The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Title: Hans Holbein the Younger, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: Arthur B. Chamberlain

Illustrator: Hans Holbein

Release date: January 3, 2021 [eBook #64208]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Tim Lindell, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

HANS HOLBEIN

Self-Portrait

Drawing in Indian ink and coloured chalks, washed with water-colour

Basel Gallery

IN this book the writer has endeavoured to give as complete an account as possible of the life and career of the younger Holbein, together with a description of every known picture painted by him, and of the more important of his drawings and designs. The earlier books devoted to the subject—such as Wornum’s Life and Works, 1867, and Dr. Woltmann’s two volumes—although they must always remain of the utmost help to the student, are now in some respects out of date. The second edition of the latter’s great work, in which he modified and corrected many passages in the earlier issue, has never been fully translated into English; while the latest book of importance on the subject published in this country, Hans Holbein the Younger, by Mr. Gerald S. Davies, M.A., 1903, is mainly devoted to the art of the painter, and does not profess to give complete biographical details of his life. In recent years many new facts as to Holbein’s career have been discovered, and fresh pictures by him unearthed, while modern criticism has reversed some of the earlier conclusions respecting the authorship of a certain number of works at one time attributed to him. Much valuable information upon the subject has been published at home and abroad, largely in periodicals devoted to such matters and in the transactions of artistic and learned societies, by various well-known students of the master in Germany and Switzerland, chief among whom must be mentioned Dr. Paul Ganz, the director of the Public Picture Collection in Basel, now recognised as the leading authority on Holbein, together with Dr. Hans Koegler, Dr. Emil Major, H. A. Schmid, and other writers too numerous to mention here; while in England equally valuable contributions to our knowledge have been made from time to time by such critics as viiiMr. Lionel Cust, M.V.O., Sir Sidney Colvin, Mr. Campbell Dodgson, Sir Claude Phillips, Miss Mary F. S. Hervey, and a number of others, in the pages of the Burlington Magazine and elsewhere. Much valuable information is also to be found in two recently-published volumes—Dr. Curt Glaser’s Hans Holbein der Ältere, 1908, and Dr. Willy Hes’ Ambrosius Holbein, 1911.

The writer has availed himself as fully as possible of the newer facts and conclusions embodied in such papers and communications, the source of information in all cases being fully acknowledged. A very careful study of the Calendars of Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, extending over a number of years, has enabled him to add some fresh items of information about the painter and certain of his sitters, and of several of the artists who were his contemporaries in England. He has dealt at some length, though necessarily in a condensed form, with the chief painters and craftsmen, both English and foreign, who were at work in London under Henry VIII, much of the information thus brought together having been hitherto scattered about in a variety of publications not always conveniently accessible to the student. He thus hopes that the book will to some extent serve the purpose for which it is primarily intended—the provision, in as concise a form as possible, of a complete biography of the painter, embodying all the more recent discoveries; and he trusts that it may be of some small service to those who are interested in Holbein, but have neither the time nor the opportunity to avail themselves of the many scattered sources of information which he has attempted to bring together within the covers of a single book.

By the gracious permission of His Majesty the King, the writer has been allowed to include among the illustrations, reproductions, in some instances in colour, of a number of pictures and drawings by Holbein in the royal collections; and he has to thank the Lord Chamberlain and Mr. Lionel Cust, M.V.O., Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, for the kind assistance they rendered him in obtaining such permission. He has also to express his grateful acknowledgments to ixa number of owners and collectors for similar permission to reproduce works by the master in their possession, among them Her Majesty the Queen of Holland, who has graciously allowed the inclusion of the beautiful miniature of an Unknown Youth; the Duke of Devonshire, G.C.V.O.; Earl Spencer, G.C.V.O.; the Earl of Radnor; Lord Leconfield; the Earl of Yarborough; Sir John Ramsden, Bt.; Sir Hugh P. Lane; the late Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan; Major Charles Palmer; and the Barber-Surgeons’ Company. Special thanks are due to Lord St. Oswald for permitting the large “More Family Group” at Nostell Priory to be photographed for the purposes of this book, and for allowing the writer to take notes from a very interesting manuscript containing a description of the various versions of the Family picture compiled by his grandfather, Mr. Charles Winn. He has also to record his great indebtedness to Mr. Ayerst H. Buttery for giving him the privilege of reproducing the recently discovered portrait of an Unknown English Lady, formerly in the possession of the Bodenham family at Rotherwas, near Hereford. His thanks also are due to Senhor José de Figueiredo, director of the National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon, for permission to include the elder Holbein’s “Fountain of Life” among the illustrations, as well as to the directors of a number of galleries and museums, including the Public Picture Collection, Basel; the National Gallery, British Museum, and Wallace Collection; the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin; the Imperial Gallery, Vienna; the Louvre, Paris; the Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague; the Metropolitan Museum of New York; the Royal Hermitage Gallery, St. Petersburg; and the Galleries of Dresden, Munich, Hanover, Rome, Florence, Solothurn, and elsewhere.

In addition, he has the pleasure of recording his great indebtedness to Mr. Lionel Cust, M.V.O., for kind assistance and advice; to Mr. Maurice W. Brockwell, for much valuable help in many directions; to Mr. Campbell Dodgson, who was good enough to assist in the selection of woodcuts from the British Museum Collection for the purposes of reproduction; to Dr. George C. Williamson, through whose kindness the writer has been able to make use of his Catalogue of the xlate Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan’s Collection of Miniatures; to the Editors of the Burlington Magazine of Fine Arts for permission to include the writer’s paper on Holbein’s visit to “High Burgony”; to Mr. James Melville for transcribing from the Balcarres MSS. a long letter from the Duchess of Guise referring to that visit; to Herr F. Engel-Gros for information about the interesting roundel in his possession, which possibly represents the painter Lucas Hornebolt; and to Dr. James H. W. Laing, of Dundee, to whom he is deeply indebted for most generously undertaking the very onerous task of reading the whole of the proofs. He wishes also to offer his grateful thanks to his publishers, and in particular to Mr. Hugh Allen, for the great care and trouble they have spent upon the book, and for their hearty co-operation in attempting to make it as complete a record as possible of the great master to whom it is devoted.

Birmingham, August 1913.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | HANS HOLBEIN THE ELDER AND HIS FAMILY | 1 |

| II. | YOUTHFUL DAYS IN AUGSBURG | 23 |

| III. | FIRST YEARS IN SWITZERLAND | 32 |

| IV. | WORK IN LUCERNE AND THE VISIT TO LOMBARDY | 57 |

| V. | CITIZEN OF BASEL | 82 |

| VI. | THE HOUSE OF THE DANCE AND THE WALL-PAINTINGS IN THE BASEL TOWN HALL | 116 |

| VII. | DESIGNS FOR PAINTED GLASS AND OTHER STUDIES | 135 |

| VIII. | PORTRAITS OF ERASMUS AND HIS CIRCLE | 162 |

| IX. | DESIGNS FOR BOOK ILLUSTRATIONS | 187 |

| X. | THE “DANCE OF DEATH” AND OLD TESTAMENT WOODCUTS | 204 |

| XI. | THE MEYER MADONNA AND THE DEPARTURE FOR ENGLAND | 232 |

| XII. | NATIVE AND FOREIGN ARTISTS IN ENGLAND DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII | 256 |

| XIII. | THE FIRST VISIT TO ENGLAND: PORTRAITS OF THE MORE FAMILY | 288 |

| XIV. | THE FIRST VISIT TO ENGLAND: OTHER PORTRAITS AND DECORATIVE WORK | 311 |

| XV. | THE RETURN TO BASEL (1528-1532) | 338 |

| Postscript to Chapter XIV. A NEWLY-DISCOVERED PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN ENGLISH LADY | 353 |

| FOOTNOTES FOR ALL CHAPTERS | 359 |

| HANS HOLBEIN: SELF-PORTRAIT | Frontispiece | |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 1. | THE BAPTISM OF ST. PAUL | 11 |

| Left-hand panel of the “Basilica of St. Paul” altar-piece. By Hans Holbein the Elder. | ||

| Museum, Augsburg. | ||

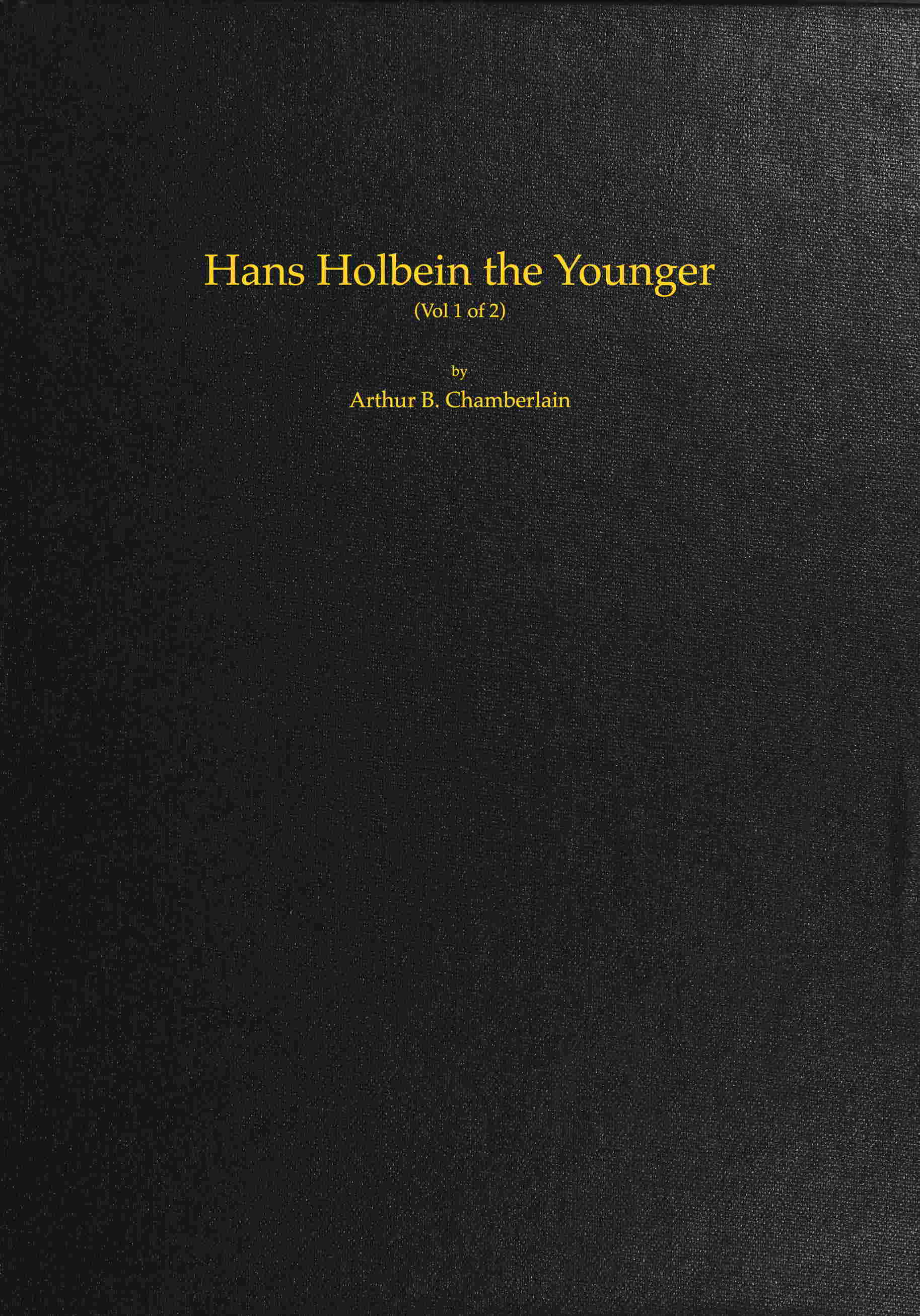

| 2. | THE ST. SEBASTIAN ALTAR-PIECE | 15 |

| Central panel. By Hans Holbein the Elder. | ||

| Alte Pinakothek, Munich. | ||

| 3. | (1) ST. BARBARA. (2) ST. ELIZABETH | 16 |

| Inner sides of the wings of the “St. Sebastian” altar-piece. By Hans Holbein the Elder. | ||

| Alte Pinakothek, Munich. | ||

| 4. | THE FOUNTAIN OF LIFE | 17 |

| By Hans Holbein the Elder. | ||

| National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon. Reproduced by kind permission of the Director, Senhor José de Figueiredo. | ||

| 5. | STUDY FOR THE PORTRAIT OF A LADY OF AUGSBURG | 21 |

| Silver-point drawing. By Hans Holbein the Elder. | ||

| British Museum. | ||

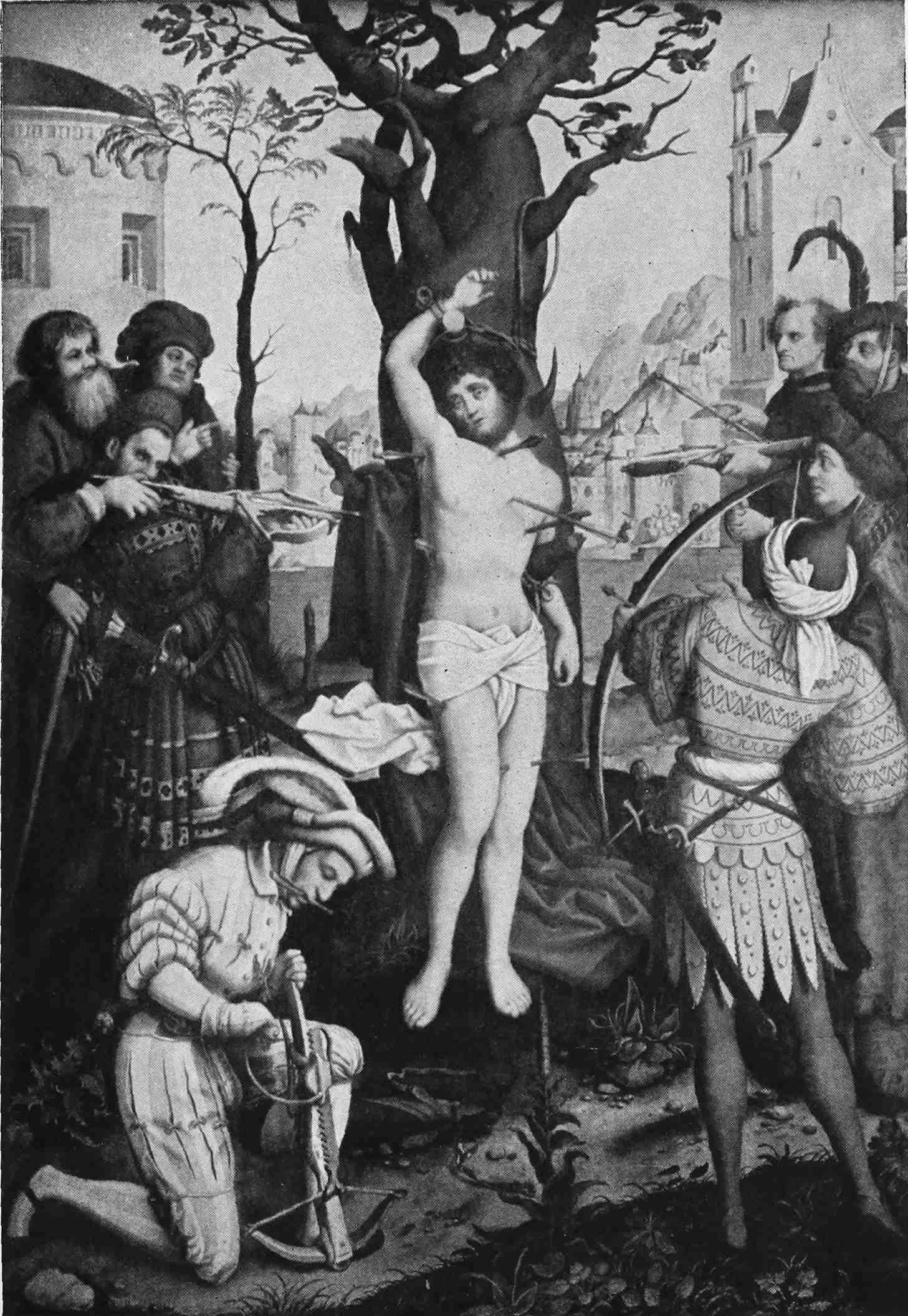

| 6. | AMBROSIUS AND HANS HOLBEIN | 25 |

| Silver-point drawing. By Hans Holbein the Elder (1511). | ||

| Royal Print Room, Berlin. | ||

| 7. | VIRGIN AND CHILD (1514) | 33 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 8. | (1) HEAD OF THE VIRGIN MARY. (2) HEAD OF ST. JOHN | 37 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 9. | THE LAST SUPPER | 40 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

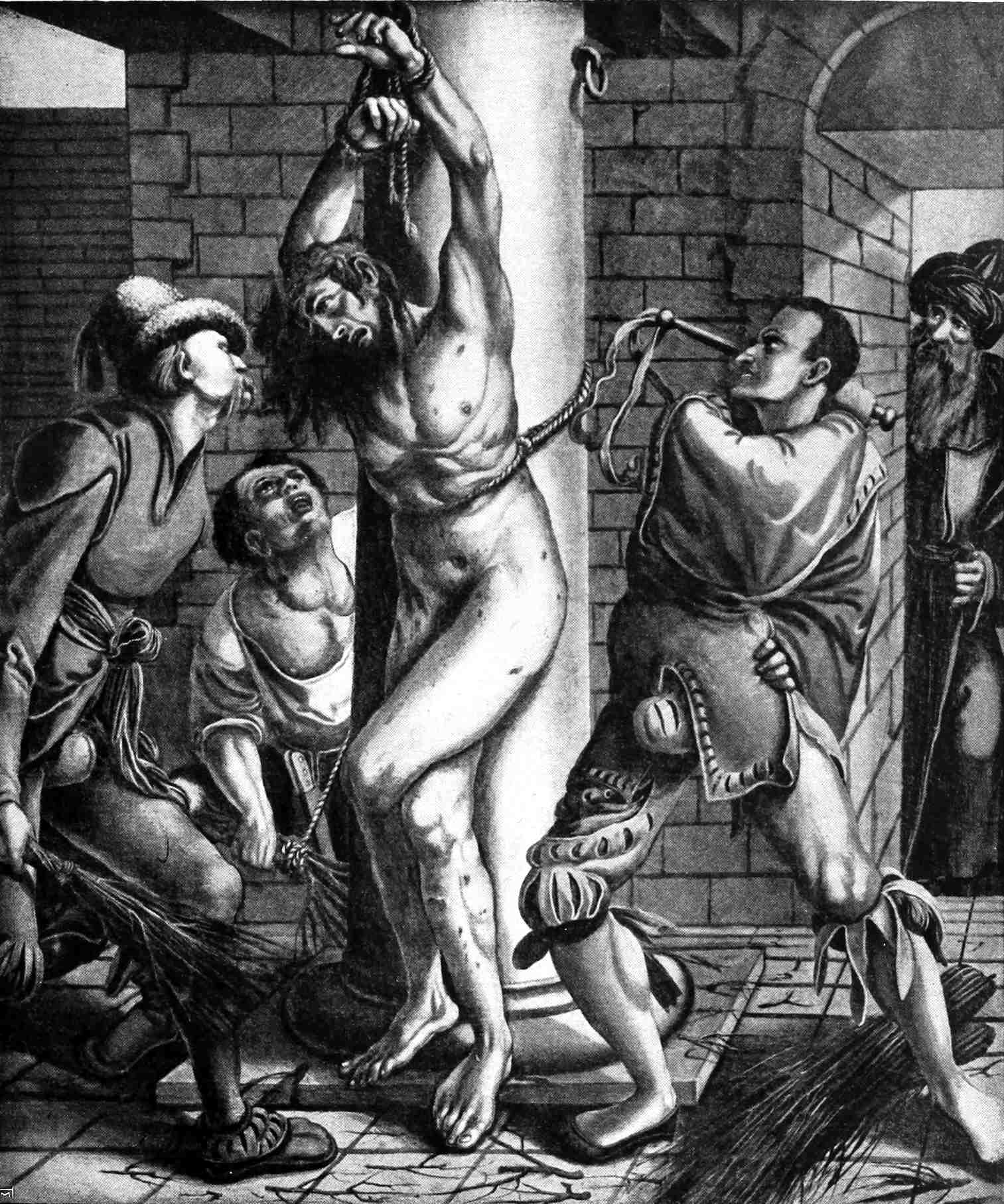

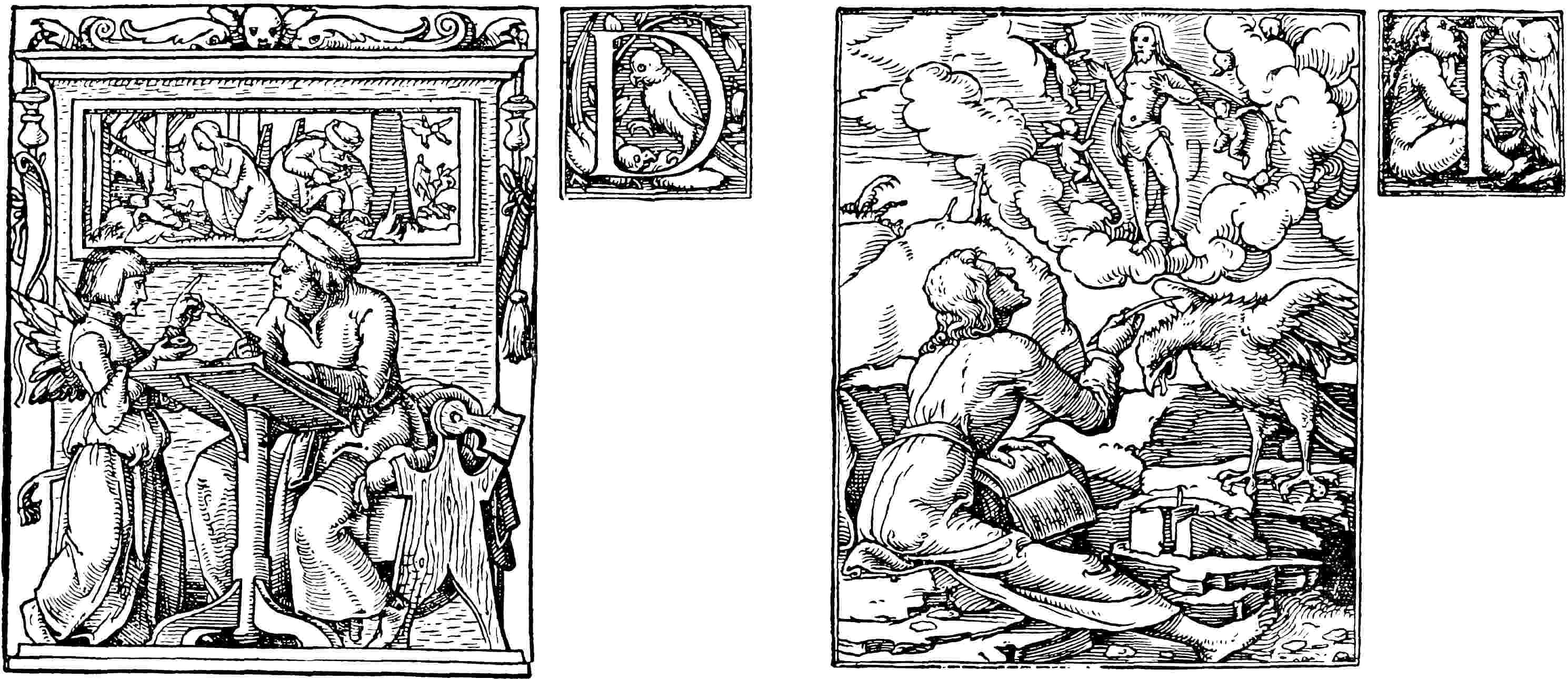

| 10. | THE SCOURGING OF CHRIST | 41 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

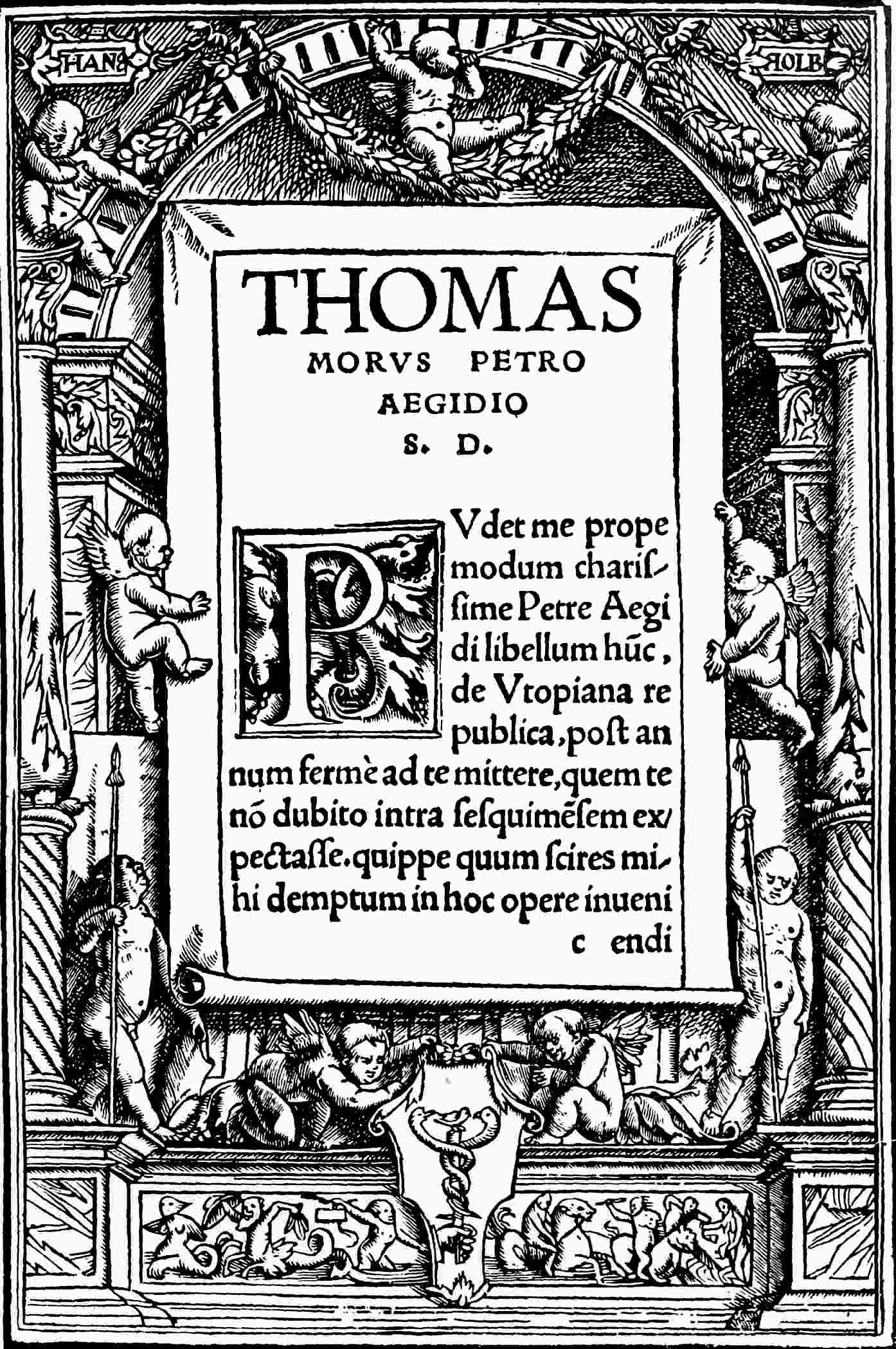

| 11. | HOLBEIN’S EARLIEST TITLE-PAGE | 45 |

| First used in 1515. | ||

| From a copy of More’s “Utopia” in the British Museum. | ||

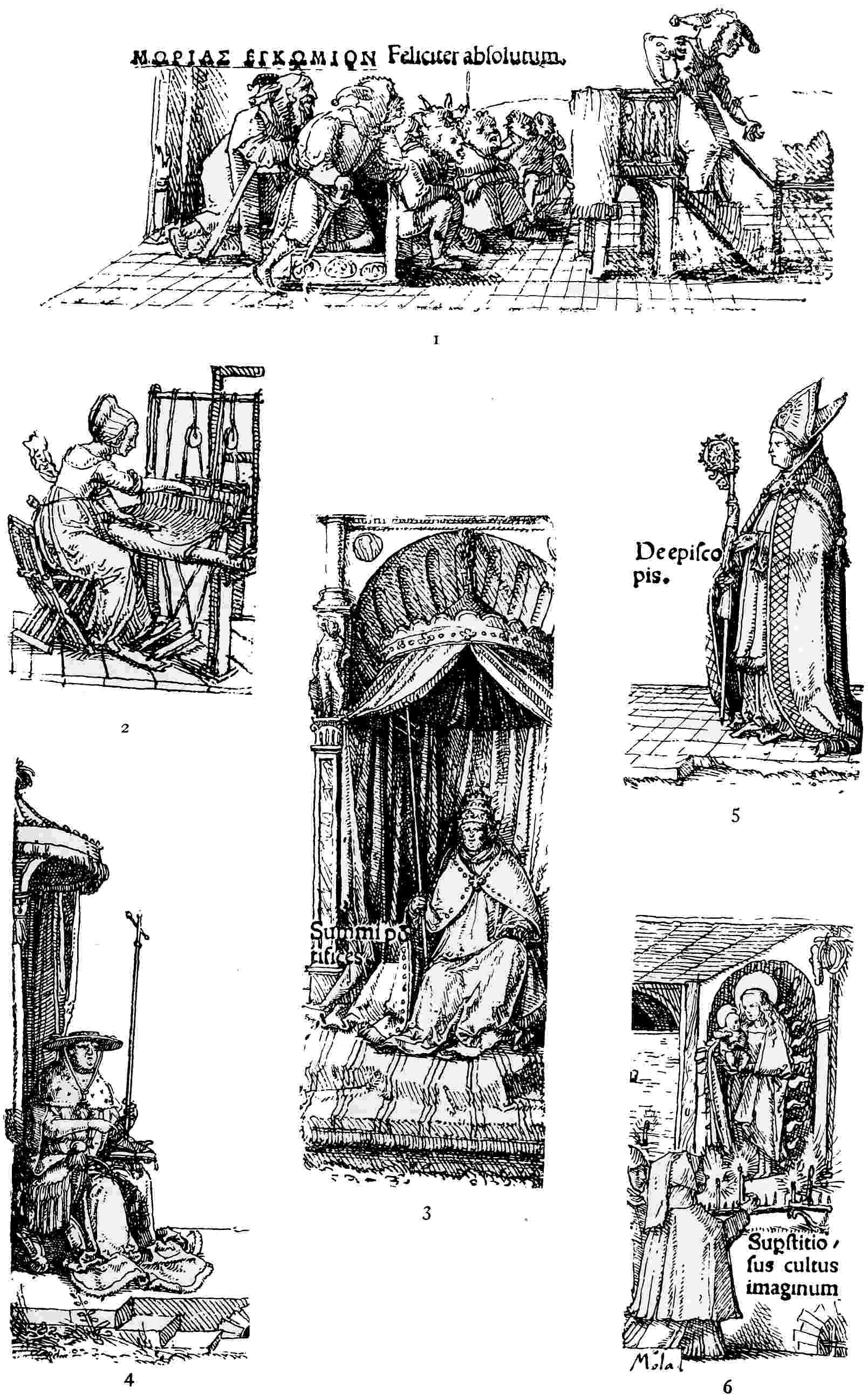

| xiii12. | MARGINAL DRAWINGS IN A COPY OF THE “PRAISE OF FOLLY” | 48 |

| (1) Folly Leaving the Pulpit. | ||

| (2) Penelope at her Loom. | ||

| (3) The Pope. | ||

| (4) The Cardinal. | ||

| (5) The Bishop. | ||

| (6) Nuns Kneeling before an Altar-piece. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

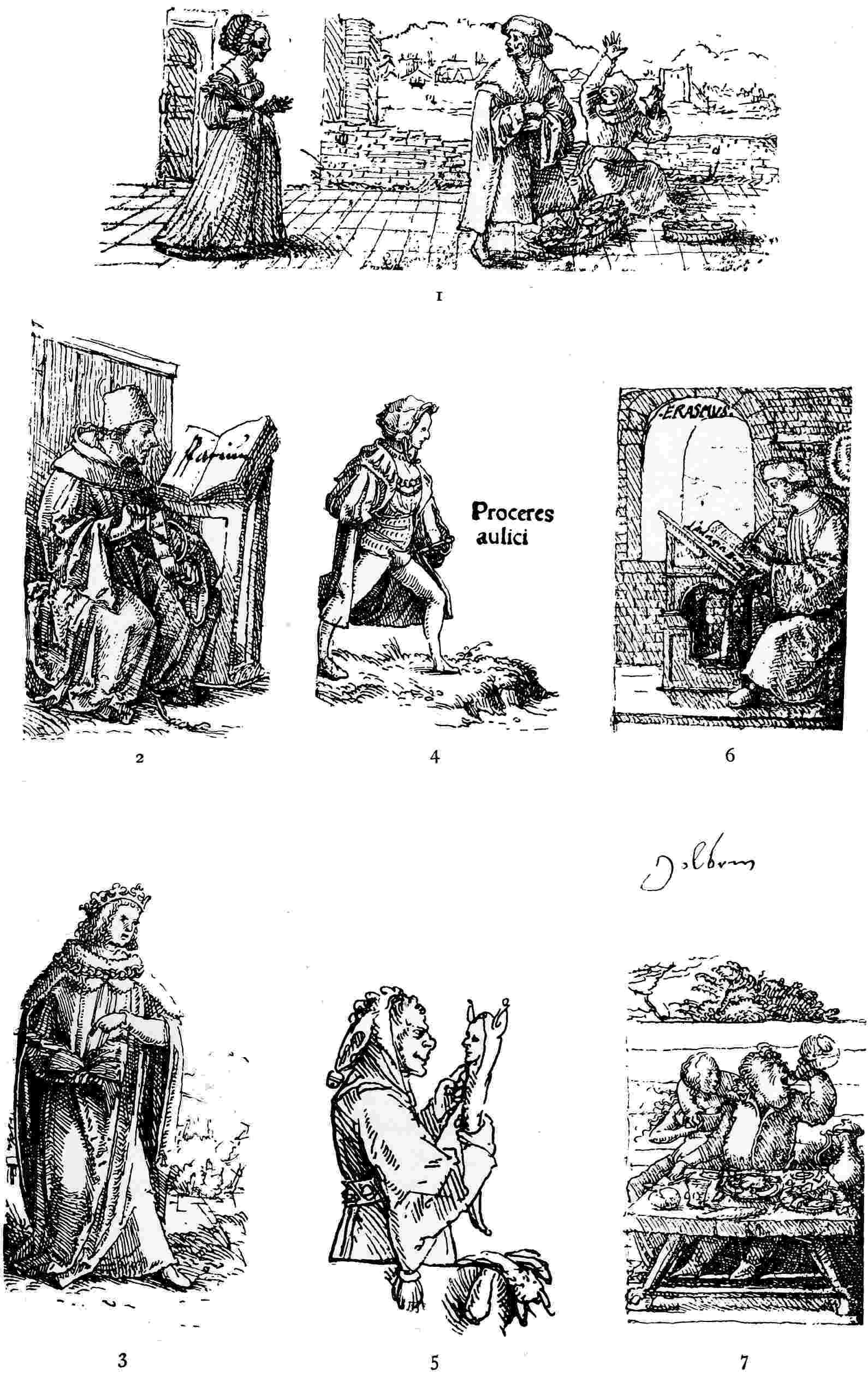

| 13. | MARGINAL DRAWINGS IN A COPY OF THE “PRAISE OF FOLLY” | 49 |

| (1) The Basket of Eggs. | ||

| (2) Nicolas de Lyra. | ||

| (3) King Solomon. | ||

| (4) Young Nobleman. | ||

| (5) Folly and his Puppet. | ||

| (6) Erasmus at his Desk. | ||

| (7) “A Fat and Splendid Pig from the Herd of Epicurus.” | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

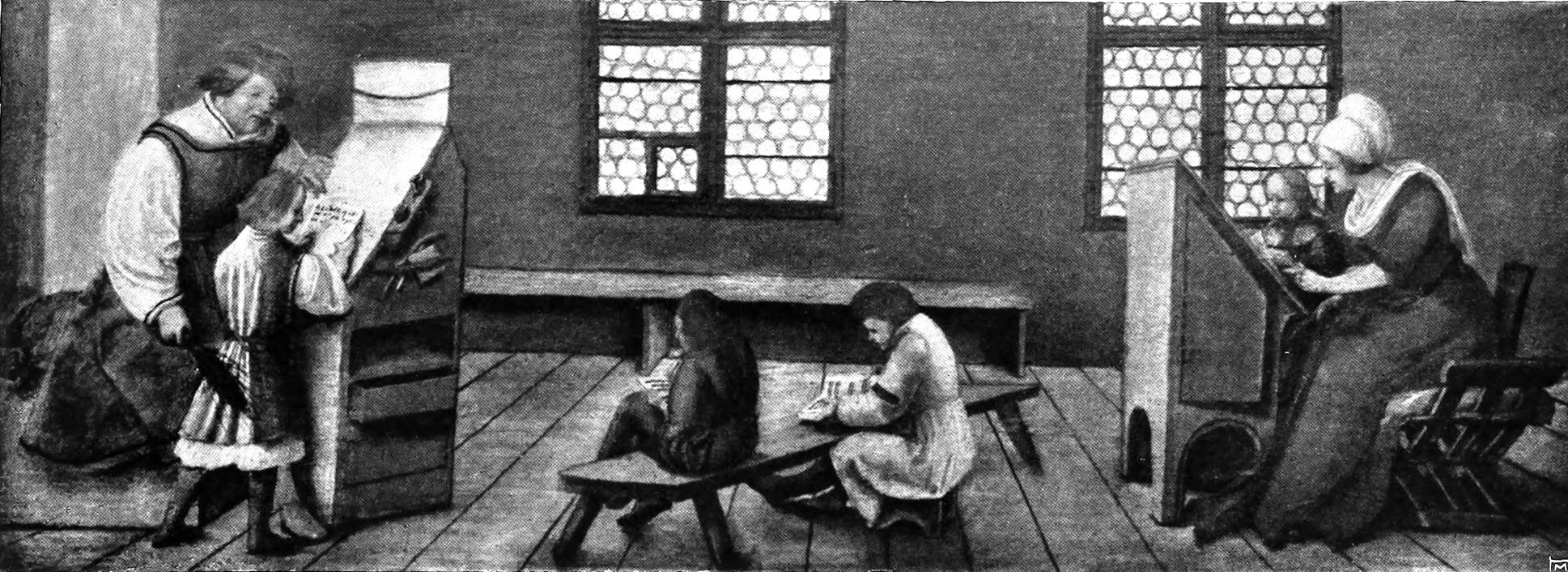

| 14. | THE TWO SIDES OF A SCHOOLMASTER’S SIGN-BOARD (1516) | 51 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 15. | DOUBLE PORTRAIT OF JAKOB MEYER AND HIS WIFE, DOROTHEA KANNENGIESSER (1516) | 52 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 16. | (1) HEAD OF JAKOB MEYER. (2) HEAD OF DOROTHEA KANNENGIESSER | 55 |

| Drawings in black and coloured chalks. Studies for the double portrait of 1516. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

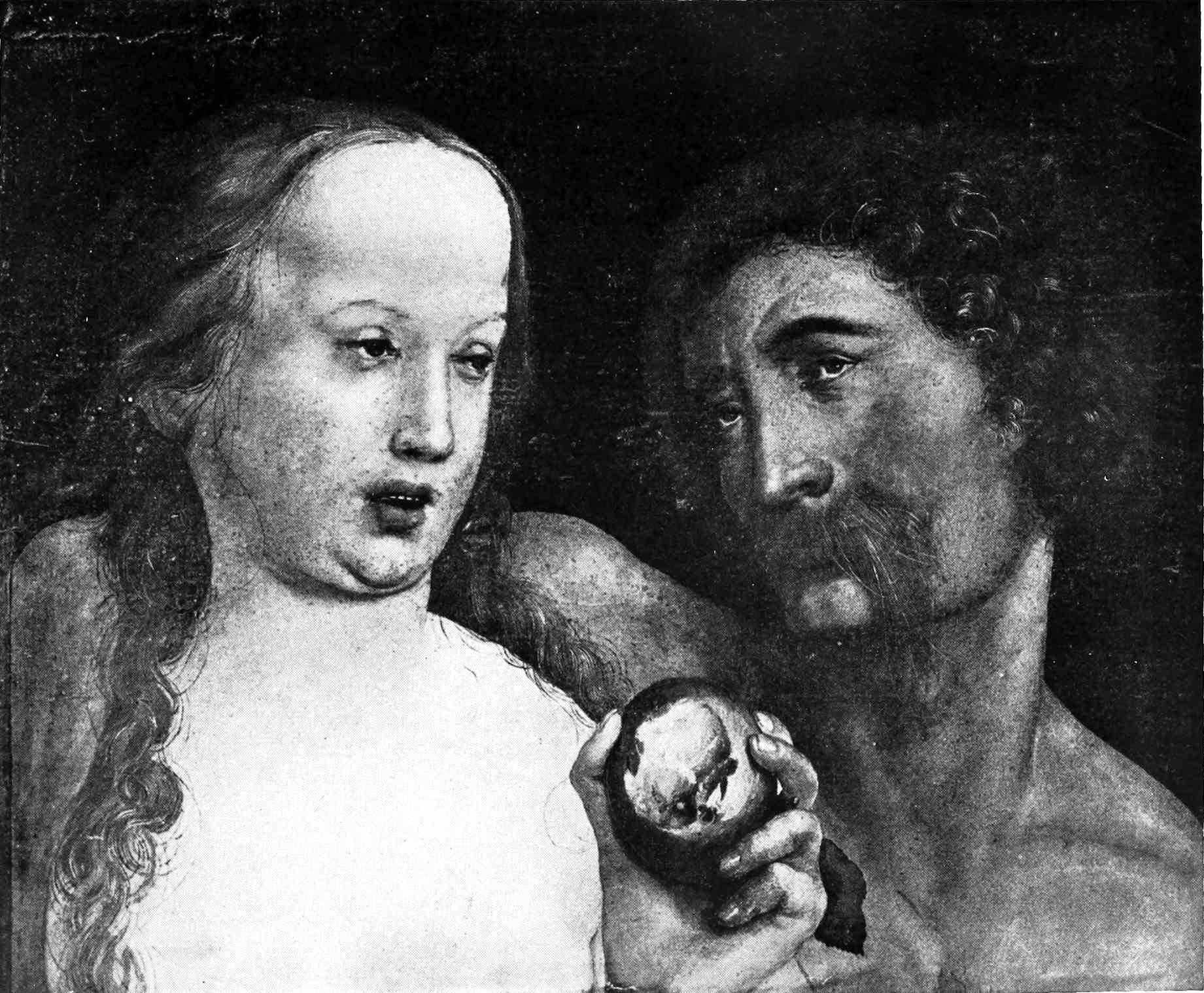

| 17. | ADAM AND EVE (1517) | 56 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 18. | PORTRAITS OF TWO BOYS | 60 |

| By Ambrosius Holbein. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 19. | STUDY OF A YOUNG GIRL NAMED “ANNE” (1518) | 61 |

| Silver-point and red chalk drawing. By Ambrosius Holbein. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 20. | THE FOUNDING OF BASEL | 61 |

| Design for painted glass. By Ambrosius Holbein. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 21. | PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN YOUNG MAN (1518) | 61 |

| By Ambrosius Holbein. | ||

| Royal Hermitage Gallery, St. Petersburg. | ||

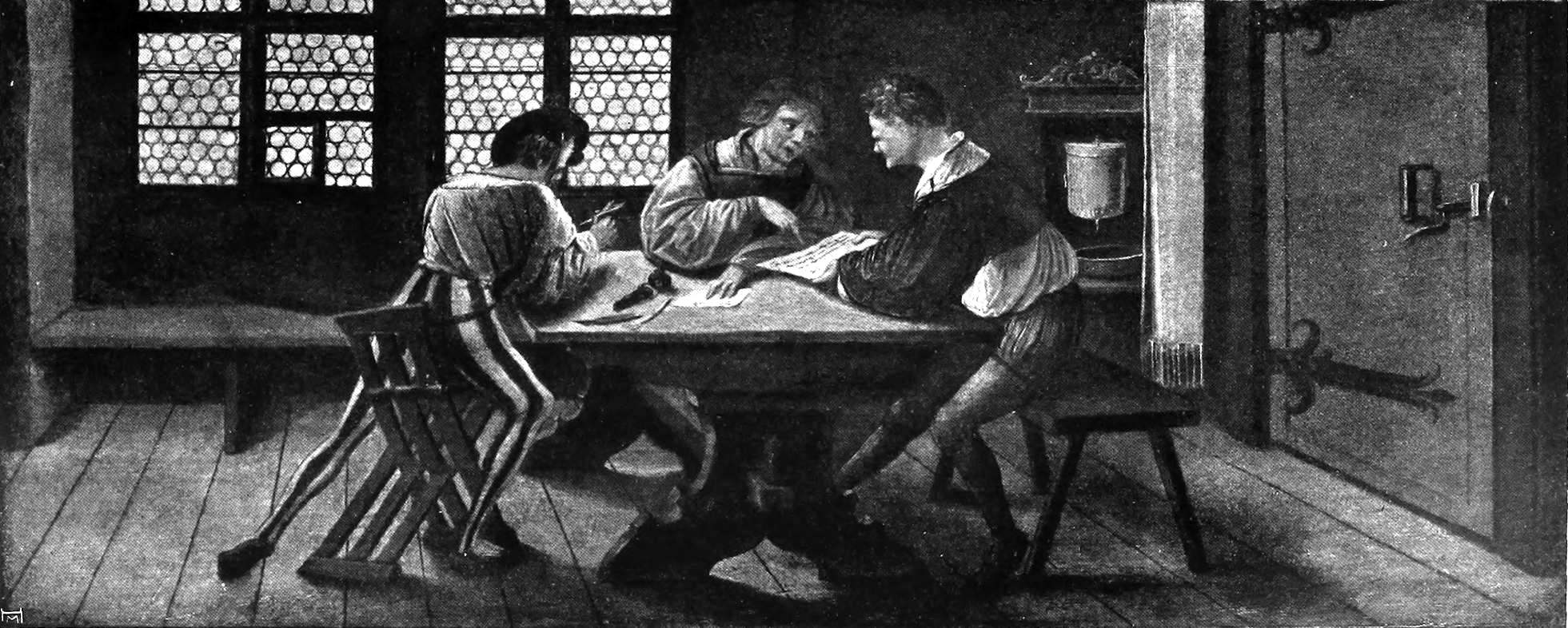

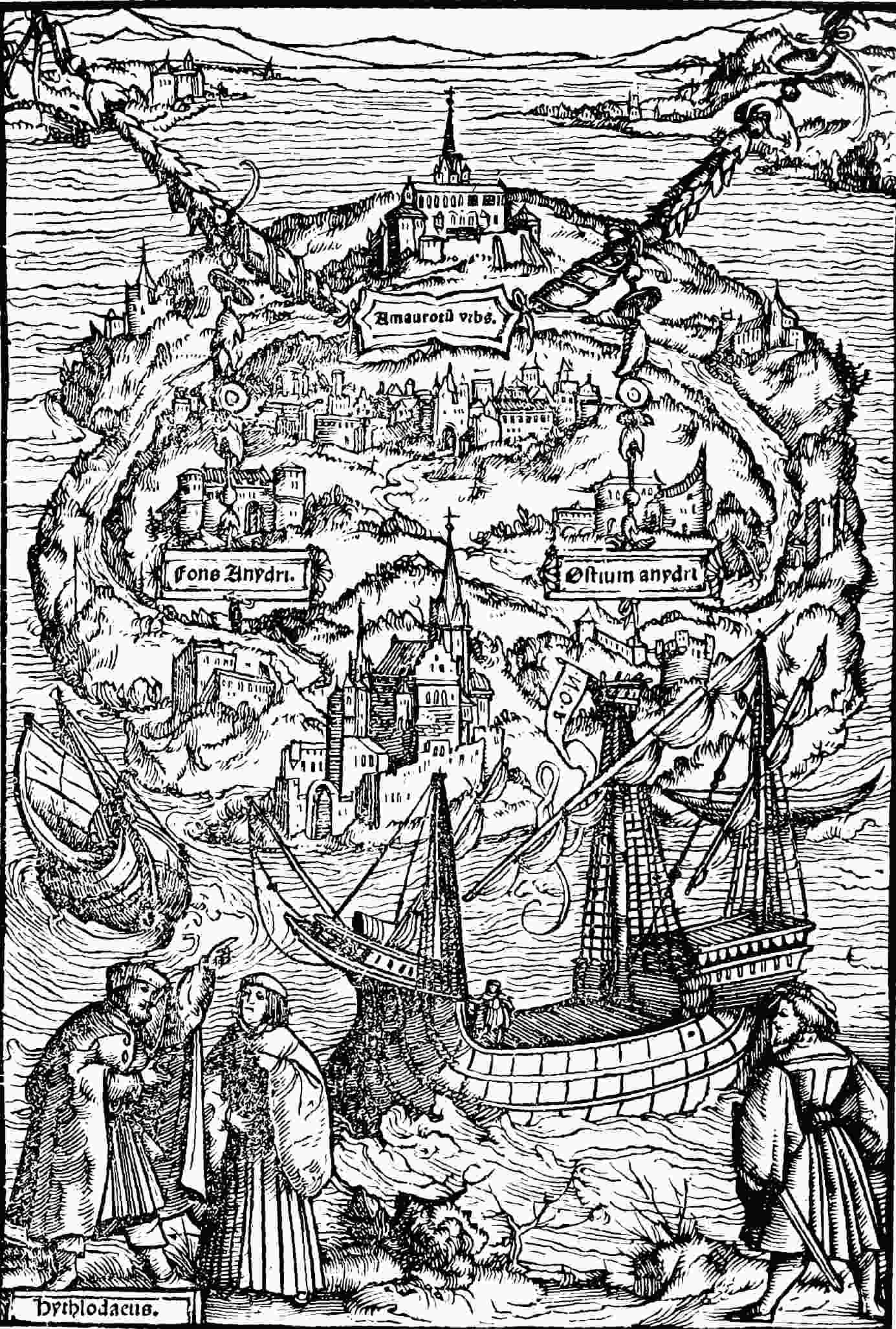

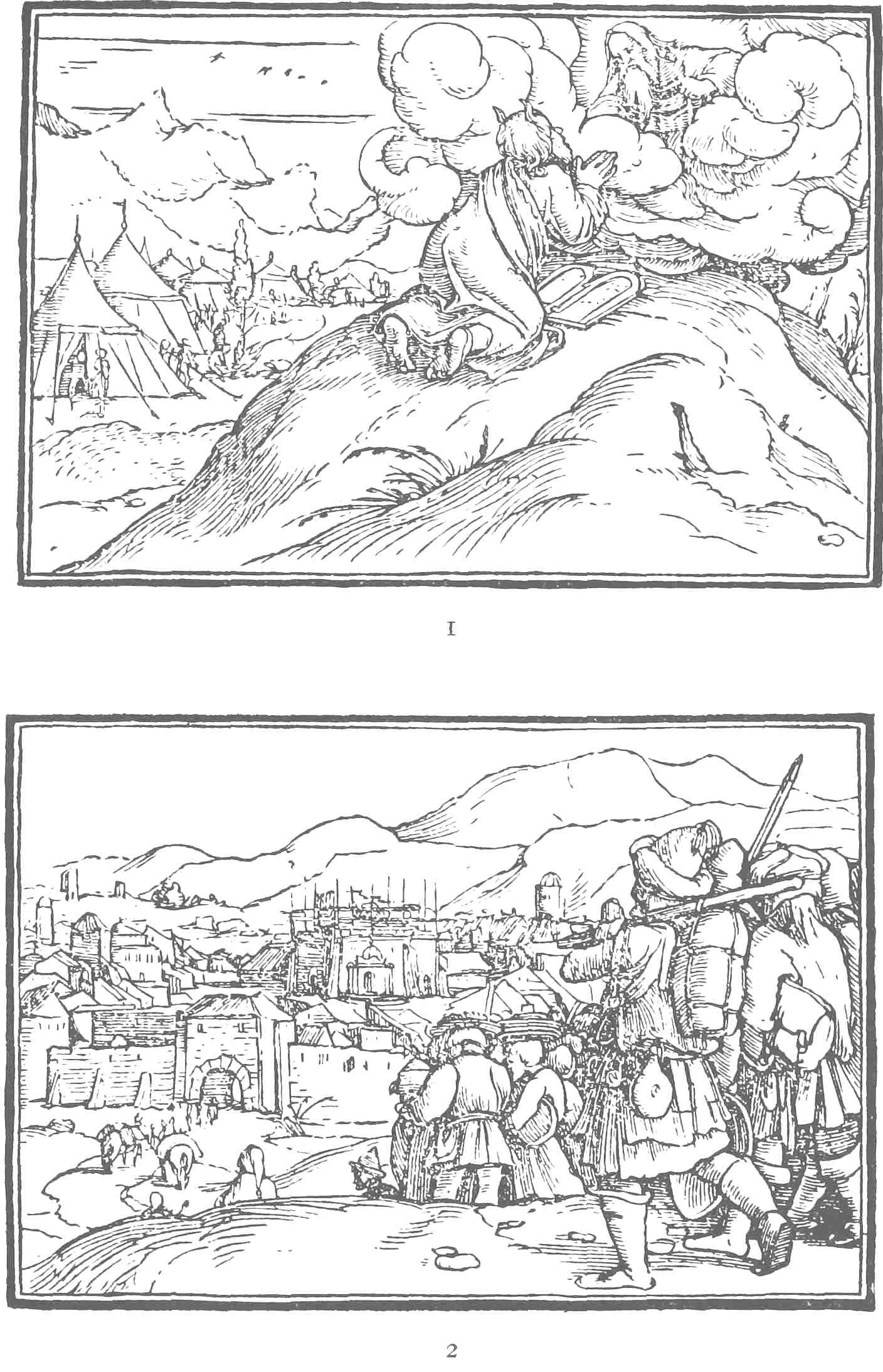

| 22. | ILLUSTRATION TO SIR THOMAS MORE’S “UTOPIA” | 62 |

| By Ambrosius Holbein. | ||

| From a woodcut in the British Museum. | ||

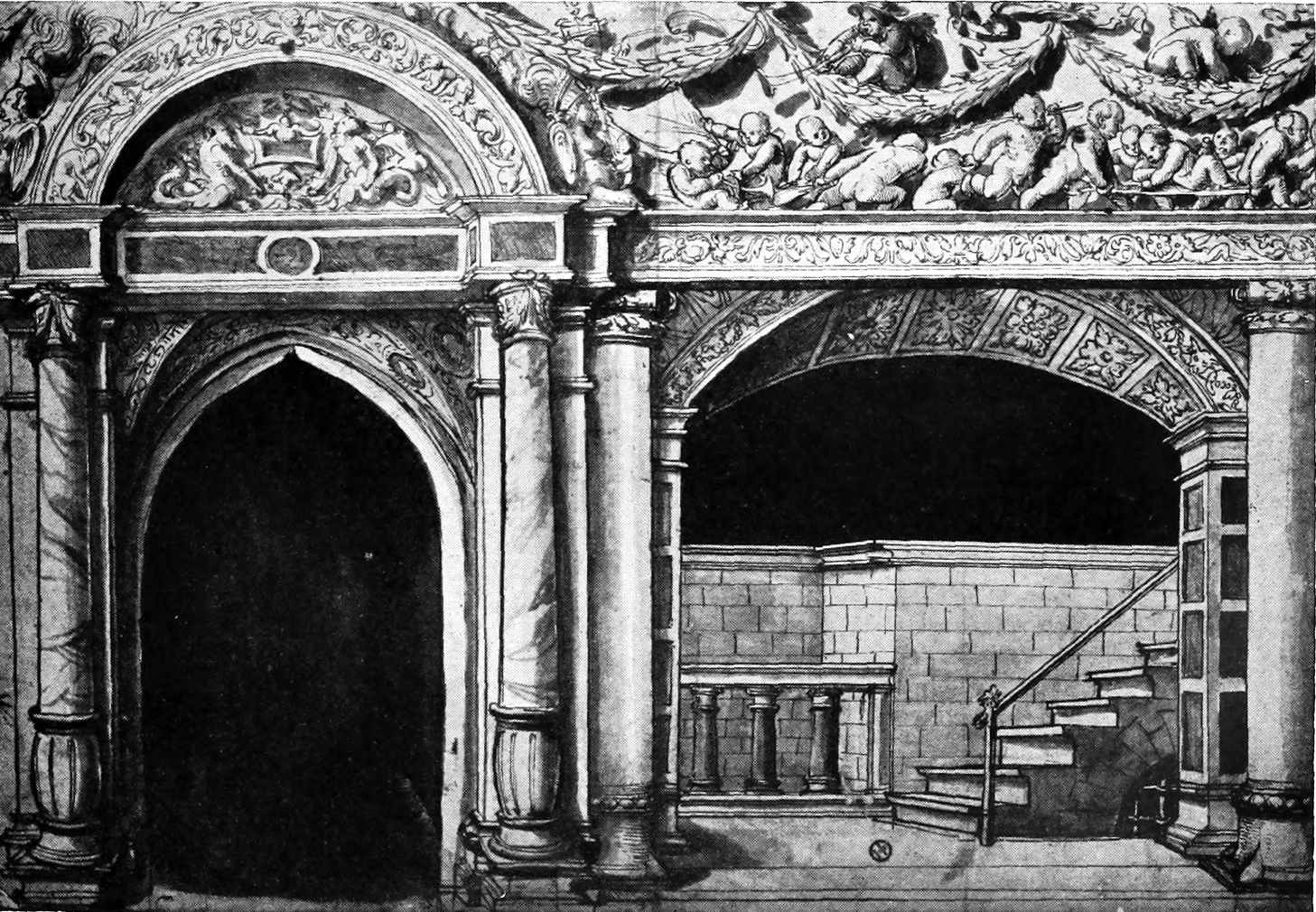

| 23. | DESIGNS FOR THE WALL-PAINTINGS OF THE HERTENSTEIN HOUSE, LUCERNE | 68 |

| (1) Leæna and the Judges. | ||

| (2) Architectural Decoration of the Ground Floor. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 24. | PORTRAIT OF BENEDIKT VON HERTENSTEIN (1517) | 72 |

| Metropolitan Museum, New York. | ||

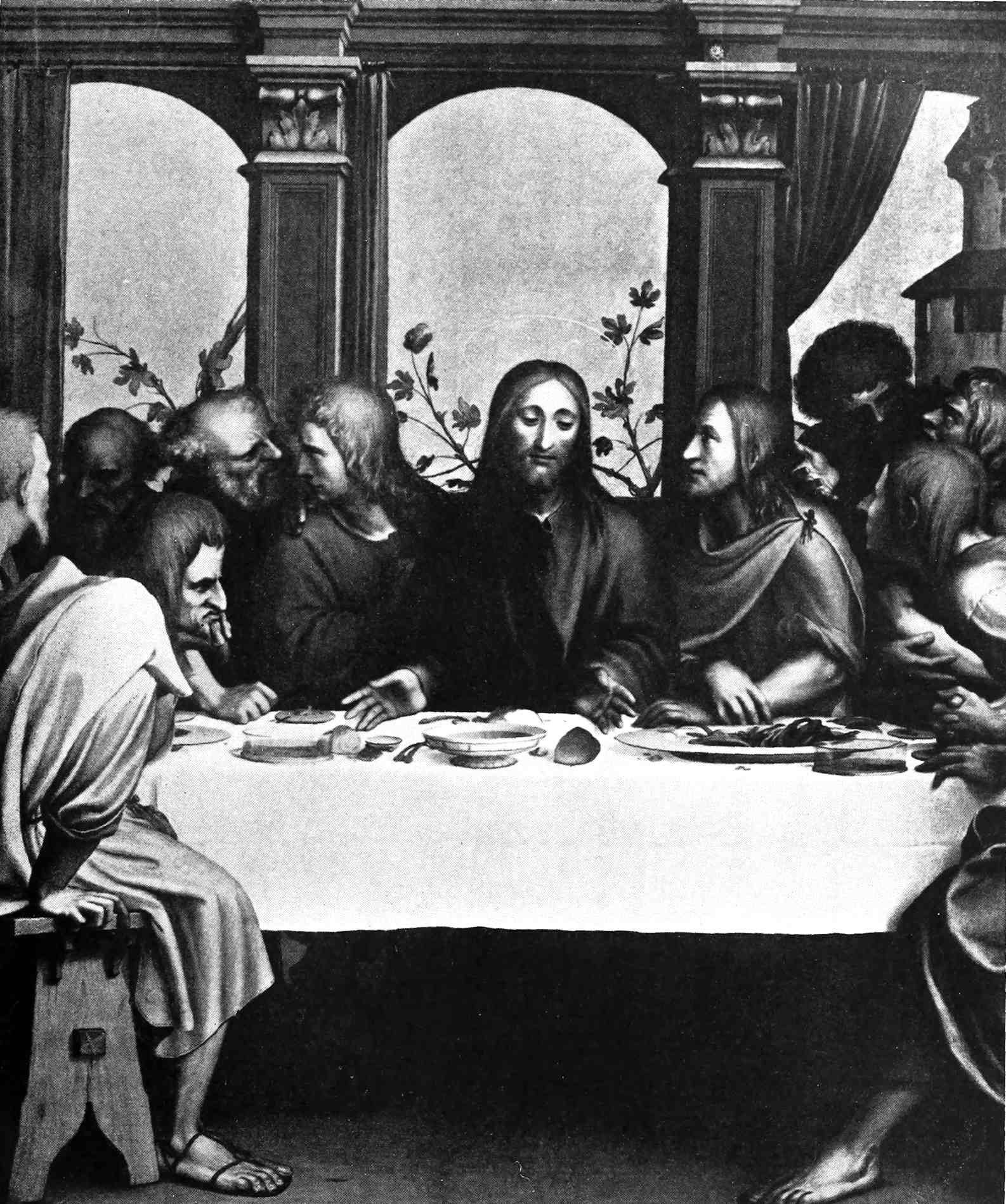

| xiv25. | THE LAST SUPPER | 75 |

| Central panel of a Triptych. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 26. | THE ARCHANGEL MICHAEL AS WEIGHER OF SOULS | 79 |

| Drawing. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 27. | MINERS AT WORK | 80 |

| Drawing in Indian ink, pen, and bistre. | ||

| British Museum. | ||

| 28. | BONIFACIUS AMERBACH (1519) | 85 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 29. | (1) ADORATION OF THE SHEPHERDS. (2) ADORATION OF THE KINGS | 88 |

| Inner sides of the wings of the Oberried altar-piece. | ||

| University Chapel, Freiburg Minster. | ||

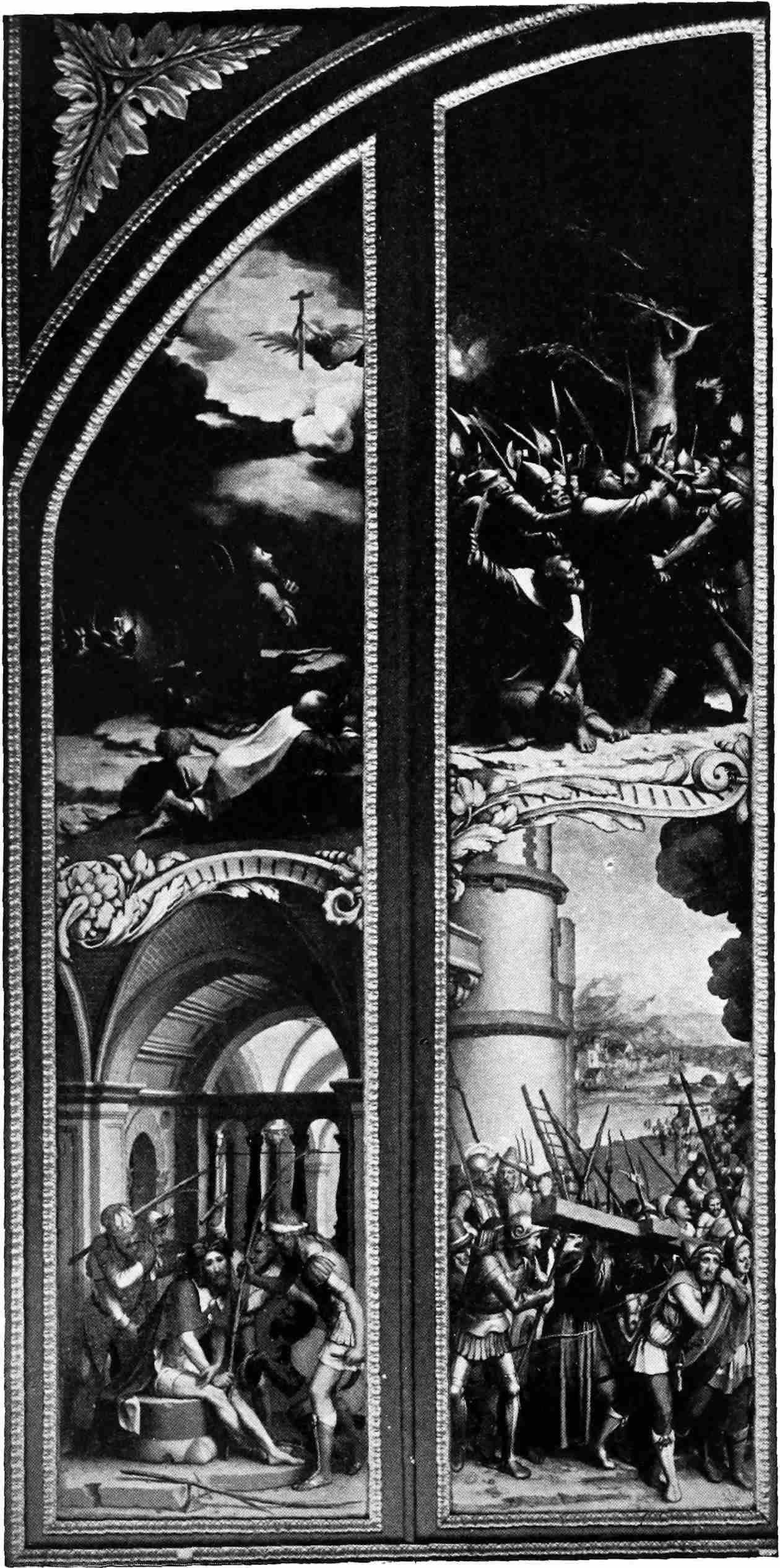

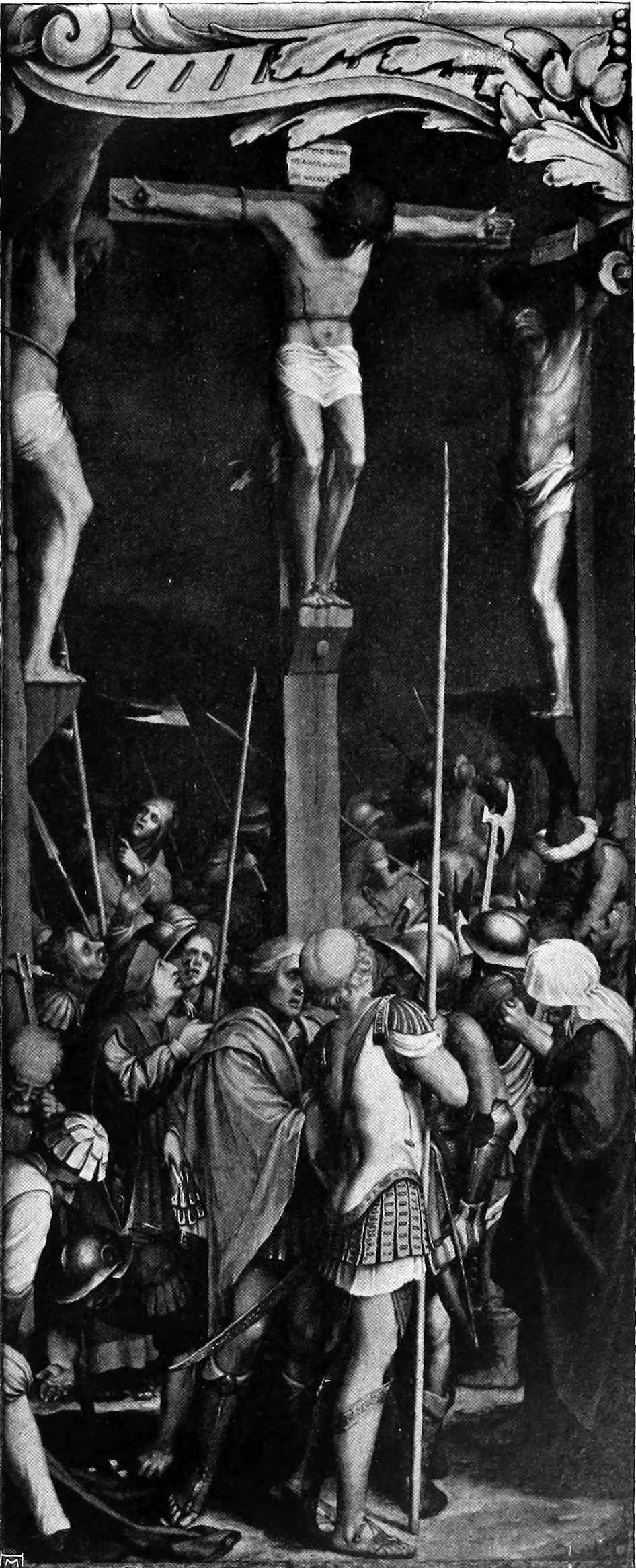

| 30. | THE PASSION OF CHRIST | 91 |

| Outer sides of the wings of an altar-piece. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

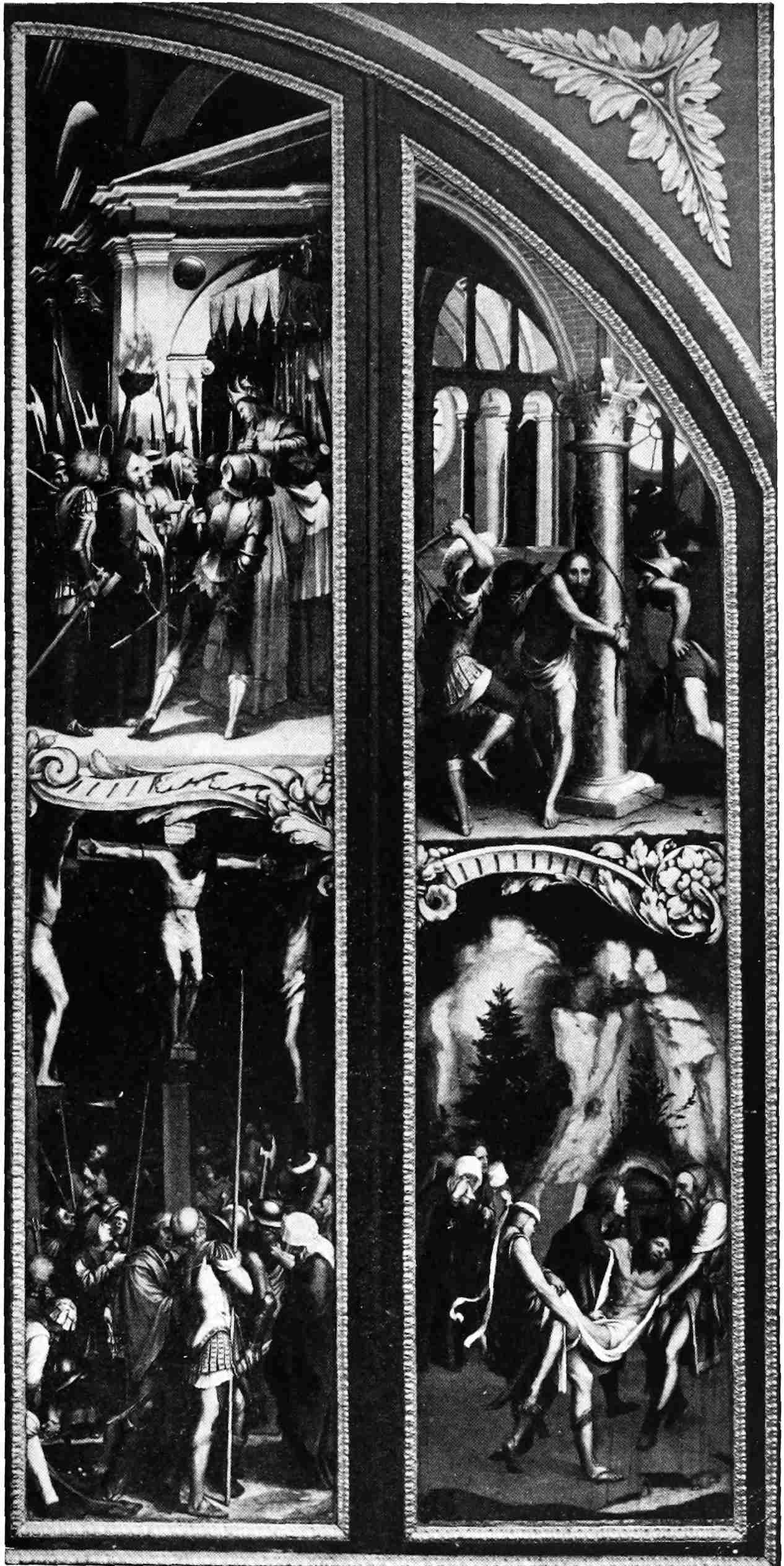

| 31. | (1) CHRIST BEARING THE CROSS. (2) THE CRUCIFIXION | 94 |

| Details of the outer sides of the wings of the “Passion” Altar-piece. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 32. | “NOLI ME TANGERE” | 95 |

| Christ appearing to Mary Magdalen. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Hampton Court Palace. | ||

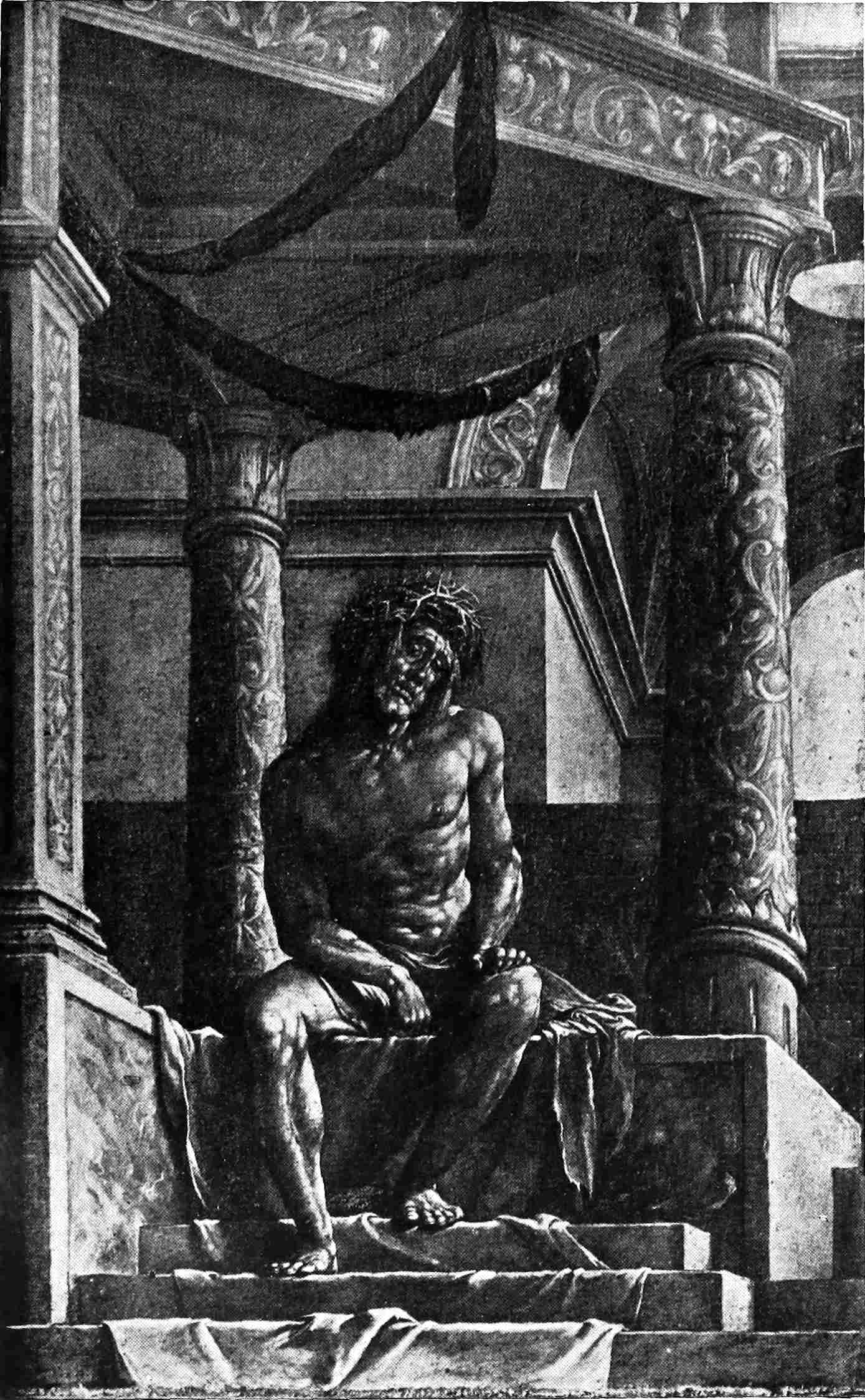

| 33. | (1) CHRIST, THE MAN OF SORROWS. (2) MARY, MATER DOLOROSA | 98 |

| Diptych, painted in brown monochrome, with blue sky. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 34. | THE HOLY FAMILY | 99 |

| Washed drawing on a red ground. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

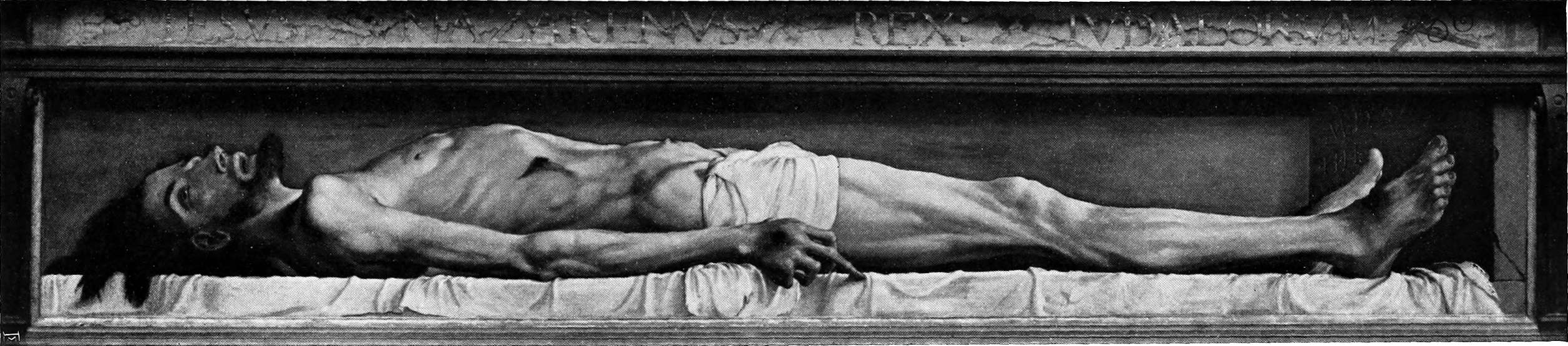

| 35. | THE DEAD CHRIST IN THE TOMB (1521) | 101 |

| Predella of an altar-piece. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 36. | THE VIRGIN AND CHILD, WITH ST. URSUS AND A HOLY BISHOP (1522) | 103 |

| Solothurn Gallery. | ||

| 37. | PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG WOMAN, POSSIBLY HOLBEIN’S WIFE | 106 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis, The Hague. | ||

| 38. | HEAD OF A YOUNG WOMAN, PROBABLY HOLBEIN’S WIFE | 108 |

| Study for the Solothurn “Madonna.” Silver-point drawing, touched with red. | ||

| Louvre, Paris. | ||

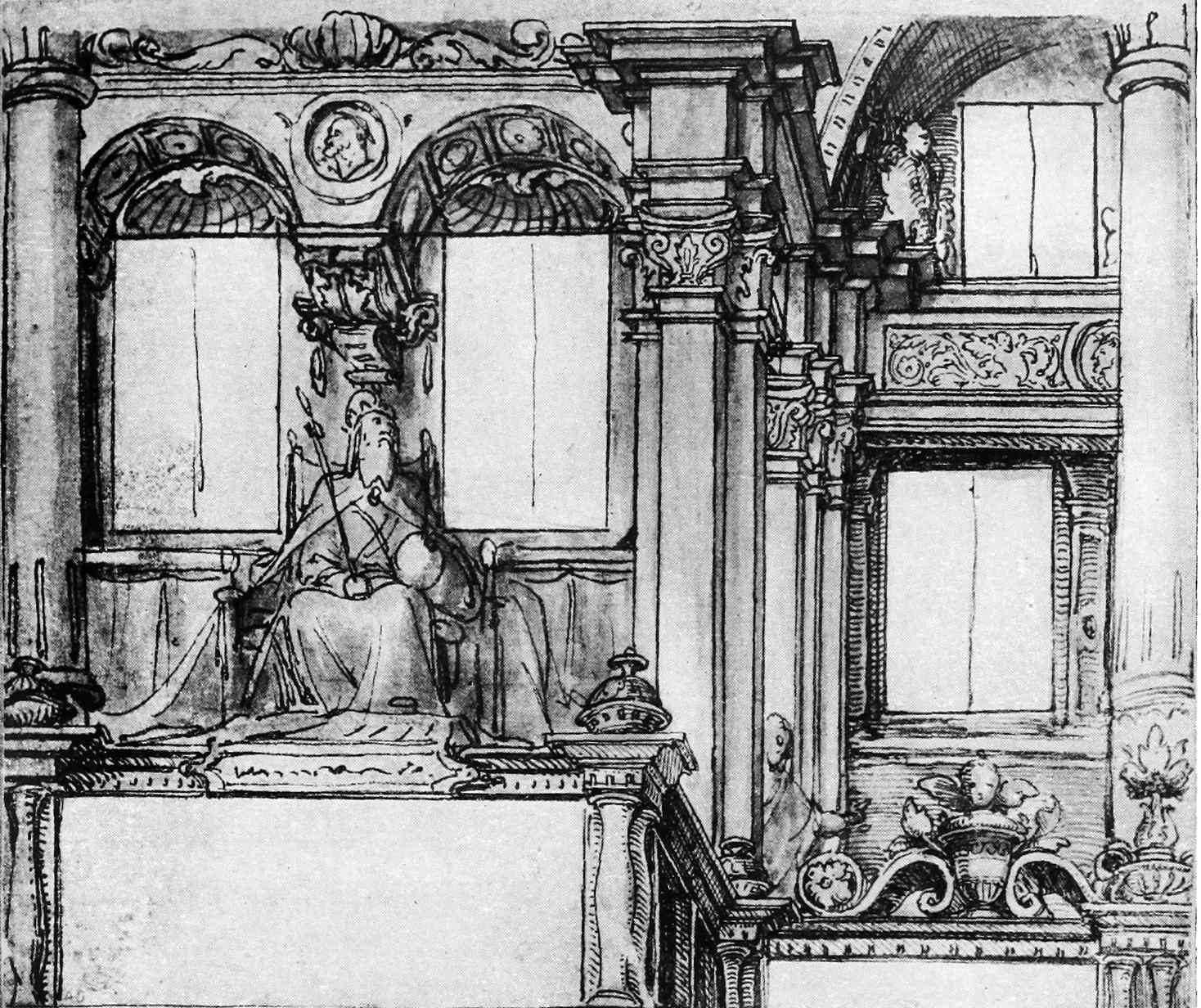

| xv39. | DESIGN FOR THE ORGAN-CASE DOORS, BASEL CATHEDRAL | 113 |

| Pen and wash drawing. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 40. | (1) STUDY FOR A PAINTED HOUSE FRONT WITH THE FIGURE OF A SEATED EMPEROR. (2) THE AMBASSADORS OF THE SAMNITES BEFORE CURIUS DENTATUS | 121 |

| The latter a fragment of the wall-painting in the Basel Town Hall. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 41. | SAPOR AND VALERIAN | 131 |

| Design for one of the wall-paintings in the Basel Town Hall. Pen and water-colour drawing. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 42. | (1) TWO LANDSKNECHTE. (2) THE PRODIGAL SON | 139 |

| Designs for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

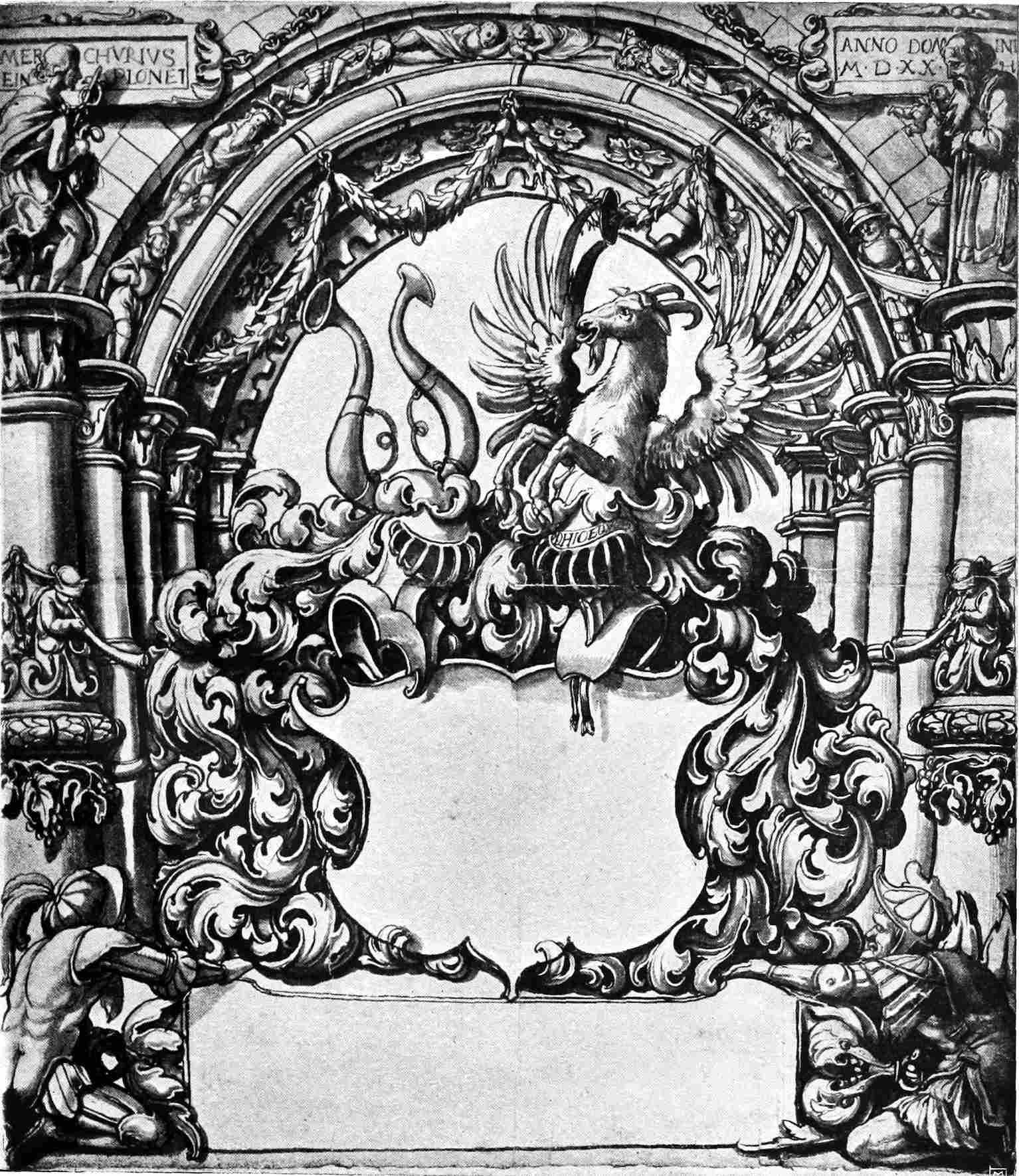

| 43. | DESIGN FOR A PAINTED WINDOW WITH THE COAT OF ARMS OF THE VON HEWEN FAMILY (1520) | 144 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 44. | ST. ELIZABETH, WITH KNEELING KNIGHT AND BEGGAR | 148 |

| Design for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 45. | THE VIRGIN AND CHILD, WITH A KNEELING DONOR | 149 |

| Design for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

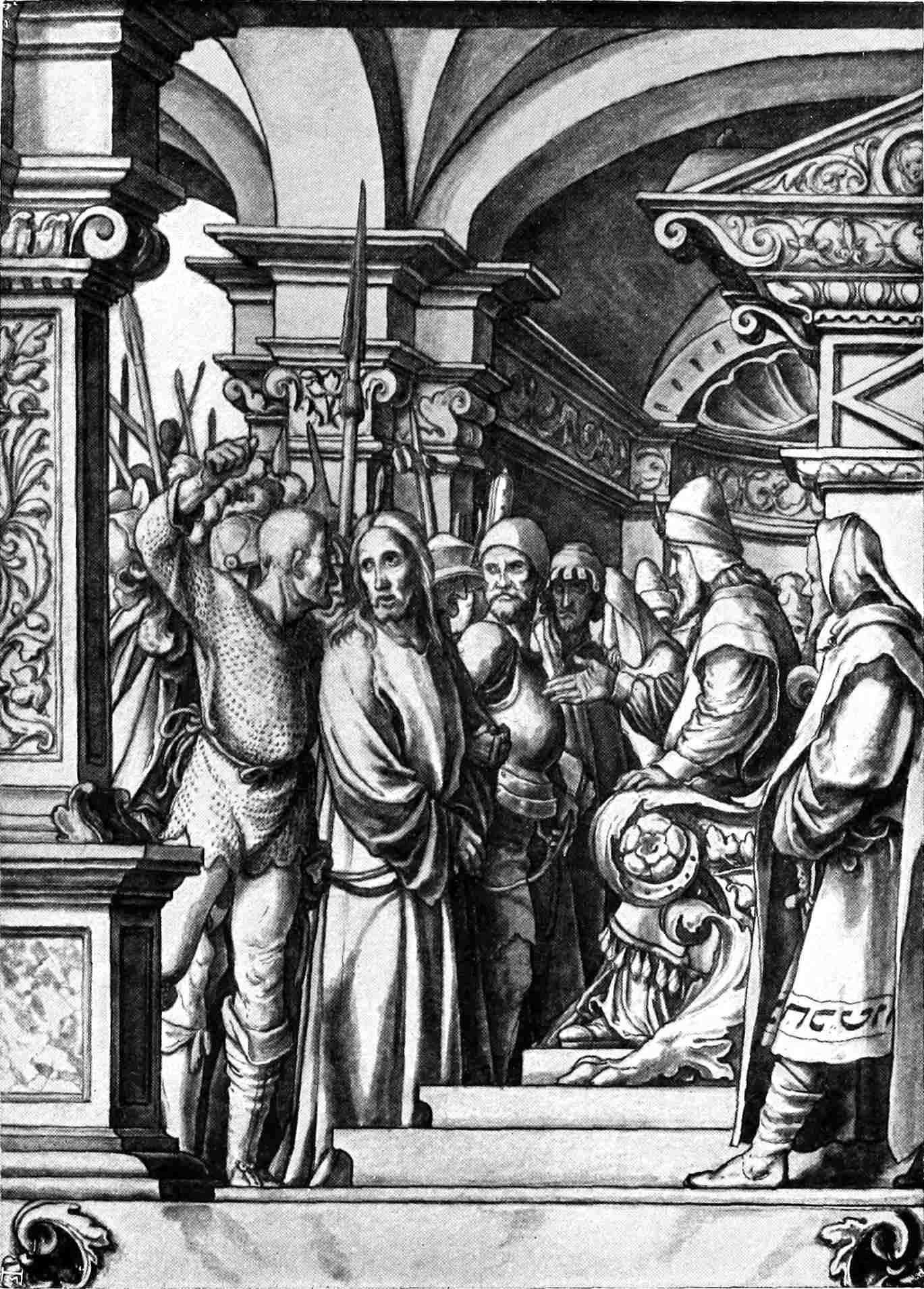

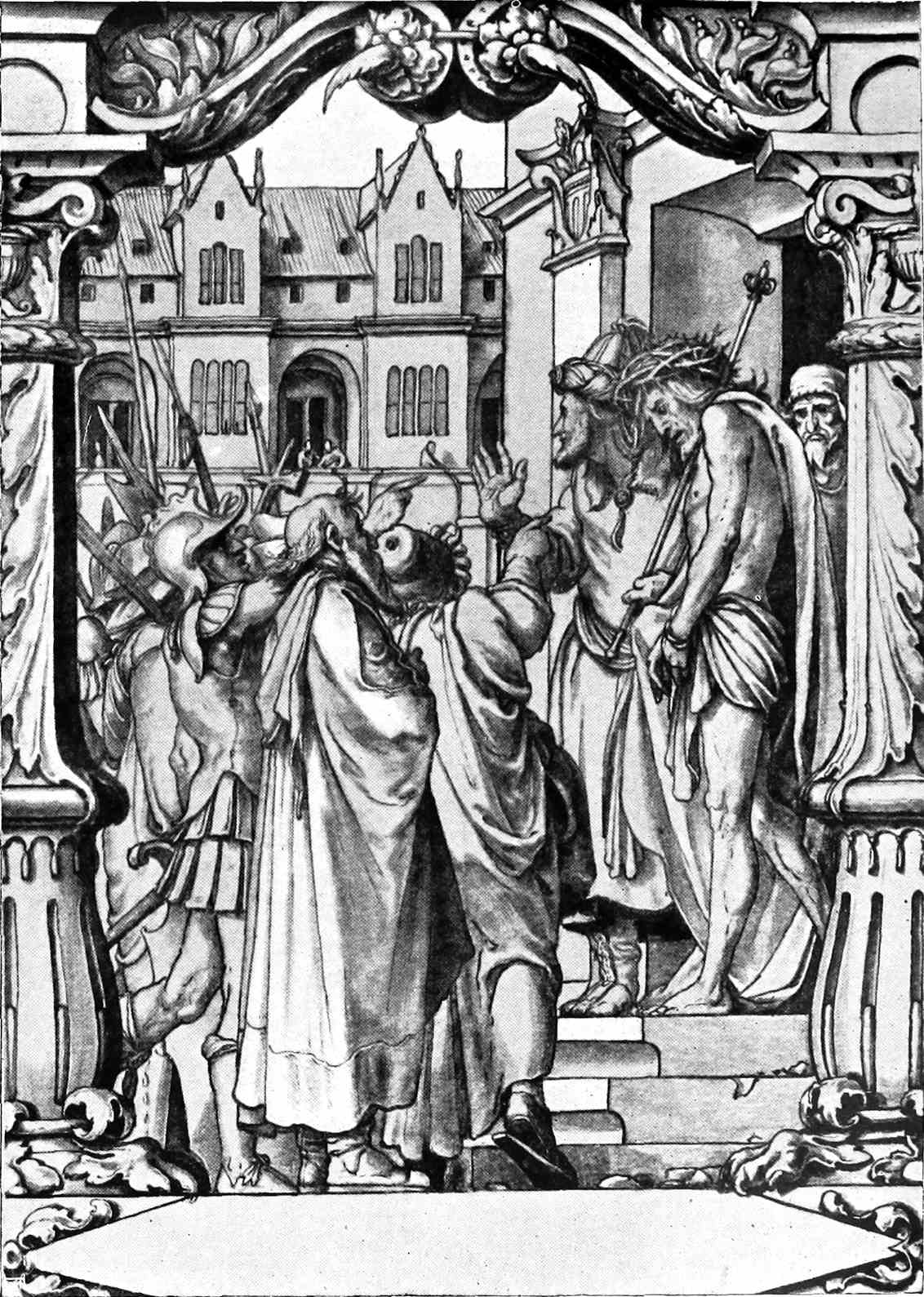

| 46. | (1) CHRIST BEFORE CAIAPHAS. (2) THE SCOURGING OF CHRIST | 151 |

| The “Passion” series of designs for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

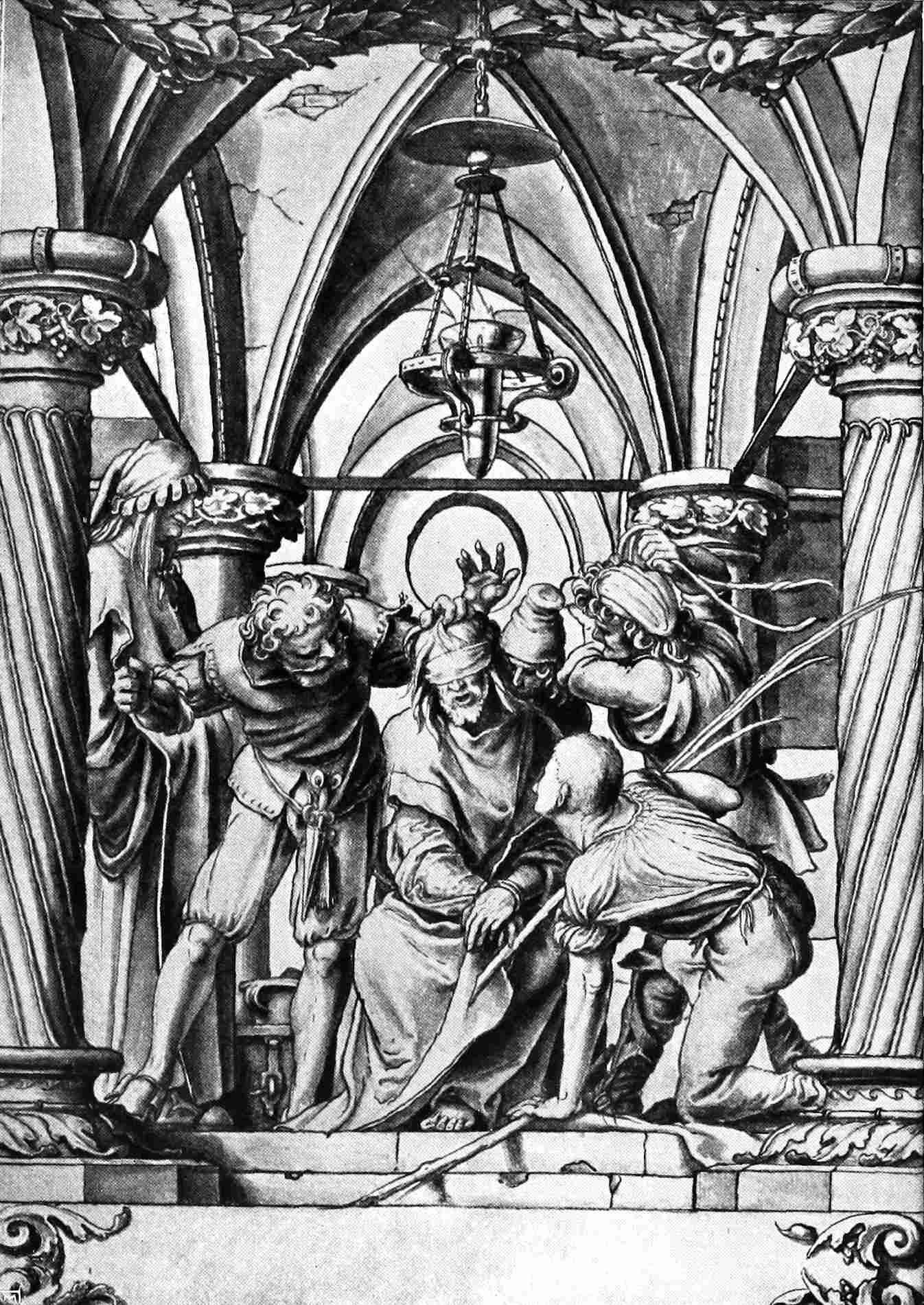

| 47. | (1) THE MOCKING OF CHRIST. (2) CHRIST CROWNED WITH THORNS | 152 |

| The “Passion” series of designs for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

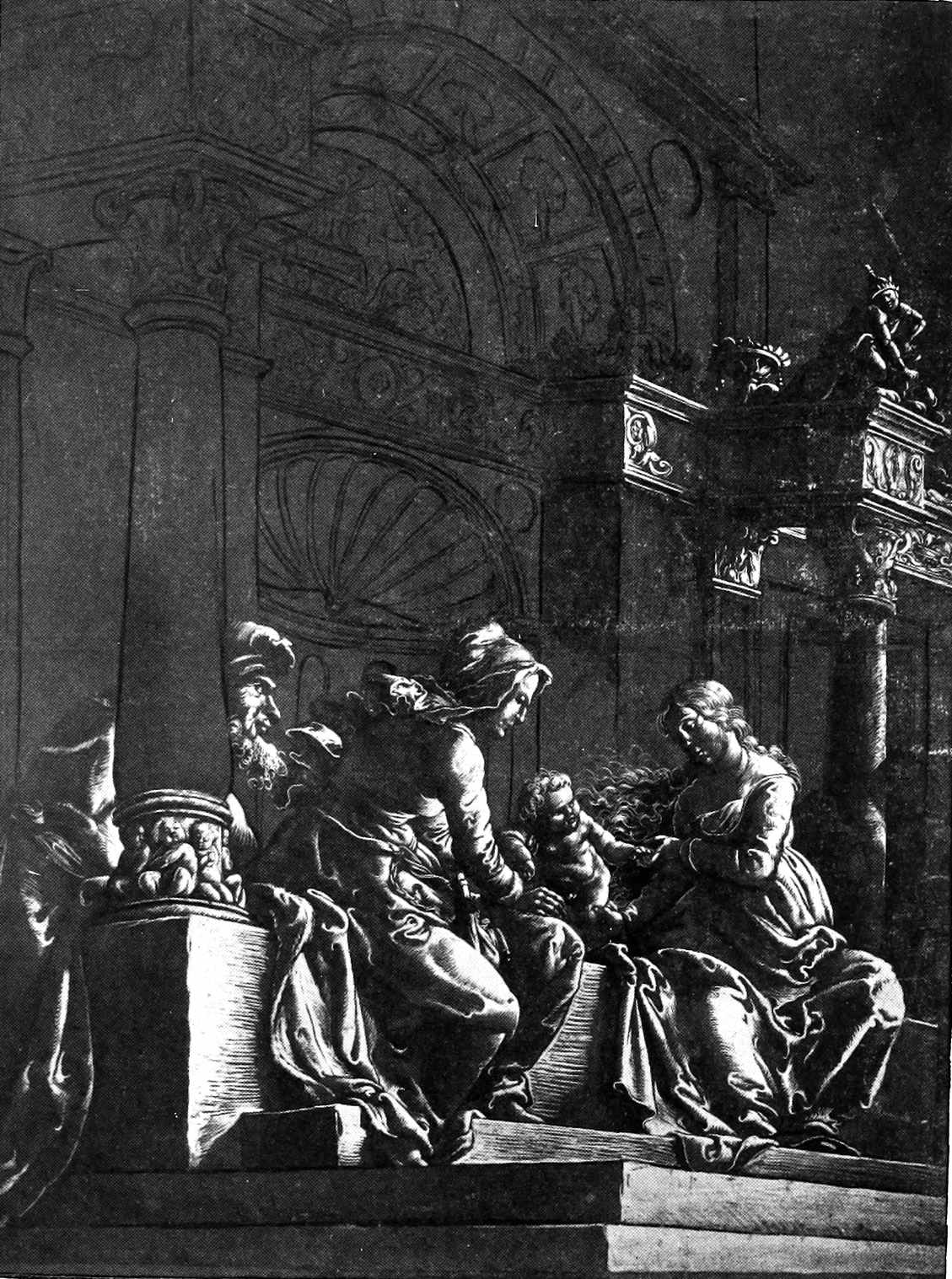

| 48. | (1) PILATE WASHING HIS HANDS. (2) ECCE HOMO | 153 |

| The “Passion” series of designs for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

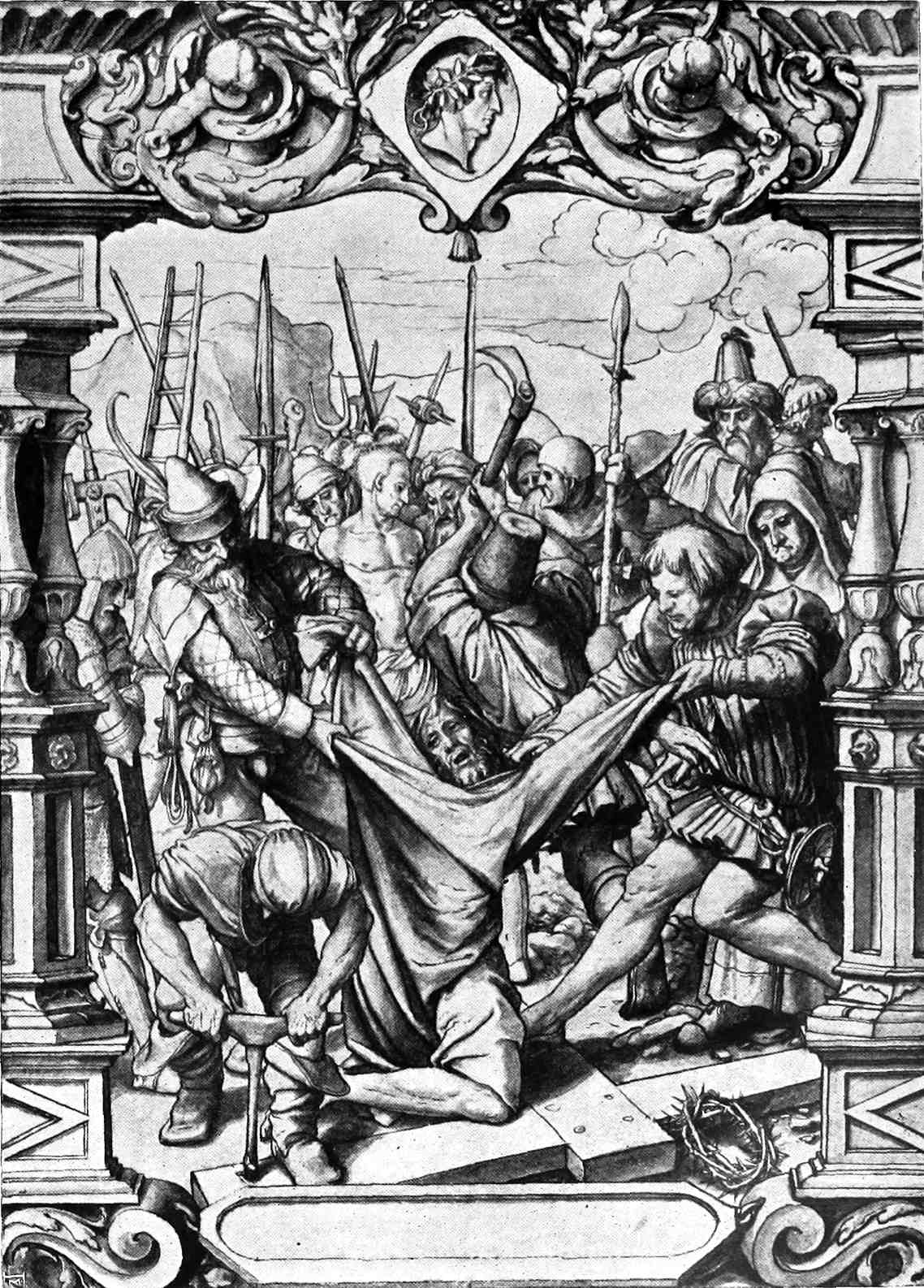

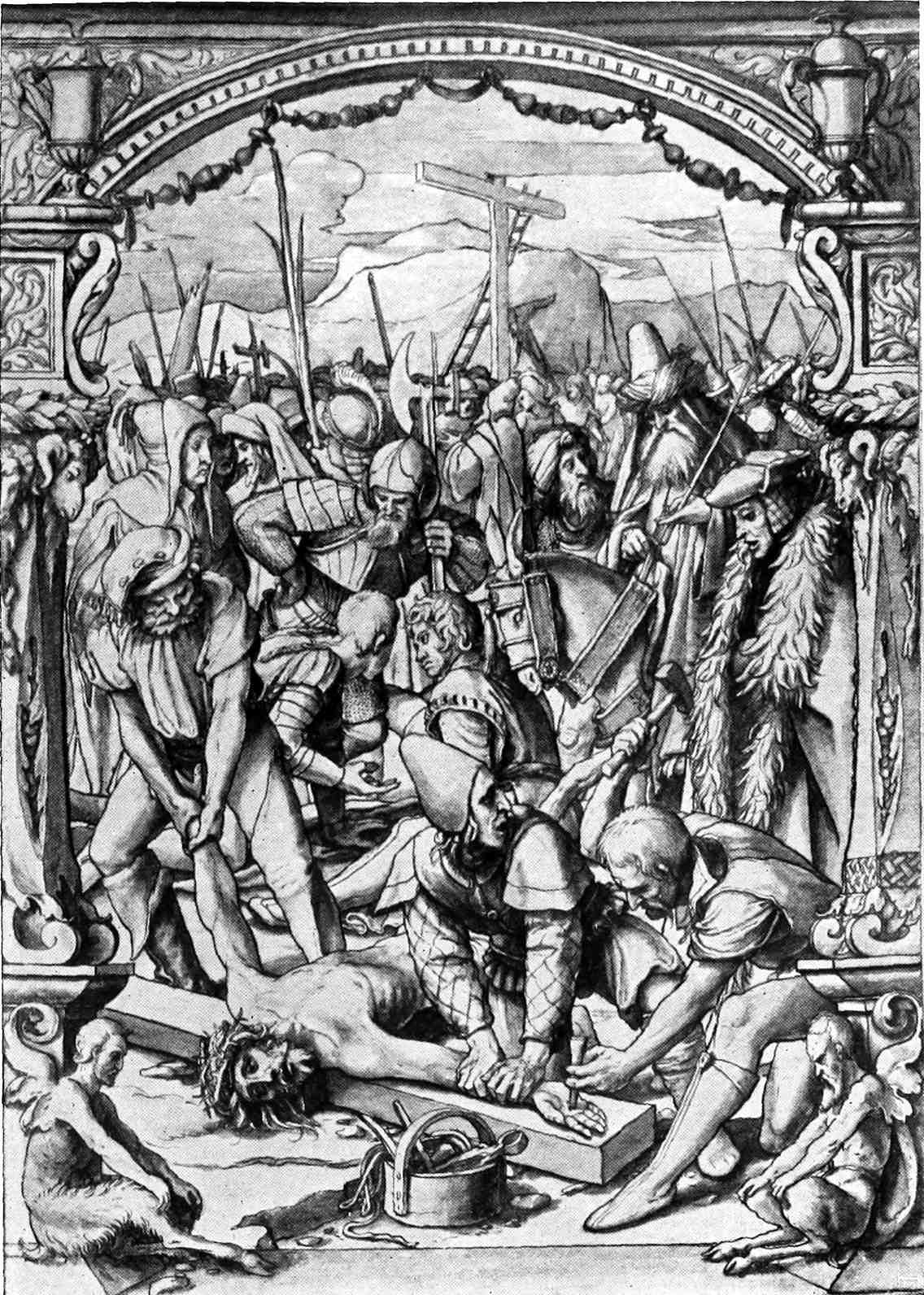

| 49. | (1) CHRIST BEARING THE CROSS. (2) THE STRIPPING OF CHRIST’S GARMENTS | 154 |

| The “Passion” series of designs for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

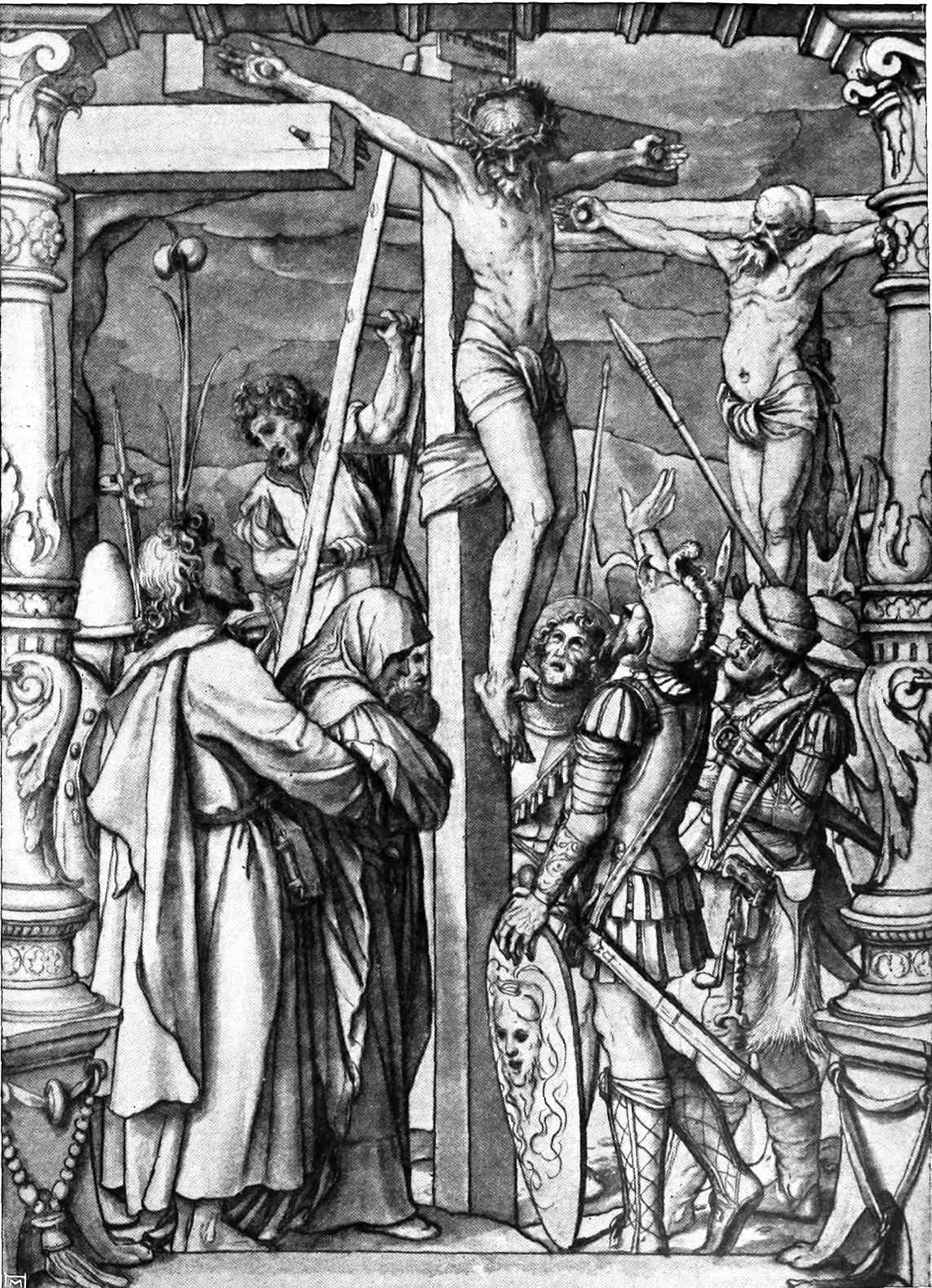

| 50. | (1) CHRIST NAILED TO THE CROSS. (2) THE CRUCIFIXION | 155 |

| The “Passion” series of designs for painted glass. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 51. | (1) COSTUME STUDY. (2) COSTUME STUDY | 157 |

| Two drawings from a set of designs of ladies’ costumes. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| xvi52. | “THE EDELDAME” | 157 |

| Drawing from a set of designs of ladies’ costumes. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

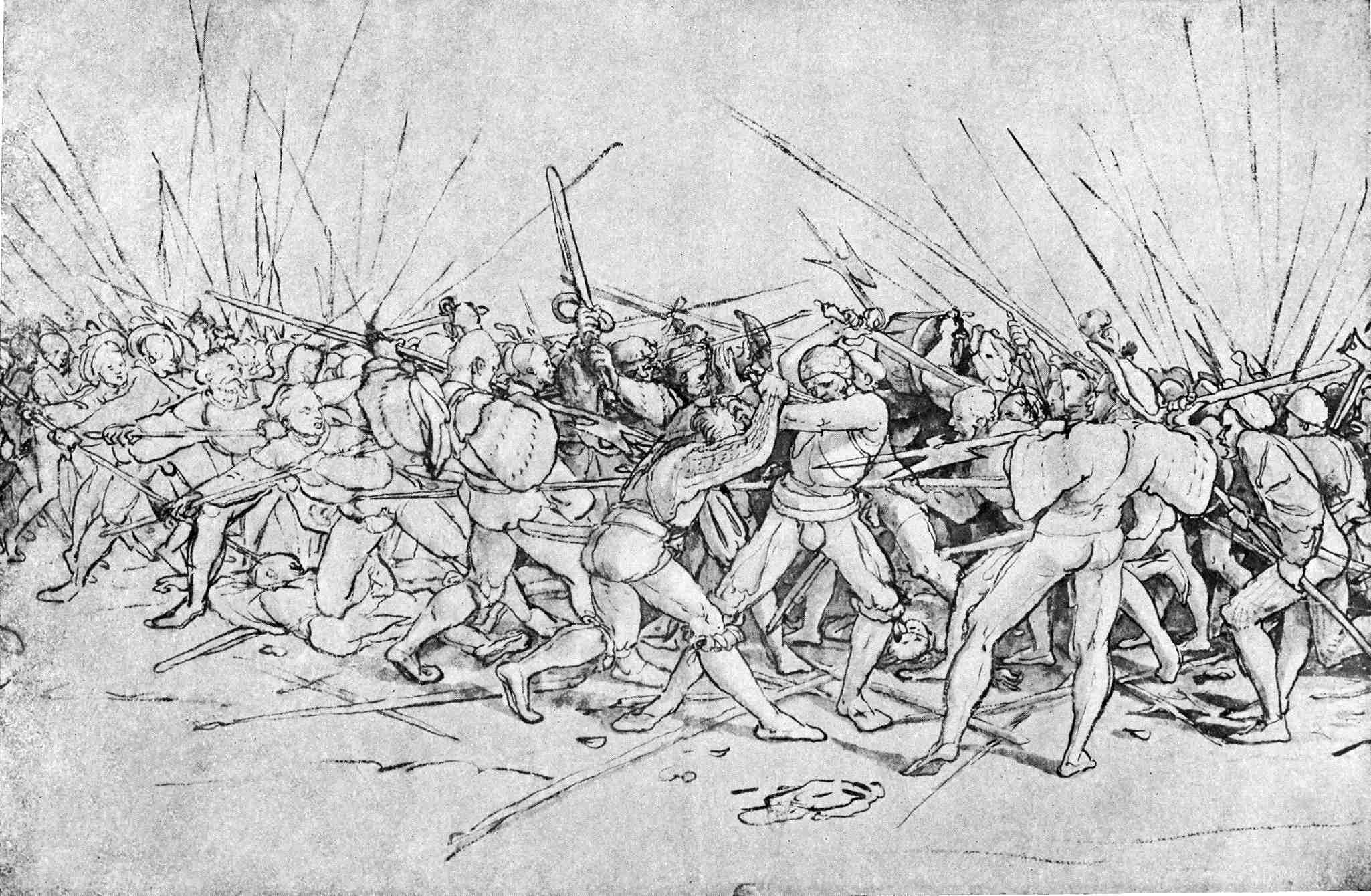

| 53. | A FIGHT BETWEEN LANDSKNECHTE | 160 |

| Drawing in Indian ink. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

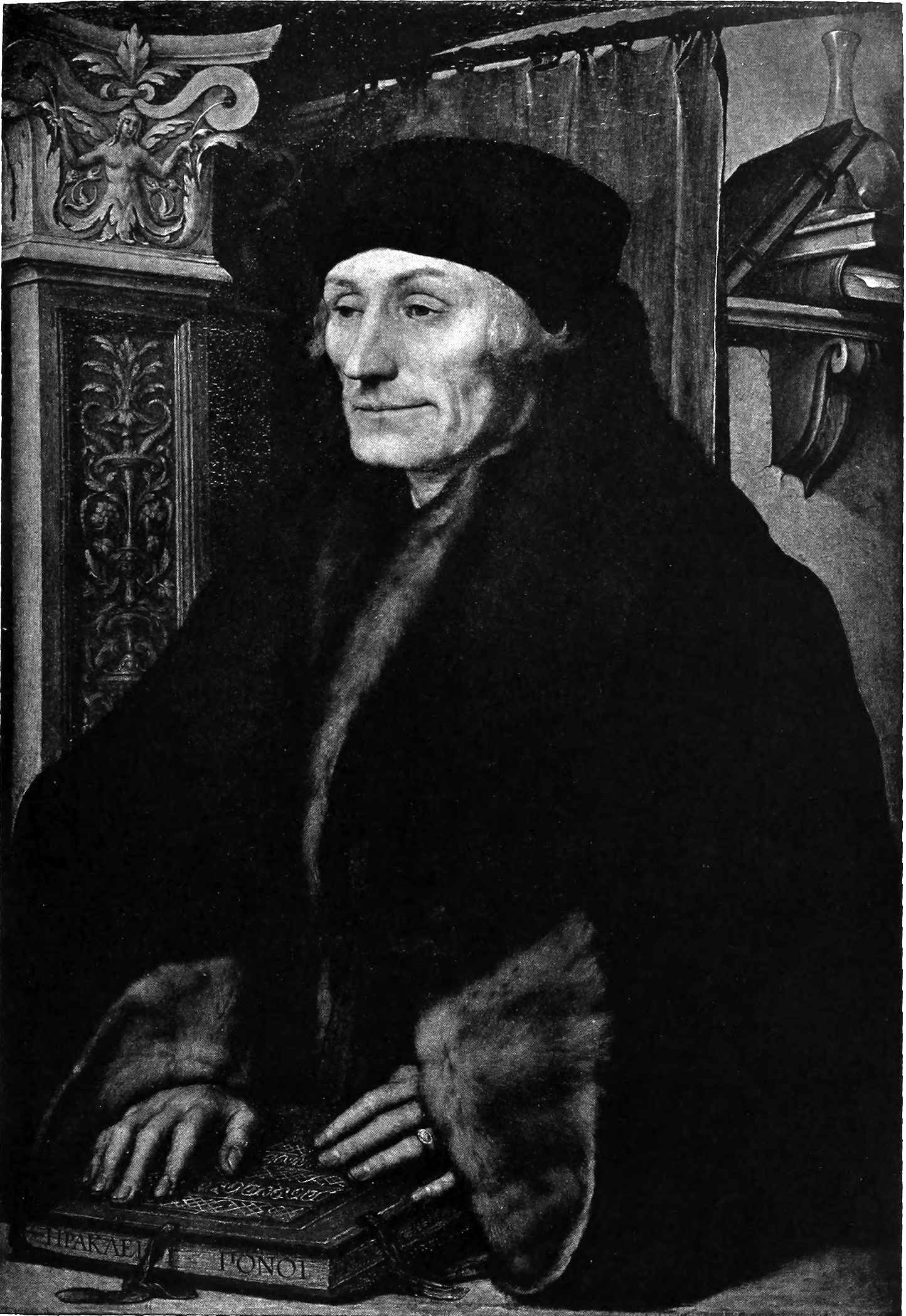

| 54. | ERASMUS (1523) | 169 |

| Reproduced by kind permission of the Earl of Radnor. | ||

| Longford Castle, Salisbury. | ||

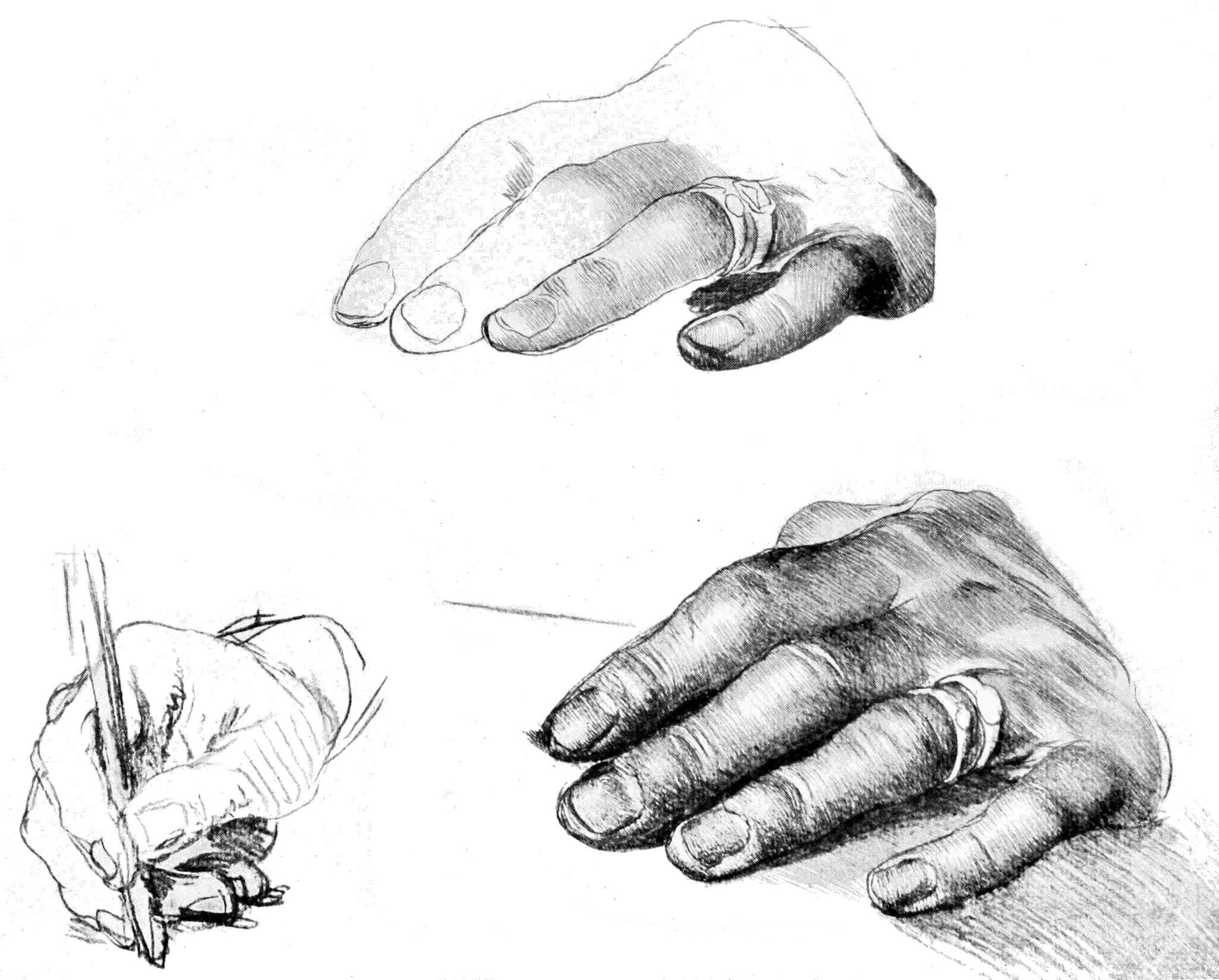

| 55. | STUDY FOR THE HANDS OF ERASMUS | 171 |

| Drawing in silver-point and red and black chalk. | ||

| Louvre, Paris. | ||

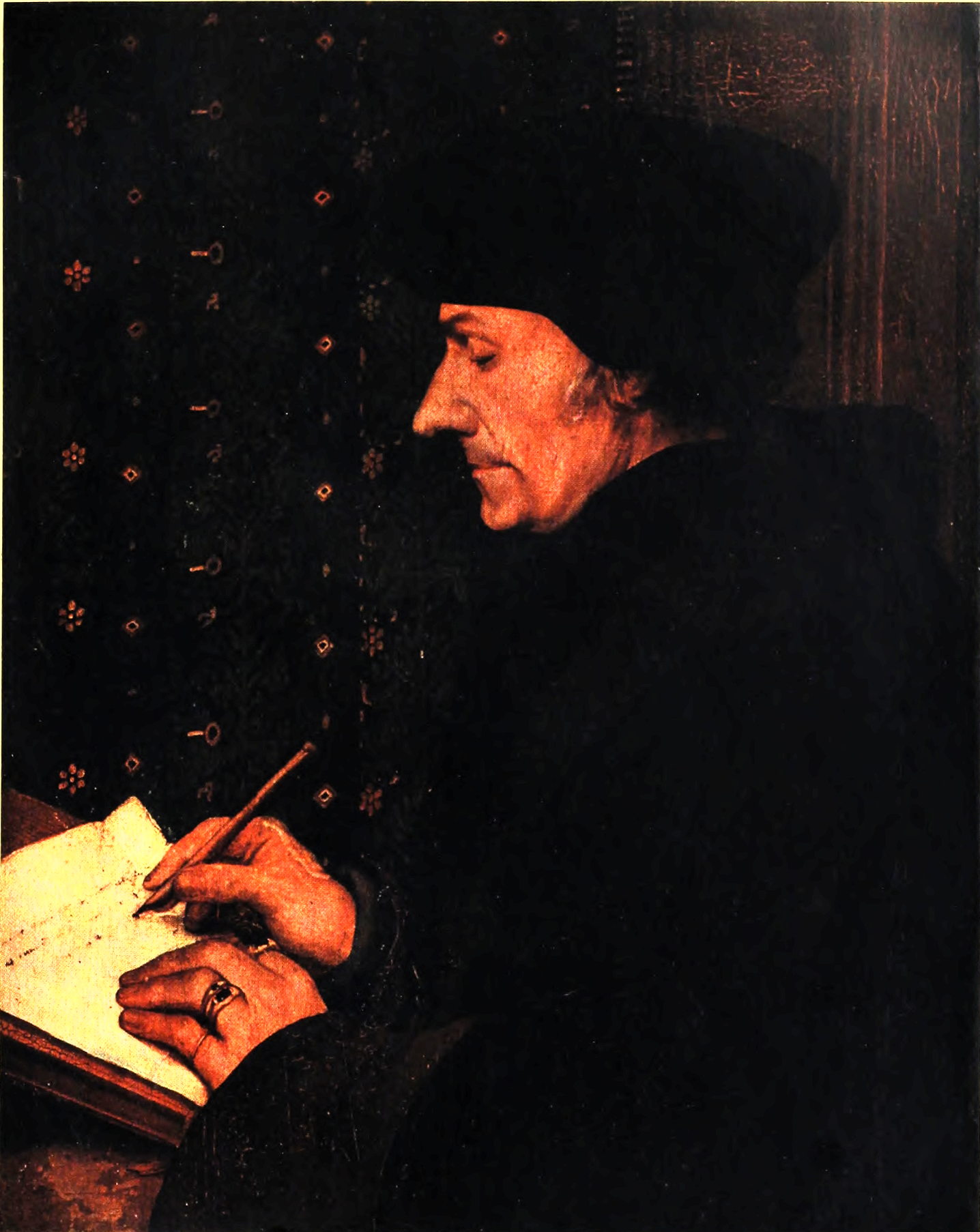

| 56. | ERASMUS (1523) | 172 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Louvre, Paris. | ||

| 57. | THE DUCHESS OF BERRY | 176 |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 58. | (1) ERASMUS | 180 |

| Roundel. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| (2) PHILIP MELANCHTHON | 180 | |

| Roundel. | ||

| Provinzial Museum, Hanover. | ||

| 59. | ERASMUS | 181 |

| From a woodcut in the British Museum. | ||

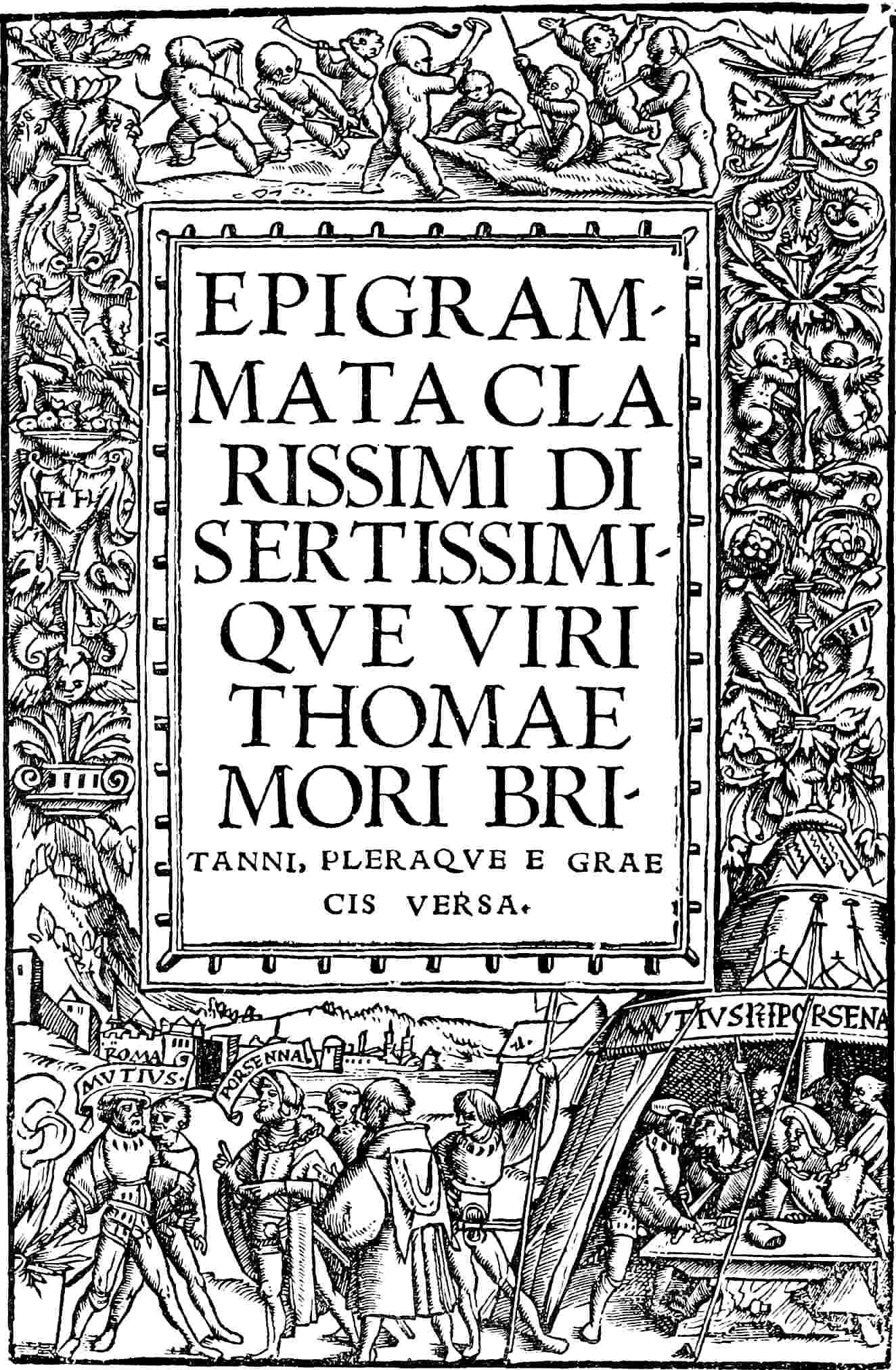

| 60. | MUCIUS SCÆVOLA AND LARS PORSENA | 191 |

| Woodcut first used in 1516. | ||

| From a copy of More’s “Epigrams” in the British Museum. | ||

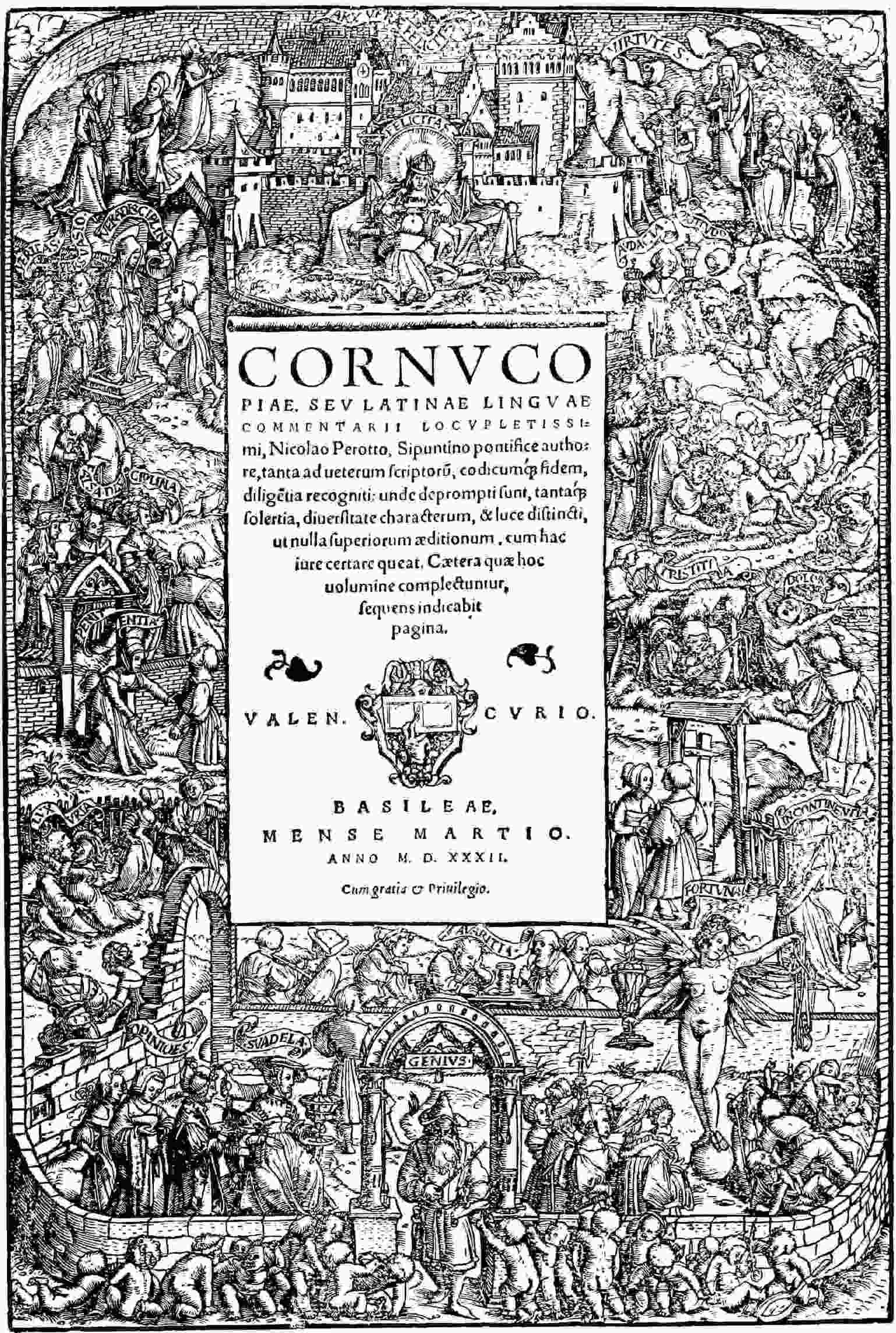

| 61. | “THE TABLE OF CEBES” | 193 |

| Woodcut first used in 1521. | ||

| From a copy of Perotto’s “Cornucopiæ” in the British Museum. | ||

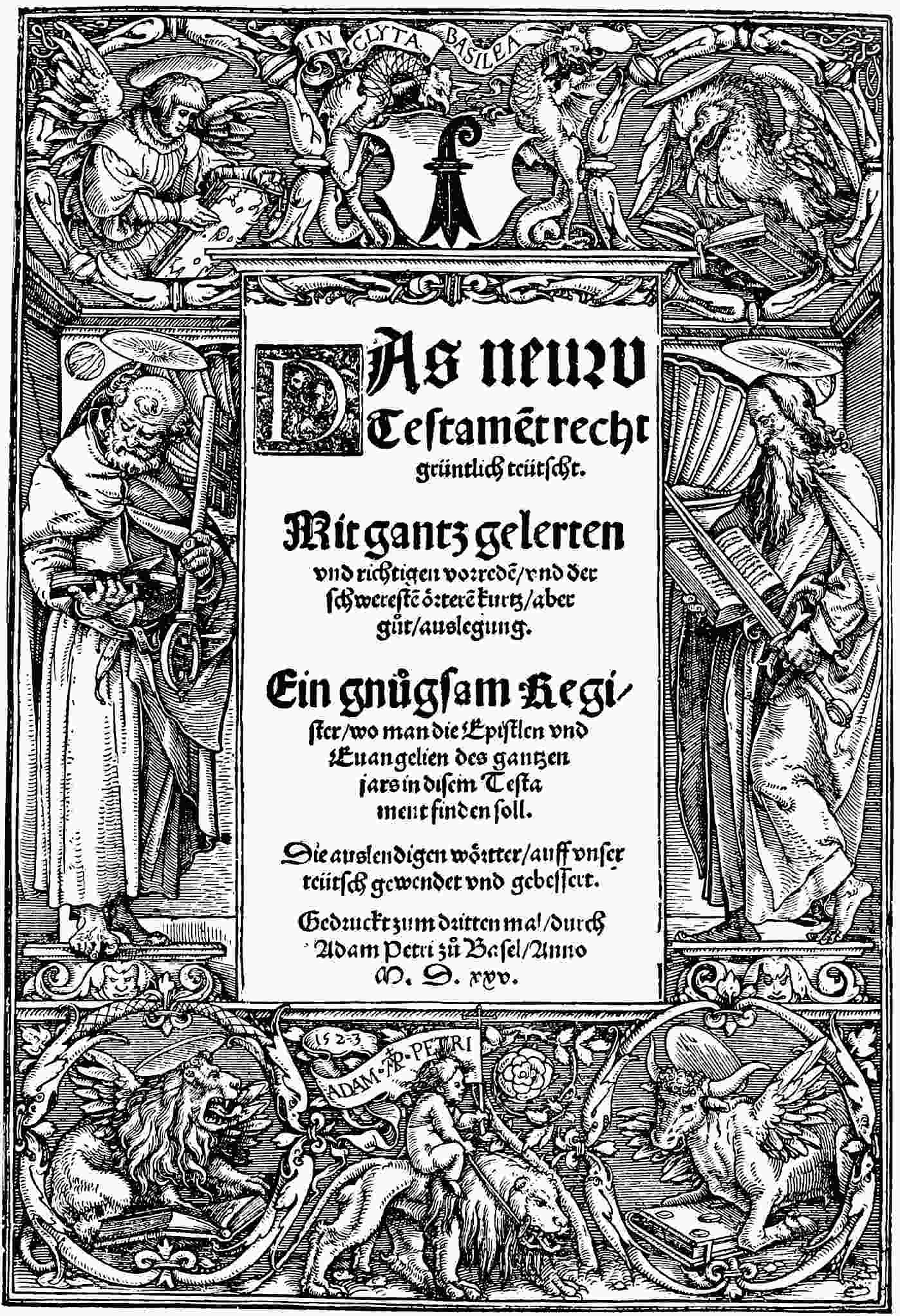

| 62. | TITLE-PAGE TO LUTHER’S “NEW TESTAMENT” | 195 |

| Woodcut first used in 1522. | ||

| From a copy in the British Museum. | ||

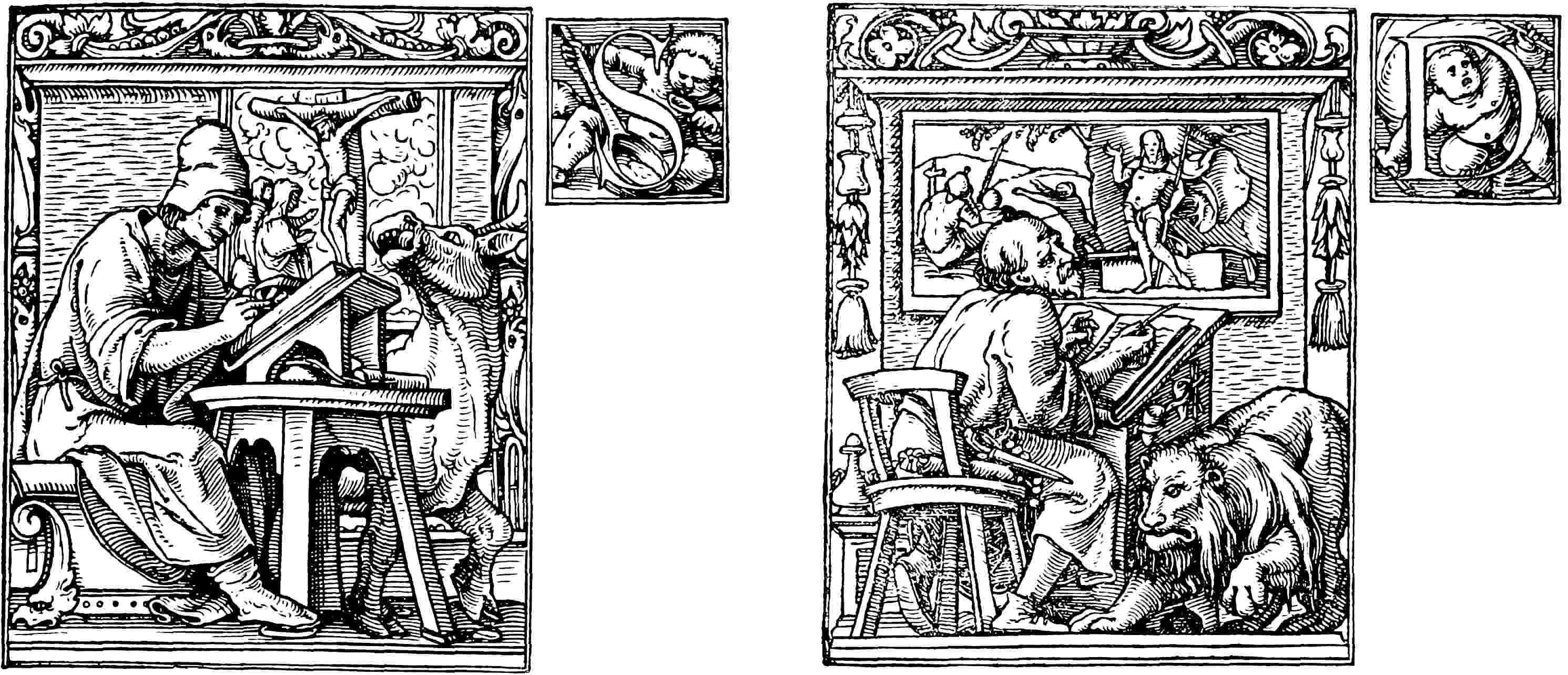

| 63. | THE FOUR EVANGELISTS | 195 |

| Woodcuts and Initial Letters used on the first page of each gospel in the 1523 edition of Luther’s “New Testament.” | ||

| From a copy in the British Museum. | ||

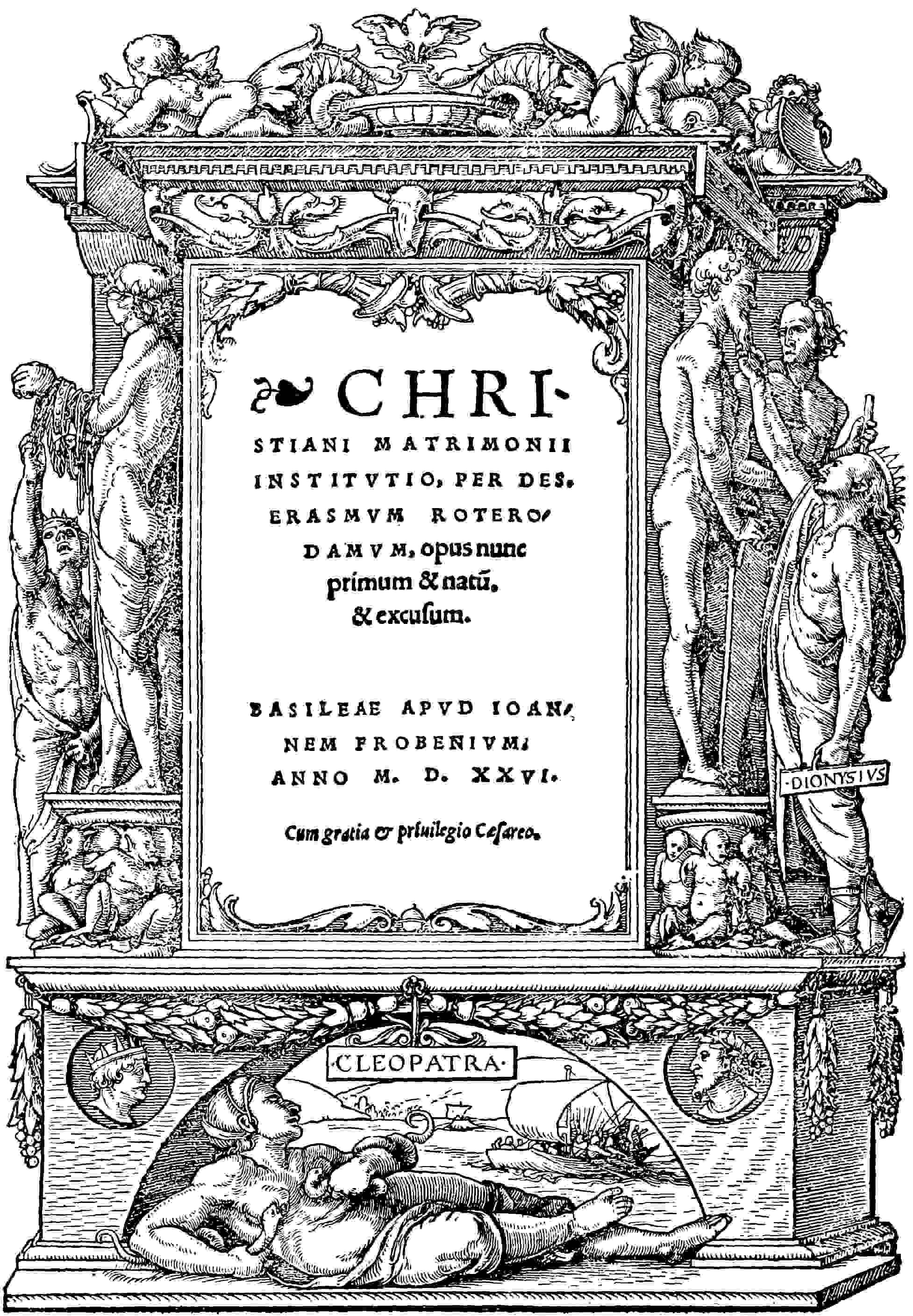

| 64. | THE “CLEOPATRA” TITLE-PAGE | 198 |

| Woodcut first used in 1523. | ||

| From a copy of Erasmus’ “Christiani Matrimonii Institutio” in the British Museum. | ||

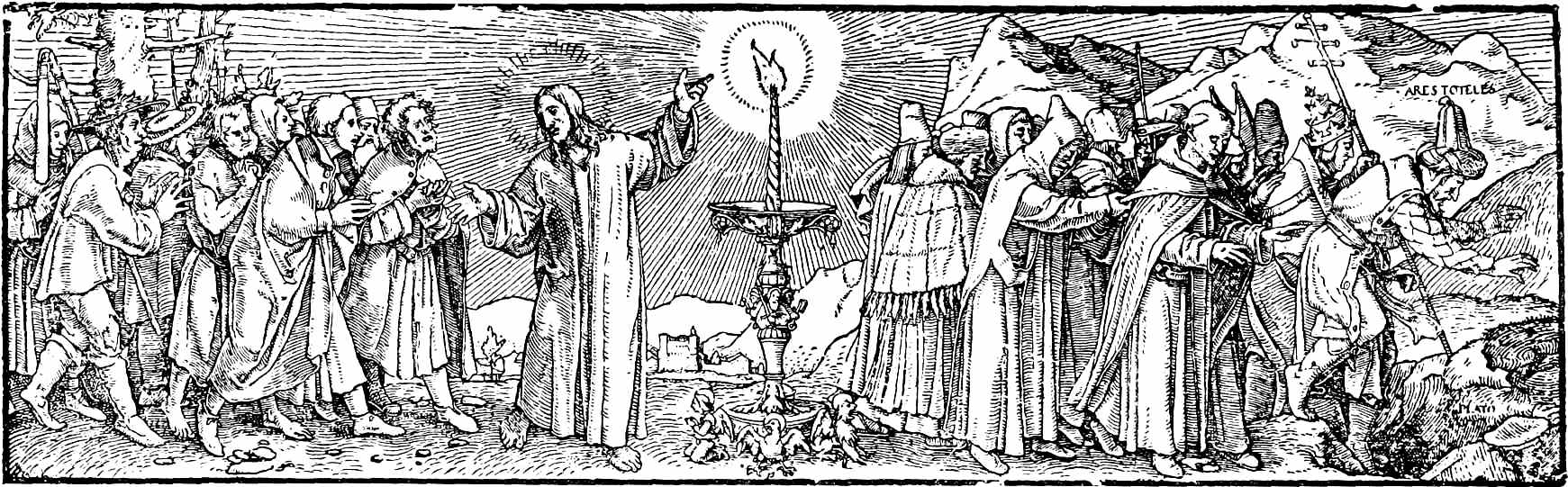

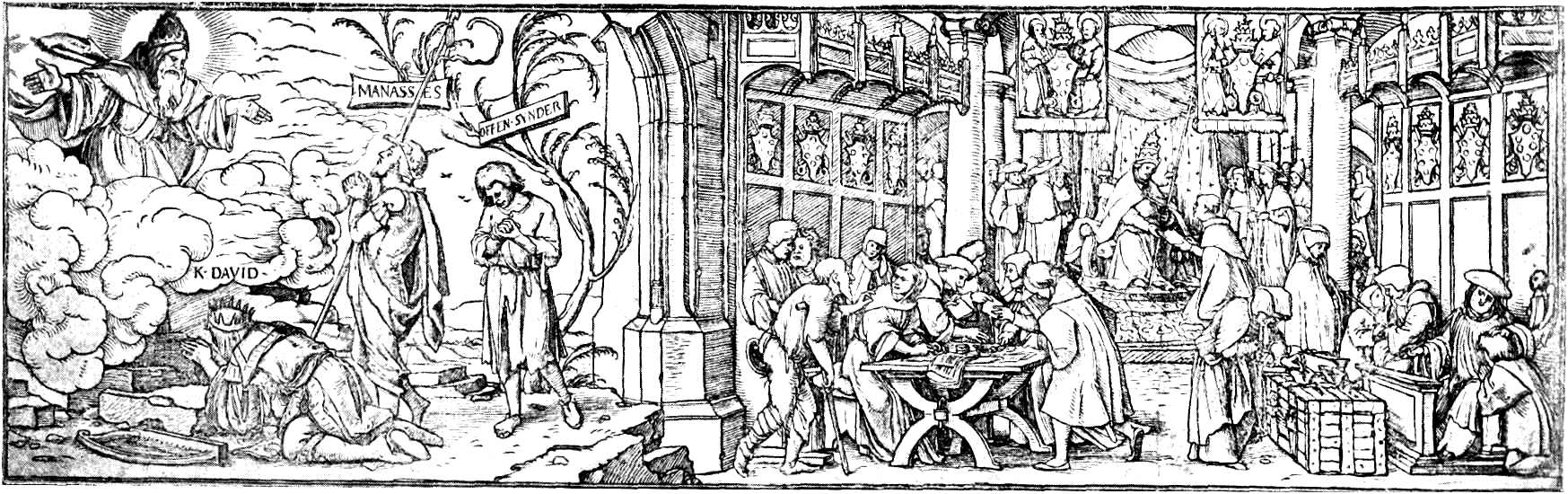

| xvii65. | (1) CHRIST THE TRUE LIGHT. (2) THE SALE OF INDULGENCES | 198 |

| Woodcuts. | ||

| From proofs in the British Museum. | ||

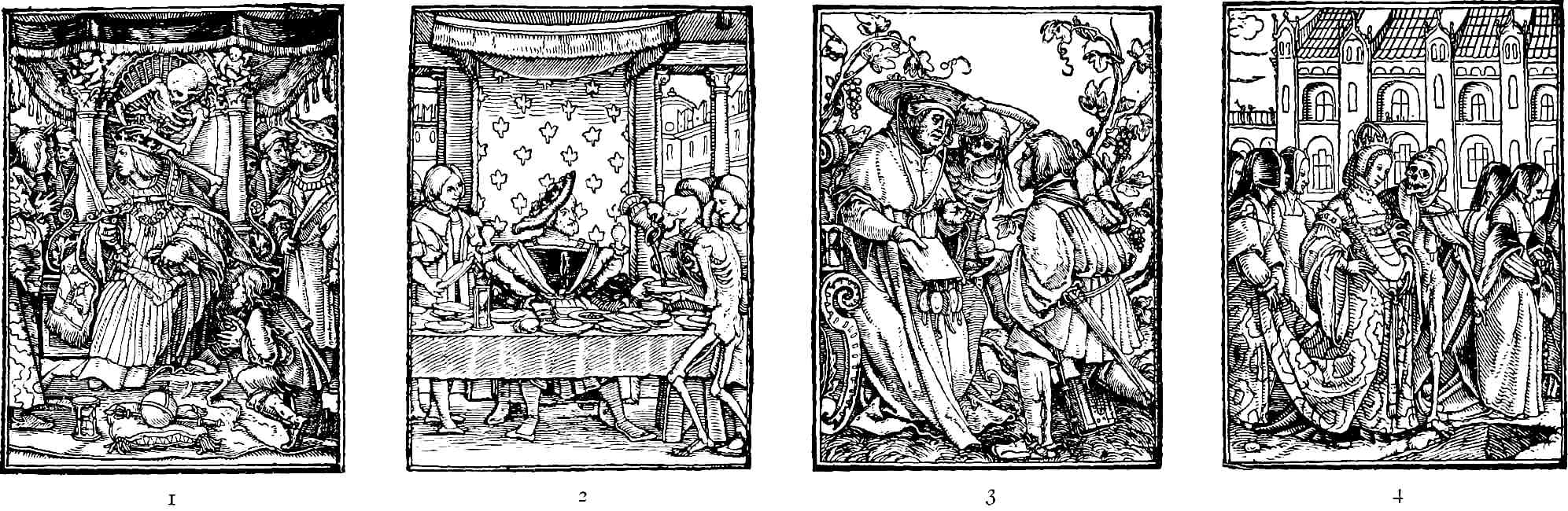

| 66. | THE DANCE OF DEATH WOODCUTS | 217 |

| (1) The Emperor. | ||

| (2) The King. | ||

| (3) The Cardinal. | ||

| (4) The Empress. | ||

| (5) The Advocate. | ||

| (6) The Counsellor. | ||

| (7) The Preacher. | ||

| (8) The Priest. | ||

| From proofs in the British Museum. | ||

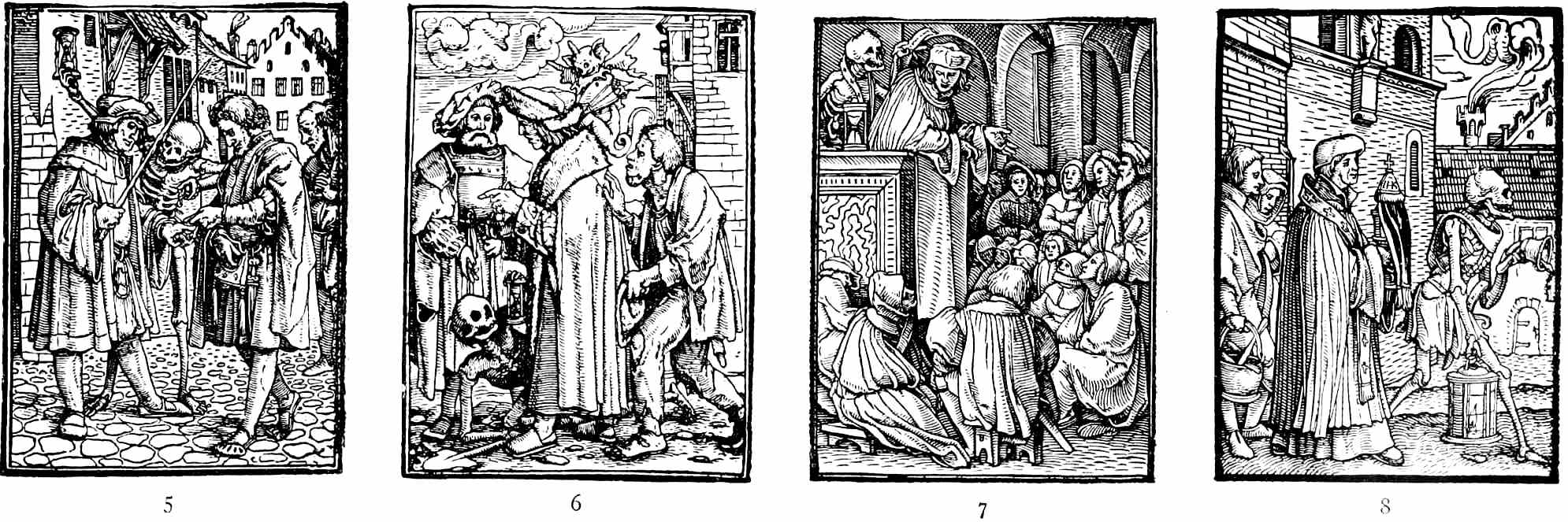

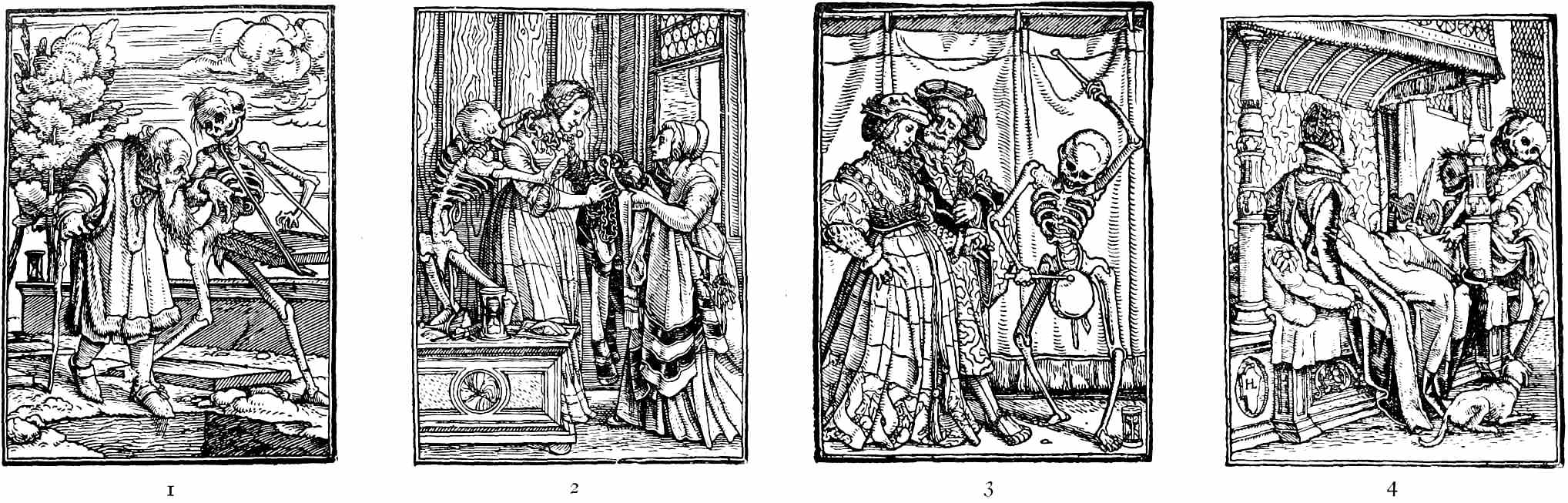

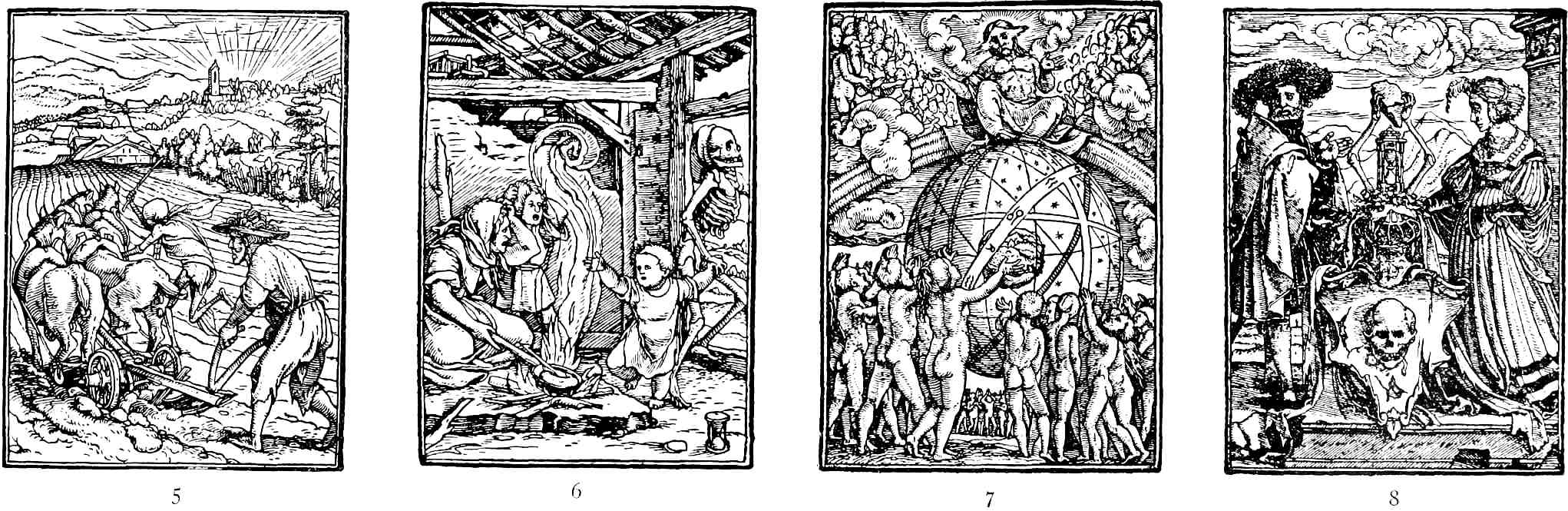

| 67. | THE DANCE OF DEATH WOODCUTS | 220 |

| (1) The Old Man. | ||

| (2) The Countess. | ||

| (3) The Noble Lady. | ||

| (4) The Duchess. | ||

| (5) The Ploughman. | ||

| (6) The Young Child. | ||

| (7) The Last Judgment. | ||

| (8) The Arms of Death. | ||

| From proofs in the British Museum. | ||

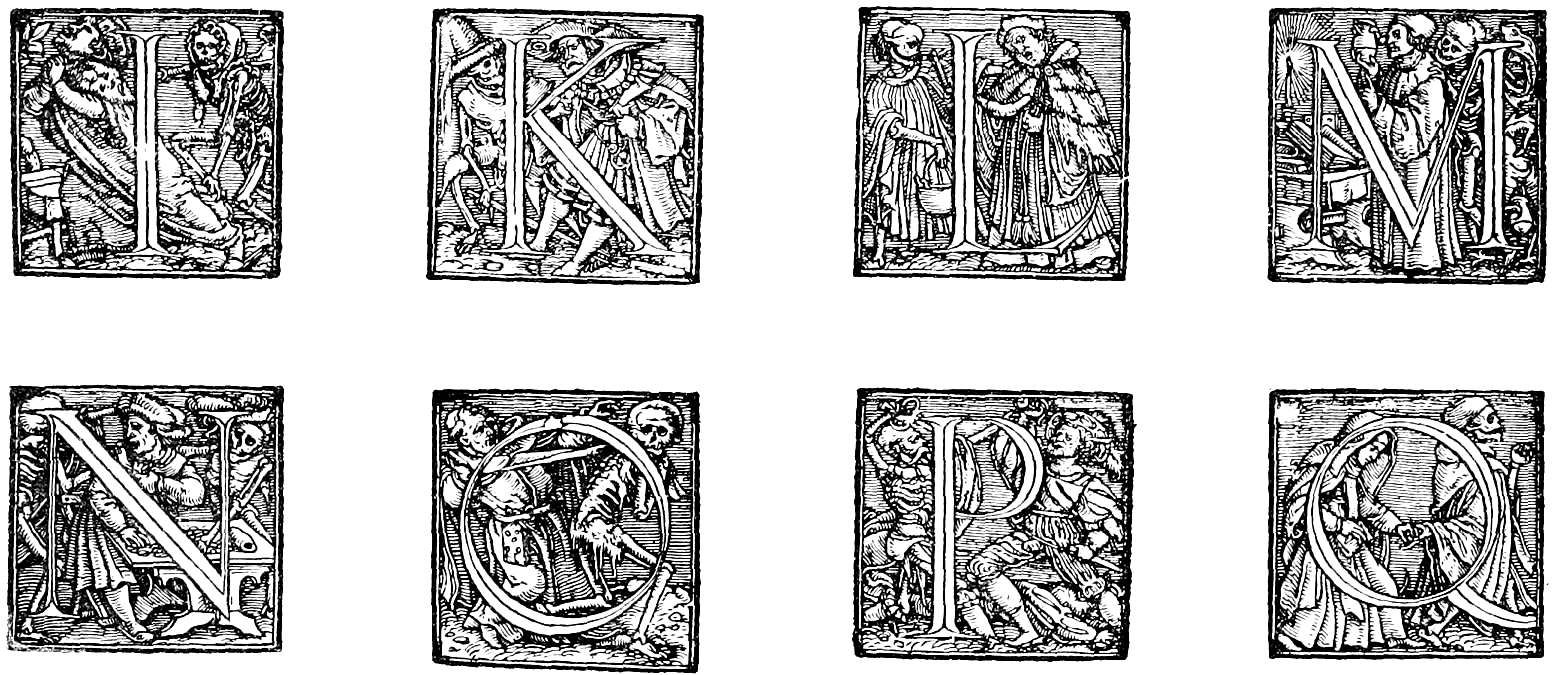

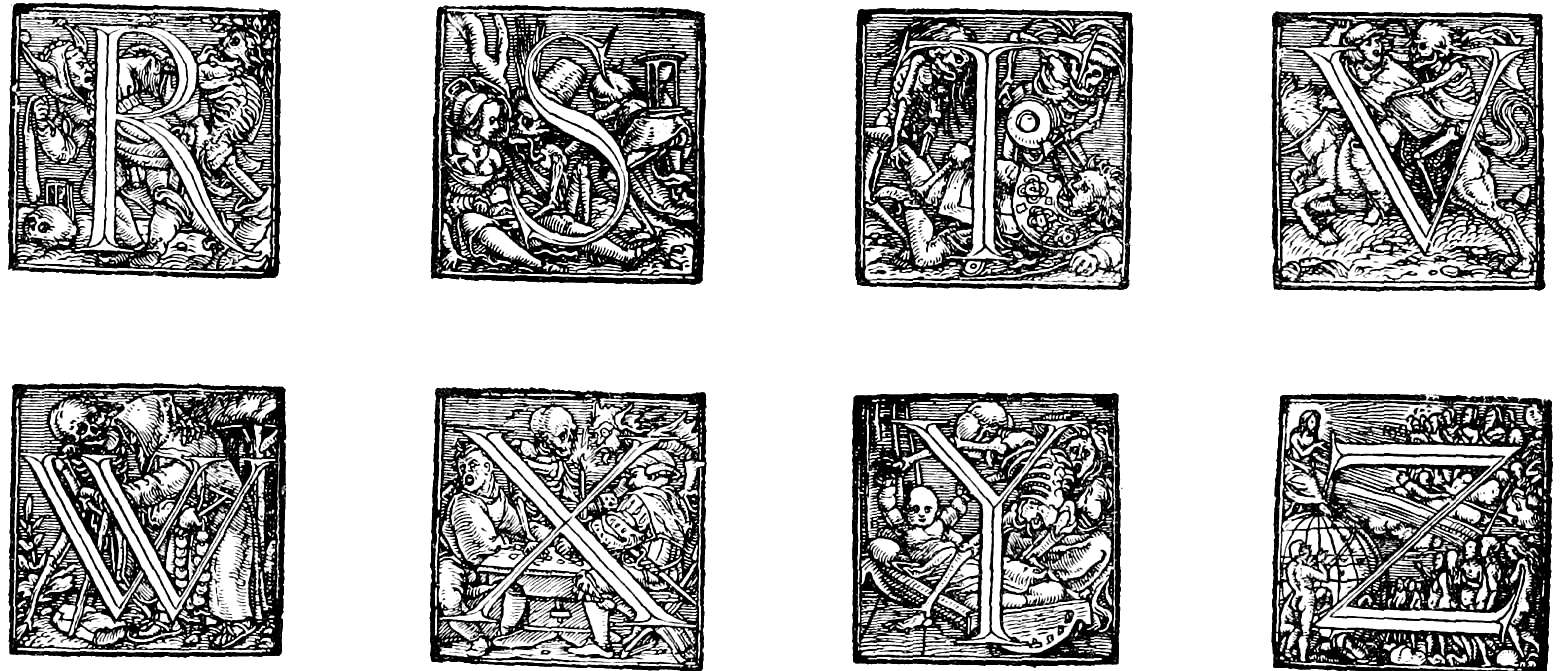

| 68. | THE DANCE OF DEATH ALPHABET | 224 |

| From a proof in the Royal Print Cabinet, Dresden. | ||

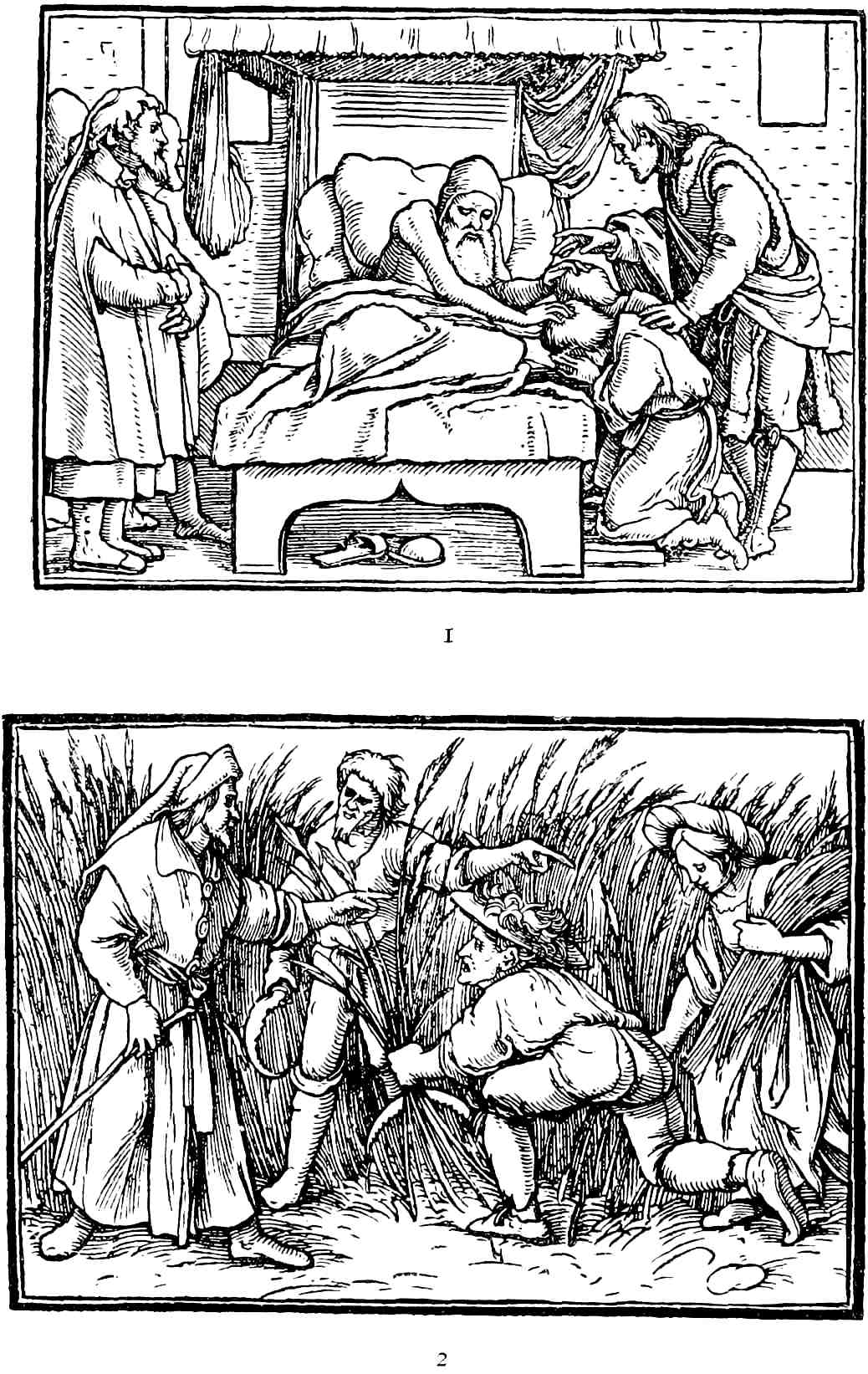

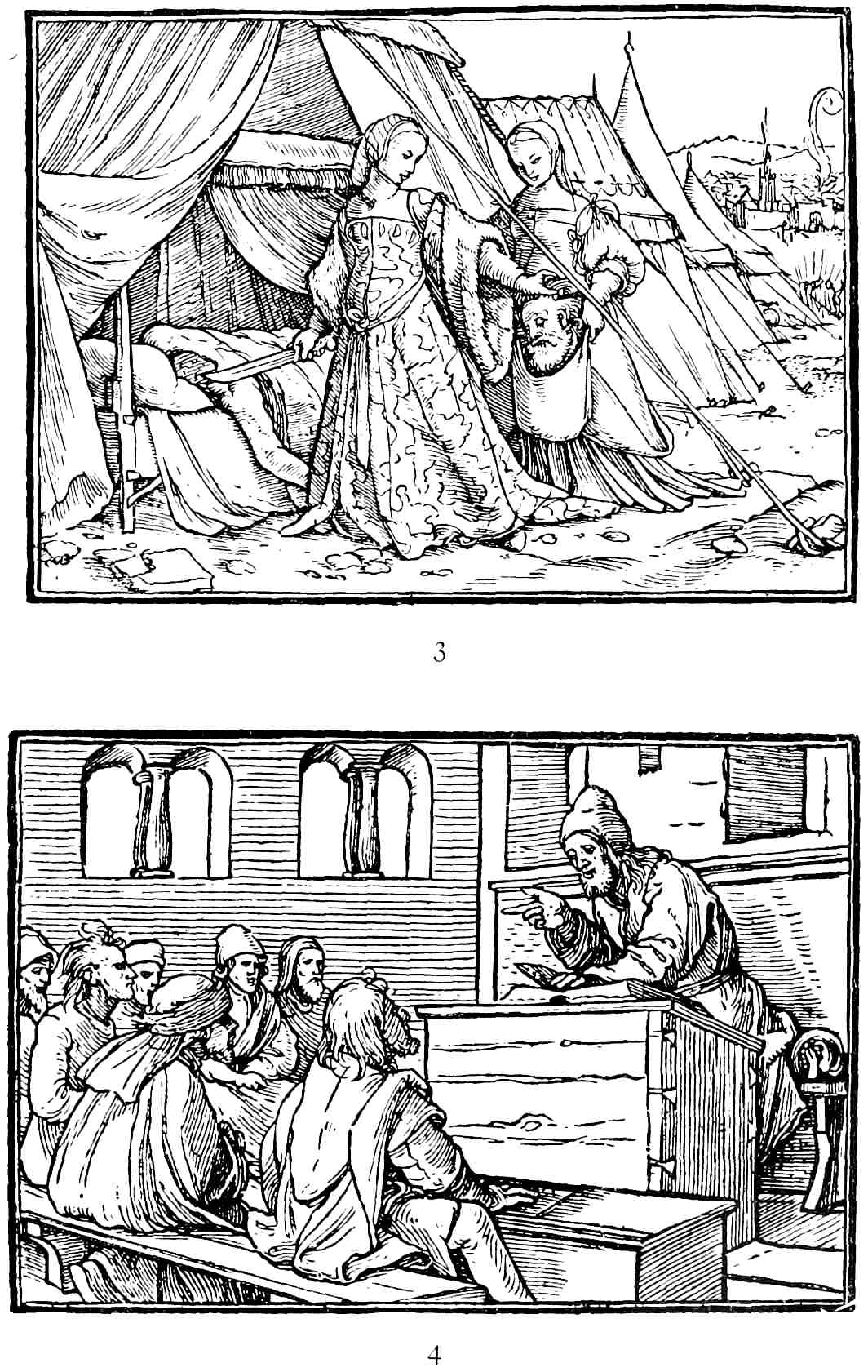

| 69. | THE OLD TESTAMENT WOODCUTS | 230 |

| (1) Jacob Blessing Ephraim and Manasseh. | ||

| (2) Ruth and Boaz. | ||

| (3) Judith with the Head of Holofernes. | ||

| (4) Amos Preaching. | ||

| From proofs in the British Museum. | ||

| 70. | THE OLD TESTAMENT WOODCUTS | 230 |

| (1) Moses receiving the Tables of the Law. | ||

| (2) The Return from the Babylonian Captivity. | ||

| From proofs in the British Museum. | ||

| (3) The Angel showing St. John the New Jerusalem (Revelation xxi.). Woodcut from Adam Petri’s “New Testament,” 1523. | ||

| From a copy in the British Museum. | ||

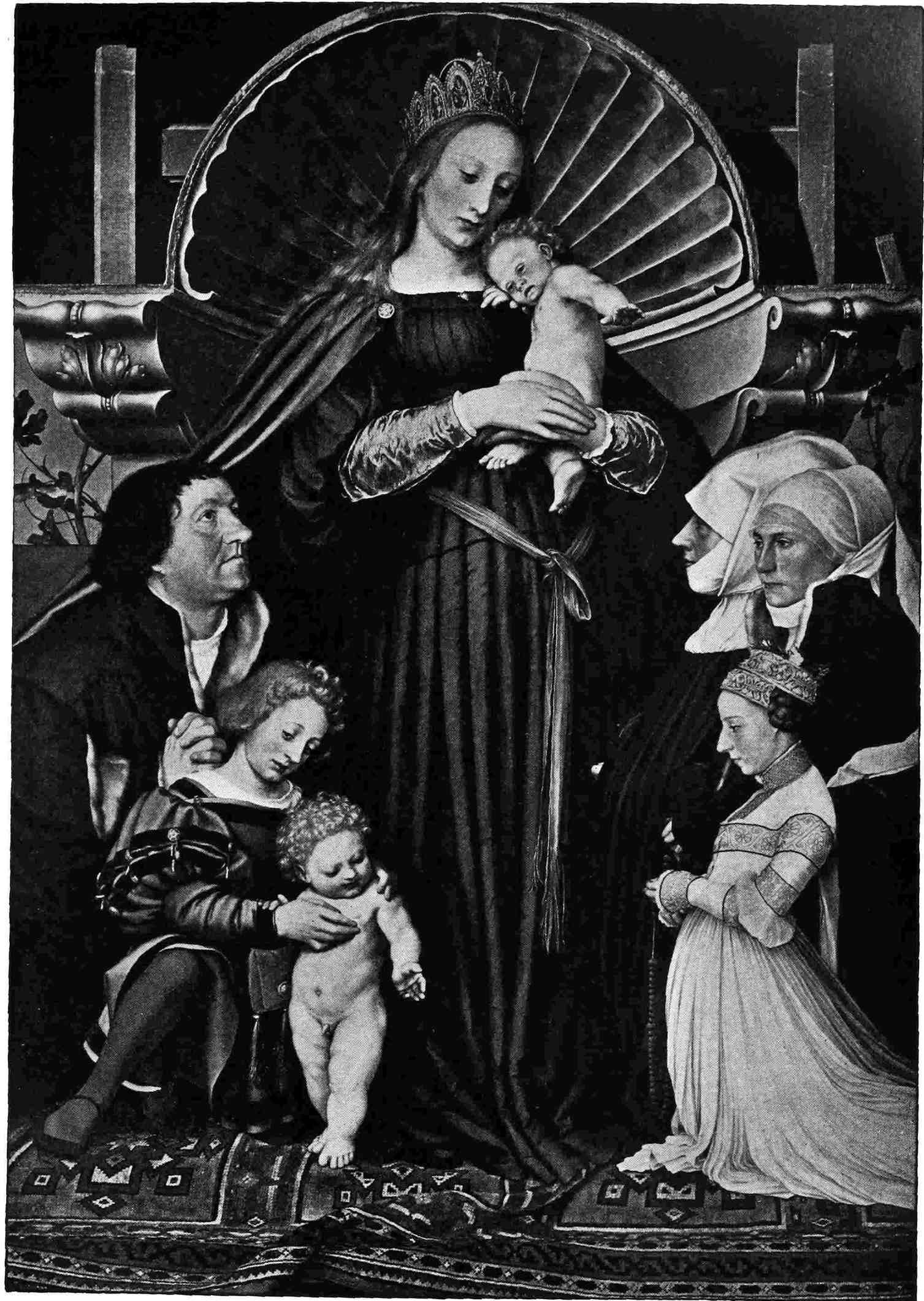

| 71. | THE MEYER MADONNA | 233 |

| Darmstadt. | ||

| 72. | (1) JAKOB MEYER. (2) DOROTHEA KANNENGIESSER | 236 |

| Studies for the Meyer Madonna. Drawings in black and coloured chalks. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 73. | (1) MAGDALENA OFFENBURG AS VENUS (1526). (2) MAGDALENA OFFENBURG AS LAÏS (1526) | 246 |

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

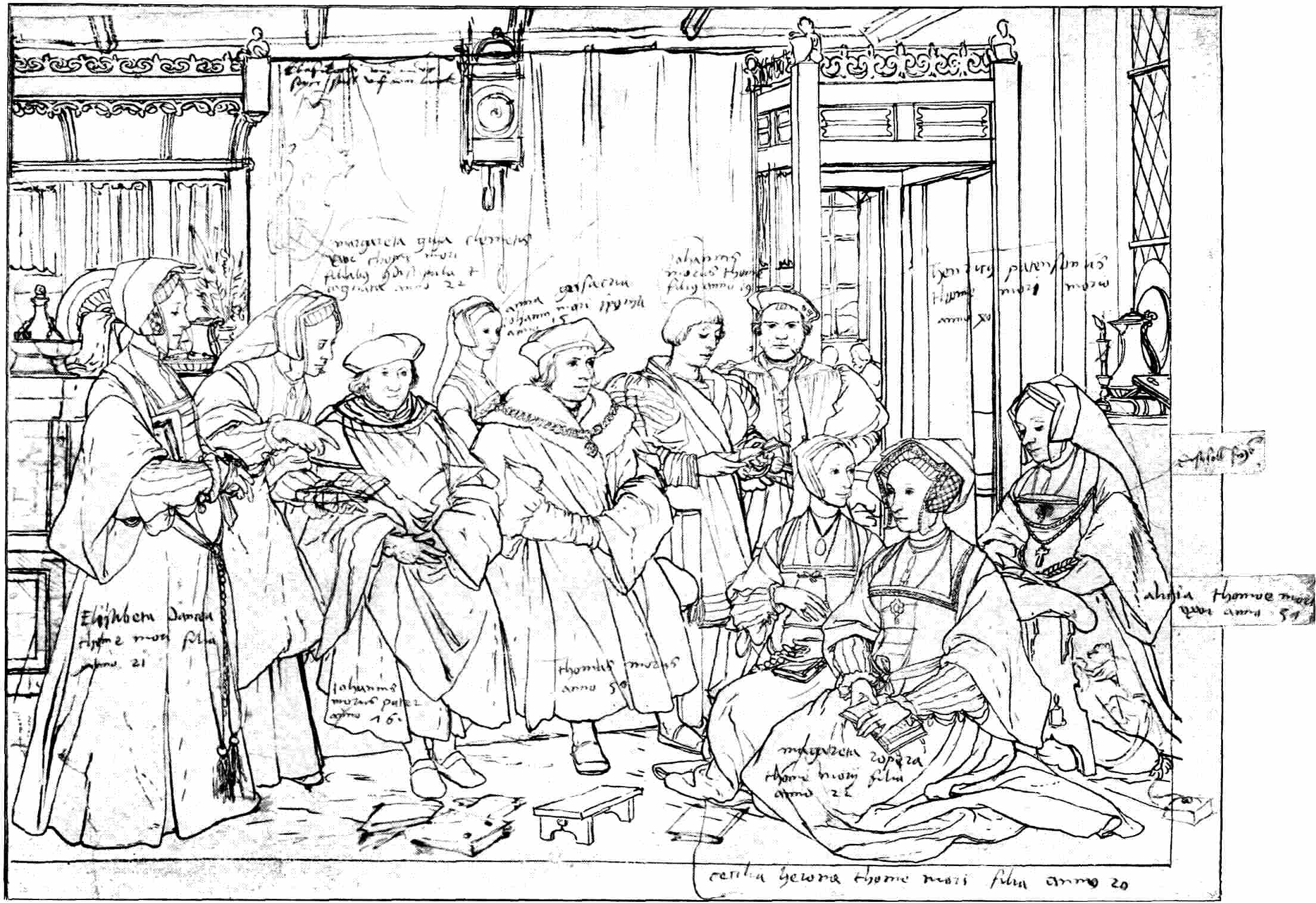

| 74. | STUDY FOR THE MORE FAMILY GROUP | 293 |

| Drawing in Indian ink, with corrections and inscriptions in brown. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 75. | THE MORE FAMILY GROUP | 295 |

| Reproduced by kind permission of Lord St. Oswald. | ||

| Nostell Priory, Wakefield. | ||

| 76. | THE MORE FAMILY GROUP | 301 |

| The version formerly at Burford Priory, now in the possession of Messrs. Parkenthorpe, London. Reproduced by kind permission of Sir Hugh P. Lane. | ||

| xviii77. | CECILIA HERON, DAUGHTER OF SIR THOMAS MORE | 303 |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Windsor Castle. | ||

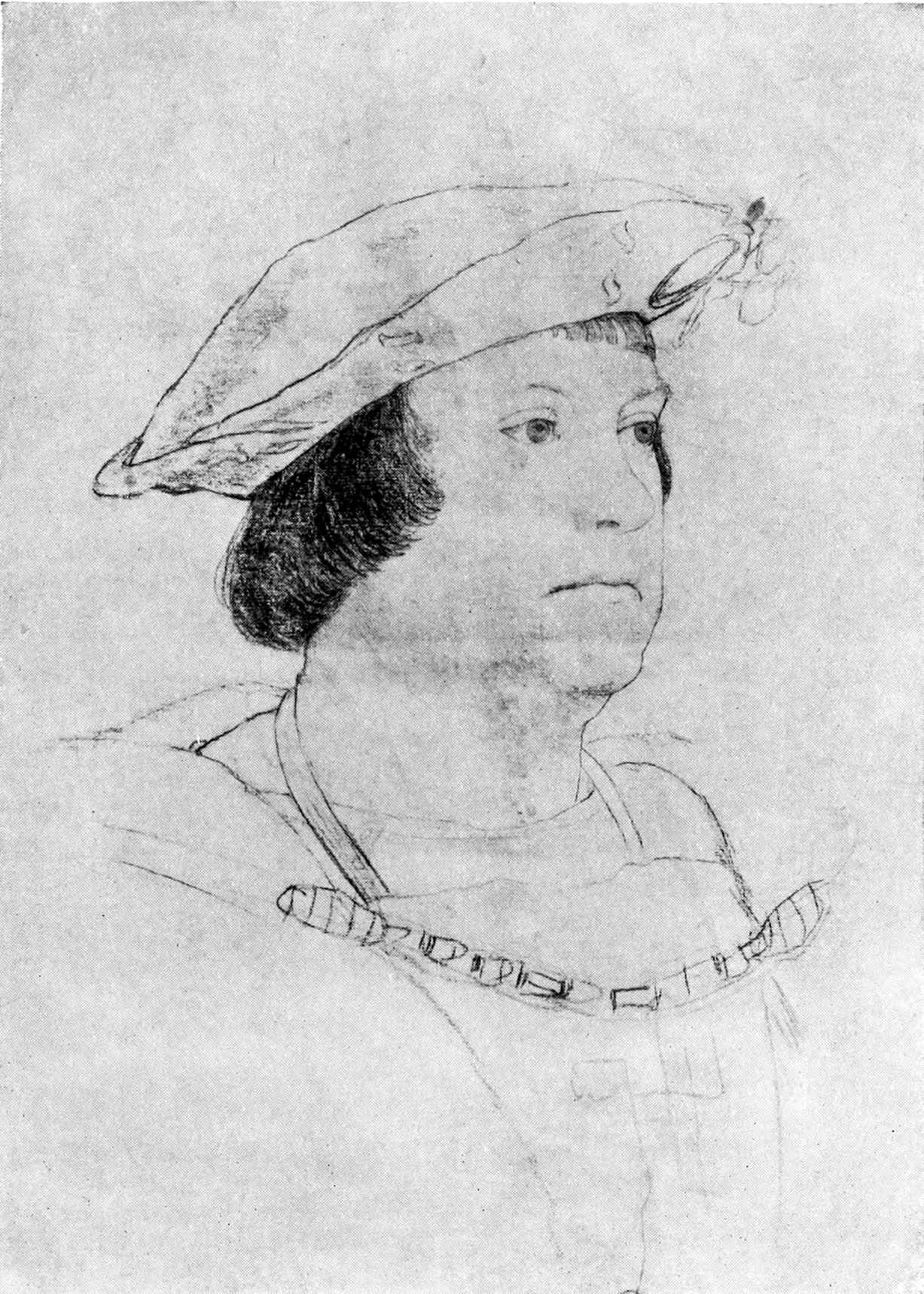

| 78. | SIR THOMAS MORE | 303 |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Windsor Castle. | ||

| 79. | PORTRAIT OF AN ENGLISH LADY | 309 |

| Drawing in black and red chalk and Indian ink. | ||

| Salting Bequest, British Museum. | ||

| 80. | SIR HENRY GULDEFORD (1527) | 317 |

| Reproduced in colour, by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Windsor Castle. | ||

| 81. | (1) JOHN FISHER, BISHOP OF ROCHESTER | 321 |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Windsor Castle. | ||

| (2) PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN ENGLISH LADY, POSSIBLY LADY GULDEFORD | 321 | |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 82. | (1) UNKNOWN ENGLISHMAN. (2) UNKNOWN ENGLISH LADY | 321 |

| Drawings in black and coloured chalks. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 83. | WILLIAM WARHAM, ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY (1527) | 322 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Louvre, Paris. | ||

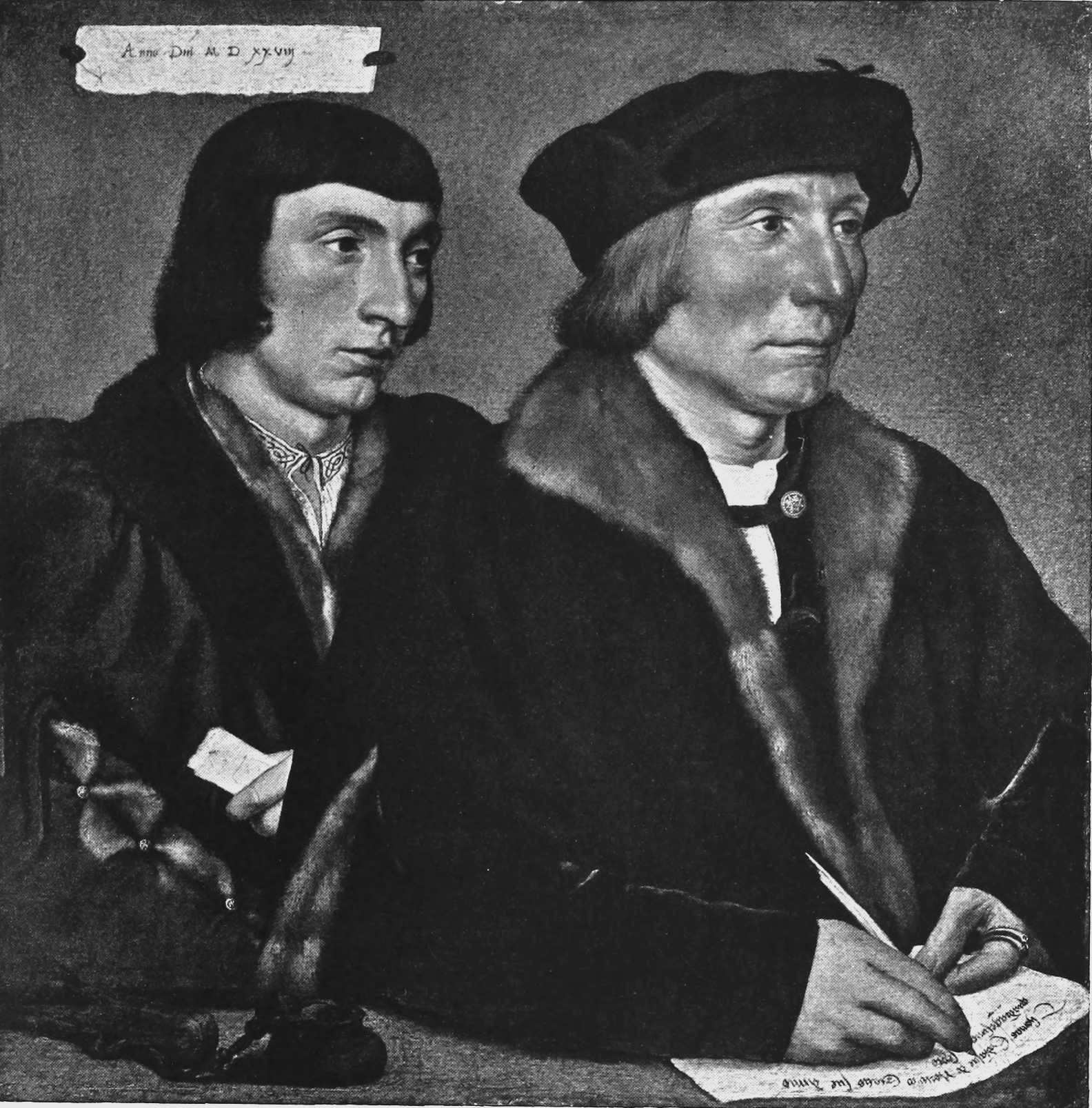

| 84. | THOMAS AND JOHN GODSALVE (1528) | 325 |

| Royal Picture Gallery, Dresden. | ||

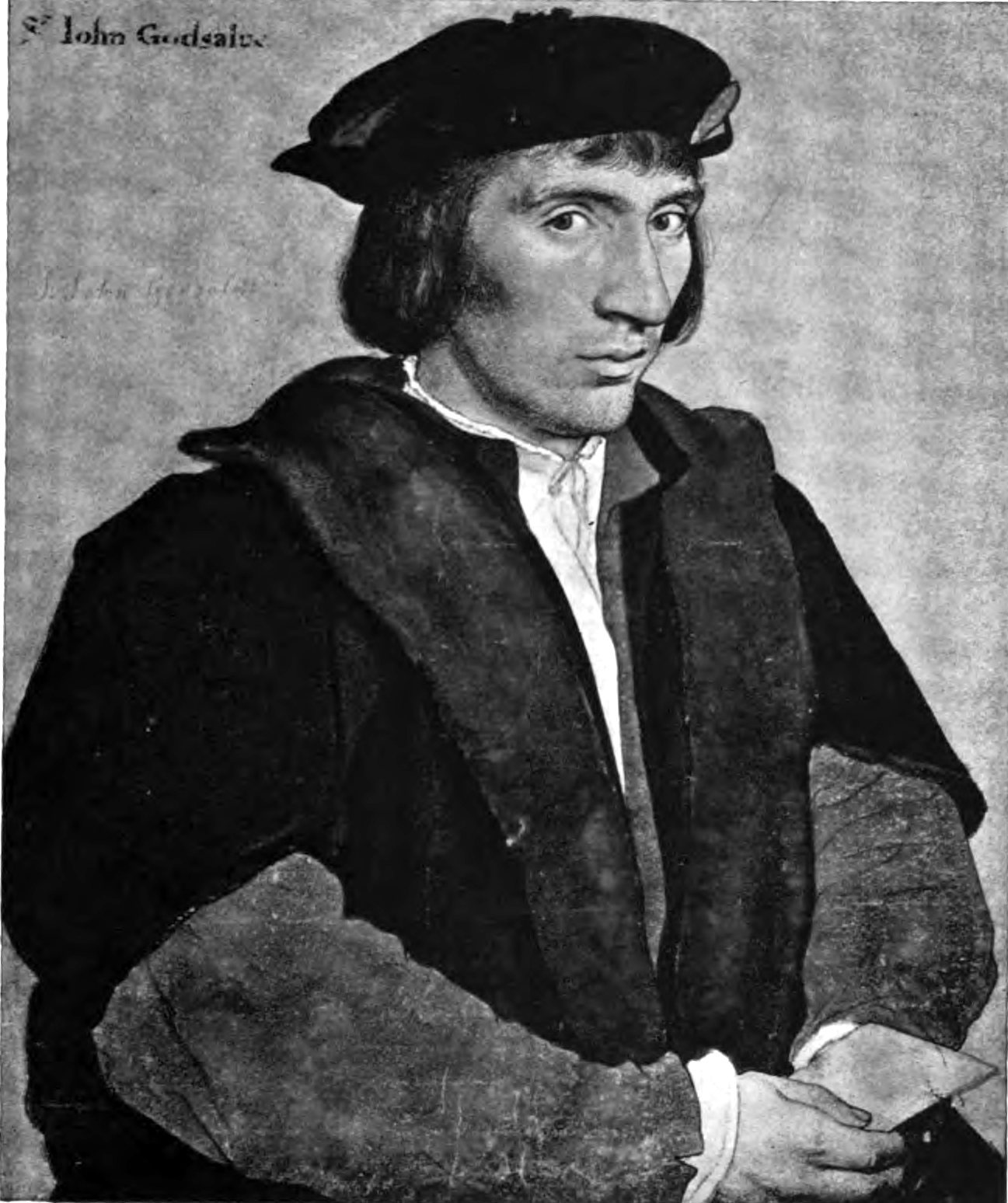

| 85. | SIR JOHN GODSALVE | 326 |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks and water-colour. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Windsor Castle. | ||

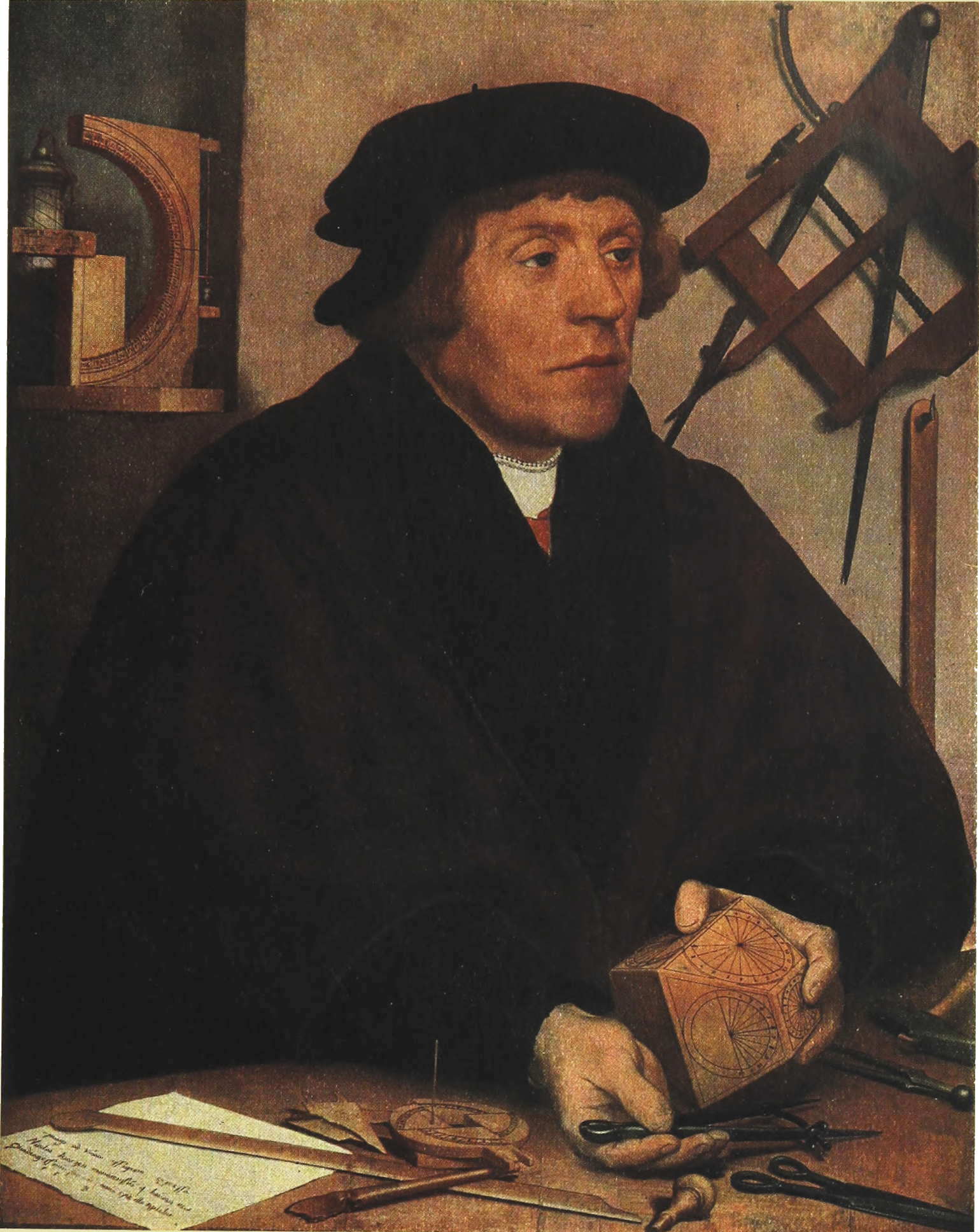

| 86. | NIKLAUS KRATZER (1528) | 327 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Louvre, Paris. | ||

| 87. | SIR BRYAN TUKE | 331 |

| Alte Pinakothek, Munich. | ||

| 88. | SIR HENRY WYAT | 335 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Louvre, Paris. | ||

| xix89. | SIR THOMAS ELYOT | 336 |

| Drawing in black and coloured chalks. Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King. | ||

| Windsor Castle. | ||

| 90. | HOLBEIN’S WIFE AND CHILDREN (1528-9) | 343 |

| Reproduced in colour. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 91. | PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG WOMAN | 346 |

| Unfinished study in oils. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

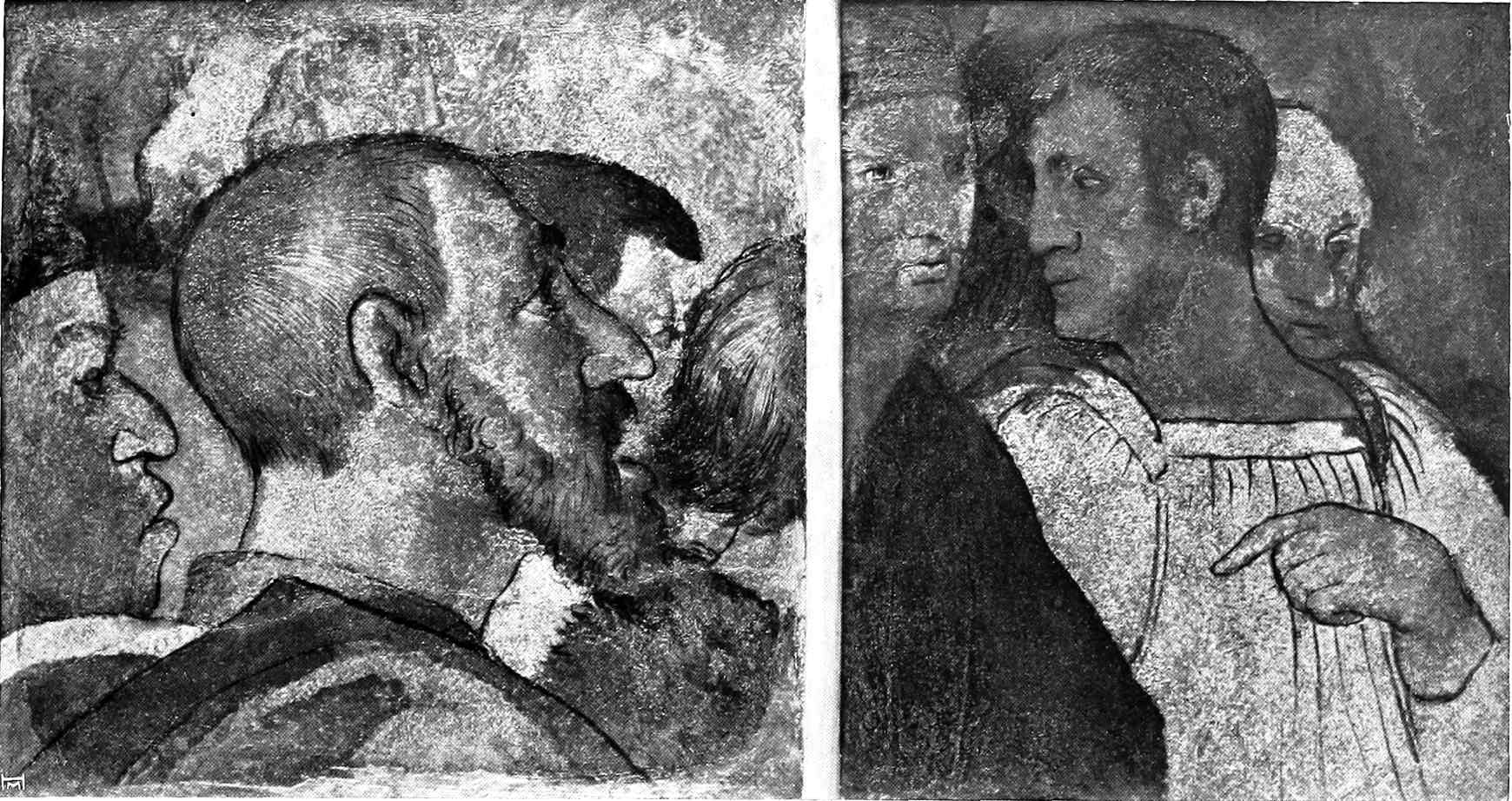

| 92. | KING REHOBOAM REBUKING THE ELDERS (1530) | 348 |

| Three fragments of the wall-painting formerly in the Basel Town Hall. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 93. | KING REHOBOAM REBUKING THE ELDERS | 348 |

| Study for the wall-painting formerly in the Basel Town Hall. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

| 94. | SAMUEL AND SAUL | 350 |

| Pen drawing in brown touched with water-colour. Study for the wall-painting formerly in the Basel Town Hall. | ||

| Public Picture Collection, Basel. | ||

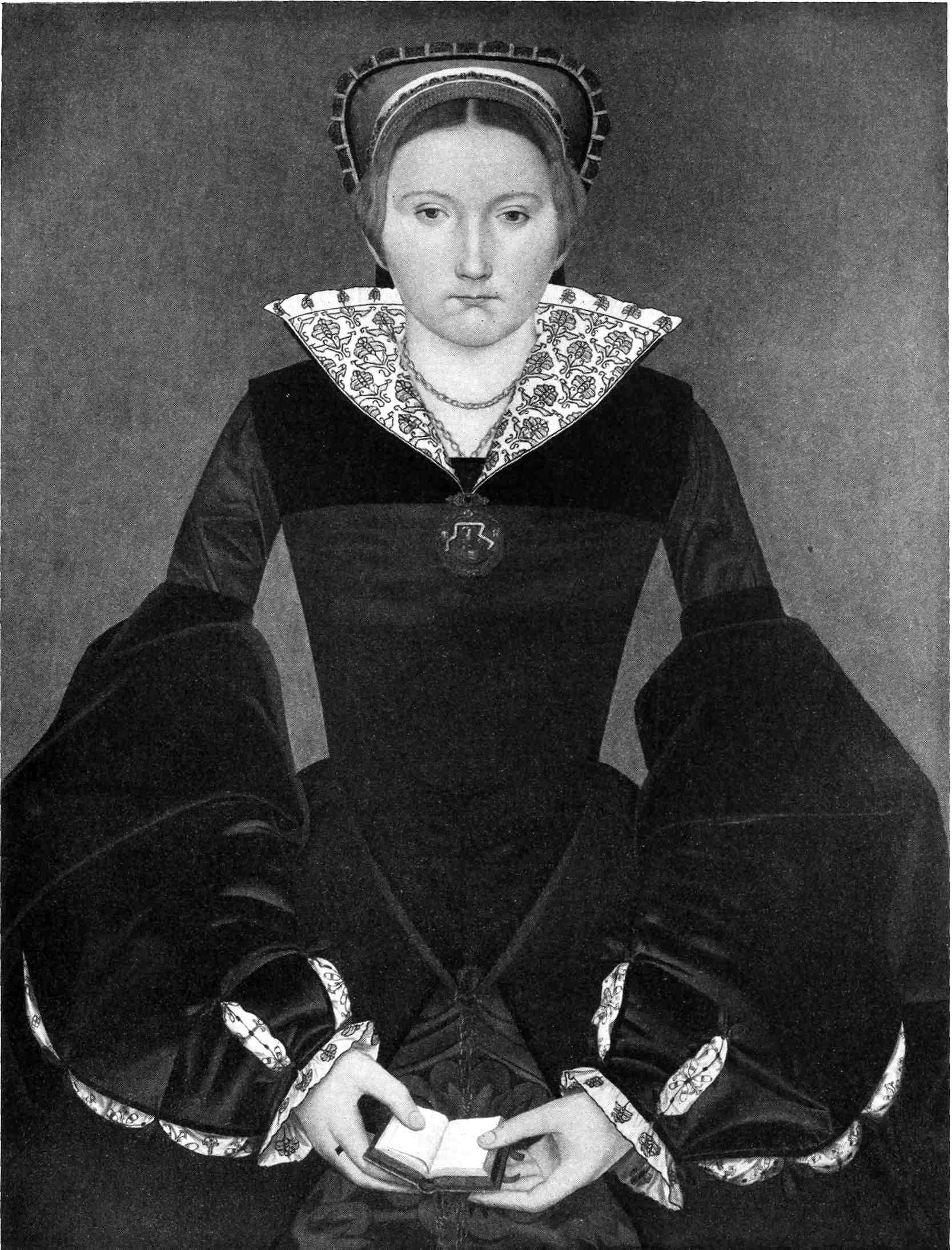

| 95. | PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN ENGLISH LADY | 354 |

| Formerly in the possession of the Bodenham family, Rotherwas Hall, Hereford. Reproduced by kind permission of Mr. Ayerst H. Buttery. | ||

| Mr. Ayerst H. Buttery, London. |

The following abbreviations are used in the footnotes to this book:—

C. L. P., for Calendars of Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII.

Davies, for Hans Holbein the Younger (Gerald S. Davies).

Ganz, Holbein, for Holbein d. J., des Meisters Gemälde in 252 Abbildungen (Klassiker der Kunst).

Ganz, Hdz. Schwz. Mstr., for Handzeichnungen Schweizerischer Meister, ed. Dr. Paul Ganz.

Ganz, Hdz. von H. H. dem Jüng., for Handzeichnungen von Hans Holbein dem Jüngeren.

Woltmann, for Holbein und seine Zeit (A. Woltmann).

Wornum, for Some Account of the Life and Works of Hans Holbein (R. N. Wornum).

In order to obviate the constant use of a somewhat long official title, the Public Picture Collection, Basel, is generally referred to in this book as the Basel Gallery.

The Holbein family in Switzerland and South Germany—Michel Holbein, the leather-dresser—Hans Holbein the Elder, citizen of Augsburg—His brother Sigmund, and his two sons, Ambrosius and Hans—The art of Hans Holbein the Elder and his position in the German School of painting—His principal pictures—Work in Ulm and Frankfurt—Paintings for the Convent of St. Catherine in Augsburg—Work for the Church of St. Moritz—Monetary difficulties—The St. Sebastian altar-piece—the “Fountain of Life” at Lisbon—His silver-point portrait drawings—His death at Isenheim.

DURING the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the name of Holbein was not uncommon in various parts of Southern Germany and Switzerland. At Ravensburg, near Lake Constance, a family of that name had settled as paper manufacturers, their trade-mark being a bull’s head, which was also used by Hans Holbein in his coat of arms. The name is also found in the records of the town of Grünstadt, in Rhenish Bavaria, during the same centuries; while for a still longer period members of a Holbein family were living in Basel, where they had a house called “Zum Papst” in the Gerbergasse. It was from this branch that the painter was in all probability descended,[1] and it is also possible that the Basel and Ravensburg Holbeins were connected. This relationship between the three branches may have been one of the reasons which induced the youthful Hans to turn his face towards Switzerland when he finally left Augsburg, the city of his birth.

In Augsburg itself the first reference to a burgher bearing the name of Holbein occurs in the middle of the fifteenth century. In 1448 a certain Michel Holbein, who had been living at Oberschönefeld, in the near neighbourhood, moved into Augsburg, and settled there permanently. In the first entry in the records in which his 2name occurs he is called “Michel von Schönenfeld,” but in 1454 his surname is given as “Holbain,” this being the common spelling of the name in Augsburg at that time, or, less frequently, “Holpain.” This Michel Holbein, who came from Oberschönefeld, and died in Augsburg about 1497, and at one time was regarded as the father of Hans Holbein the Elder, is no longer considered to be identical with the latter, who was also named Michel and was a leather-dresser by trade. From 1464 to 1475 the last named was living in a house of his own, No. 472A in the Vorderer Lech, which is spoken of as “Michel Holbains Hus,” or “Domus Michel Holbains.” After 1475 he changed his dwelling more than once, and his several removals can be traced from the rate-books, in which his addresses at various dates are given as “Salta zum Schlechtenbad,” “Vom Bilgrimhaus,” “Vom Nagengast,” “In der Prediger Garten,” and so on. All these places were in the Vorderer and Mittlerer Lech, in that part of the city to the east of the Maximilianstrasse known as the Diepold, in the neighbourhood of the Lech canals and streams, by which Augsburg is watered, along the banks of which most of the smaller trades of the city were carried on and the workshops of the artificers and metal-workers were situated. In the years 1479, 1481, and 1482 Michel Holbein was absent from Augsburg, and appears to have left his wife behind him, for in 1481 it is noted against her in the rate-book that her husband was not with her (“Ihr Mann nicht bei ihr”). Michel Holbein died probably about the year 1484.[2] His widow, whose name first occurs in the town records in 1469, continued to move from house to house, her addresses being given as “in der Strasse Am Judenberg,” “Von Sant Anthonino,” “Vom Diepolt,” and beyond the Sträfinger Gate.

The name of “Hanns Holbain” first appears in the records in the year 1494. This was the painter usually known as Hans Holbein the Elder, to distinguish him from his more celebrated son. Although there is no actual proof of the relationship, there is every reason to believe that Hans the Elder was one of the sons of Michel the currier. He lived in the same quarter of the city as the latter, his address in 1494 being in the “Strasse vom Diepolt,” and two years later in the “Salta zum Schlechtenbad.” More than once Hans Holbein’s mother is mentioned as living with him, thus evidently at that time 3a widow, which affords further proof in favour of the connection.[3] In 1504 it is recorded that Sigmund, his brother, was living in the same house with Hans, which confirms the statement by J. von Sandrart, one of the earliest of Holbein’s biographers, in his Teutsche Akademie (1675), that the elder Hans Holbein and Sigmund were brothers, a relationship of which absolute proof is to be found in the latter’s will. Sigmund was born after 1477, was of age in 1503, and died in Berne in 1540.[4] The two painter brothers had several sisters. Between 1478 and 1480 the records speak of a daughter, Barbara von Oberhausen, as living with her mother, Michel Holbainin, and a few years later a second daughter, Anna Holbainin, who is sometimes called by the diminutive name “Endlin.” There appear to have been four sisters in all, but Sigmund Holbein mentions only three of them in his will, Barbara being apparently dead—Ursel (Ursula) Nepperschmid, of Augsburg; Anna Elchinger, living by St. Ursula am Schwall, in the same city; and Margreth Herwart, at Esslingen. The name of this last sister, Margaret, occurs in the town records from 1502 as “Gret” or “Margreth Holbainin.” In 1493 there is a reference to an “Ottilia Holbainlin,” but the use of the diminutive in this case suggests that she was a small child, and, therefore, more probably a daughter rather than a sister of Hans Holbein the Elder.

At one time, before these authentic records of the Holbein family had been unearthed from the Steuerbücher and Gerichtsbücher of Augsburg, it was believed that a third painter named Hans Holbein had existed, the father of Hans Holbein the Elder. Attention was first called to him by Passavant in 1846, in connection with a painting then in the possession of Herr Samm of Mergenthau, and now in the Augsburg Museum. This picture, which represents the Virgin Mary seated on a grassy bank by a wall, with the Infant Christ in her arms, is signed “Hans Holbein, C.A. (i.e. Civis Augustanus) 1459,” a date too early for the picture to have been painted by Hans Holbein the Elder; but the inscription has been proved to be a forgery. Further proof of the existence of this painter was thought to have been discovered in connection with a second picture, forty years later in date, and in reality from the hand of Hans Holbein the Elder. It is one of a series of six pictures representing the principal basilicas of 4Rome, ordered by the nuns of St. Catherine in Augsburg in 1496, on the occasion of the reconstruction of their convent. The names of the several donors of these pictures, with the prices and other details, are preserved in the annals of the convent, compiled by the nun Dominica Erhardt from old records and documents. Extracts from this work were supplied to Passavant, including one with reference to the picture of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, now in the Augsburg Gallery (Nos. 62-64), which is signed “Hans Holbain” on the two bells in the tower, and bears the date 1499. The passage in question is as follows:—

“Item Dorothea Rölingerin hat lassen machen unser lieben frauen Taffel, die gestatt oder steht 45 gulden. Vom alten Hans Holbein hie.” (Item. Dorothea Rölingerin has ordered of old Hans Holbein a panel painting of our dear Lady for the sum of 45 gulden.)

The term “old Holbein,” Passavant thought, could only be applied to the grandfather of the family, for in 1499 Hans Holbein the Younger was still a little child, and his father too young a man to be termed “the old.” Later researches, however, proved that the extracts supplied to Passavant were incorrect, containing numerous amplifications and spurious additions not to be found in the original document, which, after considerable search, was discovered by Dr. Woltmann in the Episcopal Library in Augsburg. In the original record the price paid for the picture is given as 60 gulden, and neither the name of “old Holbein” nor of any other painter occurs, so that the myth of the grandfather Hans was finally demolished.

There is no record of the birth of Hans Holbein the Elder; but as the earliest dated picture by him so far discovered was painted in 1493, it is supposed to have taken place about 1473-4.[5] There is equal lack of information as to the date of his marriage or the name of his wife. It was believed at one time, on the authority of Paul von Stetten, that she was the daughter of Thomas Burgkmair, and sister of the more famous Hans Burgkmair, and that the young couple lived with their father-in-law; but no confirmation of this legend has been discovered. The two families dwelt in the same street, “Vom Diepolt,” but Burgkmair’s house was No. 7, while Holbein’s was No. 17. His family, as far as is known, consisted only of his two sons, Ambrosius and Hans. A third son, Bruno, is mentioned 5by Remigius Faesch (1651) in his manuscript notes preserved in the Basel Library, compiled from information supplied to him from the Amerbach papers; but beyond this short notice, and a repetition of it by Patin, there is no trace of a Bruno Holbein to be found. There are two silver-point drawings, one of the head of a child in the Bernburg Library,[6] and the other of a mitred bishop in the Albertina, Vienna,[7] both dated 1515 and signed with the letters B. H. in monogram, which it has been suggested are the work of the supposed Bruno. Dr. Woltmann, however, considered them to be by Ambrosius Holbein. The latter, he says, was known by the diminutive name of “Prosy” in the family circle, and as at that time in Germany the letters p and b were often used indifferently—as can be seen in the spelling of Holbein’s own name in the Augsburg records, where it is sometimes given as “Holbain,” and sometimes as “Holpain”—it may well be that the monogram on these two drawings is that of “Prosy” or “Brosy” Holbein.[8] Modern criticism, however, has shown that the attribution of these two drawings to Ambrosius is a wrong one.[9]

Hans Holbein the Elder, whose exceptional ability as an artist has always been overshadowed by the greater genius of his celebrated son, was one of the most representative painters of the Swabian School at the close of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century. His art, more particularly, but not only, in its earlier manifestations, shows the influence of Martin Schongauer, and, through Schongauer, that of Rogier van der Weyden and the Flemish School. The influence of Schongauer upon him is at times so marked that it has been suggested that he may have studied under him at Colmar during his younger days. Whether this be true or not, it is evident that Holbein was still under the spell of Schongauer’s painting during his stay in Isenheim towards the end of his life. The “Fountain of Life,” painted there in 1519, owed much of its inspiration to Schongauer’s “Madonna in the Rose Garden,” which Holbein must have seen in the not far-distant city of Colmar. Both in the types of his figures and the management of his draperies, as well as in the arrangement of his compositions, there is an echo of Schongauer’s art, which, however, may not have been derived through personal contact with that painter, but largely from the study of his numerous engravings, 6which were widely popular throughout Southern Germany. Schongauer himself, whose father, Kasper Schongauer, was an Augsburg painter, had studied, or, at least, had come much under the influence of, Rogier van der Weyden at Tournai, and had caught from him something of the sweetness and grace which characterised the finest Flemish art of that day. These characteristics, and others representative of the school, he handed on in his turn to the Swabian painters, the elder Holbein among them. Hans Burgkmair was one of Schongauer’s pupils, and was afterwards a near neighbour of Holbein, so that he also may have been an inspiring force in the moulding of the art of both the older and the younger Hans. Another of Schongauer’s followers, Bartolomaeus Zeitblom of Ulm, is also considered to have had some influence upon the elder Holbein’s painting. The latter, at one period of his career, became a citizen of Ulm, where he must have encountered Zeitblom, the leading painter of that city. Thus his earlier works show a gradual fusion of the methods of the old German or Rhenish School with those of the Flemings. He began to paint in the days when German art was almost uninfluenced by the great Italian Renaissance, which was gradually but surely spreading over Europe, but before the close of his career he had succumbed to its spell. A chronological examination of his later works shows what a vitalising force his study of Italian models had upon his style, though he did not accept these changes as easily or as rapidly as some of his contemporaries, such as Burgkmair. Unlike the latter, however, he never paid a visit to Italy, but he nevertheless found it impossible in the end to resist the new artistic impulses with which that country was then flooding the rest of Europe. It was not necessary for him, however, to cross the Alps in order to experience the magic spell of the new teaching, for Augsburg was one of the first of the South German towns to feel the effects of the Renaissance. The two chief routes from Italy, the western one from Milan, and the eastern road from Venice, met at its gates. The greater part of the trade between the Venetian States and Germany passed through the city, and its leading merchants had business branches in Venice and other North Italian towns. Many members of the Fugger and other patrician families of Augsburg spent long periods in the districts immediately south of the Alps, for the purpose of extending their trade connections; and the active commercial intercourse 7with Italy which resulted brought not only riches to the Augsburgers, but knowledge and love of the new culture as well, and thus through the old free city of Swabia the intellectual and artistic wealth of the Renaissance made its way into Germany. The elder Holbein was among those who reaped advantage from this intercourse between the two countries. Without entirely abandoning the solid German groundwork of his art, he stripped it, more particularly in his management of draperies, of many of its hardnesses. His colour grew more harmonious, and his handling broader and more free. His figures became less attenuated, and his heads, treated with greater realism, displayed more character, while the general composition of his pictures showed a greater dignity of conception and a deeper sense of beauty. In addition to these gradual changes in his art, the new influence wrought a complete alteration in his methods of dealing with all accessories and with the architectural backgrounds against which his subjects were placed, Renaissance forms and ornamentation taking the place of the earlier Gothic settings.

The earliest dated pictures which can be ascribed to him with any certainty are four altar-panels in the Cathedral of Augsburg, of the year 1493, which at one time formed the two wings of an altar-piece in the Abbey of Weingarten, representing Joachim’s Sacrifice, the Birth and the Presentation of Mary in the Temple, and the Presentation of Christ.[10] They display a strong Flemish influence, with a warm, luminous colour, and considerable dignity and sense of beauty in the figures.

His next pictures of which the date is certain are of the year 1499,[11] and include the picture of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore,[12] the work already mentioned as ordered by Dorothea Rölingerin[13] for the Convent of St. Catherine in Augsburg, and at one time attributed to the mythical grandfather Hans. It is a panel in the form of a broad pointed arch, corresponding, like the five other pictures of the series, with the vaulting of the chamber for which 8it was painted. It contains four scenes in three sections, divided from one another by gilded Gothic ornamentation. The lower half of the central compartment contains a view of the church, with a pilgrim kneeling at the altar. On the two bells is inscribed “Hans Holba—in 1499,” while an “H” is on one of the tombstones, and the date is repeated on the outer wall of the church. The upper part of the arch is filled with the Crowning of the Virgin. The division on the left contains St. Joseph and the Virgin adoring the Child in the stable, that on the right the Martyrdom of St. Dorothea, in honour of the donor of the picture, who is represented, a small figure, kneeling in prayer behind the saint. This picture is now in the Augsburg Museum (Nos. 62-64).

A second work in the same gallery (No. 61), of the same date, is, however, far inferior to the foregoing, the execution being careless and perfunctory. It was a commission from the nun Walburg Vetter, also for the Convent of St. Catherine, as an offering from herself, and in memory of her two sisters, Veronica and Christina, all three of whom lived, died, and were buried in the convent; and the indifference of the workmanship has been attributed to the fact that Holbein received extremely poor payment for it, only 26 gulden in all. It has an arched top, and is divided into a number of small compartments, with the Crowning of the Virgin above, and six roughly-painted scenes from Christ’s Passion below, in which the figures, more particularly of the executioners, are extremely repulsive. It is dated, and contains a long inscription.[14]

Shortly after he had sent out this very inferior example of his art from his workshop, Holbein appears to have left Augsburg for a year or two, and to have settled in Ulm. His name is found in the Augsburg rate-books every year from 1494 to 1499, but is missing in 1500 and 1501, while there is a document in the Augsburg archives, dated Wednesday, November 6, 1499, which proves that in that year he had become for the time being a citizen of Ulm (“Hannsen Holbain dem Maller, jetzo Bürger zu Ulm”),[15] though no traces remain of any work undertaken by him in that city. This entry is in connection with the contract for the purchase of a house in Augsburg from which Holbein received interest.

9In 1501 he was in Frankfurt, engaged upon an altar-piece for the Dominican convent church. Two large panels, which once formed the back of the centre portion of this work, represent the genealogy of Christ and that of the Dominicans,[16] each in two divisions. On the first there is a Latin inscription stating that the work was executed in 1501 to the order of the Superior, one “I. W.,” and concluding with the words, “Hans Hoilbayn de Avgvsta me pinxit.” These panels are now in the Städtisches Museum in Frankfurt, together with seven out of eight scenes of “Christ’s Passion,” which originally covered the outer and inner sides of the wings of the same altar-piece.[17]

10In 1502 he was back again in Augsburg, at work upon a large altar-piece for the monastery of Kaisheim at Donauwörth. Sixteen portions of it, which formed the inner and outer panels of the folding doors, are now in the Munich Gallery (Nos. 193-208).[18] Between the years 1490 and 1509 the Abbot Georg Kastner spent much money on the adornment of the fine Gothic church of this famous imperial monastery, and in an old manuscript chronicle which has survived, there is a passage referring to this particular altar-piece, from which it is to be gathered that two other artificers of Augsburg, the sculptor Gregorius and the joiner Adolph Kastner, were associated with Holbein in the work. It speaks of them as three masters of Augsburg, who were the best masters far and near. The panels from the outer sides of the shutters represent scenes from the Passion, those from the inner ones incidents in the life of the Virgin and the childhood of Christ. The former are of inferior workmanship to the latter, and were no doubt produced wholly or in great part by an apprentice or assistant, for they display many exaggerated and grotesque types and a general lack of taste in composition. The inner panels show a far higher standard, and are from the hand of the elder Holbein himself, whose signature occurs no less than three times as “J. H.,” “Hans Holbon,” and finally the inscription, “Depictum per Johannem Holbain Augustensem 1502.” Studies for some of the heads are to be found in his sketch-book in the Basel Gallery. Several panels representing the martyrdom of the Apostles, at Nuremberg, Schleissheim, and elsewhere, have much in common with the Kaisheim altar-piece.

In the same year (1502) Holbein was engaged for a second time upon work for the Convent of St. Catherine in Augsburg. This was a panel, in three compartments, representing the Transfiguration of Christ,[19] a commission from a leading Augsburg citizen, Ulrich Walther, whose daughters, Anna and Maria, were inmates of the convent, the former being the prioress. It is now in the Augsburg Gallery (Nos. 65-67). It was ordered to be made “to the praise of God and in honour of his two daughters,” and the price paid was 54 gulden 30 kreuzers. Walther, who, dying at the age of eighty-six in 1505, left behind him one hundred and thirty-three living descendants, is represented kneeling in the lower part of the left-hand compartment, with eight sons behind him; and in the corresponding part of the opposite compartment are his wife, the two nuns, and twelve others, daughters and daughters-in-law, also kneeling in prayer. These portraits, of which those of the younger children in particular are of considerable charm, form the happiest part of the painting. In the central subject, the movements by which the Apostles express their surprise at the transfiguration of their Master are exaggerated almost to the point of caricature. The side panels represent the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, and the Healing of the Possessed Youth.

A much finer work, painted for the same convent, is the “Basilica of St. Paul,”[20] like the “Transfiguration,” now in the Augsburg Gallery (Nos. 68-70). Although undated, it is usually ascribed to the year 1504. It was ordered by Veronica Weiser, daughter of the Burgomaster Bartholomäus Welser. She was one of the wealthiest of the sisters, and was at that time secretary to the convent, and afterwards succeeded Anna Walther as prioress. It follows the shape of the other pictures in the cloisters, that of a broad pointed arch, and is divided into a central and two side panels, separated by late Gothic gilded ornamentation. It depicts scenes from the life of St. Paul. In the upper arched portion is the Mocking of Christ, while the lower compartments contain the Conversion, Baptism, Martyrdom, and Burial of St. Paul, with other events in his life in the background. In the central division Holbein has shown the donor seated in a chair in front of the basilica with her back to the spectator, an evident portrait, although the face is not visible. The name “Thecla” is 11written on the chair-back. The division on the left hand is of much greater interest, for it contains portraits of the Holbein family, including the earliest but one known of Hans Holbein the Younger. The subject is the Baptism of St. Paul (Pl. 1), who is represented, a nude figure, standing in a stone font in the foreground. In the right-hand foreground the artist has placed a group of three spectators, a middle-aged man and two small boys, representing, according to old tradition, the painter himself and his two sons, Ambrosius and Hans. The truth of this tradition is confirmed by three drawings by the elder Holbein which still exist—one, a head of himself, a study for the St. Sebastian altar-piece, inscribed “Hanns Holbain maler—Der alt,” now in the Aumale Collection at Chantilly;[21] and the others, in the Berlin Print Room, representing the two boys in the years 1502 and 1511.[22] In the picture the painter himself, with long hair and a flowing beard, but the upper lip shaved, and dressed in a fur-lined coat, stands with his right hand resting upon the head of the younger boy, and with the first finger of his left points towards him as though wishing to draw particular attention to him. Ambrosius, with his hair curling upon his shoulders, stands with his right hand placed affectionately upon his younger brother’s shoulder, and with his left clasps the other’s hand. Both boys are dressed in grey cloth gowns, with gaiters and thick shoes, the elder having a pen-case and ink-bottle suspended from his girdle. Hans, a big-headed, round-faced, chubby little lad, six or seven years old, has shorter hair. One hand is raised to his chest, and the other grasps a stick. The father’s face is not a highly intellectual one, but is sensitive and amiable; that of the boy Hans is stronger in character, with a fine forehead and good mouth. On the opposite side of the picture there stands a lady, seen in profile, with plaited golden hair and a white head-dress. Her costume is a rich one, with brocaded sleeves, and the lower part of her skirts edged with pearls. Tradition, which is possibly correct, declares this lady to be the mother of the two boys. There is considerable likeness between her and Ambrosius, and it is evident that she is taking no part in the incident of the Baptism beyond that of a very passive spectator. The 12costume she wears precludes her from being the donor of the picture, who, indeed, is already represented in the central compartment. Holbein apparently introduced his whole family into the work. The only reason for throwing doubt on the tradition lies in the elaborate dress she is wearing, which seems too sumptuous for a poor painter’s wife; for the elder Holbein at this period of his life was in frequent difficulties over money. Mr. Gerald Davies draws attention to a drawing by him in coloured chalks in the Munich Print Room, which, he thinks, represents the wife some years earlier, perhaps before her marriage.[23] “It is,” he says, “a very charming drawing of a young woman, not of any special beauty beyond that which belongs to every young face which has the sparkle of happy pleasure in the lips and eyes; the hair is partly covered with a white cap, into which some delicate yellow is touched, and she wears yellow sleeves and bands of the same colour across the white chest front. Allowing for some years’ difference in age, this may well, I think, be the same person as she who appears in the Augsburg picture. But, whether it be the mother of the great painter or no, it is certainly a study which shows Hans Holbein the Elder to have been possessed in some degree of those very qualities in which his son afterwards stood supreme. There is something of the same sympathetic power of seeing, and the same completeness of recording what has been seen, without pedantries and without makeshifts, all that gives to any given human face its charm and its interest.... There is in it something of inspiration which neither care nor industry nor strength—and there are certainly artists stronger than he—can give. There is in this drawing the germ, and something more than the germ, of the spirit of his great son.”[24]

This altar-piece, in which the figures are represented at about one-third the size of life, marks a considerable advance in Holbein’s art, both in technical qualities, the harmony of colouring, and in the drawing of the figures and natural arrangement of the draperies. When ordering the picture, Veronica Welser at the same time commissioned Hans Burgkmair to paint one of the Basilica of Santa Croce and the legend of St. Ursula. Only one payment, 187 gulden, is recorded for the two. As Burgkmair’s picture is dated 1504, it is natural to suppose that Holbein’s altar-piece was painted at about the same time.

THE BAPTISM OF ST. PAUL

Left-hand panel of the “St. Paul” Altar-piece, with portraits of the Holbein Family

Hans Holbein the Elder

Augsburg Gallery

13Between the years 1504 and 1508 Holbein found frequent employment in connection with the Church of St. Moritz in Augsburg. Various payments are recorded in the church account books, but the pictures he painted cannot now be traced. Among them appear to have been two large altar-pieces, for which he frequently received small sums in advance at his own request. On the 28th October 1506, he agreed to supply four altar-panels for 100 gulden, receiving 10 gulden on account. Money was evidently scarce in the Holbein household in these years; he was even obliged to borrow 3 gulden from the churchwarden’s wife. For the second altar-piece, commissioned on the 16th March 1508, he was to receive the considerable sum of 325 gulden; but, as he was evidently still in debt, the whole of the money was not paid directly to him, but was handed over to various creditors; thus 74 gulden was paid to one Thomas Freihamer. On the same occasion Holbein’s wife received a present of 5 gulden from the church authorities, and his son, no doubt Ambrosius, one gulden.[25]

The elder Holbein, indeed, was often in monetary difficulties, more particularly towards the end of his life. From time to time he was sued for small sums by impatient creditors. In 1503 he went to law with a neighbour, Paulson Mair, and on the 10th May 1515 he was sued by his butcher, Ludwig Smid, for one gulden. In the following year he was twice in the courts, the second time at the suit of one Jörg Lotter for the small amount of 32 kreuzers. On the 12th January 1517 his own brother, Sigmund, was obliged to take proceedings against him for a debt of 34 florins, money advanced to enable Holbein to move his painting materials to “Eysznen”—that is, Isenheim in Alsace—to which place he went towards the end of 1516 for the purpose of painting an altar-piece for the monastery of St. Anthony. Once again, in 1521, a certain Hans Kämlin sued him before the justices for two sums of 40 kreuzers, and 2 florins 40 kreuzers. Thus, in spite of numerous commissions, which, however, were not always well-paid ones, he often had great difficulty in supporting his household in comfort.[26]

The scope of this book does not permit a detailed description, 14or even a bare list, of his numerous works. Two only of his later, and probably his finest, paintings must be alluded to briefly—the “Martyrdom of St. Sebastian,” in the Munich Gallery (Nos. 209-211), painted shortly before his departure from Augsburg to Isenheim, and the “Fountain of Life,” in Lisbon, both of which were at one time ascribed to his younger son.[27] The “St. Sebastian” altar-piece,[28] which in earlier days was rightly regarded as a work of the elder Holbein, is thought to have been one of several commissions given to him by the nuns of St. Catherine in Augsburg. The entry in the archives which is supposed to refer to it merely states that “Sister Magdalena Imhoff has given 3 gulden to the new Sebastian, for the Holy Cross on the altar, and the lay sisters 2 florins. This is the cost of the said picture.” Neither the name of the artist who was employed upon it nor the date of the order is given, and from the wording of the entry, and the very small price paid, it seems evident that it cannot refer to so important a painting as the “St. Sebastian.” Dr. Woltmann was probably right in suggesting that what was ordered was merely a painted wooden figure of the saint, which was to be added to a carved group of the Crucifixion on the altar of the church.[29] The picture was first attributed to the younger Holbein by Passavant and Dr. Waagen, who were misled by the forged extracts from the St. Catherine annals, in which the passage quoted above was considerably amplified, the “St. Sebastian” being definitely described as a picture “by the skilful painter Holbein,” with the additional information that it was ordered in 1515, and placed in the church in 1517, after its rebuilding, and that Magdalena Imhoff paid 10 gulden towards it, and the other lay sisters 2 gulden each. As a result of this falsification, the authorship of the picture was taken from the father and given to the son, and, in consequence, it was regarded for a number of years as an extraordinary manifestation of youthful genius. Even when the forgery was discovered, such critics as Dr. Woltmann and Mr. Wornum continued, from considerations of style, to uphold the picture as an early Augsburg work of the younger Holbein. The 15inner and outer panels of the wings, in particular, were considered to afford undoubted proof, by their high artistic merit and their method of handling, that they were from the brush of the son; and some modern critics still maintain that, if not entirely his work, they were nevertheless carried out by him under his father’s supervision, although they show a much more finished and mature style than is to be found in the first sacred paintings he produced in his early Basel days. Professor Karl Voll of Munich holds that no one but the younger Hans could have painted the lovely figures of St. Elizabeth and St. Barbara. Dr. Glaser, on the other hand, is of opinion that the whole altar-piece is the work of Hans Holbein the Elder. The picture is undated, though Passavant states that it is inscribed “1516.” According to Förster, in 1840 the old frame bore the inscription “1516, H. Holbain.” Dr. Woltmann placed it in the year 1515, but at that date the younger Hans had already left Augsburg for Basel. From considerations of style, however, and the strong Renaissance influence it displays, it is now generally considered to have been executed by Hans Holbein the Elder in or about 1516, prior to his departure from Augsburg to Isenheim.

Judged by his authentic works of this date in Basel, it is difficult to allow that the younger Holbein had any serious part in the painting of this altar-piece, though he may have worked on some of the details under his father’s direction. Whether originally painted to the order of the nuns of St. Catherine or not, the picture is said to have been found in their possession on the abolition of the convent. It was acquired in 1809 from the church of St. Sauveur in Augsburg.

The central panel (Pl. 2) shows the nude figure of the saint, transfixed with arrows, his right arm fastened by a chain above his head to a fig-tree. Four archers at very close quarters are shooting at him, the one kneeling in the left foreground, in the act of bending his bow, being dressed in a striped costume of blue and white, the colours of Bavaria, the hereditary enemy of Augsburg. Behind them stand spectators in rich costumes, two on either side, the foremost one on the right being the officer of the Emperor Diocletian, who is directing the execution. In the background is a river, on the far side of which rise the towers and buildings of a city, with the Alps beyond. The outer panels of the shutters are painted with the “Annunciation to the Virgin,” and the inner ones with the figures of St. Barbara and 16St. Elizabeth (Pl. 3). St. Barbara, who is attired in a purple mantle, a blue dress embroidered with gold, and wide white puffed sleeves, holds a cup with the Host hovering over it. St. Elizabeth has also a purple mantle, and a dress edged with fur. With her left hand she gathers up her cloak, in which she is carrying bread for the poor, and with the other pours wine from a tankard into a shallow bowl held by one of the two beggars crouching at her feet. These two suppliants, both of whom are afflicted with leprosy, have been painted with extreme and even repulsive realism. Behind the leper on the right appears the head of the painter himself, kneeling in adoration. The background in both these panels is similar in character to the central one, that behind St. Elizabeth representing, so it is said, a view of the Wartburg, near Eisenach; while above and below are deep bands of rich Renaissance ornamentation, of the type of design which the younger Holbein afterwards carried to so high a degree of excellence. The whole work, though still retaining many indications of the earlier influences which moulded the elder Holbein’s art, is strongly imbued with the newer conception of painting received from Italy. The drawing of the nude displays greater knowledge than in the “St. Paul” altar-piece, the colour is finer, and the figures of the two saints on the shutters possess much grace and beauty. There are several silver-point studies for the picture in the Copenhagen Museum, while the study for the head of Holbein himself is, as already pointed out, at Chantilly.

THE MARTYRDOM OF ST. SEBASTIAN

Central Panel

Hans Holbein the Elder

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

ST. BARBARA ST. ELIZABETH

Inner sides of the wings of the St. Sebastian Altar-piece

Hans Holbein the Elder

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

It is in the “Fountain of Life” (Pl. 4),[30] painted in 1519,[31] that the strongest proofs of the elder Holbein’s final surrender to the influences of the Italian Renaissance are to be discovered. This picture, like more than one other of his works, was formerly ascribed to the son. Nothing is known of its earlier history, but it is said[32] to have been taken from England to Portugal by Catherine of Braganza, daughter of John IV of Portugal, and wife of Charles II, when she returned home a widow after the king’s death in 1685, and that it was presented by her to the chapel of the castle of Bemposta, where it remained until removed to the royal palace in Lisbon forty or fifty years ago. It thus appears to have belonged to the royal collections 17of England in Charles II’s time, but no traces of it are to be found in any inventory. If the picture ever was in this country, it can have been only for a short time, for about the year 1628 it was in the collection of the Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria, and is very carefully described in a manuscript catalogue of his pictures of that date, with the measurements, the date, and the name of the artist—“von Hanns Holpain ao 1519 gemalt.”[33] It is signed “Iohannes Holbein Fecit 1519,” but from its present condition this signature seems to have been painted over an older one. Attention was first called to the picture by Pietro Guarienti, keeper of the Dresden Gallery, who was in Portugal from 1733 to 1736. He read the name as “Holtein,” and considered it to be the work of one of Holbein’s pupils. This would indicate that the signature was then becoming illegible, and that it was renovated some time after Guarienti saw it. On the inner edge of the circular fountain in the foreground there is also an inscription, “Pvtevs Aqvarvm Viventivm,” which has also been retouched by some clumsy hand, for the older writing, white on a brown ground, can still be seen beneath it.

The background, which occupies the upper half of the picture, is filled with a building or open loggia of very elaborate architecture in the style of the Italian Renaissance, with pillars of vari-coloured marbles, and capitals and friezes richly carved and decorated. In the central foreground, on the steps which ascend to this building, the Virgin appears, enthroned. The Infant Christ sits astride her right arm, firmly clasped against her breast. The Virgin appears to have been painted from the same model as the Virgin on the outer shutters of the “St. Sebastian” altar-piece. The Fountain of Life drips from a marble Cupid’s mask on the step below her feet into a small circular basin, on the edge of which is placed a tall vase with a spray of white lilies. Behind her carved chair stand St. Joseph and St. Anne, and on either side of her are groups of three saints, the two foremost ones being seated, with the folds of their dresses spread over the flower-strewn grass. On the right is St. Dorothy, in a richly-brocaded costume, and behind her kneels St. Catherine of Alexandria with her right hand stretched towards the Infant Christ, as a sign of their betrothal. On the left St. Margaret is seated, with a book and a long cross, and a dragon at her feet, and behind her St. Barbara is 18kneeling, holding the cup with the Host. Two other saints complete the near groups, and in the background a number of other saints are placed on either side. One of the figures is not unlike the so-called wife of Holbein in the “St. Paul” altar-piece. Still farther off, beyond the rails of the portico or temple, are three groups of singing and playing angels with vari-coloured wings. In the distance is an elaborate landscape, with a tall palm-tree, classical ruins, and a view of sea and mountains. Bands of dark cloud stretch across the sky, and the evening light still lingers over the waters, producing a peaceful and rather sombre effect. The composition is the most considerable to be found in any of the elder Holbein’s works, and is well grouped and arranged. The influence of Martin Schongauer can be very clearly traced in it, and the unusual position in which the Virgin is holding the Child is directly derived from Schongauer’s beautiful “Madonna in the Rose Garden,” which Holbein must have studied in the neighbouring city of Colmar.[34] There were also altar-panels by Schongauer in the Isenheim Monastery itself, where Holbein appears to have been working when he painted the “Fountain of Life.” In addition to this direct influence, others, both Flemish and Italian, are to be traced in it, but well fused, so that the whole composition is unforced and natural, and contains passages of much beauty. There is delicacy and warmth in the flesh tints, and the sincerity of feeling which pervades all the principal figures is one of its chief charms. The rich architecture of the background shows good understanding and appreciation of the Italian models upon which it is based, and in all ways the picture indicates that when the elder Holbein put forth his greatest powers he was worthy of being ranked among the best German painters of the early sixteenth century.

THE FOUNTAIN OF LIFE

Hans Holbein the Elder

National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon

Although he does not appear to have had many opportunities of exercising his skill as a portrait-painter, his very numerous studies in this branch of art show abilities of a very high order, and possess many of the qualities, though in a lesser degree, which his son afterwards developed to so high a pitch of perfection. Indeed, in these portrait-studies of men his art attains its greatest strength and finest accomplishment. Sixty-nine of his drawings of heads are preserved in the Imhoff Collection in the Berlin Museum. They are on the leaves of sketch-books, and were made between 1509 and 1516, in 19silver-point and pencil, some of them strengthened with white and with red chalk. A smaller number of heads from the same series are in the Copenhagen Museum, and at Basel and Bamberg, while isolated examples are to be found in the print rooms of more than one European museum. Some of the Basel drawings were made before 1508, and in the collection of M. Léon Bonnat, which contains several fine silver-points by the elder Hans, there is one of the Augsburg goldsmith, Jörig Seld, dated 1497.

These drawings, which at one time were all ascribed to his son, and are so attributed in the first edition of Dr. Woltmann’s book, represent citizens of Augsburg in all classes of life, many of them, no doubt, personal friends of the painter, who, in a number of cases, has written their names on the sketches. There is no evidence to show that the majority of them were preliminary studies for portraits for which he had received commissions; they were done partly for his own amusement and practice, and partly to serve as models for figures in his sacred paintings. They form, nevertheless, a very valuable record of the Augsburg life of his day, and so may be compared, in the wideness of their range at least, with the more brilliant series of drawings by his son. In numerous instances the same sitter has been drawn two or three times; of Johannes Schrott[35] and Hans Griesher,[36] monks of St. Ulrich, there are no less than seven and six respectively. Among them there are portraits of the Emperor Maximilian,[37] on horseback, in helmet, and with sword, and of his grandson, afterwards Charles V,[38] with a falcon on his wrist, inscribed “herzog karl vo burgundy.” As Charles became Duke of Burgundy in 1515, and King of Castile in 1516, the drawing must have been made in the former year. There are several portraits of members of the great Fugger family, among them Jacob Fugger,[39] the head of the clan; his nephews, Raimund[40] and Anton[41]; his cousin, Ulrich Fugger the Younger,[42] and his wife, Veronica Gassner[43]; and several more. Other leading Augsburg families are represented in heads of Gumprecht Rauner,[44] Hans Nell,[45] Hans Pfleger,[46] and Hans Herlins,[47] and members of the court circle by such men as Kunz von der Rosen,[48] 20the Emperor Maximilian’s lifelong friend and adviser. Included among these drawings are representations of more than one of Holbein’s fellow-workers in art, such as Hans Schwartz[49] the wood-carver, and Burkhart Engelberg,[50] stone-carver and architect. Representatives of more lowly pursuits are Gumpret Schwartz,[51] schoolmaster, and one Grün,[52] a tailor, and certain “merry fellows” of the artisan class. The heads of ladies are not very numerous, but one of them, the wife of the Guildmaster Schwartzensteiner,[53] a typical example of the “good wife” of Augsburg, has been drawn no less than three times. A less reputable personage among them is Anna, known as “the Lomentlin,”[54] who was twice expelled from the town for serious misconduct, and returned in the end apparently repentant, afterwards posing as a saint, and professing to be able to live without meat or drink. One of the most important groups in this series of drawings represents the monks of St. Ulrich, Augsburg’s famous monastery—Heinrich Grün,[55] Leonhard Wagner,[56] Conrad Merlin,[57] Johannes Schrott, Hans Griesher, and others. Finally, there are a few studies of heads of members of the artist’s family, including his own likeness, that of his brother Sigmund,[58] and the double portraits of his two sons, which have been already mentioned.

There is a small finished portrait of a lady of Augsburg, whose Christian name only, Maria, is known, in the collection of Sir Frederick Cook, at Richmond, which is the sole example of portraiture by the elder Holbein in England; and, indeed, with the exception of the portrait of a man, dated 1513, in the Lanckoronski Collection in Vienna,[59] which is also attributed to him, it is very possibly the only specimen of such work by him in existence. This portrait is of particular interest, because it conflicts with the statement of Dr. Glaser, that he never painted an independent portrait.[60] It was formerly attributed to the younger Holbein, but most critics failed to see his hand in it; and, when exhibited at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1906, it was described as of the South German School, with a note recording that the names of Schaffner and Ambrosius Holbein had been tentatively suggested in connection with it. Dr. Friedländer, 21however, considered it to be a work of the younger Holbein in his early Basel period. In 1908 Dr. Carl Giehlow suggested that the older painter was its real author, and drew attention for the first time to the fact that a fine study for it exists in the British Museum (Pl. 5); and further evidence in favour of this attribution has been brought forward by Mr. Campbell Dodgson.[61]

The picture is on panel, 13¾ by 10½ inches. The sitter wears a white cap with embroidered margin of fleur-de-lis pattern. Her yellow bodice, trimmed at the edges with a broad band of black velvet, opens in front to show a white under-garment patterned in black and gold. The girdle is studded with gold ornaments. The hands are hidden, being pushed within the sleeves, as though for warmth. The background is plain blue, and on the back of the panel is painted “Maria” in an abbreviated form, evidently the sitter’s Christian name. On the front of the old original frame is inscribed: “Also.was.ich.vir.war.in.dem. 34. iar.” (So was I in truth in my thirty-fourth year.)

The silver-point drawing in the British Museum is, says Mr. Dodgson, “a delicate piece of work, in perfect preservation, and so fresh and spontaneous that it must be regarded as a study from life, preparatory to the picture, and not as a copy from the latter. It is significant that only the main outlines of the costume are noted, and that ornamental details, which it would have taken a long time to draw, are reserved for the final execution of the portrait in oils; nothing of the kind is even suggested except the fleur-de-lis pattern on the cap. All the essential outlines of the figure itself, on the other hand, are drawn with a careful and expressive line, which notes the folds of the flesh beneath the chin more accurately than the creases of the sleeve at the elbow.” This drawing, like the portrait itself, is neither signed nor dated, so that it may be suggested, by those who see in the finished work the hand of the younger Holbein, that the drawing also is the work of the son. There is, however, a second drawing of the same lady in the Berlin Museum,[62] one of the series of the elder Holbein’s studies, in which she is represented in almost the same position, and wearing the same dress, though apparently several years older.[63] 22It does not seem to be a repetition of the earlier drawing, but a fresh portrait from life made after a considerable interval. The Berlin drawing is undoubtedly the work of the elder painter, while the one in the British Museum is closer to his style than to that of his son at the period in question, when the latter was still in his teens, as shown in such early Basel drawings as the studies of Meyer and his wife. The new attribution, therefore, appears to be the correct one, the evidence in favour of the elder Holbein being, if not conclusive, at least very strong.

STUDY FOR THE PORTRAIT OF A LADY OF AUGSBURG

Silver-point drawing

Hans Holbein the Elder

British Museum

Little is known of the last eight years of his life. The “Fountain of Life” is the only picture painted by him during that period which has survived.[64] It is supposed that he never returned to Augsburg, but died in Isenheim; but that he spent the whole period there seems unlikely. Isenheim is close to Basel, and it is not impossible that his last days were passed under the roof of his son Hans in the latter city. A letter, dated 4th July 1526, and addressed to the Vicar of the Order of St. Anthony in Isenheim by the burgomaster of Basel, Heinrich Meltinger, bears out this supposition.[65] It was written on behalf of Hans Holbein the Younger, and by means of it he made a final attempt to obtain possession of, or compensation for, his father’s painting materials, which the latter had left behind him, or which had been detained for some purpose by the monastery authorities. From this letter it appears, also, that the son had made more than one previous attempt, during his father’s lifetime, and at the elder painter’s request, to get the goods returned; from which it is to be inferred that for some considerable time prior to his death Hans Holbein the Elder had left Isenheim. In 1521, as already pointed out, he was sued by Hans Kämlin for a small debt, but this does not necessarily indicate that the painter himself was in Augsburg at the time. His death took place in 1524, as is proved by an entry in the Handwerksbuch of the Augsburg Painters’ Guild of that year, in which “Hannss Holbain maller” is noted as deceased; but this again does not prove that his actual death occurred in that city.

Birth of Hans Holbein the Younger—Forgeries of dates on early pictures attributed to him—Various portraits bearing on the question of the year of his birth—His early life in Augsburg—The family house on the Vorderer Lech—Early training in his father’s studio—Hans Burgkmair—Augsburg and the decorative arts.