![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Spanish Painting

Author: A. de Beruete y Moret

Editor: C. Geoffrey Holme

Translator: Lewis Spence

Release date: March 12, 2021 [eBook #64796]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

TEXT BY A. DE BERUETE Y MORET

(DIRECTOR OF THE PRADO MUSEUM, MADRID)

| 1921 |

EDITED BY GEOFFREY HOLME “THE STUDIO,” Ltd., LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK

HE exhibition of Spanish Painting held in London in the galleries of

the Royal Academy from November to January last, excited a lively

interest in the English public and inspired numerous articles on the

subject in English journals and reviews. If all of these were not in

accord on certain issues and critics adopted various points of view, it

may still be said that the crowds of visitors which it attracted and the

manifold expressions of opinion it evoked supply the clearest evidence

that the exhibition aroused the curiosity of the English public, and

consequently may be regarded as a triumph for Spanish art and a success

for its promoters.

HE exhibition of Spanish Painting held in London in the galleries of

the Royal Academy from November to January last, excited a lively

interest in the English public and inspired numerous articles on the

subject in English journals and reviews. If all of these were not in

accord on certain issues and critics adopted various points of view, it

may still be said that the crowds of visitors which it attracted and the

manifold expressions of opinion it evoked supply the clearest evidence

that the exhibition aroused the curiosity of the English public, and

consequently may be regarded as a triumph for Spanish art and a success

for its promoters.

The reasons underlying the interest which Spanish art awakens to-day in enlightened circles (this is the second exhibition of the kind which Spain has of late witnessed beyond her borders, recalling that of Paris in 1920) are worthy of reflection and may be said to have inspired the Royal Academy’s exhibition.

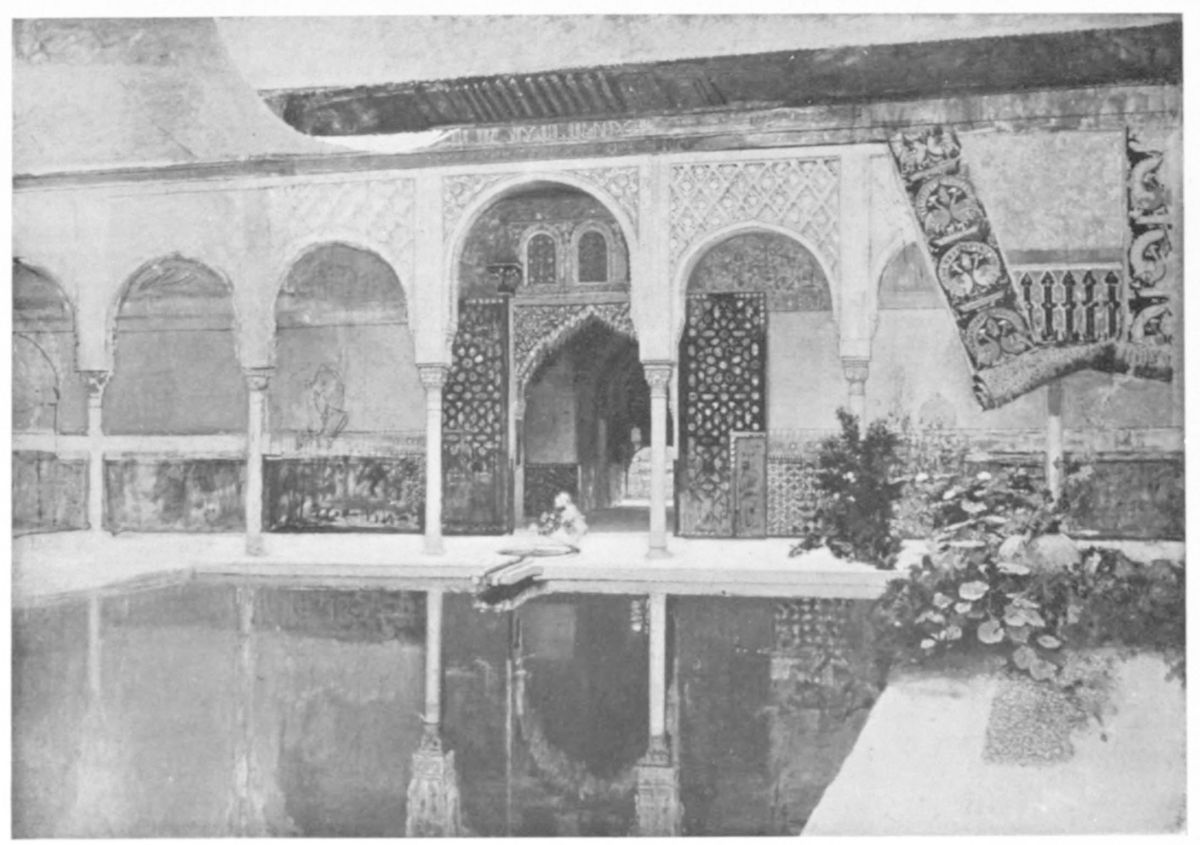

Spain—her life, history, customs, art—is often regarded subjectively as though enveloped in a haze, or through the medium of legend, which, however accommodating it may be to literary expression, is by no means conformable to the facts of history or present realities. Viewed in this picturesque manner and because of the isolation in which the country remained for generations, and perhaps still remains, it has attracted the attention of writers and poets, and even scientists and philosophers, unfamiliar with their theme and dubious in their assertions. Doubtless the typical, the true native spirit has not been misunderstood by the outside world. Thus in the case of Cervantes and Velázquez, their names are household words in every land. But the kind of knowledge to which we allude is not usually imparted by such lofty spirits, who speak to humanity from the heights, without distinctions of race or frontier. That which they accomplish is only a part of the national achievement. It is the medium in which it is fashioned, the environment in which it comes into being, its artistic matrix, which determines the precise type of racial endeavour. To its national character the new Spain cleaves, and by its light her ideas will be readjusted, her history interpreted, her present respected as in line with her tradition, which, in the sphere of things{2} artistic, Spaniards regard as a potent factor in the advancement of world art.

Spain is familiarly spoken of as a country of distinctive character, and is so not only because of its geographical situation, which has kept it somewhat apart from frequented routes, but because it aspires to such a reputation. At the present time it is incessantly productive of art, its output exhibiting a specific character of its own, obvious and intelligible to those who examine it with sufficient care. Undoubtedly it has been influenced at certain periods by extraneous currents, but during the sixteenth century, when the true Spanish school was created, it was notably independent and unique. Its productions, these national qualities which above all determine that which is called a school, possess a character of their own, a special determinative essence, which can only be explained by metaphysical processes. But at the same time they display external manifestations, an ultimate expression, a speech, an idiom, so to speak, peculiarly national. And this speech in art is quite as fundamental as the spirit which determines the nature of the creation. All-powerful, or at least very great, is the spiritual capacity for creating mighty works in mente. But the various schools of art came into being not only because they enshrined an idea, but because they were able to give it form. The characteristics of the expression, not of the idea, of form, not of essence, these it is to which the critic should address himself in the first instance when he desires to differentiate between the works of one school and another, and when trying to distinguish the work typical of one artist from that of others of the same school, who have been less successful in following a common master. The creative idea, the spirit which animates every work, is distinct, according to the period of its origin, even in the case of the productions of the same race at different periods; but in expression its form is always similar, its ideas the same. As in literature writers of one nationality have to employ a common tongue, so in painting an expression equally conclusive, a palette, a technique, an idiom quite as definitive, determines the compositions typical of each race. If we find scattered throughout a museum where there are examples of all schools, a Saint by Greco, an ascetic figure by Ribera, a portrait by Velázquez, an image by Zurbarán, a visionary subject by Valdes Leal, a Virgin by Murillo, and a woman by Goya, it is probable that these works will contrast with one another too forcibly, or at least will not blend harmoniously. Each of them belongs to an epoch, and possesses a distinct creative and æsthetic spirit. But, even so, we will find that although the works belong to different schools, and variations and dissimilarities abound, all have one speech, one ultimate idiom in common; in a word, all have been painted in Spanish.{3}

It is not easy to state precisely in what this ultimate expression consists, but on general lines it is possible to affirm of Spanish artists that their work is characterised by a decided tendency towards sincerity, simplicity of composition and tonal harmonies in grey. Velázquez appears to have fixed the character of the Spanish palette and technique: the scale of very subtle greys, the harmonies of grey and silver, the use of certain carmines and violets, first encountered in the work of Greco, were tested and employed by him, as were those coloured earths especially indigenous to Spain, the earth of Seville and the preparation of animal charcoal, the use of which is noticeable in his canvases. These determined the material elements by the aid of which was developed a method of painting as simple as characteristic. Velázquez, like the painters of the great Italian school and the schools of the North, grew tired of conventionalism in colour and perspective, and, employing an exuberant palette and gifted with vision of extraordinary keenness, turned to the natural, and, with the lesson of Greco before him, and by aid of his own gifts of observation, sincerity, and a supreme simplicity, did not employ more than the necessary colours to obtain those gradations of tone which to our eyes appear so natural and present the harmony afforded by reality, the master by choice and temperament inclining to those in which were combined all the shades of grey. He created by his unique palette the true and unmistakable Spanish style. Goya, more than a hundred years after him, during the close of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, a period when the national characteristics tended towards insipidity, maintained this traditional spirit and thus saved Spanish painting from becoming confounded with the works of his contemporaries in France and England.

The years which followed those of Goya, the remainder of the nineteenth century, those years of easy communication, of rapid transit, of frequent travelling, of international study and residence abroad, so much more advanced in some respects, were less rich for Spanish painting. Spanish artists, absent from their country, engaged in many departments of work and instruction, lost something of their former qualities. At the present time, in which there seems to have been born into the world a new assertion and exaltation of nationality, Spaniards have regained their ancient spirit, and while aspiring to absolute modernity, remain faithful to a tradition which is peculiarly their own, which makes for national individuality, and has caused them to be regarded with that interest which always accrues to the original, the characteristic, the intelligent, and consequently arouses attention and anticipation.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

England has ever followed the progress of Spanish art with enthusiasm{4} and interest. During the nineteenth century, the majority of the works of art which left Spain found a resting place in England. In London within recent years three exhibitions of Spanish painting ante-dated that of 1920—one in the New Gallery (1891), another in the Guildhall (1901), and the last in the Grafton Gallery (1913). All of them were rich in results, more especially the third, which was remarkable for its modern section. The difference in character between the exhibition of 1913 and that of the Royal Academy in 1920 consists more especially in the display of works belonging to English collections, the latter being composed for the most part of examples sent from Spain as an act of homage to the English people, and to assure them once more of the existence of a spiritual bond or tie between the two countries, which with the passage of time aspire to a more intimate relationship.

It was at first the intention of the organisers of the exhibition of 1920 not to send as representative of the older art any except the works of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and a few pictures by Goya, as examples of the golden age of Spanish painting, and especially in view of the exceptional interest in Goya. But it was ultimately decided to furnish an exhibit completely representative of all epochs. At the same time the Spanish Committee recognised that the section devoted to Primitive Art—in which among the many artists represented the most remarkable was Ribera—was lacking in distinction. This it regretted and felt a pleasure in its ability to compensate for the omission by providing a full representation of the greater Spanish painters, and in being able to lend ten Grecos and twenty-one Goyas, preserved in Spain, to Burlington House, a thing until now impossible of accomplishment and which it will not be easy to repeat.

The works of the primitive period placed on view, though all of peculiar interest, and several of striking character, were still inadequate to give a just idea of the development of early art in the Iberian Peninsula. The first essays of Spanish art were indeed lacking in national characteristics. At a time when Italy and Flanders produced painters of distinctive note, Spain, and perhaps the whole Peninsula—for in this connection we must not forget Portugal—filled its churches, monasteries and convents with panels and altarpieces. With the exception of the names of several artists now identified, all of its productions are of doubtful paternity, its style is borrowed and in general is distinguished only by the possession of regional characteristics of a minor kind. Therefore the paintings on panel that it produced are to-day referred to, in order to distinguish them one from another, as belonging to the Castilian, Portuguese, Catalan, Aragonese or Valencian Schools. For this there is an historical reason. The Peninsula, at the time in which its early art was produced, was{5} divided into different kingdoms and states, each absolutely independent and having its own history and traditions. Thus the kingdom of Aragon, with Valencia, was intimately connected with the Mediterranean, and came within the sphere of Italian influence. Castile was more closely related to the states of Flanders and the Rhine, admitting and developing Flemish and German tendencies. Catalonia possessed an art very similar to that of Provence. But I believe that all this work, chaotic, lacking in national expression, and in determinative characteristics, presents a difficult problem for its investigators. Add to this that these panels and altarpieces were often the joint work of several artists, one painting costumes, others specialising in heads and hands, others in drapery, still others in backgrounds, so that the whole resulted frequently in a composition confused and equivocal. All that can be said with any degree of certainty is that the production of this time was large, rich and of great merit, so far as that can be attained by a race of colourists who were lacking in discipline and insight.

This manifestation of pictorial art did not obtrude itself in any decided manner until the fourteenth century. To discover its origin we may have to compare it with the miniatures in the manuscripts of San Isidor, or the archaic mural decorations traceable by Byzantine art, and it would seem to possess a greater archæological than artistic interest.

Spanish art during the last years of the thirteenth century and until two centuries later is so incomplete in its details, presents so many diverse aspects, and the circumstances of its rise and tendency are so vague, that to venture any general opinions regarding it would be unwise. Its study has recently been confined to short monographs by various critics and scholars, both Spanish and foreign, which do not go beyond the discussion of specific works and artists, and the particular investigation of obscure titles and documents exhumed from the archives.

The arrival of Starnina and the Florentine Dello at the Court of Juan I of Castile in the second half of the fourteenth century, appears to have given a very great impetus to that style to which the Spanish painters were growing accustomed. But this Italianism notwithstanding, Flemish influences penetrated, if more lately, still more rapidly into Spain. The early Spaniards pursued and sought a realism in art which they were unable to find in that of Italy, hence their predilection for the style and manner of the Flemish and German painters and those of other countries whom they came to call painters of the North. The appearance of Van Eyck in the Peninsula in 1428, and that of other Flemish painters who arrived there about that time, aroused a true enthusiasm and imparted to Spanish art a tendency to copy faithfully from nature which henceforth came to be one of the characteristics which have never left it. Among{6} these painters of the North it is strange to find, a little before the middle of the fifteenth century, an artist called Jorge Inglés (George the Englishman), so named, without doubt, from his origin, who did some important work, especially in the hospital of Buitrago, the study of which we heartily commend to the English public and critics. We should like to have sent this work to the exhibition of the Royal Academy, but its enormous dimensions, as well as other circumstances, rendered this impracticable.

During this epoch, the composition of Spanish works begins to show the use of colours prepared with oil, thus permitting the development of a technique more in conformity with the Spanish temperament. Consequently the new medium appears in the works of many masters, among the first of these recorded being La Virgen de los Consellers, painted and signed by Luis Dalmau in 1445.

Andalusia, a region which has come in more recent times to be regarded as the cradle of Spanish artists, produced at this time not a few painters. The work, Saint Michael, of the master Bartolomé de Cárdenas, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy, pertains to this rich and flourishing period, which gave an impetus to the forces then impelling all Spanish life toward the national union which came to pass in the reign of the Catholic kings. Two new centres of activity arose at this epoch, which greatly fostered the rise of Spanish civilisation and favoured the development of pictorial art—two cities glorious and historical in Spain—Toledo and Salamanca.

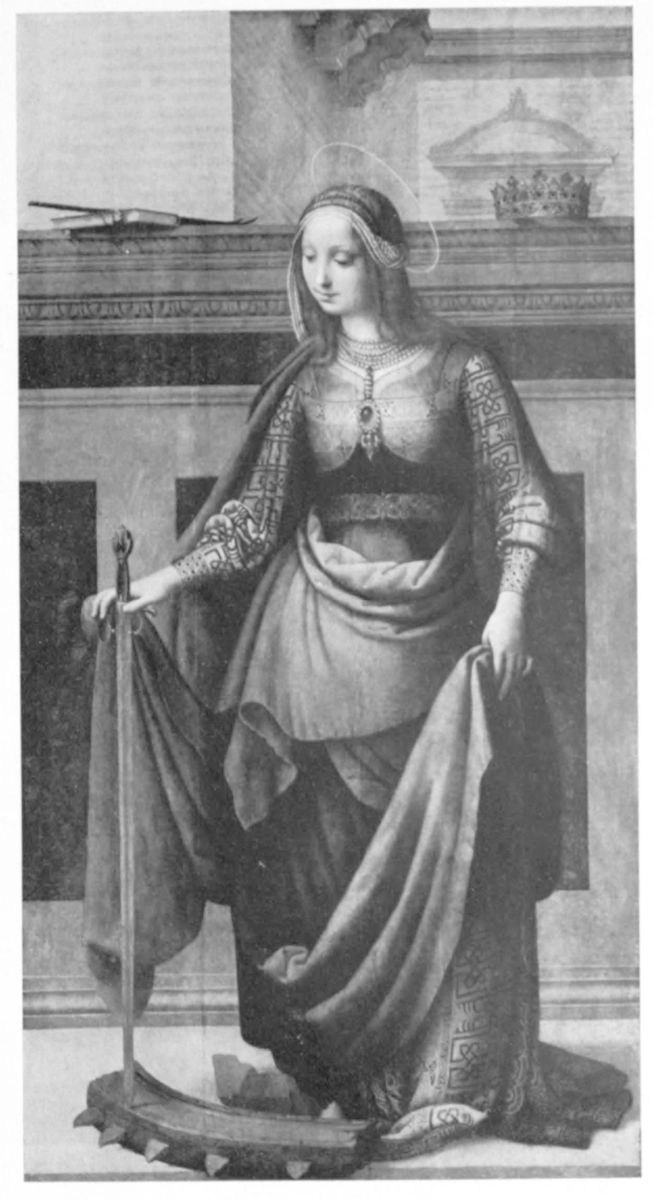

Side by side with this budding art—which was in a certain sense inspired by the schools of the north, but nevertheless began to display a national tendency—a few isolated artists, either by preference or training, still retained the Italian style. We recall the Santa Catalina of Hernando Yáñez de la Almedina (Plate I.), shown at the exhibition, a work which has not been sufficiently appreciated and must be regarded as a beautiful example of that period.

Arising at the close of the epoch of national unity, the House of Austria, in the person of its most exalted representative, the Emperor Charles V, commenced to govern the destinies of Spain. The victorious expansion of Spanish arms, both in the Old World and the New, during the first half of the sixteenth century, had but little influence upon artistic effort, and none of the Spanish painters of this period are regarded as the equals of their Italian, Flemish, German or Dutch contemporaries. And our artists, at a time when the entire national fortunes were hazarded in campaign after campaign, had enough to do to maintain an epoch of gestation, to comprehend the laws and trace the spiritual current of the Renaissance which now dawned upon the world of culture. This great{7} movement failed also to take a national direction with Spanish artists, and the few books and treatises on art printed in Spain during this period are poor in conception and lacking in information.

Even to mention the names of the painters of the period, it would be necessary to burden this critical sketch with a list of artists of secondary importance. In his art Alonso Berruguete was certainly Italian, but in spite of this, he gave to his works a marked national stamp, maintaining in the central portion of the Peninsula a patriotic inspiration which resulted later in a separate school of culture. Valencia, with artists trained in Italy, was preparing a great reputation for the future, and then a painter of individuality, isolated in a minor province, and having few relations with the Court, created with his brush an austere art, a little dry and stiff, ascetic in its inspiration and scarcely suggestive at first sight, but striking in its individuality, and reflecting that spirit of Spanish theology and mysticism which was to dawn somewhat later. I refer to Luis de Morales, the maker of all these Dolorosas and Ecce Homos, so unmistakable and so much esteemed in Spain.

We come now to the reign of the son of Charles V, Philip II, a man whose memory has had to endure much criticism, but to whom, from the point of view of art, his country owes not a few of those works which it treasures most. The portraits of Moro, a wealth of Flemish and Italian paintings and, among others, a very complete collection of Titians, are due to the commands of Philip II, who, before he shut himself up in the Monastery of the Escurial, and during his visits to Italy, Germany and Flanders, was gathering choice examples of the art of that time, and of the period immediately preceding it, installing in the castles of Spain those paintings which are to-day the most important of the foreign collections housed in the Prado Museum.

But meanwhile the true national output of those years, mostly of religious pictures, was destined for the churches and convents, and must no longer be regarded as of minor importance. Meanwhile, also, by royal command, there arrived in Spain the works of foreign masters, and in Court circles there arose a style of painting exclusively devoted to the genre of the portrait, and which is known to-day as the school of portraitists of Philip II and Philip III. Its origin is known to us. It is due to the teaching which our painters received from that famous Hollander, Antonis Moor, who had so close a relation with our country that his name has become hispanicised, and who is equally well known to-day by his Dutch name, as by the more Spanish-sounding Antonio Moro. Patronised by Philip II, he gave instruction to certain Spanish painters, especially to one, Alonso Sanchez Coello, who was his disciple and successor in art. Another Spanish follower of his, besides Coello, was Pantoja de la Cruz,{8} and the third and last of those who maintained this school and who completed its cycle, was Bartolomé González, who flourished during the first years of the reign of Philip IV. Other portrait painters, disciples and imitators of these might be mentioned, but the artists alluded to typify this school, brief in its development, very distinguished and typical, though, as we have said, not of Spanish origin. Their characteristics are quite unmistakable. They paint a life-like portrait, dry, hard, minute in execution, and complete in all its details, to the treatment of which they pay much attention, especially as regards personality. But although skilful and sincere, their school degenerated and the last of its manifestations is practically an imitation of the first, possessing little excellence and scanty inspiration. Portrait painters of the Court, as we have indicated, the works of these men, though in general replete with strong personality, especially as regards the royal family portraits, have been scattered throughout the world, and were practically confined to the palaces of other reigning houses.

In the London exhibition we were able to study the most important of these several works, for example that of Pantoja, Portrait of Philip II (Plate II.), who is represented as elderly and on foot, a full-length portrait which faithfully reflects the appearance of this monarch, and which is housed in the Monastery of the Escurial. It appeared at the Royal Academy, being lent for the purpose by His Majesty the King of Spain. There were others, the property of His Britannic Majesty, which are housed in Buckingham Palace, the portraits by Sánchez Coello of the Archdukes of Austria, Wenceslaus, Rudolf and Ernest, the Portrait of the Infante Don Diego, and that of Margaret of Austria. That by Pantoja, Portrait of a Lady of the Palavicino Family (regarding the authorship of which various doubts have arisen), though not of artistic importance, certainly presents a critical problem, for while the art of portrait painting was being developed in Spain, in other countries and particularly in Italy, the disciples of the school of Moor created works which might at times be confounded with those of Spanish painters. Bartolomé González was also represented by the portrait of the Cardinal Infante Don Fernando of Austria, lent by the Marquis de Viana.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

About the year 1575 there came from Italy to the city of Toledo, a young artist, scarcely thirty years of age, born in the island of Crete, of Greek parents. He was called Domenico Theotocopuli, and was known then, as he is to-day throughout the whole world, as El Greco (“the Greek.”) There was reserved for this man the mission of shaping and, in the course of time, perfecting through the medium of his works, a technique, especially as regards execution, performance and character, which is{9} manifest in all his creations, and the great enthusiasm which the lovers of Spanish Art evince for it is natural and explicable. The fame which the first works of El Greco aroused in Toledo reached the Court, and Philip II commanded him to work in the Monastery of the Escurial on pictures for the Church. They were at issue from time to time, the King and the painter, and do not quite seem to have understood one another. Philip II, used to an Italian and Flemish artistic atmosphere, and an enthusiastic admirer of Titian, was unable to comprehend the work of El Greco, which, though of the Venetian tradition, represented an innovation profound and complete, and to-day, as four centuries ago, it perplexes many people. But lovers of Spain, those who apprehend her true genius and have studied her characteristics and idiosyncrasies, see in El Greco one of the most interesting figures in international art. In the spirit which appears in his works, the genius with which they have been performed, the marvellous technique developed in them, and the workmanship which gives such brilliance and quality to the colour, so that it appears at times to have been executed with enamels, he triumphs, disarming criticism, making us not only forget, but even applaud the extravagances and lack of proportion of which his works are full.

The work of El Greco may be divided into two distinct groups: one comprising human figures in general, portraits; the other divine figures, images, and religious paintings. In one work, the most complete and important of all, the Burial of the Count of Orgaz (Plate V.), these two aspects are joined. The upper portion, the heavenly, which it would seem the painter suffused with his idealism, is peopled with divine figures, symbolic and incorporeal. In the lower part, which represents an earthly scene, the form and colouring have the qualities of things terrestrial. In the exhibition of the Royal Academy, in the salon set apart for the works of El Greco, there were gathered ten examples eloquent of these two phases of his effort. His Self-portrait and A Trinitarian exhibit the second; The Annunciation and the Christ embracing the Cross the first. Another canvas which occurs to one as affording a good example of his brilliance of colouring and individuality is the picture full of miniature figures, The “Glory” of Philip II (Plate III.), sent to London by His Majesty King Alfonso XIII.

In this collection of his works, as indeed, in all those from the brush of this master, one could study the origin of the greyish tonality characteristic of the Spanish school which he was the first to introduce and give effect to, and to which Velázquez, in later years, gave definite form, thus founding a technical characteristic of the school. It may interest those curious regarding such problems of painting that the shadows which abound in the works of El Greco, though intense, are never black,{10} and this lends to them a singular profundity and atmosphere. From this relation of the light and shade, never attaining a pure black or white, there results a wonderful transparency and corporality, and all this is attained with fluid colours, in most instances blurred and rubbed and nearly always rather soft, slight only in the brighter places and in the points of light. He observes and understands that the reproduction of these things in the art of the painter is not due to faithful copying alone. The atmosphere, the light, the reflections, which these objects display to our sight, change according to conditions, and are represented on canvas not as they actually appear, but according to the aspect they present to the vision, modified by external agencies. Only thus is it possible to obtain the impression of truth, of movement, of depth. In the work of the copyist the objects and figures are petrifications, rigid and dead, in one and the same plane, in which, perhaps, the ability of the artist can more readily be appreciated, but which never gives the impression of movement or of life.

Distinctive as a creator, originator and master of technique, statements regarding El Greco’s artistic antecedents are debatable, as for example the relationship to other masters of Byzantinism which some profess to be able to discern in his pictures. But it remains clear that in his typical works he is above all the true interpreter of the Spain that was noble, pious and mystical, and the most sympathetic delineator of the spirit of the time in which he lived. We believe that it is correct to regard him as the adopted son of the Spain of his day.

Although his work has been discussed since the times of Philip II, to-day it ought to be regarded as consecrated. It is not only among painters that we should seek the true influence of El Greco. It is more extensive, and embraces diverse manifestations, therefore the causes which animate it are diverse. And so, in the studios of painters, in the studies of the cultured, among wise and refined critics, among literati, we may discover the most fervent and impassioned lovers of El Greco. There exists, without doubt, an invisible bond between this painter and the world of modern intellectualism, and this is owing in great part to the enthusiasm which his works arouse, to the peculiar mystery in which they are enveloped—which we do not find in any other painter—to the suggestive power which he wields, to something which impassions and completely subdues us. It is for this reason that disciples of El Greco, who in past years were scarce, are to-day a legion in number, and their pictures, once unknown and without value, are now celebrated and occupy prominent positions in museums and private collections.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Neither Tristan, nor Mayno, nor Jorge Manuel Theotocopuli are figures{11} sufficiently important to allow us to say that El Greco, their master, founded a school, much less that he formed with them the so-called Toledan school, which, in reality, had no existence and did not give rise to an output from that city possessing those marked characteristics which would place it in the category of a school.

It has to be recorded that in the last years of the sixteenth century Philip II brought from Italy several Italian decorative artists to paint in fresco the extensive walls of the Monastery of the Escurial. He may have wished to bring with him for the purpose some celebrated foreign masters, but this was not possible, for the most important epoch of the Italian Renaissance had come to an end; and instead of great masters, there came others, decadents, facile “hacks,” who in a short time covered these enormous wall-spaces with compositions of scanty inspiration. We mention the visit of these painters to Spain, not because of any importance it has in itself, but in order to show that Spanish painters, even those of standing, have in all times been lacking in the qualities which especially characterise the decorative painter. Philip II might have encouraged Spanish artists. But whom—Morales, El Greco, the artists of the Court, the lesser followers of El Greco in Toledo? No, none of these appear to have been qualified to bring such a task to a conclusion. This and nothing else was the cause of the coming of the Italians; and for the rest the King favoured the works of various Spaniards, placing many examples of their work in his palaces and in the religious houses he founded. And so Spanish painting remained in this particular position to the close of the sixteenth century and during the first years of the seventeenth, which is regarded as its golden century, when, in the midst of fruitful invention there arose four great figures, each to-day world-renowned—Ribera, Zurbarán, Velázquez and Murillo. What centres of artistic life did Spain possess at this time? Two, fundamentally; those two cities which have since produced the greatest number of painters and the most able—Seville, the capital of Andalusia, the open gate to the New World, and Valencia, a Mediterranean port exposed to the influences of that which had been the classical world, and in close and direct communication with Italy, which bequeathed to it the last sparks of the marvellous life of the Renaissance. In Valencia, Francisco Ribalta, a conscientious painter, who had studied in Italy, introduced a style of colouring after the manner of Ribera. In Seville, frequented by all the Andalusian intellectuals, Pacheco, a most cultured artist, came later on to be the master of Velázquez and Zurbarán. In the exhibition with which we are concerned Ribalta and Pacheco, more famous for the disciples they left than for the works they produced, were represented, the first by Saint Peter (Plate VII.) and his portrait of himself as Saint Luke painting the Virgin;{12} and the second by the Portrait of a Knight of Santiago.

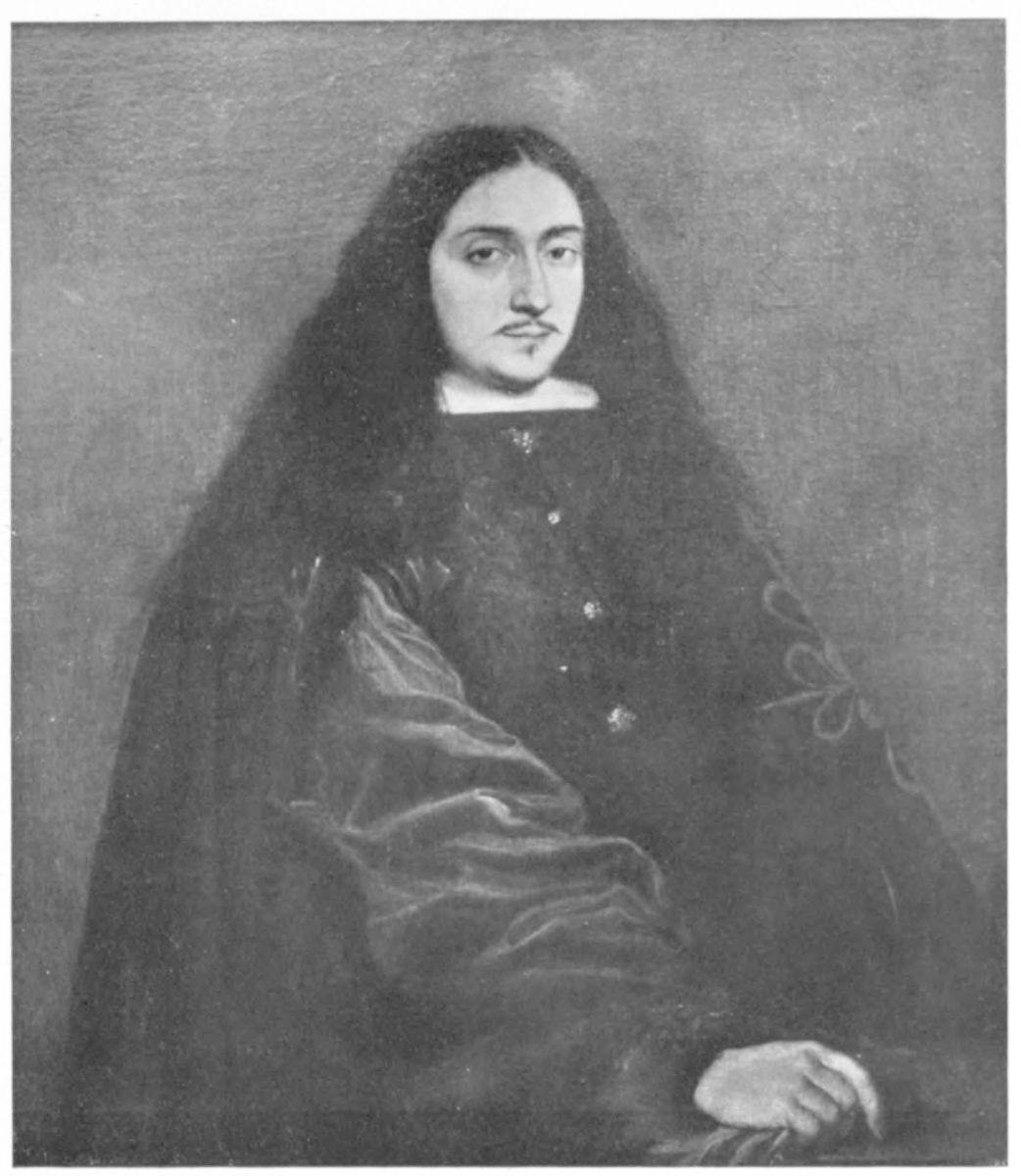

A disciple of Ribalta, the figure of Ribera rises suddenly like that of a great master, with all the distinction which the title implies. Going to Italy while yet very young, he passed the greater part of his life there, and was known as “Lo Spagnoletto” (the little Spaniard). The Italians have tried to appropriate this artist to themselves, but his truly Spanish character is so manifest that no one can entertain any doubt upon the point. On arriving in Italy, he studied the works of Raphael and Correggio, finding his true métier at last in the energy and the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, who then opposed a realistic style to the pseudo-classicism so noticeable at this time. Ribera, whose work exhibits the attributes of Spanish technique, and who above all excelled in drawing, a quality which distinguished him while still very young, naturally found in Caravaggio, the master of the chiaroscuro, more inspiration than in others of the classical painters and those Bolognese eclectics who were afterwards his imitators and rivals. He went to Naples, where he quickly achieved a fame which spread throughout Italy and Spain, his native land, with which he had never lost the most intimate relations as an artist, and here, in Naples, flattered by fortune and with riches heaped upon him, he continued to produce his admirable canvases, until the seduction of his daughter, the most beautiful of all his models, by the second Don John of Austria, the natural son of Philip IV, hastened his end.

The frequency with which he represented tatterdemalions, beggars, martyrs, saints, scenes of violence, of torture, of asceticism, marks, as everyone knows, the style of Ribera in its more superficial sense, and there is scarcely a scene of horror nor a picture of exaggerated tenebrosity belonging to that period and of Spanish tendency, which has not been attributed to him by persons of slight experience, so typical of him are these qualities, in which, moreover, he has no equal. Quite as exceptional are his vigour, his skilful modelling—which has the appearance of sculpture—and the anatomical construction of his figures, the effects of lighting which he knows how to achieve, and the exact appearance of reality, accentuated, but never repugnant, which he accomplishes. Always in touch with reality, two styles are apparent in his work: one, in which he appears to have revelled in violence of contrast, seeking out scenes of grief, old age or death; and another, less frequent it is true, in which he represents the more serene and placid aspects of reality.

It is a pity that the London exhibition did not have a full and brilliant display of the work of this master, as thereby his fame, which to-day is, in our judgment, less than he merits, for reasons expressed above, might have been securely founded. It is necessary to mention among the Valencians of this period Espinosa and Orrente.{13}

In Seville, as we have said, Pacheco was at the height of his fame, the master of all, the fount of culture. But the technique of this school at that time was under the influence of a man of a perplexing and stubborn genius, little suited by character as a guide for youth, but still animated by the Spanish spirit, subtle in technique and possessing a notable force of expression. The young men followed his style, which was in consonance with the progressive tendency of their years. We refer to Herrera el Viejo (the elder) one of the most remarkable painters Spain has ever produced. But it is a curious circumstance that those disciples who worked in the atelier of Herrera, unable to get much guidance from the master, soon betook themselves to the house of Pacheco, who, intelligent and comprehensive, did not attempt to misdirect the temperament and the inclinations of his young pupils, but set them to the task of faithfully interpreting nature.

Zurbarán and Velázquez, the most notable by far of all their contemporaries, protested against the conventionalisms of scholasticism. They did not seek to embellish the rude form, which the living model frequently presents to the eyes of the artist in search of a higher ideal, but to copy it as they beheld it, as it was presented to them, without distortion or falsity, was the purpose which they maintained faithfully all their lives. Pacheco appreciated the talent and outlook of these young men, he protected it as much as he could, and above all cultivated those qualities which seemed to him the most striking. Velázquez said to him: “I hold to the principle that nature ought to be the chief master and swear neither to draw nor to paint anything which is not before me”; and Pacheco, encouraged by the tendency towards a frankly naturalistic style which his disciple showed, and observing the qualities which he evinced, made Velázquez his son-in-law before he had arrived at the age of nineteen.

Among such tendencies the art of Zurbarán and Velázquez was evolved. The works of their youth were almost alike. They are sufficiently distinguished later because, while the first hardly ever left the neighbourhood of Seville, expanding but little, Velázquez, as is known, developed a whole pictorial technique.

Zurbarán was born in 1598. He was therefore a year older than Velázquez. By birth he did not belong to Seville, but to the province of Estremadura. But this notwithstanding, he grew up among the artistic influences of Andalusia, for the young painter arrived in Seville at the age of sixteen years, so that he is regarded as one of the greatest figures of the Sevillean School. For twenty-five years the artist was famous for his figures of virgins and saints, realistic in character, powerful, well drawn, vigorous and conceived without exaggeration, full of life and individu{14}ality. We mention as a work great in conception the Apotheosis of Saint Thomas, housed in the Museum of Seville. It is characteristic of Zurbarán the refractory, who refused to be inspired either by foreign or national influences. This lent him individuality and rendered his productions a series of continuous links between which but little difference can be remarked. He is famous, moreover, for his religious paintings, his monastic visions. These figures of monks in white sheets, which arouse admiration and appear to be carved, such is the relief of their draped folds, are characteristic and full of grandeur, feeling and austerity, and ought to be regarded in the light of actual documents of the monastic life of the Spain of the seventeenth century.

The distinctive feature of the technique of Zurbarán is the luminosity rendered by means of strong contrasts of light and shade. High lights without crudity and shadows without blackness are noticeable, as in the works of Ribera. The grey tones are never heavy, and their quality, harmonious in its blending, diminishes the hardness of the lines of profile, suppressing all rigidity. Zurbarán is, moreover, a painter easily understood, who rarely has recourse to a symbolism more or less appropriate for the expression of thought, and his ideal aspirations always present, in all that refers to form, a manifest passion for reality.

This master was well represented at the Royal Academy. Perhaps there was nothing of great distinction, but the nine works from his brush, all of one kind, were in general very typical and individual, comprising images, saints and figures realistic in character (Plate VIII.).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

We have alluded to the manner of Velázquez’s appearance in Seville and the influences under which he commenced his apprenticeship. A multitude of studies seriously executed, some in black chalk, some in colour, were his first essays. While still a youth he painted a number of those works which still astonish by their reality, by their masterly drawing—a quality with which he was naturally endowed—by their sculptural relief, and by their sobriety. Two works may serve as typical of these, both well-known in England, where they now are, The Old Woman Frying Eggs in Sir Herbert Cook’s collection, and the Water-Carrier of Seville, the property of the Duke of Wellington, which we quote as an example of the style and resolution which the artist bestowed during these years upon works of a popular character, and which, to judge from its subject and models, was then a novelty in a school of painting which had produced scarcely anything except portraits and paintings of a religious kind. Other works of a naturalistic tendency, vulgarly called bodegones, or “eating-house” sketches, and some of a religious character, complete the production of those first years of Velázquez, which was so limited in his{15} later years, that he must be described as a painter whose output was relatively small.

When the artist was twenty-four years of age, his father-in-law, Pacheco, a man of influence, advised him to leave Seville, and himself introduced him to the Court of Philip IV, in whose service Velázquez remained for the rest of his life. He was immediately granted a position and salary at the Court, and his first portraits of the Sovereign and members of the Royal Family aroused surprise and admiration. These, and his first subject compositions painted in Madrid, especially that known as Los Borrachos (“The Topers”), in their high excellence show the culmination of all the qualities found in the works painted in Seville during his first years of apprenticeship. Never has the Spanish picaresque spirit, which forms such a brilliant page in the literature of those times, been given a more genuine representation than is to be observed in the canvas just mentioned. If Velázquez had died after painting Los Borrachos, this work alone would have sufficed to have given him supremacy and the title of leader of a school previously indefinite and lacking a fixed and individual point of view.

A little later, at the command of his King, Velázquez went for the first time to Italy. The influence which Italian art exercised upon him has been the subject of discussion. It is not possible in an essay such as this to try to elucidate this point, but it appears manifest that if Italian art was naturally absorbed by his talent, it did not greatly affect his native qualities; and to judge from his subsequent work, it would seem that he showed a constant and single-minded solicitude to achieve an interpretation always actively faithful to nature.

The picture Las Lanzas (“The Lances”); the equestrian portraits of kings, princes and others, in which these personages appear dressed in hunting costume; those of the buffoons of the Court; the Scenes of the Chase in the mountains of El Pardo; and some others of a different type, such as the Christ on the Cross, in the Prado Museum, make up the tale of his output after his brief stay in Italy, and compose what critics have called the second style of Velázquez, more ample and grand than that of his youth, and, as time advances, enriching all the works which come from his brush with those definite grey harmonies which are occasionally almost silvery in tone, so characteristic and so unmistakable.

The painter was for a second time in Italy in the period of his maturity. He then painted the portrait of Pope Innocent X, and executed a bust of Juán de Pareja, which was on view in the exhibition at Burlington House. Returning soon afterwards to Spain, he there addressed himself to the accomplishment of his greater works, which truly reveal a superior art, somewhat enigmatical in its very simplicity, a sublime style which at{16} first sight does not seem to require much comprehension and the view-point of which has given to the Spanish School of all times, as well as to other schools, rich legacies, excellent examples and notable fruits. There belongs to this epoch of his artistry the portraits of kings and princes, the second series of the court dwarfs, even more rich and astonishing than those of the period of his middle years, some religious pictures, mythological works and, lastly, the two great works Las Hilanderas (“The Spinners”) and Las Meninas (“The Maids of Honour”) (Plates X. and Plates XI..), supreme monuments of a school, models of synthetic art, of astonishing simplicity in their composition, of delicate harmony, eloquent of the study of values, masterpieces, in short, of sublime painting, which, of an apparent modesty, are, notwithstanding, magical works, spontaneous creations, which shew neither exertion, weakness, nor weariness, and which seem to us the result of an art serene and calm, contrary to the influences of great idealistic conceptions, but which, essentially objective, reproduce the natural with a truth which is unsurpassed.

In the exhibition at Burlington House Velázquez was not adequately represented. But there were reasons for this. The undoubted pictures from his brush which are privately owned in England, and to some of which we have already alluded, are well-known and have figured in recent exhibitions of Spanish art, so that it was not deemed necessary to expose them again; while of those in Spain, the greater part is housed in the Prado Museum (and could not of course be sent to England), and those belonging to private persons are very scarce.

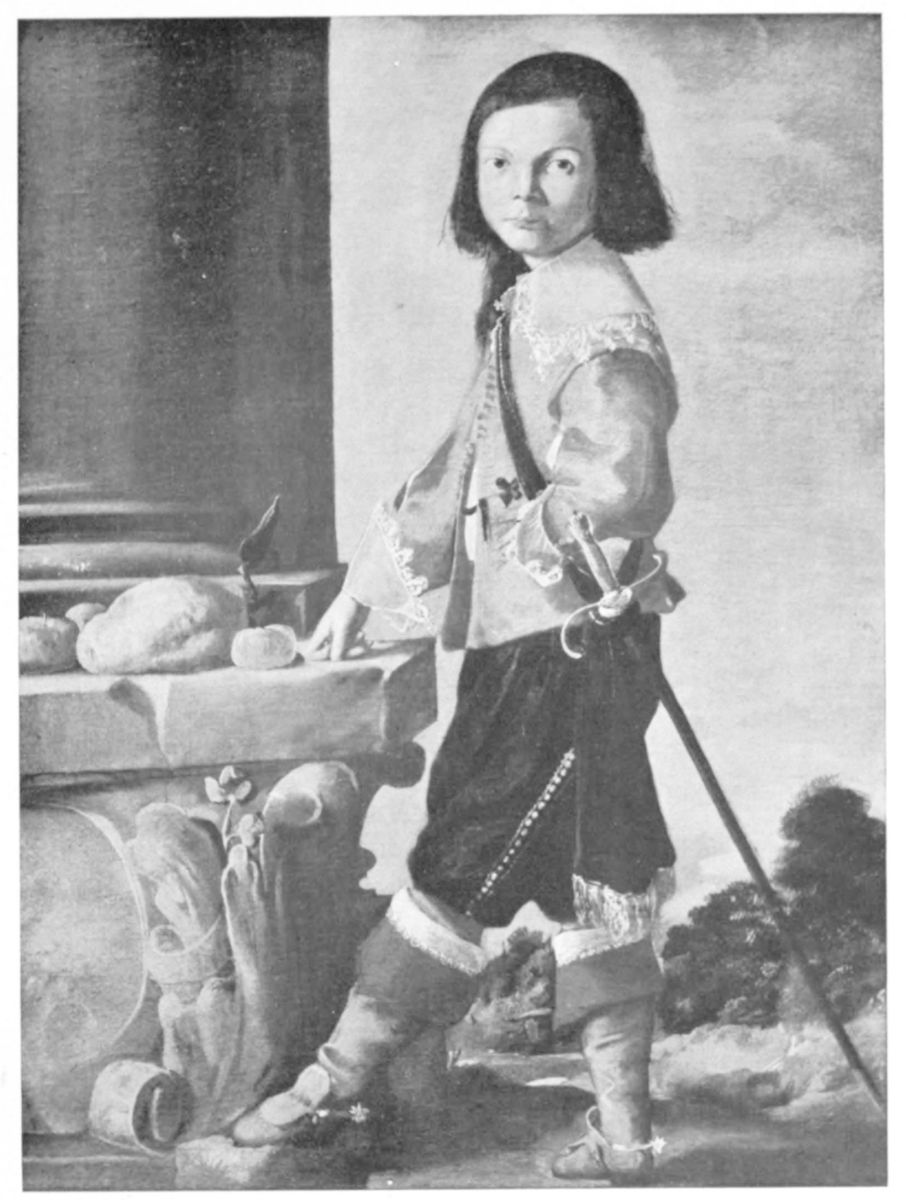

The examples from English collections were the magnificent portrait of Juán de Pareja, the Painter, from Longford Castle; the bust of A Spanish Gentleman, the property of the Duke of Wellington; Calabacillas, the Buffoon (Plate IX.) which has recently passed into Sir Herbert Cook’s collection; The Kitchen Maid, in Sir Otto Beit’s collection—all representative of a period of the artist—as well as the portrait of Don Baltasar Carlos, Infante of Spain, which His Majesty the King of England lent from Buckingham Palace.

Of this last special mention must be made. In our judgment it is an undoubted Velázquez and, moreover, a most beautiful example. Every part of the armour, of the legs, of the body, and, above all, the adjustment of the figure and the design are typical of Velázquez. How has it come to be regarded in England as a work of Mazo, where the master is so justly esteemed and where, owing, doubtless to enthusiasm for Velázquez, nearly all the pictures of Mazo are attributed to Velázquez? Or is it that some have arrived at false conclusions concerning Mazo and Velázquez, and when they are confronted by an original and undoubted Velázquez, are dubious of it because it does not appear sufficiently typi{17}cal of Mazo? It has not, to the best of our belief, elsewhere been observed that the head of this portrait is somewhat faint and flat.

From Spain there were sent The Hand of an Ecclesiastic, lent by His Majesty the King of Spain, a fragment, without doubt, from a portrait of which the remainder was lost in the burning of the Alcazar of Madrid. The special interest of the said fragment is that the hand holds a paper on which is the signature of Velázquez, assuredly, one of the three authentic signatures of this artist which remain to us, the others being found on the portrait of Philip IV, in the National Gallery, London, and that of Pope Innocent X, in the Doria Gallery at Rome. Concerning the portrait of Pulido Pareja in the National Gallery, London, we have already written at some length on another occasion, with the intention of proving that this portrait is by Mazo, and that the signature is consequently apocryphal. The Portrait of the Artist, from the Fine Art Museum, Valencia, is a beautiful example, if somewhat damaged and blackened, and the other three works shown have been more frequently exhibited and studied than those which are of undoubted authenticity. Among others of outstanding interest is the Head of a Cleric, the property of the Count of Fuenclara, which, although its attribution is not unquestioned, is remembered above all as a beautiful piece of work.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

We must now commence the rather complex study of those paintings which compose the Madrid School. We say complex, because, composed as it was of painters who came from one or the other part of the Peninsula, it does not possess a precise and regional character, but is the resultant of the work of many artists whose names we must not forget, as, for example, Carducho, Caxes and Nardi, of Italian origin, who, or perhaps their fathers, were brought to Spain as decorative painters. It seems natural that they should have had imitators or disciples, as it was precisely in the country of their adoption that artists of this genre were awanting. But, on the contrary, they were absorbed by the environment, and produced and achieved a sober and realistic style, forgetful of the circumstances of their apprenticeship, and, we may say, hispanicised.

Velázquez was the chief representative of the Madrid school, its creator, and, more, its prototype, marking the apogee of Spanish painting. His aim was always to simplify, a purpose which is clearly obvious from the methods he employed from his youth to his last work, constantly simplifying his technique and, consequently, his palette. To the study of his palette alone we have dedicated a work of a purely technical character (of which The Studio of November 1920 printed an extract) which space does not permit us to reproduce here, but which we take occasion to refer to since the simplification of the palette of this artist, the creator of{18} a school, must be regarded as of exceptional importance, as characteristic of almost all later Spanish artistic achievement, endowing it with great individuality and distinguishing it from all other schools. This circumstance is worthy of recognition by all who wish to arrive at the true significance of Spanish painting, so far as its outward manifestations are concerned.

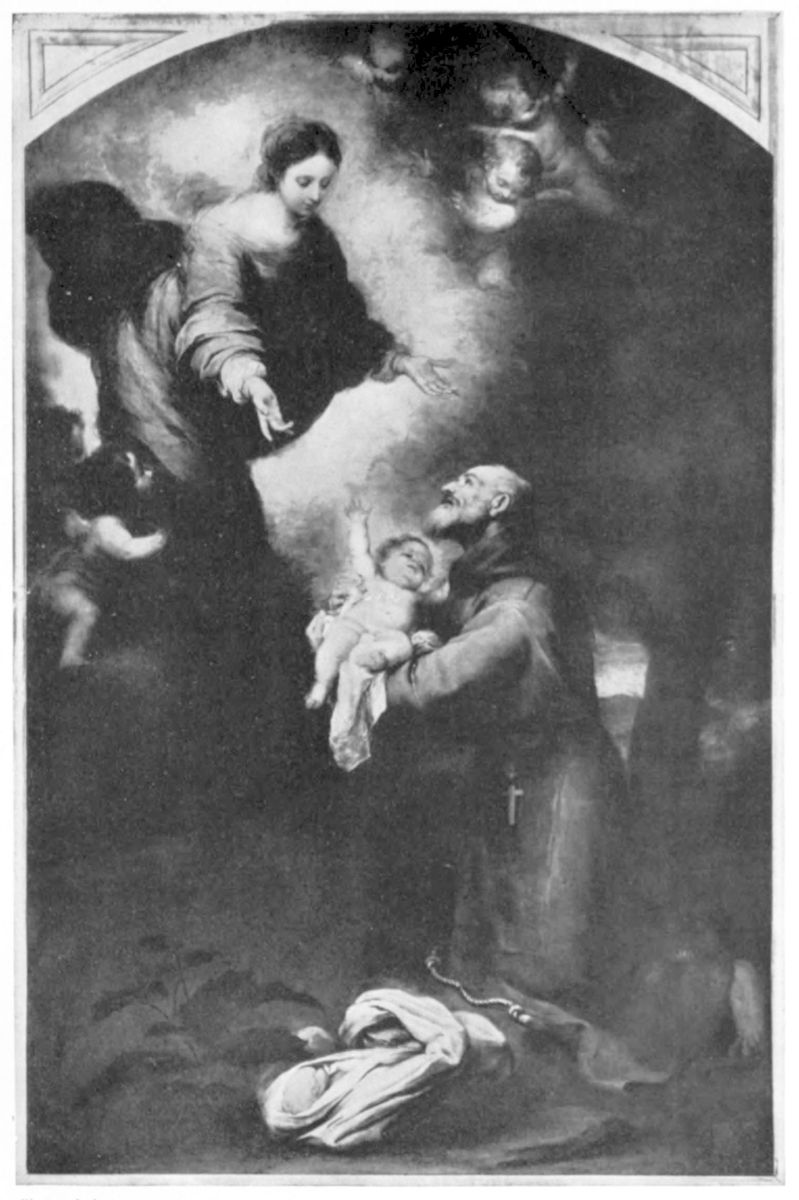

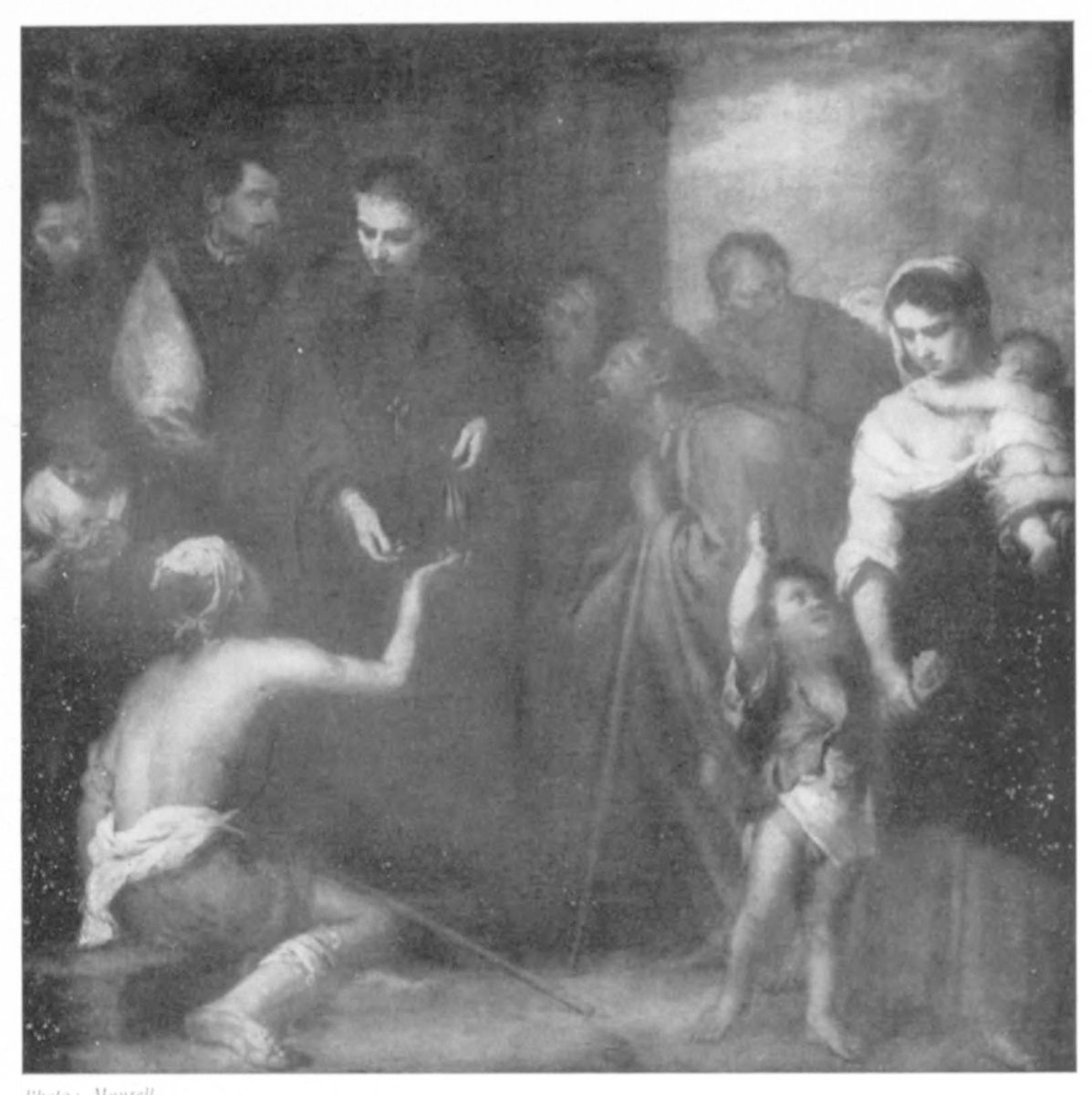

Before dealing with the continuators of Velázquez, we must briefly refer to painting in Andalusia, where Murillo appears as a great force in Seville, years after Velázquez had been so in Madrid. Murillo, at first a disciple of his kinsman Castillo, was soon afterwards a follower of Pedro Moya. The painter passed during his youth through a whole gamut of influences, that of Van Dyck especially, alternating at times with that of Ribera. At twenty-four he was in Madrid, where Velázquez worked and taught, though only for a short time. When he returned to Seville he did not forget the lessons of Velázquez, and from this period date those popular figures, full of character, which began to bring him fame. Later, Murillo altered his methods, and for the rest of his life employed a style suave and soft as the Andalusian accent, graceful and suggestive. His religious works, his Virgins, and, above all, his Conceptions were soon famous, and, an incessant worker, he left a multitude of paintings which bear a personal and unmistakable stamp, and reveal an adequate technique, ample in treatment, in a tonality of varying greys, warm and glowing and without exaggeration.

But in truth the art of Murillo is of less interest than formerly, owing to present-day preferences, which seek spirituality in art, a force and even a restlessness which we do not find in the work of this artist. But his fame in his own day was very great, and for a long time he was considered as the foremost of Spanish painters. What gave him such a great reputation? The illustrious Spanish critic, Señor Cossío, has asked the same question regarding the causes underlying a style so direct and simple. Murillo’s subject-matter, says Señor Cossío, in the background as in the thing portrayed, represents always the soft and agreeable side of life. In the sphere of spontaneous creation, in that which does not require profundity, nor reflection, Murillo always exerts an irresistible attraction. His Conceptions are beautiful but superficial. There is in them no more skilful groundwork, dramatic impulse, nor exaltation than appears at first sight. To comprehend and enjoy them it is not necessary to think, their contemplation leaves the beholder tranquil, they do not possess the power to distract, they have no warmth, nor that distinction which makes a work unique, and as they hold just that degree of cultured mediocrity which in thought and feeling is the patrimony of the majority of people, they are able to please accordingly. If there be added to this a pious{19} and poetic sentiment and the celestial and suave expression of his figures, it is easy to understand the great, indisputable and just popularity which Murillo has enjoyed. Velázquez thought profoundly, but with ideality; Murillo has not idealism, nor is he profound. Both are realists, and if one represents the masculine feeling in Spanish painting, the other shows at its highest the feminine tendency.

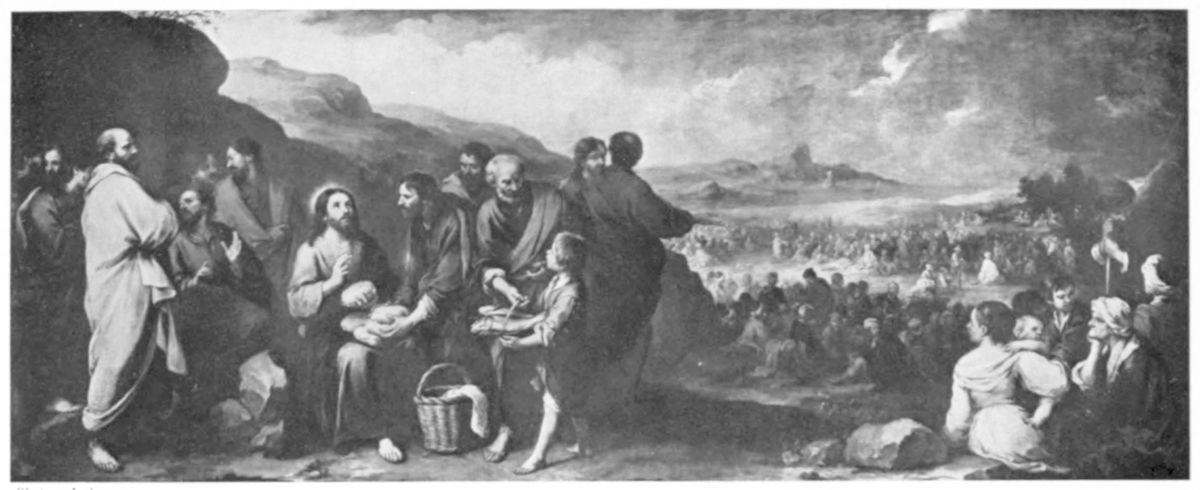

At the Royal Academy seven pictures of Murillo, some of real importance, were shown. Amongst these religious subjects predominated, San Leandro and San Buenaventura, from the Museum of Seville, and The Triumph of the Holy Eucharist, lent by Lord Faringdon. Among the portraits were that of the artist, the property of Earl Spencer; Gabriel Esteban Murillo, sent by the Duke of Alba and Berwick; and Don Diego Félix de Esquivel y Aldama, from a private collection in Madrid.

In alluding to the Sevillean school, we must mention a contemporary of Murillo, though somewhat his junior, of singular talent. His name is little known outside of Spain, and this is doubtless the reason why so few of his pictures have left the country. We believe it a mistake to allude to him, as is sometimes done, as one of those Spanish painters whose work is no longer of interest, such is his expression, his distinctive note, his creative boldness and individuality. We refer to Valdes Leal. His harsh outlook, his frequent inaccuracies, his thought, profound and almost always obscure, and above all, his subjects, at times macabre and bizarre, at times graceful, provide reasons for his unpopularity, no less than the still scanty knowledge we possess regarding this singular man, the circumstances of whose work and life are presented to us almost in a legendary manner, as in the case of his friend and patron, Don Juán de Mañara, who has been incarnated in the popular imagination as the Don Juán of tradition.

In Granada, Alonso Cano, as great a sculptor as painter, maintained, with other artists of lesser note and standing, a flourishing school which had links with that of Seville.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

We turn again to Madrid, to the Court where Velázquez, as we have indicated, stamped such character on painting and informed it with such excellence that artists flocked from all parts of the Peninsula to the capital. This resulted in the flourishing period of art—ending with the seventeenth century—fruitful and various, which is associated with the School of Madrid. It is not precisely the school of Velázquez, although equivocally so called. Velázquez had disciples who followed him, imitating and copying him, as his servant Pareja, the mulatto, did. But this notwithstanding, other painters of talent worked during these years{20} in the capital, helping to form the school, even if they did not follow him in any decided manner. Nevertheless, he is its greatest figure, for he it was who gained the title of a school for the work of his contemporaries, and for the generation which followed him. The impulse which he gave by his technique and the composition of his palette, simple and sober, are characteristic of all this period. His son-in-law, Mazo, followed him blindly, and, working in his studio, was constantly impressed by the productions of his master, making use of the same methods—the same canvas, colours, brushes, and, giving rein to an extraordinarily imitative talent, he tried to make, and occasionally produced, actual facsimiles of his master’s works. The study of this curious problem of painting, of the distinctive note, the inclination of the time, as shown in the art of father-in-law and son-in-law, has been the subject of several works from our pen. We have not insisted on the point in these, nor have we space to do so in this brief synthesis; but we flatter ourselves that several paintings, especially those which belong to museums, have come to be more correctly attributed to Mazo rather than to Velázquez, and that those who are interested in these problems have come to distinguish the external aspect of the work of the one from that of the other, substantial and inimitable. We must remark, however, that Mazo had, besides the mere qualities of an imitator, a talent of his own of singular excellence, that of a landscape painter, which represented a relative novelty in the art of Spain at that period.

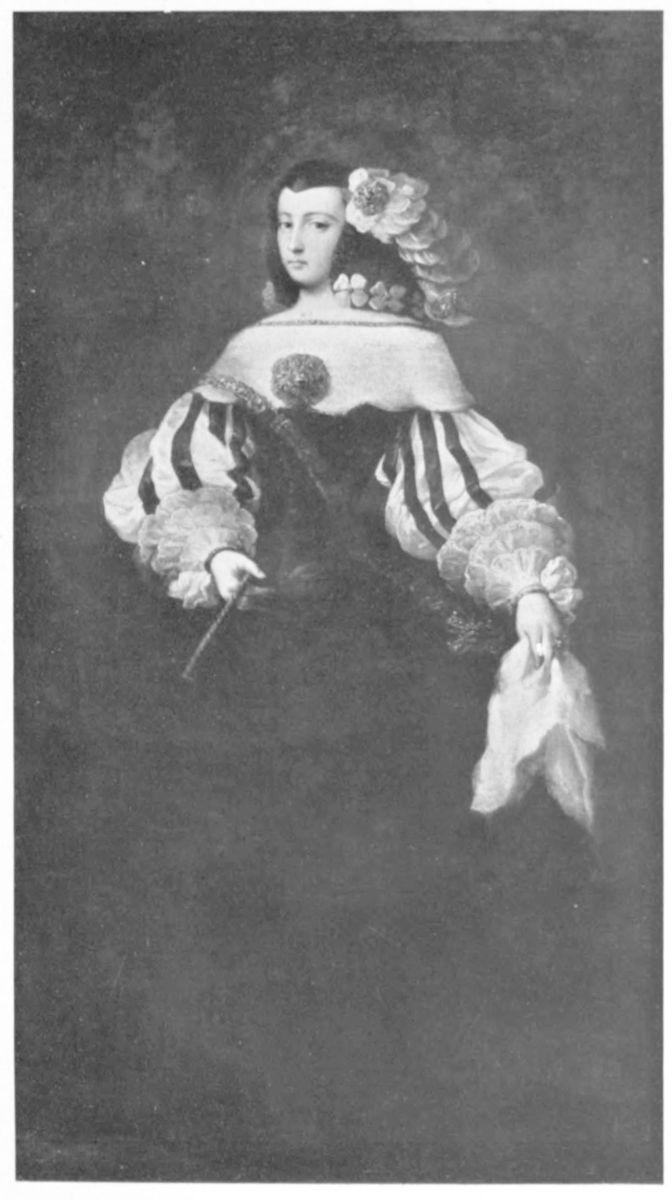

After Velázquez the most important painter of the School of Madrid is, beyond dispute, Carreño. Though his religious canvases are numerous, Carreño was, above all, a portrait painter. The relative influence of the work of Van Dyck, which extended as far as Seville, also reached Madrid, and Carreño came under it at times and discreetly made use of it. We say discreetly, for he had lost his national qualities. He borrowed from Velázquez the basic colours of his palette, but sought to enrich them with certain warm, golden tones, and he was enamoured of russets and, above all, of carmines, generally those which approximate to the colouring of the Flemings, but which appear cloying beside the works of Van Dyck. The portraits by Carreño were represented at the exhibition by that of A Young Lady (Plate XXII.), belonging to the Duke of Medinaceli, which might almost be described as a black-and-white from its colouring and the evident purpose of the artist to preserve this tonality throughout the work; that of The Queen of Spain, Doña Mariana de Austria, the property of Don Ramón de la Sota, a most beautiful example, from which, without doubt, have been taken the many repetitions which are known of it besides other variants; and that of The Marchioness of Santa Cruz, which is of great importance and very characteristic. Of religious{21} pictures it is necessary to mention The Apparition of the Virgin to Saint Bernard, sent from Bilbao by Don Antonio Plasencia.

The two brothers Rizi, Juan and Francisco, were of Italian origin; both were decorative painters and worked in the style of Carducho and Caxes. Juan, the elder, was a monk, and was one of the prototypes of the School of Madrid, following Velázquez in his work, soberly and simply. Francisco seems at times to display the qualities of his Italian origin, and though sufficiently Spanish, gave to his creations a certain quality which may have influenced the Spanish decorative painters of the time. It is a curious problem of influence. In any case this artist, who achieved fame in his time, is an interesting study to-day, and it would seem that the critic must scrutinize the beginnings of the question before he tries to explain its results. Pereda, Collantes and Leonardo are also notable, if lacking the character of their school, which clearly shows them to be among the disciples of Carreño, among whom, perhaps, the most notable were Cerezo and Cabezalero, who unfortunately died young. Cerezo seems to be the most striking figure of those years, and his brilliant colour and fine style initiated a tendency which made for the enrichment of the Spanish palette, the sobriety of which we admire in the masters, but which degenerates into a certain poverty at times in the hands of their disciples. With Cerezo we should mention Antolínez, who also died before he reached artistic maturity.

We now reach that era of painting which flourished at the Court of Spain during the remainder of the seventeenth century. A long list of names of artists could be made, all estimable and some remarkable, who exhibited the proverbial vigour and picturesque temperament of the race, which, skilfully directed, and having received a noble and traditional tendency, commenced its onward progress without faltering. We mention, however, only Claudio Coello, who seems to close this period. A disciple of Rizi, whose decorative tendency he followed, he was more an artist in a general sense than a portrait painter, and above all he produced many religious subjects. By his work The Sacred Form, which is kept in the Escurial, he seems to be sealed to the School of Madrid. This picture is obviously a result of the atmosphere and the taste of the period in its fidelity to character and its happy solution of problems of perspective and effects of light.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For Spain the eighteenth century was a period of misfortune. The reasons for this are simple and evident. Grace and good taste—in the best sense of the term—lightness, came to be the characteristics of this century, and these qualities were displayed in a perfect manner in French art. And it was precisely these attributes which Spanish artists most{22} lacked, and still lack. They are robust, strong and sincere, but without gracefulness, facility of expression or volatility. A propos of this, it must be recalled that Spanish artistic expression appears to have been more or less influenced in its development by foreign tendencies which were allowed to work freely and with absolute spontaneity. The eighteenth century was a period in which the most powerful external influences, especially the French, the least adaptable to the Spanish temperament, had full play. These external influences were wholly ordained by the rule of the House of Bourbon, and incarnated in the first of its monarchs, Philip V, nephew of Louis XIV, who, doubtless meaning well, seemed to think it possible to transplant Versailles, with its marvellous spirit and exquisite culture, to the Castilian cities, which were still dominated by the sobriety and asceticism of the mystics of past centuries.

As regards painting, these influences commenced with the arrival at the Court of Lucas Jordán, who represented the influence of the great Italian decorative artists. Afterwards came Tiépolo, who left many marvellous works, quite inimitable by Spanish artists. The Bourbons introduced Van Loo, Ranc, Houasse and other French representatives of the art of the time; and lastly came Mengs, bringing with him a spirit wholly distinct from that of the French, a style erudite and academic which was not sufficiently powerful to create an artistic output of any importance in Spain, but which possessed much destructive power, although that was limited as regards time to about a century, during which period the national production was weak, despite the number of artists, of whom those most worthy to be mentioned are Maella, the Bayeus and Paret.

Such was the condition of Spanish painting when, without precedent, reason or motive, appeared in the province of Aragon, a region which years afterwards came to typify the resistance to foreign invasion, a figure of great significance in Spanish art, and worthy of comparison with the greatest masters of the preceding centuries—Francisco de Goya.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

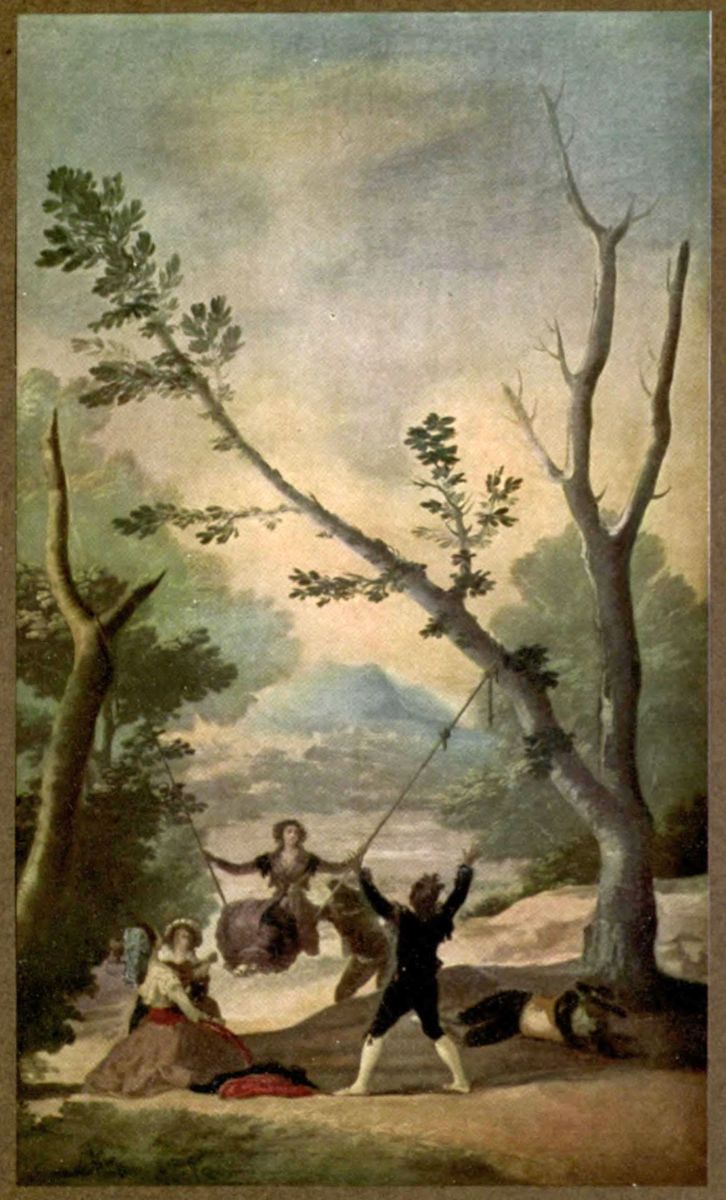

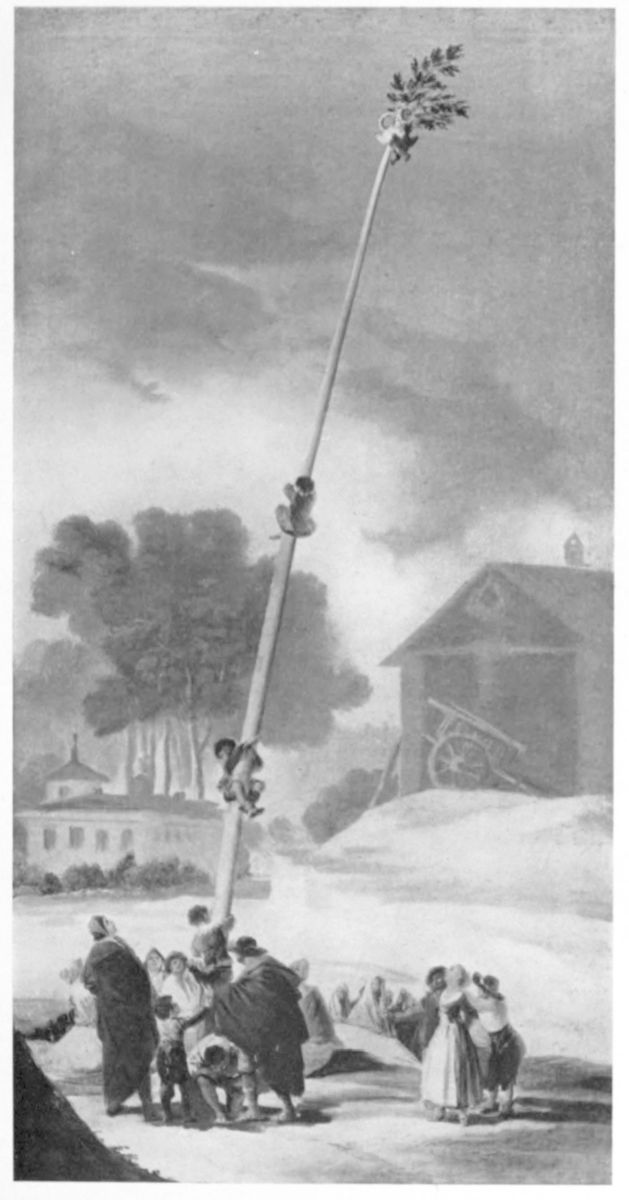

The long life of Goya coincides with an epoch which divides two ages. The critic is somewhat at a loss how to place his work and personality, to conclude whether he is the last of the old masters or the first of the moderns. His greatness is so obvious, his performance so vast and its gradual evolution so manifest, that we may be justified in holding that the first portion of his effort belongs to the old order of things, while the second must be associated with the origins of modern painting. In his advance, in the manner and development of it, it is noticeable—as we have already said in certain of our works which deal with Goya—that he substituted for the picturesque, agreeable and suggestive note of his younger days, another more intense and more embracive. It would{23} seem that the French invasion of the Peninsula, the horrors of which he experienced and depicted, influenced him profoundly in the alteration of his style. There is a Goya of the eighteenth century and a Goya of the nineteenth. But this is not entirely due to variation in technique, to mere artistic development, it is more justly to be traced to a change in creative outlook, in character, in view-point, which underwent a rude and violent transformation. Compare the subjects of his tapestries or of his festive canvases, joyful and gallant, facile in conception and at times almost trivial, with the tragic and macabre scenes of his old age, and with the drawings of this period and the compositions known as “The Disasters of War.”

His spirit was fortified and nourished by the warmth of his imagination, and assisted by an adequate technique, marvellously suited to the expression of his ideas, he produced the colossal art of his later years. If his performance is studied with reference to the vicissitudes and the adventures of which it is eloquent, the influence upon his works of the times in which they were created is obvious. The changes in his life, the transference from those gay and tranquil years to others full of the horrors of blood and fire, of shame and banishment, tended, without doubt, to discipline his spirit and excite his intelligence. His natural bias to the fantastic and his tendency to adapt the world to his visions seized upon the propitious occasion in a time of invasion and war to exalt itself, or, as he himself expressed it, “the dream of reason produces prodigies.”

An artist and creator more as regards expression than form, especially in the second phase of his work, unequal in achievement and at times inaccurate, he sacrificed much to divest himself of these faults. He deliberately set himself to discipline his ideas and develop that degree of boldness with which he longed to infuse them. But he was not quite able to subject himself to reality, and, as he was forgetful and indolent, that which naturally dominated him began to show itself in quite other productions of consummate mastery. This art, imaginative in expression and idea, is more striking as regards its individual and original qualities, than for any degree of discipline which it shows.

To follow Goya throughout the vicissitudes of his long life is not a matter of difficulty. The man to whom modern Spanish art owes its being was born in the little village of Fuendetodos and lived whilst a child at Saragossa. He came to Madrid at an early age, and before his thirtieth year went to Rome with the object of perfecting himself in his art. But he failed to obtain much direction at the academies in Parma, and having but little enthusiasm for the Italian masters of that time, returned to Spain, settling at Madrid. Until this time the artist had not evinced any exceptional gifts. Goya was not precocious. The first works to assist his repu{24}tation were a series of cartoons for tapestries to be woven at the Royal Factory. They were destined for the walls of the royal palaces of Aranjuez, the Escurial and the Prado, which Carlos IV desired to renovate according to the fashion of the time. These works, which brought fame to Goya, showed two distinctive qualities. One of them evinces the originality of his subjects, in which appear gallants, blacksmiths, beggars, labourers, popular types in short, who for the first time appeared in the decoration of Spanish palaces and castles, which, until then, had known only religious paintings, military scenes, the portraits of the Royal Family and stately hidalgos. Goya, in this sense, democratized art. The other note to be observed in his work is a certain distinction of craftsmanship, the alertness which it reveals, which is, perhaps, due to the lightness of his colouring. On canvases prepared with tones of a light red hue, which he retained as the basis of his picture, he sketched his figures and backgrounds with light brushes and velatures, retaining, where possible, the tone of the ground. This light touch, rendered necessary by the extensive character of the design and the rapidity with which it had to be executed, gave to the artist a freedom and quickness in all he drew, and from it his later works, much more important than these early essays though they were, profited not a little.

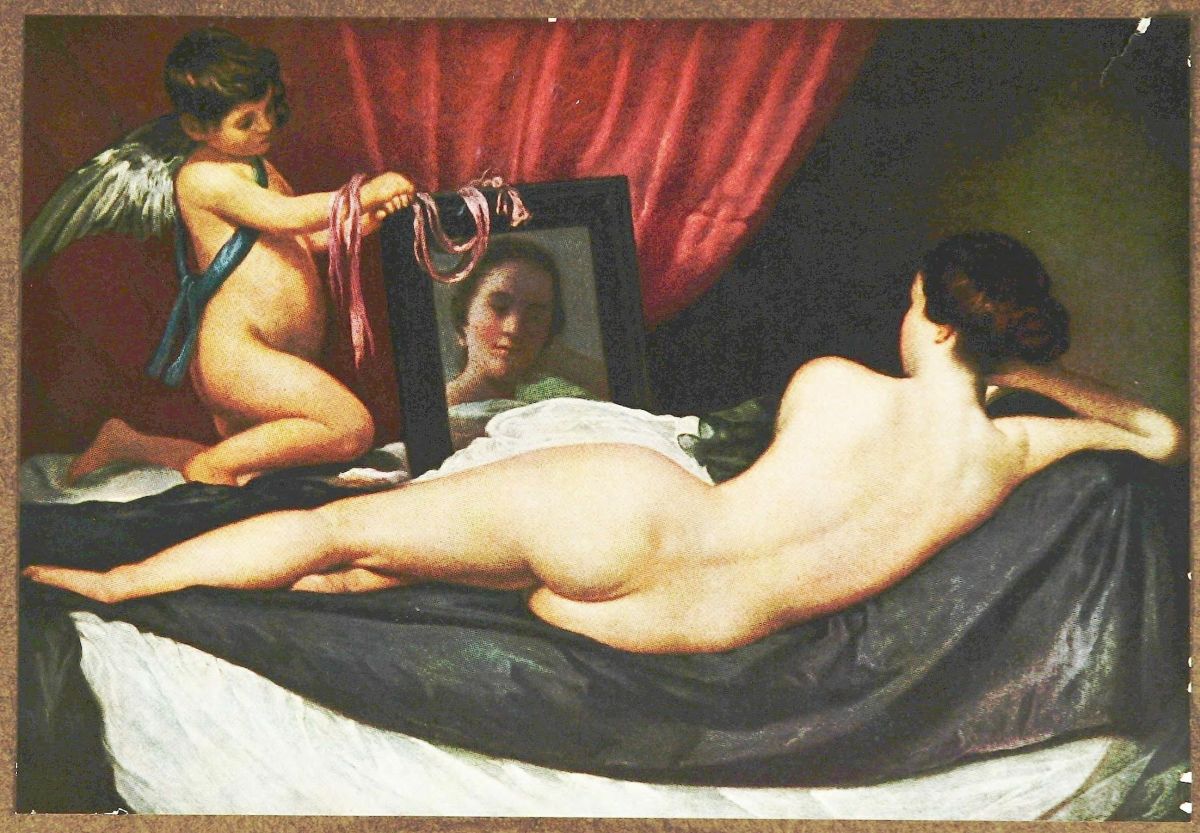

Already during these earlier years he had commenced to paint portraits which did much to enhance his reputation, and shortly afterwards he entered the royal service as first painter to the Court, where he addressed himself to the execution of that vast collection of works of all kinds which arouse such interest to-day. The list is interminable and embraces the portraits of Carlos IV and of the Queen Maria Louisa, those of the members of the Royal Family, of all the aristocracy, of the Albas, Osunas, Benaventes, Montellanos, Pignatellis, Fernán-Núñezs, the greatest wits and intellectuals of the day, especially those of Jovellanos, Moratin, and Meléndez Valdés, three men who profoundly influenced the thought of Goya in a progressive and almost revolutionary manner, in spite of his connection with the Court and the aristocracy. He also painted many portraits of popular persons, both men and women, among whom may be mentioned La Tirana, the bookseller of the Calle de Carretas, and that most mysterious and adventurous of femmes galantes of whom, now clothed, now nude, the artist has bequeathed to us those souvenirs which hang on the walls of the Prado Museum. In these the artist has for all time fixed and immortalized the finest physical type of Spanish womanhood, in which an occasional lack of perfect proportion is compensated for by elegance, grace, and unexaggerated curve and figure, without doubt one of the most exquisite feminine types which has been produced by any race. Besides these, the artist produced many lesser canvases{25} containing tiny figures full of wonderful grace and gallantry, and having rural backgrounds, frequently of the banks of the Manzanares, and others of larger proportions and scope, among the most excellent of which is that of the family of Carlos IV, treasured in the Prado Museum as one of its most precious jewels. Along with The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (Plate V.) and Las Meninas (Plate X.), this picture may be regarded as the most complete and astonishing which Spanish art has given us. It is not a “picture” in the ordinary sense of the word, but an absolute solution of the problem of how colour harmonies are to be attained, and a most striking essay in impressionism, in which an infinity of bold and varied shades and colours blend in a magnificent symphony.

Goya, triumphant and rejoicing in a life ample and satisfying, received on all sides the flatteries of the great, and, caressed by reigning beauties, lived in the tranquil pursuit of his art, which, though intense, was yet graceful and gallant, and, as we have said, still adhered to the manner of the eighteenth century, when a profound shock agitated the national life—the war with Napoleon and the French invasion. The first painter to the Court of Carlos IV, a fugitive, deaf, and already old, life, as he then experienced it, might have seemed to him a happy dream with a terrible awakening. His possessions, his pictures, and his models were dispersed and maltreated; the Court seemed to have finished its career, for his royal master was banished by force, many of the nobility were condemned to death, and Countesses, Duchesses and Maids of Honour vanished like the easy and enjoyable existence he had known. Above all, Saragossa, that heroic city, beleaguered on every side, was closed to him; a depleted army defended the strategical points of the Peninsula, and the people—the people whom Goya loved and who had so often served him as models for his damsels, his bull-fighters, his wenches, his little children—were wandering over the length and breadth of Spain, only to be shot as guerillas and stone-throwers by the soldiers of Napoleon. It was at this moment that the true development of the artist began. The painter, like his race, was not to be conquered. The old Goya remained, strong in the creation of a lofty art. The last twenty years of his life were full indeed, and represented its most vigorous phase, the most energetic in the whole course of his achievement. Scenes of war and disaster occupied almost the whole of this important period, full of a profound pessimism, which still does not lack a certain graceful style, and displays unceasingly some of the saddest thoughts which man has ever known. These works of Goya are not of any party, are not political nor sectarian. They are simply human. For his greatness is all-embracive and his might enduring. Typical of his work in this last respect are The Fusiliers, of 1808, and his lesser efforts, those scenes of brigandage, madness, plague{26} and famine which occur so frequently in his paintings during the years which followed the war.

We do not mean to make any hard and fast assertion that Goya would not have developed in intensity of feeling if he had not personally experienced and suffered the horrors of the invasion, but merely to indicate that it was this which brought about the revulsion within him and powerfully exalted him. His last years in Madrid, and afterwards in Bordeaux, where he died, were always characterized by the note of pessimism, and at times, of horror, as is shown in the paintings which once decorated his house and are now preserved in the Prado Museum. Not a few portraits of these years also show that the artist gained in intensity and in individual style. It is precisely these works, so advanced for their time and so progressive, that provided inspiration to painters like Manet, who achieved such progress in the nineteenth century, and who were enamoured of the visions of Goya, of his technique and his methods, naturalistic, perhaps, but always replete with observation and individual expression.

We must not forget to mention that Goya produced a decorative masterpiece of extraordinary distinction and supreme originality—the mural painting of the Chapel of St. Antonio of Florida, in Madrid. Nor is it less fitting to record his fecundity in the art of etching, in which, as in his painting, it is easy to observe the development of their author from a style gallant and spirited to an interpretation of deep intensity, such as is to be witnessed in the collection of “The Caprices” and “The Follies,” if these are compared with the so-called “Proverbs” and especially with “The Disasters of War.”

The pictures representing Goya at Burlington House were composed of some twenty works. Among those which belonged to his first period were the portraits of the Marchioness of Lazan, the Duchess of Alba, lent by the Duke of Alba, “La Tirana,” from the Academy of St. Fernando, the Countess of Haro, belonging to the Duchess of San Carlos, four of the smaller paintings of rural scenes, the property of the Duke of Montellano, and An Amorous Parley (“Coloquio Galante”), the property of the Marquis de la Romana, the prototype of the Spanish feeling for gallantry in the eighteenth century. As representative of the second phase, of that which holds a note intense and pessimistic, may be taken A Pest House, lent by the Marquis de la Romana, and those truly dramatic scenes, the property of the Marquis of Villagonzalo.

Of portraits of the artist by himself two were exhibited, one small in size painted in his youth (Plate XXVI.), in which the full figure is shown, and the other a head, done in 1815, which gives us a good idea of the expression and temperament of this extraordinary man.{27}

The influence of the art of Goya was not immediate. A contemporary of his is to be remembered in Esteve, who assisted him and copied from him. Later, an artist of considerable talent, Leonardo Alenza, who died very young and had no time to develop his art, was happily inspired by him. With regard to Lucas, a well-known painter whose production was very large, and who flourished many years later, and is now known to have followed Goya, he can scarcely be considered as one of his continuators, but rather as an imitator—by no means the same thing. For he imitated Goya, as, on other occasions, he imitated Velázquez and other artists. Lucas is much more praiseworthy when he follows his own instincts and does original work. His picture The Auto de Fé, the property of M. Labat, which was shown at the London exhibition in the room dedicated to artists of the nineteenth century, is one of the best that we know of from his brush.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

If the eighteenth century was for Spanish painting an epoch of external influences, the nineteenth century, especially its second half, must be characterized as one which sought for foreign direction. During this period the greater number of painters of talent sought for inspiration from foreign masters. This was a grave mistake, not because in Spain there were artists of much ability or even good instructors, but because this exodus of Spanish painters was a sign that they had lost faith and confidence in themselves and were strangers to that native force which in the end triumphs in painting as in everything else. First Paris, then Rome, the two most important centres of the art of this period, were undoubtedly centres of a lamentable distortion of Spanish art.

The organizing committee did not wish the London exhibition to be lacking in examples of this period of prolific production, to which they dedicated a room in which were shown examples of the painters of the nineteenth century. We mention some of the many artists of talent of the Spain of those days, and indicate their individual characteristics; but we are unable to allude to their general outlook and the characterization of their schools, which we do not think existed among them to any great extent.

The most famous painter who succeeded Goya was Vincente López, better known for his portraits than for his other canvases, a skilful artist with a perfect knowledge of technique, conscientious, fecund, minute in detail, who has left us the reflection of a whole generation.