Title: U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950-1953, Volume 5 (of 5)

Creator: United States. Marine Corps

Author: Pat Meid

James M. Yingling

Release date: April 6, 2021 [eBook #65011]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

Cover created by Transcriber, using the original cover and the text of the Title page, and placed into the Public Domain.

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

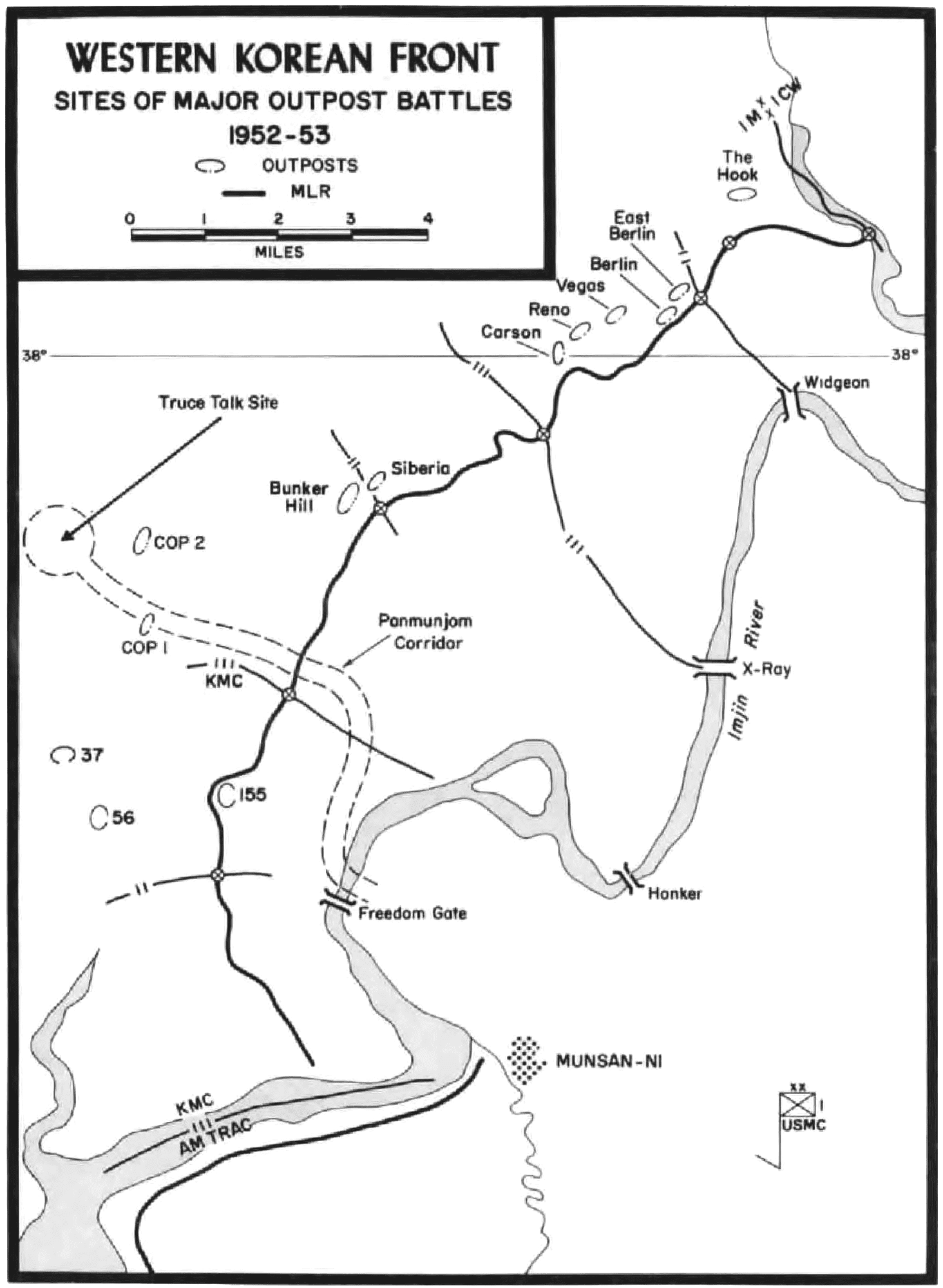

WESTERN KOREAN FRONT

SITES OF MAJOR OUTPOST BATTLES

1952–53

by

LIEUTENANT COLONEL PAT MEID, USMCR

and

MAJOR JAMES M. YINGLING, USMC

Historical Division

Headquarters, U. S. Marine Corps

Washington, D. C., 1972

Preceding Volumes of

U. S. Marine Operations in Korea

Volume I, “The Pusan Perimeter”

Volume II, “The Inchon-Seoul Campaign”

Volume III, “The Chosin Reservoir Campaign”

Volume IV, “The East-Central Front”

Library of Congress Catalogue Number: 55-60727

For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents

U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402—Price $4.50 (Cloth)

Stock Number 0855-0059

iii

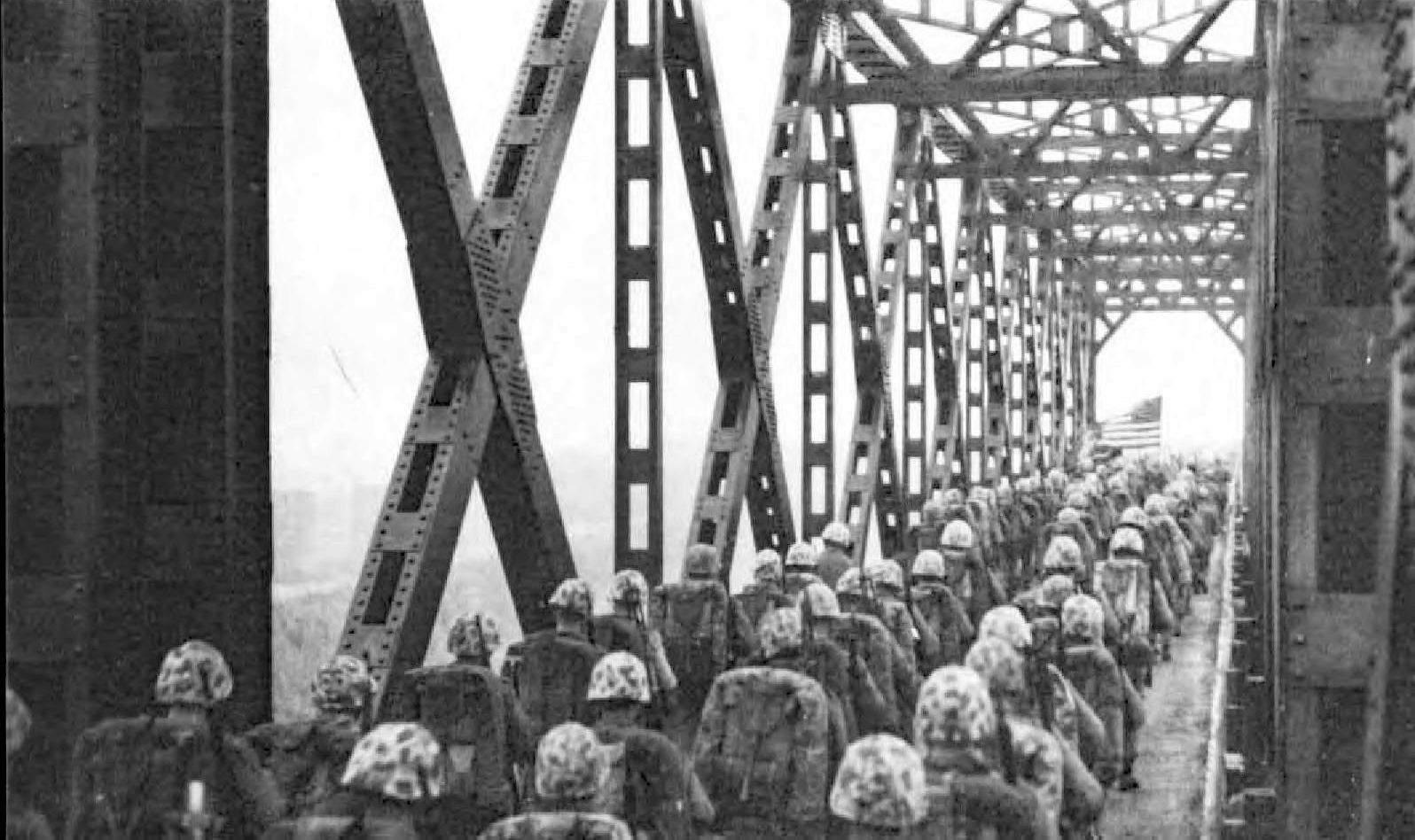

Mention the Korean War and almost immediately it evokes the memory of Marines at Pusan, Inchon, Chosin Reservoir, or the Punchbowl. Americans everywhere remember the Marine Corps’ combat readiness, courage, and military skills that were largely responsible for the success of these early operations in 1950–1951. Not as dramatic or well-known are the important accomplishments of the Marines during the latter part of the Korean War.

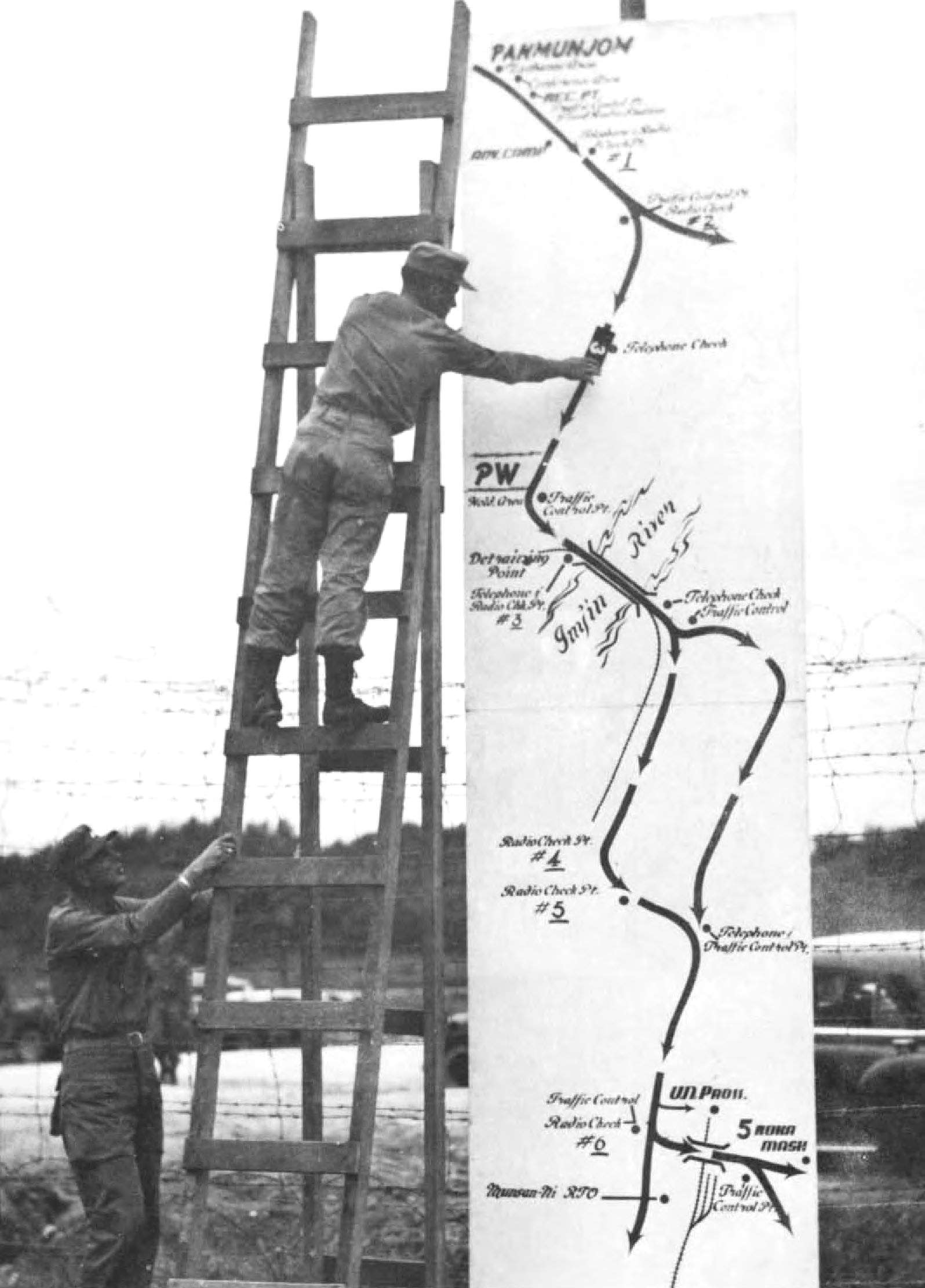

In March 1952 the 1st Marine Division redeployed from the East-Central front to West Korea. This new sector, nearly 35 miles in length, anchored the far western end of I Corps and was one of the most critical of the entire Eighth Army line. Here the Marines blocked the enemy’s goal of penetrating to Seoul, the South Korean capital. Northwest of the Marine Main Line of Resistance, less than five miles distant, lay Panmunjom, site of the sporadic truce negotiations.

Defense of their strategic area exposed the Marines to continuous and deadly Communist probes and limited objective attacks. These bitter and costly contests for key outposts bore such names as Bunker Hill, the Hook, the Nevadas (Carson-Reno-Vegas), and Boulder City. For the ground Marines, supported by 1st Marine Aircraft Wing squadrons, the fighting continued until the last day of the war, 27 July 1953.

The Korean War marked the first real test of Free World solidarity in the face of Communist force. In repulsing this attempted Communist aggression, the United Nations, led by the United States, served notice that it would not hesitate to aid those nations whose freedom and independence were under attack.

As events have subsequently proven, holding the line against Communist encroachment is a battle whose end is not yet in sight. Enemy aggression may explode brazenly upon the world scene, with an overt act of invasion, as it did in Korea in June 1950, or it mayiv take the form of a murderous guerrilla war as it has more recently, for over a decade, in Vietnam.

Whatever guise the enemy of the United States chooses or wherever he draws his battleline, he will find the Marines with their age-old answer. Today, as in the Korean era, Marine Corps readiness and professionalism are prepared to apply the cutting edge against any threat to American security.

L. F. Chapman, Jr.

General, U.S. Marine Corps,

Commandant of the Marine Corps

Reviewed and approved: 12 May 1971.

v

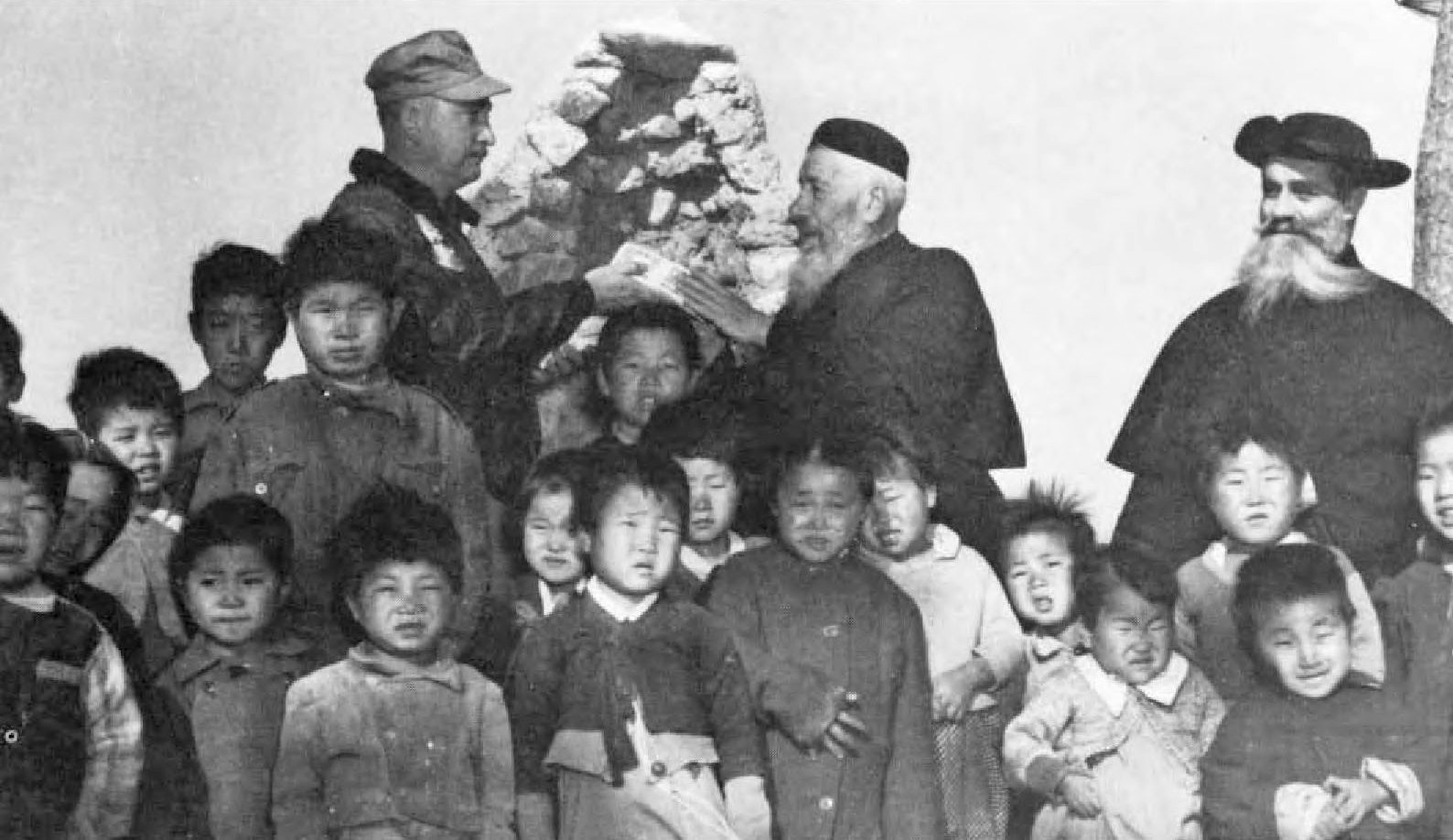

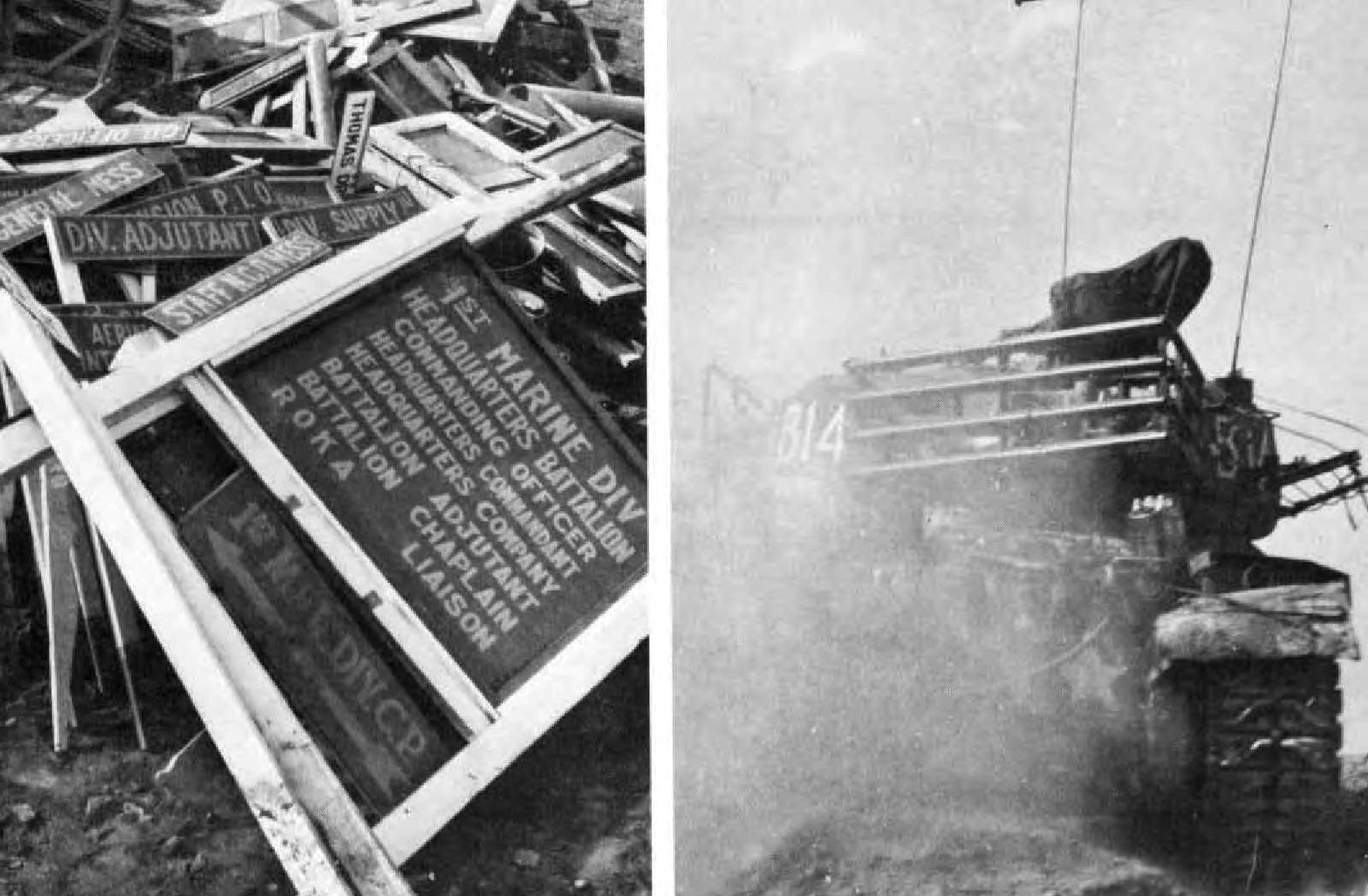

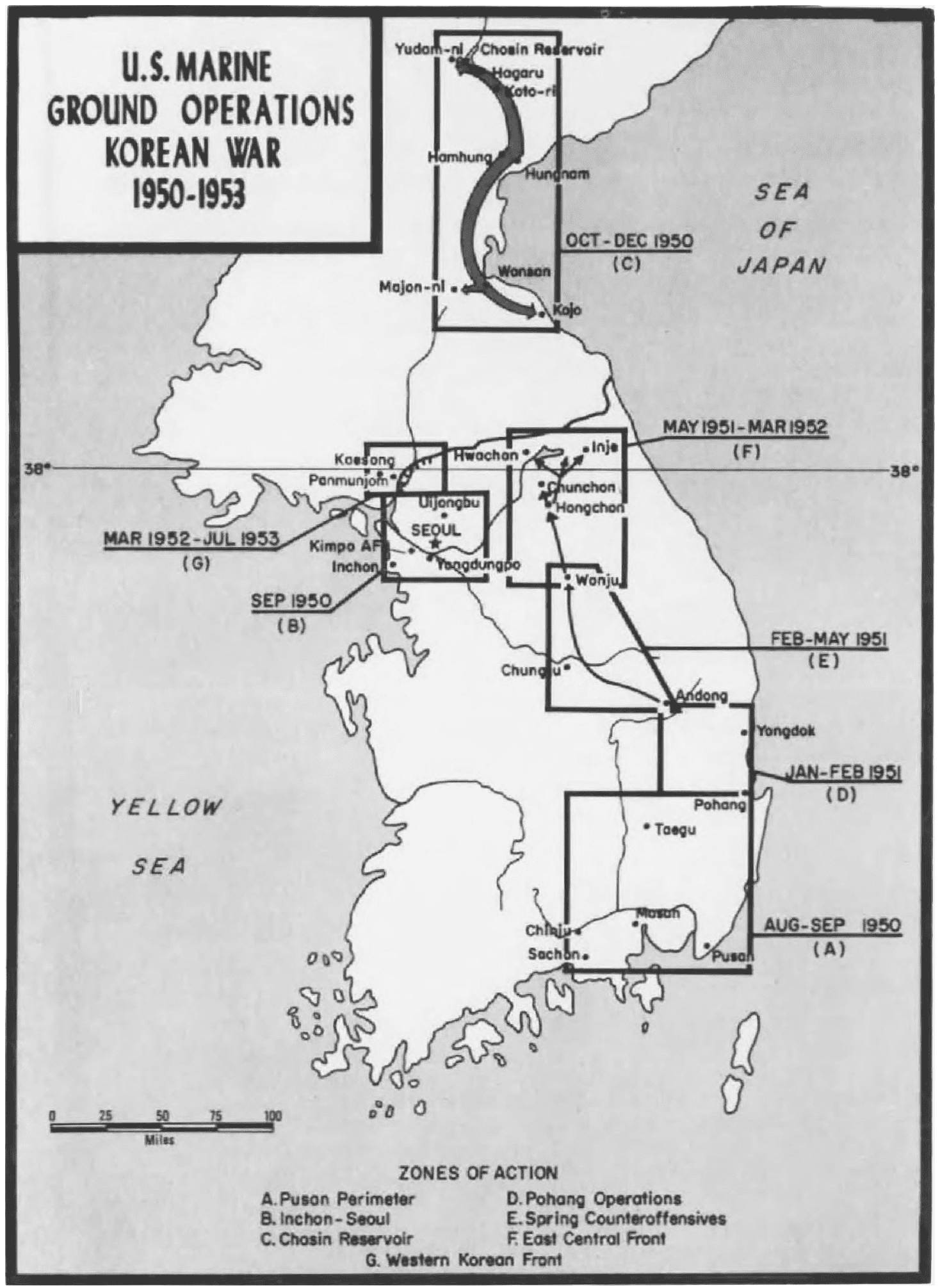

This is the concluding volume of a five-part series dealing with operations of United States Marines in Korea between 2 August 1950 and 27 July 1953. Volume V provides a definitive account of operations of the 1st Marine Division and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing during 1952–1953, the final phase of the Korean War. At this time the division operated under Eighth U.S. Army in Korea (EUSAK) control in the far western sector of I Corps, while Marine aviators and squadrons functioned as a component of the Fifth Air Force (FAF).

The period covered by this history begins in March 1952, when the Marine division moved west to occupy positions defending the approaches to Seoul, the South Korean capital. As it had for most of the war the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, operating under FAF, flew close support missions not only for the Marines but for as many as 19 other Allied frontline divisions. Included in the narrative is a detailed account of Marine POWs, a discussion of the new defense mission of Marine units in the immediate postwar period, and an evaluation of Marine Corps contributions to the Korean War.

Marines, both ground and aviation, comprised an integral part of the United Nations Command in Korea. Since this is primarily a Marine Corps history, actions of the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force are presented only in sufficient detail to place Marine operations in their proper perspective.

Official Marine Corps combat records form the basis for the book. This primary source material has been further supplemented by comments and interviews from key participants in the action described. More than 180 persons reviewed the draft chapters. Their technical knowledge and advice have been invaluable. Although the full details of these comments could not be used in the text, this material has been placed in Marine Corps archives for possible use by future historians.

The manuscript of this volume was prepared during the tenure of Colonel Frank C. Caldwell, Director of Marine Corps History,vi Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps. Production was accomplished under the direction of Mr. Henry I. Shaw, Jr., Deputy Director and Chief Historian, who also outlined the volume. Preliminary drafts were written by the late Lynn Montross, prime author of this series, and Major Hubard D. Kuokka. Major James M. Yingling researched and wrote chapters 1–6 and compiled the Command and Staff List. Lieutenant Colonel Pat Meid researched and wrote chapters 7–12, prepared appendices, processed photographs and maps, and did the final editing of the book.

Historical Division staff members, past or present, who freely lent suggestions or provided information include Lieutenant Colonel John J. Cahill, Captain Charles B. Collins, Mr. Ralph W. Donnelly, Mr. Benis M. Frank, Mr. George W. Garand, Mr. Rowland P. Gill, Captain Robert J. Kane, Major Jack K. Ringler, and Major Lloyd E. Tatem. Warrant Officer Dennis Egan was Administrative Officer during the final stages of preparation and production of this book.

The many exacting administrative duties involved in processing the volume from first draft manuscripts through the final printed form, including the formidable task of indexing the book, were handled expertly and cheerfully by Miss Kay P. Sue. Mrs. Frances J. Rubright also furnished gracious and speedy assistance in obtaining the tomes of official Marine Corps records. The maps were prepared by Sergeants Kenneth W. White and Ernest L. Wilson. Official Department of Defense photographs illustrate the book.

A major contribution to the history was made by the Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army; the Naval History Division, Department of the Navy; and the Office of Air Force History, Department of the Air Force. Military history offices of England, Canada, and South Korea provided additional details that add to the accuracy and interest of this concluding volume of the Korean series.

F. C. Caldwell

Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps (Retired)

Director of Marine Corps History

vii

| Page | ||

| I | Operations in West Korea Begin | 1 |

| From Cairo to JAMESTOWN—The Marines’ Home in West Korea—Organization of the 1st Marine Division Area—The 1st Marine Aircraft Wing—The Enemy—Initial CCF Attack—Subsequent CCF Attacks—Strengthening the Line—Marine Air Operations—Supporting the Division and the Wing—Different Area, Different Problem | ||

| II | Defending the Line | 51 |

| UN Command Activities—Defense of East and West Coast Korean Islands—Marine Air Operations—Spring 1952 on JAMESTOWN—End of the Second Year of War—A Long Fourth of July—Changes in the Lineup—Replacement and Rotation—Logistical Operations, Summer 1952 | ||

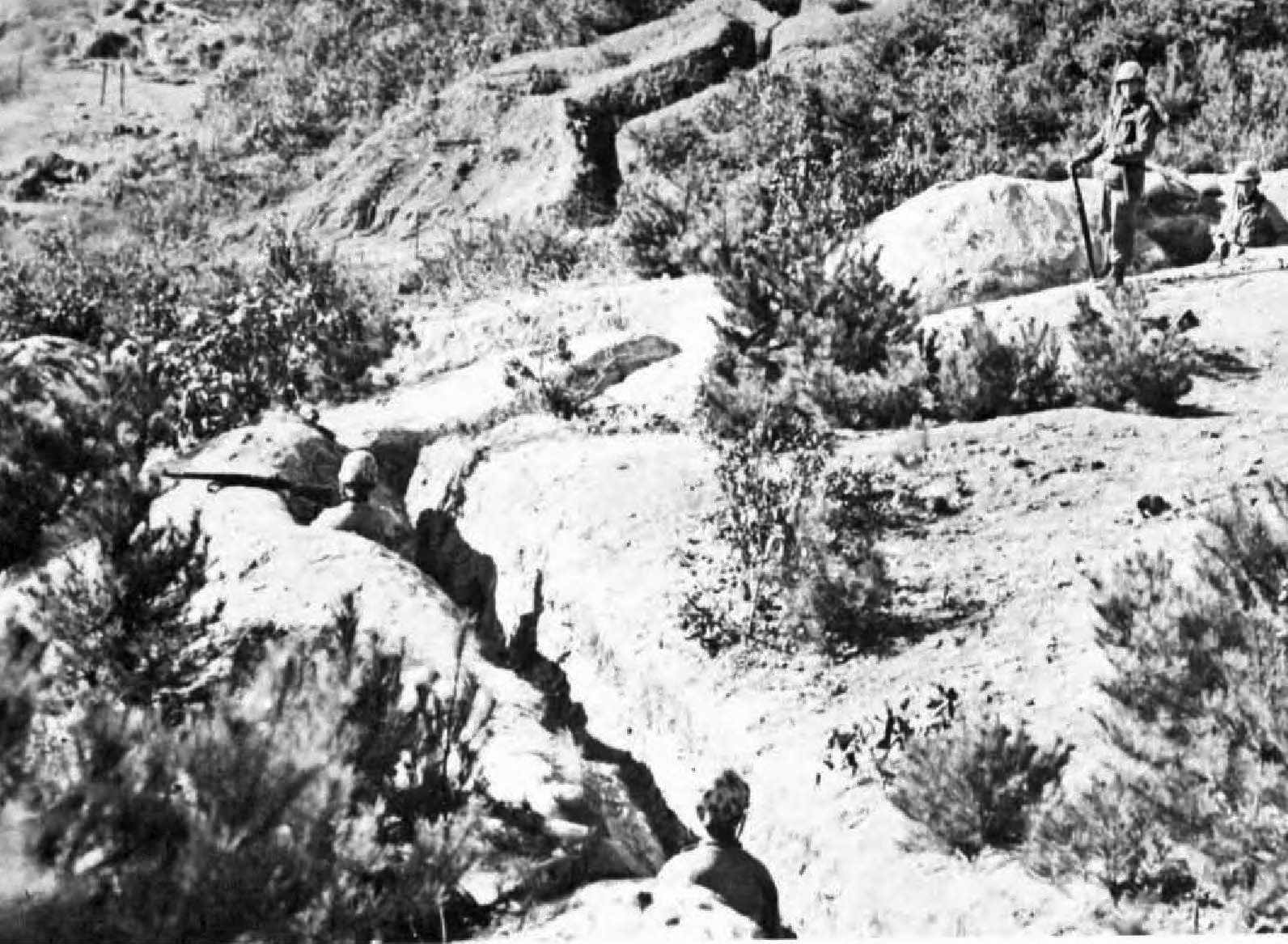

| III | The Battle of Bunker Hill | 103 |

| The Participants and the Battlefield—Preliminary Action on Siberia—The Attack on Bunker Hill—Consolidating the Defense of Bunker Hill—Company B Returns to Bunker Hill—Supporting Arms at Bunker Hill—In Retrospect | ||

| IV | Outpost Fighting Expanded | 145 |

| From the Center Sector to the Right—Early September Outpost Clashes—Korean COPs Hit Again—More Enemy Assaults in Late September—Chinese Intensify Their Outpost Attacks—More PRESSURE, More CAS, More Accomplishments—Rockets, Resupply, and Radios | ||

| V | The Hook | 185 |

| Before the Battle—Preparations for Attack and Defense—Attack on the Hook—Reno Demonstration—Counterattack—Overview | ||

| VI | Positional Warfare | 217 |

| A Successful Korean Defense—Six Months on the UNC Line—Events on the Diplomatic Front—The Marine Commandsviii During the Third Winter—1st MAW Operations 1952–1953—Behind the Lines—The Quiet Sectors—Changes in the Concept of Ground Defense—Before the Nevadas Battle | ||

| VII | Vegas | 263 |

| The Nevada Cities—Supporting Arms—Defense Organization at the Outposts—Chinese Attack on 26 March—Reinforcements Dispatched—Massed Counterattack the Next Day—Push to the Summit—Other Communist Probes—Three CCF Attempts for the Outpost—Vegas Consolidation Begins—Aftermath | ||

| VIII | Marking Time (April-June 1953) | 313 |

| The Peace Talks Resume—Operation LITTLE SWITCH—Interval Before the Marines Go Off the Line—The May Relief—Training While in Reserve and Division Change of Command—Heavy May-June Fighting—Developments in Marine Air—Other Marine Defense Activities—The Division Is Ordered Back to the Front | ||

| IX | Heavy Fighting Before the Armistice | 363 |

| Relief of the 25th Division—Initial Attacks on Outposts Berlin and East Berlin—Enemy Probes, 11–18 July—Marine Air Operations—Fall of the Berlins—Renewal of Heavy Fighting, 24–26 July—Last Day of the War | ||

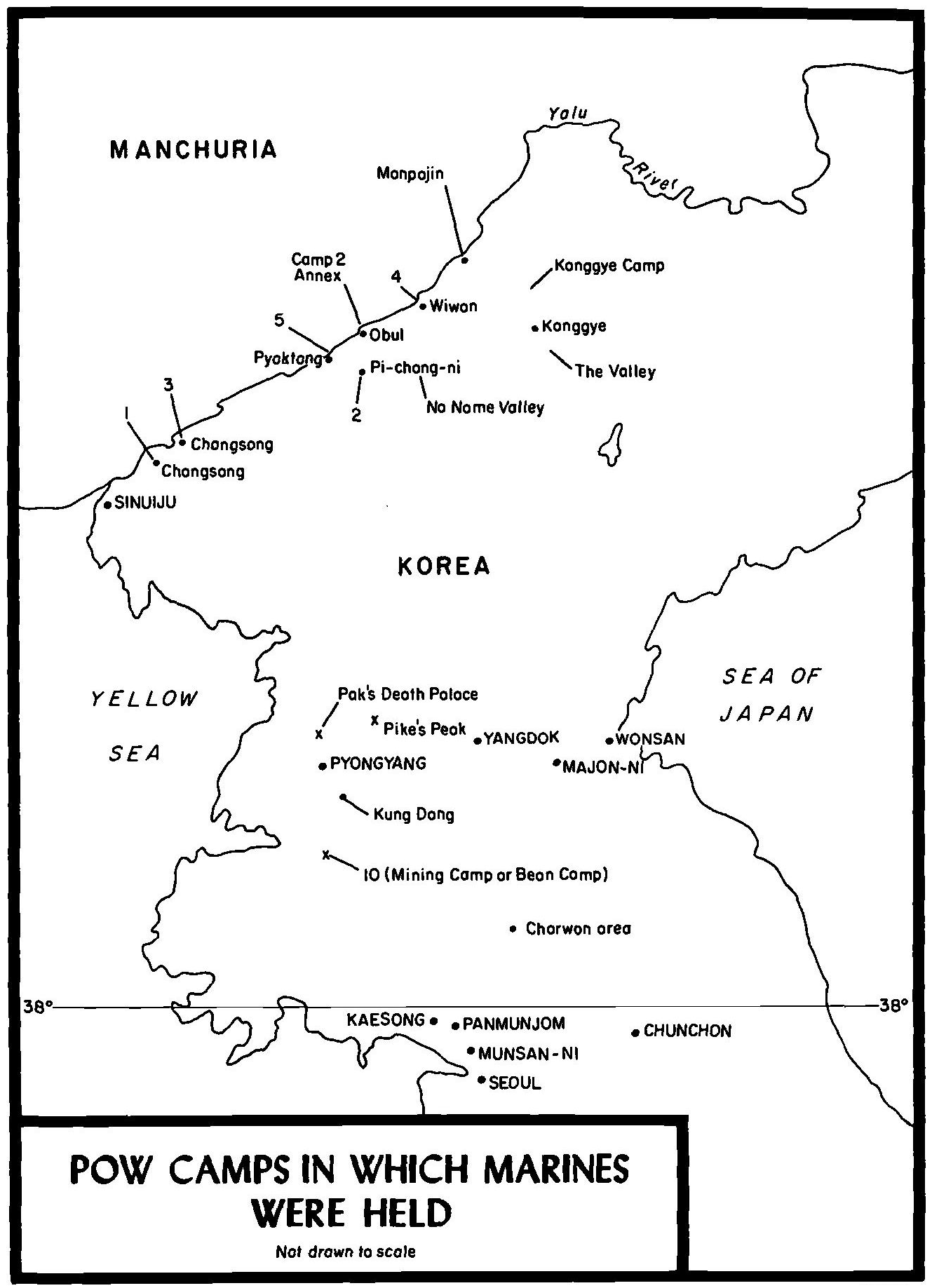

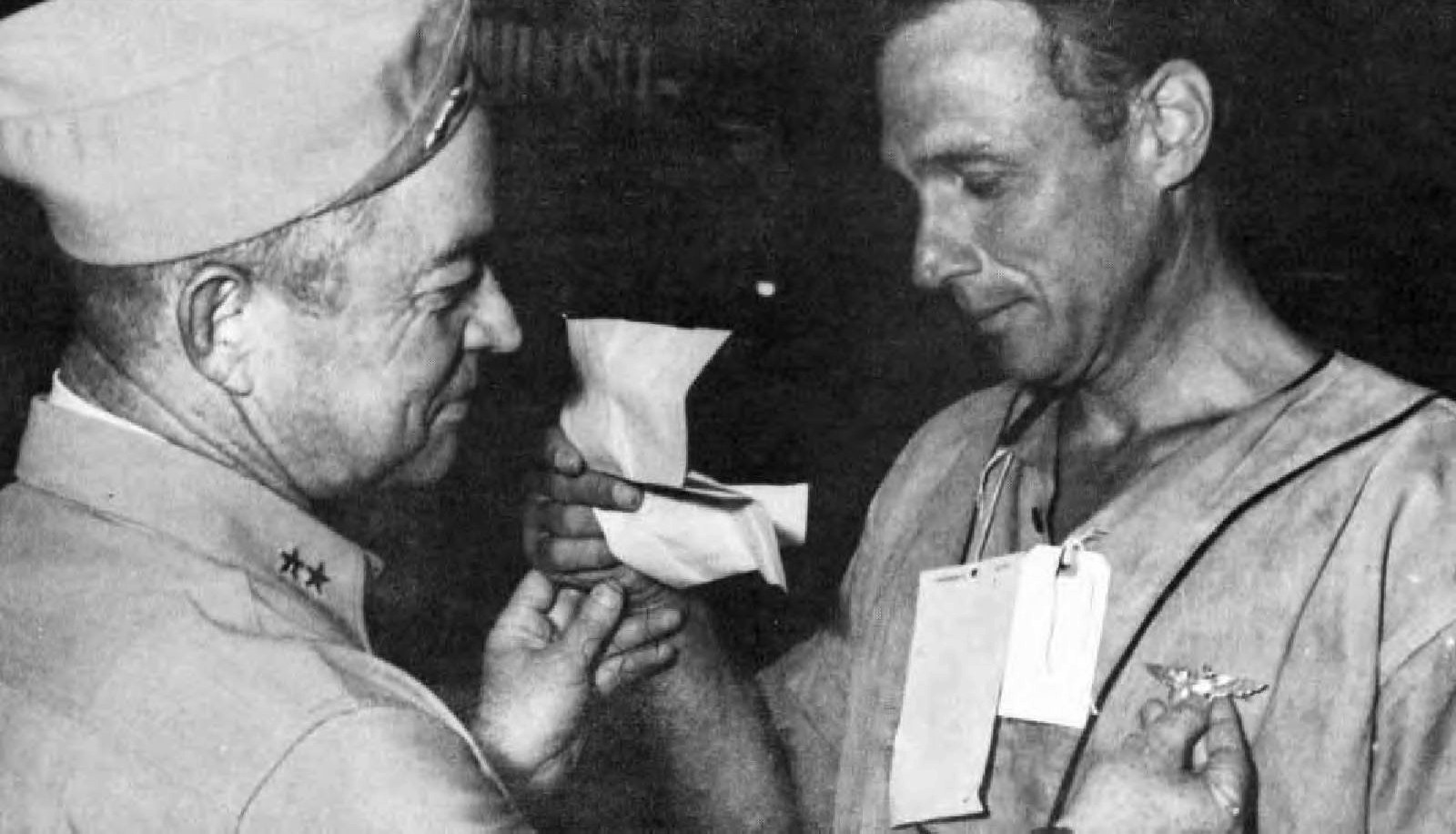

| X | Return of the Prisoners of War | 399 |

| Operation BIG SWITCH—Circumstances of Capture—The Communist POW Camps—CCF “Lenient Policy” and Indoctrination Attempts—The Germ Warfare Issue—Problems and Performance of Marine POWs—Marine Escape Attempts—Evaluation and Aftermath | ||

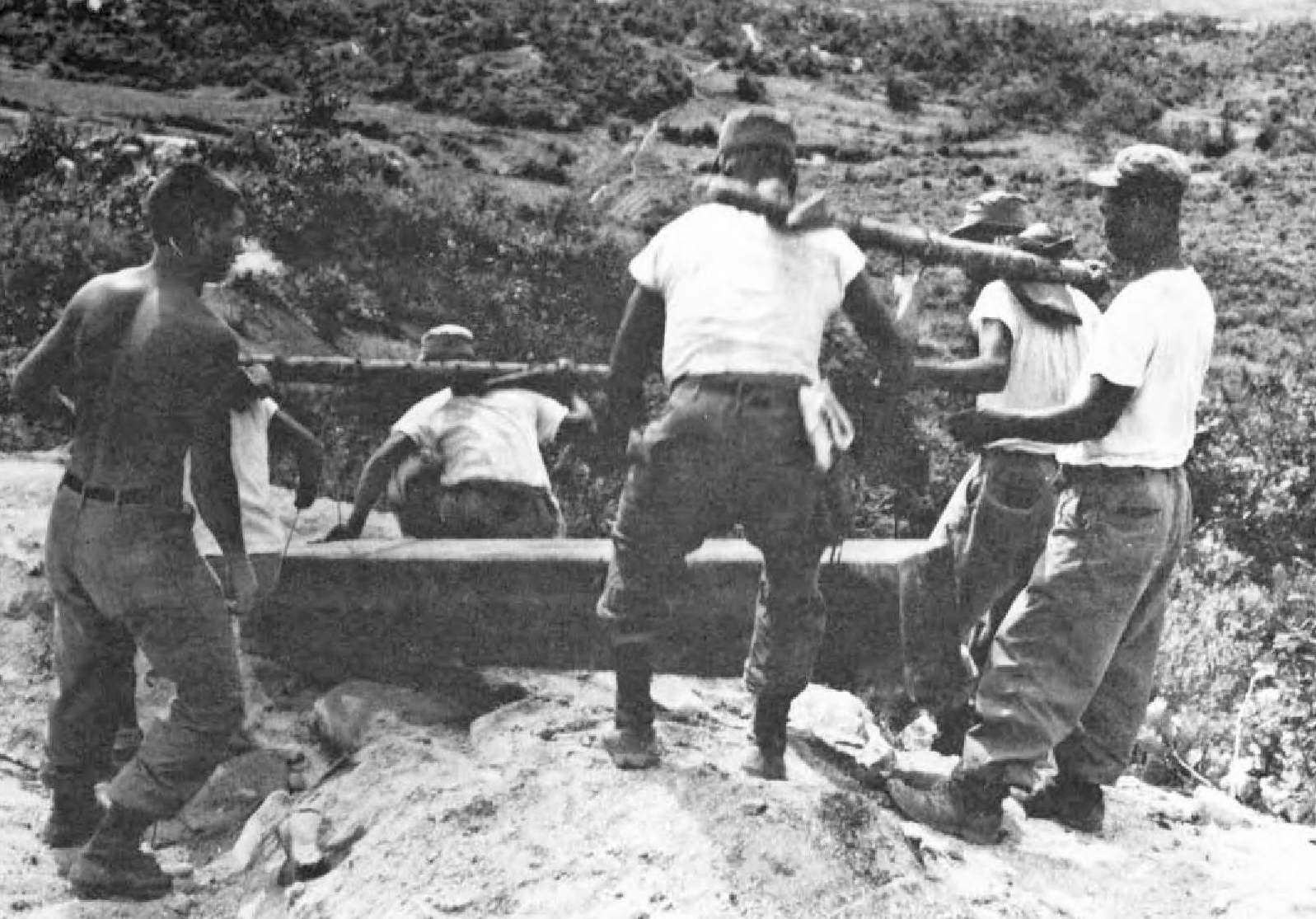

| XI | While Guns Cool | 445 |

| The Postwar Transition—Control of the DMZ and the Military Police Company—Organization of New Defense Positions—Postwar Employment of Marine Units in FECOM | ||

| XII | Korean Reflection | 475 |

| Marine Corps Role and Contributions to the Korean War: Ground, Air, Helicopter—FMF and Readiness Posture—Problems Peculiar to the Korean War—Korean Lessons |

ix

| Page | ||

| A | Glossary of Technical Terms and Abbreviations | 537 |

| B | Korean War Chronology | 541 |

| C | Command and Staff List | 549 |

| D | Effective Strength, 1st Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing | 573 |

| E | Marine Corps Casualties | 575 |

| F | Marine Pilots and Enemy Aircraft Downed in Korean War | 577 |

| G | Unit Citations (during 1952–1953 period) | 579 |

| H | Armistice Agreement | 587 |

| Bibliography | 611 | |

| Index | 617 | |

x

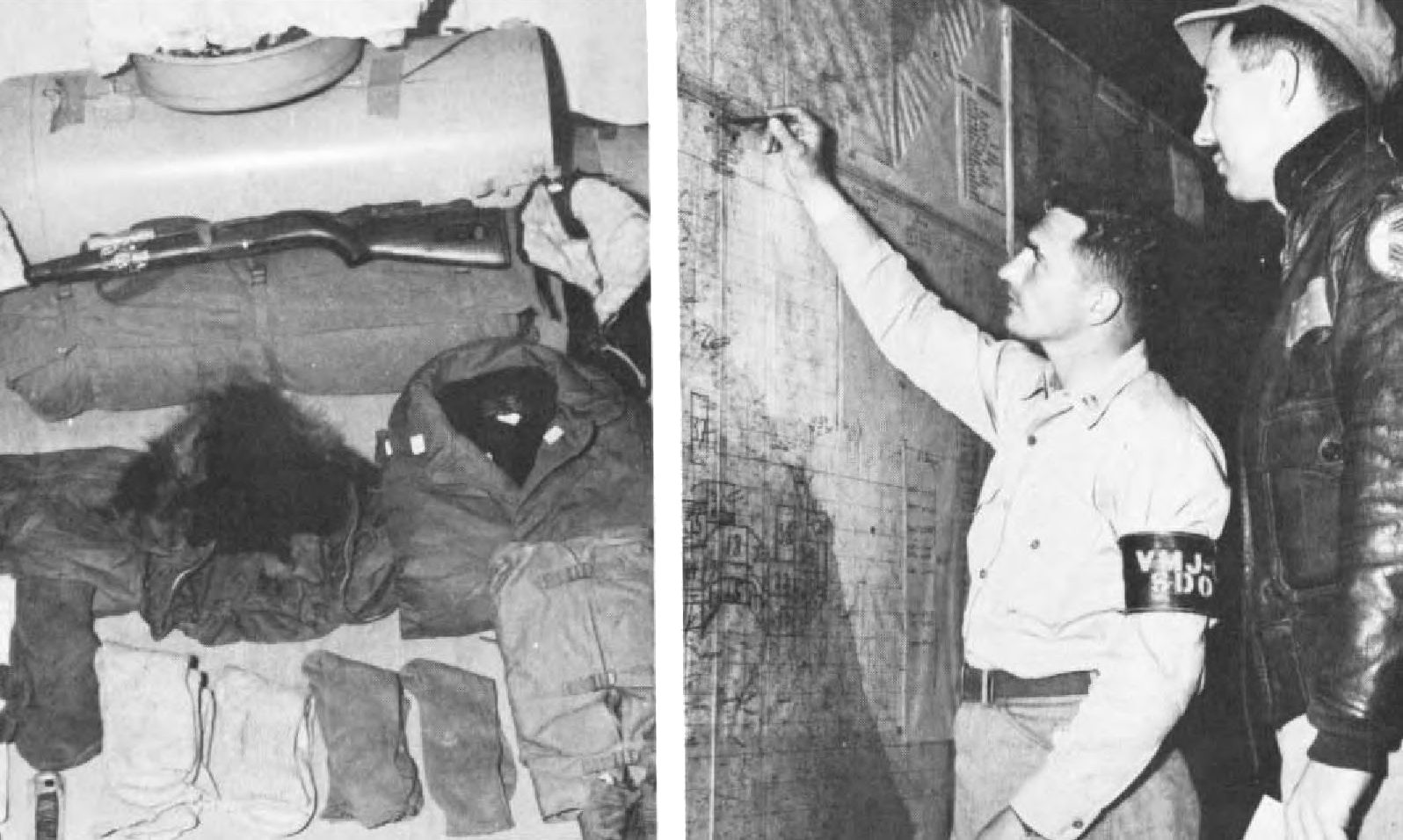

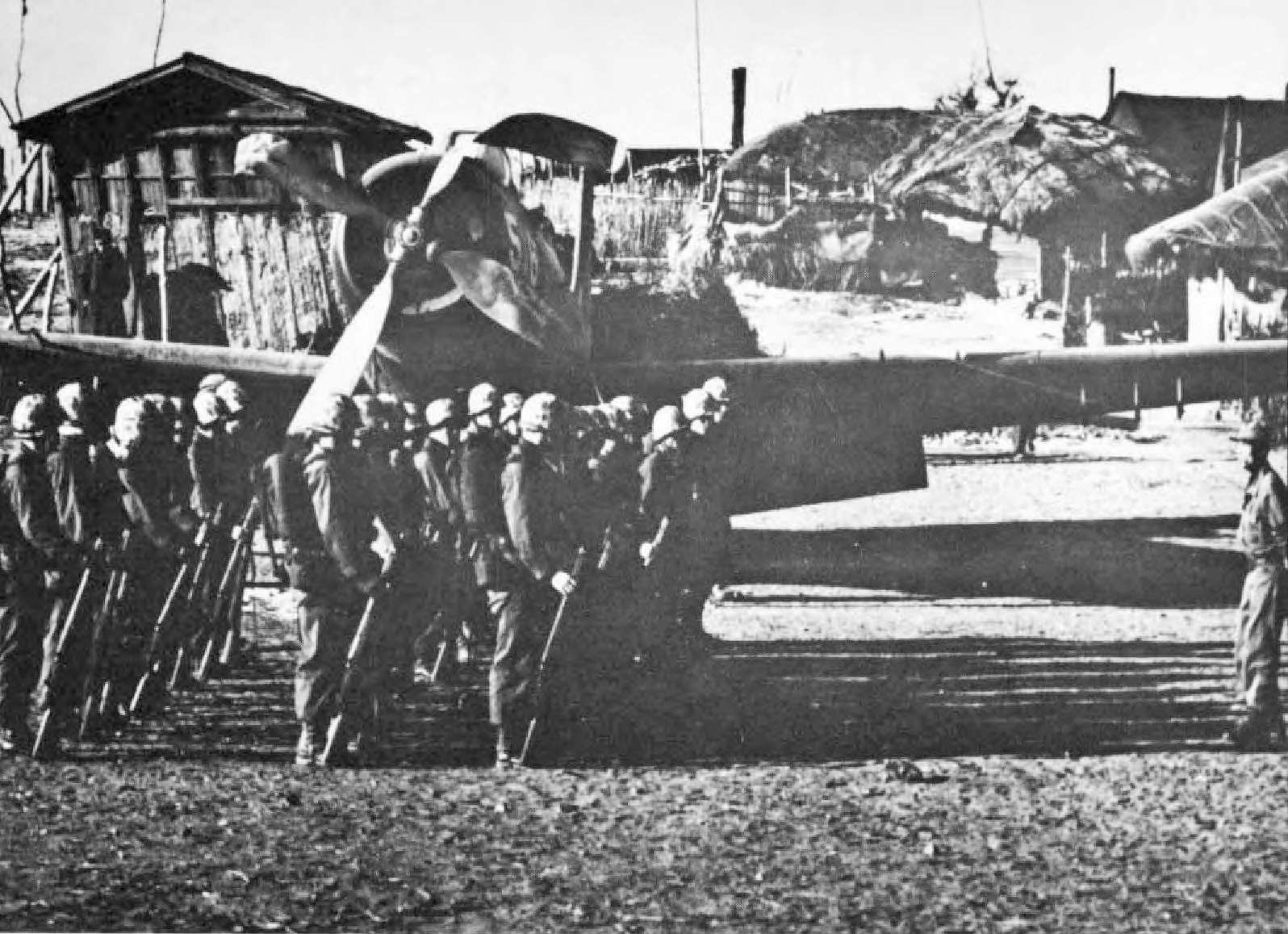

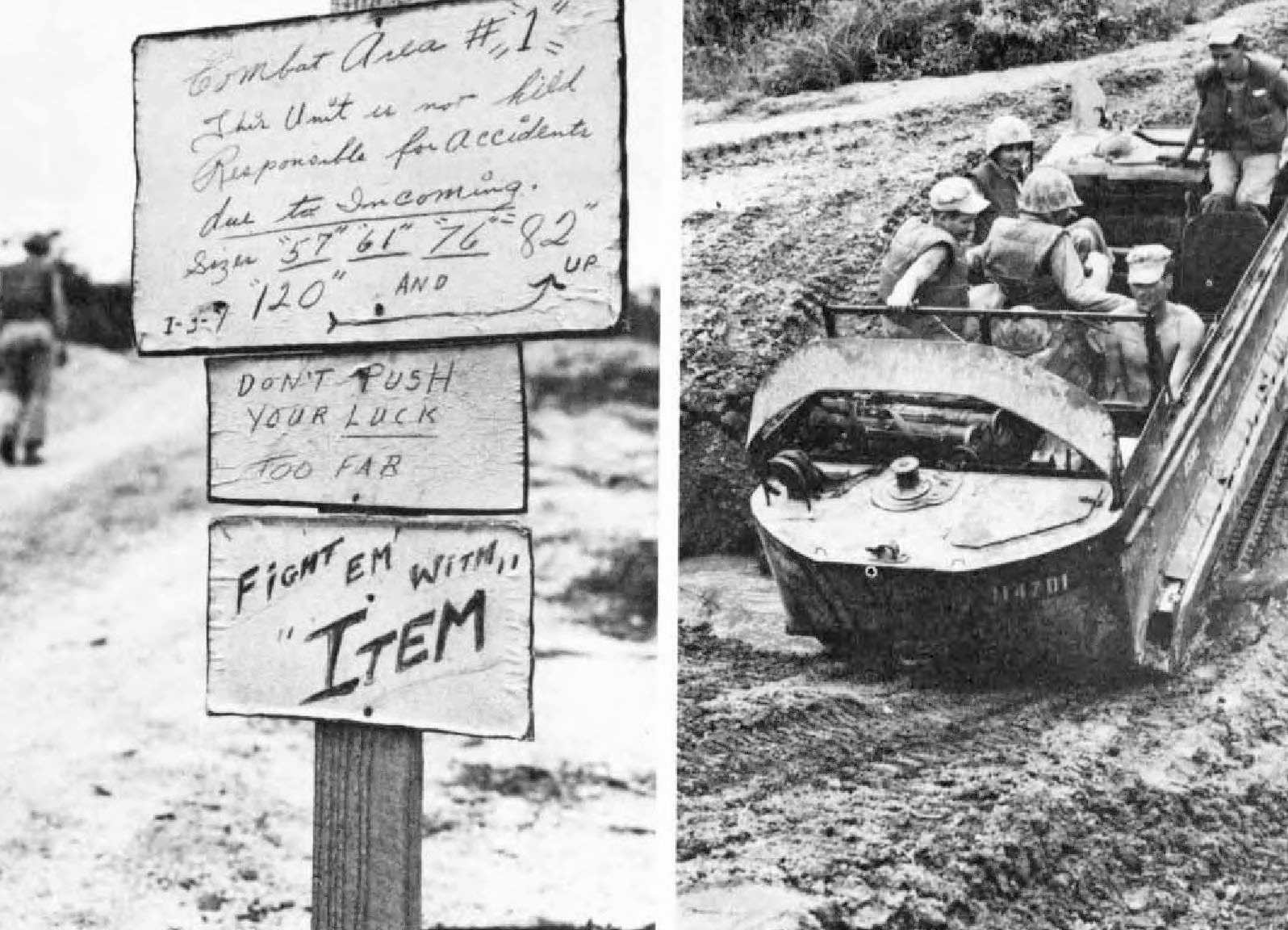

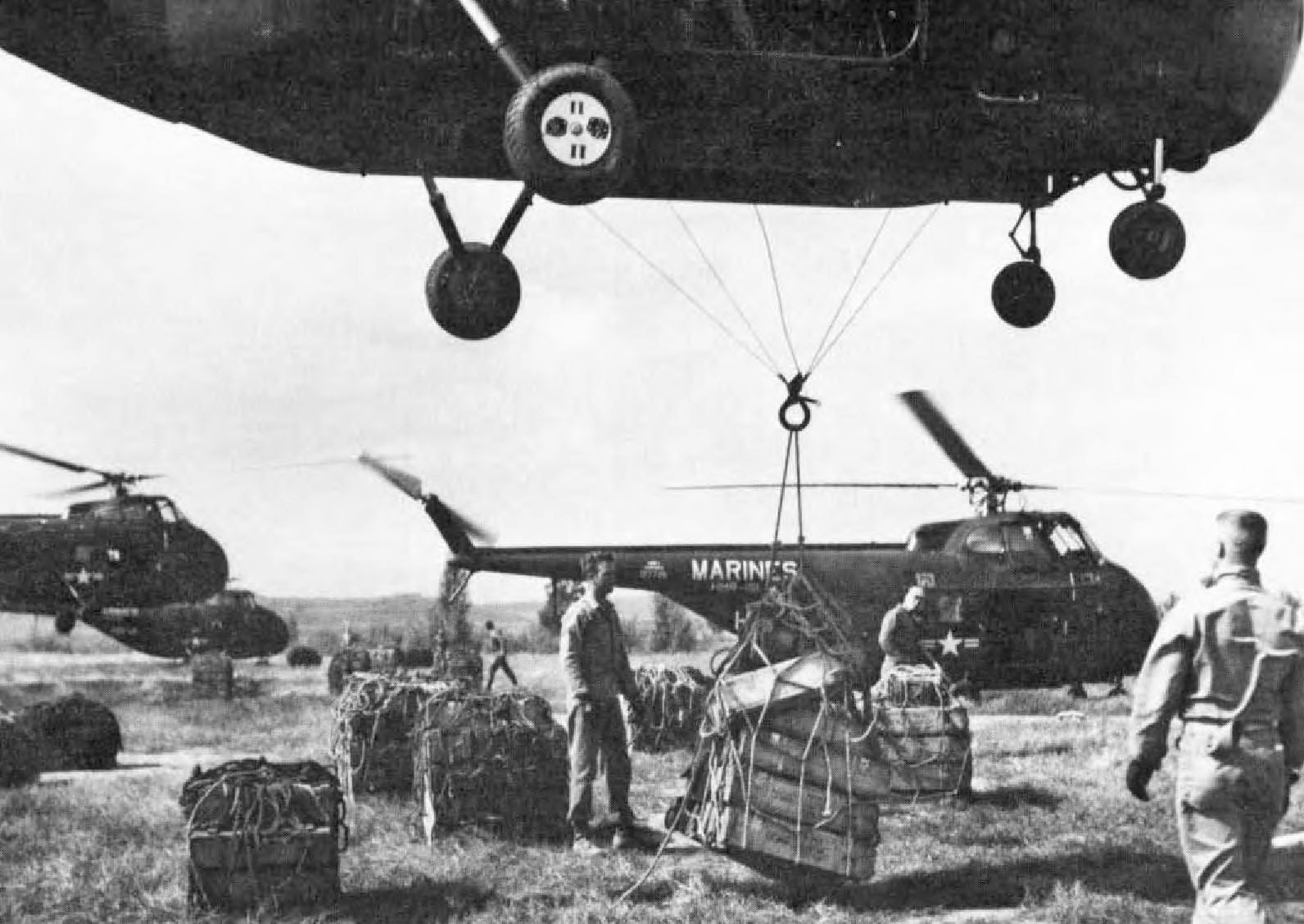

Photographs

Sixteen-page sections of photographs following pages 212 and 436

Maps and Sketches

| Page | ||

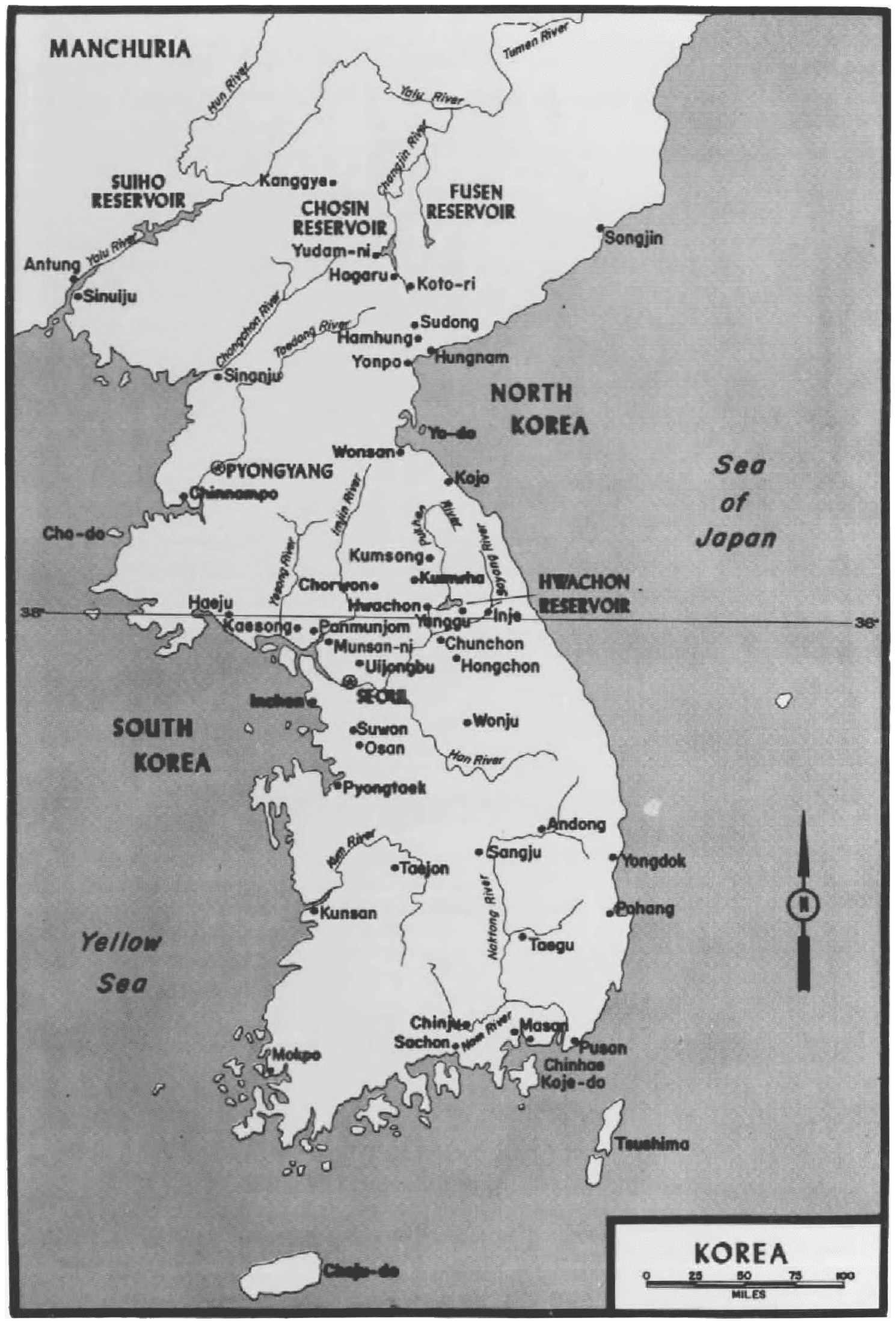

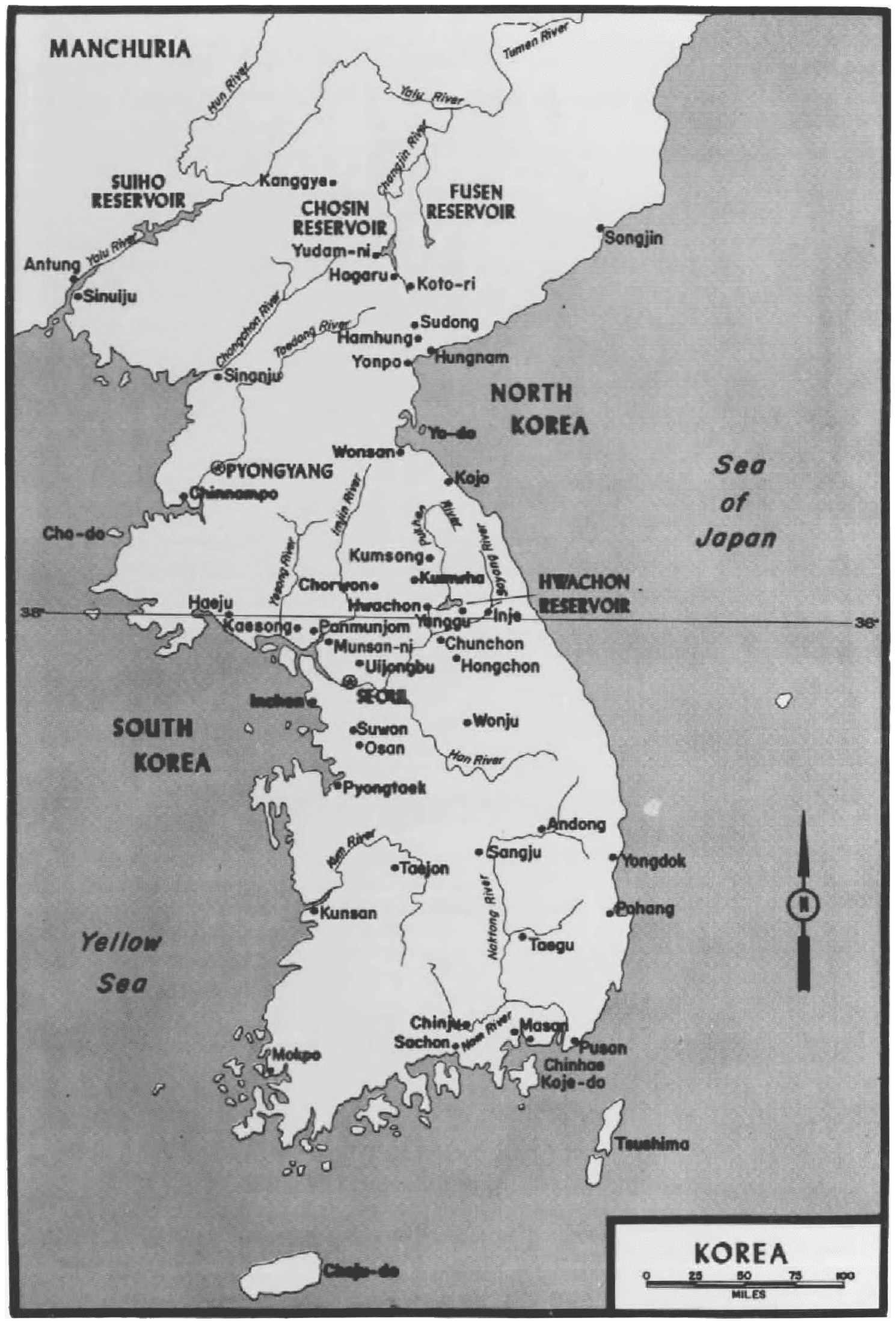

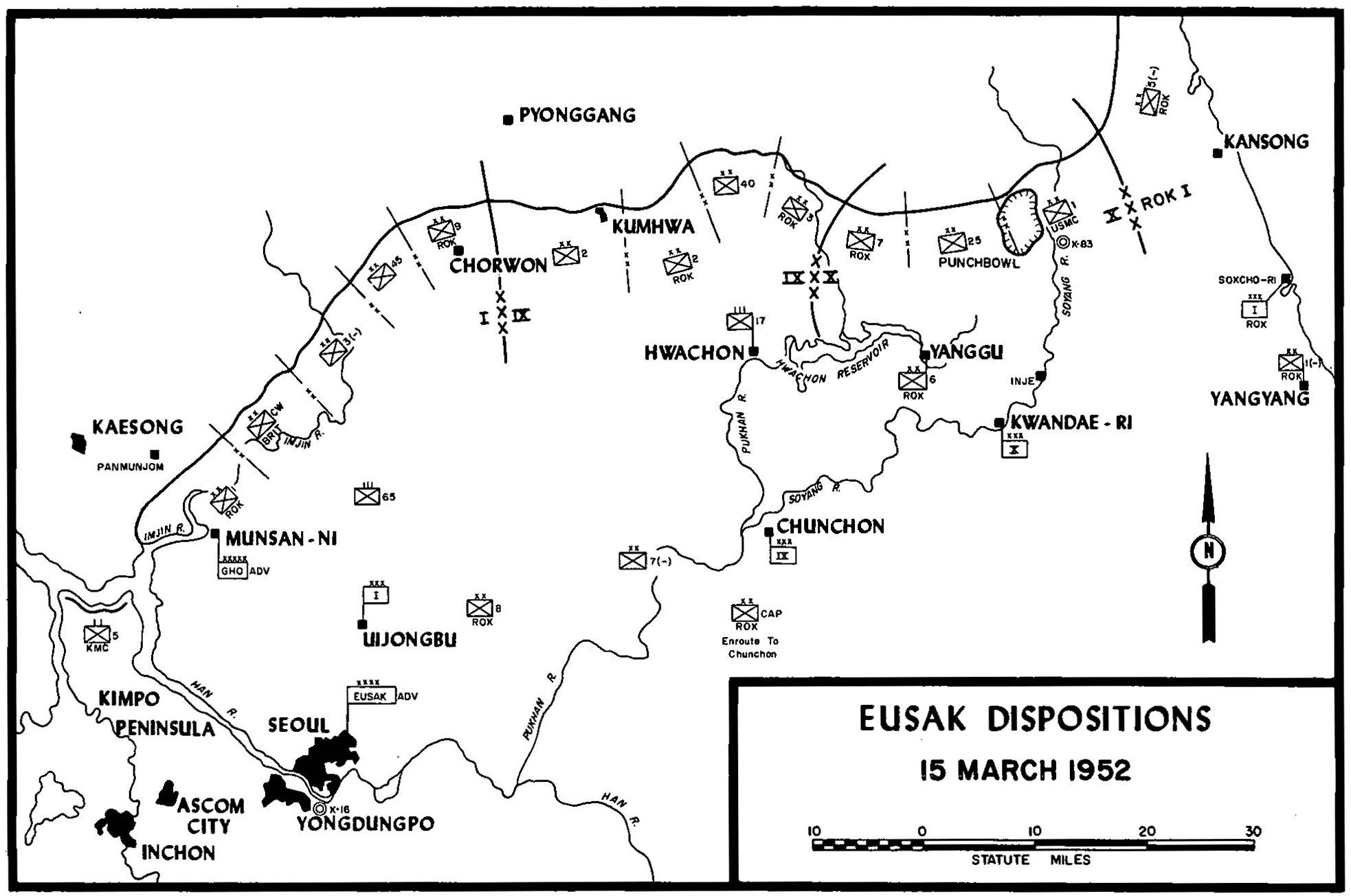

| 1 | EUSAK Dispositions—15 March 1952 | 9 |

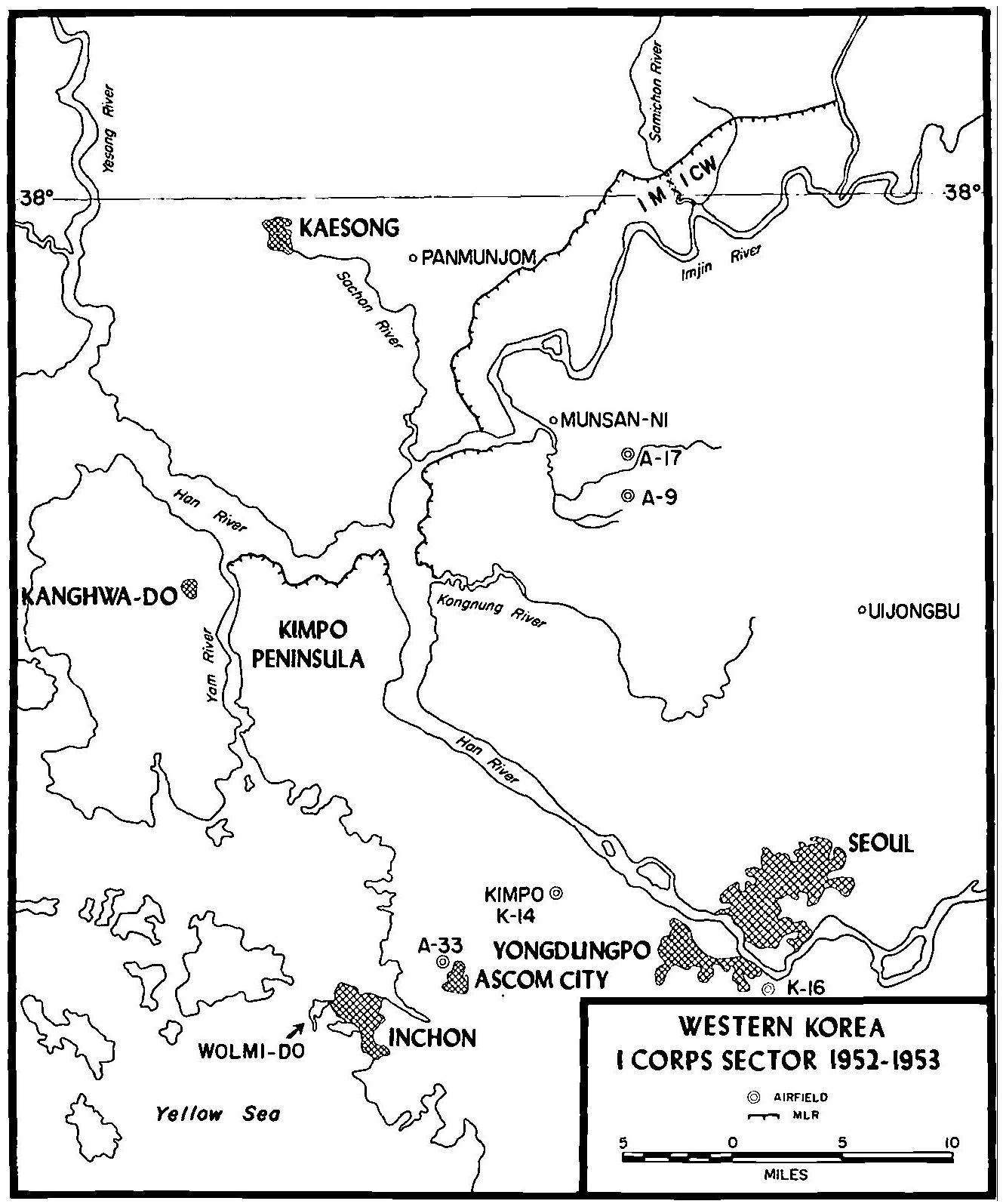

| 2 | Western Korea—I Corps Sector—1952–1953 | 14 |

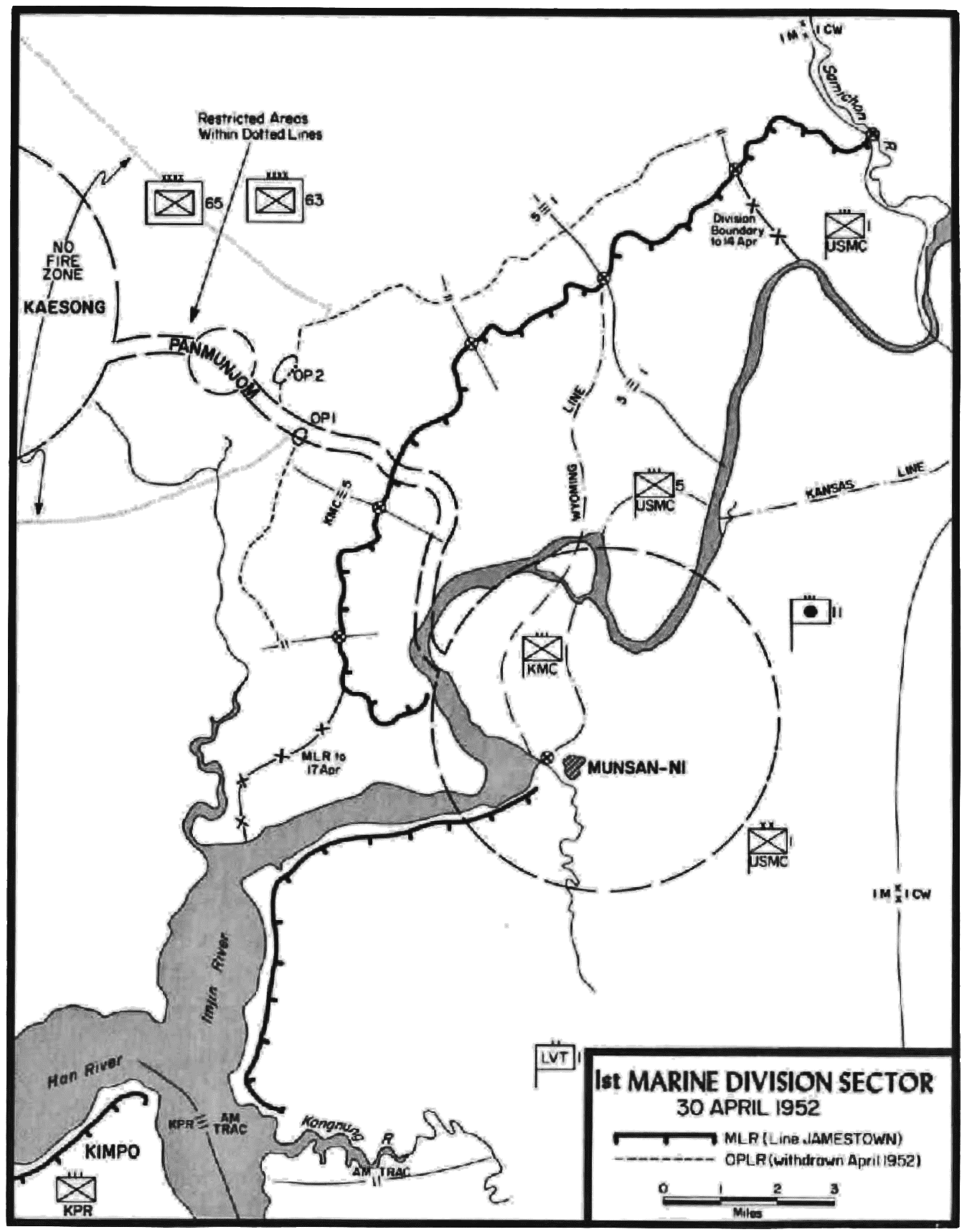

| 3 | 1st Marine Division Sector—30 April 1952 | 23 |

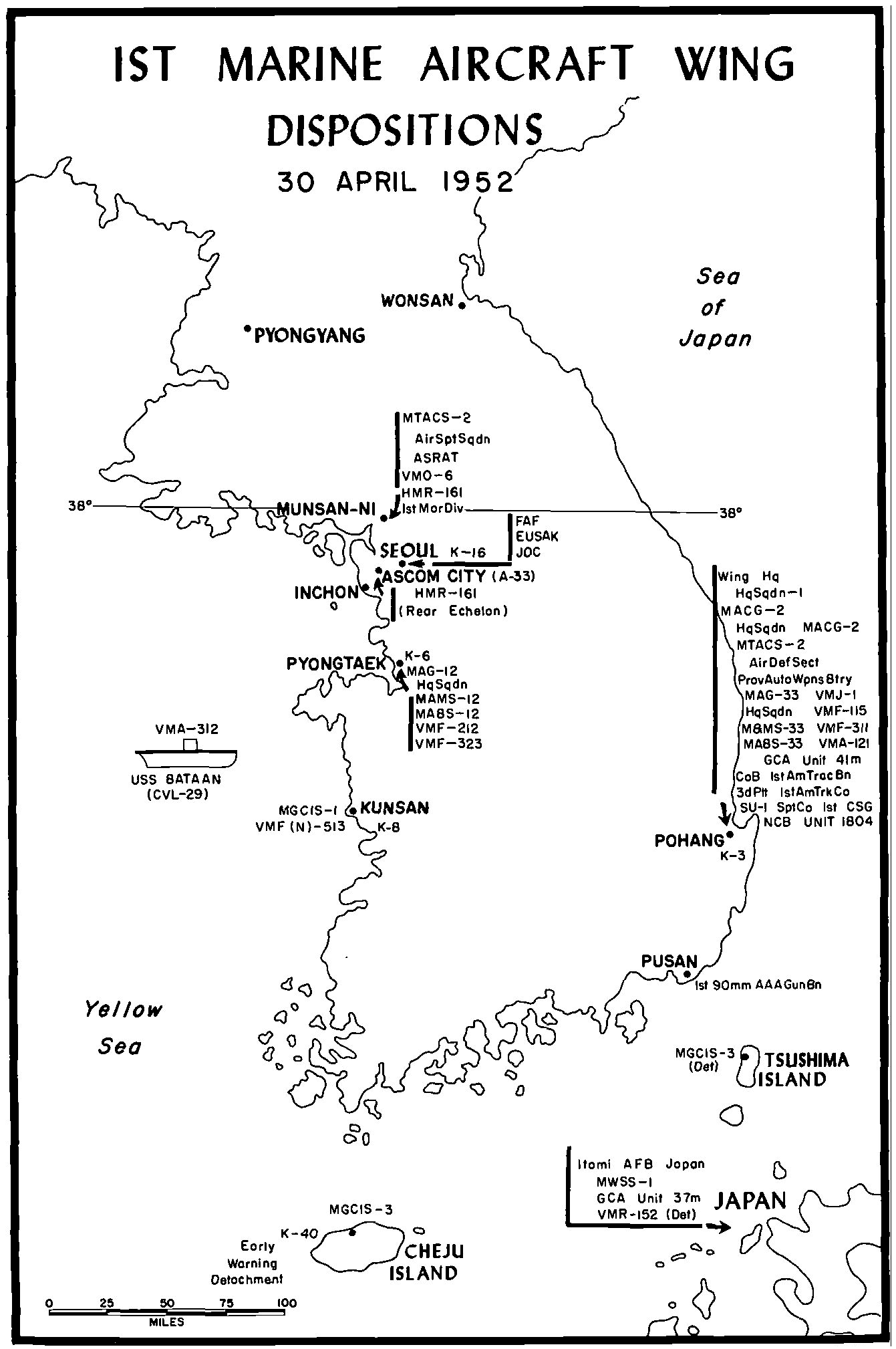

| 4 | 1st Marine Aircraft Wing Dispositions—30 April 1952 | 25 |

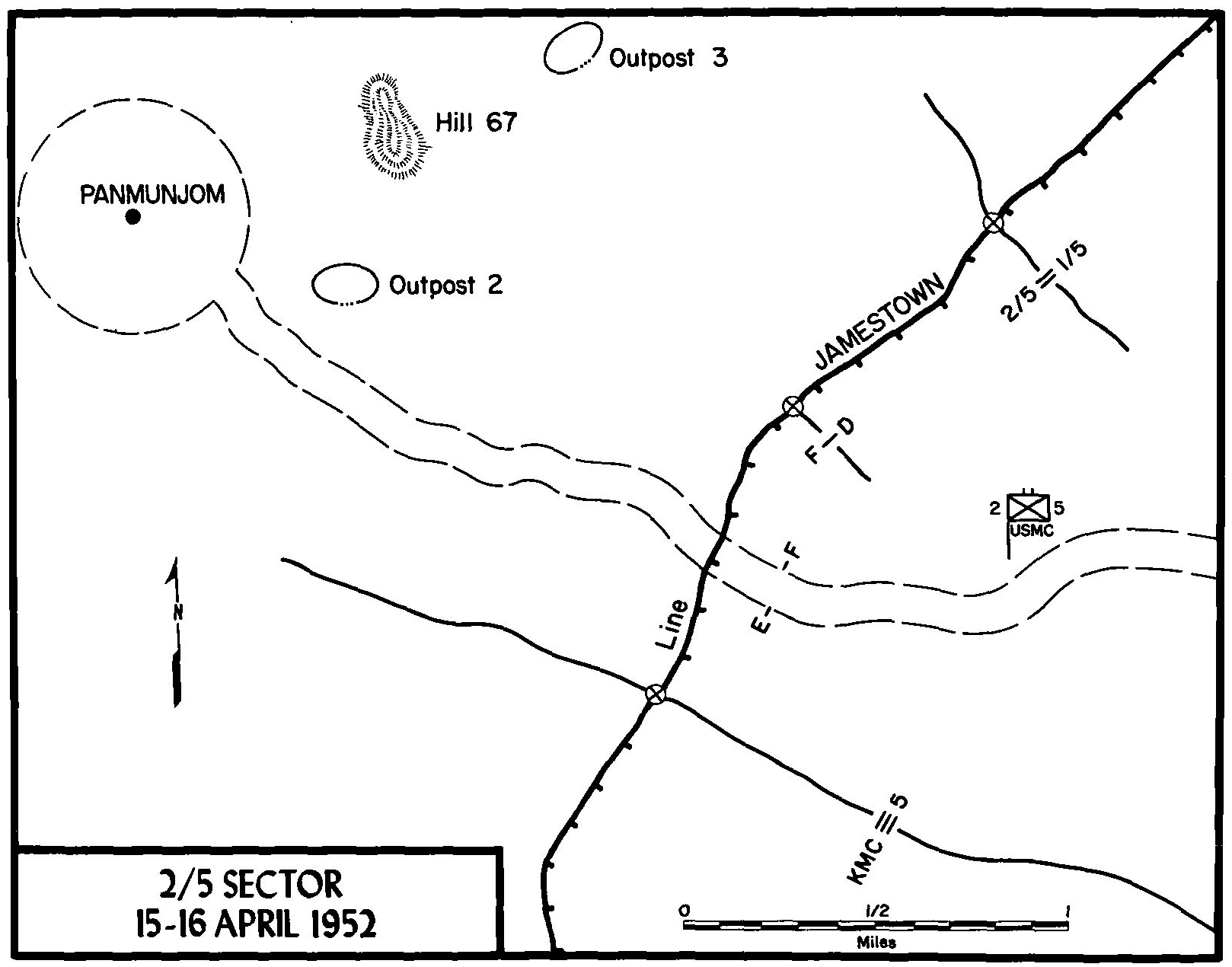

| 5 | 2/5 Sector—15–16 April 1952 | 35 |

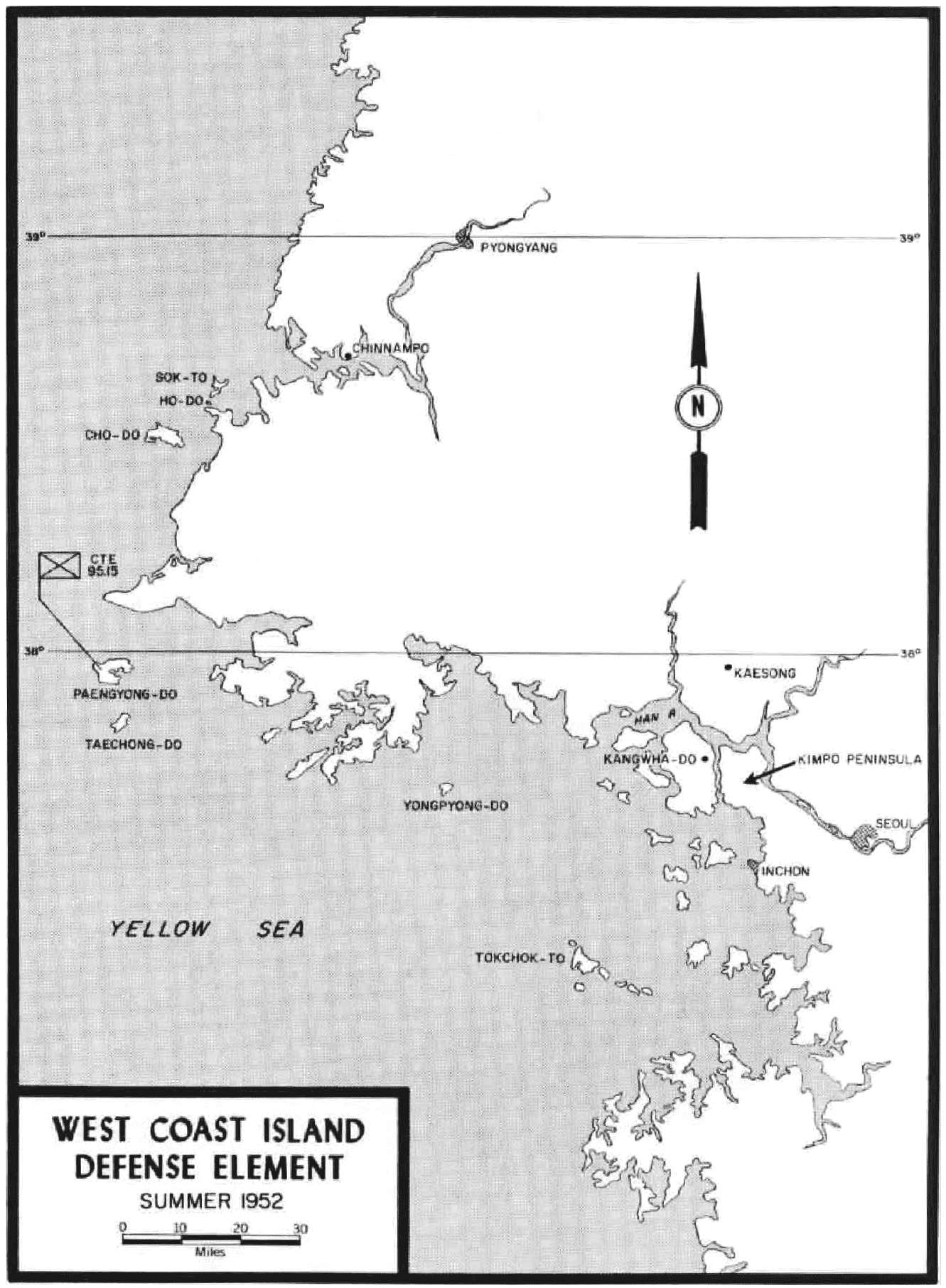

| 6 | West Coast Island Defense Element—Summer 1952 | 54 |

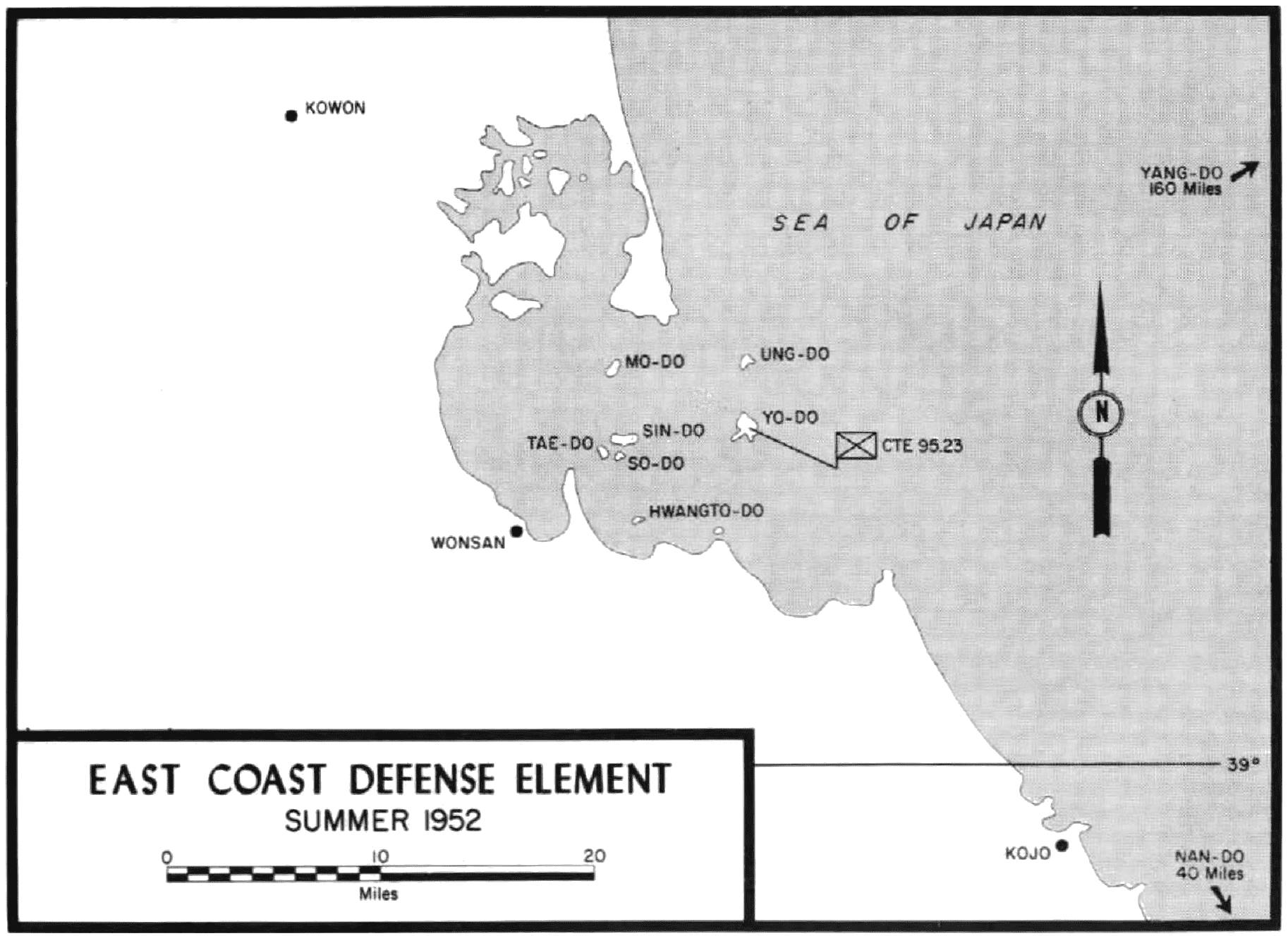

| 7 | East Coast Island Defense Element—Summer 1952 | 57 |

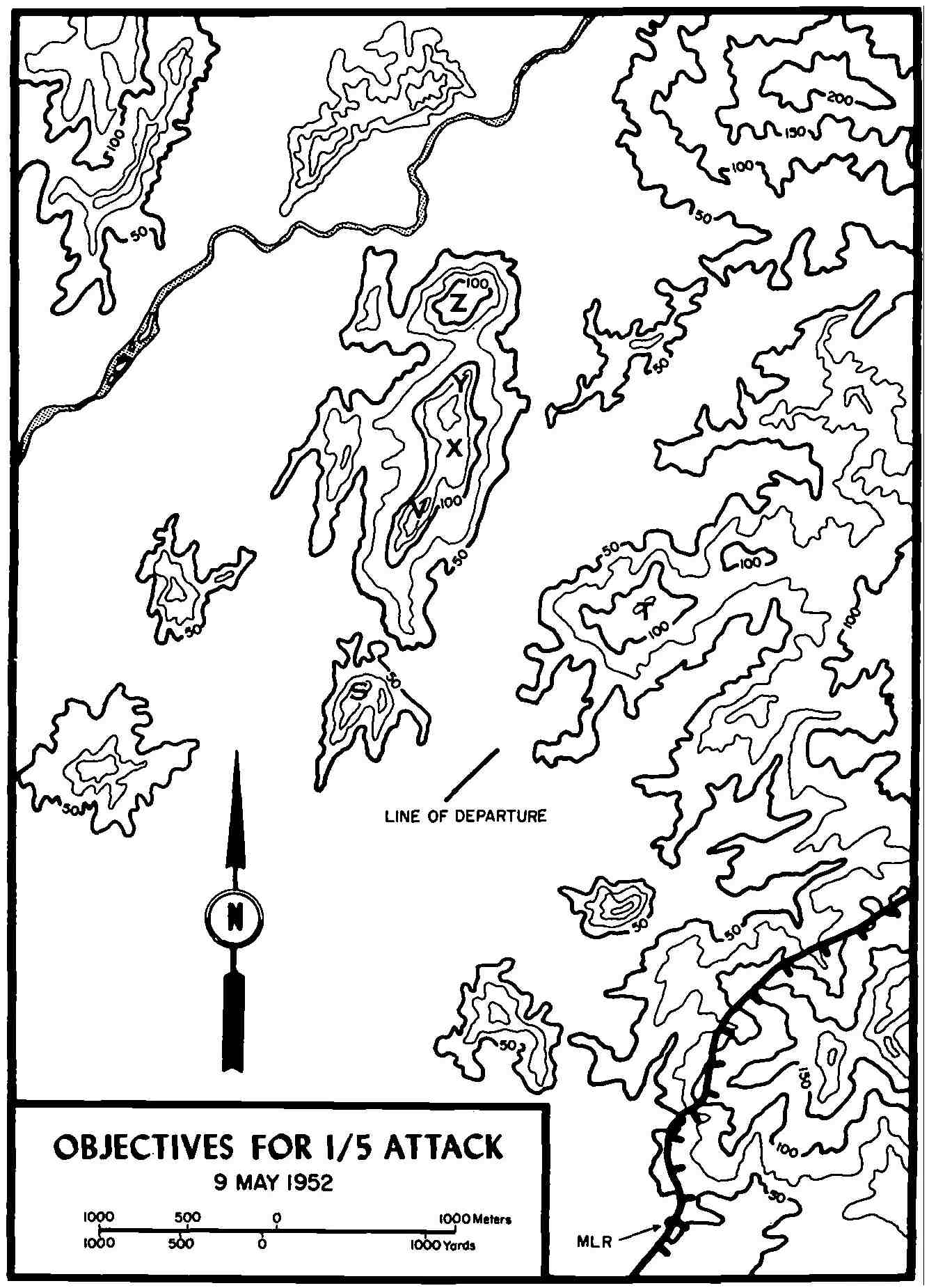

| 8 | Objectives for 1/5 Attack—9 May 1952 | 78 |

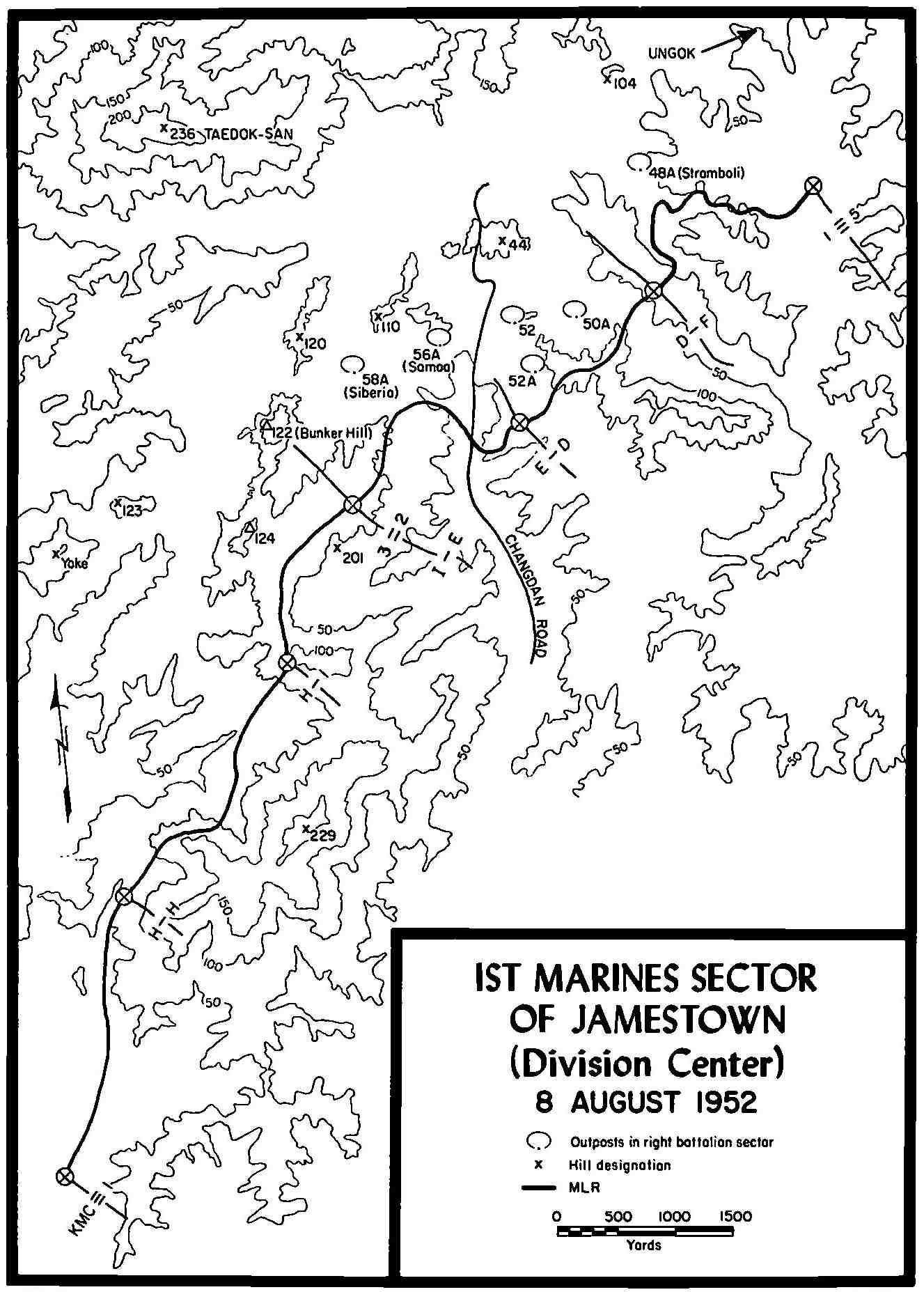

| 9 | 1st Marines Sector of JAMESTOWN (Division Center)—8 August 1952 | 110 |

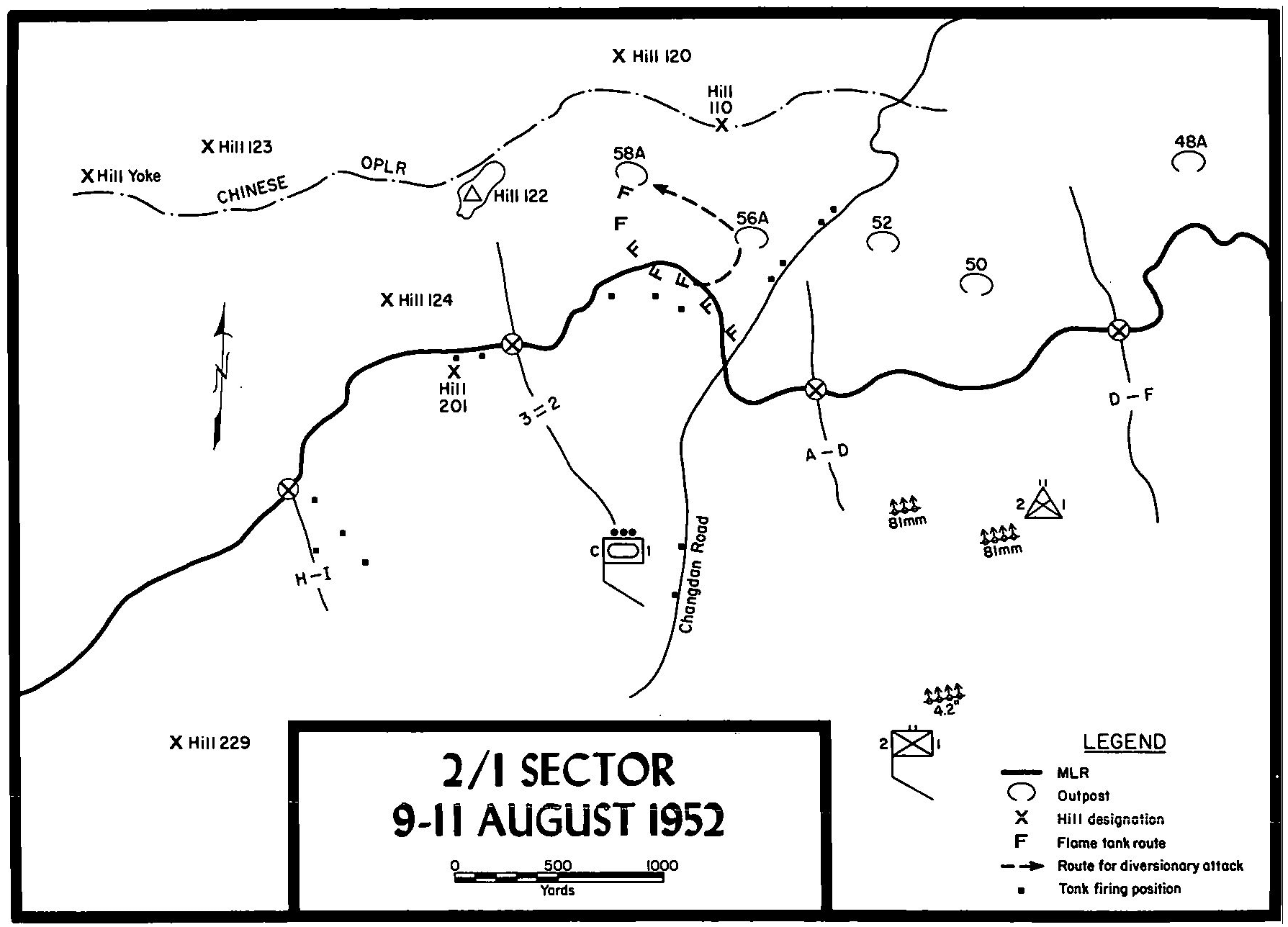

| 10 | 2/1 Sector—9–11 August 1952 | 115 |

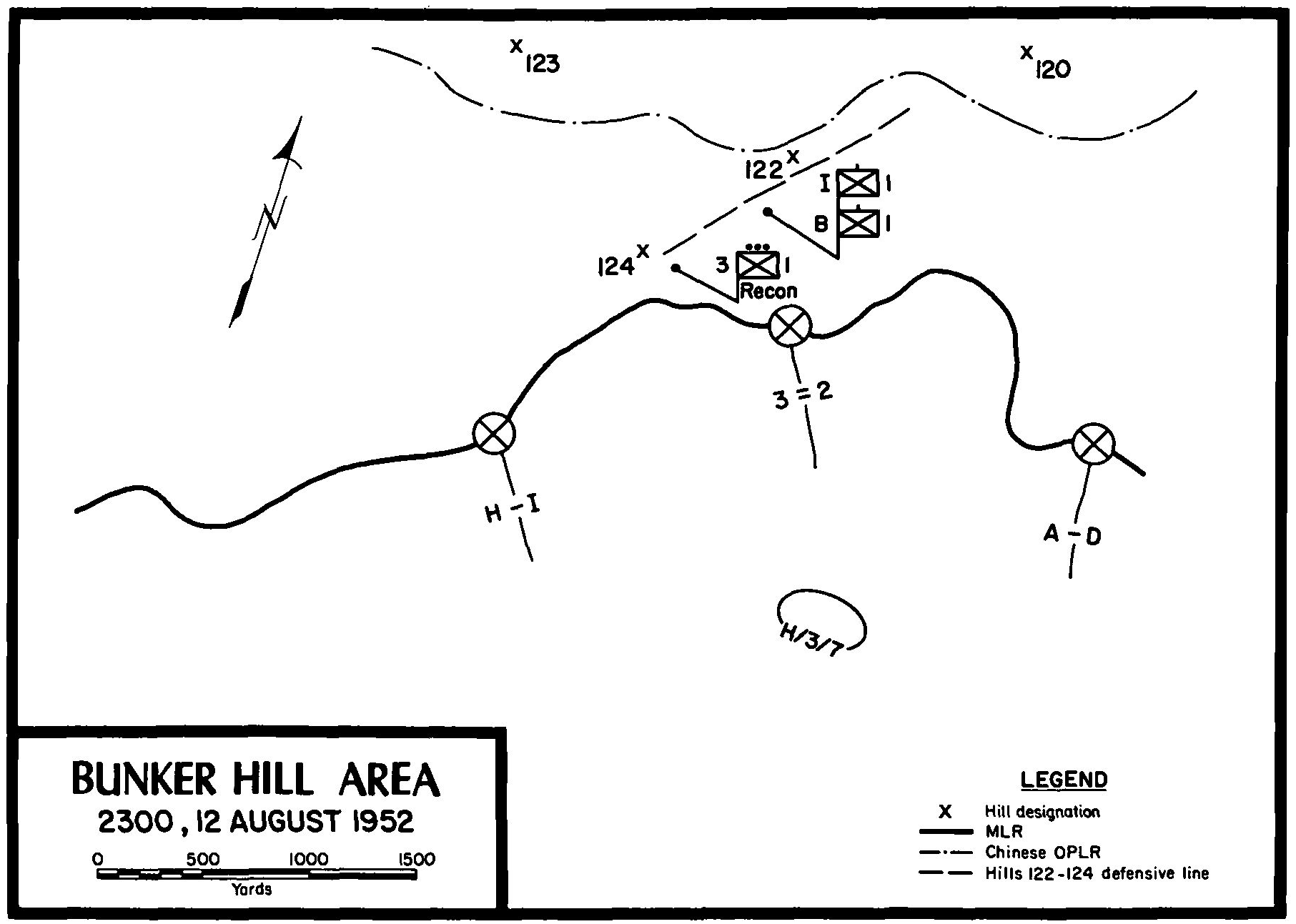

| 11 | Bunker Hill Area—2300, 12 August 1952 | 120 |

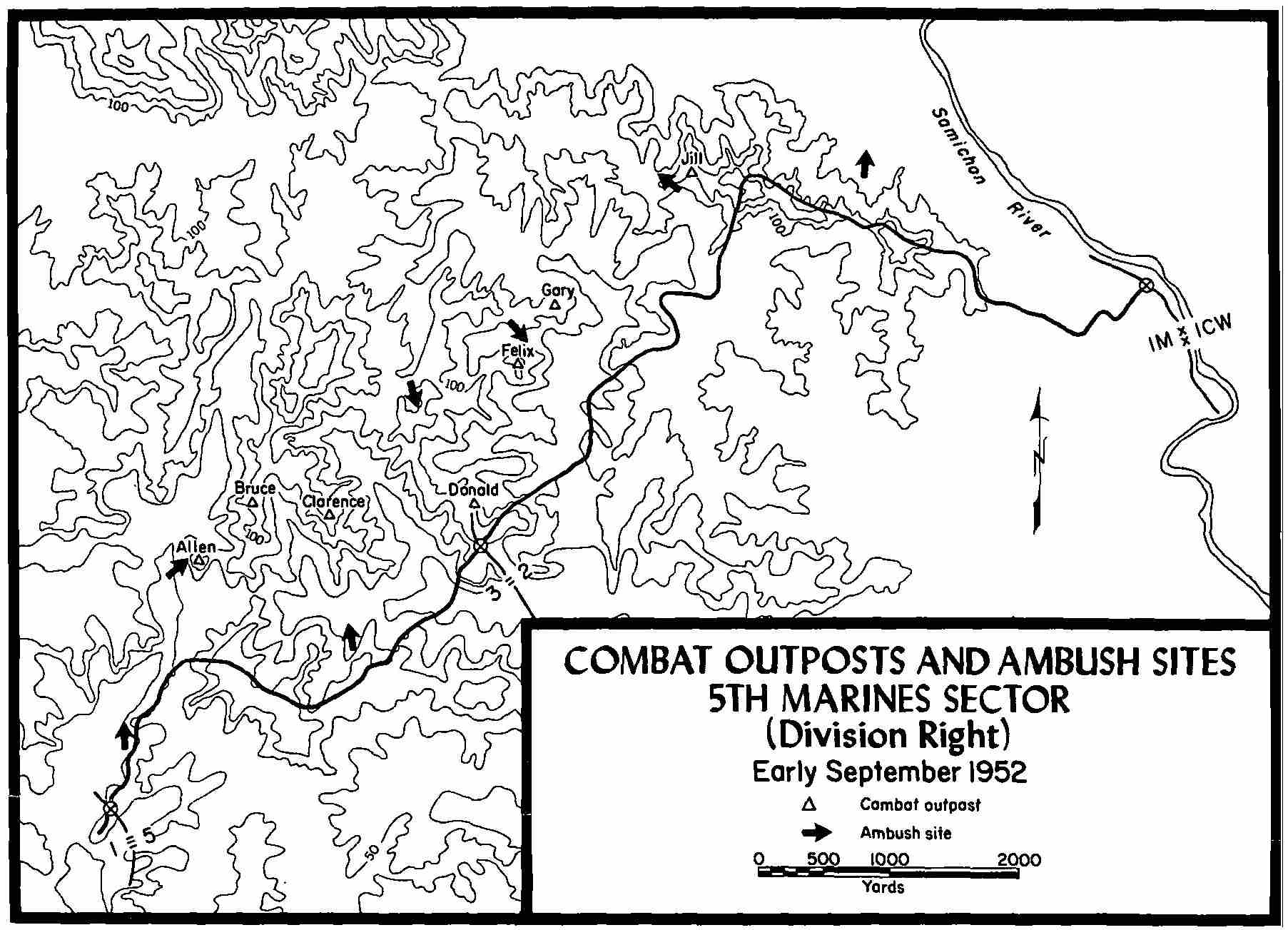

| 12 | Combat Outposts and Ambush Sites—5th Marines Sector (Division Right)—Early September 1952 | 151 |

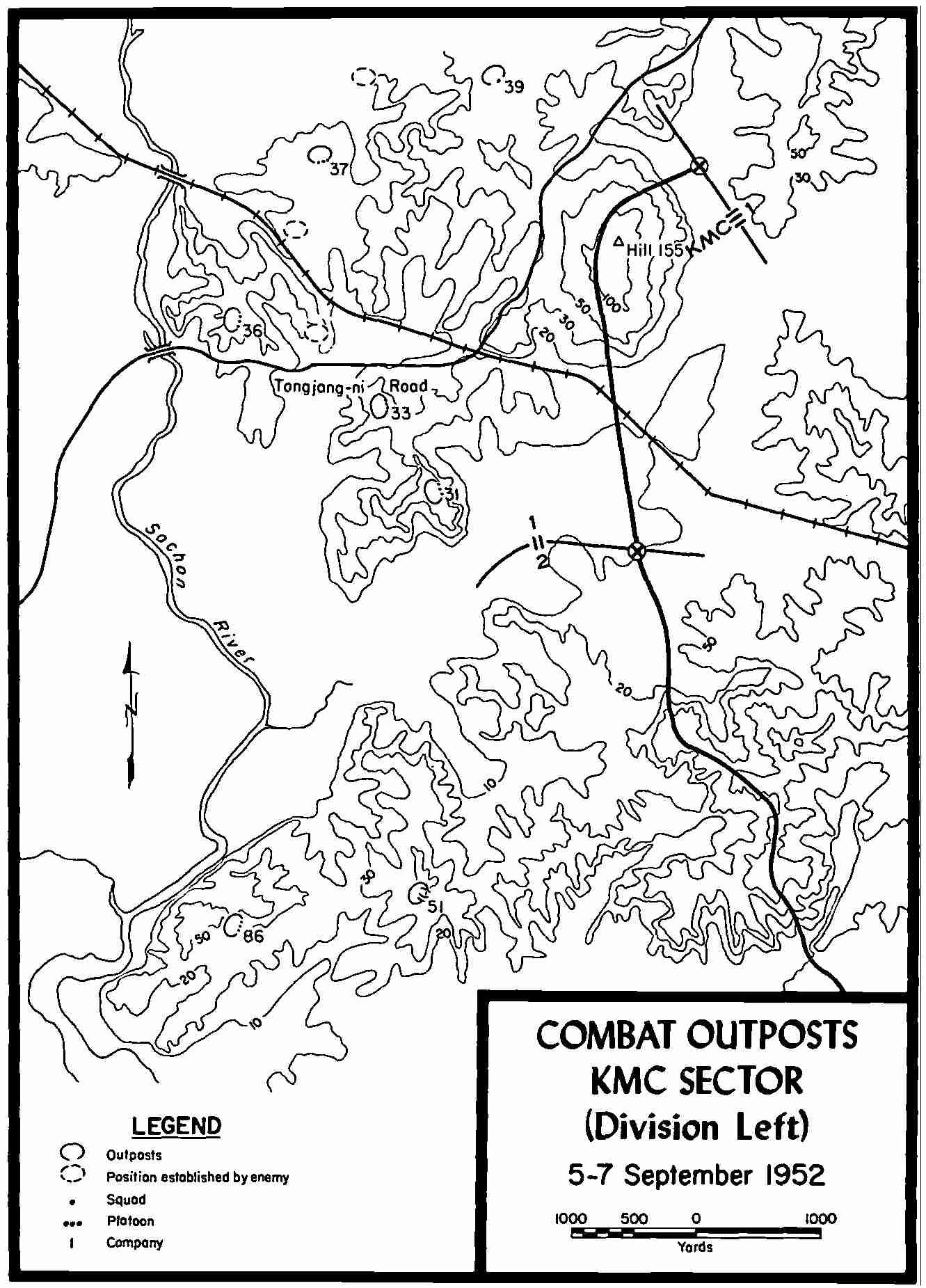

| 13 | Combat Outposts—KMC Sector (Division Left)—5–7 September 1952 | 154 |

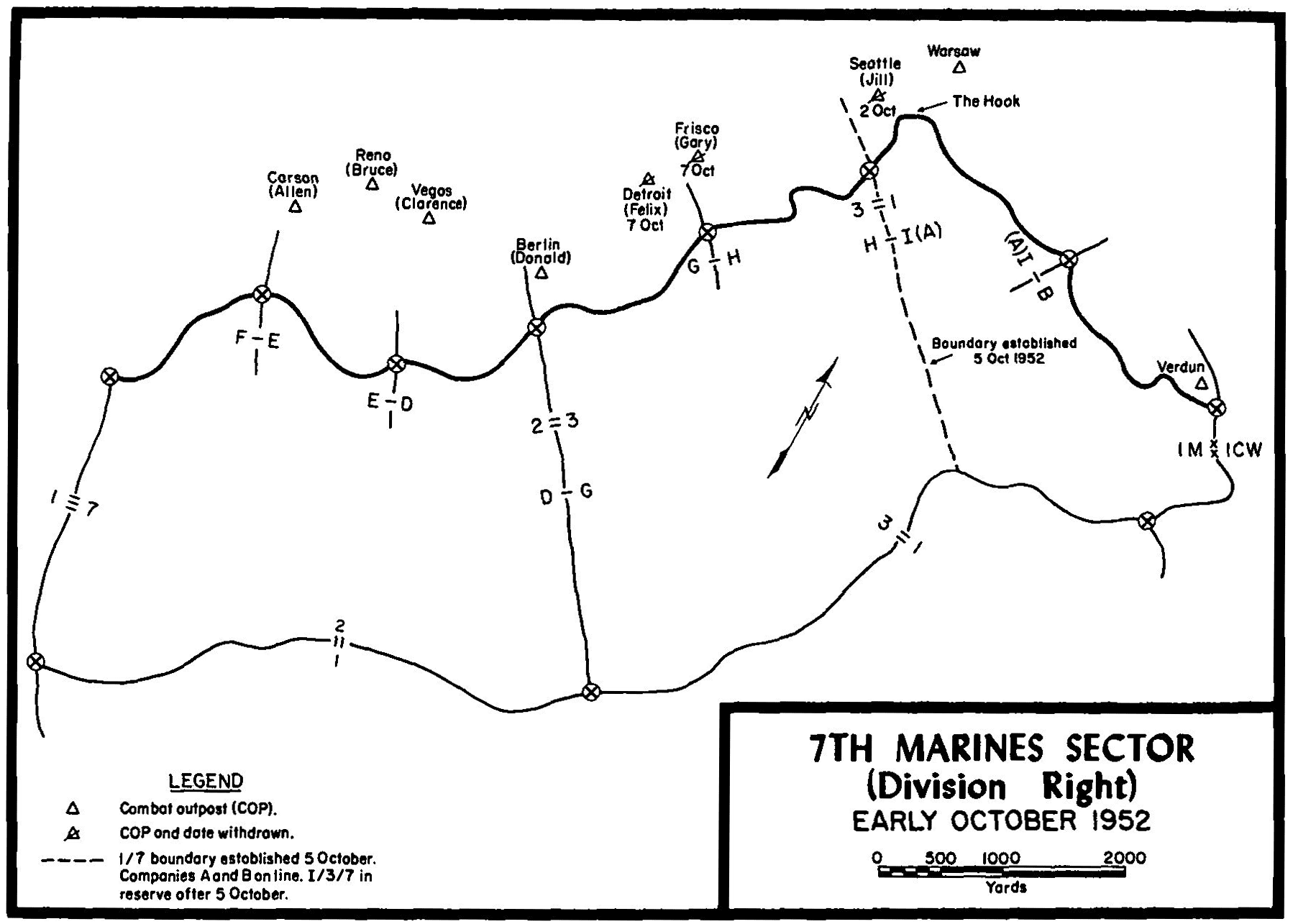

| 14 | 7th Marines Sector (Division Right)—Early October 1952 | 164 |

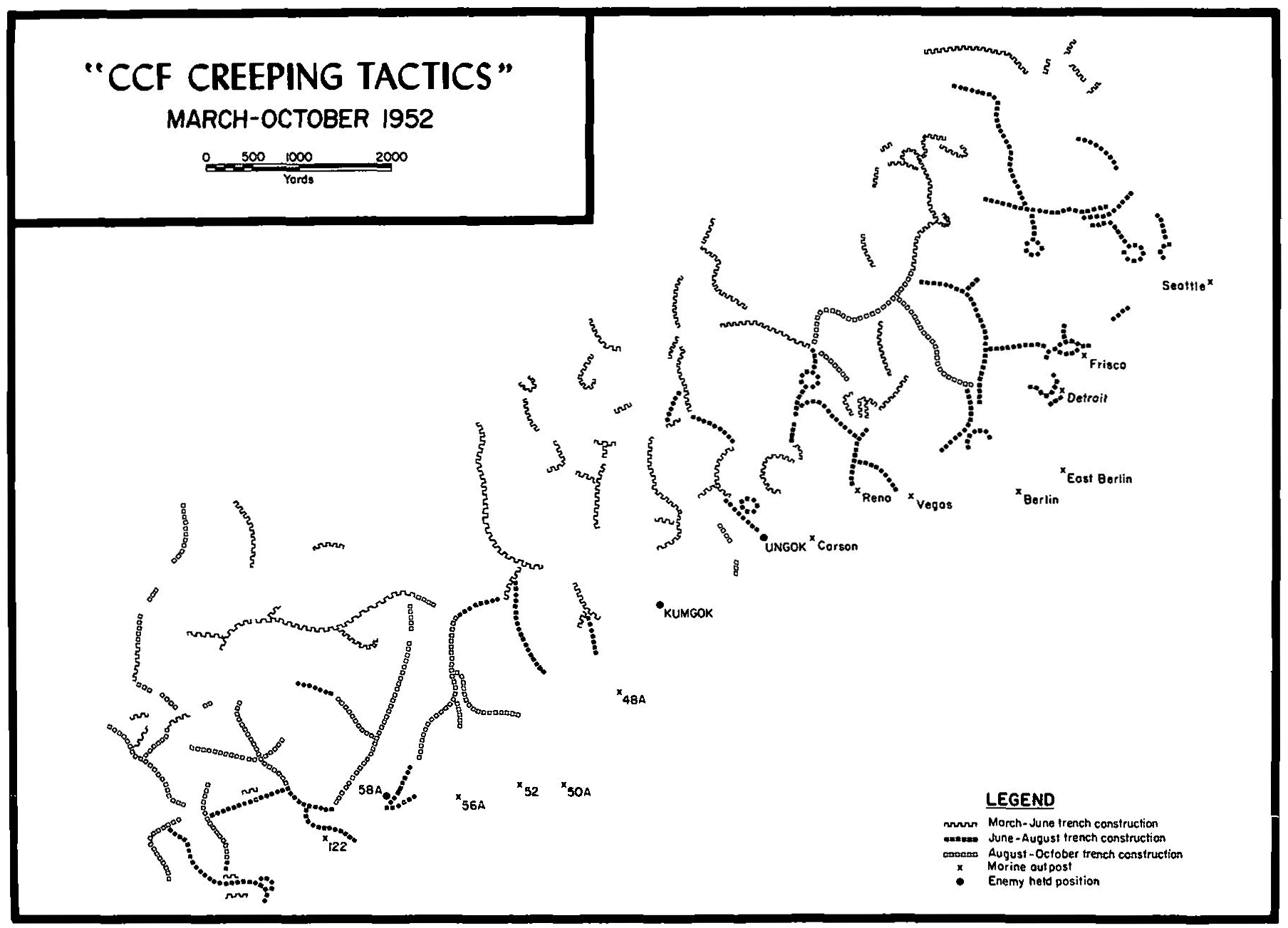

| 15 | “CCF Creeping Tactics”—March-October 1952 | 189 |

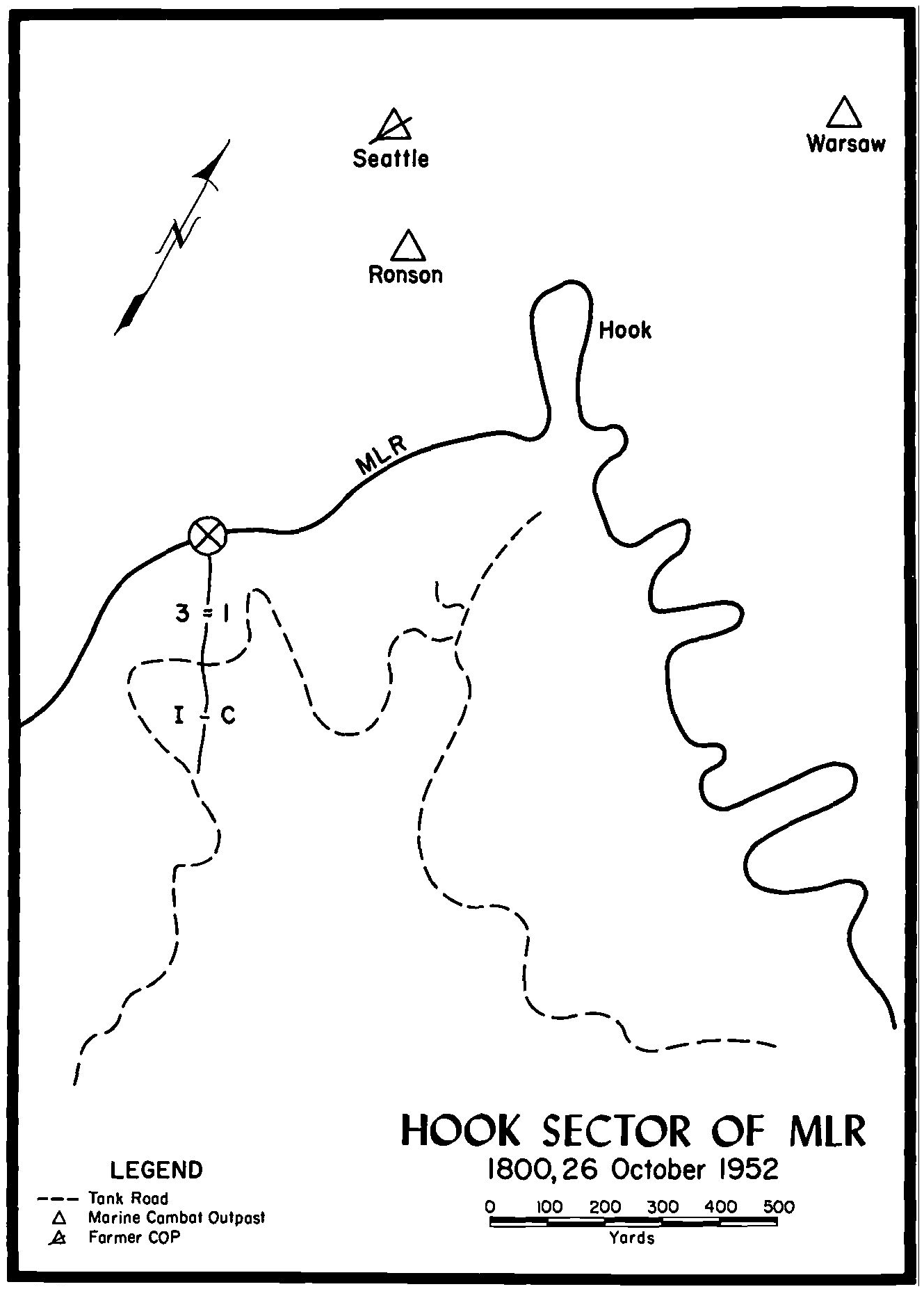

| 16 | Hook Sector of MLR—1800, 26 October 1952 | 198 |

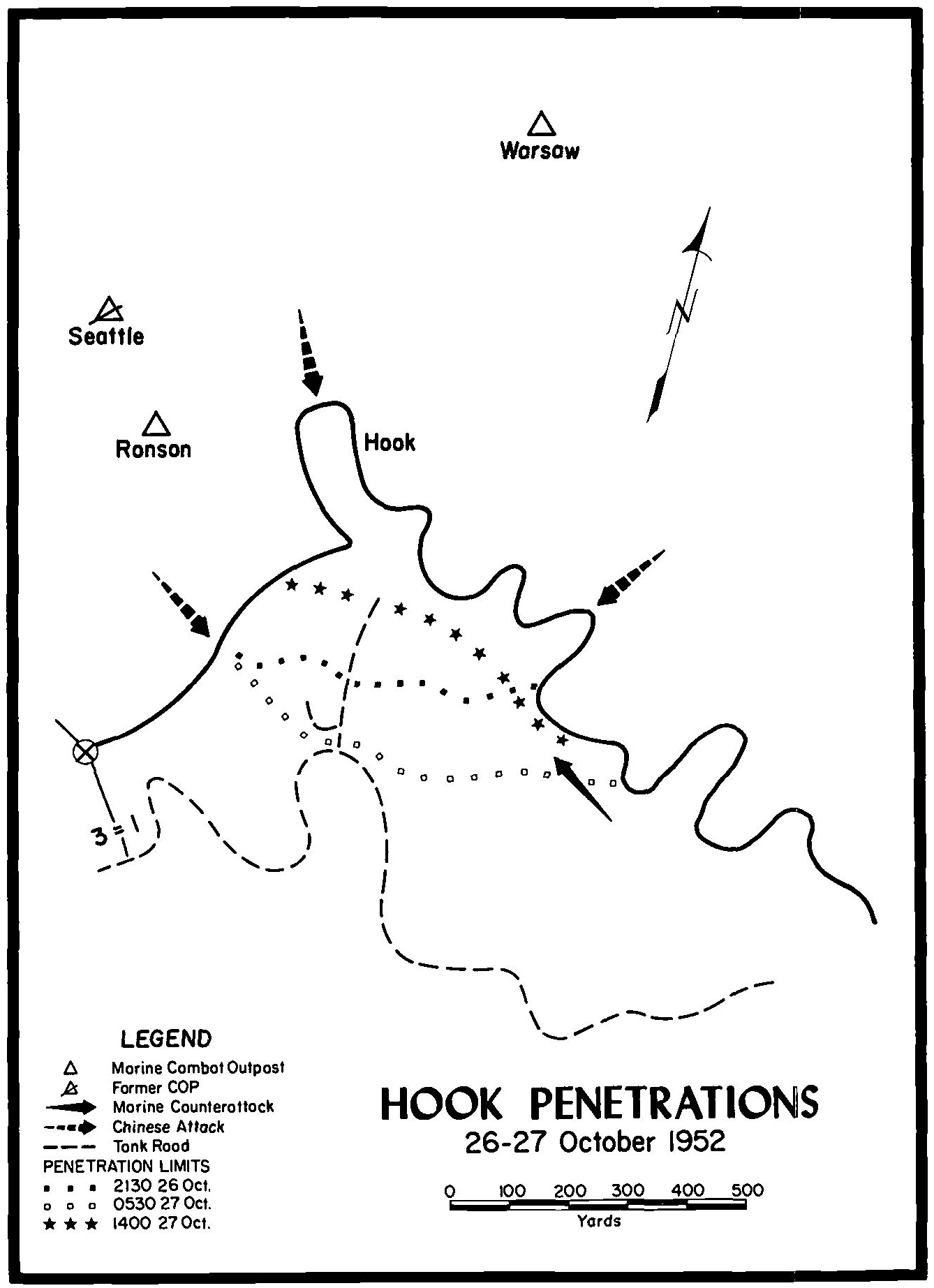

| 17 | Hook Penetrations—26–27 October 1952 | 201 |

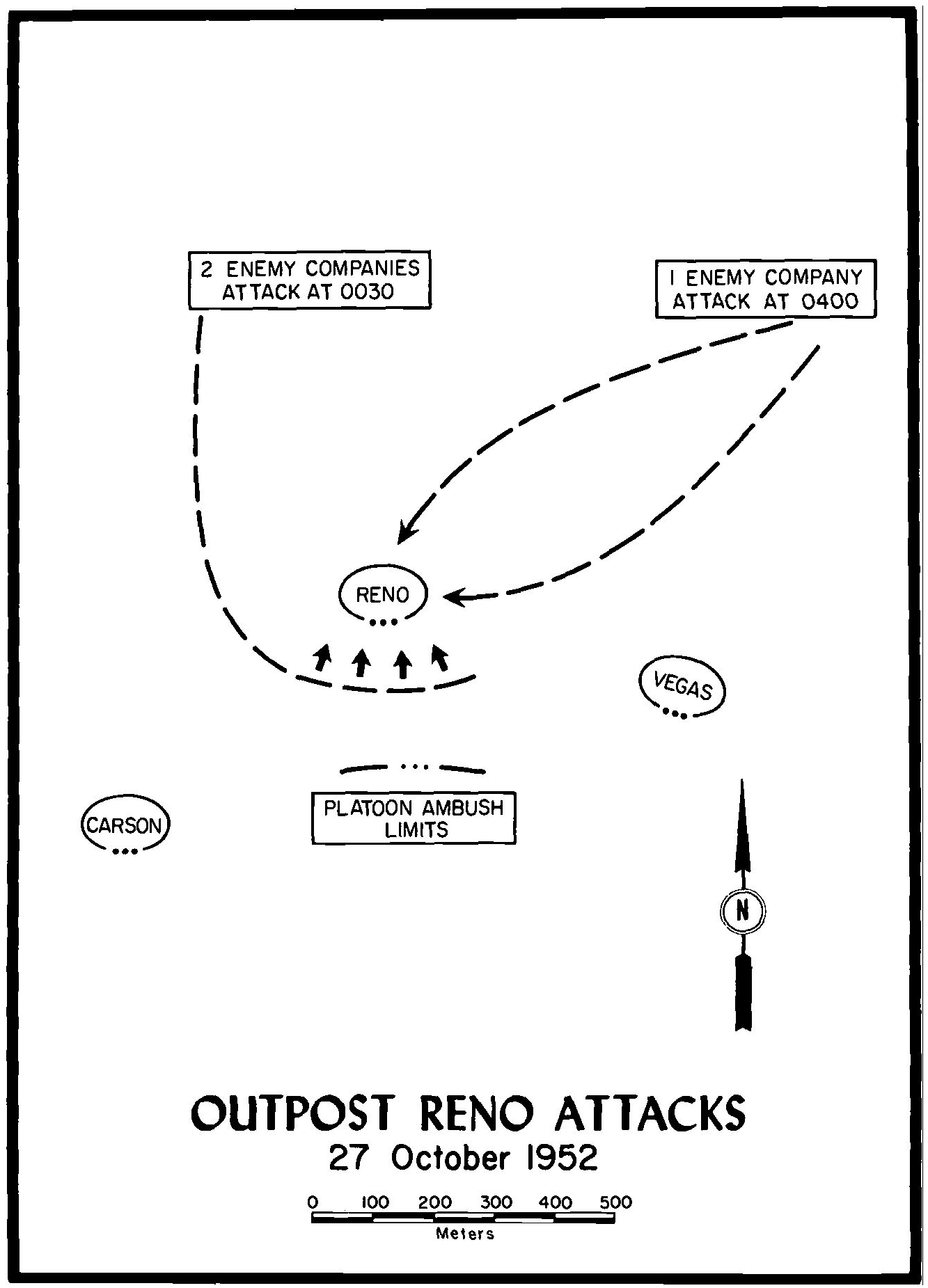

| 18 | Outpost Reno Attacks—27 October 1952 | 204 |

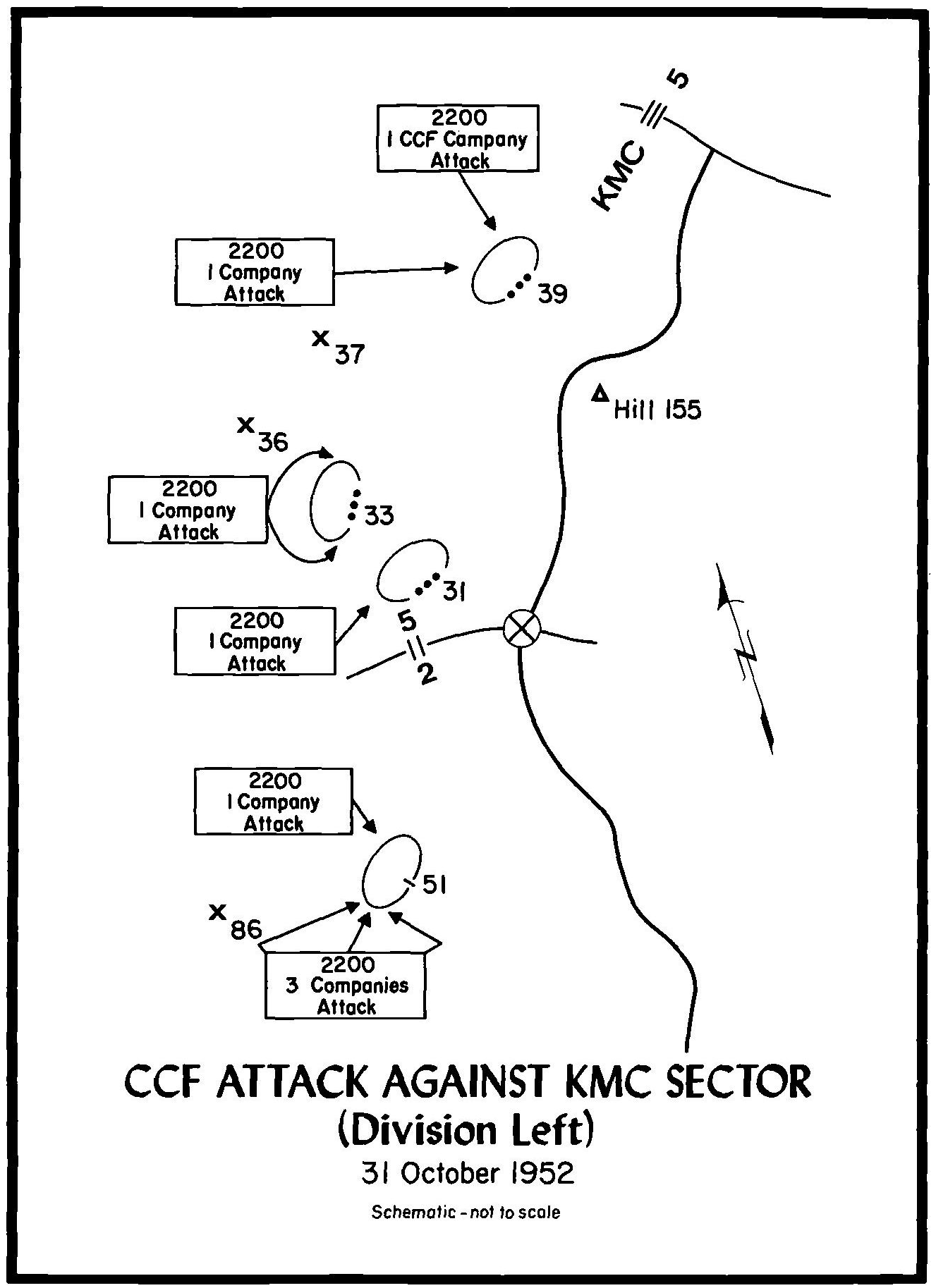

| 19 | CCF Attack Against KMC Sector (Division Left)—31 October 1952 | 219 |

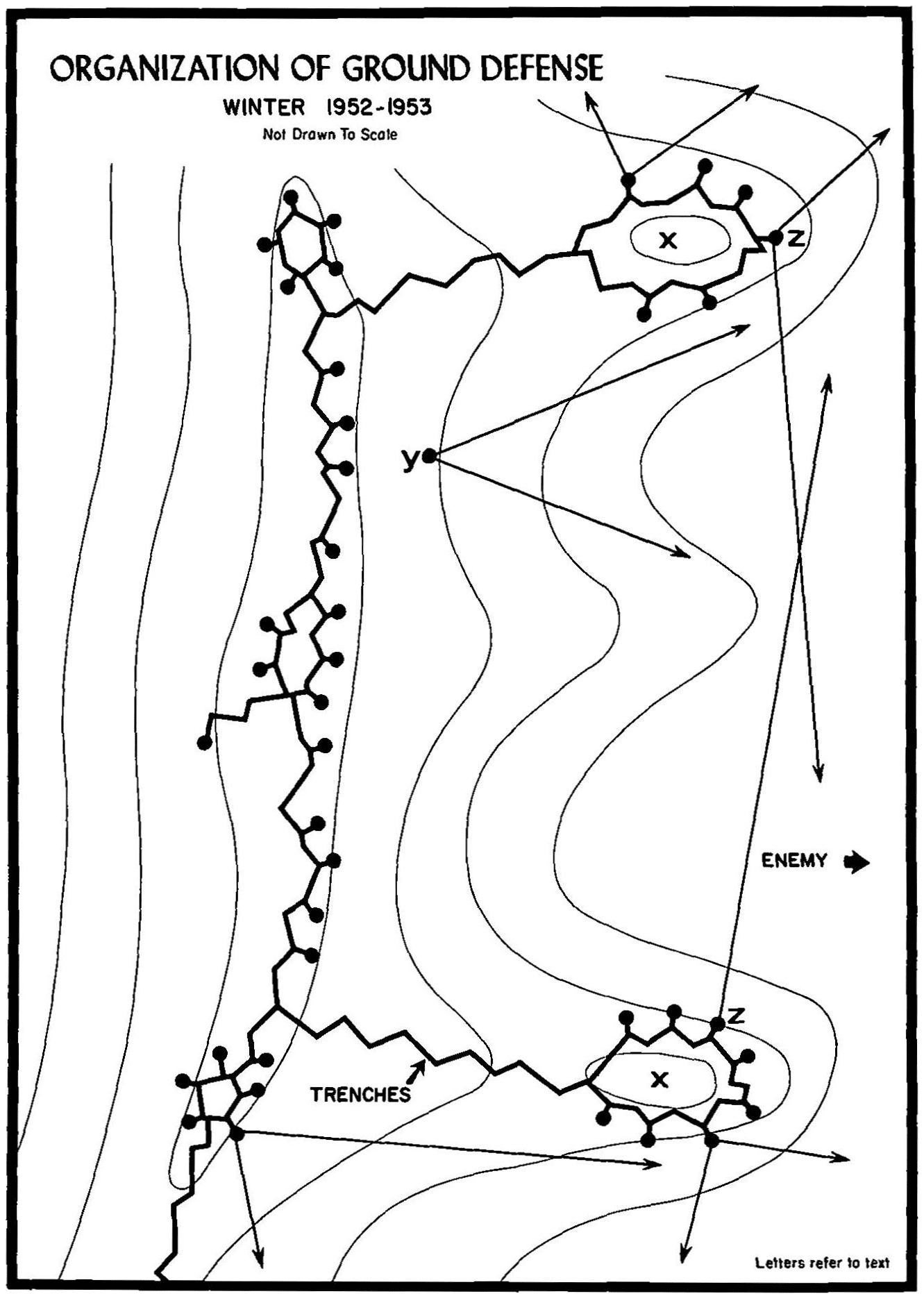

| 20 | Organization of Ground Defense—Winter 1952–1953 | 252 |

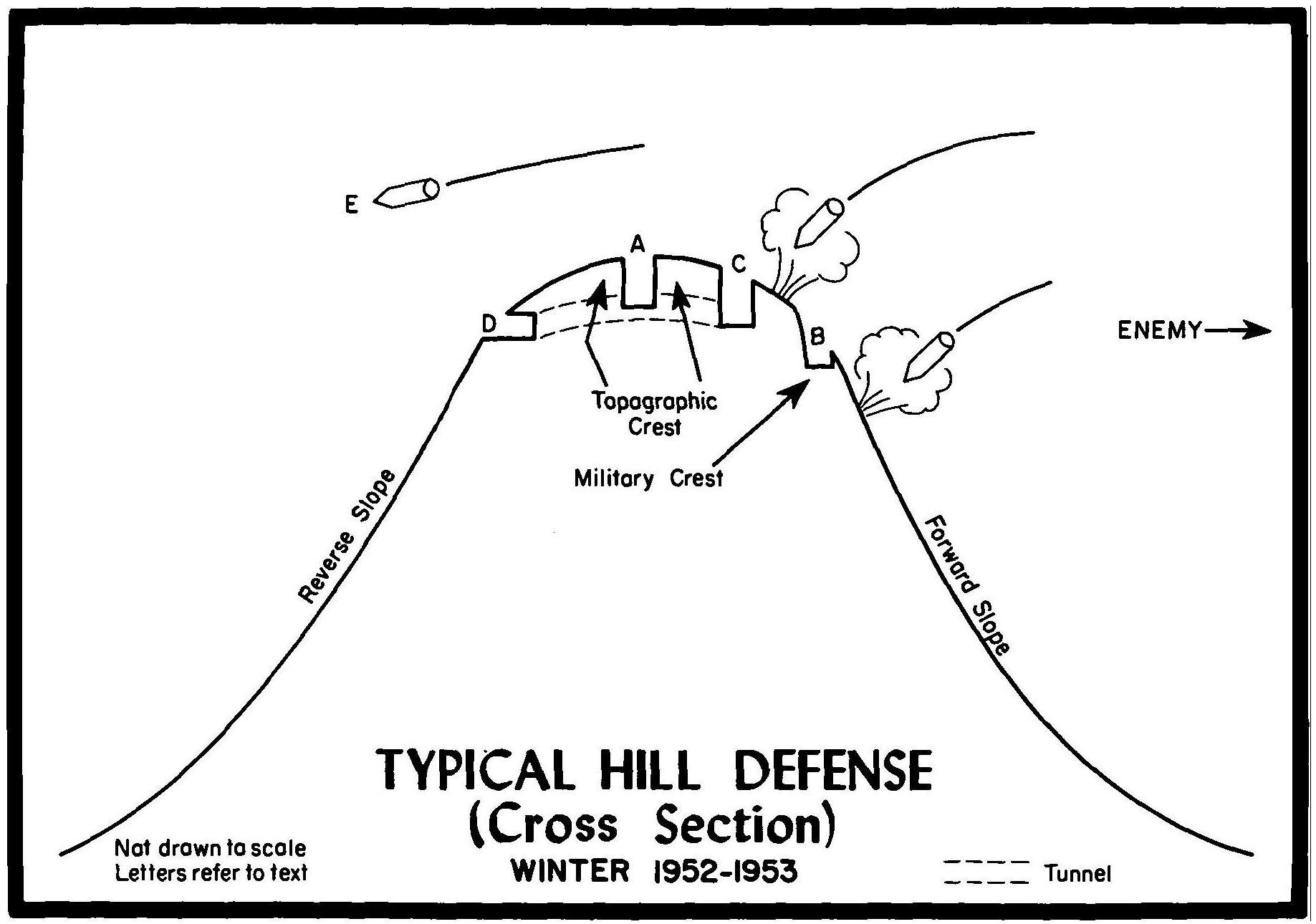

| 21 | Typical Hill Defense (Cross Section)—Winter 1952–1953 | 254 |

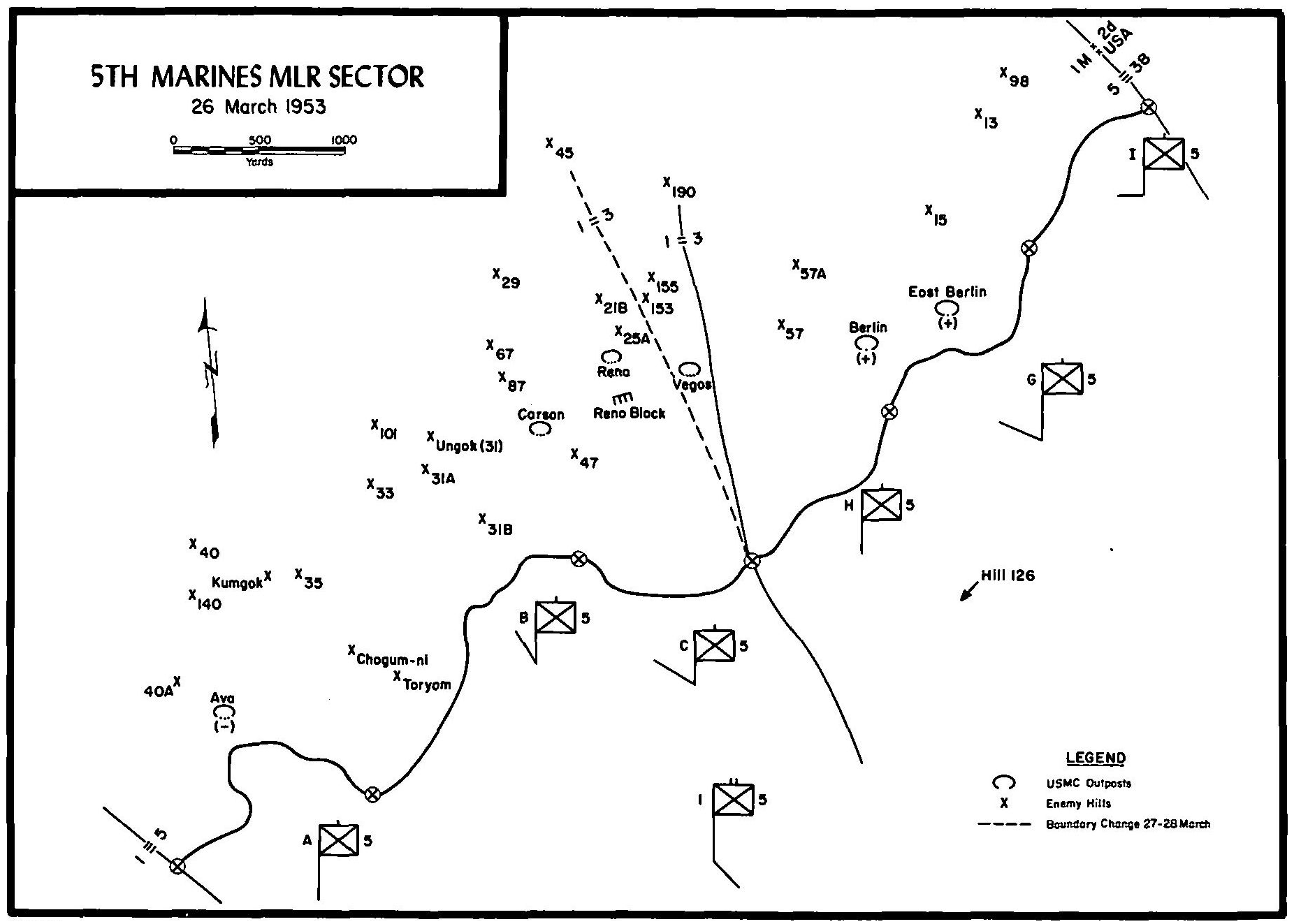

| 22 | 5th Marines MLR Sector—26 March 1953 | 266 |

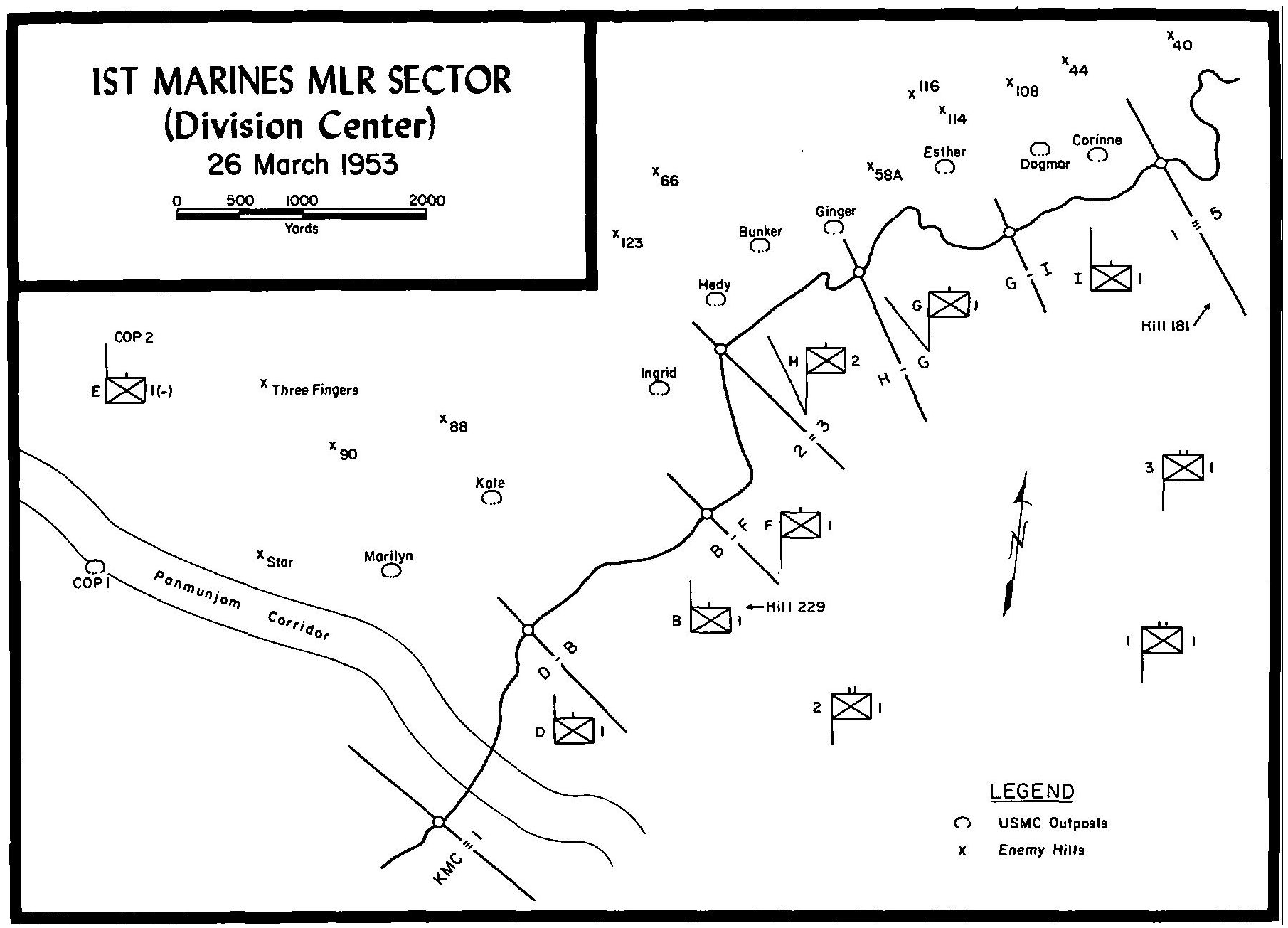

| 23 | 1st Marines MLR Sector (Division Center)—26 March 1953 | 269 |

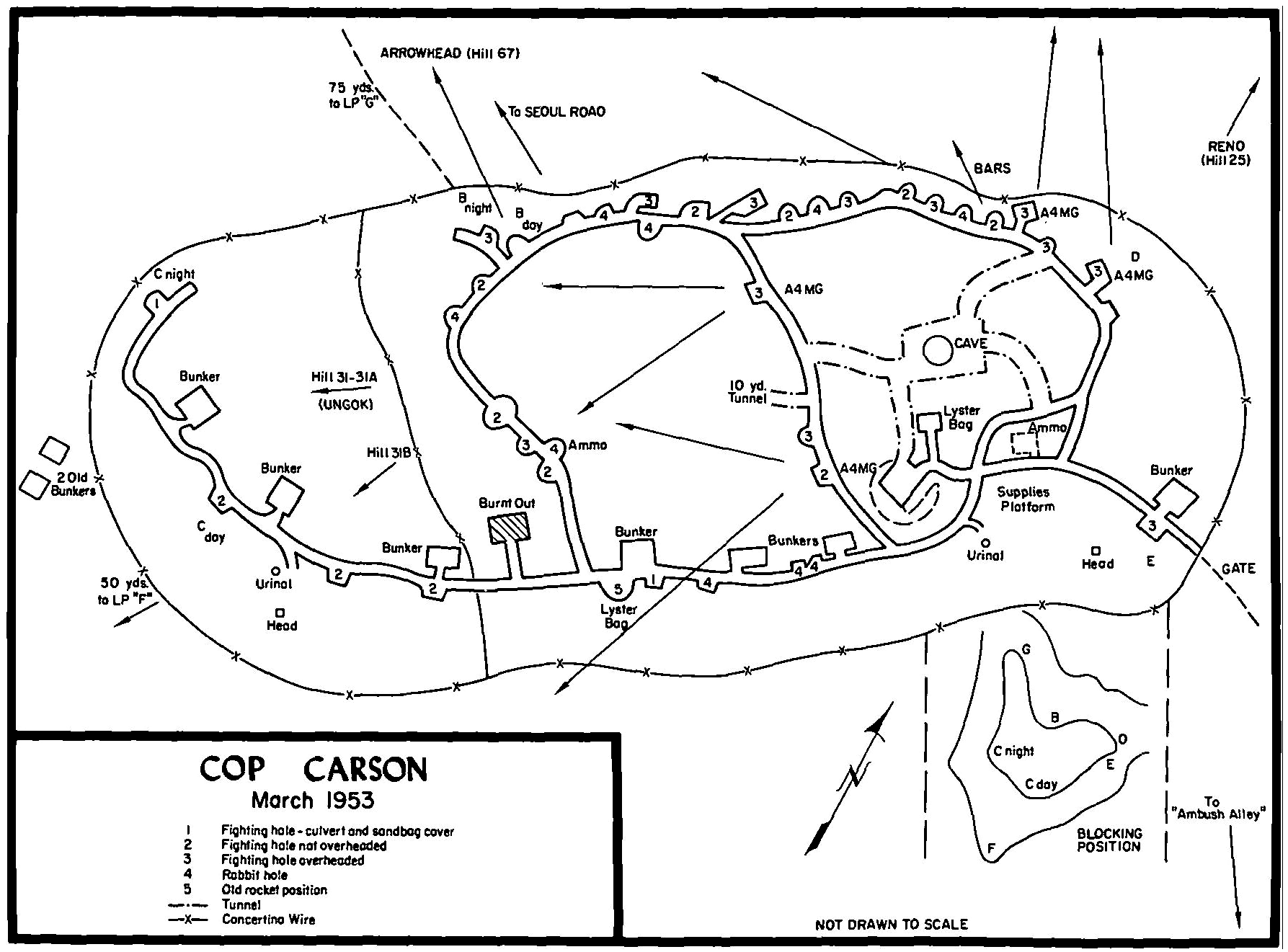

| 24 | COP Carson—March 1953 | 272 |

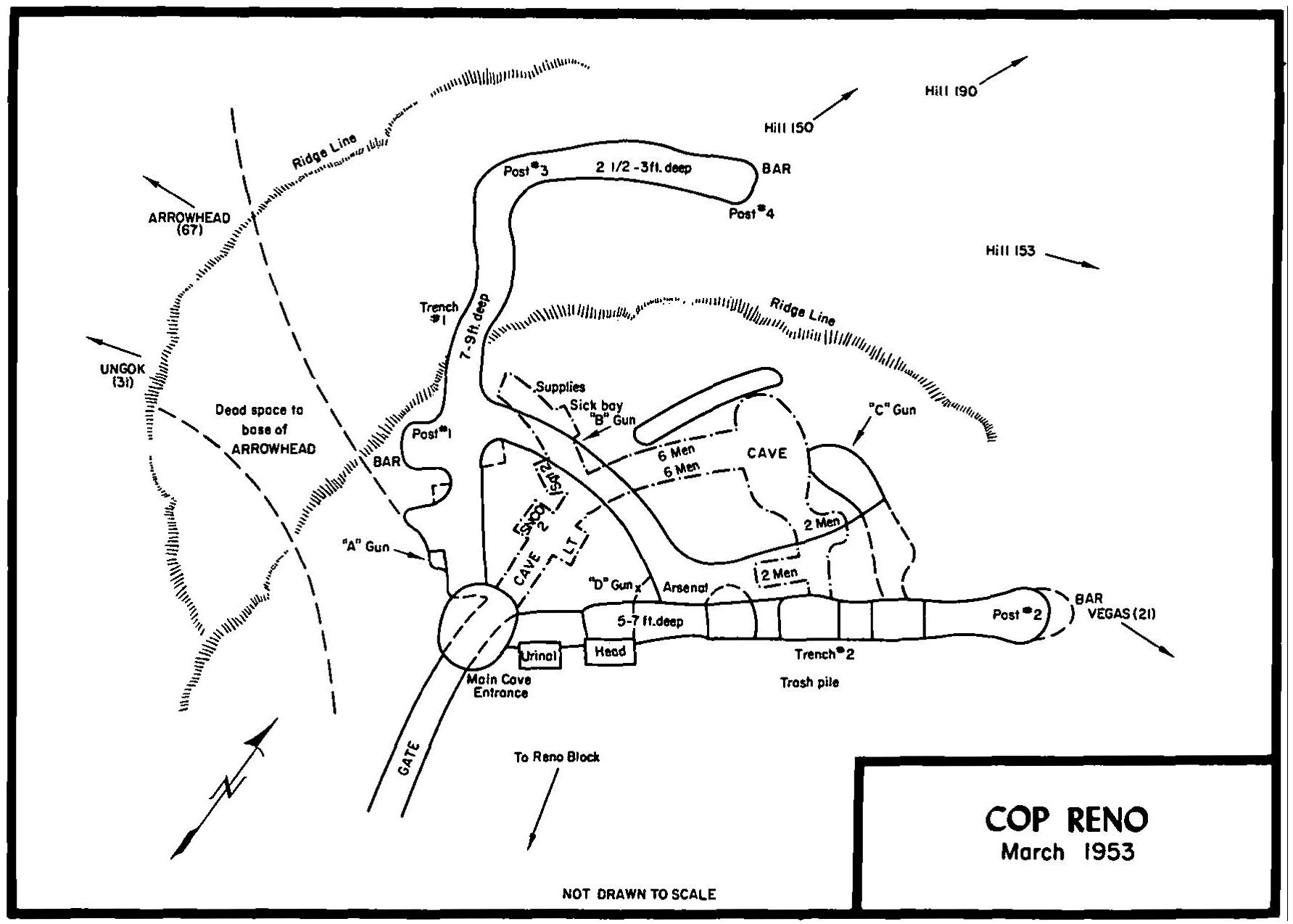

| 25 | COP Reno—March 1953 | 274 |

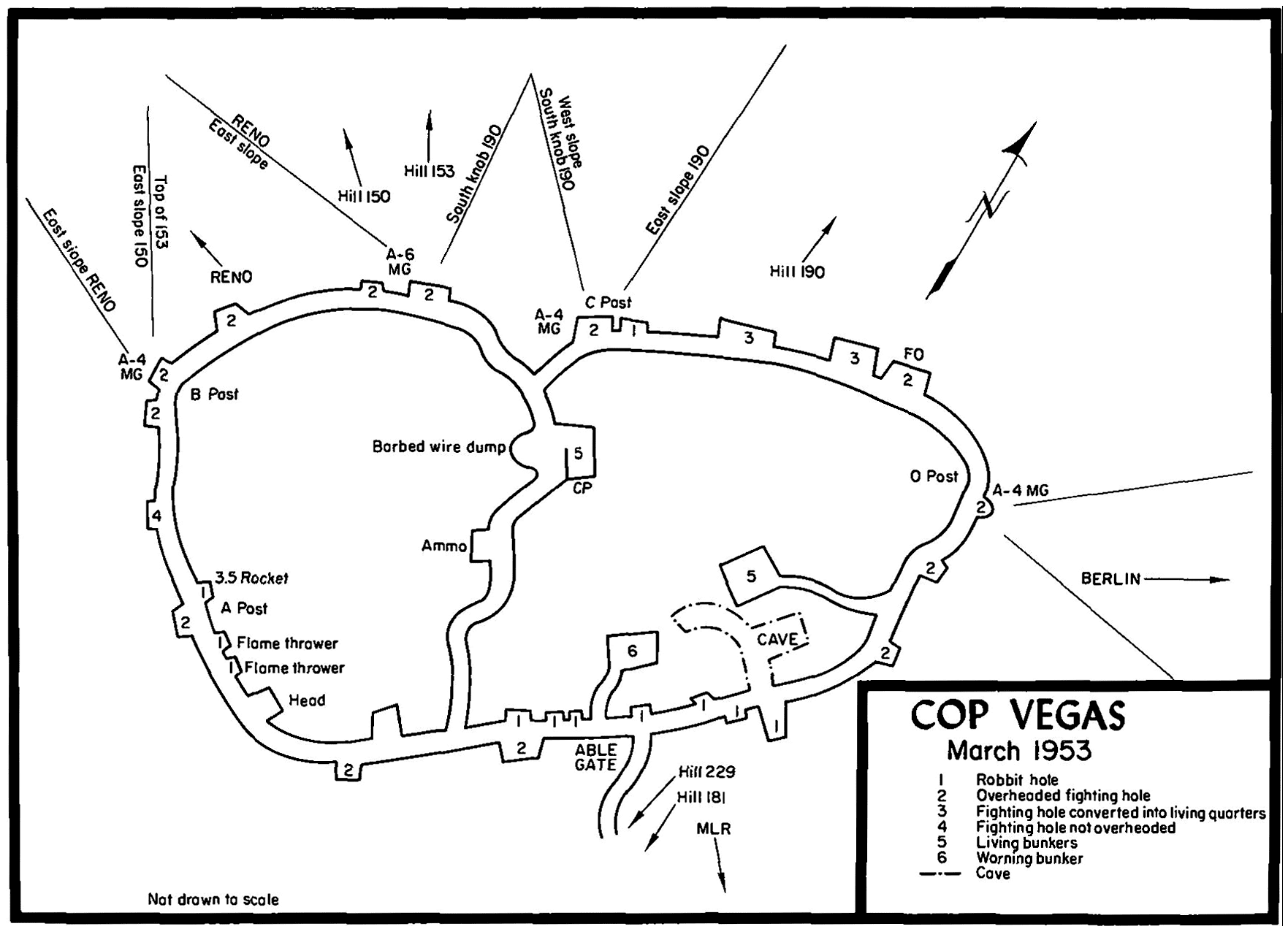

| 26 | COP Vegas—March 1953 | 277xi |

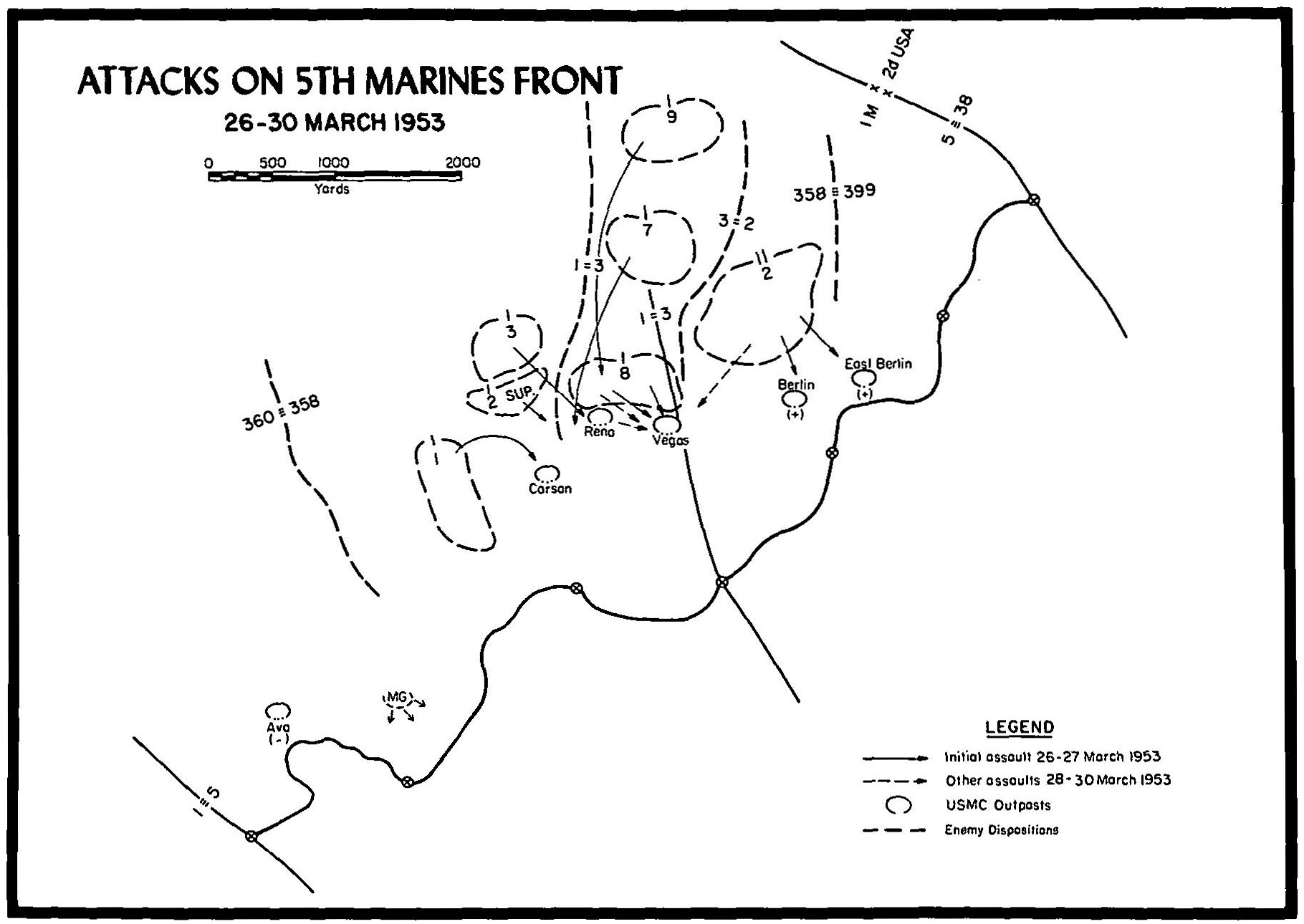

| 27 | Attack on 5th Marines Front—26–30 March 1953 | 282 |

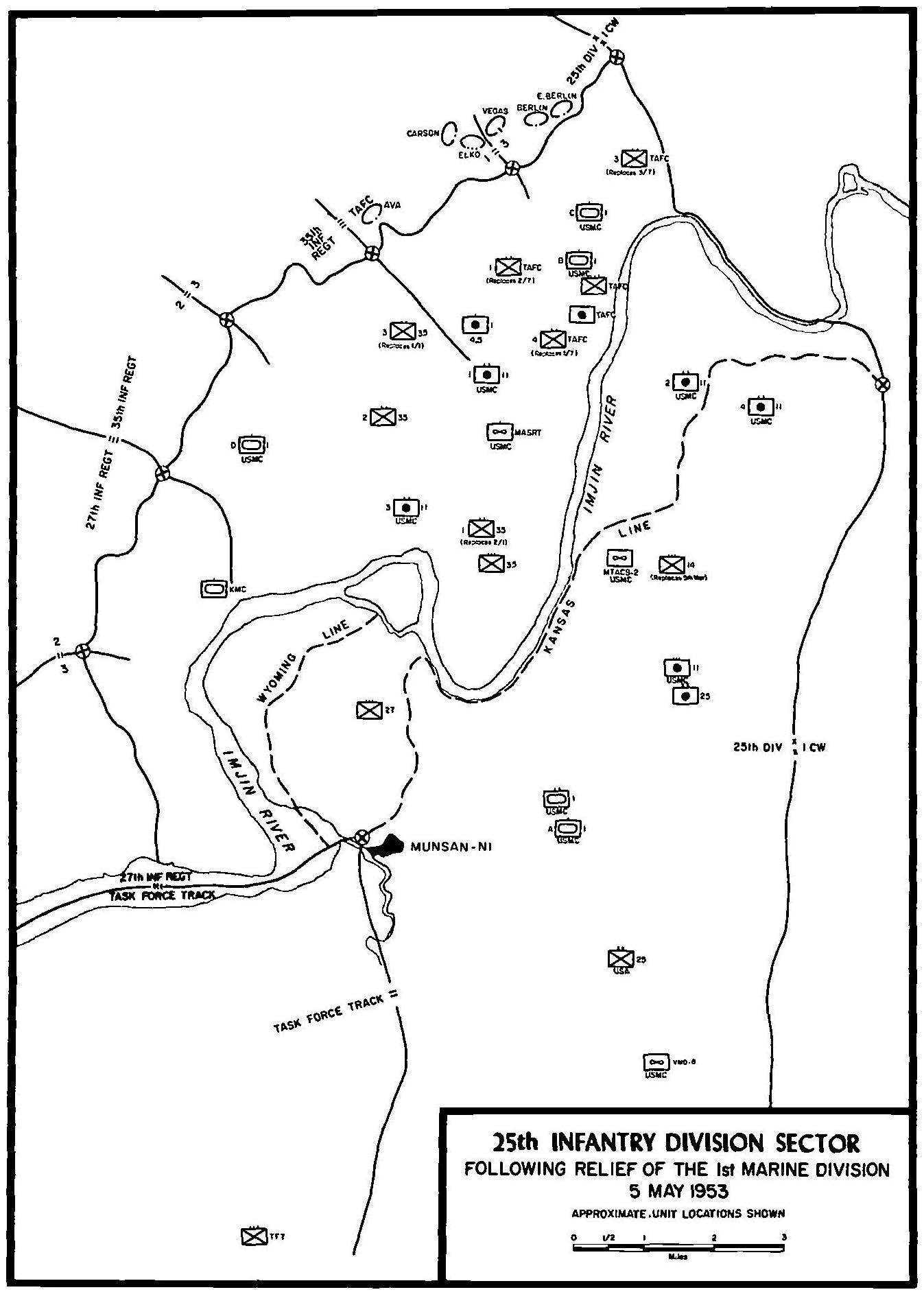

| 28 | 25th Infantry Division Sector (Following Relief of the 1st Marine Division)—5 May 1953 | 330 |

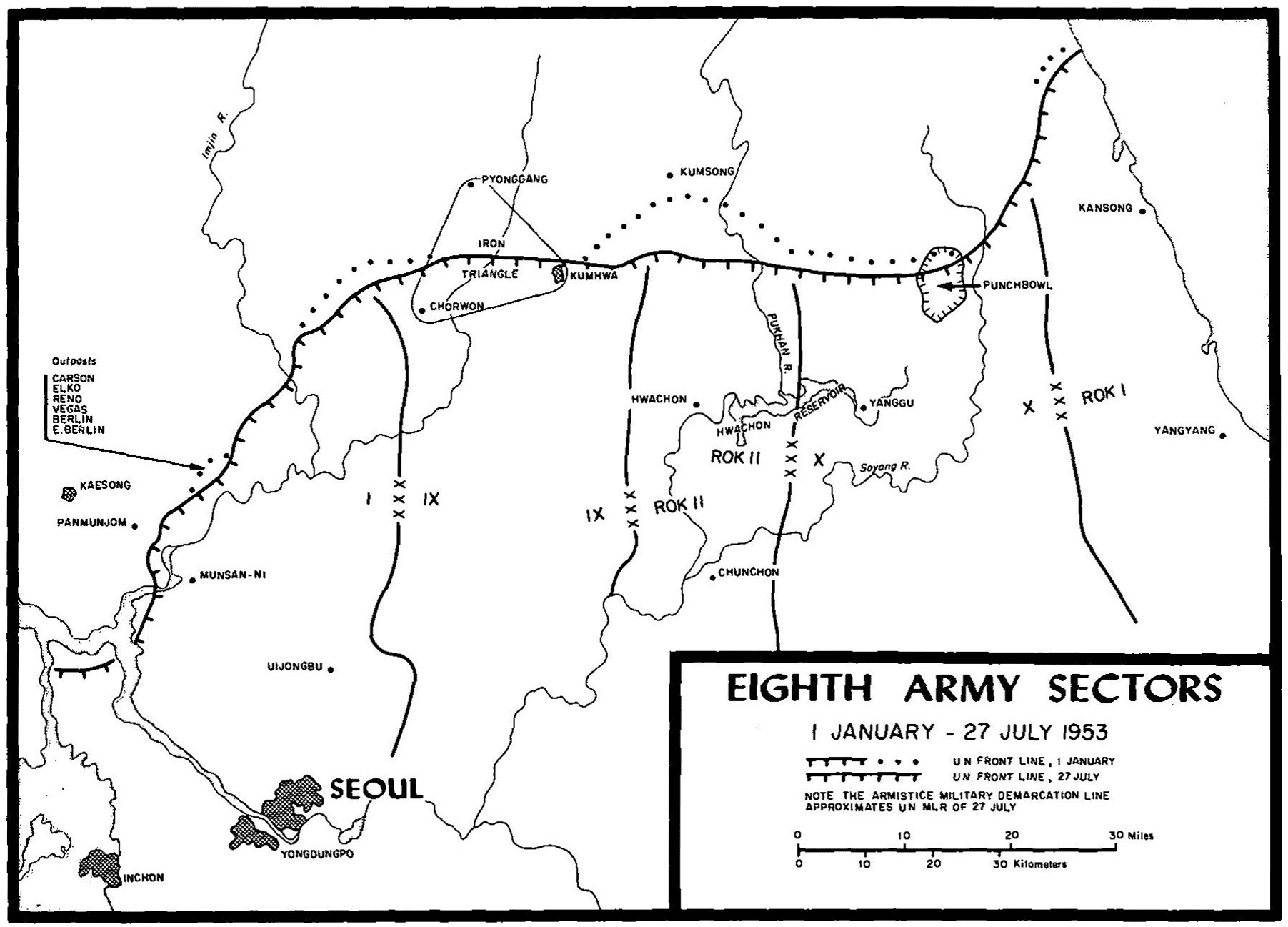

| 29 | Eighth Army Sector—1 January-27 July 1953 | 343 |

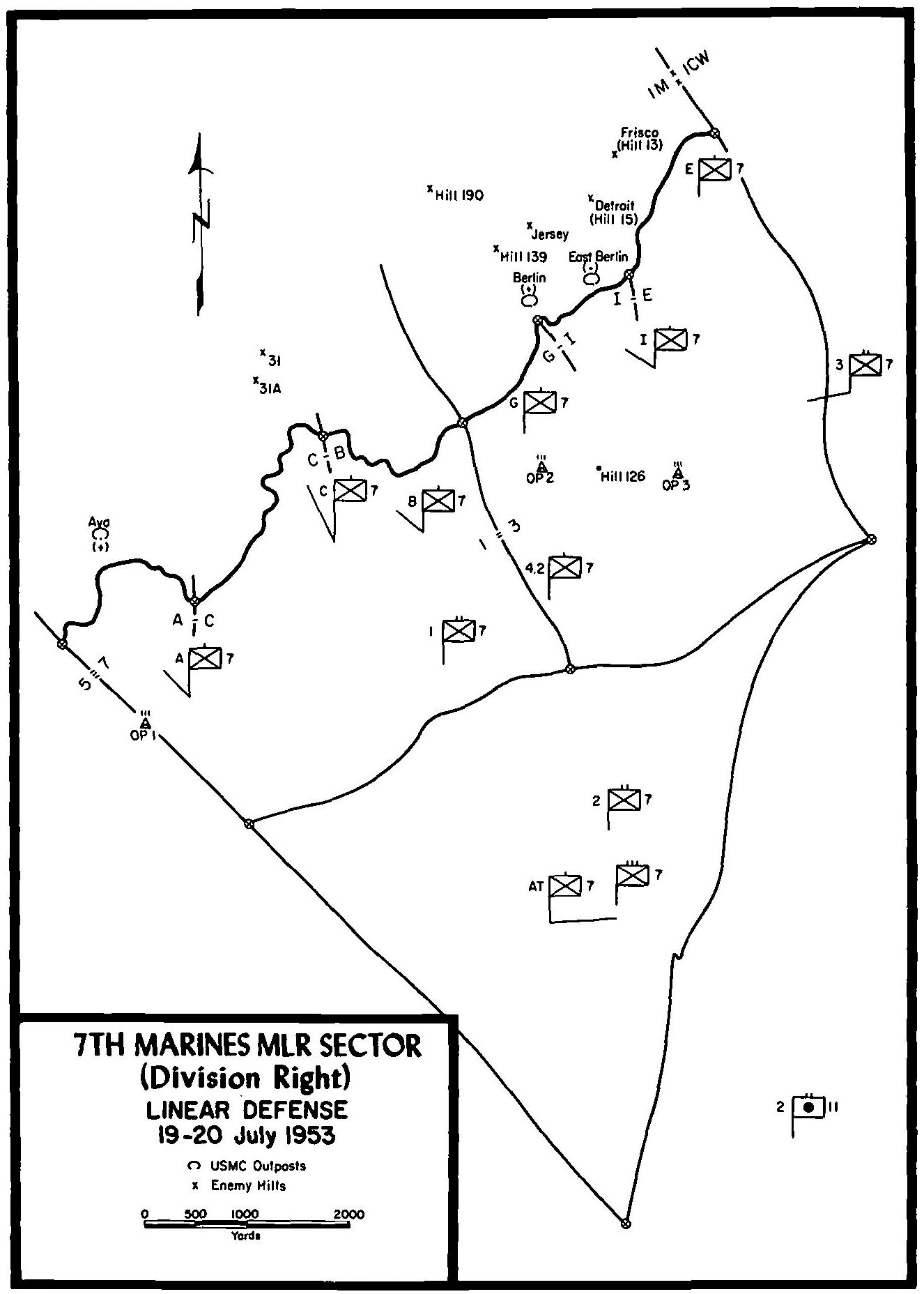

| 30 | 7th Marines MLR Sector (Division Right)—Linear Defense—19–20 July 1953 | 380 |

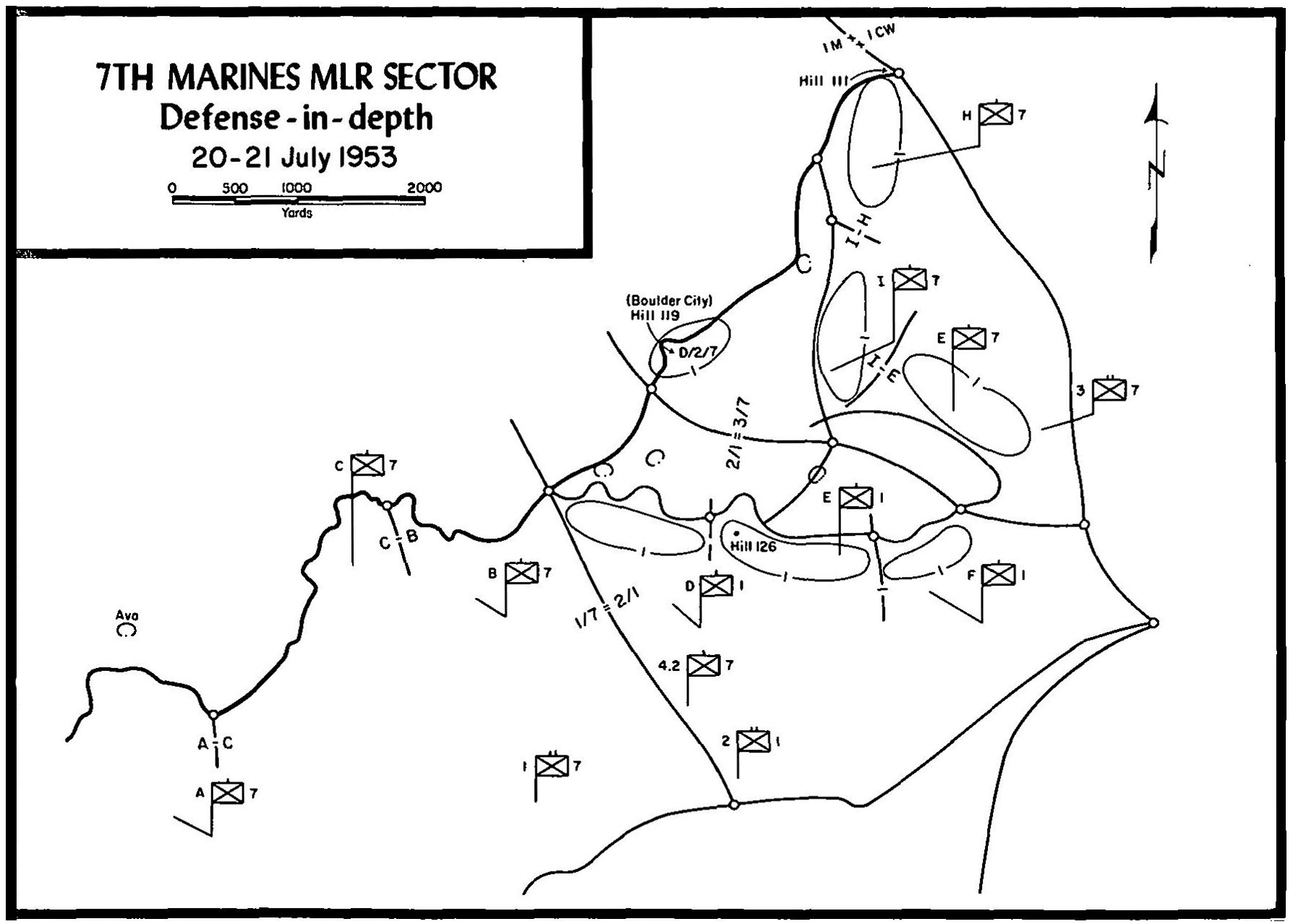

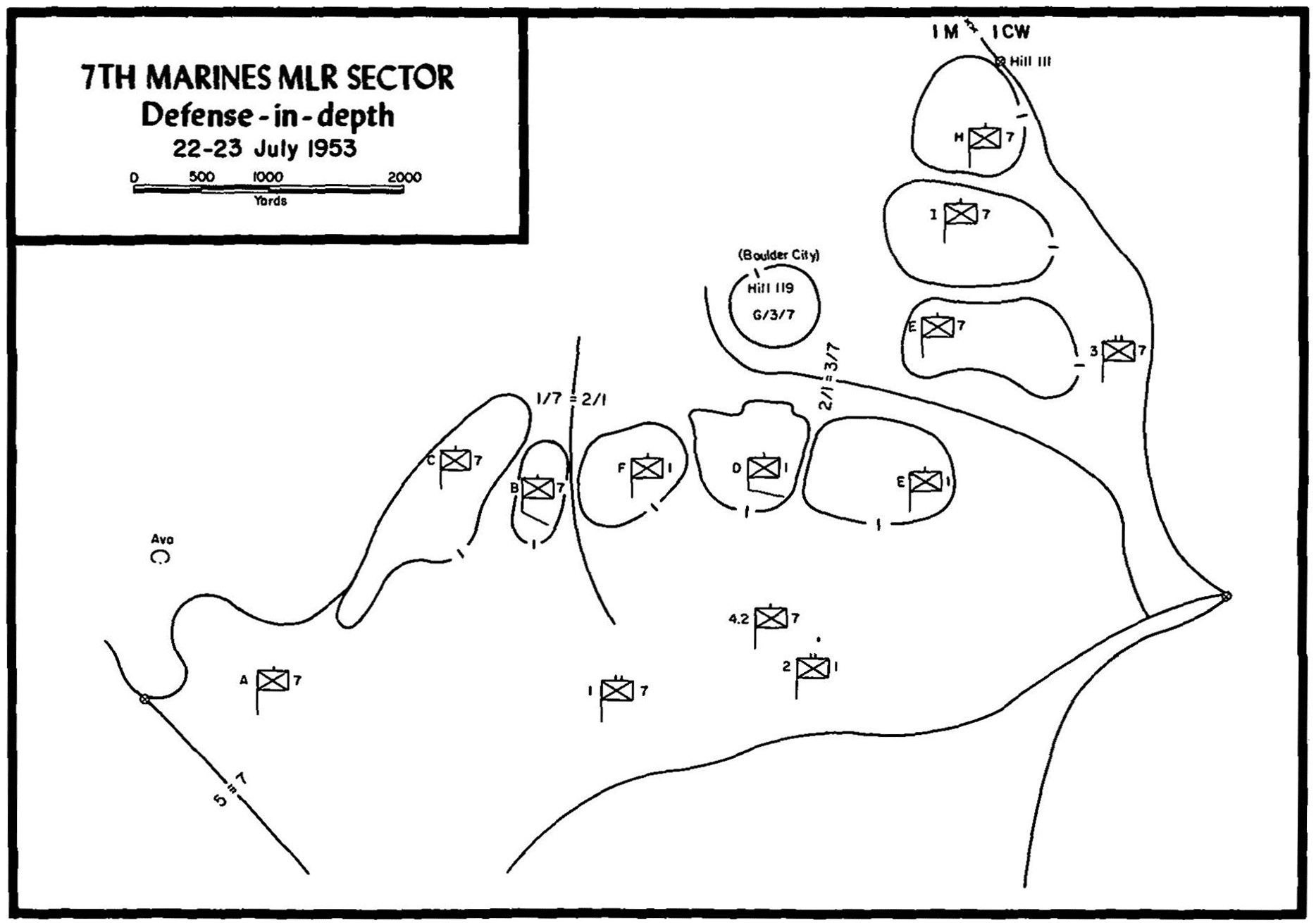

| 31 | 7th Marines MLR Sector—Defense-in-Depth—20–21 July 1953 | 382 |

| 32 | 7th Marines MLR Sector—Defense-in-Depth—22–23 July 1953 | 384 |

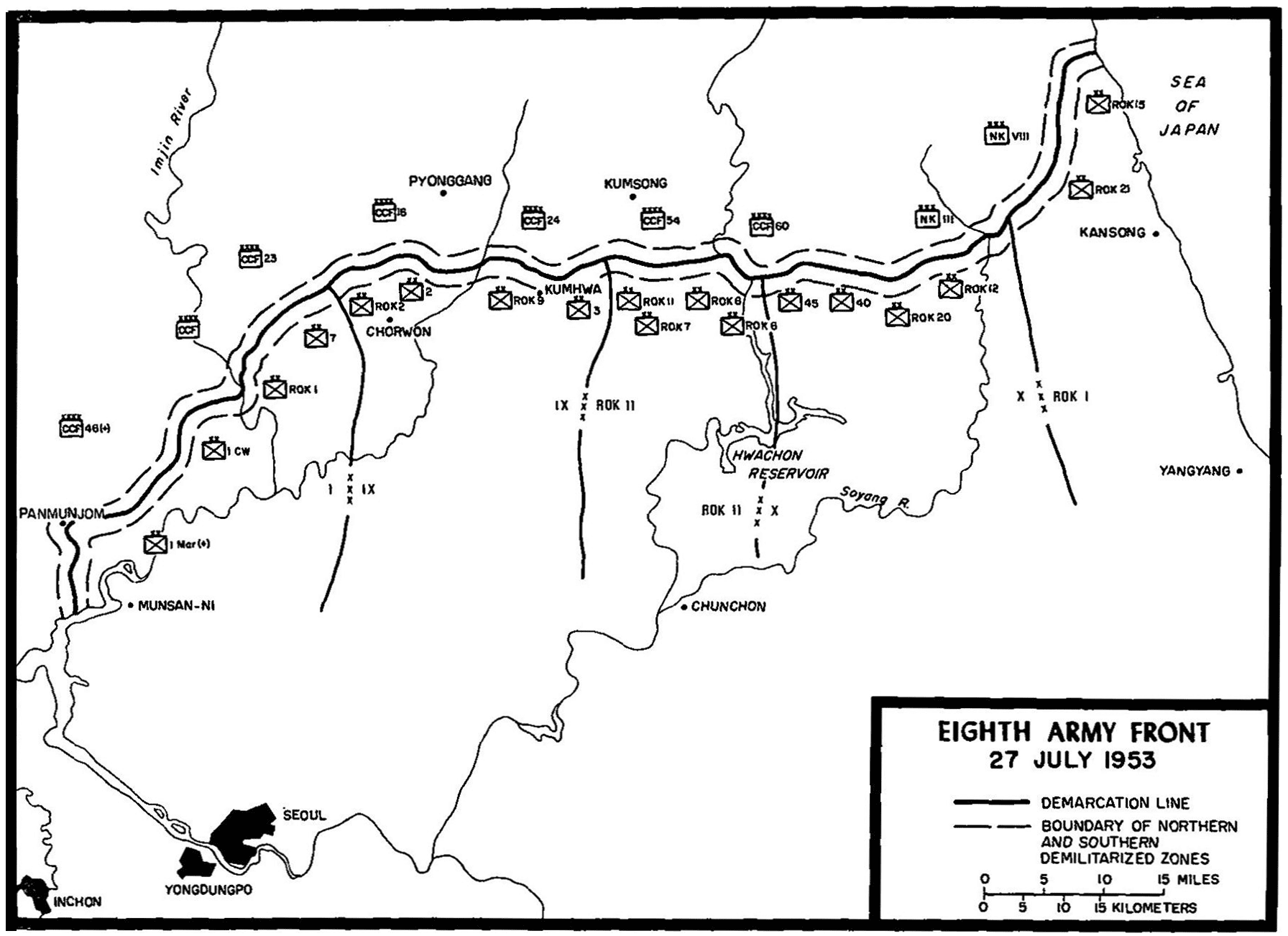

| 33 | Eighth Army Front—27 July 1953 | 395 |

| 34 | POW Camps in which Marines Were Held | 417 |

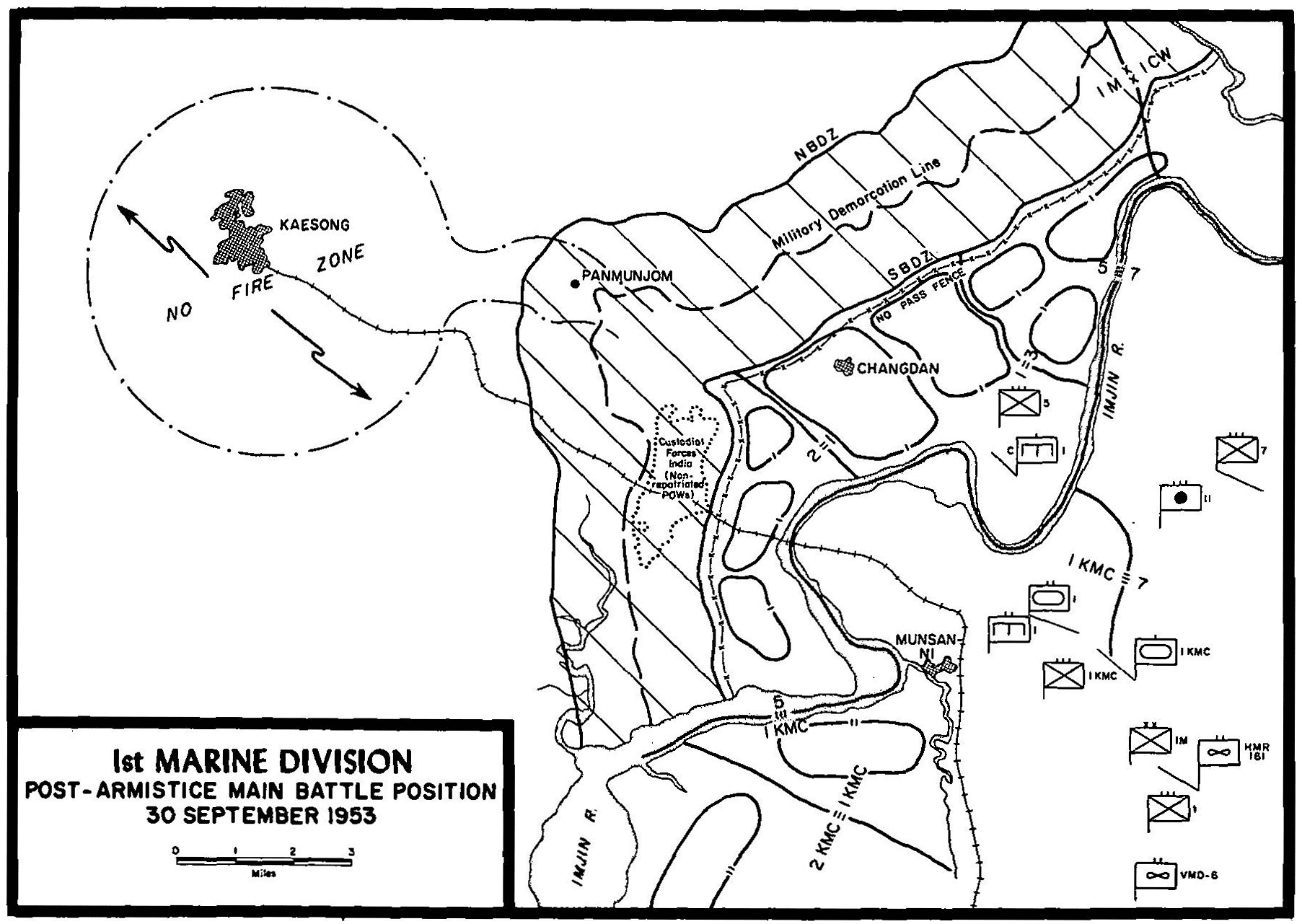

| 35 | 1st Marine Division Post-Armistice Main Battle Position—30 September 1953 | 462 |

From Cairo to JAMESTOWN—The Marines’ Home in West Korea—Organization of the 1st Marine Division Area—The 1st Marine Aircraft Wing—The Enemy—Initial CCF Attack—Subsequent CCF Attacks—Strengthening the Line—Marine Air Operations—Supporting the Division and the Wing—Different Area, Different Problem

1 Unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is derived from: 1st Marine Division Staff Report, titled “Notes for Major General J. T. Selden, Commanding General, First Marine Division, Korea,” dtd 20 Aug 52, hereafter Selden, Div. Staff Rpt; the four previous volumes of the series U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953, namely, Lynn Montross and Capt Nicholas A. Canzona, The Pusan Perimeter, v. I; The Inchon-Seoul Operation, v. II; The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, v. III; Lynn Montross, Maj Hubard D. Kuokka, and Maj Norman W. Hicks, The East-Central Front, v. IV (Washington. HistBr, G-3 Div, HQMC, 1954–1962), hereafter Montross, Kuokka, and Hicks, USMC Ops Korea—Central Front, v. IV; Department of Military Art and Engineering, U.S. Military Academy, Operations in Korea (West Point, N.Y.: 1956), hereafter USMA, Korea; David Rees, Korea: The Limited War (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1964), hereafter Rees, Korea, quoted with permission of the publisher. Unless otherwise noted, all documentary material cited is on file at, or obtainable through, the Archives of the Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps.

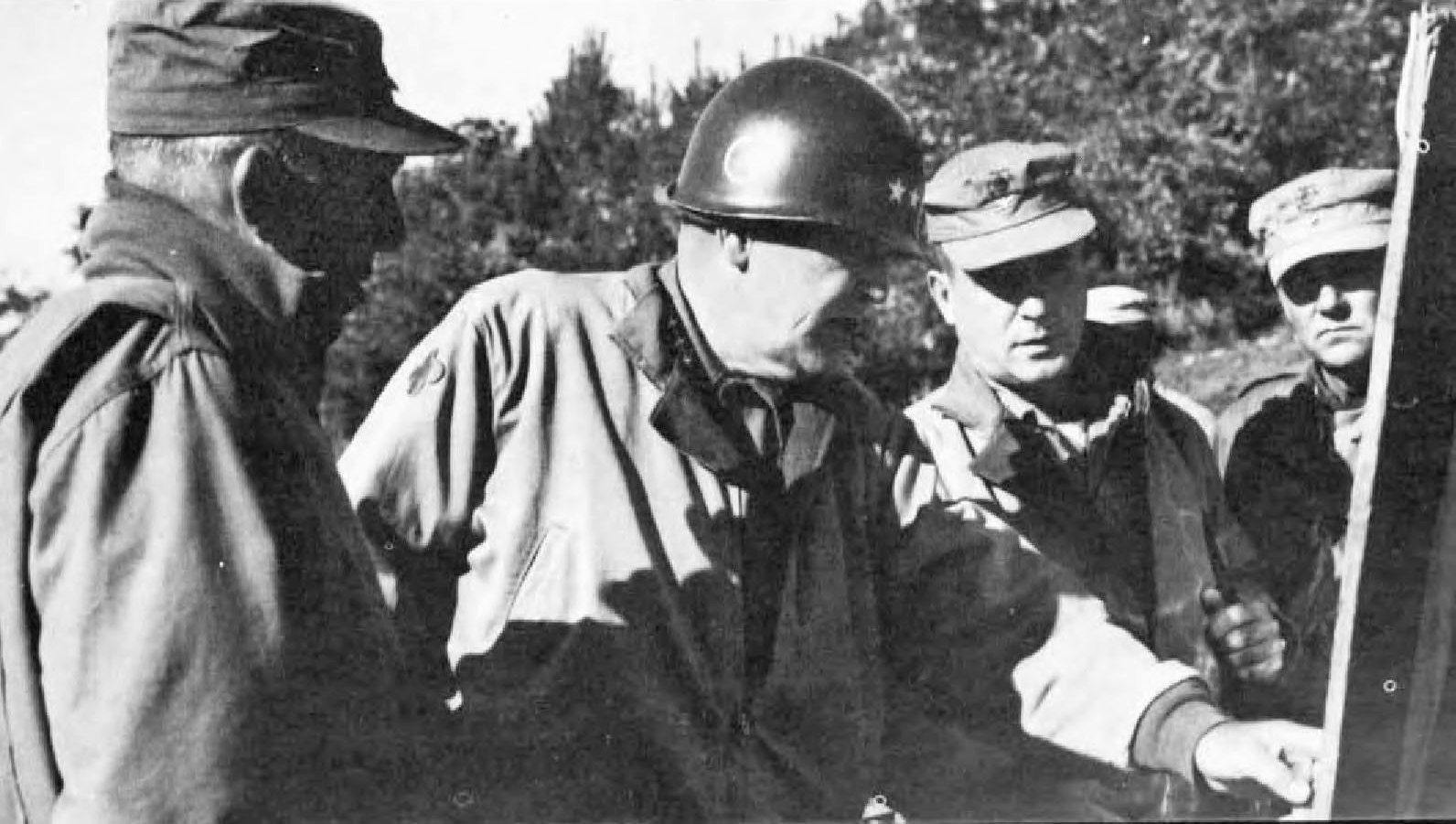

During the latter part of March 1952, the 1st Marine Division, a component of the U.S. Eighth Army in Korea (EUSAK), pulled out of its positions astride the Soyang River in east-central Korea and moved to the far western part of the country in the I Corps sector. There the Marines took over the EUSAK left flank, guarding the most likely enemy approaches to the South Korean capital city, Seoul, and improving the ground defense in their sector to comply with the strict requirements which the division2 commander, Major General John T. Selden, had set down. Except for a brief period in reserve, the Marine division would remain in the Korean front lines until a cease-fire agreement in July 1953 ended active hostilities.

The division CG, Major General Selden,2 had assumed command of the 25,000-man 1st Marine Division two months earlier, on 11 January, from Major General Gerald C. Thomas while the Marines were still in the eastern X Corps sector. The new Marine commander was a 37-year veteran of Marine Corps service, having enlisted as a private in 1915, serving shortly thereafter in Haiti. During World War I he was commissioned a second lieutenant, in 1918, while on convoy duty. Between the two world wars, his overseas service had included a second assignment to Haiti, two China tours, and sea duty. When the United States entered World War II, Lieutenant Colonel Selden was an intelligence officer aboard the carrier Lexington. Later in the war Colonel Selden led the 5th Marines in the New Britain fighting and was Chief of Staff of the 1st Marine Division in the Peleliu campaign. He was promoted to brigadier general in 1948 and received his second star in 1951, prior to his combat assignment in Korea.

2 DivInfo, HQMC, Biography of MajGen John T. Selden, Mar 54.

American concern in the 1950s for South Korea’s struggle to preserve its independence stemmed from a World War II agreement between the United States, the United Kingdom, and China. In December 1943, the three powers had signed the Cairo Declaration and bound themselves to ensure the freedom of the Korean people, then under the yoke of the Japanese Empire. At the Potsdam Conference, held on the outskirts of Berlin, Germany in July 1945, the United States, China,3 and Britain renewed their Cairo promise.

3 China did not attend. Instead, it received an advance copy of the proposed text. President Chiang Kai-shek signified Chinese approval on 26 July. A few hours later, the Potsdam Declaration was made public. Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Cairo and Teheran, 1943 (Department of State publication 7187), pp. 448–449; The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, v. II (Department of State publication 7163), pp. 1278, 1282–1283, 1474–1476.

When the Soviet Union agreed to join forces against Japan, on 8 August, the USSR also became a party to the Cairo Declaration. According to terms of the Japanese capitulation on 11 August, the Soviets were to accept surrender of the defeated forces north of the 38th Parallel in Korea. South of that line, the commander of the3 American occupation forces would receive the surrender. The Russians wasted no time and on 12 August had their troops in northern Korea. American combat units, deployed throughout the Pacific, did not enter Korea until 8 September. Then they found the Soviet soldiers so firmly established they even refused to permit U.S. occupation officials from the south to cross over into the Russian sector. A December conference in Moscow led to a Russo-American commission to work out the postwar problems of Korean independence.

Meeting for the first time in March 1946, the commission was short-lived. Its failure, due to lack of Russian cooperation, paved the way for politico-military factions within the country that set up two separate Koreas. In the north the Communists, under Kim Il Sung, and in the south the Korean nationalists, led by Dr. Syngman Rhee, organized independent governments early in 1947. In May of that year, a second joint commission failed to unify the country. As a result the Korean problem was presented to the United Nations (UN). This postwar international agency was no more successful in resolving the differences between the disputing factions. It did, however, recognize the Rhee government in December 1948 as the representative one of the two dissident groups.

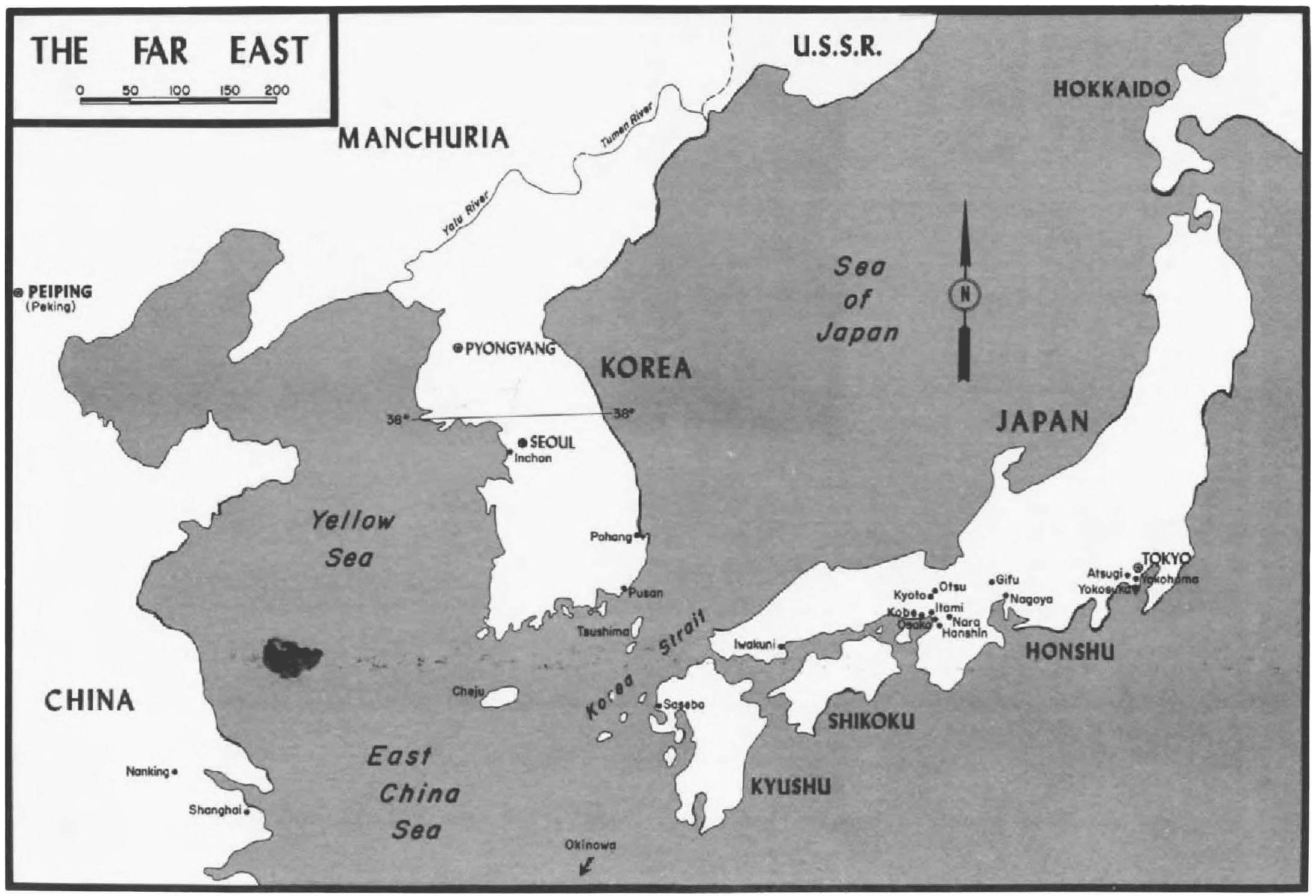

In June 1950, the North Koreans attempted to force unification of Korea under Communist control by crossing the 38th Parallel with seven infantry divisions heavily supported by artillery and tanks. Acting on a resolution presented by the United States, the United Nations responded by declaring the North Korean action a “breach of the peace” and called upon its members to assist the South Koreans in ousting the invaders. Many free countries around the globe offered their aid. In the United States, President Harry S. Truman authorized the use of U.S. air and naval units and, shortly thereafter, ground forces to evict the aggressors and restore the status quo. Under the command of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, then Far East Commander, U.S. Eighth Army occupation troops in Japan embarked to South Korea.

The first combat unit sent from America to Korea was a Marine air-ground team, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, formed at Camp Pendleton, California on 7 July 1950, under Brigadier General Edward A. Craig. The same day the UN Security Council passed a resolution creating the United Nations Command (UNC) which was to exercise operational control over the international military forces4 rallying to the defense of South Korea. The Council asked the United States to appoint a commander of the UN forces; on the 8th, President Truman named his Far East Commander, General MacArthur, as Commander in Chief, United Nations Command (CinCUNC).

In Korea the Marines soon became known as the firemen of the Pusan Perimeter, for they were shifted from one trouble spot to the next all along the defensive ring around Pusan, the last United Nations stronghold in southeastern Korea during the early days of the fighting. A bold tactical stroke planned for mid-September was designed to relieve enemy pressure on Pusan and weaken the strength of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA). As envisioned by General MacArthur, an amphibious landing at Inchon on the west coast, far to the enemy rear, would threaten the entire North Korean position south of the 38th Parallel. To help effect this coup, the UN Commander directed that the Marine brigade be pulled out of the Pusan area to take part in the landing at Inchon.

MacArthur’s assault force consisted of the 1st Marine Division, less one of its three regiments,4 but including the 1st Korean Marine Corps (KMC) Regiment. Marine ground and aviation units were to assist in retaking Seoul, the South Korean capital, and to cut the supply line sustaining the NKPA divisions.

4 The 7th Marines was on its way to Korea at the time of the Inchon landing. The brigade, however, joined the 1st Division at sea en route to the objective to provide elements of the 5th Regimental Combat Team (RCT).

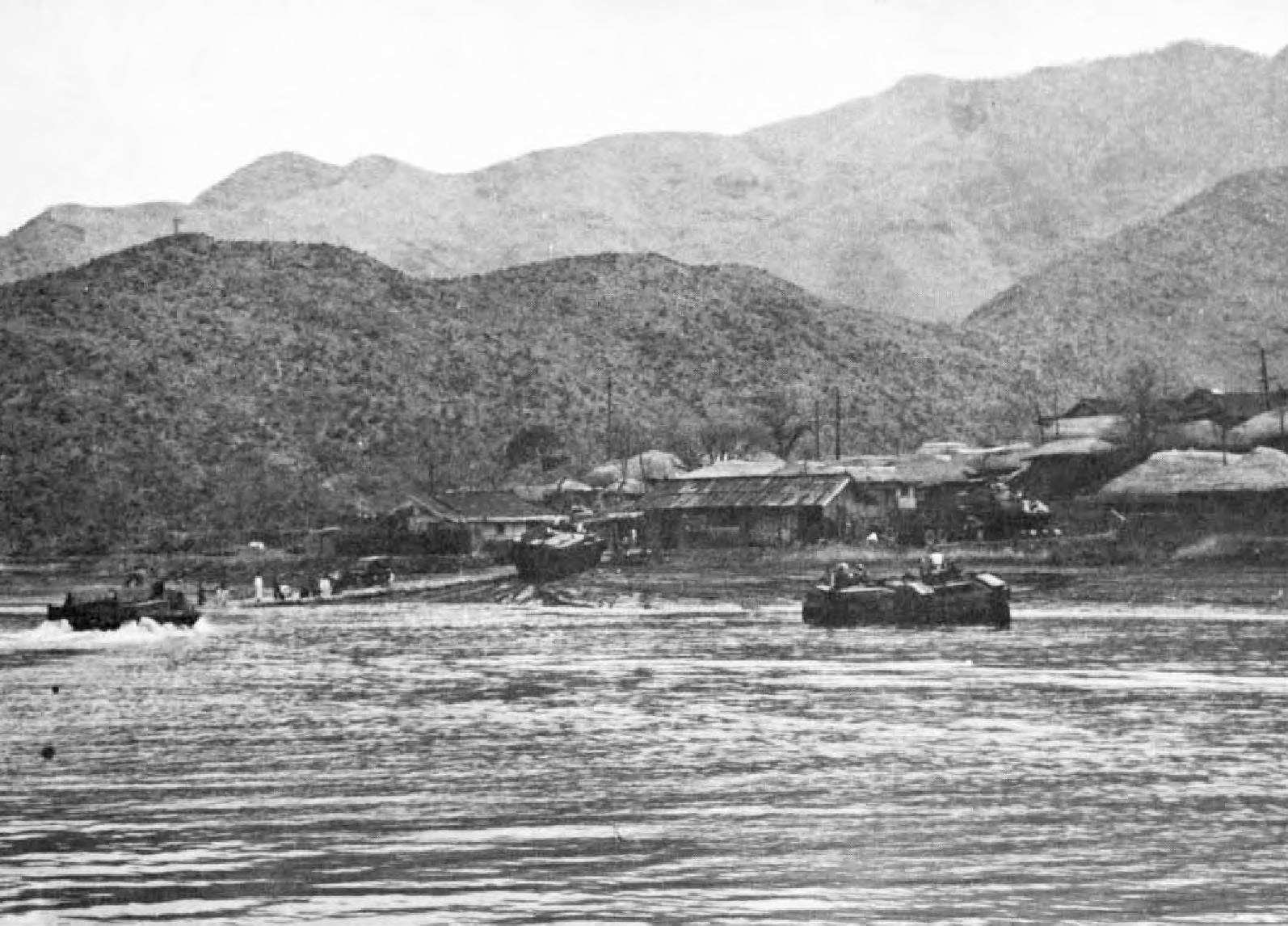

On 15 September, Marines stormed ashore on three Inchon beaches. Despite difficulties inherent in effecting a landing there,5 it was an outstandingly successful amphibious assault. The 1st and 5th Marines, with 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (1st MAW) assault squadrons providing close air support, quickly captured the port city of Inchon, Ascom City6 to the east, and Kimpo Airfield. Advancing eastward the Marines approached the Han River that separates Kimpo Peninsula from the Korean mainland. Crossing this obstacle in amphibian vehicles, 1st Division Marines converged on Seoul from three directions. By 27 September, the Marines had captured5 the South Korean government complex and, together with the U.S. Army 7th Infantry Division, had severed the enemy’s main supply route (MSR) to Pusan. In heavy, close fighting near the city, other United Nations troops pursued and cut off major units of the NKPA.

5 For a discussion of the hardships facing the landing force, see Montross and Canzona, USMC Ops Korea—Inchon, v. II, op. cit., pp. 41–42, 59–60, 62–64.

6 In World War II, the Japanese developed a logistical base east of Inchon. When the Japanese surrendered, the Army Service Command temporarily took over the installation, naming it Ascom City. Maj Robert K. Sawyer, Military Advisers in Korea: KMAG in Peace and War (Washington: OCMH, DA, 1962), p. 43n.

Ordered back to East Korea, the Marine division re-embarked at Inchon in October and made an administrative landing at Wonsan on the North Korean coast 75 miles above the 38th Parallel. As part of the U.S. X Corps, the 1st Marine Division was to move the 5th and 7th Marines (Reinforced) to the vicinity of the Chosin Reservoir, from where they were to continue the advance northward toward the North Korean-Manchurian border. The 1st Marines and support troops were to remain in the Wonsan area.

While the bulk of the division moved northward, an unforeseen development was in the making that was to change materially the military situation in Korea overnight. Aware that the North Koreans were on the brink of military disaster, Communist China had decided to enter the fighting. Nine Chinese divisions had been dispatched into the area with the specific mission of destroying the 1st Marine Division.7 Without prior warning, on the night of 27 November, hordes of Chinese Communist Forces (CCF, or “Chinese People’s Volunteers” as they called themselves) assaulted the unsuspecting Marines and nearly succeeding in trapping the two Marine regiments. The enemy’s failure to do so was due to the military discipline and courage displayed by able-bodied and wounded Marines alike, as well as effective support furnished by Marine aviation. Under conditions of great hardship, the division fought its way out over 78 miles of frozen ground from Chosin to the port of Hungnam, where transports stood by to evacuate the weary men and the equipment they had salvaged.

7 Montross and Canzona, USMC Ops Korea—Chosin, v. III, p. 161.

This Chinese offensive had wrested victory from the grasp of General MacArthur just as the successful completion of the campaign seemed assured. In the west, the bulk of the Eighth Army paced its withdrawal with that of the X Corps. The UNC established a major line of defense across the country generally following the 38th Parallel. On Christmas Day, massed Chinese forces crossed the parallel, and within a week the UN positions were bearing the full brunt of the enemy assault. Driving southward, the Communists6 recaptured Seoul, but by mid-February 1951 the advance had been slowed down, the result of determined Eighth Army stands from a series of successive defensive lines.8

8 On 9 January 1951, General MacArthur was “directed to defend himself in successive positions, inflicting maximum damage to hostile forces in Korea subject to the primary consideration of the safety of his troops and his basic mission of protecting Japan.” Carl Berger, The Korea Knot—A Military-Political History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957), pp. 131–132, hereafter Berger, Korea Knot, quoted with permission of the publisher.

Following its evacuation from Hungnam, the 1st Marine Division early in 1951 underwent a brief period of rehabilitation and training in the vicinity of Masan, west of Pusan. From there, the division moved northeast to an area beyond Pohang on the east coast. Under operational control of Eighth Army, the Marines, with the 1st Korean Marine Corps Regiment attached for most of the period, protected 75 miles of a vital supply route from attack by bands of guerrillas. In addition, the Marines conducted patrols to locate, trap, and destroy the enemy. The Pohang guerrilla hunt also provided valuable training for several thousand recently arrived Marine division replacements.

In mid-February the 1st Marine Division was assigned to the U.S. IX Corps, then operating in east-central Korea near Wonju. Initially without the KMCs,9 the Marine division helped push the corps line across the 38th Parallel into North Korea. On 22 April, the Chinese unleashed a gigantic offensive, which again forced UN troops back into South Korea. By the end of the month, however, the Allies had halted the 40-mile-wide enemy spring offensive.

9 The 1st KMC Regiment was again attached to the Marine Division on 17 March 1951 and remained under its operational control for the remainder of the war. CinCPacFlt Interim Evaluation Rpt No. 4, Chap 9, p. 9-53, hereafter PacFlt EvalRpt with number and chapter.

Once again, in May, the Marine division was assigned to the U.S. X Corps, east of the IX Corps sector. Shortly thereafter the Communists launched another major offensive. Heavy casualties inflicted by UNC forces slowed this new enemy drive. Marine, Army, and Korean troops not only repelled the Chinese onslaught but immediately launched a counteroffensive, routing the enemy back into North Korea until the rough, mountainous terrain and stiffening resistance conspired to slow the Allied advance.

In addition to these combat difficulties, the Marine division began to encounter increasing trouble in obtaining what it considered7 sufficient and timely close air support (CAS). Most attack and fighter aircraft of the 1st MAW, commanded by Major General Field Harris10 and operating since the Chosin Reservoir days under Fifth Air Force (FAF), had been employed primarily in a program of interdicting North Korean supply routes. Due to this diversion of Marine air from its primary CAS mission, both the division and wing suffered—the latter by its pilots’ limited experience in performing precision CAS sorties. Despite the difficulties, the Marine division drove northward reaching, by 20 June, a grotesque scooped-out terrain feature on the east-central front appropriately dubbed the Punchbowl.

10 Command responsibility of 1st MAW changed on 29 May 51 when Brigadier General Thomas J. Cushman succeeded General Harris.

Eighth Army advances into North Korea had caused the enemy to reappraise his military situation. On 23 June, the Russian delegate to the United Nations, Jacob Malik, hinted that the Korean differences might be settled at the conference table. Subsequently, United Nations Command and Communist leaders agreed that truce negotiations would begin on 7 July at Kaesong, located in West Korea immediately south of the 38th Parallel, but under Communist control. The Communists broke off the talks on 22 August. Without offering any credible evidence, they declared that UNC aircraft had violated the neutrality zone surrounding the conference area.11 Military and political observers then realized that the enemy’s overture to peace negotiations had served its intended purpose of permitting him to slow his retreat, regroup his forces, and prepare his ground defenses for a new determined stand.

11 The Senior Delegate and Chief of the United Nations Command Delegation to the Korean Armistice Commission, Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy, USN, has described how the Communists in Korea concocted incidents “calculated to provide advantage for their negotiating efforts or for their basic propaganda objectives, or for both.” Examples of such duplicity are given in Chapter IV of his book, How Communists Negotiate (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1955), hereafter Joy, Truce Negotiations, quoted with permission of the publisher. The quote above appears on p. 30.

The lull in military offensive activity during the mid-1951 truce talks presaged the kind of warfare that would soon typify the final phase of the Korean conflict. Before the fighting settled into positional trench warfare reminiscent of World War I, the Marines participated in the final UN offensive. In a bitter struggle, the division hacked its way northward through, over, and around the Punchbowl, and in September 1951 occupied a series of commanding terrain8 positions that became part of the MINNESOTA Line, the Eighth Army main defensive line. Beginning on the 20th of that month, it became the primary mission of frontline units to organize, construct, and defend positions they held on MINNESOTA. To show good faith at the peace table, the UNC outlawed large-scale attacks against the enemy. Intent upon not appearing the aggressor and determined to keep the door open for future truce negotiations, the United Nations Command in late 1951 decreed a new military policy of limited offensives and an aggressive defense of its line. This change in Allied strategy, due to politico-military considerations, from a moving battle situation to stabilized warfare would affect both the tactics and future of the Korean War.

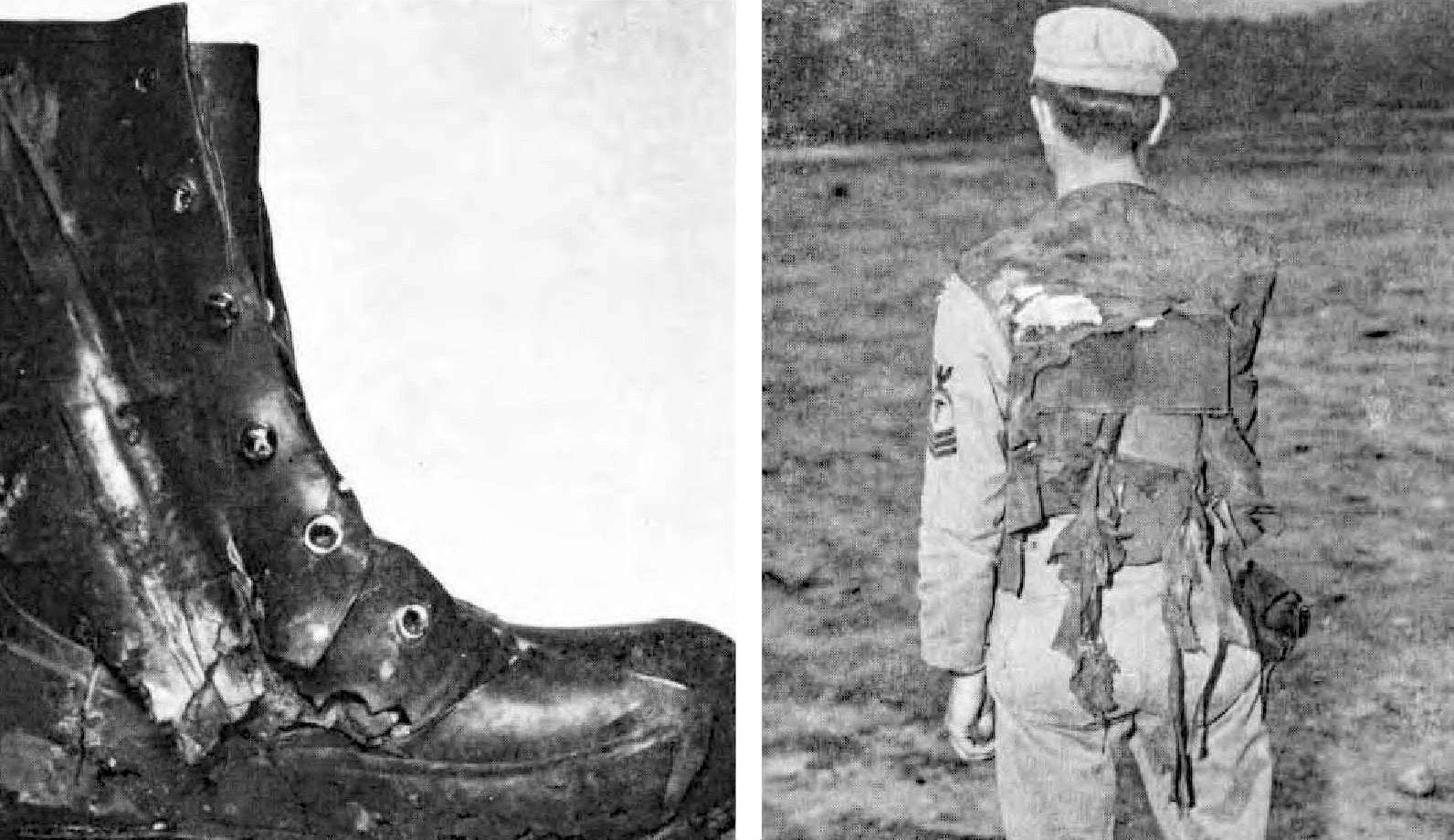

Even as Allied major tactical offensive operations and the era of fire and maneuver in Korea was passing into oblivion, several innovations were coming into use. One was the Marine Corps employment of helicopters. First used for evacuation of casualties from Pusan in August 1950, the versatile aircraft had also been adopted by the Marine brigade commander, General Craig, as an airborne jeep. On 13 September 1951, Marines made a significant contribution to the military profession when they introduced helicopters for large-scale resupply combat operations. This mission was followed one week later by the first use of helicopters for a combat zone troop lift. These revolutionary air tactics were contemporary with two new Marine Corps developments in ground equipment—body armor and insulated combat boots, which underwent extensive combat testing that summer and fall. The latter were to be especially welcomed for field use during the 1951–1952 winter.

Along the MINNESOTA Line, neither the freezing cold of a Korean winter nor blazing summer heat altered the daily routine. Ground defense operations consisted of dispatching patrols and raiding parties, laying ambushes, and improving the physical defenses. The enemy seemed reluctant to engage UN forces, and on one occasion to draw him into the open, EUSAK ordered Operation CLAM-UP across the entire UN front, beginning 10 February. Under cover of darkness, reserve battalions moved forward; then, during daylight, they pulled back, simulating a withdrawal of the main defenses. At the same time, frontline troops had explicit orders not to fire or even show themselves.912

12 Col Franklin B. Nihart comments on draft MS, Sep 66, hereafter Nihart comments.

MAP 1 K. WHITE

EUSAK DISPOSITIONS

15 MARCH 1952

10

It was hoped that the rearward movement of units from the front line and the subsequent inactivity there would cause the enemy to come out of his trenches to investigate the apparent large-scale withdrawal of UNC troops. Then Marine and other EUSAK troops could open fire and inflict maximum casualties from covered positions. On the fifth day of the operation, CLAM-UP was ended. The North Koreans were lured out of their defenses, but not in the numbers expected. CLAM-UP was the last action in the X Corps sector for the 1st Marine Division, which would begin its cross-country relocation the following month. (See Map 1.)

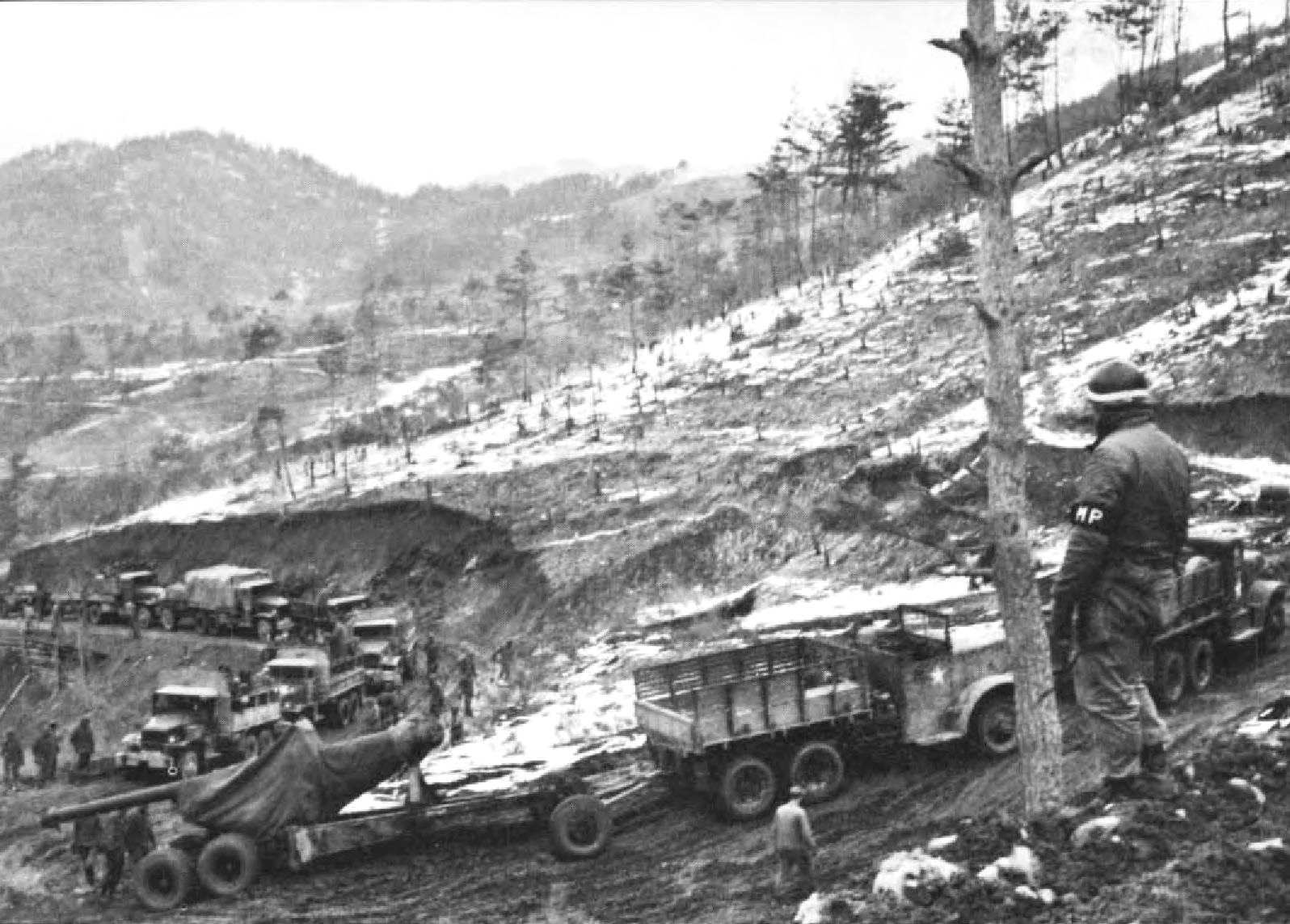

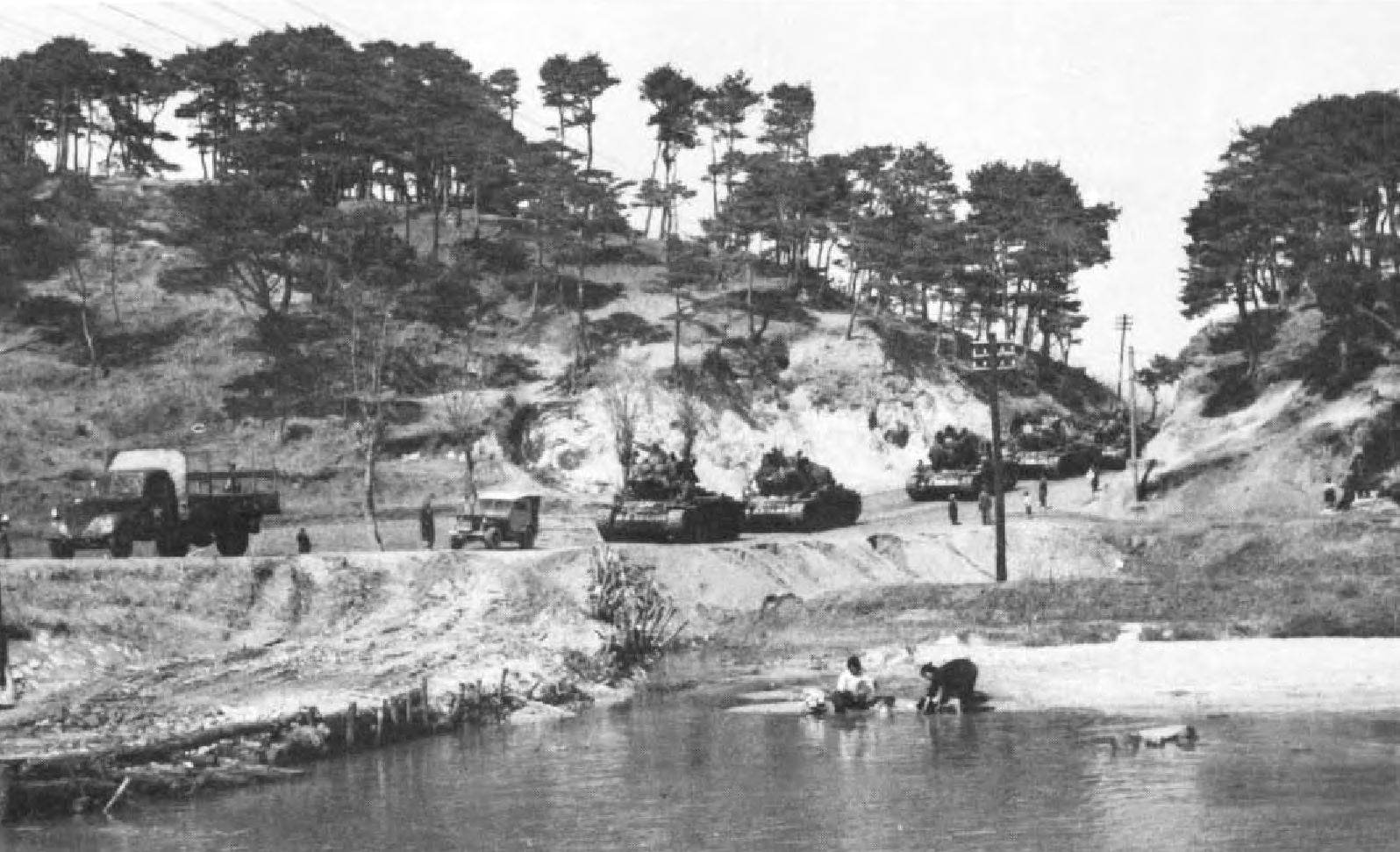

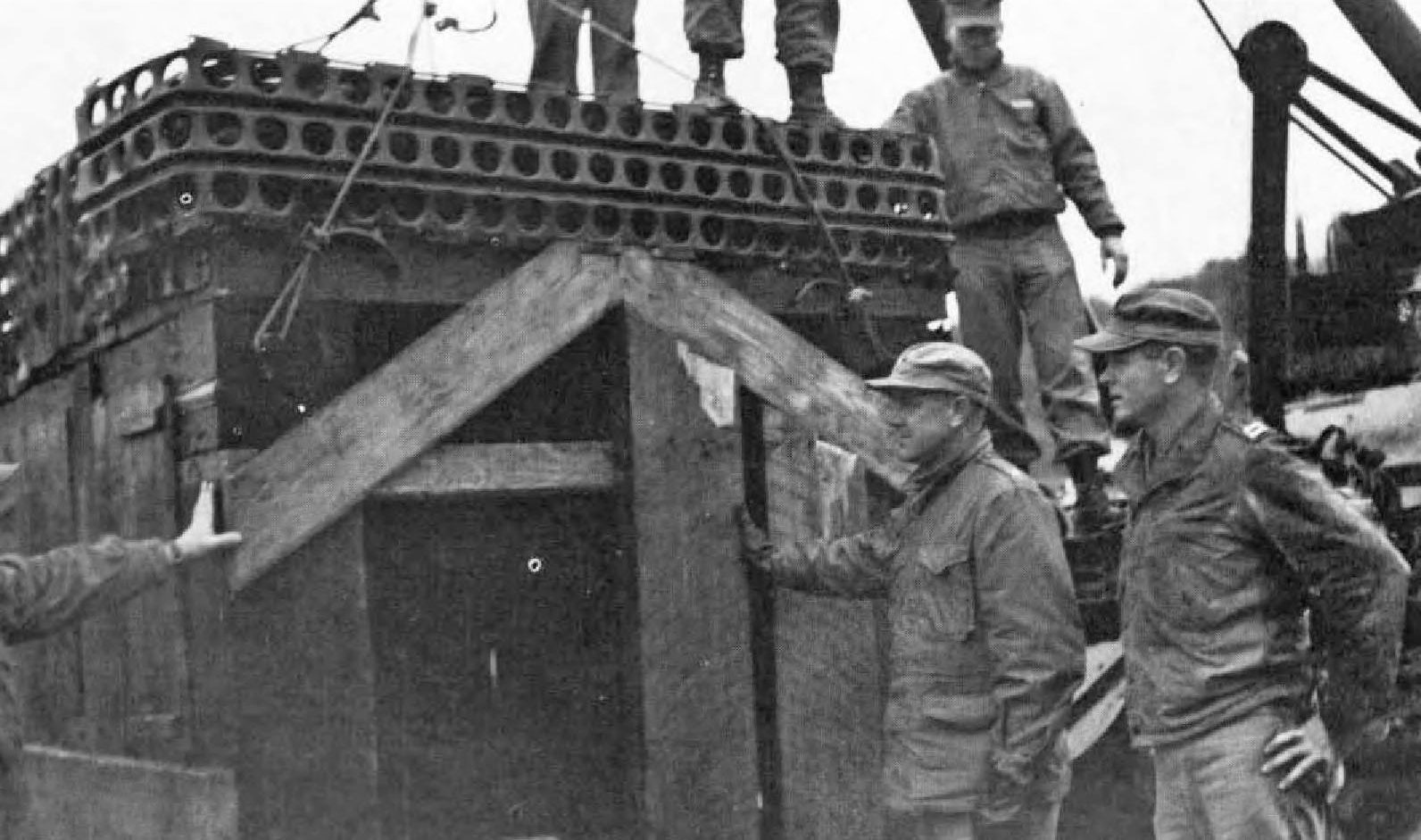

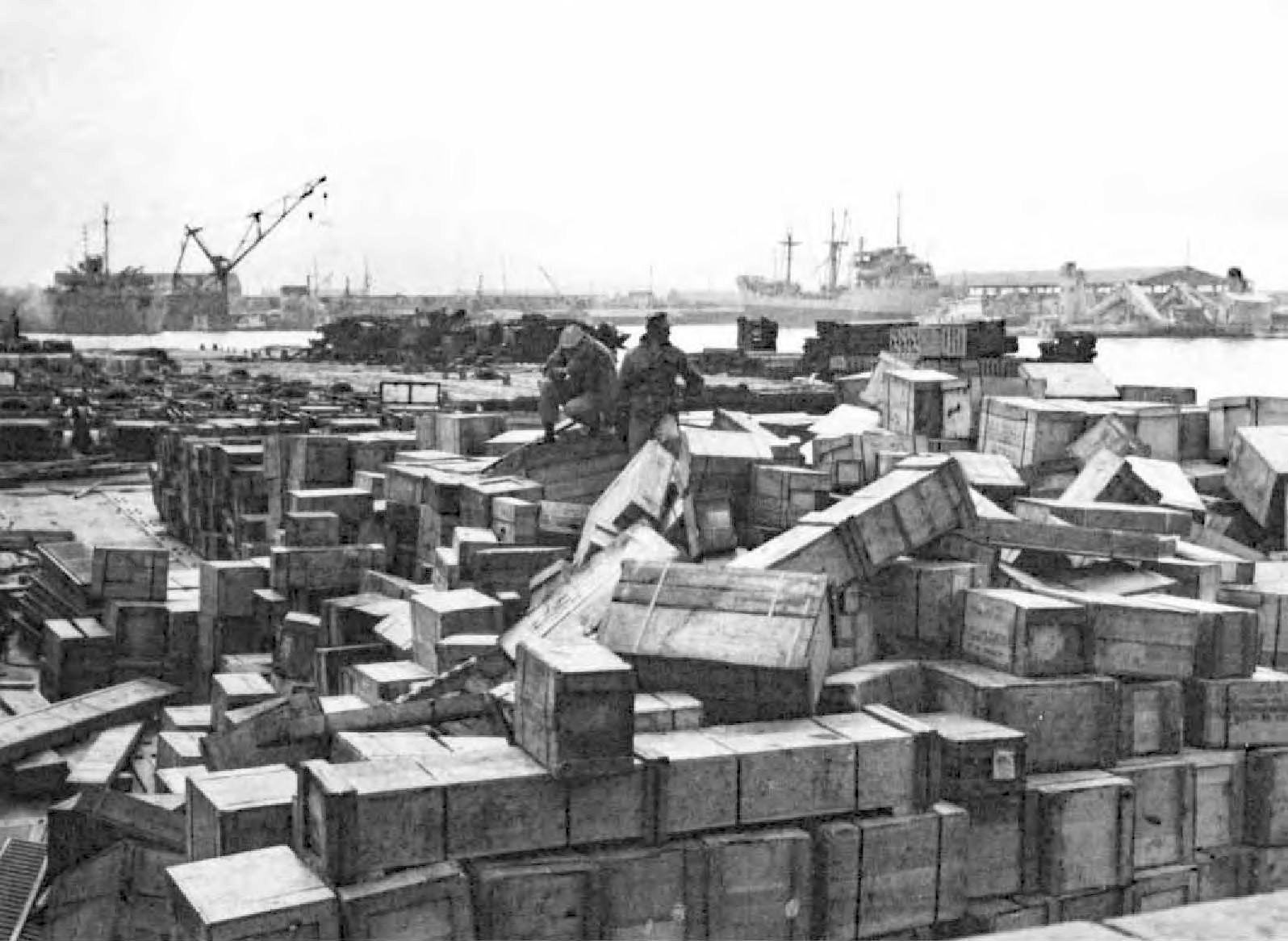

Code-named Operation MIXMASTER, the transfer of the 1st Marine Division began on 17 March when major infantry units began to move out of their eastern X Corps positions, after their relief on line by the 8th Republic of Korea (ROK) Division. Regiments of the Marine division relocated in the following order: the 1st KMCs, 1st, 7th, and 5th Marines. The division’s artillery regiment, the 11th Marines, made the shift by battalions at two-day intervals. In the motor march to West Korea, Marine units traveled approximately 140 miles over narrow, mountainous, and frequently mud-clogged primitive roads. Day and night, division transport augmented by a motor transport battalion attached from Fleet Marine Force, Pacific (FMFPac) and one company from the 1st Combat Service Group (CSG) rolled through rain, snow, sleet, and occasional good weather.

Marines employed 5,800 truck and DUKW (amphibious truck) loads to move most of the division personnel, gear, and supplies. Sixty-three flatbed trailers, 83 railroad cars, 14 landing ships, 2 transport aircraft, the vehicles of 4 Army truck companies, as well as hundreds of smaller jeep trailers and jeeps were utilized. The division estimated that these carriers moved about 50,000 tons of equipment and vehicles,13 with some of the support units making as many as a dozen round trips. The MIXMASTER move was made primarily by truck and by ship14 or rail for units with heavy vehicles.

11

13 Marine commanders and staff officers involved in the planning and execution of the division move were alarmed at the amount of additional equipment that infantry units had acquired during the static battle situation. Many had become overburdened with “nice-to-have” items in excess of actual T/E (Table of Equipment) allowances. Col William P. Pala comments on draft MS, 5 Sep 66, hereafter Pala comments.

14 Heavy equipment and tracked vehicles were loaded aboard LSDs and LSTs which sailed from Sokcho-ri to Inchon.

Impressive as these figures are, they almost pall in significance compared with the meticulous planning and precision logistics required by the week-long move. It was made, without mishap, over main routes that supplied nearly a dozen other divisions on the EUSAK line and thus had to be executed so as not to interfere with combat support. Although the transfer of the 1st Marine Division from the eastern to western front was the longest transplacement of any EUSAK division, MIXMASTER was a complicated tactical maneuver that involved realignment of UNC divisions across the entire Korean front. Some 200,000 men and their combat equipment had to be relocated as part of a master plan to strengthen the Allied front and deploy more troops on line.

Upon its arrival in West Korea, the 1st Marine Division was under orders to relieve the 1st ROK Division and take over a sector at the extreme left of the Eighth Army line, under I Corps control, where the weaknesses of Kimpo Peninsula defenses had been of considerable concern to EUSAK and its commander, General James A. Van Fleet. As division units reached their new sector, they moved to locations pre-selected in accordance with their assigned mission. First Marine unit into the I Corps main defensive position, the JAMESTOWN Line, was the 1st KMC Regiment attached to the division, with its organic artillery battalion. The KMCs, as well as 1/11, began to move into their new positions on 18 March. At 1400 on 20 March, the Korean Marines completed the relief of the 15th Republic of Korea Regiment in the left sector of the MLR (main line of resistance). Next into the division line, occupying the right regimental sector adjacent to the 1st Commonwealth Division, was Colonel Sidney S. Wade’s 1st Marines with three battalions forward and 2/5 attached as the regimental reserve. Relief of the 1st ROK Division was completed on the night of 24–25 March. At 0400 on 25 March the Commanding General, 1st Marine Division assumed responsibility for the defense of 32 miles of the JAMESTOWN Line. That same date the remainder of the Marine artillery battalions also relocated in their new positions.

As the division took over its new I Corps mission on 25 March, the Marine commander had one regiment of the 1st ROK Division attached as division reserve while his 5th Marines was still in the east. Operational plans originally had called for the 5th Marines, less a battalion, to locate in the Kimpo Peninsula area where it was12 anticipated Marine reserve units would be able to conduct extensive amphibious training. So overextended was the assigned battlefront position that General Selden realized this regiment would also be needed to man the line. He quickly alerted the 5th Marines commanding officer, Colonel Thomas A. Culhane, Jr., to deploy his regiment, then en route to western Korea, to take over a section of the JAMESTOWN front line instead of assuming reserve positions at Kimpo as originally assigned. General Selden believed that putting another regiment on the main line was essential to carrying out the division’s mission, to aggressively defend JAMESTOWN Line, not merely to delay a Communist advance.

Only a few hours after the 5th Marines had begun its trans-Korea move, helicopters picked up Colonel Culhane, his battalion commanders, and key regimental staff officers and flew them to the relocated division command post (CP) in the west. Here, on 26 March, the regimental commander officially received the change in the 5th Marines mission. Following this briefing, 5th Marines officers reconnoitered the newly assigned area15 while awaiting the arrival of their units. When the regiment arrived on the 28th, plans had been completed for it to relieve a part of the thinly-held 1st Marines line. On 29 March, the 5th Marines took over the center regimental sector while the 1st Marines, on the right regimental flank, compressed its ranks for a more solid defense.

15 Col Thomas A. Culhane, Jr. ltr to Hd, HistBr, G-3 Div, HQMC, dtd 16 Sep 59, hereafter Culhane ltr.

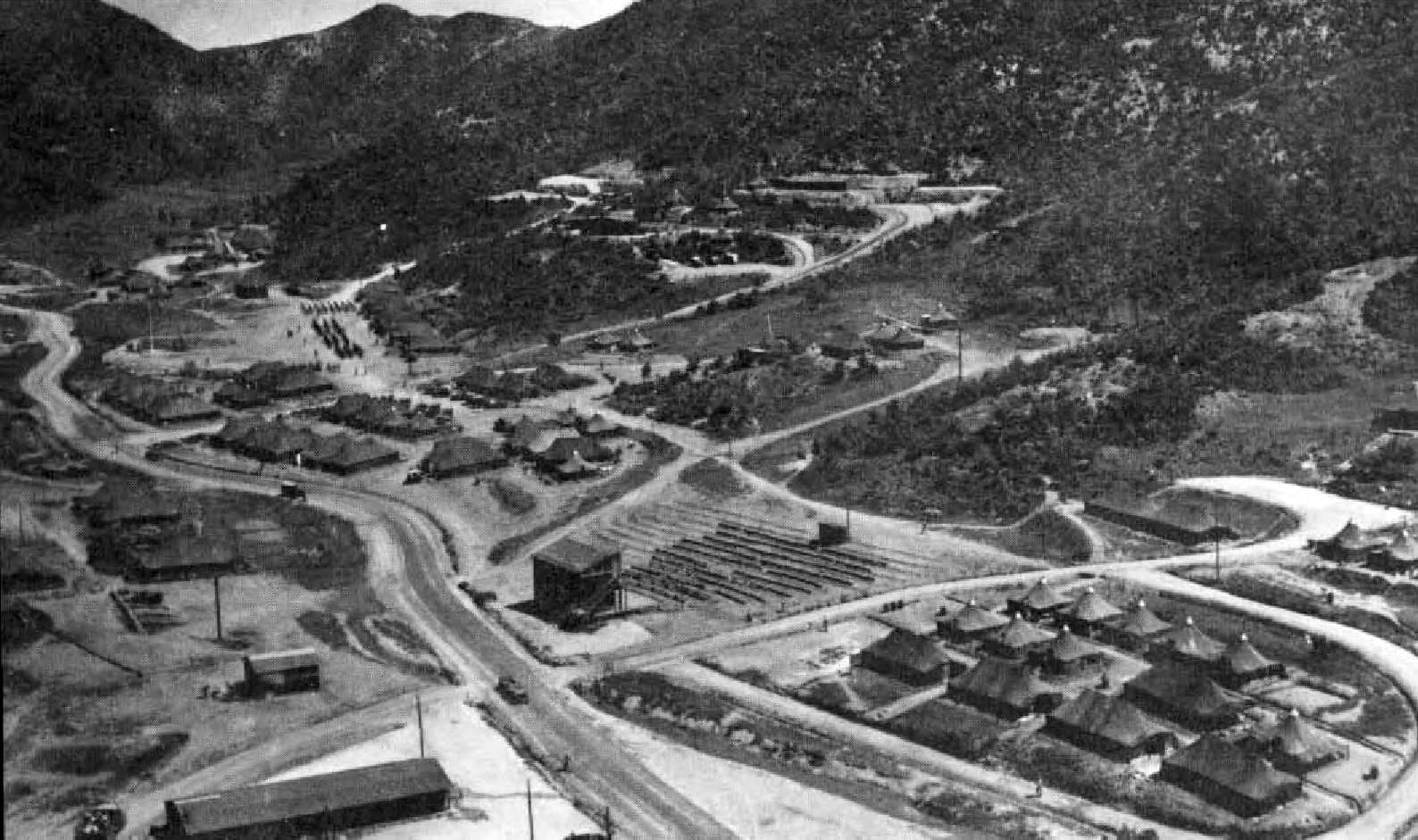

Frontline units, from the west, were the 1st KMCs, the 5th, and 1st Marines. To the rear, the 7th Marines, designated as division reserve, together with organic and attached units of the division, had established an extensive support and supply area. As a temporary measure, a battalion of the division reserve, 2/7, was detached for defense of the Kimpo Peninsula pending a reorganization of forces in this area. Major logistical facilities were the division airhead, located at K-16 airfield, just southwest of Seoul, and the railhead at Munsan-ni, 25 miles northwest of the capital city and about five miles to the rear of the division sector at its nearest point. Forward of the 1st Marine Division line, outposts were established to enhance the division’s security. In the rear area the support facilities, secondary defense lines, and unit command posts kept pace with development of defensive installations on the MLR. Throughout the 1st13 Marine Division sector outpost security, field fortifications, and the ground defense net were thorough and intended to deny the enemy access to Seoul.

16 Unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is derived from: 1stMarDiv ComdD, Mar 52; CIA, NIS 41B, South Korea, Chap I, Brief, Section 21, Military Geographic Regions, Section 24, Topography (Washington: 1957–1962); Map, Korea, 1:50,000, AMS Series L 751, Sheets 6526 I and IV, 6527 I, II, III, and IV, 6528 II and III, 6627 III and IV, and 6628 III (prepared by the Engineer, HQ, AFFE, and AFFE/8A, 1952–1954).

In western Korea, the home of the 1st Marine Division lay in a particularly significant area. (See Map 2.) Within the Marine boundaries ran the route that invaders through the ages had used in their drive south to Seoul. It was the 1st Marine Division’s mission to block any such future attempts. One of the reasons for moving the Marines to the west17 was that the terrain there had to be held at all costs; land in the east, mountainous and less valuable, could better be sacrificed if a partial withdrawal in Korea became necessary. At the end of March 1952, the division main line of resistance stretched across difficult terrain for more than 30 miles, from Kimpo to the British Commonwealth sector on the east, a frontage far in excess of the textbook concept.

17 The two other reasons were the weakness of the Kimpo defenses and abandonment of plans for an amphibious strike along the east coast. Montross, Kuokka, and Hicks, USMC Ops Korea, v. IV, p. 253. Planning for a Marine-led assault had been directed by the EUSAK commander, General Van Fleet, early in 1952. The Marine division CG, General Selden, had given the task to his intelligence and operations deputies, Colonel James H. Tinsley and Lieutenant Colonel Gordon D. Gayle. On 12 March General Van Fleet came to the Marine Division CP for a briefing on the proposed amphibious assault. At the conclusion of the meeting the EUSAK commander revealed his concern for a possible enemy attack down the Korean west coast and told the Marine commander to prepare, in utmost secrecy, to move his division to the west coast. Lynn Montross, draft MS.

Although Seoul was not actually within the area of Marine Corps responsibility, the capital city was only 33 air miles south of the right limiting point of the division MLR and 26 miles southeast of the left. The port of Inchon lay but 19 air miles south of the western end of the division sector. Kaesong, the original site of the truce negotiations, was 13 miles northwest of the nearest part of the 1st Marine Division frontline while Panmunjom was less than 5 miles away and within the area of Marine forward outpost security. From15 the far northeastern end of the JAMESTOWN Line, which roughly paralleled the Imjin River, distances were correspondingly lengthened: Inchon, thus being 39 miles southwest and Kaesong, about 17 miles west.

MAP 2 K. WHITE

WESTERN KOREA

I CORPS SECTOR 1952–1953

The area to which the Marines had moved was situated in the western coastal lowlands and highlands area of northwestern South Korea. On the left flank, the division MLR hooked around the northwest tip of the Kimpo Peninsula, moved east across the high ground overlooking the Han River, and bent around the northeast cap of the peninsula. At a point opposite the mouth of the Kongnung River, the MLR traversed the Han to the mainland, proceeding north alongside that river to its confluence with the Imjin. Crossing north over the Imjin, JAMESTOWN followed the high ground on the east bank of the Sachon River for nearly two miles to where the river valley widened. There the MLR turned abruptly to the northeast and generally pursued that direction to the end of the Marine sector, meandering frequently, however, to take advantage of key terrain. Approximately 2½ miles west of the 1st Commonwealth Division boundary, the JAMESTOWN Line intersected the 38th Parallel near the tiny village of Madam-ni.

Within the Marine division sector to the north of Seoul lay the junction of two major rivers, the Imjin and the Han, and a portion of the broad fertile valley fed by the latter. Flowing into the division area from the east, the Imjin River snaked its way southwestward to the rear of JAMESTOWN. At the northeastern tip of the Kimpo Peninsula, the Imjin joined the Han. The latter there changed its course from south to west, flowed past Kimpo and neighboring Kanghwa-do Island, and emptied eventually into the Yellow Sea. At the far western end of the division sector the Yom River formed a natural boundary, separating Kanghwa and Kimpo, as it ran into the Han River and south to the Yellow Sea. To the east, the Sachon River streamed into the Imjin, while the Kongnung emptied into the Han where the MLR crossed from the mainland to Kimpo.

In addition, two north-south oriented rivers flanked enemy positions opposite the Marines and emptied into major rivers in the Marine sector. Northwest of Kimpo, the Yesong River ran south to the Han; far to the northeast, just beyond the March 1952 division right boundary, the Samichon River flowed into the Imjin.

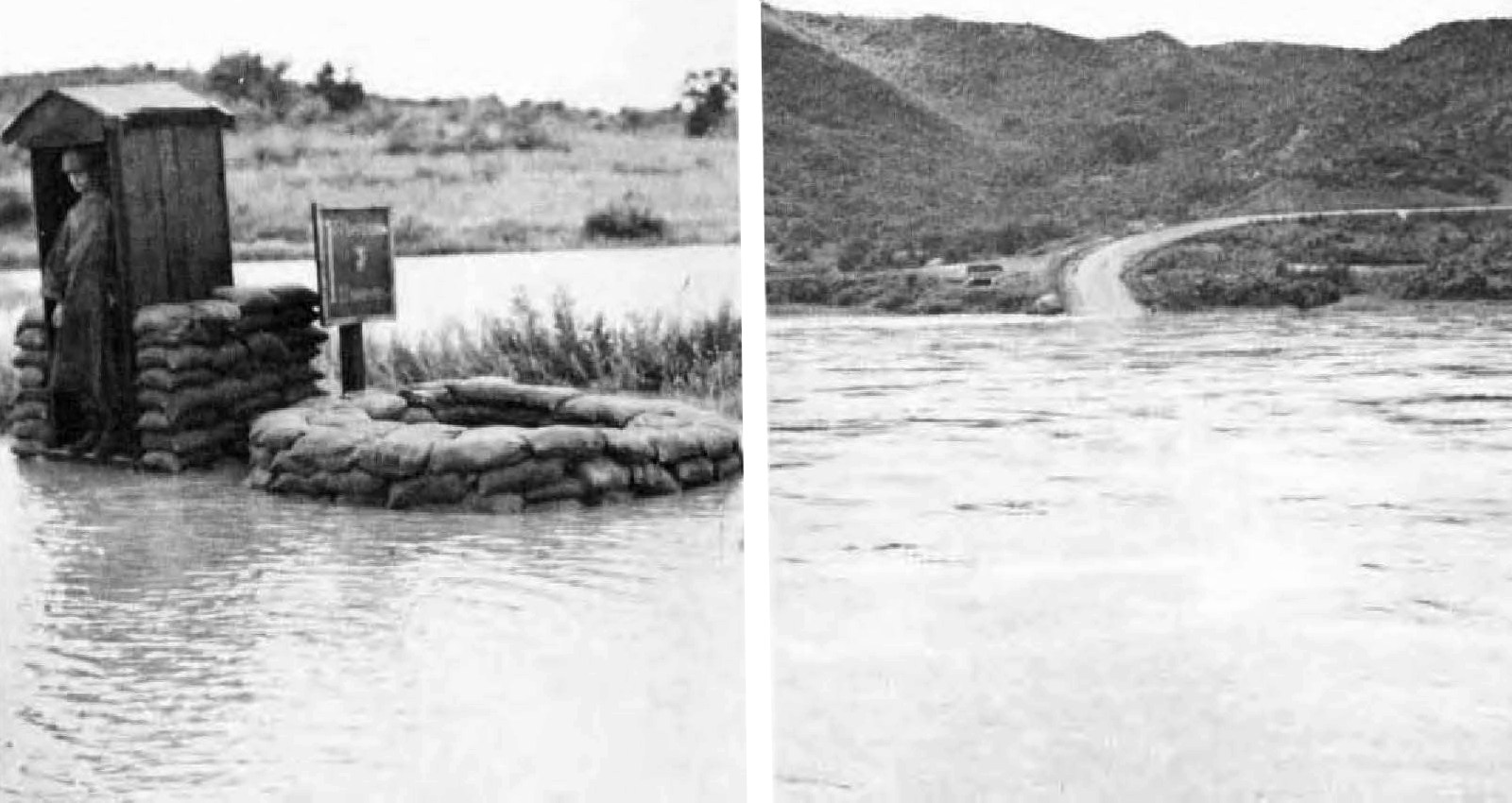

Although the rivers in the Marine division were navigable, they16 were little used for supply or transportation. The railroads, too, were considered secondary ways, for there was but one line, which ran north out of Seoul to Munsan-ni and then continued towards Kaesong. Below the division railhead, located at Munsan-ni, a spur cut off to Ascom City. Roads, the chief means of surface transport, were numerous but lacked sufficient width and durability for supporting heavy military traffic. Within the sector occupied by the Marines, the main route generally paralleled the railroad. Most of the existing roads south of JAMESTOWN eventually found their way to the logistic center at Munsan-ni. Immediately across the Imjin, the road net was more dense but not of any better construction.

From the logistical point of view, the Imjin River was a critical factor. Spanning it and connecting the division forward and rear support areas in March 1952 were only three bridges, which were vulnerable to river flooding conditions and possible enemy attack. Besides intersecting the Marine sector, the Imjin formed a barrier to the rear of much of the division MLR, thereby increasing the difficulty of normal defense and resupply operations.

When the Marines moved to the west, the winter was just ending. It had begun in November and was characterized by frequent light snowfalls but otherwise generally clear skies. Snow and wind storms seldom occurred in western Korea. From November to March the mean daily minimum Fahrenheit readings ranged from 15° to 30° above zero. The mean daily maximums during the summer were between the upper 70s and mid-80s. Extensive cloud cover, fog, and heavy rains were frequent during the summer season. Hot weather periods were also characterized by occasional severe winds. Spring and fall were moderate transitional seasons.

Steep-sided hills and mountains, which sloped abruptly into narrow valleys pierced by many of the rivers and larger streams, predominated the terrain in the I Corps sector where the Marines located. The most rugged terrain was to the rear of the JAMESTOWN Line; six miles northeast of the Munsan-ni railhead was a 1,948-foot mountain, far higher than any other elevation on the Marine or Chinese MLR but lower than the rear area peaks supporting the Communist defenses. Ground cover in the division sector consisted of grass, scrub brush, and, occasionally, small trees. Rice fields crowded the valley floors. Mud flats were prevalent in many areas immediately adjacent to the larger rivers which intersected the17 division territory or virtually paralleled the east and western boundaries of the Marine sector.

The transfer from the Punchbowl in the east to western Korea thus resulted in a distinct change of scene for the Marines, who went from a rugged mountainous area to comparatively level terrain. Instead of facing a line held by predominantly North Korean forces the division was now confronted by the Chinese Communists. The Marines also went from a front that had been characterized by lively patrol action to one that in March 1952 was relatively dormant. With the arrival of the 1st Marine Division, this critical I Corps sector would witness sharply renewed activity and become a focal point of action in the UNC line.

18 Unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is derived from: PacFlt EvalRpt No. 4, Chap. 9; 1stMarDiv, 1stMar, 5thMar, 7thMar, 11thMar ComdDs, Mar 52; 1st KMC RCT Daily Intelligence and Operations Rpts, hereafter KMC Regt UnitRpts, Mar 52; Kimpo ProvRegt ComdDs, hereafter KPR ComdDs, Mar-Apr 52.

“To defend” were the key words in the 1st Marine Division mission—“to organize, occupy, and actively defend its sector of Line JAMESTOWN”—in West Korea. General Selden’s force to prevent enemy penetration of JAMESTOWN numbered 1,364 Marine officers, 24,846 enlisted Marines, 1,100 naval personnel, and 4,400 Koreans of the attached 1st KMC Regiment. The division also had operational control of several I Corps reinforcing artillery units in its sector. On 31 March, another major infantry unit, the Kimpo Provisional Regiment (KPR) was organized. The division then assumed responsibility for the Kimpo Peninsula defense on the west flank with this Marine-Korean force.

A major reason for transfer of the 1st Marine Division to the west, it will be remembered, had been the weakness of the Kimpo defense. Several units, the 5th KMC Battalion, the Marine 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, and the 13th ROK Security Battalion (less one company), had been charged with the protection of the peninsula. Their operations, although coordinated by I Corps, were conducted independently. The fixed nature of the Kimpo defenses provided for neither a reserve maneuver element to help repel any18 enemy action that might develop nor a single commander to coordinate the operations of the defending units.

These weaknesses become more critical in consideration of the type of facilities at Kimpo and their proximity to the South Korean Capital. Seoul lay just east of the base of Kimpo Peninsula, separated from it only by the Han River. Located on Kimpo was the key port of Inchon and two other vital installations, the logistical complex at Ascom City and the Kimpo Airfield (K-14). All of these facilities were indispensable to the United Nations Command.

To improve the security of Kimpo and provide a cohesive, integrated defense line, CG, 1st Marine Division formed the independent commands into the Kimpo Provisional Regiment. Colonel Edward M. Staab, Jr., was named the first KPR commander. His small headquarters functioned in a tactical capacity only without major administrative duties. The detachments that comprised the KPR upon its formation were:

Headquarters and Service Company, with regimental and company headquarters and a communication platoon;

1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, as supporting artillery;

5th KMC Battalion;

13th ROK Security Battalion (-);

One battalion from the reserve regiment of the 1st Marine Division (2/7), as the maneuver element;

Company A, 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion;

Company B, 1st Shore Party Battalion, as engineers;

Company D, 1st Medical Battalion;

Reconnaissance Company (-), 1st Marine Division;

Detachment, Air and Naval Gunfire Liaison Company (ANGLICO), 1st Signal Battalion;

Detachment, 181st Counterintelligence Corps Unit, USA;

Detachment, 61st Engineer Searchlight Company, USA; and the

163rd Military Intelligence Service Detachment, USA.

The Kimpo Regiment, in addition to maintaining security of the division left flank, was assigned the mission to “protect supporting and communication installations in that sector against airborne or ground attack.”19 Within the division, both the artillery regiment and19 the motor transport battalion were to be prepared to support tactical operations of Colonel Staab’s organization.

19 KPR ComdD, Mar 52, p. 13.

For defense purposes, the KPR commander divided the peninsula into three sectors. The northern one was manned by the KMC battalion, which occupied commanding terrain and organized the area for defense. The southern part was defended by the ROK Army battalion, charged specifically with protection of the Kimpo Airfield and containment of any attempted enemy attack from the north. Both forces provided for the security of supply and communication installations within their areas. The western sector, held by the amphibian tractor company, less two platoons, had the mission of screening traffic along the east bank of the Yom River, that flanked the western part of the peninsula. Providing flexibility to the defense plan was the maneuver unit, the battalion assigned from the 1st Marine Division reserve.

The unit adjacent to the KPR20 in the division line in late March was the 1st Korean Marine Corps Regiment, which had been the first division unit to deploy along JAMESTOWN. The KMC Regiment, command by Colonel Kim Dong Ha,21 had assumed responsibility for its portion of JAMESTOWN at 0400 on 20 March with orders to organize and defend its sector. The regiment placed two battalions, the 3d and 1st, on the MLR and the 2d in the rear. Holding down the regimental right of the sector was the 1st Battalion, which had shared its eastern boundary with that of Colonel Wade’s 1st Marines until 29 March when the 5th Marines was emplaced on the MLR between the 1st KMC and 1st Marines.

20 The following month the 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion would be added to the four regiments on line, making a total of five major units manning the 1stMarDiv front. It was inserted between the Kimpo and 1st KMC regiments.

21 Commandant, Korean Marine Corps ltr to CMC, dtd 20 Sep 66, hereafter CKMC ltr.

The 1st Marines regimental right boundary, which on the MLR was 1,100 yards north of the 38th Parallel, separated the 1st Marine Division area from the western end of the 1st Commonwealth Division, then held by the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade. In late March, Colonel Wade’s 2/1 (Lieutenant Colonel Thell H. Fisher) and 3/1 (Lieutenant Colonel Spencer H. Pratt) manned the frontline positions while 1/1 (Lieutenant Colonel John H. Papurca), less Company A, was in reserve. The regiment was committed to the defense of its part of the division area and improvement of its ground20 positions. In the division center sector Colonel Culhane’s 1/5 (Lieutenant Colonel Franklin B. Nihart) and 3/5 (Lieutenant Colonel William S. McLaughlin) manned the left and right battalion MLR positions, with 2/5 (Lieutenant Colonel William H. Cushing) in reserve. The latter unit was to be prepared either to relieve the MLR battalions or for use as a counterattack force.

It did not take the Marines long to discover the existence of serious flaws in the area defense which made it questionable whether the Allied line here could have successfully withstood an enemy attack. While his Marine units were effecting their relief of JAMESTOWN, Colonel Wade noted that “field fortifications were practically nonexistent in some sections.”22 General Selden later pointed out that “populated villages existed between opposing lines. Farmers were cultivating their fields in full view of both forces. Traffic across the river was brisk.”23 A member of the division staff reported that there was “even a school operating in one area ahead of the Marine lines.”24 In addition to these indications of sector weakness, there was still another. Although the ROK division had placed three regiments in the line, when the two Marine regiments relieved them there were then more men on JAMESTOWN due to the greater personnel strength of a Marine regiment. Nevertheless, the division commander was still appalled at the width of the defense sector assigned to so few Marines.

22 1stMar ComdD, Mar 52, p. 2.

23 1stMarDiv ComdD, Jun 52, App IX, p. 1.

24 LtCol Harry W. Edwards comments on preliminary draft MS, ca. Sep 59.

At division level, the reserve mission was filled by Colonel Russell E. Honsowetz’, 7th Marines, minus 2/7 (Lieutenant Colonel Noel C. Gregory), which on 30 March became the maneuver force for the Kimpo Regiment. As the division reserve, the regiment was to be prepared to assume at any time either a defensive or offensive mission of any of the frontline regiments. In addition, the reserve regiment was to draw up counterattack plans, protect the division rear, improve secondary line defenses, and conduct training, including tank-infantry coordination, for units in reserve. The 7th Marines, with 3/7 (Lieutenant Colonel Houston Stiff) on the left and 1/7 (Lieutenant Colonel George W. E. Daughtry) on the right, was emplaced in the vicinity of the secondary defense lines, WYOMING and KANSAS, to the rear of the 5th and 1st Marines.

21

Another regiment located in the rear area was the 11th Marines. Its artillery battalions had begun displacement on 17 March and completed their move by 25 March. Early on the 26th, the 11th Marines resumed support of the 1st Marine Division. While the Marine artillery had been en route, U.S. Army artillery from I Corps supported the division. With the arrival on the 29th of the administrative rear echelon, the Marine artillery regiment was fully positioned in the west.

For Colonel Frederick P. Henderson, who became the division artillery commander on 27 March, operational problems in western Korea differed somewhat from those experienced in the east by his predecessor, Colonel Bruce T. Hemphill. The most critical difficulty, however, was the same situation that confronted General Selden—the vast amount of ground to be covered and defended, and the insufficient number of units to accomplish this mission. To the artillery, the wide division front resulted in spreading the available fire support dangerously thin. Placement of 11th Marines units to best support the MLR regiments created wide gaps between each artillery battalion, caused communication and resupply difficulties, prevented a maximum massing of fires, and made redeployment difficult.25

25 Col Frederick P. Henderson ltr to Hd, HistBr, G-3 Div, HQMC, dtd 25 Aug 59, hereafter Henderson ltr I.

In making use of all available fire support, the artillery regiment had to guard not only against the duplication of effort in planning or delivery of fires, but also against firing in the Panmunjom peace corridor restricted areas, located near the sector held by the Marine division’s center regiment. Moreover, the artillerymen had to maintain a flexibility sufficient to place the weight of available fire support on call into any zone of action.

Other difficulties were more directly associated with the nature of the sector rather than with its broad expanse. The positioning of the division in the west, although close to the coast, put the Marines beyond the range of protective naval gunfire. The sparse and inadequate road net further aggravated the tactical and logistical problems caused by wide separation of units. Finally, the cannoneers had exceptionally heavy demands placed on them due to the restricted amount of close air support allocated to frontline troops under operational procedures employed by Fifth Air Force. This command22 had jurisdiction over the entire Korean air defense system, including Marine squadrons.

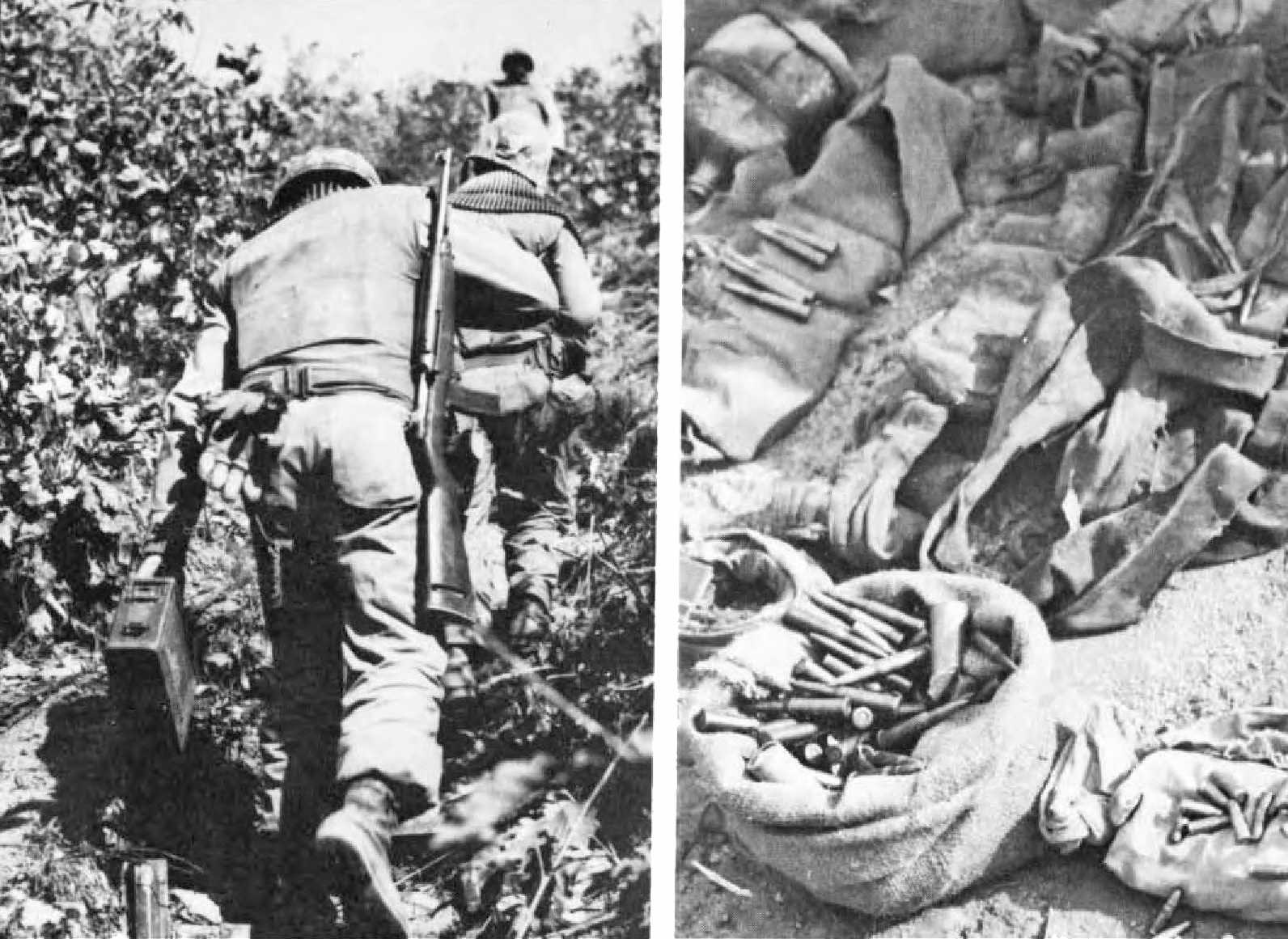

Manning the main line of resistance also frequently presented perplexing situations to the infantry. There had been little time for a thorough reconnaissance and selection of positions by any of the frontline regiments. When the 1st Marines moved into its assigned position on the MLR, the troops soon discovered many minefields, “some marked, some poorly marked, and some not marked at all.”26 Uncharted mines caused the regiment to suffer “some casualties the first night of our move and more the second and third days.”27 As it was to turn out, during the first weeks in the I Corps sector, mines of all types caused 50 percent of total Marine casualties.

26 Col Sidney S. Wade ltr to Deputy AsstCofS, G-3, HQMC, dtd 25 Aug 59.

27 Ibid.

A heavy drain on the limited manpower of Marine infantry regiments defending JAMESTOWN was caused by the need to occupy an additional position, an outpost line of resistance (OPLR). This defensive line to the front of the Marine MLR provided additional security against the enemy, but decreased the strength of the regimental reserve battalion, which furnished the OPLR troops. The outposts manned by the Marines consisted of a series of strongpoints built largely around commanding terrain features that screened the 1st Marine Division area. The OPLR across the division front was, on the average, about 2,500 yards forward of the MLR. (See Map 3.)

To the rear of the main line were two secondary defensive lines, WYOMING and KANSAS. Both had been established before the Marines arrived and both required considerable work, primarily construction of bunkers and weapons emplacements, to meet General Selden’s strict requirement for a strong defensive sector. Work in improving the lines, exercises in rapid battalion tactical deployment by helicopter, and actual manning of the lines were among the many tasks assigned to the division reserve regiment.

MAP 3 K. White

1st MARINE DIVISION SECTOR

30 APRIL 1952

Rear and frontline units alike found that new regulations affected combat operations with the enemy in West Korea. These restrictions were a result of the truce talks that had taken place first at Kaesong and, later, at Panmunjom. In line with agreements reached in October 1951:

Panmunjom was designated as the center of a circular neutral zone of a 1,000 yard radius, and a three mile radius around Munsan and Kaesong was24 also neutralized, as well as two hundred meters on either side of the Kaesong-Munsan road.28

28 Rees, Korea, p. 295.

To prevent the occurrence of any hostile act within this sanctuary, Lieutenant General John W. O’Daniel, I Corps commander, ordered that an additional area, forward of the OPLR, be set aside. This megaphone-shaped zone “could not be fired into, out of, or over.”29 It was adjacent to the OPLR in the division center regimental sector, near its left boundary, and took a generally northwest course. Marines reported that the Communists knew of this restricted zone and frequently used it for assembly areas and artillery emplacements.

29 1stMarDiv ComdD, Mar 52, p. 7.

30 Unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is derived from PacFlt EvalRpt No. 4, Chap. 10; 1stMarDiv ComdD, Mar 52; 1st MAW ComdDs, Mar-Apr 52.

When the 1st Marine Division moved to western Korea in March 1952, the two 1st Marine Aircraft Wing units that had been in direct support of the ground Marines also relocated. Marine Observation Squadron 6 (VMO-6) and Marine Helicopter Transport Squadron 161 (HMR-161) completed their displacements by 24 March from their eastern airfield (X-83) to sites in the vicinity of the new division CP. HMR-161, headed by Colonel Keith B. McCutcheon, set up headquarters at A-17,31 on a hillside 3½ miles southeast of Munsan-ni, the division railhead, “using a couple of rice paddies as our L. Z. (Landing Zone).”32 The squadron rear echelon, including the machine shops, was maintained at A-33, near Ascom City. About 2½ miles south of the helicopter forward site was an old landing strip, A-9, which Lieutenant Colonel William T. Herring’s observation squadron used as home field for its fixed and rotary wing aircraft. (For location of 1st MAW units see Map 4.) In West Korea, VMO-6 and HMR-161 continued to provide air transport for tactical and logistical missions. Both squadrons were under operational control of the division, but administered by the wing.

31 In Korea, fields near U.S. Army installations were known as “A”; major airfields carried a “K” designation; and auxiliary strips were the “X” category.

32 MajGen Keith B. McCutcheon comments on draft MS, dtd 1 Sep 66.

Commanding General of the 1st MAW, since 27 July 1951,26 was Major General Christian F. Schilt,33 a Marine airman who had brought to Korea a vast amount of experience as a flying officer. Entering the Marine Corps in June 1917, he had served as an enlisted man with the 1st Marine Aeronautical Company in the Azores during World War I. Commissioned in 1919, he served in a variety of training and overseas naval air assignments. As a first lieutenant in Nicaragua, he had been awarded the Medal of Honor in 1928 for his bravery and “almost superhuman skill” in flying out Marines wounded at Quilali.34 During World War II, General Schilt had served as 1st MAW Assistant Chief of Staff, at Guadalcanal, was later CO of Marine Aircraft Group 11, and participated in the consolidation of the Southern Solomons and air defense of Peleliu and Okinawa.

33 DivInfo, HQMC, Biography of General Christian F. Schilt, USMC (Ret.), Jun 59 rev.

34 Robert Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (Washington: Combat Forces Press, 1952), p. 26, hereafter Sherrod, Marine Aviation.

MAP 4 E. WILSON

1ST MARINE AIRCRAFT WING DISPOSITIONS

30 APRIL 1952

As in past months, the majority of General Schilt’s Marine aircraft in Korea during March 1952 continued to be under operational control of Fifth Air Force. In turn, FAF was the largest subordinate command of Far East Air Forces (FEAF), headquartered at Tokyo. The latter was the U.S. Air Force component of the Far East Command and encompassed all USAF installations in the Far East. The FAF-EUSAK Joint Operations Center (JOC) at Seoul coordinated and controlled all Allied air operations in Korea. Marine fighter and attack squadrons were employed by FAF to:

Maintain air superiority.

Furnish close support for ground units.

Provide escort [for attack aircraft].

Conduct day and night reconnaissance and fulfill requests.

Effect the complete interdiction of North Korean and Chinese Communist forces and other military targets that have an immediate effect upon the current tactical situation.35

35 1st MAW ComdD, Mar 52, p. 2.

Squadrons carrying out these assignments were attached to Marine Aircraft Groups (MAGs) 12 and 33. Commanded by Colonel Luther S. Moore, MAG-12 and its two day attack squadrons (VMF-212 and VMF-323) in March 1952 was still located in eastern Korea (K-18, Kangnung). The Marine night-fighters of VMF(N)-513 were also here as part of the MAG-12 group. Farther removed from the immediate battlefront was Colonel Martin27 A. Severson’s MAG-33, located at K-3 (Pohang), with its two powerful jet fighter squadrons (VMFs-115 and -311) and an attack squadron (VMA-121). A new MAG-33 unit was Marine Photographic Squadron 1 (VMJ-1), just formed in February 1952 and commanded by Major Robert R. Read.

In addition to its land-based squadrons, one 1st MAW unit was assigned to Commander, West Coast Blockading and Patrol Group, designated Commander, Task Group 95.1 (CTG 95.1). He in turn assigned this Marine unit to Commander, Task Element 95.11 (CTE 95.11), whose ships comprised the West Coast Carrier Element. Marine Attack Squadron 312 (VMA-312) was at this time assigned to CTE 95.11. In late March squadron aircraft were based on the escort carrier USS Bairoko but transferred on 21 April to the light carrier Bataan.36 Operating normally with a complement of 21 F4U-4 propeller-driven Corsair aircraft, VMA-312 had the following missions:

To conduct armed air reconnaissance of the West Coast of Korea from the United Nations front lines northward to latitude 39°/15´ N.

Attack enemy shipping and destroy mines.

Maintain surveillance of enemy airfields in the Haeju-Chinnampo region.37

Provide air spot services to naval units on request.

Provide close air support and armed air reconnaissance services as requested by Joint Operations Center, Korea (JOC KOREA).

Conduct air strikes against coastal and inland targets of opportunity at discretion.

Be prepared to provide combat air patrol to friendly naval forces operating off the West Coast of Korea.

Render SAR [search and rescue] assistance.

36 Unit commanders also changed about this time. Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Smith, Jr. assumed command of the Checkerboard squadron from Lieutenant Colonel Joe H. McGlothlin, on 9 April.

37 PacFlt EvalRpt No. 4, p. 10-75. The Haeju-Chinnampo region, noted in the surveillance mission, is a coastal area in southwestern North Korea between the 38th and 39th Parallels.

Because they were under operational control of Fifth Air Force, 1st MAW flying squadrons, except those assigned to CTG 95.1 and 1st Marine Division control, did not change their dispositions in March. Plans were under way at this time, however, to relocate one of the aircraft groups, MAG-12, to the west.

On 30 March the ground element of the night-fighters redeployed28 from its east coast home field to K-8 (Kunsan), on the west coast, 105 miles south of Seoul. Lieutenant Colonel John R. Burnett’s VMF (N)-513 completed this relocation by 11 April without loss of a single day of flight operations. On 20 April the rest of MAG-12,38 newly commanded since the first of the month by Colonel Elmer T. Dorsey, moved to K-6 (Pyongtaek), located 30 miles directly south of the South Korean capital.

38 VMFs-212 (LtCol Robert L. Bryson) and -323 (LtCol Richard L. Blume) left an east coast field for a flight mission over North Korea and landed at K-6 thereafter, also completing the move without closing down combat operations. The relocation in airfields was designed to keep several squadrons of support aircraft close to the 1st Marine Division. Col E. T. Dorsey ltr to Hd, HistBr, G-3 Div, HQMC, dtd 7 Sep 66.

Marine aircraft support units were also located at K-3 and at Itami Air Force Base, on Honshu, Japan. Under direct 1st MAW control were four ground-type logistical support units with MAG-33, a Provisional Automatic Weapons Battery from Marine Air Control Group 2 (MACG-2), and most of wing headquarters. This last unit, commanded by Colonel Frederick R. Payne, Jr., included the 1st 90mm AAA Gun Battalion (based at Pusan and led by Colonel Max C. Chapman), and a detachment of Marine Transport Squadron 152 (VMR-152), which had seven Douglas four-engine R5D transports. This element and the wing service squadron were based at Itami.

Marines, and others flying in western Korea, found themselves restricted much as Marines on the ground were. One limitation resulted from a FAF-EUSAK agreement in November 1951 limiting the number of daily close air support sorties across the entire Eighth Army line. This policy had restricted air activity along the 155-mile Korean front to 96 sorties per day. The curtailment seriously interfered with the Marine type of close air support teamwork evolved during World War II, and its execution had an adverse effect on Marine ground operations as well. A second restriction, also detrimental to Marine division and wing efficiency, was the prohibitive cushion Fifth Air Force had placed around the United Nations peace corridor area north of the Marine MLR. This buffer no-fly, no-fire zone which had been added to prevent violation of the UN sanctuary by stray hits did not apply, of course, to the Communists.

29

39 Unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is derived from: PacFlt EvalRpt No. 4, Chaps. 9, 10; 1stMarDiv ComdD, Mar 52.

Directly beyond the 1st Marine Division sector, to the west and north, were two first-rate units of the Chinese Communist Forces, the 65th and 63d CCF Armies. Together, they totaled approximately 49,800 troops in late March 1952. Opposite the west and center of the Marine division front was the 65th CCF Army, with elements of the 193d Division across from the KPR and the 194th Division holding positions opposing the KMC regiment. Across from the Marine line in the center was the 195th Division of the 65th CCF Army, which had placed two regiments forward. North of the division right sector lay the 188th Division, 63d CCF Army, also with two regiments forward. The estimated 15 infantry battalions facing the Marine division were supported by 10 organic artillery battalions, numbering 106 guns, and varying in caliber from 75 to 155mm.40 In addition, intelligence reported that the 1st CCF Armored Division and an unidentified airborne brigade were located near enough to aid enemy operations.

40 The Korean Marine Corps placed the artillery count at 240 weapons ranging from 57 to 122mm. CKMC ltr.

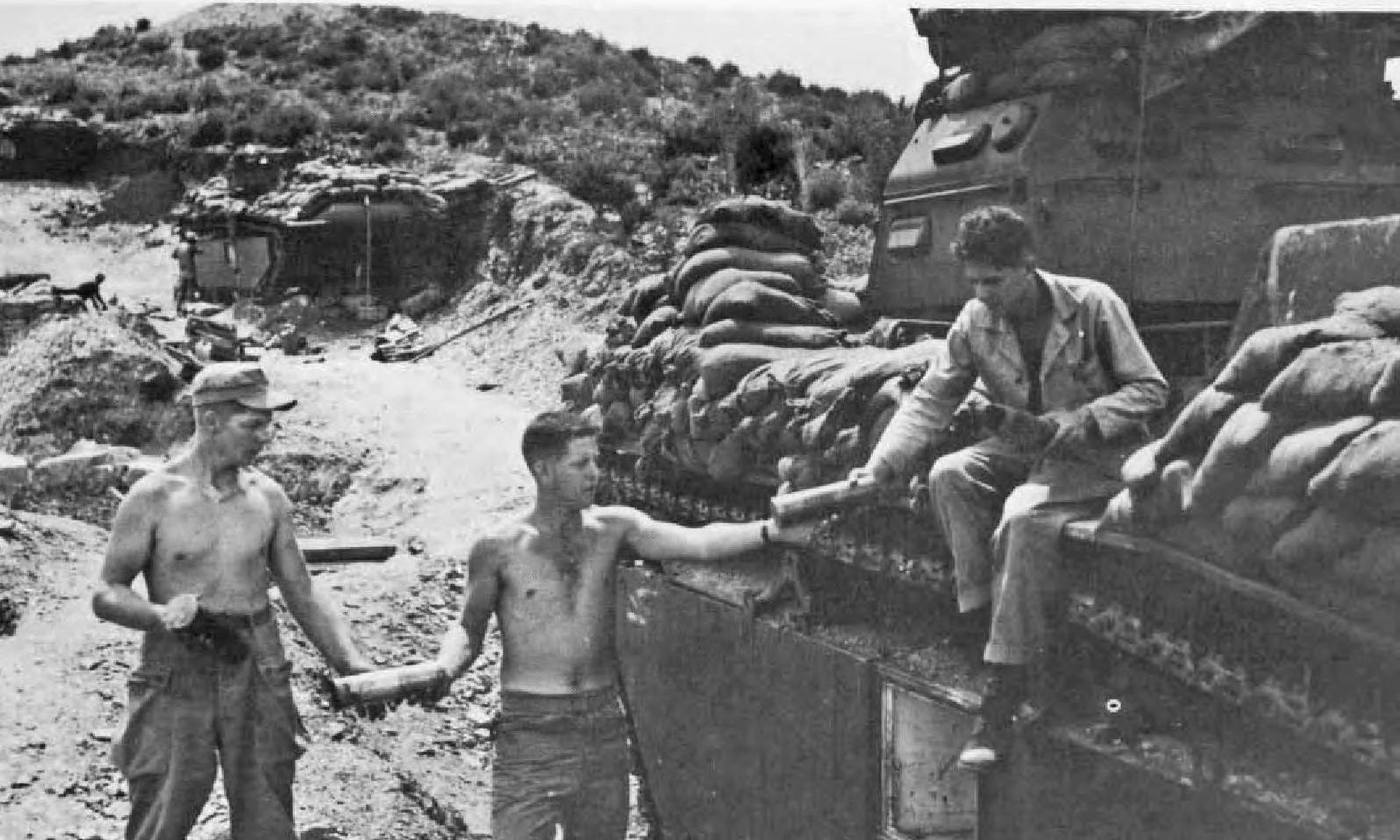

Chinese infantry units were not only solidly entrenched across their front line opposite the Marine division but were also in depth. Their successive defensive lines, protected by minefields, wire, and other obstacles, were supported by artillery and had been, as a result of activities in recent months, supplied sufficiently to conduct continuous operations. Not only were enemy ground units well-supplied, but their CCF soldiers were well disciplined and well led. Their morale was officially evaluated as ranging from good to excellent. In all, the CCF was a determined adversary of considerable ability, with their greatest strength being in plentiful combat manpower.

Air opposition to Marine pilots in Korea was of unknown quantity and only on occasion did the caliber of enemy pilots approach that of the Americans. Pilots reported that their Chinese counterparts generally lacked overall combat proficiency, but that at times their “aggressiveness, sheer weight of numbers, and utter disregard for losses have counterbalanced any apparent deficiencies.”41 The30 Communists had built their offensive potential around the Russian MIG-15 jet fighter-interceptor. Use of this aircraft for ground support or ground attack was believed to be in the training stage only. The Chinese had also based their air defense on the same MIG plus various types of ground antiaircraft (AA) weapons, particularly the mobile 37mm automatic weapons and machine guns that protected their main supply routes. In use of these ground AA weapons, enemy forces north of the 38th Parallel had become most proficient. Their defense system against UNC planes had been steadily built up and improved since stabilization of the battle lines in 1951, and by March 1952 was reaching a formidable state.

41 PacFlt EvalRpt, No. 4, p. 10-38.

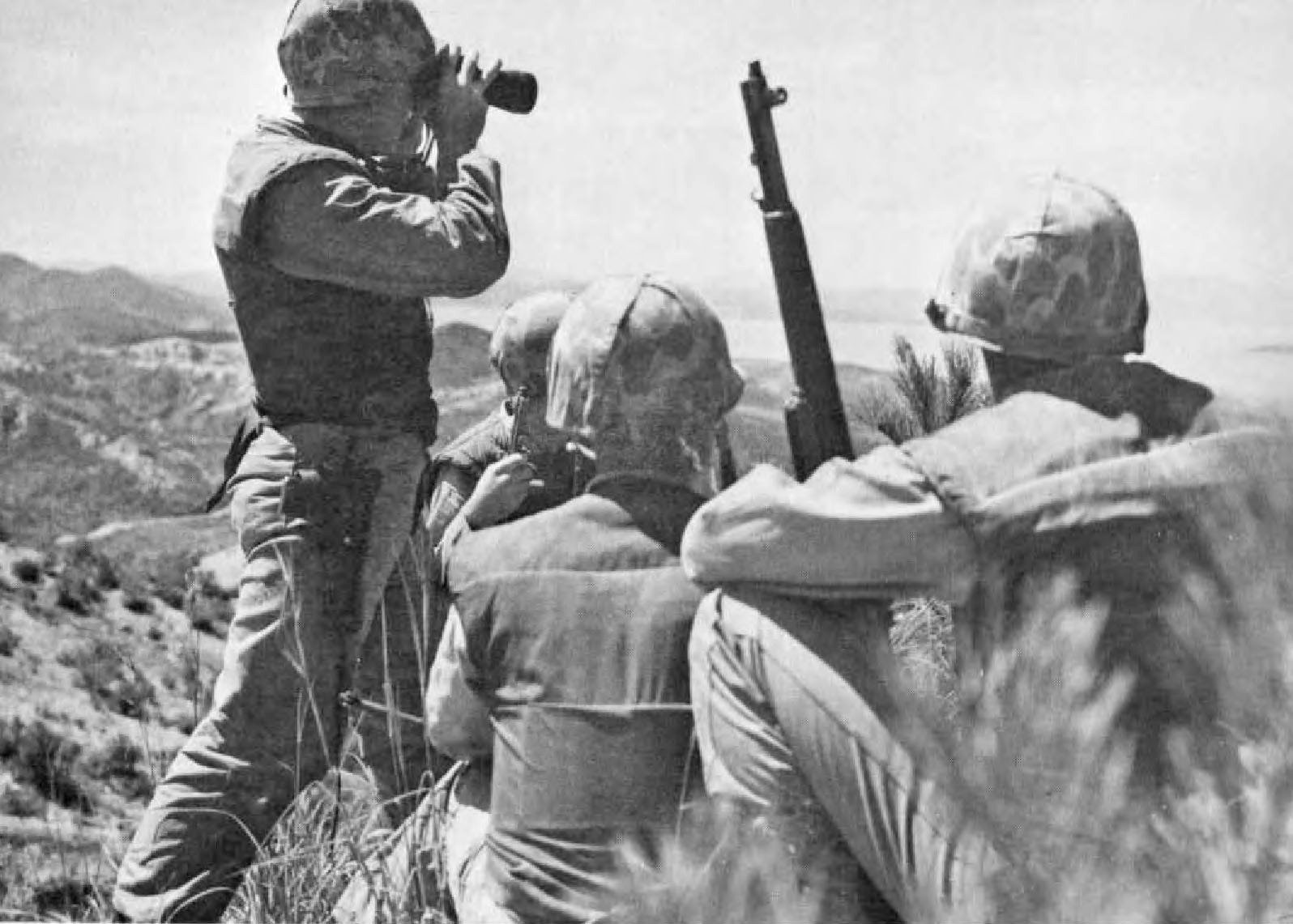

As the more favorable weather for ground combat approached toward the end of March, the CCF was well prepared to continue and expand its operations. Enemy soldiers were considered able to defend their sector easily with infantry and support units. Division intelligence also reported that Chinese ground troops had the capability for launching limited objective attacks to improve their observation of Marine MLR rear areas.

42 Unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is derived from: 1stMarDiv ComdDs, Mar-Apr 52; KMC Regt UnitRpt 31, dtd 2 Apr 52.

Whether by intent or default, the Chinese infantry occupying the enemy forward positions did not interfere with the Marine relief. With assumption of sector responsibility by the division early on 25 March, the initial enemy contact came from Chinese supporting weapons. Later that day the two division frontline regiments, the 1st and 5th Marines, received 189 mortar and artillery shells in their sectors which wounded 10 Marines. One man in the 1st Marines was killed by sniper fire on 25 March; in the same regiment, another Marine was fatally wounded the following day. Forward of the lines, the day after the division took over, there was no ground action by either side.

During the rest of the month, the tempo of activities on both sides increased. Marines began regular patrol actions to probe and ambush the enemy. Division artillery increased its number of observed missions by the end of the month. By this time the CCF had also begun31 to probe the lines of the Marine regimental sectors. In these ground actions to reconnoiter and test division defenses, the Chinese became increasingly bold, with the most activity on 28 March. Between 25–31 March, the first week on JAMESTOWN, some 100 Chinese engaged in 5 different probing actions. Most of these were against the 1st KMC Regiment on the left flank of the division MLR.

It was no wonder that the Chinese concentrated their effort against the Korean Marines, for they held the area containing Freedom Gate, the best of the three bridges spanning the Imjin. Both of the other two, X-Ray and Widgeon, were further east in the division sector. If the enemy could exploit a weak point in the KMC lines, he could attack in strength, capture the bridge, and turn the division left flank, after which he would have a direct route to Seoul.43 Without the bridge in the KMC sector, the division would be hard pressed, even with helicopter lift, to maneuver or maintain the regiments north of the Imjin.

43 Henderson ltr I.