Title: Under the Polar Star; or, The Young Explorers

Author: Dwight Weldon

Release date: October 25, 2020 [eBook #63549]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

Chapter II. Captain Stephen Morris.

Chapter IV. The Adventures of a Night.

Chapter VII. Strange Companions.

Chapter XI. Imprisoned by Wolves.

Chapter XIV. A Friend in Need.

Chapter XVIII. On Board the Whaler.

Chapter XIX. The Breaking Ice.

Chapter XX. Cast Away in the Cold.

Chapter XXII. On the Mainland.

Chapter XXIV. The Wrecked Ship.

Chapter XXV. A Thrilling Episode.

Chapter XXVI. The Young Explorers.

Chapter XXVII. The Snow Storm.

Chapter XXX. Captain Alan Bertram.

Chapter XXXI. A Terrible Experience.

Chapter XXXV. The Rescued Castaways.

Chapter XXXVII. Will’s Escape.

Golden Library

Of choice reading for Boys and Girls.

Price 10 cts

Copyrighted at Washington, D. C., by Albert Sibley & Co. Entered at the post-office at New York as second-class mail-matter.

Vol. I.—No. 3. NEW YORK. Nov. 1, 1886.

By DWIGHT WELDON.

NEW YORK:

ALBERT SIBLEY & CO.,

18 Rose Street.

1886.

Chip! chip!

All day long that same monotonous sound, chip, chip—chip, chip, had echoed through Solomon Bertram’s work room.

He called himself a ship carpenter, and he was one, for no member of that craft ever did finer work than that he was now engaged on. Before him, upon the bench, fast assuming artistic proportions, was what had been a rough block of wood, what was now very nearly a carved animal’s head.

The old man’s eyes filled with tears and his thin hand trembled more than once as he viewed the few tools at his command, and ever and anon glanced past the half open door which led into the living rooms of the humble cottage he called home.

For at the present moment grim poverty and want hovered over that threshold, and his brave heart that had never faltered before, became sad and oppressed.

From the window he could see the quaint Maine town and the shipping in the harbor. Here in Watertown he had lived, man and boy, for nearly half a century, had brought up a happy family, had accumulated almost a fortune.

Within two years that family had been sadly bereaved, the fortune cut down to a pittance, and one trouble succeeding another rapidly, had made Solomon Bertram a prematurely old man.

Chip, chip!

The mallet and chisel moved less deftly now, for the hand that wielded them was fast growing weary, and the task was almost completed.

There was a sudden interruption that made the work cease entirely. Followed by the smart, quick tramp of hurrying footsteps on the walk outside, a boisterous form dashed through the house and the work-room door,[4] and a bright, boyish face intruded itself upon the carpenter’s solitude.

“Is the ship’s head done, father?” its possessor asked eagerly, with a glance at the work bench.

“Almost, Will. Where have you been, and what does that mean?”

The boy’s eyes danced with delight and his face flushed excitedly as he laid several small silver coins on the bench.

“It means money, father,” he cried; “it means that I heard you tell mother this morning that there was not enough in the house to buy a pound of flour, and I made up my mind to earn some. Look, father, nearly four shillings!”

The old man’s eyes were suffused with tears as the boy rattled on volubly, and something choked in his voice as he sought to murmur, “My brave boy!”

“You know I’m old enough to begin work, father, and I know it too. There is not much chance for employment in the town, though, unless it’s among the shipping, and you won’t hear of my going to sea.”

“No, no!”

“Not even when the old tars say I’m a natural sailor and nimble as a monkey among the rigging?”

“Not even then, Will. The sea cost me one brave son. I can’t spare the other.”

“Well, I remembered that, and went among the shops. No work anywhere. Finally I came to the new building they are putting up on the public square, and there I met my luck, as the boys say.”

“How, Will?” inquired the interested Mr. Bertram.

“They were just putting on the spire to the tower, and, ready to arrange the tackle and climb the ropes, was the steeple Jack.”

“What’s a steeple Jack?” inquired the mystified old man.

“He’s a professional climber who makes a business of going up to high places like steeples and towers. They had sent to Portland for him. He wanted one of the workmen to help him by going to the top of the tower, but they said it was too risky, and they were more used to platforms than ropes. Well, to make a long story short, I offered my services.”

“Oh, Will, always venturesome and running into danger!” spoke a reproachful voice.

Will turned and surveyed his mother, who had come unobserved to the door, with a quizzical smile.

“Now, don’t scold, mother,” he said. “I’m at home among the ropes, as the man soon found. I was on the tower before he was half way up, and when he had set the vane on the tower, two hours later, he told me he wished he had me for an apprentice. Anyway, I earned a little money, and there it is. To-morrow I’ll start in for more, and then you’ll receive pay for the ship’s head, father, and we’ll get along famously.”

Old Solomon Bertram shook his head sadly.

“I shall get no pay for that work, Will,” he said.

“No pay, when you’ve put a week’s time on it! Why, what do you mean, father?”

Mr. Bertram looked anxiously at his wife as if silently questioning her. She nodded intelligently and withdrew.

“Sit down near me, Will,” said Mr. Bertram, seriously. “I promised to have the figure head done to-day, so I will have to work while I talk. You’re a good boy, Will; a dutiful son and a help and comfort to your old parents, and I don’t feel like clouding your life with our troubles.”

“Don’t worry about that, father,” cried Will, eagerly. “If there are any clouds we’ll drive them away.”

Mr. Bertram smiled at Will’s boyish enthusiasm and said:

“Well, up to two years ago, when your brother Alan sailed away for the far north on a whaling voyage, we were happy and comfortable. I owned the house and lot here and another piece of property, besides having two thousand dollars in bank. This I put together and purchased a share in the Albatross. That was the ship poor Alan was captain of.”

“Yes, I remember,” assented Will murmuringly.

“If the whaling voyage proved a success I should have made enough to buy Alan a ship of his own. Alas, my son, the staunch old Albatross and its brave captain never came back to Watertown again!”

Mr. Bertram stopped his work to wipe away a tear that trickled down his furrowed cheek.

“But one year afterwards,” he finally resumed, “the mate of the doomed ship returned—Stephen Morris. He told a thrilling tale of adventure. The Albatross, he said, had gone far north beyond the icebergs, but had met its fate among the glaciers, and all on board had been crushed in an ice floe but himself.”

“Do you believe him, father?” asked Will, a look of dislike in his face at the mention of Morris’ name.

[5]

“He surely would have no object in spreading a wholesale falsehood. No, no, his story seemed true. He said that he saw ship and men ground under a mighty wall of ice, and that he miraculously escaped by being on the ice floe away from the ship when the catastrophe occurred. For months he froze and starved amid a horrible solitude, and one day was discovered and rescued by a whaler. He landed at Boston, but came here at once and told the story of his adventures.”

“And he has been here since, hasn’t he, father?”

“Yes, Will, and that is the strange part of it. Stephen Morris went away a poor man. He came back a comparatively rich one. He claimed that a relative had died leaving him heir to a large fortune. Be that as it may, from mate he rose to captain and ship owner. He has an interest in several coasters, and is sole proprietor of the ocean ship the Golden Moose. It’s for that ship I’m making this figure head,” and Mr. Bertram resumed work on the same, while Will sat for some moments deeply absorbed in thought.

He had never liked the coarse, rough man his father had named, and despite himself he seemed to trace some dark mystery in his solitary rescue and the possession of sudden wealth.

“Is that all, father?” he asked after a pause.

“No, for in addition to Stephen Morris’ other possessions, he seems to have also purchased a mortgage on this house and lot, representing some of the money I borrowed to buy the Albatross. He has been very hard with me about it, for I have had to scrape and save to pay the interest regularly, and this figure head just makes out the amount to pay him this six months’ interest.”

“And I’ll be ready to pay the next,” cried Will, staunchly. “Father, I’m glad you told me just how we stand. I’m going to be a man and help you, and I’m going to find out just where Stephen Morris got all his money, for I have a suspicion that he is hiding the entire truth. You know how people dislike him. Suppose my brother Alan and the crew never perished at all?”

“No, no, Will,” cried his father, suspensefully, “don’t awaken my hopes only to be plunged in despair again. No man would be so cruel as to deceive a parent like that. Stephen Morris is hard-hearted and rough in his ways, but he would not dare to return with a false story about the Albatross. You are to take this figure head to Captain Morris. It is to take the place of the moose head that was broken in the last storm.”

“All right, father,” said Will, cheerily, but he kept thinking of the strange story he had heard.

“Tell Captain Morris to have it gilded at Portland when he goes there. It can’t be done, you know, in Watertown. There, it’s done at last!”

The old man drew back and surveyed his handiwork with some little pride as he gave it a last finishing touch with a chisel.

Then he smoothed off the rough edges and lifted it into Will’s arms.

It was quite a bulky object, but Will professed to be able without difficulty to convey it to its destination.

He carried it carefully by the doorway so as not to injure the broad-spreading antlers and walked down the street in the direction of the harbor.

His young mind was busy forming plans of how he should best secure work and rescue his parents from the poverty that threatened them.

“I will put school days and play days aside,” he said, resolutely, “and begin life in earnest.”

Mark him well, reader, this boy with honest face and manly bearing and noble determination to win his way in the world, for ere this story ends he is destined to meet with many strange and varied adventures.

“Look out there!”

Will Bertram dodged aside as he was walking along the wharf, near where the Golden Moose lay at anchorage and a broad rope-loop was thrown around a dock post from a yawl coming ashore.

“Ah, it’s you, my lad,” cried the same hearty voice. “What’s that you’ve got?” and fat and jolly Jack Marcy, boatswain of the Golden Moose, clambered ashore and confronted the lad.

“A new figure-head,” explained the latter. “The last one was lost in the storm.”

“And a great storm it was, boy. Where are you going—down to the ship?”

“Yes; I want to find Captain Morris.”

“Well, you’ll find him in squally temper, I tell you that, but not at the ship.”

“Where is he, then?”

“At the shipping office down the wharf. Come along, lad, I’ll show the way and help you, if you don’t mind.”

“It ain’t heavy, Jack,” replied Will, as he trudged along in the boatswain’s wake. “When does the Moose sail?”

[6]

“To-night, up the coast.”

“Oh, how I wish I was going!”

“Don’t I wish it too, lad. We’ve got one youngster on board, but he is no earthly good, except to get into mischief.”

“Tom Dalton?”

“Exactly; a shiftless, lazy piece of furniture. Here we are, my boy. I’ll go in first. Hear that; what did I tell you? The captain’s in one of his tantrums and no mistake.”

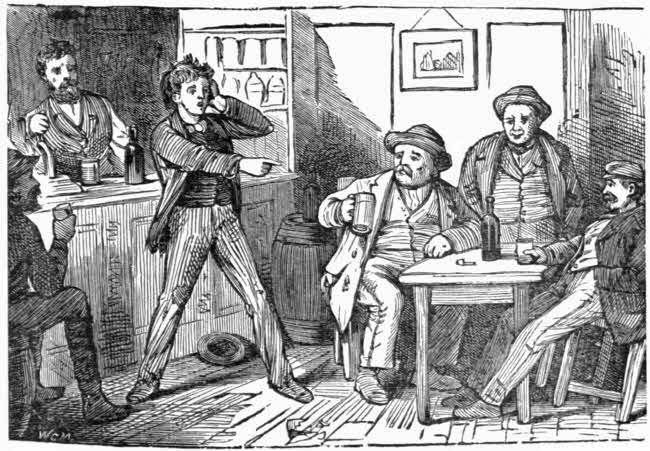

They had reached the door of the dilapidated structure where the shipping office was situated, and as the boatswain pushed it open an exciting scene was revealed to the vision of the two intruders.

Jack nimbly rounded a desk and got to the other side of the room unperceived by its occupants, while Will stood staring over the burden in his arms at Captain Morris and his clerk and general business manager, Donald Parker.

The latter lay at full length on the floor amid a wreck of the office furniture.

Glowering down at him, his face alive with brutal rage, was Captain Morris. He seemed beside himself with passion, and his beard fairly bristled as he clenched his fists.

“Say that again,” he shouted, “will you? I’m an imposter, am I? You know that I lied about the Albatross, do you? You can tell the public that, where my money came from, eh?”

“Don’t Captain, I didn’t mean anything, sure I didn’t,” pleaded the prostrate Parker, fearful of a second onslaught.

“You ungrateful scoundrel!” roared Morris, “I’ve a good mind to send you to jail, where you belong.”

“No, no!” cried the affrighted Parker.

“Yes I have. You might talk too freely. See here, Donald Parker, I saved you from prison and gave you a snug berth here, and how do you reward me—threatening to betray my secrets? I trust you no longer. You get ready to take a voyage with me, and a long one, too. You’re safer afloat, under my eye.”

“I don’t like the ocean,” whined Parker.

“You’ll like it or go to jail. As to what you pretend to know about the Albatross and my fortune, you lisp one single word outside and I’ll make you sorry for it. What do you want?”

Captain Morris directed this question to Will Bertram as he caught sight of him, but Will’s face was so obscured by the figurehead he did not at once recognize him.

“I’ve brought the moose head, sir.”

Captain Morris muttered an alarmed interjection under his breath and sprang to Will’s side.

“See here, you young Paul Pry, how long have you been sneaking around here listening to other people’s business?”

He seized Will’s shoulder in a cruel grasp as he spoke.

“I don’t sneak around anywhere,” retorted Will in a nettled tone, smarting under the man’s grip, and wrenching himself free.

Captain Morris scowled fearfully at the boy.

“Well, what do you want?” he demanded. “Oh, the figurehead! Take it to the ship, do you hear? What business have you to rush in here with it?”

“It’s my business to deliver it to you personally.”

“No sauce, you young Jackanapes. You’d better go slow or I’ll not only give your father no work, but I’ll put the clamps on him and close him out. Get out!”

He pushed Will rudely from the threshold and slammed the door in his face.

“He’s a perfect bear,” murmured Will, indignantly, as he started toward the ship. “I believed him to be a villain before and I know it now. He spoke of the Albatross as if there was some secret about it he hadn’t told. Oh, if I only knew! I will know, if watching and working can bring it out.”

The Golden Moose was a fine, seaworthy craft, and despite his unpleasant experience with its owner, Will felt a thrill of pleasure and interest as he crossed its broad deck.

He delivered the figure-head to the mate and was absorbed for some time in watching the sailors manipulate the rigging and sails.

There had always been a fascination about shipping for Will Bertram, and he glanced at a boy about his own age who was greasing some ropes with positive envy.

“I’d like to take Tom Dalton’s place for a trip or two,” he thought, but he changed his mind a moment later, as Captain Morris came walking briskly from the shipping office toward the ship.

At the sight of him the ship’s boy, Tom Dalton, whose head had been bent over his work, uttered a howl of terror, and, springing to the rigging, ensconced himself twenty feet from the decks, where he sat pale and sniveling.

A gloom seemed to come over every man on deck as Captain Morris stepped aboard. He had a reputation for excessive rudeness and brutality, and his gleaming eyes and flushed face told that he was half intoxicated and ugly.

“Aha, you’ve run away, have you?” he[7] yelled at the terrified Tom, shaking his fist at him; “well, so much the worse for you. I told you if you went ashore without my permission I’d treat you to the cat of nine tails, and I mean to keep my word. Come down, there!”

But the cabin boy only broke into wilder sobs and tears.

“Get the whip!” ordered Morris of the mate.

[8]

The latter went into the forecastle and returned with the dreaded instrument of torture with which the cruel captain occasionally terrorized the delinquent members of the ship’s crew.

Will Bertram shuddered as he took it from the mate’s hand and slashed it around a mast with a whistling, cutting sound, a look of fiendish satisfaction on his brutal face.

“Now, Tom Dalton,” he yelled up into the rigging, “it’s ten lashes if you take your punishment like a man.”

“Oh, captain, let me off, please let me off this time,” cried Tom, frantically.

“Come down, I tell you.”

“It will kill me—I can’t stand it.”

Captain Morris coolly consulted his watch.

“For every minute you stay up there I’ll give you an extra cut.”

Amid violent moanings and with streaming eyes, the wretched cabin boy began to slowly descend to the deck.

He shrank back as the captain made a vicious grasp for him, and growled out:

“Take off your jacket and shirt.”

“Oh, captain; dear captain,” shrieked the unhappy Tom, “for mercy’s sake not that; oh, please, please, and I’ll never, never disobey the rules again!”

He groveled at the captain’s feet, he writhed in an agony of fright and dread torture.

A low murmur of disapprobation swept from the lips of the watching crew, but not one of them dared to openly manifest his disapproval of the captain’s course.

Will Bertram alone, boiling over with indignation, murmured audibly, with flushed face and flashing eyes:

“Shame!”

Captain Morris spurned the suppliant boy with his feet, glowered defiantly at the sullen faced crew, and then turned fiercely on Will.

“I’ll show you how I punish insolent and disobedient boys, my pert young friend,” he sneered, malignantly. “Off with your jacket, I tell you!” he thundered at the half-crazed Tom.

“Don’t let him whip me. Save me, save me!” shrieked the tormented boy, appealing to the silent sailors.

And then espying Will, he sprang to his side and caught his hand frantically.

There was not a fibre in Will Bertram’s frame that did not tremble with indignation. He was overwhelmed with sympathy for the friendless Tom, and burning with resentment against the brutal Morris.

One sentence, quickly and impulsively, he whispered into Tom’s ear:

“Run for it!”

A suggestion from an outsider, a hope clutched at eagerly, the words seemed to arouse him to action.

With one bound he was over the rail and on the wharf. Before Captain Morris could comprehend what had occurred, Tom Dalton was flying down the wharf like one mad.

“You young jackanapes,” he yelled, advancing with uplifted whip toward Will, “I’ll teach you to raise a mutiny on my ship.”

“Captain Morris, don’t you dare to strike me.”

Erect, defiant, flinching not one whit, the spirited boy faced the enraged captain.

“You’ll help my crew to desert, will you? Take that.”

The whip cut the air, but not so quickly but that Will Bertram evaded its circling stroke.

He leaped aside, and seized the first article for defense that came to hand.

It proved to be a bucket half full of soft soap with which a sailor had been washing the decks, but he did not notice that amid his excited determination to resent Captain Morris’ exercise of authority.

Lifting it threateningly aloft on a level with the captain’s form, he cried out:

“Don’t you strike me, Captain Morris; I am not your slave, if that poor boy is.”

“Drop that!”

At the captain’s foaming, rage-filled tones Will Bertram did drop it.

The bucket fell between them. Its contents splattering far and wide, and trickling over the deck, made the captain retreat summarily.

In so doing the soft, slimy substance gave him a slippery foothold. He slid forward with a muttered imprecation and fell.

Will Bertram experienced a vague alarm as the captain picked himself up.

From head to foot the soft soap clung to his clothing, while from his nose and mouth the blood spurted freely.

“I’ve done it,” muttered Will, apprehensively. “I’d better keep out of his way now.”

It was well that he clambered ashore at that moment, for the captain, frenzied with rage, was rushing towards the spot where he had stood.

“I’ll make you pay for this!” Will heard him yell as he hurried down the wharf in the direction Tom Dalton had gone, “I’ll make you and all your family suffer for this!”

Time proved to Will Bertram how cruelly Captain Morris kept his word.

[9]

Will Bertram satisfied himself on two points before he relaxed the rapid pace with which he had left the deck of the Golden Moose.

The first was to learn that Captain Morris was not following him, and the next that Tom Dalton had got out of sight.

“I don’t know whether I have done right or wrong in incurring Captain Morris’ enmity,” he soliloquized, “but I couldn’t stand it to see him abuse poor Tom, and I wouldn’t let him whip me. I wonder what father will say when I tell him what has occurred.”

This thought worried Will considerably, and, revolving the episodes of the day over and over in his mind, he found himself wandering considerably from a straight course homewards.

An exciting divertisement for the time being took his thoughts into new channels. As he reached the public square he observed quite a throng of people gathered around a large structure just in course of completion, and went towards them to learn the cause of the curiosity and excitement their actions manifested.

A moment’s lingering on the outskirts of the throng gave Will an intelligent hint as to their interest in the spot.

“It’s up yonder,” a man said, pointing up at the high spire which crowned the summit of the tower of the structure.

It was just getting towards dusk, but as Will looked upwards he could make out a white fluttering object. It seemed to be impaled upon the pointed vane of the spire, and Will, straining his vision, made out that it resembled a large ocean bird.

“What is it?” he asked.

“A white osprey.”

“How did it get there?”

“Flew against the point, I guess,” replied the man.

The dying daylight gleaming down the valley showed the bird making frantic efforts to release itself.

Its strange, weird cries could be faintly heard from where Will stood.

The crowd kept increasing every moment, and among them Will noticed a strange, well-dressed, gentlemanly looking person who seemed very much interested in the aerial scene above.

“It’s a fine specimen of a bird,” he remarked. “Is there not some way of releasing it from its plight?”

“Yes, climb up and catch it,” responded a pert young man.

The stranger was not discomfitted at the jeering proposition.

He calmly took out his pocket book and drew from it a ten dollar bill.

“Why not?” he asked complacently. “Suppose you try, since you suggest it. I will willingly give that money for the bird.”

The crowd laughed. It became the young man’s turn to look embarrassed.

“You ain’t in earnest,” he said.

“But I am.”

“Well, I guess no one in this crowd cares to risk his neck, even for ten dollars.”

“Steeple Jack would,” broke in a boy.

“Where is he?” asked the stranger.

“Oh, he’s left town after fixing the spire.”

Will Bertram, an interested listener to all that had been said, stepped forward impulsively.

His heart beat more quickly as he thought of how much good the money might do his family, yet he trembled at his own boldness, as he asked:

“Is the offer open to anybody, sir?”

“Yes.”

“I’ll earn it. I’ll get the bird for you.”

“Here, come back! I don’t want a reckless boy to risk his life,” began the stranger, alarmed at the result of his careless offer.

But Will was gone, and a moment later after disappearing in the basement, appeared on the ledge of the third story of the building, waving his hand to the people below.

A new element of excitement was awakened by his rashness. When he appeared in view again at the base of the tower an apprehensive hush fell over the throng.

He glanced down once at the upturned faces and then looked upwards. But that he did not care to expose himself to ridicule and the charge of cowardice he would have returned below.

He remembered how he had seen the Steeple Jack nimbly climb the tower and by means of a rope work himself slowly round and round the tiled ornamental steeple.

Here and there in it were small holes bored, the only means of sustaining the weight of his body.

At that dizzy height a misstep or a slip of the hand meant certain death.

Will Bertram summoned all his courage, gained the base of the steeple, and tying the rope he had secured on a floor below around the steeple, rested his back against it and began pulling himself sideways and upwards along the smooth, even surface of the steeple.

[10]

The throng below had lost a casual, idle curiosity in the feat of daring now. Interest had succeeded, and then, as they saw that speck of diminishing humanity slowly, laboriously round the point of blackness against the darkening sky, a shuddering apprehension filled the strongest heart.

The clinging form would appear and disappear. It reached the narrowing summit of the steeple, and a hand clasped firmly the lower gilded bar of the spire.

There was a moment of awful suspense, and eyes strained and wearied by piercing the enveloping gloom of dusk, grew dimmer.

For a moment the figure rested at the base of the spire, then it was drawn a foot or two higher.

Darkness in earnest had come down over the earth, but one last glint of the dying sunlight far in the fading west illumined the gilded spire.

It showed the huddled form of the boy, his hand extended towards the vane. That hand clasped the bird, released it, and then swinging clear of the spire, dropped it flutteringly downward.

A faint cheer tinged with dread went up from the suspenseful throng. The daylight faded utterly—night came down over all the impressive scene, and only very dimly visible was the form of Will Bertram, returning to earth by the way he had left it.

At last tower, steeple and boy were a black blur against the darkened sky. A timid watcher shrieked outright as some object from above went whirling past him.

“What is it?” inquired a dozen eager voices.

“The rope! he has reached the base of the tower! he is safe!”

The stranger who had offered the money had grown very pale. His hat, dropped off in the excitement and suspense for the boy, was disregarded.

He turned to the side of the building and an exclamation of delight parted his lips as past a ledge of masonry a form came down a rope.

The rope was not long enough to reach the ground.

“Drop!” he cried, stretching out his arms.

One minute later, the centre of a surging, excited throng, Will Bertram had regained terra firma in safety.

Will uttered a great sigh of relief as the stranger led him towards the anxious throng.

“Here’s your money, my little man,” he said, extending a bill towards Will. “I wouldn’t go through the suspense I’ve suffered again, though, for ten ospreys.”

Will took the money deprecatingly, and his murmured words to the effect that “it was too much,” were lost amid the busy hum of talk around him.

“Where’s the bird?” demanded the stranger, abruptly.

“They’re chasing it yonder, still alive.”

“Yes, but it can’t fly. Here they come with it.”

Will Bertram took this opportunity, while attention was diverted from himself, to slip away from the throng.

Clasping the ten dollar bill tightly in his hands, which were not a little bruised by climbing, he thought only of the benefit its possession would afford his parents.

He burst into the house just as his father and mother were sitting down to their humble evening meal, and wondering what had detained him so long beyond his usual time.

Impulsive, excited boy that he was, Will could not keep the climax of his adventure of the afternoon and evening as a denouement to a continuous narrative, but, flushed with delight at imparting surprise and pleasure to others, he laid the crisp, new bill at his mother’s plate.

“Will! Will!” she cried, in utter amazement, “where did you get this?”

“Earned it.”

The incredulous, almost anxious, expression in his mother’s face made Will hasten his explanation.

The repast was deferred, as with bated breath and wondering faces his parents listened to his recital.

He saw his father’s face grow grave as he told of his encounter with Captain Morris, and that of his mother blanch with anxiety when he described his ascent of the steeple.

No chiding words fell from his father’s lips when he had concluded his narrative. Instead, he said, calmly:

“It is not a question of incurring Captain Morris’ enmity, Will, it is a simple question of right and wrong. His conduct to poor Tom Dalton was cruel in the extreme, and I am afraid I should have done just as you did in telling him to run away. As to defying Morris and trying to resist his anger as you did, hereafter I would simply keep out the way of such men.”

“He cannot injure you, father, as he threatened?” inquired Will, anxiously.

“No, Will, at least not until the next interest note is due, six months hence, and by[11] that time it looks as if my brave boy intends to have enough money to settle the claim for good.”

“I will, father, see if I don’t,” cried Will, enthusiastically. “I’m bound to work, and I don’t intend to get into trouble and peril to do it as I did to-day, either. Don’t think me lacking in respect to my elders, father, because I defied Captain Morris, but he is a bad-hearted, malignant man, and I could not control my indignation at his conduct.”

“And where is Tom Dalton?” inquired Mrs. Bertram.

“I don’t know,” responded Will. “Poor fellow, I must hunt him up as soon as the Moose sails, for he’ll keep in hiding until then. Captain Morris says I’m helping a mutiny and breaking his discipline, but I think it’s a mighty bad discipline he’s got, father.”

“Well, come, Will, your supper is ready, and there’s plenty of time to discuss the affair later,” urged Mrs. Bertram, as she bestowed a tender look on her son and carefully folded away the bill.

They sat down at the table, but Will’s tongue would run over the exciting events of the day. They had scarcely completed the meal when a quick knock sounded at the door.

Mrs. Bertram looked inquiringly at the well-dressed stranger who stood revealed on the threshold as she answered the knock.

“Does Mr. Bertram live here?” he inquired, and then, as she nodded assent, he continued: “I am looking for Will Bertram.”

Will recognized the voice and hastened to the door.

“Oh! it’s the gentleman who wanted the osprey,” he explained.

“Come in, sir,” spoke Mrs. Bertram, while the husband tendered him a chair.

The stranger nodded pleasantly to Will.

“Yes, he’s the person I’m looking for. The people directed me here. I suppose he has told you of my recklessness in hiring him to risk his neck for the sake of a bird?”

Mrs. Bertram paled concernedly.

“He is very venturesome,” she said, solicitously.

“He is a natural acrobat,” broke in the stranger, enthusiastically. “Mind me, madam, not that I want to encourage him to these feats of danger, but the agility, courage and manliness he exhibits should not be suppressed.”

Will’s cheek flushed at the honest compliment the stranger bestowed upon him.

“And now to business,” continued the stranger, “for I didn’t come here from idle curiosity. My name is Robert Hunter, and I am an agent for the North American Menagerie and Museum. Every year we send out agents to secure material for our institution from all quarters of the globe. I myself am now on my way to the great northern forests of Maine. We shall remain there for some two months and endeavor to trap a large number and variety of animals, such as the deer, the moose, the otter, the beaver, the catamount, the wolf, the bear, the fox, the lynx, and also such large birds as can be found. For this expedition we are very nearly entirely equipped, and I am expected to-morrow to join the wagons containing our outfit, traps, and men, at a town some few miles north of here.”

Will Bertram had listened with breathless attention. His eyes glittered with excitement as Mr. Hunter’s words suggested to him a fascinating field of adventure.

“I’ve taken a rare fancy to your boy Will,” continued Hunter. “He’s just the lad we need for handy little tasks, and I’ve come to make him an offer to accompany us on our expedition.”

Mr. Bertram’s face had grown serious, while Mrs. Bertram’s hand stole caressingly, anxiously, around that of Will, who sat near her.

“You want him to go away,—to leave us?” she murmured, tremulously.

“If he wants to go and you are willing. Don’t fear, madam. I’ll lead him into no danger, and the wild life he’ll see will benefit him. We carry everything for comfort, and, aside from once in a while climbing a hill to prospect, or a tree to get some bird’s nest——”

Will looked his disapproval at this suggestion, and the keen-eyed stranger, quick to notice it, laid his hand kindly on his arm and said:

“Don’t misunderstand me, lad. I mean no nest-robbing expedition—only the securing of abandoned nests to fit up a fancy aviary in the museum. A man who has lived long with animals and birds for his daily companions learns to be kind to them, and we allow no wanton killing of harmless beasts. It was pity, as much as curiosity, that made me want the osprey. Come, madam, I’m ready to make your boy an offer. What do you say?”

Mrs. Bertram was mute, but glanced tearfully at Will, and then inquiringly at her husband.

[12]

Will took their silence as a token of encouragement.

“What will I be paid?” he asked. “You see, my father is old and there is a debt on the little home. As their help and support, I would not leave them for the mere pleasure of the expedition.”

“Spoken like the true lad I believe you to be,” said Mr. Hunter, heartily, “and business-like, in the bargain. Well, Master Will, aside from the premiums I will give you for any important discovery or capture, I will pay you fifteen dollars a month, and I’ll relieve your anxiety about your parents by paying you two months in advance.”

“Thirty dollars! Oh, father, think what a help it would be!” cried Will, breathlessly.

Mr. Hunter arose to his feet, hat in hand.

“I will leave the hotel here to join the expedition at ten o’clock to-morrow morning. If you want to go, let me hear from you early in the day. Think it over, Mrs. Bertram, and rest assured if you agree I’ll take good care of him and return him safe and sound when the expedition is over.”

He bade them good-night and was gone without another word, leaving Mrs. Bertram in tears, her husband anxious and silent, and Will excited and undecided over the strange proposition he had made.

“It seems like Providence, father,” he said finally, after an oppressive silence. “With what I got to-day, the two months’ wages will support you for a long time, and you won’t have to work so hard. Besides, if there’s any extra money to earn, I will not miss it. Why, at the stores here I couldn’t earn half the amount, and I get my living free.”

“We will have to think and talk it over, Will,” replied Mr. Bertram, gravely, and at a motion Mrs. Bertram followed him into the next apartment.

Will could hear the low, serious sound of their voices in earnest consultation, even after they had softly closed the door connecting the two rooms.

He took up a book and tried to read, but the exciting thoughts that would come about the expedition distracted his mind completely.

“I hope they’ll let me go,” he breathed fervently. “It’s even better than the ocean. Hello, what is that?”

There had come a quick, metallic tap at the window, and Will fixed his eyes in its direction.

“It’s the wind, I guess,” he finally decided. “No, there it is again.”

Will arose, put on his cap, and, walking to the door, opened it, stepped outside, and looked searchingly around.

A low whistle from the direction of the woodshed told him that some one was there—some one, he theorized, who had thrown the pebbles against the window to attract his attention, and who did not care to manifest himself openly—in all probability, Tom Dalton.

Will found his suspicions verified as he approached the shed, and a disorderly figure stepped from behind the door.

“Tom?” he queried, peering into the face of the other.

“Yes, it’s me,” came the low, dogged response. “I hadn’t ought to bother you, Will, but I’m nigh starved.”

“Hungry, eh, Tom?”

“I should say so. Bring me a hunk of bread and meat, and I’ll get out of town and your way.”

Poor Tom had become so used to being in people’s way that he could not regard his association with any human being as otherwise than a disagreeable tolerance.

“You ain’t in my way, Tom,” said Will, kindly, “and I’ll not only get you something to eat, but I’ll find a place for you to sleep to-night. Wait a minute.”

Will returned to the house, and, when he came back, tendered his belated companion the promised “hunk” of bread and meat, which Tom seized and devoured ravenously.

“Well, Tom,” said Will, finally, as the runaway bolted the last morsel of food with a sigh of intense satisfaction, “what are your plans?”

“Ain’t got any.”

“You won’t go back to the Moose?”

“Not much. Do you think I want to get killed? I tell you, Will, you don’t know what a brute the captain is.”

“Won’t they look for you?”

“Of course they will. They were down the street searching for me everywhere half an hour ago.”

“Who?”

“Captain Morris and two of the sailors in one party, and the mate and the boatswain in another.”

Will reflected. He had intended to obtain permission of his parents to allow Tom to sleep in the house that night, but if Captain Morris was looking for him it would be unsafe.

“If I can only keep out of the way until the Golden Moose sails, I shall be all right,” said Tom, confidently.

[13]

“Keep quiet, Tom; some one is coming,” whispered Will, warningly.

Some one was coming, sure enough, for as he spoke the heavy tramp of footsteps at the side of the house was followed by a thundering knock at the back door as the forms of two men loomed into view.

“What did I tell you?” quavered Tom, beginning to tremble violently.

“Keep quiet and listen,” repeated Will, peremptorily.

At that moment Mrs. Bertram, in answer to the knock, opened the door.

The lamplight fell upon the faces of two members of the crew of the Golden Moose—the boatswain and mate in quest of Tom Dalton, the runaway.

The first question asked by the mate of the Golden Moose referred to Will Bertram, as the watching lad had expected.

“Is your son at home, Mrs. Bertram?” were his words.

“He was a moment since,” replied Will’s mother, a slight shade of anxiety in her face as she glanced around the room. “He seems to have gone.”

“Where to?”

“I do not know. Maybe to visit some neighbor’s boy. Was it anything particular, sir?”

“Well, yes. You see he got our cabin boy at the ship, Tom Dalton, to run away to-day, and we’re ready to sail.”

“Oh, I am certain he does not know where he is,” Mrs. Bertram hastened to say.

“Trust a keen-witted boy like him for that,” incredulously remarked the mate.

“At least he has been busy or at home since he was at the ship this afternoon.”

“Well, I guess if we find Will Bertram we’ll place Tom Dalton,” said the mate, confidently. “Come, Jack, we won’t break our necks looking for the lads, but, of course, we must follow orders.”

The watching boys did not move until the two sailors were well out of sight. Tom was crying bitterly.

“Be a man, Tom,” urged Will, encouragingly. “What are you crying about?”

“Because they hunt me down so, and will be sure to catch me. Everybody’s against me.”

“Well I ain’t, Tom. Now, instead of mourning uselessly, put your wits together and decide what you’re going to do.”

“I don’t know,” responded Tom, hopelessly.

“Is there not some acquaintance you could stay with to-night?”

“I ain’t got any friends.”

Will pondered deeply for a moment or two. Finally he said:

“Look here, Tom; I think I know a place where you could go.”

“Where?”

“You know the old mill down the river?”

“Yes. I’ve been there lots of times.”

“Well, I suggest that you hide there for to-night.”

“They’ll never think of searching for me there. I’ll go, Will, if we can get there without being seen.”

“Come along, then.”

Will took the most retired route he could think of to reach the mill. As he went along he talked seriously to Tom about his future, and advised him to find his way to an uncle who lived some distance down the coast, and from whose charge Tom, who was an orphan, had run away to gain a seafaring experience at bitter cost.

“Won’t I see you to-morrow?” inquired Tom, lugubriously, somewhat depressed at being left to his own resources.

“I expect not.”

“Are you going away?”

“I may, Tom,” and Will told of Mr. Hunter’s offer.

Tom’s face grew animated and his eyes flashed eagerly as Will enthusiastically referred to the plans of the expedition.

“Oh, if I could only go with you!” he ejaculated.

“I don’t know that I am going myself, Tom.”

“Oh, Will!”

They were crossing a vacant lot when Tom brought Will to an abrupt halt with a startled exclamation, at the same time clutching his arm alarmedly.

“What’s the matter, Tom?” inquired Will.

“Look yonder. There is the Captain and two of his men.”

Will grew a little excited as he glanced in the direction his affrighted companion had indicated.

“It’s them, sure enough, Tom. Now don’t get frightened, but walk fast.”

He hoped to evade the scrutiny of the trio, who were some distance away, by getting out of their range of vision.

A shout behind him, however, told him that their identity was suspected, and he saw the three men break into a run.

Will followed their example, urging his companion to do the same, and directing the[14] way to the old ruined mill, the outline of which was visible a short distance ahead of them.

They gained on their pursuers, and, reaching the mill itself, observed with satisfaction that their pursuers were almost invisible in the darkness.

“Maybe they won’t trace us here, Tom,” said Will; “now you keep close to me, and when we’ve found a snug spot we’ll keep quiet and await developments.”

The dilapidated old structure, gone to wreck and ruin many a year agone, was a familiar place to the boys of Watertown. Will clasped Tom’s hand and led the way through the doorless entrance to its lower floor.

As he did so Tom uttered a frightened cry.

“Some one’s here,” he whispered.

Some one certainly was there, for at that moment a flashing light in one corner of the place showed dimly its entire interior.

Will soon made out the cause of the unexpected illumination. On a heap of straw sat a trampish-looking individual. He had just lighted a match preparatory to taking a smoke from his pipe, and did not apparently notice the intruders.

“It’s some old tramp,” whispered Will. “Come, Tom: yonder’s a ladder leading to the next story. Go slow on it, for it’s old and rickety. Here we are.”

He crept up a creaking ladder and Tom followed him. Will took the precaution to pull the ladder up after them, and closed the broken trap door over their means of entrance.

“Now we’ll sit down and wait,” he said, and both boys slid to the floor.

It was so still that they could hear every near sound. Will felt Tom tremble as from the outside echoed faintly the gruff, harsh voice of Captain Morris.

A minute later there was a quick cry and a sudden commotion below as if the sailors had discovered the old tramp, and then, as a light showed distinctly through the cracks of the floor, Tom quavered, gaspingly:

“They’ve traced us here, and have got a light and are looking for us!”

Will Bertram placed his eye to an interstice in the floor to ascertain what was going on below.

He arose suddenly to his feet with a startled cry.

“Quick, Tom, open the trap door and get the ladder down!”

“What for?”

“It is no light below, but a fire!”

“A fire?” echoed Tom, wildly.

“Yes; quick, I say; the trap! the ladder!”

Will himself was compelled to lift the trap door, for Tom was paralyzed with terror and utter helplessness in their dilemma.

He staggered back as he drew the trap open. A dense volume of smoke issued from below, while the crackling of burning wood and a ruddy glare told that the careless tramp had precipitated a catastrophe.

“Oh, Will! what shall we do?”

“Keep cool and get out of this,” replied Will, bravely. “Stay where you are for a minute.”

He flung the trap shut and groped his way to the window.

It was now an open aperture, but, as he well knew, looked down upon a deep pit by the side of the structure.

“There used to be some ladder steps nailed to the side of the building,” he said, as he leaned out of the window.

He peered searchingly forth, and with his hand felt for the means of escape he had described.

A murmur of concern swept his lips as he made a thrilling discovery.

The ladder steps were gone!

Wind and weather or the destructive freak of some careless boy had certainly cut off the one avenue of escape for the imprisoned boys from the burning building.

Had not the pit yawned far below the ground surface Will would have trusted to a flying jump in the darkness.

Tom Dalton, utterly overwhelmed, sat huddled together on the floor quaking with terror.

The encroaching fire showed through the cracks so plainly now that they could see each other’s face.

Already the fire was burning the floor beneath them. They could not descend.

“We must climb higher,” said Will, forming a quick resolution. “There is the old stairs yonder. Follow me, Tom.”

The cabin boy obeyed Will’s order mutely, and they found themselves in a large loft at the top story of the building.

Will began to reconnoitre at once, but he found that the distance from the windows to the ground was too great to encourage him to take a dangerous leap downwards.

They might reach the attic or the roof, but that only made their dilemma worse.

[15]

At last, after a rapid inspection, he lit a match and surveyed critically an aperture in the side of the building.

The smoke and heat had now become well-nigh intolerable, and occasionally some timber burning in two would make the weakened structure topple and tremble.

“Oh! what shall we do?” moaned Tom, despairingly.

“Get out of this when it comes to the worst.”

“How?”

“By jumping from the window.”

“And kill ourselves by the fall!” cried Tom. “Can’t we call for help?”

“There’s no one in sight on this side of the building, and besides they couldn’t reach us from the river end. Now, listen carefully to me, Tom, for our safety depends on our own efforts.”

“What is it, Will?”

“In the corner yonder there’s an old shute leading to the river.”

“What’s a shute?”

“A long, tightly-boarded box. They used it to send rubbish down to the river. It slants down the side of the building about forty feet.”

“You don’t mean to slide down it?”

“Yes, I do. It’s our only chance of escape.”

It seemed a perilous one, and as Will held a match over the end of the shute and explained that a swift descent might terminate in a cold plunge in the river, Tom drew back in dismay.

“I’ll go first,” said Will. “You’ll follow.”

“I’m afraid, Will.”

“Then we’re lost, for the fire—hear that!”

“I’ll do it! I’ll do it!” cried Tom, starting, as one side of the building, the lower props burned away, sagged to one side.

It was high time for action. Will climbed over the extending top of the shute and lowered himself into it.

Clinging to the edge he gave Tom a warning word:

“Don’t delay a moment in following me.”

“I won’t.”

“Here goes, then!”

Will Bertram experienced a strange sensation as, relaxing his grasp, he shot vertically downwards.

His breath seemed taken away, and his hands, sweeping the bottom of the shute seemed to gather a thousand little slivers.

Then, with a gasp, he felt his body strike the water and become entirely submerged. He was chilled by the shock, but he puffed and struggled, and then clung at a rock and drew himself to the shore, breathless and exhausted.

Splash!

A second echoing plunge followed his own, and in the radiating illumination he made out a struggling figure in the water.

Tom Dalton had followed his example, and just in time, for a crash told of a floor giving way in the structure they had vacated.

“Tom! Tom! this way!” called Will, cautiously.

But his companion in peril either did not hear him or had determined to follow his own course. He struck out deliberately to cross the river, swam vigorously forward, and, reaching the opposite shore, cast a quick look in the direction of the burning mill, and then disappeared in the darkness outside the radius of its light.

“He’s probably afraid the captain will catch him,” theorized Will. “At all events, he’s safe.”

Will shook the water from his clothes and made a wide detour of the burning.

As he looked back he saw quite a crowd gathered around the building, but determined to evade them, and made his way homeward, walking briskly to restore the circulation to his chilled frame.

He found the lamp turned down when he reached home, and was glad to know that his father and mother had retired for the night.

“There’s no use worrying them about what’s happened to-night,” he soliloquized, and he made up a good fire in the kitchen and spread out his soaked garments to dry.

“Is that you, Will?” Mrs. Bertram called from her chamber.

“Yes, mother.”

“Where have you been?”

“With Tom Dalton. The poor fellow was afraid Captain Morris would find him, and I went with him to try and find him a place to sleep,” and with this vague explanation Will bade his parents good-night and repaired to his own room.

He dozed restlessly the first portion of the night, and then, unable to sleep, his mind filled with thoughts of his varied adventures and the anticipated expedition of the morning, he wrapped a blanket around himself and stole silently to the kitchen.

He devoted the remainder of the night to drying his clothes. With the first break of dawn he had donned them and attended to various little chores around the house.

His curiosity impelled him to proceed a[16] little distance down the street, whence a view of the harbor could be obtained.

He was familiar enough with the various craft at anchorage to miss the trim sails and masts of Captain Morris’ ship.

The Golden Moose had sailed during the night; but where was poor Tom Dalton, the runaway?

Will Bertram studied his mother’s face searchingly as he sat down to breakfast that morning. The sad, patient features gave no indication of the decision arrived at regarding the proposed expedition, however, and Will was compelled to wait until the morning meal was over before the subject was referred to.

“Well, my son, your mother and I have talked over the matter of your going away,” said Mr. Bertram.

Will looked suspenseful.

“We have decided, since your heart seems so set upon it, to let you do as you please.”

“Oh, father, I am so glad!” cried Will, rapturously. “Of course I long for the adventurous life the expedition offers—what boy wouldn’t?—but, honestly, I want to help you, and in a business point of view it’s the best thing open to me.”

He promised his mother to indulge in no reckless or dangerous exploits, and to evade companionship with any evil persons he might meet.

Then, while his mother was making up a package of his clothes, Will went to the hotel.

Mr. Hunter expressed a keen satisfaction at his decision. He drew a sort of contract between them, and, as he had promised, advanced the two months’ wages, and bade Will return by ten o’clock to leave home for good.

Will paid the money over to his mother, and took occasion to relate his adventures of the night previous. She trembled at the stirring recital. He listened attentively to her parting words of advice. Mrs. Bertram was not the woman to show her anxiety and grief at his departure, but kissed him good-by with cheering words and hopeful smiles.

Little did either dream of the long, weary months destined to intervene ere they again clasped hands.

Will’s step was quick and elastic, and his heart thrilled with pleasure as he again reached the hotel, his bundle of clothing strapped over his shoulder.

Youth does not cherish sadness, and his exuberant spirits regarded the parting with his parents tenderly rather than with forebodings of distress.

“Well, my boy, all ready?” asked Mr. Hunter, as he welcomed Will.

“Yes, sir.”

“If we ride to the meeting place where the expedition is we will have to wait for a stage. It’s barely ten miles. What do you say to a walk?”

Will expressed himself eminently satisfied with this arrangement, and the two set out at a brisk gait.

Watertown was soon left behind them. The morning was clear and frosty, and as they trudged along Mr. Hunter entered into numerous details regarding the expedition.

Will found him one of the most entertaining talkers he had ever met. He told of all the practical operations of museum, menagerie and circus life, and revealed to his companion the fact that under the artificial glitter and tinsel of circus experience existed hard realities, of which securing the collection of animals was one.

The caravan bound for the expedition was reached shortly after noon. Mr. Hunter pointed it out to Will as they reached the edge of the town where he was to meet it.

Will Bertram was amazed to find that there were nearly twenty wagons and as many men.

Mr. Hunter noticed his surprise.

“Are you going to use all those wagons?” inquired Will.

“Yes, and possibly we will have to secure more before the expedition is ended. When we reach the northern limit of settlements half the wagons will remain there. The others will go on and again divide. When we come down to actual operations we will have only two wagons with us, one with cages for the animals we capture, and one for our own use. As soon as the former is filled we send it back to the last station, and the train moves forward the entire line, one station. Thus we will have a progressive and return caravan, the wagon with the animals going back to the nearest railroad town, shipping its cages, and coming back again.”

For over an hour Will studied the caravan in all its appointments. He found the men composing it rough, good natured people, who answered his numerous questions cheerfully.

They showed him the four living vehicles, as they were called, stout, boarded wagons, with heavy wheels and a stove and bunks inside,[17] as also the supply or provision cart and the cage wagons. These latter were provided with barred cages, and in some of them were animals that had already been purchased from people along the route, consisting of a tame fox, a pet bear, and quite a number of birds.

The wounded osprey Will had rescued the night previous, and which Mr. Hunter had sent on early that morning, was being fed and nursed by a member of the caravan.

Up to this stage of the journey the party had remained at a hotel when they reached a town, but as villages grew less frequent it was designed to cook, eat and sleep in the living wagons.

This nomadic life pleased Will from its very novelty, and he longed for the journey to begin, anticipating rare sport when they reached the wilderness, and marveling at the immense wagon load of traps and snares carried by the caravan.

Mr. Hunter ordered an immediate start. There were several extra horses, and he and Will rode two of them ahead of the train.

At dusk they halted in a little stretch of timber, no near town being visible. Huge torches were planted in the ground, the wagons drawn in a circle, the horses tethered, and an immense camp-fire built for the night.

It was a novel and busy sight for the interested Will, and he watched the preparations for supper with a keen appetite and rare enjoyment of the scene.

Suddenly, at one of the wagons, where a man was taking some feed for the horses, there was a quick commotion.

“Hello! Mr. Hunter,” he cried, “here’s a discovery.”

“What is it?” inquired Mr. Hunter, coming to the wagon, Will pressing close to his side.

Amid a mass of straw was a form, which kicked vigorously as the man endeavored to drag it from the wagon.

“A stowaway!” cried the man.

“True enough,” replied Mr. Hunter. “Pull him out, and let us have a look at him.”

“Let me go! Let me go! I tell you I haven’t done anything wrong!” cried a voice that fell familiarly on Will’s startled ear.

The man drew its possessor out of the wagon, and wheeled him around to the camp-fire.

Mr. Hunter stared amusedly at the form thus revealed.

An amazed ejaculation swept Will Bertram’s lips as he recognized him.

“Why, its Tom Dalton!” he cried, breathlessly.

Will Bertram’s expressive face must have betrayed to Mr. Hunter that the stowaway was a friend, for that gentleman regarded Tom with a critical, amused smile, and then asked Will:

“You know this boy?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Who is he?”

“Tom Dalton. He is from Watertown, but how he came here is more than I can tell.”

Tom stood sullenly regarding the curious men around him, half-cowering, as if expecting the usual beating he had received on board the Golden Moose for any delinquency.

“Come to the fire and warm yourself, and get something to eat,” said Mr. Hunter, in a kindly tone, to the friendless runaway.

Tom crept to the camp-fire with a look of infinite relief. He evaded Will’s glance sheepishly, and was entirely silent until the rude, but plentiful, evening repast was finished.

Will was consumed with curiosity to learn by what strange series of circumstances Tom had become a member of the wagon train, but no opportunity presented itself to question him.

Mr. Hunter himself, however, took Tom in hand and drew from him the story of his escapade.

Briefly related, it was to the effect that after the fire at the mill, concerning which Will had spoken freely to Mr. Hunter, he had wandered away from Watertown.

Tom remembered all Will had told him about the proposed expedition, recalling even the location of the meeting place.

The temptations offered by the expected trip to the wilderness were too much for Tom. He climbed into a wagon, and had lain snugly ensconced in his hiding place until now.

“And what do you expect I’m going to do with you?” inquired Mr. Hunter.

“Let me work for you, sir,” responded Tom, promptly.

“Good! I will,” and, to the infinite delight of Tom, he was accepted as a member of the caravan and assigned to a bunk in the same wagon with Will.

The evening around the camp-fire, during which rare stories of adventure held the boys spellbound, the jaunt through a strange country, and the zest of anticipated pleasure when hunting and trapping should begin,[18] made the time pass rapidly to Will and Tom.

The history of each succeeding day tallied with its predecessor in the main details of incident, except that the caravan was penetrating farther and farther into the belt of the uninhabited territory where their actual operations were to begin.

The weather had been clear and cold, but the rivers they passed, so far, were free of ice, and the roads were not blocked with snow.

Mr. Hunter had predicted a change, and one evening it came. Since morning they had passed only one solitary hut, and he explained that they were entering a section of timber where some game might be found.

At any rate, the caravan was divided, and minute instructions given for the future. Then the main party struck off into the wilderness.

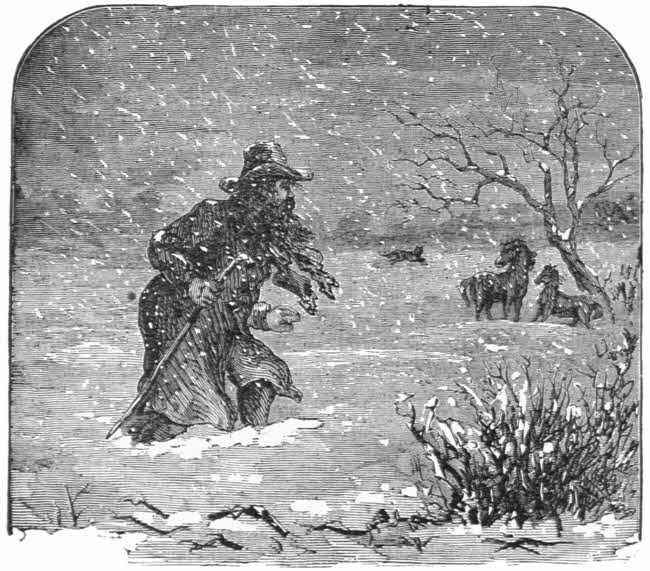

The flakes began to fall thick and heavy as darkness came down. Mr. Hunter expressed his satisfaction at this.

“If we have a heavy fall of snow and it continues cold,” he said, “it will be just right for trapping. At any rate, we’ll stay here a day or two and reconnoitre.”

No camp-fire was built that night, the men huddling around their stoves in the living wagons.

It was cozy and warm for Will and Tom, but one of the drivers, whose horses had got loose and had to be hunted up, reported a severe experience.

“The snow’s getting terribly deep and blinding,” he said, “and, as I came up to the horses, I’m sure I heard and saw a wolf.”

“We’ll keep a watch on the horses, then,” said Mr. Hunter. “Are the traps all ready for use?” he inquired of the man who had charge of the equipment wagon.

“Yes, sir.”

“Very well; we’ll devote to-morrow and the next day to a search for animals. If the signs are plentiful we’ll make our first station here.”

Bright and early the two boys were awake and up. They found the ground foot deep with snow, and the vast forests, now covered with a mantle of white, presenting the aspect of a vast, untraversed wilderness.

Mr. Hunter joined them as they gathered a lot of wood for a fire, and invited them to take a brief tour of inspection with him.

His practiced eyes passed by no marks in the snow, and whenever he came to a series of tracks he examined them closely.

“Plenty of small animals,” he remarked; “and an occasional fox and wolf.”

“What is this?” inquired Will.

He pointed to a deep, heavy furrow in the snow, which looked as if some object had been dragged over its surface.

Mr. Hunter proceeded at once to follow the marks. Here and there a hole like that made by a horse’s foot would appear outside of the smooth indentation.

It led direct to a dark ravine, and terminated at a cave-like aperture in a mound covered with stunted trees.

Here Mr. Hunter paused.

“You’ve made quite a discovery, Will,” he said.

“Is it an animal, sir?”

“Yes. Its footmarks are obscured by the object it seems to have been dragging along by its mouth.”

“And you think it’s in the cave there?”

“Undoubtedly.”

“What is it—a wolf or fox?”

“No, a bear.”

The announcement excited both boys tremendously.

“Let’s catch him,” cried Tom.

Mr. Hunter smiled.

“He’d catch us if he saw us unarmed as we are. No, we’ll get back to camp and get the traps out. Maybe by morning Mr. Bruin will walk into the one we shall set for him.”

After breakfast there was a busy time among the men. At Mr. Hunter’s direction traps and snares were set in various places, and Will and Tom were employed in gathering tree moss and abandoned nests for the aviary. A hawk and an owl were captured during the day, but it was the following morning that Mr. Hunter expected to find quite a number of animals in the traps baited over night.

The large bear trap left at the entrance to the cave was a great objective point of interest to the boys, and they visited the spot several times, hoping to be the first to announce the capture of bruin should that important event occur.

They stood before the entrance to the cave late in the afternoon regarding the set trap curiously.

“Do you see?” remarked Will, pointing to it.

“What?” inquired Tom.

“The meat is gone. It must be a cunning bear. He has sniffed the bait and cautiously eaten it off without putting his feet in.”

It certainly seemed that what Will said was true, for the marks of the animal’s feet could be traced in the snow that had blown into the entrance to its den.

[19]

Will left Tom at the place and announced his intention of going around the mound.

He made a new discovery as he came to the other side of the mound. A double track in the snow led to and from a clump of bushes, and these latter were brushed aside and broken as if recently passed over.

Will thrilled at his discovery. The cave had two entrances, and the bear, too keen-witted to step into the trap, was using this one as a means of entrance and exit.

“I believe I’ll have a look into the place,” murmured Will.

He parted the brushes and found a large aperture looking down into complete darkness.

Will’s curiosity overcame his prudence, and there being no indication of the presence of the bear, he withdrew his head, and, cutting a large, resinous knot from a tree near at hand, proceeded to ignite it with a match.

When it flared up sufficiently, he again approached the rear opening to the cave, brushed aside the bushes, and extended it far into the darkness.

Its radiance showed the clay floor of the cave a few feet below. Straining his eyes to pierce the darkness, Will met with an unexpected accident.

The bush he was holding to gave way, and he fell forward precipitately. The torch was hurled downwards, while he himself plunged head foremost into the cave.

Bruised and startled, he scrambled to his feet.

At that moment a terrific roar echoed through the darkness and gloom of the cave.

Will Bertram discovered two things as he thrilled to a realization of his true position.

Some ten feet away was daylight penetrating through the main aperture to the cave, while directly in front of him and against this light was the great, crouching body of the bear itself.

Its eyes, like two sparks of yellow fire, glared fixedly upon him, while its low grumblings told that its rage was fully aroused.

[20]

Will stood rooted to the spot, but only for a moment, for a movement on the part of the bear aroused him to sudden action.

Springing forward, the animal brought its huge foot across the intruder’s arm, tearing the sleeve of his coat into shreds.

The torch had fallen to the floor of the cave, and still flickered brightly. With no weapon to defend himself, Will stooped and seized it, and brandished it squarely in the bear’s face.

With a growl the animal retreated a step or two, but maintained a strict and entire guardianship of the way leading to the main exit from the cave.

Will gave a quick glance behind him, but instantly abandoned all thoughts of escaping by the way he had come.

The aperture was at the end of a slanting decline and several feet above his head.

To climb up that would consume time, and bruin, more agile than he, would certainly overtake him ere he had accomplished the exit.

In a flash, Will decided that but one way of escape lay open to him, and that was by dashing past the bear through the main entrance, beyond which a glance revealed Tom Dalton.

The cave narrowed as it came to this spot, and this passage way was almost completely filled by the bear’s enormous body.

The animal seemed ready for a second onslaught on the intruder, when Will, waving the torch so as to cause it to flame still more, again thrust it into the animal’s face.

Bruin roared with pain and rage and showed his horrible fangs, but retreated slowly.

“If I could only drive him to the open air,” murmured Will, tumultuously.

There seemed but little hope of this, however, for the bear at last appeared to make a sullen stand, and half-raised himself, as if to spring on Will.

The latter could see open daylight beyond. A few feet more and he believed he could rush past the bear in safety.

With a last, desperate movement he flung the burning torch square at the head of the bear.

The animal crouched back, and then turned with a frightful howl.

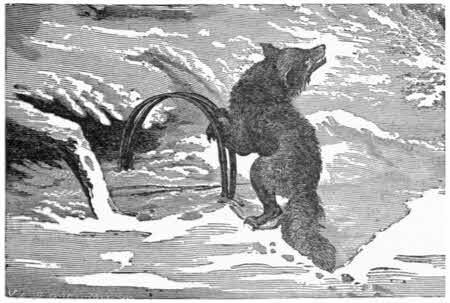

A sudden, clicking snap echoed on the air, and the bear seemed struggling and floundering in a strange way.

“The trap!” cried Will, wildly.

His excited words expressed the bear’s dilemma. Bruin, enraged and retreating, had walked into the very snare he had before avoided.

He was foaming with rage, and, his hind legs firmly caught between the clamps of the immense steel trap set at the mouth of the cave, was struggling wildly to release himself.

With a shout of relief and joy, Will darted past the imprisoned bear and into the open air.

He found Tom Dalton standing staring at the bear in open-mouthed wonderment.

The trap was secured by an iron chain around a tree, and, although it allowed bruin a certain range of action, it held him a prisoner.

Tom was struck on the arm, and came very near within the bear’s floundering grasp, but Will pulled him aside in time to avoid a crushing blow from the animal’s heavy paw.

Will entertained his companion with a vivid account of his adventure.

“You run to the camp and tell Mr. Hunter what has occurred,” he said, when he had concluded his story. “I’ll stay and watch the bear.”

Mr. Hunter and several of the men arrived soon. He complimented Will on his capture, and pronounced the bear a fine specimen of his species.

Will watched the men interestedly as, with the aid of poles and hooks, they secured bruin so that he could not injure them, when they conveyed him to a cage wagon which was sent for.

Some chloroform on a sponge robbed bruin of his natural fierceness, and he was finally safely caged.

The ensuing morning a fox and a wolf were found, with other smaller animals, in the traps, set in various places around the camp.

The history of one day was that of all the week spent at the camp. One wagon was ready to send back, and then Mr. Hunter announced that they would push on still further into the wilderness.

It was an exciting and interesting tramp for the two boys. The ensuing three weeks were the busiest ones they had ever known.

They learned how the moose, the deer, the otter, the catamount and other animals were captured, and many a thrilling experience was theirs in a quest for rare birds amid the lonely forests.

When the snow became compact, rude runners were substituted for wheels on the wagons, and several of the vehicles left the expedition filled with captured animals and birds.

[21]

When they were traveling it would sometimes be entire days ere they would come across a settlement, or even a house.

It was just about a month after leaving Watertown when, one day, an incident occurred which materially changed all the plans of the two boys who had so strangely become members of the expedition.

They had orders to prepare for a new move that night, and early in the day had gone back by the route they had come to a place where a rocky formation in the landscape had suggested the idea of successful bird hunting.

Several eagles had been noticed by the boys, and it was to capture one of these that they determined to make the expedition on their own account.

The weather had become mild, and the snow had almost disappeared. Mr. Hunter warned them not to go too far from the camp, as a storm was threatened.

Provided with ropes and snares, Will and Tom reached the spot they had in view, and for over an hour wandered about the place.

At last, some distance away, they made out several large birds circling about a rocky point of land.

Will suggested that they visit the spot, and this took them still farther away from the camp.

Clambering over the rocks, exploring this and that secluded aerie, and endeavoring to snare some of the birds, which they thought to be eagles, the hours passed so rapidly away that dusk grew upon them before they realized how the day had advanced.

“Why, Will, it’s getting dark!” suddenly exclaimed Tom.

They abandoned their efforts at catching the birds and descended to the level plain beneath.

The scenery around them seemed utterly unfamiliar, and Will was somewhat alarmed, as he found that he was considerably confused as to the points of the compass.

However, he finally decided upon what he supposed to be the direction in which the camp lay, and they started forward on their way.

Darkness came on, and, although they had progressed several miles, they were more bewildered than ever concerning their real whereabouts.

Any person who has been lost knows how, in the effort to regain some familiar landmark, the mind becomes affrighted and bewildered, and the feet wander unconsciously and aimlessly.

It was so with Will and Tom. It must have been nearly morning before they came to a halt.

They built a fire in a thicket and determined to wait until daybreak before they attempted again to ascertain their bearings or endeavored to reach the camp.

Will had not imparted his real anxieties to Tom, but when, the ensuing day, several hours’ wandering failed to reveal any trace of the camp or its proximity, he began to exhibit a deep concern.

“See here, Tom,” he said, frankly, at last, “I’ve led you to believe that it was only a matter of time in reaching the camp.”

“Yes, Will.”

“Well, I thought it was, but I’ve changed my mind.”

“You said the opening here looked like one near our last camping place.”

“I was mistaken.”

“Then you don’t think we’ll reach camp to-night?”

“I’m afraid not, Tom. There’s no use evading the true condition of affairs. We’ve been going in a wrong direction all day. We are lost!”

It was a dreary prospect for the tired and hungry boys, and Tom’s face lengthened as he realized the hardship and privation in store for them.

They had eaten the last morsel of food they had brought with them the day before, and the danger of actual starvation stared them in the face.

“We may have wandered miles from the camp, and Mr. Hunter may be looking for us in an entirely different direction,” said Will, seriously.

“Can’t we reach some town or settlement?” inquired Tom, hopefully.

“There may not be a house within a hundred miles, and there may be one within ten. All we can do is to struggle on, and as it’s getting night and looks like snow, we had better hurry away from this level prairie.”

In the far distance trees were visible, and the boys, keeping them in view, trudged wearily onwards.

Snow began to fall late in the afternoon, and this caused Will to urge the lagging Tom to hasten his pace, and endeavor to reach the timber ere night and storm overtook them.

They reached a scattering woods finally. Seeking a place to camp for the night, Tom[22] startled his companion with a welcome discovery.

It was the track of horses’ feet and wagon wheels along the edge of the timber, and they were quite fresh.

“Some vehicle has passed here lately, sure,” said Will, quite excitedly.

“Let us follow up the tracks,—they may lead to some town,” suggested Tom.

This course seemed a wise one, and was immediately followed, but when the road diverged to the opening all traces were hidden by the fast falling snow.

Darkness coming down showed a dreary waste of snow lying before them far as the eye could reach.

“We had better find a camp for the night,” said Will.

They devoted some time to searching for a convenient spot. The snow had become heavy and blinding, and penetrated even the timber.

“We’ll find a clump of screening bushes somewhere,” said Will, and they kept on through the woods.

At a little opening they paused, wet, chilled and discouraged.

Suddenly Will started.

“Hark!” he said, impressively.

Tom bent his ear to catch an ominous noise echoing strangely through the silent woods.

A distant baying sound was borne upon the breeze, becoming augmented in volume and nearness as they listened.

“What is it, Will?” inquired Tom, in awe-stricken tones.

“Wolves.”

Tom’s face grew pale and his hands began trembling violently.

“Oh, Will, what shall we do if they come here?”

“They probably will come here, but we won’t let them catch us just yet.”

“What shall we do?”

“Build a fire and climb the highest tree we can find.”

Will began at once to gather leaves and wood, but paused with a cry of delight.

“Come this way quick, Tom. Do you see yonder?”

“In the opening?”

“Yes. It’s a house. Run, Tom, for the wolves are coming nearer.”

The baying sound seemed directly in the timber as they dashed across the snowy waste.

In the centre of the opening stood a structure of some kind. As they neared it the rude outlines of a log cabin were revealed.

The single door was open. Through the roofless top the snow came down heavily.

But it was a welcome house of refuge amid peril. Will pushed the door shut and propped a heavy log lying inside against it.

As he did so he saw, breaking from the cover of the forest, a dozen or more wolves.

“Just in time,” he murmured, relievedly, as he glanced around at the stout timbers enclosing the cabin.

Tom Dalton could not overcome the terror he experienced at the near proximity of the wolves until Will assured him that they were safe.

“They can’t break in the door nor reach the roof.”

“But we’ll have to stay here all night.”