Title: China and the Chinese

Author: Edmond Plauchut

Translator: N. D'Anvers

Release date: November 12, 2020 [eBook #63733]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Tom Cosmas from files generously made available by The

Internet Archive. All resultant materials are placed in the

Public Domain.

China

AND THE CHINESE

BY

EDMUND PLAUCHUT

TRANSLATED AND EDITED

BY

Mrs. ARTHUR BELL (N. D'Anvers)

AUTHOR OF 'THE ELEMENTARY HISTORY OF ART,' 'LIFE OF GAINSBOROUGH,'

'THE SCIENCE LADDERS,' ETC.

WITH FIFTY-EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

HURST AND BLACKETT, LIMITED

13 GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET

1899

All rights reserved.

This brightly written little book by the well-known French author, Edmund Plauchut, who has spent many years in China, is the first of the new series known as the "Livres d'or de la Science" recently commenced by MM. Schleicher Frères of Paris. It gives in a succinct form a very complete account of the Chinese, both past and present, their religion, their literature, and their time-honoured customs. Touching but lightly on the many vexed questions of modern diplomacy, it yet presents a very true picture of the problems European statesmen have to solve in connection with the inevitable partition of the Celestial Empire, and will, it is hoped, be found of real service to those who wish to be abreast with the times, yet who have not the leisure to read the longer and more exhaustive books on the subject which are continually appearing.

Nancy Bell,

Southbourne-on-Sea,

May 1899.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| The delight of exploring unknown lands—Saint Louis and the Tartars of olden times—The Anglo-French force enters Pekin—Terror of the "Red Devils"—The "Cup of Immortality"—The "Sons of Heaven"—Hong-Kong as it was and is—The Treaty of Tien-tsin—The game of "Morra"—First Tea-party in the Palace of Pekin—Chinese agriculture and love of flowers—Chinese literati—An awkward meeting between two of them—Love of poetry in China—Voltaire's letter to the poet-king—The Chinese army—The Shu-King, or sacred book of China—Yao and his work—Chung, the lowly-born Emperor—The Hoang-Ho, or "China's Sorrow"—Yu the engineer and his work—Chung chooses Yu to reign after him—The foundation of the hereditary monarchy in China | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Trip up the Shu-Kiang river—My fellow-passengers and their costumes—A damaged bell—Female peasants on the river-banks—I am caught up and carried off by a laughing virago—Arrival at Canton—Early trading between China and Ceylon and Africa, etc.—The Empress Lui-Tseu teaching the people to rear silk-worms—The treaties of Nanking and Tien-tsin—Bombardment of Canton—Murder of a French sailor and terrible revenge—M. Vaucher and I explore Canton—The fétes in honour of the Divinity of the North and of the Queen of Heaven—General appearance of Canton—An emperor's recipe for making tea—How tea is grown in China—The Fatim garden—A dutiful son—Scene of the murder of the Tai-Ping rebels—The Temple of the five hundred Genii—Suicide of a young engineer—Return of his spirit in the form of a snake | 33 |

| [viii] CHAPTER III | |

| General Tcheng-Ki-Tong and his book on China—The monuments of China—Those the Chinese delight to honour—A Chinese heroine—Ingredients of the "Cup of Immortality"—Avenues of colossal statues and monsters in cemeteries—Imperial edict in honour of K'wo-Fan—Proclamation of the eighteenth century—The Emperor takes his people's sins upon himself—Reasons for Chinese indifference to matters of faith—Lao-Tsze, or the old philosopher—His early life—His book, the Tao-Teh-King—His theory of the creation—Affinity of his doctrine with Christianity—Quotations from his book | 57 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Lao-Tsze and Confucius compared—The appearance of Kilin, the fabulous dragon, to the father of Confucius—Early life of the Philosopher—The death and funeral of his mother—His views on funeral ceremonies—His visit to the King of Lu and discourse on the nature of man—Confucius advocates gymnasium exercises—His love of music—His summary of the whole duty of woman—He describes the life of a widow—He gives a list of the classes of men to be avoided in marriage—The seven legitimate reasons for the divorce of a wife—The three exceptions rendering divorce illegal—The missionary Gutzlaff's opinion of Confucius' view of woman's position—The Philosopher meets a man about to commit suicide—He rescues him from despair—He loses thirteen of his own followers | 73 |

| [ix] CHAPTER V | |

| My voyage to Macao—General appearance of the port—Gambling propensities of the Chinese—Compulsory emigration—Cruel treatment of coolies on board ship—Disaster on the Paracelses reefs—The Baracouns—The grotto of Camoens—The Lusiads—Contrast between Chinese and Japanese—Origin of the yellow races: their appearance and language—Relation of the dwellers in the Arctic regions to the people of China—Russian and Dutch intercourse with the Celestials—East India Company's monopoly of trade—Disputes on the opium question—Expiration of charter—Death of Lord Napier of a broken heart—Lin-Tseh-Hsu as Governor of the Kwang provinces—The result of his measures to suppress trade in opium—Treaty of Nanking—War of 1856-1858—Treaty of Tien-tsin and Convention of Pekin—Immense increase in exports and imports resulting from them | 97 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| French aspirations in Tonkin—Margary receives his instructions—Work already done on the Yang-tse—Margary is insulted at Paï-Chou—He awaits instructions in vain at Lo-Shan—The Tung-Ting lake—A Chinese caravanserai—The explorer leaves the river to proceed by land—He meets a starving missionary—Kwei-Chou and the French bishop there—A terrible road—Arrival at the capital of Yunnan—Armed escort from Bhâmo—Meeting between Margary and Colonel Browne—Threatening attitude of natives—Margary crosses the frontier alone—Colonel Browne's camp surrounded—Murder of Margary outside Manwyne—Importance of Yunnan and Szechuan to Europeans | 118 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Sir Thomas Wade demands his passports—Retires to man-of-war off Tien-tsin—Interviews with Li-Hung-Chang—Convention of Che-Foo—Description of Ichang on the Yang-tse—The Manchester of Western China—Pak-hoï and its harbour—A magnificent pagoda—Ceremony of opening the port to foreign trade—New Year's féte at Pak-hoï—The game of Morra—Description of Wenchow—Temples and pagodas turned into inns—Wahn and its native officials—Dislike of mandarins, etc., to missionaries—Beautiful surroundings of the town—An eclipse of the moon expected—The eclipse does not keep time—Excitement of the people—The dragon attacks the moon at last—Threatening message from the Emperor to the astronomers—Two astronomers beheaded in B.C. 2155—Reasons for importance attached to eclipses in China | 135 |

| [x] CHAPTER VIII | |

| I land at Shanghai—The Celestial who had never heard of Napoleon—Total value of exports and imports to and from Shanghai—What those exports and imports are—The devotion of the Chinese to their native land—The true yellow danger of the future—I am invited to a Chinese dinner at Shanghai—My yellow guests—The ladies find me amusing—Their small feet and difficulty in walking—A wealthy mandarin explains why the feet are mutilated—Sale of girls in China—Position of women discussed—A mandarin accepts a Bible—Our host takes us to a flower-boat—Description of boat—My first attempt at opium-smoking—A Celestial in an opium dream | 151 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Great commercial value of opium—Cultivation of the poppy—Exports of opium from India—What opium is—Preparation of the drug—Opinions on the English monopoly of the trade in it—Ingenious mode of smuggling opium—Efforts of Chinese Government to check its importation—Proclamation of the Viceroy Wang—Opinion of Li-Shi-Shen on the properties of opium—The worst form of opium smoking—Its introduction to Formosa by the Dutch—Depopulation of the island—Punishments inflicted on opium-smokers—Opinions of doctors on the effects of opium-eating or smoking—Chinese prisoners deprived of their usual pipe—The real danger to the poor of indulgence in opium—Evidence of Archibald Little—The Chinese and European pipe contrasted | 166 |

| [xi] CHAPTER X | |

| Missionary effort in China—First arrival of the Jesuits—Landing of Michael Roger—Adam Schaal appointed Chief Minister of State—The scientific work of the Jesuits—Affection of the young Emperor Kang-Hi for them—Arrival of other monks—Fatal disputes between them and the Jesuits—The Pope interferes—Fatal results for the Christians—Speech of Kang-Hi—Expulsion of the Jesuits—Concessions to Europeans in newly-opened ports—Hatred of foreigners at Tien-tsin—Arrival of French nuns—Their mistakes in ignoring native feeling—Chinese children bought by the Abbé Chevrier—A Chinese merchant's views on the situation—Terrible accusations against the Sisters—Murder of the French Consul and his assistant—The Governor of Tien-tsin responsible—Massacre of the Abbé Chevrier and one hundred children—The Lady Superior and her nuns cut to pieces and burnt—The guilty Governor Chung-Ho sent to Paris as envoy—No proper vengeance exacted by the French—Other sisters go to Tien-tsin | 184 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Great Wall—Its failure as a defence—Forced labour—Mode of construction—Shih-Hwang-Ti orders all books to be burnt—Mandarins flung into the flames—The Shu-King is saved—How the sacred books came to be written—The sedan-chair and its uses—Modern hotels at Pekin—Examination of students for degrees—Cells in which they are confined—Kublai Khan conquers China—Makes Pekin his capital—Introduces paper currency—The Great Canal—Address to the three Philosophers—Marco Polo's visit to Pekin—His description of the Emperor—Kublai Khan's wife—Foundation of the Academy of Pekin—Hin-Heng and his acquirements—Death of Kublai Khan—Inferiority of his successors—Shun-Ti the last Mongol Emperor—Pekin in the time of the Mongols—When seen by Lord Macartney—The city as it is now | 205 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Fall of the Mongol dynasty—The son of a labourer chosen Emperor—He founds the Ming dynasty—Choo becomes Tae-tsoo, and rules with great wisdom—He dies and leaves his kingdom to his grandson—Young-lo attacks and takes Nanking—The young Emperor burnt to death—Young-lo is proclaimed Emperor, and makes Pekin his capital—First European visits China—Tartar chief usurps supreme power—Dies soon after—Foundation of present dynasty—Accession of Shun-Che—Chinese compelled to shave their heads—The old style of coiffure in China—Care of the modern pig-tail | 227 |

| [xii] CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Founder of the Ch'ing dynasty—A broken-hearted widower—The Louis XIV. of China—The Will of Kang-Hy—Young-t-Ching appointed his successor—The character of the new Emperor—Mission of Lord Macartney—He refuses to perform the Ko-too, or nine prostrations—Interview with Young-t-Ching—Results of the Mission to England—Accession of Kien-Long—He resolves to abdicate when he has reigned sixty years—Accession of Taou-Kwang—The beginning of the end—An adopted brother—War against China declared by England—The Pekin Treaty—Prince Hassan goes to visit Queen Victoria—The Regents and Tung-Che—Foreign Ministers compel the young Emperor to receive them | 235 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| A child of four chosen Emperor—The power of the Empress Dowager—The Palace feud—The Palace at Pekin—A Frenchman's interview with the Emperor—The Emperor's person held sacred—Coming of age of the Emperor—An enlightened proclamation—Reception of the foreign ministers in 1889—Education of the young monarch—He goes to do homage at the tombs of his ancestors—A wife is chosen for him—His secondary wives—China, the battle-ground of the future—Railway concessions | 251 |

| FIG. | PAGE | |

| 1. | VIEW OF HONG-KONG TAKEN FROM ABOVE THE TOWN | 3 |

| 2. | CHINESE SOLDIERS | 5 |

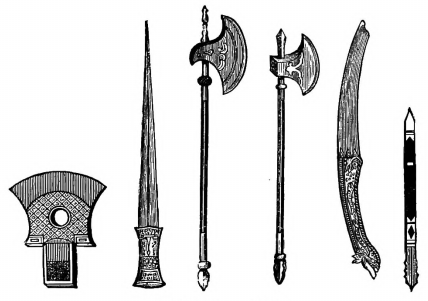

| 3. | CHINESE WEAPONS | 6 |

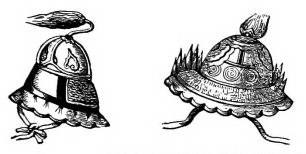

| 4. | CHINESE HELMET AND QUIVER | 7 |

| 5. | A YOUNG CHINESE WOMAN | 8 |

| 6. | A CHINESE COURTESAN | 9 |

| 7. | HWANG-TIEN-SHANG-TI, THE GOD OF HEAVEN | 11 |

| 8. | A CHINESE MANDARIN | 15 |

| 9. | ANCIENT CHINESE COSTUMES | 17 |

| 10. | ANCIENT CHINESE COSTUMES | 18 |

| 11. | A YOUNG CHINESE POET | 21 |

| 12. | A NAUGHTY PUPIL | 28 |

| 13. | A CHINESE BRIDGE SPANNING THE HOANG-HO | 31 |

| 14. | A PAGODA | 34 |

| 15. | A STREET IN CANTON | 40 |

| 16. | A WOMAN OF THE PEOPLE WITH HER BABY | 41 |

| 17. | A CHINESE MANDARIN | 42 |

| 18. | A GONG-RINGER | 43 |

| 19. | A CHINESE ACTOR | 44 |

| 20. | A CHINESE ACTOR IN A TRAGIC PART | 47 |

| 21. | A VILLA NEAR CANTON | 51 |

| 22. | GENERAL TCHENG-KI-TONG | 58 |

| 23. | LAO-TSZE | 67 |

| 24. | THE HOUSE IN WHICH CONFUCIUS WAS BORN | 75 |

| 25. | PORTRAIT OF CONFUCIUS | 76 |

| 26. | A FUNERAL PROCESSION IN CHINA | 77 |

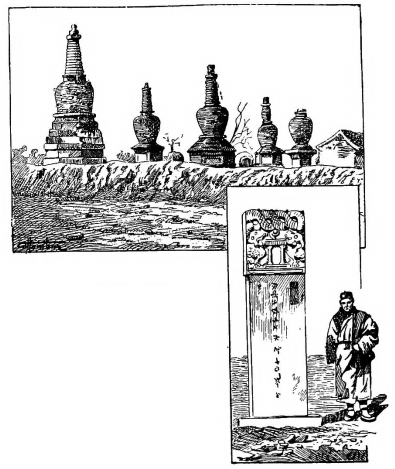

| 27. | CHINESE TOMBS | 78 |

| 28. | A CHINESE CEMETERY[xiv] | 80 |

| 29. | A YOUNG CHINESE MARRIED LADY | 88 |

| 30. | A MARRIAGE PROCESSION | 92 |

| 31. | A DESPERATE MAN | 94 |

| 32. | THE TOMB OF CONFUCIUS | 95 |

| 33. | CHINESE PEASANT CRUSHING RICE | 122 |

| 34. | A CHINESE FERRYMAN | 124 |

| 35. | A MANDARIN'S HOUSE | 127 |

| 36. | PORTRAIT OF HIS EXCELLENCY LI-HUNG-CHANG | 138 |

| 37. | ICHANG | 141 |

| 38. | A CHINESE DYER AT WORK | 143 |

| 39. | A CHINESE VISITING CARD | 144 |

| 40. | A CHINESE RESTAURANT. AFTER THE REPAST | 156 |

| 41. | A CHINESE JUNK | 165 |

| 42. | AN OPIUM-SMOKER | 179 |

| 43. | OPIUM PIPES | 181 |

| 44. | REQUISITES FOR OPIUM-SMOKING | 183 |

| 45. | A TEMPLE AT TIEN-TSIN | 195 |

| 46. | THE GREAT WALL | 206 |

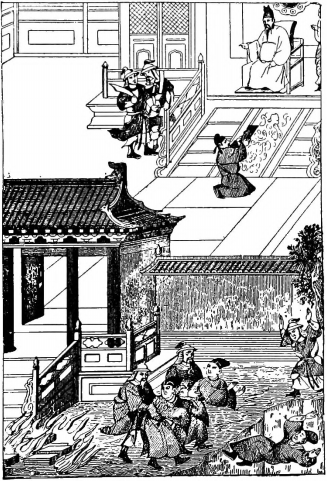

| 47. | BURNING OF MANDARINS AND HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS, BY ORDER OF SHIH-KWANG-TI | 209 |

| 48. | A STREET IN PEKIN | 214 |

| 49. | NIGHT-WATCHMEN IN PEKIN | 216 |

| 50. | A CHINESE GENERAL IN HIS WAR-CHARIOT | 220 |

| 51. | PORCELAIN TOWER AT NANKING | 222 |

| 52. | MONOLITHS AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE TOMBS OF THE MING EMPERORS | 231 |

| 53. | CHINESE BRONZES | 233 |

| 54. | PORTRAIT OF ONE OF THE CHINESE EMPERORS OF THE CH'ING DYNASTY, PROBABLY KIEN-LONG | 242 |

| 55. | ONE OF THE REGENTS DURING THE MINORITY OF TUNG-CHE | 249 |

| 56. | A CHINESE SEDAN-CHAIR AND BEARERS | 255 |

| 57. | A BONZE TORTURING HIMSELF IN A TEMPLE, AFTER A CHINESE PAINTING | 260 |

| 58. | THE TOWN AND BRIDGE OF FUCHAN | 265 |

The delight of exploring unknown lands—Saint Louis and the Tartars of olden times—The Anglo-French force enters Pekin—Terror of the "Red Devils"—The "Cup of Immortality"—The "Sons of Heaven"—Hong-Kong as it was and is—The Treaty of Tien-tsin—The game of "Morra"—First Tea-party in the Palace of Pekin—Chinese agriculture and love of flowers—Chinese literati—An awkward meeting between two of them—Love of poetry in China—Voltaire's letter to the poet-king—The Chinese army—The Shu-King, or sacred book of China—Yao and his work—Chung, the lowly-born Emperor—The Hoang-Ho, or "China's Sorrow"—Yu the engineer and his work—Chung chooses Yu to reign after him—The foundation of the hereditary monarchy in China.

I do not deny the happiness of a life spent beneath the shadow of the belfry of one's native place, in all the unruffled peace of one's own home, surrounded by one's own family; but, after all, what are such joys as these compared to those of the explorer who goes forth to meet the unknown [2] ready for all that may betide, making fresh discoveries at every turn, gladly facing all dangers and rejoicing in the ever-changing, ever-widening horizon before him? Who would care to forego the joys of memory, the power of living over again in old age the adventures of youth, of seeing once more with the mind's eye the wonders of the far-distant lands visited when the mind was still buoyant, the sight still undimmed, the limbs still in all the vigour of manhood? Happy mortal indeed is he who, thoroughly imbued with the spirit of the discoverer, looks upon death itself not as the end of all things, but the threshold of a new world, the beginning of yet another journey fraught with the deepest interest, to a bourne all the more fascinating because of the deep mystery in which it is shrouded.

This was how I reasoned with myself when I was a mere lad eagerly devouring the accounts of the work of the great early explorers, Marco Polo, the Dupleix, La Pérouse, Bougainville, Dumont D'Urville, Christopher Columbus, Mungo Park, the Landers, etc., not to speak of Swift's fascinating romance Gulliver's Travels, and the yet more thrilling Robinson Crusoe of Defoe. Like all boys with vivid imaginations, I was fired with a longing to emulate all these heroes, and said to my mother: "I have made up my mind to be a sailor!"

My ardour was, however, quickly quenched when I saw my mother's beautiful eyes fill with tears at the thought of parting from me. This did not prevent me from leaving France a few years later, for I found myself whilst still quite a young man free to go whither I would, and I made up my mind to make many a long and interesting journey. Of course I expected to meet with dangers and misfortunes, but I felt sure that any such drawbacks would be more than counterbalanced by the grand sights it would be my privilege to witness. My anticipations were in every way fully realized, and if after wandering all over the world I refrain from saying with Terence: "I am a man, and nothing in the nature of man is strange to me;" it is merely because poets alone are privileged to speak with such egotistical assurance.

I had already spent a considerable time in Oceania and a few months in Egypt, when I landed at Hong-Kong on the very threshold of the ancient Chinese Empire, which, according to well-authenticated annals, is older even than the mighty and venerable Egypt of the Pharaohs. I went to China as much to study her past on the spot as to be one of the first to hail that transformation which, when I arrived, was already on the eve of its inauguration, and is now rapidly becoming an accomplished fact. There was, indeed, urgent need for haste if I wished to study that moribund China so long closed to Europeans before the great change came, and cared to gaze upon her far-stretching table-lands girt about by heights crowned with never-melting snow, ere their solitudes were broken in upon by the desecrating [5] steam-engine, in districts whence in mediæval times great hordes of yellow-skinned, fierce-eyed barbarians, their long black hair floating on their shoulders, swept westward to devastate Europe.

In those days five hundred thousand Tartars invaded Russia, took possession of Moscow, burnt Cracow, and penetrated as far as Hungary. Saint Louis of France, who was then on the throne, stood in the greatest dread of them, but this did not prevent him from making a joke about them, quoted by the Sieur de Joinville, which, considering [6] the state of affairs at the time, speaks well for his pluck and sense of humour. "Mother," he said to Queen Blanche of Castille, "if these Tartars come here, we must make them go back to the Tartarus from which they come!"

FIG. 3.—CHINESE WEAPONS. |

|

FIG. 4.—CHINESE HELMET AND QUIVER. |

Time, however, never fails to bring about the poetic justice of revenge. Six centuries after the sack of Cracow a little Anglo-French force entered Pekin with drums beating and flags flying, pillaged the Imperial Palaces, and returned to Europe laden with rich spoil. Chinese, Tartars, Mongols, and Manchus had all alike allowed themselves to be beaten by a mere handful of resolute men. What had they to oppose to European tactics, European weapons, and above all European discipline? Bows [7] and arrows, old-fashioned muskets, spears, and shields adorned with fantastic; designs. There, was nothing for them to do but to run away; not that they were cowards, for they never have any fear of death, but simply because resistance was hopeless. Most of the generals in command of the army followed the usual custom in cases of defeat, and voluntarily emptied the bowl of poisoned opium to save themselves from being triumphed over by their enemies. At Pekin, Canton, and many other centres of population in the vast Empire, the terrified women flung themselves into the wells to escape the violent death they expected the "red devils" would otherwise have inflicted on them. Only some forty years ago what did that immense multitude of Asiatic men and women know about us Europeans? Just about as much and no more than we did of them. One thing only is certain, that in the heroic days of the founders of the dynasty, from Hwang-Ti, the yellow Emperor, to Khiang-Luanh, the poet sovereign [8] more than one ruler of China had drunk from the cup of immortality, that is to say, the cup of poison, rather than live to see the enemy enter his palaces as a conqueror. Enervated by a long course of self-indulgence, the Sons of Heaven, as the Emperors of China proudly style themselves, have degenerated terribly, and what with their own weakness and the arrogant encroachments of the eunuchs who guard the Imperial harem, many of the sovereigns would have been deposed, but for the intervention, now of an Empress-Dowager, now of some favourite wife, who, seizing the reins of power, has wielded the sceptre with virile strength and skill.

In 1851, when the English took possession of the island of Hong-Kong, it was but a rugged conical-shaped rock, dreary and forbidding in appearance. The Chinese then living on it were enraged at the intrusion of the foreigners, and one of them, the only baker on the island, resolved to dispose of all the intruders at one blow. He decided to poison them, and with this end in view he put arsenic into all the bread he supplied to [9] the foreigners. He over-reached himself, for the dose was too strong, and suspicion was at once aroused. Those who tasted the bread escaped with violent sickness, and the English were not going to abandon the place for a reason so insignificant as that.

Hong-Kong is now a maritime port of the first rank, and its harbour is one of the finest and most beautiful in the whole world. The town boasts of hotels managed on the European system, and the slopes of the rocks are covered from the sea-shore to the highest point of the island with tasty villas. It is to opium, that other poison responsible for the death of so many Celestials, and as potent in its effects as the arsenic with which the patriotic baker tried to kill off all the foreigners, that Hong-Kong owes its immense prosperity. The French did much to aid the English in inaugurating that prosperity in 1857 and 1858, when they joined them as allies in the brief campaign which resulted in the taking of Canton and the signing of the celebrated Treaty of Tien-tsin. The various stipulations of that treaty, the full significance of which the Chinese do not seem to have realized at the time, included the right to [10] the allies of appointing diplomatic agents to the Court of Pekin, and the opening of five fresh ports to European commerce, whilst a strip of territory on the mainland, opposite to the island of Hong-Kong, was ceded to the British colony. The benefits which accrued to France were small, but the increase of British trade was enormous, and from that time to this the grand harbour has been: one of the chief naval stations of the East.

In spite of its prosperity and importance, however, the town is anything but a pleasant place to stop in, and the foreign visitor soon gets tired of being jostled about by busy coolies and tipsy sailors. The great delight of the latter is to get drunk in the brandy-stores of Victoria Street, and then to dance, not, strange to say, with women, but without partners, to the music of a violin and a big drum. In the evening the floating and resident population alike resort in crowds to the opium-dens and houses of ill fame in the upper portions of the town. No one seems to feel any shame at being seen to enter these places, the windows of which are wide open, so that all can look into the brightly illuminated rooms, whence proceeds the sound of oaths in all manner of languages, whilst the loud clash of gongs mingles with the muffled songs of the Chinese beauties, and every now and then a shower of crackers is flung into the street below, bursting into zigzags of fire on the heads of the startled passers-by. In the eyes of the masters of the island, the intense commercial activity [11] of the day atones for the dissipations of the night.

Contact with Europeans has, however, done little if anything to modify the ideas and customs of the Chinese. A few of the great native merchants, it is true, are willing now and then to drink a glass of champagne with the representatives of foreign houses, and teach them the game of Morra, which, strange to say, is to all intents and purposes the same as that played all over Italy, and is so well described by Mrs. Eaton in her Rome in the Nineteenth Century. "Morra," she says, "is played by the men, and merely consists in holding up in rapid succession any number of fingers they please, calling out at the same time the number their antagonist shows.... Morra seems to differ in no respect from the Micure Digitis of the Ancient Romans." If it be a fact, as some assert, that the various races of the world are more truly themselves in their games than in their work, this similarity in a pastime played by people so different as the Chinese and the Italians, would have a deep psychological significance.

However that may be, drinking champagne and playing Morra together do not lead to any real friendship or intimacy between the Celestials and their hated foreign guests. There is not, and it seems as if there never could be, any true rapprochement, and this fact is at the root of the anxiety of statesmen for the future, in spite of the apparent progress made in the introduction of European ideas into the very stronghold of Chinese fanaticism, the Palace of Pekin, where a few months ago, on the occasion of her birthday, the Dowager Empress held that first reception of European ladies which was hailed by the European press as the commencement of a new era for China. An account of this historic tea-party may well be added here, for its being given was truly among the most remarkable events which have taken place in the century now so near its close. It seems that Lady Macdonald, the wife of the British Minister, was the prime mover in bringing about this startling innovation in the customs of the most conservative of all modern nations. The fact that it was the guests themselves who compelled the hostess to invite them, detracted not at all from the cordiality of their reception. Received at the entrance to the precincts of the Palace by numerous mandarins in brilliant costumes, the visitors were carried on State chairs to the electric tramway, strange anomaly in such a stronghold of retrogression as the capital of the Celestial Empire, and thence escorted to the audience-chamber [13] by a group of ladies of the Court specially selected to attend them.

In the throne-room, the Empress and her unfortunate son, the nominal ruler of China, were seated side by side on a raised dais, behind a table decorated with apples and chrysanthemums in the simple but effective Chinese manner. Presents and compliments were exchanged, a grand luncheon was served, over which the Princess Ching presided, and when tea was handed round later the Dowager Empress again appeared and sipped a little of the national beverage from the cup of each minister's wife. Finally, when the time for leave-taking came, the astute Dowager, giving way to an apparently uncontrollable burst of emotion, embraced all her visitors in turn. Time alone can prove whether this kiss were indeed one of peace or of future betrayal. In the eyes of the Court officials and their ladies it must have appeared far more startling than any of the political changes with which the air is rife.

The Chinese people, who know next to nothing of what is going on, and are more ignorant of the transformation taking place than even illiterate Europeans, are as indifferent to the past as to the future; they have been accustomed for centuries to obey unchanging laws of a wisdom acknowledged by even hostile critics; and startling innovation touching their own lives is the one thing which moves them out of their constitutional apathy.

Agriculture is the favourite occupation of the [14] Chinese, and they consider the tilling of the ground almost a religious duty. It has been customary for many ages for the supreme ruler to turn over a few furrows at the beginning of the agricultural year, that is to say the spring, and in all the provinces of the vast empire a similar ceremony is performed by the delegate of the Emperor. Flowers are everywhere cultivated, though generally in pots, with an enthusiasm amounting to passion, and marvellous skill is shown in the growing of dwarf trees, which produce quantities of fruit. In a word, vegetation in China is stamped with an originality setting it apart from that of any other country. In irrigation and the use of manure Chinese gardeners were long far in advance of western nations.

The chief ambition of every native of China is to leave behind him sons who on his death will give to his memory the homage he himself rendered to that of his own father, for it is in the reverence in which ancestors are held that the Chinese concentrate all their religious feeling. Even Shang-Ti, or the God of Heaven, Buddha, Lao-tsze, and Confucius only take secondary rank as compared with these ancestors.

The Literati, or scholars of China, have won their much-coveted distinction by many very severe examinations in the so-called King, or the five sacred books, and in the works of the great philosophers. Armed with the diploma securing to him the rank of a scholar, its fortunate [15] possessor may aspire to the very highest functions of the empire. So very many win that diploma, however, and the numbers increase so rapidly every year, that, as in France and in England, there are not enough appointments for those qualified to receive them. In spite of this, the scholar even when out of place commands the respect of all who have not been promoted to the grade he has won. In his interesting account of his travels in Asia, Marcel Monnier gives a very pregnant illustration of the state of things I have been describing.

"As I was leaving the rampart," he says, "I witnessed a curious scene illustrative of the esteem in which—in this land where an hereditary aristocracy does not exist—is held the one ennobling rank, that of being the owner of a paper diploma. My bearers had just entered a very narrow causeway between two rice-fields, when they were suddenly brought to a halt by another chair coming from the opposite direction. This chair was occupied by a young man in elegant attire, wearing spectacles, and with a general air about him of being pleased with himself. Apparently he was a scholar fresh from examinations. The bearers on each side parleyed together, but neither seemed [16] disposed to yield place to the others. The discussion seemed likely to be interminable, when the scholar intervened, and addressing the chief of my bearers, shouted haughtily to him:

"'Why don't you get out of the way of a licentiate of Kan-Su?'

"My chief porter, a big sturdy fellow of about forty, did not move, but without budging an inch replied with equal haughtiness:

"'A licentiate? And of what year, pray?'

"Then without giving the other time to answer, he quickly dived into the little leather-bag hanging from his waist-band, brought out a greasy paper, and proudly unfolded it as if it were a flag, before the eyes of his astonished questioner.

"'Look!' he said.

"The young man took the paper with the very tips of his fingers, but he had scarcely glanced at the magic inscription on it before he handed it back with a respectful inclination of the head, at the same time ordering his men to withdraw. My porter, too, had his diploma, and he had had it for a long time. That of recent date had to give way to the earlier one. My chair passed on in triumph, whilst that of the newly-created scholar humbly waited at the side of the road in the rice-field."

The Chinese have the trading instinct as fully developed as have the descendants of Shem. They carry on commerce with the same wonderful finesse, the same keen eye for a bargain, and they are as fond of money as the Jews themselves. At the same time in really important affairs they are as much to be trusted, as thoroughly loyal to the other side, as any great merchant of the City of London, or the Rue du Sentier in the French capital. These Chinese traders gave credit for enormous sums to the first foreign firms which had the audacity to found the Canton factories. On the faith of their signatures alone guaranteeing eventual payment, the heads of these foreign firms [18] found themselves trusted with whole cargoes of tea and silks. After the failure of the Union Bank, of the Comptoir national d'Escompte, and certain great American houses, this giving of credit was discontinued, but that it was ever granted remains a most significant fact. One proof of the extreme caution which succeeded the extraordinary confidence is, that there are no branches of the great Chinese firms of Shanghai and Hong-Kong in Paris, Marseilles, or Lyons. This is really no great loss, for the West will be invaded all too soon by the yellow races.

In Asia there are many more mystic dreamers and poets than is generally supposed. A Chinese mystic is called a bonze, or talapoin, the former word being of Japanese origin, introduced to China by Europeans. Women who devote themselves to a religious life are called bonzesses, but as certain abuses crept in of a kind which can readily be imagined, a very wise law was passed some time ago forbidding any woman to become a priestess till after her fortieth year, and certain censors have long advocated a yet further higher limit of age.

Amongst young women of the higher classes in the remote East, especially amongst those whose beauty destines them for the harem, poetry is held in high esteem. On the richly-lacquered screens and on the delicately-coloured fans so popular in China, are many representations of frail Chinese or Japanese beauties, tracing certain letters of the Mandarin alphabet with a fine pencil held in their tapering fingers with the characteristic pink nails. The words formed by these letters make up poetic phrases imbued with all the freshness and grace of the fair young girls who transcribe them. In them are sung the praises of the flowers of the hawthorn, the peach-tree, the sweet-briar, and even of a certain savoury tea. More than one Chinese Emperor has done homage to the Muses, and the most celebrated of these crowned [20] poets was Khian-Lung, of the Tartar Manchu dynasty, who died at the end of the eighteenth century, and to whom Voltaire addressed the celebrated letter in verse of which the royal recipient was probably only able to understand, and that with considerable difficulty, the last few lines of which are quoted here:

The fame of two other Chinese poets, who flourished in the eighth century of our era, has also come down to us. These were Tchu-Fu and Li-Tai-Pé, who, as was Malherbe in France, were the first to reform poetry in their native land, laying down certain rules, which are still observed in the present day.

The peace enjoyed for so long a period by the country under consideration has led to the profession of arms being held of small account. Until quite recently all the "warriors" had to do was to put down local revolts, or to win for themselves a good drubbing from some aggrieved foreigner.

The weakness and defective organization of Asiatic armies is well known, and is proved afresh at every contact with a European force. The thorough inefficiency of that of China was forcibly brought out in the recent war with Japan, when the latter country showed itself to be so far in advance of its antagonist in every way. Nothing but drilling by European officers, for at least half a century, could make Chinese soldiers at all formidable to white troops. It is just the same with the people of the Corea, Annam, Tonquin, and Siam. It will, of course, be urged: but look at the Japanese, they too belong to the despised yellow races, yet have they not proved themselves able to organize a campaign? are they not full of warlike energy and martial ability? do they not also take high rank as imaginative [22] artists? In what do the white races excel? To all these queries we reply, the assumption that the Japanese belong to the same race as the yellow natives of the continent of Asia has to be proved. The children of the land of chrysanthemums and of the rising sun indignantly repel this hypothesis, and such authorities on ethnology as Kœmpfer, Golownin, Klaproth, and Siebold also reject it. Moreover, in this world everything is relative, and because the Japanese troops, armed with weapons of precision, were able to beat the badly-equipped Chinese forces, it does not follow that they could do the same if pitted against European soldiers. Whether they could or not still remains to be proved.

Before penetrating into the interior of the country, and studying the actual customs of the inhabitants at the present day, it will be well to glance back to the remote times when China first became a nation. Very interesting details of those early days have been preserved in the traditions of the Celestials, and from them we gather that the first dwellers in the land lived, as did so many of the races of Europe, in the forests, or in caves, clothing themselves in the skins of the wild beasts slain in the chase, whose flesh supplied them with food.

The first efforts at civilization appear to have been made in the North-west of the vast country, amongst the tribes camped on the banks of the Hoang-Ho, or Yellow River. The chiefs of these [23] tribes gradually contracted the habit of making regular marriages, and living a home life with their families. To protect their wives and children they built huts; they discovered how to make fire, and with its aid to fashion agricultural implements and weapons. They knew how to distinguish plants good for food from those dangerous to human life; they fixed precise dates for the commencement of each of the four seasons; invented various systems of calligraphy, finally adopting the one still in use; and they acquired the art of weaving silk and cotton, which, according to the eminent sinologist, Leblois of Strasburg, recently deceased, they learnt from watching spiders at work.

Until the third century B.C. China was divided into small states, the weaker tributary to the stronger, the latter independent. The too-celebrated Emperor Thsin-Chi-Hwang-Ti, who two hundred years before the Christian era ordered the destruction by fire of all books, united the various little kingdoms into one, and it was only in his time that the Chinese Empire properly so called began. At this period, too, the name of Thsina, or China, originally that of the district governed by the incendiary, came to be given to the whole country.

The most important historical documents are those making up what is called the Shu-King, dating from about B.C. 500, and written by a certain Kwang-Tsen. This valuable book has been translated into French by P. Gaubil and L. Biot, and its history is very romantic. It was [24] supposed that every copy had been burnt by the agents of Thsin-Chi-Hwang-Ti, but an old literate, Fu Chang by name, had learnt it by heart, and later, one copy engraved on pieces of bamboo was found hidden in the wall of an old house which was being pulled down.

This sacred book, which is indeed a literary treasure, is now more than 2300 years old, and it contains extracts from works yet more ancient, so that it is the very best guide in existence to the early history of China.

It begins with a description of a chief named Yao, who, according to official Chinese chronology, flourished some 2350 years before the Christian era. If the portrait is not flattered, Yao must have been a perfect man. He lived in the province now known as Chen-si, and, like some great illumination, he attracted to himself all the barbaric hordes in the neighbourhood. His first care was to teach them to honour the Shang Ti, or Tien, that is to say, the Supreme God. He also employed certain men to watch the course of the heavenly bodies, or rather to continue the study of the stars begun before his time, not from any curiosity as to the science of astronomy strictly so called, but that agriculturists might learn the right seasons for the work they had to perform. According to the Shu-King the year was already divided in China into 366 days, and these days into four very strictly-defined periods, beginning at the times enumerated below:

1. The day and night of equal length, marking the middle of the spring season, or what is now known in Europe as the Equinox.

2. The longest day, marking the middle of the summer, now called the summer solstice.

3. The day and night of equal length, marking the middle of the autumn.

4. The shortest day, marking the middle of the winter solstice.

Yao having asked for a man capable of aiding him to govern his people well, his own son was the first to be suggested as a suitable person, but he was rejected, the father saying: "He is deficient in rectitude, and fond of disputing." Another candidate was sent away because he did a great deal of unnecessary talking about things of no value, and pretended to be humble although his pride was really boundless. Then a certain Chung was brought forward, renowned for his virtues in spite of his obscure birth. Although he was the son of a blind father and of a wicked mother who treated him cruelly, whilst his brother was puffed up with excessive pride, Chung yet loyally performed his filial duties, and even succeeded as it were unconsciously in correcting the errors of his relations, and saving them from the commission of serious crimes. He was quoted as the greatest known example of the practice of that most honoured of all virtues in China, filial piety, which is looked upon by the Celestials as the source of every good action of justice and of humanity.

Chung therefore was chosen, and he did not disappoint the hopes Yao had founded upon his rectitude and ability. The sacred book praises the justice of his administration, and he succeeded Yao on that great ruler's death, proving that the hereditary principle was considered dangerous in China even at that remote date. He commenced his reign by offering to the Supreme God, and performed the customary ceremonies in honour of the mountains, the flowers and the spirits, then held in veneration. He took the greatest pains to ensure that justice should be done to all. It is evident that there were schools in his day, for he gave orders that nothing but the bamboo should be used for the correction of insubordinate pupils. Chung wished faults committed without malice prepense to be pardoned, but severe punishments to be inflicted on the incorrigible and on those who abused their strength or their authority. He was anxious, however, that judges under him should temper their justice with mercy.

The ministers of state had names suggesting a pastoral origin, for they were all called Mon, a word answering to our shepherd. When Chung gave them their appointments, he would say to them: "You must treat those who come from a distance with humanity, instruct those who are near to you, esteem and encourage men of talent, believe in the virtuous and charitable and confide in them, and lastly have nothing to do with those whose manners are corrupt." He would also say [27] to them sometimes: "If I do wrong you must tell me of it; you would be to blame if you praise me to my face and speak differently of me when my back is turned."

The Shu-King tells us further that having appointed a man skilled in music to teach that art to the children of the great ones of his kingdom, Chung said to him: "See that your pupils are sincere and polite, ready to make allowances for others, obliging and sedate; teach them to be firm without being cruel; inculcate discernment, but take care that they do not become conceited." He appointed a censor to preside over public meetings where speeches were made, saying to him: "I have an extreme aversion for those who use inflammatory language; their harangues sow discord, and do much to injure the work of those who endeavour to do good; the excitement and the fears they arouse lead to public disorders."

Would it not be well for a similar formula to be pasted up in every place of public meeting at the present day?

Every three years Chung instituted an inquiry into the conduct of the officials in his dominions, recompensing those who had done well, and punishing those who had done ill. Few other sovereigns have merited the eulogy pronounced on Chung by one of his ministers: "His virtues, said the critic, are not tarnished by faults. In the care he takes of his subjects, he shows great moderation, and in his government his grandeur [28] of soul is manifest If he has to punish, the punishment does not descend from parents to children; but if he has to give a reward, the benefit extends to the descendants of those recompensed. With regard to involuntary errors, he pardons them without inquiring whether they are great or small. Voluntary faults, however apparently trivial, he punishes. In doubtful cases the penalty inflicted is light, but if a service rendered is in question, the reward is great. He would rather run the risk of letting a criminal escape the legal punishment than of putting an innocent person to death." The same minister thus defines a fortunate man: "He is one who knows how to combine prudence with indulgence, determination with integrity, reserve with frankness, humility with great talents, consistency with complaisance, justice and accuracy with gentleness, moderation with discernment, a high spirit with docility, and power with equity."

The Hoang-Ho, or Yellow River, the mighty [29] stream which rises in Thibet and flings itself into the Gulf of Pechili after a course of some 3000 miles, had from time immemorial been the cause of constant and terrible catastrophes in the districts it traversed. Chung therefore sent for a talented engineer named Yu, and ordered him to superintend the work of making canals and embankments to remedy the evil. There had been a specially destructive inundation just before this appointment, and the sacred book contains Yu's own account of what he had accomplished, couched, it must be owned, in anything but modest terms. "When," he says, "the great flood reached to heaven; when it surrounded the mountains and covered the hills, the unfortunate inhabitants were overwhelmed by the waters. Then I climbed on to the four means of transport. I followed the mountains, and I cut through the woods. I laid up stores of grain and meat to feed the people. I made channels for the river, compelling them to flow towards the sea. In the country I dug canals to connect the rivers with each other. I planted seed in the earth, and by dint of work something to live upon was won from the soil."

The memory of these vast undertakings has remained engraven on the minds of the Chinese, and they still think of Yu with undying gratitude. For all that, however, the Hoang-Ho has continued to be a menace to the Empire, for in 1789, and again in 1819, it overflowed its banks, causing a considerable amount of damage to property, and killing countless numbers of the river-side population. Only [30] twelve years ago the wayward river, justly called by the sufferers from its ravages "China's sorrow," burst its southern embankment near Chang-Chan in the inland province of Shen-Hsi, and poured in one great mass over the whole of the densely-populated Honan, drowning millions of helpless people, and undoing the work of centuries. In a word, what the erratic river will do next is one of the chief problems of the physical future of China. It has already shifted its course no less than nine times in its troubled career; and on account of the great rapidity of its stream it is of little use for navigation. Could Yu have foreseen the destruction of all the grand works of which he boasted, he would probably have taken a less exalted view of what he had accomplished.

However that may be, his contemporaries were so impressed by his ability, and the great Chung so admired his virtue and talent, that he was chosen as heir in the life-time of that mighty sovereign. The dialogue said to have taken place between the Emperor and his subject on the question of the succession to the throne is curious and interesting:

"Come," said Chung to Yu, "I have been reigning for thirty-three years; my advanced age and growing infirmities prevent me from giving the necessary application to affairs of state. I wish you to reign instead. Do your utmost to acquit yourself worthily of the task."

"I am not virtuous enough to govern well," replied Yu; "the people will not obey me."

He then recommended some one else.

Chung, however, insisted in the following terms:

"When we had everything to fear from the great inundation, you worked with eagerness and rectitude; you rendered the greatest services, and your talents and wisdom were made manifest throughout the whole country. Although you have led an unassuming life with your family, although you have served the State well, you have not considered that a reason to dispense with work, and this is no ordinary virtue. You have no pride; there is no one in the country superior to you in good qualities. None other has done such great things, and yet you do not set a high value on your own conduct. There is no one in the country whose merit excels your own."

So Yu became chief ruler, and his name was [32] associated by posterity with that of Yao and of Chung. The sacred book has preserved many of his sayings, and I will quote the most beautiful here:

"He who obeys reason is happy, he who resists it is unhappy. Virtue is the foundation of good government; the first task of government is to provide the people governed with all that is necessary for their subsistence and preservation. The next thing is to make the population virtuous; to teach them the proper use of everything; and lastly, to protect them from all which jeopardizes their health or their life. The prince who understands men well will appoint none to public offices but those who are wise; his generous heart and liberality will win him love."

When Yu died, the chiefs of the people unfortunately failed to carry on the custom of choosing as a successor to the throne the wisest and most illustrious of their number. The law of hereditary right was recognized, and dynasties henceforth succeeded each other in China as elsewhere, each lasting a long or short time according to whether the people were or were not satisfied. There was, however, one salutary exception to the usual interpretation of the hereditary principle. The reigning Emperor could choose as his successor the son he considered the most intelligent of his children; and as a Chinese ruler generally has at least fifty children, without counting the girls, there is no difficulty in making a selection.

Trip up the Shu-Kiang river—My fellow-passengers and their costumes—A damaged bell—Female peasants on the river-banks—I am caught up and carried off by a laughing virago—Arrival at Canton—Early trading between China and Ceylon and Africa, etc.—The Empress Lui-Tseu teaching the people to rear silk-worms—The treaties of Nanking and Tien-tsin—Bombardment of Canton—Murder of a French sailor and terrible revenge—M. Vaucher and I explore Canton—The fétes in honour of the Divinity of the North and of the Queen of Heaven—General appearance of Canton—An emperor's recipe for making tea—How tea is grown in China—The Fatim garden—A dutiful son—Scene of the murder of the Tai-Ping rebels—The Temple of the five hundred Genii—Suicide of a young engineer—Return of his spirit in the form of a snake.

Well-built, comfortable steamers leave Hong-Kong daily for Canton. I embarked in one of them one fine spring morning, when a fresh sea-breeze was blowing, such as gives new life to those enervated by too long a residence in the tropics. I did not see a single white face amongst the passengers, for European trade is all transferred to Hong-Kong, now driven away from Canton by the burning by the Celestials of the fine factories [34] built outside the gates of the city by European contractors.

My fellow-passengers, all Chinese, wore loose garments of blue cotton, thick-soled shoes, and a skull-cap, from which a long pig-tail, in many cases of false hair, hung down the back, reaching to the heels. The crew of American sailors as they navigated the vessel kept a watchful eye upon the passengers, for though the latter looked peaceable enough, there had been more than one instance of the sudden transformation of inoffensive travellers into daring pirates, who, after pillaging and burning the ship, had made for the nearest shore and escaped the vengeance of those they had robbed.

Before entering the great Shu-Kiang river, on the north bank of which Canton is built, we passed the ruins of a fort dating from the time of the Dutch supremacy. Beyond it the stream is bordered by green rice plantations with little hills [35] rising up here and there surmounted by isolated pagodas of several storeys high. On one of them I noticed standing out against the sky from the fifth storey the fragment of a bell, one-half of which had been shot away by a ball from a French cannon. Great indeed must have been the astonishment of the Chinese, posted on this particular pagoda to watch the movements of the enemies' troops, when the projectile struck the sonorous mass of bronze and shivered it to splinters. The catastrophe must have been to them a warning full of sinister yet salutary meaning.

The river rushes proudly along towards its final home in the ocean, but narrows before it reaches its actual mouth, the water becoming yellow, as does that of the Nile at the time of its rising. Even without glasses I could quite clearly make out several poor-looking villages, the houses with their dull red roofs occupied no doubt by fishermen and their families. Oh, how different were the surroundings of these water-highways of China to those of the Seine, the Rhone, and of the charming Gironde! How much I preferred even the Nile, which I had but recently left, to this so-called Pearl of the East, for in spite of the ugly black mud-huts of the fellaheen, there is something beautiful about the river-side scenery. I like the graceful date-tree far better than the bamboo with its self-conscious uprightness, and I considerably prefer the slim and supple Egyptian women to the clumsy, heavy-limbed female peasants of China, such as I saw on the banks of the Shu-Kiang, [36] dragging heavy loads behind them as they strode along in a manner which made me doubtful as to their sex, especially as their faces were hidden by the great hats they wore. A few more turns of the paddle-wheels of our steamer, and it stopped opposite Canton. In a moment a virago, such as those I had been looking at with anything but admiration, was on the deck, and seizing me in her strong arms as if I were a delicate baby, she quickly deposited me at the bottom of her own boat, roaring with laughter over my embarrassment. I had no longer any doubt as to her sex, as with a few vigorous strokes of her oars she ran her boat ashore, and with the same maternal care as she had shown before she landed me upon the wharf of the little island of Hainan where I was expected.

There is no particular historic interest attached to Canton except that it was the very first Chinese town to enter into relations with foreigners. We know that this opening of intercourse took place in the year 618 A.D., but whence the foreigners came is not so certain. Possibly some of them were from Ceylon, and undoubtedly others were from the continent of Africa, as proved by the fact that elephants' tusks, the horns of the rhinoceros, coral, pearls, redwood, and medicines were brought into the city by the strangers, who received metals in exchange—that is to say, copper, tin, and gold, and silk—especially silk—for it was manufactured in the Celestial Empire twenty-seven centuries before the Christian era. It was Lui-Tseu, the [37] wife of the great Emperor Kwang-Ti, or the Yellow ruler, who taught the people the art of rearing the silk-worm and spinning the material it produced. The industry of silk-weaving has brought such wealth to China that Lui-Tseu has been raised to the rank of a beneficent genius, and is honoured under the name of the "Spirit of the mulberry-tree and the silk-worm."

In 1127 an edict was issued forbidding the exportation of metal, and ordering all payments to be made from henceforth in money alone. It is recorded in Chinese annals that at a considerably later date a French vessel came up the river Shu-Kiang and fired her cannons in an aggressive manner, so that relations with foreigners were broken off.

In 1425, however, an embassy from Portugal resulted in the re-admission of foreigners to Canton, and a century later the Dutch also obtained a footing in the city.

They in their turn were, however, supplanted by the English, who practically enjoyed a monopoly of trade from the beginning of the eighteenth century until 1834. At that date their prosperity began to decline, one dispute succeeding another, and in 1839 open war broke out between England and China. In 1841 Hong-Kong was ceded to the former power, and in 1842 the Treaty of Nanking was signed, opening to British traders the five ports of Canton, Amoy, Fuchau, Ningpo, and Shanghai. Fresh friction was caused by the arrogant assumptions [38] of the Chinese and the vacillating policy of the English, culminating in the war of 1856, the immediate cause of which was the capture by the Chinese of a lorcha, or small hybrid vessel of European build, with the rigging of a Chinese junk flying the British flag. After a fierce struggle a peace was again patched up, but the factories outside Canton had all been destroyed by the mob, and prosperity has never since fully returned to the city. It was not until 1860, when the Convention of Pekin was signed, ratifying the Treaty of Tien-tsin, that anything like cordial relations were established between England and China, and since then these relations have been again and again disturbed.

Before the bombardment of Canton by the united fleets of England and France every foreigner found within the walls of that inhospitable town was beheaded at once. Naturally, with the memory of all that had so recently happened fresh in my mind, I hesitated when M. Vaucher, representative on the island of Hainan, of the Swiss house of the same name, suggested that we should go together through the streets of Canton in sedan chairs. I did not like to allude to the danger I might run myself, but I asked if I should not be exposing him to peril. "No," was his reply, "your fellow-countrymen have won the permanent respect of the people for all foreigners, and you will be able to boast on your return home of having explored the vast city with no other protector than myself."

M. Vaucher then told me the following story:

"After the allied fleets had taken possession of Canton, the commanders used to send a party of men every morning to get fresh fruit for the table of the officers, and rarely did a day pass without at least one Englishman being absent at calling over. Any sailor, who to satisfy his curiosity was foolish enough to leave his comrades for a moment, was at once set upon by Chinese soldiers and murdered in the open street. Vainly did the Admiral of the English fleet threaten to make bloody reprisals if the authorities did not punish the offenders. The same kind of thing happened again and again. At last one day five or six sailors belonging to a French frigate landed and made their way into Canton. As they turned into a street they missed one of their party, and presently they found his headless corpse lying on the ground. When the crime became known to the French, the second in command of the fleet collected fifty volunteers, armed them with revolvers and hatchets, and landing with them, marched them into Canton. On arriving in the street where the murder had been committed, some of the men were told off to guard the entrances to it, whilst the rest made their way into the houses and killed all the Chinese they found in them except one, who, though he had already been hit by six bullets, calmly walked up the middle of the street without quickening his pace or even turning his head to the right or the left at the sound of the renewed firing. The leader [40] of the expedition at last ran up to him and gave him a smart blow on the shoulder. The fearless Celestial merely turned his pale face towards his assailant, looking at him without a smile. He did not even tremble in the grasp of his enemy. Touched by his courage the officer spared his life handing him over to two sailors with orders to do him no harm.

"After this bloody punishment, which was very hostilely criticized by the English press of Hong-Kong and Shanghai, Europeans, whatever their [41] nationality, have been able to wander about unmolested either alone or in parties in the streets of Canton."

After listening to this tale, I had an eager desire to explore the town, which, since the departure of the allied fleets, had rarely been entered by Europeans. I watched anxiously for the first symptom in the faces of the inhabitants of the hereditary hatred of white men, which had most likely been greatly intensified by the bombardment of the town, and by the punishment inflicted for the murder of the French sailors, a punishment by no means excessive, terrible as it was. I am bound to add, however, that as M. Vaucher and I were carried rapidly through the crowded streets by our coolies, in our respective chairs, we noted no hostility in the placid faces of those we encountered. The people stood aside to let us pass, and showed rather benevolent curiosity than insulting [42] indifference. The Chinese children, with their round heads and strongly-marked eyebrows, who are so aggressive and impudent in the interior of the country, here remained perfectly silent. Only the old women tottering along on their deformed feet paused in their painful walk now and then, to lean against the walls of the houses, and look at us in a mocking though not exactly a hostile manner. Our progress was only once arrested for a moment, when we met a great military mandarin in a narrow street, escorted by some ten warriors bearing their halberds on their shoulders. The mandarin stopped, and we passed without difficulty, giving him a military salute in return for his courtesy.

I confess that this unexpected complaisance put me into a very good humour, and after this incident I gave myself up without reserve to the enjoyment of my first visit to a Chinese town.

|

|

| FIG. 17.—A CHINESE MANDARIN. | FIG. 18.—A GONG-RINGER. |

By a lucky chance I had arrived at the very moment when the inhabitants were celebrating two of their greatest festivals. The first, in honour of the beautiful Paktai, the fair Divinity of the North, was simply remarkable for the immense crowds flocking to the pagodas, crowds made up of bonzes, bonzesses, portly mandarins, cooks and barbers vigorously plying their trades, æsthetes with effeminate faces, young girls full of delight at getting out of their palanquins for once, and at being able to totter about on the flag-stones of the temples for a few minutes on their poor mutilated feet.

When the gilded pedestal upholding the shrine of Paktai was completely hidden beneath the flowers flung upon it by the crowds, the worshippers all repaired en masse to see the theatrical representations which take place after the religious ceremony. Not until midnight did every one go home, only to meet again the next day, when a great procession passed through the city, in the midst of which the venerated idol was carried with the greatest pomp. Some on horseback, others in sedan chairs, were many young boys and girls wearing the costumes in vogue amongst the heroes and heroines of the earliest days of the Celestial Empire. Many too were the banners of beautiful [44] silk embroidered with various devices or inscriptions in golden letters, and still more numerous were the bearers of the large gongs, some of which were of such an immense circumference that it took two strong coolies to carry them.

All Asiatics love a deafening noise, and the delight of the Chinese may be imagined when the accumulated din of these great bronze disks becomes one continuous roar like thunder.

The second féte I witnessed was celebrated in the Honan suburb in honour of Tien-Ho, the Queen of Heaven, and the protectress of sailors. All the ship-owners of the populous city of Canton, all the pilots, all the captains of junks and sampans, all the fishermen, boatmen, and boatwomen,—in [45] fact, every human creature connected in the remotest degree with anything like shipping or boats, were collected in front of the sanctuary of the goddess. Her statue too was covered with flowers, and, as in the case of the féte of the Divinity of the North, the theatre opened directly the pagoda of the Queen of Heaven closed. The stage was erected about a hundred yards from the pagoda, so that the devout had only to turn round to pass at once from the sacred to the profane.

A grand spectacular drama, called the Marriage of the Ocean and the Earth, extended over twelve consecutive evenings; the only plot was, however, the presentation to each other by the betrothed couple of the vast treasures at their disposal.

The Earth began by a grand show of tigers, lions, elephants, ostriches, etc.—in a word, of all the big animals which our ancestor Noah took with him into the ark. Then the Ocean, not to be outdone, paraded in his turn his dolphins, his turtles, the vessels he had engulfed, his corals, and great bunches of all the most wonderful growths of his submarine gardens. All these marvels were, however, nothing but a prelude to the great final surprise, when an enormous whale reeled into view, and as it flopped about shot out a great volume of water over the whole stage. It would be impossible to describe the enthusiastic delight of the spectators, who all shouted like madmen. Has! Hung haho! (excellent! perfect!) and if M. [46] Vaucher and I had not applauded too we should have been stoned.

The beautiful river on which Canton is built presented for many days a most picturesque appearance. I could wish those of my readers who love the marvellous, who enjoy looking at crowds and do not mind noise, no better pleasure than to gaze, if but for a moment, upon the Pearl of the East at this féte of the protectress of those who do their business on the great waters, thronged as its surface then is with junks dressed with flags, brilliantly illuminated flower-boats, little vessels transformed for the nonce into miniature pagodas, gliding mysteriously along as do the gondolas of Venice. I was told that on these occasions more than one lovely young Celestial maiden is worshipped in these pagodas of a day, with a ritual very different from that of the public ceremony we had witnessed at the shrine of the goddess.

Canton consists of a great number of narrow streets, each house in which is adorned with coloured signs, giving a very quaint and charming appearance to the façades, especially of an evening, when the gilt lettering on the red and black lacquer ground is lit up by the rays of the setting sun. As was the case in European towns in mediæval times, and is still customary in the Orient, each district of the city has its own special industry, and is closed at nightfall by a bamboo barrier. The cobblers' quarter seemed to me to be the most densely populated; a great multitude of workers, [47] naked to the waist, zealously plying their trade, chattering like magpies the while. Close to the cobblers live the coffin-makers, who are even noisier than their neighbours, and quite as happy over their work. Yet another quarter dear to the lovers of bric-à -brac, is sacred to the manufacture of porcelain, bronzes, cloisonné enamels, beautifully lacquered or delicately carved boxes in ebony, ivory, and other materials, plain and figured silks, etc., which are sent to Hong-Kong for trans-shipment to Europe and America.

You can of course get all these things without going all the way to China for them, and they are to be seen in Paris in the Guimet and Cernuschi Museums, and at various Oriental houses in London and New York. Many Chinese are very wealthy, and keep for themselves and their heirs the art treasures they buy or have inherited from their ancestors.

In spite of the fact that you can see Chinese curios at home, it would be a pity to miss the [48] pleasure of rummaging, in the shops. The owner of those you enter will receive you with apparent cordiality, but at the same time with a certain distrustful politeness, and you will be carefully watched as you turn over the goods for sale. If you accept the cup of tea which every merchant delights to offer to his visitors, and you seem to appreciate the superior quality of the beverage, you will win the golden opinion of the donor, for to the Celestial tea is a divine plant. The drink made from it as a matter of fact quenches thirst better than any other, not only in the heat of summer, but also in the extreme cold of the heights of the Himalayas or of the desert of Gobi, where the traveller is exposed to the icy blast of the north wind. From the east to the west, from the north to the south of the vast Empire, we meet with the hospitable tea-house; it is perhaps not quite such a fascinating place as it is in Japan, but beneath its shelter the traveller is always sure of finding the cheering beverage which will put new strength into him for his further journey. There is not a Chinese poet who has failed to sing the praises of the precious shrub. Even an illustrious Emperor wrote directions in verse (reproduced below in dull prose) for the preparation of a cup of tea, and described the salutary effect it has upon the mind:

"Put a tripod pot, the colour and form of which testifies to long service, upon a moderate fire; fill this pot with the pure water of melted snow, and heat this water to the degree [49] needed for turning fish white or crabs red, and then pour it at once into a cup containing the tender leaves of a choice tea; leave it to simmer until the steam, which will at first rise up copiously, forms thick clouds which gradually disperse, till all that is left is a light mist upon the surface; then sip the delicious liquor slowly; it will effectually dissipate all the causes for anxiety which are worrying you. You can taste, you can feel the peaceful bliss which results from imbibing the liquid thus prepared, but it is perfectly impossible to describe it. Already, however, I hear the ringing of the curfew-bell; the freshness of the night is increasing; the moonbeams penetrate through the slits in my tent, and light up the few pieces of furniture adorning it. I am without anxiety and without fatigue, my digestion is perfect; I can give myself to repose without fear. These verses were written to the best of my small ability, in the spring of the tenth month of the year Ping-yn (1746) of my reign.

(Signed) Khian-Lung."

The tea-plant is a shrub requiring very little care. A siliceous soil suits it best, and in it it attains its fullest development. Great quantities of seed are sown in September and October, and when the plants are about nine inches high they are transplanted and placed about twenty inches apart. When the leaves have reached their fullest development they are gathered, carefully washed to remove any earth which may have clung to them, and they are then exposed to the rays of the sun, the day chosen for this part of the preparation being the very hottest in the year. In the evening the dry leaves are taken up with every precaution against injury, placed in boxes, and protected from the air by sheets of lead. Millions of cases of tea thus packed are dispersed all over the world, but [50] it is needless to add that the Chinese keep the best leaves for their own consumption. Green, or as they themselves call it, white tea, is put into boxes directly it is picked, without any drying or other preparation, and black tea is produced by placing the leaves in a brazier over a slow fire, these leaves being constantly turned over with the hands by the men in charge of them, to prevent them from sticking together or drying too quickly. When taken from the brazier they are placed in a sieve and still further manipulated, always with the greatest care and delicacy. Lastly, they are once more exposed to heat in the brazier to give them the brown colour so much esteemed by many consumers. It is in this last stage of the preparation that the skill of the manipulator is put to the severest test, for if the tea is too much burnt it will have no taste at all, and if it is not sufficiently burnt it will be bitter and heating.

I forget now in whose house it was, but I was on one occasion stupid enough, when the guest of a mandarin, to say I had once at the residence of a clergyman drunk an excellent cup of tea mixed with rum and sweetened with sugar.

"Sugar and rum!" cried my host, who was terribly shocked. "We must take care not to offer our best teas to you, for you would certainly not be able to appreciate them."

I stopped eight days at Canton; more than enough to visit everything worth seeing in that now uninteresting city. I saw the endless rice-fields stretching away beyond its gates; I went to look at the French concession, where there is not a single French inhabitant, though the names of the streets, such as the Rue de la Fusée, the Rue de la Dordogne, and the Rue de la Charente, recall the vessels once manned by the brave sailors who had for a brief time sojourned in this remote Chinese town. One curiosity which every visitor to Canton ought to see, is the so-called Fatim garden, where each tree represents some fantastic animal, and in which prowl herds of pigs, more quaint in appearance than the shrubs tended by pale-faced young bonzes wearing yellow garments.

The cemetery of Canton is of vast extent, and every year in the month of May, the pious Celestials all flock to it in white robes, to lay offerings of rice, fruit, and flowers on the graves of those they have lost. The gifts would be left unmolested for a long time, but for the fact that they are presented in the spring, just when countless birds are nesting in the branches of the lofty bamboos growing in the neighbourhood, and who consequently look upon the rice and fruit as provided especially for them.

It is not only after the death of those near and dear to them, that the Chinese show the deep filial love for their parents which is one of their most striking characteristics. The Pekin Gazette gave a very touching instance of this reverent affection, communicated to the official organ of the Celestial Empire by the Governor of Schantung, which made such a sensation that it reached the ears of the Emperor himself. Here is the story:

A certain native of China, Li-Hsien-Ju by name, whose father had died at Feï-Chang, immediately sold the piece of land he inherited in order to give a grand funeral in honour of his beloved and lamented father. The time of mourning had not yet expired when a terrible famine took place in the town where the ceremonies were going on. Provisions became so scarce and so dear, that Li-Hsien-Ju found himself quite unable to provide properly for his aged mother, so he decided to carry her on his back to another province where the ground was less sterile. This he did, begging [53] his way as he went, and supporting himself and his sacred charge on alms alone.

This model son, laden as he was, actually traversed the fabulous distance of four hundred French leagues, finally arriving at Honan, where he and his mother settled down. A year after this the poor mother was taken ill, and Li-Hsien-Ju, fearing that she might die in a strange land, of which every Chinese has the greatest horror, resolved to take her home to her native country in the same manner as he had brought her from it, so he started back again with his sacred burden, begging his way once more. The two got back again to Feï-Chang at last, but had scarcely reached their home before the old mother died. It is impossible to tell how many nights the heart-broken son spent on the tomb of the lost one, but we know that, thanks to his pious efforts, the bones of his father were laid beside the body of his mother. A few days after the death of the latter, the grief of the orphan became so terrible that he wept tears of blood. He is now sixty years old, but he still mourns for his parents, and in the month of May when the féte of the dead is held, he never fails to drag himself to the cemetery and place upon the tomb, according to custom, a bowl of smoking rice of gleaming whiteness.

There are no Monthyon prizes, such as those given by the French Academy for acts of disinterested goodness, or surely this unselfish son would have received one.

M. Vaucher and I went to visit the quay outside Canton, which was the scene of the massacre of 100,000 Tai-Ping rebels, after the defeat of Hung-Hsiu-ch'wan in 1865. The ferocious mandarin Yeh had them all decapitated at the edge of the river Kwan-Tung, their heads falling into the muddy stream. A Dutchman, who had belonged to a factory in Canton at the time, told me that he witnessed the terrible scene from his window, and had been greatly struck by the extraordinary composure with which the victims met their fate. Motionless and with bowed heads they knelt at the edge of the quay, awaiting the fatal stroke of the sword. "I had some idea," added the Dutchman, "of sending the poor fellows some packets of cigarettes to cheer their last moments, but I should have been completely ruined, for their numbers increased every day."