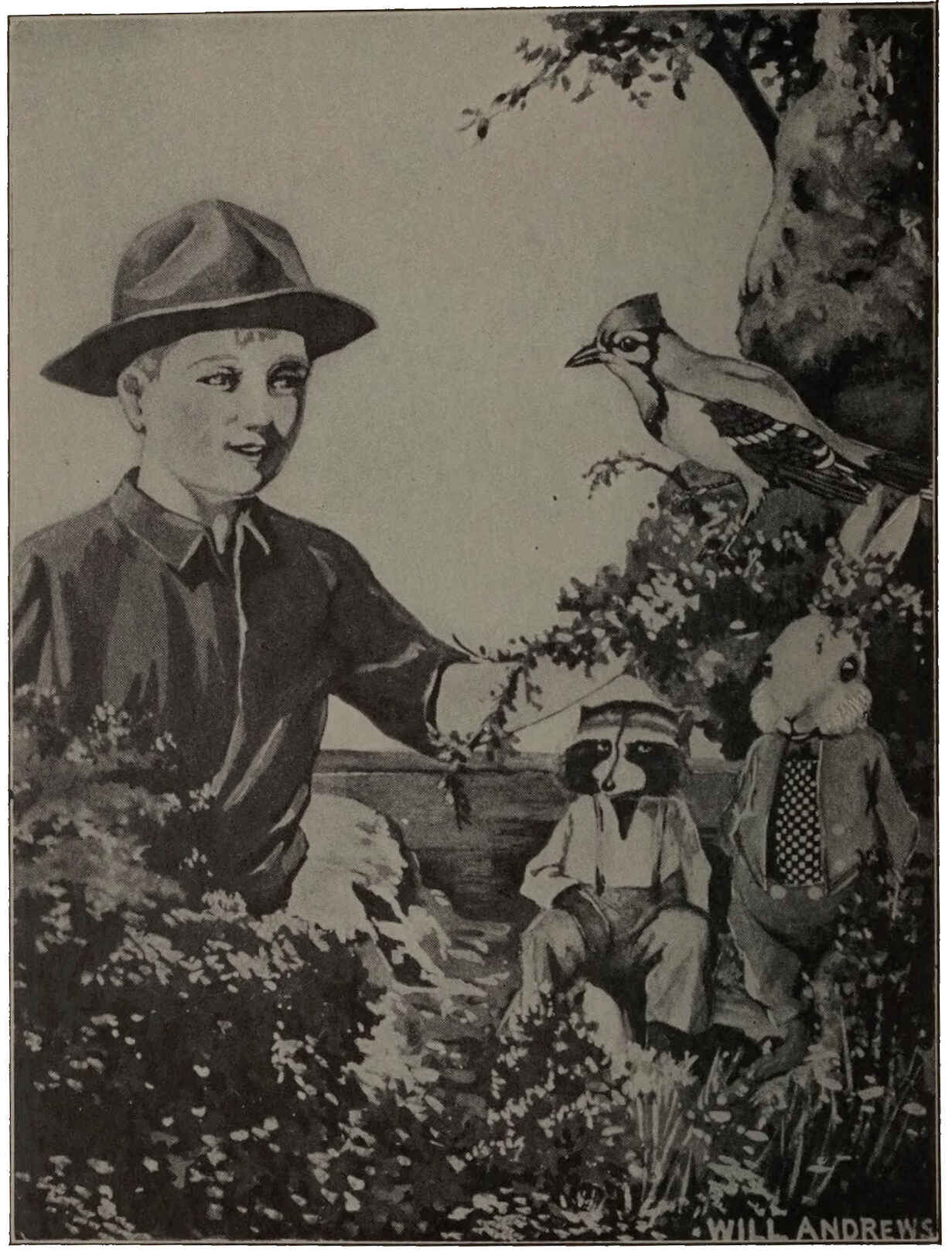

Louie Thomson and his tame Jay Bird.

Title: The Jay Bird Who Went Tame

Author: John Breck

Illustrator: William T. Andrews

Release date: February 17, 2021 [eBook #64586]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Roger Frank

Louie Thomson and his tame Jay Bird.

Prob’ly you’re all wondering what happened to Chaik Jay and Tad Coon when the big rain began to fall. Chaik had hurt his wing. He’d have had a bad time with it if he’d tried to stay in the pickery thorn bush, in the Quail’s Thicket, down by Dr. Muskrat’s Pond. Tad Coon knew a thing or two when he advised the bird to let Louie Thomson catch him. Well, when Louie burst into his mother’s kitchen with Chaik holding on tight to his fat, warm finger he was ’most bursting with pride. You know just how you’d feel if you were Louie. Chaik felt just a little fluttery, but he knew he was safe so long as the little boy held him. He waved his well wing and put up his crest, but he never let go his hold on the funniest perch he’d ever sat on.

Of course, Louie’s mother forgot all about the supper she was cooking. “Oh, wherever did you catch him?” she asked. “Isn’t he a pretty thing? I never knew they had purple on their necks—just like grapes hanging in the sun. How do you s’pose he keeps all that white in his wings so clean?”

“He takes a bath every morning,” said Louie. “I’ve seen him.”

Tad was out in the woodshed, by the pussycat’s dish, snubbing his shiny black nose against the screen. He was sniffing the hot Johnnycake he could smell baking in the oven. You know Louie promised him some—with syrup on it, too. Pretty soon Chaik had his beak pointed at the stove; he knew what Johnny cake was, because he’d had a taste of the piece Louie brought to the pond. He was ’most as interested as Tad Coon.

Then Louie’s mother smelled it. “Heavens!” she exclaimed. “I clean forgot my oven!” She opened the door and took the Johnnycake out, hot and steaming. Louie took a nice crusty corner, right away quick. Of course Chaik thought that this was the signal for him, so he picked up a crumb—and his eyes fairly popped because he wasn’t used to eating hot things. Then didn’t she laugh! “The smart thing!” said she. “He’s just like folks. But your pa’ll be here in a minute and he won’t think this kitchen’s any place for birds—not if I know him. Quick, Louie! Put him down cellar in the cage so the cats can’t get at him. Here’s enough for him and the coon.”

Down cellar they went, but Louie was careful to leave the door open so Tad could run down and see him. And Chaik didn’t mind the cage so very much.

In fact, he was as comfortable as though he’d been at home. More comfortable, maybe, because it was pretty scary sleeping in the woods with Killer the Weasel sniffing about to find his hiding holes. Anyway, he was too full and too sleepy to think about it.

But Tad Coon wasn’t sleepy a bit.

He licked the last crumb of Johnnycake, and the last drop of syrup Louie had put on it, out of his whiskers, and was just cleaning the stickiness off his little handy paws when he heard something that pricked his ears straight up. “Huh! That’s a funny noise in the henhouse,” he said to himself. “It isn’t Louie, and it isn’t his father—I believe I’ll take a look.” So off he marched, stepping most carefully in the hard middle of the path where the men walk so he wouldn’t make his tracks plain for any one to follow.

He thought about it because the evening was so dark he couldn’t see very far ahead of him, but he could smell plain as plain. It was so fresh and cool all his own fur wanted to puff out, but he wouldn’t let it; he didn’t want anybody to get a smell of him. Snf, snf, snf! “What’s that in the woodpile?” Over he jumped, so softly he didn’t make even the scritch of a claw, then——

“Hey! If this happened to our quail folk out by the pond there would be a fine goings on!” For it was the remains of a chicken. He craned his neck to see who had put it there, but he couldn’t notice anything but the feather smell. “That bird wasn’t killed to-night,” thought he. “That was last night’s work. It wasn’t any owl. It wasn’t a cat—they’re horrid, spitty creatures, but they don’t steal. Hist! I’ll know who it was in about two whisks of a mouse’s tail—he’s doing it again!”

Pit, pit, pit, he tiptoed over to the henhouse. All the birds were shrieking and cackling. “Help! Murder-r! Thieves!” The ones on the far-up back perches were squawking. “Spur him! Peck him!” But the ones who were down in front were only fluttering hard to keep high off the floor on their clumsy wings.

Tad squinted through a crack. He could just make out a limp white heap of feathers being dragged. He couldn’t see who was doing the dragging, but—sniff! He went galloping around and around the house whining: “Where did he get in; oh, wherever DID he get in?”

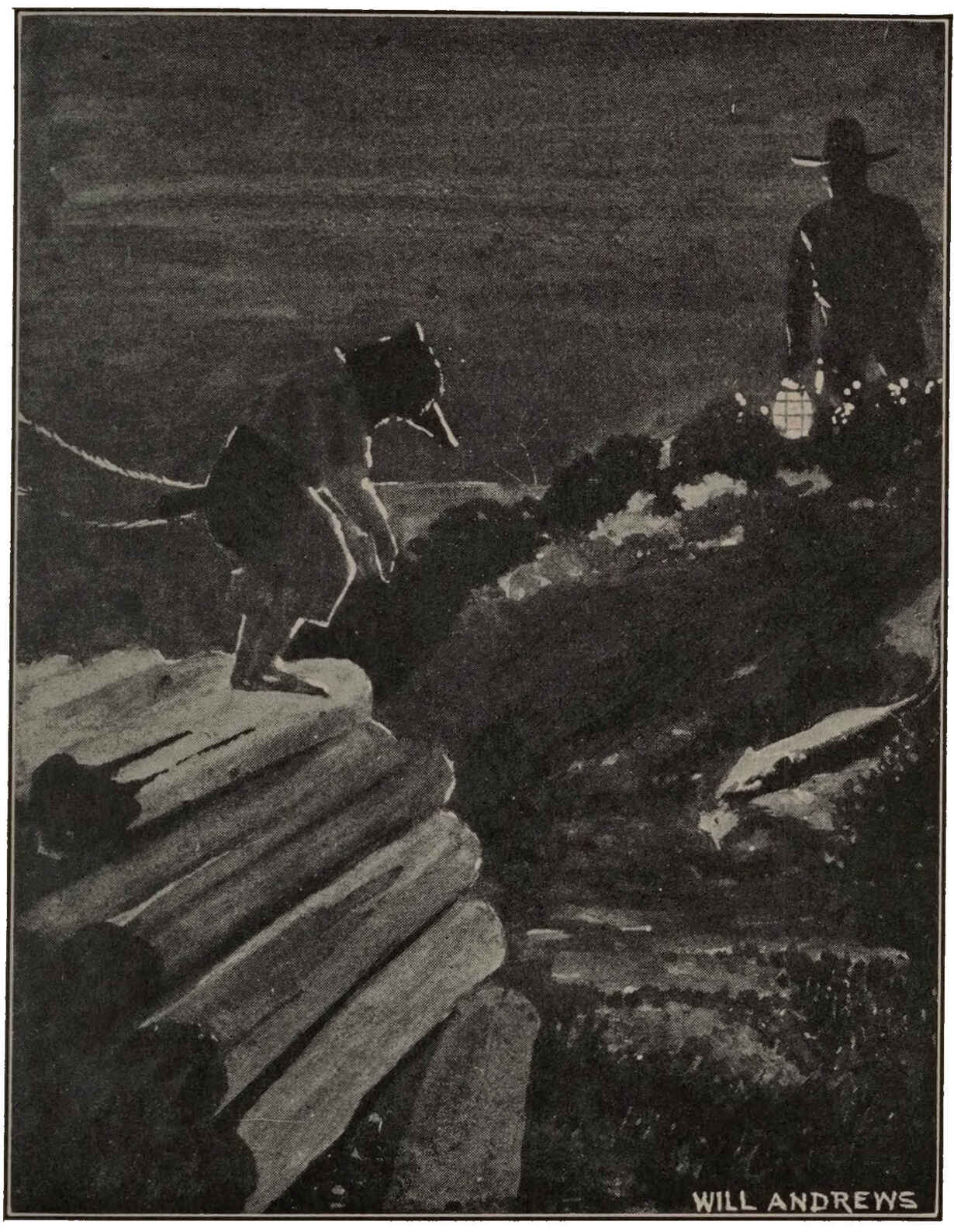

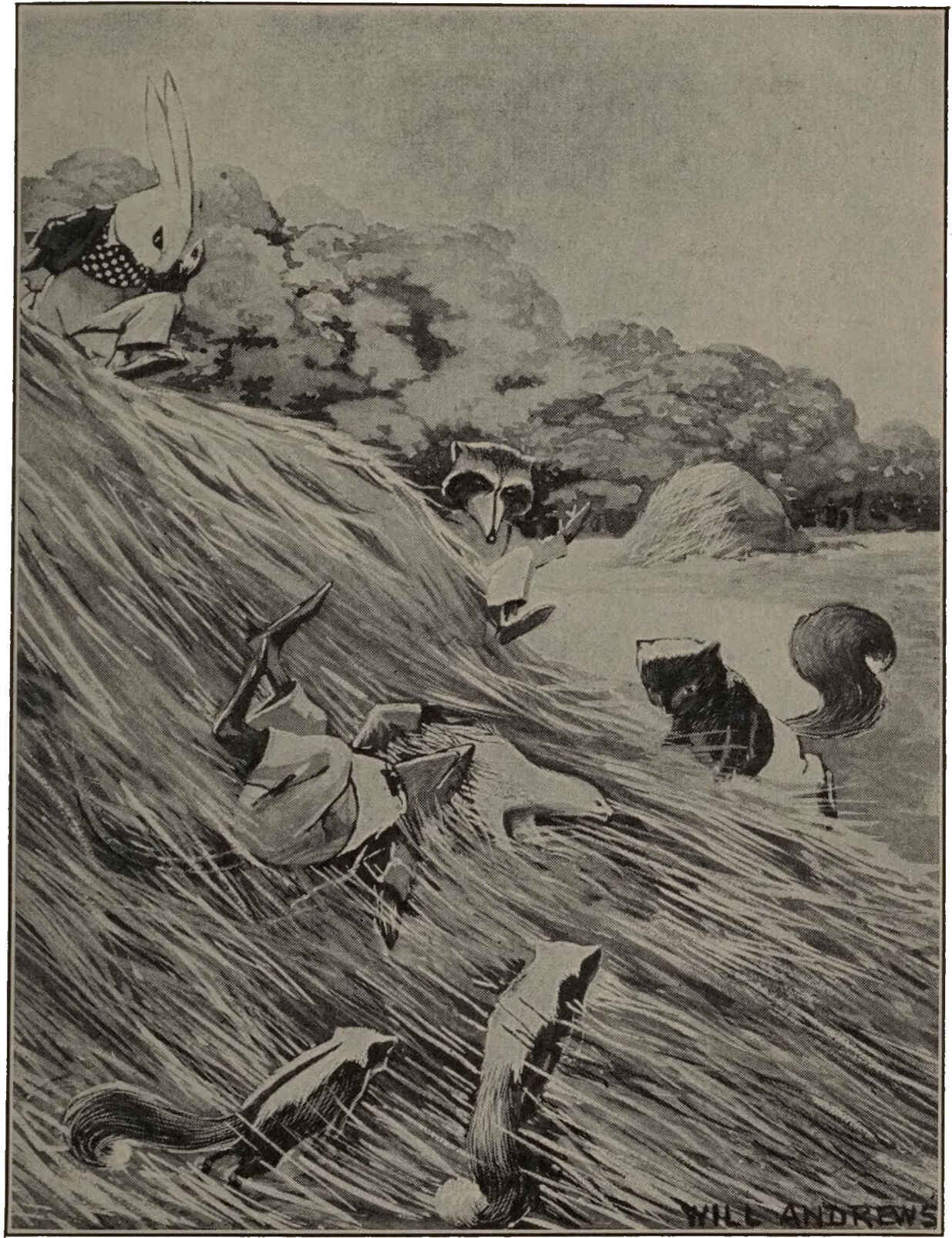

Tad catches the rat that was killing the chickens.

For that thief was the biggest, oldest, grayest rat he’d ever seen, and the wisest, too; he’d hunted right under the noses of Louie’s cats for so long he had a whole lot more tricks than Tad had hairs in his whiskers. But Tad played a brand-new one on him. Suddenly he stopped right still. “What a cub I am!” he snickered to himself. “Old Sharptooth will take that bird right back to the woodpile where he ate the other one. That’s the place for me to wait for him.” In about three jumps he was on top of it with his ears cocked, listening for the rat to come.

He was listening so hard he didn’t pay any attention when the kitchen door slammed. Louie’s father was going to take a last look at his barns to make sure the big rain that was coming wouldn’t do any harm to them, and Louie was with him to carry the lantern. He swung it as he walked and the light set all the shadows dancing. Tad Coon didn’t pay any attention to that, either; he’d learned all about it down by Doctor Muskrat’s Pond. But the rat did.

Pit-pat, pit-pat, swish. Tad could hear him coming, dragging his chicken. In one lantern swing his eyes lit up like the headlights of a little automobile, and he saw Tad’s ears, pointed right toward him. He dropped his bird and jumped at the very same breath as Tad Coon. In the next swing Louie Thomson’s father saw the white feathers lying on the ground—and he saw the fluffy tail and frilly fur pantaloons of Tad Coon diving down a big crown crock for a drain he was just going to dig.

“Here!” he roared. “That’s who’s been——” He was going to finish “killing our chickens,” and he was going to lay it to Tad Coon, but he didn’t have time. The crocks were laid out across the yard, ready to put in. The first three were so close together even a rat couldn’t squeeze out between them. Louie’s father caught up a shovel and slapped it over the open end of the third one.

“We-e-ak, we-e-ak, snarl, snap, scuffle, scratch, wee-e-ee——!” What a thumping and bumping was inside that crock! Then it was quiet. He moved his shovel to peek in. He looked into the smiley face of Tad Coon, but Tad’s smile had rat hanging down from either side.

“Well, I swan!” exclaimed Louie Thomson’s father. He said some more things like that; the words didn’t make much sense, because he didn’t know exactly what he did mean. But you ought to have heard Louie Thomson! “Hooray!” he squealed. “Hooray for my coon! That’s the rat we saw stealing an egg out from under the hen who set in the grain room last spring. It’s the very same one. You said he was too smart for the cats and they’d never catch him. But my coon got him! He sure did!”

“That’s some coon!” said his father at last. “Some coon! But how do you know he doesn’t kill chickens, too?”

“Because he’s friends with all the birds down by the pond,” Louie insisted. “I’ve never seen him eat a single one. Not even my jay with the hurt wing—I’m pretty sure he could have caught him just as easy as I did.”

“Your jay!” said his father. “Where do you keep him?” He thought he knew everything there was on the farm.

“Down cellar,” said Louie. He was just a little scared that maybe his father would be angry if Chaik made a noise, because he had got so angry when Tad Coon did. “He’ll be quiet—I know he will—but I couldn’t bear to leave him out in the rain. The minute it stops I’ll let him go again—truly I will.”

“Hm! First thing I know I’ll have a menagerie instead of a farm,” was all the man answered to that. “Give me the lantern. I’ll tend to locking up the barns so the doors won’t blow off their hinges. You take a couple of blocks from that woodpile and fix the cellar door so your coon isn’t locked out. I guess it won’t rain in. And put some corn down there. The mice are very bad again. He’s a mighty good beast to have around—that is, if I don’t catch him after my chickens——”

But Louie was gone to fix a fine place for Tad to hide from the storm.

Bang! Smash! Crash! Splash! The thunder roared and the lightning went scuttling and dodging across the sky as though it wanted a place of its own to hide and couldn’t find one. Chaik Jay woke up in the black dark and looked around. For a minute he couldn’t think where he was. He could hear the wind howling, but the stick he perched on didn’t move in it and his feathers didn’t ruffle. He could hear the rain pounding and not a single drop fell on him. He was perfectly comfortable, only he felt just a little scared and lonely, though he was still too sleepy to think why.

Pretty soon he heard a whistle. Then he knew just where he was. That was Louie whistling to let Tad Coon know he had left some corn by the cellar door for him.

I tell you Chaik was glad to know Louie was right there, almost beside him. He began to call and flutter his wings. “There, there, jay bird,” said the little boy in his very nicest voice, “I won’t forget you. Are you ready to eat again?” He rattled some seeds on the floor of Chaik’s cage. But Chaik went on fluttering. It wasn’t food he wanted, it was company. If he couldn’t have Tad Coon (Tad was still eating the rat) then Louie’s nice warm finger was the next best thing. Louie didn’t particularly like staying down there in the dark; it was nicer in the bright, warm kitchen. Besides, now he’d told his father about Chaik Jay he thought maybe he’d like to see the handsome bird. Maybe he’d make friends like he did with Tad Coon.

In about one minute Chaik was blinking in the light of the kitchen lamp. It was really very much like the lantern Louie had for his feast down by Doctor Muskrat’s pond, only there weren’t nearly so many beetles flying around it. That was because the screen kept them out, but Chaik didn’t know about screens. He had to leave Louie’s finger to catch that first beetle.

“I guess you couldn’t see to eat down there in the dark,” apologized the thoughtful boy, so he sprinkled some food on the table.

“Land o’ love, what’s that bird doing now?” Chaik looked up, but it was just Louie’s mother talking, and he didn’t mind her a bit. He went right on doing it. He wasn’t swallowing his corn whole. He was neatly turning back its shiny jacket and picking the little sweet heart out of each kernel. I tell you he was making a fine mess of that table—but who cared? Not Louie or his mother; they thought he was too smart for anything.

Chaik begins to find out that living with house-folks is really great fun.

Pick, peck, pick! Every once in a while he would give a shake of his head and scatter his little pile of grain so he could see the ones he hadn’t picked over yet. Louie and his mother were just giggling over his antics; but he didn’t care.

Puff! The kitchen door opened and let in a great gust of wind. It caught Chaik from behind; it spread out his tail like a turkey-feather fan and sent him skating and sliding because the table was covered with slippery oilcloth, and his claws wouldn’t catch. But the door closed right away and the wind was shut out again. Louie’s father had just come in.

Chaik wasn’t scared—he was cross, he thought they’d played a joke on him. He balanced himself on his feet and then he gave a big shake to settle his feathers. He looked around very severely, as much as to say, “Don’t you dare do that again. I won’t stand it!” Then he marched into a little shady corner on the window sill, behind the curtain, and sulked.

He sulked! That’s exactly what he was doing. But nobody paid any attention to him at all—which is the right way to treat any one who does such a foolish thing. Louie’s father sat down and opened up the evening paper. It made a fine crackling. Louie’s mother stirred up some yeast (it smelled like mushrooms) into the bread she was going to bake next morning. Then she began flouring the raisins she was going to put in it. Chaik began to get so interested in what was going on he forgot he was sulking.

First he peeked out from behind the curtain. Then he clawed his way sidewise across to the plate where the raisins were. Pretty soon he made a dive with his sharp beak; he did it so quickly she didn’t see what he was up to. Fine! Chaik liked that raisin. But he didn’t like it quite so dusty. He picked up another one, but he didn’t gulp it in such a hurry. He bounced it on the table to shake the flour off it again.

Louie started to laugh. “Shh!” whispered his mother. “Let’s see what he’s going to do next.” And what do you think that was? He began storing them away in his nice dark corner so he’d have some left for breakfast in the morning. He tucked a whole row of them into the crack of the window so neatly you could hardly see them. He began to find out that living with house-folks is really great fun.

All the time Chaik was hiding the raisins Louie and his mother were ’most bursting their buttons laughing at him. Louie’s father had picked up the paper while Chaik was sulking. And he dozed off in his chair with the paper in front of him all the time Chaik was stealing.

When his wife thought Chaik had enough for two birds, she whisked the plate away. He couldn’t think where it had gone to, because she did it when his tail feathers were turned. So he had to look for something else; he began trying experiments with the newspaper, pick, peck, picking, to see if he couldn’t get a taste of those little black specks. He didn’t know it was printing, of course; he thought those nice even lines were cracks and the little black specks were very neatly tucked in—so neatly it would be great fun to pick them out again. Pretty soon he got excited and used his claws. The paper began tearing; that woke up Mr. Thomson.

Slam went the paper on the table; that sent Chaik fluttering, but in a minute he was back at it again busier than ever. And when the big man saw him he burst out laughing—and he didn’t laugh very often. He laughed so hard Chaik scuttled back into his corner with his crest tucked down.

But as soon as Mr. Thomson picked up his paper again Chaik began to cock his head. “Eh?” he thought. “He’s hiding, too. He’s hiding from me!” Wasn’t he just conceited? Out he sneaked. Pick, peck, pick—he tore off the whole corner that time. Then he got his claws in it and danced around like a cat on a sheet of flypaper. That man reached out his finger, carefully as he could, and held it down so Chaik could untangle his feet.

Chaik misunderstood. “You needn’t be afraid,” said he in his politest bird talk. “I won’t peck you.”

Mr. Thomson misunderstood, too. He said: “The nerve of that bird! He isn’t a bit afraid of me.” So of course from that very minute they began to be friends—the first friend Louie’s father ever had among the Woodsfolk.

I don’t s’pose you could guess who had the most fun that evening. It wasn’t Chaik—but he’d have insisted it was if any one had asked him. Didn’t he just have a lovely time? He found all sorts of interesting things. He rather wanted to hide some of them away so he could play with them again, but there weren’t so many good places to hide them. Take that little shiny cup for instance. It reminded him very much of an acorn with the top gone. You know what that was—it was a thimble. “Too bad it’s empty,” he sighed. “Now I wonder where house-folk keep their acorns—they must have a hole for them.” No jay could go housekeeping without one. But of course he couldn’t find it.

He thought of burying his treasure in the earth beneath one of the geraniums in a row of pots on the window sill. Just then he discovered the coffee pot; Louie’s mother was measuring the coffee into it for the morning, so its lid was open. Chaik was so pleased. He dropped his shiny acorn right in. Snap! shut the top. It wouldn’t come out again.

Didn’t he just make an awful fuss? He hopped all around it. He sat on the handle and he tried to sit on the little round button on the lid, but his feet kept slipping off. He tried to peek down the spout or to reach his beak in. Finally he got so cross he gave the stubborn old thing a peck. It made such a tinny sound he jumped away and perked up his crest at it. He’d just about decided that was a lost acorn when somebody got it out for him.

Whoever do you think it was? It wasn’t Louie, and it wasn’t his mother —it was Mr. Thomson! And it wasn’t just because he and Chaik had made friends; it was because everything that foolish bird tried to do set the big man laughing. And then Chaik would stop and look very hard at him as though he thought Louie’s father were trying to talk to him, so of course he had to pay attention. That’s manners in a boy or a bird.

He let Chaik peck a lead pencil into splinters to see what he could find, because that ignorant bird thought the lead was a worm-hole. He let him peck the button out of a chair cushion, just because it was fun to pull at. And when Chaik came tumbling off the table to pull at the shiny tag on the end of his shoe lace—you’d have thought he really believed he was being helped by that impudent bird. He grumbled a lot more than Louie when Louie’s mother wound up the clock and made them all go to bed.

I just tell you Chaik and Tad didn’t mind that rain. Tad Coon had a big, dry cellar to hunt in and a fine supply of mice who came to nibble his corn. Chaik Jay slept in his corner of the window sill in the kitchen behind the curtain. It wasn’t quite so convenient as perching, for his long claws got in his way, but he found the varnished back of a chair too slippery; besides, he wanted to keep an eye on his raisins. Those thieving mice once tried to steal them. He gave one of them a good peck; it ran off squealing with one leg up, and after that they knew better than to bother him.

When Louie’s father came padding in and began putting on his shoes that he had left under the stove to dry the night before he danced and flapped good morning. And wasn’t the man just flattered to death to have a wild bird out of the woods as friendly as that?

When Chaik flapped he got more excited than ever. “My wing is well again!” he squawked. “Yah! My wing is well again!” Then didn’t he have some fun? He could fly over the stove and perch on the handle of the teakettle while Mr. Thomson laid the fire for breakfast.

But all the man said was, “You think you own this house, don’t you? Well, I dunno but you’re about right, you sassy thing!”

Chaik just answered, “Hey?” That’s all he said when Mr. Thomson opened the door to go out and Chaik’s well wing brushed against his ear as he slipped out beside him. “Now look what I’ve done,” said the man who didn’t like Woodsfolk. “I s’pose that’s the last we’ll see of you.” And he felt so lonesome as he watched Chaik go flitting off through the rain that he remembered about bringing back something from the barn for Tad Coon’s breakfast. He wanted Tad to stay.

But he needn’t have worried about never seeing Chaik Jay again. Chaik knew when he was well off. He just wanted to take a good flippity-flap with his well wing to be sure it worked right, and he was ’most afraid to try it in the house for fear he’d hit something with it. My, but it was fun to fly up high and come sliding down the air again; it was fun even if it was still raining.

But he didn’t stay out in the rain long enough to get very wet. He went over to the barn and poked around. He was a little scary at first about going in the dark doorway, but after he’d been in there a little while he just had to hunt up Tad Coon. Tad was so full of mice he was dozing off to sleep in the cellar; he came out when he heard Chaik calling.

“Oh, Tad!” Chaik exclaimed, bobbing his head and flirting his tail because he was too excited to keep still even while he was talking. “This is a wonderful place. That big barn where the cows live is perfectly safe for birds. Those swallows have left their nests all over it, and they’re such scary fellows they wouldn’t stay a minute if anything happened to one of them. I found a robin’s nest, too, a mud one, but it’s round, not flat on one side like a swallow’s, and it’s too big for a phoebe bird—I sat in it to see. (Tad Coon grinned at that.) Besides, it hasn’t any cocoons or moss in it.”

“I thought you’d like the barn,” Tad nodded. “But where were you last night? I couldn’t find you anywhere. And your supper is still in your cage. Did you get anything to eat?”

“Did I get anything to eat? Why, these house-folks have more things stored away to eat than all the Jays in the Deep Woods put together. That trap where they keep the corn doesn’t catch me. I can walk in and out any time I want to. (He meant the corn crib; the slats wouldn’t hold him any more than they would a mouse.) And I found a knothole into the biggest pile of wheat you ever dreamed about. (That was the grain room, of course.) And there’s dusty stuff the cows are eating (meal and bran), and some little wrinkly sweet wild grapes I hid in a special place. I’ll give you a taste.” (He meant his raisins in the kitchen window.)

“I guess you had plenty to eat, all right enough,” remarked Tad, “but you never told me where you slept.”

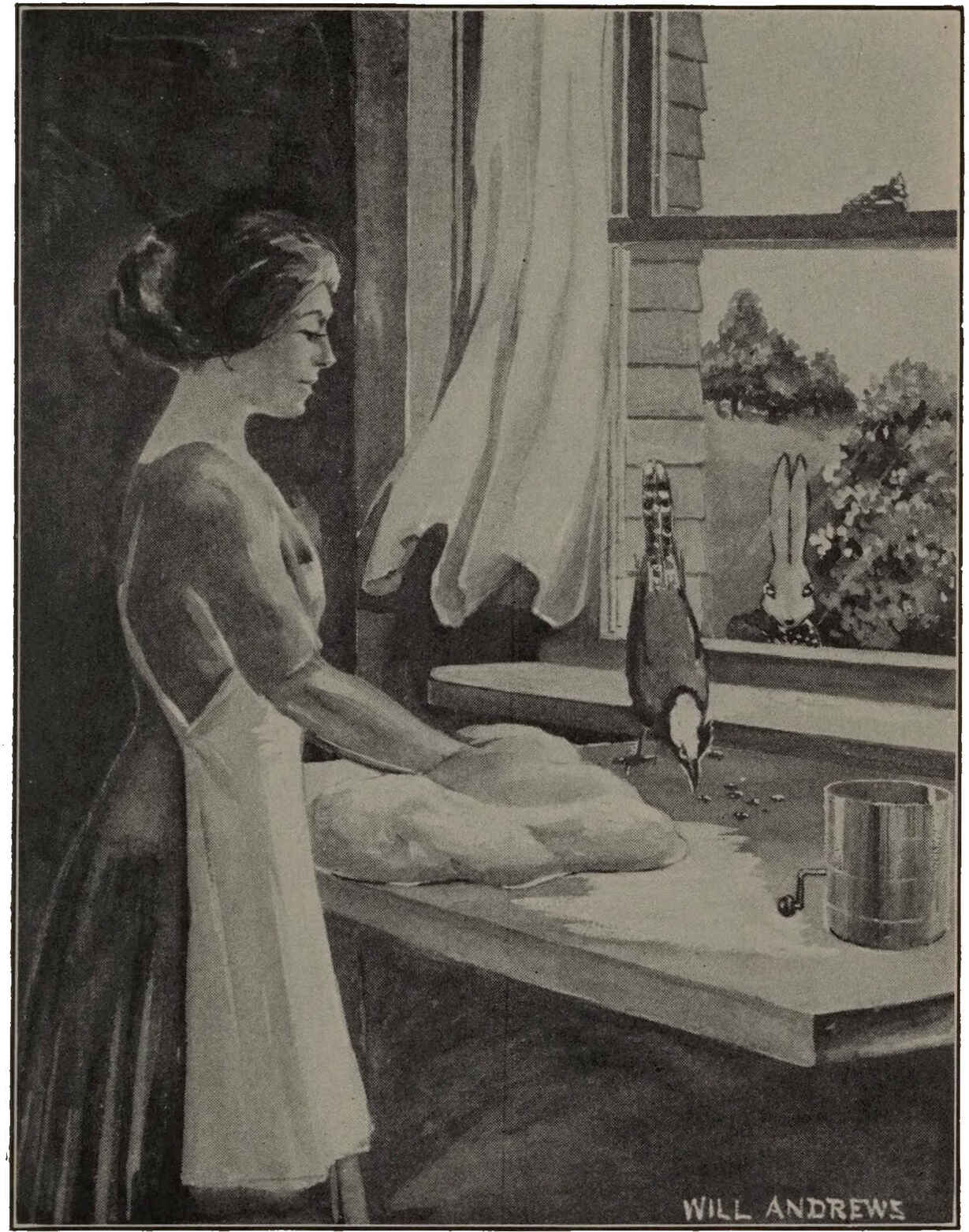

“Hey?” chuckled Chaik with his most mischievous air, “I wouldn’t dare; you wouldn’t believe me. I’ll just have to show you. Come along.” And he flapped right up to the kitchen window. Then wasn’t he the puzzled bird? He could see Louie’s mother moving around inside, getting the breakfast. He could see the raisins poked into the crack. But he couldn’t get in there to get them. He walked all the way up the screen, fluttering and scratching. Pretty soon he perched on the sill and began to think it over.

“That’s the second time this has happened,” he said. “I hid a little shiny hollow acorn last night, and then I couldn’t get it again. I knew right where it was, too. Now I can see those little wrinkly grapes, right where I put them, but I can’t get them either. It’s very queer.”

“You mean you were in the house?” gasped Tad. “Right up inside it, with the traps shut?” (He meant with the doors closed; he hadn’t learned all the proper house names for things yet.) “But that wasn’t safe. What if that big man wanted to hit you like he did me and Louie?” Tad didn’t quite trust him yet.

“He didn’t,” said Chaik. “He’s not a bit peckish, even if he does make more noise than Watch the Dog when he barks.” (That was what Chaik thought of Mr. Thomson’s laughing.) “Yeah! Hey!” he called suddenly because he saw Louie.

Louie looked up. He was feeling quite scared because he didn’t see anything of his bird—not even a little pile of feathers to show that the cats had caught him. “Why, however did you get there?” he asked, and he ran to open the window and shove up the screen.

In hopped Chaik. All his nice raisins had dropped out of the crack when Louie opened the window for him, but he didn’t care. He just ate a few himself and shoved a taste of them down to Tad. “That happened, too,” he said thoughtfully as he gulped a raisin. “The minute I stopped worrying about my acorn, one of the house-folks gave it to me. A house isn’t fixed for birds. But it’s very interesting—and full of smells.” He turned his beak toward the stove where Louie’s mother was frying bacon.

“Mmn! Mmn! Lovely ones,” sniffed Tad, twitching his nose around until he made such funny faces Louie began to giggle at him. He could smell that bacon right through the window.

Louie’s father came back from the barn carrying the milk pails all full and frothing. He had more milk than usual that morning—he remembered about that a long time afterward. He didn’t know it yet, but his luck began to turn on that farm the very day he made friends with the Woodsfolk. You’ll see.

“Why didn’t you wake me up?” asked Louie in a very surprised voice. The little boy could sleep right through all the racket of the alarm clock, even if Chaik Jay couldn’t. His father almost always called him to help with the milking.

“Oh, I just guessed you might as well sleep,” said his father. “You can feed the calf if you’ve a mind to.” He knew Louie liked to do that. It isn’t nearly as hard work either. “I kind of wish I had, though,” the big man went on. “I let your bird out. He was over in the barn this morning. Maybe we could catch him again, but I don’t know. He was flying pretty strong.”

“Hey?” asked Chaik, before Louie could even answer. He half guessed they would be talking about him—conceited thing!

“That was all right,” said the little boy. “I let him in again. He came back, just like my coon.”

Louie’s father stared at Chaik, sitting on the window sill with the window open behind him so he could go out and in. Then he peeked out and saw Tad Coon down below with his nose all wiggling because he smelled the bacon Louie’s mother was cooking. “Hm! Looks like we had company to breakfast,” was all he said.

But it wasn’t all he did. He gave Chaik some nice crisp bacon crumbs—he insisted it was just to see if the bird really would eat them. And Louie’s mother caught him right in the act of slipping a good slice out to Tad Coon. “Here,” she laughed, “there’s no need for you to feed that fellow. I’m frying up some cracklings for him and the cats.” She made a delicious mixture of odds and ends of bacon and bread and such things. But when Louie went to carry it out, the poor cats climbed up on the shelf in the shed and spat and whined because they hadn’t made any compact with any coon. So they said. Really it was because they were afraid of him.

Tad didn’t care. He wasn’t hungry, anyway. Only he liked the taste of new things. He ate his share on the cellar steps. And the mice, who had run away to hide because he was hunting them, all crept to the mouth of the holes and sat there sniffing until their whiskers trembled.

“I say,” thought Louie Thomson to himself as he started off to school, “I just must talk with Tommy Peele. He knows about the wild things.” Only Louie wasn’t thinking about a wild thing, but about his father who used to be crosser than Tad Coon in a cage.

You needn’t think, just because you’ve been hearing about Chaik Jay’s foolishness, that he and Tad Coon had all the fun there was. Not a bit of it. Things were happening round Tommy Peele’s barn at the very same time.

Of course Tommy Peele knew about most of them. And maybe you think he wasn’t puzzled! The very first morning, while it was still raining, he came sloshing down to the barn with his tall rubber boots on—because it was so wet he needed them. And splash! went somebody into the trough where the cattle drink. Of course it was Doctor Muskrat. He was just examining it because it was the queerest kind of a pond he’d ever seen, and he was a little bit scary because he didn’t feel at home yet.

He swam all the way down it in about two paw-strokes, hunting for a lily leaf to hide under while he peeked out to see who was coming. Of course there wasn’t any lily leaf. There was no mud for one to grow in—because Tommy kept the trough too clean. And there weren’t any snails, or water beetles, or anything but just water, as fresh as the water out in the cool, deep middle of his own pond. It was a great deal warmer, and it had a queer, woody taste that came from the rain water dripping in from the shingles of the barn. No wonder the wise old fellow was puzzled.

The doctor climbed up on the edge of the trough and settled his fur for a comfortable visit with his little boy friend. But he didn’t stay there, for Tommy had already unlocked the gate and the cows came rushing in, shouldering each other to get the first drink. The wise old muskrat slipped between the trough and the barn to wait until they were gone again.

That was really sensible, because he’d done something to make the cows angry with him—though he didn’t mean to. They began snorting and puffing. “Ugh! What an awful smell!” mooed one of them. “Somebody’s been bathing in our drink. I’d like to get my horn on whoever it was! I’d teach him not to do a trick like that again!”

“Mff-ff-ff!” sniffed the Red Cow—she was a big, happy-looking one by now, not a bit like the wild, scary thing who ran away from Tommy in the spring. “I like that smell. It reminds me of the kindest beast I ever knew, excepting dear little Nibble Rabbit. It reminds me of wise old Doctor Muskrat, who owns the pond at the end of the woods and fields.” And she took a sentimental sip of it.

Doctor Muskrat examines the White Cow’s drinking pond.

Doctor Muskrat was fearfully ruffled because the cows made all that fuss over his dip into their drinking trough. He thought they were just putting on airs. He put up his head between the trough and the barn, where he knew they couldn’t hurt him. “Hoot-toot!” said he severely. “What’s all this about a dive that didn’t wet my fur? Many’s the time you’ve stepped into my pond. Did I ever snap a word at you?”

“Yes, indeed!” put in the Red Cow. “Step in! I’ve seen you stamping flies in it till you had it so muddy you couldn’t see your own hooves. I’ll teach you to sniff at my friends!” She laid her horn into the cow who did the first complaining with a shove that sent her staggering. There might have been some lively argument if the wise White Cow hadn’t stopped them.

“Here, here!” she interrupted. “We didn’t know who we were sniffing at. A sensible beast like Doctor Muskrat will understand there was no offense meant.” She lowered her head respectfully and spoke in her flutiest voice. “You’ll pardon me for explaining, sir, that this isn’t a pond. The water doesn’t run through it. The wind doesn’t blow over it; it goes stale as fast as a mud puddle.”

“You don’t say!” exclaimed the doctor. “Forgive my mistake, madam. If I’d seen the least trace of green scum, which is the usual sign of still water, I wouldn’t have put my paw in it, I do assure you.”

“Nor we our noses,” mooed the cow, still very politely.

“To be sure! To be sure!” nodded Doctor Muskrat sagely. “A sour drink makes sorry fur. But what’s to be done? And what will Tommy Peele think of me?” He was more embarrassed than ever when the little boy came squeezing in between the cows, as though he wanted a drink, too.

But Tommy had just noticed the cows weren’t drinking. It didn’t take him long to guess why, but he never thought of blaming his wild friend. “Why, Doctor Muskrat!” he exclaimed, as glad as Bobby Robin when he sees a worm, “whatever are you doing here?” And he knocked out the plug in the bottom of the trough and let the spoiled water go whirling and gurgling out through a hole. Doctor Muskrat’s eyes popped at that, I can tell you, but when Tommy turned on the tap and let fresh water come splashing in, the old fellow couldn’t understand it at all. He climbed up to examine it; he tried the pipe with his chisel teeth, and he licked the drops that splashed on his whiskers.

“Well!” he gasped. “I’ve seen maple sap drip from a twig in the spring, but this is no twig, and it’s no sap that’s dripping from it. What is it?”

But if Doctor Muskrat was excited about seeing the water run, you ought to have seen him when Tommy turned it off again. He bit it and he licked it and he squeezed it and he squinted up the hole, first with one eye, and then with the other. At last he sat down to watch it, like Tad Coon watches a mouse hole. He watched it till he got a crick in his neck, but still he wouldn’t take his eye off it. He was going to know about it the next time it began. He had an idea the rain was doing it—somehow or other. He couldn’t imagine a puddle that wasn’t made by the rain.

The stale water Tommy had let run out on the ground made a fine big puddle for the raindrops to patter in. But by and by the pattering grew into a splashing, and the splashing into a quacking. He just had to look away to see what that noise was. Three big white ducks were playing in it. “Quack!” one shouted. “I got a drowned earth worm!”

“Quawk!” called back another. “I’ve got a grain of corn and a daddy-longlegs!”

The third was silent for a moment over his beakful. Then he spit it out and said quite cheerfully: “I had a nice round pebble, but I guess it’s too big to swallow. Flapper wins this time.”

“Hooray!” shouted Flapper, standing up on his toes and beating the air with his wings as though he were going to fly. But he didn’t. He just settled down on his feet again, gave a shake of his tail and would have waddled right off if he hadn’t caught sight of Doctor Muskrat’s shiny black eyes staring at him. “Who’s that?” he asked in duck talk. And they all stared at the brown, furry beast.

“It’s Doctor Muskrat. Who are you, and whatever were you doing?”

Didn’t those ducks just blink their yellow eyes when that brown, furry beast answered them back in their own language? He’d learned it from the mallards who visit his pond.

“We’re the jolly old waddle ducks,” quacked the one they called Flapper. “We’re playing a game of fish the puddle. Since you can talk duck talk so well, you might as well come along and learn it. It’s lots of fun. Come on!”

“Come along,” teased another. “We’ll show you all the ponds—lots of them are deep enough to swim in now. We’ll show you where the apples have dropped in the orchard, and where the garden snails have hidden, and the leak in the corn crib where the grains fall through——”

“Quawk! There isn’t much about this place we don’t get a beak into. We even pick over the pigs’ pail before they ever see it. Just now we got a drink of the warm milk they feed the calf. Ho! but this is a fine place to live!” laughed the third, his fat body shaking and the little curly feathers sticking up so cheerfully in his tail.

“Do you live here always?” asked Doctor Muskrat in surprise. “Don’t you ever fly away?” All the ducks he knew flew south for the winter.

“We’re not wild ducks,” Flapper explained. “We’re tame. We hear great tales from the wild ones. Some of them stop in and have a feed with us most every season. Great tales! That must be a gay life. But we’re so fat we can’t keep up with them.” He sighed, but he blinked so mischievously Doctor Muskrat could see he wasn’t breaking his heart about it.

“You’re just as well off,” said Doctor Muskrat. “White birds are so easy to see somebody always catches them.”

“Are you wild yourself?” they asked curiously. “Tell us what it’s like.”

So Doctor Muskrat strolled along with them, and fine friends they were, I can tell you, always happy and good-natured. They made the old doctor feel almost as much at home as he did in his own pond.

Doctor Muskrat makes friends with the ducks.

If Tommy Peele wondered what Doctor Muskrat was doing up at the watering trough just outside his barn door, he did a lot more wondering when he stepped inside. For there, on top of the feed bin, with her fur all puffed out and her tail as prickly as a caterpillar, perched the House Cat. And beneath her, thumping very severely, with a fine wad of pussycat fur in each of his hind toenails, sat Nibble Rabbit.

The cat was whining: “Aw, please let me go! I didn’t mean to. Honest I thought it was a rat!”

Nibble gave his ears a big flop. “No, ma’am!” he was stating decidedly. “You can’t fool me. A bunny doesn’t smell the least bit in the world like any rat. You were trying to hunt my children. But you won’t mean to next time. I know that. I only rolled you over, this time, just to show you that a rabbit can fight. Next time——”

“Next time,” squawked Chirp Sparrow, who had his first nest robbed by that very same Tabby Tiptoes; “next time he’ll set you spinning three ways at once until your brains are as addled as a frosted egg.”

“Me-waur-r!” begged the poor pussy. “Please, Tommy Peele, let me out and I’ll run back to the house. Truly I will.”

“I hope these wild things will teach you some manners,” said Tommy Peele. “Whatever Nibble did to you is nothing to what you’ll get if you try your tricks on Doctor Muskrat.” He carried her away down past the gate so she wouldn’t meet him.

“Good Clover-leaves!” whispered Nibble in surprise, when he saw how gently Tommy treated his enemy. “Do you s’pose he’ll be cross with me for what I’ve done?”

“Don’t flutter yourself,” Chirp assured him. “Tommy never takes sides between his friends. Though why he’s friends with that cat, when he knows the things she does, is more than I can tell you. You’ll have to ask Watch the Dog about it.”

Sure enough, when Tommy came back to the barn, he put out a handful of feed for his rabbit, just as though there hadn’t been the least bit of trouble. And his eyes didn’t open so very wide when Silk-ears and all her bunnies began to pop out from under the mangers and inside the hay and beneath the box he used for a milking-stool. And he didn’t have to look at the dust on their whiskers to know they’d been dipping into the cows’ breakfast. Some of the cows were telling him so.

But it doesn’t take much to start some folks sniffing and moaning. A nice clean bunny-paw never spoiled the Red Cow’s appetite. And the White Cow gave Tommy a nudge while he was milking her that said plain as words: “Isn’t it fun to have Nibble with us again?”

Now Doctor Muskrat and Nibble Rabbit weren’t having any livelier time than Stripes Skunk and his kittens were in the bottom of the haystack, hunting the rats they found there.

A rat is pretty dangerous for a skunk kitten to hunt—as dangerous as though a small boy went hunting bobcats—but it’s the skunk kitten’s business to take chances, and it isn’t the small boy’s.

There aren’t very many rats in the woods; sometimes one goes sneaking down the high grass beside a fence or snoops into a twiggy bush after baby birds in nesting time; sometimes one picks up tadpoles when the muddy ponds they hatched in begin to dry up; but mostly rats live very close to men. (Why they do is a special secret I’ll tell you some winter night.) So you see Stripes Skunk’s kittens hadn’t much chance to deal with such big game. They were awfully proud and excited about it.

It didn’t take the rats in the haystack very long to find it was a very poor place to be. They can eat hay—if they have to—but they can’t live on it like a fieldmouse can. They got hungry. But every time one ventured its whiskers out of a hole, Stripes Skunk’s kittens would pounce on it. It didn’t matter how creepy-crawly quiet they were—a kitten was sure to hear them. At last the wisest of them thought of a plan.

“Greywhisker,” said he, “you take one hole, Brokentooth the next, Scarfoot the next, and Eggeater the last. Each of you will scrabble about inside his burrow as though he meant to run, the minute he is quiet the one to the windy side of him must take his turn. That will keep those striped beasts running round and round the stack. Every third turn, run to the centre and all squeak as though you were fighting. That will keep them interested. They won’t hear me make a brand-new hole, and then we’ll plan how we can sneak out while they aren’t looking.”

Now do you know what that rat (his name was Snatch) meant to do? He meant to keep them all busy while he dug that new hole for himself and then sneak out without telling them. That’s rat for you! They cheat each other just as much as they do anybody else! But the others couldn’t think of any better plan, so they trusted him.

Only they made one mistake. The skunks weren’t running round and round that haystack. They were sitting perfectly still, each one with his nose at a hole. But one after another pricked up his ears as the rat pretended to come out, and dropped them when he scuttled back again. Wise old Papa Stripes was tiptoeing around finding all their trails so if one did get by a kitten he’d know where it was likely to go. “Hm!” he sniffed. “They’re playing a game, are they? We’ll just see who’s IT.”

Scrabble! Scratch! Squeak! went Brokentooth, Scarfoot, and Eggeater, each in turn. Each time the kitten stationed outside his hole pricked up its ears, and its wavy tail would tremble to the tip, and its claws would catch for a leap. Dig and gnaw, gnaw and dig, went the selfish Snatch, the cleverest rat of them all, making himself a new hole to sneak out through. They were helping him, but he wasn’t going to help them—not he.

Papa Stripes laid his head on one side and considered the case. Then a sly smile raised his whiskers. Pit-pat, pit-pat, he marched round the stack, whispering to each of his kittens in turn. “You see the slit in the old elm tree?” he asked one. The kitten nodded. “Did you notice the rat path under the chicken coop?” he asked the next. “Looks to me like a rat hole under that corn crib, eh?” he asked the third. He didn’t give any orders like “You do this,” or “You do that,” because he wanted the kittens to think for themselves. But he did show them what to think about.

Nip, slip, came Snatch, creeping out of the new hole he’d just made for himself. Pounce! Stripes closed it up behind him. “Now, rat,” he chuckled, “let’s see you run! And let’s see who catches you!”

“Wee-e-e-ak!” Snatch made for the slit in the elm. A kitten was there before him. The chicken-coop, then? No! The corn crib! Was Tommy’s barnyard all full of hunting skunks? A hole! A hole! He’d find one in the barn—under the grain bin! He raced for the door, the kittens after him, gaining at every bound, with their father ’most scared to death he wouldn’t be on time to lend a tooth if they needed it.

That’s how Snatch came to dive right between Tommy’s tall rubber boots as he stepped out the barn door with a milkpail in his hand. That’s how the skunk kittens came to flash past before the milk he slopped over could fall on them. “My land!” he exclaimed. “What are you doing here?” As though he couldn’t see for himself.

They were all three scrimmaging with Snatch the Rat at the very mouth of the rat hole. They never knew which of them killed him.

“Ee-e-e-yow!” squealed Stripes, prancing in his pride. “Isn’t that some hunting!” Then back they all romped to catch those poor hungry fellows in the haystack who thought Snatch was taking a mighty long time to make their new hole for them.

The most puzzled little boy you ever saw tramping off to school on a rainy morning was certainly Tommy Peele. Unless it was Louie Thomson. “Hey, Tommy,” he called, when he heard Tommy’s tall rubber boots splashing along behind him, “I want to ask you something.”

“Hey, yourself,” Tommy called back, “I want to ask you something, too. What have you done to make my muskrat run away from his pond? And all my skunks? And the rabbits? Huh? They’re all up at my barn!”

Louie’s eyes grew big and round. “I didn’t do a thing. Cross my heart didn’t—’cepting to feed them, like you showed me. The coon and the jay bird are living up at mine.”

“They are!” exclaimed Tommy. “Then I guess you didn’t do anything to them.”

“Do you s’pose they wanted to see what it was like to be tame—just like I tried being wild?” Louie wondered.

“N-n-no,” drawled Tommy thoughtfully. “My rabbit’s tried it before. But he always goes wild again. I guess he likes it best.”

“Now that fox is back by Doctor Muskrat’s pond—I’ll bet you anything!”

The two boys wouldn’t have been so puzzled if they had known how the Bad Little Owls had invited Killer the Weasel to Tommy’s Woods and Fields. It was to avoid him that all the Woodsfolk had come to stay with the boys for a while; indeed, they had even warned the obstinate mice to leave, so that Killer and the Bad Little Owls would have to go hungry.

Killer and the Bad Little Owls were hungry—Killer especially. He wasn’t enjoying his visit to the Woods and Fields one bit. For it rained and it rained, and it rained and it kept on raining. And nobody with fur can hunt in the rain because the water washes away all the trails; you can’t see where they come from or where they’re going to; you can’t even smell them.

It was way along in the afternoon before he poked out his wicked nose and found the sun was out, too, and the leaves were dancing. But he didn’t want to dance; his poor skin was doing it for him and he didn’t like it a bit; he was shivering because he was empty as a drum and the wind was thumping him. He crept down and tiptoed over to Doctor Muskrat’s pond. He walked all around it, but he didn’t see a single footprint. He didn’t even see a frog. By this time he was hungry enough to eat one, but they were all buried down in the warm mud. The only fellow he found was the Hop-toad.

The Hop-toad was very happy. Most every leaf that blew down in the wind had under it a fine fat angleworm who had come up to nibble a pleasant change from the grass-blades they eat all summer. Besides, they were simply loaded with bug cradles of every sort.

As a result, the Hop-toad was so full he could hardly squeeze his fat yellow vest into his own front door beneath his own big stone; so he just sat and blinked his ruby eyes at Killer and grinned. Who else in all the Woods and Fields would have dared to do that?

“Hail, Sharptooth!” began the hop-toad in his deep scary croak that rumbled like thunder in the back of his stony cave. “Have you come to hear your fortune? You have come in time. There were signs and omens brewing in the battle between the frost and the rain this morning.”

Now the weasel didn’t know what an omen was—it’s a sort of bad news, like the dark clouds that foretold the Big Rain and the Terrible Storm. He doesn’t sit by the week like the Hop-toad does, just thinking and remembering things. He hasn’t any more education than a pollywog, in spite of all his experiences. All the same the weasel knew more than to own up that he wanted to eat the Hop-toad. So he thought, “I’ll pretend that’s just what I came for, to hear my fortune, and he’ll never guess.”

“No one can follow a wet trail on a cloudy night so truly as the Hop-toad,” Killer said. The Hop-toad never follows a trail at all. That was only the silly weasel’s way of pretending he thought the Hop-toad was smarter than he.

Of course the Hop-toad knew Killer was just making it up. “Two can play at that game,” he blinked to himself. “I’ll scare him away and then my good friends will come back again.” Then he said out loud: “Oh, me, that sounds just like my wise friend Silvertip the Fox. He used to say, ‘The bones of yesterday lie where even the blind ants can find them, but the bones of tomorrow—only the Hop-toad knows whose skins they run in.’ He knew I could foretell what was coming. But he listened to the owls instead of listening to me—see what happened to him!”

“What did happen?” demanded Killer. You remember the Owl’s Wife lied to him. She said Silvertip was hunting in the Big Marsh, the other side of the Deep Woods!

Killer wasn’t enjoying his visit to the Woods and Fields a bit.

“He went where no ant ever gnawed his bones,” answered the wise hop-toad. “That’s why no tooth hunts by Doctor Muskrat’s pond.”

When the Hop-toad croaked these words in the dark cave under the big stone, every little crack seemed to have a scary little echo hidden in it to whisper them after him. Killer the Weasel shook to the tip ends of his fur.

“Is he dead?” asked the wicked thing in a husky voice.

“Who knows?” said the Hop-toad. He knew, himself, but he didn’t want to say so. “If he is, neither fur, scale, nor feather did the killing.” That’s true. You know it was Grandpop Snappingturtle, and he isn’t a beast or a fish or a bird.

The weasel thought a minute. Then he remembered that Louie Thomson had been living by the pond and those same lying little owls, who told him Silvertip was still alive, said he couldn’t hurt any one. “Ho,” he said, “I know! It was a man?”

“Certainly not!” snapped the hop-toad as though he were cross over such a foolish question. “How could those toothless, clawless man-tadpoles hurt any one?”

“Oh-h-h!” exclaimed Killer in a long shivery breath. “I know what you mean. He’s a ghost Owl. Eh?” But the Hop-toad never answered a word.

The beautiful Duck had told Nibble Rabbit, the day before the Terrible Storm, that everything was afraid of something. Killer the Weasel was afraid of two things—Silvertip the Fox and the Ghost Owl.

Now the Ghost Owl is a real bird. It is a big white Owl who comes down from far-away north where the storms grow. At night it hunts Killer, and the minks and the bad skunks, and all the wicked folk who prowl around trying to catch Mother Nature’s own children while they’re asleep. In the daytime it goes off to some river and catches fish. Nobody knows when or where it sleeps.

Whenever a weasel disappears you can be pretty sure the fox or the owl has caught him. So the weasel-folk got the two so mixed up in their minds at last they decided they were the same. They thought the Ghost Owl was a fox who turned into an owl because it was better hunting. If a fox died and they saw his bones they knew that was the end of him. If he just disappeared—well, they couldn’t be sure he did turn into an owl, but they couldn’t be sure he didn’t.

So Killer the Weasel thought if Silvertip just disappeared and the ants didn’t gnaw his bones, as the Hop-toad said, Tommy Peele’s Woods and Fields were no place for him.

“Hop-toad,” he whined, “I know what you mean. You mean that Silvertip isn’t dead at all. He’s hunting these Woods and Fields in a Ghost Owl’s skin.”

“What an idea!” croaked the hidden Hop-toad. “Who ever told you that?”

“Aha! You needn’t pretend to me!” sniffed Killer. “We weasels know a lot of things. We know that no real owl can stand the sunlight. The Ghost Owl can. Many a mink has seen it diving for fish like a kingfisher in the daytime. Many a weasel has felt its claws in his ribs in the dead of night. Yet whose tooth has ever found its magic throat? Can you name me one who has ever picked its bones? No! Nor will there ever be such a one. For the Ghost Owl has no mate, it builds no nest, it hatches no young. It is born in a fox’s skin until the magic shedding when feathers instead of fur prick through its hide. It never dies. It lives on us who are strongest, swiftest, cleverest of hunters—we Folk from under-the-Earth whom Mother Nature herself cannot govern.”

You just ought to have seen Croaker Hop-toad’s side shake at the idea. He didn’t know a thing about the Ghost Owl, except that there was one, but he knew more than to believe what Killer was telling him. It’s what we call a “tall story” and the Woodsfolk a “tail-ruffler.” Only an ignorant creature like the weasel could pretend it was true. He hadn’t told Killer what really did kill Silvertip because he knew Killer would be a lot more frightened at what he didn’t know than at what really did happen. But he hadn’t dreamed of scaring him as hard as all this. It was great fun. He wanted Killer to go on talking about it. So he said, “It’s very good of you to explain all these things to me. I wouldn’t see them for myself, living as I do under my stone. But if the Ghost Owl never dies, what becomes of it?”

“Ah,” said Killer. “Nobody knows but the crazy loon. But sometimes, when there’s a fearful storm, you hear it squawking and its feathers come fluttering down. They aren’t real feathers, you know; they’re only frozen. That’s why it only comes in ice-time. So we think—Ssh! Who’s coming?”

But Killer never finished. He’d scared himself ’most to death telling about the Ghost Owl; so when he did hear a sound he made a frantic scratching to squeeze into the crack in the Hop-toad’s stone, where he’d been talking, and then he bounced off at full speed for his own safe crack between the two stones on the bank of Doctor Muskrat’s pond. “Ah-h-h!” he breathed. “Safe at last! Even the Ghost Owl’s claw cannot find me here. Tooth cannot bite, and paw cannot dig to disturb me. If only I weren’t so desperate, starvation hungry. I do wish I’d caught the Hop-toad. I do wish I’d eaten those owls—but I’ll do it next summer when it’s safe to hunt here. To-night I’ll go back to the Deep Woods and stay—if I have to live on acorns.”

As soon as the Hop-toad was perfectly sure Killer had gone, he hopped to the narrow crack that was the door of his cave and squeezed out again. He cocked his deaf ears and felt with his little gloved paws on the ground. Then he began to laugh himself right out of his skin. “Ho, ho! It’s only those harmless man-tadpoles.” That’s what Croaker Toad calls Tommy Peele and Louie Thomson.

Croaker could feel them tramping along the lane. Killer had heard them whistling. They were calling Watch to help them find out who it was that had chased Nibble Rabbit and Tad Coon and Stripes Skunk and Doctor Muskrat, and all the rest of them out of Tommy’s Woods and Fields. Watch was busy about something else, way far off, when he heard them. Mighty busy, too.

But they didn’t need him. Killer had gone padding up and down the banks of Doctor Muskrat’s pond looking for tracks of someone he could eat, and he’d left his own. He’d left a clear trail from the Hop-toad’s home to his own. “Lessee who’s here!” said Tommy Peele. He tried to lift one of Killer’s big stones.

“Try this,” said Louie Thomson. He picked up a big stick and poked it into the crack between them. Then both little boys began to shove on the stick. Slowly it pried the crack apart. One of the big stones reared up on end and fell over backward. And there sat snaky-slim, bristly whiskered, snarly toothed Killer, with his wicked eyes rage-red and his wicked claws set to spring at them!

Why didn’t he do it? Well, it was the same reason Stripes Skunk explained to Nibble Rabbit and Nibble tried on the cat. They weren’t afraid of him.

Indeed they weren’t even angry, for they didn’t know all the harm he’d been doing and there wasn’t anybody in all the Woods and Fields who could tell them. Tommy said: “What’s that?” and Louie answered, “First time I ever saw him,” and they just stood still and stared at him.

Killer certainly was afraid of them. His wits were as muddled as a pollywog’s puddle when a duck goes fishing in it. First place, what had happened to his nice safe home? Tooth nor toenail couldn’t dig into it. Then why did that great big stone flop right over on its back and leave him without a place to hide in? He didn’t know it was because the little boys used a stick to pry it with just like the First Man used a stick to pry the stone that shut up the pass to his little island against the wolves in the First-off Beginning of Things.

Killer was as bad as any wolf, but the little boys didn’t know that. They didn’t know enough to be afraid of the wicked little beast who scrouched down at their very feet, snarling and swearing at them. All they thought of was the funny faces he was making. They were snarlier and funnier than any Stripes Skunk could ever make, or even Tad Coon.

“Te-hee,” giggled Louie. “My, but he thinks he’s big!”

“Ho-ho!” laughed Tommy, thinking of the fight between Nibble Rabbit and the cat that morning, “I’d like to see what our old Tabby would say to him.”

That was too much for Killer. He did jump. But he didn’t jump at them. He went leaping off into the Woods, spitting like a firecracker and looking for a new place to hide from them. And he found—the Big Oak that was blown down in the Terrible Storm where the Bad Little Owls were hidden! Wow! But wasn’t Killer mad when he bounced into the hole of the Big Oak!

He hadn’t more than poked his whiskers inside the hollow tree than he smelled owl. He smelled other things, too, but he was too mad to think about them.

“Yah!” he snarled, sniffing viciously. “So that’s where you are, you lying little flap-wings. Just you wait until I get my breath and I’ll teach you a few things. You told me it was good hunting here, you did! Well, there isn’t so much as a mouse-tail swishing, or a feather flying, or even a frog hopping by your fine pond. Not a trail has been made since the big rain that almost washed me out of my snug stones.

“And, next, did you think I wouldn’t hear what happened to Silvertip the Fox? He isn’t dead. He’s turned into the worst enemy we weasels have; he’s a Ghost Owl and he’s haunting these very Woods and Fields. That’s why all the other creatures have gone.”

“He isn’t! Truly he isn’t,” wailed Screecher’s wife. “Grandpop Snappingturtle ate him.”

“Hm. So that’s the story you’re telling now, is it?” snapped Killer. “I thought you said he was hunting duck in the Big Marsh over on the other side of the Deep Woods. Didn’t you?”

“Ye-es,” sniffed the owl. (She did, you know.) “But——”

Now if Killer had let her say another word she would have told him why she lied and she’d have explained that Grandpop Snappingturtle was gone, and things might have been very different whether he believed her or not. But he didn’t. He began crouching, creeping toward the very darkest end of the long log where he could hear the scared little birds squirming in terror. His eyes gleamed red in the blackness, with green flashes, as he peered for them.

But you surely haven’t forgotten that this was the very tree where Stripes Skunk found the honey that helped him make friends with Tad Coon and Tommy Peele.

The bees were fast asleep. They woke up all right enough when those scared little owls began scratching scared little claws into their nice neat home. “Brzz?” they began to call. “What’s happening? Call out the guard. Shake a wing, there! See who’s attacking us!”

Did the little Screecher Owls pay any attention? They did not. Killer the Weasel was gnashing his teeth at them and glaring his eyes in the black dark. “Whe-e-e!” moaned the owl’s wife as she climbed up the soft comb until she bumped her head against the top of the log, right by the little hole. “Who-o-o,” shivered her mate, scrambling after her. “Ur-r-rk!” she squawked as the first of the bee guards got his sting between her feathers.

She gave a flounce—and the honeycomb broke away. She could see the sky through the hole! Scuttle, scramble, scratch, and flutter—my, but it was a tight fit! All the same she did just manage to squeeze through, and her mate grabbed hold of her tight new tailfeathers and dragged through behind her. But Killer didn’t!

Killer couldn’t even see to try. He was a regular ball of angry bees, and he hadn’t bee-proof fur like Stripes Skunk, even if he did claim to be Stripes’ cousin. He went bouncing down that long hollow trunk, bumping into every jagged splinter on the whole inside of it. He went racing for Doctor Muskrat’s pond, just like any other Wild Thing, and plunged in. Because he knew no bee would dare plunge in after him. Only the very few whose stings were tangled in his fur wet their wings.

But he hadn’t more than got his head under water than he was in just as much of a hurry to get out again. What if the owl had told the truth for once? What if Silvertip the Fox was eaten by Grandpop Snappingturtle?

When he came out his nose was beginning to swell, but it wasn’t so swelled that he couldn’t smell Tommy and Louie, hunting for him. His eyes were beginning to close, but they weren’t shut so tight he couldn’t see them. He turned his head to look and ran right spang into Tad Coon’s tree. Up it he climbed and out across the limb where Chatter Squirrel comes over from his hickory when he wants a drink from the pond. Up that he climbed—high up. He wanted to squint across the bare limbs to see where the squirrel roads ran so he could follow them through the tree-tops.

Killer climbs the big hickory tree after Chatter Squirrel.

But high up in that hickory is where Chatter Squirrel made his winter nest of leaves, all woven together and neatly tucked in around the edges. It’s the best place in the world to hide because it looks like an old crow’s nest that the leaves have blown into.

Chatter wasn’t asleep. The Bad Little Owls had wakened him and Killer splashing in the pond had kept him awake.

“Here,” thought Chatter, who’s the most curious somebody on toepads, “something’s going on. I guess I’ll stretch my legs. It isn’t so very cold. I’d kind of like to know how long I’ve been asleep—it must be more’n a week.” So out popped his head.

Scritchy, scritchy came claws up his very own tree. Chatter pricked his ears. Then he squirmed far enough out of his front door so he could look down on—the big bulging whiskers of Killer the Weasel. Hm! You ought to have heard Chatter Squirrel. The little owls weren’t in it at all when he began screeching!

Chatter Squirrel scrambled up to the very tippest twig of his tree and there he hung while he told Killer all about himself. “Slit-throat!” and “Furred-snake!” and “Mud-belly!” were about the only things I dare to repeat. And all the time he kept rocking that springy treetop until Killer was fairly seasick.

Did Tommy Peele and Louie Thomson hear him? You know they did. The Hop-toad didn’t try to tell them about Killer because they didn’t talk his language. Chatter didn’t try either. He was just speaking out his mind and he didn’t care who happened to be listening. All the same, those two little boys didn’t have to know squirrel talk to understand.

But it wasn’t a safe thing for Chatter to do. He made Killer so terribly angry that he forgot to be scared and he forgot to be hungry and he forgot to be seasick—all he wanted was to hush up that squirrel. Up he came, foot over paw.

Up he came—and Chatter hadn’t any higher place to climb! He’d lost his temper, too. But as soon as he saw what a pickle he was in he found it again, and his wits with it. He rocked until his perch had a good long swing and then he let himself go. Out he leaped, all paws spread, sailing like a bird, then down—down——

Down went Chatter Squirrel. He kept right side up for he had his tail to help him. There was a big branch right beyond him. One good flick of his rudder, like a swimming fish, and his toes caught it. He swung right around it, like a trapeze man in a circus, scratched his nose on a twig, and then clamped his poor kicking hind feet against the bark. There he stuck with his poor little sides panting.

Down went Killer the Weasel. His measly little scrump of a tail was mighty little use to him. He went toes over ears. He never so much as got a claw on any twig because he couldn’t see to catch them; but he knew where every one of them was. They whipped him and switched him from behind and before as he whirled through them. He got a terrible spank when he found his branch, for he found it wrong side first and went bouncing off again, bing, into Nibble Rabbit’s Pickery Things. “Yip! Yeaur-r-r!” Rip! Tear! Blam! he hit the earth at last.

There he lay. For a minute he thought he was dead—right then. Then he began to breathe; before he really knew what to do next he found his legs were running, running, just like Nibble Rabbit runs when Killer is after him. And he let them go. Past the Brushpile he ran, across the Clover-patch, through the Corn. Suddenly right before him he saw the stone-pile. Down a crack he dove and pulled his tail in after him.

He found a little bed of dry grass no wind had ever blown in there, but he didn’t stop to think about it then. He was so weak and tired and bumped about he couldn’t keep his eyes open. He hardly hit the bottom before he was sound asleep.

Now some of the fieldmice who ran away from Doctor Muskrat’s pond before the Big Rain had chosen that stone-pile to live in—those who didn’t go all the way up to the barn. If Killer hadn’t been more hurt than he was hungry and more tired than he was hurt, he wouldn’t have had to smell very far to find out it was a mouse’s own bed he’d fallen asleep on.

The mice knew soon enough, and then of all the wailing and weeping and sniffing and squeaking you ever heard tell of—well! Of course, they called a meeting. They held it outside, in the cold wind that was whistling through the stones. But not all of the mice would come.

One mad old mother mouse decided to stay and run the risk of being eaten rather than go to new dangers; and one greedy weepy mouse refused to leave his second set of winter stores.

Poor old Great-grandfather Fieldmouse, who’s so old his ears are all crinkled, sat all hunched up with his whiskers drooping and his tail as straight as a sick pig’s. But he was very wise for a fieldmouse. “Mice,” said he, lifting a shaky paw, “we must not think; we must run. And

So here is our road.” He turned his old back to the breeze and began to hump himself along, though even a mouse wouldn’t have called it running. He was lucky, too, for the wind blew him right into the straw-stack where all the rest of the mice had settled the night they ran away from Doctor Muskrat’s pond. They thought they had found mouse-heaven because the stack wasn’t thrashed yet. But the mice who tried to do something different, right out of their foolish heads—you can guess what happened to them!

It was in the middle of the night when Killer the Weasel woke up. The stone-pile was a whole lot quieter than it had been that evening when he flopped into it, and for a minute he thought he was back in his own snug home between two stones on the bank of Doctor Muskrat’s pond.

Just then one of the little mice, who belonged to the fat old mamma mouse who was too stubborn to leave, began to squall. “Eh? What’s that?” Killer pricked up his ears. “Where am I, anyhow?” He began to look himself over. He was bumps and lumps from head to foot, his fur was torn—and when he moved he snubbed his nose on all sorts of rolly little stones.

“This isn’t my home,” said he.

But he did find that foolish mother mouse and fished her children out of their nest with his slinky paw. And he did find that greedy mouse, who wouldn’t leave his stores. He was sticking in a crack too small for his fat middle, with his feet kicking in the air. Killer felt quite full and rested after he’d eaten them all. “Mice are very nice,” he said to himself as he picked the last of their bones. “Very nice and juicy! Hunting these Woodsfolk has got me into a clawful of trouble. I believe I’ll live on mice for a while.”

Out he climbed and went sniffing all the trails until he found the big clear wide one where the mice ran away from him. “So-ho,” said he. “Now I wonder where these fellows went to.” Sniff, sniff, he went gliding off into the darkness, down the wind, hiding in every grass-clump to be sure nobody was after him, until he crawled into the very bottom of the straw-stack where the mice were living. How rich and mousy it smelled! If the fat grains seemed like heaven to the mice, the fat mice all around him seemed like heaven to him.

In the meantime, while Watch the Dog was busy in the barn, Stripes Skunk’s kittens came dashing up calling, “Come! Quick, quick! Come!” And what do you suppose they’d found? An oil-can that fell off the mowing machine and got raked up in the hay. Its spout was broken off so it didn’t hold any more oil, but it wasn’t empty. Great Grass-seeds, no!

It held a mouse. And she was squealing away inside, making the funniest, tinniest sound, like talking into a teapot. “I’m Nibble Rabbit’s friend! I’ve got something dreadfully important to tell him. Call Nibble Rabbit!”

They did call Nibble. He came a-hopping. He squeezed in as close as ever he could get to that oil-can. “Well!” he exclaimed, “if it isn’t the lady mouse who saved my life when Ouphe the Rat was after me! You needn’t worry, Ma’am. My hunting friends won’t hurt you.”

“They can’t,” chuckled the mouse. “Even Ouphe’s wicked grandsons couldn’t. They gnawed my front door till their teeth ached but they couldn’t make it any bigger, and even their grabby paws wouldn’t reach to the bottom of it. But I’ve sat here listening and listening and squirming in my skin because they were listening, too, so I couldn’t get out to warn you. This is what I heard:

“All the mice from the Woods and Fields are living in the stack of grain Tommy Peele’s father grew to feed the cows in the winter time. Not just a few of us, like other years, but hundreds and hundreds all nibbling and destroying it. Before long there won’t be anything left. Then, the rats say, the cows will go wild and the men will starve, and the mice will have all these houses and barns and everything else that’s in them. But the rats will rule over them. You know what that means. I’d rather have men.”

Nibble Rabbit’s face was as long as his ears when he backed out of the haystack. And he repeated every word the lady mouse had just been telling him.

“Hm!” remarked Stripes Skunk who had been listening with his head on one side. “Looks to me as if it was time for us Woodsfolk to do something. Let’s call a meeting. Doctor Muskrat, Chaik Jay, and Tad Coon are still to be heard from. Here, sons,” he waved a paw, “go bring them.” And off scuttled his three kittens.

Well, to make a long story short, a meeting they had. But little good did it do them. The mice were in the stack; they didn’t have to leave it for any reason, and unless they did, none of the Woodsfolk could catch them.

“Urr-wrr!” growled Watch uneasily after the fiftieth time they’d been over the question. “We might do something if we could make the cat talk with us.”

You ought to have seen the Woodsfolk prick up their ears when Watch the Dog spoke of the cat. Nobody else knew a single thing about her, but instead of listening to what Watch had to say they all began to talk at once—isn’t that always the way?

“What good can that cat do? She’s a sneak and a liar,” said Nibble Rabbit.

“A cat has no friends—she always hunts alone,” put in Stripes Skunk.

“She’s a lazy, greedy, ill-mannered brute,” said Tad.

“Dear me,” grinned Watch, “what an awful creature she must be, to hear you tell about her. Let’s have Doctor Muskrat’s opinion.”

“I don’t know anything,” answered the wise old beast, “but I suspect she’s like these white ducks I’ve been hunting with the last few days. They’d be dreadful fools to a wild duck’s way of thinking, but they’ve taught me a lot. Maybe that cat would teach us a lot more. Eh, Watch? What about her?”

“You’re all of you right,” sniffed Watch, thoughtfully cocking one ear. “For the first three months I spent on this farm I don’t think I was ever without one of her claw-marks on me. So I used to hate her. And you’re all of you wrong, too.” He cocked the other ear. “Once she taught me to chase my own rats and gnaw my own bones I learned there isn’t a creature in fur honester or with better manners. She’s friends with nobody, yet I feel mighty friendly toward her. Man-ways or beast-ways, she knows more than all of us put together. She could teach us a lot, but she won’t. Yet if she chose to advise us, without giving a single reason, I’d do exactly what she said and trust her for the rest. She’s clever!”

“Well, Watch,” came a purring voice from nowhere in particular (it was pretty dark by now), “if that’s the way you feel, I’ll tell you this. Be on foot here tomorrow night and you’ll see the last mouse blow to the woods on the sunset wind.” The voice stopped. It certainly was Mrs. Tabitha Puss-cat who had been talking, but crane their necks as they would, nobody could see a sign of her.

Nibble sat down and scratched his collar with his hind foot, he was that puzzled about it. “Well,” he gasped, “what do you s’pose she meant?”

“I don’t know,” Watch answered, “but she must have had a reason of her own.”

“I did,” said the puss-cat voice, and there Mrs. Tabitha stood right beside him, purring. “Until we get these mice cleaned off this farm I want to make a compact with your friends. If they won’t hunt me I won’t hunt them.” She looked specially at Tad Coon.

“By the curl in the bull-frog’s tail.” Tad exclaimed admiringly. “You are a clever one. Oh, mice, what a lot of claws you’ll find a-waiting for you.” Of course the Woodsfolk were willing to be friends.

But the cat hadn’t told all her reason. She knew Killer the Weasel had just crawled into that mouse’s straw-stack. She didn’t want to be the one to fight him when he came out again. And she knew just when and why he was coming. That was a secret, too.

How did Mrs. Tabitha Puss-Cat know the mice were going to leave their straw-stack at sundown the very next evening? Because she knew there wouldn’t be any stack left for them to stay in, or any grain left to eat. Up at the house Tommy Peele’s father had just been saying: “Better go to bed early, young fellow, if you’re going to stay home from school tomorrow to help me with the thrashing.”

You know what thrashing is. A great big engine comes puffing into the barnyard with a great big machine that shakes all the fat little grains out of their thin little chaff overcoats. Tommy Peele’s father thrashed at the very last, latest end of the season, because he knew those fat little grains would keep on getting fatter even after their stems were cut off, if he just piled them up into a nice stack and let them go quietly off to sleep for the winter. They hide a lot of good food in their hollow stems; the furry folk aren’t the only ones who get ready for the hungry season.

“Toot-toot!” whistled the engine. “Fsssh!” it sent up a cloud of steam. “Clank, clank, squeak, squeak, cough!” went the thrashing machine. Then “Wurr-wurr-wurr,” its tongue began to lick up the bundles of straw with the grains all wrapped up on the ends of their stalks. It licked so fast that the men who were feeding it could hardly keep up with its appetite. “Whish,” came the straw tumbling out of a long hollow arm with a crook on the end of it that spread the straw into a new pile.

And you ought to have seen the little overcoats go sailing off in the wind. But the sleepy little grains didn’t know anything about it. They came pouring out of the side of that machine, all nice and warm, and snuggled together in a comfortable sack, ready to be stored away—where the mice couldn’t get them—for Tommy’s own hungry season.

Watch wanted to shake himself by the scruff of his own furry neck for not thinking about it. Now he knew what that cat meant. The new strawpile grew bigger and bigger; the old stack, where the mice were hidden, grew smaller and smaller. Those foolish mice soon wouldn’t have any stack left to hide in. Pretty soon they’d have to begin coming out—but he didn’t know who else was coming! The cat didn’t tell him.

Tommy Peele was mighty busy the day of the thrashing. He had to run for oil, and monkey wrenches, and drinks for the men, and I don’t know what else, all day long. So were the men. So was that noisy, hungry old thrashing machine that kept eat, eat, eating up the mouse’s stack, shaking out the grain for Tommy’s winter food, and the pigs’ and cows’ and the chickens’. But none of them was any busier than Watch.

The mouse’s stack grew smaller and smaller. Every time a man lifted off any straw, the mice beneath it dived deep down into the little low heap there was left, until it really held more mice than grain. And something else. For Killer was hiding down in the very deepest bottom of it.

He couldn’t think what was going on. The noise outside frightened him. When he put out his nose to see what was happening, there was a man standing right in front of him; so he pulled back in a great hurry. The next time he tried it, he found the big green eyes of the cat staring right at him. They made shivers run up his spine and took away his appetite. How he wished he’d never come away from home! But all he could do now was to sit still and listen.

Awful things began to happen. Whole families of baby mice, too little to run, went into the maw of that machine, and nobody knew what became of them. Mice began bursting out of the crowded stack. Some of them ran any which way. Some of them saw the new strawpile and scuttled over there. Then——

“Squeak—wee-ee-ak!” That was the end of them. For it hid Tad Coon and Stripes Skunk and his three kittens. That’s what Watch had been doing. He’d been sneaking them in there when nobody was looking. And Doctor Muskrat was there, too, with those three jolly white ducks who’ll gobble a mouse gladly if any one will kill it for them. And Nibble Rabbit and the whole bunny family were on guard to make sure nobody got past the fighters while they were busy.

Mrs. Tabitha Puss-Cat knew that’s what would happen when the thrashing machine ate up the straw from over the very heads of the mice. But she was the only one who was clever enough to think about it.

Yet she wasn’t proud. She was worried. She’d seen Killer the Weasel run into that stack. Where was he if he wasn’t hiding in the little bit of it that was left? And if he was—well, she didn’t want the Woodsfolk to spend their time catching mice and leave her to fight him. She wanted them to do it. That’s why she took the trouble to make friends with them. So she kept walking about on top of it saying “Mewaur-r-r. Mewaur-r-r,” in a troubled voice.

“What’s up now?” asked Watch, bouncing over to hear what the old cat was saying. But she felt so sneaky about what she’d been hiding from them all that now she didn’t care to explain. She just danced about like someone was biting her toes on the bottom and yowled. So of course he began sniffing and digging.

“There’s something else here,” said Tommy’s father. “Let’s see.” He took up his fork and made the straw fly. The other men came to help him. They kept the old cat jumping.

The Woodsfolk began bursting out of the straw pile, in and out and up and down.

“Yaur-r!” she squalled. Her tail swelled up with fright and her eyes began to gleam. A dark streak had shot out of the straw—the very thing she had been looking for—Killer the Weasel! My, but he was going!

And nobody seemed to have any wits about him. Nobody you’d expect to have them. Nobody but little Tommy Peele and Stripes Skunk’s children. They thought Killer was a rat, and they just had to hunt him. They weren’t afraid of men; the only men they knew were Tommy Peele and Louie Thomson, and they were good friends. Wow! but just didn’t they take after him!

The Woodsfolk began bursting out of that strawpile.