Title: Conservation Archaeology of the Richland/Chambers Dam and Reservoir

Author: L. Mark Raab

Randall W. Moir

Release date: November 7, 2020 [eBook #63671]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

PRODUCED BY

Archaeology Research Program

Department of Anthropology

Southern Methodist University

WITH FUNDS PROVIDED BY

Tarrant County Water Control and

Improvement District Number 1

written by:

L. Mark Raab

and

Randall W. Moir

typesetting by:

James E. Bruseth

graphic layout by:

Chris Christopher

1981

Archaeology[1] has a number of popular stereotypes usually involving expeditions to remote parts of the Earth in search of ancient tombs, lost cities or long-extinct races of Man. The archaeologist is seen working a “dig” for years, looking for bits of bone or stone of little importance to anyone but other scientists.

In reality, however, archaeology departs from this picture considerably. Many modern archaeologists work in their own communities on projects that include things familiar to most of us. The scope of their studies may range from 10,000 year old American Indian sites to early twentieth century farms. Excavations are carried out with the aid of tools, including small dental instruments, large earth-moving machines, and electronic computers. Often, archaeologists do not dig at all, but gather information from maps, photographs, written histories, and living informants. In fact, more time by far is spent working on artifacts in a laboratory, and especially in writing reports of excavations, than is spent in the field. Even more surprising, many archaeologists today work in cooperation with private and governmental agencies to protect archaeological remains, as required by state and federal laws. A specialized field of archaeology, called public or conservation archaeology, has come into existence in the last twenty years to meet this need.

The archaeological studies in the Richland Creek Reservoir area are a good example of conservation archaeology in action. This report explains what the Richland Creek Archaeological Project (RCAP) is, how it works, and what it has accomplished thus far. Above all, the report tries to show why conservation of our archaeological heritage is important to us all, and to future generations.

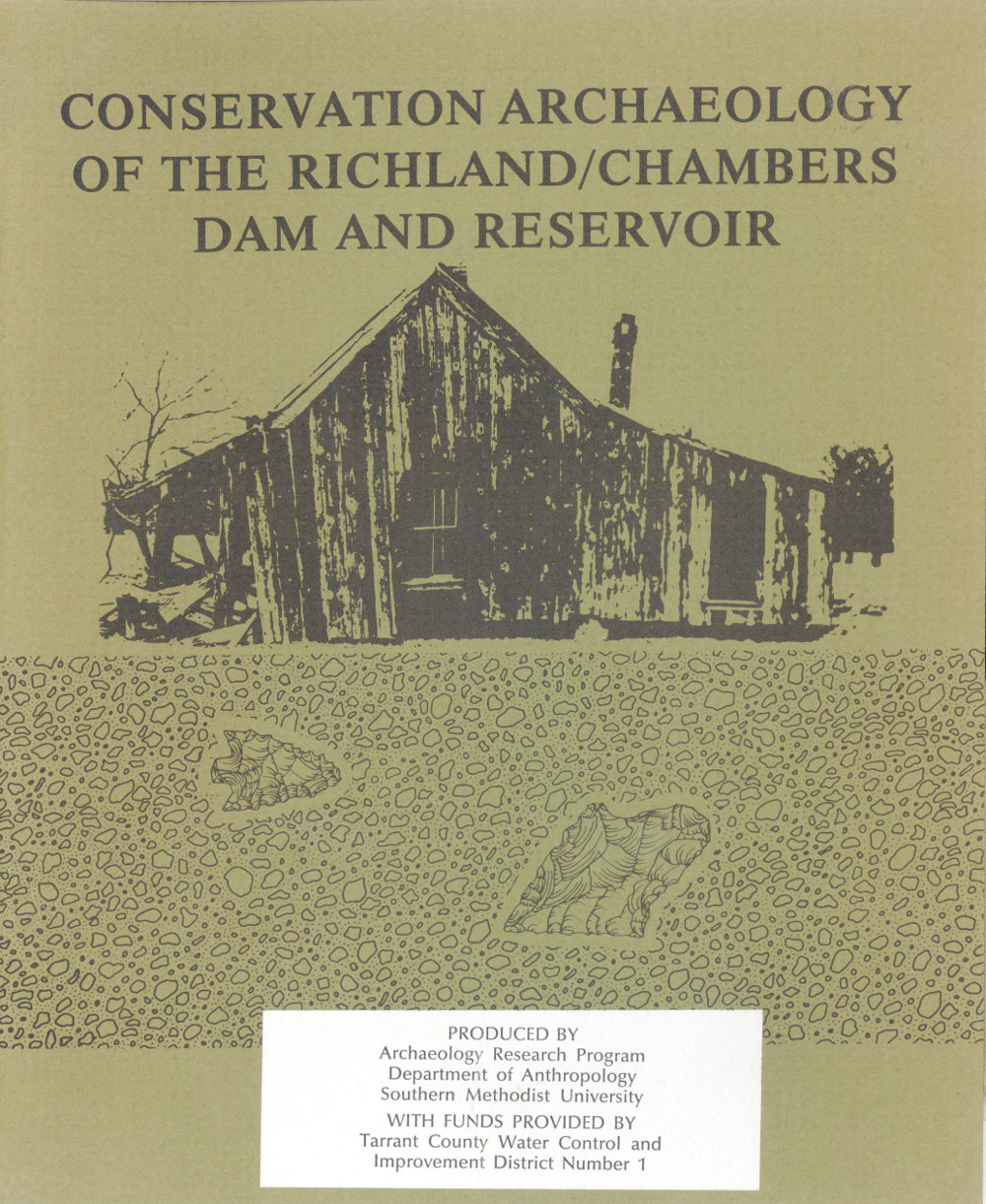

A series of archaeological studies are planned for the Richland-Chambers Dam and Reservoir area near Corsicana, Texas (Figure 1). The first phase of those studies was carried out during 1980-81. The Tarrant County Water Control and Improvement District Number 1, developer of the Reservoir, employed Southern Methodist University[2] to conduct archaeological studies. Like other construction projects requiring state and federal permits, the Reservoir cannot be completed unless state and federal laws pertaining to archaeological and historical sites are adhered to. Since 1906, several federal and state laws have been enacted to protect important archaeological sites. Particularly during the last two decades, these laws have defined archaeological remains as an important cultural resource that should be conserved for future generations.

In recent decades legislators and the public have come to realize that the expansion of our urban-industrial society is rapidly destroying the archaeological resources of the country. In many regions of the United States this destruction has reached crisis proportions. Experts point out that within another generation, given current rates of resource destruction from industry, agriculture, and other land-modification projects, intact archaeological resources will virtually cease to exist within large areas of the nation.

Archaeological resources are fragile and nonrenewable. Much of the scientific value of archaeological resources is lost if they cannot be studied in 2 an undisturbed context. Objects excavated from a site have little meaning unless they can be related to specific soil layers (stratigraphy) and other evidence of former activities of people, such as hearths, trash deposits, house remains and other features. Any activity that disturbs the soil may destroy this context.

Fig. 1. Richland-Chambers Dam and Reservoir, Navarro and Freestone Counties, Texas.

The primary objective of archaeologists working in cultural resource management is archaeological conservation. As in the case of other non-renewable natural resources, the emphasis is on resource preservation. In the case of archaeological sites, that 3 means digging as a last resort. The first priority of the conservation archaeologist is to preserve in an intact state a reasonable number of archaeological sites for future generations of scientists and the public. Sometimes sites can be preserved by selecting a construction design which avoids them. In other instances adverse impact is unavoidable—a case in which excavations are carried out to recover scientific information contained in the sites prior to their destruction. Recovery of this information is one way of conserving the resource. Preservation through data recovery will be required in the Reservoir, and will be the focus of work in years to come.

One way of understanding the RCAP is to look at how archaeologists work. People frequently ask what is an archaeological site? How do you find sites? How do you excavate and what do you look for? What do you do with the things that you collect?

During 1980-81, an archaeological survey (Figure 2) was completed in the project area. During the survey, an effort was made to develop the most complete inventory possible of prehistoric and historic sites. Sites were recorded by examining the entire project area on foot, consulting landowners, amateur archaeologists, written records, museum collections, aerial photographs, and other sources of information. No survey could guarantee discovery of every archaeological site, but every effort was made to construct a representative picture of the archaeological resources in the project. Next, limited-scale excavations (testing) were conducted on a sample of sites that were thought to contain information best suited to answering specific scientific questions. Once more, the intent was not to dig every site, but to understand a representative sample of archaeological resources within the project.

Archaeologists find sites by a variety of means. Naturally, how one defines an archaeological site has an important bearing on what is considered as representative. In the Reservoir, a site was defined as any evidence of past human occupation, predating 1930. The 1930 cut-off date reflects a legal definition of sites in the National Register of Historic places, a federal office that records important historical and archaeological properties. To be eligible for inclusion in the Register, a site must generally be at least 50 years old, and must meet a number of other criteria. Applying this definition to archaeological sites, they may be as different as isolated pieces of prehistoric stone tools and an early twentieth century farm house. Why such concern for these seemingly isolated tools or for dwellings that are so recent? One of the things that archaeologists have learned is that sometimes bits of information that are incomprehensible taken one at a time form meaningful patterns when many pieces are put together.

For example, it has been learned that when isolated projectile points dropped by prehistoric hunters are plotted on a map, their distribution may correlate with patterns of vegetation or topography, giving clues about the kinds of animals that they were hunting and the size of their hunting territories. More recent things, such as old farm houses, are worth recording because, as we discuss later, they represent the remnants of a way of life that is largely gone from rural Texas. In another generation these buildings, so familiar as to escape notice by most of us, will be gone for the most part, victims of decay, vandalism, and land modification. To future generations, these “artifacts” will be of as much interest as 4 nineteenth century houses are to us today. There is a danger that what is so common to us will fail to be recorded. Contrary to what many suppose, the rather common aspects of early twentieth century Texas culture are most in danger of being lost without adequate record. Often histories and other documents reflect the lives and architecture of the wealthy and well-known rather than the common people. Still, the buildings and farms of the latter reflect distinctive regional styles, and tell us many interesting things about the lives of the people who built and lived in them.

Fig. 2. Members of the Richland Creek Archaeological Project inspecting the banks of Richland Creek for archaeological remains. The project area was examined by teams of archaeologists for prehistoric and historic archaeological resources.

Once we know what we are looking for, actually finding sites requires a variety of methods. The most effective technique is the trained observer walking over the ground. Prehistoric sites, that is sites occupied prior to written history in the project area (about A.D. 1650), can be found by observing distinctive bits of stone (debitage) produced during manufacture and use of stone tools. Before contact 5 with Europeans, the Indians of Texas had no metals for making tools, and relied upon stone for many kinds of implements. In other instances, pieces of prehistoric pottery (potsherds), animal bone or shell, or stained soil deposits (middens) signal prehistoric sites. Many of these clues are easily overlooked except by a trained archaeologist.

In addition to ground survey, aerial photographs and geological studies may be helpful in finding sites. In the RCAP, for example, a soils scientist studied the geological history of the project area, and was able to give the archaeologists a good idea where and how deeply archaeological sites might be buried. One of the most valuable means of locating archaeological sites was talking to local people and amateur archaeologists. Many of these people are keen observers and reported the location of many prehistoric and historic sites.

Excavating sites is a complex task. There is no single technique for digging. The kinds of methods employed vary from excavation of test pits or trenches with shovels and trowels, to making larger exposures with heavy equipment. Sometimes the shape and placement of these excavations is determined by statistical sampling considerations; and they are always conditioned by the specific information that the archaeologist hopes to get from a site. That is really the most important point: excavations are aimed at recovering information, not things per se. As we pointed out earlier in the mention of archaeological context, artifacts have little meaning taken out of their setting. This fact creates one of the most striking aspects of an archaeological excavation to many people. There is a tremendous amount of record keeping that goes on in a dig—maps of the site and of the test pit walls (profiles), sheets describing artifacts and soil characteristics, photographs and many others (Figure 3). The object is to keep enough records that, if necessary, the archaeological site could be reconstructed in detail. A parallel set of record keeping comes into play, too, once things from the field reach the archaeological lab.

The demanding nature of excavation is a good reason why the untrained should not attempt to excavate sites. Without proper controls, digging can only result in loss of archaeological resources. Those who are interested in learning proper archaeological methods can contact organizations listed at the end of this report (Appendix I).

People invariably want to know what happens to the things that are collected by archaeologists. Do archaeologists add artifacts to their private collections, for example? Among professional archaeologists, keeping of private collections is actively discouraged. The reason for this is that archaeological remains are considered a scientific and public resource that should not be held for personal reasons. As scientists, archaeologists are interested in artifacts as sources of information rather than as objects with intrinsic value. All artifacts collected in the Reservoir, as is the case with all conservation archaeology projects, will be stored in permanent institutional repositories, where they can be studied by future generations of scientists. Also, plans are underway to return some of this material to the local area in the form of a museum display, for the benefit of the public.

Fig. 3. A test pit being excavated in a site within the Richland Project. Note the square pit walls, and screening for artifacts. Many kinds of records are kept during digging.

Recent studies suggest that humans have occupied North America for at least 20,000 years. These prehistoric Indians were the first people to live in North America, probably entering the New World first by way of a great land bridge between what is now Siberia and Alaska. True pioneers, they entered a vast land that had never before contained humans. Once in the New World, their culture developed over thousands of years into several successive stages and spread over the whole of North America and into South America. In the United States the development of prehistoric American Indian cultures is a fascinating story of a people’s increasingly complex culture and adaptations to the wealth of natural resources offered by our continent. Since this development occurred before these people developed systems of writing, their history is available to us only through archaeology and other sciences. Without an effort to understand this story, the history of a whole people will disappear without record.

The peopling of the New World represents a kind of huge laboratory for understanding how human societies develop over long periods of time. Since the first people in North America entered a new land that did not contain human competitors except themselves, we can study the development of their culture over thousands of years in a relatively simple frame of analysis. Archaeologists currently recognize four basic culture stages of prehistoric Indian development in North America. These stages are represented, in varying ways and degrees, by the archaeology of the Richland-Chambers project.

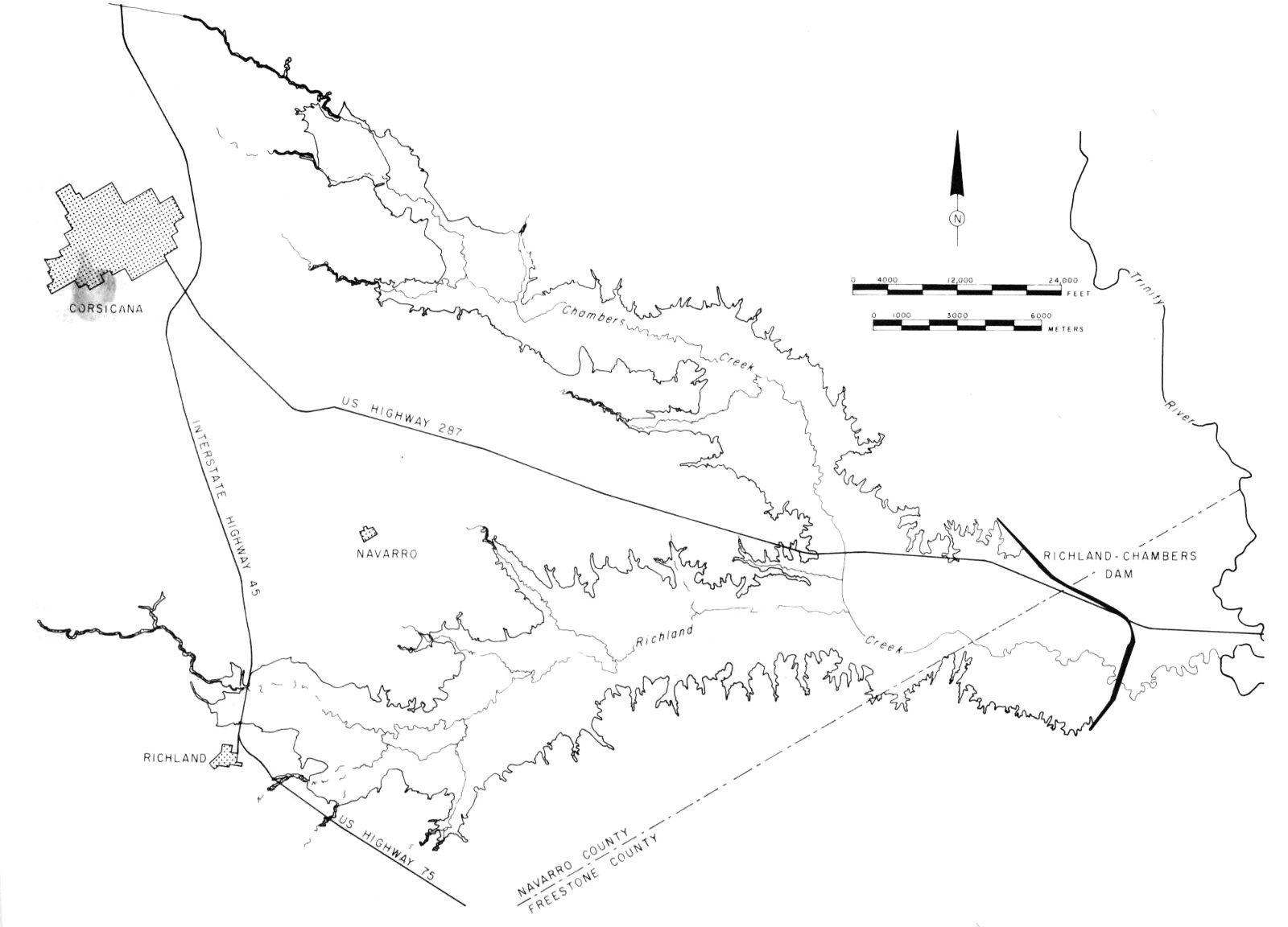

Since 1925, when flint spear points were found embedded in the bones of a kind of long-extinct bison, scientists have known that Native Americans lived in this country for tens-of-thousands of years. We call these people the “Paleo” Indians, after the Greek word for ancient, to refer to the oldest inhabitants of this continent. Intriguing as these people are, however, we understand little about them because we have found few traces of their habitations. The most distinctive trait of these people is chipped stone spear points with characteristic “flutes,” or long flake scars, on their surfaces (probably helping to lash the spear point to a shaft). These are unlike anything made by their descendants over the thousands of years to follow. Beautifully made, these artifacts are obviously stone tools of hunters, who depended on their weapons for a livelihood (Figure 4).

At first, it appears that the population grew slowly in the newly-inhabited continent of North America. The people in this period were apparently nomadic, frequently moving in search of game animals, seasonal plant foods and raw materials. Since there were not many of them, and they moved frequently, they did not leave many remains for the archaeologist to find. In the project area, only the base portion of a fluted point has been found but this artifact is an unmistakable but faint clue to the presence of Paleo-Indian inhabitants. With further work, more evidence may come to light. As matters now stand, we understand little of these people’s 8 economy, religion, society, settlement pattern and other things that made up their culture.

Fig. 4. Drawing of a Paleo-Indian fluted point (Clovis type).

Following the Paleo-Indian stage of cultural development, we know that population continued to grow steadily over thousands of years. We know this trend occurred because we find many more sites. In the project area, for example, we find that about half of all prehistoric sites that can be related to a cultural stage are from the Archaic stage (over 300 prehistoric sites were recorded during 1980-81). Even though these sites were occupied over thousands of years, they are a striking contrast to the scanty evidence of Paleo-Indian groups.

Another thing that makes it easier to find Archaic stage sites is that the Archaic peoples’ way of life had changed from that of the Paleo-Indians. The hallmark of Archaic culture was a round of occupation from one site to another in a regular cycle timed to the changing seasons. We suspect, for example, that during the fall, families moved to camps on river terraces where they could gather acorns and other nuts for winter food and hunt deer. In the spring and summer, they may have moved to camps on streams, where they could fish and gather roots, berries and mussels. By coming back to their sites again and again over hundreds or thousands of years, a great deal of waste materials was deposited leaving evidence to be found by archaeologists.

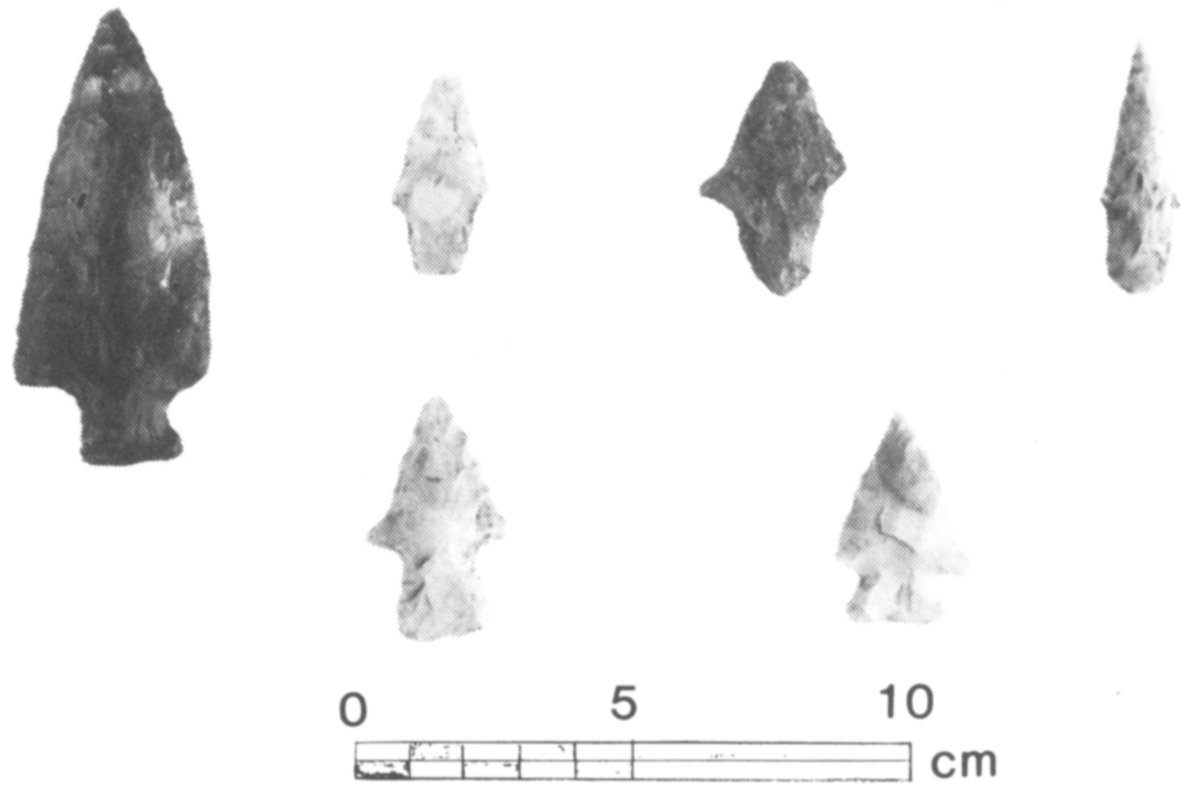

At present, only the barest outline of this culture is understood. Yet through study of their burial patterns, discarded food materials and many other aspects of the archaeological sites they left behind, we can come to a much fuller understanding of their culture (Figure 5).

Throughout much of eastern North America we know that tremendous cultural changes occurred in the few centuries before and after the time of Christ. The society of simple hunters and gatherers in Archaic times gave way to a much more advanced type of society for reasons that are not entirely understood at present. We do know that Woodland stage peoples began building huge earthworks; sometimes as burial mounds, sometimes in the forms of animals such as snakes. From a social point of view, big changes occurred. We find the first evidence of social ranking in which a few powerful people were 9 buried in mounds with great wealth and ceremony. In certain respects, this development was a clear step toward the eventual emergence of civilizations. We know that this kind of change has occurred independently in many parts of the world but we do not yet know why. It is clearly an important development with consequences for all human societies.

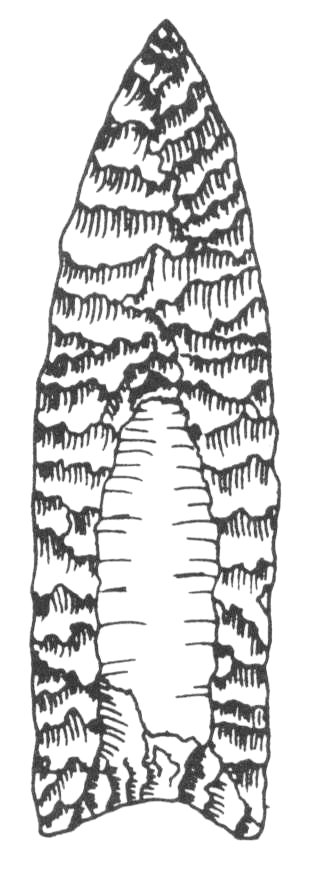

Fig. 5. Projectile points excavated from an Archaic stage site in the Richland project. Some of the stone from which these points were made was imported by the Indians from many miles away from the project.

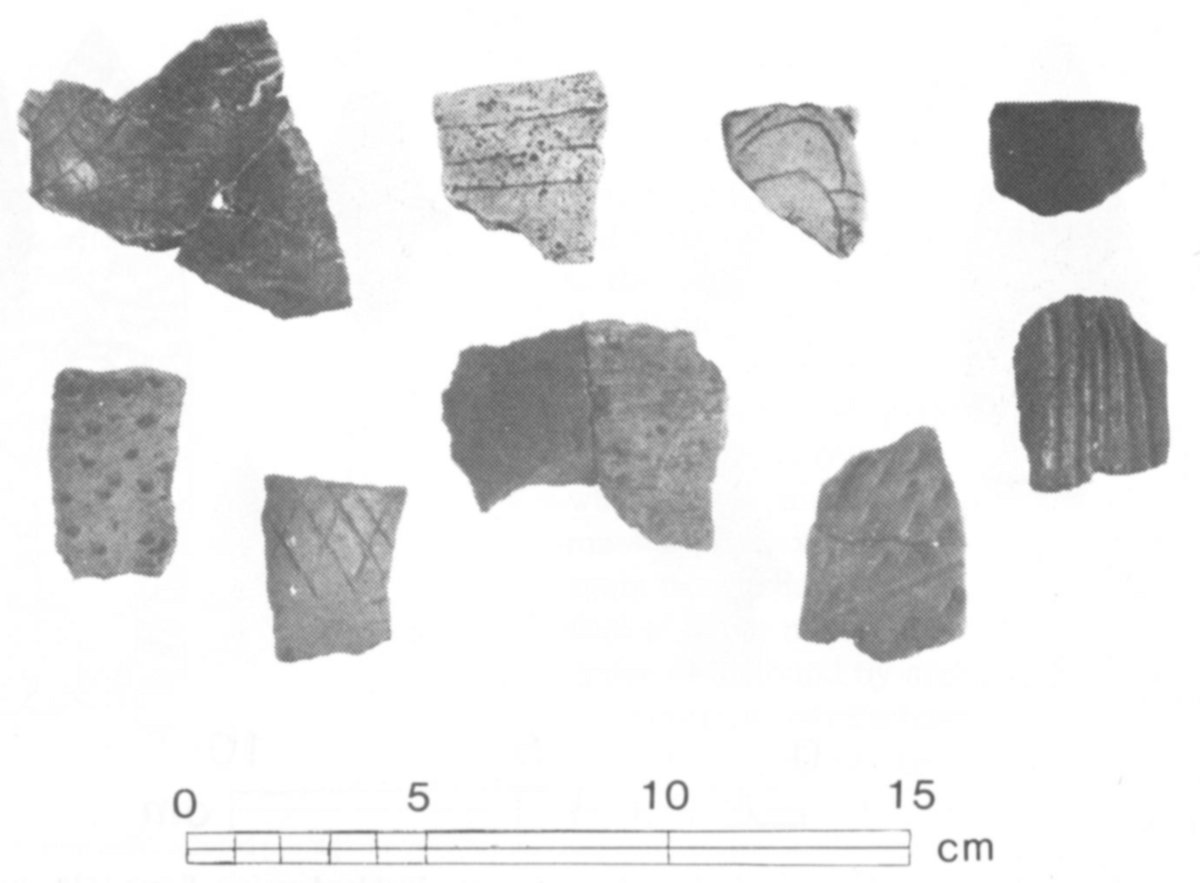

The Woodland stage also saw major technological advances. It was in this period that the bow and arrow, making of pottery (Figure 6) and agriculture (though this may have occurred during Archaic times, too) make their appearance.

The interesting aspect of the project area is that some of these things (e.g., the bow and arrow and pottery) appear to have been adopted, but not others, including the settled village life, agriculture, earth works and social complexity of other prehistoric peoples to the east and north (e.g., the prehistoric Caddo Indians). In many ways, it appears that the relatively simpler life of Archaic times persisted, with a few items borrowed from more advanced outsiders. This pattern is one that deserves an explanation.

The Neo-American stage, also called the Mississippian stage in the eastern U.S., was the last 10 prehistoric culture stage, and the one with the most complex culture. During this stage, large pyramid-shaped earthen mounds, complex ceremonialism, long-distance trade, heavy reliance on crops such as corn and squash, and a complex social order, with powerful chiefs at the top of the ranking system, all merged. The prehistoric Caddo Indians of East Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana are an excellent example of this type of culture.

Fig. 6. Pieces of prehistoric earthen pottery (potsherds) that were made during the Neo-American cultural stage in the project. Note the different types of surface decorations.

Yet, for all of the vigor and influence of this type of culture, its influence was not felt to the same degree everywhere. In the project area, there are only a few sites that suggest substantial contact with the most developed Neo-American cultures. In those cases we find certain kinds of prehistoric pottery vessels that, if not actually obtained from more culturally advanced peoples to the east and north, were modelled after ceramics of neighboring peoples.

These facts raise many questions. Were the inhabitants of the project area during Neo-American times carrying on an older style of life, modelled economically after the earlier Archaic-type of economy? Were the resources available in the project insufficient to support a thoroughly agricultural type of economy? Equipped only with simple hand tools, only certain kinds of soils allowed agriculture by 11 these ancient peoples. The tough prairie grasses, for example, would have made certain kinds of soils difficult, if not impossible to cultivate.

Fig. 7. This trench is one of those excavated in two “Wylie focus” pits discovered in the project. Since these prehistoric pits are about 100 feet in diameter, it is difficult to show their extent in a photograph. Much information on the age, construction sequence and content of the pits was gained from test trenches such as this one.

There is also the question of environmental influences. We know that over a period of thousands of years the climate of Texas, in fact of all of North America, has changed a great deal. Part of the ongoing research in the RCAP is the study of past environments. Some of the most promising results here are from the fields of geology and palynology (the study of pollen records). Many people do not know that pollen from ancient plants may be preserved in the soil for thousands of years, and can be recovered with certain laboratory methods. If this pollen from past periods is found, it can help to understand the kinds of vegetation that were present at different points in time. The present evidence from the project is exciting. It suggests, for example, that a drought far worse than anything recorded in the history of Texas occurred sometime between A.D. 1000 to 1300. The severity of the drought may have caused prehistoric people to change their way of life, including abandoning the project area.

Another major scientific discovery has been made in the project, and is dated to the Neo-American stage. For forty years archaeologists have known that an area on the Elm Fork of the Trinity River, north of Dallas, contained large, man-made pits dating to the Neo-American stage. These were called Wylie focus pits, after a system of classification of sites used by archaeologists. These pits are truly large, some measuring up to 100 feet in diameter and up to 10 feet deep in the center (Figure 7). Moreover, these pits generally contain many human burials placed in the pit over a period of time. One pit even contained the skeleton of a young bear. All of these pits were excavated by hand with simple 12 digging implements.

During the Richland project’s first season of work two of these pits were located and excavated. The discovery of these pits extended the known range of these unique cultural features over 100 miles from the region of their original occurrence.

At present, it is unclear what prehistoric culture constructed these monumental works or what their function may have been. It is safe to say, however, that these kinds of sites are unique to the north Texas area, and constitute a major point of archaeological interest. Work will be continuing on these sites in the next few years.

The archaeological story of people in this area during the last 150 years is no less exciting than its prehistoric counterpart. From the material remains, sites, and structures that these people have left behind, we see a picture of the rapid taming of a frontier, its rural agricultural florescence at the turn of this century, and then its decline under adverse economic conditions. Much of the rural landscape still contains a significant percentage of early twentieth century structures in varying degrees of abandonment and preservation. The following sections briefly look at the archaeological record for the historic period in the RCAP area as we know it today. The archaeological record provides us with a tangible and materially rich picture of specific aspects of daily life. The record left behind by the area’s past inhabitants provides much detailed information about their dwellings, farms, personal belongings, daily activities and lifeways. Although we have only begun to decipher the information, some results are already available from the 194 historic sites tested and the several dozen individuals interviewed to date.

Before entering into a discussion of the historic period, let us step back from the results and answer several major questions. What important and unique qualities emerge from the historic archaeological record for this area? Does the record tell us the same story that it would for other areas? What insight does the record provide that is distinct and unique to this part of Texas?

Unfortunately, not much is available from other areas of the country for making comparisons to the study area, but from what is known a general picture can be formed. The rural communities in this area consisted mainly of farms from the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. The sites representing these former farms indicate that lifeways were amazingly stable and relatively unaffected by influences coming from urban cultures. Since 1940, however, much of the distinctive culture of this rural area, unfortunately, has succumbed to the same urban American values found over other broad regions. The archaeological record suggests that before mass transportation and electricity entered the local scene, this area would have ranked among the richest of late nineteenth century areas in terms of local folk cultures and rural lifeways. Today, much of the rural culture has been lost. An objective of the Richland Creek Archaeological Project has been to record some of this information through interviews with senior residents over the next several years.

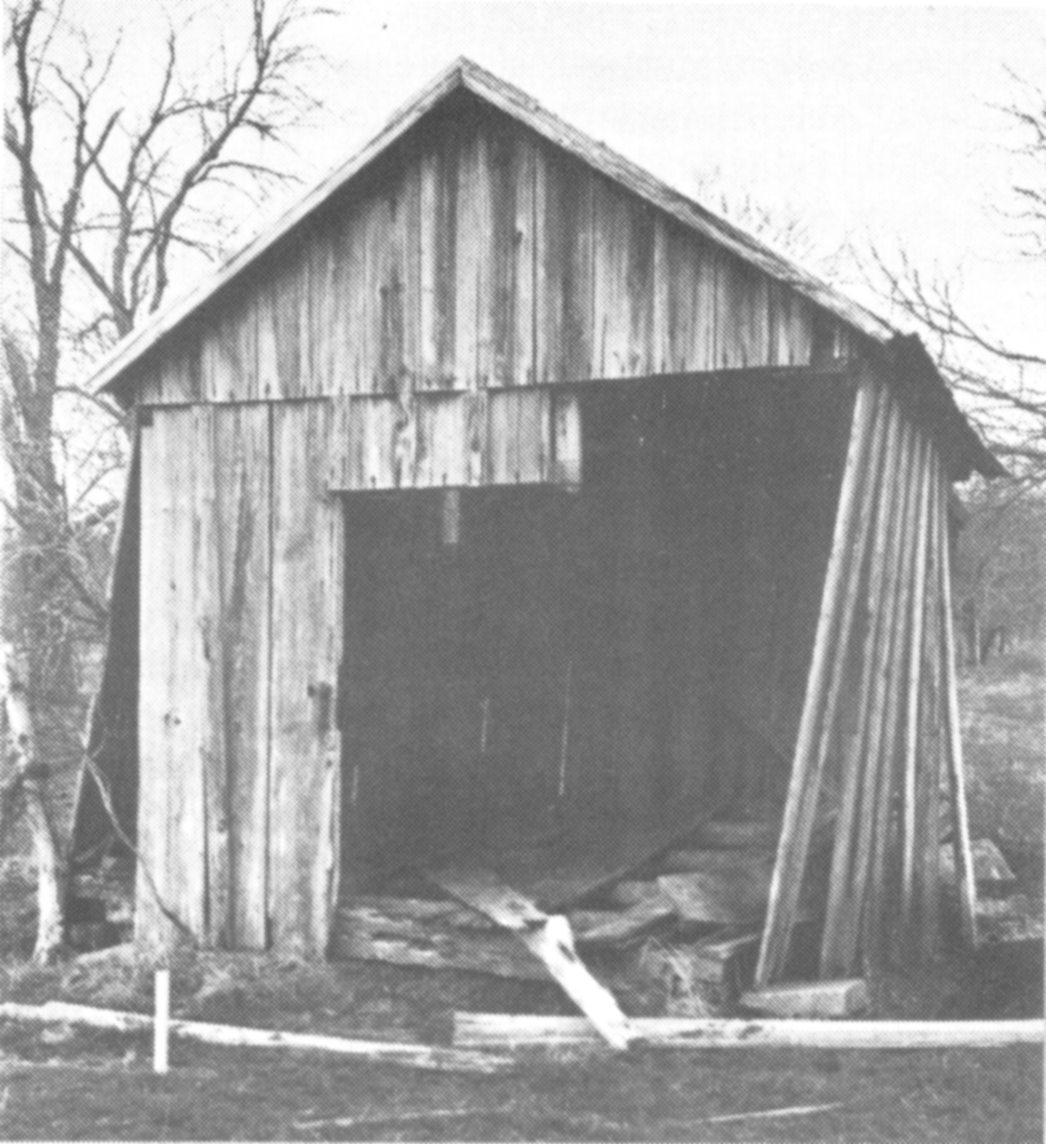

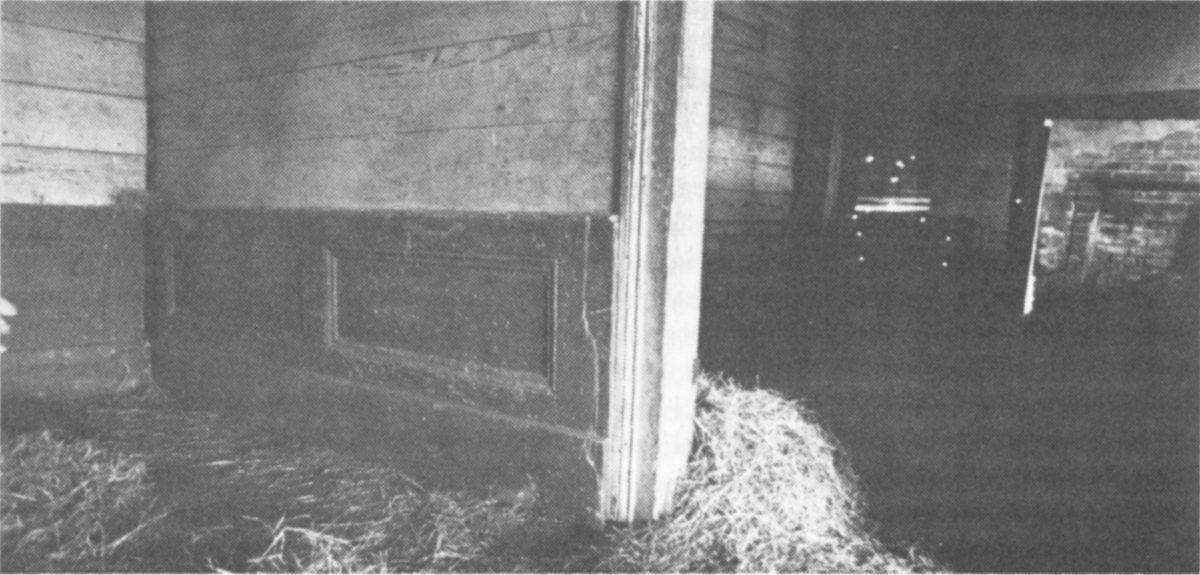

Results of some of the work conducted in the study of past lifeways portray the area’s past residents as a group of people who often made efficient and wise use of their local natural resources. This is illustrated in one aspect of their building construction. 13 As bottomland forests were cut and less wood was available locally, many individuals adopted the practice of recycling major elements of older structures into new ones. Figure 8 is an example of recycling older beams. Reuse of older structures underscores a keen awareness of optimizing local resources. Undoubtedly, other examples of the efficient use of local resources will emerge as structures and sites are studied in greater detail.

Fig. 8. Twentieth century shed constructed with hand hewn and reused sills and joists. This is a prime example of the recycling of older building parts.

What can we expect to gain from looking at broken pieces of plates, bottles, animal bones, buttons, and window glass 50 or a 100 years old? Aren’t museum collections and written histories adequate for providing information about rural life from 1870 to 1910? Unfortunately, there is a big difference between the type of information available through antiques, books, people, and archaeology. 14 Artifacts represent fragments generally resulting from the discarding or breaking of common items. Most antiques represent whole items recognized as having some intrinsic value which afforded them greater care or curation and less utilitarian usage. Most artifacts, on the other hand, represent common household items or possessions that did not receive special care or handling. No fragments of elaborately cut crystal wine glasses were among the 30,000 historic artifacts recovered from the project area, but fragments of inexpensive, undecorated tumblers were present. Similarly, only several dozen fragments of porcelain vessels were among the nearly 1,200 ceramic fragments excavated. Does this mean that cut wine glasses or porcelain cups were seldom available? No, more likely it represents a difference in handling and caring for these more expensive items. As an example, try counting the number of porcelain tablewares (plates, dishes, cups, etc.) in the household of an elderly person. In most cases, porcelain will be very frequent and often 50 years old or even older. These items have been saved from common use and now serve decorative or very special functions. The point of this example is to emphasize that the items fifty or more years old in households or museums today are not representative of the items lying broken and scattered around historic sites.

Can the written record provide us with much of the information we need to know? The richness of the written record is not to be underrated. However, in many areas, the written record is not without its problems. Often objective details about daily activities or observations about common material possessions, farm layouts, folkways or folk technologies are hard to locate. Diaries, travelers’ accounts, and written histories, on the other hand, frequently provide interesting personal or anecdotal kinds of information. The position that archaeologists wish to emphasize is that we should not rely solely on the written record in an attempt to understand the past. The picture conveyed for a group of people from their sites and material remains can be strikingly different from their own story told in writings. The archaeological record provides a direct and often objective source of information which is consistent over long periods of time. The record of your own life as revealed in the items you discard may be quite different than what you portray to others. This fact makes some aspects of the archaeological record both interesting and important for reconstructing past lifeways.

These major points all contribute to the value of the archaeological record. For nineteenth century rural East-central Texas, written records, oral folk knowledge, and antiques leave much of the story untold. The archaeology of historic sites in the proposed Reservoir area will begin to illuminate much of the former lifeways of these small rural agricultural communities. Without preserving some of this information, future generations will have little to study in order to probe the past of this nearly 100 square miles. The displacement of people and the submergence of places and sites so familiar today means oblivion for many former homesteads and communities. The task of the historic archaeologist is to select and preserve important aspects of the past record so that this information is available to future generations.

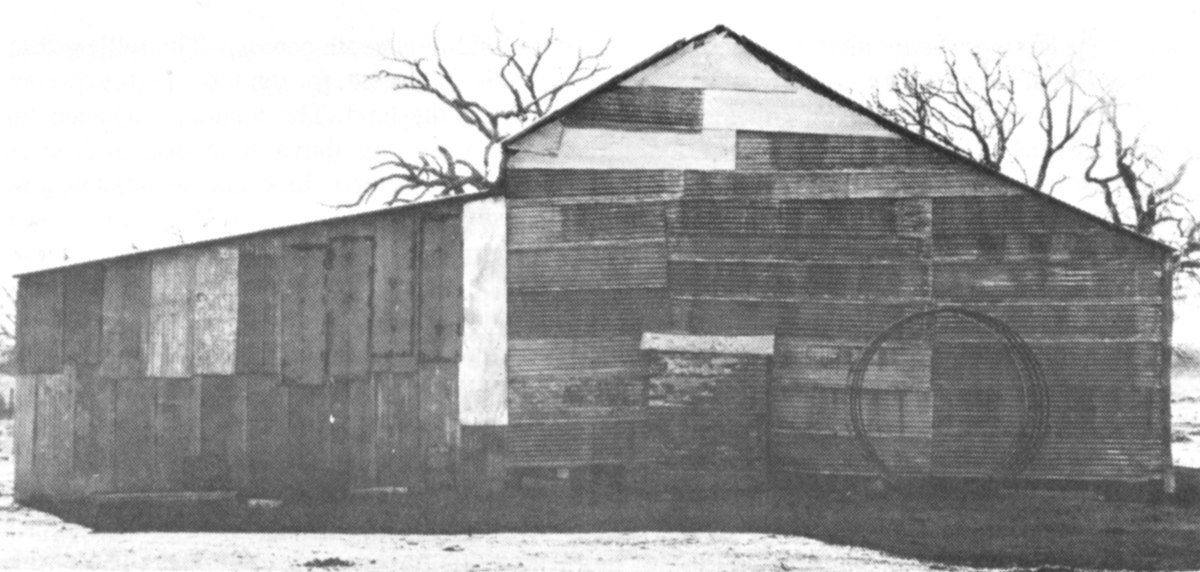

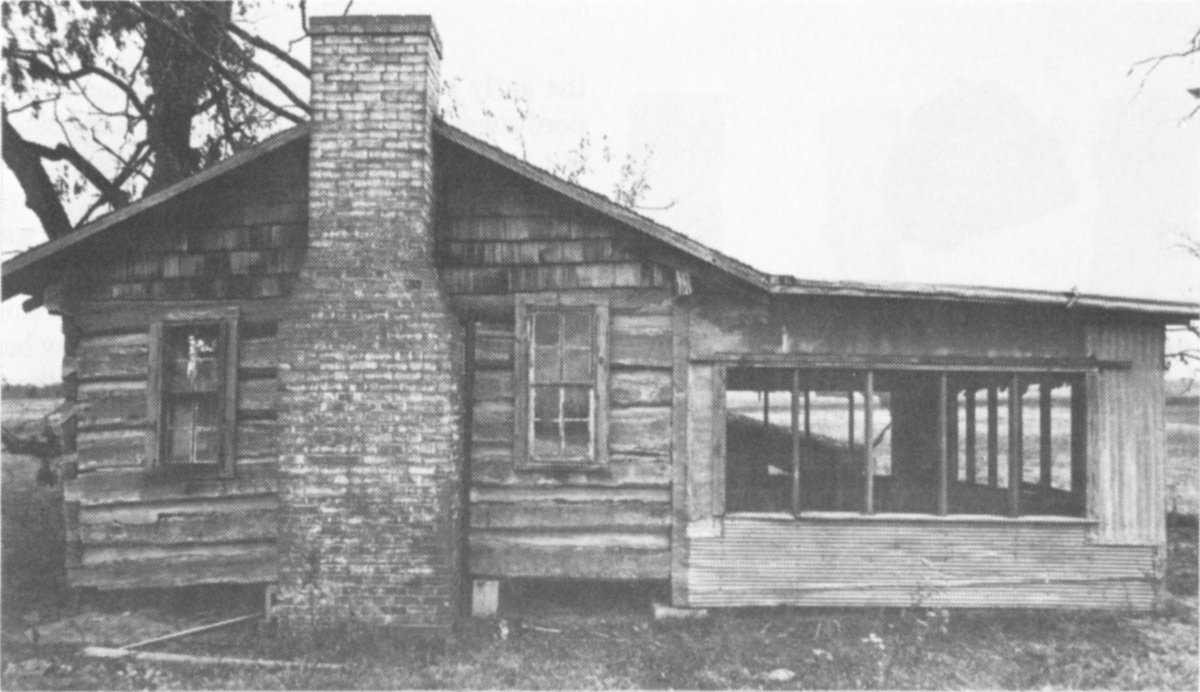

The first few permanent settlers came to this area soon after Texas declared its independence from Mexico in 1836. Settlement increased tremendously after Texas achieved statehood as families migrated westward. Most of these earliest settlers constructed log cabins for dwellings. About ten log cabin sites possibly dating to the mid-nineteenth century have been located in the area. Overall, however, we see a picture of families with widely different resources facing the same rural frontier. On the upper end were relatively affluent frontier plantation owners, such as the Burlesons and Blackmons, who settled along Richland Creek, or the Ingrams along the Trinity River to the north. The location of these affluent households were similar. They were located well above the creek bottoms and in the vicinity of good cotton land. Even the crude plantation houses themselves were similar in that each presented an air of important social status. Through the architecture of these dwellings each owner presented a visual display of his personal wealth and social status. Although these houses were far less sophisticated than those found further east in Louisiana or Mississippi, they were the mark of status in this area. The Burleson plantation house is shown in Figures 9 and 10. Compared to the simple, small, unpretentious log cabin shown in Figure 11, the crude frontier plantation house of East-central Texas fulfilled its social role as needed.

In the reservoir area, the former sites of several simple log cabins have been found. Figure 12 shows the remains of one log cabin as found today. These sites indicate that life was orderly yet simple during the mid-nineteenth century. The settlers that came to this area were, for the most part, experienced in reading the land. The locations selected for each cabin were well above the bottomlands in order to avoid the danger of floods, but at the same time close to rich farmland and water. Fifty years later people were much less concerned about selecting the proper location for a dwelling. As a consequence, many log cabins have endured over a century of harsh weather and have outlasted more recent structures.

By 1870, several dozen small communities, (Petty’s Chapel, Birdston, Rush Creek, Wadeville, Pisgah Ridge, Rural Shade, Re, and Providence) dotted the landscape. The railroad penetrated the area in 1871 and brought about many changes in the area that have lasted until today. There was, however, a price to be paid for this modern convenience of trade and travel. For some of the small communities, the railroad brought financial death and abandonment. The archaeological record shows this pattern clearly. New communities seem to have grown up overnight (e.g., Richland, Navarro, Cheneyboro, Streetman, and Kerens) while others, which had been around for 30 or 40 years, deteriorated rapidly (e.g. Wadeville, Pisgah Ridge, Winkler, and Re).

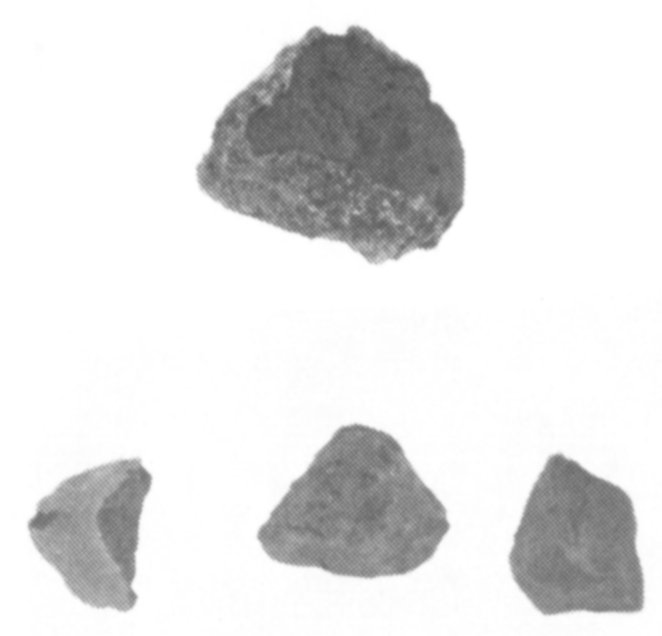

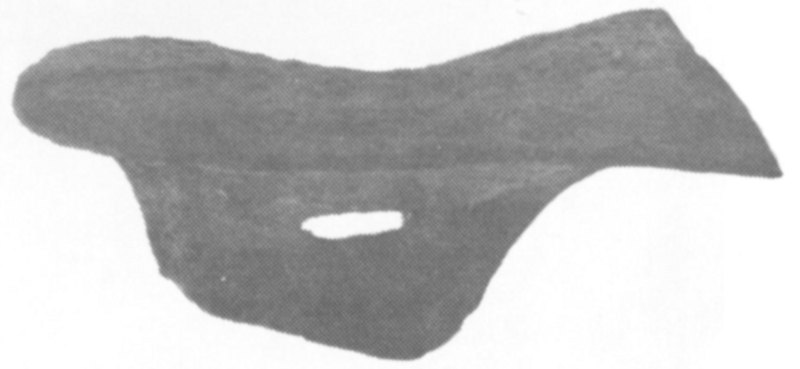

In addition to causing a shift in rural populations, the railroads also brought another major change. Prior to the railroads, these rural communities had become nearly self sufficient. The remains of a kiln for firing hand made bricks found in the project area stands as an example of rural folk industry (some fragments of glazed handmade bricks from the kiln are shown in Figure 13). Other craftsmen also may have been dispersed over this rural countryside. The shoe last (iron form used in shoe repair) found at one site suggests that a rural cobbler may have once stayed at the site (Figure 14). The railroads symbolized the start of a new era where mass produced goods, brick, lumber, shoes and commercial products could be transported cheaply into the area. Along with these goods came better living conditions and prosperity for many farmers and merchants. As a consequence some rural folk industries such as brick making disappeared and were replaced by commercial establishments. Even the need for a rural cobbler may have been eclipsed by the railroads.

Fig. 9. Burleson Plantation house as seen today. This mid-nineteenth century upper class dwelling, although covered with sheet metal, is much larger than contemporary log cabins.

Fig. 10. Interior of the mid-nineteenth century Burleson Plantation house illustrating architectural details more elaborate than less affluent dwellings of the same era.

Fig. 11. Mid-nineteenth century log cabin partially restored for use as a hunting cabin.

Fig. 12. The remains of a log cabin as seen today. Several such sites were found during the survey of the project area.

Fig. 13. Fragments of hand made bricks from a brick kiln site. Brick fragment at center top is covered with a crusty burned coating. Brick fragment at bottom lower left has a smooth light green-gray glaze on its outer surface.

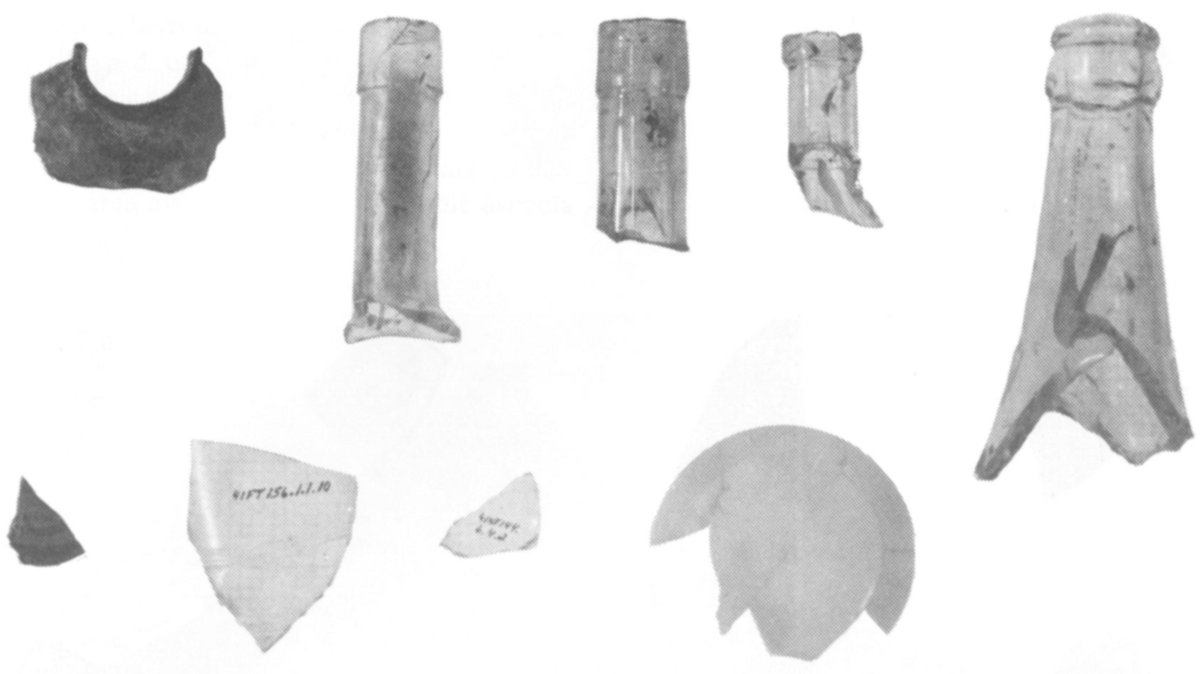

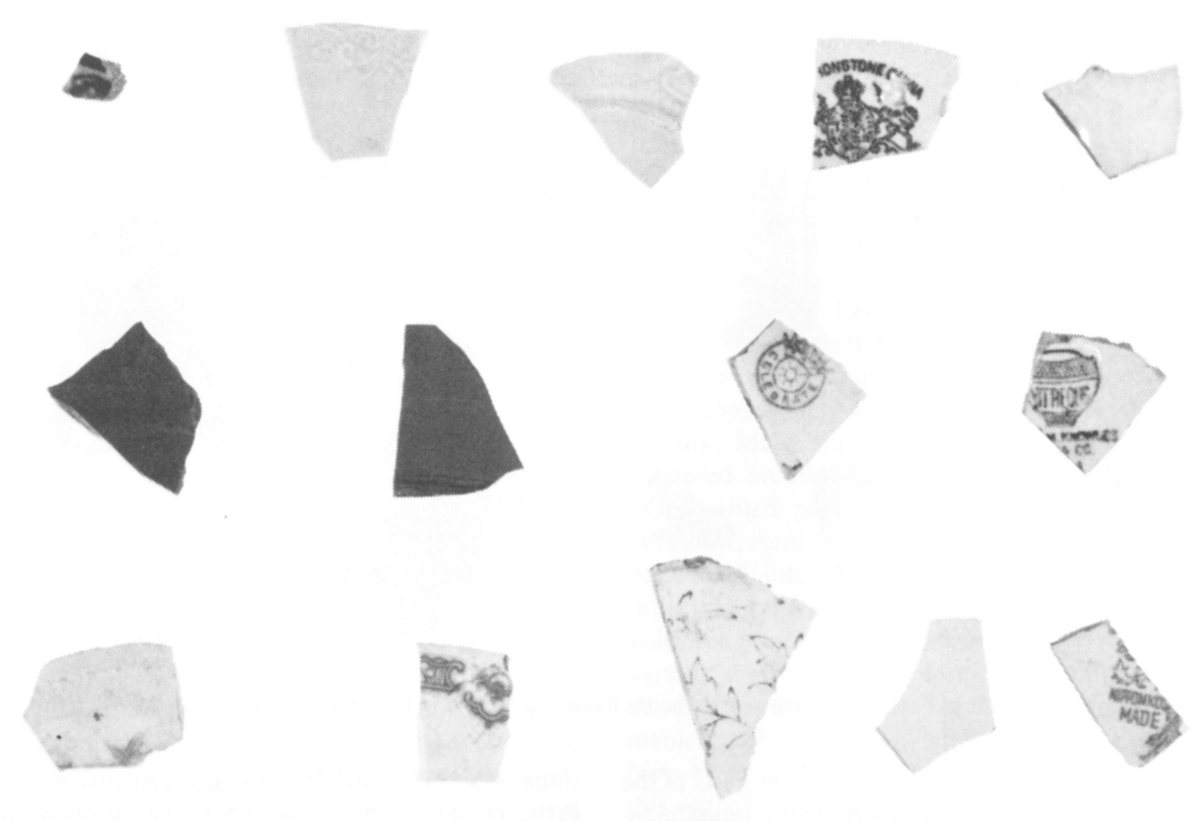

The archaeological record shows another effect of railroads on the local residents. Investigations so far suggest that there was an increase in the consumption of such items as bottles (Figure 15), plates (Figure 16), personal possessions and the like in the few decades after the railroads entered this area. By the early twentieth century, the archaeological record suggests that rural households had been partly, but not entirely incorporated into the patterns of commercial consumption. It seems that many were able to retain some of their rural folkways well into the twentieth century.

Fig. 14. Iron shoe last used in cobbler work from a historic site.

The battle played locally between rural American lifeways and their urban counterparts may be inferred from a close look at the sites, structures, and artifacts these people have left behind. For example, the pattern of intensive yard use by families in this area remains unchanged until well into the twentieth century. Many fragments of pottery and glass lie scattered around these rural dwellings. In other more settled parts of the country, such as the northeast, rural farmers had shifted away from this pattern of intensive yard use toward a pattern reflecting commercial consumption. In the Reservoir area, swept dirt yards were still being used for various daily activities, from processing food to discarding refuse, while cosmetically treated and manicured lawns were being kept in New England, New York, and much of the mid-Atlantic region. In this regard, domestic life in much of East-central 19 Texas had changed very little. In other parts of the country, archaeology reveals dramatic reorganization to keep pace with a society moving towards increased consumption and disposable material culture. Denser rural populations and a greater consumption of disposable material culture forced many communities to organize town dumps and mass collections to cope with the excess products. The Richland Creek area did not experience this transition until well into the twentieth century. Lower population density and a stronger tie to more traditional lifeways kept many aspects of rural life the same until the advent of better roads and electricity in the mid-1930s.

Fig. 15. Late nineteenth and early twentieth century bottle fragments recovered from historic sites in the project area.

The persistence of an unpretentious and traditional aspect of rural life in this area can be observed in the dwellings found throughout. The Cumberland and Hipped Roof Bungalows found here reveal a blend of traditional southern lifeways and local folk elements. Figures 17 and 18 show two examples of early twentieth century dwellings. Figure 19 illustrates the traditional cultural overtones of this region and shows an early twentieth century log barn.

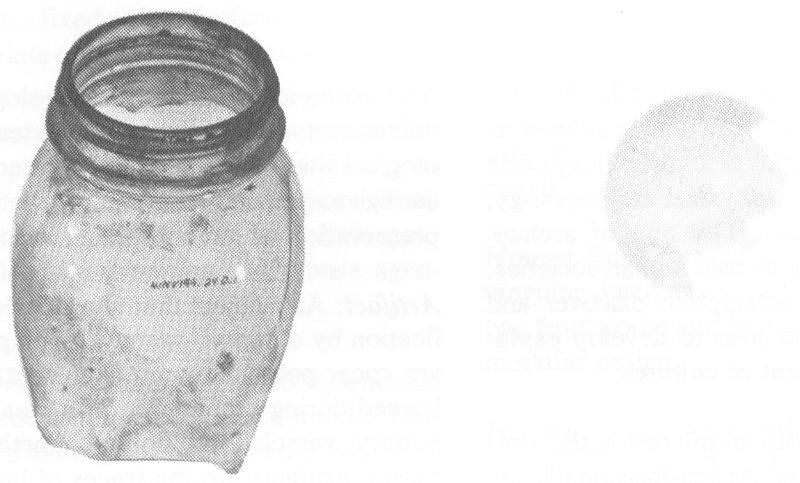

Several other aspects of traditional Southern lifeways have been captured in the archaeological record. The sites in the Richland Creek area indicate that foodways did not change as quickly in this area as in others. For example, the archaeological record suggests that home canning with commercial fruit canning (Figure 20) jars was slow to penetrate this 20 area. Wide use of glass fruit jars does not appear until the second decade of this century, unlike other parts of the country that used them as early as 1870 or 1880.

Fig. 16. Fragments of late nineteenth and early twentieth century ceramics. The printed marks designate the manufacturer. The mark seen in the top row is typical of many late nineteenth century British potteries.

Last of all, the consumption of commercially produced alcoholic beverages, liquors, and patent medicines does not appear to be anywhere near that observed in the refuse discarded by contemporaneous residents of the northeast or frontier southwest. Whether this indicates local adherence to southern temperance or the widespread use of “homemade” products is not known at this time.

When segments of the archaeological record are combined, the picture emerges of an area rich in 21 traditional Southern lifeways. From dwellings and patterns of yard use to foodways and the late participation in a society based on consumption, the archaeological record reveals a rural style of life that changed little for a period of about 100 years. In this regard, this area avoided the less desirable aspects of changing popular American culture and allowed local folk cultures to flourish. After the great depression and World War II, all of this changed. Today rural East-central Texas is not much different than many other parts of the country, but has an archaeological heritage of which to be proud.

Fig. 17. An example of an early twentieth century tenant farm dwelling; in this case, a four room Cumberland (side view).

Fig. 18. An example of an early twentieth century Hipped Roof Bungalow. This was the dwelling of a local land owner and is more elaborate than the simple Cumberland (Fig. 17).

Fig. 19. An example of the rebirth of log barns in rural folk construction in the early twentieth century.

Fig. 20. Early twentieth century glass fruit jar (bottom) with milk glass cap liner (top). If one were to pick a single artifact representative of twentieth century tenant farming lifeway, it would undoubtably be the home glass canning jar.

Archaeology (also spelled archeology): In the United States, archaeology is taught and practiced as one of the four major subfields of anthropology (with anthropological linguistics, physical anthropology, and cultural anthropology). The aim of archaeology is the understanding of past human societies. Archaeologists not only attempt to discover and describe past cultures, but also to develop explanations for the development of cultures.

Archaeologist: Anyone with an interest in the aims and methods of archaeology. At a professional level, the archaeologist usually holds a degree in anthropology, with a specialization in archaeology (see Archaeology). The professional archaeologist is one who is capable of collecting archaeological information in a proper scientific way, and interpreting that information in light of existing scientific theories and methods.

Archaeological Survey: The archaeological survey is a study intended to compile an inventory of archaeological remains within a given area. Usually a survey is an extensive rather than an intensive phase of archaeological study. The objective is to form the most complete and representative picture possible of the archaeological remains found within a defined area. Surveys may be based upon a wide variety of methods, including on-foot examinations of the ground surface, brief digging, talking with people who know where archaeological sites are to be found, consulting historical records, and looking at satellite photos of an area.

Archaeological Testing: Archaeological testing involves carrying out limited-scale testing of archaeological sites (see Site). Testing attempts to dig only enough to determine the extent, content and state of preservation within an archaeological site.

Artifact: Any object that shows evidence of modification by a human agency. Examples of artifacts are spear points chipped from flint, animal bones burned during preparation of a meal, fragments of pottery vessels and coins. Whether ancient or recent, artifacts are the traces of human behavior, and therefore one of the prime categories of things studied by archaeologists (see also Context).

Conservation Archaeology: A subfield of archaeology whose primary objective is informed management of archaeological remains and information. Working with private and public agencies, conservation archaeologists provide information that will allow archaeological properties and information to be effectively managed for the benefit of future generations. In this context, archaeological values are a natural resource of the nation, to be wisely conserved for the future (see Cultural Resource Management).

Context, or Archaeological Context: The setting from which archaeological objects (see Artifacts) are taken. Usually the meaning of archaeological objects cannot be discerned without information about their setting. One example is determining how old an object is, given that the age of objects 25 excavated from a site varies with their depth in the ground. Unless the depth of an object is carefully recorded against a fixed point of reference, it may be impossible to relate objects to the dimension of time.

Cultural Resource Management: Development of programs and policies aimed at conservation of archaeological properties and information. Such programs exist within the federal and state governments, academic institutions and private agencies.

Cumberland Dwelling: An architectural style named for its common occurrence throughout middle Tennessee. These dwellings have two front rooms of about equal size and front doors, with any additional rooms added onto the rear of the building.

Data Recovery: In the context of cultural resource management (see definition) studies, data recovery refers to relatively large-scale excavation designed to remove important objects and information from an archaeological site prior to its planned destruction. Data recovery is only undertaken after it is shown that preservation of the site in place is not a feasible course of action in the project in question. Scientific data are recovered to answer important scientific and cultural questions.

Debitage: A term meaning the characteristic types of stone flakes produced from manufacture of prehistoric stone tools by chipping (as, for example, stone spear and arrow points). One of the most common types of prehistoric artifacts, these distinctive flakes frequently alert the archaeologist to the presence of a prehistoric site.

Feature, or Archaeological Feature: Many things of archaeological interest are portable, such as fragments of bone, pottery and stone tools. However, archaeological sites frequently contain man-made things that are not portable, but are part of the earth itself. Examples of these features are hearths, foundations of buildings, storage pits, grave pits and canals.

Hipped Roof Bungalow: These are square to rectangular dwellings with hipped gable roofs, one or two front doors and four to five rooms arranged in a modular design.

Historic Sites: Archaeological sites dating to the historic era, or after about the early seventeenth century in the project area. The distinguishing characteristic of this period is availability of written documents. This era extends from the earliest period mentioned in histories to the present.

Midden: A word (adopted from the Danish language) meaning refuse heap. In many instances, one of the most apparent aspects of an archaeological site is “midden”, or a soil layer stained to a dark color by decomposition of organic refuse, and containing food bones, fragments of stone tools, charcoal, pieces of pottery or other discards. Archaeologists can learn a great deal about people’s lifeways by studying their middens.

Potsherds (or sherds): Pieces of ceramic vessels. Since the making of pottery did not begin in the project area until the first few centuries A.D., the presence of potsherds is a useful index of time. Also, the composition of the sherds and their decorative motifs are a highly useful way of detecting different 26 prehistoric cultural groups, since manufacture and design of pottery varied with cultural groups.

Prehistoric Sites: Archaeological sites (see Site) that date to a time prior to European contact (that is, before written history). In the project area that would be prior to the early seventeenth century. Prehistory is a relative concept, varying from one area to another, depending on the first intrusion of Americans or Europeans.

Profiles: Detailed maps of the walls of test pits and test trenches (see definitions). These are key records in understanding a site’s layers (stratigraphy) and distribution and age of artifacts.

Site: A site, or archaeological site, is the location of past human behavior. Sites vary tremendously in their size and content, ranging from cities to a few flakes of stone indicating the manufacture of a stone tool. As a relative concept, sites are defined in relation to specific research problems and needs.

Stratigraphy: A number of normal processes caused the earth’s surface to be built up over time in layer-cake fashion. Sometimes this is caused by floods or wind-carried soil. In other cases it may result from people piling up refuse of one kind or another. The layering effect here is called stratigraphy, and is a major interpretive tool of the archaeologist. Within a given stratigraphic sequence the most deeply buried layers are usually the oldest, and things found within a given level were usually from the same points in time. Stratigraphy is therefore a means of telling time (in a relative sense) for the archaeologist.

Test Pits: Rectilinear pits dug during excavation of a site (see Archaeological Testing). The archaeologist works with square or rectangular pits because they aid in keeping records of changes in soil types and other variables with depth. Extensive records, drawings and maps are kept of test pits. The function of the test pit is to provide a sample of a site’s contents at a particular point.

Test Trenches: Serving much the same function as a test pit, the test trench give a more continuous record of a site’s contents over a larger distance than a pit. Trenches are useful for tracing stratigraphy (see definition) over distance.

There are several organizations that encourage interest and education in archaeology by members of the public. Some of these organizations are listed below.

The first is the Texas Archaeological Society, Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78285. This society is composed of avocational archaeologists from all walks of life. It holds an annual meeting in the fall during which members present papers on various aspects of Texas archaeology. Each summer the society also organizes a field school where members can participate in excavation of an archaeological site under the supervision of a professional archaeologist. The society also publishes a high-quality bulletin about Texas archaeology.

Another organization that promotes archaeology is the Archaeological Institute of America. This organization has its national headquarters in Washington, D.C., and schedules national lecture tours by archaeologists who visit local chapters in major cities. The lectures are offered six times a year, and present the results of archaeological investigations world-wide.

In addition, local or county archaeological societies can be contacted for information about archaeology in Texas. If such an organization does not currently exist in your community, perhaps you could start one!

Discovery of archaeological remains, particularly destruction of archaeological properties, deserves official attention. To report such events and to obtain information about the State’s efforts in protecting archaeological and historical resources, contact: Texas Historical Commission, P.O. Box 12276, Capitol Station, Austin, TX, 78711.