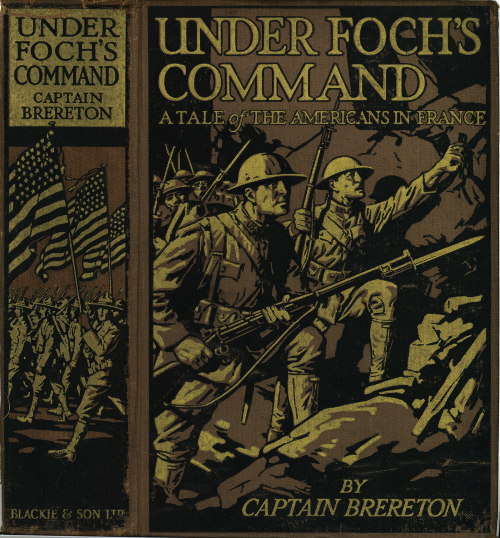

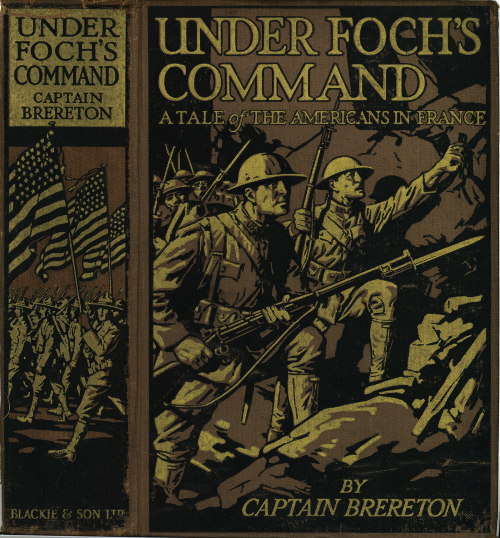

Title: Under Foch's Command: A Tale of the Americans in France

Author: F. S. Brereton

Illustrator: Walter Paget

Release date: January 8, 2021 [eBook #64236]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Juliet Sutherland, Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

THE GERMAN "GOT HIM" AT ONCE

UNDER

FOCH'S COMMAND

A Tale of the Americans

in France

BY

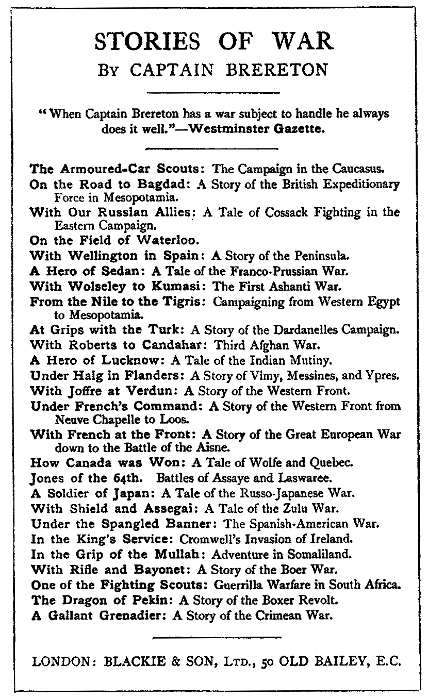

CAPTAIN F. S. BRERETON

Author of "The Armoured-car Scouts"

"From the Nile to the Tigris"

"Under Haig in Flanders"

&c. &c.

Illustrated by Wal Paget

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | An American Declaration | 9 |

| II. | The Sheriff's Posse | 21 |

| III. | In the Mine Shafts | 37 |

| IV. | "En Route" for Europe | 53 |

| V. | A German Agent | 68 |

| VI. | Bombed in Mid-ocean | 81 |

| VII. | Aboard a U-boat | 95 |

| VIII. | Capture of the Trawler | 109 |

| IX. | A Hard Fight | 124 |

| X. | The European Conflict | 137 |

| XI. | On Convoy Duty | 150 |

| XII. | Germany's Greatest Effort | 162 |

| XIII. | Surrounded | 176 |

| XIV. | Where Men fought for Empire | 191 |

| XV. | Attacked from All Sides | 206 |

| XVI. | Heinrich Hilker, Master Spy | 221 |

| XVII. | An American Encampment | 236 |

| XVIII. | In Search of Liberty | 251 |

| XIX. | Plots within Plots | 262 |

| XX. | A Turn in the Tide | 275 |

| Page | |

| The German "got him" at once Frontispiece | |

| One of the three fell with a dull thud | 40 |

| The three friends are hauled aboard the u-boat | 88 |

| A lucky shot took away a portion of the bridge | 128 |

| Bill, tying a somewhat dirty handkerchief to the top of his bayonet, waved it |

216 |

| The man beside him was a maniac, he told himself | 272 |

UNDER FOCH'S COMMAND

It was one of those glorious days which they enjoy so frequently west of the giant range of the Rocky Mountains, an exhilarating day when one rises from one's bed and issues into the open to discover a snap in the air. For spring was but just coming, and the mountains were still clad in snow and in hoar frost; the atmosphere positively sparkled, while the rays of the sun coming aslant through a giant canyon swept across the steep slopes of the mountain, where it encompassed the apparently sleeping city down below, and were reflected from thousands of minute angles, from masses of virgin snow, and from icicles which had gathered since the previous evening. Could one have clambered into those mountains, or into the canyon we have mentioned, one would have found here and there[Pg 10] spring flowers already pushing their tender buds through the coating of snow, here far thinner than higher up towards the peaks of the range. In a hundred hollows little rivulets were running, while towards the centre of the canyon to which all progressed, some at speed and some leisurely, there raced a brook, gathering size at an inordinate pace, sweeping on its surface masses of half-melted snow, flashing here and there as the rays struck upon bubbling eddies, and then plunging beneath an arch of snow, to go tumbling over rocks farther down, and so speed on towards the city.

Compare this scene with the peaks above, still ice-bound, with spring hardly come as yet, so that residence at that elevation was not to be encouraged. Compare it with the city down below: a city of wide, well-swept, tree-edged streets, of big houses and wide open spaces, green already. Down there was a different scene, throbbing with life, though from the heights above it appeared to be slumbering; with busy cars clanging their way and motor-cars dashing hither and thither. Seen from the heights above it presented a whitish blotch, picked out by red roofs here and there, and by dark streaks which represented the roads. It appeared to be a gigantic gridiron, for every block of houses was square, and the roads intersected one another at right angles.

Out beyond it see the glimmer from a vast expanse of water—a lake—the first glimpse of which astounded and delighted the eyes of Brigham[Pg 11] Young and those pioneers who, forsaking the East, fought their way across the prairie to discover a new land, and, peeping downward at the sight we are presenting to our reader, imagined they had gained a fertile country—a country flowing with milk and honey. Fertile indeed it looks from the mountains: trees by the thousand stretch out on every hand, casting a delightful shade, and farther afield green patches of vast extent hug the lake and stretch away into the open country, with brown squares here and there, on which fruit farms abound, and where dairy-men work for their living. But hasten to the lake, dip a hand in it, and taste the water. It is brine. For down there is a huge salt lake, which gives its name to the city. Down below there is Utah, which, for all its salt lake and its salt desert, has been termed "God's own country".

Ten miles away perhaps, beyond the smoke of the city, yet surrounded in the smoke and dust which it itself creates, lies a copper-mine of world-wide notoriety. Rails run hither and thither; tubs and trucks clank over them; while the mountain side, which the active hands of man and the never-ceasing grinding of machinery is eating away at a rapid pace, presents a series of steps, as it were, along which other rails are laid, where locomotives grunt, where trucks screech their way past the wide openings which give admission to the centre of the mountain.

"And that is you, Jim," said one young fellow[Pg 12] as he dropped out of a passing truck and accosted another; "just coming off, eh? Then let's walk home together. It takes longer, I know, for we could ride in the trucks down to the bottom of the mountain; but a walk's a walk; it does one good at this hour in the morning."

"Sure," the other answered, with that drawl common to men of his country. "While we walk we can talk about the situation. What'll you do, eh? I've been itching this two years past to be up and away. Of course I know that some people must work, for copper's needed, and so are thousands of other articles, but——"

"But," said Dan, looking sharply round at him—"but for us young chaps the time's come for fighting."

They trudged on down the rocky slope along which the rails ran, descending gradually and by an easy grade to the bottom, and thence to the smelting plant, where the ore was crushed and treated. They walked between the rails which carried, every day and all day and night too, long lines of trucks, heavily laden, needing no locomotive to carry them to their destination, they stepped aside now and again at some siding to pass another train, this time of empty trucks being dragged up by a smoking engine, and for a while they did not exchange another word. For their thoughts, like the thoughts of everyone in America at that moment, whether East or West, North or South, were filled to overflowing.

Armageddon, the world war which had broken out with such irresistible violence and so unexpectedly—at least unexpectedly to Americans—in the year 1914, had progressed through long weary months to this eventful year of 1917. Tales of tragedy had reached America; thousands of men had heard or read of atrocities committed by the Germans in Belgium, and had ground their teeth and become almost violent. Still more thousands of men had taken a firm grip of themselves and had looked at the situation as dispassionately as was possible.

"No! Not yet—not yet," they had told themselves. "America loves peace; we are a democratic nation, all men, from the President downwards, are equal—as good the one as the other; we wish no harm to anyone in the world; we desire only to work, to thrive, to live surrounded by freedom and justice, only——"

And then heads wagged, men looked doubtful, some cursed. The women, fearful of what might follow, fearful lest America should be drawn into this gigantic conflict, and their men-folk—their husbands and their sons—take up the cudgels, yet perhaps more susceptible than the men, feeling more acutely the sufferings of their distant sisters, spoke out:

"What of the Lusitania? Are American women and children then to be sent to the bottom of the ocean because the Kaiser ordains that none but German ships shall sail the seas? Is no American[Pg 14] vessel to make its way to England, to France, or any other country without fear that the torpedo of a German submarine may explode beneath her? Is that the idea that American men hold of freedom and justice?"

"Bah!" American men were getting out of hand; even the wonderful patience of President Wilson was becoming exhausted. For see, since the Lusitania had been sunk on a peaceful voyage in 1915, other vessels had followed the same way; more lives had been lost, citizens of the great Republic of America had fallen victims to the ruthless acts of German pirates; and now the Kaiser had ordained that America must cease her traffic on the ocean altogether. She might by his consent send a few vessels across to Europe, and these must be painted in vivid colours, must follow certain tracks, must obey the orders of the "All-Highest".

"And this is his idea of freedom, eh?" Jim Carpenter shouted all of a sudden, catching Dan Holman by the shoulder, his face flushed a deep red, his eyes glowing as through a mist. "I say, who's going to put up with that sort of bullying, for bullying it is sure? Say now, Dan, supposing you and I lived in Salt Lake City, and you were to say to me: 'Here you, clear out!—slick off! Salt Lake City ain't the place to hold both you and me. Quit!—without more talking!'"

"Huh!" growled Dan, and walked on. "Huh!"[Pg 15] he repeated, and there was more than disgust in his voice.

"Just so," said Jim, proceeding. "You and I are chums, Dan, and such a thing ain't likely to happen; only, supposing it was the other way, just sort of half-friendly, as Germany and America are supposed to be at this moment, and you out with such orders, d'you think——?"

"Do I think!" growled Dan, almost shouted it. "Don't I know that you'd tell me to mind my own business—to quit talking nonsense, that you'd up and say that you was as good a man, and that if I wanted to turn you out of the city, why, I'd better get to business. And that's the answer all of us hope the President will send to this Kaiser."

From west to east and north to south they were discussing the same theme, the men in their clubs, in their hotels, and their offices and elsewhere; and the women, keeping the tidy homes which America possesses, were wondering, hoping against hope many of them still, that war might be averted, while praying that nothing might happen to sully the honour of America.

In the capital, at Washington, on this very day, there were collected all the wise heads of the community, all the nominated representatives of the States of this vast country. Even as Jim and Dan reached the valley below, and trudged along towards the hostel where they boarded, the decision of America was being taken, the wires were singing with the words transmitted over them, telephones were[Pg 16] buzzing, and that noble speech which President Wilson delivered to Congress was being swept to the far corners of the country.

"It is war!" said a man who suddenly emerged from a store that the two young fellows were passing, waving his hat over his head—an uncouth, rough individual wearing a slouch hat, a somewhat frayed coat with many stains about it, a pair of blue trousers tucked into big, high boots, and a tie red enough in all conscience. "War!" he shouted. "The President ain't goin' to stand any more o' this nonsense. He's told the Kaiser slick that if America wants to send ships over the sea, and of course she wants to do so, she'll do it without permission from him or any other man who likes to style himself 'All-Highest'. He's told that German crowd that his patience is worn out, that America, although she hates war, is going to war for the principles that are dearer to her than almost to anyone. He's intimated to the Kaiser that he'll call upon him somewhere in France and on the sea too, and fight the question out till one of 'em's top dog, and that'll be America and her allies."

The fellow threw his hat into the air, and, running up to Jim and Dan, shook them by the hand. "I know what you think," he said, bubbling over with enthusiasm—"you two young chaps that's often chatted it over with me; you've been waiting for the day. You, like thousands and thousands more of us, will go across yonder to take the President's message to the Kaiser—eh?"

They shook hands eagerly on it, and for a while stood there chatting. For they had each of them much to say. Indeed, there were groups eagerly talking everywhere in this mining encampment: in the houses wherein the married people had their quarters, in the hostels where bachelors roomed and boarded, and farther away, where the ore from this giant copper mountain was smelted, in the hostels there, and amongst the clanking machinery.

"War! America's at war!"

In spite of the fact that thousands of them had anticipated the event, it struck them like a whirlwind, left them almost speechless, or, contrariwise, set them shouting. Pass along the street and see men dressed as they are in those parts—their hands in leather gloves, their coats wide open, and often their shirts too at the neck, arguing, speaking in loud tones and most emphatically, or talking in some quiet corner to a group of friends who listen intently. In the stores along the street they had stopped business, and customers and men behind the counter exchanged views on the situation. In the saloons, where spirits and other liquors were served, there was excitement; much, it must be confessed, in one of them which bore no very enviable reputation. For into this place a motley throng lounged or swaggered every day of the week: Spaniards, who had come to America to delve a way to fortune; Poles, and Greeks, and Russians, who had come from their own lands to make wealth more rapidly; Austrians,[Pg 18] Turks, and Germans also come here to seek a short road to prosperity. They were seated at tables along one wall, or stood at the bar talking heatedly like those others outside, or whispered to one another. But behind the bar there was no whispering on the part of the ruddy-faced and jovial tender whose duty it was to serve drinks to those thirsty mining people.

"War!" he shouted, and brought a big brawny fist down upon the counter with a bang which set glasses jingling. "War at last, and not too soon neither. Down with Germans and all that's German, say I, and I've said it these months past. Down with the Kaiser!"

A man lounging there not six feet from him, a huge hat over his eyes, and collar turned up as if to hide his features, leaned across the counter and tapped the bar-tender on the shoulder.

"Say," he drawled, and with a distinctly guttural accent. "You vos for war? Ha! And you haf said: 'Down mit the Germans and Germany!'"

"Sure!" shouted the barman, rocking with laughter; "and so says every one of us. I'm not one for politics; I'm just a plain straightforward American, with plenty of friends and a good home, but I bar the slaughter of women, and I don't take orders from no one. Nor shall America! That's why I'm glad that it's going to be war. That's why I say: 'Down with the Germans!'"

Men raised their heads as they sat at the tables, and looked across at the bar-tender; many of them[Pg 19] smiled, some nodded, and others laughed outright.

"Just Charles," one of them said, "the brightest, jolliest fellow we've ever had. It does one good to look at him. And he's downright. Say, Charles!" he called out, "I'm with you. Down with the Germans! I'm glad it's war. Let's get in and whop 'em."

The man leaning against the bar counter turned his head towards the speaker and scowled.

"A German," another of the customers at a table near at hand observed, sotto voce, to his comrade. "It's said that he's been over this side only a matter of six months, and chances are that he's a German agent, though he'd tell you that he's American to the backbone. A sulky-looking beggar."

"Say!" that individual began again, as he stretched over the bar, and once more tapped the bar-tender on the shoulder, "you said down mit Germans and Germany?"

"Aye, sure!"

"And what then? And down mit the Kaiser also?"

"Of course," flashed Charlie, "him first of all, because then it'll be easier to knock sense into the heads of the Germans."

There was a flash, a loud report, and a column of smoke just where the bar-tender had been standing. Men sprang to their feet; one rushed across to support the tottering figure of Charlie, while a second man sprang towards the individual who had[Pg 20] been leaning against the counter. Then he recoiled, for a revolver muzzle looked steadily at him.

"Don't move," came in even tones from the rascal who had just fired. "Stand back every one of you, I mean business."

He backed to the door of the saloon, and pushed his way through it; then, turning on his heel, and thrusting his still smoking weapon into his pocket, he sped down the street, passed Jim and Dan, who were still discussing the question of war with animation, and so towards the mountain.

Here, miles away in the heart of America as it were, the Kaiser had indirectly brought about yet another tragedy; for undoubtedly one of his emissaries had carried the war far afield, and had done here, as ruthlessly as could well be imagined, the wishes of his master.

Imagine the commotion that ensued in the mining city which lay at the foot of that giant mountain which the industry of man is slowly eating away. That shot which had rung out in the saloon near which Jim Carpenter and Dan Holman, his bosom chum, happened to be standing—listening to the harangue of that bearded and excitable person who had announced the declaration of war to them—though it was muffled by the windows of the saloon itself and by the half-door which closed the entrance, yet attracted the ears of quite a number. Nevertheless the figure which presently emerged and went off down the street escaped attention. Then an avalanche poured into the street.

"Where's he gone? Which way did he turn? Where's that German?"

"German?" asked Jim. "What's happened? We heard a shot, and guessed there must be a shindy in the saloon. Still, there have been others, so we didn't take much notice. As to seeing anyone coming out, that we did not, for we weren't[Pg 22] quite sure where the sound came from, and were looking the other way. Who's the man? What's happened?"

"What's happened!" exclaimed a heated individual, a tall, lithe, broad-shouldered and clean-shaven American, tapping Jim in friendly fashion on the shoulder. "Let me tell you, sir, the cruellest and most bloodthirsty murder that the Kaiser has ever committed!"

Dan stood back a pace and stared at the man in amazement. "The Kaiser," he exclaimed, "here? Surely——"

Another face was thrust forward into the circle now standing about Jim and Dan. "He didn't mean the Kaiser himself," this lusty miner cried. "George, here, is talking of what the Kaiser's brought about through one more of his rascally agents. Listen here: a man was standing up against the bar counter five minutes ago; a chap that's not long been in these parts, but I happen to know something about him, and that something is that he's a German. Well now, what d'you think happened? Charlie, the most jovial fellow that ever served a glass to any of us, states the case squarely and aloud, just as he's been used to: says as he's glad it's war, says as he thought it was high time we Americans were in it, and just downs the Kaiser with a bang of his fist."

"And then this here scoundrel of a German chap shoots him point-blank! Where's he got to?" shouted another.

It was less than five minutes later that the Sheriff, hastily summoned by telephone, came cantering up the street, and after him his posse, collected from all parts from men who had already been selected to act as special police in case of trouble arising, well acquainted with their duty, and hurrying from their work, from their houses, from wherever they might have been, all mounted on horseback, and making for the centre of the mining city.

Let us say that though the old mining cities and villages of America now wear a totally different aspect, and lead a supremely different life from that common in the '40's, yet "hold-ups" still occur in places; ruffians even now are come across, and every now and again there is a broil, and some tragedy or crime is perpetrated. Here then was one, and already the Sheriff and his men were seeking for the culprit.

"He came right round along the street down here," a man bellowed, running up a few moments later; "a dark man, with his coat collar turned up and hat pulled over his eyes?"

"That's the one," they shouted.

"And hops into one of the trucks making up the mountain; it'll be well up the slope now. He's setting his tracks for the workings."

At once there was an exodus; the crowd broke up, the Sheriff and his men galloping off to ascend the mountain by a winding track, whilst Jim and Dan and twenty more dived for their own homes,[Pg 24] then, armed with the best weapons they possessed, turned out again, and, clambering aboard a train of empty trucks going upwards, made for one of the tunnels which had been cut into the heart of the mountain.

"We've telephoned round to the other side to tell 'em to close the exit, and I've told off parties of men to watch every one of the openings on this side," the Sheriff told them as they alighted opposite one of the huge galleries which gave access to the mountain. "Next thing is to have a confab. We've got to get that fellow out, but we'd best remember it's dark in there, there are cuttings this way and that, and galleries running everywhere, so lights are wanted, and, after that, guides."

Jim stepped forward and Dan with him. "How'll we do?" they asked.

"You?"

"Yep!" declared Jim, with the curt assurance of a young American. "Dan and I have worked here since we were boys, and know every tunnel and every cutting. As to lights, Mr. Sheriff, I don't know. You see——"

"How's that?" demanded the Sheriff. "No lights! Waal, that gets me!"

"You see," explained Dan, coming to the assistance of Jim, for he had seen his reasons instantly, "the man who enters the workings carrying a lamp will draw fire, if that fellow means to do more shooting."

For a moment or so there was silence, the Sheriff[Pg 25] pushing his hat back from his head and rubbing his forehead, while the men about him looked at one another and nodded.

"Mebbe all right! Say, now, I don't want to dictate to no one," declared the Sheriff, "but, draw fire or not, we've got to get a lamp to find this fellow; we've got to take our risks so as to arrest him. Waal, taking risks is in our line; we expected that when we were elected. I'll chance it."

Jim and Dan instantly agreed to do likewise.

"There's a motor-car over here," said the former at once, beginning to walk towards it. "We can remove the lamps and use those. I don't say, Mr. Sheriff, that you're not right. This is a job which means risk, and, as you say, it's your duty to get into danger. Our job is to help you, like every honest citizen will want to do. Come on, Dan, and let us see what we can make of the lamps, for the sooner we follow that beggar the better."

It chanced that the motor-car standing not far off was equipped with acetylene head-lights, being dissimilar in that respect to the majority of modern automobiles in America, and promptly they removed these lamps and brought them back to the party. Presently they had them alight, and, taking one and sending the second along to the next party, who were watching the nearest opening, they plunged boldly into the gallery which led to the inner workings, one man carrying the lamp and the rest grouped about him, the Sheriff and half a dozen of them bearing revolvers, while not a few[Pg 26] carried guns which they had hurriedly snatched from their lodgings.

Pushing on with great caution, and flashing the lamp hither and thither, so as to expose the openings to works which led off from this main gallery, the party had presently proceeded some three hundred yards, and had as yet discovered no trace of the fugitive. Then one of them gave vent to a cry, and, bending down, picked up an object.

"The hat he was wearing, I could swear," he said, lifting it. "Let's put it in front of the light. See, Mr. Sheriff, I was in the saloon there with Bill Harkness, a-talkin' about this here declaration of war that the President's made, with one eye on Harkness, as you might say, and one on the chap leanin' up against the counter. This is his hat—I'd put me boots on it."

He raised the hat till the full stream of light from the lamp fell upon it, so that all could examine it. As he lowered it again, and the beams swept on into the depths of the tunnel, there suddenly came a deafening report; the lamp went out as if drowned in water, while the man carrying it fell to the ground with a crash.

"Pick him up," said the Sheriff. "Jim Carpenter, you were right. Did any of you folks catch a sight of the varmint?"

Not one answered. As a matter of fact, the man who had fired the shot had been secreted round a corner, and, at the moment he stretched forth one arm with his weapon, the party in search of him[Pg 27] were examining the hat which he had dropped, and which was sure evidence of the fact that he had taken refuge in these workings. A second later he had dived back round the corner, and now the whole place was in darkness.

"We had best get out," said the Sheriff in low tones. "I ain't the one to be driven off by a murderer. But Jim's right, and every time we come in bearing a lamp that fellow's open to get us. He's a shot, too, for else he wouldn't 'a got his bullet in so straight. Let's get back and 'tend to our mate."

Feeling their way along the walls, they staggered back to the exit, and were presently once more in the open, where, to the relief of all, they discovered that the man they carried had been merely stunned. For he had held the lamp at arm's length and just level with his head, and the bullet which had struck it had flung it back violently against his head and so stunned him.

"And what next?" the Sheriff asked as the party gathered in a group and looked at one another enquiringly. "Young Jim Carpenter, you've been these many years in and around the works, what 'ud you do? Mebbe you can find your way round blindfold."

Jim thought the matter over for a while. It was true that he could find his way anywhere in those works blindfold, or without a lamp, and indeed would have been a dunce could he not have done so, seeing that he habitually went to his work along[Pg 28] the galleries without a light, every inch being familiar to him. Yet to find one's road in the workings within the mountain and to search for a murderer therein were two entirely different propositions. The one required no nerve, hardly any effort; the other called for something more, and promised at the least excitement and adventure.

"Guess, Mr. Sheriff," he said at last, "it's the duty of every one of us to lend a hand."

"I can't compel," came the answer. "Me and my posse were elected to look after the rights of people in this here city and surroundings, to arrest thieves and vagabonds, and to maintain order. If we are hard pressed we are entitled to call upon those nearest, but they ain't compelled to join; they are free citizens. Folks in this country are free, young Jim Carpenter."

He eyed the young fellow critically, peering at him closely from the top of his peaked hat to the soles of his sturdy mining boots, noticing the breadth of his shoulders, the depth of his chest, his firm face with the pair of glittering, frank eyes looking out from it, the strong hands and arms, bared almost to the shoulder, and the general air of strength and resolution about this young miner.

"Should say as he and Dan are just the last to refuse a request that might plunge 'em into danger," he was thinking. "They're quiet, hard-working folks, as we all know, and orphans this many a year, having earned their own grub and a good[Pg 29] deal more, and have been independent of others. Waal?" he asked bluntly.

"I've been thinking, that's all," said Jim. "It don't do to go in for a thing like this without some sort of consideration. Any way you look at it it's not an easy job; for I take it this German chap is bottled up in the mountain and has to be hunted out of any corner or hollow in which he's taken shelter. You might board up the entrances and starve him out, only the chances are there's food enough in the workings to keep him alive for quite a while; for the miners often take in a store so as to free them from the job of carrying food up every day. As to water, there's pools of it; so, as you might say, a siege like this could last for days on end, and the murderer fail to be captured. So the best and quickest way is to go in and pull him out; and bearing a lamp, as we have just now tried, ain't successful."

"Just as you warned us, I'll own," the Sheriff admitted. "Now then?"

"I'd take in a small party only," Jim said, "every one of 'em armed and good shots, and one of 'em carrying an electric torch. I'd let 'em wear rubber boots, and would warn 'em not even to whisper. They could arrange signals before they went in: a tug at the coat to warn each other that one of 'em had heard a suspicious sound. I'd let 'em creep forward till near their man, and then the one with the lamp could flash it on, while the others covered the fellow with their revolvers."

"Gee," shouted the Sheriff, "that's some talking!—some sense! Let's think it over. But what about a guide? Who'd lead 'em? Who's the chap who's a-goin' to take hold o' the torch? It means shootin', mind. That there skunk what's got inside could shoot the eye out of a horse, I reckon, so that those who go in after him will have to look mighty lively—so who's a-goin'?"

"That's settled," Jim said abruptly. "That is, of course, if you think I'll do."

"And I'll go along with him," Dan immediately chimed in. "Only we shall want someone who can shoot well: Jim and me's used a gun (revolver) at times, but we ain't no experts; but Larry, here, he's the man. If the chap who shot Charlie over the bar, and put our light out a while ago, could hit the eye out of a horse, Larry'ud shoot one out of a fly, I guess."

"Huh!" grunted the Sheriff, and cast a sharp glance at the individual in whose direction Dan had jerked a thumb. There he saw quite a diminutive person, yet looking rather terrific in his mining costume. For what with his high brown boots with their thick soles and the lacings which ran almost from the toe right up to the knee, his rough trousers cut too big for him, and a somewhat broad hat tilted right on the back of his head, to say nothing of fierce moustaches, Larry looked a terrible fellow.

Yet those who knew him knew him as a smiling,[Pg 31] happy-go-lucky individual, a miner whose chief characteristic was a penchant for spending money. Dollars fled through the unfortunate Larry's pockets as if the latter were full of holes. He was always in an impecunious position; and yet Larry had pride, for not once did he beg of his comrades. For the rest, it was on quiet half-holidays that he and a few others would betake themselves to some retreat down at the foot of the mountain, and there practise with their revolvers.

"You ain't got no cause to take on," Larry had told Jim many a time when the latter had missed a can tossed in the air, for that was his particular test applied to all who desired to become marksmen. "See here, young fellow, I tosses the can into the air, and you has your back turned to it. I says 'Go!' and round you swings, up yer arm goes, and then the gun speaks. It ain't done by aimin', it comes natural. You can't hit a can, same as that, tossed in the air, unless you've spent dollars in ammunition same as I've done. There ain't no particular difficulty in it, it's just persistence and practice—just stickin' to it. So there, and that's all there is to it."

It might be easy enough for the diminutive Larry, but it caused him no end of amusement to see the obstinate way in which Jim and others tackled the proposition, and to watch their many failures; although, to do this jovial fellow but justice, it caused him to shout with delight when finally they were able to hit the flying object. Yet, with[Pg 32] all their practice, not one came up to the redoubtable Larry.

"Yep, Sheriff," he grinned, as the latter pointed a finger at him, "I'll own up to it. It ain't that I'm of a quarrelsome sort of a disposition."

At that they all grinned.

"What's that?" demanded Larry, firing up, not understanding their humour. "Me quarrelsome! Why, I've been here about the mines this six years past and there ain't one with whom I've had a ruction."

That again was substantial truth; yet we must amplify it a little by the statement that the population working round this huge copper-mine was constantly fluctuating, and only a small proportion of the men remained there for many months together. Yet in such a community men soon gather knowledge of one another, and, though there were brawls now and again, though men came to the mine who were of a distinctly cantankerous and quarrelsome disposition, it was significant that, learning early of Larry's prowess with a gun, it was not with this diminutive little miner that they picked their quarrels.

Larry grinned widely, for now he saw that his friends were merely bantering.

"I kin git you," he laughed. "Waal, Mr. Sheriff, let's move on. I've a gun here handy," and he tapped the holster in which his revolver was resting.

"But there's the torch to be got first of all,"[Pg 33] Jim reminded them, "and then there are rubber boots or shoes. They are of as much importance almost as our friend Larry. What's the odds, Mr. Sheriff, if we set our guards at the exits from the mountain, and send down below to get all we want? I ain't the one to delay, but we are more likely to succeed if we make our preparations carefully."

There came a commotion away on their left as he was speaking: a weapon snapped sharply, there was a rush of men towards the entrance, which, like the one in front of which Jim and his friends were standing, was being watched and guarded, and then one of the Sheriff's posse approached.

"The varmint tried to make out, Mr. Sheriff," he reported. "We was there a-talkin' away and watchin' the entrance, when a man comes slinkin' along out o' the darkness, peers out at us, and lifts his revolver. It was Jacques what took a pot shot at him, and I see'd the bullet splash on the rock by his head, and our chap turned and went off like greased lightning."

The Sheriff at once went to the telephone hut near at hand and called up the parties at the other exits and warned them to be on their guard.

"You'd best get some sort of cover," he told them, "so that if the fellow tries to break out he won't have a clear shot at you. Me and my mates here are going in to search for him, and just before we move off I'll send another 'phone message to you. Keep a bright look-out."

It was perhaps half an hour later that the messenger, whom they had dispatched to the bottom of the mountain by means of one of the mine locomotives, came back on the foot-board of that same wagon bearing sundry pairs of rubber-soled shoes with him and a couple of electric torches, also he carried a basket of food and a couple of water-bottles.

"Seems to me, boss," he said, addressing the Sheriff, "that you folks might be some while in the mountain; it ain't altogether a small place, now, is it? And ef you get on the tracks of this here chap what's murdered Charlie, you won't be askin' to come back just to get a bite of food or a drink of water. You'll want to trace him and perhaps drive him out to one of the watching-parties. Ef that's so, it occurred to me that some meat and bread and a couple of cans of cold tea would meet your ticket, and here they are. Now I'm a-goin' to put on one o' these pairs of shoes, for I'm one o' the party."

It took quite an amount of argument to settle who were to go and who were to stay behind to watch the entrance into which Jim and his friends were to penetrate. Naturally enough the Sheriff must be one of the little adventurous band, and Larry was an indispensable. Jim, too, must go, for he was to guide them; and Dan would be there to assist him if need be, or to replace him in case he became a casualty. But the remainder clamoured to accompany them; and it took not a little persuasion and tactful chatter on the part of[Pg 35] the Sheriff to pick his men and to decide who should be of the party.

"It stands to reason, boys," he said, "that we are all doing our duty whether we go in or stay out here. You've seen for yourselves that this here chap we're after won't stand at anything: if he comes into the open he's as likely to shoot at you as he will at us who are goin' in after him, only, of course, I admit it's slower work stayin' out here. Guess you've put me up as Sheriff so as I should be able to talk when times like these come round."

"You bet!" they admitted, nodding their heads.

"Then I'm goin' to give orders right off. Larry and Jim and Dan and me, and Jacques there, and Tom Curtis will make the investigating-party; t'others waits here and takes cover under boulders. Our friend Tim, what's been round the mines these many years, will take charge of the lot of you, and will post a man at the 'phone ready to call up the other parties. This here young fellow, Harry Dance, will follow us in five minutes after we've started, and when he's gone for five minutes, this here Tim will make in after him, and ef we are longer still, and moving up, Frank Stebbins will take the track into the mine so as to keep in contact. It will be a sort of relay business. Ef we get held up, the message can be passed back, and ef we want help some of you can come in after us. Only mind, there's always got to be a guard standing here in case the fellow doubles; for you've got to remember that in the workings in there there are burrows in[Pg 36] all directions, and a man can leave the main gallery and turn and twist and come back on his tracks and easily avoid a search-party."

Donning the rubber shoes which had been brought for them, and each of them tucking a portion of bread and meat into his pockets, while Dan and the Sheriff shouldered the cans of tea, the party saw to their weapons. Jim made sure that the electric torch he carried was in working order, and thrust the reserve one in his pocket. Then, at a nod from the Sheriff, and a cheery "Good luck!" from the party who were to remain behind, and who watched their departure ruefully, Jim led the way into the mine, and presently he and his friends were swallowed up by the darkness.

There was dense opaqueness within the bosom of the gigantic mountain which the industry of man in Utah has honeycombed with passages, and once the search-party, with Jim at the head, had gained some distance from the exit and had turned abruptly to their left, thereby cutting themselves off, as it were, from the few stray rays of daylight which filtered in through the arched entrance, the darkness seemed to become accentuated, while the silence was positively startling.

"Stop!"

Jim touched the Sheriff on the sleeve, and the latter signalled to the next man behind him, and so they all came to a halt. There they stood listening for three or four minutes.

"Pat-a-pat! pat-a-pat!" they heard, and then a deep splash. "Pat-a-pat! pat-a-pat!" once more, and then a bubbling sound, only to give way to that same refrain: "Pat-a-pat! pat-a-pat!"

"It's——!" gasped the Sheriff, for he was an open-air man, a farmer in the neighbourhood, and these inner workings rather tended to overawe him. "What is it?" he whispered.

"Water falling from the roof into a pool; there's lots of it," Jim told him, sotto voce. "Come along!"

Once more they were threading their way onward, each man with his left hand outstretched, feeling the damp, roughly-hewn side of the tunnel, while with his other hand he held the tail of the coat of the comrade in front of him. As for Jim, he gripped the electric torch in his right hand, ready at any moment to switch the light on and project the beams in any direction. A hundred, two hundred yards they gained, five hundred yards, without having heard a single sound to disturb them, save occasionally that pat-a-pat, the often tuneful dripping of water from the roof into some rocky pool beneath, water through which their feet splashed when they came to it. Then of a sudden a rumbling roar smote upon their ears, advanced swiftly towards them, met them, as it were, and then, racing past their ears, went on along the dark gallery, and so towards the open, bringing the party to a halt.

"A shot," Jim whispered. "That fellow's fired his gun somewhere on beyond us, and a goodish way, I'd say, for the gallery carries sound like a speaking-tube, and you can hear a man shout, for instance, more than a quarter of a mile away. Let's move forward faster."

"Get in at it," the Sheriff answered.

And then they were moving again, on through the darkness, stumbling over rough tram-lines, through pools of water, over fallen boulders, round acute corners, and so on and on, while behind them[Pg 39] first one and then others of the party they had left at the entrance crept in, forming that communicating chain which the Sheriff had so thoughtfully ordered.

"H—hush!" The Sheriff's bony fingers gripped Jim's arm, and, unmindful of the fact that darkness surrounded them, he stretched forth his other hand and pointed into the void in front. "The varmint's there," he whispered hoarsely. "I heard him move. Listen!"

Yes, something or someone was moving. Whether in the near distance or far it was impossible to state definitely, though every member of the search-party stretched his ears to the fullest extent and listened eagerly, head forward, horny palm making a funnel in the endeavour to catch more sound waves, and so to unfathom what was then a mystery.

"Pit-a-pat, pit-a-pat!" went those lugubrious drops into the pools of water underfoot, "pit-a-pat!" they tumbled from the arched roof of the gallery on to the persons of that listening search-party, while water streamed down the rough-hewn sides and dribbled over the fingers which they had placed there to guide them.

Yes, someone moved.

"Farther along," Jim hardly whispered, tugging at the Sheriff's coat. "Let Larry come along!"

The giant form of the Sheriff unbent a little when he turned, stretched out a hand and gripped that youth by the shoulder.

"I heard," came a whisper. "I've got me gun, and all's well. You get in, Jim, I'm following."

The party they left heard them stumbling along, their feet making mysterious sounds as they splashed along the floor of the tunnel, and then of a sudden the blackness in front of them was illuminated by one piercing beam which cut its way through the darkness, its edges brilliant, its centre blurred. That beam hit upon the dripping side of the tunnel some yards ahead, painted a brilliant circle on it, hovered to one side, then flicked back, and later showed in its very centre the figure of a man bent almost double crouching beside the wall, a metal object on one knee gripped by one hand, an object which reflected the beam brightly.

"It's——" shouted the Sheriff, and then a sharp crack from a revolver drowned his voice and stunned the ears of all present. They saw the flash of the weapon, and a moment later watched as the crouching figure darted along the side of the tunnel, and swept round a corner, while a second shot, a second reverberation, wakened the echoes, and a bullet flicked a piece out of the edge of rock round which that crouching figure had doubled.

"Come on," shouted Jim, while Larry beat himself on the breast, vexed that he should have missed such a shot.

"It's the light," he cried angrily, "it put me out; I wasn't expecting it. Seems to me I'd better have a torch, too. Here! hand one over, Jim,[Pg 41] then I shall know when to put it on and be ready."

For five minutes or more they struggled on, running at times, and then halting to listen. Finally Larry clapped a wet and perspiring hand on Jim's shoulder.

"Gee!" he said; "it ain't no good, this here runnin' up and down like rabbits. Every time we moves the fellow hears us. This party's too big. Let's divide, or, better still, supposin' we post sentries who will block the tunnel. You see the skunk we're after is mebbe bolting round and round in a circle."

"That's true," Jim assured him. "There are burrows leading in all directions here, and it's not at all difficult to miss anyone."

"Particularly if you're anxious to avoid a meeting, same as this white-livered German," grunted the Sheriff, who was panting after his exertions.

"And you've got to remember," said Larry, "that every time we moves he hears us. Listen! There, didn't I say so? That's the varmint we're after, and mebbe he's two or three hundred yards away, yet you can hear his feet splash in a pool of water."

There echoed along the wet walls of the gallery the sound of a distant splash, and then there was silence for a few moments, broken again by the clatter of someone's heel against a piece of rock.

"Same as he hears us," growled the Sheriff. "Larry's right, and we've got to break up this party. Well then——?"

He plucked at Jim's shoulder, and the latter at once responded.

"Larry and Dan and I will go on," he said abruptly. "You, Mr. Sheriff, and the others had best divide into two—half here and half farther back. That may trap the fellow we're after. Meanwhile we three who are going on can crawl very carefully and slowly beside the wall of the gallery and halt after a while. If we hear our man we will try and get nearer, but our main object will be to get him to move nearer to us, then we'll have our lights on him in a moment."

"Not forgettin' guns," laughed Larry, "not forgettin' this here, this shooter! It's just horse sense that, Mr. Sheriff. Jim's been long enough in the mine to know his way about, and he's listened hours and hours, same as me, and knows what it is to hear a man a-comin'. When he sits down and listens to you movin' along to him, and it's a case of shootin' between two people, it's the man who sits tight and does the listening has all the chances. Shucks! Jim's given us an idea what's worth followin'."

It took but very little time to make their preparations, when Jim and Dan and Larry again crept away, this time at a much slower pace, halting when they had proceeded some two hundred yards. Here they were at a point where a smaller gallery left the main one, and ensconcing themselves at the entrance they lay down and listened.

"Seems to me as the skunk's got right away,"[Pg 43] said Larry, his patience nearly exhausted when they had lain there nearly half an hour and not a sound had reached their ears, save those made by their distant friends who were patrolling the main gallery, "suppose——"

Dan gripped him by the shoulder.

"H—h—ush!" he whispered.

Jim pushed his torch forward and made ready.

"Aye!" grunted Larry, and then there was a faint click as he prepared his revolver.

"Wait!" Someone was coming toward them. A sound of stealthy footsteps reached their ears, though whether coming from the left or the right was at that moment uncertain. Peering in both directions, the three lay there with bated breath, endeavouring to remain cool and yet almost trembling with suppressed excitement. Then, of a sudden, the sound of a splash only a few yards away arrested their attention, and caused them to start to their knees. An instant later their two torches cast beams into the gallery, and centred themselves with a flash upon an individual creeping along some twenty yards from them. It was the German without a doubt, hatless, dishevelled, sopping wet, and bearing a haunted, hunted expression. He blinked as the light fell full in his face, and then snatched at a weapon which he held concealed in a pocket. At the same moment Larry's pistol spoke, and with a howl the man dropped his left arm helpless beside him. But a moment later a flame flashed from beneath his coat, and one of[Pg 44] the three fell with a dull thud on to the wet ground which floored the tunnel, his fall pushing Larry aside and upsetting his aim so that his second bullet went wide of the mark. A moment later the man was gone, and could be heard scuttling along into the distance.

ONE OF THE THREE FELL WITH A DULL THUD

"Show a light," said Jim hoarsely, as he bent over Dan's prostrate figure; "where's he hit, Larry? Ah!—look!"

Beneath the wide-open shirt which Dan wore there was a splash of colour extending over his broad chest, a splash of red running down beneath the cotton. The young fellow's eyes were closed, his face, brilliant in the rays of the electric torch, was desperately pale, while he seemed to have ceased breathing.

"Hard hit!" said Larry. "If I don't rip the heart of that darned German! And next time I don't shoot only to wound, to make him helpless, same as I did this time, I shoot to kill, Jim, shoot to exterminate the varmint."

They debated for a while what they would do, and then whistled for the Sheriff and his party to join them.

"It's a bad do!" the latter said when he came up and looked at Dan, bending over him and feeling his pulse and then counting his breathing. "Hard hit, as you say, Larry, but he's young and strong and ain't taken to liquor; if anyone can pull through it's Dan. Only, he's got to get every chance, which means that the sooner we've got him[Pg 45] out of here the better. Let's carry him, boys; later on we'll hunt out this German."

"Later on?" said Jim, who had now recovered a little from the shock which Dan's condition had caused him. "No, Mr. Sheriff, I'm going on at once, there's no time to be lost, for when it gets dark a fellow's chance for creeping out of the mine will be enormously improved. I'm going to hunt him down and either shoot or capture him, which it don't matter."

"Same here," declared Larry, "same here, Mr. Sheriff; now's the time, as Jim says. We've winged our man, and chances are he's bled quite a heap and will be weak like and more easily taken. If we wait till to-morrow he may have got away or got his arm tied up, and be in better shape to meet us. Now's the time. You pull out, Mr. Sheriff, with Dan, for the boy's life depends on it; me and Jim's goin' forward."

They parted, the Sheriff and his men to pick Dan up with every care and bear him along as gently as they could to the entrance; there he was put in a car and hurried down to the mining hospital below, where, in case of casualties occurring, the surgeon was already in attendance.

"Hum!" he said; "a close call, Mr. Sheriff. I don't know! I don't know! Indeed," he continued, shaking his head as he bent over Dan's almost lifeless figure and put his stethoscope to his chest, "slick through—small-calibre bullet, and not over-much bleeding. Missed the heart by two or three[Pg 46] inches, which is lucky. Well, it might have been worse, Mr. Sheriff, it might have caught him right through the heart, or that bullet might have lodged in his lung and set up no end of trouble in the future. If he lives for a few days, he will pull round. You and your men get off now and leave Dan to me and the nurses; but——" he shook his head again, "but, Mr. Sheriff, don't count on anything wonderful."

Meanwhile, Jim and Larry had pushed on resolutely into the darkness of the tunnel.

"Hold hard!" said Jim after a while, when they had crawled some distance and had listened on many occasions, only to hear nothing which told them of the near presence of the man they were seeking.

To be sure, there came to their ears the steady dripping of water as it splashed into the inky-black pools on the floor of the tunnel, and now and again a distant echo which reverberated gently along the whole length of the gallery.

"It's the Sheriff talking in that big voice of his to the men in the opening," Larry explained. "This here tunnel's like a speaking-tube. Well, what is it, Jim?"

"I've been thinking. This is like hunting for a needle in a bundle of hay. We've nothing to go on, Larry, except sounds, and they're uncertain; it seems to me that we must pursue a different course."

"A different course?" asked his companion, a little astonished. "How? which way?"

"I don't mean in direction; I mean course of action. See here," said Jim, "you've winged the German."

"Winged!" said Larry, his tones now those of disgust. "If I was worth a cent with a gun I'd have drilled a hole clean through him. I could 'a done, Jim. Ef you was to put up a dollar at ten paces distant, end ways on, I'd hit it slick ten times out of ten, and I ain't boastin' now——" he ended, with a low hiss of annoyance.

"Everyone knows what you can do, Larry," Jim told him. For indeed Larry's prowess with a revolver was known throughout the mine.

"If you couldn't shoot straight you wouldn't have been able to hit his arm; for you've told us you meant only to wound him. Of course I understand that you wish now that you'd killed him, for then Dan might not have fallen, but you've winged him and probably he's bleeding. Perhaps if we use our torches, we shall be able to follow a trail if by chance he's left one."

The suggestion cannot be described as one of any brilliance, for indeed it was so very obvious; yet in the excitement of the chase it had not occurred to either of them before, and now the prospect it offered caused Larry to grip Jim by the shoulder eagerly.

"It's it! Gee," he whispered excitedly, "ef it don't offer the only chance! And then?"

"And then," said Jim, "if we get on his trail we shoot off our lights and go forward say twenty[Pg 48] yards and pick it up again. In that way, sooner or later, we may get him cornered. He'll shoot."

"Aye, he'll shoot," agreed Larry, "and we'll chance that, Jim. Only, if the chance comes, you can lay it that we'll flatten out our man with one of these bullets. Pity you ain't armed, Jim, you ought to 'a had a gun along with you; but you ain't fearful."

"Fearful! Let's move on. Now search the ground with your light."

It was not until ten minutes or more had passed that the two as they crept along the floor of the gallery came upon a patch brighter than that they had been traversing, and here on the wall, about three feet from the floor, there was the impression of a hand—a blood-stained impression. For the outline of the fingers and the palm of a man's hand were imprinted upon the stone in a brilliant red—sure sign that the German had gone in that direction.

"And here's his boot-mark in the mud at the foot of the wall," said Larry, pointing it out to Jim, "and right here's another and another. He was going along this way. See, here, Jim," he whispered, putting his lips close to the ear of the young fellow who was his companion, "ef it was me alone as was leading this expedition, I'd turn off me light here and get ready with the feet. I'd move along quick, say a hundred yards or more, and then lie low and listen."

"Same as I was going to suggest," Jim [Pg 49]answered. "Come on, let's hold hands so that we don't get separated; and after this, not a word, not a sound!"

Hurrying forward, they stopped again when they thought they had covered the distance agreed upon, and then sat down with their backs against the wall of the gallery, listening and waiting. It was some ten minutes later that the faintest whisper of a sound was heard, a whisper which appeared to be approaching them, although that was a matter for conjecture. They listened intently till both were certain that someone was approaching them, though whether in the gallery in which they themselves were waiting, or in some other of the numerous burrows which honeycombed the mountain, was a matter they could only guess at. Then, of a sudden, they became aware of the fact that whoever gave rise to the sound was very near them. Almost instantly they switched on their lights, and just as rapidly one of them went out, while at the same moment Larry gave vent to a shrill exclamation, and a flash of flame on the far side of the gallery and a loud report accompanied the cry he gave.

When Jim contrived to turn his own torch on the point where the flame of a pistol-shot had illuminated the darkness, the tunnel was bare, there was not a sign of anyone, though rapidly moving away were the sounds of retreating footsteps. By his side lay Larry, groaning and muttering and growling.

"Guess that there fox has managed to do us in again," he managed to tell Jim. "You lay hold o' me, young fellow, and carry me under yer arm. I'm only a small bit of a chap, and of no great account, but, Gee, if I get hold o' that chap! If I ever gets square face to face o' that feller!"

It was indeed a sorry finish to what might have been quite an exhilarating affair. Undoubtedly the German had got the better of the bargain. In some uncanny manner, indeed, he had contrived to hoodwink all his pursuers, and late that night was clever enough to slip out of one of the exits and escape from the mountain. All that could be heard of him after that was that he had managed to reach the Pacific coast, and had taken ship no doubt for Germany. One clue he left: a photograph of himself, which was found in his lodgings. Below the portrait the man's signature was scrawled in a calligraphy decorated with many flourishes.

"Perhaps we'll see him over t'other side," said Larry, a few days later. "Guess we'll find no difficulty in recognizing that ugly mug wherever we come across it."

"And I just hope that happy meeting 'll come along pretty quick," agreed Jim. "As soon as you are fit to move we'll get off there and make tracks."

"Aye, aye, make tracks!" cried Larry, for they had talked the matter over and decided to leave for France at the very first opportunity. "Our chaps will be trained over this side," Larry had[Pg 51] said, "but that's too slow a job for me. Reckon a man as can shoot same as I can, and same as you, will be useful over yonder. Pity Dan can't come."

Dan couldn't, and indeed would hardly be fitted for the duties of a soldier for many months to come, for the German's bullet had wounded him severely. But his place was taken almost at once by English Bill, a mere stripling.

"Son o' Charlie, down in the saloon in the camp," he told Jim. "You see, mother's an English-born woman; father came over here seven years ago, leaving me and mother to follow. I've been here just a year."

"Just a year!" repeated Larry, looking the stripling over. "And what may be your age, young feller? Yer size and yer cheek, don't yer know, make yer out to be a good twenty; yer face, and what-not, says that yer barely eighteen."

"Seventeen this last fall—old enough to come along o' you and do something to them Germans," came the quick answer. "I can shoot, too, Larry. You ain't the only one that knows how to hold a gun. Father taught me. Besides, didn't this low-down hound murder him? Wasn't he a German agent? Hasn't England been fighting Germany this last three years? What's the good of me here then? I've something to do in France, same as you have. I'll come right along."

And come right along English Bill did, stripling though he was, and made quite an excellent [Pg 52]companion for Jim and Larry. Indeed the three of them were to meet with many adventures before they reached France itself, and there, with British and French and American troops round them, were to see quite a deal of fighting.

It was three weeks after the affair of the copper mine and the runaway German, and of the murder of Charlie by this unscrupulous agent of the Kaiser, that Jim and Larry and the juvenile English Bill—William John Harkness—made definite plans for their departure.

"Yer see," said Larry, as he stood, hands thrust deep into the capacious pockets of his trousers, his head tilted forward, and his cap over his brows, "yer see, young feller, it ain't been possible before to get a move on. There's been—there's been things to do," he said rather lamely, a little diffidently.

"Huh!" Jim merely nodded and looked a little askance at Bill, who, like many a youngster, coloured as his deeper feelings were stirred.

"Yep," he blurted out a minute later, though the two of them saw him gulp. "Yep," he repeated, aping the speech of Larry; for Larry and Jim seemed to this young English lad personalities to be envied, admired, and copied. "There's been things! The burial of Father, for instance, the winding up of affairs."

"Aye," grunted Larry, "the winding up of affairs, and yours have been important, Bill."

Jim nodded, and again the young fellow beside them flushed. Indeed, the winding up of his personal affairs had been to him, if not to the others, quite a big concern, which, coming very fortunately for him immediately after the death and burial of a father whom he admired and respected and cared for deeply, had helped to distract his grief from the loss he had suffered.

Curiously enough, it turned out that Charlie, the bar tender, was by no means bereft of this world's goods. It should be noted that bar tending in America is a highly-thought-of occupation, controlled by its own particular Union, demanding high wages, and the best of surroundings and conditions. Add to this that Charlie, popular with all with whom he came in contact, was a man possessed of no small intellect, and one can gather good reasons for his becoming affluent.

"A man can work quite contented at what seems a subordinate job, young Will," he told his only son soon after he had joined him from England. "I don't mind saying I could give up this work to-morrow if need be, and live perhaps at ease like what's sometimes called a 'gentleman' back in England. But I ain't the one for living at ease. Work's what I like, and plenty of it, so long as it's congenial; and here it's that all the time. And mark you this, lad, I'm a teetotaller, though I do serve drinks over a bar, often enough to rude[Pg 55] miners. But I was sayin', a chap don't need to leave his work if he likes it, and working behind a bar don't prevent me from making a way in other directions. There's mining shares to be bought by the chap that's saved; and I've bought 'em. If yer mother had lived, she could have gone back to England and aped the lady. There's been ranch shares to buy, and them too I've taken a liking to, and done well with 'em. Think it out, me boy, a man thrifty and careful, and who works steadily most every day and most hours of the day, will have dollars to spare to put into work that other men are doing; and so it goes on till one day he turns round and finds that he's got quite a tidy sum tucked away to cover the time when he's too old for working."

It was that "tidy sum" that Larry referred to when he said that English Bill had had "affairs" to clear up, and it was those "affairs" and the attorney to whom Jim introduced him that distracted Bill's attention from the loss he had suffered, taking his mind from the gruesome act of that rascally German and forcing him to concentrate on other more humane affairs. Now everything was cleared up, the estate of the murdered Charles was either sold already or being sold, the money was banked, and there was no longer any need for Bill to be in attendance. As for Jim, he was satisfied that Dan was progressing, slowly, perhaps, but surely.

"Though he won't be fit for months yet," the doctor told him. "As it is, he's had as narrow an[Pg 56] escape as you could imagine, and it'll be months before he's able to run about, which means that it will be months before he finds his way to France to take part in smashing that villain of a Kaiser. Aye, villain!" he cried, bringing a fist down with a bang on the edge of the operating-table. "D'you think we over here don't know? Haven't I friends, American doctors, that have been over in England these months past, who joined up to help the British Medical Service? Haven't they been in France? Aren't there friends of mine who have been working for months in the French hospitals? And what's their tale?"

If Jim had waited to hear the whole tale—for the doctor was notoriously garrulous—he would have heard much that he had already read, and would certainly have gathered some new information: news of shattered villages, of smashed châteaux, of a country ravaged wherever the Hun could reach it, of the Cathedral of Reims levelled almost, of poisoned gas projected at French and British, of dastardly acts in all directions, of the bombing of towns and villages, and the slaughtering of women and innocents. But Jim knew a lot about it himself. It had not required the dastardly act of that German who murdered Charlie to rouse him to a state of indignation, to make him swear to leave for France at the earliest possible opportunity. He had read of the ravaging of Belgium; he too knew something of the diabolical acts of the Germans to their British and French prisoners. Besides, it did[Pg 57] not want a very wise man to realize that the German was no ordinary combatant. He had not hesitated to break every rule of warfare. Was not one of his infractions of the general usages his new, widely proclaimed intention to torpedo and submarine every ship afloat, whether it carried women and children, or whether only merchandise?

Jim knew his own mind, like thousands and thousands of other Americans. He had only waited the word of the President of the United States. That word was spoken, and nothing now could hold him back, after the personal experience he had so recently met with.

"Guess we can board the train to-morrow," said Larry, pushing his head a little farther forward and looking at Bill in such a truculent way that one would have thought that he meant to be pugnacious.

"Yep—the 5.45 out," came the answer. "Bags packed; got some dollars in my pocket, with a draft on a bank at Noo York."

"And then?" asked Jim, for, though the three had made up their minds to leave for France together, they had not yet discussed the details of their journey. It didn't seem to matter, in fact, so long as they did reach France, and at the earliest possible moment.

"And then?"

"Oh, and then? Yep," said Larry, opening his lips, shutting his eyes, and then grinning inanely at the two of them.

"Yep," he repeated, and looked hard at Jim.

"Yep," said Bill, looking in the same direction.

"And then—oh!—and then," said Jim, scratching his head, "well, let's get there," he added in the most practical voice. "The train will take us there without any bother, and once on the spot we'll be nearer the coast—on the water, as you might say—and could really get a move on about sailing."

See them then on the cars en route from Salt Lake City, via the Canyon, to New York, where, in the course of four days, they put in an appearance.

"First thing is to fix up quarters," said Larry as he jingled a few cents in his pockets. "Time was when I come to Noo York and gone to the best hotel. That was in good times, Jim, when I was out for a holiday and didn't mind spending. But this is business; we're on a different jaunt altogether now. Say now, we'll make right down for the docks."

Taking their "grips" (hand-bags) with them—for, like many an American, the three travelled very light, and (porters not being in evidence at the stations as they are in England) were therefore not in any difficulty—they found their way to the cars (tram-cars) which plough in all directions through the old and new portions of this premier city of America, where once the Dutch held play, and where in their turn the British dispossessed them. Presently they were down in the docking area, with warehouses about them, the masts of huge ships projecting into the air—amongst them not a few[Pg 59] which were German. Larry jerked a somewhat dirty thumb in that direction.

"There's the Vaterland and what-not yonder," he grinned. "Ships nigh thirty or more thousand tons, what the Kaiser built to beat creation on the water. Guess they'll be American soon, if they ain't already."

"Not yet," replied the critical Jim, "though in effect they do belong to the country. I was reading in the news last night that Uncle Sam has put a guard upon each of the ships belonging to Germany, and that the crews which have lived on them all these months since the war began in Europe have been sent ashore. Pity is that in the meanwhile they've damaged the engines, though our workmen will soon make that good. And—who knows?—in a few months' time they'll be taking American soldiers to France to teach the Kaiser his lesson."

To Larry and Jim the sights they saw all along the waterside were novel, for, though Larry had been to New York before, and indeed had travelled quite a considerable amount in America, the water-side had never attracted him, but now that he was likely to embark for France, ships and all that passed on the ocean were a source of interest to him. To English Bill—young Bill as they sometimes called him—the sight was a common one.

"There'll be ships and ships going across," he told his two companions. "Store-ships filled with food, some for the Belgians, who are nigh starving, other store-ships with food for Britain, because,[Pg 60] you see, being an island with a big population, she cannot very well feed them all. Besides, as folks told me before I came out, she has these many years devoted herself to manufacturing all sorts of articles. She's allowed her land to go under grass, and hasn't been growing the crops that once she used to produce. There's the Argentina, there's America, there are the wide wheatfields of Canada to supply her."

"Or were," Jim said laconically, "or were, young Bill."

"Aye," agreed Larry, with a puff of the lips, "and will be yet, Jim. You are thinking of submarines. Well, it'll take all the submarines that the Kaiser's got, and a heap more, to keep America from sending food to our British allies. But you was talkin' about ships, Bill. What then?"

"There's others full of ammunition—ammunition made in American factories—going over to be fired by British and French guns. There'll be steamers and sailing vessels. Seems to me that, as not one of us three knows one end of a ship from the other, we'd better keep away from sailing vessels. There would be jobs, perhaps, aboard one of the steamers, and we might manage to get taken on."

"You! Take you on!" said a huge upstanding figure with a ruddy face, whose curly locks protruded from beneath the blue sailor cap he was wearing. "You!" he laughed, almost scornfully, and yet with a kindly note, as he stood over English Bill and peered down at this smiling youngster.[Pg 61] "Think as we've got jobs for such as you aboard our vessel!"

Then he laughed outright, and clapped a huge hand on Bill's shoulder.

"You'll be English," he said.

"Aye. English Bill, we call him," Larry interjected.

"British!" Bill fired out, "same as these here two, only they're American."

"American, of course," the huge sailor responded, looking a little puzzled. "But British? How?"

"He means," said Jim, with one of his pleasant smiles, "that America's allied with Britain and France and all the rest of the Entente against the Kaiser and his barbarians, so that we are all one and the same—all friends, all fighting for the identical cause. Besides, Bill and we two are chums, so it don't matter whether you call us all three Americans or all three British. I ain't ashamed of being one or the other after seeing the way Britons have shown up, have come forward by the million, have fought the Hun in France and many another place. After that, why, who's going to be ashamed of being mistaken for a Briton? Not me, eh, Larry?"

"Nor me neither," jerked the latter, his head thrust forward as was his wont, his cap tilted at a most dangerous angle, his eyes screwed up, peering at the big sailor. "See here," he said, "I like yer look, stranger. Yer come from aboard that ship, do yer?"

"I do," the man admitted, and then laughed[Pg 62] uproariously. "You three just take it! And what may be yer wants? This 'ere youngster you've called English Bill has asked for a job. Well, there may be a job—two or three of 'em; only what for? What's your game? There's talk of America adopting conscription, eh?" and he looked a little slyly at them—a little sharply at Larry and Jim, whereat the former actually scowled and then smiled.

"I know what you're thinking of, but it's natural. Down at the mines, if a chap had said that to me, most likely there would have been shooting. You are right, though. There has been men elsewhere, perhaps, that has tried to escape their national duty by slipping away from their country. Well, stranger, just listen to this. We three are bound for France. We're in a hurry to join up and get a slap in at the Germans."

Thereupon they sat down on the quay-side and told their story, to which the big sailor listened intently, sometimes scowling, then nodding his head in evident approval.

"Tom's my name," he said, when the yarn was finished—"Tom Burgan, but Tom'll be good enough for you young fellows; and let me say I like yer spirit. It was a pity, though, that you didn't nail that Heinrich. I should say that he was an enemy agent. There are lots of 'em in America, as you people must know by now, seeing the way there have been fires at works which have been manufacturing munitions for us Britons. What do they call that, eh?"

"Sabotage," said Jim.

"Aye, something of that sort," agreed Tom. "'Sabitarge,' let's call it. Dirty work, whatever you calls it. Pity is, I say, that this Heinrich escaped, 'cause he's free to carry on the same sort of work elsewhere. And he shot young Bill's father, did he? And he was a good man, eh?"

Bill's lips twitched; they always did when his father was referred to.

"A good man, Tom!" he ejaculated; "there never was a better."

"And proudly spoken, too. Happy's the man that knows that his son will say that of him. Well, let's hope you'll meet this German again; only, look out for squalls if you do. As for the search you made for him, it must have been tricky business in that mine. It must have been nervy sort of work seeking for him in those dark passages. And now you're looking for more trouble. That don't surprise me. Every man that's the proper age—and the younger and more active he is, the sooner he seeks it—seeks for something over in France, on the high seas, or elsewhere, some job that he can do to put a spoke in the wheel of the German Emperor dominating the world. Well, he flooded the sea with his submarines to keep all ships from sailing. Ho, ho, ho!" laughed Tom uproariously, disdainfully, and the trio who listened to him joined in heartily. "But come aboard; we'll go and see the old man."

"Old man?" said Jim.

"Aye, old man," Tom repeated, winking at Bill, who evidently understood the meaning of the words he had employed.

"Old man?" said Larry, a puzzled look on his face. "See here, Tom, and no offence meant, I don't want to be serving under no old man."

"You come aboard," said Tom, gripping him by the shoulder and lifting Larry to his feet as if he were a child or a doll or some quite inconsiderable person. "The old man's my skipper. 'Old man' stands for skipper in the navy. You'll find him young enough even for your liking. Step aboard."

"Af'noon, sir," he said, addressing a dapper, clean-shaven, nautical individual who at that moment emerged from a companion and stepped on the deck before them. "Here's three who wants to make for France to fight the Germans. There's three jobs goin' aboard, for you're short of your complement by that and more. How'll they do? This 'ere lad's English to his toe-nails."

"Oh!" The nautical individual looked Bill up and down in that swift way that officers have, and seemed to take in every tiny feature. "To his toe-nails," he tittered, for Tom was quite a character aboard the ship, and could take certain liberties with his officers.

"Aye, sir," repeated Bill, liking his look, "from the hair of my head to the soles of my feet, and these two are Americans, just as much American as I am British."

"And what can you do?" asked the Skipper, for it was he undoubtedly. "This young fellow," and he pointed to Jim, "looks strong and steady, and could do almost any job aboard. Young Bill, here, will fit in almost anywhere, but you——" and he pointed a finger at the diminutive Larry. Even to be unusually kind to him and a little flattering, Larry, with his small attenuated figure, his ill-fitting clothes, his absurdly big head, and his somewhat buccaneering appearance, was anything but an attractive object, and certainly looked as though he were hardly capable of strenuous work. "But you——" repeated the Skipper; "now I have my doubts!"

It was like Larry to fire up at once.

"Doubts! See here, Old Man," he growled.

Whereat Jim put out a restraining hand, and Tom, enjoying the joke, roared heartily.

"He can do a day's hard work with anyone, yep," said Jim; "and if you was to get into any sort of trouble this here Larry would be a good man: he can shoot, he can. When we're out at sea he'll give you a show, and if it's a case of hitting a dollar at ten yards or of perforating a tin that's thrown in the air, why Larry's your man. And he ain't so fierce as he looks, nor so delicate neither."