Title: Pugilistica: The History of British Boxing, Volume 3 (of 3)

Author: Henry Downes Miles

Release date: December 22, 2020 [eBook #64111]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Carol Brown, deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE HISTORY

OF

BRITISH BOXING

PUGILISTICA

THE HISTORY

OF

BRITISH BOXING

CONTAINING

LIVES OF THE MOST CELEBRATED PUGILISTS; FULL REPORTS OF THEIR BATTLES FROM CONTEMPORARY NEWSPAPERS, WITH AUTHENTIC PORTRAITS, PERSONAL ANECDOTES, AND SKETCHES OF THE PRINCIPAL PATRONS OF THE PRIZE RING, FORMING A COMPLETE HISTORY OF THE RING FROM FIG AND BROUGHTON, 1719–40, TO THE LAST CHAMPIONSHIP BATTLE BETWEEN KING AND HEENAN, IN DECEMBER 1863

EDITOR OF “THE SPORTSMAN’S MAGAZINE.” AUTHOR OF “THE BOOK OF FIELD SPORTS,” “ENGLISH COUNTRY LIFE,” ETC., ETC.

VOLUME THREE

Edinburgh

JOHN GRANT

1906

TO

LEAR JAMES DREW, ESQ.,

A PATRON OF SPORT, AND A

SUPPORTER OF THE RECREATIONS OF THE PEOPLE,

THIS VOLUME OF LIVES OF THE

MODERN BOXERS IS DEDICATED, AS A

TOKEN OF FRIENDSHIP, RESPECT, AND ESTEEM,

BY

THE AUTHOR.

Wood Green.

The Reader who has attentively accompanied us through the biographies which form the contents of our first and second volumes will not find the memoirs in this third and concluding volume of less interest and variety of incident than the former.

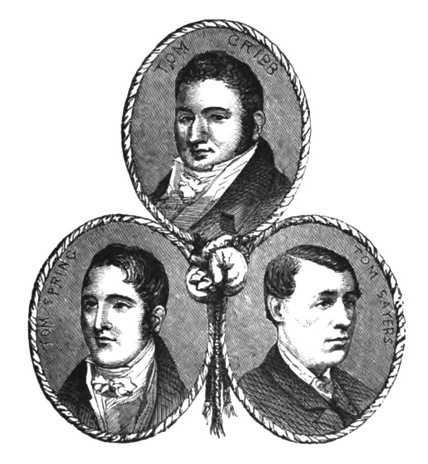

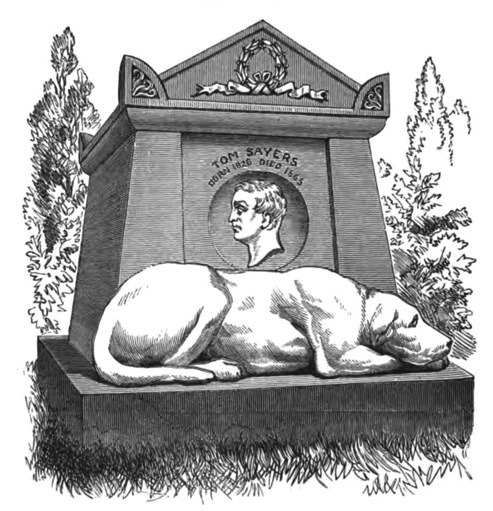

The period comprised herein extends from the year 1835 (the first appearance of Bendigo), and contains the battles of Caunt, Nick Ward, Deaf Burke, William Perry (the “Tipton”), Harry Broome, Tom Paddock, Harry Orme, Aaron Jones, Nat Langham, Tom Sayers, and Jem Mace, closing with the last Championship fight between Tom King and John Camel Heenan, on the 10th of December, 1863.

In these chapters of the “Decline and Fall” of Pugilism it has been the aim of the author to “write his annals true,” “nothing extenuate nor set down aught in malice;” leaving the deeds of each of the Champions to be judged by the “test of time, which proveth all things.”

In these pages will be found all the battles of the actual Champions, and of those who contended with them for that once-coveted distinction. It must be evident, however, that the space of three volumes thrice multiplied would not suffice to record the numerous battles of the middle and light weight men of this period; indeed, they do not come within the scope of this work. As these include some of the best battles of the later days of the P. R., and for the greater part fall within the memory of the writer of these pages, he will collect them in a series of “Pencillings of Pugilists.” These “Reminiscences” of the Ring, will form, when completed, a concurrent stream of pugilistic history, subsidiary and contemporary with this last volume of this work.

In bidding farewell to his subject the writer would plead, with the Latin poet—

PUGILISTICA

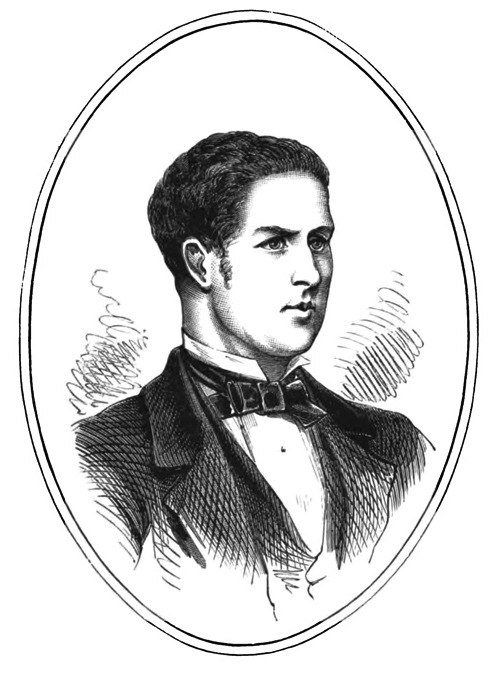

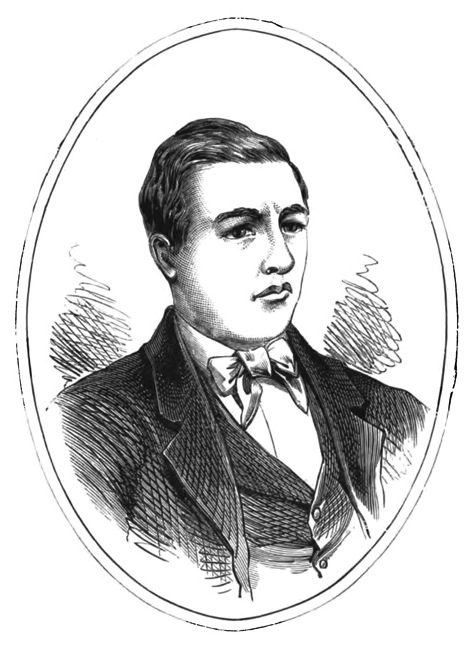

WILLIAM THOMPSON (“Bendigo”)

of Nottingham.

FROM THE CHAMPIONSHIP OF BENDIGO (WILLIAM THOMPSON) TO HIS LAST BATTLE WITH CAUNT (1845).

William Thompson, whose pseudonym of Bendigo has given its name to a district or territory of our Antipodean empire, first saw the light on the 11th day of October, in the year 1811, in the city of Nottingham, renowned, in the days of rotten boroughs and protracted contested elections, for its pugnacious populace, its riotous mobs, and rampant Radicalism, succeeded, in a like spirit, even in later “reformed” times, by its lion-like “lambs,”[2] and “tiger-Tories.” William was one of three sons at a birth, and, we are assured, of a family holding a respectable position among their neighbours, some of them filling the ministerial pulpit, and others belonging to a strait and strict denomination of dissent. The late Viscount Palmerston expressed his opinion that had not John Bright, the coadjutor of Cobden and Gladstonian Cabinet Minister of our own day, been born a Quaker, he must have grown up a pugilist; a similar reflection suggests itself to those who knew the character and genius of William Thompson; with the difference that in his case the young pugilist did grow into an elderly Methodist parson, as we shall hereafter see, while the Broadbrim secular Minister has not yet figured in the roped twenty-four feet.

4There is a closer psychological connection between fighting and fanaticism, pugnacity and Puritanism, than saints and Stigginses can afford to admit, and the readiness of wordy disputants to resort to the argumentum ad hominem, or ad baculinum, and the facile step from preachee to floggee of parsons of all sects and times, need no citations of history to prove. The young Bendigo, as we shall see hereafter, became another illustration of the wisdom of Seneca,[3] and took to theological disputation when he could no longer convince his opponents by knock-down blows.

Of the earlier portion of the career of Bendigo, previous to his first victory over the gigantic Ben Caunt, in July, 1835, much apocryphal stuff has been fabricated by an obscure biographer.

In 1832, William Thompson, then in his twenty-first year, beat Bill Faulker, a Nottingham notoriety. In April, 1833, he defeated Charley Martin, and in the following month polished off Lin Jackson, another local celebrity.

Tom Cox (of Nottingham), who had beaten Sam Merriman, was defeated easily in June, 1833; and in August of the same year (1833) Charles Skelton and Tom Burton[4] are said to have fallen beneath Bendigo’s conquering fist. Moreover (surely his biographer is poking fun at us) he is credited with beating Bill Mason in Sept. 1833, and Bill Winterflood in October! Now as we know no Bill Winterflood except Bill Moulds, the Bath champion, and he never met Bendigo at all, are we not justified in rejecting such “history”?

The last in this list is a defeat of one Bingham, who is set down as “Champion,” in January, 1834, which brings us near enough to Bendigo’s first appearance in the blue posted rails of the P. R. with Caunt on July 21st, 1835. On that day, we read—

“A fight took place in the Nottingham district between two youngsters who were both fated to develop into Champions of England. The meeting-place was near Appleby House, on the Ashbourne Road, about thirty miles from Nottingham.” Both men were natives of Nottinghamshire; the elder one, William Thompson, hailing from the county town; while the younger, Benjamin Caunt, was a native of the village of Hucknall, where his parents had been tenants of the poet, Lord Byron—a fact of which the athlete was always intensely proud. Caunt on this occasion made his first appearance in any ring, and having been born on the 22nd of March, 1815, 5 had only just completed his twenty-first year, and had therefore a very considerable disadvantage in point of age. On the other hand, he was a youngster of herculean proportions and giant strength; stood 6ft. 2in. in height, and his fighting weight was 14st. 7lb. Thus, in point of size, it was a horse to a hen; but Caunt had no science at all, while Bendigo had a very considerable share of it. The big ’un was seconded by Butler (Caunt’s uncle) and Bamford, and Bendigo by Turner and Merryman. Throughout twenty-two rounds Caunt stood up with indomitable pluck and perseverance to receive a long way the lion’s share of the punishment, while his shifty opponent always avoided the return by getting down. Caunt at last, in a rage at these tactics, which he could not counteract or endure, rushed across the ring, called on him to stand up, before the call of “Time” by the umpires, and then struck Bendigo before he rose from his second’s knee. The referee and umpires having decided that this blow was foul, the stakes, £25 a side, were awarded to Bendigo. “It was the expressed opinion of the spectators that, had Caunt kept his temper and husbanded his strength, the issue would have gone the other way, as he proved himself game to the backbone, while his opponent was made up of dodges from heel to headpiece.”

This fight had the effect of calling the attention of backers to both men. Of Bendigo’s cleverness there could be no question, while Caunt’s enormous strength and unflinching pluck were equally indisputable; and it is a curious illustration of the circular theory of events that these two men, whose pugilistic career may fairly be said to have commenced in this fight—when they were, of course, at the bottom of the ladder—should meet again when they were half-way up, and a third time when they stood on the topmost round.

This victory over the gigantic wrestler of Hucknall Torkard could not fail to bring his conqueror prominently before the eyes of the boxing world. John Leechman, alias Brassey, of Bradford (of whom hereafter), Charley Langan, Looney, of Liverpool, Bob Hampson, also of Liverpool—indeed, all the big ’uns of the “North Countrie” were anxious to have a shy at the audacious 11st. 10lb. man who had beaten Ben the Giant.

In November, 1835, Brassey, of Bradford, announced by letter in Bell’s Life, that he was prepared to meet Bendigo half-way between Nottingham and the Yorkshire town for £50 a side. But the erratic Bendigo was wandering about the country, exhibiting with Peter Taylor, Sam Pixton, Levi Eckersley, & Co., electrifying the yokels by his tricks of agility and 6 strength, and his irrepressible chaff and natural humour—gifts which made him, formidable as he really was, a sort of practical clown to the boxing ring. Hence nothing came of the challenges and appointments, although Bendigo, by a letter in a Midland sporting paper, in February, 1836, declared himself ready to make a match for £25 a side with Tom Britton or Jem Corbett—Bendigo to be under 12st. on the day. He also threw down the gauntlet to “any 12st. man in the four counties of Nottingham, Leicester, Derbyshire, and Lincolnshire; money ready at his sporting house in Sheffield”—a rather amusing challenge, as it excluded Brassey, of Bradford, and three well-known Lancashire heavy weights. Tom Britton replied to this challenge that he would not fight under £100, being engaged in business; but informed Bendigo that he could find two 12st. candidates for his favours for £25 or £50, if he would attend at the “Grapes,” Peter Street, Liverpool.

John Leechman (Brassey) now came out with a definite cartel, that he was open to fight any 12st. man within 100 miles of Bradford for £25 or £50, and that his money was ready at the “Stag’s Head,” Preston Street, Sheffield. This brought Bendigo to the scratch, and the match was made for £25 a side, to come off on Tuesday, May 24th, 1836. The deposits were duly made, and on the appointed day, May 24th, 1836, the men met nine miles from Sheffield, on the Doncaster road. No reliable report of this fight, which was for £25 a side, is extant: nothing beyond a paragraph in the following week’s papers, declaring it to be won by Bendigo, “after a severe contest of 52 rounds, in which the superiority of science was on the side of the lesser man, Bendigo weighing 11st. 12lb., Brassey nearly 13st.”

Brassey and his friends were not satisfied with this defeat, and immediately proposed a fresh match for £50; and Jem Bailey (not of Bristol, but an Irishman, afterwards twice beaten by Brassey) also challenged Bendigo. Bendigo accepted Bailey’s offer, but Paddy’s friends hung back and forfeited the deposit.

Our hero now visited London, and was for some weeks an object of some curiosity, putting up at Jem Burn’s, where he kept the company alive by his eccentric “patter.” Jem offered to back Bendigo against Fitzmaurice (who had been beaten by Deaf Burke), but Fitz’s friends also backed out. It may be remarked, par parenthese, that the Deaf ’un was in America during this paper warfare.

At this period a remarkably clever eleven stone black, hight Jem 7 Wharton, who fought under the names of “Young Molyneux,” and “The Morocco Prince,” had successively polished off Tom M’Keevor, Evans, Wilsden, and Bill Fisher, and fought a gallant drawn battle of four hours and seven minutes, and 200 rounds, with the game Tom Britton, was the talk of the provincial fancy. A match was proposed for £50, half-way between Nottingham and London. But in the interval of talk Molyneux got matched with Harry Preston, and a most interesting fight, from the crafty style of both men, was lost for ever. A forfeit in the interim was paid to Bendigo by Flint, of Coventry.

Molyneux also accepted Bendy’s offer, but insisted on raising the stakes to £100 a side, and to Bendy confining himself to 11st. 7lb. (!) Molyneux not to exceed 11st. 2lb., &c., &c.

To these stipulations Bendy replied: “My Liverpool friends will back me £100 to £80, or £50 to £40, at catch weight, against Young Molyneux. I shall be in London in a few weeks, and shall be happy to meet Luke Rogers for £50 or £100, as Looney’s match is off, owing to his being under lock and key for his day’s amusement with Bob Hampson.—Nottingham, November 25, 1836.” Molyneux got matched with Bailey, of Manchester, and this second affair fell through.

At length, in December, articles were signed with Young Langan (Charley), of Liverpool, to fight within two months, catch weight, and the day fixed for the 24th of January, 1837, when the men met at Woore, eight miles from Newcastle, in Staffordshire. At a few minutes to one o’clock Bendy appeared, esquired by Harris Birchall and Jem Corbett; Young Langan waited on by two of his countrymen. Langan weighed within 2lb. of 13st.; Bendigo 11st. 10lb. on this occasion. The battle was a characteristic one. The “long ’un,” as he was called by the bystanders, began by “forcing the fighting,” a game which suited the active and shifty Bendigo, who punished his opponent fearfully for almost every rush. Cautioned by his friends, Langan tried “out-fighting,” but Bendy was not to be cajoled into countering with so long-armed and heavy an opponent. He feigned weakness, and Langan, being encouraged to “go in,” found he had indeed “caught a Tartar.” He was upper-cut, fibbed, and thrown, until, “blind as a pup,” his seconds gave in for him at the close of the 92nd round, and one hour and thirty-three minutes.

Negotiations with Tom Britton, of Liverpool, fell through, as Britton could not come up to Bendy’s minimum of £100 a side.

Bendigo and his trainer, Peter Taylor, were now in high favour, and a 8 sparring tour among the Lancashire and Yorkshire tykes was organised and arranged. Bendigo also wrote in the London and provincial papers that he was “ready to fight any man in England at 11st. 10lb. for £50 to £100 a side; and, as he is really in want of a job, he will not refuse any 12st. customer, and will not himself exceed 11st. 10lb. Money always ready.”

At this period Looney, declaring that Bendigo had shuffled out of meeting him for £50, claimed the Championship in a boastful letter. This was too much for Jem Ward, who then kept the “Star” tavern in Williamson Square, Liverpool; so he addressed an epistle to the editor of Bell’s Life, offering to meet Mr. Looney for £200, “if there is no big ’un to save the title of Champion from the degradation into which it has fallen.”

Ward’s letter had the effect of leading to a meeting of Looney’s friends, whereat that boxer discreetly declared that he never meant to include Ward in his general challenge for £100 or £200, as he considered that Ward had retired. Barring, therefore, Ward, Mister Looney renewed his claim. Hereupon a gentleman from Nottingham, disputing Looney’s claim to fight for “a Championship stake,” offered to back Bendigo against him for £50 a side and “as much more as he could get.” This was closed with, and a deposit made. On the following Tuesday, at Matt Robinson’s, “Molly Moloney” tavern, Liverpool, articles were signed for £50 a side (afterwards increased to £100), to fight on the 13th of June, 1837, half-way between Nottingham and Liverpool. A spot near Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire, was the rendezvous, and thither the men repaired. Looney arrived in Manchester from his training-quarters at Aintree, and Bendigo from Crosby, on the overnight, when there was some spirited betting at five and occasionally six to four on Looney.

The next morning proving beautifully fine brought hundreds from distant parts to the spot, in the usual description of drags, until there was not a stable left wherein to rest a jaded prad, or a bit of hay or corn in many places to eat. Looney had fought many battles, the most conspicuous of which were with Fisher (whom he defeated twice, and another ended in a wrangle) and Bob Hampson, who suffered defeat three times by him. Bendigo, as we have seen, had scored victories over Caunt, Brassey, and young Langan. A little after eleven the magnets of the day left their hotels, and were immediately followed by an immense body on foot to the summit of a rasping hill, where a most excellent inner and outer ring was formed with new ropes and stakes, the latter being painted sky blue; near the top were 9 the letters L. P. R. (signifying Liverpool Prize Ring), encircled in a wreath of gold; the one to which the handkerchiefs were attached was, with the crown, gilt. Soon after twelve o’clock the men entered the ring amidst the cheers of their friends—Bendigo first. They good-humouredly shook hands, and proceeded to peel. Young Molyneux (who was loudly cheered), along with Joe Birchall, appeared for Looney, whilst Peter Taylor and Young Langan were the assistants of Bendigo. The colours—green and gold for Looney; blue bird’s-eye for Bendigo. A little after one o’clock, the betting being five to four on Looney, with many takers, commenced

THE FIGHT.

Round 1.—The appearance of Bendigo, on coming to the scratch, was of the first order, and as fair as a lily, whilst Looney displayed a scorbutic eruption on his back. Both seeming confident of victory put up their fives, caution and “stock-taking” for a few moments being the order of the day. Looney made a half-round right-hander, which told slightly on the ear. He then made three hits at the head and body, which Bendigo stepped away from, and dropped a little left ’un on the chin. Bendigo was not idle, but on the defensive, and succeeded in putting in two left-handers on the canister, and blood, the first, made its appearance from the mouth and under the left eye of Looney. This was a long round; in the close Bendigo was thrown.

2.—Looney, all anxious, made play left and right; one told on the ear, a scramble, both fighting; Bendigo thrown, but fell cat fashion.

3.—Bendigo put the staggers on Looney with a left-handed poke on the head; closed, and both down on their sides.

4.—Both came up smiling. Bendigo made two short hits, had his left intended for the “attic” stopped, but put in a straight one on the breast, and the round finished by both men hammering away right and left in splendid style until Looney was sent down.

5.—Two light body blows were exchanged, and Looney was thrown.

6.—Bendigo got away from two right-handers, received a little one on the left ear, and both down one over the other.

7.—Looney made two short hits with the left; Bendigo stopped his right at the ear; some capital in-fighting took place, in which Looney got his right eye out, and Bendigo slipped down.

8.—This was another good round, but in the end Bendigo got his man on the ropes in such a position as to operate pretty freely on his face, and showers of “claret” were the consequence. Looney fell through the ropes, Bendigo over him.

9.—Looney came up as gay as possible, with two to one against him, and a slashing round ended in favour of Bendigo; Looney down.

10.—Bendigo sent home a tremendous whack on the left eye, which drew claret. Looney seemed amazed, and put up his hand to “wipe away the tear.” Looney thrown.

11.—A very long struggle on the ropes, in which Looney appeared awkwardly situated, but he got down with little damage.

12.—Up to this round there was not a visible mark of punishment on Bendigo. Looney put in two hits on the left ear, but was thrown through the ropes, Bendigo over him.

13.—Looney hit short with his right on the body, but was more successful in the next effort; planted it on the ribs, and staggered Bendigo to the ropes, where both struggled down.

14.—A capital round, in which some heavy hits were exchanged, and Looney fell.

15.—Looney staggered his man again with his right, and, in making another hit, Bendigo dropped on his nether end, throwing up his legs and laughing. (Great disapprobation.)

16.—Looney again delivered his right on the ribs. Bendigo bored him to the ropes, and Looney got down.

17.—Looney put in two smart hits on the left ear, and one on the ribs. Bendigo dropped on his knees.

18.—Bendigo pressed Looney on the ropes, held him for some time in a helpless position, and gave it him severely in the face, the claret flowing copiously. He was lowered to the earth by a little stratagem on the part of his seconds.

19.—Notwithstanding the loss of blood in the last round, Looney was lively to the call, went up to his man, and knocked him through the ropes with a body blow.

20.—Looney caught his man with his right; a struggle on the ropes in favour of Bendigo. Both down.

21.—Another struggle on the ropes, in which Bendigo was forced through.

22.—A rallying round, which Looney 10 finished by knocking his man through the rope by a blow on the breast.

23.—Looney again put in his right; another struggle on the ropes, until they were forced to the ground.

24.—Looney rushed in and was going to work when Bendigo fell.

25.—Bendigo put in a smart hit on the face, caught it in return on the head, and was thrown over the ropes.

26.—Bendigo popped in three very heavy hits on the face, put three hits on the body, and went down as if weak.

27.—Looney hit short. Bendigo gave it him on the conk, and threw him a clever somersault.

28.—Looney put in his right heavily on the ribs, which compliment was returned by a stinger on the head, which staggered him down.

29.—Both got to a close, and Bendigo was thrown, coming on his head.

30.—A slashing round; give and take was “the ticket” on the ribs and head, until both went down weak.

31.—Both got to the ropes, and went down together. Ditto the next round.

33.—Bendigo put in two facers, and threw his man heavily.

34.—After an exchange, Bendigo caught hold and threw Looney heavily.

35.—Bendigo got on the ropes, and Looney dragged him down on his back.

36, 37.—Two struggling rounds at the ropes; Looney under in the falls.

38.—Looney planted a nasty one on the ribs, followed his man up, and forced Bendigo through the ropes.

39.—Looney planted three tidy hits on the head and body, as did Bendigo on the mug, again tapping the claret; but in the end was whirled on the ground.

40.—A rally in favour of Bendigo, who threw Looney.

41.—Looney caught Bendigo’s head, put in a smart upper cut, but was thrown clean.

42.—Bendigo’s left arm appeared a little black from the effects of Looney’s right, as did his ear, but with the exception of a small bump on his left eye he had not a scratch on his face, whilst Looney’s phiz began to assume a frightful aspect, his left eye completely closed, with a terrible gash over it, one under, another over his right, and his nose and mouth in a shocking state of disorder. Still he was game and confident of the victory; he rushed in, put in two sharpish hits on the head, and downed Bendigo in a heap on the grass.

43.—Body blows exchanged. Bendigo under in the fall.

44.—A rally in favour of Bendigo, in which Looney clasped him round the legs; but it was considered more by accident than design. He let go, and went down.

45.—Looney rushed in, and in the struggle went down on his nether end.

46, 47, 48, 49.—Struggling rounds—favour of Bendigo.

50.—Bendigo shot out his left, and, in going down, Looney caught his head, but, not observing Hoyle’s rule of “when in doubt take the trick,” held back his fist, and let him go.

51.—Looney popped one in the ear, but was thrown through the ropes.

52, 53, 54.—Nothing done. In the latter Looney missed a heavy upper cut, and swung himself through the ropes.

55.—Bendigo got Looney’s head in chancery, peppered away, and again the crimson stream flowed. Both down.

56.—A struggle. Both down.

57.—A close, in which Looney threw Bendigo a burster, with his head doubled under.

58.—Bendigo, being doubled on the ropes, received a few heavy hits on the ribs, but on Looney striving for his head he got away, and both went down.

59.—A close, Looney receiving a shattering throw.

60.—Looney had his man on the ropes, but was too weak to hold him, and received another burster for his pains.

61.—Looney, again on the ropes, caught pepper in the face until it assumed a frightful appearance, and the claret gushed freely; he escaped by the cords being pressed down.

62.—Looney’s right eye was now fast drawing to a close, but his game was undeniable, and he still calculated on victory; he rushed in wildly, caught Bendigo in his arms, and threw him.

63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68.—Strange to say these rounds were in favour of Looney, without any mischief, in the latter of which Bendigo was driven against one of the posts by a hit on the breast, from which he rebounded, and fell forwards on the turf.

69.—Looney rushed in, Bendigo caught his head, drew his cork, and threw him.

70, 71.—Bendigo’s optics all right, and very cautious. The first a scrambling round, Looney under. Bendigo, in the next, went to a close, and was whirled down.

72.—A little altercation took place in this round, owing to Bendigo falling on his back without a blow being struck, which was the case, but it was not done for the purpose of evading a blow. Looney was creeping up to him, and his heel, in retreating, caught a tuft of grass and threw him, which appeared to be the general opinion.

73.—Bendigo gave three facers, but was thrown.

74.—Looney bored his man to the ropes, and sent him through them by a muzzler.

75.—Bendigo slipped his left at the all but closed eye, and went down. (Cries of “Cur.”)

76.—Looney put in with his right, and gained the throw.

77.—Hugging. Looney down.

78.—Bendigo made a hit, and got down by the ropes.

79, 80.—Looney received two hits on the body, and was thrown in each.

81, 82.—In both of these rounds Looney 11 was thrown heavily, but put in a well-meant hit on the head.

83.—Bendigo, on the ropes, received a heavy hit on the ribs. Looney was about to repeat the dose, but was stopped by the cries of “Foul,” and he left him.

84.—Another rush. Bendigo whirled down.

85.—Looney was floored cleverly by a spanking hit on the chops.

Nothing particular occurred in the next six rounds; the throws, with the exception of one, being in favour of Bendigo.

92.—Bendigo showed a good feeling in this round. In the struggle Looney got seated on the under rope, but Bendigo would not take advantage, and walked away.

93, 94.—Looney down in both these rounds.

95.—Looney rallied a little, and made two hits tell with the right on the ear, and Bendigo went down rather shook.

96, 97.—Both down together. Bendigo gave a muzzler in the last, got his man on the ropes, but was too weak to hold him.

98.—Looney put in his right on the temple, but was thrown very heavily.

99, and last.—Looney came up as blind as a bat, and rushed in with his right, when Bendigo mustered up all his remaining strength and gave him another fall. Molyneux, finding it useless to prolong the contest, gave the signal of defeat, after fighting two hours and twenty-four minutes.

Remarks.—It will be seen by the above account that Bendigo won all the three events—first blood, first knock down, and the battle. He stands with his right leg foremost, has a good knowledge of wrestling, steps nimbly backwards to avoid, and hits out tremendously with his left. He was trained under the care of Jem Ward and Peter Taylor, who must have spared no pains in tutoring him, being much improved since he fought Young Langan; and no doubt will prove a troublesome customer to any 12-stone man who may meet him. He walked about a quarter of a mile to his carriage. A tint of black only appeared under his left eye, but his bodily punishment must be severe, as he could not bear to be touched on the left side. He arrived in Manchester the same evening per gig, and proceeded to Newton races the following morning. Poor Looney was terribly punished about the face, being cut under and over each eye, and his lips and nose terribly mangled: besides the loss of a grinder or two, he lost a great quantity of blood from nose, mouth, and other gashes in the face. He is possessed of most unflinching game, but is slow in his motions; he strikes very heavy with his right, but it is too long a time in arriving at its destination. All that could be done for him by his seconds, Molyneux and Birchall, was done. The ring was sometimes in great disorder, owing to want of attention on the part of the ring-keepers.

Bendigo, on the occasion of a joint benefit with Peter Taylor at the Queen’s Theatre, Liverpool—which northern city at this period appeared to have become the metropolis of milling, vice London and Bristol superseded—boldly claimed the belt. Looney disputed the claim, complaining that Bendigo had recently refused him another chance, though ready to make a new match for £50. Tom Britton also demurred to the Championship claim, and offered to fight Bendy at 11st. 10lb.; money ready to £100 at Mrs. Ford’s, “Belt Tavern,” Whitechapel, Liverpool.

Fisher, Molyneux (proposing the impossible 11st. 7lb.), and others now rushed into letter-writing, but Bendy kept up his claim and his price; and so ran out the year 1837 and part of 1838, the Championship remaining in abeyance, as Jem Ward had retired, and the Deaf ’un was still in America.

Bendy’s old opponent and fellow-townsman next re-appeared on the scene. Ben Caunt, who in the interim had beaten Ben Butler, at Stoney Stratford, in August, 1837, and Boneford, a big countryman, at Sunrise Hill, Notts, in October of the same year, proposed to meet “the self-styled Champion” for £100. Bendigo, more suo, thereupon observed, that 12 “at that price, or any other, the big, chuckle-headed navvy was as good as a gift of the money to him.”

All, therefore, went merrily; the instalments were “tabled” as agreed; Bendy was a good boy, and took care of himself; Big Ben worked hard, and got himself down to 15st. 7lb. (!), as will be seen in our account of this tourney, which, according to the plan of our work, must appear in the memoir of the victor, Ben Caunt (Chapter II., post), in the present volume. In this unequal encounter, after seventy-five rounds, Bendigo, who from a mistake had no spikes in his shoes, had the fight given against him for going down without a blow. Two to one was laid on Bendigo within four rounds of the close of the battle.

No slur on the skill, honesty, or bravery of Bendigo was cast by the umpires and referee in this battle, when they gave their decision that he had fallen without a blow, and handed over the stakes to Caunt. Bendigo proposed, before the decision, to make a match for £500, each to raise £200, to be added to the old battle-money. This Ben declined, but declared his readiness to enter into new articles for £100. Another match was accordingly made for £100 a side, to take place on Monday, July 20th, 1838. Bendigo, after bumper benefits in Liverpool, Derby, and Nottingham, now came to London, with Peter Taylor, and took up his quarters at Tom Spring’s, where he became an object of much curiosity; his animal spirits and practical joking being almost too much for Tom Winter’s quiescent and almost sedate temperament. In London he also took a benefit, “before going into strict training,” said the bills. There was “somewhat too much of this,” for Ben also was taking benefits in Notts, Leicester, and Derby. In the month of June it may be noted Deaf Burke returned from America, a fact which occasioned a hitch in Bendigo’s arrangements, as we shall presently see, for on June 24th, 1838, we read in Bell’s Life: “The match between Caunt and Bendigo is off by mutual consent, and Caunt desires us to state, that he is now open to fight any man in the world, barring neither country nor colour, for from £50 to £500. What does this mean?” The following paragraph in the ensuing week’s paper may show what it meant:—

“Bendigo and Caunt.—On the authority of a letter signed Caunt, we last week stated that this match was off by mutual consent; but we have since been informed by our Nottingham correspondent that such is not the fact, and that Caunt’s deposits are forfeited. Our correspondent adds that Caunt’s backer tried to get the match off, on the plea that it was a pity to see so little a man as Bendigo fight a giant like Caunt, who was anxious to enter the ring with Burke. He was, however, told that the fight must go on, and he promised to attend, but he neither came nor sent the deposit, but forwarded a letter to London stating that the match was off by mutual consent. As a proof that Bendigo’s backers intended the mill to go on, the deposit (£20) was received from Sheffield on the Thursday prior to the Monday, and on that very day £19 towards the next £20 deposit was raised.”

13Thus pleasantly released from his engagement with his gigantic competitor, Bendigo instantly responded to the cartel of Deaf Burke, issued on his landing from the New World, in which the Deaf ’un defied any man in the Eastern or Western hemisphere to meet him for £100 to £500, within the twenty-four feet of ropes. £100 was remitted to Peter Crawley to make the match; but lo! Burke had gone over to France (Owen Swift, Young Sam, Jack Adams, &c. were already there) with a “noble Earl,” and at two several meetings, to which the Deaf ’un was summoned, though Bendigo’s “ready” was there, there was no cash from across the water, and Jem Burn announced to Peter Crawley, that he had “a letter” from Paris that “Mister Burke,” who was on a Continental tour, could not fight for less than £200. In the midst of the ridicule and censure of this proposal, so inconsistent with his own published challenge, a gentleman offered to put down the other hundred himself for Bendigo. Crawley, however, declined to put down £50 of Bendigo’s money until guaranteed the £100. Thus the matter fell through. The public feeling in this matter was not badly expressed in a contemporaneous “squib” entitled:—

HEROIC STANZAS FROM BENDIGO TO DEAF BURKE.

September came, and the Deaf ’un was still studying “Paris graces and parley-vous,” seconding Owen Swift in his second fight with Jack Adams at Villiers, on the 5th of September, 1838. The police prosecution by the French authorities sent home the tourist, but meantime Bendy’s friends had been offended by some of his eccentric escapades, and had withdrawn the cash from Peter’s hands. In November Bendigo writes to the editor of Bell’s Life, that “he was induced to challenge Burke on the promise of certain friends at Nottingham to stand by him; but they having broken faith with him, he could not go on. His readiness and disposition to fight Burke or any other man continue the same, and, whenever friends will come 15 forward to back him, he will be found glad of the opportunity to prove that there is no unmeaning bounce about him, and that he is neither deficient in courage nor integrity.”

Such an appeal had an immediate response. The match was made at Sheffield, Burke’s friends proposing to stake £100 to £80, and a lively interest was soon awakened. On the occasion of the third deposit, on the 27th of November, at Jem Burn’s, in Great Windmill Street, the aristocratic muster was numerous, and five to four was freely laid on Burke, who was present, full of quaint fun, for the Deaf ’un, as well as Bendy, was indeed a “character.” Burke said he had “lowered his price by £50, rather than not ’commodate Mishter Bendys, as he ses his frinds is backards in comin forards.” The articles specified that the battle should take place within thirty-four miles of Nottingham, and the day to be the 15th of January, 1839. These articles were afterwards revised, and the fight postponed to February 12th, the stakes—£100 Burke to £80 Bendigo. The Deaf ’un went into training near Brighton, but removed later to Finchley; Bendigo at Crosby, near Liverpool. Here, on Sunday, January 4th, Bendigo had a narrow escape of his life, as the following paragraph records:—

“Narrow Escape of Bendigo.—During the storm on Sunday night Bendigo who is in training at Crosby, near Liverpool, narrowly escaped being ‘gathered unto his fathers.’ It appears that Peter Taylor went to meet Bendigo on Monday morning, but not finding him at the appointed place, proceeded at once to Crosby, when he discovered that the house in which he had left his friend on the previous evening was almost in ruins, the roof having been blown in, and nearly every window broken. Peter’s fears were, however, soon allayed by ascertaining that Bendigo was at a neighbouring cottage, where he found him between a pair of blankets, and looking quite chapfallen. Bendigo said that he would sooner face three Burkes than pass such another night. He went to bed about nine o’clock, but awoke about eleven, by his bed rocking under him, the wind whistling around him, and the bricks tumbling down the chimney. Every minute he expected the house to fall in upon him, and at three o’clock the hurricane increased so much in violence that he got out of bed, put on his clothes, and made his escape out of the window. He had not left the house ten minutes before the roof was blown in. A knight of the awl kindly gave him shelter, and he has since obtained fresh quarters in the same village.”

As the day approached, intense interest prevailed both in London and Liverpool, to say nothing of Nottingham, Birmingham, Derby, and Manchester, all of which towns sent their contingents of amateurs. Jem Ward undertook to give Bendy “the finishing touch,” and reported him “in prime twig,” while Burke was declared by Tommy Roundhead, his faithful red-nosed “secretary” and “esquire,” to be “strong as a rhinoceros and bold as a lion.”

At length the eventful morn of Tuesday, the 12th of February, 1839, dawned; it was Shrove Tuesday, and the concourse on all the roads to Ashby-de-la-Zouch, for which the “office” was given, was something more 16 marvellous than that which was occasioned by the “gentle passage of arms” in which Richard Cœur-de-Lion figured, for which see “Ivanhoe.” But we will leave Bell’s Life to tell the further proceedings of the tournament.

According to articles, the men were to meet within 35 miles of Nottingham, and it was finally agreed that they should meet at the “Red Lion,” at Appleby, in Warwickshire, on the Monday, to agree upon the battle-field. A centre of attraction having been thus appointed, the men were moved from their training quarters, to be near the scene of action. Burke, attended by Jem Burn, King Dick, Tommy Roundhead (his secretary), and other friends, took up his position at Atherstone, while Bendy, under the fostering care of Jem and Nick Ward and Peter Taylor, approached in an opposite direction. The contest seemed to excite extraordinary interest, and the bustle of preparation was observable in all directions. In Atherstone, a most pugnacious town by ancient charter, Burke was hailed with great favour, as a precursor of the local sports of Tuesday; for, from time “whereto the memory of man runneth not to the contrary,” on Shrove Tuesday the inhabitants of the village exercise a sort of prescriptive right to settle all disputes in fistic or other combat.

It was decided to pitch the ring as near Appleby as possible, and if practicable to have the men in the ring at ten o’clock. In the interim all sorts of vehicles were pressed into the service, horses were at a high premium, and the most ludicrous shifts were made to procure conveyances. In some instances mourning coaches, and even a hearse, were irreverently brought into use, while nags of the most unseemly description were drawn from their privacy and honoured by being hooked as leaders to post-chaises, or harnessed to any out-of-the-way kind of vehicle that fortune dictated. Beds and other accommodation were also difficult to procure, and, as in times of yore, hundreds, de necessitate, sat up all night to be up early in the morning.

Long before dawn on Tuesday multitudes were progressing towards Appleby, and at nine o’clock the assemblage in front of Burke’s domicile was immense. The crowd continued to increase steadily until the arrival of a cavalcade of “swell drags” from the direction of Leicester, which gave the signal for departure, as in and upon these were the patrician supporters of the Deaf ’un. On the arrival of these traps the Burke party instantly prepared for a start. Jem Ward and Bendigo, who were located about two miles off, were also in readiness, and lost no time in repairing to 17 the trysting-place, which, to the dismay of the toddlers and the discomfiture of the prads, proved to be at least seven miles off. The ring was formed on the top of a hill, in the parish of Heather, which spot was not reached by the Deaf ’un, owing to various impediments, until half-past eleven o’clock. A vast crowd had preceded him, and hailed his approach with cheers, but it was evident that thousands were yet to arrive, and fortunately for them an unexpected delay in the arrival of Bendigo proved favourable to their hopes, by protracting the commencement of hostilities.

It was nearly half-past twelve before the actual arrival of Bendigo was made known, and at that time, upon a moderate calculation, there were not less than 15,000 persons present of all degrees, the aristocracy forming no inconsiderable portion.

From some inexplicable delay it wanted only a quarter to one when Burke entered the ring, attended by King Dick and Jackson, and if good humour and confidence could be taken as indications of success his friends had no reason to grumble. While waiting for the arrival of Bendigo an incident occurred which produced considerable laughter: it was the approach of a well-dressed and not unlikely woman, who, forcing her way through the well-packed mass of spectators, ran up to the roped arena, and, seizing the Deaf ’un by the hand as an old acquaintance, wished him success, and, but for the intervening rope, would no doubt have added an embrace. She then seated herself in front of the inner circle, and waited the issue of the battle, subsequently cheering her favourite throughout his exertions. Shortly before one o’clock Bendigo made his salaam amidst deafening shouts, attended by Peter Taylor and Nick Ward, and, walking up to Burke, shook him heartily by the hand. The men then commenced their toilets, and on being stripped to their drawers a subject of much contention arose; Bendigo, on examining Burke’s drawers, discovered a belt round his waist, which he insisted should be taken off. In vain did Burke and his friends assure him it was merely a belt to sustain a truss which he wore in consequence of a rupture, and, as it was below his waist, was of no importance; in vain, too, did the referee pronounce it to be perfectly fair; Bendigo was not to be driven from his point, and it was not till the obnoxious belt was taken off that he was satisfied. The belt was exhibited, and fully corroborated the opinion of the referee as to its perfect inutility as a means of defence.

The signal having been given, the men threw off their great coats, and, advancing to the scratch, threw themselves into position; and now, for the 18 first time, a superficial estimate of their condition could be formed. Burke presented all that fine muscular development for which he is famed, but he was pale, and it struck us most forcibly that his flesh wanted that firmness and consistency, the sure consequence of perfect training, and to the attainment of which the mode in which he passed his time was anything but conducive; still he was playful and confident, and regarded his adversary with a look of conscious superiority. Bendigo, in point of muscularity, was inferior to Burke, especially in the shoulders, arms, and neck, but he appeared in perfect condition, and firm as iron. The colour of his skin was healthful; his countenance exhibited perfect self-possession, and wore an easy smile of confidence. The current odds, on setting to, were six to four on Burke, with plenty of takers. In Nottingham, where the physical qualities of Bendigo were better known, the odds had been as low as five to four.

THE FIGHT.

Round 1.—The position of Burke was easy and unconstrained. He stood rather square, his left foot in advance, and his arms well up, as if waiting for his antagonist to break ground. Bendigo, on the contrary, dropped his right shoulder, stooped a little, and, right foot foremost, seemed prepared to let fly left or right as the opportunity offered. After a little manœuvring, he made a catching feint with his left, but found the Deaf ’un immovably on his guard. They changed ground, both ready, when Bendigo let go his right, and caught Burke on the ribs, leaving a visible impression of his knuckles. More manœuvring. Bendigo tried his left, but was stopped. The Deaf ’un popped in his right, and caught Bendigo on the ear, but soon had a slap in return from Bendigo’s right, under the eye, as straight as an arrow. (Cheers for Bendigo.) Both steady. Bendigo made two or three feints with his left, but did not draw the Deaf ’un. Each evidently meaning mischief, and getting closer together. Counter hits with the left, when both, by mutual consent, got to a rally, and severe hits, right and left, were exchanged. The Deaf ’un closed, but Bendigo broke away, and turning round renewed the rally. Heavy exchanges followed, when they again closed, and trying for the fall both went down in the corner. (There was a cry of first blood from Bendigo’s left ear; but, although very red from the Deaf ’un’s visitations, the referee, who examined it, decided there was no claret.)

2.—Both men showed symptoms of the “ditto repeated” in the last round, although no great mischief was done, nor was there much advantage booked, each having given as good as he got. The Deaf ’un resumed his defensive position, and was steady. Bendigo again tried the feint with his left, evidently desirous of leading off with his right, but the Deaf ’un was awake to this dodge, and grinned. The Deaf ’un tried his right, but was stopped. After a pause, during which the men shifted their ground, Bendigo let go his left, but was prettily stopped. He was more successful with his right, and caught the Deaf ’un a stinger under the eye. The straightness and quickness of these right-hand deliveries were now conspicuous. Counter hits, left and right, followed, and the Deaf ’un showed a slight tinge of claret on the mouth, but it was not claimed. The Deaf ’un now made up his mind for a determined rally, and to it they went ding-dong; the stops, hits, and returns, right and left, were severe, and no flinching. Bendigo again wheeled round, but the Deaf ’un was with him, and the rally was renewed with equal vigour and good will. Bendigo, rather wild at the end, closed, and after a sharp struggle, both down. (The Deaf ’un’s chère amie, before alluded to, now cheered him, but, indifferent to her blandishments, he was carried to his corner piping a little from the severity of his exertion. Bendigo, on reaching his corner, seemed freshest, and exhibited less impression from the blows which he had received than his antagonist.)

3.—Both came up strong on their pins, but the Deaf ’un’s face, especially on the left cheek, was greatly flushed, and other marks and tokens of searching deliveries were visible. The Deaf ’un looked serious, and coughed as if the contents of his pudding-bag were not altogether satisfied with the disturbance to which they had been exposed. Sparring for a short time, when Bendigo let go his right, but was stopped; 19 it was a heavy hit, and the sound of the dashing knuckles was distinctly heard. Well-meant blows on both sides stopped. The Deaf ’un again coughed; his “cat’s meat” was clearly out of trim. Again did the Deaf ’un stop Bendigo’s right, but did not attempt to return. He now seemed to gain a little more confidence, and exhibited a few of his hanky-panky tricks, making a sort of Merry Andrew dance; but his jollity was soon stopped, for Bendigo popped in his left and right heavily, and got away. The Deaf ’un changed countenance and was more serious; Bendigo again tried his left-handed feints and was readiest to fight, but the Deaf ’un stood quiet. (Even bets offered on Bendigo.) Bendigo closed in upon his man, who waited on the defensive; but his defensive system was inexplicable, for Bendigo jobbed him four times in succession with the right under the left eye, on the old spot, jumping away each time without an attempt at return on the part of the Deaf ’un, and producing a fearful hillock on the Deaf ’un’s cheek-bone. The Deaf ’un seemed paralysed by the stinging severity of these repeated visitations and his friends called on him to go in and fight. He made an attempt with his right, but was short; at last he rushed to a rally, and some heavy hits were exchanged; Bendigo retreated, but kept hitting on the retreat. The deliveries were rapid and numerous, but those of the Deaf ’un did not tell on the hard frontispiece of his opponent. They broke away, but again joined issue, and the rally was renewed. The jobbing hits, right and left, from Bendigo were terrific, and the Deaf ’un’s nose began to weep blood for the state of his left ogle, which was now fast closing. (The question of first blood was now decided.) Bendigo broke away again, the Deaf ’un following, but Bendigo, collecting himself, jobbed severely, the Deaf ’un apparently no return, and almost standing to receive. He looked round and seemed almost stupefied, but still he kept his legs, when Bendigo went in and repeated his right-handed jobs again and again; he then closed, gave the Deaf ’un the crook, threw him, and fell on him. (The seconds immediately took up their men, and both showed distress, especially the Deaf ’un, who was obviously sick, but could not relieve his stomach, although he tried his finger for that purpose. All were astonished at his sluggishness. He seemed completely bothered, and to have lost all power of reflection and judgment.)

4.—The Deaf ’un now came up all the worse from the effects of the last rattling round, while Bendigo scarcely showed a scratch. The seconds of the Deaf ’un called on him “to go in and fight;” he obeyed the call, but again had Bendigo’s right on his damaged peeper. Bendigo fought on the retreat, hitting as he stepped back, but steadying himself he caught the Deaf ’un on the nose with his right, and sent his pimple flying backwards with the force of the blow. The Deaf ’un rushed in, hitting left and right, and in getting back Bendigo fell over the ropes out of the ring. (The fight had now lasted sixteen minutes; the Deaf ’un had all the worst of it, although Bendigo from his exertions exhibited trifling symptoms of distress.)

5.—The Deaf ’un came up boldly, but all his cleverness seemed to have left him. Bendigo, steady, was first to fight, popping in his right; exchanges followed, and in the close both went down, Burke uppermost.

6.—“Drops of brandy” were tried with the Deaf ’un, but his friends seemed to have “dropped down on their luck.” Still he came up courageously, although his right as well as his left eye was pinked. Counter-hitting, in which Bendigo’s right was on the old spot. A close at the ropes, the Deaf ’un trying for the fall, but after some pulling both went down and no harm done. (Three to one on Bendigo, but no takers.)

7.—The Deaf ’un’s left eye was now as dark as Erebus, and as a last resource he tried the rush; he rattled in to his man without waiting for the attack, but in the close, after an exchange of hits and a severe struggle, was thrown. The moment the Deaf ’un was picked up he cried “Foul!” and asserted that Bendigo had butted him, looking anxiously at the umpire and referee for a decision in his favour; but there was no pretence for the charge, as it was obvious Bendigo merely jerked back his head to relieve himself from his grasp. Like “a drowning man,” however, it was obvious he was anxious to “catch at a straw.”

8.—The Deaf ’un showed woeful punishment in the physog, although not cut. Again did he make a despairing rush, stopping Bendigo’s right, but in the second attempt he was not so fortunate, for Bendigo muzzled, closed, and threw him.

9.—The Deaf ’un’s game was now clearly all but up, for while he showed such prominent proofs of the severity of his antagonist’s visitations to his nob, the latter was but little the worse for wear. The Deaf ’un, however, was determined to cut up well, and again rattled in left and right, Bendigo retreating and jobbing as he followed, and at length hitting him down with a right-handed blow on the pimple. The Deaf ’un, with one hand and one knee on the ground, looked up, but Bendigo stood steadily looking at him, and would not repeat the blow, showing perfect coolness and self-possession.

10, and last.—The Deaf ’un, greatly distressed, still came up with a determination to produce a change if he could by in-fighting. He rushed into his man, hitting left and right, but receiving heavy jobs in return. He forced Bendigo with his back against the ropes, and, as he had him in that position, deliberately butted him twice, when both went down in the struggle for the fall. Jem Ward immediately cried 20 “Foul!” and appealed to the referee, who refused to give any decision till properly appealed to by the umpires. He stepped into the ring, where he was followed by the umpires, when he was again appealed to, and at once declared that Burke had butted, and that therefore Bendigo was entitled to the victory—a judgment in which, it is due to say, the umpire of the Deaf ’un, although anxious to protect his interests, declared in the most honourable manner he must concur. Several of Bendigo’s friends wished no advantage of this departure from the new rules to be taken, foreseeing that a few more rounds must finish the Deaf ’un; but the decision of the referee was imperative, and thus ended a contest which disappointed not only the backers of the Deaf ’un but the admirers of the Ring generally, who anticipated on the Deaf ’un’s part a different issue, or at least a better fight. With regard to the butting, of which we have no doubt, our impression is that it was done intentionally, and for the express purpose of terminating the fight in that way rather than by prolonging it to submit to additional punishment and the mortification of a more decided defeat; and we are the more inclined to this conclusion from the Deaf ’un’s readiness to claim a butt on the part of Bendigo in the seventh round, a convincing proof that he was fully sensible of its nature and consequence. An attempt was subsequently made to wrangle with the referee on the soundness of his decision, for the purpose of sustaining the character of the Deaf ’un, and exciting a spirit of discontent among his backers. This was not creditable, and to be classed among these petty expedients to which some of our modern “Ringsters” are but too willing to have recourse—namely, at all events “to win, tie, or wrangle,” a practice to which every honest man must be opposed. The time occupied in the contest was exactly four-and-twenty minutes. In no one of Burke’s former battles was he more severely punished in the face, not, it is true, in any vital part, for all Bendigo’s hits, both left and right, were as straight as a line, going straight from the shoulder and slap to their destination. There were no round hits on his part, and the body blows on both sides were few and far between.

Remarks.—Perhaps no battle on record offers a stronger illustration of the consequences of vanity and headstrong confidence than that which we have just recorded. Burke, puffed up by his former successes, and flattered by the good-natured freedom of young men of fashion, placed himself beyond the pale of instruction and advice. He was self-willed and obstinate, and quarrelled with all who presumed to guide him in the proper course. His repeated acts of imprudence while in training called forth the strongest remonstrances, but in vain; and thus he has found, when too late, that “a man who will be his own adviser” on such occasions “has a fool for his client.” Nothing but the most decided want of condition can account for the slowness which he exhibited; and, when his career from the time he went to Brighton till the day of the battle is considered, that state of constitution is sufficiently explained; and yet those besotted friends who knew all this were as prejudiced in his favour that they blindly pinned their faith to his former reputation, believed no man alive could beat him, and risked their money, as well as stultified their judgment, on we issue of his exertions. But then say these wiseacres, opening their eyes with well-feigned astonishment, “We could not have erred. It is impossible, seeing all that we have seen, and knowing what we have known of the Deaf ’un that he could have made so bad a fight, and be beaten so hollow by a countryman!” Oh no! this could not be—and what follows? Why, the old story—the honest Deaf ’un has all at once turned rogue—he had been bought and fought a cross!—he has sold his friends, and must be consigned to degradation. Why, from the third round it was seen by the merest tyro in the ring that he had not a chance. He was completely paralysed by the unexpected quickness of his adversary, who has, as Jem Ward foretold, proved himself a better man than has for some years appeared in the ring. This has been Ward’s constant cry, and had his advice been taken all the odds that were offered would have been taken. But no; the Londoners were not to be beaten out of their “propriety.” Twos to one, sevens to four, and sixes to four have, as is well known, been offered over and over again in sporting houses without takers, and many who lamented the impossibility of “getting on” before the fight, have now, after it, the consolation of feeling that they have “got off” most miraculously. And yet this was a cross; and the cunning concoctors of the robbery had the generosity to refuse the hundreds which were, as it were, forced under their noses. Verily this is “going the whole hog” with a vengeance; but from the little we know of such speculations we are inclined to think that those who hazard such an opinion will be deemed greater flats than they have proved themselves. It is an accusation unjust towards a weak, but, we believe, an honest man, and still more unjust towards Bendigo, who, throughout, proved himself, in every respect, a better fighter, as well as a harder hitter, than Burke, and who, in no part of the battle, was guilty of an act which would disentitle him to the honour and profit of his victory. But some facts seem to be altogether lost sight of in forming a just estimate of poor Burke’s pretensions, for, independent of his want of condition, it seems to be forgotten that instead of fighting or sparring for the last two years he has been confining himself to the personification of “the 21 Grecian statues,” forsooth—anything but calculated to give energy to his limbs—added to which he is ruptured. We are also informed on medical authority that the patella or knee-pan of his right leg is as weak from the fracture which he sustained in the hospital some time back that he is obliged to support it by double laced bandages, and he has been altogether precluded from taking strong walking or running exercise, never having walked more than ten miles in any one day of his training. For our own part we think his day is gone by, and, like many other great performers, he has appeared once too often; but that he intentionally deceived his friends we believe to be a most ungenerous calumny, although his friends may have deceived themselves. After the fight, Burke, who was sufficiently well to walk from the ring, returned to Appleby, and from there to “foot-ball kicking” Atherstone, where the annual sports were merrily kept up in his absence. The same night he returned to Coventry, and arrived by the mail train in London the next morning, none the worse in his bodily health from the peppering he received, however mentally he was “down on his luck.” He complained much of his arms, which, from the wrists to the elbows, were covered with bruises, the effects of stopping—and stopping blows, too, which, had they reached their destination, would have expedited his downfall. Bendigo returned to Nottingham the same night, decorated with his well-earned laurels; and it is to be hoped he will enjoy his victory with becoming modesty and civility, bearing in mind that he has yet to conquer Caunt before he can be proclaimed Champion of England.

The Deaf ’un, who showed on the Friday at Jem Burn’s, with the exception of his “nob” was all right. He complains most of having been stripped of his belt, which was attached to his truss by a loop, and the absence of which filled him with apprehension. This, combined with his admitted want of condition, he declares placed him on the wrong side the winning post. He is, however, most anxious for another trial, and instructs us to say that he still has supporters who will match him once more against Bendigo for £100 a side, the fight to come off in the same ring with Hannan and Walker; Burke to be permitted to wear his belt, as in the case of Peter Crawley and Jack Langan. It is needless to say that Burke never again faced Bendigo in the ring, getting on a match at this time with Jem Bailey.

For several months the newspapers were rife with challenges from Caunt to Bendigo and Bendigo to Caunt; each “Champion” roving about the counties in which he was most popular upon the “benefit dodge,” each with a star company, and each awakening the city or town where his company performed with a thundering challenge, while each pugilistic planet revolved in his own peculiar orbit without giving the other a chance of a “collision.”

In this interval Jem Ward presented a “Champion’s” belt to Bendigo, at the Queen’s Theatre, Liverpool, amid great acclamations, and again the tiresome game of challenging and making appointments for “a meeting to draw up articles,” at places where the challenged party never attended or meant to show, went on. Brassey, of Bradford, too, having in the interim beaten Young Langan, of Liverpool, and Jem Bailey, put in his claim and joined the chorus of challengers. Burke also offered himself for £100, which Bendigo declined, according to his published challenge. In the latter half of 1839 we read as follows:—

22“To the Editor of ‘Bell’s Life in London.’

“Sir,—Caunt states that he has been given to understand I wish to have another trial with him for £200 a side, and that his money is ready at any sporting house in Sheffield. Now, Sir, I have been to many houses that he frequents, and cannot find any one to put any money down in his behalf; and as he was in Sheffield for a fortnight previous to my going away to second Renwick, I think, if he meant fighting, he would have made the match when we were both in Sheffield. Now, Sir, what I mean to say is this—I will fight Caunt, or any other man in England, for from £200 to £500 a side, and I hope I shall not be disappointed, as I mean fighting, and nothing else; and to convince the patrons of the Prize Ring that there is no empty chaff about me, as I am going to leave Sheffield this week, my money will be ready any day or hour at Mr. Edward Daniels’, ‘Three Crowns,’ Parliament Street, Nottingham. Or if Burke wants another shy, I will fight him for £150 a side.

“WILLIAM THOMPSON, alias BENDIGO.”

This certainly looked like business, yet the next week we find Caunt declaring “I will make a match with Bendigo for £200, and I will take a sovereign to go to Nottingham, or give Bendigo the same if he will meet me at Lazarus’s house at Sheffield.” This was in July, and shortly after Bendigo writes:—

“To the Editor of ‘Bell’s Life in London.’

“Mr. Editor,—Having sent a letter to Caunt accepting his challenge on his own terms, and not receiving an answer, I wish to put that bounceable gentleman’s intentions to a public test. I am willing to fight him on his own terms, and I will give him the sovereign he requires to pay his expenses in coming to Nottingham to make the match, and let it be as early as possible. As to Deaf Burke, he is but of minor importance to me. I have no objection to give him another chance to regain his lost laurels, and will fight him for his ‘cool hundred,’ as he calls it, providing he or his friends make the first deposit £50, for my friends are not willing to stake less. Should the above not suit either of these aspirants for fistic fame, I again repeat I will fight any man in the world for £200 or £500, barring neither weight, country, nor colour. I am always to be heard of at the ‘Three Crowns,’ Parliament Street, Nottingham.

“WILLIAM THOMPSON, alias BENDIGO.

“August 3rd, 1839.”

Soon after we read:—

“Caunt and Bendigo.—Bendigo went to Nottingham to make the match with Caunt on Saturday week, but the latter could not find more than two sovereigns to put down as a deposit. Caunt, before he indulges in bounce, should reflect that he only disgraces himself and gains nothing by his ‘clap-traps.’ These benefit humbugs must be suppressed.”

No wonder that the much-enduring editor should thus express himself. Nevertheless the “benefit humbug,” like other humbugs, exhibited irrepressible vitality; 1840 wore on, and Caunt, who seemed to prefer a tourney with Brassey or Nick Ward (who had challenged him), did not close with Bendigo. Had there been a real intention, the subjoined should have brought the men together:—

“To the Editor of ‘Bell’s Life in London.’

“Sir,—I agree with you that there is more ‘talk than doing’ among the professors of ‘the art of Self-Defence’ of the present day—more challenges than acceptances—evidently for the purpose of giving to the members of the Ring, for benefits and other interested purposes, 23 fame and character which they do not always possess—I allude particularly to Caunt and Bendigo, ‘the Great Guns of the day.’ Each talks of being backed, but each, in turn, avoids ‘the scratch.’ Now to the test: I am anxious, for the sake of society, that ‘old English Boxing’ should not decline, because I am sure it is the best school for the inculcation of ‘fair play,’ and the suppression of the horrible modern use of the knife—and of this I am prepared to give proof. Bendigo says he will not fight Caunt for less than £200, which sum I presume he can find, or he, too, is carrying on ‘the game of humbug.’ Caunt says he is equally ready to fight Bendigo, but cannot come to his terms. Now to make short work of it—if Caunt can get backed for £100, I will find another £100 for him, and thus come to Bendigo’s terms. Let him communicate with Jem Burn, in whom I have confidence, and the money shall be ready at a moment’s warning. I wish for a fair, manly fight and no trickery; and my greatest pleasure will be to see the ‘best man win.’ In and out of the Ring prize-fighters ought to be friends—it is merely a struggle for supremacy, and this can be decided without personal animosity, foul play, or foul language, all of which most be disgusting to those who look to sustain a great national and, as I think, an honourable game.

“I am, &c.,

“A MEMBER OF THE NEW SPARRING CLUB AT JEM BURN’S.”

Brassey, however, was withdrawn from the controversy by an accident beyond his own control. The magistrates of Salford, determining to suppress pugilism so far as in them lay, indicted Brassey for riot in seconding Sam Pixton in a fight with Jones, of Manchester, and, obtaining a conviction, sentenced him to two months’ incarceration in the borough gaol. He was thus placed hors de combat.

Early in 1840 Bendigo was in London, with his head-quarters at Burn’s, where Nick Ward exhibited with him with the gloves in friendly emulation. The brother of the ex-champion, however, was averse to any closer engagement. Bendigo returned to the provinces, and the next week the public was informed that “Caunt’s money, to be made into a stake of £200, was lying at Tom Spring’s, but nothing has been heard from Bendigo!” The conjunction of circumstances is curious, for in the same week the subjoined paragraph appeared, which records an accident which certainly crippled Bendigo for the rest of his life. Indeed the author, who at this period saw him occasionally, did not consider him well enough to contend in the ring up to the time of his crowning struggle with the gigantic Caunt.

“Accident to Bendigo.—William Thompson, better known by his cognomen of ‘Bendigo,’ has met with an accident which is likely to cripple him for life. On Monday he had been to see the military officers’ steeplechase, near Nottingham, and on his return home he and his companions were cracking their jokes about having a steeplechase among themselves. Having duly arrived nearly opposite the Pindar’s House, on the London Road, about a mile from Nottingham, Bendigo exclaimed, ‘Now, my boys, I’ll show you how to run a steeplechase in a new style, without falling,’ and immediately threw a somersault; he felt, whilst throwing it, that he had hurt his knee, and on alighting be attempted in vain three times to rise from the ground; his companions, thinking for the moment he was joking, laughed heartily, but discovering it was no joke went to his assistance and raised him up, but the poor fellow had no use of his left leg. A gig was sent for immediately, in which he was conveyed to the house of his brother, and Messrs. Wright and Thompson, surgeons, were immediately called in. On examination of the knee we understand they pronounced the injury to the cap to be of so serious a nature that he is likely to be lame for life.

This serious mishap, which befell him on the 23rd of March, 1840, was 24 the result of those “larking” propensities for which Bendy was notorious. It shelved our hero most effectually, leaving the field open to Caunt, Nick Ward, Brassey, Deaf Burke, Tass Parker, and Co., whose several doings will be found in the proper place.

While Bendigo suffers as an im-patient under the hands of the Nottingham doctors for more than two years, we shall, before again raising the curtain, interpose a slight entr’acte in the shape of a little song to an old tune, then in the height of its popularity, “The Fine Old English Gentleman;” of which we opine we have read worse parodies than this, which was often chaunted in the parlour of Tom Spring’s “Castle,” in Holborn, at various meetings of good men and true, the patrons of fair play and of the then flourishing “Pugilistic Association,” whereof Tom was the President, and “the Bishop of Bond-street” the Honorary and Honourable Treasurer.

THE FINE OLD ENGLISH PUGILIST

By the P.L. of the P.R.

In 1842 Bendigo, maugre the advice of the medicos, made his way to London, and, putting in an appearance at a “soirée” at Jem Burn’s, solicited the honour of a glove-bout with Peter Crawley. Bendy’s resuscitation was hailed with delight, and as he declared his readiness to renew a broken-off match with Tass Parker, a spirited patron of the Ring declared that money should be no obstacle. On the Thursday week ensuing, Tass also being in town with his friends for the Derby week, all parties met at Johnny Broome’s, and articles were penned and duly signed. By these it was agreed that the men should meet on Wednesday, the 24th of August, within twenty miles of Wolverton, in the direction of Nottingham, for a stake of £200 a side.

Parker having beaten Harry Preston, the game Tom Britton, of Liverpool, and the powerful John Leechman (Brassey, of Bradford), was now at the pinnacle of his fame. His friends, too, were most confident, as Bendigo’s lameness was but too painfully apparent. Tass offered to “deposit the value of Bendigo’s belt, to be the prize of the victor.” The match went on until June 28th, when, £140 being down, it was announced at the fifth deposit that the bold Bendigo was in custody on a warrant issued by his brother (a respectable tradesman in Nottingham), who was averse to his milling pursuits. The rumour was too true. Bendy was brought before their worships, charged with intending a breach of the peace with one Hazard Parker, and held to bail to keep the peace towards all Her Majesty’s subjects for twelve months, himself in £100, and two sureties of £100 each.

During this interval, too, Ben Caunt had not been idle. He had beaten Brassey on the 27th of October, 1840, after a long, clumsy tussle of 101 26 rounds in an hour and a half, as may be read in the memoir of Caunt. He had also lost a fight with Nick Ward, by being provoked to a foul blow, and then beaten the same shifty pug. in May, 1841, thereafter departing on a tour to America, after the fashion of other modern champions. “Time and the hour wore on;” Bendy’s knee strengthened, and Big Ben returned from Yankeeshire, bringing with him, from the land of “big things,” the biggest so-called boxer that ever sported buff in the P.R., in the person of Charles Freeman, weighing 18st., and standing 6ft. 10½in. in his stocking feet. Freeman’s brief career will be found in an Appendix to that of his only antagonist William Perry, the Tipton Slasher.

At the close of 1843 Bendigo once again disputed the now established claim of Caunt to the proud title of Champion of England, when Brassey also offered himself to Bendigo’s notice. The Bradford Champion, however, does not seem to have had moneyed backers, and the business hung fire. On the 14th February, 1844, we find the following:—

VALENTINE FROM BENDIGO TO BRASSEY.

Brassey did not make a deposit, and Caunt, who was now settled at the “Coach and Horses,” St. Martin’s Lane, seemed rather given to benefits and bounce than boxing.

The rest of the year was consumed in correspondence, in which Bendigo demanded the odds offered and then retracted by Caunt, the latter having, ad interim, a row, and ridiculous challenge from Jem Burn, and an equally absurd cartel from a burly publican named Kingston, whose eccentric antics will be noticed in the memoir of Caunt.

The year 1845 was, however, destined to see the eccentric Bendigo and the ponderous Caunt brought together. All doubts and surmises were silenced when articles were signed to the effect that on the 9th of September, 1845, the men were to meet, Bendigo having closed, after innumerable difficulties, with Caunt’s terms of £200 a side and the belt.