Title: The Southern Literary Messenger, Vol. II., No. 1, December, 1835

Author: Various

Release date: March 9, 2021 [eBook #64767]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Ron Swanson

| Au gré de nos desirs bien plus qu'au gré des vents. |

| Crebillon's Electre. |

| As we will, and not as the winds will. |

OCTOBER: by Eliza

MOTHER AND CHILD: by Imogene

LINES written on one of the blank leaves of a book sent to a friend in England.: by Imogene

THE BROKEN HEART: by Eliza

HALLEY'S COMET—1760: by Miss E. Draper

EXTRACTS FROM MY MEXICAN JOURNAL

SCENES FROM AN UNPUBLISHED DRAMA: by Edgar A. Poe

AN ADDRESS ON EDUCATION, as connected with the permanence of our republican institutions: by Lucian Minor, Esq.

MACEDOINE: by the author of Other Things

LIONEL GRANBY, Chapter VI: by Theta

THE DREAM: by Sylvester

MS. FOUND IN A BOTTLE: by Edgar A. Poe

A SKETCH: by Alex. Lacey Beard, M.D.

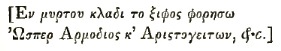

GREEK SONG: by P.

SONNET: by * * *

SPECIMENS OF LOVELETTERS in the Reign of Edward IV: by John Fenn, Esq., M.A. and F. R. S.

MARCELIA: by * * *

TO MIRA: by L. A. Wilmer

STANZAS: by Leila

CRITICAL NOTICES

THE HEROINE:

by Eaton Stannard Barrett, Esq.

HAWKS OF

HAWK-HOLLOW: by the author of Calavar and the Infidel

PEERAGE AND PEASANTRY:

edited by Lady Dacre

EDINBURGH REVIEW,

No. CXXIV, for July 1835

NUTS TO CRACK:

by the author of Facetiæ Cantabrigienses, etc.

ROBINSON'S PRACTICE:

by Conway Robinson

MEMOIR OF DR.

RICE: by William Maxwell

LIFE OF DR.

CALDWELL: by Walker Anderson, A.M.

WASHINGTONII VITA:

by Francis Glass, A.M.

NORMAN LESLIE

THE LINWOODS:

by the author of Hope Leslie, Redwood, etc.

WESTMINSTER REVIEW,

No. XLV, for July 1835

LONDON QUARTERLY REVIEW,

No. CVII, for July 1835

NORTH AMERICAN REVIEW,

No. LXXXIX, for October 1835

CRAYON MISCELLANY:

by the author of the Sketch Book

GODWIN'S NECROMANCY:

by William Godwin

REV. D. L. CARROLL'S

ADDRESS

EULOGIES ON MARSHALL

MINOR'S ADDRESS

LEGENDS OF A LOG

CABIN: by a western man

TRAITS OF AMERICAN

LIFE: by Mrs. Sarah J. Hale

WESTERN SKETCHES:

by James Hall

AMERICAN ALMANAC

CLINTON BRADSHAW

ENGLISH ANNUALS

|

The gentleman, referred to in the ninth number of the Messenger, as filling its editorial chair, retired thence with the eleventh number; and the intellectual department of the paper is now under the conduct of the Proprietor, assisted by a gentleman of distinguished literary talents. Thus seconded, he is sanguine in the hope of rendering the second volume which the present number commences, at least as deserving of support as the former was: nay, if he reads aright the tokens which are given him of the future, it teems with even richer banquets for his readers, than they have hitherto enjoyed at his board.

Some of the contributors, whose effusions have received the largest share of praise from critics, and (what is better still) have been read with most pleasure by that larger, unsophisticated class, whom Sterne loved for reading, and being pleased "they knew not why, and care not wherefore"—may be expected to continue their favors. Among these, we hope to be pardoned for singling out the name of Mr. EDGAR A. POE; not with design to make any invidious distinction, but because such a mention of him finds numberless precedents in the journals on every side, which have rung the praises of his uniquely original vein of imagination, and of humorous, delicate satire. We wish that decorum did not forbid our specifying other names also, which would afford ample guarantee for the fulfilment of larger promises than ours: but it may not be; and of our other contributors, all we can say is—"by their fruits ye shall know them."

It is a part of our present plan, to insert all original communications as editorial; that is, simply to omit the words "For the Southern Literary Messenger" at the head of such articles:—unless the contributor shall especially desire to have that caption prefixed, or there be something which requires it in the nature of the article itself. Selected articles, of course, will bear some appropriate token of their origin.

With this brief salutation to patrons and readers, we gird up ourselves for entering upon the work of another year, with zeal and energy increased, by the recollection of kindness, and by the hopes of still greater success.

About this period commenced those differences between France and the Algerine Government, which led to the overthrow of the latter, and the establishment of the French in Northern Africa; the circumstances which occasioned the dispute were however of much older date.

Between 1793 and 1798 the French Government on several occasions obtained from the Dey and merchants of Algiers, large quantities of grain on credit, for the subsistence of its armies in Italy, and the supply of the Southern Department where a great scarcity then prevailed. The creditors endeavored to have their claims on this account satisfied by the Directory, but that incapable and rapacious Government had neither the principle to admit, nor the ability to discharge such demands; every species of chicanery was in consequence employed by it in evading them, until the rupture with Turkey produced by the expedition to Egypt placing the Barbary States either really or apparently at war with the French Republic, a pretext was thus afforded for deferring their settlement indefinitely. Under the Consular regime however, a treaty of peace was concluded with Algiers on the 17th of December 1801, by the thirteenth article of which, the Government of each State engaged to cause payment to be made of all debts due by itself or its subjects to the Government or subjects of the other; the former political and commercial relations between the two countries were re-established, and the Dey restored to France the territories and privileges called the African Concessions, which had been seized by him on the breaking out of the war. This treaty was ratified by the Dey on the 5th of April 1802, and after examination of the claims on both sides, the French Government acknowledged itself debtor for a large amount to the Jewish mercantile house of Bacri and Busnach of Algiers, as representing the African creditors. Of the sum thus acknowledged to be due, only a very small portion was paid, and the Dey Hadji Ali seeing no other means of obtaining the remainder, in 1809 seized upon the Concessions; they were however of little value to France at that time, when her flag was never seen in the Mediterranean, and their confiscation merely served as a pretext for withholding farther payment. In 1813, when the star of Napoleon began to wane, and he found it necessary to assume at least the appearance of honesty, he declared that measures would be taken for the adjustment of the Algerine claims; but he fell without redeeming his promise, and on the distribution of his spoils, the Jewish merchants had not interest enough to obtain their rightful portion, which amounted to fourteen millions of francs.

Upon the return of the Bourbons to the throne of France, the government of that country became desirous to renew its former intercourse with the Barbary States, and to regain its ancient establishments and privileges in their territories, which were considered important from political as well as commercial motives. For this purpose, M. Deval a person who was educated in the East and had been long attached to the French Embassy at Constantinople, was appointed Consul General of France in Barbary, and sent to Algiers with powers to negotiate. The first result of this mission, was a convention which has never been officially published; however in consequence of it the African Concessions were restored to France, together with the exclusive right of fishing for coral on the coasts in their vicinity [p. 2] and various commercial privileges; in return for which the French were to pay annually to Algiers, the sum of sixty thousand francs. It appears also to have been understood between the parties, that no fortifications were to be erected within the ceded territories in addition to those already standing, and that arrangements should be speedily made for the examination and settlement of all their claims on both sides, not only of those for which provision was made in the treaty of 1801, but also of such as were founded on subsequent occurrences; after this mutual adjustment the treaty of 1801 confirming all former treaties was to be in force.

The annual sum required by Omar for the Concessions, was much greater than any which had been previously paid for them by France; Hussein however immediately on his elevation to the throne, raised it to two hundred thousand francs, and he moreover declared, that the debt acknowledged to be due to his subjects must be paid, before any notice were taken of claims which were still liable to be contested. In opposition to these demands, the French endeavored to prove their right to the territories of Calle and Bastion de France by reference to ancient treaties both with Algiers and the Porte, in which no mention is made of payment for them; with regard to the claims, they insisted that the only just mode of settlement, was by admitting into one statement all the demands which could be established on either side, and then balancing the account. The Dey however remained firm in his resolution, and exhibited signs of preparation to expel the French from the Concessions, when their government yielded the point concerning the amount to be annually paid.

A compromise was made respecting the claims between the French Government and the Agents of the Algerines, on the 28th of October, 1819; as the articles of this agreement have never been published, its terms are only to be gathered from the declarations of the French Ministers in the Legislative Chambers, and the semi-official communications in the Moniteur the organ of the Government. From these it appears that the French Government acknowledged itself indebted for the sum of seven millions of francs, to Messrs. Bacri and Busnach, which was to be received by them in full discharge of claims on the part of Algiers, under the thirteenth article of the treaty of 1801; from this sum however was to be retained a sufficiency to cover the demands of French subjects against Algiers under the same article, which demands were to be substantiated by the Courts of Law of France; finally, each party was to settle the claims of its own subjects against the other, founded on occurrences subsequent to the conclusion of the said treaty. The French historical writers affect to consider this arrangement entirely as a private affair between their Government and the Jewish merchants, and indeed the Ministry endeavored at first to represent it in that light to the Legislature; but they were forced to abandon this ground when they communicated its stipulations, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs declared in the Chamber of Deputies, that the Dey had formally accepted it on the 12th of April 1820, and had admitted that the treaty of 1801 was thereby fully executed.

In order to comply with this arrangement, a bill requiring an appropriation of seven millions of francs was in June, 1820, submitted by the French Ministry to the Legislative Chambers, in both of which its adoption was resisted by the small minority then opposed to the Government. The debates on this occasion are worthy of notice, as many of the arguments advanced against the appropriation, have been since employed to defeat the bill for executing the treaty of 1831 by which the United States were to be indemnified for the injuries inflicted on their commerce by Napoleon. The claims against France were in both cases pronounced antiquated and obsolete [vieilles reclamations, créances dechues] and the fact that they had long remained unsettled, was thus deemed sufficient to authorize their indefinite postponement. The great diminution to which the creditors had assented, was considered as affording strong presumption that their demands were destitute of foundation; and the probability that many of the claims, had been purchased at a low price by the actual holders, from the persons with whom the contracts were originally made, was gravely alleged as a reason for not satisfying them. The advantages secured to France by each Convention were examined in detail, and compared with the sums required for extinguishing the debts; and the Ministry were in both cases censured for not having obtained more in return for their payment. It is not surprising to hear such sentiments avowed by men educated in the service of Napoleon, but it is painful to find them supported by others distinguished for their literary merits, and for their exertions in the cause of liberty.

The bill for the appropriation of the seven millions of francs, was passed by a large majority in both Chambers, the influence of the Crown being at that period overwhelming. Four millions and a half were in consequence paid within the ensuing three years to the Jewish merchants, who having thus received the whole amount of their own demands retired to Italy; the remaining two and a half millions were retained by the Government of France in order to secure the discharge of the claims of its subjects, under the treaty of 1801, which were yet pending in the Courts of the Kingdom. At the retention of this sum, the Dey was, or affected to be at first much surprised, and he insisted that the Government should hasten the decisions of the Courts; however as years passed by without any signs of approach to a definitive settlement, his impatience became uncontrollable. Moreover in addition to the annoyance occasioned by this constant postponement, he was much dissatisfied, on account of the fortifications which the French were erecting at Calle, contrary as he insisted to the understanding between the parties at the time of its cession. To his observations and inquiries on both these subjects he received answers from the French Consul which were generally evasive and often insulting, until at length wearied by delays and having strong reason to believe that M. Deval had a personal interest in creating obstacles to an adjustment of the difficulties, he determined to address the French Government directly. Accordingly in 1826 he wrote a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of that country, in which after indignantly expressing his sense of the conduct of the French Government, in the retention of this large sum and the erection of fortresses in the Concessions, he required that the remainder of the seven millions should be immediately paid into his own hands, [p. 3] and that the French claimants should then submit their demands to him for adjustment.

No notice having been taken of the Dey's letter, the Algerine cruisers began to search French vessels in a manner contrary to the terms of existing treaties, and to plunder those of the Papal States which were by a Convention to be respected as French. Besides these acts of violence the Dey shortly after issued a proclamation declaring that all nations would be permitted on the same terms to fish for coral near the coasts of his Regency. M. Deval complained of these proceedings at a public audience on the 27th of April, 1827; Hussein in reply haughtily declared that he had been provoked to them by the bad faith of the French, and that he should no longer allow them to have a cannon in his territories, nor to enjoy a single peculiar privilege; he then demanded why his letter to the French Ministry had not been answered, and when M. Deval stated that his Government could only communicate with that of Algiers through himself, he was so much enraged that he seized a large fan from one of the attendants, with which he struck the representative of France several times before he could leave the apartment.

As soon as the French Government was informed of this outrage, a schooner was despatched to Algiers with orders to M. Deval to quit the place instantly; a squadron was also sent in the same direction, under the command of Commodore Collet who was charged to require satisfaction from the Dey. The schooner arrived in Algiers on the 11th of June, and M. Deval embarked in her on the same day, together with the other French subjects resident in the place, leaving the affairs of his office under the care of the Sardinian Consul. At the entrance of the bay the schooner met the French squadron, consisting of a ship of the line, two frigates and a corvette; M. Deval then joined the Commodore, and after consultation between them as to the nature and mode of the reparation to be demanded, the schooner was sent back to Algiers with a note containing what was declared to be the ultimatum of the French Government. This note was presented to Hussein on the 14th; in it the Dey was required to apologize for the offence committed against the dignity of France, by the insult to its representative; and in order to make the apology the more striking and complete, it was to be delivered on board the Commodore's ship, by the Minister of Marine, in the presence of M. Deval, and of all the foreign Consuls resident in Algiers, whose attendance was to be requested; the French flag was then to be displayed on the Casauba and principal forts, and M. Deval was to receive a salute of one hundred and ten guns.

The policy as well as the generosity of requiring such humiliating concessions from the Government of any country, may be questioned, but it is certainly hazardous to make the demand unless it be accompanied by the display of a force calculated to insure immediate compliance. Decatur indeed with a force perhaps inferior to that of Collet, propounded terms to Omar Dey in 1815, which were really much more onerous to Algiers than those offered on the present occasion by the French; they were accepted, and it is therefore needless to inquire what would have been his course in the other alternative. Collet was not so fortunate; his demands were rejected with scorn and defiance by Hussein, who added that if the Commodore did not within twenty-four hours land and treat with him on the subjects in dispute between the two nations, he should consider himself at war with France. The French Commander did not think proper to comply with this invitation, and declared the place in a state of blockade, under the expectation probably that the distress produced by such a measure, might occasion discontent and commotions which would either oblige the Dey to lower his tone, or lead to the destruction of so refractory an enemy. Recollecting however what had occurred at Bona in May 1816, he adopted the precaution of sending vessels to the various establishments in the Concessions, in order to bring away the Europeans who were there, under the protection of the French flag; these vessels succeeded in rescuing the people, who were transported to Corsica, but their dwellings and magazines were rifled by the Bey of the Province, who had just received orders to that effect, and the fortifications at Calle were entirely destroyed.

The preceding account of the circumstances which led to the war between France and Algiers, will be found by comparison to vary considerably from those given by the French historical writers, and to be defective and unsatisfactory with regard to several important particulars, which are stated by them with great apparent clearness and confidence. To these objections, only general replies can be made; this account has been drawn entirely from original sources, and where they failed to supply the requisite information, silence has been preferred to the introduction of statements on doubtful authority. The only publications on the subject which may be termed official, are the declarations of the French Ministers contained in the Reports of the Debates in the Legislative Chambers, and the articles on the subject in question inserted from time to time in the Moniteur, the avowed organ of the Government. From the Algerines we have nothing. The conventions of which the alleged non-fulfilment occasioned this rupture have been withheld by the French Ministry; no account has been given of the claims against Algiers brought before the French Courts, of the causes which retarded the decisions respecting them, of the amount demanded or awarded; without precise information as to these particulars, it is impossible to form a correct judgment of the case. This silence and the vagueness and reserve so apparent in the communications of the French Government, on the subject, are certainly calculated to create suspicions, as to its sincerity in maintaining its engagements, and these suspicions are increased by an examination of its conduct throughout the whole affair.

It would be incompatible with the character or plan of these Sketches, to give a review of the proceedings of the French Government; the impression produced on the mind of the author, by a diligent study of the case, is that the parties in the dispute mistrusted the intentions of each other. The French were anxious to make permanent establishments on the coast of Northern Africa, which Hussein who had much more definite ideas of policy than perhaps any of his predecessors, determined from the commencement of his reign to oppose; before resorting to violent measures however, he wished to secure the payment of the large debt [p. 4] due to himself and his subjects. The French having good reason from his conduct, to apprehend that as soon as he had received the whole of the sum, which they had engaged to pay, he would find some pretext to expel them from his dominions, may have had recourse to the old expedient of withholding a part, in order that he might be restrained from aggressions by the fear of losing it. We have no means of ascertaining the share which M. Deval may have had in producing or increasing the difficulties, but there is reason to believe that it was not inconsiderable; his conduct is admitted to have been highly imprudent and indeed improper, even by the best French authorities, and it was condemned as dishonorable by the Dey, as well as by the most respectable portion of the Consular body at Algiers.

Before entering upon the events of this war it will be proper to advert to the situation of the other Barbary States, and to notice the principal occurrences which transpired in them about this period.

It would be uninteresting to recount all the attempts made by the inferior powers of Europe to preserve peace with the Barbary Regencies; sufficient has been said to demonstrate the vainness of the expectation that the rulers of those states would be restrained from any course which promised to be immediately beneficial to their interests, by regard for engagements however solemnly taken. The King of the Netherlands by a judicious display of firmness in 1824, succeeded in preventing his country from being rendered tributary to Algiers; but he, as well as the sovereigns of Sweden and Denmark, continued to pay large annual sums to Tunis and Tripoli.

In Tunis, no events of much importance transpired during the reign of Mahmoud, which have not been already mentioned. The Regency continued at peace with foreign nations, and its situation was in general prosperous, notwithstanding the desolation produced by a plague in 1818, an extensive conspiracy headed by the Prime Minister in 1820, and the frequent contests between the adherents of Hassan and Mustapha the two sons of the Bey. Mahmoud at length died quietly on the 28th of March 1824, and Hassan succeeded without opposition.

A short time previous to the death of Mahmoud, some alterations not very material indeed, yet favorable on the whole to the United States, were made in the treaty concluded between their Government and that of Tunis in 1797. One of the amended articles provides—that no American merchant vessel shall be detained against the will of her captain in a Tunisian port, unless such port be closed for vessels of all nations, and that no American vessel of war should be so detained under any circumstances. This was considered by the British Government at variance with the terms of the engagement made with Admiral Freemantle in 1812, by which the armed vessels of nations at war with Great Britain were not to be suffered to leave a Tunisian port within twenty-four hours after the sailing of a British vessel; and the Consul was directed to ask for explanations on the subject from the Bey. Hassan who had by this time succeeded to the throne replied positively, that there was nothing contradictory in the two stipulations, and that this agreement had been made with the United States, merely in order to place them on a level with other nations. As the British Government had thought proper to make the inquiry, it is strange that it should have been satisfied with such an answer; however, under the condition of things then existing and the probabilities with respect to the future, it was certainly not worth while to press the matter further.

The Pasha of Tripoli, notwithstanding the treaties made with Lord Exmouth in behalf of Sardinia and the Two Sicilies in 1816, and his protestations to the English and French Admirals three years after, sent out armed vessels to cruise against the commerce of the Italian States. When complaint was made of these depredations, Yusuf replied that the treaties were no longer binding, and that if those nations wished to remain at peace with him, they must pay him an annual tribute. To this insolent and unreasonable pretension, the King of Sardinia replied by fitting out a squadron composed of two frigates, a corvette and a brig, which sailed from Genoa in September 1825, and arrived before Tripoli on the 25th of that month.

Before relating the proceedings of this expedition it will be proper to give some account of the place against which it was sent.

The town of Tripoli stands on a rocky point of land projecting northwardly into the Mediterranean; it is surrounded by a high and thick wall, forming an unequal pentagon or figure of five sides of different lengths, of which the two northern are washed by the sea, the other three looking upon a sandy plain but partially cultivated. The circumference of the place is about three miles, and the area enclosed within the wall does not exceed one thousand yards square.

The shore on the north-western side of the town is bordered by rocky islets, which render it almost unapproachable by vessels; but in order to secure the place effectually from attack on that quarter, a battery has been erected on one of the islets called the French fort. The harbor is on the north-eastern side; it is about two miles in length and a mile in width, and is partially enclosed by a reef of rocks extending for some distance into the sea; on these rocks are situated the principal fortifications, and by filling up the space between them, which could be done with but little labor, the reef might be converted into a continued mole. The depth of water in the harbor no where exceeds six fathoms, and great care must be taken by vessels to avoid the numerous shoals and hidden dangers which beset the entrance; the frigate Philadelphia struck in fourteen feet water on one of these shoals distant three miles and a half northeast of Tripoli, and one mile north of Kaliusa Point at the eastern extremity of the harbor.

The fortifications of Tripoli on the land side are of no value, and could not for an instant withstand an attack from a well appointed force; the wall, said to have been built by Dragut, is of great height and thickness, and provided with a rampart on which are mounted some guns, but these pieces are generally useless from rust and want of carriages. Towards the harbor the defences are more respectable, and have on many occasions as already shown, preserved the place from capture or destruction. On the shore forming the south-eastern side of the harbor, are two forts called the Dutch and English forts, and opposite them on the reef of rocks are two others, much larger and stronger, [p. 5] called the New and English forts; these have been all constructed by European engineers, and are kept in tolerable order.

There is but little appearance of wealth in Tripoli; the Moorish population amounting to about fourteen thousand are in general very poor, the trade being almost exclusively in the hands of the Jews, whose number is about two thousand. The palace contains some apartments possessing a certain degree of grandeur and furnished in a costly manner principally with French articles; in the town there are a few good stone buildings, with courts and arcades in the Italian style; these are however chiefly occupied by the foreign Consuls and merchants, the greater part of the inhabitants dwelling in mere hovels of mud but one story high. The roofs of the houses are all flat, and great care is taken to have the rain conveyed from them into cisterns, as there is not a well or spring of fresh water in the place.

A triumphant arch, the inscription on which denotes that it was erected in honor of the Roman Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, is the only remarkable monument of antiquity in the place. It is much defaced, nearly buried in the ground and encumbered with mean houses; but as far as can be ascertained, it exceeds in beauty of design, proportion and parts, any other similar relique of Roman art.

The immediate environs of Tripoli are desert; about two or three miles to the eastward is a rich and highly cultivated plain called the Messeah where the Foreign Consuls and the wealthy inhabitants of the town have their villas.

As soon as the Sardinian squadron arrived before Tripoli, the Cavaliere Sivori who commanded it immediately landed with some of his officers on the guaranty of the British Consul, and had an audience with the Pasha. Yusuf at first assured him that every thing would be accommodated, but on the day succeeding he presented a note in which his demand for tribute was unequivocally stated, accompanied by other proposals equally insulting. The Cavaliere on this took his leave, and having recommended the subjects and interests of his master to the care of the British Consul, he retired to his ships determined to assert the rights of his country by force. The sea was too rough at the time to permit the approach of the ships to the town, without danger of their being stranded; but Sivori wished to lose no time, and to effect if possible immediately the destruction of the Pasha's shipping; he accordingly manned a number of boats which entered the harbor at midnight in three divisions, commanded by Lieutenant Mamelli. The expedition was perfectly successful; a brig of twelve guns and two schooners of six guns each were boarded and set on fire, during a heavy cannonade from all the surrounding batteries; the men then landed from the boats, and endeavored to force the gates of the dock-yard and custom house, but this being found impracticable, they retreated in good order to their ships. The next day the weather proving more favorable, preparations were made for an attack on the town; but Yusuf finding that he had mistaken the character of his assailants, and not wishing to subject himself to further loss, agreed to an adjustment, and signed a convention renewing the engagements made to Lord Exmouth in 1816.

The King of the Two Sicilies was less fortunate in his attempt to bring the Pasha of Tripoli to reasonable terms. Yusuf had suspended his demands on Naples for some time after the attack made on him by the Sardinians, and it was supposed that he had abandoned them; however in the beginning of 1828, he suddenly required from His Sicilian Majesty payment of one hundred thousand dollars immediately, and an annual tribute of five thousand more, as the price of continuance of peace. King Francis considered the honor of his country too precious, or the sums demanded by the Pasha too great, for he refused to pay either present or tribute and even sent a squadron to Tripoli to bear his reply. The Sicilian force consisted of a ship of the line, two frigates, two corvettes, a brig, a schooner, and twelve gun and mortar boats, and arrived off Tripoli on the 22d of August, 1828, under the command of Baron Alphonso Sosi de Caraffa, who was authorized to treat with the Pasha respecting the future relations between the two countries. The Commander instantly landed under proper assurance of safety, and held a conference with the Pasha, in which he endeavored to induce him to adhere to the treaty of 1815; Yusuf however remained firm to his purpose, and rejected all propositions of adjustment on other terms than those he had already offered. The Sicilian flag was in consequence taken down from the Consulate, and the Consul retired with the Baron on board the squadron.

The next morning the 23d, the Sicilian squadron sailed into the harbor, and commenced an attack on the Tripoline vessels of war, twenty in number, which were drawn up in front of the reef of rocks, under the guns of the New and Spanish forts. The large ships of the squadron kept aloof from the batteries and only a few of the gun and mortar boats approached near enough to produce any effect by their fires. The injury sustained by either party was thus very slight, and a storm coming up, after a desultory contest of three hours, Caraffa thought proper to withdraw his forces, and put to sea. The storm continued for the two succeeding days; on the 26th the attack was resumed, but in the same inefficient manner; it was renewed on the 27th and 28th, during which the Sicilians expended a great deal of ammunition, but to very little purpose on account of the great distance at which their ships remained from the object of attack. At length on the 29th, the Commodore concluded that his attempts were likely to prove fruitless, and therefore resolved to return to Naples.

The Tripolines behaved with great gallantry throughout the affair, their own boats advancing frequently towards the enemy; their loss was trifling, and only two or three shots from the Sicilians reached the town, where they caused no damage. Immediately on the retreat of the squadron, Yusuf sent out his cruisers which took several Sicilian vessels, but the French Government interfered, and its Consul at Tripoli was ordered to negotiate in favor of Naples. The Pasha could not refuse such a mediation, and a Convention was in consequence signed on the 28th of October, by which the former treaty was renewed, the King of Naples however engaging to pay immediately twenty thousand dollars to Tripoli as indemnification for the expenses occasioned by the war.

Yusuf had by this time become an old man, and the decay of his body was accompanied by corresponding [p. 6] changes in his character and mental faculties. The firmness which had so long sustained him under the pressure of heavy difficulties, gave place to a disposition to temporize, inclining him to sacrifice prospects of future advantage, in order to avert a present evil; the energy which had caused him to be viewed with a certain degree of respect, notwithstanding his repeated acts of treachery and violence, now exhibited itself in undignified bursts of passion, and an insatiable desire to increase his treasures was the only remnant of his former ambition. The condition of the Regency had indeed been improved in many respects during his reign; its productiveness was increased, the communications were more easy and secure, and the affairs of internal administration, as well as the intercourse with foreign nations, were conducted with greater regularity and precision than before his accession. These reforms however served as they were intended, only to advance the personal interests of the sovereign; and the people became more wretched as the means of oppression were thus rendered more effectual by system. To obtain money had become the sole object of Yusuf's plans: if he repressed the ravages of the wandering tribes, it was only that he might levy greater contributions himself; and if the caravans traversed his dominions with unwonted security, this advantage was more than counterbalanced by the augmentation of duties on their merchandize. In imitation of the Viceroy of Egypt, whom he seems to have adopted as his model, he likewise engaged in commercial speculations, which were productive of serious evils to his subjects. These enterprises were generally carried on by the Pasha in conjunction with foreigners resident in Tripoli, or through their agency; and in order to affect the value in the market of articles which he might wish to buy or sell, the duties on their export or import were on several occasions suddenly raised or lowered, to the ruin of regular merchants. Notwithstanding these arbitrary measures, or perhaps in consequence of them, the speculations were generally unsuccessful, and the Pasha became indebted on account of their failure for immense sums, principally to subjects of France and England; these creditors, when unable to obtain settlement of their claims in any other way, were in the habit of applying to their own Governments for relief, and the unfortunate Pasha after having been long dunned by an overbearing Consul, was occasionally obliged to open his treasury on the summons of an Admiral.

These and other troubles affected the Pasha the more deeply as he could place little confidence in those who surrounded him. Mohammed D'Ghies whose kindness and integrity were worthy of being employed in a better cause, still lived and bore the title of Chief Minister; but age and blindness had long rendered him incapable of attending to business, and the duties of his office were performed by his eldest son Hassuna, of whom more will be said hereafter. The other ministers and agents of the Pasha, were persons of whose unscrupulous character he must have received too many evidences, to have supposed them attached to him by any other ties than their interests.

In the members of his own family Yusuf could place but little reliance; he whose youth had been signalized by the murder of his brother and rebellion against his father, could with an ill grace recommend fraternal affection among his children, or require of them obedience to his own authority. The attempt made by his eldest son Mohammed in 1816 to obtain possession of the throne has been already noticed; this wretch continued for ten years after his pardon in a species of exile, as Governor of Derne, while his next brother Ahmed enjoyed the title of Bey of the Regency, and was regarded as the probable successor to the crown. Ahmed however dying suddenly, Mohammed organized another conspiracy in his province, with a view to the overthrow of his father, which attempt proving like the former one unsuccessful, he again fled to Egypt where he died in 1829. Mohammed left in Tripoli a son named Emhammed who would have been the regular heir to the crown according to the customs of succession in Europe; but primogeniture is for various reasons little regarded in Oriental countries, and the reigning sovereign usually favors the pretensions of the son to whom he is the most attached, or whom he considers most capable of maintaining possession of the inheritance. For one or both of these reasons, Yusuf thought proper to set aside Emhammed, and to designate his own next surviving son Ali as the future Pasha of Tripoli; this prince was accordingly on the death of Ahmed, invested with the title of Bey, which gave him command of the troops, and in order to increase his wealth and influence, he was married to the daughter of the Chief Minister D'Ghies. These marks of favor only served to render Ali more impatient to enjoy the prize which they were intended to insure to him, and while waiting an opportunity to seize it, he gratified his own avarice by extorting as much money as he could from the people, through the aid of his myrmidons. The inhabitants thus suffering from the violent and arbitrary exactions of the Bey, in addition to the taxes and duties imposed on them by the Pasha, were frequently driven into rebellions, the suppressions of which by increasing the public expenses increased the miseries of the country.

In addition to these difficulties, Yusuf was tormented by the quarrels and jealousies of the Foreign Consuls residing in his capital, and by their interference in the affairs of his Government. Quarrels and jealousies are naturally to be expected among the members of a diplomatic corps, particularly of one in which all bear the same title and are nominally equal, while the influence possessed by each is generally commensurate with the power of the country which he represents. Thus the Consuls of France and England in Barbary have ever considered themselves superior to the representatives of other states, and have ever been rivals, each demanding the precedence on public occasions, and claiming a host of exclusive privileges either on the strength of treaties, or of custom. Their claims to superiority both in rank and privileges have been generally allowed by their European colleagues who according to circumstances range themselves under the banner of one or the other of these potentates; the Consuls of the United States have however uniformly refused to admit any inferiority on their own part, demanding for themselves the enjoyment of every substantial right granted to the representative of any other power, and abstaining from appearance on occasions of ceremony, in which a preference unfavorable to themselves may be manifested.

In Algiers and Tunis, these disputes seldom attracted the notice of the Government, and the influence which a Consul could exercise in either of those Regencies, was scarcely worth the sums which must be paid for it. In Tripoli however, and especially since 1815, the agents of Great Britain and France have each endeavored to obtain a degree of control in the affairs of the state. Colonel Warrington who has represented Great Britain during that period, is well calculated by his general intelligence and the inflexible resolution of his character to acquire this superiority; and having been always supported by his Government, many of his demands have been instantly complied with, which would otherwise have been regarded merely as the ebullitions of arrogance and presumption. On the slightest resistance to his wishes, the ships of war of his nation appeared in the harbor, the Minister who offended him sat uneasy in his place, and every aggression committed by a Tripoline upon the honor or interests of Great Britain, was speedily and severely punished.

The possession of such powers by the representative of Great Britain, would certainly not be regarded with indifference by France; as it is not so convenient however, to send squadrons on all occasions to the aid of the Consul, he is obliged to rely the more on his own resources. The French Consuls in Barbary and the East are generally persons who have been educated for the purpose, either in the embassy at Constantinople, or at some consulate in those countries. With regard to the propriety of such selections, experience seems to have shown that the advantages of acquaintance with the customs and languages of the Eastern nations, are more than counterbalanced by the loss of honorable feelings, and the disregard of moral restraints which frequently result from this mode of acquiring them. Whether Baron Rousseau who was for many years Consul of France in Tripoli, was trained in one of these schools, it is needless to inquire, but he appears to have displayed during his residence in that Regency, a talent and a disposition for intrigue, which would have done honor to the most accomplished drogaman of Pera. Between him and Warrington there was a constant struggle for influence, and the Pasha was alternately annoyed by the overbearing dictation of the British Consul, and the wily manoeuvres of Rousseau.

One of the most frequent causes of difficulties between the Governments of Barbary and the Consuls of Foreign Powers, is the right claimed by the latter to protect all persons within the walls of their residence. In those countries it is absolutely requisite for the security of the Consul and for the discharge of his duties, that the persons in his employ should not be subjected to the despotism of the Government, nor to the doubtful decisions of the tribunals; and provisions to that effect are generally inserted in the treaties between Christian nations and those of Barbary. The Consuls however insist that the privilege should extend to the protection not only of their families, servants and countrymen, but also of all other persons under their roof; and the most abandoned criminals having entered such a sanctuary, are thus frequently screened from punishment. This privilege is productive of inconvenience not only to the Government but also to the Consuls whom it frequently involves in difficulties; the representatives of the inferior powers therefore seldom attempt to maintain it, but generally surrender the fugitive, if a native of the country, to the Government, or oblige him to quit their dwelling, rather than subject themselves to the hazard of having it invaded by force; those of Great Britain and France on the contrary, make it a point of honor not to yield, except in cases where the fugitive has injured some one of their colleagues or his guilt is clearly proved; and even then they have frequently required assurances that he should be pardoned, or that his punishment should be mitigated. A circumstance of this nature occurred in 1829 which brought these two parties in direct and open collision, and for a time involved the Consul of the United States in difficulties with the Government of Tripoli; the affair was originally of a private nature, but has ultimately produced the most serious changes in the situation of the Regency.

It is well known that many efforts have been made during the last forty years, by individuals and by some European Governments, to obtain information respecting the interior of the African Continent; we are all familiar with the names and adventures of Ledyard, Parke, Burckhardt, Denham, Clapperton, Laing, Lander and others, whose labors have been important from the light thrown by them on the subject of their researches, and still more so as exhibiting instances of perseverance and moral courage with which the annals of warfare offer few parallels. Several of these heroic travellers took their departure from Tripoli, as the communications between that place and the regions which they desired to explore are comparatively easy and safe; and the Pasha, whether actuated by the expectation of obtaining some advantage from their discoveries, or by more laudable motives, appears from their accounts to have used every exertion to facilitate their movements. They likewise concur in expressing their gratitude and respect for Mohammed D'Ghies, who entertained them all hospitably in Tripoli and furnished them with letters of credit and introduction, which, says Denham, "were always duly honored throughout Northern Africa."

Hassuna and Mohammed D'Ghies the two sons of this respectable person, are also mentioned in terms of high commendation by many who visited Tripoli. Hassuna the elder was educated in France, and afterwards spent some time in England where he was much noticed in high circles, notwithstanding the assertion of the Quarterly Review to the contrary; on his return to his native country, he for some time conducted the affairs of his father's commercial house, and afterwards those of his ministerial office, in which he was distinguished for his attention to business and his apparent desire to advance the welfare of his country. Mohammed the younger son was brought up under the eye of his father at home; Captain Beechy of the British Navy who spent some time at Tripoli in 1822 while employed in surveying the adjacent coast, describes him as "an excellent young man," and as "an admirable example of true devotion to the religion of his country, united with the more extended and liberal feelings of Europeans. He daily visits the public school where young boys are taught to read the Koran, and superintends the charitable distribution of food which the bounty of his father provides for the poor who daily present themselves at his gate. Besides his [p. 8] acquaintance with English and French he is able to converse with the slaves of the family in several languages of the interior of Africa," &c. He was subsequently employed also in public affairs, and became the intimate confident of his brother-in-law the Bey Ali.

On the 17th of July 1825, Major Gordon Laing of the British Army a son-in-law of Consul Warrington, quitted Tripoli with the intention of penetrating if possible directly to Tombuctoo, and thence descending the river which is said to flow near that city, to its termination. He was amply supplied with letters by the D'Ghies family; and orders were sent to the governors and chiefs of places on his route, which were subject to the Pasha to aid him by every means in the prosecution of his journey, and to forward his letters and journals to Tripoli. For some time after his departure his communications were regularly received and bills drawn by him at various places were presented at Tripoli for payment. From these accounts it appears, that taking a south-western course he arrived on the 13th of September at Ghadamis a town of considerable trade situated in an oasis about five hundred miles from Tripoli; thence he passed to Einsalah in the country of the Tuaricks (a fierce race of wanderers) which he reached on the 3d of December and left on the 10th of January 1826. His journals up to this date were regularly received; from his few subsequent letters we learn that during the month of February, the caravan with which he travelled was suddenly attacked in the night by a band of Tuaricks, who had for some days accompanied them; many persons of the caravan were killed and the Major was dreadfully wounded, but he escaped and arrived at Tombuctoo on the 18th of August. At this place he had remained five weeks when Boubokar the Governor of the town who had previously treated him with favor, suddenly urged him to depart immediately, stating that he had received a letter from Bello the Sultan of the Foulahs a Prince of great power in the vicinity of Tombuctoo, expressing the strongest hostility to the stranger; Laing accordingly quitted Tombuctoo on the 22d of September, in company with Burbushi an Arab Sheik who had engaged to conduct him in safety to Arouan, distant about three hundred miles to the northward.

After this date nothing farther was heard from the traveller, no more of his bills were presented for payment at Tripoli, and Mr. Warrington becoming uneasy prevailed on the Pasha to have inquiries made respecting him. Messengers were accordingly despatched southward in various directions, one of whom on his return in the spring of 1827 brought an account that the Christian had been murdered soon after leaving Tombuctoo, by a party despatched from that place for the purpose. This statement was confirmed by all the other messengers on their return, and it was confidently repeated in a long article on the subject published in a Paris Journal, which gave the Prime Minister of Tripoli as authority. The other caravans and travellers however from the South contradicted these reports, and Hassuna D'Ghies on being questioned respecting the account driven in the Paris Journal, denied that he had supplied such information and asserted his total disbelief of the story. These and other circumstances induced Mr. Warrington to suspect that the Pasha or his Minister had for some interested motive suppressed Laing's communications; at his request therefore, the Commander of the British squadron in the Mediterranean sent a ship of war to Tripoli to give Yusuf notice that as the traveller had proceeded to the interior under his protection, he should hold him responsible for his safety, or at least for the delivery of his property and papers. This intimation was certainly of a most unreasonable character; the Pasha however could only exert himself to avert the threatened evil, by endeavoring to discover the traveller and at all events to disprove any unfair dealings or bad intentions on his own part with regard to him.

All doubts respecting the fate of the British traveller were however dispelled by the return to Tripoli of the servant who had accompanied him; from the statements of this man it was clearly ascertained, that the unfortunate Laing had been murdered in his sleep by his Arab conductor Burbushi on the third night after their departure from Tombuctoo, that is on the 25th of September 1826.

Some time after receiving this melancholy news, the British Consul was induced to believe that papers which were sent by his son-in-law from Tombuctoo, had actually arrived in Tripoli; and in the course of the investigations which he made in consequence, a suspicion was awakened in his mind that they had been secreted by Hassuna D'Ghies, in order to conceal some gross treachery or misconduct on his part. Under this impression Mr. Warrington urged the Pasha to have the papers secured, and not being satisfied with the means used for the purpose, he finally struck his flag, and declared that all official intercourse between himself and the Government of Tripoli, would be suspended until they were produced.

To avert the evils which might result from this measure, Yusuf labored diligently, and in the spring of 1829 he intercepted some letters sent from Ghadamis to Hassuna, which indicated a means of unravelling the mystery. Pursuing his inquiries farther, he became fully convinced of the perfidy of his Minister, and at length he declared to a friend of the British Consul, that two sealed packages sent by Laing from Tombuctoo, had been received by Hassuna and delivered by him to the French Consul in consideration of the abatement of forty per cent. in the amount of a large debt due by him to some French subjects. The fact of the receipt of the papers by Hassuna was to be proved by the evidence of the Courier who brought them from Ghadamis, and of other persons daily expected in Tripoli; the remainder of the Pasha's strange statement appears to have been founded entirely on a written deposition to that effect, of Mohammed D'Ghies the younger brother of the accused Minister, which was said to have been made in the presence of the Bey Ali and of Hadji Massen the Governor of the city.

On the strength of this declaration, Mr. Warrington insisted on the immediate apprehension of Hassuna, but he having received timely warning fled for refuge on the 20th of July, to the house of Mr. Coxe the American Consul; and immediately after to the surprise of all concerned, it was found that his brother Mohammed had likewise sought an asylum under the roof of Baron Rousseau.

October in New England is perhaps the most beautiful—certainly the most magnificent month in the year. The peculiar brilliancy of the skies and purity of the atmosphere,—the rich and variegated colors of the forest trees, and the deep, bright dyes of the flowers, are unequalled by any thing in the other seasons of the year; but the ruin wrought among the flowers by one night of those severe frosts which occur at the latter end of the month, after a day of cloudless and intense sunshine, can scarcely be imagined by one not familiar with the scene.

| Thou'rt here again, October, with that queenly look of thine— All gorgeous thine apparel and all golden thy sunshine— So brilliant and so beautiful—'tis like a fairy show— The earth in such a splendid garb, the heav'ns in such a glow. 'Tis not the loveliness of Spring—the roses and the birds, Nor Summer's soft luxuriance and her lightsome laughing words; Yet not the fresh Spring's loveliness, nor Summer's mellow glee Come o'er my spirit like the charm that's spread abroad by thee. The gaily-mottled woods that shine—all crimson, drab, and gold, With fascination strong the mind in pensive musings hold, And the rays of glorious sunshine there in saddening lustre fall— 'Tis the funeral pageant of a king with his gold and crimson pall. Thou'rt like the Indian matron, who adorns her baby fair, E'er she gives it to the Ganges' flood, all bright, to perish there; Thou callest out the trusting buds with the lustre of thy sky, And clothest them in hues of Heaven all gloriously—to die. Thou'rt like the tyrant lover, wooing soft his gentle bride— Anon the fit of passion comes—and her smitten heart hath died; The tyrant's smile may come again, and thy cheering noonday skies, But smitten hearts and flowers are woo'd, in vain, again to rise. |

* * * * * |

Thy reign was short, thou Beautiful, but they were despot's hours— The gold leaves met the forest ground, and fallen are the flowers; Ah, 'tis the bitterness of earth, that fairest, goodliest show, Comes to the heart deceitfully, and leaves the deeper wo. |

Maine.

| CHILD. |

| Where, mother, where have the fire-flies been All the day long, that their light was not seen? |

| MOTHER. |

| They've been 'mong the flowers and flown through the air, But could not be seen—for the sunshine was there. And thus, little girl, in thy morning's first light, There are many things hid from thy mind's dazzled sight, Which the ev'ning of life will too clearly reveal, And teach thee to see—or, it may be, to feel. |

| CHILD. |

| Where, mother, where will the fire-flies go When the chilling snows fall and the winter winds blow? |

| MOTHER. |

| The tempest o'ercomes them, but cannot destroy: For the spring time awakes them to sunshine and joy. And thus, little girl, when life's seasons are o'er, And thy joys and thy hopes and thy griefs are no more, May'st thou rise from death's slumbers to high worlds of light, Where all things are joyous, and all things are bright. |

| As he who sails afar on southern seas, Catches rich odor on the evening breeze, Turns to the shore whence comes the perfum'd air, And knows, though all unseen, some flower is there— Thus, when o'er ocean's wave these pages greet Thine eye, with many a line from minstrel sweet, Think of Virginia's clime far off and fair, And know, though all unseen, a friend is there |

|

... The morning dew-drop, With all its pearliness and diamond form Vanisheth. |

| * * * * * |

|

... She turned her from the gate, and walked As quietly into her father's hall, As though her lover had been true. No trace Of disappointment or of hate was found Upon the maiden's brow: but settled calm, And dignity unequalled. And they spoke To her, and she did mildly answer them And smiled: and smiling, seem'd so like an angel, That you would think the man who could desert A form so lovely, after he had won Her warm affections, must be more than demon. And though she shrunk not from the love of those Who were around her, and was never found In fretful mood—yet did they soon discover The rosy tinge upon her youthful cheek Concentrate all its radiance into one Untimely spot, and her too delicate frame Wither away beneath the false one's power. But lovelier yet, and brighter still she grew Though Death was near at hand—as the moon looks Most lovely as she sinks within the sea. Her fond devoted parents watch with care The fatal enemy: friends and physicians Exert their skill most faithfully. Alas! Could Love or Friendship bind a broken heart, The fading flower might be recalled to life. |

| * * * * * |

| She's gone, where she will chant the melody Of Seraphim and live—beyond the power Of the base. Then weep not, childless parents, weep not,— But think to meet her soon. Her smile is yet More lovely now than when a child of earth: For she has caught the ray of dazzling glory And sweet divinity, that beams all bright Upon her Saviour's face; and waits to cast That smile on thee. |

Richmond, Va.

| Good George the Third was sitting on his throne— His limbs were healthy, and his wits were sound; In gorgeous state St. James's palace shone— And bending courtiers gather'd thick around The new made monarch and his German bride, Who sat in royal splendor side by side. Pitt was haranguing in the House of Lords— Blair in the Pulpit—Blackstone at the Bar— Garrick and Foote upon the Thespian boards— [p. 10] And pious Whitfield in the open air— While nervous Cowper, shunning public cares, Sat in his study, fattening up his hares. Sterne was correcting proof-sheets—Edmund Burke Planning a register—Goldsmith and Hume Scribbling their histories—and hard at work Was honest Johnson; close at hand were some Impatient creditors, to urge the sale Of his new book, the Abyssinian tale. Italia smiled beneath her sunny skies— Her matchless works were in her classic walls; They had not gone to feast the Frenchman's eyes— They had not gone to fill Parisian halls: The Swiss was in his native Canton free, And Francis mildly ruled in Germany. Adolphus reigned in Sweden; the renown Of Denmark's Frederic overawed her foes; A gentle Empress wore the Russian crown; Amid the gilded domes of Moscow rose The ancient palace of her mighty Czars, Adorn'd with trophies of their glorious wars. Altho' the glory of the Pole was stain'd, Still Warsaw glitter'd with a courtly train, And o'er her land Augustus Frederic reign'd; Joseph in Portugal, and Charles in Spain— Louis in France, while in imperial state O'er Prussia's realm ruled Frederic the Great. In gloomy grandeur, on the Ottoman throne Sat proud Mustapha. Kerim Khan was great Amid fair Persia's sons; his sword was one That served a friend, but crush'd a rival's hate: O'er ancient China, and her countless throng, Reign'd the bold Tartar mighty Kian Long. America then held a common horde Of strange adventurers; with bloody blade The Frenchman ruled—the Englishman was lord— The haughty Spaniard, o'er his conquests sway'd— While the wild Indian, driven from his home, Ranged far and lawless, in the forest's gloom. Thus was the world when last yon Comet blazed Above our earth. On its celestial light Proudly the free American may gaze: Nations that last beheld its rapid flight Are fading fast; the rest no more are known, While his has risen to a mighty one. |

Mexico—Procession of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios—Visit to the Country—Society and Manners in Mexico—Climate.

20th June, 1825. Since our arrival on the 25th May, my occupations have been such as to prevent my seeing many of the lions of Mexico. I have, however, walked through the principal streets, and visited most of the churches, of which some are very rich and splendid—some are ancient and venerable—others are fine and gaudy—while a few of the more modern are extremely neat and handsome. The churches are numerous: these, with the convents, occupy almost every alternate square of the city; but with all this show of religion, there is a proportionate degree of vice among its population.

The city is, indeed, magnificent; many of the buildings are spacious. The streets are not wide, but well paved—clean in the most frequented, but excessively filthy in the more remote parts, and thronged with dirty, diseased, deformed, and half naked creatures. Disgusting sights every moment present themselves. At the corners of every street—each square is called a street, and bears a distinct name,—at the doors of the churches which you must be passing constantly in your walks—and sometimes in the areas of the private residences, you are importuned by miserable beggars, some of whom, not satisfied with a modest refusal, chase you into charity, which you are not assured is well bestowed.

We meet in the streets very few well dressed people; the ladies seldom walk, except to mass early in the morning, when some pretty faces are seen.

Such is the character of the street-population of Mexico. So much filth, so much vice, so much ignorance are rarely found elsewhere combined. Those who have seen the lazzaroni of Naples, may form a faint idea of the leperos of Mexico.

The leperos are most dexterous thieves—none can be more expert in relieving you of your pocket handkerchief; it is unsafe to trust them within your doors. I knew an American who had his hat stolen from under the bench on which he was seated in the Cathedral listening to a sermon!1

1 A very ingenious theft by one of this class was mentioned to me by an American who was present when it took place. At a fair in the interior of the country, two Americans were seated on a bench engaged in conversation, one of them having his hat by his side with his hand upon it for its protection. Talking earnestly he occasionally uplifted his hand from the hat. On his rising from his seat, he was surprised to find in his hand not his own beaver, but an inferior one which had been substituted for it. At an incautious moment he had ceased to guard it; a hat was there when he put down his hand—but it was not his own.

They are superstitious, too, almost to idolatry. I may here include with them the better class of people also. The recent reception of the image of Nuestra Senora de los Remedios, (Our Lady of Remedies,) I give as evidence of the justice of this remark. Her history is briefly this. She is a deity of Spanish origin—the more highly esteemed Lady of Guadalupe—the patron saint of Mexico, is indigenous. She accompanied the conquerors to the city of Muteczuma2—was lost in their disastrous retreat on the celebrated noche triste—was found some years afterwards, in 1540, seated in a maguey, by an Indian, Juan de Aguila, who carried her to his dwelling, and fed her with tortillas, (Indian corn-cakes,) which were regularly deposited in the chest where she was kept. Suddenly she fled, and was discovered on the spot where her temple now stands—the place to which Cortes retreated on the night of his flight from the city. It is an eminence to the west of Mexico, distant about five miles.

2 Cortés, in his Letters, writes the name of the Emperor of Mexico, Muteczuma. Humboldt says, I know not on what authority, that Moteuczoma was his name. The English historians always call him Montezuma.

This identical image, they say, still exists—it is about eight inches in height—it is richly decorated. It is believed to possess the power of bringing rain, and of staying the ravages of disease.

For many days previous to her entrance into the city, great preparations had been made. On the 11th inst. she was conveyed from her sanctuary in the President's coach, which was driven by a nobleman of the old regime, the Marques de Salvatierra, bare headed, and attended by a large number of coaches, and crowds of people on foot, to the parroquia de Santa Vera Cruz, a church just within the limits of the city. Here, as is usual, she was to rest one night, and on the following evening to proceed to the Cathedral. Before the appointed time, the streets leading to it were covered with canopies of canvass; draperies were suspended from every balcony, and strings of shawls and handkerchiefs stretched across, were seen fluttering in the wind. A regiment of troops marched out to form her escort, and thousands flocked to join her train. But a heavy rain began to fall, and the procession was necessarily postponed, the populace being delighted to find that the intercession of Our Lady was of so much avail, and their faith strengthened at the trifling expense of wet jackets. The procession was now appointed for an early hour the next morning, (a prudent arrangement, for it rains, in course, every evening, the rainy season having commenced,) and preparations were again made with increased zeal, proportionate with the gratitude felt at so prompt a dispensation of her Ladyship's favors. Two regiments of infantry and one of cavalry now composed the escort. The concourse of people was immense. Wax tapers, lanterns, candle-boxes, flags, and all the frippery of the churches were carried to grace the occasion; children dressed fantastically, with wings, and gay decorations upon their heads, but barefooted, with tapers in their hands, were led by their parents or nurses to take part in the pageant.

After the procession was formed, a discharge of artillery announced the departure of the holy image from the church, in which she had until now rested. The advance was a corps of cavalry, followed by flocks of ragged Indians, by respectable citizens and the civil authorities, all bearing lighted wax tapers; then followed the numerous religious orders, each order preceded by an Indian carrying on his back a huge mahogany candle-box; the higher dignitaries of the order, with their hands meekly folded on their breasts, each attended by two assistants, bringing up the rear of Carmelites, Augustines, Franciscans, Dominicans, and Mercedarians; next these were other Indians, followed by the angelic little children, who strew roses before the object of their adoration, La Santa Virgen de los Remedios, who stands majestically under a canopy, richly clothed, and surrounded by gilded ornaments, supported by four men. As she passed, the people who crowded the streets, and all who fill the windows under which she is carried, knelt, and roses are showered upon her from the roofs of the houses. Next her was another canopy, under which the Host was carried, to which the people also knelt. The troops brought up the rear, escorting Our Lady to the Cathedral, where she remains nine days. If it rain during this time, it is ascribed to her influence. If rain precede her entrance, it is because she was to be brought into the city; and if it follow her departure, it is the consequence of her late presence. The miracle, of course, never fails. After the rainy season has set in, she is introduced annually for the idolatrous worship of this ignorant, superstitious people—not only the canaille, but also the most respectable portion of the community.

14th August, 1825. I returned to the city yesterday after an excursion of a week in the vicinity of Chalco, about twenty-five or thirty miles distant. We were invited by an acquaintance to his hacienda, where he promised fine sport with our guns. Not content with abundance of deer, we were to return with the spoils of sundry wild animals, such as wild-cats, bears, panthers, wolves and tigers. Prepared for ferocious contests, we set out with all the eagerness of huntsmen who feast in their imagination on their slaughtered prey. But in fact, though to hunt was our ostensible object, from which we expected little, although entertained by our friend with extravagant hopes, we left the city chiefly for the purpose of exercise, of viewing the country, and avoiding the water, which, at this season of the year, impregnated with the soda which the heavy rains disengage from the soil, deals sadly with strangers.

A ride of five or six hours brought us to the hacienda. This, I have elsewhere said, is a country seat, generally of large extent, with a chapel forming a part of the building, and surrounded by the reed or mud huts of the Indians, who are the laborers, or, as it were, vassals of the estate. A plain, thickly strewed with these haciendas, presents the appearance of numerous villages, each with its steeple and bell. The buildings are hollow squares, extensive and commodious, and embracing in their several ranges the usual conveniences of a farm, such as stables, and yards for poultry, sheep and cattle. They all have a look of antiquity, of strength and durability, which, at a distance, is imposing; but on nearer view, they are commonly found dilapidated, and devoid of neatness, and destitute of the garden and the orchard, which give so much the appearance of comfort to the country houses of the United States.

This is their general character, as far as I have seen them, and such was the commodious dwelling to which we were now hospitably invited. It bore the air of tattered grandeur—in its dimensions and in its ruined state showing marks of pristine elegance. It was partially fortified, as were most of them, during the revolution, for protection from lawless depredation, and from the numerous bands of banditti who then roamed through the country, and were royalists or republicans, as was most expedient to accomplish their designs. Even at this time, these defences are esteemed necessary to ensure safety from the robbers who have escaped the vigilance of government by concealing themselves in the adjacent mountains.

On the day of our arrival nothing occurred particularly to attract our notice, except that, after the conclusion of dinner, the tall Indian waiter fell upon his knees in the middle of the room and gave thanks—a custom common, I am told, in the country. To our surprise, this was not repeated. He was either told that we were heretics, (as all foreigners are designated) or was deterred because some of our Catholic friends were less devout on the occasion than was to be expected from them.

It may not be amiss here to mention, that the dinner table of the Mexicans is of indefinite length, always standing in the eating room. One end only is [p. 12] commonly used. The seat of honor is at the head, where the most distinguished and most honored guest is always placed; the rest arrange themselves according to their rank and consequence; the dependants occupying the lowest seats.

After a cup of chocolate at six o'clock the next morning, we went in pursuit of game, and roamed through the hills and mountains which are contiguous, meeting with very little success. At about twelve we partook of our breakfast, which was brought to us more than two leagues from the hacienda—after which we prosecuted our hunt. Our sole reward was a heavy shower of rain—and between four and five we returned to the hacienda, well wearied, having walked at least twelve miles over steep mountains.

On the following day we set out with our mules, &c. to try our fortune higher up the mountains, and after a ride of between three and four hours, reached a herdsman's hut, where we were to lodge at night. We were unsuccessful in finding game in the evening, and after a laborious search for deer, sought our hut—a log building, about fifteen feet square, in which twelve of us, men, women and children, stowed ourselves. Annoyed by fleas, and almost frozen by the chill mountain air, within two leagues of the snow-crowned Iztaccihuatl, we passed a sleepless night.

Early next morning, whilst others of the party engaged in hunting for deer, with two companions I ascended the highest peak of this range, (except those covered with snow,) with great labor and fatigue; but we were compensated amply by the grand view beneath and around us. The adjoining peak to the south of us was the Iztaccihuatl, about a league distant. We felt very sensibly the influence of its snow. Beyond this, the Popocatepetl raised its lofty cone, while far in the southeast appeared Orizaba, around whose crest the clouds were just then gathering. The plains of Puebla and Mexico are on opposite sides of this seemingly interminable ridge on which we stood. From the latter, the clouds, which we had been long admiring far beneath us, hiding the world from our view, were gradually curling, and disclosed the distant capital with its adjoining lakes and isolated hills. The chilling wind drove us from our height, but in descending we often rested to enjoy a scene which the eyes never tire in beholding.

In the evening, we left the mountain for the hacienda, where we spent another day. Our friends were extremely kind to us, and regretted more than ourselves our ill success in quest of game. Being little of a sportsman, to me it was a trifling disappointment. I enjoyed abundant gratification in seeing the country, its people and manner of living. Whatever may be said of the bad blood of the Mexicans, I cannot but view them as a mild and amiable people—nature has bestowed her bounties liberally upon them: for their state of degradation and ignorance they are indebted not to any natural deficiencies of their own, but to the miserable and timid policy of their former Spanish masters. They are superstitious, but this arises from their education; they are jealous of strangers—the policy of Spain made them so; and they are ignorant, for in ignorance alone could they be retained in blind subjection to the mother country. If they are vicious, their vices arise from their ignorance of what is virtuous—of what is ennobling. They are indolent because they are not permitted to enjoy the fruits of industry, and nature supplies their wants so bountifully, they are compelled to exert themselves but little.

These are in fact serious defects, but the improvement of the Mexican people is daily taking place. They are beginning to be enlightened with the rays of the rising sun of liberty; and after the present generation has passed away, the succeeding one will exhibit those political and moral virtues, which are the offspring of freedom. The effects of a daily increasing intercourse with foreigners are even now perceptible, and lead me to believe, that, before many years roll over, a wonderful change must take place. Society, too, will improve: ladies will no longer gormandize or smoke—will discover that it is vulgar to attend cock-fights, and will bestow, with increased regard for their personal appearance, greater attention upon the cultivation of their minds.

In Mexico, there are few parties, either at dinner, or in the evening. None will suit but great balls, and these must occur seldom, else none but the wealthy can attend them, so expensive are the decorations and dresses of the ladies. They esteem it extremely vulgar to wear the same ball-dress more than once. Society is cut up into small tertulias or parties of intimate acquaintances, who meet invariably at the same house, and talk, play the piano, sing, dance, and smoke at their ease and pleasure.

Sometimes I attend the Theatre. This is divided into boxes, which families hire for a year. If the play be uninteresting, they visit each other's box, and pass the evening in conversation. It is diverting to observe the gentlemen take from their pockets a flint and steel for the purpose of lighting their cigars, and then to extend the favor of a light to the ladies; and sometimes the whole theatre seems as if filled with fire-flies.