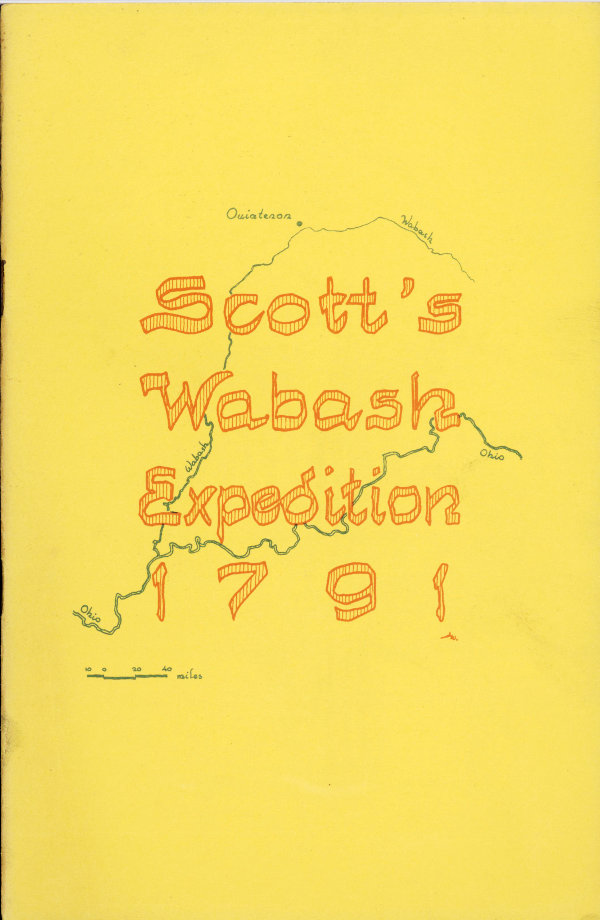

Title: Scott's Wabash Expedition, 1791

Creator: Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County

Release date: March 15, 2021 [eBook #64829]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Prepared by the staff of the

Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County

1953

One of a historical series, this pamphlet is published under the direction of the governing Boards of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE SCHOOL CITY OF FORT WAYNE

PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD FOR ALLEN COUNTY

The members of this Board include the members of the Board of Trustees of the School City of Fort Wayne (with the same officers) together with the following citizens chosen from Allen County outside the corporate City of Fort Wayne:

General Charles Scott played an active role in the establishment of the United States foothold in the Northwest Territory. He participated in General Josiah Harmar’s ill-fated expedition in 1790, in the campaign of General Arthur St. Clair in 1791, and also in General Anthony Wayne’s triumph at Fallen Timbers in 1794.

While St. Clair was preparing his army in 1791, he sent Scott, with about eight hundred Kentucky volunteers, into the Wabash region around the Indian town of Ouiatenon to distract the attention of the Indians. That Scott was more successful than his commander was destined to be is shown in his report to the Secretary of War, printed later as a letter in the INDIANAPOLIS GAZETTE. It is reprinted here with changes in grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

Sir:

In prosecution of the enterprise, I marched (with eight hundred and fifty troops under my command) four miles from the banks of the Ohio on May 23. On the twenty-fourth, I resumed my march and pushed forward with the utmost industry. I directed my route to Ouiatenon in the best manner my guides and information enabled me, though both were greatly deficient.

By May 31, I had marched one hundred and fifty miles over a country cut by four large branches of the White River and by many smaller streams with steep, muddy banks. During this march, I crossed country alternately interspersed with the most luxurious soil and with deep clay bogs from one to five miles wide, which were rendered almost impassable by brush and briers. Rain fell in torrents every day, with frequent blasts of wind and thunderstorms. These obstacles impeded my progress, wore down my horses, and destroyed my provisions.

On the morning of June 1, as the army entered an extensive prairie, I saw an Indian on horseback a few miles to the right. I immediately sent a detachment to intercept him, but he escaped. Finding myself discovered, I determined to advance with all the rapidity my circumstances would permit, rather with the hope than with the expectation of reaching the object sought that day, for my guides were strangers to the country which I occupied. At one o’clock in the afternoon, having marched by computation one hundred and fifty-five miles from the Ohio, I entered a grove which bordered on an extensive prairie and discovered two small villages to my left, two and four miles distant.

My guides now recognized the ground and informed me that the main town was four or five miles in front, behind a point of woods which jutted into the prairie. I immediately detached Colonel John Hardin, with sixty mounted infantrymen and a troop of light horse under Captain McCoy, to attack the villages to the left, while I moved on briskly with my main body, in order of battle, toward the town, the smoke of which was discernible. My guides were mistaken concerning the location of the town; instead of its standing at the edge of the plain through which I had marched, I found, in the low ground bordering on the Wabash (on turning the point of woods), just one house in front of me. Captain Price was ordered to assault that with forty men. He executed the command with great gallantry and killed two warriors.

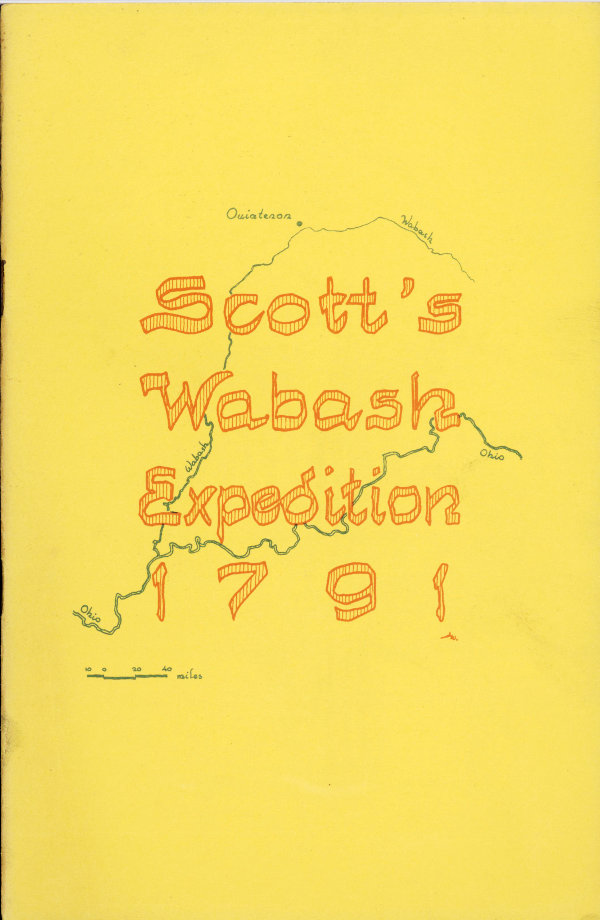

When I gained the summit of the hill which overlooks the villages on the banks of the Wabash, I discovered the enemy, in great confusion, endeavoring to make their escape over the river in canoes. I instantly ordered Lieutenant Colonel Commandant Wilkinson to rush forward with the first battalion. This detachment gained the bank of the river just as the rear of the enemy embarked. Regardless of a brisk fire kept up from a Kickapoo town on the opposite bank, well-directed rifle fire destroyed in a few minutes all the savages crowded in five canoes.

The enemy still kept possession of the Kickapoo town. I determined to dislodge them; for that purpose I ordered Captain King’s and Captain Logsdon’s companies, under the direction of Major Barbee, to march down 4 and to cross the river below the town. Several of the men swam the river, and others traveled in a small canoe. This movement was unobserved; my men had taken posts on the bank before they were discovered by the enemy, who immediately abandoned the village. About this time, word was brought me that Colonel Hardin was encumbered with prisoners and that he had discovered a stronger village (farther to my left than those I had observed), which he was proceeding to attack. I immediately detached Captain Brown with his company to support the colonel; but, as the distance was six miles, before the captain arrived the business was done. Colonel Hardin joined me a little before sunset, having killed six warriors and having taken fifty-two prisoners. Captain Bull, the warrior who discovered me in the morning, had gained the main town and had given the alarm; but the Indians of the villages to the left were uninformed of my approach and had no chance to retreat. The next morning, I decided to detach my lieutenant colonel commandant, with five hundred men, to destroy the important town of Kenapacomaqua at the mouth of the Eel River, eighteen [sic] miles from my camp and on the west side of the Wabash. But, on examination, I discovered that my men and horses were so crippled and worn down by the long, laborious march and the active exertion of the preceding day that only three hundred and sixty men could be found able to undertake the enterprise; they prepared to march on foot.

Colonel Wilkinson marched with this detachment at 5:30 p.m. and, returning to my camp the next day at 1:00 p.m., marched this six [sic] miles in about five hours and destroyed the most important settlements of the enemy in that quarter of the federal territory.

The following is Colonel Wilkinson’s report respecting the enterprise:

Sir:

The detachment under my command, ordered to attack the village of Kenapacomaqua, was put in motion at half-past five o’clock last evening. Knowing that our enemy (whose chief dependence is in his ability as a marksman and his alertness in covering himself behind trees, stumps, and other impediments to fair sight) would not hazard an action in the night, I determined to push my march until I approached the vicinity of the villages, where I knew the country to be flat and open. I gained my point without a halt twenty minutes before eleven o’clock and lay upon my arms until four o’clock in the morning; half an hour later I assaulted the town from all quarters. The enemy was vigilant, gave way on my approach, and in canoes crossed Eel Creek, which washes the northeast part of the town. The creek was not fordable. My corps dashed forward with the impetuosity suitable to volunteers and was saluted by the enemy with a brisk fire from the opposite side of the creek. Dauntlessly they rushed to the water’s edge; finding the river impassable, they returned a volley which so galled and disconcerted their antagonists that the fire of the enemy was without effect. In five minutes, the Indians were driven from their cover and fled precipitantly. I have three slightly wounded men. At half-past five, the town was in flames; and at six o’clock, I commenced my retreat.

James Wilkinson

Many of the inhabitants of Kenapacomaqua were French and lived in a state of civilization. Misunderstanding the object of a white flag (which appeared on a hill opposite me in the afternoon of the first of June), I liberated an aged squaw and sent her to inform the savages that if they would come in and surrender, their towns should be spared and they should receive good treatment. It was afterwards found that this white flag was not intended as a signal of parley, but that it was placed there to mark the burial spot of a person of distinction among the Indians. On the fourth of June, I determined to discharge sixteen of the weakest and most infirm of my prisoners with a talk to the Wabash tribes (a copy of which follows). My motives in this measure were to rid the army of a heavy encumbrance; to gratify the impulses of humanity; to increase the panic my operation had produced; and, by distracting the council of the enemy, to favor victims of government.

On the same day, after having burned the towns and adjacent villages and having destroyed the growing corn and pulse [legumes], I began my march for the rapids of the Ohio River. I arrived there on the fourteenth of June, without the loss of a single man by the enemy, and with only five wounded; I had killed thirty-two, chiefly warriors of size and figure, and had taken fifty-eight prisoners.

Charles Scott, Brigadier General

To the various tribes of the Piankashaw, and all the nations of red people living on the waters of the Wabash River:

The Sovereign Council of the Thirteen United States has long patiently borne your depredations against white settlements on this side of the great mountains, in the hope that you would see your error and would correct it by entering into bonds of amity and lasting peace. Moved by compassion and pity for your misguided councils, it has not unfrequently addressed you on this subject, but without effect. At length patience is exhausted, and it has stretched forth the arm of power against you; its mighty sons and chief warriors have at length taken up the hatchet; they have penetrated far into your country to meet your warriors and to punish you for your transgressions. But you fled before them and declined the battle, leaving your wives and children to their mercy. They have destroyed your old town, Ouiatenon, and the neighboring villages; and they have taken many prisoners. Resting here two days to give you time to collect your strength, they have proceeded to your town of Kenapacomaqua; but again you have fled before them, and that great town has been destroyed. After giving you this evidence of their power, they have stopped their hands because they are as merciful as strong. Again they indulge the hope that you will come to a sense of your true interest and determine to make a lasting peace with them and all their children forever. The United States has not desired to destroy the red people, although it has the power to do so; but should you decline this invitation and pursue your unprovoked hostilities, its strength will again be exerted against you. Your warriors will be slaughtered, your wives and children will be carried into captivity, and you may be assured that those who escape the fury of our mighty chiefs shall find no resting place on this side of the Great Lakes. The warriors of the United States do not wish to distress or destroy women, children, or old men. Although policy obliges them to retain some in captivity, yet compassion and humanity have induced them to set at liberty others, who will deliver you this talk. Those who are carried off will be left in the care of our great chief and warrior, General St. Clair, near the mouth of the Miami and opposite to the Licking River, where they will be treated with humanity and tenderness. If you wish to recover them, repair to the place by the first day of July; determine with true hearts to bury the hatchet and to smoke the pipe of peace. They will then be restored to you, and you may again sit down in security at your old towns and live in peace and happiness, unmolested by the people of the United States. They will become your friends and protectors and will be ready to furnish you with all the necessaries you may require. But should you foolishly persist in your warfare, the sons of war will be let loose against you; and the hatchet will never be buried until your country is desolated and your people humbled to the dust.

Charles Scott, Brigadier General

INDIANAPOLIS GAZETTE, September 5, 1826