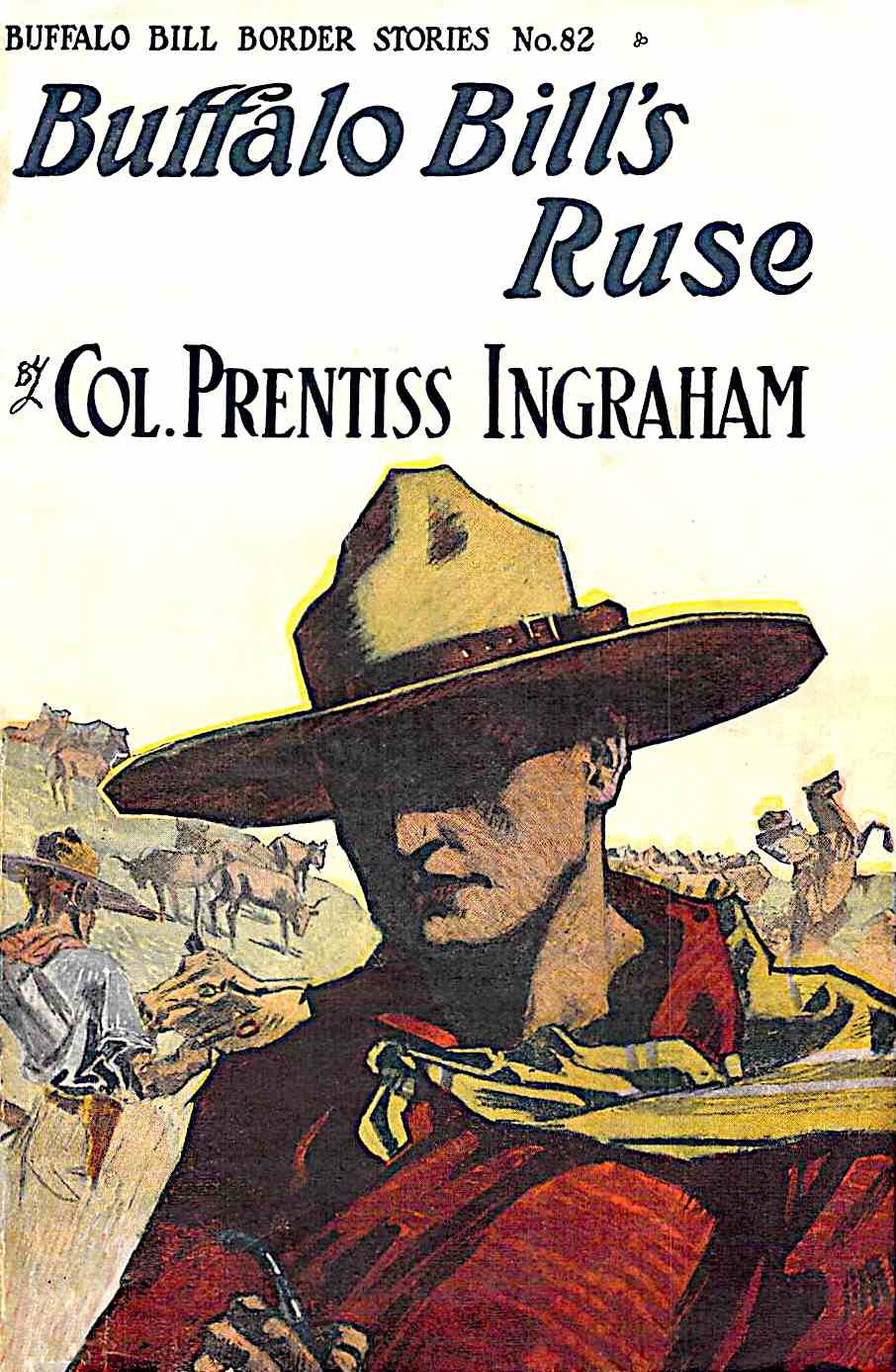

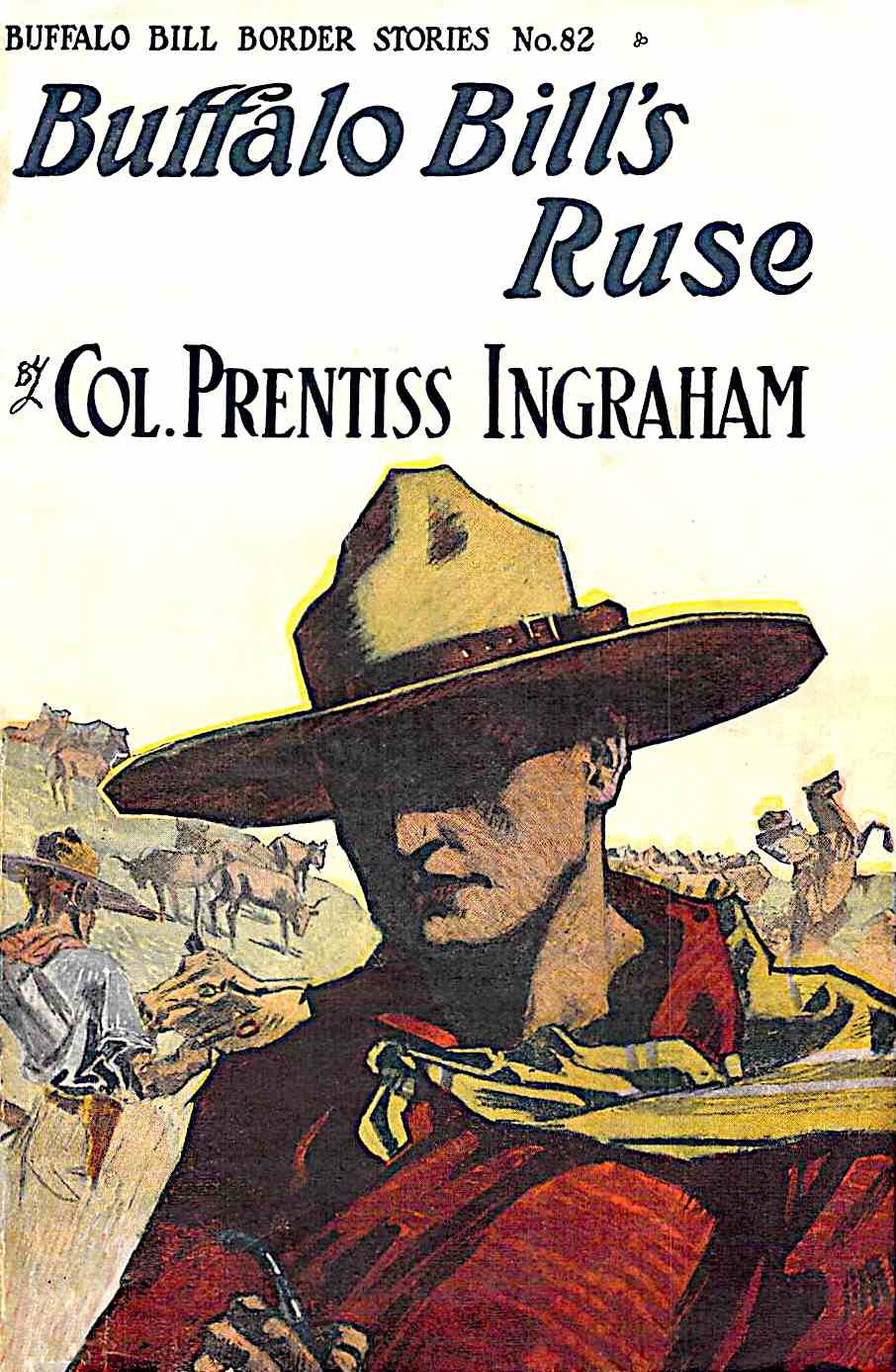

Title: Buffalo Bill's Ruse; Or, Won by Sheer Nerve

Author: Prentiss Ingraham

Release date: March 1, 2021 [eBook #64664]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Susan Carr and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BY

Colonel Prentiss Ingraham

Author of the celebrated “Buffalo Bill” stories published in the

Border Stories. For other titles see catalogue.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1906 and 1907

By STREET & SMITH

Buffalo Bill’s Ruse

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign

languages, including the Scandinavian.

| PAGE | ||

| IN APPRECIATION OF WILLIAM F. CODY | 1 | |

| I. | PIZEN KATE. | 5 |

| II. | READY TO GO. | 10 |

| III. | AN UNEXPECTED MEETING. | 14 |

| IV. | PIZEN KATE FINDS HER HUSBAND. | 19 |

| V. | MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCES. | 25 |

| VI. | INDIAN TREACHERY. | 31 |

| VII. | THE ATTACK OF THE MEXICAN | 39 |

| VIII. | THE MYSTERIOUS YOUNG WOMAN. | 43 |

| IX. | THE REDSKIN ROVERS. | 51 |

| X. | SURROUNDED AND CAPTURED. | 59 |

| XI. | ESCAPE. | 66 |

| XII. | A DESPERATE VENTURE | 73 |

| XIII. | THE FLIGHT OF THE FUGITIVES. | 78 |

| XIV. | STRANGE HAPPENINGS. | 83 |

| XV. | A DESPERATE BATTLE. | 91 |

| XVI. | AT THE HOUSE ON THE MESA. | 97 |

| XVII. | THE MYSTERY SOLVED. | 107 |

| XVIII. | THE MYSTERIOUS NUGGET. | 111 |

| XIX. | AT THE FORT. | 121 |

| XX. | BRUTALITY. | 129 |

| XXI. | ON THE BORDERS OF DISGRACE. | 132 |

| XXII. | OUTSIDE THE WALLS. | 141 |

| XXIII. | DRIVEN BY DESPERATION. | 146 |

| XXIV. | THE MAN IN THE SHADOWS. | 153 |

| XXV. | A VILLAIN IN FLIGHT. | 159 |

| XXVI. | STARTLING NEWS. | 163 |

| XXVII. | THE SKY MIRROR. | 169 |

| XXVIII. | BARLOW AND THE GIRL. | 181 |

| XXIX. | A DARING RUSE. | 192 |

| XXX. | THE CHEYENNE STAMPEDE. | 200 |

| XXXI. | THE THEFT OF THE NUGGETS. | 208 |

| XXXII. | ALCOHOL AND ELOQUENCE. | 216 |

| XXXIII. | A KINDLY WARNING. | 223 |

| XXXIV. | LURED INTO DANGER. | 230 |

| XXXV. | MOBBED AND THREATENED. | 239 |

| XXXVI. | THE WESTERN DEAD SHOT. | 245 |

| XXXVII. | THE MAN WHO INTERFERED. | 249 |

| XXXVIII. | DENTON AND DELAND. | 253 |

| XXXIX. | IN A WEB OF LIES. | 259 |

| XL. | THE RAIN MAKER. | 272 |

| XLI. | A GIRL’S HEROISM. | 284 |

| XLII. | ANOTHER STOOL PIGEON. | 292 |

| XLIII. | THE CAPTURE OF PANTHER PETE. | 297 |

| XLIV. | THE GIRL’S FLIGHT. | 304 |

| XLV. | THE FLAG OF TRUCE. | 311 |

[Pg 1]

It is now some generations since Josh Billings, Ned Buntline, and Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, intimate friends of Colonel William F. Cody, used to forgather in the office of Francis S. Smith, then proprietor of the New York Weekly. It was a dingy little office on Rose Street, New York, but the breath of the great outdoors stirred there when these old-timers got together. As a result of these conversations, Colonel Ingraham and Ned Buntline began to write of the adventures of Buffalo Bill for Street & Smith.

Colonel Cody was born in Scott County, Iowa, February 26, 1846. Before he had reached his teens, his father, Isaac Cody, with his mother and two sisters, migrated to Kansas, which at that time was little more than a wilderness.

When the elder Cody was killed shortly afterward in the Kansas “Border War,” young Bill assumed the difficult rôle of family breadwinner. During 1860, and until the outbreak of the Civil War, Cody lived the arduous life of a pony-express rider. Cody volunteered his services as government scout and guide and served throughout the Civil War with Generals McNeil and A. J. Smith. He was a distinguished member of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry.

During the Civil War, while riding through the streets of St. Louis, Cody rescued a frightened schoolgirl from a band of annoyers. In true romantic style, Cody and Louisa Federci, the girl, were married March 6, 1866.

In 1867 Cody was employed to furnish a specified amount of buffalo meat to the construction men at work on the Kansas Pacific Railroad. It was in this period that he received the sobriquet “Buffalo Bill.”

In 1868 and for four years thereafter Colonel Cody[2] served as scout and guide in campaigns against the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. It was General Sheridan who conferred on Cody the honor of chief of scouts of the command.

After completing a period of service in the Nebraska legislature, Cody joined the Fifth Cavalry in 1876, and was again appointed chief of scouts.

Colonel Cody’s fame had reached the East long before, and a great many New Yorkers went out to see him and join in his buffalo hunts, including such men as August Belmont, James Gordon Bennett, Anson Stager, and J. G. Heckscher. In entertaining these visitors at Fort McPherson, Cody was accustomed to arrange wild-West exhibitions. In return his friends invited him to visit New York. It was upon seeing his first play in the metropolis that Cody conceived the idea of going into the show business.

Assisted by Ned Buntline, novelist, and Colonel Ingraham, he started his “Wild West” show, which later developed and expanded into “A Congress of the Rough Riders of the World,” first presented at Omaha, Nebraska. In time it became a familiar yearly entertainment in the great cities of this country and Europe. Many famous personages attended the performances, and became his warm friends, including Mr. Gladstone, the Marquis of Lorne, King Edward, Queen Victoria, and the Prince of Wales, now King of England.

At the outbreak of the Sioux, in 1890 and 1891, Colonel Cody served at the head of the Nebraska National Guard. In 1895 Cody took up the development of Wyoming Valley by introducing irrigation. Not long afterward he became judge advocate general of the Wyoming National Guard.

Colonel Cody (Buffalo Bill) died in Denver, Colorado, on January 10, 1917. His legacy to a grateful world was a large share in the development of the West, and a multitude of achievements in horsemanship, marksmanship, and endurance that will live for ages. His life will continue to be a leading example of the manliness, courage, and devotion to duty that belonged to a picturesque phase of American life now passed, like the great patriot whose career it typified, into the Great Beyond.

[5]

BUFFALO BILL’S RUSE.

The ungainly female who came roaring into Eldorado in search of the husband who “run away” from her contrived to draw a crowd about her in a remarkably short time.

“I’m Pizen Kate, from Kansas City!” she yelled. “Git out of my way, er I’ll jab yer eye out with my umbreller. I’m lookin’ fer my husband, and you ain’t him. Think I’d take up with a weasel-faced, bow-legged speciment like you? Not on your tintype. I wouldn’t! So, git out o’ my way!”

The man had tried to “chaff” her and had roused her ire, but he fell back before the angry jabs of her “umbreller.”

She looked about, glaring.

She was “homely as sin.” Her features were not only irregular; they were twisted, gnarled, and seamed. A few thin hairs of an attempted beard floated from a mole on her chin, and on her upper lip there was a faint trace of a mustache. She was dressed in a soiled cotton garment, and on her head was a shapeless hat, with a faded red rose for ornament. In her muscular right hand she flourished an ancient umbrella.

“I heard my husband had come here, and I’m lookin’[6] fer him,” she declared. “He run away from me in Kansas City, and I set out to foller him; and I’ll foller him to the end o’ the earth but that I git him.”

“I’m bettin’ on you, all right!” called out some irreverent individual.

She fixed him with a glassy stare.

“Was I ’specially directin’ my langwidge to you?” she demanded. “I hate to hear a horse bray out that way. It’s sickenin’.”

“And I hate to hear the blather of a nanny goat!”

She lifted her umbrella.

“Say that ag’in, you red-headed son of a scarecrow, and I’ll ram this umbreller down yer neck and open it up inside of ye! I’d have you know that I’m a lady, and don’t allow no back talk.”

“What kind o’ lookin’ feller is your husband?” another asked.

“Well, he’s better-lookin’ than them that slanders him, if he is little and runty! He’s a small man, slim as a blacksnake, and wiry as a watch spring, and he’s a bit oldish. He was in this town less’n a week ago.”

“Kate, I reckon we ain’t met up with him.”

“Wot’s his name?” said another.

“What’s that got to do with it, if ye ain’t seen him?” she demanded.

She fixed her eyes on a man who had, a moment before, descended the steps of the Golconda Hotel, and who came now toward the crowd that hedged her in.

The man was Buffalo Bill; handsome, muscular, dressed in his border costume, and towering a full head over the other men in the street.

[7]

“That’s him, I reckon, Katie—there comes yer husband, I’m bettin’. You said he was little and runty, slim as a blacksnake, and wiry as a watch spring. I guess you hit his trail here, all right.”

It was the sort of humor this crowd could understand, and they roared hilariously.

Pizen Kate ignored them with fine scorn, and moved toward the great scout, the men falling back before her jabbing umbrella and giving her ample room. She pranced thus up in front of Buffalo Bill, and stood eying him, umbrella in one hand and the other hand on her hip.

“I think I seen you onct,” she announced, as the scout politely lifted his big hat to her.

“Possibly,” he said, smiling.

“You’re Persimmon Pete, the gazeboo what run away with my old man.”

The crowd snickered, and then roared again.

“Hardly,” said Buffalo Bill.

“Oh, I know ye!” was her vociferous assertion. “You come to Kansas City with an Injun medicine company, and lectured and sold medicine. And my old man went to your show and seen ye; and then he got magnetized by ye, somehow, and wandered off after you when you went away. He was dead gone on big men. I suppose that was because he was so durn little and runty himself. It made him like big men. And so he follered you off when you left town. Now, ain’t that so? I know ye. You’re Persimmon Pete.”

[8]

The scout lifted his hat again, flushing slightly, for he heard the roars of the crowd.

“Madam,” he said amiably, “I must deny the gentle insinuation. I never saw your husband, nor Persimmon Pete.”

“You deny it?” she shrieked.

“Certainly. I am compelled to doubt your word.”

“And you never seen my man?”

“I assure you that I never had that pleasure. What is his name?”

“If you’re goin’ to start in by lyin’, it don’t make no difference what his name is!” she declared.

“It might help in his identification,” he suggested.

“Well, then, it’s Nicholas Nomad.” She faced toward the snickering crowd. “Now laugh!” she yelled. “It’s his name, and it fits him; fer if he ain’t about next to no man I dunno it. Think of him leavin’ me in the suds there in——”

“Was ye washin’?” some one yelled.

“Well, yes, I was, though how you know it I can’t guess. I was washin’ that day fer Mrs. McGinniss and her six children, and so I had to stay at home and couldn’t watch him. He took advantage of it and skun out. But I’ll git him yit, and when I do——” She shook her red fist at the crowd.

“You’ll wallop him?”

“Wallop him? He’ll think he’s been mixed up in a barbed-wire cyclone; I won’t leave an inch of hide on him.” She turned back to Buffalo Bill. “Ye ain’t seen him, you’re sure?” she said anxiously.

“I’m sorry to say that I haven’t, madam.”

[9]

“You ain’t lyin’ to me?”

“No.”

She gave him a fierce glare, and then turned to hurl back some words of defiance to the shouting and laughing crowd.

“Don’t git too clost to me!” she warned. “I’m a lady, and I won’t stand it.”

Then she moved on up the street, looking for her husband, the crowd of amused men and boys streaming after her. Buffalo Bill followed her movements with an amused smile.

“Cody,” said the hotel clerk, who had come down into the street, “I’ve seen all sorts of females in my day, but she takes the cake.”

Buffalo Bill laughed and turned back toward the hotel.

“A bit peculiar, to say the least,” he agreed. “I don’t think I ever saw another just like her. But we’re likely to meet all kinds of queer characters out here in the West.”

[10]

The man whom Buffalo Bill had come to Eldorado to meet appeared in the town some time after this spectacular entrance of Pizen Kate, and sought the famous scout, in the latter’s room at the hotel.

The name of this man was John Latimer. He lived in isolated grandeur in a big house on Crested Mesa, for the benefit of his health, he said, which had been weakened by the damp and trying climate of the East.

He was an elderly man, of impressive appearance; gray-haired and gray-bearded. His eyes were gray, and were overhung by bushy gray eyebrows. He dressed neatly, in the Eastern fashion, and seemed very much out of place in this wild border country, at that time.

These things Buffalo Bill noted, as John Latimer came into the room, shook hands, and took the chair placed for him.

“Ah, Cody!” he said. “I was afraid you wouldn’t come, even though I had made my complaint so strong.”

“Your appeals stirred the colonel of the regiment at Fort Sinclair, and he told me to come out here and look into the thing and report to him at once; and he gave me authority, likewise, to send for a company of men, or even to organize a company of border riflemen on my own account, for quick action, if I thought necessary.”

[11]

“Very good!” said Latimer. “That pleases me. You shall have all the proofs you want.”

“I’ve already been getting some of them, on my way here.”

“You heard of that last raid made by the road agents on the Double Bar Ranch?” said Latimer.

“Yes.”

“And the attack of the Redskin Rovers on the treasure train which a week ago came out of the Bighorn Hills?”

“I heard of that, too. You have means of knowing something of the movements of these men?”

“Very little. The Redskin Rovers puzzle me.”

“Are they really Indians, or are they white men disguised as Indians?”

“Genuine Indians, I think.”

“Perhaps led by white men?”

“Perhaps so.”

“They haven’t troubled you lately?”

“Not lately.”

“Nor the white road agents?”

“They shot one of my herders less than a week ago. I believe they thought him a miner with gold. He was dressed somewhat like a miner, and he was coming out of the hills with filled saddle pouches. But the pouches held only some mineral specimens I had asked him to get for me. That trip cost him his life, poor fellow.”

“You know where that place is? We can, perhaps, find their trail there even yet.”

“You are ready to go with me, Cody?”

[12]

“That’s what I came for.”

“And I came in to get you and take you out to my place.”

“You spoke of your herder. Are you running a cattle ranch?”

“Not a ranch; but I keep a few, a very few, cattle. I am living there simply for the benefit of my health.”

His clear skin, the breadth of his shoulders, his general look of good health, in spite of gray hairs and gray beard, did not indicate that his health needed any especial care, as the scout noted.

“When will you go, Cody?” he asked.

“Any time. Now, if you like.”

“Now it is, then. We’ll start as soon as you can get ready.”

“I am ready.”

They left the room together.

In the hotel office Buffalo Bill ordered his horse brought from the stable and made ready for him, and he paid his score. Latimer’s horse had been left in the street in front of the hotel, tied to a hitching post. In a little while the scout and Latimer were mounted; and they galloped together out of the town of Eldorado, drawing many remarks from those who saw them go.

One of the witnesses of their departure was Pizen Kate. She had been having a dispute with a German shoemaker, who declared he had seen her missing husband the week before, and that he had but one leg, a statement that Pizen Kate disputed so warmly that the German was willing to modify it.

[13]

“Vell, he mighd haf had two legs,” he admitted, “but one of dem vas of wood. He come py my shop in, and ven he put oop his foot here, to have me fix his shoe, he say he is no man, as he haf but one leg.”

“But he didn’t say he was Nicholas Nomad! He didn’t say that?”

“No; I didn’t ask him vat vas his first name.”

Perhaps the German was a bit of a joker, for when he said this his blue eyes twinkled.

Pizen Kate stopped her wordy and interesting dispute with him, and stared at the horsemen who went by—Buffalo Bill and John Latimer.

“You know them men?” she snapped.

“Neider uff dhem vas the man vat I see. Neider of dhem vas your hoosbant.”

“Who said they was?” she snapped. “I said did you know ’em?”

“One I haf seen pefore. But I ton’d know heem.”

“You don’t mean Buffalo Bill, the tallest of ’em?”

“No; I ton’d know him. I neffer haf seen him. Bud I t’ink me I voult like to haf dhe chob uff making his poots for him. Dey musd cost apout dwendy-five tollars a pair.”

She left him in a hurry.

“I’m goin’ to find out why them two fellers aire ridin’ out of this place so fast,” she threw back at him. “It looks curious. I wonder if they don’t know somethin’ about my missin’ husband? Huntin’ fer missin’ husbands is terrible tryin’ work.”

[14]

When Buffalo Bill arrived with Latimer at the home of the latter on the Crested Mesa, he found a big, rambling building, with many wings, together with a number of other buildings and stables. Close by flowed a stream of water between high and rocky banks, where, Latimer said, his few cattle obtained their water. The place looked deserted.

But a great surprise came to the scout when, on riding up to the big house, he was about to dismount, and a servant came rushing out to take the horses. He stared, open-mouthed, hanging half out of his saddle, for when his eyes fell on this servant he had been swinging to the ground, and that sight had stopped all movement on his part for an instant.

The servant was a wizened little man, with a wide mouth and small, peering eyes. He was dressed in a half-border manner, and a revolver was belted to his waist.

“Nick Nomad!” was the name that came from the scout’s lips.

Old Nick Nomad seemed as much taken aback as Buffalo Bill. He halted in confusion; then laughed in his quaint cackling manner, and advanced toward the horse.

“Yours to command, Buffler!” he cried, spreading his homely mouth in a huge grin. “You didn’t reckon[15] on seein’ me, and I didn’t reckon on seein’ you, and so we’re both properly astonished. But I ain’t a-goin’ to hold it agin’ ye.”

The scout swung to the ground, and seized the little man by the hand, shaking the hand warmly.

“Nomad, I am glad to see you!”

“Ther same hyar, Buffler! I’m as glad to see ye as if I’d run a splinter in my foot. What ye doin’ hyar?”

“What are you doing here?”

“Me? Waal, I’m in hard luck jes’ now, fer a fac’. And so I’ve become a sort of hostler hyar, ye see. I look after ther hosses, and——”

John Latimer was looking on in surprise, and the garrulous old trapper subsided, seeing it.

“I’ll have a long talk with you later,” said the scout. “I’m the guest of Mr. Latimer, and shall probably be out here several days. By the way, Nomad, what do you know of Indians and road agents?”

“They’re all dead, so fur’s I know, Buffler.”

“You haven’t seen any lately?”

“Nary a pesky red, an’ not a single pizen road agent.”

“That’s strange. Mr. Latimer has reported that he had lately been raided by road agents and by the Redskin Rovers?”

“Waal, ye see how ’tis, Cody. I only come hyar yistiddy, and so I can’t be considered as bein’ ’specially up in ther happenin’s hyar and hyarabouts. But if thar’s road agents and Injuns floatin’ round, I’ll begin to feel that I’ve arrove ahead o’ time in ther happy[16] huntin’ grounds. I ain’t hed no good times at all, sense the days when you and me was huntin’ Injuns and road agents together.”

The scout, though anxious for a talk with old Nick Nomad, saw that John Latimer had dismounted and was waiting to accompany him into the house.

“Well, take my horse, Nomad,” he said. “By the way, Nick, where is old Nebuchadnezzar.”

A whinny came from the nearest stable; and old Nomad, hearing it, bent double with cackling laughter, so pleased was he.

“Thar he is, Buffler, ther ole sinner! He knows his name as well as some men know the name o’ whisky, and he answers jes’ as quick. He heard ye say ‘Nebbycudnezzar’ and he answers ye! How long’s it been, Buffler, sense that wise critter heerd your gentle voice, anyhow?”

“More than a year, I think.”

“Jes’ ther same, he’s rec’nized it. Buffler, I’ve seen wise hosses in my time, but Nebby goes ahead of ther best of ’em. He’s a-gittin’ so knowin’ that I’m acchilly askeered that some mornin’ I’ll wake up and find that he’s been translated to ther hoss heaven, if thar is one.”

Having started on his favorite subject, old Nick Nomad would have gone on indefinitely, if Buffalo Bill had not snapped one of his sentences in the middle by practically deserting him and entering the house with Latimer.

The thing that first arrested Buffalo Bill’s attention within the house was that the big, rambling structure[17] was apparently without occupants. One servant had come to the door, to admit them—a Mexican of villainous aspect and slinking mien—but aside from this one Mexican not another soul was to be seen.

“You appear to be quite alone here?” the scout suggested.

“Yes,” Latimer admitted, “quite alone.”

“You have been here alone from the first?”

“Yes. I have had a number of servants, but none of them remained with me long. The place is too isolated, and too far from the towns. So, after a short time, in each instance, they departed. I have now only that Mexican, and the man you talked with. You seemed to know him, Cody? He came to me only yesterday. He’s a stranger to me, and may not be reliable; but I needed help so badly that I took him without asking him any questions.”

“There is nothing mysterious about him,” the scout replied, as he passed through the long hall with Latimer to the latter’s rooms. “He is, in fact, as open as the day.”

“Well, I’m sure I’m glad to hear it,” Latimer confessed, with an appearance of uneasiness. “I have more than once suspected that servants who have been here have been in alliance with the Redskin Rovers, or the road agents.”

“Nomad is an old-trapper, who has been in the Western mountains more years than he can remember; and yet, in spite of the great age he claims—hear him tell it sometimes and you’d be ready to believe him a hundred years old—he is as spry as a young man,[18] and as a dead shot with rifle or revolver he has not many equals. He has helped me in a number of scouting trips, and we’ve had some very interesting experiences together. It surprised me to find him here.”

“Surprised you?”

“That he should be doing menial work. But he explained that he found himself in hard luck, and was glad to take anything that offered. I was glad to see him. He is as a friend true as steel.”

When they passed into the large rooms Latimer apologized for their apparent disorder.

“You perhaps heard him boasting of his horse,” the scout continued, still speaking of Nick Nomad.

“A bag of bones, Cody!” cried Latimer. “I wonder the brute can carry him.”

“Yet a wonderful horse. According to Nomad, it is the most wonderful horse in America, or in the world. And it really is a beast of rare intelligence. He has so trained it that its actions at times seem almost human.”

“My new hostler seems to be rather a wonderful man,” remarked Latimer, with a dry smile. “I shall have to have a talk with him myself.”

“You will find that he is a wonderful man, if you ever are able to know him as thoroughly as I do,” was the scout’s answer.

[19]

Buffalo Bill had not been in the lonesome house on the big mesa an hour before he heard a roaring shout near the stables. It drew him to the open window, and when he looked out he beheld Pizen Kate.

She had sighted Nick Nomad, and was making for him, waving her big umbrella round her head as if it were a lasso with which she meant to effect his capture.

“Run away from me, will ye?” she was bellowing. “Abandon me, yer lawful and lovin’ wedded wife, will ye? Well, you’ll perceive the sinfulness of yer sinful ways before I git through with you, you bet! You’ll know fer certain that I’m Pizen Kate, of Kansas City, and a lady that’s not to be trifled with.”

For a moment Buffalo Bill was too astonished for mirth; then he broke into a roar of laughter. Leaving the window, he descended quickly to the ground, and made his way out to where Pizen Kate was tongue-lashing her recreant spouse. She was still at it when the scout arrived.

“Me washin’ fer you, and laborin’ fer you; and then you cuttin’ right out and runnin’ away from me! Is that the way fer a man to conduct himself toward the wife of his bosom? Answer me that, you dried-up mummy, you pestiferous weasel! Why don’t you answer me?”

[20]

Nomad had backed into a corner of the adobe wall that formed part of the horse inclosure, and was defending his face with his hands from the jabbing umbrella.

“Yes, yes!” he admitted.

“Wasn’t I a true and lovin’ wife to ye?”

“Yes.”

“And you run away from me when I was workin’ fer ye?”

“Don’t!” he pleaded. “Don’t hit me in ther face with thet! Great snakes! Yes; I’m willin’ ter admit ter anything. I’m all sorts of critters that ye can think up, and more throwed in. But don’t poke me in the eye with thet.”

“I’ve a notion to ram it down yer throat and open it up inside of ye!” she threatened.

“Waal, it’d make me look fatter, ef ye did!” he declared. “Hold on—hold on! Thet thar is my arm you’re peelin’ the skin off of. Let up, can’t ye?”

“Why did you do it?” she demanded.

“I—I——”

“I ast you why did ye do it?”

“I couldn’t live with ye, and that’s a fact!” he sputtered, hopping about to evade her blows.

“Couldn’t live yith yer lovin’ and lawful wife?”

“You was too strenuous fer me, and yer temper was too peppery. So I thought I’d slide.”

Latimer had appeared, drawn by the noise.

“And there’s the feller that you went away with!” she said to Nomad. “Don’t say he ain’t, fer I know. Thet’s ther dashin’ galoot that called hisself Persimmon[21] Pete. You got stuck on him there in Kansas City, and lit out with him. Don’t say it ain’t so, er I’ll poke the p’int of this umbreller inter yer innards! Don’t say it ain’t so!”

“Waugh! I ain’t sayin’ that it ain’t so.”

“Then it is so? I knowed it was. And he lied to me in ther town, when I charged him with it. And he knowed you was out here; and out here he rid, to meet ye. I seen him go, and I follered him. Oh, I understand ye! You can’t fool Pizen Kate. Ain’t it so?”

“Anything’s so, when you says it is,” said Nomad.

She shook her umbrella at Buffalo Bill. “You lied to me there in the town!” she vociferated. “You said you wasn’t Persimmon Pete, and you perfessed that you didn’t know nothing about where my ole man was! Now, what do ye say to that? When you left Eldorado I follered ye. And here I find you two together. What do ye say to that? Answer me!”

The scout was laughing too much to reply as quickly as she wished, and this made her rave the more.

“You are mistaken,” he said finally.

“You don’t know this man?”

“Oh, yes, I know him.”

“He ain’t my lawful, wedded husband?”

“I don’t know that he isn’t, of course. It only surprises me.”

“Surprises ye, does it? Well, when I think of it, it surprises me, too. To think that I should ’a’ married a walkin’ shadder of a man like that, a living mummy that grins and acts like a baboon; and then that he[22] should run away frum me, when I stood ready to lavish all my wifely love on him. Yes, it surprises me, too.” She glared at the scout. “Why did you tell me that you wasn’t Persimmon Pete?”

“Because I am not.”

“What!” she shrieked. “You deny it?”

“Don’t deny anything, Buffler!” wailed Nomad. “It’ll be wuss fer ye. Admit everything she says. If she asks me ain’t I the man in the moon, I’m saying ‘yes’ to her every time.”

“You are married to her?” said the scout.

“Waugh! Buffler, she made me do it!”

“If you ain’t Persimmon Pete,” she demanded of the scout, “who aire ye?”

“My name is Cody. Sometimes I’m called Buffalo Bill.”

“And that’s another lie!” she declared. “I know ye. You’re Persimmon Pete. But I’ll tell ye now, that I’m goin’ to take this man back with me, and he’ll live with me as my lovin’ husband, er I’ll kill him.”

Nomad contrived to escape out of his corner while the infuriated woman talked with the scout and with Latimer, and when he had accomplished that he sprinted round the end of the wall.

She gave chase immediately; and when she found that he had hid himself somewhere, she began to search for him, vowing that she would not rest until she had forced him to return with her to her home in Kansas City. She repeated her threat, as she made her furious search.

[23]

“If he don’t go back with me, and live with me as my lovin’ husband, I’ll kill him. There ain’t goin’ to be no pore-deceived-and-weepin’-woman business with me now, you bet! I ain’t that kind of a hairpin! I’m a woman that knows her rights and is willin’ to fight fer ’em. And if he thinks he can hide, and that I’ll soon go away and leave him, why, then he is mightily mistaken.”

“Your hostler seems to have got into a good deal of trouble,” the scout remarked to Latimer, as they returned to the house together, leaving Pizen Kate hunting for Nick Nomad.

“Cody,” said Latimer, “that is the most absurd episode I ever saw, or knew about. I’m afraid that new hostler is a great rascal, in spite of what you informed me about him.”

A little later the scout saw Nomad running toward the house. Pizen Kate was not in sight. Apparently, Nomad had found a chance to get out of his hiding place unobserved by her, and was making tracks for the security of the big building.

Buffalo Bill hurried through the hall and swung the front door open to admit him.

“Cody, is she comin’?” Nomad panted.

The scout glanced out. “I think not.”

“Then, Cody,” he lowered his voice, “come into thet room over thar, fer I want a talk with ye. Fasten ther door, so that she can’t git in. And don’t let Latimer know about it. Jes’ a few minutes’ talk with ye, in thet room over thar.”

He ran on toward the door of the room indicated.

[24]

The scout stayed, in obedience to his request, to bar the outer door against the ferocious Pizen Kate. He occupied but a minute of time in doing it, and then followed on to the room, through whose door he had seen Nomad vanish. But when he entered the room Nomad was not there.

“Nomad!” he called, looking about.

There was no reply.

[25]

Nick Nomad had disappeared with such a mystery in the manner of his going that Buffalo Bill was bewildered.

The room into which Nomad had run was, apparently, but an ordinary room, with no door but the one he had gone through; and it had but one window, which was closed and locked, and which, the scout was absolutely sure, Nomad had not opened. Even a casual examination of that window was enough to show that Nomad would not have had time to open it and get through it before the scout’s appearance; and even if he could have succeeded in doing that, he could not, from the outside, have locked it, for it was locked from the inside.

Buffalo Bill stood amazed and aghast when, after much calling, he had no response, and after much examination he could not solve the mystery.

The floor, the walls, the ceiling, were solid; the window was closed tightly, and the one door had been in sight, and Nomad had not come out by it. He had gone into that room, and then had “evaporated.”

While the scout was still puzzling over this singular thing, Pizen Kate appeared at the outer door of the house, which she pushed open boldly, and entered. Figuratively, there was blood in her eye, and she was painted for the warpath. She looked suspiciously at the scout.

[26]

“Where is he?” she said. “He came in here! You been helpin’ him?”

“Madam, I wish I knew.”

“Well, if you was here, you seen him, didn’t ye? Where’d he go? Before I git through with him I’m goin’ to l’arn him a few things, you bet! Run away from me in Kansas City, he did—and jes’ now, when I was lecturin’ him on the sin of his acts, he kited out ag’in. He come in here, fer I seen him; but he outrun me. Now, where is he?”

“I wish I knew.”

“Well, why don’t you know? Didn’t you see him come in?”

“I did. He went into that room. I was to follow him, for I wanted to have a talk with him; but when I entered the room he was not in it. If you can find him, or tell what became of him, I shall be obliged to you, for I’m as anxious to know where he is as you are.”

She gave him a stare of disbelief, then she walked to the door and looked in.

“He ain’t in there,” she said, withdrawing her head, “and he never was in there, and you know it. Playin’ with my feelin’s, aire ye? And me a pore, lone woman! Well, now that’s what I’d expect of you, Persimmon Pete, and nothin’ else. You’ve hid him away, and aire laughin’ at me, thinkin’ it’s smart. But you’ll find I ain’t a lady to be trifled with. I want my husband.” She planted herself before the scout and flourished her ancient umbrella. “I want my ondutiful husband, and I want him this minute!”

[27]

The scout was too anxious and too greatly mystified to laugh.

“Madam, if I knew where he was, I shouldn’t turn him over to your tender mercies, but I don’t know where he is.”

“Do you mean to tell me he went into that room, and then drapped out o’ sight?”

“He did.”

She went to the door and looked in again.

“You used to tell some big lies, Persimmon Pete, when you was sellin’ that Injun medicine, that you said would cure about anything in creation; but you must have been practicin’ some lately, fer that’s the biggest lie that ever was told.”

“It looks it,” he admitted.

She glared at him in disbelief.

“I can’t stay to talk with you,” he added, “for I’m going to call for Latimer. He may be able to explain this thing. There must be a way out of that room which I know nothing about and cannot discover.”

“What is it?” called Latimer.

“Will you be so good as to come here?” Cody asked. “Here’s a mystery that is baffling and serious, but you may be able to make it seem quite simple.”

Latimer came forward. “Yes?” he said questioningly.

“Nomad came into this hall but a little while ago. He was hurrying, and as he came in he told me to follow him into that room, as he wished a word with me in private. I followed him to the door, and then[28] on into the room; but he wasn’t there. He did not come out by the door, for it was in my view all the time, and he could not have gone out by the window and left it locked on the inside, if he’d had time, which he had not. Will you be so good as to point out what other way he could have gone out of that room?”

Latimer hesitated.

“Will you step to the door and look in,” said the scout.

John Latimer obeyed this, but when he turned about his face showed agitation.

“It’s one of the mysteries of this strange place,” he said, in a low voice. “All of my servants have disappeared in just that way. For a while they are here working around; then they are gone. I don’t know what becomes of them. I get other servants, and they likewise disappear.”

His manner was agitated. Buffalo Bill stood aghast.

“Are you in sober earnest, Mr. Latimer?”

“Never more so,” was the answer.

Pizen Kate stared her disbelief, and then broke into a cackle of spiteful laughter.

“Do ye think it’s nice,” she said, “for two men to try to fool a pore, lone woman in that way? I found my lawful and wedded husband here, after chasin’ him all the way frum Kansas City. And you, sympathizin’ with him in his abandonment of me, his true and lovin’ wife, git up this kind of a yarn to keep me frum takin’ him back with me.”

John Latimer seemed hurt by the accusation. Buffalo[29] Bill strode again to the door, and then walked on into the room. He began to sound the walls with the butt of a revolver, and to sound the boards of the floor with his heels. Latimer followed him to the door.

Pizen Kate was still raving, accusing them of conspiring to deprive her of her husband.

“Woman, will you stop that clatter?” cried Latimer, whose nerves were jarred by her abusive talk.

“No, I will not!” she declared. “Not till I’ve found that man, and had the law on you two men fer hidin’ him away from me. Do ye suppose I’m fool enough to believe sich a story as you’re tellin’?”

Buffalo Bill came out of the room baffled. “Have these other disappearances been just in this way?” he inquired of Latimer.

“Not in just that way, Cody. I’ve twice sent servants on errands, from which they have never returned. Once, a month ago, I had a servant girl at work in my kitchen. I was in my own rooms. I heard her scream. When I got to the kitchen there was not a soul in it, and I have seen nothing of that girl since.”

Pizen Kate stared at him.

“You’re just tellin’ that to scare me away from this place.”

“I’m telling you the truth.”

“You never saw anything strange yourself?” asked the scout.

“Never.”

“And you have formed no theory to account for it?”

[30]

“I haven’t been able to, Cody.”

Pizen Kate walked into the room and began to look it over.

“I’ve had a good deal of dealings with men,” she said, as she came out, “and I know that you two fellers aire lyin’. But if you think you kin scare Pizen Kate that easy, then you don’t know her. I come here huntin’ fer my lawful husband, and I’m goin’ to stay till I find him.”

Buffalo Bill made now another inspection of the mysterious room, and this time he was accompanied in his examination of it by Latimer.

Pizen Kate stood in the door, keenly watching them, and now and then sarcastically commenting.

Buffalo Bill had never been more puzzled in his life than when he gave up further search there as a useless waste of time. He now commenced a thorough search of the house, asking Latimer’s aid, while Pizen Kate went to the outside, as if she thought she might be in a better position to see there; for she doubtless reasoned that if Nomad was still in the house, and tried to get out of it, he could not easily do so and escape her eyes.

Buffalo Bill’s search was unavailing. Nick Nomad was gone.

[31]

When Buffalo Bill gave up his profitless search and came out of the house he saw a mounted Indian ride up to the gate, some distance off, where he met John Latimer. The Indian was a painted and plumed specimen of his race, and, altogether, a glittering and jaunty figure, as he sat on his mustang, talking with Latimer.

Only a few words were said by the two men, and then the Indian wheeled his mustang and galloped away, his feathers flying, and the sun shining with brilliant effect on his beaded garments and on the painted spots on his horse.

Buffalo Bill had emerged from the big house by a side entrance. He hurried now round to the front, where he expected to meet Latimer returning from this talk with the redskin. Latimer had gone from the gate in another way, however; and the scout did not see him for several minutes, and then it was in the house itself.

“What about that Indian, Latimer?” was his question.

Latimer stared blankly. “What Indian?” he said.

“Why, the one you met out there by the gate a while ago.”

“I have seen no Indian!” said Latimer.

The answer so took the scout aback that for a moment he was at a loss what to say.

[32]

“I am sure, Latimer, I saw you out by the gate talking with a mounted Indian, not more than five minutes ago. I had just got to the steps, on the east side there, and saw the Indian ride up to the gate. You were there, and you spoke with him, and then he rode away.”

An angry look flashed over Latimer’s face.

“Cody,” he said quietly, “you are my guest here; and, therefore, I shall not try to call you to account for giving me the lie!”

“You mean that I did not see you out there talking with an Indian?”

“Certainly not.”

“Then, Latimer, I saw your very image and counterpart!”

“That may be, Cody. I can’t say as to that. You did not see me.” Latimer’s manner was strangely cold.

“You did not even know there was an Indian out there?”

“No.”

“This is as strange as the singular disappearance of my friend Nomad.”

“Don’t you think you are just a little given to imaginings, Cody? Pardon the suggestion. You saw your friend go into a room, which, according to your own story, he could not have gone into and got out of without your knowing it. And now you have seen me talking with an Indian by the front gate, when all the while I have been here in the house.”

A certain sense of giddy bewilderment attacked the[33] level-headed scout. Could he have been subject to hallucinations? The very suggestion was enough to give him a severe mental start.

“Pardon me,” he said. “I was sure of those two things. But if you say you were not out there, of course I accept your statement. But I saw some one there that I took to be you.”

Latimer laughed, and the frown vanished from his face.

“That’s more like you, Cody! I have given you no occasion to think I would lie about a matter of that kind, or would have any occasion to deceive you.”

“That is true,” the scout admitted.

“There may have been no one out at the gate,” Latimer urged.

Buffalo Bill could not admit that, puzzled as he was.

To make sure that he had not been wholly the victim of some optical delusion, as soon as he ceased talking with Latimer he walked out to the gate, and there scanned the ground, looking for tracks of the mustang. While thus looking he heard his name called by Pizen Kate.

A suggestion came to him.

“You didn’t see an Indian out here a while ago talking with Latimer?” he asked her.

“I wasn’t lookin’,” she said noncommittally. “The only thing I was lookin’ for was that no-’count husband o’ mine, that’s run away from me ag’in. I can’t find hide ner hair of him.”

“I wish you could,” said the scout, with much earnestness.

[34]

“Then you really don’t know what’s become of him?” she queried.

“Not in the least.”

“You didn’t help him to git away?”

“I didn’t.”

“Well, I thought ye did, and I was good an’ mad!”

“You didn’t see an Indian here?”

“I didn’t, for I wasn’t lookin’.”

“Nor you didn’t see Latimer come from this gate five minutes or more ago?”

“I tell ye, I wasn’t lookin’. Somethin’ queer about this place,” she added suspiciously.

“I’m beginning to think so, too.”

“Well,” she declared, “they can’t fool with me! Aire you goin’ to stay here long?”

“Until I discover what has become of Nomad.”

“Then I’m with ye! We’ll find him, if we have to tar and feather that Latimer to make him tell what he knows. I reckon I’ll go up to the house and give him a few jabs in the ribs with this old umbreller, to make him talk a bit.”

She marched angrily toward the house.

The scout began to look for the tracks of the mustang. He found them in the dust close by the gate; and on the other side of the gate he saw the imprint of shoes, which he was sure had been made by John Latimer.

“As Kate says, there is something mysterious here,” was his thought, “and it begins to look as if John Latimer were crooked. He lied to me when he said he had not been down here by this gate, and he lied[35] in saying he had not here met an Indian. I think I’ll follow this trail. It may reveal something.”

The scout started off on the trail of the mustang; and though, when he got away from the gate, other horse trails interfered, he was yet so skillful that he picked out that of the mustang from among them and continued on, finding that it led toward the hills.

The house was out of sight, and he was on a long, grassy level, when, looking up, he saw the Indian riding slowly toward him. Only one look was needed to show that this was the identical Indian who had been at the gate. He seemed to be either returning toward the house, or else, having seen that he was being followed, he had ridden back to ascertain the meaning of it.

“A word with you,” shouted Buffalo Bill.

The Indian drew rein at a little distance, and sat in silence, regarding the scout with distrust.

“You were up there at the gate a little while ago?”

The redskin did not answer.

“Tell me if that isn’t so, and if you didn’t talk there at the gate with the man who lives in that house?”

The question seemed to throw the redskin into an unaccountable rage. He drove his mustang forward without an instant’s warning, and, drawing a short rawhide whip, he aimed a blow at the scout’s face.

Though the movement was so unexpected, the scout was not caught napping. For as the enraged redskin tried to ride Buffalo Bill down and strike him in the eyes with the whip, the scout caught the mustang by[36] the head and nose, jerking its head round, and it went over in a heap, as if shot. The thing was done so quickly and cleverly that the Indian was thrown from the mustang’s back; and his right foot got caught under the falling horse.

The fall jarred a grunt from him; and then he tried to pull his foot out, but the scout leaped toward him now, drawing his revolver.

The horse had quivered as it fell, but now it lay stretched out. It had struck on its head and neck in its fall, and the weight of its body thus crushing against it had broken its neck, killing it.

The Indian stared stupidly when he saw that revolver.

“White man no shoot!” he begged.

“I don’t intend to, unless you try treachery and force me to,” was the answer, as Cody pointed the pistol at the Indian’s feathered head. “Tell me why you rode to the gate over there a while ago!” he sternly commanded.

The redskin stared stolidly, evidently inventing some answer.

“Me no go.”

“You talked there with the white man who lives in that house?”

The Indian shook his head.

“Why did you get mad and try to strike me with your whip when I asked you about it?”

“Let pore Injun go!” whined the redskin.

The scout repeated his question.

“Let pore Injun go!” was the only answer. The[37] redskin pretended he did not understand what Buffalo Bill meant.

“You may go,” said the latter, who had no desire to hold him.

The black eyes glittered. Accustomed to treachery, the Indian could not understand this, unless it spelled trickery of some kind.

Buffalo Bill seized the head of the horse and drew the body round a little, and the Indian extricated his foot, which had not been much hurt. He limped, however, when he rose to his feet.

“I’m sorry about the mustang,” said the scout, “but it was your own fault. You provoked it, when you tried to ride me down and strike me with that whip. But you may go.”

The redskin hesitated, looking at the pistol held by the scout; but when Buffalo Bill repeated his permission to go, he started off slowly, glancing back as if he feared this were but a trick to give the scout a chance to shoot him in the back.

“Here,” said the scout, “don’t you want these things?”

He pointed to the rawhide accouterments on the dead horse. The Indian looked at them doubtfully.

“White man no shoot?”

“No; come and get them.”

Buffalo Bill turned and walked away, watching the Indian, whom he could not trust. When he had gone some distance he saw that the redskin was stripping the trappings from the dead mustang.

Having secured them, the Indian slung them across[38] his shoulders and hurried away, and soon was running for the shelter of the nearest hills. He had been badly worsted, and he knew it; yet he could not understand one thing—why Cody had not killed him when he had so good a chance. Had the case been reversed, he would have killed the scout.

“Now, what does this mean?” Buffalo Bill was asking himself, as he returned to the house. “John Latimer talked with that Indian by the gate; yet he denies it. And when I suggested to the Indian that he had talked with Latimer, the fact that my question showed I had witnessed the meeting threw the redskin into a rage and he attacked me. What is the meaning of it?”

[39]

When he entered the big house Buffalo Bill did not meet Latimer. It seemed useless to search for him, to question him again, after his positive denial. Nevertheless, the feeling had grown within the scout that for some inexplicable reason Latimer was not “playing fair.”

Not finding Latimer readily, he departed from the house and strolled about the grounds. He had much to turn over in his mind. He had not, for one thing, given up solving the mysterious disappearance of Nick Nomad.

As he thus strolled about, he entered the stables where his horse was kept, and as he did so, a form dropped on him from somewhere above, knocking him to the earth; and then a brown hand clutched at his throat, and a knife flashed before his eyes.

It took him but an instant to discover that the would-be knife wielder was the Mexican servant; the only servant on the place, in addition to Nomad.

The Mexican in making his drop had evidently intended to land on the scout’s head, and thus strike him down unconscious; but his heels struck the scout’s broad shoulders; and, though Buffalo Bill went down, he was not knocked out. He writhed about as the Mexican tried to knife him, and then he set his firm fingers in the brown, lean throat, making the Mexican gasp.

[40]

However, the Mexican was strong, and he was lively and lithe as a captured snake.

The fight that followed was of brief duration, for the scout’s choking fingers subdued the little brown man in short order.

Buffalo Bill threw the Mexican against the wall. For a time the rascal lay in a heap, limp as a rag. In the meantime, the scout secured the long knife, which had fallen from the lean, brown hand. He was standing before the Mexican, when the latter tried to sit up. The Mexican was clutching at his bruised throat with a motion of pain.

“See here!” said Buffalo Bill sternly. “You would have no right to complain if I should shoot you, for on your part you tried to kill me.”

“No, no!” the fellow pleaded, his black eyes showing fright.

“Will you answer my questions?”

The Mexican stared as if he did not understand, until the scout repeated the inquiry.

“Si, señor,” he gurgled faintly.

“You were set on by some one to do this?”

“No—no, señor.”

“Why did you do it? You tried to kill me!”

“No—no, señor.”

“Then why did you attack me? Answer me straight.”

“For—for dem!”

Buffalo Bill saw that the Mexican had indicated his handsomely mounted revolvers.

“For my pistols? You wanted to rob me?”

[41]

“Si, señor,” was the bold confession.

“Well, you are cool about it!” He searched the Mexican hastily and found nothing. Standing before him he pointed the revolver and clicked the cylinder in a suggestive way.

“I think you are lying. Unless you tell the truth, I shall have to shoot you!”

The Mexican’s teeth chattered with fright and his face became an ashen brown.

“Now,” the scout went on, “did some one tell you to attack me here?”

The Mexican was so scared he could hardly speak, but he managed to stammer out another denial.

“No one told you to do it?”

“No, señor.”

“You simply wanted my pistols?”

“Si, señor.”

The scout was in a measure disappointed and baffled. He had thought that perhaps this man had been ordered to assault him. Yet he knew that the lower-class Mexicans are such liars that even their most solemn statements cannot always be believed. So he was still suspicious on that point. He threw the knife to the crouching and whining scamp.

“Clear out!” he said. “And if you trouble me again I shall certainly kill you. Clear out!”

The Mexican grabbed the knife and bolted through the door.

When Buffalo Bill had looked at his horse and had given him some hay, he left the stable. The Mexican had disappeared. On approaching the house the scout[42] once more encountered Pizen Kate, still hunting for her husband. She fairly cackled with glee, when he asked her if she had seen anything of the Mexican servant.

“Say,” she said, waving her umbrella for emphasis, “I’m believin’ that men will soon learn to fly, jedgin’ by him! He was as nigh to flyin’ as a human can git without bein’ actually a bird with wings. He went by here only hittin’ the high places. Well, he was goin’ some when I seen him! What was the matter with him?”

“I told him to get, and he was getting. He tried to murder me when I went into the stables.”

“You don’t mean it?” she cried. “Well, I thought mebby he’d seen the face of my lost husband lookin’ at him from some sing’lar place and imagined he’d seen a ghost. He tried to kill ye?”

“He made a good attempt at it.”

Then she laughed again. “Say,” she said, bending toward him earnestly, “between you and me and the gatepost, there’s somethin’ so mysterious about this here place that I think it needs investigatin’. I’ve lost my husband here and can’t find him. So I’m goin’ to be on guard round here to-night; and if there ain’t happenin’s, then I’m clean out in my reckonin’, and don’t know nothin’. Mark my words, there’ll be happenin’s round here to-night. I kin smell trouble in the air, yes’ as some men kin smell a thunderstorm when it’s comin’.”

[43]

In spite of the lugubrious prediction of Pizen Kate, Buffalo Bill retired to his own room in good season that night.

Latimer had met him, after that attack of the Mexican, and had shown great indignation when the scout told him about it. As for the Mexican, he did not return.

With no servant to wait on the table, or even to prepare the meals, Latimer went himself into the kitchen, and prepared something for supper. The scout insisted on helping him in this, urging his experience in such matters.

“Cody, I’m experienced, too,” said Latimer. “I’ve told you how my servants disappear. This isn’t the first time I’ve been left without any help. And so I’ve been forced to do for myself, not only cooking, but other things.”

“Why do you stay in such a place?” the scout could not help asking.

“I’ll tell you!” Latimer stood off, looking at him, and making a striking picture as the light of the stove fire flamed into his face. “If I should leave here, it would be because I had been driven away by superstitious fears. I refuse to become superstitious. I am not a believer in ghosts.”

“Nor I.”

[44]

“I am sure that all the things that have happened have some easy solution. Some time ago I resolved to penetrate to the bottom of the mystery. Should I leave without doing that, or not be able to do that, I should always feel that perhaps there are ghosts, and such things. So, Cody, you see I can’t afford, for myself, to go away. Besides,” he added, “I came out here for my health.” He held up his arm. “Observe that arm, firm and strong. When I came here I was a shadow, without muscle or sound nerves. To-day I am a well man. I regained my health here; and I do not propose to be driven away.”

“As we both refuse to believe in ghosts, what is your belief concerning these strange things?” the scout asked. “I can’t tell you how anxious I am about Nomad.”

“That’s where you have me,” Latimer admitted. “I can’t explain it—can’t explain anything; and when I have tried to follow out theories they were always disproved. I am just waiting to see what will come of it.”

After retiring, Buffalo Bill lay awake a long time, thinking over the singular occurrences of the day. His anxiety concerning the fate of Nick Nomad was intense. Nomad had not been out of his thoughts. It had been strange enough to discover Nomad in this place, doing the work of a menial; still stranger to hear that he had married, and married such a woman as Pizen Kate; but even these things became as nothing compared with the strangeness of Nomad’s disappearance. More and more Buffalo Bill began to suspect[45] that John Latimer was not just what he seemed; and the thought that perhaps Latimer had lured him to this place, with evil designs against him, had strong support in the dastardly attack made by the Mexican, and the other attack made by the Indian.

The scout had been here but a few hours, yet twice in that time had his life been attempted, he was sure. This made him feel that a similar attempt might be again made.

Thus reflecting, he placed his revolver ready to his hand, and lay listening.

The time was well on toward midnight, and he had grown sleepy, when he heard a sound at the door of his room. The door opened, and in the bright moonlight which flooded the room a young woman stood revealed.

The scout’s start of surprise caused her to stop on the threshold. She seemed to listen a moment; then, as he lifted his head to get a better look, she turned and fled. Instantly he leaped from the bed and ran to the door; but she had vanished, and with step so light that he could not hear her going.

Leaving the door open, the scout hurried into his clothing, and then went hastily to Latimer’s room.

“Latimer!” he called, tapping softly.

“Yes!” came the answer. Latimer’s feet were heard as they struck the floor. A moment later the door opened cautiously, and in the moonlight Latimer’s gray beard appeared.

“Ah, Cody, you startled me! Is there anything wrong?”

[46]

“Tell me, Latimer, is there a young lady in this house?”

“A young lady?” Latimer gasped.

“Yes.”

“Why, certainly not, Cody.”

“There is no woman in this house?”

“None.”

“I saw one but a minute ago. She opened the door of my room quite as though she had made a mistake in the room. The door was unlocked. She stopped, when she heard me stir, and when I half rose in the bed she fled.”

“Cody, you dreamed it!” Latimer insisted. “It couldn’t have been true.”

“I was not dreaming. I was sleepy, I’ll admit, but I was not asleep.”

“Cody, you certainly were dreaming.”

Buffalo Bill could not be convinced of this; and he made a search through the halls, and looked into some of the rooms. He confessed to a very queer feeling when he returned to his room.

“It’s almost enough to make any one believe in ghosts,” he commented to himself. “But that was not a ghost, and I was not dreaming. A young woman stood right there! She apparently came into the room by mistake; may have tried to enter for the purpose of assassinating me! Which was it? And wasn’t John Latimer lying again when he said what he did about it?”

Lying down fully dressed, the scout awaited something—he did not know what. He began to feel that[47] his nerves were badly upset. Presently, thinking he heard soft footsteps somewhere, he again left the room quietly and went in search of them.

He even went out of the house, and looked round outside, carrying his revolver ready for use, for the mystery of all these things filled him with something as near to fear as he had ever known.

As he returned to the door by which he had left the house he was startled by hearing voices; then, in the half darkness of the shaded piazza, he saw again the girl.

Here was confirmation of the fact that he had not been asleep and dreamed that he saw this woman. She was talking with some one; and the scout saw at her side a young man.

He was about to advance and demand an explanation, when the girl opened the door behind her, and she and the young man vanished into the house.

Buffalo Bill, having come out by that door, had left it unlocked. Now, when he ran up to it, he found that it was locked from the inside. He was left out of the house; and to get in he was compelled to call up John Latimer once more, doing it this time by shouting to him below his window.

Latimer appeared, coming down into the lower hall in a red dressing gown and slippers.

“What is it, Cody?”

Buffalo Bill told him.

“Come here, Cody!” He lighted a candle and led the way into a small side room, where, instead of answering Buffalo Bill’s questions, he looked at him[48] strangely, and then took down some small bottles from a shelf. “I studied medicine once, Cody, and keep medicines here for my own use. You must let me prescribe for you.”

“You mean to say I did not see and hear that young woman and young man?”

“I think you are not well, Cody,” was the evasive reply. “Permit me to prescribe for you.”

He poured some of the contents of one of the bottles into a glass.

“No!” said the scout. “I am not ill; there’s nothing the matter with me. I need no medicine.”

Latimer came and looked him closely in the face, holding up the candle.

“Cody, I insist that no young man or young woman is on this place, so far as I know. But——” He hesitated.

“Finish the sentence,” the scout urged.

“Well, what I mean to remind you of is that there have been strange happenings in this house. I’ve mentioned them. These are some of the mysterious things which I told you would make me superstitious, if there were any superstition in my nature.”

“You have seen this young man and woman?”

“Yes, I have seen them. And then I promptly dosed myself for the benefit of my nerves; not being sure then, or now, that I had seen anything at all. But if there are ghosts in this house——”

“Stuff and nonsense!” said the scout. “I saw a young man and young woman standing together on the piazza, and heard them talking. They came into[49] the house; and they locked from the inside the door I had unlocked, so that I had to call to you to get in. That wasn’t the work of ghosts. What became of them?”

“Cody,” said Latimer impressively, “what became of Nomad?” He looked at Buffalo Bill again in that peculiar manner. “Cody,” he said impressively, “I’ll tell you now something I have not hinted at. A young woman and her lover, who at the time were occupying the house here in my absence, were killed here. Who committed the murder, or why, was never shown; but I suspected the Redskin Rovers. On two occasions since then I myself have fancied that I saw a young man and a young woman here; but I knew then, and know now, that it was only fancy, a result of a heated imagination. A good many things have happened to-day to upset you, and they have excited your mind and made it morbid. So you fancied you saw the young man and the young woman.”

To Buffalo Bill it seemed that Latimer was trying to throw him off the scent. Yet he could hardly see how Latimer would expect him to believe this unlikely statement.

“No matter how excited I might be, is it probable,” he asked, “that I would chance to see the young man and the young woman that you did, when I had never so much as heard of them or their murder, and therefore they could not have been in my mind?”

“There are strange things in this world, Cody.”

“I agree with you.”

It was not the least strange to him that Latimer[50] should seek to make him believe in this ghost yarn. Again the impression was driven in on him that Latimer was concealing a great deal and was not acting in a manner that could be considered straightforward. This caused the scout to feel more strongly that great danger surrounded him, and that he must guard against it, even though he could not foresee the direction from which it would come.

[51]

Unable to sleep, for thoughts of the mysteries surrounding him, Buffalo Bill was wide awake and fully dressed when the redskins made their attack on the house.

The attack came shortly before morning, in the darkest part of the night.

There came first the clattering sound of the hoofs of mustangs. This was followed by wild and startling Indian yells, accompanied by the discharge of firearms, and the patter of bullets and arrows against the walls.

Buffalo Bill seized his revolvers and his rifle and ran out into the hall, and with quick bounds leaped down the broad stairway. He found John Latimer in the room below.

Latimer was but half dressed, but he had a rifle, and when Buffalo Bill caught sight of him he was firing with it through one of the windows, having incautiously hoisted the sash for the purpose.

A pattering shower of bullets swept through that window, and it was only luck that kept Latimer from being hit. Buffalo Bill seized him by the arm and drew him against the wall, out of range of the shots.

“That is suicidal, Latimer,” he said. “Stand back here.”

“It is Indians!” said Latimer, in great excitement.

[52]

“Yes, I know it.”

“They are attacking the house!”

“Yes, I know that, too. But you don’t want to let yourself be killed by them. Lie down here; it’s safer.”

He drew Latimer down, dropping to the floor himself.

Some of the Indian bullets were coming through the walls, showing that they had a few rifles of strong power.

Sounds of Indians trying to break into the house at the rear caused the scout to leave that spot a minute later; and John Latimer leaped up and went with him.

The Indians had broken in the kitchen door, and were raiding the kitchen and the food closets. Apparently, they were bent on looting, as much as anything else.

Latimer became so excited when he saw this that he rushed out into their midst like a wild man, striking with his clubbed rifle.

Before Buffalo Bill could prevent, Latimer had been knocked down by them, and, seeing this plight, the scout fired into the Indians he saw grouped over the fallen man.

When he jumped back to avoid the return fire, they beat a retreat from the kitchen. In going they took Latimer.

The scout heard the Indians riding round the house, yelling like fiends. Then he dimly beheld a form before him, the form of the girl whom he had seen previously.

“Come!” she cried tremulously, advancing toward[53] him, with hands extended. “Come!” she repeated. “Now is the time!”

Buffalo Bill almost forgot the howling of the Indians. Because of the darkness he could see her form but faintly, and her face not at all; but that she was young was shown by the lightness of her step and by the tones of her voice. Here was a chance to solve the baffling mystery, so far as she was concerned. He decided to attempt it.

She clutched him by the arm; and when he did not resist she began to drag him, rather than lead him, toward a room whose door opened not far off.

“Come!” she urged, in an agitated whisper, as she crossed the threshold, clinging to him, and pulling at him with nervous, almost frantic, haste.

The scout stumbled as he crossed the threshold, and her grasp of him was broken; but he tried to follow her as she fled on. Then he came to a sudden realization that this was the room into which Nick Nomad had gone and from which he had not returned.

This realization had no sooner come to him than he felt the floor sink beneath him, and heard an ominous click, which at the moment he thought the click of a revolver. He was precipitated violently downward, and, as he fell, he heard that click again.

When he struck, he landed on an earthen floor that was dry and firm. He had not fallen far, he knew, yet he felt dazed and dizzy; for, in addition to the surprise of it, the fall had been heavy and had jarred him considerably.

He no longer heard the yelling Indians. That the[54] girl was not near him he knew. He was alone. The feeling that he had been trapped—had been deliberately led by this girl into a trap—was irresistible.

As soon as he could sufficiently get his wits together, he felt for his metallic match safe. Always in this water-proof safe he kept a few matches, that were sure to be dry and reliable. One of these he struck, and by its light he looked about, without rising.

Above him were the boards of a floor. About him were the walls of a narrow tunnel. Apparently he had been dropped through a trapdoor from the room above into this tunnel.

He recalled that he had thoroughly searched that room and even had sounded the floor, but he had not found that trapdoor.

It was as plain now as anything could be that through that trapdoor Nick Nomad had dropped, in the same way as himself, and, of course, had landed in this same tunnel. It seemed probable, too, that the one who had trapped him had trapped old Nomad. He was in a fair way of solving at least one of the mysteries.

Before the light of the match went out he saw the direction and trend of the narrow tunnel, and decided to follow it. Manifestly, it would be impossible to regain the room from which he had so violently tumbled.

Being anxious, he lost no time in carrying out this resolve. He moved forward along the tunnel, feeling his way with his feet and hands. He had no desire to fall into any hole that might be there. At[55] intervals he lighted one of the matches, to reassure himself.

The tunnel was not long, though in the cautious manner in which he passed through it some time was required before he reached its end.

When he came to the end he found the little river before him, and about him a thick growth of bushes.

The river end of the tunnel opened on the side of the high, rocky bank, and was so bushed about that it could not be seen readily.

It seemed to the scout now that John Latimer must be aware of the existence of that tunnel.

Latimer had built the house, and had lived in it since its erection. Obviously, he could not have been unaware of the tunnel and the trapdoor; yet Latimer had not spoken of them when the scout was making his futile search for Nomad, nor had he hinted of their existence since. More and more it was apparent that Latimer was not “playing fair;” but even yet there was so much of mystery about the whole matter that Buffalo Bill was too bewildered to reach any clear conclusion.

The Indians had gone, and daybreak was at hand by the time Buffalo Bill got out of the tunnel and out of the river gorge, and had made his way back to the vicinity of the house and stables.

The house was silent and deserted; nevertheless, he made a cautious approach, fearing treachery.

When sure that no foes lay in wait, he entered the house, finding the kitchen door wide open.

[56]

The looting Indians had gutted the kitchen, taking everything that struck their fancy. The rest of the house they had not disturbed, there being nothing in it that they apparently cared for.

Buffalo Bill visited the room through whose floor he had made that violent plunge.

As when he had made his previous examinations of it, the hidden door was so cleverly concealed that he could not find it at first; but feeling sure now that such a door was there, he persisted, and by and by he discovered that by setting his foot in a certain place and stamping in a certain way the door dropped downward, revealing the black hole beneath.

He examined the door and the tunnel minutely, being compelled to spring the door open again, as it was weighted in such a manner that it closed instantly after being opened.

As he made his critical examination, he saw that there was a possibility that the girl had not known of the door, or intended to trap him; she might have set her foot on that particular spot by accident and thus opened the door, unintentionally precipitating him thus into the tunnel. Yet he could not make himself think she had done it without intention.

When he had made a thorough search through the big house and had found no one there, he went out to the stables.

His own horse was gone, but old Nebuchadnezzar, the horse belonging to Nomad, remained, and now whinnied the scout a recognition.

[57]

The Indians had not deemed old Nebuchadnezzar worth taking away. Indeed, the old horse would not have won favorable attention from any judge of horses. He was raw-boned, old, and seemingly had seen his best days. Yet Buffalo Bill remembered the good traits of Nebuchadnezzar, and looked on him almost with affection.

The scout recalled now that since the evening before he had not seen Pizen Kate.

Giving attention to the needs of the horse, by watering and feeding him, Buffalo Bill left him in the stall, and went out to look over the grounds. He found that the unshod hoofs of the Indian ponies had not made heavy prints in the soil, yet their marks were plain enough.

“They are the Redskin Rovers,” was his conclusion. “That is the only band operating in this section, or near it. Whether half of them, or more, are white men, I don’t know.”

He found that the Indian pony tracks came together some distance beyond the house, and that here a tolerably plain trail led away toward the hills. Having worked that out, the scout returned to the stables and brought forth Nebuchadnezzar.

The old bridle and saddle, and the saddle pouches used by Nomad, had been left undisturbed, and these the scout put on the horse.

When this had been done, he tied the horse, returned to the house, and ate some food he found there, taking some also for the saddle pouches. After that[58] he mounted Nebuchadnezzar and rode forth alone on the trail of the Redskin Rovers.

Whether he could solve any of the mysteries by following the redskins was problematical. Yet it seemed likely that Latimer was a prisoner in their hands. Possibly others were; perhaps even Nomad.

[59]

The trail of the Redskin Rovers became difficult to follow in the hills, and Buffalo Bill lost much time.

Night was approaching, and he had the feeling that the Indians were far ahead of him, a feeling which produced a lack of caution, when he suddenly found himself surrounded.

The place was a little glade in the hills, with rock walls about it. The scout had ridden into it, with head bent down and eyes searching the trail, when Nebuchadnezzar gave a quick jump of alarm, and with head up and eyes rolling in alarm, tried to stampede. The wise old brute had been taught to fear Indians, and even the scent of Indians frightened him. Only the fact that the wind was blowing strong from him to them had kept the horse from smelling them before it was too late.

Buffalo Bill knew that Indians were near when Nebuchadnezzar began his capering; and then he saw them on the rocks about him.

The redskins were well armed with rifles and bows, and Buffalo Bill recognized the futility of fighting or flight. Though he might slay a few of them, there was no doubt that they could kill him before he could get out of the glade. Hence he elevated his hands, palms outward, in token of friendship, while the Indians swarmed down the rocks upon him.

[60]

The old horse snorted angrily and rushed at the redskin who first tried to get hold of the bridle.

“Give gun!” said one of the Indians, in a commanding tone.

It was hard to do; but the scout surrendered his weapons, retaining, however, inside his hunting shirt, a little revolver, which he always kept there concealed. More than once it had escaped detection, and now again it escaped.

The only weapons left him were that small revolver, a small knife hidden in one of his boots, and a fine, thin saw embedded in the wide rim of his hat.

He handed over the other weapons with apparent cheerfulness. Then he saw in the midst of the crowding redskins the one who had attacked him the day before, and whose mustang he had killed. This Indian gave him a black look, and the scout knew that he would prove an implacable and treacherous foe.

The presence of this Indian explained, it seemed, the attack on Latimer’s house. It was hostility to Buffalo Bill, fomented by the rage of this redskin, which had brought it about. Buffalo Bill himself was the object of the attack.

The excited cries of the redskins showed full well that they understood the importance of their capture.

“Fortunately, the Indian whose mustang I killed isn’t a chief,” was the scout’s reflection. “He would have me burned at the stake!”

With feelings of uneasiness, he allowed himself to be bound and led away.

Nebuchadnezzar still snorted and showed his dislike[61] of Indians; yet he was forced to go along, and he received on his rough hide some heavy blows and kicks as the reward of his protests.

The distance which the Indians traversed was not great. They had a camp not far off, and to it they conveyed the scout, who was not greatly surprised, on arriving there, to find prisoners in the camp before him. Latimer was there, together with Nick Nomad and Pizen Kate.

Latimer maintained a gloomy silence; but Nomad received Buffalo Bill with sundry cackles, and Pizen Kate in a manner befitting her previous performances.

“That is what comes of a husband runnin’ away from the wife of his bosom,” Pizen Kate declared, with a snapping of her eyes. “If he had stayed to home, dutiful and kind, as he ort, this would never ’a’ come about; but he had to leave me alone, forlorn and forsaken, and this is the result of it. I’ve been givin’ him a piece of my mind about it, too.”

“Buffler,” said Nomad, “I’m glad to see ye, and likewise I ain’t glad to see ye. Seems a singular statement, don’t it? But I don’t need to explain.”

“I think I should like to have you do some explaining,” said the scout.

“About drappin’ through thet hole in the floor?” said Nomad. “Waal, thet war cur’us, and no mistake. I run into the room, and the floor jes’ yawned fer me, and I went through. I fell so durn hard, landin’ on the sharp p’int of my spine, that I didn’t know anything fer about a day, seemed ter me.