BISHOP W. M. WEEKLEY, D.D.

Title: Twenty Years on Horseback; or, Itinerating in West Virginia

Author: W. M. Weekley

Release date: March 9, 2021 [eBook #64765]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Twenty Years on Horseback, or Itinerating in West Virginia, by W. M. (William Marion) Weekley

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/twentyyearsonhor00week |

BISHOP W. M. WEEKLEY, D.D.

By W. M. WEEKLEY, D.D.

Author of “Getting and Giving,”

“From Life to Life,” Etc.

“Take thy part in suffering hardship as a good

soldier of Christ Jesus.”—2 Tim. 2:3

Nineteen Hundred and Seven

United Brethren Publishing House

Dayton, Ohio

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

It was not my purpose, in the preparation of this little volume, to make it an autobiography, but rather a narration of incidents connected with the twenty years of humble service which I tried to render the United Brethren Church among the mountains of West Virginia.

These incidents present an all-round view, in outline, of the real life and labors of the itinerant preacher, a third of a century ago, in an isolated section, where the most simple and primitive customs prevailed.

While some of the things related will doubtless amuse the reader, others, I trust, will lead to thoughtful reflection, and carry with them lessons inspiring and helpful. The introduction should first be carefully read by those who expect to be profited by a perusal of the pages which follow. That good may come to the church, and glory to our Redeemer through this unpretentious publication is the prayer of its

Author.

Kansas City, Mo., May 1, 1907.

I have examined the manuscript of “Twenty Years on Horseback, or Itinerating in West Virginia,” and cheerfully submit this note of commendation.

The author, Bishop W. M. Weekley, D.D., I have known for more than thirty years. He entered the ministry when young, with an undivided heart and determined purpose. During the years he served the Church in that State he traveled over almost the entire territory of the West Virginia Conference. The country then was extremely primitive; but simple as the mode of life was at that time, the field was an interesting, even an enjoyable one for a minister who could endure hardness as a good soldier of Christ. I am acquainted with nearly all the sections of the State referred to, and am therefore familiar with many of the places, facts, and persons mentioned, and can assure the reader that the author has given a faithful account of these in his book. No statement is overdrawn or warped for the sake of effect.

W. W. Rymer.

Columbus, Ohio, May 3, 1907.

An examination of the following pages caused me to live my early life over again. Having spent twenty-three years in the ministry within the bounds of the West Virginia Conference, and having been intimately associated with the author of this volume during the most of that period, I am very familiar with many of the places, persons, and events mentioned, and can testify to the correctness of the record he makes, and to the faithfulness of the pictures drawn. This book will stir the thoughts and rekindle the fire within the old itinerants, and, as well, I trust, arouse the young to larger activities in soul winning.

R. A. Hitt.

Chillicothe, Ohio, May 4, 1907.

The author of this book and myself were boys together. We were born and reared within four miles of each other, were converted in the same church, and for years were members of the same Sunday school and congregation. We were licensed to preach on the same charge, and spent the earlier years of our ministry in the same conference together. In many instances we traveled the same roads, preached in the same communities, and mingled with the same people.

After having examined the contents of this volume in manuscript form, I am sure it contains a faithful description of the varied conditions which made up the life and experiences of the United Brethren itinerant minister of that time among the hills and mountains of West Virginia.

A. Orr.

Circleville, Ohio, April 30, 1907.

| Preface | |

| Introduction | 9 |

| Chapter I | 15 |

| Chapter II | 27 |

| Chapter III | 44 |

| Chapter IV | 58 |

| Chapter V | 70 |

| Chapter VI | 86 |

| Chapter VII | 100 |

| Chapter VIII | 121 |

| Bishop W. M. Weekley (Frontispiece) |

| W. M. Weekley at Twenty Years of Age |

| W. M. Weekley at Thirty Years of Age |

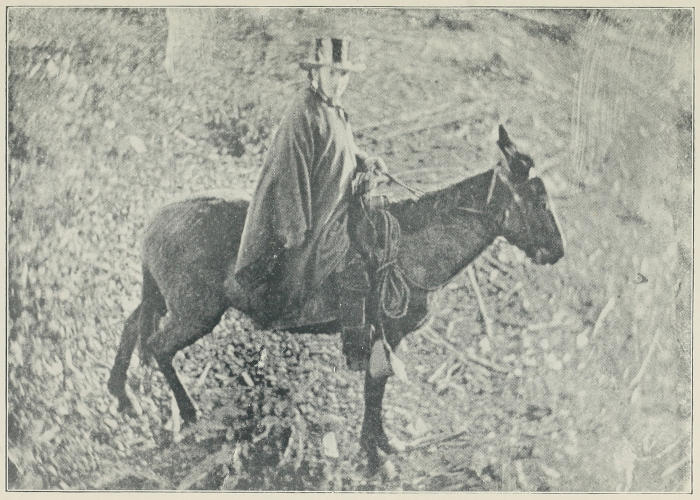

| Traveling a District |

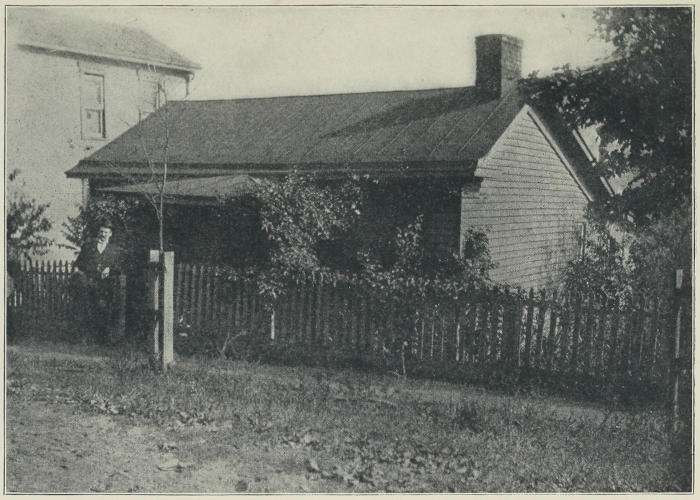

| House Where Bishop First Went To Housekeeping |

The past lives through the printed page. The ages would be blank if books were not made recording the events and achievements of men. No form of history is more interesting and profitable than that which recites the career of those who, obedient to their divine commission, proclaimed to fellowmen the sweet message of Christ’s redeeming love. The completeness of their consecration, their undaunted courage and persistency in the face of many difficulties, and their marvelous success evidence in them the presence of superhuman power. It is the genius of Christianity to inspire and develop the unselfish and heroic in men. The splendid specimens of self-sacrifice and moral courage, which adorn the pages of Christian literature, charm the reader and inspire him to more Christlike endeavor. These life-stories constitute a rich, priceless legacy for present and future generations.

In this admirable volume, Bishop Weekley has modestly removed the curtain from twenty years of his own strenuous ministerial life spent in the mountains and valleys of West Virginia, and given the reader a conception of what it meant to lift up the Christ and extend his kingdom in that rugged region. The book is biographical in character, but since “biography is the soul of history,” it is history in reality. The scenes and events which he presents suggest the character of the work which others had to do in laying the foundations of our Church in those sections.

It would be difficult to find more striking examples of Christian altruism and heroism anywhere in this country than the godly men who preached the gospel among the mountains and in the valleys of the Virginias in the early years of our denominational history. These men embodied those elements of character and graces of the Spirit which are essential to success in Christian work anywhere. Having heard the call of God, and having felt the spell of the divine spirit, they yielded themselves unreservedly to the gospel ministry. They possessed strength of conviction, singleness of aim, earnestness of purpose, and concentration of effort. As a rule these pioneer preachers had but one business—that of the King. They were so absorbed in the saving of men and women, and in extending the kingdom, that they gave but little attention to present physical comforts and future needs. Many of them were without property, and when they sang,

there was a literalness about it which would have dismayed men of less faith and consecration. Without seeking to enrich themselves in material things they labored earnestly to bring the spiritual riches of heaven to the hearts and homes of others.

They were busy men—men of action. They omitted no opportunities to do good. Intervals of rest were few and far between. The modern minister’s vacation was to them unknown. They met their “appointments” with surprising regularity. Neither storm, nor distance, nor weariness thwarted their plans. Their announcements were always made conditionally—“no preventing providence”—but they never calculated for providence to prevent them being on hand at the appointed place and hour. The strain of toil was constant, but their iron resolution, and the work itself, proved[11] a strong tonic. The success of one service was inspiration for the next. Visiting from house to house, exhorting the people to faithful Christian living, distributing religious literature, and preaching week days as well as Sundays made their lives full of heavy tasks, all of which were performed with happy hearts. They possessed the glowing and tireless zeal of the preaching friars of the Middle Ages, and with many of them the clear flame of their zeal was undimmed until the fire was turned to ashes.

They were men of thought as well as action. Their preparation was made in the college of experience, in which they proved themselves apt students. They studied few books and only the best. They cultivated and practised the perilous art of reading on horseback. They pored over books and papers in humble homes by flickering candle or pine-knot light long after the family had retired. It is remarkable what extended knowledge of the English Scriptures, methods of sermonizing, oratorical style and forceful delivery these men acquired. They knew well, and by that surest form of knowledge—the knowledge born of verified experience—all they proclaimed in message to the people. There was freshness of thought, aptness of illustration, and forcefulness of expression that was native to them. The majestic forms of nature in the regions where they toiled inspired in them the sublimest thoughts of God and his eternal truth. The marvelous results of the sermons of such men as Markwood, Glossbrenner, Bachtel, Warner, Nelson, Graham, Howe, Hott, and others proved them great preachers in the highest and truest sense.

They were men of tact as well as thought, and adjusted themselves to the conditions. They preached wherever the people would assemble—in leafy grove, by the river bank, in the humble[12] home, in the log schoolhouse, in the village hall, in the vacant storeroom, and in the unpretentious church-house. They did not always have the exhilarating and inspirational effect of great crowds, but they preached “in demonstration of the Spirit,” kindling the deepest emotions in their hearers, often arousing them to tremendous intensity and causing waves of overpowering feeling to sweep over them. Saints shouted the praises of God and penitents pleaded for mercy. These heralds of the Cross employed none of the familiar devices of modern times for securing crowds and reaching results. There were no specially-prepared and widely-scattered handbills, no local advertising committees, no daily newspapers with flashing headlines and portraits, no great choral or orchestral attractions. What made these fallible men so forceful and successful in winning others? The explanation lies in the fact of their spiritual enduement. They wrought in the name of Christ and under the influence of the Holy Spirit.

In no portion of our Zion have ministers made stronger and more lasting impression upon the people. Whenever present in a home they were the guests of honor. Their strong personalities and noble traits of character, as well as their calling itself, won for them the esteem of old and young. Parents named their children after them, and exhorted their sons to find in them their models for manhood. In thus honoring these noblemen of God they exalted the work of the ministry in the minds of the young, and prepared the way for the Lord to call them into his service. This may account, at least in part, for the great number who have gone into the ministry from these mountain districts.

Let no one fancy that somber shadows rested continually upon the pathway of these ministers. There was a joyous side to their ministerial life. When together as a class, or among their parishioners,[13] their stories and jokes were abundant, spontaneous, and of the purest type. When they met at institutes, camp-meetings, and conferences they enjoyed one round of good cheer and solid comfort. Their services of song drowned all dull cares. Their lives had shadows, but they refreshed themselves in the rifts and glorious sunbursts.

The people to whom these men of God proclaimed the gospel were not, as a rule, rich in material things, but they possessed great hearts, in which love and kindness flowed as pure and refreshing as the streams of water that rippled down the mountain side.

We rejoice that Bishop Weekley has given to the Church this book. Many aged ministers, who once toiled in the Virginias, will live over again the scenes of their lives as they read these pages. Young men will be stimulated to more earnest endeavor as they learn of the hardships and complete consecration of God’s servants in pioneer days. No one will weary in reading this excellent volume. The good Bishop has written in harmony with an established sentiment in book-making—“it is the chief of all perfections in books to be plain and brief.”

W. O. Fries.

Dayton, Ohio.

The Virginias have turned out more United Brethren preachers, perhaps, than any other section of the same size between the oceans. These pulpiteers have ranged in the scale of ability and efficiency from A to Z. Some achieved distinction in one way and another; others, though faithful and useful, were little known beyond their conference borders. Nor have all remained among the mountains. Dozens and scores of them have gone out into other parts of the Church. At this writing they are to be found in no less than nineteen different conferences, and, as a class, they are not excelled by any in devotion to the Church, in unremitting toil, and in spiritual fervor and downright enthusiasm. Some—many who spent their lives in building up the Zion of their choice among the Virginia hills, have gone to glory. Among these heroes I may mention J. Markwood, J. J. Glossbrenner, Z. Warner, J. Bachtel, J. W. Perry, J. W. Howe, S. J. Graham, I. K. Statton, and J. W. Hott. Other names, perhaps not so illustrious, but just as worthy, are to be found in God’s unerring record. The historian will never tell all about[16] them. Their labors, sacrifices, and sufferings will never be portrayed by any human tongue, no matter how eloquent, or by any pen, however versatile and fruitful it may be. Footsore and weary, dust covered and battle scarred, they reached the end of their pilgrimage and heard heaven’s “well done.” What a blessed legacy they bequeathed to their sons and daughters in the gospel!

“Old Virginia” was, in part, the field chosen by Otterbein himself, and by his devout colaborers. This was more than a hundred years ago. In 1858 the Parkersburg, now West Virginia Conference, was organized out of that part of the mother conference lying west of the Alleghanies—a territory three hundred miles long, roughly speaking, by two hundred in width. In its physical aspects the country is exceedingly rough, and difficult of travel. But the people, though mostly rural in their customs and mode of living, and many of them poor, so far as this world’s goods are concerned, are warm hearted, genial, and hospitable. When a preacher goes to fill an appointment among “mountaineers,” he is not troubled with the thought that perhaps nobody will offer him lodging, or willingly share with him the bounties of his table. I have found things different in other parts of the country.

W. M. WEEKLEY, Twenty Years of Age

Traveling Circuit

The new conference was organized at Centerville, in Tyler County, by Bishop Glossbrenner, in the month of March. Only a few ministers were present, but they were brave and good, ready to do, and, if need be, to die for their Lord. Five miles from this historic place the writer was born on the eighteenth day of September, 1851.

My parents, though poor, were honest and honorable, and toiled unceasingly to provide for and rear in respectability their ten children, of whom I was the oldest.

The neighborhood was far above the average in its religious life and moral worth. A man under the influence of liquor was seldom seen, and a profane word was hardly ever heard. The United Brethren Church was by far the leading denomination in all that country. The old log church in which we all worshiped stood on father’s farm, and our home was the stopping-place not only of preachers, but of many others who attended divine service. At times our house was so crowded that mother was compelled to make beds on the floor for the family, and not unfrequently for others as well. But to her it was a great joy to perform such a ministry for the gospel’s sake. Her loving hands could always provide for others, no matter who they were, or how many. For the[18] third of a century father was the Sunday-school superintendent in the neighborhood, and, for a longer period, teacher of the juvenile class. Thus he saw little children pass up into other and older classes, and finally to manhood and womanhood, when by and by their children came in and were given a place in “Uncle Dan’s” class.

At the age of fourteen I was born the second time, and united with the Church. The occasion was a great revival held by Rev. S. J. Graham, of precious memory. Seeing my oldest sister, Sarah, bow at the altar, greatly moved my young heart. A few moments later I observed father coming back toward the door, and thinking perhaps he was wanting to speak to me on the subject of religion, I immediately left the house. My state of mind became awful. The next evening I saw mother pressing her way toward me through the standing crowd. I knew what it meant, and sat down with the hope of concealing myself from her; but how vain the effort! What child ever hid himself away from a mother’s love? Putting her hand on my head, she said, “William, won’t you be a Christian?” I made no reply, but said to myself, “I can’t stand this; I must do something.” How her appeal, plaintive and tender, made me weep! It was really the first time she had ever[19] come to me with such directness and warmth of heart. To this very moment I can feel the touch of her hand and hear her loving appeal. The next day I talked with other boys who were with me in school, and asked them to accompany me to the “mourner’s bench,” which they did.

At that time the class, though in the country, numbered one hundred and seventy souls. Three months later, I was appointed one of its stewards, and with this office came my first experience in raising money for the Church.

The next year I was elected assistant class-leader, and though young and inexperienced, I rendered the very best service I possibly could.

My educational advantages up to this time had been only such as the common schools afforded, with the addition of a close application to study at the home fireside, aided by the historic “pine torch” and “tallow candle.”

From the day of my conversion I could not escape the thought of preaching. The duty of being a Christian was never set before me more forcibly and clearly than was the duty of preaching; but I hesitated. My ignorance, and lack of fitness otherwise for such a high calling, appeared as insurmountable barriers. I could not understand why God should pass by others, better in heart and far more capable, and choose me. So the struggle went on. In the mean[20] time I began to read such books as I could secure. The Bible, “Smith’s Bible Dictionary,” and “Dick’s Works,” constituted my library. The last named was rather heavy for a lad only in his teens, but I rather enjoyed such studies. The first book I ever purchased was “Religious Emblems,” which proved exceedingly helpful to my young life.

When seventeen I preached my first sermon, or, perhaps I should say, made my first public effort. It was in an old log church on Little Flint Run, in Doddridge County. Brother Christopher Davis, a local preacher, was holding a meeting, and at the close of the morning services announced that I would preach at night. What a day that was to me! How I tried to think and pray! When I reached the church I found it full, with many standing in the aisle about the door. I felt so unprepared—so utterly helpless—that I immediately retired to a secret place, where I again besought the Lord for help. Returning, I started in with the preliminaries, but was badly scared. No man can describe his feelings under such circumstances. Many a preacher who scans these pages will appreciate my situation. I spent a good part of the first fifteen minutes mopping my face. I seemed to be in a sweat-box; but by the time I reached my sermon, or whatever it might be[21] called, the embarrassment was all gone. I still remember the text: “And I will bring you into the land concerning the which I did swear to give it to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob; and I will give it you for an heritage. I am the Lord.” It was immense; but the most of young preachers begin just that way. At this distance from the occasion, I do not recall anything I said, and am glad I cannot. However, there was one redeeming feature about the effort, and that was its brevity. In twenty minutes I had told all I knew, and perhaps more. I have never been able to understand why the people listened so patiently. They really seemed to be interested, but why, or in what, I have never known. I have not tried that text since, and I do not think I ever shall. It is too profound to even think of as the basis of a discourse to common people.

Dr. J. L. Hensley, when pastor of Middle Island Circuit, early in the sixties, had a somewhat singular experience in this same log church. While preaching one Sabbath morning in midsummer from the text, “The seed of the woman shall bruise the serpent’s head,” the people at his left suddenly became excited, and looking around quickly for the cause, he observed a snake, about two feet long, crawling in a crevice of the wall near the pulpit. Reaching[22] for his hickory cane, which he always carried, he dealt the wily creature a blow which brought it tumbling to the floor, remarking at the same time, “The seed of the woman shall bruise the serpent’s head.” Thus in the midst of his discourse he was furnished an illustration which made a profound impression upon his hearers, and aided greatly in bringing the truth home to their hearts.

The presiding elder, Rev. S. J. Graham, my spiritual father, by authority of a quarterly conference held at the Long Run appointment, October 23, 1869, gave me a permit to exercise in public for three months. Shortly after this I was prostrated with lung fever, which soon developed the most alarming aspects. Though the ailment was outgeneraled, the process of recovery was slow. In fact, one of my lungs was so impaired that consumption was feared. A noted physician, after carefully diagnosing my case, frankly told me that nothing could be done for my lung; but I did not believe a word he told me. I had decided that I would make preaching my life work, and believed that God would give me a chance to try it. It might be noted here that ten years later this same doctor was in his grave, while I was a better specimen of physical manhood than he ever was.

“Commit thy way unto the Lord; trust also in him, and he shall bring it to pass.” What will he bring to pass? The right thing, and in the right way. Such has been my observation and experience in all the years that have come and gone since the hand of affliction was so keenly felt.

December 25, 1869, I was granted quarterly conference license in a regular way, and attended the annual conference which met in Hartford City, Mason County, the following March. Much of the time while there I was not able to walk from my stopping-place to the church, though not a half dozen blocks distant. Some of the brethren feared that I would not live to get back home again. But I wanted a circuit. With that end in view I had gone to conference, and no amount of persuasion could turn me aside from the one great purpose that had taken complete possession of my soul. I was entering the work with a full knowledge of what it meant. I had heard the brethren talk of their privations and abundant labors, and, as well, of their victories and joy of heart. The report of the year then closing was most suggestive. The eighteen fields of the conference contained one hundred and sixty-seven preaching places, and had paid twenty-four men a little less than $140 each upon an average, not[24] counting outside gifts. West Columbia Circuit paid its two pastors, Revs. W. B. Hodge and I. M. Underwood, $400. The next highest was $339.19, and was paid the brace of pastors who served the Glenville charge—Revs. W. W. Knipple and Elias Barnard. The other sixteen pastorates ranged from $267.15 down to $35, the last named amount having been received by Rev. J. W. Boggess, on Hessville Mission. The Parkersburg District paid Elder Graham $227.87, while West Columbia District only reached $152.85 for its superintendent, Rev. J. W. Perry. To the support of each of the districts, however, the parent missionary board added $100.

When the Stationing Committee reported, my name was read out as the junior preacher for Philippi Circuit, with Rev. A. L. Moore, pastor in charge. This appointment was given, as more than one assured me in later years, simply to satisfy my mind. No one expected me to go to it. As the field already had a man, my failure to reach it would make no difference in any way.

Returning home I told father what had been done, and that I must have the necessary outfit for a circuit-rider; namely, a horse, a saddle and bridle, and a pair of saddle-bags. No matter what else a man had, or did not have, in those[25] days, these things were essential to efficiency among the mountains of West Virginia.

At once I began preparations for leaving home. Mother was thoughtful enough to make me a pair of leggings which buttoned up at the sides and reached above the knees. No one article made with hands was ever more valuable to a Virginia itinerant than leggings.

Philippi Circuit was seventy-five miles distant among the mountains, and would require, owing to the bad roads, two and a half days of hard travel on horseback to reach it. At the appointed time, April 11, 1870, early in the morning, I rode out of the old lane and up the hillside. All I had of earthly possessions was in my saddle-bags. One end contained my library, (Bible, Hymn-book, “Smith’s Bible Dictionary,” “Binney’s Theological Compend,” “Religious Emblems,” and one volume of “Watson’s Institutes,”) while in the other was stored my wardrobe, scant and plain. When far up on the side of the hill I looked back and saw mother standing on the porch. She had not ceased to watch me from the moment I started. Tears unbidden filled my eyes, and with these came an appreciation of our home that I had never experienced before. The home had been humble, to be sure, but it was Christian. We had a family altar, from which the sweet incense[26] of prayer ascended daily to God. I could truthfully say:

A mile distant I joined, by a prearranged plan, Rev. G. W. Weekley, my uncle, and Rev. Isaac Davis, both of whom were also en route to their distant fields of toil.

At the end of the second day we reached Glady Fork, on Lewis Circuit, where my uncle lived. How weary after so long a ride! At that time my health was still so precarious, and my strength so limited, that I could not walk a hundred yards up grade without resting. To dismount from my horse, open and close a gate, and then get back into the saddle, exhausted me. Remaining over a few days with my uncle, I tried to preach on Sunday morning, but found myself exhausted at the end of twenty-four minutes. In a few days, however, I was sufficiently rested from my long ride to journey on to my own circuit, where I soon found the preacher in charge, and plans were discussed for the year’s work. This was historic ground. It was an old United Brethren field, having been traveled by Statton, Stickley, Warner, Hensley, and others, in the late fifties and early sixties, when it included twenty or more preaching-places, spread over portions of several counties.

Philippi Circuit contained at this time the following appointments: Romines Mills, Gnatty Creek, Peck’s Run, Indian Fork, Mt. Hebron, Green Brier, and Zeb’s Creek. Later I added two more—one on Big Run, and the other on Brushy Fort, at the home of “Mother” Simons. Two of the preaching places lay “beyond” the Middle Fork River—a rolling, dashing stream, fresh from the mountains, and at times dangerous to cross. It was so clear that a silver piece the size of a quarter could be seen at a depth of several feet. The first time I attempted to ford it I put my life in jeopardy. Because the bottom could be seen distinctly, I imagined it was not deep, but after a few paces I was in mid-side to my horse, and going deeper every step. Perceiving the danger I was in, I tried to turn my horse about, and did so only after the greatest effort, owing to the almost irresistible current which was gradually bearing horse and rider downward. Going to a house near by I made some inquiry about the stream, and was told that if I had gone ten feet farther I should have been swept away by the swift[28] running waters. How grateful I was to God for the deliverance. During the following winter my life was endangered by floating ice at the same crossing-place. Brother Moore about the same time, perhaps a little later, seeing he could not ford the stream, decided to lead his horse across the ice at a point below the regular crossing, where there was but little current; but when twenty feet from the shore toward which he was headed, the ice gave way, and the faithful animal went under. Having hold of the bridle rein, however, he managed to keep his head above the water until a passage way was broken through to dry land.

One instinctively shudders as he recalls the dangers which at times thrust themselves suddenly across the pathway of the early preachers of the Virginia and Parkersburg conferences when the fields were so large and travel so excessive. Brother Moore informed me, as we looked over the charge, that I would have to take the “outsiders” for my support, as the circuit only paid $300, and he could not get along on less and pay rent. It struck me that he was about right, so I readily agreed to his proposition. Then what? Well, at each preaching place I found a “sinner” who agreed to serve as my steward, and these men did well, everything considered. For the year I received $97, including[29] an overcoat and several pairs of yarn socks.

At one of the appointments an unfortunate episode occurred over my salary. The steward one day stepped over the line, and got after some of the church-members for money. He very well knew they were abundantly able to help, but they flatly refused. This so upset him, so I was told, that he expressed his opinion of them in language far more vigorous than polite. It is a joy, however, to note in this connection that some of these stewards soon became Christians, and active helpers in the Church.

Out of the pittance I received, possibly all, or more than I was worth, I added to my little library, which could easily be put in one end of my saddle-bags when I left home, the following books: “Bible Not of Man,” “Conversation of Jesus,” “Jesus on the Holy Mount,” “Pilgrim’s Progress,” “Dying Thoughts,” “Bible Text Book,” “Jacobus on John,” “God’s Word Written,” “Paley’s Theology,” “Our Lord’s Parables,” “Webster’s Dictionary,” “Bible True,” “Rock of Our Salvation,” “Companion to the Bible,” “Dictionary of the Bible,” “Credo,” “Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul,” and “Hand of God in History.” This, of course, was not a lavish purchase of books, but it did[30] pretty well for one with a cash income of not more than $75.

We had some good revivals that year. Ninety-nine were received into church fellowship, while many more were converted. At Indian Fork we held meeting in a little log cabin, about twenty feet square, with a great fire-place in one side. It is surprising to see how many people can be crowded into so small a place when they are anxious to attend a revival. Night after night for weeks this little room was packed like a sardine case. But the outcome was glorious. Some of the best citizens of the community were reached and won to Christ.

After a few services were held, and it was seen how insufficient the little room was to accommodate the many who wanted to come, we put on foot the project of building a church, and immediately set about the work. The plan was so unique that the whole neighborhood became interested. Some felled trees; others “scored and hewed” the logs; those who had teams volunteered to haul them, while others still made shingles, or helped with the foundation; “for the people had a mind to work.” Before the meetings closed the house was up and ready for use—an edifice which served as a place of worship for many years.

The people all over the circuit were kind and forbearing, and greatly encouraged me by waiting on my ministry, and hearing what little I had to say. I visited all classes of persons, rich and poor, and had all kinds of experiences. In some homes I enjoyed the hospitality offered; in others it was not so highly enjoyed, but keenly appreciated. At one of the preaching points a certain brother insisted upon my going home with him for dinner after the morning service, which I consented to do. It was a rainy day. He lived in a cabin of one room on the hillside. On either side of the dwelling was a shed. Under one of these he kept his corn; under the other, where we entered the house, the hogs slept and the chickens roosted. His only piece of regular furniture was a chair. As to where and when he got it I did not inquire. Long poles reaching across the room and fastened to the walls, with a forked stick under them in the center, constituted a kind of double bedstead. When I entered the door I observed a large “feather tick” piled upon these poles. Finally, something moved under it, and then a boy of ten or twelve summers, almost suffocated, crawled out and made for the door. His purpose, no doubt, was to hide from the preacher when he saw him coming, but finding he could not get his breath, decided to retreat to another place of concealment[32] where there was more fresh air. I did not eat much dinner. I told “mine host” that I was not hungry, and, in fact, was not. They had only a broken skillet in which to bake bread, fry meat, and “make gravy.” As soon as possible I excused myself, and started for my next appointment. Indeed, I was glad I had another one that day.

Many other amusing incidents occurred during the year. These always find a place in the itinerant’s life, and it is well, perhaps, that they do, as they offset in a measure his somber experiences. I am frank to confess that it is easy for me to see the funny side of a happening, if it has one, and to enjoy a joke though it be on myself.

In the early days of the West Virginia Conference, what was known as the “plug hat” was much in evidence among preachers. Such “headwear” was a distinguishing mark, hence no circuit-rider with proper self-respect, or wishing to give tone to his calling, could afford to don anything else. Being young, and somewhat ambitious to hold up the ministerial standard, at least in appearance, I determined to secure one as soon as I could get a few dollars ahead. However, the way opened for the gratification of my wish sooner than I had expected. Brother Moses Simons had one he didn’t care[33] to wear, so I bantered him for a trade. It was in first-class condition, but entirely too large for me. Even after putting a roll of paper around under the lining, it came down nearly to my ears. What was I to do? I must have a high-topped hat, but was not able to purchase a new one. At last I decided to wear it, if my ears did occasionally protest against its close proximity to them. It distinguished me from common people for the next two years, and so answered well its purpose.

One day as I was riding up a little creek between two high hills I passed a group of urchins who evidently were unused to preachers. They watched me in utter silence till I had passed them a few yards, when one of them piped out, “Lord, what a hat.” No doubt they had an interesting story to relate to their parents when they returned to their humble cabin home.

Not long after this I met a gentleman, so-called, in the road, and bade him the time of day, as was my custom. He returned the salutation with, “How are you, hat?” and passed on without another word. To me this was exceedingly offensive, for I was sure there was something in and under the hat, and any such remark was an uncalled-for reflection upon my dignity and the high calling I represented. I did not know the man, and to the best of my[34] knowledge have never seen him since, but to this day, though removed from the event more than a third of a century, I harbor the thought that if I ever do run across him I shall demand some sort of reparation for the insult.

The annual conference met in Pennsboro, Bishop Weaver presiding. During the year I had improved much in health, owing to my horseback exercise and the great amount of singing I did, which doubtless had much to do with the development of lung muscle.

At conference I went before the committee on applicants with eight others, five of whom were referred back to their respective quarterly conferences for further preparation. For some reason the examination was unusually critical. One question propounded to each was, “Do you seek admission into the conference simply to vote for a presiding elder?” There was some doubt in my case on a doctrinal point, according to the report of the chairman, Rev. W. Slaughter, an erratic old brother. He said the boy was all right, except “a little foggy on depravity.” Possibly I was, for I didn’t think much of that portion of our creed. However, I see more in it, and of it, after all these years, than I did then. In the light of my observations and experiences with men, I am not inclined to deny the doctrine.

I was appointed by this conference to Lewis Circuit, an old, run down field, embracing parts of three counties. Rev. Isaac Davis was sent along as a helper “in the Lord.” We had grown up together in the same neighborhood, and were members of the same congregation. He was a young man of sterling moral qualities, and proved himself a loyal and valuable coworker.

After spending a few days with our parents and friends, we started, early in April, for the scene of toil to which we had been assigned for the year. From the day we left home we ceased not to pray that the Lord of the harvest would give us at least one hundred souls as trophies of his grace, and to that end we labored constantly.

We found the following regular appointments: Glady Fork, Hinkleville, Union Hill, Little Skin Creek, White Oak, Waterloo, Indian Camp, Walkersville, Braxton, and Centerville. Soon we added two more, namely, Bear Run and Laurel Run. The charge agreed to pay us $210, but fell a little short, reaching only $170. Of this I received $90, and Brother Davis the remaining $80. The assessment for missions was $25, and about $10 for other purposes, which we regarded as a pretty high tax for benevolences. Yet the entire amount was raised after a most vigorous and thorough canvass of[36] all the appointments. As I now remember, no one gave more than twenty-five cents.

Our protracted meetings lasted more than six months, and resulted in the reception of one hundred and one persons into church fellowship. While in the revival at Hinkleville, a great shout occurred one night over the conversion of some far-famed sinners, during which the floor of the church gave way and went down some two feet. Before dismissing the people, I announced that we would meet and make repairs the next day. At the appointed time it seemed that nearly all the men and boys in the country round about were on hand, ready to render what service they could in repairing the house of the Lord.

This was a revival of far-reaching influence. The country for miles around was thoroughly stirred. One of the leading men became interested one night, and decided upon a new life. As he approached the church the next day he heard us singing what was then a very popular song—“Will the Angels Come?” The words and melody fairly charmed him, and kindled new hope in a life that had been given over to sin. As he opened the church door, the key of faith opened his heart’s door to the Savior, and he rushed down the aisle to tell us of his wonderful experience. It was all victory that morning.[37] The conversion of such a man profoundly affected the people, and led to many more decisions for Christ.

During this meeting my colleague arose one evening to preach. As he had the test, with book, chapter, and verse all by heart, he did not open his Bible, but began by saying, “You will find my text in Revelation, third chapter, and twentieth verse.” Just then an apple fell through a hole in his coat-pocket on to the floor. As he stooped to pick it up, another fell out. Returning them to his pocket, he again started—“Revelation, third chapter and twentieth verse,” when suddenly the two restless apples dropped out again. After picking them up, he started in the third time, “You will find my text in,”—but all was gone. He couldn’t even think of Revelation. The audience was at the point of roaring, so in the midst of his confusion he turned to me and said, “Brother Weekley, what is my text? I don’t know what nor where it is.” I answered, “Behold, I stand at the door and knock.” “Yes, yes,” he said, “I remember it now,” and proceeded with his discourse, but did not recover that evening from the knock-out blow he had received.

Preaching through such a long revival campaign was no easy thing, when I had only a few sermons in stock, and these were all “home[38] made.” I think the material in them was all right, but the mechanical construction was not according to any particular rule. I endeavored to give my hearers plenty to eat, but I did not understand how to serve the food in courses. It was like putting a lot of hominy, and pork, and cabbage, and beans into the same dish, and saying to the people, “Here it is; help yourselves.” But as a few sermons could not be made to last indefinitely, I was compelled to apply myself to study, no little of which was done on horseback. Every itinerant in West Virginia at that time had to do the same thing. While this method of study was not the most desirable, it nevertheless had its redeeming features. Ofttimes, after riding a dozen or fifteen miles over rough, hilly roads, I would alight, hitch my horse, and while the weary animal was resting, mount a log near by and practice to my heart’s content the sermon I was preparing for my next appointment. Again and again did I make the welkin ring as I preached to an audience of great trees about me. Does this appear amusing to the reader? Do you doubt that such experiences ever occurred? If so, ask some of the earlier preachers of the conference who are yet living if they ever did such a thing while circuit-riding among the mountains.

Did we ever feel lonesome as we traversed the forests or climbed the hills? Not for a moment. It was an inspiring place to be. The birds sing so sweetly there. The gurgling, murmuring streamlets are ever musical as they steal their way along through gulches, over their rocky beds. The scenery is sublime. Nature’s book stands wide open, and abounds with richest lessons and illustrations. No wonder Glossbrenner and Markwood, Warner and Howe, with a host of others, could preach! The very mountains amid which they were born and reared conspired to make them lofty characters, and majestic in their pulpit efforts. While Union Biblical Seminary, and our colleges generally, are grand, helpful schools, let it not be forgotten that “Brush College” is not without its advantages, and should be given due credit for the inspiration and rugged manliness it imparts to its students.

My home this year was with Brother James Hull, on the headwaters of French Creek, fully forty miles from the nearest railroad station. Mother Hull was one of God’s noble women. She professed sanctification, and lived it every day. I can never forget her helpfulness to me, a mere child in years and service. I must see her in heaven.

If I returned home after each Sabbath’s work, it required one hundred and fifty miles travel to make one round of the circuit. My associate also had a good home on another part of the charge; but unfortunately for him, and for some others as well, his zeal led him into trouble. Brother Mike Boyles, with whom he stayed, was a good, true man, and was ever delighted to have a preacher with him. One Sunday he went to see a friend a few miles distant, and innocently carried home on his horse a large, nice, well-matured pumpkin. His purpose, no doubt, was to prepare a special dish for his guest; but his preacher was not pleased with such an infraction of the Sabbath law. A short while after this he discoursed in the neighborhood church on the text, “I stand in doubt of you.” Among other things, he said he stood in doubt of a church-member who would go visiting on Sunday and carry “pumpkins” home with him. Brother Boyles very naturally made the application a personal one, and ever afterward refused to be reconciled.

During the year I married two couples. One of the men was a horse buyer, and was considered “away up” financially. Of course I expected no insignificant sum for my services; it ought to have been ten dollars or more; but let the reader imagine, if he can, my disappointment,[41] if not disgust, when he handed me forty cents in “shinplasters.” By “shinplasters” I mean a certain kind of currency which circulated during our civil strife in the early sixties, in the form of five, ten, twenty-five and fifty cent certificates.

Speaking of this wedding recalls the fact that it was on this circuit, while visiting my uncle the year before, that I married my first couple. I remember, too, that I approached the occasion with great trepidation. It was an awful task. But the eventful hour finally came. The parsonage, so called, where the nuptials were to be celebrated, was a log cabin of one room. The kitchen, which stood several feet from the main building, was the only place offered in which to arrange the toilet. At last I stood before the young couple and began the ceremony, which I had committed to memory. Yes, I had it sure, as I thought. I had gone over it twenty times or more. In practising for the occasion I had joined trees and fence stakes, and I know not what all, together; but at the very moment when I needed it, and couldn’t get along without it, the whole thing suddenly left me. There I was. After an extended pause and a most harrowing silence I rallied, and began by saying, “We are gathered together.” Just then my voice failed me; it seemed impossible to[42] make a noise, even. I fairly gasped for breath, for that was the one thing I seemed to need most. At last the effort was renewed. How I got through I never knew. I seemed to be in a mysterious realm, where the unknowable becomes more incomprehensible, and when all the past and future seem to unite in the present. Finally I wound up what seemed to be long-drawn out affair, and pronounced the innocent couple man and wife. I am glad they always considered themselves married. I have but little recollection of what I did or said during the ordeal. In fact, I do not care to know, since I am so far away from the occasion. Yes, that was my first wedding.

The year was not without its material enterprises, for we completed the churches at Glady Fork and Waterloo, repaired one at Indian Camp, and started a new one at Laurel Run. Some of these stand yet as moral and religious centers, and, at times, through the intervening years, have been the scenes of great spiritual awakenings.

Conference was held at New Haven, in Mason County, with Bishop D. Edwards in the chair. While our report was thought to be fairly good, I asked for a change, believing that I could do better work on another field. The[43] favor was granted, and Hessville Mission assigned me as my third charge.

At the close of this year there were thirty-one ministers employed in the conference, whose aggregate salary was $4,551.77, or an average of $147 each. The three presiding elders received, all told, $843.83. These figures indicate something of the sacrifices made by the men who gave themselves to the early work of building up the Church in the Virginias. Greater heroism of the apostolic type was never displayed by any of the sons of Otterbein, nor can any part of the country show greater achievements for the work done.

Hessville Mission embraced portions of Harrison and Marion counties, and was made up of the following preaching places: Quaker Fork, Glade Fork, Indian Run, Big Run, Little Bingamon, Ballard School-house, Salt Lick, Plumb Run, and Paw-paw. In all this territory we did not own a single church edifice. By fall I had added Dent’s Run, Bee Gum, and Glover’s Gap, making twelve appointments in all. At the last named place I held a revival in a union church. The meeting was good, and telling most favorably upon some of the best families of the town, when an unknown miscreant at an early morning hour applied the torch and reduced the building to ashes. All I lost in the conflagration was my Bible and hymn-book. Moving into a schoolhouse near by, the meeting was continued, and a class organized. By the middle of the winter there had been sixty-five accessions, but from that on till spring I had to lay by on account of measles.

At Little Bingamon we had a great meeting. The entire community was deeply stirred.[45] “Aunt Susan” Martin was my main helper and standby. While devout in life, and strong in faith, she had a blunt, honest way of saying things which often amused the people. At this meeting two of her children made a start. One was a son of some fifteen winters. He literally wore himself out by his night and day pleadings at the altar, and became so hoarse that he could scarcely talk. His mother was greatly agitated over his condition, and grew exceedingly anxious to see the intense struggle terminated. One evening she bowed at the altar with him that she might, through instruction, show him a better way. She did not believe that bodily exercise could be made to avail anything in seeking salvation. Finally, for a moment, she lost her patience, and said, “Now, if you don’t quit this kind of praying you will kill yourself. Stop it, I tell you, or I’ll box your ears good. The Lord isn’t deaf, that you should ‘holler’ so loud.” Then turning to her husband who, at the time, was a professed moralist, though faithful in attending and supporting the church services, she said: “George, you ought to be ashamed of yourself. Not a word have you for this poor child. Now come and talk to him. To stand and look on is no way to do.”

The dear sister was right, not only in thinking that the father ought to help the son, but in[46] protesting against unnecessary physical demonstrations in seeking religion. It is not the loud praying or constant pleading that saves men, but faith in the world’s Redeemer. Rev. H. R. Hess, one of the leading ministers in the West Virginia Conference, was soundly converted and received into the church during this meeting.

What a good home I had while on this charge! Brother Daniel Mason, a father in Israel, whose life was as pure as a sunbeam, took me to his home and heart, and treated me very much as the Shunammite did Elisha. He built me a little room on his porch, and put therein a bed, bookcase, table, and candlestick. The worth of such a place to a young minister is next to incalculable. Twice a day he read the Word and prayed. He was on good terms with his Lord, and talked to him with the greatest assurance. Some of the sweetest memories of my earlier ministry cluster about this Christian home. The fruition of the upper and better life he now enjoys as the reward of his faith, service, and devotion while here below.

The circuit agreed to pay me $100, and kept its contract. The first quarter I received $14.81, the second, $18.35; the third, $17.75; and the last $49.05. The conference added $50, which pushed my support up to $150. With this salary,[47] much above the average for a single man, I could afford to pay $21.50 for a new suit of clothes, and $4 for a new “two-story” silk hat.

On my way to conference a few days were spent with friends in the home neighborhood. Rev. E. Lorenz, father of the music writer, was living and preaching in Parkersburg at this time. He had organized a German congregation, and held services in the lecture-room of our English church. The Committee on Entertainment sent me to stay with him during the conference session which was held in the city. Thoughts of that superlatively Christian home linger with me to this day. I shall never forget how parents and children bowed together in prayer, morning and evening, and how each took part in the devotions. Too much emphasis cannot be placed upon the importance of prayer in the home. Nothing else, on the human side, so anchors the family and builds up character. The fact that the fire has died out on so many domestic altars is, itself, proof that family religion does not receive the attention it once did.

At this conference I was permitted to pass the second and third years’ course of reading, which put me in the class to be ordained. I can never blot from memory the prayer offered by the lamented Doctor Warner at the ordination service. He seemed to pour out his very[48] soul in petition to God for the young men being set apart to the work of the ministry. I wept like a child while he thus prayed, and anew pledged to Jesus and the Church the service of my life.

Grafton at this time was constituted a mission station, and made my field for the coming year. The town then (1873) had a population of about three thousand souls, and was located mainly on a steep hillside. In fact, it stands about the same way yet, though containing several thousand more people. We had no church-house, and no organization, though there were a few members scattered through the place. Seventy-five dollars were appropriated by the conference toward my support. A preaching-place called “Old Sandy,” some twelve miles distant, was also given me. Here we had a gracious revival. I later took up two more points—Maple Run and Glade Run—and organized a class at each. At the close of the year these country classes were formed into a separate charge, and became self-supporting.

W. M. WEEKLEY, Thirty Years of Age

Presiding Elder

At Grafton the work progressed slowly, and with some difficulty for a time. A friend gave us, free of charge, the use of a church-house which, by some means, had fallen into his hands. The first thing was to organize a Sabbath school, which started off well. When certain[49] church partisans saw the outlook, they offered to take part in the school, and adroitly got possession of the offices. When I discovered the real situation, I determined to bring the matter of control to an issue, and did. I deliberately stated that I had been sent there to organize a United Brethren Church and Sabbath school, and proposed to carry out my instructions. I was pleased to have teachers and other helpers from sister denominations join in the work, I added, but the school would be reported to my conference. The result is easily imagined. Our friends, so-called, suddenly dropped out, and from that day to this the identity of the school has never been questioned.

The seventy-five dollars appropriated by the conference was about all I received, and twenty-five dollars of that went in a lump to the centennial fund. If a kind family had not taken me in, free of cost, I could not have remained the year through. For the second year the support given was about the same. The third year there were two of us to support, hence a special effort had to be made to increase the pay. Three hundred and twelve dollars was the amount actually received, eighty dollars of which was paid on rent; but we lived well; no such thing as want seemed to be within a thousand leagues of our humble home. We were thankful for cheap[50] furniture and home-made carpet. Yea, more, we were happy. God’s ravens carried us our daily portion.

In the early spring of 1875, we began the erection of a chapel which cost, lot and all, $2,800. But a part of it had to be built the second time. Just as the frame was up and ready for roof and siding, a storm passing that way piled it in a promiscuous heap. This occurred on the seventeenth of July. Immediately, however, the work of reconstruction was undertaken, and the edifice was completed in early fall, and dedicated by Doctor Warner. Such experiences try a young man’s nerve and purpose, but invariably prove a blessing when the difficulties accompanying them are overcome.

That year I took up an appointment at the Poe School-house, two miles out of town, and organized a class. In those days the preacher was expected to look around for new openings, no matter where he was or how large his field; there is no other way to expand. My criticism of many of our young preachers to-day is that they do not try to enlarge their work. They seem never to look beyond the nest into which the conference settles them. They will live on half salary, and whine about it all year, rather than get out and look up additional territory.[51] Under fair conditions, the young man who is devout and active can secure a good living on any field. Faith and purpose and push will win every time. The year closed with fifty-three members, and ninety-five in the Sunday school.

The conference again convened in Parkersburg, with David Edwards this time as bishop—the last session he ever presided over.

At this period the battle in the Church over the secrecy question was waxing warm. West Virginia had lined up on the liberal side. The bishop, being pronouncedly “anti” in his views, determined to enforce the rules of the Church in the matter of admitting applicants into the conference. A brother who appeared for license was known to belong to some fraternal order, so the good bishop held him up. This brought on a crisis. All was excitement. Some things, it was clear, would have to be settled then and there, and they were. Doctor Warner arose, in the midst of the flurry, and demanded that the young brother be sent to the appropriate committee, which he said was thoroughly competent to deal with the question. The bishop was on his feet also with the fire of determination fairly flashing in his eyes. However, when he fully realized that, with an exception or two, the entire body was against him,[52] he gracefully yielded, thus happily bringing the unfortunate conflict to a close. By morning, matters had again assumed a normal condition, and the bishop kindly requested that all reference to the controversy be expunged from the records.

Notwithstanding Bishop Edwards’ somewhat radical position on the secrecy question, he was greatly loved by all our brethren, and by none was his death more sincerely mourned. On Sunday he preached on Elijah’s translation; a few days thereafter he was himself translated.

From Grafton I was sent to New Haven circuit, in Mason County, one hundred and sixty miles west. To get there I was compelled to borrow twenty-five dollars. Dr. J. L. Hensley kindly entertained us until a house could be found; for as yet there was not a parsonage in the conference. This was considered one of the best fields we had. The first year it paid me four hundred and sixteen dollars, and the next, four hundred and twenty-seven dollars, with a few presents in the shape of vegetables, groceries, and the like. Of course, I paid rent out of this—thirty-six dollars one year, and fifty the other. I had only four appointments—New Haven, Bachtel, Union, and Vernon, and these were close together. During the two years, one[53] hundred and thirty were received into the Church.

The next conference was held at Bachtel, which gave me my first experience in caring for such a body. Bishop Weaver presided and preached the word mightily on Sunday. He had been popular even since his first visit to that section, in 1870. By request of Hon. George W. Murdock, a wealthy business man in Hartford City, three miles west, he went down there and preached in our church on Sunday evening. Mr. Murdock was an ardent admirer of the bishop. Six years before he had entertained him in his home, and was charmed by him as a preacher and conversationalist. After spending the first hour with him, he slipped into the kitchen and said: “Wife, he is the most wonderful man I ever met. Do come in and hear him talk.” The old gentleman never forgot the bishop’s sermon on Sunday. For weeks afterward he would talk about it in his store, and elsewhere, sometimes in tears, nearly always ending with the observation, “He is a wonderful man.” It might not be out of place to note here that the good bishop more than once shared the benefactions of his wealthy friend.

During my second year on this charge, a peculiar and most trying experience came to our home. A great revival was going on at[54] the Union appointment. The altar was nightly crowded with earnest seekers, some of whom belonged to the best families in the community. Early one morning a young man came hurriedly to the place where I was stopping, and calling me out, said, “Mr. Weekley, I have been sent to tell you that your babe is dead.” Hastening home I found the faithful mother watching at the side of the withered flower, and anxiously awaiting my coming. How loving the ministry of friends had been; nor did their tender interest abate a whit until the little lifeless form was put away to sleep in the cemetery on the hillside, in the family lot of Dr. Hensley.

The reader may be anxious to know what I did under the circumstances. There was but one thing to do, that was to seek the guiding hand of duty. Our little one was gone. Just as the thoughtful florist takes his tender plants into their winter quarters before the frost appears, or the chilling winds sweep the plains, so a wise, loving, merciful Father had plucked up the little vine which had rooted itself so thoroughly and deeply in our hearts, and transplanted it in his own heavenly garden. Yes, Charley was safe; so I returned to my meeting with a tender spirit, and the work continued with great power.

More than one preacher who reads this incident will recall the time, or times, when he, too, passed under the cloud, and walked amid the shadows. Again and again I have been made to feel that some people do not sympathize with the minister and his wife, as they do with others, when the death angel tarries and lays his withering hand upon a young life. Somehow they seem to think that the cup, when administered to the preacher’s family, is not so bitter—that the thorn does not pierce so deeply. But I know better, and so do a thousand others. It is said of Dr. Daniel Curry, a great man in Methodism in his day, that he was so grieved over the death of his little boy that after returning home from the cemetery he went into the back yard, and observing his little tracks in the sand, got down on his hands and knees and kissed them. Words cannot express my sympathy for the faithful pastor and his family, and my admiration of that faith, devotion, and heroism which in so many instances are necessary to keep them in the work.

Mason County was one of the first fields occupied by the ministers who crossed the Alleghanies westward. Among these were G. W. Statton, J. Bachtel, and Moses Michael. However, prior to this, preaching had been kept up on the Virginia side by pastors of the Scioto[56] Conference. The main one was Jonas Frownfelter, whose name deserves a place alongside the heroes enumerated in the eleventh chapter of Hebrews. On one occasion, when the Ohio River was out of its banks, and too dangerous for the ferryman to venture across, he plunged in a little below the town of Syracuse, swam his horse across, and came out at Hartford City, a half mile below, singing like a conqueror:

All honor to those who put their sweat, and tears, and blood into the foundations of the conference, thus enabling others to build safely and successfully.

Early in the fifties a paper known as the Virginia Telescope, was started in West Columbia, ostensibly in the interest of the whole Church, but later developments proved that the object was to organize a Southern United Brethren Church, making the slavery question the basis of the separation. When the presiding elder, G. W. Statton, became aware of its purpose, he threw his official influence against its continuance, and succeeded, by the aid of others, in eliminating it as a disturbing factor.

The reader will pardon me for taking up these early historical threads, woven long before[57] my day as an itinerant, but I have done so with the view to preserving in permanent form interesting facts not generally known, and nowhere written into the history of the Church.

In March of 1878, the conference assembled in Grafton, with Bishop J. J. Glossbrenner as its presiding officer. At this session the brethren greatly surprised me by electing me one of the presiding elders. No thought of such a thing had ever entered my mind. I could not see the propriety of putting a young man, not yet twenty-seven, over men of age, ability, and experience, hence it was with no little diffidence that I accepted the West Columbia District, in the bounds of which I had already worked two years. The district contained only eleven charges, but these were widely scattered, embracing all or parts of Cabell, Mason, Jackson, Wood, Putnam, Kanawha, and Roane counties, and were as follows: Milton, Point Pleasant, Cross Creek, Thirteen, Jackson, Red House, Fair Plain, Sandy, New Haven, Wood, and Hartford City. Later, Walton was added.

The salary assessed the district was $425; out of this I had to pay traveling expenses, provide a house to live in, and pay a hired girl. Under such conditions I could afford a house of only[59] three rooms. I never believed in a preacher, or any one else, for that matter, living beyond his income. Debt is an awful devil for the itinerant to contend with, and should be avoided at all hazard. In all the years of my ministry I have never left a pastoral charge or district owing any one thereon a nickel. If a man is fit to be a preacher, debt will distract his mind and put a thorn in his pillow; it cannot be otherwise with a sensitive nature. God save our young men from the habit and curse of debt-making.

No little of my travel, while on the district, was by boat on the Ohio and Big Kanawha rivers. Only one of my fields was touched by a railroad, and that was sixty miles from where I lived. My custom was to go by boat to the point nearest the place of the quarterly meeting, and then walk the remaining distance, whether it be five or twenty-five miles. Often I might have secured conveyance for the asking, but I felt that it was humiliating to be always annoying somebody for favors, nor have I changed an iota in all these years in this regard. If a preacher wants to make himself a nuisance among his parishioners, he can easily do so by constantly making demands upon them which look to his own comfort and that of his family. Many a time I walked from twelve to fifteen miles in a day, held quarterly conference, and preached[60] twice. Occasionally the distance would stretch out to twenty miles. I did not mind the labor so much as I did the suffering from sore feet; walking in the hot sun or over frozen roads, hour after hour, often caused them to blister and bleed. In these experiences I was not alone; many others, some of whom yet live, suffered the same or kindred hardships.

In February of 1879 I was called home to my father’s. After a day or two I tried to return, but upon reaching Parkersburg found the river so frozen and clogged with ice that the boats could not run. It was Thursday afternoon. My quarterly was at Oakhill, fully forty miles distant, the next Saturday at two o’clock. The roads were badly frozen and almost impassable. When I saw the situation I determined to make the trip overland as best I could; if I could not find assistance along the way, I would walk it. Leaving the city at four o’clock, I traveled on till darkness overtook me, when I turned aside and knocked at the door of a humble cabin and asked for lodging, which was cheerfully granted; but I had made only a few miles. In addition to the rough roads, I was burdened with a good-sized grip and overcoat. The next morning at daydawn I resumed my journey. Once during the day I rode two or three miles in somebody’s sled, but beyond this I got no[61] help. Long after the dinner hour I secured a cold lunch, which the reader may be assured was relished by a tired, hungry man. An hour before sundown I reached Sandyville, where a warm supper was enjoyed at a little hotel. Still I was fifteen miles away from the point for which I was aiming, and felt that I could go no farther without help; but a kind friend generously agreed to loan me his horse to ride as far as Ripley, seat of justice for Jackson County, from which place the mail-carrier was to lead it back the next day; but the poor animal was shoeless, and went crippling along at a snail’s gait over the rough ground.

Two miles distant I had to cross Sandy Creek, and found it partly frozen over. It was too dark to discern the danger of fording the stream. After repeated efforts, I succeeded in getting the horse on to the ice, but as quick as a flash it fell broadside, pitching me—I never knew where nor just how far; but the horse beat me up, turned its head homeward, and disappeared in the darkness. What did I do? Well, what almost anybody else would have done under like circumstances. I took the back track and returned to the village where the animal belonged, and found that it had returned in good order. The next morning my feet were so sore that I could not wear my shoes, but was[62] fortunate in securing a pair of arctics in which to travel the rest of the journey. By noon Ripley was reached, where conveyance was secured which enabled me to make the place of meeting and call the conference on schedule time.

Some one may suggest that I was foolish for making such an effort to reach the quarterly when nothing apparently unusual was at stake; maybe I was, but such was my way of doing. I always believed that a preacher ought to fill his engagements promptly unless providentially hindered, and then he ought to be fair enough not to blame providence with too much; but few days are ever too cold and stormy, or nights too dark to keep a man from his appointments if he is anxious to preach the word and minister to his people. I here record the fact, with feelings of satisfaction and pride, that in more than a third of a century I have not disappointed a dozen congregations. As I see it, a preacher succeeds in his work just as business or other professional men succeed in their respective callings. He must bestir himself, and permit no obstacle to get between him and duty; any other policy means failure. At it everywhere and all the time, and keeping everybody else at work, are the only ways to win for the Church and maintain a good conscience before God.

Conference met in Hartford City. The chart showed that a good year had been enjoyed, 1,354 new members being reported. Of this number, 535 were credited to West Columbia District.

The second year on the district was like unto the first—full of toil, responsibility, and peril betimes.

As an indication of what was required of a presiding elder in order to aid his pastors and keep the work of the district well in hand, I relate the following experience: A rainy winter morning found me on Milton Circuit—the last charge in the southwestern part of the conference. I had an appointment that evening at Cross Creek, thirty-five miles east. The mud in some places was knee deep to my horse, but on and on I traveled, over hills and along meandering streams, sometimes walking myself up and down steep places in order to relieve my weary horse. At last, when it was nearly dark, I halted on the bank of the great Kanawha, opposite the town of Buffalo. But how was I to get across the threatening stream? The ice lay piled in great heaps on either shore; the man who tended the ferry hesitated to come after me when I called to him, but he was given to understand that in some way I must be gotten over. Finally he agreed to make the attempt, and after hard rowing, landed me on the opposite[64] side but below the regular coming-out place, and where the ice was badly gorged. Then the real difficulty of the venture was apparent. We had to get the horse up over the great blocks of ice that lay at the water’s edge, and it was to two of us an exciting time; no one can describe it on paper. Holding on to the animal, pulling my best at the bridle-rein all the while, the ferryman pushing with all his might, we finally scrambled over the ice and through narrow passageways until a place of safety was reached. How thankful I felt when it was all over, and how I loved that horse! Doctor Warner used to tell how his faithful horse once swam an angry stream, and that after the shore had been reached in safety he dismounted, put his arms around the neck of his deliverer, kissed his lips, and wept for joy. Itinerating in the early days of the West Virginia Conference meant all this, and sometimes much more.

When I got to the church, two miles farther on, I found the congregation waiting and ready to join in the service. It might be stated, in this connection, that in those days the coming of the “elder” was an extraordinary event, and seldom failed to bring out the entire community.

The following evening I had an engagement to preach at Mount Moriah, still farther east some thirty miles. It rained the day through.[65] A part of the journey I followed a single trail, popularly known as a “hog path.” Such a route relieved me somewhat from the mud, but, being in the woods, I could not carry an umbrella over me, hence had to take the rain as it came; but I must not disappoint the people. They had my word for it that I would be there, and the promise must be sacredly kept. It was a little after dark when I caught a glimpse of the lights in the old log church; but, hold! I suddenly found myself up against another serious difficulty—Parchment Creek was out of its banks. There seemed no show for getting over except to plunge in and swim my horse. I hesitated; already wet and cold, I was loath to make the attempt. I would have to carry my saddle-bags on my shoulder if I saved my Bible, hymn-book, and sermons; the water would come to my waist, to say the least. Then another trouble appeared; it was too dark to see the road or landing-place on the opposite side, and I might drift below it with the current and not get out at all. While thus cogitating, I heard some boys talking on the other side as they were going to church. Calling to them, I said, “Boys, can’t you in some way help me over the creek?” “Who are you?” was the reply. “I’m the preacher,” I answered, “and want to get to the church.” After a short consultation among[66] themselves, one of them shouted back, “All right; we’ll bring the skiff after you.” Soon I heard them push out from the shore, and in a few moments they landed near me. “Now,” said one, “you get in here with Bill, and I’ll swim your hoss over,” and in less time than it takes to pen the happenings, he was in the saddle on his knees and starting for the water. Did he get over safely? Yes, indeed; he entered the stream above the usual place of going in, hence the horse swam, not against the current, but at an angle with it. In every way possible I thanked those boys for their kindness to me, for they had certainly kept me from putting my life in peril. If they are still living and should happen to glance over these pages, they will readily recall the event.

The church was nearly full of people, and I certainly enjoyed preaching to them. The great Father had been graciously with me to guide my ways and to protect my life. How glad I will be if, on the morning of the eternal to-morrow, I shall find that the service that evening helped some soul heavenward!

Rev. W. W. Rymer, over thirty years ago, nearly lost his life in this same region on account of high waters. His horse either could not or would not swim, but plunged furiously when beyond his depth. The heroic itinerant[67] stayed in the saddle as long as he could, but was finally dislodged and went down. In the midst of it all he retained his presence of mind and aimed for the nearest shore, which was not far away. Being unable to swim, he crawled on the bottom a part of the way, and at last found himself where he could stand with his head above the water. The horse, fortunately, came out on the same side. Commenting on the incident, Mr. Rymer says: “After my deliverance, it was clear to me that I had been near death’s door, and also near heaven. Two thoughts followed; one was: ‘If I had not escaped, I would now be in glory,’ and I confess I felt good over the reflection. The other was: ‘No, it is better that I got out, for if I had drowned, my parents would have had great sorrow.’ I took it all to mean that my work was not yet done, and soon experienced great peace of mind. Almost thirty-one years have come and gone since then, but the ruling purpose of my heart all the while has been to preach Jesus. Before thirty-one years more have rolled around, I shall have gone through death’s river—yes, through to the other side, where I shall see my Lord face to face.”

Let the reader be assured that there is a profound satisfaction in looking back to those times of trial and suffering, of battle and victory, when the ways of Providence were so plain, and[68] when an unspeakable jay crowned the years of toil and service.

After another ride of twelve miles from Mount Moriah, I reached my home in Cottageville, near the Ohio River. How inexpressibly delightful to be at home again with wife and little ones! What a heavenly place home is when love and sunshine await the itinerant’s coming! While he ministers to them, they also minister tenderly to him; such mutual love and helpfulness is to be found nowhere else.

My support for the year consisted of $427.83 in salary and $22.41 in presents. Fifty dollars of this went for house rent, and fully as much more for traveling expenses. Beside these outlays, we kept hired help in the home all the time.