Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XVIII, No. 2, February 1841

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: November 7, 2020 [eBook #63665]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

from page images generously made available by the Internet

Archive (https://archive.org)

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XVIII. February, 1841. No. 2.

Contents

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| The Blind Girl of Pompeii | |

| The Reefer of ’76 (continued) | |

| My Grandmother’s Tankard | |

| The Rescued Knight | |

| The Silver Digger | |

| The Syrian Letters (continued) | |

| The Saccharineous Philosophy | |

| The Confessions of a Miser | |

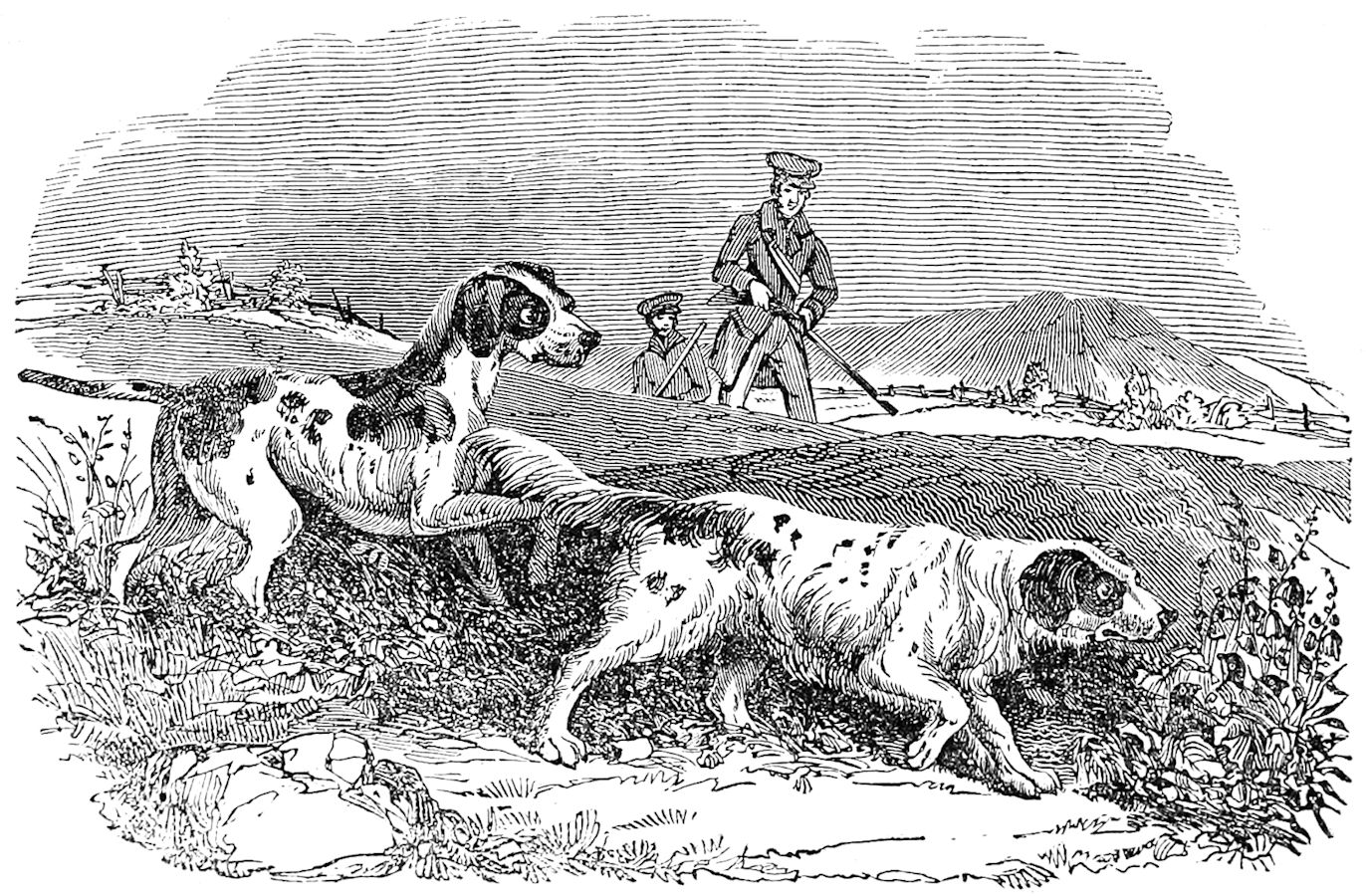

| Sports and Pastimes. Shooting | |

| Review of New Books | |

| Poetry, Music and Fashion | |

| The Dream of the Delaware | |

| Little Children | |

| Skating | |

| The Soul’s Destiny | |

| Winter | |

| The Fairy’s Home | |

| Not Lost, But Gone Before | |

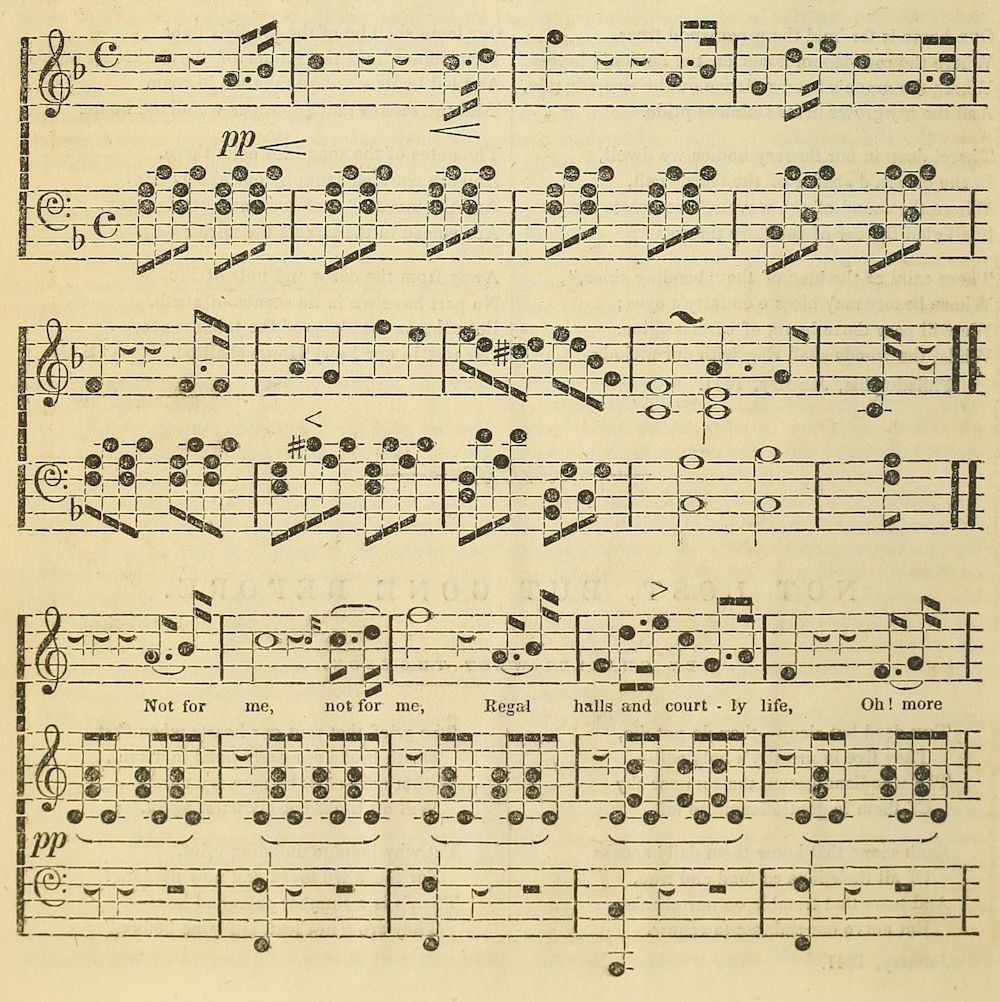

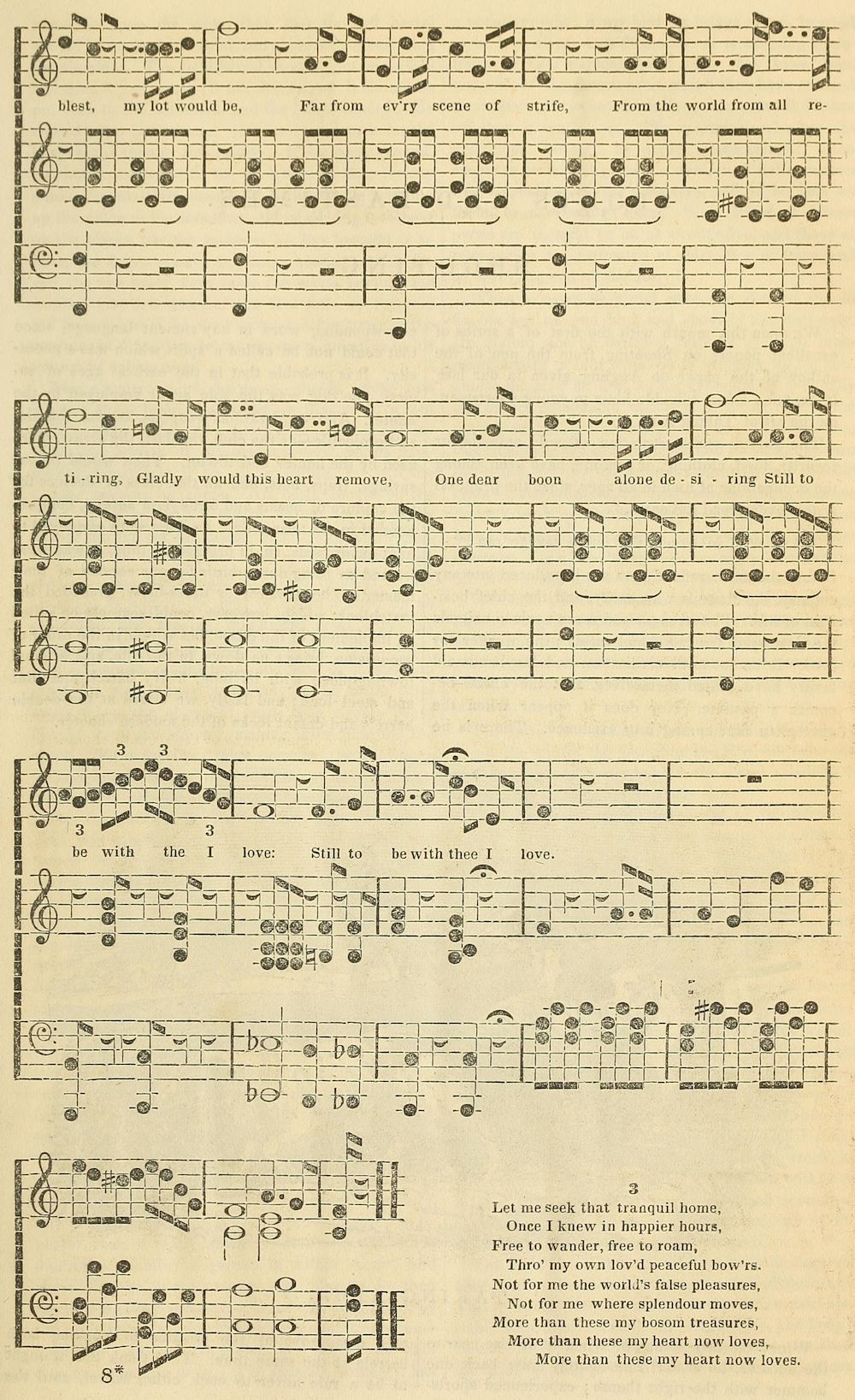

| Not for Me! Not for Me! | |

| Fashions for February, 1841 | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

J. Sartain sc.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XVIII. FEBRUARY, 1841. No. 2.

Who that has read the “Last Days of Pompeii” can forget Nydia, the blind flower-girl? So sweet, and pure, and gentle, and devoted in her unrequited love, she steals insensibly upon the heart, and wins a place therein, which even the brilliant Ione fails to obtain! Poor, artless innocent, her life, alas! was one of disappointment from its birth.

We cannot better portray the character of this guileless being than by copying the exquisite description of Bulwer. The scene opens with a company of gay, young Pompeiians—among whom is Glaucus, the hero of the story—taking a morning stroll through the town. We let the story speak for itself.

“Thus conversing, their steps were arrested by a crowd gathered round an open space where three streets met; and just where the porticoes of a light and graceful temple threw their shade, there stood a young girl, with a flower-basket on her right arm, and a small three-stringed instrument of music in the left hand, to whose low and soft tones she was modulating a wild and half-barbaric air. At every pause in the music she gracefully waved her flower basket round, inviting the loiterers to buy; and many a sesterce was showered into the basket, either in compliment to the music, or in compassion to the songstress—for she was blind.

“ ‘It is my poor Thessalian,’ said Glaucus, stopping; ‘I have not seen her since my return to Pompeii. Hush! her voice is sweet; let us listen.’

THE BLIND FLOWER GIRL’S SONG.

Buy my Flowers—O buy—I pray,

The Blind Girl comes from afar:

If the Earth be as fair as I hear them say,

These Flowers her children are!

Do they her beauty keep?

They are fresh from her lap, I know;

For I caught them fast asleep

In her arms an hour ago,

With the air which is her breath—

Her soft and delicate breath—

Over them murmuring low!—

On their lips her sweet kiss lingers yet,

And their cheeks with her tender tears are wet,

For she weeps,—that gentle mother weeps

(As morn and night her watch she keeps,

With a yearning heart and a passionate care,)

To see the young things grow so fair;

She weeps—for love she weeps—

And the dews are the tears she weeps

From the well of a mother’s love!

Ye have a world of light,

Where love in the lov’d rejoices;

But the Blind Girl’s home is the House of Night,

And its Beings are empty voices.

As one in the Realm below,

I stand by the streams of wo;

I hear the vain shadows glide,

I feel their soft breath at my side,

And I thirst the lov’d forms to see,

And I stretch my fond arms around,

And I catch but a shapeless sound,

For the Living are Ghosts to me.

Come buy—come buy!—

Hark! how the sweet things sigh

(For they have a voice like ours,)

“The breath of the Blind Girl closes

The leaves of the saddening roses—

We are tender, we sons of Light,

We shrink from this child of Night;

From the grasp of the Blind Girl free us,

We yearn for the eyes that see us—

We are for Night too gay,

In our eyes we behold the day—

O buy—O buy the Flowers!”

“ ‘I must have yon bunch of violets, sweet Nydia,’ said Glaucus, pressing through the crowd, and dropping a handful of small coins into the basket; ‘your voice is more charming than ever.’

“The blind girl started forward as she heard the Athenian’s voice—then as suddenly paused, while the blood rushed violently over neck, cheek, and temples.

“ ‘So you are returned!’ said she in a low voice; and then repeated, half to herself, ‘Glaucus is returned!’

“ ‘Yes, child, I have not been at Pompeii above a few days. My garden wants your care as before, you will visit it, I trust, to-morrow. And mind, no garlands at my house shall be woven by any hands but those of the pretty Nydia.’

“Nydia smiled joyously, but did not answer; and Glaucus, placing the violets he had selected in his breast, turned gayly and carelessly from the crowd.

“ ‘So, she is a sort of client of yours, this child?’ said Clodius.

“ ‘Ay—does she not sing prettily? She interests me, the poor slave!—besides, she is from the land of the Gods’ hill—Olympus frowned upon her cradle—she is of Thessaly.’ ”

How exquisitely is the love of Nydia told in her joy at the return of Glaucus! Only a master-hand could have described it in that blush, and start, and the glad exclamation, “Glaucus is returned!”

The revellers meanwhile pass on their way, and it is not till the following morning that the flower-girl appears again upon the scene. But though she comes even while the Athenian is musing on his mistress Ione, there is a beauty around Nydia’s every movement which makes us hail her with delight. It is her appearance at this visit which the artist has transferred to the canvass. Lo! are not the limner and the author equally inimitable?

“Longer, perhaps, had been the enamored soliloquy of Glaucus, but at that moment a shadow darkened the threshold of the chamber, and a young female, still half a child in years, broke upon his solitude. She was dressed simply in a white tunic, which reached from the neck to the ankles; under her arm she bore a basket of flowers, and in the other hand she held a bronze water vase; her features were more formed than exactly became her years, yet they were soft and feminine in their outline, and without being beautiful in themselves they were almost made so by their beauty of expression; there was something ineffably gentle, and you would say patient, in her aspect—a look of resigned sorrow, of tranquil endurance, had banished the smile, but not the sweetness, from her lips; something timid and cautious in her step—something wandering in her eyes, led you to suspect the affliction which she had suffered from her birth—she was blind; but in the orbs themselves there was no visible defect, their melancholy and subdued light was clear, cloudless, and serene. ‘They tell me that Glaucus is here,’ said she; ‘may I come in?’

“ ‘Ah, my Nydia,’ said the Greek, ‘is that you? I knew you would not neglect my invitation.’

“ ‘Glaucus did but justice to himself,’ answered Nydia, with a blush, ‘for he has always been kind to the poor blind girl.’

“ ‘Who could be otherwise?’ said Glaucus, tenderly, and in the voice of a compassionate brother.

“Nydia sighed and paused before she resumed, without replying to his remark. ‘You have but lately returned? This is the sixth sun that hath shone upon me at Pompeii. And you are well? Ah, I need not ask—for who that sees the earth which they tell me is so beautiful can be ill?’

“ ‘I am well—and you, Nydia?—how you have grown! next year you will be thinking of what answer we shall make your lovers.’

“A second blush passed over the cheek of Nydia, but this time she frowned as she blushed. ‘I have brought you some flowers,’ said she, without replying to a remark she seemed to resent, and feeling about the room till she found the table that stood by Glaucus, she laid the basket upon it: ‘they are poor, but they are fresh gathered.’

“ ‘They might come from Flora herself,’ said he, kindly; ‘and I renew again my vow to the Graces that I will wear no other garlands while thy hands can weave me such as these.’

“ ‘And how find you the flowers in your viridarium? are they thriving?’

“ ‘Wonderfully so—the Lares themselves must have tended them.’

“ ‘Ah, now you give me pleasure; for I came, as often as I could steal the leisure, to water and tend them in your absence.’

“ ‘How shall I thank thee, fair Nydia?’ said the Greek. ‘Glaucus little dreamed that he left one memory so watchful over his favorites at Pompeii.’

“The hand of the child trembled, and her breast heaved beneath her tunic. She turned around in embarrassment. ‘The sun is hot for the poor flowers,’ said she, ‘to-day, and they will miss me, for I have been ill lately, and it is nine days since I visited them.’

“ ‘Ill, Nydia! yet your cheek has more color than it had last year.’

“ ‘I am often ailing,’ said the blind girl, touchingly, ‘and as I grow up I grieve more that I am blind. But now to the flowers!’ So saying, she made a slight reverence with her head, and passing into the viridarium, busied herself with watering the flowers.

“ ‘Poor Nydia,’ thought Glaucus, gazing on her, ‘thine is a hard doom. Thou seest not the earth—nor the sun—nor the ocean—nor the stars—above all, thou canst not behold Ione.’

Nydia, too, is a slave, and to a coarse inn-keeper, who would make a profit by her beauty and her singing. How her heart breaks daily at the brutal treatment of her master, and the still more cruel language of his patrons! But at length Glaucus purchases her, and she is comparatively happy. And through all her melancholy history how does her hopeless love shine out, beautifying and making more sweet than ever, her guileless character! It is a long and mournful tale. Glaucus at length succeeds in winning Ione; they escape fortunately from the destruction of Pompeii; but Nydia, uncomplaining, yet broken-hearted, disappears mysteriously from the deck of their vessel at night. Need we tell her probable fate?

———

BY THE AUTHOR OF “CRUIZING IN THE LAST WAR.”

———

How often has the story of the heart been told! The history of the love of one bosom is that of the millions who have alternated between hope and fear since first the human heart began to throb. The gradual awakening of our affection; the first consciousness we have of our own feelings; the tumultuous emotions of doubt and certainty we experience, and the wild rapture of the moment, when, for the first time, we learn that our love is requited, have all been told by pens more graphic than mine, and in language as nervous as that of Fielding, or as moving as that of Richardson.

The daily companionship into which I was now thrown with Beatrice was, of all things, the most dangerous to my peace. From the first moment when I beheld her she had occupied a place in my thoughts; and the footing of acquaintanceship, not to say intimacy, on which we now lived, was little calculated to banish her from my mind. Oh! how I loved to linger by her side during the moonlight evenings of that balmy latitude, talking of a thousand things which, at other times, would have been void of interest, or gazing silently upon the peaceful scene around, with a hush upon our hearts it seemed almost sacrilege to break. And at such times how the merest trifle would afford us food for conversation, or how eloquent would be the quiet of that holy silence! Yes! the ripple of a wave, or the glimmer of the spray, or the twinkling of a star, or the voice of the night-wind sighing low, or the deep, mysterious language of the unquiet ocean, had, at such moments, a beauty in them, stirring every chord in our hearts, and filling us, as it were, with sympathy not only for each other, but for every thing in Nature. And when we would part for the night, I would pace for hours, my solitary watch, thinking of Beatrice, with all the rapt devotion of a first, pure love.

But this could not last. The dream was pleasant, yet it might not lead me to dishonor. Beatrice was under my protection, and was it right to avail myself of that advantage to win her heart, when I knew from the difference of our stations in life, that it was madness to think that she could ever be mine. What? the heiress of one of the richest Jamaica residents, the grand-daughter of a baron, and the near connexion of some of the wealthiest tory families of the south, to be wooed as an equal by one who not only had no fortune but his sword, but was the advocate, in the eyes of her advisers, of a rebellious cause! Nor did the service I had rendered her lessen the difficulty of my position.

These feelings, however, had rendered me more guarded, perhaps more cold, in the presence of Beatrice, for a day or two preceding our arrival in port. I felt my case hopeless: and I wished, by gradually avoiding the danger, to lessen the agony of the final separation. Besides, I knew nothing as yet of the sentiments of Beatrice toward myself. I was a novice in love; and the silent abstraction of her manner, together with the gradually increasing avoidance of my presence, filled me with uneasiness, despite the conviction of the hopelessness of my suit. But what was it to me, I would say, even if Beatrice loved me not? Was it not better that it should be so? Alas! reason and love are two very different things, and though I was better satisfied with myself when we made the lights of Charleston harbor, yet the almost total separation which had thus for nearly two days existed between Beatrice and myself, left my heart tormented with all a lover’s fears.

It was the last evening we would spend together, perhaps for years. The wind had died away, and we slowly floated upward with the tide, the shores of James Island hanging like a dark cloud on the larboard beam, and the lights of the distant city, glimmering along the horizon inboard; while no sound broke the stillness of the hour, except the occasional wash of a ripple, or the song of some negro fishermen floating across the water. As I stood by the starboard railing, gazing on this scenery, I could not help contrasting my present situation with what it had been but a few short weeks before, when I left the harbor of New York. So intensely was I wrapt in these thoughts, that I did not notice the appearance of Beatrice on deck, until the question of the helmsman, dissolving my reverie, caused me to look around me. For a moment I hesitated whether I should join her or not. My feelings at length, however, prevailed; and crossing the deck, I soon stood at her side. She did not appear to notice my presence, but with her elbow resting on the railing, and her head buried in her hand, was pensively looking down upon the tide.

“Miss Derwent!” said I, with a voice that I was conscious trembled, though I scarce knew why it did.

“Mr. Parker!” she ejaculated in a tone of surprise, her eyes sparkling, as starting suddenly around she blushed over neck and brow, and then as suddenly dropped her eyes to the deck, and began playing with her fan. For a moment we were both mutually embarrassed. A woman is, at such times, the first to speak.

“Shall we be able to land to-night?” said Beatrice.

“Not unless a breeze springs up—”

“Oh! then I hope we shall not have one,” ejaculated the guileless girl; but instantly becoming aware of the interpretation which might be put upon her remark, she blushed again, and cast her eyes anew upon the deck. A strange, joyous hope shot through my bosom; but I made a strong effort and checked my feelings. Another silence ensued, which every moment became more oppressive.

“You join, I presume, your cousin’s family on landing,” said I at length, “I will, as soon as we come to anchor, send a messenger ashore, apprising him of your presence on board.”

“How shall I ever thank you sufficiently,” said Beatrice, raising her dark eyes frankly to mine, “for your kindness? Never—never,” she continued more warmly, “shall I forget it.”

My soul thrilled to its deepest fibre at the words, and more than all, at the tone of the speaker; and it was with some difficulty that I could answer calmly,—

“The consciousness of having ever merited Miss Derwent’s thanks, is a sufficient reward for all I have done. That she will not wholly forget me is more than I could ask; but believe me, Beatrice,” said I, unable to restrain my feelings, and venturing, for the first time, to call her by that name, “though we shall soon part forever, never, never can I forget these few happy days.”

“Why—do you leave Charleston instantly?” said she, with emotion, “shall I not see you again after my landing?”

I know not how it is, but there are moments when our best resolutions vanish as though they had never been made; and now, as I looked upon the earnest countenance of Beatrice, and felt the full meaning of the words so innocently said, a wild hope once more shot across my bosom, and I said softly,—

“Why, Beatrice, would it be aught to you whether we ever met again?”

She lifted her eyes up to mine, and gazed for an instant almost reproachfully upon me, but she did not answer. There was something, however, in the look encouraging me to go on. I took her hand: she did not withdraw it: and, in a few hurried, but burning words, I poured forth my love.

“Say, Beatrice?” I said, “can you, do you love me?”

She raised her dark eyes in answer up to mine, with an expression I shall never forget, and murmured, half inaudibly,—

“You know—you know I do,” and then overcome by the consciousness of all she had done, she burst into tears.

Can words describe my feelings? Oh! if I had the eloquence of a Rosseau I could not portray the emotions of that moment. They were wild; they were almost uncontrollable. The tone, the words, everything convinced me that I was beloved; and all my well-formed resolutions were dissipated in a moment. Had we been alone I would have caught Beatrice to my bosom; but as it was, I could only press her hand in silence. I needed not to be assured, in more direct terms, of her affection. Henceforth she was to me my all. She was the star of my destiny!

The first dawn of morning beheld us abreast of the town, and at an early hour the equipage of Mr. Rochester, the relative of Beatrice, and whose guest she was now to be, was in waiting on the quay for my beautiful charge.

“You will come to-night, will you not?” said she, as I pressed her hand, on conducting her to the carriage.

I bowed affirmatively, the door was closed, and the sumptuous equipage, with its servants in livery, moved rapidly away.

It was now that I had parted with Beatrice, that the conviction of the almost utter hopelessness of my suit forced itself upon my mind. Mr. Rochester was the nearest male relative of Beatrice, being her maternal uncle. Her parents were both deceased, and the uncle, whose death I have related, together with the Carolinian nabob, were, by her father’s will, her guardians. Mr. Rochester was, therefore, her natural protector. Her fortune, though large, was fettered with a condition that she should not marry without her guardian’s consent, and I soon learned that a union had long been projected between her and the eldest son of her surviving guardian. How little hope I had before, the reader knows, but that little was now fearfully diminished. It is true Beatrice had owned that she loved me, but how could I ask her to sacrifice the comforts as well as the elegancies of life, to share her lot with a poor unfriended midshipman? I could not endure the thought. What! should I take advantage of the gratitude of a pure young being—a being, too, who had always been nourished in the lap of luxury—to subject her to privation, and perhaps to beggary? No, rather would I have lived wholly absent from her presence. I could almost have consented to lose her love, sooner than be the instrument of inflicting on her miseries so crushing. My only hope was in winning a name that would yet entitle me to ask her hand as an equal: my only fear was, lest the length of time I should be absent from her side, would gradually lose me her affection. Such is the jealous fear of a lover’s heart.

Meanwhile, however, the whole city resounded with the din of war. A despatch from the Secretary of Slate, to Gov. Eden, of Maryland, had been intercepted by Com. Barron, of the Virginia service, in the Chesapeake. From this missive, intelligence was gleaned that the capital of South Carolina was to be attacked; and on my arrival I found every exertion being made to place it in a posture of defence. I instantly volunteered, and the duties thus assumed, engrossing a large part of my time, left me little leisure, even for my suit. Still, however, I occasionally saw Beatrice, though the cold hauteur with which my visits were received by her uncle’s family, much diminished their frequency.

As the time rolled on, however, and the British fleet did not make its appearance, there were not wanting many who believed that the contemplated attack had been given up. But I was not of the number. So firm, indeed, was my conviction of the truth of the intelligence that I ran out to sea every day or two, in a smart-sailing pilot-boat, in order, if possible, to gain the first positive knowledge of the approach of our foes.

“A sail,” shouted our look-out one day, after we had been standing off and on for several hours, “a sail, broad on the weather-beam!”

Every eye was instantly turned toward the quarter indicated; spy-glasses were brought into requisition; and in a few minutes we made out distinctly nearly a dozen sail, on the larboard tack, looming up on the northern sea-board. We counted no less than six men-of-war, besides several transports. Every thing was instantly wet down to the trucks, and heading at once for Charleston harbor, we soon bore the alarming intelligence to the inhabitants of the town.

That night all was terror and bustle in the tumultuous capital. The peaceful citizens, unused to bloodshed, gazed upon the approaching conflict with mingled resolution and terror, now determining to die rather than to be conquered, and now trembling for the safety of their wives and little ones. Crowds swarmed the wharves, and even put out into the bay to catch a sight of the approaching squadron. At length it appeared off the bar, and we soon saw by their buoying out the channel, that an immediate attack was to take place by sea,—while expresses brought us hasty intelligence of the progress made by the royal troops in landing on Long Island. But want of water among our foes, and the indecision of their General, protracted the attack for more than three weeks, a delay which we eagerly improved.

At length, on the morning of the 28th of June, it became evident that our assailants were preparing to commence the attack. Eager to begin my career of fame, I sought a post under Col. Moultrie, satisfied that the fort on Sullivan’s Island would have to maintain the brunt of the conflict.

Never shall I forget the sight which presented itself to me on reaching our position. The fort we were expected to maintain, was a low building of palmetto logs, situated on a tongue of the island, and protected in the rear from the royalist troops, on Long Island, by a narrow channel, usually fordable, but now, owing to the late prevalence of easterly winds, providentially filled to a depth of some fathoms. In front of us lay the mouth of the harbor, commanded on the opposite shore, at the distance of about thirty-five hundred yards, by another fort in our possession, where Col. Gadsen, with a respectable body of troops was posted. To the right opened the bay, sweeping almost a quarter of the compass around the horizon, toward the north,—and on its extreme verge, to the north west, rose up Haddrell’s point, where General Lee, our commander-in-chief, had taken up a position. About half way around, and due west from us, lay the city, at the distance of nearly four miles, the view being partly intercepted by the low, marshy island, called Shute’s Folly, between us and the town.

“We have but twenty-eight pounds of powder, Mr. Parker, a fact I should not like generally known,” said Col. Moultrie to me, “but as you have been in action before—more than I can say of a dozen of my men—I know you may be trusted with the information.”

“Never doubt the brave continentals here, colonel,” I replied, “they are only four hundred, but we shall teach yon braggarts a lesson, before to-day is over, which they shall not soon forget.”

“Bravo, my gallant young friend! With my twenty-six eighteen and twenty four pounders, plenty of powder, and a few hundred fire-eaters like yourself I would blow the whole fleet out of water. But after all,” said he with good-humored raillery, “though you’ll not glory in rescuing Miss Derwent to-day, you’ll fight not a whit the worse for knowing that she is in Charleston, eh! But, come, don’t blush—you must be my aid—I shall want you, depend upon it, before the day is over. If those red-coats here, behind us, attempt to take us in the rear, we shall have hot work,—for by my hopes of eternal salvation, I’ll drive them back, man and officer, in spite of Gen. Lee’s fears that I cannot. But ha! there comes the first bomb.”

Looking upward as he spoke, I beheld a large, dark body flying through the air; and in the next instant, amidst a cheer from our men, it splashed into the morass behind us, simmered, and went out.

“Well sent, old Thunderer,” ejaculated the imperturbable colonel, “but, faith, many another good bomb will you throw away on the swamps and palmetto logs you sneer at. Open upon them, my brave fellows, as they come around, and teach them what Carolinians can do. Remember, you fight to-day for your wives, your children, and your liberties. The Continental Congress forever against the minions of a tyrannical court.”

The battle was now begun. One by one the British men-of-war, coming gallantly into their respective stations, and dropping their anchors with masterly coolness, opened their batteries upon us, firing with a rapidity and precision that displayed their skill. The odds against which we had to contend were indeed formidable. Directly in front of us, with springs on their cables, and supported by two frigates, were anchored a couple of two-deckers; while the three other men-of-war were working up to starboard, and endeavoring to get a position between us and the town, so as to cut off our communications with Haddrell’s Point.

“Keep it up—run her out again,” shouted the captain of a gun beside me, who was firing deliberately, but with murderous precision, every shot of his piece telling on the hull of one of the British cruizers, “huzza for Carolina!”

“Here comes the broadside of Sir Peter’s two-decker,” shouted another one, “make way for the British iron among the palmetto logs. Ha! old yellow breeches how d’ye like that?” he continued as the shot from his piece, struck the quarter of the flag-ship, knocking the splinters high into the air, and cutting transversely through and through her crowded decks.

Meanwhile the three men-of-war attempting to cut off our communications, had got entangled among the shoals to our right, and now lay utterly helpless, engaged in attempting to get afloat, and unable to fire a gun. Directly two of them ran afoul, carrying away the bowsprit of the smaller one.

“Huzza!” shouted the old bruiser again, squinting a moment in that direction, “they’re smashing each other to pieces there without our help, and so here goes at smashing their messmates in front here—what the devil,” he continued, turning smartly around to cuff a powder boy, “what are you gaping up stream for, when you should be waiting on me?—take that you varmint, and see if you can do as neat a thing as this when you’re old enough to point a gun. By the Lord Harry I’ve cut away that fore-top-mast as clean as a whistle.”

Meantime the conflict waxed hotter and hotter, and through the long summer afternoon, except during an interval when we slackened it for want of powder, our brave fellows, with the coolness of veterans, and the enthusiasm of youth, kept up their fire. A patriotic ardor burned along our lines, which only became more resistless, as the wounded were carried past in the arms of their comrades. The contest was at its height when General Lee arrived from the mainland to offer to remove us if we wished to abandon our perilous position.

“Abandon our position, General!” said Colonel Moultrie, “will your excellency but visit the guns, and ask the men whether they will give up the fort? No, we will die or conquer here.”

The eye of the Commander-in-Chief flashed proudly at this reply, and stepping out upon the plain, he approached a party who were firing with terrible precision upon the British fleet. This fearless exposure of his person called forth a cheer from the men; but without giving him time to remain long in so dangerous a position, Colonel Moultrie exclaimed,

“My brave fellows, the general has come off to offer to remove you to the main if you are tired of your post. Shall it be?”

There was a universal negative, every man declaring he would sooner die at his gun. It was a noble sight. Their eyes flashing; their chests dilated; their brawny arms bared and covered with smoke, they stood there, determined, to a man, to save their native soil at every cost, from invasion. At this moment a group appeared, carrying a poor fellow, whom it could be seen at a glance was mortally wounded. His lips were blue; his countenance ghastly; and his dim eye rolled uneasily about. He breathed heavily. But as he approached us, the shouts of his fellow soldiers falling on his ear, aroused his dying faculties, and lifting himself heavily up, his eye, after wandering inquiringly about, caught the sight of his general.

“God bless you! my poor fellow,” said Lee, compassionately, “you are, I fear, seriously hurt.”

The dying man looked at him as if not comprehending his remark, and then fixing his eye upon his general, said faintly,

“Did not some one talk of abandoning the fort?”

“Yes,” answered Lee, “I offered to remove you or let you fight it out—but I see you brave fellows would rather die than retreat.”

“Die!” said the wounded man, raising himself half upright, with sudden strength, while his eye gleamed with a brighter lustre than even in health. “I thank my God that I am dying, if we can only beat the British back. Die! I have no family, and my life is well given for the freedom of my country. No, my men, never retreat,” he continued, turning to his fellow soldiers, and waving his arm around his head, “huzza for li—i—ber—ty—huz—za—a—a,” and as the word died away, quivering in his throat, he fell back, a twitch passed over his face, and he was dead.

Need I detail the rest of that bloody day? For nine hours, without intermission, the cannonade was continued with a rapidity on the part of our foes, and a murderous precision on that of ourselves, such as I have never since seen equalled. Night did not terminate the conflict. The long afternoon wore away; the sun went down; the twilight came and vanished; darkness reigned over the distant shores around us, yet the flash of the guns, and the roar of the explosions did not cease. As the evening grew more obscure the whole horizon became illuminated by the fire of our batteries, and the long, meteor-like tracks of the shells through the sky. The crash of spars; the shouts of the men; and the thunder of the cannonade formed meanwhile a discord as terrible as it was exciting; while the lights flashing along the bay, and twinkling from our encampment at Haddrell’s Point, made the scene even picturesque.

Long was the conflict, and desperately did our enemies struggle to maintain their posts. Even when the cable of the flag-ship had been cut away, and swinging around with her stern toward us, every shot from our battery was enabled to traverse the whole length of her decks, amid terrific slaughter, she did not display a sign of fear, but doggedly maintained her position, keeping up a straggling fire upon us, for some time, from such of her guns as could be brought to bear. At length, however, a new cable was rigged upon her, and swinging around broadside on, she resumed her fire. But it was in vain. Had they fought till doomsday they could not have overcome the indomitable courage of men warring for their lives and liberties; and finding that our fire only grew more deadly at every discharge, Sir Peter Parker at length made the signal to retire. One of the frigates farther in the bay had grounded, however, so firmly on the shoals that she could not be got off; and when she was abandoned and fired next morning, our brave fellows, despite the flames wreathing already around her, boarded her, and fired at the retreating squadron until it was out of range. They had not finally deserted her more than a quarter of an hour before she blew up with a stunning shock.

The rejoicing among the inhabitants after this signal victory were long and joyous. We were thanked; feted; and became lions at once. The tory families, among which was that of Mr. Rochester, maintained, however, a sullen silence. The suspicion which such conduct created made it scarcely advisable that I should become a constant visitor at his mansion, even if the cold civility of his family had not, as I have stated before, furnished other obstacles to my seeing Beatrice. Mr. Rochester, it is true, had thanked me for the services I had rendered his ward, but he had done so in a manner frigid and reserved to the last degree, closing his expression of gratitude with an offer of pecuniary recompense, which not only made the blood tingle in my veins, but detracted from the value of what little he had said.

A fortnight had now elapsed since I had seen Beatrice, and I was still delayed at Charleston, waiting for a passage to the north, and arranging the proceeds of our prize, when I received an invitation to a ball at the house of one of the leaders of ton, who affecting a neutrality in politics, issued cards indiscriminately to both parties. Feeling a presentiment that Beatrice would be there, and doubtless unaccompanied by her uncle or cousin, I determined to go, and seek an opportunity to bid her farewell, unobserved, before my departure.

The rooms were crowded to excess. All that taste could suggest, or wealth afford, had been called into requisition to increase the splendor of the fete. Rich chandeliers; sumptuous ottomans; flowers of every hue; and an array of loveliness such as I have rarely seen equalled, made the lofty apartments almost a fairy palace. But amid that throng of beauty there was but one form which attracted my eye. It was that of Beatrice. She was surrounded by a crowd of admirers, and I felt a pang of almost jealousy, when I saw her, as I thought, smiling as gaily as the most thoughtless beauty present. But as I drew nearer I noticed that, amid all her affected gaiety, a sadness would momentarily steal over her fine countenance, like a cloud flitting over a sunny summer landscape. As I edged toward her through the crowd, her eye caught mine, and in an instant lighted up with a joyousness that was no longer assumed. I felt repaid, amply repaid by that one glance, for all the doubts I had suffered during the past fortnight; but the formalities of etiquette prevented me from doing aught except to return an answering glance, and solicit the hand of Beatrice.

“Oh! why have you been absent so long?” said the dear girl, after the dance had been concluded, and we had sauntered together, as if involuntarily, into a conservatory behind the ball room, “every one is talking of your conduct at the fort—do you know I too am a rebel—and do you then sail for the north?”

“Yes, dearest,” I replied, “and I have sought you to-night to bid you adieu for months—it may be for years. God only knows, Beatrice,” and I pressed her hand against my heart, “when we shall meet again. Perhaps you may not even hear from me; the war will doubtless cut off the communications; and sweet one, say will you still love me, though others may be willing to say that I have forgotten you?”

“Oh! how can you ask me? But you—will—write—won’t you?” and she lifted those deep, dark, liquid eyes to mine, gazing confidingly upon me, until my soul swam in ecstacy. My best answer was a renewed pressure of that small, fair hand.

“And Beatrice,” said I, venturing upon a topic, to which I had never yet alluded, “if they seek to wed you to another will you—you still be mine only?”

“How can you ask so cruel a question?” was the answer, in a tone so low and sweet, yet half reproachful, that no ear but that of a lover could have heard it. “Oh! you know better—you know,” she added, with energy, “that they have already planned a marriage between me and my cousin; but never, never can I consent to wed where my heart goes not with my hand. And now you know all,” she said tearfully, “and though they may forbid me to think of you, yet I can never forget the past. No, believe me, Beatrice Derwent where once she has plighted her faith, will never afterward betray it,” and overcome by her emotions, the fair girl leaned upon my shoulder and wept long and freely.

But I will not protract the scene. Anew we exchanged our protestations of love, and after waiting until Beatrice had grown composed we returned to the ball room. Under the plea of illness I saw her soon depart, nor was I long in following. No one, however, had noticed our absence. Her haughty uncle, in his luxurious library, little suspected the scene that had that night occurred. But his conduct, I felt, had exonerated me from every obligation to him, and I determined to win his ward, if fortune favored me, in despite of his opposition. My honor was no longer concerned against me: I felt free to act as I chose.

The British fleet meanwhile, having been seen no more upon the coast, the communication with the north, by sea, became easy again. New York, however, was in the possession of the enemy, and a squadron was daily expected at the mouth of Delaware Bay. To neither of these ports, consequently, could I obtain a passage. Nor indeed did I wish it. There was no possibility that the Fire-Fly would enter, either, to re-victual, and as I was anxious to join her, it was useless to waste time in a port where she could not enter. Newport held out the only chance to me for rejoining my vessel. It was but a day’s travel from thence to Boston, and at one or the other of these places I felt confident the Fire-Fly would appear before winter.

The very day, however, after seeing Beatrice, I obtained a passage in a brig, which had been bound to another port, but whose destination the owners had changed to Newport, almost on the eve of sailing. I instantly made arrangements for embarking in her, having already disposed of our prize, and invested the money in a manner which I knew would allow it to be distributed among the crew of the Fire-Fly at the earliest opportunity. My parting with Col. Moultrie was like parting from a father. He gave me his blessing; I carried my kit on board; and before forty-eight hours I was once more at sea.

“Sleep hath its own world,

And a wide realm of wild reality,

And dreams in their development have breath,

And tears, and tortures, and the touch of joy.”

On Alligewi’s[1] mountain height

An Indian hunter lay reclining,

Gazing upon the sunset light

In all its loveliest grace declining.

Onward the chase he had since dawn

Pursued, with swift-winged step, o’er lawn,

And pine-clad steep, and winding dell,

And deep ravine, and covert nook

Wherein the red-deer loves to dwell,

And silent cove, and brawling brook;

Yet not till twilight’s mists descending,

Had dimmed the wooded vales below,

Did he, his homeward pathway wending,

Droop ’neath his spoil, with footsteps slow.

Then, as he breathless paused, and faint,

The shout of joy that pealed on high

As broke that landscape on his eye,

Imaginings alone can paint.

Down on the granite brow, his prey,

In all its antlered glory lay.

His plumage flowed above the spoil—

His quiver, and the slackened bow,

Companions of his ceaseless toil,

Lay careless at its side below.

Oh! who might gaze, and not grow brighter,

More pure, more holy, and serene;

Who might not feel existence lighter

Beneath the power of such a scene?

Marking the blush of light ascending

From where the sun had set afar,

Tinting each fleecy cloud, and blending

With the pale azure; while each star

Came smiling forth ’mid roseate hue,

And deepened into brighter lustre

As Night, with shadowy fingers threw

Her dusky mantle round each cluster.

Purple, and floods of gold, were streaming

Around the sunset’s crimson way,

And all the impassioned west was gleaming

With the rich flush of dying day.

Far, far below the wandering sight,

Seen through the gath’ring gloom of night,

A mighty river rushing on,

Seemed dwindled to a fairy’s zone.

No bark upon its wave was seen,

Or if ’twas there, it glided by

As viewless forms, that once have been,

Will flit, half-seen, before the eye.

Long gazed the hunter on that sight,

’Till twilight darkened into night,

Dim and more dim the landscape grew,

And duskier was the empyrean blue;

Glittered a thousand stars on high,

And wailed the night-wind sadly by;

And slowly fading, one by one,

Cliff, cloud, ravine, and mountain pass

Grew darker still, and yet more dun,

’Till deep’ning to a shadowy mass,

They seemed to mingle, earth and sky,

In one wild, weird-like canopy.

Yet lo! that hunter starts, and one

Whom it were heaven to gaze upon,

A beauteous girl,—as ’twere a fawn,

So playful, wild, and gentle too,—

Came bounding o’er the shadowy lawn,

With step as light, and love as true.

It was Echucha! she, his bride,

Dearer than all of earth beside,—

For she had left her sire’s far home,

The woodland depths with him to roam

Who was that sire’s embittered foe!

And there, in loveliness alone,

With him her opening beauty shone.

But even while he gazed, that form,

As fades the lightning in the storm,

Passed quickly from his sight.

He looked again, no one was there,

No voice was on the stilly air,

No step upon the greensward fair,

But all around was night.

She past, but thro’ that hunter’s mind,

What wild’ring memories are rushing,

As harps, beneath a summer wind,

With wild, mysterious lays are gushing.

Fast came rememb’rance of that eve,

Whose first wild throb of earthly bliss

Was but to gaze, and to receive

The boon of hope so vast as this—

To clasp that being as his own,

To win her from her native bowers;

And form a spirit-land, alone

With her amid perennial flowers.

And as he thought, that dark, deep eye,

Seemed hovering as ’twas wont to bless,

When the soft hand would on him lie,

And sooth his soul to happiness.

Like the far-off stream, in its murmurings low,

Like the first warm breath of spring,

Like the Wickolis in its plaintive flow,

Or the ring-dove’s fluttering wing,

Came swelling along the balmy air,

As if a spirit itself was there,

So sweet, so soft, so rich a strain,

It might not bless the ear again,

Now breathed afar, now swelling near,

It gushed on the enraptured ear;—

And hark! was it her well-known tone?

No—naught is heard but the voice alone.

“Warrior of the Lenape race,

Thou of the oak that cannot bend,

Of noble brow and stately grace,

And agile step, of the Tamenend,

Arise—come thou with me!

Echucha waits in silent glade,

Her eyes the eagle’s gaze assume,

As daylight’s golden glories fade,

To catch afar her hunter’s plume,—

But naught, naught can she see.

Her hair is decked with ocean shell,

The vermeil bright is on her brow,

The peag zone enclasps her well,

Her heart is sad beneath it now,

She weeps, and weeps for thee.

With early dawn thou hiedst away,

In reckless sports the hours to while,

Oh! sweet as flowers, in moonlit ray,

Shall be thy look, thy voice, thy smile,

When again she looks on thee!

Oh! come, come then with me.”

Scarce ceased the strain, when silence deep,

As broods o’er an unbroken sleep,

Seemed hovering round; then slowly came

A glow athwart the darkling night,

Bursting at length to mid-day flame,

And bathing hill and vale in light.

While suddenly a form flits by

With step as fleet, as through the sky

The morning songster skims along

Preceded by his matchless song.

So glided she; yet not unseen

Her graceful gait, her brow serene,

Her finely modelled limbs so round,

Her raven tresses all unbound,

That flashing out, and hidden now,

Waved darkly on each snowy shoulder,—

As springing from the mountain’s brow,

Eager and wild that one to know,

The hunter hurried to behold her.

On, on the beauteous phantom glides

Beneath the sombre, giant pines

That stud the steep and rugged sides

Of pendant cliffs, and deep ravines;

Down many a wild descent and dell

O’ergrown with twisted lichens rude;

Yet where she passed a halo fell

To guide the footsteps that pursued,—

Like that fell wonder of the sky

That flashes o’er the starry space,

And leaves its glitt’ring wake on high,

For man portentous truths to trace.

And onward, onward still that light

Was all which beamed upon the sight.

Of figure he could naught descry,

Invisible it seemed to fly;

Alluring on with magic art

That half disclosing, hid in part.

Bright, beautiful, resistless Fate!

Oh! what is like thy magic will,

Which men in blind obedience wait,

Yet deem themselves unfettered still!

By thee impelled that hunter sped

Through shadowy wood, o’er flowery bed;

When angels else, beneath his eye,

Had passed unseen, unnoticed by.

The Indian brave! that stoic wild,

Philosophy’s untutored child,

A being, such as wisdom’s torch

Enkindled ’neath the attic porch,

Where the Phoenician stern and eld,

His wise man[2] to the world revealing,

Divined not western wildness held

Untutored ones less swayed by feeling;

Whose firm endurance fire nor stake

Nor torture’s fiercest pangs might shake.

Yes! matter, mind, the eternal whole,

In apprehension revelling free,

Evolved that fearlessness of soul

Which Greece[3] saw but in theory.

Still on that beauteous phantom fled,

And still behind the hunter sped.

Nor turned she ’till where many a rock

Lay rent as by an earthquake’s shock,

And through the midst a stream its way

Held on ’mid showers of falling spray,

Marking by one long line of foam

Its passage from its mountain home.

But now, amid the light mist glancing

Like elf or water-nymph, the maid

With ravishment of form entrancing

The spell-bound gazer, stood displayed.

So looked that Grecian maiden’s face,

So every grace and movement shone,

When ’neath the sculptor’s wild embrace,

Life, love, and rapture flushed from stone.

She paused, as if her path to trace

Through the thick mist that boiled on high,

Then turning full her unseen face,

There, there, the same, that lustrous eye,

So fawn-like in its glance and hue

As when he first had met its ray,

Echucha’s self, revealed to view—

She smiled, and shadowy sank away.

Again ’twas dawn: that hunter’s gaze

Was wand’ring o’er a wide expanse

Of inland lake, half hid in haze

That waved beneath the morning’s glance.

The circling wood, so still and deep

Its sombre hush, seemed yet asleep;

Save when at intervals from tree

A lone bird woke its minstrelsy,

Or flitting off from spray to spray

’Mid glittering dew pursued its way.

When lo! upon the list’ning ear

The rustling of a distant tread,

That pausing oft drew ever near

A causeless apprehension spread.

And from a nook, a snow-white Hind

Came bounding—beauteous of its kind!—

Seeking the silver pebbled strand

Within the tide her feet to lave,

E’re noonday’s sun should wave his wand

Of fire across the burnished wave.

Never hath mortal eye e’er seen

Such fair proportion blent with grace;

A creature with so sweet a mien

Might only find its flitting place

In that bright land far, far away

Where Indian hunters, legends say,

Pursue the all-enduring chase.

The beautifully tapered head,

The slender ear, the eye so bright,

The curving neck, the agile tread,

The strength, the eloquence, the flight

Of limbs tenuitively small,

Seemed imaged forth, a thing of light

Springing at Nature’s magic call.

The sparkling surge broke at her feet,

Rippling upon the pebbly brink,

As gracefully its waters sweet

She curved her glossy neck to drink.

Yet scarce she tasted, ere she gazed

Wildly around like one amazed,

With head erect, and eye of fear,

And trembling, quick-extended ear.

Still as the serpent’s hushed advance,

The hunter, with unmoving glance,

Wound on to where a beech-tree lay

Half buried in the snowy sand:

He crouches ’neath its sapless spray

To nerve his never-failing hand.

A whiz—a start—her rolling eye

Hath caught the danger lurking nigh.

She flies, but only for a space;

Then turns with sad reproachful face;

Then rallying forth her wonted strength,

She backward threw her matchless head,

Flung on the wind her tap’ring length,

And onward swift and swifter sped,—

O’er sward, and plain, and snowy strand,

By mossy rocks, through forests grand,

Which there for centuries had stood

Rustling in their wild solitude.

On, on, in that unwearied chase

With tireless speed imbued,

Went sweeping with an eldrich pace

Pursuing and pursued!

’Till, as the sinking orb of day,

Glowed brighter with each dying ray,

The fleetness of that form was lost,

Dark drops of blood her pathway crost,

And faint and fainter drooped that head,—

She falters—sinks—one effort more—

’Tis vain—her noontide strength has fled—

She falls upon the shore.

One eager bound—the Hunter’s knife

Sank deep to end her struggling life;

Yet, e’en as flashed the murd’rous blade,

There came a shrill and plaintive cry:

The Hind was not—a beauteous maid

Lay gasping with upbraiding eye.

The glossy head and neck were gone,

The snowy furs that clasped her round;

And in their place the peag zone,

And raven hair that all unbound

Upon her heaving bosom lies

And mingles with the rushing gore,

The sandaled foot, the fawn-like eyes;

All, all are there—he needs no more—

“Echucha—ha!” The dream hath passed;

Cold clammy drops were thick and fast

Upon the awakened warrior’s brow,

And the wild eye that flashed around

To penetrate the dark profound,

Seemed fired with Frenzy’s glow.

Yet all was still, while far above,

Nestling in calm and holy love,

The watchful stars intensely bright

Gleamed meekly through the moonless night.

The Hunter gazed,—and from his brow

Passed slowly off that fevered glow,

For what the troubled soul can bless

Like such a scene of loveliness?

He raised his quiver from his side,

And downward with his antlered prey,

To meet his lone Ojibway bride,

He gaily took his joyous way.

A. F. H.

|

The Alleghany. |

|

Zeno imagined his wise man, not only free from all sense of pleasure, but void of all passions, and emotions capable of being happy in the midst of torture. |

|

The stoics were philosophers, rather in words than in deeds. |

———

BY JESSE E. DOW.

———

My grandmother was one of the old school. She was a fine, portly built old lady, with a smart laced cap. She hated snuff and spectacles, and never lost her scissors, because she always kept them fastened to her side by a silver chain. As for scandal she never indulged in its use, believing, as she said, that truth was stranger than fiction and twice as cutting.

My grandmother had a penchant for old times and old things, she delighted to dwell upon the history of the past, and once a year on the day of thanksgiving and prayer, she appeared in all the glories of a departed age. Her head bore an enormous cushion—her waist was doubly fortified with a stomacher of whale-bone and brocade. Her skirt spread out its ample folds of brocade and embroidery below, flanked by two enormous pockets. Her well-turned ankles were covered with blue worsted stockings, with scarlet clocks, and her underpinning was completed by a pair of high quartered russet shoes mounted upon a couple of extravagant red heels. When the hour for service drew near, she added a high bonnet of antique form, made of black satin, and a long red cloak of narrow dimensions. Thus clothed, as she ascended the long slope that led to the old Presbyterian meeting house, she appeared like a British grenadier with his arms shot off, going to the pay office for his pension.

Her memory improved by age, for she doubtless recollected some things which never happened, and her powers of description were equal to those of Sir Walter Scott’s old crone, whose wild legends awoke the master’s mind to a sense of its own high powers.

My grandmother came through the revolution a buxom dame, and her legends of cow boys and tories, of white washed chimnies and tar and featherings, of battles by sea, and of “skrimmages,” as she termed them, by land, would have filled a volume as large as Fox’s book of the Martyrs, and made in the language of the day a far more readable work.

I was her pet—her auditor: I knew when to smile, and when to look grave—when to approach her, and when to retire from her presence; her pocket was my paradise, and her old cup-board my seventh heaven.

Many a red streaked apple and twisted doughnut have I munched from the former,—and many a Pisgah glimpse have I had of the bright pewter and brighter silver that garnished the latter. Among the old lady’s silver was a venerable massive tankard that had come down from the early settlers of Quinapiack, and she prized it far above many weightier and more useful vessels. This relic always attracted my notice—a coat of arms was pictured upon one side of it, and underneath it the family name in old English letters, stood out like letters upon an iron sign. It was of London manufacture, and must have been in use long before the Pilgrims sailed for Plymouth. It had, doubtless, been drained by cavaliers and roundheads in the sea girt isle,

“Ere the May flower lay

In the stormy bay,

And rocked by a barren shore.”

The history of this venerable relic was my grandmother’s hobby, and as she is no longer with us to relate the story herself, I will hand it down in print, that posterity, if so disposed, may know something also of

In the year 1636, a company of fighting men from the Massachusetts colony, pursued a party of Pequots to the borders of a swamp in the present county of Fairfield, in Connecticut, and destroyed them by fire.

The soldiers on their return to the colony spoke in rapture of a goodly land through which they passed in the south country, bordering upon a river and bay, called by the Indians Quinapiack, and by the Dutch the Vale of the Red Rocks.

In the year 1637, the New Haven company, beaten out by the toils and privations of a long and boisterous voyage across the Atlantic, landed at the mouth of the Charles River, and continued for a season inactive in the pleasant tabernacles of the early pilgrims. Hearing of the fair and goodly land beyond the Connectiquet, or Long River, and disliking the sterile shores of Massachusetts bay, the newly arrived company sent spies into the land to view the second Canaan, and bring them a true report.

In 1638, having received a favorable account from the pioneers, the company embarked, and sailed for that fair land, and at the close of the tenth day the Red Rocks appeared frowning grimly against the western horizon, and the Quinapiack spread out its silver bosom to receive them. The vessel that brought the colony, landed them on the eastern shore of a little creek now filled up and called the meadows, about twenty rods from the corner of College and George streets, in New Haven, and directly opposite to the famous old oak, under whose broad branches Mr. Davenport preached his first sermon to the settlers, “Upon the Temptations of the Wilderness.” Time, that rude old gentleman, has wrought many changes in the harbor of Quinapiack since the days of the pilgrims; and a regiment of purple cabbages are now growing where the adventurers’ bark rested her wave-worn keel.

In 1638, having laid out a city of nine squares, the company met in Newman’s barn, and formed their constitution. At this meeting it was ordered that the laws of Moses should govern the colony until the elders had time to make better ones.

Theophilus Eaton, Esq. was chosen the first governor: and the whole power of the people was vested in the governor, Mr. Davenport, the minister, his deacon, and the seven pillars of the church of Quinapiack. Here was church and state with a vengeance, and the pilgrims who sought freedom to worship God found freedom to worship him as they pleased, provided they worshipped him as Mr. Davenport directed.

The seven pillars of the church were wealthy laymen, and were its principal support; among the number I find the names of those staunch old colonists, Matthew Gilbert and John Panderson.

Governor Eaton was an eminent merchant in London, and when he arrived at Quinapiack, his ledger was transformed into a book of records for the colony. It is now to be seen with his accounts in one end of it, and the records in the other. The principal settlers of New Haven were rich London merchants. They brought with them great wealth, and calculated in the new world to engage in commerce, free from the trammels that clogged them in England. They could not be contented with the old colony location. They now found a beautiful harbor—a fine country—and a broad river: but no trade. Where all were sellers there could be no buyers. They had stores but no customers: ships but no Wapping: and they soon began to sigh for merry England, and the wharves of crowded marts. In three years after landing at New Haven, a large number of these settlers determined to return to their native land.

Accordingly a vessel was purchased in Rhode Island, a crazy old tub of a thing that bade fair to sail as fast broadside on as any way, whose sails were rotten with age, and whose timbers were pierced by the worms of years. Having brought the vessel round to New Haven, the colonists, under the direction of the old ship master Lamberton, repaired and fitted her for sea.

The day before Captain Lamberton intended to sail, Eugene Foster, the son of a wealthy merchant in London, and Grace Gilman, the daughter of one of the wealthy worthies of Quinapiack, wandered out of the settlement and ascended the East Rock.

Grace Gilman was the niece of my great, great grandmother. Possessing a brilliant mind, a lovely countenance, and a form of perfect symmetry, she occupied no small share of every single gentleman’s mind asleep or awake, in the colony. Her dark hair hung in ringlets about a neck of alabaster, and sheltered with smaller curls a cheek where the lily and the rose held sweet communion together.

Foster had followed the object of his love to her western home, and having gained Elder Gilman’s consent to his union with the flower of Quinapiack, he was now ready to return in the vessel to his native land, for the purpose of preparing for a speedy settlement in the colony.

Eugene Foster was a noble, spirited youth, of high literary attainments. Besides his frequent excursions with the scouts, had made him an experienced woodman and hunter. His countenance was pleasant; his eye possessed the fire of genius; and his form was tall and commanding.

It was a glorious morning in autumn. The whole space around the settlement was one vast forest, and the frost had tipped the leaves of the trees with russet crimson and gold. The bare sumac lifted its red core on high, and the crab apple hung its bright fruit over every crag. The maple shook its blood-colored leaves around, and the chesnut and walnut came pattering down from their lofty heights, like hail from a summer cloud. The heath hens sate drumming the morning away upon the mouldering trunks, whose tops had waved above the giants of the forest in former ages. The grey squirrel sprang from limb to limb. The flying squirrel sailed from tree to tree in his downward flight; and the growling wild cat glided swiftly down the vistas of the wood with her shrieking prey.

The blue jay piped all hands from the deep woods—and the hawk, as he sailed over the partridge’s brood, shrieked the wild death cry of the air. A haze rested upon the distant heights, and a cloud of mellow light rolled over the little settlement, and faded into silver upon the broad sound that stretched out before it.

It was nearly noon when the lovers—whose conversation on such an occasion I must leave the reader to imagine—turned from the enchanting prospect, which at this day exceeds any thing in America—to return to the settlement. Two Indians, of the Narragansett tribe, now bounded from the thicket, and before Foster could bring his musketoon to its rest—for he always went armed—they levelled him to the earth. A green withe was speedily twined around his arms, and he was apparently as powerless as a child. Grace sprang to a little path that led to the parapet of the bluff and screamed for help; that scream was her salvation, for the Indian who was binding Foster’s hands, left the withe loose, and sprang toward her. In a moment the rude hand of the red-man rested heavily upon her shoulder, and his grim look sent the blood tingling from her cheeks. Another withe was speedily passed around her arms, and then the two Narragansetts seated themselves to make a hurdle to bear the pale faced maiden away. As they were busily engaged Grace heard a whisper behind her. She turned her head half round—Foster, by great exertions, had got loose from his withe, and was crawling slowly toward his musketoon.

The Narragansetts, suspecting nothing, were sitting behind a little clump of sassafras, and nothing but their brawny chests could be seen through a small bend in the trunks of the trees that composed the thicket.

Stealthily crept the experienced Foster to the tree where his musketoon rested. Not a crackling twig, nor rustling leaf, gave the slightest evidence of his movements. The Indians spoke in their own wild gutterals of the beauty of the pale-faced squaw, and chuckled with delight at the speedy prospect of roasting the young long knife by Philip’s council fire.

The musketoon was just as he had left it: not a grain of powder had left the pan,—the match burned brightly at the butt, and every thing seemed to be as effective as possible. Foster seized it and motioned to Grace to stoop her head, so as to give him a chance to bring the red men in a range through the opening in the thicket.

Grace bent her head to the ground, while her heart beat with fearful anticipation. The young pilgrim aimed his deadly weapon, as a fine opportunity presented itself. The two savages were sitting cross-legged, side by side, and their brawny breasts were seen, one bending slightly before the other. Foster aimed so as to give each a fair proportion of slugs—for he had a charge for a panther in his barrel—and fired. A loud report rang down the aisles of the forest, and rattled in echoes over the settlement, while the two Indians bounded up with a fearful yell, and fell dead upon the half-made hurdle. Foster sprang to the side of Grace, and casting loose the withe that confined her swollen arms, bore her over the bodies of the Narragansetts, whose horrid scowls never were forgotten by the affrighted maid.

A war-whoop now rang in the usual pathway to the settlement, and Foster saw that he must take a shorter cut or die. Grace had fainted, and every thing depended upon his manliness and strength. He therefore approached the brink of the precipice. A wild grape vine, that had grown there since the morning of time, for aught he knew, extended far up the perpendicular rock, from a crag below. He bound the fair girl to his breast with his neckcloth and shot-belt, and grasping the stem of the vine, descended. As he slipped down, the vine began to yield, and just as his foot touched the narrow crag, the whole vine, with a mass of loose earth and stones, gave way with a tremendous crash, and hung, from the crevice where he stood, like a feather quivering beneath his feet. Foster was for a moment dizzy, but he cast his eyes upward, and beheld the eyes of an Indian glaring upon him from the top of the rock. He was nerved in a moment: and seeing a ledge a foot and a half broad, beyond a fissure, about eight feet over, and very deep, he determined to spring for it. Grace Gilman, however, was a dead weight to the young man, and he feared the result. The ledge seemed to run at an angle of forty-five degrees along the front of the rock, to a side hill, formed by fallen rocks and earth. A wild vine hung down over the fissure, covered with tempting fruit. He reached out his hand and grasped the main stem as it waved in the breeze,—it was strong, and its roots seemed firmly imbedded in a crevice above him. Commending himself to that Creator whose tireless eye takes in at a glance his creatures, he made his leap! The damp wind from the fissure rushed by his ears; the vine cracked and rustled above him; rich clusters of luscious fruit came tumbling upon his head; and the birds of night came shrieking out from their dark shelters in the fissure as he swung past. Foster, however, did not waver, his foot struck the ledge and he leaned forward; the vine flew back like a pendulum as he let it go, and he slid down the smooth ridge of the ledge in safety. In a short time he brought up against a heap of earth that had fallen from the mountain top, and springing up, bounded like the chamois hunter from crag to crag, until he stood upon the broad bottom, without a bruise or a scratch upon himself or his fair charge. In twenty minutes the young pilgrim entered the settlement by the forest way, with the almost lifeless form of his beloved buckled to his breast, while savage yells of disappointment came down from the summit of the East Rock, and caused the young mothers of Quinapiack to press their startled babes closer to their trembling hearts.

None had dared to follow the adventurous pilgrim’s course down the mountain’s perpendicular side: and the ledges that jut out like faint shadows from the bluff, are called Foster’s Stepping Stone by those who know the incident to this day.

The report of the musketoon was heard in the settlement. The soldiers of the colony stood to their arms, and when Foster had made his report, several strong parties went out upon a scout; but it was of no use; drops of blood only were discovered sprinkled upon the sassafras-leaves, and a heavy trail leading toward the Long River. The fighting men of Quinapiack, after a weary march, gave up the pursuit of the Narragansetts, and returned leisurely to the settlement. Night now settled like a raven upon the land—the drums beat to prayers—one by one the lights went out in the cottages of the pilgrims; and as the watch-fire sent forth its ruddy blaze from the common—now the college green—the colony slumbered in sweet forgetfulness, or wandered in visions amid the scenes of their childhood by the broad Shannon or the silver Ayr.

Who can tell the strange thoughts that agitated the sleepers’ souls? The old men, had they no pleasures of memory? The young men and the maidens, had they no dreams of joy—no bright pictures of trysting trees and lovely glens where the white lady moved in her noiseless path, or the fairies danced on the moonlight sward? Had the politician no dream of departed power? No sigh for his rapid fall? Had the soldier no dream of glory—no sound of stirring bugles melting upon his ear? Had the minister of God no dream of greatness—when before the kings and princes of the world he stood? and like Nathan of old said in Christ-like majesty to the offending monarch—

“Thou art the man.”

It was sunrise at Quinapiack, and the seven pillars were no longer seven sleepers. Eugene Foster stood beside Grace Gilman, while the old elder wrestled valiantly in prayer. When the morning service was ended, and a substantial breakfast had been stowed away with no infant’s hand, Foster imprinted a kiss upon the cheek of the bashful puritan.

“Farewell, Grace,” said he, “we are ready to sail. In a few months more the smoke shall curl from my cottage chimney, and the good people of the colony shall wait at the council board for good man Foster.”

“Eugene,” said Grace, with eyes suffused with tears, “your time will pass pleasantly in England; but, oh! how long will the period of your absence seem in this lone outpost of civilization. Do not, then, tarry in the land of your fathers beyond the time necessary for accomplishing your business. There are many Graces in England, but there are but few Fosters here.”

“Grace,” said Foster blushing, “there is no Grace in England like the Grace of Quinapiack, and he who would leave the blooming rose of the wilderness, for the sick lily of the hot-house, deserves not to enjoy the fresh blessings of Providence. The wind that blows back to the western continent shall fill my sails, and I will claim my bride.”

The old puritan now gave the young man his blessing. Foster drew from his cloak fold this silver tankard,—marked, as you now see it,—[so said my grandmother, as she held the antique vessel up to the light,] and presented it to Grace as an earnest of his love. The elder, after seeing that it was pure silver, exclaimed against the gew-gaws, and the drinking measures of a carnal world, and left the room. Two hearty kisses were now heard, even by the domestics in the Gilman family. The elder entered the breakfast room in haste; Eugene bounded out of the door—Grace glided like a fairy up stairs, and the old tankard rested upon the table.

After placing on board of the return ship the massive plate, and other valuables of the discontented merchants, those whose hearts failed them, embarked amid the tears and prayers of Davenport and his faithful associates. The sails were spread to the breeze—the old ship bowed her head to the foam, and dashed out of the harbor in gallant style. Grace watched the vessel as she departed, and when the evening came, she wept in her silent chamber, for her heart was sad.

It was a sad day for the remaining colonists when the ship dipped her topsails in the southern waves. A feeling of loneliness, such as the traveller feels when lost in a boundless wood, seized upon them, and the staunchest wept for their native land, and the air was damp with tears. The next morning the settlement became more cheerful, for what can raise the drooping soul like the still glories of a New England autumn morning? The ship would, in all probability, return in a few months with necessary stores for the colonists, and then, should the company grow weary of the new country, they could return to their native land with their wives, and recount to kind friends the perils of an ocean voyage, and of a solitary home in a savage land.

Six long and melancholy months rolled away, and no tidings of the pilgrims’ ship had reached the ears of the anxious settlers of Quinapiack. A vessel had arrived at Plymouth after a short passage, but nothing had been heard of Lamberton’s bark when she sailed. A terrible mystery hung over the ill-filled and crazy ship. Autumn now came in its beauty, and still no tidings came to cheer the sinking soul, and gladden the heavy heart. Grace Gilman now began to pine, like the fair flower, whose root the worm of destruction has struck, and whose brightness slowly fades away. At length the good people of Quinapiack could stand this state of suspense no longer, and the Rev. Mr. Davenport, and his little flock, besought the Lord with sighs and tears, and heartfelt prayers to shew them the fate of their friends by a visible sign from heaven.

Four successive Sabbaths the worthy minister strove for a revelation of the mystery, and on the afternoon of the last day, when silence brooded over the settlement; when even the barn-fowl grew silent upon his roost, and the well-trained dog lay watching by the old family clock, for sunset, and the hour of play, the cry came up from the water side,—“A sail! a sail!”—and the drums beat with a double note, and the gravest leaped for joy. The cry operated like an electric shock upon the whole mass of the people. The old and the young, the sick and the well, went out upon the shore to view the approaching stranger, and the seaman stood by the landing place ready to make her fast. Grace Gilman was in the centre of the throng, and the worthy minister, Davenport, waited silently by her side.

There is no moment so full of interest to us as that when a vessel from our native land approaches us upon a distant shore. How many anxious hearts are waiting to rise or fall, as good or bad tidings salute their ears. How many watch the faces that throng the deck, and turn from countenance to countenance with eager look, until their eyes rest upon some familiar face, and their anxiety is satisfied.

There are cold hearts also in such a crowd,—worldly men, who come to gather news. What care they for affection’s warm greeting, or the throb of sympathy? What know they of a sister’s love; aye! or of that deeper love which only exists in the breast of woman! which carried her to Pilate’s hall, to Calvary’s scene of blood, and to Joseph’s tomb? The price of cotton, of tobacco, bread-stuffs, rise of fancy stocks, election of a favorite candidate, or the death of a rich relative, are sweeter than angel whispers to their ears, and a rise of two pence on corn is enough to fill a whole exchange with raptures.

There were but few such worldlings on the landing place of Quinapiack on the Sabbath eve when the gallant vessel of the pilgrims approached the shore. Silence reigned upon the landing, and a dreadful stillness hung over the approaching ship. Gallantly she entered the harbor, and the boldest on shore trembled for her temerity in carrying such a press of canvass. Not a sail had she handed—not a man was aloft. Her course varied not—neither did the water ripple before her bows. All was now anxiety. A hail went forth from the land,—a moment of breathless curiosity passed, but no answer came. Another hail was treated with the same neglect. At length Mr. Davenport hailed the stranger. As the words slowly burst from the brazen trumpet, a bright ray of sunlight gleamed full upon the vessel. Her top-masts now faded into air—then the sails and rigging down to her courses—her ensign next rolled away upon the breeze, and when the East Rock sent back the last echo of the trumpet, the pilgrims’ ship had vanished away. A similar ship, though of much smaller dimensions, now appeared upon a heavy cloud that hung over Long Island, and faded away with the brightness of the day.

“It is the promised sign,” said Mr. Davenport.

“Our friends are lost at sea,” cried the multitude.

“Eugene is drowned!” screamed Grace Gilman, and the crowd dispersed to weep alone.

As the throng moved away from the water side, a maniac girl who had been gathering wild flowers upon the East Rock, came running in from the forest way, chaunting the following words to a plaintive air:—

She leaves the port with swelling sails,

And gaudy streamer flaunting free,

She woos the gentle western gales,

And takes her pathway o’er the sea.

The vales go down where roses bloom—

The hill tops follow green and fair;

The lofty beacon sinks in gloom,

And purpled mountains hang in air.

Along she speeds with snowy wings,

Around her breaks the foaming deep;

The tempest thro’ her rigging sings,

And weary eyes their vigils keep.

Loud thunders rattle on the ear;

Saint Elmo’s fire her yard-arms grace,

The boldest bosom sinks in fear,

While death stands watching face to face.

Months roll, and anxious friends await

Some tidings of the home-bound bark,

But ah! above her hapless fate

Mysterious shadows slumber dark.

No tidings come from Albion’s shore

To wild New England’s rocky lee;

Hope sickens, dies, and all is o’er,

The pilgrim’s bark is lost at sea.

But see around yon woody isle

A gallant vessel sweeps in pride,

Her presence bids the mourners smile,

And hope reviving marks the tide.

But ah! her topsails fade away,

Her gaudy streamer floats no more,

A shadow flits across the bay,

The pilgrim’s dying hope is o’er.