickly retorted, “But with greater pride, O Diogenes.”

One day he went about the streets carrying a lantern, though the sun was shining brightly. He seemed to be looking earnestly for something, and when asked what he was searching for he replied, “I am searching for an honest man.”

Plato gave lectures to his pupils in the Academic Gardens, and one day Diogenes was present. Plato defined man as “a two-legged animal without feathers.” Diogenes immediately seized a chicken and, having plucked its feathers, he threw it among Plato’s pupils, declaring it to be “one of Plato’s men.”

Once he was captured by pirates and sold as a slave, but even this did not subdue him, for on being asked what he could do he declared he could “govern men,” and urged the crier to ask, “Who wants to buy a master?” The man who bought him set him free, and afterwards employed him to teach his children. That is how Diogenes happened to be in Corinth when Alexander the Great was passing that way. To that great Macedonian king, who considered himself the “son of a god” and to whom all had knelt in homage almost worship, the visit to Diogenes was something of a shock. He found him in one of the poorer streets, seated in his tub, enjoying the sun and utterly indifferent as to who his visitor might be. Astonished, the king said, “I am Alexander.”

The answer came as proudly, “And I am Diogenes.”

Alexander then said, “Have you no favor to ask of me?”

“Yes,” Diogenes replied, “to get out of my sunlight.”

Far from being angry with him, Alexander seemed to respect and admire a man strong enough to be indifferent to his presence, and said, “Were I not Alexander, I would be Diogenes.”

It happened one day that the artist, Sir Edwin Landseer, passing along one of the narrower streets of London, caught a glimpse of a dirty tramp dog resting comfortably in an empty barrel and looking up with an impish gaze at a well-cared-for dog. The well-kept dog was surveying the tramp with looks of mingled haughtiness and annoyance because of his lack of respect. Immediately the thought came to the artist that here were another Alexander and Diogenes.

The well-fed and carefully cared-for pet, with his fine collar and snow-white coat, sniffs with disgust at the dirt and poverty of the tramp dog, yet is held in spite of himself by the look of indifference and disrespect on the other’s face. He, the envied dog of the neighborhood, upon whom all honors have been showered, has found here for the first time a dog who dares to disregard him. And what a dog! He is amazed, yet held, waiting to see what the tramp dog will do.

Those smaller dogs do not share the indifference of Diogenes at the presence of this great personage. They seem ready to run at the first sign of danger, yet they remain near enough to see and hear all that might happen.

The two hounds in the background, waiting so solemnly for the master, hold their heads high in the air as if the neighborhood were not good enough for them, and they of course could have no interest in what is going on.

Probably Sir Edwin Landseer meant this picture to call attention to the vanities of human nature, and to make us smile at them. The expressions on the faces of these dogs are almost human, so well do they tell their story.

The hammer and nails lying on the rough pavement near the barrel would indicate that this is not a permanent home for the tramp dog, but rather a temporary place of shelter into which he has strayed.

Notice how Landseer has centered our attention on the more important dog, by color, size, and position in the picture. The other spots of light, even that on the edge of the barrel, draw our eyes back to the proud Alexander. We might not discover Diogenes so soon if we did not follow the gaze of Alexander.

Landseer delighted in telling stories in his pictures of animals. Rosa Bonheur and other animal painters aimed to make the animals appear natural and lifelike, but Landseer wished most of all to show their relation to human beings.

This picture hangs in the National Gallery, London, England.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Who was Alexander the Great? Who was Diogenes? Tell about the life and philosophy of Diogenes. Describe his personal appearance; Plato’s dinner and his reply to Diogenes. Why did Diogenes carry a lantern in the daytime? What happened after he was captured by the pirates? How did he happen to be in Corinth when Alexander the Great was there? What opinion did Alexander have of himself? Where did he find Diogenes? What conversation did they have? Why was this picture called “Alexander and Diogenes”? Why is the name appropriate? To which class do the other dogs in the picture belong? What are they doing? Where is the scene of this picture laid? Why is this appropriate? What is there unusual about this picture? What impression do you think the artist wished to leave with us? What devices has he used to center our attention upon the more important dog? upon Diogenes? Where is the original painting?

The story of the artist. Sir Edwin Landseer’s grandfather was a jeweler, and his father also learned the jeweler’s trade. The jewelers of that day were often asked to engrave the copper plates that were used in printing pictures. Sir Edwin’s father soon decided he would rather engrave pictures than sell jewels, and he became a very skillful engraver.

At that time few people realized what an art it was to be able to cut a picture in copper so that a great many copies of it could be made from one plate. They did not even consider it an art as we do, and so engravers were not allowed to exhibit at the Royal Academy and were given no honors at all. Edwin’s father thought this was not right, and gave several lectures in defense of the art. Engraving, he said, was a kind of “sculpture performed by incision.” His talks seemed to be of no avail at the time, but in the year following his death, engravers at last received the recognition due them.

His eldest son, Thomas, also became famous as an engraver, and it is to him we are indebted for so many good prints of Sir Edwin Landseer’s paintings. This son is the one who made the engraving of the “Horse Fair” for Rosa Bonheur. Few people can afford to own great paintings, but the prints come within the means of almost all of us.

Edwin’s father taught him to draw, and he learned so quickly that even when he was only five years old he could draw remarkably well. Edwin had three sisters and two brothers. The family lived in the country, and often the father went with his boys for a walk through the fields. There were two very large fields separated from each other by a fence with an old-fashioned stile. This stile had about four steps and was built high, so that the sheep and cows pastured in the fields could not jump over. One day Edwin stopped here to admire these animals and asked his father to show him how to draw them. His father took a piece of paper and a pencil from his pocket, and showed Edwin how to draw a cow. This was the boy’s first drawing lesson. After this Edwin came here nearly every day, and his father called these two fields “Edwin’s studio.”

When he was only thirteen years old two of his pictures were exhibited at the Royal Academy. One was a painting of a mule, the other of a dog and puppy. Edwin painted from real life always, not caring to make copies from the work of others. All the sketches he made when he was a little boy were carefully kept by his father, and now, if you go to England, you may see them in the South Kensington Museum, in London.

Landseer was only sixteen years old when he exhibited his wonderful picture called “Fighting Dogs Getting Wind.” A very rich man, whose praise meant a great deal at that time, bought the picture, and Edwin’s success was assured. So many people brought their pets for him to paint that he had to keep a list and each was obliged to wait his turn.

It was about this time, too, that he painted an old white horse in the stable of another wealthy man. After the picture was finished and ready to deliver, it suddenly disappeared. It was sought everywhere, but it was not found until twenty-four years afterwards. A servant had stolen it and hidden it away in a hayloft. He was afraid to sell it, or even to keep it in his home, for every one would recognize the great artist’s work.

For a number of years Landseer lived and painted in his father’s house in a poor little room without even a carpet. All the furniture, we are told, consisted of three cheap chairs and an easel. Later he had a fine studio not far from Regent’s Park. There were a small house and garden, and the barn was made over into a studio.

Sir Edwin was not a very good business man, so he left all his financial affairs to his father, who sold his pictures for him and kept his accounts.

At twenty-four Landseer became a member of the Royal Academy, which was an unusual honor for so young a man.

This story is told of him. At a social gathering in the home of a well-known leader of society in London, where Landseer was present, the company had been talking about skill with the hands, when some one remarked that no one had ever been found who could draw two things at once. Landseer replied, “Oh, I can do that; lend me two pencils and I will show you.” Then with one hand he quickly drew the head of a horse, at the same time drawing with the other hand a deer’s head and antlers. Both sketches were so good that they might well have been drawn with the same hand and with much more care.

Landseer made a special study of lions, too. A lion died at the park menagerie, and Landseer dissected its body and studied and drew every part. He painted many pictures of lions. He modeled the lions at the base of the Nelson Monument in Trafalgar Square, London, unveiled in 1867.

When Sir Edwin Landseer went to visit Scotland one of his fellow travelers was Sir Walter Scott, the great novelist. The two became warm friends. Sir Walter Scott tells us: “Landseer’s dogs were the most magnificent things I ever saw, leaping and bounding and grinning all over the canvas.” Landseer painted Sir Walter Scott’s handsome dog, “Maida Vale,” many times, and named his studio for the dog.

Although Landseer painted so many wild animals, birds, and hunting scenes, he did not care to shoot animals or to hunt. His sketchbook was his only weapon. Sometimes he would hire guides to take him into the wildest parts of the country in search of game. But they felt quite disgusted with him when, a great deer bounding toward them, he would merely make a sketch of it in his book. He knew how to use a gun, though, and sometimes did so with great success.

But it was the study of live animals that interested him most. Sir Edwin Landseer felt that animals understand, feel, and reason just like people, so he painted them as happy, sad, gay, dignified, frivolous, rich, poor, and in all ways, just like human beings.

Landseer did and said all he could against the custom of cutting, or “cropping,” the ears of dogs. He held that nature intended to protect the ears of dogs that “dig in the dirt,” and man should not interfere. People paid attention to what he said, and the custom lost favor.

In 1850 the honor of knighthood was conferred upon the artist.

Landseer was popular alike with lovers of art and simple lovers of nature who had no knowledge of painting. No English painter has ever been more appreciated in his own country.

He died in London in 1873, at the age of seventy-one.

Other noted pictures by Landseer are: “The Highland Shepherd’s Chief Mourner,” “Suspense,” “The Connoisseurs,” “A Distinguished Member of the Royal Humane Society,” “Saved,” “My Dog,” “Dignity and Impudence,” “Sleeping Bloodhound,” “Shoeing the Bay Mare,” “Monarch of the Glen,” and “A Deer Family.”

Questions about the artist. What did Sir Edwin Landseer’s father do for a living? Tell about Edwin’s boyhood and first “studio.” For what did he name the studio “Maida Vale”? With whom did he travel through Scotland? What was Sir Edwin Landseer’s idea of hunting, and why? How did he feel about animals? What skill did he have with his left hand? Name some of his paintings.

Questions to arouse interest. Of whom is this a portrait? What are the boys doing? What expressions do you see on their faces? How does this picture show that the artist gave careful attention to details? In what ways does the picture grow more attractive the longer you look at it? How are we made to feel that the artist was in perfect sympathy with his subject? What has the pillar in the background to do with balancing the composition? Where is the center of interest and how is it held? What can you say of the light and shade? of the variety and kind of lines?

The story of the picture. The paintings of Peter Paul Rubens were in such demand that he employed a great number of skilled assistants to help him paint them. He himself worked some on each picture, making the first sketch and adding the finishing touches, but in many of them his carefully trained assistants put in the details of costume, background, and even the hands and faces. Rubens worked out a system of his own by which all were kept busy, and a remarkably large number of pictures finished in a short time. Some critics have spoken of his studio as a “manufactory for the production of religious and decorative pictures.” Knowing this, it can be readily understood how much more this picture, called “Rubens’s Sons,” is valued because the artist painted every stroke himself. He would not allow any one else to touch it, and later, owing to its great popularity, it is believed he made a copy of the painting, as there are two in existence.

The brothers, Albert and Nicholas, are so lifelike that they almost seem to breathe and move. The elder son, Albert, was twelve years old when this picture was painted, and his brother Nicholas, eight. Albert, always a studious boy, looks thoughtfully at us as he half leans against the pillar. In his gloved right hand he holds a book, while in his bare left hand, resting on his brother’s shoulder, he holds the other fur-edged glove.

The younger boy, Nicholas, is absorbed in his plaything, a goldfinch fastened by a string to a wooden perch. He shrewdly calculates the distance he must let out the string, and his alert, eager attention tells us much of the stirring, restless life of this healthy, active boy. It is difficult to keep him standing still very long.

Rubens delighted in painting rich velvets, brocades, silks, and satins, and especially in representing his wife and their children in beautiful clothes. In this picture he has certainly satisfied that desire, for the boys are dressed in most elaborate costumes even for that day, and especially so if we compare them with the simple dark suits of boys of the same age to-day. Nicholas’s suit is of gray and blue, with puffs of yellow satin, rosettes below his knees and on his shoes, lace collar and cuffs, and innumerable little buttons. Albert wears black satin slashed with white, white ruched collars and cuffs, and a soft black felt hat. At a glance we would judge them to be the sons of a gentleman, well brought up, healthy, happy, and manly.

The great studio in which Rubens worked was like a school, for many young artists came there to learn how to draw and paint. Rubens worked away at his own easel while the students and helpers were seated about the room, each carefully working out some part on the canvas before him. Occasionally he would stop his painting long enough to look at the others’ work, correct their mistakes, and help them. Often, as he worked, Rubens would have some one read aloud to him in Latin, for he was a fine scholar and liked to keep up his knowledge. The boy Albert loved to sit on a stool near his father, watching and listening, and as soon as he was able to write at all he could read and write in Latin. Always fond of reading and studying, he gained such a reputation for scholarship that when he was only sixteen years old the king of Spain, Philip IV, appointed him to a very important position—secretary to the Privy Council.

Whenever Rubens went on a long journey he brought back many curios, such as cameos, jewels, old coins, and relics of all kinds. Soon he had so many collected he put them all in one room, which he called the “museum room.” Albert loved to study the curious things in this room, and spent hours alone here while Nicholas was romping out in the great yard. When Albert grew up he wrote several books about antiquities and curios.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Who painted this picture? How old were these two boys? What were their names? Which one looks the more studious? the more active? How are they dressed? Tell something of Rubens’s studio and manner of working. Who helped him? why? In what did the elder son, Albert, become proficient? To what important position was he appointed? What books did he write? Tell about the museum.

The story of the artist. The great Flemish painter, Peter Paul Rubens, was born at Siegen, Germany, during the forced exile of his parents from their home in Antwerp, Belgium. But Rubens always claimed citizenship at Antwerp, and spent most of his life there after the death of his father.

His mother sent him to a Jesuit college, where, besides his religious training, he gained a mastery of languages. According to the customs of those times he was next sent as a page to the home of a great lady; but this was not to his liking and he soon returned home. His mother wished him to be a lawyer, as his father had been, but Rubens persuaded her to help him in his ambition to be a painter.

The next ten years he spent at home, studying under the direction of local artists, until at the age of twenty-three he was so filled with the desire to visit Italy that he set out for Venice. He spent much time copying the paintings of the Venetian masters, and it was while he was working on one of these copies that a gentleman belonging to the court of the Duke of Mantua found him, and praised his work so highly to the duke that Rubens was sent for. Then for eight years Rubens held the position of court painter for the Duke of Mantua.

In appearance he was tall, well built, and good looking, carrying himself with grace and an air of distinction. Cultured, with pleasant manners and such unusual talent, it is not strange that he made friends wherever he went.

The story is told that one day as he was painting a picture the subject of which he had chosen from Virgil, “The Struggle of Turnus with Æneas,” he recited the Latin aloud to himself. The duke, happening to pass that way, heard him, and coming into the studio spoke to him in Latin, not for an instant believing he would understand, but Rubens answered in perfect Latin. The duke was amazed, for his idea of painters did not include their having a knowledge of the classics. He then inquired about the artist’s birth and education, and so Rubens, with his great talent, was held in even greater favor at court.

Rubens made a journey to Spain for the Duke of Mantua, taking with him as presents copies of some of the celebrated Italian paintings and a number of horses to be presented to King Philip III and to the Duke of Lerma. The Duke of Mantua was famous throughout Europe for his fine horses, and it is said that those appearing so often in Rubens’s paintings were chosen from among the duke’s favorites. On this journey Rubens took the wrong road, crossing the Alps with great difficulty. The baggage, drawn by oxen over the steep mountain roads, delayed him, and the paintings were almost ruined by heavy rains, which made it necessary for him to spend many days retouching them before they could be presented. He was so successful in this task, and the journey had given them such an appearance of age, that the king thought they must be the “genuine originals of the old masters.”

The horses, however, arrived in fine condition, for, as the story goes, they had been bathed in wine several times during the journey, which greatly improved the glossiness of their coats.

After his return Rubens continued his travels through Italy, whenever he could secure a leave of absence from the duke, but was finally called back to Antwerp by the death of his mother. When he would have returned to the duke’s court he was persuaded by the Archduke Albert and his wife to remain in Antwerp, where he was offered the position of court painter at a most generous salary.

He then built a magnificent home and married Isabella Brant, whose portrait he has painted so often. This house was so arranged that he could use part of it for his school, to which students came from all parts of Europe. Each student was taught to do a certain part of a picture well, and most of them had their part in the great paintings, which were first planned and then retouched by Rubens. For this work Rubens always gave them credit, and in his list of pictures he has permitted no deception. Thus we find among his notes:

“A Prometheus bound—with an eagle who gnaws his liver. Original by my hand, eagle by Snyder.

“Leopards, painted from life, with Satyrs and Nymphs. Original by my hand, except a very beautiful landscape done by a very distinguished artist in that style.

“The Twelve Apostles and Christ, painted by my pupils after originals by my hand—they could all be retouched by my hand.”

Such a great number of pictures are attributed to Rubens and his helpers that some are to be found in every gallery in Europe.

His paintings were in demand not only in the Netherlands but in other countries. In France, Maria de Medici commissioned him to paint pictures illustrating the chief events in her life, to be placed in the gallery of the Luxembourg Palace. There were twenty-one of these pictures in all besides three portraits.

A beautiful friendship existed between the two artists, Rubens and Velasquez, although Rubens was twenty-two years older than his young friend.

Other paintings by Rubens are: “Adoration of the Magi,” “The Garland of Fruit,” “The Descent from the Cross,” “The Last Communion of St. Francis,” “Judgment of Paris,” and “Peace and War.”

Questions about the artist. Where was Rubens born? Where did he claim citizenship? why? Tell about his early education. Where did he study drawing and painting? Describe his personal appearance. Why was he such a favorite at court? Tell about his journey to Spain and the paintings and horses he took with him. Tell something of his life after his return from this journey. Name some of his important paintings.

Questions to arouse interest. What has the girl been doing? Why has she stopped? What did she hear? How does the girl seem to feel? Is she singing or listening? Why do you think so? How is she dressed? Where is she going? What has she in her hand? What occupation would this suggest? What time of day do you think it is? What can you see in the distance? What is the name of this picture?

The story of the picture. It is said that the artist, Jules Breton, was walking in the fields of France early one morning when suddenly there burst forth the joyous song of a lark singing high in the air. As he looked about him, trying to discover the bird, he soon found it by following the rapt gaze of a peasant girl who had stopped to look and listen. As you know, an English lark sings while flying high in the air instead of in the treetops as other birds do. Its song, too, is longer and far more beautiful than that of our lark, and has been the subject of many poems. Perhaps the best known are “Hark, Hark, the Lark,” by Shakespeare, and “To a Skylark,” by Shelley.

The last line of this verse by Shelley is often quoted:

Jules Breton has tried to show us what he saw that morning, and to help us find the lark through the joyous expression on the girl’s face. Her lips are parted as she listens breathlessly to the exquisite song of praise the lark is pouring forth. The sun, a huge, fiery ball, is rising just behind the trees of the distant village, and all the earth is flooded with its golden light.

This sturdy, healthy peasant girl, sickle in hand, is going forth to her work in the fields. She walks along briskly in the narrow path, her head thrown back, breathing in the fresh morning air, when suddenly her little friend, the lark, gives her the morning greeting. As we look at her we do not feel that this is the first time she has heard his sweet song, but rather that it is something she has learned to look and listen for each morning as she starts out to her day’s work.

Another Frenchman, Millet, painted the French peasant so that our feelings of pity are aroused, but Breton shows us such strong, happy, peasant girls that we are apt rather to envy them their life of outdoor freedom and healthful labor.

Millet says of these peasants, “Breton paints girls who are too beautiful to remain in the country.” Other critics declare that Breton’s wonderful sunrises and sunsets would make any figure stand out transfigured, and as he chooses as models only the most favored in strength and beauty, of course the results are unusual.

This picture is so full of joy and song that it fills us with wonder and appreciation of all that is beautiful in nature. First, there is the bird with its wonderful power to soar so high and to so fill the air with its beautiful song. Then the sun, and all that it makes possible for us in life and growth. It seems indeed a privilege for this happy-hearted peasant girl to be permitted to go out in the fields on this bright, fresh morning to do her little share in the work of the world.

Her apron is caught up about her waist to hold the heads of wheat, for, as her sickle indicates, she is going into the wheat field. A large handkerchief is fastened about her hair to protect it from the dust and dirt of the field. She is dressed for a warm day in summer. Her large, coarse hands and feet, hardened by exposure and toil, suggest health and strength and give us a feeling of admiration rather than of pity.

The details of the field and even of her dress are made secondary and unimportant compared with her face, upon which is centered our chief interest and to which our eyes are continually drawn.

In the little village faintly seen in the distance we catch a glimpse of the homes of the peasants,—simple, rude homes, yet, if we may judge by this girl’s expression, cheerful and happy homes.

Breton has avoided all possibility of monotony in his picture by the unequal division of space. Had the figure of the girl been placed exactly in the center of the landscape, or the earth and sky spaces been made equal, the picture would have lost much in interest, as you will soon discover if you cover up parts of the composition with a piece of paper. Although there is no rule stating that the center of interest should not be in the middle of a picture, most artists seem to prefer centering their interest on some person or object a little to one side of the middle.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. How did the artist happen to paint this picture? How does an English lark differ from the larks in our country? What time of day is represented in this picture? What is the girl doing? Compare the paintings of peasants by Millet and Breton. How is this girl dressed? How does she seem to feel? What can you say of the composition of this picture as to: (1) division of land and sky space; (2) center of interest; (3) placing of the figure; (4) lack of detail—the simplicity?

The story of the artist. Jules Adolphe Breton was the son of cultured, well-to-do parents. When he was only four years old his mother died and he was brought up, with other children, by his father and an uncle who came to live with them at this time. In the great yard or park about his father’s house there were four statues representing the four seasons of the year—spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Jules loved to look at these statues, and when one day a painter came and repainted them a bright green, he watched every movement of the brush with great delight. He was only six years old, but that night he announced to his father that he was going to be an artist.

When he was ten years old his father sent him to a religious school. At this school there was a large black dog named Coco, a general favorite, whose picture Jules often drew. One day he drew Coco in a black gown like the priest’s, and standing on his hind feet, holding a book in his paws. He named his picture “The Abbé Coco Reads His Breviary.” The priest, his teacher, happening to see this picture, was much displeased, and demanded, “Did you do this through impiety or to laugh at your masters?” Jules was frightened, and not knowing exactly what “impiety” meant, but feeling sure that to “laugh at your masters” would be a serious offense, he answered tremblingly, “Through impiety.”

For this he was severely whipped, much to the indignation of his father, who promptly took him out of the school. Jules was then sent to another school, where he was taught drawing, and from that time on he painted pictures which won for him great popularity.