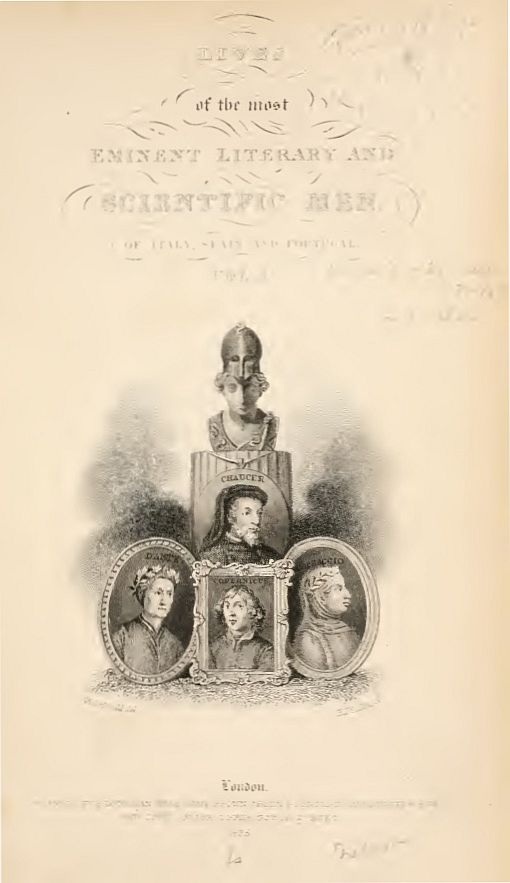

Title: Eminent literary and scientific men of Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Vol. 1 (of 3)

Author: James Montgomery

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

Editor: Dionysius Lardner

Release date: April 8, 2021 [eBook #65030]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Laura Natal Rodrigues at Free Literature (Images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

DANTE

PETRARCH

BOCCACCIO

LORENZO DE' MEDICI, &c.

BOJARDO

BERNI

ARIOSTO

MACHIAVELLI

Among the illustrious fathers of song who, in their own land, cannot cease to exercise dominion over the minds, characters, and destinies of all posterity,—and who, beyond its frontiers, must continue to influence the taste, and help to form the genius, of those who shall exercise like authority in other countries,—Dante Alighieri is, undoubtedly, one of the most remarkable.

This poet was descended from a very ancient stock, which, according to Boccaccio, traced its lineage to the Roman house of Frangipani,—one of whose members, surnamed Eliseo, was said to have been an early settler, if not a principal founder, of the restored city of Florence, in the {Pg 1} reign of Charlemagne, after it had lain desolate for several centuries, subsequently to its destruction by Attila the Hun. From this Eliseo sprang a family, of which Dante gives, in the fifteenth and sixteenth cantos of his "Paradiso," such information, as he thought proper; making Cacciaguida (one of its most distinguished chiefs, who fell fighting in the crusade under the emperor Conrad III.,) say, rather ambiguously, of those who went before him, that "who they were, and whence they came, it is more honest to keep silence than to tell,"—probably, however, intending no more than to disclaim vain boasting, but not by any means to disparage his progenitors, for whom, in the fifteenth canto of the "Inferno," he seems to claim the glory of having been of Roman descent, and fathers of Florence. Cacciaguida, having married a noble lady of Ferrara, gave to one of his sons by her the name of Aldighieri (afterwards softened to Alighieri), in honour of his consort. This Alighieri was the grandfather of Dante; and concerning him, Cacciaguida, in the last-mentioned canto, informs the poet, that, for some unnamed offence, his spirit has been more than a hundred years pacing round the first circle of the mountain of purgatory; adding,—

Dante was born in the spring of the year 1265. Benvenuta da Immola calls his father a lawyer; but little more is recorded of him except that he was twice married, and left two sons and a daughter, at an early age, to the guardianship of relatives. Dante (abridged from Durante) was born of Bella, his father's second wife, of whom, during her pregnancy, Boccaccio relates a very significant dream,—on what authority he does not say, and with what truth the reader may judge for himself. She {Pg 2} imagined herself sitting under the shade of a lofty laurel, in the midst of a green meadow, by the side of a brilliant fountain. Here she was delivered of a boy, who, in as little time as might easily happen in a dream, grew up into a man before her eyes, by feeding upon the berries that fell from the tree, and drinking of the pure stream which watered its roots. Presently he had become a shepherd; but, climbing too eagerly up the stem to gather some leaves from the laurel, with the fruit of which he had been hitherto nourished, he fell headlong to the ground, and on rising appeared no longer a man, but a magnificent peacock. It would be aggravating the offence of wasting time by quoting such a fable, were we to give the obvious interpretation. This, however, the great Boccaccio has done with most magniloquent gravity,—a task for which, of all men, he was no doubt the most competent, as it is probable that no soul living (the lady herself not excepted) besides himself was in the secret either of the vision or the moral. One point of the latter, which could not easily be guessed, may be mentioned; namely, that the spots on the peacock's tail (the hundred eyes of Argus) foreshowed the hundred cantos of the "Divina Commedia." The ingenious author of the Decameron may have borrowed the idea of this dream from Dante's own allusion to the laurel and its leaves,—the meed of poets and of princes,—in his preposterous invocation of Apollo at the commencement of the "Paradiso."

Dante himself never alludes to this notable omen, though often referring, with conscious pride, to his genius, and the circumstances by which it had been awakened and exercised. This he attributed to the benign influence of the constellation Gemini, which ruled at his nativity. In the "Paradiso," Canto XXII., mentioning his flight from the planetary system to the eighth sphere, where the fixed stars have their dwelling, he exclaims,—

Brunetto Latini (his tutor afterwards) is reported to have foretold the boy's illustrious destiny, on due consultation with the heavenly bodies that presided at his birth. Yet, superstitious as Dante appears to have been in this respect, in the twentieth canto of the "Inferno" he punishes astrologers, and those who presume to predict events, by twisting their heads over their shoulders, and making those for ever look backward who, too daringly, had looked forward into inscrutable futurity. {Pg 4}

Though early deprived of his father by death, Dante appears to have been well attended to by his relatives and guardians, who placed him for education under Brunetto Latini and other eminent tutors. He was by them instructed not only in polite letters, but in those liberal accomplishments which became his rank and prospects in life. In these he excelled; yet, while he delighted in horsemanship, falconry, and all the {Pg 5} manly as well as military exercises practised by persons of distinction in those days, he was, at the same time, so diligent a scholar, that he readily made himself master of all the crude learning then in vogue. It is stated by Pelli that, while yet a boy, he entered upon his noviciate at a convent of the Minor Friars. But his mind was too active and enterprising to enslave itself to dulness in any form; and he withdrew before the term of probation was ended.

According to Boccaccio, before he could be either student, sportsman, soldier, or monk, he became a lover; and a lover thenceforward to the end of his life he appears to have remained, with a passion so pure and unearthly, that it has been gravely questioned whether his mistress were a real or an imaginary being. The former, however, happening to be quite as probable as the latter, all true youths and maidens will naturally choose to believe that which is most pleasant, and give the credence of the heart to every eulogium which the poet, throughout his works, has lavished upon his Beatrice, whatever greybeards may think of the following story:—One fine May-day, when, according to the custom of the country, parties of both sexes used to meet in family circles, and, under the roofs of common friends, rejoice on the return of the genial season, Folco Portinari, a Florentine of no mean parentage, had invited a great number of neighbours to partake of his hospitality. As it was common on such occasions for children to accompany their relatives, Dante Alighieri, then in his ninth year, had the good fortune to be present; where, mingling with many other young folks, in their afternoon sports, he singled out, with the second sight of the future poet, that one whom his verse was destined to eternise. The little lady, a year younger than himself, was Bicè (the familiar abbreviation of Beatricè), daughter of the gentleman at whose house the festivities were held. She need not be pictured here; for premature as such a fit must have been, every one who remembers a first love, at any age, will {Pg 6} know how she looked, how she spoke, how she stepped, and how her hero felt,—growing at every instant greater and better, and braver in his own esteem, that he might become worthy of hers:—suffice it to say, from Boccaccio, that Dante, though but a boy, received her beautiful image into his heart with such fondness of affection, that, from that day, it never departed thence.

In his "Vita Nuova" (a romantic and sentimental retrospect of his youth), he has himself described his raptures and his agonies in the commencement and progress of this passion; which was not extinguished, but refined; not buried with her body, but translated with its object, (her soul,) when Beatrice died, in 1290, at the age of twenty-four years. Judging from the general tenor of his poetry, of which his mistress was at once the inspirer and the theme, it must be presumed that the lady returned his noble attachment with corresponding tenderness and delicacy; though why they were not united by marriage has never been told. He intimates, indeed, that it was long before he could learn, by any token from herself, that his faithful passion was not hopeless. As usual in cases of this kind, a most unpoetical accident has been ill-naturedly interposed, by truth or tradition, to spoil a charm almost too exquisite to be more than a charm which the breath of five words might break. On the evidence of a marriage certificate, which Time unluckily dropped in his flight, and some poring antiquary picked up a century or two afterwards, it seems as though Beatrice became the wife of a cavalier de Bardi. Dante himself, however (who pretends to no bosom-secrets too dark to be uttered), never alludes to such a blight of his prospects on this side of that threefold world which he was afterwards privileged to explore, at her spontaneous intercession, that he might be purged from every baser flame than entire affection to herself, while she gave him in the eighth heaven a heart divided only with her God. After her decease, he intimates that he was tempted to infidelity to her memory (in which she was the bride of his soul), by {Pg 7} the appearance at a window of a lady who so much resembled his "late deceased saint," that he almost forgot her in retracing her own loveliness in the features of this new apparition. His tears flowed freely at the sight; and he felt comforted by the sympathy of the beautiful stranger in his sufferings. But when, after a little while, he found love to the living symbol growing up like a serpent among the flowers, he fled in terror from it, before the gaze which had gained such power over his senses had irrevocably fascinated him to destruction; and he bewailed, in the most humiliating terms, the frailty of his heart and the wandering of his eyes. It is, moreover, the glory of his great work that the posthumous affection of Beatrice herself is represented as having so troubled her spirit, that, even amidst the blessedness of Paradise, she devised means whereby her lover might be reclaimed from the irregularities into which he had fallen after her restraining presence had been withdrawn from him on earth, and that he might be prepared, by visions of the eternal world, for future and everlasting companionship with her in heaven.

Dante, as he grew up to manhood, and for several years afterwards, continued successfully to pursue his studies in the universities of Padua, Bologna, and Paris. In the latter city he is said to have held various theological disputations, alike creditable to his learning, eloquence, and acuteness; though, from the failure of pecuniary means, he could not remain long enough there to obtain academical honours. On the authority of Giovanni da Serraville, bishop of Fermo, it has been believed that he also visited Oxford, where, as elsewhere, his different exercises gained him,—according to the respective tastes of his admirers,—from some the praise of being a great philosopher, from others a great divine, and, from the rest, a great poet. Serraville, at the request of cardinal Saluzzo and two English bishops, (Nicholas Bubwith, of Bath, and Robert Halam, of Salisbury,) whom he met at the {Pg 8} council of Constance, translated Dante's "Divina Commedia" into Latin prose; of which one manuscript copy only, with a commentary annexed, is known to be in existence, in the Vatican library. The extraordinary interest which the two English prelates took in Dante's poem may be regarded as indirect, though of course very indecisive, evidence of his having been personally known at our famous university, and having been honourably remembered there. It is, however, certain that, soon after his decease, the "Divina Commedia" was in high repute among the few in this country who, during the reigns of Edward III. and Richard II., in a chivalrous age, cultivated polite letters. This is apparent from the numerous imitations of passages in it by Chaucer, who was then attempting to do for England what his magnificent prototype had recently done for Italy.

Uncertain as the traditions concerning this portion of Dante's life (and indeed of every other) may be, there is no doubt that he became early and intimately acquainted with the reliques of all the Roman writers then known in Italy. Among these, Virgil, Ovid, and Statius were his favourites, and naturally so, as excelling (each according to his peculiar genius) in marvellous and beautiful narrative, to which their youthful admirer's own sublime and daring genius intuitively led him. At the same time, he not less courageously and patiently groped his way through the labyrinths of school divinity, and the dark caverns of what was then deemed philosophy, under the bewildering guidance of Duns Scotus and Thomas Aquinas. Full proof of the improvement which he made, both under classical and polemical tutors and prototypes, may be traced in all his compositions, prose as well as verse, from the earliest to the last: yet, that which was his own, it must be acknowledged, is ever the best; and if, in addition to a large proportion of this, there had not been a savour of originality communicated to every thing which he borrowed or had been taught, his works must have perished with those of his contemporaries, who are now either nameless, or survive only as {Pg 9} names in the titles of unread and unreadable volumes.

During this season of seed time for the mind, we are told that, notwithstanding his indefatigable labours in the acquirement and cultivation of knowledge, he appeared so cheerful, frank, and generous in deportment and disposition, that nobody would have imagined him to be such a devotee to literature in the stillness of the closet, or the open field of college exercises. On the contrary, he passed in public for a gallant and highbred man of the world; following its customs and fashions, so far as might be deemed consistent in a person of honour, and independence,—qualities on which he sufficiently prided himself; for which, also, in after life, he dearly paid the price,—and paid it, like Aristides, by banishment.

But Beatrice dying in 1290[6], her lover is reported to have fallen into such a state of despondency, that his friends, fearing the most frightful effects upon his reason not less than upon his health, persuaded him, as a last resource, to marry. Accordingly he took to wife Madonna Gemma, of the house of Donati; one of the most powerful families of Tuscany, and unhappily one of the most turbulent where few could be called pacific. By her he had five sons and a daughter. Her husband's biographers (with few exceptions) have conspired to darken this lady's memory with the stigma of being an insufferable shrew, who rendered his life a martyrdom by domestic discomforts. Aline in the "Inferno," Canto XVI., in which one of the lost spirits, Jacopo Rusticci, says,

has often been quoted as referring, with indirect bitterness, to his own miserable union with a firebrand of a woman: yet, in no passage {Pg 10} throughout the whole of his long poem, does Dante cast the slightest shade upon her character; though, with the frankness of honest censure or undisguised resentment, he spares nobody else, friend or foe, in the distribution of what he deemed impartial justice. One thing is exceedingly in favour of his own amiable and affectionate nature, in the nearest connections of life: whenever he mentions children in his similes (and he mentions them often), it is always with exquisite delicacy or endearing playfulness; while, in the tenderest tones, he descants on their beauty, their innocence, their sports, and their sufferings. Mothers, too, are among the loveliest objects which he presents in those sweet interludes of real life which he delights to bring in, and does so with consummate address, to relieve the horrors of the infernal pit, the wearying pains of purgatory, and the insufferable glories of Paradise. Concerning Dante's wife it may therefore be fairly presumed, that she was less of either termagant or tormentor than has been generally imagined by his over-zealous editors. The petulance of Boccaccio and the gravity of Aretino (two of his earliest biographers) on this subject are ludicrously contrasted. The former affects to be quite shocked at the idea of the sublime and contemplative poet being forced to lead the dull household life of other men, and submit to certain petty annoyances of daily occurrence.—On these he expatiates most pathetically, as things which might have been, though he fairly acknowledges that he does not know that any of them were, the causes of long unhappiness and final separation between the parties. Aretino, on the other hand, in sober sadness (without any reference to the ill qualities of either), justifies Dante for condescending to be married, on the ground that many illustrious philosophers, including Socrates, the greatest of all, were husbands and fathers, and held offices of state, in perfect compatibility with their intellectual pursuits!

It should not be overlooked, in mitigation of her occasional asperities, {Pg 11} that, Madonna Gemma being the near kinswoman of Corso Donati, Dante's most formidable and inveterate rival in the party feuds of Florence, some drops of the gall of political rancour may have been infused into the matrimonial cup. The poet's known and avowed passion for Beatrice, living and dead, was alone sufficient to afflict a high-minded woman with the rankling consciousness that she had not all her husband's heart. It is, moreover, no small proof of her submission to his will and pleasure, that their only daughter bore the name of his first—last—only love, if we are to believe all the protestations of his verse. Be these things as they may, it must be concluded that he was coupled with a most unpoetical yoke-mate; and she with a lord and master not easy to be ruled by her or any body else. It has been loosely stated that "the poet, not possessing the patience of Socrates, separated himself from his wife, with such vehement expressions of dislike that he never afterwards allowed her to sit down in his presence." When this happened—if it ever so happened—does not appear; nothing further seems certain, except that she did not follow her husband into exile: but Boccaccio himself acknowledges, that after that event, having secured (not without difficulty) a small portion of his effects from confiscation as her dower, she preserved herself and their little children from the wretchedness of absolute poverty, by such expedients of industry and economy as she had never before been accustomed to practise.

It has been already intimated, that, though in all the logomachies of the schools Dante was an eager and skilful disputant, yet he was left behind by none of his contemporaries in those personal accomplishments which became his station. In the mean while he cultivated with constitutional ardour and diligence those higher qualifications, which, in the sequel, enabled him to serve his country as a citizen, a soldier, and a magistrate, under circumstances that called forth all his talents, valour, firmness, wisdom, and discretion; though, judging from the {Pg 12} issue, the latter failed him oftener than the former. Eloquent, brave, and resolute he always was; but not always wise and discreet. This, indeed, might be presumed; for in the pursuit of distinction,—instead of attaching himself to the selfish and mercenary professions which oftenest lead to wealth, power, and family aggrandisement,—he preferred those generous studies which most exalt, enrich, and adorn the mind, but yet, while they gratify the taste of their votary, rather advance him in moral and intellectual eminence than to temporal and substantial prosperity. These, therefore, were exercises calculated to awaken and display the energies and resources of a temper formed to conceive, attempt, and achieve great things, so far—and perhaps so far only—as depended on his individual exertions. In the solitary case wherein he had official authority to direct difficult public affairs he failed so irrecoverably, that, during the residue of his life, he was more a sufferer than an actor in the troubles of those hideous times.

Italy, it must be observed, was still distracted with strife, in every form that strife could assume, between the factions of the Guelfs and Ghibellines;—the former, adherents of the pope; the latter, of the emperor of Germany. These factions not only arrayed state against state, but frequently divided people of the same province, the same city, and the same family against one another, in the most violent and implacable hostility,—hostility, violent in proportion as it was irrational, and implacable in proportion as it was unnatural; being, in every instance, and on both sides, contrary to the interests of their respective communities. Lombardy, especially since the Cisalpine conquests of Charlemagne, had never ceased to be a snare to his successors. The popes, who at first had affected spiritual dominion only, after the grant of territorial possessions, by that deed of Constantine to Silvester, which, having disappeared from earth, may be found, according to the veritable testimony of Ariosto, in the moon, the receptacle of {Pg 13} all lost things[7], gradually aspired to secular power. But all their ambition and influence failed, in the end, to spread their secular sovereignty beyond those provinces adjacent to Rome, which they yet retain by courtesy of the catholic potentates of Europe.

At the time of Dante's birth, the Guelf or papal party had recently recovered their ascendancy at Florence, after having been expatriated for several years, in consequence of their disastrous overthrow at the battle of Monte Aperto. The poet was therefore educated in Guelfic principles, and adhered to them till his banishment, when the perfidious interference of the pope with the independence of his native city, and the atrocious hostility of its citizens against himself and his friends, compelled him to take part with the imperialists.

The first public character in which we find the patriotic poet distinguishing himself was that of a soldier. In one of the petty wars that were perpetually occurring between the little irascible republics in the north of Italy, the Florentines gained a decisive victory over their neighbours of Arezzo (who had harboured the Ghibelline refugees), at the battle of Campaldino, A. D. 1289. On this occasion, Dante, who served among the cavalry, was not only exposed to imminent peril at the commencement of the action, when that body was partially routed by the impetuosity of the enemy's charge, but when the squadron had rallied {Pg 14} again on reaching the lines of infantry, and thence returned to the attack, he fought in the first rank, and displayed such extraordinary valour, as to claim a proud share in the glory of that day. To this conflict, and the particular service in which he had been engaged, he seems to allude in Canto XXII. of the Inferno. Having mentioned the signal given by Barbariccia (serjeant of a file of demons, appointed to escort Dante and Virgil over a certain dangerous pass on their journey,)—a signal too absurd to be repeated here, either in English or Italian, he says:—

In the following year Dante was again in the field, at the siege of Caprona. To this he alludes in Canto XXI. of the Inferno, where, under convoy of the aforementioned fiends, he compares his fears lest they {Pg 15} should break truce with him and his companion, to the apprehensions of the garrison of that fortress when they marched out on condition of being permitted to depart unmolested with their arms and property; but were so terrified, on seeing the multitude and the rage of their enemies, who cried, "Stop them! stop them! kill them! kill them!" as they passed along, that they submitted to be sent in irons, as prisoners, to Lucca, for safeguard.

During this active period of his citizenship, Dante is stated to have been frequently employed on important embassies; and, among others, to the kings of Naples, Hungary, and France; in all of which his eloquence and address enabled him to acquit himself with honour and advantage to his country: but as there is no allusion in any of his works, even to the most distinguished of these, it is very questionable whether the traditions are not, in many cases, wholly unwarranted; and probably founded upon misapprehension of the verbiage and bombast of Boccaccio, in his account of the political, philosophical, and literary labours of his hero.

In the year 1300, Dante was chosen, by the suffrages of the people, chief prior of his native city; and from that era of his arrival at the highest honour to which his ambition could aspire, he himself dated all {Pg 16} the miseries which (like the file of evil spirits above mentioned) accompanied him thenceforward to the end of his life. In one of his epistles, quoted by Aretino, he says,—"All my calamities had their origin and occasion in my unhappy priorship, of which, though I might not for my wisdom have been worthy, yet on the ground of age and fidelity was I not unworthy; ten years having elapsed since the battle of Campaldino, in which the Ghibelline party was routed and nearly exterminated; wherein, also, I proved myself no novice in arms, but experienced great perils in the various fortunes of the fight, and the highest gratification in the issue of it." Since that triumph, the Guelfs had maintained undisputed predominance in Tuscany; but the citizens of Florence split into two minor factions as bitterly opposed to each other as the Guelfs and Ghibellines.

The following circumstance (considerably varied in particulars by different narrators) has been mentioned as the origin of this schism:—Two branches of the family of Cancellieri divided the patronage of Pistoia, which was then subject to Florence, between them. The heads of these were Gulielmo and Bertaccio. In playing at snow-balls, a son of the first happened to give the son of the second a black eye. Gulielmo, knowing the savage disposition of his kinsman, immediately sent his son to offer submission for the unlucky hit. Bertaccio, eager to avail himself of a pretext for quarrelling with the rival section of his house, seized the boy, and chopped off the hand which flung the snowball, drily observing, that blows could only be compensated by blows—not with words. Another version of the story is, that the young gentlemen, quarrelling over some game, drew their swords, when one wounded the other in the face; in retribution for which, Foccacio, brother to the latter, cut off his offending cousin's hand. The father of the mutilated lad immediately called upon his friends to avenge the inhuman outrage; Bertaccio's dependants not less promptly armed {Pg 17} themselves to maintain his cause; and a civil war was ready to break out in the heart of the city. An ancestor of the Cancellieri family having married a lady named Bianchi, in honour of her one of the parties took the denomination of Bianchi (whites), when the other, in defiance, assumed the reverse, and styled themselves Neri (blacks).

This happened during the priorship of Dante, who, with the approbation of his colleagues, summoned the leaders of the antagonist factions to repair to Florence, to prevent that extremity of violence with which they threatened not Pistoia only, but the whole commonwealth. This, as Leonardo Bruni observes, was importing the plague to the capital, instead of taking means to repress it upon the spot where it had already appeared. For it so fell out, that Florence itself was principally under the influence of two great families,—the Cerchi and the Donati,—habitually jealous of one another, and each watching for opportunity to obtain the ascendancy. When, therefore, the hostages for preserving the peace of Pistoia arrived, the Bianchi were hospitably entertained by the Cerchi, and the Neri by the Donati; the natural consequence of which was, that the people of Florence were far more annoyed by the acquisition, than those of the neighbouring city were benefited by the riddance of so troublesome a crew. What these incendiary spirits had been doing in a small place, on a small scale, they forthwith began to do on a large scale, in a large place. Jealousies, fears, and antipathies were easily awakened among the families with which the partisans respectively associated. From these, through every rank of citizens down to the lowest, the contagion spread; first seizing the youth, who were sanguine and restless, but soon infecting persons of all ages; till every man who had a mind or an arm to influence or to act, enlisted himself with one side or the other. In the course of a few months, from whisperings the discontents rose to clamours, from words to blows, and from feuds in private dwellings to battles in the streets; so that not the metropolis only, but the whole {Pg 18} territory, became involved in unnatural contention.

While this was in process, the heads of the Neri held a meeting by night in the church of the Holy Trinity, at which a plan was suggested to induce pope Boniface VIII. to constitute Charles of Valois, (who was brother to Philip the Fair, king of France, and then commanded an army under his holiness against the emperor,) mediator of differences and reformer-general of abuses in the state. The Bianchi, having received information of this clandestine assembly, and the unpatriotic project which had been devised at it, took grievous umbrage, and went in a body, with arms in their hands, to the chief prior, with whom they remonstrated sharply upon what they deemed a privy conspiracy hatched for the purpose of expelling themselves and their friends from the city; at the same time demanding summary punishment on the offenders. The Neri, alarmed in their turn, flew likewise to arms, and assailed the prior with the same complaint and demand reversed,—namely, that their adversaries had plotted to drive them (the Neri) into exile under false pretences; and requiring that they (the Bianchi) should be sent into banishment, to preserve the public tranquillity.

The danger was imminent, and prompt decision to avert it indispensable. The prior and magistrates, therefore, by the advice of Dante their chief, who was the Cicero in this double conspiracy, though neither so politic nor so fortunate as his eloquent archetype, appealed to the people at large to support the executive government; and, having conciliated their favour, banished the principal instigators of tumult on both sides, including Corso Donati (Dante's wife's kinsman) of the Neri party, who, with his accomplices, was confined in the castle of Pieve in Perugia; while Guido Cavalcanti (Dante's own particular friend) and others of the Bianchi faction were sent to Serrazana.

This disturbance, and the severe remedy necessary to be adopted, painfully tried the best feelings of Dante, who seems to have acted on {Pg 19} truly independent principles in the affair, though suspected at the time of favouring the Bianchi. That, indeed, was probable; for though as chief magistrate he knew no man by his colours, yet, being a genuine Florentine,—and such he remained when Florence had banished and proscribed him,—he could not but he opposed to so preposterous a scheme as that of bringing in a stranger to lord it over his native city, under pretence of assuaging the animosities of malecontents, who cared for nothing but their own personal, family, or party aggrandisement, at the expense of the common weal.

This apparent impartiality was openly arraigned, when the Bianchi exiles were permitted to come back after a short absence, while the Neri remained under proscription. Dante vindicated himself by saying, that he had attached himself to neither party; that in condemning the heads of both he had acted solely for the public safety; and at home had used his utmost endeavours to reconcile the adverse families, who had implicated all their fellow-citizens in their feuds. With respect to the return of the Bianchi, he denied that it had been allowed on his authority, his priorate having expired before that event took place; and, moreover, that their release had been rendered necessary by the premature death of Guido Cavalcanti, who had been killed by the pestilent air of Serrazana. The pope, however, eagerly availed himself of the opportunity as a plea for sending Charles of Valois to Florence, to restore tranquillity by conciliation. That prince accordingly entered the city in triumph at the head of his troops, with a solemn assurance that liberty, property, and personal safety should in no instance be violated. In consequence of this he was well received by the people; but he had no sooner seated himself in influence than he obtained the recall of the Neri, who were his partisans. Then, having secured his authority by their presence, he threw off the mask, and began to play the part of dictator within the {Pg 20} walls, as well as throughout the adjacent territory, by causing 600 of the principal men of the Bianchi to be driven forth into exile.

At the time of this expatriation of his friends, Dante was absent, having undertaken an embassy to Rome to solicit the good offices of the pope towards pacifying his fellow-citizens without foreign interference. Boccaccio records a singular specimen at once of his self-confidence, and his disparagement of others, which, if true, betrays the most unamiable feature of his character, and throws additional light on a circumstance not otherwise well accounted for,—why, with all his admirable qualities, Dante was unhappy in domestic life, and in public life made so many and such inveterate enemies.—When his associates in the government proposed this embassy to him, he haughtily enquired,—"If I go, who will stay? If I stay, who will go?" It was fortunate for the poet that his holiness and himself, on this occasion, were unconsciously playing at cross purposes, though he was beaten in the game,—the very intervention which he had gone to deprecate taking place whilst he was on the journey. Had he been at home, it is not improbable that death, rather than banishment with the Bianchi, would have been his lot, from the exasperation of the Neri against him individually, whom they regarded as the chief agent in their disgrace and exile, as well as the patron of their rivals. It is remarkable that the pretext on which the failing party were now expelled was, that they had secretly intrigued with Pietro Ferranti, the confidant of Charles of Valois, to give him the castle of Prato, on condition that he prevailed upon his master to allow them the ascendancy under him in Florence. Charles himself countenanced the accusation, and affected high displeasure at the insulting offer, as derogatory to his immaculate purity; though the purport of it was no other than to concede to him the express object of his ambition, if he would grant to the Bianchi faction what he did grant to the perfidious Neri. A document was long preserved as the genuine letter to Ferranti, with the seals and signatures of the principal {Pg 21} Bianchi attached, containing the traitorous proposal; but Leonardo Aretino, who had himself seen it in the public archives, declares his perfect conviction that it was a forgery.

Of participation in such baseness (had his partisans been really guilty of it), Dante must stand clearly acquitted by every one who takes his character from the matter-of-fact statements, perverted as they are, of his adversaries themselves, much more from the unimpeachable evidence of his own writings;—open, undaunted, high-spirited, and generous as a friend, he was not less violent, acrimonious, and undisguisedly vindictive as an enemy. So exasperated, however, were the Neri against him, that they demolished his dwelling, confiscated his property, and decreed a fine of 8000 lire against him, with banishment for two years; not for any crime of which he had been convicted, but under pretence of contumacy, because he did not appear to a citation which had been issued when they knew him to be absent,—absent, it might be said, on their own business (his mission to Rome), where he could not be aware of the nature of his imputed offence till he heard of the condign punishment with which it had been thus prematurely visited. In the course of a few weeks a further inculpation of Dante and his associates was promulged, under which they were condemned to perpetual exile, with the merciless provision that, if any of them thereafter fell into the hands of their persecutors, they should be burnt alive. And this execrable measure seems to have been determined upon before the exiled party had made any attempt, by force of arms, to reenter Florence.

When Dante was informed at Rome of the revolution in Florence, he hastened to Siena, where, learning the full extent of his misfortune, he was driven, it may be said, by necessity to join himself to his homeless countrymen in that neighbourhood, who were concerting (though with little of mutual confidence, and miserably inadequate means) how they {Pg 22} might compel their fellow-citizens to receive them back. Arezzo, the city of the Aretines (with whom Dante had combated at Campaldino), afforded them an asylum, and became the headquarters of the Bianchi; who thenceforward, from being, like the Neri, Guelfs, transferred their affections, or rather their wrongs and their vengeance, to the Ghibellines; deeming the adherents of the emperor less the enemies of their country than their adversaries were. Their affairs were managed by a council of twelve, of whom Dante was one. Great numbers of malecontents from Bologna, Pistoia, and the adjacent provinces of Northern Italy, gradually flocking to their standard,—in the course of two years they were sufficiently strong to take the field with a force of cavalry and foot exceeding 10,000, under count Alessandro da Romena, and to commence active hostilities. By a bold and sudden march, they attempted to surprise Florence itself, and were so far successful that their advanced guard got possession of one of the gates; but the main body being attacked and defeated on the outside of the walls, the former gallant corps was overpowered by the garrison; and the enterprise itself, after the campaign of a few days, was abandoned altogether. Dante, according to general belief, accompanied this unfortunate expedition; and so did Pietro Petracco, the father of the celebrated Petrarca (Petrarch), who had been expelled with the Bianchi from Florence; and it is stated, that on the very night on which the army of the exiles marched against the city, Petracco's wife Eletta gave birth to the poet who was to succeed Dante as the glory of his country's literature.

After this miscarriage Dante quitted the confederacy, disgusted by the bickerings, jealousies, and bad faith of the heterogeneous and unmanageable multitude, which, common calamities had driven together, but could not cement by common interests. The poet refers to this motley and discordant crew in the latter lines of the celebrated passage, in which he represents his ancestor. Cacciaguida, as prophesying his future {Pg 23} banishment with the miseries and mortifications which he should suffer from the ingratitude of his countrymen:—

To the personal humiliations of which he chewed the cud in hitter secrecy, through years of heart-breaking dependence on the precarious bounty of others, there is a striking but forced allusion at the close of the eleventh canto of the "Purgatorio." Dante enquires concerning a proud spirit bent double under a huge burden of stones, which he is condemned to carry for as many years as he had lived, till he shall he sufficiently humbled to pass muster through the flames into Paradise. This is Provenzano Salvani, who for his acts of outrageous tyranny would have been doomed to a much harder penance, but for one good deed.—A {Pg 24} friend of his being kept prisoner by Charles of Anjou, and threatened with death unless a ransom of 10,000 golden florins were paid for his freedom, Salvani so far degraded himself as to stand (to kneel, say some,) in the public market-place of Siena, with a carpet spread on the ground before him, imploring, with the cries and importunity of a common beggar, the charitable contributions of every passenger towards raising the required sum. This he accomplished, and his friend was saved.

In despair of being able to force his way, sword in hand, back to Florence, Dante next endeavoured, by supplicating the good offices of individuals connected with the government, by expostulatory addresses to the people, and even by appeals to foreign princes, to obtain a reversal of his unrighteous sentence. Disappointment, however, followed upon disappointment, till, hope deferred having made the heart sick, he grew so impatient under the sense of wrong and ignominy, that he again had recourse to the summary but perilous redress of violence;—not indeed by force which he could command, though one in a million for energy, courage, and perseverance; but a powerful auxiliary having appeared in 1308, he gave up his whole soul to the main object of his desire at this time,—the chastisement of his inexorable fellow-citizens. Henry of Luxembourg, having been raised to the throne of Germany, eagerly {Pg 25} engaged, like his predecessors, in the delusive contest for the "Iron crown" of Italy, though "Luke's iron crown"[12] (placed red hot on the brow of an unsuccessful aspirant to that of Hungary) was hardly more painful or more certainly fatal than this, except that it was far more expeditious in putting the wearer out of torture. Dante now rose from the dust of self-abasement, openly professed himself a Ghibelline, and changed his tones of supplication into those of menace against his refractory countrymen. Henry himself denounced terrible retribution upon the Guelfs, and at the head of an army invaded the Florentine territory; from which, however, he was compelled to make an early retreat; and the magnificent flourish of drums and trumpets, with which the imperial actor entered, was followed by a dead march, that closed the scene before he had turned round upon the stage—except to hurry away. He died in 1313, poisoned, it was reported, by a consecrated wafer. To this prince Dante dedicated his political treatise, in Latin, "De Monarchia," in which he eloquently asserts the rights of the emperor in Italy against the usurpations of the pope. He has been accused of exciting Henry to abandon the siege of Brescia, and undertake that of Florence; though, from regard to his native land, he himself forebore to accompany the expedition. He had affected no such scruple when the Bianchi, like trodden worms, turned upon the parent foot which spurned them from the soil where they were bred. There must, therefore, have been some other motive than patriotism,—nobody will suspect that it was cowardice,—which restrained him from witnessing the expected humiliation of his persecutors.

Several of his biographers state, that after this consummation of his ruin,—a third decree having been passed against him at Florence,—the poet retired into France, and strove to reconcile his unsubdued spirit to his fate, or to forget both it and himself in those {Pg 26} fashionable theological controversies, for which he was, perhaps, better qualified than either for the council-chamber or the battle-field. This, however, is doubtful, and, in fact, very improbable, when we recollect that, next to the malice of the Neri, he was indebted for his misfortunes to Charles of Valois, their patron, who was brother to Philip the Fair, king of France. Be this as it may, the remainder of Dante's life was spent in wandering from one petty court to another, in exile and poverty, accepting the means of subsistence, almost as alms, from lukewarm friends, from hospitable strangers, and even from generous adversaries. Hence we trace him, at uncertain periods, through Lombardy, Tuscany, and Romagna, as an admitted, welcomed, admired, or merely a tolerated guest, according to the liberality or caprice of his patrons for the time being. Little more can be recorded of these "evil days" and "years," of which he was compelled to say, "I have no pleasure in them," than a few questionable anecdotes of his caustic humour, and the names of some of those who showed him kindness in his affliction.

Among the latter may be honourably mentioned Busone da Gubbio, who first afforded him shelter at Arezzo, whither he himself had been banished from Florence as an incorrigible Ghibelline; but being a brother poet, he was too noble to let political prejudice (Dante was at that time a Guelf) interfere either with his compassion towards an illustrious fugitive, or his veneration for those rare talents which ought every where to have raised the unhappy possessor above contempt, though, in some instances, they seem to have exposed him to it. Yet he knew well how to resent indignity. While residing at Verona with Can' Grande de la Scala (one of his most distinguished protectors), it happened one day, according to the rude usages of those times, that the prince's jester, or some casual buffoon about the palace, was introduced at table, to divert the high-born company there with his waggeries. In this the arch fellow succeeded so egregiously, that Dante, from scorn or {Pg 27} mortification, showed signs of chagrin, whereupon Can'Grande sarcastically asked,—"How comes it, Dante, that you, with all your learning and genius, cannot delight me and my friends half so much as this fool does with his ribaldry and grimaces?"—"Because like loves like," was the pithy retort of the poet, in the phrase of the proverb. Another story of the kind is told by Cinthio Geraldi.—On occasion of a jovial entertainment, Can' Grande, or his jester, had placed a little boy under the table, to gather all the bones that were thrown down upon the floor by the guests, and lay them about the feet of Dante. After dinner these were unexpectedly shown above board, as tokens of his feasting prowess. "You have done great things to day!" exclaimed the prince, affecting surprise at such an exhibition. "Far otherwise," returned the poet; "for if I had been a dog, (Cane, his patron's name,) I should have devoured bones and all, as it appears you have done."[13]

Other grandees, who gave the indignant wanderer an occasional asylum from the blasts of persecution, were the marchese Malespina, who, though belonging to the antagonist party, cordially entertained him in Lunigiana; the conte Guido Salvatico, of Cassentino; the signori della Faggiuolo, among the mountains of Urbino; and also the fathers of the monastery of Santa Croce di Fonte Avellana, in the district of Gubbio. In this romantic retreat, according to the Latin inscription under a marble bust of him against a wall in one of the chambers, Dante is recorded to have written a considerable portion of the "Divina Commedia." In a tower belonging to the conti Falucci, in the same territory, there is a tradition that he was often employed in the like manner. At the castle of Tulmino, the residence of the patriarch of {Pg 28} Aquileia, a rock has been pointed out as a favourite resort of the inspired poet, while engaged in that marvellous and melancholy composition.

Marius, banished from his country, and resting upon the ruins of Carthage, may have appeared a more august and mournful object; but Dante, in exile, want, and degradation, on a lonely crag, meditating thoughts, combining images, and creating a language for both in which they should for ever speak, presents a far more sublime and touching spectacle of fallen grandeur renovating itself under decay. Marius, having "mewed his mighty youth," flew back to Rome like the eagle to his quarry, surfeited himself with vengeance, and died in a debauch of blood, leaving a name to be execrated through all generations: Dante did not return to Florence; living or dead he did not return; but his name, cast out and abhorred as it had been, stands the earliest and the greatest of a long line of Tuscan poets, rivalling the most illustrious of their country, not excepting those of even Rome and Ferrara.

Dante's last and most magnanimous patron was Guido Novello da Polenta, lord of Ravenna, who was himself a poet, and a munificent benefactor of men of letters. This nobleman was the father of Francesca di Rimini, whose fatal love has given her a place on the most splendid page of the "Divina Commedia;" no other episode being told with equal beauty and pathos: yet so brief and simple is the narrative, that, even if the circumstances were as unexceptionably pure as they are insidiously delicate, translation ought hardly to be attempted; for the labour would be fruitless. Dante himself could not have given his masterpiece in precisely corresponding terms in another language; though, had any other been his own, it need not be doubted that in it he would have found words to tell his tale as well. It is not what a poet finds a language to be, but what he makes it, that constitutes the charm, not to be {Pg 29} imitated, of his style. This is the despair of translators, though few seem to have suspected the existence of such a secret.

The mental sufferings of the poet during his nineteen years of banishment, ending in death, oftener find utterance, through his writings, in bitter invectives and prophetic denunciations against his enemies and traducers, than in strains of lamentation; yet would his wounds bleed afresh, and the anguish of his spirit be renewed with all the tenderness of wronged but passionate attachment, at every endeared recollection of the land of his nativity;—the city where he had been cradled and had grown up—where Beatrice was born, beloved, and buried—where he had himself attained the highest honours of the state, and, in his own esteem, deserved the lasting gratitude of his fellow-citizens, instead of experiencing their implacable hatred. Haughty yet humbled, vindictive yet forgiving, it is manifest, even in his darkest moods, that his heart yearned for reconciliation; that he pined in home-sickness wherever he went, and would gladly have renounced all his wrath, and submitted to any self-denial consistent with honour, to be received back into his country. For, much as he loved the latter,—nay, madly as he loved it in his paroxysms of exasperation,—he wrapt himself up tighter in the mantle of his integrity as the storm raged more vehemently; and, as the conflict went harder against him, grasped his honour, like his sword, never to be surrendered but with life: to preserve these, he submitted to lose all beside.

Boccaccio says, that, at a certain time, some friend obtained from the Florentine government leave for Dante to return, on condition that he should remain a while in prison, then do penance at the principal church during a festival solemnity, and afterwards be exempt from further punishment for his offences against the state. As might be expected, he spurned the ignominious terms. A letter, preserved in the Laurentian {Pg 30} library[14], seems to refer to this circumstance, which, till the modern discovery of that document, required stronger testimony than the random verbiage of Boccaccio to confirm its credibility. It is addressed to a correspondent at Florence, whom the writer styles "father." The following are extracts; the original is in Latin. Having alluded to some overtures for pardon and return, nearly corresponding with those above mentioned, he proceeds:—

"Can such a recall to his country, after fifteen years' exile, be glorious to Dante Alighieri? Has innocence, which is manifest to every one,—have toil and fatigue in perpetuated studies, merited this? Away from the man trained up in philosophy, the dastard humiliation of an earth-born heart, that, like some petty pretender to knowledge, or other base wretch, he should endure to be delivered up in chains! Away from the man who demands justice, the thought that, after having suffered wrong, he should make terms by his money with those who have injured him, as though they had done righteously!—No, father! this is not the way of return to my country for me. Yet, if you, or any body else, can find another which shall not compromise the fame and the honour of Dante, I will not be slow to take it. But if by such an one he may not return to Florence,—to Florence he will never return. What then? May I not every where behold the sun and the stars? Can I not every where under heaven meditate on the most noble and delightful truths, without first rendering myself inglorious, aye infamous, before the people and city of Florence,—and this, for fear I should want bread!"

Far different return to Florence, and far other scene in his favourite church there, had he sometimes ventured to anticipate as possible. This we learn from the opening of the twenty-fifth canto of the "Paradiso," where, even in the presence of Beatrice and St. Peter, he thus unbosoms the long-cherished hope; conscious of high desert, as well as grievous injustice, which he would nevertheless most fervently forgive, could restoration to his country be obtained on terms "consistent with the fame and honour of Dante." {Pg 31}

In the same church here alluded to (San Giovanni), at Florence, there remained till lately a stone-remembrancer of Dante, in his prosperous days, scarcely less likely than "storied urn or animated bust," to awaken that sweet and voluntary sadness by which we love to associate dead things with the memory of those who once have lived. This was no other than an ancient bench of masonry which ran along the wall,

on which, according to long-believed tradition, the future poet of the other world was wont to

with those,

Here also, according to his own record, in rescuing a child which had fallen into the water, he accidentally broke one of the baptismal fonts,—a circumstance which seems to have been maliciously misrepresented as an act of wilful sacrilege. His stern anxiety to clear {Pg 32} himself is characteristically indicated by the brief but dignified attestation of the real fact, in the last line of the following singular parallel between objects not otherwise likely to be brought into comparison with each other. Describing the wells in which; head-downward, simoniacal offenders (among the rest pope Nicholas III.) were tormented with flames, that glanced from heel to toe along the up-turned soles of their feet, he says,—

Dante resided several years at Ravenna, with the noble-minded Guido da Polenta, who, of his own accord, had invited him thither, and who, to the last moment of his life, made him feel no other burden in his service than gratitude for benefits bestowed with such a grace as though the giver, and not the receiver, were laid under obligation. By him being sent on an embassy to Venice, with the government of which Guido had an unhappy dispute, Dante not only failed to accomplish a reconciliation, but was even refused an audience, and compelled to return by land for fear of the enemy's fleet, which had already commenced hostilities along the coast. He arrived at Ravenna broken-hearted with the disappointment, and died soon afterwards,—according to his epitaph, on the 14th of September, 1321, though some authorities date his demise in July preceding. {Pg 33}

The remains of the illustrious poet were buried with a splendour honourable to his name and worthy of his patron, who himself pronounced the funeral eulogium of his departed guest. His own countrymen, who had hardened their hearts against justice and humanity, in resistance of his return amongst them while living, soon after his death became sensible of their folly, and too late repented it. Embassy on embassy, during the two succeeding centuries, failed to recover the bones of their outcast fellow-citizen from his hospitable entertainers; and Florence has less to boast of in having given him birth, than Ravenna for having given him burial. One of those fruitless negotiations was conducted under the auspices of Leo X., and more illustriously sanctioned by Michael Angelo, an enthusiastic admirer of Dante, who offered to adorn the shrine, had the desired relics been obtained. The mighty sculptor,—himself the Dante of marble, simple, severe, sublime in style, and preternatural almost from the fulness of reality condensed in his ideal forms,—in many of his works, both of the chisel and the pencil, introduced figures suggested by images of the poet, or directly embodying such. Most conspicuous among these were the statues of Leah and Rachel, from the twenty-seventh canto of the "Purgatorio," on the monument of pope Julius II. His own copy of the "Divina Commedia" was embellished down the margin with sketches from the subjects of the text; and, had it been preserved, would surely have been classed with the most precious of those books for which collectors are eager to give ten times or more their weight in gold. The fate of this volume was not less singular than its good fortune; after having been made inestimable by the hand of Michael Angelo, it was lost at sea, and thus added to the treasures of darkness one of the richest spoils that ever went down from the light.

It was the purpose of Guido da Polenta to erect a gorgeous sepulchre over the ashes of the poet; but he neither reigned nor lived to accomplish this, being soon afterwards driven from his dominions, and {Pg 34} dying himself a banished man at Bologna. More than a hundred and fifty years later, Bernardo Bembo, father of the famous cardinal, completed Polenta's design, though upon an inferior scale; and three centuries more had elapsed, when cardinal Gonzaga raised a second and far more sumptuous monument in the same place,—Ravenna; while in Florence, to this day, there is none worthy of itself or the poet, who had been in turn "its glory and its shame." The greatest honours conferred on his memory by his native city were, the restoration to his family of his confiscated property, after a lapse of forty years, the erection of a bust crowned with laurel, at the public expense, a present from the state of ten golden florins to his daughter by the hands of Boccaccio, and the appointment of a public lecturer to expound the mysteries of the "Divina Commedia." Boccaccio was the first professor who filled this chair of poetry, philosophy, and theology. He commenced his dissertations on a Sunday, in the church of St. Stephen, but died at the end of two years, having proceeded no further than the seventeenth Canto of the "Inferno." Similar institutions were adopted in Bologna, Pisa, Venice, and other Italian towns; so that the renown of the man who had lived by sufferance, died an outlaw, and been indebted to strangers for a grave, exceeded, within two centuries, that of all his countrymen who in polite literature had gone before him, and became the load-star of all who, in any age, should follow. At Rome only the memory of the Ghibelline bard was execrated, and his writings were proscribed. His book "De Monarchia" was publicly burnt there, by order of pope John XXII., who also sent a cardinal to the successor of Guido da Polenta, to demand his bones, that they might be dealt with as those of an heretic, and the ashes scattered on the wind. How impotent is the vengeance of the great after the death of the object of their displeasure! What a refuge, especially to fame, is the grave; a sanctuary which can never be violated; for all human passions die on its threshold! {Pg 35}

Boccaccio, the earliest of his biographers, though not the most authentic, says, that in person Dante was of middle stature; that he stooped a little from the shoulders, and was remarkable for his firm and graceful gait. He always dressed in a manner peculiarly becoming his rank and years. His visage was long, with an aquiline nose, and eyes rather full than small; his cheek-bones large, and his upper lip projecting beyond the under; his complexion was dark; his hair and beard black, thick and curled; and his countenance exhibited a confirmed expression of melancholy and thoughtfulness. Hence one day, at Verona, as he passed a gateway, where several ladies were seated, one of them exclaimed, "There goes the man who can take a walk to hell, and back again, whenever he pleases, and bring us news of every thing that is doing there." On which another, with equal sagacity, added, "That must be true; for don't you see how his beard is frizzled, and his face browned, with the heat and the smoke below!" The words, whether spoken in sport or silliness, were overheard by the poet, who, as the fair slanderers meant no malice, was quite willing that they should please themselves with their own fancies. Towards the opening of the "Purgatorio" there is an allusion to the soil which his face had contracted on his journey with Virgil through the nether world:—

In his studies, Dante was so eager, earnest, and indefatigable, that his wife and family often complained of his unsocial habits. Boccaccio mentions, that once, when he was at Siena, having unexpectedly found at a shop window a book which he had not seen, but had long coveted, he placed himself on a bench before the door, at nine o'clock in the morning, and never lifted up his eyes from the volume till vespers, when he had run through the whole contents with such intense application, as to have totally disregarded the festivities of processions and music which had been passing through the streets the greater part of the day; and when questioned about what had happened even in his presence, he denied having had knowledge of any thing but what he was reading. As might be expected from his other habits, he rarely spoke, except when personally addressed, or strongly moved, and then his words were few, well chosen, weighty, and expressed in tones of voice accommodated to the subject. Yet when it was required, his eloquence brake forth with spontaneous felicity, splendour, and exuberance of diction, imagery, and thought.

Dante delighted in music. The most natural and touching incident in his "Purgatorio" is the interview between himself and his friend Casella; an eminent singer in his day, who must, notwithstanding, have been forgotten within his century, but for the extraordinary good fortune which has befallen him, to be celebrated by two of the greatest poets of their respective countries, (Dante and Milton) from whose pages his name cannot soon perish. {Pg 37}

Choosing to excel in all the elegancies of life, as well as in gentlemanly exercises and intellectual prowess, Dante attached himself to painting not less than to music, and practised it with the pencil (not, indeed, so triumphantly as with the pen, his picture-poetry being unrivalled,) with sufficient facility and grace to make it a favourite amusement in private; and none can believe that he could amuse himself with what was worthless. His four celebrated contemporaries, Cimabue, Odorigi, Franco Bolognese, and Giotto, are all honourably mentioned by him in the eleventh canto of the "Purgatorio."

There is an interesting allusion to the employment which he loved in the "Vita Nuova:—On the day that completed the year after this lady (Beatrice) had been received among the denizens of eternal life, while I was sitting alone, and recalling her form to my remembrance, I drew an angel on a certain tablet," &c. It may be incidentally observed, that Dante's angels are often painted with unsurpassable beauty as well as inexhaustible variety of delineation throughout his poem, especially in canto IX. of the "Inferno," and cantos II. VIII. XII. XV. XVII. XXIV. of the "Purgatorio." Take six lines of one of these portraits; though the inimitable original must consume the unequal version.

Leonardo Aretino, who had seen Dante's handwriting, mentions, with no small commendation, that the letters were long; slender, and exceedingly {Pg 38} distinct,—the characteristics of what is called in ornamental writing a fine Italian hand. The circumstance may seem small, but it is not insignificant as a finishing stroke in the portraiture of one who, though he was the first poet unquestionably, and not the last philosopher, was also one of the most accomplished gentlemen of his age.

Two of Dante's sons, Pietro and Jacopo, inherited a portion of their father's spirit, and were among the first commentators on his works,—an inestimable advantage to posterity, since the local and personal histories were familiar to them; for had these not been explained by contemporaries, many of the brief and more exquisite allusions must have been irrecoverably lost, and some of the most affecting passages remained as uninterpretable as though they had been carved on granite in hieroglyphics. For example, in the fifth canto of the "Purgatorio," the travellers meet three spirits together,—the first, Giacopo del Cassero of Fano, who had been assassinated by order of a prince of Ferrara, for having spoken ill of his highness;—the second, Buonconte, of Montefeltro, who had fallen fighting on the side of the Aretines, in the battle of Campaldino; and for whose soul a singular contention took place between a good angel and an evil one, in which the former happily prevailed;—the third shade was that of a female of rank, who, having quietly waited till the two gentlemen had told their tales, thus emphatically hinted hers:—

This unfortunate lady was the bride of Nello della Pietra, a grandee of Siena, who, becoming jealous of her, removed his predestined victim to the putrid marshes of Maremma, where she soon drooped and died, without suspicion on her part, or intimation on his, of the hideous purpose for which she had been hurried thither; her gloomy keeper, with a dreadful eye, watching her life go out like a lamp in a charnel-vault, and after her death abandoning himself to despair.—One of Dante's sons above mentioned (Pietro) was an eminent lawyer at Verona, and enjoyed the friendship of Petrarch, who dedicated some lines to him, at Trevizi, in 1361. Jacopo is said to have been a writer of Italian verse. Of three others, almost nothing is known, except that they died young. His daughter Beatrice, so named after his first love, took the veil in the convent of St. Stefano del' Uliva, at Ravenna.

Dante was the author of two Latin treatises,—the one already noticed, "De Monarchia;" and another, "De Vulgari Eloquio," on the structure of language in general, and that of Italy in particular. But for his celebrity he is indebted solely to his productions in the latter tongue, consisting of "La Vita Nuova," a reverie of fact and fable, in prose and rhyme, referring to his youthful love;—"Canzoni[19] and Sonnets" of which his lady was the eternal theme;—"Il Convito," a critical and mystical commentary on three of his lyrics;—and the "Divina Commedia, or Vision of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise," by the glory of which its forerunners have been at once eclipsed and kept in mid-day splendour, instead of glimmering through that doubtful twilight of obscure fame among the feeble productions of contemporaries, which must have been their lot but for such fortunate alliance.

The prose of the "Vita Nuova" and the "Convito" is deemed, at this day, {Pg 40} not only nervous and racy, but in a high degree pure and elegant Italian; while much greater praise may be unhesitatingly bestowed upon his verse. Whether employed upon the arbitrary structure of Canzoni, the love-knot form of the sonnet, or the interminable chain of terze rime, (the triple intertwisted rhyme of the "Divina Commedia," which Dante is supposed to have invented,) his language is not more antiquated to his countrymen than the English of Shakspeare is to ours. The limits of the present essay preclude further notice of his lyrics than the general remark, that they have all the stately, brief, sententious character of his heroics, with occasional strokes of natural tenderness, and not unfrequently exhibit a delicacy of thought so pure, graceful, and unaffected, that Petrarch himself has seldom reached it in his more ornate and laboured compositions.

Dante did more than either his predecessors or contemporaries had done to improve, ennoble, and refine his native idiom; indeed he was wont to speak indignantly of those who would degrade it below the Provençal, the fashionable vehicle of verse in that age of transition, when the young languages of modern Europe, begotten between the stern tongues of the north and the classic ones of the south, were growing up together, on both sides of the Alps and the Pyrenees, like children in rivalry of each other, as the nations that spoke them respectively, so often intermingled in war or in peace. At the close of canto XXVI. of the "Purgatorio," Arnauld Daniel is introduced as the master-minstrel of the age gone by, singing some lines in a "Babylonish dialect," partly Provençal and partly Catalonian; pitting infamous French against the worst kind of Spanish (according to P. P. Venturi); and these certainly present a striking contrast of barbarous dissonance with the full-toned Tuscan of the context.

Like our Spenser, Dante took many freedoms with the extant Italian, which no later writer could have used. For the sake of euphony, emphasis, or rhyme, he occasionally modified words and terminations to {Pg 41} serve a present purpose only, and which he himself rejected elsewhere. In this he was justified: he ran through the whole compass of his native vocabulary, he tried every note of the diapason, and all that were most pure, harmonious, or energetic, he sanctioned, by employing them in his song, which gave them a voice through after ages, so that few, comparatively very few, have been entirely rejected by his most fastidious successors. It was well for the poetry of his country that he wrote his immortal work in its language; for neither Petrarch nor Boccaccio could have gone so far as they did in perfecting it, if they had not had so great a model, not to equal only but to excel. They, indeed, affected to think little of their vernacular writings, and pretended merely to amuse themselves with such compositions as every body could read. Dante himself began his poem in Latin; and if he had gone forward, the finishing stroke of the last line would have been a coup-de-grace, which it could never have survived.[20]

Of the origin of the "Divina Commedia" it would be in vain to speculate here; the author himself, probably, could not have traced the first idea. Such conceptions neither come by inspiration nor by chance:—who {Pg 42} can recollect the moment when he began to think, yet all his thoughts have been consecutively allied to that? Many visions and allegories had appeared before Dante's; and in several of these were gross representations of the spiritual world, especially of purgatory, the reality of which, during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, was urged upon credulity with extraordinary zeal and perseverance by a corrupt hierarchy. By all these rather than by one his mind might have been prepared for the work.

Seven cantos of the "Inferno" are understood to have been written before the author's banishment; it is manifest, however, that if this were the case they must have been considerably altered afterwards; indeed the whole character of the poem, however the original outline may have been followed, must have undergone a very remarkable, and (afflictive as the occasion may have been for himself) a very auspicious change, from his misfortunes. To the latter, his poem owes many of its most splendid passages, and almost all its personal interest; an interest wherein consists, if not its principal, its prevailing and preserving charm. Had the whole been composed in prosperity, amidst honours, and affluence, and learned ease, in his native city, it would no doubt have been a mighty achievement of genius; but much that enhances and endears both its moral and its fable could never have been suggested, indeed would not have existed, under happier circumstances. That moral, indeed, is often as mistaken as that fable is monstrous; but the one and the other should be judged according to the times. The poet's romantic and unearthly love to Beatrice would have wanted that sombre and terrible relief which is now given to it by the gloom of his own character, the expression of his feelings under the sense of unmerited wrongs, invectives thundered out against his persecutors, and exposures of atrocities which were every-day deeds of every-day men, in those distracted countries, of which his poem has left such fearful records. {Pg 43}

Much unsatisfactory discussion has arisen upon the title "Divina Commedia," which Dante gave to his poem; it being presumed that he had never seen a regular drama either in letter or exhibition, as the Greek and Latin authors of that class were scarcely known in Italy till after his time. The religious spectacles, however, common in the darkest of the middle ages, consisting not of pantomime only, but of dialogue and song, may have suggested to him the designation as well as the subject of his strange adventure. Be this as it may, the character of the work is dramatic throughout, consisting of a series of scenes, which conduct to one catastrophe; for however miscellaneous or insulated they may seem in respect to each other,—in respect to the author (who is his own hero, and for whose warning, instruction, and final recovery from an evil course of life, the whole are collocated,) they all bear directly upon him, and accomplish by just gradations the purpose for which they were intended. Dante is a changed man when he emerges, from the infernal regions in the centre of the globe, upon the shore of the island of Purgatory at the Antipodes; and is further so refined by his ascent up that perilous mount, that when he reaches the terrestrial paradise at the top, he is prepared for translation from thence through the nine spheres of the celestial universe. Many of the interviews between the visiters of the invisible worlds which they explore, and the inhabitants of these, are scenes which involve all the peculiarities of stage-exhibitions,—dialogue, action, passion,—secrecy, surprise, interruption. Examples may be named. The meeting and conversations with Sordello, in the sixth and seventh cantos of the "Purgatorio," in which there are two instances of unexpected discoveries which bring out the whole beauty and grandeur of that mysterious personage's character; as a patriot, when at the mere sound of the word "Mantua" he embraces Virgil with transport, not yet knowing, nor even enquiring, any thing further about him, except that he is his countryman; and afterwards as a poet, when, Virgil disclosing his name, Sordello is overpowered with delightful astonishment, like one who suddenly {Pg 44} beholds something wonderful before him, and, scarcely believing his own eyes for joy, exclaims, in a breath, "It is! it is not!" (Ell' è, non è.) The parties are thus introduced to each other. Dante and Virgil are considering which road they shall take, when the latter observes:—

The reserve of Sordello is generally attributed to stubbornness or pride; but is it not manifest that, on the first sight of the strangers, he had a misgiving hope (if the phrase be allowable) which he feared might deceive him, that they were countrymen of his, wherefore, absorbed {Pg 45} in that sole idea, he disregards their question concerning the road, and directly comes to the point which he was anxious to ascertain; and this being resolved by the single word "Mantua," his soul flies forth at once to embrace the speaker?

In the tenth canto of the "Inferno," where heretics are described as being tormented in tombs of fire, the lids of which are suspended over them till the day of judgment, Dante finds Farinata d'Uberti, an illustrious commander of the Ghibellines, who, at the battle of Monte Aperto, in 1260, had so utterly defeated the Guelfs of Florence, that the city lay at the mercy of its enemies, by whom counsel was taken to raze it to the ground: but Farinata, because his bowels yearned towards his native city, stood up alone to oppose the barbarous design; and partly by menace—having drawn his sword in the midst of the assembly—and partly by persuasion, preserved the city from destruction. The interview is thus painted; but to prepare the reader for well understanding the nature of the by-play which intervenes, it is necessary to state that Cavalcante Cavalcanti, whose head appears out of an adjacent sepulchre, was the father of Guido Cavalcanti, a poet, the particular friend of Dante, and chief of the Bianchi party banished during his priorship.

The reader of these lines (however inferior the translation may be), cannot have failed to perceive by what natural action and speech the {Pg 49} paternal anxiety of Cavalcante respecting his son is indicated. On his bed of torture he hears a voice which he knows to be that of his son's friend; he starts up, looks eagerly about, as expecting to see that son; but observing the friend only, he at once interrupts the dialogue with Farinata, and in broken exclamations enquires concerning him. Dante happening to employ the past tense of a verb in reference to what his "Guido" might have done, the miserable parent instantly lays hold of that minute circumstance as an intimation of his death, and asks questions of which he dreads the answers, precisely in the manner of Macduff when he learns that his wife and children had been murdered by Macbeth. The poet hesitating to reply. Cavalcante takes the worst for granted, falls back in despair, and appears not again. Thus,