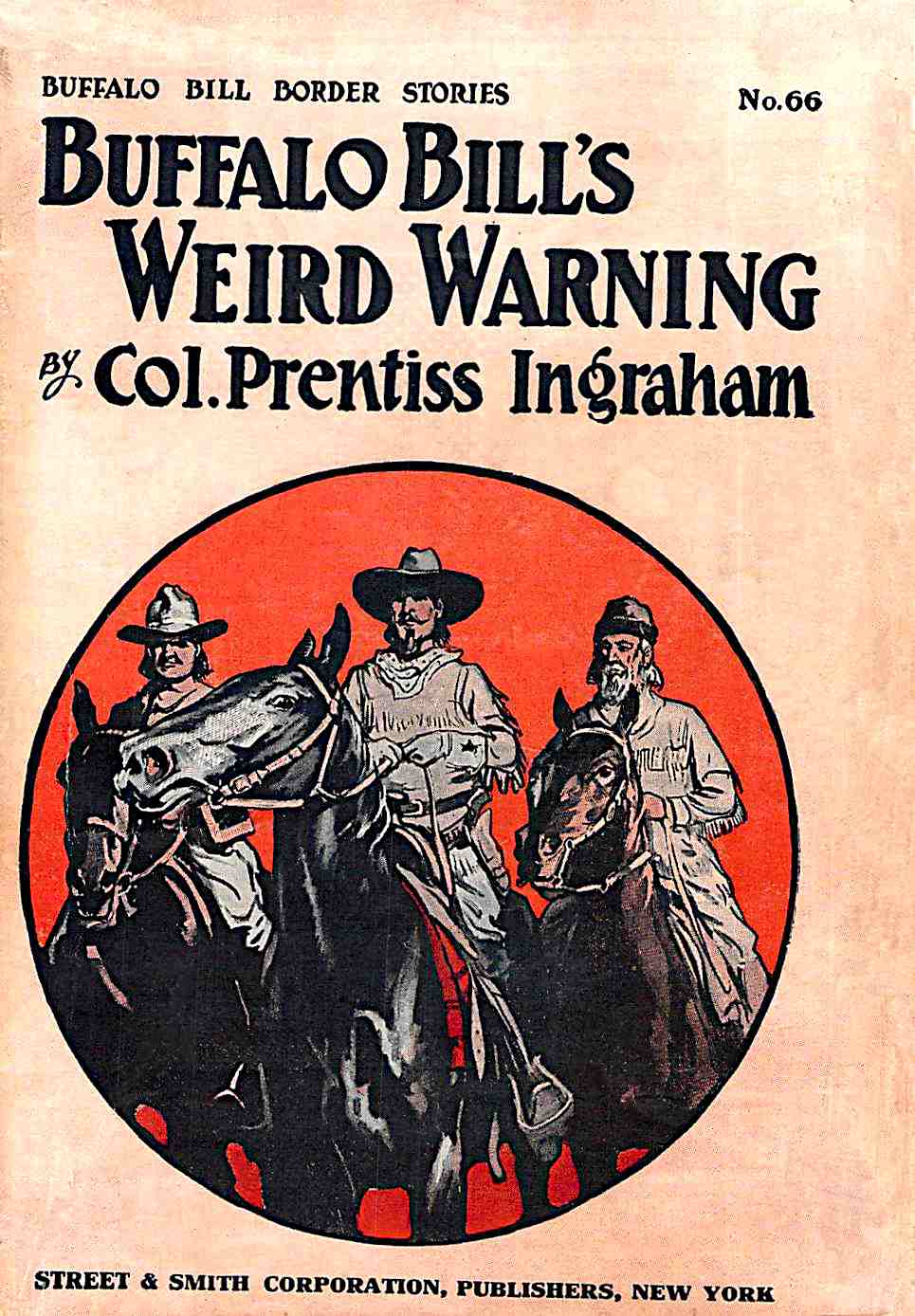

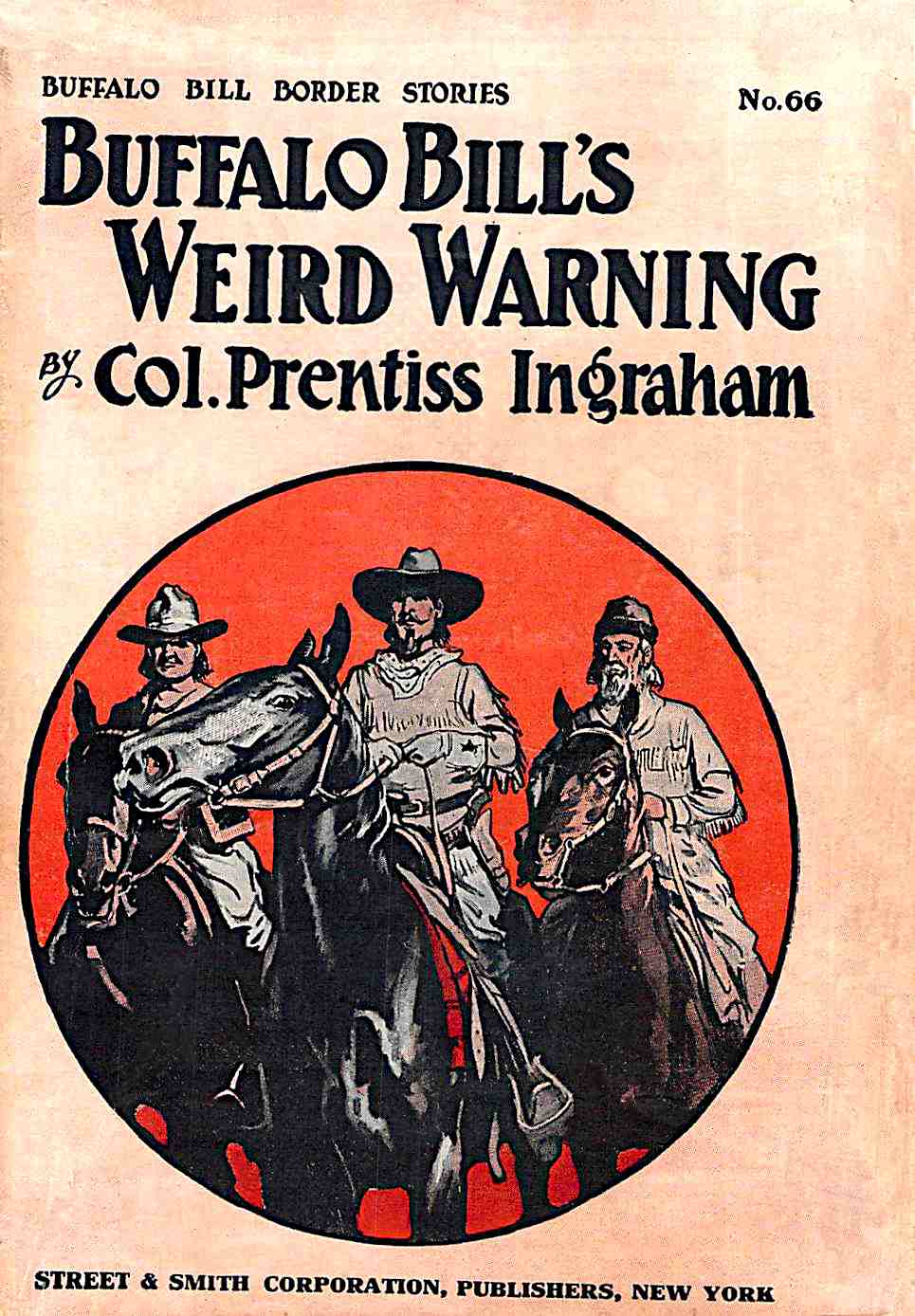

Title: Buffalo Bill's Weird Warning; Or, Dauntless Dell's Rival

Author: Prentiss Ingraham

Release date: February 23, 2021 [eBook #64613]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Susan Carr and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BY

Colonel Prentiss Ingraham

Author of the celebrated “Buffalo Bill” stories published in the

Border Stories. For other titles see catalogue.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright 1908

By STREET & SMITH

Buffalo Bill’s Weird Warning

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign

languages, including the Scandinavian.

| PAGE | ||

| IN APPRECIATION OF WILLIAM F. CODY | 1 | |

| I. | MYSTERIOUS DOINGS. | 5 |

| II. | ANOTHER STRANGER IN CAMP. | 18 |

| III. | CAPTAIN LAWLESS. | 30 |

| IV. | THE INDIAN GIRL. | 37 |

| V. | WAH-COO-TAH AGAIN. | 50 |

| VI. | AT THE FORTY THIEVES MINE. | 63 |

| VII. | LAYING THE “GHOST.” | 78 |

| VIII. | THE FIGHT AT THE ORE-DUMP. | 89 |

| IX. | DELL AND CAYUSE ALSO DELAYED. | 95 |

| X. | THE STRANGER AND THE STEER. | 107 |

| XI. | A GIFT WITH A STRING TO IT. | 119 |

| XII. | THE “FORTY THIEVES MINE.” | 131 |

| XIII. | DELL AND WAH-COO-TAH. | 144 |

| XIV. | LITTLE CAYUSE ON GUARD. | 163 |

| XV. | THE RESCUE OF NOMAD AND WILD BILL. | 176 |

| XVI. | THE CURTAIN-ROCK. | 183 |

| XVII. | THE TURN OF FORTUNE’S WHEEL. | 195 |

| XVIII. | THE ROUND-UP AT SPANGLER’S. | 202 |

| XIX. | THE STAGE FROM MONTEGORDO. | 209 |

| XX. | DOUBLE-CROSSED. | 222 |

| XXI. | BUFFALO BILL AND GENTLEMAN JIM. | 234 |

| XXII. | LETTER, RING, AND LOCKET. | 241 |

| XXIII. | PICTURE-WRITING. | 253 |

| XXIV. | ON THE WAY TO MEDICINE BLUFF. | 260 |

| XXV. | A COWED OUTLAW. | 273 |

| XXVI. | CHAVORTA GORGE AND PIMA. | 280 |

| XXVII. | A BUSY TIME FOR CAYUSE. | 293 |

| XXVIII. | A HAPPY REUNION. | 300 |

| XXIX. | CONCLUSION. | 309 |

[Pg 1]

It is now some generations since Josh Billings, Ned Buntline, and Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, intimate friends of Colonel William F. Cody, used to forgather in the office of Francis S. Smith, then proprietor of the New York Weekly. It was a dingy little office on Rose Street, New York, but the breath of the great outdoors stirred there when these old-timers got together. As a result of these conversations, Colonel Ingraham and Ned Buntline began to write of the adventures of Buffalo Bill for Street & Smith.

Colonel Cody was born in Scott County, Iowa, February 26, 1846. Before he had reached his teens, his father, Isaac Cody, with his mother and two sisters, migrated to Kansas, which at that time was little more than a wilderness.

When the elder Cody was killed shortly afterward in the Kansas “Border War,” young Bill assumed the difficult rôle of family breadwinner. During 1860, and until the outbreak of the Civil War, Cody lived the arduous life of a pony-express rider. Cody volunteered his services as government scout and guide and served throughout the Civil War with Generals McNeil and A. J. Smith. He was a distinguished member of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry.

During the Civil War, while riding through the streets of St. Louis, Cody rescued a frightened schoolgirl from a band of annoyers. In true romantic style, Cody and Louisa Federci, the girl, were married March 6, 1866.

In 1867 Cody was employed to furnish a specified amount of buffalo meat to the construction men at work on the Kansas Pacific Railroad. It was in this period that he received the sobriquet “Buffalo Bill.”

In 1868 and for four years thereafter Colonel Cody[2] served as scout and guide in campaigns against the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. It was General Sheridan who conferred on Cody the honor of chief of scouts of the command.

After completing a period of service in the Nebraska legislature, Cody joined the Fifth Cavalry in 1876, and was again appointed chief of scouts.

Colonel Cody’s fame had reached the East long before, and a great many New Yorkers went out to see him and join in his buffalo hunts, including such men as August Belmont, James Gordon Bennett, Anson Stager, and J. G. Heckscher. In entertaining these visitors at Fort McPherson, Cody was accustomed to arrange wild-West exhibitions. In return his friends invited him to visit New York. It was upon seeing his first play in the metropolis that Cody conceived the idea of going into the show business.

Assisted by Ned Buntline, novelist, and Colonel Ingraham, he started his “Wild West” show, which later developed and expanded into “A Congress of the Rough Riders of the World,” first presented at Omaha, Nebraska. In time it became a familiar yearly entertainment in the great cities of this country and Europe. Many famous personages attended the performances, and became his warm friends, including Mr. Gladstone, the Marquis of Lorne, King Edward, Queen Victoria, and the Prince of Wales, now King of England.

At the outbreak of the Sioux, in 1890 and 1891, Colonel Cody served at the head of the Nebraska National Guard. In 1895 Cody took up the development of Wyoming Valley by introducing irrigation. Not long afterward he became judge advocate general of the Wyoming National Guard.

Colonel Cody (Buffalo Bill) died in Denver, Colorado, on January 10, 1917. His legacy to a grateful world was a large share in the development of the West, and a multitude of achievements in horsemanship, marksmanship, and endurance that will live for ages. His life will continue to be a leading example of the manliness, courage, and devotion to duty that belonged to a picturesque phase of American life now passed, like the great patriot whose career it typified, into the Great Beyond.

[5]

BUFFALO BILL’S WEIRD WARNING.

“What was that, Crawling Bear?”

“Ugh! Fire-gun make um big ‘boom.’”

“It was a fire-gun, all right, but where did the report come from? That’s what I’m trying to figure out.”

Two horsemen were riding along a bleak, desolate-looking cañon, on route to the mining-camp known as Sun Dance. One was a white man, and the other an Indian. The white rider was William Hickok, of Laramie, better known as “Wild Bill,” and his companion was a Ponca warrior.

Both Wild Bill and Crawling Bear had keen ears, and the muffled report of the rifle came to them distinctly—not from right or left, from ahead or behind, or above, but seemingly from the ground under their horses’ hoofs.

Another report reached them, coming from the same place as the first, and Wild Bill, with a puzzled look, drew rein and rubbed his hand over his forehead.

“Am I locoed, or what?” he muttered. “It’s a trick of the echoes, I reckon. Somebody is having a little gun-play in this vicinity, and the bottom of the gulch picks up the sound and throws it back to us.”

The Indian made no response, although from his actions[6] it seemed quite clear that he did not accept the white man’s explanation.

Wild Bill rode on, and a sharp turn in the cañon brought him upon something which led to a revision of his theory concerning the rifle-shots.

What he saw was an ore-dump, off at one side of the cañon. The mound of broken rocks was surmounted by a plank platform. Five horses were hitched to bushes, not far from the ore-dump, but their riders were not in evidence.

Wild Bill halted his horse, once more, and looked from the ore-dump to the horses, and then around the cañon. While his eyes were busy, there came a third rifle-shot.

“By gorry!” he exclaimed, and gave a low laugh. “This thing begins to clear up a little, Crawling Bear. There’s a mine here, and probably the mine has a drift running down the gulch. The shots we heard really came from under us, but they came from the bottom of the mine.”

“Ugh!” grunted the Ponca. “Why Yellow Eyes make um shoot in mine? No got um game in mine.”

“Now you’re shouting, my redskin friend. What there is to shoot at, in that mine, is a conundrum that your Uncle William is going to work out. Maybe there’s no game to shoot at down there, but there’s a game being pulled off that needs looking into.”

Wild Bill tossed his bridle-reins to the Ponca and slipped down from the saddle.

“You go down in mine, huh?” queried Crawling Bear.

“That’s my intention,” was the answer.

“Five ponies, five Yellow Eyes down in mine. Mebbyso Crawling Bear better go with Wild Bill.”

[7]

A smile curled about Wild Bill’s lips.

“Any old day the odds of five to one make me take a back seat,” said he, “I hope some friend will hand me a good one and tell me to wake up. I’m going to hide my hand, Crawling Bear. This is a case of find out what’s doing, and then make a get-away on the q. t.—in case I can’t help some unfortunate in distress. You look out for the horses; and, if I can’t take care of myself, then I’m ready to be planted, for it will be high time.”

With that, Wild Bill stepped to the foot of the ore-dump and climbed carefully to the plank platform.

An empty ox-hide bucket stood on the platform, off to one side, but there was no windlass for hoisting the bucket, and there did not seem to be any ladders for getting down into the shaft. All this contributed still further to Wild Bill’s perplexity, and at the same time increased his determination to investigate.

But, if there were no ladders for getting into the mine, there was a rope. The upper end of the rope was made fast to the edge of the opening in the middle of the platform.

The Laramie man peered down into the shaft. The blackness was intense, and he could see nothing, not even the gleam of a candle.

“Can’t tell whether the shaft is fifty feet deep or five hundred,” he muttered, “but it’s a cinch that none of the men who came here on those five horses are anywheres around the foot of the shaft. If they were, they’d jump a piece of lead at me. With my head over the hole, like this, I’m a good target. Now to go down.”

For an instant Wild Bill sat on the platform, his feet[8] dangling over the abyss; then, slowly letting himself down, he grabbed the rope and began to slide.

The shooting continued, the echoes booming louder in Wild Bill’s ears and increasing his curiosity. Wild Bill was down fifty feet before he touched bottom. The shaft was not so deep, after all.

Leaving the lower end of the rope, he groped his way around the shaft wall until he found the opening of the level. In traversing the level, he dropped to his hands and knees, and crawled.

The level crooked to right and left, and, after Wild Bill had covered something like fifty feet of it, he began to hear voices, and to see a glow of light in the distance.

Pushing his head and shoulders around a turn, he suddenly beheld a queer scene, right at the end of the level.

Five men were there, and four of them carried lighted candles. The fifth man had no candle, but was armed with a shotgun.

The men had all the earmarks of scoundrels, and each was heeled with a brace of six-shooters. The fellow with the shotgun had a belt about his waist, above his revolver-belt, filled with brass shells.

Just as Wild Bill came within sight of the group, the man with the shotgun was “breaking” the piece at the breach, ejecting an empty shell and replacing it with one that was loaded. Having finished the loading, the man threw the gun to his shoulder and shot the charge into the breast of the level.

“We’re blowin’ a hull lot o’ good stuff inter this bloomin’ country rock, Clancy,” growled a man with a candle. “Ain’t ye done enough?”

“I started in with fifteen shells,” replied Clancy, the[9] rascal with the gun, “an’ thar’s five left. We might jest as well close up the rock with what we’ve still got.”

“How do ye know ther feller’ll take his samples from the place ye’re puttin’ them loads?”

“He’ll git his samples from the breast o’ the level, won’t he?” struck in another man with a candle. “By the time we’re done, thar won’t be a patchin’ he kin pick at but’ll hev its salt. Cap’n Lawless’ll land him, an’ thar’ll be a hundred thousand ter pass around. The ‘Forty Thieves’ Mine is a played-out propersition, but the Easterner won’t find that out until arter us fellers git our hooks on ther money. Then we’ll hike.”

Clancy banged another load into the rocks.

“Why in thunder ain’t Lawless hyer?” asked another of the candle-bearers. “He ort ter be helpin’ us, seems like.”

“Don’t you fret none erbout Lawless, Tex,” replied Clancy. “He’ll be around afore long, ready ter do the fine work an’ land the lobster. We don’t need him fer this, an’ it’s a heap better fer him not ter show up in ther cañon while this job o’ salt is bein’ pulled off. If Lawless ain’t seen around hyer, he won’t be suspected o’ any crooked work.”

“What’s Lawless doin’, anyways?” queried the man who had spoken first.

“I dunno, but I reckon he’s watchin’ thet ole flash-light warrior, Buffler Bill. Ye see, Andy, Lawless ain’t anyways eager ter tangle up with Buffler Bill an’ his pards; not but what Lawless could put ther scout an’ his friends down an’ out—fer head-work, I backs Cap’n Lawless, o’ ther Forty Thieves, ag’inst all comers, bar none—but Lawless is jest startin’ inter this hyer profitable field, an’ he don’t want ter hev no interruptions.”

[10]

“Buffler Bill is workin’ fer ther gov’ment,” said Tex. “He won’t bother none with the cap’n.”

“Ye never kin tell about him, Tex,” averred Clancy. “Wharever Buffler scents any unlawful doin’s, he’s li’ble ter butt in; an’ we don’t want ter give him no chance ter git fracasin’ round with us.”

“But if he does,” said Tex, “we’re goin’ ter do him up?”

“We are,” declared Clancy; “him an’ his pards—Nomad an’ ther Injun kid, Leetle Cayuse. I’m close ter the last ca’tridge, Tex, an’ you an’ Andy better go up an’ have ther hosses ready. We won’t linger around ther ore-dump none, arter we come out.”

Wild Bill, screened by the corner of rock, had heard every word of this talk. The mysterious doings, in the light of the conversation among the scoundrels, was now clearly explained.

The five men were “salting” the worthless mine; that is, they had loaded the shotgun-shells with fine gold, and were blowing the gold into the breast of the level. When the intended victim came to take his samples of the vein, he would chip off pieces of the doctored rock, and when the rock was assayed, it would show the mine to be a heavy “gold-producer.” On this showing, unless the intended victim was warned, a hundred thousand dollars would change hands, and Captain Lawless, of the Forty Thieves, whoever he was, would be that much richer.

“I’ll nip this little scheme in the bud,” thought Wild Bill, as he drew back and crouched against the wall for Tex and Andy to pass.

The passing of the men, with their candles, was filled with considerable danger for Wild Bill. If the two ruffians saw him, there was bound to be a fight, for it would[11] not do to let Wild Bill get away with the information he had discovered.

Wild Bill drew his revolvers and made himself as small as possible. Had there been time, he would have hastened back to the shaft, along the level, and climbed the rope. But he knew he could not have gotten half-way up before Tex and Andy would have located him. It was better for Wild Bill to stay right where he was, and hope for the best.

The whole affair, as Wild Bill had planned it, was reckless in the extreme; but he was daring by nature, and rarely counted the cost before making a leap in the dark.

This must have been his evil day, and the beginning of a series of evil days, as will soon appear. Tex and Andy were stumbling past him, when the former, tripping on a stone that lay on the bottom of the level, fell sideways, dropping his candle and falling full on the man from Laramie.

The candle was extinguished, but Tex, encountering the intruder, gave vent to a wild yell of alarm. Wild Bill’s fist shot out, and Tex crumpled flat along the floor of the level; the blow was followed by another, which landed on the point of Andy’s jaw, and threw him against the hanging wall. His candle also dropped, and Wild Bill set his foot on the sputtering flame.

By then Clancy and the other three had started at a run to see what was the trouble. Wild Bill, berating his hard luck, rushed toward the shaft, but he was running in the dark—a circumstance which brought him many a bruise and bump. Behind him came three men with two candles, but Tex and Andy were temporarily out of the race.

[12]

From time to time, as he stumbled onward, Wild Bill looked backward over his shoulder. Suddenly he saw Clancy halt, lift the shotgun, and shoot along the level.

Quick as a flash, Wild Bill dropped flat. He had no desire to stop a charge from a brass shell, even though it was of gold.

The fine yellow metal whistled over his head. As the echo of the shot clamored in the level, Wild Bill sprang up and forged onward with a reckless laugh.

“They can’t salt me,” he muttered, “but I may be able to salt one of them with lead.”

He paused long enough to chance a shot from his six-shooter. A yell of pain came from Clancy. The shotgun clattered to the rocks, and he grabbed at his right arm.

The other two men thereupon began using their revolvers, accompanying their shooting with savage yells.

Wild Bill, pushing flat against the foot wall, deliberately snuffed the two candles that remained alight. His wrist had been grazed by one of the ruffians’ bullets, but it was a small injury, and he gave it scant attention.

As soon as the level was entirely plunged in darkness, he ran on to the shaft which, by then, was only a few feet away.

The time had passed for fighting. It was up to him to retreat, and to see how quick he could get to the top of the shaft, and out of it.

Jabbing his revolver back into his belt, he laid hold of the rope and started aloft, hand over hand.

Clancy and the rest, meanwhile, had not remained inactive. They must have been considerably in the dark as to the identity of their enemy, but they realized that he had caught them red-handed, and that the success[13] of their whole plot might hang on their capturing him. Therefore they pushed forward desperately, Clancy in a rage because of his wound. Tex and Andy, having revived sufficiently from the sledge-hammer blows they had received, had joined the others.

“Don’t strike any matches,” Wild Bill heard Clancy yell, “and don’t light no candles. We don’t want the whelp ter make targets o’ us. Ketch him, thet’s all! Consarn his picter! he’s given me a game arm. I want ter play even fer thet, anyhow.”

Above him, Wild Bill could see a square patch of daylight as he climbed. His progress was slow, however, and he knew that when Clancy and the rest got to the shaft, they would see him swinging in mid-air between them and the lighted background.

As Wild Bill looked up, he saw the head of Crawling Bear leaning over the opening and looking down.

“Cover that hole, Crawling Bear!” roared Wild Bill. “They’re after me, the whole five of ’em. Look alive, now.”

The Ponca was quick-witted, and must have realized the situation. His head vanished from the patch of light the instant Wild Bill ceased speaking.

Climbing hand over hand was slow work. Wild Bill’s arms were strong, and he did his best, but his best did not carry him upward nearly so swiftly as he could have wished.

Sounds of scrambling feet came from below him, followed by the voice of Tex.

“Thar he is! See him squirm, will ye? Pepper him! Turn loose at him!”

Just then the hole above suddenly darkened. Wild Bill was still a target, but not so plain.

[14]

The shaft echoed with a patter of reports. A sharp, stinging blow struck the heel of Wild Bill’s boot, the broad brim of his hat shook, and he was raked along one side as by a red-hot iron.

“Wow!” he muttered; “if they put a piece of lead into one of my arms——”

And just then that is exactly what they did. It was Wild Bill’s left arm. The strength went out of the arm in a flash, and Wild Bill only saved himself from dropping back to the bottom of the shaft by a fierce grip on the rope with his right hand.

How could he climb now? The outlook was anything but reassuring.

All this time the Laramie man felt a movement of the rope, as though Crawling Bear, at the top of the shaft, was tinkering with it under the cover he had placed over the opening.

“I reckon he ain’t climbin’ no more,” roared the voice of Clancy, from the depths. “Lay holt, thar, Tex, an’ see if ye kain’t crawl up an’ haul ther whelp back. He’s winged, mebby, an’ kain’t climb.”

This, as we know, was Wild Bill’s condition. He had twisted the rope about one of his legs, and was able to maintain his place, but, if he did not drop downward, neither could he move upward an inch.

Tex, evidently, had grabbed the rope, for it tightened cruelly around Wild Bill’s leg.

The Laramie man’s arm did not seem to have been very seriously injured. So far as he could judge, what the arm was suffering from, more than anything else, was the shock of the bullet.

Twisting the arm about the rope, he drew his knife from its scabbard at his belt, and bent downward. A[15] quick slash severed the rope in twain, and a heavy fall and a chorus of oaths came from the shaft’s bottom. Tex had dropped upon some of his companions, for the moment demoralizing them.

This move of Wild Bill’s, while necessary for his safety, almost proved disastrous to him as well as to Tex.

Wild Bill’s left arm was not to be depended upon. At the critical moment it gave with him; and, had he not dropped the knife and gripped the rope with his right hand, he would have followed Tex onto the heads of Clancy and the others.

Before the disorder at the bottom of the shaft could be righted, and the scoundrels again begin their revolver-work, Wild Bill felt himself started upward with a jerk.

Crawling Bear was taking a hand! Just what he had done Wild Bill did not know, but that his means, whatever they were, were effectual, was proved by the swiftness with which Wild Bill was hauled to the platform.

In less than half a minute after Wild Bill started upward, his head struck against a blanket covering the mouth of the shaft, and he was snaked out onto the planks, and lay blinking in the sun.

At the foot of the ore-dump stood the Ponca with a hand on the bridle of Wild Bill’s horse. The Laramie man saw in an instant what his red companion had done.

After covering the mouth of the shaft with his blanket, he had secured the picket-rope from Wild Bill’s saddle and had tied one end to the horn; the other end he had secured to the rope leading down into the shaft, and had then cut the shaft-rope. By leading Wild Bill’s horse across the cañon from the foot of the ore-dump,[16] the Ponca had been able to get his white companion to the surface by horse-power.

“You’re all to the good, Crawling Bear!” declared Wild Bill, sitting up at the edge of the ore-dump and pulling off his coat. “I had a close call, down there, and I reckon those yaps would have got me if it hadn’t been for you.”

Crawling Bear untied the rope from the saddle-horn and began coiling it in. When he had removed the rope spliced to the end of the picket-rope, he hung the coil in its proper place at Wild Bill’s saddle.

“Wild Bill hurt, huh?” he asked, mounting the side of the dump.

“A gouge through the fleshy part of the arm, that’s all,” the Laramie man answered, examining the injury. “The bullet flickered along the muscles and went on about its business.”

Wild Bill had cut away the sleeve of his flannel shirt in order to examine the injury. Out of the bottom of the sleeve he improvised a bandage, and Crawling Bear helped him put it in place.

When the arm was roughly bandaged, Wild Bill thrust his hand into the breast of his shirt.

“I’m worth a dozen dead men yet,” he went on, “but that outfit sure had it in for me. Don’t know as I can blame them, though, as they’ve got a hundred thousand at stake. I’m going to fool them out of that hundred thousand—watch my smoke.”

He looked at the bullet-hole through the brim of his hat, then at his left boot, from which the heel was missing, and finally at the place where a bullet had raked along the side of his clothes, after which he laughed grimly.

[17]

“They had a good many chances at me, Crawling Bear,” he proceeded, “but they didn’t make good. We’ve got ’em bottled up in that mine now, and we’ll keep ’em there until I can get Pard Cody to Sun Dance. I’ve got a notion he’ll enjoy meeting that gang of trouble-makers.”

The Ponca picked up his blanket from the platform and threw it over his shoulders.

“Yellow Eyes?” he queried.

“You bet! They’re white tinhorns, every last man of them. It’s up to you and me to call their little game. It’s a salting proposition, with a tenderfoot standing to lose a hundred thousand in good, hard money. Let’s ride for Sun Dance and get there as quick as we can.”

“What about um five caballos?” asked the Ponca, his small, beady eyes gloating over the five horses belonging to Clancy and his outfit.

“Oh, we’ll leave them. Haven’t time to bother with ’em, anyhow.”

Wild Bill descended the slope lamely and climbed into his saddle. A few moments later, he and the Ponca were continuing on along the cañon toward Sun Dance.

[18]

Sun Dance was a very small mining-camp, perched on a shelf up the side of Sun Dance Cañon. “Six ’dobies stuck on a side hill,” was the trite and not very elegant way the camp was often described.

The sort of mining indulged in was both quartz and placer—placer-mining in the gulch and quartz-mining in the neighboring hills. Only the placer-miners lived in the camp; the quartz-miners had camps of their own, and only came to Sun Dance for supplies.

The camp could be reached in two ways: From the bottom of the cañon by a steep climb, and from the top by a stiff descent.

The stage from Montegordo reached camp by way of the cañon’s rim, which was its only feasible route; but Wild Bill and Crawling Bear came from below, and gained the settlement by spurring their horses up the slope.

Just where the trail crawled over the edge of the flat, there was a sign-board with the rudely lettered words: “No Shootin’ Aloud in Sun Dance.” As an indication of how seriously the sign was taken, it may be mentioned that the lettering could hardly be read for bullet-holes.

By day the camp was practically dead, all the miners being at work on their placers, and only storekeepers, gamblers, resort proprietors, and the man who “ran” the hotel being visible. For the most part, these worthies[19] smoked their pipes and cigarettes during the day, or played cards among themselves merely to pass the time.

With night everything changed. The camp became a boisterous, rollicking place.

Miners flocked in, bet their yellow dust on the turn of a card or a whirl of the wheel, sampled the camp’s “red-eye,” and very often forgot the warning of the sign, and indulged in shooting that was very loud and occasionally fatal.

The name of the one hotel in the camp was the “Lucky Strike.” The proprietor was one Abijah Spangler, a leviathan measuring six foot ten, up and down, and ten foot six—or so it was said—east and west at his girth-line. Anyway, Abijah Spangler weighed 300 pounds, and when he sat down it took two chairs to hold him.

When Wild Bill and Crawling Bear halted in front of the Lucky Strike, Bije Spangler was sitting down, dripping with perspiration and agitating the air with a ragged palm-leaf fan.

“You the boss of this hangout?” inquired Wild Bill, surveying Spangler’s huge bulk with much interest.

“I run it, you bet,” answered Spangler, ruffling his double-chin and wondering at the red handkerchief about Wild Bill’s arm.

“Got accommodations for two?” queried the Laramie man.

“Fer two whites, yes—meals, four bits, and a bed, a dollar. But”—and here Bije Spangler cast a disapproving eye on the Ponca—“I don’t feed or house Injuns fer no money. Not meanin’ any disrespect fer yerself, neighbor,” added Spangler hastily, noting the glint that[20] rose in Wild Bill’s eye, “but I couldn’t keep open house fer reds without sp’ilin’ the repertation o’ my hotel.”

The Ponca sat up stiff and straight on his horse.

“Where I stay, he stays,” averred Wild Bill; “what’s good enough for him is good enough for me. He’s plum white, all but his skin.”

“So’s a Greaser,” grunted Spangler, “or a Chink. Sorry to appear disobligin’, ’specially as you-all seems to have run inter trouble somewheres. You’re welcome to stop, but the Injun’ll have ter camp out in the chaparral.”

Wild Bill was in no mood for arguing the case, and he was about to ride on, when the Ponca leaned forward and stopped him.

“You want um Ponca take paper-talk to Pa-e-has-ka, hey?” he asked.

“Sure I do, Crawling Bear,” replied Wild Bill, “but I don’t want you to start for Sill until you have rested yourself and your horse.”

“Ugh! no want um rest. Feel plenty fine. Me take um paper-talk now.”

Wild Bill saw that Crawling Bear meant what he said. The camp not appearing to be a very safe place for a red man, anyhow, the Laramie man decided to let his companion have his way.

“Got a place where I can write?” inquired Wild Bill.

“Go through the office an’ inter the bar,” replied Spangler. “You can write on one of the tables, an’ I reckon the barkeep can skeer up a patchin’ o’ paper and a lead-pencil.”

Leaving his horse with the Ponca, Wild Bill went into the barroom, and had soon written a few words to Buffalo Bill, asking him to come to Sun Dance as soon[21] as possible. Returning to Crawling Bear, Wild Bill handed him the folded note and a dozen silver dollars.

“Why you give um Ponca dinero?” asked the Indian.

“That’s for carrying the message to Buffalo Bill,” said the Laramie man.

“Buffalo Bill?” wheezed Spangler, stirring a little in his chair. “You a friend of Buffalo Bill’s?”

“Yes,” answered Wild Bill, whirling on the fat man. “My name’s Hickok.”

“Wild Bill!” muttered Spangler. “Say, that’s different. Any Injun friend o’ Wild Bill’s can stop with me. I’ll break my rules for you, and——”

Hoofs clattered. Crawling Bear, not waiting further, was off for the edge of the “flat” on his return journey to Sill.

“You’re too late,” said Wild Bill curtly. “What’s your label.”

“Spangler is my handle.”

“Any strangers in town, Spangler?”

“Only you.”

“When’s the next stage due from Montegordo?”

“To-morrow afternoon.”

“Well, I’m going to stay with you until to-morrow afternoon, anyhow. Call some one to take care of my horse; and if I can have a room all to myself, I want it.”

“That’ll cost extry,” said Spangler. “If ye’re goin’ to throw on style with a private room, you’ll have to bleed ten dollars’ worth.”

“That’s the size of my stack. Hustle, now. I’m fagged, and want to lie down.”

Spangler lifted his voice and gave a husky yell. In answer to the signal, a Mexican showed himself around[22] the corner of the house, who took Wild Bill’s horse. Then once more Spangler indulged in a wheezy shout. This was the signal for a Chinaman to present himself. After a few words with Spangler, the Chinaman led Wild Bill into the house, through the office and the drinking-part of the establishment, and into a small, corner room, with a window looking out upon the street.

There was a cot in the room, and Wild Bill flung himself down wearily upon it. In a few minutes he was fast asleep.

He awoke in time for supper, put a fresh bandage around his arm, and went out into the hotel dining-room. Everything about the Lucky Strike was exceedingly primitive, and the table, the service, and the food were about what one would expect in a pioneer mining-camp. Wild Bill, however, was used to such accommodations and fare.

Following the meal, he smoked a couple of pipes in front of the hotel, saying nothing to anybody, but keeping up a lot of thinking.

The Forty Thieves—so ran the current of his thoughts—was a played-out mine. Those five men, under orders from one Captain Lawless, were salting it. The name of the mine was suggestive, and so was the name of the man who was engineering the salting operations.

“Captain Lawless, of the Forty Thieves!” said Wild Bill to himself. “That has sure got a regular rough-house sound. When Pard Cody hears it, I’ll bet money it will ruffle his hair the wrong way. Crawling Bear will get that paper-talk through some time to-night, and Cody will be here to-morrow afternoon. When he arrives, we’ll prance out to the Forty Thieves and snake[23] those five trouble-makers out of that hole in the ground; then, if Captain Lawless wants to take a whack at us, he’s welcome.”

Wild Bill took no part in the hilarious doings of the camp that night. By 10 o’clock he had locked himself in his room and got into bed. His arm was a bit painful, so that he was an hour or more in getting to sleep. When he was once asleep, however, he did not wake until morning.

His arm felt better. He could use his hand as well as usual. There was some pain in the arm, but it was not severe.

Following breakfast, he went to one of the general stores and bought a new flannel shirt, a pair of boots, and a bowie, to take the place of the one he had lost in the mine.

After that, he sat in front of the Lucky Strike and smoked until dinner-time; and, after dinner, he smoked until four-thirty, when the stage pulled over the rim of the cañon and slid down the slope with the hind wheels tied.

The stage drew up in front of the hotel, and a mail-bag was thrown off. There was one passenger, a man in a linen duster, and clearly a stranger.

“He’s the one,” said Wild Bill to himself, knocking the ashes out of his pipe and getting out of his chair. “The chap doesn’t look much like an easy mark, though. I wonder if he has any notion he’s taking long chances with that hundred thousand of his?”

Just then Wild Bill experienced something like a jolt. A man rode up along the trail that led from the cañon bottom, drew rein in front of the hotel, dismounted,[24] dropped his bridle-reins over a hitching-post, and followed the stranger into the Lucky Strike.

The man had his right arm in a sling, and it didn’t take two looks to inform Wild Bill that the fellow was none other than Clancy! Clancy, the man who had been blowing gold into the Forty Thieves with a shotgun! Clancy, the man Wild Bill had left, with four others, bottled up in the Forty Thieves’ shaft!

Clancy did not pay any attention to Wild Bill. It seemed very probable that neither Clancy, nor any of those with him in the mine, had been able to see Wild Bill distinctly enough to recognize him in another place and in broad day.

Then, too, the Laramie man had a new shirt of a different color from the blue one he had worn in the mine, and he showed no sign of injury. All this would help to keep Clancy from recognizing him, even if he had got a tolerably good look at him in the Forty Thieves.

Reassured on this point, Wild Bill fell to canvassing another. How had Clancy managed to escape from the shaft?

Clancy and the rest must have had help. Some other member of the gang must have been abroad in the cañon, and no doubt happened along and gave his aid.

Wild Bill was disappointed. He had hoped the five would be kept in the Forty Thieves until Buffalo Bill reached Sun Dance.

Strolling into the office of the hotel, Wild Bill saw Clancy in close conversation with the man in the linen duster. They were off by themselves in one corner, and were conversing in low, animated tones.

“Clancy is going to hold the man until this Captain Lawless shows up,” thought Wild Bill. “I must have a[25] word with that tenderfoot and show him how he is going to be gold-bricked. I’d hate myself to death if I ever allowed that gang of robbers to get away with his hundred thousand.”

Wild Bill, having settled the situation in his mind, strolled out to the front of the hotel, filled his pipe again, and seated himself in the chair he had occupied for most of the day.

He was waiting for the stranger, and he had not long to wait. Clancy came out, unhitched his horse, climbed into the saddle, and clattered back toward the bottom of the cañon. A few minutes later the stranger followed, pulled up a chair a few feet from Wild Bill’s, and seated himself.

“Howdy,” said Wild Bill, with a friendly nod, by way of breaking the ice.

“How do you do, sir?” answered the stranger, with all the elaborate courtesy of an Easterner. “Will you try one of these?”

He offered Wild Bill a cigar, and the latter accepted it amiably.

“Stranger, I take it?” pursued Wild Bill.

“Well, yes,” answered the other. “I came in on the afternoon stage from Montegordo.”

“Looking up the mines?”

A suspicious look crossed the stranger’s face.

“Figuring on examining the Forty Thieves,” pursued Wild Bill, “with the intention of handing out one hundred thousand cold plunks for the same?”

The stranger laughed.

“You seem to be pretty well informed,” he remarked. “I haven’t told a soul about my business here, but you reel it right off, first clatter out of the box.”

[26]

“Steer wide of the Forty Thieves, pilgrim,” said Wild Bill earnestly. “That proposition is a trap for the unwary. I know. It cost me some trouble to find out what I’m telling you, but you take my word for it, and let the property alone.”

“Who are you?” inquired the stranger, with sudden interest.

“My name’s Hickok, William Hickok.”

The stranger hitched restlessly in his chair.

“The man I’ve heard so much about under the sobriquet of Wild Bill?” he asked.

“Tally! That’s the time you got your bean on the right number.”

The stranger fell silent for a space.

“My name is Smith,” said he finally; “J. Algernon Smith, of Chicago, and what you tell me is mighty surprising.” He drew his chair closer. “Would you mind telling me just what you have found out?”

“Sure I wouldn’t mind. I’m hungry to cut into this game, and even up with the pack of tinhorns that gave me a hot half-hour yesterday.”

And thereupon Wild Bill began telling what he had seen and heard in the level of the Forty Thieves. When he had finished, J. Algernon Smith was wide-eyed and staring.

“Really,” he managed to gasp, “this is most astounding.”

“I reckon it’s all that,” mildly answered Wild Bill. “The very name of that mine, though, is enough to make a man think some. Who’s the fellow you’re going to deal with?”

“His name, I believe, is James Lawless.”

“That’s another name that’s bad medicine.”

[27]

“I’d never thought of the names in that light.”

“That fellow that was talking with you, right after you got out of the stage, was Clancy, the scoundrel that was blowing gold into the rock with a shotgun. What did he want?”

“Why, he was telling me that Lawless hadn’t got here yet, and he was warning me not to say anything to anybody about my business in Sun Dance.”

“You couldn’t blame him for that,” remarked Wild Bill dryly.

“He asked me to meet him at the foot of the slope, in the bottom of the cañon, immediately after supper,” went on the stranger, “so we could have a quiet talk.”

“You can see how they’re working it, can’t you?” returned Wild Bill. “They’re trying to keep this business dark until Lawless shows up, and meanwhile Clancy is going to keep your interest at fever-heat by all kinds of stringing. Any objection to my going along with you when you meet Clancy?”

“No, indeed, Wild Bill. I was about to suggest that myself. I am sure I’m very much obliged to you for your interest in me, and——”

“Stow that,” interrupted Wild Bill. “It isn’t my interest in you, particularly, that leads me to take a hand, but it’s more a desire to see every man get what’s coming to him. Sabe?”

At that moment the Chinaman came out in front of the hotel and pounded on a gong.

“Suppa leddy!” he announced.

The stranger did not remove his linen duster. It covered him from his neck to his heels, and Wild Bill thought he kept it on so as not to soil his Eastern[28] clothes. He and the Laramie man sat at the same table, and next to each other.

When the meal was over, J. Algernon Smith excused himself for a minute, and said he would rejoin Wild Bill in front of the hotel, and they would at once take their way down the slope to the bottom of the cañon.

Wild Bill waited for five minutes before J. Algernon Smith rejoined him, and they started across the “flat” toward the top of the slope.

“A tenderfoot has got to keep his eyes skinned,” said Wild Bill, “or he’ll collide with more trouble, in this western country, than he ever dreamed was turned loose.”

“I presume you are right,” said J. Algernon Smith. “Only fancy blowing gold into a mine with a shotgun!” He laughed a little. “If they knew that, back in Chicago, they’d make game of me,” he added. “You haven’t told any one about this, have you?”

“Not a soul but you.”

“I’m glad of that, I can tell you. I’d hate to have the business get out. Of course, I hadn’t bought the mine yet. I was going to take samples, you know, and have them assayed; then, if the assays showed up well, the deal would have been made.”

It was very dark, at that hour, on the slope leading down into the cañon. Bushes fringed the horse-trail, in places, and there was quite a patch of chaparral at the foot of the slope.

Here Wild Bill and J. Algernon Smith came to a halt.

“Clancy doesn’t seem to be around,” said Wild Bill. “Maybe you’d better tune up with a whistle, or a yell, so that he’ll know where you are.”

J. Algernon Smith stared into the depths of a thicket.

[29]

“It looks to me as though there was a man in there,” said he. “Can you see any one, Mr. Hickok?”

Wild Bill took a step forward. His back was to his companion, and, while he was peering into the bushes, he heard a hasty step behind him.

He started to turn; and, at that precise instant, a heavy blow, dealt with some hard instrument, landed on the back of his head.

He staggered, but, with a fierce effort, rallied all his strength, and turned around. In the darkness he saw the yellow duster pressing upon him. It was Smith, and Smith was about to land another treacherous blow.

Wild Bill’s head was reeling, but he had sense enough left to understand that he had made some sort of a mistake, and that Smith was other than he had seemed.

Evading the blow aimed at him, the Laramie man gripped Smith by the throat. Ultimately, in spite of his unsteady condition, Wild Bill might have got the best of his antagonist had not Clancy taken a part in the struggle.

The latter plunged through the bushes and assaulted Wild Bill from behind.

At Clancy’s second blow, Wild Bill’s reason fled, and he dropped helplessly on the rocks.

[30]

How long Wild Bill remained unconscious he never knew, but it must have been a considerable time. He had been struck down at the foot of the rocky slope, and when he opened his eyes he was lying in the level of the Forty Thieves.

Wild Bill had no difficulty in recognizing the level, for three or four candles were burning in niches of the rock, and lighted the place sufficiently for him to make observations.

The Laramie man’s unconsciousness had lasted long enough for his captors to remove him from the slope four or five miles down the cañon and lower him into the mine.

His hands and feet were bound, and a savage pain from his left arm, cramped around behind him, in no wise mitigated the discomforts of his situation. His head, too, was aching, and his brain was still dizzy.

He was surrounded by seven men, all but one of whom he recognized. Clancy was one, Tex was another, and Andy was a third. The faces of two more he remembered to have seen in the level with Clancy the day before.

Another of the men, of course, was J. Algernon Smith, in his linen duster.

The seventh of the outfit was the fellow whose face was strange to Wild Bill.

The prisoner lay snugly against the hanging wall of[31] the level. He had made no stir when he opened his eyes, and his captors did not know that he had recovered his senses. They were talking, and Wild Bill was content to lie quietly and listen.

“He got away from you,” Smith was saying, “and when he went he took the rope with him. How did you get out?”

“We was in hyer all night, cap’n,” replied Clancy; “me with this game arm, an’ all the rest more er less knocked about an’ stove up. We didn’t hev no water, er grub, er nothin’, an’ I had about calculated that we’d starve ter death; then, jest as things were lookin’ mighty dark fer us, Seth, thar, happened erlong, and we heerd him hollerin’ down the shaft.”

“I was left in Sun Dance,” spoke up Seth, who was the fellow Wild Bill had failed to recognize, “ter watch the stage an’ see if you, er Bingham, come in on it. Nothin’ came that arternoon, but the mail——”

“It will be two or three days before Bingham arrives here,” interjected Smith. “Go on, Seth.”

“As the night passed,” proceeded Seth, “an’ Clancy an’ the rest didn’t come back ter Sun Dance, I began ter feel anxious about ’em. Arter breakfast in the mornin’, I couldn’t stand the unsartinty any longer, so I saddled up an’ rode down the cañon. Seen the five hosses bunched tergether in the scrub, so I knowed the boys must be in the mine. When I climbed the ore-dump, I seen the rope layin’ on the platform, an’ I couldn’t savvy the layout, not noways. I got down on my knees, stuck my head inter the shaft, an’ let off a yell. The yell was answered, an’ it wasn’t long afore I knowed what had happened. I drapped a riata down, an’ spliced on the[32] rope layin’ on the platform, an’ purty soon the boys was on top o’ ground.”

“We all thort the game was up,” said Clancy, when Seth had finished. “The feller that had came nosin’ inter the mine had drapped his bowie, an’ we found the name, ‘Wild Bill,’ burned inter the handle. ‘Thunder!’ I says ter the boys; ‘if thet was Wild Bill we had down here, I ain’t wonderin’ none he got away. He’s a reg’lar tornader! The wonder is,’ I says, ‘thet some o’ us didn’t git killed.’ In the arternoon I rode ter Sun Dance ter meet the stage myself, an’ thet’s how I come ter meet ye, cap’n, an’ ter tell ye a leetle o’ what took place. But I reckon us fellers ain’t got any kick comin’ now.” Clancy gave a husky laugh. “Wild Bill drapped inter yore hands, cap’n, like er reg’lar tenderfoot. It was a slick play, yere bringin’ him along when ye come ter meet me at the foot o’ thet slope. The minit ye jumped at him I knowed somethin’ was up, an’ I wasn’t more’n a brace o’ shakes in takin’ a hand.”

“It was a tight squeak,” said Smith. “We came within a hair’s breadth of having this whole story get out. If it had ever reached Bingham’s ears it would have cost this gang a cool hundred thousand.”

“Ye’re sure Wild Bill didn’t do any talkin’?”

“He says he didn’t, and I believe he told the truth.”

“But thar was some ’un with him. He didn’t git out o’ the shaft without help.”

“That man was a Ponca Indian. He didn’t stop in Sun Dance long, but was sent out of camp by Wild Bill, with a paper-talk for Buffalo Bill, at Fort Sill.”

“Consarn it!” grunted Tex moodily. “Ain’t we goin’ ter work through this trick without hevin’ Buffler Bill mixed up in it?”

[33]

A muttered oath escaped the lips of Smith.

“If Buffler Bill mixes up in this,” said he, “we’ll take care of him, just as we’re going to take care of Wild Bill. There’s seven of us, and I’ve got the nerve to think I’m as good a man as Buffalo Bill.”

“You’ve got nerve enough for anything, Smith,” spoke up Wild Bill, “but when you compare yourself with Cody, you’re a little bit wide of your trail.”

A sudden silence fell over the gang. All of them turned their eyes on the prisoner, and Smith got up and stepped toward him.

“Got your wits back, have you?” Smith demanded, with a scowl.

“I didn’t have much sense when I started in to do you a friendly turn,” said Wild Bill. “That’s where I went lame. Who are you, anyhow?”

A hoarse laugh broke from the man’s lips. The next moment he had stripped away the linen duster, revealing a tall, supple form clad in gaudy costume. About the shoulders was a short jacket of black velvet, strung with silver-dollar buttons that flashed in the candlelight; about the waist was a silken sash of red, supporting a brace of silver-mounted derringers. Boots made of fancy leather arose to the knee, and a black sombrero capped the flashy apparel.

“In the first place,” said the man, with a fiendish grin, “my name is not Smith, but Lawless.”

“Well, I’ll be hanged!” muttered Wild Bill. “You’re Lawless, and I jumped right at you, in the Lucky Strike Hotel, supposing you were the tenderfoot who’s coming here to drop into your game! That’s a big one on me, and I reckon that fool play makes me deserve all I’ve[34] got coming. Well, well! This would be plumb comical if it wasn’t so blamed serious.”

“It is serious—for you,” said Captain Lawless. “What you know stands between me and my men and one hundred thousand dollars. Why did you mix up in this thing, in the first place?”

“I heard shooting down in this mine, and was curious to find out what it meant.”

“You found out—and that’s what’s going to make you trouble.”

Lawless turned away.

“Is everything ready, Clancy?” he asked.

“The fuses are all ready ter light.”

“Then snake him off down the level and we’ll finish this right up. See that you make a good job of it.”

Obeying a gesture from Clancy, Andy and Tex caught Wild Bill by the shoulders and dragged him some ten feet toward the shaft of the mine. Seth followed with a candle.

A stub crosscut opened off the level at this point, and Wild Bill was dragged into this and along it for fifteen feet, as he judged. That brought him to the end of the crosscut, which proved to be a blind wall.

“We’re going to put you in a pocket, Wild Bill,” said Lawless, who had followed, “and leave you there. You’ll not be able to bother anybody; and, of course, you’ll never live to get out, even if you’re not killed by the blast.”

“I’m not following you very clearly,” said Wild Bill. “Is it your intention to send me across the divide?”

“That’s it. You know too much, and we can’t take any chances with you. Look here.”

Lawless passed to the entrance of the crosscut and[35] waved the candle back and forth. In the candlelight. Wild Bill saw the ends of three fuses, placed on a line.

“At the end of each fuse,” explained Lawless calmly, “there’s a heavy charge of powder. Clancy loaded the holes, and he knows just what a charge will do when it’s put down in any given place. He has set this blast so as to wall up the crosscut and leave you in a rock cell. Clancy says that you won’t be hurt by the flying rock when the blast goes off, but that you’ll be walled in so you can’t get out. You’ll not have any water or food, and you’ll not have much air. That can’t be helped.”

“You’re a fiend!” gritted Wild Bill, glaring at the calm face of Lawless.

“This job of salt is going to win out. Bingham will find less gold in the Forty Thieves than he imagined; but, if he digs away the barrier we’re going to throw up, he’ll find something else here that will surprise him.”

“Why can’t you use a bullet or a knife, if you’re bound to put me out of the way?” called Wild Bill. “What do you want to go to all this trouble for?”

“This will look like an accident, if you’re ever found.”

“Look like an accident!” answered Wild Bill ironically. “How do you figure that, if I’m ever found with my hands and feet tied?”

“If Clancy is right, and you’re not hit by flying rock, or smothered before an hour or two, you’ll get rid of the ropes.”

“And you’re white!” muttered Wild Bill, as though it was hard for him to couple such a murderous act with a man of that color. “Why, you inhuman scoundrel, you ought to be black as the ace of spades, and to wear[36] horns! This may be the end of me, but it won’t be the end of this business for you. My pard, Bill Cody, is coming to Sun Dance Cañon to meet me. If he doesn’t meet me, he’ll know something is wrong, and when he runs out the trail, you’ll owe him something. And whatever you owe Cody, you’ll pay!”

“If I ever owe Cody anything,” scowled Lawless, “I’ll pay him just as I’m paying you. I didn’t pip my shell yesterday. You’re wide of your trail, Hickok, if you think I’m not able to take care of myself.”

Lawless disappeared from the mouth of the crosscut.

“Touch off the blasts,” Wild Bill heard him say to Clancy; “all the rest of you,” he added, “go on to the shaft. We’ve got to make a quick getaway as soon as the fuses are fired.”

Then, with staring eyes, Wild Bill saw Clancy take a candle and bend down. From one fuse to another went the candle gleam, leaving a sputtering blue flame at the end of each fuse.

Having finished his work, Clancy whirled and raced after Lawless and the rest, who had already started for the shaft.

Turning on his side, with his face against the rocks, Wild Bill waited for the deafening detonation which was to throw a barrier of rock across the mouth of the crosscut and wall him up in a living tomb.

[37]

“Whatever d’ye think Wild Bill wants us fur, Buffler?”

“I haven’t any idea, Nick, but he’ll think we’re a long time getting to Sun Dance.”

“That paper-tork o’ his had a hard time reachin’ us, an’ we’ve had er hard time gittin’ through ter Sun Dance—leastways, you an’ Dell hev had. But we kain’t be so pizen fur from ther camp now.”

“This short cut we’re taking through the hills will bring us into the cañon above the camp. Dell and Cayuse will come in below. We ought to get to the place we’re going a good two hours ahead of them.”

The king of scouts, and his old trapper pard, Nick Nomad, were riding through the rough country on their way to Sun Dance.

It was early morning, and the trapper and his pards had been in the saddle all night.

A number of things had conspired to delay them in taking the trail in answer to Wild Bill’s “paper-talk.” Among other things, Crawling Bear had been slain by hostile Cheyennes, and Hickok’s note had come into the scout’s hands by another messenger.

Some distance back on the Sun Dance trail, the scout and Nomad had separated from Dell Dauntless, Buffalo Bill’s girl pard, and the Piute boy, Little Cayuse, the scout and the trapper to travel “’cross lots,” and Dell and Cayuse to follow the regular trail.

[38]

This would bring Buffalo Bill and Nomad into Sun Dance a little earlier than if they had kept to the trail, and they were already so late that they were anxious to save even an hour or two.

The course they took was a rugged one, and they had to climb steep hills and ridges, and urge their mounts over ground that would have tried the strongest nerves.

But it was all for Pard Hickok, and no loyal pard ever called on Buffalo Bill in vain.

The scout, however, was vastly puzzled to account for the business that had led to the call. In his note, Wild Bill had not written a word about that.

“Wild Bill must hev tangled up with somethin’ purty fierce,” remarked Nomad, “or he’d never hev sent in a hurry-up call like thet.”

“It may not be anything that concerns Wild Bill, Nick, but something that concerns us,” the scout returned. “Hickok may not be in trouble; on the contrary, he may know something we’ve got to know in order to avoid trouble ourselves.”

“Kerect, Buffler. I hadn’t thort o’ ther thing in thet light afore. We ain’t neither of us very much in ther habit o’ side-steppin’ when trouble hits ther pike an’ p’ints fer us. This hyar trouble is er quare thing, pard; plumb quare. Some o’ the people has trouble all ther time, an’ all ther people has trouble some o’ the time, but all ther people kain’t hev trouble all ther time.”

The scout laughed.

“What of it, anyhow, Nick?” he asked.

“Nothin’. I was jest torkin’ ter give my bazoo exercise. No man knows jest when trouble is goin’ ter hit him. Sometimes he kin see et a good ways off, like er choo-choo train. He kin hyer ther bell an’ ther whistle,[39] an’ ef he’s a-walkin’ on ther track, he’s er ijut ef he don’t step off, an’ let et go by. An’ then, ag’in, trouble comes on ye around a sharp curve. The despatcher mixes orders, er somethin’, an’ afore ye know et ye’re tangled up in a head-on collision. Now, thet’s what I call——”

Nomad was interrupted. As if to illustrate his rambling remarks, the crack of a rifle was heard in the distance, followed by a shrill scream.

The two pards, at that moment, were on the crest of a rocky ridge. Instinctively they stopped their horses and shot their glances in the direction from which the report and the scream reached them. What they saw set their pulses to a swifter beat.

Speeding toward them along the foot of the ridge was an Indian girl. She was mounted on a sorrel cayuse, and the pony was getting over the ground like a streak. The girl was bending forward, her blanket flying in the wind behind, and her quirt was dropping on the pony’s withers with lightninglike rapidity.

She was being pursued by an Indian buck, armed with a rifle. The buck seemed savagely determined to overtake the girl. He was mounted on a larger, and evidently a fleeter, horse, for at every stride he came a shade closer.

“Is thet ther ceremony o’ ther fastest hoss, Buffler?” queried the startled Nomad. “Ef ther buck ketches ther gal, will she marry him? Hey?”

“That isn’t the ceremony of the fastest horse, Nick,” answered the scout. “The buck wouldn’t be shooting at the girl if it was.”

“Mebbyso he was jest shootin’ ter skeer her.”

“It’s not the right way to win a bride—or a Cheyenne[40] bride. As near as I can make out, those two are Cheyennes.”

“Ther gal’s a Cheyenne, but at this distance I take ther buck fer a Ponca.”

“I reckon you’re right, Nick. The buck is a Ponca and the girl a Cheyenne. There’s a good deal of bad blood between the Cheyennes and the Poncas just now, and we can’t overlook the fact that the under dog, in this case, is a squaw. We’ll save her.”

“Shore we’ll save her!” averred Nomad. “I knowed ye’d be fer doin’ thet all along. We’re jest fixed right ter slide down this hill and sashay in between ther two.”

“That Ponca is getting ready to shoot again!” exclaimed Buffalo Bill, as he started his horse, Bear Paw, down the descent. “The next bullet may not go as wide as the first, and I reckon we’d better give the buck something to think about, so he’ll let the girl alone.”

As he charged down the slope, Buffalo Bill pulled his forty-five out of his belt and shook a load in the Ponca’s direction.

The range was too great for pistol-work, but the scout succeeded in his design of giving the buck “something to think about.”

The crack of the revolver and the “sing” of the bullet caused the buck to lower the rifle he had half-raised, and to turn his eyes in the direction of the white men. The girl also, for the first time, saw that help was near. She flung up one hand in a mute appeal.

“Don’t ye fret none, gal!” roared Nomad. “We’ll look out fer you!”

The girl, apparently taking courage from the shot fired in the buck’s direction, and from the reassuring tone of Nomad’s voice, slowed down her pony.

[41]

A few moments later the pards reached the foot of the ridge and laid their horses across the Ponca’s path. The Ponca, without speaking, tried to go around them. This was the girl’s signal to turn her pony and circle back until she was under the lee of Bear Paw.

“No, ye don’t, Injun!” cried the trapper, kicking in with his spurred heels and getting in front of the Ponca at a jump. “Mebbyso ye kin git eround me, but ye kain’t git eround this!” and Nomad leveled a revolver.

The Indian sat back on his horse and glared angrily at Nomad, at the scout, and at the girl.

“Me take um squaw,” grunted the Ponca. “Her b’long to Ponca.”

“She’s a Cheyenne,” said the scout. “How can a Cheyenne belong to a Ponca?”

“Me buy um squaw with ponies,” asserted the Indian. “Me take her from Cheyenne village, and she make um run. Ugh! Give Big Thunder squaw.”

“You bought this girl of the Cheyennes?” demanded the scout.

“Wuh! Pay um all same so many ponies.”

The Ponca held up five fingers.

Buffalo Bill looked at the girl attentively. He had never seen a prettier Indian girl. Her features were regular, and her large, liquid-black eyes gave her countenance almost a Spanish cast. Her garments were of buckskin, beaded and fringed, and her blanket was of a subdued color, clean and new. Broad silver bands encircled her forearms and her shapely wrists, and her hands were small and delicately formed.

The buck, on the other hand, was a rough-looking specimen of a Ponca.

“Speakin’ free an’ free, as between men an’ feller[42] sports,” observed Nomad, “I kain’t blame ther gal none fer runnin’ erway.”

“Me know um Pa-c-has-ka,” said Big Thunder calmly. “Him friend of Poncas, and him got good heart. Him no let squaw get away from Ponca brave.”

“What is your name?” asked the scout of the girl.

“Wah-coo-tah,” was the answer.

“That’s a Sioux name.”

“Me Cheyenne, no Sioux. Name Wah-coo-tah.”

The girl had a rippling, musical voice, very different from the usually hard, strident voices of Indian women.

“Very well, Wah-coo-tah,” said the scout, “I’ll take your word for it. Why was the Ponca chasing you?”

“Me no like um.”

“Did your father sell you to the Ponca?”

“Ai. Me no like um, me run ’way. Him ketch Wah-coo-tah, then Wah-coo-tah kill herself.”

Here was a knotty point for the scout. Having bought the girl, by the girl’s own admission, the Ponca certainly had a right to take her for his squaw. But the scout could not justify himself in his own mind if he allowed the vicious-looking Ponca to take the fair Cheyenne.

“Where will you go, Wah-coo-tah, if you get away from the Ponca?”

“Me go where me be safe,” she said.

“How much time do you want to get away?”

The girl turned on her pony’s back and pointed to the top of a distant hill.

“So far,” she answered.

“All right. We’ll hang onto the Ponca until you get there.”

Before the scout could stop her, Wah-coo-tah caught[43] his hand and pressed it to her lips. Then she turned her pony and galloped off.

Big Thunder sat silently on his horse for a space, his eyes glittering fiendishly. Suddenly he jerked his rifle to his shoulder. Nomad, watching him like a cat, struck up the barrel, and the bullet plunged skyward.

Quick as a catamount the Ponca dropped the weapon and hurled himself from his horse’s back—not at Nomad, but at Buffalo Bill. He had a drawn knife in his hand, and, as he landed on the scout’s horse, he made a venomous, whole-arm stab with it.

But if the Ponca was quick, the scout was a shade quicker. Twisting about in his saddle, Buffalo Bill clutched the Ponca’s knife-wrist with his right hand, and, with his left, took a firm grip of the Ponca’s throat.

A second later and the struggle carried them both to the ground.

Big Thunder was a powerful Indian, and the nude, upper-half of his wiry body was liberally besmeared with bear’s grease. The grease made him as slippery as an eel. Nevertheless, the scout knew how to deal with him.

A crushing pressure at the wrist caused the knife to drop. With the Ponca practically disarmed, the fight became one of mere wrestling and fisticuffs.

Big Thunder slipped his oily throat clear of the scout’s fingers, but the scout’s hand, leaping upward from the throat, took a firm grip of the scalp-lock. Holding the Ponca’s head to the ground, Buffalo Bill released his wrist, and got his right hand about the throat in such a manner that it could not slip; then, kneeling on the ground, he held the Ponca in that position until he was half-throttled.

“Waugh!” jubilated Nomad. “Jest see how Pard[44] Buffler tames ther red savage. I’m darned ef et ain’t as good as a show. Goin’ ter strangle him, Buffler? Better do et. Ef ye don’t, he’ll camp on yore trail an’, sooner er later, ye’ll hev ter kill him ter prevent his takin’ yer scalp.”

The scout saw that the Indian had been punished enough for his attack, and suddenly sprang away from him.

“Don’t worry, pard,” sang out Nomad; “I’ve got him kivered.”

For a second or two the Ponca lay on the ground, gasping for breath; then, as he struggled to his feet, the point of the trapper’s revolver lifted with him, the trapper’s menacing eye gleaming along the barrel.

“Easy, thar, Ponk!” warned Nomad; “make er single hosstyle move, an’ ye’ll be er good Injun afore ye kin say Jack Robinson.”

Big Thunder, seeing how he was corralled, grunted savagely, drew himself to his full height, and folded his arms.

“Injun thought Pa-e-has-ka friend of Poncas!” he exclaimed scathingly.

“I’m the friend of the Poncas, all right, Big Thunder,” answered the scout, “but the girl did not want to go with you.”

“Ponca buy her, make um go!”

“Not while I’m around. Keep your hands off that girl, understand?”

“Ponca no keep hands off Pa-e-has-ka. Bymby, Pa-e-has-ka’s scalp dry in Big Thunder’s lodge; Big Thunder make um Cheyenne girl tie um scalp on hoop, hang um up.”

“Hyer ther pizen red!” snarled the trapper. “Hadn’t[45] I better rattle this hyar pepper-box o’ mine at ther threatenin’ varmint?”

“No.” The scout looked in the direction taken by the girl. She had got far beyond the point to which she had drawn his attention, and had vanished. “I reckon Wah-coo-tah’s all right, Nick. Put up your gun and we’ll ride on to Sun Dance.”

Unconcernedly, the scout walked to Bear Paw and mounted.

Big Thunder, still erect and with his arms folded, followed the scout’s movements with eyes of hate.

“Come on, pard,” said the scout, starting for the next “rise.”

“Mebbyso he’ll open up on ye with thet rifle o’ his, Buffler,” demurred Nomad.

“He’ll not do that,” was Buffalo Bill’s confident reply, as he spurred on.

Nomad lowered his revolver, but kept his vigilant gaze on the Ponca as he followed his pard. When they crossed the next hill, the last they saw of Big Thunder he was still glaring after them.

“Ye’ve made er enemy out o’ thet red, Buffler,” observed the trapper, pushing his revolver back into its holster.

“I suppose so,” said the scout thoughtfully. “The worst of it is, Nick, I can’t blame the Indian. According to the laws and customs of the red man he is in the right. I had no business interfering between him and Wah-coo-tah.”

“Any white man would hev done et!” asserted the trapper.

“Any white man who had the right kind of a heart,” qualified the scout.

[46]

“Wah-coo-tah ain’t er common Injun squaw.”

“That’s why I helped her.”

“All this hyar,” commented Nomad, “on’y illustrates what I was er sayin’ erbout trouble. This excitement come around ther curve, full-tilt, an’ hit us squar’ in ther face. Thar wasn’t no dodgin’ et.”

Half an hour later the pards descended into Sun Dance Cañon, and an hour’s ride down the cañon brought them to the foot of the slope leading to the “flat,” and the mining-camp.

“We’re a good two hours ahead o’ Dell an’ Cayuse,” asserted Nomad, while they were climbing the slope.

“I hope we’re in time for Hickok’s business, whatever it is,” answered the scout.

Bije Spangler, as usual, was occupying a couple of chairs in front of the Lucky Strike. The ragged, palm-leaf fan was working slowly, and he watched the pards approach with a speculative eye. Spangler had no difficulty in detecting that they were persons of consequence.

“‘Lucky Strike Hotel,’” said the scout, reading from the sign. “Are you the proprietor?” he went on, dropping his eyes to the huge bulk of humanity in the two chairs.

“I run this joint,” wheezed Spangler, “but I ain’t high-toned enough ter call myself a proprietor.”

“Can we stop here?”

“Can if ye got the price.”

“We want a room by ourselves.”

“Only got one private room, an’ that was took by a feller that vamosed last night without settlin’ up. Reckon ye kin hev that, seein’ as I don’t know whether the feller’s ever comin’ back er not. J. Algernon Smith[47] sorter opined he’d like a room by hisself, too, so I reckon he’d think he had fust claim on the room, on’y he vamosed as myster’ously as Wild Bill.”

“What’s that?” demanded the scout, pulling himself together with a jerk, and peering sharply into the flabby face of Spangler. “Was Wild Bill Hickok staying here?”

“He was.”

“And you say he left last night?”

“Him an’ J. Algernon went away tergether. That was right after supper last night, an’ neither of ’em has come back yet.”

“How long has Wild Bill been here?”

“He come day before yesterday, on hossback, with er Injun. J. Algernon come yesterday arternoon, on the Montegordo stage. Both of ’em’s skedaddled. Who might you be, neighbor?”

“Cody’s my name——”

Spangler tried to express his surprise and delight, but only succeeded in emitting a throaty gurgle; he likewise tried to get up and grab the scout’s hand, but his sudden flop displaced one of the chairs, and he slumped to the ground in a quivering heap.

Nomad got behind him and boosted him up.

“This hyar camp must be er healthy place,” remarked Nomad, “ef et grows many ombrays o’ yore size.”

“It ain’t as healthy as it looks,” said Spangler. “Buffalo Bill, I’m glad ter meet ye. Ye kin have this hull hotel if ye want it. I’ll call a man ter take keer o’ yer hosses.”

“I take care of my horse myself,” replied Buffalo Bill. “Show me the stable, Spangler.”

[48]

Spangler waddled to the corner of the house and pointed to a brush shelter in the rear.

“What d’ye think o’ this, Buffler?” asked the trapper perplexedly, as he and his pard led their mounts to the stable.

“I don’t know what to think of it yet,” answered the scout, with a troubled frown.

“Wild Bill was hyar, an’ vanished last night.”

“He vanished with a man called J. Algernon Smith. If we’re to believe Spangler, both Smith and Hickok departed unexpectedly. It looks bad, on the face of it, but——”

The rear of the stable was open. As the scout looked in, he saw and recognized Wild Bill’s horse.

“Et’s Wild Bill’s animile, shore enough,” muttered Nomad, following the scout’s eyes with his own. “Hickok wouldn’t pull out ter go any great distance without his hoss.”

“It wouldn’t seem so,” the scout answered, leading Bear Paw into an empty stall.

Removing the saddle, he rubbed Bear Paw down carefully with the saddle-blanket, then tore off a layer of hay from a bale, and loosened it out in the manger.

Nomad, deeply thoughtful, had been caring for his own horse in the same way.

Presently the pards left the stable and walked back to the front of the hotel.

Spangler was again seated on his chairs, plying the fan. He was talking with a man in a long linen duster.

“Buffalo Bill,” called Spangler, “shake hands with J. Algernon Smith, of Chicago. Smith,” went on Spangler, blowing like a porpoise, “this here is the Buffalo Bill ye read so much about.”

[49]

The scout’s eyes instantly engaged the face of J. Algernon Smith. Smith, after a moment’s hesitation, stretched out his hand.

The scout was an expert in character-reading, and, inasmuch as Smith was the last man seen with Wild Bill, he gave him keen attention.

“Well!” exclaimed Smith, “you’re the gentleman Wild Bill has been expecting. He told me about you.”

[50]

“Oh, he did, eh?” queried the scout. “Do you happen to know, Mr. Smith, where Wild Bill is now?”

“Why,” fluttered Smith, “isn’t he here?”

“No. He left here last night, right after supper, and hasn’t been back since.”

“Say, but that’s odd!”

“Spangler, here, says that you went with him.”

“I did go with him, as far as the slope leading down into the cañon. I have a friend living above here—a man I used to know in Chicago—and I called on him. He insisted that I should stay all night in his cabin, and I did so.”

“What is your friend’s name, Mr. Smith?”

“Seth Coomby.”

“Do you know such a man, Spangler?” asked the scout, turning to the hotel proprietor.

“Sure I know him,” answered Spangler. “He has a little, three-dollar-a-day placer up the gulch.”

“You say,” went on Buffalo Bill, once more facing Smith, “that you left Wild Bill on the slope leading into the cañon?”

“Yes.”

“And you haven’t seen him since?”

“Why, no. I supposed he was here. You don’t think he met with foul play, do you? I took a big liking to Wild Bill.”

“You didn’t have him very long, did you?” asked the[51] scout keenly. “I understand you only arrived in camp yesterday afternoon, and that you and Wild Bill started for the slope right after supper. Not much time to take a liking to a man. Did you know Wild Bill before you came to Sun Dance?”

“No; never saw him before I got here. We got acquainted with each other before supper, and had a little talk over our cigars. Then we ate supper together, and then I started for Coomby’s, and Wild Bill walked with me as far as the slope. Say, I’m all broke up about this.”

“Wasn’t you talkin’ with a feller in the office afore ye got ter talkin’ with Wild Bill?” put in Spangler.

“That was Clancy,” said Smith.

“Yep,” returned Spangler, with a shake of his fat sides, “I know him, all right; and”—here Spangler gave the scout a significant glance—“Clancy ain’t got none too good a repertation in this camp.”

“You surprise me!” exclaimed J. Algernon Smith.

The fellow’s actions were ingenuous. He talked and acted like an Easterner, but he looked like a Westerner, for all that.

“You understand, Mr. Smith,” pursued the scout, with the glint in his eyes that had taken the nerve of many a wily schemer, “that Wild Bill is my friend, and that I am anxious about him. If he has met with foul play, as you just suggested, I shall have something to say to the scoundrels back of it—later. Just now, though, I want all the information I can get. You will pardon me if I ask you what this Clancy had to say to you.”

Smith stiffened.

“What Clancy had to say, Buffalo Bill,” he replied, “is, of course, my own business. Nevertheless, under the[52] circumstances, I recognize your right to press inquiries. If you will step aside with me, I will explain.”

Buffalo Bill walked apart with Smith.

“In order to figure this matter down to where you will have a thorough understanding of it, Buffalo Bill,” went on Smith, in a tone that seemed perfectly frank and open, “I shall have to tell you my business in this camp—and that business is one I was told to keep dark. I have come here from Chicago to examine a mine with the view of purchasing it. Clancy came to me from the owner of the mine, who is shortly expected in this camp. What Clancy told me was that the owner would be here to-morrow or next day, and Clancy advised me not to tell any one why I was here. That is all. It is news to me if Clancy does not bear a good reputation. But I don’t suppose that affects the mine, anyway. I shall not purchase the property until I take my ore-samples and have them assayed. Then——”

“What is the name of the mine?” broke in the scout.

“It is called the Forty Thieves.”

“Queer name for an honest mine,” said the scout.

“That’s right; but they have queer names for mines—some of them almost laughable. For instance, I have heard of the Pauper’s Dream, the P. D. Q., the——”

“Who owns this mine, Mr. Smith?”

“A man by the name of Lawless; Captain Lawless he calls himself.”

The scout started.

“Have you heard of the fellow?” asked Smith eagerly.

“I have heard of a squawman who calls himself by that name, but whom the Indians call ‘Fire-hand.’ He is said to be an out-and-out rascal.”

“Great glory!” cried Smith. “It looks as though I[53] had landed right in the hands of the Philistines. Have you ever seen this Captain Lawless, Buffalo Bill?”

“Never. One of my pards, Little Cayuse, has seen him, but I have not.”

“When will your pard, Little Cayuse, be here?”

The scout’s eyes narrowed.

“What is that to you, Mr. Smith?” he demanded.

“Why, merely that I should like to have Lawless pointed out to me before I talk with him. If I don’t like his looks, I’ll get away from here without examining the Forty Thieves.”

These words were the only ones spoken by Smith that struck the scout as peculiar. On the whole, however, Smith had stood the scout’s questioning well.

Buffalo Bill turned away and walked back to Spangler. Smith went on into the hotel.

“What do you know about the Forty Thieves Mine, Spangler?” asked Buffalo Bill.

“I know it’s no good, Buffalo Bill,” said Spangler, with a choppy laugh.

“Where is it?”

“Five miles down the gulch.”

“Who owns it?”

“Give it up. It’s changed hands so many times there ain’t no keepin’ track o’ the owners.”

“Do you know a man who calls himself Captain Lawless?”

“I’ve heerd tell o’ such a chap, but I ain’t never seen him.”

“Well,” said the scout thoughtfully, “show me into the room Wild Bill occupied. I and my pard will stay in it till Wild Bill gets back. Go for the saddles, Nick,” the scout added. “We’ll keep them in the room with us.”

[54]

Spangler yelled for the Chinaman, and the latter showed the scout to the room recently occupied by Wild Bill. When left alone in the place, the scout looked over it carefully.

The first objects to strike his attention were a pair of boots. He picked them up and looked at them. The heel of one was missing—the reason, no doubt, the boots had been discarded.

On a chair lay a blue-flannel shirt. Wild Bill had worn such a shirt, but it might also have belonged to any number of men. The left sleeve was cut away close to the shoulder, and around the edge of the abbreviated sleeve were evidences of dried blood.